User login

Impact of Medicaid expansion on inpatient outcomes

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has greatly increased the number of Medicaid enrollees since it expanded eligibility criteria on Jan. 1, 2014. Nearly 9 million additional U.S. adults now have Medicaid coverage, mostly in the 31 states and Washington, which have opted into Medicaid expansion.

The ACA has also had an important impact on hospital payer mix, mainly by decreasing the amount of uncompensated care in Medicaid-expansion states. Previous studies have shown disparities in the quality of inpatient care based on insurance type. Patients with Medicaid insurance often have longer hospitalizations and higher in-hospital mortality than commercially-insured patients and occasionally even than uninsured patients.

In our study published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (2016 Dec. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2649), we evaluated the impact of state Medicaid expansion status on payer mix, length of stay, and in-hospital mortality for general medicine patients discharged from U.S. academic medical centers. We considered Jan. 1, 2014, to be the date of ACA implementation for all states except Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Indiana, which had unique dates of Medicaid expansion.

We were able to identify 3,144,488 discharges from 156 hospitals in 24 Medicaid-expansion states and Washington, and 1,114,464 discharges from 55 hospitals in 14 nonexpansion states between October 2012 and September 2015.

Despite this difference in payer mix trends, state Medicaid expansion status was not associated with differences in overall length of stay or in-hospital mortality in our study. More precisely, we looked at the length of stay and mortality indices, or ratio of observed to expected values, to control for such potential confounders as disease severity and comorbid conditions.

One possible explanation for our findings is that the higher proportion of Medicare and commercially-insured patients overshadowed the contribution of Medicaid patients to the overall length of stay and mortality indices.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to look at the effect of ACA implementation on inpatient outcomes. Early evidence suggests that Medicaid expansion has improved outpatient outcomes. Low-income adults in Medicaid-expansion states have shown greater gains in access to primary care clinics and medications and in the diagnosis of certain chronic health conditions than those in non-expansion states. However, these changes would not necessarily lead to improvements in the length of stay or mortality indices for Medicaid-expansion hospitals, since the measures account for patient acuity on admission.

The take-home message from our study for health policy makers is that state Medicaid expansion status had a neutral effect on both length of stay and mortality indices. This should be reassuring for states considering expansion of their Medicaid programs in the future.

As a next step, it would be useful to see research on the impact of ACA implementation on other inpatient outcomes that may vary with insurance type, such as readmissions or hospital-acquired complications.

The take-home message for hospitalists is that there is more work to be done in reducing disparities in inpatient care based on payer status. Though not a primary focus of our study, we did see variation in the length of stay and mortality indices based on insurance type.

It is unclear whether these differences occurred because of variation in the expertise of inpatient providers, access to invasive procedures or medical therapies, the timeliness of discharge to post-acute care facilities, or other patient- or system-level factors. However, these disparities warrant our improvement efforts moving forward.

Mary Anderson, MD, and Christine Jones, MD, are hospitalists at the University of Colorado (Aurora) Hospital and assistant professors in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has greatly increased the number of Medicaid enrollees since it expanded eligibility criteria on Jan. 1, 2014. Nearly 9 million additional U.S. adults now have Medicaid coverage, mostly in the 31 states and Washington, which have opted into Medicaid expansion.

The ACA has also had an important impact on hospital payer mix, mainly by decreasing the amount of uncompensated care in Medicaid-expansion states. Previous studies have shown disparities in the quality of inpatient care based on insurance type. Patients with Medicaid insurance often have longer hospitalizations and higher in-hospital mortality than commercially-insured patients and occasionally even than uninsured patients.

In our study published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (2016 Dec. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2649), we evaluated the impact of state Medicaid expansion status on payer mix, length of stay, and in-hospital mortality for general medicine patients discharged from U.S. academic medical centers. We considered Jan. 1, 2014, to be the date of ACA implementation for all states except Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Indiana, which had unique dates of Medicaid expansion.

We were able to identify 3,144,488 discharges from 156 hospitals in 24 Medicaid-expansion states and Washington, and 1,114,464 discharges from 55 hospitals in 14 nonexpansion states between October 2012 and September 2015.

Despite this difference in payer mix trends, state Medicaid expansion status was not associated with differences in overall length of stay or in-hospital mortality in our study. More precisely, we looked at the length of stay and mortality indices, or ratio of observed to expected values, to control for such potential confounders as disease severity and comorbid conditions.

One possible explanation for our findings is that the higher proportion of Medicare and commercially-insured patients overshadowed the contribution of Medicaid patients to the overall length of stay and mortality indices.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to look at the effect of ACA implementation on inpatient outcomes. Early evidence suggests that Medicaid expansion has improved outpatient outcomes. Low-income adults in Medicaid-expansion states have shown greater gains in access to primary care clinics and medications and in the diagnosis of certain chronic health conditions than those in non-expansion states. However, these changes would not necessarily lead to improvements in the length of stay or mortality indices for Medicaid-expansion hospitals, since the measures account for patient acuity on admission.

The take-home message from our study for health policy makers is that state Medicaid expansion status had a neutral effect on both length of stay and mortality indices. This should be reassuring for states considering expansion of their Medicaid programs in the future.

As a next step, it would be useful to see research on the impact of ACA implementation on other inpatient outcomes that may vary with insurance type, such as readmissions or hospital-acquired complications.

The take-home message for hospitalists is that there is more work to be done in reducing disparities in inpatient care based on payer status. Though not a primary focus of our study, we did see variation in the length of stay and mortality indices based on insurance type.

It is unclear whether these differences occurred because of variation in the expertise of inpatient providers, access to invasive procedures or medical therapies, the timeliness of discharge to post-acute care facilities, or other patient- or system-level factors. However, these disparities warrant our improvement efforts moving forward.

Mary Anderson, MD, and Christine Jones, MD, are hospitalists at the University of Colorado (Aurora) Hospital and assistant professors in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has greatly increased the number of Medicaid enrollees since it expanded eligibility criteria on Jan. 1, 2014. Nearly 9 million additional U.S. adults now have Medicaid coverage, mostly in the 31 states and Washington, which have opted into Medicaid expansion.

The ACA has also had an important impact on hospital payer mix, mainly by decreasing the amount of uncompensated care in Medicaid-expansion states. Previous studies have shown disparities in the quality of inpatient care based on insurance type. Patients with Medicaid insurance often have longer hospitalizations and higher in-hospital mortality than commercially-insured patients and occasionally even than uninsured patients.

In our study published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (2016 Dec. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2649), we evaluated the impact of state Medicaid expansion status on payer mix, length of stay, and in-hospital mortality for general medicine patients discharged from U.S. academic medical centers. We considered Jan. 1, 2014, to be the date of ACA implementation for all states except Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Indiana, which had unique dates of Medicaid expansion.

We were able to identify 3,144,488 discharges from 156 hospitals in 24 Medicaid-expansion states and Washington, and 1,114,464 discharges from 55 hospitals in 14 nonexpansion states between October 2012 and September 2015.

Despite this difference in payer mix trends, state Medicaid expansion status was not associated with differences in overall length of stay or in-hospital mortality in our study. More precisely, we looked at the length of stay and mortality indices, or ratio of observed to expected values, to control for such potential confounders as disease severity and comorbid conditions.

One possible explanation for our findings is that the higher proportion of Medicare and commercially-insured patients overshadowed the contribution of Medicaid patients to the overall length of stay and mortality indices.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to look at the effect of ACA implementation on inpatient outcomes. Early evidence suggests that Medicaid expansion has improved outpatient outcomes. Low-income adults in Medicaid-expansion states have shown greater gains in access to primary care clinics and medications and in the diagnosis of certain chronic health conditions than those in non-expansion states. However, these changes would not necessarily lead to improvements in the length of stay or mortality indices for Medicaid-expansion hospitals, since the measures account for patient acuity on admission.

