User login

Should psychiatrists prescribe nonpsychotropic medications?

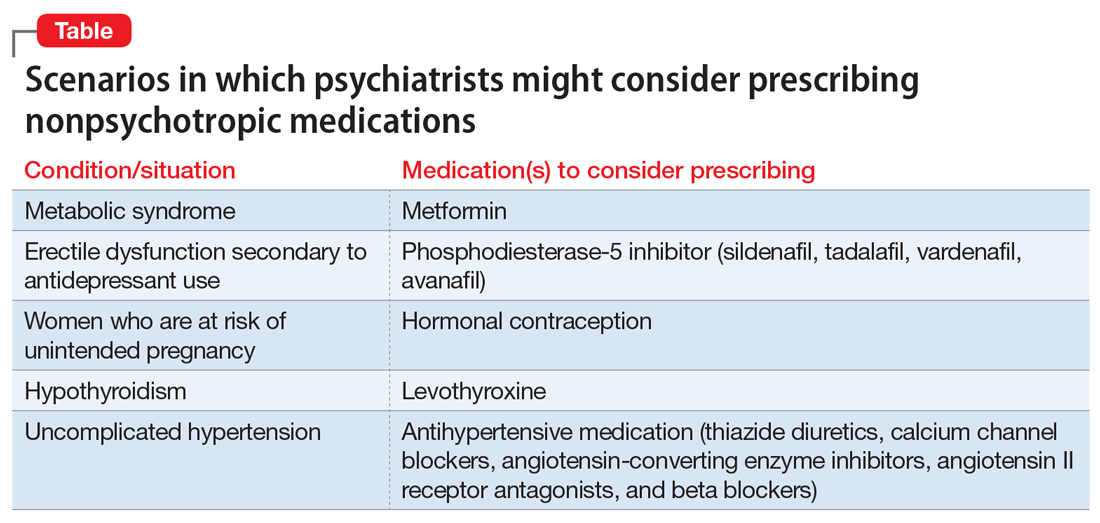

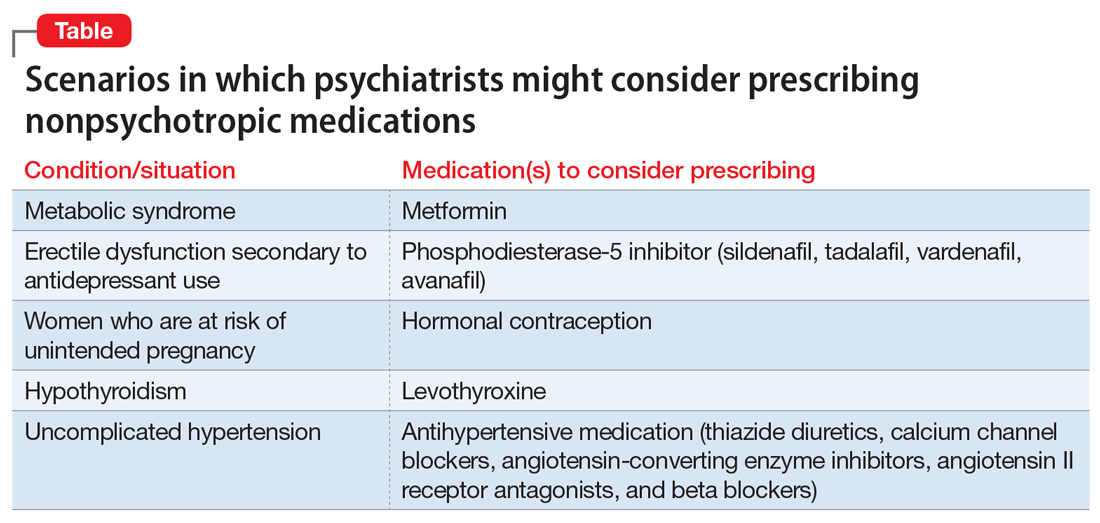

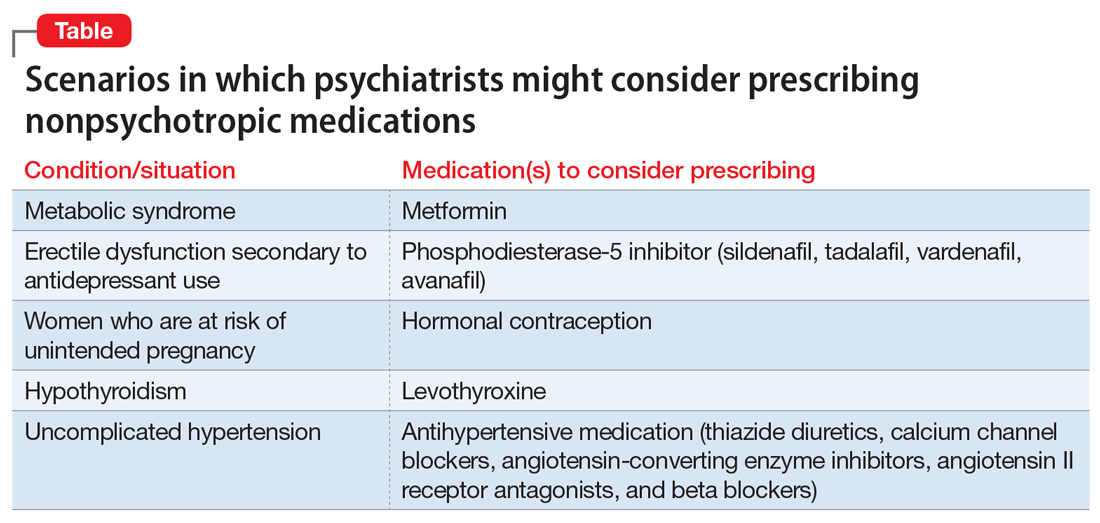

In our experience, most psychiatrists are uncomfortable with prescribing a medication when they feel that doing so would be outside their scope of practice. But there are many situations when prescribing a nonpsychotropic medication would be the correct choice. In this article, we discuss the scope of psychiatric practice, and present 4 case studies that illustrate situations in which psychiatrists should feel comfortable prescribing nonpsychotropic medications.

Defining the scope of practice

What is the scope of a psychiatrist’s practice? Scope of practice usually describes activities that a health care practitioner is allowed to undertake as defined by the terms of his/her license. A license to practice medicine does not include any stipulation restricting practice to a specific medical specialty. However, a local entity may delineate scope of practice within its organization. For instance, local practice standards held by the Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority (DWMHA) state “Psychiatrists…shall not exceed their scope of practice as per DWMHA credentialing and privileging. For example, a Psychiatrist…who [has] not been appropriately privileged to deliver services to children shall not treat children, excepting crisis situations.”1

Like physicians in other specialties, psychiatrists are not limited to prescribing only a subset of medications commonly associated with their specialty. But for many psychiatrists, prescribing nonpsychotropic medications is complicated by individual and local factors. On one hand, some psychiatrists do not feel it is their role to prescribe nonpsychotropic medications,2 or even some psychotropic medications that may be more complex to prescribe, such as lithium, clozapine, or monoamine oxidase inhibitors.3-5 However, many feel comfortable prescribing complex combinations of psychotropic medications, or prescribing in a way that does not necessarily make sense (eg, prescribing benztropine as prophylaxis for dystonia when starting an antipsychotic).

Reviewing an average day at one urban psychiatric clinic, these questions seem to come up in half of the patient population, especially in patients with chronic mental illness, multiple medical comorbidities, and limited access to health care. When a young patient walks in without an appointment with an acute dystonic reaction secondary to the initiation of antipsychotics a couple of days ago, there is no hesitation to swiftly and appropriately prescribe an IM anticholinergic medication. But why are psychiatrists often hesitant to prescribe nonpsychotropic medications to treat other adverse effects of medications? Lack of knowledge? Lack of training?

Psychiatrists who practice in hospital systems often have immediate access to consultants, and this availability may encourage them to defer to the consultant for treatment of certain adverse effects. We have seen psychiatrists consult Neurology regarding the prescription of donepezil for mild neurocognitive disorder due to Alzheimer’s disease, or Endocrinology regarding prescription of levothyroxine for lithium-induced hypothyroidism.

However, there are numerous scenarios in which psychiatrists should feel comfortable prescribing nonpsychotropic medications or managing medication adverse effects, regardless of whether they consider it to be within or outside their scope of practice. The following case examples illustrate several such situations.

CASE 1

Ms. W, age 30, has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. She requests a refill of quetiapine, 800 mg/d. This medication has been clearly beneficial in alleviating her psychotic symptoms. However, since her last visit 3 months ago, her face appears more round, and she has gained 9 kg. Further evaluation indicates that she has developed metabolic syndrome and pre-diabetes.

Continue to: Metabolic adverse effects

Metabolic adverse effects, such as metabolic syndrome, diabetic ketoacidosis, and cardiovascular disease, are well-known risks of prescribing second-generation antipsychotics.6 In such situations, psychiatrists often advise patients to modify their diet, increase physical activity, and follow up with their primary care physician to determine if other medications are needed. However, getting a patient with a serious mental illness to exercise and modify her/his diet is difficult, and many of these patients do not have a primary care physician.

For patients such as Ms. W, a psychiatrist should consider prescribing metformin. Wu et al7 found that in addition to lifestyle modifications, metformin had the greatest effect on antipsychotic-induced weight gain. In this study, metformin alone had more impact on reversing weight gain and increasing insulin sensitivity than lifestyle modifications alone.7 This is crucial because these patients are especially vulnerable to cardiac disease.8 Metformin is well tolerated and has a low risk of causing hypoglycemia. Concerns regarding lactic acidosis have abated to the extent that the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) limits for using metformin have been lowered significantly. After reviewing the contraindications, the only knowledge needed to prescribe metformin is the patient’s kidney function and a brief understanding of the titration needed to minimize gastrointestinal adverse effects.9 Thus, prescribing metformin would be a fairly logical and easy first step for managing metabolic syndrome, especially in a patient whose motivation for increasing physical activity and modifying his/her diet is doubtful.

CASE 2

Mr. B, age 45, has major depressive disorder that has been well-controlled on paroxetine, 40 mg/d, for the past 2 years. He has no history of physical illness. On his most recent visit, he appears uncomfortable and nervous. After a long discussion, he discloses that his sex life isn’t what it used to be since starting paroxetine. He is bothered by erectile problems and asks whether he can “get some Viagra.”

Sexual adverse effects, such as erectile dysfunction, are frequently associated with the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.10 Although managing these adverse effects requires careful evaluation, in most cases, psychiatrists should be able to treat them.10 The logical choice in this case would be to prescribe one of the 4 FDA-approved phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (sildenafil [Viagra], tadalafil [Cialis], vardenafil [Levitra], and avanafil [Stendra]. However, Balon et al11 found that few psychiatrists prescribe phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, although they believed that they should be prescribing to treat their patients’ sexual dysfunction. Managing these adverse effects is important not only for the patient’s quality of life and relationship with his/her partner, but also for the therapeutic alliance. In a systematic review of 23 trials, Taylor et al12 examined >1,800 patients who were prescribed a medication to address sexual dysfunction secondary to antidepressants. They found that for men, adding a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor was appropriate and effective, and for women, adding bupropion at high doses should be considered.12 Like many other adverse effects, sexual adverse effects surely play a role in medication compliance. Dording et al13 found that the addition of sildenafil, 50 to 100 mg as needed, resulted in increased treatment satisfaction and overall contentment in 102 patients who complained of sexual dysfunction in the follow-up phase of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) antidepressant trials. In most cases, with proper psychoeducation, prescription of

CASE 3

Ms. G, age 22, was recently discharged from an inpatient psychiatric unit after an episode of mania. She was prescribed carbamazepine, 600 mg/d, and ziprasidone, 40 mg twice a day, and appears to be doing well on this regimen. When asked about what led to her admission, she recalls having an elevated mood, increased energy, hypersexuality, impulsivity, and poor judgment. She reveals that she had several sexual partners during her manic episode, and worries that if such behavior occurs again, she may get pregnant. Yet Ms. G was not prescribed birth control upon discharge.

