User login

5 IUD myths dispelled

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), which include intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants, and injectables, are being offered to more and more women because of their demonstrated safety, efficacy, and convenience. In other countries, as many as 50% of all women use an IUD, but the United States has been slow to adopt this option.1 In 2002, approximately 2% of US women used an IUD.2 That percentage rose to 5.2% between 2006 and 2008, according to a recent survey.3 In that survey, women consistently expressed a high degree of satisfaction with this method of contraception.3

So why aren’t more US women using an IUD?

A general fear of the IUD persists. Women may not even know why they fear the device; they may have simply heard that it is “bad for you.” The negative press the IUD has received in this country probably is related to poor outcomes associated with use of the Dalkon Shield IUD in the 1970s. As a reminder, the Dalkon Shield was blamed for many cases of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and other negative sequelae as a result of poor patient selection. In addition, some authorities believe the design of the device was severely flawed, with a string that permitted bacteria to get from the vagina to the uterus and tubes.

Today, clinicians and many patients are better educated about the prevention of chlamydia, the primary causative organism of PID and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs); patients also are better informed about safe sex practices. We now know that women should be screened for behaviors that could increase their risk for PID and render them poor candidates for the IUD.

Clinicians also have expressed concerns about reimbursement issues related to the IUD, as well as confusion and difficulty with insertion procedures and the potential for litigation. In this article, I address some of these issues in an attempt to increase the use of this highly effective contraceptive.

What’s available today

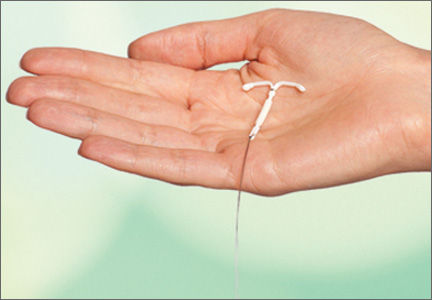

Today there are three IUDs available to US women (FIGURE):

The Copper IUD (ParaGard)—This device can be used for at least 10 years, although, in many countries, it is considered “permanent reversible contraception.” It has the advantage of being nonhormonal, making it an important option for women who cannot or will not use a hormonal contraceptive. Pregnancy is prevented through a “foreign body” effect and the spermicidal action of copper ions. The combination of these two influences prevents fertilization.4

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) (Mirena)—This IUD is recommended for 5 years of use but may remain effective for as long as 7 years. It contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of approximately 20 μg/day. In addition to the foreign body effect, this IUD prevents pregnancy through progestogenic mechanisms: It thickens cervical mucus, thins the endometrium, and reduces sperm capacitation.5

The "mini" LNG-IUS (Skyla)—This newly marketed IUD is recommended for 3 years of use. It contains 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of 14 μg/day. It has the same mechanism of action as Mirena but may be easier to insert owing to its slightly smaller size and preloaded inserter.

Myth #1: The IUD is not suitable for teens and nulliparous women

This myth arose out of concerns about the smaller uterine cavity and cervical diameter of teens and nulliparous women. Today we know that an IUD can be inserted safely in this population. Moreover, because adolescents are at high risk for unintended pregnancy, they stand to benefit uniquely from LARC options, including the IUD. As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends in a recent Committee Opinion on adolescents and LARCs, the IUD should be a “first-line” option for all women of reproductive age.6

Myth #2: An IUD should not be inserted immediately after childbirth

For many years, it was assumed that an IUD should be inserted in the postpartum period only after uterine involution was completed. However, in 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, which included the following recommendations for breastfeeding or non–breast-feeding women:

• Mirena was given a Level 2 recommendation (advantages outweigh risks) for insertion within 10 minutes after delivery of the placenta

• The copper IUD was given a Level 1 recommendation (no restrictions) for insertion within the same time interval

• From 10 minutes to 4 weeks postpartum, both devices have a Level 2 recommendation for insertion

• Beyond 4 weeks, both devices have a Level 1 recommendation for insertion.7

Immediate post-delivery insertion of an IUD has several benefits, including:

• a reduction in the risk of unintended pregnancy in women who are not breastfeeding

• providing new mothers with a LARC method.

Myth #3: Antibiotics and NSAIDs should be administered

This myth arose from concerns about PID and insertion-related pain. However, a Cochrane Database review found no benefit for prophylactic use of antibiotics prior to insertion of the copper or LNG-IUS devices to prevent PID.8

In fact, data indicate that the incidence of PID is low among women who are appropriate candidates for an IUD. Similarly, Allen and colleagues found that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) did not ameliorate symptoms of cramping during or immediately after insertion of an IUD.9

Myth #4: IUD insertion is difficult

In reality, both the copper IUD and Mirena are easy to insert. In addition, the smaller LNG-IUS (Skyla) comes more completely preloaded in its inserter. In a published Phase 2 trial comparing Mirena with two smaller, lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing devices, with the lowest-dose product corresponding to the marketed Skyla product, all 738 women given Mirena or the smaller devices experienced successful placement, with 98.5% of placements achieved on the first attempt.10

Various studies have been conducted to evaluate methods to ease insertion, including use of intracervical lidocaine, vaginal and/or oral administration of misoprostol (Cytotec), and vaginal estrogen creams. None was found to be effective in controlled trials. (See the sidebar, “Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion,” by Jennifer Gunter, MD, on page 28.) In the small percentage of women in whom it is difficult to pass a uterine sound through the external and internal os, cervical dilators may be beneficial. Gentle, progressive dilation can be accomplished easily with minimal discomfort to the patient, easing IUD insertion dramatically.

If a clinician does not insert IUDs on a frequent basis, it is prudent to look over the insertion procedure prior to the patient’s arrival. The procedure then can be reviewed with the patient as part of informed consent, which should be documented in the chart.

No steps in the recommended insertion procedure should be omitted, and charting should reflect each step:

1. Perform a bimanual exam

2. Document the appearance of the vagina and cervix

3. Use betadine or another cleansing solution on the cervical portio

4. Apply the tenaculum to the cervix (anterior lip if the uterus is anteverted, posterior lip if it is retroverted)

5. Sound the uterus to determine the optimal depth of IUD insertion. (The recommended uterine depth is 6 to 10 cm. A smaller uterus increases the likelihood of perforation, pain, and expulsion.)

6. Insert the IUD (and document the ease or difficulty of insertion)

7. Trim the string to an appropriate length

8. Assess the patient’s condition after insertion

9. Schedule a return visit in 4 weeks.

Related Article Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country Robert L. Barbieri, MD

Myth #5: Perforation is common

Uterine perforation occurs in approximately 1 in every 1,000 insertions.11 If perforation occurs with a copper IUD, remove the device to prevent the formation of intraperitoneal adhesions.12 The LNG-IUS devices do not produce this reaction, although most experts agree that they should be removed when a perforation occurs.13

Anecdotal evidence suggests that perforation may be more common among breastfeeding women, but this finding is far from definitive.

How to select an IUD for a patient: 3 case studies

CASE 1: Heavy bleeding and signs of endometriosis

Amelia, a 26-year-old nulliparous white woman, visits your office for routine examination and asks about her contraceptive options. She has no notable medical history. She has a body mass index (BMI) of 20.2 kg/m2 and exercises regularly. Menarche occurred at age 13. Her menstrual cycles are regular but are getting heavier; she now “soaks” a tampon every hour. She also complains that her cramps are more difficult to manage. She takes ibuprofen 600 mg every 6 hours during the days of heaviest bleeding and cramping, but that approach doesn’t seem to be effective lately. She is in a stable sexual relationship with her boyfriend of 2 years, now her fiancé. They have been using condoms consistently as contraception but don’t plan to start a family for a “few years.” Amelia reports that their sex life is good, although she has been experiencing pain with deep penetration for about 6 months.

