User login

Activating the Immune System to Treat Multiple Myeloma

Sagar Lonial, MD

Chief Medical Officer, Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University

Chair, Dept. of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Emory School of Medicine

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Dr. Lonial reports that he is a compensated consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb; Celgene Corporation; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; and Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Sagar Lonial, MD

Chief Medical Officer, Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University

Chair, Dept. of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Emory School of Medicine

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Dr. Lonial reports that he is a compensated consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb; Celgene Corporation; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; and Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Sagar Lonial, MD

Chief Medical Officer, Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University

Chair, Dept. of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Emory School of Medicine

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Dr. Lonial reports that he is a compensated consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb; Celgene Corporation; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; and Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Assessment of Free Flap Breast Reconstructions

Free flap autologous breast reconstruction is an excellent surgical option for breast reconstruction in select patients. A free flap involves moving skin, fat, and/or muscle from a distant part of the body, based on a named blood supply (pedicle), and attaching it to another blood supply adjacent to the acquired defect. This procedure is particularly useful in areas where local tissue supply is lacking in volume or is damaged due to trauma or radiation. These reconstructions are performed largely in high-volume centers outside the VA because of the required specialized level of surgical training, manpower, and nursing support.1 The Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville, Florida, started offering autologous free flap breast reconstruction as an option to select patients in October 2012.

The Malcom Randall VAMC operating room (OR) does not operate 24/7, and the system has limited available OR time and surgical staff compared with the volume of patients requesting care.2 Operative planning for free flap autologous breast reconstruction must occur months ahead of surgery to balance the system limitations with the ability to offer the highest level of care. Planning includes strict patient selection, preoperative imaging, practice runs with OR staff, use of venous couplers, and frequent intensive care unit (ICU) staff in-services. Planning also includes the need to keep surgeries within the allocated OR time to avoid shift changes during critical periods. Frequent and early communication occurs between the surgical scheduler, OR nurses, and the anesthesia and critical care teams.

Studies have found that the best chance of flap salvage in the event of a thrombotic event is a rapid return to the OR.3 It is essential to minimize the risk of emergent returns to the OR because it is not staffed throughout the night. Patient risk factors for perioperative vascular complications include hypercoagulable disorders, peripheral vascular disease, use of the superficial epigastric system, and smoking.4-7

A PubMed search for free flap reconstruction solely within the VA over the past 20 years found 1 article discussing the use of free flaps in head and neck reconstruction which demonstrated an impressive success rate of 93%.8

The object of this study was to assess free flap breast reconstruction results at the Malcolm Randall VAMC to determine whether it is a realistic treatment to offer in the federal system.

Methods

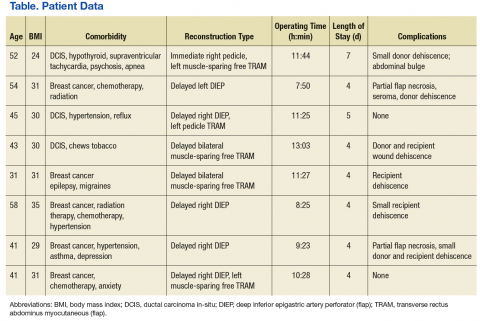

The Malcolm Randall Institutional Review Board approved a retrospective chart review of all autologous free flap breast reconstructions using CPT code 19364, performed from October 2012 to June 2016. Medical records of patients who had a free flap breast reconstruction were queried during that period. Patient age; comorbidities listed on the electronic medical record “problem list;” body mass index (BMI); type of reconstruction (delayed vs immediate); length of surgery; length of stay; and complications over a 30-day period were recorded (Table). The authors looked for documentation of preoperative imaging and unplanned returns to the OR within the 30-day period.

Of 3 full-time VA plastic surgeons on staff during the study period, 2 surgeons had advanced fellowship training in either microsurgery or hand and microsurgery. Plastic surgery fellows and general surgery interns participated in the surgeries and postoperative care. The service had 1 dedicated advanced practice registered nurse involved in the surgical scheduling and perioperative care.

Results

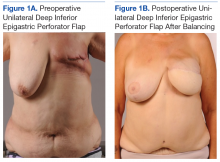

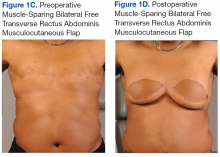

A total of 11 abdominally based free flap breast reconstructions—6 muscle-sparing transverse rectus abdominus musculocutaneous (TRAM) and 5 deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flaps—were performed in 8 patients during the study period (Figures 1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D). Patient ages ranged from 31 to 58 years with a mean of 45.6 years. Six patients had preoperative computer tomography angiography (CTA) to define the location of the abdominal wall perforators. One muscle-sparing free flap was performed immediately after mastectomy; the other free flaps were performed as delayed reconstructions. Body mass index ranged from 24 to 35, with a mean of 30. All patients reported no tobacco use during the consultation; however, 1 patient later admitted to chewing tobacco. No urinary cotinine confirmation was requested. Two patients had 1 free flap reconstruction and 1 pedicle TRAM. This bilateral combination has been recently described in the literature and was chosen as a reasonable option to balance limited resources with abdominal wall morbidity.9 Operating room time ranged from 7 hours 50 minutes to 13 hours 3 minutes. All patients went to the ICU for hourly flap monitoring.

Length of stay ranged from 4 to 7 days, with a mean of 4.5 days. The longest stay was for a patient who had immediate reconstruction using a pedicle TRAM and muscle-sparing free TRAM. She was not a DIEP candidate because poor perforator quality had been noted during preoperative imaging.

Six patients had documentation of postoperative wound complications. One patient returned to the OR on the elective schedule 3 weeks postoperatively for a partial flap debridement. Her tissue transfer was > 1,000 g, and she required a matching reduction on the other side. There were no complete flap losses or postoperative thrombotic events; no cases went back to the OR emergently.

Discussion

With the number of women veterans steadily increasing, the number of patients in need of breast cancer surgery, including reconstruction, will rise in the VA.10 Fortunately, breast reconstruction is an elective procedure. Immediate breast reconstruction is a popular option because patients can combine surgeries and potentially avoid 2 recovery periods, and a better aesthetic outcome is possible because the skin does not have time to contract. Although immediate reconstruction has been increasing in popularity, it is associated with a higher complication rate.11 Further, reconstruction can be jeopardized if the oncologic plan is changed in the early postoperative period.

Positive margins found after an autologous reconstruction result in a more complicated postoperative course and a higher rate of wound complications.12 Unexpected radiation therapy after autologous reconstruction can severely distort a tissue flap because of fat necrosis, fibrosis, and contraction.13,14 From a practical perspective in the federal system, it is very difficult to coordinate 2 surgeons’ schedules when the system is already struggling to keep up with demand. Splitting the ablative and reconstructive surgery allows the urgent problem (cancer) to be addressed first, ensuring clear margins and allowing the patient to recover and consider all reconstructive options without feeling time pressure.

A large tertiary care center will have staff and equipment redundancy, but this study had to consider limitations in resources. The preoperative lead time allows the ICU to arrange a bed for hourly flap checks and for in-servicing new nursing staff on free flap monitoring. This was well received, and patients gave positive feedback on the staff. The OR schedulers can schedule nurses and techs who are familiar with the microscope and microsurgery instruments. The micro sets were opened, and the microscope powered on for practice runs a week before the procedures to insure no broken or missing instruments.

High-procedure volume would logically improve efficiency. Although the VA is not likely to become a tertiary center for breast reconstruction, the findings of other high-volume microsurgeons can be applied to improve speed and limit complications. Efforts to limit the OR time included use of preoperative imaging and intraoperative venous couplers. Venous couplers can result in shorter OR time, fewer returns to the OR, and excellent patency rates.15,16 One microsurgeon performed his surgery using only loupe-assisted vision (x 3.5), without use of the microscope. Pannucci and colleagues have recommended this as a way to improve access and OR efficiency.17 Use of the CTA has been found to decrease the rate of partial flap necrosis and improve speed of surgery.18-20

Careful patient selection allowed a hospital stay that averaged 4.5 days and minimized risks for return to the OR. Only patients who were nonsmokers were offered the surgery. Average BMI was 30 to prevent the known operative risks in breast surgery patients who are morbidly obese.21-23 No patients had a history of thromboembolic disease. Most patients were discharged home from the ICU. They eventually returned for elective revisions, second stages, and balancing procedures.