Continue to: Contraception

Contraception. We believe that psychiatrists have an obligation to protect patients from consequences of mental illness. Much the same way that psychiatrists hope to prevent suicide in a patient who has depression, patients should be protected from risks encountered in the manic phase of bipolar disorder. Another reason to prescribe contraceptives in such patients is the teratogenic effects of mood stabilizers. Pagano et al14 reviewed 6 studies that examined common forms of hormonal birth control to determine their safety in patients with depression or bipolar disorder. They found that overall, use of hormonal contraception was not associated with a worse clinical course of disease.

Many available forms of birth control are available. When prescribing in an outpatient setting, a daily oral medication or a monthly depot injection are convenient options.

CASE 4

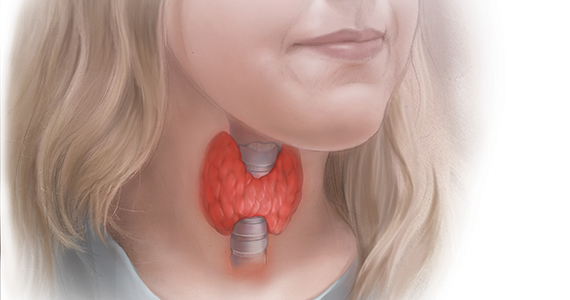

Mr. P, age 65, has bipolar I disorder and is stable on risperidone long-acting injection, 37.7 mg bimonthly, and lithium, 1,200 mg/d. He reports that he is doing well but has noticed a recent decrease in energy and weight gain without any change in mood. Laboratory testing conducted prior to this visit revealed a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 4 mU/L (normal range: 0.4 to 4.0 mU/L). Six months ago, Mr. P’s TSH level was 2.8 mU/L. The resident supervisor suggests discussing the case with an endocrinologist.

Thyroid function. The impact of lithium on the thyroid gland is well established; however, psychiatrists’ response to such changes are not.15 Gitlin16 reviewed the many adverse effects of lithium and presented various management strategies to address findings such as Mr. P’s. Two important points are that lithium should not be discontinued in light of hypothyroidism, and synthetic thyroxine (levothyroxine) can be initiated and titrated to return TSH levels to a normal range.16 Levothyroxine can be started at low doses (eg, 25 to 50 mcg/d) and increased every 6 weeks until a normal TSH level is achieved.17 Managing lithium-induced clinical or subclinical hypothyroidism can prevent further pathology and possible relapse to depression.

Incorporating integrated care

In all these cases, the prescription of a medication with which some psychiatrists are not comfortable prescribing would have been the logical, easiest, and preferable choice. Of course, when initiating any medication, boxed warnings, contraindications, and drug–drug interactions should be reviewed. Initial dosages and titration schedules can be found in every medication’s FDA-approved prescribing information document (package insert), as well as in numerous reference books and articles.

Continue to: We acknowledge...

We acknowledge that prescribing a nonpsychotropic medication is not always a psychiatrist’s best choice, and that in patients with multiple medical comorbidities and drug–drug interactions that are not clearly defined, referring to or consulting a specialist is appropriate. We in no way support reckless prescribing, but instead present an opportunity to expand the perception of what should be considered within a psychiatrist’s scope of practice, and call for further education of psychiatrists so that they are more comfortable managing these adverse effects and/or prescribing at least some nonpsychotropic medications.

We exhort integrated medical care during this time of a physician shortage; however, we do not practice this way. Interestingly, physicians in primary care, such as those in family medicine or obstetrics and gynecology, frequently attempt to treat patients with psychiatric conditions in an attempt to provide integrated care. Numerous articles have discussed these efforts.18-20 However, this type of integrated care seems less frequent in psychiatry, even though the practice of modern psychiatry in the United States shows substantial overlap with the practice of physicians in primary care specialties.21 There are few articles or practical guidelines for psychiatrists who wish to treat patients’ physical illnesses, particularly patients with severe mental illness (see Related Resources, page 56). If we practice in an integrated manner to treat one of the simple conditions we described above, we can eliminate the need for a patient to visit a second physician, pay another co-pay, pay another bus fare, and take another day off work. This can be particularly helpful for patients who at times have to decide between paying for groceries or for medications. Having one clinician manage a patient’s medications also can decrease the risk of polypharmacy.

In addition to the case scenarios described in this article, there are more clinical situations and nonpsychotropic medications that psychiatrists could manage. Considering them outside the scope of psychiatric practice and being uncomfortable or ambivalent about them is not an excuse. We hope that psychiatrists can increase their expertise in this area, and can start to practice as the primary care physicians they claim they are, and should be.

Bottom Line

Many psychiatrists are uncomfortable prescribing nonpsychotropic medications, but there are numerous clinical scenarios in which the practice would make sense. This could include cases of metabolic syndrome, sexual dysfunction secondary to antidepressant use, or other adverse effects of commonly prescribed psychotropic medications.

Related Resources

- McCarron RM, Xiong GL, Keenan CR, et al. Preventive medical care in psychiatry. A practical guide for clinicians. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2015.

- McCarron RM, Xiong GL, Keenan CR, et al. Study guide to preventive medical care in psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017.

- Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Managing the side effects of psychotropic medications. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

Drug Brand Names

Avanafil • Stendra

Benztropine • Cogentin

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Clozapine • Clozaril

Donepezil • Aricept

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthroid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metformin • Fortamet, Glucophage

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone long-acting injection • Risperdal Consta

Sildenafil • Viagra

Tadalafil • Cialis

Vardenafil • Levitra

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Detroit Wayne Integrated Health Network. DWMHA psychiatric practice standards. http://dwihn.org/files/2015/6451/9628/Psychiatric_Practice_Standards.pdf. Revised June 2018. Accessed October 8, 2019.

2. Seaman JJ, Cornfield RM, Cummings DM, et al. Exploring psychiatric prescribing practices: the relationship between the role of the provider and the appropriateness of prescribing. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1987;9(3):220-224.

3. Zivanovic O. Lithium: a classic drug—frequently discussed, but, sadly, seldom prescribed! Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(9):886-896.

4. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, et al. Geographic and clinical variation in clozapine use in the United States. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(2):186-192.

5. Balon R, Mufti R, Arfken C. A survey of prescribing practices for monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(7):945-947.

6. Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;123(2-3):225-233.

7. Wu RR, Zhao JP, Jin H, et al. Lifestyle intervention and metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(2):185-193.

8. De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52-77.

9. Kirpichnikov D, McFarlane SI, Sowers JR. Metformin: an update. Ann Internal Med. 2002;137(1):25-33.

10. Balon R. SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1504-1509.

11. Balon R, Morreale MK, Segraves RT. Prescribing of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors among psychiatrists. J Sex Marital Ther. 2014;40(3):165-169.

12. Taylor MJ, Rudkin L, Bullemor-Day P, et al. Strategies for managing sexual dysfunction induced by antidepressant medication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD003382.

13. Dording CM, LaRocca RA, Hails KA, et al. The effect of sildenafil on quality of life. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25(1):3-10.

14. Pagano HP, Zapata LB, Berry-Bibee EN, et al. Safety of hormonal contraception and intrauterine devices among women with depressive and bipolar disorders: a systematic review. Contraception. 2016;94(6):641-649.

15. Kibirige D, Luzinda K, Ssekitoleko R. Spectrum of lithium induced thyroid abnormalities: a current perspective. Thyroid Res. 2013;6(1):3.

16. Gitlin M. Lithium side effects and toxicity: prevalence and management strategies. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2016;4(1):27.

17. Devdhar M, Ousman YH, Burman KD. Hypothyroidism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36(3):595-615.

18. Hackley B, Sharma C, Kedzior A, et al. Managing mental health conditions in primary care settings. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2010;55(1):9-19.

19. Fitelson E, McGibbon C. Evaluation and management of behavioral health disorders in women: an overview of major depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, and sleep in the primary care setting. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2016;43(2):231-246.

20. Colorafi K, Vanselow J, Nelson T. Treating anxiety and depression in primary care: reducing barriers to access. Fam Pract Manag. 2017;24(4):11-16.

21. McCall WV. Defining the unique scope of psychiatric practice in 2015. J ECT. 2015;31(4):203-204.

In our experience, most psychiatrists are uncomfortable with prescribing a medication when they feel that doing so would be outside their scope of practice. But there are many situations when prescribing a nonpsychotropic medication would be the correct choice. In this article, we discuss the scope of psychiatric practice, and present 4 case studies that illustrate situations in which psychiatrists should feel comfortable prescribing nonpsychotropic medications.

Defining the scope of practice

What is the scope of a psychiatrist’s practice? Scope of practice usually describes activities that a health care practitioner is allowed to undertake as defined by the terms of his/her license. A license to practice medicine does not include any stipulation restricting practice to a specific medical specialty. However, a local entity may delineate scope of practice within its organization. For instance, local practice standards held by the Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority (DWMHA) state “Psychiatrists…shall not exceed their scope of practice as per DWMHA credentialing and privileging. For example, a Psychiatrist…who [has] not been appropriately privileged to deliver services to children shall not treat children, excepting crisis situations.”1

Like physicians in other specialties, psychiatrists are not limited to prescribing only a subset of medications commonly associated with their specialty. But for many psychiatrists, prescribing nonpsychotropic medications is complicated by individual and local factors. On one hand, some psychiatrists do not feel it is their role to prescribe nonpsychotropic medications,2 or even some psychotropic medications that may be more complex to prescribe, such as lithium, clozapine, or monoamine oxidase inhibitors.3-5 However, many feel comfortable prescribing complex combinations of psychotropic medications, or prescribing in a way that does not necessarily make sense (eg, prescribing benztropine as prophylaxis for dystonia when starting an antipsychotic).

Reviewing an average day at one urban psychiatric clinic, these questions seem to come up in half of the patient population, especially in patients with chronic mental illness, multiple medical comorbidities, and limited access to health care. When a young patient walks in without an appointment with an acute dystonic reaction secondary to the initiation of antipsychotics a couple of days ago, there is no hesitation to swiftly and appropriately prescribe an IM anticholinergic medication. But why are psychiatrists often hesitant to prescribe nonpsychotropic medications to treat other adverse effects of medications? Lack of knowledge? Lack of training?

Psychiatrists who practice in hospital systems often have immediate access to consultants, and this availability may encourage them to defer to the consultant for treatment of certain adverse effects. We have seen psychiatrists consult Neurology regarding the prescription of donepezil for mild neurocognitive disorder due to Alzheimer’s disease, or Endocrinology regarding prescription of levothyroxine for lithium-induced hypothyroidism.

However, there are numerous scenarios in which psychiatrists should feel comfortable prescribing nonpsychotropic medications or managing medication adverse effects, regardless of whether they consider it to be within or outside their scope of practice. The following case examples illustrate several such situations.

CASE 1

Ms. W, age 30, has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. She requests a refill of quetiapine, 800 mg/d. This medication has been clearly beneficial in alleviating her psychotic symptoms. However, since her last visit 3 months ago, her face appears more round, and she has gained 9 kg. Further evaluation indicates that she has developed metabolic syndrome and pre-diabetes.

