User login

Coronary Artery Calcium Linked to Cancer, Kidney Disease, COPD

Patients whose coronary artery calcium scores exceeded 400 were significantly more likely to develop cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and hip fractures, compared with adults with undetectable CAC, in an analysis of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis reported March 9 in JACC Cardiovascular Imaging.

The study is the first to examine the relationship between CAC and significant noncardiovascular diseases, said Dr. Catherine Handy of the Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Heart Disease, Baltimore. Patients with CAC scores of zero represent a unique group of “healthy agers,” she and her associates said. Conversely, 20% of initial non-CVD events occurred in the 10% of patients with CAC scores over 400, and 70% of events occurred in patients with scores greater than zero, they reported.

While CAC is an established indicator of vascular aging, CVD risk, and all-cause mortality, its relationship with non-CVD is unclear. To elucidate the issue, the researchers analyzed data from the prospective, observational Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, which included 6,814 adults aged 45-84 years from six U.S. cities. Patients had no CVD and were not receiving cancer treatment.

Over a median follow-up period of 10.2 years, and after controlling for demographic factors and predictors of CVD, patients with CAC scores exceeding 400 were significantly more likely to develop cancer (hazard ratio, 1.53), chronic kidney disease (HR, 1.70), pneumonia (HR, 1.97), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (HR, 2.71) and hip fracture (HR, 4.29), compared with patients without detectable CAC. Patients with CAC scores of zero were at significantly lower risk of these diagnoses, compared with patients with scores greater than zero (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 Mar 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.09.02).

Doubling of CAC was a modest but significant predictor of cancer, chronic kidney disease, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the subgroup of adults aged 65 years and older. However, CAC was not associated with dementia or deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

Sparse diagnoses of hip fractures and DVT/PE meant that the study might be underpowered to clearly link CAC with risk of these events, said the researchers. There also might not have been enough follow-up time to uncover risk in participants with the lowest CAC scores, they said. “At this time, our data are not powered for stratifying results based on gender or race,” they added.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The researchers had no conflicts of interest.

The current report from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis further expands the evidence base supporting the concept of coronary artery calcium as a marker of global health by examining its prognostic power across a diversity of noncardiovascular conditions.

Regardless of the directionality or magnitude of the connections between cardiovascular disease and non-CVD conditions, the extent to which coronary artery calcium–guided patient adherence to risk factor modification and lifestyle recommendations [affected] non-CVD conditions remains an additional link that should be explored further.

A synthesis of evidence, including the study by Handy et al., now supports the predictive ability of coronary artery calcium to estimate cardiac, cerebrovascular, and noncardiovascular conditions. We likely should come full circle in our discussion and acknowledge the far reaching implications of its predictive ability. Perhaps our index response that CAC should be fully integrated into all adult wellness and screening evaluations was on target after all!

Although CAC has not been without its critics and is not supported as a reimbursable procedure, its expansive evidence warrants a more thoughtful discussion within the CVD community that this powerful procedure provides valuable information to guide health care decision making.

Dr. Mosaab Awad, Dr. Parham Eshtehardi, and Leslee J. Shaw, Ph.D., of Emory University Clinical Cardiovascular Research Institute, Emory University, Atlanta, made these comments in an editorial (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 Mar 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.09.021). They had no disclosures.

The current report from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis further expands the evidence base supporting the concept of coronary artery calcium as a marker of global health by examining its prognostic power across a diversity of noncardiovascular conditions.

Regardless of the directionality or magnitude of the connections between cardiovascular disease and non-CVD conditions, the extent to which coronary artery calcium–guided patient adherence to risk factor modification and lifestyle recommendations [affected] non-CVD conditions remains an additional link that should be explored further.

A synthesis of evidence, including the study by Handy et al., now supports the predictive ability of coronary artery calcium to estimate cardiac, cerebrovascular, and noncardiovascular conditions. We likely should come full circle in our discussion and acknowledge the far reaching implications of its predictive ability. Perhaps our index response that CAC should be fully integrated into all adult wellness and screening evaluations was on target after all!

Although CAC has not been without its critics and is not supported as a reimbursable procedure, its expansive evidence warrants a more thoughtful discussion within the CVD community that this powerful procedure provides valuable information to guide health care decision making.

Dr. Mosaab Awad, Dr. Parham Eshtehardi, and Leslee J. Shaw, Ph.D., of Emory University Clinical Cardiovascular Research Institute, Emory University, Atlanta, made these comments in an editorial (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 Mar 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.09.021). They had no disclosures.

The current report from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis further expands the evidence base supporting the concept of coronary artery calcium as a marker of global health by examining its prognostic power across a diversity of noncardiovascular conditions.

Regardless of the directionality or magnitude of the connections between cardiovascular disease and non-CVD conditions, the extent to which coronary artery calcium–guided patient adherence to risk factor modification and lifestyle recommendations [affected] non-CVD conditions remains an additional link that should be explored further.

A synthesis of evidence, including the study by Handy et al., now supports the predictive ability of coronary artery calcium to estimate cardiac, cerebrovascular, and noncardiovascular conditions. We likely should come full circle in our discussion and acknowledge the far reaching implications of its predictive ability. Perhaps our index response that CAC should be fully integrated into all adult wellness and screening evaluations was on target after all!

Although CAC has not been without its critics and is not supported as a reimbursable procedure, its expansive evidence warrants a more thoughtful discussion within the CVD community that this powerful procedure provides valuable information to guide health care decision making.

Dr. Mosaab Awad, Dr. Parham Eshtehardi, and Leslee J. Shaw, Ph.D., of Emory University Clinical Cardiovascular Research Institute, Emory University, Atlanta, made these comments in an editorial (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 Mar 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.09.021). They had no disclosures.

Patients whose coronary artery calcium scores exceeded 400 were significantly more likely to develop cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and hip fractures, compared with adults with undetectable CAC, in an analysis of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis reported March 9 in JACC Cardiovascular Imaging.

The study is the first to examine the relationship between CAC and significant noncardiovascular diseases, said Dr. Catherine Handy of the Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Heart Disease, Baltimore. Patients with CAC scores of zero represent a unique group of “healthy agers,” she and her associates said. Conversely, 20% of initial non-CVD events occurred in the 10% of patients with CAC scores over 400, and 70% of events occurred in patients with scores greater than zero, they reported.

While CAC is an established indicator of vascular aging, CVD risk, and all-cause mortality, its relationship with non-CVD is unclear. To elucidate the issue, the researchers analyzed data from the prospective, observational Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, which included 6,814 adults aged 45-84 years from six U.S. cities. Patients had no CVD and were not receiving cancer treatment.

Over a median follow-up period of 10.2 years, and after controlling for demographic factors and predictors of CVD, patients with CAC scores exceeding 400 were significantly more likely to develop cancer (hazard ratio, 1.53), chronic kidney disease (HR, 1.70), pneumonia (HR, 1.97), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (HR, 2.71) and hip fracture (HR, 4.29), compared with patients without detectable CAC. Patients with CAC scores of zero were at significantly lower risk of these diagnoses, compared with patients with scores greater than zero (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 Mar 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.09.02).

Doubling of CAC was a modest but significant predictor of cancer, chronic kidney disease, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the subgroup of adults aged 65 years and older. However, CAC was not associated with dementia or deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

Sparse diagnoses of hip fractures and DVT/PE meant that the study might be underpowered to clearly link CAC with risk of these events, said the researchers. There also might not have been enough follow-up time to uncover risk in participants with the lowest CAC scores, they said. “At this time, our data are not powered for stratifying results based on gender or race,” they added.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The researchers had no conflicts of interest.

