User login

Competing Cardiovascular Outcomes

When to Worry About Incidental Renal and Adrenal Masses

› Use computed tomography studies and the Bosniak classification system to

guide management of renal cystic masses. A

› Perform laboratory tests for hypercortisolism, hyperaldosteronism, and hypersecretion of catecholamines (pheochromocytoma) on any patient with an incidental adrenal mass, regardless of signs or symptoms. C

› Refer patients with adrenal masses >4 cm for surgical evaluation. Refer any individual who has a history of malignancy and an adrenal mass for oncologic evaluation. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A. Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B. Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C. Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE Jane C, a 76-year-old patient, reports lower abdominal discomfort and increased bowel movements. Her left lower quadrant is tender to palpation, without signs of a surgical abdomen, and vital signs are normal. Laboratory studies are also normal, except for mild anemia and a positive fecal occult blood test. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT), with and without contrast, are negative for acute pathology, but a 1.7-cm lesion is found in the upper pole of the left kidney. What is your next step?

Renal or adrenal masses may be discovered during imaging studies for complaints unrelated to the kidneys or adrenals. Detection of incidentalomas has increased dramatically, keeping pace with the growing use of ultrasonography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for abdominal, chest, and back complaints.1

Family physicians can evaluate most of these masses and determine the need for referral by using clinical judgment, appropriate imaging studies, and screening laboratory tests. In the pages that follow, we present a systematic approach for evaluating these incidentalomas and determining when consultation or referral is needed.

Incidental renal masses are common

Lesions are commonly found in normal kidneys, and the incidence increases with age. Approximately one-third of individuals age 50 and older will have at least one renal cyst on CT.2

Most incidental renal masses are benign cysts requiring no further evaluation. Other possibilities include indeterminate or malignant cysts or solid masses, which may be malignant or benign. Inflammatory renal lesions from infection, infarction, or trauma also occur, but these tend to be symptomatic and are rarely found incidentally.

Classification of renal cysts—not based on size

Cysts are the most common adult renal masses. Typically they are unilocular and located in the renal cortex, frequently extending to the renal surface.3 Renal function is usually preserved, regardless of the cyst’s location or size. Careful examination of adjacent tissue is essential, as secondary cysts may form when solid tumors obstruct tubules of normal parenchyma. Cystic lesions containing enhancing soft tissue unattached to the wall or septa likely are malignant.4

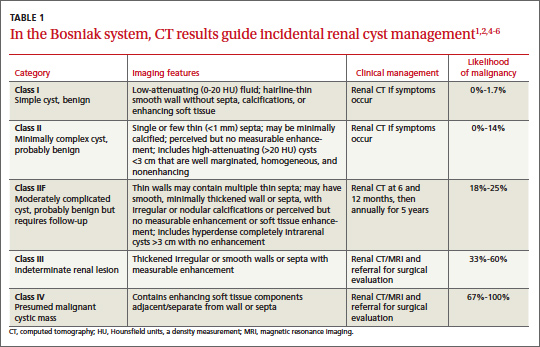

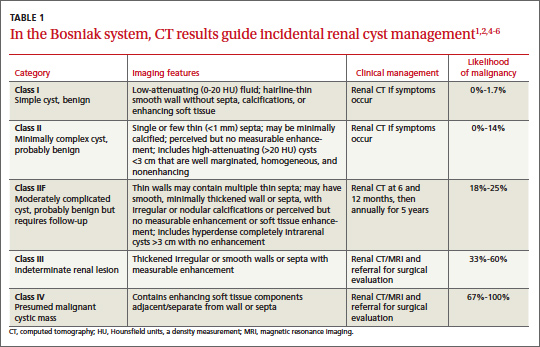

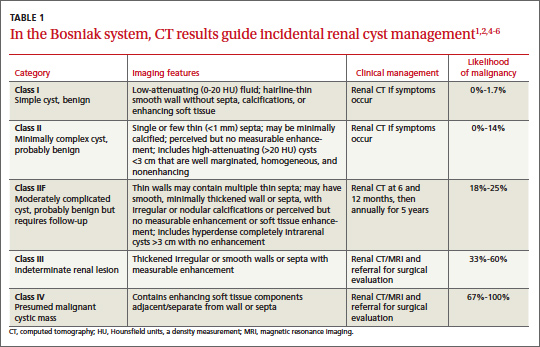

The Bosniak classification system, with 5 classes based on CT characteristics

(TABLE 1), is a useful guide for managing renal cystic lesions.4 Size is not an important feature in the Bosniak system; small cysts may be malignant and larger ones benign. Small cysts may grow into larger benign lesions, occasionally causing flank or abdominal pain, palpable masses, or hematuria.

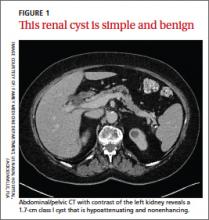

Simple cysts. Renal cysts that meet Bosniak class I criteria can be confidently labeled benign and need no further evaluation (FIGURE 1). Simple renal cysts on CT have homogenous low-attenuating fluid and thin nonenhancing walls without septa.4

On ultrasound, simple renal cysts show spherical or ovoid shape without internal echoes, a thin smooth wall separate from the surrounding parenchyma, and posterior wall enhancement caused by increased transmission through the water-filled cyst. The likelihood of malignancy is extremely low in a renal cyst that meets these criteria, which have a reported accuracy of 98% to 100%.3 Thus, no further evaluation is required if an obviously benign simple cyst is first noted on an adequate ultrasound. Inadequate ultrasound visualization or evidence of calcifications, septa, or multiple chambers calls for prompt renal CT.

CASE The mass on Ms. C’s left kidney is hypoattenuating and nonenhancing on CT. It meets Bosniak criteria for a benign simple cyst (class I) and requires no further evaluation or follow-up. Colonoscopy detects multiple colonic polyps that are removed, and the patient does well.

Mildly complicated cysts. Less diagnostic certainty characterizes cysts with mild abnormalities that keep them from being labeled as simple. Bosniak classes II and IIF describe mildly abnormal renal cysts. Class II cysts can be dismissed, whereas class IIF cysts require follow-up.

Class II cysts may contain a few hairline septa, fine calcium deposits in walls or septa, or an unmeasurable enhancement of the walls. A hyperattenuating but nonenhancing fluid also is described as category II. Small homogeneous cysts <3 cm, without enhancement but hyperattenuated, are reliably considered benign and need not be evaluated.2,7

Class IIF cysts may have multiple hairline-thin septa with unmeasurable enhancement or minimal smooth thickening or irregular/nodular calcifications of wall or septa without enhancing soft tissue components. Hyperattenuating cystic lesions >3 cm and intrarenal “noncortical” cysts are included in this category. Class IIF cysts require follow-up at 6 months with CT or MRI, then annually for at least 5 years.8

Obviously complicated cysts. Bosniak class III is indeterminate—neither benign nor clearly malignant. Class III cysts may have thickened borders or septa with measurable enhancement, or they may be multilocular, hemorrhagic, or infected. In 5 case series, 29 of 57 class III lesions proved to be malignant.5 MRI may characterize these lesions more definitively than CT prior to urologic referral.

Malignant cysts. Bosniak class IV renal lesions are clearly malignant, with large heterogeneous cysts or necrotic components, shaggy thickened walls, or enhancing soft tissue components separate from the wall or septa. Their unequivocal appearance results from solid tumor necrosis and liquefaction. Diagnosis is straightforward, and excision is indicated.2

A closer look at solid renal masses

Solid renal masses usually consist of enhancing tissue with little or no fluid. The goal of evaluation is to exclude malignancies, such as renal cell cancer, lymphomas, sarcomas, or metastasis. Benign solid masses include renal adenomas, angiomyolipomas, and oncocytomas, among others.

Several lesions can be diagnosed by appearance or symptoms:

Angiomyolipomas are recognized by their fat content within a noncalcified mass. Unenhanced CT usually is sufficient for diagnosis, unless the mass is very small or has atypical features.9

Vascular lesions can be identified because they enhance to the same degree as the vasculature. With the exception of inflammatory or vascular abnormalities, all enhancing lesions that do not contain fat should be presumed to be malignant.

In patients with a known extrarenal primary malignancy, 50% to 85% of incidental solid renal masses will represent metastatic disease.10 Percutaneous biopsy may be warranted to differentiate metastatic lesions from a secondary, primary (ie, renal cell carcinoma), or benign process.11

A study of 2770 solid renal mass excisions revealed that 12.8% were benign, with a direct relationship between malignancy and size. Masses <1 cm were benign 44% of the time.12 Early identification of small renal carcinomas may improve survival rates. Although renal cell carcinomas <3 cm in diameter have low metastatic potential, a solid, nonfat-containing mass should be evaluated for aggressive nephron-sparing surgery.6,13

Incidental adrenal masses occur infrequently

Adrenal incidentalomas are defined as radiographically identified masses >1 cm in diameter.14 They are much less common than their renal counterparts, with a reported prevalence of 0.35% to 5% on CT.15 Because the adrenal glands are hormonally active and receive substantial blood flow, metastatic, hormonally active, and nonfunctional causes for adrenal masses need to be considered.16

Adrenal pathology

Adrenal masses may be characterized by increased or normal adrenal function. Hyperfunctioning syndromes include hypercortisolism, hyperaldosteronism, adrenogenital hypersecretion of adrenocortical origin, and pheochromocytomas of the medulla. Symptom evaluation of these syndromes is important, but not sufficient to rule out a hyperfunctioning syndrome.

