User login

Pseudo-Ludwig angina

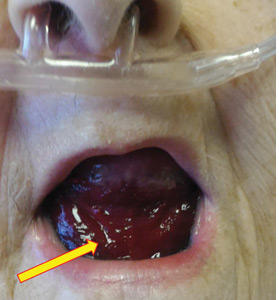

An 83-year-old woman with hypertension, hypothyroidism, and a history of depression presented to the emergency department with acute shortness of breath and hypoxia. She was found to have submassive pulmonary embolism, and a heparin infusion was started immediately.

Urgent nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy revealed a hematoma at the base of her tongue that extended into the vallecula, piriform sinuses, and aryepiglottic fold, causing acute airway obstruction. These features combined with the supratherapeutic aPTT led to the diagnosis of pseudo-Ludwig angina.

DANGER OF RAPID AIRWAY COMPROMISE

Pseudo-Ludwig angina is a rare condition in which over-anticoagulation causes sublingual swelling leading to airway obstruction, whereas true Ludwig angina is an infectious regional suppuration of the neck.

Most reported cases of pseudo-Ludwig angina have resulted from overanticogulation with warfarin or warfarin-like substances (rodenticides), or from coagulopathy due to liver disease.1–3 Early recognition is essential to avoid airway compromise.

In our patient, all anticoagulation was discontinued, and she was intubated until the hematoma began to resolve, the aPTT returned to normal, and respiratory compromise improved. At follow-up 2 months later, the sublingual hematoma had completely resolved (Figure 1). And at a 6-month follow-up visit, the pulmonary embolism had resolved, and pulmonary pressures by 2-dimensional echocardiography were normal.

- Lovallo E, Patterson S, Erickson M, Chin C, Blanc P, Durrani TS. When is “pseudo-Ludwig’s angina” associated with coagulopathy also a “pseudo” hemorrhage? J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2013; 1(2):2324709613492503. doi:10.1177/2324709613492503

- Smith RG, Parker TJ, Anderson TA. Noninfectious acute upper airway obstruction (pseudo-Ludwig phenomenon): report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 45(8):701–704. pmid:3475442

- Zacharia GS, Kandiyil S, Thomas V. Pseudo-Ludwig's phenomenon: a rare clinical manifestation in liver cirrhosis. ACG Case Rep J 2014; 2(1):53–54. doi:10.14309/crj.2014.83

An 83-year-old woman with hypertension, hypothyroidism, and a history of depression presented to the emergency department with acute shortness of breath and hypoxia. She was found to have submassive pulmonary embolism, and a heparin infusion was started immediately.

Urgent nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy revealed a hematoma at the base of her tongue that extended into the vallecula, piriform sinuses, and aryepiglottic fold, causing acute airway obstruction. These features combined with the supratherapeutic aPTT led to the diagnosis of pseudo-Ludwig angina.

DANGER OF RAPID AIRWAY COMPROMISE

Pseudo-Ludwig angina is a rare condition in which over-anticoagulation causes sublingual swelling leading to airway obstruction, whereas true Ludwig angina is an infectious regional suppuration of the neck.

Most reported cases of pseudo-Ludwig angina have resulted from overanticogulation with warfarin or warfarin-like substances (rodenticides), or from coagulopathy due to liver disease.1–3 Early recognition is essential to avoid airway compromise.

In our patient, all anticoagulation was discontinued, and she was intubated until the hematoma began to resolve, the aPTT returned to normal, and respiratory compromise improved. At follow-up 2 months later, the sublingual hematoma had completely resolved (Figure 1). And at a 6-month follow-up visit, the pulmonary embolism had resolved, and pulmonary pressures by 2-dimensional echocardiography were normal.

An 83-year-old woman with hypertension, hypothyroidism, and a history of depression presented to the emergency department with acute shortness of breath and hypoxia. She was found to have submassive pulmonary embolism, and a heparin infusion was started immediately.

Urgent nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy revealed a hematoma at the base of her tongue that extended into the vallecula, piriform sinuses, and aryepiglottic fold, causing acute airway obstruction. These features combined with the supratherapeutic aPTT led to the diagnosis of pseudo-Ludwig angina.

DANGER OF RAPID AIRWAY COMPROMISE

Pseudo-Ludwig angina is a rare condition in which over-anticoagulation causes sublingual swelling leading to airway obstruction, whereas true Ludwig angina is an infectious regional suppuration of the neck.

Most reported cases of pseudo-Ludwig angina have resulted from overanticogulation with warfarin or warfarin-like substances (rodenticides), or from coagulopathy due to liver disease.1–3 Early recognition is essential to avoid airway compromise.

In our patient, all anticoagulation was discontinued, and she was intubated until the hematoma began to resolve, the aPTT returned to normal, and respiratory compromise improved. At follow-up 2 months later, the sublingual hematoma had completely resolved (Figure 1). And at a 6-month follow-up visit, the pulmonary embolism had resolved, and pulmonary pressures by 2-dimensional echocardiography were normal.

- Lovallo E, Patterson S, Erickson M, Chin C, Blanc P, Durrani TS. When is “pseudo-Ludwig’s angina” associated with coagulopathy also a “pseudo” hemorrhage? J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2013; 1(2):2324709613492503. doi:10.1177/2324709613492503

- Smith RG, Parker TJ, Anderson TA. Noninfectious acute upper airway obstruction (pseudo-Ludwig phenomenon): report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 45(8):701–704. pmid:3475442

- Zacharia GS, Kandiyil S, Thomas V. Pseudo-Ludwig's phenomenon: a rare clinical manifestation in liver cirrhosis. ACG Case Rep J 2014; 2(1):53–54. doi:10.14309/crj.2014.83

- Lovallo E, Patterson S, Erickson M, Chin C, Blanc P, Durrani TS. When is “pseudo-Ludwig’s angina” associated with coagulopathy also a “pseudo” hemorrhage? J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2013; 1(2):2324709613492503. doi:10.1177/2324709613492503

- Smith RG, Parker TJ, Anderson TA. Noninfectious acute upper airway obstruction (pseudo-Ludwig phenomenon): report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 45(8):701–704. pmid:3475442

- Zacharia GS, Kandiyil S, Thomas V. Pseudo-Ludwig's phenomenon: a rare clinical manifestation in liver cirrhosis. ACG Case Rep J 2014; 2(1):53–54. doi:10.14309/crj.2014.83

Mediastinal granuloma due to histoplasmosis in a patient on infliximab

A 50-year-old man with Crohn disease and psoriatic arthritis treated with infliximab and methotrexate presented to a tertiary care hospital with fever, cough, and chest discomfort. The symptoms had first appeared 2 weeks earlier, and he had gone to an urgent care center, where he was prescribed a 5-day course of azithromycin and a corticosteroid, but this had not relieved his symptoms.

Bronchoscopy revealed edematous mucosa throughout, with minimal secretion. Specimens for bacterial, acid-fast bacillus, and fungal cultures were obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage. Endobronchial lymph node biopsy with ultrasonographic guidance revealed nonnecrotizing granuloma.

Bronchoalveolar lavage cultures showed no growth, but the patient’s serum histoplasma antigen was positive at 5.99 ng/dL (reference range: none detected), leading to the diagnosis of mediastinal granuloma due to histoplasmosis with possible dissemination. His immunosuppressant drugs were stopped, and oral itraconazole was started.

At a follow-up visit 2 months later, his serum antigen level had decreased to 0.68 ng/dL, and he had no symptoms whatsoever. At a visit 1 month after that, infliximab and methotrexate were restarted because of an exacerbation of Crohn disease. His oral itraconazole treatment was to be continued for at least 12 months, given the high suspicion for disseminated histoplasmosis while on immunosuppressant therapy.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF GRANULOMATOUS LUNG DISEASE AND LYMPHADENOPATHY

The differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease and lymphadenopathy is broad and includes noninfectious and infectious conditions.1

Noninfectious causes include lymphoma, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, hypersensitivity pneumonia, side effects of drugs (eg, methotrexate, etanercept), rheumatoid nodules, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, primary amyloidosis, pneumoconiosis (eg, beryllium, cobalt), and Castleman disease.

There is concern that tumor necrosis factor antagonists may increase the risk of lymphoma, but a 2017 study found no evidence of this.2

Infectious conditions associated with granulomatous lung disease include tuberculosis, nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, fungal infection (eg, Cryptococcus, Coccidioides, Histoplasma, Blastomyces), brucellosis, tularemia (respiratory type B), parasitic infection (eg, Toxocara, Leishmania, Echinococcus, Schistosoma), and Whipple disease.

HISTOPLASMOSIS

Histoplasmosis, caused by infection with Histoplasma capsulatum, is the most prevalent endemic mycotic disease in the United States.3 The fungus is commonly found in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys in the United States, and also in Central and South America and Asia.