Patients whose coronary artery calcium scores exceeded 400 were significantly more likely to develop cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and hip fractures, compared with adults with undetectable CAC, in an analysis of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis reported March 9 in JACC Cardiovascular Imaging.

The study is the first to examine the relationship between CAC and significant noncardiovascular diseases, said Dr. Catherine Handy of the Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Heart Disease, Baltimore. Patients with CAC scores of zero represent a unique group of “healthy agers,” she and her associates said. Conversely, 20% of initial non-CVD events occurred in the 10% of patients with CAC scores over 400, and 70% of events occurred in patients with scores greater than zero, they reported.

While CAC is an established indicator of vascular aging, CVD risk, and all-cause mortality, its relationship with non-CVD is unclear. To elucidate the issue, the researchers analyzed data from the prospective, observational Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, which included 6,814 adults aged 45-84 years from six U.S. cities. Patients had no CVD and were not receiving cancer treatment.

Over a median follow-up period of 10.2 years, and after controlling for demographic factors and predictors of CVD, patients with CAC scores exceeding 400 were significantly more likely to develop cancer (hazard ratio, 1.53), chronic kidney disease (HR, 1.70), pneumonia (HR, 1.97), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (HR, 2.71) and hip fracture (HR, 4.29), compared with patients without detectable CAC. Patients with CAC scores of zero were at significantly lower risk of these diagnoses, compared with patients with scores greater than zero (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 Mar 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.09.02).

Doubling of CAC was a modest but significant predictor of cancer, chronic kidney disease, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the subgroup of adults aged 65 years and older. However, CAC was not associated with dementia or deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

Sparse diagnoses of hip fractures and DVT/PE meant that the study might be underpowered to clearly link CAC with risk of these events, said the researchers. There also might not have been enough follow-up time to uncover risk in participants with the lowest CAC scores, they said. “At this time, our data are not powered for stratifying results based on gender or race,” they added.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The researchers had no conflicts of interest.

FROM JACC CARDIOVASCULAR IMAGING

AAAAI: Albuterol Dry Powder Inhaler Offers Simplified Approach for Young Kids

LOS ANGELES – Young asthmatic children on bronchodilator therapy may soon gain access to a novel albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler that’s already proved popular with teen and adult patients with reversible obstructive airway disease because of its ease of use.

A phase III randomized, double-blind multicenter trial of the albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler (MDPI) versus placebo in 184 asthmatic children aged 4-11 years not on systemic corticosteroids met its primary and secondary lung function endpoints, with safety and tolerability similar to placebo, Dr. Tushar P. Shah reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The albuterol MDPI is already marketed by Teva Pharmaceuticals as the ProAir RespiClick in patients aged 12 and older. The purpose of this phase III clinical trial was to obtain an expanded indication in 4- to 11-year-olds. The company has submitted its request to the Food and Drug Administration and anticipates smooth sailing based upon the new data, according to Dr. Shah, senior vice president for global respiratory research and development at Teva in Frazer, Pa.

The albuterol MDPI fills an unmet need for a simplified approach to rescue medication, the allergist said in an interview.

“This is a breath-actuated inhaler. Many patients – especially kids – have a hard time coordinating a conventional multidose inhaler actuation with inhalation. They have trouble getting the timing right, so the drug doesn’t get to the distal lung. That’s why this albuterol MDPI has been very well received in adults. For kids, I think it’s going to be even better because this is a very simple and intuitive device. All they do is open the cap, inhale, [and] close the cap,” he explained.

The young study participants used the albuterol MDPI at two inhalations four times daily, with a total daily albuterol dose of 720 mcg.

The primary study endpoint was the short-term improvement in lung function seen during testing performed after the very first study dose and again after the final dose of medication 3 weeks later. This was expressed as the area under the baseline-adjusted percent-predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second effect-time curve from predose to 6 hours post dose. On both occasions, a sharp jump in opening of the airways was demonstrated within 5 minutes of dosing, with the effect remaining significantly better than with placebo for more than 2 hours.

Moreover, the maximum change from baseline in peak expiratory flow rate seen within 2 hours after dosing was a 26% increase with the albuterol MDPI, a significantly better result than the 14% increase with placebo.

No adverse events attributable to the study drug were seen.

The study was sponsored by Teva Pharmaceuticals. The presenter is a senior company employee.

LOS ANGELES – Young asthmatic children on bronchodilator therapy may soon gain access to a novel albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler that’s already proved popular with teen and adult patients with reversible obstructive airway disease because of its ease of use.

A phase III randomized, double-blind multicenter trial of the albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler (MDPI) versus placebo in 184 asthmatic children aged 4-11 years not on systemic corticosteroids met its primary and secondary lung function endpoints, with safety and tolerability similar to placebo, Dr. Tushar P. Shah reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The albuterol MDPI is already marketed by Teva Pharmaceuticals as the ProAir RespiClick in patients aged 12 and older. The purpose of this phase III clinical trial was to obtain an expanded indication in 4- to 11-year-olds. The company has submitted its request to the Food and Drug Administration and anticipates smooth sailing based upon the new data, according to Dr. Shah, senior vice president for global respiratory research and development at Teva in Frazer, Pa.

The albuterol MDPI fills an unmet need for a simplified approach to rescue medication, the allergist said in an interview.

“This is a breath-actuated inhaler. Many patients – especially kids – have a hard time coordinating a conventional multidose inhaler actuation with inhalation. They have trouble getting the timing right, so the drug doesn’t get to the distal lung. That’s why this albuterol MDPI has been very well received in adults. For kids, I think it’s going to be even better because this is a very simple and intuitive device. All they do is open the cap, inhale, [and] close the cap,” he explained.

The young study participants used the albuterol MDPI at two inhalations four times daily, with a total daily albuterol dose of 720 mcg.

The primary study endpoint was the short-term improvement in lung function seen during testing performed after the very first study dose and again after the final dose of medication 3 weeks later. This was expressed as the area under the baseline-adjusted percent-predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second effect-time curve from predose to 6 hours post dose. On both occasions, a sharp jump in opening of the airways was demonstrated within 5 minutes of dosing, with the effect remaining significantly better than with placebo for more than 2 hours.

Moreover, the maximum change from baseline in peak expiratory flow rate seen within 2 hours after dosing was a 26% increase with the albuterol MDPI, a significantly better result than the 14% increase with placebo.

No adverse events attributable to the study drug were seen.

The study was sponsored by Teva Pharmaceuticals. The presenter is a senior company employee.

LOS ANGELES – Young asthmatic children on bronchodilator therapy may soon gain access to a novel albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler that’s already proved popular with teen and adult patients with reversible obstructive airway disease because of its ease of use.

A phase III randomized, double-blind multicenter trial of the albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler (MDPI) versus placebo in 184 asthmatic children aged 4-11 years not on systemic corticosteroids met its primary and secondary lung function endpoints, with safety and tolerability similar to placebo, Dr. Tushar P. Shah reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The albuterol MDPI is already marketed by Teva Pharmaceuticals as the ProAir RespiClick in patients aged 12 and older. The purpose of this phase III clinical trial was to obtain an expanded indication in 4- to 11-year-olds. The company has submitted its request to the Food and Drug Administration and anticipates smooth sailing based upon the new data, according to Dr. Shah, senior vice president for global respiratory research and development at Teva in Frazer, Pa.

The albuterol MDPI fills an unmet need for a simplified approach to rescue medication, the allergist said in an interview.

“This is a breath-actuated inhaler. Many patients – especially kids – have a hard time coordinating a conventional multidose inhaler actuation with inhalation. They have trouble getting the timing right, so the drug doesn’t get to the distal lung. That’s why this albuterol MDPI has been very well received in adults. For kids, I think it’s going to be even better because this is a very simple and intuitive device. All they do is open the cap, inhale, [and] close the cap,” he explained.

