User login

Identification of Cutaneous Warts: Cryotherapy-Induced Acetowhitelike Epithelium

To the Editor:

Cutaneous warts are benign proliferations of the epidermis that occur secondary to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The diagnosis of cutaneous warts is generally based on clinical appearance. Occasionally subtle lesions, particularly those of verruca plana, escape clinical identification leading to incomplete treatment and spreading. The acetic acid test (sometimes called the acetic acid visual inspection) causes epithelial whitening of HPV-infected areas after application of a 3% to 5% aqueous solution of acetic acid and has been used to detect subclinical HPV infection.1 Although the acetic acid test can support the diagnosis of cutaneous warts, it is more effective at detecting hyperplastic rather than flat warts and may be cumbersome to use routinely.2 We describe a simple clinical maneuver to help confirm the presence of subtle warts using gentle liquid nitrogen cryotherapy to induce epithelial whitening in areas of HPV infection.

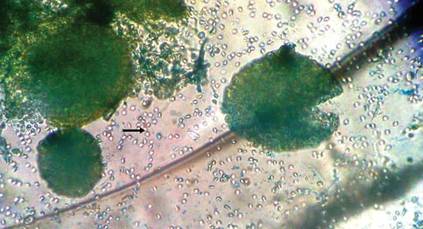

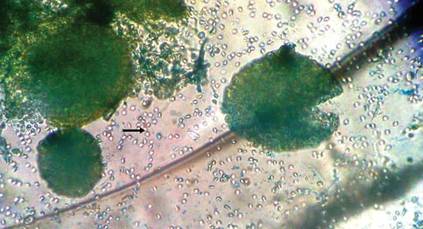

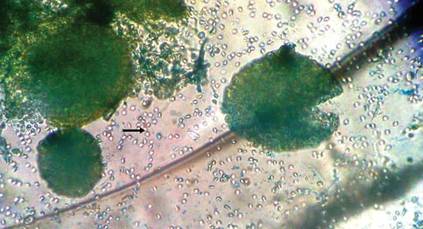

A 22-year-old man presented for evaluation of a 5-mm verrucous papule on the right wrist. He was diagnosed with verruca vulgaris. During treatment, small satellite verrucous papules were visualized by differential whitening from the surrounding uninfected skin (Figure). A brief light spray of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy (-196°C) was applied over areas containing suspicious lesions for confirmation. This acetowhitelike change from indirect collateral cryotherapy allowed for identification and treatment of these subtle warts.

Cutaneous warts represent foci of epithelial proliferation, and acetowhite changes are thought to occur from extravasation of intracellular water with subsequent tissue whitening in areas of high nuclear density.3 Acetowhite epithelium also has been reported after other ablative wart therapies.4 Similarly, acetowhitelike changes after cryotherapy may be secondary to cellular dehydration from ice crystal formation,5 with HPV-infected areas demonstrating increased susceptibility to freezing because of increased cellular water content in areas of hyperkeratosis. In addition, it has been demonstrated that cryotherapy alters the composition of the epithelium by destroying neutral and acidic mucopolysaccharides, which may subsequently induce the characteristic acetowhitelike changes in the epithelium of cutaneous warts.6

We propose that gentle painless sprays of liquid nitrogen to areas with suspicious lesions can help confirm the presence of subtle warts through cryotherapy-induced epithelial whitening. Although this test is a valuable diagnostic pearl, it should be noted that cryotherapy may accentuate an area of hyperkeratosis from causes other than an HPV infection. As such, clinical judgment is required.

1. Allan BM. Acetowhite epithelium. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:691-694.

2. Kumar B, Gupta S. The acetowhite test in genital human papillomavirus infection in men: what does it add? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:27-29.

3. O’Connor DM. A tissue basis for colposcopic findings. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35:565-582.

4. MacLean AB. Healing of the cervical epithelium after laser treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91:697-706.

5. Gage AA, Baust J. Mechanisms of tissue injury in cryosurgery. Cryobiology. 1998;37:171-186.

6. Ciecierski L. Histochemical studies on acid and neutral mucopolysaccharides in the acanthotic epidermis of warts before and after cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen. Przegl Dermatol. 1970;57:11-15.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous warts are benign proliferations of the epidermis that occur secondary to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The diagnosis of cutaneous warts is generally based on clinical appearance. Occasionally subtle lesions, particularly those of verruca plana, escape clinical identification leading to incomplete treatment and spreading. The acetic acid test (sometimes called the acetic acid visual inspection) causes epithelial whitening of HPV-infected areas after application of a 3% to 5% aqueous solution of acetic acid and has been used to detect subclinical HPV infection.1 Although the acetic acid test can support the diagnosis of cutaneous warts, it is more effective at detecting hyperplastic rather than flat warts and may be cumbersome to use routinely.2 We describe a simple clinical maneuver to help confirm the presence of subtle warts using gentle liquid nitrogen cryotherapy to induce epithelial whitening in areas of HPV infection.

A 22-year-old man presented for evaluation of a 5-mm verrucous papule on the right wrist. He was diagnosed with verruca vulgaris. During treatment, small satellite verrucous papules were visualized by differential whitening from the surrounding uninfected skin (Figure). A brief light spray of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy (-196°C) was applied over areas containing suspicious lesions for confirmation. This acetowhitelike change from indirect collateral cryotherapy allowed for identification and treatment of these subtle warts.

Cutaneous warts represent foci of epithelial proliferation, and acetowhite changes are thought to occur from extravasation of intracellular water with subsequent tissue whitening in areas of high nuclear density.3 Acetowhite epithelium also has been reported after other ablative wart therapies.4 Similarly, acetowhitelike changes after cryotherapy may be secondary to cellular dehydration from ice crystal formation,5 with HPV-infected areas demonstrating increased susceptibility to freezing because of increased cellular water content in areas of hyperkeratosis. In addition, it has been demonstrated that cryotherapy alters the composition of the epithelium by destroying neutral and acidic mucopolysaccharides, which may subsequently induce the characteristic acetowhitelike changes in the epithelium of cutaneous warts.6

We propose that gentle painless sprays of liquid nitrogen to areas with suspicious lesions can help confirm the presence of subtle warts through cryotherapy-induced epithelial whitening. Although this test is a valuable diagnostic pearl, it should be noted that cryotherapy may accentuate an area of hyperkeratosis from causes other than an HPV infection. As such, clinical judgment is required.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous warts are benign proliferations of the epidermis that occur secondary to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The diagnosis of cutaneous warts is generally based on clinical appearance. Occasionally subtle lesions, particularly those of verruca plana, escape clinical identification leading to incomplete treatment and spreading. The acetic acid test (sometimes called the acetic acid visual inspection) causes epithelial whitening of HPV-infected areas after application of a 3% to 5% aqueous solution of acetic acid and has been used to detect subclinical HPV infection.1 Although the acetic acid test can support the diagnosis of cutaneous warts, it is more effective at detecting hyperplastic rather than flat warts and may be cumbersome to use routinely.2 We describe a simple clinical maneuver to help confirm the presence of subtle warts using gentle liquid nitrogen cryotherapy to induce epithelial whitening in areas of HPV infection.

A 22-year-old man presented for evaluation of a 5-mm verrucous papule on the right wrist. He was diagnosed with verruca vulgaris. During treatment, small satellite verrucous papules were visualized by differential whitening from the surrounding uninfected skin (Figure). A brief light spray of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy (-196°C) was applied over areas containing suspicious lesions for confirmation. This acetowhitelike change from indirect collateral cryotherapy allowed for identification and treatment of these subtle warts.

Cutaneous warts represent foci of epithelial proliferation, and acetowhite changes are thought to occur from extravasation of intracellular water with subsequent tissue whitening in areas of high nuclear density.3 Acetowhite epithelium also has been reported after other ablative wart therapies.4 Similarly, acetowhitelike changes after cryotherapy may be secondary to cellular dehydration from ice crystal formation,5 with HPV-infected areas demonstrating increased susceptibility to freezing because of increased cellular water content in areas of hyperkeratosis. In addition, it has been demonstrated that cryotherapy alters the composition of the epithelium by destroying neutral and acidic mucopolysaccharides, which may subsequently induce the characteristic acetowhitelike changes in the epithelium of cutaneous warts.6

We propose that gentle painless sprays of liquid nitrogen to areas with suspicious lesions can help confirm the presence of subtle warts through cryotherapy-induced epithelial whitening. Although this test is a valuable diagnostic pearl, it should be noted that cryotherapy may accentuate an area of hyperkeratosis from causes other than an HPV infection. As such, clinical judgment is required.

1. Allan BM. Acetowhite epithelium. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:691-694.

2. Kumar B, Gupta S. The acetowhite test in genital human papillomavirus infection in men: what does it add? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:27-29.

3. O’Connor DM. A tissue basis for colposcopic findings. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35:565-582.

4. MacLean AB. Healing of the cervical epithelium after laser treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91:697-706.

5. Gage AA, Baust J. Mechanisms of tissue injury in cryosurgery. Cryobiology. 1998;37:171-186.

6. Ciecierski L. Histochemical studies on acid and neutral mucopolysaccharides in the acanthotic epidermis of warts before and after cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen. Przegl Dermatol. 1970;57:11-15.

