User login

Plexiform neurofibroma

A 19-year-old woman presented with diffuse swelling on her neck and face that had been growing gradually over the past 12 years. There was no family history of similar swelling.

Examination revealed a diffuse, hyperpigmented, nodular swelling on the right side of her neck and extending upward to the lower part of the face and the scalp (Figure 1). The rest of the physical examination was normal. A diagnosis of plexiform neurofibroma was made based on the typical clinical presentation. The patient had come primarily because of cosmetic concerns but refused surgery. She was offered genetic counseling and was scheduled for regular follow-up.

Plexiform neurofibroma is mostly associated with autosomal dominant neurofibromatosis type 1, characterized by cutaneous findings such as café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, skeletal dysplasias (usually of the tibia, fibula, ribs, and vertebrae), Lisch nodules in the eye (iris hamartomas), and neural tumors. Rarely, it may also be seen in germline p16 mutation-positive heritable melanoma and Cowden syndrome.

Diffuse plexiform neurofibroma of the face and neck rarely appears after the age of 1, and rarely develops on other parts of the body after adolescence. In contrast, deep nodular plexiform neurofibroma often originates from spinal nerve roots and usually becomes symptomatic in adulthood.

Plexiform neurofibroma has an 8% to 12% chance of changing into a malignant peripheral nerve-sheath tumor. Continuous pain in the tumor, rapid tumor growth, hardening of the tumor, or weakness or numbness in an arm or leg with a plexiform neurofibroma suggests malignant transformation.

The diagnosis is clinical, and the management involves a multidisciplinary team including a physician, geneticist, neurologist, surgeon, and ophthalmologist. Genetic counseling should be offered to patients for assessment of family risk, to look for other possible conditions such as Cowden syndrome, for marital and family planning, and whenever the diagnosis is unclear.

A 19-year-old woman presented with diffuse swelling on her neck and face that had been growing gradually over the past 12 years. There was no family history of similar swelling.

Examination revealed a diffuse, hyperpigmented, nodular swelling on the right side of her neck and extending upward to the lower part of the face and the scalp (Figure 1). The rest of the physical examination was normal. A diagnosis of plexiform neurofibroma was made based on the typical clinical presentation. The patient had come primarily because of cosmetic concerns but refused surgery. She was offered genetic counseling and was scheduled for regular follow-up.

Plexiform neurofibroma is mostly associated with autosomal dominant neurofibromatosis type 1, characterized by cutaneous findings such as café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, skeletal dysplasias (usually of the tibia, fibula, ribs, and vertebrae), Lisch nodules in the eye (iris hamartomas), and neural tumors. Rarely, it may also be seen in germline p16 mutation-positive heritable melanoma and Cowden syndrome.

Diffuse plexiform neurofibroma of the face and neck rarely appears after the age of 1, and rarely develops on other parts of the body after adolescence. In contrast, deep nodular plexiform neurofibroma often originates from spinal nerve roots and usually becomes symptomatic in adulthood.

Plexiform neurofibroma has an 8% to 12% chance of changing into a malignant peripheral nerve-sheath tumor. Continuous pain in the tumor, rapid tumor growth, hardening of the tumor, or weakness or numbness in an arm or leg with a plexiform neurofibroma suggests malignant transformation.

The diagnosis is clinical, and the management involves a multidisciplinary team including a physician, geneticist, neurologist, surgeon, and ophthalmologist. Genetic counseling should be offered to patients for assessment of family risk, to look for other possible conditions such as Cowden syndrome, for marital and family planning, and whenever the diagnosis is unclear.

A 19-year-old woman presented with diffuse swelling on her neck and face that had been growing gradually over the past 12 years. There was no family history of similar swelling.

Examination revealed a diffuse, hyperpigmented, nodular swelling on the right side of her neck and extending upward to the lower part of the face and the scalp (Figure 1). The rest of the physical examination was normal. A diagnosis of plexiform neurofibroma was made based on the typical clinical presentation. The patient had come primarily because of cosmetic concerns but refused surgery. She was offered genetic counseling and was scheduled for regular follow-up.

Plexiform neurofibroma is mostly associated with autosomal dominant neurofibromatosis type 1, characterized by cutaneous findings such as café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, skeletal dysplasias (usually of the tibia, fibula, ribs, and vertebrae), Lisch nodules in the eye (iris hamartomas), and neural tumors. Rarely, it may also be seen in germline p16 mutation-positive heritable melanoma and Cowden syndrome.

Diffuse plexiform neurofibroma of the face and neck rarely appears after the age of 1, and rarely develops on other parts of the body after adolescence. In contrast, deep nodular plexiform neurofibroma often originates from spinal nerve roots and usually becomes symptomatic in adulthood.

Plexiform neurofibroma has an 8% to 12% chance of changing into a malignant peripheral nerve-sheath tumor. Continuous pain in the tumor, rapid tumor growth, hardening of the tumor, or weakness or numbness in an arm or leg with a plexiform neurofibroma suggests malignant transformation.

The diagnosis is clinical, and the management involves a multidisciplinary team including a physician, geneticist, neurologist, surgeon, and ophthalmologist. Genetic counseling should be offered to patients for assessment of family risk, to look for other possible conditions such as Cowden syndrome, for marital and family planning, and whenever the diagnosis is unclear.

Eruptive xanthoma: Warning sign of systemic disease

A 30-year-old man presented with multiple asymptomatic skin-colored and yellowish papules and nodules over the elbows, wrists, feet, buttocks, hands, and forearms (Figure 1) that had appeared suddenly 2 weeks before.

His medical history included diabetes mellitus, Hansen disease diagnosed 6 years earlier and treated with a multibacillary regimen for 1 year, and pancreatitis diagnosed 6 months earlier.

Laboratory testing. When a serum sample was centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 15 minutes, a large lipid layer formed at the top (Figure 2). Other results:

- Triglycerides 5,742 mg/dL (reference range < 160)

- Total cholesterol 293 mg/dL (< 240 mg/dL)

- Fasting blood glucose 473 mg/dL

- Low-density and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels normal

- Complete blood cell count within normal limits.

Other testing. The electrocardiogram was normal. Retinal examination showed evidence of lipemia retinalis. Histologic study of a biopsy specimen from one of the lesions showed foamy macrophages in the superficial dermis with lymphocytic infiltrate, confirming the diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma.

An urgent medical referral was sought. The patient was started on statins and fibrates, and the treatment resulted in remarkable improvement.

ERUPTIVE XANTHOMA

Cutaneous manifestations can be warning signs of systemic disease, and physicians should be aware of the dermatologic presentations of common medical conditions.

Eruptive xanthoma is a sign of severe hypertriglyceridemia and is almost always due to an acquired cause such as hyperchylomicronemia or an inherited lipoprotein disorder (eg, lipoprotein lipase deficiency in children, common familial hypertriglyceridemia type 5 in adults).1

Chylomicronemia syndrome is characterized by triglyceride levels greater than 1,000 mg/dL in a patient with eruptive xanthoma, lipemia retinalis, or abdominal pain or pancreatitis. The syndrome has a prevalence of 1.7 out of 10,000 patients.2 Treatment is a strict low-fat diet, with a minimal role for fibrates and nicotinic acid.

Eruptive xanthoma is seen at the time of presentation in 8.5% of patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia (serum level > 1,772 mg/dL).3 In patients with serum triglyceride levels greater than 1,000 mg/dL, the risk of acute pancreatitis is 5%, and at levels above 2,000 mg/dL, the risk is 10% to 20%.4

In our patient, the diagnosis of chylomicronemia was based on the appearance of the skin lesions, his history of pancreatitis and diabetes mellitus, and the results of the initial workup, which revealed severe hypertriglyceridemia and lipemia retinalis. The presence of eruptive xanthomas should raise suspicion for a grossly elevated triglyceride level. Therefore, in view of the increased risk of acute pancreatitis and pancreatic necrosis associated with chylomicronemic syndrome,2 recognizing the cutaneous signs is mandatory.

- Chalès G, Coiffier G, Guggenbuhl P. Miscellaneous non-inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions. Rare thesaurismosis and xanthomatosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011; 25:683–701.

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121:10–12.

