User login

Bilateral thigh and knee pain • leg weakness • no history of trauma • Dx?

THE CASE

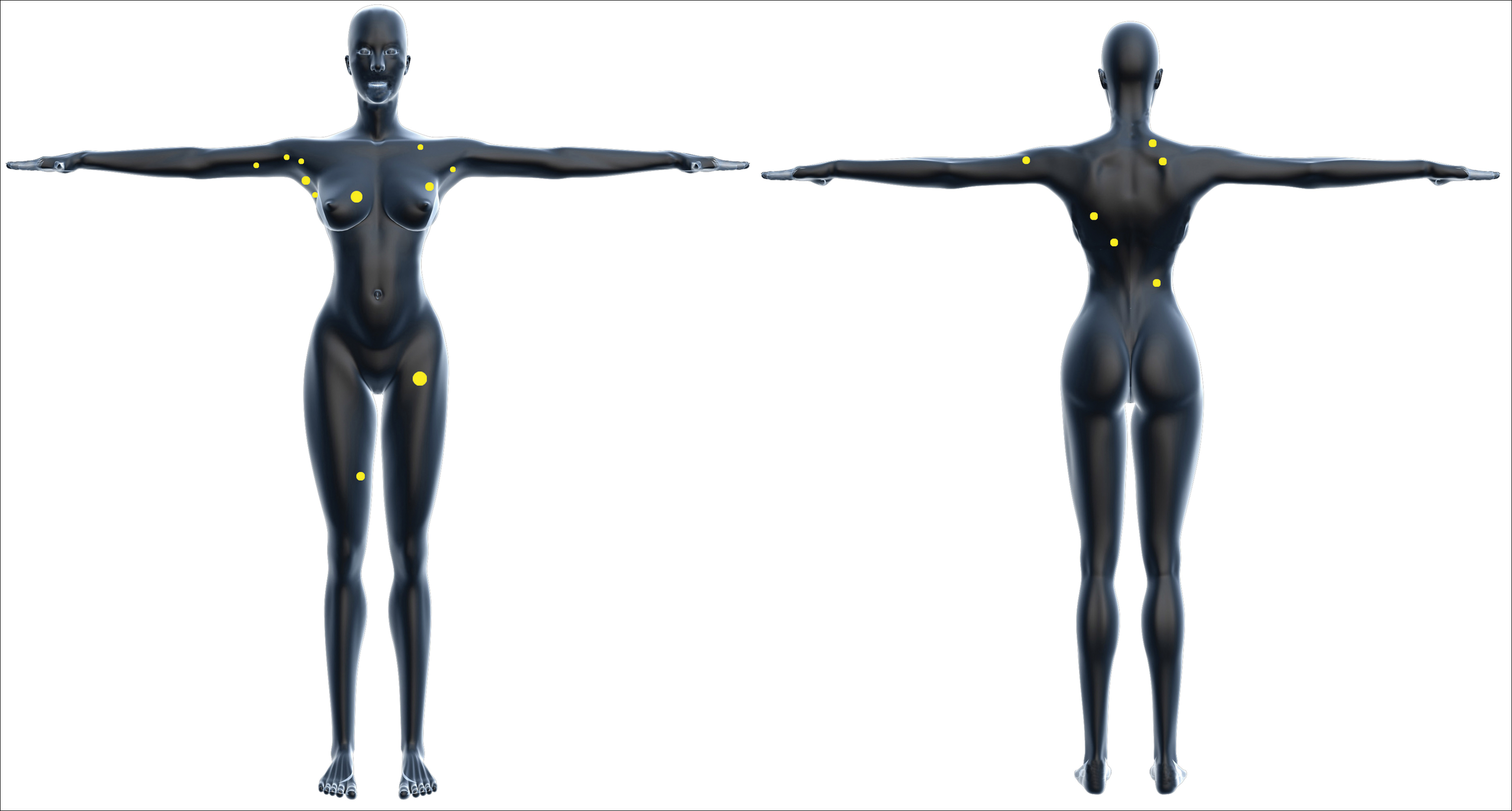

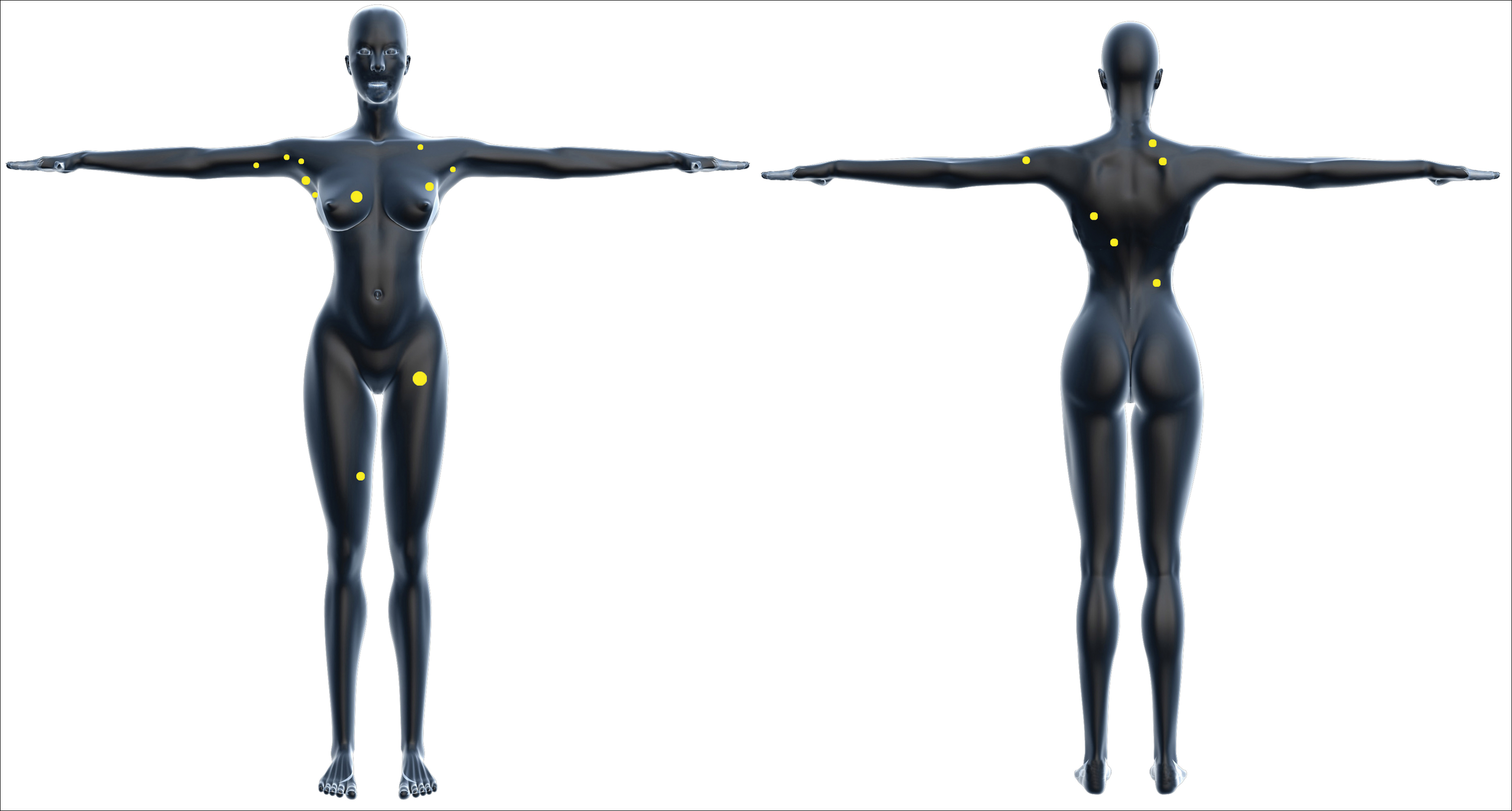

A 67-year-old woman presented to our orthopaedic clinic with a 2-year history of bilateral thigh and knee pain and weakness of her legs. She had no history of trauma, and the pain, which was localized to the distal anterior thighs and patellofemoral area, was 7/10 at rest and worse with standing and walking.

Her medical history was significant for osteoporosis (diagnosed in 2004), hypertension, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and menopause (age 54). Her original dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan did not reveal the presence of any previous fractures. She was started on calcium and vitamin D supplementation and oral alendronate (70 mg once a week). She took alendronate for 4 years until 2008, when it was stopped due to nausea. She was then started on zoledronic acid (5 mg IV annually). She received 5 infusions of zoledronic acid between 2008 and 2013; she did not have an infusion in 2012. Her medication list also included lisinopril, omeprazole, naproxen, cyclobenzaprine, and a multivitamin. She had normal renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate >60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and she did not drink alcohol or use tobacco.

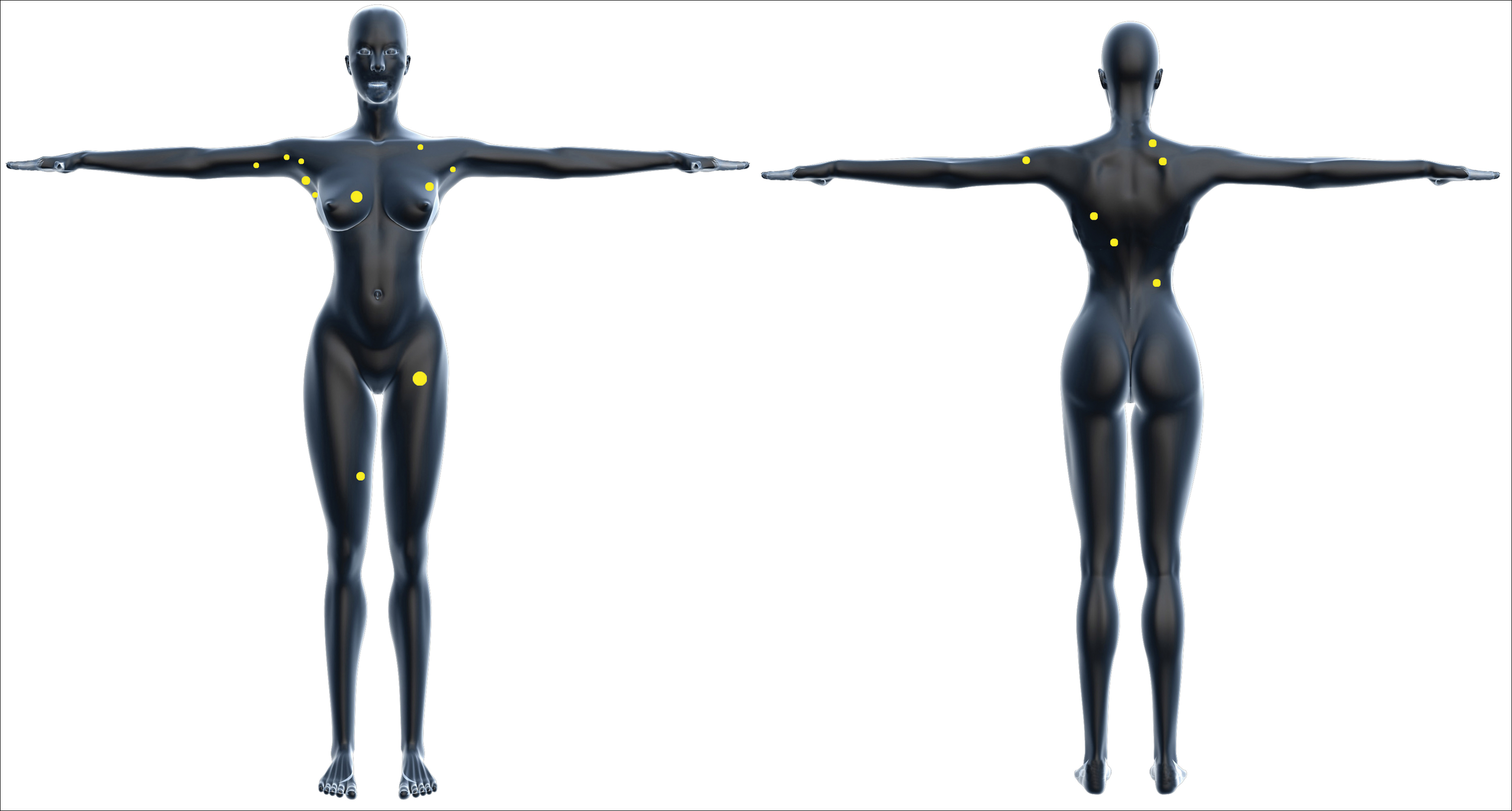

In the 2 years prior to her visit to our clinic, she had been evaluated by her primary care provider, an orthopedic sports medicine specialist, 2 spinal surgeons, and a physiatrist. She had also undergone 30 physical therapy sessions. Bilateral femur radiographs (FIGURE 1) ordered by her orthopedist 6 months earlier demonstrated no evidence of fracture, but did show an incidental enchondroma in the right distal diaphysis and bilateral thickening of the lateral femoral cortices.

Finally, with no relief in sight, her obstetrician suggested that she might be experiencing myalgias attributable to her zoledronic acid infusions. She was subsequently referred to us.

The physical exam revealed a thin female with a body mass index of 21. She had mild tenderness on palpation of the bilateral anterior thighs and knees. There was no pain with hip or knee range of motion and minimal pain in the bilateral lower extremities with axial loading. The patient had normal sensation, did not have an antalgic gait, and exhibited 5/5 strength bilaterally in all distributions of the lower extremities.

THE DIAGNOSIS

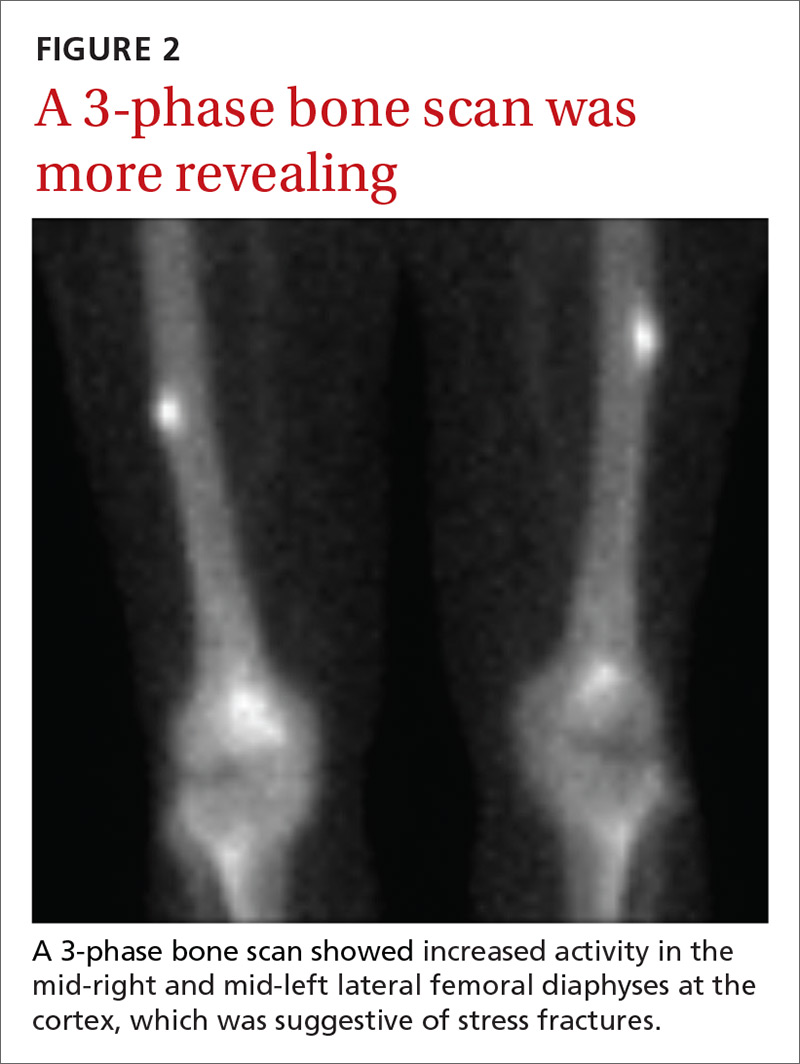

Due to continued pain despite negative x-rays, we obtained a 3-phase bone scan of the pelvis and bilateral femurs. Delayed images showed moderately increased activity in the mid-right and mid-left lateral femoral diaphyses at the cortex and confirmed stress fractures (FIGURE 2).