In a retrospective review of inapparent adrenal masses, ≤13% of pheochromocytomas were clinically silent.17 Therefore, laboratory testing is necessary for an incidental adrenal mass.

Nonfunctional lesions include adenomas, metastases, cysts, myelolipomas, hemorrhage, and adrenal carcinomas. These masses require evaluation for the possibility of cancer, the most common of which is metastasis. In patients with an extra-adrenal malignancy, the likelihood of malignancy in an incidental adrenal mass is at least 50%.18 An adrenal mass representing metastasis of a previously unrecognized cancer is exceedingly rare.19

Primary adrenal carcinoma is also rare, with an estimated incidence of 2 cases per one million in the general population. For patients with adrenal masses, the prevalence of carcinoma increases with lesion size (2% for tumors <4 cm, 6% for tumors 4-6 cm, and 25% for tumors >6 cm in diameter). 17 For this reason, tumors >4 cm in diameter are usually surgically resected in patients with no previous cancer history, unless radiologic criteria demonstrate clearly benign characteristics.

Although adrenal carcinomas are considered nonfunctioning, some evidence suggests they produce low levels of cortisol that may be associated with clinical features of metabolic syndrome.20

CT is first choice for adrenal mass evaluation

Dedicated adrenal CT with both unenhanced and delayed contrast-enhanced images is the most reliable study to evaluate an adrenal mass, according to the American College of Radiology. Consider another study only in patients with contrast allergy, renal compromise, or cancer history.21

Unenhanced CT can diagnose the approximately 70% of adenomas that are small, well-defined round masses with homogenous low-density lipid deposition.22 Delayed contrast enhancement can characterize most of the remaining 30%.23 Unenhanced CT with attenuation values of <10 Hounsfield units (HU) can diagnose adenomas with 71% specificity and 98% sensitivity,24 and can often diagnose simple cysts and myelolipomas, as well.

Other imaging options. MRI is an alternative to CT for patients with contraindications for contrast or radiation exposure. MRI provides less spatial resolution than CT, but chemical shift imaging can measure cytoplasmic lipid content similar to unenhanced CT. A small study found chemical shift MRI more reliable than unenhanced CT, but less reliable than CT with delayed contrast enhancement.25

Positron emission tomography (PET) is useful to noninvasively evaluate biochemical and physiologic processes. PET-CT incorporates unenhanced CT density measurements to improve PET accuracy. In a patient with a history of cancer, PET-CT has a sensitivity of 93% to 100% and a specificity of 95% in differentiating benign from malignant adrenal tumors.26

When to order a biopsy

The need for biopsy has decreased as imaging has improved, but biopsy is required whenever diagnostic imaging fails to differentiatea lesion as benign or malignant. CT guided biopsy provides diagnostic accuracy of 85% to 95%.27 Complications such as pneumothorax, hemorrhage, and bacteremia occur in 3% to 9% of biopsies. Before any adrenal biopsy, measure plasma-free metanephrines to exclude undiagnosed pheochromocytoma, which could precipitate a hypertensive crisis if untreated.22

These 3 laboratory screening tests are critical

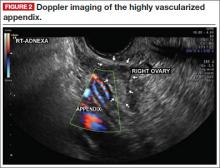

Family physicians can perform the initial biochemical evaluation of an adrenal incidentaloma. Guidance is available from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)28 and the American Academy of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) (FIGURE 2).29

Regardless of signs or symptoms, perform screening laboratory tests for 3 types of adrenal hyperfunction: hypercortisolism, hyperaldosteronism, and hypersecretion of catecholamines (pheochromocytoma). Screening tests are not recommended for androgen hypersecretion, which is extremely rare and causes recognizable symptoms such as hirsutism (Table 2).29

Hypercortisolism occurs in approximately 5% of adrenal incidentalomas.30 An overnight dexamethasone suppression test (DST) is most reliable for screening, with sensitivity >95% for Cushing syndrome.31 The patient takes a 1-mg dose of oral dexamethasone at 11 pm, and a fasting plasma cortisol sample is drawn the next day at 8 am.

Dexamethasone binds to glucocorticoid receptors in the pituitary gland, suppressing adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion. Cortisol will be depressed the next morning unless the adrenal mass produces cortisol autonomously. Patients with a DST >5 mcg/dL—highly suggestive of Cushing syndrome—require further evaluation, and we suggest referral to an endocrinologist.

Hyperaldosteronism is seen in 1% to 2% of adrenal incidentalomas.32 The aldosterone- to-renin ratio (ARR) is recommended as a screening test for hyperaldosteronism, with an ARR >20 requiring further testing.33 Medications that may affect the ARR include beta-blockers, spironolactone, clonidine, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers.29

Refer a patient with evidence of hyperaldosteronism to an endocrinologist and a surgeon with experience in managing these lesions. If the ARR test result suggests an aldosterone excess, a salt-loading test is used to verify failure of aldosterone suppression. Adrenal venous sampling is often performed prior to surgical removal to confirm that an incidentaloma is the source of hyperaldosteronism.

Pheochromocytoma. Approximately 5% of incidental adrenal lesions are pheochromocytomas.30 Many patients with these epinephrine/norepinephrine secreting tumors do not show the classic symptom triad of headache, palpitations, and diaphoresis, and approximately half have normal blood pressure.34

Identifying a pheochromocytoma is important in any patient requiring surgery or biopsy, as surgical manipulation can cause a potentially fatal intraoperative catecholamine surge. Presurgical medical management can mitigate this reaction.

A plasma-free metanephrines test, which has 95% sensitivity, is the most reliable test for pheochromocytoma.35 Medications, including tricyclic antidepressants, decongestants, amphetamines, reserpine, and phenoxybenzamine, can cause falsepositive results.29 Confirm a positive plasma-free metanephrines test with a 24-hour fractionated urine metanephrines test, and refer the patient to an endocrinologist.

Managing adrenal incidentalomas

Refer all patients with adrenal masses >4 cm for surgical evaluation because of the risk of malignancy; all patients who have a history of malignancy and an adrenal mass of any size require a referral to an oncologist. Perform the AACE-recommended 3-element biochemical workup for all masses, with the exception of definitively diagnosed cysts or myelolipomas.

Refer to an endocrinologist all patients with abnormal screening laboratory results, regardless of adrenal mass size, as well as patients with concerning clinical findings. Initiate cardiovascular, diabetes, and bone density evaluation and management for metabolic syndrome.20

Monitoring after a negative workup

Little evidence exists to guide monitoring of small adrenal incidentalomas (<4 cm) with a negative workup. The 2002 NIH report recommended annual radiologic follow-up for 5 years,28 whereas the 2009 AACE guidelines recommend radiographic follow-up at 3 to 6 months, then at one and 2 years.29

Evidence indicates that 14% of lesions will enlarge in 2 years, although the clinical significance of enlargement is unknown. Some authors argue against CT monitoring because the risk of adrenal mass progression is similar to the malignancy risk posed by 3 years of radiation exposure with CT.20

Some guidelines recommend repeat biochemical screening every 3 to 4 years.28,29 AACE guidelines quote a 47% rate of progression over 3 years, but most adrenal masses progress to subclinical Cushing syndrome— a condition of uncertain significance. Subclinical Cushing’s has not been reported to progress to the overt syndrome, and new catecholamine or aldosterone secretion is rare.

Many endocrinologists reduce the frequency of follow-up, depending on the type of adrenal mass (cyst or solid) and its size. AACE suggests CT for adenomas one to 4 cm at 12 months. AACE and NIH recommend hormonal evaluation annually for 4 years. Adrenal cysts or myelolipoma in patients without cancer need no follow-up.29

CORRESPONDENCE

James C. Higgins, DO, CAPT, MC, USN, Ret., Naval Hospital Jacksonville, Family Medicine Department, 2080 Child Street, Box 1000, Jacksonville, FL 32214;

[email protected]

1. Berland LL, Silverman SG, Gore RM, et al. Managing incidental findings on abdominal CT: white paper of the ACR incidental findings committee. J Am Coll Radiol. 2010;7:754-773.

2. Silverman S, Israel G, Herts B, et al. Management of the incidental renal mass. Radiology. 2008;249:16-31.

3. Curry NS, Bissada NK. Radiologic evaluation of small and indeterminate renal masses. Urol Clin North Am. 1997;24:493-505.

