User login

Unforgettable

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring the patient and the discussant.

A 27‐year‐old woman with a history of asthma presented to her primary care physician (PCP) with a sore throat which began after attending a party where she shared alcoholic beverages with friends. She denied any high‐risk sexual behavior. Her PCP prescribed azithromycin and methylprednisolone empirically for tonsillitis. The throat pain subsided, but in the next several days she experienced increased weakness, lethargy, poor appetite, and chills, and she returned to her PCP for reevaluation.

Two months prior she had been treated at a walk‐in clinic with a course of penicillin for a presumed streptococcal pharyngitis. Her symptoms resolved until her current presentation.

In a young woman with 2 episodes of pharyngitis in 2 months followed by an acute systemic illness, one must consider an immunocompromised state such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hematologic malignancy, or autoimmune diseases. Weakness, lethargy, anorexia, and chills in the setting of pharyngitis suggest a local process in the neck, most likely infection associated with systemic toxicity. As neck abscess and bacteremia warrant early consideration, the physical examination should focus on the neck and oropharynx, as well as neurologic exam to evaluate for bacterial spreading into the central nervous system. In addition to routine laboratory studies, a chest x‐ray (CXR) would be appropriate as upper respiratory infections may be complicated by pneumonia and present with signs and symptoms of systemic illness.

On examination by her PCP, her temperature was 99.2F and her blood pressure was 118/68. She had bilateral oropharyngeal erythema without exudates and bilateral tonsillar and anterior triangle lymphadenopathy (LAD). An oropharyngeal rapid Streptococcal antigen detection test was negative, but a Monospot test was positive for heterophile antibodies. Azithromycin and methylprednisolone were discontinued, and the patient was informed she most likely had Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) infection.

The following day, the complete blood count results returned. The platelet count was 50 K/L and the white blood cell (WBC) count was 13.0 K/L. The patient stated she had developed right‐sided flank pain upon deep inspiration and used her albuterol inhaler with minimal relief. She continued to have fever, decreased appetite, chest and abdominal pain, and difficulty swallowing due to odynophagia. She was instructed to go to the emergency department (ED) for further evaluation. In the ED, she denied any shortness of breath, but reported a slight cough and right‐sided abdominal pain.

Acute tonsillar pharyngitis and fever, as well as systemic symptoms of fatigue and abdominal pain along with positive heterophile screen are highly suggestive of EBV infection in this young female. The episode of pharyngitis 2 months prior remains unexplained and may be unrelated. Right‐sided pleuritic pain and abdominal pain may be related to EBV hepatitis. Odynophagia is consistent with EBV infection as well. Profound lethargy, however, is not a common presenting feature in mononucleosis unless infected patients are profoundly dehydrated due to inability to swallow. Her pain symptoms may be secondary to other signs of EBV infection, such as hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites, and/or right pleural effusion. A history of rash should be investigated. Initial assessment in this acutely ill patient should focus on evaluation for the presence of severe sepsis and for a primary source of infection. Given the severity of her illness, I would consider early computed tomography (CT) of her chest, abdomen, and pelvis, as well as CT of the neck to exclude a possibility of peritonsillar abscess. The complaint of chills indicates a possible bacteremia, so coverage with broad‐spectrum antibiotics is indicated. Symptomatic relief with acetaminophen and intravenous fluid rehydration is appropriate.

On exam, temperature was 101.9F, blood pressure was 111/74, heart rate was 140 beats per minute, respiratory rate was 18 per minute, and oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. She appeared drowsy, but answered questions appropriately. She had bilateral swollen tonsils, as well as anterior and posterior cervical adenopathy, with tenderness greater on the left side. Her chest exam had slightly diminished breath sounds at the bases bilaterally. Heart rhythm was regular, and there were no murmurs appreciated. On abdominal exam, she was tender to palpation in both right‐upper and left‐upper quadrants, without obvious hepatosplenomegaly. There were no petechiae noted on her skin.