Risk factors for histoplasmosis include living in or traveling to an endemic area, exposure to aerosolized soil that contains spores, and exposure to bats or birds and their droppings.4

Fewer than 5% of exposed individuals develop symptoms, which include fever, chills, headache, myalgia, anorexia, cough, and chest pain.5 Patients may experience symptoms shortly after exposure or may remain free of symptoms for years, with intermittent relapses of symptoms.6 Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy is common in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.7

The risk of disseminated histoplasmosis is greater in patients with reduced cell-mediated immunity, such as in human immunodeficiency virus infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, solid-organ or bone marrow transplant, hematologic malignancies, immunosuppression (corticosteroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and tumor necrosis factor antagonists), and congenital T-cell deficiencies.8

In a retrospective study, infliximab was the tumor necrosis factor antagonist most commonly associated with histoplasmosis.9 In a study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the disease-modifying drug most commonly associated was methotrexate.10

GOLD STANDARD FOR DIAGNOSIS

Isolation of H capsulatum from clinical specimens remains the gold standard for confirmation of histoplasmosis. The sensitivity of culture to detect H capsulatum depends on the clinical manifestations: it is 74% in patients with disseminated histoplasmosis, but only 42% in patients with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.11 The serum histoplasma antigen test has a sensitivity of 91.8% in disseminated histoplasmosis, 87.5% in chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis, and 83% in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.12

Urine testing for histoplasma antigen has generally proven to be slightly more sensitive than serum testing in all manifestations of histoplasmosis.13 Combining urine and serum testing increases the likelihood of antigen detection.

TREATMENT

Asymptomatic patients with mediastinal histoplasmosis do not require treatment. (Note: in some cases, lymphadenopathy is found incidentally, and biopsy is done to rule out malignancy.)

Standard treatment of symptomatic mediastinal histoplasmosis is oral itraconazole 200 mg, 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg orally once or twice daily for 6 to 12 weeks.14

Although stopping immunosuppressant drugs is considered the standard of care in treating histoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients, there are no guidelines on when to resume them. However, a retrospective study of 98 cases of histoplasmosis in patients on tumor necrosis factor antagonists found that resuming immunosuppressants might be safe with close monitoring during the course of antifungal therapy.9 The role of long-term suppressive therapy with antifungal agents in patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapy is still unknown and needs further study.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

- Histoplasmosis is the most prevalent endemic mycotic disease in the United States, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy is commonly seen in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.

- Histoplasmosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease in patients from an endemic area or with a history of travel to an endemic area.

- Immunosuppressive agents such as tumor necrosis factor antagonists and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs can predispose to invasive fungal infection, including histoplasmosis.

- While isolation of H capsulatum from culture remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, the histoplasma antigen tests (serum and urine) is more sensitive than culture.

- Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U, Bonella F. Differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease: clues and pitfalls: number 4 in the Series “Pathology for the clinician.” Edited by Peter Dorfmüller and Alberto Cavazza. Eur Respir Rev 2017; 26(145). doi:10.1183/16000617.0012-2017

- Mercer LK, Galloway JB, Lunt M, et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients exposed to antitumour necrosis factor therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(3):497–503. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209389

- Chu JH, Feudtner C, Heydon K, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE. Hospitalizations for endemic mycoses: a population-based national study. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42(6):822–825. doi:10.1086/500405

- Benedict K, Mody RK. Epidemiology of histoplasmosis outbreaks, United States, 1938–2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22(3):370–378. doi:10.3201/eid2203.151117

- Wheat LJ. Diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1989; 8(5):480–490. pmid:2502413

- Goodwin RA Jr, Shapiro JL, Thurman GH, Thurman SS, Des Prez RM. Disseminated histoplasmosis: clinical and pathologic correlations. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980; 59(1):1–33. pmid:7356773

- Wheat LJ, Conces D, Allen SD, Blue-Hnidy D, Loyd J. Pulmonary histoplasmosis syndromes: recognition, diagnosis, and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 25(2):129–144. doi:10.1055/s-2004-824898

- Assi MA, Sandid MS, Baddour LM, Roberts GD, Walker RC. Systemic histoplasmosis: a 15-year retrospective institutional review of 111 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007; 86(3):162–169. doi:10.1097/md.0b013e3180679130

- Vergidis P, Avery RK, Wheat LJ, et al. Histoplasmosis complicating tumor necrosis factor-a blocker therapy: a retrospective analysis of 98 cases. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(3):409–417. doi:10.1093/cid/civ299

- Olson TC, Bongartz T, Crowson CS, Roberts GD, Orenstein R, Matteson EL. Histoplasmosis infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 1998–2009. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11:145. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-145

- Hage CA, Ribes JA, Wengenack NL, et al. A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53(5):448–454. doi:10.1093/cid/cir435

- Azar MM, Hage CA. Laboratory diagnostics for histoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55(6):1612–1620. doi:10.1128/JCM.02430-16

- Swartzentruber S, Rhodes L, Kurkjian K, et al. Diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis by antigen detection. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49(12):1878–1882. doi:10.1086/648421

- Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45(7):807–825. doi:10.1086/521259

A 50-year-old man with Crohn disease and psoriatic arthritis treated with infliximab and methotrexate presented to a tertiary care hospital with fever, cough, and chest discomfort. The symptoms had first appeared 2 weeks earlier, and he had gone to an urgent care center, where he was prescribed a 5-day course of azithromycin and a corticosteroid, but this had not relieved his symptoms.

Bronchoscopy revealed edematous mucosa throughout, with minimal secretion. Specimens for bacterial, acid-fast bacillus, and fungal cultures were obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage. Endobronchial lymph node biopsy with ultrasonographic guidance revealed nonnecrotizing granuloma.

Bronchoalveolar lavage cultures showed no growth, but the patient’s serum histoplasma antigen was positive at 5.99 ng/dL (reference range: none detected), leading to the diagnosis of mediastinal granuloma due to histoplasmosis with possible dissemination. His immunosuppressant drugs were stopped, and oral itraconazole was started.

At a follow-up visit 2 months later, his serum antigen level had decreased to 0.68 ng/dL, and he had no symptoms whatsoever. At a visit 1 month after that, infliximab and methotrexate were restarted because of an exacerbation of Crohn disease. His oral itraconazole treatment was to be continued for at least 12 months, given the high suspicion for disseminated histoplasmosis while on immunosuppressant therapy.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF GRANULOMATOUS LUNG DISEASE AND LYMPHADENOPATHY

The differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease and lymphadenopathy is broad and includes noninfectious and infectious conditions.1

Noninfectious causes include lymphoma, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, hypersensitivity pneumonia, side effects of drugs (eg, methotrexate, etanercept), rheumatoid nodules, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, primary amyloidosis, pneumoconiosis (eg, beryllium, cobalt), and Castleman disease.

There is concern that tumor necrosis factor antagonists may increase the risk of lymphoma, but a 2017 study found no evidence of this.2

Infectious conditions associated with granulomatous lung disease include tuberculosis, nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, fungal infection (eg, Cryptococcus, Coccidioides, Histoplasma, Blastomyces), brucellosis, tularemia (respiratory type B), parasitic infection (eg, Toxocara, Leishmania, Echinococcus, Schistosoma), and Whipple disease.

HISTOPLASMOSIS

Histoplasmosis, caused by infection with Histoplasma capsulatum, is the most prevalent endemic mycotic disease in the United States.3 The fungus is commonly found in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys in the United States, and also in Central and South America and Asia.

Risk factors for histoplasmosis include living in or traveling to an endemic area, exposure to aerosolized soil that contains spores, and exposure to bats or birds and their droppings.4

Fewer than 5% of exposed individuals develop symptoms, which include fever, chills, headache, myalgia, anorexia, cough, and chest pain.5 Patients may experience symptoms shortly after exposure or may remain free of symptoms for years, with intermittent relapses of symptoms.6 Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy is common in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.7

The risk of disseminated histoplasmosis is greater in patients with reduced cell-mediated immunity, such as in human immunodeficiency virus infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, solid-organ or bone marrow transplant, hematologic malignancies, immunosuppression (corticosteroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and tumor necrosis factor antagonists), and congenital T-cell deficiencies.8

In a retrospective study, infliximab was the tumor necrosis factor antagonist most commonly associated with histoplasmosis.9 In a study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the disease-modifying drug most commonly associated was methotrexate.10

GOLD STANDARD FOR DIAGNOSIS

Isolation of H capsulatum from clinical specimens remains the gold standard for confirmation of histoplasmosis. The sensitivity of culture to detect H capsulatum depends on the clinical manifestations: it is 74% in patients with disseminated histoplasmosis, but only 42% in patients with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.11 The serum histoplasma antigen test has a sensitivity of 91.8% in disseminated histoplasmosis, 87.5% in chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis, and 83% in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.12

Urine testing for histoplasma antigen has generally proven to be slightly more sensitive than serum testing in all manifestations of histoplasmosis.13 Combining urine and serum testing increases the likelihood of antigen detection.