4. Bosniak MA. The current radiological approach to renal cysts. Radiology. 1986;158:1-10.

5. Harisinghani M, Maher M, Gervais D, et al. Incidence of malignancy in complex cystic renal masses (Bosniak category III): should imaging guided biopsy precede surgery? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:755-758.

6. Remzi M, Ozsoy M, Klingler HC. Are small renal tumors harmless? Analysis of histopathological features according to tumors less than 4 cm in diameter. J Urol. 2006;176:896-899.

7. Jonisch AI, Rubinowitz A, Mutalik P, et al. Can high attenuation renal cysts be differentiated from renal cell carcinoma at unenhanced computed tomography? Radiology. 2007;243:445-450.

8. Israel GM, Bosniak MA. Follow-up CT of moderately complex cystic lesions of the kidney. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181: 627-633.

9. Bosniak MA, Megibow AJ, Hulnick DH, et al. CT diagnosis of renal angiomyolipoma: the importance of detecting small amounts of fat. AJR Am J Roentengol. 1988;151:497-501.

10. Mitnick JS, Bosniak MA, Rothberg M, et al. Metastatic neoplasm to the kidney studied by computed tomography and sonogram. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1985;9:43-49.

11. Rybicki FJ, Shu KM, Cibas ES, et al. Percutaneous biopsy of renal masses: sensitivity and negative predictive value stratified by clinical setting and size of masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1281-1287.

12. Frank I, Blure MI, Cheville JC, et al. Solid renal tumors: an analysis of pathological features related to tumor size. J Urol. 2003;170:2217-2220.

13. Hollingsworth JM, Miller DC, Daignault S, et al. Rising incidence of small renal masses: a need to reassess treatment effect. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1331-1334.

14. Geelhoed GW, Spiegel CT. “Incidental” adrenal cyst: a correctable lesion possibly associated with hypertension. South Med J. 1981;74:626-630.

15. Davenport C, Liew A, Doherty B, et al. The prevalence of adrenal incidentaloma in routine clinical practice. Endocrine. 2011;40: 80-83.

16. Cook DM, Loriaux LD. The incidental adrenal mass. Am J Med. 1996;101:88 94.

17. Mansmann G, Lau J, Balk E, et al. The clinically inapparent adrenal mass: update in diagnosis and management. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:309-340.

18. Androulakis II, Kaltsas G, Piatitis G, et al. The clinical significance of adrenal incidentalomas. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41: 552-560.

19. Lee JE, Evans DB, Hickey RC, et al. Unknown primary cancer presenting as an adrenal mass: frequency and implications for diagnostic evaluation of adrenal incidentalomas. Surgery. 1998;124:1115-1122.

20. Aron D, Terzolo M, Cawood TJ. Adrenal incidentalomas. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26:69-82.

21. ACR appropriateness criteria: incidentally discovered adrenal mass. American College of Radiology. Available at: http://www.acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/AppCriteria/Diagnostic/IncidentallyDiscoveredAdrenalMass.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2012.

22. Song JH, Mayo-Smith WW. Incidentally discovered adrenal mass. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49:361-368.

23. Korobkin M, Brodeur FJ, Francis IR, et al. CT time-attenuation washout curves of adrenal adenomas and nonadenomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:747-752.

24. Boland GW, Lee MJ, Gazelle GS, et al. Characterization of adrenal masses using unenhanced CT: an analysis of the CT literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:201-204.

25. Park BK, Kim CK, Kim B, et al. Chemical shift MR imaging of hyperattenuating (>10 HU) adrenal masses: does it still have a role? Radiology. 2004;231:711-716.

26. Boland GW, Blake MA, Holakere NS, et al. PET/CT for the characterization of adrenal masses in patients with cancer: qualitative vs quantitative accuracy in 150 consecutive patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:956-962.

27. Paulsen SD, Nghiem HV, Korobkin M, et al. Changing role of imaging- guided percutaneous biopsy of adrenal masses: evaluation of 50 adrenal biopsies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1033-1037

28. Grumbach MM, Biller BMK, Braunstein GD, et al. Management of the clinically inapparent adrenal mass (“incidentalomas”). Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:424-429.

29. Zeiger MA, Thompson GB, Quan-Yang D, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Association of Endocrine Surgeons medical guidelines for the management of adrenal incidentalomas. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(suppl 1):1-20.

30. Young WF. The incidentally discovered adrenal mass. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:601-610.

31. Deutschbein T, Unger N, Hinrichs J, et al. Late-night and lowdose dexamethasone-suppressed cortisol in saliva and serum for the diagnosis of cortisol-secreting adrenal adenomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161:747-753.

32. Bernini G, Moretti A, Gianfranco A, et al. Primary aldosteronism in normokalemic patients with adrenal incidentalomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146:523-529.

33. Montori VM, Young WF Jr. Use of plasma aldosterone concentration-to-plasma renin activity ratio as a screening test for primary aldosteronism: a systematic review of the literature. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2002;31:619-632.

34. Motta-Ramirez GA, Remer EM, Herts BR, et al. Comparison of CT findings in symptomatic and incidentally discovered pheochromocytomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:684-688.

35. Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, Grossman A. The incidentally discovered adrenal mass. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2005.

› Use computed tomography studies and the Bosniak classification system to

guide management of renal cystic masses. A

› Perform laboratory tests for hypercortisolism, hyperaldosteronism, and hypersecretion of catecholamines (pheochromocytoma) on any patient with an incidental adrenal mass, regardless of signs or symptoms. C

› Refer patients with adrenal masses >4 cm for surgical evaluation. Refer any individual who has a history of malignancy and an adrenal mass for oncologic evaluation. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A. Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B. Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C. Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE Jane C, a 76-year-old patient, reports lower abdominal discomfort and increased bowel movements. Her left lower quadrant is tender to palpation, without signs of a surgical abdomen, and vital signs are normal. Laboratory studies are also normal, except for mild anemia and a positive fecal occult blood test. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT), with and without contrast, are negative for acute pathology, but a 1.7-cm lesion is found in the upper pole of the left kidney. What is your next step?

Renal or adrenal masses may be discovered during imaging studies for complaints unrelated to the kidneys or adrenals. Detection of incidentalomas has increased dramatically, keeping pace with the growing use of ultrasonography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for abdominal, chest, and back complaints.1

Family physicians can evaluate most of these masses and determine the need for referral by using clinical judgment, appropriate imaging studies, and screening laboratory tests. In the pages that follow, we present a systematic approach for evaluating these incidentalomas and determining when consultation or referral is needed.

Incidental renal masses are common

Lesions are commonly found in normal kidneys, and the incidence increases with age. Approximately one-third of individuals age 50 and older will have at least one renal cyst on CT.2

Most incidental renal masses are benign cysts requiring no further evaluation. Other possibilities include indeterminate or malignant cysts or solid masses, which may be malignant or benign. Inflammatory renal lesions from infection, infarction, or trauma also occur, but these tend to be symptomatic and are rarely found incidentally.

Classification of renal cysts—not based on size

Cysts are the most common adult renal masses. Typically they are unilocular and located in the renal cortex, frequently extending to the renal surface.3 Renal function is usually preserved, regardless of the cyst’s location or size. Careful examination of adjacent tissue is essential, as secondary cysts may form when solid tumors obstruct tubules of normal parenchyma. Cystic lesions containing enhancing soft tissue unattached to the wall or septa likely are malignant.4

The Bosniak classification system, with 5 classes based on CT characteristics

(TABLE 1), is a useful guide for managing renal cystic lesions.4 Size is not an important feature in the Bosniak system; small cysts may be malignant and larger ones benign. Small cysts may grow into larger benign lesions, occasionally causing flank or abdominal pain, palpable masses, or hematuria.

Simple cysts. Renal cysts that meet Bosniak class I criteria can be confidently labeled benign and need no further evaluation (FIGURE 1). Simple renal cysts on CT have homogenous low-attenuating fluid and thin nonenhancing walls without septa.4

On ultrasound, simple renal cysts show spherical or ovoid shape without internal echoes, a thin smooth wall separate from the surrounding parenchyma, and posterior wall enhancement caused by increased transmission through the water-filled cyst. The likelihood of malignancy is extremely low in a renal cyst that meets these criteria, which have a reported accuracy of 98% to 100%.3 Thus, no further evaluation is required if an obviously benign simple cyst is first noted on an adequate ultrasound. Inadequate ultrasound visualization or evidence of calcifications, septa, or multiple chambers calls for prompt renal CT.

CASE The mass on Ms. C’s left kidney is hypoattenuating and nonenhancing on CT. It meets Bosniak criteria for a benign simple cyst (class I) and requires no further evaluation or follow-up. Colonoscopy detects multiple colonic polyps that are removed, and the patient does well.

Mildly complicated cysts. Less diagnostic certainty characterizes cysts with mild abnormalities that keep them from being labeled as simple. Bosniak classes II and IIF describe mildly abnormal renal cysts. Class II cysts can be dismissed, whereas class IIF cysts require follow-up.

