User login

Aspergillus nidulans Causing Primary Cutaneous Aspergillosis in an Immunocompetent Patient

To the Editor:

Cutaneous aspergillosis mostly has been reported in immunosuppressed hosts and usually is caused by Aspergillus flavus or Aspergillus fumigatus. We report the occurrence of primary cutaneous aspergillosis (PCA) caused by a relatively rare species, Aspergillus nidulans, in a middle-aged patient without overt immunosuppression or history of trauma.

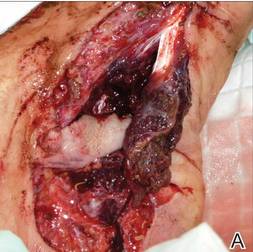

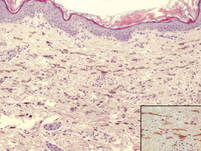

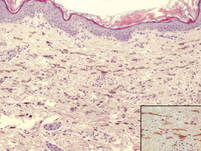

A 57-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology outpatient department for evaluation of a lesion on the right hand of 1 month's duration. On examination the lesion measured approximately 4×3 cm with central necrosis (Figure 1). Her medical history was unremarkable and routine laboratory test results were within reference range.

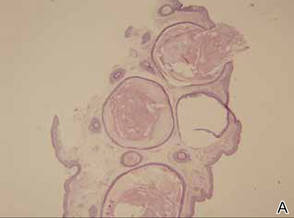

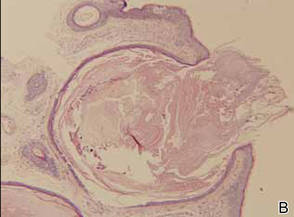

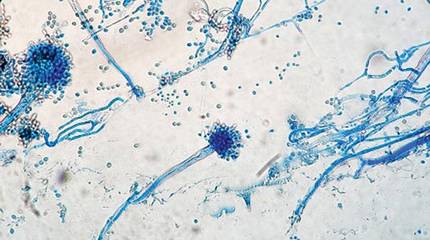

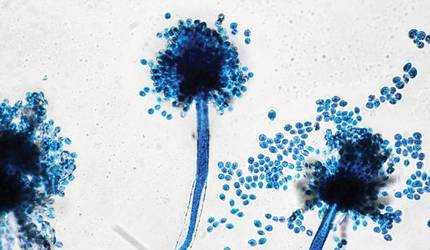

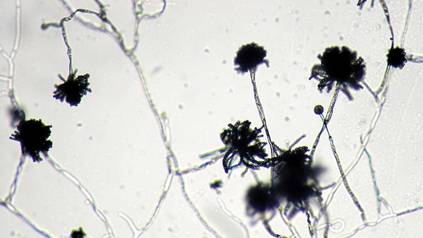

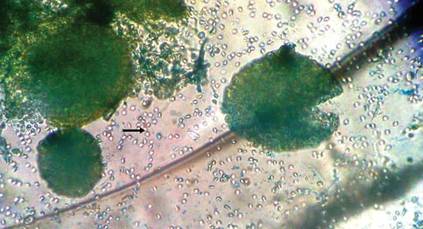

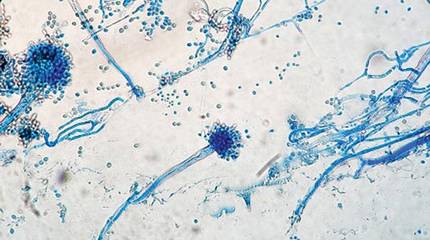

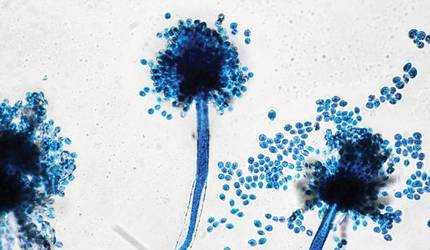

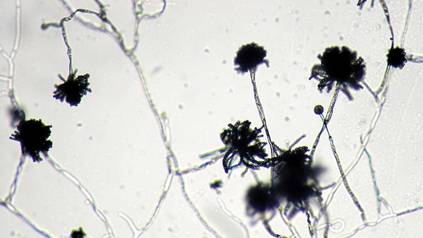

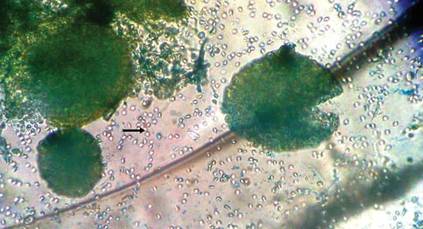

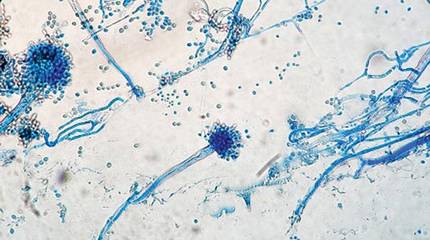

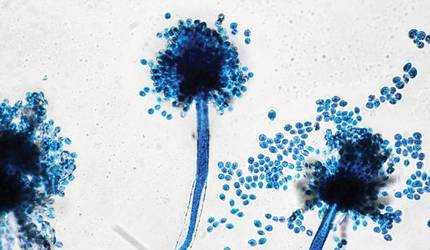

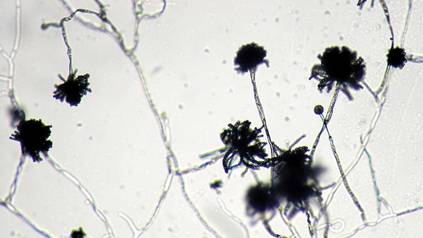

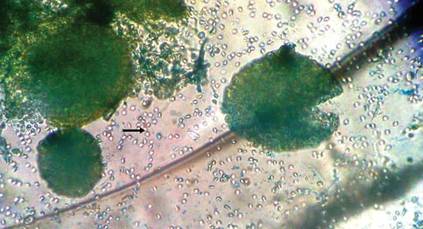

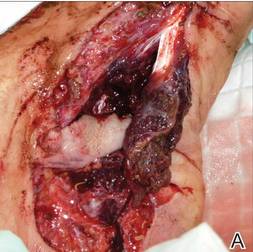

The patient was an agricultural worker with no history of trauma. Her history was unremarkable. A 20% potassium hydroxide mount of the tissue revealed septate, branched, hyaline hyphae. A soft, wooly, greenish brown growth was observed after 3 days of incubation on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Figure 2). No growth was observed on dermatophyte test medium. A lactophenol cotton blue mount revealed columnar conidial heads with brown, short, smooth-walled conidiophores (Figures 3–6). Vesicles were hemispheric and small (8–12 µm in diameter), with metulae and phialides occurring in the upper portion. Conidia were globose (3–4 µm) and rough. Based on these findings the fungus was identified as A nidulans. The patient did not respond to daily oral ketoconazole, and after 1 month of therapy the lesion did not regress. She was eventually treated with oral itraconazole and the lesion completely healed within 15 weeks.

An overwhelming majority of the cases of cutaneous aspergillosis have been reported either in immunocompromised hosts (ie, leukemia, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin disease, human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, solid-organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients) or in patients with contributing risk factors (ie, severe burns, diabetes mellitus, preterm or underweight neonates, elderly patients). Two outbreaks of this condition have been reported in neonatal intensive care units, with the source of contamination being linked to nonsterile disposable gloves, incubators, and humidity chambers.1,2 However, PCA is a relatively rare condition and often is associated with disruption of dermal integrity by trauma or maceration, followed by colonization of the wound by Aspergillus spores that are ubiquitously present in soil and decomposed vegetation.3-5 Our case was remarkable, as the patient was not immunosuppressed and did not have a history of trauma. However, we surmise that fungal inoculation might have inadvertently occurred through some trivial trauma sustained through her professional work.

The 2 species that have most commonly been associated with PCA are A flavus and A fumigatus.6,7 There have been isolated reports of PCA caused by other organisms such as Aspergillus niger,8,9 Aspergillus terreus,10Aspergillus ustus,11 or Aspergillus calidoustus.12 In a report of a neutropenic 56-year-old patient suffering from acute myeloblastic leukemia, PCA developed in association with a double-lumen Hickman catheter after a period of prolonged hospitalization.13 A study by the National Institutes of Health (1976-1997) revealed 6 life-threatening cases of A nidulans infection in patients with chronic granulomatous disease.14

We did not perform antifungal susceptibility testing on the isolate in our patient. However, we observed disease that was refractory to ketoconazole therapy but successfully resolved with oral itraconazole. Antifungal susceptibility was noted in a large number of reported cases of Aspergillus infections that were resistant to conventional treatment, such as voriconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B.15 Thus antifungal susceptibility testing is necessary before starting treatment. There also have been reports of recurrence of cutaneous aspergillosis following incomplete and irregular treatment.16 Our case of PCA also failed to respond to ketoconazole therapy, thus stressing the need for thorough mycological characterization, including the determination of an antifungal susceptibility profile, for successful and complete management of this condition.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Arunaloke Chakraborti, MD, Chandigarh, India, for the help extended for identification of the fungus.

