User login

Emergency Imaging: Severe Left Testicular Swelling

A 32-year-old man presented to the ED with acute onset of left testicular swelling and pain. He described the pain as severe, radiating to his lower back and lower abdomen. Regarding his medical history, the patient stated he had experienced similar episodes of significant testicular swelling in the past, for which he was treated with antibiotics.

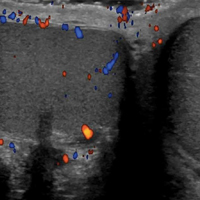

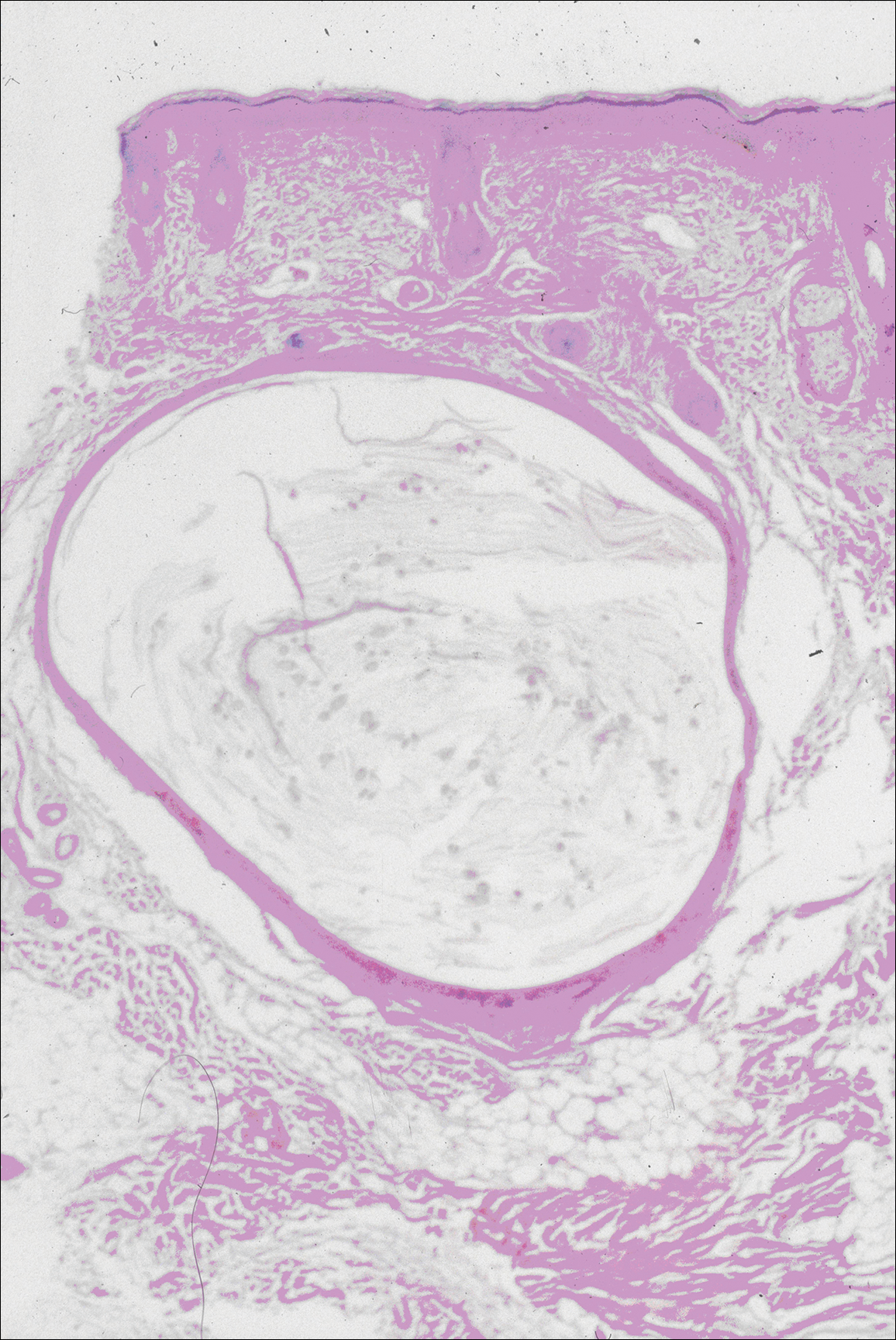

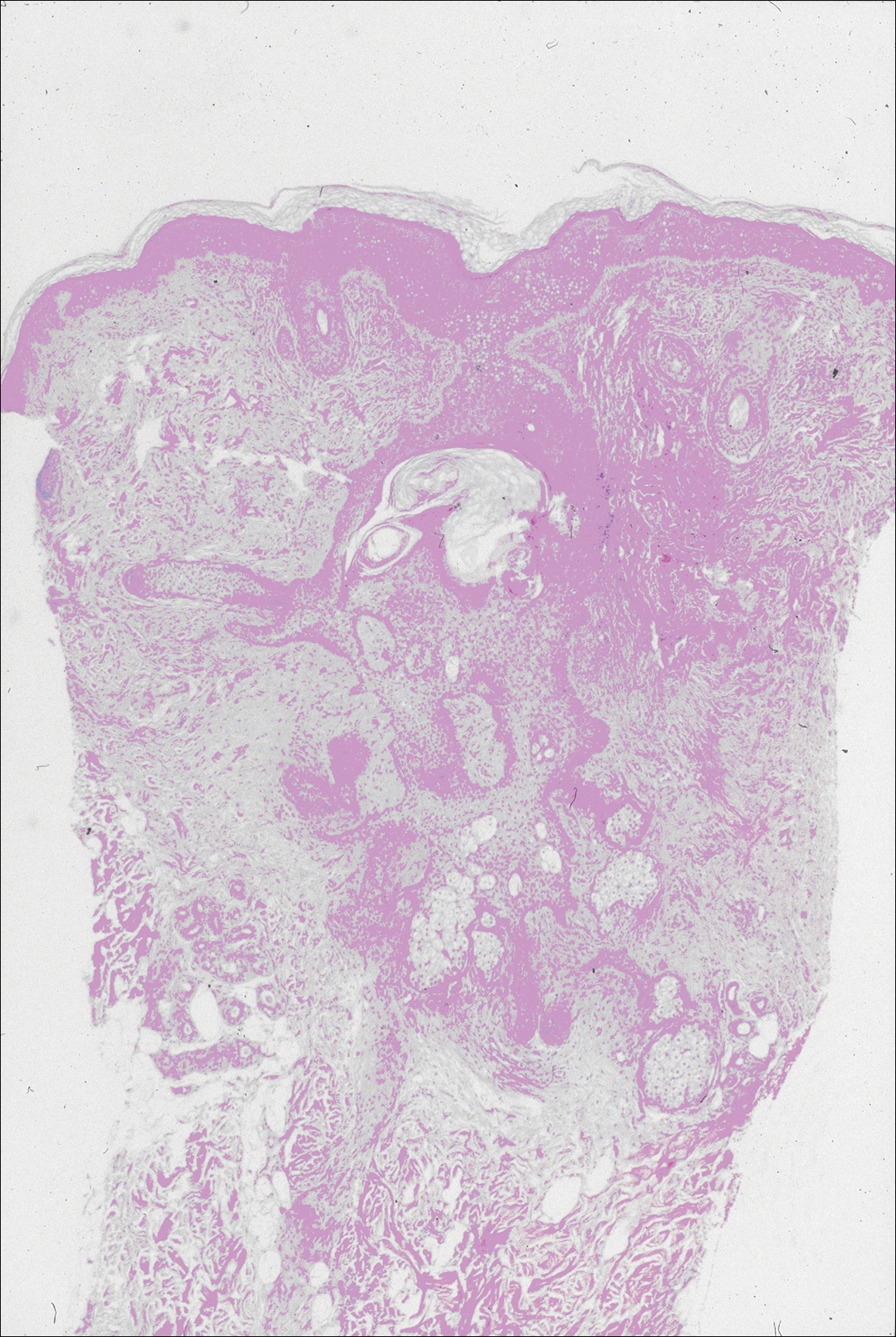

Physical examination revealed mild enlargement of the left testis with tenderness to palpation. The right testis was normal in appearance and nontender. An ultrasound study of the testicles was ordered; representative images are shown (Figures 1a-1c).

What is the diagnosis?

The transverse image of both testes demonstrated an enlarged left testicle compared to the right testicle (Figure 2a). On color-flow Doppler ultrasound, spots of color within the testicle were noted within the right testicle only. The lack of blood flow was confirmed on the sagittal image of the left testicle, which also revealed a small hydrocele (white arrows, Figure 2b). A sagittal color Doppler image of the normal right testicle showed color flow (white arrows, Figure 2c) and normal vascular waveforms (red arrow, Figure 2c) within the testis, but no hydrocele, confirming the diagnosis of left testicular torsion. The Doppler ultrasound of the right testicle (white arrows, Figure 2c) further confirmed a normal right testicle but no evidence of flow in the left testicle. These findings were further consistent with the presence of left testicular torsion.

Answer

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is a urological emergency that results from a twisting of the spermatic cord, cutting off arterial flow to, and venous drainage from, the affected testis. There are two types of testicular torsion depending on which side of the tunica vaginalis (the serous membrane pouch covering the testes) the torsion occurs: extra vaginal, seen mainly in newborns; and intravaginal, which can occur at any age, but is more common in adolescents.

“Bell clapper deformity” is a predisposing congenital condition resulting from intravaginal torsion of the testis in which the tunica vaginalis joins high on the spermatic cord, leaving the testis free to rotate.1 Testicular torsion most commonly occurs in young males, with an estimated incidence of 4.5 cases per 100,000 patients between ages 1 and 25 years.2

Clinical Presentation

Patients with testicular torsion typically experience a sudden onset of severe unilateral pain often accompanied by nausea and vomiting, which can occur spontaneously or after vigorous physical activity or trauma. Associated complaints may include urinary symptoms and/or fever.3 The affected testis may lie transversely in the scrotum and be retracted, although physical examination is often nonspecific and unreliable. Since an absence of the cremasteric reflex is neither sensitive nor specific in determining the need for surgical intervention, further diagnostic testing is required.4

Doppler Ultrasound

Ultrasound utilizing color and spectral Doppler techniques is the imaging test of choice to evaluate for testicular torsion, and has a reported sensitivity of 82% to 89%, and a specificity of 98% to 100%.5,6 Ultrasound findings include enlargement and decreased echogenicity of the affected testicle due to edema. Scrotal wall thickening and a small hydrocele also may be seen. Doppler imaging also typically demonstrates absence of flow, though hyperemia and increased flow may be present early in the disease process.