1. Allan BM. Acetowhite epithelium. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:691-694.

2. Kumar B, Gupta S. The acetowhite test in genital human papillomavirus infection in men: what does it add? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:27-29.

3. O’Connor DM. A tissue basis for colposcopic findings. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35:565-582.

4. MacLean AB. Healing of the cervical epithelium after laser treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91:697-706.

5. Gage AA, Baust J. Mechanisms of tissue injury in cryosurgery. Cryobiology. 1998;37:171-186.

6. Ciecierski L. Histochemical studies on acid and neutral mucopolysaccharides in the acanthotic epidermis of warts before and after cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen. Przegl Dermatol. 1970;57:11-15.

Subcutaneous Sarcoidosis on Ultrasonography

To the Editor:

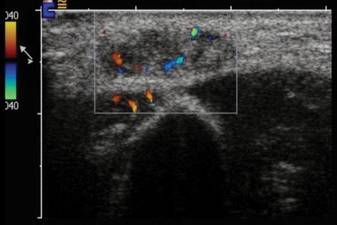

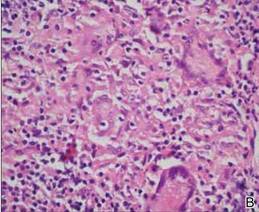

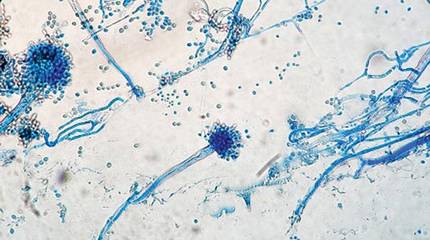

A 54-year-old woman presented with painless, firm, flesh-colored nodules measuring 1.0 to 1.5 cm in diameter on the extensor surface of the left forearm (Figure 1) and on the distal phalanx of the left thumb of 3 months’ duration. No other signs and symptoms were present. A detailed clinical examination revealed a slightly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (24 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and a high antinuclear antibody titer (1:3200 [reference range, <1:100])(anti–Sjögren syndrome anti-gen A, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anti-Ro52). Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, urinalysis, pulmonary function tests, chest radiograph, and chest computed tomography all were normal. Hepatitis B antigen and antibody tests; hepatitis C antibody tests; and tuberculin test all were negative. An ophthalmic examination revealed no abnormalities. Ultrasonography of the nodules was performed with a system using an 8- to 12-MHz linear transducer and revealed 4 heterogenous hypoechoic lesions measuring up to 1.5 cm in size. Color Doppler images showed moderate hypervascularity (Figure 2). The largest nodule was excised. Histologic examination revealed noncaseating granulomas; special stains for microorganisms were negative. The histopathologic findings confirmed a diagnosis of sarcoidosis (Figure 3). The patient refused any medication. The nodules were stable at 6-month follow-up, then spontaneously resolved.

|

Subcutaneous sarcoidosis (SS) is a rare cutaneous expression of systemic sarcoidosis. The entity was first described by French physicians Darier and Roussy in 1904 as granulomatous panniculitis. Although their original study referred to a case of tuberculosis, the term Darier-Roussy sarcoid was coined and had been applied to a true sarcoid as well as to a variety of other forms of granulomatous panniculitis including those of infectious origin. A more accurate term subcutaneous sarcoidosis was established in 1984 by Vainsencher and Winkelmann.1

The most characteristic clinical picture of this disorder consists of the presence of multiple painless, firm, mobile nodules located on the extremities, most frequently the arms. However, other sites such as the trunk, buttocks, groin, head, face, and neck also have been reported.2,3

Marcoval et al2 demonstrated SS in only 2.1% of 480 patients with systemic sarcoidosis (10 patients). In the majority of these patients, subcutaneous nodules were the initial presentation of the disease.2 Ahmed and Harshad3 reported evidence of systemic involvement in 84.9% (45/53) of patients with SS. Chest involvement was the most common finding (eg, hilar lymphadenopathy, mediastinal adenopathy, interstitial pulmonary infiltration).3 Parotitis, uveitis, neuritis, and hepatosplenomegaly also have been noted systemically.4 The vast majority of reviews have suggested that SS has a relatively good prognosis. Ahmed and Harshad3 reported a satisfactory response to steroid treatment in all patients who received corticosteroids as the primary treatment. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis usually does not herald severe systemic involvement or chronic systemic complications. Both subcutaneous granulomas and hilar adenopathy may spontaneously resolve.

Interestingly, various autoimmune disease associations were seen in 6 of 21 patients (29%) in the study by Ahmed and Harshad3 including Hashimoto thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and sicca syndrome. Barnadas et al5 reported a case of SS associated with vitiligo, pernicious anemia, and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Although our patient was not diagnosed with any particular autoimmune disease, an antinuclear antibody test was positive at a titer of 1:3200.

Our case is interesting for 2 reasons. First, it is a rare case of isolated SS. Thorough systemic evaluation showed no evidence of extracutaneous involvement. The literature only provides a few instances of isolated SS.6,7 Second, the sonographic appearance of SS is rare.8,9 Chen et al9 reported that gray-scale sonography revealed heterogenous, hypoechoic, well-demarcated plaquelike lesions with an intensive vascular pattern indicating Doppler hypervascularization. We obtained similar findings.

It has been widely acknowledged that sonographic findings of subcutaneous nodules tend to be nonspecific and overlapping. Color Doppler examination may show internal vessels both in malignant soft-tissue masses (eg, lymphoma, synovial sarcoma, liposarcoma, malignant fibrohistocytoma, metastases) and in benign lesions (eg, schwannoma, hemangioma, fibromatosis). However, the application of Doppler ultrasonography may restrict the diagnostic field, as it excludes nonvascularized benign masses such as lipomas as well as ganglion or epidermoid cysts. The ultimate diagnosis can only be made based on histopathology.

1. Vainsencher D, Winkelmann RK. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1028-1031.

2. Marcoval J, Maña J, Moreno A, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis—clinicopathological study of 10 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:790-794.

3. Ahmed I, Harshad SR. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: is it a specific subset of cutaneous sarcoidosis frequently associated with systemic disease [published online ahead of print December 2, 2005]? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:55-60.

4. Dalle Vedove C, Colato C, Girolomoni G. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: report of two cases and review of the literature [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1123-1128.

5. Barnadas MA, Rodríguez-Arias JM, Alomar A. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis associated with vitiligo, pernicious anaemia and autoimmune thyroiditis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:55-56.

6. Higgins EM, Salisbury JR, Du Vivier AW. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:65-66.

7. Heller M, Soldano AC. Sarcoidosis with subcutaneous lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:1.

8. Bosni´c D, Baresi´c M, Bagatin D, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis of the face [published online ahead of print March 15, 2010]. Intern Med. 2010;49:589-592.

9. Chen HH, Chen YM, Lan HH, et al. Sonographic appearance of subcutaneous sarcoidosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:813-816.

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old woman presented with painless, firm, flesh-colored nodules measuring 1.0 to 1.5 cm in diameter on the extensor surface of the left forearm (Figure 1) and on the distal phalanx of the left thumb of 3 months’ duration. No other signs and symptoms were present. A detailed clinical examination revealed a slightly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (24 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and a high antinuclear antibody titer (1:3200 [reference range, <1:100])(anti–Sjögren syndrome anti-gen A, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anti-Ro52). Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, urinalysis, pulmonary function tests, chest radiograph, and chest computed tomography all were normal. Hepatitis B antigen and antibody tests; hepatitis C antibody tests; and tuberculin test all were negative. An ophthalmic examination revealed no abnormalities. Ultrasonography of the nodules was performed with a system using an 8- to 12-MHz linear transducer and revealed 4 heterogenous hypoechoic lesions measuring up to 1.5 cm in size. Color Doppler images showed moderate hypervascularity (Figure 2). The largest nodule was excised. Histologic examination revealed noncaseating granulomas; special stains for microorganisms were negative. The histopathologic findings confirmed a diagnosis of sarcoidosis (Figure 3). The patient refused any medication. The nodules were stable at 6-month follow-up, then spontaneously resolved.

|

Subcutaneous sarcoidosis (SS) is a rare cutaneous expression of systemic sarcoidosis. The entity was first described by French physicians Darier and Roussy in 1904 as granulomatous panniculitis. Although their original study referred to a case of tuberculosis, the term Darier-Roussy sarcoid was coined and had been applied to a true sarcoid as well as to a variety of other forms of granulomatous panniculitis including those of infectious origin. A more accurate term subcutaneous sarcoidosis was established in 1984 by Vainsencher and Winkelmann.1

The most characteristic clinical picture of this disorder consists of the presence of multiple painless, firm, mobile nodules located on the extremities, most frequently the arms. However, other sites such as the trunk, buttocks, groin, head, face, and neck also have been reported.2,3

Marcoval et al2 demonstrated SS in only 2.1% of 480 patients with systemic sarcoidosis (10 patients). In the majority of these patients, subcutaneous nodules were the initial presentation of the disease.2 Ahmed and Harshad3 reported evidence of systemic involvement in 84.9% (45/53) of patients with SS. Chest involvement was the most common finding (eg, hilar lymphadenopathy, mediastinal adenopathy, interstitial pulmonary infiltration).3 Parotitis, uveitis, neuritis, and hepatosplenomegaly also have been noted systemically.4 The vast majority of reviews have suggested that SS has a relatively good prognosis. Ahmed and Harshad3 reported a satisfactory response to steroid treatment in all patients who received corticosteroids as the primary treatment. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis usually does not herald severe systemic involvement or chronic systemic complications. Both subcutaneous granulomas and hilar adenopathy may spontaneously resolve.

