User login

Neurologic Injuries After Total Hip Arthroplasty

CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

A common thread ties together the studies and developments highlighted here: the notion that maladaptive changes in the neurologic supply to pelvic organs may contribute to chronic pain to a greater extent than do stimuli from damaged tissue. This understanding is consistent with the general lack of any obvious relationship between the degree (i.e., volume) of tissue change in disease (e.g., endometriosis) and the intensity of associated pain. It may also open new avenues to the prevention and treatment of chronic pain.

In the future, treatments for painful conditions seen in gynecology are likely to expand beyond nonsteroidal analgesics and narcotics to include

- neuromodulatory drugs

- local anesthetics applied in novel ways

- nerve-stimulation procedures that are less invasive than methods used so far.

Furthermore, the art of treatment will involve an understanding of the most effective ways to mix and sequence these methods.

Preoperative preemptive analgesia may reduce long-term incisional pain

Mathiesen O, Moiniche S, Dahl JB. Gabapentin and post-operative pain: a qualitative and quantitative systematic review, with focus on procedure. BMC Anesthesiol. 2007;7:6.

Fassoulaki A, Stamatakis E, Petropoulos G, Siafaka I, Hassiakos D, Sarantopoulos C. Gabapentin attenuates late but not acute pain after abdominal hysterectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006;23:136–141.

The study of preemptive analgesia over the past 20 or more years has focused almost exclusively on one goal: reducing immediate postoperative pain, usually with narcotic consumption as the primary outcome measure. Results have been mixed, with few studies showing clear and clinically meaningful benefit.

More recently, several studies have focused on what may be a more important longer-term clinical outcome measure: incisional pain long after surgery. Multiple studies document an incidence of 10% to 25% of patients reporting incisional pain long after their surgery.1 Thoracotomy, reconstructive breast procedures, and abdominal incisions have all been associated with this problem. The study by Fassoulaki and associates shows that one dose of gabapentin before abdominal hysterectomy was associated with less incisional pain a full month after surgery.

Implications for patients in chronic pain

Patients who suffer chronic pain and who undergo surgery require a higher dosage of narcotic analgesics during postoperative care than other patients might. This need is usually attributed to accelerated metabolism of the drugs, brought about by longstanding use before surgery. An alternative hypothesis that would unite these observations is that pain pathways in the central nervous system are activated when surgical trauma is inflicted and that they affect the intensity of pain after surgery. For example, if the spinal cord segments associated with the pelvic reproductive organs have been involved in conducting nociceptive (pain) signals for the months or years leading to surgery, superimposed stimulus of surgery may be less well tolerated.

This hypothesis gives rise to several tantalizing questions:

- Would preoperative medication with drugs used to treat neuropathic pain reduce both visceral and somatic components of postoperative pain?

- Would these medications, given early in the clinical course, help prevent the chronic pain associated with pelvic infection and endometriosis?

- Would this approach be an avenue to reduce long-term postoperative pain in women with chronic pain before surgery?

Observations from research into preemptive analgesia are providing the impetus for what promises to be a productive and exciting area of clinical research in the treatment of pain in a variety of clinical situations in gynecology.

In chronic pain, changes in innervation may extend to peripheral organs

Atwal G, du Plessis D, Armstrong G, Slade R, Quinn M. Uterine innervation after hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain with, and without, endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1650–1655.

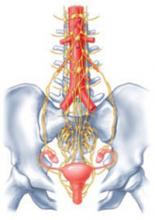

One widely accepted hypothesis is that chronic pain states are accompanied by changes in spinal cord neurophysiology at both neurochemical and neuroanatomic levels. Indeed, in animal models of chronic pain, neuronal connections are altered in the spinal cord such that touch and pressure excite true central pain fibers. New evidence suggests that changes in innervation associated with chronic pain may also affect peripheral organs (FIGURE).

For example, in the study by Atwal and associates, the uterus of women undergoing hysterectomy was stained for unmyelinated nerve fibers of the type commonly involved in visceral pain signals. Women undergoing surgery for painless conditions had a low density of pain fibers in the lower uterine segment compared with women who had chronic pain before surgery, who had a higher density of pain fibers. This was true for women who had otherwise normal pelvic anatomy, as well as for those who had endometriosis. These findings may explain the puzzling observation that hysterectomy relieves central pelvic pain in 78% of women undergoing the procedure (and improves pain in 22% of women with persistent pain) even when the uterus is histologically normal on routine pathologic examination.2

Perhaps even more intriguing is the notion that pelvic pain may ultimately be elucidated through the study of changes in neurologic systems rather than changes in gynecologic end organs themselves. If pain, initially triggered by alterations in end organs, becomes chronic and intractable by virtue of neurologic changes, this perspective may lead to entirely new approaches to preventing chronic pain.

Chronic pain may alter spinal cord neurophysiology

Under physiologic conditions, the nerves of the central nervous system guide the uterus and other organs through their respective functions. In some women, however, spinal cord neuronal circuitry becomes distorted, eliciting a pain response even when no trigger is present.

Less invasive nerve-stimulation method holds promise for pelvic pain

Nerve stimulation in a wide variety of forms has long been used to block nociceptive signals. Examples include sacral nerve root stimulators, spinal cord implants, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units. Their efficacy varies across pain syndromes, and the duration of impact (even in successfully treated women) is uncertain. The invasive nature of the implanted devices adds to the risk and often relegates them to the bottom of the list of treatment options.

Another method of peripheral nerve stimulation—posterior tibial nerve stimulation—was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of bladder irritability, and may also improve urge incontinence and pelvic pain.3,4 It involves application of electrical stimuli to a very fine (acupuncture-like) needle placed next to the posterior tibial nerve, just posterior to the medial maleolus. The nerve is generally stimulated for 30 minutes a week for a series of 12 treatments. Other protocols are bound to emerge as this method is applied more broadly.

In the case of irritability, bladder pain is also often relieved. The treatment is now being tried in women with interstitial cystitis. Even though the nerve supplies of the various pelvic and vulvar organs do not all arise from the same spinal cord segments, communications within the cord may explain the broader impact of techniques like posterior tibial nerve stimulation.

1. Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent post-surgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367:1618-1625.

2. Stovall TG, Ling FW, Crawford DA. Hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain of presumed uterine etiology. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:676-679.

3. Congregado RB, Pena OXM, Campoy MP, Leon DE, Leal LA. Peripheral afferent nerve stimulation for treatment of lower urinary tract irritative symptoms. Eur Urol. 2004;45:65-69.

4. van Balken MR, Vandoninck V, Messelink BJ, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation as neuromodulative treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol. 2003;43:158-163.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

A common thread ties together the studies and developments highlighted here: the notion that maladaptive changes in the neurologic supply to pelvic organs may contribute to chronic pain to a greater extent than do stimuli from damaged tissue. This understanding is consistent with the general lack of any obvious relationship between the degree (i.e., volume) of tissue change in disease (e.g., endometriosis) and the intensity of associated pain. It may also open new avenues to the prevention and treatment of chronic pain.

In the future, treatments for painful conditions seen in gynecology are likely to expand beyond nonsteroidal analgesics and narcotics to include

- neuromodulatory drugs

- local anesthetics applied in novel ways

- nerve-stimulation procedures that are less invasive than methods used so far.

Furthermore, the art of treatment will involve an understanding of the most effective ways to mix and sequence these methods.

Preoperative preemptive analgesia may reduce long-term incisional pain

Mathiesen O, Moiniche S, Dahl JB. Gabapentin and post-operative pain: a qualitative and quantitative systematic review, with focus on procedure. BMC Anesthesiol. 2007;7:6.

Fassoulaki A, Stamatakis E, Petropoulos G, Siafaka I, Hassiakos D, Sarantopoulos C. Gabapentin attenuates late but not acute pain after abdominal hysterectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006;23:136–141.

The study of preemptive analgesia over the past 20 or more years has focused almost exclusively on one goal: reducing immediate postoperative pain, usually with narcotic consumption as the primary outcome measure. Results have been mixed, with few studies showing clear and clinically meaningful benefit.