DISCUSSION

Bisphosphonates are considered first-line therapy for osteoporosis, according to current evidence-based guidelines.1 These medications inhibit osteoclast activity and can bind to the bone for more than 10 years.2,3 (In women with bone mineral density scores ≤ –2.5, the number needed to treat is 21.1,4)

Patients taking bisphosphonates, however, are susceptible to atypical femoral fractures (AFFs), which are stress or insufficiency fractures associated with minimal or no trauma.5 The pathophysiology remains unknown at this time, but AFFs may result from changes in bone remodeling that occur when a bone experiences repetitive microtrauma, leading to lateral cortical thickening of the femur.6,7 Incidence of AFFs in patients taking bisphosphonates is estimated to be between 3.2 and 50 cases per 100,000 person-years; however, this risk increases to approximately 100 per 100,000 person-years with long-term use.5 Other risk factors include low body weight, advancing age, rheumatoid arthritis, long-term glucocorticoid therapy, and excessive alcohol and cigarette use.8

What you’ll see

Symptoms typically include unilateral or bilateral prodromal pain with a sharp or achy character that is localized to the mid-thigh, upper thigh, or groin.9 If an AFF is suspected, we recommend performing a bilateral exam and obtaining radiographs.

If characteristic features are found (eg, signs of focal cortical thickening or beaking) and pain arises in the opposite limb, obtain a radiograph of the contralateral femur. If radiographs are negative but suspicion remains, order magnetic resonance imaging or a bone scan, to identify a cortical fracture line, bone and marrow edema, or hyperemia.5

Begin treatment by discontinuing bisphosphonates

Upon identification of an AFF, discontinue bisphosphonates and initiate calcium and vitamin D supplementation.5 Prophylactic surgical fixation may also be necessary to accelerate healing and prevent fracture propagation and further pain.

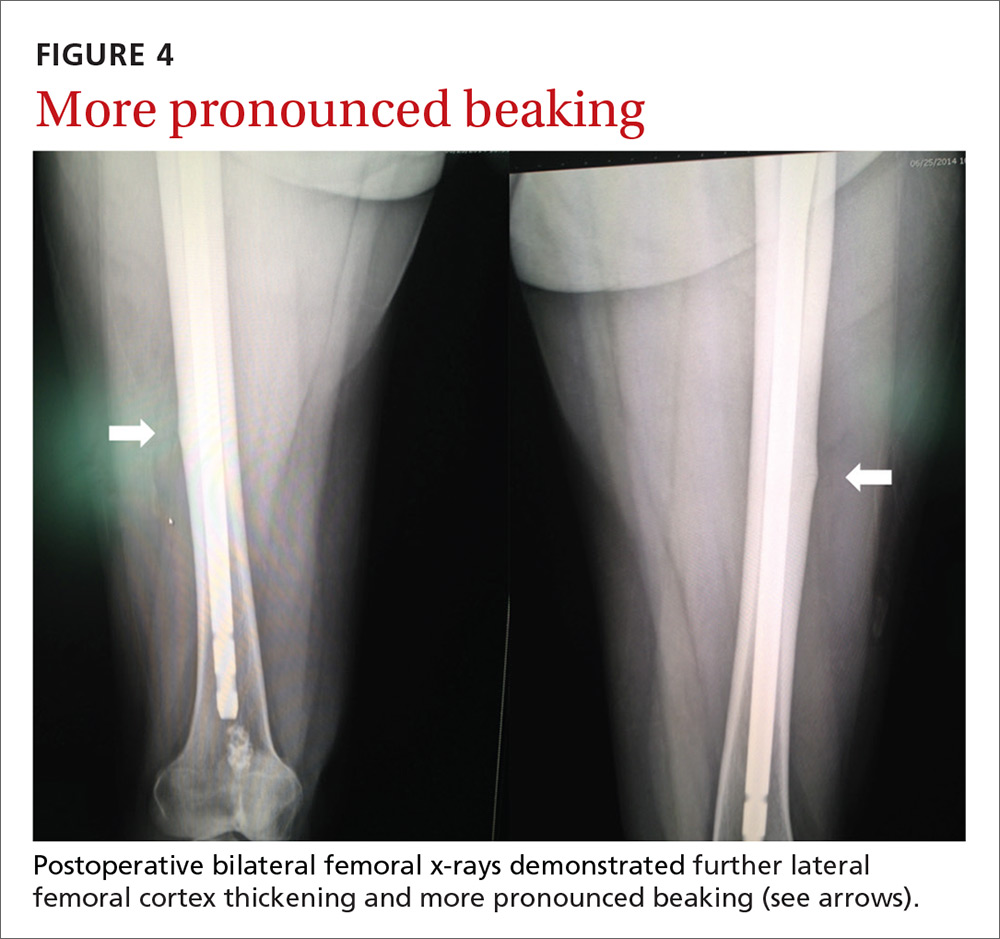

Our patient. Due to the longevity of the symptoms and the bilateral stress fractures noted on the bone scan, our patient chose to proceed with intramedullary nailing of the bilateral femurs (FIGURES 3 and 4). On postop Day 1, she was able to ambulate using a walker and to participate in bilateral weight-bearing (as tolerated). She was discharged to a skilled nursing facility, where she progressed to full weight-bearing without aid. On follow-up (one year postop), the patient reported no residual leg pain and was able to work out 5 days per week. Radiographs of her femurs demonstrated healed fractures and stable position of the intramedullary nails.

THE TAKEAWAY

An increased suspicion for AFFs due to bisphosphonate use can lead to earlier diagnosis and decreased morbidity for patients. Use of femoral imaging can promote detection and reduce financial burden.

To help prevent AFFs from occurring, we recommend reevaluating the need for continued bisphosphonate therapy after 2 to 5 years of treatment. Continued surveillance is also advisable throughout the duration of their use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Maurice Manring for his help in preparing this manuscript.

1. Watts NB, Bilezikian JP, Camacho PM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Pract. 2010;16 Suppl 3:1-37.

2. Cakmak S, Mahiroğullari M, Keklikci K, et al. Bilateral low-energy sequential femoral shaft fractures in patients on long-term bisphosphonate therapy. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2013;47:162-172.

3. Drake MT, Clarke BL, Khosla S. Bisphosphonates: mechanism of action and role in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1032-1045.

4. Black DM, Bauer DC, Schwartz AV, et al. Continuing bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis—for whom and for how long? N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2051-2053.

5. Shane E, Burr D, Abrahamsen B, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: second report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1-23.

6. Allen MR. Recent advances in understanding bisphosphonate effects on bone mechanical properties. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2018 Mar 1. [Epub ahead of print]

7. Hagino H, Endo N, Yamamoto T, et al. Treatment status and radiographic features of patients with atypical femoral fractures. J Orthop Sci. 2018;23:316-320.

8. Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, De Laet C, et al. Assessment of fracture risk. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:581-589.

9. Giusti A, Hamdy NA, Papapoulos SE. Atypical fractures of the femur and bisphosphonate therapy: a systematic review of case/case series studies. Bone. 2010;47:169-180.

THE CASE

A 67-year-old woman presented to our orthopaedic clinic with a 2-year history of bilateral thigh and knee pain and weakness of her legs. She had no history of trauma, and the pain, which was localized to the distal anterior thighs and patellofemoral area, was 7/10 at rest and worse with standing and walking.

Her medical history was significant for osteoporosis (diagnosed in 2004), hypertension, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and menopause (age 54). Her original dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan did not reveal the presence of any previous fractures. She was started on calcium and vitamin D supplementation and oral alendronate (70 mg once a week). She took alendronate for 4 years until 2008, when it was stopped due to nausea. She was then started on zoledronic acid (5 mg IV annually). She received 5 infusions of zoledronic acid between 2008 and 2013; she did not have an infusion in 2012. Her medication list also included lisinopril, omeprazole, naproxen, cyclobenzaprine, and a multivitamin. She had normal renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate >60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and she did not drink alcohol or use tobacco.

In the 2 years prior to her visit to our clinic, she had been evaluated by her primary care provider, an orthopedic sports medicine specialist, 2 spinal surgeons, and a physiatrist. She had also undergone 30 physical therapy sessions. Bilateral femur radiographs (FIGURE 1) ordered by her orthopedist 6 months earlier demonstrated no evidence of fracture, but did show an incidental enchondroma in the right distal diaphysis and bilateral thickening of the lateral femoral cortices.

Finally, with no relief in sight, her obstetrician suggested that she might be experiencing myalgias attributable to her zoledronic acid infusions. She was subsequently referred to us.

The physical exam revealed a thin female with a body mass index of 21. She had mild tenderness on palpation of the bilateral anterior thighs and knees. There was no pain with hip or knee range of motion and minimal pain in the bilateral lower extremities with axial loading. The patient had normal sensation, did not have an antalgic gait, and exhibited 5/5 strength bilaterally in all distributions of the lower extremities.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Due to continued pain despite negative x-rays, we obtained a 3-phase bone scan of the pelvis and bilateral femurs. Delayed images showed moderately increased activity in the mid-right and mid-left lateral femoral diaphyses at the cortex and confirmed stress fractures (FIGURE 2).

DISCUSSION

Bisphosphonates are considered first-line therapy for osteoporosis, according to current evidence-based guidelines.1 These medications inhibit osteoclast activity and can bind to the bone for more than 10 years.2,3 (In women with bone mineral density scores ≤ –2.5, the number needed to treat is 21.1,4)

Patients taking bisphosphonates, however, are susceptible to atypical femoral fractures (AFFs), which are stress or insufficiency fractures associated with minimal or no trauma.5 The pathophysiology remains unknown at this time, but AFFs may result from changes in bone remodeling that occur when a bone experiences repetitive microtrauma, leading to lateral cortical thickening of the femur.6,7 Incidence of AFFs in patients taking bisphosphonates is estimated to be between 3.2 and 50 cases per 100,000 person-years; however, this risk increases to approximately 100 per 100,000 person-years with long-term use.5 Other risk factors include low body weight, advancing age, rheumatoid arthritis, long-term glucocorticoid therapy, and excessive alcohol and cigarette use.8

What you’ll see

Symptoms typically include unilateral or bilateral prodromal pain with a sharp or achy character that is localized to the mid-thigh, upper thigh, or groin.9 If an AFF is suspected, we recommend performing a bilateral exam and obtaining radiographs.

If characteristic features are found (eg, signs of focal cortical thickening or beaking) and pain arises in the opposite limb, obtain a radiograph of the contralateral femur. If radiographs are negative but suspicion remains, order magnetic resonance imaging or a bone scan, to identify a cortical fracture line, bone and marrow edema, or hyperemia.5

Begin treatment by discontinuing bisphosphonates

Upon identification of an AFF, discontinue bisphosphonates and initiate calcium and vitamin D supplementation.5 Prophylactic surgical fixation may also be necessary to accelerate healing and prevent fracture propagation and further pain.

Our patient. Due to the longevity of the symptoms and the bilateral stress fractures noted on the bone scan, our patient chose to proceed with intramedullary nailing of the bilateral femurs (FIGURES 3 and 4). On postop Day 1, she was able to ambulate using a walker and to participate in bilateral weight-bearing (as tolerated). She was discharged to a skilled nursing facility, where she progressed to full weight-bearing without aid. On follow-up (one year postop), the patient reported no residual leg pain and was able to work out 5 days per week. Radiographs of her femurs demonstrated healed fractures and stable position of the intramedullary nails.

THE TAKEAWAY

An increased suspicion for AFFs due to bisphosphonate use can lead to earlier diagnosis and decreased morbidity for patients. Use of femoral imaging can promote detection and reduce financial burden.

To help prevent AFFs from occurring, we recommend reevaluating the need for continued bisphosphonate therapy after 2 to 5 years of treatment. Continued surveillance is also advisable throughout the duration of their use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Maurice Manring for his help in preparing this manuscript.

THE CASE

A 67-year-old woman presented to our orthopaedic clinic with a 2-year history of bilateral thigh and knee pain and weakness of her legs. She had no history of trauma, and the pain, which was localized to the distal anterior thighs and patellofemoral area, was 7/10 at rest and worse with standing and walking.

Her medical history was significant for osteoporosis (diagnosed in 2004), hypertension, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and menopause (age 54). Her original dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan did not reveal the presence of any previous fractures. She was started on calcium and vitamin D supplementation and oral alendronate (70 mg once a week). She took alendronate for 4 years until 2008, when it was stopped due to nausea. She was then started on zoledronic acid (5 mg IV annually). She received 5 infusions of zoledronic acid between 2008 and 2013; she did not have an infusion in 2012. Her medication list also included lisinopril, omeprazole, naproxen, cyclobenzaprine, and a multivitamin. She had normal renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate >60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and she did not drink alcohol or use tobacco.

In the 2 years prior to her visit to our clinic, she had been evaluated by her primary care provider, an orthopedic sports medicine specialist, 2 spinal surgeons, and a physiatrist. She had also undergone 30 physical therapy sessions. Bilateral femur radiographs (FIGURE 1) ordered by her orthopedist 6 months earlier demonstrated no evidence of fracture, but did show an incidental enchondroma in the right distal diaphysis and bilateral thickening of the lateral femoral cortices.

Finally, with no relief in sight, her obstetrician suggested that she might be experiencing myalgias attributable to her zoledronic acid infusions. She was subsequently referred to us.

The physical exam revealed a thin female with a body mass index of 21. She had mild tenderness on palpation of the bilateral anterior thighs and knees. There was no pain with hip or knee range of motion and minimal pain in the bilateral lower extremities with axial loading. The patient had normal sensation, did not have an antalgic gait, and exhibited 5/5 strength bilaterally in all distributions of the lower extremities.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Due to continued pain despite negative x-rays, we obtained a 3-phase bone scan of the pelvis and bilateral femurs. Delayed images showed moderately increased activity in the mid-right and mid-left lateral femoral diaphyses at the cortex and confirmed stress fractures (FIGURE 2).

DISCUSSION

Bisphosphonates are considered first-line therapy for osteoporosis, according to current evidence-based guidelines.1 These medications inhibit osteoclast activity and can bind to the bone for more than 10 years.2,3 (In women with bone mineral density scores ≤ –2.5, the number needed to treat is 21.1,4)

Patients taking bisphosphonates, however, are susceptible to atypical femoral fractures (AFFs), which are stress or insufficiency fractures associated with minimal or no trauma.5 The pathophysiology remains unknown at this time, but AFFs may result from changes in bone remodeling that occur when a bone experiences repetitive microtrauma, leading to lateral cortical thickening of the femur.6,7 Incidence of AFFs in patients taking bisphosphonates is estimated to be between 3.2 and 50 cases per 100,000 person-years; however, this risk increases to approximately 100 per 100,000 person-years with long-term use.5 Other risk factors include low body weight, advancing age, rheumatoid arthritis, long-term glucocorticoid therapy, and excessive alcohol and cigarette use.8

What you’ll see

Symptoms typically include unilateral or bilateral prodromal pain with a sharp or achy character that is localized to the mid-thigh, upper thigh, or groin.9 If an AFF is suspected, we recommend performing a bilateral exam and obtaining radiographs.

If characteristic features are found (eg, signs of focal cortical thickening or beaking) and pain arises in the opposite limb, obtain a radiograph of the contralateral femur. If radiographs are negative but suspicion remains, order magnetic resonance imaging or a bone scan, to identify a cortical fracture line, bone and marrow edema, or hyperemia.5

Begin treatment by discontinuing bisphosphonates

Upon identification of an AFF, discontinue bisphosphonates and initiate calcium and vitamin D supplementation.5 Prophylactic surgical fixation may also be necessary to accelerate healing and prevent fracture propagation and further pain.

