User login

Case Report: Acute Intermittent Porphyria

Case

A 34-year-old woman presented to the ED with severe, persistent abdominal pain that had begun 18 days earlier. She was 7 weeks pregnant and had been seen in the same ED the day before. During that visit, ultrasound had shown a single pregnancy of doubtful viability. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging was normal. She was given multiple doses of hydromorphone. The discharge diagnosis was “missed abortion.”

Since the onset of her pain, she had been hospitalized twice elsewhere, with no clear diagnosis to explain her pain. Treatment consisted of repeat doses of hydromorphone. During the second hospitalization, a sodium level of 109 mEq/L had been corrected with hypertonic saline, and a urinary tract infection (UTI) had been treated with cephalexin.

Our patient had never experienced similar abdominal pain. Her medical history included depression and asthma. Her family history was notable for an aunt who had died of lung cancer.

On this ED visit, the patient’s vital signs were normal. On examination, she was moaning in pain and clutching her abdomen. The abdomen was tender in both lower quadrants, with guarding but no rebound. Her sodium level was 125 mEq/L; the day before it had been 132 mEq/L.

Urine dipstick testing showed 2+ glucose and 2+ bilirubin; both had been within normal range (negative) the day before. An abdominal/pelvic computed tomography scan with intravenous (IV) and oral contrast did not reveal any potential cause of the patient’s pain. Multiple doses of IV hydromorphone were given, but her pain persisted.

We revisited our patient’s family history. With prompting, she remembered that as a teenager, her mother had had an illness that caused “problems with her nerves and blood vessels and turned her urine red.” When reached by phone, the patient’s mother, who lives outside the United States, said she was familiar with the term “porphyria,” but curiously, she did not state she carried the diagnosis, and had not advised her children they could be at risk.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for treatment of hyponatremia. Her mother’s history led us to suspect porphyria, so we sent a urine sample from the ED for porphobilinogen (PBG) testing. Her urine was not red at that time (on further questioning, she remembered she had had an episode of “red urine” recently). Two days later, after the PBG result came back positive, treatment was initiated for porphyria. With further stool and serum testing, the diagnosis of acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) was made.

The patient was treated with glucose loading and hemin therapy. In the ICU, 2 ampules of 50% dextrose in water solution (D50W) was administered, and she was transferred to the hematology-oncology service for hemin therapy. Soon after, she underwent a dilation and curettage. Three weeks later, she was discharged in good condition.

Discussion

The unifying diagnostic concept is that toxins damage all components of the nervous system: intestinal, central, peripheral, and autonomic. Hence, any combination of abdominal pain, vomiting, psychiatric symptoms, vital sign instability, weakness, or sensory loss may occur.1 To further confuse the diagnostician, the constellation of symptoms may vary with each episode.

Two critical laboratory clues are red urine—which often is mistaken for a UTI or hematuria—and hyponatremia.1 Another porphyria hallmark is triggers. These include drugs, carbohydrate deprivation, smoking, and stress. Common chemical inciters include alcohol, ketamine, etomidate, macrodantin, nifedipine, progesterone, and phenytoin.1 The Atkins diet (zero carbohydrates) reportedly caused an uptick in new porphyria cases.1

Attacks usually start after puberty. Women tend to experience flares during the luteal (progesterone) phase of the menstrual cycle.1 Acute intermittent porphyria can mimic Guillain-Barré syndrome and psychosis.2 Delayed diagnosis may lead to irreversible neurological damage or death.2

Despite AIP’s complexity, initial diagnostic testing is simple: a urinary PBG level obtained during an attack is virtually 100% sensitive and specific for AIP and two other acute porphyrias: hereditary coproporphyria (HCP), and variegate porphyria (VP). A positive urine PBG mandates immediate treatment—even while awaiting porphyrin and GK delta-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) levels in stool and serum to identify which porphyria (AIP, HCP, or VP) is present. The fourth (and least common) acute porphyria, ALA dehydratase porphyria (ADP), may produce no PBG elevation and requires separate porphyrin and ALA testing to make the diagnosis.

Treatment

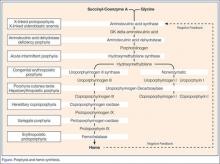

Treatment targets runaway heme precursor synthesis at its start and finish (Figure). Glucose-loading suppresses the initial enzyme, ALA synthase. Since the absence of normal end-product (heme) drives the enzymatic cascade, addition of IV hemin provides the substrate—and negative feedback—to stop it.

Conclusion

This case represents an example of AIP in which a patient presented with the characteristic abdominal pain and hyponatremia, complicated by the fact that she was pregnant and her urine was not red.

Intractable abdominal pain with negative imaging must prompt a search for red urine, neurological symptoms, porphyria medication triggers, and a family history of porphyria. Any constellation of findings should prompt immediate urine PBG testing.

In the appropriate clinical setting, it may be prudent to glucose-load a patient while waiting for confirmatory testing (which can take 1-2 days). Hemin therapy is best instituted by the hematology service after high urine PBG levels are confirmed.

- Sood GK, Anderson KE. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of acute intermittent porphyria.” Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-acute-intermittent-porphyria. Accessed February 22, 2016

- Bonkovsky HL, Siao P, Roig Z, Hedley-Whyte ET, Flotte TJ. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 20-2008. A 57-year-old woman with abdominal pain and weakness after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(26):2813-2825.

Case

A 34-year-old woman presented to the ED with severe, persistent abdominal pain that had begun 18 days earlier. She was 7 weeks pregnant and had been seen in the same ED the day before. During that visit, ultrasound had shown a single pregnancy of doubtful viability. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging was normal. She was given multiple doses of hydromorphone. The discharge diagnosis was “missed abortion.”

Since the onset of her pain, she had been hospitalized twice elsewhere, with no clear diagnosis to explain her pain. Treatment consisted of repeat doses of hydromorphone. During the second hospitalization, a sodium level of 109 mEq/L had been corrected with hypertonic saline, and a urinary tract infection (UTI) had been treated with cephalexin.

Our patient had never experienced similar abdominal pain. Her medical history included depression and asthma. Her family history was notable for an aunt who had died of lung cancer.

On this ED visit, the patient’s vital signs were normal. On examination, she was moaning in pain and clutching her abdomen. The abdomen was tender in both lower quadrants, with guarding but no rebound. Her sodium level was 125 mEq/L; the day before it had been 132 mEq/L.

Urine dipstick testing showed 2+ glucose and 2+ bilirubin; both had been within normal range (negative) the day before. An abdominal/pelvic computed tomography scan with intravenous (IV) and oral contrast did not reveal any potential cause of the patient’s pain. Multiple doses of IV hydromorphone were given, but her pain persisted.

We revisited our patient’s family history. With prompting, she remembered that as a teenager, her mother had had an illness that caused “problems with her nerves and blood vessels and turned her urine red.” When reached by phone, the patient’s mother, who lives outside the United States, said she was familiar with the term “porphyria,” but curiously, she did not state she carried the diagnosis, and had not advised her children they could be at risk.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for treatment of hyponatremia. Her mother’s history led us to suspect porphyria, so we sent a urine sample from the ED for porphobilinogen (PBG) testing. Her urine was not red at that time (on further questioning, she remembered she had had an episode of “red urine” recently). Two days later, after the PBG result came back positive, treatment was initiated for porphyria. With further stool and serum testing, the diagnosis of acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) was made.

The patient was treated with glucose loading and hemin therapy. In the ICU, 2 ampules of 50% dextrose in water solution (D50W) was administered, and she was transferred to the hematology-oncology service for hemin therapy. Soon after, she underwent a dilation and curettage. Three weeks later, she was discharged in good condition.

Discussion

The unifying diagnostic concept is that toxins damage all components of the nervous system: intestinal, central, peripheral, and autonomic. Hence, any combination of abdominal pain, vomiting, psychiatric symptoms, vital sign instability, weakness, or sensory loss may occur.1 To further confuse the diagnostician, the constellation of symptoms may vary with each episode.