The young study participants used the albuterol MDPI at two inhalations four times daily, with a total daily albuterol dose of 720 mcg.

The primary study endpoint was the short-term improvement in lung function seen during testing performed after the very first study dose and again after the final dose of medication 3 weeks later. This was expressed as the area under the baseline-adjusted percent-predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second effect-time curve from predose to 6 hours post dose. On both occasions, a sharp jump in opening of the airways was demonstrated within 5 minutes of dosing, with the effect remaining significantly better than with placebo for more than 2 hours.

Moreover, the maximum change from baseline in peak expiratory flow rate seen within 2 hours after dosing was a 26% increase with the albuterol MDPI, a significantly better result than the 14% increase with placebo.

No adverse events attributable to the study drug were seen.

The study was sponsored by Teva Pharmaceuticals. The presenter is a senior company employee.

AT 2016 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

AAAAI: Albuterol Dry Powder Inhaler Offers Simplified Approach for Young Kids

LOS ANGELES – Young asthmatic children on bronchodilator therapy may soon gain access to a novel albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler that’s already proved popular with teen and adult patients with reversible obstructive airway disease because of its ease of use.

A phase III randomized, double-blind multicenter trial of the albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler (MDPI) versus placebo in 184 asthmatic children aged 4-11 years not on systemic corticosteroids met its primary and secondary lung function endpoints, with safety and tolerability similar to placebo, Dr. Tushar P. Shah reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The albuterol MDPI is already marketed by Teva Pharmaceuticals as the ProAir RespiClick in patients aged 12 and older. The purpose of this phase III clinical trial was to obtain an expanded indication in 4- to 11-year-olds. The company has submitted its request to the Food and Drug Administration and anticipates smooth sailing based upon the new data, according to Dr. Shah, senior vice president for global respiratory research and development at Teva in Frazer, Pa.

The albuterol MDPI fills an unmet need for a simplified approach to rescue medication, the allergist said in an interview.

“This is a breath-actuated inhaler. Many patients – especially kids – have a hard time coordinating a conventional multidose inhaler actuation with inhalation. They have trouble getting the timing right, so the drug doesn’t get to the distal lung. That’s why this albuterol MDPI has been very well received in adults. For kids, I think it’s going to be even better because this is a very simple and intuitive device. All they do is open the cap, inhale, [and] close the cap,” he explained.

The young study participants used the albuterol MDPI at two inhalations four times daily, with a total daily albuterol dose of 720 mcg.

The primary study endpoint was the short-term improvement in lung function seen during testing performed after the very first study dose and again after the final dose of medication 3 weeks later. This was expressed as the area under the baseline-adjusted percent-predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second effect-time curve from predose to 6 hours post dose. On both occasions, a sharp jump in opening of the airways was demonstrated within 5 minutes of dosing, with the effect remaining significantly better than with placebo for more than 2 hours.

Moreover, the maximum change from baseline in peak expiratory flow rate seen within 2 hours after dosing was a 26% increase with the albuterol MDPI, a significantly better result than the 14% increase with placebo.

No adverse events attributable to the study drug were seen.

The study was sponsored by Teva Pharmaceuticals. The presenter is a senior company employee.

LOS ANGELES – Young asthmatic children on bronchodilator therapy may soon gain access to a novel albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler that’s already proved popular with teen and adult patients with reversible obstructive airway disease because of its ease of use.

A phase III randomized, double-blind multicenter trial of the albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler (MDPI) versus placebo in 184 asthmatic children aged 4-11 years not on systemic corticosteroids met its primary and secondary lung function endpoints, with safety and tolerability similar to placebo, Dr. Tushar P. Shah reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The albuterol MDPI is already marketed by Teva Pharmaceuticals as the ProAir RespiClick in patients aged 12 and older. The purpose of this phase III clinical trial was to obtain an expanded indication in 4- to 11-year-olds. The company has submitted its request to the Food and Drug Administration and anticipates smooth sailing based upon the new data, according to Dr. Shah, senior vice president for global respiratory research and development at Teva in Frazer, Pa.

The albuterol MDPI fills an unmet need for a simplified approach to rescue medication, the allergist said in an interview.

“This is a breath-actuated inhaler. Many patients – especially kids – have a hard time coordinating a conventional multidose inhaler actuation with inhalation. They have trouble getting the timing right, so the drug doesn’t get to the distal lung. That’s why this albuterol MDPI has been very well received in adults. For kids, I think it’s going to be even better because this is a very simple and intuitive device. All they do is open the cap, inhale, [and] close the cap,” he explained.

The young study participants used the albuterol MDPI at two inhalations four times daily, with a total daily albuterol dose of 720 mcg.

The primary study endpoint was the short-term improvement in lung function seen during testing performed after the very first study dose and again after the final dose of medication 3 weeks later. This was expressed as the area under the baseline-adjusted percent-predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second effect-time curve from predose to 6 hours post dose. On both occasions, a sharp jump in opening of the airways was demonstrated within 5 minutes of dosing, with the effect remaining significantly better than with placebo for more than 2 hours.

Moreover, the maximum change from baseline in peak expiratory flow rate seen within 2 hours after dosing was a 26% increase with the albuterol MDPI, a significantly better result than the 14% increase with placebo.

No adverse events attributable to the study drug were seen.

The study was sponsored by Teva Pharmaceuticals. The presenter is a senior company employee.

LOS ANGELES – Young asthmatic children on bronchodilator therapy may soon gain access to a novel albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler that’s already proved popular with teen and adult patients with reversible obstructive airway disease because of its ease of use.

A phase III randomized, double-blind multicenter trial of the albuterol multidose dry powder inhaler (MDPI) versus placebo in 184 asthmatic children aged 4-11 years not on systemic corticosteroids met its primary and secondary lung function endpoints, with safety and tolerability similar to placebo, Dr. Tushar P. Shah reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The albuterol MDPI is already marketed by Teva Pharmaceuticals as the ProAir RespiClick in patients aged 12 and older. The purpose of this phase III clinical trial was to obtain an expanded indication in 4- to 11-year-olds. The company has submitted its request to the Food and Drug Administration and anticipates smooth sailing based upon the new data, according to Dr. Shah, senior vice president for global respiratory research and development at Teva in Frazer, Pa.

The albuterol MDPI fills an unmet need for a simplified approach to rescue medication, the allergist said in an interview.

“This is a breath-actuated inhaler. Many patients – especially kids – have a hard time coordinating a conventional multidose inhaler actuation with inhalation. They have trouble getting the timing right, so the drug doesn’t get to the distal lung. That’s why this albuterol MDPI has been very well received in adults. For kids, I think it’s going to be even better because this is a very simple and intuitive device. All they do is open the cap, inhale, [and] close the cap,” he explained.

The young study participants used the albuterol MDPI at two inhalations four times daily, with a total daily albuterol dose of 720 mcg.

The primary study endpoint was the short-term improvement in lung function seen during testing performed after the very first study dose and again after the final dose of medication 3 weeks later. This was expressed as the area under the baseline-adjusted percent-predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second effect-time curve from predose to 6 hours post dose. On both occasions, a sharp jump in opening of the airways was demonstrated within 5 minutes of dosing, with the effect remaining significantly better than with placebo for more than 2 hours.

Moreover, the maximum change from baseline in peak expiratory flow rate seen within 2 hours after dosing was a 26% increase with the albuterol MDPI, a significantly better result than the 14% increase with placebo.

No adverse events attributable to the study drug were seen.

The study was sponsored by Teva Pharmaceuticals. The presenter is a senior company employee.

