User login

Adenomyosis: Why we need to reassess our understanding of this condition

CASE Painful, heavy menstruation and recurrent pregnancy loss

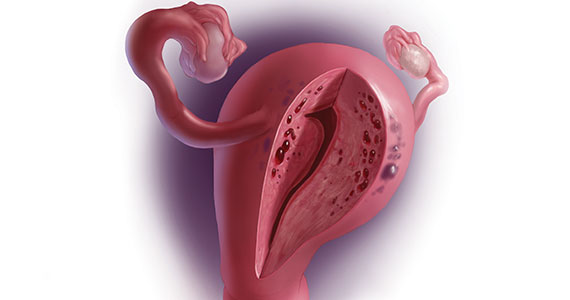

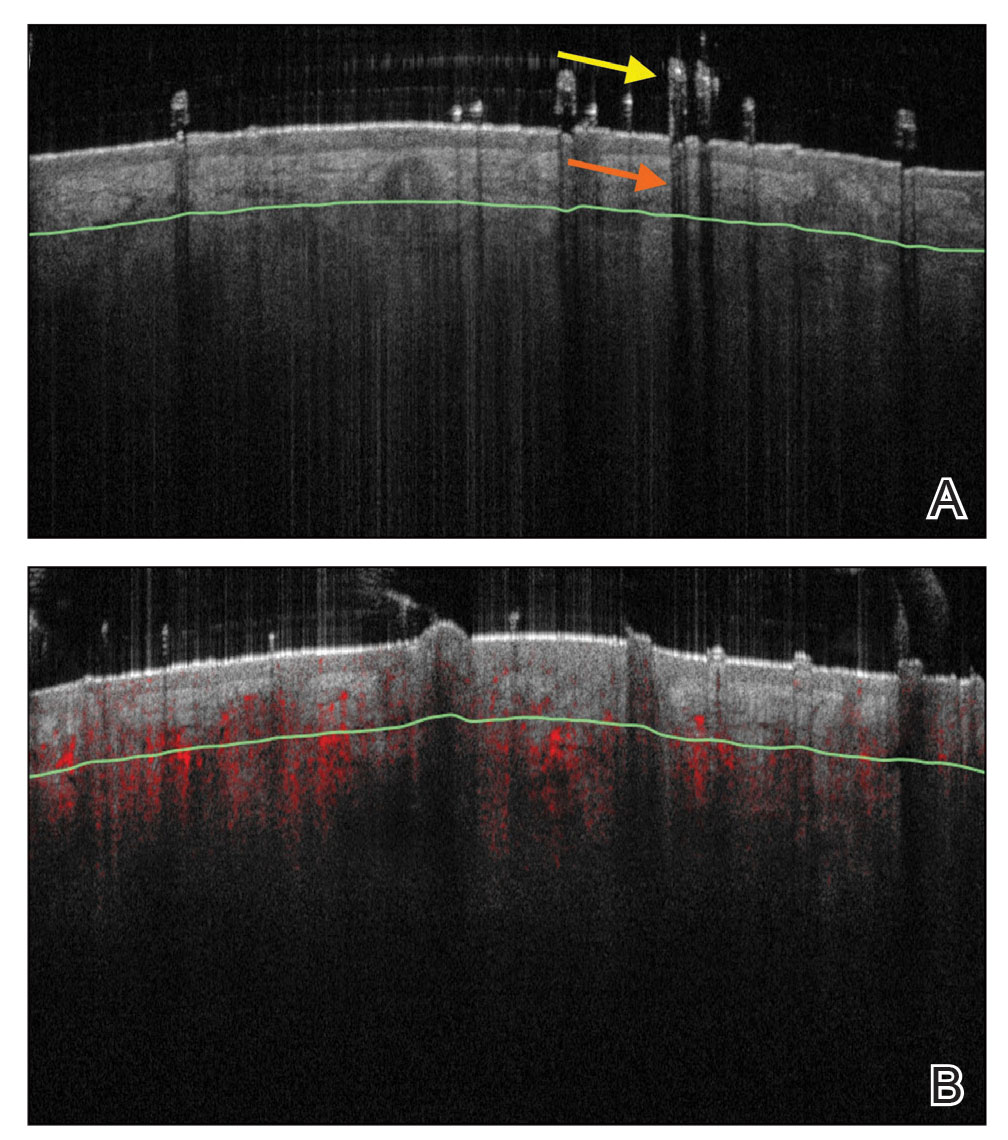

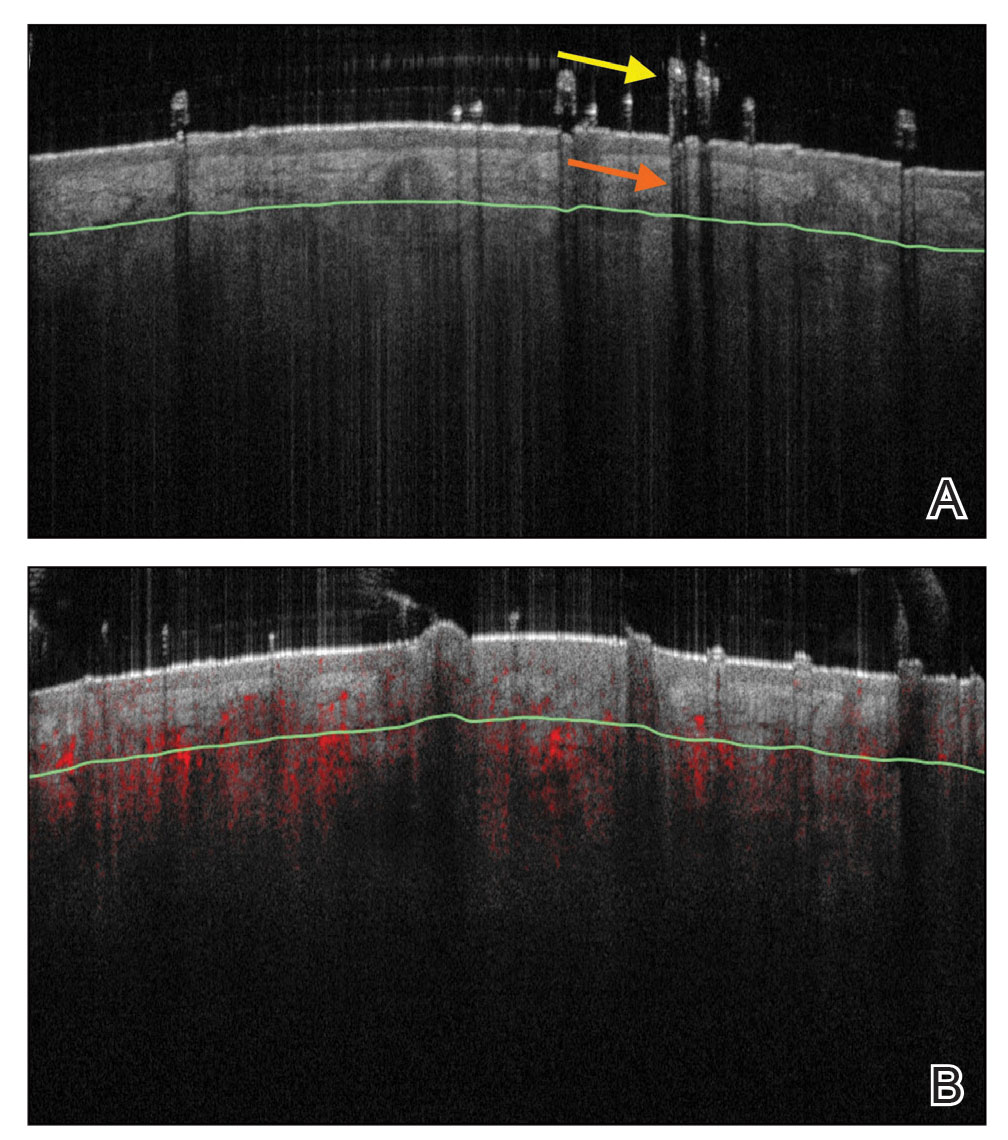

A 37-year-old woman (G3P0030) with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss presents for evaluation. She had 3 losses—most recently a miscarriage at 22 weeks with a cerclage in place. She did not undergo any surgical procedures for these losses. Hormonal and thrombophilia workup is negative and semen analysis is normal. She reports a history of painful, heavy periods for many years, as well as dyspareunia and occasional post-coital bleeding. Past medical history was otherwise unremarkable. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed focal thickening of the junctional zone up to 15 mm with 2 foci of T2 hyperintensities suggesting adenomyosis (FIGURE 1).

How do you counsel this patient regarding the MRI findings and their impact on her fertility?

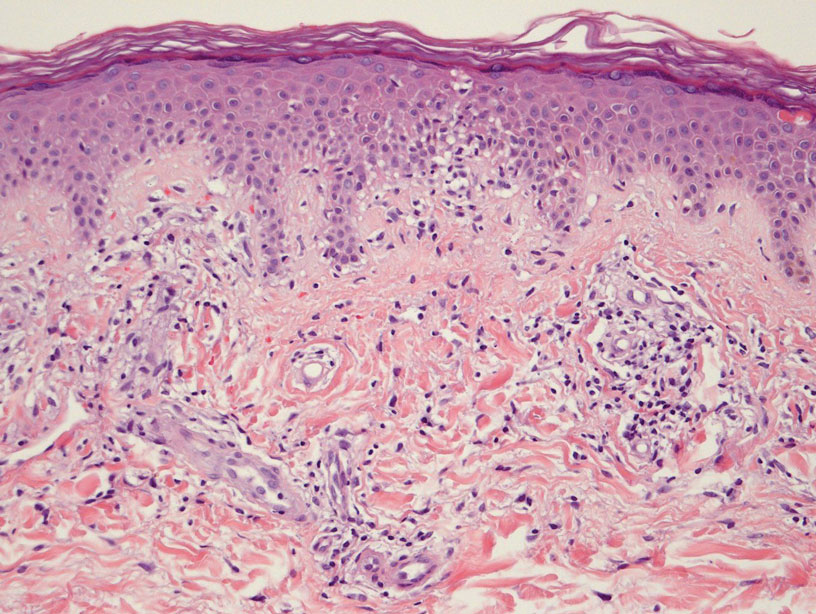

Adenomyosis is a condition in which endometrial glands and stroma are abnormally present in the uterine myometrium, resulting in smooth muscle hypertrophy and abnormal uterine contractility. Traditional teaching describes a woman in her 40s with heavy and painful menses, a “boggy uterus” on examination, who has completed childbearing and desires definitive treatment. Histologic diagnosis of adenomyosis is made from the uterine specimen at the time of hysterectomy, invariably confounding our understanding of the epidemiology of adenomyosis.

More recently, however, we are beginning to learn that this narrative is misguided. Imaging changes of adenomyosis can be seen in women who desire future fertility and in adolescents with severe dysmenorrhea, suggesting an earlier age of incidence.1 In a recent systematic review, prevalence estimates ranged from 15% to 67%, owing to varying diagnostic methods and patient inclusion criteria.2 It is increasingly being recognized as a primary contributor to infertility, with one study estimating a 30% prevalence of infertility in women with adenomyosis.3 Moreover, treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and/or surgical excision may improve fertility outcomes.4

As we learn more about this prevalent and life-altering condition, we owe it to our patients to consider this diagnosis when counseling on dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, or infertility.

Anatomy of the myometrium

The myometrium is composed of the inner and outer myometrium: the inner myometrium (IM) and endometrium are of Müllerian origin, and the outer myometrium (OM) is of mesenchymal origin. The IM thickens in response to steroid hormones during the menstrual cycle with metaplasia of endometrial stromal cells into myocytes and back again, whereas the OM is not responsive to hormones.5 Emerging literature suggests the OM is further divided into a middle and outer section based on different histologic morphologies, though the clinical implications of this are not understood.6 The term “junctional zone” (JZ) refers to the imaging appearance of what is thought to be the IM. Interestingly it cannot be identified on traditional hematoxylin and eosin staining. When the JZ is thickened or demonstrates irregular borders, it is used as a diagnostic marker for adenomyosis and is postulated to play an important role in adenomyosis pathophysiology, particularly heavy menstrual bleeding and infertility.7

Continue to: Subtypes of adenomyosis...

