User login

In the Face of It All

A 59 year‐old man was sent from urgent care clinic to the emergency room for further evaluation because of 1 month of diarrhea and an acute elevation in his serum creatinine.

Whereas acute diarrhea is commonly due to a self‐limited and often unspecified infection, diarrhea that extends beyond 23 weeks (chronic) warrants consideration of malabsorptive, inflammatory, infectious, and malignant processes. The acute renal failure likely is a consequence of dehydration, but the possibility of simultaneous gastrointestinal and renal involvement from a systemic process (eg, vasculitis) must be considered.

The patient's diarrhea began 1 month prior, shortly after having a milkshake at a fast food restaurant. The diarrhea was initially watery, occurred 8‐10 times per day, occasionally awakened him at night, and was associated with nausea. There was no mucus, blood, or steatorrhea until 1 day prior to presentation, when he developed epigastric pain and bloody stools. He denied any recent travel outside of Northern California and had no sick contacts. He had lost 10 pounds over the preceding month. He denied fevers, chills, vomiting, or jaundice, and had not taken antibiotics recently.

In the setting of chronic diarrhea, unintentional weight loss is an alarm feature but does not narrow the diagnostic possibilities significantly. The appearance of blood and pain on a single day after 1 month of symptoms renders their diagnostic value uncertain. For instance, rectal or hemorrhoidal bleeding would be a common occurrence after 1 month of frequent defecation. Sustained bloody stools might be seen in any form of erosive luminal disease, such as infection, inflammatory bowel disease, or neoplasm. Pain is compatible with inflammatory bowel disease, obstructing neoplasms, infections, or ischemia (eg, vasculitis). There are no fever or chills to support infection, and common gram‐negative enteric pathogens (such as Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Yersinia) usually do not produce symptoms for such an extended period. He has not taken antibiotics, which would predispose him to infection with Clostridum difficile, and he has no obvious exposure to parasites such as Entamoeba.

The patient had diabetes mellitus with microalbuminuria, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic low back pain, and gastritis, and had undergone a Billroth II procedure for a perforated gastric ulcer in the remote past. His medications included omeprazole, insulin glargine, simvastatin, lisinopril, amlodipine, and albuterol and beclomethasone metered‐dose inhalers. He had been married for 31 years, lived at home with his wife, was a former rigger in a shipyard and was on disability for chronic low back pain. He denied alcohol or intravenous drug use but had quit tobacco 5 years prior after more than 40 pack‐years of smoking. He had three healthy adult children and there was no family history of cancer, liver disease, or inflammatory bowel disease. There was no history of sexually transmitted diseases or unprotected sexual intercourse.

Bacterial overgrowth in the blind loop following a Billroth II operation can lead to malabsorption, but the diarrhea would not begin so abruptly this long after surgery. Medications are common causes of diarrhea. Proton‐pump inhibitors, by reducing gastric acidity, confer an increased risk of bacterial enteritis; they also are a risk factor for C difficile. Lisinopril may cause bowel angioedema months or years after initiation. Occult laxative use is a well‐recognized cause of chronic diarrhea and should also be considered. The most relevant element of his social history is the prolonged smoking and the attendant risk of cancer, although diarrhea is a rare paraneoplastic phenomenon.

On exam, temperature was 36.6C, blood pressure 125/78, pulse 88, respiratory rate 16 per minute, and oxygen saturation 97% while breathing room air. There was temporal wasting and mild scleral icterus, but no jaundice. Lungs were clear to auscultation and heart was regular in rate and rhythm without murmurs or gallops. There was no jugular venous distention. A large abdominal midline scar was present, bowel sounds were normoactive, and the abdomen was soft, nontender, and nondistended. The hard was regular in rate and rhythm the liver edge was 6 cm below costal margin; there was no splenomegaly. The patient was alert and oriented, with a normal neurologic exam.

The liver generally enlarges because of acute inflammation, congestion, or infiltration. Infiltration can be due to tumors, infections, hemochromatosis, amyloidosis, or sarcoidosis. A normal cardiac exam argues against hepatic congestion from right‐sided heart failure or pericardial disease.

The key elements of the case are diarrhea and hepatomegaly. Inflammatory bowel disease can be accompanied by sclerosing cholangitis, but this should not enlarge the liver. Mycobacterial infections and syphilis can infiltrate the liver and intestinal mucosa, causing diarrhea, but he lacks typical risk factors.

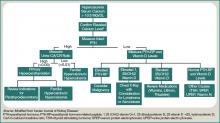

Malignancy is an increasing concern. Colon cancer commonly metastasizes to the liver and can occasionally be intensely secretory. Pancreatic cancer could account for these symptoms, especially if pancreatic exocrine insufficiency caused malabsorption. Various rare neuroendocrine tumors that arise in the pancreas can cause secretory diarrheas and liver metastases, such as carcinoid, VIPoma, and Zollinger‐Ellison syndrome.

Laboratory results revealed a serum sodium of 143 mmol/L, potassium 4.7 mmol/L, chloride 110 mmol/L, bicarbonate 25 mmol/L, urea nitrogen 24 mg/dL, and creatinine 2.5 mg/dL (baseline had been 1.2 mg/dL 2 months previously). Serum glucose was 108 mg/dL and calcium was 8.8 mg/dL. The total white blood cell count was 9300 per mm3 with a normal differential, hemoglobin was 14.4 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume was 87 fL, and the platelet count was normal. Total bilirubin was 3.7 mg/dL, and direct bilirubin was 3.1 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 122 U/L (normal range, 831), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 79 U/L (normal range, 731), alkaline phosphatase 1591 U/L (normal range, 39117), and gamma‐glutamyltransferase (GGT) 980 U/L (normal range, 57). Serum albumin was 2.5 mg/dL, prothrombin time was 16.4 seconds, and international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.6.

Urinalysis was normal except for trace hemoglobin, small bilirubin, and 70 mg/dL of protein; specific gravity was 1.007. Urine microscopy demonstrated no cells or casts. The ratio of protein to creatinine on a spot urine sample was less than 1. Chest x‐ray was normal. The electrocardiogram demonstrated sinus rhythm with an old right bundle branch block and normal QRS voltages.

The disproportionate elevation in alkaline phosphatase points to an infiltrative hepatopathy from a cancer originating in the gastrointestinal tract or infection. Other infiltrative processes such as sarcoidosis or amyloidosis usually have evidence of disease elsewhere before hepatic disease becomes apparent.

Mild proteinuria may be explained by diabetes. The specific gravity of 1.007 is atypical for dehydration and could suggest ischemic tubular injury. Although intrinsic renal diseases must continue to be entertained, hypovolemia (compounded by angiotensin‐converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitor use) is the leading explanation in light of the nondiagnostic renal studies. The preserved hemoglobin may simply indicate dehydration, but otherwise is somewhat reassuring in the context of bloody diarrhea.

The patient was admitted to the hospital. Three stool samples returned negative for C difficile toxin. No white cells were detected in the stool, and no ova or parasites were detected. Stool culture was negative for routine bacterial pathogens and for E coli O157. Tests for HIV and antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) and serologies for hepatitis A, B, and C were negative. Abdominal ultrasound demonstrated no intra‐ or extrahepatic bile duct dilatation; no hepatic masses were seen. Kidneys were normal in size and appearance without hydronephrosis. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen without intravenous contrast revealed normal‐appearing liver (with a 12‐cm span), spleen, biliary ducts, and pancreas, and there was no intra‐abdominal adenopathy.

The stool studies point away from infectious colitis. Infiltrative processes of the liver, including metastases, lymphoma, tuberculosis, syphilis, amyloidosis, and sarcoidosis, can be microscopic and therefore evade detection by ultrasound and CT scan. In conditions such as these, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopanccreatography/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (ERCP/MRCP) or liver biopsy may be required. The CT is limited without contrast but does not suggest extrahepatic disease in the abdomen.

MRCP was performed, but was a technically suboptimal study due to the presence of ascites. The serum creatinine improved to 1.4 mg/dL over the next 4 days, and the patient's diarrhea decreased to two bowel movements daily with the use of loperamide. The patient was discharged home with outpatient gastroenterology follow‐up planned to discuss further evaluation of the abnormal liver enzymes.

Prior to being seen in the Gastroenterology Clinic, the patient's nonbloody diarrhea worsened. He felt weaker and continued to lose weight. He also noted new onset of bilateral lower face numbness and burning, which was followed by swelling of his lower lip 12 hours later. He returned to the hospital.

On examination, he was afebrile. His lower lip was markedly swollen and was drooping from his face. He could not move the lip to close his mouth. The upper lip and tongue were normal size and moved without restriction. Facial sensation was intact, but there was weakness when he attempted to wrinkle both of his brows and close his eyelids. The rest of his physical examination was unchanged.

The serum creatinine had risen to 3.6 mg/dL, and the complete blood count remained normal. Serum total bilirubin was 4.6 mg/dL, AST 87 U/L, ALT 76 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase 1910 U/L. The 24‐hour urine protein measurement was 86 mg.

Lip swelling suggests angioedema. ACE inhibitors are frequent offenders, and it would be important to know whether his lisinopril was restarted at discharge. ACE‐inhibitor angioedema can also affect the intestine, causing abdominal pain and diarrhea, but does not cause a systemic wasting illness or infiltrative hepatopathy. The difficulty moving the lip may reflect the physical effects of swelling, but generalized facial weakness supports a cranial neuropathy. Basilar meningitis may produce multiple cranial neuropathies, the etiologies of which are quite similar to the previously mentioned causes of infiltrative liver disease: sarcoidosis, syphilis, tuberculosis, or lymphoma.

The patient had not resumed lisinopril since his prior hospitalization. The lower lip swelling and paralysis persisted, and new sensory paresthesias developed over the right side of his chin. A consulting neurologist found normal language and speech and moderate dysarthria. Cranial nerve exam was normal except bilateral lower motor neuron facial nerve palsy was noted with bilateral facial droop, reduced strength of eyelid closure, and diminished forehead movement bilaterally; facial sensation was normal. Extremity motor exam revealed proximal iliopsoas muscle weakness bilaterally rated as 4/5 and was otherwise normal. Sensation to pinprick was diminished in a stocking/glove distribution. Deep‐tendon reflexes were normal and plantar response was down‐going bilaterally. Coordination was intact, Romberg was negative, and gait was slowed due to weakness.

Over the next several days, the patient continued to have diarrhea and facial symptoms. The serum total bilirubin increased to 14 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase rose above 2,000 U/L, and serum creatinine increased to 5.5 mg/dL. Noncontrast CT scan of the head was normal.

