User login

Terra Firma-Forme Dermatosis Mimicking Livedo Racemosa

To the Editor:

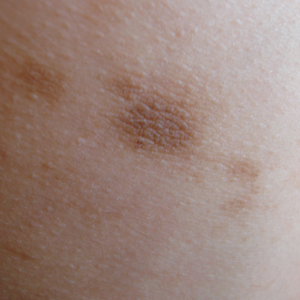

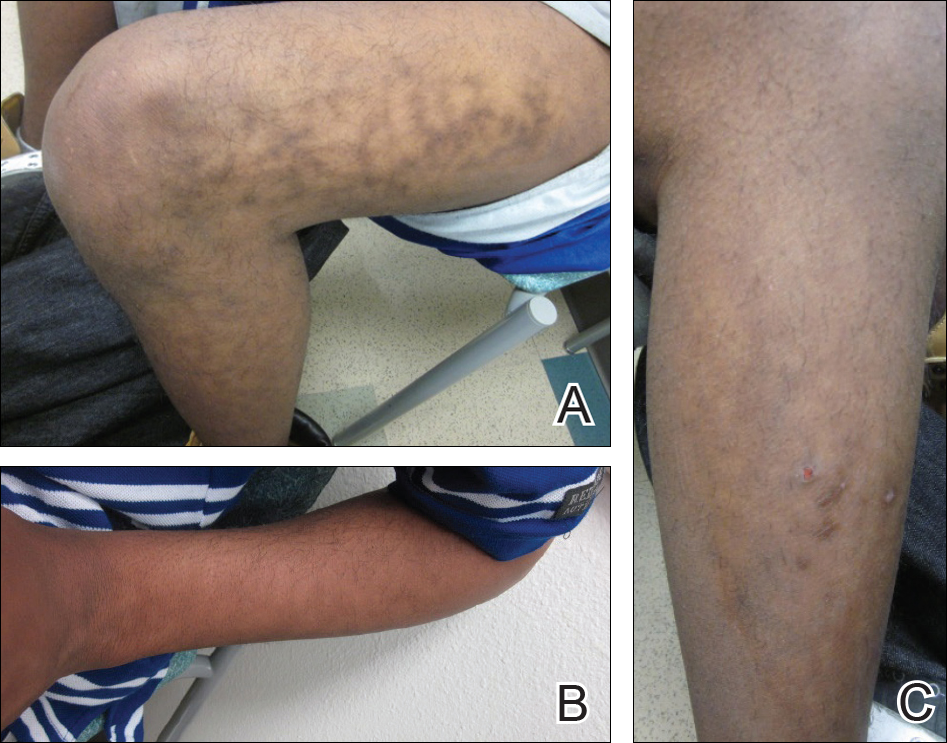

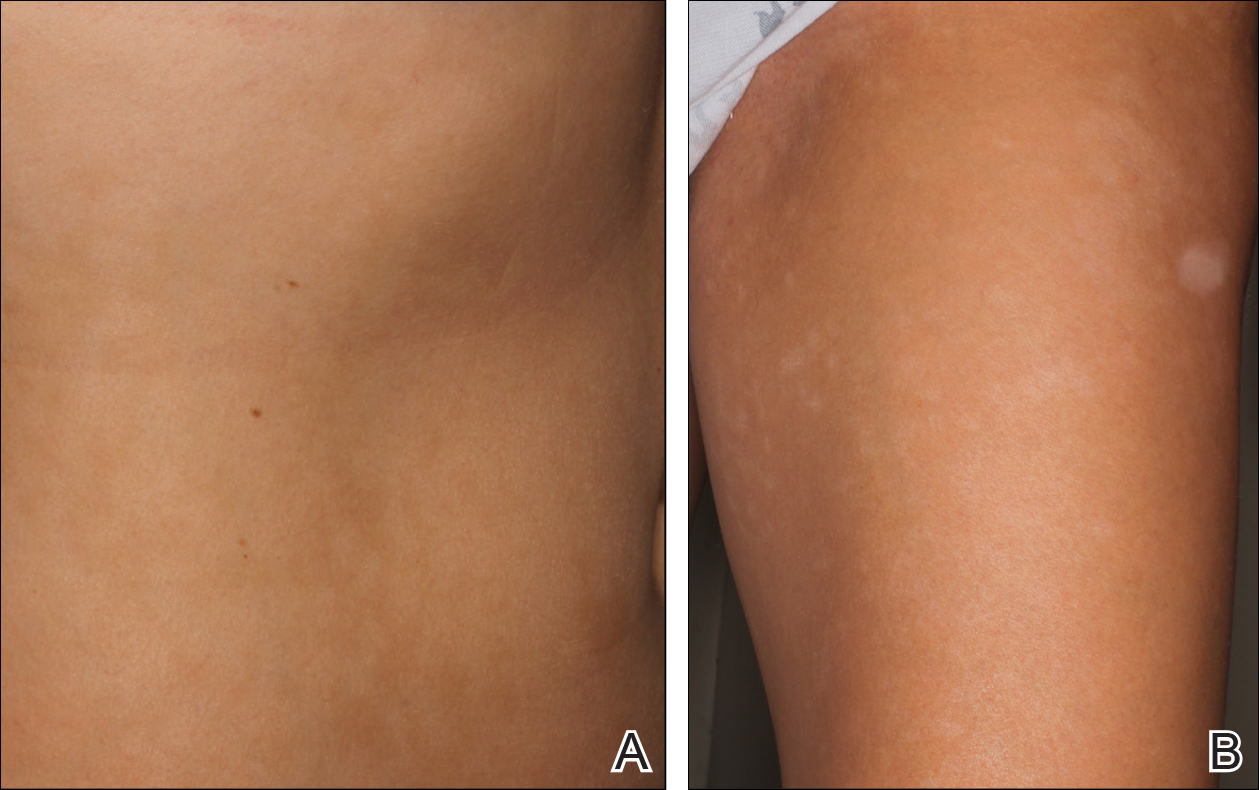

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with dark spots on the legs and back of 2 months’ duration. He was not taking any medications and the spots could not be washed away by scrubbing with soap and water. He denied symptoms, except occasional itching. Family history revealed a maternal uncle with protein C deficiency and a maternal grandmother with systemic lupus erythematosus. Review of systems was negative; the patient denied joint pain and contact with heating pads or laptop computers. Based on the initial presentation, an underlying systemic condition was suspected. Physical examination revealed reticulate, nonblanching, brown patches on the bilateral arms, legs, and back in an apparent livedoid pattern (Figure). The patient’s history and physical examination suggested terra firma-forme dermatosis, livedo racemosa, or another vasculopathic process. However, gentle rubbing of the skin with an alcohol swab removed the discoloration completely, leading to the diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Livedo racemosa appears as an irregular, focal, reticulated discoloration of the skin.1 The reticulated pattern of livedo racemosa has a branched or broken-up appearance.2 Livedo racemosa indicates a disruption in the vasculature due to inflammation or occlusion.1 The change is pathologic and does not blanch or resolve with warming.1,2 The condition can progress to pigmentation and ulceration.1 Livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of underlying vascular pathology. Due to a variety of causes, skin biopsy is nondiagnostic. Livedo racemosa can be caused by conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis, tuberculosis, polycythemia rubra vera, and Sneddon syndrome, among others.3-5

Terra firma-forme dermatosis was reported in 1987 by Duncan et al.6 The condition classically presents with an exasperated mother who is unable to clean the “dirt” off her child’s skin despite multiple vigorous scrubbing attempts. The condition most commonly occurs in the summer months on the neck, face, and ankles.7,8 Duncan et al6 reported that when the affected area was prepared for a biopsy, clean skin was revealed after wiping with an alcohol swab. No other cleansing agent has been reported to effectively remove the discoloration of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Hoping to elucidate a cause, Duncan et al6 performed both bacteriologic and fungal studies. The bacterial skin culture grew only normal flora, and fungal culture grew only normal contaminants consistent with the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scraping. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis but not parakeratosis. Staining revealed melanin in the hyperkeratotic areas.6 Although the cause of this condition largely is unknown, it is thought that the epidermis in the affected areas could undergo altered maturation, resulting in trapping melanin that causes the skin to appear hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1 In our case, wiping the skin revealed the unsuspected diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis displaying an unusual pseudolivedoid pattern. With apparently hyperpigmented processes, rubbing the skin with alcohol may help avoid unnecessary aggressive workup.

- Parsi K, Partsch H, Rabe E, et al. Reticulate eruptions: part 2. historical perspectives, morphology, terminology and classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:237-244.

- Ehrmann S. A new vascular symptom in syphilis [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1907;57:777-782.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebrovascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Golden RL. Livedo reticularis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:299-301.

- Lyell A, Church R. The cutaneous manifestations of polyarteritis nodosa. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66:335-343.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;23:297-300.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Cannavò SP. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:482-484.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with dark spots on the legs and back of 2 months’ duration. He was not taking any medications and the spots could not be washed away by scrubbing with soap and water. He denied symptoms, except occasional itching. Family history revealed a maternal uncle with protein C deficiency and a maternal grandmother with systemic lupus erythematosus. Review of systems was negative; the patient denied joint pain and contact with heating pads or laptop computers. Based on the initial presentation, an underlying systemic condition was suspected. Physical examination revealed reticulate, nonblanching, brown patches on the bilateral arms, legs, and back in an apparent livedoid pattern (Figure). The patient’s history and physical examination suggested terra firma-forme dermatosis, livedo racemosa, or another vasculopathic process. However, gentle rubbing of the skin with an alcohol swab removed the discoloration completely, leading to the diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Livedo racemosa appears as an irregular, focal, reticulated discoloration of the skin.1 The reticulated pattern of livedo racemosa has a branched or broken-up appearance.2 Livedo racemosa indicates a disruption in the vasculature due to inflammation or occlusion.1 The change is pathologic and does not blanch or resolve with warming.1,2 The condition can progress to pigmentation and ulceration.1 Livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of underlying vascular pathology. Due to a variety of causes, skin biopsy is nondiagnostic. Livedo racemosa can be caused by conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis, tuberculosis, polycythemia rubra vera, and Sneddon syndrome, among others.3-5

Terra firma-forme dermatosis was reported in 1987 by Duncan et al.6 The condition classically presents with an exasperated mother who is unable to clean the “dirt” off her child’s skin despite multiple vigorous scrubbing attempts. The condition most commonly occurs in the summer months on the neck, face, and ankles.7,8 Duncan et al6 reported that when the affected area was prepared for a biopsy, clean skin was revealed after wiping with an alcohol swab. No other cleansing agent has been reported to effectively remove the discoloration of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Hoping to elucidate a cause, Duncan et al6 performed both bacteriologic and fungal studies. The bacterial skin culture grew only normal flora, and fungal culture grew only normal contaminants consistent with the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scraping. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis but not parakeratosis. Staining revealed melanin in the hyperkeratotic areas.6 Although the cause of this condition largely is unknown, it is thought that the epidermis in the affected areas could undergo altered maturation, resulting in trapping melanin that causes the skin to appear hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1 In our case, wiping the skin revealed the unsuspected diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis displaying an unusual pseudolivedoid pattern. With apparently hyperpigmented processes, rubbing the skin with alcohol may help avoid unnecessary aggressive workup.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with dark spots on the legs and back of 2 months’ duration. He was not taking any medications and the spots could not be washed away by scrubbing with soap and water. He denied symptoms, except occasional itching. Family history revealed a maternal uncle with protein C deficiency and a maternal grandmother with systemic lupus erythematosus. Review of systems was negative; the patient denied joint pain and contact with heating pads or laptop computers. Based on the initial presentation, an underlying systemic condition was suspected. Physical examination revealed reticulate, nonblanching, brown patches on the bilateral arms, legs, and back in an apparent livedoid pattern (Figure). The patient’s history and physical examination suggested terra firma-forme dermatosis, livedo racemosa, or another vasculopathic process. However, gentle rubbing of the skin with an alcohol swab removed the discoloration completely, leading to the diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Livedo racemosa appears as an irregular, focal, reticulated discoloration of the skin.1 The reticulated pattern of livedo racemosa has a branched or broken-up appearance.2 Livedo racemosa indicates a disruption in the vasculature due to inflammation or occlusion.1 The change is pathologic and does not blanch or resolve with warming.1,2 The condition can progress to pigmentation and ulceration.1 Livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of underlying vascular pathology. Due to a variety of causes, skin biopsy is nondiagnostic. Livedo racemosa can be caused by conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis, tuberculosis, polycythemia rubra vera, and Sneddon syndrome, among others.3-5

Terra firma-forme dermatosis was reported in 1987 by Duncan et al.6 The condition classically presents with an exasperated mother who is unable to clean the “dirt” off her child’s skin despite multiple vigorous scrubbing attempts. The condition most commonly occurs in the summer months on the neck, face, and ankles.7,8 Duncan et al6 reported that when the affected area was prepared for a biopsy, clean skin was revealed after wiping with an alcohol swab. No other cleansing agent has been reported to effectively remove the discoloration of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Hoping to elucidate a cause, Duncan et al6 performed both bacteriologic and fungal studies. The bacterial skin culture grew only normal flora, and fungal culture grew only normal contaminants consistent with the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scraping. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis but not parakeratosis. Staining revealed melanin in the hyperkeratotic areas.6 Although the cause of this condition largely is unknown, it is thought that the epidermis in the affected areas could undergo altered maturation, resulting in trapping melanin that causes the skin to appear hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1 In our case, wiping the skin revealed the unsuspected diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis displaying an unusual pseudolivedoid pattern. With apparently hyperpigmented processes, rubbing the skin with alcohol may help avoid unnecessary aggressive workup.

- Parsi K, Partsch H, Rabe E, et al. Reticulate eruptions: part 2. historical perspectives, morphology, terminology and classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:237-244.

- Ehrmann S. A new vascular symptom in syphilis [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1907;57:777-782.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebrovascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Golden RL. Livedo reticularis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:299-301.

- Lyell A, Church R. The cutaneous manifestations of polyarteritis nodosa. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66:335-343.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;23:297-300.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Cannavò SP. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:482-484.