More recently, several studies have focused on what may be a more important longer-term clinical outcome measure: incisional pain long after surgery. Multiple studies document an incidence of 10% to 25% of patients reporting incisional pain long after their surgery.1 Thoracotomy, reconstructive breast procedures, and abdominal incisions have all been associated with this problem. The study by Fassoulaki and associates shows that one dose of gabapentin before abdominal hysterectomy was associated with less incisional pain a full month after surgery.

Implications for patients in chronic pain

Patients who suffer chronic pain and who undergo surgery require a higher dosage of narcotic analgesics during postoperative care than other patients might. This need is usually attributed to accelerated metabolism of the drugs, brought about by longstanding use before surgery. An alternative hypothesis that would unite these observations is that pain pathways in the central nervous system are activated when surgical trauma is inflicted and that they affect the intensity of pain after surgery. For example, if the spinal cord segments associated with the pelvic reproductive organs have been involved in conducting nociceptive (pain) signals for the months or years leading to surgery, superimposed stimulus of surgery may be less well tolerated.

This hypothesis gives rise to several tantalizing questions:

- Would preoperative medication with drugs used to treat neuropathic pain reduce both visceral and somatic components of postoperative pain?

- Would these medications, given early in the clinical course, help prevent the chronic pain associated with pelvic infection and endometriosis?

- Would this approach be an avenue to reduce long-term postoperative pain in women with chronic pain before surgery?

Observations from research into preemptive analgesia are providing the impetus for what promises to be a productive and exciting area of clinical research in the treatment of pain in a variety of clinical situations in gynecology.

In chronic pain, changes in innervation may extend to peripheral organs

Atwal G, du Plessis D, Armstrong G, Slade R, Quinn M. Uterine innervation after hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain with, and without, endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1650–1655.

One widely accepted hypothesis is that chronic pain states are accompanied by changes in spinal cord neurophysiology at both neurochemical and neuroanatomic levels. Indeed, in animal models of chronic pain, neuronal connections are altered in the spinal cord such that touch and pressure excite true central pain fibers. New evidence suggests that changes in innervation associated with chronic pain may also affect peripheral organs (FIGURE).

For example, in the study by Atwal and associates, the uterus of women undergoing hysterectomy was stained for unmyelinated nerve fibers of the type commonly involved in visceral pain signals. Women undergoing surgery for painless conditions had a low density of pain fibers in the lower uterine segment compared with women who had chronic pain before surgery, who had a higher density of pain fibers. This was true for women who had otherwise normal pelvic anatomy, as well as for those who had endometriosis. These findings may explain the puzzling observation that hysterectomy relieves central pelvic pain in 78% of women undergoing the procedure (and improves pain in 22% of women with persistent pain) even when the uterus is histologically normal on routine pathologic examination.2

Perhaps even more intriguing is the notion that pelvic pain may ultimately be elucidated through the study of changes in neurologic systems rather than changes in gynecologic end organs themselves. If pain, initially triggered by alterations in end organs, becomes chronic and intractable by virtue of neurologic changes, this perspective may lead to entirely new approaches to preventing chronic pain.

Chronic pain may alter spinal cord neurophysiology

Under physiologic conditions, the nerves of the central nervous system guide the uterus and other organs through their respective functions. In some women, however, spinal cord neuronal circuitry becomes distorted, eliciting a pain response even when no trigger is present.

Less invasive nerve-stimulation method holds promise for pelvic pain

Nerve stimulation in a wide variety of forms has long been used to block nociceptive signals. Examples include sacral nerve root stimulators, spinal cord implants, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units. Their efficacy varies across pain syndromes, and the duration of impact (even in successfully treated women) is uncertain. The invasive nature of the implanted devices adds to the risk and often relegates them to the bottom of the list of treatment options.

Another method of peripheral nerve stimulation—posterior tibial nerve stimulation—was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of bladder irritability, and may also improve urge incontinence and pelvic pain.3,4 It involves application of electrical stimuli to a very fine (acupuncture-like) needle placed next to the posterior tibial nerve, just posterior to the medial maleolus. The nerve is generally stimulated for 30 minutes a week for a series of 12 treatments. Other protocols are bound to emerge as this method is applied more broadly.

In the case of irritability, bladder pain is also often relieved. The treatment is now being tried in women with interstitial cystitis. Even though the nerve supplies of the various pelvic and vulvar organs do not all arise from the same spinal cord segments, communications within the cord may explain the broader impact of techniques like posterior tibial nerve stimulation.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

A common thread ties together the studies and developments highlighted here: the notion that maladaptive changes in the neurologic supply to pelvic organs may contribute to chronic pain to a greater extent than do stimuli from damaged tissue. This understanding is consistent with the general lack of any obvious relationship between the degree (i.e., volume) of tissue change in disease (e.g., endometriosis) and the intensity of associated pain. It may also open new avenues to the prevention and treatment of chronic pain.

In the future, treatments for painful conditions seen in gynecology are likely to expand beyond nonsteroidal analgesics and narcotics to include

- neuromodulatory drugs

- local anesthetics applied in novel ways

- nerve-stimulation procedures that are less invasive than methods used so far.

Furthermore, the art of treatment will involve an understanding of the most effective ways to mix and sequence these methods.

Preoperative preemptive analgesia may reduce long-term incisional pain

Mathiesen O, Moiniche S, Dahl JB. Gabapentin and post-operative pain: a qualitative and quantitative systematic review, with focus on procedure. BMC Anesthesiol. 2007;7:6.

Fassoulaki A, Stamatakis E, Petropoulos G, Siafaka I, Hassiakos D, Sarantopoulos C. Gabapentin attenuates late but not acute pain after abdominal hysterectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006;23:136–141.

The study of preemptive analgesia over the past 20 or more years has focused almost exclusively on one goal: reducing immediate postoperative pain, usually with narcotic consumption as the primary outcome measure. Results have been mixed, with few studies showing clear and clinically meaningful benefit.

More recently, several studies have focused on what may be a more important longer-term clinical outcome measure: incisional pain long after surgery. Multiple studies document an incidence of 10% to 25% of patients reporting incisional pain long after their surgery.1 Thoracotomy, reconstructive breast procedures, and abdominal incisions have all been associated with this problem. The study by Fassoulaki and associates shows that one dose of gabapentin before abdominal hysterectomy was associated with less incisional pain a full month after surgery.

Implications for patients in chronic pain

Patients who suffer chronic pain and who undergo surgery require a higher dosage of narcotic analgesics during postoperative care than other patients might. This need is usually attributed to accelerated metabolism of the drugs, brought about by longstanding use before surgery. An alternative hypothesis that would unite these observations is that pain pathways in the central nervous system are activated when surgical trauma is inflicted and that they affect the intensity of pain after surgery. For example, if the spinal cord segments associated with the pelvic reproductive organs have been involved in conducting nociceptive (pain) signals for the months or years leading to surgery, superimposed stimulus of surgery may be less well tolerated.

This hypothesis gives rise to several tantalizing questions:

- Would preoperative medication with drugs used to treat neuropathic pain reduce both visceral and somatic components of postoperative pain?

- Would these medications, given early in the clinical course, help prevent the chronic pain associated with pelvic infection and endometriosis?

- Would this approach be an avenue to reduce long-term postoperative pain in women with chronic pain before surgery?

Observations from research into preemptive analgesia are providing the impetus for what promises to be a productive and exciting area of clinical research in the treatment of pain in a variety of clinical situations in gynecology.

In chronic pain, changes in innervation may extend to peripheral organs

Atwal G, du Plessis D, Armstrong G, Slade R, Quinn M. Uterine innervation after hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain with, and without, endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1650–1655.

One widely accepted hypothesis is that chronic pain states are accompanied by changes in spinal cord neurophysiology at both neurochemical and neuroanatomic levels. Indeed, in animal models of chronic pain, neuronal connections are altered in the spinal cord such that touch and pressure excite true central pain fibers. New evidence suggests that changes in innervation associated with chronic pain may also affect peripheral organs (FIGURE).