Interestingly, various autoimmune disease associations were seen in 6 of 21 patients (29%) in the study by Ahmed and Harshad3 including Hashimoto thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and sicca syndrome. Barnadas et al5 reported a case of SS associated with vitiligo, pernicious anemia, and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Although our patient was not diagnosed with any particular autoimmune disease, an antinuclear antibody test was positive at a titer of 1:3200.

Our case is interesting for 2 reasons. First, it is a rare case of isolated SS. Thorough systemic evaluation showed no evidence of extracutaneous involvement. The literature only provides a few instances of isolated SS.6,7 Second, the sonographic appearance of SS is rare.8,9 Chen et al9 reported that gray-scale sonography revealed heterogenous, hypoechoic, well-demarcated plaquelike lesions with an intensive vascular pattern indicating Doppler hypervascularization. We obtained similar findings.

It has been widely acknowledged that sonographic findings of subcutaneous nodules tend to be nonspecific and overlapping. Color Doppler examination may show internal vessels both in malignant soft-tissue masses (eg, lymphoma, synovial sarcoma, liposarcoma, malignant fibrohistocytoma, metastases) and in benign lesions (eg, schwannoma, hemangioma, fibromatosis). However, the application of Doppler ultrasonography may restrict the diagnostic field, as it excludes nonvascularized benign masses such as lipomas as well as ganglion or epidermoid cysts. The ultimate diagnosis can only be made based on histopathology.

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old woman presented with painless, firm, flesh-colored nodules measuring 1.0 to 1.5 cm in diameter on the extensor surface of the left forearm (Figure 1) and on the distal phalanx of the left thumb of 3 months’ duration. No other signs and symptoms were present. A detailed clinical examination revealed a slightly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (24 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and a high antinuclear antibody titer (1:3200 [reference range, <1:100])(anti–Sjögren syndrome anti-gen A, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anti-Ro52). Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, urinalysis, pulmonary function tests, chest radiograph, and chest computed tomography all were normal. Hepatitis B antigen and antibody tests; hepatitis C antibody tests; and tuberculin test all were negative. An ophthalmic examination revealed no abnormalities. Ultrasonography of the nodules was performed with a system using an 8- to 12-MHz linear transducer and revealed 4 heterogenous hypoechoic lesions measuring up to 1.5 cm in size. Color Doppler images showed moderate hypervascularity (Figure 2). The largest nodule was excised. Histologic examination revealed noncaseating granulomas; special stains for microorganisms were negative. The histopathologic findings confirmed a diagnosis of sarcoidosis (Figure 3). The patient refused any medication. The nodules were stable at 6-month follow-up, then spontaneously resolved.

|

Subcutaneous sarcoidosis (SS) is a rare cutaneous expression of systemic sarcoidosis. The entity was first described by French physicians Darier and Roussy in 1904 as granulomatous panniculitis. Although their original study referred to a case of tuberculosis, the term Darier-Roussy sarcoid was coined and had been applied to a true sarcoid as well as to a variety of other forms of granulomatous panniculitis including those of infectious origin. A more accurate term subcutaneous sarcoidosis was established in 1984 by Vainsencher and Winkelmann.1

The most characteristic clinical picture of this disorder consists of the presence of multiple painless, firm, mobile nodules located on the extremities, most frequently the arms. However, other sites such as the trunk, buttocks, groin, head, face, and neck also have been reported.2,3

Marcoval et al2 demonstrated SS in only 2.1% of 480 patients with systemic sarcoidosis (10 patients). In the majority of these patients, subcutaneous nodules were the initial presentation of the disease.2 Ahmed and Harshad3 reported evidence of systemic involvement in 84.9% (45/53) of patients with SS. Chest involvement was the most common finding (eg, hilar lymphadenopathy, mediastinal adenopathy, interstitial pulmonary infiltration).3 Parotitis, uveitis, neuritis, and hepatosplenomegaly also have been noted systemically.4 The vast majority of reviews have suggested that SS has a relatively good prognosis. Ahmed and Harshad3 reported a satisfactory response to steroid treatment in all patients who received corticosteroids as the primary treatment. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis usually does not herald severe systemic involvement or chronic systemic complications. Both subcutaneous granulomas and hilar adenopathy may spontaneously resolve.

Interestingly, various autoimmune disease associations were seen in 6 of 21 patients (29%) in the study by Ahmed and Harshad3 including Hashimoto thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and sicca syndrome. Barnadas et al5 reported a case of SS associated with vitiligo, pernicious anemia, and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Although our patient was not diagnosed with any particular autoimmune disease, an antinuclear antibody test was positive at a titer of 1:3200.

Our case is interesting for 2 reasons. First, it is a rare case of isolated SS. Thorough systemic evaluation showed no evidence of extracutaneous involvement. The literature only provides a few instances of isolated SS.6,7 Second, the sonographic appearance of SS is rare.8,9 Chen et al9 reported that gray-scale sonography revealed heterogenous, hypoechoic, well-demarcated plaquelike lesions with an intensive vascular pattern indicating Doppler hypervascularization. We obtained similar findings.

It has been widely acknowledged that sonographic findings of subcutaneous nodules tend to be nonspecific and overlapping. Color Doppler examination may show internal vessels both in malignant soft-tissue masses (eg, lymphoma, synovial sarcoma, liposarcoma, malignant fibrohistocytoma, metastases) and in benign lesions (eg, schwannoma, hemangioma, fibromatosis). However, the application of Doppler ultrasonography may restrict the diagnostic field, as it excludes nonvascularized benign masses such as lipomas as well as ganglion or epidermoid cysts. The ultimate diagnosis can only be made based on histopathology.

1. Vainsencher D, Winkelmann RK. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1028-1031.

2. Marcoval J, Maña J, Moreno A, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis—clinicopathological study of 10 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:790-794.

3. Ahmed I, Harshad SR. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: is it a specific subset of cutaneous sarcoidosis frequently associated with systemic disease [published online ahead of print December 2, 2005]? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:55-60.

4. Dalle Vedove C, Colato C, Girolomoni G. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: report of two cases and review of the literature [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1123-1128.

5. Barnadas MA, Rodríguez-Arias JM, Alomar A. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis associated with vitiligo, pernicious anaemia and autoimmune thyroiditis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:55-56.

6. Higgins EM, Salisbury JR, Du Vivier AW. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:65-66.

7. Heller M, Soldano AC. Sarcoidosis with subcutaneous lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:1.

8. Bosni´c D, Baresi´c M, Bagatin D, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis of the face [published online ahead of print March 15, 2010]. Intern Med. 2010;49:589-592.

9. Chen HH, Chen YM, Lan HH, et al. Sonographic appearance of subcutaneous sarcoidosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:813-816.

1. Vainsencher D, Winkelmann RK. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1028-1031.

2. Marcoval J, Maña J, Moreno A, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis—clinicopathological study of 10 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:790-794.

3. Ahmed I, Harshad SR. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: is it a specific subset of cutaneous sarcoidosis frequently associated with systemic disease [published online ahead of print December 2, 2005]? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:55-60.

4. Dalle Vedove C, Colato C, Girolomoni G. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: report of two cases and review of the literature [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1123-1128.

5. Barnadas MA, Rodríguez-Arias JM, Alomar A. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis associated with vitiligo, pernicious anaemia and autoimmune thyroiditis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:55-56.

6. Higgins EM, Salisbury JR, Du Vivier AW. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:65-66.

7. Heller M, Soldano AC. Sarcoidosis with subcutaneous lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:1.

8. Bosni´c D, Baresi´c M, Bagatin D, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis of the face [published online ahead of print March 15, 2010]. Intern Med. 2010;49:589-592.

9. Chen HH, Chen YM, Lan HH, et al. Sonographic appearance of subcutaneous sarcoidosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:813-816.

Inability to Grow Long Hair: A Presentation of Trichorrhexis Nodosa

To the Editor:

First identified by Samuel Wilks in 1852, trichorrhexis nodosa (TN) is a congenital or acquired hair shaft disorder that is characterized by fragile and easily broken hair.1 Congenital TN is rare and can occur in syndromes such as pseudomonilethrix, Netherton syndrome, pili annulati,2 argininosuccinic aciduria,3 trichothiodystrophy,4 Menkes syndrome,5 and trichohepatoenteric syndrome.6 The primary congenital form of TN is inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait in some families. Acquired TN is the most common hair shaft abnormality and often is overlooked. It is provoked by hair injury, usually mechanical or physical, or chemical trauma.7,8

Chemical trauma is caused by the use of permanent hair liquids or dyes. Mechanical injuries are the result of frequent brushing, scalp massage, or lengthy backcombing, and physical damage includes excessive UV exposure or repeated application of heat. Habit tics, trichotillomania, and the scratching and pulling associated with pruritic dermatoses also can result in sufficient damage to provoke TN. Furthermore, this acquired disorder may develop from malnutrition, particularly iron deficiency, or endocrinopathy such as hypothyroidism.9 Seasonal recurrence of TN has been reported from the cumulative effect of repeated soaking in salt water and exposure to UV light. Macroscopically, hair shafts affected by TN contain small white nodes at irregular intervals throughout the length of the hair shaft. These nodes represent areas of cuticular cell disruption, which allows the underlying cortical fibers to separate and fray and gives the node the microscopic appearance of 2 brooms or paintbrushes thrusting together end-to-end by the bristles. The classic description is known as paintbrush fracture.10 Generally, complete breakage occurs at these nodes.

