User login

Should we use SSRIs to treat adolescents with depression?

Yes. Based on current evidence, fluoxetine is the most effective selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents. It is the only agent approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in children (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on meta-analysis of RCTs).

All SSRI medications increase the risk of suicidal behavior in adolescents, but do not increase the risk of completing suicide (SOR: A, based on meta-analysis of RCTs).

First, we must spot those at risk

Beth Fox, MD

East Tennessee State University, Johnson City

Family physicians are often the primary providers of healthcare for adolescents. Most health issues affecting this unique population are social and behavioral in origin. By routinely incorporating prevention and screening techniques into the adolescent visit, we can detect at-risk individuals. We need to inquire about sleep, personal interests, eating behaviors, future plans, friends and social activities, school performance, mood, and drug and alcohol use so that we can detect early symptoms of depression.

For those family physicians who like reminders, there are mnemonics and questionnaires that evaluate the social and behavioral aspects of the adolescent visit. Family physicians should also educate parents and family members about depressive signs and symptoms and the potential warning signs of suicidality.

Evidence summary

Major depressive disorder is common among adolescents and is associated with significant morbidity, including substance abuse and eating disorders. One study of survey data from 1769 adolescents found a lifetime prevalence of 15.3% for major depression. The majority of those reporting episodes of major depression in this study had recurrent symptoms and impairment in work or school.1

Fluoxetine and therapy together have the best results

A large, multicenter, randomized controlled trial evaluated the effectiveness of fluoxetine (Prozac), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), or the combination of the 2. Researchers evaluated improvement with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRSR). The CDRS-R uses adolescent and parent interviews to rate 17 symptom areas: impaired schoolwork, difficulty having fun, social withdrawal, appetite disturbance, sleep disturbance, excessive fatigue, physical complaints, irritability, excessive guilt, low self-esteem, depressed feelings, morbid ideas, suicidal ideas, excessive weeping, depressed facial affect, listless speech, and hypoactivity. Combination treatment with fluoxetine and CBT was statistically superior to placebo, CBT alone, or fluoxetine alone. In addition, fluoxetine alone was superior to CBT alone.2

A meta-analysis including both published and unpublished trials of SSRI medications found that fluoxetine was more likely than placebo to cause remission of symptoms after 7 to 8 weeks of treatment (number needed to treat [NNT]=6). Fluoxetine treatment was also associated with a reduction in symptom scores as measured with the CDRS-R (NNT=5).3

Data were conflicting for the efficacy of paroxetine (Paxil), sertraline (Zoloft), and citalopram (Celexa).3,4 No data were available for escitalopram (Lexapro).

But are SSRIs safe for adolescents?

Considerable controversy surrounds the safety of SSRIs in children due to reports of increased suicidal behavior. In 2004, the FDA conducted a meta-analysis of the suicide related adverse events from the published and unpublished trials of SSRIs including fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine (Luvox), and citalopram. A team of experts reviewed the adverse events from each trial to evaluate for suicidality including suicidal ideation, preparatory acts, self-injurious behavior, or suicide attempts. They found a risk ratio of 1.66 (95% confidence interval, 1.02–2.68) for suicidality in the treatment arms compared with placebo. There were no completed suicides in any study.5

This review led to the FDA’s October 2004 “black box” warning regarding suicidality and antidepressant medication in adolescents. However, an ecological analysis of prescription data and US Census data found an overall decline in suicide rates as the rate of prescriptions for SSRI medications increased, suggesting a beneficial correlation of SSRI medications on suicide rates.6

Recommendations from others

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) recommends psychosocial and pharmacologic intervention for depression, with psychotherapy as the preferred initial treatment for most adolescent patients.4 This organization reviewed the current published and unpublished data including the FDA analysis to formulate its conclusions regarding safety and efficacy. AACAP concluded that fluoxetine is effective for the treatment of depression in children and adolescents.

1. Kessler R, Walters E. Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depression Anxiety 1998;7:3-14.

2. March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Treatment for Adolescent Depression Study Team. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292:807-820.

3. Whittington CJ, Kendall T, Fonagy P, Cottrell D, Cotgrove A, Boddington E. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet 2004;363:1341-1345.

4. Report 10 of the Council on Scientific Affairs. Safety and Efficacy of Selective Serotonin Reup-take Inhibitors (SSRIs) in Children and Adolescents. Available at: www.aacap.org/galleries/psychiatricmedication/CSA_report_10_final.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2007

5. Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J. Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:332-339.

6. Olfson M, Shaffer D, Marcus SC, Greenberg T. Relationship between antidepressant medication treatment and suicide in adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:978-982.

Yes. Based on current evidence, fluoxetine is the most effective selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents. It is the only agent approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in children (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on meta-analysis of RCTs).

All SSRI medications increase the risk of suicidal behavior in adolescents, but do not increase the risk of completing suicide (SOR: A, based on meta-analysis of RCTs).

First, we must spot those at risk

Beth Fox, MD

East Tennessee State University, Johnson City

Family physicians are often the primary providers of healthcare for adolescents. Most health issues affecting this unique population are social and behavioral in origin. By routinely incorporating prevention and screening techniques into the adolescent visit, we can detect at-risk individuals. We need to inquire about sleep, personal interests, eating behaviors, future plans, friends and social activities, school performance, mood, and drug and alcohol use so that we can detect early symptoms of depression.

For those family physicians who like reminders, there are mnemonics and questionnaires that evaluate the social and behavioral aspects of the adolescent visit. Family physicians should also educate parents and family members about depressive signs and symptoms and the potential warning signs of suicidality.

Evidence summary

Major depressive disorder is common among adolescents and is associated with significant morbidity, including substance abuse and eating disorders. One study of survey data from 1769 adolescents found a lifetime prevalence of 15.3% for major depression. The majority of those reporting episodes of major depression in this study had recurrent symptoms and impairment in work or school.1

Fluoxetine and therapy together have the best results

A large, multicenter, randomized controlled trial evaluated the effectiveness of fluoxetine (Prozac), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), or the combination of the 2. Researchers evaluated improvement with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRSR). The CDRS-R uses adolescent and parent interviews to rate 17 symptom areas: impaired schoolwork, difficulty having fun, social withdrawal, appetite disturbance, sleep disturbance, excessive fatigue, physical complaints, irritability, excessive guilt, low self-esteem, depressed feelings, morbid ideas, suicidal ideas, excessive weeping, depressed facial affect, listless speech, and hypoactivity. Combination treatment with fluoxetine and CBT was statistically superior to placebo, CBT alone, or fluoxetine alone. In addition, fluoxetine alone was superior to CBT alone.2

A meta-analysis including both published and unpublished trials of SSRI medications found that fluoxetine was more likely than placebo to cause remission of symptoms after 7 to 8 weeks of treatment (number needed to treat [NNT]=6). Fluoxetine treatment was also associated with a reduction in symptom scores as measured with the CDRS-R (NNT=5).3

Data were conflicting for the efficacy of paroxetine (Paxil), sertraline (Zoloft), and citalopram (Celexa).3,4 No data were available for escitalopram (Lexapro).

But are SSRIs safe for adolescents?

Considerable controversy surrounds the safety of SSRIs in children due to reports of increased suicidal behavior. In 2004, the FDA conducted a meta-analysis of the suicide related adverse events from the published and unpublished trials of SSRIs including fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine (Luvox), and citalopram. A team of experts reviewed the adverse events from each trial to evaluate for suicidality including suicidal ideation, preparatory acts, self-injurious behavior, or suicide attempts. They found a risk ratio of 1.66 (95% confidence interval, 1.02–2.68) for suicidality in the treatment arms compared with placebo. There were no completed suicides in any study.5

This review led to the FDA’s October 2004 “black box” warning regarding suicidality and antidepressant medication in adolescents. However, an ecological analysis of prescription data and US Census data found an overall decline in suicide rates as the rate of prescriptions for SSRI medications increased, suggesting a beneficial correlation of SSRI medications on suicide rates.6

Recommendations from others

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) recommends psychosocial and pharmacologic intervention for depression, with psychotherapy as the preferred initial treatment for most adolescent patients.4 This organization reviewed the current published and unpublished data including the FDA analysis to formulate its conclusions regarding safety and efficacy. AACAP concluded that fluoxetine is effective for the treatment of depression in children and adolescents.