Subtypes of adenomyosis

While various disease classifications have been suggested for adenomyosis, to date there is no international consensus. Adenomyosis is typically described in 3 forms: diffuse, focal, or adenomyoma.8 As implied, the term focal adenomyosis refers to discrete lesions surrounded by normal myometrium, whereas abnormal glandular changes are pervasive throughout the myometrium in diffuse disease. Adenomyomas are a subgroup of focal adenomyosis that are thought to be surrounded by leiomyomatous smooth muscle and may be well demarcated on imaging.9

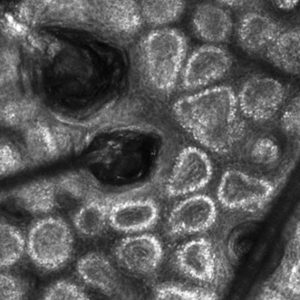

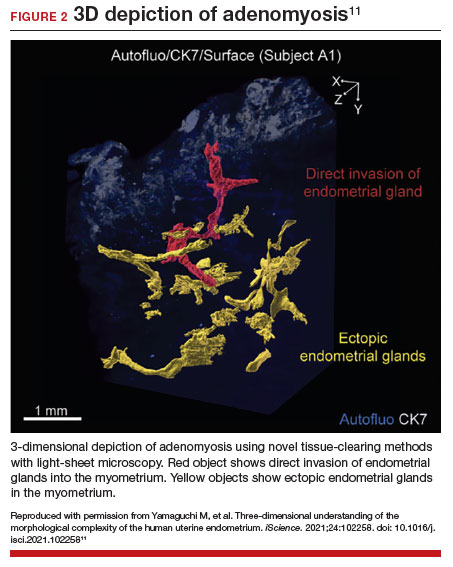

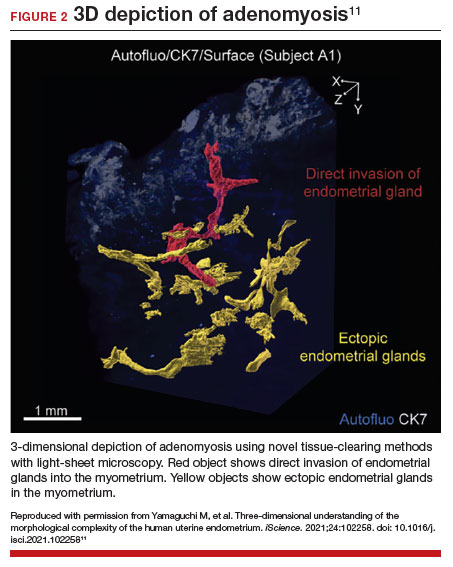

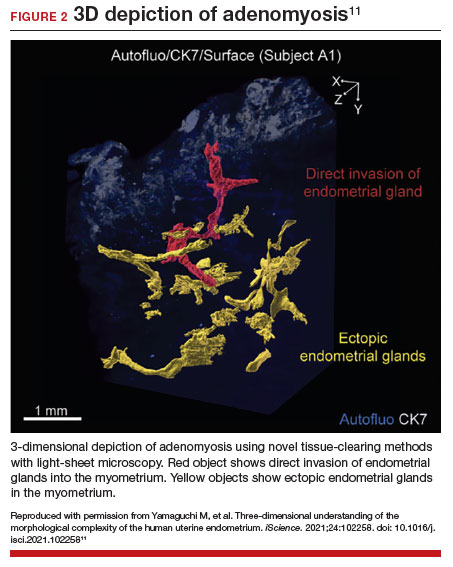

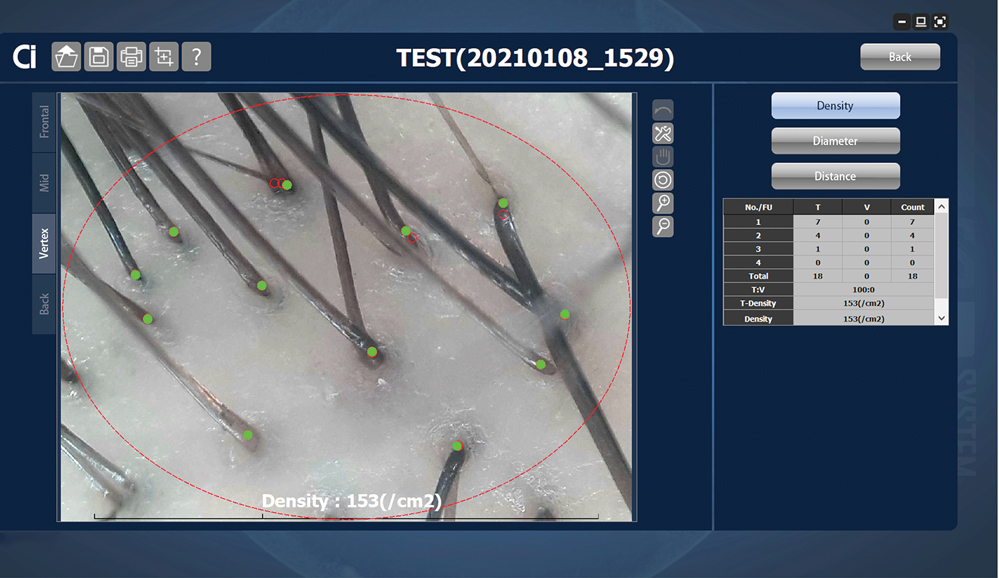

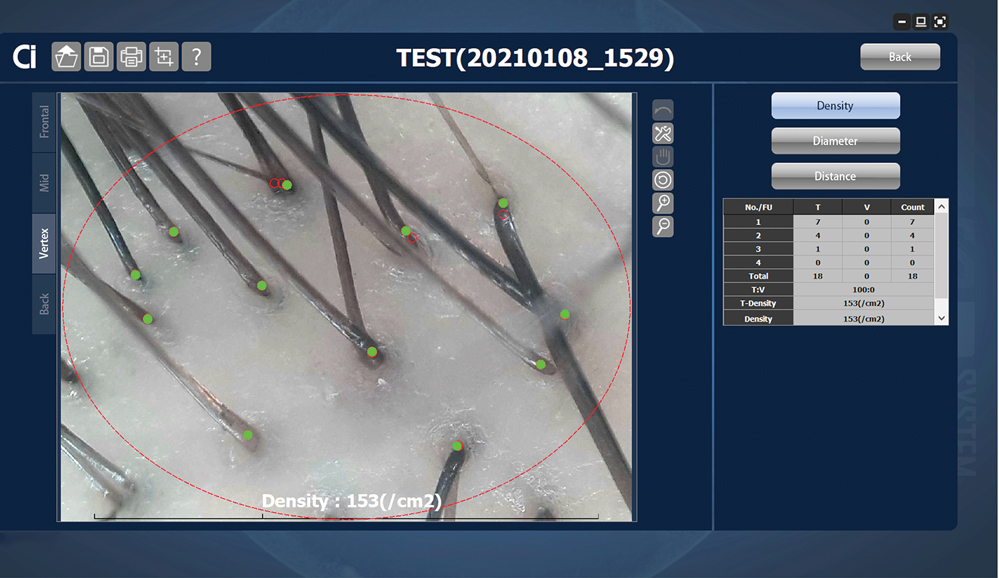

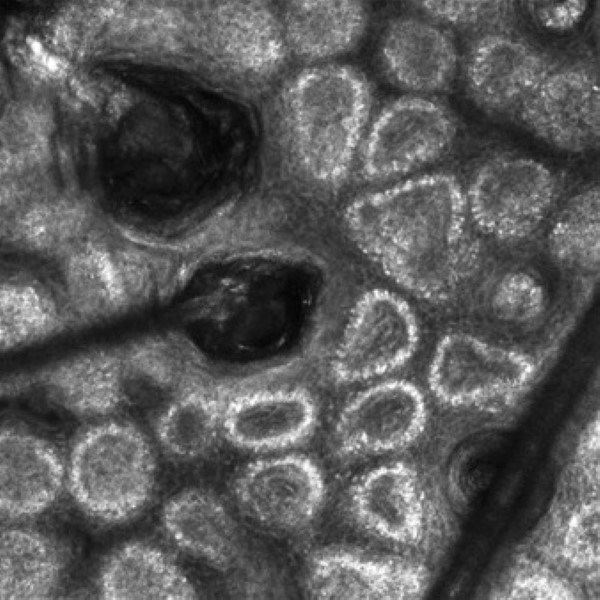

Recent research uses novel histologic imaging techniques to explore adenomyotic growth patterns in 3-dimensional (3D) reconstructions. Combining tissue-clearing methods with light-sheet fluorescence microscopy enables highly detailed 3D representations of the protein and nucleic acid structure of organs.10 For example, Yamaguchi and colleagues used this technology to explore the 3D morphological features of adenomyotic tissue and observed direct invasion of the endometrial glands into the myometrium and an “ant colony ̶ like network” of ectopic endometrial glands in the myometrium (FIGURE 2).11 These abnormal glandular networks have been visualized beyond the IM, which may not be captured on ultrasonography or MRI. While this work is still in its infancy, it has the potential to provide important insight into disease pathogenesis and to inform future therapy.

Pathogenesis

Proposed mechanisms for the development of adenomyosis include endometrial invasion, tissue injury and repair (TIAR) mechanisms, and the stem cell theory.12 According to the endometrial invasion theory, glandular epithelial cells from the basalis layer invaginate through an altered IM, slipping through weak muscle fibers and attracted by certain growth factors. In the TIAR mechanism theory, micro- or macro-trauma to the IM (whether from pregnancy, surgery, or infection) results in chronic proliferation and inflammation leading to the development of adenomyosis. Finally, the stem cell theory proposes that adenomyosis might develop from de novo ectopic endometrial tissue.

While the exact pathogenesis of adenomyosis is largely unknown, it has been associated with predictable molecular changes in the endometrium and surrounding myometrium.12 Myometrial hypercontractility is seen in patients with adenomyosis and dysmenorrhea, whereas neovascularization, high microvessel density, and abnormal uterine contractility are seen in those with abnormal uterine bleeding.13 In patients with infertility, increased inflammation, abnormal endometrial receptivity, and alterations in the myometrial architecture have been suggested to impair contractility and sperm transport.12,14

Differential growth factor expression and abnormal estrogen and progesterone signaling pathways have been observed in the IM in patients with adenomyosis, along with dysregulation of immune factors and increased inflammatory oxidative stress.12 This in turn results in myometrial hypertrophy and fibrosis, impairing normal uterine contractility patterns. This abnormal contractility may alter sperm transport and embryo implantation, and animal models that target pathways leading to fibrosis may improve endometrial receptivity.14,15 Further research is needed to elucidate specific molecular pathways and their complex interplay in this disease.

Continue to: Diagnosis...

Diagnosis

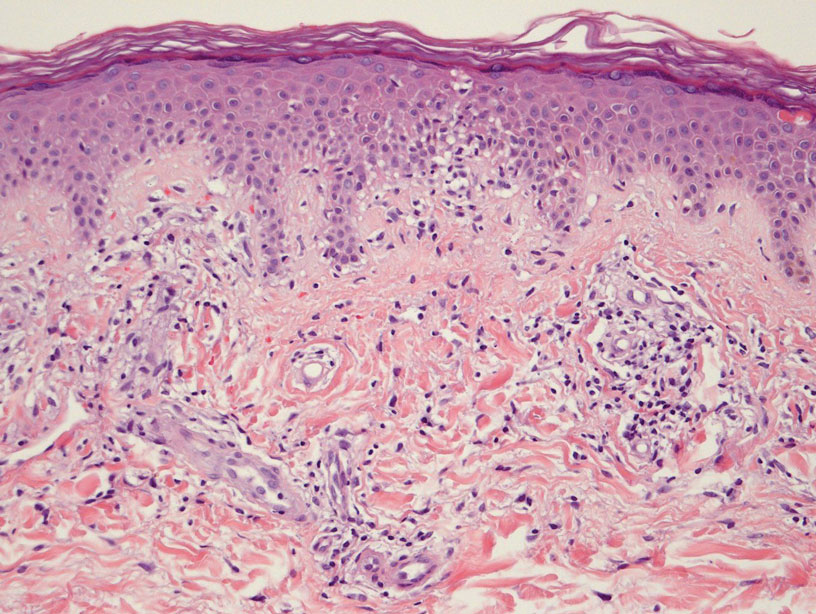

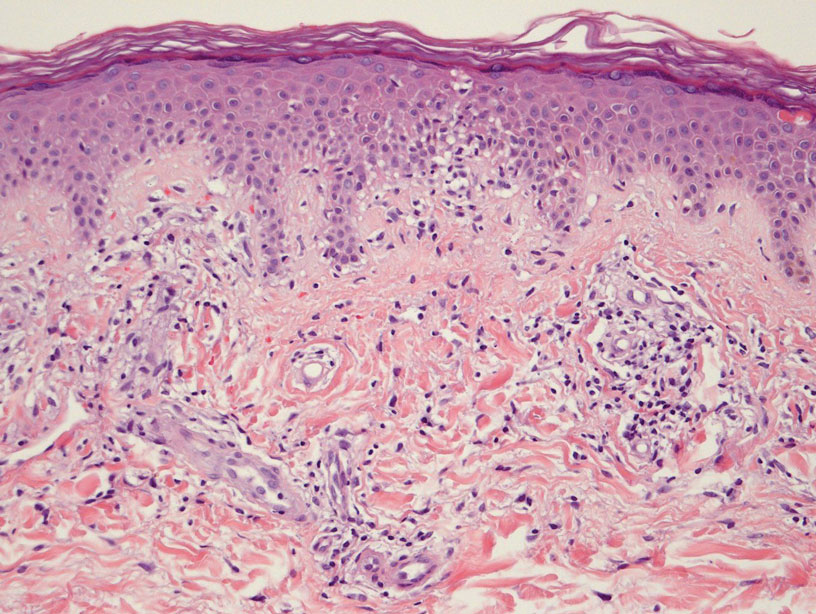

The gold standard for diagnosis of adenomyosis is histopathology from hysterectomy specimens, but specific definitions vary. Published criteria include endometrial glands within the myometrial layer greater than 0.5 to 1 low power field from the basal layer of the endometrium, endometrial glands extending deeper than 25% of the myometrial thickness, or endometrial glands a certain distance (ranging from 1-3 mm) from the basalis layer of the endometrium.16 Various methods of non-hysterectomy tissue sampling have been proposed for diagnosis, including needle, hysteroscopic, or laparoscopic sampling, but the sensitivity of these methods is poor.17 Limiting the diagnosis of adenomyosis to specimen pathology relies on invasive methods and clearly we cannot confirm the diagnosis by hysterectomy in patients with a desire for future fertility. It is for this reason that the prevalence of the disease is widely unknown.