Continue to: Metabolic adverse effects

Metabolic adverse effects, such as metabolic syndrome, diabetic ketoacidosis, and cardiovascular disease, are well-known risks of prescribing second-generation antipsychotics.6 In such situations, psychiatrists often advise patients to modify their diet, increase physical activity, and follow up with their primary care physician to determine if other medications are needed. However, getting a patient with a serious mental illness to exercise and modify her/his diet is difficult, and many of these patients do not have a primary care physician.

For patients such as Ms. W, a psychiatrist should consider prescribing metformin. Wu et al7 found that in addition to lifestyle modifications, metformin had the greatest effect on antipsychotic-induced weight gain. In this study, metformin alone had more impact on reversing weight gain and increasing insulin sensitivity than lifestyle modifications alone.7 This is crucial because these patients are especially vulnerable to cardiac disease.8 Metformin is well tolerated and has a low risk of causing hypoglycemia. Concerns regarding lactic acidosis have abated to the extent that the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) limits for using metformin have been lowered significantly. After reviewing the contraindications, the only knowledge needed to prescribe metformin is the patient’s kidney function and a brief understanding of the titration needed to minimize gastrointestinal adverse effects.9 Thus, prescribing metformin would be a fairly logical and easy first step for managing metabolic syndrome, especially in a patient whose motivation for increasing physical activity and modifying his/her diet is doubtful.

CASE 2

Mr. B, age 45, has major depressive disorder that has been well-controlled on paroxetine, 40 mg/d, for the past 2 years. He has no history of physical illness. On his most recent visit, he appears uncomfortable and nervous. After a long discussion, he discloses that his sex life isn’t what it used to be since starting paroxetine. He is bothered by erectile problems and asks whether he can “get some Viagra.”

Sexual adverse effects, such as erectile dysfunction, are frequently associated with the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.10 Although managing these adverse effects requires careful evaluation, in most cases, psychiatrists should be able to treat them.10 The logical choice in this case would be to prescribe one of the 4 FDA-approved phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (sildenafil [Viagra], tadalafil [Cialis], vardenafil [Levitra], and avanafil [Stendra]. However, Balon et al11 found that few psychiatrists prescribe phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, although they believed that they should be prescribing to treat their patients’ sexual dysfunction. Managing these adverse effects is important not only for the patient’s quality of life and relationship with his/her partner, but also for the therapeutic alliance. In a systematic review of 23 trials, Taylor et al12 examined >1,800 patients who were prescribed a medication to address sexual dysfunction secondary to antidepressants. They found that for men, adding a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor was appropriate and effective, and for women, adding bupropion at high doses should be considered.12 Like many other adverse effects, sexual adverse effects surely play a role in medication compliance. Dording et al13 found that the addition of sildenafil, 50 to 100 mg as needed, resulted in increased treatment satisfaction and overall contentment in 102 patients who complained of sexual dysfunction in the follow-up phase of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) antidepressant trials. In most cases, with proper psychoeducation, prescription of

CASE 3

Ms. G, age 22, was recently discharged from an inpatient psychiatric unit after an episode of mania. She was prescribed carbamazepine, 600 mg/d, and ziprasidone, 40 mg twice a day, and appears to be doing well on this regimen. When asked about what led to her admission, she recalls having an elevated mood, increased energy, hypersexuality, impulsivity, and poor judgment. She reveals that she had several sexual partners during her manic episode, and worries that if such behavior occurs again, she may get pregnant. Yet Ms. G was not prescribed birth control upon discharge.

Continue to: Contraception

Contraception. We believe that psychiatrists have an obligation to protect patients from consequences of mental illness. Much the same way that psychiatrists hope to prevent suicide in a patient who has depression, patients should be protected from risks encountered in the manic phase of bipolar disorder. Another reason to prescribe contraceptives in such patients is the teratogenic effects of mood stabilizers. Pagano et al14 reviewed 6 studies that examined common forms of hormonal birth control to determine their safety in patients with depression or bipolar disorder. They found that overall, use of hormonal contraception was not associated with a worse clinical course of disease.

Many available forms of birth control are available. When prescribing in an outpatient setting, a daily oral medication or a monthly depot injection are convenient options.

CASE 4

Mr. P, age 65, has bipolar I disorder and is stable on risperidone long-acting injection, 37.7 mg bimonthly, and lithium, 1,200 mg/d. He reports that he is doing well but has noticed a recent decrease in energy and weight gain without any change in mood. Laboratory testing conducted prior to this visit revealed a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 4 mU/L (normal range: 0.4 to 4.0 mU/L). Six months ago, Mr. P’s TSH level was 2.8 mU/L. The resident supervisor suggests discussing the case with an endocrinologist.

Thyroid function. The impact of lithium on the thyroid gland is well established; however, psychiatrists’ response to such changes are not.15 Gitlin16 reviewed the many adverse effects of lithium and presented various management strategies to address findings such as Mr. P’s. Two important points are that lithium should not be discontinued in light of hypothyroidism, and synthetic thyroxine (levothyroxine) can be initiated and titrated to return TSH levels to a normal range.16 Levothyroxine can be started at low doses (eg, 25 to 50 mcg/d) and increased every 6 weeks until a normal TSH level is achieved.17 Managing lithium-induced clinical or subclinical hypothyroidism can prevent further pathology and possible relapse to depression.

Incorporating integrated care

In all these cases, the prescription of a medication with which some psychiatrists are not comfortable prescribing would have been the logical, easiest, and preferable choice. Of course, when initiating any medication, boxed warnings, contraindications, and drug–drug interactions should be reviewed. Initial dosages and titration schedules can be found in every medication’s FDA-approved prescribing information document (package insert), as well as in numerous reference books and articles.

Continue to: We acknowledge...

We acknowledge that prescribing a nonpsychotropic medication is not always a psychiatrist’s best choice, and that in patients with multiple medical comorbidities and drug–drug interactions that are not clearly defined, referring to or consulting a specialist is appropriate. We in no way support reckless prescribing, but instead present an opportunity to expand the perception of what should be considered within a psychiatrist’s scope of practice, and call for further education of psychiatrists so that they are more comfortable managing these adverse effects and/or prescribing at least some nonpsychotropic medications.

We exhort integrated medical care during this time of a physician shortage; however, we do not practice this way. Interestingly, physicians in primary care, such as those in family medicine or obstetrics and gynecology, frequently attempt to treat patients with psychiatric conditions in an attempt to provide integrated care. Numerous articles have discussed these efforts.18-20 However, this type of integrated care seems less frequent in psychiatry, even though the practice of modern psychiatry in the United States shows substantial overlap with the practice of physicians in primary care specialties.21 There are few articles or practical guidelines for psychiatrists who wish to treat patients’ physical illnesses, particularly patients with severe mental illness (see Related Resources, page 56). If we practice in an integrated manner to treat one of the simple conditions we described above, we can eliminate the need for a patient to visit a second physician, pay another co-pay, pay another bus fare, and take another day off work. This can be particularly helpful for patients who at times have to decide between paying for groceries or for medications. Having one clinician manage a patient’s medications also can decrease the risk of polypharmacy.

In addition to the case scenarios described in this article, there are more clinical situations and nonpsychotropic medications that psychiatrists could manage. Considering them outside the scope of psychiatric practice and being uncomfortable or ambivalent about them is not an excuse. We hope that psychiatrists can increase their expertise in this area, and can start to practice as the primary care physicians they claim they are, and should be.

Bottom Line

Many psychiatrists are uncomfortable prescribing nonpsychotropic medications, but there are numerous clinical scenarios in which the practice would make sense. This could include cases of metabolic syndrome, sexual dysfunction secondary to antidepressant use, or other adverse effects of commonly prescribed psychotropic medications.

Related Resources

- McCarron RM, Xiong GL, Keenan CR, et al. Preventive medical care in psychiatry. A practical guide for clinicians. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2015.

- McCarron RM, Xiong GL, Keenan CR, et al. Study guide to preventive medical care in psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017.

- Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Managing the side effects of psychotropic medications. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

Drug Brand Names

Avanafil • Stendra

Benztropine • Cogentin

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Clozapine • Clozaril

Donepezil • Aricept

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthroid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metformin • Fortamet, Glucophage

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone long-acting injection • Risperdal Consta

Sildenafil • Viagra

Tadalafil • Cialis

Vardenafil • Levitra

Ziprasidone • Geodon

In our experience, most psychiatrists are uncomfortable with prescribing a medication when they feel that doing so would be outside their scope of practice. But there are many situations when prescribing a nonpsychotropic medication would be the correct choice. In this article, we discuss the scope of psychiatric practice, and present 4 case studies that illustrate situations in which psychiatrists should feel comfortable prescribing nonpsychotropic medications.

Defining the scope of practice

What is the scope of a psychiatrist’s practice? Scope of practice usually describes activities that a health care practitioner is allowed to undertake as defined by the terms of his/her license. A license to practice medicine does not include any stipulation restricting practice to a specific medical specialty. However, a local entity may delineate scope of practice within its organization. For instance, local practice standards held by the Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority (DWMHA) state “Psychiatrists…shall not exceed their scope of practice as per DWMHA credentialing and privileging. For example, a Psychiatrist…who [has] not been appropriately privileged to deliver services to children shall not treat children, excepting crisis situations.”1

Like physicians in other specialties, psychiatrists are not limited to prescribing only a subset of medications commonly associated with their specialty. But for many psychiatrists, prescribing nonpsychotropic medications is complicated by individual and local factors. On one hand, some psychiatrists do not feel it is their role to prescribe nonpsychotropic medications,2 or even some psychotropic medications that may be more complex to prescribe, such as lithium, clozapine, or monoamine oxidase inhibitors.3-5 However, many feel comfortable prescribing complex combinations of psychotropic medications, or prescribing in a way that does not necessarily make sense (eg, prescribing benztropine as prophylaxis for dystonia when starting an antipsychotic).

Reviewing an average day at one urban psychiatric clinic, these questions seem to come up in half of the patient population, especially in patients with chronic mental illness, multiple medical comorbidities, and limited access to health care. When a young patient walks in without an appointment with an acute dystonic reaction secondary to the initiation of antipsychotics a couple of days ago, there is no hesitation to swiftly and appropriately prescribe an IM anticholinergic medication. But why are psychiatrists often hesitant to prescribe nonpsychotropic medications to treat other adverse effects of medications? Lack of knowledge? Lack of training?

Psychiatrists who practice in hospital systems often have immediate access to consultants, and this availability may encourage them to defer to the consultant for treatment of certain adverse effects. We have seen psychiatrists consult Neurology regarding the prescription of donepezil for mild neurocognitive disorder due to Alzheimer’s disease, or Endocrinology regarding prescription of levothyroxine for lithium-induced hypothyroidism.

However, there are numerous scenarios in which psychiatrists should feel comfortable prescribing nonpsychotropic medications or managing medication adverse effects, regardless of whether they consider it to be within or outside their scope of practice. The following case examples illustrate several such situations.

CASE 1

Ms. W, age 30, has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. She requests a refill of quetiapine, 800 mg/d. This medication has been clearly beneficial in alleviating her psychotic symptoms. However, since her last visit 3 months ago, her face appears more round, and she has gained 9 kg. Further evaluation indicates that she has developed metabolic syndrome and pre-diabetes.

