User login

Two men with dyspnea, enlarged lymph nodes • Dx?

CASE 1

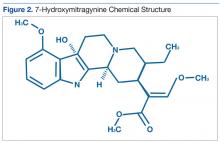

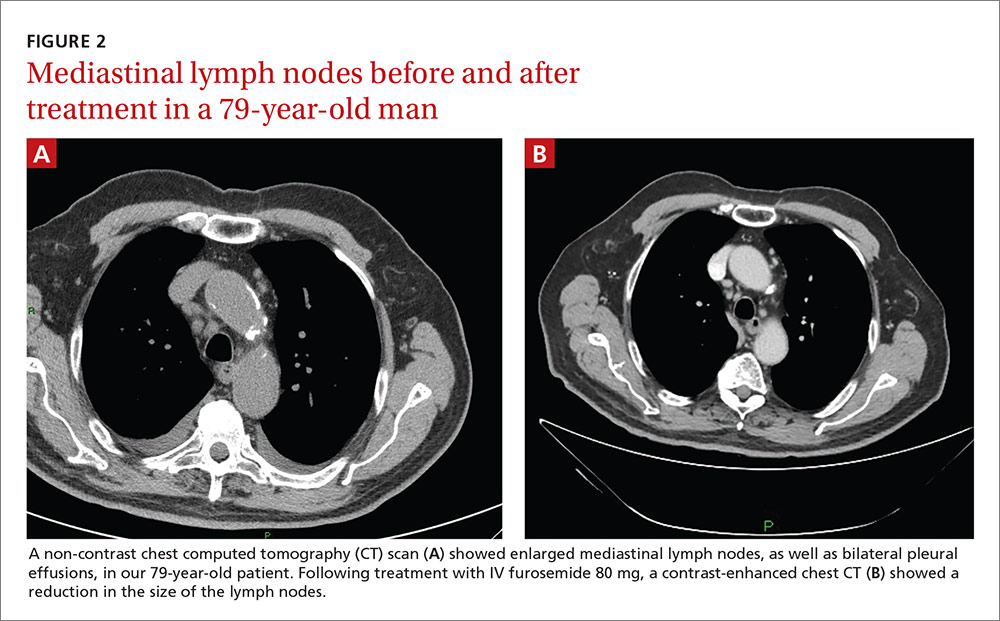

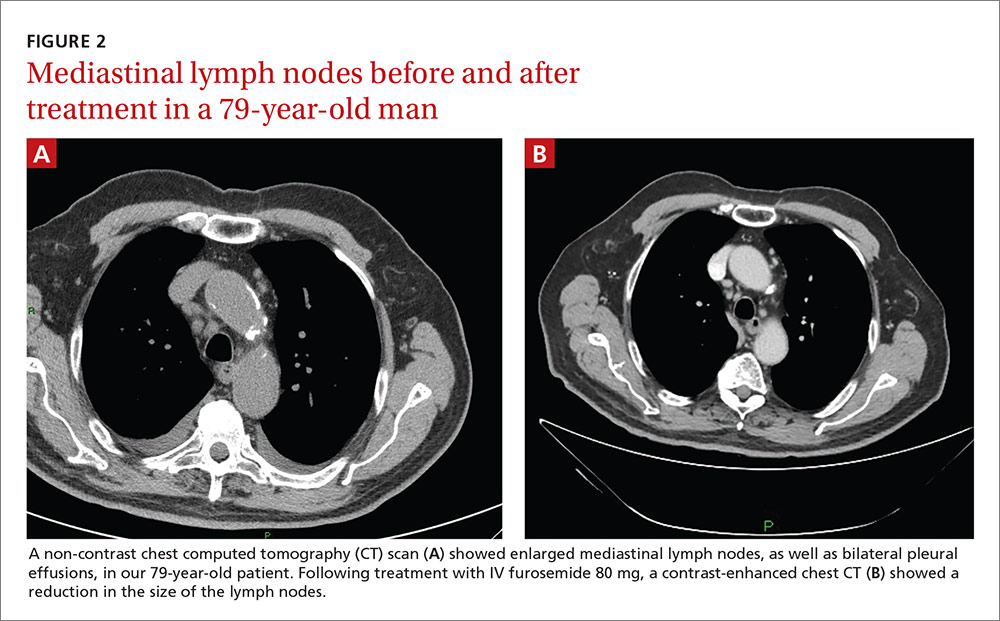

A 50-year-old man sought care for progressive dyspnea on exertion, abdominal bloating, and bilateral leg edema. He had hypertension that was being treated with atenolol, nifedipine, and enalapril. On examination, his blood pressure was 157/80 mm Hg and his heart rate was 50 beats/min. Jugular venous pressure was grossly elevated with occasional cannon A waves. The patient also had decreased breath sounds in both lower lung zones and moderate pitting edema up to the knees. A chest x-ray showed a small bilateral pleural effusion and no cardiomegaly. An electrocardiogram revealed complete atrioventricular (AV) block with a ventricular response of 50 beats/min. Computed tomography (CT) angiography revealed no evidence of a pulmonary embolus, but did show several enlarged (up to 3.5 cm in diameter) lymph nodes in the upper and middle mediastinum (FIGURE 1). We performed an echocardiogram.