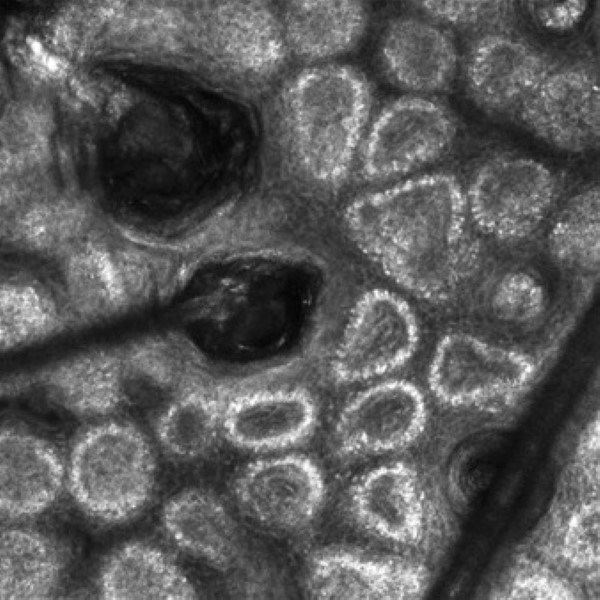

The alternative to pathologic diagnosis is to identify radiologic changes that are associated with adenomyosis via either transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) or MRI. Features suggestive of adenomyosis on MRI overlap with TVUS features, including uterine enlargement, anteroposterior myometrial asymmetry, T1- or T2-intense myometrial cysts or foci, and a thickened JZ.18 A JZ thicker than 12 mm has been thought to be predictive of adenomyosis, whereas a thickness of less than 8 mm is predictive of its absence, although the JZ may vary in thickness with the menstrual cycle.19,20 A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis comparing MRI diagnosis with histopathologic findings reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 60% and 96%, respectively.21 The reported range for sensitivity and specificity is wide: 70% to 93% for sensitivity and 67% to 93% for specificity.22-24

