User login

Total Hip Arthroplasty After Proximal Femoral Osteotomy: A Technique That Can Be Used to Address Presence of a Retained Intracortical Plate

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an effective treatment for advanced hip arthritis from a variety of causes, including osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, and sequelae of developmental disorders. It is not uncommon to perform THA in the presence of a previous proximal femoral osteotomy that may have been performed for slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or developmental dysplasia of the hip, among other conditions. These osteotomies are commonly combined with internal fixation, a plate-and-screw device. These patients are at risk for developing degenerative arthritis at an earlier age than patients with other types of arthritis and subsequently may undergo THA at a younger age.1-3 Presence of a plate can pose a technical challenge during THA surgery. THA performed after intertrochanteric osteotomy has higher rates of perioperative and postoperative complications.4 Ferguson and colleagues4 noted difficulty during hardware removal in 24% of cases. Among the complications encountered were broken hardware, stripped screws, greater trochanteric fracture, stress risers from previous screw holes, canal narrowing from endosteal hypertrophy around hardware, and lateral cortical deficiency after removal of the side plate. As intertrochanteric osteotomies are often performed in patients who have yet to reach skeletal maturity, cortical hypertrophy can lead to complete coverage of the side plate and an “intracortical” position.

This article reports on 2 THA cases in which a technique was used to avoid intracortical plate removal and the resulting problems of lateral cortical deficiency. During each THA, the plate was left in place to avoid compromise of the lateral femoral cortex. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Case 1

An adolescent with bilateral SCFE was treated first with internal fixation of the right hip and subsequently with left proximal femoral osteotomy with internal fixation. He did well until age 31 years, when he developed progressively worsening pain about the left hip. Clinical findings and imaging studies were consistent with advanced degenerative arthritis of the left hip. Radiographs showed a sliding hip screw in place, with proximal femoral deformity consisting of femoral neck shortening and posterior angulation (Figures 1A, 1B). Preoperative Harris Hip Score was 54.5.

Case 2

A 51-year-old woman presented with a history of right hip problems dating back to age 13 years, when she sustained a fracture of the right hip and was treated with internal fixation. At age 15 years, she underwent proximal femoral osteotomy to correct residual deformity. She did well until age 45 years, when she developed worsening hip symptoms. Clinical findings and imaging studies were consistent with advanced degenerative arthritis of the right hip. Radiographs showed a fixed-angle blade plate in the proximal femur, with significant proximal femoral deformity (Figures 1C, 1D). Preoperative Harris Hip Score was 53.6.

Surgical Technique

In both cases, a standard series of radiographs was obtained—an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis and AP and cross-table lateral radiographs of the operative hip (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) with a metal-artifact-reducing technique may be useful in determining amount of cortical bone remaining under the plate. CT showed limited lateral cortex beneath the side plate and bony overgrowth covering the side plate. Preoperative templating was performed using previously described techniques.5

During THA, before removing any portion of any retained hardware, the surgeon should perform 3 important actions: Dislocate the hip, perform all appropriate capsular releases, and reduce the hip. Dislocating the hip before hardware removal significantly decreases the risk for fracture caused by stress risers, as the force required for dislocation is much more controlled because of the capsular releases. After hardware removal, the hip can be easily redislocated, and the femoral neck osteotomy can be performed.

When plate and screws are in an intracortical position, the screws can be removed only after removing the small shell of cortical bone covering them. The amount of bone to be removed is minimal. After the screws are removed, the plate remains in place. A motorized device with a metal-cutting attachment is used to transect the construct at the junction of the plate and barrel (case 1) or at the bend of a fixed-angle device (case 2). Laparotomy sponges are placed around the proximal femur to minimize the amount of soft tissue that could be exposed to metal shavings. Copious irrigation is used throughout this part of the procedure. Osteotomes are used to elevate the proximal portion of the plate and the barrel, preserving the distal portion of the plate on the lateral cortex of the femoral shaft.

After the head is removed, the rest of the THA can be performed using standard press-fit insertion technique (Figures 2A-2D). Care must be taken to ensure that the distal aspect of the femoral stem bypasses the most distal screw hole by at least 2 cortical diameters in order to reduce the risk for periprosthetic fracture.

By 2-year follow-up, both patients had regained excellent range of motion, ambulation, and overall function. Postoperative Harris Hip Scores were 86.6 and 83.8, respectively. There were no radiographic signs of complications.

Discussion

THA can be challenging in the setting of previously placed internal fixation devices, particularly devices inserted during a patient’s adolescence, as significant bony overgrowth can occur. The standard approach has been to remove the internal fixation device and then perform the THA. In most cases, and particularly when the internal fixation device is in an intracortical position, the result is significant compromise of bone. This article describes a technique in which a portion of the hardware is retained to avoid compromise of the lateral femoral cortex, thereby allowing insertion of a noncemented femoral component.

THA is the most effective procedure for reducing hip pain and disability in the setting of degenerative changes.6 Patients with SCFE, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or developmental dysplasia of the hip generally are younger at the time they may be sufficiently symptomatic to consider THA.7,8 Many have had previous surgery using internal fixation devices. THAs after previous osteotomies with internal fixation devices are more technically demanding, require more operative time, are subject to more blood loss, and have a higher rate of complications, including femoral fracture. Ferguson and colleagues4 and Boos and colleagues9 found these surgeries were more difficult 33.8% and 36.8% of the time, respectively. For these reasons, some authors have recommended removing the internal fixation device as soon as the osteotomy is healed.4 However, this has not become the standard of care, and surgeons continue to perform THAs in the presence of a previous osteotomy with an internal fixation device in place.

The technique described in this article was used successfully in 2 cases. In each case, leaving the intracortical plate in place avoided compromise of the lateral femoral cortex and allowed insertion of a noncemented femoral component without complication. Of course, with the screw holes representing stress risers, careful insertion of the femoral component was required. Retaining the intracortical plate allowed it to function as part of the lateral femoral cortex, thereby maintaining the structural integrity of the femoral canal. As has been described for the 2 cases, a blade plate and plate and barrel were converted to a limited intracortical plate by removing the proximal portion of the plates—a modification that could be applied to other types of internal fixation devices that extend into the femoral neck as long as appropriate cutting tools are available.

Conclusion

THA in the setting of a retained internal fixation device is relatively common. This article describes a technique that can be used when a plate applied to the lateral femoral cortex has become intracortical as a result of extensive bony overgrowth. In using this technique to avoid plate removal, the surgeon eliminates the need for more extensive procedures aimed at compensating for deficiency of the femoral cortex in the area of plate removal. Although only 2 cases are presented here, this technique potentially can be used more broadly in these specific clinical situations.

1. Engesæter LB, Engesæter IØ, Fenstad AM, et al. Low revision rate after total hip arthroplasty in patients with pediatric hip diseases. Acta Orthop. 2012;83(5):436-441.

2. Froberg L, Christensen F, Pedersen NW, Overgaard S. The need for total hip arthroplasty in Perthes disease: a long-term study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1134-1140.

3. Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesæter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-99. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(4):579-586.

4. Ferguson GM, Cabanela ME, Ilstrup DM. Total hip arthroplasty after failed intertrochanteric osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(2):252-257.

5. Scheerlinck T. Primary hip arthroplasty templating on standard radiographs. A stepwise approach. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76(4):432-442.

6. Wroblewski BM, Siney PD. Charnley low-friction arthroplasty of the hip. Long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(292):191-201.

7. Chandler HP, Reineck FT, Wixson RL, McCarthy JC. Total hip replacement in patients younger than thirty years old. A five-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(9):1426-1434.

8. Dorr LD, Luckett M, Conaty JP. Total hip arthroplasties in patients younger than 45 years. A nine- to ten-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(260):215-219.

9. Boos N, Krushell R, Ganz R, Müller ME. Total hip arthroplasty after previous proximal femoral osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(2):247-253.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an effective treatment for advanced hip arthritis from a variety of causes, including osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, and sequelae of developmental disorders. It is not uncommon to perform THA in the presence of a previous proximal femoral osteotomy that may have been performed for slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or developmental dysplasia of the hip, among other conditions. These osteotomies are commonly combined with internal fixation, a plate-and-screw device. These patients are at risk for developing degenerative arthritis at an earlier age than patients with other types of arthritis and subsequently may undergo THA at a younger age.1-3 Presence of a plate can pose a technical challenge during THA surgery. THA performed after intertrochanteric osteotomy has higher rates of perioperative and postoperative complications.4 Ferguson and colleagues4 noted difficulty during hardware removal in 24% of cases. Among the complications encountered were broken hardware, stripped screws, greater trochanteric fracture, stress risers from previous screw holes, canal narrowing from endosteal hypertrophy around hardware, and lateral cortical deficiency after removal of the side plate. As intertrochanteric osteotomies are often performed in patients who have yet to reach skeletal maturity, cortical hypertrophy can lead to complete coverage of the side plate and an “intracortical” position.

This article reports on 2 THA cases in which a technique was used to avoid intracortical plate removal and the resulting problems of lateral cortical deficiency. During each THA, the plate was left in place to avoid compromise of the lateral femoral cortex. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Case 1

An adolescent with bilateral SCFE was treated first with internal fixation of the right hip and subsequently with left proximal femoral osteotomy with internal fixation. He did well until age 31 years, when he developed progressively worsening pain about the left hip. Clinical findings and imaging studies were consistent with advanced degenerative arthritis of the left hip. Radiographs showed a sliding hip screw in place, with proximal femoral deformity consisting of femoral neck shortening and posterior angulation (Figures 1A, 1B). Preoperative Harris Hip Score was 54.5.

Case 2

A 51-year-old woman presented with a history of right hip problems dating back to age 13 years, when she sustained a fracture of the right hip and was treated with internal fixation. At age 15 years, she underwent proximal femoral osteotomy to correct residual deformity. She did well until age 45 years, when she developed worsening hip symptoms. Clinical findings and imaging studies were consistent with advanced degenerative arthritis of the right hip. Radiographs showed a fixed-angle blade plate in the proximal femur, with significant proximal femoral deformity (Figures 1C, 1D). Preoperative Harris Hip Score was 53.6.

Surgical Technique

In both cases, a standard series of radiographs was obtained—an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis and AP and cross-table lateral radiographs of the operative hip (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) with a metal-artifact-reducing technique may be useful in determining amount of cortical bone remaining under the plate. CT showed limited lateral cortex beneath the side plate and bony overgrowth covering the side plate. Preoperative templating was performed using previously described techniques.5

During THA, before removing any portion of any retained hardware, the surgeon should perform 3 important actions: Dislocate the hip, perform all appropriate capsular releases, and reduce the hip. Dislocating the hip before hardware removal significantly decreases the risk for fracture caused by stress risers, as the force required for dislocation is much more controlled because of the capsular releases. After hardware removal, the hip can be easily redislocated, and the femoral neck osteotomy can be performed.

When plate and screws are in an intracortical position, the screws can be removed only after removing the small shell of cortical bone covering them. The amount of bone to be removed is minimal. After the screws are removed, the plate remains in place. A motorized device with a metal-cutting attachment is used to transect the construct at the junction of the plate and barrel (case 1) or at the bend of a fixed-angle device (case 2). Laparotomy sponges are placed around the proximal femur to minimize the amount of soft tissue that could be exposed to metal shavings. Copious irrigation is used throughout this part of the procedure. Osteotomes are used to elevate the proximal portion of the plate and the barrel, preserving the distal portion of the plate on the lateral cortex of the femoral shaft.

After the head is removed, the rest of the THA can be performed using standard press-fit insertion technique (Figures 2A-2D). Care must be taken to ensure that the distal aspect of the femoral stem bypasses the most distal screw hole by at least 2 cortical diameters in order to reduce the risk for periprosthetic fracture.

By 2-year follow-up, both patients had regained excellent range of motion, ambulation, and overall function. Postoperative Harris Hip Scores were 86.6 and 83.8, respectively. There were no radiographic signs of complications.

Discussion

THA can be challenging in the setting of previously placed internal fixation devices, particularly devices inserted during a patient’s adolescence, as significant bony overgrowth can occur. The standard approach has been to remove the internal fixation device and then perform the THA. In most cases, and particularly when the internal fixation device is in an intracortical position, the result is significant compromise of bone. This article describes a technique in which a portion of the hardware is retained to avoid compromise of the lateral femoral cortex, thereby allowing insertion of a noncemented femoral component.