The take-home message from our study for health policy makers is that state Medicaid expansion status had a neutral effect on both length of stay and mortality indices. This should be reassuring for states considering expansion of their Medicaid programs in the future.

As a next step, it would be useful to see research on the impact of ACA implementation on other inpatient outcomes that may vary with insurance type, such as readmissions or hospital-acquired complications.

The take-home message for hospitalists is that there is more work to be done in reducing disparities in inpatient care based on payer status. Though not a primary focus of our study, we did see variation in the length of stay and mortality indices based on insurance type.

It is unclear whether these differences occurred because of variation in the expertise of inpatient providers, access to invasive procedures or medical therapies, the timeliness of discharge to post-acute care facilities, or other patient- or system-level factors. However, these disparities warrant our improvement efforts moving forward.

Mary Anderson, MD, and Christine Jones, MD, are hospitalists at the University of Colorado (Aurora) Hospital and assistant professors in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado.

OA drug development needs patient-focused approach to biomarkers and outcome measures

Advances in our understanding of the development and treatment of osteoarthritis have led to renewed interest in leveraging these insights to establish more ways to evaluate potential drug candidates in clinical trials, particularly through the use of qualified biomarkers as meaningful outcome measures.

It is with this goal in mind that the Arthritis Foundation and the Food and Drug Administration held the Accelerating Osteoarthritis Clinical Trials Workshop in Atlanta in February 2016,1 to discuss ways of enhancing the likelihood of successful OA trials, including possible “qualification” of biomarkers that can be used as endpoints in trials of OA treatments. Clinical trial endpoints would ideally be known to be clinically meaningful to the patient (such as pain, fatigue, functional status, etc.)2 and would reflect treatments that enable patients to feel and function better.

Patient engagement in different steps of the development process might be possible through patient registries, social media communities, smart phones, and wearable devices to be used as tools for capturing patient perceptions and mobility. These means for capturing dynamic data about domains of high interest to OA patients may lead to the development of better outcome measures that can be used as clinical trial endpoints.4 Researchers at the workshop presented new ways in which they are beginning to specialize in these techniques and methods that will be useful for turning the patient experience into usable data to aid in precision medicine.

Imaging outcomes and biomarkers are attractive for their potential to demonstrate an effect on the structural and pathophysiologic elements of OA in the time frame of a clinical trial, but rely on well-characterized relationships between those structural and pathophysiologic elements of OA and the clinical outcomes of OA. A recent advance is data showing that semiquantitative knee joint features, including cartilage thickness and surface area, meniscal morphology, and bone marrow lesions, were associated with clinically relevant OA progression and could be potentially useful as measures of efficacy in clinical trials of disease-modifying interventions.5 Being able to describe the clinical benefit to be expected from such changes is essential to use these outcomes in the benefit-risk assessment. How to include structural outcomes in OA trials will depend on the level of information available to characterize clinical benefit. With less information, structural outcomes may still be useful as adjunct or secondary endpoints. To be used as the primary endpoint to support approval, a high level of characterization would be needed about the relationship of the endpoint to anticipated clinical benefit. The FDA recommends that sponsors proposing such a primary endpoint should engage with the agency early in the development program.

Another option discussed was to study an accelerated OA population, that is, subjects (prior to joint replacement) with a history of trauma to a joint and other injuries predictive of early OA. In that setting, the study duration needed to demonstrate the relationship of structural and clinical outcomes may be more feasible.

A third option discussed was an end-stage OA trial that could enroll subjects who meet criteria for joint replacement. Such a study could possibly have outcomes that include delay in time to surgery, reduction in need for surgery, and clinical outcomes, such as need for concomitant analgesics, patient pain, and patient function. In any OA population, demonstrating a treatment’s effectiveness on clinical outcomes could be the sole basis for approval, in the context of an acceptable safety profile.

Dr. Niskar is national scientific director of the Arthritis Foundation. Dr. Yim is supervisory associate director of the division of pulmonary, allergy, and rheumatology products in the Office of New Drugs at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Dr. Kraus is professor of medicine, pathology, and orthopedic surgery at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and is a faculty member of the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute. Dr. Tuan is director of the Center for Cellular and Molecular Engineering and Distinguished Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Niskar reports that the Arthritis Foundation received a donation from Samumed and a cosponsorship grant from the FDA to implement the Accelerating OA Clinical Trials Workshop. Dr. Kraus reports an Arthritis Foundation Delivering on Discovery Award that is outside of this editorial. Dr. Yim and Dr. Tuan disclosed no conflicts. Dr. Yim is relaying her personal views in this editorial, and they are not intended to convey official FDA policy, and no official support or endorsement by the FDA is provided or should be inferred. Samumed did not have a role in the writing of this editorial.

References

1. Bioworld. 2016;27:1-4.

2. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015 May;23[5]:677-85.

3. Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative. PG engagement across the research & development continuum. 2015.

4. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:336ps11.

5. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Oct;68[10]:2422-31.

Advances in our understanding of the development and treatment of osteoarthritis have led to renewed interest in leveraging these insights to establish more ways to evaluate potential drug candidates in clinical trials, particularly through the use of qualified biomarkers as meaningful outcome measures.

It is with this goal in mind that the Arthritis Foundation and the Food and Drug Administration held the Accelerating Osteoarthritis Clinical Trials Workshop in Atlanta in February 2016,1 to discuss ways of enhancing the likelihood of successful OA trials, including possible “qualification” of biomarkers that can be used as endpoints in trials of OA treatments. Clinical trial endpoints would ideally be known to be clinically meaningful to the patient (such as pain, fatigue, functional status, etc.)2 and would reflect treatments that enable patients to feel and function better.

Patient engagement in different steps of the development process might be possible through patient registries, social media communities, smart phones, and wearable devices to be used as tools for capturing patient perceptions and mobility. These means for capturing dynamic data about domains of high interest to OA patients may lead to the development of better outcome measures that can be used as clinical trial endpoints.4 Researchers at the workshop presented new ways in which they are beginning to specialize in these techniques and methods that will be useful for turning the patient experience into usable data to aid in precision medicine.

Imaging outcomes and biomarkers are attractive for their potential to demonstrate an effect on the structural and pathophysiologic elements of OA in the time frame of a clinical trial, but rely on well-characterized relationships between those structural and pathophysiologic elements of OA and the clinical outcomes of OA. A recent advance is data showing that semiquantitative knee joint features, including cartilage thickness and surface area, meniscal morphology, and bone marrow lesions, were associated with clinically relevant OA progression and could be potentially useful as measures of efficacy in clinical trials of disease-modifying interventions.5 Being able to describe the clinical benefit to be expected from such changes is essential to use these outcomes in the benefit-risk assessment. How to include structural outcomes in OA trials will depend on the level of information available to characterize clinical benefit. With less information, structural outcomes may still be useful as adjunct or secondary endpoints. To be used as the primary endpoint to support approval, a high level of characterization would be needed about the relationship of the endpoint to anticipated clinical benefit. The FDA recommends that sponsors proposing such a primary endpoint should engage with the agency early in the development program.

Another option discussed was to study an accelerated OA population, that is, subjects (prior to joint replacement) with a history of trauma to a joint and other injuries predictive of early OA. In that setting, the study duration needed to demonstrate the relationship of structural and clinical outcomes may be more feasible.