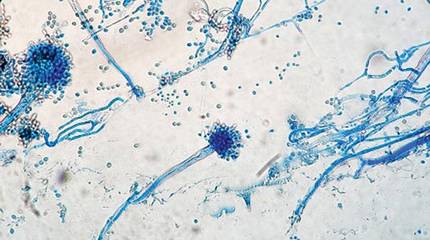

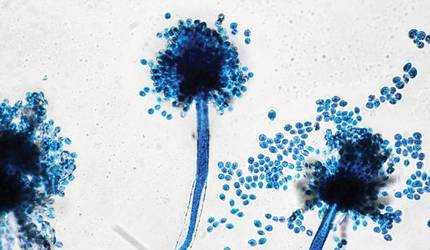

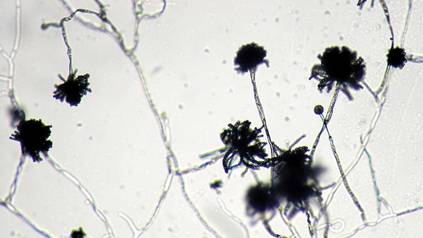

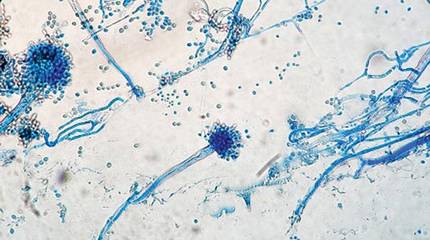

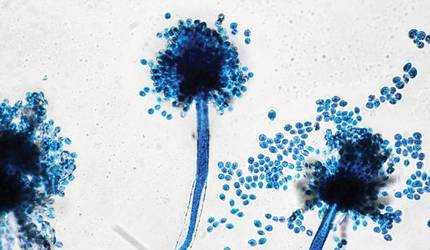

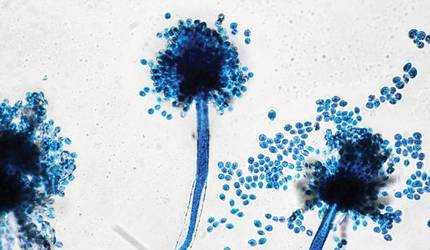

A 21-year-old white woman presented to our clinic with hair fragility and inability to grow long hair of 2 years’ duration. The hair was lusterless and dry. Dermoscopic examination revealed broken blunt-ended hair of uneven length with minute pinpoint grayish white nodules (Figure 1). Small fragments could be easily broken off with gentle tugging on the distal ends. She reported a history of severe sunlight and seawater exposure during the last 2 summers and the continuous use of a flat iron in the last year. Microscopic examination of hair samples with a scanning electron microscope showed the characteristic paintbrush fracture (Figure 2). She had no history of diseases, and blood examinations including complete blood cell count, thyroid function test, and iron levels were within reference range.

|

We hypothesize that the seasonal damage caused by exposure to UV light and salt water with repeated trauma from the heat of the flat iron caused distal TN. The patient was given an explanation about the diagnosis of TN and was instructed to avoid the practices that were suspected causes of the condition. Use of a gentle shampoo and conditioner also was recommended. At 6-month follow-up, we noticed an improvement of the quality of hair with a reduction in the whitish nodules and a revival of hair growth.

Acquired TN has been classified into 3 clinical forms: proximal, distal, and localized.1 Proximal TN is common in black individuals who use caustic chemicals when styling the hair. The involved hairs develop the characteristic nodes that break within a few centimeters from the scalp, especially in areas subject to friction from combing or sleeping. Distal TN primarily occurs in white or Asian individuals. In this disorder, nodes and breakage occur near the ends of the hairs that appear dull, dry, and uneven. Breakage commonly is associated with trichoptilosis, or longitudinal splitting, commonly referred to as split ends. This breakage may reflect frequent use of shampoo or heat treatments. The distal acquired form may simulate dandruff or pediculosis and the detection of this hair defect often is casual.

Localized TN, described by Raymond Sabouraud in 1921, is a rare disorder. It occurs in a patch that is usually a few centimeters long. It generally is accompanied by a pruritic dermatosis, such as circumscribed neurodermatitis, contact dermatitis, or atopic dermatitis. Scratching and rubbing most likely are the ultimate causes.

Trichorrhexis nodosa can spontaneously resolve. In all cases, diagnosis depends on careful microscopy examination and, if possible, scanning electron microscopy. Treatment is aimed at minimizing mechanical and physical injury, and chemical trauma. Excessive brushing, hot-combing, permanent waving, and other harsh hair treatments should be avoided. If the hair is long and the damage is distal, it may be sufficient to cut the distal fraction and to change cosmetic practices to prevent relapse.

Dermatologists who see patients with hair fragility and inability to grow long hair should consider the diagnosis of TN. Acquired TN often is reversible. Complete resolution may take 2 to 4 years depending on the growth of new anagen hairs. All patients with a history of white flecking on the scalp, abnormal fragility of the hair, and failure to attain normal hair length should be questioned about their routine hair care habits as well as environmental or chemical exposures to determine and remove the source of physical or chemical trauma.

1. Whiting DA. Structural abnormalities of hair shaft. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(1, pt 1):1-25.

2. Leider M. Multiple simultaneous anomalies of the hair; report of a case exhibiting trichorrhexis nodosa, pili annulati and trichostasis spinulosa. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:510-514.

3. Allan JD, Cusworth DC, Dent CE, et al. A disease, probably hereditary characterised by severe mental deficiency and a constant gross abnormality of aminoacid metabolism. Lancet. 1958;1:182-187.

4. Liang C, Morris A, Schlücker S, et al. Structural and molecular hair abnormalities in trichothiodystrophy [published online ahead of print May 25, 2006]. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2210-2216.

5. Taylor CJ, Green SH. Menkes’ syndrome (trichopoliodystrophy): use of scanning electron-microscope in diagnosis and carrier identification. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1981;23:361-368.

6. Hartley JL, Zachos NC, Dawood B, et al. Mutations in TTC37 cause trichohepatoenteric syndrome (phenotypic diarrhea of infancy)[published online ahead of print February 20, 2010]. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2388-2398.

7. Chernosky ME, Owens DW. Trichorrhexis nodosa. clinical and investigative studies. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:577-585.

8. Owens DW, Chernosky ME. Trichorrhexis nodosa; in vitro reproduction. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:586-588.

9. Lurie R, Hodak E, Ginzburg A, et al. Trichorrhexis nodosa: a manifestation of hypothyroidism. Cutis. 1996;57:358-359.

10. Miyamoto M, Tsuboi R, Oh-I T. Case of acquired trichorrhexis nodosa: scanning electron microscopic observation. J Dermatol. 2009;36:109-110.

To the Editor:

First identified by Samuel Wilks in 1852, trichorrhexis nodosa (TN) is a congenital or acquired hair shaft disorder that is characterized by fragile and easily broken hair.1 Congenital TN is rare and can occur in syndromes such as pseudomonilethrix, Netherton syndrome, pili annulati,2 argininosuccinic aciduria,3 trichothiodystrophy,4 Menkes syndrome,5 and trichohepatoenteric syndrome.6 The primary congenital form of TN is inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait in some families. Acquired TN is the most common hair shaft abnormality and often is overlooked. It is provoked by hair injury, usually mechanical or physical, or chemical trauma.7,8

Chemical trauma is caused by the use of permanent hair liquids or dyes. Mechanical injuries are the result of frequent brushing, scalp massage, or lengthy backcombing, and physical damage includes excessive UV exposure or repeated application of heat. Habit tics, trichotillomania, and the scratching and pulling associated with pruritic dermatoses also can result in sufficient damage to provoke TN. Furthermore, this acquired disorder may develop from malnutrition, particularly iron deficiency, or endocrinopathy such as hypothyroidism.9 Seasonal recurrence of TN has been reported from the cumulative effect of repeated soaking in salt water and exposure to UV light. Macroscopically, hair shafts affected by TN contain small white nodes at irregular intervals throughout the length of the hair shaft. These nodes represent areas of cuticular cell disruption, which allows the underlying cortical fibers to separate and fray and gives the node the microscopic appearance of 2 brooms or paintbrushes thrusting together end-to-end by the bristles. The classic description is known as paintbrush fracture.10 Generally, complete breakage occurs at these nodes.