It is important to note that torsion may be intermittent; therefore, imaging studies can appear normal during periods of intermittent perfusion. If there is incomplete torsion and some arterial flow persists in the affected testis, comparison of the two testes using transverse views is very useful in making the diagnosis.7

With respect to the differential diagnoses, ultrasound imaging studies are also useful in diagnosing other conditions associated with testicular pain, including torsion of the appendix testis, epididymitis, orchitis, trauma, varicocele, and tumors.

Treatment

Rapid diagnosis of testicular torsion is important, as delay in diagnosis may lead to irreversible damage and loss of the testicle. Infertility can result even with a normal contralateral testis.8 When surgical intervention is performed within 6 hours from onset of torsion, salvage of the testicle has been reported to be 90% to 100%, but only 50% and 10% at 12 and 24 hours, respectively.3 The patient in this case was taken immediately for emergent surgical detorsion, and the left testicle was salvaged.

1. Caesar RE, Kaplan GW. Incidence of the bell-clapper deformity in an autopsy series. Urology. 1994;44 (1):114-116.

2. Mansbach JM, Forbes P, Peters C. Testicular torsion and risk factors for orchiectomy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1167-1171. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1167.

3. Sharp VJ, Kieran K, Arlen AM. Testicular torsion: diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(12):835-840.

4. Mellick LB. Torsion of the testicle: It is time to stop tossing the dice. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:80Y86. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31823f5ed9.

5. Baker LA, Sigman D, Mathews RI, Benson J, Docimo SG. An analysis of clinical outcomes using color doppler testicular ultrasound for testicular torsion. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3 Pt 1):604-607.

6. Burks DD, Markey BJ, Burkhard TK, Balsara ZN, Haluszka MM, Canning DA. Suspected testicular torsion and ischemia: evaluation with color Doppler sonography. Radiology. 1990;175(3):815-821. doi:10.1148/radiology.175.3.2188301.

7. Aso C, Enríquez G, Fité M, et al. Gray-scale and color doppler sonography of scrotal disorders in children: an update. Radiographics. 2005;25(5):1197-1214. doi:10.1148/rg.255045109.

8. Hadziselimovic F, Geneto R, Emmons LR. Increased apoptosis in the contralateral testes of patients with testicular torsion as a factor for infertility. J Urol. 1998;160(3 Pt 2):1158-1160.

A 32-year-old man presented to the ED with acute onset of left testicular swelling and pain. He described the pain as severe, radiating to his lower back and lower abdomen. Regarding his medical history, the patient stated he had experienced similar episodes of significant testicular swelling in the past, for which he was treated with antibiotics.

Physical examination revealed mild enlargement of the left testis with tenderness to palpation. The right testis was normal in appearance and nontender. An ultrasound study of the testicles was ordered; representative images are shown (Figures 1a-1c).

What is the diagnosis?

The transverse image of both testes demonstrated an enlarged left testicle compared to the right testicle (Figure 2a). On color-flow Doppler ultrasound, spots of color within the testicle were noted within the right testicle only. The lack of blood flow was confirmed on the sagittal image of the left testicle, which also revealed a small hydrocele (white arrows, Figure 2b). A sagittal color Doppler image of the normal right testicle showed color flow (white arrows, Figure 2c) and normal vascular waveforms (red arrow, Figure 2c) within the testis, but no hydrocele, confirming the diagnosis of left testicular torsion. The Doppler ultrasound of the right testicle (white arrows, Figure 2c) further confirmed a normal right testicle but no evidence of flow in the left testicle. These findings were further consistent with the presence of left testicular torsion.

Answer

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is a urological emergency that results from a twisting of the spermatic cord, cutting off arterial flow to, and venous drainage from, the affected testis. There are two types of testicular torsion depending on which side of the tunica vaginalis (the serous membrane pouch covering the testes) the torsion occurs: extra vaginal, seen mainly in newborns; and intravaginal, which can occur at any age, but is more common in adolescents.

“Bell clapper deformity” is a predisposing congenital condition resulting from intravaginal torsion of the testis in which the tunica vaginalis joins high on the spermatic cord, leaving the testis free to rotate.1 Testicular torsion most commonly occurs in young males, with an estimated incidence of 4.5 cases per 100,000 patients between ages 1 and 25 years.2

Clinical Presentation

Patients with testicular torsion typically experience a sudden onset of severe unilateral pain often accompanied by nausea and vomiting, which can occur spontaneously or after vigorous physical activity or trauma. Associated complaints may include urinary symptoms and/or fever.3 The affected testis may lie transversely in the scrotum and be retracted, although physical examination is often nonspecific and unreliable. Since an absence of the cremasteric reflex is neither sensitive nor specific in determining the need for surgical intervention, further diagnostic testing is required.4

Doppler Ultrasound

Ultrasound utilizing color and spectral Doppler techniques is the imaging test of choice to evaluate for testicular torsion, and has a reported sensitivity of 82% to 89%, and a specificity of 98% to 100%.5,6 Ultrasound findings include enlargement and decreased echogenicity of the affected testicle due to edema. Scrotal wall thickening and a small hydrocele also may be seen. Doppler imaging also typically demonstrates absence of flow, though hyperemia and increased flow may be present early in the disease process.

It is important to note that torsion may be intermittent; therefore, imaging studies can appear normal during periods of intermittent perfusion. If there is incomplete torsion and some arterial flow persists in the affected testis, comparison of the two testes using transverse views is very useful in making the diagnosis.7

With respect to the differential diagnoses, ultrasound imaging studies are also useful in diagnosing other conditions associated with testicular pain, including torsion of the appendix testis, epididymitis, orchitis, trauma, varicocele, and tumors.

Treatment

Rapid diagnosis of testicular torsion is important, as delay in diagnosis may lead to irreversible damage and loss of the testicle. Infertility can result even with a normal contralateral testis.8 When surgical intervention is performed within 6 hours from onset of torsion, salvage of the testicle has been reported to be 90% to 100%, but only 50% and 10% at 12 and 24 hours, respectively.3 The patient in this case was taken immediately for emergent surgical detorsion, and the left testicle was salvaged.

A 32-year-old man presented to the ED with acute onset of left testicular swelling and pain. He described the pain as severe, radiating to his lower back and lower abdomen. Regarding his medical history, the patient stated he had experienced similar episodes of significant testicular swelling in the past, for which he was treated with antibiotics.

Physical examination revealed mild enlargement of the left testis with tenderness to palpation. The right testis was normal in appearance and nontender. An ultrasound study of the testicles was ordered; representative images are shown (Figures 1a-1c).

What is the diagnosis?

The transverse image of both testes demonstrated an enlarged left testicle compared to the right testicle (Figure 2a). On color-flow Doppler ultrasound, spots of color within the testicle were noted within the right testicle only. The lack of blood flow was confirmed on the sagittal image of the left testicle, which also revealed a small hydrocele (white arrows, Figure 2b). A sagittal color Doppler image of the normal right testicle showed color flow (white arrows, Figure 2c) and normal vascular waveforms (red arrow, Figure 2c) within the testis, but no hydrocele, confirming the diagnosis of left testicular torsion. The Doppler ultrasound of the right testicle (white arrows, Figure 2c) further confirmed a normal right testicle but no evidence of flow in the left testicle. These findings were further consistent with the presence of left testicular torsion.

Answer

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is a urological emergency that results from a twisting of the spermatic cord, cutting off arterial flow to, and venous drainage from, the affected testis. There are two types of testicular torsion depending on which side of the tunica vaginalis (the serous membrane pouch covering the testes) the torsion occurs: extra vaginal, seen mainly in newborns; and intravaginal, which can occur at any age, but is more common in adolescents.

“Bell clapper deformity” is a predisposing congenital condition resulting from intravaginal torsion of the testis in which the tunica vaginalis joins high on the spermatic cord, leaving the testis free to rotate.1 Testicular torsion most commonly occurs in young males, with an estimated incidence of 4.5 cases per 100,000 patients between ages 1 and 25 years.2

Clinical Presentation

Patients with testicular torsion typically experience a sudden onset of severe unilateral pain often accompanied by nausea and vomiting, which can occur spontaneously or after vigorous physical activity or trauma. Associated complaints may include urinary symptoms and/or fever.3 The affected testis may lie transversely in the scrotum and be retracted, although physical examination is often nonspecific and unreliable. Since an absence of the cremasteric reflex is neither sensitive nor specific in determining the need for surgical intervention, further diagnostic testing is required.4

Doppler Ultrasound

Ultrasound utilizing color and spectral Doppler techniques is the imaging test of choice to evaluate for testicular torsion, and has a reported sensitivity of 82% to 89%, and a specificity of 98% to 100%.5,6 Ultrasound findings include enlargement and decreased echogenicity of the affected testicle due to edema. Scrotal wall thickening and a small hydrocele also may be seen. Doppler imaging also typically demonstrates absence of flow, though hyperemia and increased flow may be present early in the disease process.

It is important to note that torsion may be intermittent; therefore, imaging studies can appear normal during periods of intermittent perfusion. If there is incomplete torsion and some arterial flow persists in the affected testis, comparison of the two testes using transverse views is very useful in making the diagnosis.7

With respect to the differential diagnoses, ultrasound imaging studies are also useful in diagnosing other conditions associated with testicular pain, including torsion of the appendix testis, epididymitis, orchitis, trauma, varicocele, and tumors.

Treatment

Rapid diagnosis of testicular torsion is important, as delay in diagnosis may lead to irreversible damage and loss of the testicle. Infertility can result even with a normal contralateral testis.8 When surgical intervention is performed within 6 hours from onset of torsion, salvage of the testicle has been reported to be 90% to 100%, but only 50% and 10% at 12 and 24 hours, respectively.3 The patient in this case was taken immediately for emergent surgical detorsion, and the left testicle was salvaged.

