User login

Fungal Melanonychia Caused by Trichophyton rubrum and the Value of Dermoscopy

To the Editor:

Longitudinal melanonychia encompasses a broad spectrum of diseases and often is a complex diagnostic problem. Differential diagnoses include ethnic-type nail pigmentation, which is more frequently seen in darker-skinned individuals; drug-induced pigmentation; subungual hemorrhage; fungal or bacterial infection; nevus; and melanoma.1,2 Fungal melan-onychia is an uncommon presentation of onychomycosis. Dermoscopy can assist in the evaluation of nail pigmentation caused by fungi to avoid unnecessary nail biopsies.

A 39-year-old man visited the dermatology clinic with a concern for melanoma because of blackish pigmentation of the toenails of 1 month’s duration. He denied history of trauma and was not taking any medications. On physical examination the second and third toenails revealed a 2-mm longitudinal band of black pigment on the lateral side; the fifth toenail showed diffuse black pigment (Figure 1A). The nail plates were thickened. Dermoscopy revealed prominent subungual hyperkeratosis, a homogeneous brown-black band with wide yellow streaks that were wider in the distal ends, and some focal reddish hue. No visible melanin inclusions were observed (Figure 2). These findings were suggestive of fungal infection. Cultures from the diseased nail grew a fungus identified as Trichophyton rubrum. The patient was treated with itraconazole 200 mg daily for 3 months. Clinical cure with disappearance of pigment was obtained at 5-month follow-up (Figure 1B).

|

|

| Figure 1. Blackish discoloration of the right second, third, and fifth toenails (A). Resolution of pigmentation and subungual hyperkeratosis was achieved at 5-month follow-up after treatment (B). |

|

|

| Figure 2. Top view (A) and front view (B) of a homogeneous brown-black band with subungual hyperkeratosis and wide intervening yellow streaks. Each ruler mark denotes 1 mm. |

Our patient illustrates the value of dermoscopy in evaluating melanonychia. The pigmentation of adult-onset melanonychia involving multiple fingers can be divided into nonmelanocytic or melanocytic origin. Causes of the former include subungual hematoma, fungal or bacterial infection, and exogenous pigmentation. The nonmelanocytic pigment often is homogeneously distributed without melanin inclusions under the dermoscope.2

On the contrary, melanin inclusions can be detected as fine granules in pigmentation of melanocytic origin, either from focal melanocytic activation or melanocyte proliferation. Causes of focal melanocytic activation include ethnic-type nail hyperpigmentation; inflammatory nail diseases; or drug-, radiation-, and friction-induced hyperpigmentation. The characteristic dermoscopic features are thin longitudinal gray lines with regular thickness and spacing in a grayish background.1-3

Melanocyte proliferation can result in a nevus or melanoma of the nail apparatus. Both share dermoscopic features of brown-black longitudinal lines in a brown background. However, the longitudinal lines in melanoma are irregular in coloration, spacing, thickness, and parallelism, in contrast with the regular pattern of a nevus.1-4 Although patients often are concerned about melanoma, involvement of multiple fingers at the same time is less likely.

In our patient, the homogeneous deep brown color without melanin inclusions favored a nonmel-anocytic origin. The distally wider pigmentation suggested fungal infection because most ungual infections extend from the distal to the proximal part of the nail.5,6 The focal reddish hue may be related with traumatic hemorrhage from subungual hyperkeratosis.

Cases of fungal melanonychia are being reported at an increasing rate. Some fungal strains are capable of synthesizing melanin, which is associated with virulence and acts as a fungal armor against toxic insults.5 In T rubrum, the melanoid variant, the diffusible black pigment infiltrates the nail plate and attributes to the black nail clinically.4 The most frequently isolated fungi in fungal melanonychia are T rubrum and Scytalidium dimidiatum6; however, Candida species,7,8 dematiaceous fungus,9 and other dermatophytes such as Trichophyton soudanense10 have been reported to be the cause.5

Our patient presented with fungal melanonychia due to T rubrum with dermoscopic features. The prominent subungual hyperkeratosis, distally wider homogeneous brown-black pigmented band, and wide yellow streaks with focal reddish hue all suggested fungal melanonychia. The diagnosis was further confirmed by a good response to antifungal agents.

1. Ronger S, Touzet S, Ligeron C, et al. Dermoscopic examination of nail pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1327-1333.

2. Braun RP, Baran R, Le Gal FA, et al. Diagnosis and management of nail pigmentations [published online ahead of print February 22, 2007]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:835-847.

3. Koga H, Saida T, Uhara H. Key point in dermoscopic differentiation between early nail apparatus melanoma and benign longitudinal melanonychia. J Dermatol. 2011;38:45-52.

4. Phan A, Dalle S, Touzet S, et al. Dermoscopic features of acral lentiginous melanoma in a large series of 110 cases in a white population [published online ahead of print November 18, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:765-771.

5. Finch J, Arenas R, Baran R. Fungal melanonychia [published online ahead of print January 17, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:830-841.

6. Lee SW, Kim YC, Kim DK, et al. Fungal melanonychia. J Dermatol. 2004;31:904-909.

7. Parlak AH, Goksugur N, Karabay O. A case of melanonychia due to Candida albicans. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:398-400.

8. Gautret P, Rodier MH, Kauffmann-Lacroix C, et al. Case report and review. onychomycosis due to Candida parapsilosis. Mycoses. 2000;43:433-435.

9. Barua P, Barua S, Borkakoty B, et al. Onychomycosis by Scytalidium dimidiatum in green tea leaf pluckers: report of two cases [published online ahead of print July 20, 2007]. Mycopathologia. 2007;164:193-195.

10. Ricci C, Monod M, Baudraz-Rosselet F. Onychomycosis due to Trichophyton soudanense in Switzerland. Dermatology. 1998;197:297-298.

To the Editor:

Longitudinal melanonychia encompasses a broad spectrum of diseases and often is a complex diagnostic problem. Differential diagnoses include ethnic-type nail pigmentation, which is more frequently seen in darker-skinned individuals; drug-induced pigmentation; subungual hemorrhage; fungal or bacterial infection; nevus; and melanoma.1,2 Fungal melan-onychia is an uncommon presentation of onychomycosis. Dermoscopy can assist in the evaluation of nail pigmentation caused by fungi to avoid unnecessary nail biopsies.

A 39-year-old man visited the dermatology clinic with a concern for melanoma because of blackish pigmentation of the toenails of 1 month’s duration. He denied history of trauma and was not taking any medications. On physical examination the second and third toenails revealed a 2-mm longitudinal band of black pigment on the lateral side; the fifth toenail showed diffuse black pigment (Figure 1A). The nail plates were thickened. Dermoscopy revealed prominent subungual hyperkeratosis, a homogeneous brown-black band with wide yellow streaks that were wider in the distal ends, and some focal reddish hue. No visible melanin inclusions were observed (Figure 2). These findings were suggestive of fungal infection. Cultures from the diseased nail grew a fungus identified as Trichophyton rubrum. The patient was treated with itraconazole 200 mg daily for 3 months. Clinical cure with disappearance of pigment was obtained at 5-month follow-up (Figure 1B).

|

|

| Figure 1. Blackish discoloration of the right second, third, and fifth toenails (A). Resolution of pigmentation and subungual hyperkeratosis was achieved at 5-month follow-up after treatment (B). |

|

|

| Figure 2. Top view (A) and front view (B) of a homogeneous brown-black band with subungual hyperkeratosis and wide intervening yellow streaks. Each ruler mark denotes 1 mm. |

Our patient illustrates the value of dermoscopy in evaluating melanonychia. The pigmentation of adult-onset melanonychia involving multiple fingers can be divided into nonmelanocytic or melanocytic origin. Causes of the former include subungual hematoma, fungal or bacterial infection, and exogenous pigmentation. The nonmelanocytic pigment often is homogeneously distributed without melanin inclusions under the dermoscope.2

On the contrary, melanin inclusions can be detected as fine granules in pigmentation of melanocytic origin, either from focal melanocytic activation or melanocyte proliferation. Causes of focal melanocytic activation include ethnic-type nail hyperpigmentation; inflammatory nail diseases; or drug-, radiation-, and friction-induced hyperpigmentation. The characteristic dermoscopic features are thin longitudinal gray lines with regular thickness and spacing in a grayish background.1-3

Melanocyte proliferation can result in a nevus or melanoma of the nail apparatus. Both share dermoscopic features of brown-black longitudinal lines in a brown background. However, the longitudinal lines in melanoma are irregular in coloration, spacing, thickness, and parallelism, in contrast with the regular pattern of a nevus.1-4 Although patients often are concerned about melanoma, involvement of multiple fingers at the same time is less likely.

In our patient, the homogeneous deep brown color without melanin inclusions favored a nonmel-anocytic origin. The distally wider pigmentation suggested fungal infection because most ungual infections extend from the distal to the proximal part of the nail.5,6 The focal reddish hue may be related with traumatic hemorrhage from subungual hyperkeratosis.

Cases of fungal melanonychia are being reported at an increasing rate. Some fungal strains are capable of synthesizing melanin, which is associated with virulence and acts as a fungal armor against toxic insults.5 In T rubrum, the melanoid variant, the diffusible black pigment infiltrates the nail plate and attributes to the black nail clinically.4 The most frequently isolated fungi in fungal melanonychia are T rubrum and Scytalidium dimidiatum6; however, Candida species,7,8 dematiaceous fungus,9 and other dermatophytes such as Trichophyton soudanense10 have been reported to be the cause.5

Our patient presented with fungal melanonychia due to T rubrum with dermoscopic features. The prominent subungual hyperkeratosis, distally wider homogeneous brown-black pigmented band, and wide yellow streaks with focal reddish hue all suggested fungal melanonychia. The diagnosis was further confirmed by a good response to antifungal agents.