CASE 2

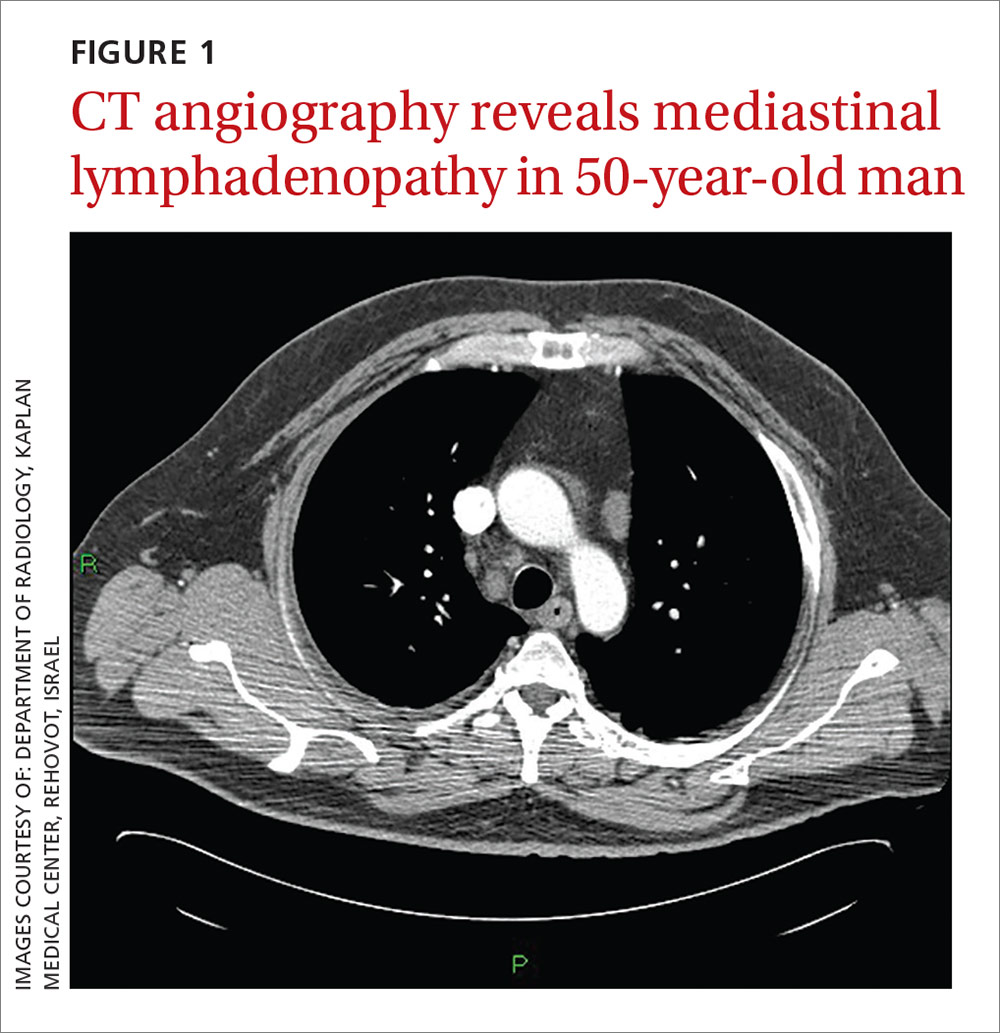

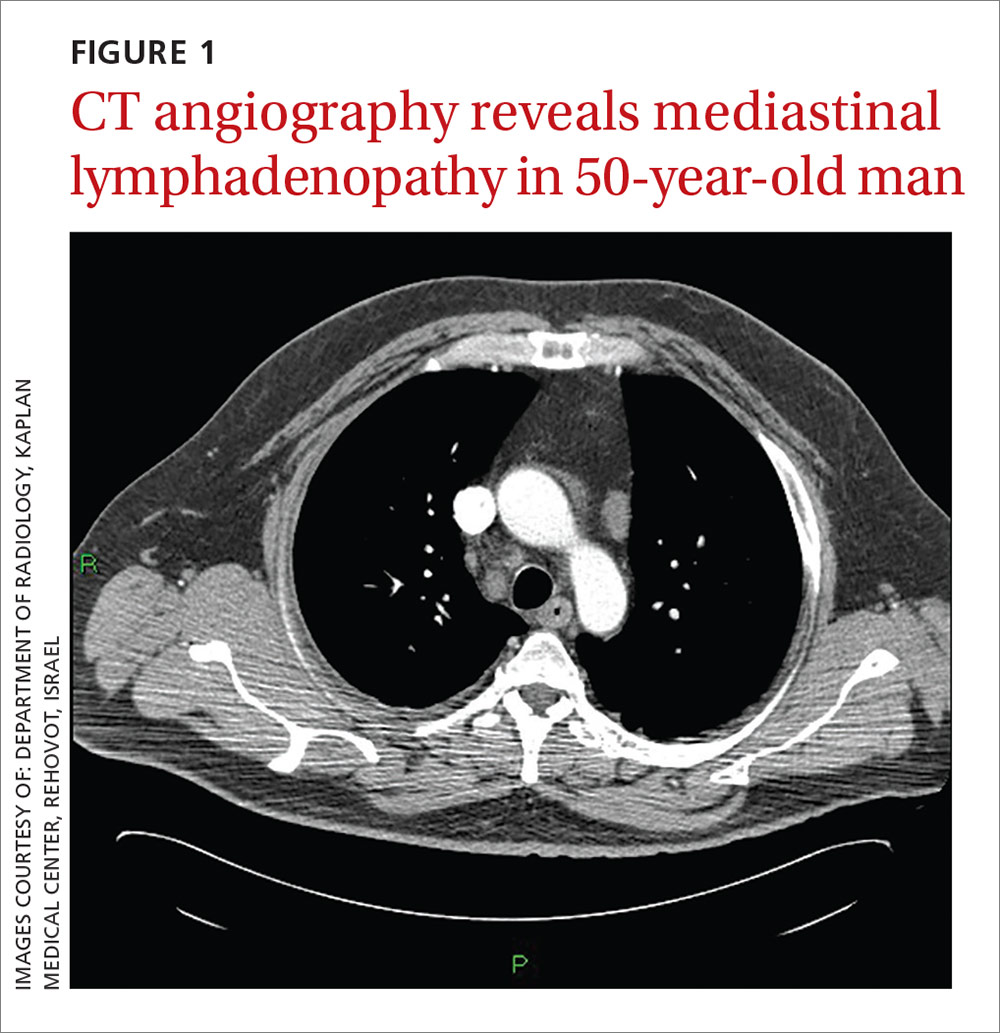

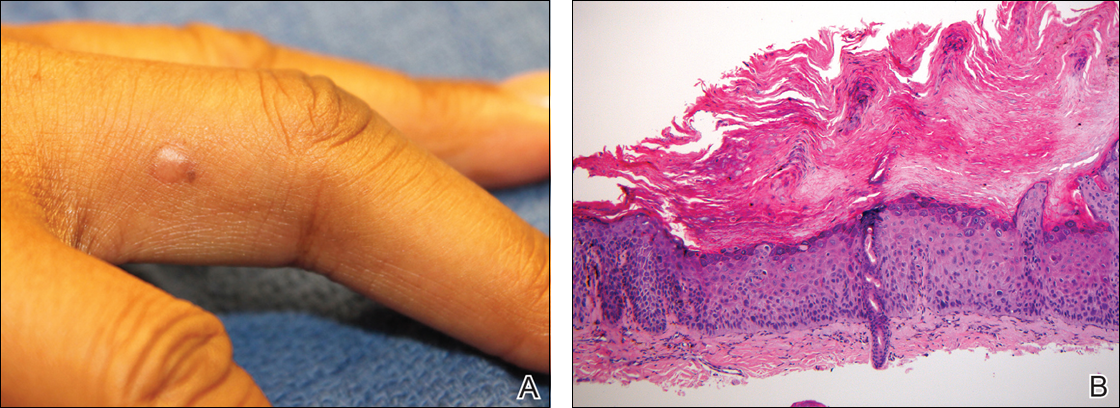

A 79-year-old man with hypertension and diabetes presented to our medical center with acute dyspnea. During the physical examination, we noted bilateral diminished breath sounds with expiratory wheezes and an irregular pulse. Chest x-ray showed mild pulmonary congestion. A chest CT demonstrated bilateral small pleural effusions and multiple enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes with a maximal diameter of 2.4 cm (FIGURE 2A). One week later, the patient’s shortness of breath increased and he was hospitalized. A chest x-ray at that time showed moderate pulmonary congestion, so we performed an echocardiogram.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The echocardiogram for the 50-year-old patient in Case 1 revealed a mildly dilated left ventricle with normal systolic function, diastolic left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and mild pulmonary hypertension. Extensive testing for malignancy and tuberculosis was negative.

For the 79-year-old patient in Case 2, echocardiography demonstrated concentric LV hypertrophy, mild dilatation of the left ventricle, normal LV systolic function, LV diastolic dysfunction with elevated LV diastolic filling pressure, and mild-to-moderate pulmonary hypertension.

Based on these results, we diagnosed both patients with diastolic heart failure. The patient in the second case had features of cardiac asthma, as well. Both patients had also developed reversible mediastinal lymphadenopathy (MLN), of which the diastolic heart failure was the only apparent cause. In both cases, radiologists did not note any suspicious findings for malignancy beyond the MLN.

DISCUSSION

Systolic heart failure has been previously recognized as a cause of MLN.1,2 Other causes of MLN include sarcoidosis, various malignancies, pulmonary infections, and occupational lung diseases. There are, however, no reports of MLN in patients with diastolic heart failure.

Heart failure and MLN. Slanetz et al reported one series of 46 patients who had undergone CT of the chest during periods of congestive heart failure (CHF).1 There was mediastinal lymph node enlargement in 55% of these patients. In a subset of 17 patients who had elevated capillary wedge pressure, 82% had some degree of lymphadenopathy.

Erly et al2 retrospectively studied 44 patients who had a thoracic CT performed before cardiac transplantation. Twenty-nine (66%) had at least one enlarged mediastinal lymph node (>1 cm). Eighty-one percent of patients with an ejection fraction <35% had lymphadenopathy, while none of the patients with an ejection fraction >35% had lymphadenopathy. Most enlarged lymph nodes were pretracheal, with a mean short axis diameter of 1.3 cm.

However, Storto et al reported that an association between CHF and MLN was not found in 7 patients undergoing high-resolution CT imaging.3 There are also cases of MLN in patients with pulmonary hypertension without systolic dysfunction.4

Chabbert et al studied 31 consecutive patients with subacute left heart failure (mean ejection fraction, 39%).5 Enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes were present in 13 patients (42%). Other radiographic features included blurred contour of the lymph nodes in 5 patients (16%) and hazy mediastinal fat in one patient (3%). Follow-up CT showed a significant decrease in the size of the lymph nodes in 8 of 13 patients (62%) following initiation of treatment.

Heart failure and malignancy. A PubMed search with the keywords “diastolic dysfunction” and “lymphoma” found 7 references in the English language. There is a report of 125 survivors of childhood lymphomas treated with mediastinal radiotherapy and anthracyclines,6 another of 44 children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma7, a report of 294 patients who had received mediastinal irradiation for the treatment of Hodgkin’s disease,8 and another of 106 survivors of non-Hodgkin’s and Hodgkin’s lymphomas.9 None of these reports, however, made any mention of mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

What caused the lymphadenopathy in our patients?

Our 2 patients had volume overload due to diastolic dysfunction with elevated LV end diastolic pressure. Our first patient also had a loss of AV synchronization—which was reversible upon pacemaker insertion—that probably exacerbated the heart failure.

The mechanism for the lymphadenopathy is not clear, but may be due to cardiogenic pulmonary edema causing distension of the pulmonary lymphatic vessels and pulmonary hypertension. In a study of patients with severe systolic dysfunction undergoing evaluation for cardiac transplant, there was a relationship (albeit weak), between MLN and mitral regurgitation, tricuspid regurgitation, elevated mean pulmonary artery pressure, elevated pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and elevated right atrial pressure.10

How to accurately detect and treat MLN

MLN may be detected by chest x-ray, CT, magnetic resonance imaging, or endoscopic ultrasound examinations. The clinical situation will dictate the imaging modality used. Keep in mind that it is difficult to make a comparison between a finding of lymphadenopathy on one modality and another, especially if one is looking for a change in size.

If clinically appropriate, a trial of diuretics, such as intravenous (IV) furosemide 80 mg,

Our patients. The 50-year-old man in Case 1 responded well to 80 mg of IV furosemide after one hour and improved further upon receipt of a pacemaker the next day. A repeat thoracic CT one month later showed complete resolution of the MLN.

The 79-year-old man in Case 2 also received 80 mg of IV furosemide and improved within 3 hours. A month later, a repeat thoracic CT showed a significant reduction in the size of all the enlarged lymph nodes (FIGURE 2B).

THE TAKEAWAY

The importance of these 2 cases is that they show that heart failure—even diastolic alone—can produce enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes. In patients with heart failure in whom unexpected MLN is detected, consideration should be given to performing a repeat imaging examination after the administration of diuretics.

1. Slanetz PJ, Truong M, Shepard JA, et al. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy and hazy mediastinal fat: new CT findings of congestive heart failure. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1307-1309.

2. Erly WK, Borders RJ, Outwater EK, et al. Location, size, and distribution of mediastinal lymph node enlargement in chronic congestive heart failure. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:485-489.

3. Storto ML, Kee ST, Golden JA, et al. Hydrostatic pulmonary edema: high-resolution CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:817-820.

4. Moua T, Levin DL, Carmona EM, et al. Frequency of mediastinal lymphadenopathy in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2013;143:344-348.

5. Chabbert V, Canevet G, Baixas C, et al. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in congestive heart failure: a sequential CT evaluation with clinical and echocardiographic correlations. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:881-889.

6. Christiansen JR, Hamre H, Massey R, et al. Left ventricular function in long-term survivors of childhood lymphoma. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:483-490.

7. Krawczuk-Rybak M, Dakowicz L, Hryniewicz A, et al. Cardiac function in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47:455-459.

8. Heidenreich PA, Hancock SL, Vagelos RH, et al. Diastolic dysfunction after mediastinal irradiation. Am Heart J. 2005;150:977-982.

9. Elbl L, Vasova I, Tomaskova I, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the evaluation of functional capacity after treatment of lymphomas in adults. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:843-851.

10. Pastis NJ Jr, Van Bakel AB, Brand TM, et al. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in patients undergoing cardiac transplant evaluation. Chest. 2011;139:1451-1457.

CASE 1

A 50-year-old man sought care for progressive dyspnea on exertion, abdominal bloating, and bilateral leg edema. He had hypertension that was being treated with atenolol, nifedipine, and enalapril. On examination, his blood pressure was 157/80 mm Hg and his heart rate was 50 beats/min. Jugular venous pressure was grossly elevated with occasional cannon A waves. The patient also had decreased breath sounds in both lower lung zones and moderate pitting edema up to the knees. A chest x-ray showed a small bilateral pleural effusion and no cardiomegaly. An electrocardiogram revealed complete atrioventricular (AV) block with a ventricular response of 50 beats/min. Computed tomography (CT) angiography revealed no evidence of a pulmonary embolus, but did show several enlarged (up to 3.5 cm in diameter) lymph nodes in the upper and middle mediastinum (FIGURE 1). We performed an echocardiogram.

CASE 2

A 79-year-old man with hypertension and diabetes presented to our medical center with acute dyspnea. During the physical examination, we noted bilateral diminished breath sounds with expiratory wheezes and an irregular pulse. Chest x-ray showed mild pulmonary congestion. A chest CT demonstrated bilateral small pleural effusions and multiple enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes with a maximal diameter of 2.4 cm (FIGURE 2A). One week later, the patient’s shortness of breath increased and he was hospitalized. A chest x-ray at that time showed moderate pulmonary congestion, so we performed an echocardiogram.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The echocardiogram for the 50-year-old patient in Case 1 revealed a mildly dilated left ventricle with normal systolic function, diastolic left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and mild pulmonary hypertension. Extensive testing for malignancy and tuberculosis was negative.

For the 79-year-old patient in Case 2, echocardiography demonstrated concentric LV hypertrophy, mild dilatation of the left ventricle, normal LV systolic function, LV diastolic dysfunction with elevated LV diastolic filling pressure, and mild-to-moderate pulmonary hypertension.

Based on these results, we diagnosed both patients with diastolic heart failure. The patient in the second case had features of cardiac asthma, as well. Both patients had also developed reversible mediastinal lymphadenopathy (MLN), of which the diastolic heart failure was the only apparent cause. In both cases, radiologists did not note any suspicious findings for malignancy beyond the MLN.

DISCUSSION

Systolic heart failure has been previously recognized as a cause of MLN.1,2 Other causes of MLN include sarcoidosis, various malignancies, pulmonary infections, and occupational lung diseases. There are, however, no reports of MLN in patients with diastolic heart failure.

Heart failure and MLN. Slanetz et al reported one series of 46 patients who had undergone CT of the chest during periods of congestive heart failure (CHF).1 There was mediastinal lymph node enlargement in 55% of these patients. In a subset of 17 patients who had elevated capillary wedge pressure, 82% had some degree of lymphadenopathy.

Erly et al2 retrospectively studied 44 patients who had a thoracic CT performed before cardiac transplantation. Twenty-nine (66%) had at least one enlarged mediastinal lymph node (>1 cm). Eighty-one percent of patients with an ejection fraction <35% had lymphadenopathy, while none of the patients with an ejection fraction >35% had lymphadenopathy. Most enlarged lymph nodes were pretracheal, with a mean short axis diameter of 1.3 cm.

However, Storto et al reported that an association between CHF and MLN was not found in 7 patients undergoing high-resolution CT imaging.3 There are also cases of MLN in patients with pulmonary hypertension without systolic dysfunction.4

Chabbert et al studied 31 consecutive patients with subacute left heart failure (mean ejection fraction, 39%).5 Enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes were present in 13 patients (42%). Other radiographic features included blurred contour of the lymph nodes in 5 patients (16%) and hazy mediastinal fat in one patient (3%). Follow-up CT showed a significant decrease in the size of the lymph nodes in 8 of 13 patients (62%) following initiation of treatment.

Heart failure and malignancy. A PubMed search with the keywords “diastolic dysfunction” and “lymphoma” found 7 references in the English language. There is a report of 125 survivors of childhood lymphomas treated with mediastinal radiotherapy and anthracyclines,6 another of 44 children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma7, a report of 294 patients who had received mediastinal irradiation for the treatment of Hodgkin’s disease,8 and another of 106 survivors of non-Hodgkin’s and Hodgkin’s lymphomas.9 None of these reports, however, made any mention of mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

What caused the lymphadenopathy in our patients?

Our 2 patients had volume overload due to diastolic dysfunction with elevated LV end diastolic pressure. Our first patient also had a loss of AV synchronization—which was reversible upon pacemaker insertion—that probably exacerbated the heart failure.

