User login

Increased syncopal episodes post surgery • Dx?

THE CASE

A 58-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for recurrent syncopal and near-syncopal events following surgical repair of a left hip fracture. The first syncopal event occurred one day post-surgery shortly after standing and was attributed to orthostatic hypotension. Subsequently, the patient experienced 2 events during her hospital stay. Both events occurred in the upright position and were preceded by lightheadedness, warmth, and diaphoresis. They were short in duration (<30 seconds) with spontaneous and complete recovery. The patient had no associated chest pain or palpitations.

The patient’s past medical history included osteopenia, dyslipidemia, and vasovagal syncope, averaging one to 2 events per year. Given her past history, the physicians caring for her assumed that she was having recurrences of her vasovagal syncope. She was discharged home on fludrocortisone 0.1 mg/d, sodium chloride 1 g tid, enoxaparin 40 mg/d, and acetaminophen and oxycodone as needed for pain.

One week later, the patient experienced another syncopal event at home, prompting her to visit our clinic for further evaluation. On arrival, her vital signs were stable. Her oxygen saturation level was 98%, she was not orthostatic, and her physical exam and blood studies were unremarkable. An echocardiogram showed preserved left ventricular function with no evidence of right ventricular dilatation or strain.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s revised Geneva Score for pulmonary embolism (PE) was 2 to 5 depending on the heart rate used (66-80 beats per minute), putting her in a low-to-intermediate risk group with an estimated PE prevalence between 8% and 28%.1 Given her recent surgery and the increase in the frequency of her vasovagal events, a computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CT-PA) was performed. The CT-PA showed a PE in the lateral and posterior basal subsegmental branches of the right lower lobe. Doppler ultrasound revealed no evidence of acute deep vein thrombosis.

DISCUSSION

Syncope may develop in 9% to 19% of patients with PE.2-6 While syncope in patients with PE is often attributed to reduced cardiac filling secondary to massive emboli, it is important to recognize that patients can also present with vasovagal syncope in the absence of massive emboli.

One mechanism for the development of syncope is right ventricular failure with subsequent impairment of left ventricular filling, leading to arterial hypotension. Indeed, the majority of patients with PE and syncope have a massive embolism defined as greater than a 50% reduction in the pulmonary circulation.7 In one study, 60% of patients with PE who presented with syncope had a massive PE compared to 39% of patients presenting without syncope (P=.036).8

Another reported mechanism for syncope in a patient with PE is transient high-degree atrioventricular (AV) block.9 Sudden increases in right-sided pressure can lead to transient right bundle branch block, which may result in complete heart block in the setting of baseline left bundle branch block.

Lastly, patients with PE may develop a vasovagal-like reaction, such as the Bezold-Jarisch reflex, which results in transient arterial hypotension and cerebral hypoperfusion.10 In such instances, the postulated mechanism is activation of cardiac vagal afferents, which results in an increase in vagal tone and peripheral sympathetic withdrawal leading to hypotension and syncope. It is important to note that this mechanism can occur in the absence of massive PE. In one study, up to 40% of patients with PE and syncope did not have a massive PE, and almost 6% had thrombi only in small branches of the pulmonary artery.8

This patient had isolated subsegmental defects, identified on the CT-PA. The sensitivity of CT-PA to detect subsegmental PE ranges from 53% to 100%.11 While this test has its limitations, the introduction of the multi-detector CT technique has significantly increased the rate of detection with a specificity of 96%.12,13

Was PE the cause of the syncope, or just an incidental finding?

In this case, we believe the CT-PA findings were diagnostic for PE. What is less clear is whether the PE was the cause of the syncope.

Asymptomatic post-operative PE with isolated subsegmental defects has been reported.14-16 When compared to patients with a defect at a segmental or more proximal level, these patients often have less dyspnea, are less likely to be classified as having a high clinical probability of PE, and have a lower prevalence of proximal deep vein thrombosis (3.3% vs 43.8%; P<.0001).17 Therefore, one could argue that the PE finding in our case was incidental. While this is a possibility, we believe the patient’s syncope was due to PE for the following reasons.

First, several investigators have reported transient increases in vagal tone and syncope following PE consistent with a vasovagal-like response.7,18 Therefore, it is possible that the reduction in preload associated with PE triggered a Bezold-Jarisch-like reflex leading to syncope. The patient’s history of vasovagal syncope was certainly indicative of increased susceptibility to reflex-mediated events, thus supporting our hypothesis.

Second, our patient had a cluster of events following surgery compared to the one to 2 events she experienced per year prior to surgery. The increased incidence of events would be an unusual progression of her syncope in the absence of clear triggers, again rendering our hypothesis more plausible.

The patient was admitted to our hospital and started on a higher dose of enoxaparin (60 mg twice daily). She was subsequently discharged home on rivaroxaban 15 mg twice daily and midodrine 2.5 mg twice daily in addition to the medications she was already taking. At her 6-week follow-up visit, she reported no recurrences.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case demonstrates that non-massive PE can present as vasovagal syncope. Recognizing that PE could lead to reflex-mediated syncope in the absence of massive emboli, it is important to rule it out in the evaluation of patients with vasovagal syncope when risk factors for PE are present.

1. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:165-171.

2. Calvo-Romero JM, Pérez-Miranda M, Bureo-Dacal P. Syncope in acute pulmonary embolism. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:208-209.

3. Castelli R, Tarsia P, Tantardini C, et al. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism: comparison between patients with syncope as the presenting symptom of pulmonary embolism and patients with pulmonary embolism without syncope. Vasc Med. 2003;8:257-261.

4. Kasper W, Konstantinides S, Geibel A, et al. Management strategies and determinants of outcome in acute major pulmonary embolism: results of a multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1165-1171.

5. Koutkia P, Wachtel TJ. Pulmonary embolism presenting as syncope: case report and review of the literature. Heart Lung. 1999;28:342-347.

6. Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276-2315.

7. Thames MD, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1977;238:2509-2511.

8. Duplyakov D, Kurakina E, Pavlova T, et al. Value of syncope in patients with high-to-intermediate risk pulmonary artery embolism. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2015;4:353-358.

9. Wilner C, Garnier-Crussard JP, Huygue De Mahenge A, et al. [Paroxysmal atrioventricular block, cause of syncope in pulmonary embolism. 2 cases]. Presse Med. 1983;12:2987-2989.

10. Frink RJ, James TN. Intracardiac route of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. Am J Physiol. 1971;221:1464-1469.

11. Rathbun SW, Raskob GE, Whitsett TL. Sensitivity and specificity of helical computed tomography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:227-232.

12. Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, et al; PIOPED II Investigators. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2317-2327.

13. Vedovati MC, Becattini C, Agnelli G, et al. Multidetector CT scan for acute pulmonary embolism: embolic burden and clinical outcome. Chest. 2012;142:1417-1424.

14. Musset D, Parent F, Meyer G, et al; Evaluation du Scanner Spiralé dans l’Embolie Pulmonaire study group. Diagnostic strategy for patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a prospective multicentre outcome study. Lancet. 2002;360:1914-1920.

15. Simpson RJ Jr, Podolak R, Mangano CA Jr, et al. Vagal syncope during recurrent pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1983;249:390-393.

16. Perrier A, Roy PM, Sanchez O, et al. Multidetector-row computed tomography in suspected pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1760-1768.

17. Le Gal G, Righini M, Parent F, et al. Diagnosis and management of subsegmental pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:724-731.

18. Eldadah ZA, Najjar SS, Ziegelstein RC. A patient with syncope, only “vagally” related to the heart. Chest. 2000;117:1801-1803.

THE CASE

A 58-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for recurrent syncopal and near-syncopal events following surgical repair of a left hip fracture. The first syncopal event occurred one day post-surgery shortly after standing and was attributed to orthostatic hypotension. Subsequently, the patient experienced 2 events during her hospital stay. Both events occurred in the upright position and were preceded by lightheadedness, warmth, and diaphoresis. They were short in duration (<30 seconds) with spontaneous and complete recovery. The patient had no associated chest pain or palpitations.

The patient’s past medical history included osteopenia, dyslipidemia, and vasovagal syncope, averaging one to 2 events per year. Given her past history, the physicians caring for her assumed that she was having recurrences of her vasovagal syncope. She was discharged home on fludrocortisone 0.1 mg/d, sodium chloride 1 g tid, enoxaparin 40 mg/d, and acetaminophen and oxycodone as needed for pain.

One week later, the patient experienced another syncopal event at home, prompting her to visit our clinic for further evaluation. On arrival, her vital signs were stable. Her oxygen saturation level was 98%, she was not orthostatic, and her physical exam and blood studies were unremarkable. An echocardiogram showed preserved left ventricular function with no evidence of right ventricular dilatation or strain.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s revised Geneva Score for pulmonary embolism (PE) was 2 to 5 depending on the heart rate used (66-80 beats per minute), putting her in a low-to-intermediate risk group with an estimated PE prevalence between 8% and 28%.1 Given her recent surgery and the increase in the frequency of her vasovagal events, a computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CT-PA) was performed. The CT-PA showed a PE in the lateral and posterior basal subsegmental branches of the right lower lobe. Doppler ultrasound revealed no evidence of acute deep vein thrombosis.