Along with a mild peripheral sensory neuropathy, the exam indicates bilateral palsies of the facial nerve. Lyme disease is a frequent etiology, but this patient is not from an endemic area. I am most suspicious of bilateral infiltration of cranial nerve VII. I am thinking analogically to the numb chin syndrome, wherein lymphoma or breast cancer infiltration along the mental branch of V3 causes sensory loss, and perhaps these disorders can produce infiltrative facial neuropathy. At this point I am most concerned about lymphomatous meningitis with cranial nerve involvement. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis (including cytology) would be informative.

Lumbar puncture demonstrated clear CSF with one white blood cell per mm3 and no red blood cells. Glucose was normal, and protein was 95.5 (normal range, 15‐45 mg/dL). Gram stain and culture for bacteria were negative, as were polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for herpes simplex virus, mycobacterial and fungal stains and cultures, and cytology. Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated severe concentric left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, normal LV systolic function, and impaired LV relaxation. CT scan of the chest identified no adenopathy or other abnormality.

The CSF analysis does not support basilar meningitis, although the cytoalbuminologic dissociation makes me wonder whether there is some intrathecal antibody production or an autoimmune process we have yet to uncover. The absence of lymphadenopathy anywhere in the body and the negative CSF cytology now point away from lymphoma. As the case for lymphoma or an infection diminishes, systemic amyloidosis rises to the top of possibilities in this afebrile man who is losing weight, has infiltrative liver and nerve abnormalities, renal failure, cardiac enlargement, and suspected gastrointestinal luminal abnormality. Although the echocardiographic findings are most likely explained by hypertension, they are compatible with amyloid infiltration. A tissue specimen is needed, and either colonoscopy or liver biopsy should be suitable.