Our patient. Due to the longevity of the symptoms and the bilateral stress fractures noted on the bone scan, our patient chose to proceed with intramedullary nailing of the bilateral femurs (FIGURES 3 and 4). On postop Day 1, she was able to ambulate using a walker and to participate in bilateral weight-bearing (as tolerated). She was discharged to a skilled nursing facility, where she progressed to full weight-bearing without aid. On follow-up (one year postop), the patient reported no residual leg pain and was able to work out 5 days per week. Radiographs of her femurs demonstrated healed fractures and stable position of the intramedullary nails.

THE TAKEAWAY

An increased suspicion for AFFs due to bisphosphonate use can lead to earlier diagnosis and decreased morbidity for patients. Use of femoral imaging can promote detection and reduce financial burden.

To help prevent AFFs from occurring, we recommend reevaluating the need for continued bisphosphonate therapy after 2 to 5 years of treatment. Continued surveillance is also advisable throughout the duration of their use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Maurice Manring for his help in preparing this manuscript.

1. Watts NB, Bilezikian JP, Camacho PM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Pract. 2010;16 Suppl 3:1-37.

2. Cakmak S, Mahiroğullari M, Keklikci K, et al. Bilateral low-energy sequential femoral shaft fractures in patients on long-term bisphosphonate therapy. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2013;47:162-172.

3. Drake MT, Clarke BL, Khosla S. Bisphosphonates: mechanism of action and role in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1032-1045.

4. Black DM, Bauer DC, Schwartz AV, et al. Continuing bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis—for whom and for how long? N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2051-2053.

5. Shane E, Burr D, Abrahamsen B, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: second report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1-23.

6. Allen MR. Recent advances in understanding bisphosphonate effects on bone mechanical properties. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2018 Mar 1. [Epub ahead of print]

7. Hagino H, Endo N, Yamamoto T, et al. Treatment status and radiographic features of patients with atypical femoral fractures. J Orthop Sci. 2018;23:316-320.

8. Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, De Laet C, et al. Assessment of fracture risk. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:581-589.

9. Giusti A, Hamdy NA, Papapoulos SE. Atypical fractures of the femur and bisphosphonate therapy: a systematic review of case/case series studies. Bone. 2010;47:169-180.

1. Watts NB, Bilezikian JP, Camacho PM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Pract. 2010;16 Suppl 3:1-37.

2. Cakmak S, Mahiroğullari M, Keklikci K, et al. Bilateral low-energy sequential femoral shaft fractures in patients on long-term bisphosphonate therapy. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2013;47:162-172.

3. Drake MT, Clarke BL, Khosla S. Bisphosphonates: mechanism of action and role in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1032-1045.

4. Black DM, Bauer DC, Schwartz AV, et al. Continuing bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis—for whom and for how long? N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2051-2053.

5. Shane E, Burr D, Abrahamsen B, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: second report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1-23.

6. Allen MR. Recent advances in understanding bisphosphonate effects on bone mechanical properties. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2018 Mar 1. [Epub ahead of print]

7. Hagino H, Endo N, Yamamoto T, et al. Treatment status and radiographic features of patients with atypical femoral fractures. J Orthop Sci. 2018;23:316-320.

8. Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, De Laet C, et al. Assessment of fracture risk. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:581-589.

9. Giusti A, Hamdy NA, Papapoulos SE. Atypical fractures of the femur and bisphosphonate therapy: a systematic review of case/case series studies. Bone. 2010;47:169-180.

Severe right upper chest pain • tender right sternoclavicular joint • Dx?

THE CASE

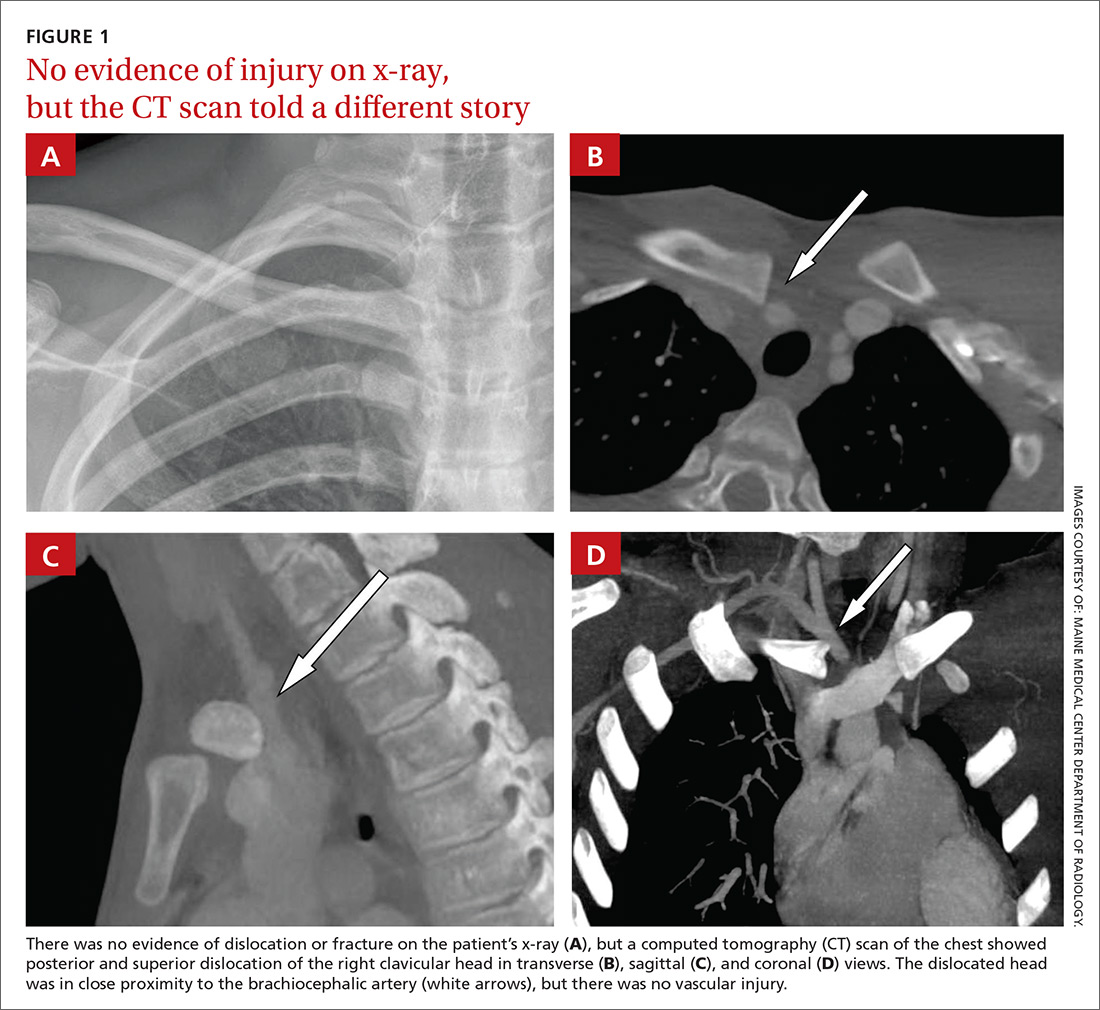

A 16-year-old hockey player presented to our emergency department with sharp pain in his right upper chest after “checking” another player during a game. The pain did not resolve with rest and was worse with movement and breathing. The patient did not have dysphagia, dyspnea, paresthesias, or hoarseness. The physical examination revealed tenderness over the right sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) without swelling or deformity. A distal neurovascular exam was intact, and a chest x-ray showed no evidence of dislocation or fracture (FIGURE 1A). The patient’s pain was refractory to multiple intravenous (IV) pain medications.

THE DIAGNOSIS

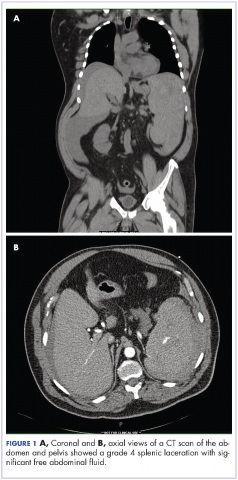

A computed tomography (CT) scan with IV contrast of the chest demonstrated posterior and superior dislocation of the right clavicular head. Despite the close proximity of the dislocated head to the brachiocephalic artery (FIGURE 1B-1D), there was no vascular injury.

DISCUSSION

Posterior sternoclavicular dislocations (PSCDs) can be difficult to diagnose. Edema can mask the characteristic skin depression that one would expect with a posterior dislocation.1 Chest radiographs are often normal (as was true in this case). Patients may present with an abnormal pulse, paresthesias, hoarseness, dysphagia, and/or dyspnea. However, for more than half of these patients, their only signs and symptoms will be pain, swelling, and limited range of motion.1 As a result, a PSCD may be misdiagnosed as a ligamentous or soft tissue injury.1

An uncommon injury that can result in serious complications

PSCDs represent 3% to 5% of all SCJ dislocations, which comprise <5% of all shoulder girdle injuries.1 Nevertheless, prompt and accurate diagnosis is critical, as these dislocations involve a high risk for injury to the posterior structures, particularly the brachiocephalic vein, right common carotid artery, and aortic arch.

One study found that nearly 75% of patients had a significant structure <1 cm posterior to the SCJ.2This proximity can result in neurovascular complications—some of which are devastating—in up to 30% of patients with PSCDs.3 A case report from 2011, for example, describes a 19-year-old man who had an undiagnosed PSCD that caused a pseudoaneurysm in his subclavian artery and a subsequent thrombotic cerebrovascular accident.4

Which injuries should raise your suspicions? Injuries in which lateral compression on the shoulder has caused it to roll forward and those in which a posteriorly directed force has been applied to the medial clavicle (as might occur in tackle sports or motor vehicle rollovers) should increase suspicion of a PSCD.1

Proper diagnosis requires CT angiography of the chest to assess the injury and evaluate the underlying structures. If CT is not available, additional chest film views, such as a serendipity view (anteroposterior view with 40° cephalic tilt) or Heinig view (oblique projection perpendicular to SCJ), may be obtained; an ultrasound is also an option.5

PSCD = surgical emergency

Following diagnosis, immediate orthopedic consultation is required. A PSCD is a surgical emergency. Reduction (open or closed) must be performed under general anesthesia with vascular and/or cardiothoracic surgery specialists available, as the reduction itself could injure one of the great vessels. Fortunately, most patients do quite well following surgery, with the majority achieving good-to-excellent results.6

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and underwent orthopedic surgery the following morning. Vascular and cardiothoracic surgeons were consulted and available in the event of a complication. A Salter-Harris type 2 fracture of the medial clavicle was identified intraoperatively, and an open reduction with internal fixation was performed. The patient had an uneventful recovery and resumed his usual activities, including playing hockey.

THE TAKEAWAY

PSCDs, although uncommon, can be life-threatening. Since the physical exam is unreliable and standard radiographs are often normal, accurate diagnosis relies largely on increased clinical suspicion. When there is a history of shoulder trauma, medial clavicle pain, and SCJ edema or tenderness, a PSCD should be suspected.7

Confirm the diagnosis with CT angiogram, and remember that a PSCD is a surgical emergency that requires coordination with orthopedic and vascular/cardiothoracic surgeons.

1. Chaudhry S. Pediatric posterior sternoclavicular joint injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:468-475.

2. Ponce BA, Kundukulam JA, Pflugner R, et al. Sternoclavicular joint surgery: how far does danger lurk below? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:993-999.

3. Daya MR, Bengtzen RR. Shoulder. In: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:618-642.

4. Marcus MS, Tan V. Cerebrovascular accident in a 19-year-old patient: a case report of posterior sternoclavicular dislocation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:e1-e4.

5. Morell DJ, Thyagarajan DS. Sternoclavicular joint dislocation and its management: a review of the literature. World J Orthop. 2016;7:244-250.

6. Boesmueller S, Wech M, Tiefenboeck TM, et al. Incidence, characteristics, and long-term follow-up of sternoclavicular injuries: an epidemiologic analysis of 92 cases. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:289-295.

7. Roepke C, Kleiner M, Jhun P, et al. Chest pain bounce-back: posterior sternoclavicular dislocation. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:559-561.

THE CASE

A 16-year-old hockey player presented to our emergency department with sharp pain in his right upper chest after “checking” another player during a game. The pain did not resolve with rest and was worse with movement and breathing. The patient did not have dysphagia, dyspnea, paresthesias, or hoarseness. The physical examination revealed tenderness over the right sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) without swelling or deformity. A distal neurovascular exam was intact, and a chest x-ray showed no evidence of dislocation or fracture (FIGURE 1A). The patient’s pain was refractory to multiple intravenous (IV) pain medications.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A computed tomography (CT) scan with IV contrast of the chest demonstrated posterior and superior dislocation of the right clavicular head. Despite the close proximity of the dislocated head to the brachiocephalic artery (FIGURE 1B-1D), there was no vascular injury.

DISCUSSION

Posterior sternoclavicular dislocations (PSCDs) can be difficult to diagnose. Edema can mask the characteristic skin depression that one would expect with a posterior dislocation.1 Chest radiographs are often normal (as was true in this case). Patients may present with an abnormal pulse, paresthesias, hoarseness, dysphagia, and/or dyspnea. However, for more than half of these patients, their only signs and symptoms will be pain, swelling, and limited range of motion.1 As a result, a PSCD may be misdiagnosed as a ligamentous or soft tissue injury.1

An uncommon injury that can result in serious complications

PSCDs represent 3% to 5% of all SCJ dislocations, which comprise <5% of all shoulder girdle injuries.1 Nevertheless, prompt and accurate diagnosis is critical, as these dislocations involve a high risk for injury to the posterior structures, particularly the brachiocephalic vein, right common carotid artery, and aortic arch.

One study found that nearly 75% of patients had a significant structure <1 cm posterior to the SCJ.2This proximity can result in neurovascular complications—some of which are devastating—in up to 30% of patients with PSCDs.3 A case report from 2011, for example, describes a 19-year-old man who had an undiagnosed PSCD that caused a pseudoaneurysm in his subclavian artery and a subsequent thrombotic cerebrovascular accident.4

Which injuries should raise your suspicions? Injuries in which lateral compression on the shoulder has caused it to roll forward and those in which a posteriorly directed force has been applied to the medial clavicle (as might occur in tackle sports or motor vehicle rollovers) should increase suspicion of a PSCD.1

Proper diagnosis requires CT angiography of the chest to assess the injury and evaluate the underlying structures. If CT is not available, additional chest film views, such as a serendipity view (anteroposterior view with 40° cephalic tilt) or Heinig view (oblique projection perpendicular to SCJ), may be obtained; an ultrasound is also an option.5

PSCD = surgical emergency

Following diagnosis, immediate orthopedic consultation is required. A PSCD is a surgical emergency. Reduction (open or closed) must be performed under general anesthesia with vascular and/or cardiothoracic surgery specialists available, as the reduction itself could injure one of the great vessels. Fortunately, most patients do quite well following surgery, with the majority achieving good-to-excellent results.6

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and underwent orthopedic surgery the following morning. Vascular and cardiothoracic surgeons were consulted and available in the event of a complication. A Salter-Harris type 2 fracture of the medial clavicle was identified intraoperatively, and an open reduction with internal fixation was performed. The patient had an uneventful recovery and resumed his usual activities, including playing hockey.

THE TAKEAWAY

PSCDs, although uncommon, can be life-threatening. Since the physical exam is unreliable and standard radiographs are often normal, accurate diagnosis relies largely on increased clinical suspicion. When there is a history of shoulder trauma, medial clavicle pain, and SCJ edema or tenderness, a PSCD should be suspected.7

Confirm the diagnosis with CT angiogram, and remember that a PSCD is a surgical emergency that requires coordination with orthopedic and vascular/cardiothoracic surgeons.

THE CASE

A 16-year-old hockey player presented to our emergency department with sharp pain in his right upper chest after “checking” another player during a game. The pain did not resolve with rest and was worse with movement and breathing. The patient did not have dysphagia, dyspnea, paresthesias, or hoarseness. The physical examination revealed tenderness over the right sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) without swelling or deformity. A distal neurovascular exam was intact, and a chest x-ray showed no evidence of dislocation or fracture (FIGURE 1A). The patient’s pain was refractory to multiple intravenous (IV) pain medications.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A computed tomography (CT) scan with IV contrast of the chest demonstrated posterior and superior dislocation of the right clavicular head. Despite the close proximity of the dislocated head to the brachiocephalic artery (FIGURE 1B-1D), there was no vascular injury.

