User login

The Role of Process Improvements in Reducing Heart Failure Readmissions

From the Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL.

Objective: To review selected process-of-care interventions that can be applied both during the hospitalization and during the transitional care period to help address the persistent challenge of heart failure readmissions.

Methods: Review of the literature.

Results: Process-of-care interventions that can be implemented to reduce readmissions of heart failure patients include: accurately identifying heart failure patients; providing disease education; titrating guideline-directed medical therapy; ensuring discharge readiness; arranging close discharge follow-up; identifying and addressing social barriers; following up by telephone; using home health; and addressing comorbidities. Importantly, the heart failure hospitalization is an opportunity to set up outpatient success, and setting up feedback loops can aid in post-discharge monitoring.

Conclusion: We encourage teams to consider local capabilities when selecting processes to improve; begin by improving something small to build capacity and team morale, and continually iterate and reexamine processes, as health care systems are continually evolving.

Keywords: heart failure; process improvement; quality improvement; readmission; rehospitalization; transitional care.

The growing population of patients affected by heart failure continues to challenge health systems. The increasing prevalence is paralleled by the rising costs of managing heart failure, which are projected to grow from $30.7 billion in 2012 to $69.8 billion in 2030.1 A significant portion of these costs relate to readmission after an index heart failure hospitalization. The statistics are staggering: for patients hospitalized with heart failure, approximately 15% to 20% are readmitted within 30 days.2,3 Though recent temporal trends suggest a modest reduction in readmission rates, there is a concerning correlation with increasing mortality,3 and a recognition that readmission rate decreases may relate to subtle changes in coding-based risk adjustment.4 Despite these concerns, efforts to reduce readmissions after heart failure hospitalization command significant attention.

Process improvement methodologies may be helpful in reducing hospital readmissions. Various approaches have been employed, and results have been mixed. An analysis of 70 participating hospitals in the American Heart Association’s Get With the Guidelines initiative found that, while overall readmission rates declined by 1.0% over 3 years, only 1 hospital achieved a 20% reduction in readmission rates.5

It is notably difficult to reduce readmissions after heart failure hospitalization. One challenge is that patients with heart failure often have multiple comorbidities, and approximately 50% to 60% of 30-day readmissions after heart failure hospitalization arise from noncardiac causes.1 Another challenge is that a significant fraction of readmissions in general—perhaps 75%—may not be avoidable.6

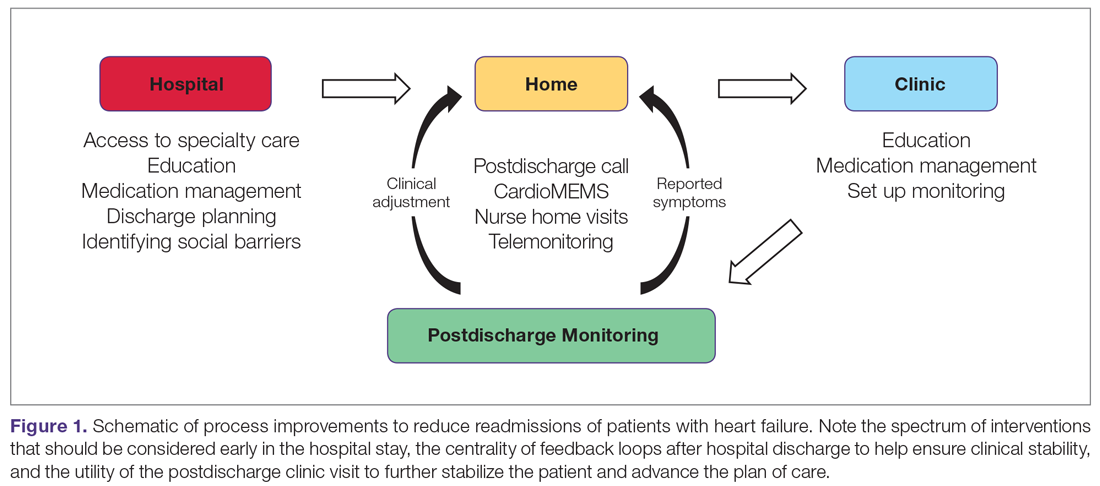

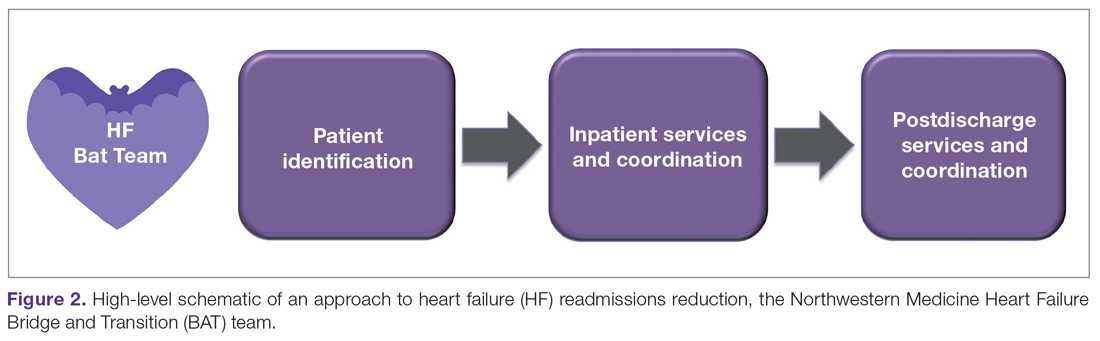

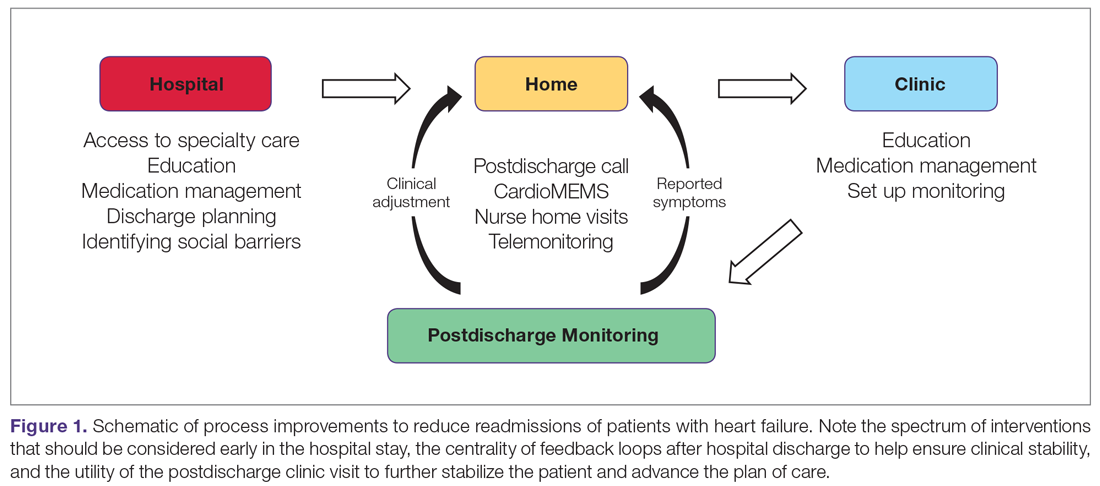

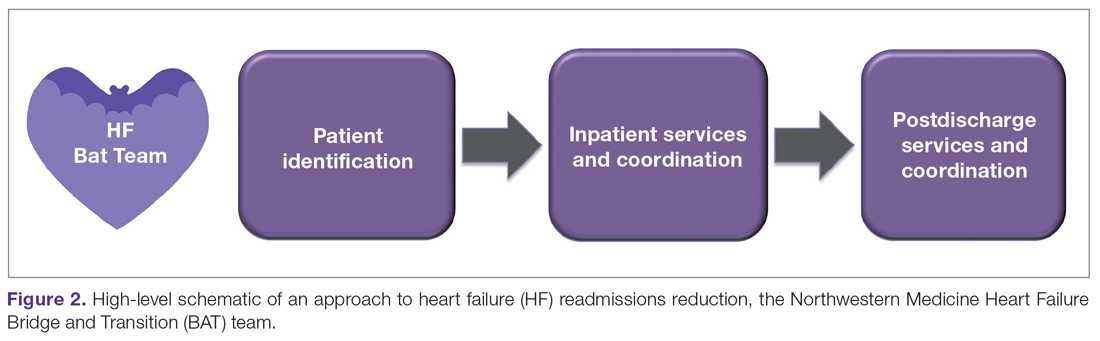

Recent excellent systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide comprehensive overviews of process improvement strategies that can be used to reduce readmissions after heart failure hospitalizations.7-9 Yet despite this extensive knowledge, few reports discuss the process of actually implementing these changes: the process of process improvement. Here, we seek to not only highlight some of the most promising potential interventions to reduce heart failure readmissions, but also to discuss a process improvement framework to help engender success, using our experience as a case study. We schematize process improvement efforts as having several distinct phases (Figure 1): processes delivered during the hospitalization and prior to discharge; feedback loops set up to maintain clinical stability at home; and the postdischarge clinic visit as an opportunity to further stabilize the patient and advance the plan of care. The discussion of these interventions follows this organization.

