User login

Evaluating the Clinical and Demographic Features of Extrafacial Granuloma Faciale

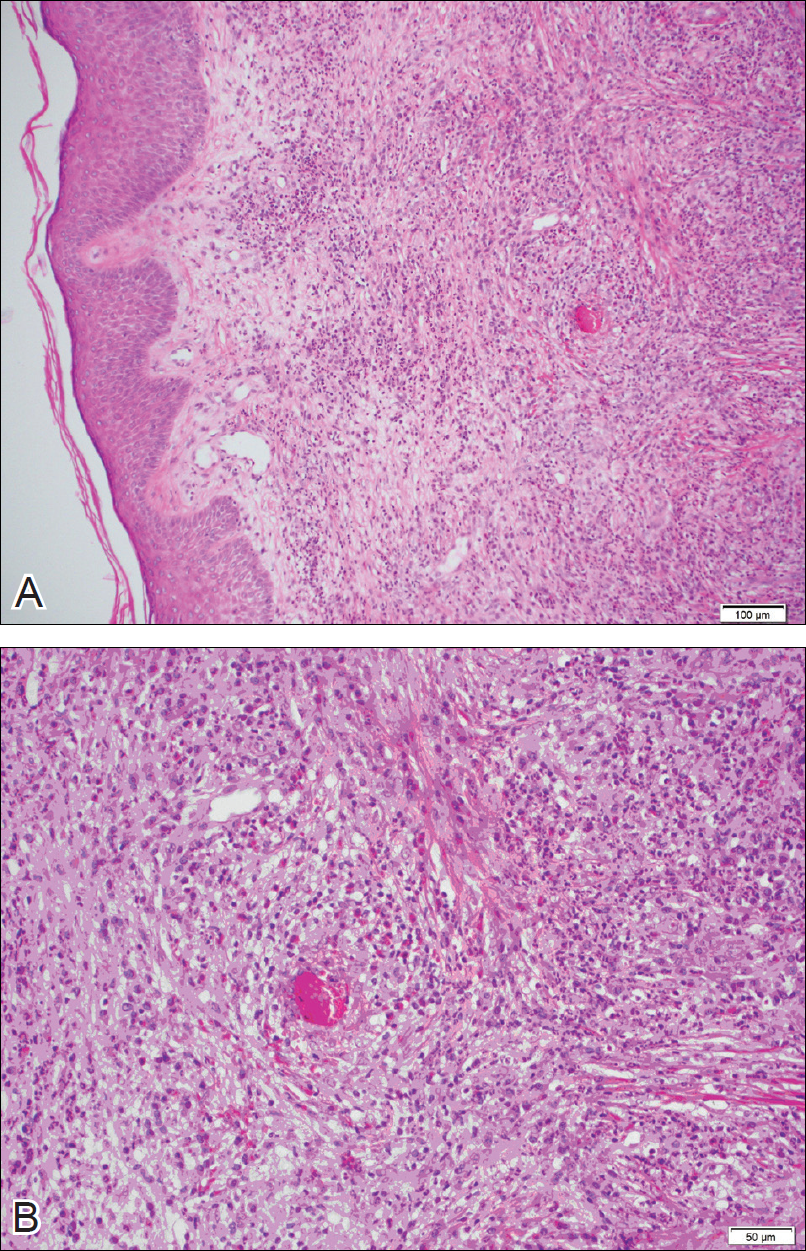

Granuloma faciale (GF) is a chronic benign leukocytoclastic vasculitis that can be difficult to treat. It is characterized by single or multiple, soft, well-circumscribed papules, plaques, or nodules ranging in color from red, violet, or yellow to brown that may darken with sun exposure.1 Lesions usually are smooth with follicular orifices that are accentuated, thus producing a peau d’orange appearance. Lesions generally are slow to develop and asymptomatic, though some patients report pruritus or burning.2,3 Diagnosis of GF is based on the presence of distinct histologic features. The epidermis usually is spared, with a prominent grenz zone of normal collagen separating the epidermis from a dense infiltrate of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. This mixed inflammatory infiltrate is seen mainly in the superficial dermis but occasionally spreads to the lower dermis and subcutaneous tissues.4

As the name implies, GF usually is confined to the face but occasionally involves extrafacial sites.5-15 The clinical characteristics of these rare extrafacial lesions are not well understood. The purpose of this study was to identify the clinical and demographic features of extrafacial GF in patients treated at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) during a 54-year period.

Methods

This study was approved by the Mayo institutional review board. We searched the Mayo Clinic Rochester dermatology database for all patients with a diagnosis of GF from 1959 through 2013. All histopathology slides were reviewed by a board-certified dermatologist (A.G.B.) and dermatopathologist (A.G.B.) before inclusion in this study. Histologic criteria for diagnosis of GF included the presence of a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes in the superficial or deep dermis; a prominent grenz zone separating the uninvolved epidermis; and the presence of vascular damage, as seen by fibrin deposition in dermal blood vessels.

Medical records were reviewed for patient demographics and for history pertinent to the diagnosis of GF, including sites involved, appearance, histopathology reports, symptoms, treatments, and outcomes.

Literature Search Strategy

A computerized Ovid MEDLINE database search was undertaken to identify English-language articles concerning GF in humans using the search terms granuloma faciale with extrafacial or disseminated. To ensure that no articles were overlooked, we conducted another search for English-language articles in the Embase database (1946-2013) using the terms granuloma faciale and extrafacial or disseminated.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive clinical and histopathologic data were summarized using means, medians, and ranges or proportions as appropriate; statistical analysis was performed using SAS software (JMP package).

Results

Ninety-six patients with a diagnosis of GF were identified, and 12 (13%) had a diagnosis of extrafacial GF. Of them, 2 patients had a diagnosis of extrafacial GF supported only by histopathology slides without accompanying clinical records and therefore were excluded from the study. Thus, 10 cases of extrafacial GF were identified from our search and were included in the study group. Clinical data for these patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 58.7 years (range, 26–87 years). Six (60%) patients were male, and all patients were white. Seven patients (70%) had facial GF in addition to extrafacial GF. Six patients reported no symptoms (60%), and 4 (40%) reported pruritus, discomfort, or both associated with their GF lesions.

Extrafacial GF was diagnosed in the following anatomic locations: scalp (n=3 [30%]), posterior auricular area (n=3 [30%]), mid upper back (n=1 [10%]), right shoulder (n=1 [10%]), both ears (n=1 [10%]), right elbow (n=1 [10%]), and left infra-auricular area (n=1 [10%]). Only 1 (10%) patient had multiple extrafacial sites identified.