- Sandhu S, Al-Sarraf A, Taraboanta C, Frohlich J, Francis GA. Incidence of pancreatitis, secondary causes, and treatment of patients referred to a specialty lipid clinic with severe hypertriglyceridemia: a retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis 2011; 10:157.

- Scherer J, Singh VP, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D. Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014; 48:195–203.

A 30-year-old man presented with multiple asymptomatic skin-colored and yellowish papules and nodules over the elbows, wrists, feet, buttocks, hands, and forearms (Figure 1) that had appeared suddenly 2 weeks before.

His medical history included diabetes mellitus, Hansen disease diagnosed 6 years earlier and treated with a multibacillary regimen for 1 year, and pancreatitis diagnosed 6 months earlier.

Laboratory testing. When a serum sample was centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 15 minutes, a large lipid layer formed at the top (Figure 2). Other results:

- Triglycerides 5,742 mg/dL (reference range < 160)

- Total cholesterol 293 mg/dL (< 240 mg/dL)

- Fasting blood glucose 473 mg/dL

- Low-density and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels normal

- Complete blood cell count within normal limits.

Other testing. The electrocardiogram was normal. Retinal examination showed evidence of lipemia retinalis. Histologic study of a biopsy specimen from one of the lesions showed foamy macrophages in the superficial dermis with lymphocytic infiltrate, confirming the diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma.

An urgent medical referral was sought. The patient was started on statins and fibrates, and the treatment resulted in remarkable improvement.

ERUPTIVE XANTHOMA

Cutaneous manifestations can be warning signs of systemic disease, and physicians should be aware of the dermatologic presentations of common medical conditions.

Eruptive xanthoma is a sign of severe hypertriglyceridemia and is almost always due to an acquired cause such as hyperchylomicronemia or an inherited lipoprotein disorder (eg, lipoprotein lipase deficiency in children, common familial hypertriglyceridemia type 5 in adults).1

Chylomicronemia syndrome is characterized by triglyceride levels greater than 1,000 mg/dL in a patient with eruptive xanthoma, lipemia retinalis, or abdominal pain or pancreatitis. The syndrome has a prevalence of 1.7 out of 10,000 patients.2 Treatment is a strict low-fat diet, with a minimal role for fibrates and nicotinic acid.

Eruptive xanthoma is seen at the time of presentation in 8.5% of patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia (serum level > 1,772 mg/dL).3 In patients with serum triglyceride levels greater than 1,000 mg/dL, the risk of acute pancreatitis is 5%, and at levels above 2,000 mg/dL, the risk is 10% to 20%.4

In our patient, the diagnosis of chylomicronemia was based on the appearance of the skin lesions, his history of pancreatitis and diabetes mellitus, and the results of the initial workup, which revealed severe hypertriglyceridemia and lipemia retinalis. The presence of eruptive xanthomas should raise suspicion for a grossly elevated triglyceride level. Therefore, in view of the increased risk of acute pancreatitis and pancreatic necrosis associated with chylomicronemic syndrome,2 recognizing the cutaneous signs is mandatory.

A 30-year-old man presented with multiple asymptomatic skin-colored and yellowish papules and nodules over the elbows, wrists, feet, buttocks, hands, and forearms (Figure 1) that had appeared suddenly 2 weeks before.

His medical history included diabetes mellitus, Hansen disease diagnosed 6 years earlier and treated with a multibacillary regimen for 1 year, and pancreatitis diagnosed 6 months earlier.

Laboratory testing. When a serum sample was centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 15 minutes, a large lipid layer formed at the top (Figure 2). Other results:

- Triglycerides 5,742 mg/dL (reference range < 160)

- Total cholesterol 293 mg/dL (< 240 mg/dL)

- Fasting blood glucose 473 mg/dL

- Low-density and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels normal

- Complete blood cell count within normal limits.

Other testing. The electrocardiogram was normal. Retinal examination showed evidence of lipemia retinalis. Histologic study of a biopsy specimen from one of the lesions showed foamy macrophages in the superficial dermis with lymphocytic infiltrate, confirming the diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma.

An urgent medical referral was sought. The patient was started on statins and fibrates, and the treatment resulted in remarkable improvement.

ERUPTIVE XANTHOMA

Cutaneous manifestations can be warning signs of systemic disease, and physicians should be aware of the dermatologic presentations of common medical conditions.

Eruptive xanthoma is a sign of severe hypertriglyceridemia and is almost always due to an acquired cause such as hyperchylomicronemia or an inherited lipoprotein disorder (eg, lipoprotein lipase deficiency in children, common familial hypertriglyceridemia type 5 in adults).1

Chylomicronemia syndrome is characterized by triglyceride levels greater than 1,000 mg/dL in a patient with eruptive xanthoma, lipemia retinalis, or abdominal pain or pancreatitis. The syndrome has a prevalence of 1.7 out of 10,000 patients.2 Treatment is a strict low-fat diet, with a minimal role for fibrates and nicotinic acid.

Eruptive xanthoma is seen at the time of presentation in 8.5% of patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia (serum level > 1,772 mg/dL).3 In patients with serum triglyceride levels greater than 1,000 mg/dL, the risk of acute pancreatitis is 5%, and at levels above 2,000 mg/dL, the risk is 10% to 20%.4

In our patient, the diagnosis of chylomicronemia was based on the appearance of the skin lesions, his history of pancreatitis and diabetes mellitus, and the results of the initial workup, which revealed severe hypertriglyceridemia and lipemia retinalis. The presence of eruptive xanthomas should raise suspicion for a grossly elevated triglyceride level. Therefore, in view of the increased risk of acute pancreatitis and pancreatic necrosis associated with chylomicronemic syndrome,2 recognizing the cutaneous signs is mandatory.

- Chalès G, Coiffier G, Guggenbuhl P. Miscellaneous non-inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions. Rare thesaurismosis and xanthomatosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011; 25:683–701.

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121:10–12.

- Sandhu S, Al-Sarraf A, Taraboanta C, Frohlich J, Francis GA. Incidence of pancreatitis, secondary causes, and treatment of patients referred to a specialty lipid clinic with severe hypertriglyceridemia: a retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis 2011; 10:157.

- Scherer J, Singh VP, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D. Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014; 48:195–203.

- Chalès G, Coiffier G, Guggenbuhl P. Miscellaneous non-inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions. Rare thesaurismosis and xanthomatosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011; 25:683–701.

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121:10–12.

- Sandhu S, Al-Sarraf A, Taraboanta C, Frohlich J, Francis GA. Incidence of pancreatitis, secondary causes, and treatment of patients referred to a specialty lipid clinic with severe hypertriglyceridemia: a retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis 2011; 10:157.

- Scherer J, Singh VP, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D. Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014; 48:195–203.

Concurrent uvulitis and epiglottitis

A 66-year-old woman presented with fever, cough, odynophagia, and anterior neck pain.

Examination of the oral cavity showed a swollen, erythematous uvula with exudate consistent with uvulitis (Figure 1). A lateral radiograph of the neck showed minimal thickening of the epiglottis (Figure 2). Fiberoptic laryngoscopy showed ulcerations along the base of the tongue, epiglottis, and aryepiglottic folds.

Intravenous antibiotics (ceftriaxone and vancomycin), intravenous corticosteroids, and acyclovir were started empirically, and the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for observation of her respiratory status.

Results of rapid testing for group A streptococci were negative. Routine throat cultures were positive for group G beta-hemolytic streptococci. Viral throat cultures were negative for herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction testing of a nasopharyngeal specimen was negative for a variety of respiratory viral pathogens. No organisms were identified on blood cultures.

Her fever and symptoms resolved. She was discharged home on an oral course of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and acyclovir. Acyclovir was given based on the ulcerative lesions suggestive of herpetic infection. No recurrence was reported.

KEY FEATURES AND MANAGEMENT

Uvulitis is an uncommon infection, usually caused by Streptococcus pyogenes, S pneumoniae, or Haemophilus influenzae.1–3 It can be an isolated finding or associated with concurrent pharyngitis and epiglottitis.1–3

Uvulitis and epiglottitis can have similar presenting symptoms such as fever, sore throat, and odynophagia. Lateral neck radiography looking for an enlarged epiglottis (“thumb” sign) is recommended, given the similarities in presentation to uvulitis and the seriousness of epiglottitis if missed. If there are signs of airway obstruction, laryngoscopy should be performed in a controlled setting such as the intensive care unit, as it may precipitate sudden airway obstruction.