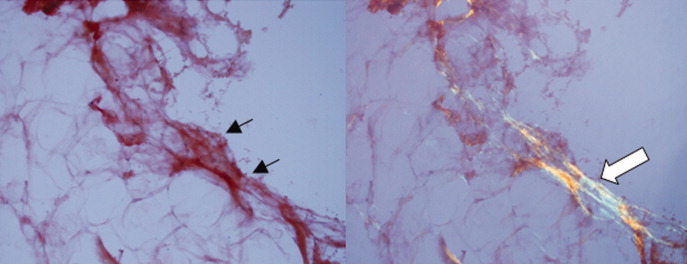

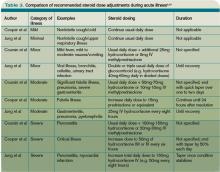

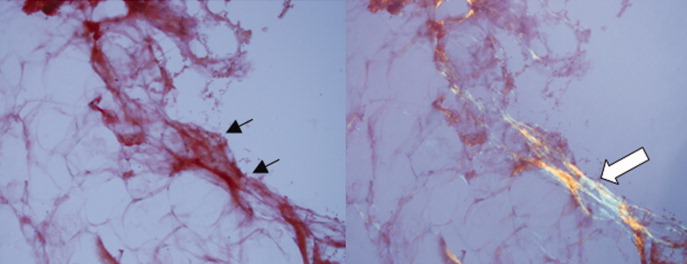

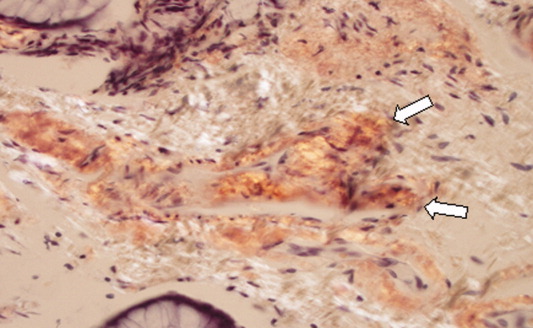

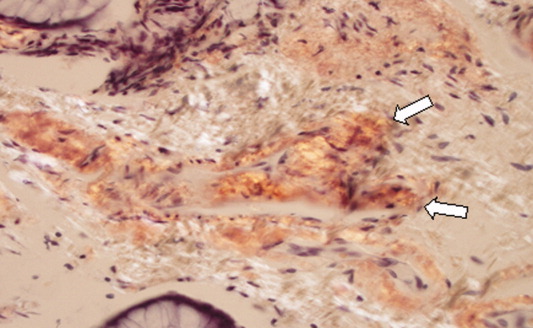

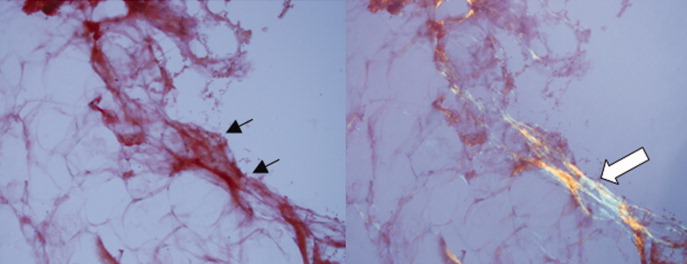

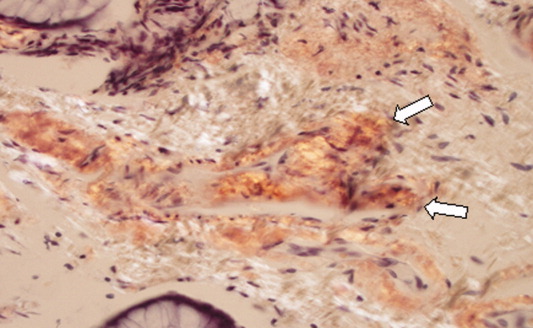

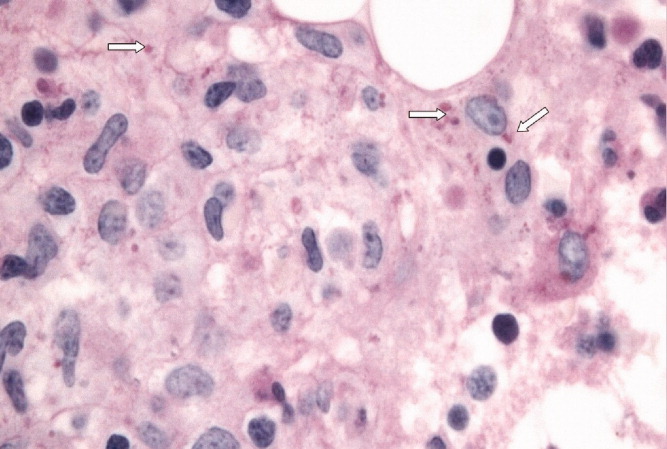

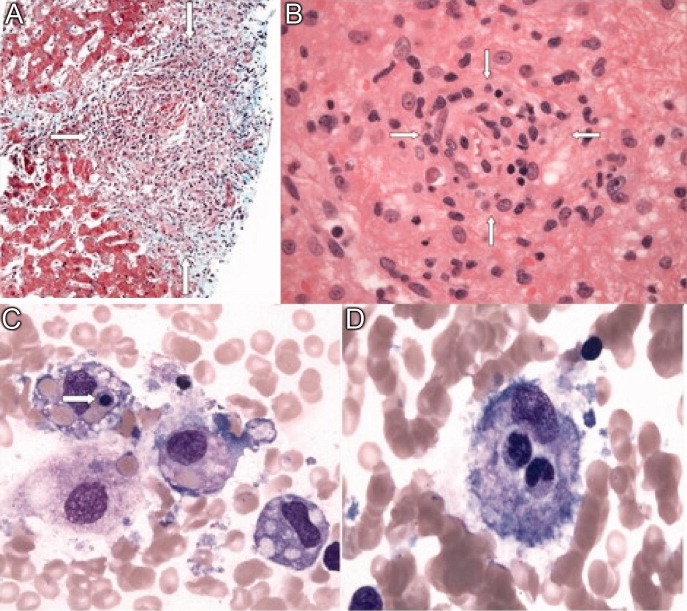

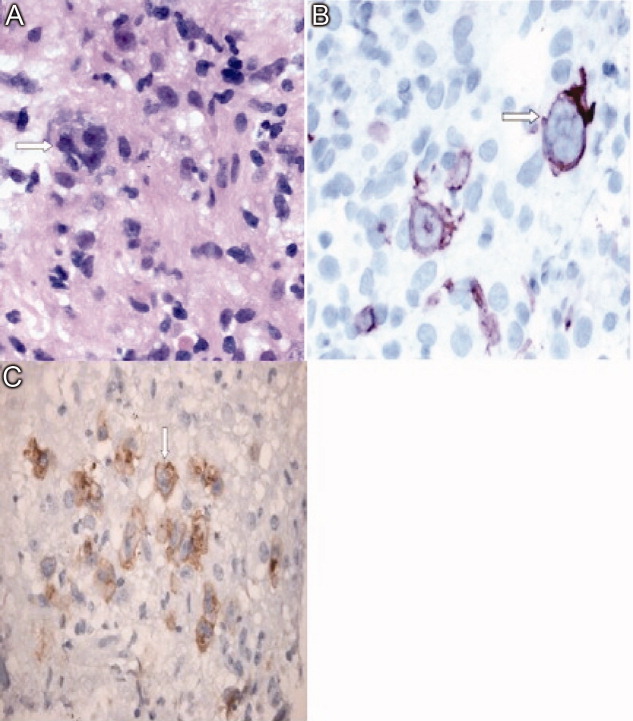

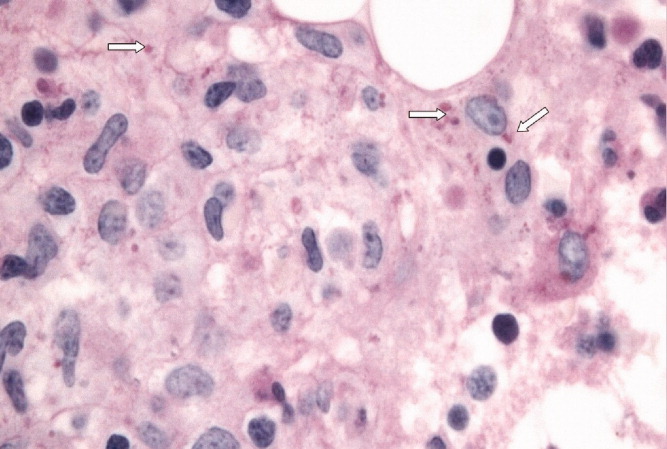

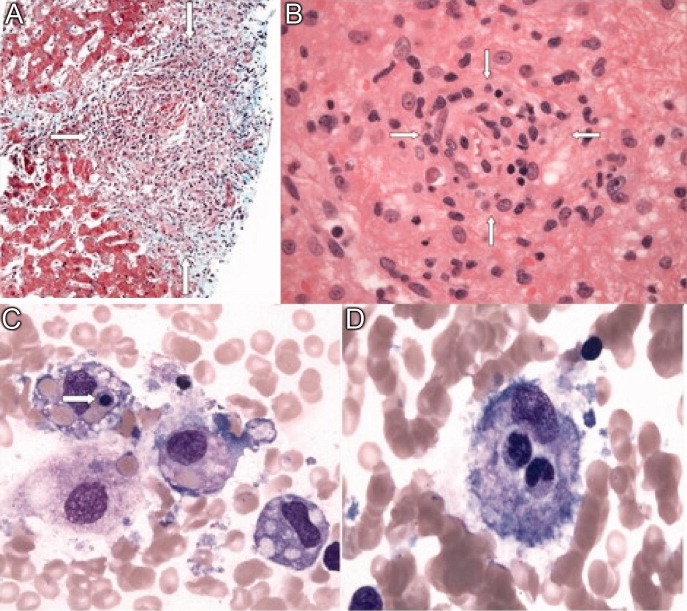

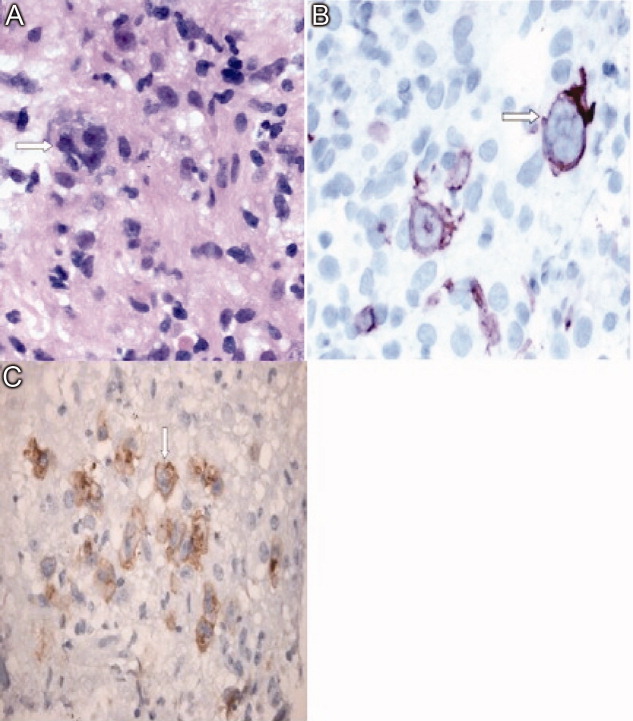

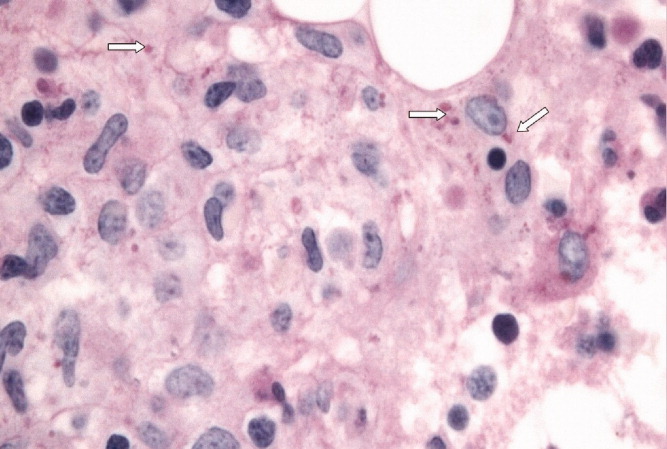

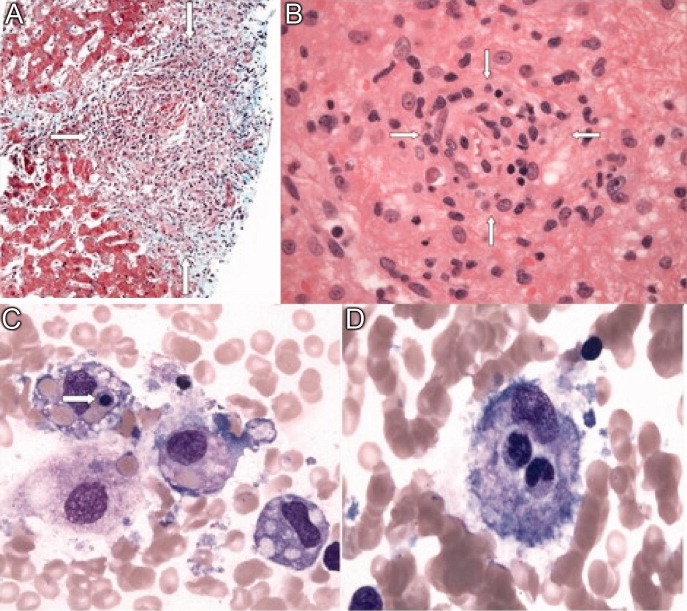

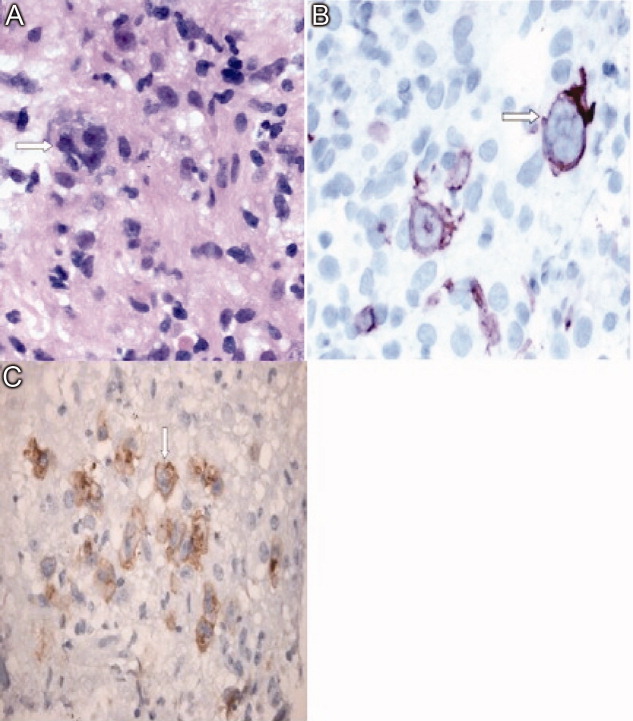

A pathologist performed a fat pad biopsy that demonstrated scant congophilic and birefringent material associated with blood vessels, suggestive of amyloid (Fig. 1). Colonoscopy demonstrated normal mucosa, and a rectal biopsy revealed congophilic material within the blood vessels consistent with amyloid (Fig. 2). No monoclonal band was present on serum protein electrophoresis. Urine protein electrophoresis identified a homogenous band in the gamma region, and urine kappa and lambda free light chains were increased: kappa was 10.7 mg/dL (normal range, 2), and lambda was 4.25 mg/dL (normal range, 2).

After extensive discussion among the patient, his wife, and a palliative care physician, the patient declined chemotherapy and elected to go home. Two days after discharge (7 weeks after his initial admission for diarrhea) he died in his sleep at home. Permission for a postmortem examination was not granted.

Discussion

Amyloidosis refers to abnormal extracellular deposition of fibril. There are many types of amyloidosis including primary amyloidosis (AL amyloidosis), secondary amyloidosis (AA amyloidosis), and hereditary causes. Systemic AL amyloidosis is a rare plasma cell disorder characterized by misfolding of insoluble extracellular fibrillar proteins derived from immunoglobulin light chains. These insoluble proteins typically deposit in the kidney, heart, and nervous system.1 Although the mechanism of organ dysfunction is debated, deposition of these proteins may disrupt the tissue architecture by interacting with local receptors and causing apoptosis.1

Table 1 indicates the most common findings in patients with AL amyloidosis.2 While our patient ultimately developed many common findings of AL amyloidosis, several features were atypical, including the marked hyperbilirubinemia, profound diarrhea, and bilateral facial diplegia.

| Organ Involvement | Incidence of Organ Involvement (%) | Symptoms | Signs | Laboratory/Test Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| General | Malaise, weight loss | |||

| Renal | 33 | Fatigue | Peripheral edema | Proteinuria with or without renal insufficiency, pleural effusion, hypercholesterolemia |

| Cardiac | 20 | Palpitations, dyspnea | Elevated jugular venous pressure, S3, peripheral edema, hepatomegaly | Low‐voltage or atrial fibrillation on electrocardiogram; echocardiogram: thickened ventricles, dilated atria |

| Neurological | 20 | Paresthesias, numbness, weakness, autonomic insufficiency | Carpal tunnel syndrome, postural hypotension | |

| Gastrointestinal and Hepatic | 16 | Diarrhea, nausea, weight loss | Macroglossia, hepatomegaly | Elevated alkaline phosphatase |

| Hematology | Rare | Bleeding | Periorbital purpura (raccoon eyes) | Prolonged prothrombin time, Factor X deficiency |

Up to 70% of patients with amyloidosis will have detectable liver deposits, typically involving portal vessels, portal stroma, central vein, and sinusoidal parenchyma.3 Clinically overt hepatic dysfunction from amyloid is less frequent,4 and the most characteristic findings are hepatomegaly with a markedly elevated serum alkaline phosphatase concentration; jaundice is rare. Palpable hepatic enlargement without abnormal liver enzymes should be interpreted with caution. The finding of a palpable liver edge correlates poorly with frank hepatomegaly, with a positive likelihood ratio of just 1.7.5 In the patient under discussion, suspected hepatomegaly was not confirmed on a subsequent CT scan. Nonetheless, the elevated alkaline phosphatase represented an important clue to potential infiltrative liver disease. In a series of amyloidosis patients from the Mayo Clinic, 81% had hepatomegaly on physical exam, and the mean alkaline phosphatase level was 1,029 U/L (normal, 250 U/L), while the mean serum bilirubin and AST levels were only modestly elevated, at 3.2 mg/dL and 72 U/L respectively. The prothrombin time was prolonged in 35% of patients.

Upper gastrointestinal tract involvement by AL amyloid may be found in up to a third of cases at autopsy, but clinically significant gastrointestinal features are seen in fewer than 5% of patients.6 Predominant intestinal manifestations are unintentional weight loss (average 7 kg) and diarrhea, nonspecific features that result in delayed diagnosis for a median of 7 months after symptom onset.7 Diarrhea in AL amyloid may stem from several mechanisms: small intestine mucosal infiltration, steatorrhea from pancreatic insufficiency, autonomic neuropathy leading to pseudo‐obstruction and bacterial overgrowth, bile acid malabsorption, or rapid transit time. Diarrhea in AL amyloid is often resistant to treatment and may be the primary cause of death.7

Systemic amyloidosis commonly produces peripheral neuropathies. Involvement of small unmyelinated fibers causes paresthesias and progressive sensory loss in a pattern that is usually distal, symmetric, and progressive.6, 9 Our patient presented with bilateral sensory paresthesias of the chin, suggesting the numb chin syndrome (NCS). NCS is characterized by facial numbness along the distribution of the mental branch of the trigeminal nerve. While dental disorders and infiltration from malignant tumors (mostly lung and breast cancer) account for most cases, amyloidosis and other infiltrative disorders are known to cause NCS as well.10, 11 Our patient's sensory paresthesias may have represented amyloid infiltration of peripheral nerves.

