User login

Responding to pseudoscience

The Internet has been a transformative means of transmitting information. Alas, the information is often not vetted, so the effects on science, truth, and health literacy have been mixed. Unfortunately, Facebook spawned a billion dollar industry that transmits gossip. Twitter distributes information based on celebrity rather than intelligence or expertise.

Listservs and Google groups have allowed small communities to form unrestricted by the physical locations of the members. A listserv for pediatric hospitalists, with 3,800 members, provides quick access to a vast body of knowledge, an extensive array of experience, and insightful clinical wisdom. Discussions on this listserv resource have inspired several of my columns, including this one. The professionalism of the listserv members ensures the accuracy of the messages. Because many of the members work nights, it is possible to post a question and receive five consults from peers, even at 1 a.m. When I first started office practice in rural areas, all I had available was my memory, Rudolph’s Pediatrics textbook, and The Harriet Lane Handbook.

Misinformation has led to vaccine hesitancy and the reemergence of diseases such as measles that had been essentially eliminated. Because people haven’t seen these diseases, they are prone to believing any critique about the risk of vaccines. More recently, parents have been refusing the vitamin K shot that is provided to all newborns to prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, now called vitamin K deficiency bleeding. The incidence of this bleeding disorder is relatively rare. However, when it occurs, the results can be disastrous, with life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeds and disabling brain hemorrhages. As with vaccine hesitancy, the corruption of scientific knowledge has led to bad outcomes that once were nearly eliminated by modern health care.

Part of being a professional is communicating in a manner that helps parents understand small risks. I compare newborn vitamin K deficiency to the risk of driving the newborn around for the first 30 days of life without a car seat. The vast majority of people will not have an accident in that time and their babies will be fine. But emergency department doctors would see so many preventable cases of injury that they would strongly advocate for car seats. I also note that if the baby has a stroke due to vitamin K deficiency, we can’t catch it early and fix it.

One issue that comes up in the nursery is whether the physician should refuse to perform a circumcision on a newborn who has not received vitamin K. The risk of bleeding is increased further when circumcisions are done as outpatient procedures a few days after birth. When this topic was discussed on the hospitalist’s listserv, most respondents took a hard line and would not perform the procedure. I am more ambivalent because of my strong personal value of accommodating diverse views and perhaps because I have never experienced a severe case of postop bleeding. The absolute risk is low.

The ethical issues are similar to those involved in maintaining or dismissing families from your practice panel if they refuse vaccines. Some physicians think the threat of having to find another doctor is the only way to appear credible when advocating the use of vaccines. Actions speak louder than words. Other physicians are dedicated to accommodating diverse viewpoints. They try to persuade over time. This is a complex subject and the American Academy of Pediatrics’ position on this changed 2 years ago to consider dismissal as a viable option as long as it adheres to relevant state laws that prohibit abandonment of patients.1

Respect for science has diminished since the era when men walked on the moon. There are myriad reasons for this. They exceed what can be covered here. All human endeavors wax and wane in their prestige and credibility. The 1960s was an era of great technological progress in many areas, including space flight and medicine. Since then, the credibility of science has been harmed by mercenary scientists who do research not to illuminate truth but to sow doubt.2 This doubt has impeded educating the public about the risks of smoking, lead paint, and climate change.

Physicians themselves have contributed to this diminished credibility of scientists. Recommendations have been published and later withdrawn in areas such as dietary cholesterol, salt, and saturated fats, estrogen replacement therapy, and screening for prostate and breast cancers. In modern America, even small inconsistencies and errors get blown up into conspiracy plots.

The era of expecting patients to blindly follow a doctor’s orders has long since passed. Parents will search the Internet for answers. The modern physician needs to guide them to good ones.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2146.

2. “Doubt is Their Product,” by David Michaels, Oxford University Press, 2008, and “Merchants of Doubt,” by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Bloomsbury Press, 2011.

The Internet has been a transformative means of transmitting information. Alas, the information is often not vetted, so the effects on science, truth, and health literacy have been mixed. Unfortunately, Facebook spawned a billion dollar industry that transmits gossip. Twitter distributes information based on celebrity rather than intelligence or expertise.

Listservs and Google groups have allowed small communities to form unrestricted by the physical locations of the members. A listserv for pediatric hospitalists, with 3,800 members, provides quick access to a vast body of knowledge, an extensive array of experience, and insightful clinical wisdom. Discussions on this listserv resource have inspired several of my columns, including this one. The professionalism of the listserv members ensures the accuracy of the messages. Because many of the members work nights, it is possible to post a question and receive five consults from peers, even at 1 a.m. When I first started office practice in rural areas, all I had available was my memory, Rudolph’s Pediatrics textbook, and The Harriet Lane Handbook.

Misinformation has led to vaccine hesitancy and the reemergence of diseases such as measles that had been essentially eliminated. Because people haven’t seen these diseases, they are prone to believing any critique about the risk of vaccines. More recently, parents have been refusing the vitamin K shot that is provided to all newborns to prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, now called vitamin K deficiency bleeding. The incidence of this bleeding disorder is relatively rare. However, when it occurs, the results can be disastrous, with life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeds and disabling brain hemorrhages. As with vaccine hesitancy, the corruption of scientific knowledge has led to bad outcomes that once were nearly eliminated by modern health care.

Part of being a professional is communicating in a manner that helps parents understand small risks. I compare newborn vitamin K deficiency to the risk of driving the newborn around for the first 30 days of life without a car seat. The vast majority of people will not have an accident in that time and their babies will be fine. But emergency department doctors would see so many preventable cases of injury that they would strongly advocate for car seats. I also note that if the baby has a stroke due to vitamin K deficiency, we can’t catch it early and fix it.

One issue that comes up in the nursery is whether the physician should refuse to perform a circumcision on a newborn who has not received vitamin K. The risk of bleeding is increased further when circumcisions are done as outpatient procedures a few days after birth. When this topic was discussed on the hospitalist’s listserv, most respondents took a hard line and would not perform the procedure. I am more ambivalent because of my strong personal value of accommodating diverse views and perhaps because I have never experienced a severe case of postop bleeding. The absolute risk is low.

The ethical issues are similar to those involved in maintaining or dismissing families from your practice panel if they refuse vaccines. Some physicians think the threat of having to find another doctor is the only way to appear credible when advocating the use of vaccines. Actions speak louder than words. Other physicians are dedicated to accommodating diverse viewpoints. They try to persuade over time. This is a complex subject and the American Academy of Pediatrics’ position on this changed 2 years ago to consider dismissal as a viable option as long as it adheres to relevant state laws that prohibit abandonment of patients.1

Respect for science has diminished since the era when men walked on the moon. There are myriad reasons for this. They exceed what can be covered here. All human endeavors wax and wane in their prestige and credibility. The 1960s was an era of great technological progress in many areas, including space flight and medicine. Since then, the credibility of science has been harmed by mercenary scientists who do research not to illuminate truth but to sow doubt.2 This doubt has impeded educating the public about the risks of smoking, lead paint, and climate change.

Physicians themselves have contributed to this diminished credibility of scientists. Recommendations have been published and later withdrawn in areas such as dietary cholesterol, salt, and saturated fats, estrogen replacement therapy, and screening for prostate and breast cancers. In modern America, even small inconsistencies and errors get blown up into conspiracy plots.

The era of expecting patients to blindly follow a doctor’s orders has long since passed. Parents will search the Internet for answers. The modern physician needs to guide them to good ones.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2146.

2. “Doubt is Their Product,” by David Michaels, Oxford University Press, 2008, and “Merchants of Doubt,” by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Bloomsbury Press, 2011.

The Internet has been a transformative means of transmitting information. Alas, the information is often not vetted, so the effects on science, truth, and health literacy have been mixed. Unfortunately, Facebook spawned a billion dollar industry that transmits gossip. Twitter distributes information based on celebrity rather than intelligence or expertise.

Listservs and Google groups have allowed small communities to form unrestricted by the physical locations of the members. A listserv for pediatric hospitalists, with 3,800 members, provides quick access to a vast body of knowledge, an extensive array of experience, and insightful clinical wisdom. Discussions on this listserv resource have inspired several of my columns, including this one. The professionalism of the listserv members ensures the accuracy of the messages. Because many of the members work nights, it is possible to post a question and receive five consults from peers, even at 1 a.m. When I first started office practice in rural areas, all I had available was my memory, Rudolph’s Pediatrics textbook, and The Harriet Lane Handbook.

Misinformation has led to vaccine hesitancy and the reemergence of diseases such as measles that had been essentially eliminated. Because people haven’t seen these diseases, they are prone to believing any critique about the risk of vaccines. More recently, parents have been refusing the vitamin K shot that is provided to all newborns to prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, now called vitamin K deficiency bleeding. The incidence of this bleeding disorder is relatively rare. However, when it occurs, the results can be disastrous, with life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeds and disabling brain hemorrhages. As with vaccine hesitancy, the corruption of scientific knowledge has led to bad outcomes that once were nearly eliminated by modern health care.

Part of being a professional is communicating in a manner that helps parents understand small risks. I compare newborn vitamin K deficiency to the risk of driving the newborn around for the first 30 days of life without a car seat. The vast majority of people will not have an accident in that time and their babies will be fine. But emergency department doctors would see so many preventable cases of injury that they would strongly advocate for car seats. I also note that if the baby has a stroke due to vitamin K deficiency, we can’t catch it early and fix it.

One issue that comes up in the nursery is whether the physician should refuse to perform a circumcision on a newborn who has not received vitamin K. The risk of bleeding is increased further when circumcisions are done as outpatient procedures a few days after birth. When this topic was discussed on the hospitalist’s listserv, most respondents took a hard line and would not perform the procedure. I am more ambivalent because of my strong personal value of accommodating diverse views and perhaps because I have never experienced a severe case of postop bleeding. The absolute risk is low.

The ethical issues are similar to those involved in maintaining or dismissing families from your practice panel if they refuse vaccines. Some physicians think the threat of having to find another doctor is the only way to appear credible when advocating the use of vaccines. Actions speak louder than words. Other physicians are dedicated to accommodating diverse viewpoints. They try to persuade over time. This is a complex subject and the American Academy of Pediatrics’ position on this changed 2 years ago to consider dismissal as a viable option as long as it adheres to relevant state laws that prohibit abandonment of patients.1

Respect for science has diminished since the era when men walked on the moon. There are myriad reasons for this. They exceed what can be covered here. All human endeavors wax and wane in their prestige and credibility. The 1960s was an era of great technological progress in many areas, including space flight and medicine. Since then, the credibility of science has been harmed by mercenary scientists who do research not to illuminate truth but to sow doubt.2 This doubt has impeded educating the public about the risks of smoking, lead paint, and climate change.

Physicians themselves have contributed to this diminished credibility of scientists. Recommendations have been published and later withdrawn in areas such as dietary cholesterol, salt, and saturated fats, estrogen replacement therapy, and screening for prostate and breast cancers. In modern America, even small inconsistencies and errors get blown up into conspiracy plots.

The era of expecting patients to blindly follow a doctor’s orders has long since passed. Parents will search the Internet for answers. The modern physician needs to guide them to good ones.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2146.

2. “Doubt is Their Product,” by David Michaels, Oxford University Press, 2008, and “Merchants of Doubt,” by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Bloomsbury Press, 2011.

Ghost busting in pediatric primary care

As clinicians trained in the care of children, we have struggled in recent years with how much care is appropriate to provide to the parents of our young charges.

Gradual progression has occurred from recognizing postpartum depression as affecting infants, to recommending screening, to creation of a billing code for screening as “for the benefit of” the child, and increasingly even being paid for that code. We now see referral of depressed parents as within our scope of practice with the goal of protecting the child’s emotional development from the caregiver’s altered mental condition, as well as relieving the parent’s suffering. Some of us even provide treatment ourselves.

While the family history has been our standard way of assessing “transgenerational transmission” of risk for physical and mental health conditions, parenting practices are a more direct transmission threat, and one more amenable to our intervention.

Aversive parenting acts happen to many people growing up, but how the parent thinks about these seems to make the difference between consciously protecting the child from similar experiences or unconsciously playing them out in the child’s life. With 64% of U.S. adults reporting at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE), many of which were acts or omissions by their parents, we need to be vigilant to track their translation of past events, “the ghosts,” into present parenting.

Just ask

“I barely have time to talk about the child,” you may be saying, “how can I have time to dig into the parent’s issues, much less know what to do?” Exploring for connections to the parent’s past in primary care is most crucial when the parent-child relationship is strained, or the parent’s handling of typical or problematic child behaviors is abnormal, clinically symptomatic, or dangerous. Nonetheless, helping all parents make these connections enriches life and meaning for families, and dramatically strengthens the doctor-family relationship. Then all of our care is more effective.

In my experience, this valuable connection is not difficult to make – it lives just below the surface for most parents. We may want to ask permission first, noting that “our ideas about how to parent tend to be shaped by how we were parented.” By simply asking, “May I ask how your parents would have handled this [behavior or situation]?” we may hear a description of a reasonable approach (sent to my room), denial that this ever came up (I was never as hardheaded as this kid!), blanking out (Things were tough. I have tried to block it all out), or clues to a pattern better not repeated (Oh, my father would have beat me ...). This question also may be useful in elucidating cultural or generational differences between what was done to them and their own intentions that can be hard to bridge. All of these are opportunities for promoting positive parenting by creating empathy for that child of the past to carry forward to the own child in the present.

While we may be lucky to have even one parent at the visit, we should ask the one present the equivalent question of the partner’s past. Even if one parent had a model that he or she wanted to emulate or a ghost to bust, the other may not agree. Conflict between partners undermines management and can create harmful tension. If the parent does not know, this is an important homework assignment to being collaborative coparents.

Empathize

After hearing about the past experiences, we should empathize with the parent regarding pain experienced as a child in the past (“That would be very scary for any child”) and ask “How much is this a burden for you now?” to see if help is needed. But this is a key educational moment for us as child development experts to suggest how children of the age they were then might process the events. For example, one might explain reaction to abandonment by a father by saying, “Any 6-year-old whose father left would feel sad and mad, but also might think he had done something wrong or wasn’t worth staying around for.” One might react to a story of abusive discipline by saying, “Children need to feel safe and protected at home. Not knowing when your parent is going to hurt you could produce lifelong anxiety and trouble trusting your closest relationships.” Watch to see if this connects for them.

Selma Fraiberg, in the classic article “Ghosts in the Nursery,”1 noted that if parents have come to empathize with their past hurting selves, they will work to prevent similar pain for their own children. If they have dealt with these experiences by identifying with the aggressive or neglectful adult or blanking the memory, they are more likely to act out similar practices with their children.

For some, being able to tolerate reviewing these painful times enough to experience empathy for the child may require years of work with a trusted therapist. We should be prepared to refer if the parents are in distress. But for many, getting our help to understand how a child might feel and later act after these experiences may be enough to interrupt the transmission. We can try to elicit current impact of the past (“How are those experiences affecting your parenting now?”). This question, expecting impact, often causes parents to stop short and think. While at first denying impact, if I have been compassionate and nonjudgmental in asking, they often return with more insight.

Help with parenting issues

After eliciting perceptions of the past, I find it useful to ask, “So, what have (the two of) you decided” about how to manage [the problematic parenting situation]?” The implication is that parenting actions are decisions. Making this decision process overt may reveal that they are having blank out moments of impulsive action, or ambivalence with thoughts and feelings in conflict, or arguments resulting in standoffs. A common reaction to hurts in the past is for parents to strongly avoid doing as their own parents did, but then have no plan at all, get increasingly emotional, and finally blow up and scream or hit or storm off ineffectually. We can help them pick out one or two stressful situations, often perceived disrespect or defiance by the child, and plan steps for when it comes up again – as hot-button issues always do. It is important to let them know that their “emotion brain” is likely to speak up first under stress and the “thinking brain” takes longer. We, and they, need to be patient and congratulate them for little bits of progress in having rationality win.

Don’t forget that children adapt to the parenting they receive and develop reactions that may interfere with seeing their parents in a new mode of trust and kindness. A child may have defended him/herself from the emotional pain of not feeling safe or protected by the parent who is acting out a ghost and may react by laughing, running, spitting, hitting, shutting down, pushing the parent away, or saying “I don’t care.” The child’s reaction, too, takes time and consistent responsiveness to change to accept new parenting patterns. It can be painful to the newly-aware parents to recognize these behaviors are caused, at least in part, by their own actions, especially when it is a repetition of their own childhood experiences. We can be the patient, empathic coach – believing in their good intentions as they develop as parents – just as they would have wanted from their parents when they were growing up.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert for MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

Reference

1. “Ghosts in the Nursery: A Psychoanalytic Approach to the Problems of Impaired Infant-Mother Relationships,” J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1975 Summer;14(3);387-421.

As clinicians trained in the care of children, we have struggled in recent years with how much care is appropriate to provide to the parents of our young charges.

Gradual progression has occurred from recognizing postpartum depression as affecting infants, to recommending screening, to creation of a billing code for screening as “for the benefit of” the child, and increasingly even being paid for that code. We now see referral of depressed parents as within our scope of practice with the goal of protecting the child’s emotional development from the caregiver’s altered mental condition, as well as relieving the parent’s suffering. Some of us even provide treatment ourselves.

While the family history has been our standard way of assessing “transgenerational transmission” of risk for physical and mental health conditions, parenting practices are a more direct transmission threat, and one more amenable to our intervention.

Aversive parenting acts happen to many people growing up, but how the parent thinks about these seems to make the difference between consciously protecting the child from similar experiences or unconsciously playing them out in the child’s life. With 64% of U.S. adults reporting at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE), many of which were acts or omissions by their parents, we need to be vigilant to track their translation of past events, “the ghosts,” into present parenting.

Just ask

“I barely have time to talk about the child,” you may be saying, “how can I have time to dig into the parent’s issues, much less know what to do?” Exploring for connections to the parent’s past in primary care is most crucial when the parent-child relationship is strained, or the parent’s handling of typical or problematic child behaviors is abnormal, clinically symptomatic, or dangerous. Nonetheless, helping all parents make these connections enriches life and meaning for families, and dramatically strengthens the doctor-family relationship. Then all of our care is more effective.

In my experience, this valuable connection is not difficult to make – it lives just below the surface for most parents. We may want to ask permission first, noting that “our ideas about how to parent tend to be shaped by how we were parented.” By simply asking, “May I ask how your parents would have handled this [behavior or situation]?” we may hear a description of a reasonable approach (sent to my room), denial that this ever came up (I was never as hardheaded as this kid!), blanking out (Things were tough. I have tried to block it all out), or clues to a pattern better not repeated (Oh, my father would have beat me ...). This question also may be useful in elucidating cultural or generational differences between what was done to them and their own intentions that can be hard to bridge. All of these are opportunities for promoting positive parenting by creating empathy for that child of the past to carry forward to the own child in the present.

While we may be lucky to have even one parent at the visit, we should ask the one present the equivalent question of the partner’s past. Even if one parent had a model that he or she wanted to emulate or a ghost to bust, the other may not agree. Conflict between partners undermines management and can create harmful tension. If the parent does not know, this is an important homework assignment to being collaborative coparents.

Empathize

After hearing about the past experiences, we should empathize with the parent regarding pain experienced as a child in the past (“That would be very scary for any child”) and ask “How much is this a burden for you now?” to see if help is needed. But this is a key educational moment for us as child development experts to suggest how children of the age they were then might process the events. For example, one might explain reaction to abandonment by a father by saying, “Any 6-year-old whose father left would feel sad and mad, but also might think he had done something wrong or wasn’t worth staying around for.” One might react to a story of abusive discipline by saying, “Children need to feel safe and protected at home. Not knowing when your parent is going to hurt you could produce lifelong anxiety and trouble trusting your closest relationships.” Watch to see if this connects for them.

Selma Fraiberg, in the classic article “Ghosts in the Nursery,”1 noted that if parents have come to empathize with their past hurting selves, they will work to prevent similar pain for their own children. If they have dealt with these experiences by identifying with the aggressive or neglectful adult or blanking the memory, they are more likely to act out similar practices with their children.

For some, being able to tolerate reviewing these painful times enough to experience empathy for the child may require years of work with a trusted therapist. We should be prepared to refer if the parents are in distress. But for many, getting our help to understand how a child might feel and later act after these experiences may be enough to interrupt the transmission. We can try to elicit current impact of the past (“How are those experiences affecting your parenting now?”). This question, expecting impact, often causes parents to stop short and think. While at first denying impact, if I have been compassionate and nonjudgmental in asking, they often return with more insight.

Help with parenting issues

After eliciting perceptions of the past, I find it useful to ask, “So, what have (the two of) you decided” about how to manage [the problematic parenting situation]?” The implication is that parenting actions are decisions. Making this decision process overt may reveal that they are having blank out moments of impulsive action, or ambivalence with thoughts and feelings in conflict, or arguments resulting in standoffs. A common reaction to hurts in the past is for parents to strongly avoid doing as their own parents did, but then have no plan at all, get increasingly emotional, and finally blow up and scream or hit or storm off ineffectually. We can help them pick out one or two stressful situations, often perceived disrespect or defiance by the child, and plan steps for when it comes up again – as hot-button issues always do. It is important to let them know that their “emotion brain” is likely to speak up first under stress and the “thinking brain” takes longer. We, and they, need to be patient and congratulate them for little bits of progress in having rationality win.

Don’t forget that children adapt to the parenting they receive and develop reactions that may interfere with seeing their parents in a new mode of trust and kindness. A child may have defended him/herself from the emotional pain of not feeling safe or protected by the parent who is acting out a ghost and may react by laughing, running, spitting, hitting, shutting down, pushing the parent away, or saying “I don’t care.” The child’s reaction, too, takes time and consistent responsiveness to change to accept new parenting patterns. It can be painful to the newly-aware parents to recognize these behaviors are caused, at least in part, by their own actions, especially when it is a repetition of their own childhood experiences. We can be the patient, empathic coach – believing in their good intentions as they develop as parents – just as they would have wanted from their parents when they were growing up.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert for MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

Reference

1. “Ghosts in the Nursery: A Psychoanalytic Approach to the Problems of Impaired Infant-Mother Relationships,” J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1975 Summer;14(3);387-421.

As clinicians trained in the care of children, we have struggled in recent years with how much care is appropriate to provide to the parents of our young charges.

Gradual progression has occurred from recognizing postpartum depression as affecting infants, to recommending screening, to creation of a billing code for screening as “for the benefit of” the child, and increasingly even being paid for that code. We now see referral of depressed parents as within our scope of practice with the goal of protecting the child’s emotional development from the caregiver’s altered mental condition, as well as relieving the parent’s suffering. Some of us even provide treatment ourselves.

While the family history has been our standard way of assessing “transgenerational transmission” of risk for physical and mental health conditions, parenting practices are a more direct transmission threat, and one more amenable to our intervention.

Aversive parenting acts happen to many people growing up, but how the parent thinks about these seems to make the difference between consciously protecting the child from similar experiences or unconsciously playing them out in the child’s life. With 64% of U.S. adults reporting at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE), many of which were acts or omissions by their parents, we need to be vigilant to track their translation of past events, “the ghosts,” into present parenting.