Close observation in the intensive care unit is recommended in adults presenting with epiglottitis because of the risk of rapid deterioration and the need to secure the airway. Empirical therapy with intravenous antibiotics (eg, a third-generation cephalosporin or a beta-lactamase inhibitor combination) to cover the common pathogens mentioned above is recommended and should then be tailored according to the results of blood culture testing.

- Kotloff KL, Wald ER. Uvulitis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis 1983; 2:392–393.

- Westerman EL, Hutton JP. Acute uvulitis associated with epiglottitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1986; 112:448–449.

- Rapkin RH. Simultaneous uvulitis and epiglottitis. JAMA 1980; 243:1843.

A 66-year-old woman presented with fever, cough, odynophagia, and anterior neck pain.

Examination of the oral cavity showed a swollen, erythematous uvula with exudate consistent with uvulitis (Figure 1). A lateral radiograph of the neck showed minimal thickening of the epiglottis (Figure 2). Fiberoptic laryngoscopy showed ulcerations along the base of the tongue, epiglottis, and aryepiglottic folds.

Intravenous antibiotics (ceftriaxone and vancomycin), intravenous corticosteroids, and acyclovir were started empirically, and the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for observation of her respiratory status.

Results of rapid testing for group A streptococci were negative. Routine throat cultures were positive for group G beta-hemolytic streptococci. Viral throat cultures were negative for herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction testing of a nasopharyngeal specimen was negative for a variety of respiratory viral pathogens. No organisms were identified on blood cultures.

Her fever and symptoms resolved. She was discharged home on an oral course of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and acyclovir. Acyclovir was given based on the ulcerative lesions suggestive of herpetic infection. No recurrence was reported.

KEY FEATURES AND MANAGEMENT

Uvulitis is an uncommon infection, usually caused by Streptococcus pyogenes, S pneumoniae, or Haemophilus influenzae.1–3 It can be an isolated finding or associated with concurrent pharyngitis and epiglottitis.1–3

Uvulitis and epiglottitis can have similar presenting symptoms such as fever, sore throat, and odynophagia. Lateral neck radiography looking for an enlarged epiglottis (“thumb” sign) is recommended, given the similarities in presentation to uvulitis and the seriousness of epiglottitis if missed. If there are signs of airway obstruction, laryngoscopy should be performed in a controlled setting such as the intensive care unit, as it may precipitate sudden airway obstruction.

Close observation in the intensive care unit is recommended in adults presenting with epiglottitis because of the risk of rapid deterioration and the need to secure the airway. Empirical therapy with intravenous antibiotics (eg, a third-generation cephalosporin or a beta-lactamase inhibitor combination) to cover the common pathogens mentioned above is recommended and should then be tailored according to the results of blood culture testing.

A 66-year-old woman presented with fever, cough, odynophagia, and anterior neck pain.

Examination of the oral cavity showed a swollen, erythematous uvula with exudate consistent with uvulitis (Figure 1). A lateral radiograph of the neck showed minimal thickening of the epiglottis (Figure 2). Fiberoptic laryngoscopy showed ulcerations along the base of the tongue, epiglottis, and aryepiglottic folds.

Intravenous antibiotics (ceftriaxone and vancomycin), intravenous corticosteroids, and acyclovir were started empirically, and the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for observation of her respiratory status.

Results of rapid testing for group A streptococci were negative. Routine throat cultures were positive for group G beta-hemolytic streptococci. Viral throat cultures were negative for herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction testing of a nasopharyngeal specimen was negative for a variety of respiratory viral pathogens. No organisms were identified on blood cultures.

Her fever and symptoms resolved. She was discharged home on an oral course of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and acyclovir. Acyclovir was given based on the ulcerative lesions suggestive of herpetic infection. No recurrence was reported.

KEY FEATURES AND MANAGEMENT

Uvulitis is an uncommon infection, usually caused by Streptococcus pyogenes, S pneumoniae, or Haemophilus influenzae.1–3 It can be an isolated finding or associated with concurrent pharyngitis and epiglottitis.1–3

Uvulitis and epiglottitis can have similar presenting symptoms such as fever, sore throat, and odynophagia. Lateral neck radiography looking for an enlarged epiglottis (“thumb” sign) is recommended, given the similarities in presentation to uvulitis and the seriousness of epiglottitis if missed. If there are signs of airway obstruction, laryngoscopy should be performed in a controlled setting such as the intensive care unit, as it may precipitate sudden airway obstruction.

Close observation in the intensive care unit is recommended in adults presenting with epiglottitis because of the risk of rapid deterioration and the need to secure the airway. Empirical therapy with intravenous antibiotics (eg, a third-generation cephalosporin or a beta-lactamase inhibitor combination) to cover the common pathogens mentioned above is recommended and should then be tailored according to the results of blood culture testing.

- Kotloff KL, Wald ER. Uvulitis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis 1983; 2:392–393.

- Westerman EL, Hutton JP. Acute uvulitis associated with epiglottitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1986; 112:448–449.

- Rapkin RH. Simultaneous uvulitis and epiglottitis. JAMA 1980; 243:1843.

- Kotloff KL, Wald ER. Uvulitis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis 1983; 2:392–393.

- Westerman EL, Hutton JP. Acute uvulitis associated with epiglottitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1986; 112:448–449.

- Rapkin RH. Simultaneous uvulitis and epiglottitis. JAMA 1980; 243:1843.

Air leakage in multiple compartments after endoscopy

A 68-year-old man with metastatic periampullary adenocarcinoma presented to his usual clinic for a scheduled biliary stent exchange by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The stent had been placed 5 months before, and no complications had been reported during that procedure.

During the stent exchange procedure, the endoscopist advanced the scope to the second part of the duodenum, where a large, ulcerated, friable mass was visualized surrounding the ampulla, consistent with patient’s known periampullary cancer. The biliary stent was removed without much difficulty. However, several attempts to cannulate the common bile duct with a preloaded guidewire failed because of extensive edema and tissue friability, and to avoid further discomfort to the patient, the procedure was aborted. No perforation was visualized during or at the end of the procedure.

During the first hour after the procedure was stopped, the patient suddenly developed abdominal pain and distention and crepitus of the right chest wall. Supine abdominal radiography showed extensive pneumoperitoneum and subcutaneous emphysema in the chest. A nasogastric tube was placed for decompression, and the patient was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit at our hospital.

EVIDENCE OF PERFORATION NOTED

On arrival, the patient’s oxygen saturation was 99% while receiving oxygen at 2 L/minute by nasal cannula. The physical examination revealed neck swelling, abdominal distention, and crepitus in the neck, abdomen, scrotum, and right lower extremity.

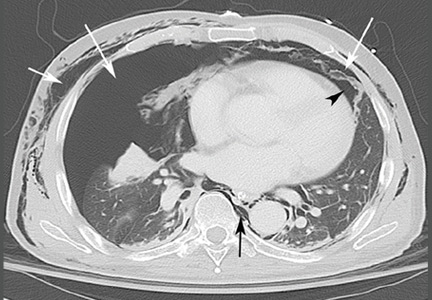

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast revealed widespread pneumoretroperitoneum, pneumoperitoneum, and air along the intermuscular planes in the right lower extremity, with no evidence of extravasation of oral contrast (Figure 1). Also noted were bilateral pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, and extensive subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 2).

Despite these impressive findings, the patient remained hemodynamically stable and was managed conservatively with broad-spectrum antibiotics, gastric decompression, and bowel rest. But repeat chest radiography 5 hours after admission to the hospital revealed an enlarging right pneumothorax, which was treated with placement of a pigtail catheter. The patient continued to improve with conservative management and was discharged on the 6th day of hospitalization.