With the exception of carpal tunnel syndrome, motor or cranial neuropathy is uncommon in amyloid, and when present usually heralds advanced disease.12 Descriptions of bilateral facial weakness, also known as facial diplegia, from amyloidosis are limited to case reports.1315 Other causes of this rare finding include sarcoidosis, Guillain‐Barr syndrome, and Lyme disease.16

The diagnosis of primary amyloidosis requires histologic evidence of amyloid from a tissue biopsy specimen (demonstrating positive Congo red staining and pathognomonic green birefringence under cross‐polarized light microscopy), and the presence of a clonal plasma cell disorder. While biopsy of an affected organ is diagnostic, more easily obtained samples such as fat pad biopsy and rectal biopsy yield positive results in up to 80% of cases.2 Serum and urine protein electrophoresis with immunofixation identify an underlying plasma cell disorder in 90% of cases of primary amyloidosis. When these tests are inconclusive, serum or urine free light chain assays or bone marrow aspirate and biopsy are useful aids to detect underlying plasma cell dyscrasia.2 AL amyloidosis is a progressive disease with median survival of about 12 years.8 Poorer prognosis is associated with substantial echocardiographic findings, autonomic neuropathy, and liver involvement.2 Hyperbilirubinemia is associated with a poor prognosis, with a median survival of 8.5 months.4 Proteinuria or peripheral neuropathy portends a less ominous course.6

Treatment goals include reducing production and deposition of fibril proteins and contending with organ dysfunction (eg, congestive heart failure [CHF] management). Selected patients with AL amyloidosis may be candidates for high‐dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation.

It would not be reasonable for clinicians to suspect amyloidosis in cases of diarrhea until two conditions are met: 1) the absence of evidence for the typical etiologies of diarrhea; and 2) the evolving picture of an infiltrative disorder. The latter was heralded by the elevated alkaline phosphatase, and was supported by the subsequent multiorgan involvement. Conceptualizing the disease as infiltrative still required a diligent exclusion of infection and invasive tumor cells, which invade disparate organs far more commonly than amyloidosis. Their absence and the organ pattern that is typical of AL amyloidosis (heart, kidney, and peripheral nerve involvement) allowed the discussant to reason by analogy that amyloidosis was also responsible for the most symptomatic phenomena, namely, the diarrhea and facial diplegia (and numb chin syndrome).

Key Teaching Points

-

Hospitalists should consider systemic amyloidosis in cases of unexplained diarrhea when other clinical features of AL amyloidosis are present, including nephrotic syndrome with or without renal insufficiency, cardiomyopathy, peripheral neuropathy, and hepatomegaly.

-

Hepatic amyloidosis should be suspected when weight loss, hepatomegaly, and elevated alkaline phosphatase are present. Although jaundice is rare in amyloidosis, liver involvement and hyperbilirubinemia portend a poorer prognosis.

-

Numb chin syndrome and bilateral facial diplegia are rare manifestations of AL amyloid deposition in peripheral nerves.

- ,.Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis.N Engl J Med.2003;349(6):583–596.

- Guidelines Working Group of UK Myeloma Forum; British Committee for Standards in Haematology, British Society for Haematology.Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of AL amyloidosis.Br J Haematol.2004;125:681–700.

- ,.Hepatic amyloidosis: morphologic differences between systemic AL and AA types.Hum Pathol.1991;22(9):904–907.

- ,,, et al.Primary (AL) hepatic amyloidosis clinical features and natural history in 98 patients.Medicine.2003;82(5):291–298.

- .Evidence‐Based Physical Diagnosis.Philadelphia, PA:WB Saunders;2001:595–599.

- ,,, et al.Definition of organ involvement and treatment response in immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL): a consensus opinion from the 10th International Symposium on Amyloid and Amyloidosis.Am J Hematol.2005;79:319–328.

- .Primary (AL) amyloidosis with gastrointestinal involvement.Scand J Gastroenterol.2009;44(6):708–711.

- ,.Gastrointestinal manifestations of amyloid.Am J Gastroenterol.2008;103:776–787.

- ,.Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases.Semin Hematol.1995;32:45–59.

- ,,,,.Chin numbness: a symptom that should not be underestimated: a review of 12 cases.Am J Med Sci.2009;337:407–410.

- .Numb chin syndrome: a possible clue to serious illness.Hosp Physician.2000;54–56.

- .Autonomic peripheral neuropathy.Neurol Clin.2007;25:277–301.

- ,.Facial diplegia due to amyloidosis.South Med J.1986;79(11):1458–1459.

- ,,,,.Familial amyloidosis with cranial neuropathy and corneal lattice dystrophy.Neurology.1986;36:432–435.

- ,,.Crainal neuropathy associated with primary amyloidosis.Ann Neurol.1991;29:451–454.

- .Bilateral seventh nerve palsy: analysis of 43 cases and review of the literature.Neurology.1994;44:1198–202.

A 59 year‐old man was sent from urgent care clinic to the emergency room for further evaluation because of 1 month of diarrhea and an acute elevation in his serum creatinine.

Whereas acute diarrhea is commonly due to a self‐limited and often unspecified infection, diarrhea that extends beyond 23 weeks (chronic) warrants consideration of malabsorptive, inflammatory, infectious, and malignant processes. The acute renal failure likely is a consequence of dehydration, but the possibility of simultaneous gastrointestinal and renal involvement from a systemic process (eg, vasculitis) must be considered.

The patient's diarrhea began 1 month prior, shortly after having a milkshake at a fast food restaurant. The diarrhea was initially watery, occurred 8‐10 times per day, occasionally awakened him at night, and was associated with nausea. There was no mucus, blood, or steatorrhea until 1 day prior to presentation, when he developed epigastric pain and bloody stools. He denied any recent travel outside of Northern California and had no sick contacts. He had lost 10 pounds over the preceding month. He denied fevers, chills, vomiting, or jaundice, and had not taken antibiotics recently.

In the setting of chronic diarrhea, unintentional weight loss is an alarm feature but does not narrow the diagnostic possibilities significantly. The appearance of blood and pain on a single day after 1 month of symptoms renders their diagnostic value uncertain. For instance, rectal or hemorrhoidal bleeding would be a common occurrence after 1 month of frequent defecation. Sustained bloody stools might be seen in any form of erosive luminal disease, such as infection, inflammatory bowel disease, or neoplasm. Pain is compatible with inflammatory bowel disease, obstructing neoplasms, infections, or ischemia (eg, vasculitis). There are no fever or chills to support infection, and common gram‐negative enteric pathogens (such as Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Yersinia) usually do not produce symptoms for such an extended period. He has not taken antibiotics, which would predispose him to infection with Clostridum difficile, and he has no obvious exposure to parasites such as Entamoeba.

The patient had diabetes mellitus with microalbuminuria, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic low back pain, and gastritis, and had undergone a Billroth II procedure for a perforated gastric ulcer in the remote past. His medications included omeprazole, insulin glargine, simvastatin, lisinopril, amlodipine, and albuterol and beclomethasone metered‐dose inhalers. He had been married for 31 years, lived at home with his wife, was a former rigger in a shipyard and was on disability for chronic low back pain. He denied alcohol or intravenous drug use but had quit tobacco 5 years prior after more than 40 pack‐years of smoking. He had three healthy adult children and there was no family history of cancer, liver disease, or inflammatory bowel disease. There was no history of sexually transmitted diseases or unprotected sexual intercourse.

Bacterial overgrowth in the blind loop following a Billroth II operation can lead to malabsorption, but the diarrhea would not begin so abruptly this long after surgery. Medications are common causes of diarrhea. Proton‐pump inhibitors, by reducing gastric acidity, confer an increased risk of bacterial enteritis; they also are a risk factor for C difficile. Lisinopril may cause bowel angioedema months or years after initiation. Occult laxative use is a well‐recognized cause of chronic diarrhea and should also be considered. The most relevant element of his social history is the prolonged smoking and the attendant risk of cancer, although diarrhea is a rare paraneoplastic phenomenon.

On exam, temperature was 36.6C, blood pressure 125/78, pulse 88, respiratory rate 16 per minute, and oxygen saturation 97% while breathing room air. There was temporal wasting and mild scleral icterus, but no jaundice. Lungs were clear to auscultation and heart was regular in rate and rhythm without murmurs or gallops. There was no jugular venous distention. A large abdominal midline scar was present, bowel sounds were normoactive, and the abdomen was soft, nontender, and nondistended. The hard was regular in rate and rhythm the liver edge was 6 cm below costal margin; there was no splenomegaly. The patient was alert and oriented, with a normal neurologic exam.

The liver generally enlarges because of acute inflammation, congestion, or infiltration. Infiltration can be due to tumors, infections, hemochromatosis, amyloidosis, or sarcoidosis. A normal cardiac exam argues against hepatic congestion from right‐sided heart failure or pericardial disease.

The key elements of the case are diarrhea and hepatomegaly. Inflammatory bowel disease can be accompanied by sclerosing cholangitis, but this should not enlarge the liver. Mycobacterial infections and syphilis can infiltrate the liver and intestinal mucosa, causing diarrhea, but he lacks typical risk factors.

Malignancy is an increasing concern. Colon cancer commonly metastasizes to the liver and can occasionally be intensely secretory. Pancreatic cancer could account for these symptoms, especially if pancreatic exocrine insufficiency caused malabsorption. Various rare neuroendocrine tumors that arise in the pancreas can cause secretory diarrheas and liver metastases, such as carcinoid, VIPoma, and Zollinger‐Ellison syndrome.

Laboratory results revealed a serum sodium of 143 mmol/L, potassium 4.7 mmol/L, chloride 110 mmol/L, bicarbonate 25 mmol/L, urea nitrogen 24 mg/dL, and creatinine 2.5 mg/dL (baseline had been 1.2 mg/dL 2 months previously). Serum glucose was 108 mg/dL and calcium was 8.8 mg/dL. The total white blood cell count was 9300 per mm3 with a normal differential, hemoglobin was 14.4 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume was 87 fL, and the platelet count was normal. Total bilirubin was 3.7 mg/dL, and direct bilirubin was 3.1 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 122 U/L (normal range, 831), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 79 U/L (normal range, 731), alkaline phosphatase 1591 U/L (normal range, 39117), and gamma‐glutamyltransferase (GGT) 980 U/L (normal range, 57). Serum albumin was 2.5 mg/dL, prothrombin time was 16.4 seconds, and international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.6.

