User login

Pyoderma gangrenosum mistaken for diabetic ulcer

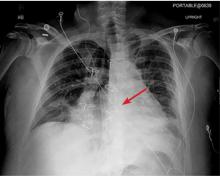

A 55-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, anemia, and ulcerative colitis presented to the emergency department with an ulcer on his left leg (Figure 1). He said the lesion had started as a “large pimple” that ruptured one night while he was sleeping and then became drastically worse over the past week. He said the lesion was painful and was “oozing blood.”

On examination, the lesion was 7 cm by 6.5 cm, with fibrinous, necrotic tissue, purulence, and a violaceous tint at the borders. The patient’s body temperature was 100.5°F (38.1°C) and the white blood cell count was 8.1 x 109/L (reference range 4.0–11.0).

Based on the patient’s medical history, the lesion was initially diagnosed as an infected diabetic ulcer. He was admitted to the hospital and intravenous (IV) vancomycin and clindamycin were started. During this time, the lesion expanded in size, and a second lesion appeared on the right anterior thigh, in similar fashion to how the original lesion had started. The original lesion expanded to 8 cm by 8.5 cm by hospital day 2. The patient continued to have episodes of low-grade fever without leukocytosis.

Cultures of blood and tissue from the lesions were negative, ruling out bacterial infection. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left tibia was negative for osteomyelitis. Punch biopsy of the ulcer border was done on day 3 to evaluate for pyoderma gangrenosum.

On hospital day 5, the patient developed acute kidney injury, with a creatinine increase to 2.17 mg/dL over 24 hours from a baseline value of 0.82 mg/dL. The IV antibiotics were discontinued, and IV fluid hydration was started. At this time, diabetic ulcer secondary to infection and osteomyelitis were ruled out. The lesions were diagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum.

The patient was started on prednisone 30 mg twice daily. After 2 days, the low-grade fevers resolved, both lesions began to heal, and his creatinine level returned to baseline (Figure 2). He was discharged on hospital day 10. The prednisone was tapered over 1 month, with wet-to-dry dressing changes for wound care.

After discharge, he remained adherent to his steroid regimen. At a follow-up visit to his dermatologist, the ulcers had fully closed, and the skin had begun to heal. Results of the punch biopsy study came back 2 days after the patient was discharged and further confirmed the diagnosis, with a mixed lymphocytic composition composed primarily of neutrophils.

APPROACH TO DIAGNOSIS

Pyoderma gangrenosum is rare, with an incidence of 3 to 10 cases per million people per year.1 It is a rapidly progressive ulcerative condition typically associated with inflammatory bowel disease.2 Despite its name, the condition involves neither gangrene nor infection. The ulcer typically appears on the legs and is rapidly growing, painful, and purulent, with tissue necrosis and a violaceous border.3

Pyoderma gangrenosum is often misdiagnosed as infective ulcer and inappropriately treated with antibiotics.2 It can also be mistreated with surgical debridement, which can result in severe complications such as pathergy.1

The differential diagnosis includes diabetic ulcer, peripheral vascular disease, vasculitis, bacterial infection, osteomyelitis, and malignancy. Because it presents as an open, necrotic ulcer, ruling out infection is a top priority.3 However, an initial workup to rule out infection or other conditions can delay diagnosis and treatment,1 and treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics poses the risk of nephrotoxicity and new complications during the hospital stay.

Diagnosis requires meeting 2 major criteria—ie, presence of the characteristic ulcerous lesion, and exclusion of other causes of skin ulceration—and at least 2 minor criteria including histologic confirmation of neutrophil infiltrate at the ulcer border, the presence of a systemic disease associated with pyoderma gangrenosum, and a rapid response to steroid treatment.4,5

Our patient was at high risk for an infected diabetic ulcer. After infection was ruled out, clinical suspicion for pyoderma gangrenosum was high, given the patient’s presentation and his history of ulcerative colitis.

TREATMENT

Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum begins with systemic corticosteroids, as was done in this patient. Additional measures depend on whether the disease is localized or extensive and can include wound care, topical treatments, immunosuppressants, and immunomodulators.1

- Bhat RM. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an update. Indian Dermatol Online J 2012; 3(1):7–13. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.93482

- Marinopoulos S, Theofanakis C, Zacharouli T, Sotiropoulou M, Dimitrakakis C. Pyoderma gangrenosum of the breast: a case report study. Int J Surg Case Rep 2017; 31:203–205. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.01.036

- Gameiro A, Pereira N, Cardoso JC, Gonçalo M. Pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2015; 8:285–293. doi:10.2147/CCID.S61202

- Su WP, David MD, Weenig RH, Powell FC, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43(11):790–800. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02128.x

- von den Driesch P. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a report of 44 cases with follow-up. Br J Dermatol 1997; 137(6):1000–1005. pmid:9470924

A 55-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, anemia, and ulcerative colitis presented to the emergency department with an ulcer on his left leg (Figure 1). He said the lesion had started as a “large pimple” that ruptured one night while he was sleeping and then became drastically worse over the past week. He said the lesion was painful and was “oozing blood.”

On examination, the lesion was 7 cm by 6.5 cm, with fibrinous, necrotic tissue, purulence, and a violaceous tint at the borders. The patient’s body temperature was 100.5°F (38.1°C) and the white blood cell count was 8.1 x 109/L (reference range 4.0–11.0).

Based on the patient’s medical history, the lesion was initially diagnosed as an infected diabetic ulcer. He was admitted to the hospital and intravenous (IV) vancomycin and clindamycin were started. During this time, the lesion expanded in size, and a second lesion appeared on the right anterior thigh, in similar fashion to how the original lesion had started. The original lesion expanded to 8 cm by 8.5 cm by hospital day 2. The patient continued to have episodes of low-grade fever without leukocytosis.

Cultures of blood and tissue from the lesions were negative, ruling out bacterial infection. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left tibia was negative for osteomyelitis. Punch biopsy of the ulcer border was done on day 3 to evaluate for pyoderma gangrenosum.

On hospital day 5, the patient developed acute kidney injury, with a creatinine increase to 2.17 mg/dL over 24 hours from a baseline value of 0.82 mg/dL. The IV antibiotics were discontinued, and IV fluid hydration was started. At this time, diabetic ulcer secondary to infection and osteomyelitis were ruled out. The lesions were diagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum.

