User login

Failure to Reduce: Small Bowel Obstruction Hidden Within a Chronic Umbilical Hernia Sac

Strangulated hernias are a medical emergency that can lead to small bowel obstruction (SBO), bowel necrosis, and death. Practitioners look for signs of strangulation on examination to guide the urgency of management. If the hernia is soft and reducible without overlying skin changes or signs of obstruction, patients may be monitored for years.1 However, there is increasing evidence that even asymptomatic hernias should be repaired rather than monitored to avoid the need for emergent surgical intervention.1

We present a case of a patient with a chronic umbilical hernia who experienced acute worsening of pain at the site of her hernia but with few additional objective signs of strangulation. Prior to this presentation, she had been recently evaluated at our ED for the “same” pain, which included a computed tomography (CT) scan that was negative for an acute surgical emergency. The patient’s second ED visit led to a diagnostic dilemma: Practitioners are encouraged to avoid “unnecessary” radiation—especially in cases of chronic pain—and to rely on history, physical examination findings, and prior recent imaging studies, as appropriate. In this case, repeat imaging ultimately revealed a surgical emergency with an unusual underlying pathology likely related to the chronicity of the patient’s hernia, and explained her repeat presentation to the ED.

Case

A 45-year-old obese woman (body mass index, 46 kg/m2) with a medical history of an umbilical hernia, tubal ligation, and chronic pelvic pain presented a second time to our ED with pain at the site of her hernia, which she stated began 5 hours prior to presentation. Although the pain was associated with nausea and vomiting, the patient said her bowel movements were normal. She first noticed the hernia more than 5 years ago, but experienced her first episode of acute pain related to the hernia with associated nausea and vomiting 3 weeks earlier, which prompted her initial presentation. During this first ED visit, a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis was obtained as part of her evaluation and was significant for umbilical herniation of bowel without evidence of strangulation. Bedside reduction was successful, and the patient was discharged home and informed of the need to follow-up with a surgeon for an elective repair. She returned to the ED prior to her scheduled operation due to recurrent pain of similar character, but increased severity.

On physical examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Her vital signs were: heart rate, 84 beats/min; blood pressure, 113/68 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air.

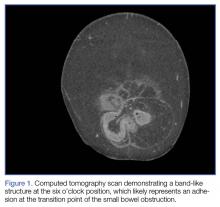

The abdomen was soft with tenderness to palpation over a 13-cm x 8-cm soft hernia to the left of the umbilicus without overlying skin changes. The patient’s pain was controlled with 1 mg of intravenous hydromorphone, after which bedside reduction was attempted. During reduction attempts, there was palpable bowel within the hernia sac, and a periumbilical defect was appreciated. Although the defect in the abdominal wall was estimated to be large enough to allow reduction, the hernia reduced only partially. Because imaging studies from the patient’s previous ED visit showed no visualized strangulation or obstruction, we deliberated over the need for a repeat CT scan prior to further attempts at reduction by general surgery services. Ultimately, we ordered a repeat CT scan, which was significant for a “mechanical small bowel obstruction with focal transition zone located within the hernia sac itself, not the neck of the umbilical hernia.”

Small bowel obstruction is commonly caused by strangulation at the neck of a hernia. In this case, however, the patient had developed an adhesion within the hernia sac itself, which caused the obstruction. This explains why none of the overlying skin changes commonly found in strangulation were visible, and why we were unable to reduce the bowel even though we could palpate the large abdominal wall defect.

Following evaluation by general surgery services, the patient was admitted for laparoscopic hernia repair. Her case was transitioned to an open repair due to extensive intra-abdominal adhesions. The hernia was closed with mesh, and the patient recovered appropriately postoperatively.

Discussion

Abdominal wall hernias are a common pathology, with more than 700,000 repairs performed every year in the United States.2 Patients most commonly present to the ED with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Less frequently, they present with obstruction, incarceration, strangulation, or rupture.3 Umbilical hernias are caused by increasing intra-abdominal pressure. As the incidence of obesity in the United States has continued to increase, the proportion of hernias that are umbilical or periumbilical has also increased.2,4 Unfortunately, even though umbilical hernias are becoming more common, they are often given less attention than other types of hernias.5 The practice of solely monitoring umbilical hernias can lead to serious outcomes. For example, in a case presentation from Spain, a morbidly obese patient died due to a strangulated umbilical hernia that had progressed over a 15-year period without treatment.6

Compared to elective surgery, emergent operative repair is associated with a higher rate of postoperative complications,1 and a growing body of evidence suggests that patients with symptomatic hernias should be encouraged to undergo operative repair.1,6

Conclusion

Umbilical hernias have become more common with increasing rates of obesity. These hernias have the potential to lead to serious medical emergencies, and the common practice of monitoring chronic hernias may increase the patient’s risk of serious complications. Emergency physicians use the physical examination to help determine the urgency of repair; however, imaging should be considered to assess hernias that cannot easily be reduced to evaluate for obstructed, strangulated, or incarcerated bowel and to help determine the urgency of surgical repair.

1. Davies M, Davies C, Morris-Stiff G, Shute K. Emergency presentation of abdominal hernias: outcome and reasons for delay in treatment-a prospective study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(1):47-50.

2. Dabbas N, Adams K, Pearson K, Royle G. Frequency of abdominal wall hernias: is classical teaching out of date? JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2(1):5. doi:10.1258/shorts.2010.010071.

3. Rodriguez JA, Hinder RA. Surgical management of umbilical hernia. Operat Tech Gen Surg. 2004;6(3):156-164.

4. Aslani N, Brown CJ. Does mesh offer an advantage over tissue in the open repair of umbilical hernias? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hernia. 2010;14(5):455-462. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.11.015.

5. Arroyo A, García P, Pérez F, Andreu J, Candela F, Calpena R. Randomized clinical trial comparing suture and mesh repair of umbilical hernia in adults. Br J Surgery. 2001;8(10):1321-1323.

6. Rodríguez-Hermosa JI, Codina-Cazador A, Ruiz-Feliú B, Roig-García J, Albiol-Quer M, Planellas-Giné P. Incarcerated umbilical hernia in a super-super-obese patient. Obes Surg. 2008;18(7):893-895. doi:10.1007/s11695-007-9397-3.

Strangulated hernias are a medical emergency that can lead to small bowel obstruction (SBO), bowel necrosis, and death. Practitioners look for signs of strangulation on examination to guide the urgency of management. If the hernia is soft and reducible without overlying skin changes or signs of obstruction, patients may be monitored for years.1 However, there is increasing evidence that even asymptomatic hernias should be repaired rather than monitored to avoid the need for emergent surgical intervention.1

We present a case of a patient with a chronic umbilical hernia who experienced acute worsening of pain at the site of her hernia but with few additional objective signs of strangulation. Prior to this presentation, she had been recently evaluated at our ED for the “same” pain, which included a computed tomography (CT) scan that was negative for an acute surgical emergency. The patient’s second ED visit led to a diagnostic dilemma: Practitioners are encouraged to avoid “unnecessary” radiation—especially in cases of chronic pain—and to rely on history, physical examination findings, and prior recent imaging studies, as appropriate. In this case, repeat imaging ultimately revealed a surgical emergency with an unusual underlying pathology likely related to the chronicity of the patient’s hernia, and explained her repeat presentation to the ED.

Case

A 45-year-old obese woman (body mass index, 46 kg/m2) with a medical history of an umbilical hernia, tubal ligation, and chronic pelvic pain presented a second time to our ED with pain at the site of her hernia, which she stated began 5 hours prior to presentation. Although the pain was associated with nausea and vomiting, the patient said her bowel movements were normal. She first noticed the hernia more than 5 years ago, but experienced her first episode of acute pain related to the hernia with associated nausea and vomiting 3 weeks earlier, which prompted her initial presentation. During this first ED visit, a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis was obtained as part of her evaluation and was significant for umbilical herniation of bowel without evidence of strangulation. Bedside reduction was successful, and the patient was discharged home and informed of the need to follow-up with a surgeon for an elective repair. She returned to the ED prior to her scheduled operation due to recurrent pain of similar character, but increased severity.

On physical examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Her vital signs were: heart rate, 84 beats/min; blood pressure, 113/68 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air.