TREATMENT

Asymptomatic patients with mediastinal histoplasmosis do not require treatment. (Note: in some cases, lymphadenopathy is found incidentally, and biopsy is done to rule out malignancy.)

Standard treatment of symptomatic mediastinal histoplasmosis is oral itraconazole 200 mg, 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg orally once or twice daily for 6 to 12 weeks.14

Although stopping immunosuppressant drugs is considered the standard of care in treating histoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients, there are no guidelines on when to resume them. However, a retrospective study of 98 cases of histoplasmosis in patients on tumor necrosis factor antagonists found that resuming immunosuppressants might be safe with close monitoring during the course of antifungal therapy.9 The role of long-term suppressive therapy with antifungal agents in patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapy is still unknown and needs further study.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

- Histoplasmosis is the most prevalent endemic mycotic disease in the United States, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy is commonly seen in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.

- Histoplasmosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease in patients from an endemic area or with a history of travel to an endemic area.

- Immunosuppressive agents such as tumor necrosis factor antagonists and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs can predispose to invasive fungal infection, including histoplasmosis.

- While isolation of H capsulatum from culture remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, the histoplasma antigen tests (serum and urine) is more sensitive than culture.

A 50-year-old man with Crohn disease and psoriatic arthritis treated with infliximab and methotrexate presented to a tertiary care hospital with fever, cough, and chest discomfort. The symptoms had first appeared 2 weeks earlier, and he had gone to an urgent care center, where he was prescribed a 5-day course of azithromycin and a corticosteroid, but this had not relieved his symptoms.

Bronchoscopy revealed edematous mucosa throughout, with minimal secretion. Specimens for bacterial, acid-fast bacillus, and fungal cultures were obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage. Endobronchial lymph node biopsy with ultrasonographic guidance revealed nonnecrotizing granuloma.

Bronchoalveolar lavage cultures showed no growth, but the patient’s serum histoplasma antigen was positive at 5.99 ng/dL (reference range: none detected), leading to the diagnosis of mediastinal granuloma due to histoplasmosis with possible dissemination. His immunosuppressant drugs were stopped, and oral itraconazole was started.

At a follow-up visit 2 months later, his serum antigen level had decreased to 0.68 ng/dL, and he had no symptoms whatsoever. At a visit 1 month after that, infliximab and methotrexate were restarted because of an exacerbation of Crohn disease. His oral itraconazole treatment was to be continued for at least 12 months, given the high suspicion for disseminated histoplasmosis while on immunosuppressant therapy.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF GRANULOMATOUS LUNG DISEASE AND LYMPHADENOPATHY

The differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease and lymphadenopathy is broad and includes noninfectious and infectious conditions.1

Noninfectious causes include lymphoma, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, hypersensitivity pneumonia, side effects of drugs (eg, methotrexate, etanercept), rheumatoid nodules, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, primary amyloidosis, pneumoconiosis (eg, beryllium, cobalt), and Castleman disease.

There is concern that tumor necrosis factor antagonists may increase the risk of lymphoma, but a 2017 study found no evidence of this.2

Infectious conditions associated with granulomatous lung disease include tuberculosis, nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, fungal infection (eg, Cryptococcus, Coccidioides, Histoplasma, Blastomyces), brucellosis, tularemia (respiratory type B), parasitic infection (eg, Toxocara, Leishmania, Echinococcus, Schistosoma), and Whipple disease.

HISTOPLASMOSIS

Histoplasmosis, caused by infection with Histoplasma capsulatum, is the most prevalent endemic mycotic disease in the United States.3 The fungus is commonly found in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys in the United States, and also in Central and South America and Asia.

Risk factors for histoplasmosis include living in or traveling to an endemic area, exposure to aerosolized soil that contains spores, and exposure to bats or birds and their droppings.4

Fewer than 5% of exposed individuals develop symptoms, which include fever, chills, headache, myalgia, anorexia, cough, and chest pain.5 Patients may experience symptoms shortly after exposure or may remain free of symptoms for years, with intermittent relapses of symptoms.6 Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy is common in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.7

The risk of disseminated histoplasmosis is greater in patients with reduced cell-mediated immunity, such as in human immunodeficiency virus infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, solid-organ or bone marrow transplant, hematologic malignancies, immunosuppression (corticosteroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and tumor necrosis factor antagonists), and congenital T-cell deficiencies.8

In a retrospective study, infliximab was the tumor necrosis factor antagonist most commonly associated with histoplasmosis.9 In a study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the disease-modifying drug most commonly associated was methotrexate.10

GOLD STANDARD FOR DIAGNOSIS

Isolation of H capsulatum from clinical specimens remains the gold standard for confirmation of histoplasmosis. The sensitivity of culture to detect H capsulatum depends on the clinical manifestations: it is 74% in patients with disseminated histoplasmosis, but only 42% in patients with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.11 The serum histoplasma antigen test has a sensitivity of 91.8% in disseminated histoplasmosis, 87.5% in chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis, and 83% in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.12

Urine testing for histoplasma antigen has generally proven to be slightly more sensitive than serum testing in all manifestations of histoplasmosis.13 Combining urine and serum testing increases the likelihood of antigen detection.

TREATMENT

Asymptomatic patients with mediastinal histoplasmosis do not require treatment. (Note: in some cases, lymphadenopathy is found incidentally, and biopsy is done to rule out malignancy.)

Standard treatment of symptomatic mediastinal histoplasmosis is oral itraconazole 200 mg, 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg orally once or twice daily for 6 to 12 weeks.14

Although stopping immunosuppressant drugs is considered the standard of care in treating histoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients, there are no guidelines on when to resume them. However, a retrospective study of 98 cases of histoplasmosis in patients on tumor necrosis factor antagonists found that resuming immunosuppressants might be safe with close monitoring during the course of antifungal therapy.9 The role of long-term suppressive therapy with antifungal agents in patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapy is still unknown and needs further study.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

- Histoplasmosis is the most prevalent endemic mycotic disease in the United States, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy is commonly seen in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.

- Histoplasmosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease in patients from an endemic area or with a history of travel to an endemic area.

- Immunosuppressive agents such as tumor necrosis factor antagonists and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs can predispose to invasive fungal infection, including histoplasmosis.

- While isolation of H capsulatum from culture remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, the histoplasma antigen tests (serum and urine) is more sensitive than culture.

- Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U, Bonella F. Differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease: clues and pitfalls: number 4 in the Series “Pathology for the clinician.” Edited by Peter Dorfmüller and Alberto Cavazza. Eur Respir Rev 2017; 26(145). doi:10.1183/16000617.0012-2017

- Mercer LK, Galloway JB, Lunt M, et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients exposed to antitumour necrosis factor therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(3):497–503. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209389

- Chu JH, Feudtner C, Heydon K, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE. Hospitalizations for endemic mycoses: a population-based national study. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42(6):822–825. doi:10.1086/500405

- Benedict K, Mody RK. Epidemiology of histoplasmosis outbreaks, United States, 1938–2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22(3):370–378. doi:10.3201/eid2203.151117

- Wheat LJ. Diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1989; 8(5):480–490. pmid:2502413

- Goodwin RA Jr, Shapiro JL, Thurman GH, Thurman SS, Des Prez RM. Disseminated histoplasmosis: clinical and pathologic correlations. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980; 59(1):1–33. pmid:7356773

- Wheat LJ, Conces D, Allen SD, Blue-Hnidy D, Loyd J. Pulmonary histoplasmosis syndromes: recognition, diagnosis, and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 25(2):129–144. doi:10.1055/s-2004-824898

- Assi MA, Sandid MS, Baddour LM, Roberts GD, Walker RC. Systemic histoplasmosis: a 15-year retrospective institutional review of 111 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007; 86(3):162–169. doi:10.1097/md.0b013e3180679130

- Vergidis P, Avery RK, Wheat LJ, et al. Histoplasmosis complicating tumor necrosis factor-a blocker therapy: a retrospective analysis of 98 cases. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(3):409–417. doi:10.1093/cid/civ299

- Olson TC, Bongartz T, Crowson CS, Roberts GD, Orenstein R, Matteson EL. Histoplasmosis infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 1998–2009. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11:145. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-145

- Hage CA, Ribes JA, Wengenack NL, et al. A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53(5):448–454. doi:10.1093/cid/cir435

- Azar MM, Hage CA. Laboratory diagnostics for histoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55(6):1612–1620. doi:10.1128/JCM.02430-16

- Swartzentruber S, Rhodes L, Kurkjian K, et al. Diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis by antigen detection. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49(12):1878–1882. doi:10.1086/648421

- Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45(7):807–825. doi:10.1086/521259

- Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U, Bonella F. Differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease: clues and pitfalls: number 4 in the Series “Pathology for the clinician.” Edited by Peter Dorfmüller and Alberto Cavazza. Eur Respir Rev 2017; 26(145). doi:10.1183/16000617.0012-2017