The patient was started on prednisone 30 mg twice daily. After 2 days, the low-grade fevers resolved, both lesions began to heal, and his creatinine level returned to baseline (Figure 2). He was discharged on hospital day 10. The prednisone was tapered over 1 month, with wet-to-dry dressing changes for wound care.

After discharge, he remained adherent to his steroid regimen. At a follow-up visit to his dermatologist, the ulcers had fully closed, and the skin had begun to heal. Results of the punch biopsy study came back 2 days after the patient was discharged and further confirmed the diagnosis, with a mixed lymphocytic composition composed primarily of neutrophils.

APPROACH TO DIAGNOSIS

Pyoderma gangrenosum is rare, with an incidence of 3 to 10 cases per million people per year.1 It is a rapidly progressive ulcerative condition typically associated with inflammatory bowel disease.2 Despite its name, the condition involves neither gangrene nor infection. The ulcer typically appears on the legs and is rapidly growing, painful, and purulent, with tissue necrosis and a violaceous border.3

Pyoderma gangrenosum is often misdiagnosed as infective ulcer and inappropriately treated with antibiotics.2 It can also be mistreated with surgical debridement, which can result in severe complications such as pathergy.1

The differential diagnosis includes diabetic ulcer, peripheral vascular disease, vasculitis, bacterial infection, osteomyelitis, and malignancy. Because it presents as an open, necrotic ulcer, ruling out infection is a top priority.3 However, an initial workup to rule out infection or other conditions can delay diagnosis and treatment,1 and treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics poses the risk of nephrotoxicity and new complications during the hospital stay.

Diagnosis requires meeting 2 major criteria—ie, presence of the characteristic ulcerous lesion, and exclusion of other causes of skin ulceration—and at least 2 minor criteria including histologic confirmation of neutrophil infiltrate at the ulcer border, the presence of a systemic disease associated with pyoderma gangrenosum, and a rapid response to steroid treatment.4,5

Our patient was at high risk for an infected diabetic ulcer. After infection was ruled out, clinical suspicion for pyoderma gangrenosum was high, given the patient’s presentation and his history of ulcerative colitis.

TREATMENT

Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum begins with systemic corticosteroids, as was done in this patient. Additional measures depend on whether the disease is localized or extensive and can include wound care, topical treatments, immunosuppressants, and immunomodulators.1

A 55-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, anemia, and ulcerative colitis presented to the emergency department with an ulcer on his left leg (Figure 1). He said the lesion had started as a “large pimple” that ruptured one night while he was sleeping and then became drastically worse over the past week. He said the lesion was painful and was “oozing blood.”

On examination, the lesion was 7 cm by 6.5 cm, with fibrinous, necrotic tissue, purulence, and a violaceous tint at the borders. The patient’s body temperature was 100.5°F (38.1°C) and the white blood cell count was 8.1 x 109/L (reference range 4.0–11.0).

Based on the patient’s medical history, the lesion was initially diagnosed as an infected diabetic ulcer. He was admitted to the hospital and intravenous (IV) vancomycin and clindamycin were started. During this time, the lesion expanded in size, and a second lesion appeared on the right anterior thigh, in similar fashion to how the original lesion had started. The original lesion expanded to 8 cm by 8.5 cm by hospital day 2. The patient continued to have episodes of low-grade fever without leukocytosis.

Cultures of blood and tissue from the lesions were negative, ruling out bacterial infection. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left tibia was negative for osteomyelitis. Punch biopsy of the ulcer border was done on day 3 to evaluate for pyoderma gangrenosum.

On hospital day 5, the patient developed acute kidney injury, with a creatinine increase to 2.17 mg/dL over 24 hours from a baseline value of 0.82 mg/dL. The IV antibiotics were discontinued, and IV fluid hydration was started. At this time, diabetic ulcer secondary to infection and osteomyelitis were ruled out. The lesions were diagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum.

The patient was started on prednisone 30 mg twice daily. After 2 days, the low-grade fevers resolved, both lesions began to heal, and his creatinine level returned to baseline (Figure 2). He was discharged on hospital day 10. The prednisone was tapered over 1 month, with wet-to-dry dressing changes for wound care.

After discharge, he remained adherent to his steroid regimen. At a follow-up visit to his dermatologist, the ulcers had fully closed, and the skin had begun to heal. Results of the punch biopsy study came back 2 days after the patient was discharged and further confirmed the diagnosis, with a mixed lymphocytic composition composed primarily of neutrophils.

APPROACH TO DIAGNOSIS

Pyoderma gangrenosum is rare, with an incidence of 3 to 10 cases per million people per year.1 It is a rapidly progressive ulcerative condition typically associated with inflammatory bowel disease.2 Despite its name, the condition involves neither gangrene nor infection. The ulcer typically appears on the legs and is rapidly growing, painful, and purulent, with tissue necrosis and a violaceous border.3

Pyoderma gangrenosum is often misdiagnosed as infective ulcer and inappropriately treated with antibiotics.2 It can also be mistreated with surgical debridement, which can result in severe complications such as pathergy.1

The differential diagnosis includes diabetic ulcer, peripheral vascular disease, vasculitis, bacterial infection, osteomyelitis, and malignancy. Because it presents as an open, necrotic ulcer, ruling out infection is a top priority.3 However, an initial workup to rule out infection or other conditions can delay diagnosis and treatment,1 and treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics poses the risk of nephrotoxicity and new complications during the hospital stay.

Diagnosis requires meeting 2 major criteria—ie, presence of the characteristic ulcerous lesion, and exclusion of other causes of skin ulceration—and at least 2 minor criteria including histologic confirmation of neutrophil infiltrate at the ulcer border, the presence of a systemic disease associated with pyoderma gangrenosum, and a rapid response to steroid treatment.4,5

Our patient was at high risk for an infected diabetic ulcer. After infection was ruled out, clinical suspicion for pyoderma gangrenosum was high, given the patient’s presentation and his history of ulcerative colitis.