THA is the most effective procedure for reducing hip pain and disability in the setting of degenerative changes.6 Patients with SCFE, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or developmental dysplasia of the hip generally are younger at the time they may be sufficiently symptomatic to consider THA.7,8 Many have had previous surgery using internal fixation devices. THAs after previous osteotomies with internal fixation devices are more technically demanding, require more operative time, are subject to more blood loss, and have a higher rate of complications, including femoral fracture. Ferguson and colleagues4 and Boos and colleagues9 found these surgeries were more difficult 33.8% and 36.8% of the time, respectively. For these reasons, some authors have recommended removing the internal fixation device as soon as the osteotomy is healed.4 However, this has not become the standard of care, and surgeons continue to perform THAs in the presence of a previous osteotomy with an internal fixation device in place.

The technique described in this article was used successfully in 2 cases. In each case, leaving the intracortical plate in place avoided compromise of the lateral femoral cortex and allowed insertion of a noncemented femoral component without complication. Of course, with the screw holes representing stress risers, careful insertion of the femoral component was required. Retaining the intracortical plate allowed it to function as part of the lateral femoral cortex, thereby maintaining the structural integrity of the femoral canal. As has been described for the 2 cases, a blade plate and plate and barrel were converted to a limited intracortical plate by removing the proximal portion of the plates—a modification that could be applied to other types of internal fixation devices that extend into the femoral neck as long as appropriate cutting tools are available.

Conclusion

THA in the setting of a retained internal fixation device is relatively common. This article describes a technique that can be used when a plate applied to the lateral femoral cortex has become intracortical as a result of extensive bony overgrowth. In using this technique to avoid plate removal, the surgeon eliminates the need for more extensive procedures aimed at compensating for deficiency of the femoral cortex in the area of plate removal. Although only 2 cases are presented here, this technique potentially can be used more broadly in these specific clinical situations.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an effective treatment for advanced hip arthritis from a variety of causes, including osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, and sequelae of developmental disorders. It is not uncommon to perform THA in the presence of a previous proximal femoral osteotomy that may have been performed for slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or developmental dysplasia of the hip, among other conditions. These osteotomies are commonly combined with internal fixation, a plate-and-screw device. These patients are at risk for developing degenerative arthritis at an earlier age than patients with other types of arthritis and subsequently may undergo THA at a younger age.1-3 Presence of a plate can pose a technical challenge during THA surgery. THA performed after intertrochanteric osteotomy has higher rates of perioperative and postoperative complications.4 Ferguson and colleagues4 noted difficulty during hardware removal in 24% of cases. Among the complications encountered were broken hardware, stripped screws, greater trochanteric fracture, stress risers from previous screw holes, canal narrowing from endosteal hypertrophy around hardware, and lateral cortical deficiency after removal of the side plate. As intertrochanteric osteotomies are often performed in patients who have yet to reach skeletal maturity, cortical hypertrophy can lead to complete coverage of the side plate and an “intracortical” position.

This article reports on 2 THA cases in which a technique was used to avoid intracortical plate removal and the resulting problems of lateral cortical deficiency. During each THA, the plate was left in place to avoid compromise of the lateral femoral cortex. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Case 1

An adolescent with bilateral SCFE was treated first with internal fixation of the right hip and subsequently with left proximal femoral osteotomy with internal fixation. He did well until age 31 years, when he developed progressively worsening pain about the left hip. Clinical findings and imaging studies were consistent with advanced degenerative arthritis of the left hip. Radiographs showed a sliding hip screw in place, with proximal femoral deformity consisting of femoral neck shortening and posterior angulation (Figures 1A, 1B). Preoperative Harris Hip Score was 54.5.

Case 2

A 51-year-old woman presented with a history of right hip problems dating back to age 13 years, when she sustained a fracture of the right hip and was treated with internal fixation. At age 15 years, she underwent proximal femoral osteotomy to correct residual deformity. She did well until age 45 years, when she developed worsening hip symptoms. Clinical findings and imaging studies were consistent with advanced degenerative arthritis of the right hip. Radiographs showed a fixed-angle blade plate in the proximal femur, with significant proximal femoral deformity (Figures 1C, 1D). Preoperative Harris Hip Score was 53.6.

Surgical Technique

In both cases, a standard series of radiographs was obtained—an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis and AP and cross-table lateral radiographs of the operative hip (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) with a metal-artifact-reducing technique may be useful in determining amount of cortical bone remaining under the plate. CT showed limited lateral cortex beneath the side plate and bony overgrowth covering the side plate. Preoperative templating was performed using previously described techniques.5

During THA, before removing any portion of any retained hardware, the surgeon should perform 3 important actions: Dislocate the hip, perform all appropriate capsular releases, and reduce the hip. Dislocating the hip before hardware removal significantly decreases the risk for fracture caused by stress risers, as the force required for dislocation is much more controlled because of the capsular releases. After hardware removal, the hip can be easily redislocated, and the femoral neck osteotomy can be performed.

When plate and screws are in an intracortical position, the screws can be removed only after removing the small shell of cortical bone covering them. The amount of bone to be removed is minimal. After the screws are removed, the plate remains in place. A motorized device with a metal-cutting attachment is used to transect the construct at the junction of the plate and barrel (case 1) or at the bend of a fixed-angle device (case 2). Laparotomy sponges are placed around the proximal femur to minimize the amount of soft tissue that could be exposed to metal shavings. Copious irrigation is used throughout this part of the procedure. Osteotomes are used to elevate the proximal portion of the plate and the barrel, preserving the distal portion of the plate on the lateral cortex of the femoral shaft.

After the head is removed, the rest of the THA can be performed using standard press-fit insertion technique (Figures 2A-2D). Care must be taken to ensure that the distal aspect of the femoral stem bypasses the most distal screw hole by at least 2 cortical diameters in order to reduce the risk for periprosthetic fracture.

By 2-year follow-up, both patients had regained excellent range of motion, ambulation, and overall function. Postoperative Harris Hip Scores were 86.6 and 83.8, respectively. There were no radiographic signs of complications.

Discussion

THA can be challenging in the setting of previously placed internal fixation devices, particularly devices inserted during a patient’s adolescence, as significant bony overgrowth can occur. The standard approach has been to remove the internal fixation device and then perform the THA. In most cases, and particularly when the internal fixation device is in an intracortical position, the result is significant compromise of bone. This article describes a technique in which a portion of the hardware is retained to avoid compromise of the lateral femoral cortex, thereby allowing insertion of a noncemented femoral component.

THA is the most effective procedure for reducing hip pain and disability in the setting of degenerative changes.6 Patients with SCFE, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or developmental dysplasia of the hip generally are younger at the time they may be sufficiently symptomatic to consider THA.7,8 Many have had previous surgery using internal fixation devices. THAs after previous osteotomies with internal fixation devices are more technically demanding, require more operative time, are subject to more blood loss, and have a higher rate of complications, including femoral fracture. Ferguson and colleagues4 and Boos and colleagues9 found these surgeries were more difficult 33.8% and 36.8% of the time, respectively. For these reasons, some authors have recommended removing the internal fixation device as soon as the osteotomy is healed.4 However, this has not become the standard of care, and surgeons continue to perform THAs in the presence of a previous osteotomy with an internal fixation device in place.

The technique described in this article was used successfully in 2 cases. In each case, leaving the intracortical plate in place avoided compromise of the lateral femoral cortex and allowed insertion of a noncemented femoral component without complication. Of course, with the screw holes representing stress risers, careful insertion of the femoral component was required. Retaining the intracortical plate allowed it to function as part of the lateral femoral cortex, thereby maintaining the structural integrity of the femoral canal. As has been described for the 2 cases, a blade plate and plate and barrel were converted to a limited intracortical plate by removing the proximal portion of the plates—a modification that could be applied to other types of internal fixation devices that extend into the femoral neck as long as appropriate cutting tools are available.

Conclusion

THA in the setting of a retained internal fixation device is relatively common. This article describes a technique that can be used when a plate applied to the lateral femoral cortex has become intracortical as a result of extensive bony overgrowth. In using this technique to avoid plate removal, the surgeon eliminates the need for more extensive procedures aimed at compensating for deficiency of the femoral cortex in the area of plate removal. Although only 2 cases are presented here, this technique potentially can be used more broadly in these specific clinical situations.

1. Engesæter LB, Engesæter IØ, Fenstad AM, et al. Low revision rate after total hip arthroplasty in patients with pediatric hip diseases. Acta Orthop. 2012;83(5):436-441.

2. Froberg L, Christensen F, Pedersen NW, Overgaard S. The need for total hip arthroplasty in Perthes disease: a long-term study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1134-1140.

3. Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesæter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-99. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(4):579-586.

4. Ferguson GM, Cabanela ME, Ilstrup DM. Total hip arthroplasty after failed intertrochanteric osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(2):252-257.

5. Scheerlinck T. Primary hip arthroplasty templating on standard radiographs. A stepwise approach. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76(4):432-442.

6. Wroblewski BM, Siney PD. Charnley low-friction arthroplasty of the hip. Long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(292):191-201.

7. Chandler HP, Reineck FT, Wixson RL, McCarthy JC. Total hip replacement in patients younger than thirty years old. A five-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(9):1426-1434.

8. Dorr LD, Luckett M, Conaty JP. Total hip arthroplasties in patients younger than 45 years. A nine- to ten-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(260):215-219.

9. Boos N, Krushell R, Ganz R, Müller ME. Total hip arthroplasty after previous proximal femoral osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(2):247-253.

1. Engesæter LB, Engesæter IØ, Fenstad AM, et al. Low revision rate after total hip arthroplasty in patients with pediatric hip diseases. Acta Orthop. 2012;83(5):436-441.

2. Froberg L, Christensen F, Pedersen NW, Overgaard S. The need for total hip arthroplasty in Perthes disease: a long-term study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1134-1140.

3. Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesæter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-99. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(4):579-586.

4. Ferguson GM, Cabanela ME, Ilstrup DM. Total hip arthroplasty after failed intertrochanteric osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(2):252-257.

5. Scheerlinck T. Primary hip arthroplasty templating on standard radiographs. A stepwise approach. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76(4):432-442.

6. Wroblewski BM, Siney PD. Charnley low-friction arthroplasty of the hip. Long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(292):191-201.

7. Chandler HP, Reineck FT, Wixson RL, McCarthy JC. Total hip replacement in patients younger than thirty years old. A five-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(9):1426-1434.

8. Dorr LD, Luckett M, Conaty JP. Total hip arthroplasties in patients younger than 45 years. A nine- to ten-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(260):215-219.

9. Boos N, Krushell R, Ganz R, Müller ME. Total hip arthroplasty after previous proximal femoral osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(2):247-253.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Vein Graft Donor Site

