User login

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

To the Editor:

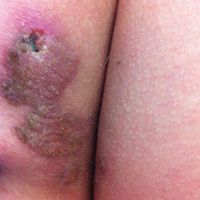

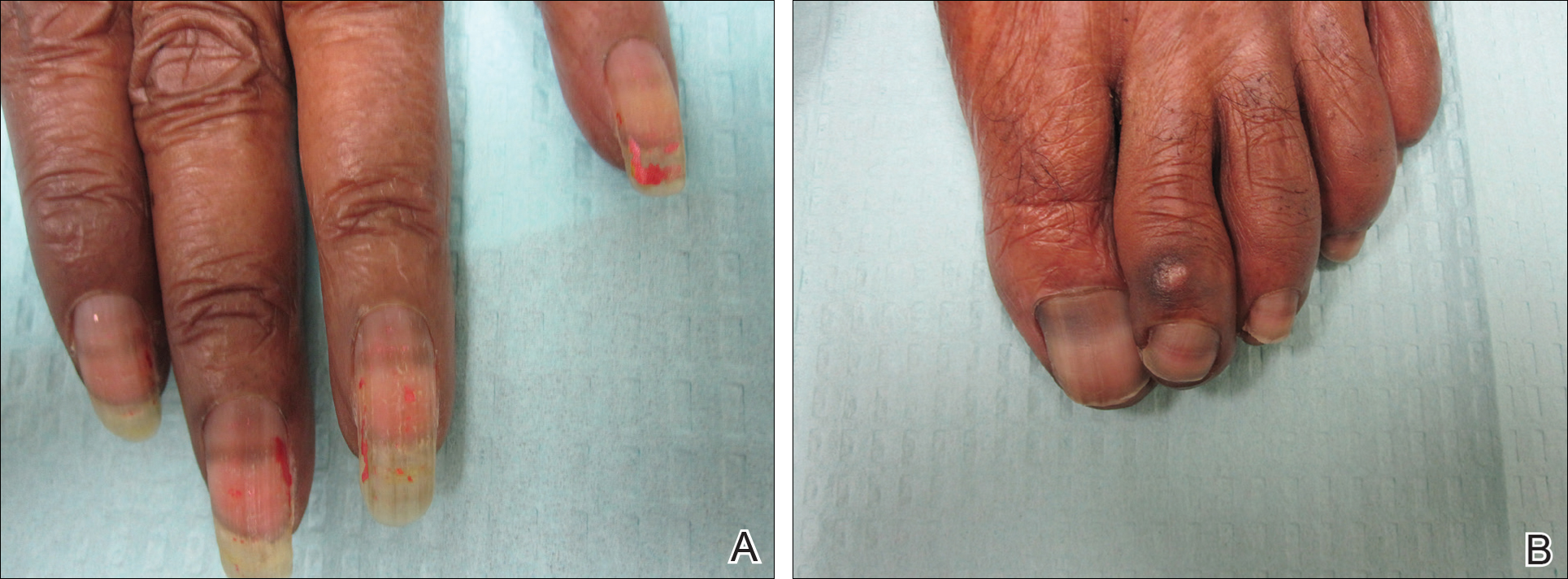

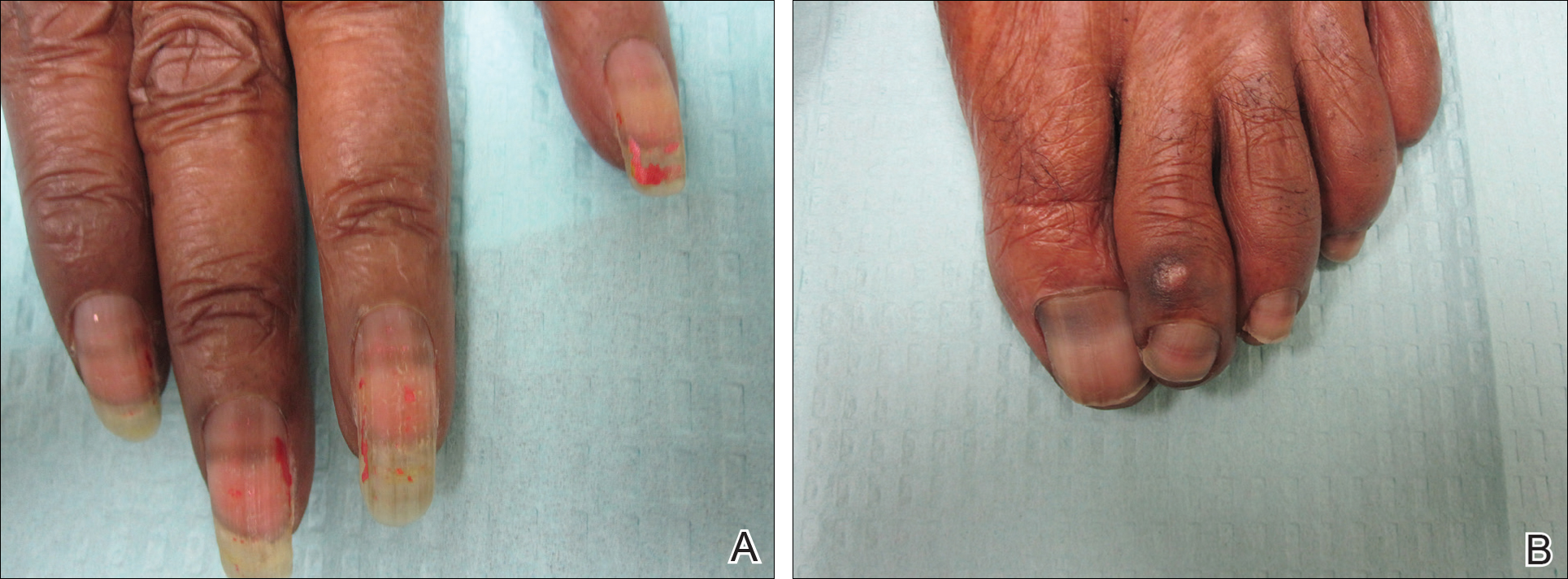

A 41-year-old man presented with a slowly enlarging, tender, firm lesion on the left hallux of approximately 5 months' duration that initially appeared to be a blister. He reported no history of keloids or trauma to the left foot. On examination, a 3.5-cm, flesh-colored, pedunculated, firm nodule was present on the lateral aspect of the left great hallux (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was found. The lesion was diagnosed at that time as a keloid and treated with intralesional steroids without response. The patient was lost to follow-up, and after 5 months he presented again with pain and drainage from the lesion. Acute drainage resolved after antibiotic therapy. A shave biopsy was performed, which revealed findings consistent with a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). A chest radiograph was unremarkable. Re-excision was performed with negative margins on frozen section but with positive peripheral and deep margins on permanent sections. The patient subsequently underwent amputation of the left great toe and was lost to follow-up after the initial postoperative period.

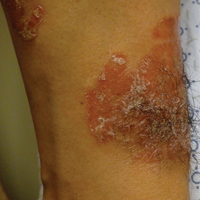

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a polypoid spindle cell tumor that filled the dermis and invaded into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 2). The spindle cells had tapered nuclei in a honeycomb arrangement with only mild nuclear pleomorphism arranged in fascicles with a herringbone formation. Areas showed a myxoid stroma with abundant mucin (Figure 3). Immunostaining demonstrated cells strongly positive for CD34 and negative for MART (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells), S-100, and smooth muscle actin immunostains.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a sarcoma that is locally aggressive and tends to recur after surgical excision, though rare cases of metastasis involving the lungs have been reported.12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually affects young to middle-aged adults. Acral DFSP is rare in adults, with tumors most commonly occurring on the trunk (50%-60%), proximal extremities (20%-30%), or the head and neck (10%-15%).1,2 A higher rate of acral DFSP has been found in children, which may be due to the increased rate of extremity trauma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans commonly presents as an asymptomatic, slowly growing, indurated plaque that may be flesh colored or hyperpigmented, followed by development of erythematous firm nodules of up to several centimeters.1,3 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may be associated with a purulent exudate or ulceration, and pain may develop as the lesion grows.