Class II cysts may contain a few hairline septa, fine calcium deposits in walls or septa, or an unmeasurable enhancement of the walls. A hyperattenuating but nonenhancing fluid also is described as category II. Small homogeneous cysts <3 cm, without enhancement but hyperattenuated, are reliably considered benign and need not be evaluated.2,7

Class IIF cysts may have multiple hairline-thin septa with unmeasurable enhancement or minimal smooth thickening or irregular/nodular calcifications of wall or septa without enhancing soft tissue components. Hyperattenuating cystic lesions >3 cm and intrarenal “noncortical” cysts are included in this category. Class IIF cysts require follow-up at 6 months with CT or MRI, then annually for at least 5 years.8

Obviously complicated cysts. Bosniak class III is indeterminate—neither benign nor clearly malignant. Class III cysts may have thickened borders or septa with measurable enhancement, or they may be multilocular, hemorrhagic, or infected. In 5 case series, 29 of 57 class III lesions proved to be malignant.5 MRI may characterize these lesions more definitively than CT prior to urologic referral.

Malignant cysts. Bosniak class IV renal lesions are clearly malignant, with large heterogeneous cysts or necrotic components, shaggy thickened walls, or enhancing soft tissue components separate from the wall or septa. Their unequivocal appearance results from solid tumor necrosis and liquefaction. Diagnosis is straightforward, and excision is indicated.2

A closer look at solid renal masses

Solid renal masses usually consist of enhancing tissue with little or no fluid. The goal of evaluation is to exclude malignancies, such as renal cell cancer, lymphomas, sarcomas, or metastasis. Benign solid masses include renal adenomas, angiomyolipomas, and oncocytomas, among others.

Several lesions can be diagnosed by appearance or symptoms:

Angiomyolipomas are recognized by their fat content within a noncalcified mass. Unenhanced CT usually is sufficient for diagnosis, unless the mass is very small or has atypical features.9

Vascular lesions can be identified because they enhance to the same degree as the vasculature. With the exception of inflammatory or vascular abnormalities, all enhancing lesions that do not contain fat should be presumed to be malignant.

In patients with a known extrarenal primary malignancy, 50% to 85% of incidental solid renal masses will represent metastatic disease.10 Percutaneous biopsy may be warranted to differentiate metastatic lesions from a secondary, primary (ie, renal cell carcinoma), or benign process.11

A study of 2770 solid renal mass excisions revealed that 12.8% were benign, with a direct relationship between malignancy and size. Masses <1 cm were benign 44% of the time.12 Early identification of small renal carcinomas may improve survival rates. Although renal cell carcinomas <3 cm in diameter have low metastatic potential, a solid, nonfat-containing mass should be evaluated for aggressive nephron-sparing surgery.6,13

Incidental adrenal masses occur infrequently

Adrenal incidentalomas are defined as radiographically identified masses >1 cm in diameter.14 They are much less common than their renal counterparts, with a reported prevalence of 0.35% to 5% on CT.15 Because the adrenal glands are hormonally active and receive substantial blood flow, metastatic, hormonally active, and nonfunctional causes for adrenal masses need to be considered.16

Adrenal pathology

Adrenal masses may be characterized by increased or normal adrenal function. Hyperfunctioning syndromes include hypercortisolism, hyperaldosteronism, adrenogenital hypersecretion of adrenocortical origin, and pheochromocytomas of the medulla. Symptom evaluation of these syndromes is important, but not sufficient to rule out a hyperfunctioning syndrome.

In a retrospective review of inapparent adrenal masses, ≤13% of pheochromocytomas were clinically silent.17 Therefore, laboratory testing is necessary for an incidental adrenal mass.

Nonfunctional lesions include adenomas, metastases, cysts, myelolipomas, hemorrhage, and adrenal carcinomas. These masses require evaluation for the possibility of cancer, the most common of which is metastasis. In patients with an extra-adrenal malignancy, the likelihood of malignancy in an incidental adrenal mass is at least 50%.18 An adrenal mass representing metastasis of a previously unrecognized cancer is exceedingly rare.19

Primary adrenal carcinoma is also rare, with an estimated incidence of 2 cases per one million in the general population. For patients with adrenal masses, the prevalence of carcinoma increases with lesion size (2% for tumors <4 cm, 6% for tumors 4-6 cm, and 25% for tumors >6 cm in diameter). 17 For this reason, tumors >4 cm in diameter are usually surgically resected in patients with no previous cancer history, unless radiologic criteria demonstrate clearly benign characteristics.

Although adrenal carcinomas are considered nonfunctioning, some evidence suggests they produce low levels of cortisol that may be associated with clinical features of metabolic syndrome.20

CT is first choice for adrenal mass evaluation

Dedicated adrenal CT with both unenhanced and delayed contrast-enhanced images is the most reliable study to evaluate an adrenal mass, according to the American College of Radiology. Consider another study only in patients with contrast allergy, renal compromise, or cancer history.21

Unenhanced CT can diagnose the approximately 70% of adenomas that are small, well-defined round masses with homogenous low-density lipid deposition.22 Delayed contrast enhancement can characterize most of the remaining 30%.23 Unenhanced CT with attenuation values of <10 Hounsfield units (HU) can diagnose adenomas with 71% specificity and 98% sensitivity,24 and can often diagnose simple cysts and myelolipomas, as well.

Other imaging options. MRI is an alternative to CT for patients with contraindications for contrast or radiation exposure. MRI provides less spatial resolution than CT, but chemical shift imaging can measure cytoplasmic lipid content similar to unenhanced CT. A small study found chemical shift MRI more reliable than unenhanced CT, but less reliable than CT with delayed contrast enhancement.25

Positron emission tomography (PET) is useful to noninvasively evaluate biochemical and physiologic processes. PET-CT incorporates unenhanced CT density measurements to improve PET accuracy. In a patient with a history of cancer, PET-CT has a sensitivity of 93% to 100% and a specificity of 95% in differentiating benign from malignant adrenal tumors.26

When to order a biopsy

The need for biopsy has decreased as imaging has improved, but biopsy is required whenever diagnostic imaging fails to differentiatea lesion as benign or malignant. CT guided biopsy provides diagnostic accuracy of 85% to 95%.27 Complications such as pneumothorax, hemorrhage, and bacteremia occur in 3% to 9% of biopsies. Before any adrenal biopsy, measure plasma-free metanephrines to exclude undiagnosed pheochromocytoma, which could precipitate a hypertensive crisis if untreated.22

These 3 laboratory screening tests are critical

Family physicians can perform the initial biochemical evaluation of an adrenal incidentaloma. Guidance is available from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)28 and the American Academy of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) (FIGURE 2).29

Regardless of signs or symptoms, perform screening laboratory tests for 3 types of adrenal hyperfunction: hypercortisolism, hyperaldosteronism, and hypersecretion of catecholamines (pheochromocytoma). Screening tests are not recommended for androgen hypersecretion, which is extremely rare and causes recognizable symptoms such as hirsutism (Table 2).29

Hypercortisolism occurs in approximately 5% of adrenal incidentalomas.30 An overnight dexamethasone suppression test (DST) is most reliable for screening, with sensitivity >95% for Cushing syndrome.31 The patient takes a 1-mg dose of oral dexamethasone at 11 pm, and a fasting plasma cortisol sample is drawn the next day at 8 am.

Dexamethasone binds to glucocorticoid receptors in the pituitary gland, suppressing adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion. Cortisol will be depressed the next morning unless the adrenal mass produces cortisol autonomously. Patients with a DST >5 mcg/dL—highly suggestive of Cushing syndrome—require further evaluation, and we suggest referral to an endocrinologist.

Hyperaldosteronism is seen in 1% to 2% of adrenal incidentalomas.32 The aldosterone- to-renin ratio (ARR) is recommended as a screening test for hyperaldosteronism, with an ARR >20 requiring further testing.33 Medications that may affect the ARR include beta-blockers, spironolactone, clonidine, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers.29

Refer a patient with evidence of hyperaldosteronism to an endocrinologist and a surgeon with experience in managing these lesions. If the ARR test result suggests an aldosterone excess, a salt-loading test is used to verify failure of aldosterone suppression. Adrenal venous sampling is often performed prior to surgical removal to confirm that an incidentaloma is the source of hyperaldosteronism.

Pheochromocytoma. Approximately 5% of incidental adrenal lesions are pheochromocytomas.30 Many patients with these epinephrine/norepinephrine secreting tumors do not show the classic symptom triad of headache, palpitations, and diaphoresis, and approximately half have normal blood pressure.34

Identifying a pheochromocytoma is important in any patient requiring surgery or biopsy, as surgical manipulation can cause a potentially fatal intraoperative catecholamine surge. Presurgical medical management can mitigate this reaction.

A plasma-free metanephrines test, which has 95% sensitivity, is the most reliable test for pheochromocytoma.35 Medications, including tricyclic antidepressants, decongestants, amphetamines, reserpine, and phenoxybenzamine, can cause falsepositive results.29 Confirm a positive plasma-free metanephrines test with a 24-hour fractionated urine metanephrines test, and refer the patient to an endocrinologist.