Case Report

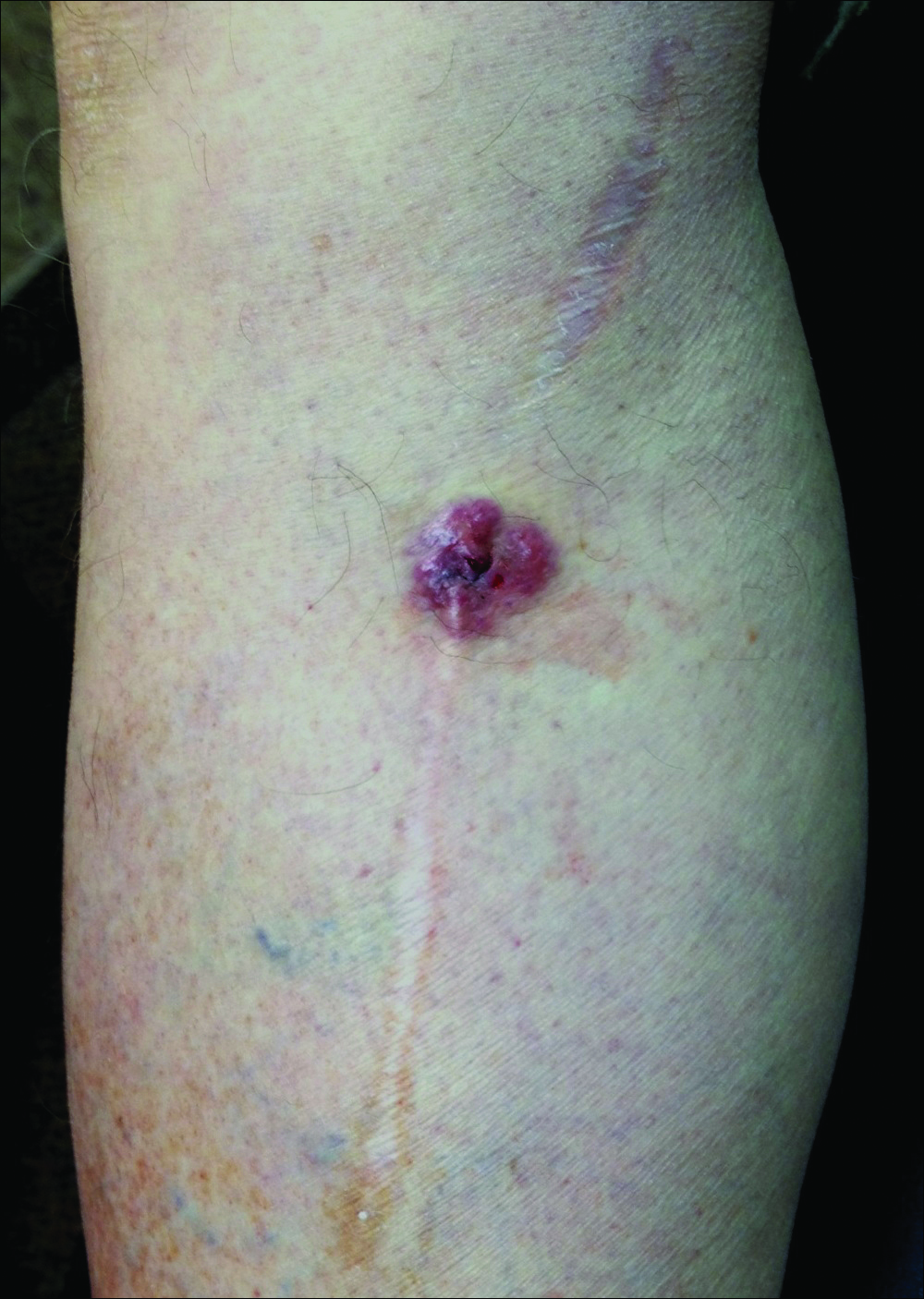

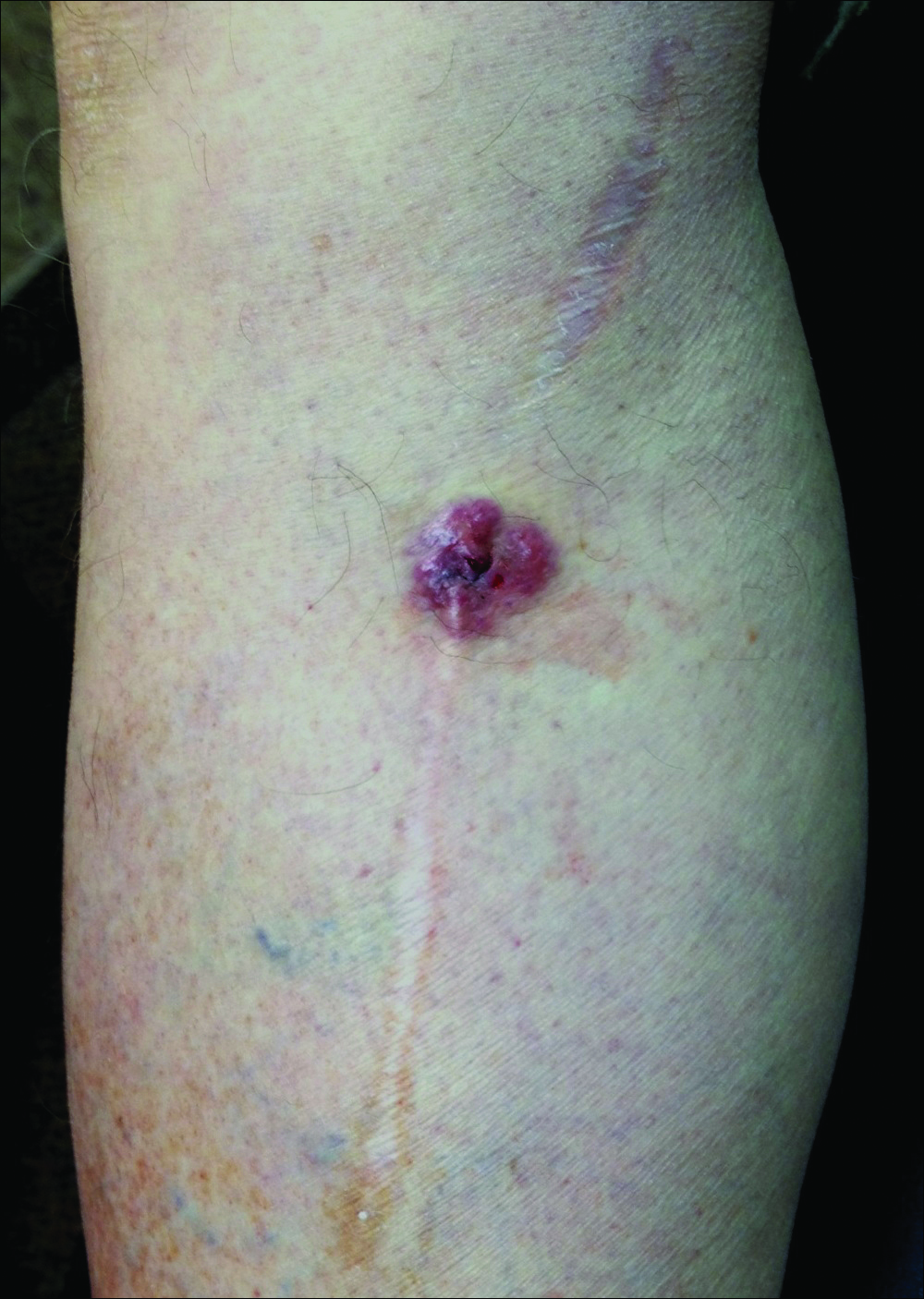

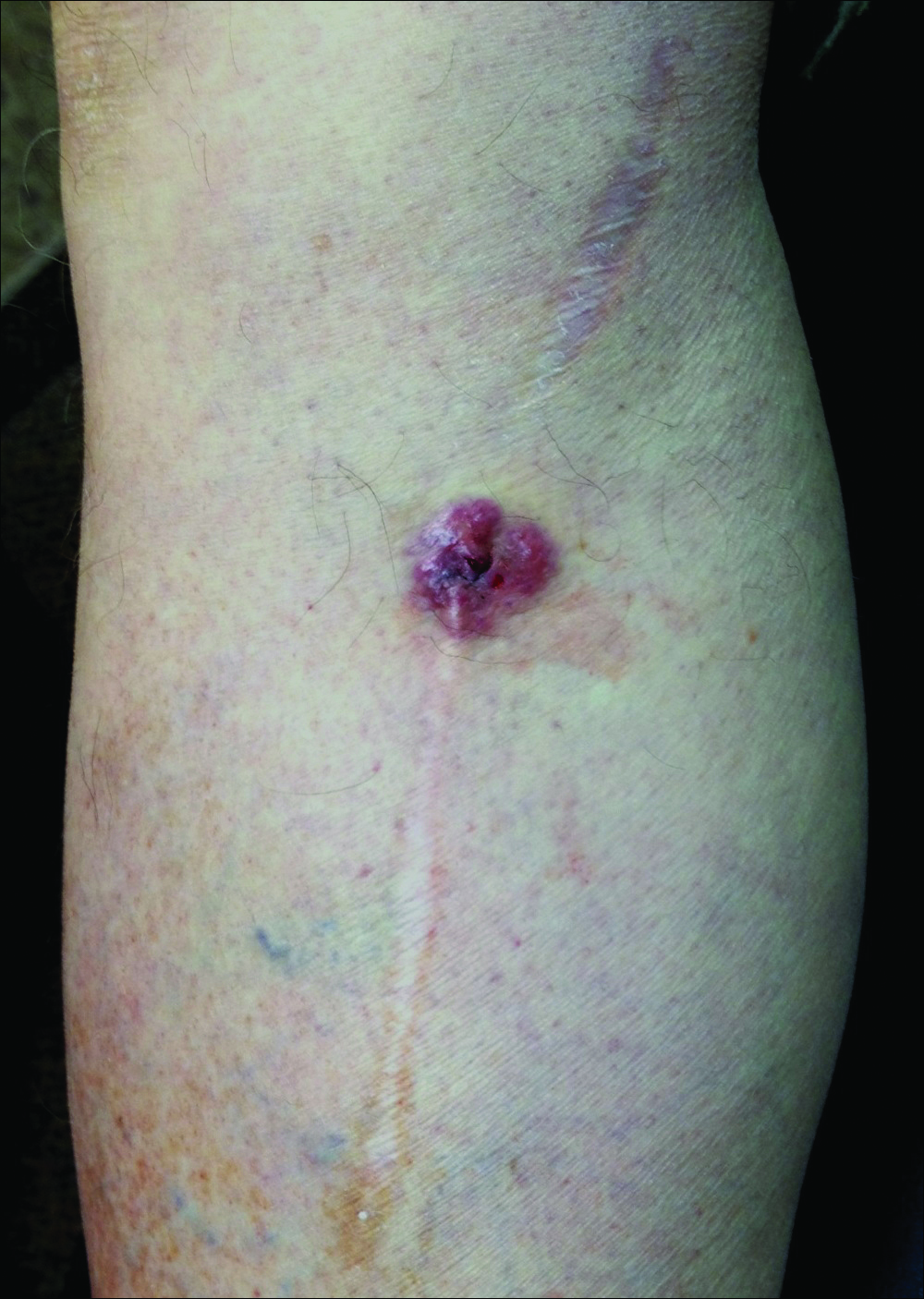

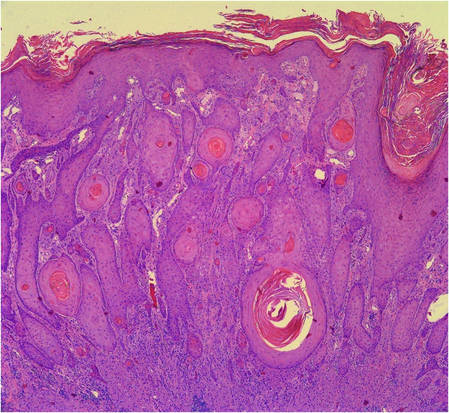

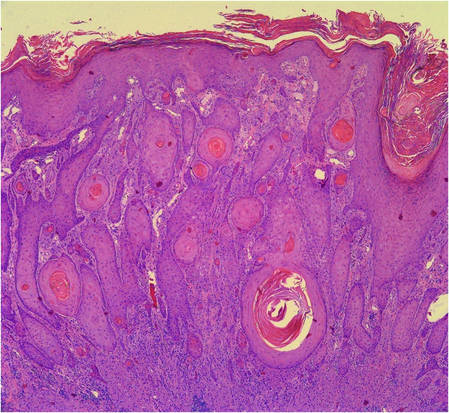

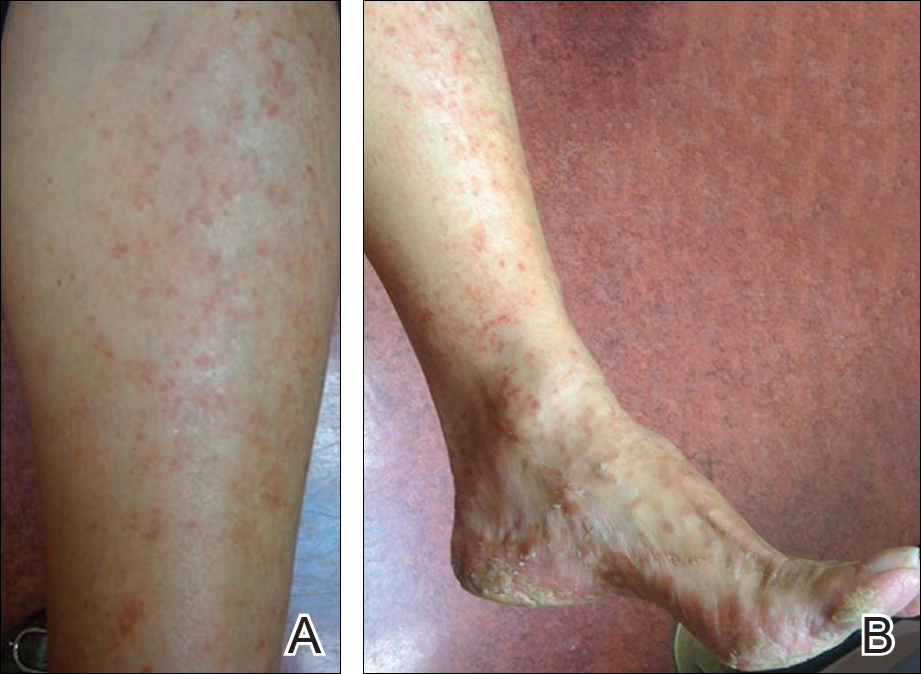

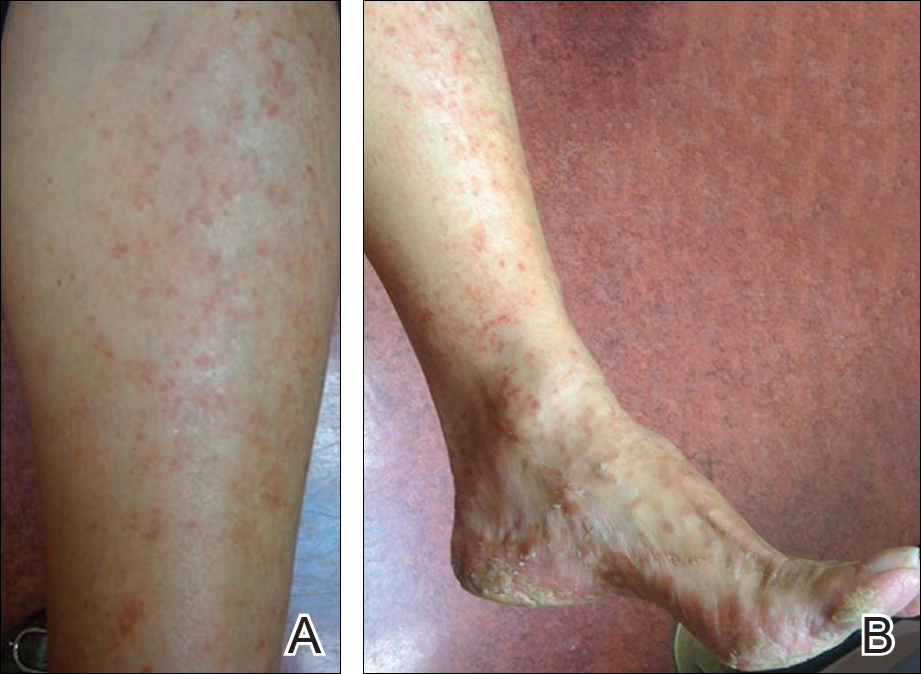

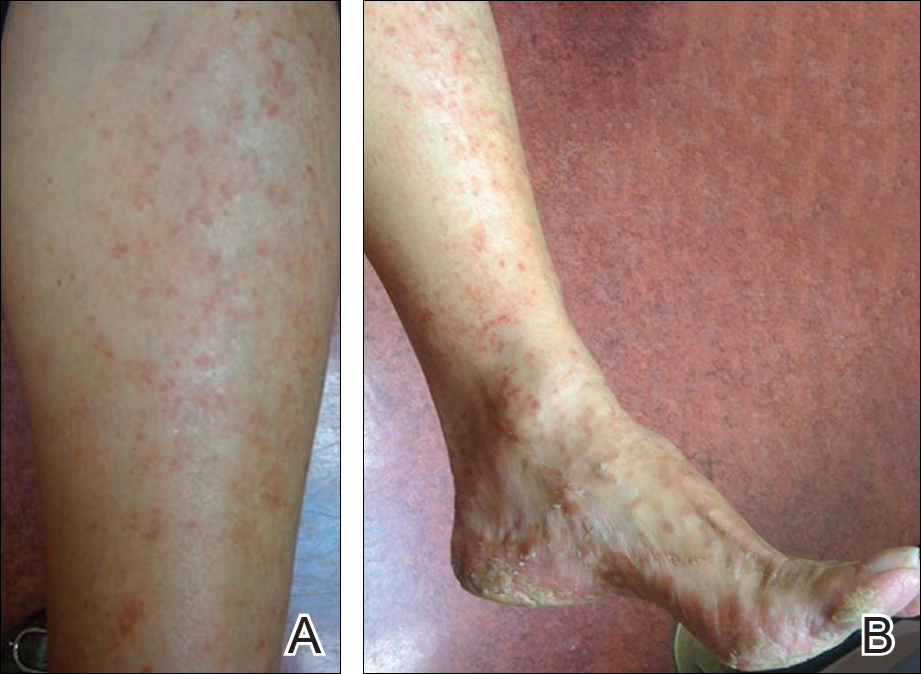

A 70-year-old man with history of coronary artery disease presented with a growing lesion on the right leg of 1 year’s duration. The lesion developed at a vein graft donor site for a coronary artery bypass that had been performed 18 years prior to presentation. The patient reported that the lesion was sensitive to touch. Physical examination revealed a 27-mm, firm, violaceous plaque on the medial aspect of the right upper shin (Figure 1). Mild pitting edema also was noted on both lower legs but was more prominent on the right leg. A 6-mm punch biopsy was performed.