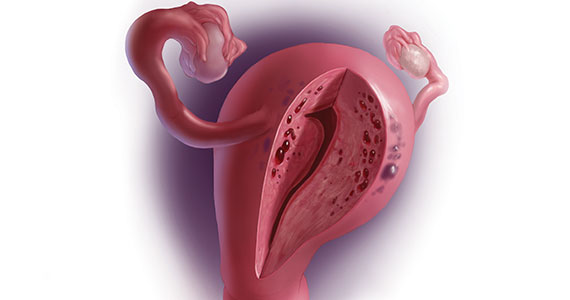

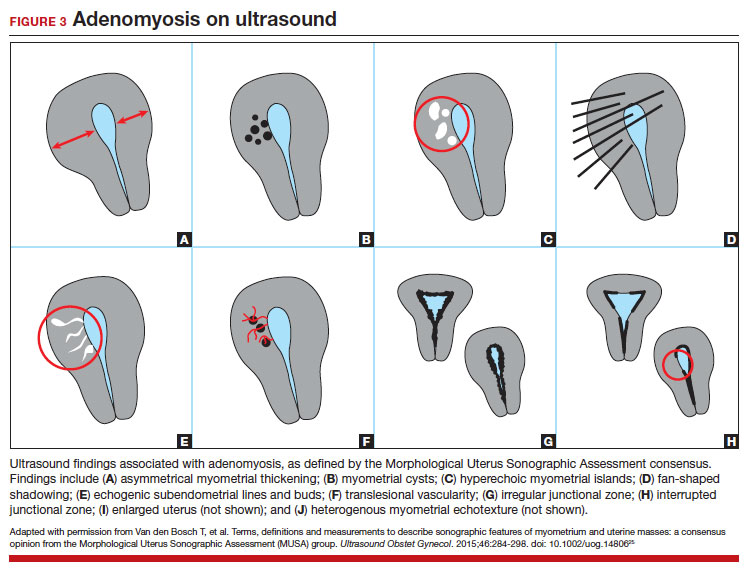

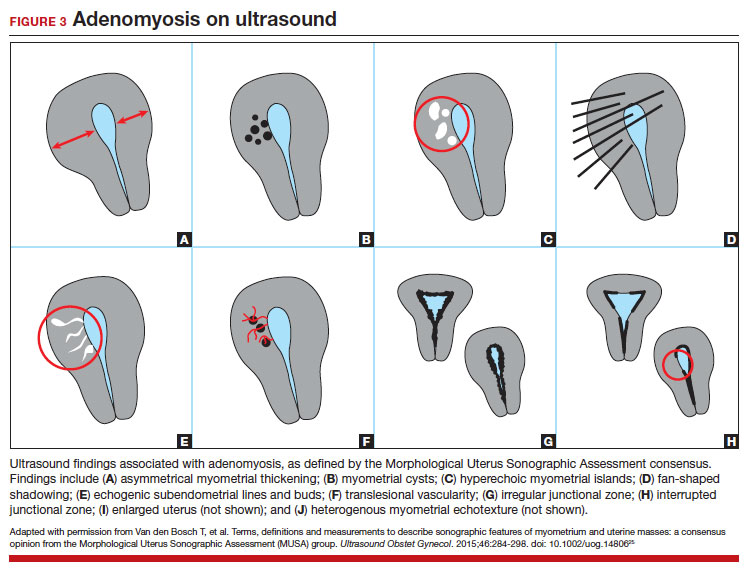

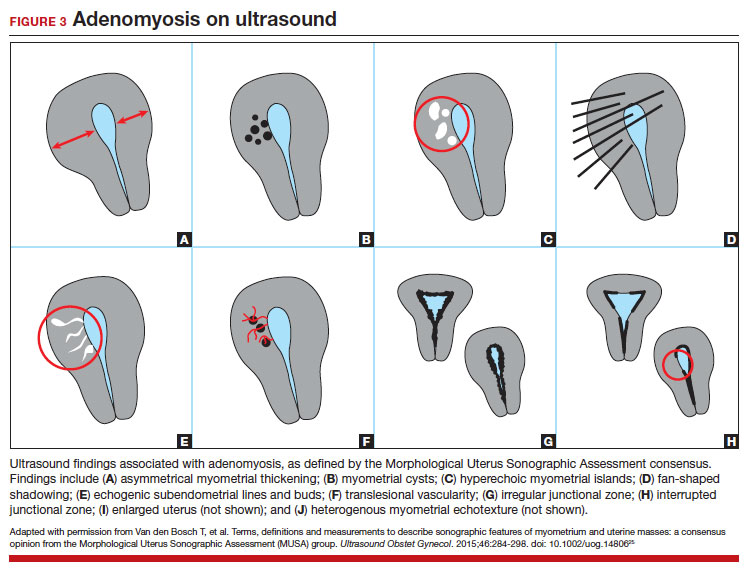

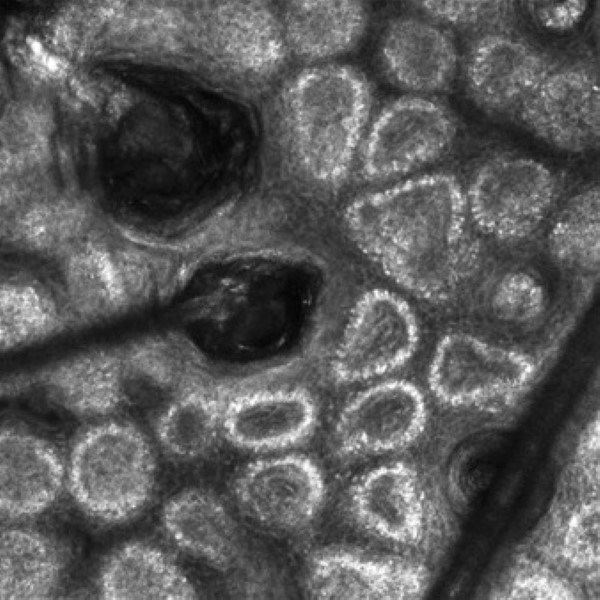

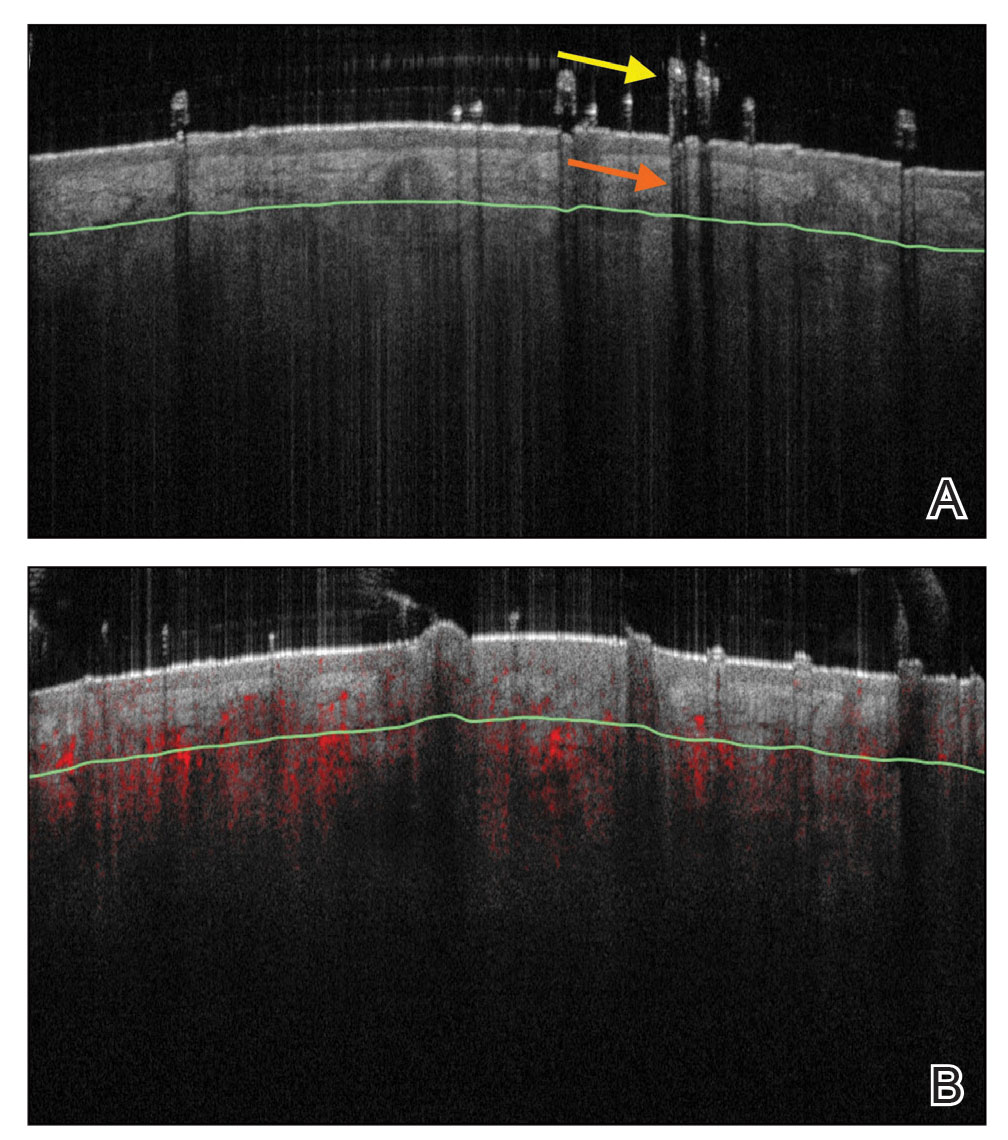

Key TVUS features associated with adenomyosis were defined in 2015 in a consensus statement released by the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group.25 These include a globally enlarged uterus, anteroposterior myometrial asymmetry, myometrial cysts, fan-shaped shadowing, mixed myometrial echogenicity, translesional vascularity, echogenic subendometrial lines and buds, and a thickened, irregular or discontinuous JZ (FIGURES 3 and 4).25 The accuracy of ultrasonographic diagnosis of adenomyosis using these features has been investigated in multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses, most recently by Liu and colleagues who found a pooled sensitivity of TVUS of 81% and pooled specificity of 87%.23 The range for ultrasonographic sensitivity and specificity is wide, however, ranging from 33% to 84% for sensitivity and 64% to 100% for specificity.22 Consensus is lacking as to which TVUS features are most predictive of adenomyosis, but in general, the combination of multiple MUSA criteria (particularly myometrial cysts and irregular JZ on 3D imaging) appears to be more accurate than any one feature alone.23 The presence of fibroids may decrease the sensitivity of TVUS, and one study suggested elastography may increase the accuracy of TVUS.24,26 Moreover, given that most radiologists receive limited training on the MUSA criteria, it behooves gynecologists to become familiar with these sonographic features to be able to identify adenomyosis in our patients.

Adenomyosis also may be suspected based on hysteroscopic findings, although a normal hysteroscopy cannot rule out the disease and data are lacking to support these markers as diagnostic. Visual findings can include a “strawberry” pattern, mucosal elevation, cystic hemorrhagic lesions, localized vascularity, or endometrial defects.27 Hysteroscopy may be effective in the treatment of localized lesions, although that discussion is beyond the scope of this review.

Clinical presentation

While many women who are later diagnosed with adenomyosis are asymptomatic, the disease can present with heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea, which occur in 50% and 30% of patients, respectively.28 Other symptoms include dyspareunia and infertility. Symptoms were previously reported to develop between the ages of 40 and 50 years; however, this is biased by diagnosis at the time of hysterectomy and the fact that younger patients are less likely to undergo definitive surgery. When using imaging criteria for diagnosis, adenomyosis might be more responsible for dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain in younger patients than previously appreciated.1,29 In a recent study reviewing TVUS in 270 adolescents for any reason, adenomyosis was present in 5% of cases and this increased up to 44% in the presence of endometriosis.30

Adenomyosis often co-exists and shares similar clinical presentations with other gynecologic pathologies such as endometriosis and fibroids, making diagnosis on symptomatology alone challenging. Concurrent adenomyosis has been found in up to 73% and 57% of patients with suspected or diagnosed endometriosis and fibroids, respectively.31,32 Accumulating evidence suggests that pelvic pain previously attributed to endometriosis may in fact be a result of adenomyosis; for example, persistent pelvic pain after optimal resection of endometriosis may be confounded by the presence of adenomyosis.29 In one study of 155 patients with complete resection of deep infiltrating endometriosis, persistent pelvic pain was significantly associated with the presence of adenomyosis on imaging.33

Adenomyosis is increasingly being recognized at the time of infertility evaluation with an estimated prevalence of 30% in women with infertility.3 Among women with infertility, adenomyosis has been associated with a lower clinical pregnancy rate, higher miscarriage rate, and lower live birth rate, as well as obstetric complications such as abnormal placentation.34-36 A study of 37 baboons found the histologic diagnosis of adenomyosis alone at necropsy was associated with a 20-fold increased risk of lifelong infertility (odds ratio [OR], 20.1; 95% CI, 2.1-921), whereas presence of endometriosis was associated with a nonsignificant 3-fold risk of lifelong infertility (OR, 3.6; 95% CI, 0.9-15.8).37

In women with endometriosis and infertility, co-existing adenomyosis portends worse fertility outcomes. In a retrospective study of 244 women who underwent endometriosis surgery, more than five features of adenomyosis on imaging was associated with higher rates of infertility, in vitro fertilization treatments, and a higher number of in vitro fertilization cycles.31 Moreover, in women who underwent surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis, the presence of adenomyosis on imaging was associated with a 68% reduction in likelihood of pregnancy after surgery.38

Conclusion

As we begin to learn about adenomyosis, our misconceptions become more evident. The notion that it largely affects women at the end of their reproductive lives is biased by using histopathology at hysterectomy as the gold standard for diagnosis. Lack of definitive histologic or imaging criteria and biopsy techniques add to the diagnostic challenge. This in turn leads to inaccurate estimates of incidence and prevalence, as we assume patients’ symptoms must be attributable to what we can see at the time of surgery (for example, Stage I or II endometriosis), rather than what we cannot see. We now know that adenomyosis is present in women of all ages, including adolescents, and can significantly contribute to reduced fertility and quality of life. We owe it to our patients to consider this condition in the differential diagnosis of dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, dyspareunia, and infertility.

CASE Resolved

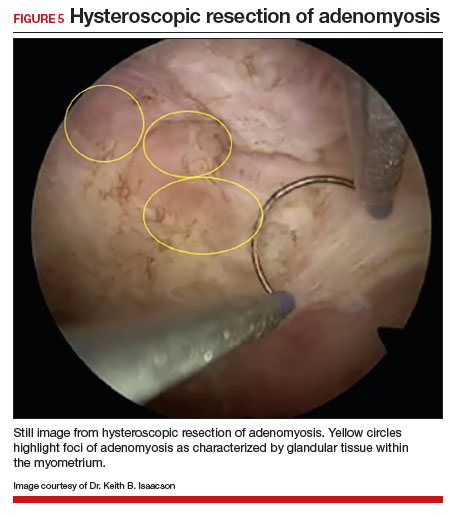

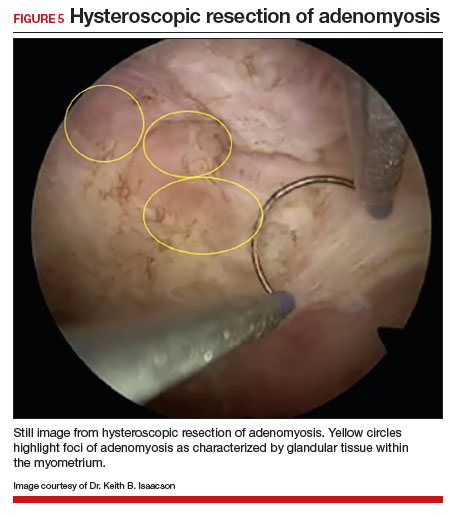

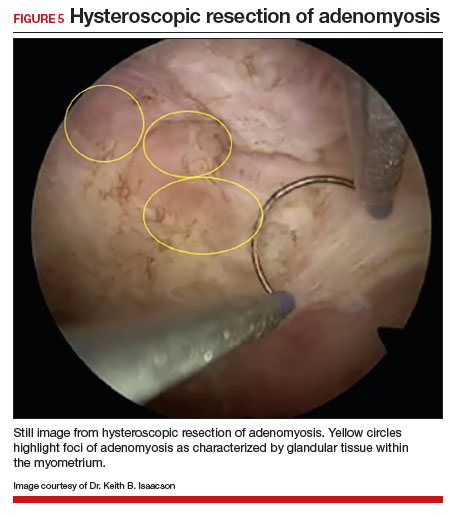

The patient underwent targeted hysteroscopic resection of adenomyosis (FIGURE 5) and conceived spontaneously the following year. ●

- Exacoustos C, Lazzeri L, Martire FG, et al. Ultrasound findings of adenomyosis in adolescents: type and grade of the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;29:291.e1-299.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2021.08.023

- Loring M, Chen TY, Isaacson KB. A systematic review of adenomyosis: it is time to reassess what we thought we knew about the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:644655. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.10.012

- Bourdon M, Santulli P, Oliveira J, et al. Focal adenomyosis is associated with primary infertility. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:1271-1277. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.06.018

- Lan J, Wu Y, Wu Z, et al. Ultra-long GnRH agonist protocol during IVF/ICSI improves pregnancy outcomes in women with adenomyosis: a retrospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:609771. doi: 10.3389 /fendo.2021.609771

- Gnecco JS, Brown AT, Kan EL, et al. Physiomimetic models of adenomyosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2020;38:179-196. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1719084

- Harmsen MJ, Trommelen LM, de Leeuw RA, et al. Uterine junctional zone and adenomyosis: comparison of MRI, transvaginal ultrasound and histology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023;62:42-60. doi: 10.1002/uog.26117

- Xie T, Xu X, Yang Y, et al. The role of abnormal uterine junction zone in the occurrence and development of adenomyosis. Reprod Sci. 2022;29:2719-2730. doi: 10.1007/s43032-021 -00684-2

- Lazzeri L, Morosetti G, Centini G, et al. A sonographic classification of adenomyosis: interobserver reproducibility in the evaluation of type and degree of the myometrial involvement. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:1154-1161.e3. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2018.06.031

- Tahlan A, Nanda A, Mohan H. Uterine adenomyoma: a clinicopathologic review of 26 cases and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25:361-365. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000209570.08716.b3

- Chung K, Wallace J, Kim S-Y, et al. Structural and molecular interrogation of intact biological systems. Nature. 2013;497:332-337. doi: 10.1038/nature12107

- Yamaguchi M, Yoshihara K, Suda K, et al. Three-dimensional understanding of the morphological complexity of the human uterine endometrium. iScience. 2021;24:102258. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102258

- Vannuccini S, Tosti C, Carmona F, et al. Pathogenesis of adenomyosis: an update on molecular mechanisms. Reprod Biomed Online. 2017;35:592-601. doi: 10.1016 /j.rbmo.2017.06.016

- Zhai J, Vannuccini S, Petraglia F, et al. Adenomyosis: mechanisms and pathogenesis. Semin Reprod Med. 2020;38:129-143. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1716687

- Munro MG. Uterine polyps, adenomyosis, leiomyomas, and endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:629-640. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.02.008

- Kay N, Huang C-Y, Shiu L-Y, et al. TGF-β1 neutralization improves pregnancy outcomes by restoring endometrial receptivity in mice with adenomyosis. Reprod Sci. 2021;28:877-887. doi: 10.1007/s43032-020-00308-1

- Habiba M, Benagiano G. Classifying adenomyosis: progress and challenges. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:12386. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312386

- Movilla P, Morris S, Isaacson K. A systematic review of tissue sampling techniques for the diagnosis of adenomyosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:344-351. doi: 10.1016 /j.jmig.2019.09.001

- Agostinho L, Cruz R, Osório F, et al. MRI for adenomyosis: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging. 2017;8:549-556. doi: 10.1007/s13244-017-0576-z

- Bazot M, Cortez A, Darai E, et al. Ultrasonography compared with magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: correlation with histopathology. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2427-2433. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.11.2427

- Reinhold C, Tafazoli F, Mehio A, et al. Uterine adenomyosis: endovaginal US and MR imaging features with histopathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:S147-S160. doi: 10.1148 /radiographics.19.suppl_1.g99oc13s147

- Rees CO, Nederend J, Mischi M, et al. Objective measures of adenomyosis on MRI and their diagnostic accuracy—a systematic review & meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:1377-1391.

- Chapron C, Vannuccini S, Santulli P, et al. Diagnosing adenomyosis: an integrated clinical and imaging approach. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:392-411. doi: 10.1093 /humupd/dmz049

- Liu L, Li W, Leonardi M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging for adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis and review of sonographic diagnostic criteria. J Ultrasound Med. 2021;40:2289-2306. doi: 10.1002/jum.15635

- Bazot M, Daraï E. Role of transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:389-397. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2018.01.024

- Van den Bosch T, Dueholm M, Leone FPG, et al. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe sonographic features of myometrium and uterine masses: a consensus opinion from the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46:284-298. doi: 10.1002/uog.14806

- Săsăran V, Turdean S, Gliga M, et al. Value of strainratio elastography in the diagnosis and differentiation of uterine fibroids and adenomyosis. J Pers Med. 2021;11:824. doi: 10.3390/jpm11080824

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Calagna G, Santangelo F, et al. The role of hysteroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of adenomyosis. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:2518396. doi: 10.1155/2017/2518396

- Azzi R. Adenomyosis: current perspectives. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:221-235.