PERFORATION DURING ERCP: INCIDENCE AND COMPLICATIONS

Although perforation is an uncommon complication of ERCP, with an incidence of 1%, mortality rates as high as 18% have been reported.1 Older age, longer procedural time, anatomic variations, and diseases of the duodenum and common bile duct can increase the risk of perforation.2

Types of perforation

Stapfer et al1 classified perforation during ERCP into four types, based on etiology and site of perforation. Type 1 is perforation of the lateral or medial duodenal wall caused by excessive pressure from the endoscope or its acute angulation. Type 2 is periampullary injury, often associated with sphincterotomy or difficulty accessing the biliary tree. Type 3 is injury to the common bile duct or pancreatic duct caused by instrumentation. Type 4 is the presence of retroperitoneal free air with no evidence of actual perforation; this is usually an incidental finding and is of little or no clinical consequence.1

In 2015, a review of 18 studies described the distribution of ERCP perforation according to the Stapfer classification: 25% were type 1, 46% were type 2, and 22% were type 3.3

Effects of air insufflation

ERCP requires air insufflation for optimal visualization. During difficult or prolonged procedures, a larger amount of air may be insufflated to maintain bowel lumen visibility. Depending on the site and size of the defect, a variable amount of air can leak under pressure once the perforation occurs. A rapid retroperitoneal air leak can spread to multiple body compartments, including the mediastinum, pleura, neck, subcutaneous tissues, scrotum, and musculature by tracking through various fascial planes. Rarely, rapid ingress of air in these areas can lead to compartment syndrome.4

Small perforations tend to close spontaneously and may remain clinically silent, but large or persistent perforations are known to cause subcutaneous emphysema, sepsis, and respiratory failure.5

Our patient’s type 2 perforation

We presumed that our patient had a type 2 perforation, given the finding of retroperitoneal air. Difficulty cannulating the biliary tree via the friable malignant tissue at the site of the major papilla likely caused punctate perforations, resulting in air leakage into the retroperitoneum. Punctate perforations typically do not allow contrast extravasation, explaining the absence of oral contrast leakage on CT.

TREATMENT OF ENDOSCOPY-RELATED PERFORATION

Conventional supine and upright abdominal radiography is an appropriate initial imaging modality to confirm the diagnosis. However, CT is more sensitive and accurate, especially when air leakage is confined to the retroperitoneum. Intravenous or oral contrast is not necessary but may help localize the perforation and better delineate fluid collections and abscesses.2

Once perforation is suspected, treatment with a broad-spectrum antibiotic, bowel rest, and stomach decompression is imperative.6 Further management depends on the type of perforation and the overall clinical picture. Type 1 perforations usually require immediate surgical intervention. Type 2 perforations often seal spontaneously within 2 to 3 days and thus are managed conservatively (ie, a broad-spectrum antibiotic, gastric decompression, and bowel rest), unless there is a persistent leak or a large fluid collection. Type 3 perforations rarely require surgery since most are very small and close spontaneously, and so they are managed conservatively. Type 4 perforations are the least serious. They result in retroperitoneal free air that is thought be related to the use of compressed air for lumen patency. They require only conservative measures.1

- Stapfer M, Selby RR, Stain SC, et al. Management of duodenal perforation after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy. Ann Surg 2000; 232:191–198.

- Enns M, Eloubeidi K, Mergener P, et al. ERCP-related perforations: risk factors and management. Endoscopy 2002; 34:293–298.

- Vezakis A, Fragulidis G, Polydorou A. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related perforations: diagnosis and management. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7:1135–1341.

- Frias Vilaca A, Reis AM, Vidal IM. The anatomical compartments and their connections as demonstrated by ectopic air. Insights Imaging 2013; 4:759–772.

- Machado N. Management of duodenal perforation post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. When and whom to operate and what factors determine the outcome? A review article. JOP (Online) 2012; 13:18–25.

- Dubecz A, Ottmann J, Schweigert M, et al. Management of ERCP-related small bowel perforations: the pivotal role of physical investigation. Can J Surg 2012; 55:99–104.

A 68-year-old man with metastatic periampullary adenocarcinoma presented to his usual clinic for a scheduled biliary stent exchange by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The stent had been placed 5 months before, and no complications had been reported during that procedure.

During the stent exchange procedure, the endoscopist advanced the scope to the second part of the duodenum, where a large, ulcerated, friable mass was visualized surrounding the ampulla, consistent with patient’s known periampullary cancer. The biliary stent was removed without much difficulty. However, several attempts to cannulate the common bile duct with a preloaded guidewire failed because of extensive edema and tissue friability, and to avoid further discomfort to the patient, the procedure was aborted. No perforation was visualized during or at the end of the procedure.

During the first hour after the procedure was stopped, the patient suddenly developed abdominal pain and distention and crepitus of the right chest wall. Supine abdominal radiography showed extensive pneumoperitoneum and subcutaneous emphysema in the chest. A nasogastric tube was placed for decompression, and the patient was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit at our hospital.

EVIDENCE OF PERFORATION NOTED

On arrival, the patient’s oxygen saturation was 99% while receiving oxygen at 2 L/minute by nasal cannula. The physical examination revealed neck swelling, abdominal distention, and crepitus in the neck, abdomen, scrotum, and right lower extremity.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast revealed widespread pneumoretroperitoneum, pneumoperitoneum, and air along the intermuscular planes in the right lower extremity, with no evidence of extravasation of oral contrast (Figure 1). Also noted were bilateral pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, and extensive subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 2).

Despite these impressive findings, the patient remained hemodynamically stable and was managed conservatively with broad-spectrum antibiotics, gastric decompression, and bowel rest. But repeat chest radiography 5 hours after admission to the hospital revealed an enlarging right pneumothorax, which was treated with placement of a pigtail catheter. The patient continued to improve with conservative management and was discharged on the 6th day of hospitalization.

PERFORATION DURING ERCP: INCIDENCE AND COMPLICATIONS

Although perforation is an uncommon complication of ERCP, with an incidence of 1%, mortality rates as high as 18% have been reported.1 Older age, longer procedural time, anatomic variations, and diseases of the duodenum and common bile duct can increase the risk of perforation.2

Types of perforation

Stapfer et al1 classified perforation during ERCP into four types, based on etiology and site of perforation. Type 1 is perforation of the lateral or medial duodenal wall caused by excessive pressure from the endoscope or its acute angulation. Type 2 is periampullary injury, often associated with sphincterotomy or difficulty accessing the biliary tree. Type 3 is injury to the common bile duct or pancreatic duct caused by instrumentation. Type 4 is the presence of retroperitoneal free air with no evidence of actual perforation; this is usually an incidental finding and is of little or no clinical consequence.1

In 2015, a review of 18 studies described the distribution of ERCP perforation according to the Stapfer classification: 25% were type 1, 46% were type 2, and 22% were type 3.3

Effects of air insufflation

ERCP requires air insufflation for optimal visualization. During difficult or prolonged procedures, a larger amount of air may be insufflated to maintain bowel lumen visibility. Depending on the site and size of the defect, a variable amount of air can leak under pressure once the perforation occurs. A rapid retroperitoneal air leak can spread to multiple body compartments, including the mediastinum, pleura, neck, subcutaneous tissues, scrotum, and musculature by tracking through various fascial planes. Rarely, rapid ingress of air in these areas can lead to compartment syndrome.4

Small perforations tend to close spontaneously and may remain clinically silent, but large or persistent perforations are known to cause subcutaneous emphysema, sepsis, and respiratory failure.5

Our patient’s type 2 perforation

We presumed that our patient had a type 2 perforation, given the finding of retroperitoneal air. Difficulty cannulating the biliary tree via the friable malignant tissue at the site of the major papilla likely caused punctate perforations, resulting in air leakage into the retroperitoneum. Punctate perforations typically do not allow contrast extravasation, explaining the absence of oral contrast leakage on CT.

TREATMENT OF ENDOSCOPY-RELATED PERFORATION

Conventional supine and upright abdominal radiography is an appropriate initial imaging modality to confirm the diagnosis. However, CT is more sensitive and accurate, especially when air leakage is confined to the retroperitoneum. Intravenous or oral contrast is not necessary but may help localize the perforation and better delineate fluid collections and abscesses.2

Once perforation is suspected, treatment with a broad-spectrum antibiotic, bowel rest, and stomach decompression is imperative.6 Further management depends on the type of perforation and the overall clinical picture. Type 1 perforations usually require immediate surgical intervention. Type 2 perforations often seal spontaneously within 2 to 3 days and thus are managed conservatively (ie, a broad-spectrum antibiotic, gastric decompression, and bowel rest), unless there is a persistent leak or a large fluid collection. Type 3 perforations rarely require surgery since most are very small and close spontaneously, and so they are managed conservatively. Type 4 perforations are the least serious. They result in retroperitoneal free air that is thought be related to the use of compressed air for lumen patency. They require only conservative measures.1

A 68-year-old man with metastatic periampullary adenocarcinoma presented to his usual clinic for a scheduled biliary stent exchange by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The stent had been placed 5 months before, and no complications had been reported during that procedure.