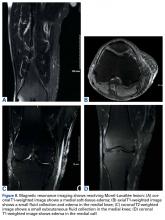

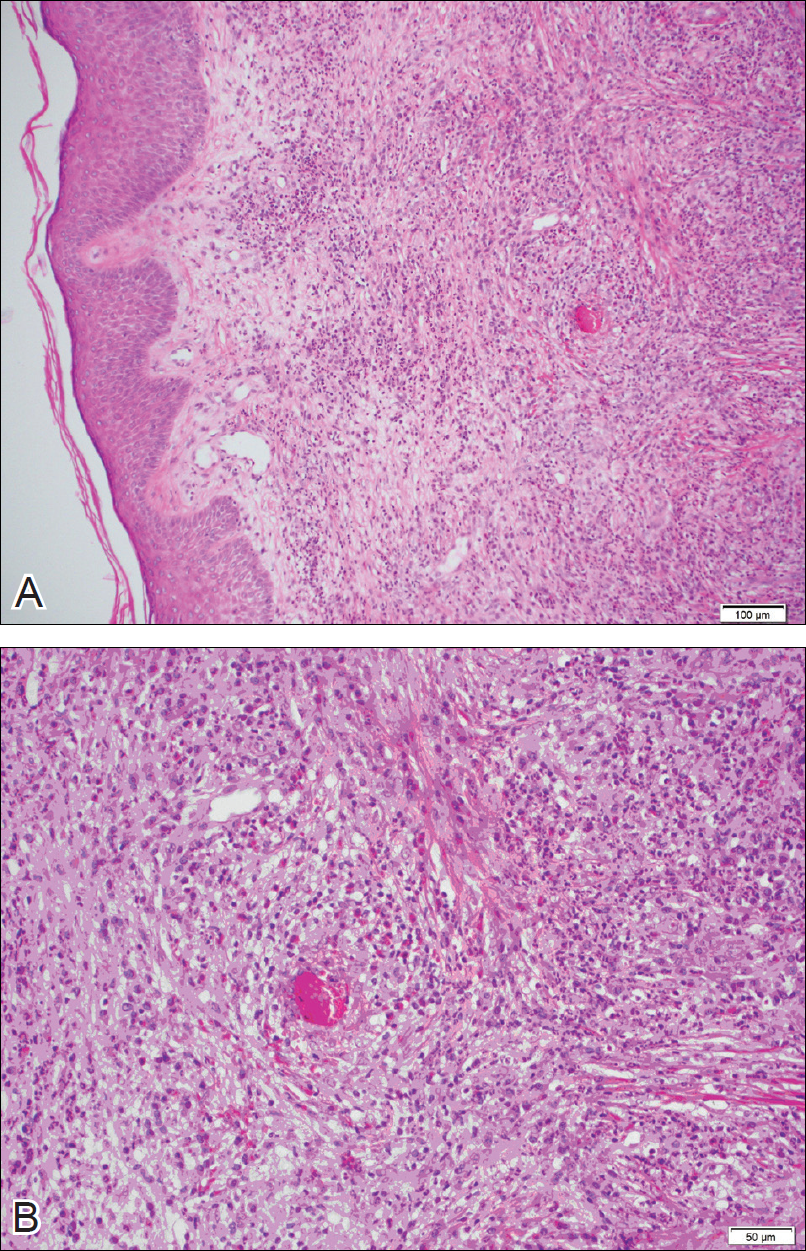

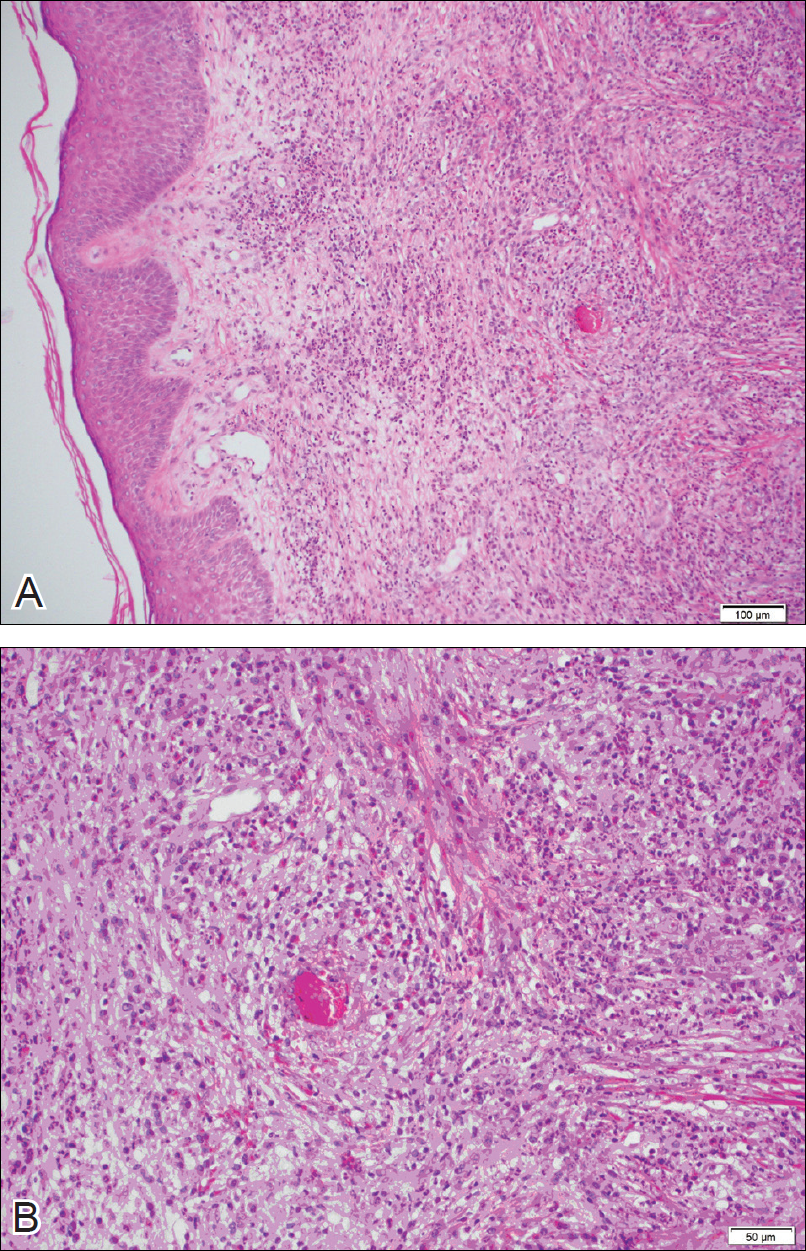

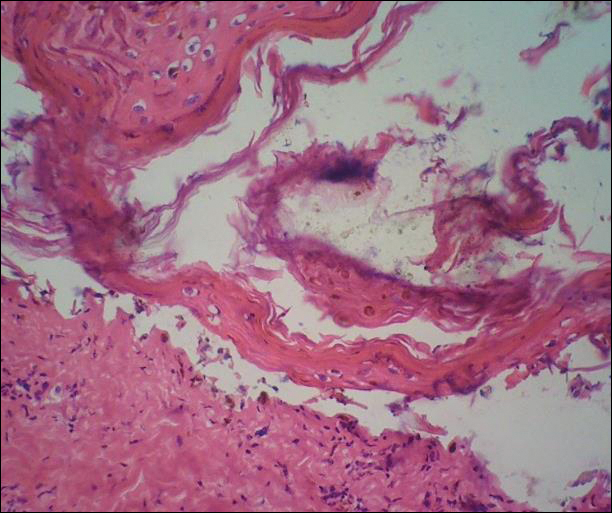

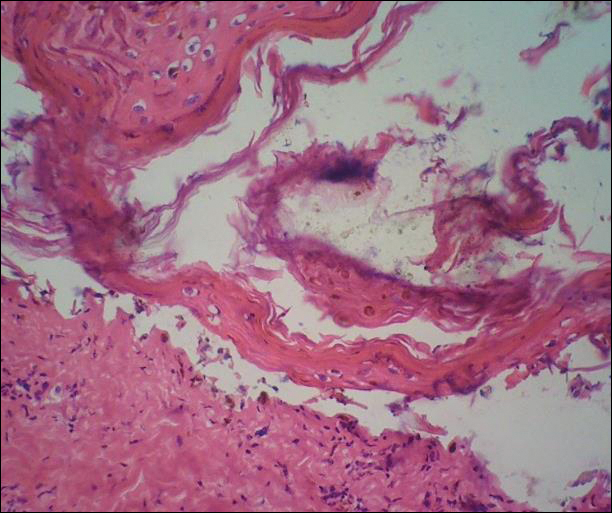

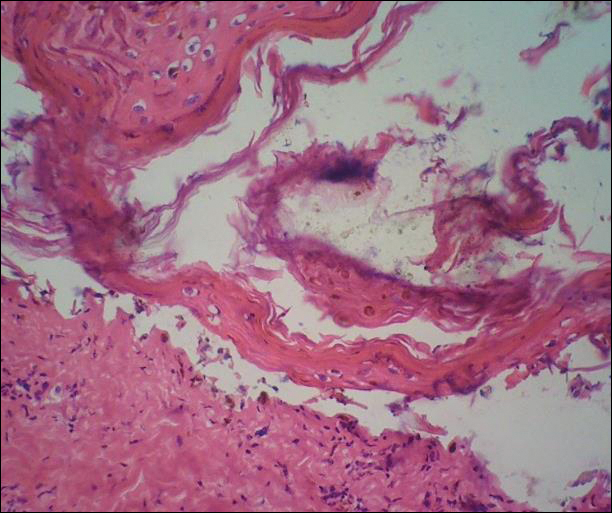

The lesions were characterized clinically as violet, red, and yellow to brown smooth papules, plaques, and nodules (Figure 1). Biopsies from these lesions showed a subepidermal and adnexal grenz zone; a polymorphous perivascular and periadnexal dermal infiltrate composed of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells; and a mild subtle leukocytoclastic vasculitis with subtle mild vascular necrosis (Figure 2).

For the 9 patients who elected to undergo GF treatment, the average number of treatments attempted was 2.8 (range, 1–5). The most common method of treatment was a combination of intralesional and topical corticosteroids (n=5 [50%]). Other methods included surgery (n=3 [30%]), dapsone (n=2 [20%]), radiation therapy (n=2 [20%]), cryosurgery (n=1 [10%]), nitrogen mustard (n=1 [10%]), liquid nitrogen (n=1 [10%]), and tar shampoo and fluocinolone acetonide solution 0.01% (n=1 [10%]).

Treatment outcomes were available for 8 of 9 treated patients. Three patients (patients 7, 8, and 10) had long-term successful resolution of their lesions. Patient 7 had an extrafacial lesion that was successfully treated with intralesional and topical corticosteroids, but the facial lesions recurred. The extrafacial GF lesion in patient 8 was found adjacent to a squamous cell carcinoma and was removed with a wide surgical excision that included both lesions. Patient 10 was successfully treated with a combination of liquid nitrogen and topical corticosteroid. Patients 2 and 4 were well controlled while on dapsone; however, once the treatment was discontinued, primarily due to adverse effects, the lesions returned.

