User login

Gene associated with vision loss also linked to COVID: Study

age-related macular degeneration.

The findings show that COVID and AMD were associated with variations in what is called the PDGFB gene, which has a role in new blood vessel formation and is linked to abnormal blood vessel changes that occur in AMD. The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine. The analysis included genetic data from more than 16,000 people with AMD, more than 50,000 people with COVID, plus control groups.

Age-related macular degeneration is a vision problem that occurs when a part of the retina – the macula – is damaged, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology. The result is that central vision is lost, but peripheral vision remains normal, so it is difficult to see fine details. For example, a person with AMD can see a clock’s numbers but not its hands.

“Our analysis lends credence to previously reported clinical studies that found those with AMD have a higher risk for COVID-19 infection and severe disease, and that this increased risk may have a genetic basis,” Boston University researcher Lindsay Farrer, PhD, chief of biomedical genetics, explained in a news release.

Previous research has shown that people with AMD have a 25% increased risk of respiratory failure or death due to COVID, which is higher than other well-known risk factors such as type 2 diabetes (21%) or obesity (13%), according to the news release.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

age-related macular degeneration.

The findings show that COVID and AMD were associated with variations in what is called the PDGFB gene, which has a role in new blood vessel formation and is linked to abnormal blood vessel changes that occur in AMD. The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine. The analysis included genetic data from more than 16,000 people with AMD, more than 50,000 people with COVID, plus control groups.

Age-related macular degeneration is a vision problem that occurs when a part of the retina – the macula – is damaged, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology. The result is that central vision is lost, but peripheral vision remains normal, so it is difficult to see fine details. For example, a person with AMD can see a clock’s numbers but not its hands.

“Our analysis lends credence to previously reported clinical studies that found those with AMD have a higher risk for COVID-19 infection and severe disease, and that this increased risk may have a genetic basis,” Boston University researcher Lindsay Farrer, PhD, chief of biomedical genetics, explained in a news release.

Previous research has shown that people with AMD have a 25% increased risk of respiratory failure or death due to COVID, which is higher than other well-known risk factors such as type 2 diabetes (21%) or obesity (13%), according to the news release.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

age-related macular degeneration.

The findings show that COVID and AMD were associated with variations in what is called the PDGFB gene, which has a role in new blood vessel formation and is linked to abnormal blood vessel changes that occur in AMD. The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine. The analysis included genetic data from more than 16,000 people with AMD, more than 50,000 people with COVID, plus control groups.

Age-related macular degeneration is a vision problem that occurs when a part of the retina – the macula – is damaged, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology. The result is that central vision is lost, but peripheral vision remains normal, so it is difficult to see fine details. For example, a person with AMD can see a clock’s numbers but not its hands.

“Our analysis lends credence to previously reported clinical studies that found those with AMD have a higher risk for COVID-19 infection and severe disease, and that this increased risk may have a genetic basis,” Boston University researcher Lindsay Farrer, PhD, chief of biomedical genetics, explained in a news release.

Previous research has shown that people with AMD have a 25% increased risk of respiratory failure or death due to COVID, which is higher than other well-known risk factors such as type 2 diabetes (21%) or obesity (13%), according to the news release.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MEDICINE

Study of beliefs about what causes cancer sparks debate

The study, entitled, “Everything Causes Cancer? Beliefs and Attitudes Towards Cancer Prevention Among Anti-Vaxxers, Flat Earthers, and Reptilian Conspiracists: Online Cross Sectional Survey,” was published in the Christmas 2022 issue of The British Medical Journal (BMJ).

The authors explain that they set out to evaluate “the patterns of beliefs about cancer among people who believed in conspiracies, rejected the COVID-19 vaccine, or preferred alternative medicine.”

They sought such people on social media and online chat platforms and asked them questions about real and mythical causes of cancer.

Almost half of survey participants agreed with the statement, “It seems like everything causes cancer.”

Overall, among all participants, awareness of the actual causes of cancer was greater than awareness of the mythical causes of cancer, the authors report. However, awareness of the actual causes of cancer was lower among the unvaccinated and members of conspiracy groups than among their counterparts.

The authors are concerned that their findings suggest “a direct connection between digital misinformation and consequent potential erroneous health decisions, which may represent a further preventable fraction of cancer.”

Backlash and criticism

The study “highlights the difficulty society encounters in distinguishing the actual causes of cancer from mythical causes,” The BMJ commented on Twitter.

However, both the study and the journal received some backlash.

This is a “horrible article seeking to smear people with concerns about COVID vaccines,” commented Clare Craig, a British consultant pathologist who specializes in cancer diagnostics.

The study and its methodology were also harshly criticized on Twitter by Normal Fenton, professor of risk information management at the Queen Mary University of London.

The senior author of the study, Laura Costas, a medical epidemiologist with the Catalan Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, told this news organization that the naysayers on social media, many of whom focused their comments on the COVID-19 vaccine, prove the purpose of the study – that misinformation spreads widely on the internet.

“Most comments focused on spreading COVID-19 myths, which were not the direct subject of the study, and questioned the motivations of BMJ authors and the scientific community, assuming they had a common malevolent hidden agenda,” Ms. Costas said.

“They stated the need of having critical thinking, a trait in common with the scientific method, but dogmatically dismissed any information that comes from official sources,” she added.

Ms. Costas commented that “society encounters difficulty in differentiating actual from mythical causes of cancer owing to mass information. We therefore planned this study with a certain satire, which is in line with the essence of The BMJ Christmas issue.”

The BMJ has a long history of publishing a lighthearted Christmas edition full of original, satirical, and nontraditional studies. Previous years have seen studies that explored potential harms from holly and ivy, survival time of chocolates on hospital wards, and the question, “Were James Bond’s drinks shaken because of alcohol induced tremor?”

Study details

Ms. Costas and colleagues sought participants for their survey from online forums that included 4chan and Reddit, which are known for their controversial content posted by anonymous users. Data were also collected from ForoCoches and HispaChan, well-known Spanish online forums. These online sites were intentionally chosen because researchers thought “conspiracy beliefs would be more prevalent,” according to Ms. Costas.

Across the multiple forums, there were 1,494 participants. Of these, 209 participants were unvaccinated against COVID-19, 112 preferred alternatives rather than conventional medicine, and 62 reported that they believed the earth was flat or believed that humanoids take reptilian forms to manipulate human societies.

The team then sought to assess beliefs about actual and mythical (nonestablished) causes of cancer by presenting the participants with the closed risk factor questions on two validated scales – the Cancer Awareness Measure (CAM) and CAM–Mythical Causes Scale (CAM-MYCS).

Responses to both were recorded on a five-point scale; answers ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

The CAM assesses cancer risk perceptions of 11 established risk factors for cancer: smoking actively or passively, consuming alcohol, low levels of physical activity, consuming red or processed meat, getting sunburnt as a child, family history of cancer, human papillomavirus infection, being overweight, age greater than or equal to 70 years, and low vegetable and fruit consumption.

The CAM-MYCS measure includes 12 questions on risk perceptions of mythical causes of cancer – nonestablished causes that are commonly believed to cause cancer but for which there is no supporting scientific evidence, the authors explain. These items include drinking from plastic bottles; eating food containing artificial sweeteners or additives and genetically modified food; using microwave ovens, aerosol containers, mobile phones, and cleaning products; living near power lines; feeling stressed; experiencing physical trauma; and being exposed to electromagnetic frequencies/non-ionizing radiation, such as wi-fi networks, radio, and television.

The most endorsed mythical causes of cancer were eating food containing additives (63.9%) or sweeteners (50.7%), feeling stressed (59.7%), and eating genetically modified foods (38.4%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study, entitled, “Everything Causes Cancer? Beliefs and Attitudes Towards Cancer Prevention Among Anti-Vaxxers, Flat Earthers, and Reptilian Conspiracists: Online Cross Sectional Survey,” was published in the Christmas 2022 issue of The British Medical Journal (BMJ).

The authors explain that they set out to evaluate “the patterns of beliefs about cancer among people who believed in conspiracies, rejected the COVID-19 vaccine, or preferred alternative medicine.”

They sought such people on social media and online chat platforms and asked them questions about real and mythical causes of cancer.

Almost half of survey participants agreed with the statement, “It seems like everything causes cancer.”