Histopathologic evaluation shows an early plaque stage characterized by low cellularity, minimal nuclear atypia, and rare mitotic figures.4 In the nodular stage, the spindle cells are arranged as short fascicles in a storiform arrangement and infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomb pattern with hyperchromatic nuclei and mitotic figures. The nodules may develop myxomatous areas as well as less-differentiated foci with intersecting fascicles in a herringbone pattern. Anti-CD34 antibody immunostaining demonstrates strongly positive spindle cells, while DFSP is negative for stromelysin 3, factor XIIIa, and D2-40, which can help to differentiate DFSP from dermatofibroma.5 The myxoid subtype of DFSP does not differ clinically or prognostically from conventional DFSP, though its recognition can be of use in differentiating other myxoid tumors. Myxoid DFSP is nearly always positive for CD34 and negative for the neural marker S-100 protein.6

Some reports have demonstrated that Mohs micrographic surgery is superior to wide local excision in treatment of DFSP, as it results in fewer local recurrences and metastases.7,8 Because of cytogenic abnormalities such as a reciprocal chromosomal (17;22) translocation or supernumerary ring chromosome derived from t(17;22) that place the PDGFB gene under the control of COL1A1 promoter, imatinib mesylate has been tested in DFSP and resulted in dramatic responses in both adults and children.9,10 Suggested uses of imatinib include metastatic disease and locally invasive disease not suitable for surgical excision as well as a method to debulk tumors prior to resection.11

- Gloster HM Jr. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):355-374; quiz 375-376.

- Do AN, Goleno K, Geisse JK. Mohs micrographic surgery and partial amputation preserving function and aesthetics in digits: case reports of invasive melanoma and digital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1516-1521.

- Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

- Kamino H, Reddy VB, Pui J. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2012:1961-1977.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Monteagudo C, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a comprehensive review and update of diagnosis and management. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2013;30:13-28.

- Paradisi A, Abeni D, Rusciani A, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: wide local excision vs. Mohs micrographic surgery. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:728-736.

- Foroozan M, Sei JF, Amini M, et al. Efficacy of Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1055-1063.

- Patel KU, Szaebo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- McArthur GA, Demetri GD, van Oosterom A, et al. Molecular and clinical analysis of locally advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans treated with imatinib: Imatinib Target Exploration Consortium Study B2225. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:866-873.

- Rutkowski P, Van Glabbeke M, Rankin CJ, et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue/Bone Sarcoma Group, Southwest Oncology Group. Imatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trials [published online March 1, 2010]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1772-1779.

- Mentzel T, Beham A, Katenkamp D, et al. Fibrosarcomatous ("high-grade") dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of a series of 41 cases with emphasis on prognostic significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:576-587.

To the Editor:

A 41-year-old man presented with a slowly enlarging, tender, firm lesion on the left hallux of approximately 5 months' duration that initially appeared to be a blister. He reported no history of keloids or trauma to the left foot. On examination, a 3.5-cm, flesh-colored, pedunculated, firm nodule was present on the lateral aspect of the left great hallux (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was found. The lesion was diagnosed at that time as a keloid and treated with intralesional steroids without response. The patient was lost to follow-up, and after 5 months he presented again with pain and drainage from the lesion. Acute drainage resolved after antibiotic therapy. A shave biopsy was performed, which revealed findings consistent with a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). A chest radiograph was unremarkable. Re-excision was performed with negative margins on frozen section but with positive peripheral and deep margins on permanent sections. The patient subsequently underwent amputation of the left great toe and was lost to follow-up after the initial postoperative period.

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a polypoid spindle cell tumor that filled the dermis and invaded into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 2). The spindle cells had tapered nuclei in a honeycomb arrangement with only mild nuclear pleomorphism arranged in fascicles with a herringbone formation. Areas showed a myxoid stroma with abundant mucin (Figure 3). Immunostaining demonstrated cells strongly positive for CD34 and negative for MART (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells), S-100, and smooth muscle actin immunostains.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a sarcoma that is locally aggressive and tends to recur after surgical excision, though rare cases of metastasis involving the lungs have been reported.12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually affects young to middle-aged adults. Acral DFSP is rare in adults, with tumors most commonly occurring on the trunk (50%-60%), proximal extremities (20%-30%), or the head and neck (10%-15%).1,2 A higher rate of acral DFSP has been found in children, which may be due to the increased rate of extremity trauma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans commonly presents as an asymptomatic, slowly growing, indurated plaque that may be flesh colored or hyperpigmented, followed by development of erythematous firm nodules of up to several centimeters.1,3 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may be associated with a purulent exudate or ulceration, and pain may develop as the lesion grows.

Histopathologic evaluation shows an early plaque stage characterized by low cellularity, minimal nuclear atypia, and rare mitotic figures.4 In the nodular stage, the spindle cells are arranged as short fascicles in a storiform arrangement and infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomb pattern with hyperchromatic nuclei and mitotic figures. The nodules may develop myxomatous areas as well as less-differentiated foci with intersecting fascicles in a herringbone pattern. Anti-CD34 antibody immunostaining demonstrates strongly positive spindle cells, while DFSP is negative for stromelysin 3, factor XIIIa, and D2-40, which can help to differentiate DFSP from dermatofibroma.5 The myxoid subtype of DFSP does not differ clinically or prognostically from conventional DFSP, though its recognition can be of use in differentiating other myxoid tumors. Myxoid DFSP is nearly always positive for CD34 and negative for the neural marker S-100 protein.6

Some reports have demonstrated that Mohs micrographic surgery is superior to wide local excision in treatment of DFSP, as it results in fewer local recurrences and metastases.7,8 Because of cytogenic abnormalities such as a reciprocal chromosomal (17;22) translocation or supernumerary ring chromosome derived from t(17;22) that place the PDGFB gene under the control of COL1A1 promoter, imatinib mesylate has been tested in DFSP and resulted in dramatic responses in both adults and children.9,10 Suggested uses of imatinib include metastatic disease and locally invasive disease not suitable for surgical excision as well as a method to debulk tumors prior to resection.11

To the Editor:

A 41-year-old man presented with a slowly enlarging, tender, firm lesion on the left hallux of approximately 5 months' duration that initially appeared to be a blister. He reported no history of keloids or trauma to the left foot. On examination, a 3.5-cm, flesh-colored, pedunculated, firm nodule was present on the lateral aspect of the left great hallux (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was found. The lesion was diagnosed at that time as a keloid and treated with intralesional steroids without response. The patient was lost to follow-up, and after 5 months he presented again with pain and drainage from the lesion. Acute drainage resolved after antibiotic therapy. A shave biopsy was performed, which revealed findings consistent with a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). A chest radiograph was unremarkable. Re-excision was performed with negative margins on frozen section but with positive peripheral and deep margins on permanent sections. The patient subsequently underwent amputation of the left great toe and was lost to follow-up after the initial postoperative period.

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a polypoid spindle cell tumor that filled the dermis and invaded into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 2). The spindle cells had tapered nuclei in a honeycomb arrangement with only mild nuclear pleomorphism arranged in fascicles with a herringbone formation. Areas showed a myxoid stroma with abundant mucin (Figure 3). Immunostaining demonstrated cells strongly positive for CD34 and negative for MART (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells), S-100, and smooth muscle actin immunostains.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a sarcoma that is locally aggressive and tends to recur after surgical excision, though rare cases of metastasis involving the lungs have been reported.12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually affects young to middle-aged adults. Acral DFSP is rare in adults, with tumors most commonly occurring on the trunk (50%-60%), proximal extremities (20%-30%), or the head and neck (10%-15%).1,2 A higher rate of acral DFSP has been found in children, which may be due to the increased rate of extremity trauma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans commonly presents as an asymptomatic, slowly growing, indurated plaque that may be flesh colored or hyperpigmented, followed by development of erythematous firm nodules of up to several centimeters.1,3 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans may be associated with a purulent exudate or ulceration, and pain may develop as the lesion grows.

Histopathologic evaluation shows an early plaque stage characterized by low cellularity, minimal nuclear atypia, and rare mitotic figures.4 In the nodular stage, the spindle cells are arranged as short fascicles in a storiform arrangement and infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomb pattern with hyperchromatic nuclei and mitotic figures. The nodules may develop myxomatous areas as well as less-differentiated foci with intersecting fascicles in a herringbone pattern. Anti-CD34 antibody immunostaining demonstrates strongly positive spindle cells, while DFSP is negative for stromelysin 3, factor XIIIa, and D2-40, which can help to differentiate DFSP from dermatofibroma.5 The myxoid subtype of DFSP does not differ clinically or prognostically from conventional DFSP, though its recognition can be of use in differentiating other myxoid tumors. Myxoid DFSP is nearly always positive for CD34 and negative for the neural marker S-100 protein.6

Some reports have demonstrated that Mohs micrographic surgery is superior to wide local excision in treatment of DFSP, as it results in fewer local recurrences and metastases.7,8 Because of cytogenic abnormalities such as a reciprocal chromosomal (17;22) translocation or supernumerary ring chromosome derived from t(17;22) that place the PDGFB gene under the control of COL1A1 promoter, imatinib mesylate has been tested in DFSP and resulted in dramatic responses in both adults and children.9,10 Suggested uses of imatinib include metastatic disease and locally invasive disease not suitable for surgical excision as well as a method to debulk tumors prior to resection.11

- Gloster HM Jr. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):355-374; quiz 375-376.