During Hospitalization

The heart failure hospitalization can be used as an opportunity to set up outpatient success, with several goals to target during the index admission. One goal is identifying the root causes of the heart failure syndrome and correcting those root causes, if possible. For example, patients in whom the heart failure syndrome is secondary to valvular heart disease may benefit from transcatheter aortic valve replacement.10 Another clinical goal is decongesting the patient, which is associated with lower readmission rates.11,12 These goals focus on the medical aspects of heart failure care. However, beyond these medical aspects, a patient must be equipped to successfully manage the disease at home.

To support medical and nonmedical interventions for hospitalized heart failure patients, a critical first step is identifying patients with heart failure. This accomplishes at least 2 objectives. First, early identification allows early initiation of interventions, such as heart failure education and social work evaluation. Early initiation of these interventions allows sufficient time during the hospitalization to make meaningful progress on these fronts. Second, early identification allows an opportunity for the delivery of cardiology specialty care, which may help with identifying and correcting root causes of the heart failure syndrome. Such access to cardiology has been shown to improve inpatient mortality and readmission rates.13

In smaller hospitals, identification of patients with heart failure can be as simple as reviewing overnight admissions. More advanced strategies, such as screeners based on brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels and administration of intravenous diuretics, can be employed.14,15 In the near future, deep learning-based natural language processing will be applied to mine full-text data in the electronic health record to identify heart failure hospitalizations.16

In the hospital, patients can also receive education about heart failure disease management. This education is a cornerstone of reducing heart failure readmissions. A recent systematic review of nurse education interventions demonstrated reductions in readmissions, hospitalizations, and costs.17 However, the efficacy of heart failure education hinges on many other variables. For patients to adhere to water restriction and daily weights, for example, there must also be patient understanding, compliance, and accessibility to providers to recommend how to strike the fluid balance. Education is therefore necessary, but not sufficient, for setting up outpatient success.

The hospitalization also represents an important time to start or uptitrate guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for heart failure. Doing so takes advantage of an important opportunity to reduce the risk of readmission and even reverse the disease process.18 Uptitration of GDMT in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction is associated with a decreased risk of mortality, while discontinuation is associated with an increased risk of mortality.19 However, recent registry data indicate that intensity of GDMT is just as likely to be decreased as increased during the hospitalization.20 Nevertheless, predischarge initiation of medications may be associated with higher attained doses in follow-up.21

Preparing for Discharge

Preparing a patient for discharge after a heart failure hospitalization involves stabilizing the medical condition as well as ensuring that the patient and caregivers have the medication, equipment, and self-care resources at home necessary to manage the condition. Several frameworks have been put forth to help care teams analyze a patient’s readiness for discharge. One is the B-PREPARED score,22 a validated instrument to discriminate among patients with regard to their readiness to discharge from the hospital. This instrument highlights the importance of several key factors that should be addressed during the discharge process, including counseling and written instructions about medications and their side effects; information about equipment needs and community resources; and information on activity levels and restrictions. Nurse education and discharge coordination can improve patients’ perception of discharge readiness,23 although whether this discharge readiness translates into improved readmission rates appears to depend on the specific follow-up intervention design.9

Prior to discharge, it is important to arrange postdischarge follow-up appointments, as emphasized by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines.24 The use of nurse navigators can help with planning follow-up appointments. For example, the ACC Patient Navigator Program was applied in a single-center study of 120 patients randomized to the program versus usual care.25 This study found a significant increase in patient education and follow-up appointments compared to usual care, and a numerical decrease in hospital readmissions, although the finding was not statistically significant.25

A third critical component of preparing for discharge is identifying and addressing social barriers to care. In a study of patients stratified by household income, patients in the lowest income quartile had a higher readmission rate than patients in the highest income quartile.26 Poverty also correlates with heart failure mortality.27 Social factors play an important role in many aspects of patients’ ability to manage their health, including self-care, medication adherence, and ability to follow-up. Identifying these social factors prior to discharge is the first step to addressing them. While few studies specifically address the role of social workers in the management of heart failure care, the general medical literature suggests that social workers embedded in transitional care teams can augment readmission reduction efforts.28

After Discharge

Patients recently discharged from the hospital who have not yet attended their postdischarge appointment are in an incredibly vulnerable phase of care. Patients who are discharged from the hospital may not yet be connected with outpatient care. During this initial transitional care period, feedback loops involving patient communication back to the clinic, and clinic communication back to the patient, are critical to helping patients remain stable. For example, consider monitoring weights daily after hospital discharge. A patient at home can report increasing weights to a provider, who can then recommend an increased dose of diuretic. The patient can complete the feedback loop by taking the extra medication and monitoring the return of weight back to normal.

While daily weight monitoring is a simple process improvement that relies on the principle of establishing feedback loops, many other strategies exist. One commonly employed tool is the postdischarge telephone follow-up call, which is often coupled with other interventions in a comprehensive care bundle.8 During the telephone call, several process-of-care defects can be corrected, including missing medications or missing information on appointment times.

Beyond the telephone, newer technologies show promise for helping develop feedback loops for patients at home. One such technology is telemonitoring, whereby physiologic information such as weight, heart rate, and blood pressure is collected and sent back to a monitoring center. While the principle holds promise, several studies have not demonstrated significantly different outcomes as compared to usual care.13,29 Another promising technology is the CardioMEMS device (Abbott, Inc., Atlanta, GA), which can remotely transmit the pulmonary artery pressure, a physiologic signal which correlates with volume overload. There is now strong evidence supporting the efficacy of pulmonary artery pressure–guided heart failure management.30,31

Finally, home visits can be an efficient way to communicate symptoms, enable clinical assessment, and provide recommendations. One program that implemented home visits, 24-hour nurses available by call, and telephone follow-up showed a statistically significant reduction in readmissions.32 Furthermore, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing home health to usual care showed decreased readmissions and mortality.33 The efficacy may be in strengthening the feedback loop—home care improves compliance with weight monitoring, fluid restriction, and medications.34 These studies provide a strong rationale for the benefits of home health in stabilizing heart failure patients postdischarge. Indeed, nurse home visits were 1 of the 2 process interventions in a Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials that were shown to statistically significantly decrease readmissions and mortality.9 These data underscore the importance of feedback loops for helping ensure patients are clinically stable.

Postdischarge Follow-Up Clinic Visit

The first clinic appointment postdischarge is an important check-in to help advance patient care. Several key tasks can be achieved during the postdischarge visit. First, the patient can be clinically stabilized by adjusting diuretic therapy. If the patient is clinically stable, GDMT can be uptitrated. Second, education around symptoms, medications, diet, and exercise can be reinforced. Finally, clinicians can help connect patients to other members of the multidisciplinary care team, including specialist care, home health, or cardiac rehabilitation.

Achieving 7-day follow-up visits after discharge has been a point of emphasis in national guidelines.24 The ACC promotes a “See You in 7” challenge, advising that all patients discharged with a diagnosis of heart failure have a follow-up appointment within 7 days. Yet based on the latest available data, arrival rates to the postdischarge clinic are dismal, hovering around 30%.35 In a multicenter observational study of hospitals participating in the “See You in 7” collaborative, hospitals were able to increase their 7-day follow-up appointment rates by 2% to 3%, and also noted an absolute decrease in readmission rates by 1% to 2%.36 We have demonstrated, using a mathematical approach called queuing theory, that discharge appointment wait times and clinic access can be significantly improved by providing a modest capacity buffer to clinic availability.37 Those interested in applying this model to their own clinical practice may do so with a free online calculator at http://hfresearch.org.