The abdomen was soft with tenderness to palpation over a 13-cm x 8-cm soft hernia to the left of the umbilicus without overlying skin changes. The patient’s pain was controlled with 1 mg of intravenous hydromorphone, after which bedside reduction was attempted. During reduction attempts, there was palpable bowel within the hernia sac, and a periumbilical defect was appreciated. Although the defect in the abdominal wall was estimated to be large enough to allow reduction, the hernia reduced only partially. Because imaging studies from the patient’s previous ED visit showed no visualized strangulation or obstruction, we deliberated over the need for a repeat CT scan prior to further attempts at reduction by general surgery services. Ultimately, we ordered a repeat CT scan, which was significant for a “mechanical small bowel obstruction with focal transition zone located within the hernia sac itself, not the neck of the umbilical hernia.”

Small bowel obstruction is commonly caused by strangulation at the neck of a hernia. In this case, however, the patient had developed an adhesion within the hernia sac itself, which caused the obstruction. This explains why none of the overlying skin changes commonly found in strangulation were visible, and why we were unable to reduce the bowel even though we could palpate the large abdominal wall defect.

Following evaluation by general surgery services, the patient was admitted for laparoscopic hernia repair. Her case was transitioned to an open repair due to extensive intra-abdominal adhesions. The hernia was closed with mesh, and the patient recovered appropriately postoperatively.

Discussion

Abdominal wall hernias are a common pathology, with more than 700,000 repairs performed every year in the United States.2 Patients most commonly present to the ED with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Less frequently, they present with obstruction, incarceration, strangulation, or rupture.3 Umbilical hernias are caused by increasing intra-abdominal pressure. As the incidence of obesity in the United States has continued to increase, the proportion of hernias that are umbilical or periumbilical has also increased.2,4 Unfortunately, even though umbilical hernias are becoming more common, they are often given less attention than other types of hernias.5 The practice of solely monitoring umbilical hernias can lead to serious outcomes. For example, in a case presentation from Spain, a morbidly obese patient died due to a strangulated umbilical hernia that had progressed over a 15-year period without treatment.6

Compared to elective surgery, emergent operative repair is associated with a higher rate of postoperative complications,1 and a growing body of evidence suggests that patients with symptomatic hernias should be encouraged to undergo operative repair.1,6

Conclusion

Umbilical hernias have become more common with increasing rates of obesity. These hernias have the potential to lead to serious medical emergencies, and the common practice of monitoring chronic hernias may increase the patient’s risk of serious complications. Emergency physicians use the physical examination to help determine the urgency of repair; however, imaging should be considered to assess hernias that cannot easily be reduced to evaluate for obstructed, strangulated, or incarcerated bowel and to help determine the urgency of surgical repair.

Strangulated hernias are a medical emergency that can lead to small bowel obstruction (SBO), bowel necrosis, and death. Practitioners look for signs of strangulation on examination to guide the urgency of management. If the hernia is soft and reducible without overlying skin changes or signs of obstruction, patients may be monitored for years.1 However, there is increasing evidence that even asymptomatic hernias should be repaired rather than monitored to avoid the need for emergent surgical intervention.1

We present a case of a patient with a chronic umbilical hernia who experienced acute worsening of pain at the site of her hernia but with few additional objective signs of strangulation. Prior to this presentation, she had been recently evaluated at our ED for the “same” pain, which included a computed tomography (CT) scan that was negative for an acute surgical emergency. The patient’s second ED visit led to a diagnostic dilemma: Practitioners are encouraged to avoid “unnecessary” radiation—especially in cases of chronic pain—and to rely on history, physical examination findings, and prior recent imaging studies, as appropriate. In this case, repeat imaging ultimately revealed a surgical emergency with an unusual underlying pathology likely related to the chronicity of the patient’s hernia, and explained her repeat presentation to the ED.

Case

A 45-year-old obese woman (body mass index, 46 kg/m2) with a medical history of an umbilical hernia, tubal ligation, and chronic pelvic pain presented a second time to our ED with pain at the site of her hernia, which she stated began 5 hours prior to presentation. Although the pain was associated with nausea and vomiting, the patient said her bowel movements were normal. She first noticed the hernia more than 5 years ago, but experienced her first episode of acute pain related to the hernia with associated nausea and vomiting 3 weeks earlier, which prompted her initial presentation. During this first ED visit, a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis was obtained as part of her evaluation and was significant for umbilical herniation of bowel without evidence of strangulation. Bedside reduction was successful, and the patient was discharged home and informed of the need to follow-up with a surgeon for an elective repair. She returned to the ED prior to her scheduled operation due to recurrent pain of similar character, but increased severity.

On physical examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Her vital signs were: heart rate, 84 beats/min; blood pressure, 113/68 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air.

The abdomen was soft with tenderness to palpation over a 13-cm x 8-cm soft hernia to the left of the umbilicus without overlying skin changes. The patient’s pain was controlled with 1 mg of intravenous hydromorphone, after which bedside reduction was attempted. During reduction attempts, there was palpable bowel within the hernia sac, and a periumbilical defect was appreciated. Although the defect in the abdominal wall was estimated to be large enough to allow reduction, the hernia reduced only partially. Because imaging studies from the patient’s previous ED visit showed no visualized strangulation or obstruction, we deliberated over the need for a repeat CT scan prior to further attempts at reduction by general surgery services. Ultimately, we ordered a repeat CT scan, which was significant for a “mechanical small bowel obstruction with focal transition zone located within the hernia sac itself, not the neck of the umbilical hernia.”

Small bowel obstruction is commonly caused by strangulation at the neck of a hernia. In this case, however, the patient had developed an adhesion within the hernia sac itself, which caused the obstruction. This explains why none of the overlying skin changes commonly found in strangulation were visible, and why we were unable to reduce the bowel even though we could palpate the large abdominal wall defect.

Following evaluation by general surgery services, the patient was admitted for laparoscopic hernia repair. Her case was transitioned to an open repair due to extensive intra-abdominal adhesions. The hernia was closed with mesh, and the patient recovered appropriately postoperatively.

Discussion

Abdominal wall hernias are a common pathology, with more than 700,000 repairs performed every year in the United States.2 Patients most commonly present to the ED with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Less frequently, they present with obstruction, incarceration, strangulation, or rupture.3 Umbilical hernias are caused by increasing intra-abdominal pressure. As the incidence of obesity in the United States has continued to increase, the proportion of hernias that are umbilical or periumbilical has also increased.2,4 Unfortunately, even though umbilical hernias are becoming more common, they are often given less attention than other types of hernias.5 The practice of solely monitoring umbilical hernias can lead to serious outcomes. For example, in a case presentation from Spain, a morbidly obese patient died due to a strangulated umbilical hernia that had progressed over a 15-year period without treatment.6

Compared to elective surgery, emergent operative repair is associated with a higher rate of postoperative complications,1 and a growing body of evidence suggests that patients with symptomatic hernias should be encouraged to undergo operative repair.1,6

Conclusion

Umbilical hernias have become more common with increasing rates of obesity. These hernias have the potential to lead to serious medical emergencies, and the common practice of monitoring chronic hernias may increase the patient’s risk of serious complications. Emergency physicians use the physical examination to help determine the urgency of repair; however, imaging should be considered to assess hernias that cannot easily be reduced to evaluate for obstructed, strangulated, or incarcerated bowel and to help determine the urgency of surgical repair.

1. Davies M, Davies C, Morris-Stiff G, Shute K. Emergency presentation of abdominal hernias: outcome and reasons for delay in treatment-a prospective study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(1):47-50.

2. Dabbas N, Adams K, Pearson K, Royle G. Frequency of abdominal wall hernias: is classical teaching out of date? JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2(1):5. doi:10.1258/shorts.2010.010071.

3. Rodriguez JA, Hinder RA. Surgical management of umbilical hernia. Operat Tech Gen Surg. 2004;6(3):156-164.

4. Aslani N, Brown CJ. Does mesh offer an advantage over tissue in the open repair of umbilical hernias? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hernia. 2010;14(5):455-462. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.11.015.

5. Arroyo A, García P, Pérez F, Andreu J, Candela F, Calpena R. Randomized clinical trial comparing suture and mesh repair of umbilical hernia in adults. Br J Surgery. 2001;8(10):1321-1323.

6. Rodríguez-Hermosa JI, Codina-Cazador A, Ruiz-Feliú B, Roig-García J, Albiol-Quer M, Planellas-Giné P. Incarcerated umbilical hernia in a super-super-obese patient. Obes Surg. 2008;18(7):893-895. doi:10.1007/s11695-007-9397-3.

1. Davies M, Davies C, Morris-Stiff G, Shute K. Emergency presentation of abdominal hernias: outcome and reasons for delay in treatment-a prospective study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(1):47-50.

2. Dabbas N, Adams K, Pearson K, Royle G. Frequency of abdominal wall hernias: is classical teaching out of date? JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2(1):5. doi:10.1258/shorts.2010.010071.

