User login

Multiple Keratoacanthomas Occurring in Surgical Margins and De Novo Treated With Intralesional Methotrexate

Keratoacanthomas (KAs) are rapidly growing tumors most prominently found on sun-exposed areas of the skin. The normal progression of a KA is to show rapid growth followed by spontaneous resolution.1 Most KAs are solitary; however, there are several variants of multiple KAs including the familial Ferguson-Smith type, Gryzbowski syndrome (generalized eruptive KAs), KA centrifugum marginatum, Muir-Torre syndrome, and xeroderma pigmentosum.2-4 Keratoacanthomas also may develop in areas of trauma, including burns, laser treatment, radiation, and surgical margins from excisional biopsies or skin grafting.5 Treatment of multiple KAs can be difficult due to a potentially large field size and number of lesions.6 We present a case of multiple KAs developing both in the surgical margins and de novo that responded dramatically to treatment with intralesional methotrexate (MTX).

Case Report

A 55-year-old man with a history of a surgically treated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the anterior aspect of the right leg developed multiple nodules involving the surgical scar. He previously underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS); within a month after the second surgery the patient noticed increased pruritus along with scaly pink changes at the site of the surgical scar.

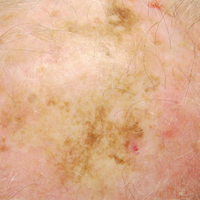

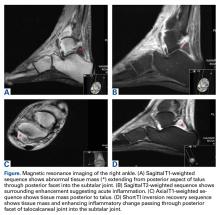

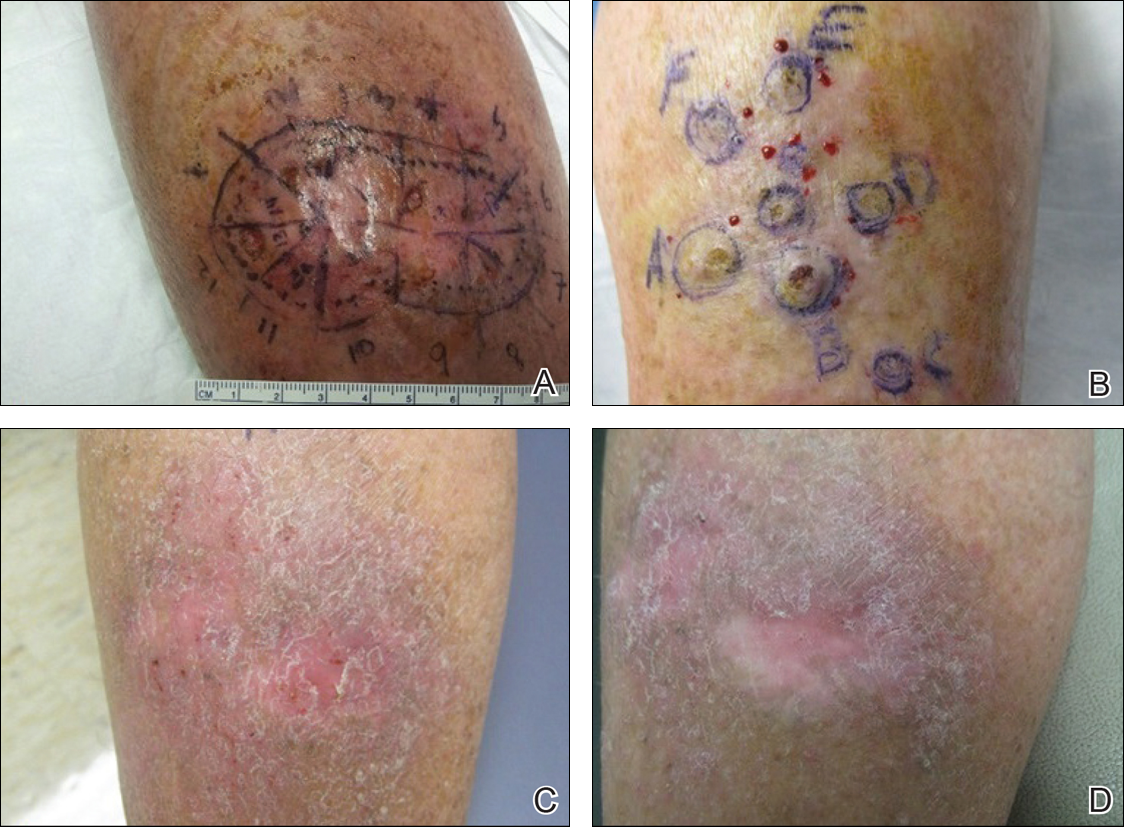

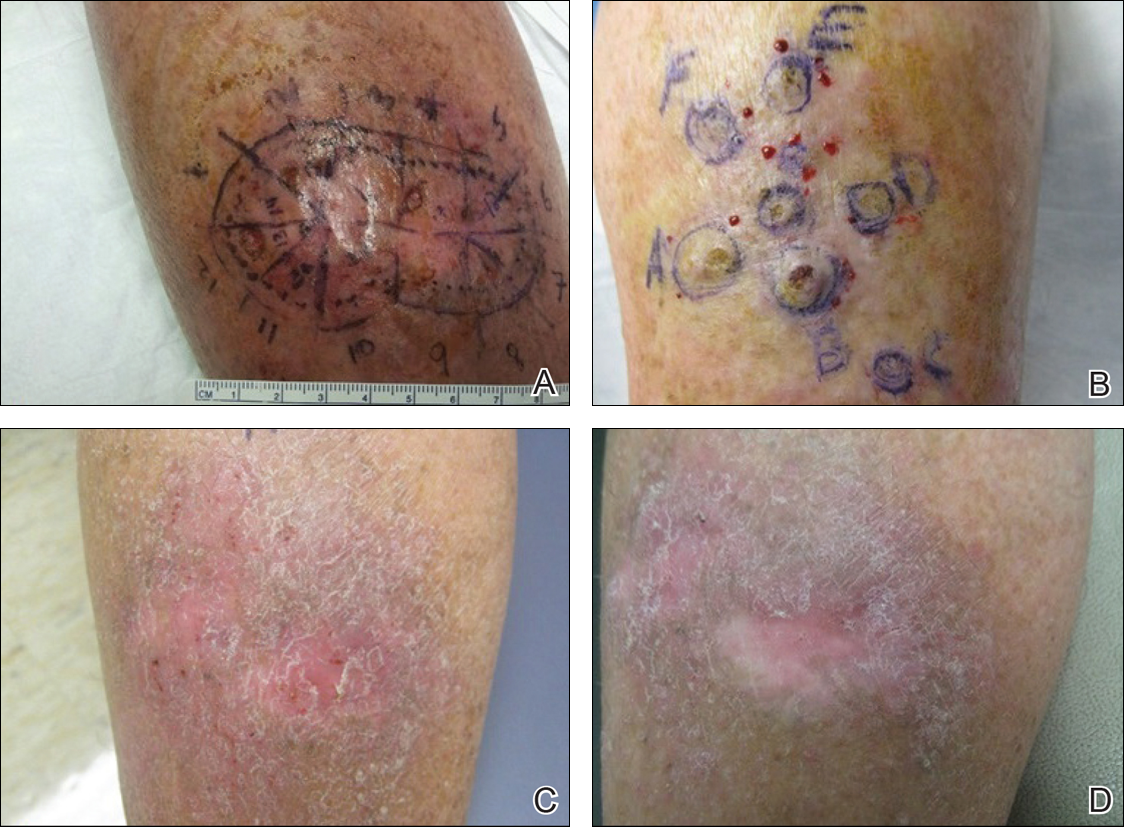

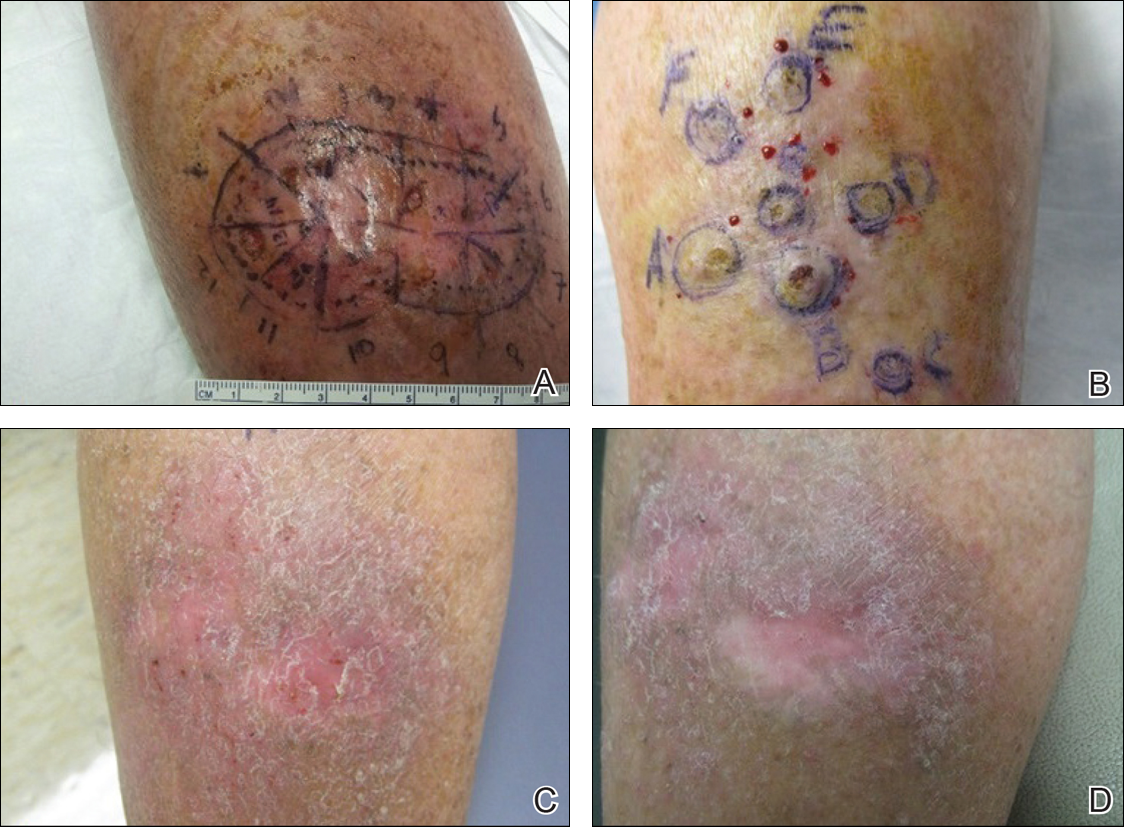

One month prior to presentation, biopsies from the anterior aspect of the right leg demonstrated well-differentiated SCC and he was subsequently treated with MMS; however, examination 1 month after MMS revealed an 11×7-cm indurated plaque with multiple nodules ranging from 1 to 2 cm near the periphery of the plaque with central atrophy and scarring, reminiscent of KA centrifugum marginatum (Figure, A). In a similar fashion, an 8×5-cm plaque composed of 7 nodular areas was noted on the posterior aspect of the right leg (Figure, B). The patient denied any history of trauma to this area. There was no palpable regional lymphadenopathy and the remainder of the skin examination was normal, except for signs of venous stasis in both legs.

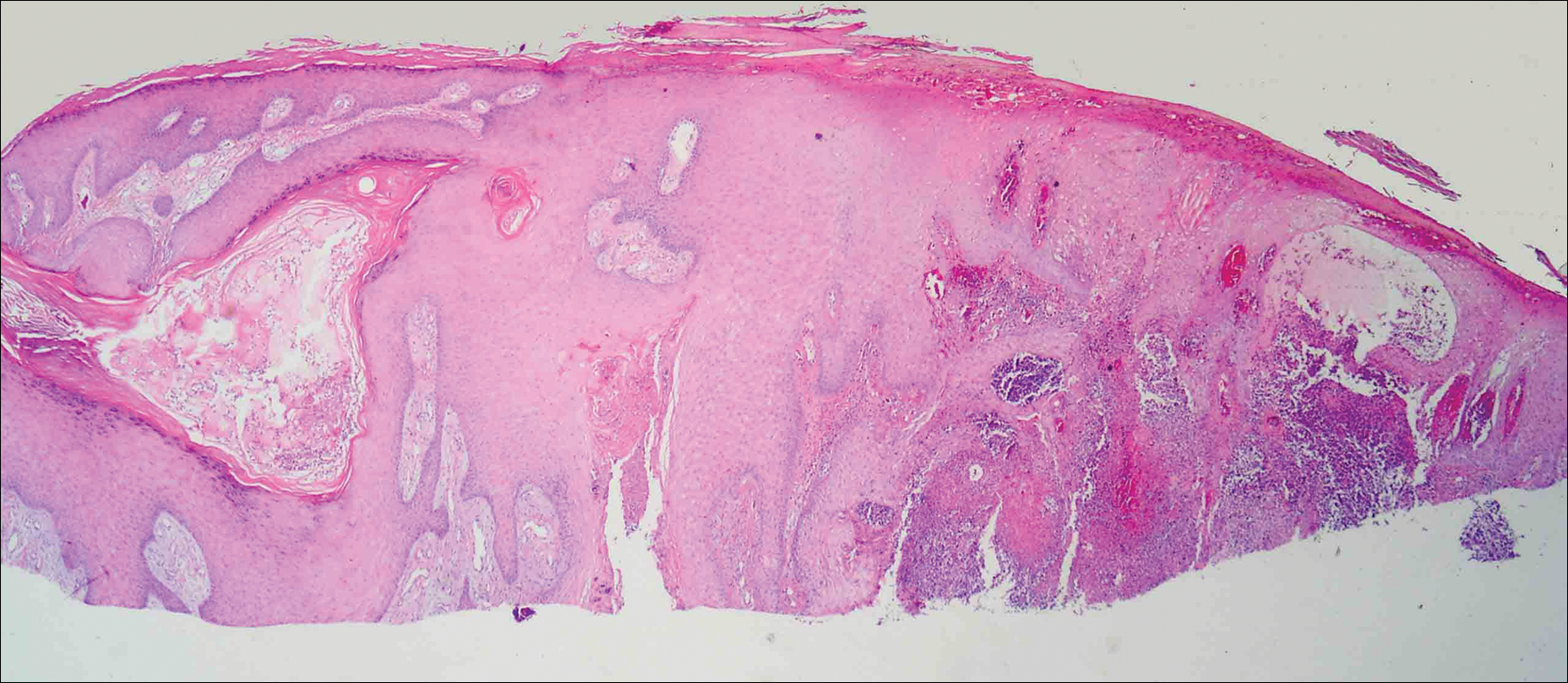

Based on the location and morphology of the lesions, the clinical presentation was consistent with multiple KAs. Histologic examination from punch biopsies taken from the plaque's periphery demonstrated well-differentiated SCC (KA type), as well as a lichenoid inflammatory process, epidermal hyperplasia, and cystic and endophytic squamous proliferation suggestive of hypertrophic lichen planus (HLP).