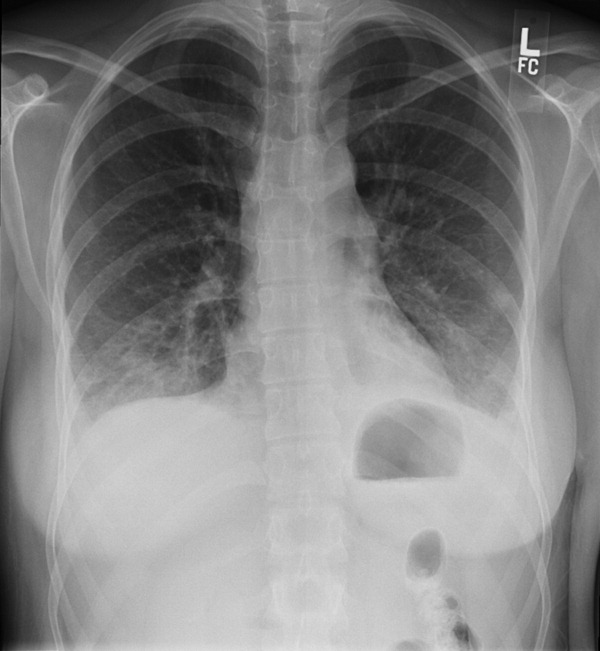

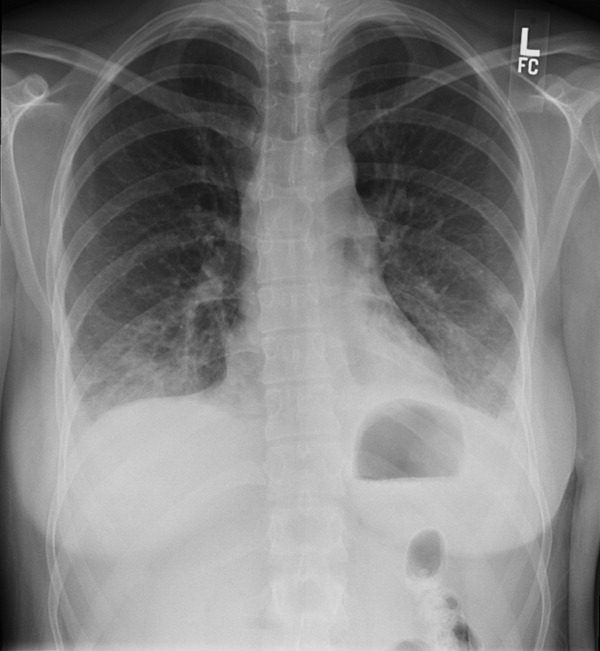

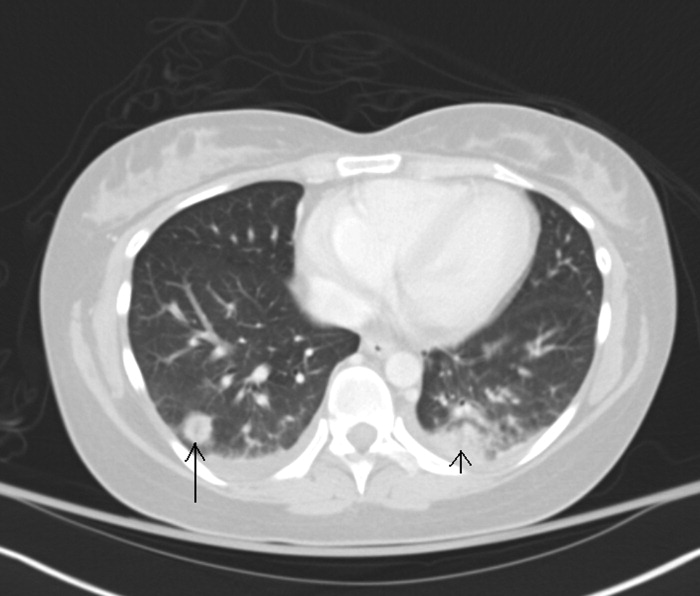

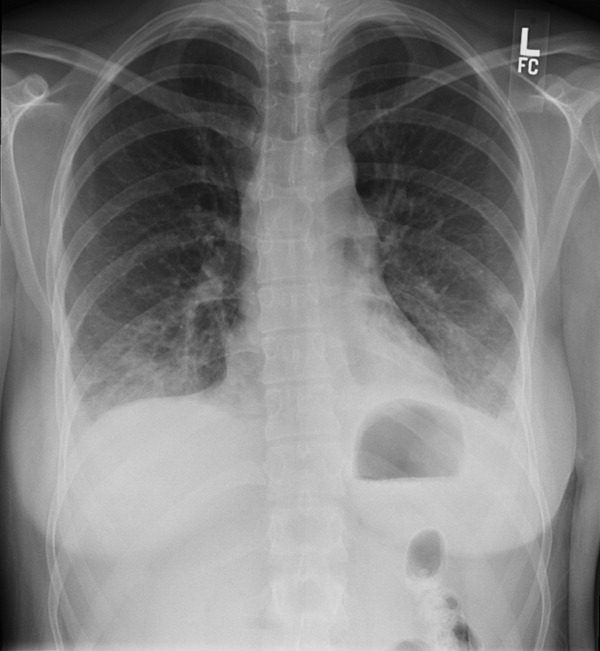

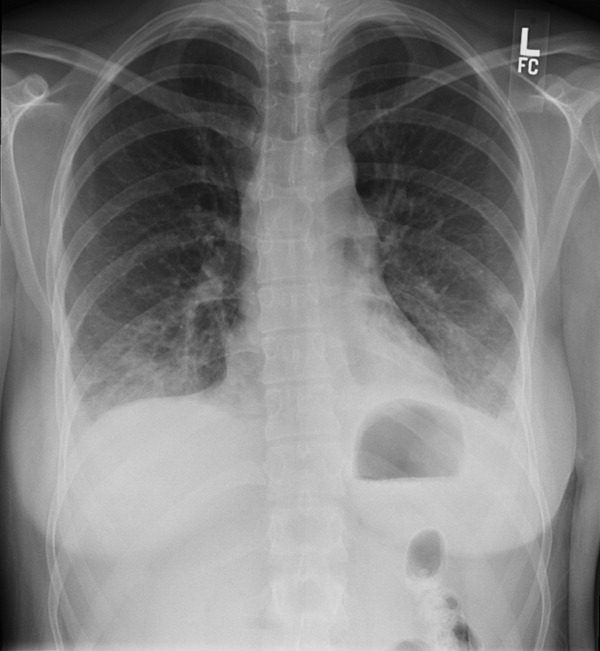

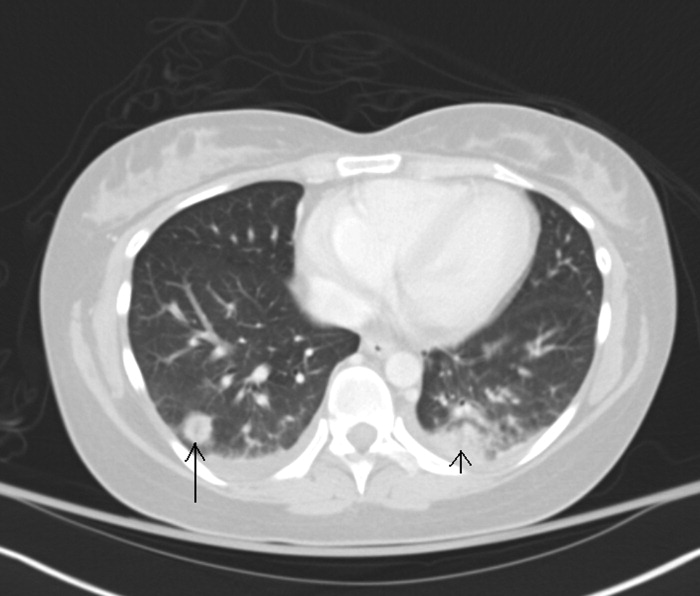

The WBC was 17.6 K/L, with 89% neutrophils and 5% lymphocytes, platelet count was 22 K/L, and hemoglobin was 13.8 g/dL. A D‐dimer test was elevated at 1344 ng/mL. Peripheral blood smear showed thrombocytopenia and neutrophilia, but demonstrated no schistocytes. The serum potassium was 3.2 mEq/L, bicarbonate was 29 mEq/L, blood urea nitrogen was 15 mg/dL and the creatinine was 1.29 mg/dL. Transaminases were within normal limits, but total bilirubin was 1.8 mg/dL. Her urinalysis was normal. Blood cultures were sent. A CXR showed bibasilar consolidations and pleural effusions (Figure 1). A CT of the chest with contrast was obtained that showed multiple confluent and patchy foci of consolidation in the lung bases, with trace bilateral pleural effusions (Figure 2). A CT of the abdomen showed a spleen at the upper limits of normal in size, measuring 13 cm in length, but was otherwise normal.

Leukocytosis with lymphopenia is not consistent with EBV infection and another process needs to be considered. This patient meets criteria for sepsis syndrome and should receive broad spectrum antibiotics, such as vancomycin and piperacillin‐tazobactam immediately after the blood cultures are sent, in addition to further evaluation to determine the source of sepsis. Depending on her mental status response to initial measures such as acetaminophen and hydration, one should consider a lumbar puncture, which would require platelet transfusion and may therefore not be done immediately. HIV serology should be performed, since acute retroviral syndrome can mimic this presentation. With neck tenderness that is more localized to her left side, a CT of her neck to evaluate for an abscess may be helpful.

She was admitted for presumed community‐acquired pneumonia complicating an upper respiratory tract infection. Her pharyngitis was thought to be of viral etiology. Moxifloxacin was started and intravenous fluids were administered. She was started on prednisone 60 mg daily for presumed immune‐mediated thrombocytopenia related to EBV infection. An HIV antibody test and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were both negative. The EBV immunoglobulin G (IgG) titer was positive (>1:10), but the IgM titer was negative. Her mental status improved after starting moxifloxacin and fluids. Her creatinine and bilirubin normalized to 0.97 mg/dL and 0.8 mg/dL respectively. She continued to have a tender left‐sided submandibular swelling. Blood cultures grew Gram‐negative bacilli in 2 anaerobic bottles.

I am uncomfortable with moxifloxacin as initial empiric therapy because at presentation she had sepsis syndrome as well as a suspected immunocompromised state. In addition, moxifloxacin would not be adequate coverage for anaerobic organisms if a peritonsillar abscess was involved. At this point, she needs a CT of her neck to look for a focus of infection which may require surgical management and, if negative, further imaging such as a tagged white blood scan to identify the source of the anaerobes.

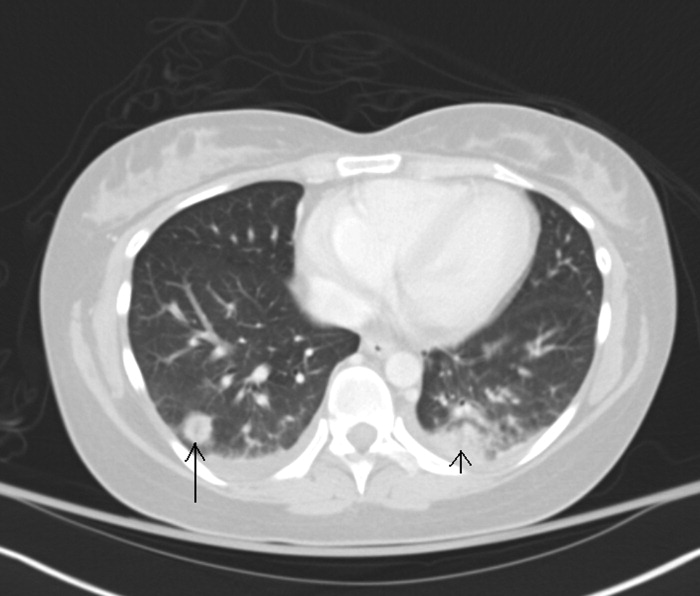

Moxifloxacin was switched to piperacillin‐tazobactam and prednisone was discontinued. By day 4 of hospitalization her platelet count had risen to 261 K/L. Her WBC continued to rise to a peak of 21.5 K/L and she continued to have fevers and diffuse pains, although her repeat blood cultures were negative. She continued to have tenderness of the cervical lymph nodes, left greater than right. A repeat CXR showed patchy air space disease bilaterally and pleural effusions, both of which had progressed compared with the prior film. Clindamycin was empirically added to her antibiotic regimen in light of her progressing pneumonia and evidence of anaerobic infection. A repeat CT scan of her chest revealed multiple nodular opacities scattered throughout the lung fields, some of which were cavitary, predominating in the lung bases. The CT scan of her neck revealed a left peritonsillar abscess and phlegmon in the left retropharyngeal and deep neck area along the sternocleidomastoid and internal jugular vein (IJV). There also was noted a large thrombus within the left IJV extending superiorly to involve the jugular bulb, sigmoid sinus, and distal left transverse sinus; and inferiorly to near the origin of the brachiocephalic vein (see Figure 3). An echocardiogram did not reveal any vegetations.

The combination of recent pharyngitis, septic pulmonary emboli, and IJV thrombosis is consistent with a diagnosis of Lemierre's syndrome (LS). This is a life threatening condition, even if diagnosis is made early and appropriate treatment is started. The most likely causative agent is Fusobacterium necrophorum. In this case it was important to realize that clinical presentation was not consistent with EBV infection, even though heterophile screen was positive. Early initiation of broad spectrum antibiotics as well as CT scan of the neck would have been appropriate.

The diagnosis of LS was made. The blood culture speciation revealed Fusobacterium nucleatum, which was too fastidious to perform antimicrobial sensitivities. Her symptoms improved significantly with the addition of clindamycin to piperacillin‐tazobactam, which was postulated to be the result of bacterial beta‐lactamase activity mitigating the efficacy of piperacillin‐tazobactam. Thoracentesis of her pleural effusion did not reveal an empyema. Due to her large thrombus burden, she was started on anticoagulation with heparin and transitioned to outpatient coumadin. She was switched to metronidazole as a single agent antibiotic for 6 weeks, and on outpatient follow‐up was doing well.

Commentary

LS was described by Dr. Andre Lemierre in 1936.6 The syndrome consists of a primary oropharyngeal infection, thrombosis of the IJV, bacteremia, and septic metastatic foci, usually involving the lungs.1, 2 LS is a form of necrobacillosis, which is a systemic infection resulting from F. necrophorum.3, 4 In classic LS, the initial pharyngitis is usually a tonsillar or peritonsillar abscess, and is followed by intense fever and rigors after 4 days to 2 weeks.1, 3 This is followed by a unilateral painful submaxillary LAD and IJV thrombophlebitisthe cord sign.2 Finally, bacteremia and distant metastatic pyogenic abscesses develop.1 (see Table 1).