3. Rodriguez JA, Hinder RA. Surgical management of umbilical hernia. Operat Tech Gen Surg. 2004;6(3):156-164.

4. Aslani N, Brown CJ. Does mesh offer an advantage over tissue in the open repair of umbilical hernias? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hernia. 2010;14(5):455-462. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.11.015.

5. Arroyo A, García P, Pérez F, Andreu J, Candela F, Calpena R. Randomized clinical trial comparing suture and mesh repair of umbilical hernia in adults. Br J Surgery. 2001;8(10):1321-1323.

6. Rodríguez-Hermosa JI, Codina-Cazador A, Ruiz-Feliú B, Roig-García J, Albiol-Quer M, Planellas-Giné P. Incarcerated umbilical hernia in a super-super-obese patient. Obes Surg. 2008;18(7):893-895. doi:10.1007/s11695-007-9397-3.

Case Studies in Toxicology: Somehow…It’s Always Lupus

Case

A 14-year-old girl with no known medical history presented to the ED via emergency medical services (EMS) approximately 1.5 hours after intentionally ingesting what she described as “a handful or two” of her mother’s lupus prescription medication in a suicide attempt. Initial vital signs and physical examination were normal, and her only complaint was nausea.

Thirty minutes after presentation, the patient suffered acute cardiovascular (CV) collapse: blood pressure, 57/39 mm Hg; heart rate, 90 beats/min. An initial electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed QRS duration of 123 milliseconds and QTc duration of 510 milliseconds, along with nonspecific T-wave abnormalities. A 150-mEq intravenous (IV) bolus of sodium bicarbonate and a 40-mEq potassium chloride IV infusion were administered, and both epinephrine and norepinephrine IV infusions were also initiated. A basic metabolic panel obtained prior to medication administration showed a potassium concentration of 1.9 mmol/L.

What is the differential diagnosis of toxicological hypokalemia?

Hypokalemia may be reflective of diminished whole body potassium stores or a transient alteration of intravascular potassium concentrations. In acute ingestions and overdose, the etiology of the hypokalemia is often electrolyte redistribution through either blockade of constitutive outward potassium leakage (eg, barium, insulin, quinine) or through increased activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase pump (eg, catecholamines, insulin, methylxanthines). This activity has little effect on whole body potassium stores, but can result in a profound fall in the serum potassium. While mild hypokalemia is generally well tolerated, more severe potassium abnormalities can cause muscular weakness, areflexic paralysis, respiratory failure, and life-threatening dysrhythmias. Common ECG findings include decreased T-wave amplitudes, ST-segment depression, and the presence or amplification of U waves.

Case Continuation

While the emergency physicians were stabilizing the patient, her mother provided additional information. Approximately 30 minutes after the exposure, the patient had become nauseated and told her mother what she had done. Her mother called EMS, and the patient was transported to the hospital, where she rapidly became symptomatic. Despite CV decompensation, she remained neurologically intact. On further questioning, the patient admitted to ingesting 6 g of her mother’s prescription of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in a suicide attempt but denied taking any other medications. She was stabilized on vasopressors and admitted to the intensive care unit.

What characterizes hydroxychloroquine toxicity?

Hydroxychloroquine is an aminoquinoline antibiotic that is classically used as an antimalarial to treat infection with Plasmodium vivax, P ovale, P malariae, and susceptible strains of P falciparum. In the United States, it is more commonly used to manage both rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), debilitating diseases which are estimated to affect anywhere from 161,000 to 322,000 Americans.1 Hydroxychloroquine is considered first-line therapy for SLE, but its mechanism of action in treating SLE-associated arthralgias is unclear.

Hydroxychloroquine is structurally similar to quinine and chloroquine (CQ), and not surprisingly exerts quinidine-like effects on the CV system with resultant negative inotropy and vasodilation. Its toxicity is characterized by rapid onset of clinical effects including central nervous system depression, seizures, apnea, hypotension, and arrhythmia. After large overdoses, cardiac arrest and death can occur within hours.

Hypokalemia is another hallmark of HCQ toxicity. It is thought to develop secondary to potassium channel blockade, which slows the constitutive release of potassium from the myocytes.2 As noted, the hypokalemia is transient and does not reflect whole-body depletion. With CQ, which is considered more toxic, there appears to be a correlation between the quantity of CQ ingested and both the degree of hypokalemia and the severity of the outcome. It is reasonable to assume the same for HCQ. There are little data to support that hypokalemia itself causes cardiotoxicity in patients with CQ or HCQ overdose.

Although lethal doses are not well established, animal studies suggest that HCQ is much less toxic than CQ, for which the clinical toxicity is better understood due to its more widespread use in overdose abroad.3 In children, the reported therapeutic dose is 10 mg/kg, but the minimum reported lethal dose was a single 300-mg tablet (30 mg/kg in a toddler). In adults, the toxic dose is reported as 20 mg/kg with lethal doses suggested to be as low as 30 mg/kg.

What are the treatment modalities for patients with hydroxychloroquine toxicity?

By analogy with the treatment of CQ poisoning, the mainstay of HCQ therapy is supportive care, including early intubation and ventilation to minimize metabolic demand. Direct-acting inotropes and vasopressors should be administered after saline to treat hypotension. Because of its large volume of distribution, extracorporeal removal has not proved to be of clinical value.4,5 Though data are sparse to determine its efficacy, there may be a role for giving activated charcoal, particularly following large overdoses—if it is given early after exposure and the patient has normal consciousness. If the patient is intubated and aspiration risk is minimized, gastric lavage may also be beneficial—especially when performed within an hour of the overdose. Syrup of ipecac should not be used.

High-dose diazepam is typically recommended, again by analogy with CQ, although there is no clear mechanism of action and its use remains controversial. Its protective effect in patients with CQ overdose is based on swine and rat models that demonstrated dose dependent relationships between diazepam and survival.6,7 A prospective study of CQ toxicity in humans reported improved survival rates when high-dose diazepam was given in combination with epinephrine.8 However, this study is limited by its comparison of prospectively studied patients with a retrospective control. A subsequent prospective study of moderately CQ-intoxicated patients did not find a benefit from treatment with diazepam.9 Furthermore, it remains unclear if the proposed benefit from high-dose diazepam in CQ toxicity may be extrapolated to HCQ, and cases of even massive HCQ ingestions report good outcomes without the use of high-dose diazepam.10

How aggressively should hypokalemia in hydroxychloroquine toxicity be treated?

As noted earlier, hypokalemia resulting from HCQ toxicity is transient, and aggressive repletion may result in rebound hyperkalemia once toxicity resolves. However, these dangers should be balanced with risks of hypokalemia-induced ventricular arrhythmias. Additionally, hypokalemia may be worsened by sodium bicarbonate that is administered to correct QRS prolongations, increasing the risk of dysrhythmia. Correction of hypokalemia in these cases is necessary but should be done with care and monitoring of serum potassium concentrations to minimize risk of hyperkalemia-induced ventricular arrhythmia.11

Case Conclusion

Throughout treatment, the patient remained neurologically intact. She did not receive benzodiazepines. The epinephrine and norepinephrine infusions were weaned, and she was discharged on hospital day 3 with no neurological or cardiac sequelae. She received an inpatient psychiatric evaluation and was referred to outpatient services for ongoing care.

1. Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15-25. doi:10.1002/art.23177.

2. Clemessy JL, Favier C, Borron SW, Hantson PE, Vicaut E, Baud FJ. Hypokalaemia related to acute chloroquine ingestion. Lancet. 1995;3469(8979):877-880.

3. McChesney EW. Animal toxicity and pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine sulfate. Am J Med. 1983;75(suppl 1A):11-18.

4. Carmichael SJ, Charles B, Tett SE. Population pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Drug Monit. 2003;25(6):671-681.

5. Marquardt K, Albertson TE. Treatment of hydroxychloroquine overdose. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19(5):420-424.

6. Crouzette J, Vicaut E, Palombo S, Girre C, Fournier PE. Experimental assessment of the protective activity of diazepam on the acute toxicity of chloroquine. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1983;20(3):271-279.

7. Riou B, Lecarpentier Y, Barriot P, Viars P. Diazepam does not improve the mechanical performance of rat cardiac papillary muscle exposed to chloroquine in vitro. Intensive Care Med. 1989;15:390-3955.

8. Riou B, Barriot P, Rimailho A, Baud FJ. Treatment of severe chloroquine poisoning. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(1):1-6.