- Parker JD, Leondires M, Sinaii N, et al. Persistence of dysmenorrhea and nonmenstrual pain after optimal endometriosis surgery may indicate adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:711-715. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.030

- Martire FG, Lazzeri L, Conway F, et al. Adolescence and endometriosis: symptoms, ultrasound signs and early diagnosis. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:1049-1057. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2020.06.012

- Decter D, Arbib N, Markovitz H, et al. Sonographic signs of adenomyosis in women with endometriosis are associated with infertility. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2355. doi: 10.3390 /jcm10112355

- Brucker SY, Huebner M, Wallwiener M, et al. Clinical characteristics indicating adenomyosis coexisting with leiomyomas: a retrospective, questionnaire-based study. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:237-241.e1. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2013.09.038

- Perelló MF, Martínez-Zamora MÁ, Torres X, et al. Endometriotic pain is associated with adenomyosis but not with the compartments affected by deep infiltrating endometriosis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2017;82:240-246. doi: 10.1159/000447633

- Younes G, Tulandi T. Effects of adenomyosis on in vitro fertilization treatment outcomes: a metaanalysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:483-490.e3. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2017.06.025

- Nirgianakis K, Kalaitzopoulos DR, Schwartz ASK, et al. Fertility, pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of patients with adenomyosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod BioMed Online. 2021;42:185-206. doi: 10.1016 /j.rbmo.2020.09.023

- Ono Y, Ota H, Takimoto K, et al. Perinatal outcomes associated with the positional relationship between the placenta and the adenomyosis lesion. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:102114. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2021.102114

- Barrier BF, Malinowski MJ, Dick EJ Jr, et al. Adenomyosis in the baboon is associated with primary infertility. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(suppl 3):1091-1094. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2003.11.065

- Vercellini P, Consonni D, Barbara G, et al. Adenomyosis and reproductive performance after surgery for rectovaginal and colorectal endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28:704-713. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.02.006

CASE Painful, heavy menstruation and recurrent pregnancy loss

A 37-year-old woman (G3P0030) with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss presents for evaluation. She had 3 losses—most recently a miscarriage at 22 weeks with a cerclage in place. She did not undergo any surgical procedures for these losses. Hormonal and thrombophilia workup is negative and semen analysis is normal. She reports a history of painful, heavy periods for many years, as well as dyspareunia and occasional post-coital bleeding. Past medical history was otherwise unremarkable. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed focal thickening of the junctional zone up to 15 mm with 2 foci of T2 hyperintensities suggesting adenomyosis (FIGURE 1).

How do you counsel this patient regarding the MRI findings and their impact on her fertility?

Adenomyosis is a condition in which endometrial glands and stroma are abnormally present in the uterine myometrium, resulting in smooth muscle hypertrophy and abnormal uterine contractility. Traditional teaching describes a woman in her 40s with heavy and painful menses, a “boggy uterus” on examination, who has completed childbearing and desires definitive treatment. Histologic diagnosis of adenomyosis is made from the uterine specimen at the time of hysterectomy, invariably confounding our understanding of the epidemiology of adenomyosis.

More recently, however, we are beginning to learn that this narrative is misguided. Imaging changes of adenomyosis can be seen in women who desire future fertility and in adolescents with severe dysmenorrhea, suggesting an earlier age of incidence.1 In a recent systematic review, prevalence estimates ranged from 15% to 67%, owing to varying diagnostic methods and patient inclusion criteria.2 It is increasingly being recognized as a primary contributor to infertility, with one study estimating a 30% prevalence of infertility in women with adenomyosis.3 Moreover, treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and/or surgical excision may improve fertility outcomes.4

As we learn more about this prevalent and life-altering condition, we owe it to our patients to consider this diagnosis when counseling on dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, or infertility.

Anatomy of the myometrium

The myometrium is composed of the inner and outer myometrium: the inner myometrium (IM) and endometrium are of Müllerian origin, and the outer myometrium (OM) is of mesenchymal origin. The IM thickens in response to steroid hormones during the menstrual cycle with metaplasia of endometrial stromal cells into myocytes and back again, whereas the OM is not responsive to hormones.5 Emerging literature suggests the OM is further divided into a middle and outer section based on different histologic morphologies, though the clinical implications of this are not understood.6 The term “junctional zone” (JZ) refers to the imaging appearance of what is thought to be the IM. Interestingly it cannot be identified on traditional hematoxylin and eosin staining. When the JZ is thickened or demonstrates irregular borders, it is used as a diagnostic marker for adenomyosis and is postulated to play an important role in adenomyosis pathophysiology, particularly heavy menstrual bleeding and infertility.7

Continue to: Subtypes of adenomyosis...

Subtypes of adenomyosis

While various disease classifications have been suggested for adenomyosis, to date there is no international consensus. Adenomyosis is typically described in 3 forms: diffuse, focal, or adenomyoma.8 As implied, the term focal adenomyosis refers to discrete lesions surrounded by normal myometrium, whereas abnormal glandular changes are pervasive throughout the myometrium in diffuse disease. Adenomyomas are a subgroup of focal adenomyosis that are thought to be surrounded by leiomyomatous smooth muscle and may be well demarcated on imaging.9

Recent research uses novel histologic imaging techniques to explore adenomyotic growth patterns in 3-dimensional (3D) reconstructions. Combining tissue-clearing methods with light-sheet fluorescence microscopy enables highly detailed 3D representations of the protein and nucleic acid structure of organs.10 For example, Yamaguchi and colleagues used this technology to explore the 3D morphological features of adenomyotic tissue and observed direct invasion of the endometrial glands into the myometrium and an “ant colony ̶ like network” of ectopic endometrial glands in the myometrium (FIGURE 2).11 These abnormal glandular networks have been visualized beyond the IM, which may not be captured on ultrasonography or MRI. While this work is still in its infancy, it has the potential to provide important insight into disease pathogenesis and to inform future therapy.

Pathogenesis

Proposed mechanisms for the development of adenomyosis include endometrial invasion, tissue injury and repair (TIAR) mechanisms, and the stem cell theory.12 According to the endometrial invasion theory, glandular epithelial cells from the basalis layer invaginate through an altered IM, slipping through weak muscle fibers and attracted by certain growth factors. In the TIAR mechanism theory, micro- or macro-trauma to the IM (whether from pregnancy, surgery, or infection) results in chronic proliferation and inflammation leading to the development of adenomyosis. Finally, the stem cell theory proposes that adenomyosis might develop from de novo ectopic endometrial tissue.

While the exact pathogenesis of adenomyosis is largely unknown, it has been associated with predictable molecular changes in the endometrium and surrounding myometrium.12 Myometrial hypercontractility is seen in patients with adenomyosis and dysmenorrhea, whereas neovascularization, high microvessel density, and abnormal uterine contractility are seen in those with abnormal uterine bleeding.13 In patients with infertility, increased inflammation, abnormal endometrial receptivity, and alterations in the myometrial architecture have been suggested to impair contractility and sperm transport.12,14

Differential growth factor expression and abnormal estrogen and progesterone signaling pathways have been observed in the IM in patients with adenomyosis, along with dysregulation of immune factors and increased inflammatory oxidative stress.12 This in turn results in myometrial hypertrophy and fibrosis, impairing normal uterine contractility patterns. This abnormal contractility may alter sperm transport and embryo implantation, and animal models that target pathways leading to fibrosis may improve endometrial receptivity.14,15 Further research is needed to elucidate specific molecular pathways and their complex interplay in this disease.

Continue to: Diagnosis...

Diagnosis

The gold standard for diagnosis of adenomyosis is histopathology from hysterectomy specimens, but specific definitions vary. Published criteria include endometrial glands within the myometrial layer greater than 0.5 to 1 low power field from the basal layer of the endometrium, endometrial glands extending deeper than 25% of the myometrial thickness, or endometrial glands a certain distance (ranging from 1-3 mm) from the basalis layer of the endometrium.16 Various methods of non-hysterectomy tissue sampling have been proposed for diagnosis, including needle, hysteroscopic, or laparoscopic sampling, but the sensitivity of these methods is poor.17 Limiting the diagnosis of adenomyosis to specimen pathology relies on invasive methods and clearly we cannot confirm the diagnosis by hysterectomy in patients with a desire for future fertility. It is for this reason that the prevalence of the disease is widely unknown.

The alternative to pathologic diagnosis is to identify radiologic changes that are associated with adenomyosis via either transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) or MRI. Features suggestive of adenomyosis on MRI overlap with TVUS features, including uterine enlargement, anteroposterior myometrial asymmetry, T1- or T2-intense myometrial cysts or foci, and a thickened JZ.18 A JZ thicker than 12 mm has been thought to be predictive of adenomyosis, whereas a thickness of less than 8 mm is predictive of its absence, although the JZ may vary in thickness with the menstrual cycle.19,20 A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis comparing MRI diagnosis with histopathologic findings reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 60% and 96%, respectively.21 The reported range for sensitivity and specificity is wide: 70% to 93% for sensitivity and 67% to 93% for specificity.22-24

Key TVUS features associated with adenomyosis were defined in 2015 in a consensus statement released by the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group.25 These include a globally enlarged uterus, anteroposterior myometrial asymmetry, myometrial cysts, fan-shaped shadowing, mixed myometrial echogenicity, translesional vascularity, echogenic subendometrial lines and buds, and a thickened, irregular or discontinuous JZ (FIGURES 3 and 4).25 The accuracy of ultrasonographic diagnosis of adenomyosis using these features has been investigated in multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses, most recently by Liu and colleagues who found a pooled sensitivity of TVUS of 81% and pooled specificity of 87%.23 The range for ultrasonographic sensitivity and specificity is wide, however, ranging from 33% to 84% for sensitivity and 64% to 100% for specificity.22 Consensus is lacking as to which TVUS features are most predictive of adenomyosis, but in general, the combination of multiple MUSA criteria (particularly myometrial cysts and irregular JZ on 3D imaging) appears to be more accurate than any one feature alone.23 The presence of fibroids may decrease the sensitivity of TVUS, and one study suggested elastography may increase the accuracy of TVUS.24,26 Moreover, given that most radiologists receive limited training on the MUSA criteria, it behooves gynecologists to become familiar with these sonographic features to be able to identify adenomyosis in our patients.

Adenomyosis also may be suspected based on hysteroscopic findings, although a normal hysteroscopy cannot rule out the disease and data are lacking to support these markers as diagnostic. Visual findings can include a “strawberry” pattern, mucosal elevation, cystic hemorrhagic lesions, localized vascularity, or endometrial defects.27 Hysteroscopy may be effective in the treatment of localized lesions, although that discussion is beyond the scope of this review.

Clinical presentation

While many women who are later diagnosed with adenomyosis are asymptomatic, the disease can present with heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea, which occur in 50% and 30% of patients, respectively.28 Other symptoms include dyspareunia and infertility. Symptoms were previously reported to develop between the ages of 40 and 50 years; however, this is biased by diagnosis at the time of hysterectomy and the fact that younger patients are less likely to undergo definitive surgery. When using imaging criteria for diagnosis, adenomyosis might be more responsible for dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain in younger patients than previously appreciated.1,29 In a recent study reviewing TVUS in 270 adolescents for any reason, adenomyosis was present in 5% of cases and this increased up to 44% in the presence of endometriosis.30

Adenomyosis often co-exists and shares similar clinical presentations with other gynecologic pathologies such as endometriosis and fibroids, making diagnosis on symptomatology alone challenging. Concurrent adenomyosis has been found in up to 73% and 57% of patients with suspected or diagnosed endometriosis and fibroids, respectively.31,32 Accumulating evidence suggests that pelvic pain previously attributed to endometriosis may in fact be a result of adenomyosis; for example, persistent pelvic pain after optimal resection of endometriosis may be confounded by the presence of adenomyosis.29 In one study of 155 patients with complete resection of deep infiltrating endometriosis, persistent pelvic pain was significantly associated with the presence of adenomyosis on imaging.33

Adenomyosis is increasingly being recognized at the time of infertility evaluation with an estimated prevalence of 30% in women with infertility.3 Among women with infertility, adenomyosis has been associated with a lower clinical pregnancy rate, higher miscarriage rate, and lower live birth rate, as well as obstetric complications such as abnormal placentation.34-36 A study of 37 baboons found the histologic diagnosis of adenomyosis alone at necropsy was associated with a 20-fold increased risk of lifelong infertility (odds ratio [OR], 20.1; 95% CI, 2.1-921), whereas presence of endometriosis was associated with a nonsignificant 3-fold risk of lifelong infertility (OR, 3.6; 95% CI, 0.9-15.8).37

In women with endometriosis and infertility, co-existing adenomyosis portends worse fertility outcomes. In a retrospective study of 244 women who underwent endometriosis surgery, more than five features of adenomyosis on imaging was associated with higher rates of infertility, in vitro fertilization treatments, and a higher number of in vitro fertilization cycles.31 Moreover, in women who underwent surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis, the presence of adenomyosis on imaging was associated with a 68% reduction in likelihood of pregnancy after surgery.38

Conclusion

As we begin to learn about adenomyosis, our misconceptions become more evident. The notion that it largely affects women at the end of their reproductive lives is biased by using histopathology at hysterectomy as the gold standard for diagnosis. Lack of definitive histologic or imaging criteria and biopsy techniques add to the diagnostic challenge. This in turn leads to inaccurate estimates of incidence and prevalence, as we assume patients’ symptoms must be attributable to what we can see at the time of surgery (for example, Stage I or II endometriosis), rather than what we cannot see. We now know that adenomyosis is present in women of all ages, including adolescents, and can significantly contribute to reduced fertility and quality of life. We owe it to our patients to consider this condition in the differential diagnosis of dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, dyspareunia, and infertility.

