User login

Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty for Distal Femur Fractures: A Systematic Review of Indications, Implants, Techniques, and Results

Take-Home Points

- Arthroplasty is a rarely utilized and, therefore, a rarely reported treatment for distal femur fractures.

- Arthroplasty carries certain advantages over fixation, including earlier weight-bearing, a benefit for elderly individuals.

- Arthroplasty is more often described in situations of comminution, often necessitating constrained prostheses.

- It is not unreasonable to utilize arthroplasty in extra-articular fractures in poor-quality bone, which can take the form of unconstrained prosthesis and supplemental fixation.

- The true complication rate is unclear, given that the few papers reporting high complication rates were in sicker populations.

Distal femur fractures (DFFs) in the elderly historically were difficult to treat because of osteoporotic bone, comminution, and intra-articular involvement. DFFs in minimally ambulatory patients were once treated nonoperatively, with traction or immobilization,1,2 but surgery is now considered for displaced and unstable fractures, even in myelopathic and nonambulatory patients, to provide pain relief, ease mobility, and decrease the risks associated with prolonged bed rest.1 Options are constantly evolving, but poor knee function, malunion, nonunion, prolonged immobilization, implant failure, and high morbidity and mortality rates have been reported in several studies regardless of fixation method.

Arthritis after DFF has been reported at rates of 36% to 50% by long-term follow-up.3-5 However, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for posttraumatic arthritis is more complex because of scarring, arthrofibrosis, malunion, nonunion, and the frequent need for hardware removal. These cases have a higher incidence of infection, aseptic loosening, stiffness,6 and skin necrosis.7 Primary TKA is a rarely used treatment for acute DFF. Several authors have recommended primary TKA for patients with intra-articular DFFs and preexisting osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, severe comminution, or poor bone stock.7-22 Compared with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), primary TKA may allow for earlier mobility and weight-bearing and thereby reduce the rates of complications (eg, respiratory failure, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism) associated with prolonged immobilization.23As the literature on TKA for acute DFF is scant, and to our knowledge there are no clear indications or guidelines, we performed a systematic review to determine whether TKA has been successful in relieving pain and restoring knee function. In this article, we discuss the indications, implant options, technical considerations, complications, and results (eg, range of motion [ROM], ambulatory status) associated with these procedures.

Methods

On December 1, 2015, we searched the major databases Medline, EMBASE (Excerpta Medica dataBASE), and the Cochrane Library for articles published since 1950. In our searches, we used the conjoint term knee arthroplasty with femur fracture, and knee replacement with femur fracture. Specifically, we queried: ((“knee replacement” OR “knee arthroplasty”) AND (intercondylar OR supracondylar OR femoral OR femur) AND fracture) NOT arthrodesis NOT periprosthetic NOT “posttraumatic arthritis” NOT osteotomy. We also hand-searched the current website of JBJS [Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery] Case Connector, a major case-report repository that was launched in 2011 but is not currently indexed by Medline.

All citations were imported to RefWorks for management and for removal of duplicates. Each article underwent screening and review by Dr. Chen and Dr. Li. Articles were included if titles were relevant to arthroplasty as treatment for acute (within 1 month) DFF. Articles and cases were excluded if they were reviews, published in languages other than English, animal studies, studies regarding nonacute (>3 months or nonunion) DFFs or periprosthetic fractures, or studies that considered only treatments other than TKA (ie, plate osteosynthesis).

Full-text publications were obtained and independently reviewed by Dr. Chen and Dr. Li for relevance and satisfaction of inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Given the rarity of publications on the treatment, all study designs from level I to level IV were included.

The same 2 reviewers extracted the data into prearranged summary tables. Data included study size, patient demographics, AO/OTA (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Orthopaedic Trauma Association) fracture type either reported or assessed by description and imaging (33A, extra-articular; 33B, partial articular with 1 intact condyle; 33C, complete articular with both condyles involved), baseline comorbidity, implant used and fracture treatment (if separate from arthroplasty), postoperative regimen, respective outcomes, and complication rates.

Results

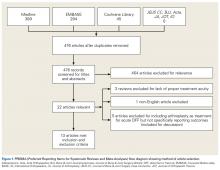

We identified 728 articles: 389 through Medline, 294 through EMBASE, and 45 through the Cochrane Library (Figure 1).

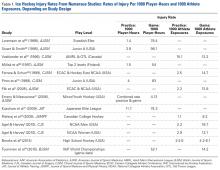

The current evidence regarding primary TKA for acute DFF is primarily level IV (Table 1). Only 1 level III study16 compared TKA with ORIF. Three case series11,19,24 met our inclusion criteria (Table 1, Table 2). In addition, 5 case series involved patients who met our criteria, but these studies did not separately report results for DFFs and proximal tibia fractures,9,20-22 or separately for acute fractures and nonunions or ORIF failures.8

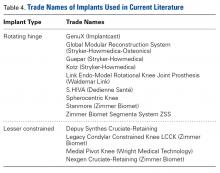

Modular, hinged, and tumor-type arthroplasty designs accounted for 83% of the treatments included in this review. Trade names are listed in Table 4. Authors who used these implants took a more aggressive approach, often resecting the entire femoral epiphyseal-metaphyseal area, menisci, and collateral ligaments.9,13,15,16,18 The majority of patients who underwent resection had 33C fractures (Tables 1, 3).

The majority of authors who treated fractures with resection and modular implants allowed their patients full weight-bearing soon after surgery (Table 1),11,12,15-18,24 whereas authors who treated their patients partly with fracture fixation often had to delay weight-bearing (Table 1).

Cement use was universally described in the literature. Some authors avoided placing cement in the fracture site (to reduce the risk of nonunion),7,19 whereas others used bone cement to fill metaphyseal defects that remained after fracture resection and implantation.11,24Complication rates were modest, and there were no reports specifically on implant loosening or fracture nonunion.7,10,12-19 The majority of complications were recorded in 2 studies that used megaprostheses in sicker populations: Bell and colleagues11 noted debilitating illnesses in all their patients, and Appleton and colleagues24 included 9 nonambulatory patients and 36 patients who required 2 assistants to ambulate. All deaths were attributed to medical comorbidities and disseminated malignancy. Contrarily, studies by Pearse and colleagues16 and Choi and colleagues19 included previously ambulatory patients and reported no deaths or complications (Table 2). Likewise, in studies that combined results of DFFs and proximal tibia fractures, death and complication rates varied from 7% to 31% (Table 3).

Discussion

DFFs in the elderly historically were difficult to treat. Reported outcomes are largely favorable, but, even with newer plate designs, catastrophic failures still occur in the absence of bony union.26,27 After ORIF, patients’ weight-bearing is often restricted for 12 weeks or longer28—a protocol that is undesirable in elderly patients, especially given that the rate of mortality 1 year after these fractures has been found to be as high as 25%.29

Arthroplasty for DFFs—performed either with ORIF, or independently with a constrained implant—is a documented treatment modality, but the evidence is poor, and results have been mixed. Patients who received hinged TKA with major fracture resection had higher complication rates.8,11,22,24 However, the problems were mostly medical, not associated with surgical technique. Appleton and colleagues24 found a higher than expected 1-year mortality rate, 41%, but used an unhealthy baseline population (44% cognitive impairment, 17% nonambulatory before injury).Although Boureau and colleagues22 found a 1-year mortality rate of 30%, only 1 in 10 deaths was attributable to a perioperative complication. Among the remaining cases involving resection and megaprostheses for previously ambulatory patients, only 1 perioperative death was recorded (Table 2).11,12,16,18 Therefore, the risks associated with patients’ baseline health and ambulatory status must be weighed against the benefits of aggressive arthroplasty.

An overwhelming majority of 33C fractures were treated with megaprostheses—a finding perhaps attributable to the higher likelihood that patients with osteoporosis have intra-articular, comminuted injuries. In addition, surgeons may have been more likely to indicate 33C fractures for joint replacement, whereas 33A and 33B patterns were more amenable to fracture fixation.17,18 Interestingly, few type B fractures (0 in primary analysis and only 9 of 67 cases in Table 3) were treated with megaprostheses. In these situations, 1 condyle and ligamentous constraint remain intact, reducing the need for a constrained implant.

There were no reports of atraumatic or aseptic loosening, though use of rotating platforms with linked prostheses helps minimize this complication. Also surprising is the lack of nonunions in any of the reviewed studies, as nonunion is one of the most devastating complications of ORIF. Only 1 superficial and 2 deep infections were reported in all of the literature—representing 1.8% of all cases, which is comparable to the rate for elective primary TKA.30In elderly patients with significant comorbidities, the main surgical goals are to minimize operative time and reduce time to mobility. It is therefore imperative to keep in mind that arthroplasty is elective. However, functional results of primary TKA for DFF may be more encouraging for healthier patients, as many can achieve satisfactory ROM and early weight-bearing. Therefore, TKA for DFF may benefit healthy and ambulatory patients in the setting of intra-articular comminution. Whether this treatment affects mortality rates remains to be seen.

There were several limitations to this study. First, the literature on the topic is scant. Second, exclusion criteria were kept lax to allow for inclusion of all treatments. This came at a cost to internal validity, given the heterogeneous population and differences in comorbidities between studies. Fracture classification was inconsistent as well: Although AO/OTA classification was dominant, descriptive classifications were used in several cases7,10,12 (these descriptions, however, were sufficient for assigning equivalent AO/OTA classes). Details on preoperative functional status and comorbidity status and on postoperative protocols were also limited, though ROM and ambulatory status were provided in most studies. Last, most of these studies were single case reports or case series, so there may be reporting bias in the body of the literature, as reflected in the discrepancies between encouraging case reports and concerning case series with longer follow-up. Such bias can be avoided with larger, controlled sampling and adequate follow-up.

TKA should be considered for acute DFF in patients who have knee arthritis and are able to tolerate the physiological load of the surgery. In the choice of implant design, several factors should be considered, including bone quality, articular involvement, degree of comminution, and ligamentous injury. Unconstrained knee designs should be considered in cases in which the fracture pattern appears stable and the collateral ligaments are intact (eg, 33A and 33BB fractures). Megaprostheses, which may allow for immediate weight-bearing but require considerable bone resection, would be beneficial in 33C fractures and in fractures with ligamentous compromise. However, their complication rates are unclear, and comparative studies are needed to investigate whether the rates are higher for these patients than for patients treated more traditionally.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):E163-E171. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Cass J, Sems SA. Operative versus nonoperative management of distal femur fracture in myelopathic, nonambulatory patients. Orthopedics. 2008;31(11):1091.

2. Eichenholtz SN. Management of long-bone fracture in paraplegic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;45(2):299-310.

3. Thomson AB, Driver R, Kregor PJ, Obremskey WT. Long-term functional outcomes after intra-articular distal femur fractures: ORIF versus retrograde intramedullary nailing. Orthopedics. 2008;31(8):748-750.

4. Rademakers MV, Kerkhoffs GM, Sierevelt IN, Raaymakers EL, Marti RK. Intra-articular fractures of the distal femur: a long-term follow-up study of surgically treated patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(4):213-219.

5. Schenker ML, Mauck RL, Ahn J, Mehta S. Pathogenesis and prevention of posttraumatic osteoarthritis after intra-articular fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(1):20-28.

6. Papadopoulos EC, Parvizi J, Lai CH, Lewallen DG. Total knee arthroplasty following prior distal femoral fracture. Knee. 2002;9(4):267-274.

7. Yoshino N, Takai S, Watanabe Y, Fujiwara H, Ohshima Y, Hirasawa Y. Primary total knee arthroplasty for supracondylar/condylar femoral fracture in osteoarthritic knees. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(4):471-475.

