User login

Incredible edibles … Guilty as charged

“We should not consider marijuana ‘innocent until proven guilty,’ given what we already know about the harms to adolescents,”1 Sharon Levy, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Abuse, said in an AAP press release, speaking of the legalization of marijuana in Washington and Colorado. The press release was issued in 2015 when the AAP updated its policy on the impact of marijuana policies on youth (Pediatrics. 2015. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-4146), reaffirming its opposition to legalization of marijuana because it contended that limited studies had been done on “medical marijuana” in adults, and that there were no published studies either on the form of marijuana or other preparations that involved children.

Marijuana is a schedule I controlled substance, so the Food and Drug Administration does not regulate marijuana edibles, resulting in poor labeling and unregulated formulations.2

Edibles are marijuana-infused foods. Extraction of the cannabinoid THC, the major psychoactive ingredient, from the cannabis plant involves heating the flowers from the female plant in an oil base liquid. As it is heated, the inactive tetrahydrocannabinoid acid (THCA) is converted to THC and dissolves into the oil base liquids, and it is this additive that is used in food products to create the edible. A safe “serving size,” was determined to be 10 mg of THC,3 but an edible may contain 100 mg of THC if consumed in its entirety.

Many prefer ingesting edibles, compared with smoking, because there are no toxic effects from the inhalation of smoke, no odors, it’s more potent, and its duration of action is longer.3 The downside is the onset of action is slower, compared with smoking, so many will consume more before the “high” begins, and therefore there is a greater risk for intoxication. For example, a chocolate bar may contain 100 mg of THC, and despite the “serving size” stated as one square, a person might consume the entire bar before the onset of the high begins. Improved labeling and warning of intoxication now are required on packaging, but this does little to reduce the risk.3

Edibles also are made in way that is attractive to children. Commonly, they come in packaging and forms that resemble candy, such as gummies and chocolate bars. Although laws have been put in place to require them to be sold in childproof containers, 3,4 As feared, once cannabis oil is obtained legally, there is little control over what it is put in.

As for medicinal purposes, edibles have a great advantage for children when used for that purpose. Ease of administration, long duration of action, and a great taste are all positive attributes. As with all good things, there is a downside when used inappropriately.

Marijuana overdoses can result in cognitive and motor impairment, extreme sedation, agitation, anxiety, cardiac stress, and vomiting. High quantities of THC have been reported to cause transient psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, and anxiety.3

As pediatricians, it is essential to educate teens and their families on the harmful effects of marijuana and dispel the myth that is benign. They need to be informed of the negative impact of marijuana, which leads to impairment of memory and executive function, on the developing brain. Parents also need to be aware of the current trends of use and formulations, so they can be aware of potential exposures.5

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. “American Academy of Pediatrics Reaffirms Opposition to Legalizing Marijuana for Recreational or Medical Use,” AAP press release on Jan. 26, 2015.

2. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:989-91.

3. Methods Rep RTI Press. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.3768/rtipress.2016.op.0035.1611.

4. JAMA. 2015;313(3):241-2.

5. Pediatrics. 2017 Mar;139(3):e20164069.

“We should not consider marijuana ‘innocent until proven guilty,’ given what we already know about the harms to adolescents,”1 Sharon Levy, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Abuse, said in an AAP press release, speaking of the legalization of marijuana in Washington and Colorado. The press release was issued in 2015 when the AAP updated its policy on the impact of marijuana policies on youth (Pediatrics. 2015. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-4146), reaffirming its opposition to legalization of marijuana because it contended that limited studies had been done on “medical marijuana” in adults, and that there were no published studies either on the form of marijuana or other preparations that involved children.

Marijuana is a schedule I controlled substance, so the Food and Drug Administration does not regulate marijuana edibles, resulting in poor labeling and unregulated formulations.2

Edibles are marijuana-infused foods. Extraction of the cannabinoid THC, the major psychoactive ingredient, from the cannabis plant involves heating the flowers from the female plant in an oil base liquid. As it is heated, the inactive tetrahydrocannabinoid acid (THCA) is converted to THC and dissolves into the oil base liquids, and it is this additive that is used in food products to create the edible. A safe “serving size,” was determined to be 10 mg of THC,3 but an edible may contain 100 mg of THC if consumed in its entirety.

Many prefer ingesting edibles, compared with smoking, because there are no toxic effects from the inhalation of smoke, no odors, it’s more potent, and its duration of action is longer.3 The downside is the onset of action is slower, compared with smoking, so many will consume more before the “high” begins, and therefore there is a greater risk for intoxication. For example, a chocolate bar may contain 100 mg of THC, and despite the “serving size” stated as one square, a person might consume the entire bar before the onset of the high begins. Improved labeling and warning of intoxication now are required on packaging, but this does little to reduce the risk.3

Edibles also are made in way that is attractive to children. Commonly, they come in packaging and forms that resemble candy, such as gummies and chocolate bars. Although laws have been put in place to require them to be sold in childproof containers, 3,4 As feared, once cannabis oil is obtained legally, there is little control over what it is put in.

As for medicinal purposes, edibles have a great advantage for children when used for that purpose. Ease of administration, long duration of action, and a great taste are all positive attributes. As with all good things, there is a downside when used inappropriately.

Marijuana overdoses can result in cognitive and motor impairment, extreme sedation, agitation, anxiety, cardiac stress, and vomiting. High quantities of THC have been reported to cause transient psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, and anxiety.3

As pediatricians, it is essential to educate teens and their families on the harmful effects of marijuana and dispel the myth that is benign. They need to be informed of the negative impact of marijuana, which leads to impairment of memory and executive function, on the developing brain. Parents also need to be aware of the current trends of use and formulations, so they can be aware of potential exposures.5

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. “American Academy of Pediatrics Reaffirms Opposition to Legalizing Marijuana for Recreational or Medical Use,” AAP press release on Jan. 26, 2015.

2. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:989-91.

3. Methods Rep RTI Press. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.3768/rtipress.2016.op.0035.1611.

4. JAMA. 2015;313(3):241-2.

5. Pediatrics. 2017 Mar;139(3):e20164069.

“We should not consider marijuana ‘innocent until proven guilty,’ given what we already know about the harms to adolescents,”1 Sharon Levy, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Abuse, said in an AAP press release, speaking of the legalization of marijuana in Washington and Colorado. The press release was issued in 2015 when the AAP updated its policy on the impact of marijuana policies on youth (Pediatrics. 2015. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-4146), reaffirming its opposition to legalization of marijuana because it contended that limited studies had been done on “medical marijuana” in adults, and that there were no published studies either on the form of marijuana or other preparations that involved children.

Marijuana is a schedule I controlled substance, so the Food and Drug Administration does not regulate marijuana edibles, resulting in poor labeling and unregulated formulations.2

Edibles are marijuana-infused foods. Extraction of the cannabinoid THC, the major psychoactive ingredient, from the cannabis plant involves heating the flowers from the female plant in an oil base liquid. As it is heated, the inactive tetrahydrocannabinoid acid (THCA) is converted to THC and dissolves into the oil base liquids, and it is this additive that is used in food products to create the edible. A safe “serving size,” was determined to be 10 mg of THC,3 but an edible may contain 100 mg of THC if consumed in its entirety.

Many prefer ingesting edibles, compared with smoking, because there are no toxic effects from the inhalation of smoke, no odors, it’s more potent, and its duration of action is longer.3 The downside is the onset of action is slower, compared with smoking, so many will consume more before the “high” begins, and therefore there is a greater risk for intoxication. For example, a chocolate bar may contain 100 mg of THC, and despite the “serving size” stated as one square, a person might consume the entire bar before the onset of the high begins. Improved labeling and warning of intoxication now are required on packaging, but this does little to reduce the risk.3

Edibles also are made in way that is attractive to children. Commonly, they come in packaging and forms that resemble candy, such as gummies and chocolate bars. Although laws have been put in place to require them to be sold in childproof containers, 3,4 As feared, once cannabis oil is obtained legally, there is little control over what it is put in.