The mechanism for the lymphadenopathy is not clear, but may be due to cardiogenic pulmonary edema causing distension of the pulmonary lymphatic vessels and pulmonary hypertension. In a study of patients with severe systolic dysfunction undergoing evaluation for cardiac transplant, there was a relationship (albeit weak), between MLN and mitral regurgitation, tricuspid regurgitation, elevated mean pulmonary artery pressure, elevated pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and elevated right atrial pressure.10

How to accurately detect and treat MLN

MLN may be detected by chest x-ray, CT, magnetic resonance imaging, or endoscopic ultrasound examinations. The clinical situation will dictate the imaging modality used. Keep in mind that it is difficult to make a comparison between a finding of lymphadenopathy on one modality and another, especially if one is looking for a change in size.

If clinically appropriate, a trial of diuretics, such as intravenous (IV) furosemide 80 mg,

Our patients. The 50-year-old man in Case 1 responded well to 80 mg of IV furosemide after one hour and improved further upon receipt of a pacemaker the next day. A repeat thoracic CT one month later showed complete resolution of the MLN.

The 79-year-old man in Case 2 also received 80 mg of IV furosemide and improved within 3 hours. A month later, a repeat thoracic CT showed a significant reduction in the size of all the enlarged lymph nodes (FIGURE 2B).

THE TAKEAWAY

The importance of these 2 cases is that they show that heart failure—even diastolic alone—can produce enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes. In patients with heart failure in whom unexpected MLN is detected, consideration should be given to performing a repeat imaging examination after the administration of diuretics.

CASE 1

A 50-year-old man sought care for progressive dyspnea on exertion, abdominal bloating, and bilateral leg edema. He had hypertension that was being treated with atenolol, nifedipine, and enalapril. On examination, his blood pressure was 157/80 mm Hg and his heart rate was 50 beats/min. Jugular venous pressure was grossly elevated with occasional cannon A waves. The patient also had decreased breath sounds in both lower lung zones and moderate pitting edema up to the knees. A chest x-ray showed a small bilateral pleural effusion and no cardiomegaly. An electrocardiogram revealed complete atrioventricular (AV) block with a ventricular response of 50 beats/min. Computed tomography (CT) angiography revealed no evidence of a pulmonary embolus, but did show several enlarged (up to 3.5 cm in diameter) lymph nodes in the upper and middle mediastinum (FIGURE 1). We performed an echocardiogram.

CASE 2

A 79-year-old man with hypertension and diabetes presented to our medical center with acute dyspnea. During the physical examination, we noted bilateral diminished breath sounds with expiratory wheezes and an irregular pulse. Chest x-ray showed mild pulmonary congestion. A chest CT demonstrated bilateral small pleural effusions and multiple enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes with a maximal diameter of 2.4 cm (FIGURE 2A). One week later, the patient’s shortness of breath increased and he was hospitalized. A chest x-ray at that time showed moderate pulmonary congestion, so we performed an echocardiogram.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The echocardiogram for the 50-year-old patient in Case 1 revealed a mildly dilated left ventricle with normal systolic function, diastolic left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and mild pulmonary hypertension. Extensive testing for malignancy and tuberculosis was negative.

For the 79-year-old patient in Case 2, echocardiography demonstrated concentric LV hypertrophy, mild dilatation of the left ventricle, normal LV systolic function, LV diastolic dysfunction with elevated LV diastolic filling pressure, and mild-to-moderate pulmonary hypertension.

Based on these results, we diagnosed both patients with diastolic heart failure. The patient in the second case had features of cardiac asthma, as well. Both patients had also developed reversible mediastinal lymphadenopathy (MLN), of which the diastolic heart failure was the only apparent cause. In both cases, radiologists did not note any suspicious findings for malignancy beyond the MLN.

DISCUSSION

Systolic heart failure has been previously recognized as a cause of MLN.1,2 Other causes of MLN include sarcoidosis, various malignancies, pulmonary infections, and occupational lung diseases. There are, however, no reports of MLN in patients with diastolic heart failure.

Heart failure and MLN. Slanetz et al reported one series of 46 patients who had undergone CT of the chest during periods of congestive heart failure (CHF).1 There was mediastinal lymph node enlargement in 55% of these patients. In a subset of 17 patients who had elevated capillary wedge pressure, 82% had some degree of lymphadenopathy.

Erly et al2 retrospectively studied 44 patients who had a thoracic CT performed before cardiac transplantation. Twenty-nine (66%) had at least one enlarged mediastinal lymph node (>1 cm). Eighty-one percent of patients with an ejection fraction <35% had lymphadenopathy, while none of the patients with an ejection fraction >35% had lymphadenopathy. Most enlarged lymph nodes were pretracheal, with a mean short axis diameter of 1.3 cm.

However, Storto et al reported that an association between CHF and MLN was not found in 7 patients undergoing high-resolution CT imaging.3 There are also cases of MLN in patients with pulmonary hypertension without systolic dysfunction.4

Chabbert et al studied 31 consecutive patients with subacute left heart failure (mean ejection fraction, 39%).5 Enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes were present in 13 patients (42%). Other radiographic features included blurred contour of the lymph nodes in 5 patients (16%) and hazy mediastinal fat in one patient (3%). Follow-up CT showed a significant decrease in the size of the lymph nodes in 8 of 13 patients (62%) following initiation of treatment.

Heart failure and malignancy. A PubMed search with the keywords “diastolic dysfunction” and “lymphoma” found 7 references in the English language. There is a report of 125 survivors of childhood lymphomas treated with mediastinal radiotherapy and anthracyclines,6 another of 44 children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma7, a report of 294 patients who had received mediastinal irradiation for the treatment of Hodgkin’s disease,8 and another of 106 survivors of non-Hodgkin’s and Hodgkin’s lymphomas.9 None of these reports, however, made any mention of mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

What caused the lymphadenopathy in our patients?

Our 2 patients had volume overload due to diastolic dysfunction with elevated LV end diastolic pressure. Our first patient also had a loss of AV synchronization—which was reversible upon pacemaker insertion—that probably exacerbated the heart failure.

The mechanism for the lymphadenopathy is not clear, but may be due to cardiogenic pulmonary edema causing distension of the pulmonary lymphatic vessels and pulmonary hypertension. In a study of patients with severe systolic dysfunction undergoing evaluation for cardiac transplant, there was a relationship (albeit weak), between MLN and mitral regurgitation, tricuspid regurgitation, elevated mean pulmonary artery pressure, elevated pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and elevated right atrial pressure.10

How to accurately detect and treat MLN

MLN may be detected by chest x-ray, CT, magnetic resonance imaging, or endoscopic ultrasound examinations. The clinical situation will dictate the imaging modality used. Keep in mind that it is difficult to make a comparison between a finding of lymphadenopathy on one modality and another, especially if one is looking for a change in size.

If clinically appropriate, a trial of diuretics, such as intravenous (IV) furosemide 80 mg,

Our patients. The 50-year-old man in Case 1 responded well to 80 mg of IV furosemide after one hour and improved further upon receipt of a pacemaker the next day. A repeat thoracic CT one month later showed complete resolution of the MLN.

The 79-year-old man in Case 2 also received 80 mg of IV furosemide and improved within 3 hours. A month later, a repeat thoracic CT showed a significant reduction in the size of all the enlarged lymph nodes (FIGURE 2B).

THE TAKEAWAY

The importance of these 2 cases is that they show that heart failure—even diastolic alone—can produce enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes. In patients with heart failure in whom unexpected MLN is detected, consideration should be given to performing a repeat imaging examination after the administration of diuretics.

1. Slanetz PJ, Truong M, Shepard JA, et al. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy and hazy mediastinal fat: new CT findings of congestive heart failure. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1307-1309.

2. Erly WK, Borders RJ, Outwater EK, et al. Location, size, and distribution of mediastinal lymph node enlargement in chronic congestive heart failure. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:485-489.

3. Storto ML, Kee ST, Golden JA, et al. Hydrostatic pulmonary edema: high-resolution CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:817-820.

4. Moua T, Levin DL, Carmona EM, et al. Frequency of mediastinal lymphadenopathy in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2013;143:344-348.

5. Chabbert V, Canevet G, Baixas C, et al. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in congestive heart failure: a sequential CT evaluation with clinical and echocardiographic correlations. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:881-889.

6. Christiansen JR, Hamre H, Massey R, et al. Left ventricular function in long-term survivors of childhood lymphoma. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:483-490.

7. Krawczuk-Rybak M, Dakowicz L, Hryniewicz A, et al. Cardiac function in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47:455-459.

8. Heidenreich PA, Hancock SL, Vagelos RH, et al. Diastolic dysfunction after mediastinal irradiation. Am Heart J. 2005;150:977-982.

9. Elbl L, Vasova I, Tomaskova I, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the evaluation of functional capacity after treatment of lymphomas in adults. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:843-851.

10. Pastis NJ Jr, Van Bakel AB, Brand TM, et al. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in patients undergoing cardiac transplant evaluation. Chest. 2011;139:1451-1457.

1. Slanetz PJ, Truong M, Shepard JA, et al. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy and hazy mediastinal fat: new CT findings of congestive heart failure. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1307-1309.

2. Erly WK, Borders RJ, Outwater EK, et al. Location, size, and distribution of mediastinal lymph node enlargement in chronic congestive heart failure. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:485-489.

3. Storto ML, Kee ST, Golden JA, et al. Hydrostatic pulmonary edema: high-resolution CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:817-820.

4. Moua T, Levin DL, Carmona EM, et al. Frequency of mediastinal lymphadenopathy in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2013;143:344-348.

5. Chabbert V, Canevet G, Baixas C, et al. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in congestive heart failure: a sequential CT evaluation with clinical and echocardiographic correlations. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:881-889.

6. Christiansen JR, Hamre H, Massey R, et al. Left ventricular function in long-term survivors of childhood lymphoma. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:483-490.

7. Krawczuk-Rybak M, Dakowicz L, Hryniewicz A, et al. Cardiac function in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47:455-459.

8. Heidenreich PA, Hancock SL, Vagelos RH, et al. Diastolic dysfunction after mediastinal irradiation. Am Heart J. 2005;150:977-982.

9. Elbl L, Vasova I, Tomaskova I, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the evaluation of functional capacity after treatment of lymphomas in adults. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:843-851.

10. Pastis NJ Jr, Van Bakel AB, Brand TM, et al. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in patients undergoing cardiac transplant evaluation. Chest. 2011;139:1451-1457.