- Do AN, Goleno K, Geisse JK. Mohs micrographic surgery and partial amputation preserving function and aesthetics in digits: case reports of invasive melanoma and digital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1516-1521.

- Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

- Kamino H, Reddy VB, Pui J. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2012:1961-1977.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Monteagudo C, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a comprehensive review and update of diagnosis and management. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2013;30:13-28.

- Paradisi A, Abeni D, Rusciani A, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: wide local excision vs. Mohs micrographic surgery. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:728-736.

- Foroozan M, Sei JF, Amini M, et al. Efficacy of Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1055-1063.

- Patel KU, Szaebo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- McArthur GA, Demetri GD, van Oosterom A, et al. Molecular and clinical analysis of locally advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans treated with imatinib: Imatinib Target Exploration Consortium Study B2225. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:866-873.

- Rutkowski P, Van Glabbeke M, Rankin CJ, et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue/Bone Sarcoma Group, Southwest Oncology Group. Imatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trials [published online March 1, 2010]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1772-1779.

- Mentzel T, Beham A, Katenkamp D, et al. Fibrosarcomatous ("high-grade") dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of a series of 41 cases with emphasis on prognostic significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:576-587.

- Gloster HM Jr. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):355-374; quiz 375-376.

- Do AN, Goleno K, Geisse JK. Mohs micrographic surgery and partial amputation preserving function and aesthetics in digits: case reports of invasive melanoma and digital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1516-1521.

- Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

- Kamino H, Reddy VB, Pui J. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2012:1961-1977.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Monteagudo C, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a comprehensive review and update of diagnosis and management. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2013;30:13-28.

- Paradisi A, Abeni D, Rusciani A, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: wide local excision vs. Mohs micrographic surgery. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:728-736.

- Foroozan M, Sei JF, Amini M, et al. Efficacy of Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1055-1063.

- Patel KU, Szaebo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- McArthur GA, Demetri GD, van Oosterom A, et al. Molecular and clinical analysis of locally advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans treated with imatinib: Imatinib Target Exploration Consortium Study B2225. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:866-873.

- Rutkowski P, Van Glabbeke M, Rankin CJ, et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue/Bone Sarcoma Group, Southwest Oncology Group. Imatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trials [published online March 1, 2010]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1772-1779.

- Mentzel T, Beham A, Katenkamp D, et al. Fibrosarcomatous ("high-grade") dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of a series of 41 cases with emphasis on prognostic significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:576-587.

Practice Points

- Consider dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans for a keloidlike enlarging lesion when there is no history of trauma or prior keloid formation.

- Treatments such as Mohs micrographic surgery or oral imatinib mesylate can provide lower recurrence rates in appropriate patients as stand-alone or adjuvant therapy.

Temporal Triangular Alopecia Acquired in Adulthood

To the Editor:

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), a condition first described by Sabouraud1 in 1905, is a circumscribed nonscarring form of alopecia. Also referred to as congenital triangular alopecia, TTA presents as a triangular or lancet-shaped area of hair loss involving the frontotemporal hairline. Temporal triangular alopecia is characterized histologically by a normal number of miniaturized hair follicles without notable inflammation.2 Although the majority of cases arise between birth and 9 years of age,3,4 rare cases of adult-onset TTA also have been reported.5,6 Adult-onset cases can cause notable diagnostic confusion and inappropriate treatment, as reported in our patient.

A 25-year-old woman with a history of Hashimoto thyroiditis presented with hair loss affecting the right temporal scalp of 3 years' duration that was first noticed by her husband. The lesion was an asymptomatic, 6×8-cm, roughly lancet-shaped patch of alopecia located on the right temporal scalp, bordering on the frontal hairline (Figure 1). Centrally, the patch appeared almost hairless with a few retained terminal hairs. The frontal hairline was thinned but still present. There was no scaling or erythema, and fine vellus hairs and a few isolated terminal hairs covered the area. The corresponding skin on the contralateral temporal scalp showed normal hair density. The patient insisted that she had normal hair at the affected area until 22 years of age, and she denied a history of trauma or tight hairstyles. Initially diagnosed with alopecia areata by her primary care provider, the patient was treated with topical corticosteroids for 6 months without benefit. She was subsequently referred to a dermatologist who again offered a diagnosis of alopecia areata and treated the lesions with 2 intralesional corticosteroid injections without benefit. No biopsies of the affected area were performed, and the patient was given a trial of topical minoxidil.

The patient consulted a new primary care provider and was diagnosed with scarring alopecia. She was referred to our dermatology department for further treatment. An initial biopsy at the edge of the affected area was interpreted as normal, but after failing additional intralesional corticosteroid injections, she was referred to our hair clinic where another biopsy was performed in the central portion of the lesion. A 4-mm diameter punch biopsy specimen revealed a normal epidermis and dermis; however, in the lower dermis only a single terminal follicle was seen (Figure 2). Sections through the upper dermis (Figure 3) showed that the total number of hairs was normal or nearly normal with at least 22 follicles, but most were vellus and indeterminate hairs with only a single terminal hair. The dermal architecture was otherwise normal. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of TTA was made. Subsequent to the diagnosis, the patient did not pursue any additional treatment options and preferred to style her hair so that the area of TTA remained covered.

The differential diagnosis in adults presenting with a patch of localized alopecia includes alopecia areata, trichotillomania, pressure-induced alopecia, traction alopecia, lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus erythematosus, and rarely TTA. Temporal triangular alopecia is a fairly common, if underreported, nonscarring form of alopecia that mainly affects young children. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms temporal triangular alopecia or congenital triangular alopecia or triangular alopecia documented only 76 cases of TTA including our own, with the majority of patients diagnosed before 9 years of age. Only 2 cases of adult-onset TTA have been reported,5,6 possibly leading to misdiagnosis of adult patients who present with similar areas of hair loss. As with some prior cases of TTA,5,7 our patient was misdiagnosed with alopecia areata and scarring alopecia, both treated unsuccessfully before a diagnosis of TTA was considered. Clues to the diagnosis included the location, the lack of change in size and shape, the lack of response to intralesional corticosteroids, and the presence of numerous vellus hairs on the surface. A biopsy of the visibly hairless zone was confirmatory. The normal or nearly normal number of miniaturized hairs in specimens of TTA suggest that topical minoxidil therapy (eg, 5% solution twice daily for at least 6 months) might be useful, but the authors have tried it on a few other patients with clinically typical TTA without discernible benefit. When lesions are small, excision provides a fast and permanent solution to the problem, albeit with the usual risks of minor surgery.

- Sabouraud RJA. Manuel Élémentaire de Dermatologie Topographique Régionale. Paris, France: Masson & Cie; 1905:197.

- Trakimas C, Sperling LC, Skelton HG 3rd, et al. Clinical and histologic findings in temporal triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:205-209.

- Yamazaki M, Irisawa R, Tsuboi R. Temporal triangular alopecia and a review of 52 past cases. J Dermatol. 2010;37:360-362.

- Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C, et al. Prevalence of scalp disorders and hair loss in children. Cutis. 2012;90:225-229.

- Trakimas CA, Sperling LC. Temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:842-844.

- Akan IM, Yildirim S, Avci G, et al. Bilateral temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1616-1617.

- Gupta LK, Khare AK, Garg A, et al. Congenital triangular alopecia--a close mimicker of alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:40-41.

To the Editor:

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), a condition first described by Sabouraud1 in 1905, is a circumscribed nonscarring form of alopecia. Also referred to as congenital triangular alopecia, TTA presents as a triangular or lancet-shaped area of hair loss involving the frontotemporal hairline. Temporal triangular alopecia is characterized histologically by a normal number of miniaturized hair follicles without notable inflammation.2 Although the majority of cases arise between birth and 9 years of age,3,4 rare cases of adult-onset TTA also have been reported.5,6 Adult-onset cases can cause notable diagnostic confusion and inappropriate treatment, as reported in our patient.