Yes. Based on current evidence, fluoxetine is the most effective selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents. It is the only agent approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in children (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on meta-analysis of RCTs).

All SSRI medications increase the risk of suicidal behavior in adolescents, but do not increase the risk of completing suicide (SOR: A, based on meta-analysis of RCTs).

First, we must spot those at risk

Beth Fox, MD

East Tennessee State University, Johnson City

Family physicians are often the primary providers of healthcare for adolescents. Most health issues affecting this unique population are social and behavioral in origin. By routinely incorporating prevention and screening techniques into the adolescent visit, we can detect at-risk individuals. We need to inquire about sleep, personal interests, eating behaviors, future plans, friends and social activities, school performance, mood, and drug and alcohol use so that we can detect early symptoms of depression.

For those family physicians who like reminders, there are mnemonics and questionnaires that evaluate the social and behavioral aspects of the adolescent visit. Family physicians should also educate parents and family members about depressive signs and symptoms and the potential warning signs of suicidality.

Evidence summary

Major depressive disorder is common among adolescents and is associated with significant morbidity, including substance abuse and eating disorders. One study of survey data from 1769 adolescents found a lifetime prevalence of 15.3% for major depression. The majority of those reporting episodes of major depression in this study had recurrent symptoms and impairment in work or school.1

Fluoxetine and therapy together have the best results

A large, multicenter, randomized controlled trial evaluated the effectiveness of fluoxetine (Prozac), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), or the combination of the 2. Researchers evaluated improvement with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRSR). The CDRS-R uses adolescent and parent interviews to rate 17 symptom areas: impaired schoolwork, difficulty having fun, social withdrawal, appetite disturbance, sleep disturbance, excessive fatigue, physical complaints, irritability, excessive guilt, low self-esteem, depressed feelings, morbid ideas, suicidal ideas, excessive weeping, depressed facial affect, listless speech, and hypoactivity. Combination treatment with fluoxetine and CBT was statistically superior to placebo, CBT alone, or fluoxetine alone. In addition, fluoxetine alone was superior to CBT alone.2

A meta-analysis including both published and unpublished trials of SSRI medications found that fluoxetine was more likely than placebo to cause remission of symptoms after 7 to 8 weeks of treatment (number needed to treat [NNT]=6). Fluoxetine treatment was also associated with a reduction in symptom scores as measured with the CDRS-R (NNT=5).3

Data were conflicting for the efficacy of paroxetine (Paxil), sertraline (Zoloft), and citalopram (Celexa).3,4 No data were available for escitalopram (Lexapro).

But are SSRIs safe for adolescents?

Considerable controversy surrounds the safety of SSRIs in children due to reports of increased suicidal behavior. In 2004, the FDA conducted a meta-analysis of the suicide related adverse events from the published and unpublished trials of SSRIs including fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine (Luvox), and citalopram. A team of experts reviewed the adverse events from each trial to evaluate for suicidality including suicidal ideation, preparatory acts, self-injurious behavior, or suicide attempts. They found a risk ratio of 1.66 (95% confidence interval, 1.02–2.68) for suicidality in the treatment arms compared with placebo. There were no completed suicides in any study.5

This review led to the FDA’s October 2004 “black box” warning regarding suicidality and antidepressant medication in adolescents. However, an ecological analysis of prescription data and US Census data found an overall decline in suicide rates as the rate of prescriptions for SSRI medications increased, suggesting a beneficial correlation of SSRI medications on suicide rates.6

Recommendations from others

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) recommends psychosocial and pharmacologic intervention for depression, with psychotherapy as the preferred initial treatment for most adolescent patients.4 This organization reviewed the current published and unpublished data including the FDA analysis to formulate its conclusions regarding safety and efficacy. AACAP concluded that fluoxetine is effective for the treatment of depression in children and adolescents.

1. Kessler R, Walters E. Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depression Anxiety 1998;7:3-14.

2. March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Treatment for Adolescent Depression Study Team. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292:807-820.

3. Whittington CJ, Kendall T, Fonagy P, Cottrell D, Cotgrove A, Boddington E. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet 2004;363:1341-1345.

4. Report 10 of the Council on Scientific Affairs. Safety and Efficacy of Selective Serotonin Reup-take Inhibitors (SSRIs) in Children and Adolescents. Available at: www.aacap.org/galleries/psychiatricmedication/CSA_report_10_final.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2007

5. Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J. Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:332-339.

6. Olfson M, Shaffer D, Marcus SC, Greenberg T. Relationship between antidepressant medication treatment and suicide in adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:978-982.

1. Kessler R, Walters E. Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depression Anxiety 1998;7:3-14.

2. March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Treatment for Adolescent Depression Study Team. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292:807-820.

3. Whittington CJ, Kendall T, Fonagy P, Cottrell D, Cotgrove A, Boddington E. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet 2004;363:1341-1345.

4. Report 10 of the Council on Scientific Affairs. Safety and Efficacy of Selective Serotonin Reup-take Inhibitors (SSRIs) in Children and Adolescents. Available at: www.aacap.org/galleries/psychiatricmedication/CSA_report_10_final.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2007

5. Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J. Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:332-339.

6. Olfson M, Shaffer D, Marcus SC, Greenberg T. Relationship between antidepressant medication treatment and suicide in adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:978-982.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What’s the best treatment for gestational diabetes?

There is no single approach to glycemic control that is better than another for reducing neonatal mortality and morbidity. Glycemic control—regardless of whether it involves diet, glyburide, or insulin—leads to fewer cases of shoulder dystocia, hyperbilirubinemia requiring phototherapy, nerve palsy, bone fracture, being large for gestational age, and fetal macrosomia (strength of recommendation: A).

Customize the intervention

Jon O. Neher, MD

Valley Family Medicine, Renton, Wash

Achieving solid glucose control for patients with gestational diabetes should be easy—most patients are healthy and motivated to do what is best for their babies. But a new diagnosis and blood sugar monitoring requirements can be daunting. Lifestyle changes and medications can quickly add to the sense of being overwhelmed. Fortunately, whatever brings down the blood sugar will do as therapy, so the patient can negotiate with her doctor to develop an intervention—be it diet, exercise, oral medications, insulin, or a combination—that works for her.

Evidence summary

Findings from 2 studies support the notion that the treatment of gestational diabetes decreases neonatal morbidity and mortality (TABLE).1,2 Both studies found a decrease in neonatal morbidity and mortality for those patients treated either with diet or insulin. One study found a higher rate of NICU admission in the treatment group, but the authors attributed this to physician awareness of the patient having gestational diabetes.1

TABLE

Treatment of gestational diabetes reduces neonatal morbidity and mortality

| TYPE OF STUDY | CONTROL(S) | INTERVENTION | MEONATAL MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY | ADMISSIONS TO NICU | NNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT1 | GDM routine care (N=510) | GDM treated with diet or insulin (N=490) | Control: 4% Intervention: 1% | 71% diet and insulin vs 61% routine care NNH: 100 | 34 |

| Cohort2 | 1) No GDM (N=1110) | GDM treated diet or insulin (N=1110) | Control 1: 11% Control 2: 59% | Not reported | 2* |

| 2) GDM not treated (due to late entry to care) (N=555) | Intervention: 15% | ||||

| *Compared with patients presenting late. | |||||

| GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; NNH, number needed to harm; NNT, number needed to treat. | |||||

Glyburide vs insulin

A high-quality randomized controlled trial comparing glyburide with insulin among 404 women found no difference in maternal hypoglycemia, neonatal mortality, or neonatal features and outcomes (including birthweight, NICU admissions, hyperbilirubinemia, and hypoglycemia; P ≥.25).3 Although this was a fairly large trial, it may have been underpowered since it found small differences in such rare outcomes.