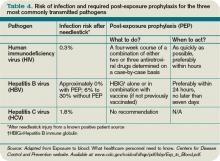

| Lemierre's Syndrome typical features |

| Antecedent head and neck infection, typically an oropharyngeal infection prior to deterioration |

| Thrombophlebitis, typically of internal jugular vein (present in only 1/3 of cases) |

| Bacteremia (Fusobacterium necrophorum most commonly) |

| Septic metastatic foci, typically to lungs |

| Usual Presentation |

| Pharyngitis |

| Fevers |

| Rigors |

| Neck involvement: tenderness, swelling, tender internal jugular vein thrombus (cord sign) |

| Pulmonary infiltrates which cavitate |

With the advent of antibiotics, LS is now rare with an incidence of 0.9 per million persons per year. In Lemierre's time, the disease was fulminant and led to death within 2 weeks, but in the antibiotic age the mortality rate is 4.9%.1, 3 The median age of an LS patient is 19 years, with a higher incidence in males.1, 35 Although in the literature it is referred to as the forgotten disease, there is evidence the incidence is increasing.3, 4, 6, 8

There are variations of classic LS. Bacteremia may occur much later than the initial pharyngitis, the disease may be less aggressive, the thrombus may be in the external jugular vein, or there may be no identified thrombus.3, 4, 8 In fact, a thrombus is only identified in 36% of cases.9 The primary infection may be a head and neck infection that is not pharyngitis, such as an odontogenic infection,4 or may not be identified.10 Despite variations, the fundamentals of diagnosis are prior head and neck infection, presumed thrombophlebitis and bacteremia, and evidence of septic metastatic foci.

The genus Fusobacterium comprises anaerobic, nonspore forming gram negative bacilli.1, 35, 11 F. necrophorum and F. nucleatum are 2 species within this genus. F. nucleatum causes the majority of reported human bacteremias by Fusobacterium species, but it is F. necrophorum that is most associated with anaerobic oropharyngeal infections, thrombocytopenia, clot formation, and LS.35, 8, 9

It is unknown if Fusobacterium species directly cause the sore throat, or rather are bystanders which thrive once a favorable anaerobic environment is created via endotoxins and exotoxins.35 A break in oral mucosa via trauma or coinfection with bacteria/viruses (especially EBV) is also thought to play a role with infection.2, 3, 5 One‐third of LS cases have coinfection with other oropharyngeal flora. Thus, one must reexamine the anaerobic blood cultures after an organism has been identified in suspect cases.3, 4

There is an increased association of LS with EBV infection, likely due to viral‐induced and steroid‐induced immunosuppression.24 False positive heterophile tests are reported with LS, so the specific antibody tests for EBV must be checked.3, 4

Once thrombophlebitis occurs, the bacteria can metastasize to distant sites. In 80% to 92% of LS cases, the metastatic complication is a pleuro‐pulmonary infection, consisting of septic pulmonary emboli, empyema, and pleural effusions, but extra‐pulmonary lesions occur.1, 3, 9, 12 Abdominal pain usually results from abdominal microabscesses or thrombophlebitis.4 Mild renal impairment and abnormal liver function tests are common.3, 4 Cranial nerve palsies and Horner's syndrome are rare and indicate carotid sheath involvement.3, 12 An elevated C‐reactive protein can distinguish bacterial from uncomplicated viral pharyngitis.3, 4 Also, rigors are unusual in tonsillitis, and their presence indicate bacterial entry into the circulation.3

CXRs may reveal the pulmonary septic emboli. Ultrasound of the IJV is inexpensive and noninvasive, but may have limited sensitivity for an acute thrombus. CT scan allows increased visualization of anatomy, but can have decreased sensitivity and specificity for thrombosis.3 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended if LS results from mastoiditis, to exclude an intracerebral vein thrombosis.9

Antibiotics have both dramatically decreased the incidence of LS and improved its prognosis. The recent rise in incidence may be due to a renewed interest in restricting the use of antibiotics in cases of pharyngitis, as well as an increased use of macrolides, to which F. necrophorum is frequently resistant.3 Decreased tonsillectomies may also have a role, as LS is more common with retained tonsils.1, 3

No trials have evaluated the optimal antibiotic regimen. Fusobacterium species are sensitive to penicillin, but 23% have beta‐lactamase activity as reported clinically by several authors.3, 5 F. necrophorum is also sensitive to metronidazole, ticarcillin‐clavulanate, cefoxitin, amoxicillin‐clavulanate, imipenem, and clindamycin. There is a high resistance to macrolides and gentamicin, and the activity of tetracyclines is poor. For treatment, most authors suggest a carbapenem, a penicillin/beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination, or metronidazole. Clindamycin has weaker bactericidal activity than metronidazole or imipenem. Metronidazole is preferred because of its activity against all Fusobacterium species, good penetration into tissues, bactericidal activity, low minimum inhibitory concentration, and ability to achieve high concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid if meningitis occurs. An effective regimen is metronidazole with a penicillinase‐resistant penicillin to cover for mixed coinfection with streptococci or staphylococci.3, 4, 12 A 6‐week antibiotic course is given for adequate penetration into the protective fibrin clots.4

Reports have shown good outcomes both with and without the use of anticoagulation.3, 4, 8 Support for anticoagulation is extrapolated from experience with septic pelvic thrombophlebitis, in which anticoagulation results in more rapid resolution of symptoms.13 Given the lack of firm evidence in cases of LS, anticoagulation is typically reserved for poor clinical response despite 2 to 3 days of antibiotic therapy or propagation of thromboses into the cavernous sinus. It is generally given for 3 months.4, 13

Prior to the antibiotic era, surgical ligation or excision of the IJV was done without clear benefit. Today, surgery is reserved for cases of continued septic emboli or extension of thrombus despite aggressive medical therapy.3 If mediastinitis develops, then surgical intervention is essential.4

Lemierre stated that the symptoms and signs of LS are so characteristic that it permits diagnosis before bacteriological examination.1 However, today it may go unrecognized by physicians until a blood culture shows anaerobes or Fusobacterium species. For a young patient admitted with pneumonia preceded by pharyngitis, hospitalists must remain vigilant for the presence of LS.

Key Points for Hospitalists/Teaching Points

-

The triad of LS is pharyngitis, thrombophlebitis, and distant metastatic pyogenic emboli.

-

Suspect LS in a young, otherwise healthy patient who clinically deteriorates in the setting of a recent pharyngeal infection.

-

With the modern decrease in antibiotic use for pharyngitis, LS may be on the rise.

- .On certain septicaemias due to anaerobic organisms.Lancet.1936;1:701–703.

- ,.Lemierre's syndrome: more judicious antibiotic prescribing habits may lead to the clinical reappearance of this often forgotten disease.Am J Med.2006;119(3):e7–e9.

- .Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre's syndrome.Clin Microbiol Rev.2007;20(4):622–659.

- ,.Human necrobacillosis, with emphasis on Lemierre's syndrome.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31(2):524–532.

- ,.Fusobacterial infections: clinical spectrum and incidence of invasive disease.J Infect.2008;57(4):283–289.

- .Human infections with Fusobacterium necrophorum.Anaerobe.2006;12(4):165–172.

- ,,, et al.Increased diagnosis of Lemierre Syndrome and other Fusobacterium necrophorum infections at a Children's Hospital.Pediatrics.2003;112(5):e380.

- ,,.Unusual presentation of Lemierre's syndrome due to Fusobacterium nucleatum.J Clin Microbiol.2003;41(7):3445–3448.

- ,,,.The evolution of Lemierre Syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature.Medicine (Baltimore).2002;81(6):458–465.

- ,.An unusual case of Lemierre's syndrome presenting as pyomyositis.Am J Med Sci.2008;335(6):499–501.

- .Update on the taxonomy and clinical aspects of the genus Fusobacterium.Clin Infect Dis.2002;35(Suppl 1):S22–S27.

- ,,,,.Lemierre syndrome: two cases and a review.Laryngosope.2007;117(9):1605–1610.

- ,,.Lemierre's syndrome (necrobacillosis).Postgrad Med J.1999;75(881):141–144.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring the patient and the discussant.

A 27‐year‐old woman with a history of asthma presented to her primary care physician (PCP) with a sore throat which began after attending a party where she shared alcoholic beverages with friends. She denied any high‐risk sexual behavior. Her PCP prescribed azithromycin and methylprednisolone empirically for tonsillitis. The throat pain subsided, but in the next several days she experienced increased weakness, lethargy, poor appetite, and chills, and she returned to her PCP for reevaluation.

Two months prior she had been treated at a walk‐in clinic with a course of penicillin for a presumed streptococcal pharyngitis. Her symptoms resolved until her current presentation.

In a young woman with 2 episodes of pharyngitis in 2 months followed by an acute systemic illness, one must consider an immunocompromised state such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hematologic malignancy, or autoimmune diseases. Weakness, lethargy, anorexia, and chills in the setting of pharyngitis suggest a local process in the neck, most likely infection associated with systemic toxicity. As neck abscess and bacteremia warrant early consideration, the physical examination should focus on the neck and oropharynx, as well as neurologic exam to evaluate for bacterial spreading into the central nervous system. In addition to routine laboratory studies, a chest x‐ray (CXR) would be appropriate as upper respiratory infections may be complicated by pneumonia and present with signs and symptoms of systemic illness.

On examination by her PCP, her temperature was 99.2F and her blood pressure was 118/68. She had bilateral oropharyngeal erythema without exudates and bilateral tonsillar and anterior triangle lymphadenopathy (LAD). An oropharyngeal rapid Streptococcal antigen detection test was negative, but a Monospot test was positive for heterophile antibodies. Azithromycin and methylprednisolone were discontinued, and the patient was informed she most likely had Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) infection.

The following day, the complete blood count results returned. The platelet count was 50 K/L and the white blood cell (WBC) count was 13.0 K/L. The patient stated she had developed right‐sided flank pain upon deep inspiration and used her albuterol inhaler with minimal relief. She continued to have fever, decreased appetite, chest and abdominal pain, and difficulty swallowing due to odynophagia. She was instructed to go to the emergency department (ED) for further evaluation. In the ED, she denied any shortness of breath, but reported a slight cough and right‐sided abdominal pain.