1. Caesar RE, Kaplan GW. Incidence of the bell-clapper deformity in an autopsy series. Urology. 1994;44 (1):114-116.

2. Mansbach JM, Forbes P, Peters C. Testicular torsion and risk factors for orchiectomy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1167-1171. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1167.

3. Sharp VJ, Kieran K, Arlen AM. Testicular torsion: diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(12):835-840.

4. Mellick LB. Torsion of the testicle: It is time to stop tossing the dice. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:80Y86. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31823f5ed9.

5. Baker LA, Sigman D, Mathews RI, Benson J, Docimo SG. An analysis of clinical outcomes using color doppler testicular ultrasound for testicular torsion. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3 Pt 1):604-607.

6. Burks DD, Markey BJ, Burkhard TK, Balsara ZN, Haluszka MM, Canning DA. Suspected testicular torsion and ischemia: evaluation with color Doppler sonography. Radiology. 1990;175(3):815-821. doi:10.1148/radiology.175.3.2188301.

7. Aso C, Enríquez G, Fité M, et al. Gray-scale and color doppler sonography of scrotal disorders in children: an update. Radiographics. 2005;25(5):1197-1214. doi:10.1148/rg.255045109.

8. Hadziselimovic F, Geneto R, Emmons LR. Increased apoptosis in the contralateral testes of patients with testicular torsion as a factor for infertility. J Urol. 1998;160(3 Pt 2):1158-1160.

1. Caesar RE, Kaplan GW. Incidence of the bell-clapper deformity in an autopsy series. Urology. 1994;44 (1):114-116.

2. Mansbach JM, Forbes P, Peters C. Testicular torsion and risk factors for orchiectomy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1167-1171. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1167.

3. Sharp VJ, Kieran K, Arlen AM. Testicular torsion: diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(12):835-840.

4. Mellick LB. Torsion of the testicle: It is time to stop tossing the dice. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:80Y86. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31823f5ed9.

5. Baker LA, Sigman D, Mathews RI, Benson J, Docimo SG. An analysis of clinical outcomes using color doppler testicular ultrasound for testicular torsion. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3 Pt 1):604-607.

6. Burks DD, Markey BJ, Burkhard TK, Balsara ZN, Haluszka MM, Canning DA. Suspected testicular torsion and ischemia: evaluation with color Doppler sonography. Radiology. 1990;175(3):815-821. doi:10.1148/radiology.175.3.2188301.

7. Aso C, Enríquez G, Fité M, et al. Gray-scale and color doppler sonography of scrotal disorders in children: an update. Radiographics. 2005;25(5):1197-1214. doi:10.1148/rg.255045109.

8. Hadziselimovic F, Geneto R, Emmons LR. Increased apoptosis in the contralateral testes of patients with testicular torsion as a factor for infertility. J Urol. 1998;160(3 Pt 2):1158-1160.

Parkinsonism and Vitamin C Deficiency

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) deficiency is known to affect brain function and is associated with parkinsonism.1 In 1752, James Lind, MD, described emotional and behavioral changes that herald the onset of scurvy and precede hemorrhagic findings.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) today refers to this stage as latent scurvy.3 The 2 case studies that follow present examples of patients with vitamin C deficiencies whose parkinsonism responded robustly to vitamin C replacement. These cases suggest that vitamin C deficiency may be a treatable cause of parkinsonism.

Case 1

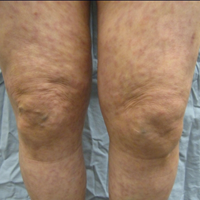

Mr. A, a 60-year-old white male, was admitted to the Medicine Service for alcohol detoxification. The patient had a history of alcohol dependence, alcohol withdrawal seizures, tobacco dependence, and hyperlipidemia. He took no medications as an outpatient. On admission Mr. A’s body mass index (BMI) was 27.2. An initial examination revealed a marked resting tremor of the patient’s right hand with cogwheeling, which had not been present in examinations conducted in the previous 3 years. Mr. A had no prior history of a tremor. He had no cerebellar findings and no evidence of asterixis or of tremulousness associated with high-output cardiac states, such as de Musset sign.

Mr. A reported he had experienced the tremor for a month and that it had been worsening. He also was having difficulty using his dominant right hand, for routine daily activities. Mr. A was oriented, and his short-term memory was intact. He was ill-appearing, irritable with psychomotor slowing, and did not wish to rise from his bed. He had no gingival or periungual bleeding and did not bruise easily. He had no corkscrew hairs. The patient was started on no medications known to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS).

In the hospital, the tremor persisted unabated for 2 days. On the third day, Mr. A was started on 1,000 mg vitamin C IV twice daily. He received a total of 2,000 mg IV that day, but the IV fell out, and he refused its replacement. Several hours later, Mr. A stated that he felt much better, got out of bed, and asked to go outside to smoke. The author noted complete resolution of the right hand tremor and cogwheeling 20 hours after starting the vitamin C IV. Mr. A refused a repeat serum vitamin C assay.

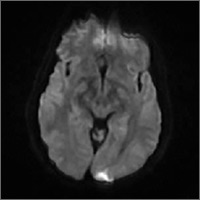

Laboratory studies initially revealed that Mr. A had hyponatremia with a serum sodium of 121 mmol/L (normal range: 133 to 145 mmol/L) as well as hypokalemia with a serum potassium of 3.2 mmol/L (normal range: 3.5 to 5.0 mmol/L). He was hypoosmolar, with a serum osmolality of 276 mOsm/kg (normal range: 278 to 305 mOsm/kg). His vitamin C level was low at 0.2 mg/dL (normal range: 0.4 to 2.0 mg/dL). Mr. A also had a serum vitamin C level drawn 2 years prior that showed no symptoms of EPS, and at that time, the reading was 0.7 mg/dL. At admission to Medicine Services, Mr. A had a serum alcohol level of 211 mg/dL. Neuroimaging revealed diffuse cerebral and cerebellar volume loss.

Normal laboratory results included serum levels of vitamin B12, red cell folate, homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, free and total carnitine, alkaline phosphatase, manganese, and zinc. A urine drug screen was negative.

Case 2

Mr. B, a 69-year-old black male, was admitted to the hospital for depression complicated by alcohol dependence. He also had tobacco dependence, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and gout. The patient’s BMI at admission was 16.1. Mr. B appeared ill, was worried about his health, and remained recumbent unless asked to move. He reported that his right hand had begun to shake at rest in the month prior to admission. The tremor made it difficult for him to drink. He pointed out stains on his hospital gurney from an attempt to drink orange juice prior to being assessed.

A physical examination revealed a distinct resting tremor with cogwheeling of the right hand; there was no other evidence of EPS, nor was there evidence of cognitive, cerebellar, or skin abnormalities, such as hemorrhages or corkscrew hairs. Asterixis was absent as was evidence of a high-output cardiac state that might produce a tremor, such as de Musset sign. A serum vitamin C level was obtained and returned at 0.0 mg/dL. A head computed tomography scan obtained the next day revealed mild cerebellar volume loss. A serum alkaline phosphatase level was elevated slightly at 136 U/L (normal range: 42 to 113 U/L). Normal serum values were returned for zinc, vitamins B12 and folate, rapid plasma reagin, sodium, and serum osmolality. A urine drug screen was negative, and serum alcohol level was < 5.0 mg/dL.

Mr. B took no medications expected to cause EPS. He received no micronutrient replacement until the day after admission when he began receiving oral vitamin C 1,000 mg twice a day. After receiving 3 doses, Mr. B’s resting tremor and cogwheeling completely resolved. He noticed he had stopped shaking and could now drink without spilling fluids. He also got out of bed and began interacting with others. Mr. B said he felt he was “doing well.” A repeat serum vitamin C level was 0.2 mg/dL on that day. The improvement was sustained over 3 days, and Mr. B was discharged to home.

Discussion

Both Mr. A and Mr. B presented with a typical picture of latent scurvy and the additional finding of parkinsonism. These cases are important for 2 reasons. First, the swift and full response of these patients’ parkinsonism to vitamin C replacement underscores the importance of considering a vitamin C deficiency when confronted with EPS. And second, both patients lacked signs of bleeding or of impaired collagen synthesis. This differs from the classic presentation of scurvy as a disorder primarily of collagen metabolism.4

Lind described the onset of scurvy as one in which striking emotional and behavior changes developed and later were followed by abnormal bleeding and even death.2 These early changes also were recognized by Shapter in 1847.5 Furthermore, the evidence that exists about the time-course of scurvy’s development suggests that neuropsychiatric findings precede the hemorrhagic.6 Indeed, classic skin findings, such as petechiae or corkscrew hairs, may develop years after the onset of neuropsychiatric changes.7,8

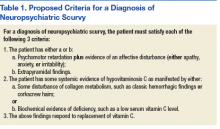

Despite WHO characterizing it as latent scurvy, the distinct syndromal presentation of hypovitaminosis C with parkinsonism along with the rapid response to vitamin C replacement argues for its recognition as a distinct clinical entity and not just a prelude to the hemorrhagic state. To assist in recognizing neuropsychiatric scurvy, the author suggests the operationalized approach described in Table 1.9

Pathophysiology

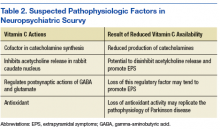

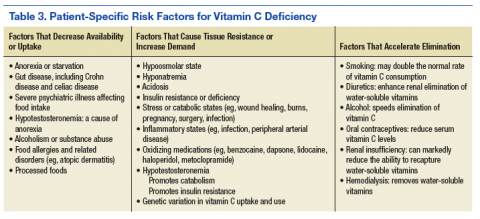

Vitamin C has an intimate role in the normal functioning of the basal ganglia. It is involved in the synthesis of catechecholamines, the regulation of the release and postsynaptic activities of various neurotransmitters, and managing the oxyradical toxicity of aerobic metabolism. Table 2 outlines some of the normal brain functions of vitamin C and the potential consequences of inadequate central vitamin C.9,10 Risk factors for vitamin C deficiency include those affecting the uptake, response to, and elimination of this vitamin (Table 3).11-14

The potential role of alcohol use by both patients also warrants mention. Current data suggest a nonlinear relationship between alcohol use and neurotoxicity. Epidemiologic data show that moderate alcohol consumption protects against the development of such neurodegenerative processes as Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease.15,16 But the cases here reflect excessive use of alcohol. In this situation, a variety of progressive insults, such as those caused by oxyradical toxicity as well as malnutrition may foster the development of basal ganglia dysfunction.17

Measuring Deficiency

A deficiency of vitamin C may be determined in several ways. The most frequently used laboratory measure of vitamin C status is the serum vitamin C level. This level is included in the WHO’s recommendations for diagnosis.3 However, this assay is limited because when facing total body depletion, the kidneys may restrict the elimination of vitamin C and tend to maintain serum vitamin C levels even as target tissue levels fall. An interesting example of this is the 0.2 mg/dL value that each patient registered. In Mr. A’s case, this reflected a systemic deficit of vitamin C, while in Mr. B’s case it correlated with the onset of effective repletion of body’s stores.

