User login

The Burden of Cardiac Complications in Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia

From the Division of Infectious Diseases, School of Medicine, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY.

Abstract

- Objective: To summarize the published literature on cardiac complications in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) as well as provide a historical context for the topic; and to provide recommendations concerning preventing and anticipating cardiac complications in patients with CAP.

- Methods: Literature review.

- Results: CAP patients are at increased risk for arrhythmias (~5%), myocardial infarction (~5%), and congestive heart failure (~14%). Oxygenation, the level of heart conditioning, local (pulmonary) and systemic (cytokines) inflammation, and medication all contribute to the pathophysiology of cardiac complications in CAP patients. A high Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) can be used to screen for risk of cardiac complications in CAP patients; however, a new but less studied clinical rule developed to risk stratify patient hospitalized for CAP was shown to outperform the PSI. A troponin test and ECG should be obtained in all patients admitted for CAP while a cardiac echocardiogram may be reserved for higher-risk patients.

- Conclusions: Cardiac complications, including arrhythmias, myocardial infarctions, and congestive heart failure, are a significant burden among patients hospitalized for CAP. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination should be emphasized among appropriate patients. Preliminary data suggest that those with CAP may be helped if they are already on aspirin or a statin. Early recognition of cardiac complications and treatment may improve clinical outcomes for patients with CAP.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a common condition in the United States and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality [1,2], with medical costs exceeding $10 billion in 2011 [3]. The mortality rate is much higher for those aged 65 years and older [4]. Men have a higher death rate than women (18.6 vs. 13.9 per 100,000 population), and death rate varies based on ethnicity, with mortality rates for American Indian/Alaska natives at 19.2, blacks at 17.1, whites at 15.9, Asian/Pacific Islanders at 15.0, and Hispanics at 13.1 (all rates per 100,000) [2]. CAP causes considerable worldwide mortality, with differences in mortality varying according to world region [5].

Cardiovascular complications and death from other comorbidities cause a substantial proportion of CAP-associated mortality. In Mortensen et al’s study, among patients with CAP who died, at least one third had a cardiac complication, and 13% had a cardiac-related cause of death [6]. One study showed that hospitalized patients with CAP complicated by heart disease were 30% more likely to die than patients hospitalized with CAP alone [7]. In this article, we discuss the burden of cardiac complications in adults with CAP, including underlying pathophysiological processes and strategies to prevent their occurence.

Pathophysiological Processes of Heart Disease Caused by CAP

The pathophysiology of cardiac complications as a result of CAP is made up of several hypotheses, including (1) declining oxygen provision by the lungs in the face of increasing demand by the heart, (2) a lack of reserve for stress because of cardiac comorbidities and (3) localized (pulmonary) inflammation leading to systemic (including cardiac) complications by the release of cytokines or other chemicals. Any of these may result in cardiac complications occurring before, during, or after a patient has been hospitalized for CAP. Antimicrobial treatment, specifically azithromycin, has also been implicated in myocardial adverse effects. Although azithromycin is most noted for causing QT prolongation, it was associated with myocardial infarction (MI) in a study of 73,690 patients with pneumonia [8]. A higher proportion of those who received azithromycin had an MI compared to those who did not (5.1% vs 4.4%; OR 1.17; 95% CI, 1.08–1.25), but there was no statistical difference in cardiac arrhythmias, and the 90-day mortality was actually better in the azithromycin group (17.4% vs 22.3%; odds ratio [OR], 0.73; 95% CI, 0.70–0.76).

Systemic inflammation is the result of several molecules, such as cytokines, chemokines and reactive oxidant species. Reactive oxidant species may determine oxidation of proteins, lipids and DNA, which leads to cell death. The hypothesis also purports that they also cause destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques leading to MIs. Other reactions as a result of inflammation lead to arrhythmias with or without compromised cardiac function, causing congestive heart failure (CHF). For this reason, some authors have approached the pathophysiology of cardiac complications by considering them to be either plaque-related or plaque-unrelated events [9].

A few studies have linked specific inflammatory molecules to cardiac toxicity. NOX2 is chemically unstable and may provoke cellular damage, thus maintaining a certain redox balance is crucial for cardiomyocyte health. In 248 patients with CAP, an elevated troponin T was present in 135 patients and among those, NOX2 correlated with the troponin T values (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.08–1.17; P < 0.001) [10]. Both disrupting the equilibrium of the redox balance by upregulating NOX2, and finding NOX2 to be associated with troponin T suggest that oxidative stress is implicated in damage to the myocardium during CAP. In another study of 432 patients with CAP, 41 developed atrial fibrillation within 24 to 72 hours of admission and showed higher blood levels of NOX2 than those who had CAP without atrial fibrillation [11]. Oxidative stress has been shown to cause hypertrophy, dysfunction, apoptotic cell death, and fibrosis in the myocardium [12].

There is likely a high level of variability in how individual patients respond to a predisposing factor for a cardiac complication. For example, one patient may tolerate a mild hypoxia while another is sensitive. The association of inflammatory markers with the presence of cardiac markers, however, would support that once there are systemic reactions, the complications increase. Macrolides, however, were not found to contribute to long-term mortality due to cardiac complications.

Cardiac Complications of CAP

After the H1N1 influenza outbreak of 1918, it was noted that all-cause mortality increased during the outbreak as did influenza-related deaths. This prompted inquiry as to whether there was an actual association between the outbreak and increased overall mortality, or whether the 2 occurrences were simply coincidental [14]. Near that time, arrhythmias in CAP patients were studied. T-wave changes were found to be associated with CAP [15]. Among 92 patients studied, 449 electrocardiograms (ECGs) were reviewed. T-wave changes were the most common ECG changes. They were found in 5 of 10 of the patients who died, and in 35 of the 82 patients who lived. Twelve living patients had persistent ECG changes, and although they were all thought to have had underlying myocardial disease, 2 of them certainly did as they each had an acute MI (and the ECG was included as a figure for one of them).

A study in the 1980s that reported 3 of 38 CAP patients with CHF interrupted the paucity of data at the time that showed that having a cardiac complication during CAP was a known entity [16]. By the end of the 20th century, Meier et al noted that among case patients who had an MI, an acute respiratory tract infection preceded the MI in 2.8% while in only 0.9% of control patients [17]. They also noted that patients who had an acute respiratory tract infection were 2.7 times more likely to have an MI in the following 10 days than control patients.

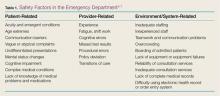

Further study by Musher et al revealed that MI was associated with pneumococcal pneumonia in 12 (7%) of 170 veteran patients [18]. An MI was defined on the basis of ECG abnormalities (Q waves or ST segment elevation or depression) with troponin I levels ≥ 0.5 ng/mL. They also evaluated arrhythmias and CHF. They included atrial fibrillation or flutter and ventricular tachycardia while excluding terminal arrhythmias. An arrhythmia was found in 8 (5%) patients. CHF was based on Framingham criteria (Table 1) [19]. New or worsening CHF was determined by comparing physical findings, laboratory values, chest radiograph, and echocardiogram reports in medical records. CHF was found in 13 (19%) patients. Ramirez et al found that MI was associated with CAP in 29 (5.8%) of 500 similar veteran patients [20].

Further study by Musher et al revealed that MI was associated with pneumococcal pneumonia in 12 (7%) of 170 veteran patients [18]. An MI was defined on the basis of ECG abnormalities (Q waves or ST segment elevation or depression) with troponin I levels ≥ 0.5 ng/mL. They also evaluated arrhythmias and CHF. They included atrial fibrillation or flutter and ventricular tachycardia while excluding terminal arrhythmias. An arrhythmia was found in 8 (5%) patients. CHF was based on Framingham criteria (Table 1) [19]. New or worsening CHF was determined by comparing physical findings, laboratory values, chest radiograph, and echocardiogram reports in medical records. CHF was found in 13 (19%) patients. Ramirez et al found that MI was associated with CAP in 29 (5.8%) of 500 similar veteran patients [20].

