User login

Benign Cephalic Histiocytosis

To the Editor:

Benign cephalic histiocytosis (BCH) falls into the group of non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis (non-LCH), which is characterized by a benign course and tendency toward spontaneous remission. Apart from BCH, the main types of non-LCH include juvenile xanthogranuloma, generalized eruptive histiocytoma, and xanthoma disseminatum.1

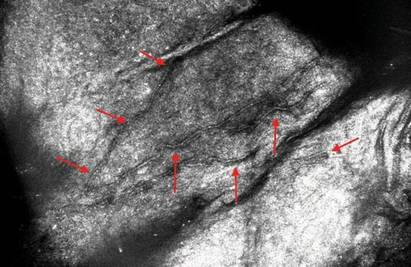

Benign cephalic histiocytosis is a rare form of cutaneous histiocytosis in young children. It presents as a papular eruption on the head and has not been associated with internal organ involvement.2-4 It was described in 1971 by Gianotti et al5 and was named infantile histiocytosis with intracytoplasmic worm-like bodies because electron microscopy revealed histiocytes with large cytoplasmatic inclusions composed of wormlike membranous profiles and absence of Birbeck granules. In BCH, skin lesions are located on the head including the face and sometimes on the neck. Lesions occasionally may appear on the trunk, buttocks, and thighs. Mucous membranes are not involved. The onset of disease is typical in the first year of life; however, the disease may begin within the first 3 years of life. An eruption is characterized by small, 2- to 8-mm, discrete, asymptomatic, tan to red-brown macules and papules. The lesions may persist for several months or years and subsequently flatten, becoming hyperpigmented briefly. They often completely resolve with time. Most children are otherwise healthy and developmentally normal6-9; however, diabetes insipidus has been reported in some children with BCH.10

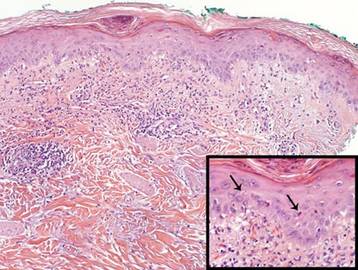

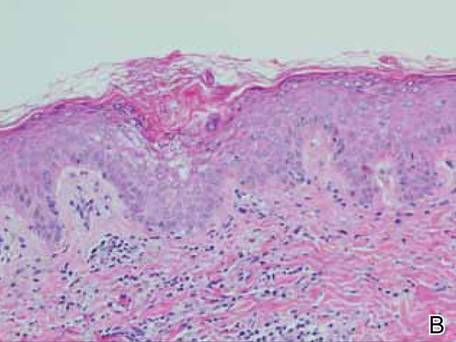

Histologic examination of skin samples reveals the infiltrate of histiocytes, which closely approaches the epidermis, accompanied by scattered lymphocytes and a few eosinophils.1,2,11 The histiocytes express a typical macrophage marker CD68, whereas immunostaining for Langerhans cell markers such as CD1a and S-100 is negative.3,9,12,13

A 2.5-year-old boy was admitted to our dermatology department with suspected cutaneous mastocytosis (CM). Since the age of 13 months, he had developed small, 4- to 8-mm, dark pinkish macules and papules localized on the cheeks (Figure 1). Physical examination performed in our center revealed yellowish macules and flat papules limited to the cheeks. Darier sign was negative. The boy was otherwise healthy and developmentally normal. All laboratory tests were within reference range and his family history was uneventful.

Figure 1. Maculopapular eruption of benign cephalic histiocytosis on the cheeks (A and B). |

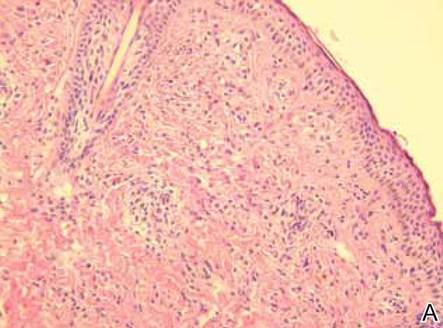

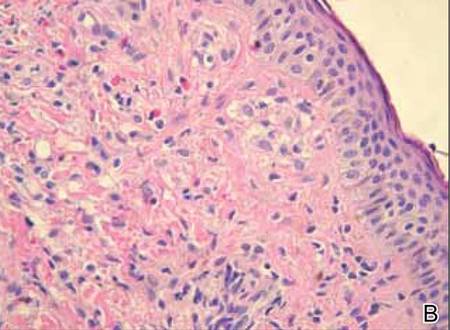

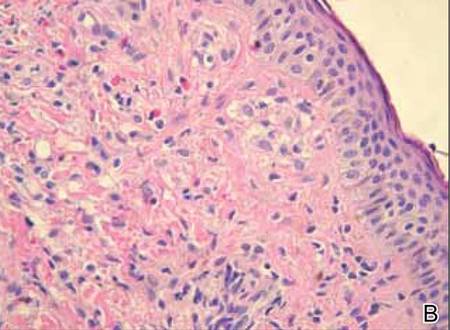

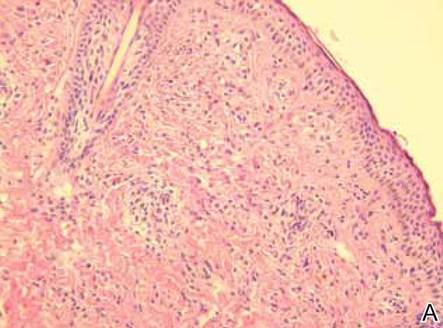

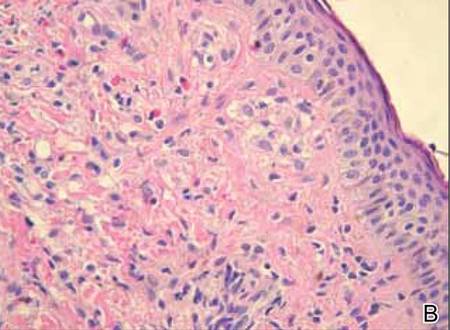

Histopathologic examination of the skin sample revealed a normotypic epidermis and scattered subepidermal infiltrates in the upper dermis. The infiltrates were composed of predominating histiocytes and a few mast cells and eosinophils (Figure 2). The histiocytes were slightly pleomorphic and had abundant clear cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mitoses were absent in these cells. The majority of cells within the infiltrate expressed CD68 and were CD1a- and S-100-. However, occasional CD1a+ cells were seen. Immunostaining for mast cell marker CD117 was negative. Cutaneous mastocytosis was excluded and non-LCH was recognized. Based on the typical location, morphology, and immunophenotype of skin lesions, BCH was diagnosed. At 24-month follow-up, spontaneous regression of skin lesions was observed.

Gianotti et al7 described BCH as a separate entity of the non-LCH group of disorders and established its diagnostic criteria: (1) onset of disease within the first 3 years of life; (2) location of skin lesions on the scalp and lack of lesions on the hands, feet, mucous membranes, and internal organ involvement; (3) spontaneous complete remission of symptoms; and (4) monomorphic infiltration of histiocytes that do not express S-100 and CD1a.

The macular and flat, papular, pink-yellow or orange lesions visible on the face of our patient are characteristic of BCH. Moreover, the cheeks are the most typical location of a BCH eruption, as noted in our patient.6,7,12 The presence of histiocytic infiltrates composed of CD68+ cells strongly support the diagnosis.3,4,9-13 In contrast to other reports, occasional CD1a+ cells of Langerhans phenotype were found in our case.3,9,11,12 The proliferation of Langerhans cells in the skin and internal organs and presence of langerin are characteristic of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).1,4,14 The presence of a few CD1a cells in cases with clinical features compatible with non-LCH may suggest that some of these cases may represent a papular self-healing variant of LCH or may indicate that there is an overlap among the histiocytic syndromes (eg, non-LCH and LCH). Furthermore, many of benign histiocytic lesions may evolve over the course of time into the others.12,13 Differential diagnosis of BCH should include other benign forms of cutaneous histiocytosis, particularly the small nodular variant of juvenile xanthogranuloma and generalized eruptive histiocytoma (GEH). Juvenile xanthogranuloma pre-sents as disseminated, yellowish, nodular lesions and may be associated with ocular involvement, whereas GEH is characterized by rapid onset of the disease and disseminated nodular eruption.1,4