Overall, among all participants, awareness of the actual causes of cancer was greater than awareness of the mythical causes of cancer, the authors report. However, awareness of the actual causes of cancer was lower among the unvaccinated and members of conspiracy groups than among their counterparts.

The authors are concerned that their findings suggest “a direct connection between digital misinformation and consequent potential erroneous health decisions, which may represent a further preventable fraction of cancer.”

Backlash and criticism

The study “highlights the difficulty society encounters in distinguishing the actual causes of cancer from mythical causes,” The BMJ commented on Twitter.

However, both the study and the journal received some backlash.

This is a “horrible article seeking to smear people with concerns about COVID vaccines,” commented Clare Craig, a British consultant pathologist who specializes in cancer diagnostics.

The study and its methodology were also harshly criticized on Twitter by Normal Fenton, professor of risk information management at the Queen Mary University of London.

The senior author of the study, Laura Costas, a medical epidemiologist with the Catalan Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, told this news organization that the naysayers on social media, many of whom focused their comments on the COVID-19 vaccine, prove the purpose of the study – that misinformation spreads widely on the internet.

“Most comments focused on spreading COVID-19 myths, which were not the direct subject of the study, and questioned the motivations of BMJ authors and the scientific community, assuming they had a common malevolent hidden agenda,” Ms. Costas said.

“They stated the need of having critical thinking, a trait in common with the scientific method, but dogmatically dismissed any information that comes from official sources,” she added.

Ms. Costas commented that “society encounters difficulty in differentiating actual from mythical causes of cancer owing to mass information. We therefore planned this study with a certain satire, which is in line with the essence of The BMJ Christmas issue.”

The BMJ has a long history of publishing a lighthearted Christmas edition full of original, satirical, and nontraditional studies. Previous years have seen studies that explored potential harms from holly and ivy, survival time of chocolates on hospital wards, and the question, “Were James Bond’s drinks shaken because of alcohol induced tremor?”

Study details

Ms. Costas and colleagues sought participants for their survey from online forums that included 4chan and Reddit, which are known for their controversial content posted by anonymous users. Data were also collected from ForoCoches and HispaChan, well-known Spanish online forums. These online sites were intentionally chosen because researchers thought “conspiracy beliefs would be more prevalent,” according to Ms. Costas.

Across the multiple forums, there were 1,494 participants. Of these, 209 participants were unvaccinated against COVID-19, 112 preferred alternatives rather than conventional medicine, and 62 reported that they believed the earth was flat or believed that humanoids take reptilian forms to manipulate human societies.

The team then sought to assess beliefs about actual and mythical (nonestablished) causes of cancer by presenting the participants with the closed risk factor questions on two validated scales – the Cancer Awareness Measure (CAM) and CAM–Mythical Causes Scale (CAM-MYCS).

Responses to both were recorded on a five-point scale; answers ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

The CAM assesses cancer risk perceptions of 11 established risk factors for cancer: smoking actively or passively, consuming alcohol, low levels of physical activity, consuming red or processed meat, getting sunburnt as a child, family history of cancer, human papillomavirus infection, being overweight, age greater than or equal to 70 years, and low vegetable and fruit consumption.

The CAM-MYCS measure includes 12 questions on risk perceptions of mythical causes of cancer – nonestablished causes that are commonly believed to cause cancer but for which there is no supporting scientific evidence, the authors explain. These items include drinking from plastic bottles; eating food containing artificial sweeteners or additives and genetically modified food; using microwave ovens, aerosol containers, mobile phones, and cleaning products; living near power lines; feeling stressed; experiencing physical trauma; and being exposed to electromagnetic frequencies/non-ionizing radiation, such as wi-fi networks, radio, and television.

The most endorsed mythical causes of cancer were eating food containing additives (63.9%) or sweeteners (50.7%), feeling stressed (59.7%), and eating genetically modified foods (38.4%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study, entitled, “Everything Causes Cancer? Beliefs and Attitudes Towards Cancer Prevention Among Anti-Vaxxers, Flat Earthers, and Reptilian Conspiracists: Online Cross Sectional Survey,” was published in the Christmas 2022 issue of The British Medical Journal (BMJ).

The authors explain that they set out to evaluate “the patterns of beliefs about cancer among people who believed in conspiracies, rejected the COVID-19 vaccine, or preferred alternative medicine.”

They sought such people on social media and online chat platforms and asked them questions about real and mythical causes of cancer.

Almost half of survey participants agreed with the statement, “It seems like everything causes cancer.”

Overall, among all participants, awareness of the actual causes of cancer was greater than awareness of the mythical causes of cancer, the authors report. However, awareness of the actual causes of cancer was lower among the unvaccinated and members of conspiracy groups than among their counterparts.

The authors are concerned that their findings suggest “a direct connection between digital misinformation and consequent potential erroneous health decisions, which may represent a further preventable fraction of cancer.”

Backlash and criticism

The study “highlights the difficulty society encounters in distinguishing the actual causes of cancer from mythical causes,” The BMJ commented on Twitter.

However, both the study and the journal received some backlash.

This is a “horrible article seeking to smear people with concerns about COVID vaccines,” commented Clare Craig, a British consultant pathologist who specializes in cancer diagnostics.

The study and its methodology were also harshly criticized on Twitter by Normal Fenton, professor of risk information management at the Queen Mary University of London.

The senior author of the study, Laura Costas, a medical epidemiologist with the Catalan Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, told this news organization that the naysayers on social media, many of whom focused their comments on the COVID-19 vaccine, prove the purpose of the study – that misinformation spreads widely on the internet.

“Most comments focused on spreading COVID-19 myths, which were not the direct subject of the study, and questioned the motivations of BMJ authors and the scientific community, assuming they had a common malevolent hidden agenda,” Ms. Costas said.

“They stated the need of having critical thinking, a trait in common with the scientific method, but dogmatically dismissed any information that comes from official sources,” she added.

Ms. Costas commented that “society encounters difficulty in differentiating actual from mythical causes of cancer owing to mass information. We therefore planned this study with a certain satire, which is in line with the essence of The BMJ Christmas issue.”

The BMJ has a long history of publishing a lighthearted Christmas edition full of original, satirical, and nontraditional studies. Previous years have seen studies that explored potential harms from holly and ivy, survival time of chocolates on hospital wards, and the question, “Were James Bond’s drinks shaken because of alcohol induced tremor?”

Study details

Ms. Costas and colleagues sought participants for their survey from online forums that included 4chan and Reddit, which are known for their controversial content posted by anonymous users. Data were also collected from ForoCoches and HispaChan, well-known Spanish online forums. These online sites were intentionally chosen because researchers thought “conspiracy beliefs would be more prevalent,” according to Ms. Costas.

Across the multiple forums, there were 1,494 participants. Of these, 209 participants were unvaccinated against COVID-19, 112 preferred alternatives rather than conventional medicine, and 62 reported that they believed the earth was flat or believed that humanoids take reptilian forms to manipulate human societies.

The team then sought to assess beliefs about actual and mythical (nonestablished) causes of cancer by presenting the participants with the closed risk factor questions on two validated scales – the Cancer Awareness Measure (CAM) and CAM–Mythical Causes Scale (CAM-MYCS).

Responses to both were recorded on a five-point scale; answers ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

The CAM assesses cancer risk perceptions of 11 established risk factors for cancer: smoking actively or passively, consuming alcohol, low levels of physical activity, consuming red or processed meat, getting sunburnt as a child, family history of cancer, human papillomavirus infection, being overweight, age greater than or equal to 70 years, and low vegetable and fruit consumption.

The CAM-MYCS measure includes 12 questions on risk perceptions of mythical causes of cancer – nonestablished causes that are commonly believed to cause cancer but for which there is no supporting scientific evidence, the authors explain. These items include drinking from plastic bottles; eating food containing artificial sweeteners or additives and genetically modified food; using microwave ovens, aerosol containers, mobile phones, and cleaning products; living near power lines; feeling stressed; experiencing physical trauma; and being exposed to electromagnetic frequencies/non-ionizing radiation, such as wi-fi networks, radio, and television.

The most endorsed mythical causes of cancer were eating food containing additives (63.9%) or sweeteners (50.7%), feeling stressed (59.7%), and eating genetically modified foods (38.4%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiac injury caused by COVID-19 less common than thought

The study examined cardiac MRI scans in 31 patients before and after having COVID-19 infection and found no new evidence of myocardial injury in the post-COVID scans relative to the pre-COVID scans.