In consideration of the size and number of the lesions as well as the prolonged wound healing with prior surgery, the patient consented to treatment with intralesional MTX (1 mL of 12.5 mg/mL every 2 weeks) rather than undergoing further surgery. The MTX injection was distributed between the lesions on the anterior and posterior aspects of the lower right leg. At each injection session, the size, thickness, and nodularity of the tumor decreased with markedly less pruritus and symptomatic relief was achieved. After 3 injection sessions, resulting in a total of 3 mL of 12.5 mg/mL of MTX, biopsies were taken from the residual atrophic scar on the anterior aspect of the right leg and the remaining 3 papules on the posterior aspect of the right leg to rule out HLP and invasive SCC. The pathology report commented on the presence of prurigo nodules without any evidence of SCC.

At 3-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated no new lesions or recurrence (Figure, C and D). The right leg continued to heal with scarring and postinflammatory pigmentary changes. The patient was monitored for recurrence and to determine the diagnosis of HLP.

Comment

We report the development of multiple KAs arising both from within surgical margins and de novo, and resolution with intralesional MTX. Keratoacanthomas, especially various KA types, have been observed to develop due to various types of trauma, including sites of surgical scars, lichen planus, tattoos, thermal burns, radiation, and discoid lupus erythematosus, and within skin grafts and donor sites.5-19

Hypertrophic lichen planus is a chronic variant of lichen planus that often is found on the pretibial areas of the lower legs.13 Both SCC and reactive KAs have been observed to develop within lesions of HLP.14 Our pathologist commented on the presence of a lichenoid infiltrate with necrotic keratinocytes and epidermal hyperplasia suspicious for HLP, with a small focus of cystic and endophytic squamous proliferation. The latter lacked notable atypia or an invasive component and could represent an irritated infundibular cyst versus an early evolving KA.

The lichenoid inflammation is suspicious for HLP, which has been associated with eruptive KAs13-16 and may have contributed to the development of persistent KAs in our patient, both in sites of surgical scars (the anterior aspect of the leg) and in uninvolved skin (the posterior aspect of the leg). Trauma from the prior surgery may have stimulated a local inflammatory response and, if coupled with a preexisting underlying chronic inflammatory condition such as HLP, may have triggered the development of new lesions on the posterior leg. Skin pathergy reactions also are caused by an upregulated inflammatory response, which is reduced with immunosuppressive agents such as MTX.12

In our patient, there was both an isotopic and isomorphic response. The term isotopic response refers to the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of another unrelated and already healed skin disease. It was first defined by Wolf and Wolf20 in 1985 and hence is also known as Wolf isotopic response. The isotopic response in our patient occurred in the setting of lichen planus. The isomorphic response indicates the appearance of typical skin lesions of an existing dermatosis at sites of other skin injuries.

Initially, we thought the patient had recurrence of SCC, but with the rapid development of multiple lesions, the diagnosis of multiple KAs was more likely. Kimyai-Asadi et al8 demonstrated that surgical trauma can precede the development of KAs, as they reported a patient who developed a KA at an excision site. Tamir et al7 reported the simultaneous appearance of KAs in burn scars and skin graft donor sites 4 months after a 40% total body surface area burn. Hamilton et al11 described surgical trauma from a split-skin graft donor site as a trigger for the onset of a KA.

Multiple treatment alternatives exist for KAs, with the standard of care for large or high-risk KAs being excisional surgery21,22; however, other approaches may need to be considered in certain cases, such as with multiple KAs in which lesions may be large and extensive, thereby yielding poor cosmetic outcomes, or with increased surgical risk.23 Furthermore, multiple KAs that develop in the setting of surgical scars require special consideration. Topical 5-fluorouracil, various systemic and intralesional agents (eg, retinoids, interferon, bleomycin, MTX), laser therapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, radiotherapy, and photodynamic therapy all have been reported as methods employed for the treatment of KA.23-27 Goldberg et al5 reported cases of resolution of eruptive KAs arising in both surgical and nonsurgical sites with a combination of deep shave excision, MMS, curettage and desiccation, and oral isotretinoin.

For our patient, we opted for treatment with intralesional MTX, both due to its effectiveness for solitary KAs and reasonably decreased risk of morbidity compared to surgical excision of regions of the pretibial calves. Treatment with MTX would not have been attempted if there was any clinical doubt that the lesions were not the well-differentiated KA type. Also, we had a low threshold for discontinuing therapy and reverting to MMS treatment if any of the lesions displayed a paradoxical growth post-MTX treatment or failed to respond after 3 treatments. Intralesional MTX is less invasive, relatively inexpensive, and a treatment modality with decreased morbidity for KAs, especially for multiple KAs. It should be considered as a potential alternative to surgery in such cases.23-27

- Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:1-19.

- Feldman RJ, Maize JC. Multiple keratoacanthomas in a young woman: report of a case emphasizing medical management and a review of the spectrum of multiple keratoacanthomas. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:77-79.

- Ereaux LP, Schopflocher P, Fornier CJ. Keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1955;71:73-83.

- Lloyd KM, Madsen DK, Lin PY. Grzybowski's eruptive keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(5, pt 1):1023-1024.

- Goldberg LH, Silapunt S, Beyrau KK, et al. Keratoacanthoma as a postoperative complication of skin cancer excision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:753-758.

- Pillsbury DM, Beerman H. Multiple keratoacanthoma. Am J Med Sci. 1958;236:614-623.

- Tamir G, Morgenstern S, Ben-Amitay D, et al. Synchronous appearance of keratoacanthomas in burn scar and skin graft donor site shortly after injury. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;400(5, pt 2):870-871.

- Kimyai-Asadi A, Shaffer C, Levine VJ, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising from an excisional surgery scar. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:193-194.

- Pattee SF, Silvis NG. Keratoacanthoma developing in sites of previous trauma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(suppl 2):S35-S38.

- Hendricks WM. Sudden appearance of multiple keratoacanthomas three weeks after thermal burns. Cutis. 1991;47:410-412.

- Hamilton SA, Dickson WA, O'Brien CJ. Keratoacanthoma developing in a split skin graft donor site. Br J Plast Surg. 1997;50:560-561.

- Bangash SJ, Green WH, Dolson DJ, et al. Eruptive postoperative squamous cell carcinomas exhibiting a pathergy-like reaction around surgical wound sites. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:892-897.

- Badell A, Marcoval J, Gallego I, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising in hypertrophic lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:370-393.

- Chave TA, Graham-Brown RAC. Keratoacanthoma developing in hypertrophic lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:592.

- Epstein R. Treatment of keratoacanthoma arising from hypertrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(3, suppl 1):AB28.

- Giesecke LM, Reid CM, James CL, et al. Giant keratoacanthoma arising in hypertrophic lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:267-269.

- Toll A, Salgado R, Espinet B, et al. "Eruptive postoperative squamous cell carcinomas" or "Hypertrophic lichen planus-like reactions combined with infundibulocystic hyperplasia"? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:910-911.

- Fanti PA, Tosti A, Peluso AM, et al. Multiple keratoacanthoma in discoid lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(4, pt 1):809-810.

- Kossard S, Thompson C, Duncan GM. Hypertrophic lichen planus-like reactions combined with infundibulocystic hyperplasia: pathway to neoplasia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1262-1267.

- Wolf R, Wolf D. Tinea in a site of healed herpes zoster (Isoloci response). Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:539.

- Larson PO. Keratoacanthomas treated with Mohs' micrographic surgery (chemosurgery): a review of forty-three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1040-1044.

- Benest L, Kaplan RP, Salit R, et al. Keratoacanthoma centrifugum marginatum of the lower extremity treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:501-502.

- Remling R, Mempel M, Schnopp N, et al. Intralesional methotrexate injection: an effective time and cost saving therapy alternative in keratoacanthomas that are difficult to treat surgically. Hautarzt. 2000;51:612-614.

- Annest NM, VanBeek MJ, Arpey CJ, et al. Intralesional methotrexate treatment for keratoacanthoma tumors: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:989-993.

- Melton JL, Nelson BR, Stough DB, et al. Treatment of keratoacanthoma with intralesional methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1017-1023.

- Cuesta-Romero C, de Grado-Pena J. Intralesional methotrexate in solitary keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:513-514.

- Richard MA, Gachon J, Choux R, et al. Treatment of keratoacanthoma with intralesional methotrexate injections. An Dermatol Venereol. 2000;127:1097.

Keratoacanthomas (KAs) are rapidly growing tumors most prominently found on sun-exposed areas of the skin. The normal progression of a KA is to show rapid growth followed by spontaneous resolution.1 Most KAs are solitary; however, there are several variants of multiple KAs including the familial Ferguson-Smith type, Gryzbowski syndrome (generalized eruptive KAs), KA centrifugum marginatum, Muir-Torre syndrome, and xeroderma pigmentosum.2-4 Keratoacanthomas also may develop in areas of trauma, including burns, laser treatment, radiation, and surgical margins from excisional biopsies or skin grafting.5 Treatment of multiple KAs can be difficult due to a potentially large field size and number of lesions.6 We present a case of multiple KAs developing both in the surgical margins and de novo that responded dramatically to treatment with intralesional methotrexate (MTX).

Case Report

A 55-year-old man with a history of a surgically treated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the anterior aspect of the right leg developed multiple nodules involving the surgical scar. He previously underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS); within a month after the second surgery the patient noticed increased pruritus along with scaly pink changes at the site of the surgical scar.

One month prior to presentation, biopsies from the anterior aspect of the right leg demonstrated well-differentiated SCC and he was subsequently treated with MMS; however, examination 1 month after MMS revealed an 11×7-cm indurated plaque with multiple nodules ranging from 1 to 2 cm near the periphery of the plaque with central atrophy and scarring, reminiscent of KA centrifugum marginatum (Figure, A). In a similar fashion, an 8×5-cm plaque composed of 7 nodular areas was noted on the posterior aspect of the right leg (Figure, B). The patient denied any history of trauma to this area. There was no palpable regional lymphadenopathy and the remainder of the skin examination was normal, except for signs of venous stasis in both legs.

Based on the location and morphology of the lesions, the clinical presentation was consistent with multiple KAs. Histologic examination from punch biopsies taken from the plaque's periphery demonstrated well-differentiated SCC (KA type), as well as a lichenoid inflammatory process, epidermal hyperplasia, and cystic and endophytic squamous proliferation suggestive of hypertrophic lichen planus (HLP).

In consideration of the size and number of the lesions as well as the prolonged wound healing with prior surgery, the patient consented to treatment with intralesional MTX (1 mL of 12.5 mg/mL every 2 weeks) rather than undergoing further surgery. The MTX injection was distributed between the lesions on the anterior and posterior aspects of the lower right leg. At each injection session, the size, thickness, and nodularity of the tumor decreased with markedly less pruritus and symptomatic relief was achieved. After 3 injection sessions, resulting in a total of 3 mL of 12.5 mg/mL of MTX, biopsies were taken from the residual atrophic scar on the anterior aspect of the right leg and the remaining 3 papules on the posterior aspect of the right leg to rule out HLP and invasive SCC. The pathology report commented on the presence of prurigo nodules without any evidence of SCC.

At 3-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated no new lesions or recurrence (Figure, C and D). The right leg continued to heal with scarring and postinflammatory pigmentary changes. The patient was monitored for recurrence and to determine the diagnosis of HLP.

Comment

We report the development of multiple KAs arising both from within surgical margins and de novo, and resolution with intralesional MTX. Keratoacanthomas, especially various KA types, have been observed to develop due to various types of trauma, including sites of surgical scars, lichen planus, tattoos, thermal burns, radiation, and discoid lupus erythematosus, and within skin grafts and donor sites.5-19

Hypertrophic lichen planus is a chronic variant of lichen planus that often is found on the pretibial areas of the lower legs.13 Both SCC and reactive KAs have been observed to develop within lesions of HLP.14 Our pathologist commented on the presence of a lichenoid infiltrate with necrotic keratinocytes and epidermal hyperplasia suspicious for HLP, with a small focus of cystic and endophytic squamous proliferation. The latter lacked notable atypia or an invasive component and could represent an irritated infundibular cyst versus an early evolving KA.