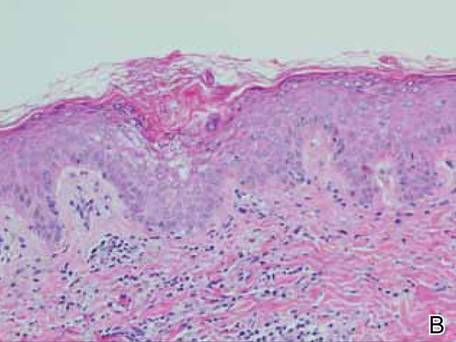

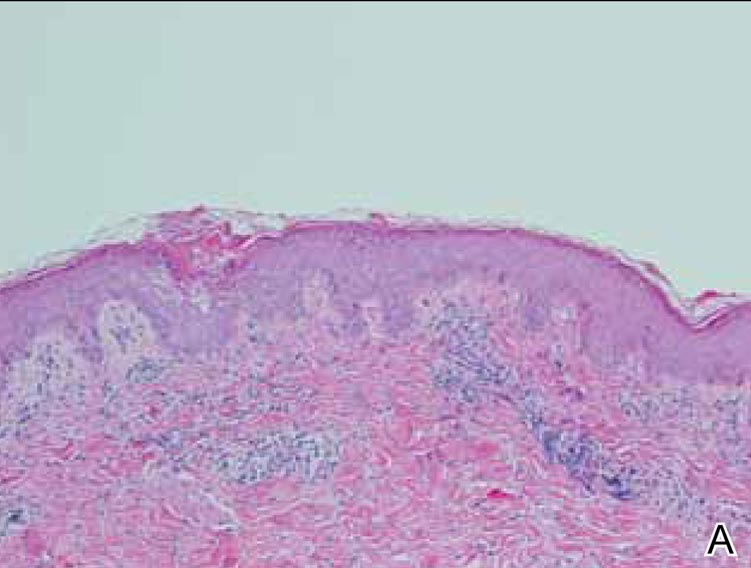

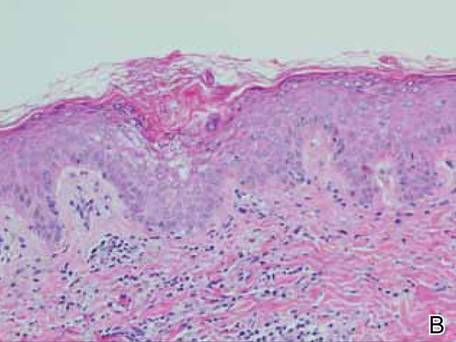

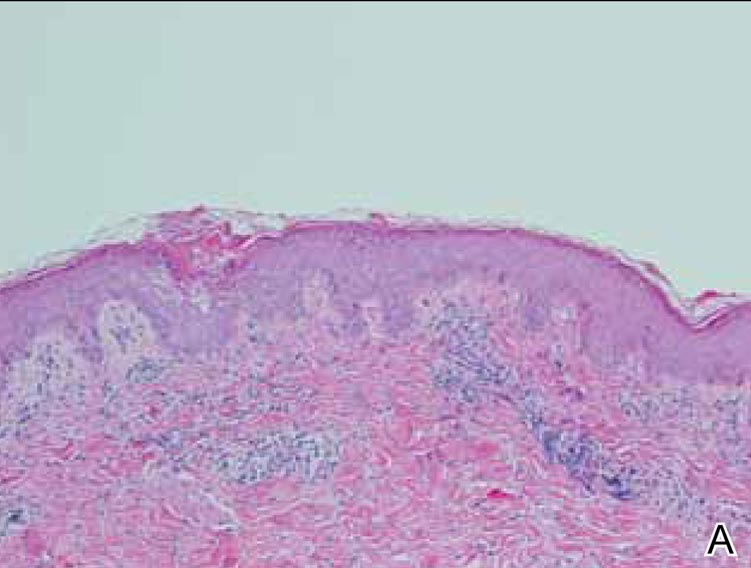

Figure 2. Skin section showing the upper and mid dermis infiltrated with slightly pleomorphic epithelioid histiocytic cells with clear cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei. Few accompanying lymphocytes and eosinophils were visible (H&E, original magnifications ×200 and ×400). |

A close histologic relationship and presence of overlapping symptoms observed among BCH, GEH, and juvenile xanthogranuloma indicate that these entities fall into a spectrum of the same disorder. However, the presence of a uniform infiltrate of large foamy histiocytes readily distinguishes xanthomas from BCH.4 In some unusual clinical presentations of CM or in cases of the nodular form of the condition, there is a need to distinguish between non-LCH and CM, as in our patient. Darier sign, consisting of urtication and erythema appearing after mechanical irritation of the skin lesion, is pathognomonic for CM. Nevertheless, Darier sign is not sufficient to confirm CM when it is not pronounced. Therefore, histologic examination with the use of immunostaining plays a key role in the differential diagnosis of these disorders in children.15 Treatment of BCH is not recommended because of spontaneous remission of the disease.1-5

Benign cephalic histiocytosis is a rare clinical form of non-LCH. No systemic or mucosal involvement has been described. Lesions often are confused with plane warts, but a biopsy is definitive. Therapy is not effective but fortunately none is necessary.

1. Gianotti F, Caputo R. Histiocytic syndromes: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:383-404.

2. Jih DM, Salcedo SL, Jaworsky C. Benign cephalic histiocytosis: a case report and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:908-913.

3. Dadzie O, Hopster D, Cerio R, et al. Benign cephalic histiocytosis in a British-African child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:444-446.

4. Goodman WT, Barret TL. Histiocytoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Hong Kong, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1527-1546.

5. Gianotti F, Caputo R, Ermacora E. Singular infantile histiocytosis with cells with intracytoplasmic vermiform particles [in French]. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1971;78:232-233.

6. Barsky B, Lao I, Barsky S, et al. Benign cephalic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:650-655.

7. Gianotti F, Caputo R, Ermacora E, et al. Benign cephalic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1038-1043.

8. Zelger BW, Sidoroff A, Orchard G, et al. Non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. a new unifying concept. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:490-504.

9. Hasegawa S, Deguchi M, Chiba-Okada S, et al. Japanese case of benign cephalic histiocytosis. J Dermatol. 2009;36:69-71.

10. Weston WL, Travers SH, Mierau GW, et al. Benign cephalic histiocytosis with diabetes insipidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:296-298.

11. Gianotti R, Alessi E, Caputo R. Benign cephalic histiocytosis: a distinct entity or a part of a wide spectrum of histiocytic proliferative disorders of children? a histopathological study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:315-319.

12. Rodriguez-Jurado R, Duran-McKinster C, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Benign cephalic histiocytosis progressing into juvenile xanthogranuloma: a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis transforming under the influence of a virus? Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:70-74.

13. Sidwell RU, Francis N, Slater DN, et al. Is disseminated juvenile xanthogranulomatosis benign cephalic histiocytosis? Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:40-43.

14. Favara BE, Jaffe R. The histopathology of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1994;23:S17-S23.

15. Heide R, Beishuizen A, De Groot H, et al. Mastocytosis in children: a protocol for management. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:493-500.

To the Editor:

Benign cephalic histiocytosis (BCH) falls into the group of non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis (non-LCH), which is characterized by a benign course and tendency toward spontaneous remission. Apart from BCH, the main types of non-LCH include juvenile xanthogranuloma, generalized eruptive histiocytoma, and xanthoma disseminatum.1

Benign cephalic histiocytosis is a rare form of cutaneous histiocytosis in young children. It presents as a papular eruption on the head and has not been associated with internal organ involvement.2-4 It was described in 1971 by Gianotti et al5 and was named infantile histiocytosis with intracytoplasmic worm-like bodies because electron microscopy revealed histiocytes with large cytoplasmatic inclusions composed of wormlike membranous profiles and absence of Birbeck granules. In BCH, skin lesions are located on the head including the face and sometimes on the neck. Lesions occasionally may appear on the trunk, buttocks, and thighs. Mucous membranes are not involved. The onset of disease is typical in the first year of life; however, the disease may begin within the first 3 years of life. An eruption is characterized by small, 2- to 8-mm, discrete, asymptomatic, tan to red-brown macules and papules. The lesions may persist for several months or years and subsequently flatten, becoming hyperpigmented briefly. They often completely resolve with time. Most children are otherwise healthy and developmentally normal6-9; however, diabetes insipidus has been reported in some children with BCH.10

Histologic examination of skin samples reveals the infiltrate of histiocytes, which closely approaches the epidermis, accompanied by scattered lymphocytes and a few eosinophils.1,2,11 The histiocytes express a typical macrophage marker CD68, whereas immunostaining for Langerhans cell markers such as CD1a and S-100 is negative.3,9,12,13

A 2.5-year-old boy was admitted to our dermatology department with suspected cutaneous mastocytosis (CM). Since the age of 13 months, he had developed small, 4- to 8-mm, dark pinkish macules and papules localized on the cheeks (Figure 1). Physical examination performed in our center revealed yellowish macules and flat papules limited to the cheeks. Darier sign was negative. The boy was otherwise healthy and developmentally normal. All laboratory tests were within reference range and his family history was uneventful.

Figure 1. Maculopapular eruption of benign cephalic histiocytosis on the cheeks (A and B). |

Histopathologic examination of the skin sample revealed a normotypic epidermis and scattered subepidermal infiltrates in the upper dermis. The infiltrates were composed of predominating histiocytes and a few mast cells and eosinophils (Figure 2). The histiocytes were slightly pleomorphic and had abundant clear cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mitoses were absent in these cells. The majority of cells within the infiltrate expressed CD68 and were CD1a- and S-100-. However, occasional CD1a+ cells were seen. Immunostaining for mast cell marker CD117 was negative. Cutaneous mastocytosis was excluded and non-LCH was recognized. Based on the typical location, morphology, and immunophenotype of skin lesions, BCH was diagnosed. At 24-month follow-up, spontaneous regression of skin lesions was observed.

Gianotti et al7 described BCH as a separate entity of the non-LCH group of disorders and established its diagnostic criteria: (1) onset of disease within the first 3 years of life; (2) location of skin lesions on the scalp and lack of lesions on the hands, feet, mucous membranes, and internal organ involvement; (3) spontaneous complete remission of symptoms; and (4) monomorphic infiltration of histiocytes that do not express S-100 and CD1a.