“To the best of our knowledge this is the first cardiac MRI study to assess myocardial injury pre- and post-COVID-19,” the authors stated.

They say that while this study cannot rule out the possibility of rare events of COVID-19–induced myocardial injury, “the complete absence of de novo late gadolinium enhancement lesions after COVID-19 in this cohort indicates that outside special circumstances, COVID-19–induced myocardial injury may be much less common than suggested by previous studies.”

The study was published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

Coauthor Till F. Althoff, MD, Cardiovascular Institute, Clínic–University Hospital Barcelona, said in an interview that previous reports have found a high rate of cardiac lesions in patients undergoing imaging after having had COVID-19 infection.

“In some reports, this has been as high as 80% of patients even though they have not had severe COVID disease. These reports have been interpreted as showing the majority of patients have some COVID-induced cardiac damage, which is an alarming message,” he commented.

However, he pointed out that the patients in these reports did not undergo a cardiac MRI scan before they had COVID-19 so it wasn’t known whether these cardiac lesions were present before infection or not.

To try and gain more accurate information, the current study examined cardiac MRI scans in the same patients before and after they had COVID-19.

The researchers, from an arrhythmia unit, made use of the fact that all their patients have cardiac MRI data, so they used their large registry of patients in whom cardiac MRI had been performed, and cross referenced this to a health care database to identify those patients who had confirmed COVID-19 after they obtaining a cardiac scan at the arrhythmia unit. They then conducted another cardiac MRI scan in the 31 patients identified a median of 5 months after their COVID-19 infection.

“These 31 patients had a cardiac MRI scan pre-COVID and post COVID using exactly the same scanner with identical sequences, so the scans were absolutely comparable,” Dr. Althoff noted.

Of these 31 patients, 7 had been hospitalized at the time of acute presentation with COVID-19, of whom 2 required intensive care. Most patients (29) had been symptomatic, but none reported cardiac symptoms.

Results showed that, on the post–COVID-19 scan, late gadolinium enhancement lesions indicative of residual myocardial injury were encountered in 15 of the 31 patients (48%), which the researchers said is in line with previous reports.

However, intraindividual comparison with the pre–COVID-19 cardiac MRI scans showed all these lesions were preexisting with identical localization, pattern, and transmural distribution, and thus not COVID-19 related.

Quantitative analyses, performed independently, detected no increase in the size of individual lesions nor in the global left ventricular late gadolinium enhancement extent.

Comparison of pre- and post COVID-19 imaging sequences did not show any differences in ventricular functional or structural parameters.

“While this study only has 31 patients, the fact that we are conducting intra-individual comparisons, which rules out bias, means that we don’t need a large number of patients for reliable results,” Dr. Althoff said.

“These types of lesions are normal to see. We know that individuals without cardiac disease have these types of lesions, and they are not necessarily an indication of any specific pathology. I was kind of surprised by the interpretation of previous data, which is why we did the current study,” he added.

Dr. Althoff acknowledged that some cardiac injury may have been seen if much larger numbers of patients had been included. “But I think we can say from this data that COVID-induced cardiac damage is much less of an issue than we may have previously thought,” he added.

He also noted that most of the patients in this study had mild COVID-19, so the results cannot be extrapolated to severe COVID-19 infection.

However, Dr. Althoff pointed out that all the patients already had atrial fibrillation, so would have been at higher risk of cardiac injury from COVID-19.

“These patients had preexisting cardiac risk factors, and thus they would have been more susceptible to both a more severe course of COVID and an increased risk of myocardial damage due to COVID. The fact that we don’t find any myocardial injury due to COVID in this group is even more reassuring. The general population will be at even lower risk,” he commented.

“I think we can say that, in COVID patients who do not have any cardiac symptoms, our study suggests that the incidence of cardiac injury is very low,” Dr. Althoff said.

“Even in patients with severe COVID and myocardial involvement reflected by increased troponin levels, I wouldn’t be sure that they have any residual cardiac injury. While it has been reported that cardiac lesions have been found in such patients, pre-COVID MRI scans were not available so we don’t know if they were there before,” he added.

“We do not know the true incidence of cardiac injury after COVID, but I think we can say from this data that it is definitely not anywhere near the 40%-50% or even greater that some of the previous reports have suggested,” he stated.

Dr. Althoff suggested that, based on these data, some of the recommendations based on previous reports such the need for follow-up cardiac scans and caution about partaking in sports again after COVID-19 infection, are probably not necessary.

“Our data suggest that these concerns are unfounded, and we need to step back a bit and stop alarming patients about the risk of cardiac damage after COVID,” he said. “Yes, if patients have cardiac symptoms during or after COVID infection they should get checked out, but I do not think we need to do a cardiac risk assessment in patients without cardiac symptoms in COVID.”

This work is supported in part by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Spanish government, Madrid, and Fundació la Marató de TV3 in Catalonia. Dr. Althoff has received research grants for investigator-initiated trials from Biosense Webster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study examined cardiac MRI scans in 31 patients before and after having COVID-19 infection and found no new evidence of myocardial injury in the post-COVID scans relative to the pre-COVID scans.

“To the best of our knowledge this is the first cardiac MRI study to assess myocardial injury pre- and post-COVID-19,” the authors stated.

They say that while this study cannot rule out the possibility of rare events of COVID-19–induced myocardial injury, “the complete absence of de novo late gadolinium enhancement lesions after COVID-19 in this cohort indicates that outside special circumstances, COVID-19–induced myocardial injury may be much less common than suggested by previous studies.”

The study was published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

Coauthor Till F. Althoff, MD, Cardiovascular Institute, Clínic–University Hospital Barcelona, said in an interview that previous reports have found a high rate of cardiac lesions in patients undergoing imaging after having had COVID-19 infection.

“In some reports, this has been as high as 80% of patients even though they have not had severe COVID disease. These reports have been interpreted as showing the majority of patients have some COVID-induced cardiac damage, which is an alarming message,” he commented.

However, he pointed out that the patients in these reports did not undergo a cardiac MRI scan before they had COVID-19 so it wasn’t known whether these cardiac lesions were present before infection or not.

To try and gain more accurate information, the current study examined cardiac MRI scans in the same patients before and after they had COVID-19.

The researchers, from an arrhythmia unit, made use of the fact that all their patients have cardiac MRI data, so they used their large registry of patients in whom cardiac MRI had been performed, and cross referenced this to a health care database to identify those patients who had confirmed COVID-19 after they obtaining a cardiac scan at the arrhythmia unit. They then conducted another cardiac MRI scan in the 31 patients identified a median of 5 months after their COVID-19 infection.

“These 31 patients had a cardiac MRI scan pre-COVID and post COVID using exactly the same scanner with identical sequences, so the scans were absolutely comparable,” Dr. Althoff noted.

Of these 31 patients, 7 had been hospitalized at the time of acute presentation with COVID-19, of whom 2 required intensive care. Most patients (29) had been symptomatic, but none reported cardiac symptoms.

Results showed that, on the post–COVID-19 scan, late gadolinium enhancement lesions indicative of residual myocardial injury were encountered in 15 of the 31 patients (48%), which the researchers said is in line with previous reports.

However, intraindividual comparison with the pre–COVID-19 cardiac MRI scans showed all these lesions were preexisting with identical localization, pattern, and transmural distribution, and thus not COVID-19 related.

Quantitative analyses, performed independently, detected no increase in the size of individual lesions nor in the global left ventricular late gadolinium enhancement extent.

Comparison of pre- and post COVID-19 imaging sequences did not show any differences in ventricular functional or structural parameters.

“While this study only has 31 patients, the fact that we are conducting intra-individual comparisons, which rules out bias, means that we don’t need a large number of patients for reliable results,” Dr. Althoff said.

“These types of lesions are normal to see. We know that individuals without cardiac disease have these types of lesions, and they are not necessarily an indication of any specific pathology. I was kind of surprised by the interpretation of previous data, which is why we did the current study,” he added.

Dr. Althoff acknowledged that some cardiac injury may have been seen if much larger numbers of patients had been included. “But I think we can say from this data that COVID-induced cardiac damage is much less of an issue than we may have previously thought,” he added.