A third option discussed was an end-stage OA trial that could enroll subjects who meet criteria for joint replacement. Such a study could possibly have outcomes that include delay in time to surgery, reduction in need for surgery, and clinical outcomes, such as need for concomitant analgesics, patient pain, and patient function. In any OA population, demonstrating a treatment’s effectiveness on clinical outcomes could be the sole basis for approval, in the context of an acceptable safety profile.

Dr. Niskar is national scientific director of the Arthritis Foundation. Dr. Yim is supervisory associate director of the division of pulmonary, allergy, and rheumatology products in the Office of New Drugs at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Dr. Kraus is professor of medicine, pathology, and orthopedic surgery at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and is a faculty member of the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute. Dr. Tuan is director of the Center for Cellular and Molecular Engineering and Distinguished Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Niskar reports that the Arthritis Foundation received a donation from Samumed and a cosponsorship grant from the FDA to implement the Accelerating OA Clinical Trials Workshop. Dr. Kraus reports an Arthritis Foundation Delivering on Discovery Award that is outside of this editorial. Dr. Yim and Dr. Tuan disclosed no conflicts. Dr. Yim is relaying her personal views in this editorial, and they are not intended to convey official FDA policy, and no official support or endorsement by the FDA is provided or should be inferred. Samumed did not have a role in the writing of this editorial.

References

1. Bioworld. 2016;27:1-4.

2. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015 May;23[5]:677-85.

3. Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative. PG engagement across the research & development continuum. 2015.

4. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:336ps11.

5. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Oct;68[10]:2422-31.

Advances in our understanding of the development and treatment of osteoarthritis have led to renewed interest in leveraging these insights to establish more ways to evaluate potential drug candidates in clinical trials, particularly through the use of qualified biomarkers as meaningful outcome measures.

It is with this goal in mind that the Arthritis Foundation and the Food and Drug Administration held the Accelerating Osteoarthritis Clinical Trials Workshop in Atlanta in February 2016,1 to discuss ways of enhancing the likelihood of successful OA trials, including possible “qualification” of biomarkers that can be used as endpoints in trials of OA treatments. Clinical trial endpoints would ideally be known to be clinically meaningful to the patient (such as pain, fatigue, functional status, etc.)2 and would reflect treatments that enable patients to feel and function better.

Patient engagement in different steps of the development process might be possible through patient registries, social media communities, smart phones, and wearable devices to be used as tools for capturing patient perceptions and mobility. These means for capturing dynamic data about domains of high interest to OA patients may lead to the development of better outcome measures that can be used as clinical trial endpoints.4 Researchers at the workshop presented new ways in which they are beginning to specialize in these techniques and methods that will be useful for turning the patient experience into usable data to aid in precision medicine.

Imaging outcomes and biomarkers are attractive for their potential to demonstrate an effect on the structural and pathophysiologic elements of OA in the time frame of a clinical trial, but rely on well-characterized relationships between those structural and pathophysiologic elements of OA and the clinical outcomes of OA. A recent advance is data showing that semiquantitative knee joint features, including cartilage thickness and surface area, meniscal morphology, and bone marrow lesions, were associated with clinically relevant OA progression and could be potentially useful as measures of efficacy in clinical trials of disease-modifying interventions.5 Being able to describe the clinical benefit to be expected from such changes is essential to use these outcomes in the benefit-risk assessment. How to include structural outcomes in OA trials will depend on the level of information available to characterize clinical benefit. With less information, structural outcomes may still be useful as adjunct or secondary endpoints. To be used as the primary endpoint to support approval, a high level of characterization would be needed about the relationship of the endpoint to anticipated clinical benefit. The FDA recommends that sponsors proposing such a primary endpoint should engage with the agency early in the development program.

Another option discussed was to study an accelerated OA population, that is, subjects (prior to joint replacement) with a history of trauma to a joint and other injuries predictive of early OA. In that setting, the study duration needed to demonstrate the relationship of structural and clinical outcomes may be more feasible.

A third option discussed was an end-stage OA trial that could enroll subjects who meet criteria for joint replacement. Such a study could possibly have outcomes that include delay in time to surgery, reduction in need for surgery, and clinical outcomes, such as need for concomitant analgesics, patient pain, and patient function. In any OA population, demonstrating a treatment’s effectiveness on clinical outcomes could be the sole basis for approval, in the context of an acceptable safety profile.

Dr. Niskar is national scientific director of the Arthritis Foundation. Dr. Yim is supervisory associate director of the division of pulmonary, allergy, and rheumatology products in the Office of New Drugs at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Dr. Kraus is professor of medicine, pathology, and orthopedic surgery at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and is a faculty member of the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute. Dr. Tuan is director of the Center for Cellular and Molecular Engineering and Distinguished Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Niskar reports that the Arthritis Foundation received a donation from Samumed and a cosponsorship grant from the FDA to implement the Accelerating OA Clinical Trials Workshop. Dr. Kraus reports an Arthritis Foundation Delivering on Discovery Award that is outside of this editorial. Dr. Yim and Dr. Tuan disclosed no conflicts. Dr. Yim is relaying her personal views in this editorial, and they are not intended to convey official FDA policy, and no official support or endorsement by the FDA is provided or should be inferred. Samumed did not have a role in the writing of this editorial.

References

1. Bioworld. 2016;27:1-4.

2. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015 May;23[5]:677-85.

3. Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative. PG engagement across the research & development continuum. 2015.

4. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:336ps11.

5. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Oct;68[10]:2422-31.

The Death of a Dream: Closing an NP Practice

For many nurse practitioners, having your own practice is the culmination of many years of planning and anticipation. I worked as an NP for 14 years in practices operated by others—hospitals and physicians—before I opened my own practice. During those years, I had observed which ways of doing things appeared productive and healing to me and which did not.

When the time came, having seen a need for more affordable health care that was not predicated on the assumption that every patient had health insurance, I opened a cash-only practice in the town where I resided. By eliminating the need for personnel and apparatus dedicated to insurance filing, I was able to charge about half of what other practices in the same location did for identical services. My chief goal was to be of service to the community, not to make the most money possible. I anticipated that volume would make up for the lower prices in the long run.

For about four years, our revenue grew slowly. I decided to risk all and stop teaching part-time in order to focus exclusively on my practice. This proved to be a good decision—for about one year. Then the recession hit my part of the country. Suddenly, the operation of a “cash-only” practice became an oxymoron, as many of the patients with already limited funds lost their jobs. These patients started to seek “free” care at area emergency departments, and the practice income plummeted. My revenue fell by one-half the first year and then one-half of that the next year.

In what would turn out to be my final year of practice ownership, I decided to accept a full-time position as faculty of a distance FNP program. I was practicing “on the side,” although in reality I was in my office full-time and teaching from there. I was already recognizing the difficulties of juggling my roles and responsibilities when a student in one of my classes asked what it would take for me to decide to close my practice, since I was (by this point) making no money from it.

As I pondered that question (my initial response was a quite honest “I don’t know”), I stepped onto the road toward closing my practice. From a business perspective, there was little point in keeping the practice open. However, from an emotional point of view, I had invested so much in building my dream—and, by extension, so had my family—that closing the practice seemed unthinkable.

THE DECISION

Opening a practice is a time of joy, pride, and a sense of accomplishment; closing that same practice induces a period of reflection, sadness, and even anger that circumstances did not allow continued operation. While financial considerations play a significant role in the decision to close a practice, they may not be the only, or the deciding, factor.