- Stock C, Veyrier M, Raberin H, et al. Severe cutaneous aspergillosis in a premature neonate linked to nonsterile disposable glove contamination [published online ahead of print August 31, 2011]? Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:465-467.

- Etienne KA, Subudhi CP, Chadwick PR, et al. Investigation of a cluster of cutaneous aspergillosis in a neonatal intensive care unit [published online ahead of print August 12, 2011]. J Hosp Infect. 2011;79:344-348.

- Isaac M. Cutaneous aspergillosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:137-140.

- Cahill KM, Mofty AM, Kawaguchi TP. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:545-547.

- Carlile JR, Millet RE, Cho CT, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis in a leukemic child. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:78-80.

- John PU, Shadomy HJ. Deep fungal infections. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al, eds. Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1987:2266-2268.

- Chakrabarti A, Gupta V, Biswas G, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis: our experience in 10 years. J Infect. 1998;37:24-27.

- Robinson A, Fien S, Grassi MA. Nonhealing scalp wound infected with Aspergillus niger in an elderly patient. Cutis. 2011;87:197-200.

- Thomas LM, Rand HK, Miller JL, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis in a patient with a solid organ transplant: case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2008;81:127-130.

- Yuanjie Z, Jingxia D, Hai W, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis in a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [published online ahead of print October 22, 2008]. Mycoses. 2009;52:462-464.

- Krishnan-Natesan S, Chandrasekar PH, Manavathu EK, et al. Successful treatment of primary cutaneous Aspergillus ustus infection with surgical debridement and a combination of voriconazole and terbinafine [published online ahead of print October 7, 2008]. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62:443-446.

- Sato Y, Suzino K, Suzuki A, et al. Case of primary cutaneous Aspergillus calidoustus infection caused by nerve block therapy [in Japanese]. Med Mycol J. 2011;52:239-244.

- Lucas GM, Tucker P, Merz WG. Primary cutaneous Aspergillus nidulans infection associated with a Hickman catheter in a patient with neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1594-1596.

- Segal BH, DeCarlo ES, Kwon-Chung KJ, et al. Aspergillus nidulans infection in chronic granulomatous disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77:345-354.

- Woodruff CA, Hebert AA. Neonatal primary cutaneous aspergillosis: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:439-444.

- Mohapatra S, Xess I, Swetha JV, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis due to Aspergillus niger in an immunocompetent patient. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:367-370.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous aspergillosis mostly has been reported in immunosuppressed hosts and usually is caused by Aspergillus flavus or Aspergillus fumigatus. We report the occurrence of primary cutaneous aspergillosis (PCA) caused by a relatively rare species, Aspergillus nidulans, in a middle-aged patient without overt immunosuppression or history of trauma.

A 57-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology outpatient department for evaluation of a lesion on the right hand of 1 month's duration. On examination the lesion measured approximately 4×3 cm with central necrosis (Figure 1). Her medical history was unremarkable and routine laboratory test results were within reference range.

The patient was an agricultural worker with no history of trauma. Her history was unremarkable. A 20% potassium hydroxide mount of the tissue revealed septate, branched, hyaline hyphae. A soft, wooly, greenish brown growth was observed after 3 days of incubation on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Figure 2). No growth was observed on dermatophyte test medium. A lactophenol cotton blue mount revealed columnar conidial heads with brown, short, smooth-walled conidiophores (Figures 3–6). Vesicles were hemispheric and small (8–12 µm in diameter), with metulae and phialides occurring in the upper portion. Conidia were globose (3–4 µm) and rough. Based on these findings the fungus was identified as A nidulans. The patient did not respond to daily oral ketoconazole, and after 1 month of therapy the lesion did not regress. She was eventually treated with oral itraconazole and the lesion completely healed within 15 weeks.

An overwhelming majority of the cases of cutaneous aspergillosis have been reported either in immunocompromised hosts (ie, leukemia, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin disease, human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, solid-organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients) or in patients with contributing risk factors (ie, severe burns, diabetes mellitus, preterm or underweight neonates, elderly patients). Two outbreaks of this condition have been reported in neonatal intensive care units, with the source of contamination being linked to nonsterile disposable gloves, incubators, and humidity chambers.1,2 However, PCA is a relatively rare condition and often is associated with disruption of dermal integrity by trauma or maceration, followed by colonization of the wound by Aspergillus spores that are ubiquitously present in soil and decomposed vegetation.3-5 Our case was remarkable, as the patient was not immunosuppressed and did not have a history of trauma. However, we surmise that fungal inoculation might have inadvertently occurred through some trivial trauma sustained through her professional work.

The 2 species that have most commonly been associated with PCA are A flavus and A fumigatus.6,7 There have been isolated reports of PCA caused by other organisms such as Aspergillus niger,8,9 Aspergillus terreus,10Aspergillus ustus,11 or Aspergillus calidoustus.12 In a report of a neutropenic 56-year-old patient suffering from acute myeloblastic leukemia, PCA developed in association with a double-lumen Hickman catheter after a period of prolonged hospitalization.13 A study by the National Institutes of Health (1976-1997) revealed 6 life-threatening cases of A nidulans infection in patients with chronic granulomatous disease.14

We did not perform antifungal susceptibility testing on the isolate in our patient. However, we observed disease that was refractory to ketoconazole therapy but successfully resolved with oral itraconazole. Antifungal susceptibility was noted in a large number of reported cases of Aspergillus infections that were resistant to conventional treatment, such as voriconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B.15 Thus antifungal susceptibility testing is necessary before starting treatment. There also have been reports of recurrence of cutaneous aspergillosis following incomplete and irregular treatment.16 Our case of PCA also failed to respond to ketoconazole therapy, thus stressing the need for thorough mycological characterization, including the determination of an antifungal susceptibility profile, for successful and complete management of this condition.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Arunaloke Chakraborti, MD, Chandigarh, India, for the help extended for identification of the fungus.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous aspergillosis mostly has been reported in immunosuppressed hosts and usually is caused by Aspergillus flavus or Aspergillus fumigatus. We report the occurrence of primary cutaneous aspergillosis (PCA) caused by a relatively rare species, Aspergillus nidulans, in a middle-aged patient without overt immunosuppression or history of trauma.

A 57-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology outpatient department for evaluation of a lesion on the right hand of 1 month's duration. On examination the lesion measured approximately 4×3 cm with central necrosis (Figure 1). Her medical history was unremarkable and routine laboratory test results were within reference range.

The patient was an agricultural worker with no history of trauma. Her history was unremarkable. A 20% potassium hydroxide mount of the tissue revealed septate, branched, hyaline hyphae. A soft, wooly, greenish brown growth was observed after 3 days of incubation on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Figure 2). No growth was observed on dermatophyte test medium. A lactophenol cotton blue mount revealed columnar conidial heads with brown, short, smooth-walled conidiophores (Figures 3–6). Vesicles were hemispheric and small (8–12 µm in diameter), with metulae and phialides occurring in the upper portion. Conidia were globose (3–4 µm) and rough. Based on these findings the fungus was identified as A nidulans. The patient did not respond to daily oral ketoconazole, and after 1 month of therapy the lesion did not regress. She was eventually treated with oral itraconazole and the lesion completely healed within 15 weeks.

An overwhelming majority of the cases of cutaneous aspergillosis have been reported either in immunocompromised hosts (ie, leukemia, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin disease, human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, solid-organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients) or in patients with contributing risk factors (ie, severe burns, diabetes mellitus, preterm or underweight neonates, elderly patients). Two outbreaks of this condition have been reported in neonatal intensive care units, with the source of contamination being linked to nonsterile disposable gloves, incubators, and humidity chambers.1,2 However, PCA is a relatively rare condition and often is associated with disruption of dermal integrity by trauma or maceration, followed by colonization of the wound by Aspergillus spores that are ubiquitously present in soil and decomposed vegetation.3-5 Our case was remarkable, as the patient was not immunosuppressed and did not have a history of trauma. However, we surmise that fungal inoculation might have inadvertently occurred through some trivial trauma sustained through her professional work.

The 2 species that have most commonly been associated with PCA are A flavus and A fumigatus.6,7 There have been isolated reports of PCA caused by other organisms such as Aspergillus niger,8,9 Aspergillus terreus,10Aspergillus ustus,11 or Aspergillus calidoustus.12 In a report of a neutropenic 56-year-old patient suffering from acute myeloblastic leukemia, PCA developed in association with a double-lumen Hickman catheter after a period of prolonged hospitalization.13 A study by the National Institutes of Health (1976-1997) revealed 6 life-threatening cases of A nidulans infection in patients with chronic granulomatous disease.14

We did not perform antifungal susceptibility testing on the isolate in our patient. However, we observed disease that was refractory to ketoconazole therapy but successfully resolved with oral itraconazole. Antifungal susceptibility was noted in a large number of reported cases of Aspergillus infections that were resistant to conventional treatment, such as voriconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B.15 Thus antifungal susceptibility testing is necessary before starting treatment. There also have been reports of recurrence of cutaneous aspergillosis following incomplete and irregular treatment.16 Our case of PCA also failed to respond to ketoconazole therapy, thus stressing the need for thorough mycological characterization, including the determination of an antifungal susceptibility profile, for successful and complete management of this condition.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Arunaloke Chakraborti, MD, Chandigarh, India, for the help extended for identification of the fungus.