For example, in the study by Atwal and associates, the uterus of women undergoing hysterectomy was stained for unmyelinated nerve fibers of the type commonly involved in visceral pain signals. Women undergoing surgery for painless conditions had a low density of pain fibers in the lower uterine segment compared with women who had chronic pain before surgery, who had a higher density of pain fibers. This was true for women who had otherwise normal pelvic anatomy, as well as for those who had endometriosis. These findings may explain the puzzling observation that hysterectomy relieves central pelvic pain in 78% of women undergoing the procedure (and improves pain in 22% of women with persistent pain) even when the uterus is histologically normal on routine pathologic examination.2

Perhaps even more intriguing is the notion that pelvic pain may ultimately be elucidated through the study of changes in neurologic systems rather than changes in gynecologic end organs themselves. If pain, initially triggered by alterations in end organs, becomes chronic and intractable by virtue of neurologic changes, this perspective may lead to entirely new approaches to preventing chronic pain.

Chronic pain may alter spinal cord neurophysiology

Under physiologic conditions, the nerves of the central nervous system guide the uterus and other organs through their respective functions. In some women, however, spinal cord neuronal circuitry becomes distorted, eliciting a pain response even when no trigger is present.

Less invasive nerve-stimulation method holds promise for pelvic pain

Nerve stimulation in a wide variety of forms has long been used to block nociceptive signals. Examples include sacral nerve root stimulators, spinal cord implants, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units. Their efficacy varies across pain syndromes, and the duration of impact (even in successfully treated women) is uncertain. The invasive nature of the implanted devices adds to the risk and often relegates them to the bottom of the list of treatment options.

Another method of peripheral nerve stimulation—posterior tibial nerve stimulation—was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of bladder irritability, and may also improve urge incontinence and pelvic pain.3,4 It involves application of electrical stimuli to a very fine (acupuncture-like) needle placed next to the posterior tibial nerve, just posterior to the medial maleolus. The nerve is generally stimulated for 30 minutes a week for a series of 12 treatments. Other protocols are bound to emerge as this method is applied more broadly.

In the case of irritability, bladder pain is also often relieved. The treatment is now being tried in women with interstitial cystitis. Even though the nerve supplies of the various pelvic and vulvar organs do not all arise from the same spinal cord segments, communications within the cord may explain the broader impact of techniques like posterior tibial nerve stimulation.

1. Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent post-surgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367:1618-1625.

2. Stovall TG, Ling FW, Crawford DA. Hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain of presumed uterine etiology. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:676-679.

3. Congregado RB, Pena OXM, Campoy MP, Leon DE, Leal LA. Peripheral afferent nerve stimulation for treatment of lower urinary tract irritative symptoms. Eur Urol. 2004;45:65-69.

4. van Balken MR, Vandoninck V, Messelink BJ, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation as neuromodulative treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol. 2003;43:158-163.

1. Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent post-surgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367:1618-1625.

2. Stovall TG, Ling FW, Crawford DA. Hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain of presumed uterine etiology. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:676-679.

3. Congregado RB, Pena OXM, Campoy MP, Leon DE, Leal LA. Peripheral afferent nerve stimulation for treatment of lower urinary tract irritative symptoms. Eur Urol. 2004;45:65-69.

4. van Balken MR, Vandoninck V, Messelink BJ, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation as neuromodulative treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol. 2003;43:158-163.

Managing preterm birth to lower the risk of cerebral palsy

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

- Intrapartum hypoxia, once considered an important cause of cerebral palsy (CP), is responsible for only 8% to 10% of cases.

- Increasingly, evidence suggests that the primary cause of CP lies in the relationship among intrauterine infection and inflammation, preterm labor, preterm premature rupture of membranes (pPROM), and neonatal white matter disease.

- This review focuses on that relationship and its implications for managing preterm birth with intact membranes or pPROM.

Cerebral palsy is a complex disease characterized by aberrant control of movement or posture that results from an insult to the developing central nervous system (CNS). In addition to motor abnormalities, some patients have seizures, cognitive impairment, and extrapyramidal abnormalities.

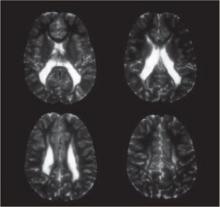

Clinical and epidemiologic evidence points to white matter lesions and severe intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH)—detected by neonatal neurosonography—as the key determinants of CP. The lesions are the sonographic antecedent or counterpart of periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), a cerebral lesion characterized by foci of necrosis in the white matter near the ventricles (FIGURE).

The principal risk factor is prematurity

A precise cause for CP has not been identified in more than 75% of cases. The leading identifiable risk factor is prematurity. The prevalence of CP at 3 years of age is 4.4% among infants born earlier than 27 weeks of gestation, compared with 0.06% among babies born at term.1

FIGURE Periventricular leukomalacia

Four axial magnetic resonance images of the brain of an infant show the usual appearance of this cerebral lesion, characterized by foci of necrosis of white matter near the ventricles.

How inflammation leads to premature birth

Any condition that increases the incidence of prematurity can be expected to increase the incidence of CP. More than 80% of premature births follow preterm labor or pPROM. Clinical and experimental evidence suggests that most of these births reflect one or more of four major pathogenic processes, which lead to uterine contractions and cervical changes, with or without premature rupture of membranes2:

- local or systemic inflammatory immune response

- activation of the maternal or fetal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

- decidual hemorrhage (abruption)

- pathologic distention of the uterus.

Two or more of these processes often occur simultaneously, ultimately converging on a final common biochemical pathway that leads to degradation of the extracellular matrix in the cervix and fetal membranes and activation of the uterine myometrium. This process leads in turn to cervical dilation, rupture of membranes, and uterine contractions.

The “inflammatory pathway” is activated in most cases of spontaneous preterm labor and pPROM. As many as 50% of women with preterm labor and intact membranes have histologic chorioamnionitis; the rate is even higher in pPROM. The incidence of chorioamnionitis increases with decreasing gestational age.

Invading microorganisms in gestational tissues often cause intrauterine inflammation and preterm birth. Highly sensitive molecular techniques detect bacteria in the amniotic fluid of as many as half of patients with preterm labor with intact membranes3 and even more women with pPROM. As with chorioamnionitis, the lower the gestational age, the higher the bacterial isolation rates—45% at 23 to 26 weeks compared with 17% at 27 to 30 weeks.4 The microorganisms isolated are often those colonizing the vagina—most commonly anaerobes, gram-negative rods, Gardnerella vaginalis, group B streptococci, Mycoplasma hominis, and Ureaplasma urealyticum.

Infection doesn’t always lead to inflammation

Bacterial products—particularly endotoxin, a major constituent of gram-negative bacteria—bind to a specific pattern-recognition receptor, known as a toll-like receptor, on cell surfaces. This activates innate immunity and stimulates a proinflammatory immune response. Endotoxin is a potent stimulant for proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which promote the release of chemoattractant cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8. Different white blood cells migrate into the inflamed tissue and become activated at the same time.

The uterine cavity is thought to be sterile, and microorganisms there are universally associated with inflammation. Recent studies challenge this assumption. One found bacteria in as many as 90% of endometrial samples from nonpregnant women, but histologic endometritis in only 40%.5 Another noted bacteria in as many as 80% of gestational tissues delivered electively by cesarean section at term or before 32 weeks because of preeclampsia, but histologic assessment showed no or minimal inflammation.6

Why don’t all women develop inflammation?