Managing adrenal incidentalomas

Refer all patients with adrenal masses >4 cm for surgical evaluation because of the risk of malignancy; all patients who have a history of malignancy and an adrenal mass of any size require a referral to an oncologist. Perform the AACE-recommended 3-element biochemical workup for all masses, with the exception of definitively diagnosed cysts or myelolipomas.

Refer to an endocrinologist all patients with abnormal screening laboratory results, regardless of adrenal mass size, as well as patients with concerning clinical findings. Initiate cardiovascular, diabetes, and bone density evaluation and management for metabolic syndrome.20

Monitoring after a negative workup

Little evidence exists to guide monitoring of small adrenal incidentalomas (<4 cm) with a negative workup. The 2002 NIH report recommended annual radiologic follow-up for 5 years,28 whereas the 2009 AACE guidelines recommend radiographic follow-up at 3 to 6 months, then at one and 2 years.29

Evidence indicates that 14% of lesions will enlarge in 2 years, although the clinical significance of enlargement is unknown. Some authors argue against CT monitoring because the risk of adrenal mass progression is similar to the malignancy risk posed by 3 years of radiation exposure with CT.20

Some guidelines recommend repeat biochemical screening every 3 to 4 years.28,29 AACE guidelines quote a 47% rate of progression over 3 years, but most adrenal masses progress to subclinical Cushing syndrome— a condition of uncertain significance. Subclinical Cushing’s has not been reported to progress to the overt syndrome, and new catecholamine or aldosterone secretion is rare.

Many endocrinologists reduce the frequency of follow-up, depending on the type of adrenal mass (cyst or solid) and its size. AACE suggests CT for adenomas one to 4 cm at 12 months. AACE and NIH recommend hormonal evaluation annually for 4 years. Adrenal cysts or myelolipoma in patients without cancer need no follow-up.29

CORRESPONDENCE

James C. Higgins, DO, CAPT, MC, USN, Ret., Naval Hospital Jacksonville, Family Medicine Department, 2080 Child Street, Box 1000, Jacksonville, FL 32214;

[email protected]

› Use computed tomography studies and the Bosniak classification system to

guide management of renal cystic masses. A

› Perform laboratory tests for hypercortisolism, hyperaldosteronism, and hypersecretion of catecholamines (pheochromocytoma) on any patient with an incidental adrenal mass, regardless of signs or symptoms. C

› Refer patients with adrenal masses >4 cm for surgical evaluation. Refer any individual who has a history of malignancy and an adrenal mass for oncologic evaluation. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A. Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B. Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C. Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE Jane C, a 76-year-old patient, reports lower abdominal discomfort and increased bowel movements. Her left lower quadrant is tender to palpation, without signs of a surgical abdomen, and vital signs are normal. Laboratory studies are also normal, except for mild anemia and a positive fecal occult blood test. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT), with and without contrast, are negative for acute pathology, but a 1.7-cm lesion is found in the upper pole of the left kidney. What is your next step?

Renal or adrenal masses may be discovered during imaging studies for complaints unrelated to the kidneys or adrenals. Detection of incidentalomas has increased dramatically, keeping pace with the growing use of ultrasonography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for abdominal, chest, and back complaints.1

Family physicians can evaluate most of these masses and determine the need for referral by using clinical judgment, appropriate imaging studies, and screening laboratory tests. In the pages that follow, we present a systematic approach for evaluating these incidentalomas and determining when consultation or referral is needed.

Incidental renal masses are common

Lesions are commonly found in normal kidneys, and the incidence increases with age. Approximately one-third of individuals age 50 and older will have at least one renal cyst on CT.2

Most incidental renal masses are benign cysts requiring no further evaluation. Other possibilities include indeterminate or malignant cysts or solid masses, which may be malignant or benign. Inflammatory renal lesions from infection, infarction, or trauma also occur, but these tend to be symptomatic and are rarely found incidentally.

Classification of renal cysts—not based on size

Cysts are the most common adult renal masses. Typically they are unilocular and located in the renal cortex, frequently extending to the renal surface.3 Renal function is usually preserved, regardless of the cyst’s location or size. Careful examination of adjacent tissue is essential, as secondary cysts may form when solid tumors obstruct tubules of normal parenchyma. Cystic lesions containing enhancing soft tissue unattached to the wall or septa likely are malignant.4

The Bosniak classification system, with 5 classes based on CT characteristics

(TABLE 1), is a useful guide for managing renal cystic lesions.4 Size is not an important feature in the Bosniak system; small cysts may be malignant and larger ones benign. Small cysts may grow into larger benign lesions, occasionally causing flank or abdominal pain, palpable masses, or hematuria.

Simple cysts. Renal cysts that meet Bosniak class I criteria can be confidently labeled benign and need no further evaluation (FIGURE 1). Simple renal cysts on CT have homogenous low-attenuating fluid and thin nonenhancing walls without septa.4

On ultrasound, simple renal cysts show spherical or ovoid shape without internal echoes, a thin smooth wall separate from the surrounding parenchyma, and posterior wall enhancement caused by increased transmission through the water-filled cyst. The likelihood of malignancy is extremely low in a renal cyst that meets these criteria, which have a reported accuracy of 98% to 100%.3 Thus, no further evaluation is required if an obviously benign simple cyst is first noted on an adequate ultrasound. Inadequate ultrasound visualization or evidence of calcifications, septa, or multiple chambers calls for prompt renal CT.

CASE The mass on Ms. C’s left kidney is hypoattenuating and nonenhancing on CT. It meets Bosniak criteria for a benign simple cyst (class I) and requires no further evaluation or follow-up. Colonoscopy detects multiple colonic polyps that are removed, and the patient does well.

Mildly complicated cysts. Less diagnostic certainty characterizes cysts with mild abnormalities that keep them from being labeled as simple. Bosniak classes II and IIF describe mildly abnormal renal cysts. Class II cysts can be dismissed, whereas class IIF cysts require follow-up.

Class II cysts may contain a few hairline septa, fine calcium deposits in walls or septa, or an unmeasurable enhancement of the walls. A hyperattenuating but nonenhancing fluid also is described as category II. Small homogeneous cysts <3 cm, without enhancement but hyperattenuated, are reliably considered benign and need not be evaluated.2,7

Class IIF cysts may have multiple hairline-thin septa with unmeasurable enhancement or minimal smooth thickening or irregular/nodular calcifications of wall or septa without enhancing soft tissue components. Hyperattenuating cystic lesions >3 cm and intrarenal “noncortical” cysts are included in this category. Class IIF cysts require follow-up at 6 months with CT or MRI, then annually for at least 5 years.8

Obviously complicated cysts. Bosniak class III is indeterminate—neither benign nor clearly malignant. Class III cysts may have thickened borders or septa with measurable enhancement, or they may be multilocular, hemorrhagic, or infected. In 5 case series, 29 of 57 class III lesions proved to be malignant.5 MRI may characterize these lesions more definitively than CT prior to urologic referral.

Malignant cysts. Bosniak class IV renal lesions are clearly malignant, with large heterogeneous cysts or necrotic components, shaggy thickened walls, or enhancing soft tissue components separate from the wall or septa. Their unequivocal appearance results from solid tumor necrosis and liquefaction. Diagnosis is straightforward, and excision is indicated.2

A closer look at solid renal masses

Solid renal masses usually consist of enhancing tissue with little or no fluid. The goal of evaluation is to exclude malignancies, such as renal cell cancer, lymphomas, sarcomas, or metastasis. Benign solid masses include renal adenomas, angiomyolipomas, and oncocytomas, among others.

Several lesions can be diagnosed by appearance or symptoms:

Angiomyolipomas are recognized by their fat content within a noncalcified mass. Unenhanced CT usually is sufficient for diagnosis, unless the mass is very small or has atypical features.9

Vascular lesions can be identified because they enhance to the same degree as the vasculature. With the exception of inflammatory or vascular abnormalities, all enhancing lesions that do not contain fat should be presumed to be malignant.

In patients with a known extrarenal primary malignancy, 50% to 85% of incidental solid renal masses will represent metastatic disease.10 Percutaneous biopsy may be warranted to differentiate metastatic lesions from a secondary, primary (ie, renal cell carcinoma), or benign process.11

A study of 2770 solid renal mass excisions revealed that 12.8% were benign, with a direct relationship between malignancy and size. Masses <1 cm were benign 44% of the time.12 Early identification of small renal carcinomas may improve survival rates. Although renal cell carcinomas <3 cm in diameter have low metastatic potential, a solid, nonfat-containing mass should be evaluated for aggressive nephron-sparing surgery.6,13

Incidental adrenal masses occur infrequently

Adrenal incidentalomas are defined as radiographically identified masses >1 cm in diameter.14 They are much less common than their renal counterparts, with a reported prevalence of 0.35% to 5% on CT.15 Because the adrenal glands are hormonally active and receive substantial blood flow, metastatic, hormonally active, and nonfunctional causes for adrenal masses need to be considered.16

Adrenal pathology

Adrenal masses may be characterized by increased or normal adrenal function. Hyperfunctioning syndromes include hypercortisolism, hyperaldosteronism, adrenogenital hypersecretion of adrenocortical origin, and pheochromocytomas of the medulla. Symptom evaluation of these syndromes is important, but not sufficient to rule out a hyperfunctioning syndrome.