- Parsi K, Partsch H, Rabe E, et al. Reticulate eruptions: part 2. historical perspectives, morphology, terminology and classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:237-244.

- Ehrmann S. A new vascular symptom in syphilis [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1907;57:777-782.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebrovascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Golden RL. Livedo reticularis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:299-301.

- Lyell A, Church R. The cutaneous manifestations of polyarteritis nodosa. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66:335-343.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;23:297-300.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Cannavò SP. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:482-484.

Practice Points

- Clinicians should include terra firma-forme dermatosis in the differential diagnosis of any hyperpigmented condition, regardless of pattern of presentation.

- Clean the skin with an alcohol wipe to rule out a diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma of the External Auditory Canal

To the Editor:

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), described by Goldstein et al1 in 1982, is a relatively uncommon cutaneous neoplasm. This locally aggressive malignant adnexal tumor has high potential for local recurrence. The skin of the head, particularly in the nasolabial and periorbital regions, most often is involved.2 Involvement of the external auditory canal (EAC) is relatively rare. We report a case of MAC of the EAC.

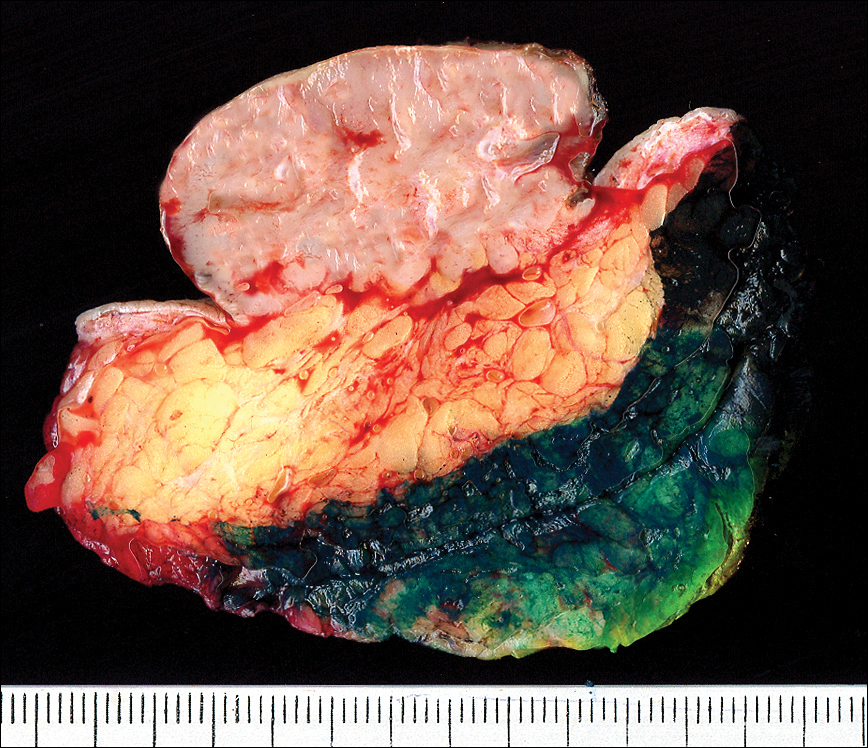

A 52-year-old man presented with 1 palpable nodule on the right EAC of approximately 1 year’s duration. The lesion was asymptomatic, and the patient had no history of radiation exposure. The patient was an airport employee required to wear an earplug in the right ear. Endoscopic examination identified a 1×1 cm2 erythematous nodule on the anterior inferior quadrant of the right external ear canal orifice (Figure 1). Axial and coronal computed tomography demonstrated a soft tissue mass in the right EAC without any bony erosion. No clinical signs of regional lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis were present. Excision was performed under microscopic visualization.