The lichenoid inflammation is suspicious for HLP, which has been associated with eruptive KAs13-16 and may have contributed to the development of persistent KAs in our patient, both in sites of surgical scars (the anterior aspect of the leg) and in uninvolved skin (the posterior aspect of the leg). Trauma from the prior surgery may have stimulated a local inflammatory response and, if coupled with a preexisting underlying chronic inflammatory condition such as HLP, may have triggered the development of new lesions on the posterior leg. Skin pathergy reactions also are caused by an upregulated inflammatory response, which is reduced with immunosuppressive agents such as MTX.12

In our patient, there was both an isotopic and isomorphic response. The term isotopic response refers to the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of another unrelated and already healed skin disease. It was first defined by Wolf and Wolf20 in 1985 and hence is also known as Wolf isotopic response. The isotopic response in our patient occurred in the setting of lichen planus. The isomorphic response indicates the appearance of typical skin lesions of an existing dermatosis at sites of other skin injuries.

Initially, we thought the patient had recurrence of SCC, but with the rapid development of multiple lesions, the diagnosis of multiple KAs was more likely. Kimyai-Asadi et al8 demonstrated that surgical trauma can precede the development of KAs, as they reported a patient who developed a KA at an excision site. Tamir et al7 reported the simultaneous appearance of KAs in burn scars and skin graft donor sites 4 months after a 40% total body surface area burn. Hamilton et al11 described surgical trauma from a split-skin graft donor site as a trigger for the onset of a KA.

Multiple treatment alternatives exist for KAs, with the standard of care for large or high-risk KAs being excisional surgery21,22; however, other approaches may need to be considered in certain cases, such as with multiple KAs in which lesions may be large and extensive, thereby yielding poor cosmetic outcomes, or with increased surgical risk.23 Furthermore, multiple KAs that develop in the setting of surgical scars require special consideration. Topical 5-fluorouracil, various systemic and intralesional agents (eg, retinoids, interferon, bleomycin, MTX), laser therapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, radiotherapy, and photodynamic therapy all have been reported as methods employed for the treatment of KA.23-27 Goldberg et al5 reported cases of resolution of eruptive KAs arising in both surgical and nonsurgical sites with a combination of deep shave excision, MMS, curettage and desiccation, and oral isotretinoin.

For our patient, we opted for treatment with intralesional MTX, both due to its effectiveness for solitary KAs and reasonably decreased risk of morbidity compared to surgical excision of regions of the pretibial calves. Treatment with MTX would not have been attempted if there was any clinical doubt that the lesions were not the well-differentiated KA type. Also, we had a low threshold for discontinuing therapy and reverting to MMS treatment if any of the lesions displayed a paradoxical growth post-MTX treatment or failed to respond after 3 treatments. Intralesional MTX is less invasive, relatively inexpensive, and a treatment modality with decreased morbidity for KAs, especially for multiple KAs. It should be considered as a potential alternative to surgery in such cases.23-27

Keratoacanthomas (KAs) are rapidly growing tumors most prominently found on sun-exposed areas of the skin. The normal progression of a KA is to show rapid growth followed by spontaneous resolution.1 Most KAs are solitary; however, there are several variants of multiple KAs including the familial Ferguson-Smith type, Gryzbowski syndrome (generalized eruptive KAs), KA centrifugum marginatum, Muir-Torre syndrome, and xeroderma pigmentosum.2-4 Keratoacanthomas also may develop in areas of trauma, including burns, laser treatment, radiation, and surgical margins from excisional biopsies or skin grafting.5 Treatment of multiple KAs can be difficult due to a potentially large field size and number of lesions.6 We present a case of multiple KAs developing both in the surgical margins and de novo that responded dramatically to treatment with intralesional methotrexate (MTX).

Case Report

A 55-year-old man with a history of a surgically treated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the anterior aspect of the right leg developed multiple nodules involving the surgical scar. He previously underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS); within a month after the second surgery the patient noticed increased pruritus along with scaly pink changes at the site of the surgical scar.

One month prior to presentation, biopsies from the anterior aspect of the right leg demonstrated well-differentiated SCC and he was subsequently treated with MMS; however, examination 1 month after MMS revealed an 11×7-cm indurated plaque with multiple nodules ranging from 1 to 2 cm near the periphery of the plaque with central atrophy and scarring, reminiscent of KA centrifugum marginatum (Figure, A). In a similar fashion, an 8×5-cm plaque composed of 7 nodular areas was noted on the posterior aspect of the right leg (Figure, B). The patient denied any history of trauma to this area. There was no palpable regional lymphadenopathy and the remainder of the skin examination was normal, except for signs of venous stasis in both legs.

Based on the location and morphology of the lesions, the clinical presentation was consistent with multiple KAs. Histologic examination from punch biopsies taken from the plaque's periphery demonstrated well-differentiated SCC (KA type), as well as a lichenoid inflammatory process, epidermal hyperplasia, and cystic and endophytic squamous proliferation suggestive of hypertrophic lichen planus (HLP).

In consideration of the size and number of the lesions as well as the prolonged wound healing with prior surgery, the patient consented to treatment with intralesional MTX (1 mL of 12.5 mg/mL every 2 weeks) rather than undergoing further surgery. The MTX injection was distributed between the lesions on the anterior and posterior aspects of the lower right leg. At each injection session, the size, thickness, and nodularity of the tumor decreased with markedly less pruritus and symptomatic relief was achieved. After 3 injection sessions, resulting in a total of 3 mL of 12.5 mg/mL of MTX, biopsies were taken from the residual atrophic scar on the anterior aspect of the right leg and the remaining 3 papules on the posterior aspect of the right leg to rule out HLP and invasive SCC. The pathology report commented on the presence of prurigo nodules without any evidence of SCC.

At 3-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated no new lesions or recurrence (Figure, C and D). The right leg continued to heal with scarring and postinflammatory pigmentary changes. The patient was monitored for recurrence and to determine the diagnosis of HLP.

Comment

We report the development of multiple KAs arising both from within surgical margins and de novo, and resolution with intralesional MTX. Keratoacanthomas, especially various KA types, have been observed to develop due to various types of trauma, including sites of surgical scars, lichen planus, tattoos, thermal burns, radiation, and discoid lupus erythematosus, and within skin grafts and donor sites.5-19

Hypertrophic lichen planus is a chronic variant of lichen planus that often is found on the pretibial areas of the lower legs.13 Both SCC and reactive KAs have been observed to develop within lesions of HLP.14 Our pathologist commented on the presence of a lichenoid infiltrate with necrotic keratinocytes and epidermal hyperplasia suspicious for HLP, with a small focus of cystic and endophytic squamous proliferation. The latter lacked notable atypia or an invasive component and could represent an irritated infundibular cyst versus an early evolving KA.

The lichenoid inflammation is suspicious for HLP, which has been associated with eruptive KAs13-16 and may have contributed to the development of persistent KAs in our patient, both in sites of surgical scars (the anterior aspect of the leg) and in uninvolved skin (the posterior aspect of the leg). Trauma from the prior surgery may have stimulated a local inflammatory response and, if coupled with a preexisting underlying chronic inflammatory condition such as HLP, may have triggered the development of new lesions on the posterior leg. Skin pathergy reactions also are caused by an upregulated inflammatory response, which is reduced with immunosuppressive agents such as MTX.12

In our patient, there was both an isotopic and isomorphic response. The term isotopic response refers to the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of another unrelated and already healed skin disease. It was first defined by Wolf and Wolf20 in 1985 and hence is also known as Wolf isotopic response. The isotopic response in our patient occurred in the setting of lichen planus. The isomorphic response indicates the appearance of typical skin lesions of an existing dermatosis at sites of other skin injuries.

Initially, we thought the patient had recurrence of SCC, but with the rapid development of multiple lesions, the diagnosis of multiple KAs was more likely. Kimyai-Asadi et al8 demonstrated that surgical trauma can precede the development of KAs, as they reported a patient who developed a KA at an excision site. Tamir et al7 reported the simultaneous appearance of KAs in burn scars and skin graft donor sites 4 months after a 40% total body surface area burn. Hamilton et al11 described surgical trauma from a split-skin graft donor site as a trigger for the onset of a KA.

Multiple treatment alternatives exist for KAs, with the standard of care for large or high-risk KAs being excisional surgery21,22; however, other approaches may need to be considered in certain cases, such as with multiple KAs in which lesions may be large and extensive, thereby yielding poor cosmetic outcomes, or with increased surgical risk.23 Furthermore, multiple KAs that develop in the setting of surgical scars require special consideration. Topical 5-fluorouracil, various systemic and intralesional agents (eg, retinoids, interferon, bleomycin, MTX), laser therapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, radiotherapy, and photodynamic therapy all have been reported as methods employed for the treatment of KA.23-27 Goldberg et al5 reported cases of resolution of eruptive KAs arising in both surgical and nonsurgical sites with a combination of deep shave excision, MMS, curettage and desiccation, and oral isotretinoin.

For our patient, we opted for treatment with intralesional MTX, both due to its effectiveness for solitary KAs and reasonably decreased risk of morbidity compared to surgical excision of regions of the pretibial calves. Treatment with MTX would not have been attempted if there was any clinical doubt that the lesions were not the well-differentiated KA type. Also, we had a low threshold for discontinuing therapy and reverting to MMS treatment if any of the lesions displayed a paradoxical growth post-MTX treatment or failed to respond after 3 treatments. Intralesional MTX is less invasive, relatively inexpensive, and a treatment modality with decreased morbidity for KAs, especially for multiple KAs. It should be considered as a potential alternative to surgery in such cases.23-27

- Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:1-19.

- Feldman RJ, Maize JC. Multiple keratoacanthomas in a young woman: report of a case emphasizing medical management and a review of the spectrum of multiple keratoacanthomas. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:77-79.

- Ereaux LP, Schopflocher P, Fornier CJ. Keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1955;71:73-83.

- Lloyd KM, Madsen DK, Lin PY. Grzybowski's eruptive keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(5, pt 1):1023-1024.

- Goldberg LH, Silapunt S, Beyrau KK, et al. Keratoacanthoma as a postoperative complication of skin cancer excision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:753-758.

- Pillsbury DM, Beerman H. Multiple keratoacanthoma. Am J Med Sci. 1958;236:614-623.

- Tamir G, Morgenstern S, Ben-Amitay D, et al. Synchronous appearance of keratoacanthomas in burn scar and skin graft donor site shortly after injury. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;400(5, pt 2):870-871.

- Kimyai-Asadi A, Shaffer C, Levine VJ, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising from an excisional surgery scar. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:193-194.

- Pattee SF, Silvis NG. Keratoacanthoma developing in sites of previous trauma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(suppl 2):S35-S38.

- Hendricks WM. Sudden appearance of multiple keratoacanthomas three weeks after thermal burns. Cutis. 1991;47:410-412.

- Hamilton SA, Dickson WA, O'Brien CJ. Keratoacanthoma developing in a split skin graft donor site. Br J Plast Surg. 1997;50:560-561.

- Bangash SJ, Green WH, Dolson DJ, et al. Eruptive postoperative squamous cell carcinomas exhibiting a pathergy-like reaction around surgical wound sites. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:892-897.

- Badell A, Marcoval J, Gallego I, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising in hypertrophic lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:370-393.

- Chave TA, Graham-Brown RAC. Keratoacanthoma developing in hypertrophic lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:592.

- Epstein R. Treatment of keratoacanthoma arising from hypertrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(3, suppl 1):AB28.

- Giesecke LM, Reid CM, James CL, et al. Giant keratoacanthoma arising in hypertrophic lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:267-269.

- Toll A, Salgado R, Espinet B, et al. "Eruptive postoperative squamous cell carcinomas" or "Hypertrophic lichen planus-like reactions combined with infundibulocystic hyperplasia"? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:910-911.

- Fanti PA, Tosti A, Peluso AM, et al. Multiple keratoacanthoma in discoid lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(4, pt 1):809-810.

- Kossard S, Thompson C, Duncan GM. Hypertrophic lichen planus-like reactions combined with infundibulocystic hyperplasia: pathway to neoplasia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1262-1267.

- Wolf R, Wolf D. Tinea in a site of healed herpes zoster (Isoloci response). Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:539.

- Larson PO. Keratoacanthomas treated with Mohs' micrographic surgery (chemosurgery): a review of forty-three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1040-1044.

- Benest L, Kaplan RP, Salit R, et al. Keratoacanthoma centrifugum marginatum of the lower extremity treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:501-502.

- Remling R, Mempel M, Schnopp N, et al. Intralesional methotrexate injection: an effective time and cost saving therapy alternative in keratoacanthomas that are difficult to treat surgically. Hautarzt. 2000;51:612-614.

- Annest NM, VanBeek MJ, Arpey CJ, et al. Intralesional methotrexate treatment for keratoacanthoma tumors: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:989-993.

- Melton JL, Nelson BR, Stough DB, et al. Treatment of keratoacanthoma with intralesional methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1017-1023.

- Cuesta-Romero C, de Grado-Pena J. Intralesional methotrexate in solitary keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:513-514.

- Richard MA, Gachon J, Choux R, et al. Treatment of keratoacanthoma with intralesional methotrexate injections. An Dermatol Venereol. 2000;127:1097.

- Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:1-19.

- Feldman RJ, Maize JC. Multiple keratoacanthomas in a young woman: report of a case emphasizing medical management and a review of the spectrum of multiple keratoacanthomas. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:77-79.

- Ereaux LP, Schopflocher P, Fornier CJ. Keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1955;71:73-83.

- Lloyd KM, Madsen DK, Lin PY. Grzybowski's eruptive keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(5, pt 1):1023-1024.

- Goldberg LH, Silapunt S, Beyrau KK, et al. Keratoacanthoma as a postoperative complication of skin cancer excision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:753-758.