- Stock C, Veyrier M, Raberin H, et al. Severe cutaneous aspergillosis in a premature neonate linked to nonsterile disposable glove contamination [published online ahead of print August 31, 2011]? Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:465-467.

- Etienne KA, Subudhi CP, Chadwick PR, et al. Investigation of a cluster of cutaneous aspergillosis in a neonatal intensive care unit [published online ahead of print August 12, 2011]. J Hosp Infect. 2011;79:344-348.

- Isaac M. Cutaneous aspergillosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:137-140.

- Cahill KM, Mofty AM, Kawaguchi TP. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:545-547.

- Carlile JR, Millet RE, Cho CT, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis in a leukemic child. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:78-80.

- John PU, Shadomy HJ. Deep fungal infections. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al, eds. Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1987:2266-2268.

- Chakrabarti A, Gupta V, Biswas G, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis: our experience in 10 years. J Infect. 1998;37:24-27.

- Robinson A, Fien S, Grassi MA. Nonhealing scalp wound infected with Aspergillus niger in an elderly patient. Cutis. 2011;87:197-200.

- Thomas LM, Rand HK, Miller JL, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis in a patient with a solid organ transplant: case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2008;81:127-130.

- Yuanjie Z, Jingxia D, Hai W, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis in a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [published online ahead of print October 22, 2008]. Mycoses. 2009;52:462-464.

- Krishnan-Natesan S, Chandrasekar PH, Manavathu EK, et al. Successful treatment of primary cutaneous Aspergillus ustus infection with surgical debridement and a combination of voriconazole and terbinafine [published online ahead of print October 7, 2008]. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62:443-446.

- Sato Y, Suzino K, Suzuki A, et al. Case of primary cutaneous Aspergillus calidoustus infection caused by nerve block therapy [in Japanese]. Med Mycol J. 2011;52:239-244.

- Lucas GM, Tucker P, Merz WG. Primary cutaneous Aspergillus nidulans infection associated with a Hickman catheter in a patient with neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1594-1596.

- Segal BH, DeCarlo ES, Kwon-Chung KJ, et al. Aspergillus nidulans infection in chronic granulomatous disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77:345-354.

- Woodruff CA, Hebert AA. Neonatal primary cutaneous aspergillosis: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:439-444.

- Mohapatra S, Xess I, Swetha JV, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis due to Aspergillus niger in an immunocompetent patient. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:367-370.

- Stock C, Veyrier M, Raberin H, et al. Severe cutaneous aspergillosis in a premature neonate linked to nonsterile disposable glove contamination [published online ahead of print August 31, 2011]? Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:465-467.

- Etienne KA, Subudhi CP, Chadwick PR, et al. Investigation of a cluster of cutaneous aspergillosis in a neonatal intensive care unit [published online ahead of print August 12, 2011]. J Hosp Infect. 2011;79:344-348.

- Isaac M. Cutaneous aspergillosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:137-140.

- Cahill KM, Mofty AM, Kawaguchi TP. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:545-547.

- Carlile JR, Millet RE, Cho CT, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis in a leukemic child. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:78-80.

- John PU, Shadomy HJ. Deep fungal infections. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al, eds. Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1987:2266-2268.

- Chakrabarti A, Gupta V, Biswas G, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis: our experience in 10 years. J Infect. 1998;37:24-27.

- Robinson A, Fien S, Grassi MA. Nonhealing scalp wound infected with Aspergillus niger in an elderly patient. Cutis. 2011;87:197-200.

- Thomas LM, Rand HK, Miller JL, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis in a patient with a solid organ transplant: case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2008;81:127-130.

- Yuanjie Z, Jingxia D, Hai W, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis in a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [published online ahead of print October 22, 2008]. Mycoses. 2009;52:462-464.

- Krishnan-Natesan S, Chandrasekar PH, Manavathu EK, et al. Successful treatment of primary cutaneous Aspergillus ustus infection with surgical debridement and a combination of voriconazole and terbinafine [published online ahead of print October 7, 2008]. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62:443-446.

- Sato Y, Suzino K, Suzuki A, et al. Case of primary cutaneous Aspergillus calidoustus infection caused by nerve block therapy [in Japanese]. Med Mycol J. 2011;52:239-244.

- Lucas GM, Tucker P, Merz WG. Primary cutaneous Aspergillus nidulans infection associated with a Hickman catheter in a patient with neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1594-1596.

- Segal BH, DeCarlo ES, Kwon-Chung KJ, et al. Aspergillus nidulans infection in chronic granulomatous disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77:345-354.

- Woodruff CA, Hebert AA. Neonatal primary cutaneous aspergillosis: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:439-444.

- Mohapatra S, Xess I, Swetha JV, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis due to Aspergillus niger in an immunocompetent patient. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:367-370.

Onychomycosis: Current and Investigational Therapies

To the Editor:

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nail plate by dermatophytes, yeasts, and nondermatophyte molds. It is a common problem with a prevalence of 10% to 12% in the United States.1,2 The clinical presentation of onychomycosis is shown in the Figure. Although some patients may have mild asymptomatic cases of onychomycosis and do not inquire about treatment, many will have more advanced cases, presenting with pain and discomfort, secondary infection, unattractive appearance, or problems performing everyday functions. The goal of onychomycosis treatment is to eliminate the fungus, if possible, which usually restores the nail to its normal state when it fully grows out. Patients should be counseled that it is a long process that may take 6 months or more for fingernails and 12 to 18 months for toenails. These estimates are based on a growth rate of 2 to 3 mm per month for fingernails and 1 to 2 mm per month for toenails.3 Nails grow fastest during the teenaged years and slow down with advancing age.4 It should be noted that advanced cases of onychomycosis affecting the nail matrix may cause permanent scarring; therefore, the nail unit may still appear dystrophic after the causative organism is eliminated. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines a complete cure as negative potassium hydroxide preparation and negative fungal culture plus a completely normal appearance of the nail.

Treatment of onychomycosis poses a number of challenges. First, hyperkeratosis and the fungal mass may limit the delivery of topical and systemic drugs to the source of the infection. In addition, high rates of relapse and reinfection after treatment may be due to residual hyphae or spores.5 Furthermore, the extended length of treatment limits patient adherence and many patients are unwilling to forego wearing nail cosmetics during the course of some of the treatments.

There are 4 approved classes of antifungal drugs for the treatment of onychomycosis: allylamines, azoles, morpholines, and hydroxypyridinones.6 The allylamines (eg, terbinafine) inhibit squalene epoxidase.7 Oral terbinafine (250 mg daily) taken for 6 weeks for fingernails and 12 weeks for toenails is considered the current systemic treatment preference in onychomycosis therapy8 with complete cure rates in 12-week studies of approximately 38%9 and 49%.10

The second class of drugs is the azoles, which inhibit lanosterol 14a-demethylase, a step in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway.6 Two members of this class that are widely used in treating onychomycosis are oral itraconazole11 and off-label oral fluconazole.12 The approved dose for oral itraconazole is 200 mg daily for 3 months (or an alternative pulse regimen) with a reported complete cure rate of 14%.11 Although fluconazole is not FDA approved for the treatment of onychomycosis in the United States, it is used extensively in other countries and to some extent off label in the United States. In a study of 362 patients with onychomycosis treated with oral fluconazole, complete cure rates were 48% in patients who received 450 mg weekly, 46% in those who received 300 mg weekly, and 37% in those who received 150 mg weekly for up to 9 months.12 It should be noted that several oral triazole antifungals, namely albaconazole,13 posaconazole,14 and ravuconazole,15 have undergone phase 1 and 2 studies for the treatment of onychomycosis and have shown some efficacy.

Another class of antifungals are the morpholines including topical amorolfine, which is approved for use in Europe but not in North America.16 Amorolfine inhibits D14 reductase and D7-D8 isomerase, thus depleting ergosterol.17 In one randomized controlled study, the combination of amorolfine nail lacquer and oral terbinafine compared to oral terbinafine alone resulted in a higher clinical cure rate with the combination (59.2% vs 46%); complete cure rate was not reported.16

Finally, the hydroxypyridinone class includes topical ciclopirox, which has a poorly understood mechanism of action but may involve iron chelation or oxidative damage.18,19 Ciclopirox nail lacquer 8% was approved by the FDA in 1999 and has reported complete cure rates of 5.5% to 8.5% with monthly nail debridement.20

Based on the poor efficacy of many of the currently available treatments and time-consuming treatment courses, it is clear that there is a need for alternative and novel therapies. There has been a greater emphasis on topical agents due to their more favorable side-effect profile and lower risk for drug-drug interactions. Although there are many agents for the treatment of onychomycosis currently in development, many are in vitro studies or phase 1 and 2 studies. However, we will focus on drugs that are further along in phase 3 studies and those that were recently FDA approved.