Another important aspect of postdischarge follow-up is appropriate management of the comorbidity burden, which, as noted, is often significant in patients hospitalized with heart failure.38 For instance, in recent cohorts of hospitalized heart failure patients, the incidence of hypertension was 78%, coronary artery disease was more than 50%, atrial fibrillation was more than 40%, and diabetes was nearly 40%.39 Given this burden of comorbidity, it is not surprising that only 35% of readmissions after an index heart failure hospitalization are for recurrent heart failure.40 Coordinating care among primary care physicians and relevant subspecialists is thus essential. Phone calls and secure electronic messages are very helpful in achieving this. There is increasing interest in more nimble care models, such as the patient-centered specialty practice41 or the dyspnea clinic, to help bring coordinated resources to the patient.42

Process of Process Improvement: Our Experiences

The previous sections outline a series of potential process improvements clinical teams and health systems can implement to impact heart failure readmissions. A plan on paper, however, does not equal a plan in actuality. How does one go about implementing these changes? We offer our local experience starting a heart failure transitional care program as a case study, then draw lessons learned as a set of practical tips for local teams to employ. What we hope to highlight is that there is a large difference between a completed process for transitional care of heart failure patients, and the process of developing that process itself. The former is the hardware, the latter is the software. The latter does not typically get highlighted, but it is absolutely critical to unlocking the capabilities of a team and the institution.

In 2015, Northwestern Memorial Hospital adopted a novel payment arrangement from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services for Medicare patients being discharged from the hospital with heart failure. Known as Bundled Payments for Care Improvement,43 this bundled payment model incentivized Northwestern Memorial Hospital charge, principally by reducing hospital readmissions and by collaborating with skilled nursing facilities to control length of stay.

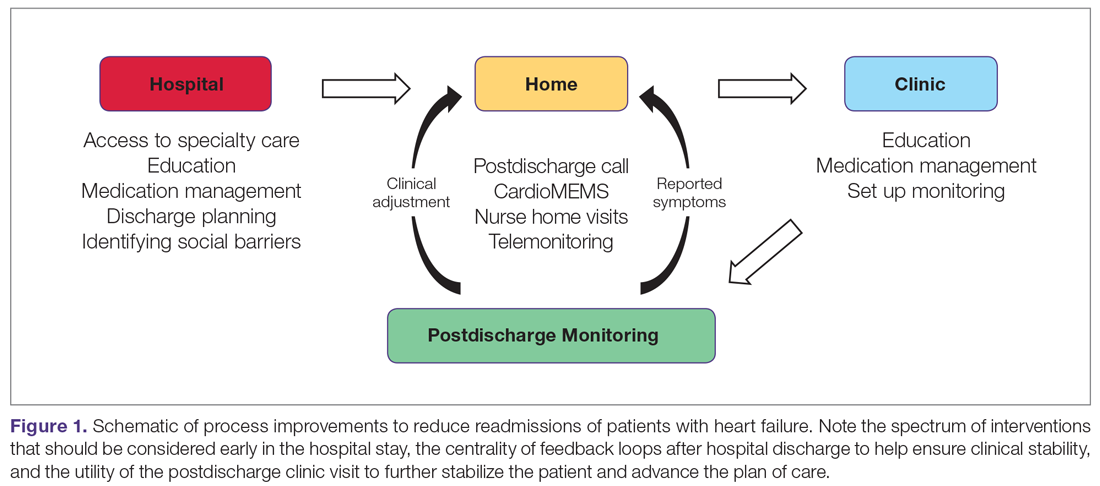

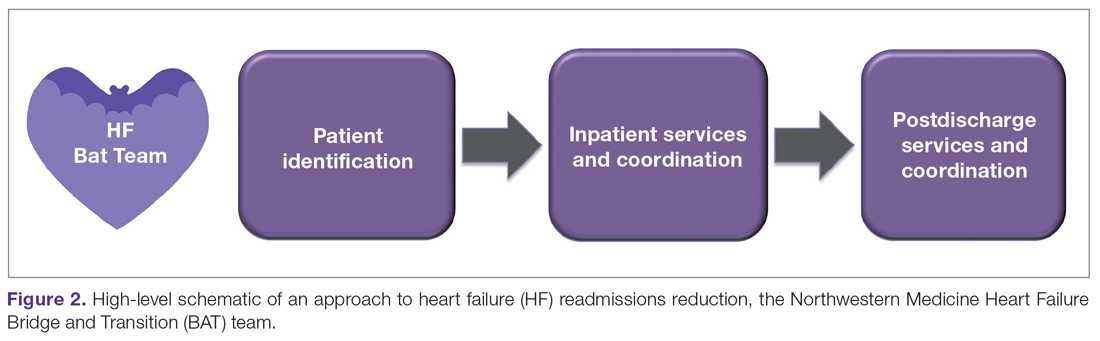

We approached this problem by drawing on the available literature,44,45 and by first creating a schematic of our high-level approach, which comprised 3 major elements (Figure 2): identification of hospitalized heart failure patients, delivery of a care bundle to hospitalized heart failure patients in hospital, and coordinating postdischarge care, centered on a telephone call and a postdischarge visit.

We then proceeded by building out, in stepwise fashion, each component of our value chain, using Agile techniques as a guiding principle.46 Agile, a productivity and process improvement mindset with roots in software development, emphasizes tackling 1 problem at a time, building out new features sequentially and completely, recognizing that the end user does not derive value from a program until new functionality is available for use. Rather than wholesale monolithic change, Agile emphasizes rapid iteration, prototyping, and discarding innovations not found to be helpful. The notion is to stand up new, incremental features rapidly, with each incremental improvement delivering value and helping to accelerate overall change.

Our experience building a robust way to identify heart failure cases is a good example of Agile process improvement in practice. At our hospital, identification of patients with heart failure was a challenge because more than half of heart failure patients are admitted to noncardiology floors. We developed a simple electronic health record query to detect heart failure patients, relying on parameters such as administration of intravenous diuretic or levels of BNP exceeding 100 ng/dL. We deployed this query, finding very high sensitivity for detection of heart failure patients.14 Patients found to have heart failure were then populated into a list in the electronic health record, which made patients’ heart failure status visible to all members of the health care team. Using this list, we were able to automate several processes necessary for heart failure care. For example, the list made it possible for cardiologists to know if there was a patient who perhaps needed cardiology consultation. Nurse navigators could know which patients needed heart failure education without having to be actively consulted by the admitting team. The same nurse navigators could then know upon discharge which patients needed a follow-up telephone call at 48 hours.

This list of heart failure patients was the end product, which was built through prototyping and iteration. For example, with our initial BNP cutoff of 300 ng/dL, we recognized we were missing several cases, and lowered the cutoff for the screener to 100 ng/dL. When we were satisfied this process was working well, we moved on to the next problem to tackle, avoiding trying to work on too many things at once. By doing so, we were able to focus our process improvement resources on 1 problem at a time, building up a suite of interventions. For our hospital, we settled on a bundle of interventions, captured by the mnemonic HEART:

Heart doctor sees patient in the hospital

Education about heart failure in the hospital

After-visit summary with 7-day appointment printed

Reach out to the patient by telephone within 72 hours

Treat the patient in clinic by the 7-day visit

Conclusion

We would like to emphasize that the elements of our heart failure readmissions interventions were not all put in place at once. This was an iterative process that proceeded in a stepwise fashion, with each step improving the care of our patients. We learned a number of lessons from our experience. First, we would advise that teams not try to do everything. One program simply cannot implement all possible readmission reduction interventions, and certainly not all at once. Trade-offs should be made, and interventions more likely to succeed in the local environment should be prioritized. In addition, interventions that do not fit and do not create synergy with the local practice environment should not be pursued.

Second, we would advise teams to start small, tackling a known problem in heart failure transitions of care first. This initial intuition is often right. An example might be improving 7-day appointments upon discharge. Starting with a problem that can be tackled builds process improvement muscle and improves team morale. Third, we would advise teams to consistently iterate on designs, tweaking and improving performance. Complex organizations always evolve; processes that work 1 year may fail the next because another element of the organization may have changed.