In my case, the financial shortfall of the practice led me to accept a teaching position in order to earn living expenses. The result of that decision was that my attention became divided: Sometimes I was in meetings or interacting with students—and for a few weeks per year, I was out of town—which meant less time devoted to seeing patients. Conversely, if I was with a patient, I of course could not be available to my students. Over time, I started to feel that I was not giving my all to either role as I shifted back and forth. Having given 100% to each of these roles at previous points in my career, I now felt that I was cheating my patients and my students.

The decision to close a practice may take months or even years before the actual process is started. I lived with my conundrum for about a year before I made the decision to close. I was exhausted—and while I was relieved to have the burden of deciding off my shoulders, it was now time to do the work of closing a practice.

NOTIFYING YOUR STAKEHOLDERS

Once the decision to close a practice is reached, the provider/owner ceases to exist in a vacuum. There are stakeholders who need to be notified—some obvious, some less so.

I started by breaking the news to my family, the people who had supported me in opening my practice (and even helped me find and refurbish furniture for my waiting room!). Although they had been aware of my internal debate, they had not lived with the decision process as I had. Having resolved at least some of my own emotions, I now had to watch others experience many of those same feelings.

Next, I had to tell my employees of the decision. Through attrition, my staff had already shrunk to two: a receptionist and a part-time licensed vocational nurse (LVN). Like my family, they had to process their own emotions about the closure. I had anticipated that the people who worked for me, concerned about their future, might choose to accept another job before we officially closed. My LVN—who had observed the practice dwindling in the preceding two years—seemed prepared for my decision. She stuck it out with me until the end and was a huge help with the influx of patients requesting records. (My MD—required by Texas law to delegate prescriptive authority to me—had already relocated his practice and was ill, so he was content with my decision.)

Of course, the biggest stakeholders in a practice are the patients. Notifying them of the impending closure is the most important action you will take (aside from making the decision to close). Although you can place notices in the local media (newspapers, TV, radio) to announce the closure of your practice to the community, you should send a notification letter directly to your patients. It should be sent at least 60 to 90 days before the closure date—and certainly not less than 30 days in any case—giving patients adequate time to find new providers and arrange for their records to be transferred.1,2 The letter should include

- A statement of gratitude for the patient’s business

- The dates of the transition period

- What is expected of the patient (eg, does he/she need to come and pick up his/her records?)

- An explanation for the closure3

I composed a letter to be sent to all patients who had been seen within the past 18 months. In it, I thanked them for being a part of the practice and gave them 60 days’ notice of the intent to close. For many patients, this was an emotional time; many understandably worried how their health care needs would be met in the future. Some responded with sadness that I had not been able to make the practice a success.

AVOIDING “ABANDONMENT”

Ideally, a provider who wants to get out of the business should seek to sell the practice—but this is not always feasible.3,4 When closure is the best (or only) option, it is important to avoid even the appearance of abandonment.

Besides giving adequate notice of practice closure, providers must have a plan for the dispersal of patients.1 Be prepared to give recommendations for new providers. Depending on the practice location (rural or urban), options may vary.

I made a concerted effort to refer patients to new providers, with the caveat that if the patient did not feel a particular provider was a good match, he/she should seek another provider of his/her choosing. Unlike in a purchased practice, where patients “go with” the practice, patients from a closed practice may be referred to one, several, or even many other providers.5

Provisions must be made to store patient records so that they are retrievable for a specified period of time. The requirements vary by state, so consultation of the state board’s rules and regulations—and/or an attorney—is in order.3 In general, the proscribed time period is seven to 10 years for adults and seven to 10 years after the patient turns 18 for pediatric patients.2 In some states, the retention time may be as short as three years for adults.1

OTHER PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

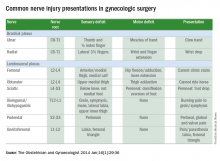

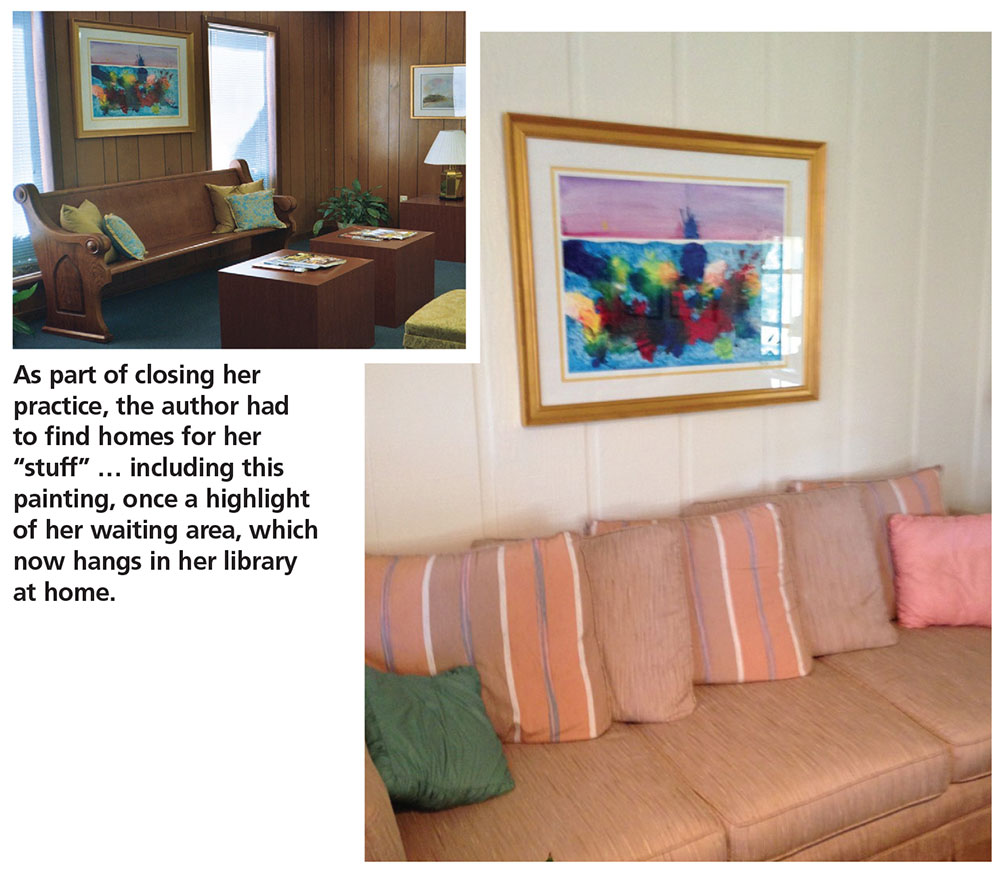

While people will be your priority as you work through the process of closing, you will have “stuff” to deal with. What will you do with the furnishings and equipment? Obviously, anything that was borrowed can be returned. Beyond that, your options are to sell (to another provider or even a patient), donate, or repurpose items.

The orthopedic exam table from my practice went to a private school for their athletic training facility. Screens went to my neighbor, a chiropractor. My preschool-aged grandsons were thrilled to be given the children’s art supplies and books that had once graced my waiting area. One of my patients bought some decorative vases and a bookcase. The painting that had been carefully chosen to pull together my waiting room now hangs in my library at home.

As the closure date approaches, the practice environment may begin to look bare as furnishings are sold or moved. One item you will want to buy, however, is a fresh ink cartridge for your copier/printer. As patients request documents, you’ll use it!

RESPONSE AND AFTERMATH

The practice may be very busy immediately following the receipt of notification letters—but don’t be fooled into thinking you have made the wrong decision. The first month after the letters went out advising of the closure, my practice was busier than it had ever been! This tapered off in the second month, though.

Most patients, once they’ve heard the news, will want prescription refills and/or their records. Some may just want to know what happened to result in the closure. Remember that to the patient, this seems like a sudden decision—no matter how long you have deliberated about it.