To the Editor:

Longitudinal melanonychia encompasses a broad spectrum of diseases and often is a complex diagnostic problem. Differential diagnoses include ethnic-type nail pigmentation, which is more frequently seen in darker-skinned individuals; drug-induced pigmentation; subungual hemorrhage; fungal or bacterial infection; nevus; and melanoma.1,2 Fungal melan-onychia is an uncommon presentation of onychomycosis. Dermoscopy can assist in the evaluation of nail pigmentation caused by fungi to avoid unnecessary nail biopsies.

A 39-year-old man visited the dermatology clinic with a concern for melanoma because of blackish pigmentation of the toenails of 1 month’s duration. He denied history of trauma and was not taking any medications. On physical examination the second and third toenails revealed a 2-mm longitudinal band of black pigment on the lateral side; the fifth toenail showed diffuse black pigment (Figure 1A). The nail plates were thickened. Dermoscopy revealed prominent subungual hyperkeratosis, a homogeneous brown-black band with wide yellow streaks that were wider in the distal ends, and some focal reddish hue. No visible melanin inclusions were observed (Figure 2). These findings were suggestive of fungal infection. Cultures from the diseased nail grew a fungus identified as Trichophyton rubrum. The patient was treated with itraconazole 200 mg daily for 3 months. Clinical cure with disappearance of pigment was obtained at 5-month follow-up (Figure 1B).

|

|

| Figure 1. Blackish discoloration of the right second, third, and fifth toenails (A). Resolution of pigmentation and subungual hyperkeratosis was achieved at 5-month follow-up after treatment (B). |

|

|

| Figure 2. Top view (A) and front view (B) of a homogeneous brown-black band with subungual hyperkeratosis and wide intervening yellow streaks. Each ruler mark denotes 1 mm. |

Our patient illustrates the value of dermoscopy in evaluating melanonychia. The pigmentation of adult-onset melanonychia involving multiple fingers can be divided into nonmelanocytic or melanocytic origin. Causes of the former include subungual hematoma, fungal or bacterial infection, and exogenous pigmentation. The nonmelanocytic pigment often is homogeneously distributed without melanin inclusions under the dermoscope.2

On the contrary, melanin inclusions can be detected as fine granules in pigmentation of melanocytic origin, either from focal melanocytic activation or melanocyte proliferation. Causes of focal melanocytic activation include ethnic-type nail hyperpigmentation; inflammatory nail diseases; or drug-, radiation-, and friction-induced hyperpigmentation. The characteristic dermoscopic features are thin longitudinal gray lines with regular thickness and spacing in a grayish background.1-3

Melanocyte proliferation can result in a nevus or melanoma of the nail apparatus. Both share dermoscopic features of brown-black longitudinal lines in a brown background. However, the longitudinal lines in melanoma are irregular in coloration, spacing, thickness, and parallelism, in contrast with the regular pattern of a nevus.1-4 Although patients often are concerned about melanoma, involvement of multiple fingers at the same time is less likely.

In our patient, the homogeneous deep brown color without melanin inclusions favored a nonmel-anocytic origin. The distally wider pigmentation suggested fungal infection because most ungual infections extend from the distal to the proximal part of the nail.5,6 The focal reddish hue may be related with traumatic hemorrhage from subungual hyperkeratosis.

Cases of fungal melanonychia are being reported at an increasing rate. Some fungal strains are capable of synthesizing melanin, which is associated with virulence and acts as a fungal armor against toxic insults.5 In T rubrum, the melanoid variant, the diffusible black pigment infiltrates the nail plate and attributes to the black nail clinically.4 The most frequently isolated fungi in fungal melanonychia are T rubrum and Scytalidium dimidiatum6; however, Candida species,7,8 dematiaceous fungus,9 and other dermatophytes such as Trichophyton soudanense10 have been reported to be the cause.5

Our patient presented with fungal melanonychia due to T rubrum with dermoscopic features. The prominent subungual hyperkeratosis, distally wider homogeneous brown-black pigmented band, and wide yellow streaks with focal reddish hue all suggested fungal melanonychia. The diagnosis was further confirmed by a good response to antifungal agents.

1. Ronger S, Touzet S, Ligeron C, et al. Dermoscopic examination of nail pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1327-1333.

2. Braun RP, Baran R, Le Gal FA, et al. Diagnosis and management of nail pigmentations [published online ahead of print February 22, 2007]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:835-847.

3. Koga H, Saida T, Uhara H. Key point in dermoscopic differentiation between early nail apparatus melanoma and benign longitudinal melanonychia. J Dermatol. 2011;38:45-52.

4. Phan A, Dalle S, Touzet S, et al. Dermoscopic features of acral lentiginous melanoma in a large series of 110 cases in a white population [published online ahead of print November 18, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:765-771.

5. Finch J, Arenas R, Baran R. Fungal melanonychia [published online ahead of print January 17, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:830-841.

6. Lee SW, Kim YC, Kim DK, et al. Fungal melanonychia. J Dermatol. 2004;31:904-909.

7. Parlak AH, Goksugur N, Karabay O. A case of melanonychia due to Candida albicans. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:398-400.

8. Gautret P, Rodier MH, Kauffmann-Lacroix C, et al. Case report and review. onychomycosis due to Candida parapsilosis. Mycoses. 2000;43:433-435.

9. Barua P, Barua S, Borkakoty B, et al. Onychomycosis by Scytalidium dimidiatum in green tea leaf pluckers: report of two cases [published online ahead of print July 20, 2007]. Mycopathologia. 2007;164:193-195.

10. Ricci C, Monod M, Baudraz-Rosselet F. Onychomycosis due to Trichophyton soudanense in Switzerland. Dermatology. 1998;197:297-298.

1. Ronger S, Touzet S, Ligeron C, et al. Dermoscopic examination of nail pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1327-1333.

2. Braun RP, Baran R, Le Gal FA, et al. Diagnosis and management of nail pigmentations [published online ahead of print February 22, 2007]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:835-847.

3. Koga H, Saida T, Uhara H. Key point in dermoscopic differentiation between early nail apparatus melanoma and benign longitudinal melanonychia. J Dermatol. 2011;38:45-52.

4. Phan A, Dalle S, Touzet S, et al. Dermoscopic features of acral lentiginous melanoma in a large series of 110 cases in a white population [published online ahead of print November 18, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:765-771.

5. Finch J, Arenas R, Baran R. Fungal melanonychia [published online ahead of print January 17, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:830-841.

6. Lee SW, Kim YC, Kim DK, et al. Fungal melanonychia. J Dermatol. 2004;31:904-909.

7. Parlak AH, Goksugur N, Karabay O. A case of melanonychia due to Candida albicans. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:398-400.

8. Gautret P, Rodier MH, Kauffmann-Lacroix C, et al. Case report and review. onychomycosis due to Candida parapsilosis. Mycoses. 2000;43:433-435.

9. Barua P, Barua S, Borkakoty B, et al. Onychomycosis by Scytalidium dimidiatum in green tea leaf pluckers: report of two cases [published online ahead of print July 20, 2007]. Mycopathologia. 2007;164:193-195.

10. Ricci C, Monod M, Baudraz-Rosselet F. Onychomycosis due to Trichophyton soudanense in Switzerland. Dermatology. 1998;197:297-298.

Narrow-Toed Shoes and the Toe-to-Toe Sign

To the Editor:

Macro- or microtrauma to nails can cause and/or exacerbate chronic diseases such as ingrown nails, onycholysis, onychauxis, onychogryposis, and hallux valgus (bunions). This trauma also can break the anatomic barrier of the hyponychium, thereby creating a portal for dermatophytes and other organisms to penetrate the nail apparatus.1

For many years, one author (C.R.D.) has used the following demonstration to communicate to patients how improper shoe fit may cause toenail trauma. The patient’s shoe is flipped 180° and placed toe-to-toe with the patient’s foot (Figure). Most patients can comprehend the relationship between their shoe fit and their toenail disease when they see this demonstration. We have termed it toe-to-toe sign.

|

|

| The foot and shoe are toe-to-toe, demonstrating the narrow toe box in comparison to the actual toes (A). This comparison is accentuated when the shoe is placed over the foot with toes splayed from standing (B). |

Narrow toe box is the usual culprit. The toe-to-toe sign best emphasizes this relationship. This sign serves as a powerful tool when demonstrating how much the foot widens when bearing full weight, and how forces of ambulation and foot strike can damage the nails with narrow-toed footwear. This trauma is compounded with high-heeled shoes that force the toes forward. However, proper shoe fit may compete with idealized shoe style. It is not until patients realize the relationship between improper shoe fit, foot strike, and toe/toenail trauma that they can make long-term decisions that favorably impact their toes and toenails.

Reference

1. Daniel CR 3rd, Jellinek NJ. The pedal fungus reservoir. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1344-1346.