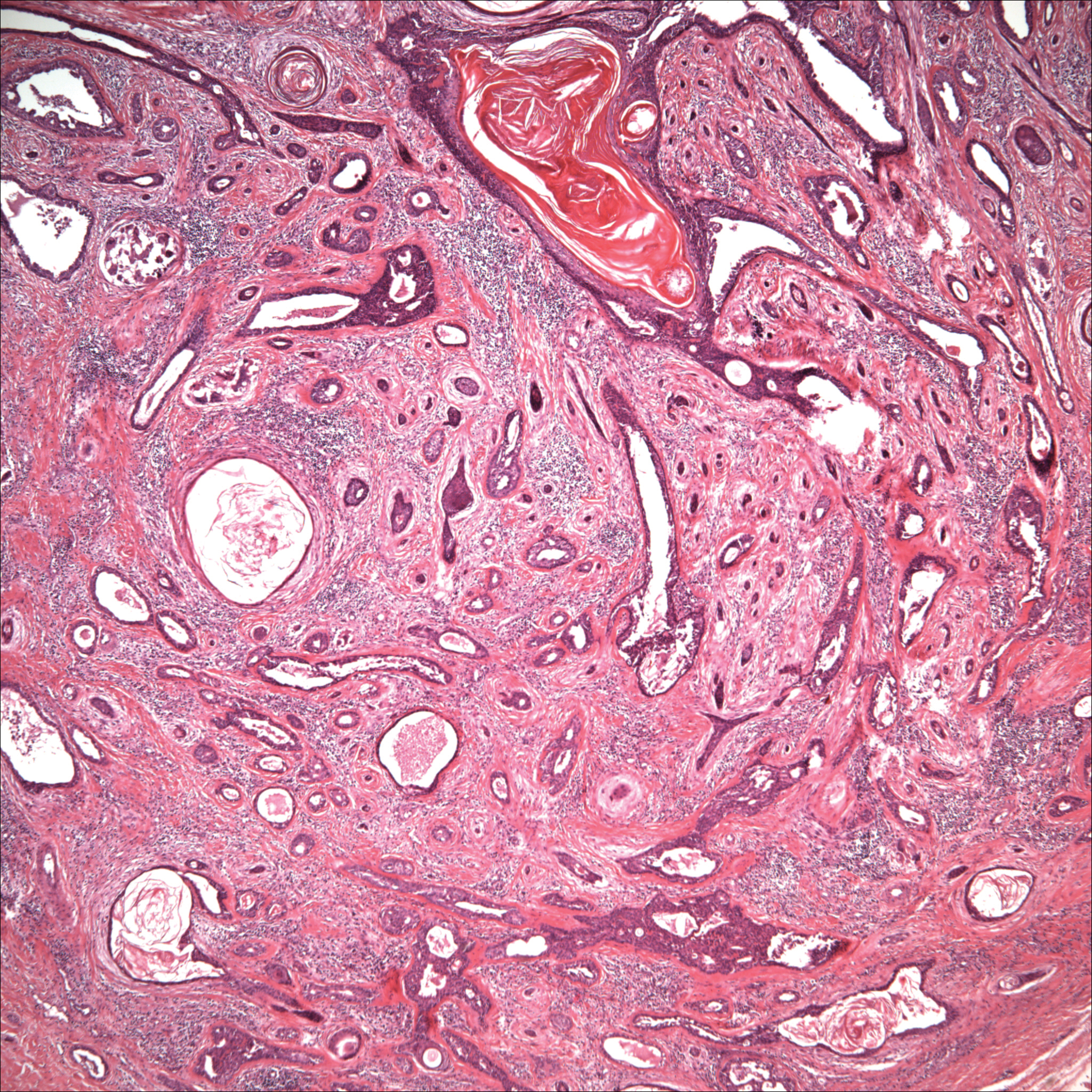

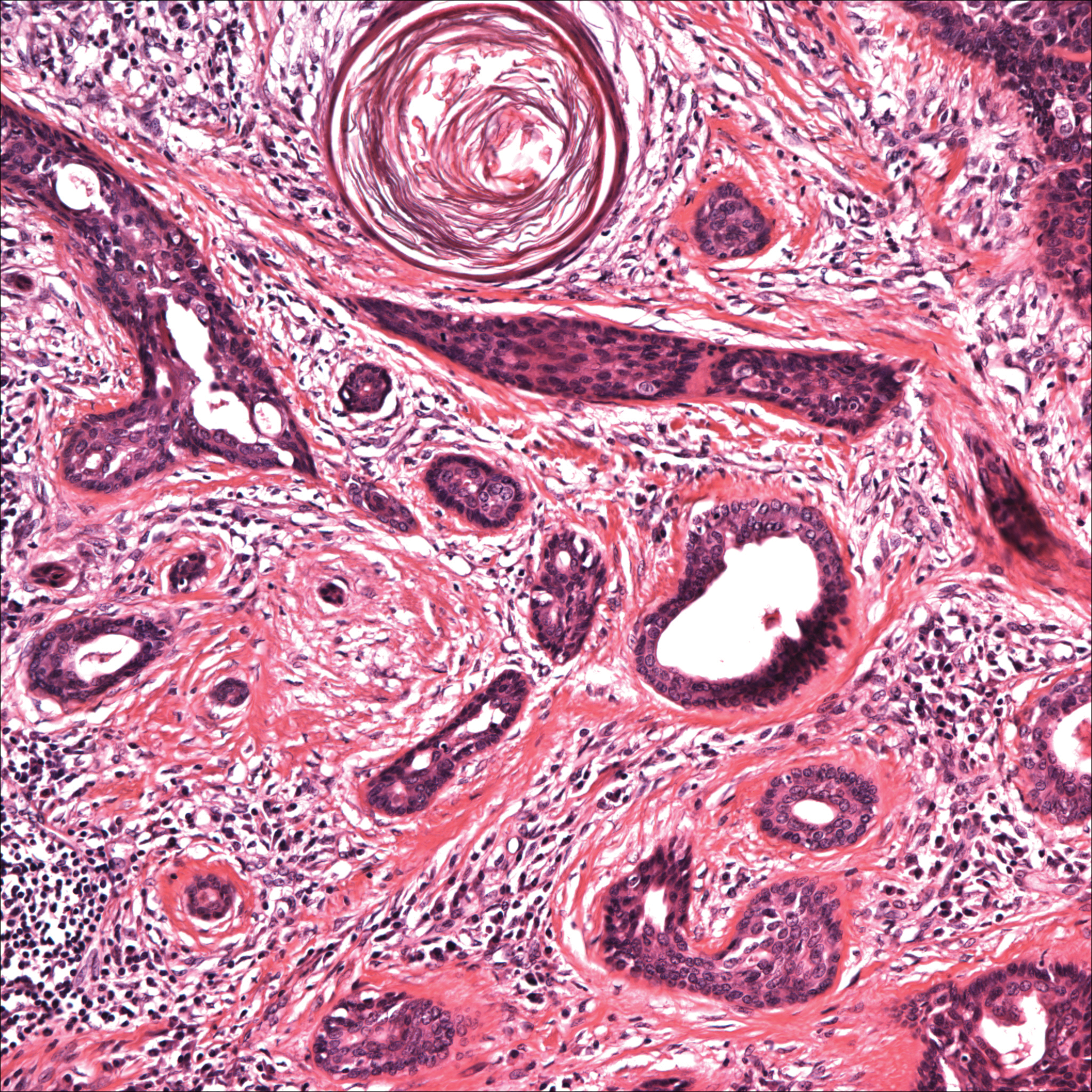

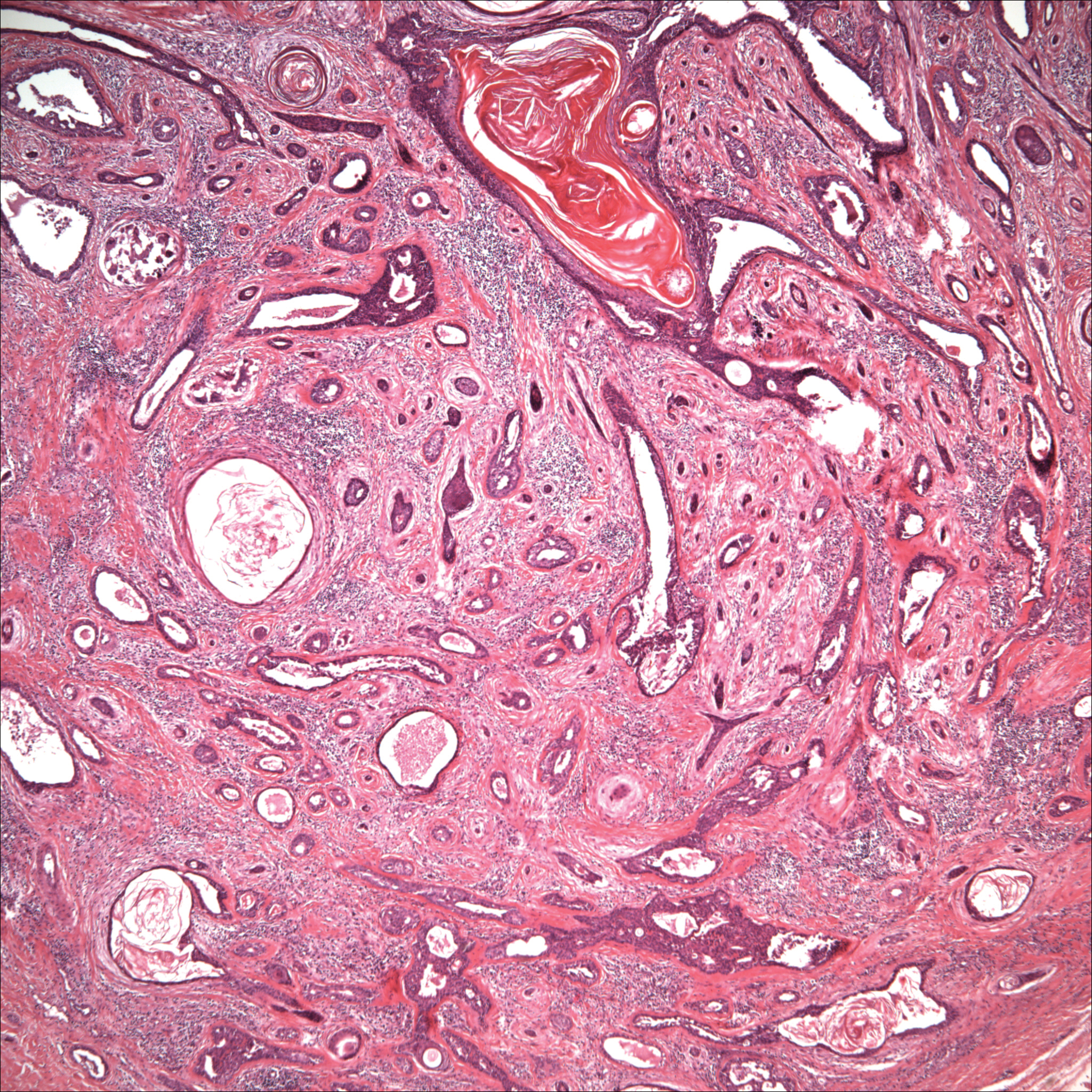

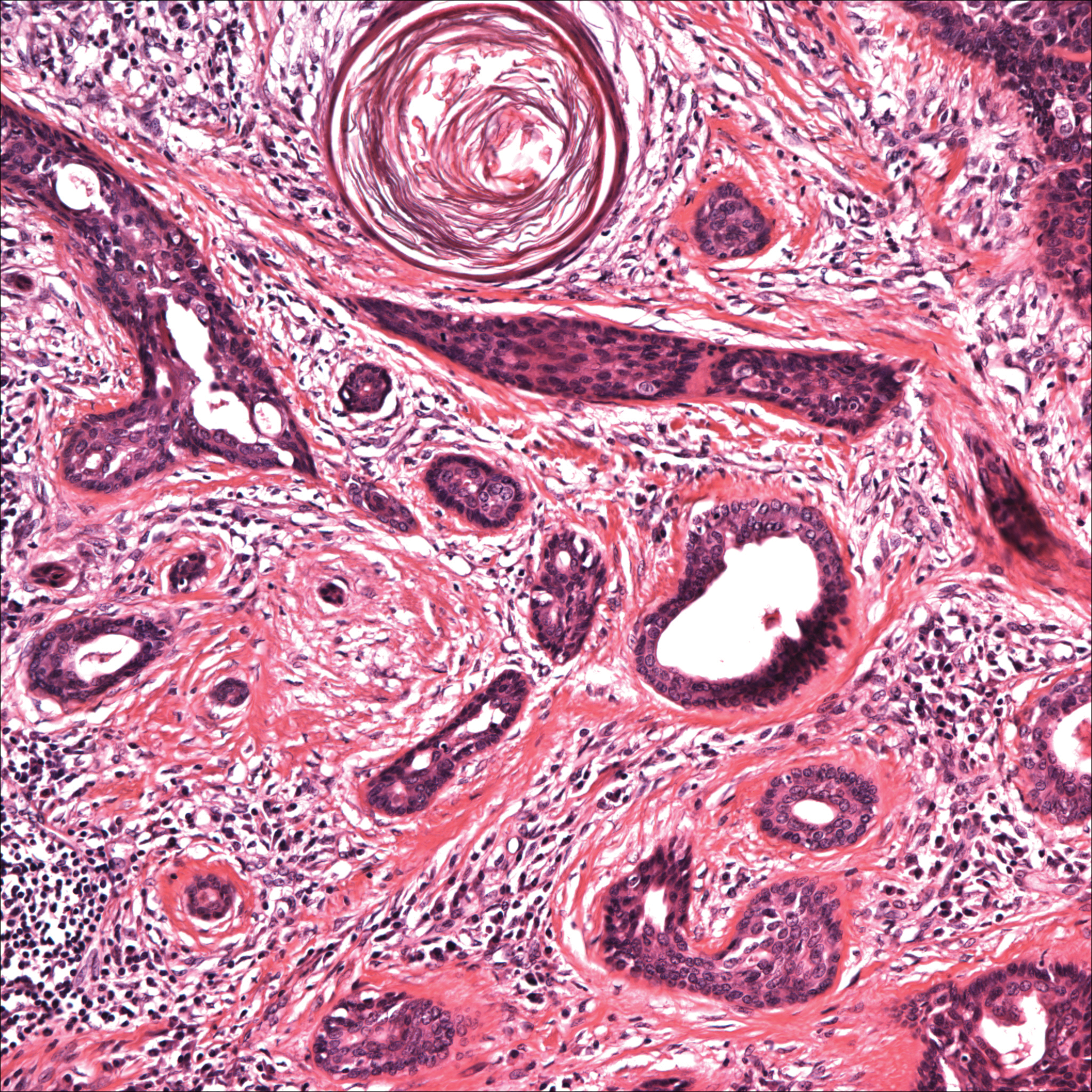

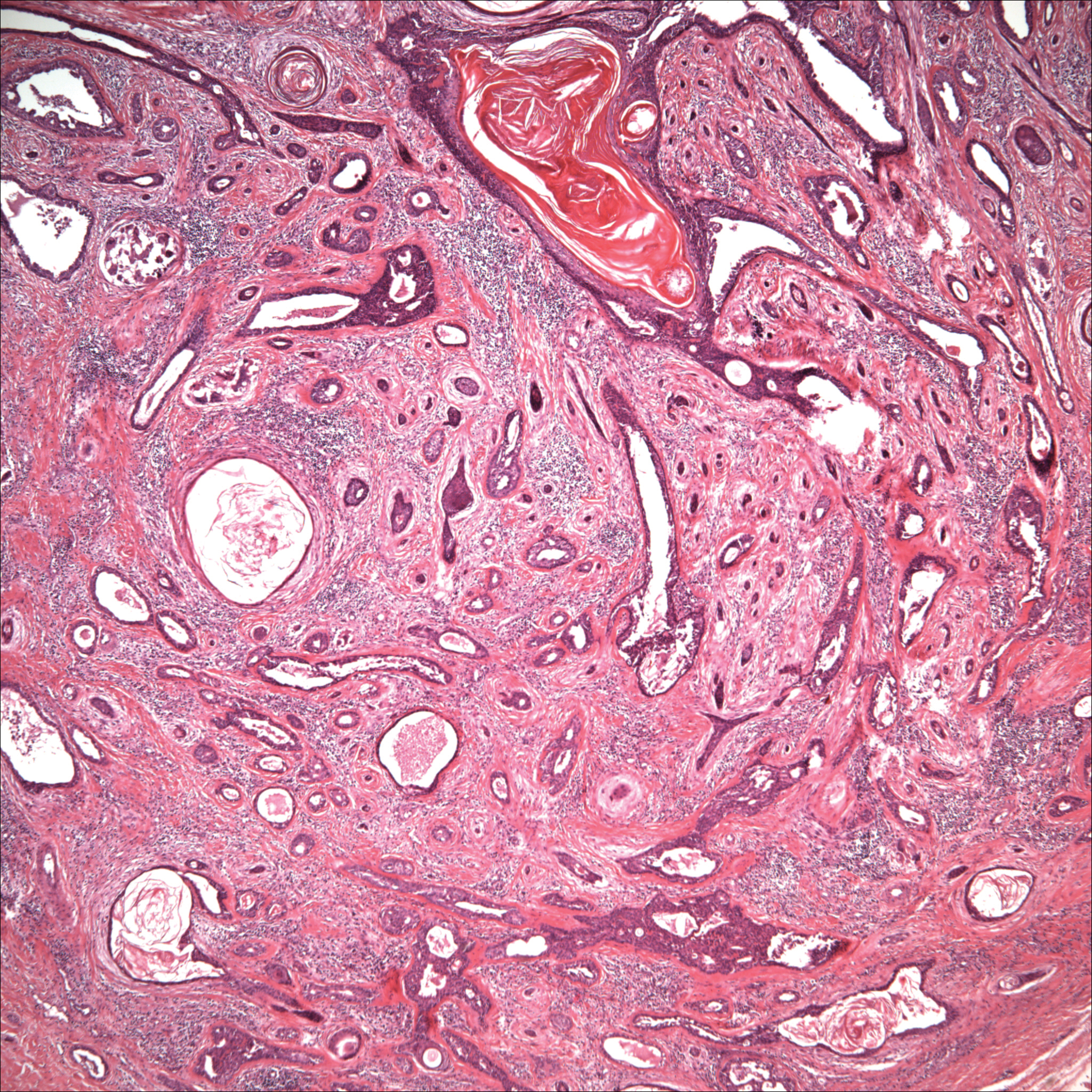

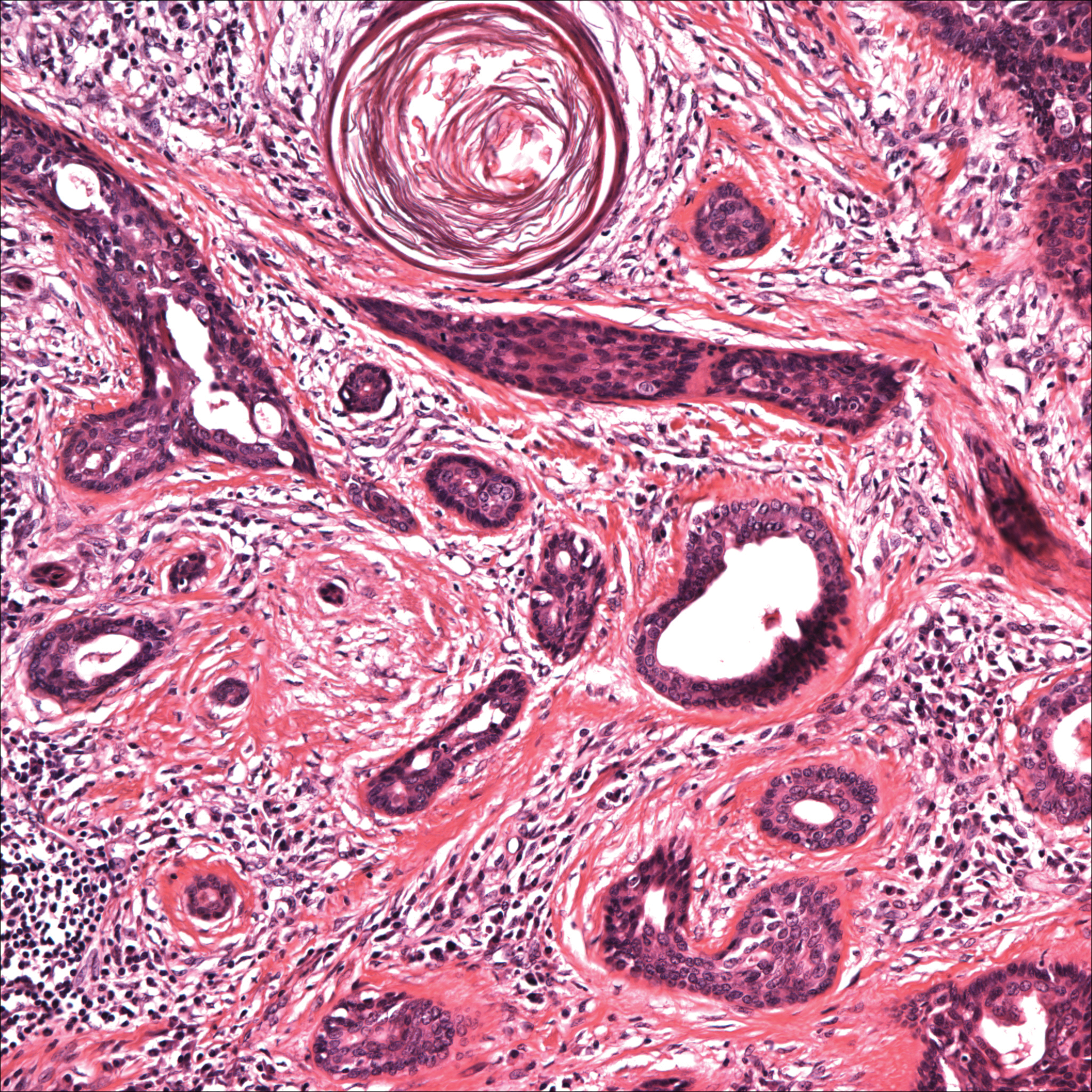

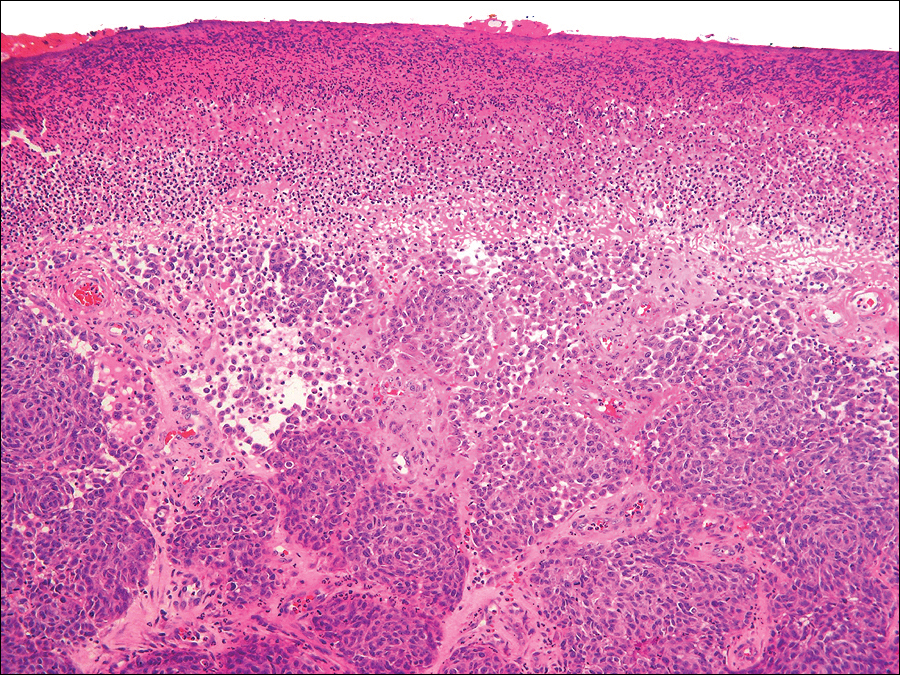

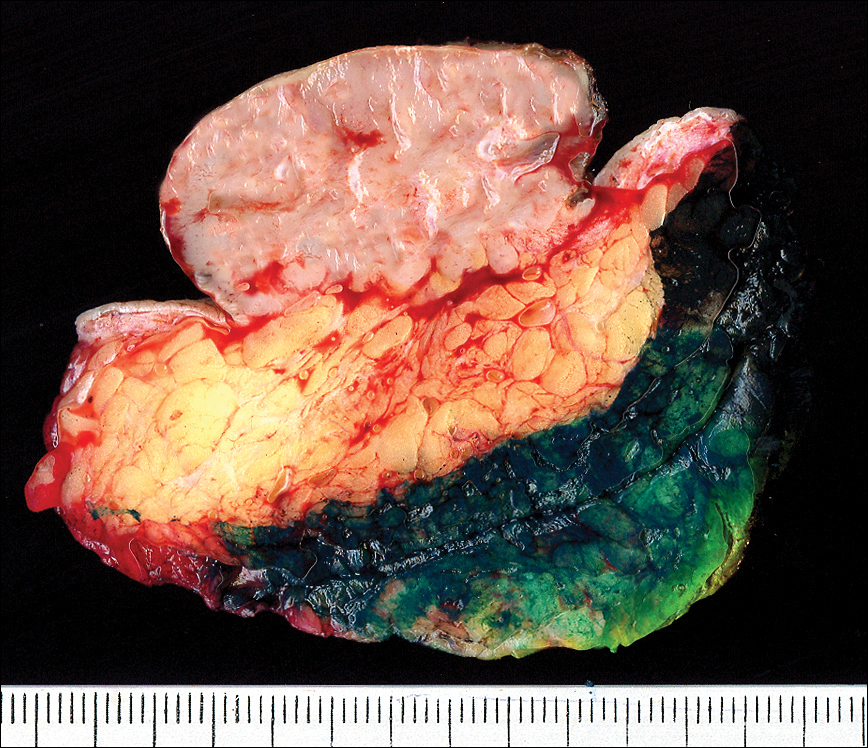

Histopathology of the nodule showed marked proliferation of multiple keratin-containing cysts, irregular ductal structures, and solid epithelial nests in the deep dermis (Figure 2). Irregular ductal structures with 2 cell layer walls and several epithelial strands or small nests of tumor cells within desmoplastic stroma were noted (Figure 3). No perineural infiltration or tumor infiltration existed at the margin. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the final diagnosis was MAC. Complete resolution was noted after the excision. The patient returned for regular follow-up and no signs of recurrence were noted for 7 years postoperatively.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma, also known as sclerosing sweat duct (syringomatous) carcinoma, malignant syringoma, and syringoid eccrine carcinoma, is characterized by slow and locally aggressive growth with high likelihood of perineural invasion and frequent recurrence.2 Regional lymph node metastasis is uncommon, and systemic metastasis is rare.2-4

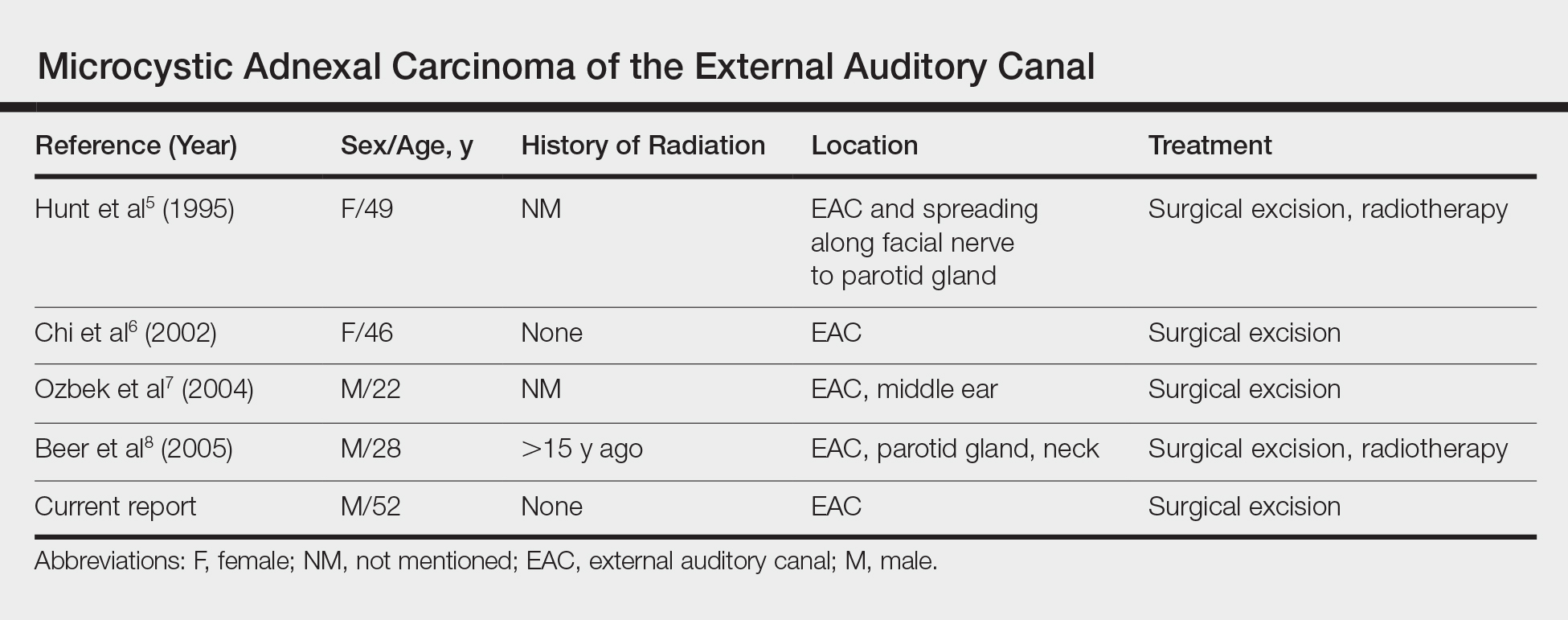

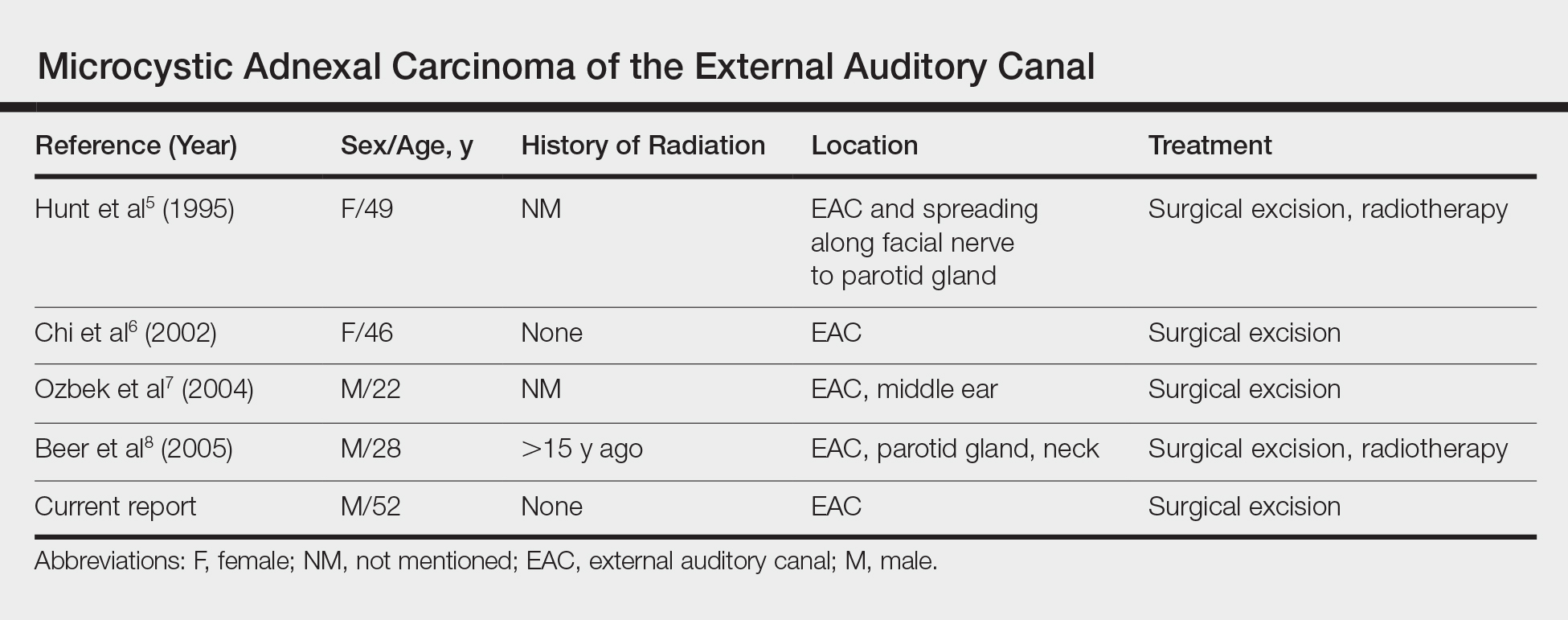

Although the head most often is involved, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms microcystic adnexal carcinoma and external auditory canal revealed 4 cases (Table).5-8 Our report adds another case of MAC arising solely in the EAC. Although the etiology of MAC is unknown, prior studies indicated that radiotherapy is a risk factor for MAC. Other possible risk factors include UV light exposure and immunodeficiency.2 Our patient had no history of these factors and experienced chronic friction caused by use of an occupational unilateral earplug, which may be a notable factor. Locations of MAC arising outside the head region include the axilla, vulva, breast, palm, toe, perianal skin, buttock, chest, and an ovarian cystic teratoma.3,9 Friction commonly occurs in many of these areas. Therefore, we propose that friction may be a risk factor for MAC.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of any slowly growing cutaneous tumor, even in the EAC. Once diagnosed, the tumor should be surgically excised. Because local recurrence is common and may occur several decades after excision, lifetime follow-up for recurrence signs is essential.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Brenn T, Mckee PH. Tumors of the sweat glands. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, eds. Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1647-1651.

- Ohtsuka H, Nagamatsu S. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of 51 Japanese patients. Dermatology. 2002;204:190-193.

- Yu JB, Blitzblau RC, Patel SC, et al. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database analysis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma) of the skin. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:125-127.

