User login

A Holiday Visit to the ED (With Apologies to Clement Clarke Moore)

‘Twas the night before New Year, when all through the land

Every ED was busy—Can you give us a hand?

Treating chest pains, and traumas, and hot swollen knees,

While clinics were shuttered, along with UCs.

The handoffs were done with hardly a frown,

In hopes that the volume soon would slow down.

Babies were nestled all snug in a sheet,

Watching sutures applied to their hands and their feet.

And amateur athletes unpadded, uncapped,

Had brains that were rattled after balls had been snapped.

When out on the deck there arose such a clatter

We sprang from the doc box to help with the matter.

To Resusc room 1 we flew in a flash,

Tearing open the curtain before the patient could crash.

The leads on the breast of the now-fallen fellow,

Made lustrous white circles near sclerae bright yellow.

When what to our wondering ears did we hear,

But an overhead page that inspired some fear:

Notifications of a Level 1 trauma,

And several ODs, to add to the drama.

More rapid than eagles the new patients came,

All victims of poisons with rather strange names:

Poinsettia, and holly, and dried mistletoe,

Angel hair, leaded tinsel, polyacrylate snow.

And a man who was tarnished with ashes and soot,

With a cherry red color from his head to his foot.

Smoke inhalation and a toxic epoxide?

Or alcohol, cyanide, carbon monoxide?

But “Holiday Poisonings” on the pages ahead,

Soon reassured us we had nothing to dread…

When patients were discharged to families waiting,

They promised to give us all a good rating.

So to all EMTs, NPs, and PAs,

RNs, and EPs who work holidays,

And to all ED staffs who “fight the good fight,”

Have a Happy New Year, and a nice quiet night!

—Neal Flomenbaum, MD

‘Twas the night before New Year, when all through the land

Every ED was busy—Can you give us a hand?

Treating chest pains, and traumas, and hot swollen knees,

While clinics were shuttered, along with UCs.

The handoffs were done with hardly a frown,

In hopes that the volume soon would slow down.

Babies were nestled all snug in a sheet,

Watching sutures applied to their hands and their feet.

And amateur athletes unpadded, uncapped,

Had brains that were rattled after balls had been snapped.

When out on the deck there arose such a clatter

We sprang from the doc box to help with the matter.

To Resusc room 1 we flew in a flash,

Tearing open the curtain before the patient could crash.

The leads on the breast of the now-fallen fellow,

Made lustrous white circles near sclerae bright yellow.

When what to our wondering ears did we hear,

But an overhead page that inspired some fear:

Notifications of a Level 1 trauma,

And several ODs, to add to the drama.

More rapid than eagles the new patients came,

All victims of poisons with rather strange names:

Poinsettia, and holly, and dried mistletoe,

Angel hair, leaded tinsel, polyacrylate snow.

And a man who was tarnished with ashes and soot,

With a cherry red color from his head to his foot.

Smoke inhalation and a toxic epoxide?

Or alcohol, cyanide, carbon monoxide?

But “Holiday Poisonings” on the pages ahead,

Soon reassured us we had nothing to dread…

When patients were discharged to families waiting,

They promised to give us all a good rating.

So to all EMTs, NPs, and PAs,

RNs, and EPs who work holidays,

And to all ED staffs who “fight the good fight,”

Have a Happy New Year, and a nice quiet night!

—Neal Flomenbaum, MD

‘Twas the night before New Year, when all through the land

Every ED was busy—Can you give us a hand?

Treating chest pains, and traumas, and hot swollen knees,

While clinics were shuttered, along with UCs.

The handoffs were done with hardly a frown,

In hopes that the volume soon would slow down.

Babies were nestled all snug in a sheet,

Watching sutures applied to their hands and their feet.

And amateur athletes unpadded, uncapped,

Had brains that were rattled after balls had been snapped.

When out on the deck there arose such a clatter

We sprang from the doc box to help with the matter.

To Resusc room 1 we flew in a flash,

Tearing open the curtain before the patient could crash.