9. Clemessy JL, Angel G, Borron SW, et al. Therapeutic trial of diazepam versus placebo in acute chloroquine intoxications of moderate gravity. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:1400-1405.

10. Yanturali S. Diazepam for treatment of massive chloroquine intoxication. Resuscitation. 2004;63(3):347-348.

11. Ling Ngan Wong A, Tsz Fung Cheung I, Graham CA. Hydroxychloroquine overdose: case report and recommendations for management. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008;15(1):16-8. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3280adcb56.

Case

A 14-year-old girl with no known medical history presented to the ED via emergency medical services (EMS) approximately 1.5 hours after intentionally ingesting what she described as “a handful or two” of her mother’s lupus prescription medication in a suicide attempt. Initial vital signs and physical examination were normal, and her only complaint was nausea.

Thirty minutes after presentation, the patient suffered acute cardiovascular (CV) collapse: blood pressure, 57/39 mm Hg; heart rate, 90 beats/min. An initial electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed QRS duration of 123 milliseconds and QTc duration of 510 milliseconds, along with nonspecific T-wave abnormalities. A 150-mEq intravenous (IV) bolus of sodium bicarbonate and a 40-mEq potassium chloride IV infusion were administered, and both epinephrine and norepinephrine IV infusions were also initiated. A basic metabolic panel obtained prior to medication administration showed a potassium concentration of 1.9 mmol/L.

What is the differential diagnosis of toxicological hypokalemia?

Hypokalemia may be reflective of diminished whole body potassium stores or a transient alteration of intravascular potassium concentrations. In acute ingestions and overdose, the etiology of the hypokalemia is often electrolyte redistribution through either blockade of constitutive outward potassium leakage (eg, barium, insulin, quinine) or through increased activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase pump (eg, catecholamines, insulin, methylxanthines). This activity has little effect on whole body potassium stores, but can result in a profound fall in the serum potassium. While mild hypokalemia is generally well tolerated, more severe potassium abnormalities can cause muscular weakness, areflexic paralysis, respiratory failure, and life-threatening dysrhythmias. Common ECG findings include decreased T-wave amplitudes, ST-segment depression, and the presence or amplification of U waves.

Case Continuation

While the emergency physicians were stabilizing the patient, her mother provided additional information. Approximately 30 minutes after the exposure, the patient had become nauseated and told her mother what she had done. Her mother called EMS, and the patient was transported to the hospital, where she rapidly became symptomatic. Despite CV decompensation, she remained neurologically intact. On further questioning, the patient admitted to ingesting 6 g of her mother’s prescription of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in a suicide attempt but denied taking any other medications. She was stabilized on vasopressors and admitted to the intensive care unit.

What characterizes hydroxychloroquine toxicity?

Hydroxychloroquine is an aminoquinoline antibiotic that is classically used as an antimalarial to treat infection with Plasmodium vivax, P ovale, P malariae, and susceptible strains of P falciparum. In the United States, it is more commonly used to manage both rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), debilitating diseases which are estimated to affect anywhere from 161,000 to 322,000 Americans.1 Hydroxychloroquine is considered first-line therapy for SLE, but its mechanism of action in treating SLE-associated arthralgias is unclear.

Hydroxychloroquine is structurally similar to quinine and chloroquine (CQ), and not surprisingly exerts quinidine-like effects on the CV system with resultant negative inotropy and vasodilation. Its toxicity is characterized by rapid onset of clinical effects including central nervous system depression, seizures, apnea, hypotension, and arrhythmia. After large overdoses, cardiac arrest and death can occur within hours.

Hypokalemia is another hallmark of HCQ toxicity. It is thought to develop secondary to potassium channel blockade, which slows the constitutive release of potassium from the myocytes.2 As noted, the hypokalemia is transient and does not reflect whole-body depletion. With CQ, which is considered more toxic, there appears to be a correlation between the quantity of CQ ingested and both the degree of hypokalemia and the severity of the outcome. It is reasonable to assume the same for HCQ. There are little data to support that hypokalemia itself causes cardiotoxicity in patients with CQ or HCQ overdose.

Although lethal doses are not well established, animal studies suggest that HCQ is much less toxic than CQ, for which the clinical toxicity is better understood due to its more widespread use in overdose abroad.3 In children, the reported therapeutic dose is 10 mg/kg, but the minimum reported lethal dose was a single 300-mg tablet (30 mg/kg in a toddler). In adults, the toxic dose is reported as 20 mg/kg with lethal doses suggested to be as low as 30 mg/kg.

What are the treatment modalities for patients with hydroxychloroquine toxicity?

By analogy with the treatment of CQ poisoning, the mainstay of HCQ therapy is supportive care, including early intubation and ventilation to minimize metabolic demand. Direct-acting inotropes and vasopressors should be administered after saline to treat hypotension. Because of its large volume of distribution, extracorporeal removal has not proved to be of clinical value.4,5 Though data are sparse to determine its efficacy, there may be a role for giving activated charcoal, particularly following large overdoses—if it is given early after exposure and the patient has normal consciousness. If the patient is intubated and aspiration risk is minimized, gastric lavage may also be beneficial—especially when performed within an hour of the overdose. Syrup of ipecac should not be used.

High-dose diazepam is typically recommended, again by analogy with CQ, although there is no clear mechanism of action and its use remains controversial. Its protective effect in patients with CQ overdose is based on swine and rat models that demonstrated dose dependent relationships between diazepam and survival.6,7 A prospective study of CQ toxicity in humans reported improved survival rates when high-dose diazepam was given in combination with epinephrine.8 However, this study is limited by its comparison of prospectively studied patients with a retrospective control. A subsequent prospective study of moderately CQ-intoxicated patients did not find a benefit from treatment with diazepam.9 Furthermore, it remains unclear if the proposed benefit from high-dose diazepam in CQ toxicity may be extrapolated to HCQ, and cases of even massive HCQ ingestions report good outcomes without the use of high-dose diazepam.10

How aggressively should hypokalemia in hydroxychloroquine toxicity be treated?

As noted earlier, hypokalemia resulting from HCQ toxicity is transient, and aggressive repletion may result in rebound hyperkalemia once toxicity resolves. However, these dangers should be balanced with risks of hypokalemia-induced ventricular arrhythmias. Additionally, hypokalemia may be worsened by sodium bicarbonate that is administered to correct QRS prolongations, increasing the risk of dysrhythmia. Correction of hypokalemia in these cases is necessary but should be done with care and monitoring of serum potassium concentrations to minimize risk of hyperkalemia-induced ventricular arrhythmia.11

Case Conclusion

Throughout treatment, the patient remained neurologically intact. She did not receive benzodiazepines. The epinephrine and norepinephrine infusions were weaned, and she was discharged on hospital day 3 with no neurological or cardiac sequelae. She received an inpatient psychiatric evaluation and was referred to outpatient services for ongoing care.

Case

A 14-year-old girl with no known medical history presented to the ED via emergency medical services (EMS) approximately 1.5 hours after intentionally ingesting what she described as “a handful or two” of her mother’s lupus prescription medication in a suicide attempt. Initial vital signs and physical examination were normal, and her only complaint was nausea.

Thirty minutes after presentation, the patient suffered acute cardiovascular (CV) collapse: blood pressure, 57/39 mm Hg; heart rate, 90 beats/min. An initial electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed QRS duration of 123 milliseconds and QTc duration of 510 milliseconds, along with nonspecific T-wave abnormalities. A 150-mEq intravenous (IV) bolus of sodium bicarbonate and a 40-mEq potassium chloride IV infusion were administered, and both epinephrine and norepinephrine IV infusions were also initiated. A basic metabolic panel obtained prior to medication administration showed a potassium concentration of 1.9 mmol/L.

What is the differential diagnosis of toxicological hypokalemia?

Hypokalemia may be reflective of diminished whole body potassium stores or a transient alteration of intravascular potassium concentrations. In acute ingestions and overdose, the etiology of the hypokalemia is often electrolyte redistribution through either blockade of constitutive outward potassium leakage (eg, barium, insulin, quinine) or through increased activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase pump (eg, catecholamines, insulin, methylxanthines). This activity has little effect on whole body potassium stores, but can result in a profound fall in the serum potassium. While mild hypokalemia is generally well tolerated, more severe potassium abnormalities can cause muscular weakness, areflexic paralysis, respiratory failure, and life-threatening dysrhythmias. Common ECG findings include decreased T-wave amplitudes, ST-segment depression, and the presence or amplification of U waves.