Literature Search

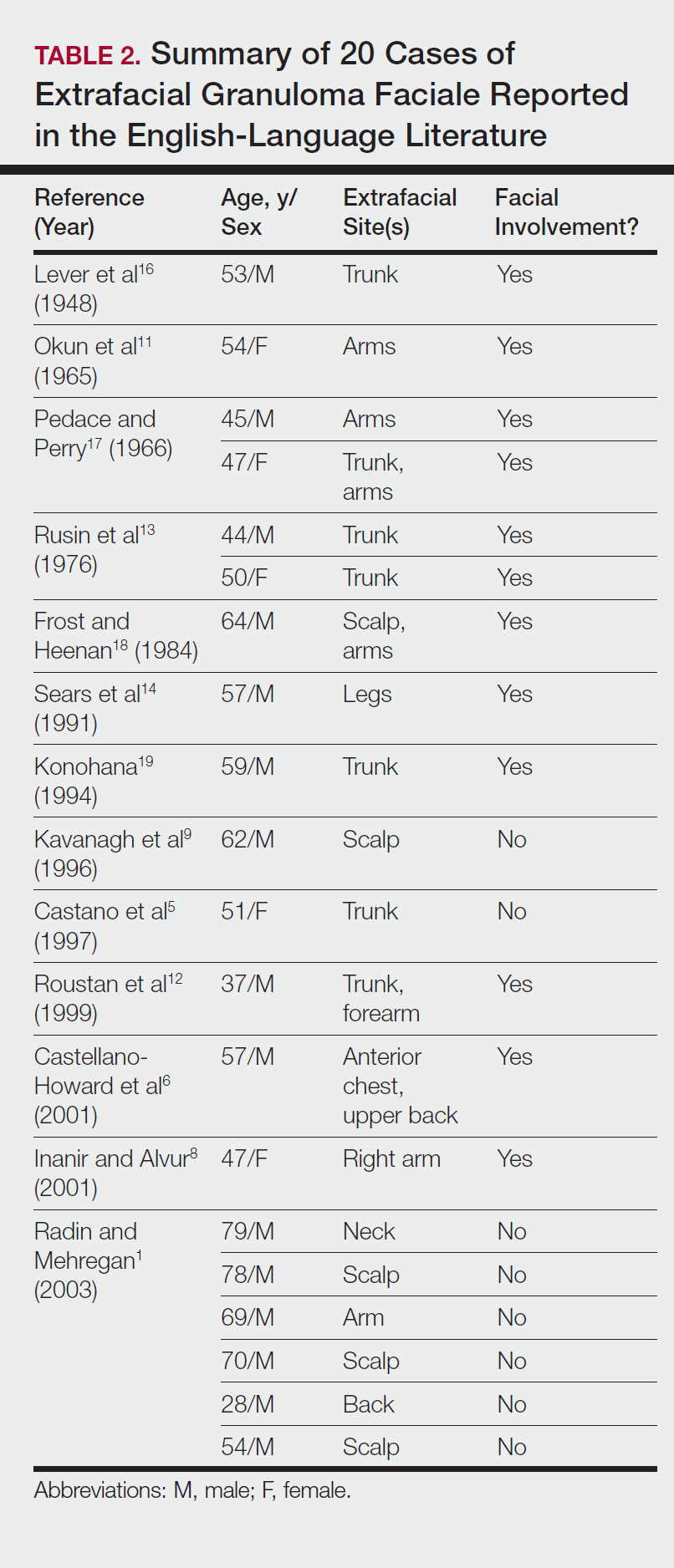

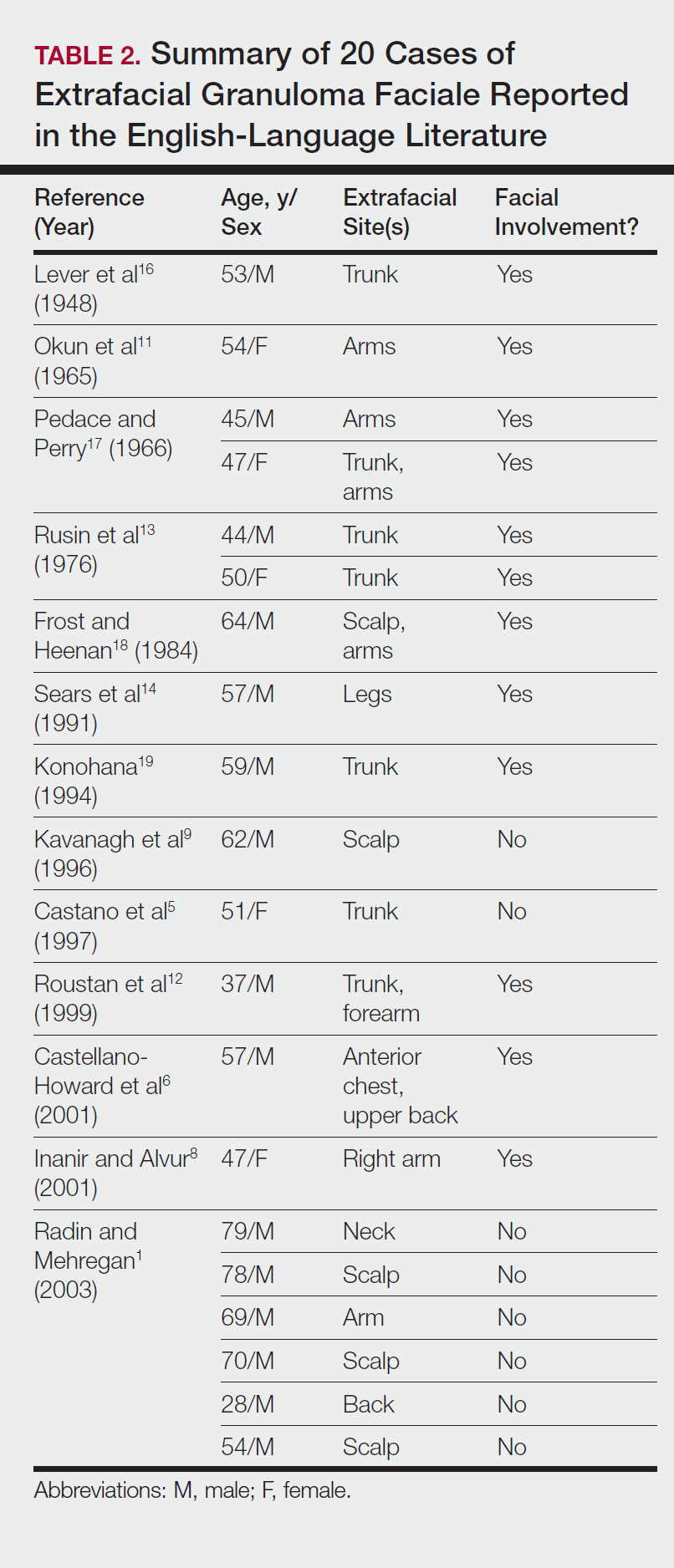

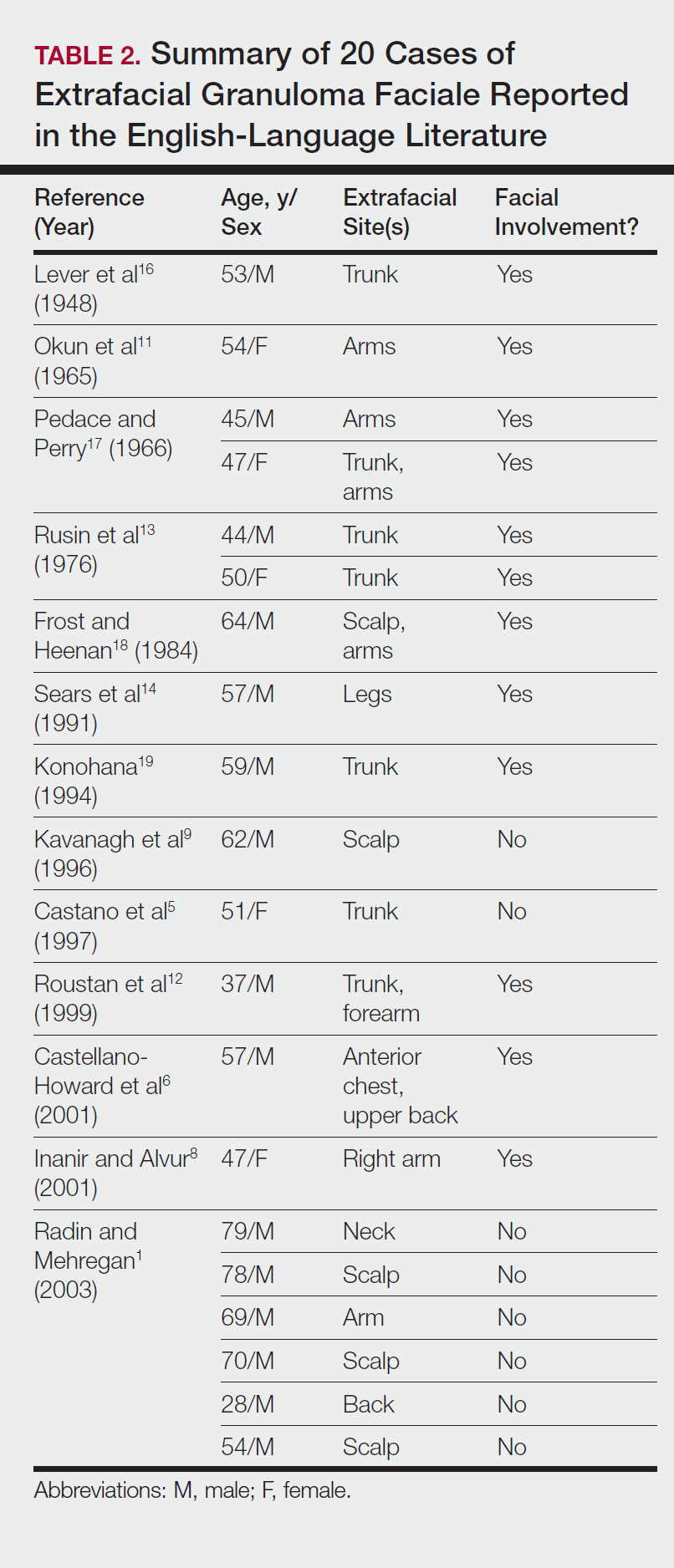

Our search of the English-language literature identified 20 patients with extrafacial GF (Table 2). Fifteen (75%) patients were male, which was similar to our study (6/10 [60%]). Our patient population was slightly older with a mean age of 58.7 years compared to a median age of 54 years among those identified in the literature. Additionally, 3 (30%) patients in our study had no facial lesions, as seen in classic GF, which is comparable to 8 (40%) patients identified in the literature.

Comment

Extrafacial GF primarily affects white individuals and is more prevalent in men, as demonstrated in our study. Extrafacial GF was most often found in association with facial lesions, with only 3 patients having exclusively extrafacial sites.

Data from the current study indicate that diverse modalities were used to treat extrafacial GF with variable outcomes (chronic recurrence to complete resolution). The most common first-line treatment, intralesional corticosteroid injection, was used in 5 (50%) patients but resulted in only 1 (10%) successful resolution. Other methods frequently used in our study and prior studies were surgical excision, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, and dermabrasion.1,20 These treatments do not appear to be uniformly definitive, and the ablative methods may result in scarring.1 Different laser treatments are emerging for the management of GF lesions. Prior reports of treating facial GF with argon and CO2 lasers have indicated minimized residual scarring and pigmentation.21-23 The use of pulsed dye lasers has resulted in complete clearance of facial GF lesions, without recurrence on long-term follow-up.20,24-26

The latest investigations of immunomodulatory drugs indicate these agents are promising for the management of facial GF. Eetam et al27 reported the successful use of topical tacrolimus to treat facial GF. The relatively low cost and ease of use make these topical medications a competitive alternative to currently available surgical and laser methods. The appearance of all of these novel therapeutic modalities creates the necessity for a randomized trial to establish their efficacy on extrafacial GF lesions.

The wide array of treatments reflects the recalcitrant nature of extrafacial GF lesions. Further insight into the etiology of these lesions is needed to understand their tendency to recur. The important contribution of our study is the observed

Conclusion

The findings from this study and the cases reviewed in the literature provide a unique contribution to the understanding of the clinical and demographic characteristics of extrafacial GF. The rarity of this condition is the single most important constraint of our study, reflected in the emblematic limitations of a retrospective analysis in a select group of patients. The results of analysis of data from our patients were similar to the findings reported in the English-language medical literature. Serious consideration should be given to the development of a national registry for patients with GF. A database containing the clinicopathologic features, treatments, and outcomes for patients with both facial and extrafacial manifestations of GF may be invaluable in evaluating various treatment options and increasing understanding of the etiology and epidemiology of the disease.

- Radin DA, Mehregan DR. Granuloma faciale: distribution of the lesions and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;72:213-219.

- Dowlati B, Firooz A, Dowlati Y. Granuloma faciale: successful treatment of nine cases with a combination of cryotherapy and intralesional corticosteroid injection. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:548-551.

- Guill MA, Aton JK. Facial granuloma responsive to dapsone therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:332-335.

- Ryan TJ. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, et al, eds. Rook/Wilkins/Ebling Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; 2004.

- Castano E, Segurado A, Iglesias L, et al. Granuloma faciale entirely in an extrafacial location. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:978-979.

- Castellano-Howard L, Fairbee SI, Hogan DJ, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case and response to treatment. Cutis. 2001;67:413-415.

- Cecchi R, Paoli S, Giomi A. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:438.

- Inanir I, Alvur Y. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2001;14:360-362.

- Kavanagh GM, McLaren KM, Hunter JA. Extensive extrafacial granuloma faciale of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:595-596.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Okun MR, Bauman L, Minor D. Granuloma faciale with lesions on the face and hand. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:78-80.

- Roustan G, Sanchez Yus E, Salas C, et al. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Dermatology. 1999;198:79-82.

- Rusin LJ, Dubin HV, Taylor WB. Disseminated granuloma faciale. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1575-1577.

- Sears JK, Gitter DG, Stone MS. Extrafacial granuloma faciale. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:742-743.

- Zargari O. Disseminated granuloma faciale. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:210-212.

- Lever WF, Lane CG, Downing JG, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma of the skin: report of three cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1948;58:430-438.

- Pedace FJ, Perry HO. Granuloma faciale: a clinical and histopathologic review. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:387-395.

- Frost FA, Heenan PJ. Facial granuloma. Australas J Dermatol. 1984;25:121-124.

Konohana A. Extrafacial granuloma faciale. J Dermatol. 1994;21:680-682.- Ludwig E, Allam JP, Bieber T, et al. New treatment modalities for granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:634-637.

- Apfelberg DB, Druker D, Maser MR, et al. Granuloma faciale: treatment with the argon laser. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:573-576.

- Apfelberg DB, Maser MR, Lash H, et al. Expanded role of the argon laser in plastic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1983;9:145-151.

- Wheeland RG, Ashley JR, Smith DA, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of granuloma faciale. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1984;10:730-733.

- Cheung ST, Lanigan SW. Granuloma faciale treated with the pulsed-dye laser: a case series. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:373-375.