CASE Resolved

The patient underwent targeted hysteroscopic resection of adenomyosis (FIGURE 5) and conceived spontaneously the following year. ●

CASE Painful, heavy menstruation and recurrent pregnancy loss

A 37-year-old woman (G3P0030) with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss presents for evaluation. She had 3 losses—most recently a miscarriage at 22 weeks with a cerclage in place. She did not undergo any surgical procedures for these losses. Hormonal and thrombophilia workup is negative and semen analysis is normal. She reports a history of painful, heavy periods for many years, as well as dyspareunia and occasional post-coital bleeding. Past medical history was otherwise unremarkable. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed focal thickening of the junctional zone up to 15 mm with 2 foci of T2 hyperintensities suggesting adenomyosis (FIGURE 1).

How do you counsel this patient regarding the MRI findings and their impact on her fertility?

Adenomyosis is a condition in which endometrial glands and stroma are abnormally present in the uterine myometrium, resulting in smooth muscle hypertrophy and abnormal uterine contractility. Traditional teaching describes a woman in her 40s with heavy and painful menses, a “boggy uterus” on examination, who has completed childbearing and desires definitive treatment. Histologic diagnosis of adenomyosis is made from the uterine specimen at the time of hysterectomy, invariably confounding our understanding of the epidemiology of adenomyosis.

More recently, however, we are beginning to learn that this narrative is misguided. Imaging changes of adenomyosis can be seen in women who desire future fertility and in adolescents with severe dysmenorrhea, suggesting an earlier age of incidence.1 In a recent systematic review, prevalence estimates ranged from 15% to 67%, owing to varying diagnostic methods and patient inclusion criteria.2 It is increasingly being recognized as a primary contributor to infertility, with one study estimating a 30% prevalence of infertility in women with adenomyosis.3 Moreover, treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and/or surgical excision may improve fertility outcomes.4

As we learn more about this prevalent and life-altering condition, we owe it to our patients to consider this diagnosis when counseling on dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, or infertility.

Anatomy of the myometrium

The myometrium is composed of the inner and outer myometrium: the inner myometrium (IM) and endometrium are of Müllerian origin, and the outer myometrium (OM) is of mesenchymal origin. The IM thickens in response to steroid hormones during the menstrual cycle with metaplasia of endometrial stromal cells into myocytes and back again, whereas the OM is not responsive to hormones.5 Emerging literature suggests the OM is further divided into a middle and outer section based on different histologic morphologies, though the clinical implications of this are not understood.6 The term “junctional zone” (JZ) refers to the imaging appearance of what is thought to be the IM. Interestingly it cannot be identified on traditional hematoxylin and eosin staining. When the JZ is thickened or demonstrates irregular borders, it is used as a diagnostic marker for adenomyosis and is postulated to play an important role in adenomyosis pathophysiology, particularly heavy menstrual bleeding and infertility.7

Continue to: Subtypes of adenomyosis...

Subtypes of adenomyosis

While various disease classifications have been suggested for adenomyosis, to date there is no international consensus. Adenomyosis is typically described in 3 forms: diffuse, focal, or adenomyoma.8 As implied, the term focal adenomyosis refers to discrete lesions surrounded by normal myometrium, whereas abnormal glandular changes are pervasive throughout the myometrium in diffuse disease. Adenomyomas are a subgroup of focal adenomyosis that are thought to be surrounded by leiomyomatous smooth muscle and may be well demarcated on imaging.9

Recent research uses novel histologic imaging techniques to explore adenomyotic growth patterns in 3-dimensional (3D) reconstructions. Combining tissue-clearing methods with light-sheet fluorescence microscopy enables highly detailed 3D representations of the protein and nucleic acid structure of organs.10 For example, Yamaguchi and colleagues used this technology to explore the 3D morphological features of adenomyotic tissue and observed direct invasion of the endometrial glands into the myometrium and an “ant colony ̶ like network” of ectopic endometrial glands in the myometrium (FIGURE 2).11 These abnormal glandular networks have been visualized beyond the IM, which may not be captured on ultrasonography or MRI. While this work is still in its infancy, it has the potential to provide important insight into disease pathogenesis and to inform future therapy.

Pathogenesis

Proposed mechanisms for the development of adenomyosis include endometrial invasion, tissue injury and repair (TIAR) mechanisms, and the stem cell theory.12 According to the endometrial invasion theory, glandular epithelial cells from the basalis layer invaginate through an altered IM, slipping through weak muscle fibers and attracted by certain growth factors. In the TIAR mechanism theory, micro- or macro-trauma to the IM (whether from pregnancy, surgery, or infection) results in chronic proliferation and inflammation leading to the development of adenomyosis. Finally, the stem cell theory proposes that adenomyosis might develop from de novo ectopic endometrial tissue.

While the exact pathogenesis of adenomyosis is largely unknown, it has been associated with predictable molecular changes in the endometrium and surrounding myometrium.12 Myometrial hypercontractility is seen in patients with adenomyosis and dysmenorrhea, whereas neovascularization, high microvessel density, and abnormal uterine contractility are seen in those with abnormal uterine bleeding.13 In patients with infertility, increased inflammation, abnormal endometrial receptivity, and alterations in the myometrial architecture have been suggested to impair contractility and sperm transport.12,14

Differential growth factor expression and abnormal estrogen and progesterone signaling pathways have been observed in the IM in patients with adenomyosis, along with dysregulation of immune factors and increased inflammatory oxidative stress.12 This in turn results in myometrial hypertrophy and fibrosis, impairing normal uterine contractility patterns. This abnormal contractility may alter sperm transport and embryo implantation, and animal models that target pathways leading to fibrosis may improve endometrial receptivity.14,15 Further research is needed to elucidate specific molecular pathways and their complex interplay in this disease.

Continue to: Diagnosis...

Diagnosis

The gold standard for diagnosis of adenomyosis is histopathology from hysterectomy specimens, but specific definitions vary. Published criteria include endometrial glands within the myometrial layer greater than 0.5 to 1 low power field from the basal layer of the endometrium, endometrial glands extending deeper than 25% of the myometrial thickness, or endometrial glands a certain distance (ranging from 1-3 mm) from the basalis layer of the endometrium.16 Various methods of non-hysterectomy tissue sampling have been proposed for diagnosis, including needle, hysteroscopic, or laparoscopic sampling, but the sensitivity of these methods is poor.17 Limiting the diagnosis of adenomyosis to specimen pathology relies on invasive methods and clearly we cannot confirm the diagnosis by hysterectomy in patients with a desire for future fertility. It is for this reason that the prevalence of the disease is widely unknown.

The alternative to pathologic diagnosis is to identify radiologic changes that are associated with adenomyosis via either transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) or MRI. Features suggestive of adenomyosis on MRI overlap with TVUS features, including uterine enlargement, anteroposterior myometrial asymmetry, T1- or T2-intense myometrial cysts or foci, and a thickened JZ.18 A JZ thicker than 12 mm has been thought to be predictive of adenomyosis, whereas a thickness of less than 8 mm is predictive of its absence, although the JZ may vary in thickness with the menstrual cycle.19,20 A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis comparing MRI diagnosis with histopathologic findings reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 60% and 96%, respectively.21 The reported range for sensitivity and specificity is wide: 70% to 93% for sensitivity and 67% to 93% for specificity.22-24

Key TVUS features associated with adenomyosis were defined in 2015 in a consensus statement released by the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group.25 These include a globally enlarged uterus, anteroposterior myometrial asymmetry, myometrial cysts, fan-shaped shadowing, mixed myometrial echogenicity, translesional vascularity, echogenic subendometrial lines and buds, and a thickened, irregular or discontinuous JZ (FIGURES 3 and 4).25 The accuracy of ultrasonographic diagnosis of adenomyosis using these features has been investigated in multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses, most recently by Liu and colleagues who found a pooled sensitivity of TVUS of 81% and pooled specificity of 87%.23 The range for ultrasonographic sensitivity and specificity is wide, however, ranging from 33% to 84% for sensitivity and 64% to 100% for specificity.22 Consensus is lacking as to which TVUS features are most predictive of adenomyosis, but in general, the combination of multiple MUSA criteria (particularly myometrial cysts and irregular JZ on 3D imaging) appears to be more accurate than any one feature alone.23 The presence of fibroids may decrease the sensitivity of TVUS, and one study suggested elastography may increase the accuracy of TVUS.24,26 Moreover, given that most radiologists receive limited training on the MUSA criteria, it behooves gynecologists to become familiar with these sonographic features to be able to identify adenomyosis in our patients.

Adenomyosis also may be suspected based on hysteroscopic findings, although a normal hysteroscopy cannot rule out the disease and data are lacking to support these markers as diagnostic. Visual findings can include a “strawberry” pattern, mucosal elevation, cystic hemorrhagic lesions, localized vascularity, or endometrial defects.27 Hysteroscopy may be effective in the treatment of localized lesions, although that discussion is beyond the scope of this review.

Clinical presentation

While many women who are later diagnosed with adenomyosis are asymptomatic, the disease can present with heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea, which occur in 50% and 30% of patients, respectively.28 Other symptoms include dyspareunia and infertility. Symptoms were previously reported to develop between the ages of 40 and 50 years; however, this is biased by diagnosis at the time of hysterectomy and the fact that younger patients are less likely to undergo definitive surgery. When using imaging criteria for diagnosis, adenomyosis might be more responsible for dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain in younger patients than previously appreciated.1,29 In a recent study reviewing TVUS in 270 adolescents for any reason, adenomyosis was present in 5% of cases and this increased up to 44% in the presence of endometriosis.30

Adenomyosis often co-exists and shares similar clinical presentations with other gynecologic pathologies such as endometriosis and fibroids, making diagnosis on symptomatology alone challenging. Concurrent adenomyosis has been found in up to 73% and 57% of patients with suspected or diagnosed endometriosis and fibroids, respectively.31,32 Accumulating evidence suggests that pelvic pain previously attributed to endometriosis may in fact be a result of adenomyosis; for example, persistent pelvic pain after optimal resection of endometriosis may be confounded by the presence of adenomyosis.29 In one study of 155 patients with complete resection of deep infiltrating endometriosis, persistent pelvic pain was significantly associated with the presence of adenomyosis on imaging.33

Adenomyosis is increasingly being recognized at the time of infertility evaluation with an estimated prevalence of 30% in women with infertility.3 Among women with infertility, adenomyosis has been associated with a lower clinical pregnancy rate, higher miscarriage rate, and lower live birth rate, as well as obstetric complications such as abnormal placentation.34-36 A study of 37 baboons found the histologic diagnosis of adenomyosis alone at necropsy was associated with a 20-fold increased risk of lifelong infertility (odds ratio [OR], 20.1; 95% CI, 2.1-921), whereas presence of endometriosis was associated with a nonsignificant 3-fold risk of lifelong infertility (OR, 3.6; 95% CI, 0.9-15.8).37

In women with endometriosis and infertility, co-existing adenomyosis portends worse fertility outcomes. In a retrospective study of 244 women who underwent endometriosis surgery, more than five features of adenomyosis on imaging was associated with higher rates of infertility, in vitro fertilization treatments, and a higher number of in vitro fertilization cycles.31 Moreover, in women who underwent surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis, the presence of adenomyosis on imaging was associated with a 68% reduction in likelihood of pregnancy after surgery.38

Conclusion

As we begin to learn about adenomyosis, our misconceptions become more evident. The notion that it largely affects women at the end of their reproductive lives is biased by using histopathology at hysterectomy as the gold standard for diagnosis. Lack of definitive histologic or imaging criteria and biopsy techniques add to the diagnostic challenge. This in turn leads to inaccurate estimates of incidence and prevalence, as we assume patients’ symptoms must be attributable to what we can see at the time of surgery (for example, Stage I or II endometriosis), rather than what we cannot see. We now know that adenomyosis is present in women of all ages, including adolescents, and can significantly contribute to reduced fertility and quality of life. We owe it to our patients to consider this condition in the differential diagnosis of dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, dyspareunia, and infertility.