A critical question is why some pregnant women with microbial invasion of gestational tissues develop inflammation, whereas others do not. Susceptibility depends, in part, on the pathogenicity and amount of invading bacteria. Endotoxin-containing gram-negative bacteria elicit an especially potent inflammatory response. The strength of the response correlates with the amount of endotoxin-containing bacteria in the environment.7

The isolation rate of bacteria from the intrauterine cavity is higher in women with bacterial vaginosis (BV), a condition characterized by malodorous vaginal discharge, vaginal pH higher than 4.5, and a shift from a Lactobacilli-dominant vaginal flora toward predominance of G vaginalis, anaerobic bacteria, and M hominis. The greater number of bacteria may account, in part, for a twofold greater risk of preterm delivery among women diagnosed with BV during pregnancy.8

Genetics may also play a role. Intrauterine inflammation and morbidity are partly influenced by common variations (polymorphisms) in immunoregulatory genes. Preliminary evidence suggests that some women who carry a variant of the TNF-α gene can mount an exaggerated immune response to BV-related organisms (hyper-responders),9 increasing their risk of preterm delivery.10

Inflammation alone is a risk factor for CP

Growing evidence suggests that intrauterine inflammation increases the risk of neonatal white matter disease and subsequent development of CP beyond the risk conferred by gestational age at birth. The relative risk (RR) for CP in preterm infants born after intrauterine infection and inflammation or inflammation alone is 1.9 and 1.6, respectively.11

The association between inflammation, neonatal white matter disease, and CP is strongest in fetuses with funisitis and a plasma IL-6 level greater than 11 ng/mL12—a condition known as fetal inflammatory response syndrome (FIRS). FIRS is also associated with other sequelae of prematurity, including bronchopulmonary dysplasia, respiratory distress syndrome, and myocardial dysfunction.

Can we diagnose subacute inflammation and infection?

Diagnosing and treating intrauterine inflammation promptly may decrease the risk of CP. No single sign, symptom, or test accurately predicts intrauterine infection and inflammation in the pregnant patient. Maternal signs and symptoms such as fundal tenderness, tachycardia, and fever, along with laboratory findings such as an elevated C-reactive protein level and an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count in peripheral blood, indicate overt chorioamnionitis and systemic maternal infection. However, these tests are not especially useful for diagnosing subacute intrauterine infection and inflammation in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes or pPROM. Some authorities advocate amniocentesis for these patients.

- Prematurity is the leading risk factor for cerebral palsy (CP)

- Subacute intrauterine infection and inflammation are common causes of preterm delivery

- Intrauterine inflammation may lower the threshold at which hypoxia becomes neurotoxic in the fetus

- No single sign, symptom, or test accurately predicts intrauterine infection and inflammation in the pregnant patient

- A biophysical profile (BPP) score of 7 or lower predicts infection-related neonatal outcomes better than any single component of the BPP

- In a pregnancy complicated by pPROM, adjunctive antibiotics prolong pregnancy for as long as 10 days, but do not affect neonatal neurologic outcome

- Adjunctive antibiotics have no proven benefit in managing preterm labor with intact membranes

- Screening for and treating bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy are not useful

- Prophylactic antibiotic treatment during the periconceptional period has no proven benefit

- A single course of antenatal steroids in preterm labor with intact membranes or pPROM significantly decreases neonatal mortality and neurologic morbidity without raising the risk of neonatal sepsis—even in the presence of intrauterine infection

- Tocolysis with magnesium sulfate or a calcium-channel blocker to stop preterm labor with intact membranes may decrease neurologic morbidity in neonates

- Consider delivery after 32 weeks if fetal lung maturity is confirmed because 1) expectant management of pPROM beyond 32 completed weeks of gestation does not have a clear benefit and 2) intrauterine inflammation associated with white matter disease is common in pPROM

A positive bacterial culture or gram-stained slide of amniotic fluid confirms intra-amniotic infection but detects fewer than 50% of cases. Other diagnostic criteria, such as an elevated WBC count, high level of lactate dehydrogenase activity, high protein level, and low glucose concentration in amniotic fluid, are more sensitive, but nonspecific, for amniotic infection and inflammation.

Elevated inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 in amniotic fluid and fetal blood have been associated with intrauterine inflammation and neonatal white matter disease in women with preterm labor and intact membranes or pPROM, but they are not significantly more accurate than the previously mentioned biomarkers.13,14 An amniotic fluid pocket may not be accessible by the abdominal approach in most patients with pPROM because of significant oligohydramnios. Testing amniotic fluid from the vagina is an alternative. Low glucose in vaginal samples is a specific, but not a sensitive, marker for intra-amniotic infection.15

Using the BPP. The biophysical profile has been used to identify fetuses at risk of FIRS in the presence of pPROM. Oligohydramnios—especially when the largest vertical amniotic fluid pocket is smaller than 1 cm—and diminished fetal breathing and body movement are associated with chorioamnionitis and suspected or proven neonatal sepsis. A nonreactive nonstress test is specific but not sensitive.

Although each component of the BPP provides useful information, a BPP score of 7 or lower predicts infection-related outcome much better than any single finding. In a population with an infection-related outcome of 30%, a BPP score of 7 or lower within 24 hours of delivery had a positive predictive value of 95% and a negative predictive value of 97%.16 A retrospective case-control study found that women who were followed with daily BPP and delivered within 24 hours after a BPP score of 7 or lower on two examinations 2 hours apart had a lower rate of neonatal sepsis than women who were managed expectantly or had a single amniocentesis on admission to the hospital.17

How management tactics affect neurologic outcome

Options for women in preterm labor with intact membranes or pPROM include antibiotics, antenatal steroids, tocolytics, or early delivery.

Antibiotics in cases of pPROM only

The findings of two large clinical trials powerful enough to evaluate adjunctive antibiotics in women with pPROM are in agreement: Such treatment prolongs the pregnancy briefly (as long as 10 days).18,19

NICHD-MFMU study. In a trial conducted by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units (NICHD-MFMU) Research Network, 48 hours of intravenous therapy with ampicillin and erythromycin followed by 5 days of oral amoxicillin and enteric-coated erythromycin given to 614 women between 24 and 32 weeks’ gestation decreased the number of infants who died or suffered a major morbidity, including respiratory distress syndrome, early sepsis, severe IVH, or severe necrotizing enterocolitis.18

ORACLE I. The results of the larger ORACLE I trial, which included 4,826 women, were less impressive.19 Patients who developed pPROM before 37 weeks’ gestation received erythromycin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, or both, or placebo for up to 10 days. Although antibiotic therapy prolonged pregnancy briefly, it did not have a major impact on neonatal mortality or any major morbidity, including cerebral abnormality on ultrasonography (US). In contrast to the NICHD-MFMU Research Network study, treatment with oral amoxicillin-clavulanic acid increased the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis.

ORACLE II. The ORACLE II trial evaluated the benefit of adjunctive antibiotics for 6,295 women in spontaneous preterm labor before 37 weeks’ gestation who had intact membranes and no evidence of clinical infection.20 The women received erythromycin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, or both, or placebo for as long as 10 days. Compared with placebo, none of the antibiotics was associated with a lower rate of the composite primary outcome, which included major cerebral abnormality on US before discharge from the hospital.

Prophylaxis. It has been suggested that antibiotics are more likely to prevent preterm birth if they are given long before contractions start or membranes rupture. Studies of antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent preterm birth and related sequelae don’t support this notion. A Cochrane meta-analysis of six randomized clinical trials involving 2,184 asymptomatic women who received prophylactic antibiotics in the second or third trimester found no reduction in the risk of subsequent preterm birth.21 In fact, intervention increased the risk of neonatal sepsis (odds ratio [OR]=8.07, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.36 to 47.77). Another meta-analysis of the effect of antibiotics on BV during pregnancy drew similar conclusions.22 This analysis of 15 randomized clinical trials with a total of 5,888 patients showed that treating BV did not reduce the risk of preterm birth. The trials reported very few perinatal deaths, and none reported substantive neonatal morbidity.

Another hypothesis argues that the events leading to preterm birth begin in very early stages of pregnancy, including conception and implantation of the embryo. To test this hypothesis, 241 women with a history of spontaneous preterm birth or pPROM between 16 and 34 weeks’ gestation were randomized to receive an oral course of azithromycin and metronidazole or placebo every 4 months until conception.23 The 124 women who conceived and were available for follow-up showed no difference in the rate of preterm birth between the treatment and placebo groups. In fact, women who received an antibiotic tended to have a shorter pregnancy and a lower-birth-weight baby than those given placebo.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the role of inflammation in neonatal white matter disease. Microorganisms and microbial products can gain access to the fetus and activate inflammatory cytokines, increasing the permeability of the blood–brain barrier and facilitating passage of the cytokines into the brain.