DISCUSSION

Syncope may develop in 9% to 19% of patients with PE.2-6 While syncope in patients with PE is often attributed to reduced cardiac filling secondary to massive emboli, it is important to recognize that patients can also present with vasovagal syncope in the absence of massive emboli.

One mechanism for the development of syncope is right ventricular failure with subsequent impairment of left ventricular filling, leading to arterial hypotension. Indeed, the majority of patients with PE and syncope have a massive embolism defined as greater than a 50% reduction in the pulmonary circulation.7 In one study, 60% of patients with PE who presented with syncope had a massive PE compared to 39% of patients presenting without syncope (P=.036).8

Another reported mechanism for syncope in a patient with PE is transient high-degree atrioventricular (AV) block.9 Sudden increases in right-sided pressure can lead to transient right bundle branch block, which may result in complete heart block in the setting of baseline left bundle branch block.

Lastly, patients with PE may develop a vasovagal-like reaction, such as the Bezold-Jarisch reflex, which results in transient arterial hypotension and cerebral hypoperfusion.10 In such instances, the postulated mechanism is activation of cardiac vagal afferents, which results in an increase in vagal tone and peripheral sympathetic withdrawal leading to hypotension and syncope. It is important to note that this mechanism can occur in the absence of massive PE. In one study, up to 40% of patients with PE and syncope did not have a massive PE, and almost 6% had thrombi only in small branches of the pulmonary artery.8

This patient had isolated subsegmental defects, identified on the CT-PA. The sensitivity of CT-PA to detect subsegmental PE ranges from 53% to 100%.11 While this test has its limitations, the introduction of the multi-detector CT technique has significantly increased the rate of detection with a specificity of 96%.12,13

Was PE the cause of the syncope, or just an incidental finding?

In this case, we believe the CT-PA findings were diagnostic for PE. What is less clear is whether the PE was the cause of the syncope.

Asymptomatic post-operative PE with isolated subsegmental defects has been reported.14-16 When compared to patients with a defect at a segmental or more proximal level, these patients often have less dyspnea, are less likely to be classified as having a high clinical probability of PE, and have a lower prevalence of proximal deep vein thrombosis (3.3% vs 43.8%; P<.0001).17 Therefore, one could argue that the PE finding in our case was incidental. While this is a possibility, we believe the patient’s syncope was due to PE for the following reasons.

First, several investigators have reported transient increases in vagal tone and syncope following PE consistent with a vasovagal-like response.7,18 Therefore, it is possible that the reduction in preload associated with PE triggered a Bezold-Jarisch-like reflex leading to syncope. The patient’s history of vasovagal syncope was certainly indicative of increased susceptibility to reflex-mediated events, thus supporting our hypothesis.

Second, our patient had a cluster of events following surgery compared to the one to 2 events she experienced per year prior to surgery. The increased incidence of events would be an unusual progression of her syncope in the absence of clear triggers, again rendering our hypothesis more plausible.

The patient was admitted to our hospital and started on a higher dose of enoxaparin (60 mg twice daily). She was subsequently discharged home on rivaroxaban 15 mg twice daily and midodrine 2.5 mg twice daily in addition to the medications she was already taking. At her 6-week follow-up visit, she reported no recurrences.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case demonstrates that non-massive PE can present as vasovagal syncope. Recognizing that PE could lead to reflex-mediated syncope in the absence of massive emboli, it is important to rule it out in the evaluation of patients with vasovagal syncope when risk factors for PE are present.

THE CASE

A 58-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for recurrent syncopal and near-syncopal events following surgical repair of a left hip fracture. The first syncopal event occurred one day post-surgery shortly after standing and was attributed to orthostatic hypotension. Subsequently, the patient experienced 2 events during her hospital stay. Both events occurred in the upright position and were preceded by lightheadedness, warmth, and diaphoresis. They were short in duration (<30 seconds) with spontaneous and complete recovery. The patient had no associated chest pain or palpitations.

The patient’s past medical history included osteopenia, dyslipidemia, and vasovagal syncope, averaging one to 2 events per year. Given her past history, the physicians caring for her assumed that she was having recurrences of her vasovagal syncope. She was discharged home on fludrocortisone 0.1 mg/d, sodium chloride 1 g tid, enoxaparin 40 mg/d, and acetaminophen and oxycodone as needed for pain.

One week later, the patient experienced another syncopal event at home, prompting her to visit our clinic for further evaluation. On arrival, her vital signs were stable. Her oxygen saturation level was 98%, she was not orthostatic, and her physical exam and blood studies were unremarkable. An echocardiogram showed preserved left ventricular function with no evidence of right ventricular dilatation or strain.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s revised Geneva Score for pulmonary embolism (PE) was 2 to 5 depending on the heart rate used (66-80 beats per minute), putting her in a low-to-intermediate risk group with an estimated PE prevalence between 8% and 28%.1 Given her recent surgery and the increase in the frequency of her vasovagal events, a computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CT-PA) was performed. The CT-PA showed a PE in the lateral and posterior basal subsegmental branches of the right lower lobe. Doppler ultrasound revealed no evidence of acute deep vein thrombosis.

DISCUSSION

Syncope may develop in 9% to 19% of patients with PE.2-6 While syncope in patients with PE is often attributed to reduced cardiac filling secondary to massive emboli, it is important to recognize that patients can also present with vasovagal syncope in the absence of massive emboli.

One mechanism for the development of syncope is right ventricular failure with subsequent impairment of left ventricular filling, leading to arterial hypotension. Indeed, the majority of patients with PE and syncope have a massive embolism defined as greater than a 50% reduction in the pulmonary circulation.7 In one study, 60% of patients with PE who presented with syncope had a massive PE compared to 39% of patients presenting without syncope (P=.036).8

Another reported mechanism for syncope in a patient with PE is transient high-degree atrioventricular (AV) block.9 Sudden increases in right-sided pressure can lead to transient right bundle branch block, which may result in complete heart block in the setting of baseline left bundle branch block.

Lastly, patients with PE may develop a vasovagal-like reaction, such as the Bezold-Jarisch reflex, which results in transient arterial hypotension and cerebral hypoperfusion.10 In such instances, the postulated mechanism is activation of cardiac vagal afferents, which results in an increase in vagal tone and peripheral sympathetic withdrawal leading to hypotension and syncope. It is important to note that this mechanism can occur in the absence of massive PE. In one study, up to 40% of patients with PE and syncope did not have a massive PE, and almost 6% had thrombi only in small branches of the pulmonary artery.8

This patient had isolated subsegmental defects, identified on the CT-PA. The sensitivity of CT-PA to detect subsegmental PE ranges from 53% to 100%.11 While this test has its limitations, the introduction of the multi-detector CT technique has significantly increased the rate of detection with a specificity of 96%.12,13

Was PE the cause of the syncope, or just an incidental finding?

In this case, we believe the CT-PA findings were diagnostic for PE. What is less clear is whether the PE was the cause of the syncope.

Asymptomatic post-operative PE with isolated subsegmental defects has been reported.14-16 When compared to patients with a defect at a segmental or more proximal level, these patients often have less dyspnea, are less likely to be classified as having a high clinical probability of PE, and have a lower prevalence of proximal deep vein thrombosis (3.3% vs 43.8%; P<.0001).17 Therefore, one could argue that the PE finding in our case was incidental. While this is a possibility, we believe the patient’s syncope was due to PE for the following reasons.

First, several investigators have reported transient increases in vagal tone and syncope following PE consistent with a vasovagal-like response.7,18 Therefore, it is possible that the reduction in preload associated with PE triggered a Bezold-Jarisch-like reflex leading to syncope. The patient’s history of vasovagal syncope was certainly indicative of increased susceptibility to reflex-mediated events, thus supporting our hypothesis.

Second, our patient had a cluster of events following surgery compared to the one to 2 events she experienced per year prior to surgery. The increased incidence of events would be an unusual progression of her syncope in the absence of clear triggers, again rendering our hypothesis more plausible.

The patient was admitted to our hospital and started on a higher dose of enoxaparin (60 mg twice daily). She was subsequently discharged home on rivaroxaban 15 mg twice daily and midodrine 2.5 mg twice daily in addition to the medications she was already taking. At her 6-week follow-up visit, she reported no recurrences.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case demonstrates that non-massive PE can present as vasovagal syncope. Recognizing that PE could lead to reflex-mediated syncope in the absence of massive emboli, it is important to rule it out in the evaluation of patients with vasovagal syncope when risk factors for PE are present.

1. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:165-171.