Finally, the framework presented in Figure 1 may be helpful in guiding how to structure interventions. Considering interventions to be delivered in the hospital, interventions to be delivered in the clinic, and how to set up feedback loops to support patients as outpatients help develop a comprehensive heart failure readmissions reduction program.

Corresponding author: R. Kannan Mutharasan, MD, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 676 North Saint Clair St., Arkes Pavilion, Suite 7-038, Chicago, IL 60611;[email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC. The prevention of hospital readmissions in heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58:379-385.

2. Kwok CS, Seferovic PM, Van Spall HG, et al. Early unplanned readmissions after admission to hospital with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124:736-745.

3. Fonarow GC, Konstam MA, Yancy CW. The hospital readmission reduction program is associated with fewer readmissions, more deaths: time to reconsider. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1931-1934.

4. Ody C, Msall L, Dafny LS, et al. Decreases in readmissions credited to medicare’s program to reduce hospital readmissions have been overstated. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38:36-43.

5. Bergethon KE, Ju C, DeVore AD, et al. Trends in 30-day readmission rates for patients hospitalized with heart failure: findings from the Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure Registry. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9.

6. van Walraven C, Jennings A, Forster AJ. A meta-analysis of hospital 30-day avoidable readmission rates. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(6):1211-1218.

7. Albert NM. A systematic review of transitional-care strategies to reduce rehospitalization in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2016;45:100-113.

8. Takeda A, Martin N, Taylor RS, Taylor SJ. Disease management interventions for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD002752.

9. Van Spall HGC, Rahman T, Mytton O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of transitional care services in patients discharged from the hospital with heart failure: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1427-1443.

10. Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, et al. Surgical or transcatheter aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1321-1331.

11. Lala A, McNulty SE, Mentz RJ, et al. Relief and recurrence of congestion during and after hospitalization for acute heart failure: insights from Diuretic Optimization Strategy Evaluation in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (DOSE-AHF) and Cardiorenal Rescue Study in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (CARESS-HF). Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:741-748.

12. Ambrosy AP, Pang PS, Khan S, et al. Clinical course and predictive value of congestion during hospitalization in patients admitted for worsening signs and symptoms of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: findings from the EVEREST trial. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:835-843.

13. Driscoll A, Meagher S, Kennedy R, et al. What is the impact of systems of care for heart failure on patients diagnosed with heart failure: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16(1):195.

14. Ahmad FS, Wehbe RM, Kansal P, et al. Targeting the correct population when designing transitional care programs for medicare patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1274-1275.

15. Blecker S, Sontag D, Horwitz LI, et al. Early identification of patients with acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2018;24:357-362.

16. Lee J, Yoon W, Kim S, et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:1234-1240.

17. Rice H, Say R, Betihavas V. The effect of nurse-led education on hospitalisation, readmission, quality of life and cost in adults with heart failure. A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:363-374.

18. Hollenberg SM, Warner Stevenson L, Ahmad T, et al. 2019 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on risk assessment, management, and clinical trajectory of patients hospitalized with heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1966-2011.

19. Tran RH, Aldemerdash A, Chang P, et al. Guideline-directed medical therapy and survival following hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38:406-416.

20. Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, DeVore AD, et al. Titration of medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2365-2383.

21. Gattis WA, O’Connor CM, Gallup DS, et al;, IMPACT-HF Investigators and Coordinators. Predischarge initiation of carvedilol in patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure: results of the Initiation Management Predischarge: Process for Assessment of Carvedilol Therapy in Heart Failure (IMPACT-HF) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1534-1541.

22. Graumlich JF, Novotny NL, Aldag JC. Brief scale measuring patient preparedness for hospital discharge to home: Psychometric properties. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:446-454.

23. Van Spall HGC, Lee SF, Xie F, et al. Effect of patient-centered transitional care services on clinical outcomes in patients hospitalized for heart failure: The PACT-HF Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321:753-761.

24. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240-327.

25. Di Palo KE, Patel K, Assafin M, Piña IL. Implementation of a patient navigator program to reduce 30-day heart failure readmission rate. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;60:259-266.

26. Patil S, Shah M, Patel B, et al. Readmissions among patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure based on income quartiles. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1939-1950.

27. Ahmad K, Chen EW, Nazir U, et al. Regional variation in the association of poverty and heart failure mortality in the 3135 counties of the united states. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012422.

28. Bellon JE, Bilderback A, Ahuja-Yende NS, et al. University of Pittsburgh medical center home transitions multidisciplinary care coordination reduces readmissions for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:156-163.

29. Rosen D, McCall JD, Primack BA. Telehealth protocol to prevent readmission among high-risk patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Med. 2017;130:1326-1330.

30. Heywood JT, Jermyn R, Shavelle D, et al. Impact of practice-based management of pulmonary artery pressures in 2000 patients implanted with the CardioMEMS sensor. Circulation. 2017;135:1509-1517.

31. Abraham WT, Adamson PB, Bourge RC, et al. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:658-666.

32. Drozda JP, Smith DA, Freiman PC, et al. Heart failure readmission reduction. Am J Med Qual. 2017;32:134-140.

33. Malik AH, Malik SS, Aronow WS; MAGIC (Meta-analysis And oriGinal Investigation in Cardiology) investigators. Effect of home-based follow-up intervention on readmissions and mortality in heart failure patients: a meta-analysis. Future Cardiol. 2019;15:377-386.

34. Strano A, Briggs A, Powell N, et al. Home healthcare visits following hospital discharge: does the timing of visits affect 30-day hospital readmission rates for heart failure patients? Home Healthc Now. 2019;37:152-157.

35. DeVore AD, Cox M, Eapen ZJ, et al. Temporal trends and variation in early scheduled follow-up after a hospitalization for heart failure: findings from get with the guidelines-heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9.

36. Baker H, Oliver-McNeil S, Deng L, Hummel SL. Regional hospital collaboration and outcomes in medicare heart failure patients: see you in 7. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3:765-773.

37. Mutharasan RK, Ahmad FS, Gurvich I, et al. Buffer or suffer: redesigning heart failure postdischarge clinic using queuing theory. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:e004351.

38. Ziaeian B, Hernandez AF, DeVore AD, et al. Long-term outcomes for heart failure patients with and without diabetes: From the Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure Registry. Am Heart J. 2019;211:1-10.

39. Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, et al. Medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: The CHAMP-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:351-366.

40. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309:355-363.

41. Ward L, Powell RE, Scharf ML, et al. Patient-centered specialty practice: defining the role of specialists in value-based health care. Chest. 2017;151:930-935.

42. Ryan JJ, Waxman AB. The dyspnea clinic. Circulation. 2018;137:1994-1996.

43. Oseran AS, Howard SE, Blumenthal DM. Factors associated with participation in cardiac episode payments included in medicare’s bundled payments for care improvement initiative. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:761-766.

44. Takeda A, Taylor SJC, Taylor RS, et al. Clinical service organisation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD002752.

45. Albert NM, Barnason S, Deswal A, et al. Transitions of care in heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:384-409.

46. Manifesto for Agile Software Development. http://agilemanifesto.org/ Accessed March 6, 2020.

From the Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL.

Objective: To review selected process-of-care interventions that can be applied both during the hospitalization and during the transitional care period to help address the persistent challenge of heart failure readmissions.

Methods: Review of the literature.

Results: Process-of-care interventions that can be implemented to reduce readmissions of heart failure patients include: accurately identifying heart failure patients; providing disease education; titrating guideline-directed medical therapy; ensuring discharge readiness; arranging close discharge follow-up; identifying and addressing social barriers; following up by telephone; using home health; and addressing comorbidities. Importantly, the heart failure hospitalization is an opportunity to set up outpatient success, and setting up feedback loops can aid in post-discharge monitoring.

Conclusion: We encourage teams to consider local capabilities when selecting processes to improve; begin by improving something small to build capacity and team morale, and continually iterate and reexamine processes, as health care systems are continually evolving.

Keywords: heart failure; process improvement; quality improvement; readmission; rehospitalization; transitional care.

The growing population of patients affected by heart failure continues to challenge health systems. The increasing prevalence is paralleled by the rising costs of managing heart failure, which are projected to grow from $30.7 billion in 2012 to $69.8 billion in 2030.1 A significant portion of these costs relate to readmission after an index heart failure hospitalization. The statistics are staggering: for patients hospitalized with heart failure, approximately 15% to 20% are readmitted within 30 days.2,3 Though recent temporal trends suggest a modest reduction in readmission rates, there is a concerning correlation with increasing mortality,3 and a recognition that readmission rate decreases may relate to subtle changes in coding-based risk adjustment.4 Despite these concerns, efforts to reduce readmissions after heart failure hospitalization command significant attention.