- Chatrath V, Rohrer TE. Granuloma faciale successfully treated with long-pulsed tunable dye laser. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:527-529.

- Elston DM. Treatment of granuloma faciale with the pulsed dye laser. Cutis. 2000;65:97-98.

- Eetam I, Ertekin B, Unal I, et al. Granuloma faciale: is it a new indication for pimecrolimus? a case report. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17:238-240.

- Johnson WC, Higdon RS, Helwig EB. Granuloma faciale. AMA Arch Derm. 1959;79:42-52.

Granuloma faciale (GF) is a chronic benign leukocytoclastic vasculitis that can be difficult to treat. It is characterized by single or multiple, soft, well-circumscribed papules, plaques, or nodules ranging in color from red, violet, or yellow to brown that may darken with sun exposure.1 Lesions usually are smooth with follicular orifices that are accentuated, thus producing a peau d’orange appearance. Lesions generally are slow to develop and asymptomatic, though some patients report pruritus or burning.2,3 Diagnosis of GF is based on the presence of distinct histologic features. The epidermis usually is spared, with a prominent grenz zone of normal collagen separating the epidermis from a dense infiltrate of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. This mixed inflammatory infiltrate is seen mainly in the superficial dermis but occasionally spreads to the lower dermis and subcutaneous tissues.4

As the name implies, GF usually is confined to the face but occasionally involves extrafacial sites.5-15 The clinical characteristics of these rare extrafacial lesions are not well understood. The purpose of this study was to identify the clinical and demographic features of extrafacial GF in patients treated at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) during a 54-year period.

Methods

This study was approved by the Mayo institutional review board. We searched the Mayo Clinic Rochester dermatology database for all patients with a diagnosis of GF from 1959 through 2013. All histopathology slides were reviewed by a board-certified dermatologist (A.G.B.) and dermatopathologist (A.G.B.) before inclusion in this study. Histologic criteria for diagnosis of GF included the presence of a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes in the superficial or deep dermis; a prominent grenz zone separating the uninvolved epidermis; and the presence of vascular damage, as seen by fibrin deposition in dermal blood vessels.

Medical records were reviewed for patient demographics and for history pertinent to the diagnosis of GF, including sites involved, appearance, histopathology reports, symptoms, treatments, and outcomes.

Literature Search Strategy

A computerized Ovid MEDLINE database search was undertaken to identify English-language articles concerning GF in humans using the search terms granuloma faciale with extrafacial or disseminated. To ensure that no articles were overlooked, we conducted another search for English-language articles in the Embase database (1946-2013) using the terms granuloma faciale and extrafacial or disseminated.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive clinical and histopathologic data were summarized using means, medians, and ranges or proportions as appropriate; statistical analysis was performed using SAS software (JMP package).

Results

Ninety-six patients with a diagnosis of GF were identified, and 12 (13%) had a diagnosis of extrafacial GF. Of them, 2 patients had a diagnosis of extrafacial GF supported only by histopathology slides without accompanying clinical records and therefore were excluded from the study. Thus, 10 cases of extrafacial GF were identified from our search and were included in the study group. Clinical data for these patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 58.7 years (range, 26–87 years). Six (60%) patients were male, and all patients were white. Seven patients (70%) had facial GF in addition to extrafacial GF. Six patients reported no symptoms (60%), and 4 (40%) reported pruritus, discomfort, or both associated with their GF lesions.

Extrafacial GF was diagnosed in the following anatomic locations: scalp (n=3 [30%]), posterior auricular area (n=3 [30%]), mid upper back (n=1 [10%]), right shoulder (n=1 [10%]), both ears (n=1 [10%]), right elbow (n=1 [10%]), and left infra-auricular area (n=1 [10%]). Only 1 (10%) patient had multiple extrafacial sites identified.

The lesions were characterized clinically as violet, red, and yellow to brown smooth papules, plaques, and nodules (Figure 1). Biopsies from these lesions showed a subepidermal and adnexal grenz zone; a polymorphous perivascular and periadnexal dermal infiltrate composed of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells; and a mild subtle leukocytoclastic vasculitis with subtle mild vascular necrosis (Figure 2).

For the 9 patients who elected to undergo GF treatment, the average number of treatments attempted was 2.8 (range, 1–5). The most common method of treatment was a combination of intralesional and topical corticosteroids (n=5 [50%]). Other methods included surgery (n=3 [30%]), dapsone (n=2 [20%]), radiation therapy (n=2 [20%]), cryosurgery (n=1 [10%]), nitrogen mustard (n=1 [10%]), liquid nitrogen (n=1 [10%]), and tar shampoo and fluocinolone acetonide solution 0.01% (n=1 [10%]).

Treatment outcomes were available for 8 of 9 treated patients. Three patients (patients 7, 8, and 10) had long-term successful resolution of their lesions. Patient 7 had an extrafacial lesion that was successfully treated with intralesional and topical corticosteroids, but the facial lesions recurred. The extrafacial GF lesion in patient 8 was found adjacent to a squamous cell carcinoma and was removed with a wide surgical excision that included both lesions. Patient 10 was successfully treated with a combination of liquid nitrogen and topical corticosteroid. Patients 2 and 4 were well controlled while on dapsone; however, once the treatment was discontinued, primarily due to adverse effects, the lesions returned.

Literature Search

Our search of the English-language literature identified 20 patients with extrafacial GF (Table 2). Fifteen (75%) patients were male, which was similar to our study (6/10 [60%]). Our patient population was slightly older with a mean age of 58.7 years compared to a median age of 54 years among those identified in the literature. Additionally, 3 (30%) patients in our study had no facial lesions, as seen in classic GF, which is comparable to 8 (40%) patients identified in the literature.

Comment

Extrafacial GF primarily affects white individuals and is more prevalent in men, as demonstrated in our study. Extrafacial GF was most often found in association with facial lesions, with only 3 patients having exclusively extrafacial sites.

Data from the current study indicate that diverse modalities were used to treat extrafacial GF with variable outcomes (chronic recurrence to complete resolution). The most common first-line treatment, intralesional corticosteroid injection, was used in 5 (50%) patients but resulted in only 1 (10%) successful resolution. Other methods frequently used in our study and prior studies were surgical excision, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, and dermabrasion.1,20 These treatments do not appear to be uniformly definitive, and the ablative methods may result in scarring.1 Different laser treatments are emerging for the management of GF lesions. Prior reports of treating facial GF with argon and CO2 lasers have indicated minimized residual scarring and pigmentation.21-23 The use of pulsed dye lasers has resulted in complete clearance of facial GF lesions, without recurrence on long-term follow-up.20,24-26

The latest investigations of immunomodulatory drugs indicate these agents are promising for the management of facial GF. Eetam et al27 reported the successful use of topical tacrolimus to treat facial GF. The relatively low cost and ease of use make these topical medications a competitive alternative to currently available surgical and laser methods. The appearance of all of these novel therapeutic modalities creates the necessity for a randomized trial to establish their efficacy on extrafacial GF lesions.

The wide array of treatments reflects the recalcitrant nature of extrafacial GF lesions. Further insight into the etiology of these lesions is needed to understand their tendency to recur. The important contribution of our study is the observed

Conclusion

The findings from this study and the cases reviewed in the literature provide a unique contribution to the understanding of the clinical and demographic characteristics of extrafacial GF. The rarity of this condition is the single most important constraint of our study, reflected in the emblematic limitations of a retrospective analysis in a select group of patients. The results of analysis of data from our patients were similar to the findings reported in the English-language medical literature. Serious consideration should be given to the development of a national registry for patients with GF. A database containing the clinicopathologic features, treatments, and outcomes for patients with both facial and extrafacial manifestations of GF may be invaluable in evaluating various treatment options and increasing understanding of the etiology and epidemiology of the disease.

Granuloma faciale (GF) is a chronic benign leukocytoclastic vasculitis that can be difficult to treat. It is characterized by single or multiple, soft, well-circumscribed papules, plaques, or nodules ranging in color from red, violet, or yellow to brown that may darken with sun exposure.1 Lesions usually are smooth with follicular orifices that are accentuated, thus producing a peau d’orange appearance. Lesions generally are slow to develop and asymptomatic, though some patients report pruritus or burning.2,3 Diagnosis of GF is based on the presence of distinct histologic features. The epidermis usually is spared, with a prominent grenz zone of normal collagen separating the epidermis from a dense infiltrate of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. This mixed inflammatory infiltrate is seen mainly in the superficial dermis but occasionally spreads to the lower dermis and subcutaneous tissues.4

As the name implies, GF usually is confined to the face but occasionally involves extrafacial sites.5-15 The clinical characteristics of these rare extrafacial lesions are not well understood. The purpose of this study was to identify the clinical and demographic features of extrafacial GF in patients treated at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) during a 54-year period.

Methods

This study was approved by the Mayo institutional review board. We searched the Mayo Clinic Rochester dermatology database for all patients with a diagnosis of GF from 1959 through 2013. All histopathology slides were reviewed by a board-certified dermatologist (A.G.B.) and dermatopathologist (A.G.B.) before inclusion in this study. Histologic criteria for diagnosis of GF included the presence of a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes in the superficial or deep dermis; a prominent grenz zone separating the uninvolved epidermis; and the presence of vascular damage, as seen by fibrin deposition in dermal blood vessels.

Medical records were reviewed for patient demographics and for history pertinent to the diagnosis of GF, including sites involved, appearance, histopathology reports, symptoms, treatments, and outcomes.

Literature Search Strategy

A computerized Ovid MEDLINE database search was undertaken to identify English-language articles concerning GF in humans using the search terms granuloma faciale with extrafacial or disseminated. To ensure that no articles were overlooked, we conducted another search for English-language articles in the Embase database (1946-2013) using the terms granuloma faciale and extrafacial or disseminated.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive clinical and histopathologic data were summarized using means, medians, and ranges or proportions as appropriate; statistical analysis was performed using SAS software (JMP package).

Results

Ninety-six patients with a diagnosis of GF were identified, and 12 (13%) had a diagnosis of extrafacial GF. Of them, 2 patients had a diagnosis of extrafacial GF supported only by histopathology slides without accompanying clinical records and therefore were excluded from the study. Thus, 10 cases of extrafacial GF were identified from our search and were included in the study group. Clinical data for these patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 58.7 years (range, 26–87 years). Six (60%) patients were male, and all patients were white. Seven patients (70%) had facial GF in addition to extrafacial GF. Six patients reported no symptoms (60%), and 4 (40%) reported pruritus, discomfort, or both associated with their GF lesions.

Extrafacial GF was diagnosed in the following anatomic locations: scalp (n=3 [30%]), posterior auricular area (n=3 [30%]), mid upper back (n=1 [10%]), right shoulder (n=1 [10%]), both ears (n=1 [10%]), right elbow (n=1 [10%]), and left infra-auricular area (n=1 [10%]). Only 1 (10%) patient had multiple extrafacial sites identified.