A 25-year-old woman with a history of Hashimoto thyroiditis presented with hair loss affecting the right temporal scalp of 3 years' duration that was first noticed by her husband. The lesion was an asymptomatic, 6×8-cm, roughly lancet-shaped patch of alopecia located on the right temporal scalp, bordering on the frontal hairline (Figure 1). Centrally, the patch appeared almost hairless with a few retained terminal hairs. The frontal hairline was thinned but still present. There was no scaling or erythema, and fine vellus hairs and a few isolated terminal hairs covered the area. The corresponding skin on the contralateral temporal scalp showed normal hair density. The patient insisted that she had normal hair at the affected area until 22 years of age, and she denied a history of trauma or tight hairstyles. Initially diagnosed with alopecia areata by her primary care provider, the patient was treated with topical corticosteroids for 6 months without benefit. She was subsequently referred to a dermatologist who again offered a diagnosis of alopecia areata and treated the lesions with 2 intralesional corticosteroid injections without benefit. No biopsies of the affected area were performed, and the patient was given a trial of topical minoxidil.

The patient consulted a new primary care provider and was diagnosed with scarring alopecia. She was referred to our dermatology department for further treatment. An initial biopsy at the edge of the affected area was interpreted as normal, but after failing additional intralesional corticosteroid injections, she was referred to our hair clinic where another biopsy was performed in the central portion of the lesion. A 4-mm diameter punch biopsy specimen revealed a normal epidermis and dermis; however, in the lower dermis only a single terminal follicle was seen (Figure 2). Sections through the upper dermis (Figure 3) showed that the total number of hairs was normal or nearly normal with at least 22 follicles, but most were vellus and indeterminate hairs with only a single terminal hair. The dermal architecture was otherwise normal. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of TTA was made. Subsequent to the diagnosis, the patient did not pursue any additional treatment options and preferred to style her hair so that the area of TTA remained covered.

The differential diagnosis in adults presenting with a patch of localized alopecia includes alopecia areata, trichotillomania, pressure-induced alopecia, traction alopecia, lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus erythematosus, and rarely TTA. Temporal triangular alopecia is a fairly common, if underreported, nonscarring form of alopecia that mainly affects young children. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms temporal triangular alopecia or congenital triangular alopecia or triangular alopecia documented only 76 cases of TTA including our own, with the majority of patients diagnosed before 9 years of age. Only 2 cases of adult-onset TTA have been reported,5,6 possibly leading to misdiagnosis of adult patients who present with similar areas of hair loss. As with some prior cases of TTA,5,7 our patient was misdiagnosed with alopecia areata and scarring alopecia, both treated unsuccessfully before a diagnosis of TTA was considered. Clues to the diagnosis included the location, the lack of change in size and shape, the lack of response to intralesional corticosteroids, and the presence of numerous vellus hairs on the surface. A biopsy of the visibly hairless zone was confirmatory. The normal or nearly normal number of miniaturized hairs in specimens of TTA suggest that topical minoxidil therapy (eg, 5% solution twice daily for at least 6 months) might be useful, but the authors have tried it on a few other patients with clinically typical TTA without discernible benefit. When lesions are small, excision provides a fast and permanent solution to the problem, albeit with the usual risks of minor surgery.

To the Editor:

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), a condition first described by Sabouraud1 in 1905, is a circumscribed nonscarring form of alopecia. Also referred to as congenital triangular alopecia, TTA presents as a triangular or lancet-shaped area of hair loss involving the frontotemporal hairline. Temporal triangular alopecia is characterized histologically by a normal number of miniaturized hair follicles without notable inflammation.2 Although the majority of cases arise between birth and 9 years of age,3,4 rare cases of adult-onset TTA also have been reported.5,6 Adult-onset cases can cause notable diagnostic confusion and inappropriate treatment, as reported in our patient.

A 25-year-old woman with a history of Hashimoto thyroiditis presented with hair loss affecting the right temporal scalp of 3 years' duration that was first noticed by her husband. The lesion was an asymptomatic, 6×8-cm, roughly lancet-shaped patch of alopecia located on the right temporal scalp, bordering on the frontal hairline (Figure 1). Centrally, the patch appeared almost hairless with a few retained terminal hairs. The frontal hairline was thinned but still present. There was no scaling or erythema, and fine vellus hairs and a few isolated terminal hairs covered the area. The corresponding skin on the contralateral temporal scalp showed normal hair density. The patient insisted that she had normal hair at the affected area until 22 years of age, and she denied a history of trauma or tight hairstyles. Initially diagnosed with alopecia areata by her primary care provider, the patient was treated with topical corticosteroids for 6 months without benefit. She was subsequently referred to a dermatologist who again offered a diagnosis of alopecia areata and treated the lesions with 2 intralesional corticosteroid injections without benefit. No biopsies of the affected area were performed, and the patient was given a trial of topical minoxidil.

The patient consulted a new primary care provider and was diagnosed with scarring alopecia. She was referred to our dermatology department for further treatment. An initial biopsy at the edge of the affected area was interpreted as normal, but after failing additional intralesional corticosteroid injections, she was referred to our hair clinic where another biopsy was performed in the central portion of the lesion. A 4-mm diameter punch biopsy specimen revealed a normal epidermis and dermis; however, in the lower dermis only a single terminal follicle was seen (Figure 2). Sections through the upper dermis (Figure 3) showed that the total number of hairs was normal or nearly normal with at least 22 follicles, but most were vellus and indeterminate hairs with only a single terminal hair. The dermal architecture was otherwise normal. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of TTA was made. Subsequent to the diagnosis, the patient did not pursue any additional treatment options and preferred to style her hair so that the area of TTA remained covered.

The differential diagnosis in adults presenting with a patch of localized alopecia includes alopecia areata, trichotillomania, pressure-induced alopecia, traction alopecia, lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus erythematosus, and rarely TTA. Temporal triangular alopecia is a fairly common, if underreported, nonscarring form of alopecia that mainly affects young children. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms temporal triangular alopecia or congenital triangular alopecia or triangular alopecia documented only 76 cases of TTA including our own, with the majority of patients diagnosed before 9 years of age. Only 2 cases of adult-onset TTA have been reported,5,6 possibly leading to misdiagnosis of adult patients who present with similar areas of hair loss. As with some prior cases of TTA,5,7 our patient was misdiagnosed with alopecia areata and scarring alopecia, both treated unsuccessfully before a diagnosis of TTA was considered. Clues to the diagnosis included the location, the lack of change in size and shape, the lack of response to intralesional corticosteroids, and the presence of numerous vellus hairs on the surface. A biopsy of the visibly hairless zone was confirmatory. The normal or nearly normal number of miniaturized hairs in specimens of TTA suggest that topical minoxidil therapy (eg, 5% solution twice daily for at least 6 months) might be useful, but the authors have tried it on a few other patients with clinically typical TTA without discernible benefit. When lesions are small, excision provides a fast and permanent solution to the problem, albeit with the usual risks of minor surgery.

- Sabouraud RJA. Manuel Élémentaire de Dermatologie Topographique Régionale. Paris, France: Masson & Cie; 1905:197.

- Trakimas C, Sperling LC, Skelton HG 3rd, et al. Clinical and histologic findings in temporal triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:205-209.

- Yamazaki M, Irisawa R, Tsuboi R. Temporal triangular alopecia and a review of 52 past cases. J Dermatol. 2010;37:360-362.

- Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C, et al. Prevalence of scalp disorders and hair loss in children. Cutis. 2012;90:225-229.

- Trakimas CA, Sperling LC. Temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:842-844.

- Akan IM, Yildirim S, Avci G, et al. Bilateral temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1616-1617.

- Gupta LK, Khare AK, Garg A, et al. Congenital triangular alopecia--a close mimicker of alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:40-41.

- Sabouraud RJA. Manuel Élémentaire de Dermatologie Topographique Régionale. Paris, France: Masson & Cie; 1905:197.

- Trakimas C, Sperling LC, Skelton HG 3rd, et al. Clinical and histologic findings in temporal triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:205-209.

- Yamazaki M, Irisawa R, Tsuboi R. Temporal triangular alopecia and a review of 52 past cases. J Dermatol. 2010;37:360-362.

- Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C, et al. Prevalence of scalp disorders and hair loss in children. Cutis. 2012;90:225-229.

- Trakimas CA, Sperling LC. Temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:842-844.

- Akan IM, Yildirim S, Avci G, et al. Bilateral temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1616-1617.

- Gupta LK, Khare AK, Garg A, et al. Congenital triangular alopecia--a close mimicker of alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:40-41.

Practice Points

- Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA) in adults often is confused with alopecia areata.