Urinalysis was normal except for trace hemoglobin, small bilirubin, and 70 mg/dL of protein; specific gravity was 1.007. Urine microscopy demonstrated no cells or casts. The ratio of protein to creatinine on a spot urine sample was less than 1. Chest x‐ray was normal. The electrocardiogram demonstrated sinus rhythm with an old right bundle branch block and normal QRS voltages.

The disproportionate elevation in alkaline phosphatase points to an infiltrative hepatopathy from a cancer originating in the gastrointestinal tract or infection. Other infiltrative processes such as sarcoidosis or amyloidosis usually have evidence of disease elsewhere before hepatic disease becomes apparent.

Mild proteinuria may be explained by diabetes. The specific gravity of 1.007 is atypical for dehydration and could suggest ischemic tubular injury. Although intrinsic renal diseases must continue to be entertained, hypovolemia (compounded by angiotensin‐converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitor use) is the leading explanation in light of the nondiagnostic renal studies. The preserved hemoglobin may simply indicate dehydration, but otherwise is somewhat reassuring in the context of bloody diarrhea.

The patient was admitted to the hospital. Three stool samples returned negative for C difficile toxin. No white cells were detected in the stool, and no ova or parasites were detected. Stool culture was negative for routine bacterial pathogens and for E coli O157. Tests for HIV and antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) and serologies for hepatitis A, B, and C were negative. Abdominal ultrasound demonstrated no intra‐ or extrahepatic bile duct dilatation; no hepatic masses were seen. Kidneys were normal in size and appearance without hydronephrosis. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen without intravenous contrast revealed normal‐appearing liver (with a 12‐cm span), spleen, biliary ducts, and pancreas, and there was no intra‐abdominal adenopathy.

The stool studies point away from infectious colitis. Infiltrative processes of the liver, including metastases, lymphoma, tuberculosis, syphilis, amyloidosis, and sarcoidosis, can be microscopic and therefore evade detection by ultrasound and CT scan. In conditions such as these, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopanccreatography/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (ERCP/MRCP) or liver biopsy may be required. The CT is limited without contrast but does not suggest extrahepatic disease in the abdomen.

MRCP was performed, but was a technically suboptimal study due to the presence of ascites. The serum creatinine improved to 1.4 mg/dL over the next 4 days, and the patient's diarrhea decreased to two bowel movements daily with the use of loperamide. The patient was discharged home with outpatient gastroenterology follow‐up planned to discuss further evaluation of the abnormal liver enzymes.

Prior to being seen in the Gastroenterology Clinic, the patient's nonbloody diarrhea worsened. He felt weaker and continued to lose weight. He also noted new onset of bilateral lower face numbness and burning, which was followed by swelling of his lower lip 12 hours later. He returned to the hospital.

On examination, he was afebrile. His lower lip was markedly swollen and was drooping from his face. He could not move the lip to close his mouth. The upper lip and tongue were normal size and moved without restriction. Facial sensation was intact, but there was weakness when he attempted to wrinkle both of his brows and close his eyelids. The rest of his physical examination was unchanged.

The serum creatinine had risen to 3.6 mg/dL, and the complete blood count remained normal. Serum total bilirubin was 4.6 mg/dL, AST 87 U/L, ALT 76 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase 1910 U/L. The 24‐hour urine protein measurement was 86 mg.

Lip swelling suggests angioedema. ACE inhibitors are frequent offenders, and it would be important to know whether his lisinopril was restarted at discharge. ACE‐inhibitor angioedema can also affect the intestine, causing abdominal pain and diarrhea, but does not cause a systemic wasting illness or infiltrative hepatopathy. The difficulty moving the lip may reflect the physical effects of swelling, but generalized facial weakness supports a cranial neuropathy. Basilar meningitis may produce multiple cranial neuropathies, the etiologies of which are quite similar to the previously mentioned causes of infiltrative liver disease: sarcoidosis, syphilis, tuberculosis, or lymphoma.

The patient had not resumed lisinopril since his prior hospitalization. The lower lip swelling and paralysis persisted, and new sensory paresthesias developed over the right side of his chin. A consulting neurologist found normal language and speech and moderate dysarthria. Cranial nerve exam was normal except bilateral lower motor neuron facial nerve palsy was noted with bilateral facial droop, reduced strength of eyelid closure, and diminished forehead movement bilaterally; facial sensation was normal. Extremity motor exam revealed proximal iliopsoas muscle weakness bilaterally rated as 4/5 and was otherwise normal. Sensation to pinprick was diminished in a stocking/glove distribution. Deep‐tendon reflexes were normal and plantar response was down‐going bilaterally. Coordination was intact, Romberg was negative, and gait was slowed due to weakness.

Over the next several days, the patient continued to have diarrhea and facial symptoms. The serum total bilirubin increased to 14 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase rose above 2,000 U/L, and serum creatinine increased to 5.5 mg/dL. Noncontrast CT scan of the head was normal.

Along with a mild peripheral sensory neuropathy, the exam indicates bilateral palsies of the facial nerve. Lyme disease is a frequent etiology, but this patient is not from an endemic area. I am most suspicious of bilateral infiltration of cranial nerve VII. I am thinking analogically to the numb chin syndrome, wherein lymphoma or breast cancer infiltration along the mental branch of V3 causes sensory loss, and perhaps these disorders can produce infiltrative facial neuropathy. At this point I am most concerned about lymphomatous meningitis with cranial nerve involvement. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis (including cytology) would be informative.

Lumbar puncture demonstrated clear CSF with one white blood cell per mm3 and no red blood cells. Glucose was normal, and protein was 95.5 (normal range, 15‐45 mg/dL). Gram stain and culture for bacteria were negative, as were polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for herpes simplex virus, mycobacterial and fungal stains and cultures, and cytology. Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated severe concentric left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, normal LV systolic function, and impaired LV relaxation. CT scan of the chest identified no adenopathy or other abnormality.

The CSF analysis does not support basilar meningitis, although the cytoalbuminologic dissociation makes me wonder whether there is some intrathecal antibody production or an autoimmune process we have yet to uncover. The absence of lymphadenopathy anywhere in the body and the negative CSF cytology now point away from lymphoma. As the case for lymphoma or an infection diminishes, systemic amyloidosis rises to the top of possibilities in this afebrile man who is losing weight, has infiltrative liver and nerve abnormalities, renal failure, cardiac enlargement, and suspected gastrointestinal luminal abnormality. Although the echocardiographic findings are most likely explained by hypertension, they are compatible with amyloid infiltration. A tissue specimen is needed, and either colonoscopy or liver biopsy should be suitable.

A pathologist performed a fat pad biopsy that demonstrated scant congophilic and birefringent material associated with blood vessels, suggestive of amyloid (Fig. 1). Colonoscopy demonstrated normal mucosa, and a rectal biopsy revealed congophilic material within the blood vessels consistent with amyloid (Fig. 2). No monoclonal band was present on serum protein electrophoresis. Urine protein electrophoresis identified a homogenous band in the gamma region, and urine kappa and lambda free light chains were increased: kappa was 10.7 mg/dL (normal range, 2), and lambda was 4.25 mg/dL (normal range, 2).

After extensive discussion among the patient, his wife, and a palliative care physician, the patient declined chemotherapy and elected to go home. Two days after discharge (7 weeks after his initial admission for diarrhea) he died in his sleep at home. Permission for a postmortem examination was not granted.

Discussion

Amyloidosis refers to abnormal extracellular deposition of fibril. There are many types of amyloidosis including primary amyloidosis (AL amyloidosis), secondary amyloidosis (AA amyloidosis), and hereditary causes. Systemic AL amyloidosis is a rare plasma cell disorder characterized by misfolding of insoluble extracellular fibrillar proteins derived from immunoglobulin light chains. These insoluble proteins typically deposit in the kidney, heart, and nervous system.1 Although the mechanism of organ dysfunction is debated, deposition of these proteins may disrupt the tissue architecture by interacting with local receptors and causing apoptosis.1

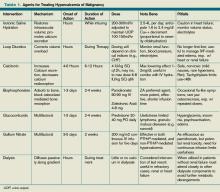

Table 1 indicates the most common findings in patients with AL amyloidosis.2 While our patient ultimately developed many common findings of AL amyloidosis, several features were atypical, including the marked hyperbilirubinemia, profound diarrhea, and bilateral facial diplegia.

| Organ Involvement | Incidence of Organ Involvement (%) | Symptoms | Signs | Laboratory/Test Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| General | Malaise, weight loss | |||

| Renal | 33 | Fatigue | Peripheral edema | Proteinuria with or without renal insufficiency, pleural effusion, hypercholesterolemia |

| Cardiac | 20 | Palpitations, dyspnea | Elevated jugular venous pressure, S3, peripheral edema, hepatomegaly | Low‐voltage or atrial fibrillation on electrocardiogram; echocardiogram: thickened ventricles, dilated atria |

| Neurological | 20 | Paresthesias, numbness, weakness, autonomic insufficiency | Carpal tunnel syndrome, postural hypotension | |

| Gastrointestinal and Hepatic | 16 | Diarrhea, nausea, weight loss | Macroglossia, hepatomegaly | Elevated alkaline phosphatase |

| Hematology | Rare | Bleeding | Periorbital purpura (raccoon eyes) | Prolonged prothrombin time, Factor X deficiency |

Up to 70% of patients with amyloidosis will have detectable liver deposits, typically involving portal vessels, portal stroma, central vein, and sinusoidal parenchyma.3 Clinically overt hepatic dysfunction from amyloid is less frequent,4 and the most characteristic findings are hepatomegaly with a markedly elevated serum alkaline phosphatase concentration; jaundice is rare. Palpable hepatic enlargement without abnormal liver enzymes should be interpreted with caution. The finding of a palpable liver edge correlates poorly with frank hepatomegaly, with a positive likelihood ratio of just 1.7.5 In the patient under discussion, suspected hepatomegaly was not confirmed on a subsequent CT scan. Nonetheless, the elevated alkaline phosphatase represented an important clue to potential infiltrative liver disease. In a series of amyloidosis patients from the Mayo Clinic, 81% had hepatomegaly on physical exam, and the mean alkaline phosphatase level was 1,029 U/L (normal, 250 U/L), while the mean serum bilirubin and AST levels were only modestly elevated, at 3.2 mg/dL and 72 U/L respectively. The prothrombin time was prolonged in 35% of patients.