TREATMENT

Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum begins with systemic corticosteroids, as was done in this patient. Additional measures depend on whether the disease is localized or extensive and can include wound care, topical treatments, immunosuppressants, and immunomodulators.1

- Bhat RM. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an update. Indian Dermatol Online J 2012; 3(1):7–13. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.93482

- Marinopoulos S, Theofanakis C, Zacharouli T, Sotiropoulou M, Dimitrakakis C. Pyoderma gangrenosum of the breast: a case report study. Int J Surg Case Rep 2017; 31:203–205. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.01.036

- Gameiro A, Pereira N, Cardoso JC, Gonçalo M. Pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2015; 8:285–293. doi:10.2147/CCID.S61202

- Su WP, David MD, Weenig RH, Powell FC, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43(11):790–800. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02128.x

- von den Driesch P. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a report of 44 cases with follow-up. Br J Dermatol 1997; 137(6):1000–1005. pmid:9470924

- Bhat RM. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an update. Indian Dermatol Online J 2012; 3(1):7–13. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.93482

- Marinopoulos S, Theofanakis C, Zacharouli T, Sotiropoulou M, Dimitrakakis C. Pyoderma gangrenosum of the breast: a case report study. Int J Surg Case Rep 2017; 31:203–205. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.01.036

- Gameiro A, Pereira N, Cardoso JC, Gonçalo M. Pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2015; 8:285–293. doi:10.2147/CCID.S61202

- Su WP, David MD, Weenig RH, Powell FC, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43(11):790–800. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02128.x

- von den Driesch P. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a report of 44 cases with follow-up. Br J Dermatol 1997; 137(6):1000–1005. pmid:9470924

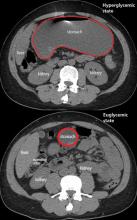

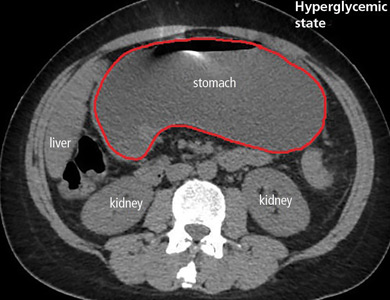

Gastroparesis in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

Flu or strep? Rapid tests can mislead

A 62-year-old woman presented to our emergency department with fever, chills, hoarseness, pain on swallowing, and a painful neck. Her symptoms had begun 1 day earlier. Because acetaminophen brought no improvement, she went to an urgent care facility, where a nasal swab polymerase chain reaction test was positive for influenza A, and a throat swab rapid test was positive for group A streptococci. She was then referred to our emergency department.

She reported no pre-existing conditions predisposing her to infection. Her temperature was 99.9°F (37.7°C), pulse 112 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. The physical examination was unremarkable except for bilateral anterior cervical adenopathy and bilateral anterior neck tenderness. Her pharynx was not injected, and no exudate, palatal edema, or petechiae were noted.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- White blood cell count 20.5 × 109/L (reference range 3.9–11)

- Neutrophils 76% (42%–75%)

- Bands 15% (0%–5%)

- Lymphocytes 3% (21%–51%)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 75 mm/h (< 20 mm/h)

- C-reactive protein 247.14 mg/L (≤ 3 mg/L)

- Serum aminotransferase levels were normal.

- Polymerase chain reaction testing of a nasal swab was negative for viral infection.

Throat swabs and blood samples were sent for culture.

She was started on ceftriaxone 1 g intravenously every 24 hours, with close observation in the medical intensive care unit, where she was admitted because of epiglottitis. On hospital day 3, the throat culture was reported as negative, but the blood culture was reported as positive for Haemophilus influenzae. Thus, the clinical diagnosis was acute epiglottitis due to H influenzae, not group A streptococci.

The patient completed 10 days of ceftriaxone therapy; her recovery was uneventful, and she was discharged on hospital day 10.

INFLUENZA: CHALLENGES TO PROMPT, ACCURATE DIAGNOSIS

During influenza season, emergency departments are inundated with adults with influenza A and other viral respiratory infections. This makes prompt, accurate diagnosis a challenge,1 given the broad differential diagnosis.2,3 Adults with influenza and its complications as well as unrelated conditions can present a special challenge.4

Our patient presented with acute-onset influenza A and was then found to have acute epiglottitis, an unexpected complication of influenza A.5 A positive rapid test for group A streptococci done at an urgent care facility led emergency department physicians to assume that the acute epiglottitis was due to group A streptococci. Unless correlated with clinical findings, results of rapid diagnostic tests may mislead the unwary practitioner. Accurate diagnosis should be based mainly on the history and physical findings. Results of rapid diagnostic tests can be helpful if interpreted in the clinical context.6–8

The rapid test for streptococci is appropriate for the diagnosis of pharyngitis due to group A streptococci in people under age 30 with acute-onset sore throat, fever, and bilateral acute cervical adenopathy, without fatigue or myalgias. However, the rapid test does not differentiate colonization from infection. Group A streptococci are common colonizers with viral pharyngitis. In 30% of cases of Epstein-Barr virus pharyngitis, there is colonization with group A streptococci. A positive rapid test in such cases can result in the wrong diagnosis, ie, pharyngitis due to group A streptococci rather than Epstein-Barr virus.

- Cunha BA. The clinical diagnosis of severe viral influenza A. Infection 2008; 36(1):92–93. doi:10.1007/s15010-007-7255-9

- Cunha BA, Klein NC, Strollo S, Syed U, Mickail N, Laguerre M. Legionnaires’ disease mimicking swine influenza (H1N1) pneumonia during the “herald wave” of the pandemic. Heart Lung 2010; 39(3):242–248. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.10.009

- Cunha BA, Raza M. During influenza season: all influenza-like illnesses are not due to influenza: dengue mimicking influenza. J Emerg Med 2015; 48(5):e117–e120. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.12.051

- Cunha CB. Infectious disease differential diagnosis. In: Cunha CB, Cunha BA, eds. Antibiotic Essentials. Jaypee Brothers Medical Pub: New Delhi, India; 2017:493–526.

- Cunha BA. Pharyngitis. In: Cunha CB, Cunha BA, eds. Antibiotic Essentials. Jaypee Brothers Medical Pub: New Delhi, India; 2017:42–47.