- Mercer LK, Galloway JB, Lunt M, et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients exposed to antitumour necrosis factor therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(3):497–503. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209389

- Chu JH, Feudtner C, Heydon K, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE. Hospitalizations for endemic mycoses: a population-based national study. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42(6):822–825. doi:10.1086/500405

- Benedict K, Mody RK. Epidemiology of histoplasmosis outbreaks, United States, 1938–2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22(3):370–378. doi:10.3201/eid2203.151117

- Wheat LJ. Diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1989; 8(5):480–490. pmid:2502413

- Goodwin RA Jr, Shapiro JL, Thurman GH, Thurman SS, Des Prez RM. Disseminated histoplasmosis: clinical and pathologic correlations. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980; 59(1):1–33. pmid:7356773

- Wheat LJ, Conces D, Allen SD, Blue-Hnidy D, Loyd J. Pulmonary histoplasmosis syndromes: recognition, diagnosis, and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 25(2):129–144. doi:10.1055/s-2004-824898

- Assi MA, Sandid MS, Baddour LM, Roberts GD, Walker RC. Systemic histoplasmosis: a 15-year retrospective institutional review of 111 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007; 86(3):162–169. doi:10.1097/md.0b013e3180679130

- Vergidis P, Avery RK, Wheat LJ, et al. Histoplasmosis complicating tumor necrosis factor-a blocker therapy: a retrospective analysis of 98 cases. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(3):409–417. doi:10.1093/cid/civ299

- Olson TC, Bongartz T, Crowson CS, Roberts GD, Orenstein R, Matteson EL. Histoplasmosis infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 1998–2009. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11:145. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-145

- Hage CA, Ribes JA, Wengenack NL, et al. A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53(5):448–454. doi:10.1093/cid/cir435

- Azar MM, Hage CA. Laboratory diagnostics for histoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55(6):1612–1620. doi:10.1128/JCM.02430-16

- Swartzentruber S, Rhodes L, Kurkjian K, et al. Diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis by antigen detection. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49(12):1878–1882. doi:10.1086/648421

- Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45(7):807–825. doi:10.1086/521259

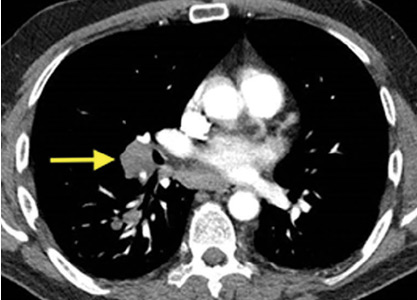

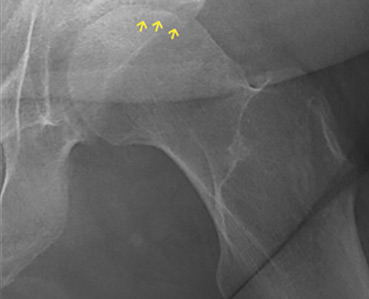

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head with subchondral collapse

A 45-year-old woman with a history of multiple organ transplants presented with a 1-month history of anterior left hip pain with insidious onset. Although she was able to perform activities of daily living, she reported increasing difficulty with weight-bearing activities.

RISK FACTORS

Osteonecrosis of the hip is caused by prolonged interruption of blood flow to the femoral head.2 While idiopathic osteonecrosis is not uncommon, the condition is often associated with alcohol abuse or, as in our patient, long-term corticosteroid use after organ transplant.3 Corticosteroid use is also the most frequently reported risk factor for multifocal osteonecrosis.

Less common risk factors include systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid antibodies, coagulopathies, sickle cell disease, Gaucher disease, trauma, and external-beam therapy.

Young age is also associated with osteonecrosis, as nearly 75% of patients are between age 30 and 60.4

APPROACH TO DIAGNOSIS

Our patient had a typical clinical presentation of this disease: she was relatively young, was on long-term corticosteroids, and had acute anterior groin pain followed by progressive functional impairment.

The diagnostic evaluation consists of a detailed history, with attention to specific risk factors, and a thorough clinical examination followed by imaging, usually with plain radiography. However, plain radiographs are often unremarkable when the condition is in the early stages. In such cases, magnetic resonance imaging is recommended if clinical suspicion for osteonecrosis is high. It is far more sensitive (> 99%) and specific (> 99%) than plain radiography, and it detects early changes in the femoral head such as focal lesions and bone marrow edema.5

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Treatment of osteonecrosis is surgical and depends on the stage of disease.6

Joint preservation may be an option for small to medium-sized lesions before subchondral collapse has occurred; options include core decompression, bone grafting, and femoral osteotomy to preserve the native femoral head. These procedures have a higher success rate in young patients.

Subchondral collapse usually warrants hip replacement.

OUR PATIENT’S TREATMENT

- Pappas JN. The musculoskeletal crescent sign. Radiology 2000; 217(1):213–214. doi:10.1148/radiology.217.1.r00oc22213

- Shah KN, Racine J, Jones LC, Aaron RK. Pathophysiology and risk factors for osteonecrosis. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2015; 8(3):201–209. doi:10.1007/s12178-015-9277-8

- Moya-Angeler J, Gianakos AL, Villa JC, Ni A, Lane JM. Current concepts on osteonecrosis of the femoral head. World J Orthop 2015; 6(8):590–601. doi:10.5312/wjo.v6.i8.590

- Assouline-Dayan Y, Chang C, Greenspan A, Shoenfeld Y, Gershwin ME. Pathogenesis and natural history of osteonecrosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002; 32(2):94–124. pmid:12430099

- Pierce TP, Jauregui JJ, Cherian JJ, Elmallah RK, Mont MA. Imaging evaluation of patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2015; 8(3):221–227. doi:10.1007/s12178-015-9279-6

- Chughtai M, Piuzzi NS, Khlopas A, Jones LC, Goodman SB, Mont MA. An evidence-based guide to the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Bone Joint J 2017; 99-B(10):1267–1279. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.99B10.BJJ-2017-0233.R2

A 45-year-old woman with a history of multiple organ transplants presented with a 1-month history of anterior left hip pain with insidious onset. Although she was able to perform activities of daily living, she reported increasing difficulty with weight-bearing activities.

RISK FACTORS

Osteonecrosis of the hip is caused by prolonged interruption of blood flow to the femoral head.2 While idiopathic osteonecrosis is not uncommon, the condition is often associated with alcohol abuse or, as in our patient, long-term corticosteroid use after organ transplant.3 Corticosteroid use is also the most frequently reported risk factor for multifocal osteonecrosis.

Less common risk factors include systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid antibodies, coagulopathies, sickle cell disease, Gaucher disease, trauma, and external-beam therapy.

Young age is also associated with osteonecrosis, as nearly 75% of patients are between age 30 and 60.4

APPROACH TO DIAGNOSIS

Our patient had a typical clinical presentation of this disease: she was relatively young, was on long-term corticosteroids, and had acute anterior groin pain followed by progressive functional impairment.

The diagnostic evaluation consists of a detailed history, with attention to specific risk factors, and a thorough clinical examination followed by imaging, usually with plain radiography. However, plain radiographs are often unremarkable when the condition is in the early stages. In such cases, magnetic resonance imaging is recommended if clinical suspicion for osteonecrosis is high. It is far more sensitive (> 99%) and specific (> 99%) than plain radiography, and it detects early changes in the femoral head such as focal lesions and bone marrow edema.5

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Treatment of osteonecrosis is surgical and depends on the stage of disease.6

Joint preservation may be an option for small to medium-sized lesions before subchondral collapse has occurred; options include core decompression, bone grafting, and femoral osteotomy to preserve the native femoral head. These procedures have a higher success rate in young patients.

Subchondral collapse usually warrants hip replacement.

OUR PATIENT’S TREATMENT

A 45-year-old woman with a history of multiple organ transplants presented with a 1-month history of anterior left hip pain with insidious onset. Although she was able to perform activities of daily living, she reported increasing difficulty with weight-bearing activities.

RISK FACTORS

Osteonecrosis of the hip is caused by prolonged interruption of blood flow to the femoral head.2 While idiopathic osteonecrosis is not uncommon, the condition is often associated with alcohol abuse or, as in our patient, long-term corticosteroid use after organ transplant.3 Corticosteroid use is also the most frequently reported risk factor for multifocal osteonecrosis.

Less common risk factors include systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid antibodies, coagulopathies, sickle cell disease, Gaucher disease, trauma, and external-beam therapy.

Young age is also associated with osteonecrosis, as nearly 75% of patients are between age 30 and 60.4

APPROACH TO DIAGNOSIS

Our patient had a typical clinical presentation of this disease: she was relatively young, was on long-term corticosteroids, and had acute anterior groin pain followed by progressive functional impairment.

