User login

High prevalence of Fall Risk–Increasing Drugs in older adults after falls

Background: Falls are the leading cause of unintentional injuries and injury-related deaths among adults aged 65 years and older. FRIDs (such as antidepressants, sedatives-hypnotics, and opioids) continue to be a major contributor for risk of falls. At the same time, little is known about prevalence of use or interventions directed toward reduction of use in older adults presenting with fall.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: PubMed and Embase databases were used to search for studies published in English on or before June 30, 2019. Search terms included older adults, falls, medication classes, and hospitalizations among other related terms.

Synopsis: The review included a total of 14 articles (10 observational studies and 4 prospective intervention studies). High prevalence of FRID use (65%-93%) was seen in older adults with fall-related injury. Use of FRIDs continued to remain high at 1 month and 6 months follow-up after a fall. Antidepressants, sedative-hypnotics, opioids, and antipsychotics were the most commonly used FRIDs. Three randomized controlled trials showed no effect of reducing FRID use on reduction in falls. An outpatient clinic pre-post assessment study based on intervention by geriatrician and communication with prescribing physicians led to reduction in FRID use and falls.

Limitations of this review included high risk of bias in observational studies and unclear timeline definitions of interventions or outcome measurements in the intervention studies. In conclusion, there is a significant need for well-designed interventions targeted at reducing FRID use in conjunction with other risk factors to decrease the incidence of falls comprehensively. An aggressive approach directed toward patient education along with primary care communication may be the key to reducing FRID use in this population.

Bottom line: With limited evidence, there is a high prevalence of FRID use in older adults presenting with falls and no reduction in FRID use following the encounter.

Citation: Hart LA et al. Use of fall risk-increasing drugs around a fall-related injury in older adults: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 Feb 17. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16369.

Dr. Yarra is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UK HealthCare, Lexington, Ky.

Background: Falls are the leading cause of unintentional injuries and injury-related deaths among adults aged 65 years and older. FRIDs (such as antidepressants, sedatives-hypnotics, and opioids) continue to be a major contributor for risk of falls. At the same time, little is known about prevalence of use or interventions directed toward reduction of use in older adults presenting with fall.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: PubMed and Embase databases were used to search for studies published in English on or before June 30, 2019. Search terms included older adults, falls, medication classes, and hospitalizations among other related terms.

Synopsis: The review included a total of 14 articles (10 observational studies and 4 prospective intervention studies). High prevalence of FRID use (65%-93%) was seen in older adults with fall-related injury. Use of FRIDs continued to remain high at 1 month and 6 months follow-up after a fall. Antidepressants, sedative-hypnotics, opioids, and antipsychotics were the most commonly used FRIDs. Three randomized controlled trials showed no effect of reducing FRID use on reduction in falls. An outpatient clinic pre-post assessment study based on intervention by geriatrician and communication with prescribing physicians led to reduction in FRID use and falls.

Limitations of this review included high risk of bias in observational studies and unclear timeline definitions of interventions or outcome measurements in the intervention studies. In conclusion, there is a significant need for well-designed interventions targeted at reducing FRID use in conjunction with other risk factors to decrease the incidence of falls comprehensively. An aggressive approach directed toward patient education along with primary care communication may be the key to reducing FRID use in this population.

Bottom line: With limited evidence, there is a high prevalence of FRID use in older adults presenting with falls and no reduction in FRID use following the encounter.

Citation: Hart LA et al. Use of fall risk-increasing drugs around a fall-related injury in older adults: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 Feb 17. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16369.

Dr. Yarra is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UK HealthCare, Lexington, Ky.

Background: Falls are the leading cause of unintentional injuries and injury-related deaths among adults aged 65 years and older. FRIDs (such as antidepressants, sedatives-hypnotics, and opioids) continue to be a major contributor for risk of falls. At the same time, little is known about prevalence of use or interventions directed toward reduction of use in older adults presenting with fall.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: PubMed and Embase databases were used to search for studies published in English on or before June 30, 2019. Search terms included older adults, falls, medication classes, and hospitalizations among other related terms.

Synopsis: The review included a total of 14 articles (10 observational studies and 4 prospective intervention studies). High prevalence of FRID use (65%-93%) was seen in older adults with fall-related injury. Use of FRIDs continued to remain high at 1 month and 6 months follow-up after a fall. Antidepressants, sedative-hypnotics, opioids, and antipsychotics were the most commonly used FRIDs. Three randomized controlled trials showed no effect of reducing FRID use on reduction in falls. An outpatient clinic pre-post assessment study based on intervention by geriatrician and communication with prescribing physicians led to reduction in FRID use and falls.

Limitations of this review included high risk of bias in observational studies and unclear timeline definitions of interventions or outcome measurements in the intervention studies. In conclusion, there is a significant need for well-designed interventions targeted at reducing FRID use in conjunction with other risk factors to decrease the incidence of falls comprehensively. An aggressive approach directed toward patient education along with primary care communication may be the key to reducing FRID use in this population.

Bottom line: With limited evidence, there is a high prevalence of FRID use in older adults presenting with falls and no reduction in FRID use following the encounter.

Citation: Hart LA et al. Use of fall risk-increasing drugs around a fall-related injury in older adults: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 Feb 17. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16369.

Dr. Yarra is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UK HealthCare, Lexington, Ky.