What surprised me most, however, was that new patients continued to present to the practice, seeking care for acute issues. While I did provide this, I made them aware from the beginning that the practice was in the process of closing and that I could not assume the responsibility of being their primary provider. I made sure to provide these patients with recommendations for other providers.

Slowly the rush will settle down, as patients start to move on to other providers. A few may drop in to see you socially. On the day I closed my practice, several patients came in just to say goodbye and wish me well.

The last things I did in my practice were turn off the lights and leave a sign on the door stating that the practice was now closed.

RECOVERY

The time needed to recover from the closure of a practice will differ. Factors include how long the practice was open and how the clinician normally deals with a setback.6 For some, relief that the pressures of ownership are over may be the predominant emotion. Having a steady, stable salary in a new position goes a long way toward making the transition easier! Although if possible, take some time between closing the practice and starting a new job.

Do not be surprised if negative emotions manifest at odd times, as feelings of sadness, regret, and even a sense of failure are worked through. Life does go on—and nurse practitioners are resilient. Find a way to use the knowledge gained from your practice in your new endeavors, whatever they may be.

For me, the healing process would have started sooner if I had acknowledged how difficult giving up the dream of having my own practice was. If I had sought out others with similar experience or even talked with a counselor, my journey through this process could have been expedited. When I started to share my story, one frequently asked question was “How did you get through this?” This showed me that others could learn from my experience.

1. Tatooles JJ, Brunell A. What you need to know before leaving a medical practice: a primer for moving on. AAOS NOW. 2015;22-23.

2. Kern SI. Take these steps if selling or closing a practice. Med Econ. 2010;87(20):66.

3. Weiss GG. How to close a practice. Med Econ. 2004;81:69.

4. Zaumeyer C. How to Start an Independent Practice: The Nurse Practitioner’s Guide to Success. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, Publishers; 2003.

5. Barrett W. The legal corner: Eleven essential steps to purchasing or selling a medical practice. J Med Pract Manage. 2014;29(5):275-277.

6. McBride JL. Personal issues to consider before leaving independent practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20(4):9-12.

For many nurse practitioners, having your own practice is the culmination of many years of planning and anticipation. I worked as an NP for 14 years in practices operated by others—hospitals and physicians—before I opened my own practice. During those years, I had observed which ways of doing things appeared productive and healing to me and which did not.

When the time came, having seen a need for more affordable health care that was not predicated on the assumption that every patient had health insurance, I opened a cash-only practice in the town where I resided. By eliminating the need for personnel and apparatus dedicated to insurance filing, I was able to charge about half of what other practices in the same location did for identical services. My chief goal was to be of service to the community, not to make the most money possible. I anticipated that volume would make up for the lower prices in the long run.

For about four years, our revenue grew slowly. I decided to risk all and stop teaching part-time in order to focus exclusively on my practice. This proved to be a good decision—for about one year. Then the recession hit my part of the country. Suddenly, the operation of a “cash-only” practice became an oxymoron, as many of the patients with already limited funds lost their jobs. These patients started to seek “free” care at area emergency departments, and the practice income plummeted. My revenue fell by one-half the first year and then one-half of that the next year.

In what would turn out to be my final year of practice ownership, I decided to accept a full-time position as faculty of a distance FNP program. I was practicing “on the side,” although in reality I was in my office full-time and teaching from there. I was already recognizing the difficulties of juggling my roles and responsibilities when a student in one of my classes asked what it would take for me to decide to close my practice, since I was (by this point) making no money from it.

As I pondered that question (my initial response was a quite honest “I don’t know”), I stepped onto the road toward closing my practice. From a business perspective, there was little point in keeping the practice open. However, from an emotional point of view, I had invested so much in building my dream—and, by extension, so had my family—that closing the practice seemed unthinkable.

THE DECISION

Opening a practice is a time of joy, pride, and a sense of accomplishment; closing that same practice induces a period of reflection, sadness, and even anger that circumstances did not allow continued operation. While financial considerations play a significant role in the decision to close a practice, they may not be the only, or the deciding, factor.

In my case, the financial shortfall of the practice led me to accept a teaching position in order to earn living expenses. The result of that decision was that my attention became divided: Sometimes I was in meetings or interacting with students—and for a few weeks per year, I was out of town—which meant less time devoted to seeing patients. Conversely, if I was with a patient, I of course could not be available to my students. Over time, I started to feel that I was not giving my all to either role as I shifted back and forth. Having given 100% to each of these roles at previous points in my career, I now felt that I was cheating my patients and my students.

The decision to close a practice may take months or even years before the actual process is started. I lived with my conundrum for about a year before I made the decision to close. I was exhausted—and while I was relieved to have the burden of deciding off my shoulders, it was now time to do the work of closing a practice.

NOTIFYING YOUR STAKEHOLDERS

Once the decision to close a practice is reached, the provider/owner ceases to exist in a vacuum. There are stakeholders who need to be notified—some obvious, some less so.

I started by breaking the news to my family, the people who had supported me in opening my practice (and even helped me find and refurbish furniture for my waiting room!). Although they had been aware of my internal debate, they had not lived with the decision process as I had. Having resolved at least some of my own emotions, I now had to watch others experience many of those same feelings.

Next, I had to tell my employees of the decision. Through attrition, my staff had already shrunk to two: a receptionist and a part-time licensed vocational nurse (LVN). Like my family, they had to process their own emotions about the closure. I had anticipated that the people who worked for me, concerned about their future, might choose to accept another job before we officially closed. My LVN—who had observed the practice dwindling in the preceding two years—seemed prepared for my decision. She stuck it out with me until the end and was a huge help with the influx of patients requesting records. (My MD—required by Texas law to delegate prescriptive authority to me—had already relocated his practice and was ill, so he was content with my decision.)

Of course, the biggest stakeholders in a practice are the patients. Notifying them of the impending closure is the most important action you will take (aside from making the decision to close). Although you can place notices in the local media (newspapers, TV, radio) to announce the closure of your practice to the community, you should send a notification letter directly to your patients. It should be sent at least 60 to 90 days before the closure date—and certainly not less than 30 days in any case—giving patients adequate time to find new providers and arrange for their records to be transferred.1,2 The letter should include

- A statement of gratitude for the patient’s business

- The dates of the transition period

- What is expected of the patient (eg, does he/she need to come and pick up his/her records?)

- An explanation for the closure3

I composed a letter to be sent to all patients who had been seen within the past 18 months. In it, I thanked them for being a part of the practice and gave them 60 days’ notice of the intent to close. For many patients, this was an emotional time; many understandably worried how their health care needs would be met in the future. Some responded with sadness that I had not been able to make the practice a success.

AVOIDING “ABANDONMENT”

Ideally, a provider who wants to get out of the business should seek to sell the practice—but this is not always feasible.3,4 When closure is the best (or only) option, it is important to avoid even the appearance of abandonment.

Besides giving adequate notice of practice closure, providers must have a plan for the dispersal of patients.1 Be prepared to give recommendations for new providers. Depending on the practice location (rural or urban), options may vary.

I made a concerted effort to refer patients to new providers, with the caveat that if the patient did not feel a particular provider was a good match, he/she should seek another provider of his/her choosing. Unlike in a purchased practice, where patients “go with” the practice, patients from a closed practice may be referred to one, several, or even many other providers.5

Provisions must be made to store patient records so that they are retrievable for a specified period of time. The requirements vary by state, so consultation of the state board’s rules and regulations—and/or an attorney—is in order.3 In general, the proscribed time period is seven to 10 years for adults and seven to 10 years after the patient turns 18 for pediatric patients.2 In some states, the retention time may be as short as three years for adults.1

OTHER PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

While people will be your priority as you work through the process of closing, you will have “stuff” to deal with. What will you do with the furnishings and equipment? Obviously, anything that was borrowed can be returned. Beyond that, your options are to sell (to another provider or even a patient), donate, or repurpose items.