- An acquired, persistent, unchanging, circumscribed hairless spot in an adult that does not respond to intralesional corticosteroids may represent TTA.

- Hair miniaturization without peribulbar inflammation is consistent with a diagnosis of TTA.

Netherton Syndrome in Association With Vitamin D Deficiency

To the Editor:

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare genodermatosis that presents with erythroderma accompanied with failure to thrive in the neonatal period. Ichthyosis linearis circumflexa, or double-edged scale, is a typical skin finding. Chronic severe atopic dermatitis with diffuse generalized xerosis usually develops and often is associated with elevated IgE levels; however, a feature most associated with and crucial for the diagnosis of NS is trichorrhexis invaginata, or bamboo hair, that causes patchy hair thinning. The triad of ichthyosis linearis circumflexa, atopic dermatitis, and trichorrhexis invaginata is diagnostic of NS. Several other clinical features, including delayed growth, skeletal age delay, and short stature also can develop during its clinical course.1

Netherton syndrome is an autosomal-recessive disorder resulting from a mutation in the SPINK5 gene, which encodes a serine protease inhibitor important in skin barrier formation and immunity.2 Thus, frequent infections are common in these patients. Current treatment options include emollients and topical anti-inflammatory agents to minimize and control the classic manifestations of NS.

A 10-year-old girl with a history of allergic rhinitis and multiple food allergies presented to the dermatology clinic with a long history of diffuse generalized xerosis and erythema with areas of lichenification and scaly patches on the face, trunk, and extremities. She was born prematurely at 34 weeks and developed scaling and erythema involving most of the body shortly after birth. She exhibited severe failure to thrive that necessitated placement of a gastrostomy feeding tube at 8 months of age, resulting in satisfactory weight gain and the tube was later removed. A liver biopsy obtained at that time revealed early intrahepatic duct obstruction and early cirrhosis. She continued to have severe atopic dermatitis, poor growth, milk intolerance, and frequent infections. She had a history of dysfunctional voiding, necessitating the use of oxybutynin. The patient also was taking desmopressin to help with insensible water losses. She had no family history of dermatologic disorders.

At presentation she had diffuse scaling and erythema around the nasal vestibule and bilateral oral commissures. She also was noted to have coarse, brittle, and sparse scalp hair and eyebrows. Her current medications included hydrocortisone cream 2.5%, loratadine 10 mg daily, desmopressin 0.1 mg twice daily, and oxybutynin. Laboratory DNA analysis revealed 2 deletion mutations involving the SPINK5 gene that combined with physical findings led to the diagnosis of NS. Due to her severe growth retardation (approximately 6 SDs below the mean), she was referred to the pediatric endocrinology department. Our patient’s skeletal age was markedly delayed (6.5 years), and she was vitamin D deficient with a total vitamin D level of 16 ng/mL (reference range, 30–80 ng/mL). She is now under the care of a dietitian and taking a vitamin D supplement of 2000 IU of vitamin D3 daily. Growth hormone therapy trials have not been helpful.

An important feature of NS is growth retardation, which is multifactorial, resulting from increased caloric requirements, percutaneous fluid loss, and food allergies. Komatsu et al3 proposed that the SPINK5 inhibitory domain in addition to its role in skin barrier function is involved in regulating proteolytic processing of growth hormone in the pituitary gland. Its dysfunction may lead to a decrease in human growth hormone levels, resulting in short stature.3 This association suggested that our patient would be a good candidate for growth hormone therapy.

Furthermore, our patient was found to be vitamin D deficient, which was not surprising, as cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) is synthesized in the epidermis with UV exposure. This finding suggests that vitamin D deficiency should be suspected in patients with an impaired skin barrier. In addition to calcium regulation and bone mineralization, vitamin D plays a preventative role in cardiovascular disease, autoimmune diseases such as Crohn disease and multiple sclerosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and influenza, and many cancers.4

Vitamin D has 2 primary derivatives: (1) vitamin D3 from the skin and dietary animal sources, and (2) ergocalciferol (vitamin D2), which is obtained primarily from dietary plant sources and fortified foods. The most common test for vitamin D sufficiency is an assay for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) concentration; 25(OH)D is derived primarily from vitamin D3, which is 3 times more potent than vitamin D2 in the production of 25(OH)D.5 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends vitamin D replacement therapy for children with 25(OH)D levels less than 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) or in children who are clinically symptomatic.6 The Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines suggest screening for vitamin D deficiency only in individuals at risk.7 We suggest that serum vitamin D testing should be routine in children with NS and other atopic dermatitis conditions in which UV absorption may be impaired.

- Sun J, Linden K. Netherton syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:693-697.

- Bitoun E, Chavanas S, Irvine AD, et al. Netherton syndrome: disease expression and spectrum of SPINK5 mutations in 21 families. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:352-361.

- Komatsu N, Saijoh K, Otsuki N, et al. Proteolytic processing of human growth hormone by multiple tissue kallikreins and regulation by the serine protease inhibitor Kazal-Type5 (SPINK5) protein. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;377:228-236.

- Wacker M, Holick MF. Vitamin D—effects on skeletal and extraskeletal health and the need for supplementation. Nutrients. 2013;5:111-148.

- Armas LA, Hollis BW, Heaney RP. Vitamin D2 is much less effective than vitamin D3 in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5387-5391.

- Madhusmita M, Pacaud D, Collett-Solberg PF, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in children and its management: review of current knowledge and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2008;122:398-417.

- Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bisckoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911-1930.

To the Editor:

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare genodermatosis that presents with erythroderma accompanied with failure to thrive in the neonatal period. Ichthyosis linearis circumflexa, or double-edged scale, is a typical skin finding. Chronic severe atopic dermatitis with diffuse generalized xerosis usually develops and often is associated with elevated IgE levels; however, a feature most associated with and crucial for the diagnosis of NS is trichorrhexis invaginata, or bamboo hair, that causes patchy hair thinning. The triad of ichthyosis linearis circumflexa, atopic dermatitis, and trichorrhexis invaginata is diagnostic of NS. Several other clinical features, including delayed growth, skeletal age delay, and short stature also can develop during its clinical course.1

Netherton syndrome is an autosomal-recessive disorder resulting from a mutation in the SPINK5 gene, which encodes a serine protease inhibitor important in skin barrier formation and immunity.2 Thus, frequent infections are common in these patients. Current treatment options include emollients and topical anti-inflammatory agents to minimize and control the classic manifestations of NS.

A 10-year-old girl with a history of allergic rhinitis and multiple food allergies presented to the dermatology clinic with a long history of diffuse generalized xerosis and erythema with areas of lichenification and scaly patches on the face, trunk, and extremities. She was born prematurely at 34 weeks and developed scaling and erythema involving most of the body shortly after birth. She exhibited severe failure to thrive that necessitated placement of a gastrostomy feeding tube at 8 months of age, resulting in satisfactory weight gain and the tube was later removed. A liver biopsy obtained at that time revealed early intrahepatic duct obstruction and early cirrhosis. She continued to have severe atopic dermatitis, poor growth, milk intolerance, and frequent infections. She had a history of dysfunctional voiding, necessitating the use of oxybutynin. The patient also was taking desmopressin to help with insensible water losses. She had no family history of dermatologic disorders.

At presentation she had diffuse scaling and erythema around the nasal vestibule and bilateral oral commissures. She also was noted to have coarse, brittle, and sparse scalp hair and eyebrows. Her current medications included hydrocortisone cream 2.5%, loratadine 10 mg daily, desmopressin 0.1 mg twice daily, and oxybutynin. Laboratory DNA analysis revealed 2 deletion mutations involving the SPINK5 gene that combined with physical findings led to the diagnosis of NS. Due to her severe growth retardation (approximately 6 SDs below the mean), she was referred to the pediatric endocrinology department. Our patient’s skeletal age was markedly delayed (6.5 years), and she was vitamin D deficient with a total vitamin D level of 16 ng/mL (reference range, 30–80 ng/mL). She is now under the care of a dietitian and taking a vitamin D supplement of 2000 IU of vitamin D3 daily. Growth hormone therapy trials have not been helpful.

An important feature of NS is growth retardation, which is multifactorial, resulting from increased caloric requirements, percutaneous fluid loss, and food allergies. Komatsu et al3 proposed that the SPINK5 inhibitory domain in addition to its role in skin barrier function is involved in regulating proteolytic processing of growth hormone in the pituitary gland. Its dysfunction may lead to a decrease in human growth hormone levels, resulting in short stature.3 This association suggested that our patient would be a good candidate for growth hormone therapy.