AT 2016 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Helping patients with cystic fibrosis live longer

› Prescribe inhaled dornase alpha and inhaled tobramycin for maintenance pulmonary treatment of moderate to severe cystic fibrosis (CF). A

› Give aggressive nutritional supplementation to maintain a patient’s body mass index and blood sugar control and to attain maximal forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). B

› Consider prescribing cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators, which have demonstrated a 5% to 10% improvement in FEV1 for CF patients. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The focus of treatment. CF is not limited to the classic picture of lung and pancreas destruction with subsequent loss of function. The underlying pathology can occur in body epithelial tissues from the intestinal lining to sweat glands. These tissues contain cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a protein that allows for the transport of chloride across epithelial cell membranes.2 In individuals homozygous for mutated CFTR genes, chloride transport can be impaired. In addition to regulating chloride transport, CFTR is part of a larger, complex interaction of ion transport proteins such as the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and others that regulate bicarbonate secretion.2 Decreased chloride ion transport in mutant CFTR negatively affects the ion transport complex; the result is a higher-than-normal viscosity of secreted body fluids.

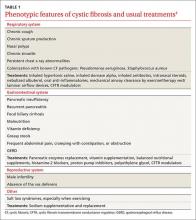

Reason for hope. It is this impairment of chloride ion transport that leads to the classic phenotypic features of CF (eg, pulmonary function decline, pancreatic insufficiency, malnutrition, chronic respiratory infection), and is the target of both established and emerging therapies3—both of which I will review here.

When to consider a CF diagnosis

Cystic fibrosis remains a clinical diagnosis when evidence of at least one phenotypic feature of the disease (TABLE 1) exists in the presence of laboratory evidence of a CFTR abnormality.4 Confirmation of CFTR dysfunction is demonstrated by an abnormality on sweat testing or identification of a CF-causing mutation in each copy of CFTR (ie, one on each chromosome).5 All 50 states now have neonatal laboratory screening programs;4 despite this, 30% of cases in 2012 were still diagnosed in those older than 1 year of age, with 3% to 5% diagnosed after age 18.1

A sweat chloride reading in the abnormal range (>60 mmol/L) is present in 90% of patients diagnosed with CF in adulthood; this test remains the gold standard in the diagnosis of CF and the initial test of choice in suspected cases.4 Newborn screening programs identify those at risk by detecting persistent hypertrypsinogenemia and referring those with positive results for definitive testing with sweat chloride evaluation. Keep CF in mind when evaluating adolescents and adults who have chronic sinusitis, chronic/recurrent pulmonary infections, chronic/recurrent pancreatitis, or infertility from absence of the vas deferens.4 When features of the CF phenotype are present, especially if there is a known positive family history of CF or CF carrier status, order sweat chloride testing.

Traditional therapies

Both maintenance and acute therapies are directed throughout the body at decreasing fluid viscosity, clearing fluid with a high viscosity, or treating the tissue destruction that results from highly-viscous fluid.3 The traditional classic picture of CF is one of lung and pancreas destruction with subsequent loss of function. However, CF is, in reality, a full-body disease.

Respiratory system: Lungs

CFTR dysfunction in the lungs results in thick pulmonary secretions as the aqueous surface layer (ASL) lining the alveolar epithelium becomes dehydrated and creates a prime environment for the development of chronic infection. What ensues is a recurrent cycle of chronic infection, inflammation, and tissue destruction with loss of lung volume and function. Current therapies interrupt this cycle at multiple points.6

Airway clearance is one of the hallmarks of CF therapy, using both chemical and mechanical treatments. Daily, most patients will use either a therapy vest that administers sheering forces to the chest cavity or an airflow device that creates positive expiratory pressure and laminar flow to aid in expectorating pulmonary secretions.7 Because exercise has yielded comparable results to mechanical or airflow clearance devices, it is recommended that all CF patients who are not otherwise prohibited engage in regular, vigorous exercise in accordance with standard recommendations for the general public.7

Mechanical therapies are often preceded by airway dilation with short- and long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled steroids that open airways for optimal airway clearance.4 Thick secretions can be treated directly and enzymatically with nebulized dornase alpha,4,8 which is also best administered before mechanical clearance therapy. Finally, viscosity of airway secretions can be decreased by improving the hydration of the ASL with nebulized 7% hypertonic saline.4,8

Infection suppression. Thickened pulmonary secretions create a fertile environment for the development of chronic infection. By the time most CF patients reach adulthood, many are colonized with mucoid producing strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.4,8-10 Many may also have chronic infection with Staphylococcus aureus, some strains of which may be methicillin-resistant. Quarterly culture and sensitivity results can be essential in directing acute antibiotic therapy, both in the hospital and ambulatory settings. In addition, in the case of Pseudomonas, inhaled antibiotics suppress chronic infection, improve lung function, decrease pulmonary secretions, and reduce inflammation.

Formulations are available for tobramycin and aztreonam, both of which are administered every other month to reduce toxicities and to deter antibiotic resistance. Some patients may use a single agent or may alternate agents every month. When acute antibiotic therapy is necessary for a pulmonary exacerbation, the inhaled agent is generally withheld. If outpatient treatment is warranted, the only available oral antibiotics with anti-pseudomonal activity are ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin.4,8-10S aureus can be treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline.4,8-10

Inflammation reduction is addressed with high-dose ibuprofen twice daily, azithromycin daily or 3 times weekly, or both. Children up to age 18 benefit from ibuprofen, which also improves forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) to a greater extent than azithromycin.8 Adults, however, face the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal dysfunction with ibuprofen, which must be weighed against its potential anti-inflammatory benefit. Both populations, however, benefit from chronic azithromycin, whose mechanism of action in this setting is believed to be more anti-inflammatory than bacterial suppression, since it has no direct bactericidal effect on the primary colonizing microbe, P aeruginosa.4,11

Gastrointestinal system: Pancreas

Cystic fibrosis was first comprehensively described in 1938 and was named for the diseased appearance of the pancreas.12 As happens in the lungs, thick pancreatic duct secretions create a cycle of tissue destruction, inflammation, and dysfunction.2 CF patients lack adequate secretion of pancreatic enzymes and bicarbonate into the small bowel, which progressively leads to pancreatic dysfunction in most patients.

As malabsorption of nutrients advances, patients suffer varying degrees of malnutrition and vitamin deficiency, especially of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. Over 85% of CF patients have deficient pancreatic function, requiring pancreatic enzyme supplementation with all food intake and daily vitamin supplementation.2

Ensuring adequate nutrition. Most CF patients experience a chronic mismatch of dietary intake against caloric expenditure and benefit from aggressive nutritional management featuring a high-calorie diet with supplementation in the form of nutrition shakes or bars.2 There is a well-documented linear relationship between BMI and FEV1. Lung function declines in CF when a man’s body mass index (BMI) falls below 23 kg/m2 and a woman’s BMI drops below 22 kg/m2.2 For this reason, the goal for caloric intake can be as high as 200% of the customary recommended daily allowance.2

Watch for CF-related diabetes. Since the pancreas is also the major source of endogenous insulin, nearly half of adults with CF will develop cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) as pancreatic deficiency progresses.13 Similar to the relationship between BMI and FEV1, there is a relationship between glucose intolerance and FEV1. For this reason, annual diabetes screening is recommended for all CF patients ages 10 years and older.13 Because glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) may not accurately reflect low levels of glucose intolerance, screen for CFRD with a 2-hour 75-g oral glucose tolerance test.13 Early insulin therapy can help maintain BMI and lower average blood sugar in support of FEV1. Once CFRD is diagnosed, the goals and recommendations for control are largely the same as those recommended by the American Diabetes Association for other forms of diabetes.13

Cystic Fibrosis Resources

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation

www.cff.org

Consensus report on cystic fibrosis management

Yankaskas JR, Marchall BC, Sufian B, et al. Cystic fibrosis adult care. Chest. 2004;125:1S-39S.