- Hunt JT, Stack BC Jr, Futran ND, et al. Pathologic quiz case 1. microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:1430-1433.

- Chi J, Jung YG, Rho YS, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of external auditory canal: report of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:241-242.

- Ozbek C, Celikkanat S, Beriat K, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the external ear canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:148-150.

- Beer KT, Bühler SS, Mullis P, et al. A microcystic adnexal carcinoma in the auditory canal 15 years after radiotherapy of a 12-year-old boy with nasopharynx carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:405-410.

- Nadiminti H, Nadiminti U, Washington C. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma in African Americans. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1384-1387.

To the Editor:

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), described by Goldstein et al1 in 1982, is a relatively uncommon cutaneous neoplasm. This locally aggressive malignant adnexal tumor has high potential for local recurrence. The skin of the head, particularly in the nasolabial and periorbital regions, most often is involved.2 Involvement of the external auditory canal (EAC) is relatively rare. We report a case of MAC of the EAC.

A 52-year-old man presented with 1 palpable nodule on the right EAC of approximately 1 year’s duration. The lesion was asymptomatic, and the patient had no history of radiation exposure. The patient was an airport employee required to wear an earplug in the right ear. Endoscopic examination identified a 1×1 cm2 erythematous nodule on the anterior inferior quadrant of the right external ear canal orifice (Figure 1). Axial and coronal computed tomography demonstrated a soft tissue mass in the right EAC without any bony erosion. No clinical signs of regional lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis were present. Excision was performed under microscopic visualization.

Histopathology of the nodule showed marked proliferation of multiple keratin-containing cysts, irregular ductal structures, and solid epithelial nests in the deep dermis (Figure 2). Irregular ductal structures with 2 cell layer walls and several epithelial strands or small nests of tumor cells within desmoplastic stroma were noted (Figure 3). No perineural infiltration or tumor infiltration existed at the margin. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the final diagnosis was MAC. Complete resolution was noted after the excision. The patient returned for regular follow-up and no signs of recurrence were noted for 7 years postoperatively.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma, also known as sclerosing sweat duct (syringomatous) carcinoma, malignant syringoma, and syringoid eccrine carcinoma, is characterized by slow and locally aggressive growth with high likelihood of perineural invasion and frequent recurrence.2 Regional lymph node metastasis is uncommon, and systemic metastasis is rare.2-4