Examination reveals a clear cervix and nontender uterus, although the uterus is retroverted. Palpation of the ovaries indicates that they are normal. Her main complaints: dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding.

What contraceptive would you suggest?

Amelia would be a good candidate for the LNG-IUS because she is in a stable relationship and wants to postpone pregnancy for several years. Although she has some symptoms suggestive of endometriosis (dyspareunia), they could be relieved by this method.14 Because thinning of the endometrial lining is an inherent mechanism of action of the LNG-IUS, this method could reduce her heavy bleeding.

She should be advised of the risks and benefits of the LNG-IUS, which can be inserted when she begins her next menstrual cycle.

CASE 2: Mother of two with no immediate desire for pregnancy

Tamika is a 19-year-old black woman (G2P2) who has arrived at your clinic for her 6-week postpartum visit. She is not breastfeeding. Her BMI is 25.7 kg/m2. She reports that her baby and 2-year-old are doing “OK” and says she does not want to get pregnant again anytime soon. She is in a relationship with the father of her baby and says he is “working a good job and taking care of me.” Her menstrual cycles have always been normal, with no cramping or heavy bleeding.

Examination reveals that her cervix is clear, her uterus is anteverted and nontender, and her ovaries appear to be normal.

Would this patient be a good candidate for a LARC?

Tamika is an excellent candidate for the copper IUD or LNG-IUS and should be educated about both methods. If she chooses an IUD, it can be inserted at the start of her next menstrual period.

These first two cases illustrate the importance of making no assumptions on the basis of general patient characteristics. Although Tamika may appear to be at greater risk for STI than Amelia, such “typecasting” may lead to inappropriate counseling.

Related Article Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene (and when you should not)

At the time of IUD insertion, both patients should be instructed to check for the IUD string periodically, and this recommendation should be documented in their charts.

CASE 3: Anovulatory patient with heavy periods

Mary, 25, is a nulliparous Hispanic woman who has been referred by her primary care provider. She has a BMI of 35.4 kg/m2 and has had menstrual problems since menarche at the age of 14. She reports that her periods are irregular and very heavy, with intermittent pelvic pain that she manages, with some success, with ibuprofen. She has never had a sexual relationship, but she has a boyfriend now and asks about her contraceptive options.

On examination, you discover that Mary has pubic hair distribution over her inner thigh, with primary escutcheon and acanthosis nigricans on the inner thigh. Her vulva is marked by multiple sebaceous cysts, and a speculum exam shows a large amount of estrogenic mucus and a clear cervix. Her uterus is anteverted and nontender. Her ovaries are palpable but may be enlarged, and transvaginal ultrasound reveals that they are cystic. Her diagnosis: hirsutism with probable polycystic ovary syndrome.

Would an IUD be appropriate?

Mary is not a good candidate for an IUD. Neither the copper IUD nor the LNG-IUS would suppress ovarian function sufficiently to reduce the growth of multiple follicles that occurs with polycystic ovary syndrome. She would benefit from a hormonal method (specifically, a combination oral contraceptive) to suppress follicular activity.

Time for a renaissance?

The IUD may be making a comeback. With the unintended pregnancy rate remaining consistently at about 50%, it is important that we offer our patients contraceptive methods that maximize efficacy, safety, and convenience. Today’s IUDs meet all these criteria.

Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion

Many patients worry about the potential for pain with IUD insertion—and this concern can dissuade them from choosing the IUD as a contraceptive. This is regrettable because the IUD has the highest satisfaction rating among reversible contraceptives, as well as the greatest efficacy.

How much pain can your patient expect? In one recent prospective study involving 40 women who received either 1.2% lidocaine or saline infused 3 minutes before IUD insertion, 33% of women reported a pain score of 5 or higher (on a scale of 0–10) at tenaculum placement. This finding means that two-thirds of women had a pain score of 4 or lower. In fact, 46% of women had a pain score of 2 or below.15 (The mean pain scores for insertion were similar with lidocaine and placebo [3.0 vs 3.7, respectively; P=.4]).

Pain reducing options

The evidence validates (or fails to disprove) the value of the following interventions to make insertion more comfortable for patients:

• Naproxen (550 mg) administration 40 minutes prior to insertion. One small study found it to be better than placebo.9

• Nonopioid pain medication. One small, randomized, double-blinded clinical trial found that tramadol was even more effective than naproxen at relieving insertion-related pain.16

• Injection of lidocaine into the cervix. Although this intervention is common, data supporting it are scarce. One small, high-quality study found no benefit, compared with placebo. However, if you have had success with this approach in the past, I would not discourage you from continuing to offer it, as a single small study is insufficient to disprove it.15 More data are needed.

• Keeping the patient calm. Anxiety increases the perception of pain. Studies have demonstrated that women who expect pain at insertion are more likely to experience it. Encourage the patient to breathe diaphragmatically, and remind her that she is likely to be very happy with her choice of the IUD.

Many other interventions don’t seem to be effective, although they may be offered frequently. Unproven methods include administration of NSAIDs other than naproxen, use of misoprostol (which can increase cramping), application of topical lidocaine to the cervix, and insertion during menses (although the LNG-IUS is inserted during the menstrual period to render it effective during the first month of use).

The studies described here come from the general population of reproductive-age women. If a patient has cervical scarring or a history of difficult or painful insertion, she may be more likely to experience pain, and these data may not apply to her.

—Jennifer Gunter, MD

Dr. Gunter is an ObGyn in San Francisco. She is the author of The Preemie Primer: A Complete Guide for Parents of Premature Babies—from Birth through the Toddler Years and Beyond (Da Capo Press, 2010). Dr. Gunter blogs at www.drjengunter.com, and you can find her on Twitter at @DrJenGunter. She is an OBG Management Contributing Editor.

Dr. Gunter reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. 2006 Pan EU study on female contraceptives [unpublished data]. Bayer Schering Pharma; 2007.

2. Moser WD, Martinex GM, Chandra A, Abma JC, Wilson SJ. Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States: 1982–2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; No. 350. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics. 2004;350:1–36.

3. Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007–2009. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(4):893–897.

4. Ortiz ME, Croxatto HB, Bardin CW. Mechanisms of action of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51(12 Suppl):S42–S51.

5. Barbosa I, Olsson SE, Odlind V, Goncalves T, Coutinho E. Ovarian function after seven years’ use of a levonorgestrel IUD. Adv Contracept. 1995;11(2):85–95.

6. Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion #539: Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):983–988.

7. CDC. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Early Release. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr59e0528.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2013.

8. Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF. Antibiotics for prevention with IUDs. Cochrane summaries. http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD001327/antibiotics-for-prevention-with-iuds. Published May 16, 2012. Accessed August 18, 2013.

9. Allen RH, Bartz D, Grimes DA, Hubacher D, O’Brien P. Interventions for pain with intrauterine device insertion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; (3):CD007373.

10. Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):616-622.e1-e3.

11. Grimes DA. Intrauterine devices (IUDs). In: Hatcher RA, ed. Contraceptive Technology. 19th ed. New York, New York: Ardent Media; 2007:117–143.

12. Hatcher RA. Contraceptive Technology. New York, New York: Ardent Media; 2011.

13. Adoni A, Ben C. The management of intrauterine devices following uterine perforation. Contraception. 1991;43(1):77.

14. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(7):1993–1998.

15. Nelson AL, Fong JK. Intrauterine infusion of lidocaine does not reduce pain scores during IUD insertion. Contraception. 2013;88(1):37–40.