As for medicinal purposes, edibles have a great advantage for children when used for that purpose. Ease of administration, long duration of action, and a great taste are all positive attributes. As with all good things, there is a downside when used inappropriately.

Marijuana overdoses can result in cognitive and motor impairment, extreme sedation, agitation, anxiety, cardiac stress, and vomiting. High quantities of THC have been reported to cause transient psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, and anxiety.3

As pediatricians, it is essential to educate teens and their families on the harmful effects of marijuana and dispel the myth that is benign. They need to be informed of the negative impact of marijuana, which leads to impairment of memory and executive function, on the developing brain. Parents also need to be aware of the current trends of use and formulations, so they can be aware of potential exposures.5

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. “American Academy of Pediatrics Reaffirms Opposition to Legalizing Marijuana for Recreational or Medical Use,” AAP press release on Jan. 26, 2015.

2. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:989-91.

3. Methods Rep RTI Press. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.3768/rtipress.2016.op.0035.1611.

4. JAMA. 2015;313(3):241-2.

5. Pediatrics. 2017 Mar;139(3):e20164069.

Insomnia – going beyond sleep hygiene

Difficulties with sleep are prevalent and significant across the developmental spectrum. Not only does poor sleep affect daytime functioning in relation to mood, focus, appetite, and emotional regulation, but ineffective bedtime routines can cause significant distress for youth and caregivers, as well. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine describes insomnia as “repeated difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite age-appropriate time and opportunity for sleep and results in daytime functional impairment for the child and/or family.’’1

Pediatric providers likely are familiar already with initial steps in the evaluation and treatment of insomnia. The emphasis here is assessment and intervention approaches beyond the foundational use of sleep hygiene recommendations.

In working with a patient such as Katie who comes laden with diagnoses and medications, stepping back to reconsider the assessment is an important starting point. Problems related to sleep are rife in psychiatric conditions, from depression, anxiety, and PTSD to bipolar disorder, ADHD, and autism.2

Next is see if there are external factors engendering insomnia. Sleep hygiene focuses on these, but sometimes recent stressors or familial conflict are overlooked, which may be linchpins to improving sleep patterns. Commonly prescribed medications (steroids, bupropion, and stimulants) and intoxication or withdrawal symptoms from substance use can contribute to wakefulness and deserve consideration. It can be useful to track sleep for a while to identify contributing factors, impediments to sleep, and ineffective patterns (see tools at sleepfoundation.org or the free app CBT-I Coach).

After assessment, the bulk of the evidence for pediatric insomnia is for behavioral treatments, mostly for infants and young children. This may be familiar territory, and it offers a good time to assess the level of motivation. Are the patient and family aware of how insomnia affects their lives on a day-to-day basis and is this problem a priority?

For adolescents who are convinced of the life-changing properties of a good night’s sleep, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-i) is developing a strong evidence base for insomnia in adolescents.3 CBT-i adds to the usual interventions for addressing insomnia in infants and young children by additionally training adolescents relaxation techniques, by addressing cognitive distortions about sleep, and by actually restricting sleep. This last technique involves initially reducing the amount of sleep in order to build a tight association between sleep and the bedroom, improve sleep efficiency, and increase sleep drive.

In general, medications are considered when other appropriate interventions have proven inadequate. There is very little evidence for using pharmacologic interventions for pediatric insomnia, so even if a medication is selected, behavioral approaches should remain a mainstay.4 Patients and caregivers should agree to specific short-term goals ahead of time when using sleep medicine, given the limited effectiveness and recommended short duration of use. Many medications change sleep architecture, and none have been clearly shown to sustainably improve sleep quality or quantity or reduce daytime symptoms of insomnia.

Prescribing guidelines for insomnia suggest selecting an agent matched to the symptoms and relevant to any comorbidities. Melatonin may be most helpful in shifting the sleep phase rather than for direct hypnotic effects; thus adolescents or patients with ADHD whose sleep schedule has naturally shifted later may benefit from a small dose of melatonin (1-3 mg) several hours before bedtime to prime their system. Beware that melatonin is not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and animal studies have shown significant alterations of the gonadal hormone axis, although this has not been examined in human trials. Alpha-2 agonists – such as clonidine and guanfacine – may be helpful for sleep initiation, especially in populations with comorbid ADHD, aggression, or tics, where these medications might be otherwise indicated. Prazosin, an alpha-1 antagonist, has some limited evidence as a treatment for nightmares and PTSD symptoms, so it may be a good choice for children with trauma-related hypervigilance.

In patients with depression, low doses of trazodone (12.5-50 mg) or mirtazapine (7.5-15 mg) may be effective. Although short-acting benzodiazepines may be useful in the short-term, particularly for sleep-onset difficulties, they generally are not recommended because of the risks of abuse, diversion, withdrawal, cognitive side effects, disinhibition, development of tolerance, and contraindication with such comorbidities as sleep apnea. However, the benzodiazepine receptor agonists such as zaleplon, zolpidem, and eszopiclone, while lacking evidence in the pediatric population, may be worthwhile considerations as their varying half-lives allow for specificity in treating sleep-onset vs. sleep-maintenance problems. Caregivers should be warned about the potential for sleepwalking or other complex sleep-related behaviors with this class of medicines.

Avoid tricyclic antidepressants because of the potential for anticholinergic effects and cardiotoxicity. Atypical antipsychotics generally are not worth the risk of serious and rapid side effects associated with this class of medications, which include metabolic syndrome.

The assessment and treatment of pediatric insomnia may require several visits to complete. But, given growing knowledge of how much sleep contributes to learning, longevity, and well-being, and the consequences of sleep deprivation with regard to safety, irritability, poor concentration, disordered metabolism and appetite, etc., the potential benefits seem well worth the time.

Dr. Rosenfeld is assistant professor of psychiatry at Vermont Center for Children, Youth & Families, at the University of Vermont Medical Center, and the University of Vermont, Burlington. He has received honorarium from Oakstone Publishing for contributing board review course content on human development.

References

1. International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic & Coding Manual. 2nd edition. (Westchester: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005).

2. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009 Oct;18(4):979-1000

3. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017, Oct 20. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12834.

4. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2009, Oct;18(4):1001-16.

Difficulties with sleep are prevalent and significant across the developmental spectrum. Not only does poor sleep affect daytime functioning in relation to mood, focus, appetite, and emotional regulation, but ineffective bedtime routines can cause significant distress for youth and caregivers, as well. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine describes insomnia as “repeated difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite age-appropriate time and opportunity for sleep and results in daytime functional impairment for the child and/or family.’’1

Pediatric providers likely are familiar already with initial steps in the evaluation and treatment of insomnia. The emphasis here is assessment and intervention approaches beyond the foundational use of sleep hygiene recommendations.

In working with a patient such as Katie who comes laden with diagnoses and medications, stepping back to reconsider the assessment is an important starting point. Problems related to sleep are rife in psychiatric conditions, from depression, anxiety, and PTSD to bipolar disorder, ADHD, and autism.2

Next is see if there are external factors engendering insomnia. Sleep hygiene focuses on these, but sometimes recent stressors or familial conflict are overlooked, which may be linchpins to improving sleep patterns. Commonly prescribed medications (steroids, bupropion, and stimulants) and intoxication or withdrawal symptoms from substance use can contribute to wakefulness and deserve consideration. It can be useful to track sleep for a while to identify contributing factors, impediments to sleep, and ineffective patterns (see tools at sleepfoundation.org or the free app CBT-I Coach).