To the Editor:

Macro- or microtrauma to nails can cause and/or exacerbate chronic diseases such as ingrown nails, onycholysis, onychauxis, onychogryposis, and hallux valgus (bunions). This trauma also can break the anatomic barrier of the hyponychium, thereby creating a portal for dermatophytes and other organisms to penetrate the nail apparatus.1

For many years, one author (C.R.D.) has used the following demonstration to communicate to patients how improper shoe fit may cause toenail trauma. The patient’s shoe is flipped 180° and placed toe-to-toe with the patient’s foot (Figure). Most patients can comprehend the relationship between their shoe fit and their toenail disease when they see this demonstration. We have termed it toe-to-toe sign.

|

|

| The foot and shoe are toe-to-toe, demonstrating the narrow toe box in comparison to the actual toes (A). This comparison is accentuated when the shoe is placed over the foot with toes splayed from standing (B). |

Narrow toe box is the usual culprit. The toe-to-toe sign best emphasizes this relationship. This sign serves as a powerful tool when demonstrating how much the foot widens when bearing full weight, and how forces of ambulation and foot strike can damage the nails with narrow-toed footwear. This trauma is compounded with high-heeled shoes that force the toes forward. However, proper shoe fit may compete with idealized shoe style. It is not until patients realize the relationship between improper shoe fit, foot strike, and toe/toenail trauma that they can make long-term decisions that favorably impact their toes and toenails.

To the Editor:

Macro- or microtrauma to nails can cause and/or exacerbate chronic diseases such as ingrown nails, onycholysis, onychauxis, onychogryposis, and hallux valgus (bunions). This trauma also can break the anatomic barrier of the hyponychium, thereby creating a portal for dermatophytes and other organisms to penetrate the nail apparatus.1

For many years, one author (C.R.D.) has used the following demonstration to communicate to patients how improper shoe fit may cause toenail trauma. The patient’s shoe is flipped 180° and placed toe-to-toe with the patient’s foot (Figure). Most patients can comprehend the relationship between their shoe fit and their toenail disease when they see this demonstration. We have termed it toe-to-toe sign.

|

|

| The foot and shoe are toe-to-toe, demonstrating the narrow toe box in comparison to the actual toes (A). This comparison is accentuated when the shoe is placed over the foot with toes splayed from standing (B). |

Narrow toe box is the usual culprit. The toe-to-toe sign best emphasizes this relationship. This sign serves as a powerful tool when demonstrating how much the foot widens when bearing full weight, and how forces of ambulation and foot strike can damage the nails with narrow-toed footwear. This trauma is compounded with high-heeled shoes that force the toes forward. However, proper shoe fit may compete with idealized shoe style. It is not until patients realize the relationship between improper shoe fit, foot strike, and toe/toenail trauma that they can make long-term decisions that favorably impact their toes and toenails.

Reference

1. Daniel CR 3rd, Jellinek NJ. The pedal fungus reservoir. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1344-1346.

Reference

1. Daniel CR 3rd, Jellinek NJ. The pedal fungus reservoir. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1344-1346.

Plaques: A Rare Presentation of Acrokeratoelastoidosis

To the Editor:

Acrokeratoelastoidosis (AKE) is a rare disease first described by Costa1 in 1953. Typically it is only a cosmetic nuisance in the majority of patients and presents as asymptomatic, small, firm, flesh-colored to yellowish, round to polygonal papules with occasional keratosis or umbilication on the radial and ulnar margins of the hands and/or feet.1-3 In some cases, the lesions occur on the anterior aspects of the wrists, fingers, or lower legs.1 The lesions are always bilaterally distributed. Acrokeratoelastoidosis is a chronic skin disorder that commonly presents during childhood or adolescence, but presentation in adulthood also has been described.3 Histologically, AKE always shows hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, decrease of elastic tissue, and elastorrhexis of remaining elastic fibers. Plaque-type lesions are rare. We describe a patient who presented with plaques on the radial and ulnar margins of the hands.

A 36-year-old Chinese woman presented with asymptomatic, small, firm papules of 6 months’ duration that initially developed on the hands and gradually increased in number, coalescing into plaques. The feet were spared. She had no medical history of hyperhidrosis, chronic trauma, friction, or excessive sun exposure, and no family history of similar symptoms. No prior therapy had been attempted.

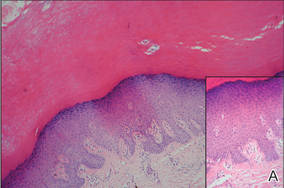

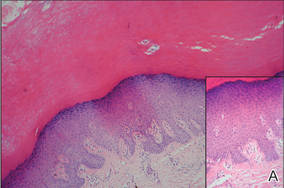

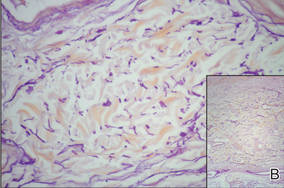

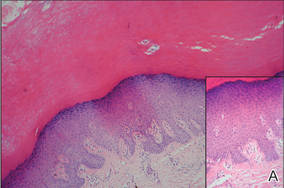

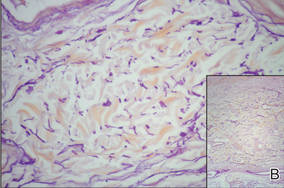

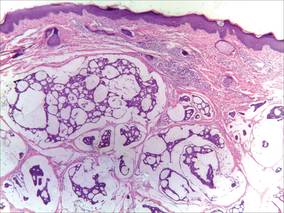

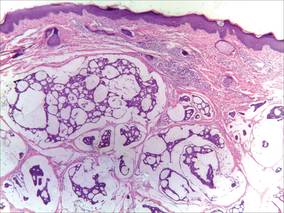

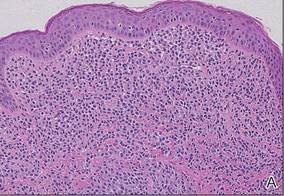

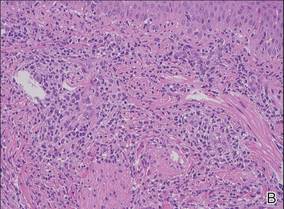

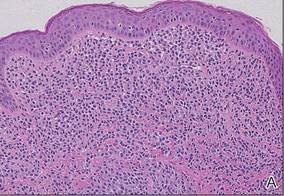

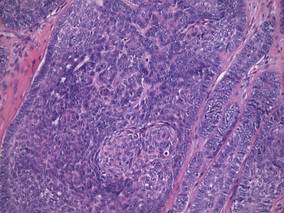

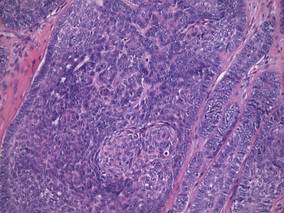

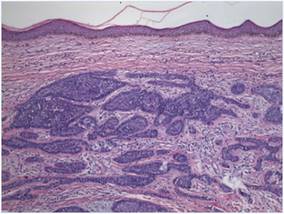

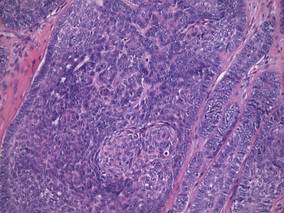

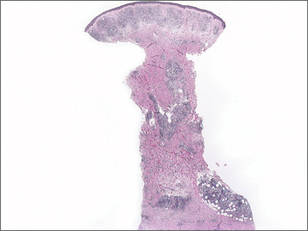

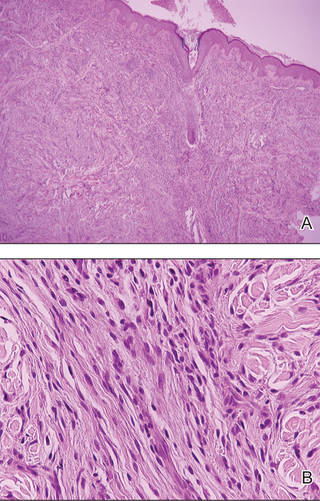

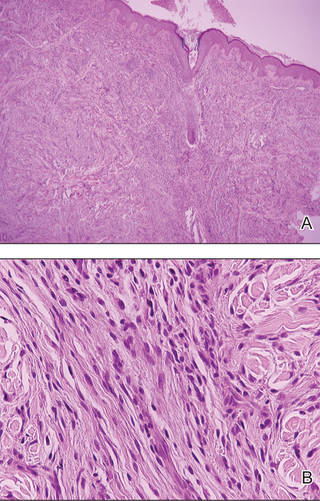

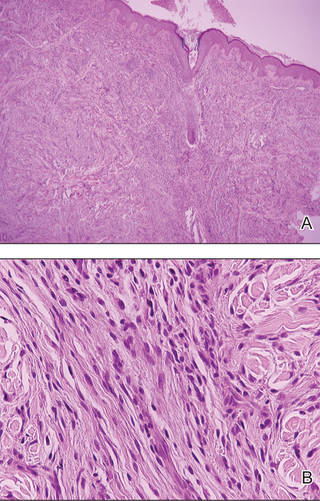

Physical examination showed nonconfluent, firm, flesh-colored to yellowish, translucent, smooth papules with wavy edges that were symmetrically distributed on the radial and ulnar margins of the hands; some papules had coalesced into plaques (Figure 1). A biopsy specimen taken from a plaque on the hypothenar eminence of the right hand revealed focal hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and mild chronic inflammation with hematoxylin and eosin stain (Figure 2A). Aldehyde fuchsin staining showed fragmented and rarefied elastic fibers in the reticular dermis (Figure 2B). The patient was diagnosed with AKE. Oral tretinoin 10 mg twice daily was initiated and resulted in an evident response after 2 weeks of treatment. However, the patient stopped taking the medication because of pruritus and dry skin and the lesions then reappeared.

|

| Figure 1. Nonconfluent, firm, flesh-colored to yellowish, translucent, smooth papules distributed on the radial margin of the hand; some of papules coalesced into plaques. |

|

|

| Figure 2. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and mild chronic inflammation (A) (H&E, original magnification ×250 [inset, original magnification ×400]), as well as fragmented elastic fibers in the reticular dermis (B) (Aldehyde fuchsin, original magnification ×400 [inset, original magnification ×100]). |

Acrokeratoelastoidosis is a rare keratotic disorder. It seems to have no racial or ethnic predilection and occurs more frequently in women.4,5 It also is rare in China, with few cases reported, all women.5 The reason for the gender predilection in China remains unknown. The course is chronic, but it may rapidly progress during pregnancy.6

The pathogenesis of AKE is still unresolved.2,3 Although many cases are sporadic,5 it appears to be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, most likely related to chromosome 2.7 Typically, AKE presents as papules that are discrete and bilaterally distributed in the palmoplantar margins,2,3 but some of the papules in our patient coalesced into plaques, which is unique. The histologic hallmarks indicated that the lesions were AKE.