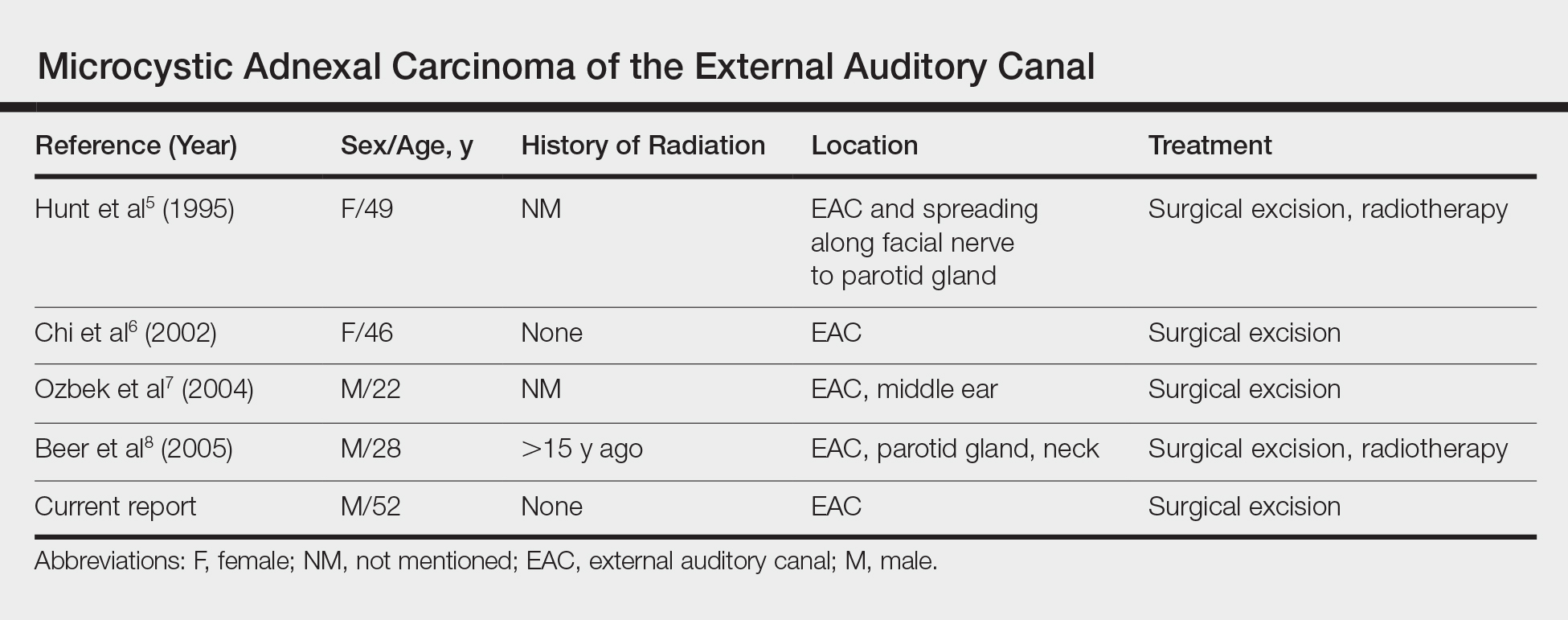

Although the head most often is involved, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms microcystic adnexal carcinoma and external auditory canal revealed 4 cases (Table).5-8 Our report adds another case of MAC arising solely in the EAC. Although the etiology of MAC is unknown, prior studies indicated that radiotherapy is a risk factor for MAC. Other possible risk factors include UV light exposure and immunodeficiency.2 Our patient had no history of these factors and experienced chronic friction caused by use of an occupational unilateral earplug, which may be a notable factor. Locations of MAC arising outside the head region include the axilla, vulva, breast, palm, toe, perianal skin, buttock, chest, and an ovarian cystic teratoma.3,9 Friction commonly occurs in many of these areas. Therefore, we propose that friction may be a risk factor for MAC.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of any slowly growing cutaneous tumor, even in the EAC. Once diagnosed, the tumor should be surgically excised. Because local recurrence is common and may occur several decades after excision, lifetime follow-up for recurrence signs is essential.

To the Editor:

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), described by Goldstein et al1 in 1982, is a relatively uncommon cutaneous neoplasm. This locally aggressive malignant adnexal tumor has high potential for local recurrence. The skin of the head, particularly in the nasolabial and periorbital regions, most often is involved.2 Involvement of the external auditory canal (EAC) is relatively rare. We report a case of MAC of the EAC.

A 52-year-old man presented with 1 palpable nodule on the right EAC of approximately 1 year’s duration. The lesion was asymptomatic, and the patient had no history of radiation exposure. The patient was an airport employee required to wear an earplug in the right ear. Endoscopic examination identified a 1×1 cm2 erythematous nodule on the anterior inferior quadrant of the right external ear canal orifice (Figure 1). Axial and coronal computed tomography demonstrated a soft tissue mass in the right EAC without any bony erosion. No clinical signs of regional lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis were present. Excision was performed under microscopic visualization.

Histopathology of the nodule showed marked proliferation of multiple keratin-containing cysts, irregular ductal structures, and solid epithelial nests in the deep dermis (Figure 2). Irregular ductal structures with 2 cell layer walls and several epithelial strands or small nests of tumor cells within desmoplastic stroma were noted (Figure 3). No perineural infiltration or tumor infiltration existed at the margin. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the final diagnosis was MAC. Complete resolution was noted after the excision. The patient returned for regular follow-up and no signs of recurrence were noted for 7 years postoperatively.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma, also known as sclerosing sweat duct (syringomatous) carcinoma, malignant syringoma, and syringoid eccrine carcinoma, is characterized by slow and locally aggressive growth with high likelihood of perineural invasion and frequent recurrence.2 Regional lymph node metastasis is uncommon, and systemic metastasis is rare.2-4

Although the head most often is involved, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms microcystic adnexal carcinoma and external auditory canal revealed 4 cases (Table).5-8 Our report adds another case of MAC arising solely in the EAC. Although the etiology of MAC is unknown, prior studies indicated that radiotherapy is a risk factor for MAC. Other possible risk factors include UV light exposure and immunodeficiency.2 Our patient had no history of these factors and experienced chronic friction caused by use of an occupational unilateral earplug, which may be a notable factor. Locations of MAC arising outside the head region include the axilla, vulva, breast, palm, toe, perianal skin, buttock, chest, and an ovarian cystic teratoma.3,9 Friction commonly occurs in many of these areas. Therefore, we propose that friction may be a risk factor for MAC.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of any slowly growing cutaneous tumor, even in the EAC. Once diagnosed, the tumor should be surgically excised. Because local recurrence is common and may occur several decades after excision, lifetime follow-up for recurrence signs is essential.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Brenn T, Mckee PH. Tumors of the sweat glands. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, eds. Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1647-1651.

- Ohtsuka H, Nagamatsu S. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of 51 Japanese patients. Dermatology. 2002;204:190-193.

- Yu JB, Blitzblau RC, Patel SC, et al. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database analysis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma) of the skin. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:125-127.

- Hunt JT, Stack BC Jr, Futran ND, et al. Pathologic quiz case 1. microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:1430-1433.

- Chi J, Jung YG, Rho YS, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of external auditory canal: report of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:241-242.

- Ozbek C, Celikkanat S, Beriat K, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the external ear canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:148-150.

- Beer KT, Bühler SS, Mullis P, et al. A microcystic adnexal carcinoma in the auditory canal 15 years after radiotherapy of a 12-year-old boy with nasopharynx carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:405-410.

- Nadiminti H, Nadiminti U, Washington C. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma in African Americans. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1384-1387.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Brenn T, Mckee PH. Tumors of the sweat glands. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, eds. Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1647-1651.

- Ohtsuka H, Nagamatsu S. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of 51 Japanese patients. Dermatology. 2002;204:190-193.

- Yu JB, Blitzblau RC, Patel SC, et al. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database analysis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma) of the skin. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:125-127.

- Hunt JT, Stack BC Jr, Futran ND, et al. Pathologic quiz case 1. microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:1430-1433.

- Chi J, Jung YG, Rho YS, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of external auditory canal: report of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:241-242.

- Ozbek C, Celikkanat S, Beriat K, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the external ear canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:148-150.

- Beer KT, Bühler SS, Mullis P, et al. A microcystic adnexal carcinoma in the auditory canal 15 years after radiotherapy of a 12-year-old boy with nasopharynx carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:405-410.

- Nadiminti H, Nadiminti U, Washington C. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma in African Americans. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1384-1387.

Practice Points

- Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a locally aggressive malignant adnexal tumor with a high potential for local recurrence.

- The skin of the head, particularly in the nasolabial and periorbital regions, most often is involved.

- Once diagnosed, the tumor should be surgically excised. Because local recurrence is common and may occur several decades after excision, lifetime follow-up for recurrence is essential.

Atrophodermalike Guttate Morphea

To the Editor:

Morphea, atrophoderma, guttate lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), anetoderma, and their subtypes are inflammatory processes ultimately leading to dermal remodeling. We report a case of a scaly, hypopigmented, macular rash that clinically appeared as an entity along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum and demonstrated unique histopathologic changes in both collagen and elastin confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis. This case is a potentially rare variant representing a combination of clinical and microscopic findings.

A 29-year-old woman presented for an increasing number of white spots distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. She denied local and systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she was stung by 100 wasps 23 years prior. Following the assault, her grandmother placed chewed tobacco leaves atop the painful erythematous wheals and flares. Upon resolution, hypopigmented macules and patches remained in their place. The patient denied associated symptoms or new lesions; she did not seek care at that time.

In her early 20s, the patient noted new, similarly distributed hypopigmented macules and patches without associated arthropod assault. She was treated by an outside dermatologist without result for presumed tinea versicolor. A follow-up superficial shave biopsy cited subtle psoriasiform dermatitis. Topical steroids did not improve the lesions. Her medical history also was remarkable for a reportedly unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear.

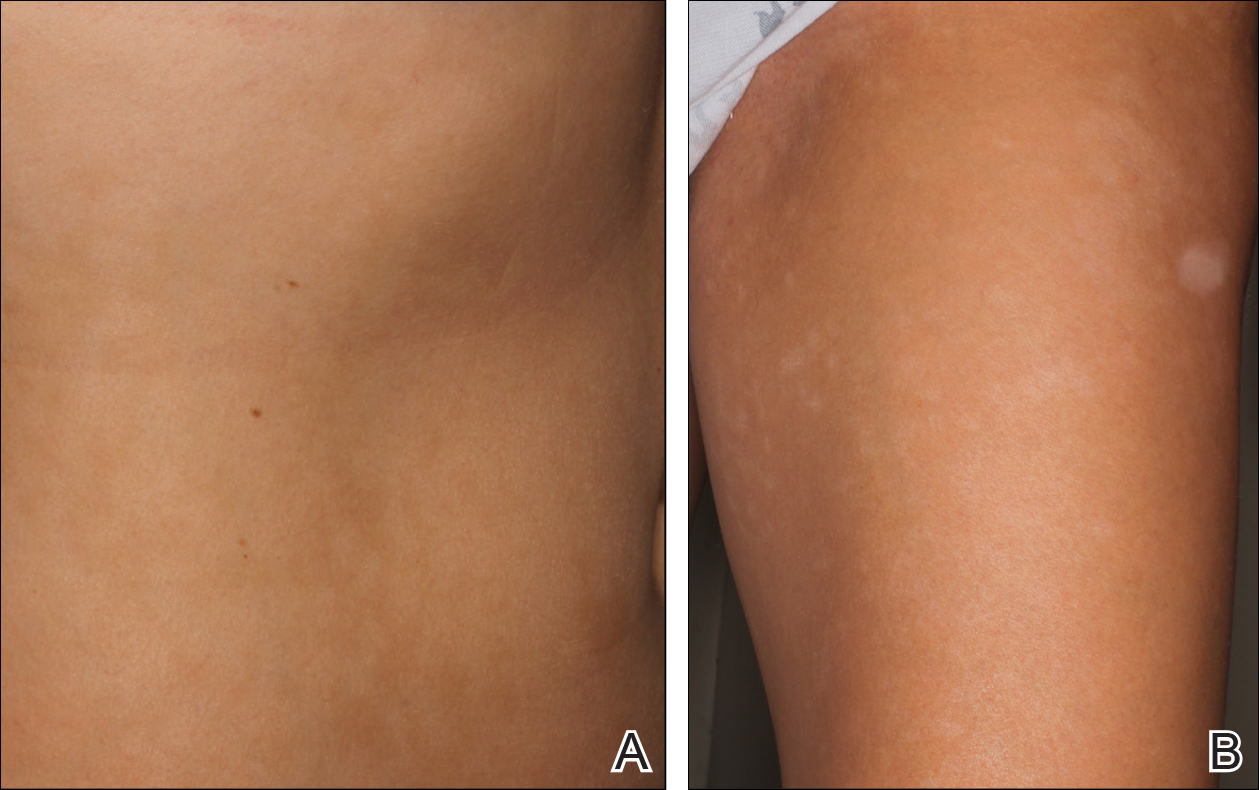

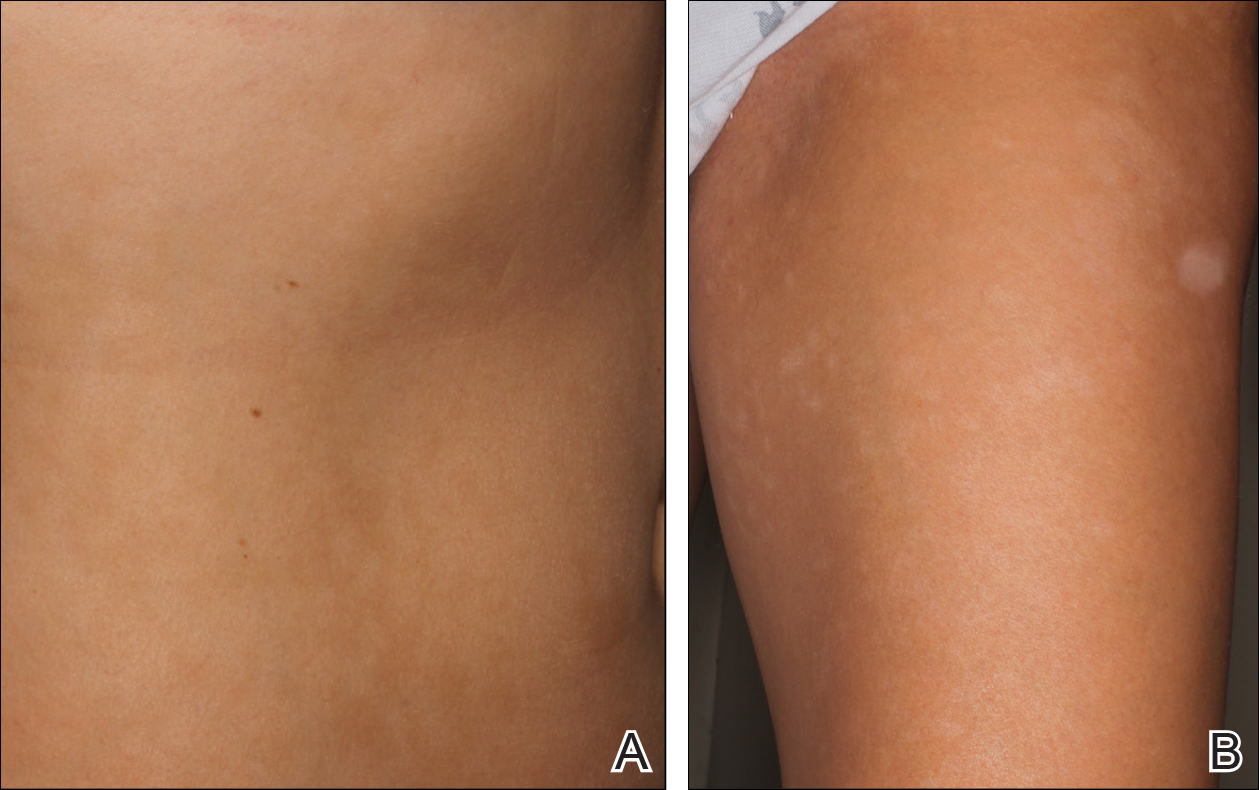

Physical examination revealed 0.5- to 2.0-cm, ill-defined, perifollicular and nonfollicular, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk, arms, and legs. There was no follicular plugging (Figure 1A). The hands, feet, face, and mucosal surfaces were spared. She had no family history of similar lesions. Although atrophic in appearance, a single lesion on the left thigh was palpably depressed (Figure 1B). Serology demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and negative Lyme titers. Light therapy and topical steroids failed to improve the lesions; calcipotriene cream 0.005% made the lesions erythematous and pruritic.