DISCUSSION

Posterior sternoclavicular dislocations (PSCDs) can be difficult to diagnose. Edema can mask the characteristic skin depression that one would expect with a posterior dislocation.1 Chest radiographs are often normal (as was true in this case). Patients may present with an abnormal pulse, paresthesias, hoarseness, dysphagia, and/or dyspnea. However, for more than half of these patients, their only signs and symptoms will be pain, swelling, and limited range of motion.1 As a result, a PSCD may be misdiagnosed as a ligamentous or soft tissue injury.1

An uncommon injury that can result in serious complications

PSCDs represent 3% to 5% of all SCJ dislocations, which comprise <5% of all shoulder girdle injuries.1 Nevertheless, prompt and accurate diagnosis is critical, as these dislocations involve a high risk for injury to the posterior structures, particularly the brachiocephalic vein, right common carotid artery, and aortic arch.

One study found that nearly 75% of patients had a significant structure <1 cm posterior to the SCJ.2This proximity can result in neurovascular complications—some of which are devastating—in up to 30% of patients with PSCDs.3 A case report from 2011, for example, describes a 19-year-old man who had an undiagnosed PSCD that caused a pseudoaneurysm in his subclavian artery and a subsequent thrombotic cerebrovascular accident.4

Which injuries should raise your suspicions? Injuries in which lateral compression on the shoulder has caused it to roll forward and those in which a posteriorly directed force has been applied to the medial clavicle (as might occur in tackle sports or motor vehicle rollovers) should increase suspicion of a PSCD.1

Proper diagnosis requires CT angiography of the chest to assess the injury and evaluate the underlying structures. If CT is not available, additional chest film views, such as a serendipity view (anteroposterior view with 40° cephalic tilt) or Heinig view (oblique projection perpendicular to SCJ), may be obtained; an ultrasound is also an option.5

PSCD = surgical emergency

Following diagnosis, immediate orthopedic consultation is required. A PSCD is a surgical emergency. Reduction (open or closed) must be performed under general anesthesia with vascular and/or cardiothoracic surgery specialists available, as the reduction itself could injure one of the great vessels. Fortunately, most patients do quite well following surgery, with the majority achieving good-to-excellent results.6

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and underwent orthopedic surgery the following morning. Vascular and cardiothoracic surgeons were consulted and available in the event of a complication. A Salter-Harris type 2 fracture of the medial clavicle was identified intraoperatively, and an open reduction with internal fixation was performed. The patient had an uneventful recovery and resumed his usual activities, including playing hockey.

THE TAKEAWAY

PSCDs, although uncommon, can be life-threatening. Since the physical exam is unreliable and standard radiographs are often normal, accurate diagnosis relies largely on increased clinical suspicion. When there is a history of shoulder trauma, medial clavicle pain, and SCJ edema or tenderness, a PSCD should be suspected.7

Confirm the diagnosis with CT angiogram, and remember that a PSCD is a surgical emergency that requires coordination with orthopedic and vascular/cardiothoracic surgeons.

1. Chaudhry S. Pediatric posterior sternoclavicular joint injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:468-475.

2. Ponce BA, Kundukulam JA, Pflugner R, et al. Sternoclavicular joint surgery: how far does danger lurk below? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:993-999.

3. Daya MR, Bengtzen RR. Shoulder. In: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:618-642.

4. Marcus MS, Tan V. Cerebrovascular accident in a 19-year-old patient: a case report of posterior sternoclavicular dislocation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:e1-e4.

5. Morell DJ, Thyagarajan DS. Sternoclavicular joint dislocation and its management: a review of the literature. World J Orthop. 2016;7:244-250.

6. Boesmueller S, Wech M, Tiefenboeck TM, et al. Incidence, characteristics, and long-term follow-up of sternoclavicular injuries: an epidemiologic analysis of 92 cases. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:289-295.

7. Roepke C, Kleiner M, Jhun P, et al. Chest pain bounce-back: posterior sternoclavicular dislocation. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:559-561.

1. Chaudhry S. Pediatric posterior sternoclavicular joint injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:468-475.

2. Ponce BA, Kundukulam JA, Pflugner R, et al. Sternoclavicular joint surgery: how far does danger lurk below? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:993-999.

3. Daya MR, Bengtzen RR. Shoulder. In: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:618-642.

4. Marcus MS, Tan V. Cerebrovascular accident in a 19-year-old patient: a case report of posterior sternoclavicular dislocation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:e1-e4.

5. Morell DJ, Thyagarajan DS. Sternoclavicular joint dislocation and its management: a review of the literature. World J Orthop. 2016;7:244-250.

6. Boesmueller S, Wech M, Tiefenboeck TM, et al. Incidence, characteristics, and long-term follow-up of sternoclavicular injuries: an epidemiologic analysis of 92 cases. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:289-295.

7. Roepke C, Kleiner M, Jhun P, et al. Chest pain bounce-back: posterior sternoclavicular dislocation. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:559-561.

Bedside Ultrasound for Pulsatile Hand Mass

Case

A 23-year-old man presented to an outside hospital’s ED for evaluation of a wound on his right hand, which he sustained after he accidentally stabbed himself with a steak knife. At presentation, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; blood pressure, 150/92 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.1°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Examination revealed a laceration on the patient’s right hand measuring 2 cm in length. The emergency physician (EP) closed the wound using four nylon sutures and administered a Boostrix shot. The patient was discharged home with a prescription for cephalexin capsule 500 mg to be taken four times daily for 5 days. He was instructed to return in 10 days for suture removal, but failed to follow-up.

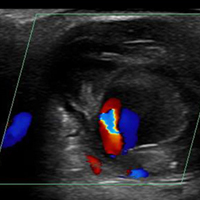

The patient presented to our ED two months after the initial injury for evaluation of a 1.5-cm round pulsatile mass on his right palm, at the base of the middle finger, from which exuded a small amount of sanguineous fluid. The patient complained of numbness and difficulty extending his right index and middle fingers.

Discussion

Palmar Pseudoaneurysms

A pseudoaneurysm, also referred to as a traumatic aneurysm, develops when a tear of the vessel wall and hemorrhage is contained by a thin-walled capsule, typically following traumatic perforation of the arterial wall. Unlike a true aneurysm, a pseudoaneurysm does not contain all three layers of intima, media, and adventitia. Thin walls lead to inevitable expansion over time; in some cases, a patient will present with a soft-tissue mass years after the initial injury. Compression of nearby structures can cause neuropathy, peripheral edema, venous thrombosis, arterial occlusion or emboli, and even bone erosion.1,2

Hand pseudoaneurysms are more likely to occur on the palmar surface, involving the superficial palmar arch,3 and are due to a penetrating injury or repetitive microtrauma. Hypothenar hammer syndrome occurs when repetitive microtrauma is applied to the ulnar artery as it passes under the hook of the hamate bone into the hand. This condition is also referred to as “hammer hand syndrome” because it frequently occurs in laborers such as mechanics, carpenters, and machinists as a result of repetitive palm trauma. Cases have also been reported in baseball players and cooks who also expose their hands to repetitive trauma.3 Likewise, elderly patients who use walking canes can also present with bilateral hammer hand syndrome,3 and patients who need crutches for a prolonged period of time may also develop axillary artery aneurysms.1,2

Although rare, there have also been cases of spontaneous hand pseudoaneurysms in patients on anticoagulation therapy;4,5 however, pseudoaneurysms are not an absolute contraindication to initiating or continuing use of anticoagulants.

Evaluation

Physical Examination. The patient’s mass in this case was clearly pulsatile on examination, but physical examination alone is not a reliable indicator of pseudoaneurysm, as patients may present only with soft-tissue swelling, pain, erythema, or neurological symptoms.3,6,7

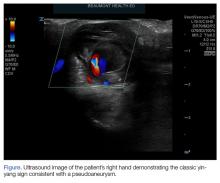

Ultrasound Imaging. In the emergency setting, POC ultrasound should be performed to evaluate any soft-tissue hand mass, especially in the context of trauma or any neurovascular findings, since palmar pseudoaneurysms can easily be confused with an abscess, foreign body, cyst, or even a tendon tear.6 Ultrasound studies using the linear vascular probe should always be done before any attempt to incise and drain the mass.

Three ultrasound characteristics of pseudoaneurysms include expansile pulsatility, turbulent flow with a classic yin-yang sign on Doppler, and a hematoma with variable echogenicity. Variable echogenicity may represent separate episodes of bleeding and rebleeding.8 A “to-and-fro” spectral waveform is pathognomonic for palmar pseudoaneurysms.8

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Angiography. Definitive imaging for operative management includes computed tomography or magnetic resonance angiography to assess for the exact location and presence of collateral circulation.

Treatment

Treatment of pseudoaneurysms includes conservative compression therapy, surgical excision, or anastomosis, and more recently, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection (UGTI).

Compression Therapy. Compression therapy is often used for femoral artery pseudoaneurysms that develop after iatrogenic injury. However, this technique is time consuming, is uncomfortable for patients, is not effective in treating large pseudoaneurysms, and is contraindicated in patients on anticoagulation therapy. Compression therapy also has a high-failure rate of resolving pseudoaneurysms. Traditionally, surgical excision or anastomosis has been the definitive treatment for palmar pseudoaneurysms.

Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. A more recent treatment option is UGTI, which is usually performed by an interventional radiologist. Although there is no consensus on exact dose of thrombin for this procedure, the literature describes UGTI to treat both the radial and ulnar arteries.9,10 One study of 83 pseudoaneurysms demonstrated a relationship between the size of the palmar pseudoaneurysm and the number of thrombin injections required to resolve it. Depending on the size of the palmar pseudoaneurysm, the effective thrombin doses ranged from 200 to 2,500 U. Regarding adverse effects and events from treatment, this study reported one case of transient distal ischemia.11

Intravascular balloon occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm neck has also been recommended for UGTI in the femoral artery if the neck is greater than 1 mm, but there is currently nothing in the literature describing its use in palmar pseudoaneurysms.12

Complications

There are more descriptions of palmar, radial, and ulnar pseudoaneurysms in critical care patients due to the frequent, but necessary, use of invasive lines. Emergency physicians frequently place radial or femoral arterial lines for hemodynamic monitoring in critically ill patients. However, the incidence of pseudoaneurysms and its sequelae from these lines are not usually observed in the ED setting.

Radial arterial lines may cause thrombosis in 19% to 57% of cases, and local infection in 1% to 18% of cases.10 In a study of 12,500 patients with radial artery catheters, the rate of radial pseudoaneurysm was only 0.05%.11 Although this is a small complication rate, pseudoaneurysms can lead to significant loss of function. To decrease the number of attempts and penetrating injuries to the arteries, ultrasound guidance for these procedures in the ED is strongly recommended. In addition to decreasing the risk of developing a pseudoaneurysm, ultrasound-guidance decreases the discomfort level of the patient and reduces the risk of bleeding, hematoma formation, and infection. Arterial line placement in the ED using ultrasound guidance decreases the risk of developing pseudoaneurysms and their sequelae, such as distal embolization.

Case Conclusion

The patient in this case underwent an arterial duplex study, which found a partially thrombosed right superficial palmar arch pseudoaneurysm measuring 1.91 cm x 2.08 cm, with an active flow area measuring 0.58 cm x 0.68 cm. The flow to the index finger medial artery and middle finger lateral artery was also diminished. The patient was discharged home with a bulky soft dressing and underwent excision and repair by hand surgery 3 days later. At the 1-month postoperative follow-up visit, the patient had full sensation but mildly decreased range of motion in his fingers.

Summary

Hand pseudoaneurysms are often associated with penetrating injuries—as demonstrated in our case—or repetitive microtrauma. Hand pseudoaneurysms can present with minimal findings such as isolated soft-tissue swelling, pain, or neuropathy. The EP should consider vascular pathology in the differential for patients who present with posttraumatic neuropathy. Regarding imaging studies, ultrasound is the best imaging modality to assess for pseudoaneurysms, and EPs should have a low threshold for its use at bedside—especially prior to attempting any invasive procedure. Patients with a confirmed pseudoaneurysm should be referred to a hand or vascular surgeon for surgical repair, or to an interventional radiologist for UGTI.

1. Newton EJ, Arora S. Peripheral vascular injury. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 1. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:502.

2. Aufderheide TP. Peripheral arteriovascular disease. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 1. 8th ed. 2014:1147-1149.

3. Anderson SE, De Monaco D, Buechler U, et al. Imaging features of pseudoaneurysms of the hand in children and adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(3):659-664. doi:10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800659.

4. Shah S, Powell-Brett S, Garnham A. Pseudoaneurysm: an unusual cause of post-traumatic hand swelling. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. pii: bcr2014208750. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208750.

5. Kitamura A, Mukohara N. Spontaneous pseudoaneurysm of the hand. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(3):739.e1-e3. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2013.04.033.

6. Huang SW, Wei TS, Liu SY, Wang WT. Spontaneous totally thrombosed pseudoaneurysm mimicking a tendon tear of the wrist. Orthopedics. 2010;33(10):776. doi:10.3928/01477447-20100826-23.

7. Belyayev L, Rich NM, McKay P, Nesti L, Wind G. Traumatic ulnar artery pseudoaneurysm following a grenade blast: report of a case. Mil Med. 2015;180(6):e725-e727. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00400.

8. Pero T, Herrick J. Pseudoaneurysm of the radial artery diagnosed by bedside ultrasound. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10(2):89-91.

9. Bosman A, Veger HTC, Doornink F, Hedeman Joosten PPA. A pseudoaneurysm of the deep palmar arch after penetrating trauma to the hand: successful exclusion by ultrasound guided percutaneous thrombin injection. EJVES Short Rep. 2016;31:9-11. doi:10.1016/j.ejvssr.2016.03.002.

10. Komorowska-Timek E, Teruya TH, Abou-Zamzam AM Jr, Papa D, Ballard JL. Treatment of radial and ulnar artery pseudoaneurysms using percutaneous thrombin injection. J Hand Surg. 2004;29A(5):936-942. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.05.009.

11. Falk PS, Scuderi PE, Sherertz RJ, Motsinger SM. Infected radial artery pseudoaneurysms occurring after percutaneous cannulation. Chest. 1992;101(2):490-495.

12. Kang SS, Labropoulos N, Mansour MA, et al. Expanded indications for ultrasound-guided thrombin injection of pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31(2):289-298.

Case

A 23-year-old man presented to an outside hospital’s ED for evaluation of a wound on his right hand, which he sustained after he accidentally stabbed himself with a steak knife. At presentation, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; blood pressure, 150/92 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.1°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Examination revealed a laceration on the patient’s right hand measuring 2 cm in length. The emergency physician (EP) closed the wound using four nylon sutures and administered a Boostrix shot. The patient was discharged home with a prescription for cephalexin capsule 500 mg to be taken four times daily for 5 days. He was instructed to return in 10 days for suture removal, but failed to follow-up.

The patient presented to our ED two months after the initial injury for evaluation of a 1.5-cm round pulsatile mass on his right palm, at the base of the middle finger, from which exuded a small amount of sanguineous fluid. The patient complained of numbness and difficulty extending his right index and middle fingers.

Discussion

Palmar Pseudoaneurysms

A pseudoaneurysm, also referred to as a traumatic aneurysm, develops when a tear of the vessel wall and hemorrhage is contained by a thin-walled capsule, typically following traumatic perforation of the arterial wall. Unlike a true aneurysm, a pseudoaneurysm does not contain all three layers of intima, media, and adventitia. Thin walls lead to inevitable expansion over time; in some cases, a patient will present with a soft-tissue mass years after the initial injury. Compression of nearby structures can cause neuropathy, peripheral edema, venous thrombosis, arterial occlusion or emboli, and even bone erosion.1,2

Hand pseudoaneurysms are more likely to occur on the palmar surface, involving the superficial palmar arch,3 and are due to a penetrating injury or repetitive microtrauma. Hypothenar hammer syndrome occurs when repetitive microtrauma is applied to the ulnar artery as it passes under the hook of the hamate bone into the hand. This condition is also referred to as “hammer hand syndrome” because it frequently occurs in laborers such as mechanics, carpenters, and machinists as a result of repetitive palm trauma. Cases have also been reported in baseball players and cooks who also expose their hands to repetitive trauma.3 Likewise, elderly patients who use walking canes can also present with bilateral hammer hand syndrome,3 and patients who need crutches for a prolonged period of time may also develop axillary artery aneurysms.1,2

Although rare, there have also been cases of spontaneous hand pseudoaneurysms in patients on anticoagulation therapy;4,5 however, pseudoaneurysms are not an absolute contraindication to initiating or continuing use of anticoagulants.