Sarcoidosis and Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Connection Documented in a Case Series of 3 Patients

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

Case Reports

Patient 1

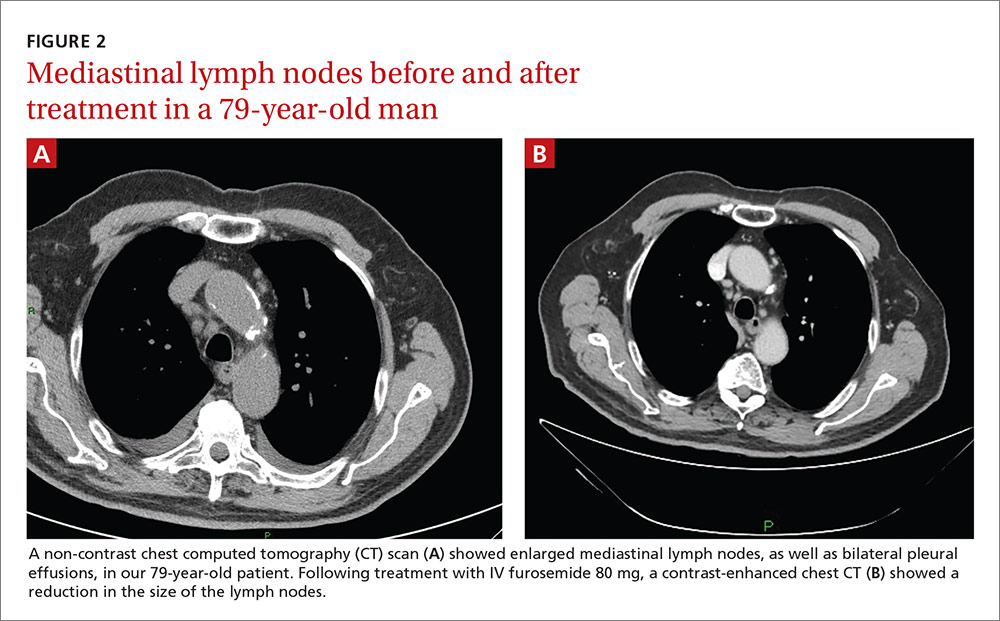

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

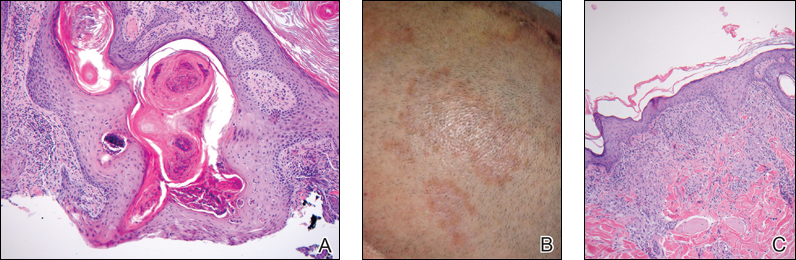

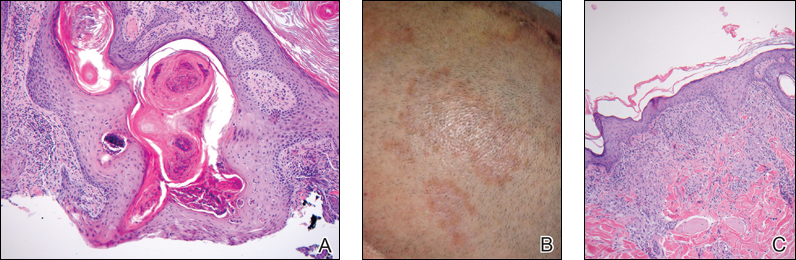

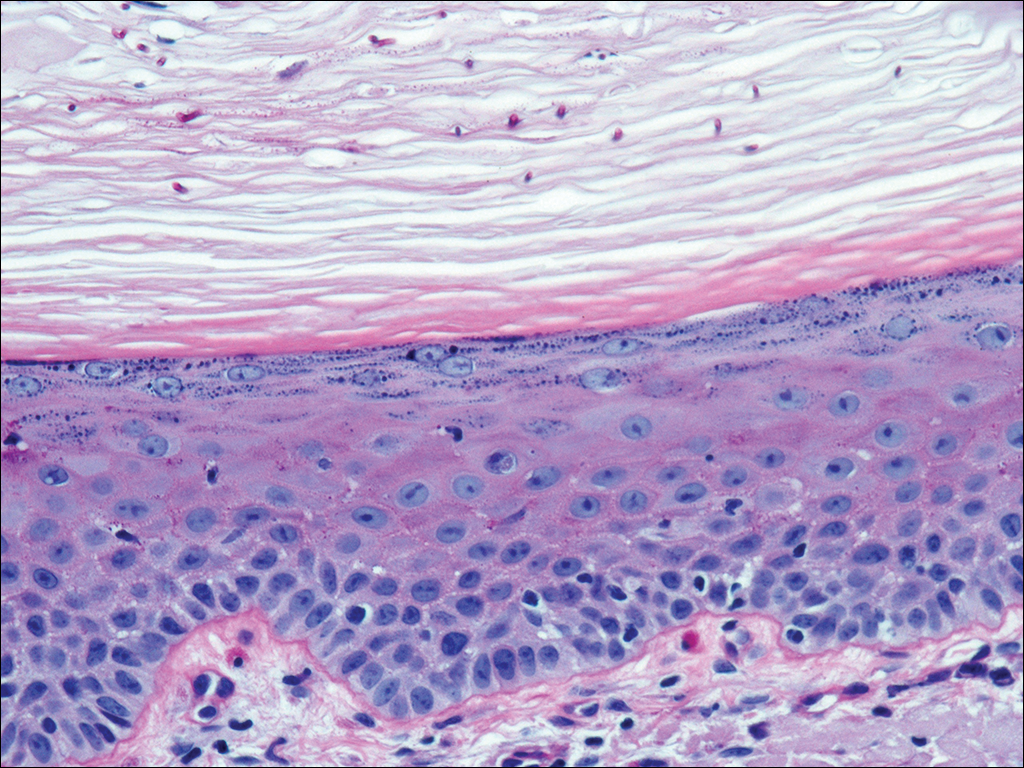

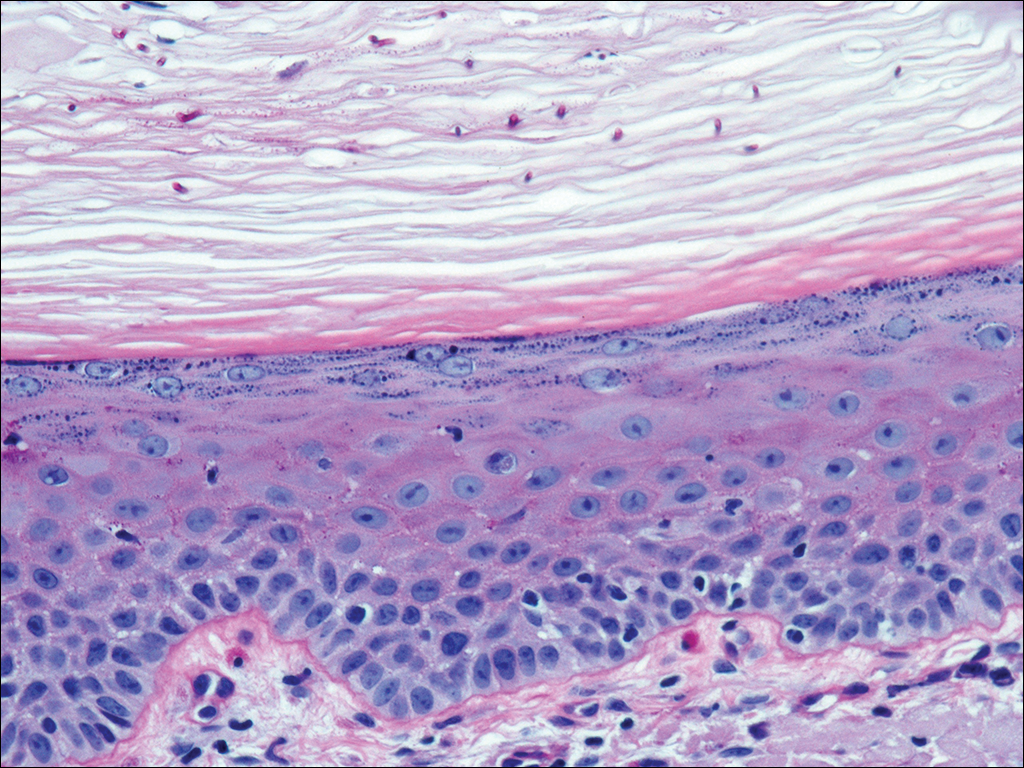

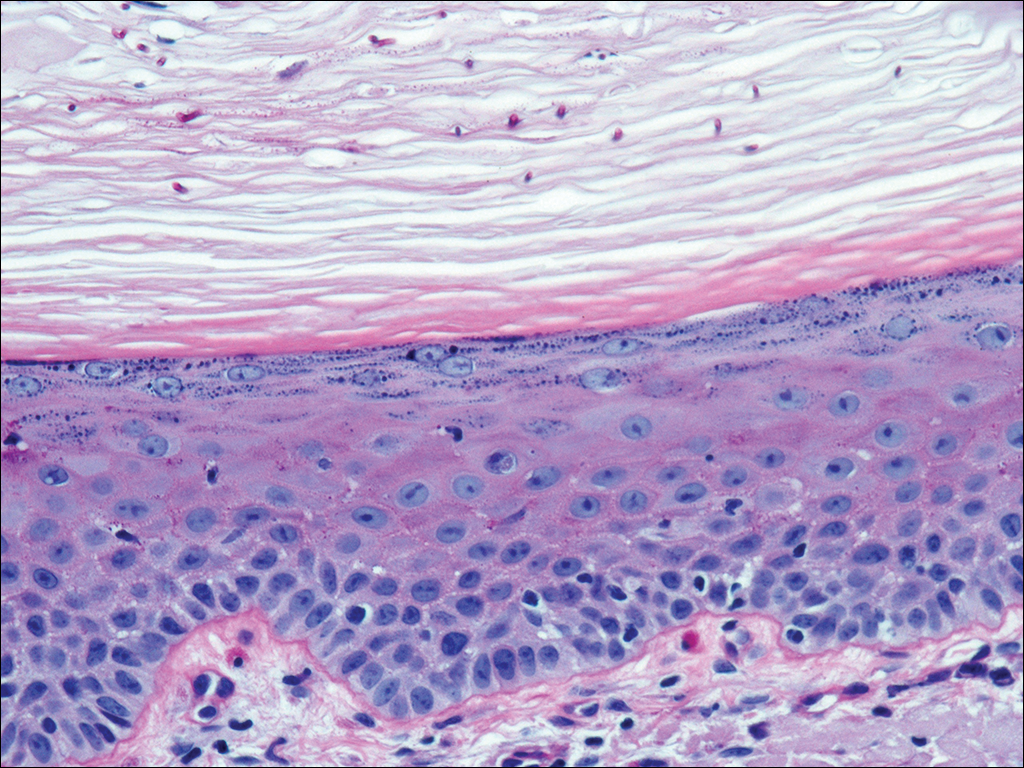

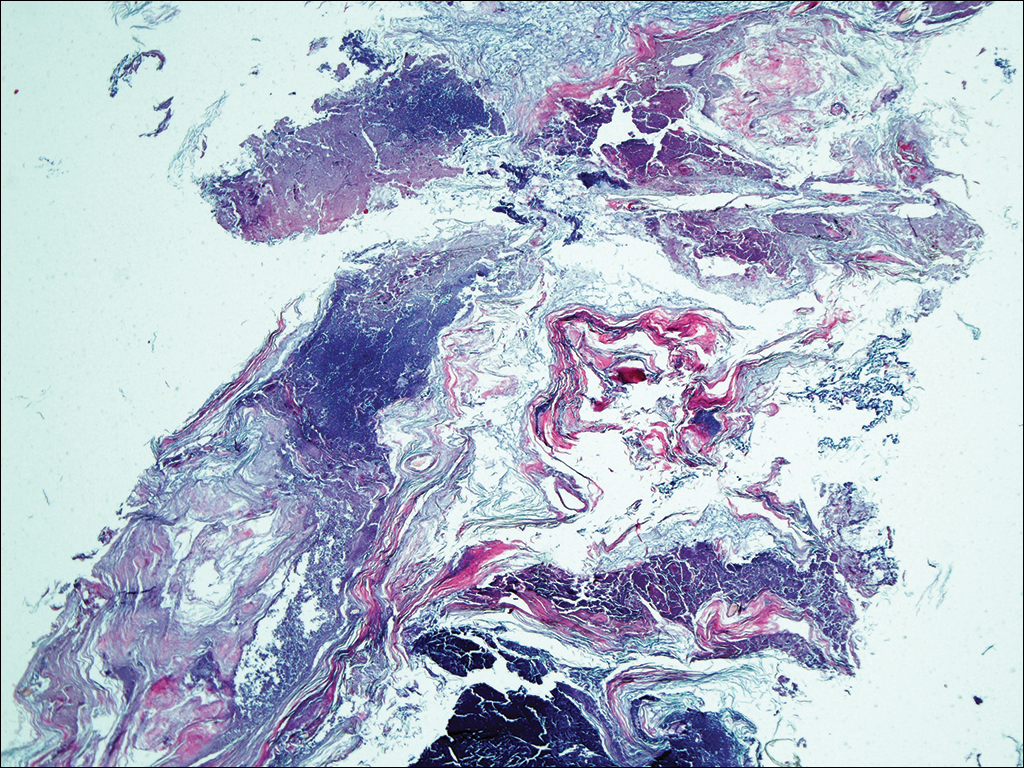

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Patient 2

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

Patient 3

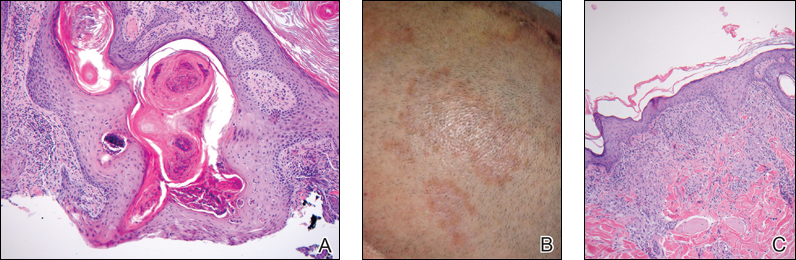

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Over the 3 years subsequent to initial presentation, the patient developed ocular inflammation attributed to his sarcoidosis and atrial fibrillation, which was determined to be unrelated. He also developed 5 scaly hyperkeratotic plaques on the vertex aspect of the scalp. Biopsy of 2 lesions revealed mild keratinocyte atypia and epidermal hyperplasia, favored to represent SCC over pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying associated granulomatous inflammation. These lesions ultimately were believed to represent new SCCs, while biopsies of 2 other lesions revealed isolated granulomatous inflammation that was believed to represent hyperkeratotic cutaneous sarcoidosis clinically resembling his SCCs. The patient was again referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and the malignancies were completely removed, while the cutaneous sarcoidosis was again treated with topical corticosteroids with complete resolution.