The diagnostic evaluation consists of a detailed history, with attention to specific risk factors, and a thorough clinical examination followed by imaging, usually with plain radiography. However, plain radiographs are often unremarkable when the condition is in the early stages. In such cases, magnetic resonance imaging is recommended if clinical suspicion for osteonecrosis is high. It is far more sensitive (> 99%) and specific (> 99%) than plain radiography, and it detects early changes in the femoral head such as focal lesions and bone marrow edema.5

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Treatment of osteonecrosis is surgical and depends on the stage of disease.6

Joint preservation may be an option for small to medium-sized lesions before subchondral collapse has occurred; options include core decompression, bone grafting, and femoral osteotomy to preserve the native femoral head. These procedures have a higher success rate in young patients.

Subchondral collapse usually warrants hip replacement.

OUR PATIENT’S TREATMENT

- Pappas JN. The musculoskeletal crescent sign. Radiology 2000; 217(1):213–214. doi:10.1148/radiology.217.1.r00oc22213

- Shah KN, Racine J, Jones LC, Aaron RK. Pathophysiology and risk factors for osteonecrosis. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2015; 8(3):201–209. doi:10.1007/s12178-015-9277-8

- Moya-Angeler J, Gianakos AL, Villa JC, Ni A, Lane JM. Current concepts on osteonecrosis of the femoral head. World J Orthop 2015; 6(8):590–601. doi:10.5312/wjo.v6.i8.590

- Assouline-Dayan Y, Chang C, Greenspan A, Shoenfeld Y, Gershwin ME. Pathogenesis and natural history of osteonecrosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002; 32(2):94–124. pmid:12430099

- Pierce TP, Jauregui JJ, Cherian JJ, Elmallah RK, Mont MA. Imaging evaluation of patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2015; 8(3):221–227. doi:10.1007/s12178-015-9279-6

- Chughtai M, Piuzzi NS, Khlopas A, Jones LC, Goodman SB, Mont MA. An evidence-based guide to the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Bone Joint J 2017; 99-B(10):1267–1279. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.99B10.BJJ-2017-0233.R2

- Pappas JN. The musculoskeletal crescent sign. Radiology 2000; 217(1):213–214. doi:10.1148/radiology.217.1.r00oc22213

- Shah KN, Racine J, Jones LC, Aaron RK. Pathophysiology and risk factors for osteonecrosis. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2015; 8(3):201–209. doi:10.1007/s12178-015-9277-8

- Moya-Angeler J, Gianakos AL, Villa JC, Ni A, Lane JM. Current concepts on osteonecrosis of the femoral head. World J Orthop 2015; 6(8):590–601. doi:10.5312/wjo.v6.i8.590

- Assouline-Dayan Y, Chang C, Greenspan A, Shoenfeld Y, Gershwin ME. Pathogenesis and natural history of osteonecrosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002; 32(2):94–124. pmid:12430099

- Pierce TP, Jauregui JJ, Cherian JJ, Elmallah RK, Mont MA. Imaging evaluation of patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2015; 8(3):221–227. doi:10.1007/s12178-015-9279-6

- Chughtai M, Piuzzi NS, Khlopas A, Jones LC, Goodman SB, Mont MA. An evidence-based guide to the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Bone Joint J 2017; 99-B(10):1267–1279. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.99B10.BJJ-2017-0233.R2

Thinker’s sign

See Mangione and Aronowitz editorials

Mechanical pressure induced by friction of the elbows on the thighs may result in proliferation of the stratum corneum and the release of hemosiderin from erythrocytes, resulting in the skin changes seen in this patient, which because of the tripod positioning are known as “thinker’s sign,” a term coined in 1963 by Rothenberg1 to describe findings in patients with chronic pulmonary disease and advanced respiratory insufficiency. It is also referred to as the Dahl sign, based on a report by Dahl of similar findings in patients with emphysema.2

- Rothenberg HJ. The thinker's sign. JAMA 1963; 184:902–903. pmid:13975358

- Dahl MV. Emphysema. Arch Dermatol 1970; 101(1):117. pmid:5416788

See Mangione and Aronowitz editorials

Mechanical pressure induced by friction of the elbows on the thighs may result in proliferation of the stratum corneum and the release of hemosiderin from erythrocytes, resulting in the skin changes seen in this patient, which because of the tripod positioning are known as “thinker’s sign,” a term coined in 1963 by Rothenberg1 to describe findings in patients with chronic pulmonary disease and advanced respiratory insufficiency. It is also referred to as the Dahl sign, based on a report by Dahl of similar findings in patients with emphysema.2

See Mangione and Aronowitz editorials

Mechanical pressure induced by friction of the elbows on the thighs may result in proliferation of the stratum corneum and the release of hemosiderin from erythrocytes, resulting in the skin changes seen in this patient, which because of the tripod positioning are known as “thinker’s sign,” a term coined in 1963 by Rothenberg1 to describe findings in patients with chronic pulmonary disease and advanced respiratory insufficiency. It is also referred to as the Dahl sign, based on a report by Dahl of similar findings in patients with emphysema.2

- Rothenberg HJ. The thinker's sign. JAMA 1963; 184:902–903. pmid:13975358

- Dahl MV. Emphysema. Arch Dermatol 1970; 101(1):117. pmid:5416788

- Rothenberg HJ. The thinker's sign. JAMA 1963; 184:902–903. pmid:13975358

- Dahl MV. Emphysema. Arch Dermatol 1970; 101(1):117. pmid:5416788

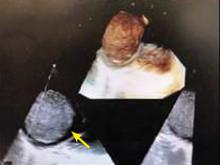

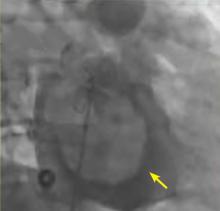

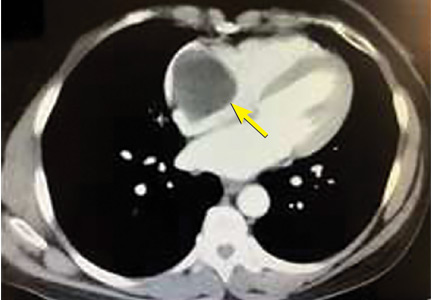

A right atrial mass

PRIMARY HEART TUMORS ARE RARE

The most common neoplasms that metastasize to the heart are malignant melanoma, lymphoma, leukemia, breast, and lung cancers. The layers of the heart affected by malignant neoplasms in order of frequency from highest to lowest are the pericardium, epicardium, myocardium, and endocardium.3

MYXOMA: A PRIMARY CARDIAC TUMOR

The most common type of primary cardiac tumor is myxoma. Most—75% to 80%—occur in the left atrium, while 15% to 20% occur in the right atrium.5 Right atrial myxomas are usually found in the intraatrial septum at the border of the fossa ovalis.6 Myxomas can occur at any age, but are most common in women between the third and sixth decades.2

The cause of atrial myxomas is currently unknown. Most cases are sporadic. However, 10% are familial, with an autosomal-dominant pattern.7

The clinical symptoms of right atrial myxoma depend on the tumor’s size, location, and mobility and on the patient’s physical activity and body position.4 Common presenting symptoms include shortness of breath, pulmonary edema, cough, hemoptysis, and fatigue. Thirty percent of patients present with constitutional symptoms.4

Auscultation may reveal a characteristic “tumor plop” early in diastole.4,7 About 35% of patients have laboratory abnormalities such as elevations in erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and globulin levels and anemia. Our patient did not.

Embolization occurs in about 10% of cases of right-sided myxoma and can result in pulmonary artery embolism or a stroke. Pulmonary artery embolism occurs with myxoma embolization to the lungs. Strokes can occur in patients who have a patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect, through which embolism to the systemic arterial circulation can occur.

The primary treatment for myxoma is complete resection of the tumor and its base with wide safety margins. This is particularly important to prevent recurrence of the myxoma and need for repeat operations, with their risk of surgical complications.9

- Dujardin KS, Click RL, Oh JK. The role of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in patients undergoing cardiac mass removal. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2000; 13(12):1080–1083. pmid:11119275

- Jang KH, Shin DH, Lee C, Jang JK, Cheong S, Yoo SY. Left atrial mass with stalk: thrombus or myxoma? J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2010; 18(4):154–156. doi:10.4250/jcu.2010.18.4.154

- Goldberg AD, Blankstein R, Padera RF. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation 2013; 128(16):1790–1794. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000790

- Aggarwal SK, Barik R, Sarma TC, et al. Clinical presentation and investigation findings in cardiac myxomas: new insights from the developing world. Am Heart J 2007; 154(6):1102–1107. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.032

- Diaz A, Di Salvo C, Lawrence D, Hayward M. Left atrial and right ventricular myxoma: an uncommon presentation of a rare tumour. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011; 12(4):622–623. doi:10.1510/icvts.2010.255661

- Reynen K. Cardiac myxomas. N Engl J Med 1995; 333(24):1610–1617. doi:10.1056/NEJM199512143332407

- Kolluru A, Desai D, Cohen GI. The etiology of atrial myxoma tumor plop. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57(21):e371. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.085