2. Calvo-Romero JM, Pérez-Miranda M, Bureo-Dacal P. Syncope in acute pulmonary embolism. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:208-209.

3. Castelli R, Tarsia P, Tantardini C, et al. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism: comparison between patients with syncope as the presenting symptom of pulmonary embolism and patients with pulmonary embolism without syncope. Vasc Med. 2003;8:257-261.

4. Kasper W, Konstantinides S, Geibel A, et al. Management strategies and determinants of outcome in acute major pulmonary embolism: results of a multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1165-1171.

5. Koutkia P, Wachtel TJ. Pulmonary embolism presenting as syncope: case report and review of the literature. Heart Lung. 1999;28:342-347.

6. Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276-2315.

7. Thames MD, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1977;238:2509-2511.

8. Duplyakov D, Kurakina E, Pavlova T, et al. Value of syncope in patients with high-to-intermediate risk pulmonary artery embolism. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2015;4:353-358.

9. Wilner C, Garnier-Crussard JP, Huygue De Mahenge A, et al. [Paroxysmal atrioventricular block, cause of syncope in pulmonary embolism. 2 cases]. Presse Med. 1983;12:2987-2989.

10. Frink RJ, James TN. Intracardiac route of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. Am J Physiol. 1971;221:1464-1469.

11. Rathbun SW, Raskob GE, Whitsett TL. Sensitivity and specificity of helical computed tomography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:227-232.

12. Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, et al; PIOPED II Investigators. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2317-2327.

13. Vedovati MC, Becattini C, Agnelli G, et al. Multidetector CT scan for acute pulmonary embolism: embolic burden and clinical outcome. Chest. 2012;142:1417-1424.

14. Musset D, Parent F, Meyer G, et al; Evaluation du Scanner Spiralé dans l’Embolie Pulmonaire study group. Diagnostic strategy for patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a prospective multicentre outcome study. Lancet. 2002;360:1914-1920.

15. Simpson RJ Jr, Podolak R, Mangano CA Jr, et al. Vagal syncope during recurrent pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1983;249:390-393.

16. Perrier A, Roy PM, Sanchez O, et al. Multidetector-row computed tomography in suspected pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1760-1768.

17. Le Gal G, Righini M, Parent F, et al. Diagnosis and management of subsegmental pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:724-731.

18. Eldadah ZA, Najjar SS, Ziegelstein RC. A patient with syncope, only “vagally” related to the heart. Chest. 2000;117:1801-1803.

1. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:165-171.

2. Calvo-Romero JM, Pérez-Miranda M, Bureo-Dacal P. Syncope in acute pulmonary embolism. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:208-209.

3. Castelli R, Tarsia P, Tantardini C, et al. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism: comparison between patients with syncope as the presenting symptom of pulmonary embolism and patients with pulmonary embolism without syncope. Vasc Med. 2003;8:257-261.

4. Kasper W, Konstantinides S, Geibel A, et al. Management strategies and determinants of outcome in acute major pulmonary embolism: results of a multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1165-1171.

5. Koutkia P, Wachtel TJ. Pulmonary embolism presenting as syncope: case report and review of the literature. Heart Lung. 1999;28:342-347.

6. Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276-2315.

7. Thames MD, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1977;238:2509-2511.

8. Duplyakov D, Kurakina E, Pavlova T, et al. Value of syncope in patients with high-to-intermediate risk pulmonary artery embolism. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2015;4:353-358.

9. Wilner C, Garnier-Crussard JP, Huygue De Mahenge A, et al. [Paroxysmal atrioventricular block, cause of syncope in pulmonary embolism. 2 cases]. Presse Med. 1983;12:2987-2989.

10. Frink RJ, James TN. Intracardiac route of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. Am J Physiol. 1971;221:1464-1469.

11. Rathbun SW, Raskob GE, Whitsett TL. Sensitivity and specificity of helical computed tomography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:227-232.

12. Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, et al; PIOPED II Investigators. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2317-2327.

13. Vedovati MC, Becattini C, Agnelli G, et al. Multidetector CT scan for acute pulmonary embolism: embolic burden and clinical outcome. Chest. 2012;142:1417-1424.

14. Musset D, Parent F, Meyer G, et al; Evaluation du Scanner Spiralé dans l’Embolie Pulmonaire study group. Diagnostic strategy for patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a prospective multicentre outcome study. Lancet. 2002;360:1914-1920.

15. Simpson RJ Jr, Podolak R, Mangano CA Jr, et al. Vagal syncope during recurrent pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1983;249:390-393.

16. Perrier A, Roy PM, Sanchez O, et al. Multidetector-row computed tomography in suspected pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1760-1768.

17. Le Gal G, Righini M, Parent F, et al. Diagnosis and management of subsegmental pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:724-731.

18. Eldadah ZA, Najjar SS, Ziegelstein RC. A patient with syncope, only “vagally” related to the heart. Chest. 2000;117:1801-1803.

Congenital Self-healing Reticulohistiocytosis: An Underreported Entity

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), also known as histiocytosis X, is a general term that describes a group of rare disorders characterized by the proliferation of Langerhans cells.1 Central to immune surveillance and the elimination of foreign substances from the body, Langerhans cells are derived from bone marrow progenitor cells and found in the epidermis but are capable of migrating from the skin to the lymph nodes. In LCH, these cells congregate on bone tissue, particularly in the head and neck region, causing a multitude of problems.2

The spectrum of LCH includes 4 variants: congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (CSHR)(also known as Hashimoto-Pritzker disease), Letterer-Siwe disease, Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, and eosinophilic granuloma (also known as pulmonary histiocytosis X)(Table). Despite the various clinical presentations and levels of severity, all variants are caused by the proliferation of Langerhans cells. We present a case of CSHR in a 6-month-old male infant that was initially diagnosed as molluscum contagiosum. We believe the actual incidence of CSHR may be underreported due to its spontaneous regression and low rate of clinical recognition.

Case Report

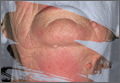

A 6-month-old male infant was referred to our clinic by his pediatrician with a generalized cutaneous eruption of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption, which followed a recent viral upper respiratory tract infection, was characterized by multiple flesh-colored to erythematous, umbilicated papules distributed along the postauricular region, scalp (Figure 1A), abdomen (Figure 1B), and anterior aspect of the neck. Due to his recent illness, the patient was diagnosed with molluscum contagiosum by the referring pediatrician that was treated symptomatically with hydrocortisone lotion, Schamberg’s cream formulated in our office (a compound mixture of zinc oxide, menthol, calcium hydroxide solution, and olive oil), and pediatric diphenhydramine as needed. During a subsequent visit 2 weeks later, a more potent topical corticosteroid and a low-dose systemic corticosteroid was prescribed for 1 week due to development of new lesions and exacerbation of existing lesions. On follow-up 1 week later, the lesions on the trunk had improved, but the patient had developed new lesions on the scalp that differed from prior findings in that they were darker (more erythematous to brown) and firmer (papules and nodules).

|

| |

Figure 1. Multiple fleshcolored to erythematous, umbilicated papules on the frontal scalp (A) and erythematous papules on the abdomen (B). | ||