Comment

The potential increased risk for malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis has been well documented.3-6 Brincker and Wilbek3 first reported this association after studying 2544 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1962 to 1971. In particular, they noted a difference between the expected and observed number of cases of malignancy, particularly lung cancer and lymphoma, in the sarcoidosis population.3 In a study of 10,037 hospitalized sarcoidosis patients from 1964 to 2004, Ji et al5 noted a 40% overall increase in the incidence of cancer and found that the risk for malignancy was highest in the year following hospitalization. Interestingly, they found that the risk for developing cutaneous SCC was elevated in sarcoidosis patients even after the first year following hospitalization.5 In a retrospective cohort study examining more than 9000 patients, Askling et al4 also confirmed the increased incidence of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, the authors found a higher than expected occurrence of skin cancer, both melanoma (standardized incidence ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (standardized incidence ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.8) in patients with sarcoidosis.4 Reich et al7 cross-matched 30,000 cases from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region Tumor Registry against a sarcoidosis registry of 243 cases to evaluate for evidence of linkage between sarcoidosis and malignancy. They concluded that there may be an etiologic relationship between sarcoidosis and malignancy in at least one-quarter of cases in which both are present and hypothesized that granulomas may be the result of a cell-mediated reaction to tumor antigens.7

Few published studies specifically address the incidence of malignancy in patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis. Cutaneous sarcoidosis includes nonspecific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, as well as specific lesions, such as papules, plaques, nodules, and lupus pernio.8 Alexandrescu et al6 evaluated 110 patients with a diagnosis of both sarcoidosis (cutaneous and noncutaneous) and malignancy. Through their analysis, they found that cutaneous sarcoidosis is seen more commonly in patients presenting with sarcoidosis and malignancy (56.4%) than in the total sarcoidosis population (20%–25%). From these findings, the authors concluded that cutaneous sarcoidosis appears to be a subtype of sarcoidosis associated with cancer.6

We report 3 cases that specifically illustrate a link between cutaneous sarcoidosis and an increased risk for cutaneous SCC. Because sarcoidosis commonly affects the skin, patients often present to dermatologists for care. Once the initial diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis is made via biopsy, it is natural to be tempted to attribute any new skin lesions to worsening or active disease; however, as cutaneous sarcoidosis may take on a variety of nonspecific forms, it is important to biopsy any unusual lesions. In our case series, patient 3 presented at several different points with scaly scalp lesions. Upon biopsy, several of these lesions were found to be SCCs, while others demonstrated regions of granulomatous inflammation consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. On further review of pathology during the preparation of this manuscript after the initial diagnoses were made, it was further noted that it is challenging to distinguish granulomatous inflammation with reactive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from SCC. The fact that these lesions were clinically indistinguishable illustrates the critical importance of appropriate-depth biopsy in this situation, and the histopathologic challenges highlighted herein are important for pathologists to remember.

Patients 1 and 2 were both black women, and the fact that these patients both presented with cutaneous SCCs—one of whom was immunosuppressed due to treatment with adalimumab, the other without systemic immunosuppression—exemplifies the need for comprehensive skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as for biopsies of new or unusual lesions.

The mechanism for the development of malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis is unknown and likely is multifactorial. Multiple theories have been proposed.1,2,5,6,8 Sarcoidosis is marked by the development of granulomas secondary to the interaction between CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells, which is mediated by various cytokines and chemokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ. Patients with sarcoidosis have been found to have oligoclonal T-cell lineages with a limited receptor repertoire, suggestive of selective immune system activation, as well as a deficiency of certain types of regulatory cells, namely natural killer cells.1,2 This immune dysregulation has been postulated to play an etiologic role in the development of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients.1,2,5 Furthermore, the chronic inflammation found in the organs commonly affected by both sarcoidosis and malignancy is another possible mechanism.6,8 Finally, immunosuppression and mutagenesis secondary to the treatment modalities used in sarcoidosis may be another contributing factor.6

Conclusion

An association between sarcoidosis and malignancy has been suggested for several decades. We specifically report 3 cases of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis who presented with concurrent cutaneous SCCs. Given the varied and often nonspecific nature of cutaneous sarcoidosis, these cases highlight the importance of biopsy when sarcoidosis patients present with new and unusual skin lesions. Additionally, they illustrate the importance of thorough skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as some of the challenges these patients pose for dermatologists.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirsten AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165.

- Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391-399.

- Brincker H, Wilbek E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br J Cancer. 1974;29:247-251.

- Askling J, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. Increased risk for cancer following sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5, pt 1):1668-1672.

- Ji J, Shu X, Li X, et al. Cancer risk in hospitalized sarcoidosis patients: a follow-up study in Sweden. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1121-1126.

- Alexandrescu DT, Kauffman CL, Ichim TE, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and malignancy: an association between sarcoidosis with skin manifestations and systemic neoplasia. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Reich JM, Mullooly JP, Johnson RE. Linkage analysis of malignancy-associated sarcoidosis. Chest. 1995;107:605-613.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sarcoidosis and malignancy. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:326-333.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

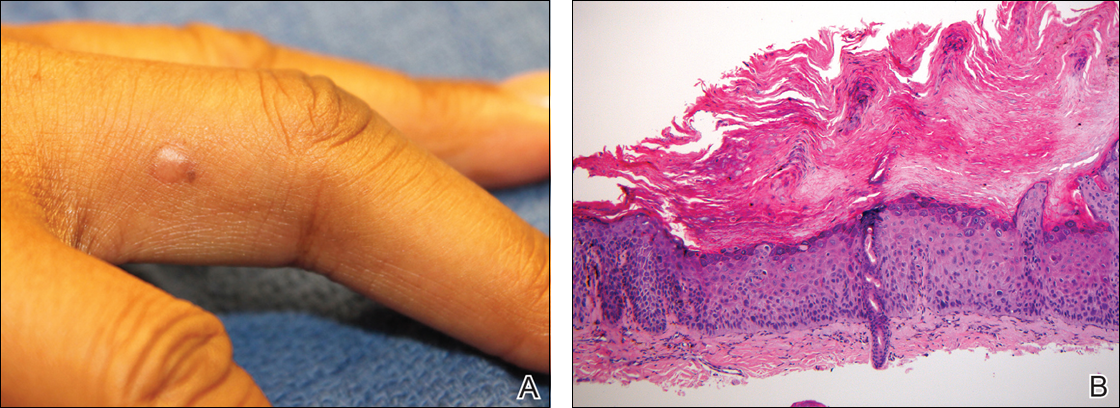

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Patient 2

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

Patient 3

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Over the 3 years subsequent to initial presentation, the patient developed ocular inflammation attributed to his sarcoidosis and atrial fibrillation, which was determined to be unrelated. He also developed 5 scaly hyperkeratotic plaques on the vertex aspect of the scalp. Biopsy of 2 lesions revealed mild keratinocyte atypia and epidermal hyperplasia, favored to represent SCC over pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying associated granulomatous inflammation. These lesions ultimately were believed to represent new SCCs, while biopsies of 2 other lesions revealed isolated granulomatous inflammation that was believed to represent hyperkeratotic cutaneous sarcoidosis clinically resembling his SCCs. The patient was again referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and the malignancies were completely removed, while the cutaneous sarcoidosis was again treated with topical corticosteroids with complete resolution.

Comment

The potential increased risk for malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis has been well documented.3-6 Brincker and Wilbek3 first reported this association after studying 2544 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1962 to 1971. In particular, they noted a difference between the expected and observed number of cases of malignancy, particularly lung cancer and lymphoma, in the sarcoidosis population.3 In a study of 10,037 hospitalized sarcoidosis patients from 1964 to 2004, Ji et al5 noted a 40% overall increase in the incidence of cancer and found that the risk for malignancy was highest in the year following hospitalization. Interestingly, they found that the risk for developing cutaneous SCC was elevated in sarcoidosis patients even after the first year following hospitalization.5 In a retrospective cohort study examining more than 9000 patients, Askling et al4 also confirmed the increased incidence of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, the authors found a higher than expected occurrence of skin cancer, both melanoma (standardized incidence ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (standardized incidence ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.8) in patients with sarcoidosis.4 Reich et al7 cross-matched 30,000 cases from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region Tumor Registry against a sarcoidosis registry of 243 cases to evaluate for evidence of linkage between sarcoidosis and malignancy. They concluded that there may be an etiologic relationship between sarcoidosis and malignancy in at least one-quarter of cases in which both are present and hypothesized that granulomas may be the result of a cell-mediated reaction to tumor antigens.7

Few published studies specifically address the incidence of malignancy in patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis. Cutaneous sarcoidosis includes nonspecific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, as well as specific lesions, such as papules, plaques, nodules, and lupus pernio.8 Alexandrescu et al6 evaluated 110 patients with a diagnosis of both sarcoidosis (cutaneous and noncutaneous) and malignancy. Through their analysis, they found that cutaneous sarcoidosis is seen more commonly in patients presenting with sarcoidosis and malignancy (56.4%) than in the total sarcoidosis population (20%–25%). From these findings, the authors concluded that cutaneous sarcoidosis appears to be a subtype of sarcoidosis associated with cancer.6

We report 3 cases that specifically illustrate a link between cutaneous sarcoidosis and an increased risk for cutaneous SCC. Because sarcoidosis commonly affects the skin, patients often present to dermatologists for care. Once the initial diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis is made via biopsy, it is natural to be tempted to attribute any new skin lesions to worsening or active disease; however, as cutaneous sarcoidosis may take on a variety of nonspecific forms, it is important to biopsy any unusual lesions. In our case series, patient 3 presented at several different points with scaly scalp lesions. Upon biopsy, several of these lesions were found to be SCCs, while others demonstrated regions of granulomatous inflammation consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. On further review of pathology during the preparation of this manuscript after the initial diagnoses were made, it was further noted that it is challenging to distinguish granulomatous inflammation with reactive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from SCC. The fact that these lesions were clinically indistinguishable illustrates the critical importance of appropriate-depth biopsy in this situation, and the histopathologic challenges highlighted herein are important for pathologists to remember.

Patients 1 and 2 were both black women, and the fact that these patients both presented with cutaneous SCCs—one of whom was immunosuppressed due to treatment with adalimumab, the other without systemic immunosuppression—exemplifies the need for comprehensive skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as for biopsies of new or unusual lesions.