- Kassab R, Wehbe L, Badaoui G, el Asmar B, Jebara V, Ashoush R. Recurrent cerebrovascular accident: unusual and isolated manifestation of myxoma of the left atrium. J Med Liban 1999; 47(4):246–250. French. pmid:10641454

- Guhathakurta S, Riordan JP. Surgical treatment of right atrial myxoma. Tex Heart Inst J 2000; 27(1):61–63. pmid:10830633

PRIMARY HEART TUMORS ARE RARE

The most common neoplasms that metastasize to the heart are malignant melanoma, lymphoma, leukemia, breast, and lung cancers. The layers of the heart affected by malignant neoplasms in order of frequency from highest to lowest are the pericardium, epicardium, myocardium, and endocardium.3

MYXOMA: A PRIMARY CARDIAC TUMOR

The most common type of primary cardiac tumor is myxoma. Most—75% to 80%—occur in the left atrium, while 15% to 20% occur in the right atrium.5 Right atrial myxomas are usually found in the intraatrial septum at the border of the fossa ovalis.6 Myxomas can occur at any age, but are most common in women between the third and sixth decades.2

The cause of atrial myxomas is currently unknown. Most cases are sporadic. However, 10% are familial, with an autosomal-dominant pattern.7

The clinical symptoms of right atrial myxoma depend on the tumor’s size, location, and mobility and on the patient’s physical activity and body position.4 Common presenting symptoms include shortness of breath, pulmonary edema, cough, hemoptysis, and fatigue. Thirty percent of patients present with constitutional symptoms.4

Auscultation may reveal a characteristic “tumor plop” early in diastole.4,7 About 35% of patients have laboratory abnormalities such as elevations in erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and globulin levels and anemia. Our patient did not.

Embolization occurs in about 10% of cases of right-sided myxoma and can result in pulmonary artery embolism or a stroke. Pulmonary artery embolism occurs with myxoma embolization to the lungs. Strokes can occur in patients who have a patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect, through which embolism to the systemic arterial circulation can occur.

The primary treatment for myxoma is complete resection of the tumor and its base with wide safety margins. This is particularly important to prevent recurrence of the myxoma and need for repeat operations, with their risk of surgical complications.9

PRIMARY HEART TUMORS ARE RARE

The most common neoplasms that metastasize to the heart are malignant melanoma, lymphoma, leukemia, breast, and lung cancers. The layers of the heart affected by malignant neoplasms in order of frequency from highest to lowest are the pericardium, epicardium, myocardium, and endocardium.3

MYXOMA: A PRIMARY CARDIAC TUMOR

The most common type of primary cardiac tumor is myxoma. Most—75% to 80%—occur in the left atrium, while 15% to 20% occur in the right atrium.5 Right atrial myxomas are usually found in the intraatrial septum at the border of the fossa ovalis.6 Myxomas can occur at any age, but are most common in women between the third and sixth decades.2

The cause of atrial myxomas is currently unknown. Most cases are sporadic. However, 10% are familial, with an autosomal-dominant pattern.7

The clinical symptoms of right atrial myxoma depend on the tumor’s size, location, and mobility and on the patient’s physical activity and body position.4 Common presenting symptoms include shortness of breath, pulmonary edema, cough, hemoptysis, and fatigue. Thirty percent of patients present with constitutional symptoms.4

Auscultation may reveal a characteristic “tumor plop” early in diastole.4,7 About 35% of patients have laboratory abnormalities such as elevations in erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and globulin levels and anemia. Our patient did not.

Embolization occurs in about 10% of cases of right-sided myxoma and can result in pulmonary artery embolism or a stroke. Pulmonary artery embolism occurs with myxoma embolization to the lungs. Strokes can occur in patients who have a patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect, through which embolism to the systemic arterial circulation can occur.

The primary treatment for myxoma is complete resection of the tumor and its base with wide safety margins. This is particularly important to prevent recurrence of the myxoma and need for repeat operations, with their risk of surgical complications.9

- Dujardin KS, Click RL, Oh JK. The role of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in patients undergoing cardiac mass removal. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2000; 13(12):1080–1083. pmid:11119275

- Jang KH, Shin DH, Lee C, Jang JK, Cheong S, Yoo SY. Left atrial mass with stalk: thrombus or myxoma? J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2010; 18(4):154–156. doi:10.4250/jcu.2010.18.4.154

- Goldberg AD, Blankstein R, Padera RF. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation 2013; 128(16):1790–1794. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000790

- Aggarwal SK, Barik R, Sarma TC, et al. Clinical presentation and investigation findings in cardiac myxomas: new insights from the developing world. Am Heart J 2007; 154(6):1102–1107. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.032

- Diaz A, Di Salvo C, Lawrence D, Hayward M. Left atrial and right ventricular myxoma: an uncommon presentation of a rare tumour. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011; 12(4):622–623. doi:10.1510/icvts.2010.255661

- Reynen K. Cardiac myxomas. N Engl J Med 1995; 333(24):1610–1617. doi:10.1056/NEJM199512143332407

- Kolluru A, Desai D, Cohen GI. The etiology of atrial myxoma tumor plop. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57(21):e371. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.085

- Kassab R, Wehbe L, Badaoui G, el Asmar B, Jebara V, Ashoush R. Recurrent cerebrovascular accident: unusual and isolated manifestation of myxoma of the left atrium. J Med Liban 1999; 47(4):246–250. French. pmid:10641454

- Guhathakurta S, Riordan JP. Surgical treatment of right atrial myxoma. Tex Heart Inst J 2000; 27(1):61–63. pmid:10830633

- Dujardin KS, Click RL, Oh JK. The role of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in patients undergoing cardiac mass removal. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2000; 13(12):1080–1083. pmid:11119275

- Jang KH, Shin DH, Lee C, Jang JK, Cheong S, Yoo SY. Left atrial mass with stalk: thrombus or myxoma? J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2010; 18(4):154–156. doi:10.4250/jcu.2010.18.4.154

- Goldberg AD, Blankstein R, Padera RF. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation 2013; 128(16):1790–1794. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000790

- Aggarwal SK, Barik R, Sarma TC, et al. Clinical presentation and investigation findings in cardiac myxomas: new insights from the developing world. Am Heart J 2007; 154(6):1102–1107. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.032

- Diaz A, Di Salvo C, Lawrence D, Hayward M. Left atrial and right ventricular myxoma: an uncommon presentation of a rare tumour. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011; 12(4):622–623. doi:10.1510/icvts.2010.255661

- Reynen K. Cardiac myxomas. N Engl J Med 1995; 333(24):1610–1617. doi:10.1056/NEJM199512143332407

- Kolluru A, Desai D, Cohen GI. The etiology of atrial myxoma tumor plop. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57(21):e371. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.085

- Kassab R, Wehbe L, Badaoui G, el Asmar B, Jebara V, Ashoush R. Recurrent cerebrovascular accident: unusual and isolated manifestation of myxoma of the left atrium. J Med Liban 1999; 47(4):246–250. French. pmid:10641454

- Guhathakurta S, Riordan JP. Surgical treatment of right atrial myxoma. Tex Heart Inst J 2000; 27(1):61–63. pmid:10830633

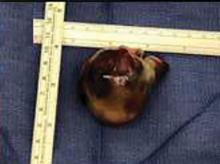

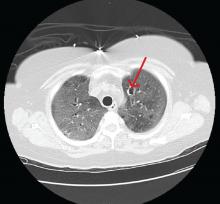

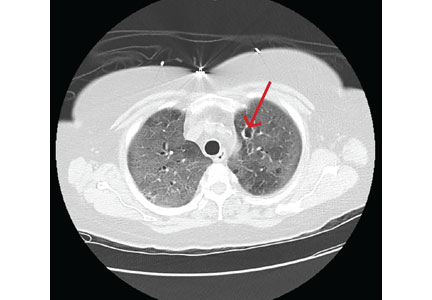

Disseminated invasive aspergillosis in an immunocompetent patient

A 57-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital for progressive hypoxic respiratory failure that developed after 10 days of empiric treatment at another hospital for an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Computed tomography (CT) showed a lesion in the upper lobe of the left lung, with new ground-glass opacities with cystic and cavitary changes raising concern for an inflammatory or infectious cause (Figure 1). Respiratory culture of expectorated secretions grew Aspergillus. Assays for beta-d-glucan and serum Aspergillus immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies were positive, although given the improvement in her oxygenation requirements and overall clinical status, these were thought to be trivial. Tests for immunoglobulin deficiencies and human immunodeficiency virus were negative, ruling out primary immunodeficiency. However, within the next 48 hours, her respiratory status declined, and voriconazole was started out of concern for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis based on results of serum IgG testing.

Despite 2 days of treatment with voriconazole, the patient developed respiratory failure. Repeat CT showed that the ground-glass opacities were more dense, especially in the lower lobes, and new patchy infiltrates were noted in the left lung. The patient developed a right tension pneumothorax requiring emergency intubation and chest tube insertion.1 She subsequently developed acute abdominal pain with worsening abdominal distention, diagnosed as pneumoperitoneum. Emergency exploratory laparotomy revealed perforations in the cecum with fecal spillage, requiring ileocecectomy and ileostomy.