The differential diagnosis of AKE includes hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma, focal acral hyperkeratosis, and keratoelastoidosis marginalis.8 Hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma also is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and shares similar acral, translucent, keratotic papules with AKE, but there is no chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, degeneration of collagenous fibers, or fragmentation of elastic fibers. The clinical appearance of focal acral hyperkeratosis is similar to AKE, but no changes are revealed in the elastic tissue.9 Because AKE, focal acral hyperkeratosis, and hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma have similar lesions and overlapping histologic changes, they may be considered variants of the same entity.4 Keratoelastoidosis marginalis, also called degenerative collagenous plaques of the hand, mainly affects white individuals aged 40 to 60 years with a history of prolonged sun exposure. Papules often are distributed over the junction of the dorsal and palmar skin and less often on the ulnar sides of the hands. The clinical lesions are similar to those in our patient, but histopathology of keratoelastoidosis marginalis shows amorphous, basophilic, elastotic masses and thickened, fragmented, calcified elastic fibers in the upper and mid dermis.

Therapies including liquid nitrogen, topical salicylic acid, methotrexate, dapsone, tar, cryotherapy, systemic prednisone, retinoic acid, clobetasone cream,5 and erbium:YAG laser10 have been applied. Thus far, no optimal treatment has been recommended and no tendency of spontaneous resolution has been previously reported in the literature. Our patient responded to tretinoin, but the lesions recurred after withdrawal of the medication; therefore, tretinoin may not be an optimal treatment option. Because the lesions are limited to the skin and AKE is only considered a cosmetic problem with a good prognosis, we recommend a wait-and-watch approach.

Acknowledgment—We thank Rashmi Sarkar, MD, New Delhi, India, for her assistance.

1. Costa OG. Akrokerato-elastoidosis; a hitherto undescribed skin disease. Dermatologica. 1953;107:164-168.

2. Bogle MA, Huang LY, Tschen JA. Acrokeratoelastoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:448-451.

3. Highet AS, Rook A, Anderson JR. Acrokeratoelastoidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:337-344.

4. Abulafia J, Vignale RA. Degenerative collagenous

plaques of the hands and acrokeratoelastoidosis: pathogenesis and relationship with knuckle pads. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:424-432.

5. Luo DQ, Zhang B, Huang YB, et al. Papules on a young woman’s hands and feet. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:451-452.

6. Nelson-Adesokan P, Mallory SB, Lombardi C, et al. Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa [published correction appears in Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:380]. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:431-433.

7. Greiner J, Krüger J, Palden L, et al. A linkage study of acrokeratoelastoidosis. possible mapping to chromosome 2. Hum Genet. 1983;63:222-227.

8. Hu W, Cook TF, Vicki GJ, et al. Acrokeratoelastoidosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:320-322.

9. Dowd PM, Harman RR, Black MM. Focal acral hyperkeratosis. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:97-103.

10. Erbil AH, Sezer E, Koç E, et al. Acrokeratoelastoidosis treated with the erbium:YAG laser [published online ahead of print November 3, 2007]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:30-31.

To the Editor:

Acrokeratoelastoidosis (AKE) is a rare disease first described by Costa1 in 1953. Typically it is only a cosmetic nuisance in the majority of patients and presents as asymptomatic, small, firm, flesh-colored to yellowish, round to polygonal papules with occasional keratosis or umbilication on the radial and ulnar margins of the hands and/or feet.1-3 In some cases, the lesions occur on the anterior aspects of the wrists, fingers, or lower legs.1 The lesions are always bilaterally distributed. Acrokeratoelastoidosis is a chronic skin disorder that commonly presents during childhood or adolescence, but presentation in adulthood also has been described.3 Histologically, AKE always shows hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, decrease of elastic tissue, and elastorrhexis of remaining elastic fibers. Plaque-type lesions are rare. We describe a patient who presented with plaques on the radial and ulnar margins of the hands.

A 36-year-old Chinese woman presented with asymptomatic, small, firm papules of 6 months’ duration that initially developed on the hands and gradually increased in number, coalescing into plaques. The feet were spared. She had no medical history of hyperhidrosis, chronic trauma, friction, or excessive sun exposure, and no family history of similar symptoms. No prior therapy had been attempted.

Physical examination showed nonconfluent, firm, flesh-colored to yellowish, translucent, smooth papules with wavy edges that were symmetrically distributed on the radial and ulnar margins of the hands; some papules had coalesced into plaques (Figure 1). A biopsy specimen taken from a plaque on the hypothenar eminence of the right hand revealed focal hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and mild chronic inflammation with hematoxylin and eosin stain (Figure 2A). Aldehyde fuchsin staining showed fragmented and rarefied elastic fibers in the reticular dermis (Figure 2B). The patient was diagnosed with AKE. Oral tretinoin 10 mg twice daily was initiated and resulted in an evident response after 2 weeks of treatment. However, the patient stopped taking the medication because of pruritus and dry skin and the lesions then reappeared.

|

| Figure 1. Nonconfluent, firm, flesh-colored to yellowish, translucent, smooth papules distributed on the radial margin of the hand; some of papules coalesced into plaques. |

|

|

| Figure 2. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and mild chronic inflammation (A) (H&E, original magnification ×250 [inset, original magnification ×400]), as well as fragmented elastic fibers in the reticular dermis (B) (Aldehyde fuchsin, original magnification ×400 [inset, original magnification ×100]). |

Acrokeratoelastoidosis is a rare keratotic disorder. It seems to have no racial or ethnic predilection and occurs more frequently in women.4,5 It also is rare in China, with few cases reported, all women.5 The reason for the gender predilection in China remains unknown. The course is chronic, but it may rapidly progress during pregnancy.6

The pathogenesis of AKE is still unresolved.2,3 Although many cases are sporadic,5 it appears to be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, most likely related to chromosome 2.7 Typically, AKE presents as papules that are discrete and bilaterally distributed in the palmoplantar margins,2,3 but some of the papules in our patient coalesced into plaques, which is unique. The histologic hallmarks indicated that the lesions were AKE.

The differential diagnosis of AKE includes hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma, focal acral hyperkeratosis, and keratoelastoidosis marginalis.8 Hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma also is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and shares similar acral, translucent, keratotic papules with AKE, but there is no chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, degeneration of collagenous fibers, or fragmentation of elastic fibers. The clinical appearance of focal acral hyperkeratosis is similar to AKE, but no changes are revealed in the elastic tissue.9 Because AKE, focal acral hyperkeratosis, and hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma have similar lesions and overlapping histologic changes, they may be considered variants of the same entity.4 Keratoelastoidosis marginalis, also called degenerative collagenous plaques of the hand, mainly affects white individuals aged 40 to 60 years with a history of prolonged sun exposure. Papules often are distributed over the junction of the dorsal and palmar skin and less often on the ulnar sides of the hands. The clinical lesions are similar to those in our patient, but histopathology of keratoelastoidosis marginalis shows amorphous, basophilic, elastotic masses and thickened, fragmented, calcified elastic fibers in the upper and mid dermis.

Therapies including liquid nitrogen, topical salicylic acid, methotrexate, dapsone, tar, cryotherapy, systemic prednisone, retinoic acid, clobetasone cream,5 and erbium:YAG laser10 have been applied. Thus far, no optimal treatment has been recommended and no tendency of spontaneous resolution has been previously reported in the literature. Our patient responded to tretinoin, but the lesions recurred after withdrawal of the medication; therefore, tretinoin may not be an optimal treatment option. Because the lesions are limited to the skin and AKE is only considered a cosmetic problem with a good prognosis, we recommend a wait-and-watch approach.

Acknowledgment—We thank Rashmi Sarkar, MD, New Delhi, India, for her assistance.

To the Editor:

Acrokeratoelastoidosis (AKE) is a rare disease first described by Costa1 in 1953. Typically it is only a cosmetic nuisance in the majority of patients and presents as asymptomatic, small, firm, flesh-colored to yellowish, round to polygonal papules with occasional keratosis or umbilication on the radial and ulnar margins of the hands and/or feet.1-3 In some cases, the lesions occur on the anterior aspects of the wrists, fingers, or lower legs.1 The lesions are always bilaterally distributed. Acrokeratoelastoidosis is a chronic skin disorder that commonly presents during childhood or adolescence, but presentation in adulthood also has been described.3 Histologically, AKE always shows hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, decrease of elastic tissue, and elastorrhexis of remaining elastic fibers. Plaque-type lesions are rare. We describe a patient who presented with plaques on the radial and ulnar margins of the hands.