He also noted that most of the patients in this study had mild COVID-19, so the results cannot be extrapolated to severe COVID-19 infection.

However, Dr. Althoff pointed out that all the patients already had atrial fibrillation, so would have been at higher risk of cardiac injury from COVID-19.

“These patients had preexisting cardiac risk factors, and thus they would have been more susceptible to both a more severe course of COVID and an increased risk of myocardial damage due to COVID. The fact that we don’t find any myocardial injury due to COVID in this group is even more reassuring. The general population will be at even lower risk,” he commented.

“I think we can say that, in COVID patients who do not have any cardiac symptoms, our study suggests that the incidence of cardiac injury is very low,” Dr. Althoff said.

“Even in patients with severe COVID and myocardial involvement reflected by increased troponin levels, I wouldn’t be sure that they have any residual cardiac injury. While it has been reported that cardiac lesions have been found in such patients, pre-COVID MRI scans were not available so we don’t know if they were there before,” he added.

“We do not know the true incidence of cardiac injury after COVID, but I think we can say from this data that it is definitely not anywhere near the 40%-50% or even greater that some of the previous reports have suggested,” he stated.

Dr. Althoff suggested that, based on these data, some of the recommendations based on previous reports such the need for follow-up cardiac scans and caution about partaking in sports again after COVID-19 infection, are probably not necessary.

“Our data suggest that these concerns are unfounded, and we need to step back a bit and stop alarming patients about the risk of cardiac damage after COVID,” he said. “Yes, if patients have cardiac symptoms during or after COVID infection they should get checked out, but I do not think we need to do a cardiac risk assessment in patients without cardiac symptoms in COVID.”

This work is supported in part by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Spanish government, Madrid, and Fundació la Marató de TV3 in Catalonia. Dr. Althoff has received research grants for investigator-initiated trials from Biosense Webster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study examined cardiac MRI scans in 31 patients before and after having COVID-19 infection and found no new evidence of myocardial injury in the post-COVID scans relative to the pre-COVID scans.

“To the best of our knowledge this is the first cardiac MRI study to assess myocardial injury pre- and post-COVID-19,” the authors stated.

They say that while this study cannot rule out the possibility of rare events of COVID-19–induced myocardial injury, “the complete absence of de novo late gadolinium enhancement lesions after COVID-19 in this cohort indicates that outside special circumstances, COVID-19–induced myocardial injury may be much less common than suggested by previous studies.”

The study was published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

Coauthor Till F. Althoff, MD, Cardiovascular Institute, Clínic–University Hospital Barcelona, said in an interview that previous reports have found a high rate of cardiac lesions in patients undergoing imaging after having had COVID-19 infection.

“In some reports, this has been as high as 80% of patients even though they have not had severe COVID disease. These reports have been interpreted as showing the majority of patients have some COVID-induced cardiac damage, which is an alarming message,” he commented.

However, he pointed out that the patients in these reports did not undergo a cardiac MRI scan before they had COVID-19 so it wasn’t known whether these cardiac lesions were present before infection or not.

To try and gain more accurate information, the current study examined cardiac MRI scans in the same patients before and after they had COVID-19.

The researchers, from an arrhythmia unit, made use of the fact that all their patients have cardiac MRI data, so they used their large registry of patients in whom cardiac MRI had been performed, and cross referenced this to a health care database to identify those patients who had confirmed COVID-19 after they obtaining a cardiac scan at the arrhythmia unit. They then conducted another cardiac MRI scan in the 31 patients identified a median of 5 months after their COVID-19 infection.

“These 31 patients had a cardiac MRI scan pre-COVID and post COVID using exactly the same scanner with identical sequences, so the scans were absolutely comparable,” Dr. Althoff noted.

Of these 31 patients, 7 had been hospitalized at the time of acute presentation with COVID-19, of whom 2 required intensive care. Most patients (29) had been symptomatic, but none reported cardiac symptoms.

Results showed that, on the post–COVID-19 scan, late gadolinium enhancement lesions indicative of residual myocardial injury were encountered in 15 of the 31 patients (48%), which the researchers said is in line with previous reports.

However, intraindividual comparison with the pre–COVID-19 cardiac MRI scans showed all these lesions were preexisting with identical localization, pattern, and transmural distribution, and thus not COVID-19 related.

Quantitative analyses, performed independently, detected no increase in the size of individual lesions nor in the global left ventricular late gadolinium enhancement extent.

Comparison of pre- and post COVID-19 imaging sequences did not show any differences in ventricular functional or structural parameters.

“While this study only has 31 patients, the fact that we are conducting intra-individual comparisons, which rules out bias, means that we don’t need a large number of patients for reliable results,” Dr. Althoff said.

“These types of lesions are normal to see. We know that individuals without cardiac disease have these types of lesions, and they are not necessarily an indication of any specific pathology. I was kind of surprised by the interpretation of previous data, which is why we did the current study,” he added.

Dr. Althoff acknowledged that some cardiac injury may have been seen if much larger numbers of patients had been included. “But I think we can say from this data that COVID-induced cardiac damage is much less of an issue than we may have previously thought,” he added.

He also noted that most of the patients in this study had mild COVID-19, so the results cannot be extrapolated to severe COVID-19 infection.

However, Dr. Althoff pointed out that all the patients already had atrial fibrillation, so would have been at higher risk of cardiac injury from COVID-19.

“These patients had preexisting cardiac risk factors, and thus they would have been more susceptible to both a more severe course of COVID and an increased risk of myocardial damage due to COVID. The fact that we don’t find any myocardial injury due to COVID in this group is even more reassuring. The general population will be at even lower risk,” he commented.

“I think we can say that, in COVID patients who do not have any cardiac symptoms, our study suggests that the incidence of cardiac injury is very low,” Dr. Althoff said.

“Even in patients with severe COVID and myocardial involvement reflected by increased troponin levels, I wouldn’t be sure that they have any residual cardiac injury. While it has been reported that cardiac lesions have been found in such patients, pre-COVID MRI scans were not available so we don’t know if they were there before,” he added.

“We do not know the true incidence of cardiac injury after COVID, but I think we can say from this data that it is definitely not anywhere near the 40%-50% or even greater that some of the previous reports have suggested,” he stated.

Dr. Althoff suggested that, based on these data, some of the recommendations based on previous reports such the need for follow-up cardiac scans and caution about partaking in sports again after COVID-19 infection, are probably not necessary.

“Our data suggest that these concerns are unfounded, and we need to step back a bit and stop alarming patients about the risk of cardiac damage after COVID,” he said. “Yes, if patients have cardiac symptoms during or after COVID infection they should get checked out, but I do not think we need to do a cardiac risk assessment in patients without cardiac symptoms in COVID.”

This work is supported in part by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Spanish government, Madrid, and Fundació la Marató de TV3 in Catalonia. Dr. Althoff has received research grants for investigator-initiated trials from Biosense Webster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR IMAGING

COVID booster shot poll: People ‘don’t think they need one’

Now, a new poll shows why so few people are willing to roll up their sleeves again.

The most common reasons people give for not getting the latest booster shot is that they “don’t think they need one” (44%) and they “don’t think the benefits are worth it” (37%), according to poll results from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The data comes amid announcements by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that boosters reduced COVID-19 hospitalizations by up to 57% for U.S. adults and by up to 84% for people age 65 and older. Those figures are just the latest in a mountain of research reporting the public health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines.

Despite all of the statistical data, health officials’ recent vaccination campaigns have proven far from compelling.

So far, just 15% of people age 12 and older have gotten the latest booster, and 36% of people age 65 and older have gotten it, the CDC’s vaccination trackershows.

Since the start of the pandemic, 1.1 million people in the U.S. have died from COVID-19, with the number of deaths currently rising by 400 per day, The New York Times COVID tracker shows.

Many experts continue to note the need for everyone to get booster shots regularly, but some advocate that perhaps a change in strategy is in order.

“What the administration should do is push for vaccinating people in high-risk groups, including those who are older, those who are immunocompromised and those who have comorbidities,” Paul Offitt, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told CNN.

Federal regulators have announced they will meet Jan. 26 with a panel of vaccine advisors to examine the current recommended vaccination schedule as well as look at the effectiveness and composition of current vaccines and boosters, with an eye toward the make-up of next-generation shots.

Vaccines are the “best available protection” against hospitalization and death caused by COVID-19, said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a statement announcing the planned meeting.