Upper gastrointestinal tract involvement by AL amyloid may be found in up to a third of cases at autopsy, but clinically significant gastrointestinal features are seen in fewer than 5% of patients.6 Predominant intestinal manifestations are unintentional weight loss (average 7 kg) and diarrhea, nonspecific features that result in delayed diagnosis for a median of 7 months after symptom onset.7 Diarrhea in AL amyloid may stem from several mechanisms: small intestine mucosal infiltration, steatorrhea from pancreatic insufficiency, autonomic neuropathy leading to pseudo‐obstruction and bacterial overgrowth, bile acid malabsorption, or rapid transit time. Diarrhea in AL amyloid is often resistant to treatment and may be the primary cause of death.7

Systemic amyloidosis commonly produces peripheral neuropathies. Involvement of small unmyelinated fibers causes paresthesias and progressive sensory loss in a pattern that is usually distal, symmetric, and progressive.6, 9 Our patient presented with bilateral sensory paresthesias of the chin, suggesting the numb chin syndrome (NCS). NCS is characterized by facial numbness along the distribution of the mental branch of the trigeminal nerve. While dental disorders and infiltration from malignant tumors (mostly lung and breast cancer) account for most cases, amyloidosis and other infiltrative disorders are known to cause NCS as well.10, 11 Our patient's sensory paresthesias may have represented amyloid infiltration of peripheral nerves.

With the exception of carpal tunnel syndrome, motor or cranial neuropathy is uncommon in amyloid, and when present usually heralds advanced disease.12 Descriptions of bilateral facial weakness, also known as facial diplegia, from amyloidosis are limited to case reports.1315 Other causes of this rare finding include sarcoidosis, Guillain‐Barr syndrome, and Lyme disease.16

The diagnosis of primary amyloidosis requires histologic evidence of amyloid from a tissue biopsy specimen (demonstrating positive Congo red staining and pathognomonic green birefringence under cross‐polarized light microscopy), and the presence of a clonal plasma cell disorder. While biopsy of an affected organ is diagnostic, more easily obtained samples such as fat pad biopsy and rectal biopsy yield positive results in up to 80% of cases.2 Serum and urine protein electrophoresis with immunofixation identify an underlying plasma cell disorder in 90% of cases of primary amyloidosis. When these tests are inconclusive, serum or urine free light chain assays or bone marrow aspirate and biopsy are useful aids to detect underlying plasma cell dyscrasia.2 AL amyloidosis is a progressive disease with median survival of about 12 years.8 Poorer prognosis is associated with substantial echocardiographic findings, autonomic neuropathy, and liver involvement.2 Hyperbilirubinemia is associated with a poor prognosis, with a median survival of 8.5 months.4 Proteinuria or peripheral neuropathy portends a less ominous course.6

Treatment goals include reducing production and deposition of fibril proteins and contending with organ dysfunction (eg, congestive heart failure [CHF] management). Selected patients with AL amyloidosis may be candidates for high‐dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation.

It would not be reasonable for clinicians to suspect amyloidosis in cases of diarrhea until two conditions are met: 1) the absence of evidence for the typical etiologies of diarrhea; and 2) the evolving picture of an infiltrative disorder. The latter was heralded by the elevated alkaline phosphatase, and was supported by the subsequent multiorgan involvement. Conceptualizing the disease as infiltrative still required a diligent exclusion of infection and invasive tumor cells, which invade disparate organs far more commonly than amyloidosis. Their absence and the organ pattern that is typical of AL amyloidosis (heart, kidney, and peripheral nerve involvement) allowed the discussant to reason by analogy that amyloidosis was also responsible for the most symptomatic phenomena, namely, the diarrhea and facial diplegia (and numb chin syndrome).

Key Teaching Points

-

Hospitalists should consider systemic amyloidosis in cases of unexplained diarrhea when other clinical features of AL amyloidosis are present, including nephrotic syndrome with or without renal insufficiency, cardiomyopathy, peripheral neuropathy, and hepatomegaly.

-

Hepatic amyloidosis should be suspected when weight loss, hepatomegaly, and elevated alkaline phosphatase are present. Although jaundice is rare in amyloidosis, liver involvement and hyperbilirubinemia portend a poorer prognosis.

-

Numb chin syndrome and bilateral facial diplegia are rare manifestations of AL amyloid deposition in peripheral nerves.

A 59 year‐old man was sent from urgent care clinic to the emergency room for further evaluation because of 1 month of diarrhea and an acute elevation in his serum creatinine.

Whereas acute diarrhea is commonly due to a self‐limited and often unspecified infection, diarrhea that extends beyond 23 weeks (chronic) warrants consideration of malabsorptive, inflammatory, infectious, and malignant processes. The acute renal failure likely is a consequence of dehydration, but the possibility of simultaneous gastrointestinal and renal involvement from a systemic process (eg, vasculitis) must be considered.

The patient's diarrhea began 1 month prior, shortly after having a milkshake at a fast food restaurant. The diarrhea was initially watery, occurred 8‐10 times per day, occasionally awakened him at night, and was associated with nausea. There was no mucus, blood, or steatorrhea until 1 day prior to presentation, when he developed epigastric pain and bloody stools. He denied any recent travel outside of Northern California and had no sick contacts. He had lost 10 pounds over the preceding month. He denied fevers, chills, vomiting, or jaundice, and had not taken antibiotics recently.

In the setting of chronic diarrhea, unintentional weight loss is an alarm feature but does not narrow the diagnostic possibilities significantly. The appearance of blood and pain on a single day after 1 month of symptoms renders their diagnostic value uncertain. For instance, rectal or hemorrhoidal bleeding would be a common occurrence after 1 month of frequent defecation. Sustained bloody stools might be seen in any form of erosive luminal disease, such as infection, inflammatory bowel disease, or neoplasm. Pain is compatible with inflammatory bowel disease, obstructing neoplasms, infections, or ischemia (eg, vasculitis). There are no fever or chills to support infection, and common gram‐negative enteric pathogens (such as Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Yersinia) usually do not produce symptoms for such an extended period. He has not taken antibiotics, which would predispose him to infection with Clostridum difficile, and he has no obvious exposure to parasites such as Entamoeba.

The patient had diabetes mellitus with microalbuminuria, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic low back pain, and gastritis, and had undergone a Billroth II procedure for a perforated gastric ulcer in the remote past. His medications included omeprazole, insulin glargine, simvastatin, lisinopril, amlodipine, and albuterol and beclomethasone metered‐dose inhalers. He had been married for 31 years, lived at home with his wife, was a former rigger in a shipyard and was on disability for chronic low back pain. He denied alcohol or intravenous drug use but had quit tobacco 5 years prior after more than 40 pack‐years of smoking. He had three healthy adult children and there was no family history of cancer, liver disease, or inflammatory bowel disease. There was no history of sexually transmitted diseases or unprotected sexual intercourse.

Bacterial overgrowth in the blind loop following a Billroth II operation can lead to malabsorption, but the diarrhea would not begin so abruptly this long after surgery. Medications are common causes of diarrhea. Proton‐pump inhibitors, by reducing gastric acidity, confer an increased risk of bacterial enteritis; they also are a risk factor for C difficile. Lisinopril may cause bowel angioedema months or years after initiation. Occult laxative use is a well‐recognized cause of chronic diarrhea and should also be considered. The most relevant element of his social history is the prolonged smoking and the attendant risk of cancer, although diarrhea is a rare paraneoplastic phenomenon.

On exam, temperature was 36.6C, blood pressure 125/78, pulse 88, respiratory rate 16 per minute, and oxygen saturation 97% while breathing room air. There was temporal wasting and mild scleral icterus, but no jaundice. Lungs were clear to auscultation and heart was regular in rate and rhythm without murmurs or gallops. There was no jugular venous distention. A large abdominal midline scar was present, bowel sounds were normoactive, and the abdomen was soft, nontender, and nondistended. The hard was regular in rate and rhythm the liver edge was 6 cm below costal margin; there was no splenomegaly. The patient was alert and oriented, with a normal neurologic exam.

The liver generally enlarges because of acute inflammation, congestion, or infiltration. Infiltration can be due to tumors, infections, hemochromatosis, amyloidosis, or sarcoidosis. A normal cardiac exam argues against hepatic congestion from right‐sided heart failure or pericardial disease.

The key elements of the case are diarrhea and hepatomegaly. Inflammatory bowel disease can be accompanied by sclerosing cholangitis, but this should not enlarge the liver. Mycobacterial infections and syphilis can infiltrate the liver and intestinal mucosa, causing diarrhea, but he lacks typical risk factors.

Malignancy is an increasing concern. Colon cancer commonly metastasizes to the liver and can occasionally be intensely secretory. Pancreatic cancer could account for these symptoms, especially if pancreatic exocrine insufficiency caused malabsorption. Various rare neuroendocrine tumors that arise in the pancreas can cause secretory diarrheas and liver metastases, such as carcinoid, VIPoma, and Zollinger‐Ellison syndrome.

Laboratory results revealed a serum sodium of 143 mmol/L, potassium 4.7 mmol/L, chloride 110 mmol/L, bicarbonate 25 mmol/L, urea nitrogen 24 mg/dL, and creatinine 2.5 mg/dL (baseline had been 1.2 mg/dL 2 months previously). Serum glucose was 108 mg/dL and calcium was 8.8 mg/dL. The total white blood cell count was 9300 per mm3 with a normal differential, hemoglobin was 14.4 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume was 87 fL, and the platelet count was normal. Total bilirubin was 3.7 mg/dL, and direct bilirubin was 3.1 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 122 U/L (normal range, 831), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 79 U/L (normal range, 731), alkaline phosphatase 1591 U/L (normal range, 39117), and gamma‐glutamyltransferase (GGT) 980 U/L (normal range, 57). Serum albumin was 2.5 mg/dL, prothrombin time was 16.4 seconds, and international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.6.

Urinalysis was normal except for trace hemoglobin, small bilirubin, and 70 mg/dL of protein; specific gravity was 1.007. Urine microscopy demonstrated no cells or casts. The ratio of protein to creatinine on a spot urine sample was less than 1. Chest x‐ray was normal. The electrocardiogram demonstrated sinus rhythm with an old right bundle branch block and normal QRS voltages.

The disproportionate elevation in alkaline phosphatase points to an infiltrative hepatopathy from a cancer originating in the gastrointestinal tract or infection. Other infiltrative processes such as sarcoidosis or amyloidosis usually have evidence of disease elsewhere before hepatic disease becomes apparent.

Mild proteinuria may be explained by diabetes. The specific gravity of 1.007 is atypical for dehydration and could suggest ischemic tubular injury. Although intrinsic renal diseases must continue to be entertained, hypovolemia (compounded by angiotensin‐converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitor use) is the leading explanation in light of the nondiagnostic renal studies. The preserved hemoglobin may simply indicate dehydration, but otherwise is somewhat reassuring in the context of bloody diarrhea.