Two critical laboratory clues are red urine—which often is mistaken for a UTI or hematuria—and hyponatremia.1 Another porphyria hallmark is triggers. These include drugs, carbohydrate deprivation, smoking, and stress. Common chemical inciters include alcohol, ketamine, etomidate, macrodantin, nifedipine, progesterone, and phenytoin.1 The Atkins diet (zero carbohydrates) reportedly caused an uptick in new porphyria cases.1

Attacks usually start after puberty. Women tend to experience flares during the luteal (progesterone) phase of the menstrual cycle.1 Acute intermittent porphyria can mimic Guillain-Barré syndrome and psychosis.2 Delayed diagnosis may lead to irreversible neurological damage or death.2

Despite AIP’s complexity, initial diagnostic testing is simple: a urinary PBG level obtained during an attack is virtually 100% sensitive and specific for AIP and two other acute porphyrias: hereditary coproporphyria (HCP), and variegate porphyria (VP). A positive urine PBG mandates immediate treatment—even while awaiting porphyrin and GK delta-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) levels in stool and serum to identify which porphyria (AIP, HCP, or VP) is present. The fourth (and least common) acute porphyria, ALA dehydratase porphyria (ADP), may produce no PBG elevation and requires separate porphyrin and ALA testing to make the diagnosis.

Treatment

Treatment targets runaway heme precursor synthesis at its start and finish (Figure). Glucose-loading suppresses the initial enzyme, ALA synthase. Since the absence of normal end-product (heme) drives the enzymatic cascade, addition of IV hemin provides the substrate—and negative feedback—to stop it.

Conclusion

This case represents an example of AIP in which a patient presented with the characteristic abdominal pain and hyponatremia, complicated by the fact that she was pregnant and her urine was not red.

Intractable abdominal pain with negative imaging must prompt a search for red urine, neurological symptoms, porphyria medication triggers, and a family history of porphyria. Any constellation of findings should prompt immediate urine PBG testing.

In the appropriate clinical setting, it may be prudent to glucose-load a patient while waiting for confirmatory testing (which can take 1-2 days). Hemin therapy is best instituted by the hematology service after high urine PBG levels are confirmed.

Case

A 34-year-old woman presented to the ED with severe, persistent abdominal pain that had begun 18 days earlier. She was 7 weeks pregnant and had been seen in the same ED the day before. During that visit, ultrasound had shown a single pregnancy of doubtful viability. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging was normal. She was given multiple doses of hydromorphone. The discharge diagnosis was “missed abortion.”

Since the onset of her pain, she had been hospitalized twice elsewhere, with no clear diagnosis to explain her pain. Treatment consisted of repeat doses of hydromorphone. During the second hospitalization, a sodium level of 109 mEq/L had been corrected with hypertonic saline, and a urinary tract infection (UTI) had been treated with cephalexin.

Our patient had never experienced similar abdominal pain. Her medical history included depression and asthma. Her family history was notable for an aunt who had died of lung cancer.

On this ED visit, the patient’s vital signs were normal. On examination, she was moaning in pain and clutching her abdomen. The abdomen was tender in both lower quadrants, with guarding but no rebound. Her sodium level was 125 mEq/L; the day before it had been 132 mEq/L.

Urine dipstick testing showed 2+ glucose and 2+ bilirubin; both had been within normal range (negative) the day before. An abdominal/pelvic computed tomography scan with intravenous (IV) and oral contrast did not reveal any potential cause of the patient’s pain. Multiple doses of IV hydromorphone were given, but her pain persisted.

We revisited our patient’s family history. With prompting, she remembered that as a teenager, her mother had had an illness that caused “problems with her nerves and blood vessels and turned her urine red.” When reached by phone, the patient’s mother, who lives outside the United States, said she was familiar with the term “porphyria,” but curiously, she did not state she carried the diagnosis, and had not advised her children they could be at risk.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for treatment of hyponatremia. Her mother’s history led us to suspect porphyria, so we sent a urine sample from the ED for porphobilinogen (PBG) testing. Her urine was not red at that time (on further questioning, she remembered she had had an episode of “red urine” recently). Two days later, after the PBG result came back positive, treatment was initiated for porphyria. With further stool and serum testing, the diagnosis of acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) was made.

The patient was treated with glucose loading and hemin therapy. In the ICU, 2 ampules of 50% dextrose in water solution (D50W) was administered, and she was transferred to the hematology-oncology service for hemin therapy. Soon after, she underwent a dilation and curettage. Three weeks later, she was discharged in good condition.

Discussion

The unifying diagnostic concept is that toxins damage all components of the nervous system: intestinal, central, peripheral, and autonomic. Hence, any combination of abdominal pain, vomiting, psychiatric symptoms, vital sign instability, weakness, or sensory loss may occur.1 To further confuse the diagnostician, the constellation of symptoms may vary with each episode.

Two critical laboratory clues are red urine—which often is mistaken for a UTI or hematuria—and hyponatremia.1 Another porphyria hallmark is triggers. These include drugs, carbohydrate deprivation, smoking, and stress. Common chemical inciters include alcohol, ketamine, etomidate, macrodantin, nifedipine, progesterone, and phenytoin.1 The Atkins diet (zero carbohydrates) reportedly caused an uptick in new porphyria cases.1

Attacks usually start after puberty. Women tend to experience flares during the luteal (progesterone) phase of the menstrual cycle.1 Acute intermittent porphyria can mimic Guillain-Barré syndrome and psychosis.2 Delayed diagnosis may lead to irreversible neurological damage or death.2

Despite AIP’s complexity, initial diagnostic testing is simple: a urinary PBG level obtained during an attack is virtually 100% sensitive and specific for AIP and two other acute porphyrias: hereditary coproporphyria (HCP), and variegate porphyria (VP). A positive urine PBG mandates immediate treatment—even while awaiting porphyrin and GK delta-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) levels in stool and serum to identify which porphyria (AIP, HCP, or VP) is present. The fourth (and least common) acute porphyria, ALA dehydratase porphyria (ADP), may produce no PBG elevation and requires separate porphyrin and ALA testing to make the diagnosis.

Treatment

Treatment targets runaway heme precursor synthesis at its start and finish (Figure). Glucose-loading suppresses the initial enzyme, ALA synthase. Since the absence of normal end-product (heme) drives the enzymatic cascade, addition of IV hemin provides the substrate—and negative feedback—to stop it.

Conclusion

This case represents an example of AIP in which a patient presented with the characteristic abdominal pain and hyponatremia, complicated by the fact that she was pregnant and her urine was not red.

Intractable abdominal pain with negative imaging must prompt a search for red urine, neurological symptoms, porphyria medication triggers, and a family history of porphyria. Any constellation of findings should prompt immediate urine PBG testing.

In the appropriate clinical setting, it may be prudent to glucose-load a patient while waiting for confirmatory testing (which can take 1-2 days). Hemin therapy is best instituted by the hematology service after high urine PBG levels are confirmed.

- Sood GK, Anderson KE. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of acute intermittent porphyria.” Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-acute-intermittent-porphyria. Accessed February 22, 2016

- Bonkovsky HL, Siao P, Roig Z, Hedley-Whyte ET, Flotte TJ. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 20-2008. A 57-year-old woman with abdominal pain and weakness after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(26):2813-2825.

- Sood GK, Anderson KE. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of acute intermittent porphyria.” Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-acute-intermittent-porphyria. Accessed February 22, 2016

- Bonkovsky HL, Siao P, Roig Z, Hedley-Whyte ET, Flotte TJ. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 20-2008. A 57-year-old woman with abdominal pain and weakness after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(26):2813-2825.

Swollen lymph nodes • patient is otherwise "healthy" • Dx?

THE CASE

A 52-year-old woman presented to our family clinic for a well woman exam. The only complaints she had were fatigue, which she attributed to a work day that began at 4 am, and hot flashes. She denied fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, medication use, or recent foreign travel. She had a history of hyperlipidemia and surgical removal of a cutaneous melanoma at age 12.

Her vital signs and physical exam were normal with the exception of 3 enlarged left inguinal lymph nodes and approximately 5 enlarged right inguinal lymph nodes. The nodes were freely moveable and non-tender. No additional lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly was found.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s work-up included a Pap smear, complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and pelvic and inguinal ultrasound. All tests were normal, except the ultrasound, which revealed 3 solid left inguinal lymph nodes measuring 1.2 to 1.6 cm and 6 solid right inguinal lymph nodes measuring 1.1 to 1.8 cm. An abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast identified nonspecific mesenteric, inguinal, retrocrural, and retroperitoneal adenopathy. An open biopsy of the largest inguinal lymph node revealed follicular lymphoma, a form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. (Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) are uncommon causes of inguinal lymphadenopathy.1)

We consulted Oncology and they recommended a positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan, which showed widespread lymphadenopathy. A bone marrow biopsy confirmed follicular lymphoma grade II, Ann Arbor stage III.