The orthopedic exam table from my practice went to a private school for their athletic training facility. Screens went to my neighbor, a chiropractor. My preschool-aged grandsons were thrilled to be given the children’s art supplies and books that had once graced my waiting area. One of my patients bought some decorative vases and a bookcase. The painting that had been carefully chosen to pull together my waiting room now hangs in my library at home.

As the closure date approaches, the practice environment may begin to look bare as furnishings are sold or moved. One item you will want to buy, however, is a fresh ink cartridge for your copier/printer. As patients request documents, you’ll use it!

RESPONSE AND AFTERMATH

The practice may be very busy immediately following the receipt of notification letters—but don’t be fooled into thinking you have made the wrong decision. The first month after the letters went out advising of the closure, my practice was busier than it had ever been! This tapered off in the second month, though.

Most patients, once they’ve heard the news, will want prescription refills and/or their records. Some may just want to know what happened to result in the closure. Remember that to the patient, this seems like a sudden decision—no matter how long you have deliberated about it.

What surprised me most, however, was that new patients continued to present to the practice, seeking care for acute issues. While I did provide this, I made them aware from the beginning that the practice was in the process of closing and that I could not assume the responsibility of being their primary provider. I made sure to provide these patients with recommendations for other providers.

Slowly the rush will settle down, as patients start to move on to other providers. A few may drop in to see you socially. On the day I closed my practice, several patients came in just to say goodbye and wish me well.

The last things I did in my practice were turn off the lights and leave a sign on the door stating that the practice was now closed.

RECOVERY

The time needed to recover from the closure of a practice will differ. Factors include how long the practice was open and how the clinician normally deals with a setback.6 For some, relief that the pressures of ownership are over may be the predominant emotion. Having a steady, stable salary in a new position goes a long way toward making the transition easier! Although if possible, take some time between closing the practice and starting a new job.

Do not be surprised if negative emotions manifest at odd times, as feelings of sadness, regret, and even a sense of failure are worked through. Life does go on—and nurse practitioners are resilient. Find a way to use the knowledge gained from your practice in your new endeavors, whatever they may be.

For me, the healing process would have started sooner if I had acknowledged how difficult giving up the dream of having my own practice was. If I had sought out others with similar experience or even talked with a counselor, my journey through this process could have been expedited. When I started to share my story, one frequently asked question was “How did you get through this?” This showed me that others could learn from my experience.

For many nurse practitioners, having your own practice is the culmination of many years of planning and anticipation. I worked as an NP for 14 years in practices operated by others—hospitals and physicians—before I opened my own practice. During those years, I had observed which ways of doing things appeared productive and healing to me and which did not.

When the time came, having seen a need for more affordable health care that was not predicated on the assumption that every patient had health insurance, I opened a cash-only practice in the town where I resided. By eliminating the need for personnel and apparatus dedicated to insurance filing, I was able to charge about half of what other practices in the same location did for identical services. My chief goal was to be of service to the community, not to make the most money possible. I anticipated that volume would make up for the lower prices in the long run.

For about four years, our revenue grew slowly. I decided to risk all and stop teaching part-time in order to focus exclusively on my practice. This proved to be a good decision—for about one year. Then the recession hit my part of the country. Suddenly, the operation of a “cash-only” practice became an oxymoron, as many of the patients with already limited funds lost their jobs. These patients started to seek “free” care at area emergency departments, and the practice income plummeted. My revenue fell by one-half the first year and then one-half of that the next year.

In what would turn out to be my final year of practice ownership, I decided to accept a full-time position as faculty of a distance FNP program. I was practicing “on the side,” although in reality I was in my office full-time and teaching from there. I was already recognizing the difficulties of juggling my roles and responsibilities when a student in one of my classes asked what it would take for me to decide to close my practice, since I was (by this point) making no money from it.

As I pondered that question (my initial response was a quite honest “I don’t know”), I stepped onto the road toward closing my practice. From a business perspective, there was little point in keeping the practice open. However, from an emotional point of view, I had invested so much in building my dream—and, by extension, so had my family—that closing the practice seemed unthinkable.

THE DECISION

Opening a practice is a time of joy, pride, and a sense of accomplishment; closing that same practice induces a period of reflection, sadness, and even anger that circumstances did not allow continued operation. While financial considerations play a significant role in the decision to close a practice, they may not be the only, or the deciding, factor.

In my case, the financial shortfall of the practice led me to accept a teaching position in order to earn living expenses. The result of that decision was that my attention became divided: Sometimes I was in meetings or interacting with students—and for a few weeks per year, I was out of town—which meant less time devoted to seeing patients. Conversely, if I was with a patient, I of course could not be available to my students. Over time, I started to feel that I was not giving my all to either role as I shifted back and forth. Having given 100% to each of these roles at previous points in my career, I now felt that I was cheating my patients and my students.

The decision to close a practice may take months or even years before the actual process is started. I lived with my conundrum for about a year before I made the decision to close. I was exhausted—and while I was relieved to have the burden of deciding off my shoulders, it was now time to do the work of closing a practice.

NOTIFYING YOUR STAKEHOLDERS

Once the decision to close a practice is reached, the provider/owner ceases to exist in a vacuum. There are stakeholders who need to be notified—some obvious, some less so.

I started by breaking the news to my family, the people who had supported me in opening my practice (and even helped me find and refurbish furniture for my waiting room!). Although they had been aware of my internal debate, they had not lived with the decision process as I had. Having resolved at least some of my own emotions, I now had to watch others experience many of those same feelings.

Next, I had to tell my employees of the decision. Through attrition, my staff had already shrunk to two: a receptionist and a part-time licensed vocational nurse (LVN). Like my family, they had to process their own emotions about the closure. I had anticipated that the people who worked for me, concerned about their future, might choose to accept another job before we officially closed. My LVN—who had observed the practice dwindling in the preceding two years—seemed prepared for my decision. She stuck it out with me until the end and was a huge help with the influx of patients requesting records. (My MD—required by Texas law to delegate prescriptive authority to me—had already relocated his practice and was ill, so he was content with my decision.)

Of course, the biggest stakeholders in a practice are the patients. Notifying them of the impending closure is the most important action you will take (aside from making the decision to close). Although you can place notices in the local media (newspapers, TV, radio) to announce the closure of your practice to the community, you should send a notification letter directly to your patients. It should be sent at least 60 to 90 days before the closure date—and certainly not less than 30 days in any case—giving patients adequate time to find new providers and arrange for their records to be transferred.1,2 The letter should include

- A statement of gratitude for the patient’s business

- The dates of the transition period

- What is expected of the patient (eg, does he/she need to come and pick up his/her records?)

- An explanation for the closure3

I composed a letter to be sent to all patients who had been seen within the past 18 months. In it, I thanked them for being a part of the practice and gave them 60 days’ notice of the intent to close. For many patients, this was an emotional time; many understandably worried how their health care needs would be met in the future. Some responded with sadness that I had not been able to make the practice a success.

AVOIDING “ABANDONMENT”

Ideally, a provider who wants to get out of the business should seek to sell the practice—but this is not always feasible.3,4 When closure is the best (or only) option, it is important to avoid even the appearance of abandonment.