Corrales-Medina et al reported cardiac complications in CAP patients in the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Team cohort study [21]. They defined MI as the presence of 2 of 3 criteria: ECG abnormalities, elevated cardiac enzymes, and chest pain. They found 43 (3.2%) of 1343 patients with an MI. Arrhythmias included atrial fibrillation or flutter, multifocal atrial tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia (≥ 3 beat run) or ventricular fibrillation. With the more inclusive list, they found a greater proportion, 137 (10%) patients affected. They defined CHF with physical examination findings plus a radiographic abnormality, and found 279 (21%) patients affected. A meta-analysis of 17 studies had pooled incidences for an MI of 5.3%, an arrhythmia of 4.7% and CHF of 14.1% [22].

In summary, the most prominent cardiac complications in patients with CAP have been found to be CHF, MI, and arrhythmia.

Timing of Cardiac Complications in Relation to CAP

While a patient is still in the community, cardiac complications may occur with the onset of CAP, or afterwards. For these patients, the primary goal is to identify the complication and manage it as soon as the patient is admitted for CAP, rather than allowing the complications to worsen only to be recognized later. Cardiac complications are rare in outpatients overall. A study of 944 outpatients found heart failure in 1.4%, arrhythmias in 1.0% and MI in 0.1% [21].

For patients who are admitted with CAP but who do not have a cardiac complication, the goals are either to prevent any complication or to recognize and manage a complication early. This also applies to patients who have been discharged after an admission for CAP. Cardiac complications have been recorded shortly after (within 30 days), and late (up to 1 year) after discharge. A study of over 50,000 veterans who were admitted for CAP were followed for any cardiovascular complication in the next 90 days. Approximately 7500 veterans were found to have a cardiac complication, including (in order of highest to lowest frequency) CHF, arrhythmia, MI, stroke and angina [23]. More than 75% of the complications were found on the day of hospitalization, but events were still measured at 30 days and 90 days.

Two other studies sought to determine an association between CAP and cardiac complications differently; not by following CAP patients prospectively for complications but by retrospectively evaluating patients for a respiratory infection among those who were admitted for a cardiovascular complication (MI or stroke). A study of over 35,000 first-time admissions for either an MI or a stroke were evaluated for a respiratory infection within the previous 90 days [24]. The incidence rates were statistically significant for every time period up to 90 days. The preceding 3 days was the time period with the highest frequency for a respiratory infection preceding an event. When the event was an MI, the incident rate was 4.95 (95% CI, 4.43–5.53). A similar study of over 20,000 first-time admissions for either an MI or stroke were evaluated for a preceding primary care visit for a respiratory infection [25]. An infection preceded 2.9% of patients with an MI and 2.8% of patients with a stroke. Statistical significance was found for the group of patients who had a respiratory infection within 7 days preceding an MI (OR 2.10 [95% CI 1.38–3.21]) or preceding a stroke (OR 1.92 [95% CI 1.24–2.97]). In fact, every time period analyzed for both complications (MI and stroke) was significant up to 1 year. Because the timing of a cardiac complication varies and can occur up to 90 days or even a year after acute infection, physicians should maintain vigilance in suspecting and screening for them.

Predictors of Cardiac Complications During CAP

Recently, Cangemi et al reviewed mortality in 301 patients admitted for CAP 6 to 60 months after they were discharged [26]. Mortality was compared between patients who experienced a cardiac complication—atrial fibrillation or an ST- or non-ST-elevation MI—during their admission and those who did not. A total of 55 (18%) patients had a cardiac complication while hospitalized. During the follow-up, 90 (30%) of the 301 patients died. Death occurred in more patients who had had a cardiac complication while hospitalized than in those who did not (32% vs 13%; P < 0.001). The study also showed that age and the pneumonia severity index (PSI) predicted death in addition to intra-hospital complication. A Cox regression analysis showed that intrahospital cardiac complications (hazard ratio [HR] 1.76 [95% CI 1.10–2.82]; P = 0.019), age (HR 1.05 [95% CI 1.03–1.08]; P < 0.001) and the PSI (HR 1.01 [95% CI 1.00–1.02] P = 0.012) independently predicted death after adjusting for possible confounders [26].

The PSI score was published in 1997, and it instructed that patients with a risk class of I or II (low risk) should be managed as outpatients. Data eventually showed that there is a portion of the population with a risk class of I or II whose hospital admission is justified [4]. Among the reasons found was “comorbidity,” including MI and other cardiac complications. The PSI prediction rule was found to be useful in novel ways, and being associated with a risk of MI in patients with CAP was one of them. The propensity-adjusted association between the PSI score and MI was significant (P < 0.05) in an observational study of the CAP Organization (CAPO) [20]. Knowing that a PSI of 80 is in the middle of risk class III (71–90), it was noted that below 80 the risk for MI was zero to 2.5%, while above 80 the risk rose from 2.5% to 12.5%. A later study using the same statistical method showed a correlation between the PSI score and cardiac complications (MI, arrhythmias and CHF) with a P value of < 0.01 [21]. Determining the probability for the combination of complications, rather than just an MI, yielded an unsurprisingly higher range of risk for the PSI below 80, which was zero to 17.5%, while risk for a PSI above 80 was 17.5% to 80%.

In a study to determine risk factors for cardiac complications among 3068 patients with CAP, Griffin et al applied a purposeful selection algorithm to a list of factors with reasonable potential to be associated with the 376 patients who actually had a cardiac complication [27]. After multivariate logistic regression analysis, hyperlipidemia, an infection with Staphlococcus aureus or Klebsiella pneumoniae, and the PSI were found to be statistically significant. In contrast, statin therapy was associated with a lower risk of an event.

In 2014, a validated score similar to the PSI and using the same database was derived to predict short-term risk for cardiac events in hospitalized patients with CAP [28]. It attributes points for age, 3 preexisting conditions, 2 vital signs and 7 radiological and laboratory values, with a point scoring system that defines 4 risk stratification classes. In the derivation cohort, the incidence of cardiac complications across the risk classes increased linearly (3%, 18%, 35%, and 72%, respectively). The score was validated in the original publication with a separate database but has not been evaluated since. The score outperformed the PSI score in predicting cardiac complications in the validation cohort (proportion of patients correctly reclassified by the new score, 44%). Potentially, the rule could help identify high-risk patients upon admission and could assist clinicians in their decision making.

Strategies to Prevent Cardiac Complications During CAP

It is now well established that there is a heavy burden of long-lasting cardiac complications among patients with CAP; therefore, preventing CAP should be a priority. This can be accomplished by counseling patients to refrain from alcohol and smoking and by administering influenza (Table 2) and pneumococcal vaccines (Figure 2). Since the 7-valent protein-polysaccharide conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (PCV-7) was released for children in 2000, there have been fewer hospitalizations in the United States [27] and improved outcomes globally;

It is now well established that there is a heavy burden of long-lasting cardiac complications among patients with CAP; therefore, preventing CAP should be a priority. This can be accomplished by counseling patients to refrain from alcohol and smoking and by administering influenza (Table 2) and pneumococcal vaccines (Figure 2). Since the 7-valent protein-polysaccharide conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (PCV-7) was released for children in 2000, there have been fewer hospitalizations in the United States [27] and improved outcomes globally;  for instance, fewer hospitalizations among children < 14 years of age in Uruguay [29], and decreased invasive pneumococcal disease among children < 5 years of age in Taiwan [30]. Furthermore, a decrease in invasive pneumococcal disease by 18% in persons aged > 65 years in the US and Canada decreased with the introduction of PCV-7 to children. Although this showed a beneficial indirect effect (herd immunity) in unvaccinated populations [31,32], there have been no randomized controlled trials in adults demonstrating a decrease in pneumococcal pneumonia or invasive pneumococcal disease which were vaccinated with PCV-13. The Food and Drug Administration approved PCV-13 for children in 2010 and for adults in 2012. Although it included fewer serotypes, it did include serotype 6A, which has a high pathogenicity and is not in 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV-23). The criteria for vaccinating adults for pneumococcal infection were recently published [33]. A study of patients with invasive pneumococcal disease, which also determined pneumococcal serotypes, included 5 patients who had CAP as well [34]. Those patients had serotypes 6A, 7C, 14, and 23F (2 patients). The patient who had serotype 14 (higher pathogenicity) died and the other 4 lived. Serotypes 14 and 23F are in both vaccines while serotype 7C is in neither. Vaccination status was not provided in the study. At this time, there is evidence to support vaccinating patients for both S. pneumoniae and influenza virus.