16. Karabayirli S, Ayrim AA, Muslu B. Comparison of the analgesic effects of oral tramadol and naproxen sodium on pain relief during IUD insertion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(5):581–584.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), which include intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants, and injectables, are being offered to more and more women because of their demonstrated safety, efficacy, and convenience. In other countries, as many as 50% of all women use an IUD, but the United States has been slow to adopt this option.1 In 2002, approximately 2% of US women used an IUD.2 That percentage rose to 5.2% between 2006 and 2008, according to a recent survey.3 In that survey, women consistently expressed a high degree of satisfaction with this method of contraception.3

So why aren’t more US women using an IUD?

A general fear of the IUD persists. Women may not even know why they fear the device; they may have simply heard that it is “bad for you.” The negative press the IUD has received in this country probably is related to poor outcomes associated with use of the Dalkon Shield IUD in the 1970s. As a reminder, the Dalkon Shield was blamed for many cases of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and other negative sequelae as a result of poor patient selection. In addition, some authorities believe the design of the device was severely flawed, with a string that permitted bacteria to get from the vagina to the uterus and tubes.

Today, clinicians and many patients are better educated about the prevention of chlamydia, the primary causative organism of PID and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs); patients also are better informed about safe sex practices. We now know that women should be screened for behaviors that could increase their risk for PID and render them poor candidates for the IUD.

Clinicians also have expressed concerns about reimbursement issues related to the IUD, as well as confusion and difficulty with insertion procedures and the potential for litigation. In this article, I address some of these issues in an attempt to increase the use of this highly effective contraceptive.

What’s available today

Today there are three IUDs available to US women (FIGURE):

The Copper IUD (ParaGard)—This device can be used for at least 10 years, although, in many countries, it is considered “permanent reversible contraception.” It has the advantage of being nonhormonal, making it an important option for women who cannot or will not use a hormonal contraceptive. Pregnancy is prevented through a “foreign body” effect and the spermicidal action of copper ions. The combination of these two influences prevents fertilization.4

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) (Mirena)—This IUD is recommended for 5 years of use but may remain effective for as long as 7 years. It contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of approximately 20 μg/day. In addition to the foreign body effect, this IUD prevents pregnancy through progestogenic mechanisms: It thickens cervical mucus, thins the endometrium, and reduces sperm capacitation.5

The "mini" LNG-IUS (Skyla)—This newly marketed IUD is recommended for 3 years of use. It contains 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of 14 μg/day. It has the same mechanism of action as Mirena but may be easier to insert owing to its slightly smaller size and preloaded inserter.

Myth #1: The IUD is not suitable for teens and nulliparous women

This myth arose out of concerns about the smaller uterine cavity and cervical diameter of teens and nulliparous women. Today we know that an IUD can be inserted safely in this population. Moreover, because adolescents are at high risk for unintended pregnancy, they stand to benefit uniquely from LARC options, including the IUD. As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends in a recent Committee Opinion on adolescents and LARCs, the IUD should be a “first-line” option for all women of reproductive age.6

Myth #2: An IUD should not be inserted immediately after childbirth

For many years, it was assumed that an IUD should be inserted in the postpartum period only after uterine involution was completed. However, in 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, which included the following recommendations for breastfeeding or non–breast-feeding women:

• Mirena was given a Level 2 recommendation (advantages outweigh risks) for insertion within 10 minutes after delivery of the placenta

• The copper IUD was given a Level 1 recommendation (no restrictions) for insertion within the same time interval

• From 10 minutes to 4 weeks postpartum, both devices have a Level 2 recommendation for insertion

• Beyond 4 weeks, both devices have a Level 1 recommendation for insertion.7

Immediate post-delivery insertion of an IUD has several benefits, including:

• a reduction in the risk of unintended pregnancy in women who are not breastfeeding

• providing new mothers with a LARC method.

Myth #3: Antibiotics and NSAIDs should be administered

This myth arose from concerns about PID and insertion-related pain. However, a Cochrane Database review found no benefit for prophylactic use of antibiotics prior to insertion of the copper or LNG-IUS devices to prevent PID.8

In fact, data indicate that the incidence of PID is low among women who are appropriate candidates for an IUD. Similarly, Allen and colleagues found that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) did not ameliorate symptoms of cramping during or immediately after insertion of an IUD.9

Myth #4: IUD insertion is difficult

In reality, both the copper IUD and Mirena are easy to insert. In addition, the smaller LNG-IUS (Skyla) comes more completely preloaded in its inserter. In a published Phase 2 trial comparing Mirena with two smaller, lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing devices, with the lowest-dose product corresponding to the marketed Skyla product, all 738 women given Mirena or the smaller devices experienced successful placement, with 98.5% of placements achieved on the first attempt.10

Various studies have been conducted to evaluate methods to ease insertion, including use of intracervical lidocaine, vaginal and/or oral administration of misoprostol (Cytotec), and vaginal estrogen creams. None was found to be effective in controlled trials. (See the sidebar, “Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion,” by Jennifer Gunter, MD, on page 28.) In the small percentage of women in whom it is difficult to pass a uterine sound through the external and internal os, cervical dilators may be beneficial. Gentle, progressive dilation can be accomplished easily with minimal discomfort to the patient, easing IUD insertion dramatically.

If a clinician does not insert IUDs on a frequent basis, it is prudent to look over the insertion procedure prior to the patient’s arrival. The procedure then can be reviewed with the patient as part of informed consent, which should be documented in the chart.

No steps in the recommended insertion procedure should be omitted, and charting should reflect each step:

1. Perform a bimanual exam

2. Document the appearance of the vagina and cervix

3. Use betadine or another cleansing solution on the cervical portio

4. Apply the tenaculum to the cervix (anterior lip if the uterus is anteverted, posterior lip if it is retroverted)

5. Sound the uterus to determine the optimal depth of IUD insertion. (The recommended uterine depth is 6 to 10 cm. A smaller uterus increases the likelihood of perforation, pain, and expulsion.)

6. Insert the IUD (and document the ease or difficulty of insertion)

7. Trim the string to an appropriate length

8. Assess the patient’s condition after insertion

9. Schedule a return visit in 4 weeks.

Related Article Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country Robert L. Barbieri, MD

Myth #5: Perforation is common

Uterine perforation occurs in approximately 1 in every 1,000 insertions.11 If perforation occurs with a copper IUD, remove the device to prevent the formation of intraperitoneal adhesions.12 The LNG-IUS devices do not produce this reaction, although most experts agree that they should be removed when a perforation occurs.13

Anecdotal evidence suggests that perforation may be more common among breastfeeding women, but this finding is far from definitive.

How to select an IUD for a patient: 3 case studies

CASE 1: Heavy bleeding and signs of endometriosis

Amelia, a 26-year-old nulliparous white woman, visits your office for routine examination and asks about her contraceptive options. She has no notable medical history. She has a body mass index (BMI) of 20.2 kg/m2 and exercises regularly. Menarche occurred at age 13. Her menstrual cycles are regular but are getting heavier; she now “soaks” a tampon every hour. She also complains that her cramps are more difficult to manage. She takes ibuprofen 600 mg every 6 hours during the days of heaviest bleeding and cramping, but that approach doesn’t seem to be effective lately. She is in a stable sexual relationship with her boyfriend of 2 years, now her fiancé. They have been using condoms consistently as contraception but don’t plan to start a family for a “few years.” Amelia reports that their sex life is good, although she has been experiencing pain with deep penetration for about 6 months.

Examination reveals a clear cervix and nontender uterus, although the uterus is retroverted. Palpation of the ovaries indicates that they are normal. Her main complaints: dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding.

What contraceptive would you suggest?

Amelia would be a good candidate for the LNG-IUS because she is in a stable relationship and wants to postpone pregnancy for several years. Although she has some symptoms suggestive of endometriosis (dyspareunia), they could be relieved by this method.14 Because thinning of the endometrial lining is an inherent mechanism of action of the LNG-IUS, this method could reduce her heavy bleeding.