Just ask

“I barely have time to talk about the child,” you may be saying, “how can I have time to dig into the parent’s issues, much less know what to do?” Exploring for connections to the parent’s past in primary care is most crucial when the parent-child relationship is strained, or the parent’s handling of typical or problematic child behaviors is abnormal, clinically symptomatic, or dangerous. Nonetheless, helping all parents make these connections enriches life and meaning for families, and dramatically strengthens the doctor-family relationship. Then all of our care is more effective.

In my experience, this valuable connection is not difficult to make – it lives just below the surface for most parents. We may want to ask permission first, noting that “our ideas about how to parent tend to be shaped by how we were parented.” By simply asking, “May I ask how your parents would have handled this [behavior or situation]?” we may hear a description of a reasonable approach (sent to my room), denial that this ever came up (I was never as hardheaded as this kid!), blanking out (Things were tough. I have tried to block it all out), or clues to a pattern better not repeated (Oh, my father would have beat me ...). This question also may be useful in elucidating cultural or generational differences between what was done to them and their own intentions that can be hard to bridge. All of these are opportunities for promoting positive parenting by creating empathy for that child of the past to carry forward to the own child in the present.

While we may be lucky to have even one parent at the visit, we should ask the one present the equivalent question of the partner’s past. Even if one parent had a model that he or she wanted to emulate or a ghost to bust, the other may not agree. Conflict between partners undermines management and can create harmful tension. If the parent does not know, this is an important homework assignment to being collaborative coparents.

Empathize

After hearing about the past experiences, we should empathize with the parent regarding pain experienced as a child in the past (“That would be very scary for any child”) and ask “How much is this a burden for you now?” to see if help is needed. But this is a key educational moment for us as child development experts to suggest how children of the age they were then might process the events. For example, one might explain reaction to abandonment by a father by saying, “Any 6-year-old whose father left would feel sad and mad, but also might think he had done something wrong or wasn’t worth staying around for.” One might react to a story of abusive discipline by saying, “Children need to feel safe and protected at home. Not knowing when your parent is going to hurt you could produce lifelong anxiety and trouble trusting your closest relationships.” Watch to see if this connects for them.

Selma Fraiberg, in the classic article “Ghosts in the Nursery,”1 noted that if parents have come to empathize with their past hurting selves, they will work to prevent similar pain for their own children. If they have dealt with these experiences by identifying with the aggressive or neglectful adult or blanking the memory, they are more likely to act out similar practices with their children.

For some, being able to tolerate reviewing these painful times enough to experience empathy for the child may require years of work with a trusted therapist. We should be prepared to refer if the parents are in distress. But for many, getting our help to understand how a child might feel and later act after these experiences may be enough to interrupt the transmission. We can try to elicit current impact of the past (“How are those experiences affecting your parenting now?”). This question, expecting impact, often causes parents to stop short and think. While at first denying impact, if I have been compassionate and nonjudgmental in asking, they often return with more insight.

Help with parenting issues

After eliciting perceptions of the past, I find it useful to ask, “So, what have (the two of) you decided” about how to manage [the problematic parenting situation]?” The implication is that parenting actions are decisions. Making this decision process overt may reveal that they are having blank out moments of impulsive action, or ambivalence with thoughts and feelings in conflict, or arguments resulting in standoffs. A common reaction to hurts in the past is for parents to strongly avoid doing as their own parents did, but then have no plan at all, get increasingly emotional, and finally blow up and scream or hit or storm off ineffectually. We can help them pick out one or two stressful situations, often perceived disrespect or defiance by the child, and plan steps for when it comes up again – as hot-button issues always do. It is important to let them know that their “emotion brain” is likely to speak up first under stress and the “thinking brain” takes longer. We, and they, need to be patient and congratulate them for little bits of progress in having rationality win.

Don’t forget that children adapt to the parenting they receive and develop reactions that may interfere with seeing their parents in a new mode of trust and kindness. A child may have defended him/herself from the emotional pain of not feeling safe or protected by the parent who is acting out a ghost and may react by laughing, running, spitting, hitting, shutting down, pushing the parent away, or saying “I don’t care.” The child’s reaction, too, takes time and consistent responsiveness to change to accept new parenting patterns. It can be painful to the newly-aware parents to recognize these behaviors are caused, at least in part, by their own actions, especially when it is a repetition of their own childhood experiences. We can be the patient, empathic coach – believing in their good intentions as they develop as parents – just as they would have wanted from their parents when they were growing up.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert for MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

Reference

1. “Ghosts in the Nursery: A Psychoanalytic Approach to the Problems of Impaired Infant-Mother Relationships,” J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1975 Summer;14(3);387-421.