“Since the initial authorizations of these vaccines, we have learned that protection wanes over time, especially as the virus rapidly mutates and new variants and subvariants emerge,” he said. “Therefore, it’s important to continue discussions about the optimal composition of COVID-19 vaccines for primary and booster vaccination, as well as the optimal interval for booster vaccination.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Now, a new poll shows why so few people are willing to roll up their sleeves again.

The most common reasons people give for not getting the latest booster shot is that they “don’t think they need one” (44%) and they “don’t think the benefits are worth it” (37%), according to poll results from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The data comes amid announcements by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that boosters reduced COVID-19 hospitalizations by up to 57% for U.S. adults and by up to 84% for people age 65 and older. Those figures are just the latest in a mountain of research reporting the public health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines.

Despite all of the statistical data, health officials’ recent vaccination campaigns have proven far from compelling.

So far, just 15% of people age 12 and older have gotten the latest booster, and 36% of people age 65 and older have gotten it, the CDC’s vaccination trackershows.

Since the start of the pandemic, 1.1 million people in the U.S. have died from COVID-19, with the number of deaths currently rising by 400 per day, The New York Times COVID tracker shows.

Many experts continue to note the need for everyone to get booster shots regularly, but some advocate that perhaps a change in strategy is in order.

“What the administration should do is push for vaccinating people in high-risk groups, including those who are older, those who are immunocompromised and those who have comorbidities,” Paul Offitt, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told CNN.

Federal regulators have announced they will meet Jan. 26 with a panel of vaccine advisors to examine the current recommended vaccination schedule as well as look at the effectiveness and composition of current vaccines and boosters, with an eye toward the make-up of next-generation shots.

Vaccines are the “best available protection” against hospitalization and death caused by COVID-19, said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a statement announcing the planned meeting.

“Since the initial authorizations of these vaccines, we have learned that protection wanes over time, especially as the virus rapidly mutates and new variants and subvariants emerge,” he said. “Therefore, it’s important to continue discussions about the optimal composition of COVID-19 vaccines for primary and booster vaccination, as well as the optimal interval for booster vaccination.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Now, a new poll shows why so few people are willing to roll up their sleeves again.

The most common reasons people give for not getting the latest booster shot is that they “don’t think they need one” (44%) and they “don’t think the benefits are worth it” (37%), according to poll results from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The data comes amid announcements by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that boosters reduced COVID-19 hospitalizations by up to 57% for U.S. adults and by up to 84% for people age 65 and older. Those figures are just the latest in a mountain of research reporting the public health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines.

Despite all of the statistical data, health officials’ recent vaccination campaigns have proven far from compelling.

So far, just 15% of people age 12 and older have gotten the latest booster, and 36% of people age 65 and older have gotten it, the CDC’s vaccination trackershows.

Since the start of the pandemic, 1.1 million people in the U.S. have died from COVID-19, with the number of deaths currently rising by 400 per day, The New York Times COVID tracker shows.

Many experts continue to note the need for everyone to get booster shots regularly, but some advocate that perhaps a change in strategy is in order.

“What the administration should do is push for vaccinating people in high-risk groups, including those who are older, those who are immunocompromised and those who have comorbidities,” Paul Offitt, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told CNN.

Federal regulators have announced they will meet Jan. 26 with a panel of vaccine advisors to examine the current recommended vaccination schedule as well as look at the effectiveness and composition of current vaccines and boosters, with an eye toward the make-up of next-generation shots.

Vaccines are the “best available protection” against hospitalization and death caused by COVID-19, said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a statement announcing the planned meeting.

“Since the initial authorizations of these vaccines, we have learned that protection wanes over time, especially as the virus rapidly mutates and new variants and subvariants emerge,” he said. “Therefore, it’s important to continue discussions about the optimal composition of COVID-19 vaccines for primary and booster vaccination, as well as the optimal interval for booster vaccination.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Multiple myeloma diagnosed more via emergency care during COVID

The study covered in this summary was published on Research Square as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaway

Why this matters

While trying to avoid COVID-19 infection, patients ultimately diagnosed with multiple myeloma may have delayed interactions with healthcare professionals and consequently delayed their cancer diagnosis.

Study design

Researchers collected data on newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma from January 2019 until July 2021 across five institutions (three universities and two hospitals) in England. In total, 323 patients with multiple myeloma were identified.

Patients were divided into two groups: those diagnosed between Jan. 1, 2019, until Jan. 31, 2020, or pre-COVID, and those diagnosed from Feb. 1, 2020, to July 31, 2021, or post COVID.

Key results

Among all patients, 80 (24.8%) were diagnosed with smoldering multiple myeloma and 243 (75.2%) were diagnosed with multiple myeloma requiring treatment.

Significantly more patients in the post-COVID group were diagnosed with myeloma through the emergency route (45.5% post COVID vs. 32.7% pre-COVID; P = .03).

Clinical complications leading to emergency admission prior to a myeloma diagnosis also differed between the two cohorts: Acute kidney injury accounted for most emergency admissions in the pre-COVID cohort while skeletal-related events, including spinal cord compression, were the major causes for diagnosis through the emergency route in the post-COVID cohort.

Patients who were diagnosed with symptomatic myeloma pre-COVID were more likely to be treated with a triplet rather than doublet combination compared with those diagnosed in the post-COVID period (triplet pre-COVID 79.1%, post COVID 63.75%; P = .014).

Overall survival at 1 year was not significantly different between the pre-COVID and post-COVID groups: 88.2% pre-COVID, compared with 87.8% post COVID.

Overall, the authors concluded that the COVID pandemic “resulted in a shift in the symptomatology, disease burden, and routes of diagnosis of patients presenting with myeloma” and “this may have significant consequences” over the long term.

Limitations

The study does not provide a clear time frame of delays in diagnosis.

Disclosures

The study authors did not report any conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The study covered in this summary was published on Research Square as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaway

Why this matters

While trying to avoid COVID-19 infection, patients ultimately diagnosed with multiple myeloma may have delayed interactions with healthcare professionals and consequently delayed their cancer diagnosis.

Study design

Researchers collected data on newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma from January 2019 until July 2021 across five institutions (three universities and two hospitals) in England. In total, 323 patients with multiple myeloma were identified.

Patients were divided into two groups: those diagnosed between Jan. 1, 2019, until Jan. 31, 2020, or pre-COVID, and those diagnosed from Feb. 1, 2020, to July 31, 2021, or post COVID.

Key results

Among all patients, 80 (24.8%) were diagnosed with smoldering multiple myeloma and 243 (75.2%) were diagnosed with multiple myeloma requiring treatment.

Significantly more patients in the post-COVID group were diagnosed with myeloma through the emergency route (45.5% post COVID vs. 32.7% pre-COVID; P = .03).

Clinical complications leading to emergency admission prior to a myeloma diagnosis also differed between the two cohorts: Acute kidney injury accounted for most emergency admissions in the pre-COVID cohort while skeletal-related events, including spinal cord compression, were the major causes for diagnosis through the emergency route in the post-COVID cohort.

Patients who were diagnosed with symptomatic myeloma pre-COVID were more likely to be treated with a triplet rather than doublet combination compared with those diagnosed in the post-COVID period (triplet pre-COVID 79.1%, post COVID 63.75%; P = .014).

Overall survival at 1 year was not significantly different between the pre-COVID and post-COVID groups: 88.2% pre-COVID, compared with 87.8% post COVID.

Overall, the authors concluded that the COVID pandemic “resulted in a shift in the symptomatology, disease burden, and routes of diagnosis of patients presenting with myeloma” and “this may have significant consequences” over the long term.

Limitations

The study does not provide a clear time frame of delays in diagnosis.

Disclosures

The study authors did not report any conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The study covered in this summary was published on Research Square as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaway

Why this matters

While trying to avoid COVID-19 infection, patients ultimately diagnosed with multiple myeloma may have delayed interactions with healthcare professionals and consequently delayed their cancer diagnosis.

Study design

Researchers collected data on newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma from January 2019 until July 2021 across five institutions (three universities and two hospitals) in England. In total, 323 patients with multiple myeloma were identified.

Patients were divided into two groups: those diagnosed between Jan. 1, 2019, until Jan. 31, 2020, or pre-COVID, and those diagnosed from Feb. 1, 2020, to July 31, 2021, or post COVID.