8. Rosen AL, Strauss E. Primary total knee arthroplasty for complex distal femur fractures in elderly patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(425):101-105.

9. Malviya A, Reed MR, Partington PF. Acute primary total knee arthroplasty for peri-articular knee fractures in patients over 65 years of age. Injury. 2011;42(11):1368-1371.

10. Wolfgang GL. Primary total knee arthroplasty for intercondylar fracture of the femur in a rheumatoid arthritic patient. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(171):80-82.

11. Bell KM, Johnstone AJ, Court-Brown CM, Hughes SP. Primary knee arthroplasty for distal femoral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74(3):400-402.

12. Shah A, Asirvatham R, Sudlow RA. Primary resection total knee arthroplasty for complicated fracture of the distal femur with an arthritic knee joint. Contemp Orthop. 1993;26(5):463-467.

13. Freedman EL, Hak DJ, Johnson EE, Eckardt JJ. Total knee replacement including a modular distal femoral component in elderly patients with acute fracture or nonunion. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(3):231-237.

14. Patterson RH, Earll M. Repair of supracondylar femur fracture and unilateral knee replacement at the same surgery. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13(5):388-390.

15. Nau T, Pflegerl E, Erhart J, Vecsei V. Primary total knee arthroplasty for periarticular fractures. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(8):968-971.

16. Pearse EO, Klass B, Bendall SP, Railton GT. Stanmore total knee replacement versus internal fixation for supracondylar fractures of the distal femur in elderly patients. Injury. 2005;36(1):163-168.

17. Mounasamy V, Ma SY, Schoderbek RJ, Mihalko WM, Saleh KJ, Brown TE. Primary total knee arthroplasty with condylar allograft and MCL reconstruction for a comminuted medial condyle fracture in an arthritic knee—a case report. Knee. 2006;13(5):400-403.

18. Mounasamy V, Cui Q, Brown TE, Saleh KJ, Mihalko WM. Primary total knee arthroplasty for a complex distal femur fracture in the elderly: a case report. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2007;17(5):491-494.

19. Choi NY, Sohn JM, Cho SG, Kim SC, In Y. Primary total knee arthroplasty for simple distal femoral fractures in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2013;25(3):141-146.

20. Parratte S, Bonnevialle P, Pietu G, Saragaglia D, Cherrier B, Lafosse JM. Primary total knee arthroplasty in the management of epiphyseal fracture around the knee. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2011;97(6 suppl):S87-S94.

21. Benazzo F, Rossi SM, Ghiara M, Zanardi A, Perticarini L, Combi A. Total knee replacement in acute and chronic traumatic events. Injury. 2014;45(suppl 6):S98-S104.

22. Boureau F, Benad K, Putman S, Dereudre G, Kern G, Chantelot C. Does primary total knee arthroplasty for acute knee joint fracture maintain autonomy in the elderly? A retrospective study of 21 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(8):947-951.

23. Bishop JA, Suarez P, Diponio L, Ota D, Curtin CM. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of femur fractures in people with spinal cord injury: an administrative analysis of risks. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(12):2357-2364.

24. Appleton P, Moran M, Houshian S, Robinson CM. Distal femoral fractures treated by hinged total knee replacement in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(8):1065-1070.

25. In Y, Koh HS, Kim SJ. Cruciate-retaining stemmed total knee arthroplasty for supracondylar-intercondylar femoral fractures in elderly patients: a report of three cases. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(7):1074-1079.

26. Kregor PJ, Stannard JA, Zlowodzki M, Cole PA. Treatment of distal femur fractures using the less invasive stabilization system: surgical experience and early clinical results in 103 fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(8):509-520.

27. Vallier HA, Hennessey TA, Sontich JK, Patterson BM. Failure of LCP condylar plate fixation in the distal part of the femur. A report of six cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(4):846-853.

28. Gwathmey FW Jr, Jones-Quaidoo SM, Kahler D, Hurwitz S, Cui Q. Distal femoral fractures: current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(10):597-607.

29. Streubel PN, Ricci WM, Wong A, Gardner MJ. Mortality after distal femur fractures in elderly patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1188-1196.

30. Peersman G, Laskin R, Davis J, Peterson M. Infection in total knee replacement: a retrospective review of 6489 total knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(392):15-23.

Take-Home Points

- Arthroplasty is a rarely utilized and, therefore, a rarely reported treatment for distal femur fractures.

- Arthroplasty carries certain advantages over fixation, including earlier weight-bearing, a benefit for elderly individuals.

- Arthroplasty is more often described in situations of comminution, often necessitating constrained prostheses.

- It is not unreasonable to utilize arthroplasty in extra-articular fractures in poor-quality bone, which can take the form of unconstrained prosthesis and supplemental fixation.

- The true complication rate is unclear, given that the few papers reporting high complication rates were in sicker populations.

Distal femur fractures (DFFs) in the elderly historically were difficult to treat because of osteoporotic bone, comminution, and intra-articular involvement. DFFs in minimally ambulatory patients were once treated nonoperatively, with traction or immobilization,1,2 but surgery is now considered for displaced and unstable fractures, even in myelopathic and nonambulatory patients, to provide pain relief, ease mobility, and decrease the risks associated with prolonged bed rest.1 Options are constantly evolving, but poor knee function, malunion, nonunion, prolonged immobilization, implant failure, and high morbidity and mortality rates have been reported in several studies regardless of fixation method.

Arthritis after DFF has been reported at rates of 36% to 50% by long-term follow-up.3-5 However, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for posttraumatic arthritis is more complex because of scarring, arthrofibrosis, malunion, nonunion, and the frequent need for hardware removal. These cases have a higher incidence of infection, aseptic loosening, stiffness,6 and skin necrosis.7 Primary TKA is a rarely used treatment for acute DFF. Several authors have recommended primary TKA for patients with intra-articular DFFs and preexisting osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, severe comminution, or poor bone stock.7-22 Compared with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), primary TKA may allow for earlier mobility and weight-bearing and thereby reduce the rates of complications (eg, respiratory failure, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism) associated with prolonged immobilization.23As the literature on TKA for acute DFF is scant, and to our knowledge there are no clear indications or guidelines, we performed a systematic review to determine whether TKA has been successful in relieving pain and restoring knee function. In this article, we discuss the indications, implant options, technical considerations, complications, and results (eg, range of motion [ROM], ambulatory status) associated with these procedures.

Methods

On December 1, 2015, we searched the major databases Medline, EMBASE (Excerpta Medica dataBASE), and the Cochrane Library for articles published since 1950. In our searches, we used the conjoint term knee arthroplasty with femur fracture, and knee replacement with femur fracture. Specifically, we queried: ((“knee replacement” OR “knee arthroplasty”) AND (intercondylar OR supracondylar OR femoral OR femur) AND fracture) NOT arthrodesis NOT periprosthetic NOT “posttraumatic arthritis” NOT osteotomy. We also hand-searched the current website of JBJS [Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery] Case Connector, a major case-report repository that was launched in 2011 but is not currently indexed by Medline.

All citations were imported to RefWorks for management and for removal of duplicates. Each article underwent screening and review by Dr. Chen and Dr. Li. Articles were included if titles were relevant to arthroplasty as treatment for acute (within 1 month) DFF. Articles and cases were excluded if they were reviews, published in languages other than English, animal studies, studies regarding nonacute (>3 months or nonunion) DFFs or periprosthetic fractures, or studies that considered only treatments other than TKA (ie, plate osteosynthesis).

Full-text publications were obtained and independently reviewed by Dr. Chen and Dr. Li for relevance and satisfaction of inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Given the rarity of publications on the treatment, all study designs from level I to level IV were included.

The same 2 reviewers extracted the data into prearranged summary tables. Data included study size, patient demographics, AO/OTA (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Orthopaedic Trauma Association) fracture type either reported or assessed by description and imaging (33A, extra-articular; 33B, partial articular with 1 intact condyle; 33C, complete articular with both condyles involved), baseline comorbidity, implant used and fracture treatment (if separate from arthroplasty), postoperative regimen, respective outcomes, and complication rates.

Results

We identified 728 articles: 389 through Medline, 294 through EMBASE, and 45 through the Cochrane Library (Figure 1).

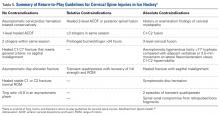

The current evidence regarding primary TKA for acute DFF is primarily level IV (Table 1). Only 1 level III study16 compared TKA with ORIF. Three case series11,19,24 met our inclusion criteria (Table 1, Table 2). In addition, 5 case series involved patients who met our criteria, but these studies did not separately report results for DFFs and proximal tibia fractures,9,20-22 or separately for acute fractures and nonunions or ORIF failures.8

Modular, hinged, and tumor-type arthroplasty designs accounted for 83% of the treatments included in this review. Trade names are listed in Table 4. Authors who used these implants took a more aggressive approach, often resecting the entire femoral epiphyseal-metaphyseal area, menisci, and collateral ligaments.9,13,15,16,18 The majority of patients who underwent resection had 33C fractures (Tables 1, 3).

The majority of authors who treated fractures with resection and modular implants allowed their patients full weight-bearing soon after surgery (Table 1),11,12,15-18,24 whereas authors who treated their patients partly with fracture fixation often had to delay weight-bearing (Table 1).

Cement use was universally described in the literature. Some authors avoided placing cement in the fracture site (to reduce the risk of nonunion),7,19 whereas others used bone cement to fill metaphyseal defects that remained after fracture resection and implantation.11,24Complication rates were modest, and there were no reports specifically on implant loosening or fracture nonunion.7,10,12-19 The majority of complications were recorded in 2 studies that used megaprostheses in sicker populations: Bell and colleagues11 noted debilitating illnesses in all their patients, and Appleton and colleagues24 included 9 nonambulatory patients and 36 patients who required 2 assistants to ambulate. All deaths were attributed to medical comorbidities and disseminated malignancy. Contrarily, studies by Pearse and colleagues16 and Choi and colleagues19 included previously ambulatory patients and reported no deaths or complications (Table 2). Likewise, in studies that combined results of DFFs and proximal tibia fractures, death and complication rates varied from 7% to 31% (Table 3).

Discussion

DFFs in the elderly historically were difficult to treat. Reported outcomes are largely favorable, but, even with newer plate designs, catastrophic failures still occur in the absence of bony union.26,27 After ORIF, patients’ weight-bearing is often restricted for 12 weeks or longer28—a protocol that is undesirable in elderly patients, especially given that the rate of mortality 1 year after these fractures has been found to be as high as 25%.29

Arthroplasty for DFFs—performed either with ORIF, or independently with a constrained implant—is a documented treatment modality, but the evidence is poor, and results have been mixed. Patients who received hinged TKA with major fracture resection had higher complication rates.8,11,22,24 However, the problems were mostly medical, not associated with surgical technique. Appleton and colleagues24 found a higher than expected 1-year mortality rate, 41%, but used an unhealthy baseline population (44% cognitive impairment, 17% nonambulatory before injury).Although Boureau and colleagues22 found a 1-year mortality rate of 30%, only 1 in 10 deaths was attributable to a perioperative complication. Among the remaining cases involving resection and megaprostheses for previously ambulatory patients, only 1 perioperative death was recorded (Table 2).11,12,16,18 Therefore, the risks associated with patients’ baseline health and ambulatory status must be weighed against the benefits of aggressive arthroplasty.