Conclusion

Free flap breast reconstruction can be offered as a treatment option with appropriate patient selection and planning. The most efficient way to provide this procedure within the federal system and to minimize the risk of flap loss and complications is by offering delayed reconstruction, obtaining preoperative CTA imaging, utilizing venous couplers, and frequently communicating with all involved practitioners from the OR to the ICU. This small study provides a good starting point to illustrate that tertiary-care reconstructive surgery can be offered to veterans within the federal system.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Gainesville, Florida.

1. Tuggle CT, Patel A, Broer N, Persing JA, Sosa JA, Au AF. Increased hospital volume is associated with improved outcomes following abdominal-based breast reconstruction. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2014;48(6):382-388.

2. Shulkin DJ. Beyond the VA crisis — becoming a high-performance network. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(11):1003-1005.

3. Novakovic D, Patel RS, Goldstein DP, Gullane PJ. Salvage of failed free flaps used in head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck Oncol. 2009;1:33.

4. Davison SP, Kessler CM, Al-Attar A. Microvascular free flap failure caused by unrecognized hypercoagulability. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):490-495.

5. Masoomi H, Clark EG, Paydar KZ, et al. Predictive risk factors of free flap thrombosis in breast reconstructive surgery. Microsurgery. 2014;34(8):589-594.

6. O’Neill AC, Haykal S, Bagher S, Zhong T, Hofer S. Predictors and consequences of intraoperative microvascular problems in autologous breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69(10):1349-1355.

7. Sanati-Mehrizy P, Massengburg BB, Rozehnal JM, Ignargiola MJ, Hernandez Rosa J, Taub PJ. Risk factors leading to free flap failure: analysis from the national surgical quality improvement program database. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(8):1956-1964.

8. Myers LL, Sumer BD, Defatta RJ, Minhajuddin A. Free tissue transfer reconstruction of the head and neck at a Veterans Affairs hospital. Head Neck. 2008;30(8):1007-1011.

9. Roslan EJ, Kelly EG, Zain MA, Basiron NH, Imran FH. Immediate simultaneous bilateral breast reconstruction with deep inferior epigastric (DIEP) flap and pedicled transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous (TRAM) pedicle flap. Med J Malaysia. 2017;72(1):85-87.

10. Leong M, Chike-Obi CJ, Basu CB, Lee EL, Albo D, Netscher DT. Effective breast reconstruction in female veterans. Am J Surg. 2009;198(5):658-663.

11. Kwok AC, Goodwin IA, Ying J, Agarwal JP. National trends and complication rates after bilateral mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction from 2005 to 2012. Am J Surg. 2015;210(3):512-516.

12. Ochoa O, Theoharis C, Pisano S, et al. Positive margin re-excision following immediate autologous breast reconstruction: morbidity, cosmetic outcome, and oncologic significance. Aesthet Surg J. 2017; [Epub ahead of print.]

13. Garvey PB, Clemens MW, Hoy AE, et al. Muscle-sparing TRAM flap does not protect breast reconstruction from post-mastectomy radiation damage compared to DIEP flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(2):223-233.

14. Kronowitz SJ. Current status of autologous tissue-based breast reconstruction in patients receiving postmastectomy radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(2):282-292.

15. Fitzgerald O’Connor E, Rozen WM, Chowdhry M, et al. The microvascular anastomotic coupler for venous anastomoses in free flap breast reconstruction improves outcomes. Gland Surg. 2016;5(2):88-92.

16. Jandali S, Wu LC, Vega SJ, Kovach SJ, Serletti JM. 1000 consecutive venous anastomoses using the microvascular anastomotic coupler in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(3):792-798.

17. Pannucci CJ, Basta MN, Kovach SJ, Kanchwala SK, Wu LC, Serletti JM. Loupes-only microsurgery is a safe alternative to the operating microscope: an analysis of 1,649 consecutive free flap breast reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2015;31(9):636-642.

18. Teunis T, Heerma van Voss MR, Kon M, van Maurik JF. CT-angiography prior to DIEP flap reconstruction: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Microsurgery. 2013;33(6):496-502.

19. Fitzgerald O’Connor E, Rozen WM, Chowdhry M, Band B, Ramakrishnan VV, Griffiths M. Preoperative computed tomography angiography for planning DIEP flap breast reconstruction reduces operative time and overall complications. Gland Surgery. 2016;5(2):93-98.

20. Malhotra A, Chhaya N, Nsiah-Sarbeng P, Mosahebi A. CT-guided deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap localization—better for the patient, the surgeon, and the hospital. Clin Radiol. 2013;68(2):131-138.

21. Ilonzo N, Tsang A, Tsantes S, Estabrook A, Thu Ma AM. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy: a ten-year analysis of trends and immediate postoperative outcomes. Breast. 2017;32:7-12.

22. McAllister P, Teo L, Chin K, Makubate B, Alexander Munnoch D. Bilateral breast reconstruction with abdominal free flaps: a single centre, single surgeon retrospective review of 55 consecutive patients. Plast Surg Int. 2016;2016:6085624.

23. Myung Y, Heo CY. Relationship between obesity and surgical complications after reduction mammoplasty: a systemic literature review and meta-analysis. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(3):308-315.

Free flap autologous breast reconstruction is an excellent surgical option for breast reconstruction in select patients. A free flap involves moving skin, fat, and/or muscle from a distant part of the body, based on a named blood supply (pedicle), and attaching it to another blood supply adjacent to the acquired defect. This procedure is particularly useful in areas where local tissue supply is lacking in volume or is damaged due to trauma or radiation. These reconstructions are performed largely in high-volume centers outside the VA because of the required specialized level of surgical training, manpower, and nursing support.1 The Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville, Florida, started offering autologous free flap breast reconstruction as an option to select patients in October 2012.

The Malcom Randall VAMC operating room (OR) does not operate 24/7, and the system has limited available OR time and surgical staff compared with the volume of patients requesting care.2 Operative planning for free flap autologous breast reconstruction must occur months ahead of surgery to balance the system limitations with the ability to offer the highest level of care. Planning includes strict patient selection, preoperative imaging, practice runs with OR staff, use of venous couplers, and frequent intensive care unit (ICU) staff in-services. Planning also includes the need to keep surgeries within the allocated OR time to avoid shift changes during critical periods. Frequent and early communication occurs between the surgical scheduler, OR nurses, and the anesthesia and critical care teams.

Studies have found that the best chance of flap salvage in the event of a thrombotic event is a rapid return to the OR.3 It is essential to minimize the risk of emergent returns to the OR because it is not staffed throughout the night. Patient risk factors for perioperative vascular complications include hypercoagulable disorders, peripheral vascular disease, use of the superficial epigastric system, and smoking.4-7

A PubMed search for free flap reconstruction solely within the VA over the past 20 years found 1 article discussing the use of free flaps in head and neck reconstruction which demonstrated an impressive success rate of 93%.8

The object of this study was to assess free flap breast reconstruction results at the Malcolm Randall VAMC to determine whether it is a realistic treatment to offer in the federal system.

Methods

The Malcolm Randall Institutional Review Board approved a retrospective chart review of all autologous free flap breast reconstructions using CPT code 19364, performed from October 2012 to June 2016. Medical records of patients who had a free flap breast reconstruction were queried during that period. Patient age; comorbidities listed on the electronic medical record “problem list;” body mass index (BMI); type of reconstruction (delayed vs immediate); length of surgery; length of stay; and complications over a 30-day period were recorded (Table). The authors looked for documentation of preoperative imaging and unplanned returns to the OR within the 30-day period.

Of 3 full-time VA plastic surgeons on staff during the study period, 2 surgeons had advanced fellowship training in either microsurgery or hand and microsurgery. Plastic surgery fellows and general surgery interns participated in the surgeries and postoperative care. The service had 1 dedicated advanced practice registered nurse involved in the surgical scheduling and perioperative care.