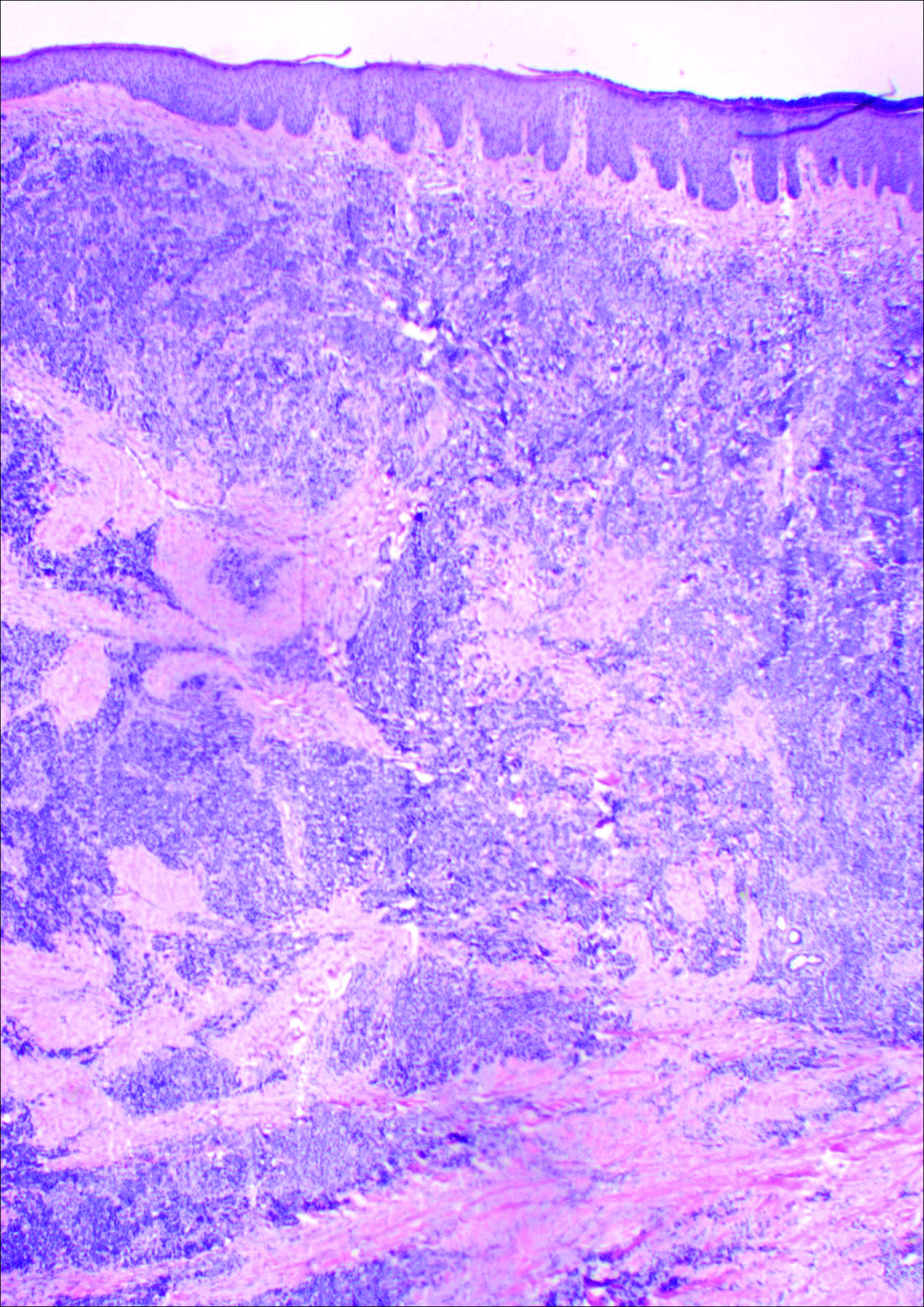

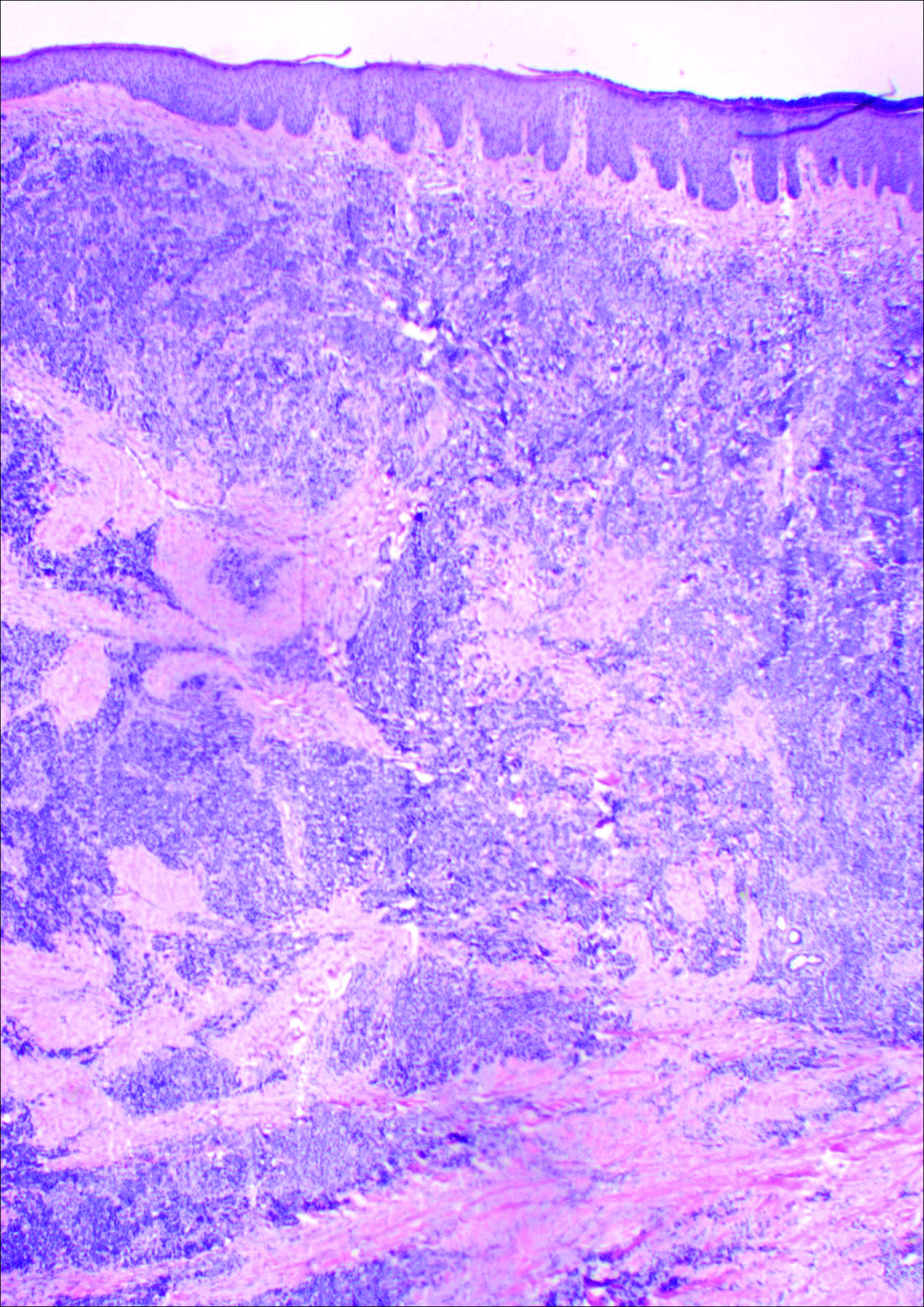

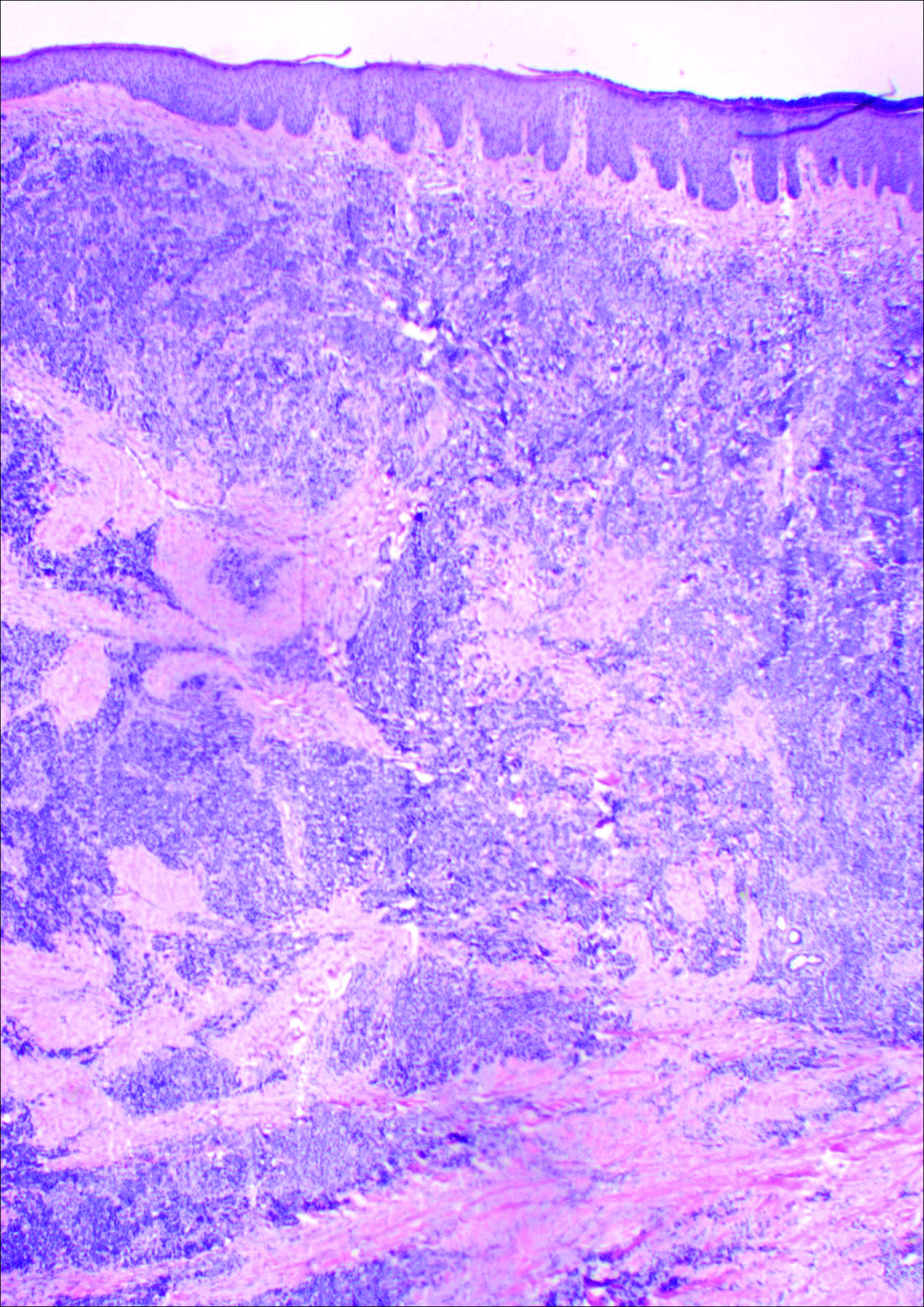

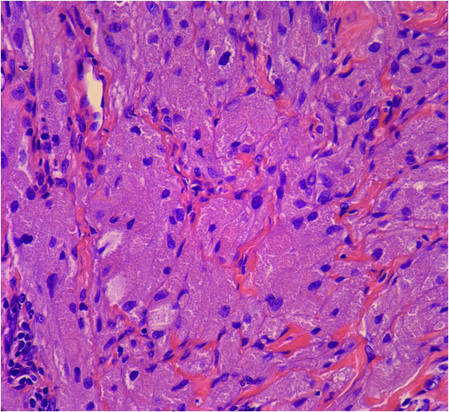

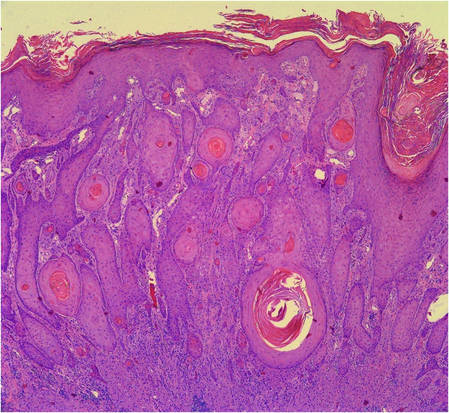

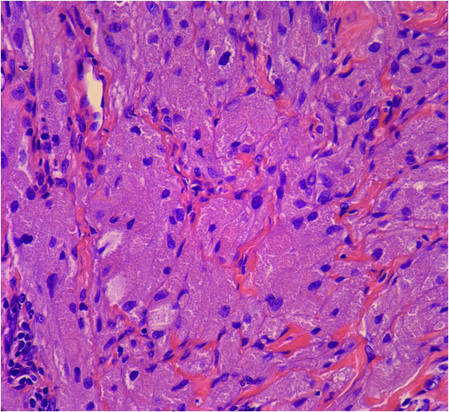

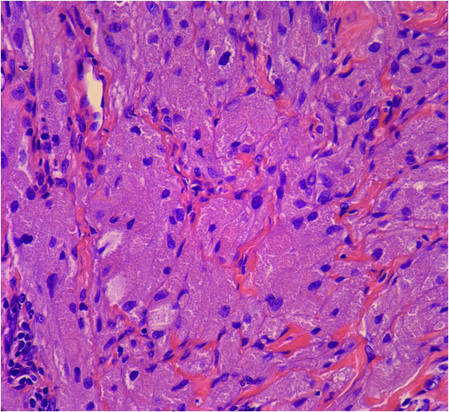

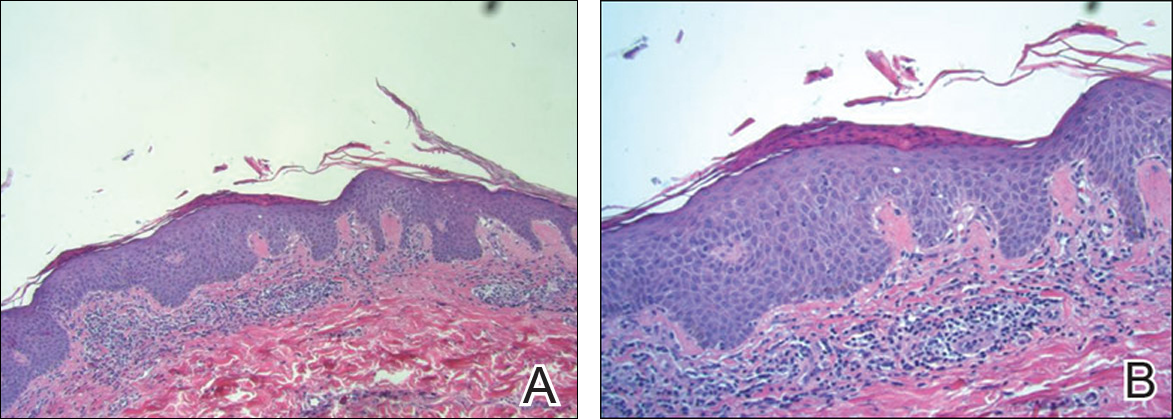

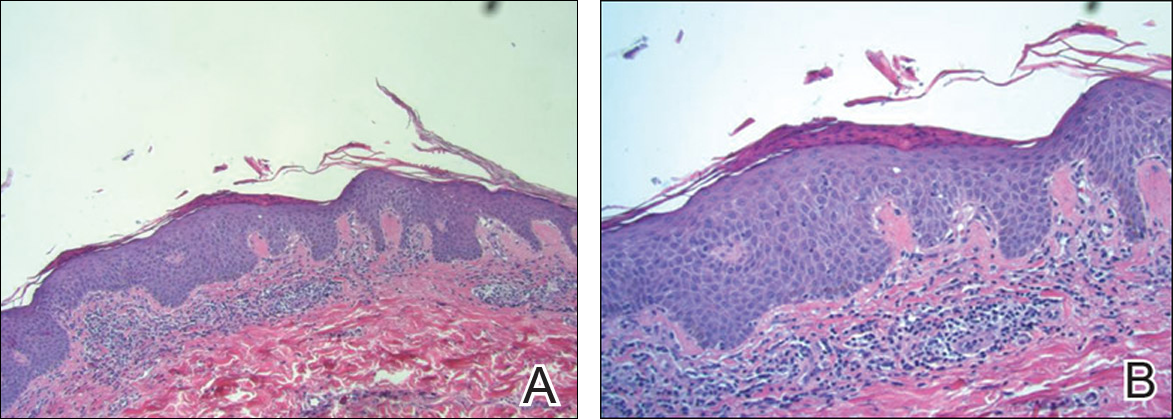

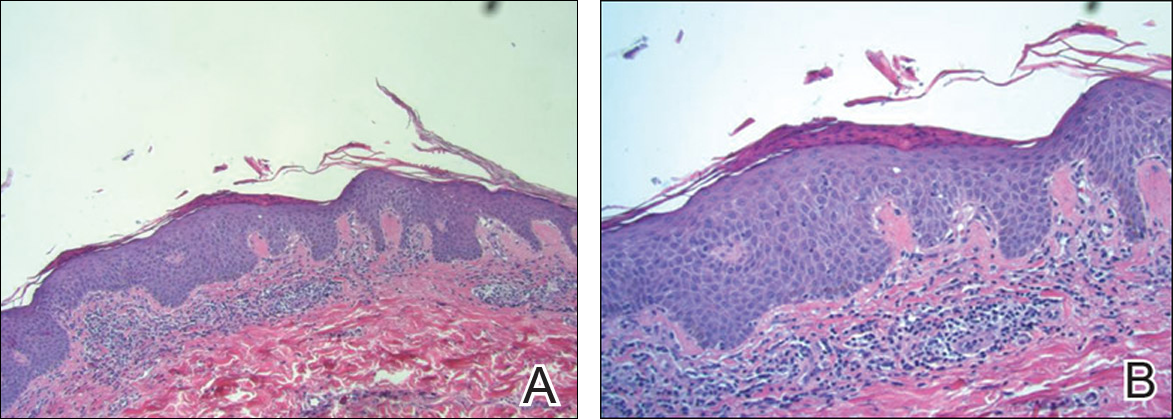

Histology showed diffuse infiltration of the dermis and subcutaneous fat by intermediate-sized atypical blue cells with scant cytoplasm (Figure 2). The tumor exhibited moderate cytologic atypia with occasional mitotic figures, and lymphovascular invasion was present. Staining for CD3 was negative within the tumor, but a few reactive lymphocytes were highlighted at the periphery. Staining for CD20 and CD30 was negative. Strong and diffuse staining for cyto-keratin 20 and pan-cytokeratin was noted within the tumor with the distinctive perinuclear pattern characteristic of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). Staining for cytokeratin 7 was negative. Synaptophysin and chromogranin were strongly and diffusely positive within the tumor, consistent with a diagnosis of MCC.

The patient was found to have stage IIA (T2N0M0) MCC. Computed tomography completed for staging showed no evidence of metastasis. Wide local excision of the lesion was performed. Margins were negative, as was a right inguinal sentinel lymph node dissection. Because of the size of the tumor and the presence of lymphovascular invasion, radiation therapy at the primary tumor site was recommended. Local radiation treatment (200 cGy daily) was administered for a total dose of 5000 cGy over 5 weeks. The patient currently is free of recurrence or metastases and is being followed by the oncology, surgery, and dermatology departments.

Comment

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare aggressive cutaneous malignancy. The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but immunosuppression and UV radiation, possibly through its immunosuppressive effects, appear to be contributing factors. More recently, the Merkel cell polyomavirus has been linked to MCC in approximately 80% of cases.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma is more common in individuals with fair skin, and the average age at diagnosis is 69 years.1 Patients typically present with an asymptomatic, firm, erythematous or violaceous, dome-shaped nodule or a small indurated plaque, most commonly on sun-exposed areas of the head and neck followed by the upper and lower extremities including the hands, feet, ankles, and wrists. Fifteen percent to 20% of MCCs develop on the legs and feet.1 Our patient presented with an MCC that developed on the right shin at a vein graft donor site.