An overwhelming majority of 33C fractures were treated with megaprostheses—a finding perhaps attributable to the higher likelihood that patients with osteoporosis have intra-articular, comminuted injuries. In addition, surgeons may have been more likely to indicate 33C fractures for joint replacement, whereas 33A and 33B patterns were more amenable to fracture fixation.17,18 Interestingly, few type B fractures (0 in primary analysis and only 9 of 67 cases in Table 3) were treated with megaprostheses. In these situations, 1 condyle and ligamentous constraint remain intact, reducing the need for a constrained implant.

There were no reports of atraumatic or aseptic loosening, though use of rotating platforms with linked prostheses helps minimize this complication. Also surprising is the lack of nonunions in any of the reviewed studies, as nonunion is one of the most devastating complications of ORIF. Only 1 superficial and 2 deep infections were reported in all of the literature—representing 1.8% of all cases, which is comparable to the rate for elective primary TKA.30In elderly patients with significant comorbidities, the main surgical goals are to minimize operative time and reduce time to mobility. It is therefore imperative to keep in mind that arthroplasty is elective. However, functional results of primary TKA for DFF may be more encouraging for healthier patients, as many can achieve satisfactory ROM and early weight-bearing. Therefore, TKA for DFF may benefit healthy and ambulatory patients in the setting of intra-articular comminution. Whether this treatment affects mortality rates remains to be seen.

There were several limitations to this study. First, the literature on the topic is scant. Second, exclusion criteria were kept lax to allow for inclusion of all treatments. This came at a cost to internal validity, given the heterogeneous population and differences in comorbidities between studies. Fracture classification was inconsistent as well: Although AO/OTA classification was dominant, descriptive classifications were used in several cases7,10,12 (these descriptions, however, were sufficient for assigning equivalent AO/OTA classes). Details on preoperative functional status and comorbidity status and on postoperative protocols were also limited, though ROM and ambulatory status were provided in most studies. Last, most of these studies were single case reports or case series, so there may be reporting bias in the body of the literature, as reflected in the discrepancies between encouraging case reports and concerning case series with longer follow-up. Such bias can be avoided with larger, controlled sampling and adequate follow-up.

TKA should be considered for acute DFF in patients who have knee arthritis and are able to tolerate the physiological load of the surgery. In the choice of implant design, several factors should be considered, including bone quality, articular involvement, degree of comminution, and ligamentous injury. Unconstrained knee designs should be considered in cases in which the fracture pattern appears stable and the collateral ligaments are intact (eg, 33A and 33BB fractures). Megaprostheses, which may allow for immediate weight-bearing but require considerable bone resection, would be beneficial in 33C fractures and in fractures with ligamentous compromise. However, their complication rates are unclear, and comparative studies are needed to investigate whether the rates are higher for these patients than for patients treated more traditionally.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):E163-E171. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Arthroplasty is a rarely utilized and, therefore, a rarely reported treatment for distal femur fractures.

- Arthroplasty carries certain advantages over fixation, including earlier weight-bearing, a benefit for elderly individuals.

- Arthroplasty is more often described in situations of comminution, often necessitating constrained prostheses.

- It is not unreasonable to utilize arthroplasty in extra-articular fractures in poor-quality bone, which can take the form of unconstrained prosthesis and supplemental fixation.

- The true complication rate is unclear, given that the few papers reporting high complication rates were in sicker populations.

Distal femur fractures (DFFs) in the elderly historically were difficult to treat because of osteoporotic bone, comminution, and intra-articular involvement. DFFs in minimally ambulatory patients were once treated nonoperatively, with traction or immobilization,1,2 but surgery is now considered for displaced and unstable fractures, even in myelopathic and nonambulatory patients, to provide pain relief, ease mobility, and decrease the risks associated with prolonged bed rest.1 Options are constantly evolving, but poor knee function, malunion, nonunion, prolonged immobilization, implant failure, and high morbidity and mortality rates have been reported in several studies regardless of fixation method.

Arthritis after DFF has been reported at rates of 36% to 50% by long-term follow-up.3-5 However, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for posttraumatic arthritis is more complex because of scarring, arthrofibrosis, malunion, nonunion, and the frequent need for hardware removal. These cases have a higher incidence of infection, aseptic loosening, stiffness,6 and skin necrosis.7 Primary TKA is a rarely used treatment for acute DFF. Several authors have recommended primary TKA for patients with intra-articular DFFs and preexisting osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, severe comminution, or poor bone stock.7-22 Compared with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), primary TKA may allow for earlier mobility and weight-bearing and thereby reduce the rates of complications (eg, respiratory failure, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism) associated with prolonged immobilization.23As the literature on TKA for acute DFF is scant, and to our knowledge there are no clear indications or guidelines, we performed a systematic review to determine whether TKA has been successful in relieving pain and restoring knee function. In this article, we discuss the indications, implant options, technical considerations, complications, and results (eg, range of motion [ROM], ambulatory status) associated with these procedures.

Methods

On December 1, 2015, we searched the major databases Medline, EMBASE (Excerpta Medica dataBASE), and the Cochrane Library for articles published since 1950. In our searches, we used the conjoint term knee arthroplasty with femur fracture, and knee replacement with femur fracture. Specifically, we queried: ((“knee replacement” OR “knee arthroplasty”) AND (intercondylar OR supracondylar OR femoral OR femur) AND fracture) NOT arthrodesis NOT periprosthetic NOT “posttraumatic arthritis” NOT osteotomy. We also hand-searched the current website of JBJS [Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery] Case Connector, a major case-report repository that was launched in 2011 but is not currently indexed by Medline.

All citations were imported to RefWorks for management and for removal of duplicates. Each article underwent screening and review by Dr. Chen and Dr. Li. Articles were included if titles were relevant to arthroplasty as treatment for acute (within 1 month) DFF. Articles and cases were excluded if they were reviews, published in languages other than English, animal studies, studies regarding nonacute (>3 months or nonunion) DFFs or periprosthetic fractures, or studies that considered only treatments other than TKA (ie, plate osteosynthesis).

Full-text publications were obtained and independently reviewed by Dr. Chen and Dr. Li for relevance and satisfaction of inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Given the rarity of publications on the treatment, all study designs from level I to level IV were included.

The same 2 reviewers extracted the data into prearranged summary tables. Data included study size, patient demographics, AO/OTA (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Orthopaedic Trauma Association) fracture type either reported or assessed by description and imaging (33A, extra-articular; 33B, partial articular with 1 intact condyle; 33C, complete articular with both condyles involved), baseline comorbidity, implant used and fracture treatment (if separate from arthroplasty), postoperative regimen, respective outcomes, and complication rates.

Results

We identified 728 articles: 389 through Medline, 294 through EMBASE, and 45 through the Cochrane Library (Figure 1).

The current evidence regarding primary TKA for acute DFF is primarily level IV (Table 1). Only 1 level III study16 compared TKA with ORIF. Three case series11,19,24 met our inclusion criteria (Table 1, Table 2). In addition, 5 case series involved patients who met our criteria, but these studies did not separately report results for DFFs and proximal tibia fractures,9,20-22 or separately for acute fractures and nonunions or ORIF failures.8

Modular, hinged, and tumor-type arthroplasty designs accounted for 83% of the treatments included in this review. Trade names are listed in Table 4. Authors who used these implants took a more aggressive approach, often resecting the entire femoral epiphyseal-metaphyseal area, menisci, and collateral ligaments.9,13,15,16,18 The majority of patients who underwent resection had 33C fractures (Tables 1, 3).

The majority of authors who treated fractures with resection and modular implants allowed their patients full weight-bearing soon after surgery (Table 1),11,12,15-18,24 whereas authors who treated their patients partly with fracture fixation often had to delay weight-bearing (Table 1).

Cement use was universally described in the literature. Some authors avoided placing cement in the fracture site (to reduce the risk of nonunion),7,19 whereas others used bone cement to fill metaphyseal defects that remained after fracture resection and implantation.11,24Complication rates were modest, and there were no reports specifically on implant loosening or fracture nonunion.7,10,12-19 The majority of complications were recorded in 2 studies that used megaprostheses in sicker populations: Bell and colleagues11 noted debilitating illnesses in all their patients, and Appleton and colleagues24 included 9 nonambulatory patients and 36 patients who required 2 assistants to ambulate. All deaths were attributed to medical comorbidities and disseminated malignancy. Contrarily, studies by Pearse and colleagues16 and Choi and colleagues19 included previously ambulatory patients and reported no deaths or complications (Table 2). Likewise, in studies that combined results of DFFs and proximal tibia fractures, death and complication rates varied from 7% to 31% (Table 3).

Discussion

DFFs in the elderly historically were difficult to treat. Reported outcomes are largely favorable, but, even with newer plate designs, catastrophic failures still occur in the absence of bony union.26,27 After ORIF, patients’ weight-bearing is often restricted for 12 weeks or longer28—a protocol that is undesirable in elderly patients, especially given that the rate of mortality 1 year after these fractures has been found to be as high as 25%.29

Arthroplasty for DFFs—performed either with ORIF, or independently with a constrained implant—is a documented treatment modality, but the evidence is poor, and results have been mixed. Patients who received hinged TKA with major fracture resection had higher complication rates.8,11,22,24 However, the problems were mostly medical, not associated with surgical technique. Appleton and colleagues24 found a higher than expected 1-year mortality rate, 41%, but used an unhealthy baseline population (44% cognitive impairment, 17% nonambulatory before injury).Although Boureau and colleagues22 found a 1-year mortality rate of 30%, only 1 in 10 deaths was attributable to a perioperative complication. Among the remaining cases involving resection and megaprostheses for previously ambulatory patients, only 1 perioperative death was recorded (Table 2).11,12,16,18 Therefore, the risks associated with patients’ baseline health and ambulatory status must be weighed against the benefits of aggressive arthroplasty.

An overwhelming majority of 33C fractures were treated with megaprostheses—a finding perhaps attributable to the higher likelihood that patients with osteoporosis have intra-articular, comminuted injuries. In addition, surgeons may have been more likely to indicate 33C fractures for joint replacement, whereas 33A and 33B patterns were more amenable to fracture fixation.17,18 Interestingly, few type B fractures (0 in primary analysis and only 9 of 67 cases in Table 3) were treated with megaprostheses. In these situations, 1 condyle and ligamentous constraint remain intact, reducing the need for a constrained implant.

There were no reports of atraumatic or aseptic loosening, though use of rotating platforms with linked prostheses helps minimize this complication. Also surprising is the lack of nonunions in any of the reviewed studies, as nonunion is one of the most devastating complications of ORIF. Only 1 superficial and 2 deep infections were reported in all of the literature—representing 1.8% of all cases, which is comparable to the rate for elective primary TKA.30In elderly patients with significant comorbidities, the main surgical goals are to minimize operative time and reduce time to mobility. It is therefore imperative to keep in mind that arthroplasty is elective. However, functional results of primary TKA for DFF may be more encouraging for healthier patients, as many can achieve satisfactory ROM and early weight-bearing. Therefore, TKA for DFF may benefit healthy and ambulatory patients in the setting of intra-articular comminution. Whether this treatment affects mortality rates remains to be seen.

There were several limitations to this study. First, the literature on the topic is scant. Second, exclusion criteria were kept lax to allow for inclusion of all treatments. This came at a cost to internal validity, given the heterogeneous population and differences in comorbidities between studies. Fracture classification was inconsistent as well: Although AO/OTA classification was dominant, descriptive classifications were used in several cases7,10,12 (these descriptions, however, were sufficient for assigning equivalent AO/OTA classes). Details on preoperative functional status and comorbidity status and on postoperative protocols were also limited, though ROM and ambulatory status were provided in most studies. Last, most of these studies were single case reports or case series, so there may be reporting bias in the body of the literature, as reflected in the discrepancies between encouraging case reports and concerning case series with longer follow-up. Such bias can be avoided with larger, controlled sampling and adequate follow-up.