- Pillsbury DM, Beerman H. Multiple keratoacanthoma. Am J Med Sci. 1958;236:614-623.

- Tamir G, Morgenstern S, Ben-Amitay D, et al. Synchronous appearance of keratoacanthomas in burn scar and skin graft donor site shortly after injury. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;400(5, pt 2):870-871.

- Kimyai-Asadi A, Shaffer C, Levine VJ, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising from an excisional surgery scar. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:193-194.

- Pattee SF, Silvis NG. Keratoacanthoma developing in sites of previous trauma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(suppl 2):S35-S38.

- Hendricks WM. Sudden appearance of multiple keratoacanthomas three weeks after thermal burns. Cutis. 1991;47:410-412.

- Hamilton SA, Dickson WA, O'Brien CJ. Keratoacanthoma developing in a split skin graft donor site. Br J Plast Surg. 1997;50:560-561.

- Bangash SJ, Green WH, Dolson DJ, et al. Eruptive postoperative squamous cell carcinomas exhibiting a pathergy-like reaction around surgical wound sites. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:892-897.

- Badell A, Marcoval J, Gallego I, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising in hypertrophic lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:370-393.

- Chave TA, Graham-Brown RAC. Keratoacanthoma developing in hypertrophic lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:592.

- Epstein R. Treatment of keratoacanthoma arising from hypertrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(3, suppl 1):AB28.

- Giesecke LM, Reid CM, James CL, et al. Giant keratoacanthoma arising in hypertrophic lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:267-269.

- Toll A, Salgado R, Espinet B, et al. "Eruptive postoperative squamous cell carcinomas" or "Hypertrophic lichen planus-like reactions combined with infundibulocystic hyperplasia"? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:910-911.

- Fanti PA, Tosti A, Peluso AM, et al. Multiple keratoacanthoma in discoid lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(4, pt 1):809-810.

- Kossard S, Thompson C, Duncan GM. Hypertrophic lichen planus-like reactions combined with infundibulocystic hyperplasia: pathway to neoplasia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1262-1267.

- Wolf R, Wolf D. Tinea in a site of healed herpes zoster (Isoloci response). Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:539.

- Larson PO. Keratoacanthomas treated with Mohs' micrographic surgery (chemosurgery): a review of forty-three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1040-1044.

- Benest L, Kaplan RP, Salit R, et al. Keratoacanthoma centrifugum marginatum of the lower extremity treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:501-502.

- Remling R, Mempel M, Schnopp N, et al. Intralesional methotrexate injection: an effective time and cost saving therapy alternative in keratoacanthomas that are difficult to treat surgically. Hautarzt. 2000;51:612-614.

- Annest NM, VanBeek MJ, Arpey CJ, et al. Intralesional methotrexate treatment for keratoacanthoma tumors: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:989-993.

- Melton JL, Nelson BR, Stough DB, et al. Treatment of keratoacanthoma with intralesional methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1017-1023.

- Cuesta-Romero C, de Grado-Pena J. Intralesional methotrexate in solitary keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:513-514.

- Richard MA, Gachon J, Choux R, et al. Treatment of keratoacanthoma with intralesional methotrexate injections. An Dermatol Venereol. 2000;127:1097.

Practice Points

- Keratoacanthomas (KAs) are rapidly growing tumors most prominently found on sun-exposed areas but also may develop in areas of trauma including burns, laser treatment, radiation, and surgical margins from excisional biopsies or skin grafting.

- Intralesional methotrexate is a potential alternative to surgical treatment of KAs as a less invasive and less costly treatment modality with decreased morbidity for multiple KAs.

- Isotopic response refers to the occurrence of a new skin disorder arising at the site of another unrelated and already healed skin disease. Isomorphic response indicates the appearance of typical skin lesions of an existing dermatosis at sites of injuries.

Topical Imiquimod Clears Invasive Melanoma

Malignant melanoma has continually shown a pattern of increased incidence and mortality over the last 50 years, especially in fair-skinned individuals. In fact, malignant melanoma has the highest mortality rate of all skin cancers in white individuals. Currently, wide local surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment of primary cutaneous melanomas.1 The margins vary in size according to the Breslow thickness (or depth) of the involved tumor. As such, advancements in melanoma treatment continue to be studied. We present the case of a patient with invasive melanoma that was cleared with topical imiquimod.