Results

A total of 11 abdominally based free flap breast reconstructions—6 muscle-sparing transverse rectus abdominus musculocutaneous (TRAM) and 5 deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flaps—were performed in 8 patients during the study period (Figures 1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D). Patient ages ranged from 31 to 58 years with a mean of 45.6 years. Six patients had preoperative computer tomography angiography (CTA) to define the location of the abdominal wall perforators. One muscle-sparing free flap was performed immediately after mastectomy; the other free flaps were performed as delayed reconstructions. Body mass index ranged from 24 to 35, with a mean of 30. All patients reported no tobacco use during the consultation; however, 1 patient later admitted to chewing tobacco. No urinary cotinine confirmation was requested. Two patients had 1 free flap reconstruction and 1 pedicle TRAM. This bilateral combination has been recently described in the literature and was chosen as a reasonable option to balance limited resources with abdominal wall morbidity.9 Operating room time ranged from 7 hours 50 minutes to 13 hours 3 minutes. All patients went to the ICU for hourly flap monitoring.

Length of stay ranged from 4 to 7 days, with a mean of 4.5 days. The longest stay was for a patient who had immediate reconstruction using a pedicle TRAM and muscle-sparing free TRAM. She was not a DIEP candidate because poor perforator quality had been noted during preoperative imaging.

Six patients had documentation of postoperative wound complications. One patient returned to the OR on the elective schedule 3 weeks postoperatively for a partial flap debridement. Her tissue transfer was > 1,000 g, and she required a matching reduction on the other side. There were no complete flap losses or postoperative thrombotic events; no cases went back to the OR emergently.

Discussion

With the number of women veterans steadily increasing, the number of patients in need of breast cancer surgery, including reconstruction, will rise in the VA.10 Fortunately, breast reconstruction is an elective procedure. Immediate breast reconstruction is a popular option because patients can combine surgeries and potentially avoid 2 recovery periods, and a better aesthetic outcome is possible because the skin does not have time to contract. Although immediate reconstruction has been increasing in popularity, it is associated with a higher complication rate.11 Further, reconstruction can be jeopardized if the oncologic plan is changed in the early postoperative period.

Positive margins found after an autologous reconstruction result in a more complicated postoperative course and a higher rate of wound complications.12 Unexpected radiation therapy after autologous reconstruction can severely distort a tissue flap because of fat necrosis, fibrosis, and contraction.13,14 From a practical perspective in the federal system, it is very difficult to coordinate 2 surgeons’ schedules when the system is already struggling to keep up with demand. Splitting the ablative and reconstructive surgery allows the urgent problem (cancer) to be addressed first, ensuring clear margins and allowing the patient to recover and consider all reconstructive options without feeling time pressure.

A large tertiary care center will have staff and equipment redundancy, but this study had to consider limitations in resources. The preoperative lead time allows the ICU to arrange a bed for hourly flap checks and for in-servicing new nursing staff on free flap monitoring. This was well received, and patients gave positive feedback on the staff. The OR schedulers can schedule nurses and techs who are familiar with the microscope and microsurgery instruments. The micro sets were opened, and the microscope powered on for practice runs a week before the procedures to insure no broken or missing instruments.

High-procedure volume would logically improve efficiency. Although the VA is not likely to become a tertiary center for breast reconstruction, the findings of other high-volume microsurgeons can be applied to improve speed and limit complications. Efforts to limit the OR time included use of preoperative imaging and intraoperative venous couplers. Venous couplers can result in shorter OR time, fewer returns to the OR, and excellent patency rates.15,16 One microsurgeon performed his surgery using only loupe-assisted vision (x 3.5), without use of the microscope. Pannucci and colleagues have recommended this as a way to improve access and OR efficiency.17 Use of the CTA has been found to decrease the rate of partial flap necrosis and improve speed of surgery.18-20

Careful patient selection allowed a hospital stay that averaged 4.5 days and minimized risks for return to the OR. Only patients who were nonsmokers were offered the surgery. Average BMI was 30 to prevent the known operative risks in breast surgery patients who are morbidly obese.21-23 No patients had a history of thromboembolic disease. Most patients were discharged home from the ICU. They eventually returned for elective revisions, second stages, and balancing procedures.

Conclusion

Free flap breast reconstruction can be offered as a treatment option with appropriate patient selection and planning. The most efficient way to provide this procedure within the federal system and to minimize the risk of flap loss and complications is by offering delayed reconstruction, obtaining preoperative CTA imaging, utilizing venous couplers, and frequently communicating with all involved practitioners from the OR to the ICU. This small study provides a good starting point to illustrate that tertiary-care reconstructive surgery can be offered to veterans within the federal system.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Gainesville, Florida.

Free flap autologous breast reconstruction is an excellent surgical option for breast reconstruction in select patients. A free flap involves moving skin, fat, and/or muscle from a distant part of the body, based on a named blood supply (pedicle), and attaching it to another blood supply adjacent to the acquired defect. This procedure is particularly useful in areas where local tissue supply is lacking in volume or is damaged due to trauma or radiation. These reconstructions are performed largely in high-volume centers outside the VA because of the required specialized level of surgical training, manpower, and nursing support.1 The Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville, Florida, started offering autologous free flap breast reconstruction as an option to select patients in October 2012.

The Malcom Randall VAMC operating room (OR) does not operate 24/7, and the system has limited available OR time and surgical staff compared with the volume of patients requesting care.2 Operative planning for free flap autologous breast reconstruction must occur months ahead of surgery to balance the system limitations with the ability to offer the highest level of care. Planning includes strict patient selection, preoperative imaging, practice runs with OR staff, use of venous couplers, and frequent intensive care unit (ICU) staff in-services. Planning also includes the need to keep surgeries within the allocated OR time to avoid shift changes during critical periods. Frequent and early communication occurs between the surgical scheduler, OR nurses, and the anesthesia and critical care teams.

Studies have found that the best chance of flap salvage in the event of a thrombotic event is a rapid return to the OR.3 It is essential to minimize the risk of emergent returns to the OR because it is not staffed throughout the night. Patient risk factors for perioperative vascular complications include hypercoagulable disorders, peripheral vascular disease, use of the superficial epigastric system, and smoking.4-7

A PubMed search for free flap reconstruction solely within the VA over the past 20 years found 1 article discussing the use of free flaps in head and neck reconstruction which demonstrated an impressive success rate of 93%.8

The object of this study was to assess free flap breast reconstruction results at the Malcolm Randall VAMC to determine whether it is a realistic treatment to offer in the federal system.

Methods

The Malcolm Randall Institutional Review Board approved a retrospective chart review of all autologous free flap breast reconstructions using CPT code 19364, performed from October 2012 to June 2016. Medical records of patients who had a free flap breast reconstruction were queried during that period. Patient age; comorbidities listed on the electronic medical record “problem list;” body mass index (BMI); type of reconstruction (delayed vs immediate); length of surgery; length of stay; and complications over a 30-day period were recorded (Table). The authors looked for documentation of preoperative imaging and unplanned returns to the OR within the 30-day period.

Of 3 full-time VA plastic surgeons on staff during the study period, 2 surgeons had advanced fellowship training in either microsurgery or hand and microsurgery. Plastic surgery fellows and general surgery interns participated in the surgeries and postoperative care. The service had 1 dedicated advanced practice registered nurse involved in the surgical scheduling and perioperative care.

Results

A total of 11 abdominally based free flap breast reconstructions—6 muscle-sparing transverse rectus abdominus musculocutaneous (TRAM) and 5 deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flaps—were performed in 8 patients during the study period (Figures 1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D). Patient ages ranged from 31 to 58 years with a mean of 45.6 years. Six patients had preoperative computer tomography angiography (CTA) to define the location of the abdominal wall perforators. One muscle-sparing free flap was performed immediately after mastectomy; the other free flaps were performed as delayed reconstructions. Body mass index ranged from 24 to 35, with a mean of 30. All patients reported no tobacco use during the consultation; however, 1 patient later admitted to chewing tobacco. No urinary cotinine confirmation was requested. Two patients had 1 free flap reconstruction and 1 pedicle TRAM. This bilateral combination has been recently described in the literature and was chosen as a reasonable option to balance limited resources with abdominal wall morbidity.9 Operating room time ranged from 7 hours 50 minutes to 13 hours 3 minutes. All patients went to the ICU for hourly flap monitoring.