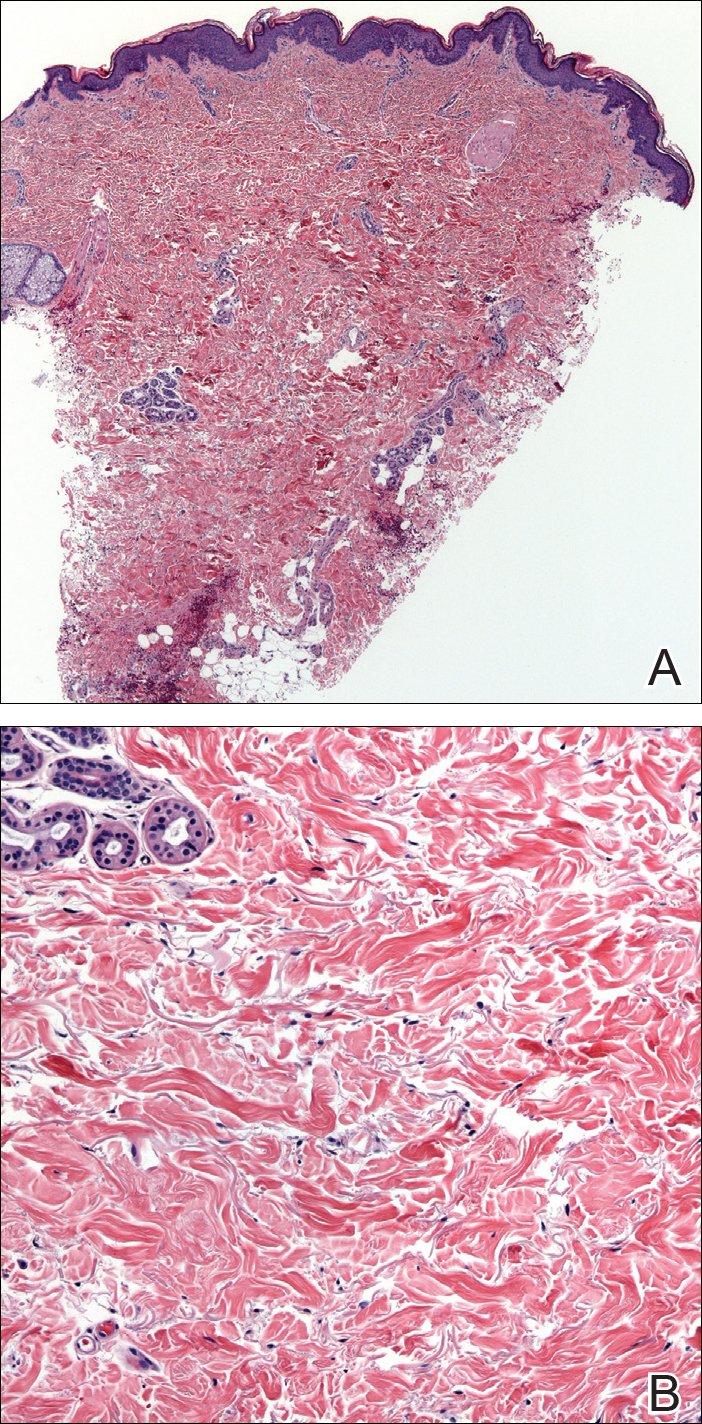

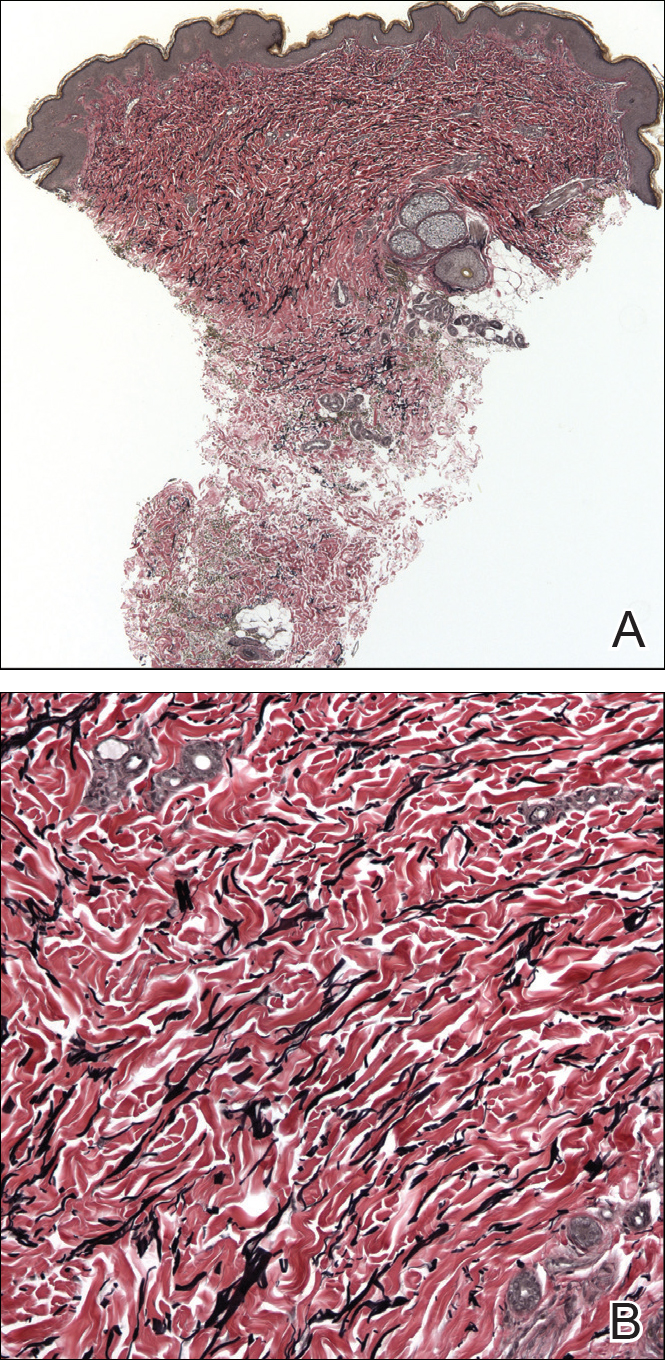

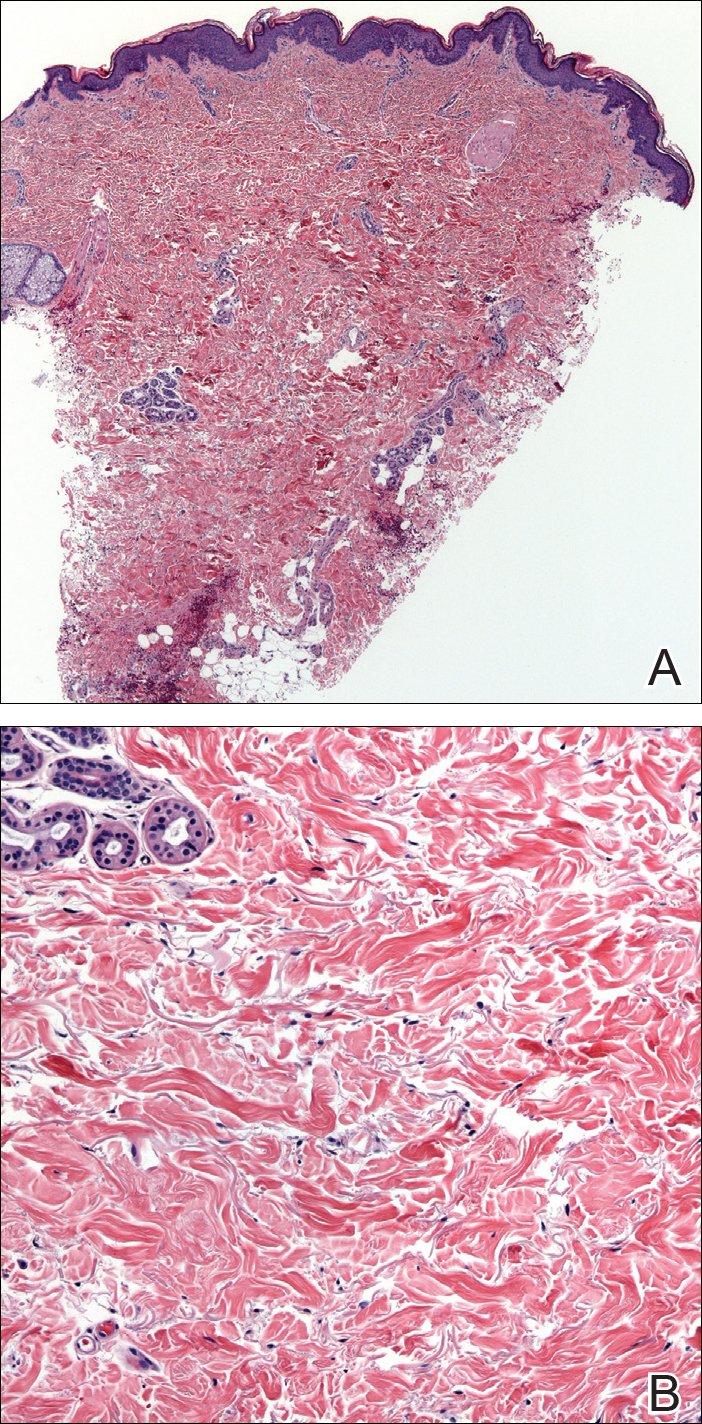

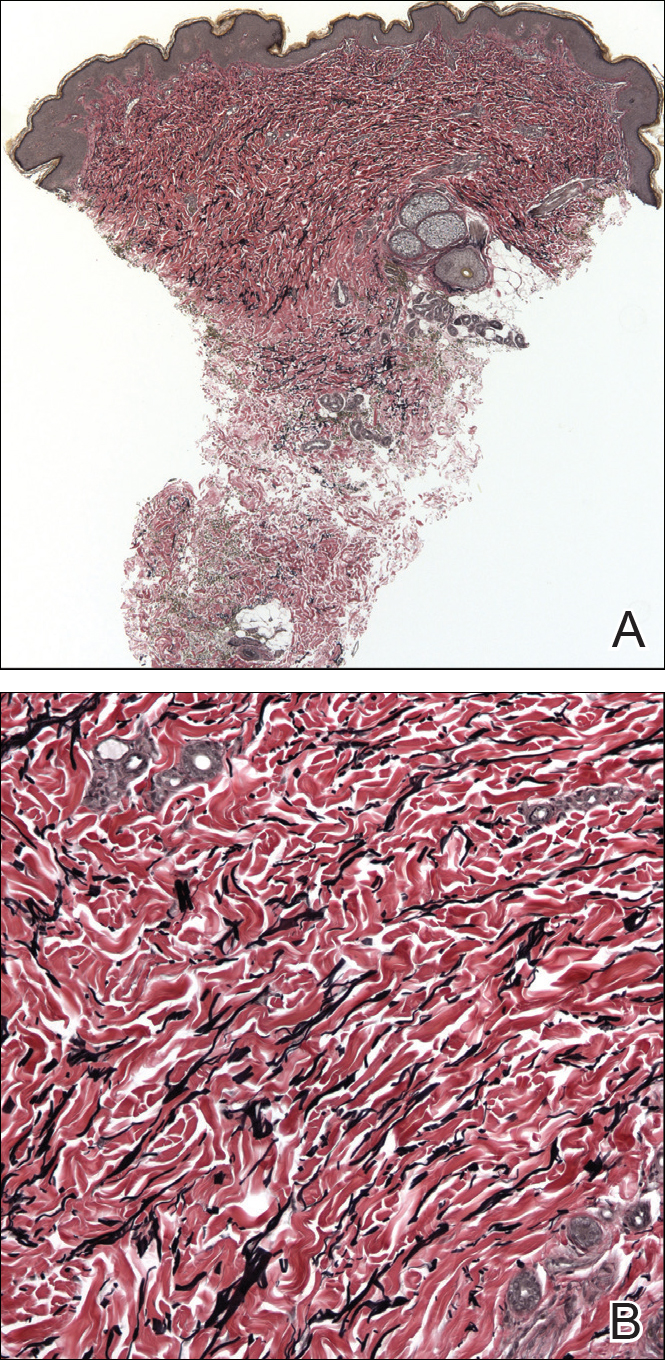

A biopsy from a flank lesion demonstrated a normal epithelium without thinning, a normal basal melanocyte population, and minimally effaced rete ridges. Thin collagen bundles were noted in the upper reticular and papillary dermis with associated fibroplasia (Figure 2). Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed decreased and fragmented elastin filaments in the same dermal distribution as the changed collagen (Figure 3). There was no evidence of primary inflammatory disease. The dermis was thinned. Periodic acid–Schiff stain confirmed the absence of hyphae and spores.