The patient was admitted to the hospital. Three stool samples returned negative for C difficile toxin. No white cells were detected in the stool, and no ova or parasites were detected. Stool culture was negative for routine bacterial pathogens and for E coli O157. Tests for HIV and antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) and serologies for hepatitis A, B, and C were negative. Abdominal ultrasound demonstrated no intra‐ or extrahepatic bile duct dilatation; no hepatic masses were seen. Kidneys were normal in size and appearance without hydronephrosis. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen without intravenous contrast revealed normal‐appearing liver (with a 12‐cm span), spleen, biliary ducts, and pancreas, and there was no intra‐abdominal adenopathy.

The stool studies point away from infectious colitis. Infiltrative processes of the liver, including metastases, lymphoma, tuberculosis, syphilis, amyloidosis, and sarcoidosis, can be microscopic and therefore evade detection by ultrasound and CT scan. In conditions such as these, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopanccreatography/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (ERCP/MRCP) or liver biopsy may be required. The CT is limited without contrast but does not suggest extrahepatic disease in the abdomen.

MRCP was performed, but was a technically suboptimal study due to the presence of ascites. The serum creatinine improved to 1.4 mg/dL over the next 4 days, and the patient's diarrhea decreased to two bowel movements daily with the use of loperamide. The patient was discharged home with outpatient gastroenterology follow‐up planned to discuss further evaluation of the abnormal liver enzymes.

Prior to being seen in the Gastroenterology Clinic, the patient's nonbloody diarrhea worsened. He felt weaker and continued to lose weight. He also noted new onset of bilateral lower face numbness and burning, which was followed by swelling of his lower lip 12 hours later. He returned to the hospital.

On examination, he was afebrile. His lower lip was markedly swollen and was drooping from his face. He could not move the lip to close his mouth. The upper lip and tongue were normal size and moved without restriction. Facial sensation was intact, but there was weakness when he attempted to wrinkle both of his brows and close his eyelids. The rest of his physical examination was unchanged.

The serum creatinine had risen to 3.6 mg/dL, and the complete blood count remained normal. Serum total bilirubin was 4.6 mg/dL, AST 87 U/L, ALT 76 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase 1910 U/L. The 24‐hour urine protein measurement was 86 mg.

Lip swelling suggests angioedema. ACE inhibitors are frequent offenders, and it would be important to know whether his lisinopril was restarted at discharge. ACE‐inhibitor angioedema can also affect the intestine, causing abdominal pain and diarrhea, but does not cause a systemic wasting illness or infiltrative hepatopathy. The difficulty moving the lip may reflect the physical effects of swelling, but generalized facial weakness supports a cranial neuropathy. Basilar meningitis may produce multiple cranial neuropathies, the etiologies of which are quite similar to the previously mentioned causes of infiltrative liver disease: sarcoidosis, syphilis, tuberculosis, or lymphoma.

The patient had not resumed lisinopril since his prior hospitalization. The lower lip swelling and paralysis persisted, and new sensory paresthesias developed over the right side of his chin. A consulting neurologist found normal language and speech and moderate dysarthria. Cranial nerve exam was normal except bilateral lower motor neuron facial nerve palsy was noted with bilateral facial droop, reduced strength of eyelid closure, and diminished forehead movement bilaterally; facial sensation was normal. Extremity motor exam revealed proximal iliopsoas muscle weakness bilaterally rated as 4/5 and was otherwise normal. Sensation to pinprick was diminished in a stocking/glove distribution. Deep‐tendon reflexes were normal and plantar response was down‐going bilaterally. Coordination was intact, Romberg was negative, and gait was slowed due to weakness.

Over the next several days, the patient continued to have diarrhea and facial symptoms. The serum total bilirubin increased to 14 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase rose above 2,000 U/L, and serum creatinine increased to 5.5 mg/dL. Noncontrast CT scan of the head was normal.

Along with a mild peripheral sensory neuropathy, the exam indicates bilateral palsies of the facial nerve. Lyme disease is a frequent etiology, but this patient is not from an endemic area. I am most suspicious of bilateral infiltration of cranial nerve VII. I am thinking analogically to the numb chin syndrome, wherein lymphoma or breast cancer infiltration along the mental branch of V3 causes sensory loss, and perhaps these disorders can produce infiltrative facial neuropathy. At this point I am most concerned about lymphomatous meningitis with cranial nerve involvement. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis (including cytology) would be informative.

Lumbar puncture demonstrated clear CSF with one white blood cell per mm3 and no red blood cells. Glucose was normal, and protein was 95.5 (normal range, 15‐45 mg/dL). Gram stain and culture for bacteria were negative, as were polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for herpes simplex virus, mycobacterial and fungal stains and cultures, and cytology. Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated severe concentric left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, normal LV systolic function, and impaired LV relaxation. CT scan of the chest identified no adenopathy or other abnormality.

The CSF analysis does not support basilar meningitis, although the cytoalbuminologic dissociation makes me wonder whether there is some intrathecal antibody production or an autoimmune process we have yet to uncover. The absence of lymphadenopathy anywhere in the body and the negative CSF cytology now point away from lymphoma. As the case for lymphoma or an infection diminishes, systemic amyloidosis rises to the top of possibilities in this afebrile man who is losing weight, has infiltrative liver and nerve abnormalities, renal failure, cardiac enlargement, and suspected gastrointestinal luminal abnormality. Although the echocardiographic findings are most likely explained by hypertension, they are compatible with amyloid infiltration. A tissue specimen is needed, and either colonoscopy or liver biopsy should be suitable.

A pathologist performed a fat pad biopsy that demonstrated scant congophilic and birefringent material associated with blood vessels, suggestive of amyloid (Fig. 1). Colonoscopy demonstrated normal mucosa, and a rectal biopsy revealed congophilic material within the blood vessels consistent with amyloid (Fig. 2). No monoclonal band was present on serum protein electrophoresis. Urine protein electrophoresis identified a homogenous band in the gamma region, and urine kappa and lambda free light chains were increased: kappa was 10.7 mg/dL (normal range, 2), and lambda was 4.25 mg/dL (normal range, 2).

After extensive discussion among the patient, his wife, and a palliative care physician, the patient declined chemotherapy and elected to go home. Two days after discharge (7 weeks after his initial admission for diarrhea) he died in his sleep at home. Permission for a postmortem examination was not granted.

Discussion

Amyloidosis refers to abnormal extracellular deposition of fibril. There are many types of amyloidosis including primary amyloidosis (AL amyloidosis), secondary amyloidosis (AA amyloidosis), and hereditary causes. Systemic AL amyloidosis is a rare plasma cell disorder characterized by misfolding of insoluble extracellular fibrillar proteins derived from immunoglobulin light chains. These insoluble proteins typically deposit in the kidney, heart, and nervous system.1 Although the mechanism of organ dysfunction is debated, deposition of these proteins may disrupt the tissue architecture by interacting with local receptors and causing apoptosis.1

Table 1 indicates the most common findings in patients with AL amyloidosis.2 While our patient ultimately developed many common findings of AL amyloidosis, several features were atypical, including the marked hyperbilirubinemia, profound diarrhea, and bilateral facial diplegia.

| Organ Involvement | Incidence of Organ Involvement (%) | Symptoms | Signs | Laboratory/Test Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| General | Malaise, weight loss | |||

| Renal | 33 | Fatigue | Peripheral edema | Proteinuria with or without renal insufficiency, pleural effusion, hypercholesterolemia |

| Cardiac | 20 | Palpitations, dyspnea | Elevated jugular venous pressure, S3, peripheral edema, hepatomegaly | Low‐voltage or atrial fibrillation on electrocardiogram; echocardiogram: thickened ventricles, dilated atria |

| Neurological | 20 | Paresthesias, numbness, weakness, autonomic insufficiency | Carpal tunnel syndrome, postural hypotension | |

| Gastrointestinal and Hepatic | 16 | Diarrhea, nausea, weight loss | Macroglossia, hepatomegaly | Elevated alkaline phosphatase |

| Hematology | Rare | Bleeding | Periorbital purpura (raccoon eyes) | Prolonged prothrombin time, Factor X deficiency |

Up to 70% of patients with amyloidosis will have detectable liver deposits, typically involving portal vessels, portal stroma, central vein, and sinusoidal parenchyma.3 Clinically overt hepatic dysfunction from amyloid is less frequent,4 and the most characteristic findings are hepatomegaly with a markedly elevated serum alkaline phosphatase concentration; jaundice is rare. Palpable hepatic enlargement without abnormal liver enzymes should be interpreted with caution. The finding of a palpable liver edge correlates poorly with frank hepatomegaly, with a positive likelihood ratio of just 1.7.5 In the patient under discussion, suspected hepatomegaly was not confirmed on a subsequent CT scan. Nonetheless, the elevated alkaline phosphatase represented an important clue to potential infiltrative liver disease. In a series of amyloidosis patients from the Mayo Clinic, 81% had hepatomegaly on physical exam, and the mean alkaline phosphatase level was 1,029 U/L (normal, 250 U/L), while the mean serum bilirubin and AST levels were only modestly elevated, at 3.2 mg/dL and 72 U/L respectively. The prothrombin time was prolonged in 35% of patients.

Upper gastrointestinal tract involvement by AL amyloid may be found in up to a third of cases at autopsy, but clinically significant gastrointestinal features are seen in fewer than 5% of patients.6 Predominant intestinal manifestations are unintentional weight loss (average 7 kg) and diarrhea, nonspecific features that result in delayed diagnosis for a median of 7 months after symptom onset.7 Diarrhea in AL amyloid may stem from several mechanisms: small intestine mucosal infiltration, steatorrhea from pancreatic insufficiency, autonomic neuropathy leading to pseudo‐obstruction and bacterial overgrowth, bile acid malabsorption, or rapid transit time. Diarrhea in AL amyloid is often resistant to treatment and may be the primary cause of death.7

Systemic amyloidosis commonly produces peripheral neuropathies. Involvement of small unmyelinated fibers causes paresthesias and progressive sensory loss in a pattern that is usually distal, symmetric, and progressive.6, 9 Our patient presented with bilateral sensory paresthesias of the chin, suggesting the numb chin syndrome (NCS). NCS is characterized by facial numbness along the distribution of the mental branch of the trigeminal nerve. While dental disorders and infiltration from malignant tumors (mostly lung and breast cancer) account for most cases, amyloidosis and other infiltrative disorders are known to cause NCS as well.10, 11 Our patient's sensory paresthesias may have represented amyloid infiltration of peripheral nerves.