A 36-year-old Chinese woman presented with asymptomatic, small, firm papules of 6 months’ duration that initially developed on the hands and gradually increased in number, coalescing into plaques. The feet were spared. She had no medical history of hyperhidrosis, chronic trauma, friction, or excessive sun exposure, and no family history of similar symptoms. No prior therapy had been attempted.

Physical examination showed nonconfluent, firm, flesh-colored to yellowish, translucent, smooth papules with wavy edges that were symmetrically distributed on the radial and ulnar margins of the hands; some papules had coalesced into plaques (Figure 1). A biopsy specimen taken from a plaque on the hypothenar eminence of the right hand revealed focal hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and mild chronic inflammation with hematoxylin and eosin stain (Figure 2A). Aldehyde fuchsin staining showed fragmented and rarefied elastic fibers in the reticular dermis (Figure 2B). The patient was diagnosed with AKE. Oral tretinoin 10 mg twice daily was initiated and resulted in an evident response after 2 weeks of treatment. However, the patient stopped taking the medication because of pruritus and dry skin and the lesions then reappeared.

|

| Figure 1. Nonconfluent, firm, flesh-colored to yellowish, translucent, smooth papules distributed on the radial margin of the hand; some of papules coalesced into plaques. |

|

|

| Figure 2. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and mild chronic inflammation (A) (H&E, original magnification ×250 [inset, original magnification ×400]), as well as fragmented elastic fibers in the reticular dermis (B) (Aldehyde fuchsin, original magnification ×400 [inset, original magnification ×100]). |

Acrokeratoelastoidosis is a rare keratotic disorder. It seems to have no racial or ethnic predilection and occurs more frequently in women.4,5 It also is rare in China, with few cases reported, all women.5 The reason for the gender predilection in China remains unknown. The course is chronic, but it may rapidly progress during pregnancy.6

The pathogenesis of AKE is still unresolved.2,3 Although many cases are sporadic,5 it appears to be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, most likely related to chromosome 2.7 Typically, AKE presents as papules that are discrete and bilaterally distributed in the palmoplantar margins,2,3 but some of the papules in our patient coalesced into plaques, which is unique. The histologic hallmarks indicated that the lesions were AKE.

The differential diagnosis of AKE includes hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma, focal acral hyperkeratosis, and keratoelastoidosis marginalis.8 Hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma also is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and shares similar acral, translucent, keratotic papules with AKE, but there is no chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, degeneration of collagenous fibers, or fragmentation of elastic fibers. The clinical appearance of focal acral hyperkeratosis is similar to AKE, but no changes are revealed in the elastic tissue.9 Because AKE, focal acral hyperkeratosis, and hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma have similar lesions and overlapping histologic changes, they may be considered variants of the same entity.4 Keratoelastoidosis marginalis, also called degenerative collagenous plaques of the hand, mainly affects white individuals aged 40 to 60 years with a history of prolonged sun exposure. Papules often are distributed over the junction of the dorsal and palmar skin and less often on the ulnar sides of the hands. The clinical lesions are similar to those in our patient, but histopathology of keratoelastoidosis marginalis shows amorphous, basophilic, elastotic masses and thickened, fragmented, calcified elastic fibers in the upper and mid dermis.

Therapies including liquid nitrogen, topical salicylic acid, methotrexate, dapsone, tar, cryotherapy, systemic prednisone, retinoic acid, clobetasone cream,5 and erbium:YAG laser10 have been applied. Thus far, no optimal treatment has been recommended and no tendency of spontaneous resolution has been previously reported in the literature. Our patient responded to tretinoin, but the lesions recurred after withdrawal of the medication; therefore, tretinoin may not be an optimal treatment option. Because the lesions are limited to the skin and AKE is only considered a cosmetic problem with a good prognosis, we recommend a wait-and-watch approach.

Acknowledgment—We thank Rashmi Sarkar, MD, New Delhi, India, for her assistance.

1. Costa OG. Akrokerato-elastoidosis; a hitherto undescribed skin disease. Dermatologica. 1953;107:164-168.

2. Bogle MA, Huang LY, Tschen JA. Acrokeratoelastoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:448-451.

3. Highet AS, Rook A, Anderson JR. Acrokeratoelastoidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:337-344.

4. Abulafia J, Vignale RA. Degenerative collagenous

plaques of the hands and acrokeratoelastoidosis: pathogenesis and relationship with knuckle pads. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:424-432.

5. Luo DQ, Zhang B, Huang YB, et al. Papules on a young woman’s hands and feet. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:451-452.

6. Nelson-Adesokan P, Mallory SB, Lombardi C, et al. Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa [published correction appears in Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:380]. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:431-433.

7. Greiner J, Krüger J, Palden L, et al. A linkage study of acrokeratoelastoidosis. possible mapping to chromosome 2. Hum Genet. 1983;63:222-227.

8. Hu W, Cook TF, Vicki GJ, et al. Acrokeratoelastoidosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:320-322.

9. Dowd PM, Harman RR, Black MM. Focal acral hyperkeratosis. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:97-103.

10. Erbil AH, Sezer E, Koç E, et al. Acrokeratoelastoidosis treated with the erbium:YAG laser [published online ahead of print November 3, 2007]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:30-31.

1. Costa OG. Akrokerato-elastoidosis; a hitherto undescribed skin disease. Dermatologica. 1953;107:164-168.

2. Bogle MA, Huang LY, Tschen JA. Acrokeratoelastoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:448-451.

3. Highet AS, Rook A, Anderson JR. Acrokeratoelastoidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:337-344.

4. Abulafia J, Vignale RA. Degenerative collagenous

plaques of the hands and acrokeratoelastoidosis: pathogenesis and relationship with knuckle pads. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:424-432.

5. Luo DQ, Zhang B, Huang YB, et al. Papules on a young woman’s hands and feet. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:451-452.

6. Nelson-Adesokan P, Mallory SB, Lombardi C, et al. Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa [published correction appears in Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:380]. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:431-433.

7. Greiner J, Krüger J, Palden L, et al. A linkage study of acrokeratoelastoidosis. possible mapping to chromosome 2. Hum Genet. 1983;63:222-227.

8. Hu W, Cook TF, Vicki GJ, et al. Acrokeratoelastoidosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:320-322.

9. Dowd PM, Harman RR, Black MM. Focal acral hyperkeratosis. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:97-103.

10. Erbil AH, Sezer E, Koç E, et al. Acrokeratoelastoidosis treated with the erbium:YAG laser [published online ahead of print November 3, 2007]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:30-31.

Primary Mucinous Carcinoma of the Skin

To the Editor:

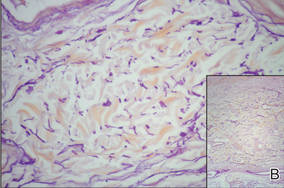

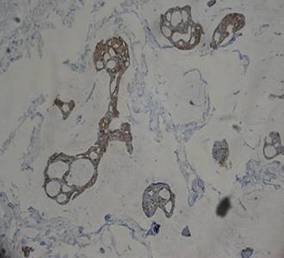

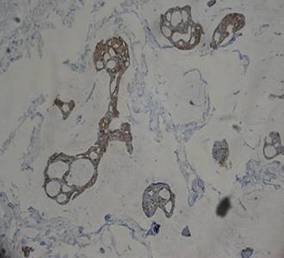

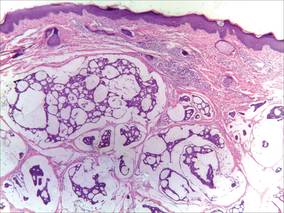

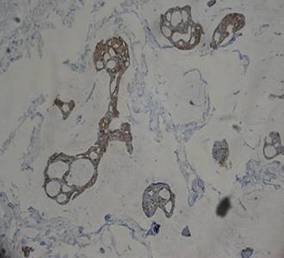

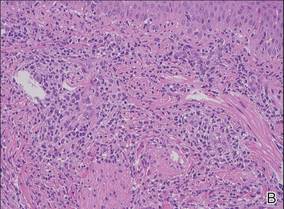

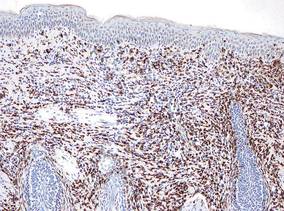

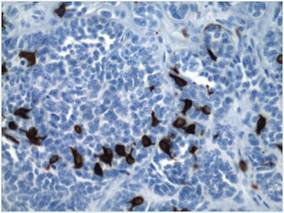

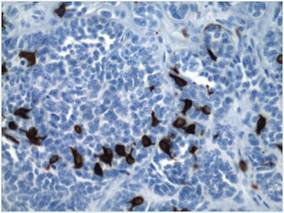

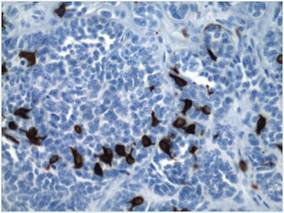

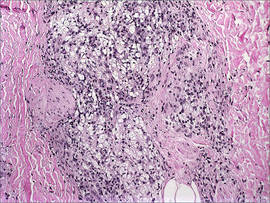

A 41-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a recurrent asymptomatic nodule on the right cheek that had gradually increased in size over 1 year. The patient underwent laser excision at an outside facility 1 year after the first presentation. Pathology reports and tissue cultures from the excision were not available. The lesion recurred in the same location 6 months following excision. The patient reported no history of pain, fever, cough, weight loss, or loss of appetite, and he denied any trauma or radiation to the affected area. Dermatologic examination revealed a 24×18-mm, slightly elevated, dome-shaped, translucent, pink-colored tumor with telangiectasia on the right cheek (Figure 1). There was no tenderness or pruritus. Clinical examination and extensive radiographic studies revealed no primary disease. A complete blood cell count, biochemical tests, and serous tumor markers were within reference range. The lesion was resected with a 2-mm margin. The margins were free of tumor cells. Histopathology showed a circumscribed tumor with large amounts of mucin compartmentalized by fibrous septa and scattered floating islands of tumor cells in the dermis. Small-sized glands were organized in some areas of the tumor cells (Figure 2). Epithelial tumor cell islands contained uniform oval nuclei and focally vacuolated cytoplasm. The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 7 (CK7) (Figure 3) and negative for cytokeratin 20 (CK20), carcinoembryonic antigen, homeobox transcription factor (CDX2), villin, mucus-associated peptides of the thyroid transcription factor (TTF1), and prostate-specific antigen, all indicating a diagnosis of primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin (PMCS). No local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, or distant metastasis was observed after resection.