DISCUSSION

Generalized lymphadenopathy involves lymph node enlargement in more than one region of the body. Lymph nodes >1 cm in adults are considered abnormal and the differential diagnosis is broad (TABLE2-5). A patient’s age is a significant factor in the evaluation of peripheral lymphadenopathy.2-5 Results from one study of 628 patients who underwent nodal biopsy for peripheral lymphadenopathy revealed approximately 80% of nodes in patients under age 30 were noncancerous and likely had an infectious cause.3 However, among patients over age 50, only 40% were noncancerous.3

Node enlargement can be palpated in the head, neck, axilla, inguinal, and popliteal areas. Inguinal lymph nodes up to 2 cm in size may be palpable in healthy patients who spend time barefoot outdoors, have chronic leg trauma or infections, or have sexually transmitted infections.6 However, any lymph node >1 cm in adults should be considered abnormal.2-5

Method of diagnosis depends on malignancy risk

A definitive diagnosis in patients with lymph nodes >1 cm can be made by open lymph node biopsy (the gold standard) or fine needle aspiration (FNA); however, these procedures are rarely needed if malignancy risk is low.

Data on the prevalence of malignant peripheral lymphadenopathy is limited.4 Fijten et al reported that among 2556 patients who presented to a family medicine clinic with unexplained lymphadenopathy, the prevalence of malignancy was as low as 1.1%.7 However, the prevalence of malignant lymph nodes among patients referred to a surgical center for biopsy by primary care physicians was approximately 40% to 60%.3 This highlights the importance of a thorough history, physical exam, and referral when appropriate to increase the yield of diagnostic biopsies.

Low risk for malignancy is suggested when lymphadenopathy is present for less than 2 weeks or persists for more than one year with no increase in size.2 Benign causes such as sexually transmitted infections, Epstein-Barr virus, or medications should be treated appropriately. With no cause identified, 4 weeks of observation is recommended before biopsy.2,4,5,8 CT, PET, and biopsy should be considered early for large, concerning masses. No evidence supports empiric antibiotic use for unknown causes.2,5

High risk for malignancy is suggested in patients who are ≥50 years, present with constitutional symptoms, have lymphadenopathy >1 cm in >2 regions of the body, history of cancer, or have nodes that are rapidly enlarging, firm, fixed, or painless.2,3,5,7,9 Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy has the highest risk for malignancy, especially in patients ≥40 years.7 Enlarged iliac, popliteal, epitrochlear, and umbilical lymph nodes are never normal.2,4,5,7,10 Biopsy should be considered early in these patients.2-4,7 FNA or core needle biopsy is acceptable for an initial diagnosis, but negative results may require open biopsy.1,5,8 Prior to biopsy, imaging with ultrasound is recommended.1,2,8,11

Our patient was offered rituximab alone or rituximab in addition to cyclophosphamide, hydroxydoxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). The patient chose rituximab alone, which resulted in a 30% reduction in the size of her intra-abdominal disease. At this point, the patient and her oncologist chose to stop treatment and monitor her clinically.

Three months later, the patient returned to our family clinic complaining of postnasal drip, throat pain, and neck fullness that she’d had for one month that weren’t responsive to over-the-counter remedies and antibiotics. A supervised osteopathic medical student’s exam revealed right tonsillar enlargement (grade 3+) with minimal erythema and no exudates. A neck CT confirmed right tonsillar enlargement. The patient was referred to Otolaryngology, and the surgeon performed a tonsillectomy that demonstrated disease progression to follicular lymphoma grade IIIa. Given the new findings, Oncology recommended R-CHOP and the patient agreed.

The patient completed R-CHOP and her cancer was in remission one year later.

THE TAKEAWAY

Peripheral lymphadenopathy presents a diagnostic challenge that requires a thorough history and physical exam. General wellness exams should incorporate a comprehensive physical that includes the palpation of lymph nodes. Exam challenges include distinguishing benign lymphadenopathy (reactive lymphadenitis) from malignant lymphadenopathy.

In patients with low risk for malignancy, a period of 4 weeks of observation is reasonable. Biopsy should be considered early for risk factors including patient’s age ≥50, constitutional symptoms, lymphadenopathy >1 cm in >2 regions of the body, history of cancer, or rapidly enlarging nodes.

1. Metzgeroth G, Schneider S, Walz C, et al. Fine needle aspiration and core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of lymphadenopathy of unknown aetiology. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1477-1484.

2. Bazemore AW, Smucker DR. Lymphadenopathy and malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:2103-2110.

3. Lee Y, Terry R, Lukes RJ. Lymph node biopsy for diagnosis: a statistical study. J Surg Oncol. 1980;14:53-60.

4. Ferrer R. Lymphadenopathy: differential diagnosis and evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:1313-1320.

5. Motyckova G, Steensma DP. Why does my patient have lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly? Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2012;26:395-408.

6. Habermann TM, Steensma DP. Lymphadenopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:723-732.

7. Fijten GH, Blijham GH. Unexplained lymphadenopathy in family practice. An evaluation of the probability of malignant causes and the effectiveness of physicians’ workup. J Fam Pract. 1988;27:373-376.

8. Chau I, Kelleher MT, Cunningham D, et al. Rapid access multidisciplinary lymph node diagnostic clinic: analysis of 550 patients. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:354-361.

9. Vassilakopoulos TP, Pangalis GA. Application of a prediction rule to select which patients presenting with lymphadenopathy should undergo a lymph node biopsy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79:338-347.

10. Dar IH, Kamili MA, Dar SH, et al. Sister Mary Joseph nodule-A case report with review of literature. J Res Med Sci. 2009;14:385-387.

11. Cui XW, Jenssen C, Saftoiu A, et al. New ultrasound techniques for lymph node evaluation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4850-4860.

THE CASE

A 52-year-old woman presented to our family clinic for a well woman exam. The only complaints she had were fatigue, which she attributed to a work day that began at 4 am, and hot flashes. She denied fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, medication use, or recent foreign travel. She had a history of hyperlipidemia and surgical removal of a cutaneous melanoma at age 12.

Her vital signs and physical exam were normal with the exception of 3 enlarged left inguinal lymph nodes and approximately 5 enlarged right inguinal lymph nodes. The nodes were freely moveable and non-tender. No additional lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly was found.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s work-up included a Pap smear, complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and pelvic and inguinal ultrasound. All tests were normal, except the ultrasound, which revealed 3 solid left inguinal lymph nodes measuring 1.2 to 1.6 cm and 6 solid right inguinal lymph nodes measuring 1.1 to 1.8 cm. An abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast identified nonspecific mesenteric, inguinal, retrocrural, and retroperitoneal adenopathy. An open biopsy of the largest inguinal lymph node revealed follicular lymphoma, a form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. (Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) are uncommon causes of inguinal lymphadenopathy.1)

We consulted Oncology and they recommended a positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan, which showed widespread lymphadenopathy. A bone marrow biopsy confirmed follicular lymphoma grade II, Ann Arbor stage III.

DISCUSSION

Generalized lymphadenopathy involves lymph node enlargement in more than one region of the body. Lymph nodes >1 cm in adults are considered abnormal and the differential diagnosis is broad (TABLE2-5). A patient’s age is a significant factor in the evaluation of peripheral lymphadenopathy.2-5 Results from one study of 628 patients who underwent nodal biopsy for peripheral lymphadenopathy revealed approximately 80% of nodes in patients under age 30 were noncancerous and likely had an infectious cause.3 However, among patients over age 50, only 40% were noncancerous.3

Node enlargement can be palpated in the head, neck, axilla, inguinal, and popliteal areas. Inguinal lymph nodes up to 2 cm in size may be palpable in healthy patients who spend time barefoot outdoors, have chronic leg trauma or infections, or have sexually transmitted infections.6 However, any lymph node >1 cm in adults should be considered abnormal.2-5

Method of diagnosis depends on malignancy risk

A definitive diagnosis in patients with lymph nodes >1 cm can be made by open lymph node biopsy (the gold standard) or fine needle aspiration (FNA); however, these procedures are rarely needed if malignancy risk is low.