She should be advised of the risks and benefits of the LNG-IUS, which can be inserted when she begins her next menstrual cycle.

CASE 2: Mother of two with no immediate desire for pregnancy

Tamika is a 19-year-old black woman (G2P2) who has arrived at your clinic for her 6-week postpartum visit. She is not breastfeeding. Her BMI is 25.7 kg/m2. She reports that her baby and 2-year-old are doing “OK” and says she does not want to get pregnant again anytime soon. She is in a relationship with the father of her baby and says he is “working a good job and taking care of me.” Her menstrual cycles have always been normal, with no cramping or heavy bleeding.

Examination reveals that her cervix is clear, her uterus is anteverted and nontender, and her ovaries appear to be normal.

Would this patient be a good candidate for a LARC?

Tamika is an excellent candidate for the copper IUD or LNG-IUS and should be educated about both methods. If she chooses an IUD, it can be inserted at the start of her next menstrual period.

These first two cases illustrate the importance of making no assumptions on the basis of general patient characteristics. Although Tamika may appear to be at greater risk for STI than Amelia, such “typecasting” may lead to inappropriate counseling.

Related Article Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene (and when you should not)

At the time of IUD insertion, both patients should be instructed to check for the IUD string periodically, and this recommendation should be documented in their charts.

CASE 3: Anovulatory patient with heavy periods

Mary, 25, is a nulliparous Hispanic woman who has been referred by her primary care provider. She has a BMI of 35.4 kg/m2 and has had menstrual problems since menarche at the age of 14. She reports that her periods are irregular and very heavy, with intermittent pelvic pain that she manages, with some success, with ibuprofen. She has never had a sexual relationship, but she has a boyfriend now and asks about her contraceptive options.

On examination, you discover that Mary has pubic hair distribution over her inner thigh, with primary escutcheon and acanthosis nigricans on the inner thigh. Her vulva is marked by multiple sebaceous cysts, and a speculum exam shows a large amount of estrogenic mucus and a clear cervix. Her uterus is anteverted and nontender. Her ovaries are palpable but may be enlarged, and transvaginal ultrasound reveals that they are cystic. Her diagnosis: hirsutism with probable polycystic ovary syndrome.

Would an IUD be appropriate?

Mary is not a good candidate for an IUD. Neither the copper IUD nor the LNG-IUS would suppress ovarian function sufficiently to reduce the growth of multiple follicles that occurs with polycystic ovary syndrome. She would benefit from a hormonal method (specifically, a combination oral contraceptive) to suppress follicular activity.

Time for a renaissance?

The IUD may be making a comeback. With the unintended pregnancy rate remaining consistently at about 50%, it is important that we offer our patients contraceptive methods that maximize efficacy, safety, and convenience. Today’s IUDs meet all these criteria.

Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion

Many patients worry about the potential for pain with IUD insertion—and this concern can dissuade them from choosing the IUD as a contraceptive. This is regrettable because the IUD has the highest satisfaction rating among reversible contraceptives, as well as the greatest efficacy.

How much pain can your patient expect? In one recent prospective study involving 40 women who received either 1.2% lidocaine or saline infused 3 minutes before IUD insertion, 33% of women reported a pain score of 5 or higher (on a scale of 0–10) at tenaculum placement. This finding means that two-thirds of women had a pain score of 4 or lower. In fact, 46% of women had a pain score of 2 or below.15 (The mean pain scores for insertion were similar with lidocaine and placebo [3.0 vs 3.7, respectively; P=.4]).

Pain reducing options

The evidence validates (or fails to disprove) the value of the following interventions to make insertion more comfortable for patients:

• Naproxen (550 mg) administration 40 minutes prior to insertion. One small study found it to be better than placebo.9

• Nonopioid pain medication. One small, randomized, double-blinded clinical trial found that tramadol was even more effective than naproxen at relieving insertion-related pain.16

• Injection of lidocaine into the cervix. Although this intervention is common, data supporting it are scarce. One small, high-quality study found no benefit, compared with placebo. However, if you have had success with this approach in the past, I would not discourage you from continuing to offer it, as a single small study is insufficient to disprove it.15 More data are needed.

• Keeping the patient calm. Anxiety increases the perception of pain. Studies have demonstrated that women who expect pain at insertion are more likely to experience it. Encourage the patient to breathe diaphragmatically, and remind her that she is likely to be very happy with her choice of the IUD.

Many other interventions don’t seem to be effective, although they may be offered frequently. Unproven methods include administration of NSAIDs other than naproxen, use of misoprostol (which can increase cramping), application of topical lidocaine to the cervix, and insertion during menses (although the LNG-IUS is inserted during the menstrual period to render it effective during the first month of use).

The studies described here come from the general population of reproductive-age women. If a patient has cervical scarring or a history of difficult or painful insertion, she may be more likely to experience pain, and these data may not apply to her.

—Jennifer Gunter, MD

Dr. Gunter is an ObGyn in San Francisco. She is the author of The Preemie Primer: A Complete Guide for Parents of Premature Babies—from Birth through the Toddler Years and Beyond (Da Capo Press, 2010). Dr. Gunter blogs at www.drjengunter.com, and you can find her on Twitter at @DrJenGunter. She is an OBG Management Contributing Editor.

Dr. Gunter reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), which include intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants, and injectables, are being offered to more and more women because of their demonstrated safety, efficacy, and convenience. In other countries, as many as 50% of all women use an IUD, but the United States has been slow to adopt this option.1 In 2002, approximately 2% of US women used an IUD.2 That percentage rose to 5.2% between 2006 and 2008, according to a recent survey.3 In that survey, women consistently expressed a high degree of satisfaction with this method of contraception.3

So why aren’t more US women using an IUD?

A general fear of the IUD persists. Women may not even know why they fear the device; they may have simply heard that it is “bad for you.” The negative press the IUD has received in this country probably is related to poor outcomes associated with use of the Dalkon Shield IUD in the 1970s. As a reminder, the Dalkon Shield was blamed for many cases of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and other negative sequelae as a result of poor patient selection. In addition, some authorities believe the design of the device was severely flawed, with a string that permitted bacteria to get from the vagina to the uterus and tubes.

Today, clinicians and many patients are better educated about the prevention of chlamydia, the primary causative organism of PID and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs); patients also are better informed about safe sex practices. We now know that women should be screened for behaviors that could increase their risk for PID and render them poor candidates for the IUD.

Clinicians also have expressed concerns about reimbursement issues related to the IUD, as well as confusion and difficulty with insertion procedures and the potential for litigation. In this article, I address some of these issues in an attempt to increase the use of this highly effective contraceptive.

What’s available today

Today there are three IUDs available to US women (FIGURE):

The Copper IUD (ParaGard)—This device can be used for at least 10 years, although, in many countries, it is considered “permanent reversible contraception.” It has the advantage of being nonhormonal, making it an important option for women who cannot or will not use a hormonal contraceptive. Pregnancy is prevented through a “foreign body” effect and the spermicidal action of copper ions. The combination of these two influences prevents fertilization.4

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) (Mirena)—This IUD is recommended for 5 years of use but may remain effective for as long as 7 years. It contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of approximately 20 μg/day. In addition to the foreign body effect, this IUD prevents pregnancy through progestogenic mechanisms: It thickens cervical mucus, thins the endometrium, and reduces sperm capacitation.5

The "mini" LNG-IUS (Skyla)—This newly marketed IUD is recommended for 3 years of use. It contains 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of 14 μg/day. It has the same mechanism of action as Mirena but may be easier to insert owing to its slightly smaller size and preloaded inserter.