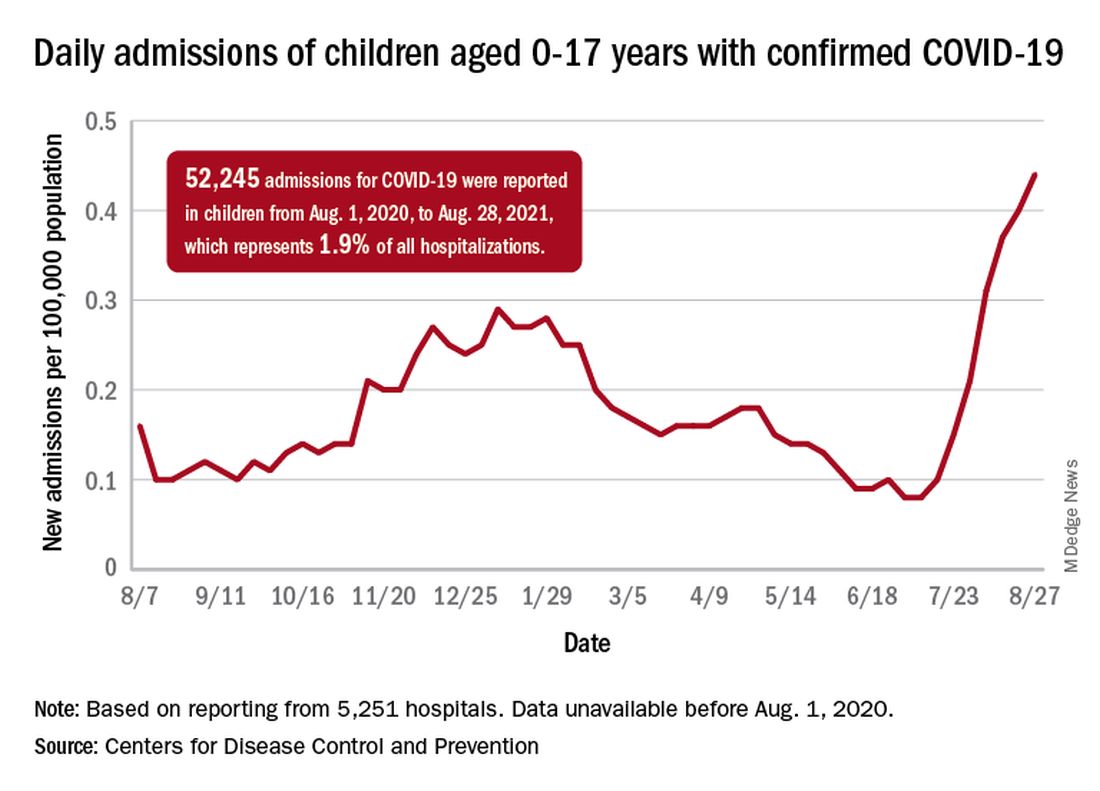

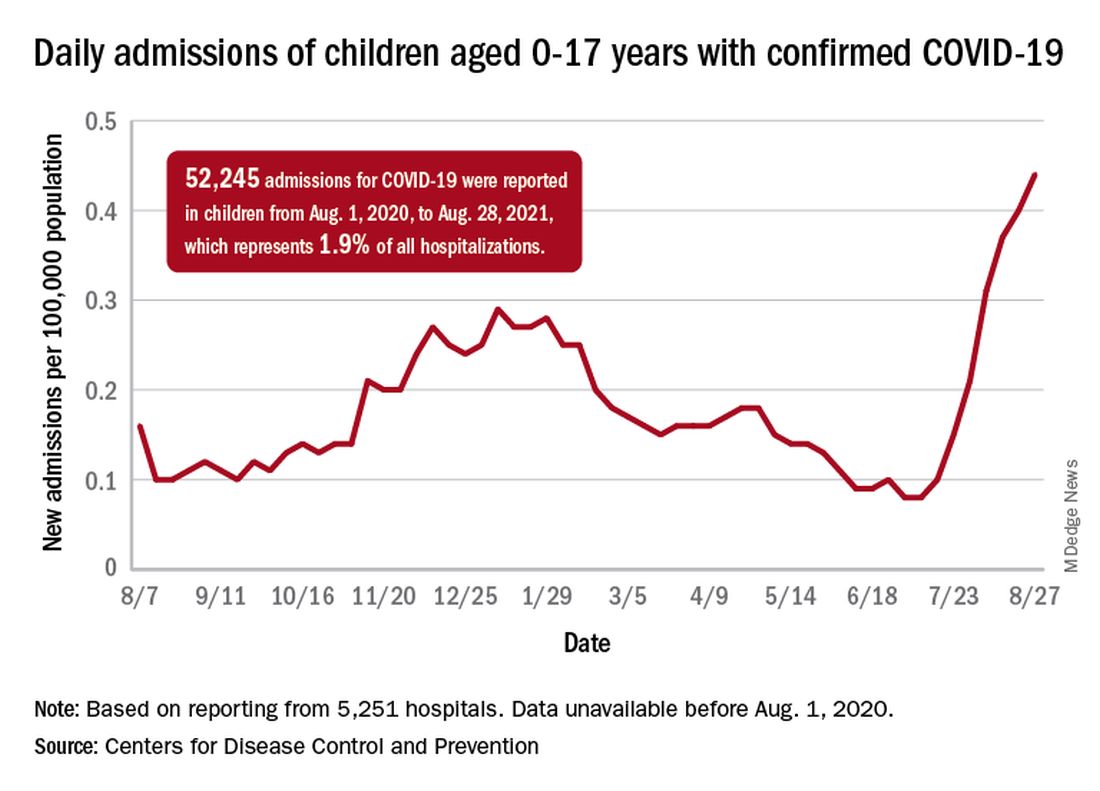

Breakthrough infections twice as likely to be asymptomatic

Individuals infected with COVID-19 after receiving their first or second dose of either the Pfizer, Moderna, or AstraZeneca vaccine experienced a lower number of symptoms in the first week of infection, compared with those who did not receive a COVID-19 vaccine, reported the authors of the report in The Lancet Infectious Diseases. These patients also had a reduced need for hospitalization, compared with their unvaccinated peers. Those who received both doses of a vaccine were less likely to experience prolonged COVID - defined as at least 28 days of symptoms in this paper - compared with unvaccinated individuals.

“We are at a critical point in the pandemic as we see cases rising worldwide due to the delta variant,” study co–lead author Dr. Claire Steves, said in a statement. “Breakthrough infections are expected and don’t diminish the fact that these vaccines are doing exactly what they were designed to do – save lives and prevent serious illness.”

For the community-based, case-control study, Dr. Steves, who is a clinical senior lecturer at King’s College London, and her colleagues analyzed and presented self-reported data on demographics, geographical location, health risk factors, COVID-19 test results, symptoms, and vaccinations from more than 1.2 million UK-based adults through the COVID Symptom Study mobile phone app.

They found that, of the 1.2 million adults who received at least one dose of either the Pfizer, Moderna, or AstraZeneca vaccine, fewer than 0.5% tested positive for COVID-19 14 days after their first dose. Of those who received a second dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, 0.2% acquired the infection more than 7 days post vaccination.

Likelihood of severe symptoms dropped after one dose

After just one COVID-19 vaccine dose, the likelihood of experiencing severe symptoms from a COVID-19 infection dropped by a quarter. The odds of their infection being asymptomatic increased by 94% after the second dose. Researchers also found that vaccinated participants in the study were more likely to be completely asymptomatic, especially if they were 60 years or older.

Furthermore, the odds of those with breakthrough infections experiencing severe disease – which is characterized by having five or more symptoms within the first week of becoming ill – dropped by approximately one-third.

When evaluating risk factors, the researchers found that those most vulnerable to a breakthrough infection after receiving a first dose of Pfizer, Moderna, or Astrazeneca COVID-19 vaccine were older adults (ages 60 years or older) who are either frail or live with underlying conditions such as asthma, lung disease, and obesity.

The findings provide substantial evidence that there are benefits after just one dose of the vaccine, said Diego Hijano, MD, MSc, pediatric infectious disease specialist at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis. However, the report also supports caution around becoming lax on protective COVID-19 measures such as physical distancing and wearing masks, especially around vulnerable groups, he said.

Findings may have implications for health policies

“It’s also important for people who are fully vaccinated to understand that these infections are expected and are happening, especially now with the Delta variant” Dr. Hijano said. “While the outcomes are favorable, you need to still protect yourself to also protect your loved ones. You want to be very mindful that, if you are vaccinated and you get infected, you can pass it on to somebody that actually has not been vaccinated or has some of these risk factors.”

The authors of the new research paper believe their findings may have implications for health policies regarding the timing between vaccine doses, COVID-19 booster shots, and for continuing personal protective measures.

The authors of the paper and Dr. Hijano disclosed no conflicts.

Individuals infected with COVID-19 after receiving their first or second dose of either the Pfizer, Moderna, or AstraZeneca vaccine experienced a lower number of symptoms in the first week of infection, compared with those who did not receive a COVID-19 vaccine, reported the authors of the report in The Lancet Infectious Diseases. These patients also had a reduced need for hospitalization, compared with their unvaccinated peers. Those who received both doses of a vaccine were less likely to experience prolonged COVID - defined as at least 28 days of symptoms in this paper - compared with unvaccinated individuals.

“We are at a critical point in the pandemic as we see cases rising worldwide due to the delta variant,” study co–lead author Dr. Claire Steves, said in a statement. “Breakthrough infections are expected and don’t diminish the fact that these vaccines are doing exactly what they were designed to do – save lives and prevent serious illness.”

For the community-based, case-control study, Dr. Steves, who is a clinical senior lecturer at King’s College London, and her colleagues analyzed and presented self-reported data on demographics, geographical location, health risk factors, COVID-19 test results, symptoms, and vaccinations from more than 1.2 million UK-based adults through the COVID Symptom Study mobile phone app.

They found that, of the 1.2 million adults who received at least one dose of either the Pfizer, Moderna, or AstraZeneca vaccine, fewer than 0.5% tested positive for COVID-19 14 days after their first dose. Of those who received a second dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, 0.2% acquired the infection more than 7 days post vaccination.

Likelihood of severe symptoms dropped after one dose

After just one COVID-19 vaccine dose, the likelihood of experiencing severe symptoms from a COVID-19 infection dropped by a quarter. The odds of their infection being asymptomatic increased by 94% after the second dose. Researchers also found that vaccinated participants in the study were more likely to be completely asymptomatic, especially if they were 60 years or older.

Furthermore, the odds of those with breakthrough infections experiencing severe disease – which is characterized by having five or more symptoms within the first week of becoming ill – dropped by approximately one-third.

When evaluating risk factors, the researchers found that those most vulnerable to a breakthrough infection after receiving a first dose of Pfizer, Moderna, or Astrazeneca COVID-19 vaccine were older adults (ages 60 years or older) who are either frail or live with underlying conditions such as asthma, lung disease, and obesity.

The findings provide substantial evidence that there are benefits after just one dose of the vaccine, said Diego Hijano, MD, MSc, pediatric infectious disease specialist at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis. However, the report also supports caution around becoming lax on protective COVID-19 measures such as physical distancing and wearing masks, especially around vulnerable groups, he said.

Findings may have implications for health policies

“It’s also important for people who are fully vaccinated to understand that these infections are expected and are happening, especially now with the Delta variant” Dr. Hijano said. “While the outcomes are favorable, you need to still protect yourself to also protect your loved ones. You want to be very mindful that, if you are vaccinated and you get infected, you can pass it on to somebody that actually has not been vaccinated or has some of these risk factors.”

The authors of the new research paper believe their findings may have implications for health policies regarding the timing between vaccine doses, COVID-19 booster shots, and for continuing personal protective measures.