Acute tonsillar pharyngitis and fever, as well as systemic symptoms of fatigue and abdominal pain along with positive heterophile screen are highly suggestive of EBV infection in this young female. The episode of pharyngitis 2 months prior remains unexplained and may be unrelated. Right‐sided pleuritic pain and abdominal pain may be related to EBV hepatitis. Odynophagia is consistent with EBV infection as well. Profound lethargy, however, is not a common presenting feature in mononucleosis unless infected patients are profoundly dehydrated due to inability to swallow. Her pain symptoms may be secondary to other signs of EBV infection, such as hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites, and/or right pleural effusion. A history of rash should be investigated. Initial assessment in this acutely ill patient should focus on evaluation for the presence of severe sepsis and for a primary source of infection. Given the severity of her illness, I would consider early computed tomography (CT) of her chest, abdomen, and pelvis, as well as CT of the neck to exclude a possibility of peritonsillar abscess. The complaint of chills indicates a possible bacteremia, so coverage with broad‐spectrum antibiotics is indicated. Symptomatic relief with acetaminophen and intravenous fluid rehydration is appropriate.

On exam, temperature was 101.9F, blood pressure was 111/74, heart rate was 140 beats per minute, respiratory rate was 18 per minute, and oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. She appeared drowsy, but answered questions appropriately. She had bilateral swollen tonsils, as well as anterior and posterior cervical adenopathy, with tenderness greater on the left side. Her chest exam had slightly diminished breath sounds at the bases bilaterally. Heart rhythm was regular, and there were no murmurs appreciated. On abdominal exam, she was tender to palpation in both right‐upper and left‐upper quadrants, without obvious hepatosplenomegaly. There were no petechiae noted on her skin.

The WBC was 17.6 K/L, with 89% neutrophils and 5% lymphocytes, platelet count was 22 K/L, and hemoglobin was 13.8 g/dL. A D‐dimer test was elevated at 1344 ng/mL. Peripheral blood smear showed thrombocytopenia and neutrophilia, but demonstrated no schistocytes. The serum potassium was 3.2 mEq/L, bicarbonate was 29 mEq/L, blood urea nitrogen was 15 mg/dL and the creatinine was 1.29 mg/dL. Transaminases were within normal limits, but total bilirubin was 1.8 mg/dL. Her urinalysis was normal. Blood cultures were sent. A CXR showed bibasilar consolidations and pleural effusions (Figure 1). A CT of the chest with contrast was obtained that showed multiple confluent and patchy foci of consolidation in the lung bases, with trace bilateral pleural effusions (Figure 2). A CT of the abdomen showed a spleen at the upper limits of normal in size, measuring 13 cm in length, but was otherwise normal.

Leukocytosis with lymphopenia is not consistent with EBV infection and another process needs to be considered. This patient meets criteria for sepsis syndrome and should receive broad spectrum antibiotics, such as vancomycin and piperacillin‐tazobactam immediately after the blood cultures are sent, in addition to further evaluation to determine the source of sepsis. Depending on her mental status response to initial measures such as acetaminophen and hydration, one should consider a lumbar puncture, which would require platelet transfusion and may therefore not be done immediately. HIV serology should be performed, since acute retroviral syndrome can mimic this presentation. With neck tenderness that is more localized to her left side, a CT of her neck to evaluate for an abscess may be helpful.

She was admitted for presumed community‐acquired pneumonia complicating an upper respiratory tract infection. Her pharyngitis was thought to be of viral etiology. Moxifloxacin was started and intravenous fluids were administered. She was started on prednisone 60 mg daily for presumed immune‐mediated thrombocytopenia related to EBV infection. An HIV antibody test and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were both negative. The EBV immunoglobulin G (IgG) titer was positive (>1:10), but the IgM titer was negative. Her mental status improved after starting moxifloxacin and fluids. Her creatinine and bilirubin normalized to 0.97 mg/dL and 0.8 mg/dL respectively. She continued to have a tender left‐sided submandibular swelling. Blood cultures grew Gram‐negative bacilli in 2 anaerobic bottles.

I am uncomfortable with moxifloxacin as initial empiric therapy because at presentation she had sepsis syndrome as well as a suspected immunocompromised state. In addition, moxifloxacin would not be adequate coverage for anaerobic organisms if a peritonsillar abscess was involved. At this point, she needs a CT of her neck to look for a focus of infection which may require surgical management and, if negative, further imaging such as a tagged white blood scan to identify the source of the anaerobes.

Moxifloxacin was switched to piperacillin‐tazobactam and prednisone was discontinued. By day 4 of hospitalization her platelet count had risen to 261 K/L. Her WBC continued to rise to a peak of 21.5 K/L and she continued to have fevers and diffuse pains, although her repeat blood cultures were negative. She continued to have tenderness of the cervical lymph nodes, left greater than right. A repeat CXR showed patchy air space disease bilaterally and pleural effusions, both of which had progressed compared with the prior film. Clindamycin was empirically added to her antibiotic regimen in light of her progressing pneumonia and evidence of anaerobic infection. A repeat CT scan of her chest revealed multiple nodular opacities scattered throughout the lung fields, some of which were cavitary, predominating in the lung bases. The CT scan of her neck revealed a left peritonsillar abscess and phlegmon in the left retropharyngeal and deep neck area along the sternocleidomastoid and internal jugular vein (IJV). There also was noted a large thrombus within the left IJV extending superiorly to involve the jugular bulb, sigmoid sinus, and distal left transverse sinus; and inferiorly to near the origin of the brachiocephalic vein (see Figure 3). An echocardiogram did not reveal any vegetations.

The combination of recent pharyngitis, septic pulmonary emboli, and IJV thrombosis is consistent with a diagnosis of Lemierre's syndrome (LS). This is a life threatening condition, even if diagnosis is made early and appropriate treatment is started. The most likely causative agent is Fusobacterium necrophorum. In this case it was important to realize that clinical presentation was not consistent with EBV infection, even though heterophile screen was positive. Early initiation of broad spectrum antibiotics as well as CT scan of the neck would have been appropriate.

The diagnosis of LS was made. The blood culture speciation revealed Fusobacterium nucleatum, which was too fastidious to perform antimicrobial sensitivities. Her symptoms improved significantly with the addition of clindamycin to piperacillin‐tazobactam, which was postulated to be the result of bacterial beta‐lactamase activity mitigating the efficacy of piperacillin‐tazobactam. Thoracentesis of her pleural effusion did not reveal an empyema. Due to her large thrombus burden, she was started on anticoagulation with heparin and transitioned to outpatient coumadin. She was switched to metronidazole as a single agent antibiotic for 6 weeks, and on outpatient follow‐up was doing well.

Commentary

LS was described by Dr. Andre Lemierre in 1936.6 The syndrome consists of a primary oropharyngeal infection, thrombosis of the IJV, bacteremia, and septic metastatic foci, usually involving the lungs.1, 2 LS is a form of necrobacillosis, which is a systemic infection resulting from F. necrophorum.3, 4 In classic LS, the initial pharyngitis is usually a tonsillar or peritonsillar abscess, and is followed by intense fever and rigors after 4 days to 2 weeks.1, 3 This is followed by a unilateral painful submaxillary LAD and IJV thrombophlebitisthe cord sign.2 Finally, bacteremia and distant metastatic pyogenic abscesses develop.1 (see Table 1).

| Lemierre's Syndrome typical features |

| Antecedent head and neck infection, typically an oropharyngeal infection prior to deterioration |

| Thrombophlebitis, typically of internal jugular vein (present in only 1/3 of cases) |

| Bacteremia (Fusobacterium necrophorum most commonly) |

| Septic metastatic foci, typically to lungs |

| Usual Presentation |

| Pharyngitis |

| Fevers |

| Rigors |

| Neck involvement: tenderness, swelling, tender internal jugular vein thrombus (cord sign) |

| Pulmonary infiltrates which cavitate |

With the advent of antibiotics, LS is now rare with an incidence of 0.9 per million persons per year. In Lemierre's time, the disease was fulminant and led to death within 2 weeks, but in the antibiotic age the mortality rate is 4.9%.1, 3 The median age of an LS patient is 19 years, with a higher incidence in males.1, 35 Although in the literature it is referred to as the forgotten disease, there is evidence the incidence is increasing.3, 4, 6, 8

There are variations of classic LS. Bacteremia may occur much later than the initial pharyngitis, the disease may be less aggressive, the thrombus may be in the external jugular vein, or there may be no identified thrombus.3, 4, 8 In fact, a thrombus is only identified in 36% of cases.9 The primary infection may be a head and neck infection that is not pharyngitis, such as an odontogenic infection,4 or may not be identified.10 Despite variations, the fundamentals of diagnosis are prior head and neck infection, presumed thrombophlebitis and bacteremia, and evidence of septic metastatic foci.