After assessment, the bulk of the evidence for pediatric insomnia is for behavioral treatments, mostly for infants and young children. This may be familiar territory, and it offers a good time to assess the level of motivation. Are the patient and family aware of how insomnia affects their lives on a day-to-day basis and is this problem a priority?

For adolescents who are convinced of the life-changing properties of a good night’s sleep, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-i) is developing a strong evidence base for insomnia in adolescents.3 CBT-i adds to the usual interventions for addressing insomnia in infants and young children by additionally training adolescents relaxation techniques, by addressing cognitive distortions about sleep, and by actually restricting sleep. This last technique involves initially reducing the amount of sleep in order to build a tight association between sleep and the bedroom, improve sleep efficiency, and increase sleep drive.

In general, medications are considered when other appropriate interventions have proven inadequate. There is very little evidence for using pharmacologic interventions for pediatric insomnia, so even if a medication is selected, behavioral approaches should remain a mainstay.4 Patients and caregivers should agree to specific short-term goals ahead of time when using sleep medicine, given the limited effectiveness and recommended short duration of use. Many medications change sleep architecture, and none have been clearly shown to sustainably improve sleep quality or quantity or reduce daytime symptoms of insomnia.

Prescribing guidelines for insomnia suggest selecting an agent matched to the symptoms and relevant to any comorbidities. Melatonin may be most helpful in shifting the sleep phase rather than for direct hypnotic effects; thus adolescents or patients with ADHD whose sleep schedule has naturally shifted later may benefit from a small dose of melatonin (1-3 mg) several hours before bedtime to prime their system. Beware that melatonin is not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and animal studies have shown significant alterations of the gonadal hormone axis, although this has not been examined in human trials. Alpha-2 agonists – such as clonidine and guanfacine – may be helpful for sleep initiation, especially in populations with comorbid ADHD, aggression, or tics, where these medications might be otherwise indicated. Prazosin, an alpha-1 antagonist, has some limited evidence as a treatment for nightmares and PTSD symptoms, so it may be a good choice for children with trauma-related hypervigilance.

In patients with depression, low doses of trazodone (12.5-50 mg) or mirtazapine (7.5-15 mg) may be effective. Although short-acting benzodiazepines may be useful in the short-term, particularly for sleep-onset difficulties, they generally are not recommended because of the risks of abuse, diversion, withdrawal, cognitive side effects, disinhibition, development of tolerance, and contraindication with such comorbidities as sleep apnea. However, the benzodiazepine receptor agonists such as zaleplon, zolpidem, and eszopiclone, while lacking evidence in the pediatric population, may be worthwhile considerations as their varying half-lives allow for specificity in treating sleep-onset vs. sleep-maintenance problems. Caregivers should be warned about the potential for sleepwalking or other complex sleep-related behaviors with this class of medicines.

Avoid tricyclic antidepressants because of the potential for anticholinergic effects and cardiotoxicity. Atypical antipsychotics generally are not worth the risk of serious and rapid side effects associated with this class of medications, which include metabolic syndrome.

The assessment and treatment of pediatric insomnia may require several visits to complete. But, given growing knowledge of how much sleep contributes to learning, longevity, and well-being, and the consequences of sleep deprivation with regard to safety, irritability, poor concentration, disordered metabolism and appetite, etc., the potential benefits seem well worth the time.

Dr. Rosenfeld is assistant professor of psychiatry at Vermont Center for Children, Youth & Families, at the University of Vermont Medical Center, and the University of Vermont, Burlington. He has received honorarium from Oakstone Publishing for contributing board review course content on human development.

References

1. International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic & Coding Manual. 2nd edition. (Westchester: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005).

2. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009 Oct;18(4):979-1000

3. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017, Oct 20. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12834.

4. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2009, Oct;18(4):1001-16.

Difficulties with sleep are prevalent and significant across the developmental spectrum. Not only does poor sleep affect daytime functioning in relation to mood, focus, appetite, and emotional regulation, but ineffective bedtime routines can cause significant distress for youth and caregivers, as well. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine describes insomnia as “repeated difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite age-appropriate time and opportunity for sleep and results in daytime functional impairment for the child and/or family.’’1

Pediatric providers likely are familiar already with initial steps in the evaluation and treatment of insomnia. The emphasis here is assessment and intervention approaches beyond the foundational use of sleep hygiene recommendations.

In working with a patient such as Katie who comes laden with diagnoses and medications, stepping back to reconsider the assessment is an important starting point. Problems related to sleep are rife in psychiatric conditions, from depression, anxiety, and PTSD to bipolar disorder, ADHD, and autism.2

Next is see if there are external factors engendering insomnia. Sleep hygiene focuses on these, but sometimes recent stressors or familial conflict are overlooked, which may be linchpins to improving sleep patterns. Commonly prescribed medications (steroids, bupropion, and stimulants) and intoxication or withdrawal symptoms from substance use can contribute to wakefulness and deserve consideration. It can be useful to track sleep for a while to identify contributing factors, impediments to sleep, and ineffective patterns (see tools at sleepfoundation.org or the free app CBT-I Coach).

After assessment, the bulk of the evidence for pediatric insomnia is for behavioral treatments, mostly for infants and young children. This may be familiar territory, and it offers a good time to assess the level of motivation. Are the patient and family aware of how insomnia affects their lives on a day-to-day basis and is this problem a priority?

For adolescents who are convinced of the life-changing properties of a good night’s sleep, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-i) is developing a strong evidence base for insomnia in adolescents.3 CBT-i adds to the usual interventions for addressing insomnia in infants and young children by additionally training adolescents relaxation techniques, by addressing cognitive distortions about sleep, and by actually restricting sleep. This last technique involves initially reducing the amount of sleep in order to build a tight association between sleep and the bedroom, improve sleep efficiency, and increase sleep drive.

In general, medications are considered when other appropriate interventions have proven inadequate. There is very little evidence for using pharmacologic interventions for pediatric insomnia, so even if a medication is selected, behavioral approaches should remain a mainstay.4 Patients and caregivers should agree to specific short-term goals ahead of time when using sleep medicine, given the limited effectiveness and recommended short duration of use. Many medications change sleep architecture, and none have been clearly shown to sustainably improve sleep quality or quantity or reduce daytime symptoms of insomnia.

Prescribing guidelines for insomnia suggest selecting an agent matched to the symptoms and relevant to any comorbidities. Melatonin may be most helpful in shifting the sleep phase rather than for direct hypnotic effects; thus adolescents or patients with ADHD whose sleep schedule has naturally shifted later may benefit from a small dose of melatonin (1-3 mg) several hours before bedtime to prime their system. Beware that melatonin is not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and animal studies have shown significant alterations of the gonadal hormone axis, although this has not been examined in human trials. Alpha-2 agonists – such as clonidine and guanfacine – may be helpful for sleep initiation, especially in populations with comorbid ADHD, aggression, or tics, where these medications might be otherwise indicated. Prazosin, an alpha-1 antagonist, has some limited evidence as a treatment for nightmares and PTSD symptoms, so it may be a good choice for children with trauma-related hypervigilance.

In patients with depression, low doses of trazodone (12.5-50 mg) or mirtazapine (7.5-15 mg) may be effective. Although short-acting benzodiazepines may be useful in the short-term, particularly for sleep-onset difficulties, they generally are not recommended because of the risks of abuse, diversion, withdrawal, cognitive side effects, disinhibition, development of tolerance, and contraindication with such comorbidities as sleep apnea. However, the benzodiazepine receptor agonists such as zaleplon, zolpidem, and eszopiclone, while lacking evidence in the pediatric population, may be worthwhile considerations as their varying half-lives allow for specificity in treating sleep-onset vs. sleep-maintenance problems. Caregivers should be warned about the potential for sleepwalking or other complex sleep-related behaviors with this class of medicines.