During the stent exchange procedure, the endoscopist advanced the scope to the second part of the duodenum, where a large, ulcerated, friable mass was visualized surrounding the ampulla, consistent with patient’s known periampullary cancer. The biliary stent was removed without much difficulty. However, several attempts to cannulate the common bile duct with a preloaded guidewire failed because of extensive edema and tissue friability, and to avoid further discomfort to the patient, the procedure was aborted. No perforation was visualized during or at the end of the procedure.

During the first hour after the procedure was stopped, the patient suddenly developed abdominal pain and distention and crepitus of the right chest wall. Supine abdominal radiography showed extensive pneumoperitoneum and subcutaneous emphysema in the chest. A nasogastric tube was placed for decompression, and the patient was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit at our hospital.

EVIDENCE OF PERFORATION NOTED

On arrival, the patient’s oxygen saturation was 99% while receiving oxygen at 2 L/minute by nasal cannula. The physical examination revealed neck swelling, abdominal distention, and crepitus in the neck, abdomen, scrotum, and right lower extremity.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast revealed widespread pneumoretroperitoneum, pneumoperitoneum, and air along the intermuscular planes in the right lower extremity, with no evidence of extravasation of oral contrast (Figure 1). Also noted were bilateral pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, and extensive subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 2).

Despite these impressive findings, the patient remained hemodynamically stable and was managed conservatively with broad-spectrum antibiotics, gastric decompression, and bowel rest. But repeat chest radiography 5 hours after admission to the hospital revealed an enlarging right pneumothorax, which was treated with placement of a pigtail catheter. The patient continued to improve with conservative management and was discharged on the 6th day of hospitalization.

PERFORATION DURING ERCP: INCIDENCE AND COMPLICATIONS

Although perforation is an uncommon complication of ERCP, with an incidence of 1%, mortality rates as high as 18% have been reported.1 Older age, longer procedural time, anatomic variations, and diseases of the duodenum and common bile duct can increase the risk of perforation.2

Types of perforation

Stapfer et al1 classified perforation during ERCP into four types, based on etiology and site of perforation. Type 1 is perforation of the lateral or medial duodenal wall caused by excessive pressure from the endoscope or its acute angulation. Type 2 is periampullary injury, often associated with sphincterotomy or difficulty accessing the biliary tree. Type 3 is injury to the common bile duct or pancreatic duct caused by instrumentation. Type 4 is the presence of retroperitoneal free air with no evidence of actual perforation; this is usually an incidental finding and is of little or no clinical consequence.1

In 2015, a review of 18 studies described the distribution of ERCP perforation according to the Stapfer classification: 25% were type 1, 46% were type 2, and 22% were type 3.3

Effects of air insufflation

ERCP requires air insufflation for optimal visualization. During difficult or prolonged procedures, a larger amount of air may be insufflated to maintain bowel lumen visibility. Depending on the site and size of the defect, a variable amount of air can leak under pressure once the perforation occurs. A rapid retroperitoneal air leak can spread to multiple body compartments, including the mediastinum, pleura, neck, subcutaneous tissues, scrotum, and musculature by tracking through various fascial planes. Rarely, rapid ingress of air in these areas can lead to compartment syndrome.4

Small perforations tend to close spontaneously and may remain clinically silent, but large or persistent perforations are known to cause subcutaneous emphysema, sepsis, and respiratory failure.5

Our patient’s type 2 perforation

We presumed that our patient had a type 2 perforation, given the finding of retroperitoneal air. Difficulty cannulating the biliary tree via the friable malignant tissue at the site of the major papilla likely caused punctate perforations, resulting in air leakage into the retroperitoneum. Punctate perforations typically do not allow contrast extravasation, explaining the absence of oral contrast leakage on CT.

TREATMENT OF ENDOSCOPY-RELATED PERFORATION

Conventional supine and upright abdominal radiography is an appropriate initial imaging modality to confirm the diagnosis. However, CT is more sensitive and accurate, especially when air leakage is confined to the retroperitoneum. Intravenous or oral contrast is not necessary but may help localize the perforation and better delineate fluid collections and abscesses.2

Once perforation is suspected, treatment with a broad-spectrum antibiotic, bowel rest, and stomach decompression is imperative.6 Further management depends on the type of perforation and the overall clinical picture. Type 1 perforations usually require immediate surgical intervention. Type 2 perforations often seal spontaneously within 2 to 3 days and thus are managed conservatively (ie, a broad-spectrum antibiotic, gastric decompression, and bowel rest), unless there is a persistent leak or a large fluid collection. Type 3 perforations rarely require surgery since most are very small and close spontaneously, and so they are managed conservatively. Type 4 perforations are the least serious. They result in retroperitoneal free air that is thought be related to the use of compressed air for lumen patency. They require only conservative measures.1

- Stapfer M, Selby RR, Stain SC, et al. Management of duodenal perforation after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy. Ann Surg 2000; 232:191–198.

- Enns M, Eloubeidi K, Mergener P, et al. ERCP-related perforations: risk factors and management. Endoscopy 2002; 34:293–298.

- Vezakis A, Fragulidis G, Polydorou A. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related perforations: diagnosis and management. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7:1135–1341.

- Frias Vilaca A, Reis AM, Vidal IM. The anatomical compartments and their connections as demonstrated by ectopic air. Insights Imaging 2013; 4:759–772.

- Machado N. Management of duodenal perforation post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. When and whom to operate and what factors determine the outcome? A review article. JOP (Online) 2012; 13:18–25.

- Dubecz A, Ottmann J, Schweigert M, et al. Management of ERCP-related small bowel perforations: the pivotal role of physical investigation. Can J Surg 2012; 55:99–104.

- Stapfer M, Selby RR, Stain SC, et al. Management of duodenal perforation after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy. Ann Surg 2000; 232:191–198.

- Enns M, Eloubeidi K, Mergener P, et al. ERCP-related perforations: risk factors and management. Endoscopy 2002; 34:293–298.

- Vezakis A, Fragulidis G, Polydorou A. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related perforations: diagnosis and management. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7:1135–1341.

- Frias Vilaca A, Reis AM, Vidal IM. The anatomical compartments and their connections as demonstrated by ectopic air. Insights Imaging 2013; 4:759–772.

- Machado N. Management of duodenal perforation post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. When and whom to operate and what factors determine the outcome? A review article. JOP (Online) 2012; 13:18–25.

- Dubecz A, Ottmann J, Schweigert M, et al. Management of ERCP-related small bowel perforations: the pivotal role of physical investigation. Can J Surg 2012; 55:99–104.

An abnormal peripheral blood smear and altered mental status

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation on anticoagulation was brought to the emergency department by her husband after 1 day of altered mental status with acute onset. Her husband reported that she had been minimally arousable, and the physical examination revealed that she was stuporous and withdrew extremities only from noxious stimuli.

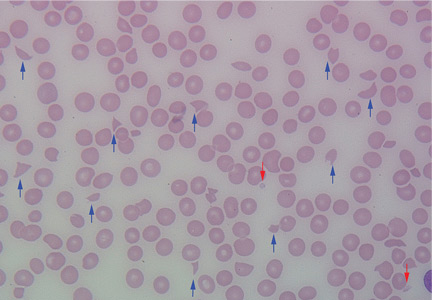

Results of initial laboratory tests revealed a creatinine level of 2.4 mg/dL (reference range 0.7–1.4), hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL (12–16), platelet count 16 × 109/L (150–400), white blood cell count of 7.7 × 109/L (3.7–11), and international normalized ratio of 2.1. A peripheral blood smear is shown in Figure 1.

Computed tomography showed evidence of chronic small vascular ischemia. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed numerous foci of restricted diffusion within the supratentorial and infratentorial areas, suggesting microembolic phenomena.