The relevant findings in our patient including the following: (1) onset of hypopigmented macules and patches following resolution of a toxic insult; (2) initially stable number of lesions that progressed in number but not size; (3) thinned collagen associated with fibroplasia in the upper reticular and papillary dermis; (4) decreased number and fragmentation of elastin filaments confined to the same region; (5) no congenital lesions or similar lesions in family members; and (6) a complete rotator cuff tear with no findings of a systemic connective-tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

We performed a literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using combinations of the terms atrophic, hypopigmented, white, spot disease, confetti-like, guttate, macules, atrophoderma, morphea, anetoderma, elastin, and collagen to identify potentially similar reports of guttate hypopigmented macules demonstrating changes of the collagen and elastin in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. Some variants, namely atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP), guttate morphea, and superficial morphea, demonstrate similar clinical and histopathologic findings.

Findings similar to our case were documented in case reports of 2 women (aged 34 and 42 years)1 presenting with asymptomatic, atrophic, well-demarcated, shiny, hypopigmented macules over the trunk and upper extremities, which demonstrated a thinned epidermis with coarse hyalinized collagen bundles in the mid and lower dermis. There was upper and diffuse dermal elastolysis (patient 1 and patient 2, respectively).1 Our patient’s lesions were hypopigmented and atrophic in appearance but were slightly scaly and also involved the extremities. Distinct from these patient reports, histopathology from our case demonstrated thin packed collagen bundles and decreased fragmented elastin filaments confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis.

Plaque morphea is the most common type of localized scleroderma.2 The subtype APP demonstrates round to ovoid, gray-brown depressions with cliff-drop borders. They may appear flesh colored or hypopigmented.3,4 These sclerodermoid lesions lack the violaceous border classic to morphea. Sclerosis and induration also are typically absent.5 Clinically, our patient’s macules resembled this entity. Histopathologically, APP shows normal epithelium with an increased basal layer pigmentation; preserved adnexal structures; and mid to lower dermal collagen edema, clumping, and homogenization.3,4 Elastic fibers classically are unchanged, with exceptions.6-11 Changes in the collagen and elastin of our patient were unlike those reported in APP, which occur in the mid to lower dermis.

Guttate morphea demonstrates small, pale, minimally indurated, coin-shaped lesions on the trunk. Histopathology reveals less sclerosis and more edema, resembling LS&A.12 The earliest descriptions of this entity describe 3 stages: ivory/chalk white, scaly, and atrophic. Follicular plugging (absent in this patient) and fine scale can exist at any stage.13,14 Flattened rete ridges mark an otherwise preserved epidermis; hyalinized collagen typically is superficial and demonstrates less sclerosis yet increased edema.12-14 Fewer elastic fibers typically are present compared to normal skin. Changes seen in this entity are more superficial, as with our patient, than classic scleroderma. However, classic edema was not found in our patient’s biopsy specimen.

Superficial morphea, occurring predominantly in females, presents with hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patches having minimal to no induration. The lesions typically are asymptomatic. Histopathologically, collagen deposition and inflammation are confined to the superficial dermis without homogenization associated with LS&A, findings that were consistent with this patient’s biopsy.15,16 However, similar to other morpheaform variants, elastic fibers are unchanged.15 Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of the biopsy (Figure 3) showed the decreased and fragmented elastin network in the upper reticular and papillary dermis, making this entity less compatible.

Guttate LS&A may present with interfollicular, bluish white macules or papules coalescing into patches or plaques. Lesions evolve to reveal atrophic thin skin with follicular plugging. Histology demonstrates a thinned epidermis with orthohypokeratosis marked by flattened rete ridges. The dermis reveals short hyalinized collagen fibrils with a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, giving a homogenized appearance. Early disease is marked by an inflammatory infiltrate.17 Most of these findings are consistent with our patient’s pathology, which was confined to the upper dermis. Lacking, however, were characteristic findings of LS&A, including upper dermal homogenization, near-total effacement of rete ridges, orthokeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction. As such, this entity is less compatible.

Atrophoderma elastolyticum discretum has clinical features of atrophoderma with elastolytic histopathologic findings.1 Anetoderma presents with outpouchings of atrophic skin with a surrounding ring of normal tissue. Histopathologically, this entity shows normal collagen with elastolysis; there also is a decrease in desmosine, an elastin cross-linker.1,3 Neither the clinical nor histopathologic findings in this patient matched these 2 entities.

The reported chronologic association of these lesions with an arthropod assault raised suspicion to their association with toxic insult or postinflammatory changes. One study reported mechanical trauma, including insect bites, as a possible inciting factor of morphea.11 These data, gathered from patient surveys, reported trauma associated to lesion development.1,17 A review of the literature regarding atrophoderma, morphea, and LS&A failed to identify pathogenic changes seen in this patient following initial trauma. Moreover, although it is difficult to prove causality in the formation of the original hypopigmented spots, the development of identical spots in a similar distribution without further trauma suggests against these etiologies to fully explain her lesions. Nonetheless, circumstance makes it difficult to prove whether the original arthropod insult spurred a smoldering reactive process that caused the newer lesions.

Hereditary connective-tissue disorders also were considered in the differential diagnosis. Because of the patient’s history of an unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was considered; however, the remainder of her examination was normal, making a syndromic systemic disorder a less likely etiology.Because of the distinct clinical and histopathologic findings, this case may represent a rare and previously unreported variant of morphea. Clinically, these hypopigmented macules and patches exist somewhere along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum. Histopathologic findings do not conform to prior reports. The name atrophodermalike guttate morphea may be an appropriate appellation. It is possible this presentation represents a variant of what dermatologists have referred to as white spot disease.18 We hope that this case may bring others to discussion, allowing for the identification of a more precise entity and etiology so that patients may receive more directed therapy.

- Aksoy B, Ustün H, Gulbahce R, et al. Confetti-like macular atrophy: a new entity? J Dermatol. 2009;36:592-597.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Bauer EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271-279.

- Buechner SA, Rufli T. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. clinical and histopathologic findings and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in thirty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:441-446.

- Saleh Z, Abbas O, Dahdah MJ, et al. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini: a clinical and histopathological study. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1108-1114.

- Canizares O, Sachs PM, Jaimovich L, et al. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Arch Dermatol. 1958;77:42-58; discussion 58-60.

- Pullara TJ, Lober CW, Fenske NA. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:643-645.

- Jablonska S, Szczepanski A. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini: is it an entity? Dermatologica. 1962;125:226-242.

- Ang G, Hyde PM, Lee JB. Unilateral congenital linear atrophoderma of the leg. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:350-354.

- Miteva L, Kadurina M. Unilateral idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1391-1393.

- Kee CE, Brothers WS, New W. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini with coexistent morphea. a case report. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:100-103.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. an international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614-620.

- Winkelmann RK. Localized cutaneous scleroderma. Semin Dermatol. 1985;4:90-103.

- Dore SE. Two cases of morphoea guttata. Proc R Soc Med. 1918;11:26-28.

- Dore SE. Guttate morphoea. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:3-5.

- McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, et al. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:315-319.

- Jacobson L, Palazij R, Jaworsky C. Superficial morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:323-325.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Bunch JL. White-spot disease (morphoea guttata). Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:24-27.

To the Editor:

Morphea, atrophoderma, guttate lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), anetoderma, and their subtypes are inflammatory processes ultimately leading to dermal remodeling. We report a case of a scaly, hypopigmented, macular rash that clinically appeared as an entity along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum and demonstrated unique histopathologic changes in both collagen and elastin confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis. This case is a potentially rare variant representing a combination of clinical and microscopic findings.

A 29-year-old woman presented for an increasing number of white spots distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. She denied local and systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she was stung by 100 wasps 23 years prior. Following the assault, her grandmother placed chewed tobacco leaves atop the painful erythematous wheals and flares. Upon resolution, hypopigmented macules and patches remained in their place. The patient denied associated symptoms or new lesions; she did not seek care at that time.

In her early 20s, the patient noted new, similarly distributed hypopigmented macules and patches without associated arthropod assault. She was treated by an outside dermatologist without result for presumed tinea versicolor. A follow-up superficial shave biopsy cited subtle psoriasiform dermatitis. Topical steroids did not improve the lesions. Her medical history also was remarkable for a reportedly unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear.

Physical examination revealed 0.5- to 2.0-cm, ill-defined, perifollicular and nonfollicular, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk, arms, and legs. There was no follicular plugging (Figure 1A). The hands, feet, face, and mucosal surfaces were spared. She had no family history of similar lesions. Although atrophic in appearance, a single lesion on the left thigh was palpably depressed (Figure 1B). Serology demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and negative Lyme titers. Light therapy and topical steroids failed to improve the lesions; calcipotriene cream 0.005% made the lesions erythematous and pruritic.

A biopsy from a flank lesion demonstrated a normal epithelium without thinning, a normal basal melanocyte population, and minimally effaced rete ridges. Thin collagen bundles were noted in the upper reticular and papillary dermis with associated fibroplasia (Figure 2). Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed decreased and fragmented elastin filaments in the same dermal distribution as the changed collagen (Figure 3). There was no evidence of primary inflammatory disease. The dermis was thinned. Periodic acid–Schiff stain confirmed the absence of hyphae and spores.

The relevant findings in our patient including the following: (1) onset of hypopigmented macules and patches following resolution of a toxic insult; (2) initially stable number of lesions that progressed in number but not size; (3) thinned collagen associated with fibroplasia in the upper reticular and papillary dermis; (4) decreased number and fragmentation of elastin filaments confined to the same region; (5) no congenital lesions or similar lesions in family members; and (6) a complete rotator cuff tear with no findings of a systemic connective-tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

We performed a literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using combinations of the terms atrophic, hypopigmented, white, spot disease, confetti-like, guttate, macules, atrophoderma, morphea, anetoderma, elastin, and collagen to identify potentially similar reports of guttate hypopigmented macules demonstrating changes of the collagen and elastin in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. Some variants, namely atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP), guttate morphea, and superficial morphea, demonstrate similar clinical and histopathologic findings.

Findings similar to our case were documented in case reports of 2 women (aged 34 and 42 years)1 presenting with asymptomatic, atrophic, well-demarcated, shiny, hypopigmented macules over the trunk and upper extremities, which demonstrated a thinned epidermis with coarse hyalinized collagen bundles in the mid and lower dermis. There was upper and diffuse dermal elastolysis (patient 1 and patient 2, respectively).1 Our patient’s lesions were hypopigmented and atrophic in appearance but were slightly scaly and also involved the extremities. Distinct from these patient reports, histopathology from our case demonstrated thin packed collagen bundles and decreased fragmented elastin filaments confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis.

Plaque morphea is the most common type of localized scleroderma.2 The subtype APP demonstrates round to ovoid, gray-brown depressions with cliff-drop borders. They may appear flesh colored or hypopigmented.3,4 These sclerodermoid lesions lack the violaceous border classic to morphea. Sclerosis and induration also are typically absent.5 Clinically, our patient’s macules resembled this entity. Histopathologically, APP shows normal epithelium with an increased basal layer pigmentation; preserved adnexal structures; and mid to lower dermal collagen edema, clumping, and homogenization.3,4 Elastic fibers classically are unchanged, with exceptions.6-11 Changes in the collagen and elastin of our patient were unlike those reported in APP, which occur in the mid to lower dermis.

Guttate morphea demonstrates small, pale, minimally indurated, coin-shaped lesions on the trunk. Histopathology reveals less sclerosis and more edema, resembling LS&A.12 The earliest descriptions of this entity describe 3 stages: ivory/chalk white, scaly, and atrophic. Follicular plugging (absent in this patient) and fine scale can exist at any stage.13,14 Flattened rete ridges mark an otherwise preserved epidermis; hyalinized collagen typically is superficial and demonstrates less sclerosis yet increased edema.12-14 Fewer elastic fibers typically are present compared to normal skin. Changes seen in this entity are more superficial, as with our patient, than classic scleroderma. However, classic edema was not found in our patient’s biopsy specimen.

Superficial morphea, occurring predominantly in females, presents with hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patches having minimal to no induration. The lesions typically are asymptomatic. Histopathologically, collagen deposition and inflammation are confined to the superficial dermis without homogenization associated with LS&A, findings that were consistent with this patient’s biopsy.15,16 However, similar to other morpheaform variants, elastic fibers are unchanged.15 Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of the biopsy (Figure 3) showed the decreased and fragmented elastin network in the upper reticular and papillary dermis, making this entity less compatible.

Guttate LS&A may present with interfollicular, bluish white macules or papules coalescing into patches or plaques. Lesions evolve to reveal atrophic thin skin with follicular plugging. Histology demonstrates a thinned epidermis with orthohypokeratosis marked by flattened rete ridges. The dermis reveals short hyalinized collagen fibrils with a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, giving a homogenized appearance. Early disease is marked by an inflammatory infiltrate.17 Most of these findings are consistent with our patient’s pathology, which was confined to the upper dermis. Lacking, however, were characteristic findings of LS&A, including upper dermal homogenization, near-total effacement of rete ridges, orthokeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction. As such, this entity is less compatible.

Atrophoderma elastolyticum discretum has clinical features of atrophoderma with elastolytic histopathologic findings.1 Anetoderma presents with outpouchings of atrophic skin with a surrounding ring of normal tissue. Histopathologically, this entity shows normal collagen with elastolysis; there also is a decrease in desmosine, an elastin cross-linker.1,3 Neither the clinical nor histopathologic findings in this patient matched these 2 entities.

The reported chronologic association of these lesions with an arthropod assault raised suspicion to their association with toxic insult or postinflammatory changes. One study reported mechanical trauma, including insect bites, as a possible inciting factor of morphea.11 These data, gathered from patient surveys, reported trauma associated to lesion development.1,17 A review of the literature regarding atrophoderma, morphea, and LS&A failed to identify pathogenic changes seen in this patient following initial trauma. Moreover, although it is difficult to prove causality in the formation of the original hypopigmented spots, the development of identical spots in a similar distribution without further trauma suggests against these etiologies to fully explain her lesions. Nonetheless, circumstance makes it difficult to prove whether the original arthropod insult spurred a smoldering reactive process that caused the newer lesions.