Continue to: Metabolic adverse effects

Metabolic adverse effects, such as metabolic syndrome, diabetic ketoacidosis, and cardiovascular disease, are well-known risks of prescribing second-generation antipsychotics.6 In such situations, psychiatrists often advise patients to modify their diet, increase physical activity, and follow up with their primary care physician to determine if other medications are needed. However, getting a patient with a serious mental illness to exercise and modify her/his diet is difficult, and many of these patients do not have a primary care physician.

For patients such as Ms. W, a psychiatrist should consider prescribing metformin. Wu et al7 found that in addition to lifestyle modifications, metformin had the greatest effect on antipsychotic-induced weight gain. In this study, metformin alone had more impact on reversing weight gain and increasing insulin sensitivity than lifestyle modifications alone.7 This is crucial because these patients are especially vulnerable to cardiac disease.8 Metformin is well tolerated and has a low risk of causing hypoglycemia. Concerns regarding lactic acidosis have abated to the extent that the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) limits for using metformin have been lowered significantly. After reviewing the contraindications, the only knowledge needed to prescribe metformin is the patient’s kidney function and a brief understanding of the titration needed to minimize gastrointestinal adverse effects.9 Thus, prescribing metformin would be a fairly logical and easy first step for managing metabolic syndrome, especially in a patient whose motivation for increasing physical activity and modifying his/her diet is doubtful.

CASE 2

Mr. B, age 45, has major depressive disorder that has been well-controlled on paroxetine, 40 mg/d, for the past 2 years. He has no history of physical illness. On his most recent visit, he appears uncomfortable and nervous. After a long discussion, he discloses that his sex life isn’t what it used to be since starting paroxetine. He is bothered by erectile problems and asks whether he can “get some Viagra.”

Sexual adverse effects, such as erectile dysfunction, are frequently associated with the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.10 Although managing these adverse effects requires careful evaluation, in most cases, psychiatrists should be able to treat them.10 The logical choice in this case would be to prescribe one of the 4 FDA-approved phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (sildenafil [Viagra], tadalafil [Cialis], vardenafil [Levitra], and avanafil [Stendra]. However, Balon et al11 found that few psychiatrists prescribe phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, although they believed that they should be prescribing to treat their patients’ sexual dysfunction. Managing these adverse effects is important not only for the patient’s quality of life and relationship with his/her partner, but also for the therapeutic alliance. In a systematic review of 23 trials, Taylor et al12 examined >1,800 patients who were prescribed a medication to address sexual dysfunction secondary to antidepressants. They found that for men, adding a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor was appropriate and effective, and for women, adding bupropion at high doses should be considered.12 Like many other adverse effects, sexual adverse effects surely play a role in medication compliance. Dording et al13 found that the addition of sildenafil, 50 to 100 mg as needed, resulted in increased treatment satisfaction and overall contentment in 102 patients who complained of sexual dysfunction in the follow-up phase of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) antidepressant trials. In most cases, with proper psychoeducation, prescription of

CASE 3

Ms. G, age 22, was recently discharged from an inpatient psychiatric unit after an episode of mania. She was prescribed carbamazepine, 600 mg/d, and ziprasidone, 40 mg twice a day, and appears to be doing well on this regimen. When asked about what led to her admission, she recalls having an elevated mood, increased energy, hypersexuality, impulsivity, and poor judgment. She reveals that she had several sexual partners during her manic episode, and worries that if such behavior occurs again, she may get pregnant. Yet Ms. G was not prescribed birth control upon discharge.

Continue to: Contraception

Contraception. We believe that psychiatrists have an obligation to protect patients from consequences of mental illness. Much the same way that psychiatrists hope to prevent suicide in a patient who has depression, patients should be protected from risks encountered in the manic phase of bipolar disorder. Another reason to prescribe contraceptives in such patients is the teratogenic effects of mood stabilizers. Pagano et al14 reviewed 6 studies that examined common forms of hormonal birth control to determine their safety in patients with depression or bipolar disorder. They found that overall, use of hormonal contraception was not associated with a worse clinical course of disease.

Many available forms of birth control are available. When prescribing in an outpatient setting, a daily oral medication or a monthly depot injection are convenient options.

CASE 4

Mr. P, age 65, has bipolar I disorder and is stable on risperidone long-acting injection, 37.7 mg bimonthly, and lithium, 1,200 mg/d. He reports that he is doing well but has noticed a recent decrease in energy and weight gain without any change in mood. Laboratory testing conducted prior to this visit revealed a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 4 mU/L (normal range: 0.4 to 4.0 mU/L). Six months ago, Mr. P’s TSH level was 2.8 mU/L. The resident supervisor suggests discussing the case with an endocrinologist.

Thyroid function. The impact of lithium on the thyroid gland is well established; however, psychiatrists’ response to such changes are not.15 Gitlin16 reviewed the many adverse effects of lithium and presented various management strategies to address findings such as Mr. P’s. Two important points are that lithium should not be discontinued in light of hypothyroidism, and synthetic thyroxine (levothyroxine) can be initiated and titrated to return TSH levels to a normal range.16 Levothyroxine can be started at low doses (eg, 25 to 50 mcg/d) and increased every 6 weeks until a normal TSH level is achieved.17 Managing lithium-induced clinical or subclinical hypothyroidism can prevent further pathology and possible relapse to depression.

Incorporating integrated care

In all these cases, the prescription of a medication with which some psychiatrists are not comfortable prescribing would have been the logical, easiest, and preferable choice. Of course, when initiating any medication, boxed warnings, contraindications, and drug–drug interactions should be reviewed. Initial dosages and titration schedules can be found in every medication’s FDA-approved prescribing information document (package insert), as well as in numerous reference books and articles.

Continue to: We acknowledge...

We acknowledge that prescribing a nonpsychotropic medication is not always a psychiatrist’s best choice, and that in patients with multiple medical comorbidities and drug–drug interactions that are not clearly defined, referring to or consulting a specialist is appropriate. We in no way support reckless prescribing, but instead present an opportunity to expand the perception of what should be considered within a psychiatrist’s scope of practice, and call for further education of psychiatrists so that they are more comfortable managing these adverse effects and/or prescribing at least some nonpsychotropic medications.

We exhort integrated medical care during this time of a physician shortage; however, we do not practice this way. Interestingly, physicians in primary care, such as those in family medicine or obstetrics and gynecology, frequently attempt to treat patients with psychiatric conditions in an attempt to provide integrated care. Numerous articles have discussed these efforts.18-20 However, this type of integrated care seems less frequent in psychiatry, even though the practice of modern psychiatry in the United States shows substantial overlap with the practice of physicians in primary care specialties.21 There are few articles or practical guidelines for psychiatrists who wish to treat patients’ physical illnesses, particularly patients with severe mental illness (see Related Resources, page 56). If we practice in an integrated manner to treat one of the simple conditions we described above, we can eliminate the need for a patient to visit a second physician, pay another co-pay, pay another bus fare, and take another day off work. This can be particularly helpful for patients who at times have to decide between paying for groceries or for medications. Having one clinician manage a patient’s medications also can decrease the risk of polypharmacy.

In addition to the case scenarios described in this article, there are more clinical situations and nonpsychotropic medications that psychiatrists could manage. Considering them outside the scope of psychiatric practice and being uncomfortable or ambivalent about them is not an excuse. We hope that psychiatrists can increase their expertise in this area, and can start to practice as the primary care physicians they claim they are, and should be.

Bottom Line

Many psychiatrists are uncomfortable prescribing nonpsychotropic medications, but there are numerous clinical scenarios in which the practice would make sense. This could include cases of metabolic syndrome, sexual dysfunction secondary to antidepressant use, or other adverse effects of commonly prescribed psychotropic medications.

Related Resources

- McCarron RM, Xiong GL, Keenan CR, et al. Preventive medical care in psychiatry. A practical guide for clinicians. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2015.

- McCarron RM, Xiong GL, Keenan CR, et al. Study guide to preventive medical care in psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017.

- Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Managing the side effects of psychotropic medications. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

Drug Brand Names

Avanafil • Stendra

Benztropine • Cogentin

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Clozapine • Clozaril

Donepezil • Aricept

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthroid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metformin • Fortamet, Glucophage

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone long-acting injection • Risperdal Consta

Sildenafil • Viagra

Tadalafil • Cialis

Vardenafil • Levitra

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Detroit Wayne Integrated Health Network. DWMHA psychiatric practice standards. http://dwihn.org/files/2015/6451/9628/Psychiatric_Practice_Standards.pdf. Revised June 2018. Accessed October 8, 2019.

2. Seaman JJ, Cornfield RM, Cummings DM, et al. Exploring psychiatric prescribing practices: the relationship between the role of the provider and the appropriateness of prescribing. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1987;9(3):220-224.

3. Zivanovic O. Lithium: a classic drug—frequently discussed, but, sadly, seldom prescribed! Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(9):886-896.

4. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, et al. Geographic and clinical variation in clozapine use in the United States. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(2):186-192.

5. Balon R, Mufti R, Arfken C. A survey of prescribing practices for monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(7):945-947.

6. Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;123(2-3):225-233.

7. Wu RR, Zhao JP, Jin H, et al. Lifestyle intervention and metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(2):185-193.

8. De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52-77.

9. Kirpichnikov D, McFarlane SI, Sowers JR. Metformin: an update. Ann Internal Med. 2002;137(1):25-33.

10. Balon R. SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1504-1509.

11. Balon R, Morreale MK, Segraves RT. Prescribing of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors among psychiatrists. J Sex Marital Ther. 2014;40(3):165-169.

12. Taylor MJ, Rudkin L, Bullemor-Day P, et al. Strategies for managing sexual dysfunction induced by antidepressant medication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD003382.

13. Dording CM, LaRocca RA, Hails KA, et al. The effect of sildenafil on quality of life. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25(1):3-10.

14. Pagano HP, Zapata LB, Berry-Bibee EN, et al. Safety of hormonal contraception and intrauterine devices among women with depressive and bipolar disorders: a systematic review. Contraception. 2016;94(6):641-649.

15. Kibirige D, Luzinda K, Ssekitoleko R. Spectrum of lithium induced thyroid abnormalities: a current perspective. Thyroid Res. 2013;6(1):3.

16. Gitlin M. Lithium side effects and toxicity: prevalence and management strategies. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2016;4(1):27.

17. Devdhar M, Ousman YH, Burman KD. Hypothyroidism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36(3):595-615.

18. Hackley B, Sharma C, Kedzior A, et al. Managing mental health conditions in primary care settings. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2010;55(1):9-19.

19. Fitelson E, McGibbon C. Evaluation and management of behavioral health disorders in women: an overview of major depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, and sleep in the primary care setting. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2016;43(2):231-246.

20. Colorafi K, Vanselow J, Nelson T. Treating anxiety and depression in primary care: reducing barriers to access. Fam Pract Manag. 2017;24(4):11-16.

21. McCall WV. Defining the unique scope of psychiatric practice in 2015. J ECT. 2015;31(4):203-204.

1. Detroit Wayne Integrated Health Network. DWMHA psychiatric practice standards. http://dwihn.org/files/2015/6451/9628/Psychiatric_Practice_Standards.pdf. Revised June 2018. Accessed October 8, 2019.

2. Seaman JJ, Cornfield RM, Cummings DM, et al. Exploring psychiatric prescribing practices: the relationship between the role of the provider and the appropriateness of prescribing. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1987;9(3):220-224.

3. Zivanovic O. Lithium: a classic drug—frequently discussed, but, sadly, seldom prescribed! Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(9):886-896.

4. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, et al. Geographic and clinical variation in clozapine use in the United States. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(2):186-192.

5. Balon R, Mufti R, Arfken C. A survey of prescribing practices for monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(7):945-947.

6. Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;123(2-3):225-233.

7. Wu RR, Zhao JP, Jin H, et al. Lifestyle intervention and metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(2):185-193.

8. De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52-77.

9. Kirpichnikov D, McFarlane SI, Sowers JR. Metformin: an update. Ann Internal Med. 2002;137(1):25-33.

10. Balon R. SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1504-1509.

11. Balon R, Morreale MK, Segraves RT. Prescribing of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors among psychiatrists. J Sex Marital Ther. 2014;40(3):165-169.

12. Taylor MJ, Rudkin L, Bullemor-Day P, et al. Strategies for managing sexual dysfunction induced by antidepressant medication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD003382.

13. Dording CM, LaRocca RA, Hails KA, et al. The effect of sildenafil on quality of life. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25(1):3-10.

14. Pagano HP, Zapata LB, Berry-Bibee EN, et al. Safety of hormonal contraception and intrauterine devices among women with depressive and bipolar disorders: a systematic review. Contraception. 2016;94(6):641-649.

15. Kibirige D, Luzinda K, Ssekitoleko R. Spectrum of lithium induced thyroid abnormalities: a current perspective. Thyroid Res. 2013;6(1):3.

16. Gitlin M. Lithium side effects and toxicity: prevalence and management strategies. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2016;4(1):27.

17. Devdhar M, Ousman YH, Burman KD. Hypothyroidism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36(3):595-615.

18. Hackley B, Sharma C, Kedzior A, et al. Managing mental health conditions in primary care settings. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2010;55(1):9-19.

19. Fitelson E, McGibbon C. Evaluation and management of behavioral health disorders in women: an overview of major depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, and sleep in the primary care setting. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2016;43(2):231-246.

20. Colorafi K, Vanselow J, Nelson T. Treating anxiety and depression in primary care: reducing barriers to access. Fam Pract Manag. 2017;24(4):11-16.