The genus Fusobacterium comprises anaerobic, nonspore forming gram negative bacilli.1, 35, 11 F. necrophorum and F. nucleatum are 2 species within this genus. F. nucleatum causes the majority of reported human bacteremias by Fusobacterium species, but it is F. necrophorum that is most associated with anaerobic oropharyngeal infections, thrombocytopenia, clot formation, and LS.35, 8, 9

It is unknown if Fusobacterium species directly cause the sore throat, or rather are bystanders which thrive once a favorable anaerobic environment is created via endotoxins and exotoxins.35 A break in oral mucosa via trauma or coinfection with bacteria/viruses (especially EBV) is also thought to play a role with infection.2, 3, 5 One‐third of LS cases have coinfection with other oropharyngeal flora. Thus, one must reexamine the anaerobic blood cultures after an organism has been identified in suspect cases.3, 4

There is an increased association of LS with EBV infection, likely due to viral‐induced and steroid‐induced immunosuppression.24 False positive heterophile tests are reported with LS, so the specific antibody tests for EBV must be checked.3, 4

Once thrombophlebitis occurs, the bacteria can metastasize to distant sites. In 80% to 92% of LS cases, the metastatic complication is a pleuro‐pulmonary infection, consisting of septic pulmonary emboli, empyema, and pleural effusions, but extra‐pulmonary lesions occur.1, 3, 9, 12 Abdominal pain usually results from abdominal microabscesses or thrombophlebitis.4 Mild renal impairment and abnormal liver function tests are common.3, 4 Cranial nerve palsies and Horner's syndrome are rare and indicate carotid sheath involvement.3, 12 An elevated C‐reactive protein can distinguish bacterial from uncomplicated viral pharyngitis.3, 4 Also, rigors are unusual in tonsillitis, and their presence indicate bacterial entry into the circulation.3

CXRs may reveal the pulmonary septic emboli. Ultrasound of the IJV is inexpensive and noninvasive, but may have limited sensitivity for an acute thrombus. CT scan allows increased visualization of anatomy, but can have decreased sensitivity and specificity for thrombosis.3 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended if LS results from mastoiditis, to exclude an intracerebral vein thrombosis.9

Antibiotics have both dramatically decreased the incidence of LS and improved its prognosis. The recent rise in incidence may be due to a renewed interest in restricting the use of antibiotics in cases of pharyngitis, as well as an increased use of macrolides, to which F. necrophorum is frequently resistant.3 Decreased tonsillectomies may also have a role, as LS is more common with retained tonsils.1, 3

No trials have evaluated the optimal antibiotic regimen. Fusobacterium species are sensitive to penicillin, but 23% have beta‐lactamase activity as reported clinically by several authors.3, 5 F. necrophorum is also sensitive to metronidazole, ticarcillin‐clavulanate, cefoxitin, amoxicillin‐clavulanate, imipenem, and clindamycin. There is a high resistance to macrolides and gentamicin, and the activity of tetracyclines is poor. For treatment, most authors suggest a carbapenem, a penicillin/beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination, or metronidazole. Clindamycin has weaker bactericidal activity than metronidazole or imipenem. Metronidazole is preferred because of its activity against all Fusobacterium species, good penetration into tissues, bactericidal activity, low minimum inhibitory concentration, and ability to achieve high concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid if meningitis occurs. An effective regimen is metronidazole with a penicillinase‐resistant penicillin to cover for mixed coinfection with streptococci or staphylococci.3, 4, 12 A 6‐week antibiotic course is given for adequate penetration into the protective fibrin clots.4

Reports have shown good outcomes both with and without the use of anticoagulation.3, 4, 8 Support for anticoagulation is extrapolated from experience with septic pelvic thrombophlebitis, in which anticoagulation results in more rapid resolution of symptoms.13 Given the lack of firm evidence in cases of LS, anticoagulation is typically reserved for poor clinical response despite 2 to 3 days of antibiotic therapy or propagation of thromboses into the cavernous sinus. It is generally given for 3 months.4, 13

Prior to the antibiotic era, surgical ligation or excision of the IJV was done without clear benefit. Today, surgery is reserved for cases of continued septic emboli or extension of thrombus despite aggressive medical therapy.3 If mediastinitis develops, then surgical intervention is essential.4

Lemierre stated that the symptoms and signs of LS are so characteristic that it permits diagnosis before bacteriological examination.1 However, today it may go unrecognized by physicians until a blood culture shows anaerobes or Fusobacterium species. For a young patient admitted with pneumonia preceded by pharyngitis, hospitalists must remain vigilant for the presence of LS.

Key Points for Hospitalists/Teaching Points

-

The triad of LS is pharyngitis, thrombophlebitis, and distant metastatic pyogenic emboli.

-

Suspect LS in a young, otherwise healthy patient who clinically deteriorates in the setting of a recent pharyngeal infection.

-

With the modern decrease in antibiotic use for pharyngitis, LS may be on the rise.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring the patient and the discussant.

A 27‐year‐old woman with a history of asthma presented to her primary care physician (PCP) with a sore throat which began after attending a party where she shared alcoholic beverages with friends. She denied any high‐risk sexual behavior. Her PCP prescribed azithromycin and methylprednisolone empirically for tonsillitis. The throat pain subsided, but in the next several days she experienced increased weakness, lethargy, poor appetite, and chills, and she returned to her PCP for reevaluation.

Two months prior she had been treated at a walk‐in clinic with a course of penicillin for a presumed streptococcal pharyngitis. Her symptoms resolved until her current presentation.

In a young woman with 2 episodes of pharyngitis in 2 months followed by an acute systemic illness, one must consider an immunocompromised state such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hematologic malignancy, or autoimmune diseases. Weakness, lethargy, anorexia, and chills in the setting of pharyngitis suggest a local process in the neck, most likely infection associated with systemic toxicity. As neck abscess and bacteremia warrant early consideration, the physical examination should focus on the neck and oropharynx, as well as neurologic exam to evaluate for bacterial spreading into the central nervous system. In addition to routine laboratory studies, a chest x‐ray (CXR) would be appropriate as upper respiratory infections may be complicated by pneumonia and present with signs and symptoms of systemic illness.

On examination by her PCP, her temperature was 99.2F and her blood pressure was 118/68. She had bilateral oropharyngeal erythema without exudates and bilateral tonsillar and anterior triangle lymphadenopathy (LAD). An oropharyngeal rapid Streptococcal antigen detection test was negative, but a Monospot test was positive for heterophile antibodies. Azithromycin and methylprednisolone were discontinued, and the patient was informed she most likely had Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) infection.

The following day, the complete blood count results returned. The platelet count was 50 K/L and the white blood cell (WBC) count was 13.0 K/L. The patient stated she had developed right‐sided flank pain upon deep inspiration and used her albuterol inhaler with minimal relief. She continued to have fever, decreased appetite, chest and abdominal pain, and difficulty swallowing due to odynophagia. She was instructed to go to the emergency department (ED) for further evaluation. In the ED, she denied any shortness of breath, but reported a slight cough and right‐sided abdominal pain.

Acute tonsillar pharyngitis and fever, as well as systemic symptoms of fatigue and abdominal pain along with positive heterophile screen are highly suggestive of EBV infection in this young female. The episode of pharyngitis 2 months prior remains unexplained and may be unrelated. Right‐sided pleuritic pain and abdominal pain may be related to EBV hepatitis. Odynophagia is consistent with EBV infection as well. Profound lethargy, however, is not a common presenting feature in mononucleosis unless infected patients are profoundly dehydrated due to inability to swallow. Her pain symptoms may be secondary to other signs of EBV infection, such as hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites, and/or right pleural effusion. A history of rash should be investigated. Initial assessment in this acutely ill patient should focus on evaluation for the presence of severe sepsis and for a primary source of infection. Given the severity of her illness, I would consider early computed tomography (CT) of her chest, abdomen, and pelvis, as well as CT of the neck to exclude a possibility of peritonsillar abscess. The complaint of chills indicates a possible bacteremia, so coverage with broad‐spectrum antibiotics is indicated. Symptomatic relief with acetaminophen and intravenous fluid rehydration is appropriate.

On exam, temperature was 101.9F, blood pressure was 111/74, heart rate was 140 beats per minute, respiratory rate was 18 per minute, and oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. She appeared drowsy, but answered questions appropriately. She had bilateral swollen tonsils, as well as anterior and posterior cervical adenopathy, with tenderness greater on the left side. Her chest exam had slightly diminished breath sounds at the bases bilaterally. Heart rhythm was regular, and there were no murmurs appreciated. On abdominal exam, she was tender to palpation in both right‐upper and left‐upper quadrants, without obvious hepatosplenomegaly. There were no petechiae noted on her skin.

The WBC was 17.6 K/L, with 89% neutrophils and 5% lymphocytes, platelet count was 22 K/L, and hemoglobin was 13.8 g/dL. A D‐dimer test was elevated at 1344 ng/mL. Peripheral blood smear showed thrombocytopenia and neutrophilia, but demonstrated no schistocytes. The serum potassium was 3.2 mEq/L, bicarbonate was 29 mEq/L, blood urea nitrogen was 15 mg/dL and the creatinine was 1.29 mg/dL. Transaminases were within normal limits, but total bilirubin was 1.8 mg/dL. Her urinalysis was normal. Blood cultures were sent. A CXR showed bibasilar consolidations and pleural effusions (Figure 1). A CT of the chest with contrast was obtained that showed multiple confluent and patchy foci of consolidation in the lung bases, with trace bilateral pleural effusions (Figure 2). A CT of the abdomen showed a spleen at the upper limits of normal in size, measuring 13 cm in length, but was otherwise normal.

Leukocytosis with lymphopenia is not consistent with EBV infection and another process needs to be considered. This patient meets criteria for sepsis syndrome and should receive broad spectrum antibiotics, such as vancomycin and piperacillin‐tazobactam immediately after the blood cultures are sent, in addition to further evaluation to determine the source of sepsis. Depending on her mental status response to initial measures such as acetaminophen and hydration, one should consider a lumbar puncture, which would require platelet transfusion and may therefore not be done immediately. HIV serology should be performed, since acute retroviral syndrome can mimic this presentation. With neck tenderness that is more localized to her left side, a CT of her neck to evaluate for an abscess may be helpful.