Furthermore, our patient was found to be vitamin D deficient, which was not surprising, as cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) is synthesized in the epidermis with UV exposure. This finding suggests that vitamin D deficiency should be suspected in patients with an impaired skin barrier. In addition to calcium regulation and bone mineralization, vitamin D plays a preventative role in cardiovascular disease, autoimmune diseases such as Crohn disease and multiple sclerosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and influenza, and many cancers.4

Vitamin D has 2 primary derivatives: (1) vitamin D3 from the skin and dietary animal sources, and (2) ergocalciferol (vitamin D2), which is obtained primarily from dietary plant sources and fortified foods. The most common test for vitamin D sufficiency is an assay for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) concentration; 25(OH)D is derived primarily from vitamin D3, which is 3 times more potent than vitamin D2 in the production of 25(OH)D.5 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends vitamin D replacement therapy for children with 25(OH)D levels less than 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) or in children who are clinically symptomatic.6 The Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines suggest screening for vitamin D deficiency only in individuals at risk.7 We suggest that serum vitamin D testing should be routine in children with NS and other atopic dermatitis conditions in which UV absorption may be impaired.

To the Editor:

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare genodermatosis that presents with erythroderma accompanied with failure to thrive in the neonatal period. Ichthyosis linearis circumflexa, or double-edged scale, is a typical skin finding. Chronic severe atopic dermatitis with diffuse generalized xerosis usually develops and often is associated with elevated IgE levels; however, a feature most associated with and crucial for the diagnosis of NS is trichorrhexis invaginata, or bamboo hair, that causes patchy hair thinning. The triad of ichthyosis linearis circumflexa, atopic dermatitis, and trichorrhexis invaginata is diagnostic of NS. Several other clinical features, including delayed growth, skeletal age delay, and short stature also can develop during its clinical course.1

Netherton syndrome is an autosomal-recessive disorder resulting from a mutation in the SPINK5 gene, which encodes a serine protease inhibitor important in skin barrier formation and immunity.2 Thus, frequent infections are common in these patients. Current treatment options include emollients and topical anti-inflammatory agents to minimize and control the classic manifestations of NS.

A 10-year-old girl with a history of allergic rhinitis and multiple food allergies presented to the dermatology clinic with a long history of diffuse generalized xerosis and erythema with areas of lichenification and scaly patches on the face, trunk, and extremities. She was born prematurely at 34 weeks and developed scaling and erythema involving most of the body shortly after birth. She exhibited severe failure to thrive that necessitated placement of a gastrostomy feeding tube at 8 months of age, resulting in satisfactory weight gain and the tube was later removed. A liver biopsy obtained at that time revealed early intrahepatic duct obstruction and early cirrhosis. She continued to have severe atopic dermatitis, poor growth, milk intolerance, and frequent infections. She had a history of dysfunctional voiding, necessitating the use of oxybutynin. The patient also was taking desmopressin to help with insensible water losses. She had no family history of dermatologic disorders.

At presentation she had diffuse scaling and erythema around the nasal vestibule and bilateral oral commissures. She also was noted to have coarse, brittle, and sparse scalp hair and eyebrows. Her current medications included hydrocortisone cream 2.5%, loratadine 10 mg daily, desmopressin 0.1 mg twice daily, and oxybutynin. Laboratory DNA analysis revealed 2 deletion mutations involving the SPINK5 gene that combined with physical findings led to the diagnosis of NS. Due to her severe growth retardation (approximately 6 SDs below the mean), she was referred to the pediatric endocrinology department. Our patient’s skeletal age was markedly delayed (6.5 years), and she was vitamin D deficient with a total vitamin D level of 16 ng/mL (reference range, 30–80 ng/mL). She is now under the care of a dietitian and taking a vitamin D supplement of 2000 IU of vitamin D3 daily. Growth hormone therapy trials have not been helpful.

An important feature of NS is growth retardation, which is multifactorial, resulting from increased caloric requirements, percutaneous fluid loss, and food allergies. Komatsu et al3 proposed that the SPINK5 inhibitory domain in addition to its role in skin barrier function is involved in regulating proteolytic processing of growth hormone in the pituitary gland. Its dysfunction may lead to a decrease in human growth hormone levels, resulting in short stature.3 This association suggested that our patient would be a good candidate for growth hormone therapy.

Furthermore, our patient was found to be vitamin D deficient, which was not surprising, as cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) is synthesized in the epidermis with UV exposure. This finding suggests that vitamin D deficiency should be suspected in patients with an impaired skin barrier. In addition to calcium regulation and bone mineralization, vitamin D plays a preventative role in cardiovascular disease, autoimmune diseases such as Crohn disease and multiple sclerosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and influenza, and many cancers.4

Vitamin D has 2 primary derivatives: (1) vitamin D3 from the skin and dietary animal sources, and (2) ergocalciferol (vitamin D2), which is obtained primarily from dietary plant sources and fortified foods. The most common test for vitamin D sufficiency is an assay for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) concentration; 25(OH)D is derived primarily from vitamin D3, which is 3 times more potent than vitamin D2 in the production of 25(OH)D.5 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends vitamin D replacement therapy for children with 25(OH)D levels less than 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) or in children who are clinically symptomatic.6 The Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines suggest screening for vitamin D deficiency only in individuals at risk.7 We suggest that serum vitamin D testing should be routine in children with NS and other atopic dermatitis conditions in which UV absorption may be impaired.

- Sun J, Linden K. Netherton syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:693-697.

- Bitoun E, Chavanas S, Irvine AD, et al. Netherton syndrome: disease expression and spectrum of SPINK5 mutations in 21 families. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:352-361.

- Komatsu N, Saijoh K, Otsuki N, et al. Proteolytic processing of human growth hormone by multiple tissue kallikreins and regulation by the serine protease inhibitor Kazal-Type5 (SPINK5) protein. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;377:228-236.

- Wacker M, Holick MF. Vitamin D—effects on skeletal and extraskeletal health and the need for supplementation. Nutrients. 2013;5:111-148.

- Armas LA, Hollis BW, Heaney RP. Vitamin D2 is much less effective than vitamin D3 in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5387-5391.

- Madhusmita M, Pacaud D, Collett-Solberg PF, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in children and its management: review of current knowledge and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2008;122:398-417.

- Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bisckoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911-1930.

- Sun J, Linden K. Netherton syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:693-697.

- Bitoun E, Chavanas S, Irvine AD, et al. Netherton syndrome: disease expression and spectrum of SPINK5 mutations in 21 families. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:352-361.

- Komatsu N, Saijoh K, Otsuki N, et al. Proteolytic processing of human growth hormone by multiple tissue kallikreins and regulation by the serine protease inhibitor Kazal-Type5 (SPINK5) protein. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;377:228-236.

- Wacker M, Holick MF. Vitamin D—effects on skeletal and extraskeletal health and the need for supplementation. Nutrients. 2013;5:111-148.

- Armas LA, Hollis BW, Heaney RP. Vitamin D2 is much less effective than vitamin D3 in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5387-5391.

- Madhusmita M, Pacaud D, Collett-Solberg PF, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in children and its management: review of current knowledge and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2008;122:398-417.

- Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bisckoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911-1930.

Practice Points

- Netherton syndrome (NS) is characterized by severe atopic dermatitis, ichthyosis linearis circumflexa, and trichorrhexis invaginata.

- Children with NS are at increased risk for vitamin D deficiency.

- Consider screening patients with chronic severe dermatitis for vitamin D deficiency.

Segmental Vitiligo–like Hypopigmentation Associated With Metastatic Melanoma

To the Editor:

Melanoma-associated hypopigmentation frequently has been reported during the disease course and can include different characteristics such as regression of the primary melanoma and/or its metastases as well as common vitiligolike hypopigmentation at sites distant from the melanoma.1,2 Among patients who present with hypopigmentation, the most common clinical presentation is hypopigmented patches in a bilateral symmetric distribution that is similar to vitiligo.1 We report a case of segmental vitiligo–like hypopigmentation associated with melanoma.