A 21-year-old white woman presented to our clinic with hair fragility and inability to grow long hair of 2 years’ duration. The hair was lusterless and dry. Dermoscopic examination revealed broken blunt-ended hair of uneven length with minute pinpoint grayish white nodules (Figure 1). Small fragments could be easily broken off with gentle tugging on the distal ends. She reported a history of severe sunlight and seawater exposure during the last 2 summers and the continuous use of a flat iron in the last year. Microscopic examination of hair samples with a scanning electron microscope showed the characteristic paintbrush fracture (Figure 2). She had no history of diseases, and blood examinations including complete blood cell count, thyroid function test, and iron levels were within reference range.

|

We hypothesize that the seasonal damage caused by exposure to UV light and salt water with repeated trauma from the heat of the flat iron caused distal TN. The patient was given an explanation about the diagnosis of TN and was instructed to avoid the practices that were suspected causes of the condition. Use of a gentle shampoo and conditioner also was recommended. At 6-month follow-up, we noticed an improvement of the quality of hair with a reduction in the whitish nodules and a revival of hair growth.

Acquired TN has been classified into 3 clinical forms: proximal, distal, and localized.1 Proximal TN is common in black individuals who use caustic chemicals when styling the hair. The involved hairs develop the characteristic nodes that break within a few centimeters from the scalp, especially in areas subject to friction from combing or sleeping. Distal TN primarily occurs in white or Asian individuals. In this disorder, nodes and breakage occur near the ends of the hairs that appear dull, dry, and uneven. Breakage commonly is associated with trichoptilosis, or longitudinal splitting, commonly referred to as split ends. This breakage may reflect frequent use of shampoo or heat treatments. The distal acquired form may simulate dandruff or pediculosis and the detection of this hair defect often is casual.

Localized TN, described by Raymond Sabouraud in 1921, is a rare disorder. It occurs in a patch that is usually a few centimeters long. It generally is accompanied by a pruritic dermatosis, such as circumscribed neurodermatitis, contact dermatitis, or atopic dermatitis. Scratching and rubbing most likely are the ultimate causes.

Trichorrhexis nodosa can spontaneously resolve. In all cases, diagnosis depends on careful microscopy examination and, if possible, scanning electron microscopy. Treatment is aimed at minimizing mechanical and physical injury, and chemical trauma. Excessive brushing, hot-combing, permanent waving, and other harsh hair treatments should be avoided. If the hair is long and the damage is distal, it may be sufficient to cut the distal fraction and to change cosmetic practices to prevent relapse.

Dermatologists who see patients with hair fragility and inability to grow long hair should consider the diagnosis of TN. Acquired TN often is reversible. Complete resolution may take 2 to 4 years depending on the growth of new anagen hairs. All patients with a history of white flecking on the scalp, abnormal fragility of the hair, and failure to attain normal hair length should be questioned about their routine hair care habits as well as environmental or chemical exposures to determine and remove the source of physical or chemical trauma.

To the Editor:

First identified by Samuel Wilks in 1852, trichorrhexis nodosa (TN) is a congenital or acquired hair shaft disorder that is characterized by fragile and easily broken hair.1 Congenital TN is rare and can occur in syndromes such as pseudomonilethrix, Netherton syndrome, pili annulati,2 argininosuccinic aciduria,3 trichothiodystrophy,4 Menkes syndrome,5 and trichohepatoenteric syndrome.6 The primary congenital form of TN is inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait in some families. Acquired TN is the most common hair shaft abnormality and often is overlooked. It is provoked by hair injury, usually mechanical or physical, or chemical trauma.7,8

Chemical trauma is caused by the use of permanent hair liquids or dyes. Mechanical injuries are the result of frequent brushing, scalp massage, or lengthy backcombing, and physical damage includes excessive UV exposure or repeated application of heat. Habit tics, trichotillomania, and the scratching and pulling associated with pruritic dermatoses also can result in sufficient damage to provoke TN. Furthermore, this acquired disorder may develop from malnutrition, particularly iron deficiency, or endocrinopathy such as hypothyroidism.9 Seasonal recurrence of TN has been reported from the cumulative effect of repeated soaking in salt water and exposure to UV light. Macroscopically, hair shafts affected by TN contain small white nodes at irregular intervals throughout the length of the hair shaft. These nodes represent areas of cuticular cell disruption, which allows the underlying cortical fibers to separate and fray and gives the node the microscopic appearance of 2 brooms or paintbrushes thrusting together end-to-end by the bristles. The classic description is known as paintbrush fracture.10 Generally, complete breakage occurs at these nodes.

A 21-year-old white woman presented to our clinic with hair fragility and inability to grow long hair of 2 years’ duration. The hair was lusterless and dry. Dermoscopic examination revealed broken blunt-ended hair of uneven length with minute pinpoint grayish white nodules (Figure 1). Small fragments could be easily broken off with gentle tugging on the distal ends. She reported a history of severe sunlight and seawater exposure during the last 2 summers and the continuous use of a flat iron in the last year. Microscopic examination of hair samples with a scanning electron microscope showed the characteristic paintbrush fracture (Figure 2). She had no history of diseases, and blood examinations including complete blood cell count, thyroid function test, and iron levels were within reference range.

|

We hypothesize that the seasonal damage caused by exposure to UV light and salt water with repeated trauma from the heat of the flat iron caused distal TN. The patient was given an explanation about the diagnosis of TN and was instructed to avoid the practices that were suspected causes of the condition. Use of a gentle shampoo and conditioner also was recommended. At 6-month follow-up, we noticed an improvement of the quality of hair with a reduction in the whitish nodules and a revival of hair growth.

Acquired TN has been classified into 3 clinical forms: proximal, distal, and localized.1 Proximal TN is common in black individuals who use caustic chemicals when styling the hair. The involved hairs develop the characteristic nodes that break within a few centimeters from the scalp, especially in areas subject to friction from combing or sleeping. Distal TN primarily occurs in white or Asian individuals. In this disorder, nodes and breakage occur near the ends of the hairs that appear dull, dry, and uneven. Breakage commonly is associated with trichoptilosis, or longitudinal splitting, commonly referred to as split ends. This breakage may reflect frequent use of shampoo or heat treatments. The distal acquired form may simulate dandruff or pediculosis and the detection of this hair defect often is casual.

Localized TN, described by Raymond Sabouraud in 1921, is a rare disorder. It occurs in a patch that is usually a few centimeters long. It generally is accompanied by a pruritic dermatosis, such as circumscribed neurodermatitis, contact dermatitis, or atopic dermatitis. Scratching and rubbing most likely are the ultimate causes.

Trichorrhexis nodosa can spontaneously resolve. In all cases, diagnosis depends on careful microscopy examination and, if possible, scanning electron microscopy. Treatment is aimed at minimizing mechanical and physical injury, and chemical trauma. Excessive brushing, hot-combing, permanent waving, and other harsh hair treatments should be avoided. If the hair is long and the damage is distal, it may be sufficient to cut the distal fraction and to change cosmetic practices to prevent relapse.

Dermatologists who see patients with hair fragility and inability to grow long hair should consider the diagnosis of TN. Acquired TN often is reversible. Complete resolution may take 2 to 4 years depending on the growth of new anagen hairs. All patients with a history of white flecking on the scalp, abnormal fragility of the hair, and failure to attain normal hair length should be questioned about their routine hair care habits as well as environmental or chemical exposures to determine and remove the source of physical or chemical trauma.

1. Whiting DA. Structural abnormalities of hair shaft. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(1, pt 1):1-25.

2. Leider M. Multiple simultaneous anomalies of the hair; report of a case exhibiting trichorrhexis nodosa, pili annulati and trichostasis spinulosa. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:510-514.

3. Allan JD, Cusworth DC, Dent CE, et al. A disease, probably hereditary characterised by severe mental deficiency and a constant gross abnormality of aminoacid metabolism. Lancet. 1958;1:182-187.

4. Liang C, Morris A, Schlücker S, et al. Structural and molecular hair abnormalities in trichothiodystrophy [published online ahead of print May 25, 2006]. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2210-2216.

5. Taylor CJ, Green SH. Menkes’ syndrome (trichopoliodystrophy): use of scanning electron-microscope in diagnosis and carrier identification. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1981;23:361-368.

6. Hartley JL, Zachos NC, Dawood B, et al. Mutations in TTC37 cause trichohepatoenteric syndrome (phenotypic diarrhea of infancy)[published online ahead of print February 20, 2010]. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2388-2398.

7. Chernosky ME, Owens DW. Trichorrhexis nodosa. clinical and investigative studies. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:577-585.

8. Owens DW, Chernosky ME. Trichorrhexis nodosa; in vitro reproduction. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:586-588.

9. Lurie R, Hodak E, Ginzburg A, et al. Trichorrhexis nodosa: a manifestation of hypothyroidism. Cutis. 1996;57:358-359.

10. Miyamoto M, Tsuboi R, Oh-I T. Case of acquired trichorrhexis nodosa: scanning electron microscopic observation. J Dermatol. 2009;36:109-110.

1. Whiting DA. Structural abnormalities of hair shaft. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(1, pt 1):1-25.

2. Leider M. Multiple simultaneous anomalies of the hair; report of a case exhibiting trichorrhexis nodosa, pili annulati and trichostasis spinulosa. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:510-514.

3. Allan JD, Cusworth DC, Dent CE, et al. A disease, probably hereditary characterised by severe mental deficiency and a constant gross abnormality of aminoacid metabolism. Lancet. 1958;1:182-187.