Efinaconazole is a member of the azole class of drugs and has completed 2 phase 3 clinical trials (study 1, N=870; study 2, N=785).21 Patients in these 2 studies were randomized to receive either efinaconazole nail solution 10% or vehicle for 48 weeks followed by a 4-week washout period. Complete cure rates in the 2 studies were 17.8% and 15.2% in the treated group and 3.3% and 5.5% in the control group. The mycological cure rates were 55.2% and 53.4% in the treated group and 16.8% and 16.9% in the control group. The side-effect profile was minimal, with the most common adverse events being application-site dermatitis and vesiculation, which were not significantly higher in the treated group versus the control group.21 Efinaconazole received FDA approval for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in June 2014.

There are some notable differences between ciclopirox and efinaconazole that may improve patient compliance with the latter. First, treatment with ciclopirox includes monthly nail debridement, which is not required with efinaconazole. Secondly, although ciclopirox lacquer must be removed weekly, efinaconazole is a solution, so no removal is necessary.

Terbinafine nail solution (TNS) is a member of the allylamine class and has completed phase 3 clinical trials.22 Three studies—2 vehicle controlled and 1 active comparator—were performed. The first compared TNS and vehicle, both applied daily for 24 weeks; the second study repeated the same for 48 weeks; and the third study compared TNS to amorolfine nail lacquer 5% daily for 48 weeks. The best results for complete cure were achieved with TNS for 48 weeks in the vehicle-controlled study with a rate of 2.2% versus 0%. The authors also concluded TNS was not more effective than amorolfine, as complete cure rates were 1.2% for TNS and 0.96% for amorolfine. The most common side effects were headache, nasopharyngitis, and influenza.22

Tavaborole is a member of the new benzoxaborole class, which inhibits protein synthesis by forming an adduct with the aminoacyl–transfer RNA synthetase.23 The topical solution was engineered to have improved penetration through the nail plate. In vitro studies showed better penetration than both ciclopirox and amorolfine.24 Two identical phase 3 randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies were completed involving 1197 patients who were treated with tavaborole topical solution 5% daily compared to vehicle for 48 weeks followed by a 4-week washout period with promising results.25 The incidence of treatment-related side effects was comparable to the vehicle. The most common adverse events were exfoliation, erythema, and dermatitis, all occurring at the application site.25 Tavaborole was approved by the FDA for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in July 2014.

Luliconazole is a member of the azole class and a phase 2b/3 clinical trial with a 10% solution involving 334 patients was completed in June 2013.26 Results from this trial are expected in early 2015.

Lasers are a developing area for onychomycosis therapy and the appeal stems from their ability to selectively deliver energy to the target tissue, thus avoiding systemic side effects. Since 2010, the FDA has approved numerous laser devices for the temporary cosmetic improvement of onychomycosis, all of which are Nd:YAG 1064-nm lasers.27,28 It was previously thought that the mechanism of action for the fungicidal effect was achieved with heat,29 but newer in vitro studies have shown that the amount of time and level of heat required to kill Trichophyton rubrum would not be tolerable to patients.30 Although the mechanism of action is poorly understood, some clinical trials have shown success using the Nd:YAG 1064-nm laser for treatment of onychomycosis. However, in a study of 8 patients treated with the Nd:YAG 1064-nm laser for 5 treatment sessions, none had a mycological or clinical cure and there was only mild clinical improvement. In addition, most patients had pain and burning during the treatments requiring many short breaks.30 Although not yet FDA approved for the treatment of onychomycosis, other types of lasers are currently being studied, including CO2, near-infrared diode, and femtosecond-infrared laser systems.3

Plasma therapy is a developing area for the treatment of onychomycosis. Plasma was shown to be fungicidal to T rubrum in an in vitro model (MOE Medical Devices, written communication, July 2012), and a clinical trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of plasma in human subjects is ongoing (registered on March 22, 2013, at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifier NCT01819051).

Onychomycosis is a common problem that increases in prevalence with advancing age. Oral terbinafine is considered the first-line treatment at this point in time.31 Two new topical agents, efinaconazole and tavaborole, were recently FDA approved and may be used for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis without the need for nail debridement. The Nd:YAG laser has shown some promise in earlier clinical studies but was ineffective in a more recent study.

1. Ghannoum MA, Hajjeh RA, Scher R, et al. A large-scale North American study of fungal isolates from nails: the frequency of onychomycosis, fungal distribution, and antifungal susceptibility patterns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:641-648.

2. Heikkila H, Stubb S. The prevalence of onychomycosis in Finland. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:699-703.

3. Scher RK, Rich P, Pariser D, et al. The epidemiology, etiology, and pathophysiology of onychomycosis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2013;32(2, suppl 1):S2-S4.

4. Abdullah L, Abbas O. Common nail changes and disorders in older people: diagnosis and management. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:173-181.

5. Scher RK, Baran R. Onychomycosis in clinical practice: factors contributing to recurrence. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(suppl 65):5-9.

6. Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E. Onychomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:151-159.

7. Gupta AK, Sauder DN, Shear NH. Antifungal agents: an overview. part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:911-933.

8. Gupta AK, Paquet M, Simpson F, et al. Terbinafine in the treatment of dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis: a meta-analysis of efficacy for continuous and intermittent regimens. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:267-272.

9. Drake LA, Shear NH, Arlette JP, et al. Oral terbinafine in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: North American multicenter trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:740-745.

10. Evans EG, Sigurgeirsson B. Double blind, randomised study of continuous terbinafine compared with intermittent itraconazole in treatment of toenail onychomycosis. the LION Study Group. BMJ. 1999;318:1031-1035.

11. Sporanox [package insert]. Macquarie Park, Australia: Janssen-Cilag Pty Ltd; 2014.

12. Scher RK, Breneman D, Rich P, et al. Once-weekly fluconazole (150, 300, or 450 mg) in the treatment of distal subungual onychomycosis of the toenail. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(6, pt 2):S77-S86.

13. Sigurgeirsson B, van Rossem K, Malahias S, et al. A phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group, dose-ranging study to investigate the efficacy and safety of 4 dose regimens of oral albaconazole in patients with distal subungual onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:416-425.

14. Elewski B, Pollak R, Ashton S, et al. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre, investigator-blinded study of four treatment regimens of posaconazole in adults with toenail onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:389-398.

15. Gupta AK, Leonardi C, Stoltz RR, et al. A phase I/II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study evaluating the efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of ravuconazole in the treatment of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:437-443.

16. Baran R, Sigurgeirsson B, de Berker D, et al. A multicentre, randomized, controlled study of the efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness of a combination therapy with amorolfine nail lacquer and oral terbinafine compared with oral terbinafine alone for the treatment of onychomycosis with matrix involvement. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:149-157.

17. Polak A. Preclinical data and mode of action of amorolfine. Dermatology. 1992;184(suppl 1):3-7.

18. Belenky P, Camacho D, Collins JJ. Fungicidal drugs induce a common oxidative-damage cellular death pathway. Cell Rep. 2013;3:350-358.

19. Lee RE, Liu TT, Barker KS, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling of the response to ciclopirox olamine in Candida albicans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:655-662.

20. Penlac [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis; 2006.

21. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

22. Elewski BE, Ghannoum MA, Mayser P, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of topical terbinafine nail solution in patients with mild-to-moderate toenail onychomycosis: results from three randomized studies using double-blind vehicle-controlled and open-label active-controlled designs. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:287-294.

23. Rock FL, Mao W, Yaremchuk A, et al. An antifungal agent inhibits an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase by trapping tRNA in the editing site. Science. 2007;316:1759-1761.

24. Hui X, Baker SJ, Wester RC, et al. In vitro penetration of a novel oxaborole antifungal (AN2690) into the human nail plate. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96:2622-2631.

25. Elewski BE, Rich P, Wiltz H, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tavaborole, a novel born-based molecule for the treatment of onychomycosis: results from two phase 3 studies. Poster presented at: Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar; October 4-6, 2013; Newport Beach, CA.

26. The solution study: Topica’s phase 2b/3 clinical trial. Topica Pharmaceuticals Inc Web site. http://www.

topicapharma.com/phase-2b3. Accessed December 2, 2014.

27. Gupta AK, Simpson FC. Medical devices for the treatment of onychomycosis. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:574-581.

28. Ortiz AE, Avram MM, Wanner MA. A review of lasers and light for the treatment of onychomycosis. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46:117-124.

29. Vural E, Winfield HL, Shingleton AW, et al. The effects of laser irradiation on Trichophyton rubrum growth. Lasers Med Sci. 2008;23:349-353.

30. Carney C, Cantrell W, Warner J, et al. Treatment of onychomycosis using a submillisecond 1064-nm neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:578-582.

31. Gupta AK, Daigle D, Paquet M. Therapies for onychomycosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of mycological cure [published online ahead of print July 17, 2014]. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. doi:10.7547/13-110.1.