for instance, fewer hospitalizations among children < 14 years of age in Uruguay [29], and decreased invasive pneumococcal disease among children < 5 years of age in Taiwan [30]. Furthermore, a decrease in invasive pneumococcal disease by 18% in persons aged > 65 years in the US and Canada decreased with the introduction of PCV-7 to children. Although this showed a beneficial indirect effect (herd immunity) in unvaccinated populations [31,32], there have been no randomized controlled trials in adults demonstrating a decrease in pneumococcal pneumonia or invasive pneumococcal disease which were vaccinated with PCV-13. The Food and Drug Administration approved PCV-13 for children in 2010 and for adults in 2012. Although it included fewer serotypes, it did include serotype 6A, which has a high pathogenicity and is not in 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV-23). The criteria for vaccinating adults for pneumococcal infection were recently published [33]. A study of patients with invasive pneumococcal disease, which also determined pneumococcal serotypes, included 5 patients who had CAP as well [34]. Those patients had serotypes 6A, 7C, 14, and 23F (2 patients). The patient who had serotype 14 (higher pathogenicity) died and the other 4 lived. Serotypes 14 and 23F are in both vaccines while serotype 7C is in neither. Vaccination status was not provided in the study. At this time, there is evidence to support vaccinating patients for both S. pneumoniae and influenza virus.

Two methods used to prevent cardiac complications in general have been administration of aspirin and statins. The anticlotting properties of aspirin help to maintain blood flow in arteries narrowed by atherosclerosis. A meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials found a statistically significant association between aspirin and a benefit on nonfatal myocardial infarctions/coronary events [35]. The associations were found with doses of 100 mg or less daily, and benefits were seen within 1 to 5 years. Statins have also been found to reduce all-cause mortality, cardiac-related mortality, and myocardial infarction [36]. A statin may stabilize coronary artery plaques that otherwise may rupture and cause myocardial ischemia or an infarct. But statins have also been found to be associated with a decreased risk of CAP. A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis found a decreased risk of CAP (OR 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74– 0.95) and decreased short-term mortality in patients with CAP (OR 0.68; 95% CI, 0.56–0.78) as a result of statin therapy [37]. The studies included any of 8 available statins. A prospective observational study found that patients who had been on a statin prior to being admitted for CAP had lower mortality, a lower incidence of complicated pneumonia and a lower C-reactive protein [38]. The lower C-reactive protein identifies decreased inflammation, which translates into improved endothelial function, modulated antioxidant effects, and a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines, hence its association with less severe CAP. Further study may reveal that a certain patient population should receive a statin to prevent CAP and improve outcomes. Overall, data support taking aspirin to prevent cardiac events regardless of CAP; further investigation of the benefits of statins to prevent cardiac complications in CAP patients is needed.

Clinical Applications

There are several implications of knowing the relationship between cardiac complications and CAP. First, physicians can better inform their patients about risks once they have been diagnosed with pneumonia. Second, physicians may be more likely to recognize a complication early and provide appropriate intervention. Third, physicians can risk stratify patients using the prediction score for cardiac complications in CAP patients [28]. In 1931 Master et al found that some patients with CAP also had PR interval or T-wave changes present for about 3 days, so they recommended obtaining an ECG to determine when a patient might be able to be discharged or declared “cured” [39]. Now, we are similarly recommending obtaining an ECG in CAP patients, but upon admission, in order to identify those who may get ischemic changes, arrhythmias or QTc prolongations. Pro-brain natriuretic peptide and troponins may be obtained independently of ECG results, and a cardiac echocardiogram may be reserved for those with a high risk of complications [40]. Finally, we recommend screening all patients for need for influenza and pneumococcal vaccines and administering according to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease and Prevention [33].

Research Implications

The fact that cardiac complications in CAP patients is a well-defined entity with a significant degree of morbidity and mortality should prompt attentiona and resources to be directed to this area. The prediction score created specifically for this subpopulation of patients [28] can improve research by allowing adequate risk stratification to efficiently design and execute studies. Studies may be designed with fewer patients required to be enrolled while maintaining statistical power by limiting subject inclusion criteria to certain risk classes. Specific areas of future investigation should include the mechanisms of pathophysiology, which are not completely understood, and other complications, such as pulmonary edema, infectious endocarditis and pericarditis. Finally, cost has not been studied in this area or the potential savings of recognizing and preventing cardiac complications.

Summary

Cardiac complications, including arrhythmias, MI, and CHF are a significant burden among patients hospitalized for CAP. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination should be emphasized among appropriate patients. The cardiac complication prediction score may be used to screen patients once admitted. A troponin and ECG should be obtained in all patients admitted for CAP while a cardiac echocardiogram may be reserved in higher-risk patients. Future research may be directed towards the subjects of pathophysiology other complications and cost.

Acknowledgment: We appreciate the critical review by Jessica Lynn Petrey, MSLS, Clinical Librarian, Kornhauser Health Sciences Library, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY.

Corresponding author: Dr. Forest Arnold, 501 E. Broadway, Suite 140 B, Louisville, KY 40202, [email protected]

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Stocks C. HCUP statistical brief #162. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2013. Most frequent conditions in U.S. hospitals, 2011. Available at www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb162.pdf..

2. FastStats deaths and mortality. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed 14 Oct 2015 at www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm.

3. Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Steiner C. HCUP statistical brief #168. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2013. Costs for hospital stays in the United States, 2011. Available at www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb168-Hospital-Costs-United-States-2011.pdf.

4. American Lung Association. Trends in pneumonia and influenza morbidity and mortality. November 2015. Available at

www.lung.org/assets/documents/research/pi-trend-report.pdf.

5. Arnold FW, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, et al. Mortality differences among hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia in three world regions: results from the Community-Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) International Cohort Study. Respir Med 2013;107:1101–11.

6. Mortensen EM, Coley CM, Singer DE, et al. Causes of death for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: results from the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1059–64.

7. Bordon J, Wiemken T, Peyrani P, et al. Decrease in long-term survival for hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest 2010;138:279–83.

8. Mortensen EM, Halm EA, Pugh MJ, et al. Association of azithromycin with mortality and cardiovascular events among older patients hospitalized with pneumonia. JAMA 2014;311:2199–208.

9. Aliberti S, Ramirez JA. Cardiac diseases complicating community-acquired pneumonia. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2014;27:295–301.

10. Cangemi R, Calvieri C, Bucci T, et al. Is NOX2 upregulation implicated in myocardial injury in patients with pneumonia? Antioxid Redox Signal 2014;20:2949–54.

11. Violi F, Carnevale R, Calvieri C, et al. Nox2 up-regulation is associated with an enhanced risk of atrial fibrillation in patients with pneumonia. Thorax 2015;70:961–6.

12. Zhang Y, Tocchetti CG, Krieg T, Moens AL. Oxidative and nitrosative stress in the maintenance of myocardial function. Free Radic Biol Med 2012;53:1531–40.

13. Brown AO, Millett ER, Quint JK, Orihuela CJ. Cardiotoxicity during invasive pneumococcal disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:739–45.

14. Collins SD. Excess mortality from causes other than influenza and pneumonia during influenza epidemics. Pub Health Rep 1932;47:2159–79.

15. Thomson KJ, Rustein DD, et al. Electrocardiographic studies during and after pneumococcus pneumonia. Am Heart J 1946;31:565–79.

16. Esposito AL. Community-acquired bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia. Effect of age on manifestations and outcome. Arch Intern Med 1984;144:945–8.

17. Meier CR, Jick SS, Derby LE, et al. Acute respiratory-tract infections and risk of first-time acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 1998;351(9114):1467–71.

18. Musher DM, Rueda AM, Kaka AS, Mapara SM. The association between pneumococcal pneumonia and acute cardiac events. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:158–65.

19. McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Kannel WB. The natural history of congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med 1971;285:1441–6.