Myth #1: The IUD is not suitable for teens and nulliparous women

This myth arose out of concerns about the smaller uterine cavity and cervical diameter of teens and nulliparous women. Today we know that an IUD can be inserted safely in this population. Moreover, because adolescents are at high risk for unintended pregnancy, they stand to benefit uniquely from LARC options, including the IUD. As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends in a recent Committee Opinion on adolescents and LARCs, the IUD should be a “first-line” option for all women of reproductive age.6

Myth #2: An IUD should not be inserted immediately after childbirth

For many years, it was assumed that an IUD should be inserted in the postpartum period only after uterine involution was completed. However, in 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, which included the following recommendations for breastfeeding or non–breast-feeding women:

• Mirena was given a Level 2 recommendation (advantages outweigh risks) for insertion within 10 minutes after delivery of the placenta

• The copper IUD was given a Level 1 recommendation (no restrictions) for insertion within the same time interval

• From 10 minutes to 4 weeks postpartum, both devices have a Level 2 recommendation for insertion

• Beyond 4 weeks, both devices have a Level 1 recommendation for insertion.7

Immediate post-delivery insertion of an IUD has several benefits, including:

• a reduction in the risk of unintended pregnancy in women who are not breastfeeding

• providing new mothers with a LARC method.

Myth #3: Antibiotics and NSAIDs should be administered

This myth arose from concerns about PID and insertion-related pain. However, a Cochrane Database review found no benefit for prophylactic use of antibiotics prior to insertion of the copper or LNG-IUS devices to prevent PID.8

In fact, data indicate that the incidence of PID is low among women who are appropriate candidates for an IUD. Similarly, Allen and colleagues found that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) did not ameliorate symptoms of cramping during or immediately after insertion of an IUD.9

Myth #4: IUD insertion is difficult

In reality, both the copper IUD and Mirena are easy to insert. In addition, the smaller LNG-IUS (Skyla) comes more completely preloaded in its inserter. In a published Phase 2 trial comparing Mirena with two smaller, lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing devices, with the lowest-dose product corresponding to the marketed Skyla product, all 738 women given Mirena or the smaller devices experienced successful placement, with 98.5% of placements achieved on the first attempt.10

Various studies have been conducted to evaluate methods to ease insertion, including use of intracervical lidocaine, vaginal and/or oral administration of misoprostol (Cytotec), and vaginal estrogen creams. None was found to be effective in controlled trials. (See the sidebar, “Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion,” by Jennifer Gunter, MD, on page 28.) In the small percentage of women in whom it is difficult to pass a uterine sound through the external and internal os, cervical dilators may be beneficial. Gentle, progressive dilation can be accomplished easily with minimal discomfort to the patient, easing IUD insertion dramatically.

If a clinician does not insert IUDs on a frequent basis, it is prudent to look over the insertion procedure prior to the patient’s arrival. The procedure then can be reviewed with the patient as part of informed consent, which should be documented in the chart.

No steps in the recommended insertion procedure should be omitted, and charting should reflect each step:

1. Perform a bimanual exam

2. Document the appearance of the vagina and cervix

3. Use betadine or another cleansing solution on the cervical portio

4. Apply the tenaculum to the cervix (anterior lip if the uterus is anteverted, posterior lip if it is retroverted)

5. Sound the uterus to determine the optimal depth of IUD insertion. (The recommended uterine depth is 6 to 10 cm. A smaller uterus increases the likelihood of perforation, pain, and expulsion.)

6. Insert the IUD (and document the ease or difficulty of insertion)

7. Trim the string to an appropriate length

8. Assess the patient’s condition after insertion

9. Schedule a return visit in 4 weeks.

Related Article Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country Robert L. Barbieri, MD

Myth #5: Perforation is common

Uterine perforation occurs in approximately 1 in every 1,000 insertions.11 If perforation occurs with a copper IUD, remove the device to prevent the formation of intraperitoneal adhesions.12 The LNG-IUS devices do not produce this reaction, although most experts agree that they should be removed when a perforation occurs.13

Anecdotal evidence suggests that perforation may be more common among breastfeeding women, but this finding is far from definitive.

How to select an IUD for a patient: 3 case studies

CASE 1: Heavy bleeding and signs of endometriosis

Amelia, a 26-year-old nulliparous white woman, visits your office for routine examination and asks about her contraceptive options. She has no notable medical history. She has a body mass index (BMI) of 20.2 kg/m2 and exercises regularly. Menarche occurred at age 13. Her menstrual cycles are regular but are getting heavier; she now “soaks” a tampon every hour. She also complains that her cramps are more difficult to manage. She takes ibuprofen 600 mg every 6 hours during the days of heaviest bleeding and cramping, but that approach doesn’t seem to be effective lately. She is in a stable sexual relationship with her boyfriend of 2 years, now her fiancé. They have been using condoms consistently as contraception but don’t plan to start a family for a “few years.” Amelia reports that their sex life is good, although she has been experiencing pain with deep penetration for about 6 months.

Examination reveals a clear cervix and nontender uterus, although the uterus is retroverted. Palpation of the ovaries indicates that they are normal. Her main complaints: dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding.

What contraceptive would you suggest?

Amelia would be a good candidate for the LNG-IUS because she is in a stable relationship and wants to postpone pregnancy for several years. Although she has some symptoms suggestive of endometriosis (dyspareunia), they could be relieved by this method.14 Because thinning of the endometrial lining is an inherent mechanism of action of the LNG-IUS, this method could reduce her heavy bleeding.

She should be advised of the risks and benefits of the LNG-IUS, which can be inserted when she begins her next menstrual cycle.

CASE 2: Mother of two with no immediate desire for pregnancy

Tamika is a 19-year-old black woman (G2P2) who has arrived at your clinic for her 6-week postpartum visit. She is not breastfeeding. Her BMI is 25.7 kg/m2. She reports that her baby and 2-year-old are doing “OK” and says she does not want to get pregnant again anytime soon. She is in a relationship with the father of her baby and says he is “working a good job and taking care of me.” Her menstrual cycles have always been normal, with no cramping or heavy bleeding.

Examination reveals that her cervix is clear, her uterus is anteverted and nontender, and her ovaries appear to be normal.

Would this patient be a good candidate for a LARC?

Tamika is an excellent candidate for the copper IUD or LNG-IUS and should be educated about both methods. If she chooses an IUD, it can be inserted at the start of her next menstrual period.

These first two cases illustrate the importance of making no assumptions on the basis of general patient characteristics. Although Tamika may appear to be at greater risk for STI than Amelia, such “typecasting” may lead to inappropriate counseling.

Related Article Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene (and when you should not)

At the time of IUD insertion, both patients should be instructed to check for the IUD string periodically, and this recommendation should be documented in their charts.

CASE 3: Anovulatory patient with heavy periods

Mary, 25, is a nulliparous Hispanic woman who has been referred by her primary care provider. She has a BMI of 35.4 kg/m2 and has had menstrual problems since menarche at the age of 14. She reports that her periods are irregular and very heavy, with intermittent pelvic pain that she manages, with some success, with ibuprofen. She has never had a sexual relationship, but she has a boyfriend now and asks about her contraceptive options.

On examination, you discover that Mary has pubic hair distribution over her inner thigh, with primary escutcheon and acanthosis nigricans on the inner thigh. Her vulva is marked by multiple sebaceous cysts, and a speculum exam shows a large amount of estrogenic mucus and a clear cervix. Her uterus is anteverted and nontender. Her ovaries are palpable but may be enlarged, and transvaginal ultrasound reveals that they are cystic. Her diagnosis: hirsutism with probable polycystic ovary syndrome.

Would an IUD be appropriate?

Mary is not a good candidate for an IUD. Neither the copper IUD nor the LNG-IUS would suppress ovarian function sufficiently to reduce the growth of multiple follicles that occurs with polycystic ovary syndrome. She would benefit from a hormonal method (specifically, a combination oral contraceptive) to suppress follicular activity.

Time for a renaissance?