Length of stay ranged from 4 to 7 days, with a mean of 4.5 days. The longest stay was for a patient who had immediate reconstruction using a pedicle TRAM and muscle-sparing free TRAM. She was not a DIEP candidate because poor perforator quality had been noted during preoperative imaging.

Six patients had documentation of postoperative wound complications. One patient returned to the OR on the elective schedule 3 weeks postoperatively for a partial flap debridement. Her tissue transfer was > 1,000 g, and she required a matching reduction on the other side. There were no complete flap losses or postoperative thrombotic events; no cases went back to the OR emergently.

Discussion

With the number of women veterans steadily increasing, the number of patients in need of breast cancer surgery, including reconstruction, will rise in the VA.10 Fortunately, breast reconstruction is an elective procedure. Immediate breast reconstruction is a popular option because patients can combine surgeries and potentially avoid 2 recovery periods, and a better aesthetic outcome is possible because the skin does not have time to contract. Although immediate reconstruction has been increasing in popularity, it is associated with a higher complication rate.11 Further, reconstruction can be jeopardized if the oncologic plan is changed in the early postoperative period.

Positive margins found after an autologous reconstruction result in a more complicated postoperative course and a higher rate of wound complications.12 Unexpected radiation therapy after autologous reconstruction can severely distort a tissue flap because of fat necrosis, fibrosis, and contraction.13,14 From a practical perspective in the federal system, it is very difficult to coordinate 2 surgeons’ schedules when the system is already struggling to keep up with demand. Splitting the ablative and reconstructive surgery allows the urgent problem (cancer) to be addressed first, ensuring clear margins and allowing the patient to recover and consider all reconstructive options without feeling time pressure.

A large tertiary care center will have staff and equipment redundancy, but this study had to consider limitations in resources. The preoperative lead time allows the ICU to arrange a bed for hourly flap checks and for in-servicing new nursing staff on free flap monitoring. This was well received, and patients gave positive feedback on the staff. The OR schedulers can schedule nurses and techs who are familiar with the microscope and microsurgery instruments. The micro sets were opened, and the microscope powered on for practice runs a week before the procedures to insure no broken or missing instruments.

High-procedure volume would logically improve efficiency. Although the VA is not likely to become a tertiary center for breast reconstruction, the findings of other high-volume microsurgeons can be applied to improve speed and limit complications. Efforts to limit the OR time included use of preoperative imaging and intraoperative venous couplers. Venous couplers can result in shorter OR time, fewer returns to the OR, and excellent patency rates.15,16 One microsurgeon performed his surgery using only loupe-assisted vision (x 3.5), without use of the microscope. Pannucci and colleagues have recommended this as a way to improve access and OR efficiency.17 Use of the CTA has been found to decrease the rate of partial flap necrosis and improve speed of surgery.18-20

Careful patient selection allowed a hospital stay that averaged 4.5 days and minimized risks for return to the OR. Only patients who were nonsmokers were offered the surgery. Average BMI was 30 to prevent the known operative risks in breast surgery patients who are morbidly obese.21-23 No patients had a history of thromboembolic disease. Most patients were discharged home from the ICU. They eventually returned for elective revisions, second stages, and balancing procedures.

Conclusion

Free flap breast reconstruction can be offered as a treatment option with appropriate patient selection and planning. The most efficient way to provide this procedure within the federal system and to minimize the risk of flap loss and complications is by offering delayed reconstruction, obtaining preoperative CTA imaging, utilizing venous couplers, and frequently communicating with all involved practitioners from the OR to the ICU. This small study provides a good starting point to illustrate that tertiary-care reconstructive surgery can be offered to veterans within the federal system.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Gainesville, Florida.

1. Tuggle CT, Patel A, Broer N, Persing JA, Sosa JA, Au AF. Increased hospital volume is associated with improved outcomes following abdominal-based breast reconstruction. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2014;48(6):382-388.

2. Shulkin DJ. Beyond the VA crisis — becoming a high-performance network. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(11):1003-1005.

3. Novakovic D, Patel RS, Goldstein DP, Gullane PJ. Salvage of failed free flaps used in head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck Oncol. 2009;1:33.

4. Davison SP, Kessler CM, Al-Attar A. Microvascular free flap failure caused by unrecognized hypercoagulability. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):490-495.

5. Masoomi H, Clark EG, Paydar KZ, et al. Predictive risk factors of free flap thrombosis in breast reconstructive surgery. Microsurgery. 2014;34(8):589-594.

6. O’Neill AC, Haykal S, Bagher S, Zhong T, Hofer S. Predictors and consequences of intraoperative microvascular problems in autologous breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69(10):1349-1355.

7. Sanati-Mehrizy P, Massengburg BB, Rozehnal JM, Ignargiola MJ, Hernandez Rosa J, Taub PJ. Risk factors leading to free flap failure: analysis from the national surgical quality improvement program database. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(8):1956-1964.

8. Myers LL, Sumer BD, Defatta RJ, Minhajuddin A. Free tissue transfer reconstruction of the head and neck at a Veterans Affairs hospital. Head Neck. 2008;30(8):1007-1011.

9. Roslan EJ, Kelly EG, Zain MA, Basiron NH, Imran FH. Immediate simultaneous bilateral breast reconstruction with deep inferior epigastric (DIEP) flap and pedicled transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous (TRAM) pedicle flap. Med J Malaysia. 2017;72(1):85-87.

10. Leong M, Chike-Obi CJ, Basu CB, Lee EL, Albo D, Netscher DT. Effective breast reconstruction in female veterans. Am J Surg. 2009;198(5):658-663.

11. Kwok AC, Goodwin IA, Ying J, Agarwal JP. National trends and complication rates after bilateral mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction from 2005 to 2012. Am J Surg. 2015;210(3):512-516.

12. Ochoa O, Theoharis C, Pisano S, et al. Positive margin re-excision following immediate autologous breast reconstruction: morbidity, cosmetic outcome, and oncologic significance. Aesthet Surg J. 2017; [Epub ahead of print.]

13. Garvey PB, Clemens MW, Hoy AE, et al. Muscle-sparing TRAM flap does not protect breast reconstruction from post-mastectomy radiation damage compared to DIEP flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(2):223-233.

14. Kronowitz SJ. Current status of autologous tissue-based breast reconstruction in patients receiving postmastectomy radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(2):282-292.

15. Fitzgerald O’Connor E, Rozen WM, Chowdhry M, et al. The microvascular anastomotic coupler for venous anastomoses in free flap breast reconstruction improves outcomes. Gland Surg. 2016;5(2):88-92.

16. Jandali S, Wu LC, Vega SJ, Kovach SJ, Serletti JM. 1000 consecutive venous anastomoses using the microvascular anastomotic coupler in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(3):792-798.

17. Pannucci CJ, Basta MN, Kovach SJ, Kanchwala SK, Wu LC, Serletti JM. Loupes-only microsurgery is a safe alternative to the operating microscope: an analysis of 1,649 consecutive free flap breast reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2015;31(9):636-642.

18. Teunis T, Heerma van Voss MR, Kon M, van Maurik JF. CT-angiography prior to DIEP flap reconstruction: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Microsurgery. 2013;33(6):496-502.

19. Fitzgerald O’Connor E, Rozen WM, Chowdhry M, Band B, Ramakrishnan VV, Griffiths M. Preoperative computed tomography angiography for planning DIEP flap breast reconstruction reduces operative time and overall complications. Gland Surgery. 2016;5(2):93-98.

20. Malhotra A, Chhaya N, Nsiah-Sarbeng P, Mosahebi A. CT-guided deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap localization—better for the patient, the surgeon, and the hospital. Clin Radiol. 2013;68(2):131-138.

21. Ilonzo N, Tsang A, Tsantes S, Estabrook A, Thu Ma AM. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy: a ten-year analysis of trends and immediate postoperative outcomes. Breast. 2017;32:7-12.

22. McAllister P, Teo L, Chin K, Makubate B, Alexander Munnoch D. Bilateral breast reconstruction with abdominal free flaps: a single centre, single surgeon retrospective review of 55 consecutive patients. Plast Surg Int. 2016;2016:6085624.

23. Myung Y, Heo CY. Relationship between obesity and surgical complications after reduction mammoplasty: a systemic literature review and meta-analysis. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(3):308-315.