The peripheral blood smear was compatible with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, which can occur in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome, malignant hypertension, scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, eclampsia, renal allograft rejection, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and severe sepsis.1,2

In addition to hemolytic anemia, the patient also had neurologic abnormalities, renal involvement, and thrombocytopenia. The hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia were sufficient to raise our suspicion of TTP and to consider initiation of plasma exchange. Only 5% of patients with TTP demonstrate the classic pentad of clinical features,1 ie, thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, fluctuating neurologic signs, renal impairment, and fever.

In 1991, when plasma exchange was introduced for TTP, the survival rate of patients increased from 10% to 78%.1,3 Thus, the diagnosis of TTP is an urgent indication for plasma exchange. We normally do plasma exchange daily until the platelet levels improve.

Our patient received methylprednisone 125 mg intravenously every 12 hours and plasma exchange daily. After three cycles of plasma exchange, she regained normal consciousness, and her platelet count had increased to 20.5 × 109/L on the day of discharge from our hospital.

TTP is a life-threatening hematologic disorder. Evidence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia on a peripheral blood smear is vital to the suspicion of TTP. The diagnosis should be confirmed by ADAMTS13 testing, which should show decreased activity (< 10%) or increased inhibition, or both. Rapid management with plasma exchange and steroids can lead to a satisfactory outcome.

Acknowledgment: We are particularly grateful to Dr. Vivian Arguello (Director of Flow Cytometry, Department of Pathology, Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia) for her kind support with the blood smear image.

- George JN. How I treat patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: 2010. Blood 2010; 116:4060–4069.

- Sadler JE. Von Willebrand factor, ADAMTS13, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 2008; 112:11–18.

- Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA, et al. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 1991; 325:393–397.

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation on anticoagulation was brought to the emergency department by her husband after 1 day of altered mental status with acute onset. Her husband reported that she had been minimally arousable, and the physical examination revealed that she was stuporous and withdrew extremities only from noxious stimuli.

Results of initial laboratory tests revealed a creatinine level of 2.4 mg/dL (reference range 0.7–1.4), hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL (12–16), platelet count 16 × 109/L (150–400), white blood cell count of 7.7 × 109/L (3.7–11), and international normalized ratio of 2.1. A peripheral blood smear is shown in Figure 1.

Computed tomography showed evidence of chronic small vascular ischemia. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed numerous foci of restricted diffusion within the supratentorial and infratentorial areas, suggesting microembolic phenomena.

The peripheral blood smear was compatible with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, which can occur in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome, malignant hypertension, scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, eclampsia, renal allograft rejection, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and severe sepsis.1,2

In addition to hemolytic anemia, the patient also had neurologic abnormalities, renal involvement, and thrombocytopenia. The hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia were sufficient to raise our suspicion of TTP and to consider initiation of plasma exchange. Only 5% of patients with TTP demonstrate the classic pentad of clinical features,1 ie, thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, fluctuating neurologic signs, renal impairment, and fever.

In 1991, when plasma exchange was introduced for TTP, the survival rate of patients increased from 10% to 78%.1,3 Thus, the diagnosis of TTP is an urgent indication for plasma exchange. We normally do plasma exchange daily until the platelet levels improve.

Our patient received methylprednisone 125 mg intravenously every 12 hours and plasma exchange daily. After three cycles of plasma exchange, she regained normal consciousness, and her platelet count had increased to 20.5 × 109/L on the day of discharge from our hospital.

TTP is a life-threatening hematologic disorder. Evidence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia on a peripheral blood smear is vital to the suspicion of TTP. The diagnosis should be confirmed by ADAMTS13 testing, which should show decreased activity (< 10%) or increased inhibition, or both. Rapid management with plasma exchange and steroids can lead to a satisfactory outcome.

Acknowledgment: We are particularly grateful to Dr. Vivian Arguello (Director of Flow Cytometry, Department of Pathology, Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia) for her kind support with the blood smear image.

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation on anticoagulation was brought to the emergency department by her husband after 1 day of altered mental status with acute onset. Her husband reported that she had been minimally arousable, and the physical examination revealed that she was stuporous and withdrew extremities only from noxious stimuli.

Results of initial laboratory tests revealed a creatinine level of 2.4 mg/dL (reference range 0.7–1.4), hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL (12–16), platelet count 16 × 109/L (150–400), white blood cell count of 7.7 × 109/L (3.7–11), and international normalized ratio of 2.1. A peripheral blood smear is shown in Figure 1.

Computed tomography showed evidence of chronic small vascular ischemia. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed numerous foci of restricted diffusion within the supratentorial and infratentorial areas, suggesting microembolic phenomena.

The peripheral blood smear was compatible with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, which can occur in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome, malignant hypertension, scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, eclampsia, renal allograft rejection, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and severe sepsis.1,2

In addition to hemolytic anemia, the patient also had neurologic abnormalities, renal involvement, and thrombocytopenia. The hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia were sufficient to raise our suspicion of TTP and to consider initiation of plasma exchange. Only 5% of patients with TTP demonstrate the classic pentad of clinical features,1 ie, thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, fluctuating neurologic signs, renal impairment, and fever.

In 1991, when plasma exchange was introduced for TTP, the survival rate of patients increased from 10% to 78%.1,3 Thus, the diagnosis of TTP is an urgent indication for plasma exchange. We normally do plasma exchange daily until the platelet levels improve.

Our patient received methylprednisone 125 mg intravenously every 12 hours and plasma exchange daily. After three cycles of plasma exchange, she regained normal consciousness, and her platelet count had increased to 20.5 × 109/L on the day of discharge from our hospital.

TTP is a life-threatening hematologic disorder. Evidence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia on a peripheral blood smear is vital to the suspicion of TTP. The diagnosis should be confirmed by ADAMTS13 testing, which should show decreased activity (< 10%) or increased inhibition, or both. Rapid management with plasma exchange and steroids can lead to a satisfactory outcome.

Acknowledgment: We are particularly grateful to Dr. Vivian Arguello (Director of Flow Cytometry, Department of Pathology, Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia) for her kind support with the blood smear image.

- George JN. How I treat patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: 2010. Blood 2010; 116:4060–4069.

- Sadler JE. Von Willebrand factor, ADAMTS13, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 2008; 112:11–18.

- Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA, et al. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 1991; 325:393–397.

- George JN. How I treat patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: 2010. Blood 2010; 116:4060–4069.

- Sadler JE. Von Willebrand factor, ADAMTS13, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 2008; 112:11–18.

- Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA, et al. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 1991; 325:393–397.

A man with HIV and papules and nodules on the knees

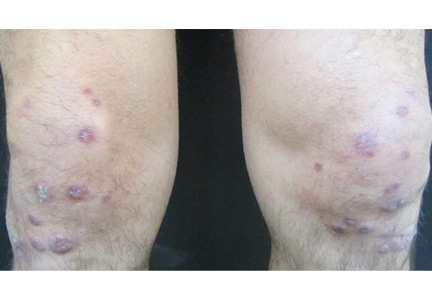

A 39-year-old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and a CD4 cell count of 528 × 106/L without treatment was referred for evaluation of periarticular, indurated, erythematous papules and nodules on the knees and elbows and purpuric lesions on the ankles (Figure 1). He has had recurrent fever, arthralgia, and mild constitutional symptoms during the past month. He also reported a diagnosis of polyclonal immunoglobulin A gammopathy.

Punch biopsy of the purpuric lesions was performed, and histologic study showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with eosinophilic necrosis of the epithelium.

Treatment with a systemic corticosteroid was started. The purpuric lesions disappeared after 3 weeks of therapy, but the nodules over the extensor surface of both knees showed no improvement (Figure 2). Subsequent biopsy of late-stage lesions (3 months after the start of therapy) demonstrated perivascular fibrosis with small, persistent foci of vasculitis, and confirmed the diagnosis of HIV-associated nodular erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). Antiretroviral therapy was started in addition to intralesional corticosteroids and topical dapsone 5% gel, with resolution of the lesions 1 month later.

ERYTHEMA ELEVATUM DIUTINUM

EED is an uncommon chronic dermatosis, classified as a fibrosing form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and characterized clinically by violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules, usually distributed acrally and symmetrically over extensor surfaces. The histopathologic picture depends on the stage of the lesion. Features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are found in early-stage lesions, while a fibrotic replacement of the dermis with small persistent foci of vasculitis is typical of late-stage lesions.

EED has clinical and histopathologic similarities to Sweet syndrome, but EED is distinguished from neutrophilic dermatosis by vasculitis.