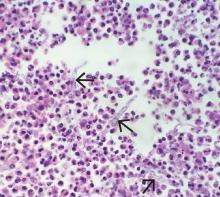

Pathologic study of bowel specimens confirmed fungal hyphae with “tree-branch” structures consistent with fungal infection in the bowel (Figure 2).

Oral voriconazole was continued. The patient’s respiratory status improved, and she no longer required supplemental oxygen. She was discharged on a regimen of oral voriconazole 200 mg twice daily. However, over the next 12 months, she had additional hospitalizations for severe sepsis from abdominal wound infections, pneumonia, and Clostridium difficile infection. She will require lifelong antifungal treatment.

INVASIVE PULMONARY ASPERGILLOSIS

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is the most severe form of aspergillosis and is most often seen in immunocompromised patients. The death rate is as high as 50% in neutropenic patients regardless of the time to diagnosis or effective treatment.2 It becomes life-threatening as the infection enters the blood stream, leading to formation of thrombi and precipitating embolism and necrosis in the lungs.3

In immunocompetent patients, COPD, tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, liver disease, severe sepsis, and diabetes mellitus predispose to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.2 Other risk factors include long-term steroid therapy at doses equivalent to prednisone 20 mg/day for at least 13 weeks4 and viral infection such as influenza.5 Chronic use of inhaled corticosteroids has been hypothesized to increase risk.4

Histopathologic confirmation of fungal elements is the gold standard for diagnosis.3 New biomarkers such as beta-d-glucan have shown promise in enabling earlier diagnosis to allow effective treatment of disseminated aspergillosis, as in our patient.6

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Although not common, invasive aspergillosis can occur in immunocompetent and near-immunocompetent patients, particularly those with COPD or other underlying lung disease.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Kimberley Woodward, MD, Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, VA, for her study of the bowel specimen and for providing the histology slide.

- Vukicevic TA, Dudvarski-Ilic A, Zugic V, Stevanovic G, Rubino S, Barac A. Subacute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis as a rare cause of pneumothorax in immunocompetent patient: brief report. Infection 2017; 45(3):377–380. doi:10.1007/s15010-017-0994-3

- Moreno-González G, Ricart de Mesones A, Tazi-Mezalek R, Marron-Moya MT, Rosell A, Mañez R. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with disseminated infection in immunocompetent patient. Can Respir J 2016; 2016:7984032. doi:10.1155/2016/7984032

- Chen L, Liu Y, Wang W, Liu K. Adrenal and hepatic aspergillosis in an immunocompetent patient. Infect Dis (Lond) 2015; 47(6):428–432. doi:10.3109/00365548.2014.995697

- Taccone FS, Van den Abeele AM, Bulpa P, et al; AspICU Study Investigators. Epidemiology of invasive aspergillosis in critically ill patients: clinical presentation, underlying conditions, and outcomes. Crit Care 2015; 19:7. doi:10.1186/s13054-014-0722-7

- Crum-Cianflone NF. Invasive aspergillosis associated with severe influenza infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3(3):ofw171. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofw171

- Ergene U, Akcali Z, Ozbalci D, Nese N, Senol S. Disseminated aspergillosis due to Aspergillus niger in immunocompetent patient: a case report. Case Rep Infect Dis 2013; 2013:385190. doi:10.1155/2013/385190

A 57-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital for progressive hypoxic respiratory failure that developed after 10 days of empiric treatment at another hospital for an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Computed tomography (CT) showed a lesion in the upper lobe of the left lung, with new ground-glass opacities with cystic and cavitary changes raising concern for an inflammatory or infectious cause (Figure 1). Respiratory culture of expectorated secretions grew Aspergillus. Assays for beta-d-glucan and serum Aspergillus immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies were positive, although given the improvement in her oxygenation requirements and overall clinical status, these were thought to be trivial. Tests for immunoglobulin deficiencies and human immunodeficiency virus were negative, ruling out primary immunodeficiency. However, within the next 48 hours, her respiratory status declined, and voriconazole was started out of concern for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis based on results of serum IgG testing.

Despite 2 days of treatment with voriconazole, the patient developed respiratory failure. Repeat CT showed that the ground-glass opacities were more dense, especially in the lower lobes, and new patchy infiltrates were noted in the left lung. The patient developed a right tension pneumothorax requiring emergency intubation and chest tube insertion.1 She subsequently developed acute abdominal pain with worsening abdominal distention, diagnosed as pneumoperitoneum. Emergency exploratory laparotomy revealed perforations in the cecum with fecal spillage, requiring ileocecectomy and ileostomy.

Pathologic study of bowel specimens confirmed fungal hyphae with “tree-branch” structures consistent with fungal infection in the bowel (Figure 2).

Oral voriconazole was continued. The patient’s respiratory status improved, and she no longer required supplemental oxygen. She was discharged on a regimen of oral voriconazole 200 mg twice daily. However, over the next 12 months, she had additional hospitalizations for severe sepsis from abdominal wound infections, pneumonia, and Clostridium difficile infection. She will require lifelong antifungal treatment.

INVASIVE PULMONARY ASPERGILLOSIS

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is the most severe form of aspergillosis and is most often seen in immunocompromised patients. The death rate is as high as 50% in neutropenic patients regardless of the time to diagnosis or effective treatment.2 It becomes life-threatening as the infection enters the blood stream, leading to formation of thrombi and precipitating embolism and necrosis in the lungs.3

In immunocompetent patients, COPD, tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, liver disease, severe sepsis, and diabetes mellitus predispose to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.2 Other risk factors include long-term steroid therapy at doses equivalent to prednisone 20 mg/day for at least 13 weeks4 and viral infection such as influenza.5 Chronic use of inhaled corticosteroids has been hypothesized to increase risk.4

Histopathologic confirmation of fungal elements is the gold standard for diagnosis.3 New biomarkers such as beta-d-glucan have shown promise in enabling earlier diagnosis to allow effective treatment of disseminated aspergillosis, as in our patient.6

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Although not common, invasive aspergillosis can occur in immunocompetent and near-immunocompetent patients, particularly those with COPD or other underlying lung disease.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Kimberley Woodward, MD, Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, VA, for her study of the bowel specimen and for providing the histology slide.

A 57-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital for progressive hypoxic respiratory failure that developed after 10 days of empiric treatment at another hospital for an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Computed tomography (CT) showed a lesion in the upper lobe of the left lung, with new ground-glass opacities with cystic and cavitary changes raising concern for an inflammatory or infectious cause (Figure 1). Respiratory culture of expectorated secretions grew Aspergillus. Assays for beta-d-glucan and serum Aspergillus immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies were positive, although given the improvement in her oxygenation requirements and overall clinical status, these were thought to be trivial. Tests for immunoglobulin deficiencies and human immunodeficiency virus were negative, ruling out primary immunodeficiency. However, within the next 48 hours, her respiratory status declined, and voriconazole was started out of concern for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis based on results of serum IgG testing.

Despite 2 days of treatment with voriconazole, the patient developed respiratory failure. Repeat CT showed that the ground-glass opacities were more dense, especially in the lower lobes, and new patchy infiltrates were noted in the left lung. The patient developed a right tension pneumothorax requiring emergency intubation and chest tube insertion.1 She subsequently developed acute abdominal pain with worsening abdominal distention, diagnosed as pneumoperitoneum. Emergency exploratory laparotomy revealed perforations in the cecum with fecal spillage, requiring ileocecectomy and ileostomy.

Pathologic study of bowel specimens confirmed fungal hyphae with “tree-branch” structures consistent with fungal infection in the bowel (Figure 2).

Oral voriconazole was continued. The patient’s respiratory status improved, and she no longer required supplemental oxygen. She was discharged on a regimen of oral voriconazole 200 mg twice daily. However, over the next 12 months, she had additional hospitalizations for severe sepsis from abdominal wound infections, pneumonia, and Clostridium difficile infection. She will require lifelong antifungal treatment.

INVASIVE PULMONARY ASPERGILLOSIS

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is the most severe form of aspergillosis and is most often seen in immunocompromised patients. The death rate is as high as 50% in neutropenic patients regardless of the time to diagnosis or effective treatment.2 It becomes life-threatening as the infection enters the blood stream, leading to formation of thrombi and precipitating embolism and necrosis in the lungs.3

In immunocompetent patients, COPD, tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, liver disease, severe sepsis, and diabetes mellitus predispose to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.2 Other risk factors include long-term steroid therapy at doses equivalent to prednisone 20 mg/day for at least 13 weeks4 and viral infection such as influenza.5 Chronic use of inhaled corticosteroids has been hypothesized to increase risk.4

Histopathologic confirmation of fungal elements is the gold standard for diagnosis.3 New biomarkers such as beta-d-glucan have shown promise in enabling earlier diagnosis to allow effective treatment of disseminated aspergillosis, as in our patient.6

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Although not common, invasive aspergillosis can occur in immunocompetent and near-immunocompetent patients, particularly those with COPD or other underlying lung disease.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Kimberley Woodward, MD, Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, VA, for her study of the bowel specimen and for providing the histology slide.