Microbial products stimulate human fetal microglia (the central nervous system [CNS] equivalent of macrophages) to produce interleukin (IL)-1 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which, in turn, stimulate proliferation of astrocytes (the CNS equivalent of fibroblasts) and production of TNF. Leviton proposed that TNF-α can damage white matter by four mechanisms:33

- inducing hypotension and brain ischemia

- stimulating the production of a tissue factor, which can activate the hemostatic system and contribute to coagulation necrosis of white matter

- inducing the release of platelet-activating factor, which can act as a membrane detergent, causing direct brain damage

- producing a direct cytotoxic effect on oligodendrocytes.

Polymorphisms in immunomodulatory genes, such as the gene encoding TNF-α, modify the immune response and the risk for white matter disease in preterm infants.34

Based on available data, treatment with a short course of antibiotics such as erythromycin or ampicillin, or both, is recommended only in cases of pPROM.

Antenatal steroids improve outcome

Antenatal steroids reduce neonatal mortality and morbidity, including IVH and PVL, in infants born between 24 and 34 weeks’ gestation. One concern raised about antenatal steroid use is whether it increases the risk of neonatal infection and morbidity when intrauterine infection and inflammation are present. A retrospective analysis of infants who weighed 1,750 g or more at birth concluded that antenatal steroids significantly decreased neonatal mortality and morbidity—including IVH, PVL, and major brain lesions—without increasing neonatal sepsis in babies delivered following preterm labor or pPROM.24

In another retrospective analysis of 457 consecutive 23- to 32-week live-born singletons, antenatal steroids weren’t associated with significant worsening of any neonatal outcome. Steroids were associated with significant reductions in respiratory distress syndrome and neonatal systemic inflammatory response syndrome in infants with positive placental cultures and elevated cord blood IL-6 levels.25

These data suggest that antenatal steroids may not be contraindicated in the face of inflammation and infection; they may, in fact, be beneficial. In women with pPROM, weekly administration of ante-natal steroids doesn’t seem to improve neonatal outcomes more than single-course therapy and may increase the risk of chorioamnionitis.26

Some tocolytics may help

Tocolytic agents are often given to women with preterm contractions to delay delivery long enough to administer a course of antenatal corticosteroids.

Magnesium sulfate is commonly used in the United States. A 2007 Cochrane meta-analysis of four trials (3,701 babies) found that antenatal magnesium sulfate had no statistically significant effect on any major pediatric outcome, including death and neurologic problems such as CP in the first few years of life.27 Nor did antenatal magnesium therapy significantly affect combined rates of mortality and neurologic outcomes. Two trials involving 2,848 infants found a significant reduction in substantial gross motor dysfunction (RR=0.56; 95% CI, 0.33 to 0.97).

Betamimetics are also widely used for tocolysis, especially in resource-poor countries. Eleven randomized controlled trials, involving 1,332 women, compared betamimetics with placebo.28 Although betamimetics decreased the number of women in preterm labor who gave birth within 48 hours, they didn’t reduce perinatal or neonatal death. Data on CP were too sparse to allow comment. Because these drugs cause many maternal side effects, they aren’t considered first-line tocolytics.

Calcium-channel blockers are attracting growing interest as potentially effective and well-tolerated tocolytic agents. A meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials involving 1,029 women suggests that calcium-channel blockers reduce the number of women giving birth within 7 days of receiving treatment, compared with other tocolytic agents (mainly betamimetics).29 They also decrease the frequency of neonatal morbidity, including IVH (RR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.36 to 0.98).

Cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors are easy to administer and cause fewer maternal side effects than conventional tocolytics. A 2005 Cochrane meta-analysis includes outcome data from 13 trials with a total of 713 women.30 Indomethacin, a non-selective COX inhibitor, was used in 10 trials. COX inhibition reduced birth before 37 weeks’ gestation more effectively than other tocolytic agents, but data were insufficient to comment on neonatal outcomes.

In women with pPROM, starting tocolysis before onset of contractions prolongs latency. However, the utility of tocolytic therapy after pPROM remains controversial pending more powerful randomized trials.

Early delivery is an option

It has been suggested that exposure to infection, especially proinflammatory cytokines, reduces the threshold at which hypoxia becomes neurotoxic, making the brain much more vulnerable to even mild hypoxic insults. A recent study found that infants with encephalopathy were more than 90 times more likely to have experienced both neonatal intrapartum acidosis and maternal intrapartum fever than infants with no encephalopathy; maternal fever or neonatal acidosis increased the risk six- and 12-fold, respectively.31 Lack of interaction between maternal fever and acidosis suggests that these are separate causal pathways to adverse neonatal outcomes. Although intrapartum fever doesn’t always correlate with intrauterine inflammation, the findings of this study suggest that fetal acidosis should be avoided when intrauterine infection and inflammation are suspected.

Conservative management of pPROM remote from term has been shown to prolong pregnancy significantly and reduce complications in the infant when prophylactic antibiotics and ante-natal steroids are given concurrently. The benefit of this strategy is less clear after 32 weeks of gestation because:

- The efficacy of antenatal steroids after 32 weeks is unclear

- Beyond 32 weeks, the risk of severe complications of prematurity, including CP, is low if fetal lung maturity has been established by amniotic fluid samples collected vaginally or by amniocentesis.

For these reasons and because sub-acute intrauterine inflammation may harm the fetus, delivery can be considered after 32 completed weeks of gestation if fetal lung maturity is confirmed. A meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials that compared intentional delivery with expectant management after pPROM between 30 and 36 weeks of gestation found no difference in neonatal outcomes.32

1. Cummins SK, Nelson KB, Grether JK, Velie EM. Cerebral palsy in four northern California counties, births 1983 through 1985. J Pediatr. 1993;123:230-237.

2. Lockwood CJ, Kuczynski E. Risk stratification and pathological mechanisms in preterm delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15 Suppl 2:78-89.

3. Gardella C, Riley DE, Hitti J, Agnew K, Krieger JN, Eschenbach D. Identification and sequencing of bacterial rDNAs in culture-negative amniotic fluid from women in premature labor. Am J Perinatol. 2004;21:319-323.

4. Watts DH, Krohn MA, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA. The association of occult amniotic fluid infection with gestational age and neonatal outcome among women in preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:351-357.

5. Andrews WW, Hauth JC, Cliver SP, Conner MG, Goldenberg RL, Goepfert AR. Association of asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis with endometrial microbial colonization and plasma cell endometritis in nonpregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1611-1616.

6. Steele JH, Malatos S, Kennea N, et al. Bacteria and inflammatory cells in fetal membranes do not always cause preterm labor. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:404-411.

7. Genc MR, Witkin SS, Delaney ML, et al. A disproportionate increase in IL-1beta over IL-1ra in cervicovaginal secretions of pregnant women with vaginal microflora correlates with preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1191-1197.

8. Leitich H, Bodner-Adler B, Brunbauer M, Kaider A, Egarter C, Husslein P. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for preterm delivery: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:139-147.

9. Genc MR, Vardhana S, Delaney ML, Witkin SS, Onderdonk AB. MAP Study Group. TNFA-308G>A polymorphism influences the TNF-alpha response to altered vaginal flora. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;134:188-191.

10. Macones GA, Parry S, Elkousy M, et al. A polymorphism in the promoter region of TNF and bacterial vaginosis: preliminary evidence of gene-environment interaction in the etiology of spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1504-1508.

11. Wu YW, Colford JM. Chorioamnionitis as a risk factor for cerebral palsy: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;284:1417-1424.

12. Gomez R, Romero R, Ghezzi F, Yoon BH, Mazor M, Berry SM. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:194-202.