A fall in urinary output of vitamin C is another marker of hypovitaminosis C. When available, this laboratory test can be used with the serum level to assess total body stores of vitamin C. Lymphocytes, neutrophils, and platelets also store vitamin C. These target tissues tend to saturate when the oral intake ranges between 100 mg to 200 mg a day. This is the same point at which serum vitamin C levels peak and level off in normal, healthy adults.18,19 Once again, the limited availability of target-tissue assays puts these studies out of reach for most clinicians.

No evaluation is complete without some assurance of what the disease is not. Deficiencies of biotin, zinc, folate, and B12 all may affect the function of the basal ganglia.20 The biotin deficiencies literature is particularly robust. Biotin deficiencies affecting basal ganglia function are best known as inherited disorders of metabolism.21 Manganese intoxication also may present as a movement disorder.22

Treatment

Treatment of neuropsychiatric scurvy has relied on IV administration of vitamin C. Although the bioavailability of oral vitamin C among healthy adult volunteers is nearly complete up to about 200 mg a day, a patient with neuropsychiatric scurvy may need substantially more than that amount to accommodate total body deficiencies and increased demands.23 The IV route allows serum vitamin C levels up to 100 times higher than by the oral route.24 Mr. B is, in fact, the first person reported in the literature with neuropsychiatric scurvy to respond to oral vitamin C replacement alone. Once repletion of vitamin C is complete, it is useful to consider a maintenance replacement dose based on a patient’s risk factors and needs.

A healthy adult should ingest about 120 mg of vitamin C daily. Smokers and pregnant women may require more, but this recommendation was intended to address their needs as well.25 Many commercial multivitamins use the old recommended daily allowance of 60 mg, so it may be safest to recommend specifically a vitamin C tablet with at least 120 mg when ordering vitamin C replacement.

Tight control of the serum vitamin C concentration means that little additional vitamin C will be taken up by the gut beyond 200 mg orally a day, which helps minimize any concerns about long-term toxicity. It takes several weeks to deplete vitamin C from the human body when vitamin C is removed from the diet, so a patient with a previously treated deficiency of vitamin C should wait a month before a repeat serum vitamin C level measurement.

The half life of vitamin C is normally ≤ 2 hours. When renal function is intact, vitamin C in excess of immediate need is lost through renal filtration. Toxicity is rare under these conditions.26 When vitamin C toxicity has been reported, it has occurred in the setting of prolonged supplementation, usually when a patient already experienced a renal injury. The main toxicities attributed to vitamin C are oxalate crystal formation with subsequent renal injury and exacerbation of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD).24

Oxalate formation due to vitamin C replacement is uncommon, but patients with preexisting calcium oxalate stones may be at risk for further stone formation when they receive additional vitamin C.27 This is most likely to occur when treatment with parenteral vitamin C is prolonged, which is not typical for patients with neuropsychiatric scurvy who tend to respond rapidly to vitamin C replenishment. Reports of acute hemolytic episodes among patient with G6PD deficiency receiving vitamin C exist, although these cases are rare.28 Furthermore, some authors advocate for the use of ascorbic acid to treat methemoglobinemia associated with G6PD deficiency, when methylene blue is not available.29 It may be reasonable to begin treatment with oral vitamin C for patients with NPS and G6PD deficiency. This is equivalent to a low-dose form of vitamin C replacement and may help avoid the theoretically pro-oxidant effects of larger, IV doses of vitamin C.30

Conclusion

The recent discovery of movement disorders in scurvy has enlarged the picture of vitamin C deficiency. The cases here demonstrate how hypovitaminosis C with central nervous system manifestations may be identified and treated. This relationship fits well within the established basic science and clinical framework for scurvy, and the clinical implications for scurvy remain in many ways unchanged. First, malnutrition must be considered even when a patient’s habitus suggests he is well fed. Also, it is more likely to see scurvy without all of the classic findings than an end-stage case of the disease.31 In the right clinical setting, it is reasonable to think of a vitamin C deficiency before the patient develops bleeding gums and corkscrew hairs. And as is typical of vitamin deficiencies, the treatment of a vitamin C deficiency usually results in swift improvement. Finally, for those who treat movement disorders or who prescribe agents such as antipsychotics that may cause movement disorders, it is important to recognize vitamin C deficiency as another potential explanation for EPS.

1. Ide K, Yamada H, Umegaki K, et al. Lymphocyte vitamin C levels as potential biomarker for progression of Parkinson’s disease. Nutrition. 2015;31(2):406-408.

2. Lind J. The diagnostics, or symptoms. A Treatise on the Scurvy, in Three Parts. 3rd ed. London: S. Crowder, D. Wilson and G. Nicholls, T. Cadell, T. Becket and Co., G. Pearch, and Woodfall; 1772:98-129.

3. World Health Organization. Scurvy and its prevention and control in major emergencies. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_NHD_99.11.pdf. Published 1999. Accessed July 6, 2017.

4. Sasseville D. Scurvy: curse and cure in New France. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(4):431.

5. Shapter T. On the recent occurrence of scurvy in Exeter and the neighbourhood. Prov Med Surg J. 1847;11(11):281-285.

6. Kinsman RA, Hood J. Some behavioral effects of ascorbic acid deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr. 1971;24(4):455-464.

7. DeSantis J. Scurvy and psychiatric symptoms. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 1993;29(1):18-22.

8. Walter JF. Scurvy resulting from a self-imposed diet. West J Med. 1979;130(2):177-179.

9. Brown TM. Neuropsychiatric scurvy. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(1):12-20.

10. Feuerstein TJ, Weinheimer G, Lang G, Ginap T, Rossner R. Inhibition by ascorbic acid of NMDA-evoked acetylcholine release in rabbit caudate nucleus. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1993;348(5):549-551.

11. Kim J, Kwon J, Noh G, Lee SS. The effects of elimination diet on nutritional status in subjects with atopic dermatitis. Nutr Res Pract. 2013;7(6):488-494.

12. Langlois M, Duprez D, Delanghe J, De Buyzere M, Clement DL. Serum vitamin C concentration is low in peripheral arterial disease and is associated with inflammation and severity of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2001;103(14):1863-1868.

13. Nappe TM, Pacelli AM, Katz K. An atypical case of methemoglobinemia due to self-administered benzocaine. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2015;2015:670979.

14. Wright AD, Stevens E, Ali M, Carroll DW, Brown TM. The neuropsychiatry of scurvy. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(2):179-185.

15. Bate C, Williams A. Ethanol protects cultured neurons against amyloid-β and α-synuclein-induced synapse damage. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61(8):1406-1412.

16. Vasanthi HR, Parameswari RP, DeLeiris J, Das DK. Health benefits of wine and alcohol from neuroprotection to heart health. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012;4:1505-1512.

17. Vaglini F, Viaggi C, Piro V, et al. Acetaldehyde and parkinsonism: role of CYP450 2E1. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:71.

18. Levine M, Wang Y, Padayatty SJ, Morrow J. A new recommended dietary allowance of vitamin C for healthy young women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(17):9842-9846.

19. Levine M, Padayatty SJ, Espey MG. Vitamin C: a concentration-function approach yields pharmacology and therapeutic discoveries. Adv Nutr. 2011;2(2):78-88.

20. Quiroga MJ, Carroll DW, Brown TM. Ascorbate- and zinc-responsive parkinsonism. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(11):1515-1520.

21. Tabarki B, Al-Shafi S, Al-Shahwan S, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease revisited: clinical, radiologic, and genetic findings. Neurology. 2013;80(3):261-267.

22. Tuschl K, Mills PB, Clayton PT. Manganese and the brain. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;110:277-312.

23. Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang Y, et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(8):3704-3709.

24. Wilson MK, Baguley BC, Wall C, Jameson MB, Findlay MP. Review of high-dose intravenous vitamin C as an anticancer agent. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10(1):22-37.

25. Carr AC, Frei B. Toward a new recommended dietary allowance for vitamin C based on antioxidant and health effects in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(6):1086-1107.

26. Nielsen TK, Højgaard M, Andersen JT, Poulsen HE, Lykkesfeldt J, Mikines KJ. Elimination of ascorbic acid after high-dose infusion in prostate cancer patients: a pharmacokinetic evaluation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;116(4):343-348.

27. Baxmann AC, De O G Mendonça C, Heilberg IP. Effect of vitamin C supplements on urinary oxalate and pH in calcium stone-forming patients. Kidney Int. 2003;63(3):1066-1071.

28. Huang YC, Chang TK, Fu YC, Jan SL. C for colored urine: acute hemolysis induced by high-dose ascorbic acid. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52(9):984.

29. Rino PB, Scolnik D, Fustiñana A, Mitelpunkt A, Glatstein M. Ascorbic acid for the treatment of methemoglobinemia: the experience of a large tertiary care pediatric hospital. Am J Ther. 2014;21(4):240-243.

30. Du J, Cullen JJ, Buettner GR. Ascorbic acid: chemistry, biology and the treatment of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826(2):443-457.

31. Fouron JC, Chicoine L. Le scorbut: aspects particuliers de l’association rachitisme-scorbut. Can Med Assoc J. 1962;86(26):1191-1196.