20. Ramirez J, Aliberti S, Mirsaeidi M, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:182–7.

21. Corrales-Medina VF, Musher DM, Wells GA, et al. Cardiac complications in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: incidence, timing, risk factors, and association with short-term mortality. Circulation 2012;125:773–81.

22. Corrales-Medina VF, Suh KN, Rose G, et al. Cardiac complications in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS Med 2011;8(6):e1001048.

23. Perry TW, Pugh MJ, Waterer GW, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular events after hospital admission for pneumonia. Am J Med 2011;124:244–51.

24. Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJ, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2611–8.

25. Clayton TC, Thompson M, Meade TW. Recent respiratory infection and risk of cardiovascular disease: case-control study through a general practice database. Eur Heart J 2008;29:96–103.

26. Cangemi R, Calvieri C, Falcone M, et al. Relation of cardiac complications in the early phase of community-acquired pneumonia to long-term mortality and cardiovascular events. Am J Cardiol 2015;116:647–51.

27. Griffin MR, Zhu Y, Moore MR, et al. U.S. hospitalizations for pneumonia after a decade of pneumococcal vaccination. N Engl J Med 2013;369:155–63.

28. Corrales-Medina VF, Taljaard M, Fine MJ, et al. Risk stratification for cardiac complications in patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia. Mayo Clin Proc 2014;89:60–8.

29. Pirez MC, Algorta G, Cedres A, et al. Impact of universal pneumococcal vaccination on hospitalizations for pneumonia and meningitis in children in Montevideo, Uruguay. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011;30:669–74.

30. Liao WH, Lin SH, Lai CC, et al. Impact of pneumococcal vaccines on invasive pneumococcal disease in Taiwan. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2010;29:489–92.

31. Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, et al. Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1737–46.

32. Kellner JD, Church DL, MacDonald J, et al. Progress in the prevention of pneumococcal infection. CMAJ 2005;173:1149–51.

33. Kim DK, Bridges CB, Harriman KH, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older: United States, 2016. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:184–94.

34. Kan B, Ries J, Normark BH, et al. Endocarditis and pericarditis complicating pneumococcal bacteraemia, with special reference to the adhesive abilities of pneumococci: results from a prospective study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006;12:338–44.

35. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 131. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015.

36. Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005;366:1267–78.

37. Khan AR, Riaz M, Bin Abdulhak AA, et al. The role of statins in prevention and treatment of community acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e52929.

38. Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Murray MP, Hill AT. Prior statin use is associated with improved outcomes in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med 2008;121:1002–7 e1.

39. Master AM, Romanoff A, Jaffe H. Electrocardiographic changes in pneumonia. Am Heart J 1931;6:696–709.

40. Corrales-Medina VF, Musher DM, Shachkina S, Chirinos JA. Acute pneumonia and the cardiovascular system. Lancet 2015;381:496–505.

From the Division of Infectious Diseases, School of Medicine, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY.

Abstract

- Objective: To summarize the published literature on cardiac complications in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) as well as provide a historical context for the topic; and to provide recommendations concerning preventing and anticipating cardiac complications in patients with CAP.

- Methods: Literature review.

- Results: CAP patients are at increased risk for arrhythmias (~5%), myocardial infarction (~5%), and congestive heart failure (~14%). Oxygenation, the level of heart conditioning, local (pulmonary) and systemic (cytokines) inflammation, and medication all contribute to the pathophysiology of cardiac complications in CAP patients. A high Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) can be used to screen for risk of cardiac complications in CAP patients; however, a new but less studied clinical rule developed to risk stratify patient hospitalized for CAP was shown to outperform the PSI. A troponin test and ECG should be obtained in all patients admitted for CAP while a cardiac echocardiogram may be reserved for higher-risk patients.

- Conclusions: Cardiac complications, including arrhythmias, myocardial infarctions, and congestive heart failure, are a significant burden among patients hospitalized for CAP. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination should be emphasized among appropriate patients. Preliminary data suggest that those with CAP may be helped if they are already on aspirin or a statin. Early recognition of cardiac complications and treatment may improve clinical outcomes for patients with CAP.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a common condition in the United States and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality [1,2], with medical costs exceeding $10 billion in 2011 [3]. The mortality rate is much higher for those aged 65 years and older [4]. Men have a higher death rate than women (18.6 vs. 13.9 per 100,000 population), and death rate varies based on ethnicity, with mortality rates for American Indian/Alaska natives at 19.2, blacks at 17.1, whites at 15.9, Asian/Pacific Islanders at 15.0, and Hispanics at 13.1 (all rates per 100,000) [2]. CAP causes considerable worldwide mortality, with differences in mortality varying according to world region [5].

Cardiovascular complications and death from other comorbidities cause a substantial proportion of CAP-associated mortality. In Mortensen et al’s study, among patients with CAP who died, at least one third had a cardiac complication, and 13% had a cardiac-related cause of death [6]. One study showed that hospitalized patients with CAP complicated by heart disease were 30% more likely to die than patients hospitalized with CAP alone [7]. In this article, we discuss the burden of cardiac complications in adults with CAP, including underlying pathophysiological processes and strategies to prevent their occurence.

Pathophysiological Processes of Heart Disease Caused by CAP

The pathophysiology of cardiac complications as a result of CAP is made up of several hypotheses, including (1) declining oxygen provision by the lungs in the face of increasing demand by the heart, (2) a lack of reserve for stress because of cardiac comorbidities and (3) localized (pulmonary) inflammation leading to systemic (including cardiac) complications by the release of cytokines or other chemicals. Any of these may result in cardiac complications occurring before, during, or after a patient has been hospitalized for CAP. Antimicrobial treatment, specifically azithromycin, has also been implicated in myocardial adverse effects. Although azithromycin is most noted for causing QT prolongation, it was associated with myocardial infarction (MI) in a study of 73,690 patients with pneumonia [8]. A higher proportion of those who received azithromycin had an MI compared to those who did not (5.1% vs 4.4%; OR 1.17; 95% CI, 1.08–1.25), but there was no statistical difference in cardiac arrhythmias, and the 90-day mortality was actually better in the azithromycin group (17.4% vs 22.3%; odds ratio [OR], 0.73; 95% CI, 0.70–0.76).

Systemic inflammation is the result of several molecules, such as cytokines, chemokines and reactive oxidant species. Reactive oxidant species may determine oxidation of proteins, lipids and DNA, which leads to cell death. The hypothesis also purports that they also cause destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques leading to MIs. Other reactions as a result of inflammation lead to arrhythmias with or without compromised cardiac function, causing congestive heart failure (CHF). For this reason, some authors have approached the pathophysiology of cardiac complications by considering them to be either plaque-related or plaque-unrelated events [9].

A few studies have linked specific inflammatory molecules to cardiac toxicity. NOX2 is chemically unstable and may provoke cellular damage, thus maintaining a certain redox balance is crucial for cardiomyocyte health. In 248 patients with CAP, an elevated troponin T was present in 135 patients and among those, NOX2 correlated with the troponin T values (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.08–1.17; P < 0.001) [10]. Both disrupting the equilibrium of the redox balance by upregulating NOX2, and finding NOX2 to be associated with troponin T suggest that oxidative stress is implicated in damage to the myocardium during CAP. In another study of 432 patients with CAP, 41 developed atrial fibrillation within 24 to 72 hours of admission and showed higher blood levels of NOX2 than those who had CAP without atrial fibrillation [11]. Oxidative stress has been shown to cause hypertrophy, dysfunction, apoptotic cell death, and fibrosis in the myocardium [12].

There is likely a high level of variability in how individual patients respond to a predisposing factor for a cardiac complication. For example, one patient may tolerate a mild hypoxia while another is sensitive. The association of inflammatory markers with the presence of cardiac markers, however, would support that once there are systemic reactions, the complications increase. Macrolides, however, were not found to contribute to long-term mortality due to cardiac complications.