13. Romero R, Yoon BH, Mazor M, et al. A comparative study of the diagnostic performance of amniotic fluid glucose, white blood cell count, interleukin-6, and gram stain in the detection of microbial invasion in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:839-851.

14. Romero R, Yoon BH, Mazor M, et al. The diagnostic and prognostic value of amniotic fluid white blood cell count, glucose, interleukin-6, and gram stain in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:805-816.

15. Buhimschi CS, Sfakianaki AK, Hamar BG, et al. A low vaginal “pool” amniotic fluid glucose measurement is a predictive but not a sensitive marker for infection in women with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:309-316.

16. Vintzileos AM, Campbell WA, Nochimson DJ, Connolly ME, Fuenfer MM, Hoehn GJ. The fetal biophysical profile in patients with premature rupture of the membranes—an early predictor of fetal infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;152:510-516.

17. Vintzileos AM, Bors-Koefoed R, Pelegano JF, et al. The use of fetal biophysical profile improves pregnancy outcome in premature rupture of the membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:236-240.

18. Mercer BM, Miodovnik M, Thurnau GR, et al. Antibiotic therapy for reduction of infant morbidity after preterm premature rupture of the membranes. A randomized controlled trial. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. JAMA. 1997;278:989-995.

19. Kenyon SL, Taylor DJ, Tarnow-Mordi W. ORACLE Collaborative Group. Broad-spectrum antibiotics for preterm, prelabour rupture of fetal membranes: the ORACLE I randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:979-988.

20. Kenyon SL, Taylor DJ, Tarnow-Mordi W. ORACLE Collaborative Group. Broad-spectrum antibiotics for spontaneous preterm labour: the ORACLE II randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:989-994.

21. Thinkhamrop J, Hofmeyr GJ, Adetoro O, Lumbiganon P. Prophylactic antibiotic administration in pregnancy to prevent infectious morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(4):CD002250.-

22. McDonald H, Brocklehurst P, Parsons J. Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD000262.-

23. Andrews WW, Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Cliver SP, Copper R, Conner M. Interconceptional antibiotics to prevent spontaneous preterm birth: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:617-623.

24. Elimian A, Verma U, Canterino J, Shah J, Visintainer P, Tejani N. Effectiveness of antenatal steroids in obstetric subgroups. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:174-179.

25. Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW, Faye-Petersen OM, Cliver SP, Goepfert AR, Hauth JC. The Alabama preterm birth study: corticosteroids and neonatal outcomes in 23- to 32-week newborns with various markers of intrauterine infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1020-1024.

26. Ghidini A, Salafia CM, Minior VK. Repeated courses of steroids in preterm membrane rupture do not increase the risk of histologic chorioamnionitis. Am J Perinatol. 1997;14:309-313.

27. Doyle LW, Crowther CA, Middleton P, Marret S. Magnesium sulphate for women at risk of preterm birth for neuroprotection of the fetus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD004661.-

28. Anotayanonth S, Subhedar NV, Garner P, Neilson JP, Harigopal S. Betamimetics for inhibiting preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(8):CD004352.-

29. King JF, Flenady VJ, Papatsonis DN, Carbonne B. Calcium channel blockers for inhibiting preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD002255.-

30. King J, Flenady V, Cole S, Thornton S. Cyclo-oxygen-ase (COX) inhibitors for treating preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001992.-

31. Impey LW, Greenwood CE, Black RS, Yeh PS, Sheil O, Doyle P. The relationship between intrapartum maternal fever and neonatal acidosis as risk factors for neonatal encephalopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:49-51.

32. Hartling L, Chari R, Friesen C, Vandermeer B, Lacaze-Masmonteil T. A systematic review of intentional delivery in women with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:177-187.

33. Leviton A. Preterm birth and cerebral palsy: is tumor necrosis factor the missing link?. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1993;35:553-558.

34. Gibson CS, MacLennan AH, Goldwater PN, Haan EA, Priest K, Dekker GA. South Australian Cerebral Palsy Research Group. The association between inherited cytokine polymorphisms and cerebral palsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:674.e1-11.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

- Intrapartum hypoxia, once considered an important cause of cerebral palsy (CP), is responsible for only 8% to 10% of cases.

- Increasingly, evidence suggests that the primary cause of CP lies in the relationship among intrauterine infection and inflammation, preterm labor, preterm premature rupture of membranes (pPROM), and neonatal white matter disease.

- This review focuses on that relationship and its implications for managing preterm birth with intact membranes or pPROM.

Cerebral palsy is a complex disease characterized by aberrant control of movement or posture that results from an insult to the developing central nervous system (CNS). In addition to motor abnormalities, some patients have seizures, cognitive impairment, and extrapyramidal abnormalities.

Clinical and epidemiologic evidence points to white matter lesions and severe intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH)—detected by neonatal neurosonography—as the key determinants of CP. The lesions are the sonographic antecedent or counterpart of periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), a cerebral lesion characterized by foci of necrosis in the white matter near the ventricles (FIGURE).

The principal risk factor is prematurity

A precise cause for CP has not been identified in more than 75% of cases. The leading identifiable risk factor is prematurity. The prevalence of CP at 3 years of age is 4.4% among infants born earlier than 27 weeks of gestation, compared with 0.06% among babies born at term.1

FIGURE Periventricular leukomalacia

Four axial magnetic resonance images of the brain of an infant show the usual appearance of this cerebral lesion, characterized by foci of necrosis of white matter near the ventricles.

How inflammation leads to premature birth

Any condition that increases the incidence of prematurity can be expected to increase the incidence of CP. More than 80% of premature births follow preterm labor or pPROM. Clinical and experimental evidence suggests that most of these births reflect one or more of four major pathogenic processes, which lead to uterine contractions and cervical changes, with or without premature rupture of membranes2:

- local or systemic inflammatory immune response

- activation of the maternal or fetal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

- decidual hemorrhage (abruption)

- pathologic distention of the uterus.

Two or more of these processes often occur simultaneously, ultimately converging on a final common biochemical pathway that leads to degradation of the extracellular matrix in the cervix and fetal membranes and activation of the uterine myometrium. This process leads in turn to cervical dilation, rupture of membranes, and uterine contractions.

The “inflammatory pathway” is activated in most cases of spontaneous preterm labor and pPROM. As many as 50% of women with preterm labor and intact membranes have histologic chorioamnionitis; the rate is even higher in pPROM. The incidence of chorioamnionitis increases with decreasing gestational age.

Invading microorganisms in gestational tissues often cause intrauterine inflammation and preterm birth. Highly sensitive molecular techniques detect bacteria in the amniotic fluid of as many as half of patients with preterm labor with intact membranes3 and even more women with pPROM. As with chorioamnionitis, the lower the gestational age, the higher the bacterial isolation rates—45% at 23 to 26 weeks compared with 17% at 27 to 30 weeks.4 The microorganisms isolated are often those colonizing the vagina—most commonly anaerobes, gram-negative rods, Gardnerella vaginalis, group B streptococci, Mycoplasma hominis, and Ureaplasma urealyticum.

Infection doesn’t always lead to inflammation

Bacterial products—particularly endotoxin, a major constituent of gram-negative bacteria—bind to a specific pattern-recognition receptor, known as a toll-like receptor, on cell surfaces. This activates innate immunity and stimulates a proinflammatory immune response. Endotoxin is a potent stimulant for proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which promote the release of chemoattractant cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8. Different white blood cells migrate into the inflamed tissue and become activated at the same time.

The uterine cavity is thought to be sterile, and microorganisms there are universally associated with inflammation. Recent studies challenge this assumption. One found bacteria in as many as 90% of endometrial samples from nonpregnant women, but histologic endometritis in only 40%.5 Another noted bacteria in as many as 80% of gestational tissues delivered electively by cesarean section at term or before 32 weeks because of preeclampsia, but histologic assessment showed no or minimal inflammation.6

Why don’t all women develop inflammation?