She was admitted for presumed community‐acquired pneumonia complicating an upper respiratory tract infection. Her pharyngitis was thought to be of viral etiology. Moxifloxacin was started and intravenous fluids were administered. She was started on prednisone 60 mg daily for presumed immune‐mediated thrombocytopenia related to EBV infection. An HIV antibody test and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were both negative. The EBV immunoglobulin G (IgG) titer was positive (>1:10), but the IgM titer was negative. Her mental status improved after starting moxifloxacin and fluids. Her creatinine and bilirubin normalized to 0.97 mg/dL and 0.8 mg/dL respectively. She continued to have a tender left‐sided submandibular swelling. Blood cultures grew Gram‐negative bacilli in 2 anaerobic bottles.

I am uncomfortable with moxifloxacin as initial empiric therapy because at presentation she had sepsis syndrome as well as a suspected immunocompromised state. In addition, moxifloxacin would not be adequate coverage for anaerobic organisms if a peritonsillar abscess was involved. At this point, she needs a CT of her neck to look for a focus of infection which may require surgical management and, if negative, further imaging such as a tagged white blood scan to identify the source of the anaerobes.

Moxifloxacin was switched to piperacillin‐tazobactam and prednisone was discontinued. By day 4 of hospitalization her platelet count had risen to 261 K/L. Her WBC continued to rise to a peak of 21.5 K/L and she continued to have fevers and diffuse pains, although her repeat blood cultures were negative. She continued to have tenderness of the cervical lymph nodes, left greater than right. A repeat CXR showed patchy air space disease bilaterally and pleural effusions, both of which had progressed compared with the prior film. Clindamycin was empirically added to her antibiotic regimen in light of her progressing pneumonia and evidence of anaerobic infection. A repeat CT scan of her chest revealed multiple nodular opacities scattered throughout the lung fields, some of which were cavitary, predominating in the lung bases. The CT scan of her neck revealed a left peritonsillar abscess and phlegmon in the left retropharyngeal and deep neck area along the sternocleidomastoid and internal jugular vein (IJV). There also was noted a large thrombus within the left IJV extending superiorly to involve the jugular bulb, sigmoid sinus, and distal left transverse sinus; and inferiorly to near the origin of the brachiocephalic vein (see Figure 3). An echocardiogram did not reveal any vegetations.

The combination of recent pharyngitis, septic pulmonary emboli, and IJV thrombosis is consistent with a diagnosis of Lemierre's syndrome (LS). This is a life threatening condition, even if diagnosis is made early and appropriate treatment is started. The most likely causative agent is Fusobacterium necrophorum. In this case it was important to realize that clinical presentation was not consistent with EBV infection, even though heterophile screen was positive. Early initiation of broad spectrum antibiotics as well as CT scan of the neck would have been appropriate.

The diagnosis of LS was made. The blood culture speciation revealed Fusobacterium nucleatum, which was too fastidious to perform antimicrobial sensitivities. Her symptoms improved significantly with the addition of clindamycin to piperacillin‐tazobactam, which was postulated to be the result of bacterial beta‐lactamase activity mitigating the efficacy of piperacillin‐tazobactam. Thoracentesis of her pleural effusion did not reveal an empyema. Due to her large thrombus burden, she was started on anticoagulation with heparin and transitioned to outpatient coumadin. She was switched to metronidazole as a single agent antibiotic for 6 weeks, and on outpatient follow‐up was doing well.

Commentary

LS was described by Dr. Andre Lemierre in 1936.6 The syndrome consists of a primary oropharyngeal infection, thrombosis of the IJV, bacteremia, and septic metastatic foci, usually involving the lungs.1, 2 LS is a form of necrobacillosis, which is a systemic infection resulting from F. necrophorum.3, 4 In classic LS, the initial pharyngitis is usually a tonsillar or peritonsillar abscess, and is followed by intense fever and rigors after 4 days to 2 weeks.1, 3 This is followed by a unilateral painful submaxillary LAD and IJV thrombophlebitisthe cord sign.2 Finally, bacteremia and distant metastatic pyogenic abscesses develop.1 (see Table 1).

| Lemierre's Syndrome typical features |

| Antecedent head and neck infection, typically an oropharyngeal infection prior to deterioration |

| Thrombophlebitis, typically of internal jugular vein (present in only 1/3 of cases) |

| Bacteremia (Fusobacterium necrophorum most commonly) |

| Septic metastatic foci, typically to lungs |

| Usual Presentation |

| Pharyngitis |

| Fevers |

| Rigors |

| Neck involvement: tenderness, swelling, tender internal jugular vein thrombus (cord sign) |

| Pulmonary infiltrates which cavitate |

With the advent of antibiotics, LS is now rare with an incidence of 0.9 per million persons per year. In Lemierre's time, the disease was fulminant and led to death within 2 weeks, but in the antibiotic age the mortality rate is 4.9%.1, 3 The median age of an LS patient is 19 years, with a higher incidence in males.1, 35 Although in the literature it is referred to as the forgotten disease, there is evidence the incidence is increasing.3, 4, 6, 8

There are variations of classic LS. Bacteremia may occur much later than the initial pharyngitis, the disease may be less aggressive, the thrombus may be in the external jugular vein, or there may be no identified thrombus.3, 4, 8 In fact, a thrombus is only identified in 36% of cases.9 The primary infection may be a head and neck infection that is not pharyngitis, such as an odontogenic infection,4 or may not be identified.10 Despite variations, the fundamentals of diagnosis are prior head and neck infection, presumed thrombophlebitis and bacteremia, and evidence of septic metastatic foci.

The genus Fusobacterium comprises anaerobic, nonspore forming gram negative bacilli.1, 35, 11 F. necrophorum and F. nucleatum are 2 species within this genus. F. nucleatum causes the majority of reported human bacteremias by Fusobacterium species, but it is F. necrophorum that is most associated with anaerobic oropharyngeal infections, thrombocytopenia, clot formation, and LS.35, 8, 9

It is unknown if Fusobacterium species directly cause the sore throat, or rather are bystanders which thrive once a favorable anaerobic environment is created via endotoxins and exotoxins.35 A break in oral mucosa via trauma or coinfection with bacteria/viruses (especially EBV) is also thought to play a role with infection.2, 3, 5 One‐third of LS cases have coinfection with other oropharyngeal flora. Thus, one must reexamine the anaerobic blood cultures after an organism has been identified in suspect cases.3, 4

There is an increased association of LS with EBV infection, likely due to viral‐induced and steroid‐induced immunosuppression.24 False positive heterophile tests are reported with LS, so the specific antibody tests for EBV must be checked.3, 4

Once thrombophlebitis occurs, the bacteria can metastasize to distant sites. In 80% to 92% of LS cases, the metastatic complication is a pleuro‐pulmonary infection, consisting of septic pulmonary emboli, empyema, and pleural effusions, but extra‐pulmonary lesions occur.1, 3, 9, 12 Abdominal pain usually results from abdominal microabscesses or thrombophlebitis.4 Mild renal impairment and abnormal liver function tests are common.3, 4 Cranial nerve palsies and Horner's syndrome are rare and indicate carotid sheath involvement.3, 12 An elevated C‐reactive protein can distinguish bacterial from uncomplicated viral pharyngitis.3, 4 Also, rigors are unusual in tonsillitis, and their presence indicate bacterial entry into the circulation.3

CXRs may reveal the pulmonary septic emboli. Ultrasound of the IJV is inexpensive and noninvasive, but may have limited sensitivity for an acute thrombus. CT scan allows increased visualization of anatomy, but can have decreased sensitivity and specificity for thrombosis.3 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended if LS results from mastoiditis, to exclude an intracerebral vein thrombosis.9

Antibiotics have both dramatically decreased the incidence of LS and improved its prognosis. The recent rise in incidence may be due to a renewed interest in restricting the use of antibiotics in cases of pharyngitis, as well as an increased use of macrolides, to which F. necrophorum is frequently resistant.3 Decreased tonsillectomies may also have a role, as LS is more common with retained tonsils.1, 3

No trials have evaluated the optimal antibiotic regimen. Fusobacterium species are sensitive to penicillin, but 23% have beta‐lactamase activity as reported clinically by several authors.3, 5 F. necrophorum is also sensitive to metronidazole, ticarcillin‐clavulanate, cefoxitin, amoxicillin‐clavulanate, imipenem, and clindamycin. There is a high resistance to macrolides and gentamicin, and the activity of tetracyclines is poor. For treatment, most authors suggest a carbapenem, a penicillin/beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination, or metronidazole. Clindamycin has weaker bactericidal activity than metronidazole or imipenem. Metronidazole is preferred because of its activity against all Fusobacterium species, good penetration into tissues, bactericidal activity, low minimum inhibitory concentration, and ability to achieve high concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid if meningitis occurs. An effective regimen is metronidazole with a penicillinase‐resistant penicillin to cover for mixed coinfection with streptococci or staphylococci.3, 4, 12 A 6‐week antibiotic course is given for adequate penetration into the protective fibrin clots.4

Reports have shown good outcomes both with and without the use of anticoagulation.3, 4, 8 Support for anticoagulation is extrapolated from experience with septic pelvic thrombophlebitis, in which anticoagulation results in more rapid resolution of symptoms.13 Given the lack of firm evidence in cases of LS, anticoagulation is typically reserved for poor clinical response despite 2 to 3 days of antibiotic therapy or propagation of thromboses into the cavernous sinus. It is generally given for 3 months.4, 13

Prior to the antibiotic era, surgical ligation or excision of the IJV was done without clear benefit. Today, surgery is reserved for cases of continued septic emboli or extension of thrombus despite aggressive medical therapy.3 If mediastinitis develops, then surgical intervention is essential.4

Lemierre stated that the symptoms and signs of LS are so characteristic that it permits diagnosis before bacteriological examination.1 However, today it may go unrecognized by physicians until a blood culture shows anaerobes or Fusobacterium species. For a young patient admitted with pneumonia preceded by pharyngitis, hospitalists must remain vigilant for the presence of LS.