4. Liang C, Morris A, Schlücker S, et al. Structural and molecular hair abnormalities in trichothiodystrophy [published online ahead of print May 25, 2006]. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2210-2216.

5. Taylor CJ, Green SH. Menkes’ syndrome (trichopoliodystrophy): use of scanning electron-microscope in diagnosis and carrier identification. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1981;23:361-368.

6. Hartley JL, Zachos NC, Dawood B, et al. Mutations in TTC37 cause trichohepatoenteric syndrome (phenotypic diarrhea of infancy)[published online ahead of print February 20, 2010]. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2388-2398.

7. Chernosky ME, Owens DW. Trichorrhexis nodosa. clinical and investigative studies. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:577-585.

8. Owens DW, Chernosky ME. Trichorrhexis nodosa; in vitro reproduction. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:586-588.

9. Lurie R, Hodak E, Ginzburg A, et al. Trichorrhexis nodosa: a manifestation of hypothyroidism. Cutis. 1996;57:358-359.

10. Miyamoto M, Tsuboi R, Oh-I T. Case of acquired trichorrhexis nodosa: scanning electron microscopic observation. J Dermatol. 2009;36:109-110.

Dermatologic Toxicity in a Patient Receiving Liposomal Doxorubicin

To the Editor:

Liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride is an anthracycline topoisomerase inhibitor indicated for ovarian cancer, AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma, and multiple myeloma.1 It also has been used with limited success in a clinical trial of previously treated patients with endometrial cancer.2 The most common adverse reactions include asthenia, fatigue, fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, stomatitis, diarrhea, constipation, hand-and-foot syndrome, rash, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia.1

A 58-year-old woman with a history of stage IIIA endometrial cancer underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy soon after diagnosis. She then completed 5 high-dose-rate brachytherapy treatments and 6 cycles of paclitaxel and carboplatin. Follow-up imaging revealed pulmonary metastasis. The patient was then enrolled in a clinical trial but was switched to 40 mg/m2 liposomal doxorubicin given once every 28 days for 5 cycles after progression of disease.

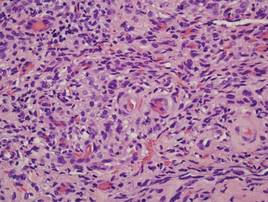

After each dose of doxorubicin, she developed redness of the palms and soles. Following the third cycle of doxorubicin, a painful rash involving the thighs and axilla appeared with some desquamation in the left axilla. Three weeks after the fourth dose of doxorubicin, she presented with severe worsening of the rash to involve the extensor elbows (Figure 1), back, and lower legs with bilateral axillary desquamation. The bilateral medial thighs were erythematous with maceration that was tender and blanchable (Figure 2). The total affected body surface area was 10% to 15%. There was no involvement of the mucosa. She was treated with hydrogel sheet dressings and silver sulfadiazine cream 1%.

|

|

The patient’s rash was thought to be due to doxorubicin toxicity; however, a 4-mm punch biopsy specimen from the left thigh was taken for culture and hemotoxylin and eosin stain to rule out other possibilities. Biopsy was consistent with a drug reaction, revealing superficial perivascular dermatitis with keratinocyte atypia of the epidermis. Doxorubicin was discontinued and the rash resolved completely within 2 weeks, except for some thickening of the skin on the palms, soles, and thighs. After a delay of approximately 1 week, doxorubicin was resumed at a lower dose of 30 mg/m2. No dermatologic symptoms followed treatment at this dose.

Four clinical patterns of doxorubicin toxicity are recognized. The most common pattern is acral erythema, also known as hand-and-foot syndrome, which is followed by desquamation of the palms and soles, occurring in approximately 50% of patients. Ten percent of patients experience a diffuse follicular rash with mild, diffuse, scaly erythema and follicular accentuation that often occurs over the lateral limbs but also may occur over the trunk. New melanotic macules may appear on the trunk or extremities including palms and soles.3 Finally, an intertrigolike eruption exacerbated by friction with erythematous patches over skin folds or in areas of friction also has been described.3-5 Our patient presented with a combination of dermatologic toxicities including acral erythema and intertrigolike eruption. Acral erythema occurred in 24 of 60 patients and intertrigolike eruption occurred in 5 of 60 patients in one study.3 Another report documented both occurring together.5

Treatment of doxorubicin skin toxicity consists of reduction of the dose of doxorubicin, supportive care, and patient education. Specific treatments include topical wound care, emollient creams, and pain management with analgesics. Other interventions include wearing loose clothing, avoiding vigorous exercise, and sitting on padded surfaces.6

Doxorubicin skin toxicity presents in several clinical patterns. Although acral erythema is the most common pattern, severe intertrigolike eruptions similar to our case may occur. Physicians caring for patients receiving doxorubicin should be aware of the variety of presentations of skin toxicity and the possible need for dose reduction to decrease symptoms.

1. Doxil [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Products, LP; 2014.

2. Muggia FM, Blessing JA, Sorosky J, et al. Phase II trial of the pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in previously treated metastatic endometrial cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2360-2364.

3. Lotem M, Hubert A, Lyass O, et al. Skin toxic effects of polyethylene glycol-coated liposomal doxorubicin. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1475-1480.

4. Korver GE, Ronald H, Petersen MJ. An intertrigo-like eruption from pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:901-902.

5. Sánchez Henarejos P, Ros Martinez S, Marín Zafra GR,

et al. Intertrigo-like eruption caused by pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD). Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:486-487.

6. von Moos R, Thuerlimann BJ, Aapro M, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-associated hand-foot syndrome: recommendations of an international panel of experts [published online ahead of print March 10, 2008]. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:781-790.

To the Editor:

Liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride is an anthracycline topoisomerase inhibitor indicated for ovarian cancer, AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma, and multiple myeloma.1 It also has been used with limited success in a clinical trial of previously treated patients with endometrial cancer.2 The most common adverse reactions include asthenia, fatigue, fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, stomatitis, diarrhea, constipation, hand-and-foot syndrome, rash, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia.1

A 58-year-old woman with a history of stage IIIA endometrial cancer underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy soon after diagnosis. She then completed 5 high-dose-rate brachytherapy treatments and 6 cycles of paclitaxel and carboplatin. Follow-up imaging revealed pulmonary metastasis. The patient was then enrolled in a clinical trial but was switched to 40 mg/m2 liposomal doxorubicin given once every 28 days for 5 cycles after progression of disease.

After each dose of doxorubicin, she developed redness of the palms and soles. Following the third cycle of doxorubicin, a painful rash involving the thighs and axilla appeared with some desquamation in the left axilla. Three weeks after the fourth dose of doxorubicin, she presented with severe worsening of the rash to involve the extensor elbows (Figure 1), back, and lower legs with bilateral axillary desquamation. The bilateral medial thighs were erythematous with maceration that was tender and blanchable (Figure 2). The total affected body surface area was 10% to 15%. There was no involvement of the mucosa. She was treated with hydrogel sheet dressings and silver sulfadiazine cream 1%.

|

|

The patient’s rash was thought to be due to doxorubicin toxicity; however, a 4-mm punch biopsy specimen from the left thigh was taken for culture and hemotoxylin and eosin stain to rule out other possibilities. Biopsy was consistent with a drug reaction, revealing superficial perivascular dermatitis with keratinocyte atypia of the epidermis. Doxorubicin was discontinued and the rash resolved completely within 2 weeks, except for some thickening of the skin on the palms, soles, and thighs. After a delay of approximately 1 week, doxorubicin was resumed at a lower dose of 30 mg/m2. No dermatologic symptoms followed treatment at this dose.

Four clinical patterns of doxorubicin toxicity are recognized. The most common pattern is acral erythema, also known as hand-and-foot syndrome, which is followed by desquamation of the palms and soles, occurring in approximately 50% of patients. Ten percent of patients experience a diffuse follicular rash with mild, diffuse, scaly erythema and follicular accentuation that often occurs over the lateral limbs but also may occur over the trunk. New melanotic macules may appear on the trunk or extremities including palms and soles.3 Finally, an intertrigolike eruption exacerbated by friction with erythematous patches over skin folds or in areas of friction also has been described.3-5 Our patient presented with a combination of dermatologic toxicities including acral erythema and intertrigolike eruption. Acral erythema occurred in 24 of 60 patients and intertrigolike eruption occurred in 5 of 60 patients in one study.3 Another report documented both occurring together.5

Treatment of doxorubicin skin toxicity consists of reduction of the dose of doxorubicin, supportive care, and patient education. Specific treatments include topical wound care, emollient creams, and pain management with analgesics. Other interventions include wearing loose clothing, avoiding vigorous exercise, and sitting on padded surfaces.6

Doxorubicin skin toxicity presents in several clinical patterns. Although acral erythema is the most common pattern, severe intertrigolike eruptions similar to our case may occur. Physicians caring for patients receiving doxorubicin should be aware of the variety of presentations of skin toxicity and the possible need for dose reduction to decrease symptoms.