- Cohen JF, Chalumeau M, Levy C, et al. Effect of clinical spectrum, inoculum size and physician characteristics on sensitivity of rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 32(6):787–793. doi:10.1007/s10096-012-1809-1

- Dimatteo LA, Lowenstein SR, Brimhall B, Reiquam W, Gonzales R. The relationship between the clinical features of pharyngitis and the sensitivity of a rapid antigen test: evidence of spectrum bias. Ann Emerg Med 2001; 38(6):648–652. doi:10.1067/mem.2001.119850

- Cunha BA. A positive rapid strep test in a young adult with acute pharyngitis: be careful what you wish for! IDCases 2017; 10:58–59. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2017.08.012

A 62-year-old woman presented to our emergency department with fever, chills, hoarseness, pain on swallowing, and a painful neck. Her symptoms had begun 1 day earlier. Because acetaminophen brought no improvement, she went to an urgent care facility, where a nasal swab polymerase chain reaction test was positive for influenza A, and a throat swab rapid test was positive for group A streptococci. She was then referred to our emergency department.

She reported no pre-existing conditions predisposing her to infection. Her temperature was 99.9°F (37.7°C), pulse 112 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. The physical examination was unremarkable except for bilateral anterior cervical adenopathy and bilateral anterior neck tenderness. Her pharynx was not injected, and no exudate, palatal edema, or petechiae were noted.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- White blood cell count 20.5 × 109/L (reference range 3.9–11)

- Neutrophils 76% (42%–75%)

- Bands 15% (0%–5%)

- Lymphocytes 3% (21%–51%)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 75 mm/h (< 20 mm/h)

- C-reactive protein 247.14 mg/L (≤ 3 mg/L)

- Serum aminotransferase levels were normal.

- Polymerase chain reaction testing of a nasal swab was negative for viral infection.

Throat swabs and blood samples were sent for culture.

She was started on ceftriaxone 1 g intravenously every 24 hours, with close observation in the medical intensive care unit, where she was admitted because of epiglottitis. On hospital day 3, the throat culture was reported as negative, but the blood culture was reported as positive for Haemophilus influenzae. Thus, the clinical diagnosis was acute epiglottitis due to H influenzae, not group A streptococci.

The patient completed 10 days of ceftriaxone therapy; her recovery was uneventful, and she was discharged on hospital day 10.

INFLUENZA: CHALLENGES TO PROMPT, ACCURATE DIAGNOSIS

During influenza season, emergency departments are inundated with adults with influenza A and other viral respiratory infections. This makes prompt, accurate diagnosis a challenge,1 given the broad differential diagnosis.2,3 Adults with influenza and its complications as well as unrelated conditions can present a special challenge.4

Our patient presented with acute-onset influenza A and was then found to have acute epiglottitis, an unexpected complication of influenza A.5 A positive rapid test for group A streptococci done at an urgent care facility led emergency department physicians to assume that the acute epiglottitis was due to group A streptococci. Unless correlated with clinical findings, results of rapid diagnostic tests may mislead the unwary practitioner. Accurate diagnosis should be based mainly on the history and physical findings. Results of rapid diagnostic tests can be helpful if interpreted in the clinical context.6–8

The rapid test for streptococci is appropriate for the diagnosis of pharyngitis due to group A streptococci in people under age 30 with acute-onset sore throat, fever, and bilateral acute cervical adenopathy, without fatigue or myalgias. However, the rapid test does not differentiate colonization from infection. Group A streptococci are common colonizers with viral pharyngitis. In 30% of cases of Epstein-Barr virus pharyngitis, there is colonization with group A streptococci. A positive rapid test in such cases can result in the wrong diagnosis, ie, pharyngitis due to group A streptococci rather than Epstein-Barr virus.

A 62-year-old woman presented to our emergency department with fever, chills, hoarseness, pain on swallowing, and a painful neck. Her symptoms had begun 1 day earlier. Because acetaminophen brought no improvement, she went to an urgent care facility, where a nasal swab polymerase chain reaction test was positive for influenza A, and a throat swab rapid test was positive for group A streptococci. She was then referred to our emergency department.

She reported no pre-existing conditions predisposing her to infection. Her temperature was 99.9°F (37.7°C), pulse 112 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. The physical examination was unremarkable except for bilateral anterior cervical adenopathy and bilateral anterior neck tenderness. Her pharynx was not injected, and no exudate, palatal edema, or petechiae were noted.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- White blood cell count 20.5 × 109/L (reference range 3.9–11)

- Neutrophils 76% (42%–75%)

- Bands 15% (0%–5%)

- Lymphocytes 3% (21%–51%)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 75 mm/h (< 20 mm/h)

- C-reactive protein 247.14 mg/L (≤ 3 mg/L)

- Serum aminotransferase levels were normal.

- Polymerase chain reaction testing of a nasal swab was negative for viral infection.

Throat swabs and blood samples were sent for culture.

She was started on ceftriaxone 1 g intravenously every 24 hours, with close observation in the medical intensive care unit, where she was admitted because of epiglottitis. On hospital day 3, the throat culture was reported as negative, but the blood culture was reported as positive for Haemophilus influenzae. Thus, the clinical diagnosis was acute epiglottitis due to H influenzae, not group A streptococci.

The patient completed 10 days of ceftriaxone therapy; her recovery was uneventful, and she was discharged on hospital day 10.

INFLUENZA: CHALLENGES TO PROMPT, ACCURATE DIAGNOSIS

During influenza season, emergency departments are inundated with adults with influenza A and other viral respiratory infections. This makes prompt, accurate diagnosis a challenge,1 given the broad differential diagnosis.2,3 Adults with influenza and its complications as well as unrelated conditions can present a special challenge.4

Our patient presented with acute-onset influenza A and was then found to have acute epiglottitis, an unexpected complication of influenza A.5 A positive rapid test for group A streptococci done at an urgent care facility led emergency department physicians to assume that the acute epiglottitis was due to group A streptococci. Unless correlated with clinical findings, results of rapid diagnostic tests may mislead the unwary practitioner. Accurate diagnosis should be based mainly on the history and physical findings. Results of rapid diagnostic tests can be helpful if interpreted in the clinical context.6–8

The rapid test for streptococci is appropriate for the diagnosis of pharyngitis due to group A streptococci in people under age 30 with acute-onset sore throat, fever, and bilateral acute cervical adenopathy, without fatigue or myalgias. However, the rapid test does not differentiate colonization from infection. Group A streptococci are common colonizers with viral pharyngitis. In 30% of cases of Epstein-Barr virus pharyngitis, there is colonization with group A streptococci. A positive rapid test in such cases can result in the wrong diagnosis, ie, pharyngitis due to group A streptococci rather than Epstein-Barr virus.