TKA should be considered for acute DFF in patients who have knee arthritis and are able to tolerate the physiological load of the surgery. In the choice of implant design, several factors should be considered, including bone quality, articular involvement, degree of comminution, and ligamentous injury. Unconstrained knee designs should be considered in cases in which the fracture pattern appears stable and the collateral ligaments are intact (eg, 33A and 33BB fractures). Megaprostheses, which may allow for immediate weight-bearing but require considerable bone resection, would be beneficial in 33C fractures and in fractures with ligamentous compromise. However, their complication rates are unclear, and comparative studies are needed to investigate whether the rates are higher for these patients than for patients treated more traditionally.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):E163-E171. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Cass J, Sems SA. Operative versus nonoperative management of distal femur fracture in myelopathic, nonambulatory patients. Orthopedics. 2008;31(11):1091.

2. Eichenholtz SN. Management of long-bone fracture in paraplegic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;45(2):299-310.

3. Thomson AB, Driver R, Kregor PJ, Obremskey WT. Long-term functional outcomes after intra-articular distal femur fractures: ORIF versus retrograde intramedullary nailing. Orthopedics. 2008;31(8):748-750.

4. Rademakers MV, Kerkhoffs GM, Sierevelt IN, Raaymakers EL, Marti RK. Intra-articular fractures of the distal femur: a long-term follow-up study of surgically treated patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(4):213-219.

5. Schenker ML, Mauck RL, Ahn J, Mehta S. Pathogenesis and prevention of posttraumatic osteoarthritis after intra-articular fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(1):20-28.

6. Papadopoulos EC, Parvizi J, Lai CH, Lewallen DG. Total knee arthroplasty following prior distal femoral fracture. Knee. 2002;9(4):267-274.

7. Yoshino N, Takai S, Watanabe Y, Fujiwara H, Ohshima Y, Hirasawa Y. Primary total knee arthroplasty for supracondylar/condylar femoral fracture in osteoarthritic knees. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(4):471-475.

8. Rosen AL, Strauss E. Primary total knee arthroplasty for complex distal femur fractures in elderly patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(425):101-105.

9. Malviya A, Reed MR, Partington PF. Acute primary total knee arthroplasty for peri-articular knee fractures in patients over 65 years of age. Injury. 2011;42(11):1368-1371.

10. Wolfgang GL. Primary total knee arthroplasty for intercondylar fracture of the femur in a rheumatoid arthritic patient. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(171):80-82.

11. Bell KM, Johnstone AJ, Court-Brown CM, Hughes SP. Primary knee arthroplasty for distal femoral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74(3):400-402.

12. Shah A, Asirvatham R, Sudlow RA. Primary resection total knee arthroplasty for complicated fracture of the distal femur with an arthritic knee joint. Contemp Orthop. 1993;26(5):463-467.

13. Freedman EL, Hak DJ, Johnson EE, Eckardt JJ. Total knee replacement including a modular distal femoral component in elderly patients with acute fracture or nonunion. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(3):231-237.

14. Patterson RH, Earll M. Repair of supracondylar femur fracture and unilateral knee replacement at the same surgery. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13(5):388-390.

15. Nau T, Pflegerl E, Erhart J, Vecsei V. Primary total knee arthroplasty for periarticular fractures. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(8):968-971.

16. Pearse EO, Klass B, Bendall SP, Railton GT. Stanmore total knee replacement versus internal fixation for supracondylar fractures of the distal femur in elderly patients. Injury. 2005;36(1):163-168.

17. Mounasamy V, Ma SY, Schoderbek RJ, Mihalko WM, Saleh KJ, Brown TE. Primary total knee arthroplasty with condylar allograft and MCL reconstruction for a comminuted medial condyle fracture in an arthritic knee—a case report. Knee. 2006;13(5):400-403.

18. Mounasamy V, Cui Q, Brown TE, Saleh KJ, Mihalko WM. Primary total knee arthroplasty for a complex distal femur fracture in the elderly: a case report. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2007;17(5):491-494.

19. Choi NY, Sohn JM, Cho SG, Kim SC, In Y. Primary total knee arthroplasty for simple distal femoral fractures in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2013;25(3):141-146.

20. Parratte S, Bonnevialle P, Pietu G, Saragaglia D, Cherrier B, Lafosse JM. Primary total knee arthroplasty in the management of epiphyseal fracture around the knee. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2011;97(6 suppl):S87-S94.

21. Benazzo F, Rossi SM, Ghiara M, Zanardi A, Perticarini L, Combi A. Total knee replacement in acute and chronic traumatic events. Injury. 2014;45(suppl 6):S98-S104.

22. Boureau F, Benad K, Putman S, Dereudre G, Kern G, Chantelot C. Does primary total knee arthroplasty for acute knee joint fracture maintain autonomy in the elderly? A retrospective study of 21 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(8):947-951.

23. Bishop JA, Suarez P, Diponio L, Ota D, Curtin CM. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of femur fractures in people with spinal cord injury: an administrative analysis of risks. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(12):2357-2364.

24. Appleton P, Moran M, Houshian S, Robinson CM. Distal femoral fractures treated by hinged total knee replacement in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(8):1065-1070.

25. In Y, Koh HS, Kim SJ. Cruciate-retaining stemmed total knee arthroplasty for supracondylar-intercondylar femoral fractures in elderly patients: a report of three cases. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(7):1074-1079.

26. Kregor PJ, Stannard JA, Zlowodzki M, Cole PA. Treatment of distal femur fractures using the less invasive stabilization system: surgical experience and early clinical results in 103 fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(8):509-520.

27. Vallier HA, Hennessey TA, Sontich JK, Patterson BM. Failure of LCP condylar plate fixation in the distal part of the femur. A report of six cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(4):846-853.

28. Gwathmey FW Jr, Jones-Quaidoo SM, Kahler D, Hurwitz S, Cui Q. Distal femoral fractures: current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(10):597-607.

29. Streubel PN, Ricci WM, Wong A, Gardner MJ. Mortality after distal femur fractures in elderly patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1188-1196.

30. Peersman G, Laskin R, Davis J, Peterson M. Infection in total knee replacement: a retrospective review of 6489 total knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(392):15-23.

1. Cass J, Sems SA. Operative versus nonoperative management of distal femur fracture in myelopathic, nonambulatory patients. Orthopedics. 2008;31(11):1091.

2. Eichenholtz SN. Management of long-bone fracture in paraplegic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;45(2):299-310.

3. Thomson AB, Driver R, Kregor PJ, Obremskey WT. Long-term functional outcomes after intra-articular distal femur fractures: ORIF versus retrograde intramedullary nailing. Orthopedics. 2008;31(8):748-750.

4. Rademakers MV, Kerkhoffs GM, Sierevelt IN, Raaymakers EL, Marti RK. Intra-articular fractures of the distal femur: a long-term follow-up study of surgically treated patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(4):213-219.

5. Schenker ML, Mauck RL, Ahn J, Mehta S. Pathogenesis and prevention of posttraumatic osteoarthritis after intra-articular fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(1):20-28.

6. Papadopoulos EC, Parvizi J, Lai CH, Lewallen DG. Total knee arthroplasty following prior distal femoral fracture. Knee. 2002;9(4):267-274.

7. Yoshino N, Takai S, Watanabe Y, Fujiwara H, Ohshima Y, Hirasawa Y. Primary total knee arthroplasty for supracondylar/condylar femoral fracture in osteoarthritic knees. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(4):471-475.

8. Rosen AL, Strauss E. Primary total knee arthroplasty for complex distal femur fractures in elderly patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(425):101-105.

9. Malviya A, Reed MR, Partington PF. Acute primary total knee arthroplasty for peri-articular knee fractures in patients over 65 years of age. Injury. 2011;42(11):1368-1371.

10. Wolfgang GL. Primary total knee arthroplasty for intercondylar fracture of the femur in a rheumatoid arthritic patient. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(171):80-82.

11. Bell KM, Johnstone AJ, Court-Brown CM, Hughes SP. Primary knee arthroplasty for distal femoral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74(3):400-402.

12. Shah A, Asirvatham R, Sudlow RA. Primary resection total knee arthroplasty for complicated fracture of the distal femur with an arthritic knee joint. Contemp Orthop. 1993;26(5):463-467.

13. Freedman EL, Hak DJ, Johnson EE, Eckardt JJ. Total knee replacement including a modular distal femoral component in elderly patients with acute fracture or nonunion. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(3):231-237.

14. Patterson RH, Earll M. Repair of supracondylar femur fracture and unilateral knee replacement at the same surgery. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13(5):388-390.

15. Nau T, Pflegerl E, Erhart J, Vecsei V. Primary total knee arthroplasty for periarticular fractures. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(8):968-971.

16. Pearse EO, Klass B, Bendall SP, Railton GT. Stanmore total knee replacement versus internal fixation for supracondylar fractures of the distal femur in elderly patients. Injury. 2005;36(1):163-168.

17. Mounasamy V, Ma SY, Schoderbek RJ, Mihalko WM, Saleh KJ, Brown TE. Primary total knee arthroplasty with condylar allograft and MCL reconstruction for a comminuted medial condyle fracture in an arthritic knee—a case report. Knee. 2006;13(5):400-403.

18. Mounasamy V, Cui Q, Brown TE, Saleh KJ, Mihalko WM. Primary total knee arthroplasty for a complex distal femur fracture in the elderly: a case report. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2007;17(5):491-494.

19. Choi NY, Sohn JM, Cho SG, Kim SC, In Y. Primary total knee arthroplasty for simple distal femoral fractures in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2013;25(3):141-146.

20. Parratte S, Bonnevialle P, Pietu G, Saragaglia D, Cherrier B, Lafosse JM. Primary total knee arthroplasty in the management of epiphyseal fracture around the knee. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2011;97(6 suppl):S87-S94.

21. Benazzo F, Rossi SM, Ghiara M, Zanardi A, Perticarini L, Combi A. Total knee replacement in acute and chronic traumatic events. Injury. 2014;45(suppl 6):S98-S104.

22. Boureau F, Benad K, Putman S, Dereudre G, Kern G, Chantelot C. Does primary total knee arthroplasty for acute knee joint fracture maintain autonomy in the elderly? A retrospective study of 21 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(8):947-951.

23. Bishop JA, Suarez P, Diponio L, Ota D, Curtin CM. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of femur fractures in people with spinal cord injury: an administrative analysis of risks. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(12):2357-2364.

24. Appleton P, Moran M, Houshian S, Robinson CM. Distal femoral fractures treated by hinged total knee replacement in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(8):1065-1070.

25. In Y, Koh HS, Kim SJ. Cruciate-retaining stemmed total knee arthroplasty for supracondylar-intercondylar femoral fractures in elderly patients: a report of three cases. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(7):1074-1079.

26. Kregor PJ, Stannard JA, Zlowodzki M, Cole PA. Treatment of distal femur fractures using the less invasive stabilization system: surgical experience and early clinical results in 103 fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(8):509-520.

27. Vallier HA, Hennessey TA, Sontich JK, Patterson BM. Failure of LCP condylar plate fixation in the distal part of the femur. A report of six cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(4):846-853.

28. Gwathmey FW Jr, Jones-Quaidoo SM, Kahler D, Hurwitz S, Cui Q. Distal femoral fractures: current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(10):597-607.

29. Streubel PN, Ricci WM, Wong A, Gardner MJ. Mortality after distal femur fractures in elderly patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1188-1196.

30. Peersman G, Laskin R, Davis J, Peterson M. Infection in total knee replacement: a retrospective review of 6489 total knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(392):15-23.