21. McCall WV. Defining the unique scope of psychiatric practice in 2015. J ECT. 2015;31(4):203-204.

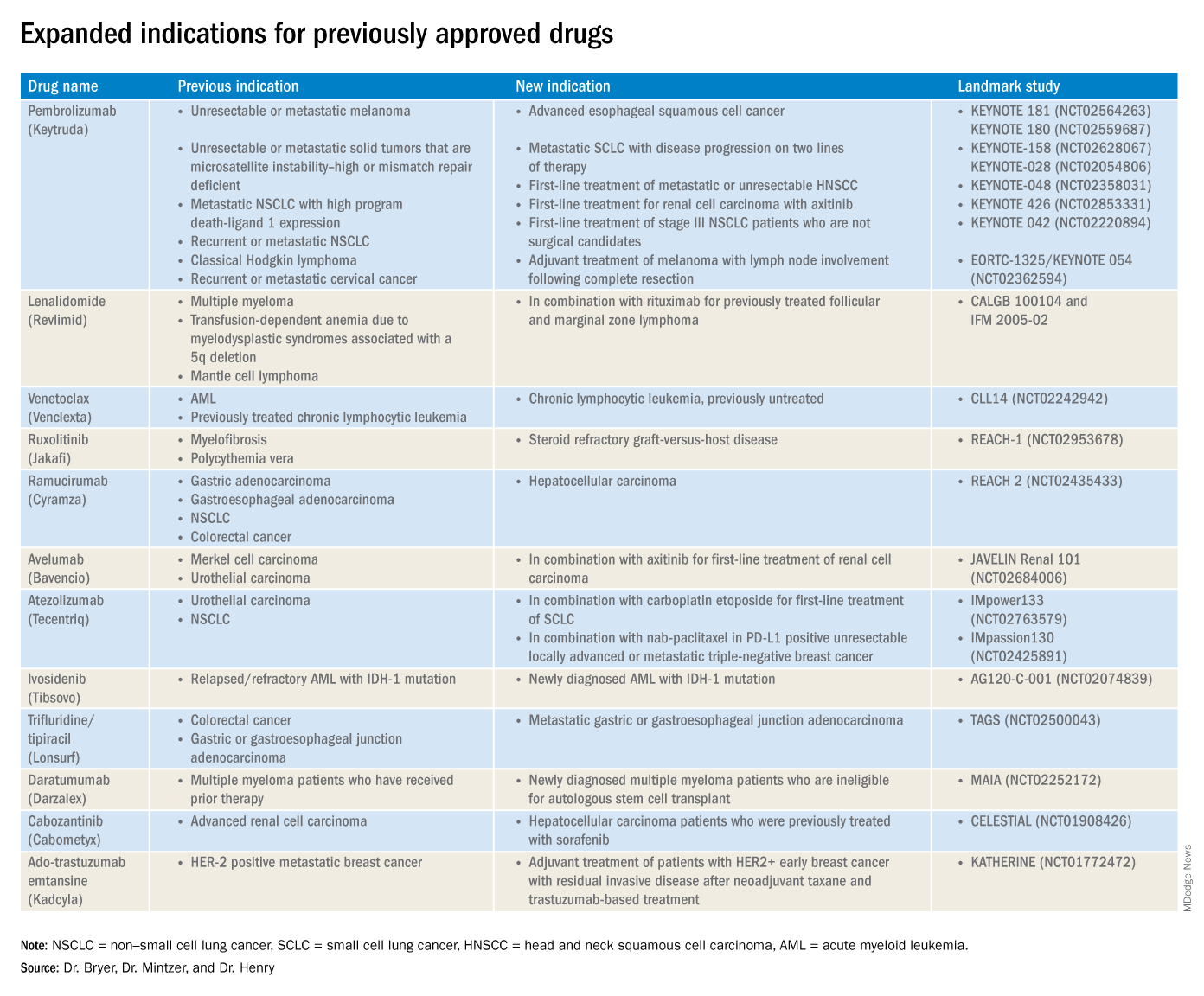

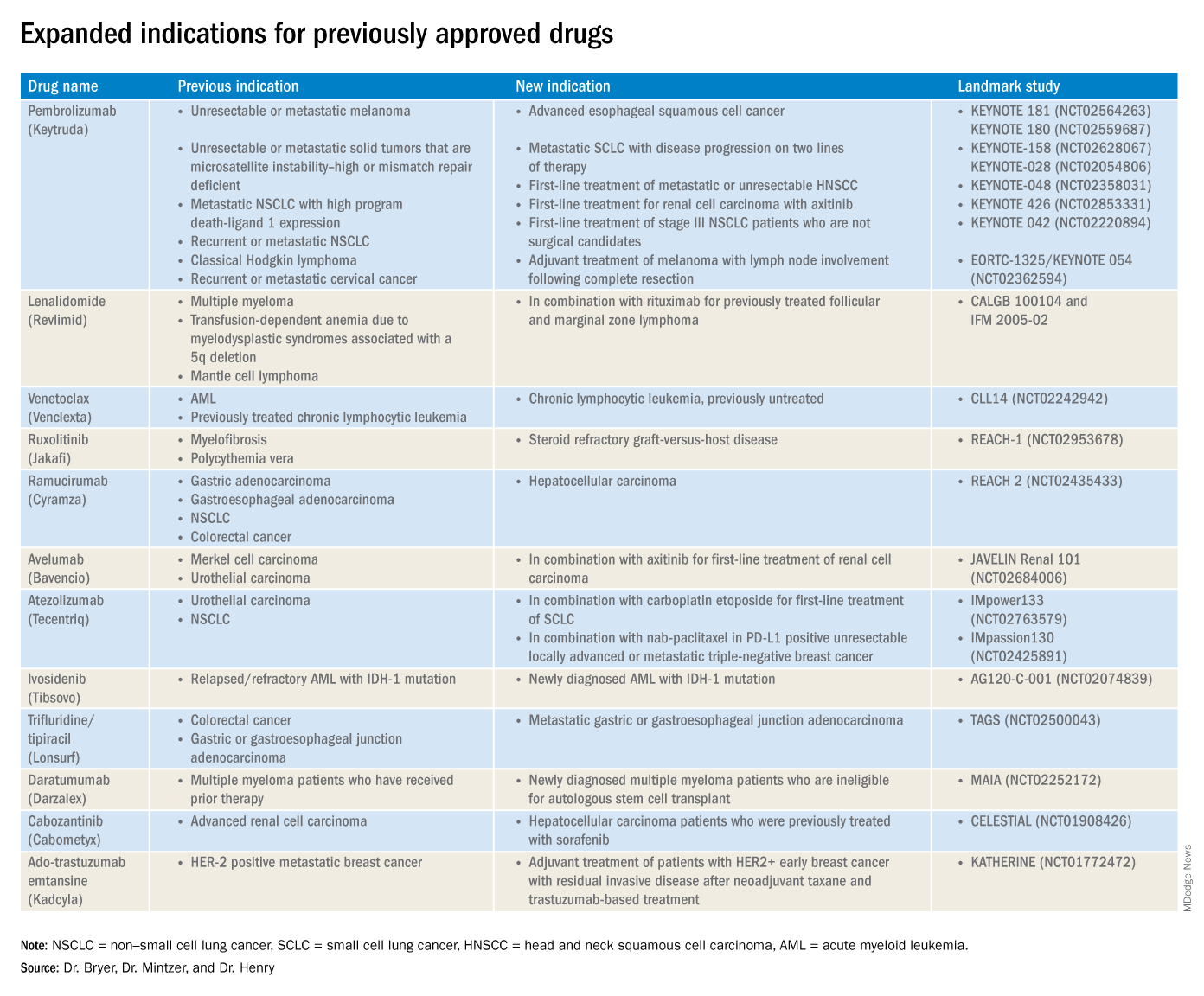

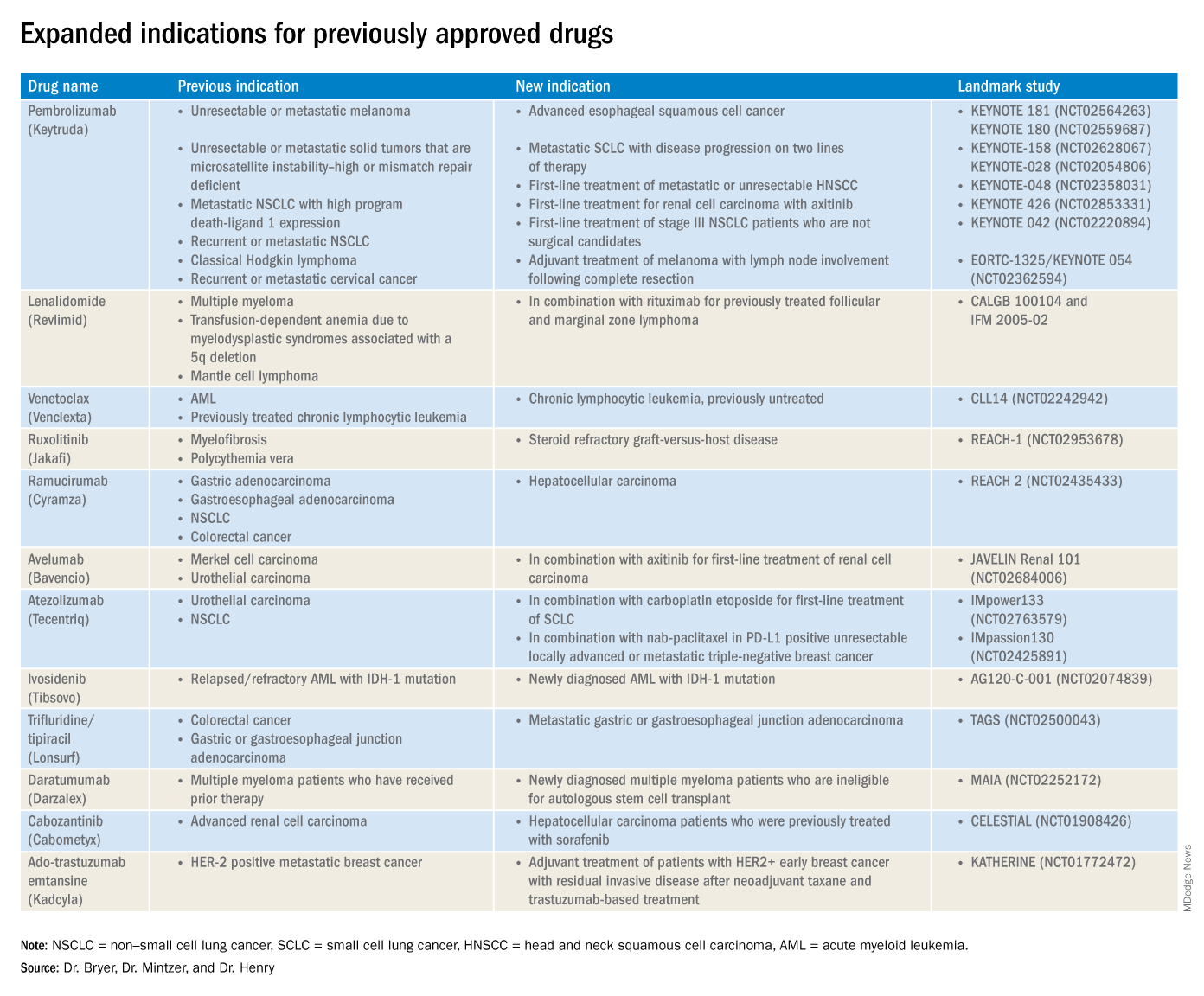

2019 at a glance: Hem-onc U.S. drug approvals

The rapid development and identification of novel drugs has translated into innovative therapies in hematology and oncology. The aim of this piece is to present newly approved drugs and expanded indications to serve as a reference guide for practicing clinicians.

This article reviews therapies that were newly approved so far in 2019, as well as those previously approved whose indications were expanded this past year. The list highlights the most clinically important approvals, as well as adverse events that are unique or especially severe.

New approvals

Fedratinib (Inrebic)

Class: JAK2 and FLT3 selective kinase inhibitor.

Disease: Intermediate or high-risk primary or secondary (postpolycythemia vera or postessential thrombocythemia) myelofibrosis.

Dose: 400 mg orally once daily, with or without food.

Adverse events (AEs): Black box warning: Fatal encephalopathy, including Wernicke’s (thiamine level monitoring suggested).

Trials: In JAKARTA (NCT01437787), 37% of patients achieved a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume and 40% received a 50% or greater reduction in myelofibrosis-related symptoms. In Jakarta-2, there was a 55% spleen response in patients resistant or intolerant to ruxolitinib.

Entrectinib (Rozlytrek)

Class: Tropomyosin receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Disease: Solid tumors that have a neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase (NTRK) gene fusion and for ROS-1 positive non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Dose: 600 mg orally once daily.

AEs: Heart failure, QT prolongation, skeletal fractures, hepatotoxicity, central nervous system effects, and hyperuricemia.

Trial: ALKA, STARTRK-1 (NCT02097810) and STARTRK-2 (NCT02568267): Overall response rate of 57% for NTRK positive patients; response rate of 77% in ROS-1 positive NSCLC.

Pexidartinib (Turalio)

Class: Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting CSF1R.

Disease: Symptomatic tenosynovial giant cell tumor.

Dose: 400 mg orally twice daily without food.

AEs: Black box warning on hepatotoxicity.

Trial: ENLIVEN (NCT02371369): Overall response rate of 38% at 25 weeks, with a 15% complete response rate and a 23% partial response rate.

Darolutamide (Nubeqa)

Class: Androgen receptor inhibitor.

Disease: Nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Dose: 600 mg orally twice daily with food with concomitant androgen deprivation therapy.

AEs: Fatigue, extremity pain, and rash.

Trial: ARAMIS (NCT02200614): Median metastasis free survival was 40.4 months for patients with darolutamide, compared with 18.4 months for controls.

Selinexor (Xpovio)

Class: Reversible inhibitor of nuclear export of tumor suppressor proteins, growth regulators, and mRNAs of oncogenic proteins.

Disease: Relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Indicated for patients who have received at least four prior therapies, including at least two immunomodulatory agents and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody.

Dose: 80 mg orally in combination with oral dexamethasone on days 1 and 3 of each week.

AEs: Thrombocytopenia, fatigue, pancytopenia, and hyponatremia.

Trial: STORM (NCT02336815): Overall response rate 25.3% with a median time to first response of 4 weeks and 3.8-month median duration of response.

Polatuzumab vedotin-piiq (Polivy)

Class: CD79b-directed antibody-drug conjugate.

Disease: Relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Indicated for patients who have had at least two prior therapies.

Dose: 1.8 mg/kg intravenous infusion every 21 days for six cycles in combination with bendamustine and a rituximab product.

AEs: Pancytopenia, peripheral neuropathy.

Trial: GO29365 (NCT02257567): Complete response rate was 40% for polatuzumab vedotin-piiq plus bendamustine/rituximab, compared with 18% with bendamustine/rituximab alone.*

Caplacizumab-yhdp (Cablivi)

Class: Monoclonal antibody fragment directed against von Willebrand factor.

Disease: Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Dose: 11 mg IV initially, then daily subcutaneously; in combination with plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy.

AEs: Epistaxis, headache, and gingival bleeding.

Trial: Hercules trial (NCT02553317): More rapid normalization of platelets, lower incidence of composite TTP-related death, and lower rate of recurrence when added to plasma exchange and steroids.

Alpelisib (Piqray)

Class: Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor.

Disease: Hormone receptor positive HER2-negative PIK3CA-mutated, advanced or metastatic breast cancer.

Dose: 300 mg orally once daily with food with concomitant fulvestrant.

AEs: Hyperglycemia, pancytopenia.

Trial: SOLAR-1 (NCT02437318): 11-month progression-free survival among patients treated with alpelisib and fulvestrant, compared with 5.7 months in fulvestrant alone control arm; overall response rate of 36% versus 16%, respectively.

Erdafitinib (Balversa)

Class: Fibroblast growth factor receptor kinase inhibitor.

Disease: Locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma with FGFR3 or FGFR2 mutations.

Dose: 8 mg orally once daily, with or without food.

AEs: Ocular disorders including retinopathy or retinal detachment.

Trial: BLC2001 (NCT02365597): Objective response rate of 32.2%, with a complete response in 2.3% of patients and partial response in 29.9% of patients.

Biosimilar approvals

Trastuzumab and hyaluronidase-oysk (Herceptin Hylecta)

Biosimilar to: Trastuzumab.

Indication: HER2-overexpressing breast cancer.

Dr. Bryer is a resident in the department of internal medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Mintzer is chief of hematology-oncology at Pennsylvania Hospital and professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Henry is a hematologist-oncologist at Pennsylvania Hospital and professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

*Correction, 11/7/2019: An earlier version of this article misstated the drug combination in the GO29365 trial.

The rapid development and identification of novel drugs has translated into innovative therapies in hematology and oncology. The aim of this piece is to present newly approved drugs and expanded indications to serve as a reference guide for practicing clinicians.

This article reviews therapies that were newly approved so far in 2019, as well as those previously approved whose indications were expanded this past year. The list highlights the most clinically important approvals, as well as adverse events that are unique or especially severe.

New approvals

Fedratinib (Inrebic)

Class: JAK2 and FLT3 selective kinase inhibitor.

Disease: Intermediate or high-risk primary or secondary (postpolycythemia vera or postessential thrombocythemia) myelofibrosis.

Dose: 400 mg orally once daily, with or without food.

Adverse events (AEs): Black box warning: Fatal encephalopathy, including Wernicke’s (thiamine level monitoring suggested).

Trials: In JAKARTA (NCT01437787), 37% of patients achieved a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume and 40% received a 50% or greater reduction in myelofibrosis-related symptoms. In Jakarta-2, there was a 55% spleen response in patients resistant or intolerant to ruxolitinib.

Entrectinib (Rozlytrek)

Class: Tropomyosin receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Disease: Solid tumors that have a neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase (NTRK) gene fusion and for ROS-1 positive non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Dose: 600 mg orally once daily.

AEs: Heart failure, QT prolongation, skeletal fractures, hepatotoxicity, central nervous system effects, and hyperuricemia.

Trial: ALKA, STARTRK-1 (NCT02097810) and STARTRK-2 (NCT02568267): Overall response rate of 57% for NTRK positive patients; response rate of 77% in ROS-1 positive NSCLC.

Pexidartinib (Turalio)

Class: Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting CSF1R.

Disease: Symptomatic tenosynovial giant cell tumor.

Dose: 400 mg orally twice daily without food.

AEs: Black box warning on hepatotoxicity.

Trial: ENLIVEN (NCT02371369): Overall response rate of 38% at 25 weeks, with a 15% complete response rate and a 23% partial response rate.

Darolutamide (Nubeqa)

Class: Androgen receptor inhibitor.

Disease: Nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Dose: 600 mg orally twice daily with food with concomitant androgen deprivation therapy.

AEs: Fatigue, extremity pain, and rash.

Trial: ARAMIS (NCT02200614): Median metastasis free survival was 40.4 months for patients with darolutamide, compared with 18.4 months for controls.

Selinexor (Xpovio)

Class: Reversible inhibitor of nuclear export of tumor suppressor proteins, growth regulators, and mRNAs of oncogenic proteins.

Disease: Relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Indicated for patients who have received at least four prior therapies, including at least two immunomodulatory agents and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody.

Dose: 80 mg orally in combination with oral dexamethasone on days 1 and 3 of each week.

AEs: Thrombocytopenia, fatigue, pancytopenia, and hyponatremia.

Trial: STORM (NCT02336815): Overall response rate 25.3% with a median time to first response of 4 weeks and 3.8-month median duration of response.

Polatuzumab vedotin-piiq (Polivy)

Class: CD79b-directed antibody-drug conjugate.

Disease: Relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Indicated for patients who have had at least two prior therapies.

Dose: 1.8 mg/kg intravenous infusion every 21 days for six cycles in combination with bendamustine and a rituximab product.

AEs: Pancytopenia, peripheral neuropathy.

Trial: GO29365 (NCT02257567): Complete response rate was 40% for polatuzumab vedotin-piiq plus bendamustine/rituximab, compared with 18% with bendamustine/rituximab alone.*

Caplacizumab-yhdp (Cablivi)

Class: Monoclonal antibody fragment directed against von Willebrand factor.

Disease: Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Dose: 11 mg IV initially, then daily subcutaneously; in combination with plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy.

AEs: Epistaxis, headache, and gingival bleeding.

Trial: Hercules trial (NCT02553317): More rapid normalization of platelets, lower incidence of composite TTP-related death, and lower rate of recurrence when added to plasma exchange and steroids.

Alpelisib (Piqray)

Class: Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor.

Disease: Hormone receptor positive HER2-negative PIK3CA-mutated, advanced or metastatic breast cancer.

Dose: 300 mg orally once daily with food with concomitant fulvestrant.

AEs: Hyperglycemia, pancytopenia.