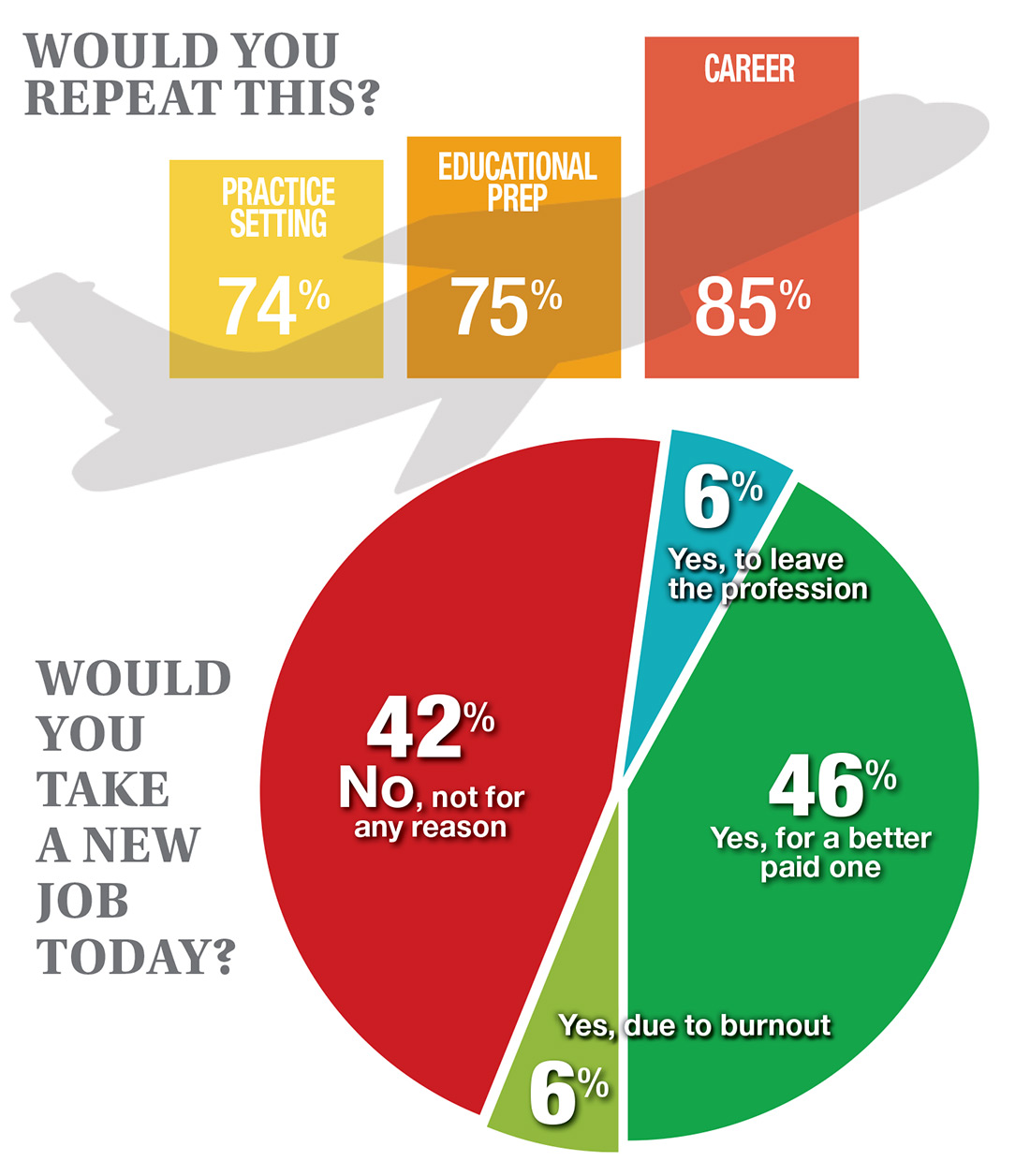

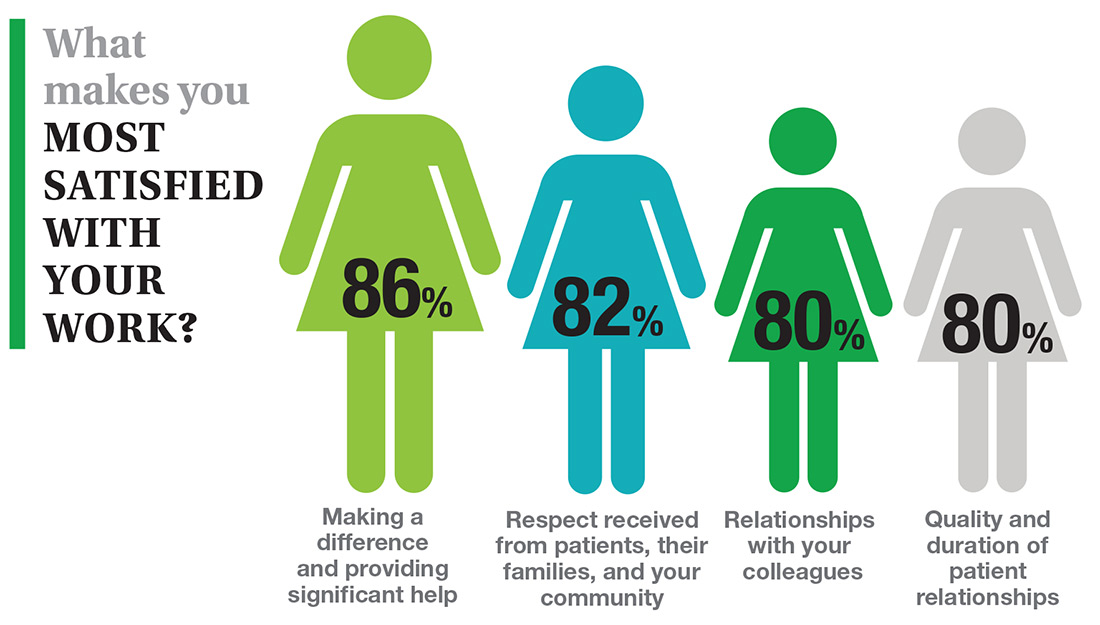

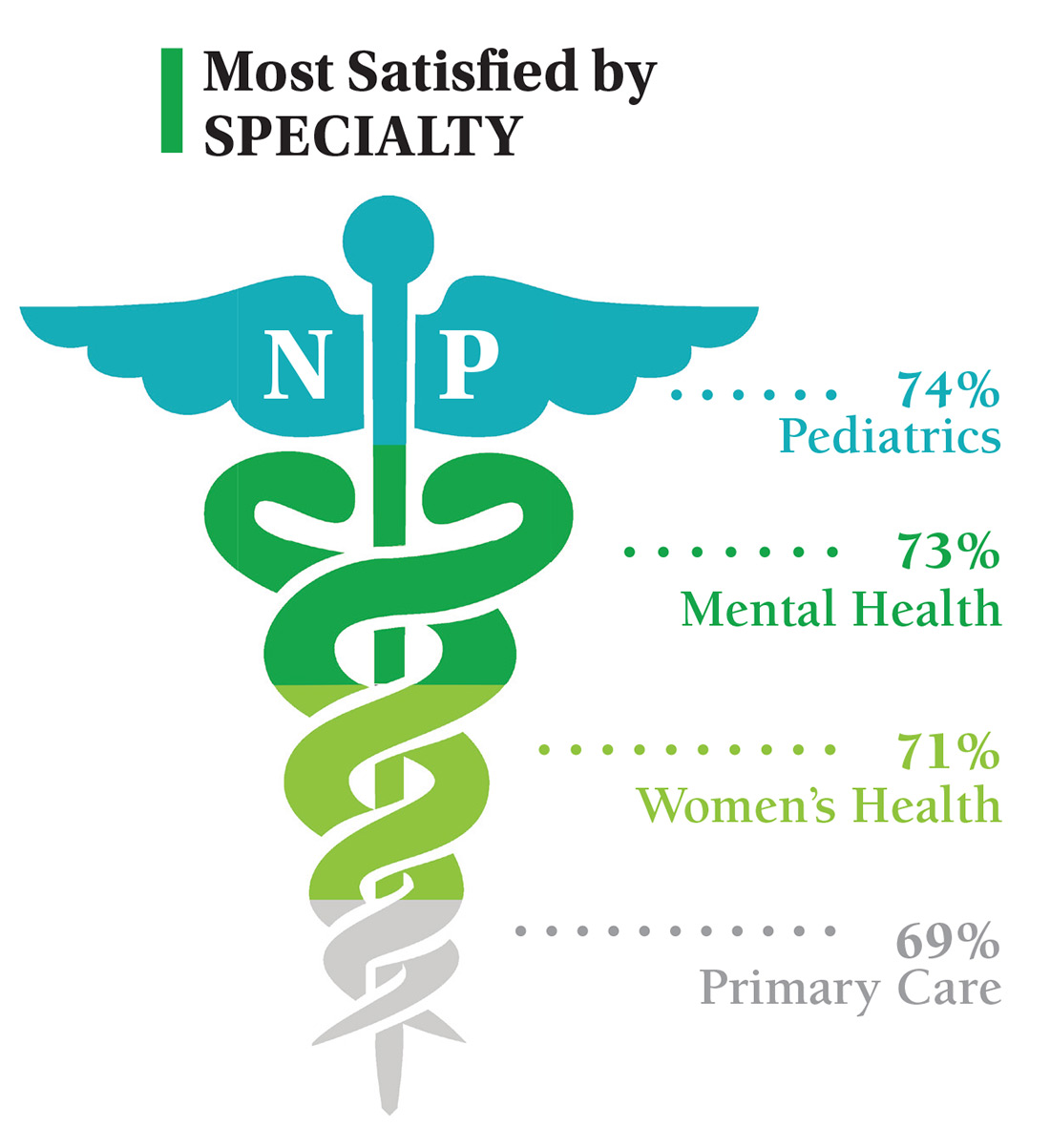

If You Had to Do It Again …

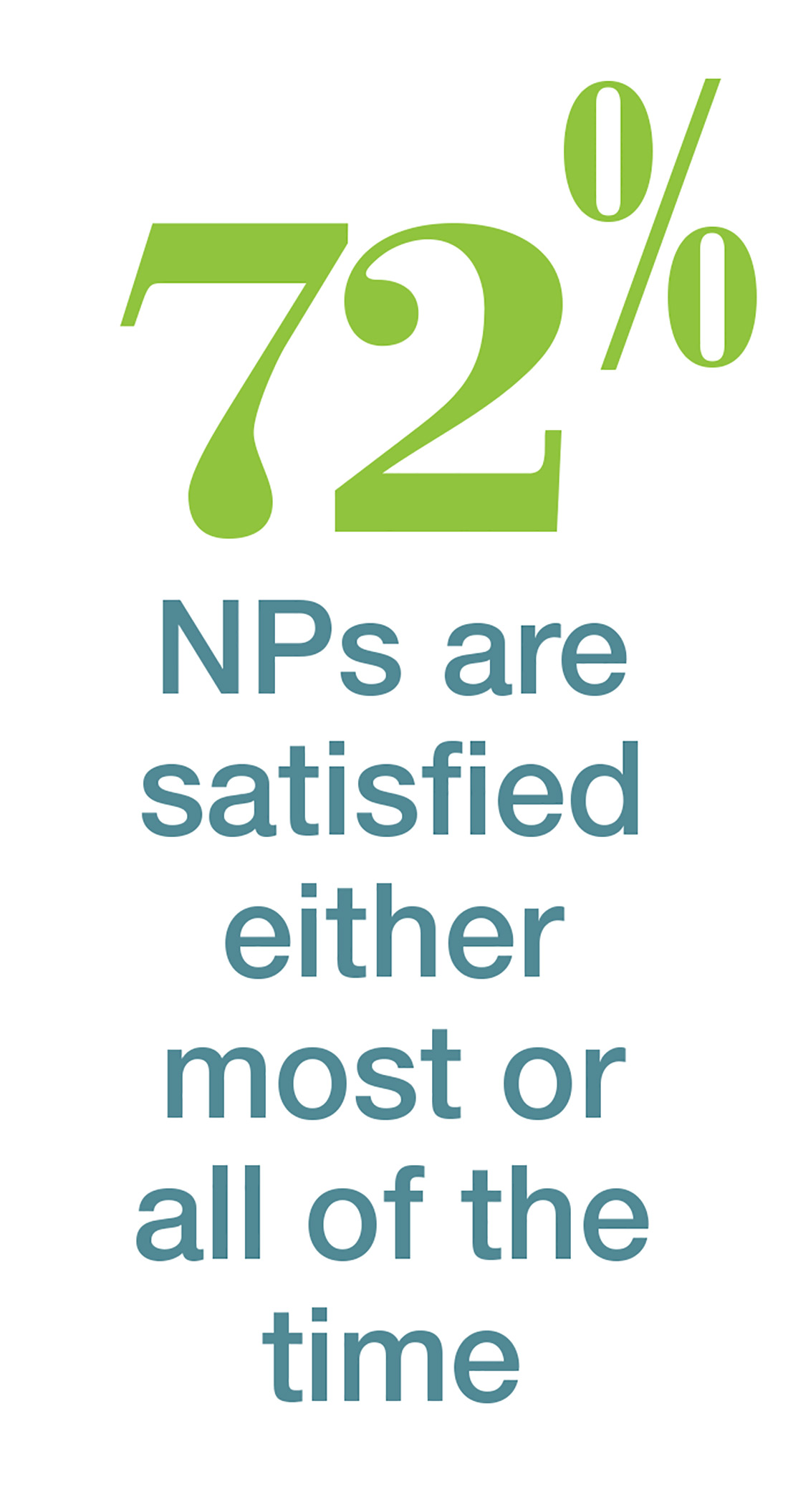

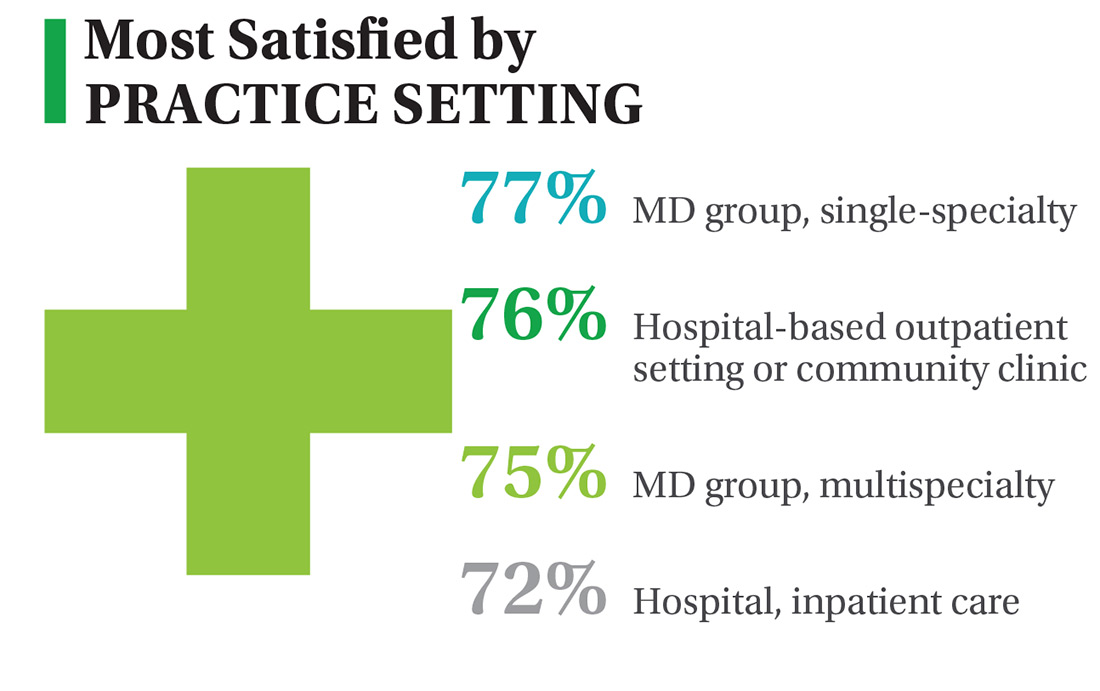

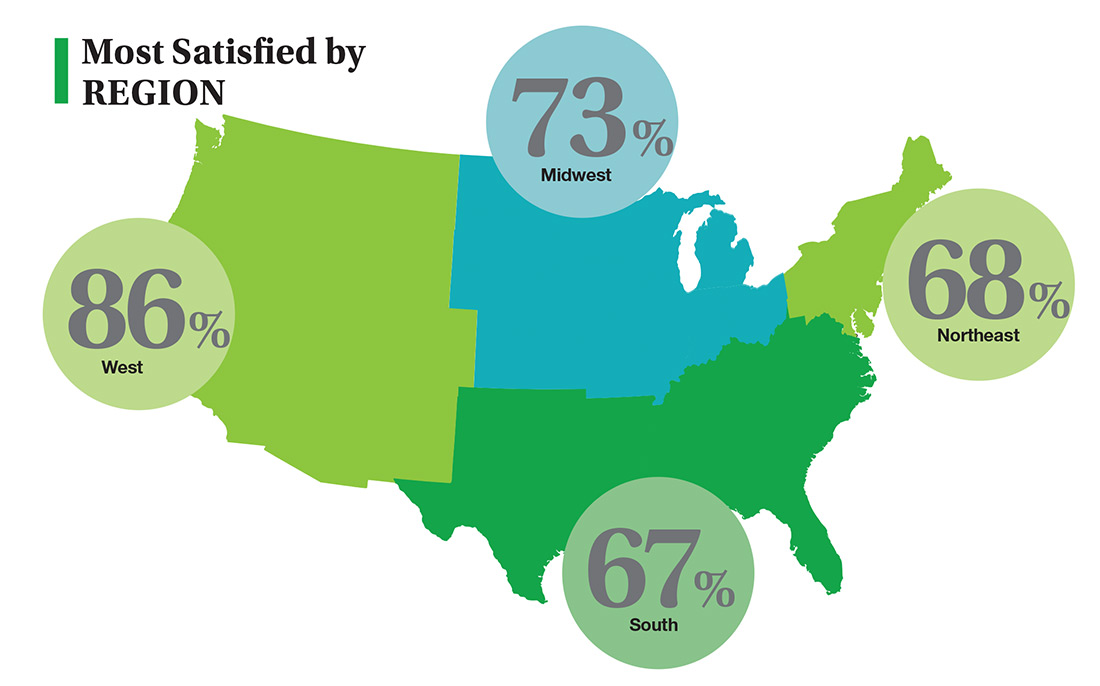

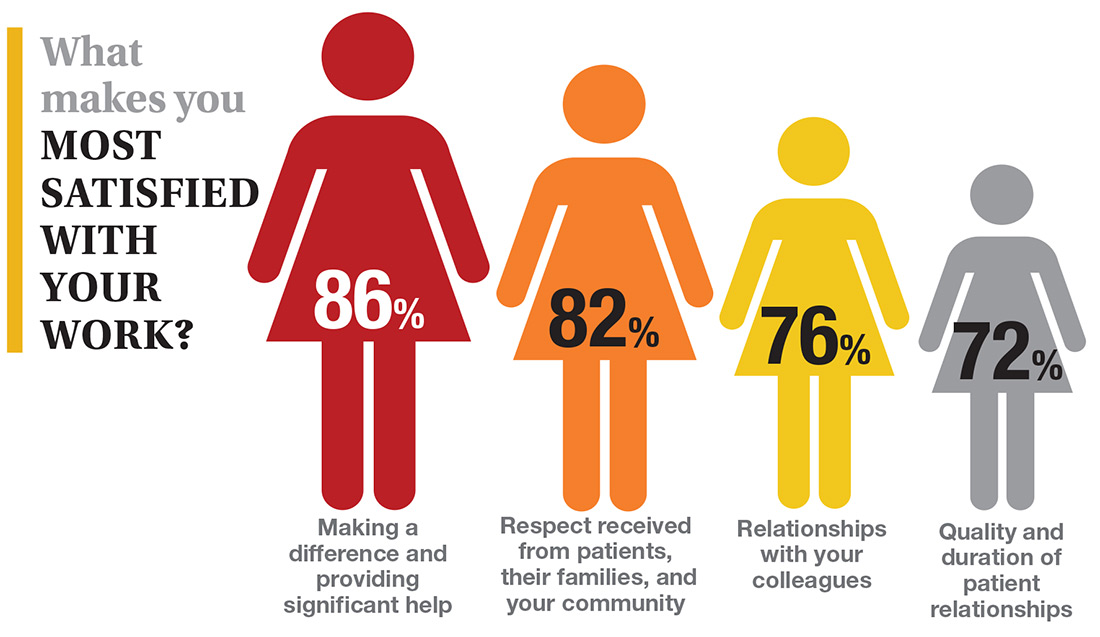

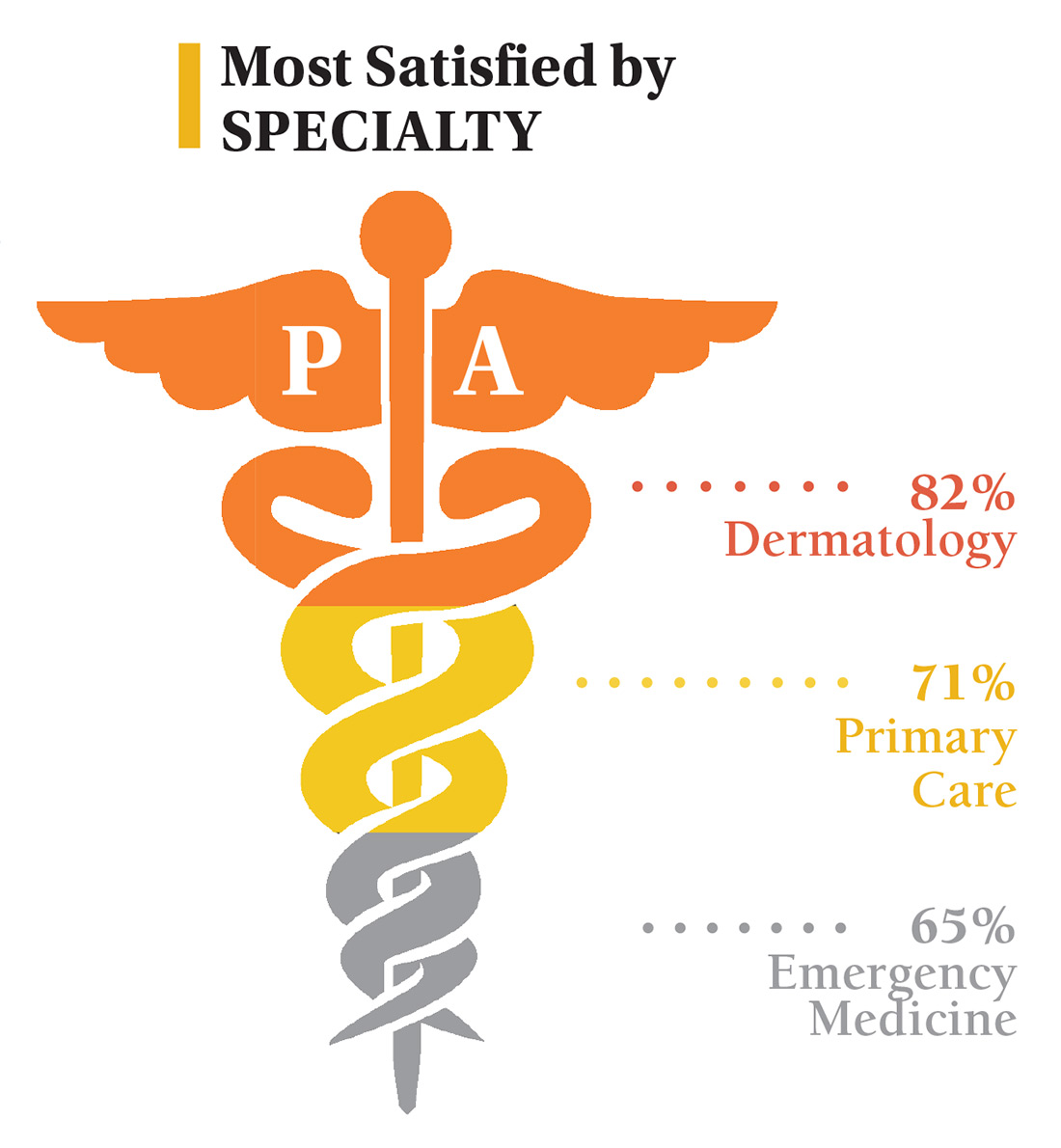

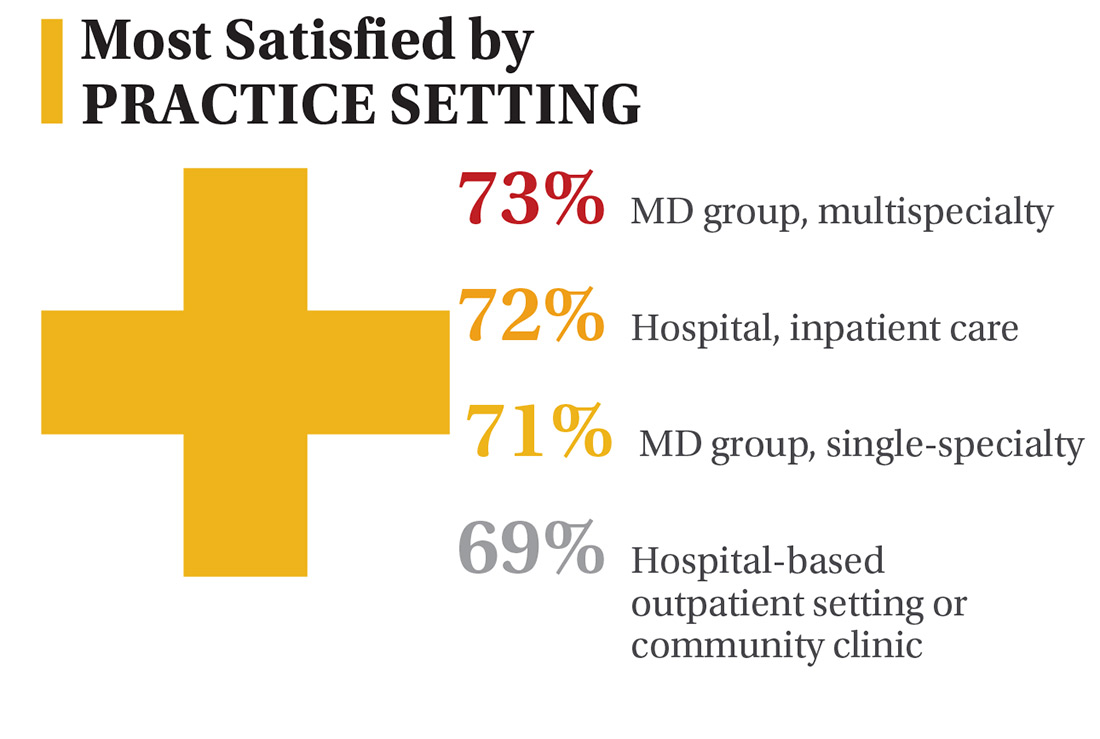