Process improvement methodologies may be helpful in reducing hospital readmissions. Various approaches have been employed, and results have been mixed. An analysis of 70 participating hospitals in the American Heart Association’s Get With the Guidelines initiative found that, while overall readmission rates declined by 1.0% over 3 years, only 1 hospital achieved a 20% reduction in readmission rates.5

It is notably difficult to reduce readmissions after heart failure hospitalization. One challenge is that patients with heart failure often have multiple comorbidities, and approximately 50% to 60% of 30-day readmissions after heart failure hospitalization arise from noncardiac causes.1 Another challenge is that a significant fraction of readmissions in general—perhaps 75%—may not be avoidable.6

Recent excellent systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide comprehensive overviews of process improvement strategies that can be used to reduce readmissions after heart failure hospitalizations.7-9 Yet despite this extensive knowledge, few reports discuss the process of actually implementing these changes: the process of process improvement. Here, we seek to not only highlight some of the most promising potential interventions to reduce heart failure readmissions, but also to discuss a process improvement framework to help engender success, using our experience as a case study. We schematize process improvement efforts as having several distinct phases (Figure 1): processes delivered during the hospitalization and prior to discharge; feedback loops set up to maintain clinical stability at home; and the postdischarge clinic visit as an opportunity to further stabilize the patient and advance the plan of care. The discussion of these interventions follows this organization.

During Hospitalization

The heart failure hospitalization can be used as an opportunity to set up outpatient success, with several goals to target during the index admission. One goal is identifying the root causes of the heart failure syndrome and correcting those root causes, if possible. For example, patients in whom the heart failure syndrome is secondary to valvular heart disease may benefit from transcatheter aortic valve replacement.10 Another clinical goal is decongesting the patient, which is associated with lower readmission rates.11,12 These goals focus on the medical aspects of heart failure care. However, beyond these medical aspects, a patient must be equipped to successfully manage the disease at home.

To support medical and nonmedical interventions for hospitalized heart failure patients, a critical first step is identifying patients with heart failure. This accomplishes at least 2 objectives. First, early identification allows early initiation of interventions, such as heart failure education and social work evaluation. Early initiation of these interventions allows sufficient time during the hospitalization to make meaningful progress on these fronts. Second, early identification allows an opportunity for the delivery of cardiology specialty care, which may help with identifying and correcting root causes of the heart failure syndrome. Such access to cardiology has been shown to improve inpatient mortality and readmission rates.13

In smaller hospitals, identification of patients with heart failure can be as simple as reviewing overnight admissions. More advanced strategies, such as screeners based on brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels and administration of intravenous diuretics, can be employed.14,15 In the near future, deep learning-based natural language processing will be applied to mine full-text data in the electronic health record to identify heart failure hospitalizations.16

In the hospital, patients can also receive education about heart failure disease management. This education is a cornerstone of reducing heart failure readmissions. A recent systematic review of nurse education interventions demonstrated reductions in readmissions, hospitalizations, and costs.17 However, the efficacy of heart failure education hinges on many other variables. For patients to adhere to water restriction and daily weights, for example, there must also be patient understanding, compliance, and accessibility to providers to recommend how to strike the fluid balance. Education is therefore necessary, but not sufficient, for setting up outpatient success.

The hospitalization also represents an important time to start or uptitrate guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for heart failure. Doing so takes advantage of an important opportunity to reduce the risk of readmission and even reverse the disease process.18 Uptitration of GDMT in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction is associated with a decreased risk of mortality, while discontinuation is associated with an increased risk of mortality.19 However, recent registry data indicate that intensity of GDMT is just as likely to be decreased as increased during the hospitalization.20 Nevertheless, predischarge initiation of medications may be associated with higher attained doses in follow-up.21

Preparing for Discharge

Preparing a patient for discharge after a heart failure hospitalization involves stabilizing the medical condition as well as ensuring that the patient and caregivers have the medication, equipment, and self-care resources at home necessary to manage the condition. Several frameworks have been put forth to help care teams analyze a patient’s readiness for discharge. One is the B-PREPARED score,22 a validated instrument to discriminate among patients with regard to their readiness to discharge from the hospital. This instrument highlights the importance of several key factors that should be addressed during the discharge process, including counseling and written instructions about medications and their side effects; information about equipment needs and community resources; and information on activity levels and restrictions. Nurse education and discharge coordination can improve patients’ perception of discharge readiness,23 although whether this discharge readiness translates into improved readmission rates appears to depend on the specific follow-up intervention design.9

Prior to discharge, it is important to arrange postdischarge follow-up appointments, as emphasized by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines.24 The use of nurse navigators can help with planning follow-up appointments. For example, the ACC Patient Navigator Program was applied in a single-center study of 120 patients randomized to the program versus usual care.25 This study found a significant increase in patient education and follow-up appointments compared to usual care, and a numerical decrease in hospital readmissions, although the finding was not statistically significant.25

A third critical component of preparing for discharge is identifying and addressing social barriers to care. In a study of patients stratified by household income, patients in the lowest income quartile had a higher readmission rate than patients in the highest income quartile.26 Poverty also correlates with heart failure mortality.27 Social factors play an important role in many aspects of patients’ ability to manage their health, including self-care, medication adherence, and ability to follow-up. Identifying these social factors prior to discharge is the first step to addressing them. While few studies specifically address the role of social workers in the management of heart failure care, the general medical literature suggests that social workers embedded in transitional care teams can augment readmission reduction efforts.28

After Discharge

Patients recently discharged from the hospital who have not yet attended their postdischarge appointment are in an incredibly vulnerable phase of care. Patients who are discharged from the hospital may not yet be connected with outpatient care. During this initial transitional care period, feedback loops involving patient communication back to the clinic, and clinic communication back to the patient, are critical to helping patients remain stable. For example, consider monitoring weights daily after hospital discharge. A patient at home can report increasing weights to a provider, who can then recommend an increased dose of diuretic. The patient can complete the feedback loop by taking the extra medication and monitoring the return of weight back to normal.

While daily weight monitoring is a simple process improvement that relies on the principle of establishing feedback loops, many other strategies exist. One commonly employed tool is the postdischarge telephone follow-up call, which is often coupled with other interventions in a comprehensive care bundle.8 During the telephone call, several process-of-care defects can be corrected, including missing medications or missing information on appointment times.

Beyond the telephone, newer technologies show promise for helping develop feedback loops for patients at home. One such technology is telemonitoring, whereby physiologic information such as weight, heart rate, and blood pressure is collected and sent back to a monitoring center. While the principle holds promise, several studies have not demonstrated significantly different outcomes as compared to usual care.13,29 Another promising technology is the CardioMEMS device (Abbott, Inc., Atlanta, GA), which can remotely transmit the pulmonary artery pressure, a physiologic signal which correlates with volume overload. There is now strong evidence supporting the efficacy of pulmonary artery pressure–guided heart failure management.30,31

Finally, home visits can be an efficient way to communicate symptoms, enable clinical assessment, and provide recommendations. One program that implemented home visits, 24-hour nurses available by call, and telephone follow-up showed a statistically significant reduction in readmissions.32 Furthermore, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing home health to usual care showed decreased readmissions and mortality.33 The efficacy may be in strengthening the feedback loop—home care improves compliance with weight monitoring, fluid restriction, and medications.34 These studies provide a strong rationale for the benefits of home health in stabilizing heart failure patients postdischarge. Indeed, nurse home visits were 1 of the 2 process interventions in a Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials that were shown to statistically significantly decrease readmissions and mortality.9 These data underscore the importance of feedback loops for helping ensure patients are clinically stable.

Postdischarge Follow-Up Clinic Visit

The first clinic appointment postdischarge is an important check-in to help advance patient care. Several key tasks can be achieved during the postdischarge visit. First, the patient can be clinically stabilized by adjusting diuretic therapy. If the patient is clinically stable, GDMT can be uptitrated. Second, education around symptoms, medications, diet, and exercise can be reinforced. Finally, clinicians can help connect patients to other members of the multidisciplinary care team, including specialist care, home health, or cardiac rehabilitation.