The macular and flat, papular, pink-yellow or orange lesions visible on the face of our patient are characteristic of BCH. Moreover, the cheeks are the most typical location of a BCH eruption, as noted in our patient.6,7,12 The presence of histiocytic infiltrates composed of CD68+ cells strongly support the diagnosis.3,4,9-13 In contrast to other reports, occasional CD1a+ cells of Langerhans phenotype were found in our case.3,9,11,12 The proliferation of Langerhans cells in the skin and internal organs and presence of langerin are characteristic of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).1,4,14 The presence of a few CD1a cells in cases with clinical features compatible with non-LCH may suggest that some of these cases may represent a papular self-healing variant of LCH or may indicate that there is an overlap among the histiocytic syndromes (eg, non-LCH and LCH). Furthermore, many of benign histiocytic lesions may evolve over the course of time into the others.12,13 Differential diagnosis of BCH should include other benign forms of cutaneous histiocytosis, particularly the small nodular variant of juvenile xanthogranuloma and generalized eruptive histiocytoma (GEH). Juvenile xanthogranuloma pre-sents as disseminated, yellowish, nodular lesions and may be associated with ocular involvement, whereas GEH is characterized by rapid onset of the disease and disseminated nodular eruption.1,4

Figure 2. Skin section showing the upper and mid dermis infiltrated with slightly pleomorphic epithelioid histiocytic cells with clear cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei. Few accompanying lymphocytes and eosinophils were visible (H&E, original magnifications ×200 and ×400). |

A close histologic relationship and presence of overlapping symptoms observed among BCH, GEH, and juvenile xanthogranuloma indicate that these entities fall into a spectrum of the same disorder. However, the presence of a uniform infiltrate of large foamy histiocytes readily distinguishes xanthomas from BCH.4 In some unusual clinical presentations of CM or in cases of the nodular form of the condition, there is a need to distinguish between non-LCH and CM, as in our patient. Darier sign, consisting of urtication and erythema appearing after mechanical irritation of the skin lesion, is pathognomonic for CM. Nevertheless, Darier sign is not sufficient to confirm CM when it is not pronounced. Therefore, histologic examination with the use of immunostaining plays a key role in the differential diagnosis of these disorders in children.15 Treatment of BCH is not recommended because of spontaneous remission of the disease.1-5

Benign cephalic histiocytosis is a rare clinical form of non-LCH. No systemic or mucosal involvement has been described. Lesions often are confused with plane warts, but a biopsy is definitive. Therapy is not effective but fortunately none is necessary.

To the Editor:

Benign cephalic histiocytosis (BCH) falls into the group of non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis (non-LCH), which is characterized by a benign course and tendency toward spontaneous remission. Apart from BCH, the main types of non-LCH include juvenile xanthogranuloma, generalized eruptive histiocytoma, and xanthoma disseminatum.1

Benign cephalic histiocytosis is a rare form of cutaneous histiocytosis in young children. It presents as a papular eruption on the head and has not been associated with internal organ involvement.2-4 It was described in 1971 by Gianotti et al5 and was named infantile histiocytosis with intracytoplasmic worm-like bodies because electron microscopy revealed histiocytes with large cytoplasmatic inclusions composed of wormlike membranous profiles and absence of Birbeck granules. In BCH, skin lesions are located on the head including the face and sometimes on the neck. Lesions occasionally may appear on the trunk, buttocks, and thighs. Mucous membranes are not involved. The onset of disease is typical in the first year of life; however, the disease may begin within the first 3 years of life. An eruption is characterized by small, 2- to 8-mm, discrete, asymptomatic, tan to red-brown macules and papules. The lesions may persist for several months or years and subsequently flatten, becoming hyperpigmented briefly. They often completely resolve with time. Most children are otherwise healthy and developmentally normal6-9; however, diabetes insipidus has been reported in some children with BCH.10

Histologic examination of skin samples reveals the infiltrate of histiocytes, which closely approaches the epidermis, accompanied by scattered lymphocytes and a few eosinophils.1,2,11 The histiocytes express a typical macrophage marker CD68, whereas immunostaining for Langerhans cell markers such as CD1a and S-100 is negative.3,9,12,13

A 2.5-year-old boy was admitted to our dermatology department with suspected cutaneous mastocytosis (CM). Since the age of 13 months, he had developed small, 4- to 8-mm, dark pinkish macules and papules localized on the cheeks (Figure 1). Physical examination performed in our center revealed yellowish macules and flat papules limited to the cheeks. Darier sign was negative. The boy was otherwise healthy and developmentally normal. All laboratory tests were within reference range and his family history was uneventful.

Figure 1. Maculopapular eruption of benign cephalic histiocytosis on the cheeks (A and B). |

Histopathologic examination of the skin sample revealed a normotypic epidermis and scattered subepidermal infiltrates in the upper dermis. The infiltrates were composed of predominating histiocytes and a few mast cells and eosinophils (Figure 2). The histiocytes were slightly pleomorphic and had abundant clear cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mitoses were absent in these cells. The majority of cells within the infiltrate expressed CD68 and were CD1a- and S-100-. However, occasional CD1a+ cells were seen. Immunostaining for mast cell marker CD117 was negative. Cutaneous mastocytosis was excluded and non-LCH was recognized. Based on the typical location, morphology, and immunophenotype of skin lesions, BCH was diagnosed. At 24-month follow-up, spontaneous regression of skin lesions was observed.

Gianotti et al7 described BCH as a separate entity of the non-LCH group of disorders and established its diagnostic criteria: (1) onset of disease within the first 3 years of life; (2) location of skin lesions on the scalp and lack of lesions on the hands, feet, mucous membranes, and internal organ involvement; (3) spontaneous complete remission of symptoms; and (4) monomorphic infiltration of histiocytes that do not express S-100 and CD1a.

The macular and flat, papular, pink-yellow or orange lesions visible on the face of our patient are characteristic of BCH. Moreover, the cheeks are the most typical location of a BCH eruption, as noted in our patient.6,7,12 The presence of histiocytic infiltrates composed of CD68+ cells strongly support the diagnosis.3,4,9-13 In contrast to other reports, occasional CD1a+ cells of Langerhans phenotype were found in our case.3,9,11,12 The proliferation of Langerhans cells in the skin and internal organs and presence of langerin are characteristic of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).1,4,14 The presence of a few CD1a cells in cases with clinical features compatible with non-LCH may suggest that some of these cases may represent a papular self-healing variant of LCH or may indicate that there is an overlap among the histiocytic syndromes (eg, non-LCH and LCH). Furthermore, many of benign histiocytic lesions may evolve over the course of time into the others.12,13 Differential diagnosis of BCH should include other benign forms of cutaneous histiocytosis, particularly the small nodular variant of juvenile xanthogranuloma and generalized eruptive histiocytoma (GEH). Juvenile xanthogranuloma pre-sents as disseminated, yellowish, nodular lesions and may be associated with ocular involvement, whereas GEH is characterized by rapid onset of the disease and disseminated nodular eruption.1,4

Figure 2. Skin section showing the upper and mid dermis infiltrated with slightly pleomorphic epithelioid histiocytic cells with clear cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei. Few accompanying lymphocytes and eosinophils were visible (H&E, original magnifications ×200 and ×400). |

A close histologic relationship and presence of overlapping symptoms observed among BCH, GEH, and juvenile xanthogranuloma indicate that these entities fall into a spectrum of the same disorder. However, the presence of a uniform infiltrate of large foamy histiocytes readily distinguishes xanthomas from BCH.4 In some unusual clinical presentations of CM or in cases of the nodular form of the condition, there is a need to distinguish between non-LCH and CM, as in our patient. Darier sign, consisting of urtication and erythema appearing after mechanical irritation of the skin lesion, is pathognomonic for CM. Nevertheless, Darier sign is not sufficient to confirm CM when it is not pronounced. Therefore, histologic examination with the use of immunostaining plays a key role in the differential diagnosis of these disorders in children.15 Treatment of BCH is not recommended because of spontaneous remission of the disease.1-5

Benign cephalic histiocytosis is a rare clinical form of non-LCH. No systemic or mucosal involvement has been described. Lesions often are confused with plane warts, but a biopsy is definitive. Therapy is not effective but fortunately none is necessary.

1. Gianotti F, Caputo R. Histiocytic syndromes: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:383-404.

2. Jih DM, Salcedo SL, Jaworsky C. Benign cephalic histiocytosis: a case report and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:908-913.

3. Dadzie O, Hopster D, Cerio R, et al. Benign cephalic histiocytosis in a British-African child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:444-446.

4. Goodman WT, Barret TL. Histiocytoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Hong Kong, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1527-1546.

5. Gianotti F, Caputo R, Ermacora E. Singular infantile histiocytosis with cells with intracytoplasmic vermiform particles [in French]. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1971;78:232-233.

6. Barsky B, Lao I, Barsky S, et al. Benign cephalic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:650-655.

7. Gianotti F, Caputo R, Ermacora E, et al. Benign cephalic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1038-1043.

8. Zelger BW, Sidoroff A, Orchard G, et al. Non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. a new unifying concept. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:490-504.

9. Hasegawa S, Deguchi M, Chiba-Okada S, et al. Japanese case of benign cephalic histiocytosis. J Dermatol. 2009;36:69-71.

10. Weston WL, Travers SH, Mierau GW, et al. Benign cephalic histiocytosis with diabetes insipidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:296-298.

11. Gianotti R, Alessi E, Caputo R. Benign cephalic histiocytosis: a distinct entity or a part of a wide spectrum of histiocytic proliferative disorders of children? a histopathological study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:315-319.

12. Rodriguez-Jurado R, Duran-McKinster C, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Benign cephalic histiocytosis progressing into juvenile xanthogranuloma: a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis transforming under the influence of a virus? Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:70-74.

13. Sidwell RU, Francis N, Slater DN, et al. Is disseminated juvenile xanthogranulomatosis benign cephalic histiocytosis? Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:40-43.

14. Favara BE, Jaffe R. The histopathology of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1994;23:S17-S23.

15. Heide R, Beishuizen A, De Groot H, et al. Mastocytosis in children: a protocol for management. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:493-500.