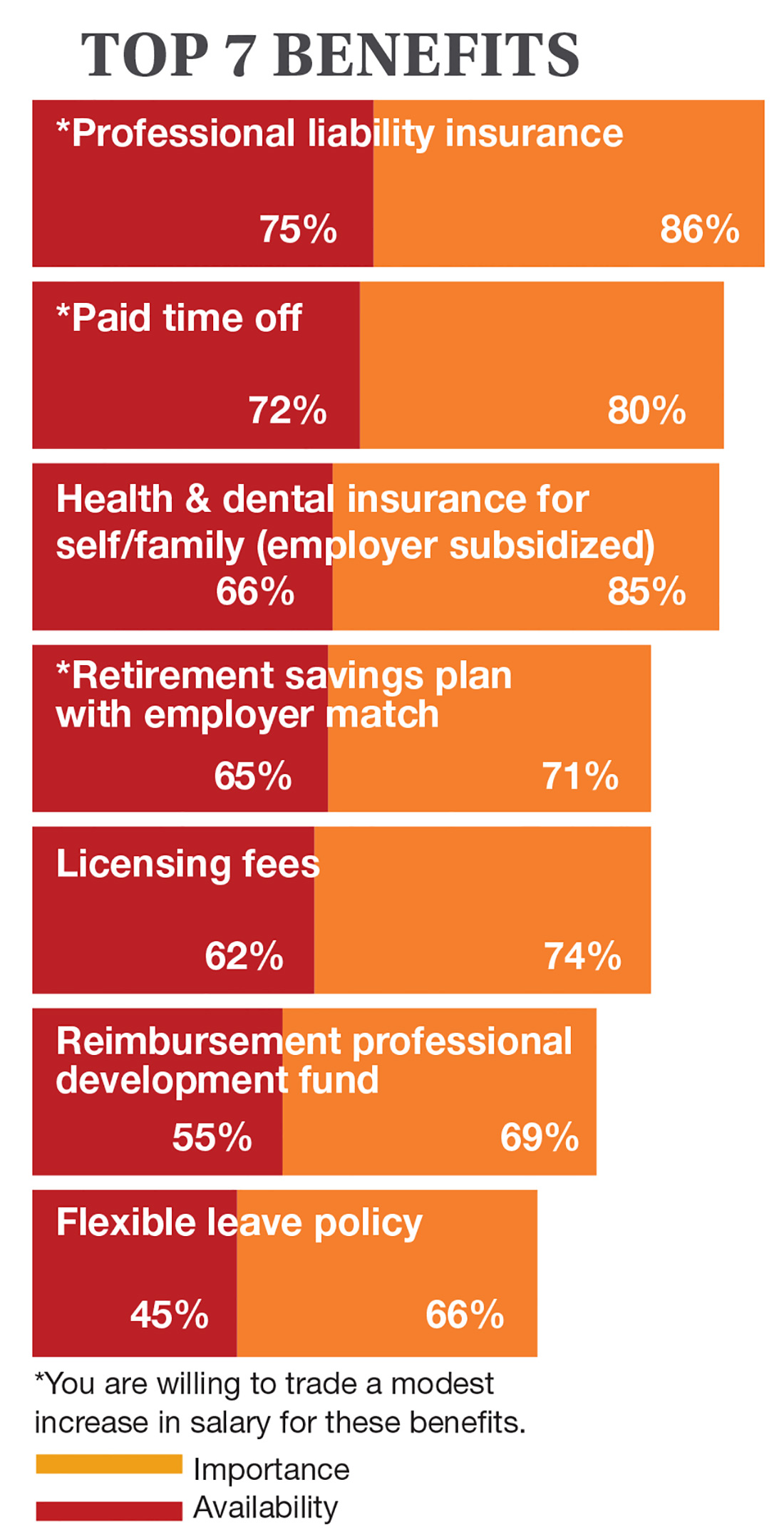

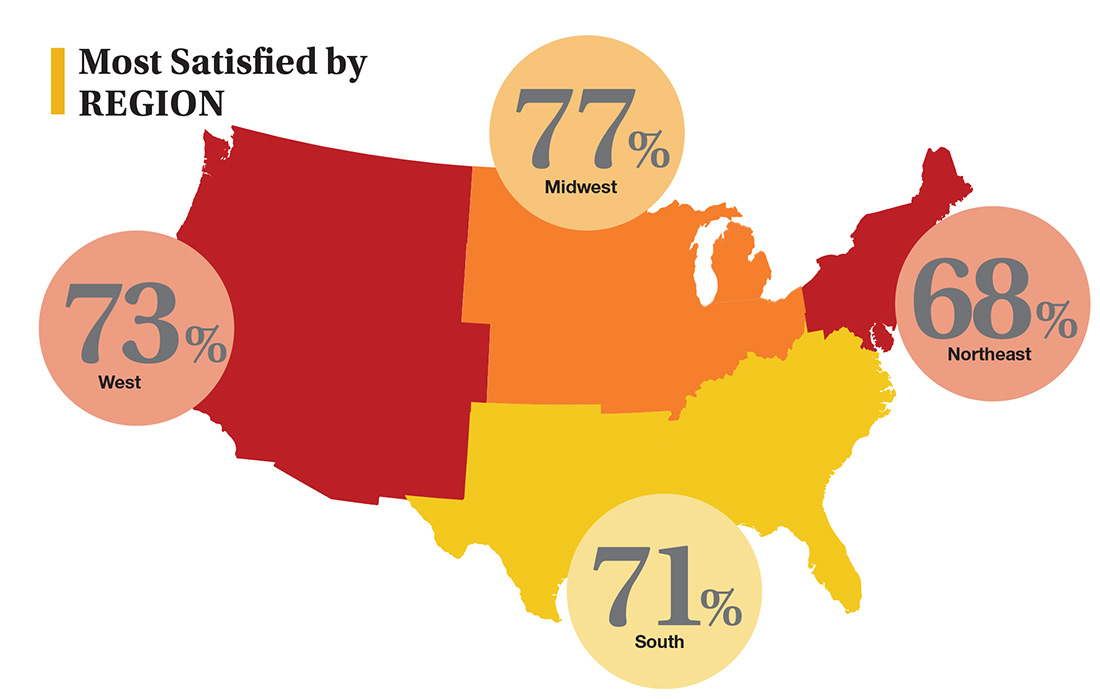

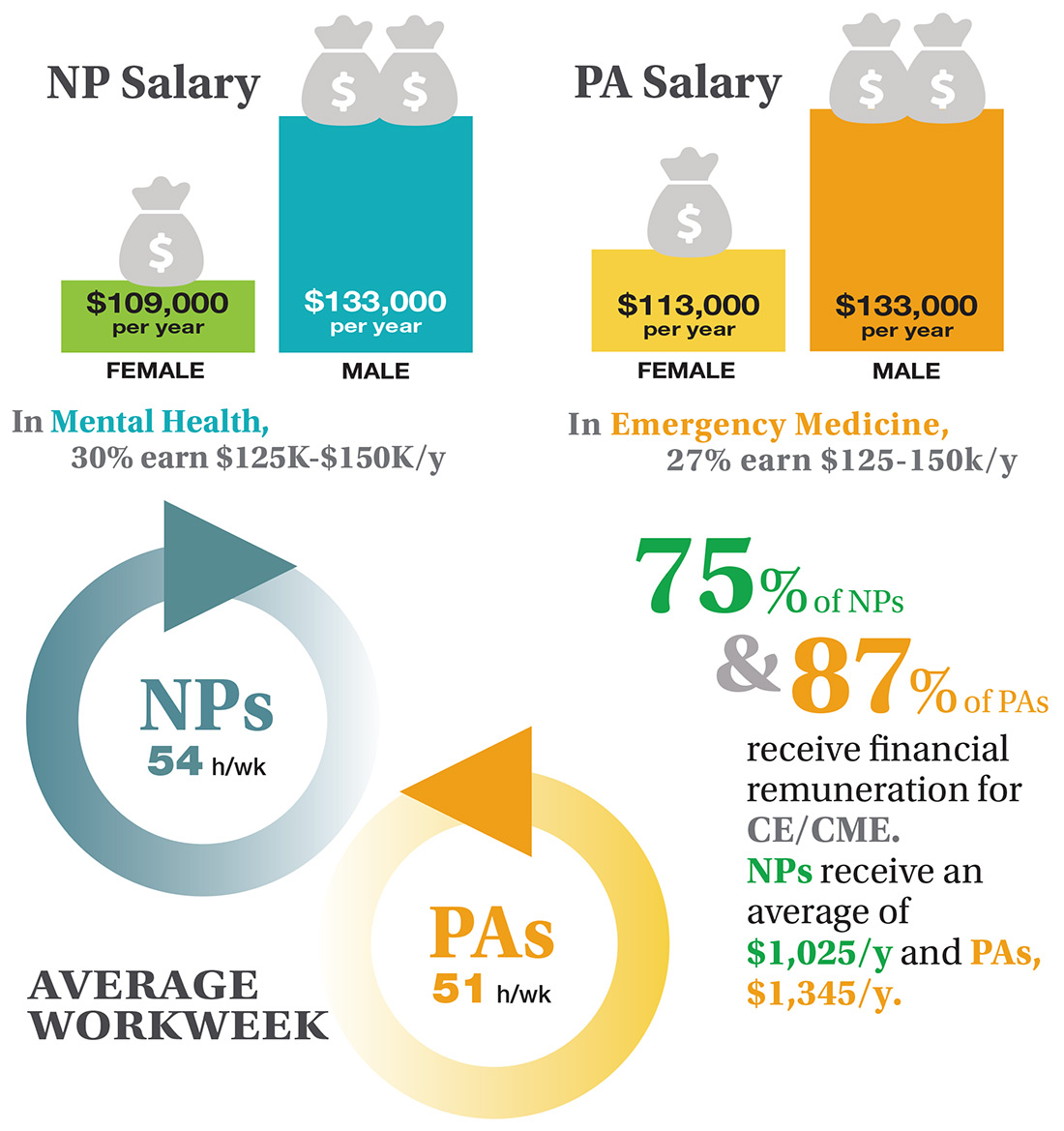

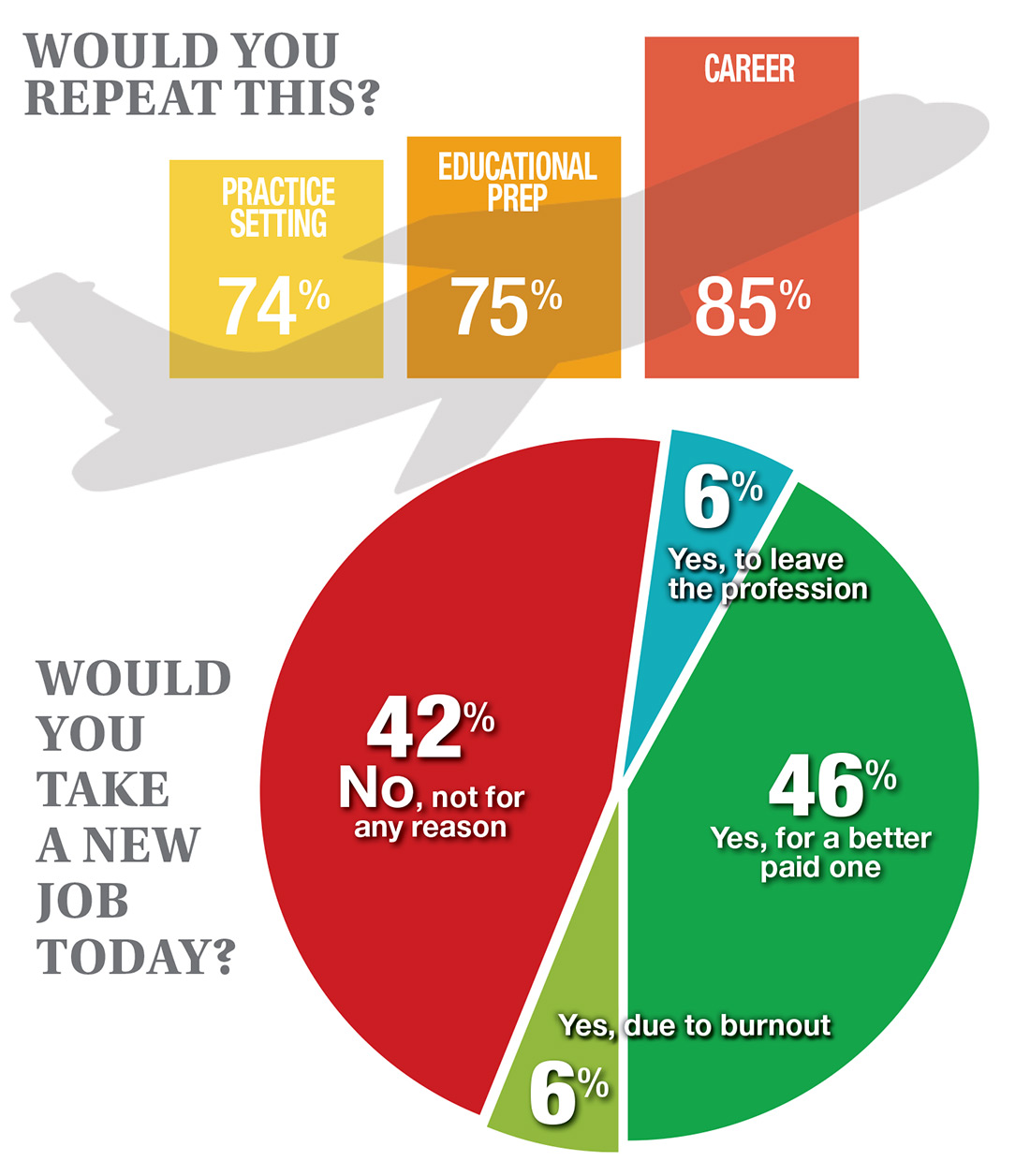

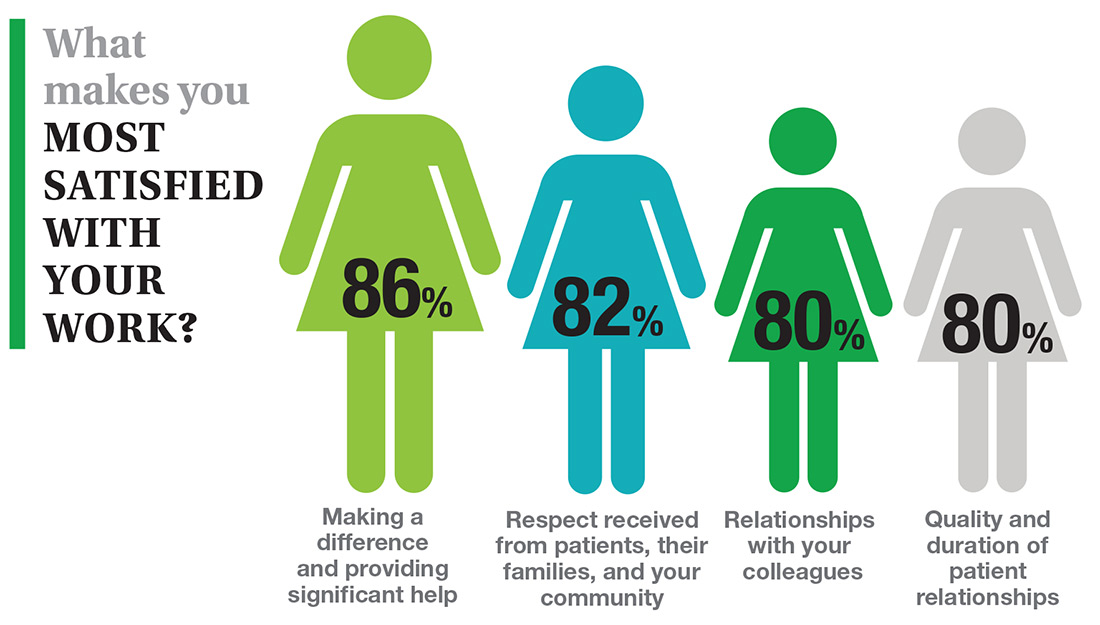

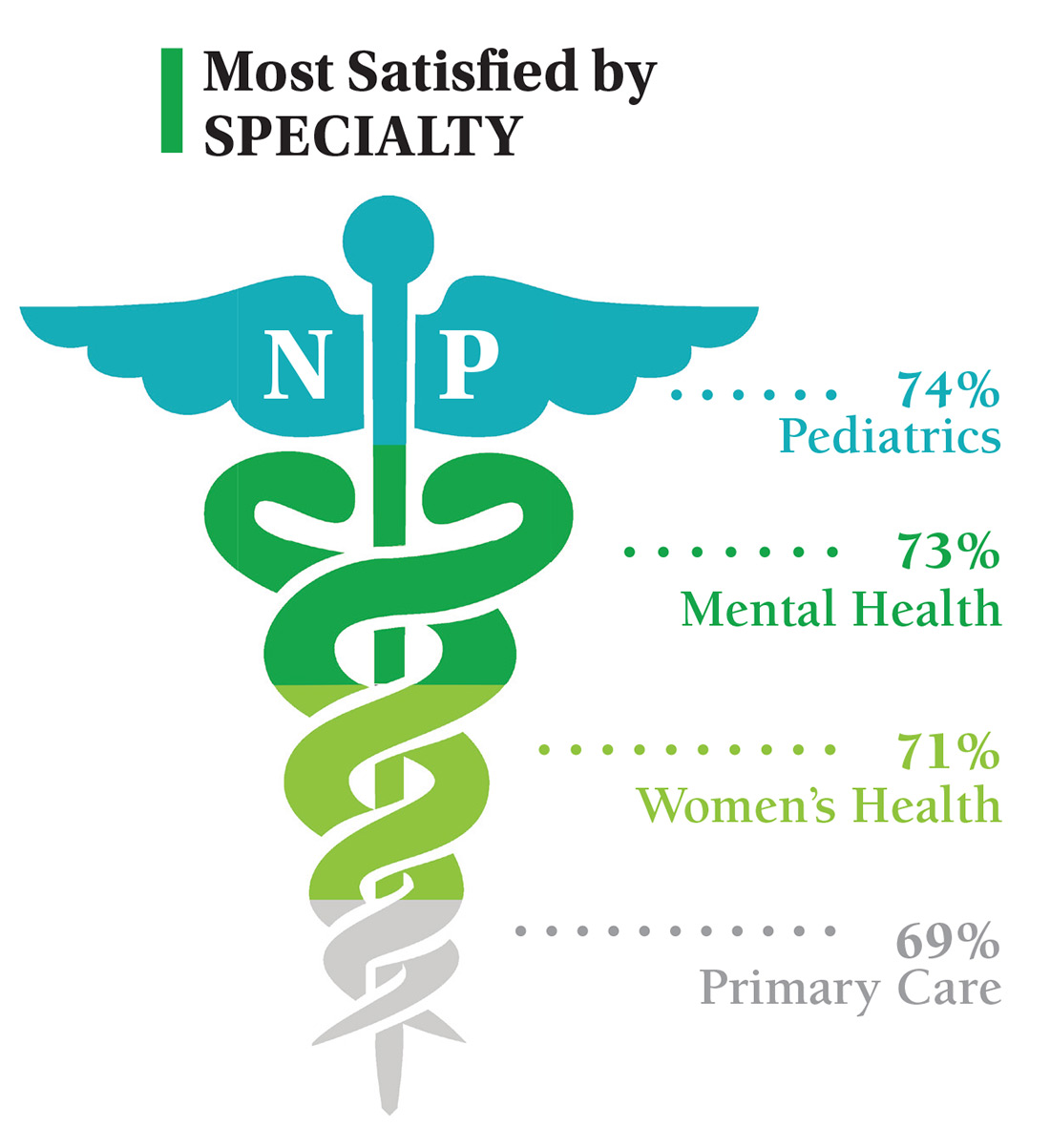

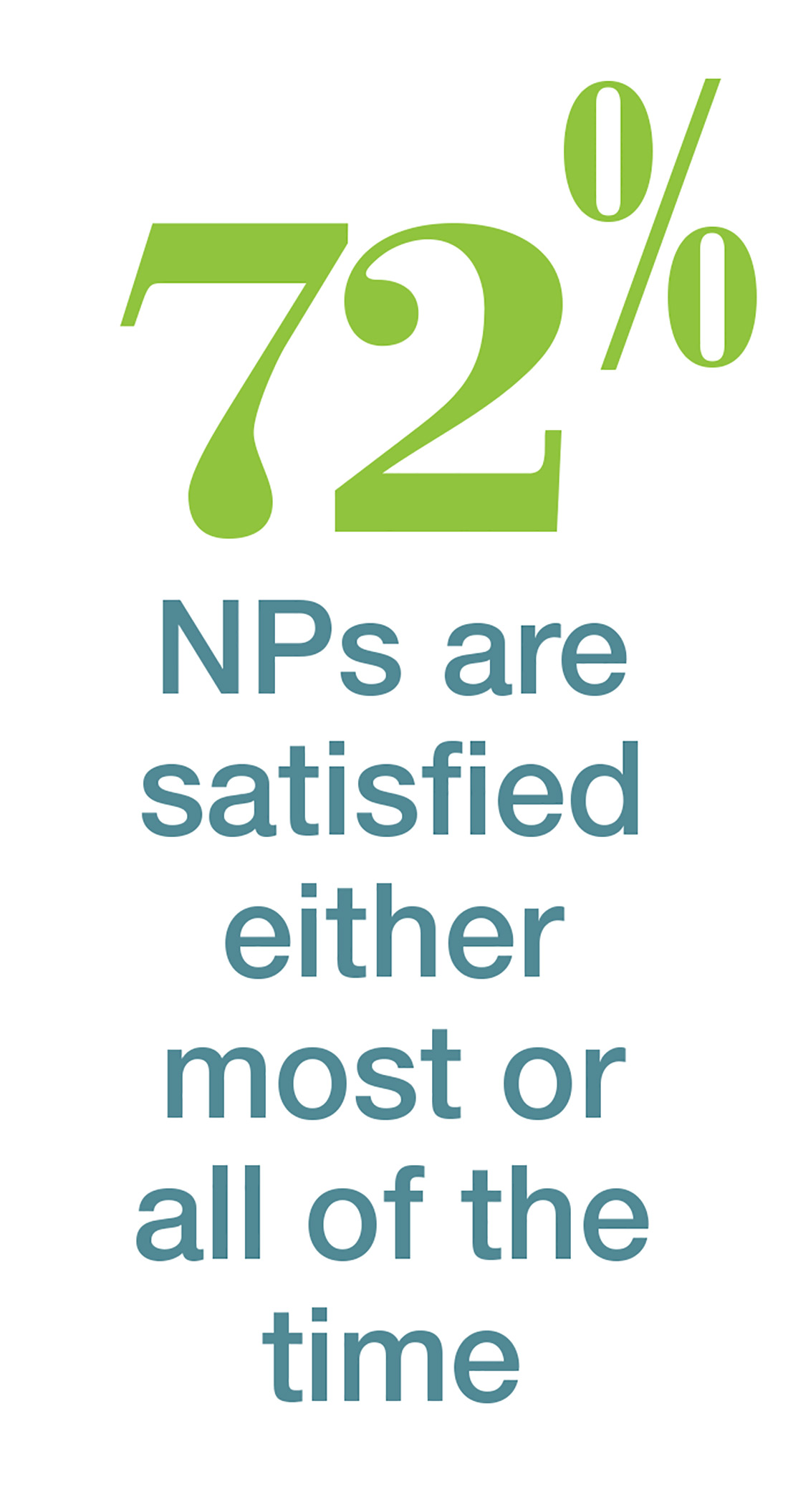

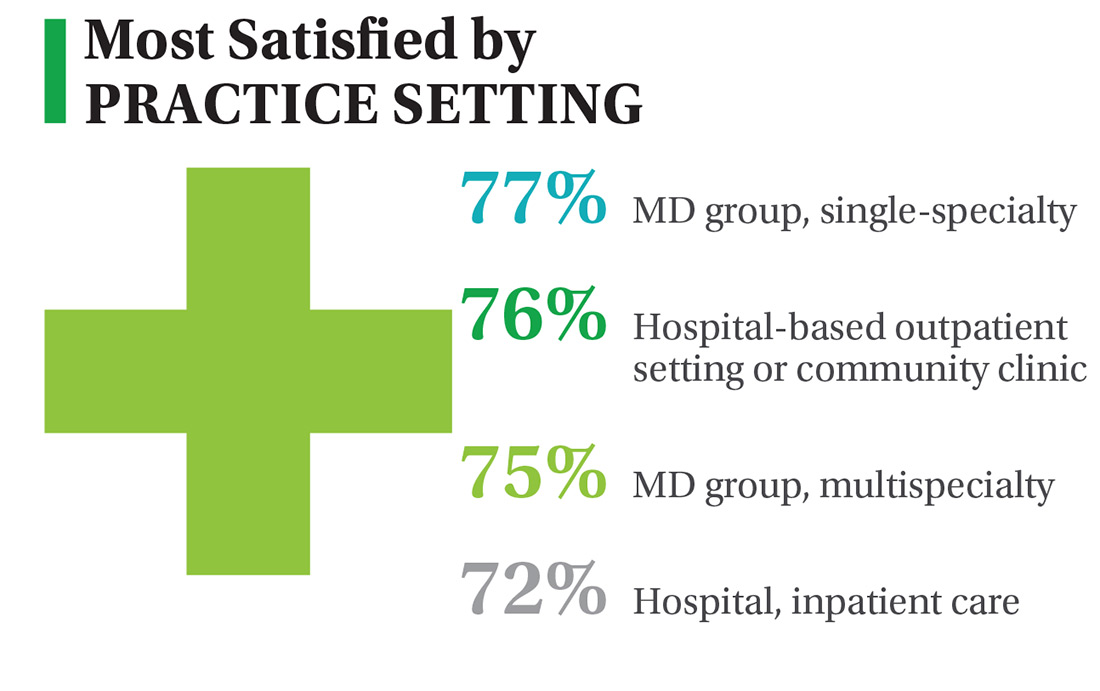

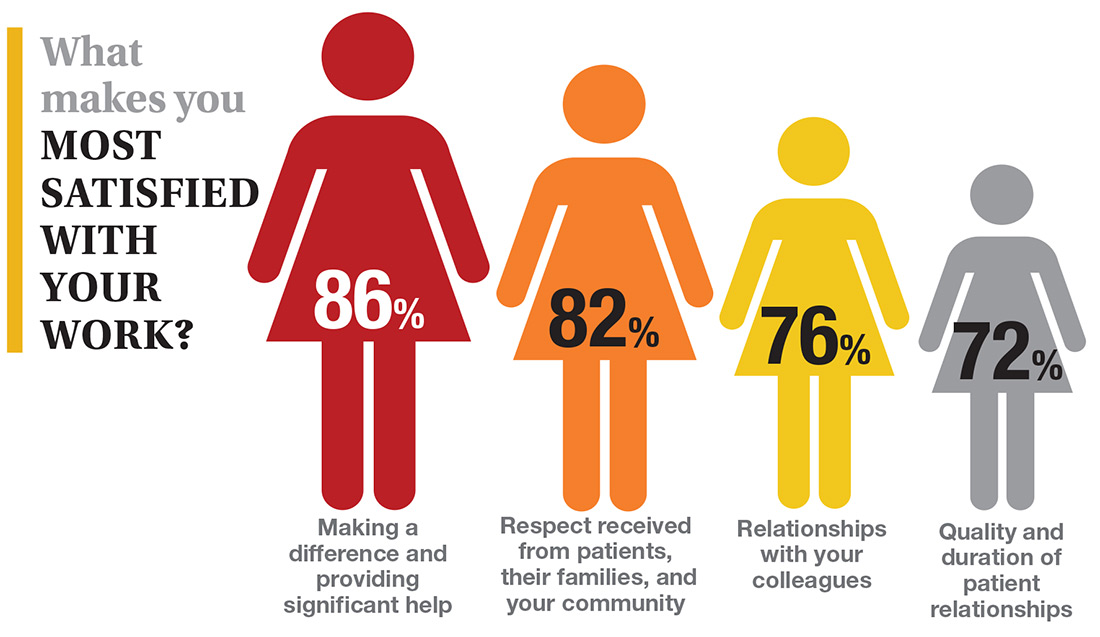

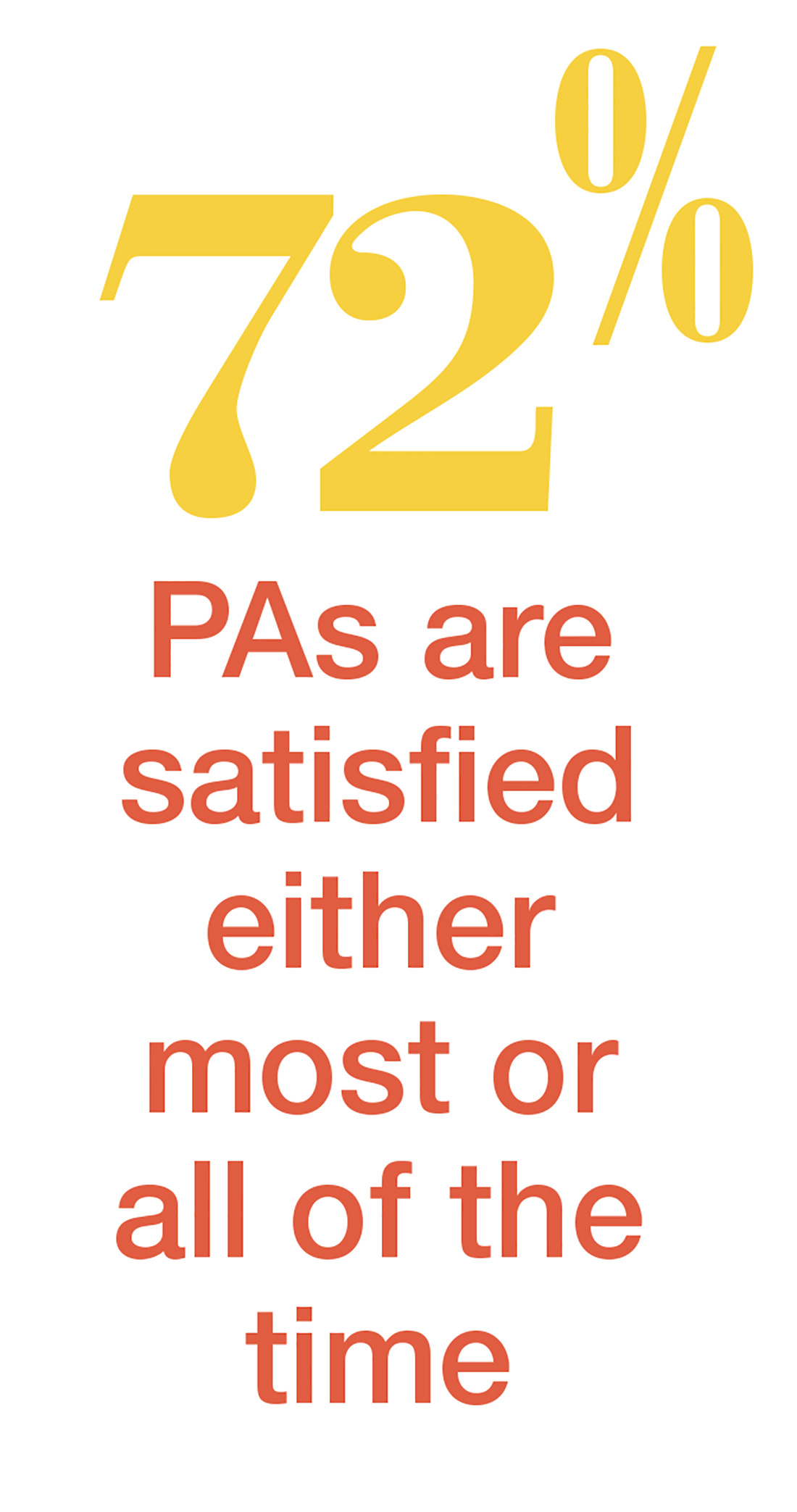