Achieving 7-day follow-up visits after discharge has been a point of emphasis in national guidelines.24 The ACC promotes a “See You in 7” challenge, advising that all patients discharged with a diagnosis of heart failure have a follow-up appointment within 7 days. Yet based on the latest available data, arrival rates to the postdischarge clinic are dismal, hovering around 30%.35 In a multicenter observational study of hospitals participating in the “See You in 7” collaborative, hospitals were able to increase their 7-day follow-up appointment rates by 2% to 3%, and also noted an absolute decrease in readmission rates by 1% to 2%.36 We have demonstrated, using a mathematical approach called queuing theory, that discharge appointment wait times and clinic access can be significantly improved by providing a modest capacity buffer to clinic availability.37 Those interested in applying this model to their own clinical practice may do so with a free online calculator at http://hfresearch.org.

Another important aspect of postdischarge follow-up is appropriate management of the comorbidity burden, which, as noted, is often significant in patients hospitalized with heart failure.38 For instance, in recent cohorts of hospitalized heart failure patients, the incidence of hypertension was 78%, coronary artery disease was more than 50%, atrial fibrillation was more than 40%, and diabetes was nearly 40%.39 Given this burden of comorbidity, it is not surprising that only 35% of readmissions after an index heart failure hospitalization are for recurrent heart failure.40 Coordinating care among primary care physicians and relevant subspecialists is thus essential. Phone calls and secure electronic messages are very helpful in achieving this. There is increasing interest in more nimble care models, such as the patient-centered specialty practice41 or the dyspnea clinic, to help bring coordinated resources to the patient.42

Process of Process Improvement: Our Experiences

The previous sections outline a series of potential process improvements clinical teams and health systems can implement to impact heart failure readmissions. A plan on paper, however, does not equal a plan in actuality. How does one go about implementing these changes? We offer our local experience starting a heart failure transitional care program as a case study, then draw lessons learned as a set of practical tips for local teams to employ. What we hope to highlight is that there is a large difference between a completed process for transitional care of heart failure patients, and the process of developing that process itself. The former is the hardware, the latter is the software. The latter does not typically get highlighted, but it is absolutely critical to unlocking the capabilities of a team and the institution.

In 2015, Northwestern Memorial Hospital adopted a novel payment arrangement from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services for Medicare patients being discharged from the hospital with heart failure. Known as Bundled Payments for Care Improvement,43 this bundled payment model incentivized Northwestern Memorial Hospital charge, principally by reducing hospital readmissions and by collaborating with skilled nursing facilities to control length of stay.

We approached this problem by drawing on the available literature,44,45 and by first creating a schematic of our high-level approach, which comprised 3 major elements (Figure 2): identification of hospitalized heart failure patients, delivery of a care bundle to hospitalized heart failure patients in hospital, and coordinating postdischarge care, centered on a telephone call and a postdischarge visit.

We then proceeded by building out, in stepwise fashion, each component of our value chain, using Agile techniques as a guiding principle.46 Agile, a productivity and process improvement mindset with roots in software development, emphasizes tackling 1 problem at a time, building out new features sequentially and completely, recognizing that the end user does not derive value from a program until new functionality is available for use. Rather than wholesale monolithic change, Agile emphasizes rapid iteration, prototyping, and discarding innovations not found to be helpful. The notion is to stand up new, incremental features rapidly, with each incremental improvement delivering value and helping to accelerate overall change.

Our experience building a robust way to identify heart failure cases is a good example of Agile process improvement in practice. At our hospital, identification of patients with heart failure was a challenge because more than half of heart failure patients are admitted to noncardiology floors. We developed a simple electronic health record query to detect heart failure patients, relying on parameters such as administration of intravenous diuretic or levels of BNP exceeding 100 ng/dL. We deployed this query, finding very high sensitivity for detection of heart failure patients.14 Patients found to have heart failure were then populated into a list in the electronic health record, which made patients’ heart failure status visible to all members of the health care team. Using this list, we were able to automate several processes necessary for heart failure care. For example, the list made it possible for cardiologists to know if there was a patient who perhaps needed cardiology consultation. Nurse navigators could know which patients needed heart failure education without having to be actively consulted by the admitting team. The same nurse navigators could then know upon discharge which patients needed a follow-up telephone call at 48 hours.

This list of heart failure patients was the end product, which was built through prototyping and iteration. For example, with our initial BNP cutoff of 300 ng/dL, we recognized we were missing several cases, and lowered the cutoff for the screener to 100 ng/dL. When we were satisfied this process was working well, we moved on to the next problem to tackle, avoiding trying to work on too many things at once. By doing so, we were able to focus our process improvement resources on 1 problem at a time, building up a suite of interventions. For our hospital, we settled on a bundle of interventions, captured by the mnemonic HEART:

Heart doctor sees patient in the hospital

Education about heart failure in the hospital

After-visit summary with 7-day appointment printed

Reach out to the patient by telephone within 72 hours

Treat the patient in clinic by the 7-day visit

Conclusion

We would like to emphasize that the elements of our heart failure readmissions interventions were not all put in place at once. This was an iterative process that proceeded in a stepwise fashion, with each step improving the care of our patients. We learned a number of lessons from our experience. First, we would advise that teams not try to do everything. One program simply cannot implement all possible readmission reduction interventions, and certainly not all at once. Trade-offs should be made, and interventions more likely to succeed in the local environment should be prioritized. In addition, interventions that do not fit and do not create synergy with the local practice environment should not be pursued.

Second, we would advise teams to start small, tackling a known problem in heart failure transitions of care first. This initial intuition is often right. An example might be improving 7-day appointments upon discharge. Starting with a problem that can be tackled builds process improvement muscle and improves team morale. Third, we would advise teams to consistently iterate on designs, tweaking and improving performance. Complex organizations always evolve; processes that work 1 year may fail the next because another element of the organization may have changed.

Finally, the framework presented in Figure 1 may be helpful in guiding how to structure interventions. Considering interventions to be delivered in the hospital, interventions to be delivered in the clinic, and how to set up feedback loops to support patients as outpatients help develop a comprehensive heart failure readmissions reduction program.

Corresponding author: R. Kannan Mutharasan, MD, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 676 North Saint Clair St., Arkes Pavilion, Suite 7-038, Chicago, IL 60611;[email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL.

Objective: To review selected process-of-care interventions that can be applied both during the hospitalization and during the transitional care period to help address the persistent challenge of heart failure readmissions.

Methods: Review of the literature.

Results: Process-of-care interventions that can be implemented to reduce readmissions of heart failure patients include: accurately identifying heart failure patients; providing disease education; titrating guideline-directed medical therapy; ensuring discharge readiness; arranging close discharge follow-up; identifying and addressing social barriers; following up by telephone; using home health; and addressing comorbidities. Importantly, the heart failure hospitalization is an opportunity to set up outpatient success, and setting up feedback loops can aid in post-discharge monitoring.

Conclusion: We encourage teams to consider local capabilities when selecting processes to improve; begin by improving something small to build capacity and team morale, and continually iterate and reexamine processes, as health care systems are continually evolving.

Keywords: heart failure; process improvement; quality improvement; readmission; rehospitalization; transitional care.

The growing population of patients affected by heart failure continues to challenge health systems. The increasing prevalence is paralleled by the rising costs of managing heart failure, which are projected to grow from $30.7 billion in 2012 to $69.8 billion in 2030.1 A significant portion of these costs relate to readmission after an index heart failure hospitalization. The statistics are staggering: for patients hospitalized with heart failure, approximately 15% to 20% are readmitted within 30 days.2,3 Though recent temporal trends suggest a modest reduction in readmission rates, there is a concerning correlation with increasing mortality,3 and a recognition that readmission rate decreases may relate to subtle changes in coding-based risk adjustment.4 Despite these concerns, efforts to reduce readmissions after heart failure hospitalization command significant attention.