The mechanism for the development of malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis is unknown and likely is multifactorial. Multiple theories have been proposed.1,2,5,6,8 Sarcoidosis is marked by the development of granulomas secondary to the interaction between CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells, which is mediated by various cytokines and chemokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ. Patients with sarcoidosis have been found to have oligoclonal T-cell lineages with a limited receptor repertoire, suggestive of selective immune system activation, as well as a deficiency of certain types of regulatory cells, namely natural killer cells.1,2 This immune dysregulation has been postulated to play an etiologic role in the development of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients.1,2,5 Furthermore, the chronic inflammation found in the organs commonly affected by both sarcoidosis and malignancy is another possible mechanism.6,8 Finally, immunosuppression and mutagenesis secondary to the treatment modalities used in sarcoidosis may be another contributing factor.6

Conclusion

An association between sarcoidosis and malignancy has been suggested for several decades. We specifically report 3 cases of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis who presented with concurrent cutaneous SCCs. Given the varied and often nonspecific nature of cutaneous sarcoidosis, these cases highlight the importance of biopsy when sarcoidosis patients present with new and unusual skin lesions. Additionally, they illustrate the importance of thorough skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as some of the challenges these patients pose for dermatologists.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Patient 2

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

Patient 3

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Over the 3 years subsequent to initial presentation, the patient developed ocular inflammation attributed to his sarcoidosis and atrial fibrillation, which was determined to be unrelated. He also developed 5 scaly hyperkeratotic plaques on the vertex aspect of the scalp. Biopsy of 2 lesions revealed mild keratinocyte atypia and epidermal hyperplasia, favored to represent SCC over pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying associated granulomatous inflammation. These lesions ultimately were believed to represent new SCCs, while biopsies of 2 other lesions revealed isolated granulomatous inflammation that was believed to represent hyperkeratotic cutaneous sarcoidosis clinically resembling his SCCs. The patient was again referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and the malignancies were completely removed, while the cutaneous sarcoidosis was again treated with topical corticosteroids with complete resolution.

Comment

The potential increased risk for malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis has been well documented.3-6 Brincker and Wilbek3 first reported this association after studying 2544 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1962 to 1971. In particular, they noted a difference between the expected and observed number of cases of malignancy, particularly lung cancer and lymphoma, in the sarcoidosis population.3 In a study of 10,037 hospitalized sarcoidosis patients from 1964 to 2004, Ji et al5 noted a 40% overall increase in the incidence of cancer and found that the risk for malignancy was highest in the year following hospitalization. Interestingly, they found that the risk for developing cutaneous SCC was elevated in sarcoidosis patients even after the first year following hospitalization.5 In a retrospective cohort study examining more than 9000 patients, Askling et al4 also confirmed the increased incidence of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, the authors found a higher than expected occurrence of skin cancer, both melanoma (standardized incidence ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (standardized incidence ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.8) in patients with sarcoidosis.4 Reich et al7 cross-matched 30,000 cases from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region Tumor Registry against a sarcoidosis registry of 243 cases to evaluate for evidence of linkage between sarcoidosis and malignancy. They concluded that there may be an etiologic relationship between sarcoidosis and malignancy in at least one-quarter of cases in which both are present and hypothesized that granulomas may be the result of a cell-mediated reaction to tumor antigens.7

Few published studies specifically address the incidence of malignancy in patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis. Cutaneous sarcoidosis includes nonspecific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, as well as specific lesions, such as papules, plaques, nodules, and lupus pernio.8 Alexandrescu et al6 evaluated 110 patients with a diagnosis of both sarcoidosis (cutaneous and noncutaneous) and malignancy. Through their analysis, they found that cutaneous sarcoidosis is seen more commonly in patients presenting with sarcoidosis and malignancy (56.4%) than in the total sarcoidosis population (20%–25%). From these findings, the authors concluded that cutaneous sarcoidosis appears to be a subtype of sarcoidosis associated with cancer.6

We report 3 cases that specifically illustrate a link between cutaneous sarcoidosis and an increased risk for cutaneous SCC. Because sarcoidosis commonly affects the skin, patients often present to dermatologists for care. Once the initial diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis is made via biopsy, it is natural to be tempted to attribute any new skin lesions to worsening or active disease; however, as cutaneous sarcoidosis may take on a variety of nonspecific forms, it is important to biopsy any unusual lesions. In our case series, patient 3 presented at several different points with scaly scalp lesions. Upon biopsy, several of these lesions were found to be SCCs, while others demonstrated regions of granulomatous inflammation consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. On further review of pathology during the preparation of this manuscript after the initial diagnoses were made, it was further noted that it is challenging to distinguish granulomatous inflammation with reactive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from SCC. The fact that these lesions were clinically indistinguishable illustrates the critical importance of appropriate-depth biopsy in this situation, and the histopathologic challenges highlighted herein are important for pathologists to remember.

Patients 1 and 2 were both black women, and the fact that these patients both presented with cutaneous SCCs—one of whom was immunosuppressed due to treatment with adalimumab, the other without systemic immunosuppression—exemplifies the need for comprehensive skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as for biopsies of new or unusual lesions.

The mechanism for the development of malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis is unknown and likely is multifactorial. Multiple theories have been proposed.1,2,5,6,8 Sarcoidosis is marked by the development of granulomas secondary to the interaction between CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells, which is mediated by various cytokines and chemokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ. Patients with sarcoidosis have been found to have oligoclonal T-cell lineages with a limited receptor repertoire, suggestive of selective immune system activation, as well as a deficiency of certain types of regulatory cells, namely natural killer cells.1,2 This immune dysregulation has been postulated to play an etiologic role in the development of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients.1,2,5 Furthermore, the chronic inflammation found in the organs commonly affected by both sarcoidosis and malignancy is another possible mechanism.6,8 Finally, immunosuppression and mutagenesis secondary to the treatment modalities used in sarcoidosis may be another contributing factor.6

Conclusion

An association between sarcoidosis and malignancy has been suggested for several decades. We specifically report 3 cases of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis who presented with concurrent cutaneous SCCs. Given the varied and often nonspecific nature of cutaneous sarcoidosis, these cases highlight the importance of biopsy when sarcoidosis patients present with new and unusual skin lesions. Additionally, they illustrate the importance of thorough skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as some of the challenges these patients pose for dermatologists.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirsten AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165.

- Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391-399.

- Brincker H, Wilbek E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br J Cancer. 1974;29:247-251.

- Askling J, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. Increased risk for cancer following sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5, pt 1):1668-1672.

- Ji J, Shu X, Li X, et al. Cancer risk in hospitalized sarcoidosis patients: a follow-up study in Sweden. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1121-1126.

- Alexandrescu DT, Kauffman CL, Ichim TE, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and malignancy: an association between sarcoidosis with skin manifestations and systemic neoplasia. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Reich JM, Mullooly JP, Johnson RE. Linkage analysis of malignancy-associated sarcoidosis. Chest. 1995;107:605-613.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sarcoidosis and malignancy. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:326-333.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirsten AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165.

- Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391-399.

- Brincker H, Wilbek E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br J Cancer. 1974;29:247-251.

- Askling J, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. Increased risk for cancer following sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5, pt 1):1668-1672.

- Ji J, Shu X, Li X, et al. Cancer risk in hospitalized sarcoidosis patients: a follow-up study in Sweden. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1121-1126.

- Alexandrescu DT, Kauffman CL, Ichim TE, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and malignancy: an association between sarcoidosis with skin manifestations and systemic neoplasia. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Reich JM, Mullooly JP, Johnson RE. Linkage analysis of malignancy-associated sarcoidosis. Chest. 1995;107:605-613.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sarcoidosis and malignancy. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:326-333.

Practice Points

- There may be an increased risk of skin cancer in patients with sarcoidosis.

- Sarcoidosis may present with multiple morphologies, including verrucous or hyperkeratotic lesions; superficial biopsy of this type of lesion may be mistaken for a squamous cell carcinoma.

- A biopsy diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in a black patient with sarcoidosis should be carefully reviewed for evidence of deeper granulomatous inflammation.

Tinea Capitis Caused by Trichophyton rubrum Mimicking Favus

In 1909, Sabouraud1 published a report delineating the clinical subsets of a chronic fungal infection of the scalp known as favus. The rarest subset was termed favus papyroide and consisted of a thin, dry, gray, parchmentlike crust up to 5 cm in diameter. Hair shafts were described as piercing the crust, with the underlying skin exhibiting erythema, moisture, and erosions. Children were reported to be affected more often than adults.1 Subsequent descriptions of patients with similar presentations have not appeared in the medical literature. In this case, an elderly woman with tinea capitis (TC) due to Trichophyton rubrum exhibited features of favus papyroide.