The lesions were characterized clinically as violet, red, and yellow to brown smooth papules, plaques, and nodules (Figure 1). Biopsies from these lesions showed a subepidermal and adnexal grenz zone; a polymorphous perivascular and periadnexal dermal infiltrate composed of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells; and a mild subtle leukocytoclastic vasculitis with subtle mild vascular necrosis (Figure 2).

For the 9 patients who elected to undergo GF treatment, the average number of treatments attempted was 2.8 (range, 1–5). The most common method of treatment was a combination of intralesional and topical corticosteroids (n=5 [50%]). Other methods included surgery (n=3 [30%]), dapsone (n=2 [20%]), radiation therapy (n=2 [20%]), cryosurgery (n=1 [10%]), nitrogen mustard (n=1 [10%]), liquid nitrogen (n=1 [10%]), and tar shampoo and fluocinolone acetonide solution 0.01% (n=1 [10%]).

Treatment outcomes were available for 8 of 9 treated patients. Three patients (patients 7, 8, and 10) had long-term successful resolution of their lesions. Patient 7 had an extrafacial lesion that was successfully treated with intralesional and topical corticosteroids, but the facial lesions recurred. The extrafacial GF lesion in patient 8 was found adjacent to a squamous cell carcinoma and was removed with a wide surgical excision that included both lesions. Patient 10 was successfully treated with a combination of liquid nitrogen and topical corticosteroid. Patients 2 and 4 were well controlled while on dapsone; however, once the treatment was discontinued, primarily due to adverse effects, the lesions returned.

Literature Search

Our search of the English-language literature identified 20 patients with extrafacial GF (Table 2). Fifteen (75%) patients were male, which was similar to our study (6/10 [60%]). Our patient population was slightly older with a mean age of 58.7 years compared to a median age of 54 years among those identified in the literature. Additionally, 3 (30%) patients in our study had no facial lesions, as seen in classic GF, which is comparable to 8 (40%) patients identified in the literature.

Comment

Extrafacial GF primarily affects white individuals and is more prevalent in men, as demonstrated in our study. Extrafacial GF was most often found in association with facial lesions, with only 3 patients having exclusively extrafacial sites.

Data from the current study indicate that diverse modalities were used to treat extrafacial GF with variable outcomes (chronic recurrence to complete resolution). The most common first-line treatment, intralesional corticosteroid injection, was used in 5 (50%) patients but resulted in only 1 (10%) successful resolution. Other methods frequently used in our study and prior studies were surgical excision, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, and dermabrasion.1,20 These treatments do not appear to be uniformly definitive, and the ablative methods may result in scarring.1 Different laser treatments are emerging for the management of GF lesions. Prior reports of treating facial GF with argon and CO2 lasers have indicated minimized residual scarring and pigmentation.21-23 The use of pulsed dye lasers has resulted in complete clearance of facial GF lesions, without recurrence on long-term follow-up.20,24-26

The latest investigations of immunomodulatory drugs indicate these agents are promising for the management of facial GF. Eetam et al27 reported the successful use of topical tacrolimus to treat facial GF. The relatively low cost and ease of use make these topical medications a competitive alternative to currently available surgical and laser methods. The appearance of all of these novel therapeutic modalities creates the necessity for a randomized trial to establish their efficacy on extrafacial GF lesions.

The wide array of treatments reflects the recalcitrant nature of extrafacial GF lesions. Further insight into the etiology of these lesions is needed to understand their tendency to recur. The important contribution of our study is the observed

Conclusion

The findings from this study and the cases reviewed in the literature provide a unique contribution to the understanding of the clinical and demographic characteristics of extrafacial GF. The rarity of this condition is the single most important constraint of our study, reflected in the emblematic limitations of a retrospective analysis in a select group of patients. The results of analysis of data from our patients were similar to the findings reported in the English-language medical literature. Serious consideration should be given to the development of a national registry for patients with GF. A database containing the clinicopathologic features, treatments, and outcomes for patients with both facial and extrafacial manifestations of GF may be invaluable in evaluating various treatment options and increasing understanding of the etiology and epidemiology of the disease.

- Radin DA, Mehregan DR. Granuloma faciale: distribution of the lesions and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;72:213-219.

- Dowlati B, Firooz A, Dowlati Y. Granuloma faciale: successful treatment of nine cases with a combination of cryotherapy and intralesional corticosteroid injection. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:548-551.

- Guill MA, Aton JK. Facial granuloma responsive to dapsone therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:332-335.

- Ryan TJ. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, et al, eds. Rook/Wilkins/Ebling Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; 2004.

- Castano E, Segurado A, Iglesias L, et al. Granuloma faciale entirely in an extrafacial location. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:978-979.

- Castellano-Howard L, Fairbee SI, Hogan DJ, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case and response to treatment. Cutis. 2001;67:413-415.

- Cecchi R, Paoli S, Giomi A. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:438.

- Inanir I, Alvur Y. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2001;14:360-362.

- Kavanagh GM, McLaren KM, Hunter JA. Extensive extrafacial granuloma faciale of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:595-596.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Okun MR, Bauman L, Minor D. Granuloma faciale with lesions on the face and hand. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:78-80.

- Roustan G, Sanchez Yus E, Salas C, et al. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Dermatology. 1999;198:79-82.

- Rusin LJ, Dubin HV, Taylor WB. Disseminated granuloma faciale. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1575-1577.

- Sears JK, Gitter DG, Stone MS. Extrafacial granuloma faciale. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:742-743.

- Zargari O. Disseminated granuloma faciale. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:210-212.

- Lever WF, Lane CG, Downing JG, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma of the skin: report of three cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1948;58:430-438.

- Pedace FJ, Perry HO. Granuloma faciale: a clinical and histopathologic review. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:387-395.

- Frost FA, Heenan PJ. Facial granuloma. Australas J Dermatol. 1984;25:121-124.

Konohana A. Extrafacial granuloma faciale. J Dermatol. 1994;21:680-682.- Ludwig E, Allam JP, Bieber T, et al. New treatment modalities for granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:634-637.

- Apfelberg DB, Druker D, Maser MR, et al. Granuloma faciale: treatment with the argon laser. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:573-576.

- Apfelberg DB, Maser MR, Lash H, et al. Expanded role of the argon laser in plastic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1983;9:145-151.

- Wheeland RG, Ashley JR, Smith DA, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of granuloma faciale. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1984;10:730-733.

- Cheung ST, Lanigan SW. Granuloma faciale treated with the pulsed-dye laser: a case series. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:373-375.

- Chatrath V, Rohrer TE. Granuloma faciale successfully treated with long-pulsed tunable dye laser. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:527-529.

- Elston DM. Treatment of granuloma faciale with the pulsed dye laser. Cutis. 2000;65:97-98.

- Eetam I, Ertekin B, Unal I, et al. Granuloma faciale: is it a new indication for pimecrolimus? a case report. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17:238-240.

- Johnson WC, Higdon RS, Helwig EB. Granuloma faciale. AMA Arch Derm. 1959;79:42-52.

- Radin DA, Mehregan DR. Granuloma faciale: distribution of the lesions and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;72:213-219.

- Dowlati B, Firooz A, Dowlati Y. Granuloma faciale: successful treatment of nine cases with a combination of cryotherapy and intralesional corticosteroid injection. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:548-551.

- Guill MA, Aton JK. Facial granuloma responsive to dapsone therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:332-335.

- Ryan TJ. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, et al, eds. Rook/Wilkins/Ebling Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; 2004.

- Castano E, Segurado A, Iglesias L, et al. Granuloma faciale entirely in an extrafacial location. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:978-979.

- Castellano-Howard L, Fairbee SI, Hogan DJ, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case and response to treatment. Cutis. 2001;67:413-415.

- Cecchi R, Paoli S, Giomi A. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:438.

- Inanir I, Alvur Y. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2001;14:360-362.

- Kavanagh GM, McLaren KM, Hunter JA. Extensive extrafacial granuloma faciale of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:595-596.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Okun MR, Bauman L, Minor D. Granuloma faciale with lesions on the face and hand. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:78-80.

- Roustan G, Sanchez Yus E, Salas C, et al. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Dermatology. 1999;198:79-82.

- Rusin LJ, Dubin HV, Taylor WB. Disseminated granuloma faciale. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1575-1577.

- Sears JK, Gitter DG, Stone MS. Extrafacial granuloma faciale. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:742-743.

- Zargari O. Disseminated granuloma faciale. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:210-212.

- Lever WF, Lane CG, Downing JG, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma of the skin: report of three cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1948;58:430-438.

- Pedace FJ, Perry HO. Granuloma faciale: a clinical and histopathologic review. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:387-395.

- Frost FA, Heenan PJ. Facial granuloma. Australas J Dermatol. 1984;25:121-124.

Konohana A. Extrafacial granuloma faciale. J Dermatol. 1994;21:680-682.- Ludwig E, Allam JP, Bieber T, et al. New treatment modalities for granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:634-637.

- Apfelberg DB, Druker D, Maser MR, et al. Granuloma faciale: treatment with the argon laser. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:573-576.

- Apfelberg DB, Maser MR, Lash H, et al. Expanded role of the argon laser in plastic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1983;9:145-151.

- Wheeland RG, Ashley JR, Smith DA, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of granuloma faciale. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1984;10:730-733.

- Cheung ST, Lanigan SW. Granuloma faciale treated with the pulsed-dye laser: a case series. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:373-375.

- Chatrath V, Rohrer TE. Granuloma faciale successfully treated with long-pulsed tunable dye laser. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:527-529.

- Elston DM. Treatment of granuloma faciale with the pulsed dye laser. Cutis. 2000;65:97-98.

- Eetam I, Ertekin B, Unal I, et al. Granuloma faciale: is it a new indication for pimecrolimus? a case report. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17:238-240.

- Johnson WC, Higdon RS, Helwig EB. Granuloma faciale. AMA Arch Derm. 1959;79:42-52.

Practice Points

- Extrafacial lesions are rare in granuloma faciale (GF).

- Extrafacial GF should be included in the differential diagnosis of well-demarcated plaques and nodules found on the trunk or extremities.

- Diagnosis of extrafacial GF is based on the presence of distinct histologic features identical to GF.

- Granuloma faciale is a chronic benign leukocytoclastic vasculitis that can be difficult to treat.

Rowell Syndrome: Targeting a True Definition

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman was admitted to the intensive care unit secondary to the acute development of an erythematous rash with tissue sloughing that involved acral sites and mucosal surfaces. Her medical history was notable for anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A (SS-A)–positive lupus erythematosus (LE) with a morphologic semblance to subacute cutaneous LE (SCLE). Prior treatment had included oral corticosteroids. In addition, she reported a concurrent history of acral and mucosal lesions that appeared to flare with her lupus. The nature of these lesions was not clear to the patient or her physicians. Before this particular episode, her primary care physician had attempted to wean her off of the corticosteroids. As she dropped below 20 mg of prednisone daily, new lesions developed. The patient stated that her social situation was poor and that these lesions did seem to develop more frequently during times of physical and emotional stress. She recounted her first episode developing during her second pregnancy. Oral prednisone and over-the-counter calcium with vitamin D were her only reported medications. She denied the use of any other medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and recent antibiotic therapy.