1. Gianotti F, Caputo R. Histiocytic syndromes: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:383-404.

2. Jih DM, Salcedo SL, Jaworsky C. Benign cephalic histiocytosis: a case report and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:908-913.

3. Dadzie O, Hopster D, Cerio R, et al. Benign cephalic histiocytosis in a British-African child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:444-446.

4. Goodman WT, Barret TL. Histiocytoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Hong Kong, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1527-1546.

5. Gianotti F, Caputo R, Ermacora E. Singular infantile histiocytosis with cells with intracytoplasmic vermiform particles [in French]. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1971;78:232-233.

6. Barsky B, Lao I, Barsky S, et al. Benign cephalic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:650-655.

7. Gianotti F, Caputo R, Ermacora E, et al. Benign cephalic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1038-1043.

8. Zelger BW, Sidoroff A, Orchard G, et al. Non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. a new unifying concept. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:490-504.

9. Hasegawa S, Deguchi M, Chiba-Okada S, et al. Japanese case of benign cephalic histiocytosis. J Dermatol. 2009;36:69-71.

10. Weston WL, Travers SH, Mierau GW, et al. Benign cephalic histiocytosis with diabetes insipidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:296-298.

11. Gianotti R, Alessi E, Caputo R. Benign cephalic histiocytosis: a distinct entity or a part of a wide spectrum of histiocytic proliferative disorders of children? a histopathological study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:315-319.

12. Rodriguez-Jurado R, Duran-McKinster C, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Benign cephalic histiocytosis progressing into juvenile xanthogranuloma: a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis transforming under the influence of a virus? Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:70-74.

13. Sidwell RU, Francis N, Slater DN, et al. Is disseminated juvenile xanthogranulomatosis benign cephalic histiocytosis? Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:40-43.

14. Favara BE, Jaffe R. The histopathology of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1994;23:S17-S23.

15. Heide R, Beishuizen A, De Groot H, et al. Mastocytosis in children: a protocol for management. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:493-500.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infection in Adults With Acute and Chronic Urticaria

To the Editor:

Mycoplasma pneumoniae has been implicated as a cause of acute urticaria (AU) in children,1 but its role in adults with AU is unknown. The aim of this retrospective study was to compare the incidence of acute M pneumoniae infection in adults with AU and chronic urticaria (CU).

A chart review was performed on adult patients with AU and CU who presented at a private dermatology practice in Singapore. Acute M pneumoniae infection was diagnosed on the basis of a single indirect microparticle agglutinin assay (MAA) titer of 1:320 or higher. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS version 13.0. P=.05 was regarded as significant. Data from 49 adults with AU and 44 adults with CU were analyzed. The distribution of MAA titers in adults with AU and CU are shown in the Figure. Microparticle agglutinin assay was negative in 10 (20.4%) of 49 adults with AU. Fifteen (30.6%) of 49 adults with AU had evidence of acute M pneumoniae infection, as indicated by an MAA titer of 1:320 or higher. The remaining 24 (49.0%) had evidence of prior infection as indicated by titers above the manufacturer’s cutoff of 1:402 and below our cutoff for acute infection of 1:320 or higher. Microparticle agglutinin assay was negative in 11 (25%) of 44 adults with CU. Three (6.8%) adults with CU were diagnosed with acute M pneumoniae infection and 30 (68.2%) were diagnosed with prior infection. The incidence of acute M pneumoniae infection was 30.6% in adults with AU compared to 6.8% in adults with CU, and the difference was statistically significant (P=.004).

Extrapulmonary complications of M pneumoniae involving practically every organ system have been described and 25% of patients develop cutaneous symptoms3 including AU. In 2007, Kano et al4 reported M pneumoniae infection-induced erythema nodosum, anaphylactoid purpura, and AU in a family of 3. This report was interesting because it showed that M pneumoniae had the ability to elicit different cutaneous reactions depending on the maturity of the adaptive immunity of a host, even among individuals of a common genetic background. A Taiwanese study found that 21 (32%) of 65 children with AU had M pneumoniae infection as determined by a positive Mycoplasma IgM test or an equivocal Mycoplasma IgM coupled with positive cold agglutinin test results.1

In our study, we found serological evidence of acute M pneumoniae infection in 15 (30.6%) of 49 adults with AU compared to 3 (6.8%) of 44 adults with CU (P=.004), suggesting that M pneumoniae also may play a role in the etiology of adult AU. Diagnosis of acute M pneumoniae infection is challenging, as it is often impossible to obtain convalescent serum that will show the 4-fold rise in titer. Single MAA titers of 1:160 or higher have been recommended for diagnosis of acute infection,5 but because of higher background activity in Singapore, we used a higher titer (>1:320). However, in doing so, we could be underestimating the true incidence of acute M pneumoniae infections.

The role of M pneumoniae in CU is uncertain. A Thai study reported that 55% of 38 children with CU had elevated M pneumoniae titers but did not provide details of actual titers or define what they meant by elevated titers.6 The incidence of acute and prior infection in our patients with CU was 6.8% and 68.2%, respectively. Unfortunately, we cannot determine the significance of the 68.2% incidence rate of prior infection in the absence of a normal control population of patients without urticaria. Another limitation of this study is that we compared M pneumoniae infection rate in AU with CU on the assumption that infection is not likely to play a significant role in CU, which may not necessarily be the case. Tests for other etiologic agents, including viruses, also were not performed. Not withstanding these limitations, this study suggests that acute M pneumoniae infection is significantly more common in adults with AU than in adults with CU.

This study showed that M pneumoniae might play a role in the etiology of AU in adults and our findings need to be confirmed by prospective studies. Several more questions must be answered before deciding whether the current practice of treating AU symptomatically without investigation needs to be changed. First, does treatment of M pneumoniae infection have any influence on the course of AU? The fact that AU usually is self-limiting suggests that treatment may not influence the disease course. Second, does treatment of underlying M pneumoniae infection shorten the course of AU? Third, do AU patients with untreated M pneumoniae infection face a higher risk for developing CU? This question is intriguing for the following reasons: (1) 30% to 50% of CU cases are autoimmune in etiology7; (2) antibodies to galactocerebroside that cross-react with glycolipids on M pneumoniae have been detected in patients with M pneumoniae–associated Guillain-Barré syndrome, suggesting a form of molecular mimicry8; and (3) antinuclear antibody also has occasionally been detected in sera of patients with M pneumoniae.9 It would be interesting to test patients with autoimmune and nonautoimmune CU for evidence of M pneumoniae serology infection.

We hope that prospective studies will be conducted in the future to confirm our findings and answer some of the questions raised.

1. Wu CC, Kuo HC, Yu HR, et al. Association of acute urticaria with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in hospitalized children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:134-139.

2. Serodia-Myco II [package insert]. Tokyo, Japan: Fujirebo; 2013.

3. Murray HW, Masur H, Senterfit LB, et al. The protean manifestations of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in adults. Am J Med. 1975;58:229-242.

4. Kano Y, Mitsuyama Y, Hirahara K, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection-induced erythema nodosum, anaphylactoid purpura, and acute urticaria in 3 people in a single family. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(suppl 2):S33-S35.

5. Daxboeck F, Krause R, Wenisch C. Laboratory diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:263-273.

6. Pongpreuksa S, Boochoo S, Kulthanan K, et al. Chronic urticaria: what is worth doing in pediatric population? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004:S134.

7. Grattan CE. Autoimmune urticaria. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004;24:163-181.

8. Kusunoki S, Shiina M, Kanazawa I. Anti-Gal-C antibodies in GBS subsequent to mycoplasma infection: evidence of molecular mimicry. Neurology. 2001;57:736-738.

9. Arikan S, Ergüven S, Ustaçelebi S, et al. Detection of antinuclear antibody (ANA) in patients with Mycoplasmal Pneumonia. Turk J Med Sci. 1998;28:97-98.

To the Editor:

Mycoplasma pneumoniae has been implicated as a cause of acute urticaria (AU) in children,1 but its role in adults with AU is unknown. The aim of this retrospective study was to compare the incidence of acute M pneumoniae infection in adults with AU and chronic urticaria (CU).

A chart review was performed on adult patients with AU and CU who presented at a private dermatology practice in Singapore. Acute M pneumoniae infection was diagnosed on the basis of a single indirect microparticle agglutinin assay (MAA) titer of 1:320 or higher. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS version 13.0. P=.05 was regarded as significant. Data from 49 adults with AU and 44 adults with CU were analyzed. The distribution of MAA titers in adults with AU and CU are shown in the Figure. Microparticle agglutinin assay was negative in 10 (20.4%) of 49 adults with AU. Fifteen (30.6%) of 49 adults with AU had evidence of acute M pneumoniae infection, as indicated by an MAA titer of 1:320 or higher. The remaining 24 (49.0%) had evidence of prior infection as indicated by titers above the manufacturer’s cutoff of 1:402 and below our cutoff for acute infection of 1:320 or higher. Microparticle agglutinin assay was negative in 11 (25%) of 44 adults with CU. Three (6.8%) adults with CU were diagnosed with acute M pneumoniae infection and 30 (68.2%) were diagnosed with prior infection. The incidence of acute M pneumoniae infection was 30.6% in adults with AU compared to 6.8% in adults with CU, and the difference was statistically significant (P=.004).