RELATED ARTICLE: Novel Melanoma Therapies and Their Side Effects

A 37-year-old man presented with achromic patches on the right side of the neck and lower face of 2 months’ duration. He had a history of melanoma (Breslow thickness, 1.37 mm; mitotic rate, 4/mm2) on the right retroauricular region that was treated by wide local excision 12 years prior; after 10 years, he began to have headaches. At that time, imaging studies including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed multiple nodules on the brain, lungs, pancreas, left scapula, and left suprarenal gland. A lung biopsy confirmed metastatic melanoma. Intr

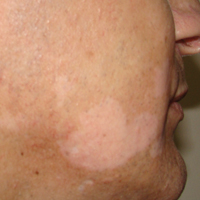

On physical examination using a Wood lamp at the current presentation 2 months later, the achromic patches were linearly distributed on the inferior portion of the right cheek (Figure). A 2×3-cm atrophic scar was present on the right retroauricular region. No regional or distant lymph nodes were enlarged or hard on examination. Although vitiligo is diagnosed using clinical findings,3 a biopsy was performed and showed absence of melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction (hematoxylin and eosin stain) and complete absence of melanin pigment (Fontana-Masson stain). The patient was treated with topical tacrolimus with poor improvement after 2 months.

The relationship between melanoma and vitiligolike hypopigmentation is a fascinating and controversial topic. Its association is considered to be a consequence of the immune-mediated response against antigens shared by normal melanocytes and melanoma cells.4 Vitiligolike hypopigmentation occurs in 2.8%2 of melanoma patients and is reported in metastatic disease1 as well as those undergoing immunotherapy with or without chemotherapy.5 Its development in patients with stage III or IV melanoma seems to represent an independent positive prognostic factor2 and correlates with a better therapeutic outcome in patients undergoing treatment with biotherapy.5

In most cases, the onset of achromic lesions follows the diagnosis of melanoma. Hypopigmentation appears on average 4.8 years after the initial diagnosis and approximately 1 to 2 years after lymph node or distant metastasis.1 In our case, it occurred 12 years after the initial diagnosis and 2 years after metastatic disease was diagnosed.

Despite having widespread metastatic melanoma, our patient only developed achromic patches on the area near the prior melanoma. However, most affected patients present with hypopigmented patches in a bilateral symmetric distribution pattern similar to common vitiligo. No correlation has been found between the hypopigmentation distribution and the location of the primary tumor.1

Because fotemustine is not likely to induce hypopigmentation, we believe that the vitiligolike hypopigmentation in our patient was related to an immune-mediated response associated with melanoma. To help explain our findings, one hypothesis considered was that cutaneous mosaicism may be involved in segmental vitiligo.6 The tumor may have triggered an immune response that affected a close susceptible area of mosaic vitiligo, leading to these clinical findings.

- Hartmann A, Bedenk C, Keikavoussi P, et al. Vitiligo and melanoma-associated hypopigmentation (MAH): shared and discriminative features. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:1053-1059.

- Quaglino P, Marenco F, Osella-Abate S, et al. Vitiligo is an independent favourable prognostic factor in stage III and IV metastatic melanoma patients: results from a single-institution hospital-based observational cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:409-414.

- Taïeb A, Picardo M, VETF Members. The definition and assessment of vitiligo: a consensus report of the Vitiligo European Task Force. Pigment Cell Res. 2007;20:27-35.

- Becker JC, Guldberg P, Zeuthen J, et al. Accumulation of identical T cells in melanoma and vitiligo-like leukoderma. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:1033-1038.

- Boasberg PD, Hoon DS, Piro LD, et al. Enhanced survival associated with vitiligo expression during maintenance biotherapy for metastatic melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2658-2663.

- Van Geel N, Speeckaert R, Melsens E, et al. The distribution pattern of segmental vitiligo: clues for somatic mosaicism. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:56-64.

To the Editor:

Melanoma-associated hypopigmentation frequently has been reported during the disease course and can include different characteristics such as regression of the primary melanoma and/or its metastases as well as common vitiligolike hypopigmentation at sites distant from the melanoma.1,2 Among patients who present with hypopigmentation, the most common clinical presentation is hypopigmented patches in a bilateral symmetric distribution that is similar to vitiligo.1 We report a case of segmental vitiligo–like hypopigmentation associated with melanoma.

RELATED ARTICLE: Novel Melanoma Therapies and Their Side Effects

A 37-year-old man presented with achromic patches on the right side of the neck and lower face of 2 months’ duration. He had a history of melanoma (Breslow thickness, 1.37 mm; mitotic rate, 4/mm2) on the right retroauricular region that was treated by wide local excision 12 years prior; after 10 years, he began to have headaches. At that time, imaging studies including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed multiple nodules on the brain, lungs, pancreas, left scapula, and left suprarenal gland. A lung biopsy confirmed metastatic melanoma. Intr

On physical examination using a Wood lamp at the current presentation 2 months later, the achromic patches were linearly distributed on the inferior portion of the right cheek (Figure). A 2×3-cm atrophic scar was present on the right retroauricular region. No regional or distant lymph nodes were enlarged or hard on examination. Although vitiligo is diagnosed using clinical findings,3 a biopsy was performed and showed absence of melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction (hematoxylin and eosin stain) and complete absence of melanin pigment (Fontana-Masson stain). The patient was treated with topical tacrolimus with poor improvement after 2 months.

The relationship between melanoma and vitiligolike hypopigmentation is a fascinating and controversial topic. Its association is considered to be a consequence of the immune-mediated response against antigens shared by normal melanocytes and melanoma cells.4 Vitiligolike hypopigmentation occurs in 2.8%2 of melanoma patients and is reported in metastatic disease1 as well as those undergoing immunotherapy with or without chemotherapy.5 Its development in patients with stage III or IV melanoma seems to represent an independent positive prognostic factor2 and correlates with a better therapeutic outcome in patients undergoing treatment with biotherapy.5

In most cases, the onset of achromic lesions follows the diagnosis of melanoma. Hypopigmentation appears on average 4.8 years after the initial diagnosis and approximately 1 to 2 years after lymph node or distant metastasis.1 In our case, it occurred 12 years after the initial diagnosis and 2 years after metastatic disease was diagnosed.

Despite having widespread metastatic melanoma, our patient only developed achromic patches on the area near the prior melanoma. However, most affected patients present with hypopigmented patches in a bilateral symmetric distribution pattern similar to common vitiligo. No correlation has been found between the hypopigmentation distribution and the location of the primary tumor.1

Because fotemustine is not likely to induce hypopigmentation, we believe that the vitiligolike hypopigmentation in our patient was related to an immune-mediated response associated with melanoma. To help explain our findings, one hypothesis considered was that cutaneous mosaicism may be involved in segmental vitiligo.6 The tumor may have triggered an immune response that affected a close susceptible area of mosaic vitiligo, leading to these clinical findings.

To the Editor:

Melanoma-associated hypopigmentation frequently has been reported during the disease course and can include different characteristics such as regression of the primary melanoma and/or its metastases as well as common vitiligolike hypopigmentation at sites distant from the melanoma.1,2 Among patients who present with hypopigmentation, the most common clinical presentation is hypopigmented patches in a bilateral symmetric distribution that is similar to vitiligo.1 We report a case of segmental vitiligo–like hypopigmentation associated with melanoma.

RELATED ARTICLE: Novel Melanoma Therapies and Their Side Effects

A 37-year-old man presented with achromic patches on the right side of the neck and lower face of 2 months’ duration. He had a history of melanoma (Breslow thickness, 1.37 mm; mitotic rate, 4/mm2) on the right retroauricular region that was treated by wide local excision 12 years prior; after 10 years, he began to have headaches. At that time, imaging studies including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed multiple nodules on the brain, lungs, pancreas, left scapula, and left suprarenal gland. A lung biopsy confirmed metastatic melanoma. Intr

On physical examination using a Wood lamp at the current presentation 2 months later, the achromic patches were linearly distributed on the inferior portion of the right cheek (Figure). A 2×3-cm atrophic scar was present on the right retroauricular region. No regional or distant lymph nodes were enlarged or hard on examination. Although vitiligo is diagnosed using clinical findings,3 a biopsy was performed and showed absence of melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction (hematoxylin and eosin stain) and complete absence of melanin pigment (Fontana-Masson stain). The patient was treated with topical tacrolimus with poor improvement after 2 months.

The relationship between melanoma and vitiligolike hypopigmentation is a fascinating and controversial topic. Its association is considered to be a consequence of the immune-mediated response against antigens shared by normal melanocytes and melanoma cells.4 Vitiligolike hypopigmentation occurs in 2.8%2 of melanoma patients and is reported in metastatic disease1 as well as those undergoing immunotherapy with or without chemotherapy.5 Its development in patients with stage III or IV melanoma seems to represent an independent positive prognostic factor2 and correlates with a better therapeutic outcome in patients undergoing treatment with biotherapy.5

In most cases, the onset of achromic lesions follows the diagnosis of melanoma. Hypopigmentation appears on average 4.8 years after the initial diagnosis and approximately 1 to 2 years after lymph node or distant metastasis.1 In our case, it occurred 12 years after the initial diagnosis and 2 years after metastatic disease was diagnosed.