To the Editor:

Liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride is an anthracycline topoisomerase inhibitor indicated for ovarian cancer, AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma, and multiple myeloma.1 It also has been used with limited success in a clinical trial of previously treated patients with endometrial cancer.2 The most common adverse reactions include asthenia, fatigue, fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, stomatitis, diarrhea, constipation, hand-and-foot syndrome, rash, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia.1

A 58-year-old woman with a history of stage IIIA endometrial cancer underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy soon after diagnosis. She then completed 5 high-dose-rate brachytherapy treatments and 6 cycles of paclitaxel and carboplatin. Follow-up imaging revealed pulmonary metastasis. The patient was then enrolled in a clinical trial but was switched to 40 mg/m2 liposomal doxorubicin given once every 28 days for 5 cycles after progression of disease.

After each dose of doxorubicin, she developed redness of the palms and soles. Following the third cycle of doxorubicin, a painful rash involving the thighs and axilla appeared with some desquamation in the left axilla. Three weeks after the fourth dose of doxorubicin, she presented with severe worsening of the rash to involve the extensor elbows (Figure 1), back, and lower legs with bilateral axillary desquamation. The bilateral medial thighs were erythematous with maceration that was tender and blanchable (Figure 2). The total affected body surface area was 10% to 15%. There was no involvement of the mucosa. She was treated with hydrogel sheet dressings and silver sulfadiazine cream 1%.

|

|

The patient’s rash was thought to be due to doxorubicin toxicity; however, a 4-mm punch biopsy specimen from the left thigh was taken for culture and hemotoxylin and eosin stain to rule out other possibilities. Biopsy was consistent with a drug reaction, revealing superficial perivascular dermatitis with keratinocyte atypia of the epidermis. Doxorubicin was discontinued and the rash resolved completely within 2 weeks, except for some thickening of the skin on the palms, soles, and thighs. After a delay of approximately 1 week, doxorubicin was resumed at a lower dose of 30 mg/m2. No dermatologic symptoms followed treatment at this dose.

Four clinical patterns of doxorubicin toxicity are recognized. The most common pattern is acral erythema, also known as hand-and-foot syndrome, which is followed by desquamation of the palms and soles, occurring in approximately 50% of patients. Ten percent of patients experience a diffuse follicular rash with mild, diffuse, scaly erythema and follicular accentuation that often occurs over the lateral limbs but also may occur over the trunk. New melanotic macules may appear on the trunk or extremities including palms and soles.3 Finally, an intertrigolike eruption exacerbated by friction with erythematous patches over skin folds or in areas of friction also has been described.3-5 Our patient presented with a combination of dermatologic toxicities including acral erythema and intertrigolike eruption. Acral erythema occurred in 24 of 60 patients and intertrigolike eruption occurred in 5 of 60 patients in one study.3 Another report documented both occurring together.5

Treatment of doxorubicin skin toxicity consists of reduction of the dose of doxorubicin, supportive care, and patient education. Specific treatments include topical wound care, emollient creams, and pain management with analgesics. Other interventions include wearing loose clothing, avoiding vigorous exercise, and sitting on padded surfaces.6

Doxorubicin skin toxicity presents in several clinical patterns. Although acral erythema is the most common pattern, severe intertrigolike eruptions similar to our case may occur. Physicians caring for patients receiving doxorubicin should be aware of the variety of presentations of skin toxicity and the possible need for dose reduction to decrease symptoms.

1. Doxil [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Products, LP; 2014.

2. Muggia FM, Blessing JA, Sorosky J, et al. Phase II trial of the pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in previously treated metastatic endometrial cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2360-2364.

3. Lotem M, Hubert A, Lyass O, et al. Skin toxic effects of polyethylene glycol-coated liposomal doxorubicin. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1475-1480.

4. Korver GE, Ronald H, Petersen MJ. An intertrigo-like eruption from pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:901-902.

5. Sánchez Henarejos P, Ros Martinez S, Marín Zafra GR,

et al. Intertrigo-like eruption caused by pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD). Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:486-487.

6. von Moos R, Thuerlimann BJ, Aapro M, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-associated hand-foot syndrome: recommendations of an international panel of experts [published online ahead of print March 10, 2008]. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:781-790.

1. Doxil [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Products, LP; 2014.

2. Muggia FM, Blessing JA, Sorosky J, et al. Phase II trial of the pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in previously treated metastatic endometrial cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2360-2364.

3. Lotem M, Hubert A, Lyass O, et al. Skin toxic effects of polyethylene glycol-coated liposomal doxorubicin. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1475-1480.

4. Korver GE, Ronald H, Petersen MJ. An intertrigo-like eruption from pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:901-902.

5. Sánchez Henarejos P, Ros Martinez S, Marín Zafra GR,

et al. Intertrigo-like eruption caused by pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD). Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:486-487.

6. von Moos R, Thuerlimann BJ, Aapro M, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-associated hand-foot syndrome: recommendations of an international panel of experts [published online ahead of print March 10, 2008]. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:781-790.

An Unusual Case of Sporadic Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome

To the Editor:

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome (HLRCCS) is a rare, highly penetrant, autosomal-dominant disorder that has been reported in approximately 200 families worldwide.1,2 More than 90% of patients with HLRCCS develop multiple cutaneous leiomyomata, frequently in a segmental distribution, that increase in number and size with age. The extent of skin lesions is variable, even within the same family. Approximately 90% of female family members also have symptomatic uterine leiomyomata; 10% to 16% of these patients develop aggressive renal cell carcinomas,3 with more than 50% dying of metastatic disease within 5 years of diagnosis. Clinical diagnosis is established by the presence of multiple cutaneous leiomyomata, at least 1 of which should be histologically confirmed, or by a single leiomyoma in the presence of a positive family history.4

Mutations of fumarate hydratase (FH), a Krebs cycle enzyme that interconverts fumarate and malate, have been implicated in this syndrome.5 The homotetrameric 50 kDa protein exists in the mitochondrial matrix and the cytoplasm. Diagnosis is confirmed by molecular genetic testing for FH mutations or rarely by demonstrating reduced activity of FH enzyme. So far, at least 155 variations in DNA sequence of FH have been identified in HLRCCS. However, no definite genotype-phenotype correlations have been established yet. We present the case of a sporadic form of HLRCCS, which is rare.

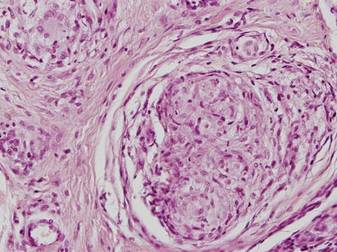

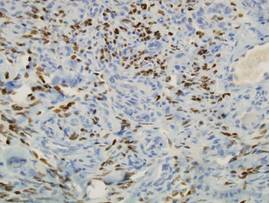

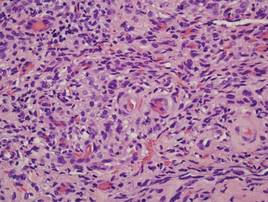

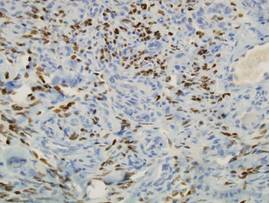

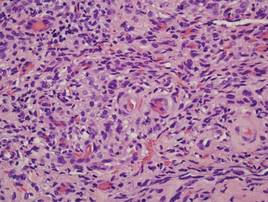

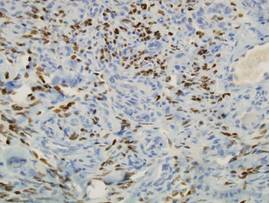

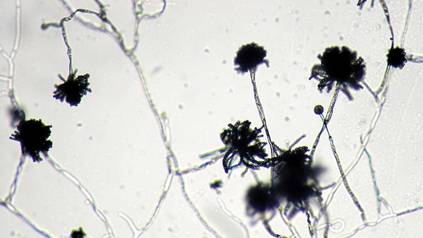

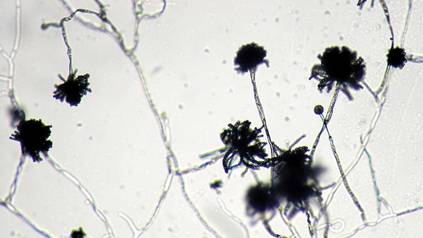

A 27-year-old man presented with multiple slowly growing, painful lesions on the chest and back of 11 years’ duration. Physical examination revealed approximately twenty 2- to 4-mm pink-tan papules on the left side of the chest and several 2- to 7-mm tan-pink papules on the upper back (Figure 1A). The lesions were tender to touch, pressure, and cold temperatures. Microscopic examination of one of the lesions on the back showed benign smooth muscle proliferation expanding the reticular dermis, consistent with a cutaneous leiomyoma (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Cluster of slow-growing, 2- to 7-mm, slightly erythematous papules on the upper back (A). Shave biopsy showed an unencapsulated dermal proliferation composed of interlacing fascicles of smooth muscle bundles with bland morphology, cigar-shaped nuclei, and lack of mitotic activity, compatible with cutaneous leiomyoma (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Based on the clinical presentation, the possibility of HLRCCS was raised. Subsequently, the FH gene was sequenced from the peripheral blood revealing a heterozygous 4-base pair frameshift deletion mutation (TGAA deleted at positions 1083 through 1086 [complementary DNA][c.1083_1086delTGAA]), confirming the diagnosis (Figure 2). There was no family history of leiomyomata of the skin or uterus or renal tumors. Therefore, this case represents sporadic HLRCCS. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed only a 0.4-cm renal cortical cyst for which he was monitored for approximately a year but was lost to follow-up.