Hereditary connective-tissue disorders also were considered in the differential diagnosis. Because of the patient’s history of an unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was considered; however, the remainder of her examination was normal, making a syndromic systemic disorder a less likely etiology.Because of the distinct clinical and histopathologic findings, this case may represent a rare and previously unreported variant of morphea. Clinically, these hypopigmented macules and patches exist somewhere along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum. Histopathologic findings do not conform to prior reports. The name atrophodermalike guttate morphea may be an appropriate appellation. It is possible this presentation represents a variant of what dermatologists have referred to as white spot disease.18 We hope that this case may bring others to discussion, allowing for the identification of a more precise entity and etiology so that patients may receive more directed therapy.

To the Editor:

Morphea, atrophoderma, guttate lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), anetoderma, and their subtypes are inflammatory processes ultimately leading to dermal remodeling. We report a case of a scaly, hypopigmented, macular rash that clinically appeared as an entity along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum and demonstrated unique histopathologic changes in both collagen and elastin confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis. This case is a potentially rare variant representing a combination of clinical and microscopic findings.

A 29-year-old woman presented for an increasing number of white spots distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. She denied local and systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she was stung by 100 wasps 23 years prior. Following the assault, her grandmother placed chewed tobacco leaves atop the painful erythematous wheals and flares. Upon resolution, hypopigmented macules and patches remained in their place. The patient denied associated symptoms or new lesions; she did not seek care at that time.

In her early 20s, the patient noted new, similarly distributed hypopigmented macules and patches without associated arthropod assault. She was treated by an outside dermatologist without result for presumed tinea versicolor. A follow-up superficial shave biopsy cited subtle psoriasiform dermatitis. Topical steroids did not improve the lesions. Her medical history also was remarkable for a reportedly unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear.

Physical examination revealed 0.5- to 2.0-cm, ill-defined, perifollicular and nonfollicular, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk, arms, and legs. There was no follicular plugging (Figure 1A). The hands, feet, face, and mucosal surfaces were spared. She had no family history of similar lesions. Although atrophic in appearance, a single lesion on the left thigh was palpably depressed (Figure 1B). Serology demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and negative Lyme titers. Light therapy and topical steroids failed to improve the lesions; calcipotriene cream 0.005% made the lesions erythematous and pruritic.

A biopsy from a flank lesion demonstrated a normal epithelium without thinning, a normal basal melanocyte population, and minimally effaced rete ridges. Thin collagen bundles were noted in the upper reticular and papillary dermis with associated fibroplasia (Figure 2). Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed decreased and fragmented elastin filaments in the same dermal distribution as the changed collagen (Figure 3). There was no evidence of primary inflammatory disease. The dermis was thinned. Periodic acid–Schiff stain confirmed the absence of hyphae and spores.

The relevant findings in our patient including the following: (1) onset of hypopigmented macules and patches following resolution of a toxic insult; (2) initially stable number of lesions that progressed in number but not size; (3) thinned collagen associated with fibroplasia in the upper reticular and papillary dermis; (4) decreased number and fragmentation of elastin filaments confined to the same region; (5) no congenital lesions or similar lesions in family members; and (6) a complete rotator cuff tear with no findings of a systemic connective-tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

We performed a literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using combinations of the terms atrophic, hypopigmented, white, spot disease, confetti-like, guttate, macules, atrophoderma, morphea, anetoderma, elastin, and collagen to identify potentially similar reports of guttate hypopigmented macules demonstrating changes of the collagen and elastin in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. Some variants, namely atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP), guttate morphea, and superficial morphea, demonstrate similar clinical and histopathologic findings.

Findings similar to our case were documented in case reports of 2 women (aged 34 and 42 years)1 presenting with asymptomatic, atrophic, well-demarcated, shiny, hypopigmented macules over the trunk and upper extremities, which demonstrated a thinned epidermis with coarse hyalinized collagen bundles in the mid and lower dermis. There was upper and diffuse dermal elastolysis (patient 1 and patient 2, respectively).1 Our patient’s lesions were hypopigmented and atrophic in appearance but were slightly scaly and also involved the extremities. Distinct from these patient reports, histopathology from our case demonstrated thin packed collagen bundles and decreased fragmented elastin filaments confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis.

Plaque morphea is the most common type of localized scleroderma.2 The subtype APP demonstrates round to ovoid, gray-brown depressions with cliff-drop borders. They may appear flesh colored or hypopigmented.3,4 These sclerodermoid lesions lack the violaceous border classic to morphea. Sclerosis and induration also are typically absent.5 Clinically, our patient’s macules resembled this entity. Histopathologically, APP shows normal epithelium with an increased basal layer pigmentation; preserved adnexal structures; and mid to lower dermal collagen edema, clumping, and homogenization.3,4 Elastic fibers classically are unchanged, with exceptions.6-11 Changes in the collagen and elastin of our patient were unlike those reported in APP, which occur in the mid to lower dermis.

Guttate morphea demonstrates small, pale, minimally indurated, coin-shaped lesions on the trunk. Histopathology reveals less sclerosis and more edema, resembling LS&A.12 The earliest descriptions of this entity describe 3 stages: ivory/chalk white, scaly, and atrophic. Follicular plugging (absent in this patient) and fine scale can exist at any stage.13,14 Flattened rete ridges mark an otherwise preserved epidermis; hyalinized collagen typically is superficial and demonstrates less sclerosis yet increased edema.12-14 Fewer elastic fibers typically are present compared to normal skin. Changes seen in this entity are more superficial, as with our patient, than classic scleroderma. However, classic edema was not found in our patient’s biopsy specimen.

Superficial morphea, occurring predominantly in females, presents with hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patches having minimal to no induration. The lesions typically are asymptomatic. Histopathologically, collagen deposition and inflammation are confined to the superficial dermis without homogenization associated with LS&A, findings that were consistent with this patient’s biopsy.15,16 However, similar to other morpheaform variants, elastic fibers are unchanged.15 Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of the biopsy (Figure 3) showed the decreased and fragmented elastin network in the upper reticular and papillary dermis, making this entity less compatible.

Guttate LS&A may present with interfollicular, bluish white macules or papules coalescing into patches or plaques. Lesions evolve to reveal atrophic thin skin with follicular plugging. Histology demonstrates a thinned epidermis with orthohypokeratosis marked by flattened rete ridges. The dermis reveals short hyalinized collagen fibrils with a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, giving a homogenized appearance. Early disease is marked by an inflammatory infiltrate.17 Most of these findings are consistent with our patient’s pathology, which was confined to the upper dermis. Lacking, however, were characteristic findings of LS&A, including upper dermal homogenization, near-total effacement of rete ridges, orthokeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction. As such, this entity is less compatible.

Atrophoderma elastolyticum discretum has clinical features of atrophoderma with elastolytic histopathologic findings.1 Anetoderma presents with outpouchings of atrophic skin with a surrounding ring of normal tissue. Histopathologically, this entity shows normal collagen with elastolysis; there also is a decrease in desmosine, an elastin cross-linker.1,3 Neither the clinical nor histopathologic findings in this patient matched these 2 entities.

The reported chronologic association of these lesions with an arthropod assault raised suspicion to their association with toxic insult or postinflammatory changes. One study reported mechanical trauma, including insect bites, as a possible inciting factor of morphea.11 These data, gathered from patient surveys, reported trauma associated to lesion development.1,17 A review of the literature regarding atrophoderma, morphea, and LS&A failed to identify pathogenic changes seen in this patient following initial trauma. Moreover, although it is difficult to prove causality in the formation of the original hypopigmented spots, the development of identical spots in a similar distribution without further trauma suggests against these etiologies to fully explain her lesions. Nonetheless, circumstance makes it difficult to prove whether the original arthropod insult spurred a smoldering reactive process that caused the newer lesions.

Hereditary connective-tissue disorders also were considered in the differential diagnosis. Because of the patient’s history of an unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was considered; however, the remainder of her examination was normal, making a syndromic systemic disorder a less likely etiology.Because of the distinct clinical and histopathologic findings, this case may represent a rare and previously unreported variant of morphea. Clinically, these hypopigmented macules and patches exist somewhere along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum. Histopathologic findings do not conform to prior reports. The name atrophodermalike guttate morphea may be an appropriate appellation. It is possible this presentation represents a variant of what dermatologists have referred to as white spot disease.18 We hope that this case may bring others to discussion, allowing for the identification of a more precise entity and etiology so that patients may receive more directed therapy.

- Aksoy B, Ustün H, Gulbahce R, et al. Confetti-like macular atrophy: a new entity? J Dermatol. 2009;36:592-597.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Bauer EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271-279.

- Buechner SA, Rufli T. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. clinical and histopathologic findings and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in thirty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:441-446.

- Saleh Z, Abbas O, Dahdah MJ, et al. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini: a clinical and histopathological study. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1108-1114.

- Canizares O, Sachs PM, Jaimovich L, et al. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Arch Dermatol. 1958;77:42-58; discussion 58-60.

- Pullara TJ, Lober CW, Fenske NA. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:643-645.

- Jablonska S, Szczepanski A. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini: is it an entity? Dermatologica. 1962;125:226-242.

- Ang G, Hyde PM, Lee JB. Unilateral congenital linear atrophoderma of the leg. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:350-354.

- Miteva L, Kadurina M. Unilateral idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1391-1393.

- Kee CE, Brothers WS, New W. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini with coexistent morphea. a case report. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:100-103.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. an international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614-620.

- Winkelmann RK. Localized cutaneous scleroderma. Semin Dermatol. 1985;4:90-103.

- Dore SE. Two cases of morphoea guttata. Proc R Soc Med. 1918;11:26-28.

- Dore SE. Guttate morphoea. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:3-5.

- McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, et al. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:315-319.

- Jacobson L, Palazij R, Jaworsky C. Superficial morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:323-325.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Bunch JL. White-spot disease (morphoea guttata). Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:24-27.

- Aksoy B, Ustün H, Gulbahce R, et al. Confetti-like macular atrophy: a new entity? J Dermatol. 2009;36:592-597.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Bauer EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271-279.

- Buechner SA, Rufli T. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. clinical and histopathologic findings and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in thirty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:441-446.

- Saleh Z, Abbas O, Dahdah MJ, et al. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini: a clinical and histopathological study. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1108-1114.

- Canizares O, Sachs PM, Jaimovich L, et al. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Arch Dermatol. 1958;77:42-58; discussion 58-60.

- Pullara TJ, Lober CW, Fenske NA. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:643-645.

- Jablonska S, Szczepanski A. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini: is it an entity? Dermatologica. 1962;125:226-242.

- Ang G, Hyde PM, Lee JB. Unilateral congenital linear atrophoderma of the leg. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:350-354.

- Miteva L, Kadurina M. Unilateral idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1391-1393.

- Kee CE, Brothers WS, New W. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini with coexistent morphea. a case report. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:100-103.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. an international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614-620.

- Winkelmann RK. Localized cutaneous scleroderma. Semin Dermatol. 1985;4:90-103.

- Dore SE. Two cases of morphoea guttata. Proc R Soc Med. 1918;11:26-28.

- Dore SE. Guttate morphoea. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:3-5.

- McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, et al. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:315-319.

- Jacobson L, Palazij R, Jaworsky C. Superficial morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:323-325.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Bunch JL. White-spot disease (morphoea guttata). Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:24-27.

Practice Points

- Atrophodermalike guttate morphea is a potentially underreported or undescribed entity consisting of a combination of clinicopathologic features.

- Widespread hypopigmented macules on the trunk and extremities marked by thinned collagen, fibroplasia, and altered fragmented elastin in the papillary dermis and upper reticular dermis are the key features.

- Atrophoderma, morphea, and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus should be ruled out during clinical workup.

Gottron Papules Mimicking Dermatomyositis: An Unusual Manifestation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

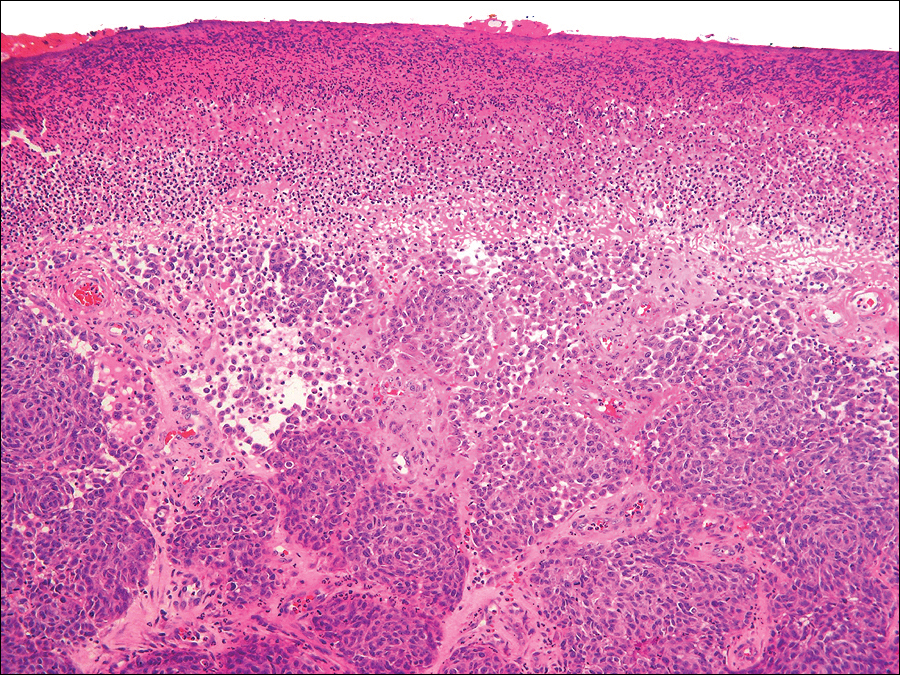

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5