To the Editor:

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nail plate by dermatophytes, yeasts, and nondermatophyte molds. It is a common problem with a prevalence of 10% to 12% in the United States.1,2 The clinical presentation of onychomycosis is shown in the Figure. Although some patients may have mild asymptomatic cases of onychomycosis and do not inquire about treatment, many will have more advanced cases, presenting with pain and discomfort, secondary infection, unattractive appearance, or problems performing everyday functions. The goal of onychomycosis treatment is to eliminate the fungus, if possible, which usually restores the nail to its normal state when it fully grows out. Patients should be counseled that it is a long process that may take 6 months or more for fingernails and 12 to 18 months for toenails. These estimates are based on a growth rate of 2 to 3 mm per month for fingernails and 1 to 2 mm per month for toenails.3 Nails grow fastest during the teenaged years and slow down with advancing age.4 It should be noted that advanced cases of onychomycosis affecting the nail matrix may cause permanent scarring; therefore, the nail unit may still appear dystrophic after the causative organism is eliminated. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines a complete cure as negative potassium hydroxide preparation and negative fungal culture plus a completely normal appearance of the nail.

Treatment of onychomycosis poses a number of challenges. First, hyperkeratosis and the fungal mass may limit the delivery of topical and systemic drugs to the source of the infection. In addition, high rates of relapse and reinfection after treatment may be due to residual hyphae or spores.5 Furthermore, the extended length of treatment limits patient adherence and many patients are unwilling to forego wearing nail cosmetics during the course of some of the treatments.

There are 4 approved classes of antifungal drugs for the treatment of onychomycosis: allylamines, azoles, morpholines, and hydroxypyridinones.6 The allylamines (eg, terbinafine) inhibit squalene epoxidase.7 Oral terbinafine (250 mg daily) taken for 6 weeks for fingernails and 12 weeks for toenails is considered the current systemic treatment preference in onychomycosis therapy8 with complete cure rates in 12-week studies of approximately 38%9 and 49%.10

The second class of drugs is the azoles, which inhibit lanosterol 14a-demethylase, a step in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway.6 Two members of this class that are widely used in treating onychomycosis are oral itraconazole11 and off-label oral fluconazole.12 The approved dose for oral itraconazole is 200 mg daily for 3 months (or an alternative pulse regimen) with a reported complete cure rate of 14%.11 Although fluconazole is not FDA approved for the treatment of onychomycosis in the United States, it is used extensively in other countries and to some extent off label in the United States. In a study of 362 patients with onychomycosis treated with oral fluconazole, complete cure rates were 48% in patients who received 450 mg weekly, 46% in those who received 300 mg weekly, and 37% in those who received 150 mg weekly for up to 9 months.12 It should be noted that several oral triazole antifungals, namely albaconazole,13 posaconazole,14 and ravuconazole,15 have undergone phase 1 and 2 studies for the treatment of onychomycosis and have shown some efficacy.

Another class of antifungals are the morpholines including topical amorolfine, which is approved for use in Europe but not in North America.16 Amorolfine inhibits D14 reductase and D7-D8 isomerase, thus depleting ergosterol.17 In one randomized controlled study, the combination of amorolfine nail lacquer and oral terbinafine compared to oral terbinafine alone resulted in a higher clinical cure rate with the combination (59.2% vs 46%); complete cure rate was not reported.16

Finally, the hydroxypyridinone class includes topical ciclopirox, which has a poorly understood mechanism of action but may involve iron chelation or oxidative damage.18,19 Ciclopirox nail lacquer 8% was approved by the FDA in 1999 and has reported complete cure rates of 5.5% to 8.5% with monthly nail debridement.20

Based on the poor efficacy of many of the currently available treatments and time-consuming treatment courses, it is clear that there is a need for alternative and novel therapies. There has been a greater emphasis on topical agents due to their more favorable side-effect profile and lower risk for drug-drug interactions. Although there are many agents for the treatment of onychomycosis currently in development, many are in vitro studies or phase 1 and 2 studies. However, we will focus on drugs that are further along in phase 3 studies and those that were recently FDA approved.

Efinaconazole is a member of the azole class of drugs and has completed 2 phase 3 clinical trials (study 1, N=870; study 2, N=785).21 Patients in these 2 studies were randomized to receive either efinaconazole nail solution 10% or vehicle for 48 weeks followed by a 4-week washout period. Complete cure rates in the 2 studies were 17.8% and 15.2% in the treated group and 3.3% and 5.5% in the control group. The mycological cure rates were 55.2% and 53.4% in the treated group and 16.8% and 16.9% in the control group. The side-effect profile was minimal, with the most common adverse events being application-site dermatitis and vesiculation, which were not significantly higher in the treated group versus the control group.21 Efinaconazole received FDA approval for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in June 2014.

There are some notable differences between ciclopirox and efinaconazole that may improve patient compliance with the latter. First, treatment with ciclopirox includes monthly nail debridement, which is not required with efinaconazole. Secondly, although ciclopirox lacquer must be removed weekly, efinaconazole is a solution, so no removal is necessary.

Terbinafine nail solution (TNS) is a member of the allylamine class and has completed phase 3 clinical trials.22 Three studies—2 vehicle controlled and 1 active comparator—were performed. The first compared TNS and vehicle, both applied daily for 24 weeks; the second study repeated the same for 48 weeks; and the third study compared TNS to amorolfine nail lacquer 5% daily for 48 weeks. The best results for complete cure were achieved with TNS for 48 weeks in the vehicle-controlled study with a rate of 2.2% versus 0%. The authors also concluded TNS was not more effective than amorolfine, as complete cure rates were 1.2% for TNS and 0.96% for amorolfine. The most common side effects were headache, nasopharyngitis, and influenza.22

Tavaborole is a member of the new benzoxaborole class, which inhibits protein synthesis by forming an adduct with the aminoacyl–transfer RNA synthetase.23 The topical solution was engineered to have improved penetration through the nail plate. In vitro studies showed better penetration than both ciclopirox and amorolfine.24 Two identical phase 3 randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies were completed involving 1197 patients who were treated with tavaborole topical solution 5% daily compared to vehicle for 48 weeks followed by a 4-week washout period with promising results.25 The incidence of treatment-related side effects was comparable to the vehicle. The most common adverse events were exfoliation, erythema, and dermatitis, all occurring at the application site.25 Tavaborole was approved by the FDA for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in July 2014.

Luliconazole is a member of the azole class and a phase 2b/3 clinical trial with a 10% solution involving 334 patients was completed in June 2013.26 Results from this trial are expected in early 2015.

Lasers are a developing area for onychomycosis therapy and the appeal stems from their ability to selectively deliver energy to the target tissue, thus avoiding systemic side effects. Since 2010, the FDA has approved numerous laser devices for the temporary cosmetic improvement of onychomycosis, all of which are Nd:YAG 1064-nm lasers.27,28 It was previously thought that the mechanism of action for the fungicidal effect was achieved with heat,29 but newer in vitro studies have shown that the amount of time and level of heat required to kill Trichophyton rubrum would not be tolerable to patients.30 Although the mechanism of action is poorly understood, some clinical trials have shown success using the Nd:YAG 1064-nm laser for treatment of onychomycosis. However, in a study of 8 patients treated with the Nd:YAG 1064-nm laser for 5 treatment sessions, none had a mycological or clinical cure and there was only mild clinical improvement. In addition, most patients had pain and burning during the treatments requiring many short breaks.30 Although not yet FDA approved for the treatment of onychomycosis, other types of lasers are currently being studied, including CO2, near-infrared diode, and femtosecond-infrared laser systems.3

Plasma therapy is a developing area for the treatment of onychomycosis. Plasma was shown to be fungicidal to T rubrum in an in vitro model (MOE Medical Devices, written communication, July 2012), and a clinical trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of plasma in human subjects is ongoing (registered on March 22, 2013, at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifier NCT01819051).

Onychomycosis is a common problem that increases in prevalence with advancing age. Oral terbinafine is considered the first-line treatment at this point in time.31 Two new topical agents, efinaconazole and tavaborole, were recently FDA approved and may be used for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis without the need for nail debridement. The Nd:YAG laser has shown some promise in earlier clinical studies but was ineffective in a more recent study.

To the Editor:

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nail plate by dermatophytes, yeasts, and nondermatophyte molds. It is a common problem with a prevalence of 10% to 12% in the United States.1,2 The clinical presentation of onychomycosis is shown in the Figure. Although some patients may have mild asymptomatic cases of onychomycosis and do not inquire about treatment, many will have more advanced cases, presenting with pain and discomfort, secondary infection, unattractive appearance, or problems performing everyday functions. The goal of onychomycosis treatment is to eliminate the fungus, if possible, which usually restores the nail to its normal state when it fully grows out. Patients should be counseled that it is a long process that may take 6 months or more for fingernails and 12 to 18 months for toenails. These estimates are based on a growth rate of 2 to 3 mm per month for fingernails and 1 to 2 mm per month for toenails.3 Nails grow fastest during the teenaged years and slow down with advancing age.4 It should be noted that advanced cases of onychomycosis affecting the nail matrix may cause permanent scarring; therefore, the nail unit may still appear dystrophic after the causative organism is eliminated. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines a complete cure as negative potassium hydroxide preparation and negative fungal culture plus a completely normal appearance of the nail.