Evaluation

Physical Examination. The patient’s mass in this case was clearly pulsatile on examination, but physical examination alone is not a reliable indicator of pseudoaneurysm, as patients may present only with soft-tissue swelling, pain, erythema, or neurological symptoms.3,6,7

Ultrasound Imaging. In the emergency setting, POC ultrasound should be performed to evaluate any soft-tissue hand mass, especially in the context of trauma or any neurovascular findings, since palmar pseudoaneurysms can easily be confused with an abscess, foreign body, cyst, or even a tendon tear.6 Ultrasound studies using the linear vascular probe should always be done before any attempt to incise and drain the mass.

Three ultrasound characteristics of pseudoaneurysms include expansile pulsatility, turbulent flow with a classic yin-yang sign on Doppler, and a hematoma with variable echogenicity. Variable echogenicity may represent separate episodes of bleeding and rebleeding.8 A “to-and-fro” spectral waveform is pathognomonic for palmar pseudoaneurysms.8

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Angiography. Definitive imaging for operative management includes computed tomography or magnetic resonance angiography to assess for the exact location and presence of collateral circulation.

Treatment

Treatment of pseudoaneurysms includes conservative compression therapy, surgical excision, or anastomosis, and more recently, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection (UGTI).

Compression Therapy. Compression therapy is often used for femoral artery pseudoaneurysms that develop after iatrogenic injury. However, this technique is time consuming, is uncomfortable for patients, is not effective in treating large pseudoaneurysms, and is contraindicated in patients on anticoagulation therapy. Compression therapy also has a high-failure rate of resolving pseudoaneurysms. Traditionally, surgical excision or anastomosis has been the definitive treatment for palmar pseudoaneurysms.

Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. A more recent treatment option is UGTI, which is usually performed by an interventional radiologist. Although there is no consensus on exact dose of thrombin for this procedure, the literature describes UGTI to treat both the radial and ulnar arteries.9,10 One study of 83 pseudoaneurysms demonstrated a relationship between the size of the palmar pseudoaneurysm and the number of thrombin injections required to resolve it. Depending on the size of the palmar pseudoaneurysm, the effective thrombin doses ranged from 200 to 2,500 U. Regarding adverse effects and events from treatment, this study reported one case of transient distal ischemia.11

Intravascular balloon occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm neck has also been recommended for UGTI in the femoral artery if the neck is greater than 1 mm, but there is currently nothing in the literature describing its use in palmar pseudoaneurysms.12

Complications

There are more descriptions of palmar, radial, and ulnar pseudoaneurysms in critical care patients due to the frequent, but necessary, use of invasive lines. Emergency physicians frequently place radial or femoral arterial lines for hemodynamic monitoring in critically ill patients. However, the incidence of pseudoaneurysms and its sequelae from these lines are not usually observed in the ED setting.

Radial arterial lines may cause thrombosis in 19% to 57% of cases, and local infection in 1% to 18% of cases.10 In a study of 12,500 patients with radial artery catheters, the rate of radial pseudoaneurysm was only 0.05%.11 Although this is a small complication rate, pseudoaneurysms can lead to significant loss of function. To decrease the number of attempts and penetrating injuries to the arteries, ultrasound guidance for these procedures in the ED is strongly recommended. In addition to decreasing the risk of developing a pseudoaneurysm, ultrasound-guidance decreases the discomfort level of the patient and reduces the risk of bleeding, hematoma formation, and infection. Arterial line placement in the ED using ultrasound guidance decreases the risk of developing pseudoaneurysms and their sequelae, such as distal embolization.

Case Conclusion

The patient in this case underwent an arterial duplex study, which found a partially thrombosed right superficial palmar arch pseudoaneurysm measuring 1.91 cm x 2.08 cm, with an active flow area measuring 0.58 cm x 0.68 cm. The flow to the index finger medial artery and middle finger lateral artery was also diminished. The patient was discharged home with a bulky soft dressing and underwent excision and repair by hand surgery 3 days later. At the 1-month postoperative follow-up visit, the patient had full sensation but mildly decreased range of motion in his fingers.

Summary

Hand pseudoaneurysms are often associated with penetrating injuries—as demonstrated in our case—or repetitive microtrauma. Hand pseudoaneurysms can present with minimal findings such as isolated soft-tissue swelling, pain, or neuropathy. The EP should consider vascular pathology in the differential for patients who present with posttraumatic neuropathy. Regarding imaging studies, ultrasound is the best imaging modality to assess for pseudoaneurysms, and EPs should have a low threshold for its use at bedside—especially prior to attempting any invasive procedure. Patients with a confirmed pseudoaneurysm should be referred to a hand or vascular surgeon for surgical repair, or to an interventional radiologist for UGTI.

Case

A 23-year-old man presented to an outside hospital’s ED for evaluation of a wound on his right hand, which he sustained after he accidentally stabbed himself with a steak knife. At presentation, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; blood pressure, 150/92 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.1°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Examination revealed a laceration on the patient’s right hand measuring 2 cm in length. The emergency physician (EP) closed the wound using four nylon sutures and administered a Boostrix shot. The patient was discharged home with a prescription for cephalexin capsule 500 mg to be taken four times daily for 5 days. He was instructed to return in 10 days for suture removal, but failed to follow-up.

The patient presented to our ED two months after the initial injury for evaluation of a 1.5-cm round pulsatile mass on his right palm, at the base of the middle finger, from which exuded a small amount of sanguineous fluid. The patient complained of numbness and difficulty extending his right index and middle fingers.

Discussion

Palmar Pseudoaneurysms

A pseudoaneurysm, also referred to as a traumatic aneurysm, develops when a tear of the vessel wall and hemorrhage is contained by a thin-walled capsule, typically following traumatic perforation of the arterial wall. Unlike a true aneurysm, a pseudoaneurysm does not contain all three layers of intima, media, and adventitia. Thin walls lead to inevitable expansion over time; in some cases, a patient will present with a soft-tissue mass years after the initial injury. Compression of nearby structures can cause neuropathy, peripheral edema, venous thrombosis, arterial occlusion or emboli, and even bone erosion.1,2

Hand pseudoaneurysms are more likely to occur on the palmar surface, involving the superficial palmar arch,3 and are due to a penetrating injury or repetitive microtrauma. Hypothenar hammer syndrome occurs when repetitive microtrauma is applied to the ulnar artery as it passes under the hook of the hamate bone into the hand. This condition is also referred to as “hammer hand syndrome” because it frequently occurs in laborers such as mechanics, carpenters, and machinists as a result of repetitive palm trauma. Cases have also been reported in baseball players and cooks who also expose their hands to repetitive trauma.3 Likewise, elderly patients who use walking canes can also present with bilateral hammer hand syndrome,3 and patients who need crutches for a prolonged period of time may also develop axillary artery aneurysms.1,2

Although rare, there have also been cases of spontaneous hand pseudoaneurysms in patients on anticoagulation therapy;4,5 however, pseudoaneurysms are not an absolute contraindication to initiating or continuing use of anticoagulants.

Evaluation

Physical Examination. The patient’s mass in this case was clearly pulsatile on examination, but physical examination alone is not a reliable indicator of pseudoaneurysm, as patients may present only with soft-tissue swelling, pain, erythema, or neurological symptoms.3,6,7

Ultrasound Imaging. In the emergency setting, POC ultrasound should be performed to evaluate any soft-tissue hand mass, especially in the context of trauma or any neurovascular findings, since palmar pseudoaneurysms can easily be confused with an abscess, foreign body, cyst, or even a tendon tear.6 Ultrasound studies using the linear vascular probe should always be done before any attempt to incise and drain the mass.

Three ultrasound characteristics of pseudoaneurysms include expansile pulsatility, turbulent flow with a classic yin-yang sign on Doppler, and a hematoma with variable echogenicity. Variable echogenicity may represent separate episodes of bleeding and rebleeding.8 A “to-and-fro” spectral waveform is pathognomonic for palmar pseudoaneurysms.8

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Angiography. Definitive imaging for operative management includes computed tomography or magnetic resonance angiography to assess for the exact location and presence of collateral circulation.

Treatment

Treatment of pseudoaneurysms includes conservative compression therapy, surgical excision, or anastomosis, and more recently, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection (UGTI).

Compression Therapy. Compression therapy is often used for femoral artery pseudoaneurysms that develop after iatrogenic injury. However, this technique is time consuming, is uncomfortable for patients, is not effective in treating large pseudoaneurysms, and is contraindicated in patients on anticoagulation therapy. Compression therapy also has a high-failure rate of resolving pseudoaneurysms. Traditionally, surgical excision or anastomosis has been the definitive treatment for palmar pseudoaneurysms.

Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. A more recent treatment option is UGTI, which is usually performed by an interventional radiologist. Although there is no consensus on exact dose of thrombin for this procedure, the literature describes UGTI to treat both the radial and ulnar arteries.9,10 One study of 83 pseudoaneurysms demonstrated a relationship between the size of the palmar pseudoaneurysm and the number of thrombin injections required to resolve it. Depending on the size of the palmar pseudoaneurysm, the effective thrombin doses ranged from 200 to 2,500 U. Regarding adverse effects and events from treatment, this study reported one case of transient distal ischemia.11

Intravascular balloon occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm neck has also been recommended for UGTI in the femoral artery if the neck is greater than 1 mm, but there is currently nothing in the literature describing its use in palmar pseudoaneurysms.12

Complications

There are more descriptions of palmar, radial, and ulnar pseudoaneurysms in critical care patients due to the frequent, but necessary, use of invasive lines. Emergency physicians frequently place radial or femoral arterial lines for hemodynamic monitoring in critically ill patients. However, the incidence of pseudoaneurysms and its sequelae from these lines are not usually observed in the ED setting.

Radial arterial lines may cause thrombosis in 19% to 57% of cases, and local infection in 1% to 18% of cases.10 In a study of 12,500 patients with radial artery catheters, the rate of radial pseudoaneurysm was only 0.05%.11 Although this is a small complication rate, pseudoaneurysms can lead to significant loss of function. To decrease the number of attempts and penetrating injuries to the arteries, ultrasound guidance for these procedures in the ED is strongly recommended. In addition to decreasing the risk of developing a pseudoaneurysm, ultrasound-guidance decreases the discomfort level of the patient and reduces the risk of bleeding, hematoma formation, and infection. Arterial line placement in the ED using ultrasound guidance decreases the risk of developing pseudoaneurysms and their sequelae, such as distal embolization.

Case Conclusion

The patient in this case underwent an arterial duplex study, which found a partially thrombosed right superficial palmar arch pseudoaneurysm measuring 1.91 cm x 2.08 cm, with an active flow area measuring 0.58 cm x 0.68 cm. The flow to the index finger medial artery and middle finger lateral artery was also diminished. The patient was discharged home with a bulky soft dressing and underwent excision and repair by hand surgery 3 days later. At the 1-month postoperative follow-up visit, the patient had full sensation but mildly decreased range of motion in his fingers.

Summary

Hand pseudoaneurysms are often associated with penetrating injuries—as demonstrated in our case—or repetitive microtrauma. Hand pseudoaneurysms can present with minimal findings such as isolated soft-tissue swelling, pain, or neuropathy. The EP should consider vascular pathology in the differential for patients who present with posttraumatic neuropathy. Regarding imaging studies, ultrasound is the best imaging modality to assess for pseudoaneurysms, and EPs should have a low threshold for its use at bedside—especially prior to attempting any invasive procedure. Patients with a confirmed pseudoaneurysm should be referred to a hand or vascular surgeon for surgical repair, or to an interventional radiologist for UGTI.

1. Newton EJ, Arora S. Peripheral vascular injury. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 1. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:502.

2. Aufderheide TP. Peripheral arteriovascular disease. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 1. 8th ed. 2014:1147-1149.

3. Anderson SE, De Monaco D, Buechler U, et al. Imaging features of pseudoaneurysms of the hand in children and adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(3):659-664. doi:10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800659.

4. Shah S, Powell-Brett S, Garnham A. Pseudoaneurysm: an unusual cause of post-traumatic hand swelling. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. pii: bcr2014208750. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208750.

5. Kitamura A, Mukohara N. Spontaneous pseudoaneurysm of the hand. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(3):739.e1-e3. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2013.04.033.

6. Huang SW, Wei TS, Liu SY, Wang WT. Spontaneous totally thrombosed pseudoaneurysm mimicking a tendon tear of the wrist. Orthopedics. 2010;33(10):776. doi:10.3928/01477447-20100826-23.

7. Belyayev L, Rich NM, McKay P, Nesti L, Wind G. Traumatic ulnar artery pseudoaneurysm following a grenade blast: report of a case. Mil Med. 2015;180(6):e725-e727. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00400.

8. Pero T, Herrick J. Pseudoaneurysm of the radial artery diagnosed by bedside ultrasound. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10(2):89-91.

9. Bosman A, Veger HTC, Doornink F, Hedeman Joosten PPA. A pseudoaneurysm of the deep palmar arch after penetrating trauma to the hand: successful exclusion by ultrasound guided percutaneous thrombin injection. EJVES Short Rep. 2016;31:9-11. doi:10.1016/j.ejvssr.2016.03.002.

10. Komorowska-Timek E, Teruya TH, Abou-Zamzam AM Jr, Papa D, Ballard JL. Treatment of radial and ulnar artery pseudoaneurysms using percutaneous thrombin injection. J Hand Surg. 2004;29A(5):936-942. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.05.009.

11. Falk PS, Scuderi PE, Sherertz RJ, Motsinger SM. Infected radial artery pseudoaneurysms occurring after percutaneous cannulation. Chest. 1992;101(2):490-495.

12. Kang SS, Labropoulos N, Mansour MA, et al. Expanded indications for ultrasound-guided thrombin injection of pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31(2):289-298.

1. Newton EJ, Arora S. Peripheral vascular injury. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 1. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:502.

2. Aufderheide TP. Peripheral arteriovascular disease. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 1. 8th ed. 2014:1147-1149.

3. Anderson SE, De Monaco D, Buechler U, et al. Imaging features of pseudoaneurysms of the hand in children and adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(3):659-664. doi:10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800659.

4. Shah S, Powell-Brett S, Garnham A. Pseudoaneurysm: an unusual cause of post-traumatic hand swelling. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. pii: bcr2014208750. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208750.

5. Kitamura A, Mukohara N. Spontaneous pseudoaneurysm of the hand. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(3):739.e1-e3. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2013.04.033.

6. Huang SW, Wei TS, Liu SY, Wang WT. Spontaneous totally thrombosed pseudoaneurysm mimicking a tendon tear of the wrist. Orthopedics. 2010;33(10):776. doi:10.3928/01477447-20100826-23.

7. Belyayev L, Rich NM, McKay P, Nesti L, Wind G. Traumatic ulnar artery pseudoaneurysm following a grenade blast: report of a case. Mil Med. 2015;180(6):e725-e727. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00400.

8. Pero T, Herrick J. Pseudoaneurysm of the radial artery diagnosed by bedside ultrasound. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10(2):89-91.

9. Bosman A, Veger HTC, Doornink F, Hedeman Joosten PPA. A pseudoaneurysm of the deep palmar arch after penetrating trauma to the hand: successful exclusion by ultrasound guided percutaneous thrombin injection. EJVES Short Rep. 2016;31:9-11. doi:10.1016/j.ejvssr.2016.03.002.

10. Komorowska-Timek E, Teruya TH, Abou-Zamzam AM Jr, Papa D, Ballard JL. Treatment of radial and ulnar artery pseudoaneurysms using percutaneous thrombin injection. J Hand Surg. 2004;29A(5):936-942. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.05.009.