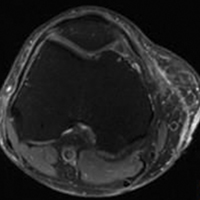

Dermatology was called in for consultation, and physical examination revealed areas of epidermal sloughing on the hands and feet. Complete clinical exposure of the underlying dermis was noted with remarkable tenderness. These lesions were noted to be in various stages of healing (Figure 1). Figure 2 displays a lesion in early development. The mucosal surfaces of the lips and eyes demonstrated hemorrhagic crusting, and some tissue sloughing was noted on the ears. A widespread erythematous exanthema with fine scaling was noted on the face, neck, chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs (Figure 3).

Laboratory evaluation revealed positive antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies, anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B (SS-B) antibodies, and anti–double-stranded DNA. The hemoglobin level was 9.4 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL) and hematocrit was 28.8% (reference range, 36%–47%). The mean corpuscular hemoglobin level was 32 pg/cell (reference range, 27–31 pg/cell), and the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration was 32.5 g/dL (reference range, 30–35 g/dL). Rheumatoid factor (RF) and herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 IgM were all found to be negative.

A deep shave biopsy obtained from the patient’s right knee revealed an atrophic interface dermatitis associated with a lymphocytic eccrine hidradenitis accompanied by abundant mesenchymal mucin deposition (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) from the same area demonstrated IgG and IgM along the dermoepidermal junction with some granular deposition. Frozen sections performed on acral lesions demonstrated epidermal necrosis (Figure 5). Direct immunofluorescence of acral lesions was negative. In light of these findings, a diagnosis of Rowell syndrome (RS) was suspected to be the most likely explanation for the presentation.

Intravenous corticosteroids and antibiotics were administered, and over a 2-week hospitalization, the lesions on the feet and hands slowly reepithelialized. Physical therapy was required to aid in ambulation. The patient was discharged on a tapering course of oral prednisone and hydroxychloroquine. After 6 months of therapy with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily, the patient continued to experience recurrent bouts of acral lesions, and pulse doses of oral prednisone were required. The lesions currently are controlled with azathioprine 50 mg twice daily and prednisone 10 mg by mouth daily.

Comment

The 4 prototypical patients identified by Rowell et al1 in 1963 in the first account of the eponymous syndrome were all females with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) and perniosis. In addition, they all displayed positive RF and saline extract of human tissue antibodies (analogous to anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B).2 Since then, at least 132 patients with clinical symptoms suspicious of RS have been identified with variations on these original criteria.3 The reported permutations of the lupus component of the disease include cutaneous LE (CLE), bullous systemic LE, necrotic lesions associated with antiphospholipid syndrome, annular/polycyclic SCLE, systemic LE (SLE) without CLE, SLE with lupus nephritis, SLE with pericarditis, SLE with systemic vasculitis, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and necrotizing lymphadenitis.2 In addition, variations of the erythema multiforme (EM)–like lesions found in reported cases include changes to their gross appearance (flat vs raised), location (acral or mucosal involvement), and resemblance to other conditions (Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis).2,3 From this information alone, it is clear that, as further cases have been chronicled, defining exact criteria for the disease has been challenging.

The essential question concerning the existence of RS hinges on the strength of its distinctiveness: Is it a unique disorder or merely another variant of lupus? Antiga et al2 concluded that it should be characterized as a variant of SCLE. Lee at al4 agreed, stating that “[i]n view of the lack of specific features that distinguish RS from LE, Kuhn et al5 suggested that [RS] is probably not a distinct entity and is now widely considered to be a variant of SCLE.” One of the primary contributors to this conclusion is that the laboratory findings of reported patients with SCLE have more closely mirrored the original cases from Rowell et al’s1 report than those of typical LE. Patients with SCLE have demonstrated positive ANA antibodies in 60% to 80% of cases, positive anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies in 40% to 100% of cases, positive anti-La/SS-B antibodies in 12% to 42% of cases, positive anti–double-stranded DNA in 1.2% to 10% of cases, and positive RF antibodies in 33% of cases.2 An argument could certainly be made to ascribe our patient’s condition to an SCLE variant, as 4 of 5 preceding laboratory findings were found to be positive; however, the majority of reported cases of SCLE have been linked to drugs (ie, hydrochlorothiazide, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, terbinafine),2 which has not commonly been the attributable etiology of other cases of RS, including the 4 cases reported by Rowell et al.1

In a review of the literature on RS since 2010 in addition to their report of 132 new cases, Torchia et al3 outlined a set of diagnostic standards for the condition consisting of major and minor criteria. According to the authors, if all 4 major and 1 minor criteria are met, the patient meets the standards for true RS. The major criteria include the following: (1) presence of chronic CLE [DLE and/or chilblain]; (2) presence of EM-like lesions [typical or atypical targets]; (3) at least 1 positivity among speckled ANA, anti-Ro/SS-A, and anti-La/SS-B antibodies; and (4) negative DIF on lesional EM-like targetoid lesions. The minor criteria include the following: (1) absence of infectious or pharmacologic triggers; (2) absence of typical EM location (acral and mucosal); and (3) presence of at least 1 additional American College of Rheumatology criterion for diagnosis of SLE8 besides discoid rash and positive ANA antibodies and excluding photosensitivity, malar rash, and oral ulcers. Using these criteria, the patient in our case met the standards for diagnosis of RS.

One area of disagreement that has been encountered in the literature is the exact histologic determination of true RS, specifically related to the microscopic findings of the EM-like lesions. Two cases presented by Modi et al6 were interpreted under the stipulation that true RS must contain histologic LE and histologic EM. Because the EM-appearing lesions revealed LE histology, the cases were concluded to be variants of LE. These cases are similar to our case in that the EM-like lesions in our patient demonstrated LE pathology. Torchia et al,3 as demonstrated in the above criteria, seemed to be less concerned about the histology of the EM-like lesions, only requiring them to show negative DIF.

Conclusion

In the search for answers concerning RS, many unanswered questions remain: Where should the line be drawn in the inclusion of so many variations of both the LE and EM components of the condition? Also, should these elements even be approached as distinct components in the first place? Viewing the majority of RS cases as simply simultaneous LE and EM, Shteyngarts et al7 concluded that “the concomitant occurrence of EM with LE did not change the course, therapy, or prognosis of either disease. SLE and DLE can coexist with EM, but the coexistence does not impart any unusual characteristic to either illness. Rowell’s syndrome is not reproducible, and the immunologic disturbances in such patients are probably coincidental.”

If the condition is a genuine pathological individuality, should we not view the seemingly separate LE and EM as the product of a single underlying biochemical process? These questions and others in the search for a true definition of the disease should continue to be debated. It is clear that further investigation is warranted in the understanding of the underlying mechanism of the pathology.

- Rowell NR, Beck JS, Anderson JR. Lupus erythematosus and erythema multiforme-like lesions: a syndrome with characteristic immunological abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:176-180.

- Antiga E, Caproni M, Bonciani D, et al. The last word on the so-called ‘Rowell’s syndrome’? Lupus. 2012;21:577-585.

- Torchia D, Romanelli P, Kerdel FA. Erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:417-421.

- Lee A, Batra P, Furer V, et al. Rowell syndrome (systemic lupus erythematosus + erythema multiforme). Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Kuhn A, Sticherling M, Bonsmann G. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:1124-1140.

- Modi GM, Shen A, Mazloom A, et al. Lupus erythematosus masquerading as erythema multiforme: does Rowell syndrome really exist? Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:5.

- Shteyngarts AR, Warner MR, Camisa C. Lupus erythematosus associated with erythema multiforme: does Rowell’s syndrome exist? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5 pt 1):773-777.

- Lupus diagnosis. Lupus Research Alliance website. http://lupusresearchinstitute.org/lupus-facts/lupus-diagnosis. Accessed July 11, 2017.

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman was admitted to the intensive care unit secondary to the acute development of an erythematous rash with tissue sloughing that involved acral sites and mucosal surfaces. Her medical history was notable for anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A (SS-A)–positive lupus erythematosus (LE) with a morphologic semblance to subacute cutaneous LE (SCLE). Prior treatment had included oral corticosteroids. In addition, she reported a concurrent history of acral and mucosal lesions that appeared to flare with her lupus. The nature of these lesions was not clear to the patient or her physicians. Before this particular episode, her primary care physician had attempted to wean her off of the corticosteroids. As she dropped below 20 mg of prednisone daily, new lesions developed. The patient stated that her social situation was poor and that these lesions did seem to develop more frequently during times of physical and emotional stress. She recounted her first episode developing during her second pregnancy. Oral prednisone and over-the-counter calcium with vitamin D were her only reported medications. She denied the use of any other medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and recent antibiotic therapy.

Dermatology was called in for consultation, and physical examination revealed areas of epidermal sloughing on the hands and feet. Complete clinical exposure of the underlying dermis was noted with remarkable tenderness. These lesions were noted to be in various stages of healing (Figure 1). Figure 2 displays a lesion in early development. The mucosal surfaces of the lips and eyes demonstrated hemorrhagic crusting, and some tissue sloughing was noted on the ears. A widespread erythematous exanthema with fine scaling was noted on the face, neck, chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs (Figure 3).

Laboratory evaluation revealed positive antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies, anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B (SS-B) antibodies, and anti–double-stranded DNA. The hemoglobin level was 9.4 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL) and hematocrit was 28.8% (reference range, 36%–47%). The mean corpuscular hemoglobin level was 32 pg/cell (reference range, 27–31 pg/cell), and the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration was 32.5 g/dL (reference range, 30–35 g/dL). Rheumatoid factor (RF) and herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 IgM were all found to be negative.

A deep shave biopsy obtained from the patient’s right knee revealed an atrophic interface dermatitis associated with a lymphocytic eccrine hidradenitis accompanied by abundant mesenchymal mucin deposition (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) from the same area demonstrated IgG and IgM along the dermoepidermal junction with some granular deposition. Frozen sections performed on acral lesions demonstrated epidermal necrosis (Figure 5). Direct immunofluorescence of acral lesions was negative. In light of these findings, a diagnosis of Rowell syndrome (RS) was suspected to be the most likely explanation for the presentation.

Intravenous corticosteroids and antibiotics were administered, and over a 2-week hospitalization, the lesions on the feet and hands slowly reepithelialized. Physical therapy was required to aid in ambulation. The patient was discharged on a tapering course of oral prednisone and hydroxychloroquine. After 6 months of therapy with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily, the patient continued to experience recurrent bouts of acral lesions, and pulse doses of oral prednisone were required. The lesions currently are controlled with azathioprine 50 mg twice daily and prednisone 10 mg by mouth daily.