Besides giving adequate notice of practice closure, providers must have a plan for the dispersal of patients.1 Be prepared to give recommendations for new providers. Depending on the practice location (rural or urban), options may vary.

I made a concerted effort to refer patients to new providers, with the caveat that if the patient did not feel a particular provider was a good match, he/she should seek another provider of his/her choosing. Unlike in a purchased practice, where patients “go with” the practice, patients from a closed practice may be referred to one, several, or even many other providers.5

Provisions must be made to store patient records so that they are retrievable for a specified period of time. The requirements vary by state, so consultation of the state board’s rules and regulations—and/or an attorney—is in order.3 In general, the proscribed time period is seven to 10 years for adults and seven to 10 years after the patient turns 18 for pediatric patients.2 In some states, the retention time may be as short as three years for adults.1

OTHER PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

While people will be your priority as you work through the process of closing, you will have “stuff” to deal with. What will you do with the furnishings and equipment? Obviously, anything that was borrowed can be returned. Beyond that, your options are to sell (to another provider or even a patient), donate, or repurpose items.

The orthopedic exam table from my practice went to a private school for their athletic training facility. Screens went to my neighbor, a chiropractor. My preschool-aged grandsons were thrilled to be given the children’s art supplies and books that had once graced my waiting area. One of my patients bought some decorative vases and a bookcase. The painting that had been carefully chosen to pull together my waiting room now hangs in my library at home.

As the closure date approaches, the practice environment may begin to look bare as furnishings are sold or moved. One item you will want to buy, however, is a fresh ink cartridge for your copier/printer. As patients request documents, you’ll use it!

RESPONSE AND AFTERMATH

The practice may be very busy immediately following the receipt of notification letters—but don’t be fooled into thinking you have made the wrong decision. The first month after the letters went out advising of the closure, my practice was busier than it had ever been! This tapered off in the second month, though.

Most patients, once they’ve heard the news, will want prescription refills and/or their records. Some may just want to know what happened to result in the closure. Remember that to the patient, this seems like a sudden decision—no matter how long you have deliberated about it.

What surprised me most, however, was that new patients continued to present to the practice, seeking care for acute issues. While I did provide this, I made them aware from the beginning that the practice was in the process of closing and that I could not assume the responsibility of being their primary provider. I made sure to provide these patients with recommendations for other providers.

Slowly the rush will settle down, as patients start to move on to other providers. A few may drop in to see you socially. On the day I closed my practice, several patients came in just to say goodbye and wish me well.

The last things I did in my practice were turn off the lights and leave a sign on the door stating that the practice was now closed.

RECOVERY

The time needed to recover from the closure of a practice will differ. Factors include how long the practice was open and how the clinician normally deals with a setback.6 For some, relief that the pressures of ownership are over may be the predominant emotion. Having a steady, stable salary in a new position goes a long way toward making the transition easier! Although if possible, take some time between closing the practice and starting a new job.

Do not be surprised if negative emotions manifest at odd times, as feelings of sadness, regret, and even a sense of failure are worked through. Life does go on—and nurse practitioners are resilient. Find a way to use the knowledge gained from your practice in your new endeavors, whatever they may be.

For me, the healing process would have started sooner if I had acknowledged how difficult giving up the dream of having my own practice was. If I had sought out others with similar experience or even talked with a counselor, my journey through this process could have been expedited. When I started to share my story, one frequently asked question was “How did you get through this?” This showed me that others could learn from my experience.

1. Tatooles JJ, Brunell A. What you need to know before leaving a medical practice: a primer for moving on. AAOS NOW. 2015;22-23.

2. Kern SI. Take these steps if selling or closing a practice. Med Econ. 2010;87(20):66.

3. Weiss GG. How to close a practice. Med Econ. 2004;81:69.

4. Zaumeyer C. How to Start an Independent Practice: The Nurse Practitioner’s Guide to Success. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, Publishers; 2003.

5. Barrett W. The legal corner: Eleven essential steps to purchasing or selling a medical practice. J Med Pract Manage. 2014;29(5):275-277.

6. McBride JL. Personal issues to consider before leaving independent practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20(4):9-12.

1. Tatooles JJ, Brunell A. What you need to know before leaving a medical practice: a primer for moving on. AAOS NOW. 2015;22-23.

2. Kern SI. Take these steps if selling or closing a practice. Med Econ. 2010;87(20):66.

3. Weiss GG. How to close a practice. Med Econ. 2004;81:69.

4. Zaumeyer C. How to Start an Independent Practice: The Nurse Practitioner’s Guide to Success. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, Publishers; 2003.

5. Barrett W. The legal corner: Eleven essential steps to purchasing or selling a medical practice. J Med Pract Manage. 2014;29(5):275-277.

6. McBride JL. Personal issues to consider before leaving independent practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20(4):9-12.

The war on pain

When your peer group is dominated by folks in their early 70s, conversations at dinner parties and lobster bakes invariably morph into storytelling competitions between the survivors of recent hospitalizations and medical procedures. I try to redirect this tedious and repetitive chatter with a topic from my standard collection of conversation re-starters that includes “How about those Red Sox?” and “How’s your granddaughter’s soccer season going?” But sadly I am not always successful.

Often embedded in these tales of medical misadventure are stories of unfortunate experiences with pain medications. Sometimes the story includes a description of how prescribed pain medication created symptoms that were far worse than the pain it was intended to treat. Vomiting, constipation, and “feeling goofy” are high on the list of complaints.

These caches of unused opioids, many of which were never needed in the first place, are evidence of why our health care has become so expensive, and also represent the seeds from which the addiction epidemic has grown. Ironically, they also are collateral damage from an unsuccessful and sometimes misguided war on pain.

It isn’t clear exactly when or where the war on pain began, but I’m sure those who fired the first shots were understandably concerned that many patients with incurable and terminal conditions were suffering needlessly because their pain was being under-treated. Coincidently came the realization that the sooner we could get postoperative patients on their feet and taking deep breaths, the fewer complications we would see. And the more adequately we treated their pain, the sooner we could get those patients moving and breathing optimally.

In a good faith effort to be more “scientific” about pain management, patients were asked to rate their pain and smiley face charts appeared. Unfortunately, somewhere along the line came the mantra that not only should no patient’s pain go unmeasured, but no patient’s pain should go unmedicated.

The federal government entered the war when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued the directive that hospitals ask patients who were being discharged if their pain had been well controlled and how often did the hospital staff do what they could to ease their pain? The answers to these questions, along with others, was collected and used in assessing a hospital’s quality of care and determining its level of reimbursement.

So far, there is insufficient data to determine how frequently this directive on pain management induced hospitals to over-prescribe medication, but it certainly hasn’t been associated with a decline in opioid abuse. It is reasonable to suspect that this salvo by the government has resulted in some collateral damage as it encouraged a steady flow of unused and unnecessary prescription narcotics out of the hospital and on to the streets.

The good news is that there has been enough concern voiced about the unintended effect of these pain management questions that the CMS has decided to eliminate financial pressure clinicians might feel to over-prescribe medications by withdrawing the questions from the patient discharge questionnaire.

The bad news is that we continue to fight the war on pain with a limited arsenal. As long as clinicians simply believe that no pain should go unmedicated, they will continue to miss opportunities to use other modalities such as counseling, physical therapy, and education that can be effective without the risk of collateral damage. Instead of asking the patient (who may not know the answer), we should be asking ourselves if we have been doing everything we could to help the patient deal with his pain. The answer is often not written on prescription pads.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

When your peer group is dominated by folks in their early 70s, conversations at dinner parties and lobster bakes invariably morph into storytelling competitions between the survivors of recent hospitalizations and medical procedures. I try to redirect this tedious and repetitive chatter with a topic from my standard collection of conversation re-starters that includes “How about those Red Sox?” and “How’s your granddaughter’s soccer season going?” But sadly I am not always successful.