In HIV-infected patients, it is important to include pruritic papular eruption in the differential diagnosis. It is characterized by chronic bilaterally symmetric pruritic papules on the trunk and extremities and is the most common cutaneous noninfectious manifestation of HIV.

The clinical presentation of EED may also be easily confused with Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis.2

AN EMERGING HIV-RELATED DERMATOSIS

EED is emerging as a specific HIV-associated dermatosis, with 20 cases reported in the medical literature as of this writing.3

The cause of EED is not known, but it is often associated with streptococcal infection, monoclonal IgA gammopathy, hematologic malignancy, cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune disease.3 The stimulus could be immune-complex deposition in blood vessels triggered by HIV infection, or by another infection acting as an antigenic stimulus.4 The nodular variant of EED is even rarer, but it evolves most often in HIV-positive individuals.5,6

Oral dapsone is the treatment of choice but is less effective in late-stage fibrotic lesions.7 Treatment courses tend to be long and recurrence is common.8 Intralesional, topical, and oral corticosteroids, topical dapsone 5% gel,9 tetracycline and nicotinamide, sulfonamides, colchicine, chloroquine, and surgical excision are other options.

Our patient’s presentation reminds us to consider EED in HIV-infected patients and illustrates the importance of histologic diagnosis to differentiate EED from assumed Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV. EED can also be the first clinical sign of HIV infection. It is important to rule out underlying disorders such as HIV infection, because directed therapy is often the best management.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:38–44.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Martín L, Barat A, Arias D. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Another clinical simulator of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127:1819–1822.

- Momen SE, Jorizzo J, Al-Niaimi F. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a review of presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28:1594–1602.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, Alessi E. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141:335–338.

- LeBoit PE, Cockerell CJ. Nodular lesions of erythema elevatum diutinum in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 28:919–922.

- Rover PA, Bittencourt C, Discacciati MP, Zaniboni MC, Arruda LH, Cintra ML. Erythema elevatum diutinum as a first clinical manifestation for diagnosing HIV infection: case history. Sao Paulo Med J 2005; 123:201–203.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, Don PC, Weinberg JM. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis 2001; 68:41–42.

- Katz SI, Gallin JL, Hertz KC, Fauci AS, Lawley TJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum: skin and systemic manifestations, immunologic studies, and successful treatment with dapsone. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977; 56:443–455.

- Frieling GW, Williams NL, Lim SJ, Rosenthal SI. Novel use of topical dapsone 5% gel for erythema elevatum diutinum: safer and effective. J Drugs Dermatol 2013; 12:481–484.

A 39-year-old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and a CD4 cell count of 528 × 106/L without treatment was referred for evaluation of periarticular, indurated, erythematous papules and nodules on the knees and elbows and purpuric lesions on the ankles (Figure 1). He has had recurrent fever, arthralgia, and mild constitutional symptoms during the past month. He also reported a diagnosis of polyclonal immunoglobulin A gammopathy.

Punch biopsy of the purpuric lesions was performed, and histologic study showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with eosinophilic necrosis of the epithelium.

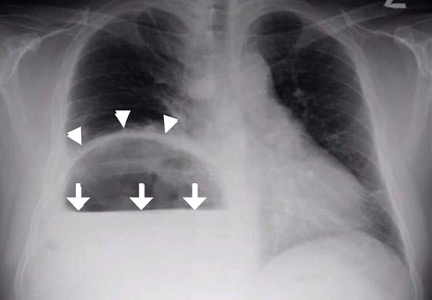

Treatment with a systemic corticosteroid was started. The purpuric lesions disappeared after 3 weeks of therapy, but the nodules over the extensor surface of both knees showed no improvement (Figure 2). Subsequent biopsy of late-stage lesions (3 months after the start of therapy) demonstrated perivascular fibrosis with small, persistent foci of vasculitis, and confirmed the diagnosis of HIV-associated nodular erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). Antiretroviral therapy was started in addition to intralesional corticosteroids and topical dapsone 5% gel, with resolution of the lesions 1 month later.

ERYTHEMA ELEVATUM DIUTINUM

EED is an uncommon chronic dermatosis, classified as a fibrosing form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and characterized clinically by violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules, usually distributed acrally and symmetrically over extensor surfaces. The histopathologic picture depends on the stage of the lesion. Features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are found in early-stage lesions, while a fibrotic replacement of the dermis with small persistent foci of vasculitis is typical of late-stage lesions.

EED has clinical and histopathologic similarities to Sweet syndrome, but EED is distinguished from neutrophilic dermatosis by vasculitis.

In HIV-infected patients, it is important to include pruritic papular eruption in the differential diagnosis. It is characterized by chronic bilaterally symmetric pruritic papules on the trunk and extremities and is the most common cutaneous noninfectious manifestation of HIV.

The clinical presentation of EED may also be easily confused with Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis.2

AN EMERGING HIV-RELATED DERMATOSIS

EED is emerging as a specific HIV-associated dermatosis, with 20 cases reported in the medical literature as of this writing.3

The cause of EED is not known, but it is often associated with streptococcal infection, monoclonal IgA gammopathy, hematologic malignancy, cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune disease.3 The stimulus could be immune-complex deposition in blood vessels triggered by HIV infection, or by another infection acting as an antigenic stimulus.4 The nodular variant of EED is even rarer, but it evolves most often in HIV-positive individuals.5,6

Oral dapsone is the treatment of choice but is less effective in late-stage fibrotic lesions.7 Treatment courses tend to be long and recurrence is common.8 Intralesional, topical, and oral corticosteroids, topical dapsone 5% gel,9 tetracycline and nicotinamide, sulfonamides, colchicine, chloroquine, and surgical excision are other options.

Our patient’s presentation reminds us to consider EED in HIV-infected patients and illustrates the importance of histologic diagnosis to differentiate EED from assumed Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV. EED can also be the first clinical sign of HIV infection. It is important to rule out underlying disorders such as HIV infection, because directed therapy is often the best management.

A 39-year-old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and a CD4 cell count of 528 × 106/L without treatment was referred for evaluation of periarticular, indurated, erythematous papules and nodules on the knees and elbows and purpuric lesions on the ankles (Figure 1). He has had recurrent fever, arthralgia, and mild constitutional symptoms during the past month. He also reported a diagnosis of polyclonal immunoglobulin A gammopathy.

Punch biopsy of the purpuric lesions was performed, and histologic study showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with eosinophilic necrosis of the epithelium.

Treatment with a systemic corticosteroid was started. The purpuric lesions disappeared after 3 weeks of therapy, but the nodules over the extensor surface of both knees showed no improvement (Figure 2). Subsequent biopsy of late-stage lesions (3 months after the start of therapy) demonstrated perivascular fibrosis with small, persistent foci of vasculitis, and confirmed the diagnosis of HIV-associated nodular erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). Antiretroviral therapy was started in addition to intralesional corticosteroids and topical dapsone 5% gel, with resolution of the lesions 1 month later.

ERYTHEMA ELEVATUM DIUTINUM

EED is an uncommon chronic dermatosis, classified as a fibrosing form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and characterized clinically by violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules, usually distributed acrally and symmetrically over extensor surfaces. The histopathologic picture depends on the stage of the lesion. Features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are found in early-stage lesions, while a fibrotic replacement of the dermis with small persistent foci of vasculitis is typical of late-stage lesions.

EED has clinical and histopathologic similarities to Sweet syndrome, but EED is distinguished from neutrophilic dermatosis by vasculitis.

In HIV-infected patients, it is important to include pruritic papular eruption in the differential diagnosis. It is characterized by chronic bilaterally symmetric pruritic papules on the trunk and extremities and is the most common cutaneous noninfectious manifestation of HIV.

The clinical presentation of EED may also be easily confused with Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis.2

AN EMERGING HIV-RELATED DERMATOSIS

EED is emerging as a specific HIV-associated dermatosis, with 20 cases reported in the medical literature as of this writing.3

The cause of EED is not known, but it is often associated with streptococcal infection, monoclonal IgA gammopathy, hematologic malignancy, cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune disease.3 The stimulus could be immune-complex deposition in blood vessels triggered by HIV infection, or by another infection acting as an antigenic stimulus.4 The nodular variant of EED is even rarer, but it evolves most often in HIV-positive individuals.5,6

Oral dapsone is the treatment of choice but is less effective in late-stage fibrotic lesions.7 Treatment courses tend to be long and recurrence is common.8 Intralesional, topical, and oral corticosteroids, topical dapsone 5% gel,9 tetracycline and nicotinamide, sulfonamides, colchicine, chloroquine, and surgical excision are other options.