Key Points for Hospitalists/Teaching Points

-

The triad of LS is pharyngitis, thrombophlebitis, and distant metastatic pyogenic emboli.

-

Suspect LS in a young, otherwise healthy patient who clinically deteriorates in the setting of a recent pharyngeal infection.

-

With the modern decrease in antibiotic use for pharyngitis, LS may be on the rise.

- .On certain septicaemias due to anaerobic organisms.Lancet.1936;1:701–703.

- ,.Lemierre's syndrome: more judicious antibiotic prescribing habits may lead to the clinical reappearance of this often forgotten disease.Am J Med.2006;119(3):e7–e9.

- .Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre's syndrome.Clin Microbiol Rev.2007;20(4):622–659.

- ,.Human necrobacillosis, with emphasis on Lemierre's syndrome.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31(2):524–532.

- ,.Fusobacterial infections: clinical spectrum and incidence of invasive disease.J Infect.2008;57(4):283–289.

- .Human infections with Fusobacterium necrophorum.Anaerobe.2006;12(4):165–172.

- ,,, et al.Increased diagnosis of Lemierre Syndrome and other Fusobacterium necrophorum infections at a Children's Hospital.Pediatrics.2003;112(5):e380.

- ,,.Unusual presentation of Lemierre's syndrome due to Fusobacterium nucleatum.J Clin Microbiol.2003;41(7):3445–3448.

- ,,,.The evolution of Lemierre Syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature.Medicine (Baltimore).2002;81(6):458–465.

- ,.An unusual case of Lemierre's syndrome presenting as pyomyositis.Am J Med Sci.2008;335(6):499–501.

- .Update on the taxonomy and clinical aspects of the genus Fusobacterium.Clin Infect Dis.2002;35(Suppl 1):S22–S27.

- ,,,,.Lemierre syndrome: two cases and a review.Laryngosope.2007;117(9):1605–1610.

- ,,.Lemierre's syndrome (necrobacillosis).Postgrad Med J.1999;75(881):141–144.

- .On certain septicaemias due to anaerobic organisms.Lancet.1936;1:701–703.

- ,.Lemierre's syndrome: more judicious antibiotic prescribing habits may lead to the clinical reappearance of this often forgotten disease.Am J Med.2006;119(3):e7–e9.

- .Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre's syndrome.Clin Microbiol Rev.2007;20(4):622–659.

- ,.Human necrobacillosis, with emphasis on Lemierre's syndrome.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31(2):524–532.

- ,.Fusobacterial infections: clinical spectrum and incidence of invasive disease.J Infect.2008;57(4):283–289.

- .Human infections with Fusobacterium necrophorum.Anaerobe.2006;12(4):165–172.

- ,,, et al.Increased diagnosis of Lemierre Syndrome and other Fusobacterium necrophorum infections at a Children's Hospital.Pediatrics.2003;112(5):e380.

- ,,.Unusual presentation of Lemierre's syndrome due to Fusobacterium nucleatum.J Clin Microbiol.2003;41(7):3445–3448.

- ,,,.The evolution of Lemierre Syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature.Medicine (Baltimore).2002;81(6):458–465.

- ,.An unusual case of Lemierre's syndrome presenting as pyomyositis.Am J Med Sci.2008;335(6):499–501.

- .Update on the taxonomy and clinical aspects of the genus Fusobacterium.Clin Infect Dis.2002;35(Suppl 1):S22–S27.

- ,,,,.Lemierre syndrome: two cases and a review.Laryngosope.2007;117(9):1605–1610.

- ,,.Lemierre's syndrome (necrobacillosis).Postgrad Med J.1999;75(881):141–144.

In the Literature: HM-Related Research You Need to Know

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Effect of early follow-up on readmission rates

- Heart rate control and outcomes in atrial fibrillation

- Pneumococcal vaccine to prevent stroke and MI

- Long-term outcomes of endovascular repair of AAA

- Insurance and outcomes in myocardial infarction

- Risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and cardiovascular outcomes with concurrent PPI and clopidogrel use

- CT in patients with suspected coronary artery disease

Reduced 30-Day Readmission Rate for Patients Discharged from Hospitals with Higher Rates of Early Follow-Up

Clinical question: Is early follow-up after discharge for heart failure associated with a reduction in readmission rates?

Background: Readmission for heart failure is very frequent and often unplanned. Early follow-up visits after discharge have been hypothesized to reduce readmissions but have been undefined.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Patients with Medicare inpatient claims data linked to the OPTIMIZE-HF and GWTG-HF registries.

Synopsis: The study included 30,136 patients >65 years old with the principal discharge diagnosis of heart failure from 2003 to 2006. Hospitals were stratified into quartiles based upon the median arrival rate to “early” (within one week after discharge) follow-up appointments. Ranges of arrival rates to these appointments ranged from Quartile 1 (Q1) (<32.4% of patients) to Q4 (>44.5%). Readmission rates were highest in the lowest quartile of “early” follow-up (Q1: 23.3%; Q2: 20.5%; Q3: 20.5%; Q4: 20.5%, P<0.001). No mortality difference was seen.

The study also examined whether the physician following the patient after discharge impacted the readmission rate for these same quartiles, comparing cardiologists to generalists and comparing the same physician at discharge and follow-up (defined as “continuity”) versus different physicians. Follow-up with continuity or a cardiologist did not reduce readmissions.

Interestingly, nearly all markers of quality were best in Q1 and Q2 hospitals, which had the lowest arrival rates to appointments, which might reflect patient-centered rather than hospital-centered issues.

Bottom line: Hospitals with low “early” follow-up appointment rates after discharge have a higher readmission rate, although causality is not established.

Citation: Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303 (17):1716-1722.

Strict Heart Rate Control Is Not Necessary in Management of Chronic Atrial Fibrillation

Clinical question: Is lenient heart rate control inferior to strict heart rate control in preventing cardiovascular events in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation?

Background: Guidelines generally call for the use of medications to achieve strict heart rate control in the management of chronic atrial fibrillation, but the optimal level of heart rate control necessary to avoid cardiovascular events remains uncertain.

Study design: Prospectively randomized, noninferiority trial.

Setting: Thirty-three medical centers in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: The study looked at 614 patients with permanent atrial fibrillation; 311 patients were randomized to lenient control and 303 to strict control. Calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, or digoxin were dose-adjusted to control heart rate below 110 beats per minute (bpm) in the lenient control group versus 80 bpm in the strict control group.

Thirty-eight patients (12.9%) in the lenient control group and 43 (14.9%) in the strict control group reached the primary composite outcome of significant cardiovascular events (death, heart failure, stroke, embolism, major bleeding, major arrhythmia, need for pacemaker, or severe drug adverse event). Although no statistical difference in the frequency of these events between groups was detected, the study was dramatically underpowered due to unanticipated low event rates.

Bottom line: Although the lenient control group had far fewer outpatient visits and a trend toward improved outcomes, no definite conclusion regarding the management of permanent atrial fibrillation can be drawn from this underpowered noninferiority trial.

Citation: Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(15):1363-1373.

Pneumococcal Vaccine Does Not Reduce the Risk of Stroke or Myocardial Infarction

Clinical question: Does pneumococcal vaccination reduce the risk of acute myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke?

Background: Studies have demonstrated that influenza vaccination reduces the risk of cardiac and cerebrovascular events. A single study has shown similar outcomes for the pneumococcal vaccination, although the study was limited by confounders and selection bias.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Large HMO in California.

Synopsis: More than 84,000 men participating in the California Men’s Health Study (CMHS) and enrolled in the Kaiser Permanente health plan were categorized as unvaccinated or vaccinated with the pneumococcal vaccine. Vaccinated patients had 10.73 first MIs and 5.30 strokes per 1,000 person-years, compared with unvaccinated patients who incurred 6.07 MIs and 1.90 strokes per 1,000 unvaccinated person-years based on ICD-9 codes.

Even with propensity scoring to minimize selection bias, no clear evidence of benefit was observed. One significant limitation is that 80% of the unvaccinated patients were younger than 60 years old, whereas 74% of the vaccinated patients were 60 or older; this might represent selection bias that cannot be overcome with propensity scoring.

Bottom line: In a population of men older than age 45, pneumococcal vaccination does not appear to reduce the risk of acute MI or stroke.

Citation: Tseng HF, Slezak JM, Quinn VP, et al. Pneumococcal vaccination and risk of acute myocardial infarction and stroke in men. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1699-1706.

No Durable Mortality Benefit from Endovascular Repair of Enlarged Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Clinical question: What is the cost and mortality benefit of endovascular versus open repair of abdominal aneurysms?

Background: Previous studies demonstrated a 30-day mortality benefit using endovascular repair over open surgical repair of large abdominal aortic aneurysms. Limited longer-term data are available assessing the durability of these findings.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Thirty-seven hospitals in the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Researchers looked at 1,252 patients who were at least 60 years old with a large abdominal aortic aneurysm (>5.5 cm) on CT scan. The patients were randomized to open versus endovascular repair and followed for a median of six years postoperatively. An early, postoperative, all-cause mortality benefit was observed for endovascular repair (1.8%) compared with open repair (4.3%), but no benefit was seen after six months of follow-up, driven by secondary aneurysm ruptures with endovascular grafts. Graft-related complications in all time periods were higher in the endovascular repair group, highest from 0 to 6 months (nearly 50% of patients), and were associated with an increased cost.