Treatment of onychomycosis poses a number of challenges. First, hyperkeratosis and the fungal mass may limit the delivery of topical and systemic drugs to the source of the infection. In addition, high rates of relapse and reinfection after treatment may be due to residual hyphae or spores.5 Furthermore, the extended length of treatment limits patient adherence and many patients are unwilling to forego wearing nail cosmetics during the course of some of the treatments.

There are 4 approved classes of antifungal drugs for the treatment of onychomycosis: allylamines, azoles, morpholines, and hydroxypyridinones.6 The allylamines (eg, terbinafine) inhibit squalene epoxidase.7 Oral terbinafine (250 mg daily) taken for 6 weeks for fingernails and 12 weeks for toenails is considered the current systemic treatment preference in onychomycosis therapy8 with complete cure rates in 12-week studies of approximately 38%9 and 49%.10

The second class of drugs is the azoles, which inhibit lanosterol 14a-demethylase, a step in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway.6 Two members of this class that are widely used in treating onychomycosis are oral itraconazole11 and off-label oral fluconazole.12 The approved dose for oral itraconazole is 200 mg daily for 3 months (or an alternative pulse regimen) with a reported complete cure rate of 14%.11 Although fluconazole is not FDA approved for the treatment of onychomycosis in the United States, it is used extensively in other countries and to some extent off label in the United States. In a study of 362 patients with onychomycosis treated with oral fluconazole, complete cure rates were 48% in patients who received 450 mg weekly, 46% in those who received 300 mg weekly, and 37% in those who received 150 mg weekly for up to 9 months.12 It should be noted that several oral triazole antifungals, namely albaconazole,13 posaconazole,14 and ravuconazole,15 have undergone phase 1 and 2 studies for the treatment of onychomycosis and have shown some efficacy.

Another class of antifungals are the morpholines including topical amorolfine, which is approved for use in Europe but not in North America.16 Amorolfine inhibits D14 reductase and D7-D8 isomerase, thus depleting ergosterol.17 In one randomized controlled study, the combination of amorolfine nail lacquer and oral terbinafine compared to oral terbinafine alone resulted in a higher clinical cure rate with the combination (59.2% vs 46%); complete cure rate was not reported.16

Finally, the hydroxypyridinone class includes topical ciclopirox, which has a poorly understood mechanism of action but may involve iron chelation or oxidative damage.18,19 Ciclopirox nail lacquer 8% was approved by the FDA in 1999 and has reported complete cure rates of 5.5% to 8.5% with monthly nail debridement.20

Based on the poor efficacy of many of the currently available treatments and time-consuming treatment courses, it is clear that there is a need for alternative and novel therapies. There has been a greater emphasis on topical agents due to their more favorable side-effect profile and lower risk for drug-drug interactions. Although there are many agents for the treatment of onychomycosis currently in development, many are in vitro studies or phase 1 and 2 studies. However, we will focus on drugs that are further along in phase 3 studies and those that were recently FDA approved.

Efinaconazole is a member of the azole class of drugs and has completed 2 phase 3 clinical trials (study 1, N=870; study 2, N=785).21 Patients in these 2 studies were randomized to receive either efinaconazole nail solution 10% or vehicle for 48 weeks followed by a 4-week washout period. Complete cure rates in the 2 studies were 17.8% and 15.2% in the treated group and 3.3% and 5.5% in the control group. The mycological cure rates were 55.2% and 53.4% in the treated group and 16.8% and 16.9% in the control group. The side-effect profile was minimal, with the most common adverse events being application-site dermatitis and vesiculation, which were not significantly higher in the treated group versus the control group.21 Efinaconazole received FDA approval for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in June 2014.

There are some notable differences between ciclopirox and efinaconazole that may improve patient compliance with the latter. First, treatment with ciclopirox includes monthly nail debridement, which is not required with efinaconazole. Secondly, although ciclopirox lacquer must be removed weekly, efinaconazole is a solution, so no removal is necessary.

Terbinafine nail solution (TNS) is a member of the allylamine class and has completed phase 3 clinical trials.22 Three studies—2 vehicle controlled and 1 active comparator—were performed. The first compared TNS and vehicle, both applied daily for 24 weeks; the second study repeated the same for 48 weeks; and the third study compared TNS to amorolfine nail lacquer 5% daily for 48 weeks. The best results for complete cure were achieved with TNS for 48 weeks in the vehicle-controlled study with a rate of 2.2% versus 0%. The authors also concluded TNS was not more effective than amorolfine, as complete cure rates were 1.2% for TNS and 0.96% for amorolfine. The most common side effects were headache, nasopharyngitis, and influenza.22

Tavaborole is a member of the new benzoxaborole class, which inhibits protein synthesis by forming an adduct with the aminoacyl–transfer RNA synthetase.23 The topical solution was engineered to have improved penetration through the nail plate. In vitro studies showed better penetration than both ciclopirox and amorolfine.24 Two identical phase 3 randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies were completed involving 1197 patients who were treated with tavaborole topical solution 5% daily compared to vehicle for 48 weeks followed by a 4-week washout period with promising results.25 The incidence of treatment-related side effects was comparable to the vehicle. The most common adverse events were exfoliation, erythema, and dermatitis, all occurring at the application site.25 Tavaborole was approved by the FDA for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in July 2014.

Luliconazole is a member of the azole class and a phase 2b/3 clinical trial with a 10% solution involving 334 patients was completed in June 2013.26 Results from this trial are expected in early 2015.

Lasers are a developing area for onychomycosis therapy and the appeal stems from their ability to selectively deliver energy to the target tissue, thus avoiding systemic side effects. Since 2010, the FDA has approved numerous laser devices for the temporary cosmetic improvement of onychomycosis, all of which are Nd:YAG 1064-nm lasers.27,28 It was previously thought that the mechanism of action for the fungicidal effect was achieved with heat,29 but newer in vitro studies have shown that the amount of time and level of heat required to kill Trichophyton rubrum would not be tolerable to patients.30 Although the mechanism of action is poorly understood, some clinical trials have shown success using the Nd:YAG 1064-nm laser for treatment of onychomycosis. However, in a study of 8 patients treated with the Nd:YAG 1064-nm laser for 5 treatment sessions, none had a mycological or clinical cure and there was only mild clinical improvement. In addition, most patients had pain and burning during the treatments requiring many short breaks.30 Although not yet FDA approved for the treatment of onychomycosis, other types of lasers are currently being studied, including CO2, near-infrared diode, and femtosecond-infrared laser systems.3

Plasma therapy is a developing area for the treatment of onychomycosis. Plasma was shown to be fungicidal to T rubrum in an in vitro model (MOE Medical Devices, written communication, July 2012), and a clinical trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of plasma in human subjects is ongoing (registered on March 22, 2013, at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifier NCT01819051).

Onychomycosis is a common problem that increases in prevalence with advancing age. Oral terbinafine is considered the first-line treatment at this point in time.31 Two new topical agents, efinaconazole and tavaborole, were recently FDA approved and may be used for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis without the need for nail debridement. The Nd:YAG laser has shown some promise in earlier clinical studies but was ineffective in a more recent study.

1. Ghannoum MA, Hajjeh RA, Scher R, et al. A large-scale North American study of fungal isolates from nails: the frequency of onychomycosis, fungal distribution, and antifungal susceptibility patterns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:641-648.

2. Heikkila H, Stubb S. The prevalence of onychomycosis in Finland. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:699-703.

3. Scher RK, Rich P, Pariser D, et al. The epidemiology, etiology, and pathophysiology of onychomycosis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2013;32(2, suppl 1):S2-S4.

4. Abdullah L, Abbas O. Common nail changes and disorders in older people: diagnosis and management. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:173-181.

5. Scher RK, Baran R. Onychomycosis in clinical practice: factors contributing to recurrence. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(suppl 65):5-9.

6. Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E. Onychomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:151-159.

7. Gupta AK, Sauder DN, Shear NH. Antifungal agents: an overview. part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:911-933.

8. Gupta AK, Paquet M, Simpson F, et al. Terbinafine in the treatment of dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis: a meta-analysis of efficacy for continuous and intermittent regimens. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:267-272.

9. Drake LA, Shear NH, Arlette JP, et al. Oral terbinafine in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: North American multicenter trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:740-745.

10. Evans EG, Sigurgeirsson B. Double blind, randomised study of continuous terbinafine compared with intermittent itraconazole in treatment of toenail onychomycosis. the LION Study Group. BMJ. 1999;318:1031-1035.

11. Sporanox [package insert]. Macquarie Park, Australia: Janssen-Cilag Pty Ltd; 2014.

12. Scher RK, Breneman D, Rich P, et al. Once-weekly fluconazole (150, 300, or 450 mg) in the treatment of distal subungual onychomycosis of the toenail. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(6, pt 2):S77-S86.