Trial: SOLAR-1 (NCT02437318): 11-month progression-free survival among patients treated with alpelisib and fulvestrant, compared with 5.7 months in fulvestrant alone control arm; overall response rate of 36% versus 16%, respectively.

Erdafitinib (Balversa)

Class: Fibroblast growth factor receptor kinase inhibitor.

Disease: Locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma with FGFR3 or FGFR2 mutations.

Dose: 8 mg orally once daily, with or without food.

AEs: Ocular disorders including retinopathy or retinal detachment.

Trial: BLC2001 (NCT02365597): Objective response rate of 32.2%, with a complete response in 2.3% of patients and partial response in 29.9% of patients.

Biosimilar approvals

Trastuzumab and hyaluronidase-oysk (Herceptin Hylecta)

Biosimilar to: Trastuzumab.

Indication: HER2-overexpressing breast cancer.

Dr. Bryer is a resident in the department of internal medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Mintzer is chief of hematology-oncology at Pennsylvania Hospital and professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Henry is a hematologist-oncologist at Pennsylvania Hospital and professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

*Correction, 11/7/2019: An earlier version of this article misstated the drug combination in the GO29365 trial.

The rapid development and identification of novel drugs has translated into innovative therapies in hematology and oncology. The aim of this piece is to present newly approved drugs and expanded indications to serve as a reference guide for practicing clinicians.

This article reviews therapies that were newly approved so far in 2019, as well as those previously approved whose indications were expanded this past year. The list highlights the most clinically important approvals, as well as adverse events that are unique or especially severe.

New approvals

Fedratinib (Inrebic)

Class: JAK2 and FLT3 selective kinase inhibitor.

Disease: Intermediate or high-risk primary or secondary (postpolycythemia vera or postessential thrombocythemia) myelofibrosis.

Dose: 400 mg orally once daily, with or without food.

Adverse events (AEs): Black box warning: Fatal encephalopathy, including Wernicke’s (thiamine level monitoring suggested).

Trials: In JAKARTA (NCT01437787), 37% of patients achieved a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume and 40% received a 50% or greater reduction in myelofibrosis-related symptoms. In Jakarta-2, there was a 55% spleen response in patients resistant or intolerant to ruxolitinib.

Entrectinib (Rozlytrek)

Class: Tropomyosin receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Disease: Solid tumors that have a neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase (NTRK) gene fusion and for ROS-1 positive non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Dose: 600 mg orally once daily.

AEs: Heart failure, QT prolongation, skeletal fractures, hepatotoxicity, central nervous system effects, and hyperuricemia.

Trial: ALKA, STARTRK-1 (NCT02097810) and STARTRK-2 (NCT02568267): Overall response rate of 57% for NTRK positive patients; response rate of 77% in ROS-1 positive NSCLC.

Pexidartinib (Turalio)

Class: Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting CSF1R.

Disease: Symptomatic tenosynovial giant cell tumor.

Dose: 400 mg orally twice daily without food.

AEs: Black box warning on hepatotoxicity.

Trial: ENLIVEN (NCT02371369): Overall response rate of 38% at 25 weeks, with a 15% complete response rate and a 23% partial response rate.

Darolutamide (Nubeqa)

Class: Androgen receptor inhibitor.

Disease: Nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Dose: 600 mg orally twice daily with food with concomitant androgen deprivation therapy.

AEs: Fatigue, extremity pain, and rash.

Trial: ARAMIS (NCT02200614): Median metastasis free survival was 40.4 months for patients with darolutamide, compared with 18.4 months for controls.

Selinexor (Xpovio)

Class: Reversible inhibitor of nuclear export of tumor suppressor proteins, growth regulators, and mRNAs of oncogenic proteins.

Disease: Relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Indicated for patients who have received at least four prior therapies, including at least two immunomodulatory agents and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody.

Dose: 80 mg orally in combination with oral dexamethasone on days 1 and 3 of each week.

AEs: Thrombocytopenia, fatigue, pancytopenia, and hyponatremia.

Trial: STORM (NCT02336815): Overall response rate 25.3% with a median time to first response of 4 weeks and 3.8-month median duration of response.

Polatuzumab vedotin-piiq (Polivy)

Class: CD79b-directed antibody-drug conjugate.

Disease: Relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Indicated for patients who have had at least two prior therapies.

Dose: 1.8 mg/kg intravenous infusion every 21 days for six cycles in combination with bendamustine and a rituximab product.

AEs: Pancytopenia, peripheral neuropathy.

Trial: GO29365 (NCT02257567): Complete response rate was 40% for polatuzumab vedotin-piiq plus bendamustine/rituximab, compared with 18% with bendamustine/rituximab alone.*

Caplacizumab-yhdp (Cablivi)

Class: Monoclonal antibody fragment directed against von Willebrand factor.

Disease: Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Dose: 11 mg IV initially, then daily subcutaneously; in combination with plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy.

AEs: Epistaxis, headache, and gingival bleeding.

Trial: Hercules trial (NCT02553317): More rapid normalization of platelets, lower incidence of composite TTP-related death, and lower rate of recurrence when added to plasma exchange and steroids.

Alpelisib (Piqray)

Class: Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor.

Disease: Hormone receptor positive HER2-negative PIK3CA-mutated, advanced or metastatic breast cancer.

Dose: 300 mg orally once daily with food with concomitant fulvestrant.

AEs: Hyperglycemia, pancytopenia.

Trial: SOLAR-1 (NCT02437318): 11-month progression-free survival among patients treated with alpelisib and fulvestrant, compared with 5.7 months in fulvestrant alone control arm; overall response rate of 36% versus 16%, respectively.

Erdafitinib (Balversa)

Class: Fibroblast growth factor receptor kinase inhibitor.

Disease: Locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma with FGFR3 or FGFR2 mutations.

Dose: 8 mg orally once daily, with or without food.

AEs: Ocular disorders including retinopathy or retinal detachment.

Trial: BLC2001 (NCT02365597): Objective response rate of 32.2%, with a complete response in 2.3% of patients and partial response in 29.9% of patients.

Biosimilar approvals

Trastuzumab and hyaluronidase-oysk (Herceptin Hylecta)

Biosimilar to: Trastuzumab.

Indication: HER2-overexpressing breast cancer.

Dr. Bryer is a resident in the department of internal medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Mintzer is chief of hematology-oncology at Pennsylvania Hospital and professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Henry is a hematologist-oncologist at Pennsylvania Hospital and professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

*Correction, 11/7/2019: An earlier version of this article misstated the drug combination in the GO29365 trial.