11. Falk PS, Scuderi PE, Sherertz RJ, Motsinger SM. Infected radial artery pseudoaneurysms occurring after percutaneous cannulation. Chest. 1992;101(2):490-495.

12. Kang SS, Labropoulos N, Mansour MA, et al. Expanded indications for ultrasound-guided thrombin injection of pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31(2):289-298.

A Recalcitrant Case of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

One of the most severe complications of systemic medications is the development of a life-threatening rash, especially toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Most patients can expect a full recovery if the complicating medication is discontinued early on in its course.1 When suspected TEN does not improve despite discontinuation of the detrimental medication, other diseases must be considered, particularly immunobullous and infectious etiologies. Treatment of these diseases differs substantially; therefore, a quick diagnosis is crucial. We present a case of a patient with an acute blistering eruption that was initially diagnosed and managed as TEN but physical examination and histopathologic confirmed another diagnosis. We review key examination findings that can help differentiate the causes of an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, allowing for earlier diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

Case Report

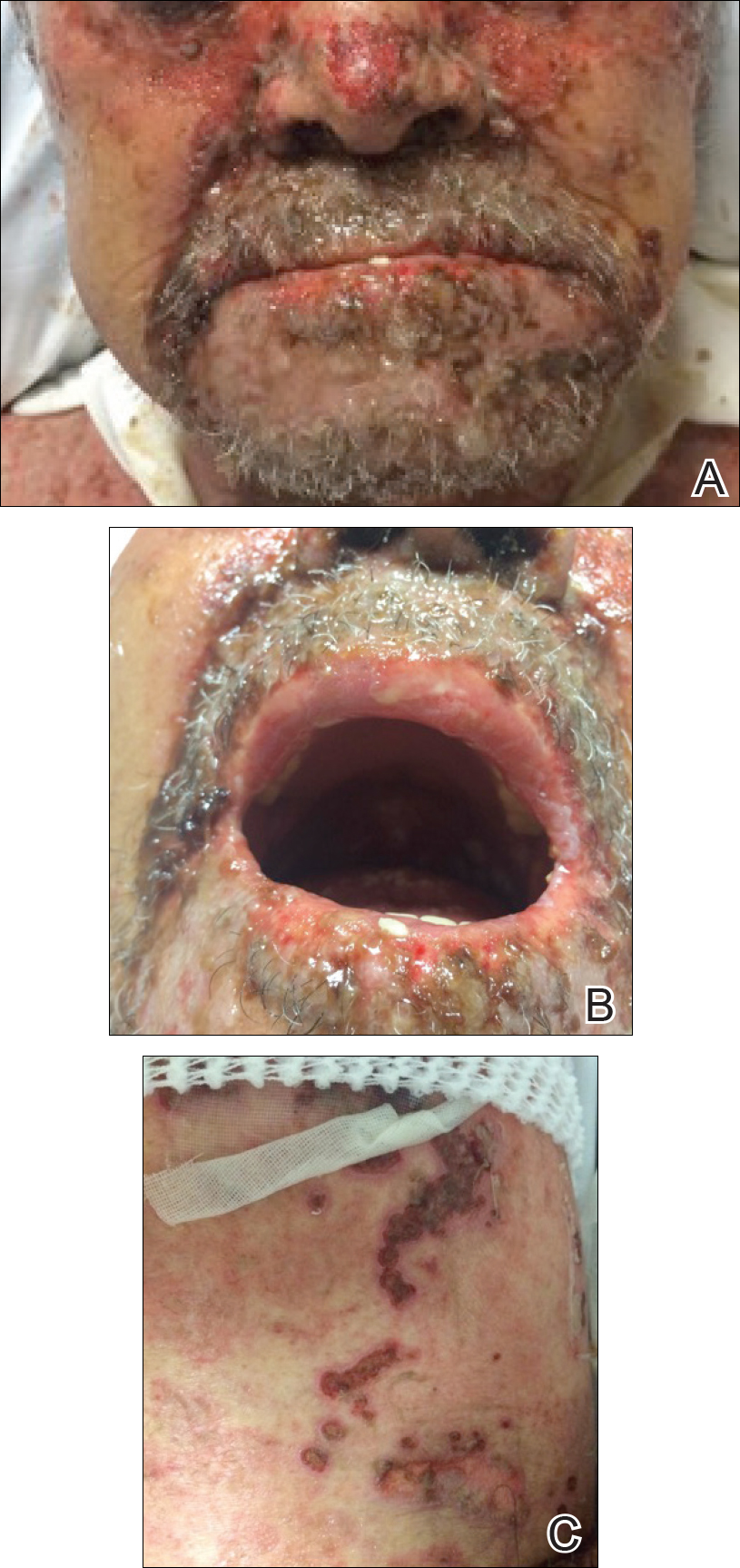

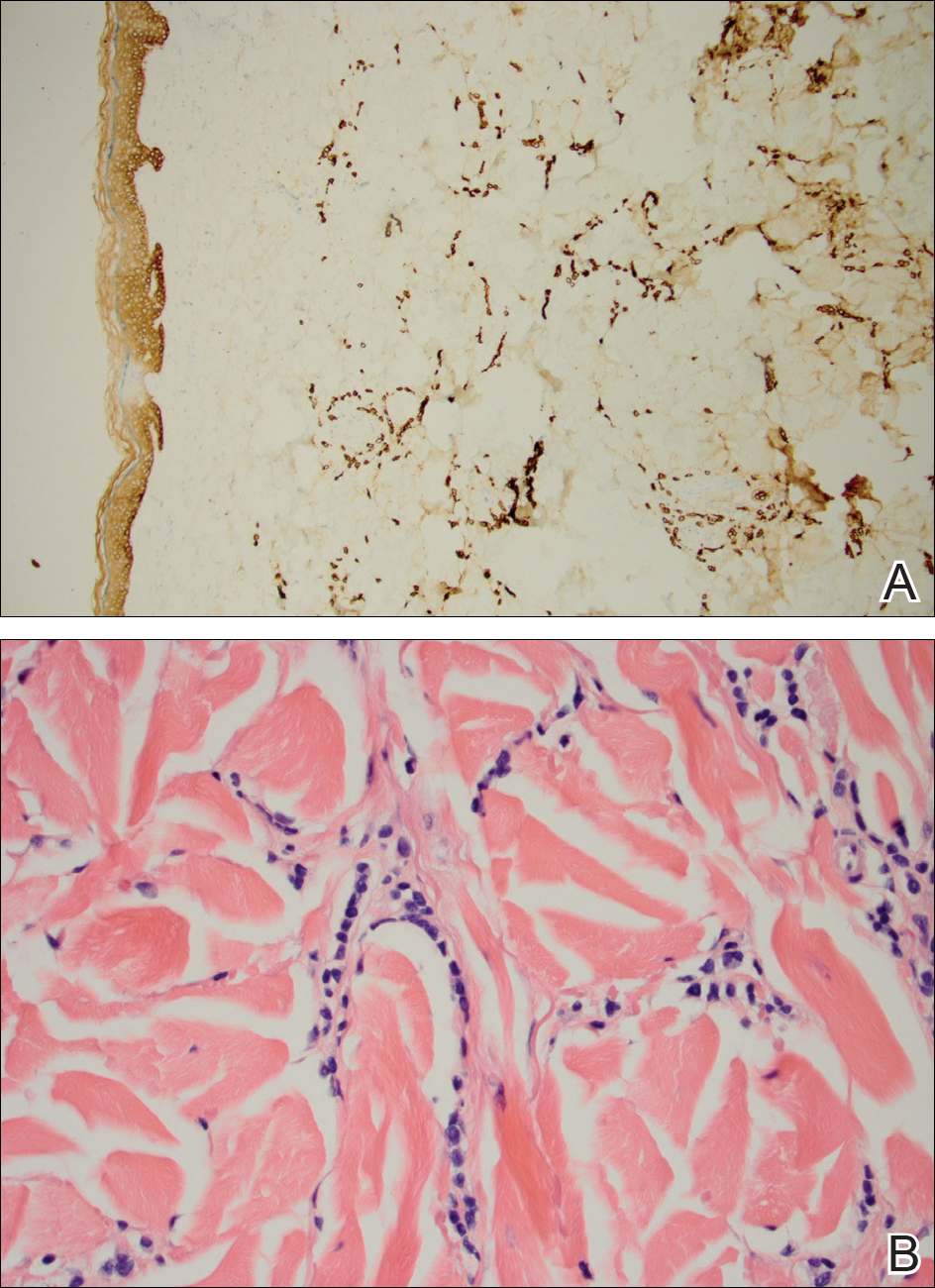

An 85-year-old immunocompetent man was admitted to an outside hospital with a pruritic blistering eruption associated with myalgia, weakness, and fatigue of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption initiated on the scalp and face and then spread down to the trunk and proximal arms and legs, with oral erosions also reported. An outside dermatologist was consulted on admission and performed a skin biopsy; the initial pathology was read as TEN. The patient was admitted to our institution on the same day, and all potentially complicating medications were stopped. He was treated with intravenous (IV)