Cardiac Complications of CAP

After the H1N1 influenza outbreak of 1918, it was noted that all-cause mortality increased during the outbreak as did influenza-related deaths. This prompted inquiry as to whether there was an actual association between the outbreak and increased overall mortality, or whether the 2 occurrences were simply coincidental [14]. Near that time, arrhythmias in CAP patients were studied. T-wave changes were found to be associated with CAP [15]. Among 92 patients studied, 449 electrocardiograms (ECGs) were reviewed. T-wave changes were the most common ECG changes. They were found in 5 of 10 of the patients who died, and in 35 of the 82 patients who lived. Twelve living patients had persistent ECG changes, and although they were all thought to have had underlying myocardial disease, 2 of them certainly did as they each had an acute MI (and the ECG was included as a figure for one of them).

A study in the 1980s that reported 3 of 38 CAP patients with CHF interrupted the paucity of data at the time that showed that having a cardiac complication during CAP was a known entity [16]. By the end of the 20th century, Meier et al noted that among case patients who had an MI, an acute respiratory tract infection preceded the MI in 2.8% while in only 0.9% of control patients [17]. They also noted that patients who had an acute respiratory tract infection were 2.7 times more likely to have an MI in the following 10 days than control patients.

Further study by Musher et al revealed that MI was associated with pneumococcal pneumonia in 12 (7%) of 170 veteran patients [18]. An MI was defined on the basis of ECG abnormalities (Q waves or ST segment elevation or depression) with troponin I levels ≥ 0.5 ng/mL. They also evaluated arrhythmias and CHF. They included atrial fibrillation or flutter and ventricular tachycardia while excluding terminal arrhythmias. An arrhythmia was found in 8 (5%) patients. CHF was based on Framingham criteria (Table 1) [19]. New or worsening CHF was determined by comparing physical findings, laboratory values, chest radiograph, and echocardiogram reports in medical records. CHF was found in 13 (19%) patients. Ramirez et al found that MI was associated with CAP in 29 (5.8%) of 500 similar veteran patients [20].

Further study by Musher et al revealed that MI was associated with pneumococcal pneumonia in 12 (7%) of 170 veteran patients [18]. An MI was defined on the basis of ECG abnormalities (Q waves or ST segment elevation or depression) with troponin I levels ≥ 0.5 ng/mL. They also evaluated arrhythmias and CHF. They included atrial fibrillation or flutter and ventricular tachycardia while excluding terminal arrhythmias. An arrhythmia was found in 8 (5%) patients. CHF was based on Framingham criteria (Table 1) [19]. New or worsening CHF was determined by comparing physical findings, laboratory values, chest radiograph, and echocardiogram reports in medical records. CHF was found in 13 (19%) patients. Ramirez et al found that MI was associated with CAP in 29 (5.8%) of 500 similar veteran patients [20].

Corrales-Medina et al reported cardiac complications in CAP patients in the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Team cohort study [21]. They defined MI as the presence of 2 of 3 criteria: ECG abnormalities, elevated cardiac enzymes, and chest pain. They found 43 (3.2%) of 1343 patients with an MI. Arrhythmias included atrial fibrillation or flutter, multifocal atrial tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia (≥ 3 beat run) or ventricular fibrillation. With the more inclusive list, they found a greater proportion, 137 (10%) patients affected. They defined CHF with physical examination findings plus a radiographic abnormality, and found 279 (21%) patients affected. A meta-analysis of 17 studies had pooled incidences for an MI of 5.3%, an arrhythmia of 4.7% and CHF of 14.1% [22].

In summary, the most prominent cardiac complications in patients with CAP have been found to be CHF, MI, and arrhythmia.

Timing of Cardiac Complications in Relation to CAP

While a patient is still in the community, cardiac complications may occur with the onset of CAP, or afterwards. For these patients, the primary goal is to identify the complication and manage it as soon as the patient is admitted for CAP, rather than allowing the complications to worsen only to be recognized later. Cardiac complications are rare in outpatients overall. A study of 944 outpatients found heart failure in 1.4%, arrhythmias in 1.0% and MI in 0.1% [21].

For patients who are admitted with CAP but who do not have a cardiac complication, the goals are either to prevent any complication or to recognize and manage a complication early. This also applies to patients who have been discharged after an admission for CAP. Cardiac complications have been recorded shortly after (within 30 days), and late (up to 1 year) after discharge. A study of over 50,000 veterans who were admitted for CAP were followed for any cardiovascular complication in the next 90 days. Approximately 7500 veterans were found to have a cardiac complication, including (in order of highest to lowest frequency) CHF, arrhythmia, MI, stroke and angina [23]. More than 75% of the complications were found on the day of hospitalization, but events were still measured at 30 days and 90 days.

Two other studies sought to determine an association between CAP and cardiac complications differently; not by following CAP patients prospectively for complications but by retrospectively evaluating patients for a respiratory infection among those who were admitted for a cardiovascular complication (MI or stroke). A study of over 35,000 first-time admissions for either an MI or a stroke were evaluated for a respiratory infection within the previous 90 days [24]. The incidence rates were statistically significant for every time period up to 90 days. The preceding 3 days was the time period with the highest frequency for a respiratory infection preceding an event. When the event was an MI, the incident rate was 4.95 (95% CI, 4.43–5.53). A similar study of over 20,000 first-time admissions for either an MI or stroke were evaluated for a preceding primary care visit for a respiratory infection [25]. An infection preceded 2.9% of patients with an MI and 2.8% of patients with a stroke. Statistical significance was found for the group of patients who had a respiratory infection within 7 days preceding an MI (OR 2.10 [95% CI 1.38–3.21]) or preceding a stroke (OR 1.92 [95% CI 1.24–2.97]). In fact, every time period analyzed for both complications (MI and stroke) was significant up to 1 year. Because the timing of a cardiac complication varies and can occur up to 90 days or even a year after acute infection, physicians should maintain vigilance in suspecting and screening for them.

Predictors of Cardiac Complications During CAP

Recently, Cangemi et al reviewed mortality in 301 patients admitted for CAP 6 to 60 months after they were discharged [26]. Mortality was compared between patients who experienced a cardiac complication—atrial fibrillation or an ST- or non-ST-elevation MI—during their admission and those who did not. A total of 55 (18%) patients had a cardiac complication while hospitalized. During the follow-up, 90 (30%) of the 301 patients died. Death occurred in more patients who had had a cardiac complication while hospitalized than in those who did not (32% vs 13%; P < 0.001). The study also showed that age and the pneumonia severity index (PSI) predicted death in addition to intra-hospital complication. A Cox regression analysis showed that intrahospital cardiac complications (hazard ratio [HR] 1.76 [95% CI 1.10–2.82]; P = 0.019), age (HR 1.05 [95% CI 1.03–1.08]; P < 0.001) and the PSI (HR 1.01 [95% CI 1.00–1.02] P = 0.012) independently predicted death after adjusting for possible confounders [26].

The PSI score was published in 1997, and it instructed that patients with a risk class of I or II (low risk) should be managed as outpatients. Data eventually showed that there is a portion of the population with a risk class of I or II whose hospital admission is justified [4]. Among the reasons found was “comorbidity,” including MI and other cardiac complications. The PSI prediction rule was found to be useful in novel ways, and being associated with a risk of MI in patients with CAP was one of them. The propensity-adjusted association between the PSI score and MI was significant (P < 0.05) in an observational study of the CAP Organization (CAPO) [20]. Knowing that a PSI of 80 is in the middle of risk class III (71–90), it was noted that below 80 the risk for MI was zero to 2.5%, while above 80 the risk rose from 2.5% to 12.5%. A later study using the same statistical method showed a correlation between the PSI score and cardiac complications (MI, arrhythmias and CHF) with a P value of < 0.01 [21]. Determining the probability for the combination of complications, rather than just an MI, yielded an unsurprisingly higher range of risk for the PSI below 80, which was zero to 17.5%, while risk for a PSI above 80 was 17.5% to 80%.

In a study to determine risk factors for cardiac complications among 3068 patients with CAP, Griffin et al applied a purposeful selection algorithm to a list of factors with reasonable potential to be associated with the 376 patients who actually had a cardiac complication [27]. After multivariate logistic regression analysis, hyperlipidemia, an infection with Staphlococcus aureus or Klebsiella pneumoniae, and the PSI were found to be statistically significant. In contrast, statin therapy was associated with a lower risk of an event.