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) deficiency is known to affect brain function and is associated with parkinsonism.1 In 1752, James Lind, MD, described emotional and behavioral changes that herald the onset of scurvy and precede hemorrhagic findings.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) today refers to this stage as latent scurvy.3 The 2 case studies that follow present examples of patients with vitamin C deficiencies whose parkinsonism responded robustly to vitamin C replacement. These cases suggest that vitamin C deficiency may be a treatable cause of parkinsonism.

Case 1

Mr. A, a 60-year-old white male, was admitted to the Medicine Service for alcohol detoxification. The patient had a history of alcohol dependence, alcohol withdrawal seizures, tobacco dependence, and hyperlipidemia. He took no medications as an outpatient. On admission Mr. A’s body mass index (BMI) was 27.2. An initial examination revealed a marked resting tremor of the patient’s right hand with cogwheeling, which had not been present in examinations conducted in the previous 3 years. Mr. A had no prior history of a tremor. He had no cerebellar findings and no evidence of asterixis or of tremulousness associated with high-output cardiac states, such as de Musset sign.

Mr. A reported he had experienced the tremor for a month and that it had been worsening. He also was having difficulty using his dominant right hand, for routine daily activities. Mr. A was oriented, and his short-term memory was intact. He was ill-appearing, irritable with psychomotor slowing, and did not wish to rise from his bed. He had no gingival or periungual bleeding and did not bruise easily. He had no corkscrew hairs. The patient was started on no medications known to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS).

In the hospital, the tremor persisted unabated for 2 days. On the third day, Mr. A was started on 1,000 mg vitamin C IV twice daily. He received a total of 2,000 mg IV that day, but the IV fell out, and he refused its replacement. Several hours later, Mr. A stated that he felt much better, got out of bed, and asked to go outside to smoke. The author noted complete resolution of the right hand tremor and cogwheeling 20 hours after starting the vitamin C IV. Mr. A refused a repeat serum vitamin C assay.

Laboratory studies initially revealed that Mr. A had hyponatremia with a serum sodium of 121 mmol/L (normal range: 133 to 145 mmol/L) as well as hypokalemia with a serum potassium of 3.2 mmol/L (normal range: 3.5 to 5.0 mmol/L). He was hypoosmolar, with a serum osmolality of 276 mOsm/kg (normal range: 278 to 305 mOsm/kg). His vitamin C level was low at 0.2 mg/dL (normal range: 0.4 to 2.0 mg/dL). Mr. A also had a serum vitamin C level drawn 2 years prior that showed no symptoms of EPS, and at that time, the reading was 0.7 mg/dL. At admission to Medicine Services, Mr. A had a serum alcohol level of 211 mg/dL. Neuroimaging revealed diffuse cerebral and cerebellar volume loss.

Normal laboratory results included serum levels of vitamin B12, red cell folate, homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, free and total carnitine, alkaline phosphatase, manganese, and zinc. A urine drug screen was negative.

Case 2

Mr. B, a 69-year-old black male, was admitted to the hospital for depression complicated by alcohol dependence. He also had tobacco dependence, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and gout. The patient’s BMI at admission was 16.1. Mr. B appeared ill, was worried about his health, and remained recumbent unless asked to move. He reported that his right hand had begun to shake at rest in the month prior to admission. The tremor made it difficult for him to drink. He pointed out stains on his hospital gurney from an attempt to drink orange juice prior to being assessed.

A physical examination revealed a distinct resting tremor with cogwheeling of the right hand; there was no other evidence of EPS, nor was there evidence of cognitive, cerebellar, or skin abnormalities, such as hemorrhages or corkscrew hairs. Asterixis was absent as was evidence of a high-output cardiac state that might produce a tremor, such as de Musset sign. A serum vitamin C level was obtained and returned at 0.0 mg/dL. A head computed tomography scan obtained the next day revealed mild cerebellar volume loss. A serum alkaline phosphatase level was elevated slightly at 136 U/L (normal range: 42 to 113 U/L). Normal serum values were returned for zinc, vitamins B12 and folate, rapid plasma reagin, sodium, and serum osmolality. A urine drug screen was negative, and serum alcohol level was < 5.0 mg/dL.

Mr. B took no medications expected to cause EPS. He received no micronutrient replacement until the day after admission when he began receiving oral vitamin C 1,000 mg twice a day. After receiving 3 doses, Mr. B’s resting tremor and cogwheeling completely resolved. He noticed he had stopped shaking and could now drink without spilling fluids. He also got out of bed and began interacting with others. Mr. B said he felt he was “doing well.” A repeat serum vitamin C level was 0.2 mg/dL on that day. The improvement was sustained over 3 days, and Mr. B was discharged to home.

Discussion

Both Mr. A and Mr. B presented with a typical picture of latent scurvy and the additional finding of parkinsonism. These cases are important for 2 reasons. First, the swift and full response of these patients’ parkinsonism to vitamin C replacement underscores the importance of considering a vitamin C deficiency when confronted with EPS. And second, both patients lacked signs of bleeding or of impaired collagen synthesis. This differs from the classic presentation of scurvy as a disorder primarily of collagen metabolism.4

Lind described the onset of scurvy as one in which striking emotional and behavior changes developed and later were followed by abnormal bleeding and even death.2 These early changes also were recognized by Shapter in 1847.5 Furthermore, the evidence that exists about the time-course of scurvy’s development suggests that neuropsychiatric findings precede the hemorrhagic.6 Indeed, classic skin findings, such as petechiae or corkscrew hairs, may develop years after the onset of neuropsychiatric changes.7,8

Despite WHO characterizing it as latent scurvy, the distinct syndromal presentation of hypovitaminosis C with parkinsonism along with the rapid response to vitamin C replacement argues for its recognition as a distinct clinical entity and not just a prelude to the hemorrhagic state. To assist in recognizing neuropsychiatric scurvy, the author suggests the operationalized approach described in Table 1.9

Pathophysiology

Vitamin C has an intimate role in the normal functioning of the basal ganglia. It is involved in the synthesis of catechecholamines, the regulation of the release and postsynaptic activities of various neurotransmitters, and managing the oxyradical toxicity of aerobic metabolism. Table 2 outlines some of the normal brain functions of vitamin C and the potential consequences of inadequate central vitamin C.9,10 Risk factors for vitamin C deficiency include those affecting the uptake, response to, and elimination of this vitamin (Table 3).11-14

The potential role of alcohol use by both patients also warrants mention. Current data suggest a nonlinear relationship between alcohol use and neurotoxicity. Epidemiologic data show that moderate alcohol consumption protects against the development of such neurodegenerative processes as Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease.15,16 But the cases here reflect excessive use of alcohol. In this situation, a variety of progressive insults, such as those caused by oxyradical toxicity as well as malnutrition may foster the development of basal ganglia dysfunction.17

Measuring Deficiency

A deficiency of vitamin C may be determined in several ways. The most frequently used laboratory measure of vitamin C status is the serum vitamin C level. This level is included in the WHO’s recommendations for diagnosis.3 However, this assay is limited because when facing total body depletion, the kidneys may restrict the elimination of vitamin C and tend to maintain serum vitamin C levels even as target tissue levels fall. An interesting example of this is the 0.2 mg/dL value that each patient registered. In Mr. A’s case, this reflected a systemic deficit of vitamin C, while in Mr. B’s case it correlated with the onset of effective repletion of body’s stores.

A fall in urinary output of vitamin C is another marker of hypovitaminosis C. When available, this laboratory test can be used with the serum level to assess total body stores of vitamin C. Lymphocytes, neutrophils, and platelets also store vitamin C. These target tissues tend to saturate when the oral intake ranges between 100 mg to 200 mg a day. This is the same point at which serum vitamin C levels peak and level off in normal, healthy adults.18,19 Once again, the limited availability of target-tissue assays puts these studies out of reach for most clinicians.

No evaluation is complete without some assurance of what the disease is not. Deficiencies of biotin, zinc, folate, and B12 all may affect the function of the basal ganglia.20 The biotin deficiencies literature is particularly robust. Biotin deficiencies affecting basal ganglia function are best known as inherited disorders of metabolism.21 Manganese intoxication also may present as a movement disorder.22

Treatment

Treatment of neuropsychiatric scurvy has relied on IV administration of vitamin C. Although the bioavailability of oral vitamin C among healthy adult volunteers is nearly complete up to about 200 mg a day, a patient with neuropsychiatric scurvy may need substantially more than that amount to accommodate total body deficiencies and increased demands.23 The IV route allows serum vitamin C levels up to 100 times higher than by the oral route.24 Mr. B is, in fact, the first person reported in the literature with neuropsychiatric scurvy to respond to oral vitamin C replacement alone. Once repletion of vitamin C is complete, it is useful to consider a maintenance replacement dose based on a patient’s risk factors and needs.

A healthy adult should ingest about 120 mg of vitamin C daily. Smokers and pregnant women may require more, but this recommendation was intended to address their needs as well.25 Many commercial multivitamins use the old recommended daily allowance of 60 mg, so it may be safest to recommend specifically a vitamin C tablet with at least 120 mg when ordering vitamin C replacement.

Tight control of the serum vitamin C concentration means that little additional vitamin C will be taken up by the gut beyond 200 mg orally a day, which helps minimize any concerns about long-term toxicity. It takes several weeks to deplete vitamin C from the human body when vitamin C is removed from the diet, so a patient with a previously treated deficiency of vitamin C should wait a month before a repeat serum vitamin C level measurement.