Key results

Among all patients, 80 (24.8%) were diagnosed with smoldering multiple myeloma and 243 (75.2%) were diagnosed with multiple myeloma requiring treatment.

Significantly more patients in the post-COVID group were diagnosed with myeloma through the emergency route (45.5% post COVID vs. 32.7% pre-COVID; P = .03).

Clinical complications leading to emergency admission prior to a myeloma diagnosis also differed between the two cohorts: Acute kidney injury accounted for most emergency admissions in the pre-COVID cohort while skeletal-related events, including spinal cord compression, were the major causes for diagnosis through the emergency route in the post-COVID cohort.

Patients who were diagnosed with symptomatic myeloma pre-COVID were more likely to be treated with a triplet rather than doublet combination compared with those diagnosed in the post-COVID period (triplet pre-COVID 79.1%, post COVID 63.75%; P = .014).

Overall survival at 1 year was not significantly different between the pre-COVID and post-COVID groups: 88.2% pre-COVID, compared with 87.8% post COVID.

Overall, the authors concluded that the COVID pandemic “resulted in a shift in the symptomatology, disease burden, and routes of diagnosis of patients presenting with myeloma” and “this may have significant consequences” over the long term.

Limitations

The study does not provide a clear time frame of delays in diagnosis.

Disclosures

The study authors did not report any conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Intermittent fasting can lead to type 2 diabetes remission

In a small randomized controlled trial of patients with type 2 diabetes in China, close to half of those who followed a novel intermittent fasting program for 3 months had diabetes remission (A1c less than 6.5% without taking antidiabetic drugs) that persisted for 1 year.

Importantly, “this study was performed under real-life conditions, and the intervention was delivered by trained nurses in primary care rather than by specialized staff at a research institute, making it a more practical and achievable way to manage” type 2 diabetes, the authors report.

Moreover, 65% of the patients in the intervention group who achieved diabetes remission had had diabetes for more than 6 years, which “suggests the possibility of remission for patients with longer duration” of diabetes, they note.

In addition, antidiabetic medication costs decreased by 77%, compared with baseline, in patients in the intermittent-fasting intervention group.

Although intermittent fasting has been studied for weight loss, it had not been investigated for effectiveness for diabetes remission.

These findings suggest that intermittent fasting “could be a paradigm shift in the management goals in diabetes care,” Xiao Yang and colleagues conclude in their study, published online in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Type 2 diabetes is not necessarily a permanent, lifelong disease,” senior author Dongbo Liu, PhD, from the Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China, added in a press release from The Endocrine Society.

“Diabetes remission is possible if patients lose weight by changing their diet and exercise habits,” Dr. Liu said.

‘Excellent outcome’

Invited to comment, Amy E. Rothberg, MD, PhD, who was not involved with the research, agreed that the study indicates that intermittent fasting works for diabetes remission.

“We know that diabetes remission is possible with calorie restriction and subsequent weight loss, and intermittent fasting is just one of the many [dietary] approaches that may be suitable, appealing, and sustainable to some individuals, and usually results in calorie restriction and therefore weight loss,” she said.

The most studied types of intermittent fasting diets are alternate-day fasting, the 5:2 diet, and time-restricted consumption, Dr. Rothberg told this news organization.

This study presented a novel type of intermittent fasting, she noted. The intervention consisted of 6 cycles (3 months) of 5 fasting days followed by 10 ad libitum days, and then 3 months of follow-up (with no fasting days).

After 3 months of the intervention plus 3 months of follow-up, 47% of the 36 patients in the intervention group achieved diabetes remission (with a mean A1c of 5.66%), compared with only 2.8% of the 36 patients in the control group.

At 12 months, 44% of patients in the intervention group had sustained diabetes remission (with a mean A1c of 6.33%).

This was “an excellent outcome,” said Dr. Rothberg, professor of nutritional sciences, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a co-author of an international consensus statement that defined diabetes remission.

On average, patients in the intermittent fasting group lost 5.93 kg (13.0 lb) in 3 months, which was sustained over 12 months. “The large amount of weight reduction is key to continuing to achieve diabetes remission,” she noted.

This contrasted with an average weight loss of just 0.27 kg (0.6 lb) in the control group.

Participants who were prescribed fewer antidiabetic medications were more likely to achieve diabetes remission. The researchers acknowledge that the study was not blinded, and they did not record physical activity (although participants were encouraged to maintain their usual physical activity).

This was a small study, Dr. Rothberg acknowledged. The researchers did not specify which specific antidiabetic drugs patients were taking, and they did not determine waist or hip circumference or assess lipids.

The diet was culturally sensitive, appropriate, and feasible in this Chinese population and would not be generalizable to non-Asians.

Nevertheless, a similar approach could be used in any population if the diet is tailored to the individual, according to Dr. Rothberg. Importantly, patients would need to receive guidance from a dietician to make sure their diet comprises all the necessary micronutrients, vitamins, and minerals on fasting days, and they would need to maintain a relatively balanced diet and not gorge themselves on feast days.

“I think we should campaign widely about lifestyle approaches to achieve diabetes remission,” she urged.

72 patients with diabetes for an average of 6.6 years

“Despite a widespread public consensus that [type 2 diabetes] is irreversible and requires drug treatment escalation, there is some evidence of the possibility of remission,” Dr. Yang and colleagues write in their article.

They aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of intermittent fasting for diabetes remission and the durability of diabetes remission at 1 year.

Diabetes remission was defined having a stable A1c less than 6.5% for at least 3 months after discontinuing all antidiabetic medications, confirmed in at least annual A1c measurements (according to a 2021 consensus statement initiated by the American Diabetes Association).

Between 2019 and 2020, the researchers enrolled 72 participants aged 38-72 years who had had type 2 diabetes (duration 1 to 11 years) and a body mass index (BMI) of 19.1-30.4 kg/m2. Patients were randomized 1:1 to the intermittent fasting group or control group.

Baseline characteristics were similar in both groups. Patients were a mean age of 53 years and roughly 60% were men. They had a mean BMI of 24 kg/m2, a mean duration of diabetes of 6.6 years, and a mean A1c of 7.6%, and they were taking an average of 1.8 glucose-lowering medications.

On fasting days, patients in the intervention group received a Chinese Medical Nutrition Therapy kit that provided approximately 840 kcal/day (46% carbohydrates, 46% fat, 8% protein). The kit included a breakfast of a fruit and vegetable gruel, lunch of a solid beverage plus a nutritional rice composite, and dinner of a solid beverage and a meal replacement biscuit, which participants reconstituted by mixing with boiling water. They were allowed to consume noncaloric beverages.

On nonfasting days, patients chose foods ad libitum based on the 2017 Dietary Guidelines for Diabetes in China, which recommend approximately 50%-65% of total energy intake from carbohydrates, 15%-20% from protein, and 20%-30% from fat, and had greater than or equal to 5 g fiber per serving.

Patients in the control group chose foods ad libitum from the dietary guidelines during the entire study.

The study received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors have reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a small randomized controlled trial of patients with type 2 diabetes in China, close to half of those who followed a novel intermittent fasting program for 3 months had diabetes remission (A1c less than 6.5% without taking antidiabetic drugs) that persisted for 1 year.

Importantly, “this study was performed under real-life conditions, and the intervention was delivered by trained nurses in primary care rather than by specialized staff at a research institute, making it a more practical and achievable way to manage” type 2 diabetes, the authors report.

Moreover, 65% of the patients in the intervention group who achieved diabetes remission had had diabetes for more than 6 years, which “suggests the possibility of remission for patients with longer duration” of diabetes, they note.

In addition, antidiabetic medication costs decreased by 77%, compared with baseline, in patients in the intermittent-fasting intervention group.

Although intermittent fasting has been studied for weight loss, it had not been investigated for effectiveness for diabetes remission.

These findings suggest that intermittent fasting “could be a paradigm shift in the management goals in diabetes care,” Xiao Yang and colleagues conclude in their study, published online in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Type 2 diabetes is not necessarily a permanent, lifelong disease,” senior author Dongbo Liu, PhD, from the Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China, added in a press release from The Endocrine Society.

“Diabetes remission is possible if patients lose weight by changing their diet and exercise habits,” Dr. Liu said.