Extrapulmonary complications of M pneumoniae involving practically every organ system have been described and 25% of patients develop cutaneous symptoms3 including AU. In 2007, Kano et al4 reported M pneumoniae infection-induced erythema nodosum, anaphylactoid purpura, and AU in a family of 3. This report was interesting because it showed that M pneumoniae had the ability to elicit different cutaneous reactions depending on the maturity of the adaptive immunity of a host, even among individuals of a common genetic background. A Taiwanese study found that 21 (32%) of 65 children with AU had M pneumoniae infection as determined by a positive Mycoplasma IgM test or an equivocal Mycoplasma IgM coupled with positive cold agglutinin test results.1

In our study, we found serological evidence of acute M pneumoniae infection in 15 (30.6%) of 49 adults with AU compared to 3 (6.8%) of 44 adults with CU (P=.004), suggesting that M pneumoniae also may play a role in the etiology of adult AU. Diagnosis of acute M pneumoniae infection is challenging, as it is often impossible to obtain convalescent serum that will show the 4-fold rise in titer. Single MAA titers of 1:160 or higher have been recommended for diagnosis of acute infection,5 but because of higher background activity in Singapore, we used a higher titer (>1:320). However, in doing so, we could be underestimating the true incidence of acute M pneumoniae infections.

The role of M pneumoniae in CU is uncertain. A Thai study reported that 55% of 38 children with CU had elevated M pneumoniae titers but did not provide details of actual titers or define what they meant by elevated titers.6 The incidence of acute and prior infection in our patients with CU was 6.8% and 68.2%, respectively. Unfortunately, we cannot determine the significance of the 68.2% incidence rate of prior infection in the absence of a normal control population of patients without urticaria. Another limitation of this study is that we compared M pneumoniae infection rate in AU with CU on the assumption that infection is not likely to play a significant role in CU, which may not necessarily be the case. Tests for other etiologic agents, including viruses, also were not performed. Not withstanding these limitations, this study suggests that acute M pneumoniae infection is significantly more common in adults with AU than in adults with CU.

This study showed that M pneumoniae might play a role in the etiology of AU in adults and our findings need to be confirmed by prospective studies. Several more questions must be answered before deciding whether the current practice of treating AU symptomatically without investigation needs to be changed. First, does treatment of M pneumoniae infection have any influence on the course of AU? The fact that AU usually is self-limiting suggests that treatment may not influence the disease course. Second, does treatment of underlying M pneumoniae infection shorten the course of AU? Third, do AU patients with untreated M pneumoniae infection face a higher risk for developing CU? This question is intriguing for the following reasons: (1) 30% to 50% of CU cases are autoimmune in etiology7; (2) antibodies to galactocerebroside that cross-react with glycolipids on M pneumoniae have been detected in patients with M pneumoniae–associated Guillain-Barré syndrome, suggesting a form of molecular mimicry8; and (3) antinuclear antibody also has occasionally been detected in sera of patients with M pneumoniae.9 It would be interesting to test patients with autoimmune and nonautoimmune CU for evidence of M pneumoniae serology infection.

We hope that prospective studies will be conducted in the future to confirm our findings and answer some of the questions raised.

To the Editor:

Mycoplasma pneumoniae has been implicated as a cause of acute urticaria (AU) in children,1 but its role in adults with AU is unknown. The aim of this retrospective study was to compare the incidence of acute M pneumoniae infection in adults with AU and chronic urticaria (CU).

A chart review was performed on adult patients with AU and CU who presented at a private dermatology practice in Singapore. Acute M pneumoniae infection was diagnosed on the basis of a single indirect microparticle agglutinin assay (MAA) titer of 1:320 or higher. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS version 13.0. P=.05 was regarded as significant. Data from 49 adults with AU and 44 adults with CU were analyzed. The distribution of MAA titers in adults with AU and CU are shown in the Figure. Microparticle agglutinin assay was negative in 10 (20.4%) of 49 adults with AU. Fifteen (30.6%) of 49 adults with AU had evidence of acute M pneumoniae infection, as indicated by an MAA titer of 1:320 or higher. The remaining 24 (49.0%) had evidence of prior infection as indicated by titers above the manufacturer’s cutoff of 1:402 and below our cutoff for acute infection of 1:320 or higher. Microparticle agglutinin assay was negative in 11 (25%) of 44 adults with CU. Three (6.8%) adults with CU were diagnosed with acute M pneumoniae infection and 30 (68.2%) were diagnosed with prior infection. The incidence of acute M pneumoniae infection was 30.6% in adults with AU compared to 6.8% in adults with CU, and the difference was statistically significant (P=.004).

Extrapulmonary complications of M pneumoniae involving practically every organ system have been described and 25% of patients develop cutaneous symptoms3 including AU. In 2007, Kano et al4 reported M pneumoniae infection-induced erythema nodosum, anaphylactoid purpura, and AU in a family of 3. This report was interesting because it showed that M pneumoniae had the ability to elicit different cutaneous reactions depending on the maturity of the adaptive immunity of a host, even among individuals of a common genetic background. A Taiwanese study found that 21 (32%) of 65 children with AU had M pneumoniae infection as determined by a positive Mycoplasma IgM test or an equivocal Mycoplasma IgM coupled with positive cold agglutinin test results.1

In our study, we found serological evidence of acute M pneumoniae infection in 15 (30.6%) of 49 adults with AU compared to 3 (6.8%) of 44 adults with CU (P=.004), suggesting that M pneumoniae also may play a role in the etiology of adult AU. Diagnosis of acute M pneumoniae infection is challenging, as it is often impossible to obtain convalescent serum that will show the 4-fold rise in titer. Single MAA titers of 1:160 or higher have been recommended for diagnosis of acute infection,5 but because of higher background activity in Singapore, we used a higher titer (>1:320). However, in doing so, we could be underestimating the true incidence of acute M pneumoniae infections.

The role of M pneumoniae in CU is uncertain. A Thai study reported that 55% of 38 children with CU had elevated M pneumoniae titers but did not provide details of actual titers or define what they meant by elevated titers.6 The incidence of acute and prior infection in our patients with CU was 6.8% and 68.2%, respectively. Unfortunately, we cannot determine the significance of the 68.2% incidence rate of prior infection in the absence of a normal control population of patients without urticaria. Another limitation of this study is that we compared M pneumoniae infection rate in AU with CU on the assumption that infection is not likely to play a significant role in CU, which may not necessarily be the case. Tests for other etiologic agents, including viruses, also were not performed. Not withstanding these limitations, this study suggests that acute M pneumoniae infection is significantly more common in adults with AU than in adults with CU.

This study showed that M pneumoniae might play a role in the etiology of AU in adults and our findings need to be confirmed by prospective studies. Several more questions must be answered before deciding whether the current practice of treating AU symptomatically without investigation needs to be changed. First, does treatment of M pneumoniae infection have any influence on the course of AU? The fact that AU usually is self-limiting suggests that treatment may not influence the disease course. Second, does treatment of underlying M pneumoniae infection shorten the course of AU? Third, do AU patients with untreated M pneumoniae infection face a higher risk for developing CU? This question is intriguing for the following reasons: (1) 30% to 50% of CU cases are autoimmune in etiology7; (2) antibodies to galactocerebroside that cross-react with glycolipids on M pneumoniae have been detected in patients with M pneumoniae–associated Guillain-Barré syndrome, suggesting a form of molecular mimicry8; and (3) antinuclear antibody also has occasionally been detected in sera of patients with M pneumoniae.9 It would be interesting to test patients with autoimmune and nonautoimmune CU for evidence of M pneumoniae serology infection.

We hope that prospective studies will be conducted in the future to confirm our findings and answer some of the questions raised.

1. Wu CC, Kuo HC, Yu HR, et al. Association of acute urticaria with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in hospitalized children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:134-139.

2. Serodia-Myco II [package insert]. Tokyo, Japan: Fujirebo; 2013.

3. Murray HW, Masur H, Senterfit LB, et al. The protean manifestations of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in adults. Am J Med. 1975;58:229-242.

4. Kano Y, Mitsuyama Y, Hirahara K, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection-induced erythema nodosum, anaphylactoid purpura, and acute urticaria in 3 people in a single family. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(suppl 2):S33-S35.

5. Daxboeck F, Krause R, Wenisch C. Laboratory diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:263-273.

6. Pongpreuksa S, Boochoo S, Kulthanan K, et al. Chronic urticaria: what is worth doing in pediatric population? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004:S134.

7. Grattan CE. Autoimmune urticaria. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004;24:163-181.

8. Kusunoki S, Shiina M, Kanazawa I. Anti-Gal-C antibodies in GBS subsequent to mycoplasma infection: evidence of molecular mimicry. Neurology. 2001;57:736-738.

9. Arikan S, Ergüven S, Ustaçelebi S, et al. Detection of antinuclear antibody (ANA) in patients with Mycoplasmal Pneumonia. Turk J Med Sci. 1998;28:97-98.

1. Wu CC, Kuo HC, Yu HR, et al. Association of acute urticaria with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in hospitalized children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:134-139.

2. Serodia-Myco II [package insert]. Tokyo, Japan: Fujirebo; 2013.

3. Murray HW, Masur H, Senterfit LB, et al. The protean manifestations of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in adults. Am J Med. 1975;58:229-242.

4. Kano Y, Mitsuyama Y, Hirahara K, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection-induced erythema nodosum, anaphylactoid purpura, and acute urticaria in 3 people in a single family. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(suppl 2):S33-S35.

5. Daxboeck F, Krause R, Wenisch C. Laboratory diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:263-273.

6. Pongpreuksa S, Boochoo S, Kulthanan K, et al. Chronic urticaria: what is worth doing in pediatric population? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004:S134.