In a retrospective review of inapparent adrenal masses, ≤13% of pheochromocytomas were clinically silent.17 Therefore, laboratory testing is necessary for an incidental adrenal mass.

Nonfunctional lesions include adenomas, metastases, cysts, myelolipomas, hemorrhage, and adrenal carcinomas. These masses require evaluation for the possibility of cancer, the most common of which is metastasis. In patients with an extra-adrenal malignancy, the likelihood of malignancy in an incidental adrenal mass is at least 50%.18 An adrenal mass representing metastasis of a previously unrecognized cancer is exceedingly rare.19

Primary adrenal carcinoma is also rare, with an estimated incidence of 2 cases per one million in the general population. For patients with adrenal masses, the prevalence of carcinoma increases with lesion size (2% for tumors <4 cm, 6% for tumors 4-6 cm, and 25% for tumors >6 cm in diameter). 17 For this reason, tumors >4 cm in diameter are usually surgically resected in patients with no previous cancer history, unless radiologic criteria demonstrate clearly benign characteristics.

Although adrenal carcinomas are considered nonfunctioning, some evidence suggests they produce low levels of cortisol that may be associated with clinical features of metabolic syndrome.20

CT is first choice for adrenal mass evaluation

Dedicated adrenal CT with both unenhanced and delayed contrast-enhanced images is the most reliable study to evaluate an adrenal mass, according to the American College of Radiology. Consider another study only in patients with contrast allergy, renal compromise, or cancer history.21

Unenhanced CT can diagnose the approximately 70% of adenomas that are small, well-defined round masses with homogenous low-density lipid deposition.22 Delayed contrast enhancement can characterize most of the remaining 30%.23 Unenhanced CT with attenuation values of <10 Hounsfield units (HU) can diagnose adenomas with 71% specificity and 98% sensitivity,24 and can often diagnose simple cysts and myelolipomas, as well.

Other imaging options. MRI is an alternative to CT for patients with contraindications for contrast or radiation exposure. MRI provides less spatial resolution than CT, but chemical shift imaging can measure cytoplasmic lipid content similar to unenhanced CT. A small study found chemical shift MRI more reliable than unenhanced CT, but less reliable than CT with delayed contrast enhancement.25

Positron emission tomography (PET) is useful to noninvasively evaluate biochemical and physiologic processes. PET-CT incorporates unenhanced CT density measurements to improve PET accuracy. In a patient with a history of cancer, PET-CT has a sensitivity of 93% to 100% and a specificity of 95% in differentiating benign from malignant adrenal tumors.26

When to order a biopsy

The need for biopsy has decreased as imaging has improved, but biopsy is required whenever diagnostic imaging fails to differentiatea lesion as benign or malignant. CT guided biopsy provides diagnostic accuracy of 85% to 95%.27 Complications such as pneumothorax, hemorrhage, and bacteremia occur in 3% to 9% of biopsies. Before any adrenal biopsy, measure plasma-free metanephrines to exclude undiagnosed pheochromocytoma, which could precipitate a hypertensive crisis if untreated.22

These 3 laboratory screening tests are critical

Family physicians can perform the initial biochemical evaluation of an adrenal incidentaloma. Guidance is available from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)28 and the American Academy of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) (FIGURE 2).29

Regardless of signs or symptoms, perform screening laboratory tests for 3 types of adrenal hyperfunction: hypercortisolism, hyperaldosteronism, and hypersecretion of catecholamines (pheochromocytoma). Screening tests are not recommended for androgen hypersecretion, which is extremely rare and causes recognizable symptoms such as hirsutism (Table 2).29

Hypercortisolism occurs in approximately 5% of adrenal incidentalomas.30 An overnight dexamethasone suppression test (DST) is most reliable for screening, with sensitivity >95% for Cushing syndrome.31 The patient takes a 1-mg dose of oral dexamethasone at 11 pm, and a fasting plasma cortisol sample is drawn the next day at 8 am.

Dexamethasone binds to glucocorticoid receptors in the pituitary gland, suppressing adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion. Cortisol will be depressed the next morning unless the adrenal mass produces cortisol autonomously. Patients with a DST >5 mcg/dL—highly suggestive of Cushing syndrome—require further evaluation, and we suggest referral to an endocrinologist.

Hyperaldosteronism is seen in 1% to 2% of adrenal incidentalomas.32 The aldosterone- to-renin ratio (ARR) is recommended as a screening test for hyperaldosteronism, with an ARR >20 requiring further testing.33 Medications that may affect the ARR include beta-blockers, spironolactone, clonidine, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers.29

Refer a patient with evidence of hyperaldosteronism to an endocrinologist and a surgeon with experience in managing these lesions. If the ARR test result suggests an aldosterone excess, a salt-loading test is used to verify failure of aldosterone suppression. Adrenal venous sampling is often performed prior to surgical removal to confirm that an incidentaloma is the source of hyperaldosteronism.

Pheochromocytoma. Approximately 5% of incidental adrenal lesions are pheochromocytomas.30 Many patients with these epinephrine/norepinephrine secreting tumors do not show the classic symptom triad of headache, palpitations, and diaphoresis, and approximately half have normal blood pressure.34

Identifying a pheochromocytoma is important in any patient requiring surgery or biopsy, as surgical manipulation can cause a potentially fatal intraoperative catecholamine surge. Presurgical medical management can mitigate this reaction.

A plasma-free metanephrines test, which has 95% sensitivity, is the most reliable test for pheochromocytoma.35 Medications, including tricyclic antidepressants, decongestants, amphetamines, reserpine, and phenoxybenzamine, can cause falsepositive results.29 Confirm a positive plasma-free metanephrines test with a 24-hour fractionated urine metanephrines test, and refer the patient to an endocrinologist.

Managing adrenal incidentalomas

Refer all patients with adrenal masses >4 cm for surgical evaluation because of the risk of malignancy; all patients who have a history of malignancy and an adrenal mass of any size require a referral to an oncologist. Perform the AACE-recommended 3-element biochemical workup for all masses, with the exception of definitively diagnosed cysts or myelolipomas.

Refer to an endocrinologist all patients with abnormal screening laboratory results, regardless of adrenal mass size, as well as patients with concerning clinical findings. Initiate cardiovascular, diabetes, and bone density evaluation and management for metabolic syndrome.20

Monitoring after a negative workup

Little evidence exists to guide monitoring of small adrenal incidentalomas (<4 cm) with a negative workup. The 2002 NIH report recommended annual radiologic follow-up for 5 years,28 whereas the 2009 AACE guidelines recommend radiographic follow-up at 3 to 6 months, then at one and 2 years.29

Evidence indicates that 14% of lesions will enlarge in 2 years, although the clinical significance of enlargement is unknown. Some authors argue against CT monitoring because the risk of adrenal mass progression is similar to the malignancy risk posed by 3 years of radiation exposure with CT.20

Some guidelines recommend repeat biochemical screening every 3 to 4 years.28,29 AACE guidelines quote a 47% rate of progression over 3 years, but most adrenal masses progress to subclinical Cushing syndrome— a condition of uncertain significance. Subclinical Cushing’s has not been reported to progress to the overt syndrome, and new catecholamine or aldosterone secretion is rare.

Many endocrinologists reduce the frequency of follow-up, depending on the type of adrenal mass (cyst or solid) and its size. AACE suggests CT for adenomas one to 4 cm at 12 months. AACE and NIH recommend hormonal evaluation annually for 4 years. Adrenal cysts or myelolipoma in patients without cancer need no follow-up.29

CORRESPONDENCE

James C. Higgins, DO, CAPT, MC, USN, Ret., Naval Hospital Jacksonville, Family Medicine Department, 2080 Child Street, Box 1000, Jacksonville, FL 32214;

[email protected]

1. Berland LL, Silverman SG, Gore RM, et al. Managing incidental findings on abdominal CT: white paper of the ACR incidental findings committee. J Am Coll Radiol. 2010;7:754-773.

2. Silverman S, Israel G, Herts B, et al. Management of the incidental renal mass. Radiology. 2008;249:16-31.

3. Curry NS, Bissada NK. Radiologic evaluation of small and indeterminate renal masses. Urol Clin North Am. 1997;24:493-505.

4. Bosniak MA. The current radiological approach to renal cysts. Radiology. 1986;158:1-10.

5. Harisinghani M, Maher M, Gervais D, et al. Incidence of malignancy in complex cystic renal masses (Bosniak category III): should imaging guided biopsy precede surgery? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:755-758.

6. Remzi M, Ozsoy M, Klingler HC. Are small renal tumors harmless? Analysis of histopathological features according to tumors less than 4 cm in diameter. J Urol. 2006;176:896-899.