Similarly, a retrospective study comparing glyburide with insulin in 584 women found little difference between the 2 approaches. Women in the glyburide group had better glycemic control, but the women in the insulin group started with higher initial blood sugars.4 The glyburide group had fewer NICU admissions than the insulin group (number needed to treat [NNT]=11), but higher rates of jaundice (number needed to harm [NNH]=25), pre-eclampsia (NNH=17), and maternal hypoglycemia (NNH=8). All other neonatal outcomes were similar between groups.

Diet alone vs diet + insulin

A meta-analysis combined 6 RCTs comparing diet alone with diet plus insulin in a total of 1281 women.5 Insulin was moderately superior to diet in preventing fetal macrosomia (NNT=11; 95% confidence interval, 6–36), but not in rates of hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hyperbilirubinemia, or congenital malformations.

Recommendations from others

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends that women diagnosed with gestational diabetes by a 3-hour glucose tolerance test receive nutritional counseling from a registered dietician. The ADA also recommends insulin therapy if diet is unsuccessful in achieving fasting glucose <105 mg/dL, 1-hour postprandial <155 mg/dL, or 2-hour postprandial <130 mg/dL.6

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends the use of diet or insulin to achieve 1-hour postprandial blood sugar of 130 mg/dL.7 Both ADA and ACOG indicate that further studies are needed to establish the safety of glyburide before general use can be recommended.

1. Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, et al. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2477-2486.

2. Langer O, Yogev Y, Most O, Xenakis EM. Gestational diabetes: The consequences of not treating. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:989-997.

3. Langer O, Conway DL, Berkus MD, Xenakis EM, Gonzales O. A comparison of glyburide and insulin in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1134-1138.

4. Jacobson GF, Ramos GA, Ching JY, Kirby RS, Ferrara A, Field DR. Comparison of glyburide and insulin for the management of gestational diabetes in a large managed care organization. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193:118-124.

5. Giuffrida FM, Castro AA, Atallah AN, Dib SA. Diet plus insulin compared to diet alone in the treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Braz J Med Biol Res 2003;36:1297-1300.

6. American Diabetes Association. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2004;27 Suppl 1:S88-S90.

7. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists. Gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:525-538.

There is no single approach to glycemic control that is better than another for reducing neonatal mortality and morbidity. Glycemic control—regardless of whether it involves diet, glyburide, or insulin—leads to fewer cases of shoulder dystocia, hyperbilirubinemia requiring phototherapy, nerve palsy, bone fracture, being large for gestational age, and fetal macrosomia (strength of recommendation: A).

Customize the intervention

Jon O. Neher, MD

Valley Family Medicine, Renton, Wash

Achieving solid glucose control for patients with gestational diabetes should be easy—most patients are healthy and motivated to do what is best for their babies. But a new diagnosis and blood sugar monitoring requirements can be daunting. Lifestyle changes and medications can quickly add to the sense of being overwhelmed. Fortunately, whatever brings down the blood sugar will do as therapy, so the patient can negotiate with her doctor to develop an intervention—be it diet, exercise, oral medications, insulin, or a combination—that works for her.

Evidence summary

Findings from 2 studies support the notion that the treatment of gestational diabetes decreases neonatal morbidity and mortality (TABLE).1,2 Both studies found a decrease in neonatal morbidity and mortality for those patients treated either with diet or insulin. One study found a higher rate of NICU admission in the treatment group, but the authors attributed this to physician awareness of the patient having gestational diabetes.1

TABLE

Treatment of gestational diabetes reduces neonatal morbidity and mortality

| TYPE OF STUDY | CONTROL(S) | INTERVENTION | MEONATAL MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY | ADMISSIONS TO NICU | NNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT1 | GDM routine care (N=510) | GDM treated with diet or insulin (N=490) | Control: 4% Intervention: 1% | 71% diet and insulin vs 61% routine care NNH: 100 | 34 |

| Cohort2 | 1) No GDM (N=1110) | GDM treated diet or insulin (N=1110) | Control 1: 11% Control 2: 59% | Not reported | 2* |

| 2) GDM not treated (due to late entry to care) (N=555) | Intervention: 15% | ||||

| *Compared with patients presenting late. | |||||

| GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; NNH, number needed to harm; NNT, number needed to treat. | |||||

Glyburide vs insulin

A high-quality randomized controlled trial comparing glyburide with insulin among 404 women found no difference in maternal hypoglycemia, neonatal mortality, or neonatal features and outcomes (including birthweight, NICU admissions, hyperbilirubinemia, and hypoglycemia; P ≥.25).3 Although this was a fairly large trial, it may have been underpowered since it found small differences in such rare outcomes.

Similarly, a retrospective study comparing glyburide with insulin in 584 women found little difference between the 2 approaches. Women in the glyburide group had better glycemic control, but the women in the insulin group started with higher initial blood sugars.4 The glyburide group had fewer NICU admissions than the insulin group (number needed to treat [NNT]=11), but higher rates of jaundice (number needed to harm [NNH]=25), pre-eclampsia (NNH=17), and maternal hypoglycemia (NNH=8). All other neonatal outcomes were similar between groups.

Diet alone vs diet + insulin

A meta-analysis combined 6 RCTs comparing diet alone with diet plus insulin in a total of 1281 women.5 Insulin was moderately superior to diet in preventing fetal macrosomia (NNT=11; 95% confidence interval, 6–36), but not in rates of hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hyperbilirubinemia, or congenital malformations.

Recommendations from others

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends that women diagnosed with gestational diabetes by a 3-hour glucose tolerance test receive nutritional counseling from a registered dietician. The ADA also recommends insulin therapy if diet is unsuccessful in achieving fasting glucose <105 mg/dL, 1-hour postprandial <155 mg/dL, or 2-hour postprandial <130 mg/dL.6

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends the use of diet or insulin to achieve 1-hour postprandial blood sugar of 130 mg/dL.7 Both ADA and ACOG indicate that further studies are needed to establish the safety of glyburide before general use can be recommended.

There is no single approach to glycemic control that is better than another for reducing neonatal mortality and morbidity. Glycemic control—regardless of whether it involves diet, glyburide, or insulin—leads to fewer cases of shoulder dystocia, hyperbilirubinemia requiring phototherapy, nerve palsy, bone fracture, being large for gestational age, and fetal macrosomia (strength of recommendation: A).

Customize the intervention

Jon O. Neher, MD

Valley Family Medicine, Renton, Wash

Achieving solid glucose control for patients with gestational diabetes should be easy—most patients are healthy and motivated to do what is best for their babies. But a new diagnosis and blood sugar monitoring requirements can be daunting. Lifestyle changes and medications can quickly add to the sense of being overwhelmed. Fortunately, whatever brings down the blood sugar will do as therapy, so the patient can negotiate with her doctor to develop an intervention—be it diet, exercise, oral medications, insulin, or a combination—that works for her.