Data on the prevalence of malignant peripheral lymphadenopathy is limited.4 Fijten et al reported that among 2556 patients who presented to a family medicine clinic with unexplained lymphadenopathy, the prevalence of malignancy was as low as 1.1%.7 However, the prevalence of malignant lymph nodes among patients referred to a surgical center for biopsy by primary care physicians was approximately 40% to 60%.3 This highlights the importance of a thorough history, physical exam, and referral when appropriate to increase the yield of diagnostic biopsies.

Low risk for malignancy is suggested when lymphadenopathy is present for less than 2 weeks or persists for more than one year with no increase in size.2 Benign causes such as sexually transmitted infections, Epstein-Barr virus, or medications should be treated appropriately. With no cause identified, 4 weeks of observation is recommended before biopsy.2,4,5,8 CT, PET, and biopsy should be considered early for large, concerning masses. No evidence supports empiric antibiotic use for unknown causes.2,5

High risk for malignancy is suggested in patients who are ≥50 years, present with constitutional symptoms, have lymphadenopathy >1 cm in >2 regions of the body, history of cancer, or have nodes that are rapidly enlarging, firm, fixed, or painless.2,3,5,7,9 Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy has the highest risk for malignancy, especially in patients ≥40 years.7 Enlarged iliac, popliteal, epitrochlear, and umbilical lymph nodes are never normal.2,4,5,7,10 Biopsy should be considered early in these patients.2-4,7 FNA or core needle biopsy is acceptable for an initial diagnosis, but negative results may require open biopsy.1,5,8 Prior to biopsy, imaging with ultrasound is recommended.1,2,8,11

Our patient was offered rituximab alone or rituximab in addition to cyclophosphamide, hydroxydoxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). The patient chose rituximab alone, which resulted in a 30% reduction in the size of her intra-abdominal disease. At this point, the patient and her oncologist chose to stop treatment and monitor her clinically.

Three months later, the patient returned to our family clinic complaining of postnasal drip, throat pain, and neck fullness that she’d had for one month that weren’t responsive to over-the-counter remedies and antibiotics. A supervised osteopathic medical student’s exam revealed right tonsillar enlargement (grade 3+) with minimal erythema and no exudates. A neck CT confirmed right tonsillar enlargement. The patient was referred to Otolaryngology, and the surgeon performed a tonsillectomy that demonstrated disease progression to follicular lymphoma grade IIIa. Given the new findings, Oncology recommended R-CHOP and the patient agreed.

The patient completed R-CHOP and her cancer was in remission one year later.

THE TAKEAWAY

Peripheral lymphadenopathy presents a diagnostic challenge that requires a thorough history and physical exam. General wellness exams should incorporate a comprehensive physical that includes the palpation of lymph nodes. Exam challenges include distinguishing benign lymphadenopathy (reactive lymphadenitis) from malignant lymphadenopathy.

In patients with low risk for malignancy, a period of 4 weeks of observation is reasonable. Biopsy should be considered early for risk factors including patient’s age ≥50, constitutional symptoms, lymphadenopathy >1 cm in >2 regions of the body, history of cancer, or rapidly enlarging nodes.

THE CASE

A 52-year-old woman presented to our family clinic for a well woman exam. The only complaints she had were fatigue, which she attributed to a work day that began at 4 am, and hot flashes. She denied fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, medication use, or recent foreign travel. She had a history of hyperlipidemia and surgical removal of a cutaneous melanoma at age 12.

Her vital signs and physical exam were normal with the exception of 3 enlarged left inguinal lymph nodes and approximately 5 enlarged right inguinal lymph nodes. The nodes were freely moveable and non-tender. No additional lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly was found.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s work-up included a Pap smear, complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and pelvic and inguinal ultrasound. All tests were normal, except the ultrasound, which revealed 3 solid left inguinal lymph nodes measuring 1.2 to 1.6 cm and 6 solid right inguinal lymph nodes measuring 1.1 to 1.8 cm. An abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast identified nonspecific mesenteric, inguinal, retrocrural, and retroperitoneal adenopathy. An open biopsy of the largest inguinal lymph node revealed follicular lymphoma, a form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. (Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) are uncommon causes of inguinal lymphadenopathy.1)

We consulted Oncology and they recommended a positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan, which showed widespread lymphadenopathy. A bone marrow biopsy confirmed follicular lymphoma grade II, Ann Arbor stage III.

DISCUSSION

Generalized lymphadenopathy involves lymph node enlargement in more than one region of the body. Lymph nodes >1 cm in adults are considered abnormal and the differential diagnosis is broad (TABLE2-5). A patient’s age is a significant factor in the evaluation of peripheral lymphadenopathy.2-5 Results from one study of 628 patients who underwent nodal biopsy for peripheral lymphadenopathy revealed approximately 80% of nodes in patients under age 30 were noncancerous and likely had an infectious cause.3 However, among patients over age 50, only 40% were noncancerous.3

Node enlargement can be palpated in the head, neck, axilla, inguinal, and popliteal areas. Inguinal lymph nodes up to 2 cm in size may be palpable in healthy patients who spend time barefoot outdoors, have chronic leg trauma or infections, or have sexually transmitted infections.6 However, any lymph node >1 cm in adults should be considered abnormal.2-5

Method of diagnosis depends on malignancy risk

A definitive diagnosis in patients with lymph nodes >1 cm can be made by open lymph node biopsy (the gold standard) or fine needle aspiration (FNA); however, these procedures are rarely needed if malignancy risk is low.

Data on the prevalence of malignant peripheral lymphadenopathy is limited.4 Fijten et al reported that among 2556 patients who presented to a family medicine clinic with unexplained lymphadenopathy, the prevalence of malignancy was as low as 1.1%.7 However, the prevalence of malignant lymph nodes among patients referred to a surgical center for biopsy by primary care physicians was approximately 40% to 60%.3 This highlights the importance of a thorough history, physical exam, and referral when appropriate to increase the yield of diagnostic biopsies.

Low risk for malignancy is suggested when lymphadenopathy is present for less than 2 weeks or persists for more than one year with no increase in size.2 Benign causes such as sexually transmitted infections, Epstein-Barr virus, or medications should be treated appropriately. With no cause identified, 4 weeks of observation is recommended before biopsy.2,4,5,8 CT, PET, and biopsy should be considered early for large, concerning masses. No evidence supports empiric antibiotic use for unknown causes.2,5

High risk for malignancy is suggested in patients who are ≥50 years, present with constitutional symptoms, have lymphadenopathy >1 cm in >2 regions of the body, history of cancer, or have nodes that are rapidly enlarging, firm, fixed, or painless.2,3,5,7,9 Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy has the highest risk for malignancy, especially in patients ≥40 years.7 Enlarged iliac, popliteal, epitrochlear, and umbilical lymph nodes are never normal.2,4,5,7,10 Biopsy should be considered early in these patients.2-4,7 FNA or core needle biopsy is acceptable for an initial diagnosis, but negative results may require open biopsy.1,5,8 Prior to biopsy, imaging with ultrasound is recommended.1,2,8,11

Our patient was offered rituximab alone or rituximab in addition to cyclophosphamide, hydroxydoxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). The patient chose rituximab alone, which resulted in a 30% reduction in the size of her intra-abdominal disease. At this point, the patient and her oncologist chose to stop treatment and monitor her clinically.

Three months later, the patient returned to our family clinic complaining of postnasal drip, throat pain, and neck fullness that she’d had for one month that weren’t responsive to over-the-counter remedies and antibiotics. A supervised osteopathic medical student’s exam revealed right tonsillar enlargement (grade 3+) with minimal erythema and no exudates. A neck CT confirmed right tonsillar enlargement. The patient was referred to Otolaryngology, and the surgeon performed a tonsillectomy that demonstrated disease progression to follicular lymphoma grade IIIa. Given the new findings, Oncology recommended R-CHOP and the patient agreed.

The patient completed R-CHOP and her cancer was in remission one year later.

THE TAKEAWAY

Peripheral lymphadenopathy presents a diagnostic challenge that requires a thorough history and physical exam. General wellness exams should incorporate a comprehensive physical that includes the palpation of lymph nodes. Exam challenges include distinguishing benign lymphadenopathy (reactive lymphadenitis) from malignant lymphadenopathy.