CASE Resolved

The patient underwent targeted hysteroscopic resection of adenomyosis (FIGURE 5) and conceived spontaneously the following year. ●

- Exacoustos C, Lazzeri L, Martire FG, et al. Ultrasound findings of adenomyosis in adolescents: type and grade of the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;29:291.e1-299.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2021.08.023

- Loring M, Chen TY, Isaacson KB. A systematic review of adenomyosis: it is time to reassess what we thought we knew about the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:644655. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.10.012

- Bourdon M, Santulli P, Oliveira J, et al. Focal adenomyosis is associated with primary infertility. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:1271-1277. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.06.018

- Lan J, Wu Y, Wu Z, et al. Ultra-long GnRH agonist protocol during IVF/ICSI improves pregnancy outcomes in women with adenomyosis: a retrospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:609771. doi: 10.3389 /fendo.2021.609771

- Gnecco JS, Brown AT, Kan EL, et al. Physiomimetic models of adenomyosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2020;38:179-196. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1719084

- Harmsen MJ, Trommelen LM, de Leeuw RA, et al. Uterine junctional zone and adenomyosis: comparison of MRI, transvaginal ultrasound and histology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023;62:42-60. doi: 10.1002/uog.26117

- Xie T, Xu X, Yang Y, et al. The role of abnormal uterine junction zone in the occurrence and development of adenomyosis. Reprod Sci. 2022;29:2719-2730. doi: 10.1007/s43032-021 -00684-2

- Lazzeri L, Morosetti G, Centini G, et al. A sonographic classification of adenomyosis: interobserver reproducibility in the evaluation of type and degree of the myometrial involvement. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:1154-1161.e3. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2018.06.031

- Tahlan A, Nanda A, Mohan H. Uterine adenomyoma: a clinicopathologic review of 26 cases and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25:361-365. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000209570.08716.b3

- Chung K, Wallace J, Kim S-Y, et al. Structural and molecular interrogation of intact biological systems. Nature. 2013;497:332-337. doi: 10.1038/nature12107

- Yamaguchi M, Yoshihara K, Suda K, et al. Three-dimensional understanding of the morphological complexity of the human uterine endometrium. iScience. 2021;24:102258. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102258

- Vannuccini S, Tosti C, Carmona F, et al. Pathogenesis of adenomyosis: an update on molecular mechanisms. Reprod Biomed Online. 2017;35:592-601. doi: 10.1016 /j.rbmo.2017.06.016

- Zhai J, Vannuccini S, Petraglia F, et al. Adenomyosis: mechanisms and pathogenesis. Semin Reprod Med. 2020;38:129-143. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1716687

- Munro MG. Uterine polyps, adenomyosis, leiomyomas, and endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:629-640. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.02.008

- Kay N, Huang C-Y, Shiu L-Y, et al. TGF-β1 neutralization improves pregnancy outcomes by restoring endometrial receptivity in mice with adenomyosis. Reprod Sci. 2021;28:877-887. doi: 10.1007/s43032-020-00308-1

- Habiba M, Benagiano G. Classifying adenomyosis: progress and challenges. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:12386. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312386

- Movilla P, Morris S, Isaacson K. A systematic review of tissue sampling techniques for the diagnosis of adenomyosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:344-351. doi: 10.1016 /j.jmig.2019.09.001

- Agostinho L, Cruz R, Osório F, et al. MRI for adenomyosis: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging. 2017;8:549-556. doi: 10.1007/s13244-017-0576-z

- Bazot M, Cortez A, Darai E, et al. Ultrasonography compared with magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: correlation with histopathology. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2427-2433. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.11.2427

- Reinhold C, Tafazoli F, Mehio A, et al. Uterine adenomyosis: endovaginal US and MR imaging features with histopathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:S147-S160. doi: 10.1148 /radiographics.19.suppl_1.g99oc13s147

- Rees CO, Nederend J, Mischi M, et al. Objective measures of adenomyosis on MRI and their diagnostic accuracy—a systematic review & meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:1377-1391.

- Chapron C, Vannuccini S, Santulli P, et al. Diagnosing adenomyosis: an integrated clinical and imaging approach. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:392-411. doi: 10.1093 /humupd/dmz049

- Liu L, Li W, Leonardi M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging for adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis and review of sonographic diagnostic criteria. J Ultrasound Med. 2021;40:2289-2306. doi: 10.1002/jum.15635

- Bazot M, Daraï E. Role of transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:389-397. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2018.01.024

- Van den Bosch T, Dueholm M, Leone FPG, et al. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe sonographic features of myometrium and uterine masses: a consensus opinion from the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46:284-298. doi: 10.1002/uog.14806

- Săsăran V, Turdean S, Gliga M, et al. Value of strainratio elastography in the diagnosis and differentiation of uterine fibroids and adenomyosis. J Pers Med. 2021;11:824. doi: 10.3390/jpm11080824

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Calagna G, Santangelo F, et al. The role of hysteroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of adenomyosis. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:2518396. doi: 10.1155/2017/2518396

- Azzi R. Adenomyosis: current perspectives. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:221-235.

- Parker JD, Leondires M, Sinaii N, et al. Persistence of dysmenorrhea and nonmenstrual pain after optimal endometriosis surgery may indicate adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:711-715. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.030

- Martire FG, Lazzeri L, Conway F, et al. Adolescence and endometriosis: symptoms, ultrasound signs and early diagnosis. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:1049-1057. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2020.06.012

- Decter D, Arbib N, Markovitz H, et al. Sonographic signs of adenomyosis in women with endometriosis are associated with infertility. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2355. doi: 10.3390 /jcm10112355

- Brucker SY, Huebner M, Wallwiener M, et al. Clinical characteristics indicating adenomyosis coexisting with leiomyomas: a retrospective, questionnaire-based study. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:237-241.e1. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2013.09.038

- Perelló MF, Martínez-Zamora MÁ, Torres X, et al. Endometriotic pain is associated with adenomyosis but not with the compartments affected by deep infiltrating endometriosis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2017;82:240-246. doi: 10.1159/000447633

- Younes G, Tulandi T. Effects of adenomyosis on in vitro fertilization treatment outcomes: a metaanalysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:483-490.e3. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2017.06.025

- Nirgianakis K, Kalaitzopoulos DR, Schwartz ASK, et al. Fertility, pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of patients with adenomyosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod BioMed Online. 2021;42:185-206. doi: 10.1016 /j.rbmo.2020.09.023

- Ono Y, Ota H, Takimoto K, et al. Perinatal outcomes associated with the positional relationship between the placenta and the adenomyosis lesion. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:102114. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2021.102114

- Barrier BF, Malinowski MJ, Dick EJ Jr, et al. Adenomyosis in the baboon is associated with primary infertility. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(suppl 3):1091-1094. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2003.11.065

- Vercellini P, Consonni D, Barbara G, et al. Adenomyosis and reproductive performance after surgery for rectovaginal and colorectal endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28:704-713. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.02.006

- Exacoustos C, Lazzeri L, Martire FG, et al. Ultrasound findings of adenomyosis in adolescents: type and grade of the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;29:291.e1-299.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2021.08.023

- Loring M, Chen TY, Isaacson KB. A systematic review of adenomyosis: it is time to reassess what we thought we knew about the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:644655. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.10.012

- Bourdon M, Santulli P, Oliveira J, et al. Focal adenomyosis is associated with primary infertility. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:1271-1277. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.06.018

- Lan J, Wu Y, Wu Z, et al. Ultra-long GnRH agonist protocol during IVF/ICSI improves pregnancy outcomes in women with adenomyosis: a retrospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:609771. doi: 10.3389 /fendo.2021.609771

- Gnecco JS, Brown AT, Kan EL, et al. Physiomimetic models of adenomyosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2020;38:179-196. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1719084

- Harmsen MJ, Trommelen LM, de Leeuw RA, et al. Uterine junctional zone and adenomyosis: comparison of MRI, transvaginal ultrasound and histology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023;62:42-60. doi: 10.1002/uog.26117

- Xie T, Xu X, Yang Y, et al. The role of abnormal uterine junction zone in the occurrence and development of adenomyosis. Reprod Sci. 2022;29:2719-2730. doi: 10.1007/s43032-021 -00684-2

- Lazzeri L, Morosetti G, Centini G, et al. A sonographic classification of adenomyosis: interobserver reproducibility in the evaluation of type and degree of the myometrial involvement. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:1154-1161.e3. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2018.06.031

- Tahlan A, Nanda A, Mohan H. Uterine adenomyoma: a clinicopathologic review of 26 cases and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25:361-365. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000209570.08716.b3

- Chung K, Wallace J, Kim S-Y, et al. Structural and molecular interrogation of intact biological systems. Nature. 2013;497:332-337. doi: 10.1038/nature12107

- Yamaguchi M, Yoshihara K, Suda K, et al. Three-dimensional understanding of the morphological complexity of the human uterine endometrium. iScience. 2021;24:102258. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102258

- Vannuccini S, Tosti C, Carmona F, et al. Pathogenesis of adenomyosis: an update on molecular mechanisms. Reprod Biomed Online. 2017;35:592-601. doi: 10.1016 /j.rbmo.2017.06.016

- Zhai J, Vannuccini S, Petraglia F, et al. Adenomyosis: mechanisms and pathogenesis. Semin Reprod Med. 2020;38:129-143. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1716687

- Munro MG. Uterine polyps, adenomyosis, leiomyomas, and endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:629-640. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.02.008

- Kay N, Huang C-Y, Shiu L-Y, et al. TGF-β1 neutralization improves pregnancy outcomes by restoring endometrial receptivity in mice with adenomyosis. Reprod Sci. 2021;28:877-887. doi: 10.1007/s43032-020-00308-1

- Habiba M, Benagiano G. Classifying adenomyosis: progress and challenges. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:12386. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312386

- Movilla P, Morris S, Isaacson K. A systematic review of tissue sampling techniques for the diagnosis of adenomyosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:344-351. doi: 10.1016 /j.jmig.2019.09.001

- Agostinho L, Cruz R, Osório F, et al. MRI for adenomyosis: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging. 2017;8:549-556. doi: 10.1007/s13244-017-0576-z

- Bazot M, Cortez A, Darai E, et al. Ultrasonography compared with magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: correlation with histopathology. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2427-2433. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.11.2427

- Reinhold C, Tafazoli F, Mehio A, et al. Uterine adenomyosis: endovaginal US and MR imaging features with histopathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:S147-S160. doi: 10.1148 /radiographics.19.suppl_1.g99oc13s147

- Rees CO, Nederend J, Mischi M, et al. Objective measures of adenomyosis on MRI and their diagnostic accuracy—a systematic review & meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:1377-1391.

- Chapron C, Vannuccini S, Santulli P, et al. Diagnosing adenomyosis: an integrated clinical and imaging approach. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:392-411. doi: 10.1093 /humupd/dmz049

- Liu L, Li W, Leonardi M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging for adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis and review of sonographic diagnostic criteria. J Ultrasound Med. 2021;40:2289-2306. doi: 10.1002/jum.15635

- Bazot M, Daraï E. Role of transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:389-397. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2018.01.024

- Van den Bosch T, Dueholm M, Leone FPG, et al. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe sonographic features of myometrium and uterine masses: a consensus opinion from the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46:284-298. doi: 10.1002/uog.14806

- Săsăran V, Turdean S, Gliga M, et al. Value of strainratio elastography in the diagnosis and differentiation of uterine fibroids and adenomyosis. J Pers Med. 2021;11:824. doi: 10.3390/jpm11080824

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Calagna G, Santangelo F, et al. The role of hysteroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of adenomyosis. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:2518396. doi: 10.1155/2017/2518396

- Azzi R. Adenomyosis: current perspectives. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:221-235.