With the exception of carpal tunnel syndrome, motor or cranial neuropathy is uncommon in amyloid, and when present usually heralds advanced disease.12 Descriptions of bilateral facial weakness, also known as facial diplegia, from amyloidosis are limited to case reports.1315 Other causes of this rare finding include sarcoidosis, Guillain‐Barr syndrome, and Lyme disease.16

The diagnosis of primary amyloidosis requires histologic evidence of amyloid from a tissue biopsy specimen (demonstrating positive Congo red staining and pathognomonic green birefringence under cross‐polarized light microscopy), and the presence of a clonal plasma cell disorder. While biopsy of an affected organ is diagnostic, more easily obtained samples such as fat pad biopsy and rectal biopsy yield positive results in up to 80% of cases.2 Serum and urine protein electrophoresis with immunofixation identify an underlying plasma cell disorder in 90% of cases of primary amyloidosis. When these tests are inconclusive, serum or urine free light chain assays or bone marrow aspirate and biopsy are useful aids to detect underlying plasma cell dyscrasia.2 AL amyloidosis is a progressive disease with median survival of about 12 years.8 Poorer prognosis is associated with substantial echocardiographic findings, autonomic neuropathy, and liver involvement.2 Hyperbilirubinemia is associated with a poor prognosis, with a median survival of 8.5 months.4 Proteinuria or peripheral neuropathy portends a less ominous course.6

Treatment goals include reducing production and deposition of fibril proteins and contending with organ dysfunction (eg, congestive heart failure [CHF] management). Selected patients with AL amyloidosis may be candidates for high‐dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation.

It would not be reasonable for clinicians to suspect amyloidosis in cases of diarrhea until two conditions are met: 1) the absence of evidence for the typical etiologies of diarrhea; and 2) the evolving picture of an infiltrative disorder. The latter was heralded by the elevated alkaline phosphatase, and was supported by the subsequent multiorgan involvement. Conceptualizing the disease as infiltrative still required a diligent exclusion of infection and invasive tumor cells, which invade disparate organs far more commonly than amyloidosis. Their absence and the organ pattern that is typical of AL amyloidosis (heart, kidney, and peripheral nerve involvement) allowed the discussant to reason by analogy that amyloidosis was also responsible for the most symptomatic phenomena, namely, the diarrhea and facial diplegia (and numb chin syndrome).

Key Teaching Points

-

Hospitalists should consider systemic amyloidosis in cases of unexplained diarrhea when other clinical features of AL amyloidosis are present, including nephrotic syndrome with or without renal insufficiency, cardiomyopathy, peripheral neuropathy, and hepatomegaly.

-

Hepatic amyloidosis should be suspected when weight loss, hepatomegaly, and elevated alkaline phosphatase are present. Although jaundice is rare in amyloidosis, liver involvement and hyperbilirubinemia portend a poorer prognosis.

-

Numb chin syndrome and bilateral facial diplegia are rare manifestations of AL amyloid deposition in peripheral nerves.

- ,.Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis.N Engl J Med.2003;349(6):583–596.

- Guidelines Working Group of UK Myeloma Forum; British Committee for Standards in Haematology, British Society for Haematology.Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of AL amyloidosis.Br J Haematol.2004;125:681–700.

- ,.Hepatic amyloidosis: morphologic differences between systemic AL and AA types.Hum Pathol.1991;22(9):904–907.

- ,,, et al.Primary (AL) hepatic amyloidosis clinical features and natural history in 98 patients.Medicine.2003;82(5):291–298.

- .Evidence‐Based Physical Diagnosis.Philadelphia, PA:WB Saunders;2001:595–599.

- ,,, et al.Definition of organ involvement and treatment response in immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL): a consensus opinion from the 10th International Symposium on Amyloid and Amyloidosis.Am J Hematol.2005;79:319–328.

- .Primary (AL) amyloidosis with gastrointestinal involvement.Scand J Gastroenterol.2009;44(6):708–711.

- ,.Gastrointestinal manifestations of amyloid.Am J Gastroenterol.2008;103:776–787.

- ,.Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases.Semin Hematol.1995;32:45–59.

- ,,,,.Chin numbness: a symptom that should not be underestimated: a review of 12 cases.Am J Med Sci.2009;337:407–410.

- .Numb chin syndrome: a possible clue to serious illness.Hosp Physician.2000;54–56.

- .Autonomic peripheral neuropathy.Neurol Clin.2007;25:277–301.

- ,.Facial diplegia due to amyloidosis.South Med J.1986;79(11):1458–1459.

- ,,,,.Familial amyloidosis with cranial neuropathy and corneal lattice dystrophy.Neurology.1986;36:432–435.

- ,,.Crainal neuropathy associated with primary amyloidosis.Ann Neurol.1991;29:451–454.

- .Bilateral seventh nerve palsy: analysis of 43 cases and review of the literature.Neurology.1994;44:1198–202.

- ,.Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis.N Engl J Med.2003;349(6):583–596.

- Guidelines Working Group of UK Myeloma Forum; British Committee for Standards in Haematology, British Society for Haematology.Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of AL amyloidosis.Br J Haematol.2004;125:681–700.

- ,.Hepatic amyloidosis: morphologic differences between systemic AL and AA types.Hum Pathol.1991;22(9):904–907.

- ,,, et al.Primary (AL) hepatic amyloidosis clinical features and natural history in 98 patients.Medicine.2003;82(5):291–298.

- .Evidence‐Based Physical Diagnosis.Philadelphia, PA:WB Saunders;2001:595–599.

- ,,, et al.Definition of organ involvement and treatment response in immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL): a consensus opinion from the 10th International Symposium on Amyloid and Amyloidosis.Am J Hematol.2005;79:319–328.

- .Primary (AL) amyloidosis with gastrointestinal involvement.Scand J Gastroenterol.2009;44(6):708–711.

- ,.Gastrointestinal manifestations of amyloid.Am J Gastroenterol.2008;103:776–787.

- ,.Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases.Semin Hematol.1995;32:45–59.

- ,,,,.Chin numbness: a symptom that should not be underestimated: a review of 12 cases.Am J Med Sci.2009;337:407–410.

- .Numb chin syndrome: a possible clue to serious illness.Hosp Physician.2000;54–56.

- .Autonomic peripheral neuropathy.Neurol Clin.2007;25:277–301.

- ,.Facial diplegia due to amyloidosis.South Med J.1986;79(11):1458–1459.

- ,,,,.Familial amyloidosis with cranial neuropathy and corneal lattice dystrophy.Neurology.1986;36:432–435.

- ,,.Crainal neuropathy associated with primary amyloidosis.Ann Neurol.1991;29:451–454.

- .Bilateral seventh nerve palsy: analysis of 43 cases and review of the literature.Neurology.1994;44:1198–202.

What Is the Role of BNP in Diagnosis and Management of Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure?

Case

A 76-year-old woman with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), and atrial fibrillation presents with shortness of breath. She is tachypneic, her pulse is 105 beats per minute, and her blood pressure is 105/60 mm/Hg. She is obese and has an immeasurable venous pressure with decreased breath sounds in both lung bases, and irregular and distant heart sounds. What is the role of brain (or B-type) natriuretic peptide (BNP) in the diagnosis and management of this patient?

Overview

Each year, more than 1 million patients are admitted to hospitals with acutely decompensated heart failure (ADHF). Although many of these patients carry a pre-admission diagnosis of CHF, their common presenting symptoms are not specific for ADHF, which leads to delays in diagnosis and therapy initiation, and increased diagnostic costs and potentially worse outcomes. Clinical risk scores from NHANES and the Framingham heart study have limited sensitivity, missing nearly 20% of patients.1,2 Moreover, these scores are underused by clinicians who depend heavily on clinical gestalt.3

Once ADHF is diagnosed, ongoing bedside assessment of volume status is a difficult and inexact science. The physiologic goal is achievement of normal left ventricular end diastolic volume; however, surrogate measures of this status, including weight change, venous pressure, and pulmonary and cardiac auscultatory findings, have significant limitations. After discharge, patients have high and heterogeneous risks of readmission, death, and other adverse events. Identifying patients with the highest risk might allow for intensive strategies to improve outcomes.

BNP is a neurohormone released from the ventricular cells in response to increased cardiac filling pressures. Plasma measurements of BNP have been shown to reflect volume status, to predict risk at admission and discharge, and to serve as a treatment guide in a variety of clinical settings.4 This simple laboratory test increasingly has been used to diagnose and manage ADHF; its utility and limitations deserve critical review.

Review of the Data

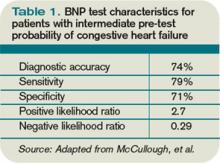

CHF diagnosis. Since introduction of the rapid BNP assay, several trials have evaluated its clinical utility in determining whether ADHF is the cause of a patient’s dyspnea. The largest of these trials, the Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study, conducted by McCullough et al, enrolled nearly 1,600 patients who presented with the primary complaint of dyspnea.5 After reviewing conventional clinical information, ED physicians were asked to determine the likelihood that ADHF was the etiology of a patient’s dyspnea. These likelihoods were classified as low (<20%), intermediate (20%-80%), or high (>80%). The admission BNP was recorded but was not available for the ED physician decisions.

The “gold standard” was the opinion of two adjudicating cardiologists who reviewed the cases retrospectively and determined whether the dyspnea resulted from ADHF. They were blinded to both the ED physician’s opinion and the BNP results. The accuracy of the ED physician’s initial assessment and the impact of the BNP results were compared with this gold standard.

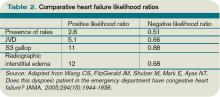

For the entire cohort, the use of BNP (with a cutoff point of 100 pg/mL) would have improved the ED physician’s assessment from 74% diagnostic accuracy to 81%, which is statistically significant. Most important, in those patients initially given an intermediate likelihood of CHF, BNP results correctly classified 75% of these patients and rarely missed ADHF cases (<10%).

Atrial fibrillation. Since the original trials that established a BNP cutoff of 100 pg/mL for determining the presence of ADHF, several adjustments have been suggested. The presence of atrial fibrillation has been shown to increase BNP values independent of cardiac filling pressures. Breidthardt et al examined patients with atrial fibrillation presenting with dyspnea.4 In their analysis, using a cutoff of 100 pg/mL remained robust in identifying patients without ADHF. However, in the 100 pg/mL-500 pg/mL range, the test was not able to discriminate between atrial fibrillation and ADHF. Values greater than 500 pg/mL proved accurate in supporting the diagnosis of ADHF.

Renal failure. Renal dysfunction also elevates BNP levels independent of filling pressures. McCullough et al re-examined data from their Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study and found that the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was inversely related to BNP levels.5 They recommend using a cutoff point of 200 pg/mL when the GFR is below 60 mg/dL. Other authors recommend not using BNP levels to diagnose ADHF when the GFR is less than 60 mg/dL due to the lack of data supporting this approach. Until clarified, clinicians should be cautious of interpreting BNP elevations in the setting of kidney disease.

Obesity. Obesity has a negative effect on BNP levels, decreasing the sensitivity of the test in these patients.6 Although no study defines how to adjust for body mass index (BMI), clinicians should be cautious about using a low BNP to rule out ADHF in a dyspneic obese patient.