1. Tuggle CT, Patel A, Broer N, Persing JA, Sosa JA, Au AF. Increased hospital volume is associated with improved outcomes following abdominal-based breast reconstruction. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2014;48(6):382-388.

2. Shulkin DJ. Beyond the VA crisis — becoming a high-performance network. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(11):1003-1005.

3. Novakovic D, Patel RS, Goldstein DP, Gullane PJ. Salvage of failed free flaps used in head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck Oncol. 2009;1:33.

4. Davison SP, Kessler CM, Al-Attar A. Microvascular free flap failure caused by unrecognized hypercoagulability. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):490-495.

5. Masoomi H, Clark EG, Paydar KZ, et al. Predictive risk factors of free flap thrombosis in breast reconstructive surgery. Microsurgery. 2014;34(8):589-594.

6. O’Neill AC, Haykal S, Bagher S, Zhong T, Hofer S. Predictors and consequences of intraoperative microvascular problems in autologous breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69(10):1349-1355.

7. Sanati-Mehrizy P, Massengburg BB, Rozehnal JM, Ignargiola MJ, Hernandez Rosa J, Taub PJ. Risk factors leading to free flap failure: analysis from the national surgical quality improvement program database. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(8):1956-1964.

8. Myers LL, Sumer BD, Defatta RJ, Minhajuddin A. Free tissue transfer reconstruction of the head and neck at a Veterans Affairs hospital. Head Neck. 2008;30(8):1007-1011.

9. Roslan EJ, Kelly EG, Zain MA, Basiron NH, Imran FH. Immediate simultaneous bilateral breast reconstruction with deep inferior epigastric (DIEP) flap and pedicled transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous (TRAM) pedicle flap. Med J Malaysia. 2017;72(1):85-87.

10. Leong M, Chike-Obi CJ, Basu CB, Lee EL, Albo D, Netscher DT. Effective breast reconstruction in female veterans. Am J Surg. 2009;198(5):658-663.

11. Kwok AC, Goodwin IA, Ying J, Agarwal JP. National trends and complication rates after bilateral mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction from 2005 to 2012. Am J Surg. 2015;210(3):512-516.

12. Ochoa O, Theoharis C, Pisano S, et al. Positive margin re-excision following immediate autologous breast reconstruction: morbidity, cosmetic outcome, and oncologic significance. Aesthet Surg J. 2017; [Epub ahead of print.]

13. Garvey PB, Clemens MW, Hoy AE, et al. Muscle-sparing TRAM flap does not protect breast reconstruction from post-mastectomy radiation damage compared to DIEP flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(2):223-233.

14. Kronowitz SJ. Current status of autologous tissue-based breast reconstruction in patients receiving postmastectomy radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(2):282-292.

15. Fitzgerald O’Connor E, Rozen WM, Chowdhry M, et al. The microvascular anastomotic coupler for venous anastomoses in free flap breast reconstruction improves outcomes. Gland Surg. 2016;5(2):88-92.

16. Jandali S, Wu LC, Vega SJ, Kovach SJ, Serletti JM. 1000 consecutive venous anastomoses using the microvascular anastomotic coupler in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(3):792-798.

17. Pannucci CJ, Basta MN, Kovach SJ, Kanchwala SK, Wu LC, Serletti JM. Loupes-only microsurgery is a safe alternative to the operating microscope: an analysis of 1,649 consecutive free flap breast reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2015;31(9):636-642.

18. Teunis T, Heerma van Voss MR, Kon M, van Maurik JF. CT-angiography prior to DIEP flap reconstruction: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Microsurgery. 2013;33(6):496-502.

19. Fitzgerald O’Connor E, Rozen WM, Chowdhry M, Band B, Ramakrishnan VV, Griffiths M. Preoperative computed tomography angiography for planning DIEP flap breast reconstruction reduces operative time and overall complications. Gland Surgery. 2016;5(2):93-98.

20. Malhotra A, Chhaya N, Nsiah-Sarbeng P, Mosahebi A. CT-guided deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap localization—better for the patient, the surgeon, and the hospital. Clin Radiol. 2013;68(2):131-138.

21. Ilonzo N, Tsang A, Tsantes S, Estabrook A, Thu Ma AM. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy: a ten-year analysis of trends and immediate postoperative outcomes. Breast. 2017;32:7-12.

22. McAllister P, Teo L, Chin K, Makubate B, Alexander Munnoch D. Bilateral breast reconstruction with abdominal free flaps: a single centre, single surgeon retrospective review of 55 consecutive patients. Plast Surg Int. 2016;2016:6085624.

23. Myung Y, Heo CY. Relationship between obesity and surgical complications after reduction mammoplasty: a systemic literature review and meta-analysis. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(3):308-315.

Is Your Practice Biosimilar Ready?

Click Here to Read the Full Supplement.

Topics include:

- The Pathway for Biosimilar Approval

- The Difference between Biosimilars and Generics

- Draft Interchangeablity Guidelines

- ACR Position Statement on Biosimilars

- Effect of the Reimbursement Model on Biosimilars

Click Here to Read the Full Supplement.

Topics include:

- The Pathway for Biosimilar Approval

- The Difference between Biosimilars and Generics

- Draft Interchangeablity Guidelines

- ACR Position Statement on Biosimilars

- Effect of the Reimbursement Model on Biosimilars

Click Here to Read the Full Supplement.

Topics include:

- The Pathway for Biosimilar Approval

- The Difference between Biosimilars and Generics

- Draft Interchangeablity Guidelines

- ACR Position Statement on Biosimilars

- Effect of the Reimbursement Model on Biosimilars

Best Practices: In the Management of Hemophilia

The treatment of patients with hemophilia has rapidly evolved from one-size-fits-all factor replacement strategies to highly individualized, patient-specific care.

Faculty:

Erik Berntorp, MD, PhD

Malmö Centre for Thrombosis and Haemostasis

Lund University

Malmö, Sweden

Faculty Disclosures:

This sponsored content was prepared by Dr. Berntorp and reviewed by Shire. Dr. Berntorp discloses that he is a consultant and on the advisory boards and speakers’ bureaus for Bayer, CSL Behring, Octapharma, Shire, and Sobi. The production of this section did not involve the news or editorial staff of Frontline Medical Communications.

S28001

2/17

Click here to read the supplement

The treatment of patients with hemophilia has rapidly evolved from one-size-fits-all factor replacement strategies to highly individualized, patient-specific care.

Faculty:

Erik Berntorp, MD, PhD

Malmö Centre for Thrombosis and Haemostasis

Lund University

Malmö, Sweden

Faculty Disclosures:

This sponsored content was prepared by Dr. Berntorp and reviewed by Shire. Dr. Berntorp discloses that he is a consultant and on the advisory boards and speakers’ bureaus for Bayer, CSL Behring, Octapharma, Shire, and Sobi. The production of this section did not involve the news or editorial staff of Frontline Medical Communications.

S28001

2/17

Click here to read the supplement

The treatment of patients with hemophilia has rapidly evolved from one-size-fits-all factor replacement strategies to highly individualized, patient-specific care.

Faculty:

Erik Berntorp, MD, PhD

Malmö Centre for Thrombosis and Haemostasis

Lund University

Malmö, Sweden

Faculty Disclosures:

This sponsored content was prepared by Dr. Berntorp and reviewed by Shire. Dr. Berntorp discloses that he is a consultant and on the advisory boards and speakers’ bureaus for Bayer, CSL Behring, Octapharma, Shire, and Sobi. The production of this section did not involve the news or editorial staff of Frontline Medical Communications.