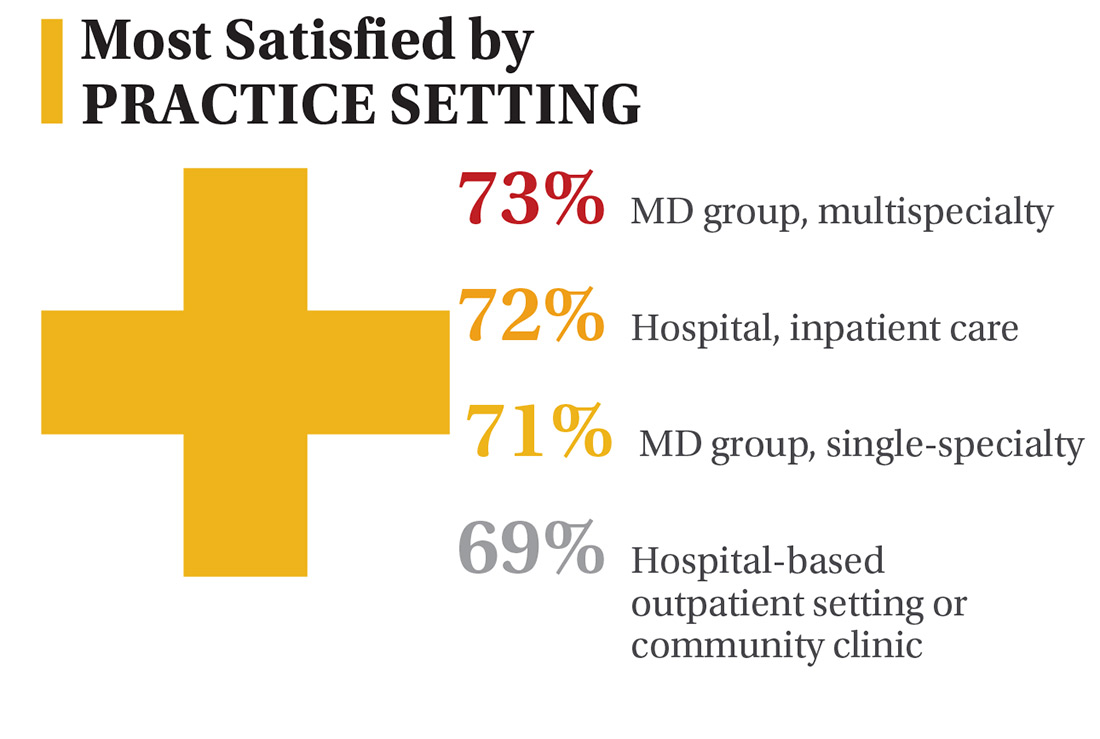

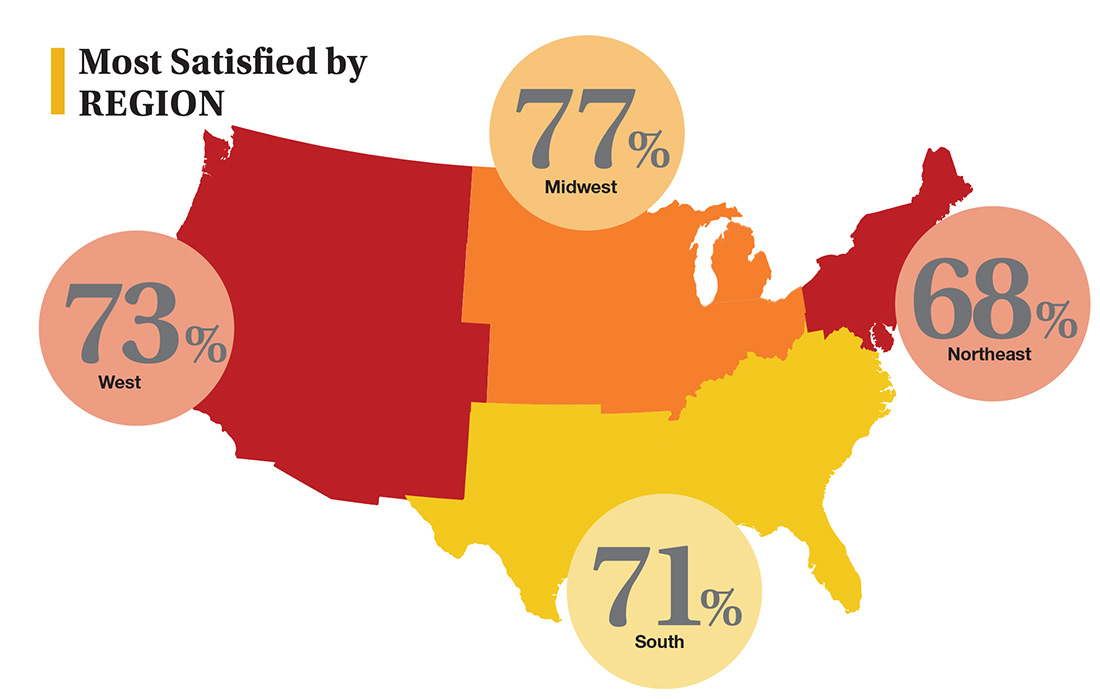

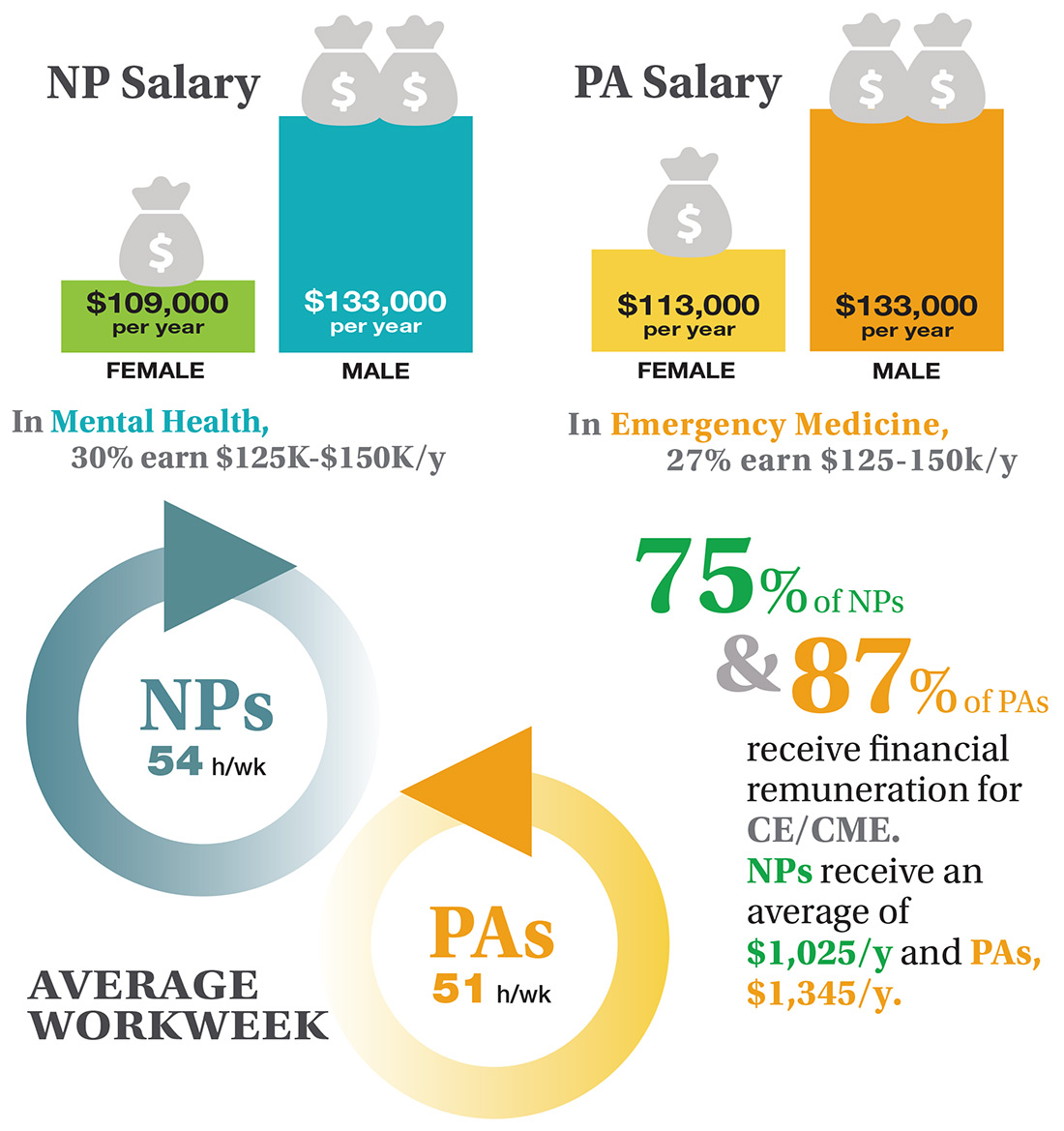

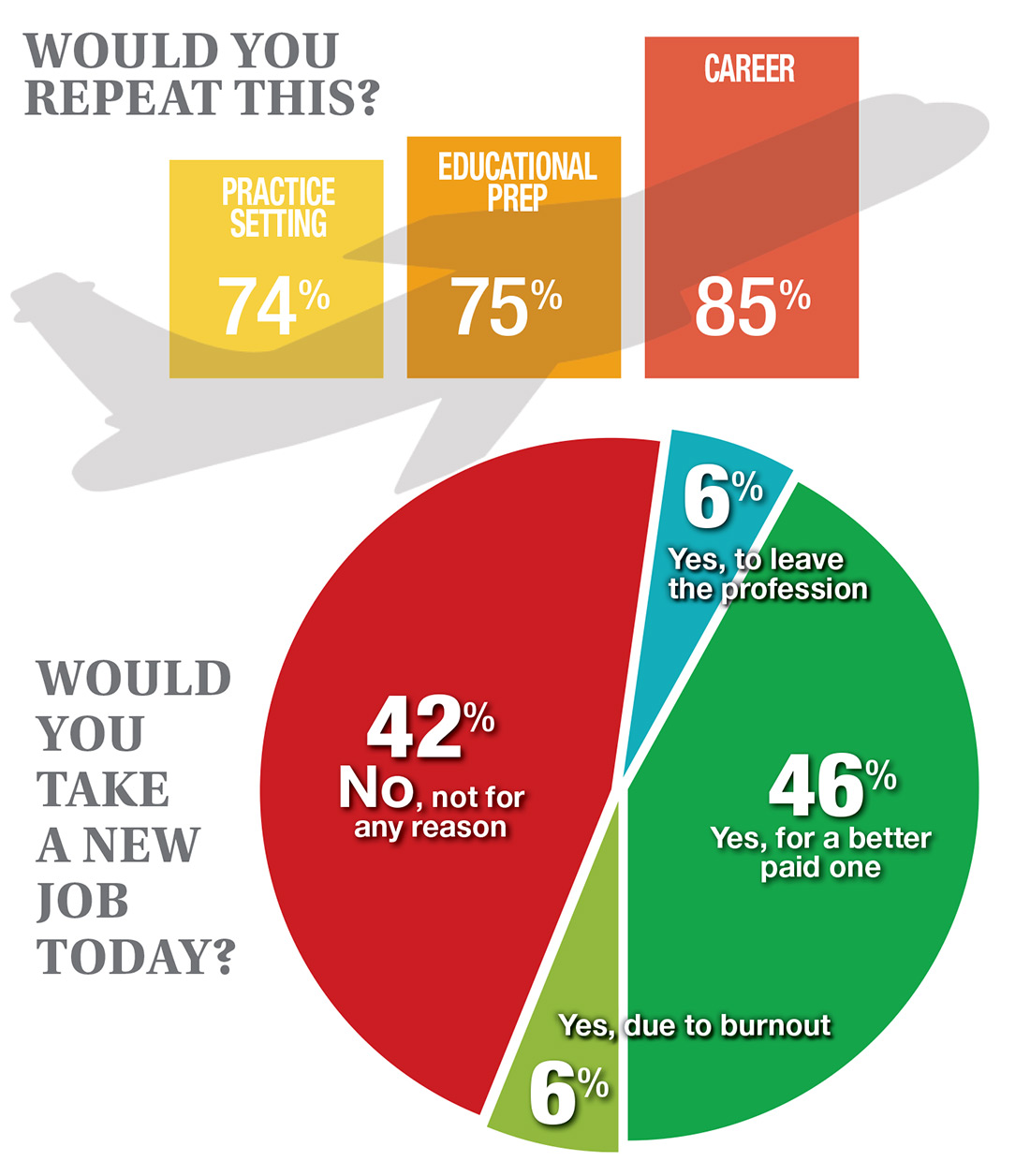

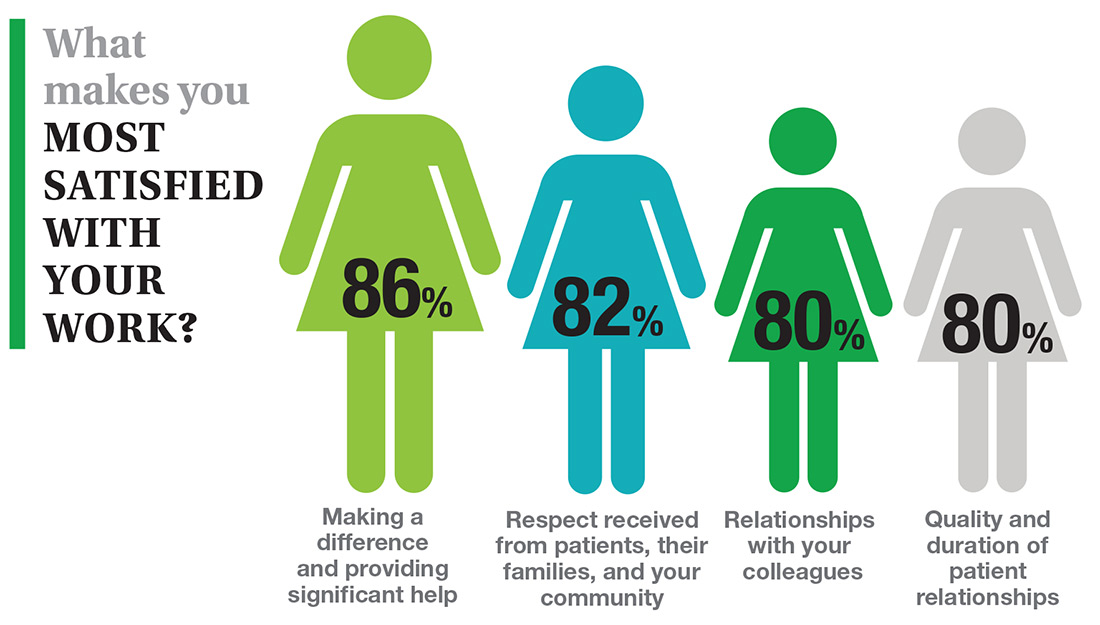

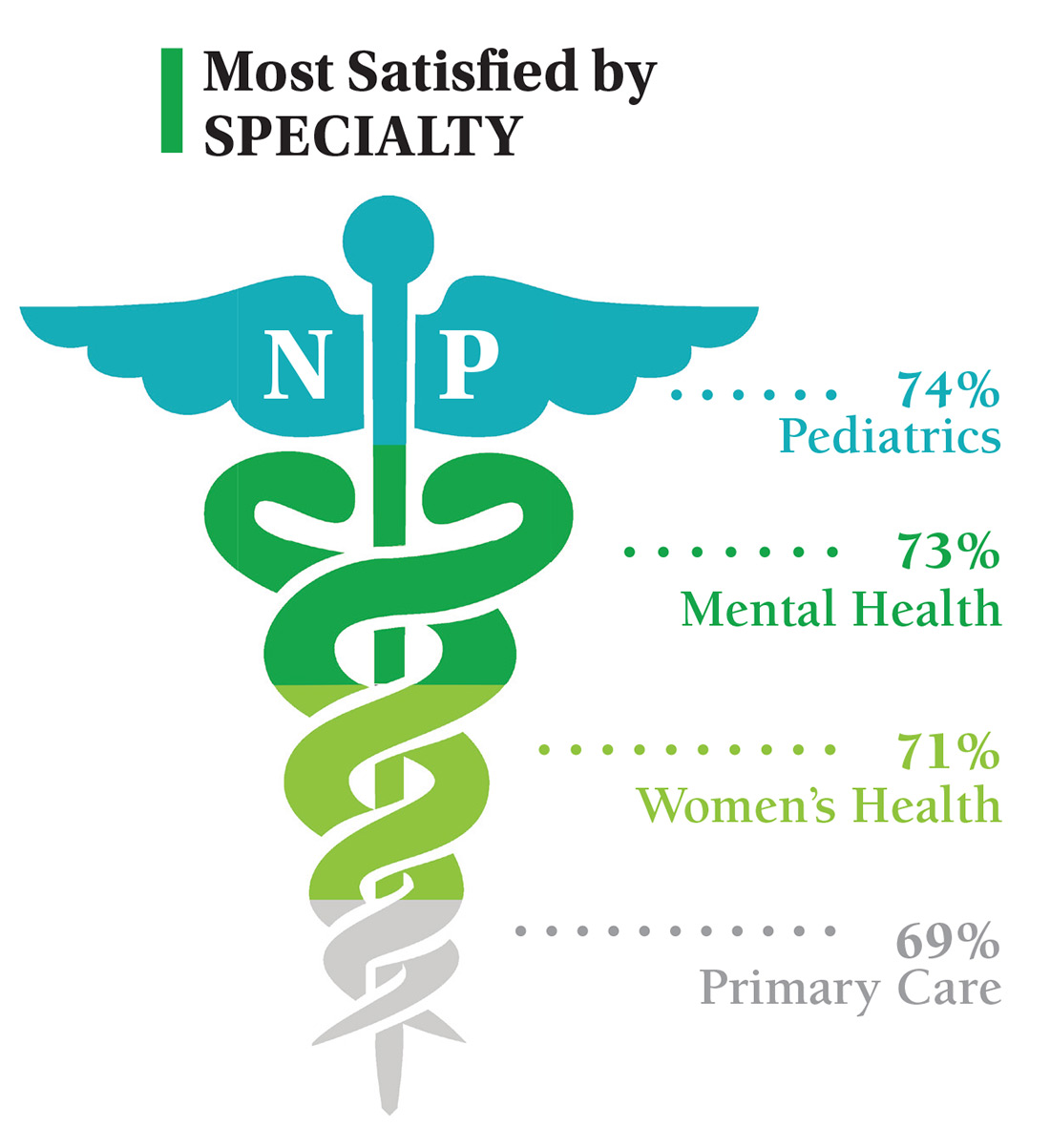

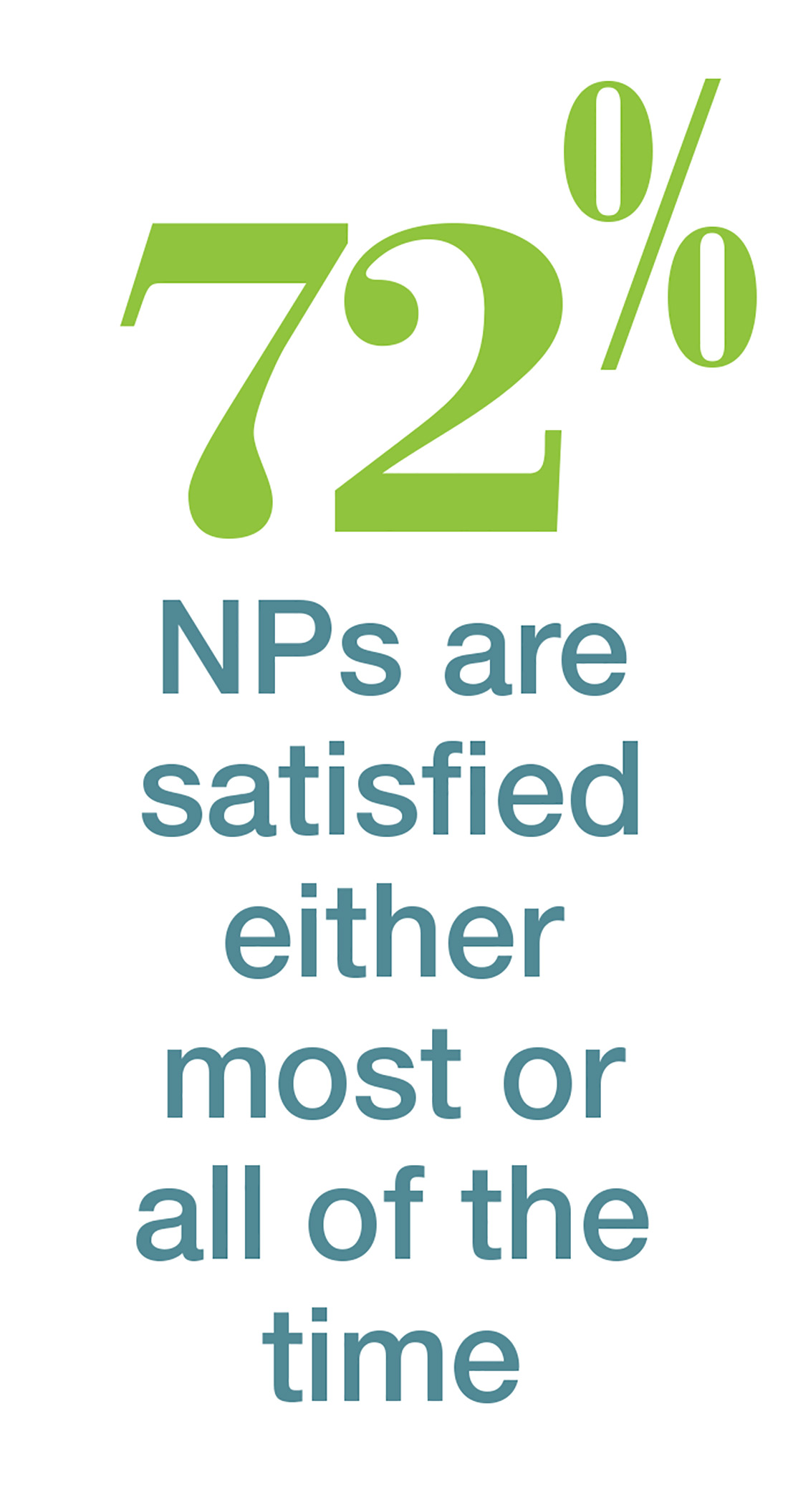

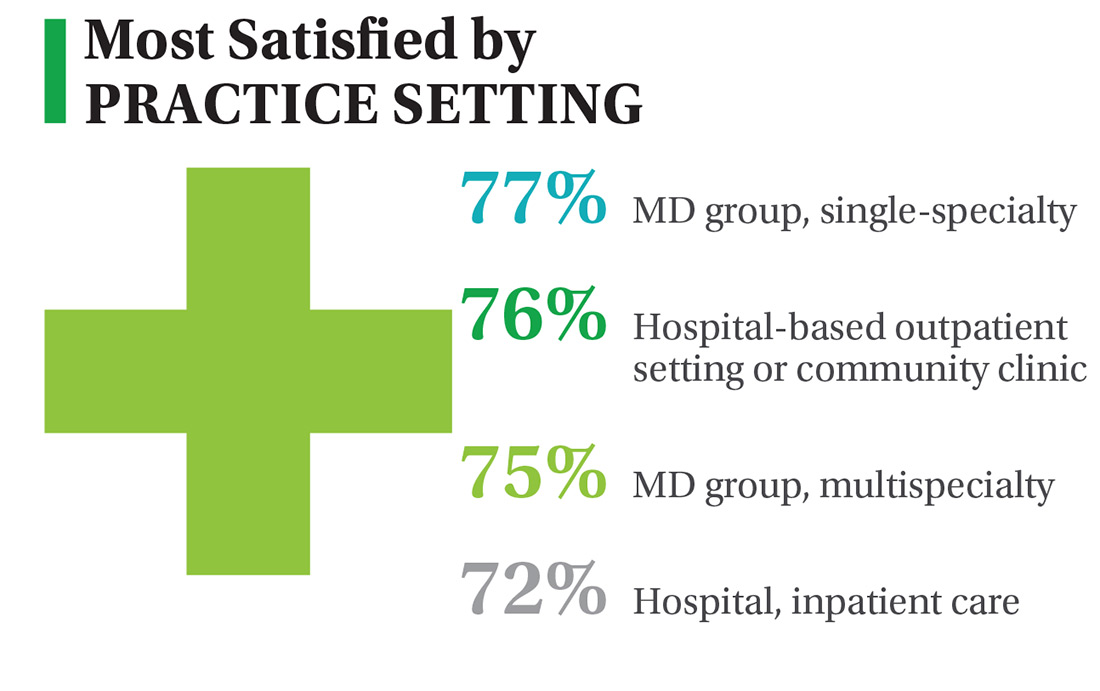

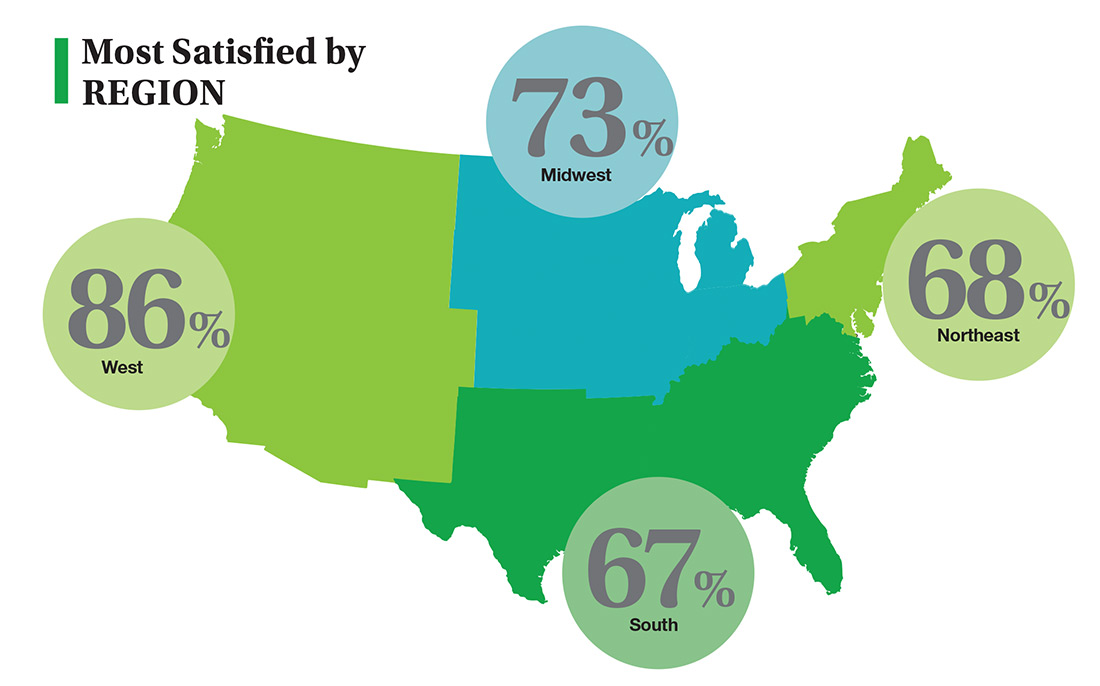

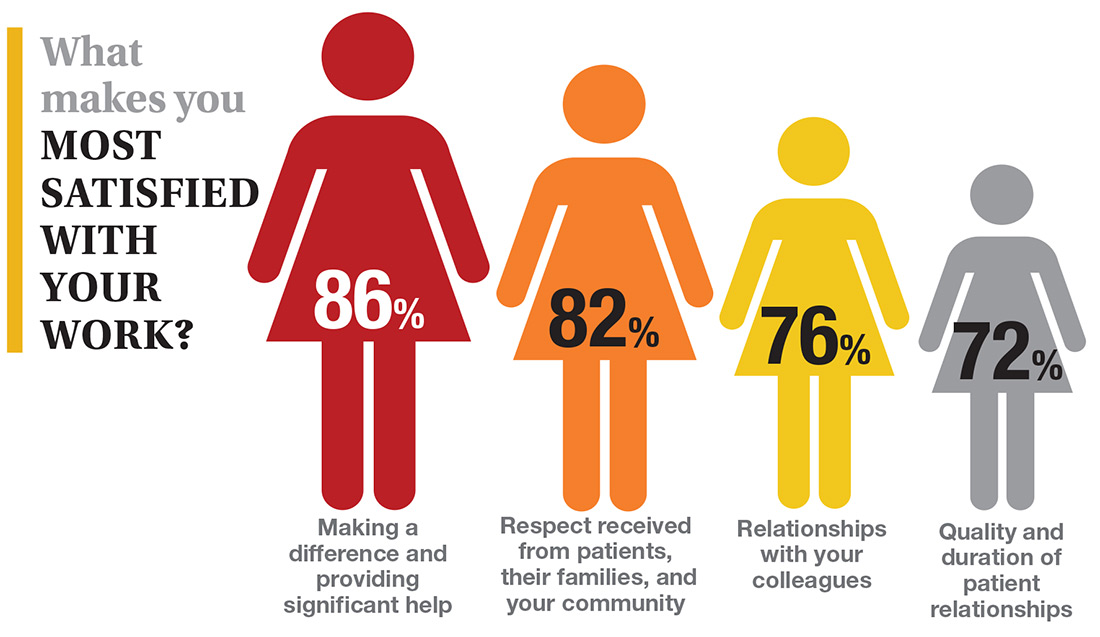