A critical question is why some pregnant women with microbial invasion of gestational tissues develop inflammation, whereas others do not. Susceptibility depends, in part, on the pathogenicity and amount of invading bacteria. Endotoxin-containing gram-negative bacteria elicit an especially potent inflammatory response. The strength of the response correlates with the amount of endotoxin-containing bacteria in the environment.7

The isolation rate of bacteria from the intrauterine cavity is higher in women with bacterial vaginosis (BV), a condition characterized by malodorous vaginal discharge, vaginal pH higher than 4.5, and a shift from a Lactobacilli-dominant vaginal flora toward predominance of G vaginalis, anaerobic bacteria, and M hominis. The greater number of bacteria may account, in part, for a twofold greater risk of preterm delivery among women diagnosed with BV during pregnancy.8

Genetics may also play a role. Intrauterine inflammation and morbidity are partly influenced by common variations (polymorphisms) in immunoregulatory genes. Preliminary evidence suggests that some women who carry a variant of the TNF-α gene can mount an exaggerated immune response to BV-related organisms (hyper-responders),9 increasing their risk of preterm delivery.10

Inflammation alone is a risk factor for CP

Growing evidence suggests that intrauterine inflammation increases the risk of neonatal white matter disease and subsequent development of CP beyond the risk conferred by gestational age at birth. The relative risk (RR) for CP in preterm infants born after intrauterine infection and inflammation or inflammation alone is 1.9 and 1.6, respectively.11

The association between inflammation, neonatal white matter disease, and CP is strongest in fetuses with funisitis and a plasma IL-6 level greater than 11 ng/mL12—a condition known as fetal inflammatory response syndrome (FIRS). FIRS is also associated with other sequelae of prematurity, including bronchopulmonary dysplasia, respiratory distress syndrome, and myocardial dysfunction.

Can we diagnose subacute inflammation and infection?

Diagnosing and treating intrauterine inflammation promptly may decrease the risk of CP. No single sign, symptom, or test accurately predicts intrauterine infection and inflammation in the pregnant patient. Maternal signs and symptoms such as fundal tenderness, tachycardia, and fever, along with laboratory findings such as an elevated C-reactive protein level and an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count in peripheral blood, indicate overt chorioamnionitis and systemic maternal infection. However, these tests are not especially useful for diagnosing subacute intrauterine infection and inflammation in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes or pPROM. Some authorities advocate amniocentesis for these patients.

- Prematurity is the leading risk factor for cerebral palsy (CP)

- Subacute intrauterine infection and inflammation are common causes of preterm delivery

- Intrauterine inflammation may lower the threshold at which hypoxia becomes neurotoxic in the fetus

- No single sign, symptom, or test accurately predicts intrauterine infection and inflammation in the pregnant patient

- A biophysical profile (BPP) score of 7 or lower predicts infection-related neonatal outcomes better than any single component of the BPP

- In a pregnancy complicated by pPROM, adjunctive antibiotics prolong pregnancy for as long as 10 days, but do not affect neonatal neurologic outcome

- Adjunctive antibiotics have no proven benefit in managing preterm labor with intact membranes

- Screening for and treating bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy are not useful

- Prophylactic antibiotic treatment during the periconceptional period has no proven benefit

- A single course of antenatal steroids in preterm labor with intact membranes or pPROM significantly decreases neonatal mortality and neurologic morbidity without raising the risk of neonatal sepsis—even in the presence of intrauterine infection

- Tocolysis with magnesium sulfate or a calcium-channel blocker to stop preterm labor with intact membranes may decrease neurologic morbidity in neonates

- Consider delivery after 32 weeks if fetal lung maturity is confirmed because 1) expectant management of pPROM beyond 32 completed weeks of gestation does not have a clear benefit and 2) intrauterine inflammation associated with white matter disease is common in pPROM

A positive bacterial culture or gram-stained slide of amniotic fluid confirms intra-amniotic infection but detects fewer than 50% of cases. Other diagnostic criteria, such as an elevated WBC count, high level of lactate dehydrogenase activity, high protein level, and low glucose concentration in amniotic fluid, are more sensitive, but nonspecific, for amniotic infection and inflammation.

Elevated inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 in amniotic fluid and fetal blood have been associated with intrauterine inflammation and neonatal white matter disease in women with preterm labor and intact membranes or pPROM, but they are not significantly more accurate than the previously mentioned biomarkers.13,14 An amniotic fluid pocket may not be accessible by the abdominal approach in most patients with pPROM because of significant oligohydramnios. Testing amniotic fluid from the vagina is an alternative. Low glucose in vaginal samples is a specific, but not a sensitive, marker for intra-amniotic infection.15

Using the BPP. The biophysical profile has been used to identify fetuses at risk of FIRS in the presence of pPROM. Oligohydramnios—especially when the largest vertical amniotic fluid pocket is smaller than 1 cm—and diminished fetal breathing and body movement are associated with chorioamnionitis and suspected or proven neonatal sepsis. A nonreactive nonstress test is specific but not sensitive.

Although each component of the BPP provides useful information, a BPP score of 7 or lower predicts infection-related outcome much better than any single finding. In a population with an infection-related outcome of 30%, a BPP score of 7 or lower within 24 hours of delivery had a positive predictive value of 95% and a negative predictive value of 97%.16 A retrospective case-control study found that women who were followed with daily BPP and delivered within 24 hours after a BPP score of 7 or lower on two examinations 2 hours apart had a lower rate of neonatal sepsis than women who were managed expectantly or had a single amniocentesis on admission to the hospital.17

How management tactics affect neurologic outcome

Options for women in preterm labor with intact membranes or pPROM include antibiotics, antenatal steroids, tocolytics, or early delivery.

Antibiotics in cases of pPROM only

The findings of two large clinical trials powerful enough to evaluate adjunctive antibiotics in women with pPROM are in agreement: Such treatment prolongs the pregnancy briefly (as long as 10 days).18,19

NICHD-MFMU study. In a trial conducted by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units (NICHD-MFMU) Research Network, 48 hours of intravenous therapy with ampicillin and erythromycin followed by 5 days of oral amoxicillin and enteric-coated erythromycin given to 614 women between 24 and 32 weeks’ gestation decreased the number of infants who died or suffered a major morbidity, including respiratory distress syndrome, early sepsis, severe IVH, or severe necrotizing enterocolitis.18

ORACLE I. The results of the larger ORACLE I trial, which included 4,826 women, were less impressive.19 Patients who developed pPROM before 37 weeks’ gestation received erythromycin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, or both, or placebo for up to 10 days. Although antibiotic therapy prolonged pregnancy briefly, it did not have a major impact on neonatal mortality or any major morbidity, including cerebral abnormality on ultrasonography (US). In contrast to the NICHD-MFMU Research Network study, treatment with oral amoxicillin-clavulanic acid increased the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis.

ORACLE II. The ORACLE II trial evaluated the benefit of adjunctive antibiotics for 6,295 women in spontaneous preterm labor before 37 weeks’ gestation who had intact membranes and no evidence of clinical infection.20 The women received erythromycin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, or both, or placebo for as long as 10 days. Compared with placebo, none of the antibiotics was associated with a lower rate of the composite primary outcome, which included major cerebral abnormality on US before discharge from the hospital.

Prophylaxis. It has been suggested that antibiotics are more likely to prevent preterm birth if they are given long before contractions start or membranes rupture. Studies of antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent preterm birth and related sequelae don’t support this notion. A Cochrane meta-analysis of six randomized clinical trials involving 2,184 asymptomatic women who received prophylactic antibiotics in the second or third trimester found no reduction in the risk of subsequent preterm birth.21 In fact, intervention increased the risk of neonatal sepsis (odds ratio [OR]=8.07, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.36 to 47.77). Another meta-analysis of the effect of antibiotics on BV during pregnancy drew similar conclusions.22 This analysis of 15 randomized clinical trials with a total of 5,888 patients showed that treating BV did not reduce the risk of preterm birth. The trials reported very few perinatal deaths, and none reported substantive neonatal morbidity.