Case Report

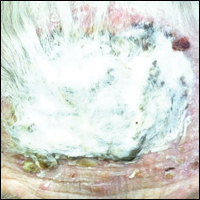

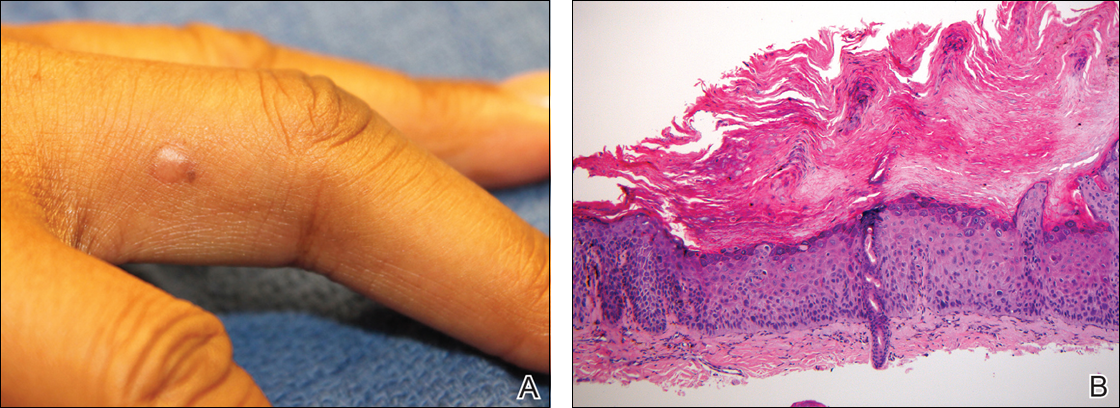

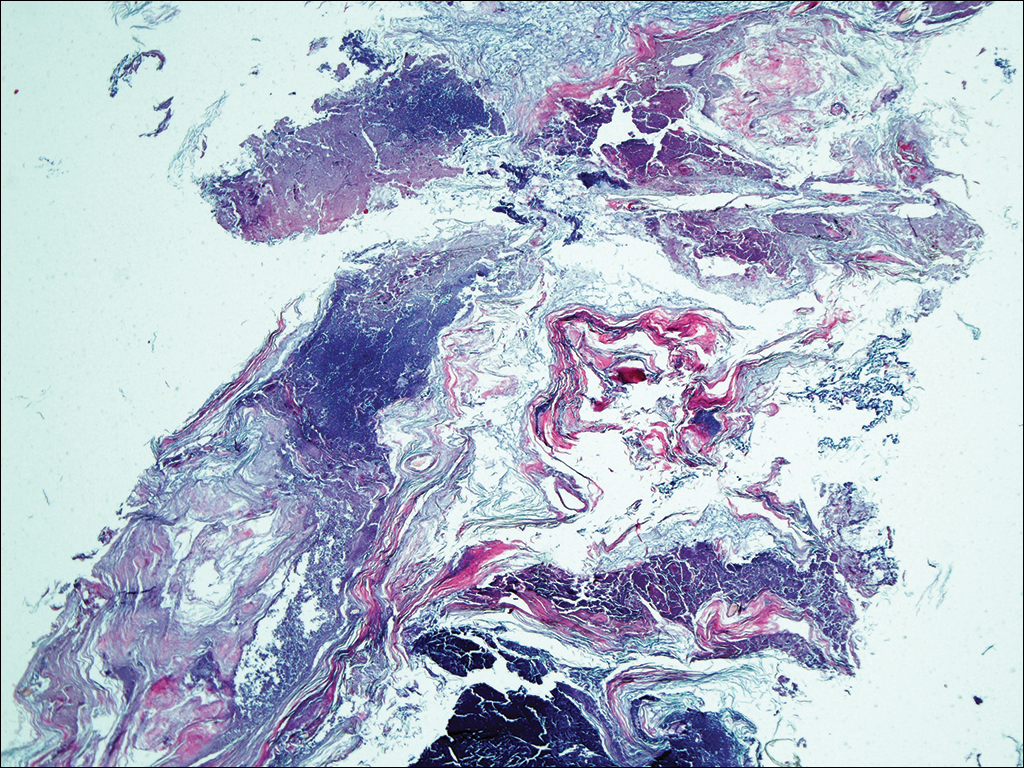

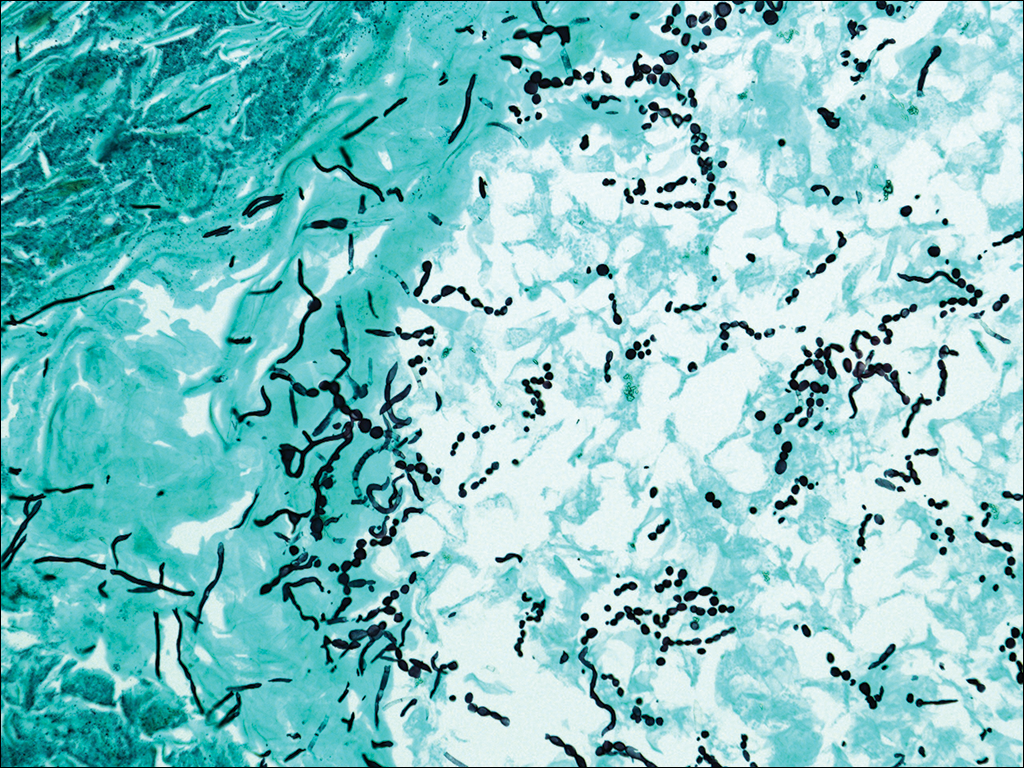

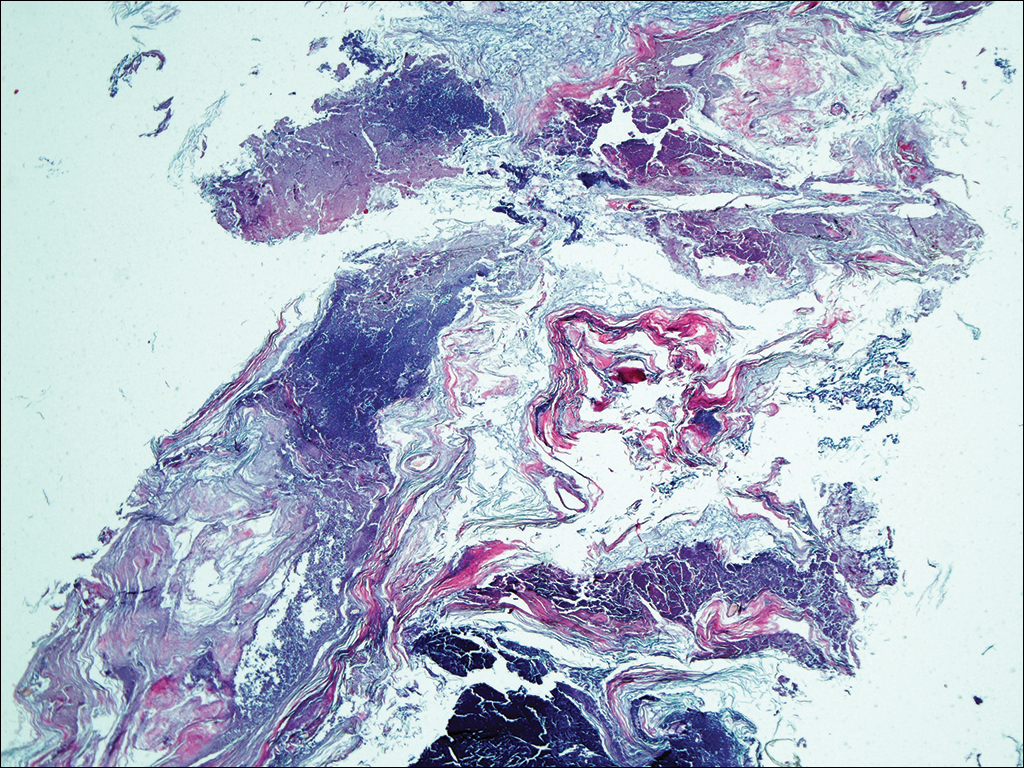

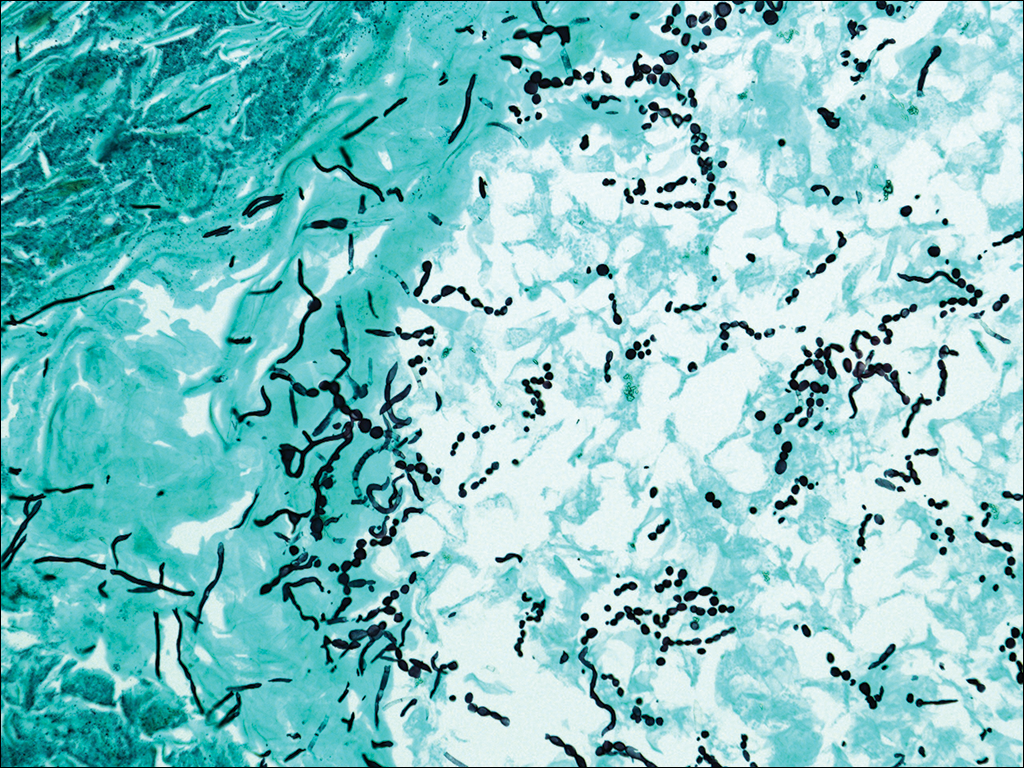

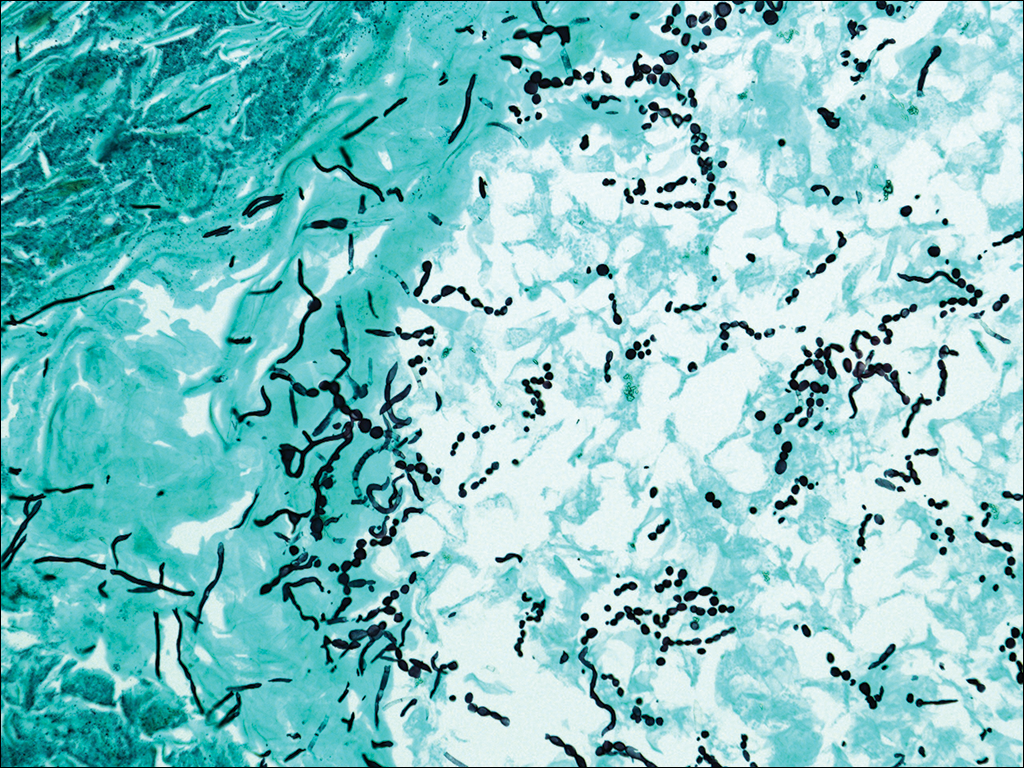

An 87-year-old woman with a long history of actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers presented to our dermatology clinic with numerous growths on the head, neck, and arms. The patient resided in a nursing home and had a history of hypertension, osteoarthritis, and mild to moderate dementia. Physical examination revealed a frail elderly woman in a wheelchair. Numerous actinic keratoses were noted on the arms and face. Examination of the scalp revealed a large, white-gray, palm-sized plaque on the crown (Figure 1) with 2 yellow, quarter-sized, hyperkeratotic nodules on the left temple and left parietal scalp. The differential diagnosis for the nodules on the temple and scalp included squamous cell carcinoma and hyperkeratotic actinic keratosis, and both lesions were biopsied. Histologically, they demonstrated pronounced hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with numerous infiltrating neutrophils. The stratum malpighii exhibited focal atypia consistent with an actinic keratosis with areas of spongiosis and pustular folliculitis but no evidence of an invasive cutaneous malignancy. Periodic acid–Schiff stains were performed on both specimens and revealed numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 2) as well as evidence of a fungal folliculitis.