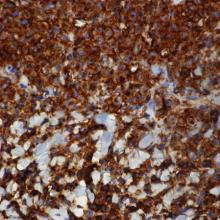

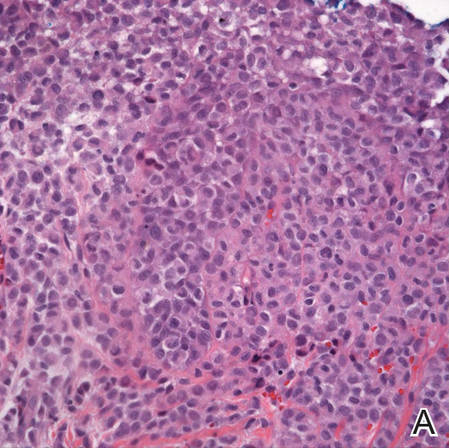

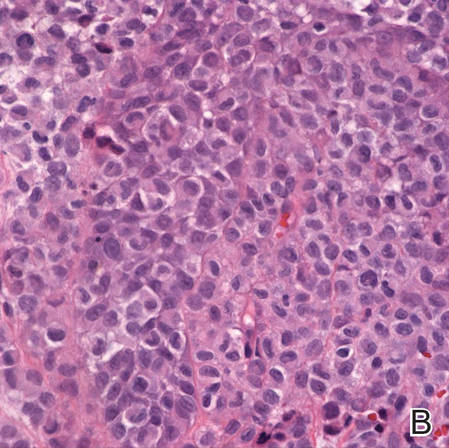

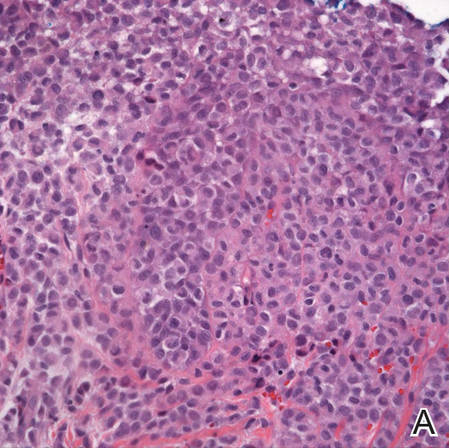

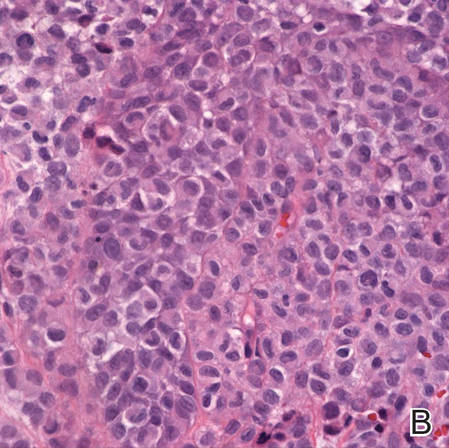

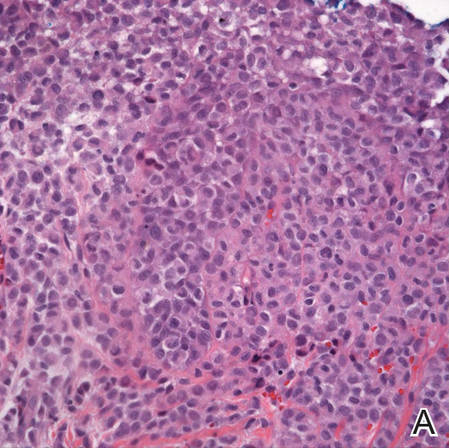

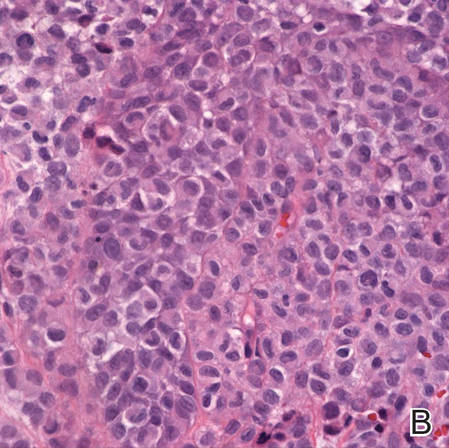

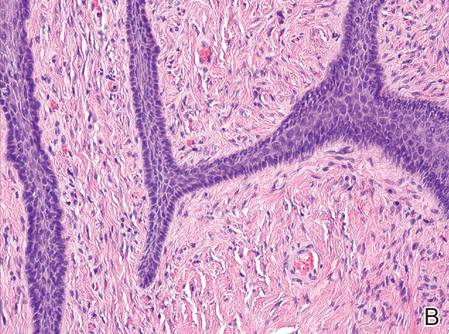

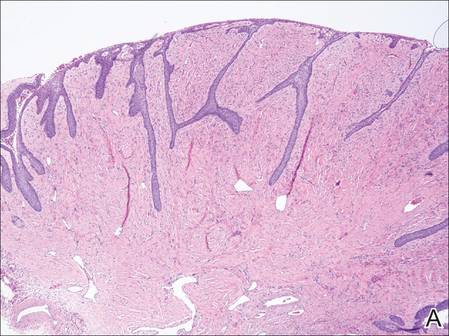

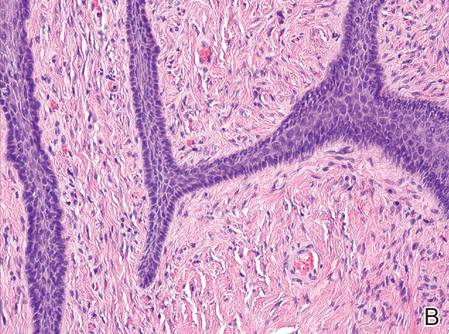

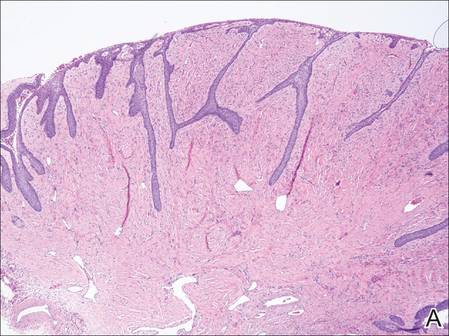

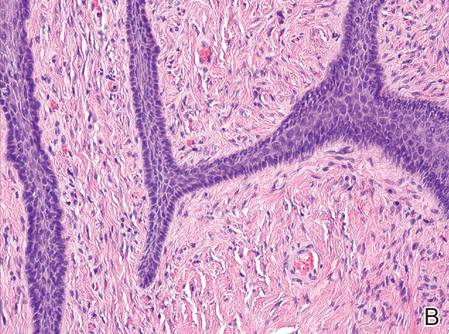

A shave biopsy was obtained from the frontal scalp to rule out LCH. Histologic examination and culture of the biopsy specimen revealed an atypical cellular infiltrate effacing the dermoepidermal junction and extensive epidermotropism. Focal erosion of the epidermis and an acute inflammatory exudate were visible. The nuclei of the cellular infiltrate were enlarged and hyperchromatic with a characteristic reniform appearance and indistinct nucleoli (Figure 2). The cells were admixed with scattered eosinophils and extravasated red blood cells.

|

| |

Figure 2. Low-power view of dermal mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100), and high-power view of enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei with a characteristic reniform appearance admixed with eosinophils and extravasated red blood cells (B) (H&E, original magnification ×400). | ||

Immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen was strongly positive for both CD1a and S-100 expression (Figure 3). Histopathologic findings were consistent with LCH. Clinicopathologic correlation strongly favored the diagnosis of CSHR.

Comment

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis is a rare, benign, congenital variant of LCH that spontaneously resolves with no systemic involvement. The more aggressive forms typically manifest at birth or during the first 2 months of life and regress within 3 to 4 months.5 Since CSHR was first described in 1973 by Hashimoto and Pritzker,5 more than 100 cases have been reported, but the true incidence is believed to be higher than reported given the high rate of spontaneous resolution and the low rate of clinical recognition.2 The first reported case of CSHR occurred in a female infant who presented at birth with multiple, diffusely distributed, red-brown papules that were 2 to 4 mm in diameter. Although the patient received no treatment, the exanthem completely resolved within 3.5 months without recurrence at 14-year follow-up.5 Most often, CSHR presents as multiple papules or nodules with occasional disseminated crusting and is followed within a few months by a dramatic and spontaneous regression. Lesions may heal with mild postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Pseudo-Darier sign, the propensity to urticate from physical manipulation, has been reported in some lesions with an increased number of mast cells.6 Extensive superficial nasal and oral mucosal erosions have been reported in 2 cases.7 Solitary lesions have been reported in 25% of cases.8

The etiology of CSHR remains unknown, though neoplastic, viral, and immunologic origins have been suggested. There have been reports that human herpesvirus 6 may contribute to the development of LCH.9 It may be postulated that our patient’s presentation of CSHR was potentiated by his recent upper respiratory tract illness. In the literature, CSHR is distributed equally among males and females. Prevalence is higher in the white population than in other racial groups.5

Although CSHR is a benign cutaneous variant of LCH, there have been reports of patients with disseminated and extracutaneous involvement. In 1 rare case, CSHR reportedly involved the eyes, producing multiple, bilateral, well-circumscribed, diffuse, yellow-white lesions of the retinal pigment epithelium throughout the posterior pole of the eyes.10 The retinal lesions spontaneously regressed along with the skin manifestations. Additionally, it was reported that a neonate in Thailand presented with CSHR at birth and 1 month later developed multiple lung cysts that had completely regressed 11 months later.11 One study reported that initial diagnoses of LCH in 18 patients with only cutaneous involvement eventually progressed to systemic LCH, requiring further management.12 When LCH is suspected, a thorough physical examination, including hematologic and coagulation evaluation, liver function tests, musculoskeletal examination, and consultation with specialists if necessary, is recommended.13

There are 3 additional variants of LCH. Letterer-Siwe disease is an acute form of LCH that accounts for 10% of all LCH cases and typically presents in children younger than 2 years. It involves multiple organs, including the bones, lungs, liver, and lymph nodes.14 Affected patients usually present with fever; hepatosplenomegaly; anemia; lymphadenopathy; extensive lytic skull lesions; and a generalized cutaneous eruption, appearing as a maculopapular scaling rash with underlying purpura on the scalp, neck, axilla, and trunk.3 Letterer-Siwe disease is inherited in an autosomal-recessive pattern. Diagnosis is confirmed by skin biopsy demonstrating a thinning of the epidermis and a collection of reticulum cells in the dermis.3 Letterer-Siwe disease is treated with radiation and chemotherapy; if left untreated, the disease is fatal.4

Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, a chronic form of LCH, is most commonly seen in children aged 2 to 6 years and accounts for 15% to 20% of all LCH cases. This LCH variant presents with a classic triad of diabetes insipidus (resulting from erosion into the sella turcica), lytic bone lesions, and exophthalmos.15 Hand-Schüller-Christian disease also affects the oral cavity, producing nodular ulcerations of the hard palate, trouble swallowing, and halitosis.4 The involvement of lytic bone lesions of the mastoid process and petrous portions of the temporal bones may cause recurrent or chronic otitis media and otitis externa. Hand-Schüller-Christian disease is treated with a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgical excision. The mortality rate is 30%.4

Eosinophilic granuloma is the most prevalent variant of LCH, accounting for 60% to 80% of all cases. Characterized by Langerhans cell granulomatous infiltration of the lungs and painful cystic bone lesions, eosinophilic granuloma primarily presents in the third or fourth decades of life.16 Some studies suggest an epidemiologic association with tobacco use.17 In the preliminary stages of this disease, Langerhans cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts infiltrate and form nodules on the terminal bronchioles in the upper and middle lung zones, damaging the airway walls.18 Fibrotic scarring progresses, ultimately resulting in alveolar destruction.10 The common signs and symptoms of eosinophilic granuloma are a nonproductive cough, dyspnea, weight loss, spontaneous pneumothorax, fever, peripheral edema, and a tricuspid regurgitation murmur.14 The prognosis of eosinophilic granuloma is variable. Although some patients progress to end-stage fibrotic lung disease requiring lung transplant, there have been reports of complete remission following cessation of cigarette smoking.17

Langerhans cells travel from the bone marrow to the epidermis where they express the CD1a protein on the surface of the antigen-presenting cell. Elevated levels of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and interleukins have been seen in patients with LCH.1 Their role in the pathogenesis of this disease remains unknown, but the elevated levels of cytokines may indicate the lack of an efficient immune system.

Histologically, hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections demonstrate an infiltrate of histiocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and an increased number of mast cells involving the papillary and reticular dermis. Infiltrating Langerhans cells have concave reniform nuclei18 and stain positive for CD1a, S-100, and CD68 antigens.15 In 10% to 30% of CSHR cases, Birbeck granules can be seen on electron microscopy and tend to transform into laminated dense bodies, signifying the degenerative changes seen in CSHR.15 The various forms of LCH exhibit no significant differences in the expression of the epithelial cadherin, the phosphorylated histone H3, and the Ki-67 proteins, indicating that they are simply different forms of the same disease represented on a spectrum.15

Conclusion

The actual incidence of CSHR may be notably underreported due to its spontaneous regression and low rate of clinical recognition. A subtype of LCH, CSHR is a diagnosis of exclusion. Although CSHR generally follows a benign clinical course, a thorough workup and evaluation for systemic disease with close follow-up is recommended after diagnosis due to the potential of LCH to involve multiple organs and to relapse at a later date after apparent regression.

1. Hussein MR. Skin-limited Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis in children. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:504-511.

2. Nakahigashi K, Ohta M, Sakai R, et al. Late-onset self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: pediatric case of Hashimoto-Pritzker type Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Dermatol. 2007;34:205-209.

3. Pant C, Madonia P, Bahna SL, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a case of Letterer Siwe disease. J La State Med Soc. 2009;161:211-212.

4. Ferreira LM, Emerich PS, Diniz LM, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Letterer-Siwe disease–the importance of dermatological diagnosis in two cases [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:405-409.

5. Hashimoto K, Pritzker MS. Electron microscopic study of reticulohistiocytoma. an unusual case of congenital, self-healing reticulohistiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:263-270.

6. Kapur P, Erickson C, Rakheja D, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (Hashimoto-Pritzker disease): ten-year experience at Dallas Children’s Medical Center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:290-294.

7. Le Bidre E, Lorette G, Delage M, et al. Extensive, erosive congenital self-healing cell histiocytosis [published online December 22, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:835-836.

8. Weiss T, Weber L, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, et al. Solitary cutaneous dendritic cell tumor in a child: role of dendritic cell markers for the diagnosis of skin Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:838-844.

9. Csire M, Mikala G, Jákó J, et al. Persistent long-term human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) infection in a patient with Langerhans cell histiocytosis [published online July 3, 2007]. Pathol Oncol Res. 2007;13:157-160.

10. Zaenglein AL, Steele MA, Kamino H, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with eye involvement. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:135-137.

11. Chunharas A, Pabunruang W, Hongeng S. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis with pulmonary involvement: spontaneous regression. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85(suppl 4):S1309-S1313.

12. Minkov M, Prosch H, Steiner M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in neonates. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:802-807.

13. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a review of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:291-295.

14. Stacher E, Beham-Schmid C, Terpe HJ, et al. Pulmonary histiocytic sarcoma mimicking pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a young adult presenting with spontaneous pneumothorax: a potential diagnostic pitfall [published online June 27, 2009]. Virchows Arch. 2009;455:187-190.

15. Scolozzi P, Lombardi T, Monnier P, et al. Multisystem Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (Hand-Schüller-Christian disease) in an adult: a case report and review of the literature [published online October 10, 2003]. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:326-330.

16. Noonan V, Kabani S, Alibhai K. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma). J Mass Dent Soc. 2011;60:35.

17. Podbielski FJ, Worley TA, Korn JM, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma of the lung and rib. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2009;17:194-195.

18. Rosso DA, Ripoli MF, Roy A, et al. Serum levels of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are elevated in children with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:480-483.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), also known as histiocytosis X, is a general term that describes a group of rare disorders characterized by the proliferation of Langerhans cells.1 Central to immune surveillance and the elimination of foreign substances from the body, Langerhans cells are derived from bone marrow progenitor cells and found in the epidermis but are capable of migrating from the skin to the lymph nodes. In LCH, these cells congregate on bone tissue, particularly in the head and neck region, causing a multitude of problems.2

The spectrum of LCH includes 4 variants: congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (CSHR)(also known as Hashimoto-Pritzker disease), Letterer-Siwe disease, Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, and eosinophilic granuloma (also known as pulmonary histiocytosis X)(Table). Despite the various clinical presentations and levels of severity, all variants are caused by the proliferation of Langerhans cells. We present a case of CSHR in a 6-month-old male infant that was initially diagnosed as molluscum contagiosum. We believe the actual incidence of CSHR may be underreported due to its spontaneous regression and low rate of clinical recognition.

Case Report

A 6-month-old male infant was referred to our clinic by his pediatrician with a generalized cutaneous eruption of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption, which followed a recent viral upper respiratory tract infection, was characterized by multiple flesh-colored to erythematous, umbilicated papules distributed along the postauricular region, scalp (Figure 1A), abdomen (Figure 1B), and anterior aspect of the neck. Due to his recent illness, the patient was diagnosed with molluscum contagiosum by the referring pediatrician that was treated symptomatically with hydrocortisone lotion, Schamberg’s cream formulated in our office (a compound mixture of zinc oxide, menthol, calcium hydroxide solution, and olive oil), and pediatric diphenhydramine as needed. During a subsequent visit 2 weeks later, a more potent topical corticosteroid and a low-dose systemic corticosteroid was prescribed for 1 week due to development of new lesions and exacerbation of existing lesions. On follow-up 1 week later, the lesions on the trunk had improved, but the patient had developed new lesions on the scalp that differed from prior findings in that they were darker (more erythematous to brown) and firmer (papules and nodules).

|

| |

Figure 1. Multiple fleshcolored to erythematous, umbilicated papules on the frontal scalp (A) and erythematous papules on the abdomen (B). | ||

A shave biopsy was obtained from the frontal scalp to rule out LCH. Histologic examination and culture of the biopsy specimen revealed an atypical cellular infiltrate effacing the dermoepidermal junction and extensive epidermotropism. Focal erosion of the epidermis and an acute inflammatory exudate were visible. The nuclei of the cellular infiltrate were enlarged and hyperchromatic with a characteristic reniform appearance and indistinct nucleoli (Figure 2). The cells were admixed with scattered eosinophils and extravasated red blood cells.

|

| |

Figure 2. Low-power view of dermal mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100), and high-power view of enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei with a characteristic reniform appearance admixed with eosinophils and extravasated red blood cells (B) (H&E, original magnification ×400). | ||

Immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen was strongly positive for both CD1a and S-100 expression (Figure 3). Histopathologic findings were consistent with LCH. Clinicopathologic correlation strongly favored the diagnosis of CSHR.