In 2014, a validated score similar to the PSI and using the same database was derived to predict short-term risk for cardiac events in hospitalized patients with CAP [28]. It attributes points for age, 3 preexisting conditions, 2 vital signs and 7 radiological and laboratory values, with a point scoring system that defines 4 risk stratification classes. In the derivation cohort, the incidence of cardiac complications across the risk classes increased linearly (3%, 18%, 35%, and 72%, respectively). The score was validated in the original publication with a separate database but has not been evaluated since. The score outperformed the PSI score in predicting cardiac complications in the validation cohort (proportion of patients correctly reclassified by the new score, 44%). Potentially, the rule could help identify high-risk patients upon admission and could assist clinicians in their decision making.

Strategies to Prevent Cardiac Complications During CAP

It is now well established that there is a heavy burden of long-lasting cardiac complications among patients with CAP; therefore, preventing CAP should be a priority. This can be accomplished by counseling patients to refrain from alcohol and smoking and by administering influenza (Table 2) and pneumococcal vaccines (Figure 2). Since the 7-valent protein-polysaccharide conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (PCV-7) was released for children in 2000, there have been fewer hospitalizations in the United States [27] and improved outcomes globally;

It is now well established that there is a heavy burden of long-lasting cardiac complications among patients with CAP; therefore, preventing CAP should be a priority. This can be accomplished by counseling patients to refrain from alcohol and smoking and by administering influenza (Table 2) and pneumococcal vaccines (Figure 2). Since the 7-valent protein-polysaccharide conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (PCV-7) was released for children in 2000, there have been fewer hospitalizations in the United States [27] and improved outcomes globally;  for instance, fewer hospitalizations among children < 14 years of age in Uruguay [29], and decreased invasive pneumococcal disease among children < 5 years of age in Taiwan [30]. Furthermore, a decrease in invasive pneumococcal disease by 18% in persons aged > 65 years in the US and Canada decreased with the introduction of PCV-7 to children. Although this showed a beneficial indirect effect (herd immunity) in unvaccinated populations [31,32], there have been no randomized controlled trials in adults demonstrating a decrease in pneumococcal pneumonia or invasive pneumococcal disease which were vaccinated with PCV-13. The Food and Drug Administration approved PCV-13 for children in 2010 and for adults in 2012. Although it included fewer serotypes, it did include serotype 6A, which has a high pathogenicity and is not in 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV-23). The criteria for vaccinating adults for pneumococcal infection were recently published [33]. A study of patients with invasive pneumococcal disease, which also determined pneumococcal serotypes, included 5 patients who had CAP as well [34]. Those patients had serotypes 6A, 7C, 14, and 23F (2 patients). The patient who had serotype 14 (higher pathogenicity) died and the other 4 lived. Serotypes 14 and 23F are in both vaccines while serotype 7C is in neither. Vaccination status was not provided in the study. At this time, there is evidence to support vaccinating patients for both S. pneumoniae and influenza virus.

for instance, fewer hospitalizations among children < 14 years of age in Uruguay [29], and decreased invasive pneumococcal disease among children < 5 years of age in Taiwan [30]. Furthermore, a decrease in invasive pneumococcal disease by 18% in persons aged > 65 years in the US and Canada decreased with the introduction of PCV-7 to children. Although this showed a beneficial indirect effect (herd immunity) in unvaccinated populations [31,32], there have been no randomized controlled trials in adults demonstrating a decrease in pneumococcal pneumonia or invasive pneumococcal disease which were vaccinated with PCV-13. The Food and Drug Administration approved PCV-13 for children in 2010 and for adults in 2012. Although it included fewer serotypes, it did include serotype 6A, which has a high pathogenicity and is not in 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV-23). The criteria for vaccinating adults for pneumococcal infection were recently published [33]. A study of patients with invasive pneumococcal disease, which also determined pneumococcal serotypes, included 5 patients who had CAP as well [34]. Those patients had serotypes 6A, 7C, 14, and 23F (2 patients). The patient who had serotype 14 (higher pathogenicity) died and the other 4 lived. Serotypes 14 and 23F are in both vaccines while serotype 7C is in neither. Vaccination status was not provided in the study. At this time, there is evidence to support vaccinating patients for both S. pneumoniae and influenza virus.

Two methods used to prevent cardiac complications in general have been administration of aspirin and statins. The anticlotting properties of aspirin help to maintain blood flow in arteries narrowed by atherosclerosis. A meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials found a statistically significant association between aspirin and a benefit on nonfatal myocardial infarctions/coronary events [35]. The associations were found with doses of 100 mg or less daily, and benefits were seen within 1 to 5 years. Statins have also been found to reduce all-cause mortality, cardiac-related mortality, and myocardial infarction [36]. A statin may stabilize coronary artery plaques that otherwise may rupture and cause myocardial ischemia or an infarct. But statins have also been found to be associated with a decreased risk of CAP. A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis found a decreased risk of CAP (OR 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74– 0.95) and decreased short-term mortality in patients with CAP (OR 0.68; 95% CI, 0.56–0.78) as a result of statin therapy [37]. The studies included any of 8 available statins. A prospective observational study found that patients who had been on a statin prior to being admitted for CAP had lower mortality, a lower incidence of complicated pneumonia and a lower C-reactive protein [38]. The lower C-reactive protein identifies decreased inflammation, which translates into improved endothelial function, modulated antioxidant effects, and a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines, hence its association with less severe CAP. Further study may reveal that a certain patient population should receive a statin to prevent CAP and improve outcomes. Overall, data support taking aspirin to prevent cardiac events regardless of CAP; further investigation of the benefits of statins to prevent cardiac complications in CAP patients is needed.

Clinical Applications

There are several implications of knowing the relationship between cardiac complications and CAP. First, physicians can better inform their patients about risks once they have been diagnosed with pneumonia. Second, physicians may be more likely to recognize a complication early and provide appropriate intervention. Third, physicians can risk stratify patients using the prediction score for cardiac complications in CAP patients [28]. In 1931 Master et al found that some patients with CAP also had PR interval or T-wave changes present for about 3 days, so they recommended obtaining an ECG to determine when a patient might be able to be discharged or declared “cured” [39]. Now, we are similarly recommending obtaining an ECG in CAP patients, but upon admission, in order to identify those who may get ischemic changes, arrhythmias or QTc prolongations. Pro-brain natriuretic peptide and troponins may be obtained independently of ECG results, and a cardiac echocardiogram may be reserved for those with a high risk of complications [40]. Finally, we recommend screening all patients for need for influenza and pneumococcal vaccines and administering according to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease and Prevention [33].

Research Implications

The fact that cardiac complications in CAP patients is a well-defined entity with a significant degree of morbidity and mortality should prompt attentiona and resources to be directed to this area. The prediction score created specifically for this subpopulation of patients [28] can improve research by allowing adequate risk stratification to efficiently design and execute studies. Studies may be designed with fewer patients required to be enrolled while maintaining statistical power by limiting subject inclusion criteria to certain risk classes. Specific areas of future investigation should include the mechanisms of pathophysiology, which are not completely understood, and other complications, such as pulmonary edema, infectious endocarditis and pericarditis. Finally, cost has not been studied in this area or the potential savings of recognizing and preventing cardiac complications.

Summary

Cardiac complications, including arrhythmias, MI, and CHF are a significant burden among patients hospitalized for CAP. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination should be emphasized among appropriate patients. The cardiac complication prediction score may be used to screen patients once admitted. A troponin and ECG should be obtained in all patients admitted for CAP while a cardiac echocardiogram may be reserved in higher-risk patients. Future research may be directed towards the subjects of pathophysiology other complications and cost.

Acknowledgment: We appreciate the critical review by Jessica Lynn Petrey, MSLS, Clinical Librarian, Kornhauser Health Sciences Library, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY.

Corresponding author: Dr. Forest Arnold, 501 E. Broadway, Suite 140 B, Louisville, KY 40202, [email protected]

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Division of Infectious Diseases, School of Medicine, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY.