7. Grattan CE. Autoimmune urticaria. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004;24:163-181.

8. Kusunoki S, Shiina M, Kanazawa I. Anti-Gal-C antibodies in GBS subsequent to mycoplasma infection: evidence of molecular mimicry. Neurology. 2001;57:736-738.

9. Arikan S, Ergüven S, Ustaçelebi S, et al. Detection of antinuclear antibody (ANA) in patients with Mycoplasmal Pneumonia. Turk J Med Sci. 1998;28:97-98.

Lupus-like Rash of Chronic Granulomatous Disease Effectively Treated With Hydroxychloroquine

To the Editor:

A 26-year-old man was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a persistent red rash to rule out cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE). The patient was diagnosed at 12 years of age with autosomal-recessive chronic granulomatous disease (CGD)(nitroblue tetrazolium test, 5.0; low normal, 20.6), type p47phox mutation. At that time the patient had recurrent fevers, sinusitis, anemia, and noncaseating granulomatous liver lesions, but he lacked any cutaneous manifestations. The patient was then treated for approximately 2 years with interferon therapy but discontinued therapy given the absence of any signs or symptoms. He remained asymptomatic until approximately 16 years of age when he experienced the onset of an intermittently painful and pruritic rash on the face that slowly spread over the ensuing years to involve the trunk, arms, forearms, and hands. Although he reported that sunlight exacerbated the rash, the rash also persisted through the winter months when the majority of the sun-exposed areas of the trunk and arms were covered. He denied exposure to topical products and denied the use of any oral medications (prescription or over-the-counter).

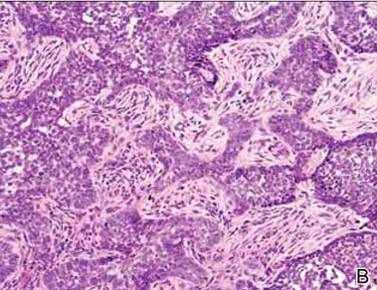

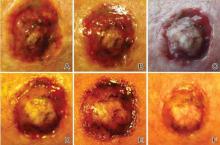

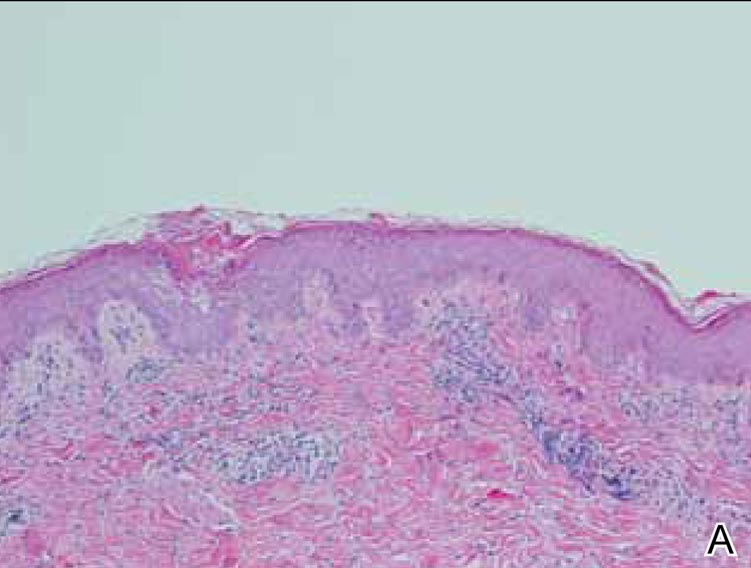

Review of systems was negative for fever, fatigue, malaise, headaches, joint pain, arthritis, oral ulcers, dyspnea, or dysuria. Physical examination revealed a well-defined exanthem comprised of erythematous, mildly indurated papules coalescing into larger plaques with white scale that were exclusively limited to the photodistributed areas of the face (Figure 1), neck, arms, forearms, hands, chest, and back. Laboratory test results included the following: minimally elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 31 mm/h (reference range, 0–15 mm/h) and rheumatoid factor of 45 IU/mL (reference range, <20 IU/mL; negative antinuclear antibody screen, Sjögren syndrome antigens A and B, double-stranded DNA, anti–extractable nuclear antigen antibody test, and anti-Jo-1 antibody; complete blood cell count revealed no abnormalities; basic metabolic panel, C3 and C4, CH50, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity, total plasma porphyrins, and testing for hepatitis B and C virus and human immunodeficiency virus serologies were negative. Skin biopsy from a lesion on the lateral arm showed features consistent with interface dermatitis (Figure 2). Additional skin biopsies for direct immunofluorescence showed linear deposition of IgG at the dermoepidermal junction, both from involved and uninvolved neck skin (more focally from the involved site). Extensive photopatch testing did not show any clinically relevant positive reactions.

|

Given the patient’s history of CGD and the extensive negative workup for rheumatologic, photoallergic, and phototoxic causes, the patient was diagnosed with a lupus-like rash of CGD. The rash failed to respond to rigorous sun avoidance and a 3-week on/1-week off regimen of high-potency class 1 topical steroids to the trunk, arms, forearms, and legs, and lower-potency class 4 topical steroid to the face, with disease flaring almost immediately on cessation of treatment during the rest weeks. Given the marked photodistribution resembling subacute cutaneous LE, oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg (5.7 mg/kg) twice daily was initiated in addition to continued topical steroid therapy.

Four months after the addition of hydroxychloroquine, the patient showed considerable improvement of the rash. Seven months after initiation of hydroxychloroquine, the photodistributed rash was completely resolved and topical steroids were stopped. The rash remained in remission for an additional 24 months with hydroxychloroquine alone, at which time hydroxychloroquine was stopped; however, the rash flared 2 months later and hydroxychloroquine was restarted at 200 mg twice daily, resulting in clearance within 3 months. The patient was maintained on this dose of hydroxychloroquine.

During treatment, the patient had an episode of extensive furunculosis caused by Staphylococcus aureus that was successfully treated with a 14-day course of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. He has since been maintained on prophylactic intranasal mupirocin ointment 2% for the first several days of each month and daily benzoyl peroxide wash 10% without further episodes. He also developed a single lesion of alopecia areata that was successfully treated with intralesional steroid injections.

Chronic granulomatous disease can either be X-linked or, less commonly, autosomal recessive, resulting from a defect in components of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase complex that is necessary to generate reactive oxygen intermediates for killing phagocytosed microbes. Cutaneous manifestations are relatively common in CGD (60%–70% of cases)1 and include infectious lesions (eg, recurrent mucous membrane infections, impetigo, carbuncles, otitis externa, suppurative lymphadenopathy) as well as the less common chronic inflammatory conditions such as lupus-like eruption, aphthous stomatitis, Raynaud phenomenon, arcuate dermal erythema, and Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate.2 The pathognomonic clinical feature of CGD is the presence of characteristic multinucleated giant cell granulomas distributed in multiple organ systems such as the gastrointestinal system, causing pyloric and/or small bowel obstruction, and the genitourinary system, causing ureter and/or bladder outlet obstruction.3

Importantly, CGD patients also demonstrate immune-related inflammatory disorders, most commonly inflammatory bowel disease, IgA nephropathy, sarcoidosis, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis.3 In addition, both CGD patients and female carriers of X-linked CGD have been reported to demonstrate lupus-like rashes that share overlapping clinical and histologic features with the rashes seen in true discoid LE and tumid LE patients without CGD.4-6 This lupus-like rash is more commonly observed in adulthood and in carriers, possibly secondary to the high childhood mortality rate of CGD patients.4,6

De Ravin et al3 proposed that autoimmune conditions arising in CGD patients who have met established criteria for a particular autoimmune disease should be treated for that condition rather than consider it as a part of the CGD spectrum. This theory has important therapeutic implications, including initiating paradoxical corticosteroid and/or steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents in this otherwise immunocompromised patient population. They reported a 21-year-old man with cutaneous LE lesions and negative lupus serologies whose lesions were refractory to topical steroids but responded to systemic prednisone, requiring a low-dose alternate-day maintenance regimen.3 Beyond the development of a true autoimmune disease associated with CGD, systemic medications, specifically voriconazole, have been implicated as an alternative etiology for this rash in CGD.7 While important to consider, our patient’s rash presented in the absence of any systemic medications, supporting the former etiology over the latter.

Our case demonstrates the utility of hydroxychloroquine to treat the lupus-like rash of CGD. Similarly, the lupus-like symptoms of female carriers of X-linked CGD, predominantly with negative lupus serologies, also have been reported to respond to hydroxychloroquine and mepacrine.4,5,8-10 Interestingly, the utility of monotherapy with hydroxychloroquine may extend beyond treating cutaneous lupus-like lesions, as this regimen also was reported to successfully treat gastric granulomatous involvement in a CGD patient.11

Chronic granulomatous disease often is fatal in early childhood or adolescence due to sequelae from infections or chronic granulomatous infiltration of internal organs. Residual reactive oxygen intermediate production was shown to be a predictor of overall survival, and CGD patients with 1% of normal reactive oxygen intermediate production by neutrophils had a greater likelihood of survival.12 In this regard, the otherwise good health of our patient at the time of presentation was consistent with his initial nitroblue tetrazolium test showing some residual oxidative activity, emphasizing the phenotypic variability of this rare genetic disorder and the importance of considering CGD in the diagnosis of seronegative cutaneous lupus-like reactions.

1. Dohil M, Prendiville JS, Crawford RI, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic granulomatous disease. a report of four cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6, pt 1):899-907.

2. Chowdhury MM, Anstey A, Matthews CN. The dermatosis of chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:190-194.

3. De Ravin SS, Naumann N, Cowen EW, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease as a risk factor for autoimmune disease [published online ahead of print September 26, 2008]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:1097-1103.