Endometriosis: From Identification to Management

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Staging endometriosis

- Medications for treating endometriosis

- Complications

Endometriosis is a gynecologic disorder characterized by the presence and growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity (ie, endometrial implants), most commonly found on the ovaries. Although its pathophysiology is not completely understood, the disease is associated with dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.1,2 Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disorder, predominantly affecting women of childbearing age. It occurs in 10% to 15% of the general female population, but prevalence is even higher (35% to 50%) among women who experience pelvic pain and/or infertility.1-4 Although endometriosis mainly affects women in their mid-to-late 20s, it can also manifest in adolescence.3,5 Nearly half of all adolescents with intractable dysmenorrhea are diagnosed with endometriosis.5

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of endometriosis, while not completely understood, is likely multifactorial. Factors that may influence its development include gene expression, tissue response to hormones, neuronal tissue involvement, lack of protective factors, inflammation, and cellular oxidative stress.6,7

Several theories regarding the etiology of endometriosis have been proposed; the most widely accepted is the transplantation theory, which suggests that endometriosis results from retrograde flow of menstrual tissue through the fallopian tubes. During menstruation, fragments of the endometrium are driven through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity, where they can implant onto the pelvic structures, leading to further growth and invasion.2,6,8 Women who have polymenorrhea, prolonged menses, and early menarche therefore have an increased risk for endometriosis.8 This theory does not account for the fact that although nearly 90% of women have some elements of retrograde menstrual flow, only a fraction of them develop endometriosis.6

Two other plausible explanations are the coelomic metaplasia and embryonic rest theories. In the coelomic metaplasia theory, the mesothelium (coelomic epithelium)—which encases the ovaries—invaginates into the ovaries and undergoes a metaplastic change to endometrial tissue. This could explain the development of endometriosis in patients with the congenital malformation Müllerian agenesis. In the embryonic rest theory, Müllerian remnants in the rectovaginal area, left behind by the Müllerian duct system, have the potential to differentiate into endometrial tissue.2,5,6,8

Another theory involving lymphatic or hematologic spread has been proposed, which would explain the presence of endometrial implants at sites distant from the uterus (eg, the pleural cavity and brain). However, this theory is not widely understood

The two most recent hypotheses on endometriosis are associated with an abnormal immune system and a possible genetic predisposition. The peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis has different levels of prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins than that of women who do not have the condition. It is uncertain whether the relationship between peritoneal fluid changes and endometriosis is causal.6 A genetic correlation has been suggested, based on an increased prevalence of endometriosis in women with an affected first-degree relative; in a case-control study on family incidence of endometriosis, 5.9% to 9.6% of first-degree relatives and 1.3% of second-degree relatives were affected.9 The Oxford Endometriosis Gene (OXEGENE) study is currently investigating susceptible loci for endometriosis genes, which could provide a better understanding of the disease process.6

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The most common symptoms of endometriosis are dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility, but 20% to 25% of affected women are asymptomatic.4,10,11 Pelvic pain in women most often heralds onset of menses and worsens during menstruation.1 Other symptoms include back pain, dyschezia, dysuria, nausea, lethargy, and chronic fatigue.4,8,10

Endometriosis is concomitant with infertility; endometrial adhesions that attach to pelvic organs cause distortion of pelvic structures and impaired ovum release and pick-up, and are believed to reduce fecundity. Additionally, women with endometriosis have low ovarian reserve and low-quality oocytes.6,8 Altered chemical elements (ie, prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins) may also contribute to endometrial-related infertility; intrapelvic growth factors could affect the fallopian tubes or pelvic environment, and thus the oocytes in a similar fashion.6

In adolescents, endometriosis can present as cyclic or acyclic pain; severe dysmenorrhea; dysmenorrhea that responds poorly to medications (eg, oral contraceptive pills [OCPs] or NSAIDs); and prolonged menstruation with premenstrual spotting.1

The physical exam may reveal tender nodules in the posterior vaginal fornix; cervical motion tenderness; a fixed uterus, cervix, or adnexa; uterine motion tenderness; thickening, pain, tenderness, or nodularity of the uterosacral ligament; or tender adnexal masses due to endometriomas.8,10

PATHOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS AND STAGING

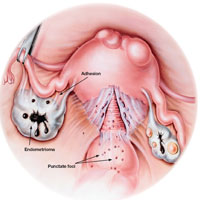

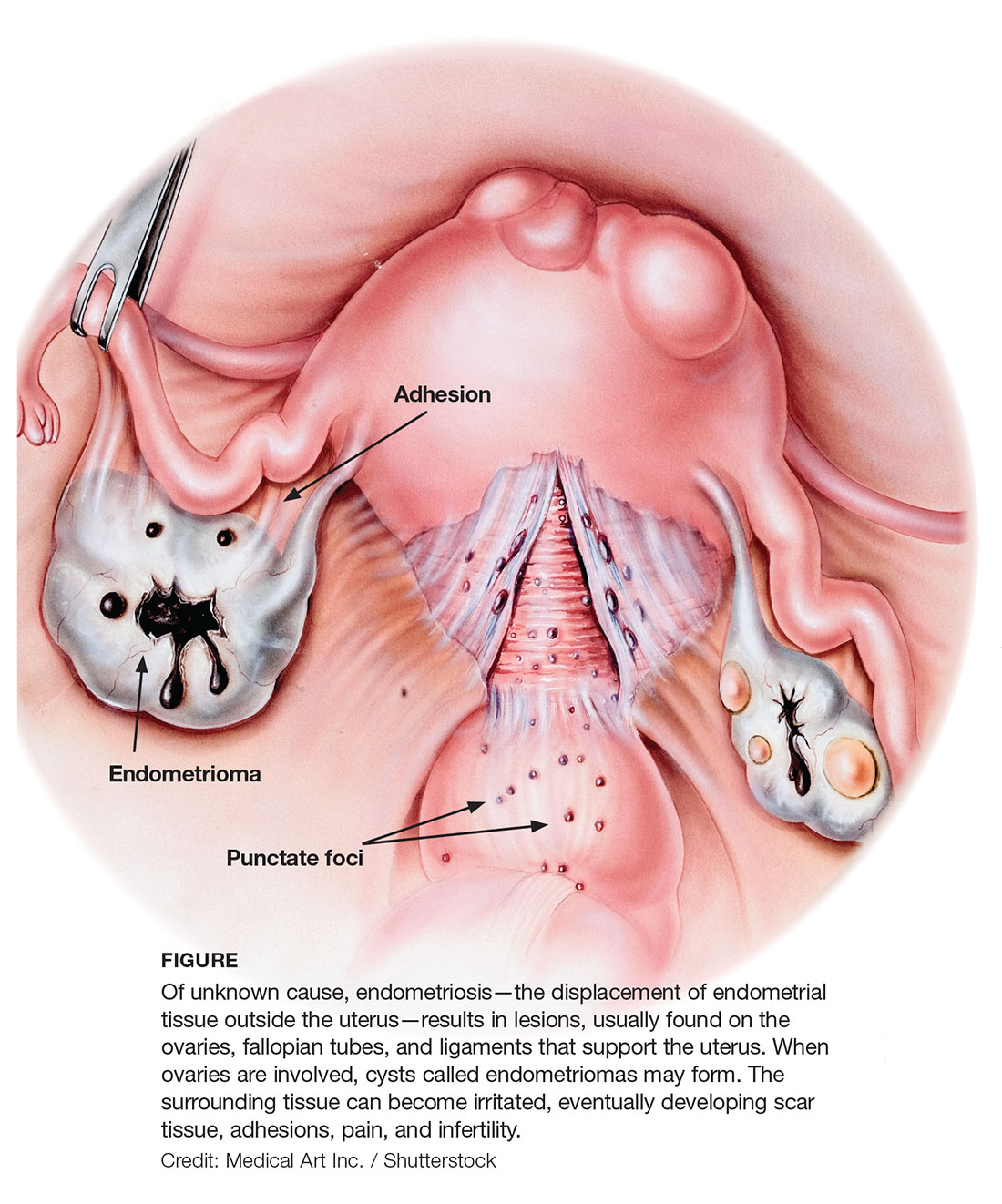

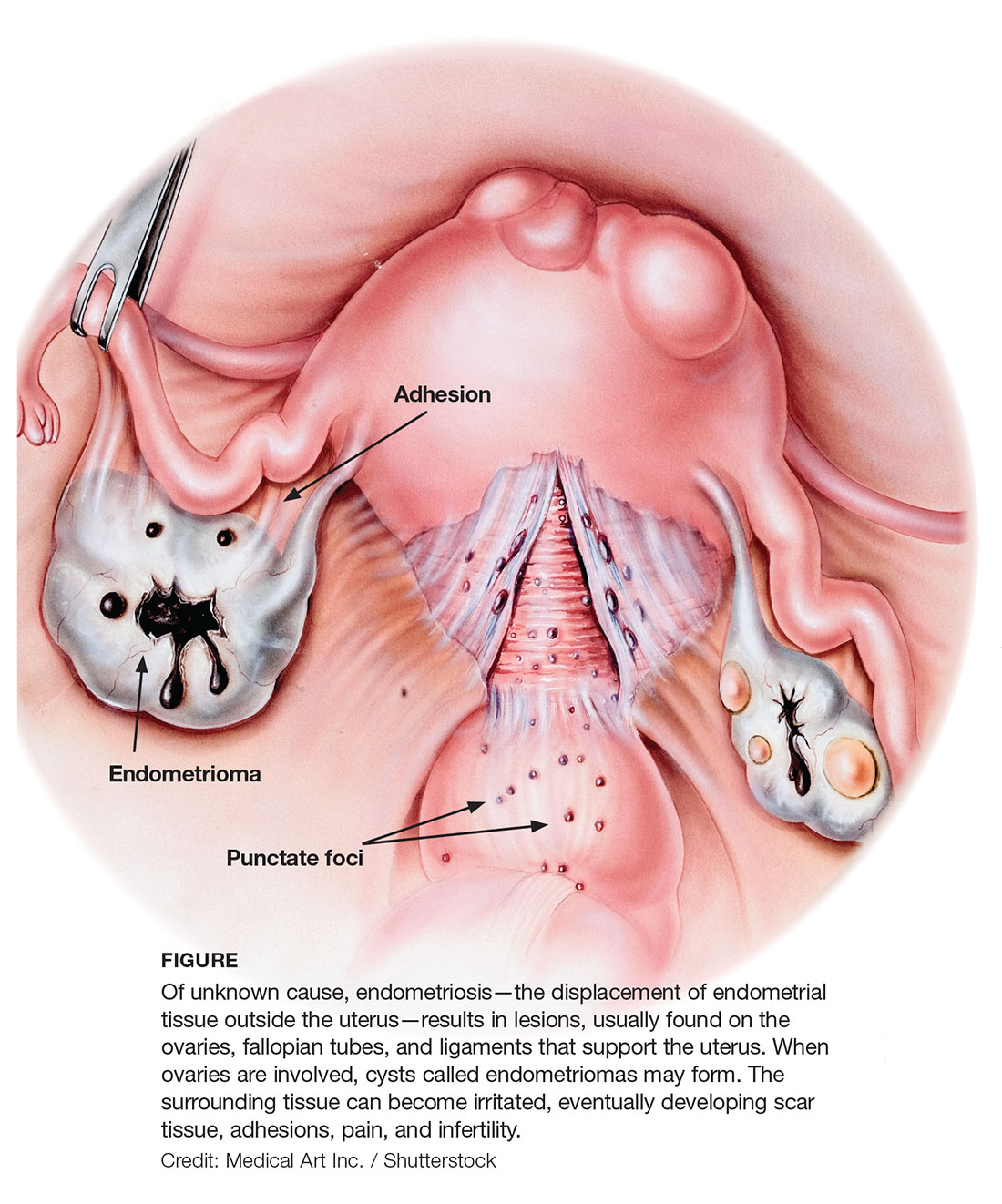

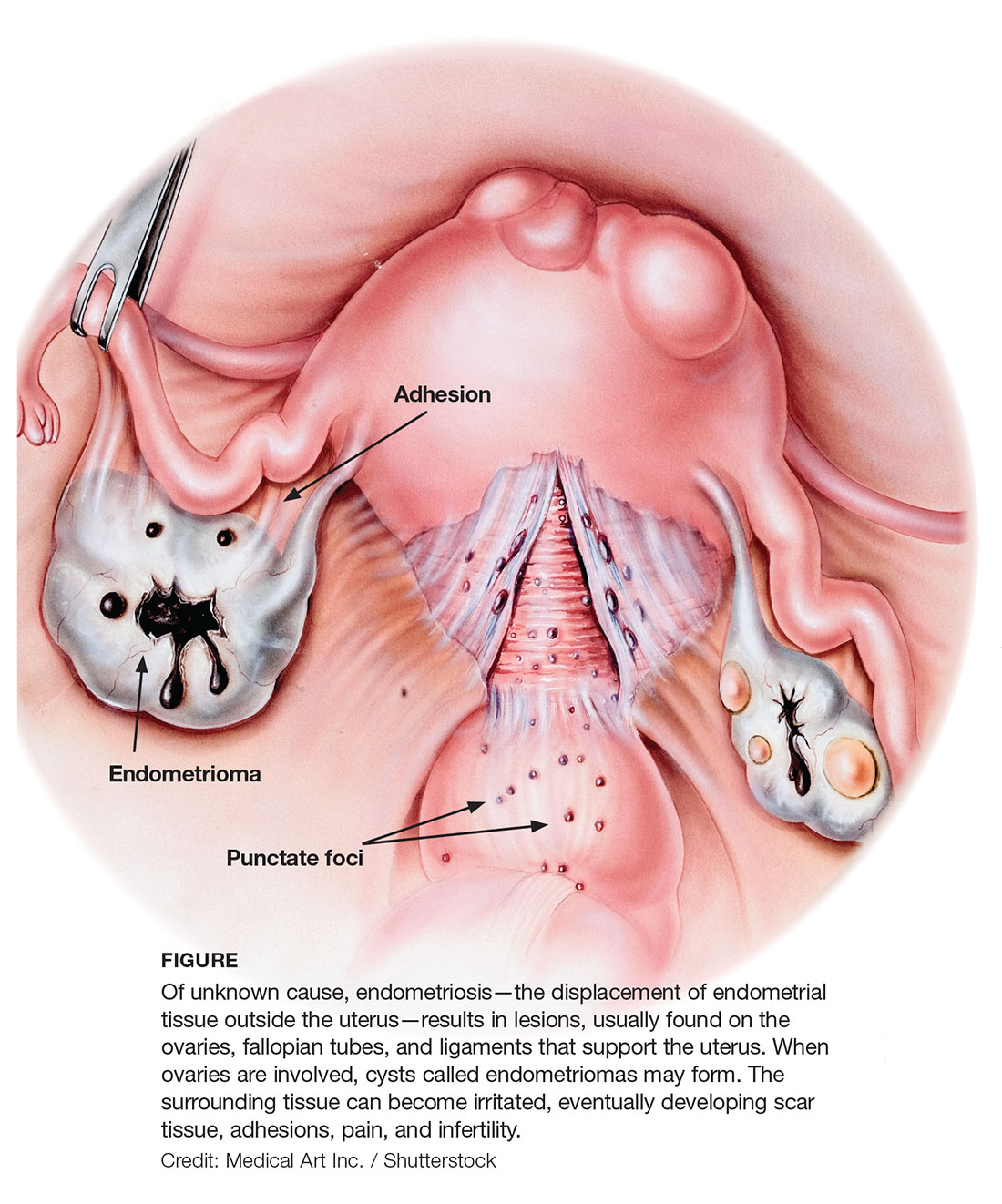

Gross pathology of endometriosis varies based on duration of disease and depth of implants or lesions. Implants range from punctate foci to small stellate patches that vary in color but typically measure less than 2 cm. They manifest most commonly in the ovaries, followed by the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac, posterior broad ligament, and uterosacral ligament. Implants can also be located on the uterus, fallopian tubes, sigmoid colon, ureter, small intestine, lungs, and brain (see Figure).3

Due to recurrent cyclic hemorrhage within a deep implant, endometriomas typically appear in the ovaries, entirely replacing normal ovarian tissue. Endometriomas are composed of dark, thick, degenerated blood products that result in a brown cyst—hence their designation as chocolate cysts. Microscopically, they are comprised of endometrial glands, stroma, and sometimes smooth muscle.3

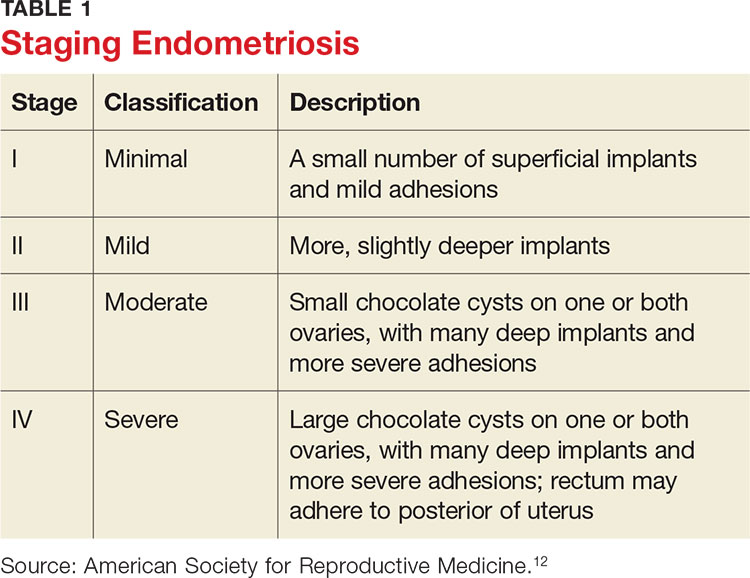

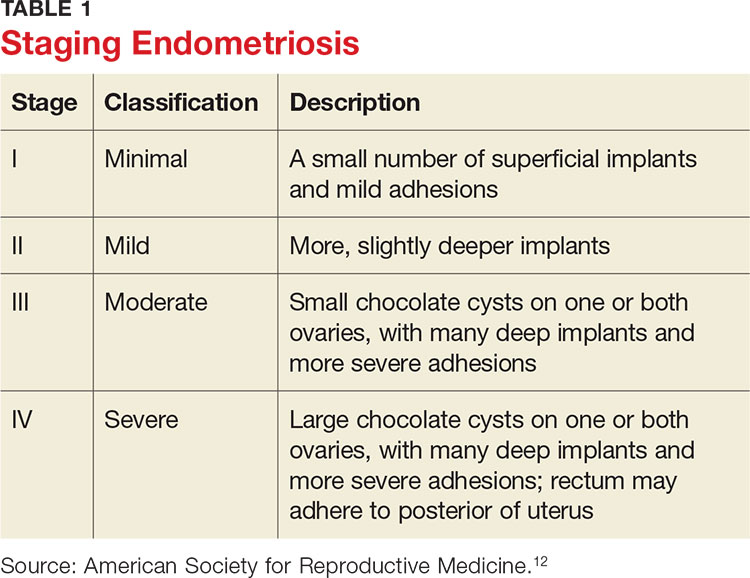

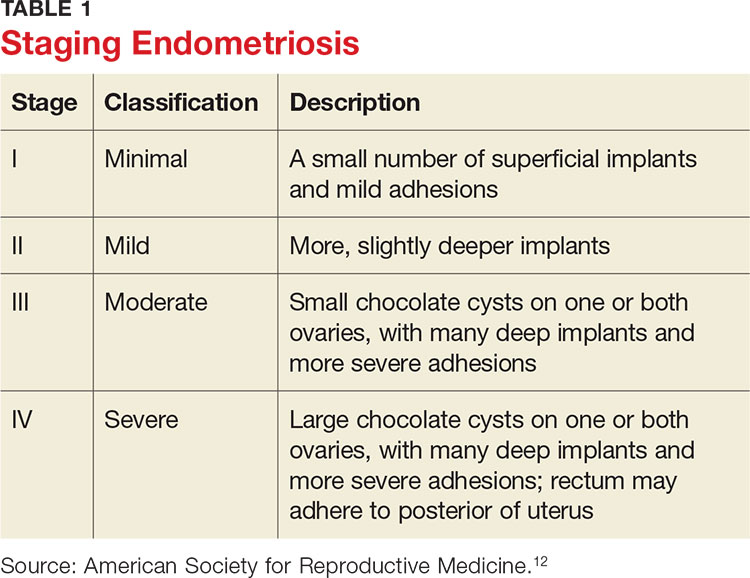

Staging of endometriosis is determined by the volume, depth, location, and size of the implants (see Table 1). It is important to note that staging does not necessarily reflect symptom severity.12

DIAGNOSIS

There are several approaches to the diagnostic evaluation of endometriosis, all of which should be guided by the clinical presentation and physical examination. Clinical characteristics can be nonspecific and highly variable, warranting more reliable diagnostic methods.

Laparoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard for endometriosis, and biopsy of implants revealing endometrial tissue is confirmatory. Less invasive diagnostic methods include ultrasound and MRI—but without confirmatory histologic sampling, these only yield a presumptive diagnosis.

With ultrasonography, a transvaginal approach should be taken. While endometriomas have a variety of presentations on ultrasound, most appear as a homogenous, hypoechoic, focal lesion within the ovary. MRI has greater specificity than ultrasound for diagnosis of endometriomas. However, “shading,” or loss of signal, within an endometrioma is a feature commonly found on MRI.3

Other tests that aid in the diagnosis, but are not definitive, include sedimentation rate and tumor marker CA-125. These are both commonly elevated in patients with endometriosis. Measurement of CA-125 is helpful for identifying patients with infertility and severe endometriosis, who would therefore benefit from early surgical intervention.8

TREATMENT

There is no permanent cure for endometriosis; treatment entails nonsurgical and surgical approaches to symptom resolution. Treatment is directed by the patient’s desire to maintain fertility.