S28001

2/17

Click here to read the supplement

Military Sexual Trauma and Sexual Health: Practice and Future Research for Mental Health Professionals

About 24% of women and 1% of men will experience military sexual trauma (MST) during their service.1 Despite the higher percentage of women reporting MST, the estimated number of men (55,491) and women (72,497) who endorse MST is relatively similar. Military sexual trauma is associated with negative psychosocial (eg, decreased quality of life) and psychiatric (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], depression) sequelae. Surís and colleagues provided a full review of sequelae, with PTSD being the most discussed consequence of MST.2 However, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) during or after MST are a consequence of growing concern.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

The link between sexual trauma and increased incidence of STIs is well established. Survivors of rape are at a higher risk of exposure to STIs due to unprotected sexual contact that may occur during the assault(s).3 Numerous studies have demonstrated that sexual trauma is directly related to greater engagement in risky sexual behaviors (eg, more sexual partners, unprotected sex, and “sex trading”).2,4

This relationship is particularly concerning given that individuals in the military tend to report sexual trauma with greater propensity than that reported in civilian populations.4 Additionally, military personnel and veteran populations tend to engage in high-risk behaviors (eg, alcohol and drug use) more often than their civilian counterparts, increasing their potential susceptibility to predatory sexual trauma(s) and victimization.2,5 Taken in aggregate, military personnel and veterans may be at increased risk for STIs compared with the civilian population due to the increased incidence of risky sexual behavior and sexual traumatization during military service.

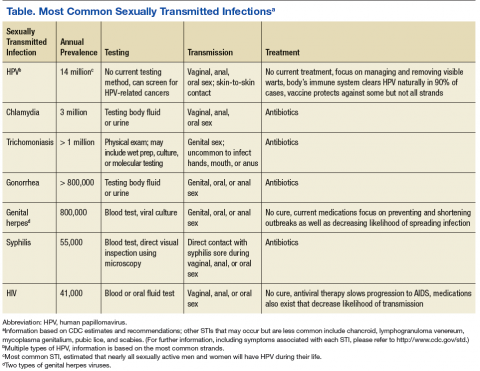

Sexually transmitted infections potentially lead to immediate-term (eg, physical discomfort, sexual dysfunction) and long-term (eg, cancer, infertility) adverse health consequences.6 Early detection is crucial in the treatment of STIs because it can aid in preventing STI transmission and allow for early intervention. See Table for a list of common STIs and their prevalence, testing method, method of sexual transmission, and treatment. Early detection is also important because many STIs may be asymptomatic (eg, HIV, human papillomavirus [HPV]), which decreases the likelihood of seeking testing or treatment as well as increases the likelihood of transmission.7

Current Research

To date, only 1 study has explicitly examined the relationship between MST and STIs. In 2011, researchers analyzed a large national database of 420,725 male and female Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans.6 In the study, both male and female OEF/OIF veterans who endorsed MST were significantly more likely than those who did not endorse MST to have a STI diagnosis. The researchers noted that this finding underscored the necessity for sexual health assessment in survivors of MST, to facilitate early detection and treatment.

STI Risk Assessment

Because military personnel and veterans often initially disclose their MST to a mental health provider (MHP), these providers operate in a unique circumstance where they may be the individual’s first point of contact for determining STI risk. In these circumstances, the MHP should consider the utility of briefly assessing the patient’s sexual health and making subsequent medical referrals as necessary.

To accurately assess a patient’s STI risk, the MHP should gather information regarding both current/acute risk (eg, “Have you had unprotected sexual contact, for instance, genital contact without a condom or oral sex without a dental dam, in the past month?”) as well as longer standing (eg, “Have you had unprotected sexual contact... in the past year?”) STI risk. Providers also should consider oral, anal, and genital modes of sexual contact as well as common STI symptoms (eg, warts, sores, genital discharge, and/or pain or burning sensation when peeing or during sex). Additionally, psychoeducation should be provided, especially information regarding the asymptomatic nature of certain STIs, such as HIV and HPV, and the risk of transmission in all forms of sexual contact, including nongenital anal contact. Appropriate referrals to sexual health education, including safe sex practices, also should be considered in order to minimize risk of future STI transmission.

Mental health providers also should determine the date of patient’s most recent STI test. Not all STIs can be detected via a blood test or routine yearly Papanicolaou (Pap test) physicals. Additionally, MHPs should be aware that risky practices, including substance misuse, are more common in survivors of MST and that there is an association between substance misuse and STIs.2,6 If testing has not occurred recently, MHPs should strongly encourage the individual to access STI testing and provide resources as necessary, such as access to low-cost STI testing. Further, if the MHP has reason to suspect the presence of an STI after the brief assessment (eg, individual endorses unprotected sexual contact or risky behaviors, including substance misuse, sex trading, and STI symptomatology; a positive STI test but the patient has not accessed treatment), an appropriate sexual health referral should be made.

During the assessment and psychoeducation processes, terminology and language plays an integral role. If a MHP assumes an individual has sexual contact only with opposite sex partners (eg, asking a male “How many women have you had sexual contact with in the past 30 days?” vs “How many partners have you had sexual contact with in the past 30 days?”), the MHP will not accurately assess the individual’s level of current risk. Additionally, it is important to remember that sexual behavior does not always align with sexual identity: A man who identifies as heterosexual may still have sexual contact with men. Due to the sensitive nature of sexual health, MHPs should be careful to use nonjudgmental language, such as using the term sex work rather than the more pejorative term prostitution, to avoid offending patients and to increase their likelihood to disclose sexual health information.

Nonjudgmental language is especially relevant when working with gender-minority veterans (eg, transgender, gender nonconforming, gender transitioning), because this clinical population has a higher risk of victimization and lower rates of help-seeking health behavior.7 In particular, a sizable portion of individuals who identify as transgender do not seek services out of fear that they will be discriminated against, humiliated, or misunderstood.7 To assuage these concerns, MHPs should ensure they refer to the veteran with the veteran’s preferred pronouns. For example, a MHP could ask “I would like to be respectful, how would you like to be addressed?” or “What name and pronoun would you like me/us to use?” Providers also should consider nonbinary pronouns when appropriate (eg, singular: ze/hir/hirs; plural: they/them/theirs). Providers also should recognize that making a mistake is not uncommon, and they should apologize to maintain rapport and maximize the patient’s comfort during this distressing process. Further, MHPs should consider additional training, education, and/or consultation if they feel uncomfortable or ill prepared when working with gender-minority veterans.

Future Research

Research has attempted to understand the consequences of MST on sexual health; however, despite these efforts, more research is necessary. The majority of published studies have focused on females even though a similar number of males have reported MST.2 This dearth of published studies likely is due to hesitation by male active-duty personnel and veterans to disclose or seek treatment for MST and because the percentage of females reporting MST is much higher. Males are less likely to report or seek treatment for MST because of stigma-based concerns (eg, shame, self-blame, privacy concerns).8,9 Therefore, it is difficult to acquire a sizable research sample to study. As previously noted, a single study has specifically examined MST and STI risk. Although this study included a sizable population of male OEF/OIF veterans, results have yet to be replicated in other clinical populations of interest, such as male military personnel and male veterans of other service eras.

Research is even more limited regarding lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and other gender-minority military personnel and veterans. Although researchers propose that these populations may experience a similar, or even heightened, likelihood of MST during their service, no empirical research yet exists to fully examine this hypothesis.10,11 It is important to note that the paucity of research attention may be related to the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (DADT) policy, which obstructed the open discussion and empirical examination of sexual and gender minorities within military populations.11 The DADT policy led to limited awareness and greater stigmatization among sexual- and gender-minority personnel, resulting in poorer sexual health outcomes in these populations.10,11 With the end of DADT in 2011, it is now imperative for future research to examine the prevalence and associated consequences of MST in sexual- and gender-minority military personnel and veterans.

Conclusion

The DoD and VA should be commended for their continued focus on understanding the health consequences of MST. These efforts have yielded substantial information regarding the negative effects of MST on sexual health; in particular, increased risk for STIs. These findings suggest that MHPs may, at times, be the first point of contact for MST-related sexual health concerns. These providers should be aware of their ability to assess for STI risk and make appropriate referrals to facilitate early detection and access to treatment. Despite the presence of MST-related sexual health research, continued research remains necessary. In particular, a broader focus that includes other genders (eg, male, transgender) and sexual minorities would further inform research and clinical practice.

1. Military Sexual Trauma Support Team. Military sexual trauma (MST) screening report fiscal year 2012. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Patient Care Services, Mental Health Services; 2013.

2. Surís A, Holliday R, Weitlauf JC, North CS; the Veteran Safety Initiative Writing Collaborative. Military sexual trauma in the context of veterans’ life experiences. Fed Pract. 2013;30(suppl 3):16S-20S.