Case Continuation

While the emergency physicians were stabilizing the patient, her mother provided additional information. Approximately 30 minutes after the exposure, the patient had become nauseated and told her mother what she had done. Her mother called EMS, and the patient was transported to the hospital, where she rapidly became symptomatic. Despite CV decompensation, she remained neurologically intact. On further questioning, the patient admitted to ingesting 6 g of her mother’s prescription of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in a suicide attempt but denied taking any other medications. She was stabilized on vasopressors and admitted to the intensive care unit.

What characterizes hydroxychloroquine toxicity?

Hydroxychloroquine is an aminoquinoline antibiotic that is classically used as an antimalarial to treat infection with Plasmodium vivax, P ovale, P malariae, and susceptible strains of P falciparum. In the United States, it is more commonly used to manage both rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), debilitating diseases which are estimated to affect anywhere from 161,000 to 322,000 Americans.1 Hydroxychloroquine is considered first-line therapy for SLE, but its mechanism of action in treating SLE-associated arthralgias is unclear.

Hydroxychloroquine is structurally similar to quinine and chloroquine (CQ), and not surprisingly exerts quinidine-like effects on the CV system with resultant negative inotropy and vasodilation. Its toxicity is characterized by rapid onset of clinical effects including central nervous system depression, seizures, apnea, hypotension, and arrhythmia. After large overdoses, cardiac arrest and death can occur within hours.

Hypokalemia is another hallmark of HCQ toxicity. It is thought to develop secondary to potassium channel blockade, which slows the constitutive release of potassium from the myocytes.2 As noted, the hypokalemia is transient and does not reflect whole-body depletion. With CQ, which is considered more toxic, there appears to be a correlation between the quantity of CQ ingested and both the degree of hypokalemia and the severity of the outcome. It is reasonable to assume the same for HCQ. There are little data to support that hypokalemia itself causes cardiotoxicity in patients with CQ or HCQ overdose.

Although lethal doses are not well established, animal studies suggest that HCQ is much less toxic than CQ, for which the clinical toxicity is better understood due to its more widespread use in overdose abroad.3 In children, the reported therapeutic dose is 10 mg/kg, but the minimum reported lethal dose was a single 300-mg tablet (30 mg/kg in a toddler). In adults, the toxic dose is reported as 20 mg/kg with lethal doses suggested to be as low as 30 mg/kg.

What are the treatment modalities for patients with hydroxychloroquine toxicity?

By analogy with the treatment of CQ poisoning, the mainstay of HCQ therapy is supportive care, including early intubation and ventilation to minimize metabolic demand. Direct-acting inotropes and vasopressors should be administered after saline to treat hypotension. Because of its large volume of distribution, extracorporeal removal has not proved to be of clinical value.4,5 Though data are sparse to determine its efficacy, there may be a role for giving activated charcoal, particularly following large overdoses—if it is given early after exposure and the patient has normal consciousness. If the patient is intubated and aspiration risk is minimized, gastric lavage may also be beneficial—especially when performed within an hour of the overdose. Syrup of ipecac should not be used.

High-dose diazepam is typically recommended, again by analogy with CQ, although there is no clear mechanism of action and its use remains controversial. Its protective effect in patients with CQ overdose is based on swine and rat models that demonstrated dose dependent relationships between diazepam and survival.6,7 A prospective study of CQ toxicity in humans reported improved survival rates when high-dose diazepam was given in combination with epinephrine.8 However, this study is limited by its comparison of prospectively studied patients with a retrospective control. A subsequent prospective study of moderately CQ-intoxicated patients did not find a benefit from treatment with diazepam.9 Furthermore, it remains unclear if the proposed benefit from high-dose diazepam in CQ toxicity may be extrapolated to HCQ, and cases of even massive HCQ ingestions report good outcomes without the use of high-dose diazepam.10

How aggressively should hypokalemia in hydroxychloroquine toxicity be treated?

As noted earlier, hypokalemia resulting from HCQ toxicity is transient, and aggressive repletion may result in rebound hyperkalemia once toxicity resolves. However, these dangers should be balanced with risks of hypokalemia-induced ventricular arrhythmias. Additionally, hypokalemia may be worsened by sodium bicarbonate that is administered to correct QRS prolongations, increasing the risk of dysrhythmia. Correction of hypokalemia in these cases is necessary but should be done with care and monitoring of serum potassium concentrations to minimize risk of hyperkalemia-induced ventricular arrhythmia.11

Case Conclusion

Throughout treatment, the patient remained neurologically intact. She did not receive benzodiazepines. The epinephrine and norepinephrine infusions were weaned, and she was discharged on hospital day 3 with no neurological or cardiac sequelae. She received an inpatient psychiatric evaluation and was referred to outpatient services for ongoing care.

1. Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15-25. doi:10.1002/art.23177.

2. Clemessy JL, Favier C, Borron SW, Hantson PE, Vicaut E, Baud FJ. Hypokalaemia related to acute chloroquine ingestion. Lancet. 1995;3469(8979):877-880.

3. McChesney EW. Animal toxicity and pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine sulfate. Am J Med. 1983;75(suppl 1A):11-18.

4. Carmichael SJ, Charles B, Tett SE. Population pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Drug Monit. 2003;25(6):671-681.

5. Marquardt K, Albertson TE. Treatment of hydroxychloroquine overdose. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19(5):420-424.

6. Crouzette J, Vicaut E, Palombo S, Girre C, Fournier PE. Experimental assessment of the protective activity of diazepam on the acute toxicity of chloroquine. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1983;20(3):271-279.

7. Riou B, Lecarpentier Y, Barriot P, Viars P. Diazepam does not improve the mechanical performance of rat cardiac papillary muscle exposed to chloroquine in vitro. Intensive Care Med. 1989;15:390-3955.

8. Riou B, Barriot P, Rimailho A, Baud FJ. Treatment of severe chloroquine poisoning. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(1):1-6.

9. Clemessy JL, Angel G, Borron SW, et al. Therapeutic trial of diazepam versus placebo in acute chloroquine intoxications of moderate gravity. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:1400-1405.

10. Yanturali S. Diazepam for treatment of massive chloroquine intoxication. Resuscitation. 2004;63(3):347-348.

11. Ling Ngan Wong A, Tsz Fung Cheung I, Graham CA. Hydroxychloroquine overdose: case report and recommendations for management. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008;15(1):16-8. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3280adcb56.

1. Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15-25. doi:10.1002/art.23177.

2. Clemessy JL, Favier C, Borron SW, Hantson PE, Vicaut E, Baud FJ. Hypokalaemia related to acute chloroquine ingestion. Lancet. 1995;3469(8979):877-880.

3. McChesney EW. Animal toxicity and pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine sulfate. Am J Med. 1983;75(suppl 1A):11-18.

4. Carmichael SJ, Charles B, Tett SE. Population pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Drug Monit. 2003;25(6):671-681.

5. Marquardt K, Albertson TE. Treatment of hydroxychloroquine overdose. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19(5):420-424.

6. Crouzette J, Vicaut E, Palombo S, Girre C, Fournier PE. Experimental assessment of the protective activity of diazepam on the acute toxicity of chloroquine. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1983;20(3):271-279.

7. Riou B, Lecarpentier Y, Barriot P, Viars P. Diazepam does not improve the mechanical performance of rat cardiac papillary muscle exposed to chloroquine in vitro. Intensive Care Med. 1989;15:390-3955.

8. Riou B, Barriot P, Rimailho A, Baud FJ. Treatment of severe chloroquine poisoning. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(1):1-6.

9. Clemessy JL, Angel G, Borron SW, et al. Therapeutic trial of diazepam versus placebo in acute chloroquine intoxications of moderate gravity. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:1400-1405.

10. Yanturali S. Diazepam for treatment of massive chloroquine intoxication. Resuscitation. 2004;63(3):347-348.

11. Ling Ngan Wong A, Tsz Fung Cheung I, Graham CA. Hydroxychloroquine overdose: case report and recommendations for management. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008;15(1):16-8. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3280adcb56.

Idiopathic Livedo Racemosa Presenting With Splenomegaly and Diffuse Lymphadenopathy

Sneddon syndrome (SS) was first described in 1965 in patients with persistent livedo racemosa and neurological events.1 Because the other manifestations of SS are nonspecific (eg, hypertension, cardiac valvulopathy, arterial and venous occlusion), the diagnosis often is delayed. Many patients who experience prodromal neurologic symptoms such as headaches, depression, anxiety, dizziness, and neuropathy often present to a physician prior to developing ischemic brain manifestations2 but seldom receive the correct diagnosis. Onset of cerebral occlusive events typically occurs in patients younger than 45 years and may present as a transient ischemic attack, stroke, or intracranial hemorrhage.3 The disease is more prevalent in females than males (2:1 ratio). The exact pathogenesis of SS is still unknown, and although it has been thought of as a separate entity from systemic lupus erythematosus and other antiphospholipid disorders, it has been postulated that an immunological dysfunction damages vessel walls leading to thrombosis.