Comment

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis is a rare, benign, congenital variant of LCH that spontaneously resolves with no systemic involvement. The more aggressive forms typically manifest at birth or during the first 2 months of life and regress within 3 to 4 months.5 Since CSHR was first described in 1973 by Hashimoto and Pritzker,5 more than 100 cases have been reported, but the true incidence is believed to be higher than reported given the high rate of spontaneous resolution and the low rate of clinical recognition.2 The first reported case of CSHR occurred in a female infant who presented at birth with multiple, diffusely distributed, red-brown papules that were 2 to 4 mm in diameter. Although the patient received no treatment, the exanthem completely resolved within 3.5 months without recurrence at 14-year follow-up.5 Most often, CSHR presents as multiple papules or nodules with occasional disseminated crusting and is followed within a few months by a dramatic and spontaneous regression. Lesions may heal with mild postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Pseudo-Darier sign, the propensity to urticate from physical manipulation, has been reported in some lesions with an increased number of mast cells.6 Extensive superficial nasal and oral mucosal erosions have been reported in 2 cases.7 Solitary lesions have been reported in 25% of cases.8

The etiology of CSHR remains unknown, though neoplastic, viral, and immunologic origins have been suggested. There have been reports that human herpesvirus 6 may contribute to the development of LCH.9 It may be postulated that our patient’s presentation of CSHR was potentiated by his recent upper respiratory tract illness. In the literature, CSHR is distributed equally among males and females. Prevalence is higher in the white population than in other racial groups.5

Although CSHR is a benign cutaneous variant of LCH, there have been reports of patients with disseminated and extracutaneous involvement. In 1 rare case, CSHR reportedly involved the eyes, producing multiple, bilateral, well-circumscribed, diffuse, yellow-white lesions of the retinal pigment epithelium throughout the posterior pole of the eyes.10 The retinal lesions spontaneously regressed along with the skin manifestations. Additionally, it was reported that a neonate in Thailand presented with CSHR at birth and 1 month later developed multiple lung cysts that had completely regressed 11 months later.11 One study reported that initial diagnoses of LCH in 18 patients with only cutaneous involvement eventually progressed to systemic LCH, requiring further management.12 When LCH is suspected, a thorough physical examination, including hematologic and coagulation evaluation, liver function tests, musculoskeletal examination, and consultation with specialists if necessary, is recommended.13

There are 3 additional variants of LCH. Letterer-Siwe disease is an acute form of LCH that accounts for 10% of all LCH cases and typically presents in children younger than 2 years. It involves multiple organs, including the bones, lungs, liver, and lymph nodes.14 Affected patients usually present with fever; hepatosplenomegaly; anemia; lymphadenopathy; extensive lytic skull lesions; and a generalized cutaneous eruption, appearing as a maculopapular scaling rash with underlying purpura on the scalp, neck, axilla, and trunk.3 Letterer-Siwe disease is inherited in an autosomal-recessive pattern. Diagnosis is confirmed by skin biopsy demonstrating a thinning of the epidermis and a collection of reticulum cells in the dermis.3 Letterer-Siwe disease is treated with radiation and chemotherapy; if left untreated, the disease is fatal.4

Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, a chronic form of LCH, is most commonly seen in children aged 2 to 6 years and accounts for 15% to 20% of all LCH cases. This LCH variant presents with a classic triad of diabetes insipidus (resulting from erosion into the sella turcica), lytic bone lesions, and exophthalmos.15 Hand-Schüller-Christian disease also affects the oral cavity, producing nodular ulcerations of the hard palate, trouble swallowing, and halitosis.4 The involvement of lytic bone lesions of the mastoid process and petrous portions of the temporal bones may cause recurrent or chronic otitis media and otitis externa. Hand-Schüller-Christian disease is treated with a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgical excision. The mortality rate is 30%.4

Eosinophilic granuloma is the most prevalent variant of LCH, accounting for 60% to 80% of all cases. Characterized by Langerhans cell granulomatous infiltration of the lungs and painful cystic bone lesions, eosinophilic granuloma primarily presents in the third or fourth decades of life.16 Some studies suggest an epidemiologic association with tobacco use.17 In the preliminary stages of this disease, Langerhans cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts infiltrate and form nodules on the terminal bronchioles in the upper and middle lung zones, damaging the airway walls.18 Fibrotic scarring progresses, ultimately resulting in alveolar destruction.10 The common signs and symptoms of eosinophilic granuloma are a nonproductive cough, dyspnea, weight loss, spontaneous pneumothorax, fever, peripheral edema, and a tricuspid regurgitation murmur.14 The prognosis of eosinophilic granuloma is variable. Although some patients progress to end-stage fibrotic lung disease requiring lung transplant, there have been reports of complete remission following cessation of cigarette smoking.17

Langerhans cells travel from the bone marrow to the epidermis where they express the CD1a protein on the surface of the antigen-presenting cell. Elevated levels of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and interleukins have been seen in patients with LCH.1 Their role in the pathogenesis of this disease remains unknown, but the elevated levels of cytokines may indicate the lack of an efficient immune system.

Histologically, hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections demonstrate an infiltrate of histiocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and an increased number of mast cells involving the papillary and reticular dermis. Infiltrating Langerhans cells have concave reniform nuclei18 and stain positive for CD1a, S-100, and CD68 antigens.15 In 10% to 30% of CSHR cases, Birbeck granules can be seen on electron microscopy and tend to transform into laminated dense bodies, signifying the degenerative changes seen in CSHR.15 The various forms of LCH exhibit no significant differences in the expression of the epithelial cadherin, the phosphorylated histone H3, and the Ki-67 proteins, indicating that they are simply different forms of the same disease represented on a spectrum.15

Conclusion

The actual incidence of CSHR may be notably underreported due to its spontaneous regression and low rate of clinical recognition. A subtype of LCH, CSHR is a diagnosis of exclusion. Although CSHR generally follows a benign clinical course, a thorough workup and evaluation for systemic disease with close follow-up is recommended after diagnosis due to the potential of LCH to involve multiple organs and to relapse at a later date after apparent regression.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), also known as histiocytosis X, is a general term that describes a group of rare disorders characterized by the proliferation of Langerhans cells.1 Central to immune surveillance and the elimination of foreign substances from the body, Langerhans cells are derived from bone marrow progenitor cells and found in the epidermis but are capable of migrating from the skin to the lymph nodes. In LCH, these cells congregate on bone tissue, particularly in the head and neck region, causing a multitude of problems.2

The spectrum of LCH includes 4 variants: congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (CSHR)(also known as Hashimoto-Pritzker disease), Letterer-Siwe disease, Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, and eosinophilic granuloma (also known as pulmonary histiocytosis X)(Table). Despite the various clinical presentations and levels of severity, all variants are caused by the proliferation of Langerhans cells. We present a case of CSHR in a 6-month-old male infant that was initially diagnosed as molluscum contagiosum. We believe the actual incidence of CSHR may be underreported due to its spontaneous regression and low rate of clinical recognition.

Case Report

A 6-month-old male infant was referred to our clinic by his pediatrician with a generalized cutaneous eruption of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption, which followed a recent viral upper respiratory tract infection, was characterized by multiple flesh-colored to erythematous, umbilicated papules distributed along the postauricular region, scalp (Figure 1A), abdomen (Figure 1B), and anterior aspect of the neck. Due to his recent illness, the patient was diagnosed with molluscum contagiosum by the referring pediatrician that was treated symptomatically with hydrocortisone lotion, Schamberg’s cream formulated in our office (a compound mixture of zinc oxide, menthol, calcium hydroxide solution, and olive oil), and pediatric diphenhydramine as needed. During a subsequent visit 2 weeks later, a more potent topical corticosteroid and a low-dose systemic corticosteroid was prescribed for 1 week due to development of new lesions and exacerbation of existing lesions. On follow-up 1 week later, the lesions on the trunk had improved, but the patient had developed new lesions on the scalp that differed from prior findings in that they were darker (more erythematous to brown) and firmer (papules and nodules).

|

| |

Figure 1. Multiple fleshcolored to erythematous, umbilicated papules on the frontal scalp (A) and erythematous papules on the abdomen (B). | ||

A shave biopsy was obtained from the frontal scalp to rule out LCH. Histologic examination and culture of the biopsy specimen revealed an atypical cellular infiltrate effacing the dermoepidermal junction and extensive epidermotropism. Focal erosion of the epidermis and an acute inflammatory exudate were visible. The nuclei of the cellular infiltrate were enlarged and hyperchromatic with a characteristic reniform appearance and indistinct nucleoli (Figure 2). The cells were admixed with scattered eosinophils and extravasated red blood cells.

|

| |

Figure 2. Low-power view of dermal mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100), and high-power view of enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei with a characteristic reniform appearance admixed with eosinophils and extravasated red blood cells (B) (H&E, original magnification ×400). | ||

Immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen was strongly positive for both CD1a and S-100 expression (Figure 3). Histopathologic findings were consistent with LCH. Clinicopathologic correlation strongly favored the diagnosis of CSHR.