Abstract

- Objective: To summarize the published literature on cardiac complications in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) as well as provide a historical context for the topic; and to provide recommendations concerning preventing and anticipating cardiac complications in patients with CAP.

- Methods: Literature review.

- Results: CAP patients are at increased risk for arrhythmias (~5%), myocardial infarction (~5%), and congestive heart failure (~14%). Oxygenation, the level of heart conditioning, local (pulmonary) and systemic (cytokines) inflammation, and medication all contribute to the pathophysiology of cardiac complications in CAP patients. A high Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) can be used to screen for risk of cardiac complications in CAP patients; however, a new but less studied clinical rule developed to risk stratify patient hospitalized for CAP was shown to outperform the PSI. A troponin test and ECG should be obtained in all patients admitted for CAP while a cardiac echocardiogram may be reserved for higher-risk patients.

- Conclusions: Cardiac complications, including arrhythmias, myocardial infarctions, and congestive heart failure, are a significant burden among patients hospitalized for CAP. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination should be emphasized among appropriate patients. Preliminary data suggest that those with CAP may be helped if they are already on aspirin or a statin. Early recognition of cardiac complications and treatment may improve clinical outcomes for patients with CAP.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a common condition in the United States and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality [1,2], with medical costs exceeding $10 billion in 2011 [3]. The mortality rate is much higher for those aged 65 years and older [4]. Men have a higher death rate than women (18.6 vs. 13.9 per 100,000 population), and death rate varies based on ethnicity, with mortality rates for American Indian/Alaska natives at 19.2, blacks at 17.1, whites at 15.9, Asian/Pacific Islanders at 15.0, and Hispanics at 13.1 (all rates per 100,000) [2]. CAP causes considerable worldwide mortality, with differences in mortality varying according to world region [5].

Cardiovascular complications and death from other comorbidities cause a substantial proportion of CAP-associated mortality. In Mortensen et al’s study, among patients with CAP who died, at least one third had a cardiac complication, and 13% had a cardiac-related cause of death [6]. One study showed that hospitalized patients with CAP complicated by heart disease were 30% more likely to die than patients hospitalized with CAP alone [7]. In this article, we discuss the burden of cardiac complications in adults with CAP, including underlying pathophysiological processes and strategies to prevent their occurence.

Pathophysiological Processes of Heart Disease Caused by CAP

The pathophysiology of cardiac complications as a result of CAP is made up of several hypotheses, including (1) declining oxygen provision by the lungs in the face of increasing demand by the heart, (2) a lack of reserve for stress because of cardiac comorbidities and (3) localized (pulmonary) inflammation leading to systemic (including cardiac) complications by the release of cytokines or other chemicals. Any of these may result in cardiac complications occurring before, during, or after a patient has been hospitalized for CAP. Antimicrobial treatment, specifically azithromycin, has also been implicated in myocardial adverse effects. Although azithromycin is most noted for causing QT prolongation, it was associated with myocardial infarction (MI) in a study of 73,690 patients with pneumonia [8]. A higher proportion of those who received azithromycin had an MI compared to those who did not (5.1% vs 4.4%; OR 1.17; 95% CI, 1.08–1.25), but there was no statistical difference in cardiac arrhythmias, and the 90-day mortality was actually better in the azithromycin group (17.4% vs 22.3%; odds ratio [OR], 0.73; 95% CI, 0.70–0.76).

Systemic inflammation is the result of several molecules, such as cytokines, chemokines and reactive oxidant species. Reactive oxidant species may determine oxidation of proteins, lipids and DNA, which leads to cell death. The hypothesis also purports that they also cause destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques leading to MIs. Other reactions as a result of inflammation lead to arrhythmias with or without compromised cardiac function, causing congestive heart failure (CHF). For this reason, some authors have approached the pathophysiology of cardiac complications by considering them to be either plaque-related or plaque-unrelated events [9].

A few studies have linked specific inflammatory molecules to cardiac toxicity. NOX2 is chemically unstable and may provoke cellular damage, thus maintaining a certain redox balance is crucial for cardiomyocyte health. In 248 patients with CAP, an elevated troponin T was present in 135 patients and among those, NOX2 correlated with the troponin T values (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.08–1.17; P < 0.001) [10]. Both disrupting the equilibrium of the redox balance by upregulating NOX2, and finding NOX2 to be associated with troponin T suggest that oxidative stress is implicated in damage to the myocardium during CAP. In another study of 432 patients with CAP, 41 developed atrial fibrillation within 24 to 72 hours of admission and showed higher blood levels of NOX2 than those who had CAP without atrial fibrillation [11]. Oxidative stress has been shown to cause hypertrophy, dysfunction, apoptotic cell death, and fibrosis in the myocardium [12].

There is likely a high level of variability in how individual patients respond to a predisposing factor for a cardiac complication. For example, one patient may tolerate a mild hypoxia while another is sensitive. The association of inflammatory markers with the presence of cardiac markers, however, would support that once there are systemic reactions, the complications increase. Macrolides, however, were not found to contribute to long-term mortality due to cardiac complications.

Cardiac Complications of CAP

After the H1N1 influenza outbreak of 1918, it was noted that all-cause mortality increased during the outbreak as did influenza-related deaths. This prompted inquiry as to whether there was an actual association between the outbreak and increased overall mortality, or whether the 2 occurrences were simply coincidental [14]. Near that time, arrhythmias in CAP patients were studied. T-wave changes were found to be associated with CAP [15]. Among 92 patients studied, 449 electrocardiograms (ECGs) were reviewed. T-wave changes were the most common ECG changes. They were found in 5 of 10 of the patients who died, and in 35 of the 82 patients who lived. Twelve living patients had persistent ECG changes, and although they were all thought to have had underlying myocardial disease, 2 of them certainly did as they each had an acute MI (and the ECG was included as a figure for one of them).

A study in the 1980s that reported 3 of 38 CAP patients with CHF interrupted the paucity of data at the time that showed that having a cardiac complication during CAP was a known entity [16]. By the end of the 20th century, Meier et al noted that among case patients who had an MI, an acute respiratory tract infection preceded the MI in 2.8% while in only 0.9% of control patients [17]. They also noted that patients who had an acute respiratory tract infection were 2.7 times more likely to have an MI in the following 10 days than control patients.

Further study by Musher et al revealed that MI was associated with pneumococcal pneumonia in 12 (7%) of 170 veteran patients [18]. An MI was defined on the basis of ECG abnormalities (Q waves or ST segment elevation or depression) with troponin I levels ≥ 0.5 ng/mL. They also evaluated arrhythmias and CHF. They included atrial fibrillation or flutter and ventricular tachycardia while excluding terminal arrhythmias. An arrhythmia was found in 8 (5%) patients. CHF was based on Framingham criteria (Table 1) [19]. New or worsening CHF was determined by comparing physical findings, laboratory values, chest radiograph, and echocardiogram reports in medical records. CHF was found in 13 (19%) patients. Ramirez et al found that MI was associated with CAP in 29 (5.8%) of 500 similar veteran patients [20].

Further study by Musher et al revealed that MI was associated with pneumococcal pneumonia in 12 (7%) of 170 veteran patients [18]. An MI was defined on the basis of ECG abnormalities (Q waves or ST segment elevation or depression) with troponin I levels ≥ 0.5 ng/mL. They also evaluated arrhythmias and CHF. They included atrial fibrillation or flutter and ventricular tachycardia while excluding terminal arrhythmias. An arrhythmia was found in 8 (5%) patients. CHF was based on Framingham criteria (Table 1) [19]. New or worsening CHF was determined by comparing physical findings, laboratory values, chest radiograph, and echocardiogram reports in medical records. CHF was found in 13 (19%) patients. Ramirez et al found that MI was associated with CAP in 29 (5.8%) of 500 similar veteran patients [20].

Corrales-Medina et al reported cardiac complications in CAP patients in the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Team cohort study [21]. They defined MI as the presence of 2 of 3 criteria: ECG abnormalities, elevated cardiac enzymes, and chest pain. They found 43 (3.2%) of 1343 patients with an MI. Arrhythmias included atrial fibrillation or flutter, multifocal atrial tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia (≥ 3 beat run) or ventricular fibrillation. With the more inclusive list, they found a greater proportion, 137 (10%) patients affected. They defined CHF with physical examination findings plus a radiographic abnormality, and found 279 (21%) patients affected. A meta-analysis of 17 studies had pooled incidences for an MI of 5.3%, an arrhythmia of 4.7% and CHF of 14.1% [22].