Avoid tricyclic antidepressants because of the potential for anticholinergic effects and cardiotoxicity. Atypical antipsychotics generally are not worth the risk of serious and rapid side effects associated with this class of medications, which include metabolic syndrome.

The assessment and treatment of pediatric insomnia may require several visits to complete. But, given growing knowledge of how much sleep contributes to learning, longevity, and well-being, and the consequences of sleep deprivation with regard to safety, irritability, poor concentration, disordered metabolism and appetite, etc., the potential benefits seem well worth the time.

Dr. Rosenfeld is assistant professor of psychiatry at Vermont Center for Children, Youth & Families, at the University of Vermont Medical Center, and the University of Vermont, Burlington. He has received honorarium from Oakstone Publishing for contributing board review course content on human development.

References

1. International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic & Coding Manual. 2nd edition. (Westchester: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005).

2. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009 Oct;18(4):979-1000

3. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017, Oct 20. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12834.

4. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2009, Oct;18(4):1001-16.

Engaging skeptical parents

While every day seems to bring extraordinary new advances in science – robotic surgery, individually targeted medications, and even gene therapy – there are many people who currently approach the science of medicine with skepticism.

While it is the right of legally competent adults in a free society to chose how best to care for their own health, to explore holistic or alternative therapies, or avoid medicine altogether, it is more complex when they are skeptical of accepted medical practice in managing the health of their children. For those parents who trust you enough to bring their children to you for care but remain skeptical of vaccines or other treatments, you have an opportunity to work with that trust and engage in a discussion so that they might reconsider their position on valuable and even life-saving treatments for their children.

In each of these cases, launching into an enthusiastic explanation of the advanced statistics that underpin your recommendation is unlikely to bridge the gap. Instead, you want to start with these parents by being curious. Resist the urge to tell, and listen instead. What is their understanding of the problem you are treating or preventing? What have they heard or read about the treatment or test in question? What do they most fear is going to happen to their child if they do or do not accept your recommendation? Are there specific events (with their child or with the health care system) that have informed this fear?

Respectfully listening to their experiences, thoughts, and feelings goes a long way toward building a trusting alliance. It can help overcome feelings of distrust or defensiveness around authority figures. And it models the thoughtful, respectful give and take that are essential to a healthy collaboration between pediatrician and parents.

Once you have information about what they think and some about how they think and make decisions, you then can offer your perspective. “You are the expert on your child, what I bring to this equation is experience with (this problem) and with assessing the scientific evidence that guides treatments in medicine. It is true that treatments often change as we learn more, but here is what the evidence currently supports.”

After learning something about how they think, you might offer more data or more warm acknowledgment of how difficult it can be to make medical decisions for your children with imperfect information. Be humble while also being accurate about your level of confidence in a recommendation. Humility is important because it is easy for parents to feel insecure and condescended to. You understand their greatest fear, now let them know what your greatest worry is for their child should they forgo a recommended treatment. Explaining all of this with humility and warmth makes it more likely that the parents will take in the facts you are trying to share with them and not be derailed by suspicion, defensiveness, or insecurity.

Make building an alliance with the parents your top priority. This does not mean that you do not offer your best recommendation for their child. Rather, it means that, if they still decline recommended treatment, you treat them with respect and invest your time in explaining what they should be watching or monitoring their child for without recommended treatment. Building trust is a long game. If you patiently stick with parents even when it’s not easy, they may be ready to trust you with a subsequent decision when the stakes are even higher.

Of course, all this thoughtful communication takes a lot of time! You may learn to block off more time for certain families. It also can be helpful to have these conversations as a team. If you and your nurse or social worker can meet with parents together, then some of the listening and learning can be done by the nurse or social worker alone, so that everyone’s time might be managed more efficiently. And managing skeptical parents as a team also can help to prevent frustration or burnout. It will not always succeed, but in some cases, your investment will pay off in a trusting alliance, mutual respect, and healthy patients.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

While every day seems to bring extraordinary new advances in science – robotic surgery, individually targeted medications, and even gene therapy – there are many people who currently approach the science of medicine with skepticism.

While it is the right of legally competent adults in a free society to chose how best to care for their own health, to explore holistic or alternative therapies, or avoid medicine altogether, it is more complex when they are skeptical of accepted medical practice in managing the health of their children. For those parents who trust you enough to bring their children to you for care but remain skeptical of vaccines or other treatments, you have an opportunity to work with that trust and engage in a discussion so that they might reconsider their position on valuable and even life-saving treatments for their children.

In each of these cases, launching into an enthusiastic explanation of the advanced statistics that underpin your recommendation is unlikely to bridge the gap. Instead, you want to start with these parents by being curious. Resist the urge to tell, and listen instead. What is their understanding of the problem you are treating or preventing? What have they heard or read about the treatment or test in question? What do they most fear is going to happen to their child if they do or do not accept your recommendation? Are there specific events (with their child or with the health care system) that have informed this fear?

Respectfully listening to their experiences, thoughts, and feelings goes a long way toward building a trusting alliance. It can help overcome feelings of distrust or defensiveness around authority figures. And it models the thoughtful, respectful give and take that are essential to a healthy collaboration between pediatrician and parents.

Once you have information about what they think and some about how they think and make decisions, you then can offer your perspective. “You are the expert on your child, what I bring to this equation is experience with (this problem) and with assessing the scientific evidence that guides treatments in medicine. It is true that treatments often change as we learn more, but here is what the evidence currently supports.”

After learning something about how they think, you might offer more data or more warm acknowledgment of how difficult it can be to make medical decisions for your children with imperfect information. Be humble while also being accurate about your level of confidence in a recommendation. Humility is important because it is easy for parents to feel insecure and condescended to. You understand their greatest fear, now let them know what your greatest worry is for their child should they forgo a recommended treatment. Explaining all of this with humility and warmth makes it more likely that the parents will take in the facts you are trying to share with them and not be derailed by suspicion, defensiveness, or insecurity.

Make building an alliance with the parents your top priority. This does not mean that you do not offer your best recommendation for their child. Rather, it means that, if they still decline recommended treatment, you treat them with respect and invest your time in explaining what they should be watching or monitoring their child for without recommended treatment. Building trust is a long game. If you patiently stick with parents even when it’s not easy, they may be ready to trust you with a subsequent decision when the stakes are even higher.

Of course, all this thoughtful communication takes a lot of time! You may learn to block off more time for certain families. It also can be helpful to have these conversations as a team. If you and your nurse or social worker can meet with parents together, then some of the listening and learning can be done by the nurse or social worker alone, so that everyone’s time might be managed more efficiently. And managing skeptical parents as a team also can help to prevent frustration or burnout. It will not always succeed, but in some cases, your investment will pay off in a trusting alliance, mutual respect, and healthy patients.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

While every day seems to bring extraordinary new advances in science – robotic surgery, individually targeted medications, and even gene therapy – there are many people who currently approach the science of medicine with skepticism.

While it is the right of legally competent adults in a free society to chose how best to care for their own health, to explore holistic or alternative therapies, or avoid medicine altogether, it is more complex when they are skeptical of accepted medical practice in managing the health of their children. For those parents who trust you enough to bring their children to you for care but remain skeptical of vaccines or other treatments, you have an opportunity to work with that trust and engage in a discussion so that they might reconsider their position on valuable and even life-saving treatments for their children.

In each of these cases, launching into an enthusiastic explanation of the advanced statistics that underpin your recommendation is unlikely to bridge the gap. Instead, you want to start with these parents by being curious. Resist the urge to tell, and listen instead. What is their understanding of the problem you are treating or preventing? What have they heard or read about the treatment or test in question? What do they most fear is going to happen to their child if they do or do not accept your recommendation? Are there specific events (with their child or with the health care system) that have informed this fear?