Evidence summary

Findings from 2 studies support the notion that the treatment of gestational diabetes decreases neonatal morbidity and mortality (TABLE).1,2 Both studies found a decrease in neonatal morbidity and mortality for those patients treated either with diet or insulin. One study found a higher rate of NICU admission in the treatment group, but the authors attributed this to physician awareness of the patient having gestational diabetes.1

TABLE

Treatment of gestational diabetes reduces neonatal morbidity and mortality

| TYPE OF STUDY | CONTROL(S) | INTERVENTION | MEONATAL MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY | ADMISSIONS TO NICU | NNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT1 | GDM routine care (N=510) | GDM treated with diet or insulin (N=490) | Control: 4% Intervention: 1% | 71% diet and insulin vs 61% routine care NNH: 100 | 34 |

| Cohort2 | 1) No GDM (N=1110) | GDM treated diet or insulin (N=1110) | Control 1: 11% Control 2: 59% | Not reported | 2* |

| 2) GDM not treated (due to late entry to care) (N=555) | Intervention: 15% | ||||

| *Compared with patients presenting late. | |||||

| GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; NNH, number needed to harm; NNT, number needed to treat. | |||||

Glyburide vs insulin

A high-quality randomized controlled trial comparing glyburide with insulin among 404 women found no difference in maternal hypoglycemia, neonatal mortality, or neonatal features and outcomes (including birthweight, NICU admissions, hyperbilirubinemia, and hypoglycemia; P ≥.25).3 Although this was a fairly large trial, it may have been underpowered since it found small differences in such rare outcomes.

Similarly, a retrospective study comparing glyburide with insulin in 584 women found little difference between the 2 approaches. Women in the glyburide group had better glycemic control, but the women in the insulin group started with higher initial blood sugars.4 The glyburide group had fewer NICU admissions than the insulin group (number needed to treat [NNT]=11), but higher rates of jaundice (number needed to harm [NNH]=25), pre-eclampsia (NNH=17), and maternal hypoglycemia (NNH=8). All other neonatal outcomes were similar between groups.

Diet alone vs diet + insulin

A meta-analysis combined 6 RCTs comparing diet alone with diet plus insulin in a total of 1281 women.5 Insulin was moderately superior to diet in preventing fetal macrosomia (NNT=11; 95% confidence interval, 6–36), but not in rates of hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hyperbilirubinemia, or congenital malformations.

Recommendations from others

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends that women diagnosed with gestational diabetes by a 3-hour glucose tolerance test receive nutritional counseling from a registered dietician. The ADA also recommends insulin therapy if diet is unsuccessful in achieving fasting glucose <105 mg/dL, 1-hour postprandial <155 mg/dL, or 2-hour postprandial <130 mg/dL.6

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends the use of diet or insulin to achieve 1-hour postprandial blood sugar of 130 mg/dL.7 Both ADA and ACOG indicate that further studies are needed to establish the safety of glyburide before general use can be recommended.

1. Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, et al. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2477-2486.

2. Langer O, Yogev Y, Most O, Xenakis EM. Gestational diabetes: The consequences of not treating. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:989-997.

3. Langer O, Conway DL, Berkus MD, Xenakis EM, Gonzales O. A comparison of glyburide and insulin in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1134-1138.

4. Jacobson GF, Ramos GA, Ching JY, Kirby RS, Ferrara A, Field DR. Comparison of glyburide and insulin for the management of gestational diabetes in a large managed care organization. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193:118-124.

5. Giuffrida FM, Castro AA, Atallah AN, Dib SA. Diet plus insulin compared to diet alone in the treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Braz J Med Biol Res 2003;36:1297-1300.

6. American Diabetes Association. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2004;27 Suppl 1:S88-S90.

7. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists. Gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:525-538.

1. Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, et al. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2477-2486.

2. Langer O, Yogev Y, Most O, Xenakis EM. Gestational diabetes: The consequences of not treating. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:989-997.

3. Langer O, Conway DL, Berkus MD, Xenakis EM, Gonzales O. A comparison of glyburide and insulin in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1134-1138.

4. Jacobson GF, Ramos GA, Ching JY, Kirby RS, Ferrara A, Field DR. Comparison of glyburide and insulin for the management of gestational diabetes in a large managed care organization. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193:118-124.

5. Giuffrida FM, Castro AA, Atallah AN, Dib SA. Diet plus insulin compared to diet alone in the treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Braz J Med Biol Res 2003;36:1297-1300.

6. American Diabetes Association. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2004;27 Suppl 1:S88-S90.

7. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists. Gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:525-538.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Can infants/toddlers get enough fluoride through brushing?

Yes. Brushing twice daily with topical fluoride toothpaste decreases the incidence of dental caries in infants and toddlers (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). High-concentration fluoride toothpaste delivers superior caries protection, but causes more dental fluorosis.

Use of high-concentration fluoride toothpaste should be targeted towards children at highest risk of dental caries, such as those living in areas without fluoridated water (SOR: B).

Brushing, yes, but what about fluoride supplementation?

Laura G. Kittinger-Aisenberg, MD

Chesterfield Family Medicine Residency Program, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond

In medical school, we were taught that infants who are breastfed should start supplemental fluoride at 6 months. Pediatric dentists generally only use supplemental fluoride if the baby’s home has well water that has been tested and found deficient. The worst outcome from a lack of fluoride supplementation is caries, which usually can be managed. However, too much fluoride also has a significant downside, fluorosis, which permanently stains the teeth.

Start fluoride toothpaste in minute amounts at 1 year of age. Don’t use fluoride supplementation—even in breastfed infants—unless they are on well water proven to be low in fluoride.

Evidence summary

Toothpaste as effective as rinse or gel

A large Cochrane review evaluated topical fluoride therapy in the form of toothpaste, mouth rinse, varnish, or gel. Based on 133 randomized or quasi-randomized controlled trials (n=65,169), the meta-analysis indicated a 26% (95% confidence interval [CI], 24%–29%) reduction in decayed, missing, and filled tooth surfaces in children.1 Another Cochrane review found 17 randomized controlled trials comparing different methods of topical fluoride application in children. The limited data suggested that fluoride toothpaste is as effective as mouth rinse or gel.2 Depending on the prevalence of caries in the population, between 1.6 and 3.7 children need to use a fluoride toothpaste to prevent 1 decayed, missing, or filled tooth.3

The risk of fluorosis

Topical fluoride use has been associated with dental fluorosis, which causes staining or pitting of the enamel tooth surface. The incidence of significant dental fluorosis varies in children—from 5% to 7% with 1450 ppm fluoride toothpaste to 2% to 4% with 440 ppm fluoride toothpaste (number needed to harm [NNH]=20–100).4,5

High-fluoride concentrations

High-fluoride-concentration toothpastes (1000 ppm F) prevent 14% more caries than low-fluoride-concentration toothpastes (250 ppm F).6 Another randomized controlled trial, carried out in an area without fluoridated water, found the high-fluoride-concentration toothpaste (1450 ppm F) resulted in 16% fewer caries in children, while the low-fluoride-concentration toothpaste (440 ppm F) was no different than placebo.7

When there’s fluoridated water

A meta-analysis found that the effect of topical fluoride was independent of water fluoridation, suggesting that topical fluoride toothpaste has a beneficial effect even in communities with fluoridated water.3 No relevant studies comparing topical fluoride toothpaste with oral fluoride supplementation were found.

Recommendations from others

Both the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend topical fluoride toothpaste for children as an adjunct to oral fluoride intake. The AAPD8 recommends a “pea-sized” amount of toothpaste for children under 6 years of age. The CDC9 recommends that you weigh the risks and possible other sources of fluoride in children under age 2, and using a pea-sized amount of toothpaste with supervised brushing for children 2 to 6 years of age.

The TABLE shows the AAPD’s recommended daily dose of fluoride supplementation based on the fluoride concentration in the local water.