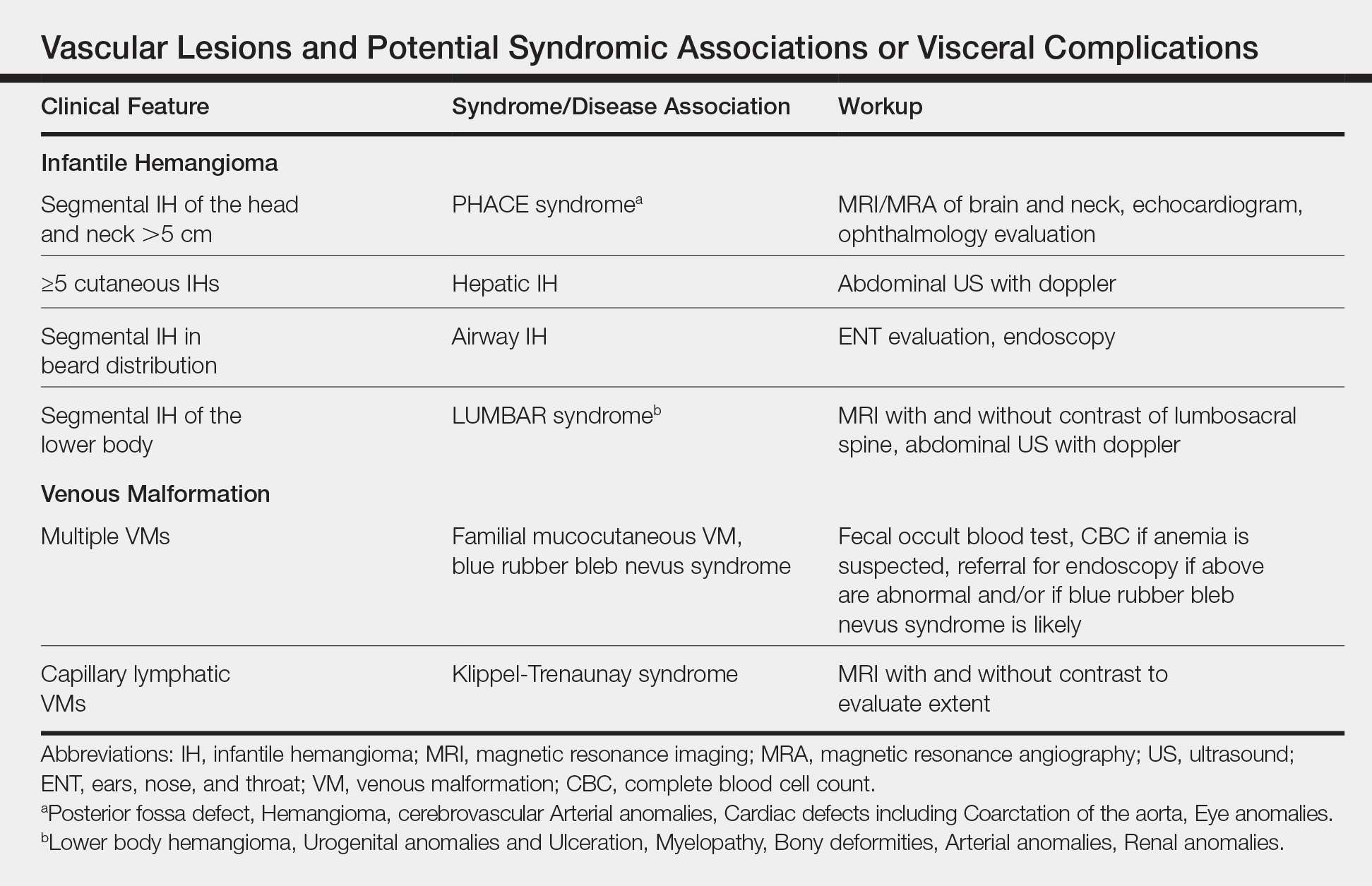

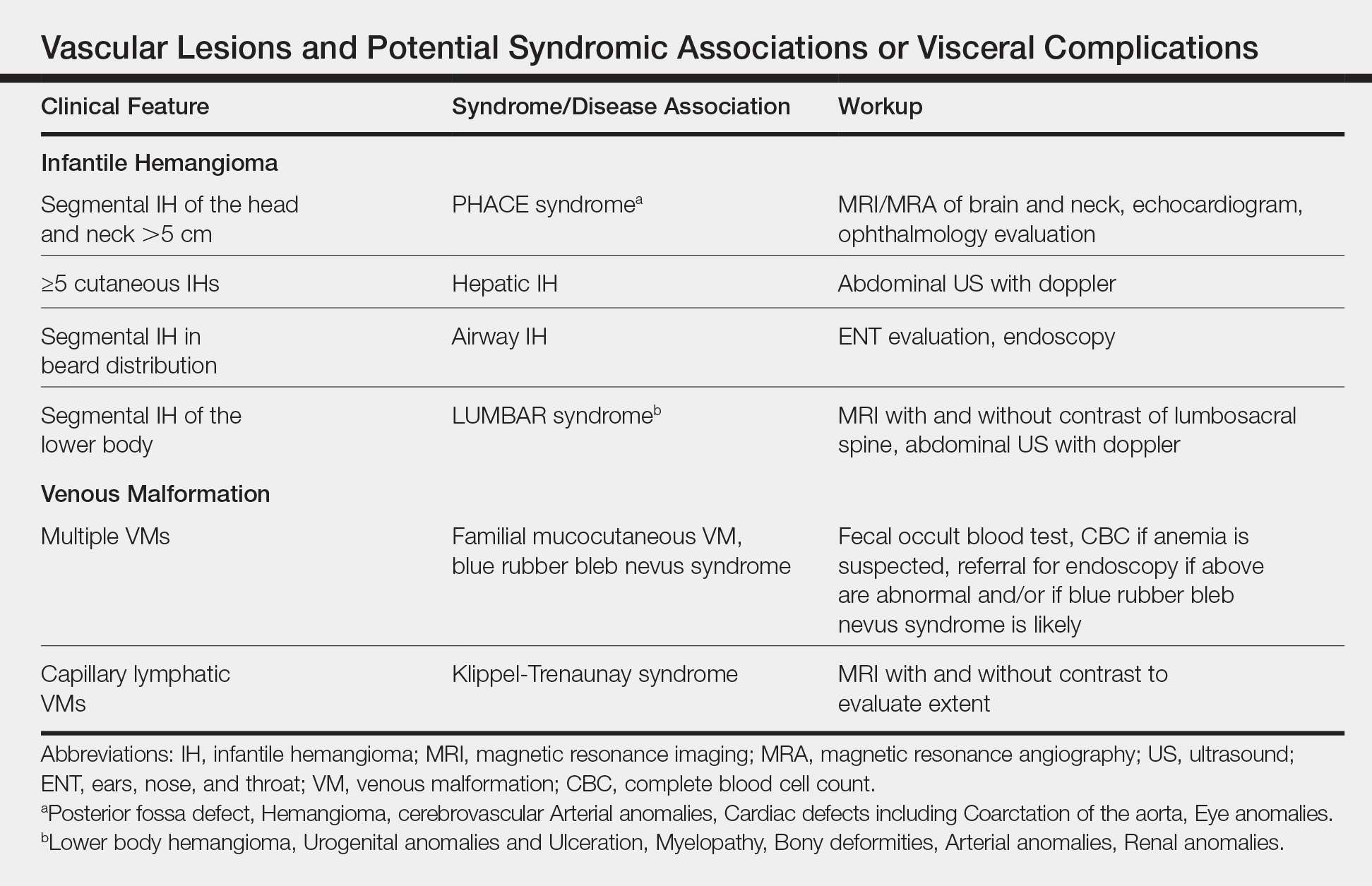

Neonatal Consultations: Vascular Lumps, Bumps, and Tumors in the Neonate

Although most neonatal vascular lumps, bumps, and tumors are benign, proper diagnosis is important for prognosis and management. Therefore, knowledge of both common and rare conditions is important when evaluating a neonatal nodule. Differential diagnosis of neonatal vascular nodules must focus on important diagnostic clues that should prompt consideration and evaluation for less common and/or potentially threatening conditions. Infantile hemangioma (IH), congenital hemangioma (CH), venous malformation (VM), lymphatic malformation (LM), kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) and tufted angioma, and malignant tumors are reviewed here.

Infantile Hemangioma

Infantile hemangioma, a benign proliferation of capillaries, is the most common tumor of infancy with reported incidence of up to 5% in neonates.1 As such, suspicion for less common lesions is often predicated on identifying features that would be atypical for an IH. A superficial IH presents as a bright red papule, nodule, or plaque, while a deep IH presents as a flesh-colored to bluish nodule. Mixed IHs combine features of both superficial and deep lesions. The distribution may be focal or segmental, with segmental lesions encompassing a larger territory–like distribution and frequently displaying a thin, coarsely telangiectatic appearance.

Knowledge of the natural history of IH generally is crucial in differentiating it from other neonatal lesions. Infantile hemangiomas display a natural history that is distinct and predictable. They typically manifest within the first few weeks of life, though up to 30% present at birth with a premonitory mark, which may be a light red, pink, bluish, or vasoconstricted patch. Thus, mere presence of a lesion at birth is not the feature that distinguishes other congenital lesions from an IH. After initial appearance, IHs undergo a period of proliferation that occurs over 4 to 6 months in most patients. In some cases, areas of proliferation may be subtle, but nonetheless the presence of some areas of increased redness and/or volumetric growth generally is required to firmly establish the diagnosis of IH. Thereafter, IH will involute, a process that begins before 1 year of age in most cases and continues over years. Although IHs undergo involution, complete clearance may not occur, as nearly 70% will leave permanent residua such as fibrofatty masses or anetodermic skin.2 Nevertheless, the presence of a proliferative phase followed by a slower period of involution is a hallmark feature of the IH.

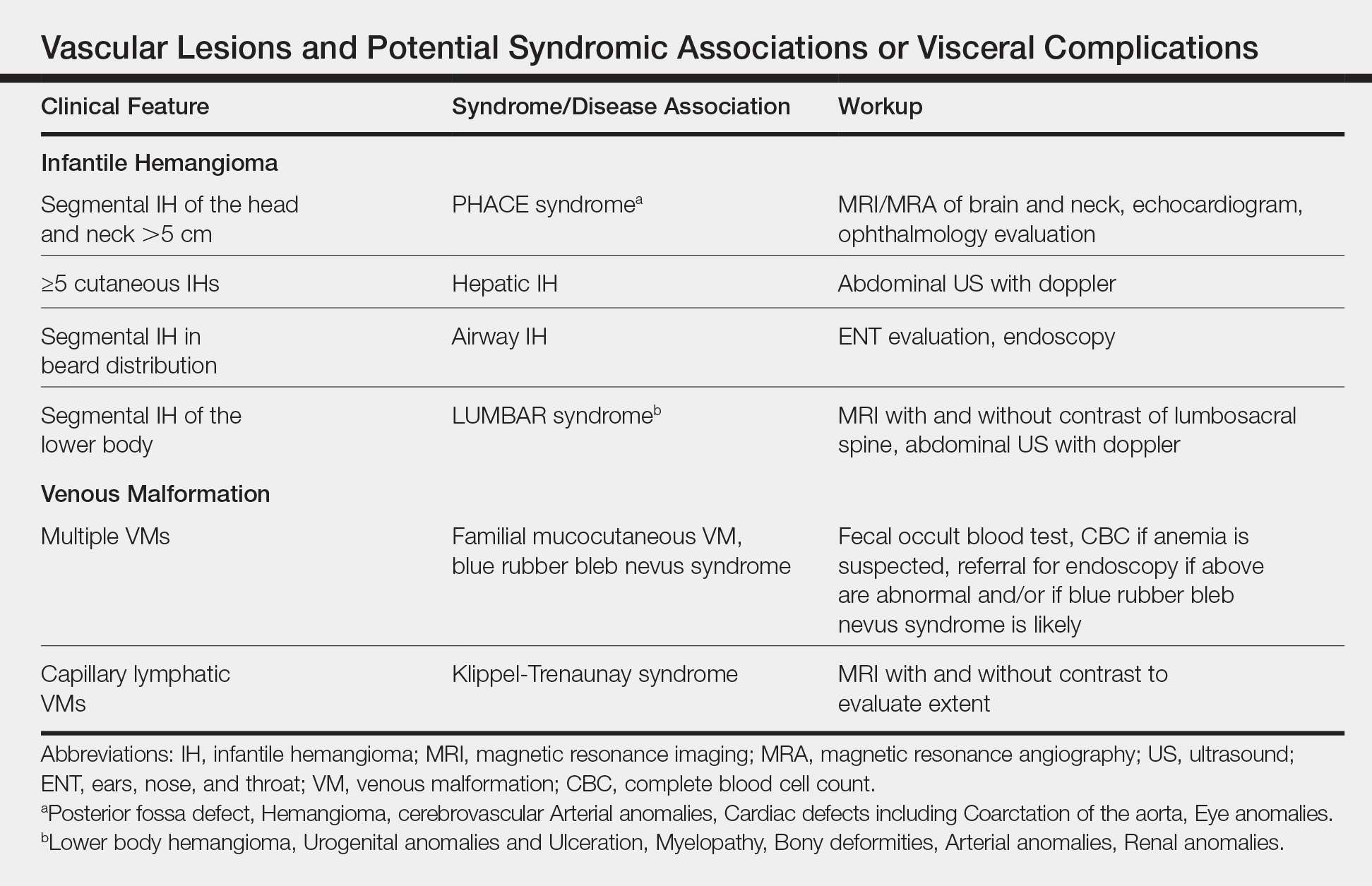

Biopsy and imaging rarely are required for establishing diagnosis of an IH. Histopathology showing a proliferation of capillaries with positive glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1) staining is characteristic. Imaging with ultrasound reveals a fast-flow lesion. Apart from exceptionally rare cases, a cutaneous IH typically does not cross muscle fascia, and thus alternative diagnoses should be considered for a cutaneous lesion that demonstrates infiltration into nerve, bone, joint, or other deeper tissues. Most IHs do not require treatment; however, a small subset may be associated with complications and thus require intervention. Complications of IH may include impairment of function (eg, vision, feeding, respiratory), ulceration, and risk for permanent disfigurement. When treatment is indicated, the most commonly employed options during the proliferative phase are the topical beta-blocker timolol and the oral beta-blocker propranolol. In addition, certain IHs may be associated with either syndromic presentations and/or visceral involvement, thus requiring further workup (Table).

Congenital Hemangioma

A CH is an uncommon benign neonatal tumor that is distinct from an IH in behavior, biology, and treatment. Congenital hemangiomas may have a rapidly involuting course, referred to as RICH (rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma), or a noninvoluting course, referred to as NICH (noninvoluting congenital hemangioma). Partially involuting types also have been described.3 A RICH typically presents as a highly vascular, red-violaceous or bluish plaque, nodule, or large mass at birth. An NICH presents as a red-violaceous or bluish, coarsely telangiectatic patch, plaque, or nodule. A characteristic feature of the CH is the rim of vasoconstriction around the lesion, which is an important diagnostic clue (Figure 1). In contrast to IH, multifocal lesions are highly unlikely in CH, though it rarely has been reported.4

Regardless of subtype, CHs are fully developed at birth. Infantile hemangiomas, on the other hand, are either minimally present or not present at birth and thereafter proliferate. After birth, a RICH rapidly involutes over the first 9 to 12 months of life. This process generally is evident even in the first few weeks of life, which would not be expected of an IH and is therefore a major distinguishing factor. A NICH, on the other hand, is expected to be persistent, for the most part neither showing signs of proliferation nor involution.

Complications of CHs may include ulceration, functional impairment, or risk for permanent disfigurement depending on location. In addition, due to their fast-flow state and potential large size, some CHs may be complicated by high-output heart failure in the neonate. Distinguishing an IH from a CH is important not only for prognosis but also treatment. Beta-blocker therapy generally is not useful for CHs, and management usually is supportive in the neonatal period.

In the majority of cases, diagnosis can be achieved solely on clinical features. Biopsy with immunohistochemistry shows negative GLUT-1 staining, which will distinguish this lesion from an IH. At times, the highly vascular nature and/or striking size of a CH may lead some to consider the potential diagnosis of an arteriovenous malformation. However, soft-tissue arteriovenous malformations involving the skin are almost never fully developed in the neonatal period and generally take years to evolve from a quiescent state to a destructive lesion.

Venous Malformation