‘Excellent outcome’

Invited to comment, Amy E. Rothberg, MD, PhD, who was not involved with the research, agreed that the study indicates that intermittent fasting works for diabetes remission.

“We know that diabetes remission is possible with calorie restriction and subsequent weight loss, and intermittent fasting is just one of the many [dietary] approaches that may be suitable, appealing, and sustainable to some individuals, and usually results in calorie restriction and therefore weight loss,” she said.

The most studied types of intermittent fasting diets are alternate-day fasting, the 5:2 diet, and time-restricted consumption, Dr. Rothberg told this news organization.

This study presented a novel type of intermittent fasting, she noted. The intervention consisted of 6 cycles (3 months) of 5 fasting days followed by 10 ad libitum days, and then 3 months of follow-up (with no fasting days).

After 3 months of the intervention plus 3 months of follow-up, 47% of the 36 patients in the intervention group achieved diabetes remission (with a mean A1c of 5.66%), compared with only 2.8% of the 36 patients in the control group.

At 12 months, 44% of patients in the intervention group had sustained diabetes remission (with a mean A1c of 6.33%).

This was “an excellent outcome,” said Dr. Rothberg, professor of nutritional sciences, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a co-author of an international consensus statement that defined diabetes remission.

On average, patients in the intermittent fasting group lost 5.93 kg (13.0 lb) in 3 months, which was sustained over 12 months. “The large amount of weight reduction is key to continuing to achieve diabetes remission,” she noted.

This contrasted with an average weight loss of just 0.27 kg (0.6 lb) in the control group.

Participants who were prescribed fewer antidiabetic medications were more likely to achieve diabetes remission. The researchers acknowledge that the study was not blinded, and they did not record physical activity (although participants were encouraged to maintain their usual physical activity).

This was a small study, Dr. Rothberg acknowledged. The researchers did not specify which specific antidiabetic drugs patients were taking, and they did not determine waist or hip circumference or assess lipids.

The diet was culturally sensitive, appropriate, and feasible in this Chinese population and would not be generalizable to non-Asians.

Nevertheless, a similar approach could be used in any population if the diet is tailored to the individual, according to Dr. Rothberg. Importantly, patients would need to receive guidance from a dietician to make sure their diet comprises all the necessary micronutrients, vitamins, and minerals on fasting days, and they would need to maintain a relatively balanced diet and not gorge themselves on feast days.

“I think we should campaign widely about lifestyle approaches to achieve diabetes remission,” she urged.

72 patients with diabetes for an average of 6.6 years

“Despite a widespread public consensus that [type 2 diabetes] is irreversible and requires drug treatment escalation, there is some evidence of the possibility of remission,” Dr. Yang and colleagues write in their article.

They aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of intermittent fasting for diabetes remission and the durability of diabetes remission at 1 year.

Diabetes remission was defined having a stable A1c less than 6.5% for at least 3 months after discontinuing all antidiabetic medications, confirmed in at least annual A1c measurements (according to a 2021 consensus statement initiated by the American Diabetes Association).

Between 2019 and 2020, the researchers enrolled 72 participants aged 38-72 years who had had type 2 diabetes (duration 1 to 11 years) and a body mass index (BMI) of 19.1-30.4 kg/m2. Patients were randomized 1:1 to the intermittent fasting group or control group.

Baseline characteristics were similar in both groups. Patients were a mean age of 53 years and roughly 60% were men. They had a mean BMI of 24 kg/m2, a mean duration of diabetes of 6.6 years, and a mean A1c of 7.6%, and they were taking an average of 1.8 glucose-lowering medications.

On fasting days, patients in the intervention group received a Chinese Medical Nutrition Therapy kit that provided approximately 840 kcal/day (46% carbohydrates, 46% fat, 8% protein). The kit included a breakfast of a fruit and vegetable gruel, lunch of a solid beverage plus a nutritional rice composite, and dinner of a solid beverage and a meal replacement biscuit, which participants reconstituted by mixing with boiling water. They were allowed to consume noncaloric beverages.

On nonfasting days, patients chose foods ad libitum based on the 2017 Dietary Guidelines for Diabetes in China, which recommend approximately 50%-65% of total energy intake from carbohydrates, 15%-20% from protein, and 20%-30% from fat, and had greater than or equal to 5 g fiber per serving.

Patients in the control group chose foods ad libitum from the dietary guidelines during the entire study.

The study received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors have reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a small randomized controlled trial of patients with type 2 diabetes in China, close to half of those who followed a novel intermittent fasting program for 3 months had diabetes remission (A1c less than 6.5% without taking antidiabetic drugs) that persisted for 1 year.

Importantly, “this study was performed under real-life conditions, and the intervention was delivered by trained nurses in primary care rather than by specialized staff at a research institute, making it a more practical and achievable way to manage” type 2 diabetes, the authors report.

Moreover, 65% of the patients in the intervention group who achieved diabetes remission had had diabetes for more than 6 years, which “suggests the possibility of remission for patients with longer duration” of diabetes, they note.

In addition, antidiabetic medication costs decreased by 77%, compared with baseline, in patients in the intermittent-fasting intervention group.

Although intermittent fasting has been studied for weight loss, it had not been investigated for effectiveness for diabetes remission.

These findings suggest that intermittent fasting “could be a paradigm shift in the management goals in diabetes care,” Xiao Yang and colleagues conclude in their study, published online in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Type 2 diabetes is not necessarily a permanent, lifelong disease,” senior author Dongbo Liu, PhD, from the Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China, added in a press release from The Endocrine Society.

“Diabetes remission is possible if patients lose weight by changing their diet and exercise habits,” Dr. Liu said.

‘Excellent outcome’

Invited to comment, Amy E. Rothberg, MD, PhD, who was not involved with the research, agreed that the study indicates that intermittent fasting works for diabetes remission.

“We know that diabetes remission is possible with calorie restriction and subsequent weight loss, and intermittent fasting is just one of the many [dietary] approaches that may be suitable, appealing, and sustainable to some individuals, and usually results in calorie restriction and therefore weight loss,” she said.

The most studied types of intermittent fasting diets are alternate-day fasting, the 5:2 diet, and time-restricted consumption, Dr. Rothberg told this news organization.

This study presented a novel type of intermittent fasting, she noted. The intervention consisted of 6 cycles (3 months) of 5 fasting days followed by 10 ad libitum days, and then 3 months of follow-up (with no fasting days).

After 3 months of the intervention plus 3 months of follow-up, 47% of the 36 patients in the intervention group achieved diabetes remission (with a mean A1c of 5.66%), compared with only 2.8% of the 36 patients in the control group.

At 12 months, 44% of patients in the intervention group had sustained diabetes remission (with a mean A1c of 6.33%).

This was “an excellent outcome,” said Dr. Rothberg, professor of nutritional sciences, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a co-author of an international consensus statement that defined diabetes remission.

On average, patients in the intermittent fasting group lost 5.93 kg (13.0 lb) in 3 months, which was sustained over 12 months. “The large amount of weight reduction is key to continuing to achieve diabetes remission,” she noted.

This contrasted with an average weight loss of just 0.27 kg (0.6 lb) in the control group.

Participants who were prescribed fewer antidiabetic medications were more likely to achieve diabetes remission. The researchers acknowledge that the study was not blinded, and they did not record physical activity (although participants were encouraged to maintain their usual physical activity).

This was a small study, Dr. Rothberg acknowledged. The researchers did not specify which specific antidiabetic drugs patients were taking, and they did not determine waist or hip circumference or assess lipids.

The diet was culturally sensitive, appropriate, and feasible in this Chinese population and would not be generalizable to non-Asians.

Nevertheless, a similar approach could be used in any population if the diet is tailored to the individual, according to Dr. Rothberg. Importantly, patients would need to receive guidance from a dietician to make sure their diet comprises all the necessary micronutrients, vitamins, and minerals on fasting days, and they would need to maintain a relatively balanced diet and not gorge themselves on feast days.

“I think we should campaign widely about lifestyle approaches to achieve diabetes remission,” she urged.

72 patients with diabetes for an average of 6.6 years

“Despite a widespread public consensus that [type 2 diabetes] is irreversible and requires drug treatment escalation, there is some evidence of the possibility of remission,” Dr. Yang and colleagues write in their article.

They aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of intermittent fasting for diabetes remission and the durability of diabetes remission at 1 year.