3. Jenny C, Hooton TM, Bowers A, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases in victims of rape. N Eng J Med. 1990;322(11):713-716.

4. Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Coury-Doniger P, Urban MA. Childhood sexual abuse and sexual risk behavior among men and women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(4):720-731.

5. Schultz JR, Bell KM, Naugle AE, Polusny MA. Child sexual abuse and adult sexual assault among military veteran and civilian women. Mil Med. 2006;171(8):723-728.

6. Turchik JA, Pavao J, Nazarian D, Iqbal S, McLean C, Kimerling R. Sexually transmitted infections and sexual dysfunctions among newly returned veterans with and without military sexual trauma. Int J Sex Health. 2012;24(1):45-59.

7. National LGBT Health Education Center. Affirmative care for transgender and gender non-conforming people: best practices for front-line health care staff. https://www.lgbthealth education.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Affirmative-Care-for-Transgender -and-Gender-Non-conforming-People-Best-Practices -for-Frontline-Health-Care-Staff.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed February 16, 2017.

8. Morris EE, Smith JC, Farooqui SY, Surís AM. Unseen battles: the recognition, assessment, and treatment issues of men with military sexual trauma (MST). Trauma Violence Abuse. 2014;15(2):94-101.

9. Turchik JA, Edwards KM. Myths about male rape: a literature review. Psychol Men Masc. 2012;13(2):211-226.

10. Mattocks KM, Kauth MR, Sandfort T, Matza AR, Sullivan JC, Shipherd J. Understanding health-care needs of sexual and gender minority veterans: how targeted research and policy can improve health. LGBT Health. 2014;1(1):50-57.

11. Burks DJ. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual victimization in the military: an unintended consequence of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”? Am Psychol. 2011;66(7):604-613.

About 24% of women and 1% of men will experience military sexual trauma (MST) during their service.1 Despite the higher percentage of women reporting MST, the estimated number of men (55,491) and women (72,497) who endorse MST is relatively similar. Military sexual trauma is associated with negative psychosocial (eg, decreased quality of life) and psychiatric (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], depression) sequelae. Surís and colleagues provided a full review of sequelae, with PTSD being the most discussed consequence of MST.2 However, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) during or after MST are a consequence of growing concern.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

The link between sexual trauma and increased incidence of STIs is well established. Survivors of rape are at a higher risk of exposure to STIs due to unprotected sexual contact that may occur during the assault(s).3 Numerous studies have demonstrated that sexual trauma is directly related to greater engagement in risky sexual behaviors (eg, more sexual partners, unprotected sex, and “sex trading”).2,4

This relationship is particularly concerning given that individuals in the military tend to report sexual trauma with greater propensity than that reported in civilian populations.4 Additionally, military personnel and veteran populations tend to engage in high-risk behaviors (eg, alcohol and drug use) more often than their civilian counterparts, increasing their potential susceptibility to predatory sexual trauma(s) and victimization.2,5 Taken in aggregate, military personnel and veterans may be at increased risk for STIs compared with the civilian population due to the increased incidence of risky sexual behavior and sexual traumatization during military service.

Sexually transmitted infections potentially lead to immediate-term (eg, physical discomfort, sexual dysfunction) and long-term (eg, cancer, infertility) adverse health consequences.6 Early detection is crucial in the treatment of STIs because it can aid in preventing STI transmission and allow for early intervention. See Table for a list of common STIs and their prevalence, testing method, method of sexual transmission, and treatment. Early detection is also important because many STIs may be asymptomatic (eg, HIV, human papillomavirus [HPV]), which decreases the likelihood of seeking testing or treatment as well as increases the likelihood of transmission.7

Current Research

To date, only 1 study has explicitly examined the relationship between MST and STIs. In 2011, researchers analyzed a large national database of 420,725 male and female Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans.6 In the study, both male and female OEF/OIF veterans who endorsed MST were significantly more likely than those who did not endorse MST to have a STI diagnosis. The researchers noted that this finding underscored the necessity for sexual health assessment in survivors of MST, to facilitate early detection and treatment.

STI Risk Assessment

Because military personnel and veterans often initially disclose their MST to a mental health provider (MHP), these providers operate in a unique circumstance where they may be the individual’s first point of contact for determining STI risk. In these circumstances, the MHP should consider the utility of briefly assessing the patient’s sexual health and making subsequent medical referrals as necessary.

To accurately assess a patient’s STI risk, the MHP should gather information regarding both current/acute risk (eg, “Have you had unprotected sexual contact, for instance, genital contact without a condom or oral sex without a dental dam, in the past month?”) as well as longer standing (eg, “Have you had unprotected sexual contact... in the past year?”) STI risk. Providers also should consider oral, anal, and genital modes of sexual contact as well as common STI symptoms (eg, warts, sores, genital discharge, and/or pain or burning sensation when peeing or during sex). Additionally, psychoeducation should be provided, especially information regarding the asymptomatic nature of certain STIs, such as HIV and HPV, and the risk of transmission in all forms of sexual contact, including nongenital anal contact. Appropriate referrals to sexual health education, including safe sex practices, also should be considered in order to minimize risk of future STI transmission.

Mental health providers also should determine the date of patient’s most recent STI test. Not all STIs can be detected via a blood test or routine yearly Papanicolaou (Pap test) physicals. Additionally, MHPs should be aware that risky practices, including substance misuse, are more common in survivors of MST and that there is an association between substance misuse and STIs.2,6 If testing has not occurred recently, MHPs should strongly encourage the individual to access STI testing and provide resources as necessary, such as access to low-cost STI testing. Further, if the MHP has reason to suspect the presence of an STI after the brief assessment (eg, individual endorses unprotected sexual contact or risky behaviors, including substance misuse, sex trading, and STI symptomatology; a positive STI test but the patient has not accessed treatment), an appropriate sexual health referral should be made.

During the assessment and psychoeducation processes, terminology and language plays an integral role. If a MHP assumes an individual has sexual contact only with opposite sex partners (eg, asking a male “How many women have you had sexual contact with in the past 30 days?” vs “How many partners have you had sexual contact with in the past 30 days?”), the MHP will not accurately assess the individual’s level of current risk. Additionally, it is important to remember that sexual behavior does not always align with sexual identity: A man who identifies as heterosexual may still have sexual contact with men. Due to the sensitive nature of sexual health, MHPs should be careful to use nonjudgmental language, such as using the term sex work rather than the more pejorative term prostitution, to avoid offending patients and to increase their likelihood to disclose sexual health information.

Nonjudgmental language is especially relevant when working with gender-minority veterans (eg, transgender, gender nonconforming, gender transitioning), because this clinical population has a higher risk of victimization and lower rates of help-seeking health behavior.7 In particular, a sizable portion of individuals who identify as transgender do not seek services out of fear that they will be discriminated against, humiliated, or misunderstood.7 To assuage these concerns, MHPs should ensure they refer to the veteran with the veteran’s preferred pronouns. For example, a MHP could ask “I would like to be respectful, how would you like to be addressed?” or “What name and pronoun would you like me/us to use?” Providers also should consider nonbinary pronouns when appropriate (eg, singular: ze/hir/hirs; plural: they/them/theirs). Providers also should recognize that making a mistake is not uncommon, and they should apologize to maintain rapport and maximize the patient’s comfort during this distressing process. Further, MHPs should consider additional training, education, and/or consultation if they feel uncomfortable or ill prepared when working with gender-minority veterans.

Future Research

Research has attempted to understand the consequences of MST on sexual health; however, despite these efforts, more research is necessary. The majority of published studies have focused on females even though a similar number of males have reported MST.2 This dearth of published studies likely is due to hesitation by male active-duty personnel and veterans to disclose or seek treatment for MST and because the percentage of females reporting MST is much higher. Males are less likely to report or seek treatment for MST because of stigma-based concerns (eg, shame, self-blame, privacy concerns).8,9 Therefore, it is difficult to acquire a sizable research sample to study. As previously noted, a single study has specifically examined MST and STI risk. Although this study included a sizable population of male OEF/OIF veterans, results have yet to be replicated in other clinical populations of interest, such as male military personnel and male veterans of other service eras.