Respectfully listening to their experiences, thoughts, and feelings goes a long way toward building a trusting alliance. It can help overcome feelings of distrust or defensiveness around authority figures. And it models the thoughtful, respectful give and take that are essential to a healthy collaboration between pediatrician and parents.

Once you have information about what they think and some about how they think and make decisions, you then can offer your perspective. “You are the expert on your child, what I bring to this equation is experience with (this problem) and with assessing the scientific evidence that guides treatments in medicine. It is true that treatments often change as we learn more, but here is what the evidence currently supports.”

After learning something about how they think, you might offer more data or more warm acknowledgment of how difficult it can be to make medical decisions for your children with imperfect information. Be humble while also being accurate about your level of confidence in a recommendation. Humility is important because it is easy for parents to feel insecure and condescended to. You understand their greatest fear, now let them know what your greatest worry is for their child should they forgo a recommended treatment. Explaining all of this with humility and warmth makes it more likely that the parents will take in the facts you are trying to share with them and not be derailed by suspicion, defensiveness, or insecurity.

Make building an alliance with the parents your top priority. This does not mean that you do not offer your best recommendation for their child. Rather, it means that, if they still decline recommended treatment, you treat them with respect and invest your time in explaining what they should be watching or monitoring their child for without recommended treatment. Building trust is a long game. If you patiently stick with parents even when it’s not easy, they may be ready to trust you with a subsequent decision when the stakes are even higher.

Of course, all this thoughtful communication takes a lot of time! You may learn to block off more time for certain families. It also can be helpful to have these conversations as a team. If you and your nurse or social worker can meet with parents together, then some of the listening and learning can be done by the nurse or social worker alone, so that everyone’s time might be managed more efficiently. And managing skeptical parents as a team also can help to prevent frustration or burnout. It will not always succeed, but in some cases, your investment will pay off in a trusting alliance, mutual respect, and healthy patients.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

Dr. T. Berry Brazelton was a pioneer of child-centered parenting

You may not realize it, but as you navigated through this morning’s hospital rounds and your busy office schedule, some of what you did and how you did it was the result of the pioneering work of Boston-based pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton, MD, who died March 13, 2018, at the age of 99.

You probably found the newborn you needed to examine in his mother’s hospital room. The 3-year-old in the croup tent was sharing his room with his father, who was sleeping on a cot at his crib side, and three out of the first four patients you saw in your office had been breastfed. These scenarios would have been unheard of 50 years ago. But Dr. Brazelton’s voice was the most widely heard, yet gentlest and persuasive in support of rooming-in and breastfeeding.

My fellow house officers and I had been accustomed to picking up infants to assess their tone. However, when Dr. Brazelton picked up a newborn, it was more like a conversation, an interview, and in a sense, it was a meeting of the minds.

It wasn’t that we had been rejecting the notion that a newborn could have a personality. It is just that we hadn’t been taught to look for it or to take it seriously. Dr. Brazelton taught us how to examine the person inside that little body and understand the importance of her temperament. By sharing what we learned from doing a Brazelton-style exam, we hoped to encourage the child’s parents to adopt more realistic expectations, and as a consequence, make parenting less mysterious and stressful.

When I first met Dr. Brazelton, he was in his mid-40s and just beginning on his trajectory toward national prominence. When we were assigned to take care of his hospitalized patients, it was obvious that his patient skills with sick children had taken a back seat to his interest in newborn temperament. He was more than willing to let us make the management decisions. In retrospect, that experience was a warning that I, like many other pediatricians, would face the similar challenge of maintaining my clinical skills in the face of a patient mix that was steadily acquiring a more behavioral and developmental flavor.

It is impossible to quantify the degree to which Dr. Brazelton’s ubiquity contributed to the popularity of a more child-centered parenting style. However, I think it would be unfair to blame him for the unfortunate phenomenon known as “helicopter parenting.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

You may not realize it, but as you navigated through this morning’s hospital rounds and your busy office schedule, some of what you did and how you did it was the result of the pioneering work of Boston-based pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton, MD, who died March 13, 2018, at the age of 99.

You probably found the newborn you needed to examine in his mother’s hospital room. The 3-year-old in the croup tent was sharing his room with his father, who was sleeping on a cot at his crib side, and three out of the first four patients you saw in your office had been breastfed. These scenarios would have been unheard of 50 years ago. But Dr. Brazelton’s voice was the most widely heard, yet gentlest and persuasive in support of rooming-in and breastfeeding.

My fellow house officers and I had been accustomed to picking up infants to assess their tone. However, when Dr. Brazelton picked up a newborn, it was more like a conversation, an interview, and in a sense, it was a meeting of the minds.

It wasn’t that we had been rejecting the notion that a newborn could have a personality. It is just that we hadn’t been taught to look for it or to take it seriously. Dr. Brazelton taught us how to examine the person inside that little body and understand the importance of her temperament. By sharing what we learned from doing a Brazelton-style exam, we hoped to encourage the child’s parents to adopt more realistic expectations, and as a consequence, make parenting less mysterious and stressful.

When I first met Dr. Brazelton, he was in his mid-40s and just beginning on his trajectory toward national prominence. When we were assigned to take care of his hospitalized patients, it was obvious that his patient skills with sick children had taken a back seat to his interest in newborn temperament. He was more than willing to let us make the management decisions. In retrospect, that experience was a warning that I, like many other pediatricians, would face the similar challenge of maintaining my clinical skills in the face of a patient mix that was steadily acquiring a more behavioral and developmental flavor.

It is impossible to quantify the degree to which Dr. Brazelton’s ubiquity contributed to the popularity of a more child-centered parenting style. However, I think it would be unfair to blame him for the unfortunate phenomenon known as “helicopter parenting.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

You may not realize it, but as you navigated through this morning’s hospital rounds and your busy office schedule, some of what you did and how you did it was the result of the pioneering work of Boston-based pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton, MD, who died March 13, 2018, at the age of 99.

You probably found the newborn you needed to examine in his mother’s hospital room. The 3-year-old in the croup tent was sharing his room with his father, who was sleeping on a cot at his crib side, and three out of the first four patients you saw in your office had been breastfed. These scenarios would have been unheard of 50 years ago. But Dr. Brazelton’s voice was the most widely heard, yet gentlest and persuasive in support of rooming-in and breastfeeding.

My fellow house officers and I had been accustomed to picking up infants to assess their tone. However, when Dr. Brazelton picked up a newborn, it was more like a conversation, an interview, and in a sense, it was a meeting of the minds.

It wasn’t that we had been rejecting the notion that a newborn could have a personality. It is just that we hadn’t been taught to look for it or to take it seriously. Dr. Brazelton taught us how to examine the person inside that little body and understand the importance of her temperament. By sharing what we learned from doing a Brazelton-style exam, we hoped to encourage the child’s parents to adopt more realistic expectations, and as a consequence, make parenting less mysterious and stressful.

When I first met Dr. Brazelton, he was in his mid-40s and just beginning on his trajectory toward national prominence. When we were assigned to take care of his hospitalized patients, it was obvious that his patient skills with sick children had taken a back seat to his interest in newborn temperament. He was more than willing to let us make the management decisions. In retrospect, that experience was a warning that I, like many other pediatricians, would face the similar challenge of maintaining my clinical skills in the face of a patient mix that was steadily acquiring a more behavioral and developmental flavor.

It is impossible to quantify the degree to which Dr. Brazelton’s ubiquity contributed to the popularity of a more child-centered parenting style. However, I think it would be unfair to blame him for the unfortunate phenomenon known as “helicopter parenting.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Sexual harassment, violence is our problem, too

This past year has seen an incredible transformation in our awareness and understanding of the extent of sexual harassment and assault in our society. The #metoo campaign and the brave women throughout the country who have come out and told us their stories have truly made a difference.