The authors of the paper and Dr. Hijano disclosed no conflicts.

Individuals infected with COVID-19 after receiving their first or second dose of either the Pfizer, Moderna, or AstraZeneca vaccine experienced a lower number of symptoms in the first week of infection, compared with those who did not receive a COVID-19 vaccine, reported the authors of the report in The Lancet Infectious Diseases. These patients also had a reduced need for hospitalization, compared with their unvaccinated peers. Those who received both doses of a vaccine were less likely to experience prolonged COVID - defined as at least 28 days of symptoms in this paper - compared with unvaccinated individuals.

“We are at a critical point in the pandemic as we see cases rising worldwide due to the delta variant,” study co–lead author Dr. Claire Steves, said in a statement. “Breakthrough infections are expected and don’t diminish the fact that these vaccines are doing exactly what they were designed to do – save lives and prevent serious illness.”

For the community-based, case-control study, Dr. Steves, who is a clinical senior lecturer at King’s College London, and her colleagues analyzed and presented self-reported data on demographics, geographical location, health risk factors, COVID-19 test results, symptoms, and vaccinations from more than 1.2 million UK-based adults through the COVID Symptom Study mobile phone app.

They found that, of the 1.2 million adults who received at least one dose of either the Pfizer, Moderna, or AstraZeneca vaccine, fewer than 0.5% tested positive for COVID-19 14 days after their first dose. Of those who received a second dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, 0.2% acquired the infection more than 7 days post vaccination.

Likelihood of severe symptoms dropped after one dose

After just one COVID-19 vaccine dose, the likelihood of experiencing severe symptoms from a COVID-19 infection dropped by a quarter. The odds of their infection being asymptomatic increased by 94% after the second dose. Researchers also found that vaccinated participants in the study were more likely to be completely asymptomatic, especially if they were 60 years or older.

Furthermore, the odds of those with breakthrough infections experiencing severe disease – which is characterized by having five or more symptoms within the first week of becoming ill – dropped by approximately one-third.

When evaluating risk factors, the researchers found that those most vulnerable to a breakthrough infection after receiving a first dose of Pfizer, Moderna, or Astrazeneca COVID-19 vaccine were older adults (ages 60 years or older) who are either frail or live with underlying conditions such as asthma, lung disease, and obesity.

The findings provide substantial evidence that there are benefits after just one dose of the vaccine, said Diego Hijano, MD, MSc, pediatric infectious disease specialist at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis. However, the report also supports caution around becoming lax on protective COVID-19 measures such as physical distancing and wearing masks, especially around vulnerable groups, he said.

Findings may have implications for health policies

“It’s also important for people who are fully vaccinated to understand that these infections are expected and are happening, especially now with the Delta variant” Dr. Hijano said. “While the outcomes are favorable, you need to still protect yourself to also protect your loved ones. You want to be very mindful that, if you are vaccinated and you get infected, you can pass it on to somebody that actually has not been vaccinated or has some of these risk factors.”

The authors of the new research paper believe their findings may have implications for health policies regarding the timing between vaccine doses, COVID-19 booster shots, and for continuing personal protective measures.

The authors of the paper and Dr. Hijano disclosed no conflicts.

FROM THE LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Another COVID-19 patient to get ivermectin after court order

Another case, another state, another judge ordering a hospital to give a patient a controversial horse deworming drug to treat a severe case of COVID-19.

, according to the Ohio Capital Journal. Judge Gregory Howard’s ruling comes after Mr. Smith’s wife sued to force the hospital to provide the controversial drug to her husband, who has been hospitalized since July 15.

Julie Smith has gotten Fred Wagshul, MD, to agree to administer ivermectin to her husband. Dr. Wagshul is known as a member of a group of doctors who say the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration are lying about ivermectin’s usefulness in fighting COVID-19. Both agencies have warned against using the drug to treat COVID-19, saying there is no evidence it works and that it can be dangerous in large amounts.

According to the Ohio Capital Journal, Dr. Wagshul accused the CDC and FDA of engaging in a “conspiracy” to prevent ivermectin’s use.

But Arthur L. Caplan, MD, professor of bioethics at New York University’s Langone Medical Center, said, “it is absurd that this order was issued,” according to an interview in Ars Technica. “If I were these doctors, I simply wouldn’t do it.”

It is not the first time a judge has ordered ivermectin’s use against a hospital’s wishes.

A 68-year-old woman with COVID-19 in an Illinois hospital started receiving the controversial drug in May after her family sued the hospital to have someone administer it.

Nurije Fype’s daughter, Desareta, filed suit against Elmhurst Hospital, part of Edward-Elmhurst Health, asking that her mother receive the treatment, which is approved as an antiparasitic drug but not approved for the treatment of COVID-19. Desareta Fype was granted temporary guardianship of her mother.

The FDA has published guidance titled “Why You Should Not Use Ivermectin to Treat or Prevent COVID-19” on its website. The National Institutes of Health said there is not enough data to recommend either for or against its use in treating COVID-19.

But DuPage County Judge James Orel ruled Ms. Fype should be allowed to get the treatment.

Three days later, according to the Daily Herald, the lawyer for the hospital, Joseph Monahan, argued the hospital could not find a hospital-affiliated doctor to administer the ivermectin.

The Herald reported the judge told the hospital to “get out of the way” and allow any board-certified doctor to administer the drug.

When Ms. Fype’s doctor was unable to administer it, the legal team found another doctor, Alan Bain, DO, to do it. Mr. Monahan said Dr. Bain was granted credentials to work at the hospital so he could administer it.

Judge Orel denied a request from Desareta Fype’s lawyer to order the hospital’s nurses to administer further doses. The judge also denied a request to hold the hospital in contempt of court.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Another case, another state, another judge ordering a hospital to give a patient a controversial horse deworming drug to treat a severe case of COVID-19.

, according to the Ohio Capital Journal. Judge Gregory Howard’s ruling comes after Mr. Smith’s wife sued to force the hospital to provide the controversial drug to her husband, who has been hospitalized since July 15.

Julie Smith has gotten Fred Wagshul, MD, to agree to administer ivermectin to her husband. Dr. Wagshul is known as a member of a group of doctors who say the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration are lying about ivermectin’s usefulness in fighting COVID-19. Both agencies have warned against using the drug to treat COVID-19, saying there is no evidence it works and that it can be dangerous in large amounts.

According to the Ohio Capital Journal, Dr. Wagshul accused the CDC and FDA of engaging in a “conspiracy” to prevent ivermectin’s use.

But Arthur L. Caplan, MD, professor of bioethics at New York University’s Langone Medical Center, said, “it is absurd that this order was issued,” according to an interview in Ars Technica. “If I were these doctors, I simply wouldn’t do it.”

It is not the first time a judge has ordered ivermectin’s use against a hospital’s wishes.

A 68-year-old woman with COVID-19 in an Illinois hospital started receiving the controversial drug in May after her family sued the hospital to have someone administer it.

Nurije Fype’s daughter, Desareta, filed suit against Elmhurst Hospital, part of Edward-Elmhurst Health, asking that her mother receive the treatment, which is approved as an antiparasitic drug but not approved for the treatment of COVID-19. Desareta Fype was granted temporary guardianship of her mother.

The FDA has published guidance titled “Why You Should Not Use Ivermectin to Treat or Prevent COVID-19” on its website. The National Institutes of Health said there is not enough data to recommend either for or against its use in treating COVID-19.

But DuPage County Judge James Orel ruled Ms. Fype should be allowed to get the treatment.

Three days later, according to the Daily Herald, the lawyer for the hospital, Joseph Monahan, argued the hospital could not find a hospital-affiliated doctor to administer the ivermectin.

The Herald reported the judge told the hospital to “get out of the way” and allow any board-certified doctor to administer the drug.

When Ms. Fype’s doctor was unable to administer it, the legal team found another doctor, Alan Bain, DO, to do it. Mr. Monahan said Dr. Bain was granted credentials to work at the hospital so he could administer it.

Judge Orel denied a request from Desareta Fype’s lawyer to order the hospital’s nurses to administer further doses. The judge also denied a request to hold the hospital in contempt of court.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Another case, another state, another judge ordering a hospital to give a patient a controversial horse deworming drug to treat a severe case of COVID-19.

, according to the Ohio Capital Journal. Judge Gregory Howard’s ruling comes after Mr. Smith’s wife sued to force the hospital to provide the controversial drug to her husband, who has been hospitalized since July 15.