Process improvement methodologies may be helpful in reducing hospital readmissions. Various approaches have been employed, and results have been mixed. An analysis of 70 participating hospitals in the American Heart Association’s Get With the Guidelines initiative found that, while overall readmission rates declined by 1.0% over 3 years, only 1 hospital achieved a 20% reduction in readmission rates.5

It is notably difficult to reduce readmissions after heart failure hospitalization. One challenge is that patients with heart failure often have multiple comorbidities, and approximately 50% to 60% of 30-day readmissions after heart failure hospitalization arise from noncardiac causes.1 Another challenge is that a significant fraction of readmissions in general—perhaps 75%—may not be avoidable.6

Recent excellent systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide comprehensive overviews of process improvement strategies that can be used to reduce readmissions after heart failure hospitalizations.7-9 Yet despite this extensive knowledge, few reports discuss the process of actually implementing these changes: the process of process improvement. Here, we seek to not only highlight some of the most promising potential interventions to reduce heart failure readmissions, but also to discuss a process improvement framework to help engender success, using our experience as a case study. We schematize process improvement efforts as having several distinct phases (Figure 1): processes delivered during the hospitalization and prior to discharge; feedback loops set up to maintain clinical stability at home; and the postdischarge clinic visit as an opportunity to further stabilize the patient and advance the plan of care. The discussion of these interventions follows this organization.

During Hospitalization

The heart failure hospitalization can be used as an opportunity to set up outpatient success, with several goals to target during the index admission. One goal is identifying the root causes of the heart failure syndrome and correcting those root causes, if possible. For example, patients in whom the heart failure syndrome is secondary to valvular heart disease may benefit from transcatheter aortic valve replacement.10 Another clinical goal is decongesting the patient, which is associated with lower readmission rates.11,12 These goals focus on the medical aspects of heart failure care. However, beyond these medical aspects, a patient must be equipped to successfully manage the disease at home.

To support medical and nonmedical interventions for hospitalized heart failure patients, a critical first step is identifying patients with heart failure. This accomplishes at least 2 objectives. First, early identification allows early initiation of interventions, such as heart failure education and social work evaluation. Early initiation of these interventions allows sufficient time during the hospitalization to make meaningful progress on these fronts. Second, early identification allows an opportunity for the delivery of cardiology specialty care, which may help with identifying and correcting root causes of the heart failure syndrome. Such access to cardiology has been shown to improve inpatient mortality and readmission rates.13

In smaller hospitals, identification of patients with heart failure can be as simple as reviewing overnight admissions. More advanced strategies, such as screeners based on brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels and administration of intravenous diuretics, can be employed.14,15 In the near future, deep learning-based natural language processing will be applied to mine full-text data in the electronic health record to identify heart failure hospitalizations.16

In the hospital, patients can also receive education about heart failure disease management. This education is a cornerstone of reducing heart failure readmissions. A recent systematic review of nurse education interventions demonstrated reductions in readmissions, hospitalizations, and costs.17 However, the efficacy of heart failure education hinges on many other variables. For patients to adhere to water restriction and daily weights, for example, there must also be patient understanding, compliance, and accessibility to providers to recommend how to strike the fluid balance. Education is therefore necessary, but not sufficient, for setting up outpatient success.

The hospitalization also represents an important time to start or uptitrate guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for heart failure. Doing so takes advantage of an important opportunity to reduce the risk of readmission and even reverse the disease process.18 Uptitration of GDMT in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction is associated with a decreased risk of mortality, while discontinuation is associated with an increased risk of mortality.19 However, recent registry data indicate that intensity of GDMT is just as likely to be decreased as increased during the hospitalization.20 Nevertheless, predischarge initiation of medications may be associated with higher attained doses in follow-up.21

Preparing for Discharge

Preparing a patient for discharge after a heart failure hospitalization involves stabilizing the medical condition as well as ensuring that the patient and caregivers have the medication, equipment, and self-care resources at home necessary to manage the condition. Several frameworks have been put forth to help care teams analyze a patient’s readiness for discharge. One is the B-PREPARED score,22 a validated instrument to discriminate among patients with regard to their readiness to discharge from the hospital. This instrument highlights the importance of several key factors that should be addressed during the discharge process, including counseling and written instructions about medications and their side effects; information about equipment needs and community resources; and information on activity levels and restrictions. Nurse education and discharge coordination can improve patients’ perception of discharge readiness,23 although whether this discharge readiness translates into improved readmission rates appears to depend on the specific follow-up intervention design.9

Prior to discharge, it is important to arrange postdischarge follow-up appointments, as emphasized by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines.24 The use of nurse navigators can help with planning follow-up appointments. For example, the ACC Patient Navigator Program was applied in a single-center study of 120 patients randomized to the program versus usual care.25 This study found a significant increase in patient education and follow-up appointments compared to usual care, and a numerical decrease in hospital readmissions, although the finding was not statistically significant.25

A third critical component of preparing for discharge is identifying and addressing social barriers to care. In a study of patients stratified by household income, patients in the lowest income quartile had a higher readmission rate than patients in the highest income quartile.26 Poverty also correlates with heart failure mortality.27 Social factors play an important role in many aspects of patients’ ability to manage their health, including self-care, medication adherence, and ability to follow-up. Identifying these social factors prior to discharge is the first step to addressing them. While few studies specifically address the role of social workers in the management of heart failure care, the general medical literature suggests that social workers embedded in transitional care teams can augment readmission reduction efforts.28

After Discharge

Patients recently discharged from the hospital who have not yet attended their postdischarge appointment are in an incredibly vulnerable phase of care. Patients who are discharged from the hospital may not yet be connected with outpatient care. During this initial transitional care period, feedback loops involving patient communication back to the clinic, and clinic communication back to the patient, are critical to helping patients remain stable. For example, consider monitoring weights daily after hospital discharge. A patient at home can report increasing weights to a provider, who can then recommend an increased dose of diuretic. The patient can complete the feedback loop by taking the extra medication and monitoring the return of weight back to normal.

While daily weight monitoring is a simple process improvement that relies on the principle of establishing feedback loops, many other strategies exist. One commonly employed tool is the postdischarge telephone follow-up call, which is often coupled with other interventions in a comprehensive care bundle.8 During the telephone call, several process-of-care defects can be corrected, including missing medications or missing information on appointment times.

Beyond the telephone, newer technologies show promise for helping develop feedback loops for patients at home. One such technology is telemonitoring, whereby physiologic information such as weight, heart rate, and blood pressure is collected and sent back to a monitoring center. While the principle holds promise, several studies have not demonstrated significantly different outcomes as compared to usual care.13,29 Another promising technology is the CardioMEMS device (Abbott, Inc., Atlanta, GA), which can remotely transmit the pulmonary artery pressure, a physiologic signal which correlates with volume overload. There is now strong evidence supporting the efficacy of pulmonary artery pressure–guided heart failure management.30,31

Finally, home visits can be an efficient way to communicate symptoms, enable clinical assessment, and provide recommendations. One program that implemented home visits, 24-hour nurses available by call, and telephone follow-up showed a statistically significant reduction in readmissions.32 Furthermore, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing home health to usual care showed decreased readmissions and mortality.33 The efficacy may be in strengthening the feedback loop—home care improves compliance with weight monitoring, fluid restriction, and medications.34 These studies provide a strong rationale for the benefits of home health in stabilizing heart failure patients postdischarge. Indeed, nurse home visits were 1 of the 2 process interventions in a Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials that were shown to statistically significantly decrease readmissions and mortality.9 These data underscore the importance of feedback loops for helping ensure patients are clinically stable.

Postdischarge Follow-Up Clinic Visit

The first clinic appointment postdischarge is an important check-in to help advance patient care. Several key tasks can be achieved during the postdischarge visit. First, the patient can be clinically stabilized by adjusting diuretic therapy. If the patient is clinically stable, GDMT can be uptitrated. Second, education around symptoms, medications, diet, and exercise can be reinforced. Finally, clinicians can help connect patients to other members of the multidisciplinary care team, including specialist care, home health, or cardiac rehabilitation.

Achieving 7-day follow-up visits after discharge has been a point of emphasis in national guidelines.24 The ACC promotes a “See You in 7” challenge, advising that all patients discharged with a diagnosis of heart failure have a follow-up appointment within 7 days. Yet based on the latest available data, arrival rates to the postdischarge clinic are dismal, hovering around 30%.35 In a multicenter observational study of hospitals participating in the “See You in 7” collaborative, hospitals were able to increase their 7-day follow-up appointment rates by 2% to 3%, and also noted an absolute decrease in readmission rates by 1% to 2%.36 We have demonstrated, using a mathematical approach called queuing theory, that discharge appointment wait times and clinic access can be significantly improved by providing a modest capacity buffer to clinic availability.37 Those interested in applying this model to their own clinical practice may do so with a free online calculator at http://hfresearch.org.