The half life of vitamin C is normally ≤ 2 hours. When renal function is intact, vitamin C in excess of immediate need is lost through renal filtration. Toxicity is rare under these conditions.26 When vitamin C toxicity has been reported, it has occurred in the setting of prolonged supplementation, usually when a patient already experienced a renal injury. The main toxicities attributed to vitamin C are oxalate crystal formation with subsequent renal injury and exacerbation of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD).24

Oxalate formation due to vitamin C replacement is uncommon, but patients with preexisting calcium oxalate stones may be at risk for further stone formation when they receive additional vitamin C.27 This is most likely to occur when treatment with parenteral vitamin C is prolonged, which is not typical for patients with neuropsychiatric scurvy who tend to respond rapidly to vitamin C replenishment. Reports of acute hemolytic episodes among patient with G6PD deficiency receiving vitamin C exist, although these cases are rare.28 Furthermore, some authors advocate for the use of ascorbic acid to treat methemoglobinemia associated with G6PD deficiency, when methylene blue is not available.29 It may be reasonable to begin treatment with oral vitamin C for patients with NPS and G6PD deficiency. This is equivalent to a low-dose form of vitamin C replacement and may help avoid the theoretically pro-oxidant effects of larger, IV doses of vitamin C.30

Conclusion

The recent discovery of movement disorders in scurvy has enlarged the picture of vitamin C deficiency. The cases here demonstrate how hypovitaminosis C with central nervous system manifestations may be identified and treated. This relationship fits well within the established basic science and clinical framework for scurvy, and the clinical implications for scurvy remain in many ways unchanged. First, malnutrition must be considered even when a patient’s habitus suggests he is well fed. Also, it is more likely to see scurvy without all of the classic findings than an end-stage case of the disease.31 In the right clinical setting, it is reasonable to think of a vitamin C deficiency before the patient develops bleeding gums and corkscrew hairs. And as is typical of vitamin deficiencies, the treatment of a vitamin C deficiency usually results in swift improvement. Finally, for those who treat movement disorders or who prescribe agents such as antipsychotics that may cause movement disorders, it is important to recognize vitamin C deficiency as another potential explanation for EPS.

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) deficiency is known to affect brain function and is associated with parkinsonism.1 In 1752, James Lind, MD, described emotional and behavioral changes that herald the onset of scurvy and precede hemorrhagic findings.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) today refers to this stage as latent scurvy.3 The 2 case studies that follow present examples of patients with vitamin C deficiencies whose parkinsonism responded robustly to vitamin C replacement. These cases suggest that vitamin C deficiency may be a treatable cause of parkinsonism.

Case 1

Mr. A, a 60-year-old white male, was admitted to the Medicine Service for alcohol detoxification. The patient had a history of alcohol dependence, alcohol withdrawal seizures, tobacco dependence, and hyperlipidemia. He took no medications as an outpatient. On admission Mr. A’s body mass index (BMI) was 27.2. An initial examination revealed a marked resting tremor of the patient’s right hand with cogwheeling, which had not been present in examinations conducted in the previous 3 years. Mr. A had no prior history of a tremor. He had no cerebellar findings and no evidence of asterixis or of tremulousness associated with high-output cardiac states, such as de Musset sign.

Mr. A reported he had experienced the tremor for a month and that it had been worsening. He also was having difficulty using his dominant right hand, for routine daily activities. Mr. A was oriented, and his short-term memory was intact. He was ill-appearing, irritable with psychomotor slowing, and did not wish to rise from his bed. He had no gingival or periungual bleeding and did not bruise easily. He had no corkscrew hairs. The patient was started on no medications known to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS).

In the hospital, the tremor persisted unabated for 2 days. On the third day, Mr. A was started on 1,000 mg vitamin C IV twice daily. He received a total of 2,000 mg IV that day, but the IV fell out, and he refused its replacement. Several hours later, Mr. A stated that he felt much better, got out of bed, and asked to go outside to smoke. The author noted complete resolution of the right hand tremor and cogwheeling 20 hours after starting the vitamin C IV. Mr. A refused a repeat serum vitamin C assay.

Laboratory studies initially revealed that Mr. A had hyponatremia with a serum sodium of 121 mmol/L (normal range: 133 to 145 mmol/L) as well as hypokalemia with a serum potassium of 3.2 mmol/L (normal range: 3.5 to 5.0 mmol/L). He was hypoosmolar, with a serum osmolality of 276 mOsm/kg (normal range: 278 to 305 mOsm/kg). His vitamin C level was low at 0.2 mg/dL (normal range: 0.4 to 2.0 mg/dL). Mr. A also had a serum vitamin C level drawn 2 years prior that showed no symptoms of EPS, and at that time, the reading was 0.7 mg/dL. At admission to Medicine Services, Mr. A had a serum alcohol level of 211 mg/dL. Neuroimaging revealed diffuse cerebral and cerebellar volume loss.

Normal laboratory results included serum levels of vitamin B12, red cell folate, homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, free and total carnitine, alkaline phosphatase, manganese, and zinc. A urine drug screen was negative.

Case 2

Mr. B, a 69-year-old black male, was admitted to the hospital for depression complicated by alcohol dependence. He also had tobacco dependence, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and gout. The patient’s BMI at admission was 16.1. Mr. B appeared ill, was worried about his health, and remained recumbent unless asked to move. He reported that his right hand had begun to shake at rest in the month prior to admission. The tremor made it difficult for him to drink. He pointed out stains on his hospital gurney from an attempt to drink orange juice prior to being assessed.

A physical examination revealed a distinct resting tremor with cogwheeling of the right hand; there was no other evidence of EPS, nor was there evidence of cognitive, cerebellar, or skin abnormalities, such as hemorrhages or corkscrew hairs. Asterixis was absent as was evidence of a high-output cardiac state that might produce a tremor, such as de Musset sign. A serum vitamin C level was obtained and returned at 0.0 mg/dL. A head computed tomography scan obtained the next day revealed mild cerebellar volume loss. A serum alkaline phosphatase level was elevated slightly at 136 U/L (normal range: 42 to 113 U/L). Normal serum values were returned for zinc, vitamins B12 and folate, rapid plasma reagin, sodium, and serum osmolality. A urine drug screen was negative, and serum alcohol level was < 5.0 mg/dL.

Mr. B took no medications expected to cause EPS. He received no micronutrient replacement until the day after admission when he began receiving oral vitamin C 1,000 mg twice a day. After receiving 3 doses, Mr. B’s resting tremor and cogwheeling completely resolved. He noticed he had stopped shaking and could now drink without spilling fluids. He also got out of bed and began interacting with others. Mr. B said he felt he was “doing well.” A repeat serum vitamin C level was 0.2 mg/dL on that day. The improvement was sustained over 3 days, and Mr. B was discharged to home.

Discussion

Both Mr. A and Mr. B presented with a typical picture of latent scurvy and the additional finding of parkinsonism. These cases are important for 2 reasons. First, the swift and full response of these patients’ parkinsonism to vitamin C replacement underscores the importance of considering a vitamin C deficiency when confronted with EPS. And second, both patients lacked signs of bleeding or of impaired collagen synthesis. This differs from the classic presentation of scurvy as a disorder primarily of collagen metabolism.4

Lind described the onset of scurvy as one in which striking emotional and behavior changes developed and later were followed by abnormal bleeding and even death.2 These early changes also were recognized by Shapter in 1847.5 Furthermore, the evidence that exists about the time-course of scurvy’s development suggests that neuropsychiatric findings precede the hemorrhagic.6 Indeed, classic skin findings, such as petechiae or corkscrew hairs, may develop years after the onset of neuropsychiatric changes.7,8

Despite WHO characterizing it as latent scurvy, the distinct syndromal presentation of hypovitaminosis C with parkinsonism along with the rapid response to vitamin C replacement argues for its recognition as a distinct clinical entity and not just a prelude to the hemorrhagic state. To assist in recognizing neuropsychiatric scurvy, the author suggests the operationalized approach described in Table 1.9

Pathophysiology

Vitamin C has an intimate role in the normal functioning of the basal ganglia. It is involved in the synthesis of catechecholamines, the regulation of the release and postsynaptic activities of various neurotransmitters, and managing the oxyradical toxicity of aerobic metabolism. Table 2 outlines some of the normal brain functions of vitamin C and the potential consequences of inadequate central vitamin C.9,10 Risk factors for vitamin C deficiency include those affecting the uptake, response to, and elimination of this vitamin (Table 3).11-14

The potential role of alcohol use by both patients also warrants mention. Current data suggest a nonlinear relationship between alcohol use and neurotoxicity. Epidemiologic data show that moderate alcohol consumption protects against the development of such neurodegenerative processes as Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease.15,16 But the cases here reflect excessive use of alcohol. In this situation, a variety of progressive insults, such as those caused by oxyradical toxicity as well as malnutrition may foster the development of basal ganglia dysfunction.17

Measuring Deficiency

A deficiency of vitamin C may be determined in several ways. The most frequently used laboratory measure of vitamin C status is the serum vitamin C level. This level is included in the WHO’s recommendations for diagnosis.3 However, this assay is limited because when facing total body depletion, the kidneys may restrict the elimination of vitamin C and tend to maintain serum vitamin C levels even as target tissue levels fall. An interesting example of this is the 0.2 mg/dL value that each patient registered. In Mr. A’s case, this reflected a systemic deficit of vitamin C, while in Mr. B’s case it correlated with the onset of effective repletion of body’s stores.

A fall in urinary output of vitamin C is another marker of hypovitaminosis C. When available, this laboratory test can be used with the serum level to assess total body stores of vitamin C. Lymphocytes, neutrophils, and platelets also store vitamin C. These target tissues tend to saturate when the oral intake ranges between 100 mg to 200 mg a day. This is the same point at which serum vitamin C levels peak and level off in normal, healthy adults.18,19 Once again, the limited availability of target-tissue assays puts these studies out of reach for most clinicians.

No evaluation is complete without some assurance of what the disease is not. Deficiencies of biotin, zinc, folate, and B12 all may affect the function of the basal ganglia.20 The biotin deficiencies literature is particularly robust. Biotin deficiencies affecting basal ganglia function are best known as inherited disorders of metabolism.21 Manganese intoxication also may present as a movement disorder.22

Treatment

Treatment of neuropsychiatric scurvy has relied on IV administration of vitamin C. Although the bioavailability of oral vitamin C among healthy adult volunteers is nearly complete up to about 200 mg a day, a patient with neuropsychiatric scurvy may need substantially more than that amount to accommodate total body deficiencies and increased demands.23 The IV route allows serum vitamin C levels up to 100 times higher than by the oral route.24 Mr. B is, in fact, the first person reported in the literature with neuropsychiatric scurvy to respond to oral vitamin C replacement alone. Once repletion of vitamin C is complete, it is useful to consider a maintenance replacement dose based on a patient’s risk factors and needs.