The leads on the breast of the now-fallen fellow,

Made lustrous white circles near sclerae bright yellow.

When what to our wondering ears did we hear,

But an overhead page that inspired some fear:

Notifications of a Level 1 trauma,

And several ODs, to add to the drama.

More rapid than eagles the new patients came,

All victims of poisons with rather strange names:

Poinsettia, and holly, and dried mistletoe,

Angel hair, leaded tinsel, polyacrylate snow.

And a man who was tarnished with ashes and soot,

With a cherry red color from his head to his foot.

Smoke inhalation and a toxic epoxide?

Or alcohol, cyanide, carbon monoxide?

But “Holiday Poisonings” on the pages ahead,

Soon reassured us we had nothing to dread…

When patients were discharged to families waiting,

They promised to give us all a good rating.

So to all EMTs, NPs, and PAs,

RNs, and EPs who work holidays,

And to all ED staffs who “fight the good fight,”

Have a Happy New Year, and a nice quiet night!

—Neal Flomenbaum, MD

Using the Blanch Sign to Differentiate Weathering Nodules From Auricular Tophaceous Gout

To the Editor:

We commend the recent report by Smith et al (Cutis. 2016;97:166, 175-176) that described multiple white nodules on the bilateral helical rims of the ears in a 40-year-old man, which was determined to be bilateral auricular tophaceous gout. Furthermore, we appreciate the inclusion of weathering nodules in the differential diagnosis and wish to share our experience with these lesions.