- Cunha BA. The clinical diagnosis of severe viral influenza A. Infection 2008; 36(1):92–93. doi:10.1007/s15010-007-7255-9

- Cunha BA, Klein NC, Strollo S, Syed U, Mickail N, Laguerre M. Legionnaires’ disease mimicking swine influenza (H1N1) pneumonia during the “herald wave” of the pandemic. Heart Lung 2010; 39(3):242–248. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.10.009

- Cunha BA, Raza M. During influenza season: all influenza-like illnesses are not due to influenza: dengue mimicking influenza. J Emerg Med 2015; 48(5):e117–e120. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.12.051

- Cunha CB. Infectious disease differential diagnosis. In: Cunha CB, Cunha BA, eds. Antibiotic Essentials. Jaypee Brothers Medical Pub: New Delhi, India; 2017:493–526.

- Cunha BA. Pharyngitis. In: Cunha CB, Cunha BA, eds. Antibiotic Essentials. Jaypee Brothers Medical Pub: New Delhi, India; 2017:42–47.

- Cohen JF, Chalumeau M, Levy C, et al. Effect of clinical spectrum, inoculum size and physician characteristics on sensitivity of rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 32(6):787–793. doi:10.1007/s10096-012-1809-1

- Dimatteo LA, Lowenstein SR, Brimhall B, Reiquam W, Gonzales R. The relationship between the clinical features of pharyngitis and the sensitivity of a rapid antigen test: evidence of spectrum bias. Ann Emerg Med 2001; 38(6):648–652. doi:10.1067/mem.2001.119850

- Cunha BA. A positive rapid strep test in a young adult with acute pharyngitis: be careful what you wish for! IDCases 2017; 10:58–59. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2017.08.012

- Cunha BA. The clinical diagnosis of severe viral influenza A. Infection 2008; 36(1):92–93. doi:10.1007/s15010-007-7255-9

- Cunha BA, Klein NC, Strollo S, Syed U, Mickail N, Laguerre M. Legionnaires’ disease mimicking swine influenza (H1N1) pneumonia during the “herald wave” of the pandemic. Heart Lung 2010; 39(3):242–248. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.10.009

- Cunha BA, Raza M. During influenza season: all influenza-like illnesses are not due to influenza: dengue mimicking influenza. J Emerg Med 2015; 48(5):e117–e120. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.12.051

- Cunha CB. Infectious disease differential diagnosis. In: Cunha CB, Cunha BA, eds. Antibiotic Essentials. Jaypee Brothers Medical Pub: New Delhi, India; 2017:493–526.

- Cunha BA. Pharyngitis. In: Cunha CB, Cunha BA, eds. Antibiotic Essentials. Jaypee Brothers Medical Pub: New Delhi, India; 2017:42–47.

- Cohen JF, Chalumeau M, Levy C, et al. Effect of clinical spectrum, inoculum size and physician characteristics on sensitivity of rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 32(6):787–793. doi:10.1007/s10096-012-1809-1

- Dimatteo LA, Lowenstein SR, Brimhall B, Reiquam W, Gonzales R. The relationship between the clinical features of pharyngitis and the sensitivity of a rapid antigen test: evidence of spectrum bias. Ann Emerg Med 2001; 38(6):648–652. doi:10.1067/mem.2001.119850

- Cunha BA. A positive rapid strep test in a young adult with acute pharyngitis: be careful what you wish for! IDCases 2017; 10:58–59. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2017.08.012

Norwegian scabies

DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT, CONTROL

The differential diagnosis of Norwegian scabies includes psoriasis, eczema, contact dermatitis, insect bites, seborrheic dermatitis, lichen planus, systemic infection, palmoplantar keratoderma, and cutaneous lymphoma.2

Treatment involves eradicating the infestation with a topical ointment consisting of permethrin, crotamiton, lindane, benzyl benzoate, and sulfur, applied directly to the skin. However, topical treatments often cannot penetrate the crusted and thickened skin, leading to treatment failure. A dose of oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg on days 1, 2, and 8 is a safe, effective, first-line treatment for Norwegian scabies, rapidly reducing scabies symptoms.3 Adverse effects of oral ivermectin are rare and usually minor.

Norwegian scabies is extremely contagious, spread by close physical contact and sharing of contaminated items such as clothing, bedding, towels, and furniture. Scabies mites can survive off the skin for 48 to 72 hours at room temperature.4 Potentially contaminated items should be decontaminated by washing in hot water and drying in a drying machine or by dry cleaning. Body contact with other contaminated items should be avoided for at least 72 hours.

Outbreaks can spread among patients, visitors, and medical staff in institutions such as nursing homes, day care centers, long-term-care facilities, and hospitals.5 Early identification facilitates appropriate management and treatment, thereby preventing infection and community-wide scabies outbreaks.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to sincerely thank Paul Williams for his editing of the article.

- Leone PA. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44(suppl 3):S153–S159. doi:10.1086/511428

- Siegfried EC, Hebert AA. Diagnosis of atopic dermatitis: mimics, overlaps, and complications. J Clin Med 2015; 4(5):884–917. doi:10.3390/jcm4050884

- Salavastru CM, Chosidow O, Boffa MJ, Janier M, Tiplica GS. European guideline for the management of scabies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31(8):1248–1253. doi:10.1111/jdv.14351

- Khalil S, Abbas O, Kibbi AG, Kurban M. Scabies in the age of increasing drug resistance. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017; 11(11):e0005920. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005920

- Anderson KL, Strowd LC. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of scabies in a dermatology office. J Am Board Fam Med 2017; 30(1):78–84. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160190

DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT, CONTROL

The differential diagnosis of Norwegian scabies includes psoriasis, eczema, contact dermatitis, insect bites, seborrheic dermatitis, lichen planus, systemic infection, palmoplantar keratoderma, and cutaneous lymphoma.2

Treatment involves eradicating the infestation with a topical ointment consisting of permethrin, crotamiton, lindane, benzyl benzoate, and sulfur, applied directly to the skin. However, topical treatments often cannot penetrate the crusted and thickened skin, leading to treatment failure. A dose of oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg on days 1, 2, and 8 is a safe, effective, first-line treatment for Norwegian scabies, rapidly reducing scabies symptoms.3 Adverse effects of oral ivermectin are rare and usually minor.