Case Report

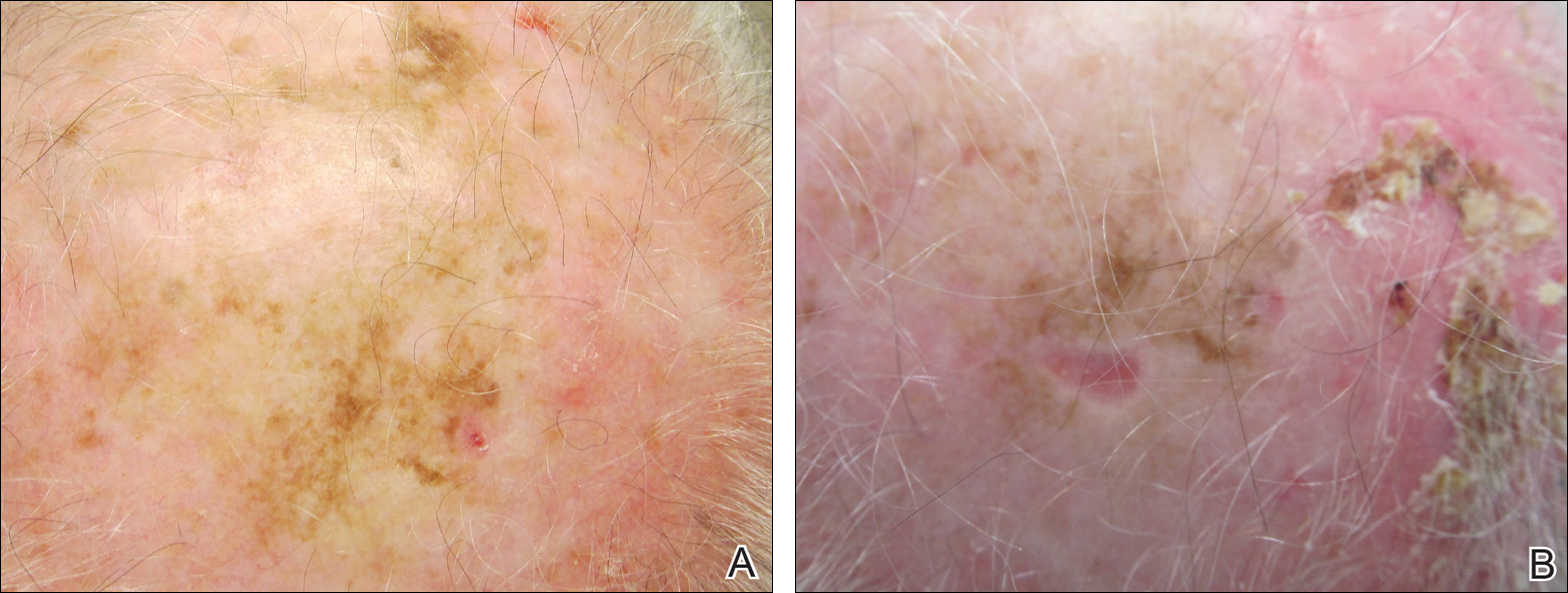

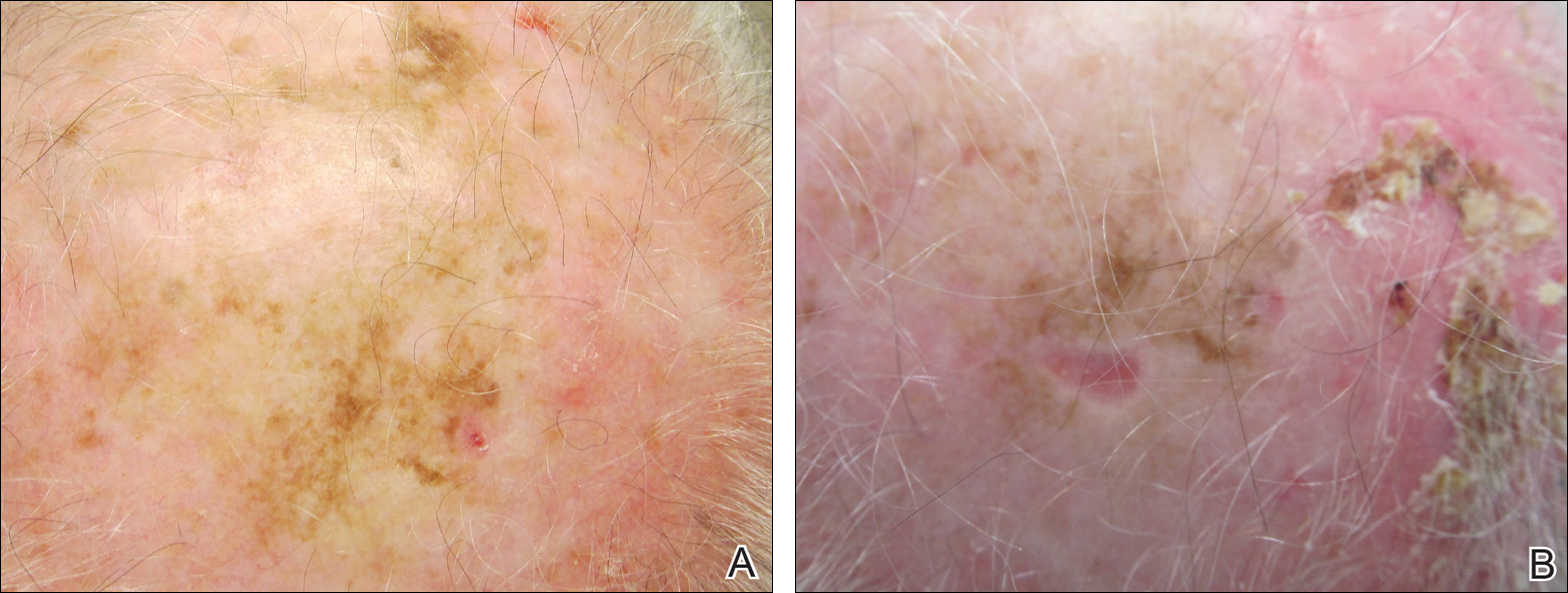

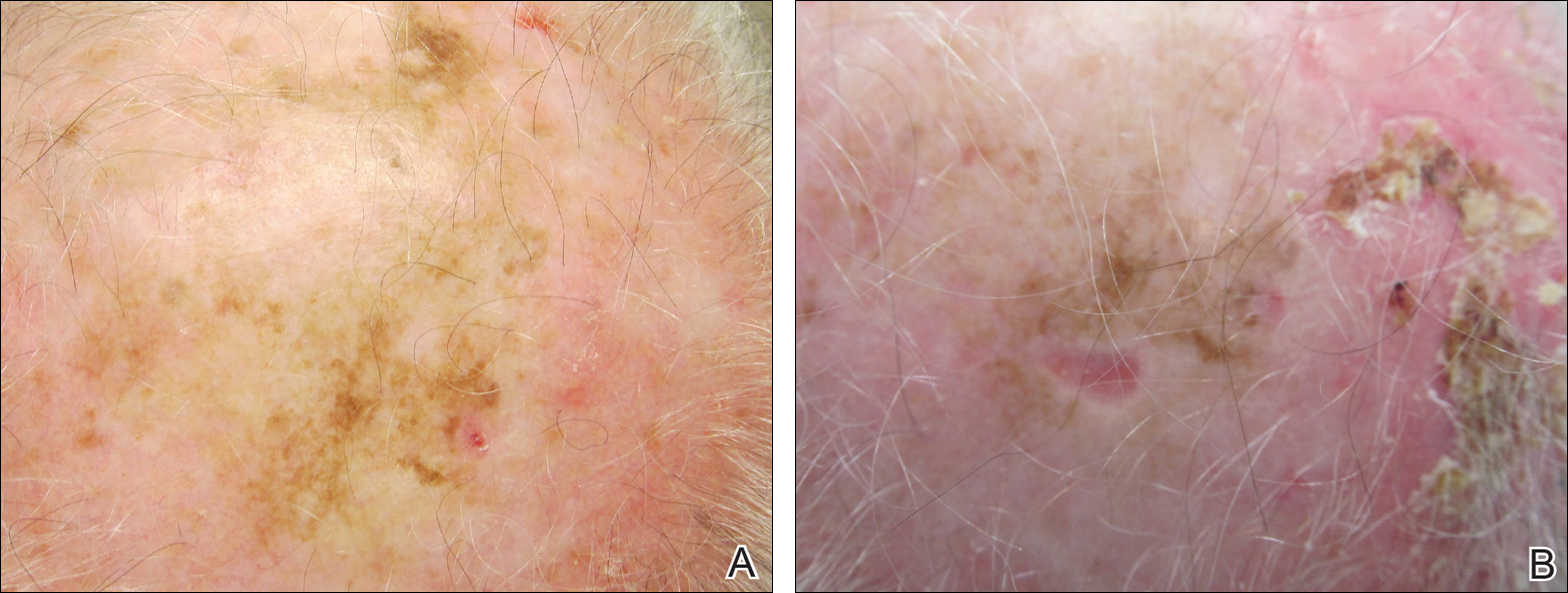

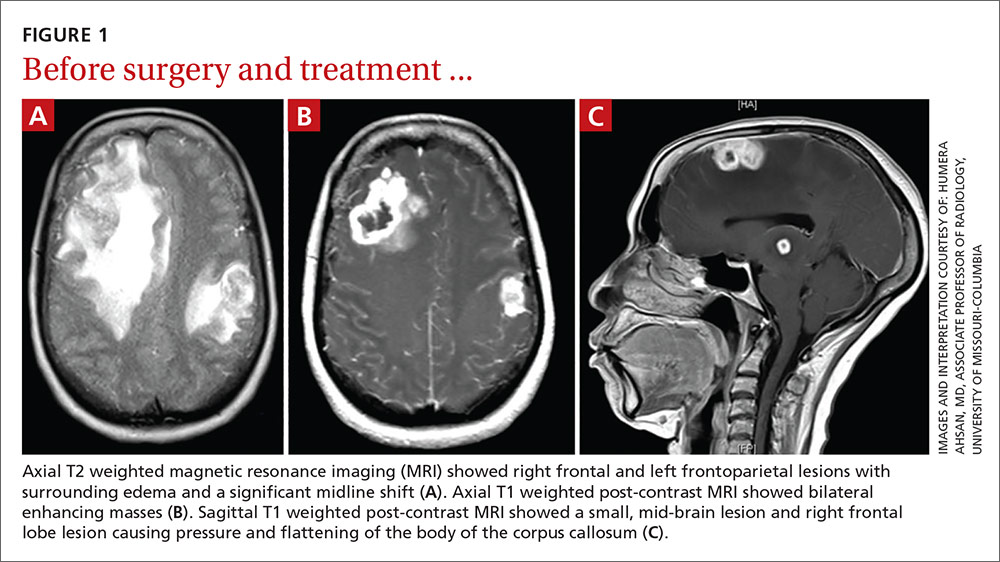

A 71-year-old man presented with biopsy-proven malignant melanoma on the right posterior scalp that was diagnosed a few weeks prior. The melanoma was invasive with a depth of 0.73 mm. The patient also had an approximately 8-cm, irregular, patchy area of hyperpigmentation involving almost the entire crown of the head (Figure 1A). The biopsy site used for melanoma diagnosis was on the right posterior aspect of the hyperpigmented area where a symptomatic pigmented papule was located. To determine if the rest of this macule represented an extension of the proven malignancy, surveillance biopsies were taken at the 12 o'clock (anterior aspect), 3 o'clock, 6 o'clock, and 9 o'clock positions on the head. All of the biopsies came back as lentigo simplex, which presented a clinical problem in that the boundaries of the invasive melanoma merged with the lentigo simplex and were not clinically apparent. Because an exact boundary could not be visualized, the entire area was treated with imiquimod cream 5% once nightly at bedtime for 4 weeks prior to excision of the original biopsy site. There was a notable decrease in hyperpigmentation in the treated area after 4 weeks of therapy (Figure 1B). The original biopsy site was then excised with a 0.6-cm margin and a complex linear repair was performed. Histologic examination of the excised specimen showed no residual melanoma.

Comment

Although surgical excision is the recommended treatment of cutaneous melanoma,1 in some cases the defect following an excision can be quite large or even disfiguring. To minimize the size of the excision site, other treatment modalities should be studied. Imiquimod is an immunomodulating agent that exerts antitumor and antiviral effects. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved imiquimod for treatment of genital warts, actinic keratoses, and superficial basal cell carcinoma.2 The most common side effects of topical imiquimod involve application-site reactions such as erythema, swelling, and crusting of the treated area. Ulceration of the skin also is possible. A small percentage of individuals have experienced systemic flulike symptoms after using topical imiquimod. Topical imiquimod has been used off label to treat noninvasive forms of melanoma. The topical therapy has been reported to clear melanoma in situ and lentigo maligna.2,3 In addition, imiquimod has been used as a palliative therapy for cutaneous metastatic melanoma.4,5 In another case of a primary melanoma that responded to topical imiquimod, clinical and histological clearance of a recurrent oral mucosa melanoma was obtained.6

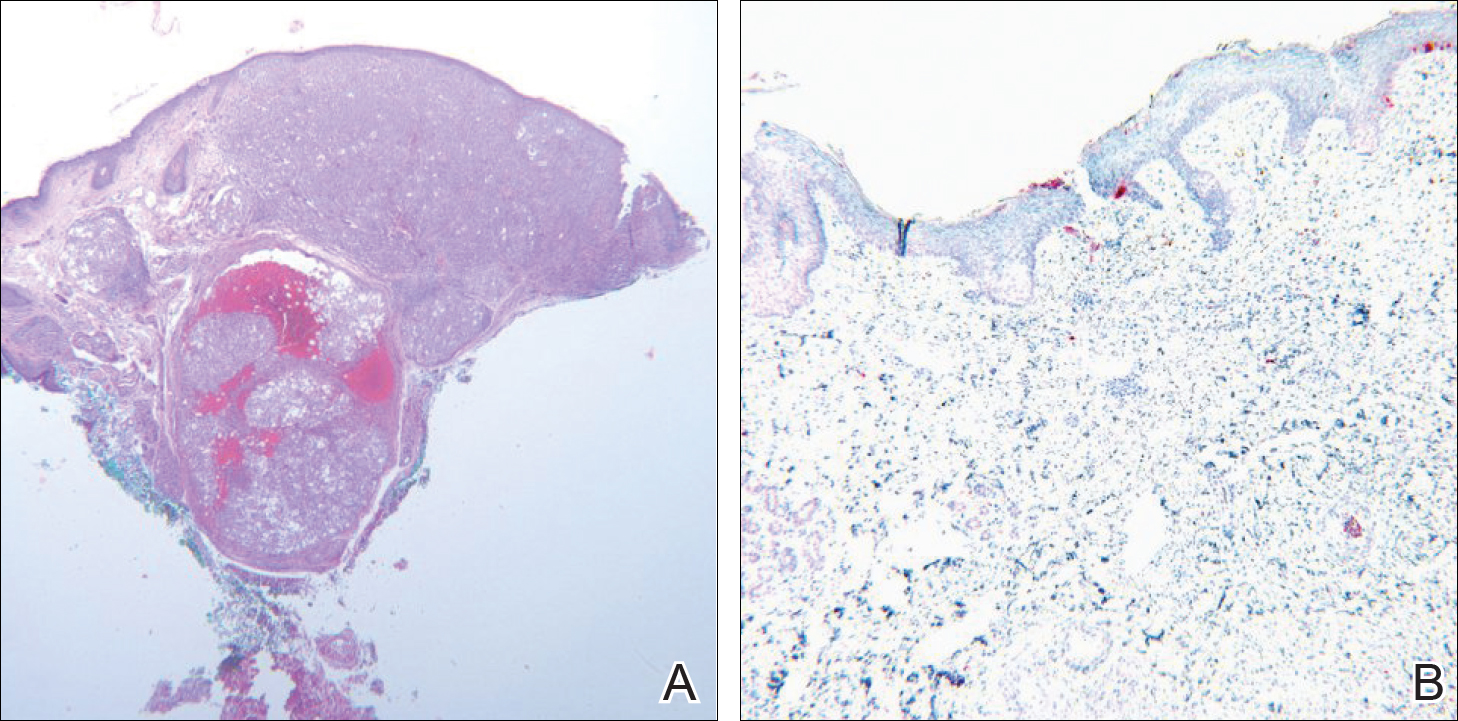

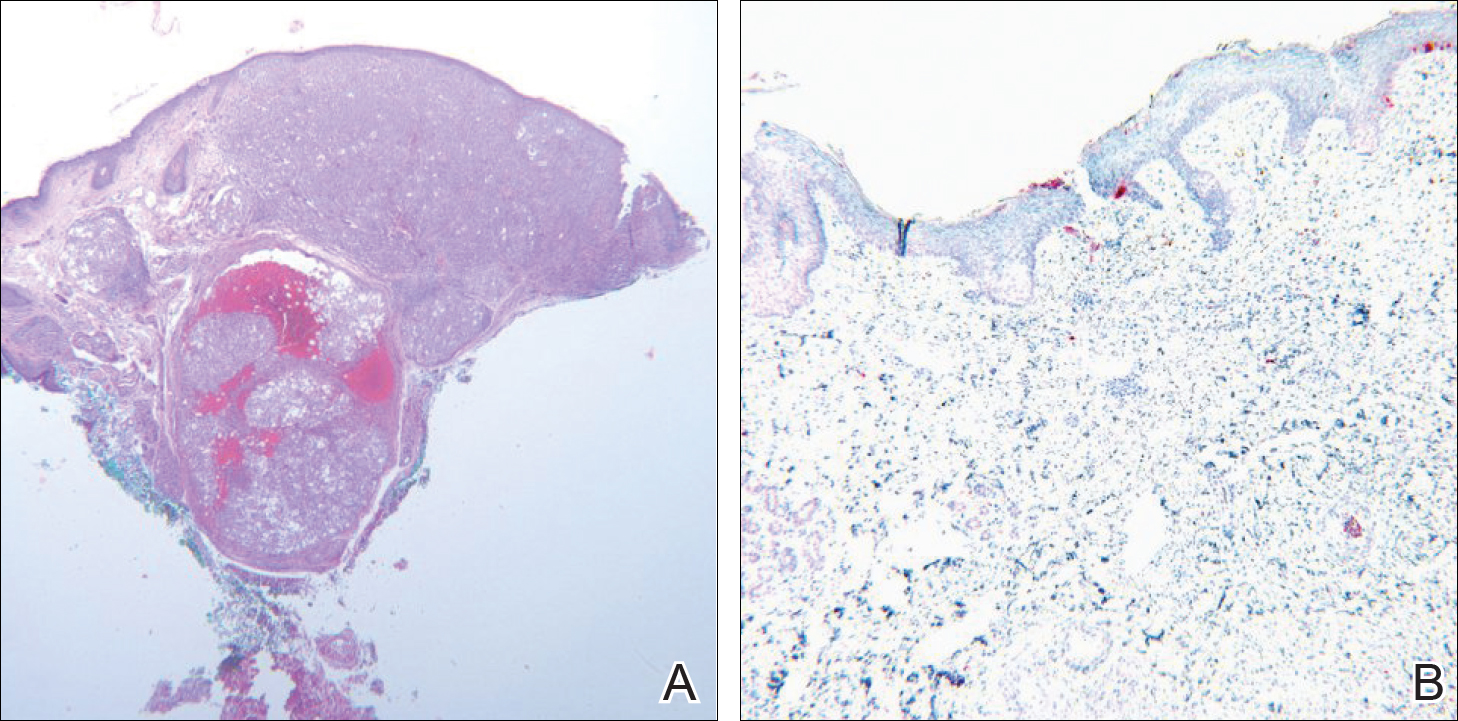

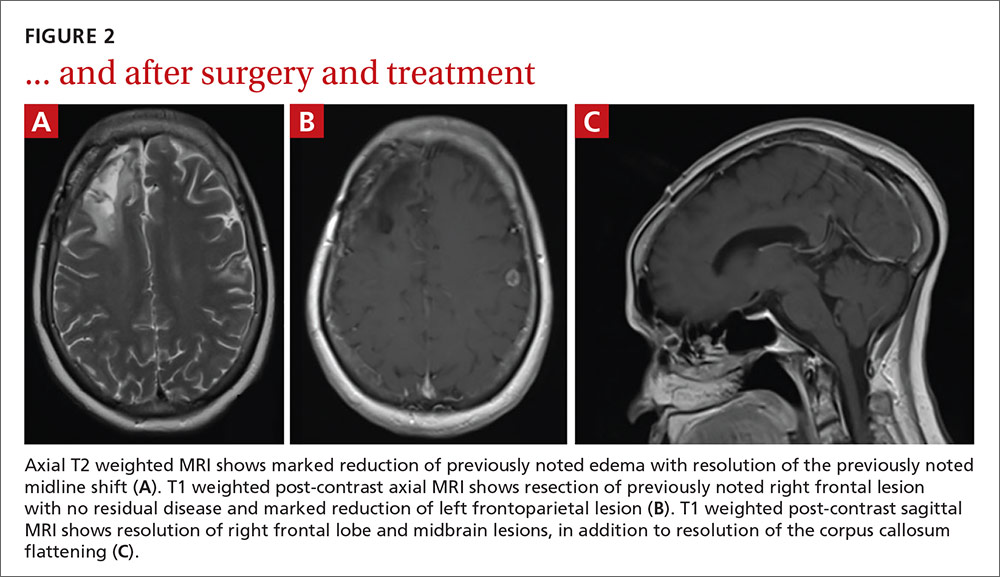

Moon and Spencer7 reported a case of an invasive melanoma that was cleared with topical imiquimod. A 93-year-old woman presented with a central 2.75-mm thick invasive melanoma surrounded by a large area of melanoma in situ involving the left cheek and eyelid. The excised tissue was stained for CD31 and D2-40 to rule out intravascular and intralymphatic spread (Figure 2A). The standard-of-care treatment for this case would involve surgical excision with 2-cm margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy, but given the morbidity involved with the surgery, an alternative treatment plan was made with the patient. The patient completed 5 weeks of topical imiquimod therapy and then underwent wide local excision with a 1-cm margin. Extensive histological examination of the excised specimen showed no residual melanoma; in fact, there was a near absence of junctional melanocytes that would normally have been seen. The specimen underwent immunoperoxidase staining for Melan-A (Figure 2B). The patient was followed for 14 months with no evidence of recurrence.7

Conclusion

We describe a patient who achieved complete histologic clearance of invasive melanoma following treatment with topical imiquimod. Four weeks of topical therapy completely cleared an invasive melanoma that was 0.73-mm thick. Follow-up was recommended for the patient because long-term outcomes of this therapy are unknown. More studies demonstrating reliability and reproducibility are needed to evaluate the role of topical imiquimod in melanoma treatment; however, our case shows the potential of this topical modality.