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, a portion of the hyperkeratotic material on the crown of the scalp was lifted free from the skin surface, removed with scissors, and submitted for histologic analysis and culture. The underlying skin exhibited substantial erythema and diffuse alopecia. The specimen consisted entirely of masses of hyperkeratotic and parakeratotic stratum corneum with numerous infiltrating neutrophils, cellular debris, and focal secondary bacterial colonization (Figure 3). Fungal hyphae and spores were readily demonstrated on Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 4). A fungal culture from this material failed to demonstrate growth at 28 days. The organism was molecularly identified as T rubrum using the Sanger sequencing assay. The patient was treated with fluconazole 150 mg once daily for 3 weeks with eventual resolution of the plaque. The patient died approximately 3 months later (unrelated to her scalp infection).

Comment

Favus, or tinea favosa, is a chronic inflammatory dermatophyte infection of the scalp, less commonly involving the skin and nails.2 The classic lesion is termed a scutulum or godet consisting of concave, cup-shaped, yellow crusts typically pierced by a single hair shaft.1 With an increase in size, the scutula may become confluent. Alopecia commonly results and infected patients may exude a “cheesy” or “mousy” odor from the lesions.3 Sabouraud1 delineated 3 clinical presentations of favus: (1) favus pityroide, the most common type consisting of a seborrheic dermatitis–like picture and scutula; (2) favus impetigoide, exhibiting honey-colored crusts reminiscent of impetigo but without appreciable scutula; and (3) favus papyroide, the rarest variant, demonstrating a dry, gray, parchmentlike crust pierced by hair shafts overlying an eroded erythematous scalp.

Favus usually is acquired in childhood or adolescence and often persists into adulthood.3 It is transmitted directly by hairs, infected keratinocytes, and fomites. Child-to-child transmission is much less common than other forms of TC.4 The responsible organism is almost always Trichophyton schoenleinii, with rare cases of Trichophyton violaceum, Trichophyton verrucosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes var quinckeanum, Microsporum canis, and Microsporum gypseum having been reported.2,5,6 This anthropophilic dermatophyte infects only humans, is capable of surviving in the same dwelling space for generations, and is believed to require prolonged exposure for transmission. Trichophyton schoenleinii was the predominant infectious cause of TC in eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but its incidence has dramatically declined in the last 50 years.7 A survey conducted in 1997 and published in 2001 of TC that was culture-positive for T schoenleinii in 19 European countries found only 3 cases among 3671 isolates (0.08%).8 Between 1980 and 2005, no cases were reported in the British Isles.9 Currently, favus generally is found in impoverished geographic regions with poor hygiene, malnutrition, and limited access to health care; however, endemic foci in Kentucky, Quebec, and Montreal have been reported in North America.10 Although favus rarely resolves spontaneously, T schoenleinii was eradicated in most of the world with the introduction of griseofulvin in 1958.7 Terbinafine and itraconazole are currently the drugs of choice for therapy.10

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection in children, with 1 in 20 US children displaying evidence of overt infection.11 Infection in adults is rare and most affected patients typically display serious illnesses with concomitant immune compromise.12 Only 3% to 5% of cases arise in patients older than 20 years.13 Adult hair appears to be relatively resistant to dermatophyte infection, probably from the fungistatic properties of long-chain fatty acids found in sebum.13 Tinea capitis in adults usually occurs in postmenopausal women, presumably from involution of sebaceous glands associated with declining estrogen levels. Patients typically exhibit erythematous scaly patches with central clearing, alopecia, varying degrees of inflammation, and few pustules, though exudative and heavily inflammatory lesions also have been described.14

In the current case, TC was not raised in the differential diagnosis. Regardless, given that scaly red patches and papules of the scalp may represent a dermatophyte infection in this patient population, clinicians are encouraged to consider this possibility. Transmission is by direct human-to-human contact and contact with objects containing fomites including brushes, combs, bedding, clothing, toys, furniture, and telephones.15 It is frequently spread among family members and classmates.16

Prior to World War II, most cases of TC in the United States were due to M canis, with Microsporum audouinii becoming more prevalent until the 1960s and 1970s when Trichophyton tonsurans began surging in incidence.12,17 Currently, the latter organism is responsible for more than 95% of TC cases in the United States.18Microsporum canis is the main causative species in Europe but varies widely by country. In the Middle East and Africa, T violaceum is responsible for many infections.

Trichophyton rubrum–associated TC appears to be a rare occurrence. A global study in 1995 noted that less than 1% of TC cases were due to T rubrum infection, most having been described in emerging nations.12 A meta-analysis of 9 studies from developed countries found only 9 of 10,145 cases of TC with a culture positive for T rubrum.14 In adults, infected patients typically exhibit either evidence of a concomitant fungal infection of the skin and/or nails or health conditions with impaired immunity, whereas in children, interfamilial spread appears more common.11

- Sabouraud R. Les favus atypiques, clinique. Paris. 1909;4:296-299.

- Olkit M. Favus of the scalp: an overview and update. Mycopathologia. 2010;170:143-154.

- Elewski BE. Tinea capitis: a current perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1-20.

- Aly R, Hay RJ, del Palacio A, et al. Epidemiology of tinea capitis. Med Mycol. 2000;38(suppl 1):183-188.

- Joly J, Delage G, Auger P, et al. Favus: twenty indigenous cases in the province of Quebec. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1647-1648.

- Garcia-Sanchez MS, Pereira M, Pereira MM, et al. Favus due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. quinckeanum. Dermatology. 1997;194:177-179.

- Seebacher C, Bouchara JP, Mignon B. Updates on the epidemiology of dermatophyte infections. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:335-352.

- Hay RJ, Robles W, Midgley MK, et al. Tinea capitis in Europe: new perspective on an old problem. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:229-233.

- Borman AM, Campbell CK, Fraser M, et al. Analysis of the dermatophyte species isolated in the British Isles between 1980 and 2005 and review of worldwide dermatophyte trends over the last three decades. Med Mycol. 2007;45:131-141.

- Rippon JW. Dermatophytosis and dermatomycosis. In: Rippon JW. Medical Mycology: The Pathogenic Fungi and the Pathogenic Actinomycetes. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1988:197-199.

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Penny J, Alander SW. Trichophyton rubrum tinea capitis in a young child. Ped Dermatol. 2004;21:63-65.

- Schwinn A, Ebert J, Brocker EB. Frequency of Trichophyton rubrum in tinea capitis. Mycoses. 1995;38:1-7.

- Ziemer A, Kohl K, Schroder G. Trichophyton rubrum induced inflammatory tinea capitis in a 63-year-old man. Mycoses. 2005;48:76-79.

- Anstey A, Lucke TW, Philpot C. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:113-115.

- Schwinn A, Ebert J, Muller I, et al. Trichophyton rubrum as the causative agent of tinea capitis in three children. Mycoses. 1995;38:9-11.

- Chang SE, Kang SK, Choi JH, et al. Tinea capitis due to Trichophyton rubrum in a neonate. Ped Dermatol. 2002;19:356-358.

- Stiller MJ, Rosenthal SA, Weinstein AS. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton rubrum in a 67-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:257-258.

- Foster KW, Ghannoum MA, Elewski BE. Epidemiologic surveillance of cutaneous fungal infection in the United States from 1999 to 2002. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:748-752.

In 1909, Sabouraud1 published a report delineating the clinical subsets of a chronic fungal infection of the scalp known as favus. The rarest subset was termed favus papyroide and consisted of a thin, dry, gray, parchmentlike crust up to 5 cm in diameter. Hair shafts were described as piercing the crust, with the underlying skin exhibiting erythema, moisture, and erosions. Children were reported to be affected more often than adults.1 Subsequent descriptions of patients with similar presentations have not appeared in the medical literature. In this case, an elderly woman with tinea capitis (TC) due to Trichophyton rubrum exhibited features of favus papyroide.

Case Report

An 87-year-old woman with a long history of actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers presented to our dermatology clinic with numerous growths on the head, neck, and arms. The patient resided in a nursing home and had a history of hypertension, osteoarthritis, and mild to moderate dementia. Physical examination revealed a frail elderly woman in a wheelchair. Numerous actinic keratoses were noted on the arms and face. Examination of the scalp revealed a large, white-gray, palm-sized plaque on the crown (Figure 1) with 2 yellow, quarter-sized, hyperkeratotic nodules on the left temple and left parietal scalp. The differential diagnosis for the nodules on the temple and scalp included squamous cell carcinoma and hyperkeratotic actinic keratosis, and both lesions were biopsied. Histologically, they demonstrated pronounced hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with numerous infiltrating neutrophils. The stratum malpighii exhibited focal atypia consistent with an actinic keratosis with areas of spongiosis and pustular folliculitis but no evidence of an invasive cutaneous malignancy. Periodic acid–Schiff stains were performed on both specimens and revealed numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 2) as well as evidence of a fungal folliculitis.

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, a portion of the hyperkeratotic material on the crown of the scalp was lifted free from the skin surface, removed with scissors, and submitted for histologic analysis and culture. The underlying skin exhibited substantial erythema and diffuse alopecia. The specimen consisted entirely of masses of hyperkeratotic and parakeratotic stratum corneum with numerous infiltrating neutrophils, cellular debris, and focal secondary bacterial colonization (Figure 3). Fungal hyphae and spores were readily demonstrated on Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 4). A fungal culture from this material failed to demonstrate growth at 28 days. The organism was molecularly identified as T rubrum using the Sanger sequencing assay. The patient was treated with fluconazole 150 mg once daily for 3 weeks with eventual resolution of the plaque. The patient died approximately 3 months later (unrelated to her scalp infection).

Comment

Favus, or tinea favosa, is a chronic inflammatory dermatophyte infection of the scalp, less commonly involving the skin and nails.2 The classic lesion is termed a scutulum or godet consisting of concave, cup-shaped, yellow crusts typically pierced by a single hair shaft.1 With an increase in size, the scutula may become confluent. Alopecia commonly results and infected patients may exude a “cheesy” or “mousy” odor from the lesions.3 Sabouraud1 delineated 3 clinical presentations of favus: (1) favus pityroide, the most common type consisting of a seborrheic dermatitis–like picture and scutula; (2) favus impetigoide, exhibiting honey-colored crusts reminiscent of impetigo but without appreciable scutula; and (3) favus papyroide, the rarest variant, demonstrating a dry, gray, parchmentlike crust pierced by hair shafts overlying an eroded erythematous scalp.

Favus usually is acquired in childhood or adolescence and often persists into adulthood.3 It is transmitted directly by hairs, infected keratinocytes, and fomites. Child-to-child transmission is much less common than other forms of TC.4 The responsible organism is almost always Trichophyton schoenleinii, with rare cases of Trichophyton violaceum, Trichophyton verrucosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes var quinckeanum, Microsporum canis, and Microsporum gypseum having been reported.2,5,6 This anthropophilic dermatophyte infects only humans, is capable of surviving in the same dwelling space for generations, and is believed to require prolonged exposure for transmission. Trichophyton schoenleinii was the predominant infectious cause of TC in eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but its incidence has dramatically declined in the last 50 years.7 A survey conducted in 1997 and published in 2001 of TC that was culture-positive for T schoenleinii in 19 European countries found only 3 cases among 3671 isolates (0.08%).8 Between 1980 and 2005, no cases were reported in the British Isles.9 Currently, favus generally is found in impoverished geographic regions with poor hygiene, malnutrition, and limited access to health care; however, endemic foci in Kentucky, Quebec, and Montreal have been reported in North America.10 Although favus rarely resolves spontaneously, T schoenleinii was eradicated in most of the world with the introduction of griseofulvin in 1958.7 Terbinafine and itraconazole are currently the drugs of choice for therapy.10

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection in children, with 1 in 20 US children displaying evidence of overt infection.11 Infection in adults is rare and most affected patients typically display serious illnesses with concomitant immune compromise.12 Only 3% to 5% of cases arise in patients older than 20 years.13 Adult hair appears to be relatively resistant to dermatophyte infection, probably from the fungistatic properties of long-chain fatty acids found in sebum.13 Tinea capitis in adults usually occurs in postmenopausal women, presumably from involution of sebaceous glands associated with declining estrogen levels. Patients typically exhibit erythematous scaly patches with central clearing, alopecia, varying degrees of inflammation, and few pustules, though exudative and heavily inflammatory lesions also have been described.14