Bottom line: Immediate postoperative mortality benefit of endovascular repair is not sustained for abdominal aortic aneurysm beyond six months postoperatively.

Citation: The United Kingdom EVAR trial investigators. Endovascular versus open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med. 2010:362(20):1863-1870.

Financial Constraints Delay Presentation in Patients Suffering from Acute Myocardial Infarction

Clinical question: Does being underinsured or uninsured delay individuals from seeking treatment for emergency medical care?

Background: The number of underinsured or uninsured Americans is growing. Studies have shown that patients with financial concerns avoid routine preventive and chronic medical care; however, similar avoidance has not been defined clearly for patients seeking emergent care.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Twenty-four urban hospitals in the U.S. included in a multisite, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) registry.

Synopsis: Of the 3,721 patients enrolled in the AMI registry, 61.7% of the cohort was insured and without financial concerns that prevented them from seeking care. These patients were less likely to have delays in care related to AMI compared with patients who were insured with financial concerns (18.5% of the cohort; OR 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.06-1.40) or uninsured (19.8%; OR 1.30; 95% CI, 1.12-1.51) in all time frames after symptom onset. Patients were less likely to undergo PCI or thrombolysis if the delay to presentation was more than six hours.

After adjustment for confounding factors, the authors concluded that uninsured and underinsured patients were likely to delay presentation to the hospital. Despite these findings, alternative etiologies for delays in care are likely to be more significant, as insurance considerations only account for an 8% difference between the well-insured group (39.3% delayed seeking care >6 hours) and the uninsured group (48.6%). These etiologies are ill-defined.

Bottom line: Underinsured or uninsured patients have a small but significant delay in seeking treatment for AMI due to financial concerns.

Citation: Smolderen KG, Spertus JA, Nallamothu BK, et al. Health care insurance, financial concerns in accessing care, and delays to hospital presentation in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2010;303 (14):1392-1400.

Concurrent Use of PPIs and Clopidogrel Decrease Hospitalizations for Gastroduodenal Bleeding without Significant Increase in Adverse Cardiovascular Events

Clinical question: Does concomitant use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) and clopidogrel affect the risks of hospitalizations for gastroduodenal bleeding and serious cardiovascular events?

Background: PPIs commonly are prescribed with clopidogrel to reduce the risk of serious gastroduodenal bleeding. Recent observational studies suggest that concurrent PPI and clopidogrel administration might increase the risk of cardiovascular events compared with clopidogrel alone.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Tennessee Medicaid program.

Synopsis: Researchers identified 20,596 patients hospitalized for acute MI, revascularization, or unstable angina, and prescribed clopidogrel. Of this cohort, 7,593 were initial concurrent PPI users—62% used pantoprazole and 9% used omeprazole. Hospitalizations for gastroduodenal bleeding were reduced by 50% (HR 0.50 [95% CI, 0.39-0.65]) in concurrent users of PPIs and clopidogrel, compared with nonusers of PPIs.

Concurrent use was not associated with a statistically significant increase in serious cardiovascular diseases (HR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.82-1.19]), defined as acute MI, sudden cardiac death, nonfatal or fatal stroke, or other cardiovascular deaths.

Subgroup analyses of individual PPIs and patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions also showed no increased risk of serious cardiovascular events. This study could differ from previous observational studies because far fewer patients were on omeprazole, the most potent inhibitor of clopidogrel.

Bottom line: In patients treated with clopidogrel, PPI users had 50% fewer hospitalizations for gastroduodenal bleeding compared with nonusers. Concurrent use of clopidogrel and PPIs, most of which was pantoprazole, was not associated with a significant increase in serious cardiovascular events.

Citation: Ray WA, Murray KT, Griffin MR, et al. Outcomes with concurrent use of clopidogrel and proton-pump inhibitors. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(6):337-345.

CTCA a Promising, Noninvasive Option in Evaluating Patients with Suspected Coronary Artery Disease

Clinical question: How does computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA) compare to noninvasive stress testing for diagnosing coronary artery disease (CAD)?

Background: CTCA is a newer, noninvasive test that has a high diagnostic accuracy for CAD, but its clinical role in the evaluation of patients with chest symptoms is unclear.

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: Single academic center in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Five hundred seventeen eligible patients were evaluated with stress testing and CTCA. The patients were classified as having a low (<20%), intermediate (20%-80%), or high (>80%) pretest probability of CAD based on the Duke clinical score. Using coronary angiography as the gold standard, stress-testing was found to be less accurate than CTCA in all of the patient groups. In patients with low and intermediate pretest probabilities, a negative CTCA had a post-test probability of 0% and 1%, respectively. On the other hand, patients with an intermediate pretest probability and a positive CTCA had a post-test probability of 94% (CI, 89%-97%). In patients with an initial high pretest probability, stress-testing and CTCA confirmed disease in most cases.

The results of this study suggest that CTCA is particularly useful in evaluating patients with an intermediate pretest probability.

Patients were ineligible in this study if they had acute coronary syndromes, previous coronary stent placement, coronary artery bypass surgery, or myocardial infarction. It is important to note that because anatomic lesions seen on imaging (CTCA and coronary angiography) are not always functionally significant, CTCA might have seemed more accurate and clinically useful than it actually is. The investigators also acknowledge that further studies are necessary before CTCA can be accepted as a first-line diagnostic test.

Bottom line: In patients with an intermediate pretest probability of CAD, a negative CTCA is valuable in excluding coronary artery disease, thereby reducing the need for invasive coronary angiography in this group.

Citation: Weustink AC, Mollet NR, Neefjes LA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility of noninvasive testing for coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(10):630-639. TH

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Effect of early follow-up on readmission rates

- Heart rate control and outcomes in atrial fibrillation

- Pneumococcal vaccine to prevent stroke and MI

- Long-term outcomes of endovascular repair of AAA

- Insurance and outcomes in myocardial infarction

- Risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and cardiovascular outcomes with concurrent PPI and clopidogrel use

- CT in patients with suspected coronary artery disease

Reduced 30-Day Readmission Rate for Patients Discharged from Hospitals with Higher Rates of Early Follow-Up

Clinical question: Is early follow-up after discharge for heart failure associated with a reduction in readmission rates?

Background: Readmission for heart failure is very frequent and often unplanned. Early follow-up visits after discharge have been hypothesized to reduce readmissions but have been undefined.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Patients with Medicare inpatient claims data linked to the OPTIMIZE-HF and GWTG-HF registries.

Synopsis: The study included 30,136 patients >65 years old with the principal discharge diagnosis of heart failure from 2003 to 2006. Hospitals were stratified into quartiles based upon the median arrival rate to “early” (within one week after discharge) follow-up appointments. Ranges of arrival rates to these appointments ranged from Quartile 1 (Q1) (<32.4% of patients) to Q4 (>44.5%). Readmission rates were highest in the lowest quartile of “early” follow-up (Q1: 23.3%; Q2: 20.5%; Q3: 20.5%; Q4: 20.5%, P<0.001). No mortality difference was seen.

The study also examined whether the physician following the patient after discharge impacted the readmission rate for these same quartiles, comparing cardiologists to generalists and comparing the same physician at discharge and follow-up (defined as “continuity”) versus different physicians. Follow-up with continuity or a cardiologist did not reduce readmissions.

Interestingly, nearly all markers of quality were best in Q1 and Q2 hospitals, which had the lowest arrival rates to appointments, which might reflect patient-centered rather than hospital-centered issues.

Bottom line: Hospitals with low “early” follow-up appointment rates after discharge have a higher readmission rate, although causality is not established.

Citation: Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303 (17):1716-1722.

Strict Heart Rate Control Is Not Necessary in Management of Chronic Atrial Fibrillation

Clinical question: Is lenient heart rate control inferior to strict heart rate control in preventing cardiovascular events in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation?

Background: Guidelines generally call for the use of medications to achieve strict heart rate control in the management of chronic atrial fibrillation, but the optimal level of heart rate control necessary to avoid cardiovascular events remains uncertain.

Study design: Prospectively randomized, noninferiority trial.

Setting: Thirty-three medical centers in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: The study looked at 614 patients with permanent atrial fibrillation; 311 patients were randomized to lenient control and 303 to strict control. Calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, or digoxin were dose-adjusted to control heart rate below 110 beats per minute (bpm) in the lenient control group versus 80 bpm in the strict control group.

Thirty-eight patients (12.9%) in the lenient control group and 43 (14.9%) in the strict control group reached the primary composite outcome of significant cardiovascular events (death, heart failure, stroke, embolism, major bleeding, major arrhythmia, need for pacemaker, or severe drug adverse event). Although no statistical difference in the frequency of these events between groups was detected, the study was dramatically underpowered due to unanticipated low event rates.

Bottom line: Although the lenient control group had far fewer outpatient visits and a trend toward improved outcomes, no definite conclusion regarding the management of permanent atrial fibrillation can be drawn from this underpowered noninferiority trial.

Citation: Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(15):1363-1373.

Pneumococcal Vaccine Does Not Reduce the Risk of Stroke or Myocardial Infarction

Clinical question: Does pneumococcal vaccination reduce the risk of acute myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke?

Background: Studies have demonstrated that influenza vaccination reduces the risk of cardiac and cerebrovascular events. A single study has shown similar outcomes for the pneumococcal vaccination, although the study was limited by confounders and selection bias.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Large HMO in California.