Julie Smith has gotten Fred Wagshul, MD, to agree to administer ivermectin to her husband. Dr. Wagshul is known as a member of a group of doctors who say the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration are lying about ivermectin’s usefulness in fighting COVID-19. Both agencies have warned against using the drug to treat COVID-19, saying there is no evidence it works and that it can be dangerous in large amounts.

According to the Ohio Capital Journal, Dr. Wagshul accused the CDC and FDA of engaging in a “conspiracy” to prevent ivermectin’s use.

But Arthur L. Caplan, MD, professor of bioethics at New York University’s Langone Medical Center, said, “it is absurd that this order was issued,” according to an interview in Ars Technica. “If I were these doctors, I simply wouldn’t do it.”

It is not the first time a judge has ordered ivermectin’s use against a hospital’s wishes.

A 68-year-old woman with COVID-19 in an Illinois hospital started receiving the controversial drug in May after her family sued the hospital to have someone administer it.

Nurije Fype’s daughter, Desareta, filed suit against Elmhurst Hospital, part of Edward-Elmhurst Health, asking that her mother receive the treatment, which is approved as an antiparasitic drug but not approved for the treatment of COVID-19. Desareta Fype was granted temporary guardianship of her mother.

The FDA has published guidance titled “Why You Should Not Use Ivermectin to Treat or Prevent COVID-19” on its website. The National Institutes of Health said there is not enough data to recommend either for or against its use in treating COVID-19.

But DuPage County Judge James Orel ruled Ms. Fype should be allowed to get the treatment.

Three days later, according to the Daily Herald, the lawyer for the hospital, Joseph Monahan, argued the hospital could not find a hospital-affiliated doctor to administer the ivermectin.

The Herald reported the judge told the hospital to “get out of the way” and allow any board-certified doctor to administer the drug.

When Ms. Fype’s doctor was unable to administer it, the legal team found another doctor, Alan Bain, DO, to do it. Mr. Monahan said Dr. Bain was granted credentials to work at the hospital so he could administer it.

Judge Orel denied a request from Desareta Fype’s lawyer to order the hospital’s nurses to administer further doses. The judge also denied a request to hold the hospital in contempt of court.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID-clogged ICUs ‘terrify’ those with chronic or emergency illness

Jessica Gosnell, MD, 41, from Portland, Oregon, lives daily with the knowledge that her rare disease — a form of hereditary angioedema — could cause a sudden, severe swelling in her throat that could require quick intubation and land her in an intensive care unit (ICU) for days.

“I’ve been hospitalized for throat swells three times in the last year,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Gosnell no longer practices medicine because of a combination of illnesses, but lives with her husband, Andrew, and two young children, and said they are all “terrified” she will have to go to the hospital amid a COVID-19 surge that had shrunk the number of available ICU beds to 152 from 780 in Oregon as of Aug. 30. Thirty percent of the beds are in use for patients with COVID-19.

She said her life depends on being near hospitals that have ICUs and having access to highly specialized medications, one of which can cost up to $50,000 for the rescue dose.

Her fear has her “literally living bedbound.” In addition to hereditary angioedema, she has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which weakens connective tissue. She wears a cervical collar 24/7 to keep from tearing tissues, as any tissue injury can trigger a swell.

Patients worry there won’t be room

As ICU beds in most states are filling with COVID-19 patients as the Delta variant spreads, fears are rising among people like Dr. Gosnell, who have chronic conditions and diseases with unpredictable emergency visits, who worry that if they need emergency care there won’t be room.

As of Aug. 30, in the United States, 79% of ICU beds nationally were in use, 30% of them for COVID-19 patients, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

In individual states, the picture is dire. Alabama has fewer than 10% of its ICU beds open across the entire state. In Florida, 93% of ICU beds are filled, 53% of them with COVID patients. In Louisiana, 87% of beds were already in use, 45% of them with COVID patients, just as category 4 hurricane Ida smashed into the coastline on Aug. 29.

News reports have told of people transported and airlifted as hospitals reach capacity.

In Bellville, Tex., U.S. Army veteran Daniel Wilkinson needed advanced care for gallstone pancreatitis that normally would take 30 minutes to treat, his Bellville doctor, Hasan Kakli, MD, told CBS News.

Mr. Wilkinson’s house was three doors from Bellville Hospital, but the hospital was not equipped to treat the condition. Calls to other hospitals found the same answer: no empty ICU beds. After a 7-hour wait on a stretcher, he was airlifted to a Veterans Affairs hospital in Houston, but it was too late. He died on August 22 at age 46.

Dr. Kakli said, “I’ve never lost a patient with this diagnosis. Ever. I’m scared that the next patient I see is someone that I can’t get to where they need to get to. We are playing musical chairs with 100 people and 10 chairs. When the music stops, what happens?”

Also in Texas in August, Joe Valdez, who was shot six times as an unlucky bystander in a domestic dispute, waited for more than a week for surgery at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, which was over capacity with COVID patients, the Washington Post reported.

Others with chronic diseases fear needing emergency services or even entering a hospital for regular care with the COVID surge.

Nicole Seefeldt, 44, from Easton, Penn., who had a double-lung transplant in 2016, said that she hasn’t been able to see her lung transplant specialists in Philadelphia — an hour-and-a-half drive — for almost 2 years because of fear of contracting COVID. Before the pandemic, she made the trip almost weekly.

“I protect my lungs like they’re children,” she said.

She relies on her local hospital for care, but has put off some needed care, such as a colonoscopy, and has relied on telemedicine because she wants to limit her hospital exposure.

Ms. Seefeldt now faces an eventual kidney transplant, as her kidney function has been reduced to 20%. In the meantime, she worries she will need emergency care for either her lungs or kidneys.

“For those of us who are chronically ill or disabled, what if we have an emergency that is not COVID-related? Are we going to be able to get a bed? Are we going to be able to get treatment? It’s not just COVID patients who come to the [emergency room],” she said.

A pandemic problem

Paul E. Casey, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said that high vaccination rates in Chicago have helped Rush continue to accommodate both non-COVID and COVID patients in the emergency department.

Though the hospital treated a large volume of COVID patients, “The vast majority of people we see and did see through the pandemic were non-COVID patents,” he said.

Dr. Casey said that in the first wave the hospital noticed a concerning drop in patients coming in for strokes and heart attacks — “things we knew hadn’t gone away.”

And the data backs it up. Over the course of the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health Interview Survey found that the percentage of Americans who reported seeing a doctor or health professional fell from 85% at the end of 2019 to about 80% in the first three months of 2021. The survey did not differentiate between in-person visits and telehealth appointments.

Medical practices and patients themselves postponed elective procedures and delayed routine visits during the early months of the crisis.

Patients also reported staying away from hospitals’ emergency departments throughout the pandemic. At the end of 2019, 22% of respondents reported visiting an emergency department in the past year. That dropped to 17% by the end of 2020, and was at 17.7% in the first 3 months of 2021.

Dr. Casey said that, in his hospital’s case, clear messaging became very important to assure patients it was safe to come back. And the message is still critical.

“We want to be loud and clear that patients should continue to seek care for those conditions,” Dr. Casey said. “Deferring healthcare only comes with the long-term sequelae of disease left untreated so we want people to be as proactive in seeking care as they always would be.”

In some cases, fears of entering emergency rooms because of excess patients and risk for infection are keeping some patients from seeking necessary care for minor injuries.

Jim Rickert, MD, an orthopedic surgeon with Indiana University Health in Bloomington, said that some of his patients have expressed fears of coming into the hospital for fractures.

Some patients, particularly elderly patients, he said, are having falls and fractures and wearing slings or braces at home rather than going into the hospital for injuries that need immediate attention.

Bones start healing incorrectly, Dr. Rickert said, and the correction becomes much more difficult.

Plea for vaccinations

Dr. Gosnell made a plea posted on her neighborhood news forum for people to get COVID vaccinations.

“It seems to me it’s easy for other people who are not in bodies like mine to take health for granted,” she said. “But there are a lot of us who live in very fragile bodies and our entire life is at the intersection of us and getting healthcare treatment. Small complications to getting treatment can be life altering.”

Dr. Gosnell, Ms. Seefeldt, Dr. Casey, and Dr. Rickert reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Jessica Gosnell, MD, 41, from Portland, Oregon, lives daily with the knowledge that her rare disease — a form of hereditary angioedema — could cause a sudden, severe swelling in her throat that could require quick intubation and land her in an intensive care unit (ICU) for days.