Norwegian scabies is extremely contagious, spread by close physical contact and sharing of contaminated items such as clothing, bedding, towels, and furniture. Scabies mites can survive off the skin for 48 to 72 hours at room temperature.4 Potentially contaminated items should be decontaminated by washing in hot water and drying in a drying machine or by dry cleaning. Body contact with other contaminated items should be avoided for at least 72 hours.

Outbreaks can spread among patients, visitors, and medical staff in institutions such as nursing homes, day care centers, long-term-care facilities, and hospitals.5 Early identification facilitates appropriate management and treatment, thereby preventing infection and community-wide scabies outbreaks.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to sincerely thank Paul Williams for his editing of the article.

DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT, CONTROL

The differential diagnosis of Norwegian scabies includes psoriasis, eczema, contact dermatitis, insect bites, seborrheic dermatitis, lichen planus, systemic infection, palmoplantar keratoderma, and cutaneous lymphoma.2

Treatment involves eradicating the infestation with a topical ointment consisting of permethrin, crotamiton, lindane, benzyl benzoate, and sulfur, applied directly to the skin. However, topical treatments often cannot penetrate the crusted and thickened skin, leading to treatment failure. A dose of oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg on days 1, 2, and 8 is a safe, effective, first-line treatment for Norwegian scabies, rapidly reducing scabies symptoms.3 Adverse effects of oral ivermectin are rare and usually minor.

Norwegian scabies is extremely contagious, spread by close physical contact and sharing of contaminated items such as clothing, bedding, towels, and furniture. Scabies mites can survive off the skin for 48 to 72 hours at room temperature.4 Potentially contaminated items should be decontaminated by washing in hot water and drying in a drying machine or by dry cleaning. Body contact with other contaminated items should be avoided for at least 72 hours.

Outbreaks can spread among patients, visitors, and medical staff in institutions such as nursing homes, day care centers, long-term-care facilities, and hospitals.5 Early identification facilitates appropriate management and treatment, thereby preventing infection and community-wide scabies outbreaks.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to sincerely thank Paul Williams for his editing of the article.

- Leone PA. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44(suppl 3):S153–S159. doi:10.1086/511428

- Siegfried EC, Hebert AA. Diagnosis of atopic dermatitis: mimics, overlaps, and complications. J Clin Med 2015; 4(5):884–917. doi:10.3390/jcm4050884

- Salavastru CM, Chosidow O, Boffa MJ, Janier M, Tiplica GS. European guideline for the management of scabies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31(8):1248–1253. doi:10.1111/jdv.14351

- Khalil S, Abbas O, Kibbi AG, Kurban M. Scabies in the age of increasing drug resistance. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017; 11(11):e0005920. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005920

- Anderson KL, Strowd LC. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of scabies in a dermatology office. J Am Board Fam Med 2017; 30(1):78–84. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160190

- Leone PA. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44(suppl 3):S153–S159. doi:10.1086/511428

- Siegfried EC, Hebert AA. Diagnosis of atopic dermatitis: mimics, overlaps, and complications. J Clin Med 2015; 4(5):884–917. doi:10.3390/jcm4050884

- Salavastru CM, Chosidow O, Boffa MJ, Janier M, Tiplica GS. European guideline for the management of scabies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31(8):1248–1253. doi:10.1111/jdv.14351

- Khalil S, Abbas O, Kibbi AG, Kurban M. Scabies in the age of increasing drug resistance. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017; 11(11):e0005920. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005920

- Anderson KL, Strowd LC. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of scabies in a dermatology office. J Am Board Fam Med 2017; 30(1):78–84. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160190

Aleukemic leukemia cutis

On examination, the numerous firm, indurated nodules ranged in size from 1 to 4 cm. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy.

Results of a peripheral blood cell count showed the following:

- Hemoglobin 12.5 g/dL (reference range 13.0–17.0)

- Platelet count 154 × 109/L (130–400)

- White blood cell count 5.0 × 109/L (4.0–11.0)

- Neutrophils 1.7 × 109/L (1.5–8.0)

- Lymphocytes 2.2 × 109/L (1.0–4.0)

- Monocytes 1.0 × 109/L (0.2–1.0)

- Eosinophils 0 (0–0.4)

- Basophils 0 (0–0.2)

- Blasts 0.

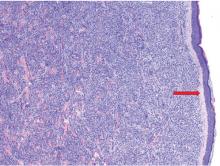

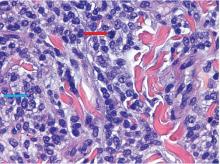

The findings were consistent with leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation. The infiltrate was unusual because leukemic infiltrates typically demonstrate a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, but in this case the malignant cells had moderate amounts of cytoplasm due to the monocytic differentiation. Also, a grenz zone is more typically seen in B-cell lymphomas, and T cells more typically demonstrate epidermotropism.

Bone marrow aspiration was performed and revealed a hypercellular bone marrow with trilineage maturation with only 2% blasts. The fluorescence in situ hybridization testing for myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia was normal. A diagnosis of aleukemic leukemia cutis was made.

After 2 months of chemotherapy with azacitidine, the nodules were less indurated. Treatment was briefly withdrawn due to the development of acute pneumonia, leading to a rapid progression of cutaneous involvement. Despite restarting chemotherapy, the patient died.

ALEUKEMIC LEUKEMIA CUTIS

The differential diagnosis of leukemia cutis is diverse and extensive. Patients often present with painless, firm, indurated nodules, papules, and plaques.1 The lesions can be small, involving a small amount of body surface area, but can also be very large and diffuse.

In our patient’s case, there were no new drugs or exposures to suggest a drug-related eruption, or pruritus or pain to suggest an inflammatory process. The rapid progression of the lesions suggested either an infectious or malignant process. The top 3 conditions in the differential diagnosis, based on his clinical presentation, were cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, and a drug-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma.

Skin biopsy is required to differentiate leukemia cutis from the other conditions. On skin biopsy study, leukemia cutis is characterized by infiltration of the skin by leukemic cells and is seen in 10% to 15% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia.2 In 5% of cases, leukemia cutis can present without bone marrow or peripheral signs of leukemia, hence the term aleukemic leukemia cutis.3 Cutaneous signs can occur before, after, or simultaneously with systemic leukemia.4

In the absence of systemic symptoms, the diagnosis is made when progressive cutaneous symptoms are present. The prognosis for aleukemic leukemia cutis is poor. Prompt diagnosis with skin biopsy is paramount to improve outcomes.