Consensus report on cystic fibrosis diagnostic guidelines

Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White RB. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4-S14.

Gastrointestinal system: Alimentary canal

CF is often mistakenly believed to be primarily a pulmonary disease since 85% of the mortality is due to lung dysfunction,7 but intermittent abdominal pain is a common experience for most patients, and disorders can range from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) to small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SBBO) to constipation. Up to 85% of adult patients experience symptoms of reflux, with as many as 40% of cases occurring silently.2 Proton pump inhibitors are a first-line treatment, but they can also contribute to intestinal bacterial overgrowth and pulmonary infections.

In SBBO, gram-negative colonic bacteria colonize the small bowel and can contribute to abdominal pain and malabsorption, weight loss, and malnutrition. Treatment requires antibiotics with activity against gram-negative organisms, or non-absorbable agents such as rifamyxin, sometimes on a chronic, recurrent, or rotating basis.2

Chronic constipation is also quite common among CF patients and many require daily administration of poly-ethylene-glycol. Before newborn screening programs were introduced, infants would on occasion present with complete distal intestinal obstruction. Adults are not immune to obstructive complications and may require hospitalization for bowel cleansing.

Gastrointestinal system: Liver

Liver disease is relatively common in CF, with up to 24% of adults experiencing hepatomegaly or persistently elevated liver function tests (LFT).4 Progressive biliary fibrosis and cirrhosis are encountered more often as the median survival age has increased. There is evidence that ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) can be a useful adjunct in the treatment of cholestasis, but it is not clear if it alters mortality or progression to cirrhosis. Only CF patients with elevated LFTs should be started on UDCA.4

Other areas of concern: Sinuses, serum sodium levels

Chronic, symptomatic sinus disease in CF patients—chiefly polyposis—is common and may require repeat surgery, although most patients with extensive nasal polyps find symptom relief with daily sinus rinses. Intranasal steroids and intranasal antibiotics are also often employed, and many CF patients need to be in regular contact with an otolaryngologist.14 For symptoms of allergic rhinitis, recommend OTC antihistamines in standard dosages.

Exercise is recommended for all CF patients, as noted earlier, and as life expectancy increases, many are engaging in more strenuous and longer duration activities.15 Due to high sweat sodium loss, CF patients are at risk for hyponatremia, especially when exercising on days with high temperatures and humidity. CF patients need to replace sodium losses in these conditions and when exercising for extended periods.

There are no evidence-based guidelines for sodium replacement. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) recommends that patients increase salt in the diet when under conditions likely to result in increased sodium loss, such as exercise. It has been thought that CF patients can easily dehydrate due to an impaired thirst mechanism and, when exercising, should consume fluids beyond the need to quench thirst.16,17 More recent evidence suggests, however, that the thirst mechanism in those with CF remains normally intact and that overconsumption of fluids beyond the level of thirst may predispose the individual to exercise-associated hyponatremia as serum sodium is diluted.15

New therapies

Small-molecule CFTR-modulating compounds are a promising development in the treatment of CF. The first such available medication was ivacaftor in 2012. Because these molecules are mutation specific, ivacaftor was available at first only for patients with at least one copy of the G551D mutation,18 which means about 5% of patients with CF.3

Ivacaftor increases the likelihood that the CFTR chloride channel will open and patients will exhibit a reduction in sweat chloride levels. In the first reported clinical trial of ivacaftor involving patients with the G551D mutation, FEV1 improvements of 10% occurred by the second week of therapy and persisted for 48 weeks.18 The drug has now been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients 12 years of age and older with at least one of the following mutations: R117H, G551D, G178R, S549N, S549R, G551S, G1244E, S1251N, S1255P, or G1349D.19

A medication combining ivacaftor with lumacaftor is also now available for patients with a copy of F508del on both chromosomes. F508del is the most common CFTR mutation, with one copy present in almost 87% of people with CF in the United States.1 Since 47% of CF patients have 2 copies of F508del,1 about half of those with CF in the United States are now eligible for small-molecule therapy. Lumacaftor acts by facilitating transport of a misfolded CFTR to the cell membrane where ivacaftor then increases the probability of an open chloride channel. This combination medication has improved lung function by about 5%.

The ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination was approved by the FDA in July 2015. Both ivacaftor and the ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination were deemed by the FDA to demonstrate statistically significant and sustained FEV1 improvements over placebo.

The CFF was instrumental in providing financial support for the development of both ivacaftor and the ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination and continues to provide significant research advancement. According to the CFF (www.cff.org), medications currently in the development pipeline include compounds that provide CFTR modulation, surface airway liquid restoration, anti-inflammation, inhaled anti-infection, and pancreatic enzyme function. For more on CFF, see "The traditional CF care model.”4,20

The traditional CF care model

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) has been a driving force behind the increased life expectancy CF patients have seen over the last 3 decades. Its contributions include the development of medication through the CFF Therapeutics Development Network (TDN) and disease management through a network of CF Care Centers throughout the United States. The CFF recommends a minimum of quarterly visits to a CF Care Center, and the primary care physician can play a critical role alongside the multidisciplinary CF team.20

At every CF Care Center encounter, the entire team (nurse, physician, dietician, social worker, psychologist) interacts with each patient and their families to maximize overall medical care. Respiratory cultures are generally obtained at each visit. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry is performed biannually. Lab work (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, glycated hemoglobin, vitamins A, D, E, and K, 2-hour glucose tolerance test), and chest x-ray are obtained at least annually (TABLE 2).4

Since CF generally involves both restrictive and obstructive lung components, complete spirometry evaluation is performed annually in the pulmonary function lab, with static lung volumes in addition to airflow measurement. Office spirometry to measure airflow alone is performed at each visit. FEV1 is tracked both as an indicator of disease progression and as a measure of current pulmonary status.

The CFF recommends that each patient receive full genetic testing and encourages patient participation in the CFF Registry, where mutation data are documented among other disease parameters to ensure that patients receive mutation specific therapies as they become available.4 The vaccine schedule recommended for CF patients is the same as for the general population.

CORRESPONDENCE

Douglas Lewis, MD, 1121 S. Clifton, Wichita, KS 67218; [email protected].

1. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Patient registry 2012 annual data report. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Web site. Available at: http://www.cff.org/UploadedFiles/research/ClinicalResearch/PatientRegistryReport/2012-CFF-Patient-Registry.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2014.

2. Haller W, Ledder O, Lewindon PJ, et al. Cystic fibrosis: An update for clinicians. Part 1: Nutrition and gastrointestinal complications. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1344-1355.

3. Hoffman LR, Ramsey BW. Cystic fibrosis therapeutics: the road ahead. Chest. 2013;143:207-213.

4. Yankaskas JR, Marshall BC, Sufian B, et al. Cystic fibrosis adult care: consensus conference report. Chest. 2004;125:1S-39S.

5. Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White TB, et al; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation consensus report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4-S14.

6. Donaldson SH, Boucher RC. Sodium channels and cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2007;132:1631-1636.

7. Flume PA, Robinson KA, O’Sullivan BP, et al; Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: airway clearance therapies. Respir Care. 2009;54:522-537.

8. Flume PA, O’Sullivan BP, Robinson KA, et al; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: chronic medications for maintenance of lung health. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:957-969.

9. Döring G, Flume P, Heijerman H, et al; Consensus Study Group. Treatment of lung infection in patients with cystic fibrosis: current and future strategies. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11:461-479.

10. Flume PA, Mogayzel PJ Jr, Robinson KA, et al; Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: treatment of pulmonary exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:802-808.