Diabetes remission was defined having a stable A1c less than 6.5% for at least 3 months after discontinuing all antidiabetic medications, confirmed in at least annual A1c measurements (according to a 2021 consensus statement initiated by the American Diabetes Association).

Between 2019 and 2020, the researchers enrolled 72 participants aged 38-72 years who had had type 2 diabetes (duration 1 to 11 years) and a body mass index (BMI) of 19.1-30.4 kg/m2. Patients were randomized 1:1 to the intermittent fasting group or control group.

Baseline characteristics were similar in both groups. Patients were a mean age of 53 years and roughly 60% were men. They had a mean BMI of 24 kg/m2, a mean duration of diabetes of 6.6 years, and a mean A1c of 7.6%, and they were taking an average of 1.8 glucose-lowering medications.

On fasting days, patients in the intervention group received a Chinese Medical Nutrition Therapy kit that provided approximately 840 kcal/day (46% carbohydrates, 46% fat, 8% protein). The kit included a breakfast of a fruit and vegetable gruel, lunch of a solid beverage plus a nutritional rice composite, and dinner of a solid beverage and a meal replacement biscuit, which participants reconstituted by mixing with boiling water. They were allowed to consume noncaloric beverages.

On nonfasting days, patients chose foods ad libitum based on the 2017 Dietary Guidelines for Diabetes in China, which recommend approximately 50%-65% of total energy intake from carbohydrates, 15%-20% from protein, and 20%-30% from fat, and had greater than or equal to 5 g fiber per serving.

Patients in the control group chose foods ad libitum from the dietary guidelines during the entire study.

The study received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors have reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. sees most flu hospitalizations in a decade

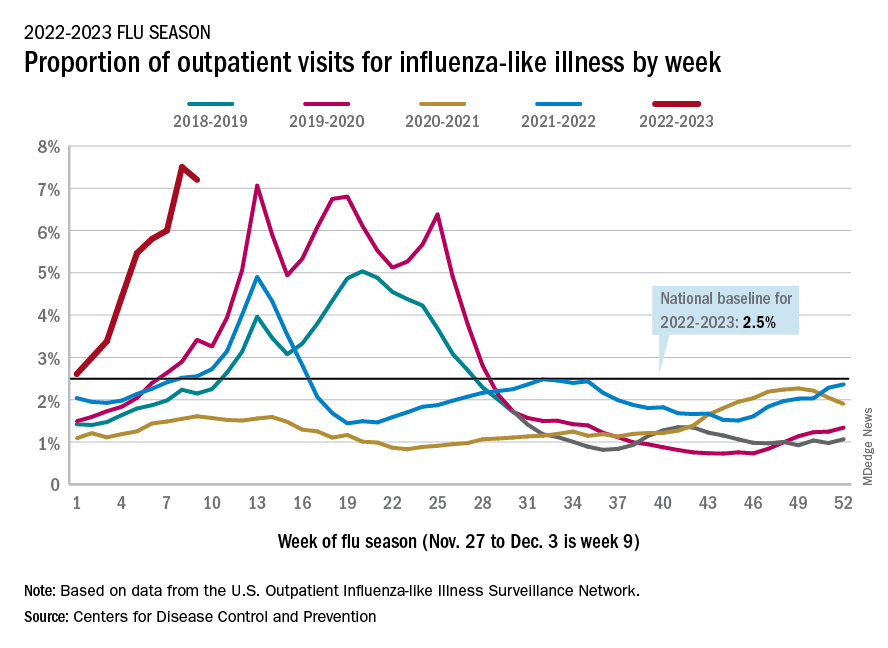

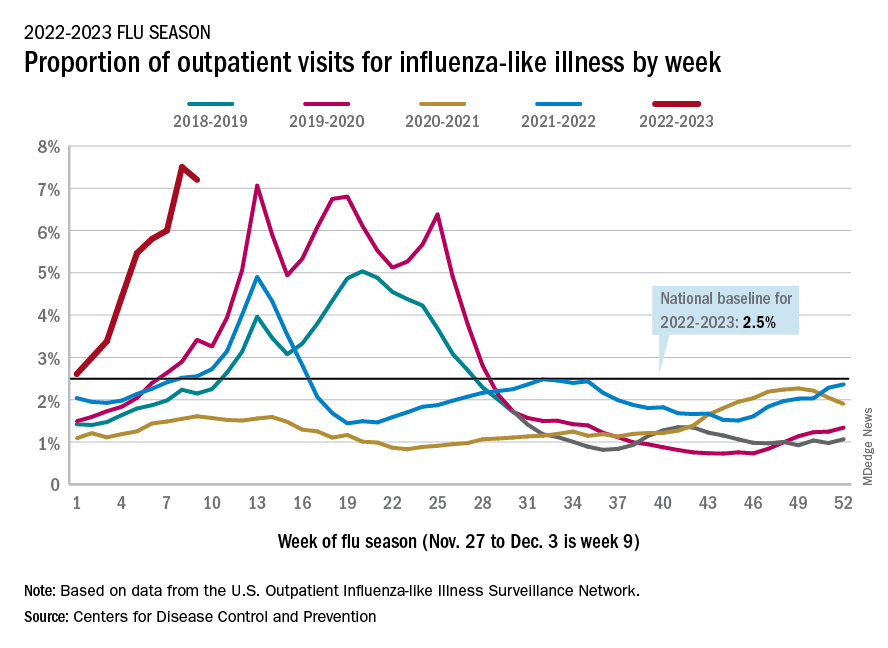

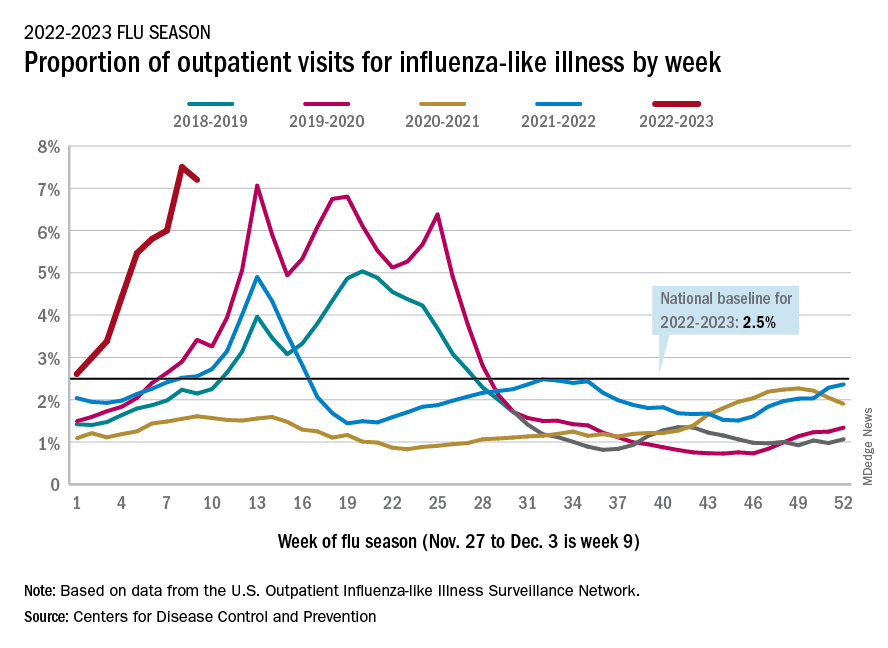

But the number of deaths and outpatient visits for flu or flu-like illnesses was down slightly from the week before, the CDC said in its weekly FluView report.

There were almost 26,000 new hospital admissions involving laboratory-confirmed influenza over those 7 days, up by over 31% from the previous week, based on data from 5,000 hospitals in the HHS Protect system, which tracks and shares COVID-19 data.

The cumulative hospitalization rate for the 2022-2023 season is 26.0 per 100,000 people, the highest seen at this time of year since 2010-2011, the CDC said, based on data from its Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network, which includes hospitals in select counties in 13 states.

At this point in the 2019-2020 season, just before the COVID-19 pandemic began, the cumulative rate was 3.1 per 100,000 people, the CDC’s data show.

On the positive side, the proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness dropped slightly to 7.2%, from 7.5% the week before. But these cases from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network are not laboratory confirmed, so the data could include people with the flu, COVID-19, or respiratory syncytial virus.