Acknowledgment: We would like to recognize Maanasa Devabhaktuni for her assistance in reporting this case.

- Yonal I, Hindilerden F, Coskun R, Dogan OI, Nalcaci M. Aleukemic leukemia cutis manifesting with disseminated nodular eruptions and a plaque preceding acute monocytic leukemia: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2011; 4(3):547–554. doi:10.1159/000334745

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, Vega F. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol 2008; 129(1):130–142. doi:10.1309/WYACYWF6NGM3WBRT

- Kang YS, Kim HS, Park HJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of 75 patients with leukemia cutis. J Korean Med Sci 2013; 28(4):614–619. doi:10.3346/jkms.2013.28.4.614

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21(8)pii:13030/qt6m18g35f. pmid:26437164

On examination, the numerous firm, indurated nodules ranged in size from 1 to 4 cm. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy.

Results of a peripheral blood cell count showed the following:

- Hemoglobin 12.5 g/dL (reference range 13.0–17.0)

- Platelet count 154 × 109/L (130–400)

- White blood cell count 5.0 × 109/L (4.0–11.0)

- Neutrophils 1.7 × 109/L (1.5–8.0)

- Lymphocytes 2.2 × 109/L (1.0–4.0)

- Monocytes 1.0 × 109/L (0.2–1.0)

- Eosinophils 0 (0–0.4)

- Basophils 0 (0–0.2)

- Blasts 0.

The findings were consistent with leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation. The infiltrate was unusual because leukemic infiltrates typically demonstrate a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, but in this case the malignant cells had moderate amounts of cytoplasm due to the monocytic differentiation. Also, a grenz zone is more typically seen in B-cell lymphomas, and T cells more typically demonstrate epidermotropism.

Bone marrow aspiration was performed and revealed a hypercellular bone marrow with trilineage maturation with only 2% blasts. The fluorescence in situ hybridization testing for myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia was normal. A diagnosis of aleukemic leukemia cutis was made.

After 2 months of chemotherapy with azacitidine, the nodules were less indurated. Treatment was briefly withdrawn due to the development of acute pneumonia, leading to a rapid progression of cutaneous involvement. Despite restarting chemotherapy, the patient died.

ALEUKEMIC LEUKEMIA CUTIS

The differential diagnosis of leukemia cutis is diverse and extensive. Patients often present with painless, firm, indurated nodules, papules, and plaques.1 The lesions can be small, involving a small amount of body surface area, but can also be very large and diffuse.

In our patient’s case, there were no new drugs or exposures to suggest a drug-related eruption, or pruritus or pain to suggest an inflammatory process. The rapid progression of the lesions suggested either an infectious or malignant process. The top 3 conditions in the differential diagnosis, based on his clinical presentation, were cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, and a drug-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma.

Skin biopsy is required to differentiate leukemia cutis from the other conditions. On skin biopsy study, leukemia cutis is characterized by infiltration of the skin by leukemic cells and is seen in 10% to 15% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia.2 In 5% of cases, leukemia cutis can present without bone marrow or peripheral signs of leukemia, hence the term aleukemic leukemia cutis.3 Cutaneous signs can occur before, after, or simultaneously with systemic leukemia.4

In the absence of systemic symptoms, the diagnosis is made when progressive cutaneous symptoms are present. The prognosis for aleukemic leukemia cutis is poor. Prompt diagnosis with skin biopsy is paramount to improve outcomes.

Acknowledgment: We would like to recognize Maanasa Devabhaktuni for her assistance in reporting this case.

On examination, the numerous firm, indurated nodules ranged in size from 1 to 4 cm. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy.

Results of a peripheral blood cell count showed the following:

- Hemoglobin 12.5 g/dL (reference range 13.0–17.0)

- Platelet count 154 × 109/L (130–400)

- White blood cell count 5.0 × 109/L (4.0–11.0)

- Neutrophils 1.7 × 109/L (1.5–8.0)

- Lymphocytes 2.2 × 109/L (1.0–4.0)

- Monocytes 1.0 × 109/L (0.2–1.0)

- Eosinophils 0 (0–0.4)

- Basophils 0 (0–0.2)

- Blasts 0.

The findings were consistent with leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation. The infiltrate was unusual because leukemic infiltrates typically demonstrate a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, but in this case the malignant cells had moderate amounts of cytoplasm due to the monocytic differentiation. Also, a grenz zone is more typically seen in B-cell lymphomas, and T cells more typically demonstrate epidermotropism.

Bone marrow aspiration was performed and revealed a hypercellular bone marrow with trilineage maturation with only 2% blasts. The fluorescence in situ hybridization testing for myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia was normal. A diagnosis of aleukemic leukemia cutis was made.

After 2 months of chemotherapy with azacitidine, the nodules were less indurated. Treatment was briefly withdrawn due to the development of acute pneumonia, leading to a rapid progression of cutaneous involvement. Despite restarting chemotherapy, the patient died.

ALEUKEMIC LEUKEMIA CUTIS

The differential diagnosis of leukemia cutis is diverse and extensive. Patients often present with painless, firm, indurated nodules, papules, and plaques.1 The lesions can be small, involving a small amount of body surface area, but can also be very large and diffuse.

In our patient’s case, there were no new drugs or exposures to suggest a drug-related eruption, or pruritus or pain to suggest an inflammatory process. The rapid progression of the lesions suggested either an infectious or malignant process. The top 3 conditions in the differential diagnosis, based on his clinical presentation, were cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, and a drug-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma.

Skin biopsy is required to differentiate leukemia cutis from the other conditions. On skin biopsy study, leukemia cutis is characterized by infiltration of the skin by leukemic cells and is seen in 10% to 15% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia.2 In 5% of cases, leukemia cutis can present without bone marrow or peripheral signs of leukemia, hence the term aleukemic leukemia cutis.3 Cutaneous signs can occur before, after, or simultaneously with systemic leukemia.4

In the absence of systemic symptoms, the diagnosis is made when progressive cutaneous symptoms are present. The prognosis for aleukemic leukemia cutis is poor. Prompt diagnosis with skin biopsy is paramount to improve outcomes.