The IUD may be making a comeback. With the unintended pregnancy rate remaining consistently at about 50%, it is important that we offer our patients contraceptive methods that maximize efficacy, safety, and convenience. Today’s IUDs meet all these criteria.

Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion

Many patients worry about the potential for pain with IUD insertion—and this concern can dissuade them from choosing the IUD as a contraceptive. This is regrettable because the IUD has the highest satisfaction rating among reversible contraceptives, as well as the greatest efficacy.

How much pain can your patient expect? In one recent prospective study involving 40 women who received either 1.2% lidocaine or saline infused 3 minutes before IUD insertion, 33% of women reported a pain score of 5 or higher (on a scale of 0–10) at tenaculum placement. This finding means that two-thirds of women had a pain score of 4 or lower. In fact, 46% of women had a pain score of 2 or below.15 (The mean pain scores for insertion were similar with lidocaine and placebo [3.0 vs 3.7, respectively; P=.4]).

Pain reducing options

The evidence validates (or fails to disprove) the value of the following interventions to make insertion more comfortable for patients:

• Naproxen (550 mg) administration 40 minutes prior to insertion. One small study found it to be better than placebo.9

• Nonopioid pain medication. One small, randomized, double-blinded clinical trial found that tramadol was even more effective than naproxen at relieving insertion-related pain.16

• Injection of lidocaine into the cervix. Although this intervention is common, data supporting it are scarce. One small, high-quality study found no benefit, compared with placebo. However, if you have had success with this approach in the past, I would not discourage you from continuing to offer it, as a single small study is insufficient to disprove it.15 More data are needed.

• Keeping the patient calm. Anxiety increases the perception of pain. Studies have demonstrated that women who expect pain at insertion are more likely to experience it. Encourage the patient to breathe diaphragmatically, and remind her that she is likely to be very happy with her choice of the IUD.

Many other interventions don’t seem to be effective, although they may be offered frequently. Unproven methods include administration of NSAIDs other than naproxen, use of misoprostol (which can increase cramping), application of topical lidocaine to the cervix, and insertion during menses (although the LNG-IUS is inserted during the menstrual period to render it effective during the first month of use).

The studies described here come from the general population of reproductive-age women. If a patient has cervical scarring or a history of difficult or painful insertion, she may be more likely to experience pain, and these data may not apply to her.

—Jennifer Gunter, MD

Dr. Gunter is an ObGyn in San Francisco. She is the author of The Preemie Primer: A Complete Guide for Parents of Premature Babies—from Birth through the Toddler Years and Beyond (Da Capo Press, 2010). Dr. Gunter blogs at www.drjengunter.com, and you can find her on Twitter at @DrJenGunter. She is an OBG Management Contributing Editor.

Dr. Gunter reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. 2006 Pan EU study on female contraceptives [unpublished data]. Bayer Schering Pharma; 2007.

2. Moser WD, Martinex GM, Chandra A, Abma JC, Wilson SJ. Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States: 1982–2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; No. 350. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics. 2004;350:1–36.

3. Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007–2009. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(4):893–897.

4. Ortiz ME, Croxatto HB, Bardin CW. Mechanisms of action of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51(12 Suppl):S42–S51.

5. Barbosa I, Olsson SE, Odlind V, Goncalves T, Coutinho E. Ovarian function after seven years’ use of a levonorgestrel IUD. Adv Contracept. 1995;11(2):85–95.

6. Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion #539: Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):983–988.

7. CDC. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Early Release. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr59e0528.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2013.

8. Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF. Antibiotics for prevention with IUDs. Cochrane summaries. http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD001327/antibiotics-for-prevention-with-iuds. Published May 16, 2012. Accessed August 18, 2013.

9. Allen RH, Bartz D, Grimes DA, Hubacher D, O’Brien P. Interventions for pain with intrauterine device insertion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; (3):CD007373.

10. Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):616-622.e1-e3.

11. Grimes DA. Intrauterine devices (IUDs). In: Hatcher RA, ed. Contraceptive Technology. 19th ed. New York, New York: Ardent Media; 2007:117–143.

12. Hatcher RA. Contraceptive Technology. New York, New York: Ardent Media; 2011.

13. Adoni A, Ben C. The management of intrauterine devices following uterine perforation. Contraception. 1991;43(1):77.

14. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(7):1993–1998.

15. Nelson AL, Fong JK. Intrauterine infusion of lidocaine does not reduce pain scores during IUD insertion. Contraception. 2013;88(1):37–40.

16. Karabayirli S, Ayrim AA, Muslu B. Comparison of the analgesic effects of oral tramadol and naproxen sodium on pain relief during IUD insertion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(5):581–584.

1. 2006 Pan EU study on female contraceptives [unpublished data]. Bayer Schering Pharma; 2007.

2. Moser WD, Martinex GM, Chandra A, Abma JC, Wilson SJ. Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States: 1982–2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; No. 350. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics. 2004;350:1–36.

3. Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007–2009. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(4):893–897.

4. Ortiz ME, Croxatto HB, Bardin CW. Mechanisms of action of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51(12 Suppl):S42–S51.

5. Barbosa I, Olsson SE, Odlind V, Goncalves T, Coutinho E. Ovarian function after seven years’ use of a levonorgestrel IUD. Adv Contracept. 1995;11(2):85–95.

6. Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion #539: Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):983–988.

7. CDC. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Early Release. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr59e0528.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2013.

8. Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF. Antibiotics for prevention with IUDs. Cochrane summaries. http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD001327/antibiotics-for-prevention-with-iuds. Published May 16, 2012. Accessed August 18, 2013.

9. Allen RH, Bartz D, Grimes DA, Hubacher D, O’Brien P. Interventions for pain with intrauterine device insertion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; (3):CD007373.

10. Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):616-622.e1-e3.

11. Grimes DA. Intrauterine devices (IUDs). In: Hatcher RA, ed. Contraceptive Technology. 19th ed. New York, New York: Ardent Media; 2007:117–143.

12. Hatcher RA. Contraceptive Technology. New York, New York: Ardent Media; 2011.

13. Adoni A, Ben C. The management of intrauterine devices following uterine perforation. Contraception. 1991;43(1):77.

14. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(7):1993–1998.

15. Nelson AL, Fong JK. Intrauterine infusion of lidocaine does not reduce pain scores during IUD insertion. Contraception. 2013;88(1):37–40.

16. Karabayirli S, Ayrim AA, Muslu B. Comparison of the analgesic effects of oral tramadol and naproxen sodium on pain relief during IUD insertion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(5):581–584.

UPDATE ON TECHNOLOGY

The development of new medical technology continues at a brisk pace—and ObGyns and our patients often are the beneficiaries. Notable technological breakthroughs of the past include hormonal contraception, in vitro fertilization, the application of minimally invasive surgical devices and techniques to gynecologic procedures, and many other innovations.

The leaders in our specialty are innovators themselves, ever vigilant for developments that can help improve health and quality of life for our patients. Regrettably, however, many technologies spread widely before they are fully validated by published studies—or continue to be used long after a superior or less invasive intervention has come along. And many claims about new technology are based on marketing information rather than reliable data.

Another common occurrence in regard to published data: Findings in one well-defined sector of the population are extrapolated to all patients. Even clinicians who are careful about adopting new technology can overlook the fact that it was tested, and proven, in a subset of patients that may not be comparable to all their patients.

In this article, I offer two case studies that illustrate some of the challenges we face when it comes to applying scientific findings to our practice and assessing medical technologies. In both settings, the health of the patient should be our primary focus.