Research is even more limited regarding lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and other gender-minority military personnel and veterans. Although researchers propose that these populations may experience a similar, or even heightened, likelihood of MST during their service, no empirical research yet exists to fully examine this hypothesis.10,11 It is important to note that the paucity of research attention may be related to the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (DADT) policy, which obstructed the open discussion and empirical examination of sexual and gender minorities within military populations.11 The DADT policy led to limited awareness and greater stigmatization among sexual- and gender-minority personnel, resulting in poorer sexual health outcomes in these populations.10,11 With the end of DADT in 2011, it is now imperative for future research to examine the prevalence and associated consequences of MST in sexual- and gender-minority military personnel and veterans.

Conclusion

The DoD and VA should be commended for their continued focus on understanding the health consequences of MST. These efforts have yielded substantial information regarding the negative effects of MST on sexual health; in particular, increased risk for STIs. These findings suggest that MHPs may, at times, be the first point of contact for MST-related sexual health concerns. These providers should be aware of their ability to assess for STI risk and make appropriate referrals to facilitate early detection and access to treatment. Despite the presence of MST-related sexual health research, continued research remains necessary. In particular, a broader focus that includes other genders (eg, male, transgender) and sexual minorities would further inform research and clinical practice.

About 24% of women and 1% of men will experience military sexual trauma (MST) during their service.1 Despite the higher percentage of women reporting MST, the estimated number of men (55,491) and women (72,497) who endorse MST is relatively similar. Military sexual trauma is associated with negative psychosocial (eg, decreased quality of life) and psychiatric (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], depression) sequelae. Surís and colleagues provided a full review of sequelae, with PTSD being the most discussed consequence of MST.2 However, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) during or after MST are a consequence of growing concern.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

The link between sexual trauma and increased incidence of STIs is well established. Survivors of rape are at a higher risk of exposure to STIs due to unprotected sexual contact that may occur during the assault(s).3 Numerous studies have demonstrated that sexual trauma is directly related to greater engagement in risky sexual behaviors (eg, more sexual partners, unprotected sex, and “sex trading”).2,4

This relationship is particularly concerning given that individuals in the military tend to report sexual trauma with greater propensity than that reported in civilian populations.4 Additionally, military personnel and veteran populations tend to engage in high-risk behaviors (eg, alcohol and drug use) more often than their civilian counterparts, increasing their potential susceptibility to predatory sexual trauma(s) and victimization.2,5 Taken in aggregate, military personnel and veterans may be at increased risk for STIs compared with the civilian population due to the increased incidence of risky sexual behavior and sexual traumatization during military service.

Sexually transmitted infections potentially lead to immediate-term (eg, physical discomfort, sexual dysfunction) and long-term (eg, cancer, infertility) adverse health consequences.6 Early detection is crucial in the treatment of STIs because it can aid in preventing STI transmission and allow for early intervention. See Table for a list of common STIs and their prevalence, testing method, method of sexual transmission, and treatment. Early detection is also important because many STIs may be asymptomatic (eg, HIV, human papillomavirus [HPV]), which decreases the likelihood of seeking testing or treatment as well as increases the likelihood of transmission.7

Current Research

To date, only 1 study has explicitly examined the relationship between MST and STIs. In 2011, researchers analyzed a large national database of 420,725 male and female Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans.6 In the study, both male and female OEF/OIF veterans who endorsed MST were significantly more likely than those who did not endorse MST to have a STI diagnosis. The researchers noted that this finding underscored the necessity for sexual health assessment in survivors of MST, to facilitate early detection and treatment.

STI Risk Assessment

Because military personnel and veterans often initially disclose their MST to a mental health provider (MHP), these providers operate in a unique circumstance where they may be the individual’s first point of contact for determining STI risk. In these circumstances, the MHP should consider the utility of briefly assessing the patient’s sexual health and making subsequent medical referrals as necessary.

To accurately assess a patient’s STI risk, the MHP should gather information regarding both current/acute risk (eg, “Have you had unprotected sexual contact, for instance, genital contact without a condom or oral sex without a dental dam, in the past month?”) as well as longer standing (eg, “Have you had unprotected sexual contact... in the past year?”) STI risk. Providers also should consider oral, anal, and genital modes of sexual contact as well as common STI symptoms (eg, warts, sores, genital discharge, and/or pain or burning sensation when peeing or during sex). Additionally, psychoeducation should be provided, especially information regarding the asymptomatic nature of certain STIs, such as HIV and HPV, and the risk of transmission in all forms of sexual contact, including nongenital anal contact. Appropriate referrals to sexual health education, including safe sex practices, also should be considered in order to minimize risk of future STI transmission.

Mental health providers also should determine the date of patient’s most recent STI test. Not all STIs can be detected via a blood test or routine yearly Papanicolaou (Pap test) physicals. Additionally, MHPs should be aware that risky practices, including substance misuse, are more common in survivors of MST and that there is an association between substance misuse and STIs.2,6 If testing has not occurred recently, MHPs should strongly encourage the individual to access STI testing and provide resources as necessary, such as access to low-cost STI testing. Further, if the MHP has reason to suspect the presence of an STI after the brief assessment (eg, individual endorses unprotected sexual contact or risky behaviors, including substance misuse, sex trading, and STI symptomatology; a positive STI test but the patient has not accessed treatment), an appropriate sexual health referral should be made.

During the assessment and psychoeducation processes, terminology and language plays an integral role. If a MHP assumes an individual has sexual contact only with opposite sex partners (eg, asking a male “How many women have you had sexual contact with in the past 30 days?” vs “How many partners have you had sexual contact with in the past 30 days?”), the MHP will not accurately assess the individual’s level of current risk. Additionally, it is important to remember that sexual behavior does not always align with sexual identity: A man who identifies as heterosexual may still have sexual contact with men. Due to the sensitive nature of sexual health, MHPs should be careful to use nonjudgmental language, such as using the term sex work rather than the more pejorative term prostitution, to avoid offending patients and to increase their likelihood to disclose sexual health information.

Nonjudgmental language is especially relevant when working with gender-minority veterans (eg, transgender, gender nonconforming, gender transitioning), because this clinical population has a higher risk of victimization and lower rates of help-seeking health behavior.7 In particular, a sizable portion of individuals who identify as transgender do not seek services out of fear that they will be discriminated against, humiliated, or misunderstood.7 To assuage these concerns, MHPs should ensure they refer to the veteran with the veteran’s preferred pronouns. For example, a MHP could ask “I would like to be respectful, how would you like to be addressed?” or “What name and pronoun would you like me/us to use?” Providers also should consider nonbinary pronouns when appropriate (eg, singular: ze/hir/hirs; plural: they/them/theirs). Providers also should recognize that making a mistake is not uncommon, and they should apologize to maintain rapport and maximize the patient’s comfort during this distressing process. Further, MHPs should consider additional training, education, and/or consultation if they feel uncomfortable or ill prepared when working with gender-minority veterans.

Future Research

Research has attempted to understand the consequences of MST on sexual health; however, despite these efforts, more research is necessary. The majority of published studies have focused on females even though a similar number of males have reported MST.2 This dearth of published studies likely is due to hesitation by male active-duty personnel and veterans to disclose or seek treatment for MST and because the percentage of females reporting MST is much higher. Males are less likely to report or seek treatment for MST because of stigma-based concerns (eg, shame, self-blame, privacy concerns).8,9 Therefore, it is difficult to acquire a sizable research sample to study. As previously noted, a single study has specifically examined MST and STI risk. Although this study included a sizable population of male OEF/OIF veterans, results have yet to be replicated in other clinical populations of interest, such as male military personnel and male veterans of other service eras.

Research is even more limited regarding lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and other gender-minority military personnel and veterans. Although researchers propose that these populations may experience a similar, or even heightened, likelihood of MST during their service, no empirical research yet exists to fully examine this hypothesis.10,11 It is important to note that the paucity of research attention may be related to the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (DADT) policy, which obstructed the open discussion and empirical examination of sexual and gender minorities within military populations.11 The DADT policy led to limited awareness and greater stigmatization among sexual- and gender-minority personnel, resulting in poorer sexual health outcomes in these populations.10,11 With the end of DADT in 2011, it is now imperative for future research to examine the prevalence and associated consequences of MST in sexual- and gender-minority military personnel and veterans.