- Vukicevic TA, Dudvarski-Ilic A, Zugic V, Stevanovic G, Rubino S, Barac A. Subacute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis as a rare cause of pneumothorax in immunocompetent patient: brief report. Infection 2017; 45(3):377–380. doi:10.1007/s15010-017-0994-3

- Moreno-González G, Ricart de Mesones A, Tazi-Mezalek R, Marron-Moya MT, Rosell A, Mañez R. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with disseminated infection in immunocompetent patient. Can Respir J 2016; 2016:7984032. doi:10.1155/2016/7984032

- Chen L, Liu Y, Wang W, Liu K. Adrenal and hepatic aspergillosis in an immunocompetent patient. Infect Dis (Lond) 2015; 47(6):428–432. doi:10.3109/00365548.2014.995697

- Taccone FS, Van den Abeele AM, Bulpa P, et al; AspICU Study Investigators. Epidemiology of invasive aspergillosis in critically ill patients: clinical presentation, underlying conditions, and outcomes. Crit Care 2015; 19:7. doi:10.1186/s13054-014-0722-7

- Crum-Cianflone NF. Invasive aspergillosis associated with severe influenza infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3(3):ofw171. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofw171

- Ergene U, Akcali Z, Ozbalci D, Nese N, Senol S. Disseminated aspergillosis due to Aspergillus niger in immunocompetent patient: a case report. Case Rep Infect Dis 2013; 2013:385190. doi:10.1155/2013/385190

- Vukicevic TA, Dudvarski-Ilic A, Zugic V, Stevanovic G, Rubino S, Barac A. Subacute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis as a rare cause of pneumothorax in immunocompetent patient: brief report. Infection 2017; 45(3):377–380. doi:10.1007/s15010-017-0994-3

- Moreno-González G, Ricart de Mesones A, Tazi-Mezalek R, Marron-Moya MT, Rosell A, Mañez R. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with disseminated infection in immunocompetent patient. Can Respir J 2016; 2016:7984032. doi:10.1155/2016/7984032

- Chen L, Liu Y, Wang W, Liu K. Adrenal and hepatic aspergillosis in an immunocompetent patient. Infect Dis (Lond) 2015; 47(6):428–432. doi:10.3109/00365548.2014.995697

- Taccone FS, Van den Abeele AM, Bulpa P, et al; AspICU Study Investigators. Epidemiology of invasive aspergillosis in critically ill patients: clinical presentation, underlying conditions, and outcomes. Crit Care 2015; 19:7. doi:10.1186/s13054-014-0722-7

- Crum-Cianflone NF. Invasive aspergillosis associated with severe influenza infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3(3):ofw171. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofw171

- Ergene U, Akcali Z, Ozbalci D, Nese N, Senol S. Disseminated aspergillosis due to Aspergillus niger in immunocompetent patient: a case report. Case Rep Infect Dis 2013; 2013:385190. doi:10.1155/2013/385190

Dabigatran-induced esophagitis

A 74-year-old man presented to the gastroenterology clinic with a 2-day history of retrosternal discomfort. His vital signs were normal, and laboratory testing showed a normal leukocyte count.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed longitudinal sloughing mucosal casts in the middle and lower esophagus (Figure 1).

The patient had been taking dabigatran 110 mg twice daily for 2 years because of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. He was also taking amlodipine 2.5 mg/day for hypertension.

DABIGATRAN-INDUCED ESOPHAGITIS

Although no study has investigated the overall prevalence of dabigatran-induced esophagitis, a retrospective database review of 91 patients taking dabigatran and undergoing upper-gastrointestinal endoscopy reported that 19 (20.9%) had endoscopic signs of dabigatran-induced esophagitis.2

Typical symptoms are the acute onset of chest pain, epigastralgia, odynophagia, and dysphagia. But patients can also have no symptoms or only mild symptoms.2,3

Despite dabigatran’s anticoagulant activity, there have been few reports of bleeding, perhaps because the lesions tend to be superficial on the surface of the esophageal mucosa.

Symptoms usually resolve within 1 week after stopping dabigatran and starting a proton pump inhibitor. To prevent mucosal injury, patients should be instructed to take dabigatran with sufficient water and to remain in an upright position for at least 30 minutes afterward.4

- Baehr PH, McDonald GB. Esophageal infections: risk factors, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 1994; 106(2):509–532. pmid:7980741

- Toya Y, Nakamura S, Tomita K, et al. Dabigatran-induced esophagitis: the prevalence and endoscopic characteristics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 31(3):610–614. doi:10.1111/jgh.13024

- Ueta E, Fujikawa T, Imagawa A. A case of a slightly symptomatic exfoliative oesophagitis. BMJ Case Rep 2015; pii:bcr2015211925. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-211925

- Ootani A, Hayashi Y, Miyagi Y. Dabigatran-induced esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12(7):e55–e56. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.010

A 74-year-old man presented to the gastroenterology clinic with a 2-day history of retrosternal discomfort. His vital signs were normal, and laboratory testing showed a normal leukocyte count.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed longitudinal sloughing mucosal casts in the middle and lower esophagus (Figure 1).

The patient had been taking dabigatran 110 mg twice daily for 2 years because of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. He was also taking amlodipine 2.5 mg/day for hypertension.

DABIGATRAN-INDUCED ESOPHAGITIS

Although no study has investigated the overall prevalence of dabigatran-induced esophagitis, a retrospective database review of 91 patients taking dabigatran and undergoing upper-gastrointestinal endoscopy reported that 19 (20.9%) had endoscopic signs of dabigatran-induced esophagitis.2

Typical symptoms are the acute onset of chest pain, epigastralgia, odynophagia, and dysphagia. But patients can also have no symptoms or only mild symptoms.2,3

Despite dabigatran’s anticoagulant activity, there have been few reports of bleeding, perhaps because the lesions tend to be superficial on the surface of the esophageal mucosa.

Symptoms usually resolve within 1 week after stopping dabigatran and starting a proton pump inhibitor. To prevent mucosal injury, patients should be instructed to take dabigatran with sufficient water and to remain in an upright position for at least 30 minutes afterward.4

A 74-year-old man presented to the gastroenterology clinic with a 2-day history of retrosternal discomfort. His vital signs were normal, and laboratory testing showed a normal leukocyte count.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed longitudinal sloughing mucosal casts in the middle and lower esophagus (Figure 1).

The patient had been taking dabigatran 110 mg twice daily for 2 years because of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. He was also taking amlodipine 2.5 mg/day for hypertension.

DABIGATRAN-INDUCED ESOPHAGITIS

Although no study has investigated the overall prevalence of dabigatran-induced esophagitis, a retrospective database review of 91 patients taking dabigatran and undergoing upper-gastrointestinal endoscopy reported that 19 (20.9%) had endoscopic signs of dabigatran-induced esophagitis.2

Typical symptoms are the acute onset of chest pain, epigastralgia, odynophagia, and dysphagia. But patients can also have no symptoms or only mild symptoms.2,3

Despite dabigatran’s anticoagulant activity, there have been few reports of bleeding, perhaps because the lesions tend to be superficial on the surface of the esophageal mucosa.

Symptoms usually resolve within 1 week after stopping dabigatran and starting a proton pump inhibitor. To prevent mucosal injury, patients should be instructed to take dabigatran with sufficient water and to remain in an upright position for at least 30 minutes afterward.4

- Baehr PH, McDonald GB. Esophageal infections: risk factors, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 1994; 106(2):509–532. pmid:7980741

- Toya Y, Nakamura S, Tomita K, et al. Dabigatran-induced esophagitis: the prevalence and endoscopic characteristics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 31(3):610–614. doi:10.1111/jgh.13024

- Ueta E, Fujikawa T, Imagawa A. A case of a slightly symptomatic exfoliative oesophagitis. BMJ Case Rep 2015; pii:bcr2015211925. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-211925

- Ootani A, Hayashi Y, Miyagi Y. Dabigatran-induced esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12(7):e55–e56. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.010

- Baehr PH, McDonald GB. Esophageal infections: risk factors, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 1994; 106(2):509–532. pmid:7980741

- Toya Y, Nakamura S, Tomita K, et al. Dabigatran-induced esophagitis: the prevalence and endoscopic characteristics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 31(3):610–614. doi:10.1111/jgh.13024

- Ueta E, Fujikawa T, Imagawa A. A case of a slightly symptomatic exfoliative oesophagitis. BMJ Case Rep 2015; pii:bcr2015211925. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-211925

- Ootani A, Hayashi Y, Miyagi Y. Dabigatran-induced esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12(7):e55–e56. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.010