Cutaneous findings associated with SS involve small- to medium-sized dermal-subdermal arteries. Histopathology in some patients demonstrates proliferation of the endothelium and fibrin deposits with subsequent obliteration of involved arteries.4 In many patients including our patient, histopathologic examination of involved skin fails to show specific abnormalities.1 Zelger et al5 reported the sequence of histopathologic skin events in a series of antiphospholipid-negative SS patients. The authors reported that only small arteries at the dermis-subcutis junction were involved and a progression of endothelial dysfunction was observed. The authors believed there were several nonspecific stages prior to fibrin occlusion of involved arteries.5 Stage I involved loosening of endothelial cells with nonspecific perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with perivascular inflammation and lymphocytic infiltration representing the prime mover of the disease.5,6 This stage is thought to be short lived, thus the reason why it has gone undetected for many years in SS patients. Stages II to IV progress through fibrin deposition and occlusion.5 Histological features of stages I to II have not been reported because of late diagnosis of SS. Stage I patients typically present with an average duration of symptoms of 6 months with few neurologic symptoms, the most common being paresthesia of the legs.5

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman with epigastric tenderness on the left side and splenomegaly seen on computed tomography was referred by a hematologist for evaluation of a reticular rash on the left side of the flank of 9 months’ duration with a presumed diagnosis of focal melanoderma. Her medical history was remarkable for a congenital ventricular septal defect and coarctation of the aorta, as well as endometriosis, myalgia, and joint stiffness that had all developed over the last year. Her medical history also was remarkable for nephrolithiasis, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic sinusitis, as well as psychiatric depression and anxiety disorders. She recently had been diagnosed with moderate hypertension and had experienced difficulty getting pregnant for the last several years with 3 consecutive miscarriages in the first trimester. Neurologic symptoms included neuropathy involving the feet, intermittent paresthesia of the legs, and a history of chronic migraine headaches for several months.

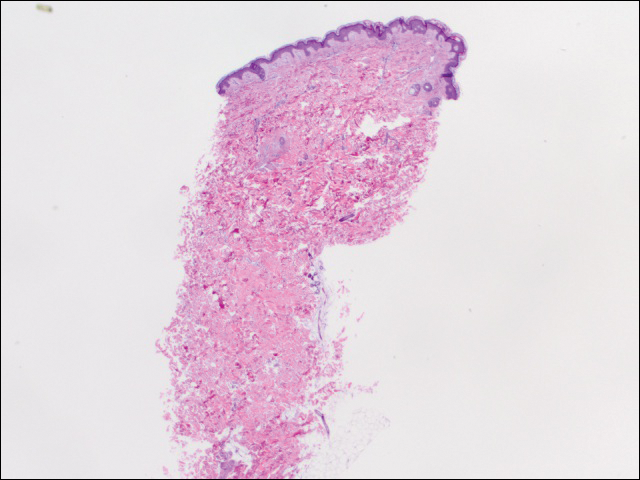

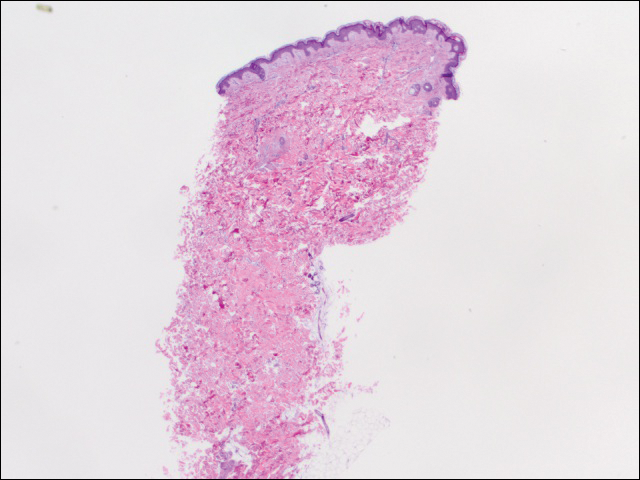

Dermatologic examination revealed a slightly overweight woman with a 25×30-cm dusky, erythematous, irregular, netlike pattern on the left side of the upper and lower trunk (Figure 1). Extensive livedo racemosa was not altered by changes in temperature and had been unchanged for more than 9 months. There were no signs of pruritus or ulcerations, and areas of livedo racemosa were slightly tender to palpation.

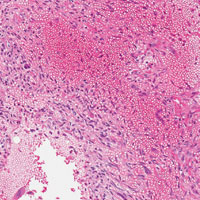

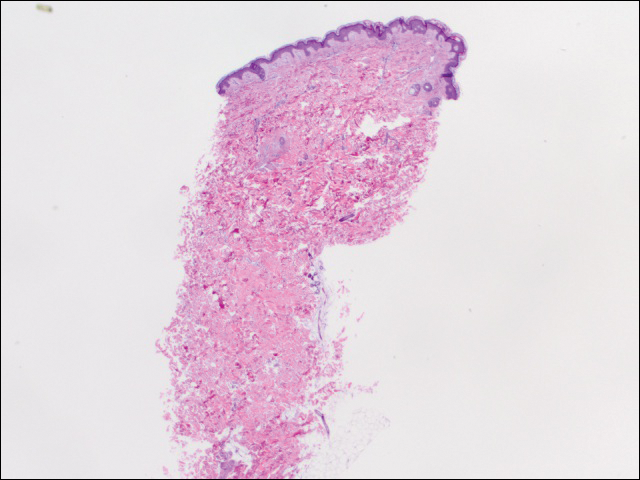

We performed 2 sets of three 4-mm biopsies. The first set targeted areas within the violaceous pattern, while the second set targeted areas of normal tissue between the mottled areas. All 6 specimens demonstrated superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with no evidence of vasculitis or connective tissue disease. The vessels showed no microthrombi or surrounding fibrosis. No eosinophils were identified within the epidermis. There was no evidence of increased dermal mucin. Both the superficial and deep vascular plexuses were unremarkable and showed no evidence of damage to the walls (Figure 2).

To rule out other possible causes of livedo racemosa, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation profile, lipase test, urinalysis, serologic testing, and immunologic workup were performed. Lipase was within reference range. The complete blood cell count revealed mild anemia, while the rest of the values were within reference range. An immunologic workup included Sjögren syndrome antigen A, Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anticardiolipin antibodies, and antinuclear antibody, which were all negative. Family history was remarkable for first-degree relatives with systemic lupus erythematosus and Crohn disease.

Computed tomography revealed enlargement of the spleen, as well as periaortic, portacaval, and porta hepatis lymphadenopathy. Based on the laboratory findings and clinical presentation as well as the patient’s medical history, the diagnosis of exclusion was idiopathic livedo racemosa with unknown progression to full-blown SS. The patient did not meet the current diagnostic criteria for SS, and her immunologic studies failed to confirm any present antibodies, but involvement of the reticuloendothelial system pointed to production of antibodies that were not yet detectable on laboratory testing.

Comment

More than 50 years after the first case of SS was diagnosed, better laboratory workup is available and more information is known about the pathophysiology. Sneddon syndrome is a rare disorder, affecting only approximately 4 patients per million each year worldwide. Seronegative antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (SNAPS) describes patients with clinical presentations of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) without detectable serological markers.7 Antiphospholipid-negative SS, which was seen in our patient, would be categorized under SNAPS. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms livedo racemosa, Sneddon syndrome, and SNAPS and splenomegaly revealed there currently are no known cases of SNAPS that have been reported with splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Our patient presented with the following clinical features of SS: livedo racemosa, history of miscarriage, psychiatric disturbances, and hypertension. Surprisingly, biopsies from affected skin did not show any fibrin deposition or microthrombi but did reveal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrations. Magnetic resonance imaging did not show any pathological lesions or vascular changes.