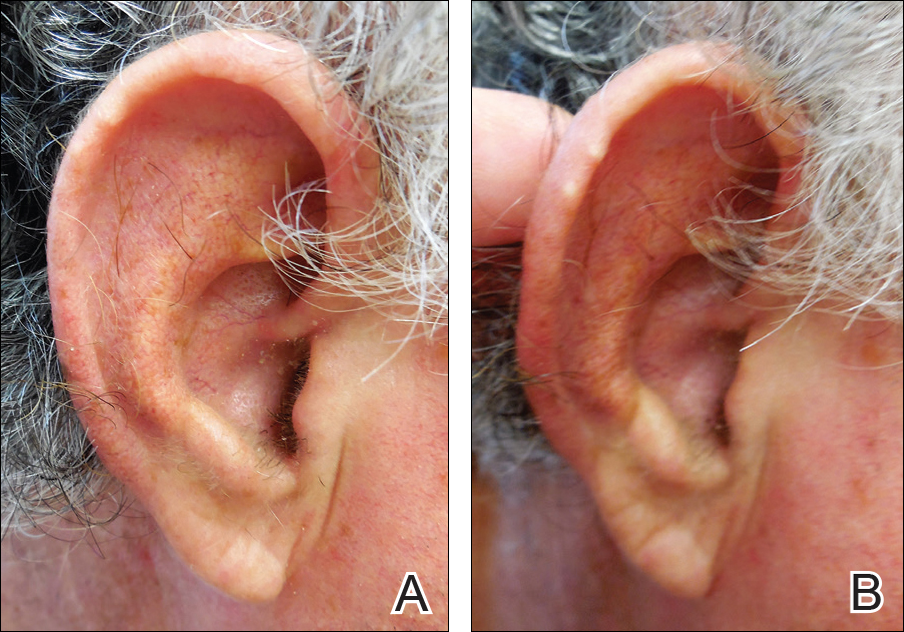

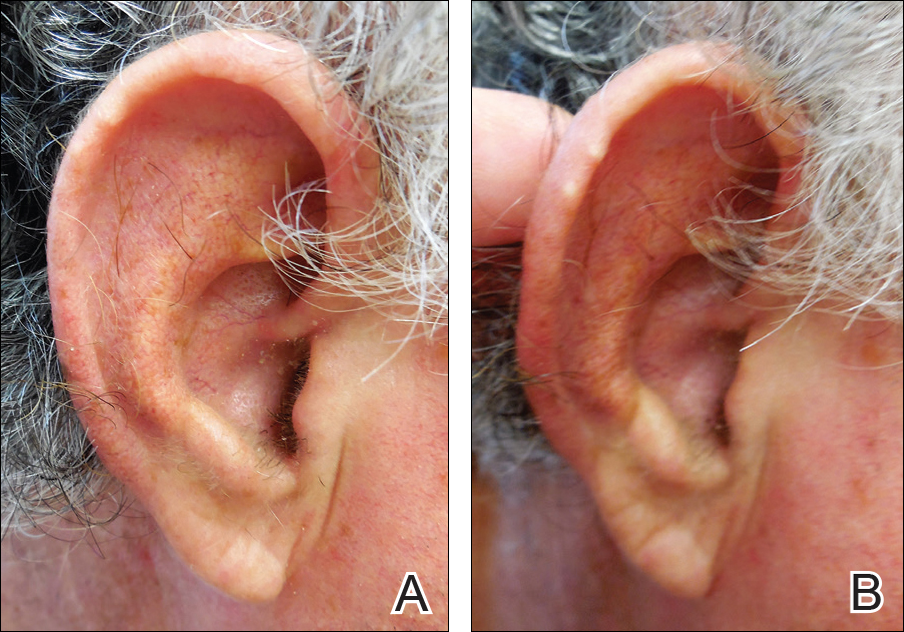

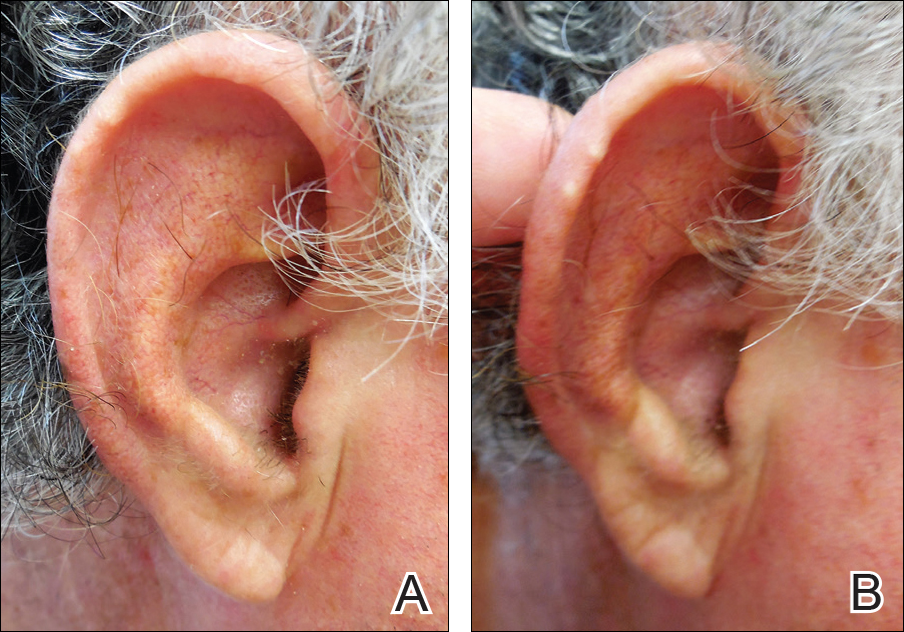

Auricular tophaceous gout and weathering nodules are clinically similar. Weathering nodules may appear as single or multiple, 2 to 3 mm in diameter and 1 to 2 mm in height, white to flesh-colored papules usually found on the helical rim of the ear (Figure 1).1 We recently described 10 patients with weathering nodules and their associated risk factors.2 We observed that the weathering nodules will blanch upon the application of pressure to the adjacent helical rim; a positive “blanch sign” may be used to differentiate weathering nodules from auricular tophaceous gout and other lesions of the ear (Figure 2). Furthermore, patients with weathering nodules typically exhibit a history of sun exposure and often have other cutaneous findings such as actinic keratoses. The pathogenesis of weathering nodules was previously thought to rely solely on actinic damage; however, we reported a pediatric case of weathering nodules that presented following radiotherapy to the ears.2

In summary, weathering nodules should be included in the differential diagnosis of auricular tophaceous gout. In addition, a positive blanch sign may be a useful clinical tool in differentiating weathering nodules from other ear lesions.