In patients with low risk for malignancy, a period of 4 weeks of observation is reasonable. Biopsy should be considered early for risk factors including patient’s age ≥50, constitutional symptoms, lymphadenopathy >1 cm in >2 regions of the body, history of cancer, or rapidly enlarging nodes.

1. Metzgeroth G, Schneider S, Walz C, et al. Fine needle aspiration and core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of lymphadenopathy of unknown aetiology. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1477-1484.

2. Bazemore AW, Smucker DR. Lymphadenopathy and malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:2103-2110.

3. Lee Y, Terry R, Lukes RJ. Lymph node biopsy for diagnosis: a statistical study. J Surg Oncol. 1980;14:53-60.

4. Ferrer R. Lymphadenopathy: differential diagnosis and evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:1313-1320.

5. Motyckova G, Steensma DP. Why does my patient have lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly? Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2012;26:395-408.

6. Habermann TM, Steensma DP. Lymphadenopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:723-732.

7. Fijten GH, Blijham GH. Unexplained lymphadenopathy in family practice. An evaluation of the probability of malignant causes and the effectiveness of physicians’ workup. J Fam Pract. 1988;27:373-376.

8. Chau I, Kelleher MT, Cunningham D, et al. Rapid access multidisciplinary lymph node diagnostic clinic: analysis of 550 patients. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:354-361.

9. Vassilakopoulos TP, Pangalis GA. Application of a prediction rule to select which patients presenting with lymphadenopathy should undergo a lymph node biopsy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79:338-347.

10. Dar IH, Kamili MA, Dar SH, et al. Sister Mary Joseph nodule-A case report with review of literature. J Res Med Sci. 2009;14:385-387.

11. Cui XW, Jenssen C, Saftoiu A, et al. New ultrasound techniques for lymph node evaluation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4850-4860.

1. Metzgeroth G, Schneider S, Walz C, et al. Fine needle aspiration and core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of lymphadenopathy of unknown aetiology. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1477-1484.

2. Bazemore AW, Smucker DR. Lymphadenopathy and malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:2103-2110.

3. Lee Y, Terry R, Lukes RJ. Lymph node biopsy for diagnosis: a statistical study. J Surg Oncol. 1980;14:53-60.

4. Ferrer R. Lymphadenopathy: differential diagnosis and evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:1313-1320.

5. Motyckova G, Steensma DP. Why does my patient have lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly? Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2012;26:395-408.

6. Habermann TM, Steensma DP. Lymphadenopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:723-732.

7. Fijten GH, Blijham GH. Unexplained lymphadenopathy in family practice. An evaluation of the probability of malignant causes and the effectiveness of physicians’ workup. J Fam Pract. 1988;27:373-376.

8. Chau I, Kelleher MT, Cunningham D, et al. Rapid access multidisciplinary lymph node diagnostic clinic: analysis of 550 patients. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:354-361.

9. Vassilakopoulos TP, Pangalis GA. Application of a prediction rule to select which patients presenting with lymphadenopathy should undergo a lymph node biopsy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79:338-347.

10. Dar IH, Kamili MA, Dar SH, et al. Sister Mary Joseph nodule-A case report with review of literature. J Res Med Sci. 2009;14:385-387.

11. Cui XW, Jenssen C, Saftoiu A, et al. New ultrasound techniques for lymph node evaluation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4850-4860.

Extreme Postinjection Flare in Response to Intra-Articular Triamcinolone Acetonide (Kenalog)

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections (CSIs) have been a common treatment for osteoarthritis since the 1950s and continue to be an option for patients who prefer nonoperative management.1 Although CSIs may improve pain secondary to osteoarthritis temporarily, they do not slow articular cartilage degradation, and many patients request multiple CSIs before total joint arthroplasty ultimately is required.1,2 Therefore, acute and chronic side effects of CSI must be considered when repeatedly administering corticosteroids.

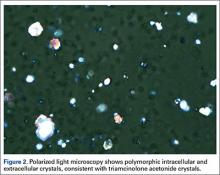

A postinjection flare, the most common acute side effect of intra-articular CSI, is characterized by a localized inflammatory response that can last 2 to 3 days. The flare occurs in 2% to 25% of CSI cases.3-5 Symptoms can range from mild joint effusion to disabling pain.6 In the present case, a severe postinjection flare occurred after intra-articular administration of triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog). This case is novel in that its acuity of onset, severity of symptoms, and synovial fluid analysis mimicked septic arthritis, which was ultimately ruled out with negative cultures and confirmation of triamcinolone acetonide crystals in the synovial aspirate, viewed by polarized light microscopy. To date, only one other case of an immediate (<2 hours) and severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone has been reported.7 As CSIs are often used in the nonoperative treatment of osteoarthritis, it is imperative for the treating physician to be aware of this potential side effect in order to appropriately inform the patient of this risk and guide treatment should the scenario arise. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, and moderate bilateral knee osteoarthritis presented with left knee pain. She had been receiving annual hylan injections for 5 years and had no adverse reactions, but the pain gradually worsened over the past 3 months. She was given an intra-articular injection of 2 mL of 1% lidocaine and 2 mL (40 mg) of triamcinolone acetonide in the left knee.

Two hours later, she experienced swelling and intense pain in the knee and was unable to ambulate. Physical examination revealed she was afebrile but was having severe pain in the knee through all range of motion. The knee had no appreciable erythema or warmth. Laboratory data were significant: White blood cell (WBC) count was 14,600, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 1 mm/h. The knee was aspirated with a return of 25 mL of “butterscotch”-colored fluid (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to rule out iatrogenic septic arthritis, or chronic, indolent septic arthritis acutely worsened by CSI, until synovial fluid analysis and cultures could be performed (Table 1).

She was treated overnight with a compressive wrap, elevation, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which provided significant pain relief. Polarized light microscopy revealed polymorphic intracellular and extracellular crystals with crystal morphology consistent with the injection of triamcinolone ester (Figure 2). Gram stain showed many WBCs but no organisms. These findings were thought to represent an exogenous crystal-induced acute inflammatory response. Given the patient’s improving clinical course, she was discharged the next morning.

Twelve days later, at clinic follow-up, she was still experiencing pain above her baseline level. Given the continued effusion, 8 mL of synovial fluid was aspirated, which appeared clear and only slightly blood-tinged. Synovial analysis showed resolution of leukocytosis, confirming a severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide.

Discussion

Although rare, side effects from repeated intra-articular CSIs include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction and steroid-induced myopathy.8,9 Acute side effects are more common and include postinjection flare, iatrogenic septic arthritis, local tissue atrophy, cartilage damage, tendon rupture, nerve atrophy, increased blood glucose, and osteonecrosis.10,11 The present case report describes an extreme example of a postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide and summarizes the characteristics of injections that cause flares.

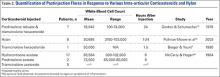

The physical properties of corticosteroids have a significant impact on their efficacy and on their potential for adverse events. Corticosteroid preparations can be water-soluble or water-insoluble. Most commonly, water-insoluble preparations that contain insoluble corticosteroid esters (eg, triamcinolone, methylprednisolone) are used in intra-articular injections. These form microcrystalline aggregates in solution, which require the patient’s own hydrolytic enzymes (esterases) to release the active moiety and thus have a longer duration of action. However, they are more commonly associated with postinjection flares compared with their more soluble and faster- acting counterparts (eg. dexamethasone, betamethasone).10 Microcrystalline aggregates, which are larger in size, induce a stronger inflammatory response, and in a dose-dependent manner.6A sterile inflammatory reaction to hydrocortisone, cortisone, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and prednisolone crystals in normal joints has been previously described,6,12,13 and crystals of the various preparations have been demonstrated within leukocytes by both polarized light and electron microscopy.12,13 Table 2 summarizes previous synovial fluid analyses after intra-articular injections of various corticosteroid preparations in normal healthy joints and in patients experiencing a postinjection flare. To date, there have been no reports of an immediate (<2 hours) and severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide, though there was a report of a postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone hexacetonide (Aristospan),7 and here the synovial fluid WBC count (30,000) was much lower.