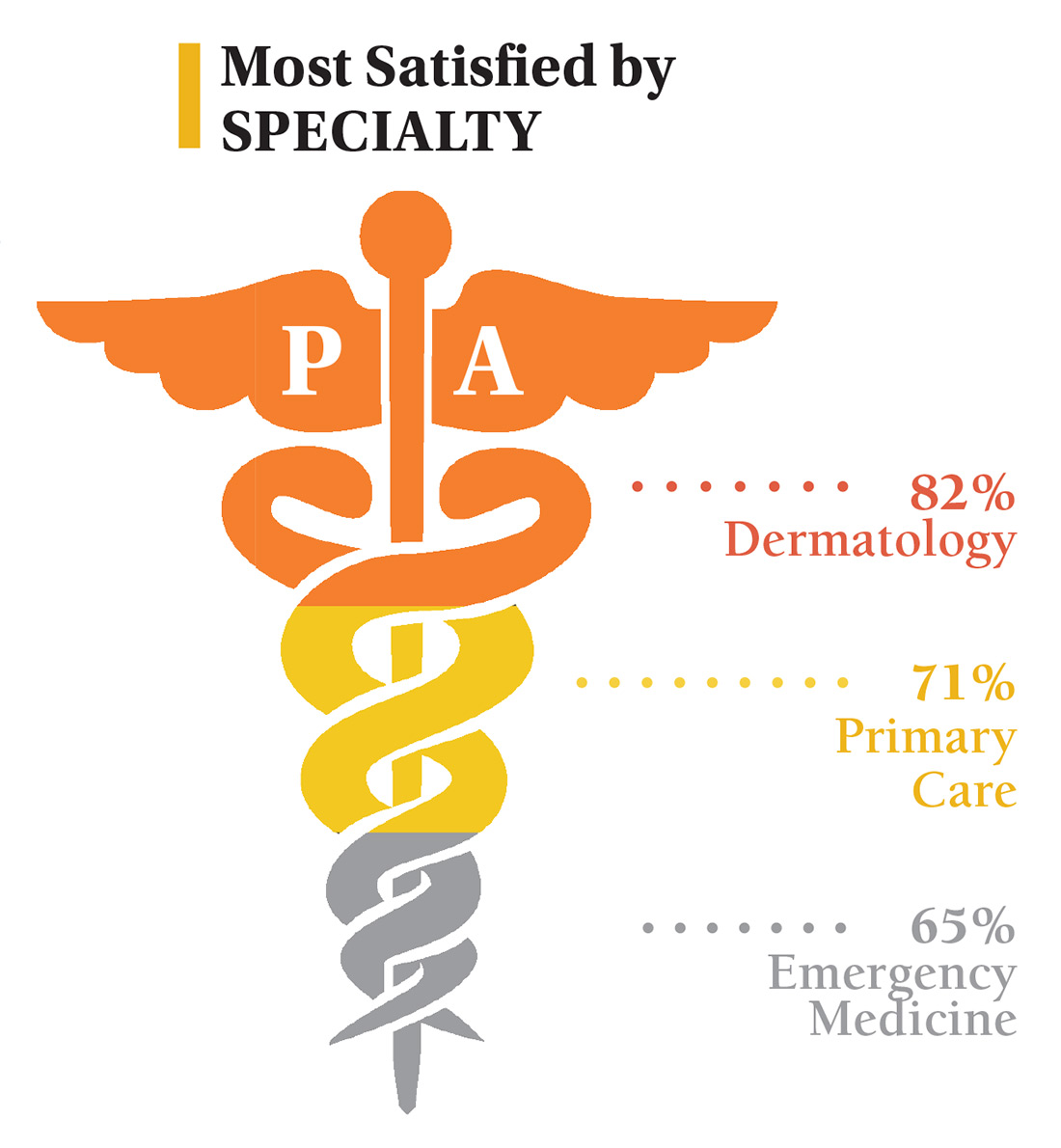

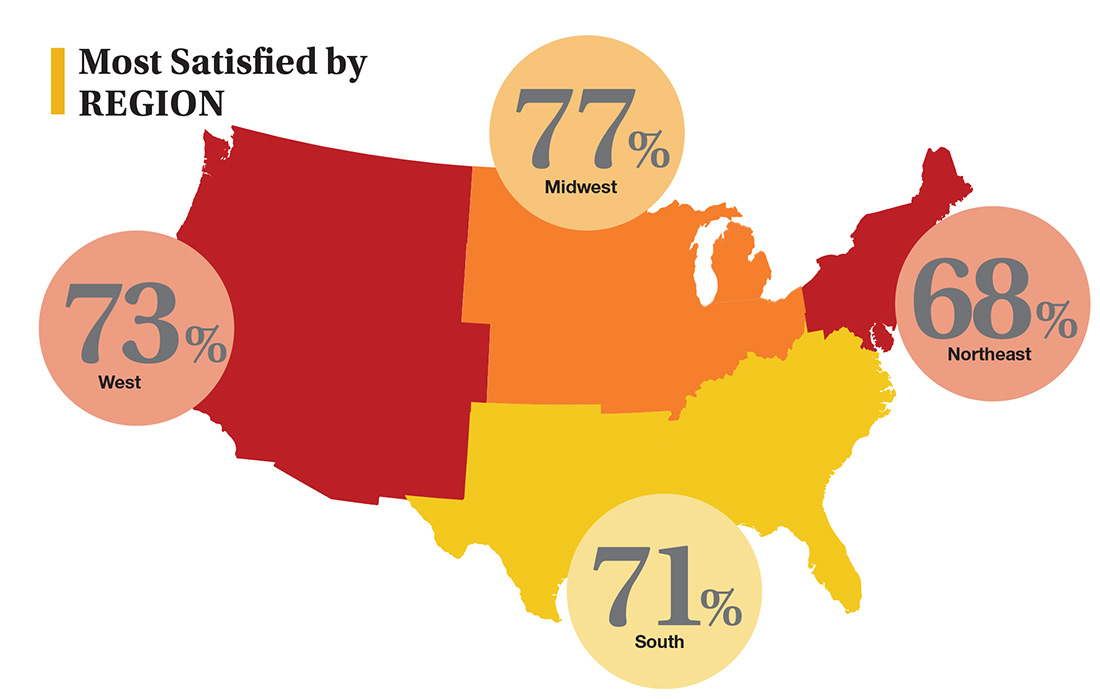

In this era of “burnout”—when a PubMed search of the term yields more than 13,000 results—it’s heartening to discover that 72% of all clinicians are always and almost always satisfied at work. In contrast to physicians, who report a 42% burnout rate, only 6% of NPs and PAs report the same.1 This bodes well for your patients’ satisfaction.2