|

| Figure 1. A 24×18-mm, slightly elevated, dome-shaped, translucent, pink-colored tumor with telangiectasia on the right cheek. |

|

| Figure 2. Histopathology showed a circumscribed tumor with large amounts of mucin compartmentalized by fibrous septa that contained scattered floating islands of tumor cells in the dermis (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

| Figure 3. The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 7 (original magnification ×400). |

Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin is a rare malignant adnexal tumor. It was first described by Lennox et al1 in 1952 and was later given its name by Mendoza and Helwig2 through summarizing clinical and histochemical characteristics based on the observation of 14 cases. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms adenocarcinoma, mucinous (Medical Subject Headings); mucinous adenocarcinoma (title/abstract); colloid carcinoma* (title/abstract); skin neoplasms (Medical Subject Headings); skin neoplasm (title/abstract); skin cancer* (title/abstract), and primary (title/abstract) revealed more than 200 reported cases of PMCS. It usually is located in the head and neck region, with the eyelids being the most common site of presentation, but rare presentations in the gluteal region, axillae, hemithoraxes, vulva, arms, and legs also have been reported.3-6 Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin mainly affects elderly patients (age range, 61–80 years), with men being affected more often than women. It often presents as a painless, solitary, nontender, sometimes ulcerated, translucent, white or reddish nodule. The tumors generally grow slowly with high rates of local recurrence and rare chances of distant metastasis.7 Most metastases involve the regional lymph nodes and lungs, but rare cases of bone marrow and parotid gland metastases also have been reported.8 Because PMCS is an indolent tumor, which may be mistaken for a benign tumor, it is not always histologically examined on initial presentation.

Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin is characterized histopathologically by floating epithelial cell nests in mucinous lakes. It is unknown if this neoplasm shows eccrine- or apocrine-type differentiation. S-100 protein seems to indicate eccrine rather than apocrine differentiation.9 Misdiagnosis of PMCS is common, as it has an uncharacteristic gross appearance and may microscopically resemble cutaneous metastasis from a mucinous carcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, ovaries, or prostate. It is important to distinguish between metastatic tumors and PMCS because PMCS generally is more benign and has a better prognosis. A variety of stains have been reported as helpful in the diagnosis of PMCS, including CK7 and CK20, D2-40, p63, and others. In some reports, labeling for CK7 and CK20 was helpful in differentiating colon carcinoma from breast or skin malignancies but did not differentiate primary skin lesions from metastasis of breast malignancies to the skin.10-13 Paradela et al5 proposed D2-40 as a reliable immunostain to detect lymphatic invasion in node-negative primary tumors. Kalebi and Hale11 and Ivan et al12 highlighted the importance of p63 in excluding metastasis to the skin, particularly from the gastrointestinal tract, pancreaticobiliary tree, and lungs.

Even though these factors may help in establishing the primary site of the tumor, a final diagnosis only can be drawn when the patient has been subjected to a thorough investigation. In our patient, clinical workup did not reveal other possible primary sites in other organs or evidence of metastasis from the skin lesion to other sites. Based on the histologic findings, the diagnosis of PMCS was made.

The recommended treatment of PMCS varies from standard excision to wide local excision including dissection of the regional lymph nodes. Alam et al14 reported that Mohs micrographic surgery may be appropriate for first-line therapy because the procedure gives complete margin control and spares tissue. Immunohistochemistry should be used as an adjunct to routine hematoxylin and eosin staining to aid in ensuring negative margins.15 Considering a high potential for recurrence following surgical excision, it is important to detect hormone receptors in this tumor because patients may be treated using antiestrogenic drugs such as tamoxifen. Moreover, recurrent or metastatic PMCS is both resistant to radiotherapy and unresponsive to chemotherapy.3 Annual follow-up is recommended due to the potential for recurrence or metastasis.

1. Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin, with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-890.

2. Mendoza S, Helwig EB. Mucinous (adenocystic) carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:68-78.

3. Breiting L, Dahlstrøm K, Christensen L, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:595-596.

4. Krishnamurthy J, Saba F, Sunila. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a rare tumor in the gluteal region. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:225-227.

5. Paradela S, Castiñeiras I, Cuevas J, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin: evaluation of lymphatic invasion with D2-40. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:504-508.

6. Laco J, Simáková E, Svobodová J, et al. Recurrent mucinous carcinoma of skin mimicking primary mucinous carcinoma of parotid gland: a diagnostic pitfall. Cesk Patol. 2009;45:79-82.

7. Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrøm K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

8. Ajithkumar TV, Nileena N, Abraham EK, et al. Bone marrow relapse in primary mucinous carcinoma of skin. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:303-304.

9. Bellezza G, Sidoni A, Bucciarelli E. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:166-170.

10. Levy G, Finkelstein A, McNiff JM. Immunohistochemical techniques to compare primary vs. metastatic mucinous carcinoma of the skin [published online ahead of print September 24, 2009]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:411-415.

11. Kalebi A, Hale M. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: usefulness of p63 in excluding metastasis and first report of psammoma bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:510.

12. Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:474-480.

13. Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

14. Alam M, Trela R, Kim N, et al. Treatment of primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: meta-analysis of 189 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:382.

15. Stranahan D, Cherpelis BS, Glass LF, et al. Immunohistochemical stains in Mohs surgery: a review [published online ahead of print April 16, 2009]. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1023-1034.

To the Editor:

A 41-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a recurrent asymptomatic nodule on the right cheek that had gradually increased in size over 1 year. The patient underwent laser excision at an outside facility 1 year after the first presentation. Pathology reports and tissue cultures from the excision were not available. The lesion recurred in the same location 6 months following excision. The patient reported no history of pain, fever, cough, weight loss, or loss of appetite, and he denied any trauma or radiation to the affected area. Dermatologic examination revealed a 24×18-mm, slightly elevated, dome-shaped, translucent, pink-colored tumor with telangiectasia on the right cheek (Figure 1). There was no tenderness or pruritus. Clinical examination and extensive radiographic studies revealed no primary disease. A complete blood cell count, biochemical tests, and serous tumor markers were within reference range. The lesion was resected with a 2-mm margin. The margins were free of tumor cells. Histopathology showed a circumscribed tumor with large amounts of mucin compartmentalized by fibrous septa and scattered floating islands of tumor cells in the dermis. Small-sized glands were organized in some areas of the tumor cells (Figure 2). Epithelial tumor cell islands contained uniform oval nuclei and focally vacuolated cytoplasm. The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 7 (CK7) (Figure 3) and negative for cytokeratin 20 (CK20), carcinoembryonic antigen, homeobox transcription factor (CDX2), villin, mucus-associated peptides of the thyroid transcription factor (TTF1), and prostate-specific antigen, all indicating a diagnosis of primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin (PMCS). No local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, or distant metastasis was observed after resection.

|

| Figure 1. A 24×18-mm, slightly elevated, dome-shaped, translucent, pink-colored tumor with telangiectasia on the right cheek. |

|

| Figure 2. Histopathology showed a circumscribed tumor with large amounts of mucin compartmentalized by fibrous septa that contained scattered floating islands of tumor cells in the dermis (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

| Figure 3. The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 7 (original magnification ×400). |

Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin is a rare malignant adnexal tumor. It was first described by Lennox et al1 in 1952 and was later given its name by Mendoza and Helwig2 through summarizing clinical and histochemical characteristics based on the observation of 14 cases. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms adenocarcinoma, mucinous (Medical Subject Headings); mucinous adenocarcinoma (title/abstract); colloid carcinoma* (title/abstract); skin neoplasms (Medical Subject Headings); skin neoplasm (title/abstract); skin cancer* (title/abstract), and primary (title/abstract) revealed more than 200 reported cases of PMCS. It usually is located in the head and neck region, with the eyelids being the most common site of presentation, but rare presentations in the gluteal region, axillae, hemithoraxes, vulva, arms, and legs also have been reported.3-6 Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin mainly affects elderly patients (age range, 61–80 years), with men being affected more often than women. It often presents as a painless, solitary, nontender, sometimes ulcerated, translucent, white or reddish nodule. The tumors generally grow slowly with high rates of local recurrence and rare chances of distant metastasis.7 Most metastases involve the regional lymph nodes and lungs, but rare cases of bone marrow and parotid gland metastases also have been reported.8 Because PMCS is an indolent tumor, which may be mistaken for a benign tumor, it is not always histologically examined on initial presentation.

Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin is characterized histopathologically by floating epithelial cell nests in mucinous lakes. It is unknown if this neoplasm shows eccrine- or apocrine-type differentiation. S-100 protein seems to indicate eccrine rather than apocrine differentiation.9 Misdiagnosis of PMCS is common, as it has an uncharacteristic gross appearance and may microscopically resemble cutaneous metastasis from a mucinous carcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, ovaries, or prostate. It is important to distinguish between metastatic tumors and PMCS because PMCS generally is more benign and has a better prognosis. A variety of stains have been reported as helpful in the diagnosis of PMCS, including CK7 and CK20, D2-40, p63, and others. In some reports, labeling for CK7 and CK20 was helpful in differentiating colon carcinoma from breast or skin malignancies but did not differentiate primary skin lesions from metastasis of breast malignancies to the skin.10-13 Paradela et al5 proposed D2-40 as a reliable immunostain to detect lymphatic invasion in node-negative primary tumors. Kalebi and Hale11 and Ivan et al12 highlighted the importance of p63 in excluding metastasis to the skin, particularly from the gastrointestinal tract, pancreaticobiliary tree, and lungs.

Even though these factors may help in establishing the primary site of the tumor, a final diagnosis only can be drawn when the patient has been subjected to a thorough investigation. In our patient, clinical workup did not reveal other possible primary sites in other organs or evidence of metastasis from the skin lesion to other sites. Based on the histologic findings, the diagnosis of PMCS was made.

The recommended treatment of PMCS varies from standard excision to wide local excision including dissection of the regional lymph nodes. Alam et al14 reported that Mohs micrographic surgery may be appropriate for first-line therapy because the procedure gives complete margin control and spares tissue. Immunohistochemistry should be used as an adjunct to routine hematoxylin and eosin staining to aid in ensuring negative margins.15 Considering a high potential for recurrence following surgical excision, it is important to detect hormone receptors in this tumor because patients may be treated using antiestrogenic drugs such as tamoxifen. Moreover, recurrent or metastatic PMCS is both resistant to radiotherapy and unresponsive to chemotherapy.3 Annual follow-up is recommended due to the potential for recurrence or metastasis.

To the Editor:

A 41-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a recurrent asymptomatic nodule on the right cheek that had gradually increased in size over 1 year. The patient underwent laser excision at an outside facility 1 year after the first presentation. Pathology reports and tissue cultures from the excision were not available. The lesion recurred in the same location 6 months following excision. The patient reported no history of pain, fever, cough, weight loss, or loss of appetite, and he denied any trauma or radiation to the affected area. Dermatologic examination revealed a 24×18-mm, slightly elevated, dome-shaped, translucent, pink-colored tumor with telangiectasia on the right cheek (Figure 1). There was no tenderness or pruritus. Clinical examination and extensive radiographic studies revealed no primary disease. A complete blood cell count, biochemical tests, and serous tumor markers were within reference range. The lesion was resected with a 2-mm margin. The margins were free of tumor cells. Histopathology showed a circumscribed tumor with large amounts of mucin compartmentalized by fibrous septa and scattered floating islands of tumor cells in the dermis. Small-sized glands were organized in some areas of the tumor cells (Figure 2). Epithelial tumor cell islands contained uniform oval nuclei and focally vacuolated cytoplasm. The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 7 (CK7) (Figure 3) and negative for cytokeratin 20 (CK20), carcinoembryonic antigen, homeobox transcription factor (CDX2), villin, mucus-associated peptides of the thyroid transcription factor (TTF1), and prostate-specific antigen, all indicating a diagnosis of primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin (PMCS). No local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, or distant metastasis was observed after resection.

|

| Figure 1. A 24×18-mm, slightly elevated, dome-shaped, translucent, pink-colored tumor with telangiectasia on the right cheek. |

|

| Figure 2. Histopathology showed a circumscribed tumor with large amounts of mucin compartmentalized by fibrous septa that contained scattered floating islands of tumor cells in the dermis (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

| Figure 3. The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 7 (original magnification ×400). |

Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin is a rare malignant adnexal tumor. It was first described by Lennox et al1 in 1952 and was later given its name by Mendoza and Helwig2 through summarizing clinical and histochemical characteristics based on the observation of 14 cases. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms adenocarcinoma, mucinous (Medical Subject Headings); mucinous adenocarcinoma (title/abstract); colloid carcinoma* (title/abstract); skin neoplasms (Medical Subject Headings); skin neoplasm (title/abstract); skin cancer* (title/abstract), and primary (title/abstract) revealed more than 200 reported cases of PMCS. It usually is located in the head and neck region, with the eyelids being the most common site of presentation, but rare presentations in the gluteal region, axillae, hemithoraxes, vulva, arms, and legs also have been reported.3-6 Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin mainly affects elderly patients (age range, 61–80 years), with men being affected more often than women. It often presents as a painless, solitary, nontender, sometimes ulcerated, translucent, white or reddish nodule. The tumors generally grow slowly with high rates of local recurrence and rare chances of distant metastasis.7 Most metastases involve the regional lymph nodes and lungs, but rare cases of bone marrow and parotid gland metastases also have been reported.8 Because PMCS is an indolent tumor, which may be mistaken for a benign tumor, it is not always histologically examined on initial presentation.

Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin is characterized histopathologically by floating epithelial cell nests in mucinous lakes. It is unknown if this neoplasm shows eccrine- or apocrine-type differentiation. S-100 protein seems to indicate eccrine rather than apocrine differentiation.9 Misdiagnosis of PMCS is common, as it has an uncharacteristic gross appearance and may microscopically resemble cutaneous metastasis from a mucinous carcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, ovaries, or prostate. It is important to distinguish between metastatic tumors and PMCS because PMCS generally is more benign and has a better prognosis. A variety of stains have been reported as helpful in the diagnosis of PMCS, including CK7 and CK20, D2-40, p63, and others. In some reports, labeling for CK7 and CK20 was helpful in differentiating colon carcinoma from breast or skin malignancies but did not differentiate primary skin lesions from metastasis of breast malignancies to the skin.10-13 Paradela et al5 proposed D2-40 as a reliable immunostain to detect lymphatic invasion in node-negative primary tumors. Kalebi and Hale11 and Ivan et al12 highlighted the importance of p63 in excluding metastasis to the skin, particularly from the gastrointestinal tract, pancreaticobiliary tree, and lungs.

Even though these factors may help in establishing the primary site of the tumor, a final diagnosis only can be drawn when the patient has been subjected to a thorough investigation. In our patient, clinical workup did not reveal other possible primary sites in other organs or evidence of metastasis from the skin lesion to other sites. Based on the histologic findings, the diagnosis of PMCS was made.

The recommended treatment of PMCS varies from standard excision to wide local excision including dissection of the regional lymph nodes. Alam et al14 reported that Mohs micrographic surgery may be appropriate for first-line therapy because the procedure gives complete margin control and spares tissue. Immunohistochemistry should be used as an adjunct to routine hematoxylin and eosin staining to aid in ensuring negative margins.15 Considering a high potential for recurrence following surgical excision, it is important to detect hormone receptors in this tumor because patients may be treated using antiestrogenic drugs such as tamoxifen. Moreover, recurrent or metastatic PMCS is both resistant to radiotherapy and unresponsive to chemotherapy.3 Annual follow-up is recommended due to the potential for recurrence or metastasis.

1. Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin, with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-890.

2. Mendoza S, Helwig EB. Mucinous (adenocystic) carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:68-78.

3. Breiting L, Dahlstrøm K, Christensen L, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:595-596.

4. Krishnamurthy J, Saba F, Sunila. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a rare tumor in the gluteal region. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:225-227.

5. Paradela S, Castiñeiras I, Cuevas J, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin: evaluation of lymphatic invasion with D2-40. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:504-508.

6. Laco J, Simáková E, Svobodová J, et al. Recurrent mucinous carcinoma of skin mimicking primary mucinous carcinoma of parotid gland: a diagnostic pitfall. Cesk Patol. 2009;45:79-82.

7. Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrøm K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

8. Ajithkumar TV, Nileena N, Abraham EK, et al. Bone marrow relapse in primary mucinous carcinoma of skin. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:303-304.

9. Bellezza G, Sidoni A, Bucciarelli E. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:166-170.

10. Levy G, Finkelstein A, McNiff JM. Immunohistochemical techniques to compare primary vs. metastatic mucinous carcinoma of the skin [published online ahead of print September 24, 2009]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:411-415.

11. Kalebi A, Hale M. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: usefulness of p63 in excluding metastasis and first report of psammoma bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:510.

12. Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:474-480.

13. Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

14. Alam M, Trela R, Kim N, et al. Treatment of primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: meta-analysis of 189 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:382.

15. Stranahan D, Cherpelis BS, Glass LF, et al. Immunohistochemical stains in Mohs surgery: a review [published online ahead of print April 16, 2009]. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1023-1034.

1. Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin, with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-890.

2. Mendoza S, Helwig EB. Mucinous (adenocystic) carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:68-78.

3. Breiting L, Dahlstrøm K, Christensen L, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:595-596.

4. Krishnamurthy J, Saba F, Sunila. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a rare tumor in the gluteal region. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:225-227.

5. Paradela S, Castiñeiras I, Cuevas J, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin: evaluation of lymphatic invasion with D2-40. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:504-508.

6. Laco J, Simáková E, Svobodová J, et al. Recurrent mucinous carcinoma of skin mimicking primary mucinous carcinoma of parotid gland: a diagnostic pitfall. Cesk Patol. 2009;45:79-82.

7. Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrøm K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

8. Ajithkumar TV, Nileena N, Abraham EK, et al. Bone marrow relapse in primary mucinous carcinoma of skin. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:303-304.