Although many cases of corticosteroid hypersensitivity have been reported, in rare cases intra-articular administration of triamcinolone has caused anaphylactic reactions and shock.14,15 Multiple case studies have determined that the specific excipient carboxymethylcellulose (found in many triamcinolone preparations), and not the corticosteroid itself, can cause an immunoglobulin E–mediated anaphylactic reaction.16-18 Therefore, performing skin-prick tests for potential corticosteroids and their excipients in patients with known postinjection flares might help prevent serious adverse reactions.18,19

The present case involved an extreme postinjection flare in response to intra-articular administration of triamcinolone acetonide. Postinjection flares are rare but significant events, and physicians using CSIs in the treatment of arthritis need to be aware of this potential reaction in order to appropriately inform patients of this risk and guide treatment should the scenario arise.

1. Hollander JL, Brown EM Jr, Jessar RA, Brown CY. Hydrocortisone and cortisone injected into arthritic joints; comparative effects of and use of hydrocortisone as a local antiarthritic agent. J Am Med Assoc. 1951;147(17):1629-1635.

2. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, Gee T, Bourne R, Wells G. Intraarticular corticosteroid for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;19(2):CD005328.

3. Friedman DM, Moore ME. The efficacy of intraarticular steroids in osteoarthritis: a double-blind study. J Rheumatol. 1980;7(6):850-856.

4. Brown EM Jr, Frain JB, Udell L, Hollander JL. Locally administered hydrocortisone in the rheumatic diseases; a summary of its use in 547 patients. Am J Med. 1953;15(5):656-665.

5. Hollander JL, Jessar RA, Brown EM Jr. Intra-synovial corticosteroid therapy: a decade of use. Bull Rheum Dis. 1961;11:239-240.

6. McCarty DJ Jr, Hogan JM. Inflammatory reaction after intrasynovial injection of microcrystalline adrenocorticosteroid esters. Arthritis Rheum. 1964;7(4):359-367.

7. Berger RG, Yount WJ. Immediate “steroid flare” from intraarticular triamcinolone hexacetonide injection: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1284-1286.

8. Mader R, Lavi I, Luboshitzky R. Evaluation of the pituitary-adrenal axis function following single intraarticular injection of methylprednisolone. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(3):924-928.

9. Raynauld JP, Buckland-Wright C, Ward R, et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term intraarticular steroid injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(2):370-377.

10. MacMahon PJ, Eustace SJ, Kavanagh EC. Injectable corticosteroid and local anesthetic preparations: a review for radiologists. Radiology. 2009;252(3):647-661.

11. Sparling M, Malleson P, Wood B, Petty R. Radiographic followup of joints injected with triamcinolone hexacetonide for the management of childhood arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(6):821-826.

12. Eymontt MJ, Gordon GV, Schumacher HR, Hansell JR. The effects on synovial permeability and synovial fluid leukocyte counts in symptomatic osteoarthritis after intraarticular corticosteroid administration. J Rheumatol. 1982;9(2):198-203.

13. Gordon GV, Schumacher HR. Electron microscopic study of depot corticosteroid crystals with clinical studies after intra-articular injection. J Rheumatol. 1979;6(1):7-14.

14. Karsh J, Yang WH. An anaphylactic reaction to intra-articular triamcinolone: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90(2):254-258.

15. Larsson LG. Anaphylactic shock after i.a. administration of triamcinolone acetonide in a 35-year-old female. Scand J Rheumatol. 1989;18(6):441-442.

16. García-Ortega P, Corominas M, Badia M. Carboxymethylcellulose allergy as a cause of suspected corticosteroid anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91(4):421.

17. Patterson DL, Yunginger JW, Dunn WF, Jones RT, Hunt LW. Anaphylaxis induced by the carboxymethylcellulose component of injectable triamcinolone acetonide suspension (Kenalog). Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995;74(2):163-166.

18. Steiner UC, Gentinetta T, Hausmann O, Pichler WJ. IgE-mediated anaphylaxis to intraarticular glucocorticoid preparations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):W156-W157.

19. Ijsselmuiden OE, Knegt-Junk KJ, van Wijk RG, van Joost T. Cutaneous adverse reactions after intra-articular injection of triamcinolone acetonide. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75(1):57-58.

20. Pullman-Mooar S, Mooar P, Sieck M, Clayburne G, Schumacher HR. Are there distinctive inflammatory flares after hylan g-f 20 intraarticular injections? J Rheumatol. 2002;29(12):2611-2614.

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections (CSIs) have been a common treatment for osteoarthritis since the 1950s and continue to be an option for patients who prefer nonoperative management.1 Although CSIs may improve pain secondary to osteoarthritis temporarily, they do not slow articular cartilage degradation, and many patients request multiple CSIs before total joint arthroplasty ultimately is required.1,2 Therefore, acute and chronic side effects of CSI must be considered when repeatedly administering corticosteroids.

A postinjection flare, the most common acute side effect of intra-articular CSI, is characterized by a localized inflammatory response that can last 2 to 3 days. The flare occurs in 2% to 25% of CSI cases.3-5 Symptoms can range from mild joint effusion to disabling pain.6 In the present case, a severe postinjection flare occurred after intra-articular administration of triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog). This case is novel in that its acuity of onset, severity of symptoms, and synovial fluid analysis mimicked septic arthritis, which was ultimately ruled out with negative cultures and confirmation of triamcinolone acetonide crystals in the synovial aspirate, viewed by polarized light microscopy. To date, only one other case of an immediate (<2 hours) and severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone has been reported.7 As CSIs are often used in the nonoperative treatment of osteoarthritis, it is imperative for the treating physician to be aware of this potential side effect in order to appropriately inform the patient of this risk and guide treatment should the scenario arise. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, and moderate bilateral knee osteoarthritis presented with left knee pain. She had been receiving annual hylan injections for 5 years and had no adverse reactions, but the pain gradually worsened over the past 3 months. She was given an intra-articular injection of 2 mL of 1% lidocaine and 2 mL (40 mg) of triamcinolone acetonide in the left knee.

Two hours later, she experienced swelling and intense pain in the knee and was unable to ambulate. Physical examination revealed she was afebrile but was having severe pain in the knee through all range of motion. The knee had no appreciable erythema or warmth. Laboratory data were significant: White blood cell (WBC) count was 14,600, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 1 mm/h. The knee was aspirated with a return of 25 mL of “butterscotch”-colored fluid (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to rule out iatrogenic septic arthritis, or chronic, indolent septic arthritis acutely worsened by CSI, until synovial fluid analysis and cultures could be performed (Table 1).

She was treated overnight with a compressive wrap, elevation, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which provided significant pain relief. Polarized light microscopy revealed polymorphic intracellular and extracellular crystals with crystal morphology consistent with the injection of triamcinolone ester (Figure 2). Gram stain showed many WBCs but no organisms. These findings were thought to represent an exogenous crystal-induced acute inflammatory response. Given the patient’s improving clinical course, she was discharged the next morning.

Twelve days later, at clinic follow-up, she was still experiencing pain above her baseline level. Given the continued effusion, 8 mL of synovial fluid was aspirated, which appeared clear and only slightly blood-tinged. Synovial analysis showed resolution of leukocytosis, confirming a severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide.

Discussion

Although rare, side effects from repeated intra-articular CSIs include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction and steroid-induced myopathy.8,9 Acute side effects are more common and include postinjection flare, iatrogenic septic arthritis, local tissue atrophy, cartilage damage, tendon rupture, nerve atrophy, increased blood glucose, and osteonecrosis.10,11 The present case report describes an extreme example of a postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide and summarizes the characteristics of injections that cause flares.

The physical properties of corticosteroids have a significant impact on their efficacy and on their potential for adverse events. Corticosteroid preparations can be water-soluble or water-insoluble. Most commonly, water-insoluble preparations that contain insoluble corticosteroid esters (eg, triamcinolone, methylprednisolone) are used in intra-articular injections. These form microcrystalline aggregates in solution, which require the patient’s own hydrolytic enzymes (esterases) to release the active moiety and thus have a longer duration of action. However, they are more commonly associated with postinjection flares compared with their more soluble and faster- acting counterparts (eg. dexamethasone, betamethasone).10 Microcrystalline aggregates, which are larger in size, induce a stronger inflammatory response, and in a dose-dependent manner.6A sterile inflammatory reaction to hydrocortisone, cortisone, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and prednisolone crystals in normal joints has been previously described,6,12,13 and crystals of the various preparations have been demonstrated within leukocytes by both polarized light and electron microscopy.12,13 Table 2 summarizes previous synovial fluid analyses after intra-articular injections of various corticosteroid preparations in normal healthy joints and in patients experiencing a postinjection flare. To date, there have been no reports of an immediate (<2 hours) and severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide, though there was a report of a postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone hexacetonide (Aristospan),7 and here the synovial fluid WBC count (30,000) was much lower.