The molecular mechanism of tumorigenesis in HLRCCS is poorly understood.6 Under normal circumstances, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is hydroxylated by HIF prolyl hydroxylase after which it is targeted for an ubiquitin-mediated degradation (Figure 3 [top panel]). In the absence of FH, there is accumulation of fumarate, an inhibitor of HIF prolyl hydroxylase, leading to an increase in intracellular levels of unhydroxylated and undegradable HIF (Figure 3 [bottom panel]). Because of insufficient malate levels, the glucose metabolism through Krebs cycle shifts toward anaerobic glycolysis, even when sufficient oxygen is present to support respiration, creating a pseudohypoxic milieu that is similar to the Warburg effect. This environment leads to further stabilization of HIF, which is a transcription factor, that upregulates the expression of angiogenic factors (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor), growth factors (eg, erythropoietin, transforming growth factor a, platelet-derived growth factor), glucose transporters (eg, glucose transporter 1), and glycolytic enzymes (eg, phosphokinase mutase 1, lactate dehydrogenase A). These alterations may favor tumor growth by increasing the availability of biosynthetic intermediates needed for cellular proliferation and survival.

Patients with renal tumor–associated hereditary syndromes may present initially to dermatologists; therefore, it is important to recognize the cutaneous manifestations of these conditions because early diagnosis of renal cancer may prove to be lifesaving.

1. Kiuru M, Launonen V, Hietala M, et al. Familial cutaneous leiomyomatosis is a two-hit condition associated with renal cell cancer of characteristic histopathology. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:825-829.

2. Launonen V, Vierimaa O, Kiuru M, et al. Inherited susceptibility to uterine leiomyomas and renal cell cancer [published online ahead of print February 27, 2001]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3387-3392.

3. Toro JR, Nickerson ML, Wei MH, et al. Mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America [published online ahead of print May 22, 2003]. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:95-106.

4. Ferzli PG, Millett CR, Newman MD, et al. The dermatologist’s guide to hereditary syndromes with renal tumors. Cutis. 2008;81:41-48.

5. Bayley JP, Launonen V, Tomlinson IP. The FH mutation database: an online database of fumarate hydratase mutations involved in the MCUL (HLRCC) tumor syndrome and congenital fumarase deficiency. BMC Med Genet. 2008;25:20.

6. Sudarshan S, Pinto PA, Neckers L, et al. Mechanisms of disease: hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer—a distinct form of hereditary kidney cancer. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2007;4:104-110.

To the Editor:

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome (HLRCCS) is a rare, highly penetrant, autosomal-dominant disorder that has been reported in approximately 200 families worldwide.1,2 More than 90% of patients with HLRCCS develop multiple cutaneous leiomyomata, frequently in a segmental distribution, that increase in number and size with age. The extent of skin lesions is variable, even within the same family. Approximately 90% of female family members also have symptomatic uterine leiomyomata; 10% to 16% of these patients develop aggressive renal cell carcinomas,3 with more than 50% dying of metastatic disease within 5 years of diagnosis. Clinical diagnosis is established by the presence of multiple cutaneous leiomyomata, at least 1 of which should be histologically confirmed, or by a single leiomyoma in the presence of a positive family history.4

Mutations of fumarate hydratase (FH), a Krebs cycle enzyme that interconverts fumarate and malate, have been implicated in this syndrome.5 The homotetrameric 50 kDa protein exists in the mitochondrial matrix and the cytoplasm. Diagnosis is confirmed by molecular genetic testing for FH mutations or rarely by demonstrating reduced activity of FH enzyme. So far, at least 155 variations in DNA sequence of FH have been identified in HLRCCS. However, no definite genotype-phenotype correlations have been established yet. We present the case of a sporadic form of HLRCCS, which is rare.

A 27-year-old man presented with multiple slowly growing, painful lesions on the chest and back of 11 years’ duration. Physical examination revealed approximately twenty 2- to 4-mm pink-tan papules on the left side of the chest and several 2- to 7-mm tan-pink papules on the upper back (Figure 1A). The lesions were tender to touch, pressure, and cold temperatures. Microscopic examination of one of the lesions on the back showed benign smooth muscle proliferation expanding the reticular dermis, consistent with a cutaneous leiomyoma (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Cluster of slow-growing, 2- to 7-mm, slightly erythematous papules on the upper back (A). Shave biopsy showed an unencapsulated dermal proliferation composed of interlacing fascicles of smooth muscle bundles with bland morphology, cigar-shaped nuclei, and lack of mitotic activity, compatible with cutaneous leiomyoma (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Based on the clinical presentation, the possibility of HLRCCS was raised. Subsequently, the FH gene was sequenced from the peripheral blood revealing a heterozygous 4-base pair frameshift deletion mutation (TGAA deleted at positions 1083 through 1086 [complementary DNA][c.1083_1086delTGAA]), confirming the diagnosis (Figure 2). There was no family history of leiomyomata of the skin or uterus or renal tumors. Therefore, this case represents sporadic HLRCCS. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed only a 0.4-cm renal cortical cyst for which he was monitored for approximately a year but was lost to follow-up.

The molecular mechanism of tumorigenesis in HLRCCS is poorly understood.6 Under normal circumstances, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is hydroxylated by HIF prolyl hydroxylase after which it is targeted for an ubiquitin-mediated degradation (Figure 3 [top panel]). In the absence of FH, there is accumulation of fumarate, an inhibitor of HIF prolyl hydroxylase, leading to an increase in intracellular levels of unhydroxylated and undegradable HIF (Figure 3 [bottom panel]). Because of insufficient malate levels, the glucose metabolism through Krebs cycle shifts toward anaerobic glycolysis, even when sufficient oxygen is present to support respiration, creating a pseudohypoxic milieu that is similar to the Warburg effect. This environment leads to further stabilization of HIF, which is a transcription factor, that upregulates the expression of angiogenic factors (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor), growth factors (eg, erythropoietin, transforming growth factor a, platelet-derived growth factor), glucose transporters (eg, glucose transporter 1), and glycolytic enzymes (eg, phosphokinase mutase 1, lactate dehydrogenase A). These alterations may favor tumor growth by increasing the availability of biosynthetic intermediates needed for cellular proliferation and survival.

Patients with renal tumor–associated hereditary syndromes may present initially to dermatologists; therefore, it is important to recognize the cutaneous manifestations of these conditions because early diagnosis of renal cancer may prove to be lifesaving.

To the Editor:

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome (HLRCCS) is a rare, highly penetrant, autosomal-dominant disorder that has been reported in approximately 200 families worldwide.1,2 More than 90% of patients with HLRCCS develop multiple cutaneous leiomyomata, frequently in a segmental distribution, that increase in number and size with age. The extent of skin lesions is variable, even within the same family. Approximately 90% of female family members also have symptomatic uterine leiomyomata; 10% to 16% of these patients develop aggressive renal cell carcinomas,3 with more than 50% dying of metastatic disease within 5 years of diagnosis. Clinical diagnosis is established by the presence of multiple cutaneous leiomyomata, at least 1 of which should be histologically confirmed, or by a single leiomyoma in the presence of a positive family history.4

Mutations of fumarate hydratase (FH), a Krebs cycle enzyme that interconverts fumarate and malate, have been implicated in this syndrome.5 The homotetrameric 50 kDa protein exists in the mitochondrial matrix and the cytoplasm. Diagnosis is confirmed by molecular genetic testing for FH mutations or rarely by demonstrating reduced activity of FH enzyme. So far, at least 155 variations in DNA sequence of FH have been identified in HLRCCS. However, no definite genotype-phenotype correlations have been established yet. We present the case of a sporadic form of HLRCCS, which is rare.

A 27-year-old man presented with multiple slowly growing, painful lesions on the chest and back of 11 years’ duration. Physical examination revealed approximately twenty 2- to 4-mm pink-tan papules on the left side of the chest and several 2- to 7-mm tan-pink papules on the upper back (Figure 1A). The lesions were tender to touch, pressure, and cold temperatures. Microscopic examination of one of the lesions on the back showed benign smooth muscle proliferation expanding the reticular dermis, consistent with a cutaneous leiomyoma (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Cluster of slow-growing, 2- to 7-mm, slightly erythematous papules on the upper back (A). Shave biopsy showed an unencapsulated dermal proliferation composed of interlacing fascicles of smooth muscle bundles with bland morphology, cigar-shaped nuclei, and lack of mitotic activity, compatible with cutaneous leiomyoma (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Based on the clinical presentation, the possibility of HLRCCS was raised. Subsequently, the FH gene was sequenced from the peripheral blood revealing a heterozygous 4-base pair frameshift deletion mutation (TGAA deleted at positions 1083 through 1086 [complementary DNA][c.1083_1086delTGAA]), confirming the diagnosis (Figure 2). There was no family history of leiomyomata of the skin or uterus or renal tumors. Therefore, this case represents sporadic HLRCCS. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed only a 0.4-cm renal cortical cyst for which he was monitored for approximately a year but was lost to follow-up.