Despite having widespread metastatic melanoma, our patient only developed achromic patches on the area near the prior melanoma. However, most affected patients present with hypopigmented patches in a bilateral symmetric distribution pattern similar to common vitiligo. No correlation has been found between the hypopigmentation distribution and the location of the primary tumor.1

Because fotemustine is not likely to induce hypopigmentation, we believe that the vitiligolike hypopigmentation in our patient was related to an immune-mediated response associated with melanoma. To help explain our findings, one hypothesis considered was that cutaneous mosaicism may be involved in segmental vitiligo.6 The tumor may have triggered an immune response that affected a close susceptible area of mosaic vitiligo, leading to these clinical findings.

- Hartmann A, Bedenk C, Keikavoussi P, et al. Vitiligo and melanoma-associated hypopigmentation (MAH): shared and discriminative features. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:1053-1059.

- Quaglino P, Marenco F, Osella-Abate S, et al. Vitiligo is an independent favourable prognostic factor in stage III and IV metastatic melanoma patients: results from a single-institution hospital-based observational cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:409-414.

- Taïeb A, Picardo M, VETF Members. The definition and assessment of vitiligo: a consensus report of the Vitiligo European Task Force. Pigment Cell Res. 2007;20:27-35.

- Becker JC, Guldberg P, Zeuthen J, et al. Accumulation of identical T cells in melanoma and vitiligo-like leukoderma. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:1033-1038.

- Boasberg PD, Hoon DS, Piro LD, et al. Enhanced survival associated with vitiligo expression during maintenance biotherapy for metastatic melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2658-2663.

- Van Geel N, Speeckaert R, Melsens E, et al. The distribution pattern of segmental vitiligo: clues for somatic mosaicism. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:56-64.

- Hartmann A, Bedenk C, Keikavoussi P, et al. Vitiligo and melanoma-associated hypopigmentation (MAH): shared and discriminative features. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:1053-1059.

- Quaglino P, Marenco F, Osella-Abate S, et al. Vitiligo is an independent favourable prognostic factor in stage III and IV metastatic melanoma patients: results from a single-institution hospital-based observational cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:409-414.

- Taïeb A, Picardo M, VETF Members. The definition and assessment of vitiligo: a consensus report of the Vitiligo European Task Force. Pigment Cell Res. 2007;20:27-35.

- Becker JC, Guldberg P, Zeuthen J, et al. Accumulation of identical T cells in melanoma and vitiligo-like leukoderma. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:1033-1038.

- Boasberg PD, Hoon DS, Piro LD, et al. Enhanced survival associated with vitiligo expression during maintenance biotherapy for metastatic melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2658-2663.

- Van Geel N, Speeckaert R, Melsens E, et al. The distribution pattern of segmental vitiligo: clues for somatic mosaicism. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:56-64.

Prac

- Melanoma-associated hypopigmentation usually manifests as common vitiligo; however, little is known about the pathophysiology of segmental vitiligo–like hypopigmentation associated with melanoma.

- This case of segmental vitiligo–like hypopigmentation associated with melanoma sheds light on possible autoimmune and mosaic disease etiology.

Granulomatous Cheilitis Mimicking Angioedema

To the Editor:

Granulomatous cheilitis (GC), also known as Miescher cheilitis, belongs to a larger class of diseases known as orofacial granulomatoses (OFGs), a set of diseases distinguished by their clinical and pathologic features of facial edema and granulomatous inflammation.1-3 Granulomatous cheilitis, a monosymptomatic variant of a more extensive disease known as Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (MRS), presents with labial swelling mimicking angioedema. Timely diagnosis of GC and MRS reduces the number of unnecessary tests, health care costs, and unnecessary patient burden. We present a case of idiopathic persistent swelling of the upper lip that was originally misdiagnosed as angioedema.

A 13-year-old white adolescent boy was referred to the allergy-immunology clinic for an alternate opinion regarding a presumed diagnosis of angioedema. He presented with prominent persistent swelling of the upper lip of 1 year’s duration associated with fissuring and discomfort while eating, which led to weight loss of more than 4.5 kg. The patient denied any history of facial asymmetry, paralysis, dental infections, or gastrointestinal tract symptoms. Additionally, he was not on any medications. His parents reported variable symptomatic worsening associated with egg ingestion, but avoiding egg did not provide any symptomatic relief. The swelling was unresponsive to multiple and prolonged courses of antihistamines and oral glucocorticoids. The patient’s medical history revealed no similar episodes of unexplained swelling, and family history was negative for angioedema. On examination, the upper lip was tender with a firm rubbery consistency. No other areas of swelling were noted. Angular cheilosis and minor labial mucosal ulcerations also were observed (Figure).

The persistent nature of the lip swelling and findings of fissures were not consistent with angioedema. Furthermore, prior laboratory studies did not reveal evidence of hereditary or acquired angioedema, and a complete blood cell count with differential was within reference range. Although the clinical suspicion for egg allergy was low, a blood test for serum-specific IgE showed a mild reactivity to egg allergen. The patient was referred to an oral surgeon for biopsy, which revealed dermal foci of noncaseating granulomas consistent with the preliminary diagnosis of GC.

Intralesional triamcinolone injections were initiated with marked improvement. Shortly after the initial improvement, however, the symptoms recurred, which necessitated several additional intralesional triamcinolone injections, again with remarkable improvement. Approximately 1.5 years later, the patient presented with recurrence of the lip swelling and admitted to having episodic diarrhea and abdominal cramps. He was referred to a pediatric gastroenterologist and a colonoscopy with biopsy confirmed Crohn disease. He was started on azathioprine followed by infliximab. A few months after this treatment was initiated, both his lip swelling and gastrointestinal tract symptoms remarkably improved. He has been maintained on this regimen and in the most recent follow-up had no recurrence of GC. He is scheduled to have another colonoscopy.

Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare chronic inflammatory condition characterized clinically by persistent lip swelling and histologically by granulomatous inflammation in the absence of systemic granulomatous disorders.4 Granulomatous cheilitis falls under the umbrella of OFGs. When it is paired with facial paralysis and fissuring of the tongue, it is specifically referred to as MRS. The prevalence of GC has historically been difficult to ascertain. In a review, an estimated incidence of 0.08% in the general population was reported with no predilection for race, sex, or age.4,5 Initially, the swelling of GC can be misdiagnosed as angioedema; therefore, it is imperative to include OFG and GC in the differential diagnosis of facial angioedema.3 Other possible diagnoses to consider include contact dermatitis, foreign-body reactions, infection, and reactions to medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.5 Chronic lymphedema and other granulomatous diseases also should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Isolated lymphedema of the head and neck, though rare, typically is seen following surgical or radiological interventions for cancer. Lymphatic fibrosis also can occur in the setting of chronic inflammatory skin conditions but is not typically the first presenting symptom, as was seen in our patient.6 Although granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis may be difficult to clinically and histologically differentiate from GC, isolated orofacial swelling in sarcoidosis is rare. If clinical suspicion for sarcoidosis does exist, however, a negative chest radiograph as well as serum calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels within reference range may help differentiate GC from sarcoidosis. In our patient, the clinical suspicion for sarcoidosis was low given his clinical history, young age, and race.

The etiology of MRS and GC currently is unknown. Genetic factors, food allergies, infectious processes, and aberrant immunologic functions all have been proposed as possible mechanisms.1-3,7,8 Genetic factors, such as HLA antigen subtypes, have been investigated but have not shown a definitive correlation.8 Numerous food allergens have been suggested as causative factors in OFG via a type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction,7 with cinnamon and benzoate reported as 2 of the most cited entities.9,10 Currently, it is believed that both of these mechanisms may play an exacerbating role to an otherwise unknown disease process.7,8 The infectious process most often associated with GC is Mycobacterium tuberculosis; however, similar to genetics and food allergens, causality has not been determined.4,7 At the present time, the best evidence points to an immunologic basis of GC with the inciting event being a random influx of inflammatory cells.7,11

There is a known association between GC and Crohn disease, especially when oral lesions are present.1,9 Granulomatous cheilitis can be considered an extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease.Up to 20% of OFG patients eventually go on to develop Crohn disease, with some reports being even higher when OFG presents in childhood.1,9 One study proposed that both GC and Crohn disease patients shared similar histopathologic and immunopathologic features including a helper T cell (TH1)–predominant inflammatory reaction.11