4. Kragballe K, Borregaard N, Brandrup F, et al. Relation of monocyte and neutrophil oxidative metabolism to skin and oral lesions in carriers of chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1981;43:390-398.

5. Barton LL, Johnson CR. Discoid lupus erythematosus and X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:376-379.

6. Córdoba-Guijarro S, Feal C, Daudén E, et al. Lupus erythematosus-like lesions in a carrier of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:409-411.

7. Gomez-Moyano E, Vera-Casaño A, Moreno-Perez D, et al. Lupus erythematosus-like lesions by voriconazole in an infant with chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:105-106.

8. Brandrup F, Koch C, Petri M, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus-like lesions and stomatitis in female carriers of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. Br J Dermatol. 1981;104:495-505.

9. Cale CM, Morton L, Goldblatt D. Cutaneous and other lupus-like symptoms in carriers of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease: incidence and autoimmune serology. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;148:79-84.

10. Levinsky RJ, Harvey BA, Roberton DM, et al. A polymorph bactericidal defect and a lupus-like syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1981;56:382-385.

11. Arlet JB, Aouba A, Suarez F, et al. Efficiency of hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of granulomatous complications in chronic granulomatous disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:142-144.

12. Kuhns DB, Alvord WG, Heller T, et al. Residual NADPH oxidase and survival in chronic granulomatous disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2600-2610.

To the Editor:

A 26-year-old man was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a persistent red rash to rule out cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE). The patient was diagnosed at 12 years of age with autosomal-recessive chronic granulomatous disease (CGD)(nitroblue tetrazolium test, 5.0; low normal, 20.6), type p47phox mutation. At that time the patient had recurrent fevers, sinusitis, anemia, and noncaseating granulomatous liver lesions, but he lacked any cutaneous manifestations. The patient was then treated for approximately 2 years with interferon therapy but discontinued therapy given the absence of any signs or symptoms. He remained asymptomatic until approximately 16 years of age when he experienced the onset of an intermittently painful and pruritic rash on the face that slowly spread over the ensuing years to involve the trunk, arms, forearms, and hands. Although he reported that sunlight exacerbated the rash, the rash also persisted through the winter months when the majority of the sun-exposed areas of the trunk and arms were covered. He denied exposure to topical products and denied the use of any oral medications (prescription or over-the-counter).

Review of systems was negative for fever, fatigue, malaise, headaches, joint pain, arthritis, oral ulcers, dyspnea, or dysuria. Physical examination revealed a well-defined exanthem comprised of erythematous, mildly indurated papules coalescing into larger plaques with white scale that were exclusively limited to the photodistributed areas of the face (Figure 1), neck, arms, forearms, hands, chest, and back. Laboratory test results included the following: minimally elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 31 mm/h (reference range, 0–15 mm/h) and rheumatoid factor of 45 IU/mL (reference range, <20 IU/mL; negative antinuclear antibody screen, Sjögren syndrome antigens A and B, double-stranded DNA, anti–extractable nuclear antigen antibody test, and anti-Jo-1 antibody; complete blood cell count revealed no abnormalities; basic metabolic panel, C3 and C4, CH50, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity, total plasma porphyrins, and testing for hepatitis B and C virus and human immunodeficiency virus serologies were negative. Skin biopsy from a lesion on the lateral arm showed features consistent with interface dermatitis (Figure 2). Additional skin biopsies for direct immunofluorescence showed linear deposition of IgG at the dermoepidermal junction, both from involved and uninvolved neck skin (more focally from the involved site). Extensive photopatch testing did not show any clinically relevant positive reactions.

|

Given the patient’s history of CGD and the extensive negative workup for rheumatologic, photoallergic, and phototoxic causes, the patient was diagnosed with a lupus-like rash of CGD. The rash failed to respond to rigorous sun avoidance and a 3-week on/1-week off regimen of high-potency class 1 topical steroids to the trunk, arms, forearms, and legs, and lower-potency class 4 topical steroid to the face, with disease flaring almost immediately on cessation of treatment during the rest weeks. Given the marked photodistribution resembling subacute cutaneous LE, oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg (5.7 mg/kg) twice daily was initiated in addition to continued topical steroid therapy.

Four months after the addition of hydroxychloroquine, the patient showed considerable improvement of the rash. Seven months after initiation of hydroxychloroquine, the photodistributed rash was completely resolved and topical steroids were stopped. The rash remained in remission for an additional 24 months with hydroxychloroquine alone, at which time hydroxychloroquine was stopped; however, the rash flared 2 months later and hydroxychloroquine was restarted at 200 mg twice daily, resulting in clearance within 3 months. The patient was maintained on this dose of hydroxychloroquine.

During treatment, the patient had an episode of extensive furunculosis caused by Staphylococcus aureus that was successfully treated with a 14-day course of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. He has since been maintained on prophylactic intranasal mupirocin ointment 2% for the first several days of each month and daily benzoyl peroxide wash 10% without further episodes. He also developed a single lesion of alopecia areata that was successfully treated with intralesional steroid injections.

Chronic granulomatous disease can either be X-linked or, less commonly, autosomal recessive, resulting from a defect in components of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase complex that is necessary to generate reactive oxygen intermediates for killing phagocytosed microbes. Cutaneous manifestations are relatively common in CGD (60%–70% of cases)1 and include infectious lesions (eg, recurrent mucous membrane infections, impetigo, carbuncles, otitis externa, suppurative lymphadenopathy) as well as the less common chronic inflammatory conditions such as lupus-like eruption, aphthous stomatitis, Raynaud phenomenon, arcuate dermal erythema, and Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate.2 The pathognomonic clinical feature of CGD is the presence of characteristic multinucleated giant cell granulomas distributed in multiple organ systems such as the gastrointestinal system, causing pyloric and/or small bowel obstruction, and the genitourinary system, causing ureter and/or bladder outlet obstruction.3

Importantly, CGD patients also demonstrate immune-related inflammatory disorders, most commonly inflammatory bowel disease, IgA nephropathy, sarcoidosis, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis.3 In addition, both CGD patients and female carriers of X-linked CGD have been reported to demonstrate lupus-like rashes that share overlapping clinical and histologic features with the rashes seen in true discoid LE and tumid LE patients without CGD.4-6 This lupus-like rash is more commonly observed in adulthood and in carriers, possibly secondary to the high childhood mortality rate of CGD patients.4,6

De Ravin et al3 proposed that autoimmune conditions arising in CGD patients who have met established criteria for a particular autoimmune disease should be treated for that condition rather than consider it as a part of the CGD spectrum. This theory has important therapeutic implications, including initiating paradoxical corticosteroid and/or steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents in this otherwise immunocompromised patient population. They reported a 21-year-old man with cutaneous LE lesions and negative lupus serologies whose lesions were refractory to topical steroids but responded to systemic prednisone, requiring a low-dose alternate-day maintenance regimen.3 Beyond the development of a true autoimmune disease associated with CGD, systemic medications, specifically voriconazole, have been implicated as an alternative etiology for this rash in CGD.7 While important to consider, our patient’s rash presented in the absence of any systemic medications, supporting the former etiology over the latter.

Our case demonstrates the utility of hydroxychloroquine to treat the lupus-like rash of CGD. Similarly, the lupus-like symptoms of female carriers of X-linked CGD, predominantly with negative lupus serologies, also have been reported to respond to hydroxychloroquine and mepacrine.4,5,8-10 Interestingly, the utility of monotherapy with hydroxychloroquine may extend beyond treating cutaneous lupus-like lesions, as this regimen also was reported to successfully treat gastric granulomatous involvement in a CGD patient.11

Chronic granulomatous disease often is fatal in early childhood or adolescence due to sequelae from infections or chronic granulomatous infiltration of internal organs. Residual reactive oxygen intermediate production was shown to be a predictor of overall survival, and CGD patients with 1% of normal reactive oxygen intermediate production by neutrophils had a greater likelihood of survival.12 In this regard, the otherwise good health of our patient at the time of presentation was consistent with his initial nitroblue tetrazolium test showing some residual oxidative activity, emphasizing the phenotypic variability of this rare genetic disorder and the importance of considering CGD in the diagnosis of seronegative cutaneous lupus-like reactions.

To the Editor:

A 26-year-old man was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a persistent red rash to rule out cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE). The patient was diagnosed at 12 years of age with autosomal-recessive chronic granulomatous disease (CGD)(nitroblue tetrazolium test, 5.0; low normal, 20.6), type p47phox mutation. At that time the patient had recurrent fevers, sinusitis, anemia, and noncaseating granulomatous liver lesions, but he lacked any cutaneous manifestations. The patient was then treated for approximately 2 years with interferon therapy but discontinued therapy given the absence of any signs or symptoms. He remained asymptomatic until approximately 16 years of age when he experienced the onset of an intermittently painful and pruritic rash on the face that slowly spread over the ensuing years to involve the trunk, arms, forearms, and hands. Although he reported that sunlight exacerbated the rash, the rash also persisted through the winter months when the majority of the sun-exposed areas of the trunk and arms were covered. He denied exposure to topical products and denied the use of any oral medications (prescription or over-the-counter).