When it comes to technology, patient selection is key

CASE 1: Anovulatory patient requests endometrial ablation

A 34-year-old woman (G2P2) who is moderately obese (body mass index of 32 kg/m2) visits your office to request endometrial ablation to manage her irregular and heavy menses. She reached menarche at age 10, and her periods have been somewhat irregular ever since. She required ovarian stimulation with clomiphene citrate to achieve each of her pregnancies, and both children were delivered by cesarean section. She currently uses condoms for contraception but does not have a steady partner, and she desires no additional pregnancies.

The patient reports that her menses occur every 2 to 6 weeks, with flow lasting from 2 to 8 days. She is housebound for 2 days each cycle because of heavy flow and cramping. She takes no medications and has no other medical conditions.

On exam, she is centrally obese with a tender uterus that is 10- to 12-weeks’ size; no adnexal masses are palpable. All other findings are normal. A recent test for diabetes was negative, but her serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels are borderline elevated.

What intervention would you recommend to address the heavy bleeding?

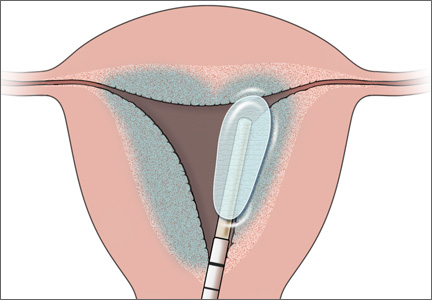

With the advent of second-generation endometrial ablation devices in the late 1990s, women with refractory menorrhagia had a safe, reliable, minimally invasive alternative to hysterectomy that made it possible to treat the endometrial cavity without the technical challenges of resectoscopic surgery. More than 10 million women report menorrhagia each year in the United States—so it is no small problem.1,2 Global endometrial ablation devices make management possible in an office setting, and recovery is significantly shorter than with hysterectomy. The three most prominent nonhysteroscopic ablation devices are (FIGURE):

• NovaSure (Hologic) uses bipolar radiofrequency energy to ablate tissue. Its probe contains stretchable gold-plated fabric that conforms to the endometrial surface.

• Gynecare Thermachoice (Ethicon) consists of an intrauterine balloon that is filled with hot liquid (temperatures of roughly 87°C) to ablate the endometrium

• Her Option (CooperSurgical) is a cryoablation system that consists of an intrauterine probe that forms an ice ball (temperatures of roughly –90°C) that destroys the uterine lining. Several applications are required to treat the majority of the cavity.

Use of these devices is widespread, although a nonsurgical alternative—the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; Mirena)—was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2009 for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Not only is the efficacy of the LNG-IUS for controlling menorrhagia equal to endometrial ablation, but it provides the additional benefits of reliable contraception and management of dysmenorrhea.

6 questions to ask before applying a technology

1. In which population was it studied?

One of the most important issues to consider when you are evaluating technology is the population in which it was studied. In other words, to whom do the findings apply?

Most endometrial ablation technologies were tested in women who had a uterus of normal size (mean, 8 cm) with no structural abnormalities (ie, no polyps or fibroids) and regular but very heavy periods. The findings from these studies now have been extrapolated in many cases to women who have hormonally induced abnormal bleeding, whose periods are irregular. That extrapolation may not be appropriate.

2. What is the diagnosis?

As the manufacturers of global endometrial ablation devices note, heavy menstrual bleeding may arise from an underlying condition, such as endometrial cancer, hormonal imbalance, fibroids, coagulopathy, and so on—and it is important to rule these conditions out before considering endometrial ablation.

For example, in Case 1, the patient is experiencing anovulatory cycles, as evidenced by her irregular menses and the need for ovulation induction to achieve her pregnancies. The success rate of endometrial ablation in the setting of chronic anovulation is unknown. Pivotal trials for all of the nonhysteroscopic endometrial ablation technologies required regular menses or failure of cyclic hormonal therapy prior to enrollment.

In addition, in Case 1, the patient has signs (an enlarged, tender uterus) that suggest the presence of adenomyosis. Endometrial ablation is not recommended as a treatment for women with this condition.

3. Will later surgery be required?

In one study from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, 21% of women who underwent endometrial ablation for menorrhagia later underwent hysterectomy, and 3.9% underwent other uterine-sparing procedures to alleviate heavy bleeding.3

In that study, women younger than age 45 were 2.1 times more likely to require hysterectomy after endometrial ablation, compared with older women (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.8–2.4). The likelihood of hysterectomy increased with each decreasing stratum of age and exceeded 40% in women aged 40 years or younger.3

In a population-based retrospective cohort study from Scotland, 2,779 (19.7%) of 11,299 women who underwent endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding required hysterectomy later.4 Again, women who required hysterectomy after endometrial ablation tended to be younger than those who did not. Overall, 26.6% of women undergoing endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding required further surgery.4

And in a 5-year follow-up of patients participating in a randomized trial of uterine balloon therapy versus rollerball ablation, roughly 30% of women required subsequent surgery for heavy menstrual bleeding.5

The need for subsequent surgery following endometrial ablation is likely to be higher among women who do not match the profile of participants in pivotal trials of the devices. All patients considering endometrial ablation should be counseled about the possible need for further surgery.

Related Article The economics of surgical gynecology: How we can not only survive, but thrive, in the 21st Century Barbara S. Levy, MD

4. What is the patient's overall health?

Before selecting an intervention for heavy menstrual bleeding, it is important to consider the patient’s overall health. What comorbidities does she have? Is pain a component of her condition? If so, might she have endometriosis or adenomyosis, as our patient does? If pain is a significant component of her menorrhagia, is it cyclical—that is, does it correspond to the days of heaviest flow? Pain related to the passage of large clots during menses may respond well to endometrial ablation. Pelvic pain occurring before and after the flow probably won’t.

Also keep in mind that the patient in Case 1 has two risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia: anovulatory cycles and obesity. If she undergoes endometrial ablation and subsequently experiences abnormal uterine bleeding, the most prominent sign of endometrial hyperplasia, how will you assess her endometrium 5 years after ablation if she develops abnormal bleeding? Will you be able to adequately sample it?

5. Have less invasive options been tried?

Many of the women studied in pivotal trials of second-generation endometrial ablation devices failed medical therapy prior to undergoing ablation. Because medical therapy is less expensive and noninvasive, it makes sense to offer it before proceeding to surgery. Common pharmacologic approaches include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), oral contraceptives, and tranexamic acid.

In addition, as I mentioned earlier, Mirena is approved for treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Medical therapy and Mirena should be offered prior to surgery because of their noninvasive, reversible nature. Most physicians now consider Mirena to be the first-line option for heavy menstrual bleeding in women who have normal anatomy.6

6. What is the cost of treatment?

With health-care expenses accelerating, we need to be mindful of the cost-effectiveness of the options we recommend.

Let’s assess the expense of managing the patient in Case 1. To address her desire for long-term contraception, we might offer tubal sterilization by laparoscopy followed by endometrial ablation (to address the heavy bleeding), which would require a general anesthetic and management in an ambulatory surgical facility.

If she opts for hysteroscopic sterilization prior to endometrial ablation, the sterilization procedure must be performed at least 3 months prior to ablation (according to FDA labeling) so that tubal occlusion can be demonstrated by hysterosalpingography (HSG) before the uterine cavity is scarred. This means that the patient would require two separate interventions. Although both procedures could be performed in an office setting, the patient would still require time away from work and family.

The cost for sterilization plus ablation in the office without anesthesia would be approximately $4,500 (including HSG) at Medicare rates. For a combined laparoscopic sterilization and endometrial ablation, costs would be higher because of the need for anesthesia and an ambulatory surgical facility. Another option that would address both the heavy bleeding and the need for contraception: oral contraceptives (OCs). The overall cost of this approach over 5 years would be $4,200 (60 months of OCs at $70/month), but it would be fully covered under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), so the patient would have no out-of-pocket expense. The cost of Mirena would be $1,000 ($850 for the device plus $150 for insertion), but it also would be fully covered under the ACA.