Another important aspect of postdischarge follow-up is appropriate management of the comorbidity burden, which, as noted, is often significant in patients hospitalized with heart failure.38 For instance, in recent cohorts of hospitalized heart failure patients, the incidence of hypertension was 78%, coronary artery disease was more than 50%, atrial fibrillation was more than 40%, and diabetes was nearly 40%.39 Given this burden of comorbidity, it is not surprising that only 35% of readmissions after an index heart failure hospitalization are for recurrent heart failure.40 Coordinating care among primary care physicians and relevant subspecialists is thus essential. Phone calls and secure electronic messages are very helpful in achieving this. There is increasing interest in more nimble care models, such as the patient-centered specialty practice41 or the dyspnea clinic, to help bring coordinated resources to the patient.42

Process of Process Improvement: Our Experiences

The previous sections outline a series of potential process improvements clinical teams and health systems can implement to impact heart failure readmissions. A plan on paper, however, does not equal a plan in actuality. How does one go about implementing these changes? We offer our local experience starting a heart failure transitional care program as a case study, then draw lessons learned as a set of practical tips for local teams to employ. What we hope to highlight is that there is a large difference between a completed process for transitional care of heart failure patients, and the process of developing that process itself. The former is the hardware, the latter is the software. The latter does not typically get highlighted, but it is absolutely critical to unlocking the capabilities of a team and the institution.

In 2015, Northwestern Memorial Hospital adopted a novel payment arrangement from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services for Medicare patients being discharged from the hospital with heart failure. Known as Bundled Payments for Care Improvement,43 this bundled payment model incentivized Northwestern Memorial Hospital charge, principally by reducing hospital readmissions and by collaborating with skilled nursing facilities to control length of stay.

We approached this problem by drawing on the available literature,44,45 and by first creating a schematic of our high-level approach, which comprised 3 major elements (Figure 2): identification of hospitalized heart failure patients, delivery of a care bundle to hospitalized heart failure patients in hospital, and coordinating postdischarge care, centered on a telephone call and a postdischarge visit.

We then proceeded by building out, in stepwise fashion, each component of our value chain, using Agile techniques as a guiding principle.46 Agile, a productivity and process improvement mindset with roots in software development, emphasizes tackling 1 problem at a time, building out new features sequentially and completely, recognizing that the end user does not derive value from a program until new functionality is available for use. Rather than wholesale monolithic change, Agile emphasizes rapid iteration, prototyping, and discarding innovations not found to be helpful. The notion is to stand up new, incremental features rapidly, with each incremental improvement delivering value and helping to accelerate overall change.

Our experience building a robust way to identify heart failure cases is a good example of Agile process improvement in practice. At our hospital, identification of patients with heart failure was a challenge because more than half of heart failure patients are admitted to noncardiology floors. We developed a simple electronic health record query to detect heart failure patients, relying on parameters such as administration of intravenous diuretic or levels of BNP exceeding 100 ng/dL. We deployed this query, finding very high sensitivity for detection of heart failure patients.14 Patients found to have heart failure were then populated into a list in the electronic health record, which made patients’ heart failure status visible to all members of the health care team. Using this list, we were able to automate several processes necessary for heart failure care. For example, the list made it possible for cardiologists to know if there was a patient who perhaps needed cardiology consultation. Nurse navigators could know which patients needed heart failure education without having to be actively consulted by the admitting team. The same nurse navigators could then know upon discharge which patients needed a follow-up telephone call at 48 hours.

This list of heart failure patients was the end product, which was built through prototyping and iteration. For example, with our initial BNP cutoff of 300 ng/dL, we recognized we were missing several cases, and lowered the cutoff for the screener to 100 ng/dL. When we were satisfied this process was working well, we moved on to the next problem to tackle, avoiding trying to work on too many things at once. By doing so, we were able to focus our process improvement resources on 1 problem at a time, building up a suite of interventions. For our hospital, we settled on a bundle of interventions, captured by the mnemonic HEART:

Heart doctor sees patient in the hospital

Education about heart failure in the hospital

After-visit summary with 7-day appointment printed

Reach out to the patient by telephone within 72 hours

Treat the patient in clinic by the 7-day visit

Conclusion

We would like to emphasize that the elements of our heart failure readmissions interventions were not all put in place at once. This was an iterative process that proceeded in a stepwise fashion, with each step improving the care of our patients. We learned a number of lessons from our experience. First, we would advise that teams not try to do everything. One program simply cannot implement all possible readmission reduction interventions, and certainly not all at once. Trade-offs should be made, and interventions more likely to succeed in the local environment should be prioritized. In addition, interventions that do not fit and do not create synergy with the local practice environment should not be pursued.

Second, we would advise teams to start small, tackling a known problem in heart failure transitions of care first. This initial intuition is often right. An example might be improving 7-day appointments upon discharge. Starting with a problem that can be tackled builds process improvement muscle and improves team morale. Third, we would advise teams to consistently iterate on designs, tweaking and improving performance. Complex organizations always evolve; processes that work 1 year may fail the next because another element of the organization may have changed.

Finally, the framework presented in Figure 1 may be helpful in guiding how to structure interventions. Considering interventions to be delivered in the hospital, interventions to be delivered in the clinic, and how to set up feedback loops to support patients as outpatients help develop a comprehensive heart failure readmissions reduction program.

Corresponding author: R. Kannan Mutharasan, MD, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 676 North Saint Clair St., Arkes Pavilion, Suite 7-038, Chicago, IL 60611;[email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC. The prevention of hospital readmissions in heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58:379-385.

2. Kwok CS, Seferovic PM, Van Spall HG, et al. Early unplanned readmissions after admission to hospital with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124:736-745.

3. Fonarow GC, Konstam MA, Yancy CW. The hospital readmission reduction program is associated with fewer readmissions, more deaths: time to reconsider. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1931-1934.

4. Ody C, Msall L, Dafny LS, et al. Decreases in readmissions credited to medicare’s program to reduce hospital readmissions have been overstated. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38:36-43.

5. Bergethon KE, Ju C, DeVore AD, et al. Trends in 30-day readmission rates for patients hospitalized with heart failure: findings from the Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure Registry. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9.

6. van Walraven C, Jennings A, Forster AJ. A meta-analysis of hospital 30-day avoidable readmission rates. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(6):1211-1218.

7. Albert NM. A systematic review of transitional-care strategies to reduce rehospitalization in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2016;45:100-113.

8. Takeda A, Martin N, Taylor RS, Taylor SJ. Disease management interventions for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD002752.

9. Van Spall HGC, Rahman T, Mytton O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of transitional care services in patients discharged from the hospital with heart failure: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1427-1443.

10. Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, et al. Surgical or transcatheter aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1321-1331.

11. Lala A, McNulty SE, Mentz RJ, et al. Relief and recurrence of congestion during and after hospitalization for acute heart failure: insights from Diuretic Optimization Strategy Evaluation in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (DOSE-AHF) and Cardiorenal Rescue Study in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (CARESS-HF). Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:741-748.

12. Ambrosy AP, Pang PS, Khan S, et al. Clinical course and predictive value of congestion during hospitalization in patients admitted for worsening signs and symptoms of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: findings from the EVEREST trial. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:835-843.

13. Driscoll A, Meagher S, Kennedy R, et al. What is the impact of systems of care for heart failure on patients diagnosed with heart failure: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16(1):195.

14. Ahmad FS, Wehbe RM, Kansal P, et al. Targeting the correct population when designing transitional care programs for medicare patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1274-1275.

15. Blecker S, Sontag D, Horwitz LI, et al. Early identification of patients with acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2018;24:357-362.

16. Lee J, Yoon W, Kim S, et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:1234-1240.

17. Rice H, Say R, Betihavas V. The effect of nurse-led education on hospitalisation, readmission, quality of life and cost in adults with heart failure. A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:363-374.

18. Hollenberg SM, Warner Stevenson L, Ahmad T, et al. 2019 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on risk assessment, management, and clinical trajectory of patients hospitalized with heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1966-2011.

19. Tran RH, Aldemerdash A, Chang P, et al. Guideline-directed medical therapy and survival following hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38:406-416.

20. Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, DeVore AD, et al. Titration of medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2365-2383.