Our patient’s presentation reminds us to consider EED in HIV-infected patients and illustrates the importance of histologic diagnosis to differentiate EED from assumed Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV. EED can also be the first clinical sign of HIV infection. It is important to rule out underlying disorders such as HIV infection, because directed therapy is often the best management.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:38–44.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Martín L, Barat A, Arias D. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Another clinical simulator of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127:1819–1822.

- Momen SE, Jorizzo J, Al-Niaimi F. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a review of presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28:1594–1602.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, Alessi E. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141:335–338.

- LeBoit PE, Cockerell CJ. Nodular lesions of erythema elevatum diutinum in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 28:919–922.

- Rover PA, Bittencourt C, Discacciati MP, Zaniboni MC, Arruda LH, Cintra ML. Erythema elevatum diutinum as a first clinical manifestation for diagnosing HIV infection: case history. Sao Paulo Med J 2005; 123:201–203.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, Don PC, Weinberg JM. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis 2001; 68:41–42.

- Katz SI, Gallin JL, Hertz KC, Fauci AS, Lawley TJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum: skin and systemic manifestations, immunologic studies, and successful treatment with dapsone. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977; 56:443–455.

- Frieling GW, Williams NL, Lim SJ, Rosenthal SI. Novel use of topical dapsone 5% gel for erythema elevatum diutinum: safer and effective. J Drugs Dermatol 2013; 12:481–484.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:38–44.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Martín L, Barat A, Arias D. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Another clinical simulator of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127:1819–1822.

- Momen SE, Jorizzo J, Al-Niaimi F. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a review of presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28:1594–1602.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, Alessi E. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141:335–338.

- LeBoit PE, Cockerell CJ. Nodular lesions of erythema elevatum diutinum in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 28:919–922.

- Rover PA, Bittencourt C, Discacciati MP, Zaniboni MC, Arruda LH, Cintra ML. Erythema elevatum diutinum as a first clinical manifestation for diagnosing HIV infection: case history. Sao Paulo Med J 2005; 123:201–203.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, Don PC, Weinberg JM. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis 2001; 68:41–42.

- Katz SI, Gallin JL, Hertz KC, Fauci AS, Lawley TJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum: skin and systemic manifestations, immunologic studies, and successful treatment with dapsone. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977; 56:443–455.

- Frieling GW, Williams NL, Lim SJ, Rosenthal SI. Novel use of topical dapsone 5% gel for erythema elevatum diutinum: safer and effective. J Drugs Dermatol 2013; 12:481–484.

‘Air-raising’: An air-fluid level in the right subphrenic region

A 39-year-old Filipino man presented with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain of 2 weeks’ duration. He did not report trauma, and he had no history of medical illness or surgery.

On arrival, his blood pressure was 123/83 mm Hg, pulse 122 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and temperature 100.7°F (38.1°C). On physical examination, he exhibited marked tenderness of the right upper quadrant on palpation. The abdomen was otherwise soft with no guarding or rebound tenderness.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Leukocyte count 17.0 × 109/L (reference range 4.5–11.0)

- Serum glucose 558 mg/dL without ketoacidosis

- Aspartate aminotransferase 109 U/L (2–40)

- Alanine aminotranferase 28 U/L (2–50)

- Total serum bilirubin 4.0 mg/dL (0.0–1.5).

Plain chest radiography showed dramatic elevation of the right hemidiaphragm with a large subphrenic air-fluid level (Figure 1). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a multiloculated hepatic abscess 18 × 13.5 cm subjacent to the diaphragm (Figure 2). Cultures of blood and the abscess yielded Klebsiella pneumoniae. The patient recovered after percutaneous drainage and a course of ceftriaxone.

PRIMARY KLEBSIELLA LIVER ABSCESS

K pneumoniae, a gram-negative aerobic encapsulated bacillus of the normal human intestinal flora, is closely related to Escherichia coli, historically the most frequent bacterial cause of pyogenic liver abscess.1 Over the last 30 years, K pneumoniae has eclipsed E coli as the most common causative agent, with the epicenter of this trend being located in Taiwan and South Korea, perhaps because rates of fecal Klebsiella carriage in that region are particularly high.1,2

Concurrently, there has been increasing recognition—initially across Asia, but lately in Europe and the Western Hemisphere—of the so-called invasive Klebsiella liver abscess (KLA) syndrome, virtually unique to the hypervirulent K1 and K2 capsular serotypes of K pneumoniae prevalent in Asia.3–6 This community-acquired syndrome is characterized by hematogenous deposition of the organism at distant sites, such as the lung, soft tissues, central nervous system, and eyes. Impairment of phagocytic function, as occurs in diabetes mellitus, and the resistance to phagocytosis conferred by the K1 and K2 serotypes have been identified as predisposing factors for dissemination.7,8 The mucoid phenotype of K pneumoniae, very common in Asian isolates of the K1 and K2 serotypes, is also associated with hypervirulence and extrahepatic spread, presumably through evasion of phagocytosis and complement-mediated opsonization.2,9

Our patient’s risk factors for KLA were his Asian origin and uncontrolled diabetes. No evidence of remote infection was detected during his hospitalization.

HEMIDIAPHRAGM ELEVATION

Acquired hemidiaphragm elevation is most commonly unilateral and typically represents an incidental radiologic finding attributable to paralysis of the corresponding diaphragm after phrenic nerve injury caused by trauma, surgery, or infection. Unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis is classically confirmed by performing a fluoroscopic sniff test, which is positive if the affected hemidiaphragm is observed in real time to paradoxically move upward during forced inhalation.10 This condition is usually asymptomatic at rest but could cause exertional dyspnea and contribute to ventilatory failure when pulmonary disease coexists.11

Occasionally, as in our patient, hemidiaphragm elevation is part of the presentation of active abdominal pathology that displaces the corresponding hemidiaphragm cephalad by mass effect. Examples of such space-occupying abdominal lesions include infections, malignancy, hepatosplenomegaly, and pneumoperitoneum from a ruptured viscus. Pneumoperitoneum is suggested by the presence of an air crescent immediately subjacent to the affected hemidiaphragm on an upright radiograph accompanied by peritoneal signs.

Although there was subphrenic air on this patient’s initial chest radiograph, it was actually part of an air-fluid level without associated peritoneal signs. An air-fluid level is characterized by a sharp horizontal demarcation between the lighter gas component floating at the top and the heavier fluid component settling on the bottom (Figure 1). The subsequent CT excluded free intra-abdominal air while identifying a large hepatic abscess as the cause of hemidiaphragm elevation. In trauma victims, CT is also helpful in ruling out diaphragmatic rupture, which can have a similar radiographic appearance.12

Our patient’s presentation was a reminder that an elevated hemidiaphragm may reflect abdominal pathology and that subphrenic air in this context need not be either “free” or a surgical emergency. Drainage of the abscess restored the normal position of our patient’s right hemidiaphragm (Figure 3).

- Huang CJ, Pitt HA, Lipsett PA, et al. Pyogenic hepatic abscess: changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg 1996; 223:600–607.

- Lin YT, Siu LK, Lin JC, et al. Seroepidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae colonizing the intestinal tract of healthy Chinese and overseas Chinese adults in Asian countries. BMC Microbiol 2012; 12:13.

- Wang JH, Liu YC, Lee SS, et al. Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 26:1434–1438.

- Pastagia M, Arumugam V. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses in a public hospital in Queens, New York. Travel Med Infect Dis 2008; 6:228–233.

- Rahimian J, Wilson T, Oram V, Holzman RS. Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:1654–1659.

- Moore R, O’Shea D, Geoghegan T, Mallon PW, Sheehan G. Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: an emerging infection in Ireland and Europe. Infection 2013; 41:681–686.

- Lecube A, Pachón G, Petriz J, Hernández C, Simó R. Phagocytic activity is impaired in type 2 diabetes mellitus and increases after metabolic improvement. PLoS One 2011; 6:e23366.