The development of a cutaneous malignancy in a chronic wound (also known as a Marjolin ulcer) is a rare but well-recognized process. These malignancies occur in previously traumatized or chronically inflamed wounds and have been found to occur most commonly in chronic burn wounds, especially in ungrafted full-thickness burns. Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are the most common malignancies to arise in chronic wounds, but basal cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, melanomas, malignant fibrous histiocytomas, adenoacanthomas, liposarcomas, and osteosarcomas also have been reported.3 There also have been a few reports of MCC associated with Bowen disease that developed in burn wounds.4 These malignancies generally occur years after injury (average, 35.5 years), but there have been reports of keratoacanthomas developing as early as 3 weeks after injury.5,6

In some reports, malignancies in skin graft donor sites are differentiated from Marjolin ulcers, as the former appear in healed surgical wounds rather than in chronic unstable wounds and tend to occur sooner (ie, in weeks to months after graft harvesting).7,8 The development of these malignancies in graft donor sites is not as well recognized and has been reported in donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs), full-thickness skin grafts, tendon grafts, and bone grafts. In addition to malignancies that arise de novo, some develop due to metastatic and iatrogenic spread. The majority of reported malignancies in tendon and bone graft donor sites have been due to metastasis or iatrogenic spread.9-14

Iatrogenic implantation of tumor cells is a well-recognized phenomenon. Hussain et al10 reported a case of implantation of SCC in an STSG donor site, most likely due to direct seeding from a hollow needle used to infiltrate local anesthetic in the tumor area and the STSG. In this case, metastasis could not be completely ruled out.10 There also have been reports of osteosarcoma, ameloblastoma, scirrhous carcinoma of the breast, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma thought to be implanted at bone graft donor sites.14-17 Iatrogenic spread of malignancies can occur through seeding from contaminated gloves or instruments such as hollow bore needles or trocar placement in laparoscopic surgery.11 Airborne spread also may be possible, as viable melanoma cells have been detected in electrocautery plume in mice.13

Metastatic malignancies including metastases from SCC, adenocarcinoma, melanoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, angiosarcoma, and osteosarcoma also have been reported to develop in graft donor sites.11,13,18,19 Many malignancies thought to have developed from iatrogenic seeding may actually be from metastasis either by hematogenous or lymphatic spread. A possible contributing factor may be surgery-induced immunosuppression, which has been linked to increased tumor metastasis formation.20 Surgery or trauma have been shown to have an effect on cellular components of the immune system, causing changes such as a shift in T lymphocytes toward immune-suppressive T lymphocytes and impaired function of natural killer cells, neutrophils, and macrophages.20 The suppression of cell-mediated immunity has been shown to decrease over days to weeks in the postoperative period.21 In addition to surgery- or trauma-induced immunosuppression, the risk for metastasis may increase due to increased vascular, including lymphatic, flow toward a skin graft donor site.13,16 Furthermore, trauma predisposes areas to a hypercoagulable state with increased sludging as well as increased platelet counts and fibrinogen levels, which may lead to localization of metastatic lesions.22 All of these factors could potentially work simultaneously to induce the development of metastasis in graft donor sites.

We found that SCCs and keratoacanthomas, which may be a variant of SCC, are among the only primary malignancies that have been reported to develop in skin graft donor sites.6-8 Malignancies in these donor sites appear to develop sooner than those found in chronic wounds and are reported to develop within weeks to several months postoperatively, even in as few as 2 weeks.6,8 Tamir et al6 reported 2 keratoacanthomas that developed simultaneously in a burn scar and STSG donor site. The investigators believed it could be a sign of reduced immune surveillance in the 2 affected areas.6 It has been hypothesized that one cause of local immune suppression in Marjolin ulcers could be due to poor lymphatic regeneration in scar tissue, which would prevent delivery of antigens and stimulated lymphocytes.23 Haik et al7 considered this possibility when discussing a case of SCC that developed at the site of an STSG. The authors did not feel it applied, however, as the donor site had only undergone a single skin harvesting procedure.7 Ponnuvelu et al8 felt that inflammation was the underlying etiology behind the 2 cases they reported of SCCs that developed in STSG donor sites. The inflammation associated with tumors has many of the same processes involved in wound healing (eg, cellular proliferation, angiogenesis). Ponnuvelu et al8 hypothesized that the local inflammation caused by graft harvesting produced an ideal environment for early carcinogenesis. Although in chronic wounds it is believed that continual repair and regeneration in recurrent ulceration contributes to neoplastic initiation, it is thought that even a single injury may lead to malignant change, which may be because prior actinic damage or another cause has made the area more susceptible to these changes.24,25 Surgery-induced immunosuppression also may play a role in development of primary malignancies in graft donor sites.

There have been a few reports of SCCs and basal cell carcinomas occurring in other surgical scars that healed without complications.24,26-28 Similar to the malignancies in graft donor sites, some authors differentiate malignancies that occur in surgical scars that heal without complications from Marjolin ulcers, as they do not occur in chronically irritated wounds. These malignancies have been reported in scars from sternotomies, an infertility procedure, hair transplantation, thyroidectomy, colostomy, cleft lip repair, inguinal hernia repair, and paraumbilical laparoscopic port site. The time between surgery and diagnosis of malignancy ranged from 9 months to 67 years.24,26-28 The development of malignancies in these surgical scars may be due to local immunosuppression, possibly from decreased lymphatic flow; additionally, the inflammation in wound healing may provide the ideal environment for carcinogenesis. Trauma in areas already susceptible to malignant change could be a contributing factor.

Conclusion

Our patient developed an MCC in a vein graft donor site 18 years after vein harvesting. It was likely a primary tumor, as vein harvesting was done for coronary artery bypass graft. There was no evidence of any other lesions on physical examination or computed tomography, making it doubtful that an MCC serving as a primary lesion for seeding or metastasis was present. If such a lesion had been present at that time, it would likely have spread well before the time of presentation to our clinic due to the fast doubling time and high rate of metastasis characteristic of MCCs, further lessening the possibility of metastasis or implantation.

The extended length of time from procedure to lesion development in our patient is much longer than for other reported malignancies in graft donor sites, but the reported time for malignancies in other postsurgical scars is more varied. Regardless of whether the MCC in our patient is classified as a Marjolin ulcer, the pathogenesis is unclear. It is thought that a single injury could lead to malignant change in predisposed skin. Our patient’s legs did not have any evidence of prior actinic damage; however, it is likely that he had local immune suppression, which may have made him more susceptible to these changes. It is unlikely that surgery-induced immunosuppression played a role in our patient, as specific cellular components of the immune system only appear to be affected over days to weeks in the postoperative period. Although poor lymphatic regeneration in scar tissue leading to decreased immune surveillance is not generally thought to contribute to malignancies in most surgical scars, our patient underwent vein harvesting. Chronic edema commonly occurs after vein harvesting and is believed to be due to trauma to the lymphatics. Local immune suppression also may have led to increased susceptibility to infection by the MCC polyomavirus, which has been found to be associated with many MCCs. In addition, the area may have been more susceptible to carcinogenesis due to changes from inflammation from wound healing. We suspect together these factors contributed to the development of our patient’s MCC. Although rare, graft donor sites should be examined periodically for the development of malignancy.

- Swann MH, Yoon J. Merkel cell carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:51-56.

- Schrama D, Ugurel S, Becker JC. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent insights and new treatment options. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:141-149.

- Kadir AR. Burn scar neoplasm. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2007;20:185-188.

- Walsh NM. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin: morphologic diversity and implications thereof. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:680-689.

- Guenther N, Menenakos C, Braumann C, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising on a skin graft 64 years after primary injury. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:27.

- Tamir G, Morgenstern S, Ben-Amitay D, et al. Synchronous appearance of keratoacanthomas in burn scar and skin graft donor site shortly after injury. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:870-871.

- Haik J, Georgiou I, Farber N, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. Burns. 2008;34:891-893.

- Ponnuvelu G, Ng MF, Connolly CM, et al. Inflammation to skin malignancy, time to rethink the link: SCC in skin graft donor sites. Surgeon. 2011;9:168-169.

- Bekar A, Kahveci R, Tolunay S, et al. Metastatic gliosarcoma mass extension to a donor fascia lata graft harvest site by tumor cell contamination. World Neurosurg. 2010;73:719-721.

- Hussain A, Ekwobi C, Watson S. Metastatic implantation squamous cell carcinoma in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:690-692.

- May JT, Patil YJ. Keratoacanthoma-type squamous cell carcinoma developing in a skin graft donor site after tumor extirpation at a distant site. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010;89:E11-E13.

- Serrano-Ortega S, Buendia-Eisman A, Ortega del Olmo RM, et al. Melanoma metastasis in donor site of full-thickness skin graft. Dermatology. 2000;201:377-378.

- Wright H, McKinnell TH, Dunkin C. Recurrence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma at remote limb donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1265-1266.

- Yip KM, Lin J, Kumta SM. A pelvic osteosarcoma with metastasis to the donor site of the bone graft. a case report. Int Orthop. 1996;20:389-391.

- Dias RG, Abudu A, Carter SR, et al. Tumour transfer to bone graft donor site: a case report and review of the literature of the mechanism of seeding. Sarcoma. 2000;4:57-59.

- Neilson D, Emerson DJ, Dunn L. Squamous cell carcinoma of skin developing in a skin graft donor site. Br J Plast Surg. 1988;41:417-419.

- Singh C, Ibrahim S, Pang KS, et al. Implantation metastasis in a 13-year-old girl: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2003;11:94-96.

- Enion DS, Scott MJ, Gouldesbrough D. Cutaneous metastasis from a malignant fibrous histiocytoma to a limb skin graft donor site. Br J Surg. 1993;80:366.

- Yamasaki O, Terao K, Asagoe K, et al. Koebner phenomenon on skin graft donor site in cutaneous angiosarcoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:584-586.

- Hogan BV, Peter MB, Shenoy HG, et al. Surgery induced immunosuppression. Surgeon. 2011;9:38-43.

- Neeman E, Ben-Eliyahu S. The perioperative period and promotion of cancer metastasis: new outlooks on mediating mechanisms and immune involvement. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):32-40.

- Agostino D, Cliffton EE. Trauma as a cause of localization of blood-borne metastases: preventive effect of heparin and fibrinolysin. Ann Surg. 1965;161:97-102.

- Hammond JS, Thomsen S, Ward CG. Scar carcinoma arising acutely in a skin graft donor site. J Trauma. 1987;27:681-683.

- Korula R, Hughes CF. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a sternotomy scar. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:667-669.

- Kennedy CTC, Burd DAR, Creamer D. Mechanical and thermal injury. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. Vol 2. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:28.1-28.94.

- Durrani AJ, Miller RJ, Davies M. Basal cell carcinoma arising in a laparoscopic port site scar at the umbilicus. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:348-350.

- Kotwal S, Madaan S, Prescott S, et al. Unusual squamous cell carcinoma of the scrotum arising from a well healed, innocuous scar of an infertility procedure: a case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:17-19.

- Ozyazgan I, Kontas O. Previous injuries or scars as risk factors for the development of basal cell carcinoma. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2004;38:11-15.

Case Report

A 70-year-old man with history of coronary artery disease presented with a growing lesion on the right leg of 1 year’s duration. The lesion developed at a vein graft donor site for a coronary artery bypass that had been performed 18 years prior to presentation. The patient reported that the lesion was sensitive to touch. Physical examination revealed a 27-mm, firm, violaceous plaque on the medial aspect of the right upper shin (Figure 1). Mild pitting edema also was noted on both lower legs but was more prominent on the right leg. A 6-mm punch biopsy was performed.

Histology showed diffuse infiltration of the dermis and subcutaneous fat by intermediate-sized atypical blue cells with scant cytoplasm (Figure 2). The tumor exhibited moderate cytologic atypia with occasional mitotic figures, and lymphovascular invasion was present. Staining for CD3 was negative within the tumor, but a few reactive lymphocytes were highlighted at the periphery. Staining for CD20 and CD30 was negative. Strong and diffuse staining for cyto-keratin 20 and pan-cytokeratin was noted within the tumor with the distinctive perinuclear pattern characteristic of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). Staining for cytokeratin 7 was negative. Synaptophysin and chromogranin were strongly and diffusely positive within the tumor, consistent with a diagnosis of MCC.

The patient was found to have stage IIA (T2N0M0) MCC. Computed tomography completed for staging showed no evidence of metastasis. Wide local excision of the lesion was performed. Margins were negative, as was a right inguinal sentinel lymph node dissection. Because of the size of the tumor and the presence of lymphovascular invasion, radiation therapy at the primary tumor site was recommended. Local radiation treatment (200 cGy daily) was administered for a total dose of 5000 cGy over 5 weeks. The patient currently is free of recurrence or metastases and is being followed by the oncology, surgery, and dermatology departments.