In summary, the most prominent cardiac complications in patients with CAP have been found to be CHF, MI, and arrhythmia.

Timing of Cardiac Complications in Relation to CAP

While a patient is still in the community, cardiac complications may occur with the onset of CAP, or afterwards. For these patients, the primary goal is to identify the complication and manage it as soon as the patient is admitted for CAP, rather than allowing the complications to worsen only to be recognized later. Cardiac complications are rare in outpatients overall. A study of 944 outpatients found heart failure in 1.4%, arrhythmias in 1.0% and MI in 0.1% [21].

For patients who are admitted with CAP but who do not have a cardiac complication, the goals are either to prevent any complication or to recognize and manage a complication early. This also applies to patients who have been discharged after an admission for CAP. Cardiac complications have been recorded shortly after (within 30 days), and late (up to 1 year) after discharge. A study of over 50,000 veterans who were admitted for CAP were followed for any cardiovascular complication in the next 90 days. Approximately 7500 veterans were found to have a cardiac complication, including (in order of highest to lowest frequency) CHF, arrhythmia, MI, stroke and angina [23]. More than 75% of the complications were found on the day of hospitalization, but events were still measured at 30 days and 90 days.

Two other studies sought to determine an association between CAP and cardiac complications differently; not by following CAP patients prospectively for complications but by retrospectively evaluating patients for a respiratory infection among those who were admitted for a cardiovascular complication (MI or stroke). A study of over 35,000 first-time admissions for either an MI or a stroke were evaluated for a respiratory infection within the previous 90 days [24]. The incidence rates were statistically significant for every time period up to 90 days. The preceding 3 days was the time period with the highest frequency for a respiratory infection preceding an event. When the event was an MI, the incident rate was 4.95 (95% CI, 4.43–5.53). A similar study of over 20,000 first-time admissions for either an MI or stroke were evaluated for a preceding primary care visit for a respiratory infection [25]. An infection preceded 2.9% of patients with an MI and 2.8% of patients with a stroke. Statistical significance was found for the group of patients who had a respiratory infection within 7 days preceding an MI (OR 2.10 [95% CI 1.38–3.21]) or preceding a stroke (OR 1.92 [95% CI 1.24–2.97]). In fact, every time period analyzed for both complications (MI and stroke) was significant up to 1 year. Because the timing of a cardiac complication varies and can occur up to 90 days or even a year after acute infection, physicians should maintain vigilance in suspecting and screening for them.

Predictors of Cardiac Complications During CAP

Recently, Cangemi et al reviewed mortality in 301 patients admitted for CAP 6 to 60 months after they were discharged [26]. Mortality was compared between patients who experienced a cardiac complication—atrial fibrillation or an ST- or non-ST-elevation MI—during their admission and those who did not. A total of 55 (18%) patients had a cardiac complication while hospitalized. During the follow-up, 90 (30%) of the 301 patients died. Death occurred in more patients who had had a cardiac complication while hospitalized than in those who did not (32% vs 13%; P < 0.001). The study also showed that age and the pneumonia severity index (PSI) predicted death in addition to intra-hospital complication. A Cox regression analysis showed that intrahospital cardiac complications (hazard ratio [HR] 1.76 [95% CI 1.10–2.82]; P = 0.019), age (HR 1.05 [95% CI 1.03–1.08]; P < 0.001) and the PSI (HR 1.01 [95% CI 1.00–1.02] P = 0.012) independently predicted death after adjusting for possible confounders [26].

The PSI score was published in 1997, and it instructed that patients with a risk class of I or II (low risk) should be managed as outpatients. Data eventually showed that there is a portion of the population with a risk class of I or II whose hospital admission is justified [4]. Among the reasons found was “comorbidity,” including MI and other cardiac complications. The PSI prediction rule was found to be useful in novel ways, and being associated with a risk of MI in patients with CAP was one of them. The propensity-adjusted association between the PSI score and MI was significant (P < 0.05) in an observational study of the CAP Organization (CAPO) [20]. Knowing that a PSI of 80 is in the middle of risk class III (71–90), it was noted that below 80 the risk for MI was zero to 2.5%, while above 80 the risk rose from 2.5% to 12.5%. A later study using the same statistical method showed a correlation between the PSI score and cardiac complications (MI, arrhythmias and CHF) with a P value of < 0.01 [21]. Determining the probability for the combination of complications, rather than just an MI, yielded an unsurprisingly higher range of risk for the PSI below 80, which was zero to 17.5%, while risk for a PSI above 80 was 17.5% to 80%.

In a study to determine risk factors for cardiac complications among 3068 patients with CAP, Griffin et al applied a purposeful selection algorithm to a list of factors with reasonable potential to be associated with the 376 patients who actually had a cardiac complication [27]. After multivariate logistic regression analysis, hyperlipidemia, an infection with Staphlococcus aureus or Klebsiella pneumoniae, and the PSI were found to be statistically significant. In contrast, statin therapy was associated with a lower risk of an event.

In 2014, a validated score similar to the PSI and using the same database was derived to predict short-term risk for cardiac events in hospitalized patients with CAP [28]. It attributes points for age, 3 preexisting conditions, 2 vital signs and 7 radiological and laboratory values, with a point scoring system that defines 4 risk stratification classes. In the derivation cohort, the incidence of cardiac complications across the risk classes increased linearly (3%, 18%, 35%, and 72%, respectively). The score was validated in the original publication with a separate database but has not been evaluated since. The score outperformed the PSI score in predicting cardiac complications in the validation cohort (proportion of patients correctly reclassified by the new score, 44%). Potentially, the rule could help identify high-risk patients upon admission and could assist clinicians in their decision making.

Strategies to Prevent Cardiac Complications During CAP

It is now well established that there is a heavy burden of long-lasting cardiac complications among patients with CAP; therefore, preventing CAP should be a priority. This can be accomplished by counseling patients to refrain from alcohol and smoking and by administering influenza (Table 2) and pneumococcal vaccines (Figure 2). Since the 7-valent protein-polysaccharide conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (PCV-7) was released for children in 2000, there have been fewer hospitalizations in the United States [27] and improved outcomes globally;

It is now well established that there is a heavy burden of long-lasting cardiac complications among patients with CAP; therefore, preventing CAP should be a priority. This can be accomplished by counseling patients to refrain from alcohol and smoking and by administering influenza (Table 2) and pneumococcal vaccines (Figure 2). Since the 7-valent protein-polysaccharide conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (PCV-7) was released for children in 2000, there have been fewer hospitalizations in the United States [27] and improved outcomes globally;  for instance, fewer hospitalizations among children < 14 years of age in Uruguay [29], and decreased invasive pneumococcal disease among children < 5 years of age in Taiwan [30]. Furthermore, a decrease in invasive pneumococcal disease by 18% in persons aged > 65 years in the US and Canada decreased with the introduction of PCV-7 to children. Although this showed a beneficial indirect effect (herd immunity) in unvaccinated populations [31,32], there have been no randomized controlled trials in adults demonstrating a decrease in pneumococcal pneumonia or invasive pneumococcal disease which were vaccinated with PCV-13. The Food and Drug Administration approved PCV-13 for children in 2010 and for adults in 2012. Although it included fewer serotypes, it did include serotype 6A, which has a high pathogenicity and is not in 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV-23). The criteria for vaccinating adults for pneumococcal infection were recently published [33]. A study of patients with invasive pneumococcal disease, which also determined pneumococcal serotypes, included 5 patients who had CAP as well [34]. Those patients had serotypes 6A, 7C, 14, and 23F (2 patients). The patient who had serotype 14 (higher pathogenicity) died and the other 4 lived. Serotypes 14 and 23F are in both vaccines while serotype 7C is in neither. Vaccination status was not provided in the study. At this time, there is evidence to support vaccinating patients for both S. pneumoniae and influenza virus.