- Rastrelli M, Alaibac M, Stramare R, et al. Melanoma m (zero): diagnosis and therapy. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:616170.

- Ellis LZ, Cohen JL, High W, et al. Melanoma in situ treated successfully using imiquimod after nonclearance with surgery: review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:937-946.

- Cotter MA, McKenna JK, Bowen GM. Treatment of lentigo maligna with imiquimod before staged excision. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:147-151.

- Li X, Naylor MF, Le H, et al. Clinical effects of in situ photoimmunotherapy on late-stage melanoma patients: a preliminary study. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:1081-1087.

- Steinmann A, Funk JO, Schuler G, et al. Topical imiquimod treatment of a cutaneous melanoma metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:555-556.

- Spieth K, Kovács A, Wolter M, et al. Topical imiquimod: effectiveness in intraepithelial melanoma of oral mucosa. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:1036-1037.

- Moon SD, Spencer JM. Clearance of invasive melanoma with topical imiquimod. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:107-108.

Malignant melanoma has continually shown a pattern of increased incidence and mortality over the last 50 years, especially in fair-skinned individuals. In fact, malignant melanoma has the highest mortality rate of all skin cancers in white individuals. Currently, wide local surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment of primary cutaneous melanomas.1 The margins vary in size according to the Breslow thickness (or depth) of the involved tumor. As such, advancements in melanoma treatment continue to be studied. We present the case of a patient with invasive melanoma that was cleared with topical imiquimod.

Case Report

A 71-year-old man presented with biopsy-proven malignant melanoma on the right posterior scalp that was diagnosed a few weeks prior. The melanoma was invasive with a depth of 0.73 mm. The patient also had an approximately 8-cm, irregular, patchy area of hyperpigmentation involving almost the entire crown of the head (Figure 1A). The biopsy site used for melanoma diagnosis was on the right posterior aspect of the hyperpigmented area where a symptomatic pigmented papule was located. To determine if the rest of this macule represented an extension of the proven malignancy, surveillance biopsies were taken at the 12 o'clock (anterior aspect), 3 o'clock, 6 o'clock, and 9 o'clock positions on the head. All of the biopsies came back as lentigo simplex, which presented a clinical problem in that the boundaries of the invasive melanoma merged with the lentigo simplex and were not clinically apparent. Because an exact boundary could not be visualized, the entire area was treated with imiquimod cream 5% once nightly at bedtime for 4 weeks prior to excision of the original biopsy site. There was a notable decrease in hyperpigmentation in the treated area after 4 weeks of therapy (Figure 1B). The original biopsy site was then excised with a 0.6-cm margin and a complex linear repair was performed. Histologic examination of the excised specimen showed no residual melanoma.

Comment

Although surgical excision is the recommended treatment of cutaneous melanoma,1 in some cases the defect following an excision can be quite large or even disfiguring. To minimize the size of the excision site, other treatment modalities should be studied. Imiquimod is an immunomodulating agent that exerts antitumor and antiviral effects. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved imiquimod for treatment of genital warts, actinic keratoses, and superficial basal cell carcinoma.2 The most common side effects of topical imiquimod involve application-site reactions such as erythema, swelling, and crusting of the treated area. Ulceration of the skin also is possible. A small percentage of individuals have experienced systemic flulike symptoms after using topical imiquimod. Topical imiquimod has been used off label to treat noninvasive forms of melanoma. The topical therapy has been reported to clear melanoma in situ and lentigo maligna.2,3 In addition, imiquimod has been used as a palliative therapy for cutaneous metastatic melanoma.4,5 In another case of a primary melanoma that responded to topical imiquimod, clinical and histological clearance of a recurrent oral mucosa melanoma was obtained.6

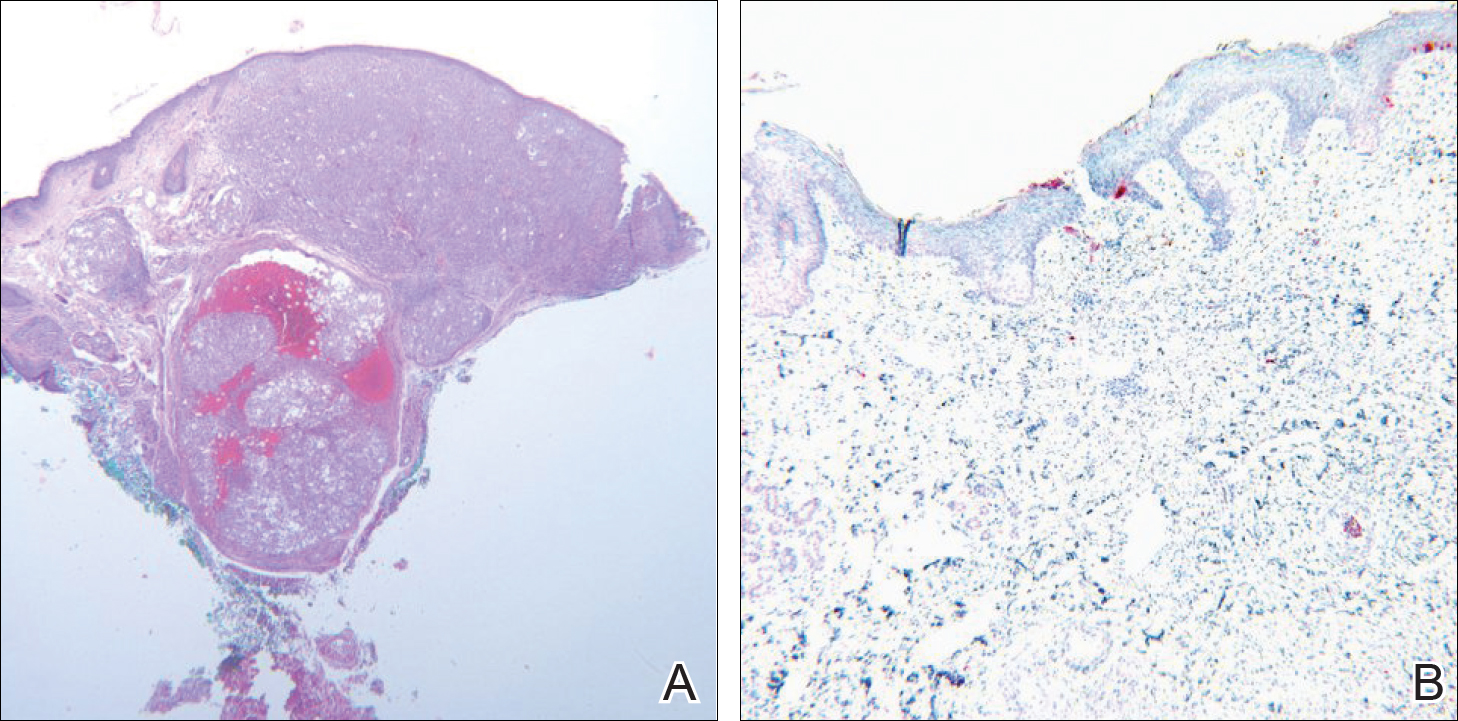

Moon and Spencer7 reported a case of an invasive melanoma that was cleared with topical imiquimod. A 93-year-old woman presented with a central 2.75-mm thick invasive melanoma surrounded by a large area of melanoma in situ involving the left cheek and eyelid. The excised tissue was stained for CD31 and D2-40 to rule out intravascular and intralymphatic spread (Figure 2A). The standard-of-care treatment for this case would involve surgical excision with 2-cm margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy, but given the morbidity involved with the surgery, an alternative treatment plan was made with the patient. The patient completed 5 weeks of topical imiquimod therapy and then underwent wide local excision with a 1-cm margin. Extensive histological examination of the excised specimen showed no residual melanoma; in fact, there was a near absence of junctional melanocytes that would normally have been seen. The specimen underwent immunoperoxidase staining for Melan-A (Figure 2B). The patient was followed for 14 months with no evidence of recurrence.7

Conclusion

We describe a patient who achieved complete histologic clearance of invasive melanoma following treatment with topical imiquimod. Four weeks of topical therapy completely cleared an invasive melanoma that was 0.73-mm thick. Follow-up was recommended for the patient because long-term outcomes of this therapy are unknown. More studies demonstrating reliability and reproducibility are needed to evaluate the role of topical imiquimod in melanoma treatment; however, our case shows the potential of this topical modality.

Malignant melanoma has continually shown a pattern of increased incidence and mortality over the last 50 years, especially in fair-skinned individuals. In fact, malignant melanoma has the highest mortality rate of all skin cancers in white individuals. Currently, wide local surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment of primary cutaneous melanomas.1 The margins vary in size according to the Breslow thickness (or depth) of the involved tumor. As such, advancements in melanoma treatment continue to be studied. We present the case of a patient with invasive melanoma that was cleared with topical imiquimod.

Case Report

A 71-year-old man presented with biopsy-proven malignant melanoma on the right posterior scalp that was diagnosed a few weeks prior. The melanoma was invasive with a depth of 0.73 mm. The patient also had an approximately 8-cm, irregular, patchy area of hyperpigmentation involving almost the entire crown of the head (Figure 1A). The biopsy site used for melanoma diagnosis was on the right posterior aspect of the hyperpigmented area where a symptomatic pigmented papule was located. To determine if the rest of this macule represented an extension of the proven malignancy, surveillance biopsies were taken at the 12 o'clock (anterior aspect), 3 o'clock, 6 o'clock, and 9 o'clock positions on the head. All of the biopsies came back as lentigo simplex, which presented a clinical problem in that the boundaries of the invasive melanoma merged with the lentigo simplex and were not clinically apparent. Because an exact boundary could not be visualized, the entire area was treated with imiquimod cream 5% once nightly at bedtime for 4 weeks prior to excision of the original biopsy site. There was a notable decrease in hyperpigmentation in the treated area after 4 weeks of therapy (Figure 1B). The original biopsy site was then excised with a 0.6-cm margin and a complex linear repair was performed. Histologic examination of the excised specimen showed no residual melanoma.

Comment

Although surgical excision is the recommended treatment of cutaneous melanoma,1 in some cases the defect following an excision can be quite large or even disfiguring. To minimize the size of the excision site, other treatment modalities should be studied. Imiquimod is an immunomodulating agent that exerts antitumor and antiviral effects. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved imiquimod for treatment of genital warts, actinic keratoses, and superficial basal cell carcinoma.2 The most common side effects of topical imiquimod involve application-site reactions such as erythema, swelling, and crusting of the treated area. Ulceration of the skin also is possible. A small percentage of individuals have experienced systemic flulike symptoms after using topical imiquimod. Topical imiquimod has been used off label to treat noninvasive forms of melanoma. The topical therapy has been reported to clear melanoma in situ and lentigo maligna.2,3 In addition, imiquimod has been used as a palliative therapy for cutaneous metastatic melanoma.4,5 In another case of a primary melanoma that responded to topical imiquimod, clinical and histological clearance of a recurrent oral mucosa melanoma was obtained.6

Moon and Spencer7 reported a case of an invasive melanoma that was cleared with topical imiquimod. A 93-year-old woman presented with a central 2.75-mm thick invasive melanoma surrounded by a large area of melanoma in situ involving the left cheek and eyelid. The excised tissue was stained for CD31 and D2-40 to rule out intravascular and intralymphatic spread (Figure 2A). The standard-of-care treatment for this case would involve surgical excision with 2-cm margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy, but given the morbidity involved with the surgery, an alternative treatment plan was made with the patient. The patient completed 5 weeks of topical imiquimod therapy and then underwent wide local excision with a 1-cm margin. Extensive histological examination of the excised specimen showed no residual melanoma; in fact, there was a near absence of junctional melanocytes that would normally have been seen. The specimen underwent immunoperoxidase staining for Melan-A (Figure 2B). The patient was followed for 14 months with no evidence of recurrence.7

Conclusion

We describe a patient who achieved complete histologic clearance of invasive melanoma following treatment with topical imiquimod. Four weeks of topical therapy completely cleared an invasive melanoma that was 0.73-mm thick. Follow-up was recommended for the patient because long-term outcomes of this therapy are unknown. More studies demonstrating reliability and reproducibility are needed to evaluate the role of topical imiquimod in melanoma treatment; however, our case shows the potential of this topical modality.

- Rastrelli M, Alaibac M, Stramare R, et al. Melanoma m (zero): diagnosis and therapy. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:616170.

- Ellis LZ, Cohen JL, High W, et al. Melanoma in situ treated successfully using imiquimod after nonclearance with surgery: review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:937-946.

- Cotter MA, McKenna JK, Bowen GM. Treatment of lentigo maligna with imiquimod before staged excision. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:147-151.

- Li X, Naylor MF, Le H, et al. Clinical effects of in situ photoimmunotherapy on late-stage melanoma patients: a preliminary study. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:1081-1087.

- Steinmann A, Funk JO, Schuler G, et al. Topical imiquimod treatment of a cutaneous melanoma metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:555-556.

- Spieth K, Kovács A, Wolter M, et al. Topical imiquimod: effectiveness in intraepithelial melanoma of oral mucosa. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:1036-1037.

- Moon SD, Spencer JM. Clearance of invasive melanoma with topical imiquimod. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:107-108.

- Rastrelli M, Alaibac M, Stramare R, et al. Melanoma m (zero): diagnosis and therapy. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:616170.

- Ellis LZ, Cohen JL, High W, et al. Melanoma in situ treated successfully using imiquimod after nonclearance with surgery: review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:937-946.

- Cotter MA, McKenna JK, Bowen GM. Treatment of lentigo maligna with imiquimod before staged excision. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:147-151.

- Li X, Naylor MF, Le H, et al. Clinical effects of in situ photoimmunotherapy on late-stage melanoma patients: a preliminary study. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:1081-1087.