For years, I, and many other pediatricians like me, have counseled teenage girls on how to stay safe as they prepare to enter college and universities. So many times, I have mentioned the shocking statistics on rape and sexual assault in college. I have cautioned these young women on how to stay safe, to stay close to their girlfriends, to not accept drinks from other people, and if drinking, not to drink so much that they don’t know what is going on around them … and so on and so forth with many dos and don’ts.

But here is something I only recently noticed: In the last 18 years of practice, my counsel to the boys was limited to how to stay safe, protect themselves against sexually transmitted infections, and how to avoid pregnancy. It did not cross my mind to counsel the teenage boys on their respective dos and don’ts, especially when it comes to their behavior with women. For example, stern advice on how to respect women, that only yes means yes, and frankly how to make sure they don’t become sexual harassers or worse.

I have questioned myself since then, wondering if I was alone with this oversight. I asked several other pediatricians as well to see if they had spoken about sexual harassment and assault in this context with their teenage male patients. The vast majority had the same experience as I did. They had all counseled the girls on how to protect themselves from becoming victims, but somehow not the boys (or girls for that matter) on how to help them not become the aggressors.

It has occurred to me that our focus as physicians has largely been limited to what the victims can do to not become victims.

As pediatricians, we counsel parents on how to keep their children safe, and how to protect them. It is our obligation to help, to guide, and to teach parents. We teach parents about discipline, limit setting, sleeping, feeding, and so many other things. We need to teach them how to talk to their boys and girls about appropriate behavior with whomever they may be interested in, about sexual harassment, and assault, and how not to become part of the problem.

It is our obligation as pediatricians to teach the children we see growing up in front of us how to behave in an adult, sexual world. We can make a bigger difference than we might think. As physicians, we promised to do no harm when we took our oath. It is now our turn also to take proactive steps to stop the harm caused by others.

Dr. Rimawi is a pediatrician in private practice in Atherton, Calif. Email her at [email protected].

This past year has seen an incredible transformation in our awareness and understanding of the extent of sexual harassment and assault in our society. The #metoo campaign and the brave women throughout the country who have come out and told us their stories have truly made a difference.

For years, I, and many other pediatricians like me, have counseled teenage girls on how to stay safe as they prepare to enter college and universities. So many times, I have mentioned the shocking statistics on rape and sexual assault in college. I have cautioned these young women on how to stay safe, to stay close to their girlfriends, to not accept drinks from other people, and if drinking, not to drink so much that they don’t know what is going on around them … and so on and so forth with many dos and don’ts.

But here is something I only recently noticed: In the last 18 years of practice, my counsel to the boys was limited to how to stay safe, protect themselves against sexually transmitted infections, and how to avoid pregnancy. It did not cross my mind to counsel the teenage boys on their respective dos and don’ts, especially when it comes to their behavior with women. For example, stern advice on how to respect women, that only yes means yes, and frankly how to make sure they don’t become sexual harassers or worse.

I have questioned myself since then, wondering if I was alone with this oversight. I asked several other pediatricians as well to see if they had spoken about sexual harassment and assault in this context with their teenage male patients. The vast majority had the same experience as I did. They had all counseled the girls on how to protect themselves from becoming victims, but somehow not the boys (or girls for that matter) on how to help them not become the aggressors.

It has occurred to me that our focus as physicians has largely been limited to what the victims can do to not become victims.

As pediatricians, we counsel parents on how to keep their children safe, and how to protect them. It is our obligation to help, to guide, and to teach parents. We teach parents about discipline, limit setting, sleeping, feeding, and so many other things. We need to teach them how to talk to their boys and girls about appropriate behavior with whomever they may be interested in, about sexual harassment, and assault, and how not to become part of the problem.

It is our obligation as pediatricians to teach the children we see growing up in front of us how to behave in an adult, sexual world. We can make a bigger difference than we might think. As physicians, we promised to do no harm when we took our oath. It is now our turn also to take proactive steps to stop the harm caused by others.

Dr. Rimawi is a pediatrician in private practice in Atherton, Calif. Email her at [email protected].

This past year has seen an incredible transformation in our awareness and understanding of the extent of sexual harassment and assault in our society. The #metoo campaign and the brave women throughout the country who have come out and told us their stories have truly made a difference.

For years, I, and many other pediatricians like me, have counseled teenage girls on how to stay safe as they prepare to enter college and universities. So many times, I have mentioned the shocking statistics on rape and sexual assault in college. I have cautioned these young women on how to stay safe, to stay close to their girlfriends, to not accept drinks from other people, and if drinking, not to drink so much that they don’t know what is going on around them … and so on and so forth with many dos and don’ts.

But here is something I only recently noticed: In the last 18 years of practice, my counsel to the boys was limited to how to stay safe, protect themselves against sexually transmitted infections, and how to avoid pregnancy. It did not cross my mind to counsel the teenage boys on their respective dos and don’ts, especially when it comes to their behavior with women. For example, stern advice on how to respect women, that only yes means yes, and frankly how to make sure they don’t become sexual harassers or worse.

I have questioned myself since then, wondering if I was alone with this oversight. I asked several other pediatricians as well to see if they had spoken about sexual harassment and assault in this context with their teenage male patients. The vast majority had the same experience as I did. They had all counseled the girls on how to protect themselves from becoming victims, but somehow not the boys (or girls for that matter) on how to help them not become the aggressors.

It has occurred to me that our focus as physicians has largely been limited to what the victims can do to not become victims.

As pediatricians, we counsel parents on how to keep their children safe, and how to protect them. It is our obligation to help, to guide, and to teach parents. We teach parents about discipline, limit setting, sleeping, feeding, and so many other things. We need to teach them how to talk to their boys and girls about appropriate behavior with whomever they may be interested in, about sexual harassment, and assault, and how not to become part of the problem.

It is our obligation as pediatricians to teach the children we see growing up in front of us how to behave in an adult, sexual world. We can make a bigger difference than we might think. As physicians, we promised to do no harm when we took our oath. It is now our turn also to take proactive steps to stop the harm caused by others.

Dr. Rimawi is a pediatrician in private practice in Atherton, Calif. Email her at [email protected].

Why isn’t smart gun technology on Parkland activists’ agenda?