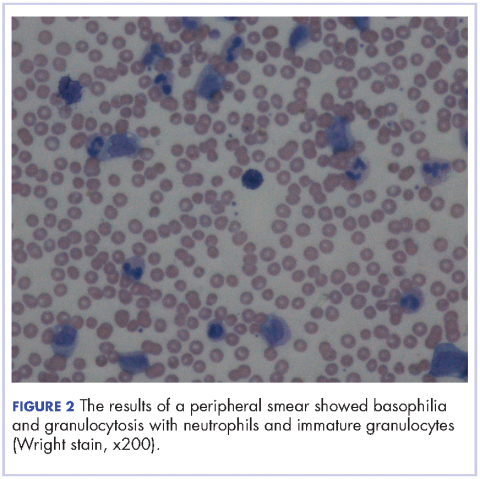

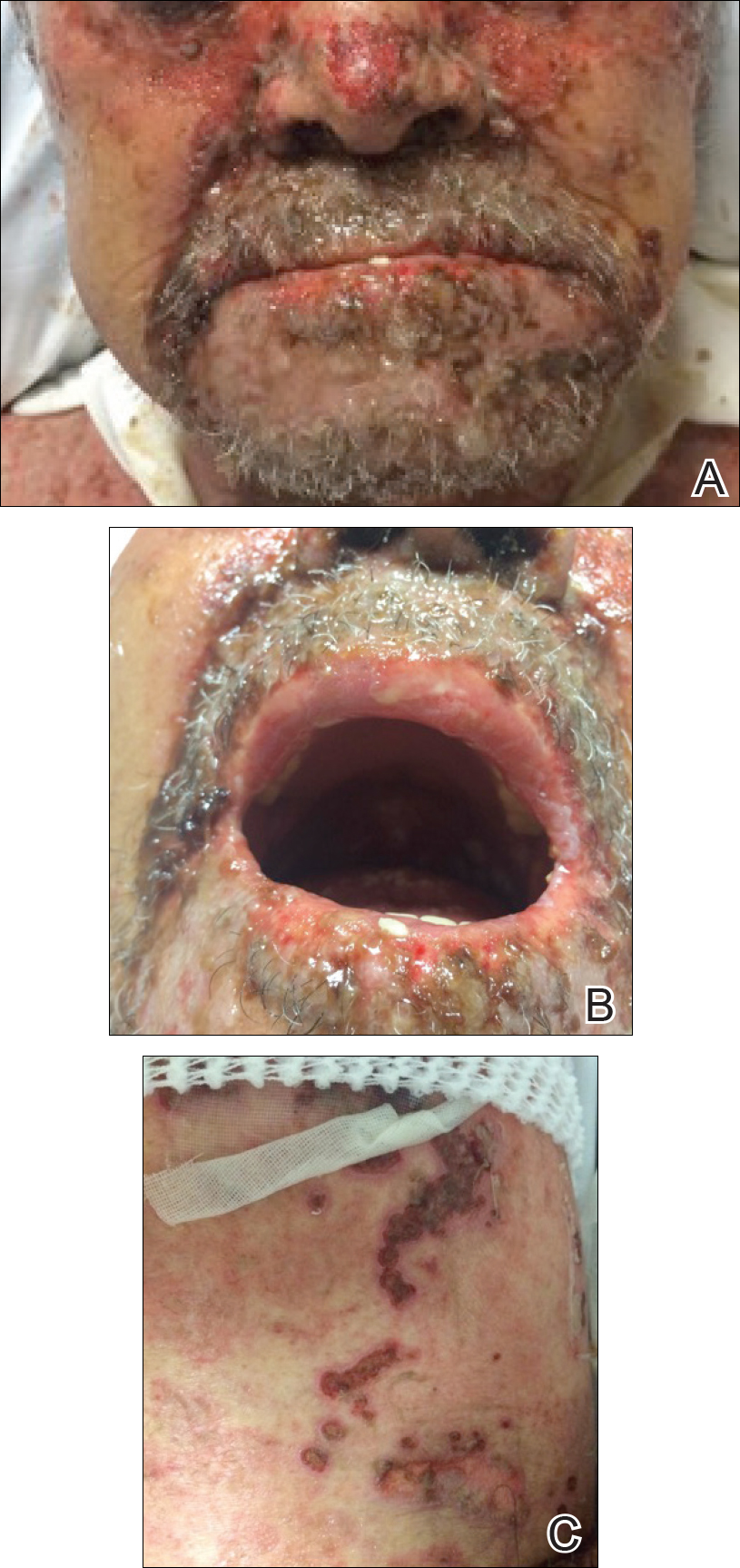

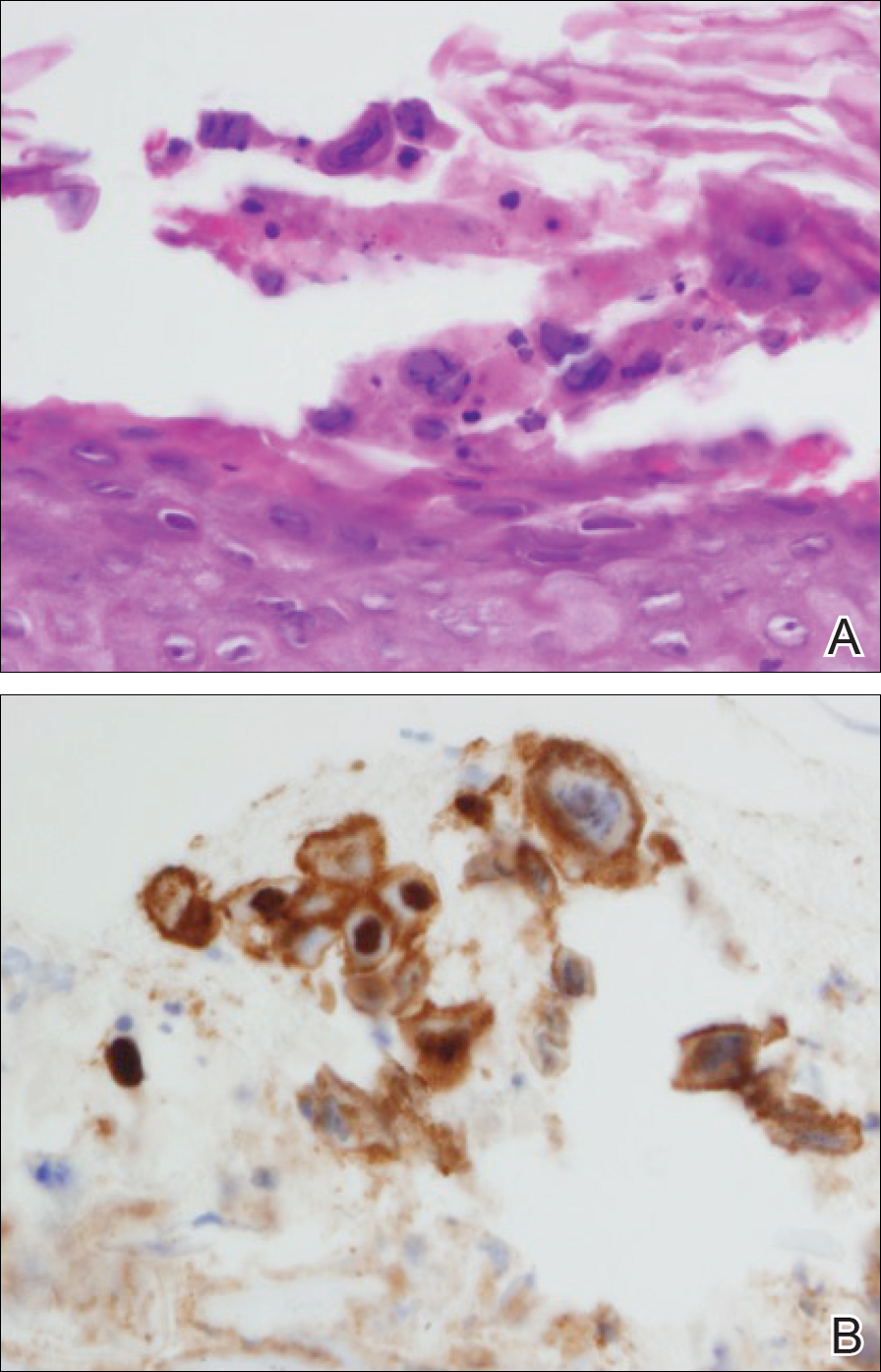

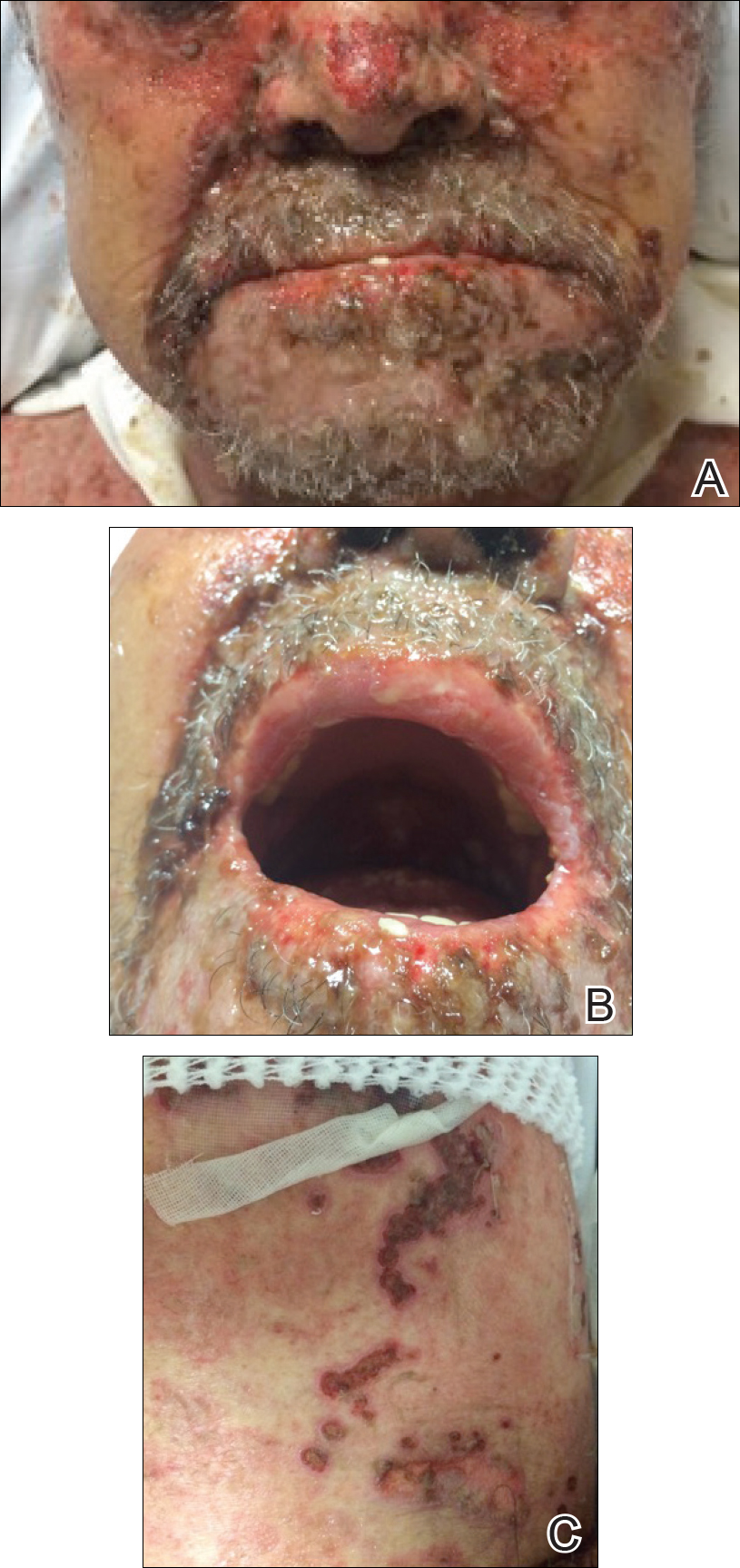

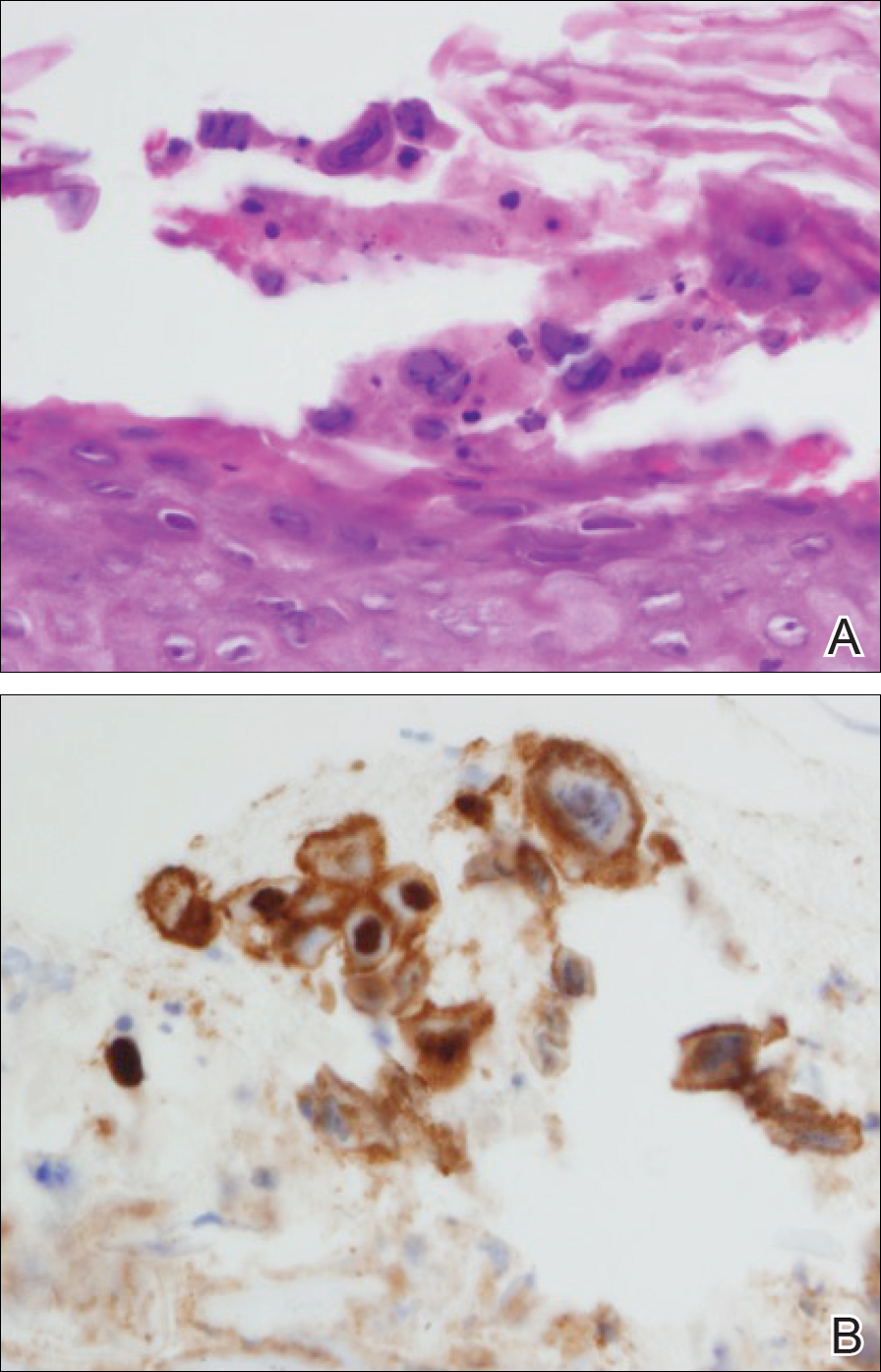

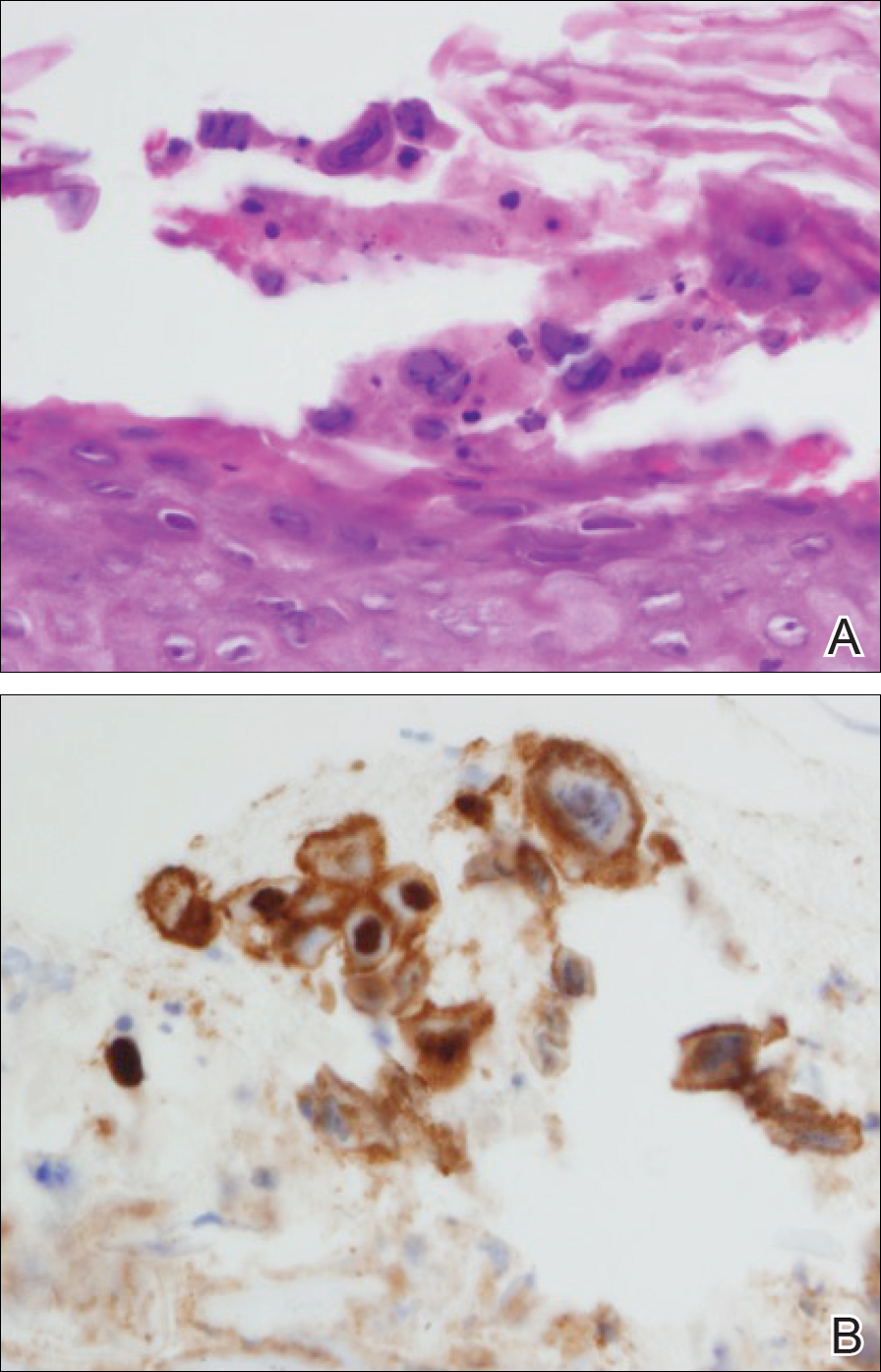

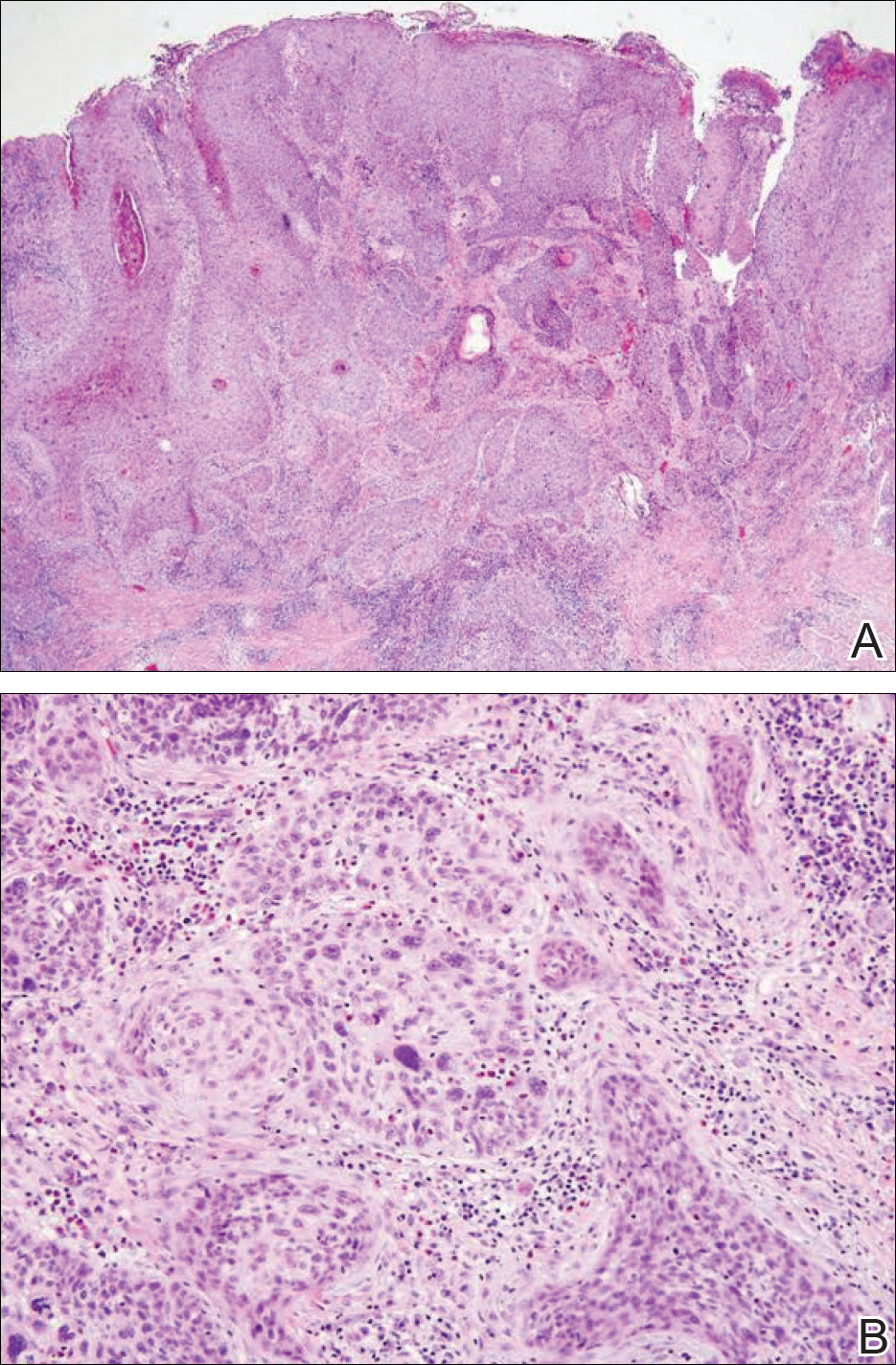

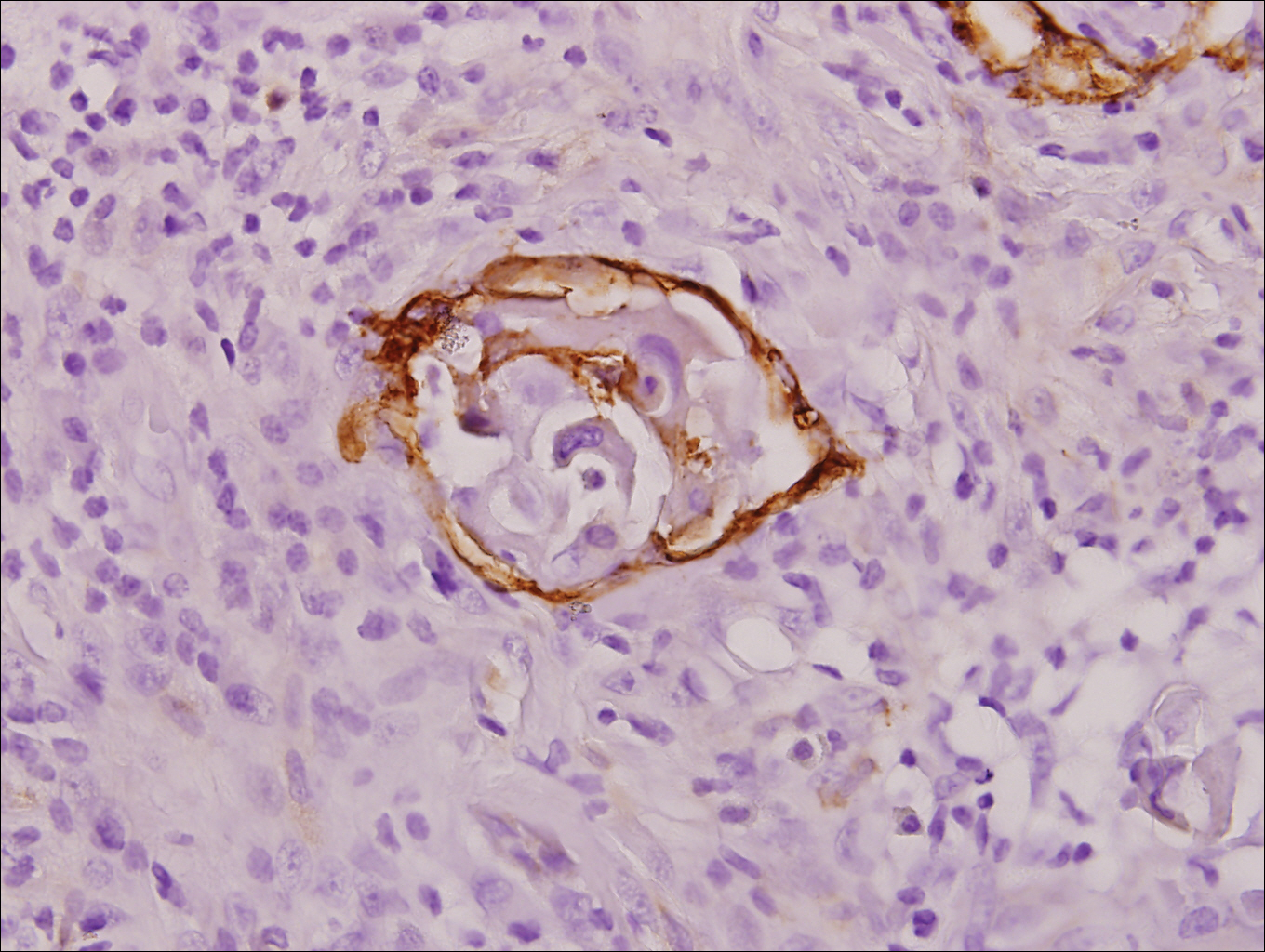

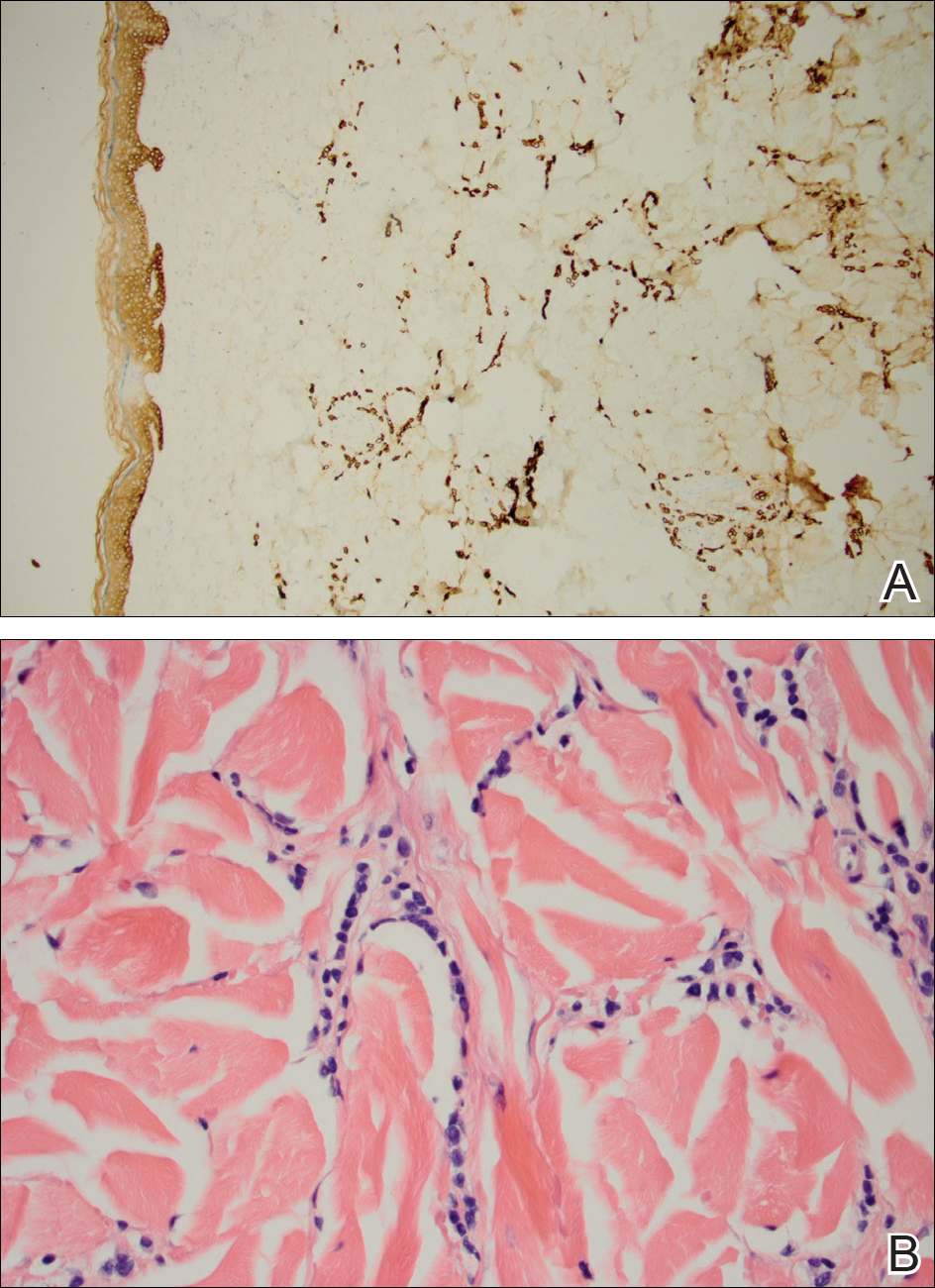

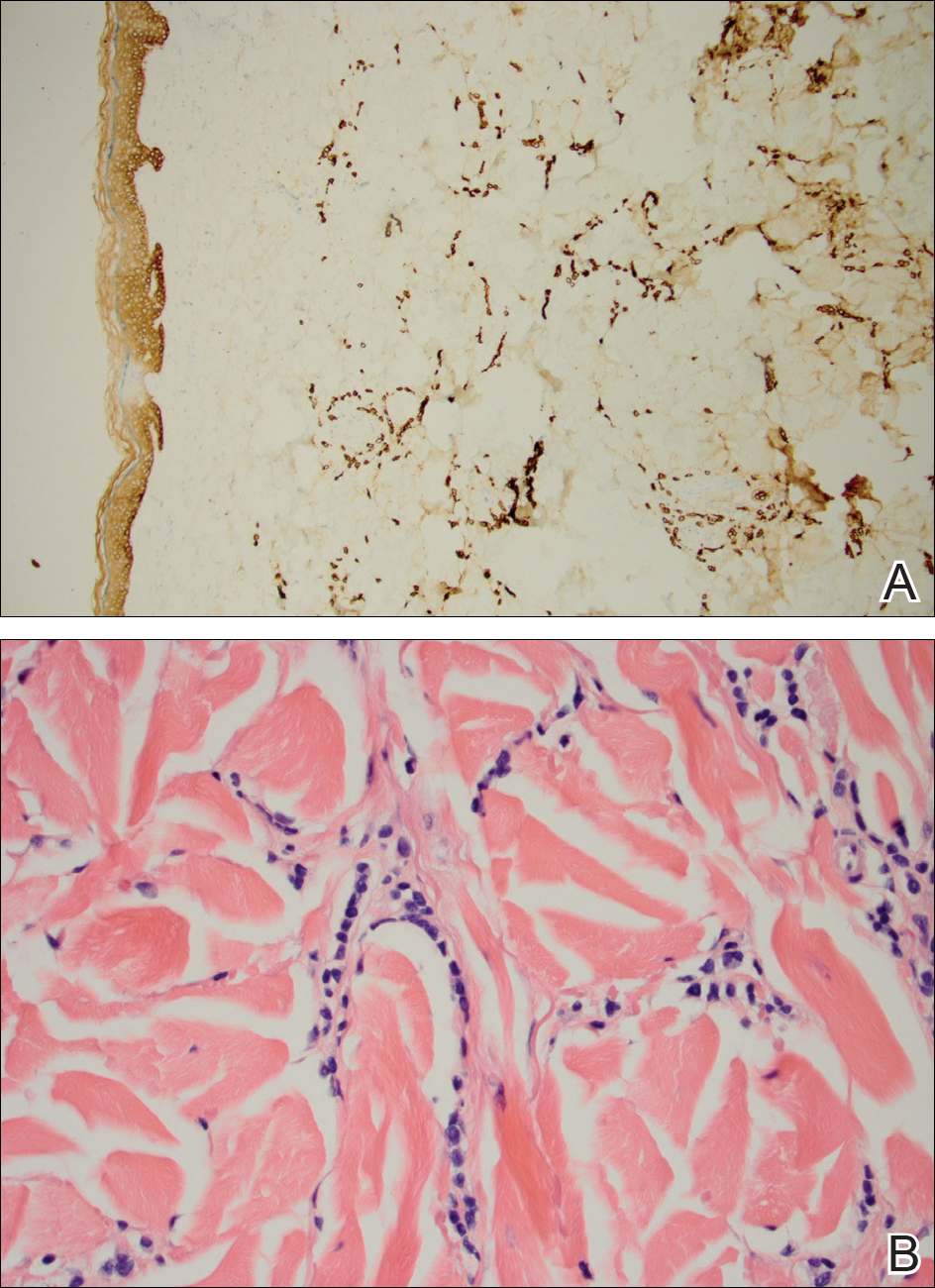

At that time, physical examination revealed numerous confluent erosions with honey-colored crust involving the entire face (Figure 1A) and sharp demarcation at the cutaneous lip (Figure 1B). There was a large erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral mucosa was spared. The trunk and proximal extremities showed numerous grouped, punched-out erosions with scalloped borders (Figure 1C). A repeat skin biopsy showed an ulcer with viral cytopathic changes. Immunoperoxidase studies demonstrated positive staining for herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (Figure 2). The original slides were a frozen section from an outside facility and could not be obtained. A tissue culture and direct fluorescent antibody also confirmed HSV-1, and the patient was diagnosed with disseminated herpes. He was rapidly tapered off of the steroids and started on IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 21 days. All prior erosions reepithelialized within 7 days of treatment (Figure 3). The patient had an otherwise uncomplicated hospital course and was discharged on hospital day 21.

Comment

A patient with an acute generalized blistering eruption requires urgent workup and treatment given the potentially devastating sequelae. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and immunobullous diseases often are the first diagnoses to be ruled out. Certainly infections such as HSV can cause a vesicular and erosive eruption, especially in the setting of a poorly controlled dermatitis, but they typically are not in the same differential as the other diagnoses.

Clinical Presentation

This case highlights 2 key physical examination findings that can alert the clinician to a possible underlying herpetic infection. First, the distribution of this patient’s oral lesions was telling. In most cases of TEN or pemphigus vulgaris, there is notable involvement of the oral mucosa, particularly the buccal and labial mucosa. Although herpes can involve any mucocutaneous surface, it does have a predilection for keratinized tissue, with the tongue and cutaneous lip commonly involved.2,3 Our patient had a solitary linear erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral cavity was strikingly spared. In addition, the erosions around the mouth stopped right at the cutaneous lip, sparing the labial mucosa (Figure 1B).

Second, the configuration of the erosions on the trunk, arms, and legs was diagnostic. Herpes classically presents as a cluster of vesicles overlying an erythematous base. When these vesicles rupture, punched-out erosions are left behind. Because these vesicles often are grouped, they can develop a scalloped border, which is a helpful indicator of HSV (Figure 1C). When these erosions become more confluent and irregular, the distinction from other conditions may not be as clear. A careful skin examination often can show areas that have preserved this herpetiform configuration.