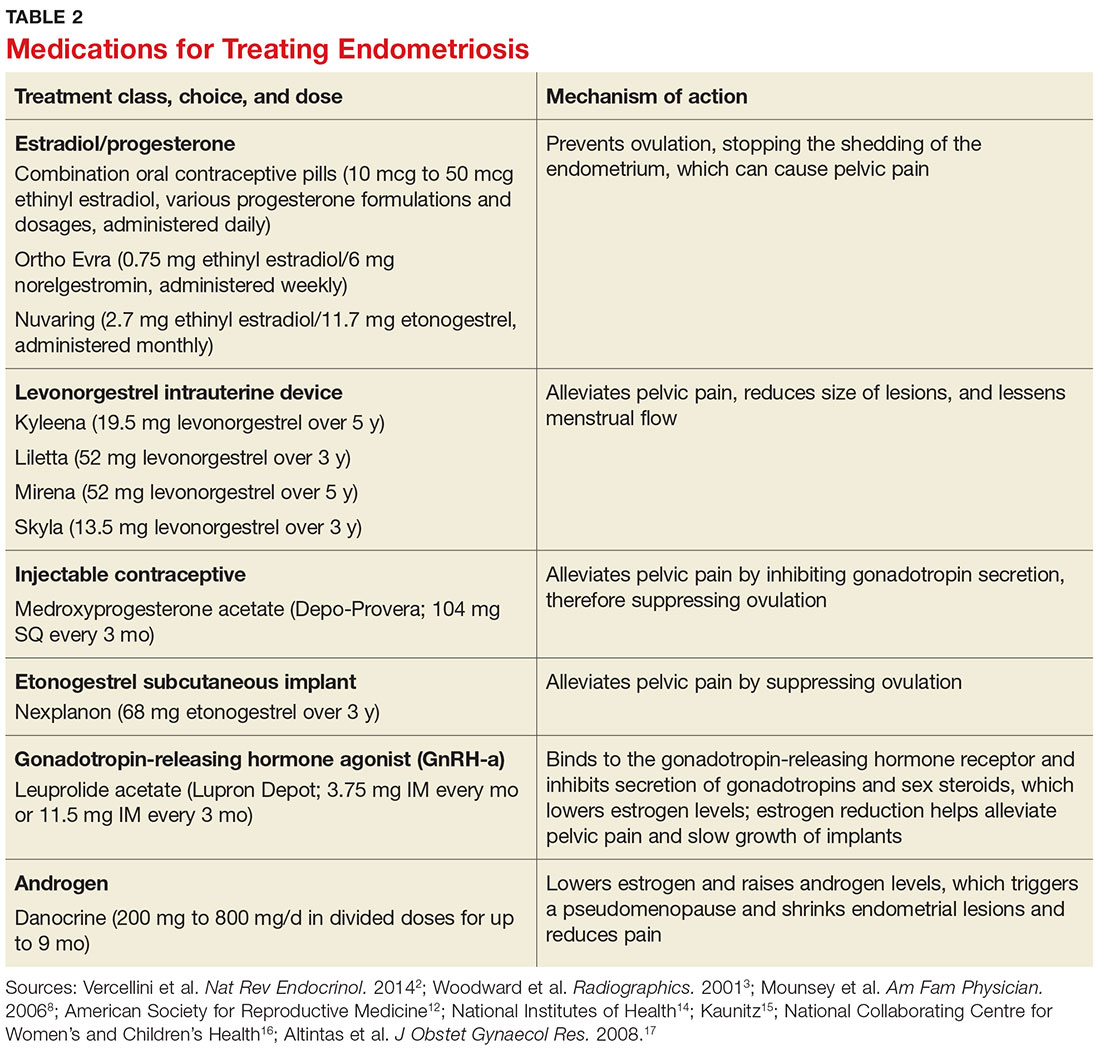

Conservative treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs is a common approach. Progestins are also used to treat pelvic pain; they create an acyclic, hypo-estrogenic environment by blocking ovarian estrogen secretion and subsequent endometrial cell proliferation. In addition to alleviating pain, progestins also prevent disease recurrence after surgery.2,13 Options include combination OCPs, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and etonogestrel implants. Combination OCPs and medroxyprogesterone acetate are considered to be firstline treatment.8

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a), such as leuprolide acetate, and androgenic agents, such as danocrine, are also indicated for relief of pain resulting from biopsy-confirmed endometriosis. Danocrine has been shown to ameliorate pain in up to 92% of patients.3,8 Other unconventional treatment modalities include aromatase inhibitors, selective estrogen receptor modulators, anti-inflammatory agents, and immunomodulators.2 For an outline of the medication choices and their mechanisms of action, see Table 2.

Surgery, or ablation of the implants, is another viable treatment option; it can be performed via laparoscopy or laparotomy. Although the success rate is high, implants recur in 28% of patients 18 months after surgery and in 40% of patients after nine years; 40% to 50% of patients have adhesion recurrence.3

Patients who have concomitant infertility can be treated with advanced reproductive techniques, including intrauterine insemination and ovarian hyperstimulation. The monthly fecundity rate with such techniques is 9% to 18%.3 Laparoscopic surgery with ablation of endometrial implants may increase fertility in patients with endometriosis.8

Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are definitive treatment options reserved for patients with intractable pain and those who do not wish to maintain fertility.3,8 Recurrent symptoms occur in 10% of patients 10 years after hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, compared with 62% of those who have hysterectomy alone.8 Complete surgical removal of endometriomas, and ovary if affected, can reduce risk for epithelial ovarian cancer in the future.2

COMPLICATIONS

Adhesions are a common complication of endometriosis. Ultrasound can be used for diagnosis and to determine whether pelvic organs are fixed (ie, fixed retroverted uterus). MRI may also be used; adhesions appear as “speculated low-signal-intensity stranding that obscures organ interfaces.”3 Other suggestive findings on MRI include posterior displacement of the pelvic organs, elevation of the posterior vaginal fornix, hydrosalpinx, loculated fluid collections, and angulated bowel loops.3

Malignant transformation is rare, affecting fewer than 1% of patients with endometriosis. Most malignancies arise from ovarian endometriosis and can be related to unopposed estrogen therapy; they are typically large and have a solid component. The most common endometriosis-related malignant neoplasm is endometrioid carcinoma, followed by clear-cell carcinoma.3

CONCLUSION

Patients with endometriosis often present with complaints such as dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain, but surgical and histologic findings indicate that symptom severity does not necessarily equate to disease severity. Definitive diagnosis requires an invasive surgical procedure.

In the absence of a cure, endometriosis treatment focuses on symptom control and improvement in quality of life. Familiarity with the disease process and knowledge of treatment options will help health care providers achieve this goal for patients who experience the potentially life-altering effects of endometriosis.

1. Janssen EB, Rijkers AC, Hoppenbrouwers K, et al. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(5):570-582.

2. Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014; 10(5):261-275.

3. Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Mezzetti TP. Endometriosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001;21(1):193-216.

4. Bulletti C, Coccia ME, Battistoni S, Borini A. Endometriosis and infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27(8):441-447.

5. Ahn SH, Monsanto SP, Miller C, et al. Pathophysiology and immune dysfunction in endometriosis. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2015:1-12.

6. Child TJ, Tan SL. Endometriosis: aetiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Drugs. 2001;61(12):1735-1750.

7. Farrell E, Garad R. Clinical update: endometriosis. Aust Nurs J. 2012;20(5):37-39.

8. Mounsey AL, Wilgus A, Slawson DC. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(4):594-600.

9. Nouri K, Ott J, Krupitz B, et al. Family incidence of endometriosis in first-, second-, and third-degree relatives: case-control study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8(85):1-7.

10. Riazi H, Tehranian N, Ziaei S, et al. Clinical diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis: a scoping review. BMC Women’s Health. 2015;15(39):1-12.

11. Acién P, Velasco I. Endometriosis: a disease that remains enigmatic. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:1-12.

12. American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Endometriosis: a guide for patients. www.conceive.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/ASRM-endometriosis.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

13. Angioni S, Cofelice V, Pontis A, et al. New trends of progestins treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014; 30(11):769-773.

14. National Institutes of Health. What are the treatments for endometriosis? www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/endometri/conditioninfo/Pages/treatment.aspx. Accessed April 19, 2017.

15. Kaunitz AM. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/depot-medroxyprogesterone-acetate-for-contraception. Accessed April 19, 2017.

16. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Long-acting reversible contraception: the effective and appropriate use of long-acting reversible contraception. London, England: RCOG Press; 2005. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK51051/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK51051.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

17. Altintas D, Kokcu A, Tosun M, Kandemir B. Comparison of the effects of cetrorelix, a GnRH antagonist, and leuprolide, a GnRH agonist, on experimental endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(6):1014-1019.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Staging endometriosis

- Medications for treating endometriosis

- Complications

Endometriosis is a gynecologic disorder characterized by the presence and growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity (ie, endometrial implants), most commonly found on the ovaries. Although its pathophysiology is not completely understood, the disease is associated with dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.1,2 Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disorder, predominantly affecting women of childbearing age. It occurs in 10% to 15% of the general female population, but prevalence is even higher (35% to 50%) among women who experience pelvic pain and/or infertility.1-4 Although endometriosis mainly affects women in their mid-to-late 20s, it can also manifest in adolescence.3,5 Nearly half of all adolescents with intractable dysmenorrhea are diagnosed with endometriosis.5

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of endometriosis, while not completely understood, is likely multifactorial. Factors that may influence its development include gene expression, tissue response to hormones, neuronal tissue involvement, lack of protective factors, inflammation, and cellular oxidative stress.6,7

Several theories regarding the etiology of endometriosis have been proposed; the most widely accepted is the transplantation theory, which suggests that endometriosis results from retrograde flow of menstrual tissue through the fallopian tubes. During menstruation, fragments of the endometrium are driven through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity, where they can implant onto the pelvic structures, leading to further growth and invasion.2,6,8 Women who have polymenorrhea, prolonged menses, and early menarche therefore have an increased risk for endometriosis.8 This theory does not account for the fact that although nearly 90% of women have some elements of retrograde menstrual flow, only a fraction of them develop endometriosis.6

Two other plausible explanations are the coelomic metaplasia and embryonic rest theories. In the coelomic metaplasia theory, the mesothelium (coelomic epithelium)—which encases the ovaries—invaginates into the ovaries and undergoes a metaplastic change to endometrial tissue. This could explain the development of endometriosis in patients with the congenital malformation Müllerian agenesis. In the embryonic rest theory, Müllerian remnants in the rectovaginal area, left behind by the Müllerian duct system, have the potential to differentiate into endometrial tissue.2,5,6,8

Another theory involving lymphatic or hematologic spread has been proposed, which would explain the presence of endometrial implants at sites distant from the uterus (eg, the pleural cavity and brain). However, this theory is not widely understood

The two most recent hypotheses on endometriosis are associated with an abnormal immune system and a possible genetic predisposition. The peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis has different levels of prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins than that of women who do not have the condition. It is uncertain whether the relationship between peritoneal fluid changes and endometriosis is causal.6 A genetic correlation has been suggested, based on an increased prevalence of endometriosis in women with an affected first-degree relative; in a case-control study on family incidence of endometriosis, 5.9% to 9.6% of first-degree relatives and 1.3% of second-degree relatives were affected.9 The Oxford Endometriosis Gene (OXEGENE) study is currently investigating susceptible loci for endometriosis genes, which could provide a better understanding of the disease process.6

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The most common symptoms of endometriosis are dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility, but 20% to 25% of affected women are asymptomatic.4,10,11 Pelvic pain in women most often heralds onset of menses and worsens during menstruation.1 Other symptoms include back pain, dyschezia, dysuria, nausea, lethargy, and chronic fatigue.4,8,10

Endometriosis is concomitant with infertility; endometrial adhesions that attach to pelvic organs cause distortion of pelvic structures and impaired ovum release and pick-up, and are believed to reduce fecundity. Additionally, women with endometriosis have low ovarian reserve and low-quality oocytes.6,8 Altered chemical elements (ie, prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins) may also contribute to endometrial-related infertility; intrapelvic growth factors could affect the fallopian tubes or pelvic environment, and thus the oocytes in a similar fashion.6

In adolescents, endometriosis can present as cyclic or acyclic pain; severe dysmenorrhea; dysmenorrhea that responds poorly to medications (eg, oral contraceptive pills [OCPs] or NSAIDs); and prolonged menstruation with premenstrual spotting.1

The physical exam may reveal tender nodules in the posterior vaginal fornix; cervical motion tenderness; a fixed uterus, cervix, or adnexa; uterine motion tenderness; thickening, pain, tenderness, or nodularity of the uterosacral ligament; or tender adnexal masses due to endometriomas.8,10

PATHOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS AND STAGING

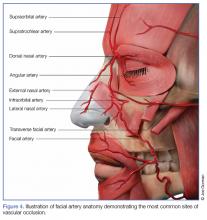

Gross pathology of endometriosis varies based on duration of disease and depth of implants or lesions. Implants range from punctate foci to small stellate patches that vary in color but typically measure less than 2 cm. They manifest most commonly in the ovaries, followed by the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac, posterior broad ligament, and uterosacral ligament. Implants can also be located on the uterus, fallopian tubes, sigmoid colon, ureter, small intestine, lungs, and brain (see Figure).3

Due to recurrent cyclic hemorrhage within a deep implant, endometriomas typically appear in the ovaries, entirely replacing normal ovarian tissue. Endometriomas are composed of dark, thick, degenerated blood products that result in a brown cyst—hence their designation as chocolate cysts. Microscopically, they are comprised of endometrial glands, stroma, and sometimes smooth muscle.3

Staging of endometriosis is determined by the volume, depth, location, and size of the implants (see Table 1). It is important to note that staging does not necessarily reflect symptom severity.12

DIAGNOSIS

There are several approaches to the diagnostic evaluation of endometriosis, all of which should be guided by the clinical presentation and physical examination. Clinical characteristics can be nonspecific and highly variable, warranting more reliable diagnostic methods.

Laparoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard for endometriosis, and biopsy of implants revealing endometrial tissue is confirmatory. Less invasive diagnostic methods include ultrasound and MRI—but without confirmatory histologic sampling, these only yield a presumptive diagnosis.

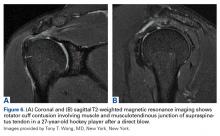

With ultrasonography, a transvaginal approach should be taken. While endometriomas have a variety of presentations on ultrasound, most appear as a homogenous, hypoechoic, focal lesion within the ovary. MRI has greater specificity than ultrasound for diagnosis of endometriomas. However, “shading,” or loss of signal, within an endometrioma is a feature commonly found on MRI.3

Other tests that aid in the diagnosis, but are not definitive, include sedimentation rate and tumor marker CA-125. These are both commonly elevated in patients with endometriosis. Measurement of CA-125 is helpful for identifying patients with infertility and severe endometriosis, who would therefore benefit from early surgical intervention.8

TREATMENT

There is no permanent cure for endometriosis; treatment entails nonsurgical and surgical approaches to symptom resolution. Treatment is directed by the patient’s desire to maintain fertility.

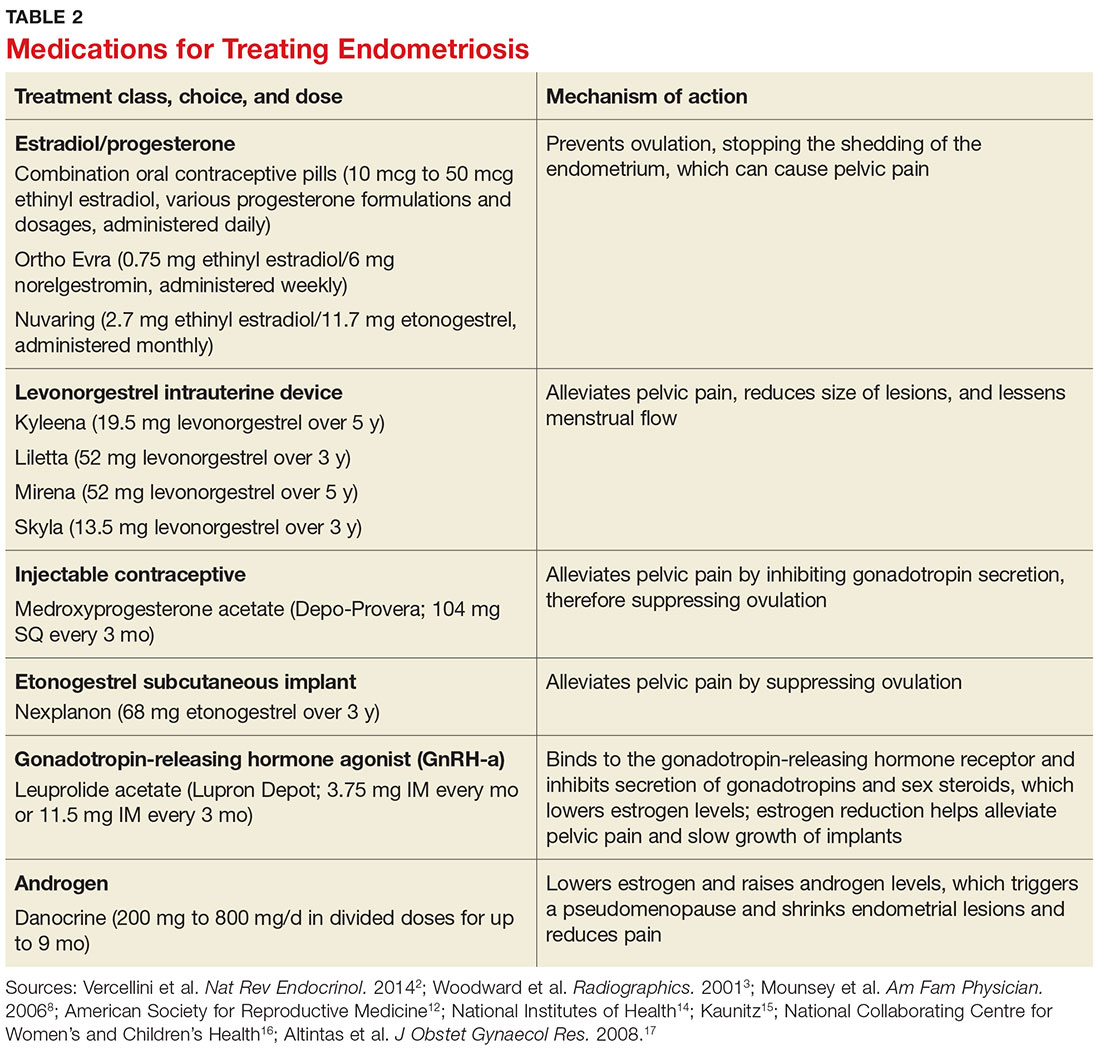

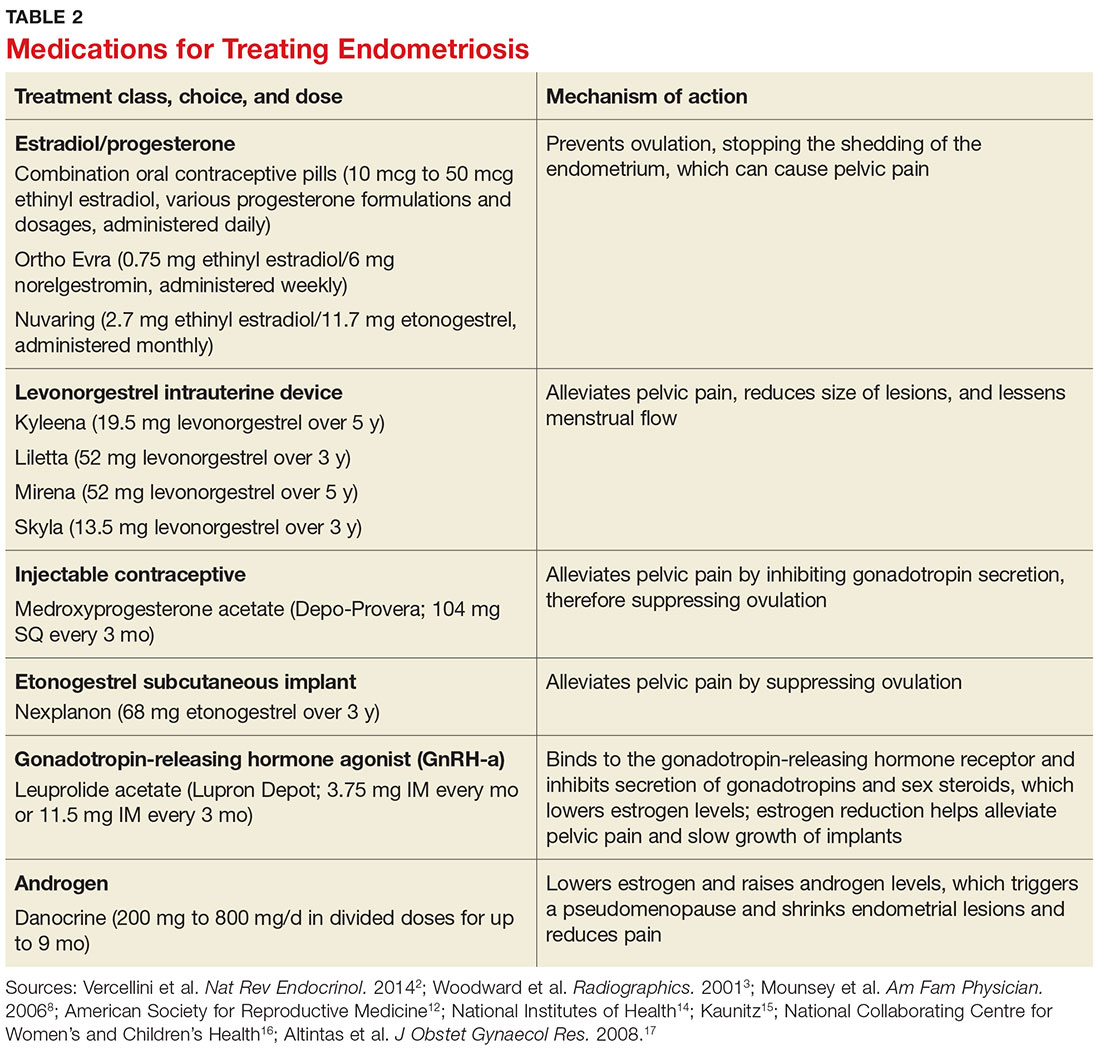

Conservative treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs is a common approach. Progestins are also used to treat pelvic pain; they create an acyclic, hypo-estrogenic environment by blocking ovarian estrogen secretion and subsequent endometrial cell proliferation. In addition to alleviating pain, progestins also prevent disease recurrence after surgery.2,13 Options include combination OCPs, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and etonogestrel implants. Combination OCPs and medroxyprogesterone acetate are considered to be firstline treatment.8

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a), such as leuprolide acetate, and androgenic agents, such as danocrine, are also indicated for relief of pain resulting from biopsy-confirmed endometriosis. Danocrine has been shown to ameliorate pain in up to 92% of patients.3,8 Other unconventional treatment modalities include aromatase inhibitors, selective estrogen receptor modulators, anti-inflammatory agents, and immunomodulators.2 For an outline of the medication choices and their mechanisms of action, see Table 2.

Surgery, or ablation of the implants, is another viable treatment option; it can be performed via laparoscopy or laparotomy. Although the success rate is high, implants recur in 28% of patients 18 months after surgery and in 40% of patients after nine years; 40% to 50% of patients have adhesion recurrence.3

Patients who have concomitant infertility can be treated with advanced reproductive techniques, including intrauterine insemination and ovarian hyperstimulation. The monthly fecundity rate with such techniques is 9% to 18%.3 Laparoscopic surgery with ablation of endometrial implants may increase fertility in patients with endometriosis.8

Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are definitive treatment options reserved for patients with intractable pain and those who do not wish to maintain fertility.3,8 Recurrent symptoms occur in 10% of patients 10 years after hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, compared with 62% of those who have hysterectomy alone.8 Complete surgical removal of endometriomas, and ovary if affected, can reduce risk for epithelial ovarian cancer in the future.2

COMPLICATIONS