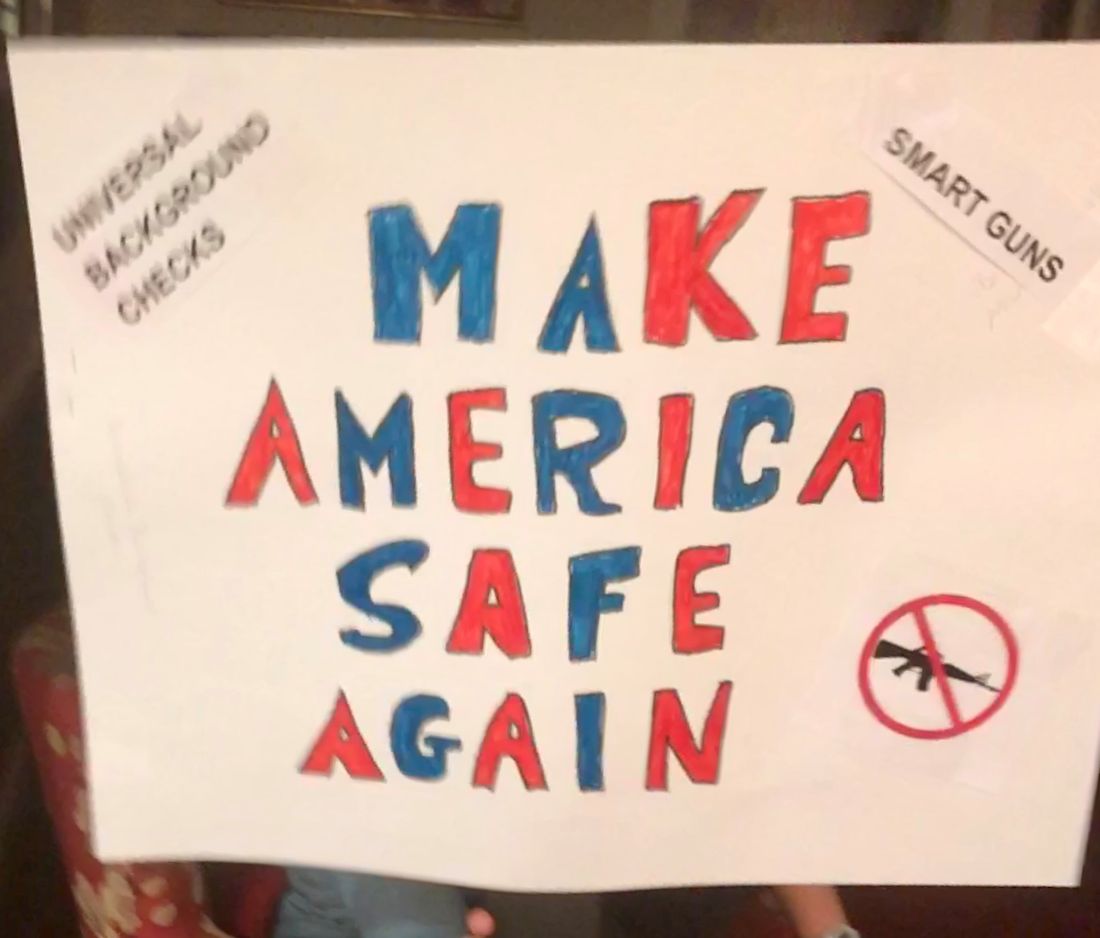

The evening before the March For Our Lives rally in Washington, I was hard at work on my sign. Making a statement is important, but at the Women’s March last January, I discovered that a sign was invaluable for keeping friends together in a crowd. Since my Women’s March sign read “Make America Kind Again,” I opted to keep with the theme, and I created a “Make America Safe Again” sign for gun control. My daughter looked at my sign skeptically. “It’s too vague and nondirective,” she declared. Now challenged, I added the following directives: “Universal Background Checks,” “Ban Assault Weapons,” and “Smart Guns.” My sign was now complete.

I was surprised when my daughter – our family Jeopardy! whiz – asked, “What’s a smart gun?” When we arrived to join friends, their daughter – a doctoral student – also looked at the sign and asked me what a smart gun is. I explained to both young women that a smart gun – like an iPhone – relies on a biometric such as a fingerprint so that it can be used only by authorized users. This technology would reduce the flow of firearms to illegal owners, prevent accidental discharge by children, protect rightful owners and law enforcement officers from having their own weapons used against them by criminals, and decrease the number of suicides by family members of gun owners. In my state of Maryland, there have been two school shootings, one as recently as March 20, and both were committed by boys who took a parent’s firearm to school.

We arrived at the rally and found a spot in front of the Newseum, with two jumbotrons in sight, right in the middle of the crowd. The young people who spoke were inspirational. Regardless of one’s political views or thoughts on gun control, they were bright, articulate, fearless, passionate, and determined. The show was stolen by Naomi Wadler, a precocious 11-year-old girl who is destined to be a member of Congress (if not president) one day, and by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 9-year-old granddaughter, Yolanda Renee King.

The rest of the speakers were teenagers, all of whom had lost someone to gunfire. There were speakers from Parkland, Fla., who talked about the raw losses they were feeling, and the student who wasn’t celebrating his 18th birthday on March 24. Matthew Soto from Newtown, Conn., talked about losing his sister, a first-grade teacher, in the Sandy Hook shooting.

But the rally wasn’t just about mass murders and school shootings: Zion Kelly talked about the death of his twin, a teen who was killed when he stopped at a convenience store on the way home from school in Washington, only to have his promising life snuffed out during a holdup. We heard about shootings in the bullet-riddled streets of Chicago and Los Angeles and the toll they have taken. The losses to gun violence have been felt most strongly in communities of color. While it was mentioned that the majority of gun deaths are suicides, there were no speakers from families of people who died from suicide. The final speaker was Emma Gonzalez, a young woman from Parkland who took the stage for 6 minutes and 20 seconds - the duration of the shooter’s rampage - and closed with a powerful moment of silence.* The rally closed with a performance of Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’ ” by Jennifer Hudson, whose mother, brother, and nephew were murdered by a gunman.

The teens talked about what changes they wanted to see enacted. They talked about closing loopholes to background checks, and I was pleased that one young man specifically mentioned keeping guns from those who are violent, but did not mention mental illness as a reason to block gun ownership. A call to resume a ban on assault weapons was made repeatedly as was a call to raise the age (to 21) at which an individual can purchase a gun. Military-style weapons are not necessary for hunting or self-defense, and they enable the rapid-fire assassinations we have seen in mass shootings, so they remain an easy target of gun control advocacy. But in terms of numbers, these firearms are responsible for a small fraction of gun deaths. I was surprised, but the teens did not mention “smart gun” legislation as a way to reduce gun deaths.

Guns, and gun deaths, are a part of American society. While the majority of Americans favor stronger regulation of gun ownership, legislation that would end gun ownership is not likely to go anywhere. Smart guns, however, are different. Forty percent of polled gun owners have said they would swap their firearm for a smart firearm. So given the appeal of a firearm that can’t be diverted or stolen, used against the owner, discharged accidentally by a child, or used for suicide or homicide by a distressed family member, why don’t these weapons exist for use by the American people? . People want these guns and the protections they offer, yet they have never been produced and made available to either the American public or to our law enforcement officers.

So where are these firearms, and why aren’t our Parkland teens asking for them? The answer to the first part of that question lies with the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the state of New Jersey. In 2003, New Jersey passed the Childproof Handgun bill, which requires that all guns sold in the state be smart guns within 3 years of their availability. The NRA has vigorously opposed any legislation that would require all guns to be smart guns. Because the availability of these weapons would trigger the New Jersey bill, California and Maryland have been prevented from importing smart firearms from a German company. Perhaps, however, New Jersey does not need to bear all the blame; in 1999, 4 years before the passage of the bill, the NRA and its members boycotted Smith & Wesson when the gun manufacturer revealed plans to develop a smart gun for the government. The NRA’s public stance is that it does not oppose smart guns for those who want them, but it opposes legislation that would eliminate the sale of conventional firearms. The organization has voiced concerns that technology fails and that it potentially slows down firing the weapon. It doesn’t talk about dead toddlers, or about police officers who’ve been killed when their weapons were taken from them.

As for the Parkland students, I don’t know why they aren’t asking for smart gun technology while they have the attention of the country. Perhaps they, like the young women I was with, don’t know it’s an option. Perhaps it’s too removed from the issue of mass murders and an assault weapon ban feels more attainable. Or perhaps the NRA’s mission has too much of a stronghold in Florida. I don’t know why they aren’t asking for smart gun production, but I know they should be.

*Correction, 3/27/2018: An earlier version of this story misstated the duration of Emma Gonzalez's moment of silence.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), 2016. She practices in Baltimore.

The evening before the March For Our Lives rally in Washington, I was hard at work on my sign. Making a statement is important, but at the Women’s March last January, I discovered that a sign was invaluable for keeping friends together in a crowd. Since my Women’s March sign read “Make America Kind Again,” I opted to keep with the theme, and I created a “Make America Safe Again” sign for gun control. My daughter looked at my sign skeptically. “It’s too vague and nondirective,” she declared. Now challenged, I added the following directives: “Universal Background Checks,” “Ban Assault Weapons,” and “Smart Guns.” My sign was now complete.