Comment

The 4 prototypical patients identified by Rowell et al1 in 1963 in the first account of the eponymous syndrome were all females with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) and perniosis. In addition, they all displayed positive RF and saline extract of human tissue antibodies (analogous to anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B).2 Since then, at least 132 patients with clinical symptoms suspicious of RS have been identified with variations on these original criteria.3 The reported permutations of the lupus component of the disease include cutaneous LE (CLE), bullous systemic LE, necrotic lesions associated with antiphospholipid syndrome, annular/polycyclic SCLE, systemic LE (SLE) without CLE, SLE with lupus nephritis, SLE with pericarditis, SLE with systemic vasculitis, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and necrotizing lymphadenitis.2 In addition, variations of the erythema multiforme (EM)–like lesions found in reported cases include changes to their gross appearance (flat vs raised), location (acral or mucosal involvement), and resemblance to other conditions (Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis).2,3 From this information alone, it is clear that, as further cases have been chronicled, defining exact criteria for the disease has been challenging.

The essential question concerning the existence of RS hinges on the strength of its distinctiveness: Is it a unique disorder or merely another variant of lupus? Antiga et al2 concluded that it should be characterized as a variant of SCLE. Lee at al4 agreed, stating that “[i]n view of the lack of specific features that distinguish RS from LE, Kuhn et al5 suggested that [RS] is probably not a distinct entity and is now widely considered to be a variant of SCLE.” One of the primary contributors to this conclusion is that the laboratory findings of reported patients with SCLE have more closely mirrored the original cases from Rowell et al’s1 report than those of typical LE. Patients with SCLE have demonstrated positive ANA antibodies in 60% to 80% of cases, positive anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies in 40% to 100% of cases, positive anti-La/SS-B antibodies in 12% to 42% of cases, positive anti–double-stranded DNA in 1.2% to 10% of cases, and positive RF antibodies in 33% of cases.2 An argument could certainly be made to ascribe our patient’s condition to an SCLE variant, as 4 of 5 preceding laboratory findings were found to be positive; however, the majority of reported cases of SCLE have been linked to drugs (ie, hydrochlorothiazide, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, terbinafine),2 which has not commonly been the attributable etiology of other cases of RS, including the 4 cases reported by Rowell et al.1

In a review of the literature on RS since 2010 in addition to their report of 132 new cases, Torchia et al3 outlined a set of diagnostic standards for the condition consisting of major and minor criteria. According to the authors, if all 4 major and 1 minor criteria are met, the patient meets the standards for true RS. The major criteria include the following: (1) presence of chronic CLE [DLE and/or chilblain]; (2) presence of EM-like lesions [typical or atypical targets]; (3) at least 1 positivity among speckled ANA, anti-Ro/SS-A, and anti-La/SS-B antibodies; and (4) negative DIF on lesional EM-like targetoid lesions. The minor criteria include the following: (1) absence of infectious or pharmacologic triggers; (2) absence of typical EM location (acral and mucosal); and (3) presence of at least 1 additional American College of Rheumatology criterion for diagnosis of SLE8 besides discoid rash and positive ANA antibodies and excluding photosensitivity, malar rash, and oral ulcers. Using these criteria, the patient in our case met the standards for diagnosis of RS.

One area of disagreement that has been encountered in the literature is the exact histologic determination of true RS, specifically related to the microscopic findings of the EM-like lesions. Two cases presented by Modi et al6 were interpreted under the stipulation that true RS must contain histologic LE and histologic EM. Because the EM-appearing lesions revealed LE histology, the cases were concluded to be variants of LE. These cases are similar to our case in that the EM-like lesions in our patient demonstrated LE pathology. Torchia et al,3 as demonstrated in the above criteria, seemed to be less concerned about the histology of the EM-like lesions, only requiring them to show negative DIF.

Conclusion

In the search for answers concerning RS, many unanswered questions remain: Where should the line be drawn in the inclusion of so many variations of both the LE and EM components of the condition? Also, should these elements even be approached as distinct components in the first place? Viewing the majority of RS cases as simply simultaneous LE and EM, Shteyngarts et al7 concluded that “the concomitant occurrence of EM with LE did not change the course, therapy, or prognosis of either disease. SLE and DLE can coexist with EM, but the coexistence does not impart any unusual characteristic to either illness. Rowell’s syndrome is not reproducible, and the immunologic disturbances in such patients are probably coincidental.”

If the condition is a genuine pathological individuality, should we not view the seemingly separate LE and EM as the product of a single underlying biochemical process? These questions and others in the search for a true definition of the disease should continue to be debated. It is clear that further investigation is warranted in the understanding of the underlying mechanism of the pathology.

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman was admitted to the intensive care unit secondary to the acute development of an erythematous rash with tissue sloughing that involved acral sites and mucosal surfaces. Her medical history was notable for anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A (SS-A)–positive lupus erythematosus (LE) with a morphologic semblance to subacute cutaneous LE (SCLE). Prior treatment had included oral corticosteroids. In addition, she reported a concurrent history of acral and mucosal lesions that appeared to flare with her lupus. The nature of these lesions was not clear to the patient or her physicians. Before this particular episode, her primary care physician had attempted to wean her off of the corticosteroids. As she dropped below 20 mg of prednisone daily, new lesions developed. The patient stated that her social situation was poor and that these lesions did seem to develop more frequently during times of physical and emotional stress. She recounted her first episode developing during her second pregnancy. Oral prednisone and over-the-counter calcium with vitamin D were her only reported medications. She denied the use of any other medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and recent antibiotic therapy.

Dermatology was called in for consultation, and physical examination revealed areas of epidermal sloughing on the hands and feet. Complete clinical exposure of the underlying dermis was noted with remarkable tenderness. These lesions were noted to be in various stages of healing (Figure 1). Figure 2 displays a lesion in early development. The mucosal surfaces of the lips and eyes demonstrated hemorrhagic crusting, and some tissue sloughing was noted on the ears. A widespread erythematous exanthema with fine scaling was noted on the face, neck, chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs (Figure 3).

Laboratory evaluation revealed positive antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies, anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B (SS-B) antibodies, and anti–double-stranded DNA. The hemoglobin level was 9.4 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL) and hematocrit was 28.8% (reference range, 36%–47%). The mean corpuscular hemoglobin level was 32 pg/cell (reference range, 27–31 pg/cell), and the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration was 32.5 g/dL (reference range, 30–35 g/dL). Rheumatoid factor (RF) and herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 IgM were all found to be negative.

A deep shave biopsy obtained from the patient’s right knee revealed an atrophic interface dermatitis associated with a lymphocytic eccrine hidradenitis accompanied by abundant mesenchymal mucin deposition (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) from the same area demonstrated IgG and IgM along the dermoepidermal junction with some granular deposition. Frozen sections performed on acral lesions demonstrated epidermal necrosis (Figure 5). Direct immunofluorescence of acral lesions was negative. In light of these findings, a diagnosis of Rowell syndrome (RS) was suspected to be the most likely explanation for the presentation.

Intravenous corticosteroids and antibiotics were administered, and over a 2-week hospitalization, the lesions on the feet and hands slowly reepithelialized. Physical therapy was required to aid in ambulation. The patient was discharged on a tapering course of oral prednisone and hydroxychloroquine. After 6 months of therapy with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily, the patient continued to experience recurrent bouts of acral lesions, and pulse doses of oral prednisone were required. The lesions currently are controlled with azathioprine 50 mg twice daily and prednisone 10 mg by mouth daily.

Comment

The 4 prototypical patients identified by Rowell et al1 in 1963 in the first account of the eponymous syndrome were all females with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) and perniosis. In addition, they all displayed positive RF and saline extract of human tissue antibodies (analogous to anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B).2 Since then, at least 132 patients with clinical symptoms suspicious of RS have been identified with variations on these original criteria.3 The reported permutations of the lupus component of the disease include cutaneous LE (CLE), bullous systemic LE, necrotic lesions associated with antiphospholipid syndrome, annular/polycyclic SCLE, systemic LE (SLE) without CLE, SLE with lupus nephritis, SLE with pericarditis, SLE with systemic vasculitis, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and necrotizing lymphadenitis.2 In addition, variations of the erythema multiforme (EM)–like lesions found in reported cases include changes to their gross appearance (flat vs raised), location (acral or mucosal involvement), and resemblance to other conditions (Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis).2,3 From this information alone, it is clear that, as further cases have been chronicled, defining exact criteria for the disease has been challenging.

The essential question concerning the existence of RS hinges on the strength of its distinctiveness: Is it a unique disorder or merely another variant of lupus? Antiga et al2 concluded that it should be characterized as a variant of SCLE. Lee at al4 agreed, stating that “[i]n view of the lack of specific features that distinguish RS from LE, Kuhn et al5 suggested that [RS] is probably not a distinct entity and is now widely considered to be a variant of SCLE.” One of the primary contributors to this conclusion is that the laboratory findings of reported patients with SCLE have more closely mirrored the original cases from Rowell et al’s1 report than those of typical LE. Patients with SCLE have demonstrated positive ANA antibodies in 60% to 80% of cases, positive anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies in 40% to 100% of cases, positive anti-La/SS-B antibodies in 12% to 42% of cases, positive anti–double-stranded DNA in 1.2% to 10% of cases, and positive RF antibodies in 33% of cases.2 An argument could certainly be made to ascribe our patient’s condition to an SCLE variant, as 4 of 5 preceding laboratory findings were found to be positive; however, the majority of reported cases of SCLE have been linked to drugs (ie, hydrochlorothiazide, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, terbinafine),2 which has not commonly been the attributable etiology of other cases of RS, including the 4 cases reported by Rowell et al.1

In a review of the literature on RS since 2010 in addition to their report of 132 new cases, Torchia et al3 outlined a set of diagnostic standards for the condition consisting of major and minor criteria. According to the authors, if all 4 major and 1 minor criteria are met, the patient meets the standards for true RS. The major criteria include the following: (1) presence of chronic CLE [DLE and/or chilblain]; (2) presence of EM-like lesions [typical or atypical targets]; (3) at least 1 positivity among speckled ANA, anti-Ro/SS-A, and anti-La/SS-B antibodies; and (4) negative DIF on lesional EM-like targetoid lesions. The minor criteria include the following: (1) absence of infectious or pharmacologic triggers; (2) absence of typical EM location (acral and mucosal); and (3) presence of at least 1 additional American College of Rheumatology criterion for diagnosis of SLE8 besides discoid rash and positive ANA antibodies and excluding photosensitivity, malar rash, and oral ulcers. Using these criteria, the patient in our case met the standards for diagnosis of RS.

One area of disagreement that has been encountered in the literature is the exact histologic determination of true RS, specifically related to the microscopic findings of the EM-like lesions. Two cases presented by Modi et al6 were interpreted under the stipulation that true RS must contain histologic LE and histologic EM. Because the EM-appearing lesions revealed LE histology, the cases were concluded to be variants of LE. These cases are similar to our case in that the EM-like lesions in our patient demonstrated LE pathology. Torchia et al,3 as demonstrated in the above criteria, seemed to be less concerned about the histology of the EM-like lesions, only requiring them to show negative DIF.