“I’ve been hospitalized for throat swells three times in the last year,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Gosnell no longer practices medicine because of a combination of illnesses, but lives with her husband, Andrew, and two young children, and said they are all “terrified” she will have to go to the hospital amid a COVID-19 surge that had shrunk the number of available ICU beds to 152 from 780 in Oregon as of Aug. 30. Thirty percent of the beds are in use for patients with COVID-19.

She said her life depends on being near hospitals that have ICUs and having access to highly specialized medications, one of which can cost up to $50,000 for the rescue dose.

Her fear has her “literally living bedbound.” In addition to hereditary angioedema, she has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which weakens connective tissue. She wears a cervical collar 24/7 to keep from tearing tissues, as any tissue injury can trigger a swell.

Patients worry there won’t be room

As ICU beds in most states are filling with COVID-19 patients as the Delta variant spreads, fears are rising among people like Dr. Gosnell, who have chronic conditions and diseases with unpredictable emergency visits, who worry that if they need emergency care there won’t be room.

As of Aug. 30, in the United States, 79% of ICU beds nationally were in use, 30% of them for COVID-19 patients, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

In individual states, the picture is dire. Alabama has fewer than 10% of its ICU beds open across the entire state. In Florida, 93% of ICU beds are filled, 53% of them with COVID patients. In Louisiana, 87% of beds were already in use, 45% of them with COVID patients, just as category 4 hurricane Ida smashed into the coastline on Aug. 29.

News reports have told of people transported and airlifted as hospitals reach capacity.

In Bellville, Tex., U.S. Army veteran Daniel Wilkinson needed advanced care for gallstone pancreatitis that normally would take 30 minutes to treat, his Bellville doctor, Hasan Kakli, MD, told CBS News.

Mr. Wilkinson’s house was three doors from Bellville Hospital, but the hospital was not equipped to treat the condition. Calls to other hospitals found the same answer: no empty ICU beds. After a 7-hour wait on a stretcher, he was airlifted to a Veterans Affairs hospital in Houston, but it was too late. He died on August 22 at age 46.

Dr. Kakli said, “I’ve never lost a patient with this diagnosis. Ever. I’m scared that the next patient I see is someone that I can’t get to where they need to get to. We are playing musical chairs with 100 people and 10 chairs. When the music stops, what happens?”

Also in Texas in August, Joe Valdez, who was shot six times as an unlucky bystander in a domestic dispute, waited for more than a week for surgery at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, which was over capacity with COVID patients, the Washington Post reported.

Others with chronic diseases fear needing emergency services or even entering a hospital for regular care with the COVID surge.

Nicole Seefeldt, 44, from Easton, Penn., who had a double-lung transplant in 2016, said that she hasn’t been able to see her lung transplant specialists in Philadelphia — an hour-and-a-half drive — for almost 2 years because of fear of contracting COVID. Before the pandemic, she made the trip almost weekly.

“I protect my lungs like they’re children,” she said.

She relies on her local hospital for care, but has put off some needed care, such as a colonoscopy, and has relied on telemedicine because she wants to limit her hospital exposure.

Ms. Seefeldt now faces an eventual kidney transplant, as her kidney function has been reduced to 20%. In the meantime, she worries she will need emergency care for either her lungs or kidneys.

“For those of us who are chronically ill or disabled, what if we have an emergency that is not COVID-related? Are we going to be able to get a bed? Are we going to be able to get treatment? It’s not just COVID patients who come to the [emergency room],” she said.

A pandemic problem

Paul E. Casey, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said that high vaccination rates in Chicago have helped Rush continue to accommodate both non-COVID and COVID patients in the emergency department.

Though the hospital treated a large volume of COVID patients, “The vast majority of people we see and did see through the pandemic were non-COVID patents,” he said.

Dr. Casey said that in the first wave the hospital noticed a concerning drop in patients coming in for strokes and heart attacks — “things we knew hadn’t gone away.”

And the data backs it up. Over the course of the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health Interview Survey found that the percentage of Americans who reported seeing a doctor or health professional fell from 85% at the end of 2019 to about 80% in the first three months of 2021. The survey did not differentiate between in-person visits and telehealth appointments.

Medical practices and patients themselves postponed elective procedures and delayed routine visits during the early months of the crisis.

Patients also reported staying away from hospitals’ emergency departments throughout the pandemic. At the end of 2019, 22% of respondents reported visiting an emergency department in the past year. That dropped to 17% by the end of 2020, and was at 17.7% in the first 3 months of 2021.

Dr. Casey said that, in his hospital’s case, clear messaging became very important to assure patients it was safe to come back. And the message is still critical.

“We want to be loud and clear that patients should continue to seek care for those conditions,” Dr. Casey said. “Deferring healthcare only comes with the long-term sequelae of disease left untreated so we want people to be as proactive in seeking care as they always would be.”

In some cases, fears of entering emergency rooms because of excess patients and risk for infection are keeping some patients from seeking necessary care for minor injuries.

Jim Rickert, MD, an orthopedic surgeon with Indiana University Health in Bloomington, said that some of his patients have expressed fears of coming into the hospital for fractures.

Some patients, particularly elderly patients, he said, are having falls and fractures and wearing slings or braces at home rather than going into the hospital for injuries that need immediate attention.

Bones start healing incorrectly, Dr. Rickert said, and the correction becomes much more difficult.

Plea for vaccinations

Dr. Gosnell made a plea posted on her neighborhood news forum for people to get COVID vaccinations.

“It seems to me it’s easy for other people who are not in bodies like mine to take health for granted,” she said. “But there are a lot of us who live in very fragile bodies and our entire life is at the intersection of us and getting healthcare treatment. Small complications to getting treatment can be life altering.”

Dr. Gosnell, Ms. Seefeldt, Dr. Casey, and Dr. Rickert reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Jessica Gosnell, MD, 41, from Portland, Oregon, lives daily with the knowledge that her rare disease — a form of hereditary angioedema — could cause a sudden, severe swelling in her throat that could require quick intubation and land her in an intensive care unit (ICU) for days.

“I’ve been hospitalized for throat swells three times in the last year,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Gosnell no longer practices medicine because of a combination of illnesses, but lives with her husband, Andrew, and two young children, and said they are all “terrified” she will have to go to the hospital amid a COVID-19 surge that had shrunk the number of available ICU beds to 152 from 780 in Oregon as of Aug. 30. Thirty percent of the beds are in use for patients with COVID-19.

She said her life depends on being near hospitals that have ICUs and having access to highly specialized medications, one of which can cost up to $50,000 for the rescue dose.

Her fear has her “literally living bedbound.” In addition to hereditary angioedema, she has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which weakens connective tissue. She wears a cervical collar 24/7 to keep from tearing tissues, as any tissue injury can trigger a swell.

Patients worry there won’t be room

As ICU beds in most states are filling with COVID-19 patients as the Delta variant spreads, fears are rising among people like Dr. Gosnell, who have chronic conditions and diseases with unpredictable emergency visits, who worry that if they need emergency care there won’t be room.

As of Aug. 30, in the United States, 79% of ICU beds nationally were in use, 30% of them for COVID-19 patients, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

In individual states, the picture is dire. Alabama has fewer than 10% of its ICU beds open across the entire state. In Florida, 93% of ICU beds are filled, 53% of them with COVID patients. In Louisiana, 87% of beds were already in use, 45% of them with COVID patients, just as category 4 hurricane Ida smashed into the coastline on Aug. 29.

News reports have told of people transported and airlifted as hospitals reach capacity.

In Bellville, Tex., U.S. Army veteran Daniel Wilkinson needed advanced care for gallstone pancreatitis that normally would take 30 minutes to treat, his Bellville doctor, Hasan Kakli, MD, told CBS News.

Mr. Wilkinson’s house was three doors from Bellville Hospital, but the hospital was not equipped to treat the condition. Calls to other hospitals found the same answer: no empty ICU beds. After a 7-hour wait on a stretcher, he was airlifted to a Veterans Affairs hospital in Houston, but it was too late. He died on August 22 at age 46.

Dr. Kakli said, “I’ve never lost a patient with this diagnosis. Ever. I’m scared that the next patient I see is someone that I can’t get to where they need to get to. We are playing musical chairs with 100 people and 10 chairs. When the music stops, what happens?”

Also in Texas in August, Joe Valdez, who was shot six times as an unlucky bystander in a domestic dispute, waited for more than a week for surgery at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, which was over capacity with COVID patients, the Washington Post reported.

Others with chronic diseases fear needing emergency services or even entering a hospital for regular care with the COVID surge.