TABLE

Oral fluoride dosing: Recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry8

| DRINKING WATER FLUORIDE LEVEL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AGE | <0.3 PPM F | 0.3–0.6 PPM F | >0.6 PPM F |

| 0–6 months | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 months – 3 years | 0.25 mg daily | 0 | 0 |

| 3–6 years | 0.5 mg daily | 0.25 mg daily | 0 |

| 6–16 years | 1 mg daily | 0.5 mg daily | 0 |

| ppm F, parts per million fluoride | |||

1. Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Logan S, Sheiham A. Topical fluoride (toothpastes, mouth rinses, gels, or varnishes) for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(4):CD002782.-

2. Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Sheiham A, Logan S. One topical fluoride (toothpastes, or mouthrinses, or gels, or varnishes) versus another for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(1):CD002780.-

3. Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Sheiham A, Logan S. Fluoride toothpastes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(1):CD002278.-

4. Tavener JA, Davies GM, Davies RM, Ellwood RP. The prevalence and severity of fluorosis in children who received toothpaste containing either 440 or 1450 ppm F from the age of 12 months in deprived and less deprived communities. Caries Res 2006;40:66-72.

5. Tavener JA, Davies GM, Davies RM, Ellwood RP. The prevalence and severity of fluorosis and other developmental defects of enamel in children who received free fluoride toothpaste containing either 440 or 1450 ppm F from the age of 12 months. Community Dent Health 2004;21:217-223.

6. Steiner M, Helfenstein U, Menghini G. Effect of 1000 ppm relative to 250 ppm fluoride toothpaste. A meta-analysis. Am J Dent 2004;17:85-88.

7. Davies GM, Worthington HV, Ellwood RP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of providing free fluoride toothpaste from the age of 12 months on reducing caries in 5-6 year old children. Community Dent Health 2002;19:131-136.

8. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Clinical guideline on fluoride therapy. Chicago, Ill: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2003. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=6272. Accessed August 6, 2007.

9. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the united States. Centers for Disease Control and prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep 2001;50:1-42.

Yes. Brushing twice daily with topical fluoride toothpaste decreases the incidence of dental caries in infants and toddlers (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). High-concentration fluoride toothpaste delivers superior caries protection, but causes more dental fluorosis.

Use of high-concentration fluoride toothpaste should be targeted towards children at highest risk of dental caries, such as those living in areas without fluoridated water (SOR: B).

Brushing, yes, but what about fluoride supplementation?

Laura G. Kittinger-Aisenberg, MD

Chesterfield Family Medicine Residency Program, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond

In medical school, we were taught that infants who are breastfed should start supplemental fluoride at 6 months. Pediatric dentists generally only use supplemental fluoride if the baby’s home has well water that has been tested and found deficient. The worst outcome from a lack of fluoride supplementation is caries, which usually can be managed. However, too much fluoride also has a significant downside, fluorosis, which permanently stains the teeth.

Start fluoride toothpaste in minute amounts at 1 year of age. Don’t use fluoride supplementation—even in breastfed infants—unless they are on well water proven to be low in fluoride.

Evidence summary

Toothpaste as effective as rinse or gel

A large Cochrane review evaluated topical fluoride therapy in the form of toothpaste, mouth rinse, varnish, or gel. Based on 133 randomized or quasi-randomized controlled trials (n=65,169), the meta-analysis indicated a 26% (95% confidence interval [CI], 24%–29%) reduction in decayed, missing, and filled tooth surfaces in children.1 Another Cochrane review found 17 randomized controlled trials comparing different methods of topical fluoride application in children. The limited data suggested that fluoride toothpaste is as effective as mouth rinse or gel.2 Depending on the prevalence of caries in the population, between 1.6 and 3.7 children need to use a fluoride toothpaste to prevent 1 decayed, missing, or filled tooth.3

The risk of fluorosis

Topical fluoride use has been associated with dental fluorosis, which causes staining or pitting of the enamel tooth surface. The incidence of significant dental fluorosis varies in children—from 5% to 7% with 1450 ppm fluoride toothpaste to 2% to 4% with 440 ppm fluoride toothpaste (number needed to harm [NNH]=20–100).4,5

High-fluoride concentrations

High-fluoride-concentration toothpastes (1000 ppm F) prevent 14% more caries than low-fluoride-concentration toothpastes (250 ppm F).6 Another randomized controlled trial, carried out in an area without fluoridated water, found the high-fluoride-concentration toothpaste (1450 ppm F) resulted in 16% fewer caries in children, while the low-fluoride-concentration toothpaste (440 ppm F) was no different than placebo.7

When there’s fluoridated water

A meta-analysis found that the effect of topical fluoride was independent of water fluoridation, suggesting that topical fluoride toothpaste has a beneficial effect even in communities with fluoridated water.3 No relevant studies comparing topical fluoride toothpaste with oral fluoride supplementation were found.

Recommendations from others

Both the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend topical fluoride toothpaste for children as an adjunct to oral fluoride intake. The AAPD8 recommends a “pea-sized” amount of toothpaste for children under 6 years of age. The CDC9 recommends that you weigh the risks and possible other sources of fluoride in children under age 2, and using a pea-sized amount of toothpaste with supervised brushing for children 2 to 6 years of age.

The TABLE shows the AAPD’s recommended daily dose of fluoride supplementation based on the fluoride concentration in the local water.

TABLE

Oral fluoride dosing: Recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry8

| DRINKING WATER FLUORIDE LEVEL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AGE | <0.3 PPM F | 0.3–0.6 PPM F | >0.6 PPM F |

| 0–6 months | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 months – 3 years | 0.25 mg daily | 0 | 0 |

| 3–6 years | 0.5 mg daily | 0.25 mg daily | 0 |

| 6–16 years | 1 mg daily | 0.5 mg daily | 0 |

| ppm F, parts per million fluoride | |||

Yes. Brushing twice daily with topical fluoride toothpaste decreases the incidence of dental caries in infants and toddlers (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). High-concentration fluoride toothpaste delivers superior caries protection, but causes more dental fluorosis.

Use of high-concentration fluoride toothpaste should be targeted towards children at highest risk of dental caries, such as those living in areas without fluoridated water (SOR: B).

Brushing, yes, but what about fluoride supplementation?

Laura G. Kittinger-Aisenberg, MD

Chesterfield Family Medicine Residency Program, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond

In medical school, we were taught that infants who are breastfed should start supplemental fluoride at 6 months. Pediatric dentists generally only use supplemental fluoride if the baby’s home has well water that has been tested and found deficient. The worst outcome from a lack of fluoride supplementation is caries, which usually can be managed. However, too much fluoride also has a significant downside, fluorosis, which permanently stains the teeth.

Start fluoride toothpaste in minute amounts at 1 year of age. Don’t use fluoride supplementation—even in breastfed infants—unless they are on well water proven to be low in fluoride.

Evidence summary

Toothpaste as effective as rinse or gel

A large Cochrane review evaluated topical fluoride therapy in the form of toothpaste, mouth rinse, varnish, or gel. Based on 133 randomized or quasi-randomized controlled trials (n=65,169), the meta-analysis indicated a 26% (95% confidence interval [CI], 24%–29%) reduction in decayed, missing, and filled tooth surfaces in children.1 Another Cochrane review found 17 randomized controlled trials comparing different methods of topical fluoride application in children. The limited data suggested that fluoride toothpaste is as effective as mouth rinse or gel.2 Depending on the prevalence of caries in the population, between 1.6 and 3.7 children need to use a fluoride toothpaste to prevent 1 decayed, missing, or filled tooth.3

The risk of fluorosis

Topical fluoride use has been associated with dental fluorosis, which causes staining or pitting of the enamel tooth surface. The incidence of significant dental fluorosis varies in children—from 5% to 7% with 1450 ppm fluoride toothpaste to 2% to 4% with 440 ppm fluoride toothpaste (number needed to harm [NNH]=20–100).4,5

High-fluoride concentrations

High-fluoride-concentration toothpastes (1000 ppm F) prevent 14% more caries than low-fluoride-concentration toothpastes (250 ppm F).6 Another randomized controlled trial, carried out in an area without fluoridated water, found the high-fluoride-concentration toothpaste (1450 ppm F) resulted in 16% fewer caries in children, while the low-fluoride-concentration toothpaste (440 ppm F) was no different than placebo.7

When there’s fluoridated water

A meta-analysis found that the effect of topical fluoride was independent of water fluoridation, suggesting that topical fluoride toothpaste has a beneficial effect even in communities with fluoridated water.3 No relevant studies comparing topical fluoride toothpaste with oral fluoride supplementation were found.