Comment

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis is a rare, benign, congenital variant of LCH that spontaneously resolves with no systemic involvement. The more aggressive forms typically manifest at birth or during the first 2 months of life and regress within 3 to 4 months.5 Since CSHR was first described in 1973 by Hashimoto and Pritzker,5 more than 100 cases have been reported, but the true incidence is believed to be higher than reported given the high rate of spontaneous resolution and the low rate of clinical recognition.2 The first reported case of CSHR occurred in a female infant who presented at birth with multiple, diffusely distributed, red-brown papules that were 2 to 4 mm in diameter. Although the patient received no treatment, the exanthem completely resolved within 3.5 months without recurrence at 14-year follow-up.5 Most often, CSHR presents as multiple papules or nodules with occasional disseminated crusting and is followed within a few months by a dramatic and spontaneous regression. Lesions may heal with mild postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Pseudo-Darier sign, the propensity to urticate from physical manipulation, has been reported in some lesions with an increased number of mast cells.6 Extensive superficial nasal and oral mucosal erosions have been reported in 2 cases.7 Solitary lesions have been reported in 25% of cases.8

The etiology of CSHR remains unknown, though neoplastic, viral, and immunologic origins have been suggested. There have been reports that human herpesvirus 6 may contribute to the development of LCH.9 It may be postulated that our patient’s presentation of CSHR was potentiated by his recent upper respiratory tract illness. In the literature, CSHR is distributed equally among males and females. Prevalence is higher in the white population than in other racial groups.5

Although CSHR is a benign cutaneous variant of LCH, there have been reports of patients with disseminated and extracutaneous involvement. In 1 rare case, CSHR reportedly involved the eyes, producing multiple, bilateral, well-circumscribed, diffuse, yellow-white lesions of the retinal pigment epithelium throughout the posterior pole of the eyes.10 The retinal lesions spontaneously regressed along with the skin manifestations. Additionally, it was reported that a neonate in Thailand presented with CSHR at birth and 1 month later developed multiple lung cysts that had completely regressed 11 months later.11 One study reported that initial diagnoses of LCH in 18 patients with only cutaneous involvement eventually progressed to systemic LCH, requiring further management.12 When LCH is suspected, a thorough physical examination, including hematologic and coagulation evaluation, liver function tests, musculoskeletal examination, and consultation with specialists if necessary, is recommended.13

There are 3 additional variants of LCH. Letterer-Siwe disease is an acute form of LCH that accounts for 10% of all LCH cases and typically presents in children younger than 2 years. It involves multiple organs, including the bones, lungs, liver, and lymph nodes.14 Affected patients usually present with fever; hepatosplenomegaly; anemia; lymphadenopathy; extensive lytic skull lesions; and a generalized cutaneous eruption, appearing as a maculopapular scaling rash with underlying purpura on the scalp, neck, axilla, and trunk.3 Letterer-Siwe disease is inherited in an autosomal-recessive pattern. Diagnosis is confirmed by skin biopsy demonstrating a thinning of the epidermis and a collection of reticulum cells in the dermis.3 Letterer-Siwe disease is treated with radiation and chemotherapy; if left untreated, the disease is fatal.4

Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, a chronic form of LCH, is most commonly seen in children aged 2 to 6 years and accounts for 15% to 20% of all LCH cases. This LCH variant presents with a classic triad of diabetes insipidus (resulting from erosion into the sella turcica), lytic bone lesions, and exophthalmos.15 Hand-Schüller-Christian disease also affects the oral cavity, producing nodular ulcerations of the hard palate, trouble swallowing, and halitosis.4 The involvement of lytic bone lesions of the mastoid process and petrous portions of the temporal bones may cause recurrent or chronic otitis media and otitis externa. Hand-Schüller-Christian disease is treated with a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgical excision. The mortality rate is 30%.4

Eosinophilic granuloma is the most prevalent variant of LCH, accounting for 60% to 80% of all cases. Characterized by Langerhans cell granulomatous infiltration of the lungs and painful cystic bone lesions, eosinophilic granuloma primarily presents in the third or fourth decades of life.16 Some studies suggest an epidemiologic association with tobacco use.17 In the preliminary stages of this disease, Langerhans cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts infiltrate and form nodules on the terminal bronchioles in the upper and middle lung zones, damaging the airway walls.18 Fibrotic scarring progresses, ultimately resulting in alveolar destruction.10 The common signs and symptoms of eosinophilic granuloma are a nonproductive cough, dyspnea, weight loss, spontaneous pneumothorax, fever, peripheral edema, and a tricuspid regurgitation murmur.14 The prognosis of eosinophilic granuloma is variable. Although some patients progress to end-stage fibrotic lung disease requiring lung transplant, there have been reports of complete remission following cessation of cigarette smoking.17

Langerhans cells travel from the bone marrow to the epidermis where they express the CD1a protein on the surface of the antigen-presenting cell. Elevated levels of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and interleukins have been seen in patients with LCH.1 Their role in the pathogenesis of this disease remains unknown, but the elevated levels of cytokines may indicate the lack of an efficient immune system.

Histologically, hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections demonstrate an infiltrate of histiocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and an increased number of mast cells involving the papillary and reticular dermis. Infiltrating Langerhans cells have concave reniform nuclei18 and stain positive for CD1a, S-100, and CD68 antigens.15 In 10% to 30% of CSHR cases, Birbeck granules can be seen on electron microscopy and tend to transform into laminated dense bodies, signifying the degenerative changes seen in CSHR.15 The various forms of LCH exhibit no significant differences in the expression of the epithelial cadherin, the phosphorylated histone H3, and the Ki-67 proteins, indicating that they are simply different forms of the same disease represented on a spectrum.15

Conclusion

The actual incidence of CSHR may be notably underreported due to its spontaneous regression and low rate of clinical recognition. A subtype of LCH, CSHR is a diagnosis of exclusion. Although CSHR generally follows a benign clinical course, a thorough workup and evaluation for systemic disease with close follow-up is recommended after diagnosis due to the potential of LCH to involve multiple organs and to relapse at a later date after apparent regression.

1. Hussein MR. Skin-limited Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis in children. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:504-511.

2. Nakahigashi K, Ohta M, Sakai R, et al. Late-onset self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: pediatric case of Hashimoto-Pritzker type Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Dermatol. 2007;34:205-209.

3. Pant C, Madonia P, Bahna SL, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a case of Letterer Siwe disease. J La State Med Soc. 2009;161:211-212.

4. Ferreira LM, Emerich PS, Diniz LM, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Letterer-Siwe disease–the importance of dermatological diagnosis in two cases [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:405-409.

5. Hashimoto K, Pritzker MS. Electron microscopic study of reticulohistiocytoma. an unusual case of congenital, self-healing reticulohistiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:263-270.

6. Kapur P, Erickson C, Rakheja D, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (Hashimoto-Pritzker disease): ten-year experience at Dallas Children’s Medical Center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:290-294.

7. Le Bidre E, Lorette G, Delage M, et al. Extensive, erosive congenital self-healing cell histiocytosis [published online December 22, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:835-836.

8. Weiss T, Weber L, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, et al. Solitary cutaneous dendritic cell tumor in a child: role of dendritic cell markers for the diagnosis of skin Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:838-844.

9. Csire M, Mikala G, Jákó J, et al. Persistent long-term human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) infection in a patient with Langerhans cell histiocytosis [published online July 3, 2007]. Pathol Oncol Res. 2007;13:157-160.

10. Zaenglein AL, Steele MA, Kamino H, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with eye involvement. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:135-137.

11. Chunharas A, Pabunruang W, Hongeng S. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis with pulmonary involvement: spontaneous regression. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85(suppl 4):S1309-S1313.

12. Minkov M, Prosch H, Steiner M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in neonates. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:802-807.

13. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a review of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:291-295.

14. Stacher E, Beham-Schmid C, Terpe HJ, et al. Pulmonary histiocytic sarcoma mimicking pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a young adult presenting with spontaneous pneumothorax: a potential diagnostic pitfall [published online June 27, 2009]. Virchows Arch. 2009;455:187-190.

15. Scolozzi P, Lombardi T, Monnier P, et al. Multisystem Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (Hand-Schüller-Christian disease) in an adult: a case report and review of the literature [published online October 10, 2003]. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:326-330.

16. Noonan V, Kabani S, Alibhai K. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma). J Mass Dent Soc. 2011;60:35.

17. Podbielski FJ, Worley TA, Korn JM, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma of the lung and rib. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2009;17:194-195.

18. Rosso DA, Ripoli MF, Roy A, et al. Serum levels of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are elevated in children with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:480-483.

1. Hussein MR. Skin-limited Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis in children. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:504-511.

2. Nakahigashi K, Ohta M, Sakai R, et al. Late-onset self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: pediatric case of Hashimoto-Pritzker type Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Dermatol. 2007;34:205-209.

3. Pant C, Madonia P, Bahna SL, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a case of Letterer Siwe disease. J La State Med Soc. 2009;161:211-212.