- Steinmann A, Funk JO, Schuler G, et al. Topical imiquimod treatment of a cutaneous melanoma metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:555-556.

- Spieth K, Kovács A, Wolter M, et al. Topical imiquimod: effectiveness in intraepithelial melanoma of oral mucosa. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:1036-1037.

- Moon SD, Spencer JM. Clearance of invasive melanoma with topical imiquimod. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:107-108.

Practice Points

- Topical imiquimod may clear invasive melanoma as well as melanoma in situ.

- Further study is required to confirm the role of topical imiquimod in melanoma treatment.

Primary Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium Complex Infection Following Squamous Cell Carcinoma Excision

Case Report

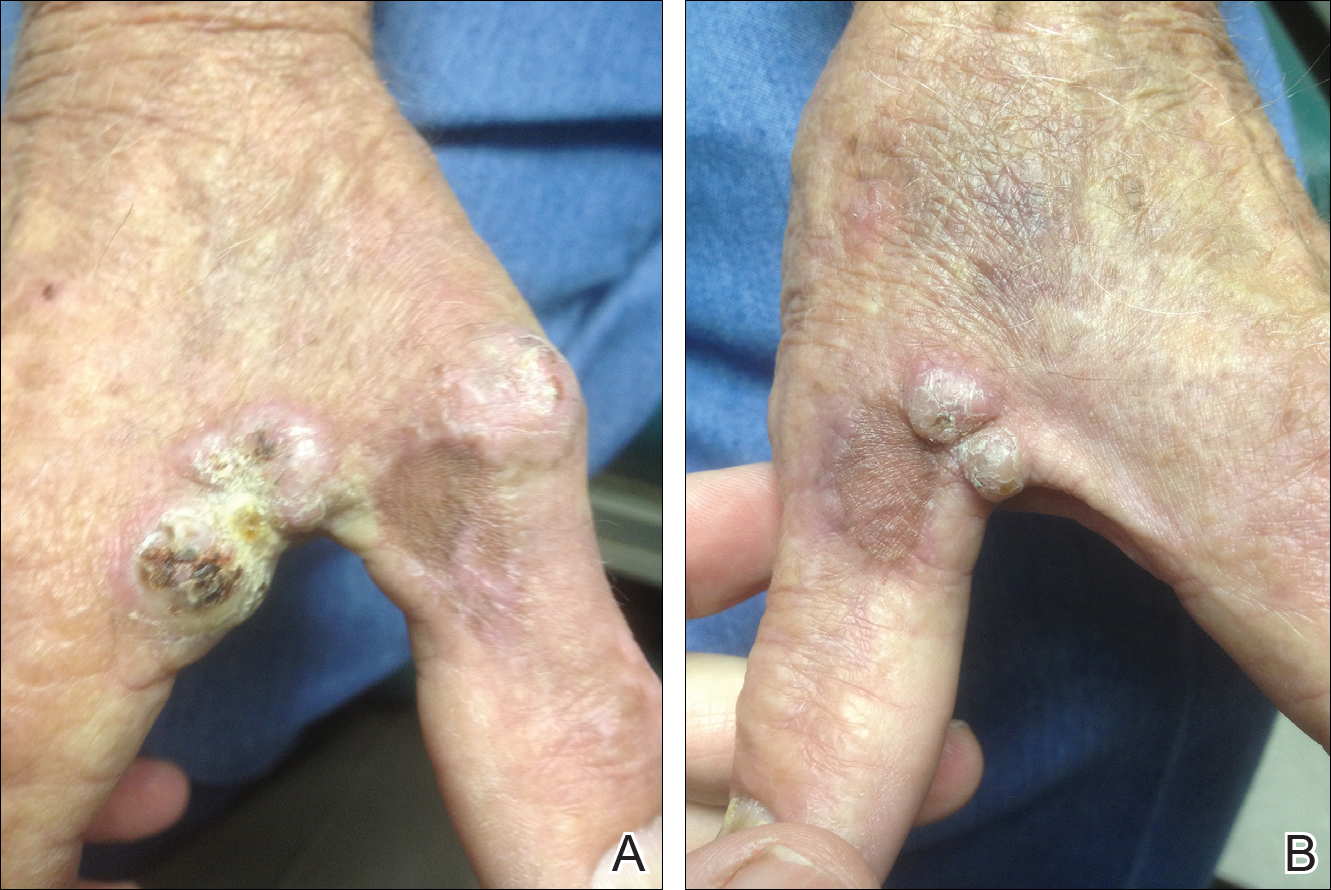

A 78-year-old man presented for evaluation of 4 painful keratotic nodules that had appeared on the dorsal aspect of the right thumb, the first web space of the right hand, and the first web space of the left hand. The nodules developed in pericicatricial skin following Mohs micrographic surgery to the affected areas for treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) 2 months prior. The patient had worked in lawn maintenance for decades and continued to garden on an avocational basis. He denied exposure to angling or aquariums.

On physical examination the lesions appeared as firm, dusky-violaceous, crusted nodules (Figure 1). Brown patches of hyperpigmentation or characteristic cornlike elevations of the palm were not present to implicate arsenic exposure. Extensive sun damage to the face, neck, forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands was noted. Epitrochlear lymphadenopathy or lymphangitic streaking were not appreciated. Routine hematologic parameters including leukocyte count were normal, except for chronic thrombocytopenia. Computerized tomography of the abdomen demonstrated no hepatosplenomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy specimens from the right thumb showed irregular squamous epithelial hyperplasia with an impetiginized scale crust and pustular tissue reaction, including suppurative abscess formation in the dermis (Figure 2). Initial acid-fast staining performed on the biopsy from the right thumb was negative for microorganisms. Given the concerning histologic features indicating infection, a tissue culture was performed. Subsequent growth on Lowenstein-Jensen culture medium confirmed infection with Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). The patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily in accordance with laboratory susceptibilities, and the cutaneous nodules improved. Unfortunately, the patient died 6 months later secondary to cardiac arrest.

Comment

The genus Mycobacterium comprises more than 130 described bacteria, including the precipitants of tuberculosis and leprosy. Mycobacterium avium complex--an umbrella term for M avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other close relatives--is a member of the genus that maintains a low pathogenicity for healthy individuals.1,2 Nonetheless, MAC accounts for more than 70% of cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in the United States.3 Mycobacterium avium complex typically acts as a respiratory pathogen, but infection may manifest with lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, hepatosplenomegaly, or skin involvement. Disseminated MAC infection can occur in patients with defective immune systems, including those with conditions such as AIDS or hairy cell leukemia and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.1,4 Although uncommon, cutaneous infection with MAC occurs via 3 possible mechanisms: (1) primary inoculation, (2) lymphogenous extension, or (3) hematologic dissemination.4 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms primary cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex and MAC skin infection, only 11 known cases of primary cutaneous MAC infection have been reported in the English-language literature,4-14 the most recent being a report by Landriscina et al.11

A Runyon group III bacillus, MAC is a slow-growing nonchromogen that is ubiquitous in nature.15 It has been isolated from soil, water, house dust, vegetables, eggs, and milk. According to Reed et al,3 occupational exposure to soil is an independent risk factor for MAC infection, with individuals reporting more than 6 years of cumulative participation in lawn and landscaping services, farming, or other occupations involving substantial exposure to dirt or dust most likely to be MAC-positive. Cutaneous MAC infection may be associated with water exposure, as Sugita et al2 described one familial outbreak of cutaneous MAC infection linked to use of a circulating, constantly heated bathwater system. With respect to US geography, individuals living in rural areas of the South seem most prone to MAC infection.3

Primary cutaneous infection with MAC occurs after a breach in the skin surface, though this fact may not be elicited by history. Modes of entry include minor abrasions after falling,1 small wounds,2 traumatic inoculation,15 and intramuscular injection.16 Clinically, cutaneous lesions of MAC are protean. In the literature, clinical presentation is described as a polymorphous appearance with scaling plaques, verrucous nodules, crusted ulcers, inflammatory nodules, dermatitis, panniculitis, draining sinuses, ecthymatous lesions, sporotrichoid growth patterns, or rosacealike papulopustules.1,15,17 Lesions may affect the arms and legs, trunk, buttocks, and face.18

The differential diagnosis of MAC infection includes lupus vulgaris, Mycobacterium marinum infection (also known as swimming pool granuloma), sporotrichosis, nocardiosis, sarcoidosis, neutrophilic dermatosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and cutaneous blastomycosis. Given its rarity and variability, diagnosis of MAC infection requires a high index of suspicion. Cutaneous MAC infection should be considered if a nodule, plaque, or ulcer fails to respond to conventional treatment, especially in patients with a history of environmental exposure and possible injury to the skin.

We report a rare case of primary cutaneous MAC infection arising in SCC excision sites in a patient without known immune deficiency. This presentation may have occurred for several reasons. First, the surgical excision sites coupled with the substantial occupational and recreational exposure to soil experienced by our patient may have served as portals for infection. Although SCCs are common on the hands, Mohs micrographic surgery is not always performed for excision; in our patient's case, this approach allowed for maximum tissue conservation and preserved manual function given the number and location of the lesions. Second, despite an overtly intact immune system, our patient may have harbored an occult immune deficiency, predisposing him to dermatologic infection with a microorganism of low intrinsic virulence and recurrent malignant neoplasms. This presentation may have been the first clinical indication of subtle immune compromise. For example, inadequate proinflammatory cytokines may contribute to both mycobacterial and malignant disease. A potential risk of inhibition of tumor necrosis factor α is the unmasking of tuberculosis or lymphoma.19,20 Likewise, IFN-γ is vital in suppressing mycobacteria and malignancy. Yonekura et al21 found that IFN-γ induces apoptosis in oral SCC lines. It follows that a paucity of IFN-γ could allow neoplastic growth. Normal function of IFN-γ prompts microbicidal activity in macrophages and stimulates granuloma formation, both of which combat mycobacterial infection.19 A final postulation is that a simmering cutaneous MAC infection precipitated neoplastic degeneration into SCC, much the same way that the human papillomavirus has been correlated in the carcinogenesis of cervical cancer. As an intracellular microbe, MAC could cause the genetic machinery of skin cells to go awry. Kullavanijaya et al18 described a patient with cutaneous MAC in association with cervical cancer.

Conclusion

This association of primary cutaneous MAC infection and cutaneous malignancy in a reportedly immunocompetent patient is rare. Cancer patients, as noted by Feld et al,22 are 3 times more likely to develop infections with mycobacteria, with SCC, lymphoma, and leukemia being most commonly indicated. A specific immune deficit in the IFN-γ receptor is known to confer a selective predisposition to mycobacterial infection.23,24 Toyoda et al25 outlined the case of a pediatric patient with IFN-γ receptor 2 deficiency who presented with disseminated MAC infection and later succumbed to multiple SCCs of the hands and face. The authors' assertion was that inherited disorders of IFN-γ-mediated immunity may be associated with SCCs.25 Unfortunately, our patient died before more specific immunological testing could be conducted. This case highlights the remarkable singularity of primary cutaneous MAC infection in association with multiple SCCs with seemingly intact immune status and offers some intriguing hypotheses regarding its occurrence.

- Hong BK, Kumar C, Marottoli RA. "MAC" attack. Am J Med. 2009;122:1096-1098.

- Sugita Y, Ishii N, Katsuno M, et al. Familial cluster of cutaneous Mycobacterium avium infection resulting from use of a circulating, constantly heated bath water system. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:789-793.

- Reed C, von Reyn CF, Chamblee S, et al. Environmental risk factors for infection with Mycobacterium avium complex [published online May 4, 2006]. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:32-40.

- Ichiki Y, Hirose M, Akiyama T, et al. Skin infection caused by Mycobacterium avium. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:260-263.

- Aboutalebi A, Shen A, Katta R, et al. Primary cutaneous infection by Mycobacterium avium: a case report and literature review. Cutis. 2012;89:175-179.

- Nassar D, Ortonne N, Grégoire-Krikorian B, et al. Chronic granulomatous Mycobacterium avium skin pseudotumor. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:136.

- Escalonilla P, Esteban J, Soriano ML, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:214-221.

- Lugo-Janer G, Cruz A, Sanchez JL. Disseminated cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium avium complex. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1108-1110.

- Schmidt JD, Yeager H Jr, Smith EB, et al. Cutaneous infection due to a Runyon group 3 atypical Mycobacterium. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1972;106:469-471.

- Carlos C, Tang YW, Adler DJ, et al. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Clin Pathol. 2012;39:795-797.

- Landriscina A, Musaev T, Amin B, et al. A surprising case of Mycobacterium avium complex skin infection in an immunocompetent patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1491-1493.

- Zhou L, Wang HS, Feng SY, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterium intracellulare infection in an immunocompetent person. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:711-714.

- Cox S, Strausbaugh L. Chronic cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium intracellulare. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:794-796.

- Sachs M, Fraimow HF, Staros EB, et al. Mycobacterium intracellulare soft tissue infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:1019-1021.

- Jogi R, Tyring SK. Therapy of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:491-498.

- Meadows JR, Carter R, Katner HP. Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection at an intramuscular injection site in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1273-1274.

- Kayal JD, McCall CO. Sporotrichoid cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S249-S250.

- Kullavanijaya P, Sirimachan S, Surarak S. Primary cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex resembling lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:264-266.

- Netea MG, Kullberg BJ, Van der Meer JW. Proinflammatory cytokines in the treatment of bacterial and fungal infections. BioDrugs. 2004;18:9-22.

- Dommasch E, Gelfand JM. Is there truly a risk of lymphoma from biologic therapies? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:418-430.