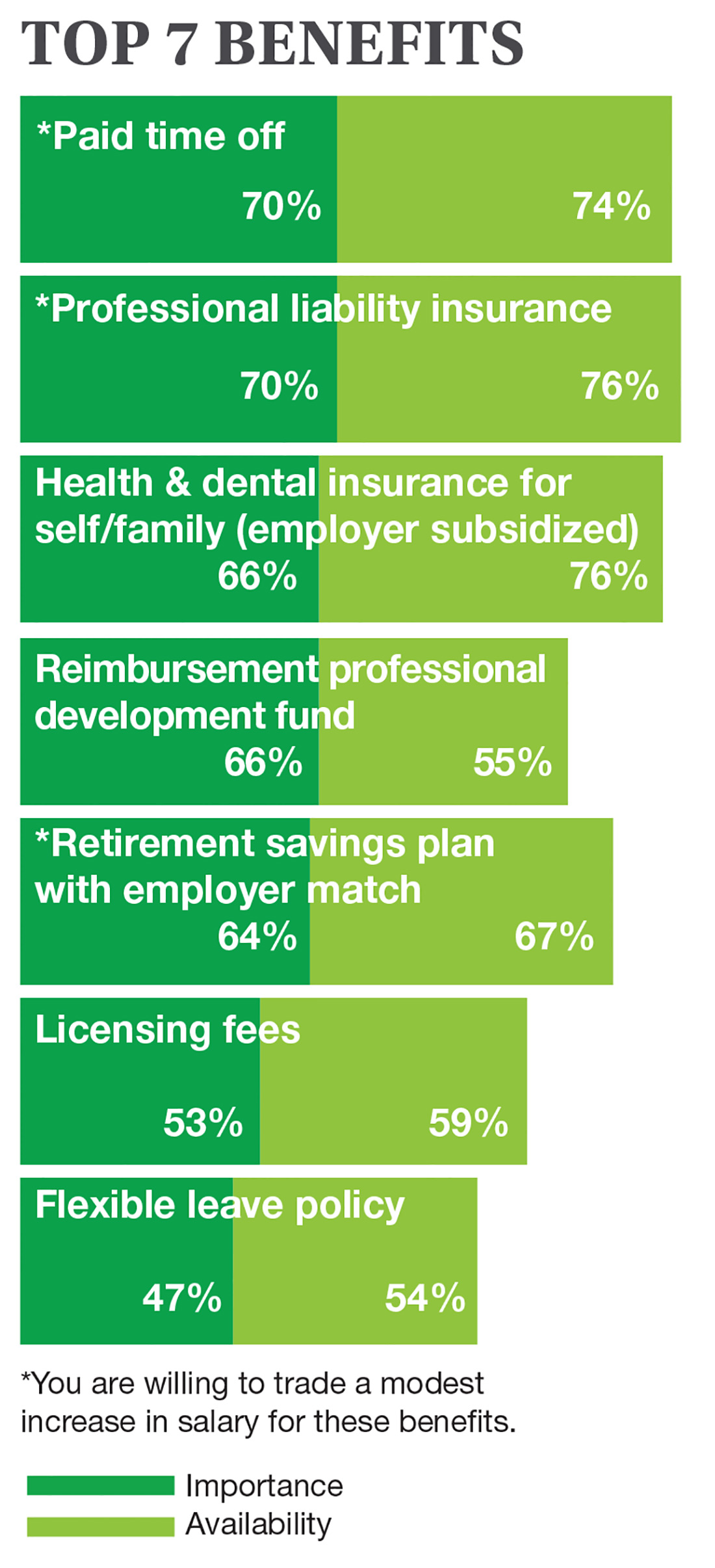

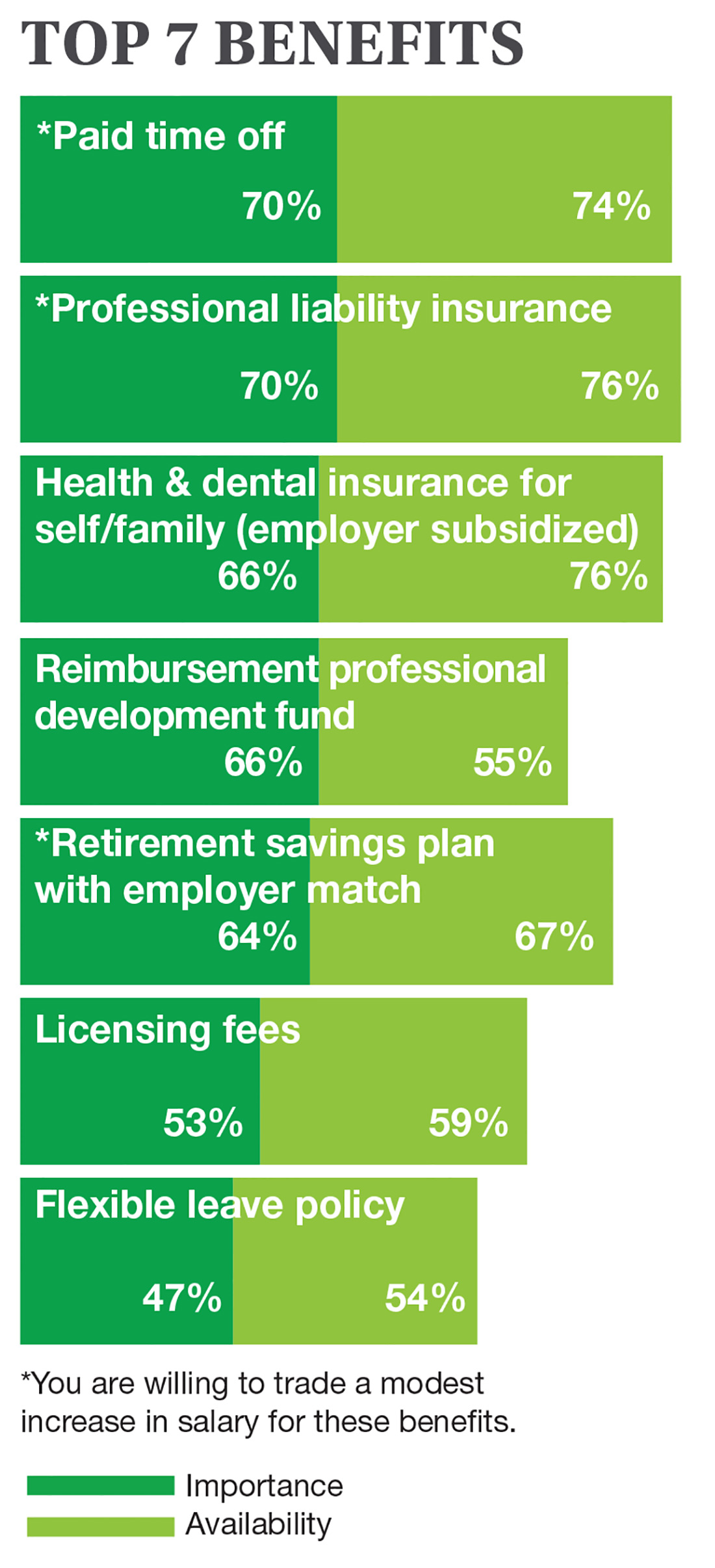

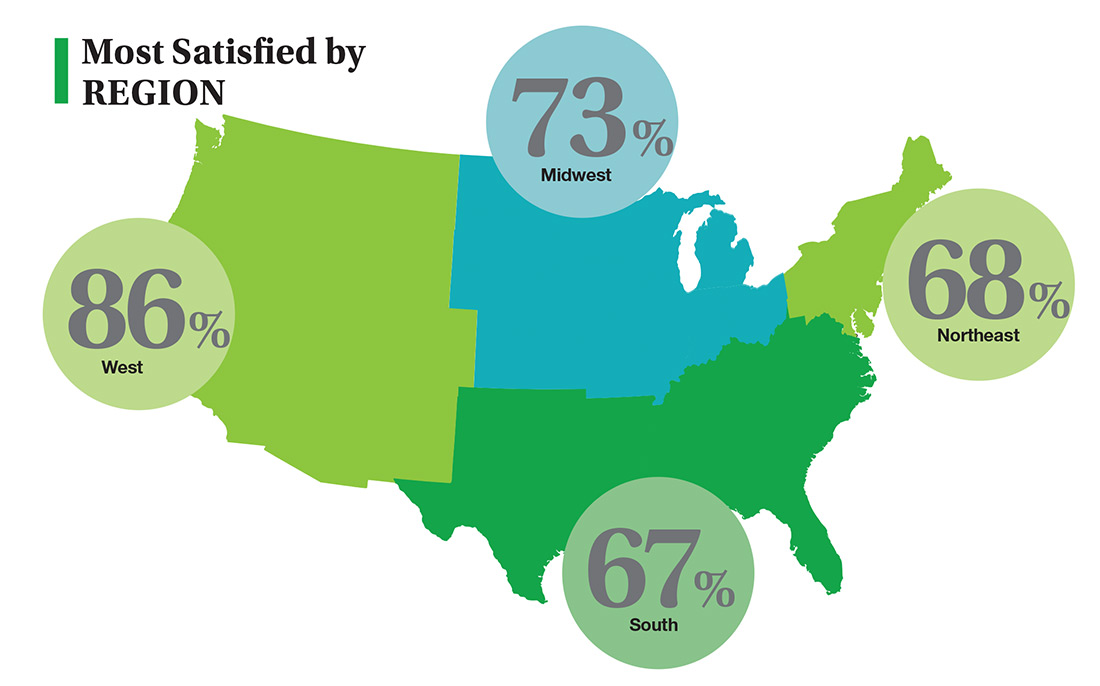

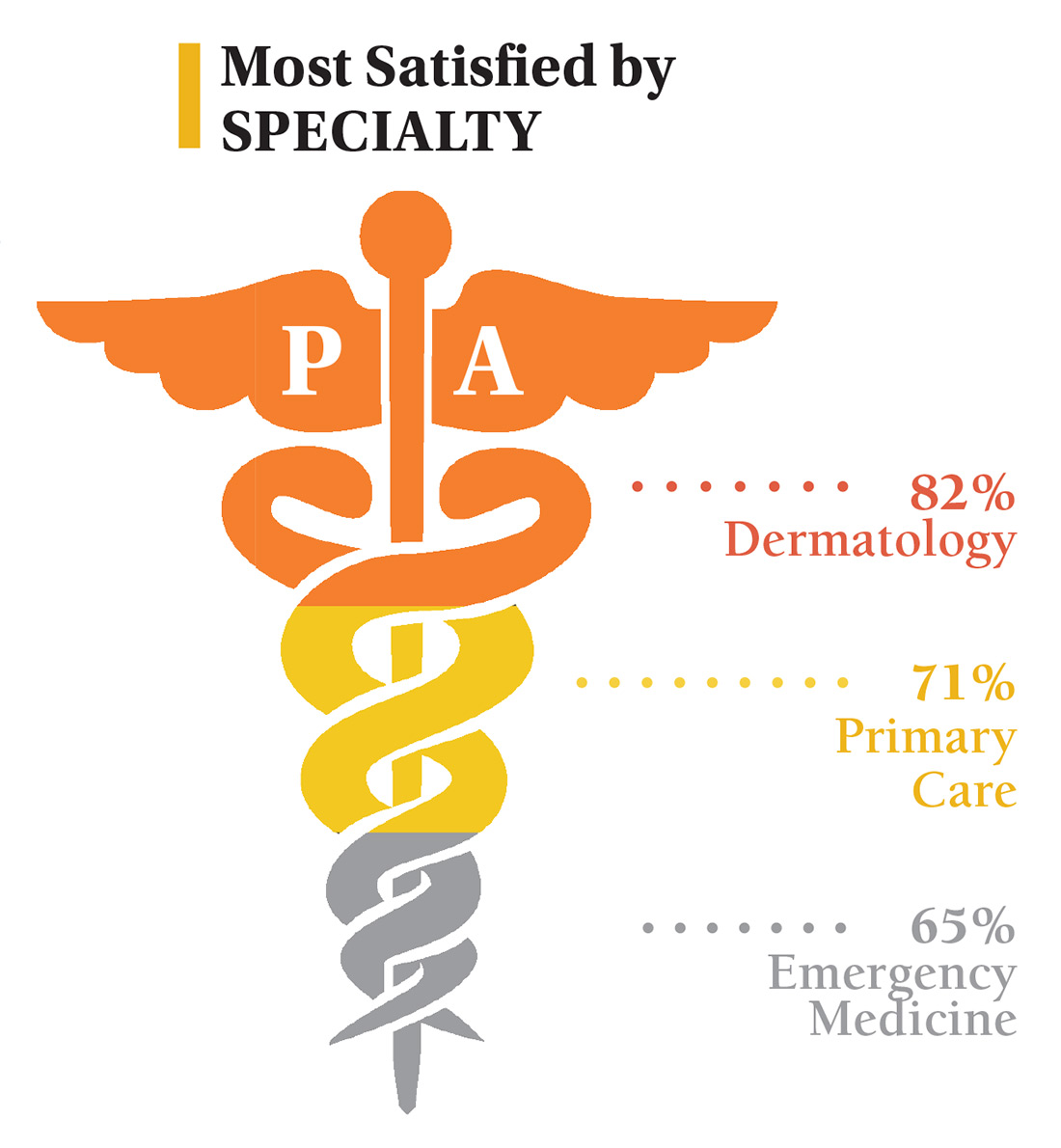

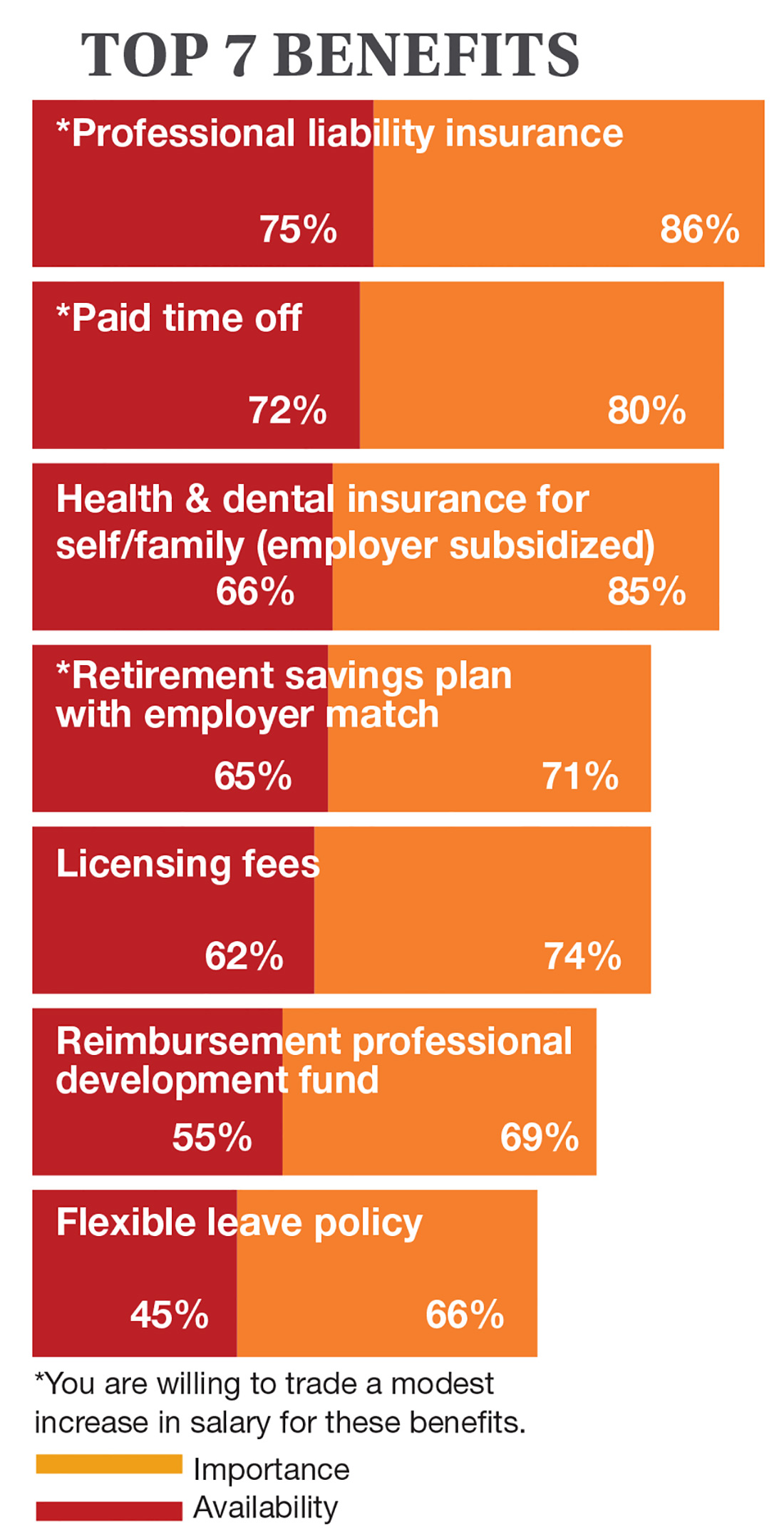

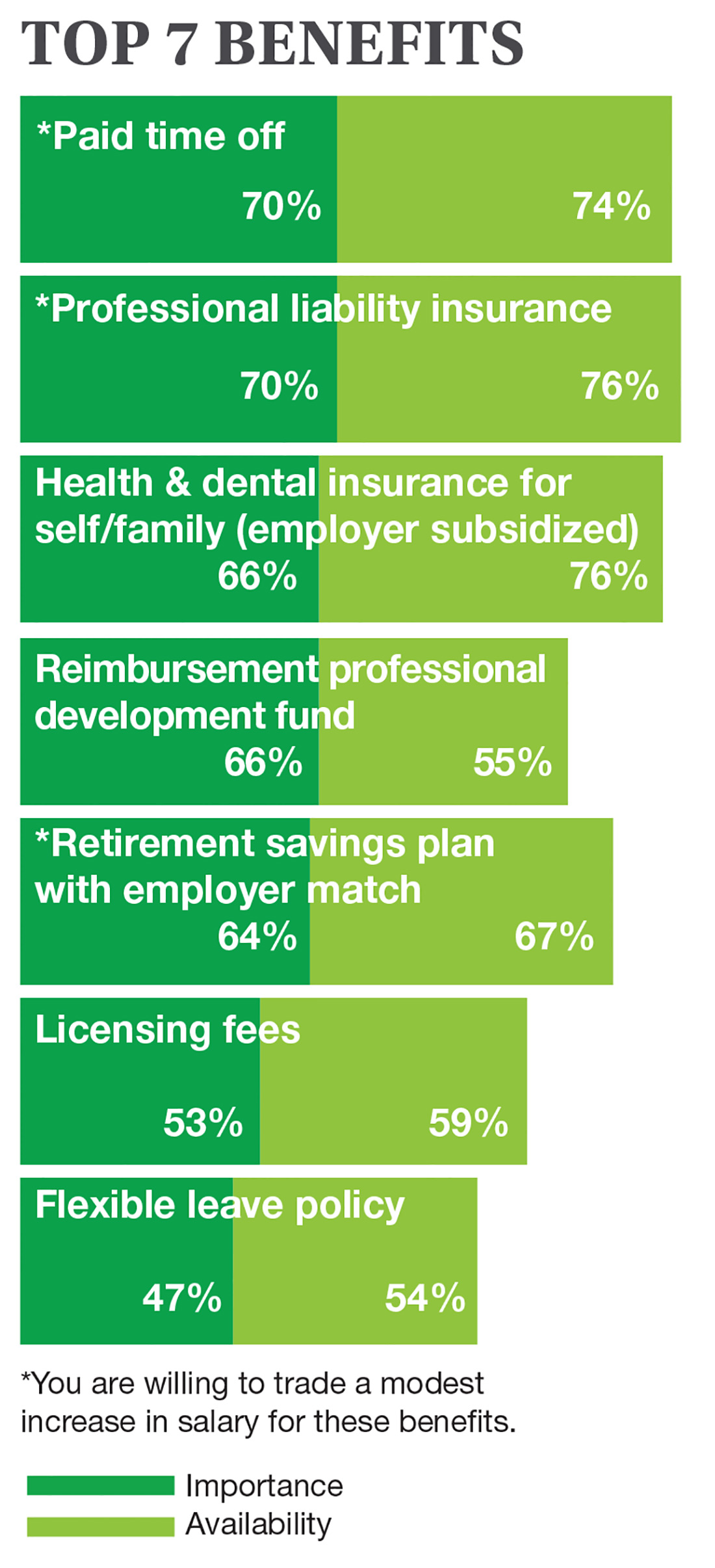

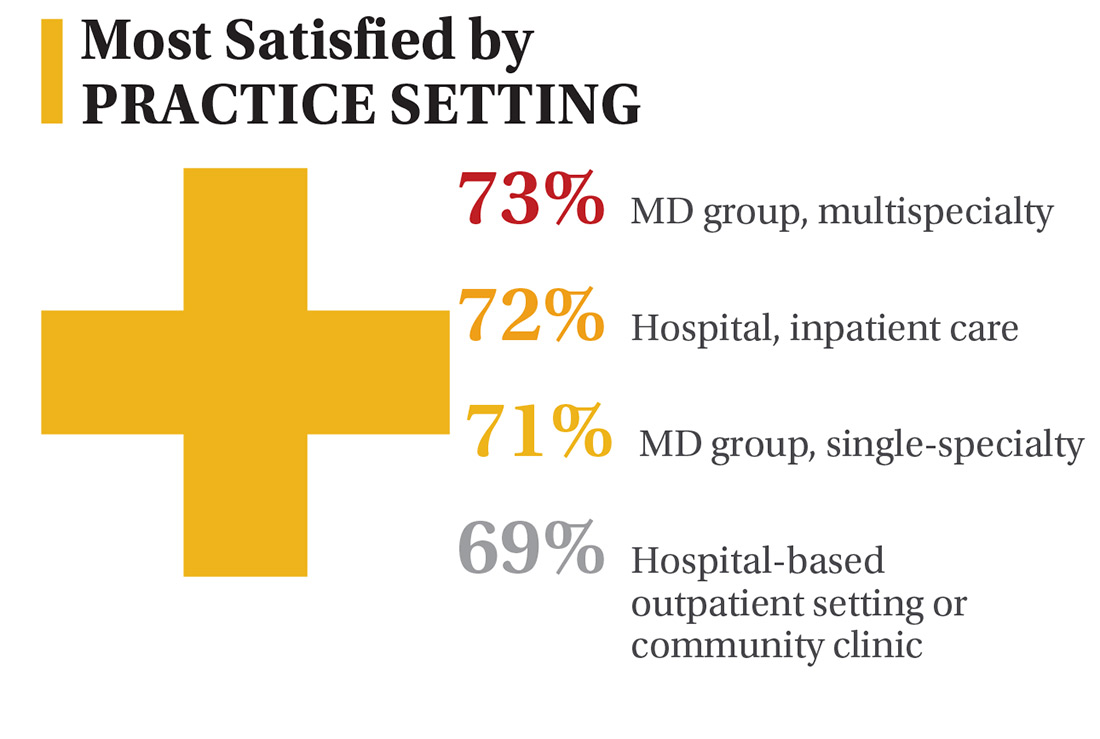

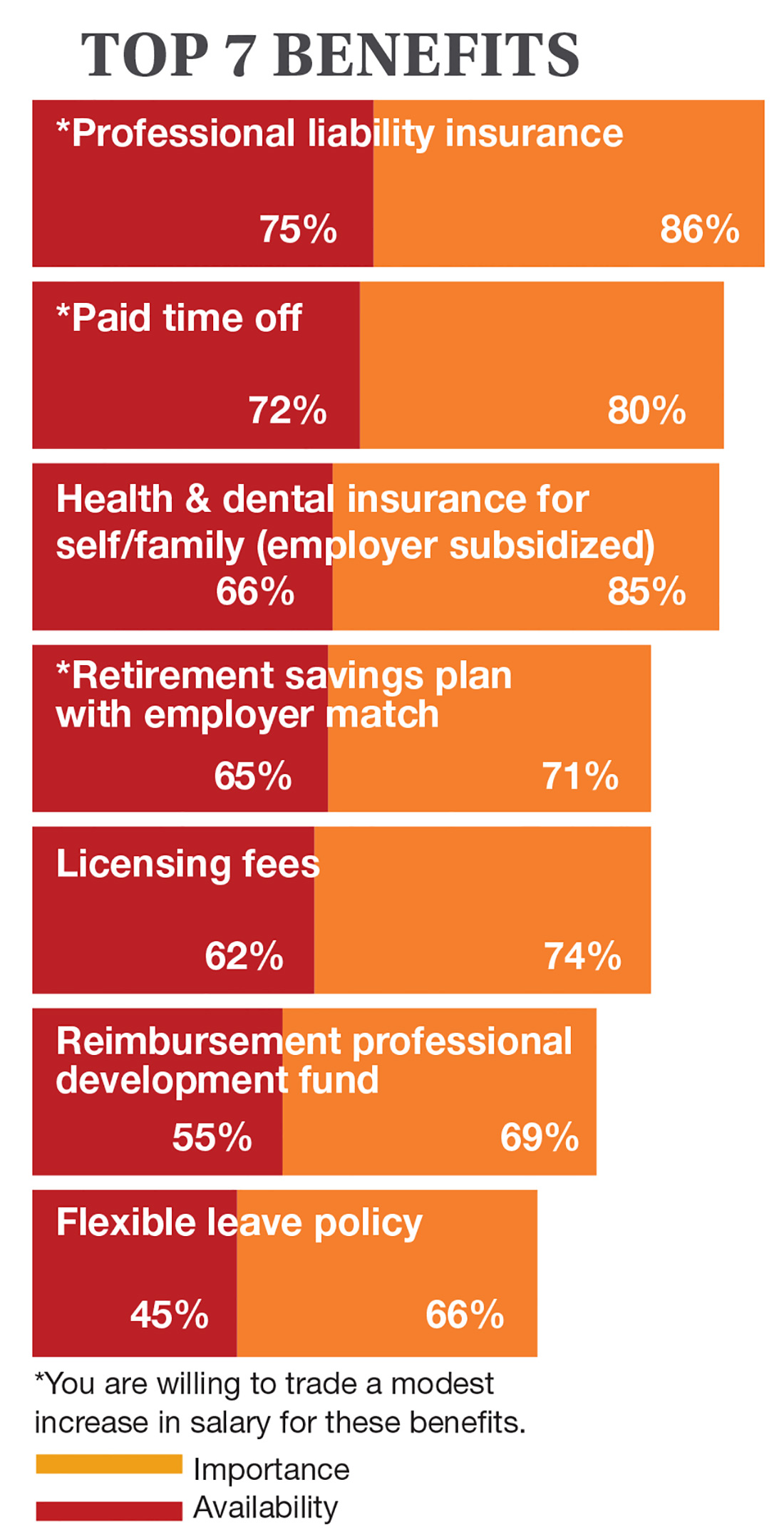

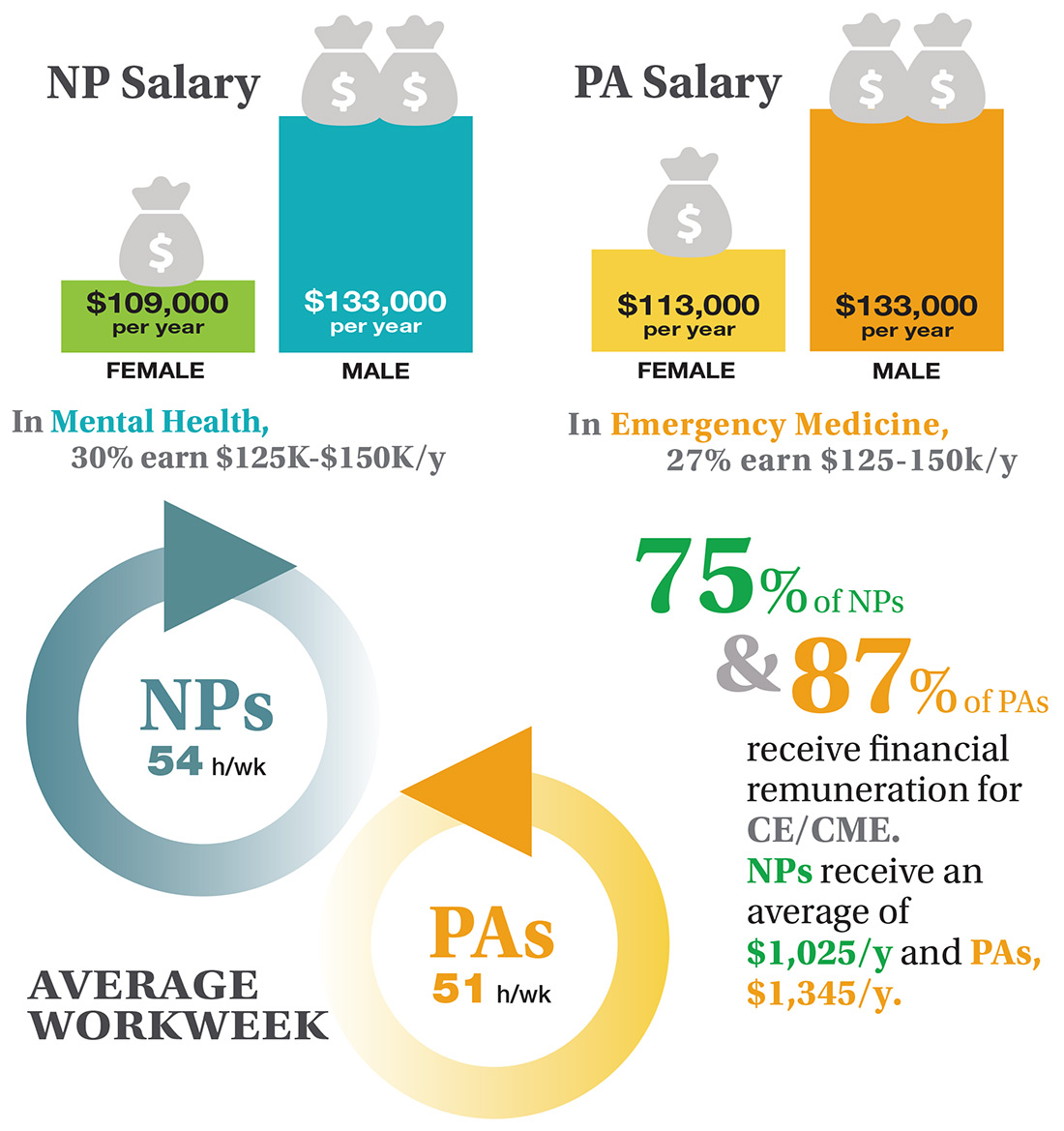

On the following pages, we focus on the details, with breakouts by specialty, region, and practice setting. Be sure to check out your top seven most desirable benefits by availability; CE/CME reimbursements; and salary information by gender and workweek.

1. Medscape National Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2018. www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnoutdepression-6009235#2. Accessed November 17, 2018.

2. The Connection Between Employee Satisfaction and Patient Satisfaction. www.amnhealthcare.com/latest-healthcare-news/459/1033. AMN Healthcare. Accessed November 17, 2018.

Continue to: Nurse Practitioners

NURSE PRACTITIONERS

Continue to: Physician Assistants

PHYSICIAN ASSISTANTS

Continue to: NPs & PAs

NPs & PAs

METHODOLOGY

Fielded electronically under the Clinician Reviews logo, an introductory email letter signed by the Editors-in-Chief invited participation in the online 3rd annual NP/PA Job Satisfaction Survey of 35 questions.

The survey was fielded October 4, 2018, to a random representative sample of 16,000 NPs and 9,000 PAs within the United States, excluding students. The first 150 respondents to complete the survey received a $25 Amazon.com gift certificate.

A total of 1,207 usable responses—a projectable sample size—were received by October 19, 2018, the final cut-off date.

Of the total respondents, 65% are NPs (789) and 35% are PAs (418), which is proportional to the universe of NPs and PAs.1,2 This summary of results is based on only those respondents who designated their profession as NP or PA.

1. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. NP Fact Sheet. www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet. Accessed November 20, 2018.

2. NCCPA. 2017 Statistical Profile of Certified Physician Assistants: an Annual Report of the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. http://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/2017StatisticalProfileofCertifiedPhysicianAssistants6.27.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2018.

In this era of “burnout”—when a PubMed search of the term yields more than 13,000 results—it’s heartening to discover that 72% of all clinicians are always and almost always satisfied at work. In contrast to physicians, who report a 42% burnout rate, only 6% of NPs and PAs report the same.1 This bodes well for your patients’ satisfaction.2

On the following pages, we focus on the details, with breakouts by specialty, region, and practice setting. Be sure to check out your top seven most desirable benefits by availability; CE/CME reimbursements; and salary information by gender and workweek.

1. Medscape National Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2018. www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnoutdepression-6009235#2. Accessed November 17, 2018.

2. The Connection Between Employee Satisfaction and Patient Satisfaction. www.amnhealthcare.com/latest-healthcare-news/459/1033. AMN Healthcare. Accessed November 17, 2018.

Continue to: Nurse Practitioners

NURSE PRACTITIONERS

Continue to: Physician Assistants

PHYSICIAN ASSISTANTS

Continue to: NPs & PAs

NPs & PAs

METHODOLOGY

Fielded electronically under the Clinician Reviews logo, an introductory email letter signed by the Editors-in-Chief invited participation in the online 3rd annual NP/PA Job Satisfaction Survey of 35 questions.

The survey was fielded October 4, 2018, to a random representative sample of 16,000 NPs and 9,000 PAs within the United States, excluding students. The first 150 respondents to complete the survey received a $25 Amazon.com gift certificate.

A total of 1,207 usable responses—a projectable sample size—were received by October 19, 2018, the final cut-off date.

Of the total respondents, 65% are NPs (789) and 35% are PAs (418), which is proportional to the universe of NPs and PAs.1,2 This summary of results is based on only those respondents who designated their profession as NP or PA.

1. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. NP Fact Sheet. www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet. Accessed November 20, 2018.

2. NCCPA. 2017 Statistical Profile of Certified Physician Assistants: an Annual Report of the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. http://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/2017StatisticalProfileofCertifiedPhysicianAssistants6.27.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2018.

In this era of “burnout”—when a PubMed search of the term yields more than 13,000 results—it’s heartening to discover that 72% of all clinicians are always and almost always satisfied at work. In contrast to physicians, who report a 42% burnout rate, only 6% of NPs and PAs report the same.1 This bodes well for your patients’ satisfaction.2

On the following pages, we focus on the details, with breakouts by specialty, region, and practice setting. Be sure to check out your top seven most desirable benefits by availability; CE/CME reimbursements; and salary information by gender and workweek.

1. Medscape National Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2018. www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnoutdepression-6009235#2. Accessed November 17, 2018.

2. The Connection Between Employee Satisfaction and Patient Satisfaction. www.amnhealthcare.com/latest-healthcare-news/459/1033. AMN Healthcare. Accessed November 17, 2018.

Continue to: Nurse Practitioners

NURSE PRACTITIONERS

Continue to: Physician Assistants

PHYSICIAN ASSISTANTS

Continue to: NPs & PAs

NPs & PAs

METHODOLOGY

Fielded electronically under the Clinician Reviews logo, an introductory email letter signed by the Editors-in-Chief invited participation in the online 3rd annual NP/PA Job Satisfaction Survey of 35 questions.

The survey was fielded October 4, 2018, to a random representative sample of 16,000 NPs and 9,000 PAs within the United States, excluding students. The first 150 respondents to complete the survey received a $25 Amazon.com gift certificate.

A total of 1,207 usable responses—a projectable sample size—were received by October 19, 2018, the final cut-off date.

Of the total respondents, 65% are NPs (789) and 35% are PAs (418), which is proportional to the universe of NPs and PAs.1,2 This summary of results is based on only those respondents who designated their profession as NP or PA.

1. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. NP Fact Sheet. www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet. Accessed November 20, 2018.

2. NCCPA. 2017 Statistical Profile of Certified Physician Assistants: an Annual Report of the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. http://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/2017StatisticalProfileofCertifiedPhysicianAssistants6.27.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2018.

Addressing patients’ complaints

. More than ever, it seems impossible to construct any sort of template for consistent, mutually satisfactory resolutions of such disputes.

But it is possible, and it’s not as complex as it appears, once you realize what the vast majority of complaints have in common: Expectations have not been met. Sometimes it’s your fault, sometimes the patient’s, and often a bit of both, but either way, the result is the same: You have an unhappy patient, and you must deal with it.

Why, you might ask? Is the expenditure of time and effort necessary to resolve complaints really worth it? Absolutely, because the old cliché is true: A satisfied patient will refer five new patients, but a dissatisfied one will chase away twenty or more. Besides, if the complaint is significant, and you decline to resolve it, the patient is likely to find someone who will; and chances are you won’t like the choice, or the venue – or the resolution.

As such, this is not a job you should delegate. Unless the complaint is trivial or purely administrative, you should address it yourself. It’s what you would want if you were the complainant, and it’s often too important to trust to a subordinate.

I have distilled this unpleasant duty down to a three-part strategy:

- Discover which expectations went unmet, and why.

- Agree on a solution.

- Learn from the experience, to prevent similar future complaints.