Another hypothesis argues that the events leading to preterm birth begin in very early stages of pregnancy, including conception and implantation of the embryo. To test this hypothesis, 241 women with a history of spontaneous preterm birth or pPROM between 16 and 34 weeks’ gestation were randomized to receive an oral course of azithromycin and metronidazole or placebo every 4 months until conception.23 The 124 women who conceived and were available for follow-up showed no difference in the rate of preterm birth between the treatment and placebo groups. In fact, women who received an antibiotic tended to have a shorter pregnancy and a lower-birth-weight baby than those given placebo.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the role of inflammation in neonatal white matter disease. Microorganisms and microbial products can gain access to the fetus and activate inflammatory cytokines, increasing the permeability of the blood–brain barrier and facilitating passage of the cytokines into the brain.

Microbial products stimulate human fetal microglia (the central nervous system [CNS] equivalent of macrophages) to produce interleukin (IL)-1 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which, in turn, stimulate proliferation of astrocytes (the CNS equivalent of fibroblasts) and production of TNF. Leviton proposed that TNF-α can damage white matter by four mechanisms:33

- inducing hypotension and brain ischemia

- stimulating the production of a tissue factor, which can activate the hemostatic system and contribute to coagulation necrosis of white matter

- inducing the release of platelet-activating factor, which can act as a membrane detergent, causing direct brain damage

- producing a direct cytotoxic effect on oligodendrocytes.

Polymorphisms in immunomodulatory genes, such as the gene encoding TNF-α, modify the immune response and the risk for white matter disease in preterm infants.34

Based on available data, treatment with a short course of antibiotics such as erythromycin or ampicillin, or both, is recommended only in cases of pPROM.

Antenatal steroids improve outcome

Antenatal steroids reduce neonatal mortality and morbidity, including IVH and PVL, in infants born between 24 and 34 weeks’ gestation. One concern raised about antenatal steroid use is whether it increases the risk of neonatal infection and morbidity when intrauterine infection and inflammation are present. A retrospective analysis of infants who weighed 1,750 g or more at birth concluded that antenatal steroids significantly decreased neonatal mortality and morbidity—including IVH, PVL, and major brain lesions—without increasing neonatal sepsis in babies delivered following preterm labor or pPROM.24

In another retrospective analysis of 457 consecutive 23- to 32-week live-born singletons, antenatal steroids weren’t associated with significant worsening of any neonatal outcome. Steroids were associated with significant reductions in respiratory distress syndrome and neonatal systemic inflammatory response syndrome in infants with positive placental cultures and elevated cord blood IL-6 levels.25

These data suggest that antenatal steroids may not be contraindicated in the face of inflammation and infection; they may, in fact, be beneficial. In women with pPROM, weekly administration of ante-natal steroids doesn’t seem to improve neonatal outcomes more than single-course therapy and may increase the risk of chorioamnionitis.26

Some tocolytics may help

Tocolytic agents are often given to women with preterm contractions to delay delivery long enough to administer a course of antenatal corticosteroids.

Magnesium sulfate is commonly used in the United States. A 2007 Cochrane meta-analysis of four trials (3,701 babies) found that antenatal magnesium sulfate had no statistically significant effect on any major pediatric outcome, including death and neurologic problems such as CP in the first few years of life.27 Nor did antenatal magnesium therapy significantly affect combined rates of mortality and neurologic outcomes. Two trials involving 2,848 infants found a significant reduction in substantial gross motor dysfunction (RR=0.56; 95% CI, 0.33 to 0.97).

Betamimetics are also widely used for tocolysis, especially in resource-poor countries. Eleven randomized controlled trials, involving 1,332 women, compared betamimetics with placebo.28 Although betamimetics decreased the number of women in preterm labor who gave birth within 48 hours, they didn’t reduce perinatal or neonatal death. Data on CP were too sparse to allow comment. Because these drugs cause many maternal side effects, they aren’t considered first-line tocolytics.

Calcium-channel blockers are attracting growing interest as potentially effective and well-tolerated tocolytic agents. A meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials involving 1,029 women suggests that calcium-channel blockers reduce the number of women giving birth within 7 days of receiving treatment, compared with other tocolytic agents (mainly betamimetics).29 They also decrease the frequency of neonatal morbidity, including IVH (RR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.36 to 0.98).

Cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors are easy to administer and cause fewer maternal side effects than conventional tocolytics. A 2005 Cochrane meta-analysis includes outcome data from 13 trials with a total of 713 women.30 Indomethacin, a non-selective COX inhibitor, was used in 10 trials. COX inhibition reduced birth before 37 weeks’ gestation more effectively than other tocolytic agents, but data were insufficient to comment on neonatal outcomes.

In women with pPROM, starting tocolysis before onset of contractions prolongs latency. However, the utility of tocolytic therapy after pPROM remains controversial pending more powerful randomized trials.

Early delivery is an option

It has been suggested that exposure to infection, especially proinflammatory cytokines, reduces the threshold at which hypoxia becomes neurotoxic, making the brain much more vulnerable to even mild hypoxic insults. A recent study found that infants with encephalopathy were more than 90 times more likely to have experienced both neonatal intrapartum acidosis and maternal intrapartum fever than infants with no encephalopathy; maternal fever or neonatal acidosis increased the risk six- and 12-fold, respectively.31 Lack of interaction between maternal fever and acidosis suggests that these are separate causal pathways to adverse neonatal outcomes. Although intrapartum fever doesn’t always correlate with intrauterine inflammation, the findings of this study suggest that fetal acidosis should be avoided when intrauterine infection and inflammation are suspected.

Conservative management of pPROM remote from term has been shown to prolong pregnancy significantly and reduce complications in the infant when prophylactic antibiotics and ante-natal steroids are given concurrently. The benefit of this strategy is less clear after 32 weeks of gestation because:

- The efficacy of antenatal steroids after 32 weeks is unclear

- Beyond 32 weeks, the risk of severe complications of prematurity, including CP, is low if fetal lung maturity has been established by amniotic fluid samples collected vaginally or by amniocentesis.

For these reasons and because sub-acute intrauterine inflammation may harm the fetus, delivery can be considered after 32 completed weeks of gestation if fetal lung maturity is confirmed. A meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials that compared intentional delivery with expectant management after pPROM between 30 and 36 weeks of gestation found no difference in neonatal outcomes.32

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

- Intrapartum hypoxia, once considered an important cause of cerebral palsy (CP), is responsible for only 8% to 10% of cases.

- Increasingly, evidence suggests that the primary cause of CP lies in the relationship among intrauterine infection and inflammation, preterm labor, preterm premature rupture of membranes (pPROM), and neonatal white matter disease.

- This review focuses on that relationship and its implications for managing preterm birth with intact membranes or pPROM.

Cerebral palsy is a complex disease characterized by aberrant control of movement or posture that results from an insult to the developing central nervous system (CNS). In addition to motor abnormalities, some patients have seizures, cognitive impairment, and extrapyramidal abnormalities.

Clinical and epidemiologic evidence points to white matter lesions and severe intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH)—detected by neonatal neurosonography—as the key determinants of CP. The lesions are the sonographic antecedent or counterpart of periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), a cerebral lesion characterized by foci of necrosis in the white matter near the ventricles (FIGURE).

The principal risk factor is prematurity

A precise cause for CP has not been identified in more than 75% of cases. The leading identifiable risk factor is prematurity. The prevalence of CP at 3 years of age is 4.4% among infants born earlier than 27 weeks of gestation, compared with 0.06% among babies born at term.1

FIGURE Periventricular leukomalacia

Four axial magnetic resonance images of the brain of an infant show the usual appearance of this cerebral lesion, characterized by foci of necrosis of white matter near the ventricles.

How inflammation leads to premature birth

Any condition that increases the incidence of prematurity can be expected to increase the incidence of CP. More than 80% of premature births follow preterm labor or pPROM. Clinical and experimental evidence suggests that most of these births reflect one or more of four major pathogenic processes, which lead to uterine contractions and cervical changes, with or without premature rupture of membranes2:

- local or systemic inflammatory immune response

- activation of the maternal or fetal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

- decidual hemorrhage (abruption)

- pathologic distention of the uterus.