- Yonekura N, Yokota S, Yonekura K, et al. Interferon-γ downregulates Hsp27 expression and suppresses the negative regulation of cell death in oral squamous cell carcinoma lines. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:313-322.

- Feld R, Bodey GP, Groschel D. Mycobacteriosis in patients with malignant disease. Arch Intern Med. 1976;136:67-70.

- Dorman S, Picard C, Lammas D, et al. Clinical features of dominant and recessive interferon γ receptor 1 deficiencies. Lancet. 2004;364:2113-2121.

- Storgaard M, Varming K, Herlin T, et al. Novel mutation in the interferon-γ receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infections. Scand J Immunol. 2006;64:137-139.

- Toyoda H, Ido M, Nakanishi K, et al. Multiple cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas in a patient with interferon γ receptor 2 (IFNγR2) deficiency [published online June 18, 2010]. J Med Genet. 2010;47:631-634.

Case Report

A 78-year-old man presented for evaluation of 4 painful keratotic nodules that had appeared on the dorsal aspect of the right thumb, the first web space of the right hand, and the first web space of the left hand. The nodules developed in pericicatricial skin following Mohs micrographic surgery to the affected areas for treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) 2 months prior. The patient had worked in lawn maintenance for decades and continued to garden on an avocational basis. He denied exposure to angling or aquariums.

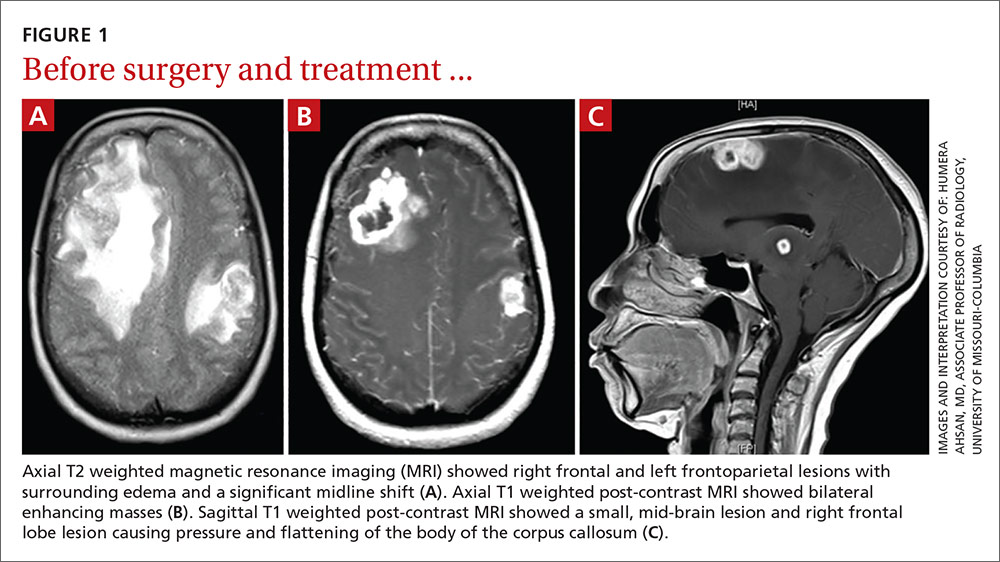

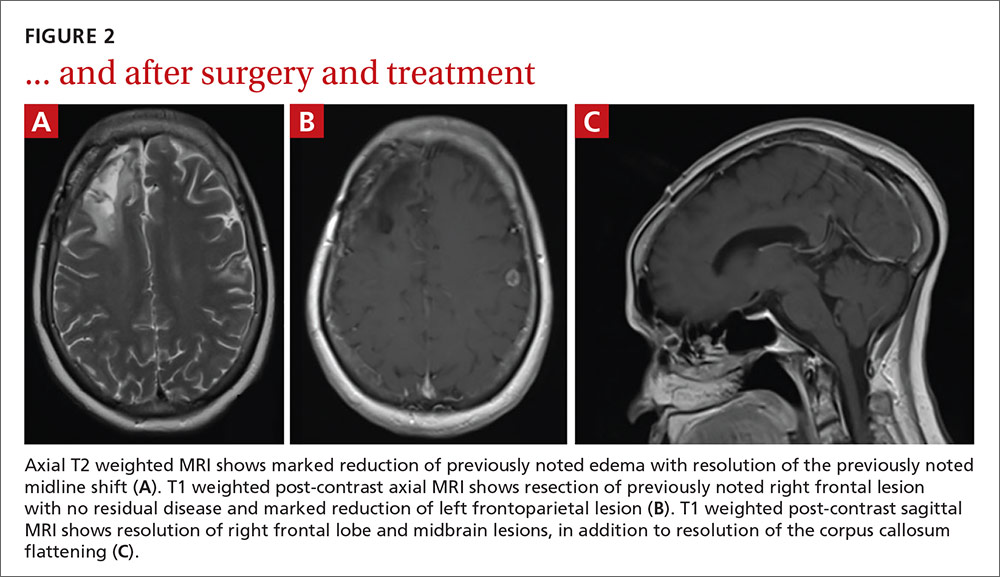

On physical examination the lesions appeared as firm, dusky-violaceous, crusted nodules (Figure 1). Brown patches of hyperpigmentation or characteristic cornlike elevations of the palm were not present to implicate arsenic exposure. Extensive sun damage to the face, neck, forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands was noted. Epitrochlear lymphadenopathy or lymphangitic streaking were not appreciated. Routine hematologic parameters including leukocyte count were normal, except for chronic thrombocytopenia. Computerized tomography of the abdomen demonstrated no hepatosplenomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy specimens from the right thumb showed irregular squamous epithelial hyperplasia with an impetiginized scale crust and pustular tissue reaction, including suppurative abscess formation in the dermis (Figure 2). Initial acid-fast staining performed on the biopsy from the right thumb was negative for microorganisms. Given the concerning histologic features indicating infection, a tissue culture was performed. Subsequent growth on Lowenstein-Jensen culture medium confirmed infection with Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). The patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily in accordance with laboratory susceptibilities, and the cutaneous nodules improved. Unfortunately, the patient died 6 months later secondary to cardiac arrest.

Comment

The genus Mycobacterium comprises more than 130 described bacteria, including the precipitants of tuberculosis and leprosy. Mycobacterium avium complex--an umbrella term for M avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other close relatives--is a member of the genus that maintains a low pathogenicity for healthy individuals.1,2 Nonetheless, MAC accounts for more than 70% of cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in the United States.3 Mycobacterium avium complex typically acts as a respiratory pathogen, but infection may manifest with lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, hepatosplenomegaly, or skin involvement. Disseminated MAC infection can occur in patients with defective immune systems, including those with conditions such as AIDS or hairy cell leukemia and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.1,4 Although uncommon, cutaneous infection with MAC occurs via 3 possible mechanisms: (1) primary inoculation, (2) lymphogenous extension, or (3) hematologic dissemination.4 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms primary cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex and MAC skin infection, only 11 known cases of primary cutaneous MAC infection have been reported in the English-language literature,4-14 the most recent being a report by Landriscina et al.11

A Runyon group III bacillus, MAC is a slow-growing nonchromogen that is ubiquitous in nature.15 It has been isolated from soil, water, house dust, vegetables, eggs, and milk. According to Reed et al,3 occupational exposure to soil is an independent risk factor for MAC infection, with individuals reporting more than 6 years of cumulative participation in lawn and landscaping services, farming, or other occupations involving substantial exposure to dirt or dust most likely to be MAC-positive. Cutaneous MAC infection may be associated with water exposure, as Sugita et al2 described one familial outbreak of cutaneous MAC infection linked to use of a circulating, constantly heated bathwater system. With respect to US geography, individuals living in rural areas of the South seem most prone to MAC infection.3

Primary cutaneous infection with MAC occurs after a breach in the skin surface, though this fact may not be elicited by history. Modes of entry include minor abrasions after falling,1 small wounds,2 traumatic inoculation,15 and intramuscular injection.16 Clinically, cutaneous lesions of MAC are protean. In the literature, clinical presentation is described as a polymorphous appearance with scaling plaques, verrucous nodules, crusted ulcers, inflammatory nodules, dermatitis, panniculitis, draining sinuses, ecthymatous lesions, sporotrichoid growth patterns, or rosacealike papulopustules.1,15,17 Lesions may affect the arms and legs, trunk, buttocks, and face.18

The differential diagnosis of MAC infection includes lupus vulgaris, Mycobacterium marinum infection (also known as swimming pool granuloma), sporotrichosis, nocardiosis, sarcoidosis, neutrophilic dermatosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and cutaneous blastomycosis. Given its rarity and variability, diagnosis of MAC infection requires a high index of suspicion. Cutaneous MAC infection should be considered if a nodule, plaque, or ulcer fails to respond to conventional treatment, especially in patients with a history of environmental exposure and possible injury to the skin.

We report a rare case of primary cutaneous MAC infection arising in SCC excision sites in a patient without known immune deficiency. This presentation may have occurred for several reasons. First, the surgical excision sites coupled with the substantial occupational and recreational exposure to soil experienced by our patient may have served as portals for infection. Although SCCs are common on the hands, Mohs micrographic surgery is not always performed for excision; in our patient's case, this approach allowed for maximum tissue conservation and preserved manual function given the number and location of the lesions. Second, despite an overtly intact immune system, our patient may have harbored an occult immune deficiency, predisposing him to dermatologic infection with a microorganism of low intrinsic virulence and recurrent malignant neoplasms. This presentation may have been the first clinical indication of subtle immune compromise. For example, inadequate proinflammatory cytokines may contribute to both mycobacterial and malignant disease. A potential risk of inhibition of tumor necrosis factor α is the unmasking of tuberculosis or lymphoma.19,20 Likewise, IFN-γ is vital in suppressing mycobacteria and malignancy. Yonekura et al21 found that IFN-γ induces apoptosis in oral SCC lines. It follows that a paucity of IFN-γ could allow neoplastic growth. Normal function of IFN-γ prompts microbicidal activity in macrophages and stimulates granuloma formation, both of which combat mycobacterial infection.19 A final postulation is that a simmering cutaneous MAC infection precipitated neoplastic degeneration into SCC, much the same way that the human papillomavirus has been correlated in the carcinogenesis of cervical cancer. As an intracellular microbe, MAC could cause the genetic machinery of skin cells to go awry. Kullavanijaya et al18 described a patient with cutaneous MAC in association with cervical cancer.

Conclusion

This association of primary cutaneous MAC infection and cutaneous malignancy in a reportedly immunocompetent patient is rare. Cancer patients, as noted by Feld et al,22 are 3 times more likely to develop infections with mycobacteria, with SCC, lymphoma, and leukemia being most commonly indicated. A specific immune deficit in the IFN-γ receptor is known to confer a selective predisposition to mycobacterial infection.23,24 Toyoda et al25 outlined the case of a pediatric patient with IFN-γ receptor 2 deficiency who presented with disseminated MAC infection and later succumbed to multiple SCCs of the hands and face. The authors' assertion was that inherited disorders of IFN-γ-mediated immunity may be associated with SCCs.25 Unfortunately, our patient died before more specific immunological testing could be conducted. This case highlights the remarkable singularity of primary cutaneous MAC infection in association with multiple SCCs with seemingly intact immune status and offers some intriguing hypotheses regarding its occurrence.

Case Report

A 78-year-old man presented for evaluation of 4 painful keratotic nodules that had appeared on the dorsal aspect of the right thumb, the first web space of the right hand, and the first web space of the left hand. The nodules developed in pericicatricial skin following Mohs micrographic surgery to the affected areas for treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) 2 months prior. The patient had worked in lawn maintenance for decades and continued to garden on an avocational basis. He denied exposure to angling or aquariums.

On physical examination the lesions appeared as firm, dusky-violaceous, crusted nodules (Figure 1). Brown patches of hyperpigmentation or characteristic cornlike elevations of the palm were not present to implicate arsenic exposure. Extensive sun damage to the face, neck, forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands was noted. Epitrochlear lymphadenopathy or lymphangitic streaking were not appreciated. Routine hematologic parameters including leukocyte count were normal, except for chronic thrombocytopenia. Computerized tomography of the abdomen demonstrated no hepatosplenomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy specimens from the right thumb showed irregular squamous epithelial hyperplasia with an impetiginized scale crust and pustular tissue reaction, including suppurative abscess formation in the dermis (Figure 2). Initial acid-fast staining performed on the biopsy from the right thumb was negative for microorganisms. Given the concerning histologic features indicating infection, a tissue culture was performed. Subsequent growth on Lowenstein-Jensen culture medium confirmed infection with Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). The patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily in accordance with laboratory susceptibilities, and the cutaneous nodules improved. Unfortunately, the patient died 6 months later secondary to cardiac arrest.

Comment

The genus Mycobacterium comprises more than 130 described bacteria, including the precipitants of tuberculosis and leprosy. Mycobacterium avium complex--an umbrella term for M avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other close relatives--is a member of the genus that maintains a low pathogenicity for healthy individuals.1,2 Nonetheless, MAC accounts for more than 70% of cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in the United States.3 Mycobacterium avium complex typically acts as a respiratory pathogen, but infection may manifest with lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, hepatosplenomegaly, or skin involvement. Disseminated MAC infection can occur in patients with defective immune systems, including those with conditions such as AIDS or hairy cell leukemia and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.1,4 Although uncommon, cutaneous infection with MAC occurs via 3 possible mechanisms: (1) primary inoculation, (2) lymphogenous extension, or (3) hematologic dissemination.4 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms primary cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex and MAC skin infection, only 11 known cases of primary cutaneous MAC infection have been reported in the English-language literature,4-14 the most recent being a report by Landriscina et al.11