Nicole Seefeldt, 44, from Easton, Penn., who had a double-lung transplant in 2016, said that she hasn’t been able to see her lung transplant specialists in Philadelphia — an hour-and-a-half drive — for almost 2 years because of fear of contracting COVID. Before the pandemic, she made the trip almost weekly.

“I protect my lungs like they’re children,” she said.

She relies on her local hospital for care, but has put off some needed care, such as a colonoscopy, and has relied on telemedicine because she wants to limit her hospital exposure.

Ms. Seefeldt now faces an eventual kidney transplant, as her kidney function has been reduced to 20%. In the meantime, she worries she will need emergency care for either her lungs or kidneys.

“For those of us who are chronically ill or disabled, what if we have an emergency that is not COVID-related? Are we going to be able to get a bed? Are we going to be able to get treatment? It’s not just COVID patients who come to the [emergency room],” she said.

A pandemic problem

Paul E. Casey, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said that high vaccination rates in Chicago have helped Rush continue to accommodate both non-COVID and COVID patients in the emergency department.

Though the hospital treated a large volume of COVID patients, “The vast majority of people we see and did see through the pandemic were non-COVID patents,” he said.

Dr. Casey said that in the first wave the hospital noticed a concerning drop in patients coming in for strokes and heart attacks — “things we knew hadn’t gone away.”

And the data backs it up. Over the course of the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health Interview Survey found that the percentage of Americans who reported seeing a doctor or health professional fell from 85% at the end of 2019 to about 80% in the first three months of 2021. The survey did not differentiate between in-person visits and telehealth appointments.

Medical practices and patients themselves postponed elective procedures and delayed routine visits during the early months of the crisis.

Patients also reported staying away from hospitals’ emergency departments throughout the pandemic. At the end of 2019, 22% of respondents reported visiting an emergency department in the past year. That dropped to 17% by the end of 2020, and was at 17.7% in the first 3 months of 2021.

Dr. Casey said that, in his hospital’s case, clear messaging became very important to assure patients it was safe to come back. And the message is still critical.

“We want to be loud and clear that patients should continue to seek care for those conditions,” Dr. Casey said. “Deferring healthcare only comes with the long-term sequelae of disease left untreated so we want people to be as proactive in seeking care as they always would be.”

In some cases, fears of entering emergency rooms because of excess patients and risk for infection are keeping some patients from seeking necessary care for minor injuries.

Jim Rickert, MD, an orthopedic surgeon with Indiana University Health in Bloomington, said that some of his patients have expressed fears of coming into the hospital for fractures.

Some patients, particularly elderly patients, he said, are having falls and fractures and wearing slings or braces at home rather than going into the hospital for injuries that need immediate attention.

Bones start healing incorrectly, Dr. Rickert said, and the correction becomes much more difficult.

Plea for vaccinations

Dr. Gosnell made a plea posted on her neighborhood news forum for people to get COVID vaccinations.

“It seems to me it’s easy for other people who are not in bodies like mine to take health for granted,” she said. “But there are a lot of us who live in very fragile bodies and our entire life is at the intersection of us and getting healthcare treatment. Small complications to getting treatment can be life altering.”

Dr. Gosnell, Ms. Seefeldt, Dr. Casey, and Dr. Rickert reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Study calls higher surgery costs at NCI centers into question

according to a recent report in JAMA Network Open.

“While acceptable to pay higher prices for care that is expected to be of higher quality, we found no differences in short-term postsurgical outcomes,” said authors led by Samuel Takvorian, MD, a medical oncologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The team looked at what insurance companies paid for incident breast, colon, and lung cancer surgeries, which together account for most cancer surgeries, among 66,878 patients treated from 2011 to 2014 at almost 3,000 U.S. hospitals.

Three-quarters had surgery at a community hospital, and 8.3% were treated at one of the nation’s 71 NCI centers, which are recognized by the NCI as meeting rigorous standards in cancer care. The remaining patients were treated at non-NCI academic hospitals.

The mean surgery-specific insurer prices paid at NCI centers was $18,526 versus $14,772 at community hospitals, a difference of $3,755 (P < .001) that was driven primarily by higher facility payments at NCI centers, a mean of $17,704 versus $14,120 at community hospitals.

Mean 90-day postdischarge payments were also $5,744 higher at NCI centers, $47,035 versus $41,291 at community hospitals (P = .006).

The team used postsurgical acute care utilization as a marker of quality but found no differences between the two settings. Mean length of stay was 5.1 days and the probability of ED utilization just over 13% in both, and both had a 90-day readmission rate of just over 10%.

Who should be treated at an NCI center?

The data didn’t allow for direct comparison of surgical quality, such as margin status, number of lymph nodes assessed, or postoperative complications, but the postsurgery utilization outcomes “suggest that quality may have been similar,” said Nancy Keating, MD, a health care policy and medicine professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in an invited commentary.

The price differences are probably because NCI centers, with their comprehensive offerings, market share, and prestige, can negotiate higher reimbursement rates from insurers, the researchers said.

There is also evidence of better outcomes at NCI centers, particularly for more advanced and complex cases. However, “this study focused on common cancer surgical procedures ... revealing that there is a premium associated with receipt of surgical cancer care at NCI centers.” Further research “is necessary to judge whether and under what circumstances the premium price of NCI centers is justified,” the investigators said.

Dr. Keating noted that “it is likely that some patients benefit from the highly specialized care available at NCI-designated cancer centers ... but it is also likely that many other patients will do equally well regardless of where they receive their care.”

Amid ever-increasing cancer care costs and the need to strategically allocate financial resources, more research is needed to “identify subgroups of patients for whom highly specialized care is particularly necessary to achieve better outcomes. Such data could also be used by payers considering tiered networks and by physician organizations participating in risk contracts for decisions about where to refer patients with cancer for treatment,” she said.

Rectifying a ‘misalignment’

The researchers also said the findings reveal competing incentives, with commercial payers wanting to steer patients away from high-cost hospitals but health systems hoping to maximize surgical volume at lucrative referral centers.

“Value-based or bundled payment reimbursement for surgical episodes, particularly when paired with mandatory reporting on surgical outcomes, could help to rectify this misalignment,” they said.

Out-of-pocket spending wasn’t analyzed in the study, so it’s unknown how the higher prices at NCI centers hit patients in the pocketbook.

Meanwhile, non-NCI academic hospitals also had higher insurer prices paid than community hospitals, but the differences were not statistically significant, nor were differences in the study’s utilization outcomes.

Over half the patients had breast cancer, about one-third had colon cancer, and the rest had lung tumors. Patients treated at NCI centers tended to be younger than those treated at community hospitals and more likely to be women, but comorbidity scores were similar between the groups.

NCI centers, compared with community hospitals, were larger with higher surgical volumes and in more populated areas. They also had higher rates of laparoscopic partial colectomies and pneumonectomies.

Data came from the Health Care Cost Institute’s national commercial claims data set, which includes claims from three of the country’s five largest commercial insurers: Aetna, Humana, and UnitedHealthcare.

The work was funded by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Takvorian and Dr. Keating didn’t have any disclosures. One of Dr. Takvorian’s coauthors reported grants and/or personal fees from several sources, including Pfizer, UnitedHealthcare, and Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina.

according to a recent report in JAMA Network Open.

“While acceptable to pay higher prices for care that is expected to be of higher quality, we found no differences in short-term postsurgical outcomes,” said authors led by Samuel Takvorian, MD, a medical oncologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The team looked at what insurance companies paid for incident breast, colon, and lung cancer surgeries, which together account for most cancer surgeries, among 66,878 patients treated from 2011 to 2014 at almost 3,000 U.S. hospitals.

Three-quarters had surgery at a community hospital, and 8.3% were treated at one of the nation’s 71 NCI centers, which are recognized by the NCI as meeting rigorous standards in cancer care. The remaining patients were treated at non-NCI academic hospitals.

The mean surgery-specific insurer prices paid at NCI centers was $18,526 versus $14,772 at community hospitals, a difference of $3,755 (P < .001) that was driven primarily by higher facility payments at NCI centers, a mean of $17,704 versus $14,120 at community hospitals.

Mean 90-day postdischarge payments were also $5,744 higher at NCI centers, $47,035 versus $41,291 at community hospitals (P = .006).

The team used postsurgical acute care utilization as a marker of quality but found no differences between the two settings. Mean length of stay was 5.1 days and the probability of ED utilization just over 13% in both, and both had a 90-day readmission rate of just over 10%.

Who should be treated at an NCI center?