11. Southern KW, Barker PM. Azithromycin for cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:834-838.

12. Andersen DH. Cystic fibrosis of the pancreas and its relation to celiac disease: a clinical and pathologic study. Am J Dis Child. 1938;56:344-399.

13. Moran A, Brunzell C, Cohen RC, et al; CFRD Guidelines Committee. Clinical care guidelines for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a clinical practice guideline of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, endorsed by the Pediatric Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2697-2708.

14. Kerem E, Conway S, Elborn S, et al; Consensus Committee. Standards of care for patients with cystic fibrosis: a European consensus. J Cyst Fibros. 2005;4:7-26.

15. Hew-Butler T, Rosner MH, Fowkes-Godek S, et al. Statement of the third international exercise-associated hyponatremia consensus development conference, Carlsbad, California, 2015. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:303-320.

16. Brown MB, McCarty NA, Millard-Stafford M. High-sweat Na+ in cystic fibrosis and healthy individuals does not diminish thirst during exercise in the heat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301:R1177-R1185.

17. Wheatley CM, Wilkins BW, Snyder EM. Exercise is medicine in cystic fibrosis. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2011;39:155-160.

18. Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, et al; VX08-770-102 Study Group. ACFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1663-1672.

19. Pettit RS, Fellner C. CFTR Modulators for the Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis. P T. 2014;39:500-511.

20. Lewis D. Role of the family physician in the management of cystic fibrosis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:822-824.

› Prescribe inhaled dornase alpha and inhaled tobramycin for maintenance pulmonary treatment of moderate to severe cystic fibrosis (CF). A

› Give aggressive nutritional supplementation to maintain a patient’s body mass index and blood sugar control and to attain maximal forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). B

› Consider prescribing cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators, which have demonstrated a 5% to 10% improvement in FEV1 for CF patients. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The focus of treatment. CF is not limited to the classic picture of lung and pancreas destruction with subsequent loss of function. The underlying pathology can occur in body epithelial tissues from the intestinal lining to sweat glands. These tissues contain cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a protein that allows for the transport of chloride across epithelial cell membranes.2 In individuals homozygous for mutated CFTR genes, chloride transport can be impaired. In addition to regulating chloride transport, CFTR is part of a larger, complex interaction of ion transport proteins such as the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and others that regulate bicarbonate secretion.2 Decreased chloride ion transport in mutant CFTR negatively affects the ion transport complex; the result is a higher-than-normal viscosity of secreted body fluids.

Reason for hope. It is this impairment of chloride ion transport that leads to the classic phenotypic features of CF (eg, pulmonary function decline, pancreatic insufficiency, malnutrition, chronic respiratory infection), and is the target of both established and emerging therapies3—both of which I will review here.

When to consider a CF diagnosis

Cystic fibrosis remains a clinical diagnosis when evidence of at least one phenotypic feature of the disease (TABLE 1) exists in the presence of laboratory evidence of a CFTR abnormality.4 Confirmation of CFTR dysfunction is demonstrated by an abnormality on sweat testing or identification of a CF-causing mutation in each copy of CFTR (ie, one on each chromosome).5 All 50 states now have neonatal laboratory screening programs;4 despite this, 30% of cases in 2012 were still diagnosed in those older than 1 year of age, with 3% to 5% diagnosed after age 18.1

A sweat chloride reading in the abnormal range (>60 mmol/L) is present in 90% of patients diagnosed with CF in adulthood; this test remains the gold standard in the diagnosis of CF and the initial test of choice in suspected cases.4 Newborn screening programs identify those at risk by detecting persistent hypertrypsinogenemia and referring those with positive results for definitive testing with sweat chloride evaluation. Keep CF in mind when evaluating adolescents and adults who have chronic sinusitis, chronic/recurrent pulmonary infections, chronic/recurrent pancreatitis, or infertility from absence of the vas deferens.4 When features of the CF phenotype are present, especially if there is a known positive family history of CF or CF carrier status, order sweat chloride testing.

Traditional therapies

Both maintenance and acute therapies are directed throughout the body at decreasing fluid viscosity, clearing fluid with a high viscosity, or treating the tissue destruction that results from highly-viscous fluid.3 The traditional classic picture of CF is one of lung and pancreas destruction with subsequent loss of function. However, CF is, in reality, a full-body disease.

Respiratory system: Lungs

CFTR dysfunction in the lungs results in thick pulmonary secretions as the aqueous surface layer (ASL) lining the alveolar epithelium becomes dehydrated and creates a prime environment for the development of chronic infection. What ensues is a recurrent cycle of chronic infection, inflammation, and tissue destruction with loss of lung volume and function. Current therapies interrupt this cycle at multiple points.6

Airway clearance is one of the hallmarks of CF therapy, using both chemical and mechanical treatments. Daily, most patients will use either a therapy vest that administers sheering forces to the chest cavity or an airflow device that creates positive expiratory pressure and laminar flow to aid in expectorating pulmonary secretions.7 Because exercise has yielded comparable results to mechanical or airflow clearance devices, it is recommended that all CF patients who are not otherwise prohibited engage in regular, vigorous exercise in accordance with standard recommendations for the general public.7

Mechanical therapies are often preceded by airway dilation with short- and long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled steroids that open airways for optimal airway clearance.4 Thick secretions can be treated directly and enzymatically with nebulized dornase alpha,4,8 which is also best administered before mechanical clearance therapy. Finally, viscosity of airway secretions can be decreased by improving the hydration of the ASL with nebulized 7% hypertonic saline.4,8

Infection suppression. Thickened pulmonary secretions create a fertile environment for the development of chronic infection. By the time most CF patients reach adulthood, many are colonized with mucoid producing strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.4,8-10 Many may also have chronic infection with Staphylococcus aureus, some strains of which may be methicillin-resistant. Quarterly culture and sensitivity results can be essential in directing acute antibiotic therapy, both in the hospital and ambulatory settings. In addition, in the case of Pseudomonas, inhaled antibiotics suppress chronic infection, improve lung function, decrease pulmonary secretions, and reduce inflammation.

Formulations are available for tobramycin and aztreonam, both of which are administered every other month to reduce toxicities and to deter antibiotic resistance. Some patients may use a single agent or may alternate agents every month. When acute antibiotic therapy is necessary for a pulmonary exacerbation, the inhaled agent is generally withheld. If outpatient treatment is warranted, the only available oral antibiotics with anti-pseudomonal activity are ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin.4,8-10S aureus can be treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline.4,8-10

Inflammation reduction is addressed with high-dose ibuprofen twice daily, azithromycin daily or 3 times weekly, or both. Children up to age 18 benefit from ibuprofen, which also improves forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) to a greater extent than azithromycin.8 Adults, however, face the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal dysfunction with ibuprofen, which must be weighed against its potential anti-inflammatory benefit. Both populations, however, benefit from chronic azithromycin, whose mechanism of action in this setting is believed to be more anti-inflammatory than bacterial suppression, since it has no direct bactericidal effect on the primary colonizing microbe, P aeruginosa.4,11

Gastrointestinal system: Pancreas

Cystic fibrosis was first comprehensively described in 1938 and was named for the diseased appearance of the pancreas.12 As happens in the lungs, thick pancreatic duct secretions create a cycle of tissue destruction, inflammation, and dysfunction.2 CF patients lack adequate secretion of pancreatic enzymes and bicarbonate into the small bowel, which progressively leads to pancreatic dysfunction in most patients.