CASE 1: Resolved

You discuss the option of cyclic OCs with the patient. This approach would help control her irregular, heavy, and painful menses while providing good contraceptive coverage.

Although sterilization plus endometrial ablation is an option, you counsel the patient that the published “success” rates do not apply to her. Given her young age, obesity, and anovulatory status, endometrial ablation has a greater likelihood of failure. Further, when abnormal bleeding recurs, it may be difficult to assess this high-risk patient’s endometrium.

You also discuss Mirena, which would provide long-term contraception and also manage her menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea; indeed, it is FDA-approved for this indication. In fact, Mirena would address all of this patient’s concerns, offering superb contraception and reliable reductions in bleeding and pelvic pain in the setting of endometriosis and adenomyosis.

Overall, this woman is best served by a highly reliable approach that manages her contraceptive needs and her menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea while reducing her risk for endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. Given the long-term endometrial-sampling problems ablation would create, it is not an optimal solution for this woman.

What this evidence means for practice

When assessing technology, consider which patients it was tested in, your patient’s diagnosis and long-term health risks, the cost and success rate of the technology, and the availability of less invasive options.

How to assess new data on a technology or procedure

Gill SE, Mills BB. Physician opinions regarding elective bilateral salpingectomy with hysterectomy and for sterilization. JMIG. 2013;20(4):517–521.

CASE 2: A healthy patient seeks permanent contraception

At her annual well-woman visit, your 42-year-old patient (G3P3) asks to discuss permanent contraception now that she has completed her family. She has used OCs for more than 10 years without problems. She is a nonsmoker of normal weight (BMI of 22 kg/m2), with normal blood pressure and vital signs. Her family history is remarkable for the health of her parents and siblings: Her mother is 68 years old and well; her father, 70, also is healthy. There is no family history of breast or ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, or significant medical illness.

What options would you offer this patient? Given recent data suggesting that ovarian cancer may originate in the fallopian tubes, would you recommend prophylactic salpingectomy as her contraceptive method of choice?

This patient has many options. In describing them to her, it would be important to focus on the breadth of safe, reversible, long-acting contraceptives now available, including their respective risks, benefits, and long-term outcomes and costs. It also is important to consider the published data on these methods, weighing their relevance to her overall health and medical history. Although some data regarding the origin of ovarian cancer in the fallopian tubes may be especially compelling, it may not be wise to extrapolate it from a specific group of women to all patients, as we shall see.

Option 1: Cyclic OCs

This option should not be excluded, despite the need for daily dosing, because the patient has used it successfully for more than 10 years. OCs are highly effective and have the added benefits of reducing menstrual blood loss, alleviating cramps, and lowering the risks of endometrial and ovarian cancer.7

Option 2: LARC

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods include the LNG-IUS, the copper intrauterine device (IUD; ParaGard, Teva), and the etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon, Merck). Each of these contraceptives is similar to sterilization in terms of efficacy. None requires the interruption of sexual activity or weekly or monthly trips to the pharmacy.

The LNG-IUS and the etonogestrel implant have the added benefits of reducing menstrual blood loss and reducing or eliminating premenstrual symptoms and cramps in most women. In addition, they may reduce the risk of unopposed estrogen stimulation of the endometrium associated with perimenopausal anovulatory cycles.

Option 3: Transcervical tubal sterilization

This hysteroscopic method (Essure, Bayer) avoids the risks of general anesthesia, but successful bilateral placement may not be possible in a small percentage of women. It also requires a 3-month interval between placement and confirmation of tubal occlusion (via HSG). During this interval, alternative contraception must be used. Once occlusion is confirmed, this method is highly reliable.

Option 4: Laparoscopic sterilization

This approach was the method of choice prior to the introduction of Essure in 2002. There now is a resurgence of interest in laparoscopic sterilization due to recent publications describing the distal portion of the fallopian tube as the “true source” of high-grade serous ovarian cancers.

In pathologic analyses of fallopian tubes removed prophylactically from women with a BRCA 1 or 2 mutation, investigators found a significant rate of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma.8 Researchers began to study the genetics of these cancers and concluded that, in women with a BRCA mutation, high-grade serous carcinomas may arise from the distal fallopian tube.

Until recently, all of the literature on these tubal carcinomas related only to women with a specific tumor suppressor gene p53 mutation in the BRCA system. Other investigators then reviewed pathology specimens from women without a BRCA mutation who had high-grade serous carcinomas that were peritoneal, tubal, or ovarian in origin. They found serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas in 33% to 59% of these women.9

“Research suggests that bilateral salpingectomy during hysterectomy for benign indications or as a sterilization procedure may have benefits, such as preventing tubal disease and cancer, without significant risks,” wrote Gill and Mills.10 In conducting a survey of US physicians to determine how widespread prophylactic salpingectomy is during benign hysterectomy or sterilization, they found that 54% of respondents performed bilateral salpingectomy during hysterectomy, usually to lower the risk of cancer (75%) and avoid the need for reoperation (49.1%). Of the 45.5% of respondents who did not perform bilateral salpingectomy during hysterectomy, most (69.4%) believed it has no benefit.10

Although 58% of respondents believed bilateral salpingectomy to be the most effective option for sterilization in women older than 35 years, they reported that they reserve it for women in whom one sterilization procedure has failed or for women who have tubal disease.10

As for the 45.5% of respondents who did not perform prophylactic salpingectomy, they offered as reasons their concern about increased operative time and the risk of complications, as well as a belief that it has no benefit.10

The lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in the general population is 1 in 70 women. Although it is possible that high-grade serous ovarian cancers originate in the distal fallopian tube, as the research to date suggests, it also is possible that we might find in-situ lesions in tissues other than the distal tube, suggesting a more global genetic defect underlying ovarian cancers in the peritoneal and müllerian tissues. Randomized trials are under way in an effort to determine whether excision of the fallopian tubes will prevent the majority of high-grade serous cancers. It will be many years, however, before the results of these trials are available.

CASE 2: Resolved

This patient has used combination OCs for more than 10 years, so her lifetime risk of ovarian cancer has been reduced by approximately 50%. Because her family history indicates that a BRCA mutation is highly unlikely, her lifetime risk of ovarian cancer now has declined from 1:70 to roughly 1:140.

Prophylactic salpingectomy might offer a very small reduction in this patient’s absolute risk of ovarian cancer—from 0.75% to 0.50% lifetime risk—but the current data are not robust enough to suggest that it should be recommended for her. The operation would carry the risks associated with general anesthesia and peritoneal access. Although these risks are small, there is a documented risk of death from laparoscopic sterilization procedures in the United States, from complications related to bowel injury, anesthesia, and hemorrhage.

For these reasons, I would counsel this patient that her best options for contraception are combination OCs, transcervical tubal sterilization, or a long-acting reversible contraceptive such as the IUD or implant.

Tell us what you think, at [email protected]. Please include your name and city and state.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Blood disor-ders in women: heavy menstrual bleeding. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/blooddisorders/women/menorrhagia.html. Updated December 12, 2011. Accessed August 15, 2013.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Blood disorders in women: research. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/blooddis orders/women/research.html. Updated December 12, 2011. Accessed August 15, 2013.

3. Longinotti K, Jacobson GF, Hung YY, Learman LA. Probability of hysterectomy after endometrial ablation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1214–1220.

4. Cooper K, Lee AJ, Chien P, Raja EA, Timmaraju V, Bhattacharya S. Outcomes following hysterectomy or endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding: retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics in Scotland. BJOG. 2011;118(10):1171–1179.

5. Loffer FD, Grainger D. Five-year follow-up of patients participating in a randomized trial of uterine balloon therapy versus rollerball ablation for treatment of menorrhagia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9(4):429–435.