The data didn’t allow for direct comparison of surgical quality, such as margin status, number of lymph nodes assessed, or postoperative complications, but the postsurgery utilization outcomes “suggest that quality may have been similar,” said Nancy Keating, MD, a health care policy and medicine professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in an invited commentary.

The price differences are probably because NCI centers, with their comprehensive offerings, market share, and prestige, can negotiate higher reimbursement rates from insurers, the researchers said.

There is also evidence of better outcomes at NCI centers, particularly for more advanced and complex cases. However, “this study focused on common cancer surgical procedures ... revealing that there is a premium associated with receipt of surgical cancer care at NCI centers.” Further research “is necessary to judge whether and under what circumstances the premium price of NCI centers is justified,” the investigators said.

Dr. Keating noted that “it is likely that some patients benefit from the highly specialized care available at NCI-designated cancer centers ... but it is also likely that many other patients will do equally well regardless of where they receive their care.”

Amid ever-increasing cancer care costs and the need to strategically allocate financial resources, more research is needed to “identify subgroups of patients for whom highly specialized care is particularly necessary to achieve better outcomes. Such data could also be used by payers considering tiered networks and by physician organizations participating in risk contracts for decisions about where to refer patients with cancer for treatment,” she said.

Rectifying a ‘misalignment’

The researchers also said the findings reveal competing incentives, with commercial payers wanting to steer patients away from high-cost hospitals but health systems hoping to maximize surgical volume at lucrative referral centers.

“Value-based or bundled payment reimbursement for surgical episodes, particularly when paired with mandatory reporting on surgical outcomes, could help to rectify this misalignment,” they said.

Out-of-pocket spending wasn’t analyzed in the study, so it’s unknown how the higher prices at NCI centers hit patients in the pocketbook.

Meanwhile, non-NCI academic hospitals also had higher insurer prices paid than community hospitals, but the differences were not statistically significant, nor were differences in the study’s utilization outcomes.

Over half the patients had breast cancer, about one-third had colon cancer, and the rest had lung tumors. Patients treated at NCI centers tended to be younger than those treated at community hospitals and more likely to be women, but comorbidity scores were similar between the groups.

NCI centers, compared with community hospitals, were larger with higher surgical volumes and in more populated areas. They also had higher rates of laparoscopic partial colectomies and pneumonectomies.

Data came from the Health Care Cost Institute’s national commercial claims data set, which includes claims from three of the country’s five largest commercial insurers: Aetna, Humana, and UnitedHealthcare.

The work was funded by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Takvorian and Dr. Keating didn’t have any disclosures. One of Dr. Takvorian’s coauthors reported grants and/or personal fees from several sources, including Pfizer, UnitedHealthcare, and Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina.

according to a recent report in JAMA Network Open.

“While acceptable to pay higher prices for care that is expected to be of higher quality, we found no differences in short-term postsurgical outcomes,” said authors led by Samuel Takvorian, MD, a medical oncologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The team looked at what insurance companies paid for incident breast, colon, and lung cancer surgeries, which together account for most cancer surgeries, among 66,878 patients treated from 2011 to 2014 at almost 3,000 U.S. hospitals.

Three-quarters had surgery at a community hospital, and 8.3% were treated at one of the nation’s 71 NCI centers, which are recognized by the NCI as meeting rigorous standards in cancer care. The remaining patients were treated at non-NCI academic hospitals.

The mean surgery-specific insurer prices paid at NCI centers was $18,526 versus $14,772 at community hospitals, a difference of $3,755 (P < .001) that was driven primarily by higher facility payments at NCI centers, a mean of $17,704 versus $14,120 at community hospitals.

Mean 90-day postdischarge payments were also $5,744 higher at NCI centers, $47,035 versus $41,291 at community hospitals (P = .006).

The team used postsurgical acute care utilization as a marker of quality but found no differences between the two settings. Mean length of stay was 5.1 days and the probability of ED utilization just over 13% in both, and both had a 90-day readmission rate of just over 10%.

Who should be treated at an NCI center?

The data didn’t allow for direct comparison of surgical quality, such as margin status, number of lymph nodes assessed, or postoperative complications, but the postsurgery utilization outcomes “suggest that quality may have been similar,” said Nancy Keating, MD, a health care policy and medicine professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in an invited commentary.

The price differences are probably because NCI centers, with their comprehensive offerings, market share, and prestige, can negotiate higher reimbursement rates from insurers, the researchers said.

There is also evidence of better outcomes at NCI centers, particularly for more advanced and complex cases. However, “this study focused on common cancer surgical procedures ... revealing that there is a premium associated with receipt of surgical cancer care at NCI centers.” Further research “is necessary to judge whether and under what circumstances the premium price of NCI centers is justified,” the investigators said.

Dr. Keating noted that “it is likely that some patients benefit from the highly specialized care available at NCI-designated cancer centers ... but it is also likely that many other patients will do equally well regardless of where they receive their care.”

Amid ever-increasing cancer care costs and the need to strategically allocate financial resources, more research is needed to “identify subgroups of patients for whom highly specialized care is particularly necessary to achieve better outcomes. Such data could also be used by payers considering tiered networks and by physician organizations participating in risk contracts for decisions about where to refer patients with cancer for treatment,” she said.

Rectifying a ‘misalignment’

The researchers also said the findings reveal competing incentives, with commercial payers wanting to steer patients away from high-cost hospitals but health systems hoping to maximize surgical volume at lucrative referral centers.

“Value-based or bundled payment reimbursement for surgical episodes, particularly when paired with mandatory reporting on surgical outcomes, could help to rectify this misalignment,” they said.

Out-of-pocket spending wasn’t analyzed in the study, so it’s unknown how the higher prices at NCI centers hit patients in the pocketbook.

Meanwhile, non-NCI academic hospitals also had higher insurer prices paid than community hospitals, but the differences were not statistically significant, nor were differences in the study’s utilization outcomes.

Over half the patients had breast cancer, about one-third had colon cancer, and the rest had lung tumors. Patients treated at NCI centers tended to be younger than those treated at community hospitals and more likely to be women, but comorbidity scores were similar between the groups.

NCI centers, compared with community hospitals, were larger with higher surgical volumes and in more populated areas. They also had higher rates of laparoscopic partial colectomies and pneumonectomies.

Data came from the Health Care Cost Institute’s national commercial claims data set, which includes claims from three of the country’s five largest commercial insurers: Aetna, Humana, and UnitedHealthcare.

The work was funded by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Takvorian and Dr. Keating didn’t have any disclosures. One of Dr. Takvorian’s coauthors reported grants and/or personal fees from several sources, including Pfizer, UnitedHealthcare, and Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Limited evidence for interventions to reduce post-op pulmonary complications

Background: Despite advances in perioperative care, postoperative pulmonary complications represent a leading cause of morbidity and mortality that are associated with increased risk of admission to critical care and prolonged length of hospital stay. There are multiple interventions that are used, despite there being no consensus guidelines aimed at reducing the risk of PPCs.

Study design: Systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Setting: Literature search from Medline, Embase, CINHAL, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from January 1990 to December 2017, including trials investigating short-term, protocolized medical interventions around noncardiac surgeries with clinical diagnostic criteria for PPC outcomes.

Synopsis: The authors reviewed 117 trials that included 21,940 participants. The meta-analysis comprised 95 randomized controlled trials with 18,062 patients. The authors identified 11 categories of perioperative care interventions that were tested to reduce PPCs. None of the interventions evaluated was supported by high-quality evidence. There were seven interventions that showed a probable reduction in PPCs. Goal-directed fluid therapy was the only one that was supported by both moderate quality evidence and trial sequential analysis. Lung protective intraoperative ventilation was supported by moderate quality evidence, but not trial sequential analysis. Five interventions had low-quality evidence of benefit: enhanced recovery pathways, prophylactic mucolytics, postoperative continuous positive airway pressure ventilation, prophylactic respiratory physiotherapy, and epidural analgesia.

Unfortunately, only a minority of the trials reviewed were large, multi-center studies with a low risk of bias. The studies were also heterogeneous, posing a challenge for meta-analysis.

Bottom line: There is limited evidence supporting the efficacy of any intervention preventing postoperative pulmonary complications, with moderate-quality evidence supporting intraoperative lung protective ventilation and goal-directed hemodynamic strategies reducing PPCs.

Citation: Odor PM et al. Perioperative interventions for prevention of postoperative pulmonary complication: Systemic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m540.

Dr. Weaver is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UK HealthCare, Lexington, Ky.