4. Ferreira LM, Emerich PS, Diniz LM, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Letterer-Siwe disease–the importance of dermatological diagnosis in two cases [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:405-409.

5. Hashimoto K, Pritzker MS. Electron microscopic study of reticulohistiocytoma. an unusual case of congenital, self-healing reticulohistiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:263-270.

6. Kapur P, Erickson C, Rakheja D, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (Hashimoto-Pritzker disease): ten-year experience at Dallas Children’s Medical Center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:290-294.

7. Le Bidre E, Lorette G, Delage M, et al. Extensive, erosive congenital self-healing cell histiocytosis [published online December 22, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:835-836.

8. Weiss T, Weber L, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, et al. Solitary cutaneous dendritic cell tumor in a child: role of dendritic cell markers for the diagnosis of skin Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:838-844.

9. Csire M, Mikala G, Jákó J, et al. Persistent long-term human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) infection in a patient with Langerhans cell histiocytosis [published online July 3, 2007]. Pathol Oncol Res. 2007;13:157-160.

10. Zaenglein AL, Steele MA, Kamino H, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with eye involvement. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:135-137.

11. Chunharas A, Pabunruang W, Hongeng S. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis with pulmonary involvement: spontaneous regression. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85(suppl 4):S1309-S1313.

12. Minkov M, Prosch H, Steiner M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in neonates. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:802-807.

13. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a review of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:291-295.

14. Stacher E, Beham-Schmid C, Terpe HJ, et al. Pulmonary histiocytic sarcoma mimicking pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a young adult presenting with spontaneous pneumothorax: a potential diagnostic pitfall [published online June 27, 2009]. Virchows Arch. 2009;455:187-190.

15. Scolozzi P, Lombardi T, Monnier P, et al. Multisystem Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (Hand-Schüller-Christian disease) in an adult: a case report and review of the literature [published online October 10, 2003]. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:326-330.

16. Noonan V, Kabani S, Alibhai K. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma). J Mass Dent Soc. 2011;60:35.

17. Podbielski FJ, Worley TA, Korn JM, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma of the lung and rib. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2009;17:194-195.

18. Rosso DA, Ripoli MF, Roy A, et al. Serum levels of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are elevated in children with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:480-483.

Practice Points

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is believed to occur in 1:200,000 children and tends to be underdiagnosed, as some patients may have no symptoms while others have symptoms that are misdiagnosed as other conditions.

- Patients with LCH usually should have long-term follow-up care to detect progression or complications of the disease or treatment.

Recurrent Abdominal Pain and Bowel Edema in a Middle-Aged Woman

A 34-year-old African American woman presented to the emergency department (ED) after several hours of sharp lower abdominal pain and cramping followed by nausea and vomiting. The pain initially began in the periumbilical region and migrated to the bilateral lower quadrants. The patient reported no fevers, chills, diarrhea, hematemesis, or hematochezia associated with these symptoms. She also reported no unusual food exposures or sick contacts.

The patient’s medical history was notable only for hypertension; her surgical history included 2 cesarean section births several years prior to presentation. Her father was diagnosed with stomach cancer in his 40s. The patient’s only medications were an oral contraceptive, lisinopril, and an antihistamine taken as needed for seasonal allergies. She had no history of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use and no known drug allergies.

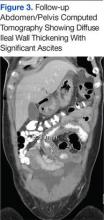

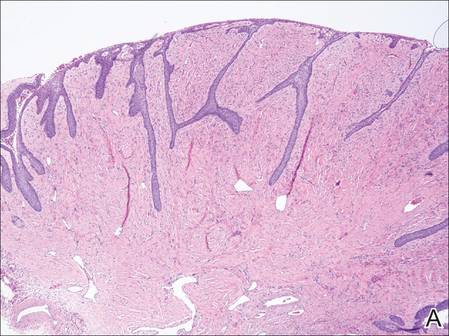

While in the ED, the patient’s physical exam revealed mild tachycardia (104 bpm on arrival, which improved with fluid resuscitation) and diffuse abdominal tenderness. Laboratory evaluation revealed a mild leukocytosis (10.7 x 103/L) but normal liver-associated enzymes, lipase, and urinalysis. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and IV contrast revealed diffuse ileal wall thickening with significant perihepatic and perisplenic ascites with pelvic free fluid suspicious for an inflammatory vs infectious enteritis (Figure 1).

The patient was treated supportively with IV fluids, antiemetics, and pain medication. Her symptoms generally improved over several days, though she did develop loose stools that prompted infectious stool studies, which were negative for typical pathogens. Follow-up laboratory testing revealed resolution of her leukocytosis.

About 2 weeks later, the patient had another acute attack of abdominal pain, again associated with nausea and vomiting.

Six weeks after her initial presentation, the patient presented to the ED for the third time with the same symptoms. A CT scan again displayed diffuse ileal wall thickening with significant ascites; slightly worse than the image from initial presentation (Figure 3).

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

[Click through to the next page to see the answer.]

Diagnosis

This patient presented with recurrent episodes of diffuse small bowel wall thickening and ascites associated with diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Her symptoms resolved spontaneously, correlating with normalization of bowel wall appearance on imaging studies. Initially, the patient’s symptoms were most concerning for infectious or inflammatory enteritis. Infection became lower on the differential as the patient’s symptoms continued to recur and then resolve spontaneously without antiviral or antibiotic treatment. She also had no fevers, and stools samples were negative for infectious causes of her symptoms.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) was considered, but direct visualization of the small bowel and colonic mucosa was unremarkable. In addition, the sporadic nature of her symptoms did not fit the typical IBD presentation. The patient had no risk factors or history that would suggest ischemic disease, vasculitis, or radiation-induced enteritis. Hereditary angioedema and acquired C1 esterase deficiency were considered given the intermittent nature and characteristic quality of her symptoms. However, serum C4 and C1 esterase inhibitor levels returned within normal limits when measured during these episodes. Finally, visceral angioedema was considered.

Visceral angioedema may be related to medications and is specifically associated with angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors as well as β-lactams and high doses of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Given the characteristic presentation with no other inciting cause, the patient’s lisinopril was felt to be the causative agent and was discontinued. Her symptoms resolved completely and never returned. The patient’s final diagnosis was ACE inhibitor-induced visceral angioedema.

About This Condition

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors were first introduced in the early 1980s and have been prescribed more frequently as the indications for their use have increased. Some estimate that ACE inhibitors are used by more than 40 million people worldwide.1 Angioedema has been reported to occur in 0.1% to 0.2% of patients taking ACE inhibitorsand accounts for 20% to 30% of all angioedema cases presenting to EDs.2,3 However, ACE inhibitors recently have been recognized as a rare cause of angioedema of the gastrointestinal tract. One of the largest literature reviews on ACE inhibitor-induced gastrointestinal angioedema describes only 27 cases.3

Prevalence seems to be highest among middle-aged or older women, particularly among African Americans.3 The interval between medication initiation and onset of symptoms can vary, ranging from 24 hours to 9 years.3,4 In many cases, lack of recognition of this condition early in the disease course led to costly and invasive procedures, such as abdominal laparotomy, before reaching a diagnosis. Other literature reviews report similar patient characteristics and initial disease manifestations: female predominance, often middle-aged, presenting with abdominal pain and emesis associated with bowel wall thickening and ascites on CT.4,5 Additionally, in the majority of cases, visceral angioedema occurred in the absence of oropharyngeal angioedema. Unlike allergic angioedema or NSAID-induced angioedema, ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema is not associated with urticaria.6

The exact pathway of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema is not completely understood but is thought to be bradykinin mediated. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors decrease the degradation of bradykinin, which ultimately leads to an increase in vascular permeability and results in an increased plasma extravasation into the interstitial space of subcutaneous or submucosal tissue.1 However, many experts believe that the exclusive role of bradykinin is unlikely. Some suggest that patients with ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema are more likely to have decreased levels or defects in other enzymes such as carboxypeptidase N and aminopeptidase P, which are involved in the breakdown of bradykinin and its metabolites.6 Given the female predominance in this patient population, it also seems reasonable to consider the role of estrogens in the pathogenesis of this disease, although none have been identified to the knowledge of the authors.

Treatment of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema is largely supportive following discontinuation of the offending medication. There have been case reports of infrequent, mild, recurrent episodes of angioedema, even after ACE inhibitor discontinuation, so these should be anticipated.7

Conclusions

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced gastrointestinal angioedema is a rare condition. It generally presents as recurrent abdominal pain and nausea with CT findings of intestinal edema and ascites. It is more common among the middle-aged, women, and minorities. ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema should be kept on the differential for patients with the aforementioned characteristics, especially if infection, inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic disease, or vasculitis is deemed unlikely. Identifying this condition early can save patients from unnecessary hospitalizations, physical and emotional discomfort, and further health care costs.