Comment

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare aggressive cutaneous malignancy. The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but immunosuppression and UV radiation, possibly through its immunosuppressive effects, appear to be contributing factors. More recently, the Merkel cell polyomavirus has been linked to MCC in approximately 80% of cases.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma is more common in individuals with fair skin, and the average age at diagnosis is 69 years.1 Patients typically present with an asymptomatic, firm, erythematous or violaceous, dome-shaped nodule or a small indurated plaque, most commonly on sun-exposed areas of the head and neck followed by the upper and lower extremities including the hands, feet, ankles, and wrists. Fifteen percent to 20% of MCCs develop on the legs and feet.1 Our patient presented with an MCC that developed on the right shin at a vein graft donor site.

The development of a cutaneous malignancy in a chronic wound (also known as a Marjolin ulcer) is a rare but well-recognized process. These malignancies occur in previously traumatized or chronically inflamed wounds and have been found to occur most commonly in chronic burn wounds, especially in ungrafted full-thickness burns. Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are the most common malignancies to arise in chronic wounds, but basal cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, melanomas, malignant fibrous histiocytomas, adenoacanthomas, liposarcomas, and osteosarcomas also have been reported.3 There also have been a few reports of MCC associated with Bowen disease that developed in burn wounds.4 These malignancies generally occur years after injury (average, 35.5 years), but there have been reports of keratoacanthomas developing as early as 3 weeks after injury.5,6

In some reports, malignancies in skin graft donor sites are differentiated from Marjolin ulcers, as the former appear in healed surgical wounds rather than in chronic unstable wounds and tend to occur sooner (ie, in weeks to months after graft harvesting).7,8 The development of these malignancies in graft donor sites is not as well recognized and has been reported in donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs), full-thickness skin grafts, tendon grafts, and bone grafts. In addition to malignancies that arise de novo, some develop due to metastatic and iatrogenic spread. The majority of reported malignancies in tendon and bone graft donor sites have been due to metastasis or iatrogenic spread.9-14

Iatrogenic implantation of tumor cells is a well-recognized phenomenon. Hussain et al10 reported a case of implantation of SCC in an STSG donor site, most likely due to direct seeding from a hollow needle used to infiltrate local anesthetic in the tumor area and the STSG. In this case, metastasis could not be completely ruled out.10 There also have been reports of osteosarcoma, ameloblastoma, scirrhous carcinoma of the breast, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma thought to be implanted at bone graft donor sites.14-17 Iatrogenic spread of malignancies can occur through seeding from contaminated gloves or instruments such as hollow bore needles or trocar placement in laparoscopic surgery.11 Airborne spread also may be possible, as viable melanoma cells have been detected in electrocautery plume in mice.13

Metastatic malignancies including metastases from SCC, adenocarcinoma, melanoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, angiosarcoma, and osteosarcoma also have been reported to develop in graft donor sites.11,13,18,19 Many malignancies thought to have developed from iatrogenic seeding may actually be from metastasis either by hematogenous or lymphatic spread. A possible contributing factor may be surgery-induced immunosuppression, which has been linked to increased tumor metastasis formation.20 Surgery or trauma have been shown to have an effect on cellular components of the immune system, causing changes such as a shift in T lymphocytes toward immune-suppressive T lymphocytes and impaired function of natural killer cells, neutrophils, and macrophages.20 The suppression of cell-mediated immunity has been shown to decrease over days to weeks in the postoperative period.21 In addition to surgery- or trauma-induced immunosuppression, the risk for metastasis may increase due to increased vascular, including lymphatic, flow toward a skin graft donor site.13,16 Furthermore, trauma predisposes areas to a hypercoagulable state with increased sludging as well as increased platelet counts and fibrinogen levels, which may lead to localization of metastatic lesions.22 All of these factors could potentially work simultaneously to induce the development of metastasis in graft donor sites.

We found that SCCs and keratoacanthomas, which may be a variant of SCC, are among the only primary malignancies that have been reported to develop in skin graft donor sites.6-8 Malignancies in these donor sites appear to develop sooner than those found in chronic wounds and are reported to develop within weeks to several months postoperatively, even in as few as 2 weeks.6,8 Tamir et al6 reported 2 keratoacanthomas that developed simultaneously in a burn scar and STSG donor site. The investigators believed it could be a sign of reduced immune surveillance in the 2 affected areas.6 It has been hypothesized that one cause of local immune suppression in Marjolin ulcers could be due to poor lymphatic regeneration in scar tissue, which would prevent delivery of antigens and stimulated lymphocytes.23 Haik et al7 considered this possibility when discussing a case of SCC that developed at the site of an STSG. The authors did not feel it applied, however, as the donor site had only undergone a single skin harvesting procedure.7 Ponnuvelu et al8 felt that inflammation was the underlying etiology behind the 2 cases they reported of SCCs that developed in STSG donor sites. The inflammation associated with tumors has many of the same processes involved in wound healing (eg, cellular proliferation, angiogenesis). Ponnuvelu et al8 hypothesized that the local inflammation caused by graft harvesting produced an ideal environment for early carcinogenesis. Although in chronic wounds it is believed that continual repair and regeneration in recurrent ulceration contributes to neoplastic initiation, it is thought that even a single injury may lead to malignant change, which may be because prior actinic damage or another cause has made the area more susceptible to these changes.24,25 Surgery-induced immunosuppression also may play a role in development of primary malignancies in graft donor sites.

There have been a few reports of SCCs and basal cell carcinomas occurring in other surgical scars that healed without complications.24,26-28 Similar to the malignancies in graft donor sites, some authors differentiate malignancies that occur in surgical scars that heal without complications from Marjolin ulcers, as they do not occur in chronically irritated wounds. These malignancies have been reported in scars from sternotomies, an infertility procedure, hair transplantation, thyroidectomy, colostomy, cleft lip repair, inguinal hernia repair, and paraumbilical laparoscopic port site. The time between surgery and diagnosis of malignancy ranged from 9 months to 67 years.24,26-28 The development of malignancies in these surgical scars may be due to local immunosuppression, possibly from decreased lymphatic flow; additionally, the inflammation in wound healing may provide the ideal environment for carcinogenesis. Trauma in areas already susceptible to malignant change could be a contributing factor.

Conclusion

Our patient developed an MCC in a vein graft donor site 18 years after vein harvesting. It was likely a primary tumor, as vein harvesting was done for coronary artery bypass graft. There was no evidence of any other lesions on physical examination or computed tomography, making it doubtful that an MCC serving as a primary lesion for seeding or metastasis was present. If such a lesion had been present at that time, it would likely have spread well before the time of presentation to our clinic due to the fast doubling time and high rate of metastasis characteristic of MCCs, further lessening the possibility of metastasis or implantation.

The extended length of time from procedure to lesion development in our patient is much longer than for other reported malignancies in graft donor sites, but the reported time for malignancies in other postsurgical scars is more varied. Regardless of whether the MCC in our patient is classified as a Marjolin ulcer, the pathogenesis is unclear. It is thought that a single injury could lead to malignant change in predisposed skin. Our patient’s legs did not have any evidence of prior actinic damage; however, it is likely that he had local immune suppression, which may have made him more susceptible to these changes. It is unlikely that surgery-induced immunosuppression played a role in our patient, as specific cellular components of the immune system only appear to be affected over days to weeks in the postoperative period. Although poor lymphatic regeneration in scar tissue leading to decreased immune surveillance is not generally thought to contribute to malignancies in most surgical scars, our patient underwent vein harvesting. Chronic edema commonly occurs after vein harvesting and is believed to be due to trauma to the lymphatics. Local immune suppression also may have led to increased susceptibility to infection by the MCC polyomavirus, which has been found to be associated with many MCCs. In addition, the area may have been more susceptible to carcinogenesis due to changes from inflammation from wound healing. We suspect together these factors contributed to the development of our patient’s MCC. Although rare, graft donor sites should be examined periodically for the development of malignancy.

Case Report

A 70-year-old man with history of coronary artery disease presented with a growing lesion on the right leg of 1 year’s duration. The lesion developed at a vein graft donor site for a coronary artery bypass that had been performed 18 years prior to presentation. The patient reported that the lesion was sensitive to touch. Physical examination revealed a 27-mm, firm, violaceous plaque on the medial aspect of the right upper shin (Figure 1). Mild pitting edema also was noted on both lower legs but was more prominent on the right leg. A 6-mm punch biopsy was performed.

Histology showed diffuse infiltration of the dermis and subcutaneous fat by intermediate-sized atypical blue cells with scant cytoplasm (Figure 2). The tumor exhibited moderate cytologic atypia with occasional mitotic figures, and lymphovascular invasion was present. Staining for CD3 was negative within the tumor, but a few reactive lymphocytes were highlighted at the periphery. Staining for CD20 and CD30 was negative. Strong and diffuse staining for cyto-keratin 20 and pan-cytokeratin was noted within the tumor with the distinctive perinuclear pattern characteristic of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). Staining for cytokeratin 7 was negative. Synaptophysin and chromogranin were strongly and diffusely positive within the tumor, consistent with a diagnosis of MCC.

The patient was found to have stage IIA (T2N0M0) MCC. Computed tomography completed for staging showed no evidence of metastasis. Wide local excision of the lesion was performed. Margins were negative, as was a right inguinal sentinel lymph node dissection. Because of the size of the tumor and the presence of lymphovascular invasion, radiation therapy at the primary tumor site was recommended. Local radiation treatment (200 cGy daily) was administered for a total dose of 5000 cGy over 5 weeks. The patient currently is free of recurrence or metastases and is being followed by the oncology, surgery, and dermatology departments.

Comment

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare aggressive cutaneous malignancy. The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but immunosuppression and UV radiation, possibly through its immunosuppressive effects, appear to be contributing factors. More recently, the Merkel cell polyomavirus has been linked to MCC in approximately 80% of cases.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma is more common in individuals with fair skin, and the average age at diagnosis is 69 years.1 Patients typically present with an asymptomatic, firm, erythematous or violaceous, dome-shaped nodule or a small indurated plaque, most commonly on sun-exposed areas of the head and neck followed by the upper and lower extremities including the hands, feet, ankles, and wrists. Fifteen percent to 20% of MCCs develop on the legs and feet.1 Our patient presented with an MCC that developed on the right shin at a vein graft donor site.

The development of a cutaneous malignancy in a chronic wound (also known as a Marjolin ulcer) is a rare but well-recognized process. These malignancies occur in previously traumatized or chronically inflamed wounds and have been found to occur most commonly in chronic burn wounds, especially in ungrafted full-thickness burns. Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are the most common malignancies to arise in chronic wounds, but basal cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, melanomas, malignant fibrous histiocytomas, adenoacanthomas, liposarcomas, and osteosarcomas also have been reported.3 There also have been a few reports of MCC associated with Bowen disease that developed in burn wounds.4 These malignancies generally occur years after injury (average, 35.5 years), but there have been reports of keratoacanthomas developing as early as 3 weeks after injury.5,6

In some reports, malignancies in skin graft donor sites are differentiated from Marjolin ulcers, as the former appear in healed surgical wounds rather than in chronic unstable wounds and tend to occur sooner (ie, in weeks to months after graft harvesting).7,8 The development of these malignancies in graft donor sites is not as well recognized and has been reported in donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs), full-thickness skin grafts, tendon grafts, and bone grafts. In addition to malignancies that arise de novo, some develop due to metastatic and iatrogenic spread. The majority of reported malignancies in tendon and bone graft donor sites have been due to metastasis or iatrogenic spread.9-14

Iatrogenic implantation of tumor cells is a well-recognized phenomenon. Hussain et al10 reported a case of implantation of SCC in an STSG donor site, most likely due to direct seeding from a hollow needle used to infiltrate local anesthetic in the tumor area and the STSG. In this case, metastasis could not be completely ruled out.10 There also have been reports of osteosarcoma, ameloblastoma, scirrhous carcinoma of the breast, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma thought to be implanted at bone graft donor sites.14-17 Iatrogenic spread of malignancies can occur through seeding from contaminated gloves or instruments such as hollow bore needles or trocar placement in laparoscopic surgery.11 Airborne spread also may be possible, as viable melanoma cells have been detected in electrocautery plume in mice.13

Metastatic malignancies including metastases from SCC, adenocarcinoma, melanoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, angiosarcoma, and osteosarcoma also have been reported to develop in graft donor sites.11,13,18,19 Many malignancies thought to have developed from iatrogenic seeding may actually be from metastasis either by hematogenous or lymphatic spread. A possible contributing factor may be surgery-induced immunosuppression, which has been linked to increased tumor metastasis formation.20 Surgery or trauma have been shown to have an effect on cellular components of the immune system, causing changes such as a shift in T lymphocytes toward immune-suppressive T lymphocytes and impaired function of natural killer cells, neutrophils, and macrophages.20 The suppression of cell-mediated immunity has been shown to decrease over days to weeks in the postoperative period.21 In addition to surgery- or trauma-induced immunosuppression, the risk for metastasis may increase due to increased vascular, including lymphatic, flow toward a skin graft donor site.13,16 Furthermore, trauma predisposes areas to a hypercoagulable state with increased sludging as well as increased platelet counts and fibrinogen levels, which may lead to localization of metastatic lesions.22 All of these factors could potentially work simultaneously to induce the development of metastasis in graft donor sites.