Recommendations from others

Both the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend topical fluoride toothpaste for children as an adjunct to oral fluoride intake. The AAPD8 recommends a “pea-sized” amount of toothpaste for children under 6 years of age. The CDC9 recommends that you weigh the risks and possible other sources of fluoride in children under age 2, and using a pea-sized amount of toothpaste with supervised brushing for children 2 to 6 years of age.

The TABLE shows the AAPD’s recommended daily dose of fluoride supplementation based on the fluoride concentration in the local water.

TABLE

Oral fluoride dosing: Recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry8

| DRINKING WATER FLUORIDE LEVEL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AGE | <0.3 PPM F | 0.3–0.6 PPM F | >0.6 PPM F |

| 0–6 months | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 months – 3 years | 0.25 mg daily | 0 | 0 |

| 3–6 years | 0.5 mg daily | 0.25 mg daily | 0 |

| 6–16 years | 1 mg daily | 0.5 mg daily | 0 |

| ppm F, parts per million fluoride | |||

1. Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Logan S, Sheiham A. Topical fluoride (toothpastes, mouth rinses, gels, or varnishes) for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(4):CD002782.-

2. Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Sheiham A, Logan S. One topical fluoride (toothpastes, or mouthrinses, or gels, or varnishes) versus another for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(1):CD002780.-

3. Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Sheiham A, Logan S. Fluoride toothpastes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(1):CD002278.-

4. Tavener JA, Davies GM, Davies RM, Ellwood RP. The prevalence and severity of fluorosis in children who received toothpaste containing either 440 or 1450 ppm F from the age of 12 months in deprived and less deprived communities. Caries Res 2006;40:66-72.

5. Tavener JA, Davies GM, Davies RM, Ellwood RP. The prevalence and severity of fluorosis and other developmental defects of enamel in children who received free fluoride toothpaste containing either 440 or 1450 ppm F from the age of 12 months. Community Dent Health 2004;21:217-223.

6. Steiner M, Helfenstein U, Menghini G. Effect of 1000 ppm relative to 250 ppm fluoride toothpaste. A meta-analysis. Am J Dent 2004;17:85-88.

7. Davies GM, Worthington HV, Ellwood RP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of providing free fluoride toothpaste from the age of 12 months on reducing caries in 5-6 year old children. Community Dent Health 2002;19:131-136.

8. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Clinical guideline on fluoride therapy. Chicago, Ill: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2003. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=6272. Accessed August 6, 2007.

9. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the united States. Centers for Disease Control and prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep 2001;50:1-42.

1. Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Logan S, Sheiham A. Topical fluoride (toothpastes, mouth rinses, gels, or varnishes) for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(4):CD002782.-

2. Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Sheiham A, Logan S. One topical fluoride (toothpastes, or mouthrinses, or gels, or varnishes) versus another for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(1):CD002780.-

3. Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Sheiham A, Logan S. Fluoride toothpastes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(1):CD002278.-

4. Tavener JA, Davies GM, Davies RM, Ellwood RP. The prevalence and severity of fluorosis in children who received toothpaste containing either 440 or 1450 ppm F from the age of 12 months in deprived and less deprived communities. Caries Res 2006;40:66-72.

5. Tavener JA, Davies GM, Davies RM, Ellwood RP. The prevalence and severity of fluorosis and other developmental defects of enamel in children who received free fluoride toothpaste containing either 440 or 1450 ppm F from the age of 12 months. Community Dent Health 2004;21:217-223.

6. Steiner M, Helfenstein U, Menghini G. Effect of 1000 ppm relative to 250 ppm fluoride toothpaste. A meta-analysis. Am J Dent 2004;17:85-88.

7. Davies GM, Worthington HV, Ellwood RP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of providing free fluoride toothpaste from the age of 12 months on reducing caries in 5-6 year old children. Community Dent Health 2002;19:131-136.

8. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Clinical guideline on fluoride therapy. Chicago, Ill: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2003. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=6272. Accessed August 6, 2007.

9. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the united States. Centers for Disease Control and prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep 2001;50:1-42.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Does the age you introduce food to an infant affect allergies later?

Yes. In children at high risk for atopy (those with a family history of allergy, asthma, or eczema in at least 1 first-degree relative), breastfeeding or giving hydrolyzed protein formula during the first 4 to 6 months reduces the risk of atopy in the first year of life, when compared with introducing cow’s milk or soy formula (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on a systematic review that included only 2 double-blinded randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

There is inconsistent evidence to show that early introduction of solid food increases the incidence of atopic disease (SOR: B, systematic review of inconsistent studies).

Begin talking about infant feeding during the first postnatal visit

Mary M. Stephens, MD, MPH

East Tennessee State University, Johnson City

Having found a surprising number of children on cereal or other solids at the 2-month visit, I make it a practice to begin talking about infant feeding during the first postnatal visit. I encourage parents to wait until at least 4 months (but not more than 6 months) to start cereal, and to wait 3 to 4 days between introducing any new foods to make sure the child does not have an adverse reaction.

I generally tell all parents to keep their child on breast milk or formula and avoid whole milk until age 1, although small amounts of cheese and yogurt are fine. Additionally, I recommend avoiding citrus, honey, and eggs until age 1 and peanut butter until age 2 or 3.

For the child at high risk of atopy, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation to wait to introduce solid foods until 6 months of age and to wait to introduce peanuts and fish until 3 years of age seems reasonable, although I’d let parents know that they could try these foods earlier if they wanted since there is no definite evidence that those changes will make a difference.

Although I’ve never recommended hydrolyzed protein formula for children at high risk of atopy, it is an option for discussion. practical considerations to bring up in the discussion are the higher cost of these formulas and the palatability. Children receiving their formula through Women, Infant and Children (WIC) programs will need a prescription that includes the indication for the formula.

Evidence summary

Systematic reviews analyzing the modification of early feeding practices to prevent atopic disease have all been limited by a paucity of double-blinded RCTs of sufficient duration.1-3

Breastfeeding, hydrolyzed formulas confer lowest atopy risk

Breastfeeding and the use of hydrolyzed protein formulas confer the lowest risk of atopy in high-risk children when compared with cow’s milk or soy-based formulas.1,3 The relative risk for wheeze or asthma in the first year of life was 0.4 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.19–0.85) for children fed hydrolyzed protein formulas when compared with cow’s milk.1 Studies have not found a significant difference among these forms of milk for infants without a strong family history of atopic disease.3

Delaying solid food may reduce allergies

There is speculation that introducing certain solid foods early increases the risk of allergies to these foods, as well as causing generalized atopic symptoms. Few studies have examined this, and no systematic reviews focus on atopic disease.4

A cohort study (n=1265) comparing children who had been given 4 or more types of solid food before 4 months of age with those whose caregivers delayed solid foods showed an increased incidence of eczema by 10 years of age (relative risk=2.35; P<.05) in the early feeding group.5

However, a prospective interventional cohort study using a retrospective cohort as a control (n=375) compared children who had strictly avoided fish and citrus products until 1 year of age with those who had an unrestricted diet. There was no difference in the frequency of allergy to these foods as quantified by history and positive challenge test, although the authors did not include a statistical analysis of their results.6

Another study randomized 165 high-risk children into groups with standard feeding practices or an allergy prophylaxis regimen, which included avoidance of milk protein until age 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and fish and peanuts until 3 years. Although prophylaxis decreased the prevalence of atopic disorders at 1 year, there was no difference in any atopic disease between the 2 groups at age 7.7

Recommendations from others

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that for high-risk infants, solid foods should not be introduced into the diet until 6 months of age, with dairy products delayed until 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and peanuts, tree nuts, and fish until 3 years of age.8

1. Ram FS, Ducharme FM, Scarlett J. Cow’s milk protein avoidance and development of childhood wheeze in children with a family history of atopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD003795.-

2. Smethurst D, Macfarlane S. Atopic eczema (web archive): prolonged breast feeding in predisposed infants. Clinical Evidence 2002;(8):1664-1682.