9. Bellezza G, Sidoni A, Bucciarelli E. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:166-170.

10. Levy G, Finkelstein A, McNiff JM. Immunohistochemical techniques to compare primary vs. metastatic mucinous carcinoma of the skin [published online ahead of print September 24, 2009]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:411-415.

11. Kalebi A, Hale M. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: usefulness of p63 in excluding metastasis and first report of psammoma bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:510.

12. Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:474-480.

13. Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

14. Alam M, Trela R, Kim N, et al. Treatment of primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: meta-analysis of 189 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:382.

15. Stranahan D, Cherpelis BS, Glass LF, et al. Immunohistochemical stains in Mohs surgery: a review [published online ahead of print April 16, 2009]. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1023-1034.

Large Plaque-Type Benign Cephalic Histiocytosis Showing Rapid Aggravation Following Vaccination

To the Editor:

Benign cephalic histiocytosis (BCH) is a rare benign dermatosis in which self-healing papular eruptions develop. This condition is classified as non-X histiocytosis and behaves as a benign histiocytic proliferation. Since the first report by Gianotti et al1 in 1971, the etiology and pathophysiology of this condition have not been elucidated. The clinical and histologic features of BCH overlap with juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) and generalized eruptive histiocytosis.2 Rodriguez-Jurado et al3 reported that BCH showed clinical evolution to JXG with varicella-zoster infection, suggesting that BCH is a part of a spectrum of diseases that non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis encompasses. We present a case of plaque-type BCH in an infant.

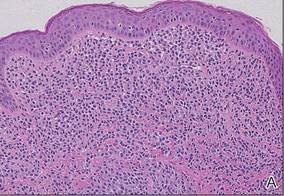

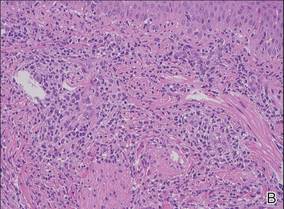

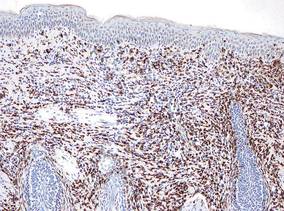

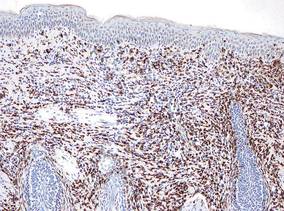

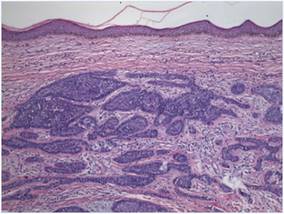

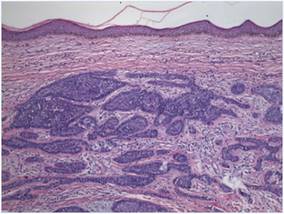

An 11-month-old male infant presented with asymptomatic, ill-defined, infiltrated plaques on the cheeks of 1 month’s duration (Figure 1). Similar red plaques were present on both ears, the left forearm, and the right middle finger. One month following the initial onset as tiny red papules, the lesions had become larger and more prominent after an episode of fever (temperature, 39°C) and immunization against rubella virus and Haemophilus influenzae type b. No therapeutic effect was observed with the application of a topical steroid at the time of presentation. A skin biopsy specimen was taken from a flat plaque on the right cheek. Histopathologic findings revealed dense cell infiltrates predominated by histiocytic cells with some vacuolization in the papillary and upper reticular dermis (Figure 2). Neither foamy histiocytic cells nor giant cells were seen. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the cells were CD68+ (Figure 3) and negative for S-100. Following 2 months of observation without any treatment, the plaques on the ears, right forearm, and right middle finger had begun to spontaneously subside. Overall, the remaining lesions showed complete remission by 21 months of age.

|

| Figure 1. Asymptomatic red, infiltrated, flat plaques on the left cheek. |

|

|

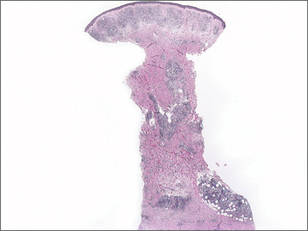

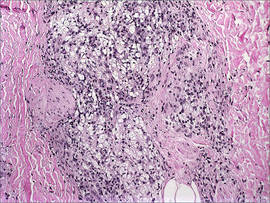

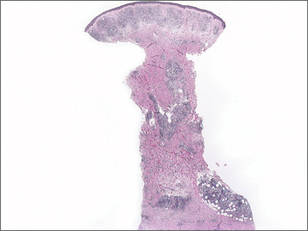

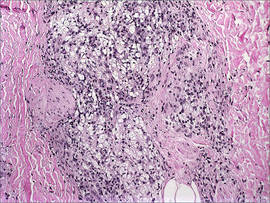

| Figure 2. A biopsy revealed an infiltrate of histiocytes with vacuolization of cells in the papillary and upper reticular dermis (A and B) (both H&E, original magnifications ×50 and ×200). |

|

| Figure 3. Immunohistochemistry revealed histiocytic infiltrate cells that were CD68+ (original magnification ×50). |

Benign cephalic histiocytosis commonly presents as smooth, round, or flat-topped papules with a diameter of 1 to 8 mm and color ranging from tan-yellow to brown-red.2 The etiology of BCH is unknown. Plaque-type BCH represented by this patient is a rare feature, suggesting sarcoidosis, perniosis, or Sjögren syndrome because the lesions are comprised of infiltrated erythematous plaques rather than papules. Rodriguez-Jurado et al3 described a transitional form of BCH to JXG in a 2-year-old girl with facial plaques after an episode of varicella-zoster virus infection. Vasconcelos et al4 also indicated that JXG is associated with cytomegalovirus infection. These findings support the notion that BCH and non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis are on the same spectrum of diseases, representing a reactive histiocytic process to an infectious agent.

The difference in clinical manifestation of each non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis subgroup may reflect the degree or stage of infection. T lymphocytes may release different cytokines and activate macrophage migration when sensitized by a virus or vaccine. As a result, BCH may show various clinical features even when confirmed by histological analysis. Our patient might have had an early stage of BCH that would transform into JXG.

1. Gianotti F, Caputo R, Ermacora E. Singular “infantile histiocytosis with cells with intracytoplasmic vermiform particles” [in French]. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1971;78:232-233.

2. Jih DM, Salcedo SL, Jaworsky C. Benign cephalic histiocytosis: a case report and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:908-913.

3. Rodriguez-Jurado R, Duran-McKinster C, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Benign cephalic histiocytosis progressing into juvenile xanthogranuloma: a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis transforming under the influence of a virus? Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:70-74.

4. Vasconcelos FO, Oliveira LA, Naves MD, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report with immunohistochemical identification of early and late cytomegalovirus antigens. J Oral Sci. 2001;43:21-25.

To the Editor:

Benign cephalic histiocytosis (BCH) is a rare benign dermatosis in which self-healing papular eruptions develop. This condition is classified as non-X histiocytosis and behaves as a benign histiocytic proliferation. Since the first report by Gianotti et al1 in 1971, the etiology and pathophysiology of this condition have not been elucidated. The clinical and histologic features of BCH overlap with juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) and generalized eruptive histiocytosis.2 Rodriguez-Jurado et al3 reported that BCH showed clinical evolution to JXG with varicella-zoster infection, suggesting that BCH is a part of a spectrum of diseases that non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis encompasses. We present a case of plaque-type BCH in an infant.

An 11-month-old male infant presented with asymptomatic, ill-defined, infiltrated plaques on the cheeks of 1 month’s duration (Figure 1). Similar red plaques were present on both ears, the left forearm, and the right middle finger. One month following the initial onset as tiny red papules, the lesions had become larger and more prominent after an episode of fever (temperature, 39°C) and immunization against rubella virus and Haemophilus influenzae type b. No therapeutic effect was observed with the application of a topical steroid at the time of presentation. A skin biopsy specimen was taken from a flat plaque on the right cheek. Histopathologic findings revealed dense cell infiltrates predominated by histiocytic cells with some vacuolization in the papillary and upper reticular dermis (Figure 2). Neither foamy histiocytic cells nor giant cells were seen. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the cells were CD68+ (Figure 3) and negative for S-100. Following 2 months of observation without any treatment, the plaques on the ears, right forearm, and right middle finger had begun to spontaneously subside. Overall, the remaining lesions showed complete remission by 21 months of age.

|

| Figure 1. Asymptomatic red, infiltrated, flat plaques on the left cheek. |

|

|

| Figure 2. A biopsy revealed an infiltrate of histiocytes with vacuolization of cells in the papillary and upper reticular dermis (A and B) (both H&E, original magnifications ×50 and ×200). |

|

| Figure 3. Immunohistochemistry revealed histiocytic infiltrate cells that were CD68+ (original magnification ×50). |

Benign cephalic histiocytosis commonly presents as smooth, round, or flat-topped papules with a diameter of 1 to 8 mm and color ranging from tan-yellow to brown-red.2 The etiology of BCH is unknown. Plaque-type BCH represented by this patient is a rare feature, suggesting sarcoidosis, perniosis, or Sjögren syndrome because the lesions are comprised of infiltrated erythematous plaques rather than papules. Rodriguez-Jurado et al3 described a transitional form of BCH to JXG in a 2-year-old girl with facial plaques after an episode of varicella-zoster virus infection. Vasconcelos et al4 also indicated that JXG is associated with cytomegalovirus infection. These findings support the notion that BCH and non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis are on the same spectrum of diseases, representing a reactive histiocytic process to an infectious agent.