A healthy adult should ingest about 120 mg of vitamin C daily. Smokers and pregnant women may require more, but this recommendation was intended to address their needs as well.25 Many commercial multivitamins use the old recommended daily allowance of 60 mg, so it may be safest to recommend specifically a vitamin C tablet with at least 120 mg when ordering vitamin C replacement.

Tight control of the serum vitamin C concentration means that little additional vitamin C will be taken up by the gut beyond 200 mg orally a day, which helps minimize any concerns about long-term toxicity. It takes several weeks to deplete vitamin C from the human body when vitamin C is removed from the diet, so a patient with a previously treated deficiency of vitamin C should wait a month before a repeat serum vitamin C level measurement.

The half life of vitamin C is normally ≤ 2 hours. When renal function is intact, vitamin C in excess of immediate need is lost through renal filtration. Toxicity is rare under these conditions.26 When vitamin C toxicity has been reported, it has occurred in the setting of prolonged supplementation, usually when a patient already experienced a renal injury. The main toxicities attributed to vitamin C are oxalate crystal formation with subsequent renal injury and exacerbation of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD).24

Oxalate formation due to vitamin C replacement is uncommon, but patients with preexisting calcium oxalate stones may be at risk for further stone formation when they receive additional vitamin C.27 This is most likely to occur when treatment with parenteral vitamin C is prolonged, which is not typical for patients with neuropsychiatric scurvy who tend to respond rapidly to vitamin C replenishment. Reports of acute hemolytic episodes among patient with G6PD deficiency receiving vitamin C exist, although these cases are rare.28 Furthermore, some authors advocate for the use of ascorbic acid to treat methemoglobinemia associated with G6PD deficiency, when methylene blue is not available.29 It may be reasonable to begin treatment with oral vitamin C for patients with NPS and G6PD deficiency. This is equivalent to a low-dose form of vitamin C replacement and may help avoid the theoretically pro-oxidant effects of larger, IV doses of vitamin C.30

Conclusion

The recent discovery of movement disorders in scurvy has enlarged the picture of vitamin C deficiency. The cases here demonstrate how hypovitaminosis C with central nervous system manifestations may be identified and treated. This relationship fits well within the established basic science and clinical framework for scurvy, and the clinical implications for scurvy remain in many ways unchanged. First, malnutrition must be considered even when a patient’s habitus suggests he is well fed. Also, it is more likely to see scurvy without all of the classic findings than an end-stage case of the disease.31 In the right clinical setting, it is reasonable to think of a vitamin C deficiency before the patient develops bleeding gums and corkscrew hairs. And as is typical of vitamin deficiencies, the treatment of a vitamin C deficiency usually results in swift improvement. Finally, for those who treat movement disorders or who prescribe agents such as antipsychotics that may cause movement disorders, it is important to recognize vitamin C deficiency as another potential explanation for EPS.

1. Ide K, Yamada H, Umegaki K, et al. Lymphocyte vitamin C levels as potential biomarker for progression of Parkinson’s disease. Nutrition. 2015;31(2):406-408.

2. Lind J. The diagnostics, or symptoms. A Treatise on the Scurvy, in Three Parts. 3rd ed. London: S. Crowder, D. Wilson and G. Nicholls, T. Cadell, T. Becket and Co., G. Pearch, and Woodfall; 1772:98-129.

3. World Health Organization. Scurvy and its prevention and control in major emergencies. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_NHD_99.11.pdf. Published 1999. Accessed July 6, 2017.

4. Sasseville D. Scurvy: curse and cure in New France. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(4):431.

5. Shapter T. On the recent occurrence of scurvy in Exeter and the neighbourhood. Prov Med Surg J. 1847;11(11):281-285.

6. Kinsman RA, Hood J. Some behavioral effects of ascorbic acid deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr. 1971;24(4):455-464.

7. DeSantis J. Scurvy and psychiatric symptoms. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 1993;29(1):18-22.

8. Walter JF. Scurvy resulting from a self-imposed diet. West J Med. 1979;130(2):177-179.

9. Brown TM. Neuropsychiatric scurvy. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(1):12-20.

10. Feuerstein TJ, Weinheimer G, Lang G, Ginap T, Rossner R. Inhibition by ascorbic acid of NMDA-evoked acetylcholine release in rabbit caudate nucleus. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1993;348(5):549-551.

11. Kim J, Kwon J, Noh G, Lee SS. The effects of elimination diet on nutritional status in subjects with atopic dermatitis. Nutr Res Pract. 2013;7(6):488-494.

12. Langlois M, Duprez D, Delanghe J, De Buyzere M, Clement DL. Serum vitamin C concentration is low in peripheral arterial disease and is associated with inflammation and severity of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2001;103(14):1863-1868.

13. Nappe TM, Pacelli AM, Katz K. An atypical case of methemoglobinemia due to self-administered benzocaine. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2015;2015:670979.

14. Wright AD, Stevens E, Ali M, Carroll DW, Brown TM. The neuropsychiatry of scurvy. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(2):179-185.

15. Bate C, Williams A. Ethanol protects cultured neurons against amyloid-β and α-synuclein-induced synapse damage. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61(8):1406-1412.

16. Vasanthi HR, Parameswari RP, DeLeiris J, Das DK. Health benefits of wine and alcohol from neuroprotection to heart health. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012;4:1505-1512.

17. Vaglini F, Viaggi C, Piro V, et al. Acetaldehyde and parkinsonism: role of CYP450 2E1. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:71.

18. Levine M, Wang Y, Padayatty SJ, Morrow J. A new recommended dietary allowance of vitamin C for healthy young women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(17):9842-9846.

19. Levine M, Padayatty SJ, Espey MG. Vitamin C: a concentration-function approach yields pharmacology and therapeutic discoveries. Adv Nutr. 2011;2(2):78-88.

20. Quiroga MJ, Carroll DW, Brown TM. Ascorbate- and zinc-responsive parkinsonism. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(11):1515-1520.

21. Tabarki B, Al-Shafi S, Al-Shahwan S, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease revisited: clinical, radiologic, and genetic findings. Neurology. 2013;80(3):261-267.

22. Tuschl K, Mills PB, Clayton PT. Manganese and the brain. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;110:277-312.

23. Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang Y, et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(8):3704-3709.

24. Wilson MK, Baguley BC, Wall C, Jameson MB, Findlay MP. Review of high-dose intravenous vitamin C as an anticancer agent. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10(1):22-37.

25. Carr AC, Frei B. Toward a new recommended dietary allowance for vitamin C based on antioxidant and health effects in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(6):1086-1107.

26. Nielsen TK, Højgaard M, Andersen JT, Poulsen HE, Lykkesfeldt J, Mikines KJ. Elimination of ascorbic acid after high-dose infusion in prostate cancer patients: a pharmacokinetic evaluation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;116(4):343-348.

27. Baxmann AC, De O G Mendonça C, Heilberg IP. Effect of vitamin C supplements on urinary oxalate and pH in calcium stone-forming patients. Kidney Int. 2003;63(3):1066-1071.

28. Huang YC, Chang TK, Fu YC, Jan SL. C for colored urine: acute hemolysis induced by high-dose ascorbic acid. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52(9):984.

29. Rino PB, Scolnik D, Fustiñana A, Mitelpunkt A, Glatstein M. Ascorbic acid for the treatment of methemoglobinemia: the experience of a large tertiary care pediatric hospital. Am J Ther. 2014;21(4):240-243.

30. Du J, Cullen JJ, Buettner GR. Ascorbic acid: chemistry, biology and the treatment of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826(2):443-457.

31. Fouron JC, Chicoine L. Le scorbut: aspects particuliers de l’association rachitisme-scorbut. Can Med Assoc J. 1962;86(26):1191-1196.

1. Ide K, Yamada H, Umegaki K, et al. Lymphocyte vitamin C levels as potential biomarker for progression of Parkinson’s disease. Nutrition. 2015;31(2):406-408.

2. Lind J. The diagnostics, or symptoms. A Treatise on the Scurvy, in Three Parts. 3rd ed. London: S. Crowder, D. Wilson and G. Nicholls, T. Cadell, T. Becket and Co., G. Pearch, and Woodfall; 1772:98-129.

3. World Health Organization. Scurvy and its prevention and control in major emergencies. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_NHD_99.11.pdf. Published 1999. Accessed July 6, 2017.

4. Sasseville D. Scurvy: curse and cure in New France. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(4):431.

5. Shapter T. On the recent occurrence of scurvy in Exeter and the neighbourhood. Prov Med Surg J. 1847;11(11):281-285.

6. Kinsman RA, Hood J. Some behavioral effects of ascorbic acid deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr. 1971;24(4):455-464.

7. DeSantis J. Scurvy and psychiatric symptoms. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 1993;29(1):18-22.

8. Walter JF. Scurvy resulting from a self-imposed diet. West J Med. 1979;130(2):177-179.

9. Brown TM. Neuropsychiatric scurvy. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(1):12-20.

10. Feuerstein TJ, Weinheimer G, Lang G, Ginap T, Rossner R. Inhibition by ascorbic acid of NMDA-evoked acetylcholine release in rabbit caudate nucleus. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1993;348(5):549-551.

11. Kim J, Kwon J, Noh G, Lee SS. The effects of elimination diet on nutritional status in subjects with atopic dermatitis. Nutr Res Pract. 2013;7(6):488-494.

12. Langlois M, Duprez D, Delanghe J, De Buyzere M, Clement DL. Serum vitamin C concentration is low in peripheral arterial disease and is associated with inflammation and severity of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2001;103(14):1863-1868.

13. Nappe TM, Pacelli AM, Katz K. An atypical case of methemoglobinemia due to self-administered benzocaine. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2015;2015:670979.

14. Wright AD, Stevens E, Ali M, Carroll DW, Brown TM. The neuropsychiatry of scurvy. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(2):179-185.

15. Bate C, Williams A. Ethanol protects cultured neurons against amyloid-β and α-synuclein-induced synapse damage. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61(8):1406-1412.

16. Vasanthi HR, Parameswari RP, DeLeiris J, Das DK. Health benefits of wine and alcohol from neuroprotection to heart health. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012;4:1505-1512.

17. Vaglini F, Viaggi C, Piro V, et al. Acetaldehyde and parkinsonism: role of CYP450 2E1. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:71.