3. Osborn DA, Sinn J. Formulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD003664.-

4. Lanigan JA, Bishop J, Kimber AC, Morgan J. Systematic review concerning the age of introduction of complementary foods to the healthy full-term infant. Eur J Clin Nutr 2001;55:309-320.

5. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Shannon FT. Early solid feeding and recurrent childhood eczema: a 10-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics 1990;86:541-546.

6. Saarinen UM, Kajosaari M. Does dietary elimination in infancy prevent or only postpone a food allergy? A study of fish and citrus allergy in 375 children. Lancet 1980;1:166-167.

7. Zeiger RS, Heller S. The development and prediction of atopy in high-risk children: follow-up at age seven years in a prospective randomized study of combined maternal and infant food allergen avoidance. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995;95:1179-1190.

8. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics 2000;106:346-349.

Yes. In children at high risk for atopy (those with a family history of allergy, asthma, or eczema in at least 1 first-degree relative), breastfeeding or giving hydrolyzed protein formula during the first 4 to 6 months reduces the risk of atopy in the first year of life, when compared with introducing cow’s milk or soy formula (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on a systematic review that included only 2 double-blinded randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

There is inconsistent evidence to show that early introduction of solid food increases the incidence of atopic disease (SOR: B, systematic review of inconsistent studies).

Begin talking about infant feeding during the first postnatal visit

Mary M. Stephens, MD, MPH

East Tennessee State University, Johnson City

Having found a surprising number of children on cereal or other solids at the 2-month visit, I make it a practice to begin talking about infant feeding during the first postnatal visit. I encourage parents to wait until at least 4 months (but not more than 6 months) to start cereal, and to wait 3 to 4 days between introducing any new foods to make sure the child does not have an adverse reaction.

I generally tell all parents to keep their child on breast milk or formula and avoid whole milk until age 1, although small amounts of cheese and yogurt are fine. Additionally, I recommend avoiding citrus, honey, and eggs until age 1 and peanut butter until age 2 or 3.

For the child at high risk of atopy, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation to wait to introduce solid foods until 6 months of age and to wait to introduce peanuts and fish until 3 years of age seems reasonable, although I’d let parents know that they could try these foods earlier if they wanted since there is no definite evidence that those changes will make a difference.

Although I’ve never recommended hydrolyzed protein formula for children at high risk of atopy, it is an option for discussion. practical considerations to bring up in the discussion are the higher cost of these formulas and the palatability. Children receiving their formula through Women, Infant and Children (WIC) programs will need a prescription that includes the indication for the formula.

Evidence summary

Systematic reviews analyzing the modification of early feeding practices to prevent atopic disease have all been limited by a paucity of double-blinded RCTs of sufficient duration.1-3

Breastfeeding, hydrolyzed formulas confer lowest atopy risk

Breastfeeding and the use of hydrolyzed protein formulas confer the lowest risk of atopy in high-risk children when compared with cow’s milk or soy-based formulas.1,3 The relative risk for wheeze or asthma in the first year of life was 0.4 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.19–0.85) for children fed hydrolyzed protein formulas when compared with cow’s milk.1 Studies have not found a significant difference among these forms of milk for infants without a strong family history of atopic disease.3

Delaying solid food may reduce allergies

There is speculation that introducing certain solid foods early increases the risk of allergies to these foods, as well as causing generalized atopic symptoms. Few studies have examined this, and no systematic reviews focus on atopic disease.4

A cohort study (n=1265) comparing children who had been given 4 or more types of solid food before 4 months of age with those whose caregivers delayed solid foods showed an increased incidence of eczema by 10 years of age (relative risk=2.35; P<.05) in the early feeding group.5

However, a prospective interventional cohort study using a retrospective cohort as a control (n=375) compared children who had strictly avoided fish and citrus products until 1 year of age with those who had an unrestricted diet. There was no difference in the frequency of allergy to these foods as quantified by history and positive challenge test, although the authors did not include a statistical analysis of their results.6

Another study randomized 165 high-risk children into groups with standard feeding practices or an allergy prophylaxis regimen, which included avoidance of milk protein until age 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and fish and peanuts until 3 years. Although prophylaxis decreased the prevalence of atopic disorders at 1 year, there was no difference in any atopic disease between the 2 groups at age 7.7

Recommendations from others

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that for high-risk infants, solid foods should not be introduced into the diet until 6 months of age, with dairy products delayed until 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and peanuts, tree nuts, and fish until 3 years of age.8

Yes. In children at high risk for atopy (those with a family history of allergy, asthma, or eczema in at least 1 first-degree relative), breastfeeding or giving hydrolyzed protein formula during the first 4 to 6 months reduces the risk of atopy in the first year of life, when compared with introducing cow’s milk or soy formula (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on a systematic review that included only 2 double-blinded randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

There is inconsistent evidence to show that early introduction of solid food increases the incidence of atopic disease (SOR: B, systematic review of inconsistent studies).

Begin talking about infant feeding during the first postnatal visit

Mary M. Stephens, MD, MPH

East Tennessee State University, Johnson City

Having found a surprising number of children on cereal or other solids at the 2-month visit, I make it a practice to begin talking about infant feeding during the first postnatal visit. I encourage parents to wait until at least 4 months (but not more than 6 months) to start cereal, and to wait 3 to 4 days between introducing any new foods to make sure the child does not have an adverse reaction.

I generally tell all parents to keep their child on breast milk or formula and avoid whole milk until age 1, although small amounts of cheese and yogurt are fine. Additionally, I recommend avoiding citrus, honey, and eggs until age 1 and peanut butter until age 2 or 3.

For the child at high risk of atopy, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation to wait to introduce solid foods until 6 months of age and to wait to introduce peanuts and fish until 3 years of age seems reasonable, although I’d let parents know that they could try these foods earlier if they wanted since there is no definite evidence that those changes will make a difference.

Although I’ve never recommended hydrolyzed protein formula for children at high risk of atopy, it is an option for discussion. practical considerations to bring up in the discussion are the higher cost of these formulas and the palatability. Children receiving their formula through Women, Infant and Children (WIC) programs will need a prescription that includes the indication for the formula.