Often embedded in these tales of medical misadventure are stories of unfortunate experiences with pain medications. Sometimes the story includes a description of how prescribed pain medication created symptoms that were far worse than the pain it was intended to treat. Vomiting, constipation, and “feeling goofy” are high on the list of complaints.

These caches of unused opioids, many of which were never needed in the first place, are evidence of why our health care has become so expensive, and also represent the seeds from which the addiction epidemic has grown. Ironically, they also are collateral damage from an unsuccessful and sometimes misguided war on pain.

It isn’t clear exactly when or where the war on pain began, but I’m sure those who fired the first shots were understandably concerned that many patients with incurable and terminal conditions were suffering needlessly because their pain was being under-treated. Coincidently came the realization that the sooner we could get postoperative patients on their feet and taking deep breaths, the fewer complications we would see. And the more adequately we treated their pain, the sooner we could get those patients moving and breathing optimally.

In a good faith effort to be more “scientific” about pain management, patients were asked to rate their pain and smiley face charts appeared. Unfortunately, somewhere along the line came the mantra that not only should no patient’s pain go unmeasured, but no patient’s pain should go unmedicated.

The federal government entered the war when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued the directive that hospitals ask patients who were being discharged if their pain had been well controlled and how often did the hospital staff do what they could to ease their pain? The answers to these questions, along with others, was collected and used in assessing a hospital’s quality of care and determining its level of reimbursement.

So far, there is insufficient data to determine how frequently this directive on pain management induced hospitals to over-prescribe medication, but it certainly hasn’t been associated with a decline in opioid abuse. It is reasonable to suspect that this salvo by the government has resulted in some collateral damage as it encouraged a steady flow of unused and unnecessary prescription narcotics out of the hospital and on to the streets.

The good news is that there has been enough concern voiced about the unintended effect of these pain management questions that the CMS has decided to eliminate financial pressure clinicians might feel to over-prescribe medications by withdrawing the questions from the patient discharge questionnaire.

The bad news is that we continue to fight the war on pain with a limited arsenal. As long as clinicians simply believe that no pain should go unmedicated, they will continue to miss opportunities to use other modalities such as counseling, physical therapy, and education that can be effective without the risk of collateral damage. Instead of asking the patient (who may not know the answer), we should be asking ourselves if we have been doing everything we could to help the patient deal with his pain. The answer is often not written on prescription pads.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

When your peer group is dominated by folks in their early 70s, conversations at dinner parties and lobster bakes invariably morph into storytelling competitions between the survivors of recent hospitalizations and medical procedures. I try to redirect this tedious and repetitive chatter with a topic from my standard collection of conversation re-starters that includes “How about those Red Sox?” and “How’s your granddaughter’s soccer season going?” But sadly I am not always successful.

Often embedded in these tales of medical misadventure are stories of unfortunate experiences with pain medications. Sometimes the story includes a description of how prescribed pain medication created symptoms that were far worse than the pain it was intended to treat. Vomiting, constipation, and “feeling goofy” are high on the list of complaints.

These caches of unused opioids, many of which were never needed in the first place, are evidence of why our health care has become so expensive, and also represent the seeds from which the addiction epidemic has grown. Ironically, they also are collateral damage from an unsuccessful and sometimes misguided war on pain.

It isn’t clear exactly when or where the war on pain began, but I’m sure those who fired the first shots were understandably concerned that many patients with incurable and terminal conditions were suffering needlessly because their pain was being under-treated. Coincidently came the realization that the sooner we could get postoperative patients on their feet and taking deep breaths, the fewer complications we would see. And the more adequately we treated their pain, the sooner we could get those patients moving and breathing optimally.

In a good faith effort to be more “scientific” about pain management, patients were asked to rate their pain and smiley face charts appeared. Unfortunately, somewhere along the line came the mantra that not only should no patient’s pain go unmeasured, but no patient’s pain should go unmedicated.

The federal government entered the war when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued the directive that hospitals ask patients who were being discharged if their pain had been well controlled and how often did the hospital staff do what they could to ease their pain? The answers to these questions, along with others, was collected and used in assessing a hospital’s quality of care and determining its level of reimbursement.

So far, there is insufficient data to determine how frequently this directive on pain management induced hospitals to over-prescribe medication, but it certainly hasn’t been associated with a decline in opioid abuse. It is reasonable to suspect that this salvo by the government has resulted in some collateral damage as it encouraged a steady flow of unused and unnecessary prescription narcotics out of the hospital and on to the streets.

The good news is that there has been enough concern voiced about the unintended effect of these pain management questions that the CMS has decided to eliminate financial pressure clinicians might feel to over-prescribe medications by withdrawing the questions from the patient discharge questionnaire.

The bad news is that we continue to fight the war on pain with a limited arsenal. As long as clinicians simply believe that no pain should go unmedicated, they will continue to miss opportunities to use other modalities such as counseling, physical therapy, and education that can be effective without the risk of collateral damage. Instead of asking the patient (who may not know the answer), we should be asking ourselves if we have been doing everything we could to help the patient deal with his pain. The answer is often not written on prescription pads.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

EMTALA – statutory law

This is the first of a two-part series.

Question: Which of the following statements regarding the Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act (EMTALA) is correct?

A. Deals with the standard of care in emergency medicine.

B. Provides safeguards for uninsured and nonpaying patients with an emergency medical condition.

C. Mandates uniform screening and treatment stabilization prior to transfer, irrespective of the hospital’s capability.

D. Is mostly directed at hospitals and emergency department staff doctors, but excludes on-call physicians.

E. Violations can result in fines, loss of Medicare provider participation, or even imprisonment.

Answer: B. In 1985, the CBS investigative news show “60 Minutes” ran an exposé on abuses in the emergency departments of U.S. hospitals, featuring the case of Eugene Barnes, a 32-year-old man brought to the Brookside Hospital emergency department (ED) in San Pablo, Calif., with a penetrating stab wound.

In another case, William Jenness, injured in an auto accident, died after a delayed transfer to a county hospital, because the original hospital required a $1,000 deposit in advance before initiating treatment.

In response to the widespread perception that uninsured patients were being denied treatment in the nation’s emergency departments, Congress enacted the Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act.1

Originally referred to as the “antidumping law,” EMTALA was designed to prevent hospitals from transferring financially undesirable patients to public hospitals without providing a medical screening examination and stabilizing treatment prior to transfer.

The purpose and intent of the law is to ensure that all patients who come to the ED have access to emergency services, although the statute itself is silent on payment ability.

EMTALA is not meant to replace or override state tort law, and does not deal with quality of care issues that may arise in the emergency department. Over the 30-year period since its enactment, EMTALA has received mixed reviews, with one scholar complaining that the statute is sloppily drafted and the premise of the statute, silly at best.2

EMTALA defines an emergency medical condition as:

1. A medical condition manifesting itself by acute symptoms of sufficient severity (including severe pain, psychiatric disturbances, and/or symptoms of substance abuse) such that the absence of immediate medical attention could reasonably be expected to result in placing the health of the individual (or, with respect to a pregnant woman, the health of the woman or her unborn child) in serious jeopardy, cause serious impairment to bodily functions, or result in serious dysfunction of any bodily organ or part.

2. With respect to a pregnant woman who is having contractions, there is inadequate time to effect a safe transfer to another hospital before delivery, or that transfer may pose a threat to the health or safety of the woman or the unborn child.3