Although many cases of corticosteroid hypersensitivity have been reported, in rare cases intra-articular administration of triamcinolone has caused anaphylactic reactions and shock.14,15 Multiple case studies have determined that the specific excipient carboxymethylcellulose (found in many triamcinolone preparations), and not the corticosteroid itself, can cause an immunoglobulin E–mediated anaphylactic reaction.16-18 Therefore, performing skin-prick tests for potential corticosteroids and their excipients in patients with known postinjection flares might help prevent serious adverse reactions.18,19

The present case involved an extreme postinjection flare in response to intra-articular administration of triamcinolone acetonide. Postinjection flares are rare but significant events, and physicians using CSIs in the treatment of arthritis need to be aware of this potential reaction in order to appropriately inform patients of this risk and guide treatment should the scenario arise.

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections (CSIs) have been a common treatment for osteoarthritis since the 1950s and continue to be an option for patients who prefer nonoperative management.1 Although CSIs may improve pain secondary to osteoarthritis temporarily, they do not slow articular cartilage degradation, and many patients request multiple CSIs before total joint arthroplasty ultimately is required.1,2 Therefore, acute and chronic side effects of CSI must be considered when repeatedly administering corticosteroids.

A postinjection flare, the most common acute side effect of intra-articular CSI, is characterized by a localized inflammatory response that can last 2 to 3 days. The flare occurs in 2% to 25% of CSI cases.3-5 Symptoms can range from mild joint effusion to disabling pain.6 In the present case, a severe postinjection flare occurred after intra-articular administration of triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog). This case is novel in that its acuity of onset, severity of symptoms, and synovial fluid analysis mimicked septic arthritis, which was ultimately ruled out with negative cultures and confirmation of triamcinolone acetonide crystals in the synovial aspirate, viewed by polarized light microscopy. To date, only one other case of an immediate (<2 hours) and severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone has been reported.7 As CSIs are often used in the nonoperative treatment of osteoarthritis, it is imperative for the treating physician to be aware of this potential side effect in order to appropriately inform the patient of this risk and guide treatment should the scenario arise. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, and moderate bilateral knee osteoarthritis presented with left knee pain. She had been receiving annual hylan injections for 5 years and had no adverse reactions, but the pain gradually worsened over the past 3 months. She was given an intra-articular injection of 2 mL of 1% lidocaine and 2 mL (40 mg) of triamcinolone acetonide in the left knee.

Two hours later, she experienced swelling and intense pain in the knee and was unable to ambulate. Physical examination revealed she was afebrile but was having severe pain in the knee through all range of motion. The knee had no appreciable erythema or warmth. Laboratory data were significant: White blood cell (WBC) count was 14,600, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 1 mm/h. The knee was aspirated with a return of 25 mL of “butterscotch”-colored fluid (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to rule out iatrogenic septic arthritis, or chronic, indolent septic arthritis acutely worsened by CSI, until synovial fluid analysis and cultures could be performed (Table 1).

She was treated overnight with a compressive wrap, elevation, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which provided significant pain relief. Polarized light microscopy revealed polymorphic intracellular and extracellular crystals with crystal morphology consistent with the injection of triamcinolone ester (Figure 2). Gram stain showed many WBCs but no organisms. These findings were thought to represent an exogenous crystal-induced acute inflammatory response. Given the patient’s improving clinical course, she was discharged the next morning.

Twelve days later, at clinic follow-up, she was still experiencing pain above her baseline level. Given the continued effusion, 8 mL of synovial fluid was aspirated, which appeared clear and only slightly blood-tinged. Synovial analysis showed resolution of leukocytosis, confirming a severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide.

Discussion

Although rare, side effects from repeated intra-articular CSIs include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction and steroid-induced myopathy.8,9 Acute side effects are more common and include postinjection flare, iatrogenic septic arthritis, local tissue atrophy, cartilage damage, tendon rupture, nerve atrophy, increased blood glucose, and osteonecrosis.10,11 The present case report describes an extreme example of a postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide and summarizes the characteristics of injections that cause flares.

The physical properties of corticosteroids have a significant impact on their efficacy and on their potential for adverse events. Corticosteroid preparations can be water-soluble or water-insoluble. Most commonly, water-insoluble preparations that contain insoluble corticosteroid esters (eg, triamcinolone, methylprednisolone) are used in intra-articular injections. These form microcrystalline aggregates in solution, which require the patient’s own hydrolytic enzymes (esterases) to release the active moiety and thus have a longer duration of action. However, they are more commonly associated with postinjection flares compared with their more soluble and faster- acting counterparts (eg. dexamethasone, betamethasone).10 Microcrystalline aggregates, which are larger in size, induce a stronger inflammatory response, and in a dose-dependent manner.6A sterile inflammatory reaction to hydrocortisone, cortisone, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and prednisolone crystals in normal joints has been previously described,6,12,13 and crystals of the various preparations have been demonstrated within leukocytes by both polarized light and electron microscopy.12,13 Table 2 summarizes previous synovial fluid analyses after intra-articular injections of various corticosteroid preparations in normal healthy joints and in patients experiencing a postinjection flare. To date, there have been no reports of an immediate (<2 hours) and severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide, though there was a report of a postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone hexacetonide (Aristospan),7 and here the synovial fluid WBC count (30,000) was much lower.

Although many cases of corticosteroid hypersensitivity have been reported, in rare cases intra-articular administration of triamcinolone has caused anaphylactic reactions and shock.14,15 Multiple case studies have determined that the specific excipient carboxymethylcellulose (found in many triamcinolone preparations), and not the corticosteroid itself, can cause an immunoglobulin E–mediated anaphylactic reaction.16-18 Therefore, performing skin-prick tests for potential corticosteroids and their excipients in patients with known postinjection flares might help prevent serious adverse reactions.18,19

The present case involved an extreme postinjection flare in response to intra-articular administration of triamcinolone acetonide. Postinjection flares are rare but significant events, and physicians using CSIs in the treatment of arthritis need to be aware of this potential reaction in order to appropriately inform patients of this risk and guide treatment should the scenario arise.

1. Hollander JL, Brown EM Jr, Jessar RA, Brown CY. Hydrocortisone and cortisone injected into arthritic joints; comparative effects of and use of hydrocortisone as a local antiarthritic agent. J Am Med Assoc. 1951;147(17):1629-1635.

2. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, Gee T, Bourne R, Wells G. Intraarticular corticosteroid for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;19(2):CD005328.

3. Friedman DM, Moore ME. The efficacy of intraarticular steroids in osteoarthritis: a double-blind study. J Rheumatol. 1980;7(6):850-856.

4. Brown EM Jr, Frain JB, Udell L, Hollander JL. Locally administered hydrocortisone in the rheumatic diseases; a summary of its use in 547 patients. Am J Med. 1953;15(5):656-665.

5. Hollander JL, Jessar RA, Brown EM Jr. Intra-synovial corticosteroid therapy: a decade of use. Bull Rheum Dis. 1961;11:239-240.

6. McCarty DJ Jr, Hogan JM. Inflammatory reaction after intrasynovial injection of microcrystalline adrenocorticosteroid esters. Arthritis Rheum. 1964;7(4):359-367.

7. Berger RG, Yount WJ. Immediate “steroid flare” from intraarticular triamcinolone hexacetonide injection: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1284-1286.

8. Mader R, Lavi I, Luboshitzky R. Evaluation of the pituitary-adrenal axis function following single intraarticular injection of methylprednisolone. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(3):924-928.

9. Raynauld JP, Buckland-Wright C, Ward R, et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term intraarticular steroid injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(2):370-377.

10. MacMahon PJ, Eustace SJ, Kavanagh EC. Injectable corticosteroid and local anesthetic preparations: a review for radiologists. Radiology. 2009;252(3):647-661.

11. Sparling M, Malleson P, Wood B, Petty R. Radiographic followup of joints injected with triamcinolone hexacetonide for the management of childhood arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(6):821-826.

12. Eymontt MJ, Gordon GV, Schumacher HR, Hansell JR. The effects on synovial permeability and synovial fluid leukocyte counts in symptomatic osteoarthritis after intraarticular corticosteroid administration. J Rheumatol. 1982;9(2):198-203.