Of course, the easiest way to deal with complaints is to prevent as many as possible in the first place. Take the time to explain all treatments and procedures, and their most likely outcomes. Nip unrealistic expectations in the bud. Make it clear (preferably in writing) that reputable practitioners cannot guarantee perfect results. And, of course, document everything you have explained. Documentation is like garlic: There is no such thing as too much of it.

Of course, despite your best efforts at prevention, there will always be complaints, and handling them is a skill set worth honing, especially the one most of us do poorly: listening to the complaint.

Before you can resolve a problem you have to know what it is, and this is precisely the wrong time to make assumptions or jump to conclusions. So listen to the entire complaint without interrupting, defending, or justifying. Angry patients don’t care why the problem occurred, and they are not interested in your side of the story. This is not about you, so listen and understand.

As you listen, the unmet expectations will become clear. When the patient is finished, I like to summarize the complaint in that context: “So if I understand you correctly, you expected ‘X’ to happen, but ‘Y’ happened instead.” If I’m wrong, I modify my summary until the patient agrees that I understand the issue.

Once you know the problem, you can talk about a solution. The patient usually has one in mind – additional treatment, a referral elsewhere, a fee adjustment, or sometimes simply an apology. Consider it.

If the patient’s solution is reasonable, by all means, agree to it; if it is unreasonable, try to offer a reasonable alternative. The temptation here is to think more about protecting yourself than making the patient happy, but that often leads to bigger problems. Don’t be defensive. Again, this is not about you.

I am often asked if a refund is a reasonable option. Some patients (and lawyers) will interpret a refund as a tacit admission of guilt, so I generally try to avoid them. However, canceling a small fee or copay for an angry patient can be an expedient solution (particularly if it is still unpaid), and in my opinion, looks exactly like what it is: an honest effort to rectify the situation. But in general, additional materials or services, at reduced or waived fees, are a better alternative than refunding money.

Once you have arrived at a mutually satisfactory solution, again, document everything but consider reserving a “private” chart area for such documentation (unless it is a bona fide clinical issue), so that it won’t go out to referrers and other third parties with copies of your clinical notes. Also, consider having the patient sign off on the documentation, acknowledging that the complaint has been resolved.

Finally, always try to learn something from the experience. Ask yourself what you can do (or avoid doing) next time, and how you might prevent similar unrealistic expectations in a future situation.

Above all, never take complaints personally – even when they are personal. It’s always worth reminding yourself that no matter how hard you try, you will never please everyone.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

. More than ever, it seems impossible to construct any sort of template for consistent, mutually satisfactory resolutions of such disputes.

But it is possible, and it’s not as complex as it appears, once you realize what the vast majority of complaints have in common: Expectations have not been met. Sometimes it’s your fault, sometimes the patient’s, and often a bit of both, but either way, the result is the same: You have an unhappy patient, and you must deal with it.

Why, you might ask? Is the expenditure of time and effort necessary to resolve complaints really worth it? Absolutely, because the old cliché is true: A satisfied patient will refer five new patients, but a dissatisfied one will chase away twenty or more. Besides, if the complaint is significant, and you decline to resolve it, the patient is likely to find someone who will; and chances are you won’t like the choice, or the venue – or the resolution.

As such, this is not a job you should delegate. Unless the complaint is trivial or purely administrative, you should address it yourself. It’s what you would want if you were the complainant, and it’s often too important to trust to a subordinate.

I have distilled this unpleasant duty down to a three-part strategy:

- Discover which expectations went unmet, and why.

- Agree on a solution.

- Learn from the experience, to prevent similar future complaints.

Of course, the easiest way to deal with complaints is to prevent as many as possible in the first place. Take the time to explain all treatments and procedures, and their most likely outcomes. Nip unrealistic expectations in the bud. Make it clear (preferably in writing) that reputable practitioners cannot guarantee perfect results. And, of course, document everything you have explained. Documentation is like garlic: There is no such thing as too much of it.

Of course, despite your best efforts at prevention, there will always be complaints, and handling them is a skill set worth honing, especially the one most of us do poorly: listening to the complaint.

Before you can resolve a problem you have to know what it is, and this is precisely the wrong time to make assumptions or jump to conclusions. So listen to the entire complaint without interrupting, defending, or justifying. Angry patients don’t care why the problem occurred, and they are not interested in your side of the story. This is not about you, so listen and understand.

As you listen, the unmet expectations will become clear. When the patient is finished, I like to summarize the complaint in that context: “So if I understand you correctly, you expected ‘X’ to happen, but ‘Y’ happened instead.” If I’m wrong, I modify my summary until the patient agrees that I understand the issue.

Once you know the problem, you can talk about a solution. The patient usually has one in mind – additional treatment, a referral elsewhere, a fee adjustment, or sometimes simply an apology. Consider it.

If the patient’s solution is reasonable, by all means, agree to it; if it is unreasonable, try to offer a reasonable alternative. The temptation here is to think more about protecting yourself than making the patient happy, but that often leads to bigger problems. Don’t be defensive. Again, this is not about you.

I am often asked if a refund is a reasonable option. Some patients (and lawyers) will interpret a refund as a tacit admission of guilt, so I generally try to avoid them. However, canceling a small fee or copay for an angry patient can be an expedient solution (particularly if it is still unpaid), and in my opinion, looks exactly like what it is: an honest effort to rectify the situation. But in general, additional materials or services, at reduced or waived fees, are a better alternative than refunding money.

Once you have arrived at a mutually satisfactory solution, again, document everything but consider reserving a “private” chart area for such documentation (unless it is a bona fide clinical issue), so that it won’t go out to referrers and other third parties with copies of your clinical notes. Also, consider having the patient sign off on the documentation, acknowledging that the complaint has been resolved.

Finally, always try to learn something from the experience. Ask yourself what you can do (or avoid doing) next time, and how you might prevent similar unrealistic expectations in a future situation.

Above all, never take complaints personally – even when they are personal. It’s always worth reminding yourself that no matter how hard you try, you will never please everyone.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

. More than ever, it seems impossible to construct any sort of template for consistent, mutually satisfactory resolutions of such disputes.

But it is possible, and it’s not as complex as it appears, once you realize what the vast majority of complaints have in common: Expectations have not been met. Sometimes it’s your fault, sometimes the patient’s, and often a bit of both, but either way, the result is the same: You have an unhappy patient, and you must deal with it.

Why, you might ask? Is the expenditure of time and effort necessary to resolve complaints really worth it? Absolutely, because the old cliché is true: A satisfied patient will refer five new patients, but a dissatisfied one will chase away twenty or more. Besides, if the complaint is significant, and you decline to resolve it, the patient is likely to find someone who will; and chances are you won’t like the choice, or the venue – or the resolution.

As such, this is not a job you should delegate. Unless the complaint is trivial or purely administrative, you should address it yourself. It’s what you would want if you were the complainant, and it’s often too important to trust to a subordinate.

I have distilled this unpleasant duty down to a three-part strategy:

- Discover which expectations went unmet, and why.

- Agree on a solution.

- Learn from the experience, to prevent similar future complaints.

Of course, the easiest way to deal with complaints is to prevent as many as possible in the first place. Take the time to explain all treatments and procedures, and their most likely outcomes. Nip unrealistic expectations in the bud. Make it clear (preferably in writing) that reputable practitioners cannot guarantee perfect results. And, of course, document everything you have explained. Documentation is like garlic: There is no such thing as too much of it.

Of course, despite your best efforts at prevention, there will always be complaints, and handling them is a skill set worth honing, especially the one most of us do poorly: listening to the complaint.

Before you can resolve a problem you have to know what it is, and this is precisely the wrong time to make assumptions or jump to conclusions. So listen to the entire complaint without interrupting, defending, or justifying. Angry patients don’t care why the problem occurred, and they are not interested in your side of the story. This is not about you, so listen and understand.

As you listen, the unmet expectations will become clear. When the patient is finished, I like to summarize the complaint in that context: “So if I understand you correctly, you expected ‘X’ to happen, but ‘Y’ happened instead.” If I’m wrong, I modify my summary until the patient agrees that I understand the issue.

Once you know the problem, you can talk about a solution. The patient usually has one in mind – additional treatment, a referral elsewhere, a fee adjustment, or sometimes simply an apology. Consider it.

If the patient’s solution is reasonable, by all means, agree to it; if it is unreasonable, try to offer a reasonable alternative. The temptation here is to think more about protecting yourself than making the patient happy, but that often leads to bigger problems. Don’t be defensive. Again, this is not about you.

I am often asked if a refund is a reasonable option. Some patients (and lawyers) will interpret a refund as a tacit admission of guilt, so I generally try to avoid them. However, canceling a small fee or copay for an angry patient can be an expedient solution (particularly if it is still unpaid), and in my opinion, looks exactly like what it is: an honest effort to rectify the situation. But in general, additional materials or services, at reduced or waived fees, are a better alternative than refunding money.

Once you have arrived at a mutually satisfactory solution, again, document everything but consider reserving a “private” chart area for such documentation (unless it is a bona fide clinical issue), so that it won’t go out to referrers and other third parties with copies of your clinical notes. Also, consider having the patient sign off on the documentation, acknowledging that the complaint has been resolved.

Finally, always try to learn something from the experience. Ask yourself what you can do (or avoid doing) next time, and how you might prevent similar unrealistic expectations in a future situation.

Above all, never take complaints personally – even when they are personal. It’s always worth reminding yourself that no matter how hard you try, you will never please everyone.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

The Gift and the Thought Both Count

It is that time of year when federal compliance officers, clinical ethicists, and staff counsels are flooded with queries about the legal and ethical acceptability of gifts. And no wonder, all the winter holidays often involve giving gifts. The simple and spontaneous acts of giving and receiving gifts become more complicated and deliberative in the federal health care system. Both legal rules and ethical values bear upon who can offer and accept what gift to whom upon what occasion and in what amount. The “Standards of Ethical Conduct for Employees of the Executive Branch” devotes 2 entire subparts to the subject of gifts.1 We will examine a small section of the document that can become a big issue for federal practitioners during that holiday—gifts from patients.

First, veterans (patients) are “prohibited sources” in section 5 CFR §2635.203 (d).1 And since VA employees are subject to restrictions on accepting gifts from sources outside the government, unless an exception applies, federal employees may not accept a gift because of their official position (eg, Federal Practitioner, editor-in-chief) or a gift from a patient (prohibited source; [5 CFR §2635.201]).

It might seem like this is going to be a very short column this month, as gifts from patients are forbidden. Yet, a Christmas card or homemade fudge isn’t really a gift, is it?

5 CFR §2635.203 (b) defines what is and is not a gift: For example, minor items of food or items like a thank-you card are specifically excluded in section (b) 1-10.

Is Christmas an exception or are just types of gifts excluded?

There are exceptions to the general regulation about accepting gifts from prohibited sources. Many staff will recall hearing about the “$20 rule,” which is actually the “$20-50” rule stating that a federal employee may accept a gift from a patient (prohibited source) if the value of said gift is under $20 and the employee does not accept more than $50 from any single source in a calendar year. §2635.204 lists the exceptions. However, starting in 2017, the regulations changed to require that federal employees also consider not just whether they could accept a gift but—ethically—they should take the gift even if it was permitted under the law. The Office of Government Ethics made this change because it wanted to emphasize the importance of considering not just how things are but how things appear to be. The regulations contain detailed descriptions of what employees should think about and stipulates that the decisions will not be further scrutinized (5 CFR §2635.201[b]).1

Based on this new emphasis on appearances, ethically, no doctor or nurse should accept the keys to a new BMW from a patient who owns a luxury car dealership. But what about more prosaic and probable presents: the holiday cookies a single father made with his children for the nurse practitioner who has been his primary care practitioner for years; the birdhouse a Vietnam veteran made in her crafts class for the surgeon who removed her gallbladder; or even the store-bought but no less heartfelt tin of popcorn from an elderly veteran for the hospitalist who saw him through a rough bought of pneumonia?

Related: Happy Federal New Year

The rules about practitioners accepting patient gifts are rational and unambiguous: It is the values conflict surrounding patient gifts that is often emotion driven and muddled; it may be easier and safer to adopt the “just say no” policy. And yet, while this might seem the most unassailable position to avoid a conflict of interest, could this possibly be a more practitioner- than patient-centered standard? Authoritative sources in the ethics literature are equally divided and ambivalent on the question.2,3 The American College of Physicians Ethics Manual states: “In deciding whether to accept a gift from a patient, the physician should consider the nature of the gift and its value to the patient, the potential implications for the patient-physician relationship of accepting or refusing it, and the patient’s probable intention and expectations.”4 A small gift as a token of appreciation is not ethically problematic. Favored treatment as a result of acceptance of any gift is problematic, undermines professionalism, and may interfere with objectivity in the care of the patient.4

Related: Am I My Brother’s/Sister’s Keeper?

Many an ethics commentator have cautioned, “beware of patients bearing gifts.”5 In making an ethical assessment of whether or not to accept the gift, a key question a practitioner needs to ask him or herself is about the patient’s motive. Even the patient may be unaware of the reasons behind their giving, and the wise practitioner will take a mindful moment to think about the context and timing of the gift and the nature of his or her relationship to the patient. Sadly, many of our patients are lonely especially at this family time of year and on some level may hope the gift will help slide the professional relationship toward a more personal one. Some patients may think a gift might earn them preferential treatment. Finally, a few patients may have a romantic or sexual attraction toward a clinician.

Often in the latter 2 cases, a pattern will develop that discloses the patient’s true intent. Very expensive gifts, monetary gifts, excessively personal gifts, or frequent gifts should alert the practitioner that more may be going on. A kind reminder to the patient that providing good care is the only reward needed may be sufficient. For practitioners whose ethical code does not permit them to accept gifts, then a genuine thank you and an explanation of the rules and/or values behind the refusal may be necessary. There are other times when the practitioner or a supervisor/advisor may need to reset the boundaries or even to transfer the patient to another practitioner. The norms in mental health care and psychotherapy are more stringent because of the intimacy of the relationship and the potential vulnerability of patients.6

For gifts that seem genuine and generous or cost a trivial amount, then there is an ethical argument to be made for accepting them with gratitude. In many cultures, hospitality is a tradition, and expressing appreciation a virtue, so when a practitioner refuses to graciously take a small gift, they risk offending the patient. Rejection of a gift can be seen as disrespectful and could cause a rupture in an otherwise sound practitioner-patient relationship. Other patients experience strong feelings of gratitude and admiration for their practitioners, stronger than most of us recognize. The ability for a patient to give their practitioner a holiday gift, particularly one they invested time and energy in creating or choosing, can enhance their sense of self-worth and individual agency. These gifts are not so much an attempt to diminish the professional power differential but to close the gap between 2 human beings in an unequal relationship that is yet one of shared decision making. All practitioners should be aware of the often underappreciated social power of a gift to influence decisions.

Related: Caring Under a Microscope

At the same time, clinicians can strive to be sensitively attuned to the reality that, sometimes the cookie is just a cookie so eat and enjoy, just remember to share with your group. External judgments are often cited as practical rules of thumb for determining the ethical acceptability of a gift: Would you want your mother, newspaper, or colleague to know you took the present? I prefer an internal moral compass that steers always to the true north of is accepting this gift really in the patient’s best interest?

1. Standards of ethical conduct for employees of the executive branch. Fed Regist. 2016;81(223):81641-81657. To be codified at 5 CFR §2635.

2. Spence SA. Patients bearing gifts: are there strings attached. BMJ. 2005;331.

3. American Medical Association. American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 1.2.8. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/code-medical-ethics-patient-physician-relationships. Accessed November 27, 2018.

4. Snyder L; Ethics, Professionalism, and Human Rights Committee. American College of Physicians Ethics Manual, 6th ed. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(1, Part 2):73-104.

5. Levine A, Valeriote T. Beware the patient bearing gifts. http://epmonthly.com/article/beware-patient-bearing-gifts. Published December 14, 2016. Accessed November 27, 2018.

6. Brendel DH, Chu J, Radden J, et al. The price of a gift: an approach to receiving gifts from psychiatric patients. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2007;15(2):43-51.

It is that time of year when federal compliance officers, clinical ethicists, and staff counsels are flooded with queries about the legal and ethical acceptability of gifts. And no wonder, all the winter holidays often involve giving gifts. The simple and spontaneous acts of giving and receiving gifts become more complicated and deliberative in the federal health care system. Both legal rules and ethical values bear upon who can offer and accept what gift to whom upon what occasion and in what amount. The “Standards of Ethical Conduct for Employees of the Executive Branch” devotes 2 entire subparts to the subject of gifts.1 We will examine a small section of the document that can become a big issue for federal practitioners during that holiday—gifts from patients.

First, veterans (patients) are “prohibited sources” in section 5 CFR §2635.203 (d).1 And since VA employees are subject to restrictions on accepting gifts from sources outside the government, unless an exception applies, federal employees may not accept a gift because of their official position (eg, Federal Practitioner, editor-in-chief) or a gift from a patient (prohibited source; [5 CFR §2635.201]).

It might seem like this is going to be a very short column this month, as gifts from patients are forbidden. Yet, a Christmas card or homemade fudge isn’t really a gift, is it?

5 CFR §2635.203 (b) defines what is and is not a gift: For example, minor items of food or items like a thank-you card are specifically excluded in section (b) 1-10.

Is Christmas an exception or are just types of gifts excluded?

There are exceptions to the general regulation about accepting gifts from prohibited sources. Many staff will recall hearing about the “$20 rule,” which is actually the “$20-50” rule stating that a federal employee may accept a gift from a patient (prohibited source) if the value of said gift is under $20 and the employee does not accept more than $50 from any single source in a calendar year. §2635.204 lists the exceptions. However, starting in 2017, the regulations changed to require that federal employees also consider not just whether they could accept a gift but—ethically—they should take the gift even if it was permitted under the law. The Office of Government Ethics made this change because it wanted to emphasize the importance of considering not just how things are but how things appear to be. The regulations contain detailed descriptions of what employees should think about and stipulates that the decisions will not be further scrutinized (5 CFR §2635.201[b]).1

Based on this new emphasis on appearances, ethically, no doctor or nurse should accept the keys to a new BMW from a patient who owns a luxury car dealership. But what about more prosaic and probable presents: the holiday cookies a single father made with his children for the nurse practitioner who has been his primary care practitioner for years; the birdhouse a Vietnam veteran made in her crafts class for the surgeon who removed her gallbladder; or even the store-bought but no less heartfelt tin of popcorn from an elderly veteran for the hospitalist who saw him through a rough bought of pneumonia?

Related: Happy Federal New Year

The rules about practitioners accepting patient gifts are rational and unambiguous: It is the values conflict surrounding patient gifts that is often emotion driven and muddled; it may be easier and safer to adopt the “just say no” policy. And yet, while this might seem the most unassailable position to avoid a conflict of interest, could this possibly be a more practitioner- than patient-centered standard? Authoritative sources in the ethics literature are equally divided and ambivalent on the question.2,3 The American College of Physicians Ethics Manual states: “In deciding whether to accept a gift from a patient, the physician should consider the nature of the gift and its value to the patient, the potential implications for the patient-physician relationship of accepting or refusing it, and the patient’s probable intention and expectations.”4 A small gift as a token of appreciation is not ethically problematic. Favored treatment as a result of acceptance of any gift is problematic, undermines professionalism, and may interfere with objectivity in the care of the patient.4

Related: Am I My Brother’s/Sister’s Keeper?

Many an ethics commentator have cautioned, “beware of patients bearing gifts.”5 In making an ethical assessment of whether or not to accept the gift, a key question a practitioner needs to ask him or herself is about the patient’s motive. Even the patient may be unaware of the reasons behind their giving, and the wise practitioner will take a mindful moment to think about the context and timing of the gift and the nature of his or her relationship to the patient. Sadly, many of our patients are lonely especially at this family time of year and on some level may hope the gift will help slide the professional relationship toward a more personal one. Some patients may think a gift might earn them preferential treatment. Finally, a few patients may have a romantic or sexual attraction toward a clinician.

Often in the latter 2 cases, a pattern will develop that discloses the patient’s true intent. Very expensive gifts, monetary gifts, excessively personal gifts, or frequent gifts should alert the practitioner that more may be going on. A kind reminder to the patient that providing good care is the only reward needed may be sufficient. For practitioners whose ethical code does not permit them to accept gifts, then a genuine thank you and an explanation of the rules and/or values behind the refusal may be necessary. There are other times when the practitioner or a supervisor/advisor may need to reset the boundaries or even to transfer the patient to another practitioner. The norms in mental health care and psychotherapy are more stringent because of the intimacy of the relationship and the potential vulnerability of patients.6

For gifts that seem genuine and generous or cost a trivial amount, then there is an ethical argument to be made for accepting them with gratitude. In many cultures, hospitality is a tradition, and expressing appreciation a virtue, so when a practitioner refuses to graciously take a small gift, they risk offending the patient. Rejection of a gift can be seen as disrespectful and could cause a rupture in an otherwise sound practitioner-patient relationship. Other patients experience strong feelings of gratitude and admiration for their practitioners, stronger than most of us recognize. The ability for a patient to give their practitioner a holiday gift, particularly one they invested time and energy in creating or choosing, can enhance their sense of self-worth and individual agency. These gifts are not so much an attempt to diminish the professional power differential but to close the gap between 2 human beings in an unequal relationship that is yet one of shared decision making. All practitioners should be aware of the often underappreciated social power of a gift to influence decisions.

Related: Caring Under a Microscope

At the same time, clinicians can strive to be sensitively attuned to the reality that, sometimes the cookie is just a cookie so eat and enjoy, just remember to share with your group. External judgments are often cited as practical rules of thumb for determining the ethical acceptability of a gift: Would you want your mother, newspaper, or colleague to know you took the present? I prefer an internal moral compass that steers always to the true north of is accepting this gift really in the patient’s best interest?

It is that time of year when federal compliance officers, clinical ethicists, and staff counsels are flooded with queries about the legal and ethical acceptability of gifts. And no wonder, all the winter holidays often involve giving gifts. The simple and spontaneous acts of giving and receiving gifts become more complicated and deliberative in the federal health care system. Both legal rules and ethical values bear upon who can offer and accept what gift to whom upon what occasion and in what amount. The “Standards of Ethical Conduct for Employees of the Executive Branch” devotes 2 entire subparts to the subject of gifts.1 We will examine a small section of the document that can become a big issue for federal practitioners during that holiday—gifts from patients.

First, veterans (patients) are “prohibited sources” in section 5 CFR §2635.203 (d).1 And since VA employees are subject to restrictions on accepting gifts from sources outside the government, unless an exception applies, federal employees may not accept a gift because of their official position (eg, Federal Practitioner, editor-in-chief) or a gift from a patient (prohibited source; [5 CFR §2635.201]).

It might seem like this is going to be a very short column this month, as gifts from patients are forbidden. Yet, a Christmas card or homemade fudge isn’t really a gift, is it?

5 CFR §2635.203 (b) defines what is and is not a gift: For example, minor items of food or items like a thank-you card are specifically excluded in section (b) 1-10.

Is Christmas an exception or are just types of gifts excluded?