Immune Compromise

Additionally, this case is illustrative of how immunosuppression and immunocompromise can affect the clinical presentation of HSV infection. Herpetic infections in the immunocompromised host tend to have a more protracted course, with chronic enlarging ulcers involving multiple sites.

Conclusion

This case is a good reminder that not everything that blisters and involves the mucosa is due to a hypersensitivity state such as TEN and Stevens-Johnson syndrome or an immunobullous disorder such as pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus vegetans. The fact that this patient was worsening despite drug cessation, high-dose steroids, and IV immunoglobulin should have indicated a misdiagnosis. This case also shows that the early histopathologic findings of disseminated HSV and TEN can be nonspecific, and viral cytopathic changes may not always be obvious early in the disease.

Disseminated HSV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient with an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, and careful history and physical examination should be taken to rule out a viral etiology.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173.e1-173.e13.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008.

- Woo SB, Lee SF. Oral recrudescent herpes simplex virus infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:239-243.

One of the most severe complications of systemic medications is the development of a life-threatening rash, especially toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Most patients can expect a full recovery if the complicating medication is discontinued early on in its course.1 When suspected TEN does not improve despite discontinuation of the detrimental medication, other diseases must be considered, particularly immunobullous and infectious etiologies. Treatment of these diseases differs substantially; therefore, a quick diagnosis is crucial. We present a case of a patient with an acute blistering eruption that was initially diagnosed and managed as TEN but physical examination and histopathologic confirmed another diagnosis. We review key examination findings that can help differentiate the causes of an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, allowing for earlier diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

Case Report

An 85-year-old immunocompetent man was admitted to an outside hospital with a pruritic blistering eruption associated with myalgia, weakness, and fatigue of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption initiated on the scalp and face and then spread down to the trunk and proximal arms and legs, with oral erosions also reported. An outside dermatologist was consulted on admission and performed a skin biopsy; the initial pathology was read as TEN. The patient was admitted to our institution on the same day, and all potentially complicating medications were stopped. He was treated with intravenous (IV)