We found that SCCs and keratoacanthomas, which may be a variant of SCC, are among the only primary malignancies that have been reported to develop in skin graft donor sites.6-8 Malignancies in these donor sites appear to develop sooner than those found in chronic wounds and are reported to develop within weeks to several months postoperatively, even in as few as 2 weeks.6,8 Tamir et al6 reported 2 keratoacanthomas that developed simultaneously in a burn scar and STSG donor site. The investigators believed it could be a sign of reduced immune surveillance in the 2 affected areas.6 It has been hypothesized that one cause of local immune suppression in Marjolin ulcers could be due to poor lymphatic regeneration in scar tissue, which would prevent delivery of antigens and stimulated lymphocytes.23 Haik et al7 considered this possibility when discussing a case of SCC that developed at the site of an STSG. The authors did not feel it applied, however, as the donor site had only undergone a single skin harvesting procedure.7 Ponnuvelu et al8 felt that inflammation was the underlying etiology behind the 2 cases they reported of SCCs that developed in STSG donor sites. The inflammation associated with tumors has many of the same processes involved in wound healing (eg, cellular proliferation, angiogenesis). Ponnuvelu et al8 hypothesized that the local inflammation caused by graft harvesting produced an ideal environment for early carcinogenesis. Although in chronic wounds it is believed that continual repair and regeneration in recurrent ulceration contributes to neoplastic initiation, it is thought that even a single injury may lead to malignant change, which may be because prior actinic damage or another cause has made the area more susceptible to these changes.24,25 Surgery-induced immunosuppression also may play a role in development of primary malignancies in graft donor sites.

There have been a few reports of SCCs and basal cell carcinomas occurring in other surgical scars that healed without complications.24,26-28 Similar to the malignancies in graft donor sites, some authors differentiate malignancies that occur in surgical scars that heal without complications from Marjolin ulcers, as they do not occur in chronically irritated wounds. These malignancies have been reported in scars from sternotomies, an infertility procedure, hair transplantation, thyroidectomy, colostomy, cleft lip repair, inguinal hernia repair, and paraumbilical laparoscopic port site. The time between surgery and diagnosis of malignancy ranged from 9 months to 67 years.24,26-28 The development of malignancies in these surgical scars may be due to local immunosuppression, possibly from decreased lymphatic flow; additionally, the inflammation in wound healing may provide the ideal environment for carcinogenesis. Trauma in areas already susceptible to malignant change could be a contributing factor.

Conclusion

Our patient developed an MCC in a vein graft donor site 18 years after vein harvesting. It was likely a primary tumor, as vein harvesting was done for coronary artery bypass graft. There was no evidence of any other lesions on physical examination or computed tomography, making it doubtful that an MCC serving as a primary lesion for seeding or metastasis was present. If such a lesion had been present at that time, it would likely have spread well before the time of presentation to our clinic due to the fast doubling time and high rate of metastasis characteristic of MCCs, further lessening the possibility of metastasis or implantation.

The extended length of time from procedure to lesion development in our patient is much longer than for other reported malignancies in graft donor sites, but the reported time for malignancies in other postsurgical scars is more varied. Regardless of whether the MCC in our patient is classified as a Marjolin ulcer, the pathogenesis is unclear. It is thought that a single injury could lead to malignant change in predisposed skin. Our patient’s legs did not have any evidence of prior actinic damage; however, it is likely that he had local immune suppression, which may have made him more susceptible to these changes. It is unlikely that surgery-induced immunosuppression played a role in our patient, as specific cellular components of the immune system only appear to be affected over days to weeks in the postoperative period. Although poor lymphatic regeneration in scar tissue leading to decreased immune surveillance is not generally thought to contribute to malignancies in most surgical scars, our patient underwent vein harvesting. Chronic edema commonly occurs after vein harvesting and is believed to be due to trauma to the lymphatics. Local immune suppression also may have led to increased susceptibility to infection by the MCC polyomavirus, which has been found to be associated with many MCCs. In addition, the area may have been more susceptible to carcinogenesis due to changes from inflammation from wound healing. We suspect together these factors contributed to the development of our patient’s MCC. Although rare, graft donor sites should be examined periodically for the development of malignancy.

- Swann MH, Yoon J. Merkel cell carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:51-56.

- Schrama D, Ugurel S, Becker JC. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent insights and new treatment options. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:141-149.

- Kadir AR. Burn scar neoplasm. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2007;20:185-188.

- Walsh NM. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin: morphologic diversity and implications thereof. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:680-689.

- Guenther N, Menenakos C, Braumann C, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising on a skin graft 64 years after primary injury. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:27.

- Tamir G, Morgenstern S, Ben-Amitay D, et al. Synchronous appearance of keratoacanthomas in burn scar and skin graft donor site shortly after injury. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:870-871.

- Haik J, Georgiou I, Farber N, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. Burns. 2008;34:891-893.

- Ponnuvelu G, Ng MF, Connolly CM, et al. Inflammation to skin malignancy, time to rethink the link: SCC in skin graft donor sites. Surgeon. 2011;9:168-169.

- Bekar A, Kahveci R, Tolunay S, et al. Metastatic gliosarcoma mass extension to a donor fascia lata graft harvest site by tumor cell contamination. World Neurosurg. 2010;73:719-721.

- Hussain A, Ekwobi C, Watson S. Metastatic implantation squamous cell carcinoma in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:690-692.

- May JT, Patil YJ. Keratoacanthoma-type squamous cell carcinoma developing in a skin graft donor site after tumor extirpation at a distant site. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010;89:E11-E13.

- Serrano-Ortega S, Buendia-Eisman A, Ortega del Olmo RM, et al. Melanoma metastasis in donor site of full-thickness skin graft. Dermatology. 2000;201:377-378.

- Wright H, McKinnell TH, Dunkin C. Recurrence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma at remote limb donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1265-1266.

- Yip KM, Lin J, Kumta SM. A pelvic osteosarcoma with metastasis to the donor site of the bone graft. a case report. Int Orthop. 1996;20:389-391.

- Dias RG, Abudu A, Carter SR, et al. Tumour transfer to bone graft donor site: a case report and review of the literature of the mechanism of seeding. Sarcoma. 2000;4:57-59.

- Neilson D, Emerson DJ, Dunn L. Squamous cell carcinoma of skin developing in a skin graft donor site. Br J Plast Surg. 1988;41:417-419.

- Singh C, Ibrahim S, Pang KS, et al. Implantation metastasis in a 13-year-old girl: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2003;11:94-96.

- Enion DS, Scott MJ, Gouldesbrough D. Cutaneous metastasis from a malignant fibrous histiocytoma to a limb skin graft donor site. Br J Surg. 1993;80:366.

- Yamasaki O, Terao K, Asagoe K, et al. Koebner phenomenon on skin graft donor site in cutaneous angiosarcoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:584-586.

- Hogan BV, Peter MB, Shenoy HG, et al. Surgery induced immunosuppression. Surgeon. 2011;9:38-43.

- Neeman E, Ben-Eliyahu S. The perioperative period and promotion of cancer metastasis: new outlooks on mediating mechanisms and immune involvement. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):32-40.

- Agostino D, Cliffton EE. Trauma as a cause of localization of blood-borne metastases: preventive effect of heparin and fibrinolysin. Ann Surg. 1965;161:97-102.

- Hammond JS, Thomsen S, Ward CG. Scar carcinoma arising acutely in a skin graft donor site. J Trauma. 1987;27:681-683.

- Korula R, Hughes CF. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a sternotomy scar. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:667-669.

- Kennedy CTC, Burd DAR, Creamer D. Mechanical and thermal injury. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. Vol 2. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:28.1-28.94.

- Durrani AJ, Miller RJ, Davies M. Basal cell carcinoma arising in a laparoscopic port site scar at the umbilicus. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:348-350.

- Kotwal S, Madaan S, Prescott S, et al. Unusual squamous cell carcinoma of the scrotum arising from a well healed, innocuous scar of an infertility procedure: a case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:17-19.

- Ozyazgan I, Kontas O. Previous injuries or scars as risk factors for the development of basal cell carcinoma. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2004;38:11-15.

- Swann MH, Yoon J. Merkel cell carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:51-56.

- Schrama D, Ugurel S, Becker JC. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent insights and new treatment options. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:141-149.

- Kadir AR. Burn scar neoplasm. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2007;20:185-188.

- Walsh NM. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin: morphologic diversity and implications thereof. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:680-689.

- Guenther N, Menenakos C, Braumann C, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising on a skin graft 64 years after primary injury. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:27.

- Tamir G, Morgenstern S, Ben-Amitay D, et al. Synchronous appearance of keratoacanthomas in burn scar and skin graft donor site shortly after injury. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:870-871.

- Haik J, Georgiou I, Farber N, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. Burns. 2008;34:891-893.

- Ponnuvelu G, Ng MF, Connolly CM, et al. Inflammation to skin malignancy, time to rethink the link: SCC in skin graft donor sites. Surgeon. 2011;9:168-169.

- Bekar A, Kahveci R, Tolunay S, et al. Metastatic gliosarcoma mass extension to a donor fascia lata graft harvest site by tumor cell contamination. World Neurosurg. 2010;73:719-721.

- Hussain A, Ekwobi C, Watson S. Metastatic implantation squamous cell carcinoma in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:690-692.

- May JT, Patil YJ. Keratoacanthoma-type squamous cell carcinoma developing in a skin graft donor site after tumor extirpation at a distant site. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010;89:E11-E13.

- Serrano-Ortega S, Buendia-Eisman A, Ortega del Olmo RM, et al. Melanoma metastasis in donor site of full-thickness skin graft. Dermatology. 2000;201:377-378.

- Wright H, McKinnell TH, Dunkin C. Recurrence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma at remote limb donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1265-1266.

- Yip KM, Lin J, Kumta SM. A pelvic osteosarcoma with metastasis to the donor site of the bone graft. a case report. Int Orthop. 1996;20:389-391.

- Dias RG, Abudu A, Carter SR, et al. Tumour transfer to bone graft donor site: a case report and review of the literature of the mechanism of seeding. Sarcoma. 2000;4:57-59.

- Neilson D, Emerson DJ, Dunn L. Squamous cell carcinoma of skin developing in a skin graft donor site. Br J Plast Surg. 1988;41:417-419.

- Singh C, Ibrahim S, Pang KS, et al. Implantation metastasis in a 13-year-old girl: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2003;11:94-96.

- Enion DS, Scott MJ, Gouldesbrough D. Cutaneous metastasis from a malignant fibrous histiocytoma to a limb skin graft donor site. Br J Surg. 1993;80:366.

- Yamasaki O, Terao K, Asagoe K, et al. Koebner phenomenon on skin graft donor site in cutaneous angiosarcoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:584-586.

- Hogan BV, Peter MB, Shenoy HG, et al. Surgery induced immunosuppression. Surgeon. 2011;9:38-43.

- Neeman E, Ben-Eliyahu S. The perioperative period and promotion of cancer metastasis: new outlooks on mediating mechanisms and immune involvement. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):32-40.

- Agostino D, Cliffton EE. Trauma as a cause of localization of blood-borne metastases: preventive effect of heparin and fibrinolysin. Ann Surg. 1965;161:97-102.

- Hammond JS, Thomsen S, Ward CG. Scar carcinoma arising acutely in a skin graft donor site. J Trauma. 1987;27:681-683.

- Korula R, Hughes CF. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a sternotomy scar. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:667-669.

- Kennedy CTC, Burd DAR, Creamer D. Mechanical and thermal injury. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. Vol 2. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:28.1-28.94.

- Durrani AJ, Miller RJ, Davies M. Basal cell carcinoma arising in a laparoscopic port site scar at the umbilicus. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:348-350.