7. Jonisch AI, Rubinowitz A, Mutalik P, et al. Can high attenuation renal cysts be differentiated from renal cell carcinoma at unenhanced computed tomography? Radiology. 2007;243:445-450.

8. Israel GM, Bosniak MA. Follow-up CT of moderately complex cystic lesions of the kidney. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181: 627-633.

9. Bosniak MA, Megibow AJ, Hulnick DH, et al. CT diagnosis of renal angiomyolipoma: the importance of detecting small amounts of fat. AJR Am J Roentengol. 1988;151:497-501.

10. Mitnick JS, Bosniak MA, Rothberg M, et al. Metastatic neoplasm to the kidney studied by computed tomography and sonogram. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1985;9:43-49.

11. Rybicki FJ, Shu KM, Cibas ES, et al. Percutaneous biopsy of renal masses: sensitivity and negative predictive value stratified by clinical setting and size of masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1281-1287.

12. Frank I, Blure MI, Cheville JC, et al. Solid renal tumors: an analysis of pathological features related to tumor size. J Urol. 2003;170:2217-2220.

13. Hollingsworth JM, Miller DC, Daignault S, et al. Rising incidence of small renal masses: a need to reassess treatment effect. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1331-1334.

14. Geelhoed GW, Spiegel CT. “Incidental” adrenal cyst: a correctable lesion possibly associated with hypertension. South Med J. 1981;74:626-630.

15. Davenport C, Liew A, Doherty B, et al. The prevalence of adrenal incidentaloma in routine clinical practice. Endocrine. 2011;40: 80-83.

16. Cook DM, Loriaux LD. The incidental adrenal mass. Am J Med. 1996;101:88 94.

17. Mansmann G, Lau J, Balk E, et al. The clinically inapparent adrenal mass: update in diagnosis and management. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:309-340.

18. Androulakis II, Kaltsas G, Piatitis G, et al. The clinical significance of adrenal incidentalomas. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41: 552-560.

19. Lee JE, Evans DB, Hickey RC, et al. Unknown primary cancer presenting as an adrenal mass: frequency and implications for diagnostic evaluation of adrenal incidentalomas. Surgery. 1998;124:1115-1122.

20. Aron D, Terzolo M, Cawood TJ. Adrenal incidentalomas. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26:69-82.

21. ACR appropriateness criteria: incidentally discovered adrenal mass. American College of Radiology. Available at: http://www.acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/AppCriteria/Diagnostic/IncidentallyDiscoveredAdrenalMass.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2012.

22. Song JH, Mayo-Smith WW. Incidentally discovered adrenal mass. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49:361-368.

23. Korobkin M, Brodeur FJ, Francis IR, et al. CT time-attenuation washout curves of adrenal adenomas and nonadenomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:747-752.

24. Boland GW, Lee MJ, Gazelle GS, et al. Characterization of adrenal masses using unenhanced CT: an analysis of the CT literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:201-204.

25. Park BK, Kim CK, Kim B, et al. Chemical shift MR imaging of hyperattenuating (>10 HU) adrenal masses: does it still have a role? Radiology. 2004;231:711-716.

26. Boland GW, Blake MA, Holakere NS, et al. PET/CT for the characterization of adrenal masses in patients with cancer: qualitative vs quantitative accuracy in 150 consecutive patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:956-962.

27. Paulsen SD, Nghiem HV, Korobkin M, et al. Changing role of imaging- guided percutaneous biopsy of adrenal masses: evaluation of 50 adrenal biopsies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1033-1037

28. Grumbach MM, Biller BMK, Braunstein GD, et al. Management of the clinically inapparent adrenal mass (“incidentalomas”). Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:424-429.

29. Zeiger MA, Thompson GB, Quan-Yang D, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Association of Endocrine Surgeons medical guidelines for the management of adrenal incidentalomas. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(suppl 1):1-20.

30. Young WF. The incidentally discovered adrenal mass. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:601-610.

31. Deutschbein T, Unger N, Hinrichs J, et al. Late-night and lowdose dexamethasone-suppressed cortisol in saliva and serum for the diagnosis of cortisol-secreting adrenal adenomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161:747-753.

32. Bernini G, Moretti A, Gianfranco A, et al. Primary aldosteronism in normokalemic patients with adrenal incidentalomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146:523-529.

33. Montori VM, Young WF Jr. Use of plasma aldosterone concentration-to-plasma renin activity ratio as a screening test for primary aldosteronism: a systematic review of the literature. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2002;31:619-632.

34. Motta-Ramirez GA, Remer EM, Herts BR, et al. Comparison of CT findings in symptomatic and incidentally discovered pheochromocytomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:684-688.

35. Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, Grossman A. The incidentally discovered adrenal mass. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2005.

1. Berland LL, Silverman SG, Gore RM, et al. Managing incidental findings on abdominal CT: white paper of the ACR incidental findings committee. J Am Coll Radiol. 2010;7:754-773.

2. Silverman S, Israel G, Herts B, et al. Management of the incidental renal mass. Radiology. 2008;249:16-31.

3. Curry NS, Bissada NK. Radiologic evaluation of small and indeterminate renal masses. Urol Clin North Am. 1997;24:493-505.

4. Bosniak MA. The current radiological approach to renal cysts. Radiology. 1986;158:1-10.

5. Harisinghani M, Maher M, Gervais D, et al. Incidence of malignancy in complex cystic renal masses (Bosniak category III): should imaging guided biopsy precede surgery? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:755-758.

6. Remzi M, Ozsoy M, Klingler HC. Are small renal tumors harmless? Analysis of histopathological features according to tumors less than 4 cm in diameter. J Urol. 2006;176:896-899.

7. Jonisch AI, Rubinowitz A, Mutalik P, et al. Can high attenuation renal cysts be differentiated from renal cell carcinoma at unenhanced computed tomography? Radiology. 2007;243:445-450.

8. Israel GM, Bosniak MA. Follow-up CT of moderately complex cystic lesions of the kidney. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181: 627-633.

9. Bosniak MA, Megibow AJ, Hulnick DH, et al. CT diagnosis of renal angiomyolipoma: the importance of detecting small amounts of fat. AJR Am J Roentengol. 1988;151:497-501.

10. Mitnick JS, Bosniak MA, Rothberg M, et al. Metastatic neoplasm to the kidney studied by computed tomography and sonogram. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1985;9:43-49.

11. Rybicki FJ, Shu KM, Cibas ES, et al. Percutaneous biopsy of renal masses: sensitivity and negative predictive value stratified by clinical setting and size of masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1281-1287.

12. Frank I, Blure MI, Cheville JC, et al. Solid renal tumors: an analysis of pathological features related to tumor size. J Urol. 2003;170:2217-2220.

13. Hollingsworth JM, Miller DC, Daignault S, et al. Rising incidence of small renal masses: a need to reassess treatment effect. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1331-1334.

14. Geelhoed GW, Spiegel CT. “Incidental” adrenal cyst: a correctable lesion possibly associated with hypertension. South Med J. 1981;74:626-630.

15. Davenport C, Liew A, Doherty B, et al. The prevalence of adrenal incidentaloma in routine clinical practice. Endocrine. 2011;40: 80-83.

16. Cook DM, Loriaux LD. The incidental adrenal mass. Am J Med. 1996;101:88 94.

17. Mansmann G, Lau J, Balk E, et al. The clinically inapparent adrenal mass: update in diagnosis and management. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:309-340.

18. Androulakis II, Kaltsas G, Piatitis G, et al. The clinical significance of adrenal incidentalomas. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41: 552-560.

19. Lee JE, Evans DB, Hickey RC, et al. Unknown primary cancer presenting as an adrenal mass: frequency and implications for diagnostic evaluation of adrenal incidentalomas. Surgery. 1998;124:1115-1122.

20. Aron D, Terzolo M, Cawood TJ. Adrenal incidentalomas. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26:69-82.

21. ACR appropriateness criteria: incidentally discovered adrenal mass. American College of Radiology. Available at: http://www.acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/AppCriteria/Diagnostic/IncidentallyDiscoveredAdrenalMass.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2012.

22. Song JH, Mayo-Smith WW. Incidentally discovered adrenal mass. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49:361-368.

23. Korobkin M, Brodeur FJ, Francis IR, et al. CT time-attenuation washout curves of adrenal adenomas and nonadenomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:747-752.

24. Boland GW, Lee MJ, Gazelle GS, et al. Characterization of adrenal masses using unenhanced CT: an analysis of the CT literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:201-204.

25. Park BK, Kim CK, Kim B, et al. Chemical shift MR imaging of hyperattenuating (>10 HU) adrenal masses: does it still have a role? Radiology. 2004;231:711-716.

26. Boland GW, Blake MA, Holakere NS, et al. PET/CT for the characterization of adrenal masses in patients with cancer: qualitative vs quantitative accuracy in 150 consecutive patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:956-962.