Acknowledgment: We would like to recognize Maanasa Devabhaktuni for her assistance in reporting this case.

- Yonal I, Hindilerden F, Coskun R, Dogan OI, Nalcaci M. Aleukemic leukemia cutis manifesting with disseminated nodular eruptions and a plaque preceding acute monocytic leukemia: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2011; 4(3):547–554. doi:10.1159/000334745

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, Vega F. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol 2008; 129(1):130–142. doi:10.1309/WYACYWF6NGM3WBRT

- Kang YS, Kim HS, Park HJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of 75 patients with leukemia cutis. J Korean Med Sci 2013; 28(4):614–619. doi:10.3346/jkms.2013.28.4.614

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21(8)pii:13030/qt6m18g35f. pmid:26437164

- Yonal I, Hindilerden F, Coskun R, Dogan OI, Nalcaci M. Aleukemic leukemia cutis manifesting with disseminated nodular eruptions and a plaque preceding acute monocytic leukemia: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2011; 4(3):547–554. doi:10.1159/000334745

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, Vega F. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol 2008; 129(1):130–142. doi:10.1309/WYACYWF6NGM3WBRT

- Kang YS, Kim HS, Park HJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of 75 patients with leukemia cutis. J Korean Med Sci 2013; 28(4):614–619. doi:10.3346/jkms.2013.28.4.614

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21(8)pii:13030/qt6m18g35f. pmid:26437164

Dancing sternal wires: A radiologic sign of sternal dehiscence

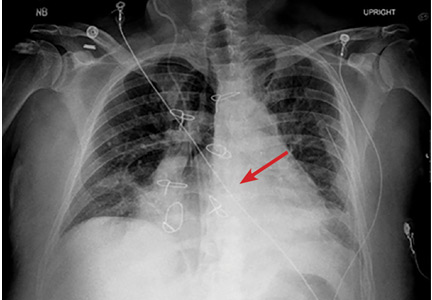

The next day, routine radiography showed widely separated sternal wires (Figure 3), indicating significant progression of sternal dehiscence. The patient subsequently underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the sternum.

STERNAL DEHISCENCE

Physical examination may reveal tenderness to palpation, but findings that are more characteristic are an audible click and rocking of the sternum with coughing or forced chest movements.3

Plain chest radiography can clearly show early signs of sternal dehiscence; however, physicians rarely scrutinize the films for wire placement. Subtle signs include loss of sternal alignment with shifting of the segments and central sternal lucency. Gross signs start to appear when 2 or more wires are displaced; these signs are dramatic and rarely missed.

Loss of alignment and central sternal lucency are the earliest radiographic signs of dehiscence. Awareness of early subtle signs can lead to prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent progression to gross sternal dehiscence.

- Olbrecht VA, Barreiro CJ, Bonde PN, et al. Clinical outcomes of noninfectious sternal dehiscence after median sternotomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 82(3):902–907. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.04.058

- Efthymiou CA, Kay PH, Nair UR. Repair of spontaneous right ventricular rupture following sternal dehiscence. A novel technique. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010; 10(1):12–13. doi:10.1510/icvts.2009.217810

- Santarpino G, Pfeiffer S, Concistré G, Fischlein T. Sternal wound dehiscence from intense coughing in a cardiac surgery patient: could it be prevented? G Chir 2013; 34(4):112-113. pmid:23660161

The next day, routine radiography showed widely separated sternal wires (Figure 3), indicating significant progression of sternal dehiscence. The patient subsequently underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the sternum.

STERNAL DEHISCENCE

Physical examination may reveal tenderness to palpation, but findings that are more characteristic are an audible click and rocking of the sternum with coughing or forced chest movements.3

Plain chest radiography can clearly show early signs of sternal dehiscence; however, physicians rarely scrutinize the films for wire placement. Subtle signs include loss of sternal alignment with shifting of the segments and central sternal lucency. Gross signs start to appear when 2 or more wires are displaced; these signs are dramatic and rarely missed.

Loss of alignment and central sternal lucency are the earliest radiographic signs of dehiscence. Awareness of early subtle signs can lead to prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent progression to gross sternal dehiscence.

The next day, routine radiography showed widely separated sternal wires (Figure 3), indicating significant progression of sternal dehiscence. The patient subsequently underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the sternum.

STERNAL DEHISCENCE

Physical examination may reveal tenderness to palpation, but findings that are more characteristic are an audible click and rocking of the sternum with coughing or forced chest movements.3

Plain chest radiography can clearly show early signs of sternal dehiscence; however, physicians rarely scrutinize the films for wire placement. Subtle signs include loss of sternal alignment with shifting of the segments and central sternal lucency. Gross signs start to appear when 2 or more wires are displaced; these signs are dramatic and rarely missed.

Loss of alignment and central sternal lucency are the earliest radiographic signs of dehiscence. Awareness of early subtle signs can lead to prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent progression to gross sternal dehiscence.

- Olbrecht VA, Barreiro CJ, Bonde PN, et al. Clinical outcomes of noninfectious sternal dehiscence after median sternotomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 82(3):902–907. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.04.058

- Efthymiou CA, Kay PH, Nair UR. Repair of spontaneous right ventricular rupture following sternal dehiscence. A novel technique. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010; 10(1):12–13. doi:10.1510/icvts.2009.217810

- Santarpino G, Pfeiffer S, Concistré G, Fischlein T. Sternal wound dehiscence from intense coughing in a cardiac surgery patient: could it be prevented? G Chir 2013; 34(4):112-113. pmid:23660161

- Olbrecht VA, Barreiro CJ, Bonde PN, et al. Clinical outcomes of noninfectious sternal dehiscence after median sternotomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 82(3):902–907. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.04.058

- Efthymiou CA, Kay PH, Nair UR. Repair of spontaneous right ventricular rupture following sternal dehiscence. A novel technique. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010; 10(1):12–13. doi:10.1510/icvts.2009.217810

- Santarpino G, Pfeiffer S, Concistré G, Fischlein T. Sternal wound dehiscence from intense coughing in a cardiac surgery patient: could it be prevented? G Chir 2013; 34(4):112-113. pmid:23660161