Sneddon syndrome and APS share a common pathway to occlusive arteriolopathy for which 4 stages have been described by Zelger et al.5 Stage I involves a nonspecific Langerhans cell infiltrate with polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The tunica media and elastic lamina usually are unaltered at this early stage, while the surrounding connective tissue may appear edematous.5 This early stage of histopathology has not been evaluated in SS patients, primarily because of delay of diagnosis. Late stages III and IV will show fibrin deposition and shrinkage of affected vessels.7

A PubMed search using the terms Sneddon syndrome, lymphadenopathy and livedo racemosa, and Sneddon syndrome and lymphadenopathy revealed that splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy have not been reported in patients with SS. In patients with antiphospholipid-negative SS, one can assume that antibodies to other phospholipids not tested must exist because of striking similarities between APS and antiphospholipid-negative SS.8 Although our patient did not test positive for any of these antibodies, she did present with lymphadenopathy and splenic enlargement, leading us to believe that involvement of the reticuloendothelial system may be a feature of SS that has not been previously reported. Further studies are required to name specific antigens responsible for clinical manifestations in SS.

Currently, no single diagnostic test for SS exists, thus delaying both diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Histopathologic examination may be helpful, but in many cases it is nonspecific, as are serologic markers. Neuroradiological confirmation of involvement usually is the confirmatory feature in many patients with late-stage diagnosis.2 A diagnostic schematic for SS, which was first described by Daoud et al,2 illustrates classification of symptoms and aids in diagnosis. A working diagnosis of idiopathic livedo racemosa is made after ruling out other causes of SS in a patient with nonspecific biopsy findings and negative magnetic resonance imaging results with prodromal symptoms. The prognosis for such patients progressing to full SS is unknown with or without management using anticoagulant therapy.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis of livedo racemosa and SS is essential, as prevention of cerebrovascular accidents, myocardial infarction, and other thromboembolic diseases can be minimized by attacking risk factors such as smoking, taking oral contraceptive pills, becoming pregnant,9 and by initiating either antiplatelet or anticoagulation treatments. These treatments have been shown to delay the development of neurovascular damage and early-onset dementia. We present this case to demonstrate the variability of early-presenting symptoms in idiopathic livedo racemosa. Recognizing some of the early manifestations can lead to early diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebro-vascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Daoud MS, Wilmoth GJ, Su WP, et al. Sneddon syndrome. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:166-172.

- Besnier R, Francès C, Ankri A, et al. Factor V Leiden mutation in Sneddon syndrome. Lupus. 2003;12:406-408.

- K aragülle AT, Karadağ D, Erden A, et al. Sneddon’s syndrome: MR imaging findings. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:144-146.

- Zelg er B, Sepp N, Schmid KW, et al. Life-history of cutaneous vascular-lesions in Sneddon’s syndrome. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:668-675.

- Ayoub N, Esposito G, Barete S, et al. Protein Z deficiency in antiphospholipid-negative Sneddon’s syndrome. Stroke. 2004;35:1329-1332.

- Duva l A, Darnige L, Glowacki F, et al. Livedo, dementia, thrombocytopenia, and endotheliitis without antiphospholipid antibodies: seronegative antiphospholipid-like syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1076-1078.

- Kala shnikova LA, Nasonov EL, Kushekbaeva AE, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies in Sneddon’s syndrome. Neurology. 1990;40:464-467.

- Wohl rab J, Fischer M, Wolter M, et al. Diagnostic impact and sensitivity of skin biopsies in Sneddon’s syndrome. a report of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:285-288.

Sneddon syndrome (SS) was first described in 1965 in patients with persistent livedo racemosa and neurological events.1 Because the other manifestations of SS are nonspecific (eg, hypertension, cardiac valvulopathy, arterial and venous occlusion), the diagnosis often is delayed. Many patients who experience prodromal neurologic symptoms such as headaches, depression, anxiety, dizziness, and neuropathy often present to a physician prior to developing ischemic brain manifestations2 but seldom receive the correct diagnosis. Onset of cerebral occlusive events typically occurs in patients younger than 45 years and may present as a transient ischemic attack, stroke, or intracranial hemorrhage.3 The disease is more prevalent in females than males (2:1 ratio). The exact pathogenesis of SS is still unknown, and although it has been thought of as a separate entity from systemic lupus erythematosus and other antiphospholipid disorders, it has been postulated that an immunological dysfunction damages vessel walls leading to thrombosis.

Cutaneous findings associated with SS involve small- to medium-sized dermal-subdermal arteries. Histopathology in some patients demonstrates proliferation of the endothelium and fibrin deposits with subsequent obliteration of involved arteries.4 In many patients including our patient, histopathologic examination of involved skin fails to show specific abnormalities.1 Zelger et al5 reported the sequence of histopathologic skin events in a series of antiphospholipid-negative SS patients. The authors reported that only small arteries at the dermis-subcutis junction were involved and a progression of endothelial dysfunction was observed. The authors believed there were several nonspecific stages prior to fibrin occlusion of involved arteries.5 Stage I involved loosening of endothelial cells with nonspecific perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with perivascular inflammation and lymphocytic infiltration representing the prime mover of the disease.5,6 This stage is thought to be short lived, thus the reason why it has gone undetected for many years in SS patients. Stages II to IV progress through fibrin deposition and occlusion.5 Histological features of stages I to II have not been reported because of late diagnosis of SS. Stage I patients typically present with an average duration of symptoms of 6 months with few neurologic symptoms, the most common being paresthesia of the legs.5

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman with epigastric tenderness on the left side and splenomegaly seen on computed tomography was referred by a hematologist for evaluation of a reticular rash on the left side of the flank of 9 months’ duration with a presumed diagnosis of focal melanoderma. Her medical history was remarkable for a congenital ventricular septal defect and coarctation of the aorta, as well as endometriosis, myalgia, and joint stiffness that had all developed over the last year. Her medical history also was remarkable for nephrolithiasis, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic sinusitis, as well as psychiatric depression and anxiety disorders. She recently had been diagnosed with moderate hypertension and had experienced difficulty getting pregnant for the last several years with 3 consecutive miscarriages in the first trimester. Neurologic symptoms included neuropathy involving the feet, intermittent paresthesia of the legs, and a history of chronic migraine headaches for several months.

Dermatologic examination revealed a slightly overweight woman with a 25×30-cm dusky, erythematous, irregular, netlike pattern on the left side of the upper and lower trunk (Figure 1). Extensive livedo racemosa was not altered by changes in temperature and had been unchanged for more than 9 months. There were no signs of pruritus or ulcerations, and areas of livedo racemosa were slightly tender to palpation.

We performed 2 sets of three 4-mm biopsies. The first set targeted areas within the violaceous pattern, while the second set targeted areas of normal tissue between the mottled areas. All 6 specimens demonstrated superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with no evidence of vasculitis or connective tissue disease. The vessels showed no microthrombi or surrounding fibrosis. No eosinophils were identified within the epidermis. There was no evidence of increased dermal mucin. Both the superficial and deep vascular plexuses were unremarkable and showed no evidence of damage to the walls (Figure 2).

To rule out other possible causes of livedo racemosa, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation profile, lipase test, urinalysis, serologic testing, and immunologic workup were performed. Lipase was within reference range. The complete blood cell count revealed mild anemia, while the rest of the values were within reference range. An immunologic workup included Sjögren syndrome antigen A, Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anticardiolipin antibodies, and antinuclear antibody, which were all negative. Family history was remarkable for first-degree relatives with systemic lupus erythematosus and Crohn disease.

Computed tomography revealed enlargement of the spleen, as well as periaortic, portacaval, and porta hepatis lymphadenopathy. Based on the laboratory findings and clinical presentation as well as the patient’s medical history, the diagnosis of exclusion was idiopathic livedo racemosa with unknown progression to full-blown SS. The patient did not meet the current diagnostic criteria for SS, and her immunologic studies failed to confirm any present antibodies, but involvement of the reticuloendothelial system pointed to production of antibodies that were not yet detectable on laboratory testing.

Comment

More than 50 years after the first case of SS was diagnosed, better laboratory workup is available and more information is known about the pathophysiology. Sneddon syndrome is a rare disorder, affecting only approximately 4 patients per million each year worldwide. Seronegative antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (SNAPS) describes patients with clinical presentations of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) without detectable serological markers.7 Antiphospholipid-negative SS, which was seen in our patient, would be categorized under SNAPS. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms livedo racemosa, Sneddon syndrome, and SNAPS and splenomegaly revealed there currently are no known cases of SNAPS that have been reported with splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Our patient presented with the following clinical features of SS: livedo racemosa, history of miscarriage, psychiatric disturbances, and hypertension. Surprisingly, biopsies from affected skin did not show any fibrin deposition or microthrombi but did reveal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrations. Magnetic resonance imaging did not show any pathological lesions or vascular changes.