Conclusion

In the search for answers concerning RS, many unanswered questions remain: Where should the line be drawn in the inclusion of so many variations of both the LE and EM components of the condition? Also, should these elements even be approached as distinct components in the first place? Viewing the majority of RS cases as simply simultaneous LE and EM, Shteyngarts et al7 concluded that “the concomitant occurrence of EM with LE did not change the course, therapy, or prognosis of either disease. SLE and DLE can coexist with EM, but the coexistence does not impart any unusual characteristic to either illness. Rowell’s syndrome is not reproducible, and the immunologic disturbances in such patients are probably coincidental.”

If the condition is a genuine pathological individuality, should we not view the seemingly separate LE and EM as the product of a single underlying biochemical process? These questions and others in the search for a true definition of the disease should continue to be debated. It is clear that further investigation is warranted in the understanding of the underlying mechanism of the pathology.

- Rowell NR, Beck JS, Anderson JR. Lupus erythematosus and erythema multiforme-like lesions: a syndrome with characteristic immunological abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:176-180.

- Antiga E, Caproni M, Bonciani D, et al. The last word on the so-called ‘Rowell’s syndrome’? Lupus. 2012;21:577-585.

- Torchia D, Romanelli P, Kerdel FA. Erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:417-421.

- Lee A, Batra P, Furer V, et al. Rowell syndrome (systemic lupus erythematosus + erythema multiforme). Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Kuhn A, Sticherling M, Bonsmann G. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:1124-1140.

- Modi GM, Shen A, Mazloom A, et al. Lupus erythematosus masquerading as erythema multiforme: does Rowell syndrome really exist? Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:5.

- Shteyngarts AR, Warner MR, Camisa C. Lupus erythematosus associated with erythema multiforme: does Rowell’s syndrome exist? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5 pt 1):773-777.

- Lupus diagnosis. Lupus Research Alliance website. http://lupusresearchinstitute.org/lupus-facts/lupus-diagnosis. Accessed July 11, 2017.

- Rowell NR, Beck JS, Anderson JR. Lupus erythematosus and erythema multiforme-like lesions: a syndrome with characteristic immunological abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:176-180.

- Antiga E, Caproni M, Bonciani D, et al. The last word on the so-called ‘Rowell’s syndrome’? Lupus. 2012;21:577-585.

- Torchia D, Romanelli P, Kerdel FA. Erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:417-421.

- Lee A, Batra P, Furer V, et al. Rowell syndrome (systemic lupus erythematosus + erythema multiforme). Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Kuhn A, Sticherling M, Bonsmann G. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:1124-1140.

- Modi GM, Shen A, Mazloom A, et al. Lupus erythematosus masquerading as erythema multiforme: does Rowell syndrome really exist? Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:5.

- Shteyngarts AR, Warner MR, Camisa C. Lupus erythematosus associated with erythema multiforme: does Rowell’s syndrome exist? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5 pt 1):773-777.

- Lupus diagnosis. Lupus Research Alliance website. http://lupusresearchinstitute.org/lupus-facts/lupus-diagnosis. Accessed July 11, 2017.

Practice Points

- Rowell syndrome (RS) is an often unrecognized unique presentation of lupus erythematosus.

- There have been a variety of historical criteria that have sought to characterize RS.

Lower Limb Morel-Lavallée Lesion Treated With Short-Stretch Compression Bandaging

Take-Home Points

- Have a high-index of suspicion for MLLs and initiate treatment early.

- Compression needs to occur through short-stretch bandaging over a conventional Ace wrap in order to be successful.

- Apply the short-stretch compression with care to avoid shearing underlying tissue.

- Nonoperative treatment modalities require high patient compliance.

- MLLs need close monitoring until final healing occurs.

Morel-Lavallée lesions (MLLs) are traumatic degloving injuries resulting from separation of subcutaneous fat from underlying fascia. MLLs occur in association with acetabular fractures and are also associated with low-velocity crush injuries.1,2 Shearing creates a “false” space that is filled with hemorrhaged blood, fat, and lymphatic tissue.3 Disruption of the lymphatics leads to cavity formation and, eventually, a fibrotic pseudocapsule.4The pseudocapsule prevents resorption, leading to a chronic fluid collection, which potentiates the risk of infection or tissue necrosis.3,5,6 Skin necrosis may occur through direct-pressure compromise of the dermal vascular plexus.4 Necrotic skin may require multiple débridements, negative-pressure wound therapy or soft-tissue coverage, and may ultimately result in infection. MLLs classically occur in the greater trochanteric region, lateral thigh, buttocks, and back but also appear in the prepatellar region.1,3 Patients present with soft-tissue swelling, bruising, bulging, decreased cutaneous sensation over the region, and a palpable, fluctuant subcutaneous fluid collection with mobile skin.2,4,7 The mechanism of injury may cause a concomitant fracture. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the preferred imaging modality, shows a discrete fluid collection between subcutaneous fat and underlying fascia. Ultrasonography may reveal a thickened capsule surrounding either a hypoechoic area or an anechoic area but its accuracy is user-dependent.7

Large MLLs may be treated with open serial débridement and healing by secondary intention; infection rates, however, are high. Authors have described several other treatment modalities, including percutaneous débridement with a brush followed by use of a large-bore drain and antibiotics; open débridement with meticulous dead-space closure; elastic compression bandaging; aspiration; and doxycycline sclerodesis.1,5,6,8,9 Modifications of short-stretch compression bandaging were recently described in edema control for hindfoot trauma, ankle trauma, and total ankle arthroplasty, but not for MLLs.10,11 Nickerson and colleagues4 retrospectively reviewed 87 MLLs, found that fluid aspirate of >50 mL predicted recurrence and failure with conservative measures, and recommended operative intervention for any MLL with >50 mL of fluid aspirated.

We report the case of an MLL that occurred in an unusual anatomical region, and we describe a novel application of a conservative treatment, which was selected on the basis of its success in lymphedema management. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 66-year-old man was injured when a parked vehicle began moving, pulled him under, and ran over his lower right leg. In the emergency department, no fractures or major injuries were noted (Figures 1A, 1B), and the patient was discharged.

About 10 days after injury, profuse ecchymosis and swelling were noted running from the distal medial thigh to the proximal medial calf (Figures 2A-2C).

Given the size of the MLL, the fluid collection reaccumulated. The patient was evaluated by an orthopedic traumatologist 3 days after the aspiration (17 days after injury).

Another orthopedic traumatologist confirmed the low likelihood that compression would resolve the MLL, given its size (Figures 4A, 4B).

After the second orthopedic consultation, the patient saw a physical therapist trained in complete decongestive therapy. The therapist suggested placing short-stretch bandage wraps over the conventional long-stretch Ace bandage currently being used—a treatment common in lymphedema. The patient was wrapped from toe to groin without an initial layer of padding (Figures 6A, 6B), and the response was immediate.

Nine weeks after injury, the leg was significantly improved, and clinical signs resolved (Figure 7).

Discussion

Short-stretch bandaging has been performed mainly in lymphedema and ulcer management.

Compression bandaging reduces volume in lymphedematous limbs by reducing capillary filtration, shifting fluid into noncompressed parts of the body, increasing lymphatic reabsorption and lymphatic transport stimulation, improving venous pumping, and breaking down fibrosclerotic tissue.15 We think containment, improved venous flow, and enhanced muscle contraction contributed to the effectiveness of short-stretch bandaging as treatment for our patient’s MLL. Because MLLs also contain disrupted lymphatics, lymphedema management strategies (eg, short-stretch bandages) can be used. Our patient rapidly improved after conversion to short-stretch bandages.

These bandages are applied with 50% overlap to ensure even pressures throughout.16 Multiple layers are applied using a combination of spiral and figure-of-8 techniques, first clockwise and then counterclockwise, to avoid shearing underlying tissue.17 This method is very important in MLL treatment, given the degloving involved and the highly mobile skin and subcutaneous fat.

In standard lymphedema management, a foam padding layer is applied before the short-stretch bandage in order to reshape the limb and avoid proximal constrictions.13 In our patient’s case, the short-stretch wrap was applied without padding. Because his condition was acute, and the limb contour was preserved, limb reshaping and thus padding were not necessary.

Given the rapid, high-volume reduction that occurs within the first 1 to 2 weeks, bandages are reapplied daily to effectively adjust for the decreased swelling and altered limb shape.17 Most improvement is expected within the first few weeks—consistent with our patient’s case. Bandages usually are applied to the entire limb. For partial cases, the bandaging must extend past the area of swelling and incorporate the knee to prevent displacement of fluid into the joint.17 Feet and ankles are bandaged in dorsiflexion.17Several factors must be considered with short-stretch wraps. For example, pressure may need to be adjusted in patients with peripheral vascular disease. In patients with ankle-brachial indexes >0.5, it is safe to apply pressure up to 40 mm Hg.12 Reduced pressure is recommended for patients with arterial disease, sensory disturbance, lipoedema, poor mobility, frailty, or palliative needs.13The unusual location of our patient’s MLL accounts for the delay in diagnosis. To our knowledge, no other authors have reported such a large MLL in this location. A few series and case reports have listed MLLs in the calf near the gastrocnemius muscle, in the ankle, in the prepatellar area, and in the suprapatellar region, including the thigh,1,3,18-20 but there are no reports of MLLs running from medial thigh to proximal calf. MLLs of this size classically are treated surgically, but our patient selected nonoperative management.

To our knowledge, there are no earlier reports of using this nonoperative technique to treat MLLs. Conservative treatment with compression has been discussed, but no case involved short-stretch bandages. Large MLLs are thought to require surgery plus some type of drainage. The success of using short-stretch bandages in our patient’s case should prompt further investigation of use in adherent patients—which could ultimately result in reduced surgical needs, improved wound care (surgery is avoided), and a maintained low risk of infection. Although more work is needed to come to a more definitive verdict on this treatment method, it is a promising option that warrants consideration.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):E213-E218. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Tejwani SG, Cohen SB, Bradley JP. Management of Morel-Lavallee lesion of the knee: twenty-seven cases in the National Football League. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1162-1167.

2. Tsur A, Galin A, Kogan L, Loberant N. Morel-Lavallee syndrome after crush injury [in Hebrew]. Harefuah. 2006;145(2):111-113.

3. Ciaschini M, Sundaram M. Radiologic case study. Prepatellar Morel-Lavallée lesion. Orthopedics. 2008;31(7):626, 719-721.

4. Nickerson TP, Zielinski MD, Jenkins DH, Schiller HJ. The Mayo Clinic experience with Morel-Lavallée lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(2):493-497.

5. Bansal A, Bhatia N, Singh A, Singh AK. Doxycycline sclerodesis as a treatment option for persistent Morel-Lavallée lesions. Injury. 2013;44(1):66-69.

6. Carlson DA, Simmons J, Sando W, Weber T, Clements B. Morel-Lavalée lesions treated with debridement and meticulous dead space closure: surgical technique. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(2):140-144.

7. Miller J, Daggett J, Ambay R, Payne WG. Morel-Lavallée lesion. Eplasty. 2014;14:ic12.

8. Tseng S, Tornetta P 3rd. Percutaneous management of Morel-Lavallee lesions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(1):92-96.