13. Sigurgeirsson B, van Rossem K, Malahias S, et al. A phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group, dose-ranging study to investigate the efficacy and safety of 4 dose regimens of oral albaconazole in patients with distal subungual onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:416-425.

14. Elewski B, Pollak R, Ashton S, et al. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre, investigator-blinded study of four treatment regimens of posaconazole in adults with toenail onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:389-398.

15. Gupta AK, Leonardi C, Stoltz RR, et al. A phase I/II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study evaluating the efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of ravuconazole in the treatment of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:437-443.

16. Baran R, Sigurgeirsson B, de Berker D, et al. A multicentre, randomized, controlled study of the efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness of a combination therapy with amorolfine nail lacquer and oral terbinafine compared with oral terbinafine alone for the treatment of onychomycosis with matrix involvement. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:149-157.

17. Polak A. Preclinical data and mode of action of amorolfine. Dermatology. 1992;184(suppl 1):3-7.

18. Belenky P, Camacho D, Collins JJ. Fungicidal drugs induce a common oxidative-damage cellular death pathway. Cell Rep. 2013;3:350-358.

19. Lee RE, Liu TT, Barker KS, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling of the response to ciclopirox olamine in Candida albicans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:655-662.

20. Penlac [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis; 2006.

21. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

22. Elewski BE, Ghannoum MA, Mayser P, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of topical terbinafine nail solution in patients with mild-to-moderate toenail onychomycosis: results from three randomized studies using double-blind vehicle-controlled and open-label active-controlled designs. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:287-294.

23. Rock FL, Mao W, Yaremchuk A, et al. An antifungal agent inhibits an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase by trapping tRNA in the editing site. Science. 2007;316:1759-1761.

24. Hui X, Baker SJ, Wester RC, et al. In vitro penetration of a novel oxaborole antifungal (AN2690) into the human nail plate. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96:2622-2631.

25. Elewski BE, Rich P, Wiltz H, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tavaborole, a novel born-based molecule for the treatment of onychomycosis: results from two phase 3 studies. Poster presented at: Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar; October 4-6, 2013; Newport Beach, CA.

26. The solution study: Topica’s phase 2b/3 clinical trial. Topica Pharmaceuticals Inc Web site. http://www.

topicapharma.com/phase-2b3. Accessed December 2, 2014.

27. Gupta AK, Simpson FC. Medical devices for the treatment of onychomycosis. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:574-581.

28. Ortiz AE, Avram MM, Wanner MA. A review of lasers and light for the treatment of onychomycosis. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46:117-124.

29. Vural E, Winfield HL, Shingleton AW, et al. The effects of laser irradiation on Trichophyton rubrum growth. Lasers Med Sci. 2008;23:349-353.

30. Carney C, Cantrell W, Warner J, et al. Treatment of onychomycosis using a submillisecond 1064-nm neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:578-582.

31. Gupta AK, Daigle D, Paquet M. Therapies for onychomycosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of mycological cure [published online ahead of print July 17, 2014]. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. doi:10.7547/13-110.1.

1. Ghannoum MA, Hajjeh RA, Scher R, et al. A large-scale North American study of fungal isolates from nails: the frequency of onychomycosis, fungal distribution, and antifungal susceptibility patterns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:641-648.

2. Heikkila H, Stubb S. The prevalence of onychomycosis in Finland. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:699-703.

3. Scher RK, Rich P, Pariser D, et al. The epidemiology, etiology, and pathophysiology of onychomycosis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2013;32(2, suppl 1):S2-S4.

4. Abdullah L, Abbas O. Common nail changes and disorders in older people: diagnosis and management. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:173-181.

5. Scher RK, Baran R. Onychomycosis in clinical practice: factors contributing to recurrence. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(suppl 65):5-9.

6. Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E. Onychomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:151-159.

7. Gupta AK, Sauder DN, Shear NH. Antifungal agents: an overview. part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:911-933.

8. Gupta AK, Paquet M, Simpson F, et al. Terbinafine in the treatment of dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis: a meta-analysis of efficacy for continuous and intermittent regimens. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:267-272.

9. Drake LA, Shear NH, Arlette JP, et al. Oral terbinafine in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: North American multicenter trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:740-745.

10. Evans EG, Sigurgeirsson B. Double blind, randomised study of continuous terbinafine compared with intermittent itraconazole in treatment of toenail onychomycosis. the LION Study Group. BMJ. 1999;318:1031-1035.

11. Sporanox [package insert]. Macquarie Park, Australia: Janssen-Cilag Pty Ltd; 2014.

12. Scher RK, Breneman D, Rich P, et al. Once-weekly fluconazole (150, 300, or 450 mg) in the treatment of distal subungual onychomycosis of the toenail. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(6, pt 2):S77-S86.

13. Sigurgeirsson B, van Rossem K, Malahias S, et al. A phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group, dose-ranging study to investigate the efficacy and safety of 4 dose regimens of oral albaconazole in patients with distal subungual onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:416-425.

14. Elewski B, Pollak R, Ashton S, et al. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre, investigator-blinded study of four treatment regimens of posaconazole in adults with toenail onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:389-398.

15. Gupta AK, Leonardi C, Stoltz RR, et al. A phase I/II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study evaluating the efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of ravuconazole in the treatment of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:437-443.

16. Baran R, Sigurgeirsson B, de Berker D, et al. A multicentre, randomized, controlled study of the efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness of a combination therapy with amorolfine nail lacquer and oral terbinafine compared with oral terbinafine alone for the treatment of onychomycosis with matrix involvement. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:149-157.

17. Polak A. Preclinical data and mode of action of amorolfine. Dermatology. 1992;184(suppl 1):3-7.

18. Belenky P, Camacho D, Collins JJ. Fungicidal drugs induce a common oxidative-damage cellular death pathway. Cell Rep. 2013;3:350-358.

19. Lee RE, Liu TT, Barker KS, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling of the response to ciclopirox olamine in Candida albicans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:655-662.

20. Penlac [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis; 2006.

21. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

22. Elewski BE, Ghannoum MA, Mayser P, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of topical terbinafine nail solution in patients with mild-to-moderate toenail onychomycosis: results from three randomized studies using double-blind vehicle-controlled and open-label active-controlled designs. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:287-294.

23. Rock FL, Mao W, Yaremchuk A, et al. An antifungal agent inhibits an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase by trapping tRNA in the editing site. Science. 2007;316:1759-1761.

24. Hui X, Baker SJ, Wester RC, et al. In vitro penetration of a novel oxaborole antifungal (AN2690) into the human nail plate. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96:2622-2631.

25. Elewski BE, Rich P, Wiltz H, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tavaborole, a novel born-based molecule for the treatment of onychomycosis: results from two phase 3 studies. Poster presented at: Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar; October 4-6, 2013; Newport Beach, CA.

26. The solution study: Topica’s phase 2b/3 clinical trial. Topica Pharmaceuticals Inc Web site. http://www.

topicapharma.com/phase-2b3. Accessed December 2, 2014.

27. Gupta AK, Simpson FC. Medical devices for the treatment of onychomycosis. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:574-581.

28. Ortiz AE, Avram MM, Wanner MA. A review of lasers and light for the treatment of onychomycosis. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46:117-124.

29. Vural E, Winfield HL, Shingleton AW, et al. The effects of laser irradiation on Trichophyton rubrum growth. Lasers Med Sci. 2008;23:349-353.

30. Carney C, Cantrell W, Warner J, et al. Treatment of onychomycosis using a submillisecond 1064-nm neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:578-582.

31. Gupta AK, Daigle D, Paquet M. Therapies for onychomycosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of mycological cure [published online ahead of print July 17, 2014]. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. doi:10.7547/13-110.1.