13. Gordon GV, Schumacher HR. Electron microscopic study of depot corticosteroid crystals with clinical studies after intra-articular injection. J Rheumatol. 1979;6(1):7-14.

14. Karsh J, Yang WH. An anaphylactic reaction to intra-articular triamcinolone: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90(2):254-258.

15. Larsson LG. Anaphylactic shock after i.a. administration of triamcinolone acetonide in a 35-year-old female. Scand J Rheumatol. 1989;18(6):441-442.

16. García-Ortega P, Corominas M, Badia M. Carboxymethylcellulose allergy as a cause of suspected corticosteroid anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91(4):421.

17. Patterson DL, Yunginger JW, Dunn WF, Jones RT, Hunt LW. Anaphylaxis induced by the carboxymethylcellulose component of injectable triamcinolone acetonide suspension (Kenalog). Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995;74(2):163-166.

18. Steiner UC, Gentinetta T, Hausmann O, Pichler WJ. IgE-mediated anaphylaxis to intraarticular glucocorticoid preparations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):W156-W157.

19. Ijsselmuiden OE, Knegt-Junk KJ, van Wijk RG, van Joost T. Cutaneous adverse reactions after intra-articular injection of triamcinolone acetonide. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75(1):57-58.

20. Pullman-Mooar S, Mooar P, Sieck M, Clayburne G, Schumacher HR. Are there distinctive inflammatory flares after hylan g-f 20 intraarticular injections? J Rheumatol. 2002;29(12):2611-2614.

1. Hollander JL, Brown EM Jr, Jessar RA, Brown CY. Hydrocortisone and cortisone injected into arthritic joints; comparative effects of and use of hydrocortisone as a local antiarthritic agent. J Am Med Assoc. 1951;147(17):1629-1635.

2. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, Gee T, Bourne R, Wells G. Intraarticular corticosteroid for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;19(2):CD005328.

3. Friedman DM, Moore ME. The efficacy of intraarticular steroids in osteoarthritis: a double-blind study. J Rheumatol. 1980;7(6):850-856.

4. Brown EM Jr, Frain JB, Udell L, Hollander JL. Locally administered hydrocortisone in the rheumatic diseases; a summary of its use in 547 patients. Am J Med. 1953;15(5):656-665.

5. Hollander JL, Jessar RA, Brown EM Jr. Intra-synovial corticosteroid therapy: a decade of use. Bull Rheum Dis. 1961;11:239-240.

6. McCarty DJ Jr, Hogan JM. Inflammatory reaction after intrasynovial injection of microcrystalline adrenocorticosteroid esters. Arthritis Rheum. 1964;7(4):359-367.

7. Berger RG, Yount WJ. Immediate “steroid flare” from intraarticular triamcinolone hexacetonide injection: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1284-1286.

8. Mader R, Lavi I, Luboshitzky R. Evaluation of the pituitary-adrenal axis function following single intraarticular injection of methylprednisolone. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(3):924-928.

9. Raynauld JP, Buckland-Wright C, Ward R, et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term intraarticular steroid injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(2):370-377.

10. MacMahon PJ, Eustace SJ, Kavanagh EC. Injectable corticosteroid and local anesthetic preparations: a review for radiologists. Radiology. 2009;252(3):647-661.

11. Sparling M, Malleson P, Wood B, Petty R. Radiographic followup of joints injected with triamcinolone hexacetonide for the management of childhood arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(6):821-826.

12. Eymontt MJ, Gordon GV, Schumacher HR, Hansell JR. The effects on synovial permeability and synovial fluid leukocyte counts in symptomatic osteoarthritis after intraarticular corticosteroid administration. J Rheumatol. 1982;9(2):198-203.

13. Gordon GV, Schumacher HR. Electron microscopic study of depot corticosteroid crystals with clinical studies after intra-articular injection. J Rheumatol. 1979;6(1):7-14.

14. Karsh J, Yang WH. An anaphylactic reaction to intra-articular triamcinolone: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90(2):254-258.

15. Larsson LG. Anaphylactic shock after i.a. administration of triamcinolone acetonide in a 35-year-old female. Scand J Rheumatol. 1989;18(6):441-442.

16. García-Ortega P, Corominas M, Badia M. Carboxymethylcellulose allergy as a cause of suspected corticosteroid anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91(4):421.

17. Patterson DL, Yunginger JW, Dunn WF, Jones RT, Hunt LW. Anaphylaxis induced by the carboxymethylcellulose component of injectable triamcinolone acetonide suspension (Kenalog). Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995;74(2):163-166.

18. Steiner UC, Gentinetta T, Hausmann O, Pichler WJ. IgE-mediated anaphylaxis to intraarticular glucocorticoid preparations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):W156-W157.

19. Ijsselmuiden OE, Knegt-Junk KJ, van Wijk RG, van Joost T. Cutaneous adverse reactions after intra-articular injection of triamcinolone acetonide. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75(1):57-58.

20. Pullman-Mooar S, Mooar P, Sieck M, Clayburne G, Schumacher HR. Are there distinctive inflammatory flares after hylan g-f 20 intraarticular injections? J Rheumatol. 2002;29(12):2611-2614.

Tibialis Posterior Tendon Entrapment Within Posterior Malleolar Fracture Fragment

Irreducible ankle fracture-dislocation secondary to tibialis posterior tendon interposition is a rare but documented complication most commonly associated with Lauge-Hansen classification pronation–external rotation ankle fractures.1-4 Entrapment of the tibialis posterior tendon has been documented in the syndesmosis (tibiotalar joint)1,2,4 and within a medial malleolus fracture.5 To our knowledge, however, there are no case reports of entrapment of the tibialis posterior tendon in a posterior malleolus fracture.

Ankle arthroscopy performed at time of fracture fixation is gaining in popularity because of its enhanced ability to document and treat intra-articular pathology associated with the initial injury.6,7 In addition, percutaneous fixation of a posterior malleolar fragment with arthroscopic assessment of the articular surface reduction may be valuable, as evaluation of tibial plafond fracture reduction by plain radiographs and fluoroscopy has proved to have limitations.8,9

In this article, we present the case of a patient who underwent attempted arthroscopy-assisted reduction of the posterior malleolus with entrapment of the tibialis posterior tendon within the posterior malleolar fracture fragment. The tendon was irreducible with arthroscopic techniques, necessitating posteromedial incision and subsequent open reduction of the incarcerated structure. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man slipped and fell on ice while jogging and subsequently presented to the emergency department with a closed bimalleolar ankle fracture-dislocation. Plain radiography (Figure 1) and computed tomography (CT) showed an oblique lateral malleolar fracture and a large posterior malleolar fracture. Further examination of the CT scan revealed entrapment of the tibialis posterior tendon within the posterior malleolar fracture (Figure 2).

Two days after injury, the patient was taken to the operating room for ankle arthroscopy with planned extrication of the entrapped tibialis posterior tendon and possible arthroscopy-assisted percutaneous fixation of the posterior malleolar fracture and open fixation of the distal fibula fracture. Diagnostic arthroscopy revealed a deltoid ligament injury (Figure 3) and a loose piece of articular cartilage (~1 cm in diameter), which was excised. No donor site for this cartilage fragment was identified with further arthroscopic evaluation. During arthroscopic examination, the tibialis posterior tendon was visualized within the joint, incarcerated within the posterior malleolar fracture (Figure 4). Attempts to release the tibialis posterior tendon from the fracture site using arthroscopic instruments and closed reduction techniques were unsuccessful, both with and without noninvasive skeletal traction applied to the ankle.

After multiple unsuccessful attempts to extract the tibialis posterior tendon arthroscopically, traction was removed, and a separate incision was made over the posteromedial aspect of the ankle. The tibialis posterior tendon was identified within the fracture site and was removed using an angled clamp (Figure 5). The fracture was reduced and held provisionally with a large tenaculum clamp. Two anterior-to-posterior, partially threaded cannulated screws were placed for fixation after adequate fracture reduction was confirmed on fluoroscopy. As a medial incision was made to extract the tibialis posterior tendon, the joint could not retain arthroscopic fluid, and visualization of the posterior fracture fragment after tendon removal was difficult. Therefore, arthroscopy-assisted reduction could not be completed.