Background: Despite advances in perioperative care, postoperative pulmonary complications represent a leading cause of morbidity and mortality that are associated with increased risk of admission to critical care and prolonged length of hospital stay. There are multiple interventions that are used, despite there being no consensus guidelines aimed at reducing the risk of PPCs.

Study design: Systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Setting: Literature search from Medline, Embase, CINHAL, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from January 1990 to December 2017, including trials investigating short-term, protocolized medical interventions around noncardiac surgeries with clinical diagnostic criteria for PPC outcomes.

Synopsis: The authors reviewed 117 trials that included 21,940 participants. The meta-analysis comprised 95 randomized controlled trials with 18,062 patients. The authors identified 11 categories of perioperative care interventions that were tested to reduce PPCs. None of the interventions evaluated was supported by high-quality evidence. There were seven interventions that showed a probable reduction in PPCs. Goal-directed fluid therapy was the only one that was supported by both moderate quality evidence and trial sequential analysis. Lung protective intraoperative ventilation was supported by moderate quality evidence, but not trial sequential analysis. Five interventions had low-quality evidence of benefit: enhanced recovery pathways, prophylactic mucolytics, postoperative continuous positive airway pressure ventilation, prophylactic respiratory physiotherapy, and epidural analgesia.

Unfortunately, only a minority of the trials reviewed were large, multi-center studies with a low risk of bias. The studies were also heterogeneous, posing a challenge for meta-analysis.

Bottom line: There is limited evidence supporting the efficacy of any intervention preventing postoperative pulmonary complications, with moderate-quality evidence supporting intraoperative lung protective ventilation and goal-directed hemodynamic strategies reducing PPCs.

Citation: Odor PM et al. Perioperative interventions for prevention of postoperative pulmonary complication: Systemic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m540.

Dr. Weaver is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UK HealthCare, Lexington, Ky.

Background: Despite advances in perioperative care, postoperative pulmonary complications represent a leading cause of morbidity and mortality that are associated with increased risk of admission to critical care and prolonged length of hospital stay. There are multiple interventions that are used, despite there being no consensus guidelines aimed at reducing the risk of PPCs.

Study design: Systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Setting: Literature search from Medline, Embase, CINHAL, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from January 1990 to December 2017, including trials investigating short-term, protocolized medical interventions around noncardiac surgeries with clinical diagnostic criteria for PPC outcomes.

Synopsis: The authors reviewed 117 trials that included 21,940 participants. The meta-analysis comprised 95 randomized controlled trials with 18,062 patients. The authors identified 11 categories of perioperative care interventions that were tested to reduce PPCs. None of the interventions evaluated was supported by high-quality evidence. There were seven interventions that showed a probable reduction in PPCs. Goal-directed fluid therapy was the only one that was supported by both moderate quality evidence and trial sequential analysis. Lung protective intraoperative ventilation was supported by moderate quality evidence, but not trial sequential analysis. Five interventions had low-quality evidence of benefit: enhanced recovery pathways, prophylactic mucolytics, postoperative continuous positive airway pressure ventilation, prophylactic respiratory physiotherapy, and epidural analgesia.

Unfortunately, only a minority of the trials reviewed were large, multi-center studies with a low risk of bias. The studies were also heterogeneous, posing a challenge for meta-analysis.

Bottom line: There is limited evidence supporting the efficacy of any intervention preventing postoperative pulmonary complications, with moderate-quality evidence supporting intraoperative lung protective ventilation and goal-directed hemodynamic strategies reducing PPCs.

Citation: Odor PM et al. Perioperative interventions for prevention of postoperative pulmonary complication: Systemic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m540.

Dr. Weaver is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UK HealthCare, Lexington, Ky.

Two swings, two misses with colchicine, Vascepa in COVID-19

The anti-inflammatory agents colchicine and icosapent ethyl (Vascepa; Amarin) failed to provide substantial benefits in separate randomized COVID-19 trials.

Both were reported at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress 2021.

The open-label ECLA PHRI COLCOVID trial randomized 1,277 hospitalized adults (mean age 62 years) to usual care alone or with colchicine at a loading dose of 1.5 mg for 2 hours followed by 0.5 mg on day 1 and then 0.5 mg twice daily for 14 days or until discharge.

The investigators hypothesized that colchicine, which is widely used to treat gout and other inflammatory conditions, might modulate the hyperinflammatory syndrome, or cytokine storm, associated with COVID-19.

Results showed that the need for mechanical ventilation or death occurred in 25.0% of patients receiving colchicine and 28.8% with usual care (P = .08).

The coprimary endpoint of death at 28 days was also not significantly different between groups (20.5% vs. 22.2%), principal investigator Rafael Diaz, MD, said in a late-breaking COVID-19 trials session at the congress.

Among the secondary outcomes at 28 days, colchicine significantly reduced the incidence of new intubation or death from respiratory failure from 27.0% to 22.3% (hazard ratio, 0.79; 95% confidence interval, 0.63-0.99) but not mortality from respiratory failure (19.5% vs. 16.8%).

The only important adverse effect was severe diarrhea, which was reported in 11.3% of the colchicine group vs. 4.5% in the control group, said Dr. Diaz, director of Estudios Clínicos Latinoamérica (ECLA), Rosario, Argentina.

The results are consistent with those from the massive RECOVERY trial, which earlier this year stopped enrollment in the colchicine arm for lack of efficacy in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, and COLCORONA, which missed its primary endpoint using colchicine among nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19.

Session chair and COLCORONA principal investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, pointed out that, as clinicians, it’s fairly uncommon to combine systemic steroids with colchicine, which was the case in 92% of patients in ECLA PHRI COLCOVID.

“I think it is an inherent limitation of testing colchicine on top of steroids,” said Dr. Tardif, of the Montreal Heart Institute.

Icosapent ethyl in PREPARE-IT

Dr. Diaz returned in the ESC session to present the results of the PREPARE-IT trial, which tested whether icosapent ethyl – at a loading dose of 8 grams (4 capsules) for the first 3 days and 4 g/d on days 4-60 – could reduce the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection in 2,041 health care and other public workers in Argentina at high risk for infection (mean age 40.5 years).

Vascepa was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2012 for the reduction of elevated triglyceride levels, with an added indication in 2019 to reduce cardiovascular (CV) events in people with elevated triglycerides and established CV disease or diabetes with other CV risk factors.

The rationale for using the high-dose prescription eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) preparation includes its anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic effects, and that unsaturated fatty acids, especially EPA, might inactivate the enveloped virus, he explained.

Among 1,712 participants followed for up to 60 days, however, the SARS-CoV-2 infection rate was 7.9% with icosapent ethyl vs. 7.1% with a mineral oil placebo (P = .58).

There were also no significant changes from baseline in the icosapent ethyl and placebo groups for the secondary outcomes of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (0 vs. 0), triglycerides (median –2 mg/dL vs. 7 mg/dL), or Influenza Patient-Reported Outcome (FLU-PRO) questionnaire scores (median 0.01 vs. 0.03).

The use of a mineral oil placebo has been the subject of controversy in previous fish oil trials, but, Dr. Diaz noted, it did not have a significant proinflammatory effect or cause any excess adverse events.

Overall, adverse events were similar between the active and placebo groups, including atrial fibrillation (none), major bleeding (none), minor bleeding (7 events vs. 10 events), gastrointestinal symptoms (6.8% vs. 7.0%), and diarrhea (8.6% vs. 7.7%).

Although it missed the primary endpoint, Dr. Diaz said, “this is the first large, randomized blinded trial to demonstrate excellent safety and tolerability of an 8-gram-per-day loading dose of icosapent ethyl, opening up the potential for acute use in randomized trials of myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndromes, strokes, and revascularization.”

During a discussion of the results, Dr. Diaz said the Delta variant was not present at the time of the analysis and that the second half of the trial will report on whether icosapent ethyl can reduce the risk for hospitalization or death in participants diagnosed with COVID-19.

ECLA PHRI COLCOVID was supported by the Estudios Clínicos Latinoamérica Population Health Research Institute. PREPARE-IT was supported by Estudios Clínicos Latinoamérica with collaboration from Amarin. Dr. Diaz reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The anti-inflammatory agents colchicine and icosapent ethyl (Vascepa; Amarin) failed to provide substantial benefits in separate randomized COVID-19 trials.

Both were reported at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress 2021.

The open-label ECLA PHRI COLCOVID trial randomized 1,277 hospitalized adults (mean age 62 years) to usual care alone or with colchicine at a loading dose of 1.5 mg for 2 hours followed by 0.5 mg on day 1 and then 0.5 mg twice daily for 14 days or until discharge.