18. Levine M, Wang Y, Padayatty SJ, Morrow J. A new recommended dietary allowance of vitamin C for healthy young women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(17):9842-9846.

19. Levine M, Padayatty SJ, Espey MG. Vitamin C: a concentration-function approach yields pharmacology and therapeutic discoveries. Adv Nutr. 2011;2(2):78-88.

20. Quiroga MJ, Carroll DW, Brown TM. Ascorbate- and zinc-responsive parkinsonism. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(11):1515-1520.

21. Tabarki B, Al-Shafi S, Al-Shahwan S, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease revisited: clinical, radiologic, and genetic findings. Neurology. 2013;80(3):261-267.

22. Tuschl K, Mills PB, Clayton PT. Manganese and the brain. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;110:277-312.

23. Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang Y, et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(8):3704-3709.

24. Wilson MK, Baguley BC, Wall C, Jameson MB, Findlay MP. Review of high-dose intravenous vitamin C as an anticancer agent. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10(1):22-37.

25. Carr AC, Frei B. Toward a new recommended dietary allowance for vitamin C based on antioxidant and health effects in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(6):1086-1107.

26. Nielsen TK, Højgaard M, Andersen JT, Poulsen HE, Lykkesfeldt J, Mikines KJ. Elimination of ascorbic acid after high-dose infusion in prostate cancer patients: a pharmacokinetic evaluation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;116(4):343-348.

27. Baxmann AC, De O G Mendonça C, Heilberg IP. Effect of vitamin C supplements on urinary oxalate and pH in calcium stone-forming patients. Kidney Int. 2003;63(3):1066-1071.

28. Huang YC, Chang TK, Fu YC, Jan SL. C for colored urine: acute hemolysis induced by high-dose ascorbic acid. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52(9):984.

29. Rino PB, Scolnik D, Fustiñana A, Mitelpunkt A, Glatstein M. Ascorbic acid for the treatment of methemoglobinemia: the experience of a large tertiary care pediatric hospital. Am J Ther. 2014;21(4):240-243.

30. Du J, Cullen JJ, Buettner GR. Ascorbic acid: chemistry, biology and the treatment of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826(2):443-457.

31. Fouron JC, Chicoine L. Le scorbut: aspects particuliers de l’association rachitisme-scorbut. Can Med Assoc J. 1962;86(26):1191-1196.

Hyaluronic Acid Gel Filler for Nipple Enhancement Following Breast Reconstruction

The most frequently used surgical techniques in nipple-areola complex (NAC) reconstruction involve the use of local tissue flaps and yield the fewest complications, though these techniques can be associated with up to a 75% loss in nipple projection over time.1 In a best-case scenario for both the surgeon and the patient, the NAC is preserved during mastectomy; however, even when the tissues are spared, an eventual loss of nipple projection is expected due to atrophy and contraction of the healing skin.2 Loss of nipple projection is the most common attribute that patients dislike regarding their NAC reconstruction results.Additional efforts made to restore the natural look and feel of the NAC provides undeniable benefit to the patient in the form of improved body image and psychosocial well-being.3

Augmentation with a grafted material can include cartilage or fat (autologous grafts), calcium hydroxylapatite or polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)(alloplastic grafts), and acellular dermal matrix or biologic collagen (allografts). Among these options, successive treatment with autologous fat has been shown to provide satisfactory projections over time with minimal complications.4 However, an additional consideration associated with graft augmentation is the need for an additional surgical site (autologous grafts) or the possibility that graft material may not be compatible with subsequent breast examination techniques. For example, calcium hydroxylapatite is a radiopaque material that may interfere with the interpretation of radiography and mammography.5

The use of injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) dermal fillers to enhance nipple projection represents a noninvasive procedure with immediate and adjustable results. A variety of dermal fillers that do not interfere with subsequent breast imaging needs have already been successfully used for nipple reconstruction including HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40%, PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel, and poly-L-lactic acid.5-7

The results achieved with HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40% were as much as a 2.5-mm mean increase in nipple projection after 12 months for 70 nipples reconstructed using a small wedge from the labia minora.5 In these treatments, an initial injection of 0.1 to 0.3 mL of filler into each nipple along with a 0.2-mL injection at the base of each nipple was made. Further optional treatments at 2 and 4 months after the initial injection were made using up to 0.3 mL additional volume depending on filler reabsorption.5 Results achieved with PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel included a 1.6-mm mean increase in nipple projection at 9 months versus baseline for 33 nipples in 23 patients, which involved up to 2 injections at baseline and again at 3 months.6 Treatment with poly-L-lactic acid provided a 2.3-mm mean increase in nipple projection for 12 patients after 1 year of treatment, which involved 0.5-mL injections every 4 weeks over a series of 4 treatments.7

This report describes the technique and cosmetic outcome using an injectable HA gel to postoperatively restore the 3-dimensional contour of the nipple following surgical breast reconstruction. This chemically cross-linked, stabilized HA gel suspended in phosphate-buffered saline at a pH of 7 and a concentration of 20 mg/mL with lidocaine 0.3% is indicated for mid to deep dermal implantation for the correction of moderate to severe facial wrinkles and folds, such as the nasolabial folds.8

Case Report

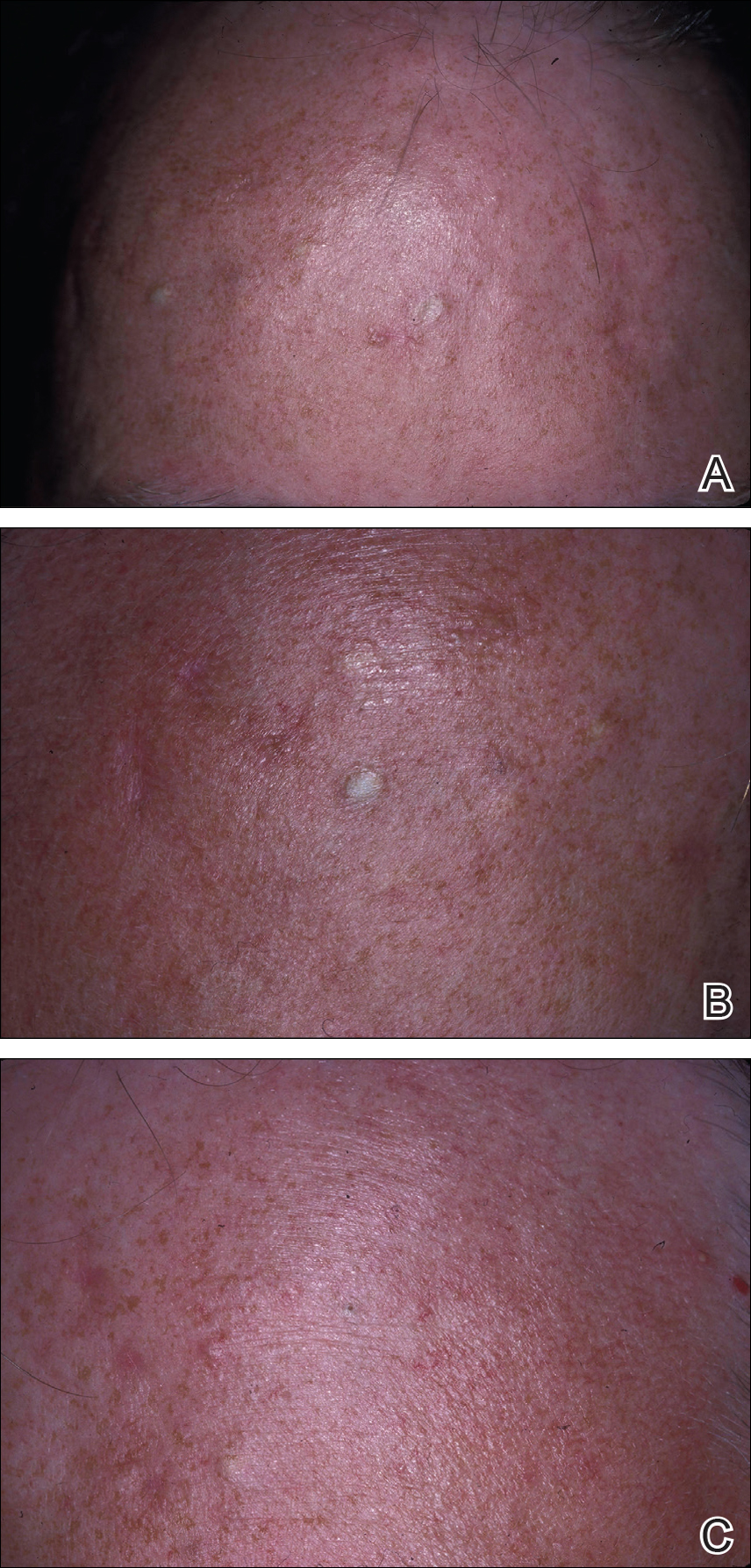

A 49-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer with a focal, high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ underwent a complete bilateral mastectomy. The sentinel lymph nodes were negative at the time of mastectomy. One year later, the patient elected to have breast and nipple-areola (flap) reconstruction. Following the reconstructive surgery, her nipples had become visibly atrophic and flat, and she was interested in cosmetic enhancement.

After informed consent had been obtained from the patient, a baseline measurement of each nipple was made while the patient was standing. Each nipple was then injected with up to 0.1 to 0.2 mL of HA gel filler using a 30-gauge needle inserted 2-mm deep (bilaterally) into each nipple. The patient tolerated the procedure well with no pain, bleeding, or bruising. Although HA gel filler contains lidocaine 0.3% and tricaine can further be used to ensure patient comfort, the nipple reconstruction surgery left the patient with little sensation in the treatment area. Rubbing alcohol was used to prepare the skin prior to the procedure, and fractionated coconut oil spray with a nonadherent dressing was used postprocedure.

Following the injection, an immediate increase of 1.6 and 1.5 mm in nipple projection in the right and left breasts, respectively, was achieved with HA gel. The nipple projection of the right breast was 1.7 mm before injection (Figure, A) and 3.3 mm immediately postinjection (Figure, C). The nipple projection of the left breast was 1.8 mm before injection (Figure, B) and 3.3 mm immediately postinjection (Figure, D).

Comment