Review of systems was negative for fever, fatigue, malaise, headaches, joint pain, arthritis, oral ulcers, dyspnea, or dysuria. Physical examination revealed a well-defined exanthem comprised of erythematous, mildly indurated papules coalescing into larger plaques with white scale that were exclusively limited to the photodistributed areas of the face (Figure 1), neck, arms, forearms, hands, chest, and back. Laboratory test results included the following: minimally elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 31 mm/h (reference range, 0–15 mm/h) and rheumatoid factor of 45 IU/mL (reference range, <20 IU/mL; negative antinuclear antibody screen, Sjögren syndrome antigens A and B, double-stranded DNA, anti–extractable nuclear antigen antibody test, and anti-Jo-1 antibody; complete blood cell count revealed no abnormalities; basic metabolic panel, C3 and C4, CH50, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity, total plasma porphyrins, and testing for hepatitis B and C virus and human immunodeficiency virus serologies were negative. Skin biopsy from a lesion on the lateral arm showed features consistent with interface dermatitis (Figure 2). Additional skin biopsies for direct immunofluorescence showed linear deposition of IgG at the dermoepidermal junction, both from involved and uninvolved neck skin (more focally from the involved site). Extensive photopatch testing did not show any clinically relevant positive reactions.

|

Given the patient’s history of CGD and the extensive negative workup for rheumatologic, photoallergic, and phototoxic causes, the patient was diagnosed with a lupus-like rash of CGD. The rash failed to respond to rigorous sun avoidance and a 3-week on/1-week off regimen of high-potency class 1 topical steroids to the trunk, arms, forearms, and legs, and lower-potency class 4 topical steroid to the face, with disease flaring almost immediately on cessation of treatment during the rest weeks. Given the marked photodistribution resembling subacute cutaneous LE, oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg (5.7 mg/kg) twice daily was initiated in addition to continued topical steroid therapy.

Four months after the addition of hydroxychloroquine, the patient showed considerable improvement of the rash. Seven months after initiation of hydroxychloroquine, the photodistributed rash was completely resolved and topical steroids were stopped. The rash remained in remission for an additional 24 months with hydroxychloroquine alone, at which time hydroxychloroquine was stopped; however, the rash flared 2 months later and hydroxychloroquine was restarted at 200 mg twice daily, resulting in clearance within 3 months. The patient was maintained on this dose of hydroxychloroquine.

During treatment, the patient had an episode of extensive furunculosis caused by Staphylococcus aureus that was successfully treated with a 14-day course of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. He has since been maintained on prophylactic intranasal mupirocin ointment 2% for the first several days of each month and daily benzoyl peroxide wash 10% without further episodes. He also developed a single lesion of alopecia areata that was successfully treated with intralesional steroid injections.

Chronic granulomatous disease can either be X-linked or, less commonly, autosomal recessive, resulting from a defect in components of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase complex that is necessary to generate reactive oxygen intermediates for killing phagocytosed microbes. Cutaneous manifestations are relatively common in CGD (60%–70% of cases)1 and include infectious lesions (eg, recurrent mucous membrane infections, impetigo, carbuncles, otitis externa, suppurative lymphadenopathy) as well as the less common chronic inflammatory conditions such as lupus-like eruption, aphthous stomatitis, Raynaud phenomenon, arcuate dermal erythema, and Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate.2 The pathognomonic clinical feature of CGD is the presence of characteristic multinucleated giant cell granulomas distributed in multiple organ systems such as the gastrointestinal system, causing pyloric and/or small bowel obstruction, and the genitourinary system, causing ureter and/or bladder outlet obstruction.3

Importantly, CGD patients also demonstrate immune-related inflammatory disorders, most commonly inflammatory bowel disease, IgA nephropathy, sarcoidosis, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis.3 In addition, both CGD patients and female carriers of X-linked CGD have been reported to demonstrate lupus-like rashes that share overlapping clinical and histologic features with the rashes seen in true discoid LE and tumid LE patients without CGD.4-6 This lupus-like rash is more commonly observed in adulthood and in carriers, possibly secondary to the high childhood mortality rate of CGD patients.4,6

De Ravin et al3 proposed that autoimmune conditions arising in CGD patients who have met established criteria for a particular autoimmune disease should be treated for that condition rather than consider it as a part of the CGD spectrum. This theory has important therapeutic implications, including initiating paradoxical corticosteroid and/or steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents in this otherwise immunocompromised patient population. They reported a 21-year-old man with cutaneous LE lesions and negative lupus serologies whose lesions were refractory to topical steroids but responded to systemic prednisone, requiring a low-dose alternate-day maintenance regimen.3 Beyond the development of a true autoimmune disease associated with CGD, systemic medications, specifically voriconazole, have been implicated as an alternative etiology for this rash in CGD.7 While important to consider, our patient’s rash presented in the absence of any systemic medications, supporting the former etiology over the latter.

Our case demonstrates the utility of hydroxychloroquine to treat the lupus-like rash of CGD. Similarly, the lupus-like symptoms of female carriers of X-linked CGD, predominantly with negative lupus serologies, also have been reported to respond to hydroxychloroquine and mepacrine.4,5,8-10 Interestingly, the utility of monotherapy with hydroxychloroquine may extend beyond treating cutaneous lupus-like lesions, as this regimen also was reported to successfully treat gastric granulomatous involvement in a CGD patient.11

Chronic granulomatous disease often is fatal in early childhood or adolescence due to sequelae from infections or chronic granulomatous infiltration of internal organs. Residual reactive oxygen intermediate production was shown to be a predictor of overall survival, and CGD patients with 1% of normal reactive oxygen intermediate production by neutrophils had a greater likelihood of survival.12 In this regard, the otherwise good health of our patient at the time of presentation was consistent with his initial nitroblue tetrazolium test showing some residual oxidative activity, emphasizing the phenotypic variability of this rare genetic disorder and the importance of considering CGD in the diagnosis of seronegative cutaneous lupus-like reactions.

1. Dohil M, Prendiville JS, Crawford RI, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic granulomatous disease. a report of four cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6, pt 1):899-907.

2. Chowdhury MM, Anstey A, Matthews CN. The dermatosis of chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:190-194.

3. De Ravin SS, Naumann N, Cowen EW, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease as a risk factor for autoimmune disease [published online ahead of print September 26, 2008]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:1097-1103.

4. Kragballe K, Borregaard N, Brandrup F, et al. Relation of monocyte and neutrophil oxidative metabolism to skin and oral lesions in carriers of chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1981;43:390-398.

5. Barton LL, Johnson CR. Discoid lupus erythematosus and X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:376-379.

6. Córdoba-Guijarro S, Feal C, Daudén E, et al. Lupus erythematosus-like lesions in a carrier of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:409-411.

7. Gomez-Moyano E, Vera-Casaño A, Moreno-Perez D, et al. Lupus erythematosus-like lesions by voriconazole in an infant with chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:105-106.

8. Brandrup F, Koch C, Petri M, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus-like lesions and stomatitis in female carriers of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. Br J Dermatol. 1981;104:495-505.

9. Cale CM, Morton L, Goldblatt D. Cutaneous and other lupus-like symptoms in carriers of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease: incidence and autoimmune serology. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;148:79-84.

10. Levinsky RJ, Harvey BA, Roberton DM, et al. A polymorph bactericidal defect and a lupus-like syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1981;56:382-385.

11. Arlet JB, Aouba A, Suarez F, et al. Efficiency of hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of granulomatous complications in chronic granulomatous disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:142-144.

12. Kuhns DB, Alvord WG, Heller T, et al. Residual NADPH oxidase and survival in chronic granulomatous disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2600-2610.

1. Dohil M, Prendiville JS, Crawford RI, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic granulomatous disease. a report of four cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6, pt 1):899-907.

2. Chowdhury MM, Anstey A, Matthews CN. The dermatosis of chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:190-194.

3. De Ravin SS, Naumann N, Cowen EW, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease as a risk factor for autoimmune disease [published online ahead of print September 26, 2008]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:1097-1103.

4. Kragballe K, Borregaard N, Brandrup F, et al. Relation of monocyte and neutrophil oxidative metabolism to skin and oral lesions in carriers of chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1981;43:390-398.

5. Barton LL, Johnson CR. Discoid lupus erythematosus and X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:376-379.

6. Córdoba-Guijarro S, Feal C, Daudén E, et al. Lupus erythematosus-like lesions in a carrier of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:409-411.

7. Gomez-Moyano E, Vera-Casaño A, Moreno-Perez D, et al. Lupus erythematosus-like lesions by voriconazole in an infant with chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:105-106.

8. Brandrup F, Koch C, Petri M, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus-like lesions and stomatitis in female carriers of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. Br J Dermatol. 1981;104:495-505.

9. Cale CM, Morton L, Goldblatt D. Cutaneous and other lupus-like symptoms in carriers of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease: incidence and autoimmune serology. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;148:79-84.

10. Levinsky RJ, Harvey BA, Roberton DM, et al. A polymorph bactericidal defect and a lupus-like syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1981;56:382-385.

11. Arlet JB, Aouba A, Suarez F, et al. Efficiency of hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of granulomatous complications in chronic granulomatous disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:142-144.

12. Kuhns DB, Alvord WG, Heller T, et al. Residual NADPH oxidase and survival in chronic granulomatous disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2600-2610.

Shiitake Mushroom Dermatitis

To the Editor:

The shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes) is a popular Asian food and represents the second most consumed mushroom in the world. It is known for having a range of strong health benefits including antihypertensive, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects. Especially in Asia, this mushroom has been used in patients with cancers of the gastrointestinal tract and also may be helpful in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus.1,2 The source of these effects is lentinan, a polysaccharide in the mushroom. However, lentinan also can cause a toxic reaction of the skin when the mushrooms are eaten raw or undercooked. These reactions are mainly reported in Asia, but more cases have been published in the last decade in Europe and the United States, evidence that the incidence of this adverse effect has increased in the Western world.