- Parker JD, Leondires M, Sinaii N, et al. Persistence of dysmenorrhea and nonmenstrual pain after optimal endometriosis surgery may indicate adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:711-715. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.030

- Martire FG, Lazzeri L, Conway F, et al. Adolescence and endometriosis: symptoms, ultrasound signs and early diagnosis. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:1049-1057. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2020.06.012

- Decter D, Arbib N, Markovitz H, et al. Sonographic signs of adenomyosis in women with endometriosis are associated with infertility. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2355. doi: 10.3390 /jcm10112355

- Brucker SY, Huebner M, Wallwiener M, et al. Clinical characteristics indicating adenomyosis coexisting with leiomyomas: a retrospective, questionnaire-based study. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:237-241.e1. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2013.09.038

- Perelló MF, Martínez-Zamora MÁ, Torres X, et al. Endometriotic pain is associated with adenomyosis but not with the compartments affected by deep infiltrating endometriosis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2017;82:240-246. doi: 10.1159/000447633

- Younes G, Tulandi T. Effects of adenomyosis on in vitro fertilization treatment outcomes: a metaanalysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:483-490.e3. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2017.06.025

- Nirgianakis K, Kalaitzopoulos DR, Schwartz ASK, et al. Fertility, pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of patients with adenomyosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod BioMed Online. 2021;42:185-206. doi: 10.1016 /j.rbmo.2020.09.023

- Ono Y, Ota H, Takimoto K, et al. Perinatal outcomes associated with the positional relationship between the placenta and the adenomyosis lesion. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:102114. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2021.102114

- Barrier BF, Malinowski MJ, Dick EJ Jr, et al. Adenomyosis in the baboon is associated with primary infertility. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(suppl 3):1091-1094. doi: 10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2003.11.065

- Vercellini P, Consonni D, Barbara G, et al. Adenomyosis and reproductive performance after surgery for rectovaginal and colorectal endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28:704-713. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.02.006

Managing intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

CASE Pregnant woman with intense itching

A 28-year-old woman (G1P0) is seen for a routine prenatal visit at 32 3/7 weeks’ gestation. She reports having generalized intense itching, including on her palms and soles, that is most intense at night and has been present for approximately 1 week. Her pregnancy is otherwise uncomplicated to date. Physical exam is within normal limits, with no evidence of a skin rash. Cholestasis of pregnancy is suspected, and laboratory tests are ordered, including bile acids and liver transaminases. Test results show that her aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels are mildly elevated at 55 IU/L and 41 IU/L, respectively, and several days later her bile acid level result is 21 µmol/L.

How should this patient be managed?

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) affects 0.5% to 0.7% of pregnant individuals and results in maternal pruritus and elevated serum bile acid levels.1-3 Pruritus in ICP typically is generalized, including occurrence on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, and it often is reported to be worse at night.4 Up to 25% of pregnant women will develop pruritus during pregnancy but the majority will not have ICP.2,5 Patients with ICP have no associated rash, but clinicians may note excoriations on exam. ICP typically presents in the third trimester of pregnancy but has been reported to occur earlier in gestation.6

Making a diagnosis of ICP

The presence of maternal pruritus in the absence of a skin condition along with elevated levels of serum bile acids are required for the diagnosis of ICP.7 Thus, a thorough history and physical exam is recommended to rule out another skin condition that could potentially explain the patient’s pruritus.

Some controversy exists regarding the bile acid level cutoff that should be used to make a diagnosis of ICP.8 It has been noted that nonfasting serum bile acid levels in pregnancy are considerably higher than those in in the nonpregnant state, and an upper limit of 18 µmol/L has been proposed as a cutoff in pregnancy.9 However, nonfasting total serum bile acids also have been shown to vary considerably by race, with levels 25.8% higher in Black women compared with those in White women and 24.3% higher in Black women compared with those in south Asian women.9 This raises the question of whether we should be using race-specific bile acid values to make a diagnosis of ICP.

Bile acid levels also vary based on whether a patient is in a fasting or postprandial state.10 Despite this variation, most guidelines do not recommend testing fasting bile acid levels as the postprandial state effect overall is small.7,9,11 The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) recommends that if a pregnancy-specific bile acid range is available from the laboratory, then the upper limit of normal for pregnancy should be used when making a diagnosis of ICP.7 The SMFM guidelines also acknowledge, however, that pregnancy-specific values rarely are available, and in this case, levels above the upper limit of normal—often 10 µmol/L should be considered diagnostic for ICP until further evidence regarding optimal bile acid cutoff levels in pregnancy becomes available.7

For patients with suspected ICP, liver transaminase levels should be measured in addition to nonfasting serum bile acid levels.7 A thorough history should include assessment for additional symptoms of liver disease, such as changes in weight, appetite, jaundice, excessive fatigue, malaise, and abdominal pain.7 Elevated transaminases levels may be associated with ICP, but they are not necessary for diagnosis. In the absence of additional clinical symptoms that suggest underlying liver disease or severe early onset ICP, additional evaluation beyond nonfasting serum bile acids and liver transaminase levels, such as liver ultrasonography or evaluation for viral or autoimmune hepatitis, is not recommended.7 Obstetric care clinicians should be aware that there is an increased incidence of preeclampsia among patients with ICP, although no specific guidance regarding further recommendations for screening is provided.7

Continue to: Risks associated with ICP...

Risks associated with ICP

For both patients and clinicians, the greatest concern among patients with ICP is the increased risk of stillbirth. Stillbirth risk in ICP appears to be related to serum bile acid levels and has been reported to be highest in patients with bile acid levels greater than 100 µmol/L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of ICP studies demonstrated no increased risk of stillbirth among patients with bile acid levels less than 100 µmol/L.12 These results, however, must be interpreted with extreme caution as the majority of studies included patients with ICP who were actively managed with attempts to mitigate the risk of stillbirth.7

In the absence of additional pregnancy risk factors, the risk of stillbirth among patients with ICP and serum bile acid levels between 19 and 39 µmol/L does not appear to be elevated above their baseline risk.11 The same is true for pregnant individuals with ICP and no additional pregnancy risk factors with serum bile acid levels between 40 and 99 µmol/L until approximately 38 weeks’ gestation, when the risk of stillbirth is elevated.11 The risk of stillbirth is elevated in ICP with peak bile acid levels greater than 100 µmol/L, with an absolute risk of 3.44%.11

Management of patients with ICP

Laboratory evaluation

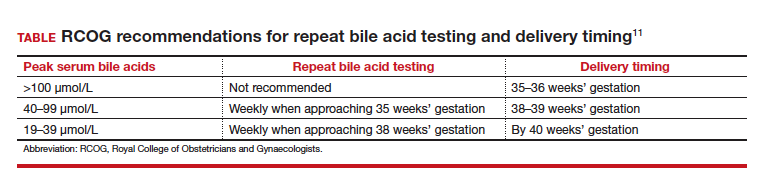

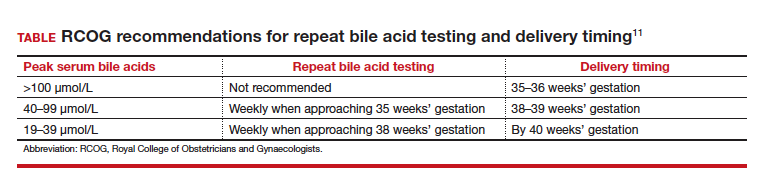

There is no consensus on the need for repeat testing of bile acid levels in patients with ICP. SMFM advises that follow-up testing of bile acid levels may help to guide delivery timing, especially in cases of severe ICP, but the society recommends against serial testing.7 By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) provides a detailed algorithm regarding time intervals between serum bile acid level testing to guide delivery timing.11 The TABLE lists the strategy for reassessment of serum bile acid levels in ICP as recommended by the RCOG.11

In the United States, bile acid testing traditionally takes several days as the testing is commonly performed at reference laboratories. We therefore suggest that clinicians consider repeating bile acid level testing in situations in which the timing of delivery may be altered if further elevations of bile acid levels were noted. This is particularly relevant for patients diagnosed with ICP early in the third trimester when repeat bile acid levels would still allow for an adjustment in delivery timing.

Antepartum fetal surveillance

Unfortunately, antepartum fetal testing for pregnant patients with ICP does not appear to reliably predict or prevent stillbirth as several studies have reported stillbirths within days of normal fetal testing.13-16 It is therefore important to counsel pregnant patients regarding monitoring of fetal movements and advise them to present for evaluation if concerns arise.

Currently, SMFM recommends that patients with ICP should begin antenatal fetal surveillance at a gestational age when abnormal fetal testing would result in delivery.7 Patients should be counseled, however, regarding the unpredictability of stillbirth with ICP in the setting of a low absolute risk of such.

Medications

While SMFM recommends a starting dose of ursodeoxycholic acid 10 to 15 mg/kg per day divided into 2 or 3 daily doses as first-line therapy for the treatment of maternal symptoms of ICP, it is important to acknowledge that the goal of treatment is to alleviate maternal symptoms as there is no evidence that ursodeoxycholic acid improves either maternal serum bile acid levels or perinatal outcomes.7,17,18 Since publication of the guidelines, ursodeoxycholic acid’s lack of benefit has been further confirmed in a meta-analysis, and thus discontinuation is not unreasonable in the absence of any improvement in maternal symptoms.18

Timing of delivery

The optimal management of ICP remains unknown. SMFM recommends delivery based on peak serum bile acid levels. Delivery is recommended at 36 weeks’ gestation with ICP and total bile acid levels greater than 100 µmol/L as these patients have the greatest risk of stillbirth.7 For patients with ICP and bile acid levels less than 100 µmol/L, delivery is recommended between 36 0/7 and 39 0/7 weeks’ gestation.7 This is a wide gestational age window for clinicians to consider timing of delivery, and certainly the risks of stillbirth should be carefully balanced with the morbidity associated with a preterm or early term delivery.

For patients with ICP who have bile acid levels greater than 40 µmol/L, it is reasonable to consider delivery earlier in the gestational age window, given an evidence of increased risk of stillbirth after 38 weeks.7,12 For patients with ICP who have bile acid levels less than 40 µmol/L, delivery closer to 39 weeks’ gestation is recommended, as the risk of stillbirth does not appear to be increased above the baseline risk.7,12 Clinicians should be aware that the presence of concomitant morbidities, such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, are associated with an increased risk of stillbirth and should be considered for delivery planning.19

Postpartum follow-up

Routine laboratory evaluation following delivery is not recommended.7 However, in the presence of persistent pruritus or other signs and symptoms of hepatobiliary disease, liver function tests should be repeated with referral to hepatology if results are persistently abnormal 4 to 6 weeks postpartum.7

CASE Patient follow-up and outcomes

- Abedin P, Weaver JB, Egginton E. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: prevalence and ethnic distribution. Ethn Health. 1999;4:35-37.

- Kenyon AP, Tribe RM, Nelson-Piercy C, et al. Pruritus in pregnancy: a study of anatomical distribution and prevalence in relation to the development of obstetric cholestasis. Obstet Med. 2010;3:25-29.

- Wikstrom Shemer E, Marschall HU, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and associated adverse pregnancy and fetal outcomes: a 12-year population-based cohort study. BJOG. 2013;120:717-723.

- Ambros-Rudolph CM, Glatz M, Trauner M, et al. The importance of serum bile acid level analysis and treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a case series from central Europe. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:757-762.

- Szczech J, Wiatrowski A, Hirnle L, et al. Prevalence and relevance of pruritus in pregnancy. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4238139.

- Geenes V, Williamson C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2049-2066.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Lee RH, Greenberg M, Metz TD, et al. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #53: intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: replaces Consult #13, April 2011. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:B2-B9.

- Horgan R, Bitas C, Abuhamad A. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a comparison of Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5:100838.

- Mitchell AL, Ovadia C, Syngelaki A, et al. Re-evaluating diagnostic thresholds for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: case-control and cohort study. BJOG. 2021;128:1635-1644.

- Adams A, Jacobs K, Vogel RI, et al. Bile acid determination after standardized glucose load in pregnant women. AJP Rep. 2015;5:e168-e171.

- Girling J, Knight CL, Chappell L; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Green-top guideline no. 43, June 2022. BJOG. 2022;129:e95-e114.

- Ovadia C, Seed PT, Sklavounos A, et al. Association of adverse perinatal outcomes of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with biochemical markers: results of aggregate and individual patient data meta-analyses. Lancet. 2019;393:899-909.

- Alsulyman OM, Ouzounian JG, Ames-Castro M, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: perinatal outcome associated with expectant management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:957-960.

- Herrera CA, Manuck TA, Stoddard GJ, et al. Perinatal outcomes associated with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:1913-1920.