As malabsorption of nutrients advances, patients suffer varying degrees of malnutrition and vitamin deficiency, especially of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. Over 85% of CF patients have deficient pancreatic function, requiring pancreatic enzyme supplementation with all food intake and daily vitamin supplementation.2

Ensuring adequate nutrition. Most CF patients experience a chronic mismatch of dietary intake against caloric expenditure and benefit from aggressive nutritional management featuring a high-calorie diet with supplementation in the form of nutrition shakes or bars.2 There is a well-documented linear relationship between BMI and FEV1. Lung function declines in CF when a man’s body mass index (BMI) falls below 23 kg/m2 and a woman’s BMI drops below 22 kg/m2.2 For this reason, the goal for caloric intake can be as high as 200% of the customary recommended daily allowance.2

Watch for CF-related diabetes. Since the pancreas is also the major source of endogenous insulin, nearly half of adults with CF will develop cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) as pancreatic deficiency progresses.13 Similar to the relationship between BMI and FEV1, there is a relationship between glucose intolerance and FEV1. For this reason, annual diabetes screening is recommended for all CF patients ages 10 years and older.13 Because glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) may not accurately reflect low levels of glucose intolerance, screen for CFRD with a 2-hour 75-g oral glucose tolerance test.13 Early insulin therapy can help maintain BMI and lower average blood sugar in support of FEV1. Once CFRD is diagnosed, the goals and recommendations for control are largely the same as those recommended by the American Diabetes Association for other forms of diabetes.13

Cystic Fibrosis Resources

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation

www.cff.org

Consensus report on cystic fibrosis management

Yankaskas JR, Marchall BC, Sufian B, et al. Cystic fibrosis adult care. Chest. 2004;125:1S-39S.

Consensus report on cystic fibrosis diagnostic guidelines

Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White RB. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4-S14.

Gastrointestinal system: Alimentary canal

CF is often mistakenly believed to be primarily a pulmonary disease since 85% of the mortality is due to lung dysfunction,7 but intermittent abdominal pain is a common experience for most patients, and disorders can range from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) to small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SBBO) to constipation. Up to 85% of adult patients experience symptoms of reflux, with as many as 40% of cases occurring silently.2 Proton pump inhibitors are a first-line treatment, but they can also contribute to intestinal bacterial overgrowth and pulmonary infections.

In SBBO, gram-negative colonic bacteria colonize the small bowel and can contribute to abdominal pain and malabsorption, weight loss, and malnutrition. Treatment requires antibiotics with activity against gram-negative organisms, or non-absorbable agents such as rifamyxin, sometimes on a chronic, recurrent, or rotating basis.2

Chronic constipation is also quite common among CF patients and many require daily administration of poly-ethylene-glycol. Before newborn screening programs were introduced, infants would on occasion present with complete distal intestinal obstruction. Adults are not immune to obstructive complications and may require hospitalization for bowel cleansing.

Gastrointestinal system: Liver

Liver disease is relatively common in CF, with up to 24% of adults experiencing hepatomegaly or persistently elevated liver function tests (LFT).4 Progressive biliary fibrosis and cirrhosis are encountered more often as the median survival age has increased. There is evidence that ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) can be a useful adjunct in the treatment of cholestasis, but it is not clear if it alters mortality or progression to cirrhosis. Only CF patients with elevated LFTs should be started on UDCA.4

Other areas of concern: Sinuses, serum sodium levels

Chronic, symptomatic sinus disease in CF patients—chiefly polyposis—is common and may require repeat surgery, although most patients with extensive nasal polyps find symptom relief with daily sinus rinses. Intranasal steroids and intranasal antibiotics are also often employed, and many CF patients need to be in regular contact with an otolaryngologist.14 For symptoms of allergic rhinitis, recommend OTC antihistamines in standard dosages.

Exercise is recommended for all CF patients, as noted earlier, and as life expectancy increases, many are engaging in more strenuous and longer duration activities.15 Due to high sweat sodium loss, CF patients are at risk for hyponatremia, especially when exercising on days with high temperatures and humidity. CF patients need to replace sodium losses in these conditions and when exercising for extended periods.

There are no evidence-based guidelines for sodium replacement. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) recommends that patients increase salt in the diet when under conditions likely to result in increased sodium loss, such as exercise. It has been thought that CF patients can easily dehydrate due to an impaired thirst mechanism and, when exercising, should consume fluids beyond the need to quench thirst.16,17 More recent evidence suggests, however, that the thirst mechanism in those with CF remains normally intact and that overconsumption of fluids beyond the level of thirst may predispose the individual to exercise-associated hyponatremia as serum sodium is diluted.15

New therapies

Small-molecule CFTR-modulating compounds are a promising development in the treatment of CF. The first such available medication was ivacaftor in 2012. Because these molecules are mutation specific, ivacaftor was available at first only for patients with at least one copy of the G551D mutation,18 which means about 5% of patients with CF.3

Ivacaftor increases the likelihood that the CFTR chloride channel will open and patients will exhibit a reduction in sweat chloride levels. In the first reported clinical trial of ivacaftor involving patients with the G551D mutation, FEV1 improvements of 10% occurred by the second week of therapy and persisted for 48 weeks.18 The drug has now been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients 12 years of age and older with at least one of the following mutations: R117H, G551D, G178R, S549N, S549R, G551S, G1244E, S1251N, S1255P, or G1349D.19

A medication combining ivacaftor with lumacaftor is also now available for patients with a copy of F508del on both chromosomes. F508del is the most common CFTR mutation, with one copy present in almost 87% of people with CF in the United States.1 Since 47% of CF patients have 2 copies of F508del,1 about half of those with CF in the United States are now eligible for small-molecule therapy. Lumacaftor acts by facilitating transport of a misfolded CFTR to the cell membrane where ivacaftor then increases the probability of an open chloride channel. This combination medication has improved lung function by about 5%.

The ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination was approved by the FDA in July 2015. Both ivacaftor and the ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination were deemed by the FDA to demonstrate statistically significant and sustained FEV1 improvements over placebo.

The CFF was instrumental in providing financial support for the development of both ivacaftor and the ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination and continues to provide significant research advancement. According to the CFF (www.cff.org), medications currently in the development pipeline include compounds that provide CFTR modulation, surface airway liquid restoration, anti-inflammation, inhaled anti-infection, and pancreatic enzyme function. For more on CFF, see "The traditional CF care model.”4,20

The traditional CF care model

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) has been a driving force behind the increased life expectancy CF patients have seen over the last 3 decades. Its contributions include the development of medication through the CFF Therapeutics Development Network (TDN) and disease management through a network of CF Care Centers throughout the United States. The CFF recommends a minimum of quarterly visits to a CF Care Center, and the primary care physician can play a critical role alongside the multidisciplinary CF team.20

At every CF Care Center encounter, the entire team (nurse, physician, dietician, social worker, psychologist) interacts with each patient and their families to maximize overall medical care. Respiratory cultures are generally obtained at each visit. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry is performed biannually. Lab work (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, glycated hemoglobin, vitamins A, D, E, and K, 2-hour glucose tolerance test), and chest x-ray are obtained at least annually (TABLE 2).4

Since CF generally involves both restrictive and obstructive lung components, complete spirometry evaluation is performed annually in the pulmonary function lab, with static lung volumes in addition to airflow measurement. Office spirometry to measure airflow alone is performed at each visit. FEV1 is tracked both as an indicator of disease progression and as a measure of current pulmonary status.

The CFF recommends that each patient receive full genetic testing and encourages patient participation in the CFF Registry, where mutation data are documented among other disease parameters to ensure that patients receive mutation specific therapies as they become available.4 The vaccine schedule recommended for CF patients is the same as for the general population.

CORRESPONDENCE

Douglas Lewis, MD, 1121 S. Clifton, Wichita, KS 67218; [email protected].