Hemorrhagic Bullous Lesions Due to Bacillus cereus in a Cirrhotic Patient

To the Editor:

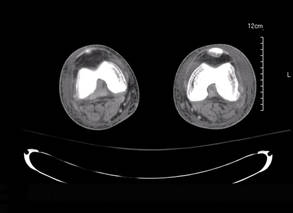

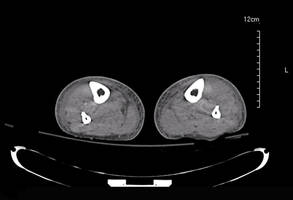

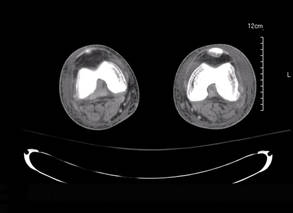

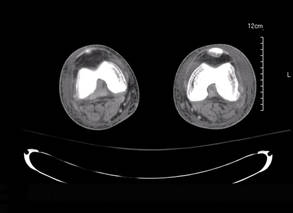

A 42-year-old man with hypertension, hypothyroidism, and alcohol-related cirrhosis was admitted for evaluation of rapidly deteriorating mental status. He was referred from a rehabilitation facility where he had been admitted 4 days earlier after a hospitalization for hepatorenal syndrome and pneumonia. He was alert and ambulating until the day of the current admission. On arrival he was hypotensive(54/42 mm Hg); hypothermic (35°C, rectally); and unresponsive, except to painful stimuli. Jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, and bilateral lower extremity edema were noted. There were multiple tense and flaccid bullous lesions containing serosanguineous fluid over both tibias and calves, without crepitus (Figure 1).

|

|

|

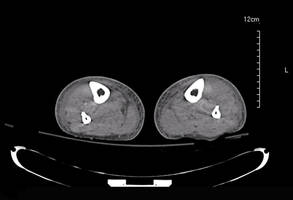

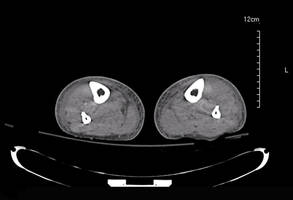

Laboratory test results revealed leukocytosis (total leukocytes, 10,900/mm3 [reference range, 4500–10,800/mm3), hypoglycemia (glucose, <20 mg/dL [reference range, 74–106 mg/dL]), renal insufficiency (serum creatinine, 2.5 mg/dL [reference range, 0.66–1.25 mg/dL]), metabolic acidosis (pH, 7.1 [reference range, 7.35–7.45]; bicarbonate, 13 mmol/L [reference range, 22–30 mmol/L]; lactic acid, 11.9 mmol/L [reference range, 0.7–2.1 mmol/L]), liver dysfunction (aspartate aminotransferase, 576 IU/L [reference range, 15–46 IU/L]), and coagulopathy with evidence of diffuse intravascular coagulation (total platelets, 75,000/mm3 [reference range, 150,000–450,000/mm3]; international normalized ratio, 9.5 [reference range, 0.8–1.2]; partial thromboplastin time, 108 seconds [reference range 23.0–35.0 seconds]; fibrinogen, 145 mg/dL [reference range, 228–501 mg/dL]; D-dimer, >20 µg/mL [reference range, 0.01–0.58 μg/mL]). Computed tomography of the pelvis and legs showed ascites, extensive subcutaneous edema, and cutaneous blisterlike lesions superior to the level of the ankles bilaterally. No gas, foreign bodies, collections, asymmetric facial thickening, or evidence of infection across tissue planes was present (Figures 2 and 3).

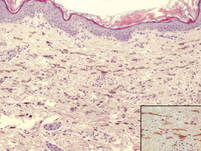

Specimens of blood and aspirates from the bullae at multiple lower leg sites were sent for microbiologic evaluation. The blood specimens were inoculated at bedside into aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles and incubated in an automated blood culture system. The aspirate samples were inoculated to trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood, Columbia-nalidixic acid agar, chocolate agar, MacConkey agar, and thioglycollate broth, which were incubated at 37ºC in air supplemented with 5% CO2, and to CDC anaerobic blood agar, which was incubated under anaerobic conditions. Gram-stained smears of the aspirates from the bullae demonstrated few granulocytes and numerous large gram-positive bacilli (Figure 4). By the next day, growth of large gram-positive bacilli was detected in both aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles and in pure culture from all the bullae samples. The bacterial colonies on sheep blood agar were opaque and white-gray in color, with a rough surface, undulate margins, and surrounding β hemolysis. The isolate was a motile, catalase-positive, arginine-positive, salicin-positive, lecithinase-positive, and penicillin-resistant organism that was identified as Bacillus cereus.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing for B cereus has not been standardized, but evaluation by broth microdilution suggested decreased susceptibility to penicillin (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC], 2 µg/mL) and clindamycin (MIC, 2 µg/mL), but retained susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (MIC, ≤0.25 µg/mL), tetracycline (MIC, ≤1 µg/mL), rifampin (MIC, ≤1 µg/mL), and vancomycin (MIC, ≤2 µg/mL).

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and was treated initially with fluid resuscitation; transfusions; ventilatory support; and intravenous vancomycin, clindamycin, and imipenem. This regimen was changed to vancomycin and ciprofloxacin when culture and susceptibility results became available to complete a 14-day course. Signs of sepsis resolved and the mental status and skin lesions improved. Ultimately, the patient died due to complications of hepatic failure.

Bacillus cereus is a rod-shaped, gram-positive, facultative, aerobic organism that is widely distributed in the environment.1 Spore formation makes B cereus resistant to most physical and chemical disinfection methods; as a consequence, it is a frequent contaminant in materials (eg, plants, dust, soil, sediment), foodstuffs, and clinical specimens.1

Traditionally considered in the context of foodborne illness, B cereus is recognized increasingly as a cause of systemic and local infections in both immunosuppressed and immunocompetent patients. Nongastrointestinal infections reported include fulminant bacteremia, pneumonia, meningitis, brain abscesses, endophthalmitis, necrotizing fasciitis, and central line catheter–related and cutaneous infections.1,2

Cutaneous lesions may have a variety of forms and appearance at initial presentation, including small papules or vesicles that progress into a rapidly spreading cellulitis1,2 with a characteristic serosanguineous draining fluid,2 single necrotic bullae,3 and gas-gangrenelike infections with extensive soft tissue involvement resembling clostridial myonecrosis.1,4 Single or multiple papulovesicular lesions can even mimic cutaneous anthrax.1-4 Necrotic or hemorrhagic bullous lesions,3 such as those observed in our patient, are rare.

Exposed areas such as extremities and digits are most often affected, presumably due to entrance of spores from soil, water, decaying organic material, or fomites through skin microabrasions or trauma-induced wounds.1 Once in the tissue, the crystalline surface protein layer (S-layer) of the bacilli promotes adhesion to human epithelial cells and neutrophils,5 followed by release of virulence factors including proteases, collagenases, lecithinaselike enzymes, necrotizing exotoxinlike hemolysins, phospholipases, and most importantly a dermonecrotic vascular permeability factor.1,5 Toxins produced by B cereus are similar to those closely related to Bacillus anthracis, the agent of anthrax.1,2

When large gram-positive bacilli are observed in tissue or wound specimens, initial therapy should address both aerobic (Bacillus species) and anaerobic (Clostridium species) organisms.1,4,6 Once B cereus is recovered, treatment should rely on susceptibility testing of the isolate. Bacillus cereus produces ß-lactamase, thus penicillin and cephalosporin should be avoided.1 Vancomycin, clindamycin, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones are the drugs of choice.1,3,4,6 Daptomycin and linezolid also are active in vitro,1 but clinical experience with these agents is limited. Necrotic infection or deep tissue involvement requires surgical intervention.

Numerous other organisms can cause cellulitis and soft tissue infections with hemorrhagic bullae.1,3,6 Streptococci, particularly Streptococcus pyogenes, and occasionally staphylococci are the primary consideration in normal hosts without trauma.3,6 In immunocompromised patients, including those with cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, and malignancy, Clostridium perfringens and gram-negative organisms such as Escherichia coli, other enteric bacteria including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Aeromonas, and halophilic Vibrio species are more frequent.3,6

We describe a patient with underlying cirrhosis who developed bilateral lower extremity hemorrhagic bullous lesions and sepsis due to infection with B cereus, an emerging cause of serious infections in patients with underlying immunocompromising conditions such as cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, and malignancy. Hemorrhagic bullae in immunocompromised patients are associated with sepsis and rapidly progressive illness, and rapid treatment is essential. Bacillus cereus should be included as a consideration in the differential diagnosis and management of patients presenting with bullous cellulitis and sepsis.

1. Bottone EJ. Bacillus cereus, a volatile human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:382-398.

2. Henrickson KJ. A second species of bacillus causing primary cutaneous disease. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:19-20.

3. Liu BM, Hsiao CT, Chung KJ, et al. Hemorrhagic bullae represent an ominous sign for cirrhotic patients [published online ahead of print November 5, 2007]. J Emer Med. 2008;34:277-281.

4. Meredith FT, Fowler VG, Gautier M, et al. Bacillus cereus necrotizing cellulitis mimicking clostridial myonecrosis: case report and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 1997;29:528-529.

5. Kotiranta A, Lounatmaa K, Haapasalo M. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Bacillus cereus infections. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:189-198.

6. Lee CC, Chi CH, Lee NY, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis in patients with liver cirrhosis: predominance of monomicrobial gram-negative bacillary infections [published online ahead of print July 23, 2008]. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62:219-225.

To the Editor:

A 42-year-old man with hypertension, hypothyroidism, and alcohol-related cirrhosis was admitted for evaluation of rapidly deteriorating mental status. He was referred from a rehabilitation facility where he had been admitted 4 days earlier after a hospitalization for hepatorenal syndrome and pneumonia. He was alert and ambulating until the day of the current admission. On arrival he was hypotensive(54/42 mm Hg); hypothermic (35°C, rectally); and unresponsive, except to painful stimuli. Jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, and bilateral lower extremity edema were noted. There were multiple tense and flaccid bullous lesions containing serosanguineous fluid over both tibias and calves, without crepitus (Figure 1).

|

|

|