I was surprised when my daughter – our family Jeopardy! whiz – asked, “What’s a smart gun?” When we arrived to join friends, their daughter – a doctoral student – also looked at the sign and asked me what a smart gun is. I explained to both young women that a smart gun – like an iPhone – relies on a biometric such as a fingerprint so that it can be used only by authorized users. This technology would reduce the flow of firearms to illegal owners, prevent accidental discharge by children, protect rightful owners and law enforcement officers from having their own weapons used against them by criminals, and decrease the number of suicides by family members of gun owners. In my state of Maryland, there have been two school shootings, one as recently as March 20, and both were committed by boys who took a parent’s firearm to school.

We arrived at the rally and found a spot in front of the Newseum, with two jumbotrons in sight, right in the middle of the crowd. The young people who spoke were inspirational. Regardless of one’s political views or thoughts on gun control, they were bright, articulate, fearless, passionate, and determined. The show was stolen by Naomi Wadler, a precocious 11-year-old girl who is destined to be a member of Congress (if not president) one day, and by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 9-year-old granddaughter, Yolanda Renee King.

The rest of the speakers were teenagers, all of whom had lost someone to gunfire. There were speakers from Parkland, Fla., who talked about the raw losses they were feeling, and the student who wasn’t celebrating his 18th birthday on March 24. Matthew Soto from Newtown, Conn., talked about losing his sister, a first-grade teacher, in the Sandy Hook shooting.

But the rally wasn’t just about mass murders and school shootings: Zion Kelly talked about the death of his twin, a teen who was killed when he stopped at a convenience store on the way home from school in Washington, only to have his promising life snuffed out during a holdup. We heard about shootings in the bullet-riddled streets of Chicago and Los Angeles and the toll they have taken. The losses to gun violence have been felt most strongly in communities of color. While it was mentioned that the majority of gun deaths are suicides, there were no speakers from families of people who died from suicide. The final speaker was Emma Gonzalez, a young woman from Parkland who took the stage for 6 minutes and 20 seconds - the duration of the shooter’s rampage - and closed with a powerful moment of silence.* The rally closed with a performance of Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’ ” by Jennifer Hudson, whose mother, brother, and nephew were murdered by a gunman.

The teens talked about what changes they wanted to see enacted. They talked about closing loopholes to background checks, and I was pleased that one young man specifically mentioned keeping guns from those who are violent, but did not mention mental illness as a reason to block gun ownership. A call to resume a ban on assault weapons was made repeatedly as was a call to raise the age (to 21) at which an individual can purchase a gun. Military-style weapons are not necessary for hunting or self-defense, and they enable the rapid-fire assassinations we have seen in mass shootings, so they remain an easy target of gun control advocacy. But in terms of numbers, these firearms are responsible for a small fraction of gun deaths. I was surprised, but the teens did not mention “smart gun” legislation as a way to reduce gun deaths.

Guns, and gun deaths, are a part of American society. While the majority of Americans favor stronger regulation of gun ownership, legislation that would end gun ownership is not likely to go anywhere. Smart guns, however, are different. Forty percent of polled gun owners have said they would swap their firearm for a smart firearm. So given the appeal of a firearm that can’t be diverted or stolen, used against the owner, discharged accidentally by a child, or used for suicide or homicide by a distressed family member, why don’t these weapons exist for use by the American people? . People want these guns and the protections they offer, yet they have never been produced and made available to either the American public or to our law enforcement officers.

So where are these firearms, and why aren’t our Parkland teens asking for them? The answer to the first part of that question lies with the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the state of New Jersey. In 2003, New Jersey passed the Childproof Handgun bill, which requires that all guns sold in the state be smart guns within 3 years of their availability. The NRA has vigorously opposed any legislation that would require all guns to be smart guns. Because the availability of these weapons would trigger the New Jersey bill, California and Maryland have been prevented from importing smart firearms from a German company. Perhaps, however, New Jersey does not need to bear all the blame; in 1999, 4 years before the passage of the bill, the NRA and its members boycotted Smith & Wesson when the gun manufacturer revealed plans to develop a smart gun for the government. The NRA’s public stance is that it does not oppose smart guns for those who want them, but it opposes legislation that would eliminate the sale of conventional firearms. The organization has voiced concerns that technology fails and that it potentially slows down firing the weapon. It doesn’t talk about dead toddlers, or about police officers who’ve been killed when their weapons were taken from them.

As for the Parkland students, I don’t know why they aren’t asking for smart gun technology while they have the attention of the country. Perhaps they, like the young women I was with, don’t know it’s an option. Perhaps it’s too removed from the issue of mass murders and an assault weapon ban feels more attainable. Or perhaps the NRA’s mission has too much of a stronghold in Florida. I don’t know why they aren’t asking for smart gun production, but I know they should be.

*Correction, 3/27/2018: An earlier version of this story misstated the duration of Emma Gonzalez's moment of silence.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), 2016. She practices in Baltimore.

The evening before the March For Our Lives rally in Washington, I was hard at work on my sign. Making a statement is important, but at the Women’s March last January, I discovered that a sign was invaluable for keeping friends together in a crowd. Since my Women’s March sign read “Make America Kind Again,” I opted to keep with the theme, and I created a “Make America Safe Again” sign for gun control. My daughter looked at my sign skeptically. “It’s too vague and nondirective,” she declared. Now challenged, I added the following directives: “Universal Background Checks,” “Ban Assault Weapons,” and “Smart Guns.” My sign was now complete.

I was surprised when my daughter – our family Jeopardy! whiz – asked, “What’s a smart gun?” When we arrived to join friends, their daughter – a doctoral student – also looked at the sign and asked me what a smart gun is. I explained to both young women that a smart gun – like an iPhone – relies on a biometric such as a fingerprint so that it can be used only by authorized users. This technology would reduce the flow of firearms to illegal owners, prevent accidental discharge by children, protect rightful owners and law enforcement officers from having their own weapons used against them by criminals, and decrease the number of suicides by family members of gun owners. In my state of Maryland, there have been two school shootings, one as recently as March 20, and both were committed by boys who took a parent’s firearm to school.

We arrived at the rally and found a spot in front of the Newseum, with two jumbotrons in sight, right in the middle of the crowd. The young people who spoke were inspirational. Regardless of one’s political views or thoughts on gun control, they were bright, articulate, fearless, passionate, and determined. The show was stolen by Naomi Wadler, a precocious 11-year-old girl who is destined to be a member of Congress (if not president) one day, and by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 9-year-old granddaughter, Yolanda Renee King.

The rest of the speakers were teenagers, all of whom had lost someone to gunfire. There were speakers from Parkland, Fla., who talked about the raw losses they were feeling, and the student who wasn’t celebrating his 18th birthday on March 24. Matthew Soto from Newtown, Conn., talked about losing his sister, a first-grade teacher, in the Sandy Hook shooting.

But the rally wasn’t just about mass murders and school shootings: Zion Kelly talked about the death of his twin, a teen who was killed when he stopped at a convenience store on the way home from school in Washington, only to have his promising life snuffed out during a holdup. We heard about shootings in the bullet-riddled streets of Chicago and Los Angeles and the toll they have taken. The losses to gun violence have been felt most strongly in communities of color. While it was mentioned that the majority of gun deaths are suicides, there were no speakers from families of people who died from suicide. The final speaker was Emma Gonzalez, a young woman from Parkland who took the stage for 6 minutes and 20 seconds - the duration of the shooter’s rampage - and closed with a powerful moment of silence.* The rally closed with a performance of Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’ ” by Jennifer Hudson, whose mother, brother, and nephew were murdered by a gunman.