› Prescribe inhaled dornase alpha and inhaled tobramycin for maintenance pulmonary treatment of moderate to severe cystic fibrosis (CF). A

› Give aggressive nutritional supplementation to maintain a patient’s body mass index and blood sugar control and to attain maximal forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). B

› Consider prescribing cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators, which have demonstrated a 5% to 10% improvement in FEV1 for CF patients. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The focus of treatment. CF is not limited to the classic picture of lung and pancreas destruction with subsequent loss of function. The underlying pathology can occur in body epithelial tissues from the intestinal lining to sweat glands. These tissues contain cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a protein that allows for the transport of chloride across epithelial cell membranes.2 In individuals homozygous for mutated CFTR genes, chloride transport can be impaired. In addition to regulating chloride transport, CFTR is part of a larger, complex interaction of ion transport proteins such as the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and others that regulate bicarbonate secretion.2 Decreased chloride ion transport in mutant CFTR negatively affects the ion transport complex; the result is a higher-than-normal viscosity of secreted body fluids.

Reason for hope. It is this impairment of chloride ion transport that leads to the classic phenotypic features of CF (eg, pulmonary function decline, pancreatic insufficiency, malnutrition, chronic respiratory infection), and is the target of both established and emerging therapies3—both of which I will review here.

When to consider a CF diagnosis

Cystic fibrosis remains a clinical diagnosis when evidence of at least one phenotypic feature of the disease (TABLE 1) exists in the presence of laboratory evidence of a CFTR abnormality.4 Confirmation of CFTR dysfunction is demonstrated by an abnormality on sweat testing or identification of a CF-causing mutation in each copy of CFTR (ie, one on each chromosome).5 All 50 states now have neonatal laboratory screening programs;4 despite this, 30% of cases in 2012 were still diagnosed in those older than 1 year of age, with 3% to 5% diagnosed after age 18.1

A sweat chloride reading in the abnormal range (>60 mmol/L) is present in 90% of patients diagnosed with CF in adulthood; this test remains the gold standard in the diagnosis of CF and the initial test of choice in suspected cases.4 Newborn screening programs identify those at risk by detecting persistent hypertrypsinogenemia and referring those with positive results for definitive testing with sweat chloride evaluation. Keep CF in mind when evaluating adolescents and adults who have chronic sinusitis, chronic/recurrent pulmonary infections, chronic/recurrent pancreatitis, or infertility from absence of the vas deferens.4 When features of the CF phenotype are present, especially if there is a known positive family history of CF or CF carrier status, order sweat chloride testing.

Traditional therapies

Both maintenance and acute therapies are directed throughout the body at decreasing fluid viscosity, clearing fluid with a high viscosity, or treating the tissue destruction that results from highly-viscous fluid.3 The traditional classic picture of CF is one of lung and pancreas destruction with subsequent loss of function. However, CF is, in reality, a full-body disease.

Respiratory system: Lungs

CFTR dysfunction in the lungs results in thick pulmonary secretions as the aqueous surface layer (ASL) lining the alveolar epithelium becomes dehydrated and creates a prime environment for the development of chronic infection. What ensues is a recurrent cycle of chronic infection, inflammation, and tissue destruction with loss of lung volume and function. Current therapies interrupt this cycle at multiple points.6

Airway clearance is one of the hallmarks of CF therapy, using both chemical and mechanical treatments. Daily, most patients will use either a therapy vest that administers sheering forces to the chest cavity or an airflow device that creates positive expiratory pressure and laminar flow to aid in expectorating pulmonary secretions.7 Because exercise has yielded comparable results to mechanical or airflow clearance devices, it is recommended that all CF patients who are not otherwise prohibited engage in regular, vigorous exercise in accordance with standard recommendations for the general public.7

Mechanical therapies are often preceded by airway dilation with short- and long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled steroids that open airways for optimal airway clearance.4 Thick secretions can be treated directly and enzymatically with nebulized dornase alpha,4,8 which is also best administered before mechanical clearance therapy. Finally, viscosity of airway secretions can be decreased by improving the hydration of the ASL with nebulized 7% hypertonic saline.4,8

Infection suppression. Thickened pulmonary secretions create a fertile environment for the development of chronic infection. By the time most CF patients reach adulthood, many are colonized with mucoid producing strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.4,8-10 Many may also have chronic infection with Staphylococcus aureus, some strains of which may be methicillin-resistant. Quarterly culture and sensitivity results can be essential in directing acute antibiotic therapy, both in the hospital and ambulatory settings. In addition, in the case of Pseudomonas, inhaled antibiotics suppress chronic infection, improve lung function, decrease pulmonary secretions, and reduce inflammation.

Formulations are available for tobramycin and aztreonam, both of which are administered every other month to reduce toxicities and to deter antibiotic resistance. Some patients may use a single agent or may alternate agents every month. When acute antibiotic therapy is necessary for a pulmonary exacerbation, the inhaled agent is generally withheld. If outpatient treatment is warranted, the only available oral antibiotics with anti-pseudomonal activity are ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin.4,8-10S aureus can be treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline.4,8-10

Inflammation reduction is addressed with high-dose ibuprofen twice daily, azithromycin daily or 3 times weekly, or both. Children up to age 18 benefit from ibuprofen, which also improves forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) to a greater extent than azithromycin.8 Adults, however, face the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal dysfunction with ibuprofen, which must be weighed against its potential anti-inflammatory benefit. Both populations, however, benefit from chronic azithromycin, whose mechanism of action in this setting is believed to be more anti-inflammatory than bacterial suppression, since it has no direct bactericidal effect on the primary colonizing microbe, P aeruginosa.4,11

Gastrointestinal system: Pancreas

Cystic fibrosis was first comprehensively described in 1938 and was named for the diseased appearance of the pancreas.12 As happens in the lungs, thick pancreatic duct secretions create a cycle of tissue destruction, inflammation, and dysfunction.2 CF patients lack adequate secretion of pancreatic enzymes and bicarbonate into the small bowel, which progressively leads to pancreatic dysfunction in most patients.

As malabsorption of nutrients advances, patients suffer varying degrees of malnutrition and vitamin deficiency, especially of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. Over 85% of CF patients have deficient pancreatic function, requiring pancreatic enzyme supplementation with all food intake and daily vitamin supplementation.2

Ensuring adequate nutrition. Most CF patients experience a chronic mismatch of dietary intake against caloric expenditure and benefit from aggressive nutritional management featuring a high-calorie diet with supplementation in the form of nutrition shakes or bars.2 There is a well-documented linear relationship between BMI and FEV1. Lung function declines in CF when a man’s body mass index (BMI) falls below 23 kg/m2 and a woman’s BMI drops below 22 kg/m2.2 For this reason, the goal for caloric intake can be as high as 200% of the customary recommended daily allowance.2

Watch for CF-related diabetes. Since the pancreas is also the major source of endogenous insulin, nearly half of adults with CF will develop cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) as pancreatic deficiency progresses.13 Similar to the relationship between BMI and FEV1, there is a relationship between glucose intolerance and FEV1. For this reason, annual diabetes screening is recommended for all CF patients ages 10 years and older.13 Because glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) may not accurately reflect low levels of glucose intolerance, screen for CFRD with a 2-hour 75-g oral glucose tolerance test.13 Early insulin therapy can help maintain BMI and lower average blood sugar in support of FEV1. Once CFRD is diagnosed, the goals and recommendations for control are largely the same as those recommended by the American Diabetes Association for other forms of diabetes.13

Cystic Fibrosis Resources

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation

www.cff.org

Consensus report on cystic fibrosis management

Yankaskas JR, Marchall BC, Sufian B, et al. Cystic fibrosis adult care. Chest. 2004;125:1S-39S.

Consensus report on cystic fibrosis diagnostic guidelines

Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White RB. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4-S14.

Gastrointestinal system: Alimentary canal