27. Paulsen SD, Nghiem HV, Korobkin M, et al. Changing role of imaging- guided percutaneous biopsy of adrenal masses: evaluation of 50 adrenal biopsies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1033-1037

28. Grumbach MM, Biller BMK, Braunstein GD, et al. Management of the clinically inapparent adrenal mass (“incidentalomas”). Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:424-429.

29. Zeiger MA, Thompson GB, Quan-Yang D, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Association of Endocrine Surgeons medical guidelines for the management of adrenal incidentalomas. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(suppl 1):1-20.

30. Young WF. The incidentally discovered adrenal mass. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:601-610.

31. Deutschbein T, Unger N, Hinrichs J, et al. Late-night and lowdose dexamethasone-suppressed cortisol in saliva and serum for the diagnosis of cortisol-secreting adrenal adenomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161:747-753.

32. Bernini G, Moretti A, Gianfranco A, et al. Primary aldosteronism in normokalemic patients with adrenal incidentalomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146:523-529.

33. Montori VM, Young WF Jr. Use of plasma aldosterone concentration-to-plasma renin activity ratio as a screening test for primary aldosteronism: a systematic review of the literature. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2002;31:619-632.

34. Motta-Ramirez GA, Remer EM, Herts BR, et al. Comparison of CT findings in symptomatic and incidentally discovered pheochromocytomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:684-688.

35. Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, Grossman A. The incidentally discovered adrenal mass. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2005.

Plantar Fasciitis: How Best to Treat?

› Use plantar fascia specific stretching to decrease pain in patients with plantar fasciitis. A

› Consider recommending prefabricated orthoses, including night splints, to decrease pain. A

› Consider using extracorporeal shock wave therapy for plantar fascial pain. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A. Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B. Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C. Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE A 43-year-old obese woman seeks advice for left heel pain she has had for 2 months. Before the onset of pain, her activity level had increased as part of a weight loss program. Her pain is at its worst in the morning, with her first few steps; it decreases with continued walking and intensifies again after being on her feet all day. There is no history of trauma, and she reports no paresthesias or radiation of the pain. Her medical history is otherwise unremarkable. She has used ibuprofen sparingly, with limited relief.

If you were this patient’s physician, how would you proceed with her care?

Plantar fasciitis (PF) is a common cause of heel pain that affects up to 10% of the US population and accounts for approximately 600,000 outpatient visits annually.1 The plantar fascia is a dense, fibrous membrane spanning the length of the foot. It originates at the medial calcaneal tubercle, attaches to the phalanges, and provides stability and arch support to the foot. The etiology of PF is unknown, but predisposing factors include overtraining, obesity, pes planus, decreased ankle dorsiflexion, and inappropriate footwear.2 Limited dorsiflexion due to tightness of the Achilles tendon strains the plantar fascia and can lead to PF. Histology shows minimal inflammatory changes, and some experts advocate the term plantar fasciosis to counter the misperception that it is primarily an inflammatory condition.3

A patient’s history and physical exam findings are the basis for confirming or dismissing a diagnosis of PF. Radiologic studies, used judiciously, can rule out important alternative diagnoses that should not be overlooked. Multiple treatment options range from conservative to surgical interventions, although studies of the effectiveness of each modality have had conflicting results. Clinical practice guidelines generally advocate a stepwise approach to treatment.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of PF (TABLE) includes significant disorders such as calcaneal stress fracture, entrapment neuropathies (eg, tarsal tunnel syndrome), calcaneal tumor, Paget’s disease, and systemic arthritidies.4,5

What to look for in the history and physical exam

Severe heel pain upon initial weight bearing in the morning or after prolonged periods of inactivity is pathognomonic for PF.2 Initially the pain presents diffusely, but over time it localizes to the area of the medial calcaneal tubercle. Pain typically subsides with activity but may return with prolonged weight bearing, as it did with the patient in the opening case.

Test range of motion of the foot and ankle. Although this is not needed for diagnosing PF, some patients will exhibit limited ankle dorsiflexion, a predisposing factor for PF.4,6 Look for heel pad swelling, inflammation, or atrophy, and palpate the heel, plantar fascia, and calcaneal tubercle. Lastly, evaluate for gait abnormalities and the presence of sensory deficits or hypesthesias.4

The most common exam finding in PF is pain at the medial calcaneal tubercle, which may be exacerbated with passive ankle dorsiflexion or first digit extension.2,4 If paresthesias occur with percussion inferior to the medial malleolus, suspect possible nerve entrapment or tarsal tunnel syndrome. Tenderness with heel compression (squeeze test) may indicate a calcaneal fracture or apophysitis.

Imaging is useful to rule out alternative disorders

Radiologic studies generally do not contribute to the diagnosis or management of PF, but they can assist in ruling out alternative causes of heel pain or in reevaluation if symptoms of PF persist after 3 to 6 months of treatment.

Plain films lack the sensitivity to detect plantar fasciitis. While a plantar calcaneal spur is often seen on radiography, it does not confirm the diagnosis, correlate with severity of symptoms, or predict prognosis.4 Despite this deficiency, plain radiography remains the initial choice of imaging modalities, particularly to rule out other conditions.

Ultrasound accurately diagnoses plantar fasciitis. Plantar fascia thickness of more than 4.0 mm is diagnostic of PF.7 Additionally, a decrease in plantar fascia thickness correlates with a decrease in pain levels, and thus ultrasound can aid in monitoring treatment progress.8 If results of plain films and ultrasound are inconclusive and clinical concern for an alternative diagnosis warrants additional expense, consider arranging for magnetic resonance imaging.9

Noninvasive treatments

Conservative therapies remain the preferred approach to treating PF, successfully managing 85% to 90% of cases.10,11 A 2010 clinical practice guideline from the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons recommends conservative treatments such as nonsteroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), stretching, and prefabricated orthotics for the initial management of plantar heel pain.4 Emphasize to patients that it may take 6 to 12 months for symptoms to resolve.4

Stretching and trigger-point manual therapy are effective

The traditional primary treatment modality for PF has been early initiation of an Achilles-soleus (heel-cord) muscle–stretching program. However, studies have shown that plantar fascia–specific stretching (PFSS) (FIGURE) significantly diminishes or eliminates heel pain when compared with traditional stretching movements, and is useful in treating chronic recalcitrant heel pain.12,13 PFSS has also yielded results superior to low-dose shock wave therapy.14

In a 2011 study, adding myofascial trigger-point manual therapy to a PFSS routine improved self-reported physical function and pain vs stretching alone.15 This manual therapy technique is specialized and should be administered only by trained physical therapists. Data are limited and mixed regarding the effectiveness of deep tissue massage, iontophoresis, or eccentric stretching of the plantar fascia to alleviate plantar fascial pain. Support for therapies such as rest, ice, heat, and massage has largely been anecdotal.

NSAIDs for PF lack good evidence

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often prescribed to treat PF, despite a lack of evidence supporting their use. A small randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind study established a trend toward improvement in pain and disability scores with the use of NSAIDs. However, no statistically significant difference was noted in the measures between the NSAID and placebo groups at 1, 2, and 6 months.16 We found no studies that demonstrate a significant reduction in pain or improvement in function with the use of NSAIDs alone.

Although NSAIDs carry their own risks, they may work for some patients. And studies showing a lack of significant pain reduction may have been underpowered. If patients are willing to accept the risks of NSAID use, it would be reasonable to prescribe a therapeutic trial.

Orthotics and night splints can help, depending on comfort and compliance

Foot orthotics help prevent overpronation and attenuate tensile forces on the plantar fascia. A 2009 meta-analysis confirmed that both prefabricated and custom-made foot orthotics can decrease pain.17 One prospective study showed that 95% of patients had improvement in PF symptoms after 8 weeks of treatment with prefabricated orthotics.18 A Cochrane review found no difference in pain reduction between custom and prefabricated foot orthotics.19 A recent study demonstrated that rocker sole shoes—a type of therapeutic footwear with a more rounded outsole contour—combined with custom orthotics significantly reduced pain during walking compared with either modality alone.20 More research needs to be conducted into the use of rocker sole shoes before recommending them to PF patients.

Night splints help keep the foot and ankle in a neutral position, or slightly dorsiflexed, while patients sleep. Several studies have shown a reduction in pain with the use of night splints alone.17,21,22 Patient comfort and compliance tend to be the limiting factors in their use. Anterior splints are better tolerated than posterior splints.23

Shock wave therapy has better long-term results than steroid injections

Shock waves used to treat PF are thought to invoke extracellular responses that cause neovascularization and induce tissue repair and regeneration. A 2012 review article concluded that most research confirms that extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) reduces PF pain and improves function in 34% to 88% of cases.24 ESWT is comparable to surgical plantar fasciotomy without the operative risks, and yields better long-term effects in recalcitrant PF compared with corticosteroid injections (CSI).24 Many studies are underway to validate the effectiveness of ESWT. Currently, expense or lack of availability limits its use in some communities.

Invasive treatments

Corticosteroid injections may be used for more than just refractory pain