Evidence summary

Systematic reviews analyzing the modification of early feeding practices to prevent atopic disease have all been limited by a paucity of double-blinded RCTs of sufficient duration.1-3

Breastfeeding, hydrolyzed formulas confer lowest atopy risk

Breastfeeding and the use of hydrolyzed protein formulas confer the lowest risk of atopy in high-risk children when compared with cow’s milk or soy-based formulas.1,3 The relative risk for wheeze or asthma in the first year of life was 0.4 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.19–0.85) for children fed hydrolyzed protein formulas when compared with cow’s milk.1 Studies have not found a significant difference among these forms of milk for infants without a strong family history of atopic disease.3

Delaying solid food may reduce allergies

There is speculation that introducing certain solid foods early increases the risk of allergies to these foods, as well as causing generalized atopic symptoms. Few studies have examined this, and no systematic reviews focus on atopic disease.4

A cohort study (n=1265) comparing children who had been given 4 or more types of solid food before 4 months of age with those whose caregivers delayed solid foods showed an increased incidence of eczema by 10 years of age (relative risk=2.35; P<.05) in the early feeding group.5

However, a prospective interventional cohort study using a retrospective cohort as a control (n=375) compared children who had strictly avoided fish and citrus products until 1 year of age with those who had an unrestricted diet. There was no difference in the frequency of allergy to these foods as quantified by history and positive challenge test, although the authors did not include a statistical analysis of their results.6

Another study randomized 165 high-risk children into groups with standard feeding practices or an allergy prophylaxis regimen, which included avoidance of milk protein until age 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and fish and peanuts until 3 years. Although prophylaxis decreased the prevalence of atopic disorders at 1 year, there was no difference in any atopic disease between the 2 groups at age 7.7

Recommendations from others

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that for high-risk infants, solid foods should not be introduced into the diet until 6 months of age, with dairy products delayed until 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and peanuts, tree nuts, and fish until 3 years of age.8

1. Ram FS, Ducharme FM, Scarlett J. Cow’s milk protein avoidance and development of childhood wheeze in children with a family history of atopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD003795.-

2. Smethurst D, Macfarlane S. Atopic eczema (web archive): prolonged breast feeding in predisposed infants. Clinical Evidence 2002;(8):1664-1682.

3. Osborn DA, Sinn J. Formulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD003664.-

4. Lanigan JA, Bishop J, Kimber AC, Morgan J. Systematic review concerning the age of introduction of complementary foods to the healthy full-term infant. Eur J Clin Nutr 2001;55:309-320.

5. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Shannon FT. Early solid feeding and recurrent childhood eczema: a 10-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics 1990;86:541-546.

6. Saarinen UM, Kajosaari M. Does dietary elimination in infancy prevent or only postpone a food allergy? A study of fish and citrus allergy in 375 children. Lancet 1980;1:166-167.

7. Zeiger RS, Heller S. The development and prediction of atopy in high-risk children: follow-up at age seven years in a prospective randomized study of combined maternal and infant food allergen avoidance. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995;95:1179-1190.

8. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics 2000;106:346-349.

1. Ram FS, Ducharme FM, Scarlett J. Cow’s milk protein avoidance and development of childhood wheeze in children with a family history of atopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD003795.-

2. Smethurst D, Macfarlane S. Atopic eczema (web archive): prolonged breast feeding in predisposed infants. Clinical Evidence 2002;(8):1664-1682.

3. Osborn DA, Sinn J. Formulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD003664.-

4. Lanigan JA, Bishop J, Kimber AC, Morgan J. Systematic review concerning the age of introduction of complementary foods to the healthy full-term infant. Eur J Clin Nutr 2001;55:309-320.

5. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Shannon FT. Early solid feeding and recurrent childhood eczema: a 10-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics 1990;86:541-546.

6. Saarinen UM, Kajosaari M. Does dietary elimination in infancy prevent or only postpone a food allergy? A study of fish and citrus allergy in 375 children. Lancet 1980;1:166-167.

7. Zeiger RS, Heller S. The development and prediction of atopy in high-risk children: follow-up at age seven years in a prospective randomized study of combined maternal and infant food allergen avoidance. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995;95:1179-1190.

8. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics 2000;106:346-349.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

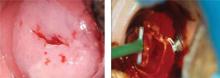

Which technique for removing nevi is least scarring?

A shave biopsy with a razor blade or #15 scalpel is the best approach for a facial nevus, assuming malignancy is not suspected. the resulting scar is usually flat, smaller than the lesion, has no suture lines, and—if shaved in mid or upper dermis—has a low risk of producing a hypertrophic or hypotrophic scar (strength of recommendation: C, expert opinion, committee guidelines).

Shave biopsies are quick and well-tolerated

Parul Harsora, MD

University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas

If you suspect malignancy in a nevus, obtain an excisional or incisional biopsy. Shave biopsies are best suited for raised, flesh-colored nevi and are generally quick, well-tolerated, and cost-effective. tissue from a shave biopsy can be submitted for histological evaluation.

Shave biopsies are preferred by patients because there are no sutures and scarring is minimized. the site may be pink and may take several months to develop a normal appearance. the final result may be unnoticeable, or leave an indentation or be hypo- or hyperpigmented.

Hairy, pigmented, and compound nevi are likely to do better with a punch biopsy. to prevent recurrence, seek histologic confirmation that the entire nevus has been removed.

Evidence summary

Numerous reports and guidelines indicate that if a nevus is even slightly suspicious for malignancy, it should be removed by excisional biopsy or sampled for diagnosis by punch or incisional biopsy. There are no randomized controlled trials or cohort studies comparing techniques for removing raised nevi from the face.

Shave biopsy has good outcomes

Expert opinion and individual prospective case series show acceptable outcomes for shave biopsy. One prospective study followed 55 patients after removal of nevi from the head and neck. These nevi were removed using a shave procedure with a#15 scalpel and hot cautery for bleeding. Of the 55 sites, 4 retained pigment and 30 had a visible scar with a mean diameter of 5 mm at 6- to 8-month follow-up.1 The mean diameter of the original lesions was 6 mm. There was no difference between the size of those lesions that scarred and those that didn’t.

Researchers conducting a second retrospective study, done at least 1 year after the procedure, used a questionnaire to ask 76 patients (with a total of 83 nevi removed from the face by shave excision) about their perceptions of the scar.2 Patients described their lesions as: no scar (33%), white and flat (25%), depressed (19%), raised (15%), and pigmented (7%). Eighty-six percent thought their scars looked better than the nevus and 79% were “happy with the way the scar looks now.” Two additional studies, based on both patient and provider perceptions, with similar conclusions, are presented in the (TABLE).3,4

TABLE

Favorable cosmetic results following shave biopsy of facial nevi

| STUDY | NO. PTS/NEVI | % WITH RET AINED PIGMENT OR RECURRENCE | % WITH VISIBLE SCARRING | FOLLOW-UP INTERVAL | EVALUATION/DONE BY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hudson-Peacock1 | 55/55 | 13 | 55 | 6-8 mo | Cosmetically acceptable/patients |

| Bong2 | 76/83 | 28 | 67 | ≥1 yr | 86%: better than nevus/patients |

| Zanardini3 | 206/ 215 | 4 | 9 | 3 mo | 90%: excellent* 9%: good/surgeons |

| Ferrandiz4 | Not known/59 | 20† | 67 | 3 mo | 98%: better than nevus/pts; 92%: excellent or acceptable‡/surgeons |

| Excellent=no noticeable scar, good=slightly noticeable scar with normochromia or hypochromia, poor=depressed scar or intense dyschromia. | |||||

| † Some lesions not papular. | |||||

| ‡ Excellent cosmetic result=imperceptible scar without erythema, hyper- or hypo-pigmentation, hypertrophy or atrophy. Acceptable=scar better than original mole. poor=left scar worse than original mole. | |||||

Atypical lesions should be excised

Atypical lesions require excisional biopsy. The depth and architecture of the lesion, if melanoma, cannot be determined by shave biopsy, and both treatment and prognosis depend on those characteristics.

These guidelines derive from well-designed, nonexperimental descriptive studies.5 However, a recent retrospective study compared the Breslow depth determination of 4 different biopsy techniques, performed by experienced dermatologists, with the subsequent depth on definitive surgery for melanoma. This study found that superficial shave, deep shave, and punch biopsy predicted the Breslow depth 88% (95/108) of the time.6 As expected, excisional biopsy predicted the depth 100% (30/30) of the time. The location of the biopsy sites were not reported. The choice of biopsy was influenced by the suspicion of melanoma; thin (< 1 mm) melanomas were more likely to be superficially shaved than deep-shaved or punched.

Recommendations from others

Guidelines on nevocellular nevi from the American Academy of Dermatology recommend a simple excisional or incisional biopsy; they do not discuss the method of removal for benign appearing facial lesions.7