Sneddon syndrome and APS share a common pathway to occlusive arteriolopathy for which 4 stages have been described by Zelger et al.5 Stage I involves a nonspecific Langerhans cell infiltrate with polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The tunica media and elastic lamina usually are unaltered at this early stage, while the surrounding connective tissue may appear edematous.5 This early stage of histopathology has not been evaluated in SS patients, primarily because of delay of diagnosis. Late stages III and IV will show fibrin deposition and shrinkage of affected vessels.7

A PubMed search using the terms Sneddon syndrome, lymphadenopathy and livedo racemosa, and Sneddon syndrome and lymphadenopathy revealed that splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy have not been reported in patients with SS. In patients with antiphospholipid-negative SS, one can assume that antibodies to other phospholipids not tested must exist because of striking similarities between APS and antiphospholipid-negative SS.8 Although our patient did not test positive for any of these antibodies, she did present with lymphadenopathy and splenic enlargement, leading us to believe that involvement of the reticuloendothelial system may be a feature of SS that has not been previously reported. Further studies are required to name specific antigens responsible for clinical manifestations in SS.

Currently, no single diagnostic test for SS exists, thus delaying both diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Histopathologic examination may be helpful, but in many cases it is nonspecific, as are serologic markers. Neuroradiological confirmation of involvement usually is the confirmatory feature in many patients with late-stage diagnosis.2 A diagnostic schematic for SS, which was first described by Daoud et al,2 illustrates classification of symptoms and aids in diagnosis. A working diagnosis of idiopathic livedo racemosa is made after ruling out other causes of SS in a patient with nonspecific biopsy findings and negative magnetic resonance imaging results with prodromal symptoms. The prognosis for such patients progressing to full SS is unknown with or without management using anticoagulant therapy.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis of livedo racemosa and SS is essential, as prevention of cerebrovascular accidents, myocardial infarction, and other thromboembolic diseases can be minimized by attacking risk factors such as smoking, taking oral contraceptive pills, becoming pregnant,9 and by initiating either antiplatelet or anticoagulation treatments. These treatments have been shown to delay the development of neurovascular damage and early-onset dementia. We present this case to demonstrate the variability of early-presenting symptoms in idiopathic livedo racemosa. Recognizing some of the early manifestations can lead to early diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

Sneddon syndrome (SS) was first described in 1965 in patients with persistent livedo racemosa and neurological events.1 Because the other manifestations of SS are nonspecific (eg, hypertension, cardiac valvulopathy, arterial and venous occlusion), the diagnosis often is delayed. Many patients who experience prodromal neurologic symptoms such as headaches, depression, anxiety, dizziness, and neuropathy often present to a physician prior to developing ischemic brain manifestations2 but seldom receive the correct diagnosis. Onset of cerebral occlusive events typically occurs in patients younger than 45 years and may present as a transient ischemic attack, stroke, or intracranial hemorrhage.3 The disease is more prevalent in females than males (2:1 ratio). The exact pathogenesis of SS is still unknown, and although it has been thought of as a separate entity from systemic lupus erythematosus and other antiphospholipid disorders, it has been postulated that an immunological dysfunction damages vessel walls leading to thrombosis.

Cutaneous findings associated with SS involve small- to medium-sized dermal-subdermal arteries. Histopathology in some patients demonstrates proliferation of the endothelium and fibrin deposits with subsequent obliteration of involved arteries.4 In many patients including our patient, histopathologic examination of involved skin fails to show specific abnormalities.1 Zelger et al5 reported the sequence of histopathologic skin events in a series of antiphospholipid-negative SS patients. The authors reported that only small arteries at the dermis-subcutis junction were involved and a progression of endothelial dysfunction was observed. The authors believed there were several nonspecific stages prior to fibrin occlusion of involved arteries.5 Stage I involved loosening of endothelial cells with nonspecific perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with perivascular inflammation and lymphocytic infiltration representing the prime mover of the disease.5,6 This stage is thought to be short lived, thus the reason why it has gone undetected for many years in SS patients. Stages II to IV progress through fibrin deposition and occlusion.5 Histological features of stages I to II have not been reported because of late diagnosis of SS. Stage I patients typically present with an average duration of symptoms of 6 months with few neurologic symptoms, the most common being paresthesia of the legs.5

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman with epigastric tenderness on the left side and splenomegaly seen on computed tomography was referred by a hematologist for evaluation of a reticular rash on the left side of the flank of 9 months’ duration with a presumed diagnosis of focal melanoderma. Her medical history was remarkable for a congenital ventricular septal defect and coarctation of the aorta, as well as endometriosis, myalgia, and joint stiffness that had all developed over the last year. Her medical history also was remarkable for nephrolithiasis, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic sinusitis, as well as psychiatric depression and anxiety disorders. She recently had been diagnosed with moderate hypertension and had experienced difficulty getting pregnant for the last several years with 3 consecutive miscarriages in the first trimester. Neurologic symptoms included neuropathy involving the feet, intermittent paresthesia of the legs, and a history of chronic migraine headaches for several months.

Dermatologic examination revealed a slightly overweight woman with a 25×30-cm dusky, erythematous, irregular, netlike pattern on the left side of the upper and lower trunk (Figure 1). Extensive livedo racemosa was not altered by changes in temperature and had been unchanged for more than 9 months. There were no signs of pruritus or ulcerations, and areas of livedo racemosa were slightly tender to palpation.

We performed 2 sets of three 4-mm biopsies. The first set targeted areas within the violaceous pattern, while the second set targeted areas of normal tissue between the mottled areas. All 6 specimens demonstrated superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with no evidence of vasculitis or connective tissue disease. The vessels showed no microthrombi or surrounding fibrosis. No eosinophils were identified within the epidermis. There was no evidence of increased dermal mucin. Both the superficial and deep vascular plexuses were unremarkable and showed no evidence of damage to the walls (Figure 2).

To rule out other possible causes of livedo racemosa, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation profile, lipase test, urinalysis, serologic testing, and immunologic workup were performed. Lipase was within reference range. The complete blood cell count revealed mild anemia, while the rest of the values were within reference range. An immunologic workup included Sjögren syndrome antigen A, Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anticardiolipin antibodies, and antinuclear antibody, which were all negative. Family history was remarkable for first-degree relatives with systemic lupus erythematosus and Crohn disease.

Computed tomography revealed enlargement of the spleen, as well as periaortic, portacaval, and porta hepatis lymphadenopathy. Based on the laboratory findings and clinical presentation as well as the patient’s medical history, the diagnosis of exclusion was idiopathic livedo racemosa with unknown progression to full-blown SS. The patient did not meet the current diagnostic criteria for SS, and her immunologic studies failed to confirm any present antibodies, but involvement of the reticuloendothelial system pointed to production of antibodies that were not yet detectable on laboratory testing.

Comment

More than 50 years after the first case of SS was diagnosed, better laboratory workup is available and more information is known about the pathophysiology. Sneddon syndrome is a rare disorder, affecting only approximately 4 patients per million each year worldwide. Seronegative antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (SNAPS) describes patients with clinical presentations of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) without detectable serological markers.7 Antiphospholipid-negative SS, which was seen in our patient, would be categorized under SNAPS. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms livedo racemosa, Sneddon syndrome, and SNAPS and splenomegaly revealed there currently are no known cases of SNAPS that have been reported with splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Our patient presented with the following clinical features of SS: livedo racemosa, history of miscarriage, psychiatric disturbances, and hypertension. Surprisingly, biopsies from affected skin did not show any fibrin deposition or microthrombi but did reveal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrations. Magnetic resonance imaging did not show any pathological lesions or vascular changes.

Sneddon syndrome and APS share a common pathway to occlusive arteriolopathy for which 4 stages have been described by Zelger et al.5 Stage I involves a nonspecific Langerhans cell infiltrate with polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The tunica media and elastic lamina usually are unaltered at this early stage, while the surrounding connective tissue may appear edematous.5 This early stage of histopathology has not been evaluated in SS patients, primarily because of delay of diagnosis. Late stages III and IV will show fibrin deposition and shrinkage of affected vessels.7

A PubMed search using the terms Sneddon syndrome, lymphadenopathy and livedo racemosa, and Sneddon syndrome and lymphadenopathy revealed that splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy have not been reported in patients with SS. In patients with antiphospholipid-negative SS, one can assume that antibodies to other phospholipids not tested must exist because of striking similarities between APS and antiphospholipid-negative SS.8 Although our patient did not test positive for any of these antibodies, she did present with lymphadenopathy and splenic enlargement, leading us to believe that involvement of the reticuloendothelial system may be a feature of SS that has not been previously reported. Further studies are required to name specific antigens responsible for clinical manifestations in SS.