- Kavanagh GM, Bradfield JW, Collins CM, et al. Weathering nodules of the ear: a clinicopathological study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:550-554.

- Udkoff J, Cohen PR. Weathering nodules: a report of ten individuals with weathering nodules and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:433-436.

To the Editor:

We commend the recent report by Smith et al (Cutis. 2016;97:166, 175-176) that described multiple white nodules on the bilateral helical rims of the ears in a 40-year-old man, which was determined to be bilateral auricular tophaceous gout. Furthermore, we appreciate the inclusion of weathering nodules in the differential diagnosis and wish to share our experience with these lesions.

Auricular tophaceous gout and weathering nodules are clinically similar. Weathering nodules may appear as single or multiple, 2 to 3 mm in diameter and 1 to 2 mm in height, white to flesh-colored papules usually found on the helical rim of the ear (Figure 1).1 We recently described 10 patients with weathering nodules and their associated risk factors.2 We observed that the weathering nodules will blanch upon the application of pressure to the adjacent helical rim; a positive “blanch sign” may be used to differentiate weathering nodules from auricular tophaceous gout and other lesions of the ear (Figure 2). Furthermore, patients with weathering nodules typically exhibit a history of sun exposure and often have other cutaneous findings such as actinic keratoses. The pathogenesis of weathering nodules was previously thought to rely solely on actinic damage; however, we reported a pediatric case of weathering nodules that presented following radiotherapy to the ears.2

In summary, weathering nodules should be included in the differential diagnosis of auricular tophaceous gout. In addition, a positive blanch sign may be a useful clinical tool in differentiating weathering nodules from other ear lesions.

To the Editor:

We commend the recent report by Smith et al (Cutis. 2016;97:166, 175-176) that described multiple white nodules on the bilateral helical rims of the ears in a 40-year-old man, which was determined to be bilateral auricular tophaceous gout. Furthermore, we appreciate the inclusion of weathering nodules in the differential diagnosis and wish to share our experience with these lesions.

Auricular tophaceous gout and weathering nodules are clinically similar. Weathering nodules may appear as single or multiple, 2 to 3 mm in diameter and 1 to 2 mm in height, white to flesh-colored papules usually found on the helical rim of the ear (Figure 1).1 We recently described 10 patients with weathering nodules and their associated risk factors.2 We observed that the weathering nodules will blanch upon the application of pressure to the adjacent helical rim; a positive “blanch sign” may be used to differentiate weathering nodules from auricular tophaceous gout and other lesions of the ear (Figure 2). Furthermore, patients with weathering nodules typically exhibit a history of sun exposure and often have other cutaneous findings such as actinic keratoses. The pathogenesis of weathering nodules was previously thought to rely solely on actinic damage; however, we reported a pediatric case of weathering nodules that presented following radiotherapy to the ears.2

In summary, weathering nodules should be included in the differential diagnosis of auricular tophaceous gout. In addition, a positive blanch sign may be a useful clinical tool in differentiating weathering nodules from other ear lesions.

- Kavanagh GM, Bradfield JW, Collins CM, et al. Weathering nodules of the ear: a clinicopathological study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:550-554.

- Udkoff J, Cohen PR. Weathering nodules: a report of ten individuals with weathering nodules and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:433-436.

- Kavanagh GM, Bradfield JW, Collins CM, et al. Weathering nodules of the ear: a clinicopathological study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:550-554.

- Udkoff J, Cohen PR. Weathering nodules: a report of ten individuals with weathering nodules and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:433-436.

How Can We Say Thank You?

And remember: you must never, under any circumstances, despair. To hope and to act, these are our duties in misfortune.

—Boris Pasternak, Doctor Zhivago

This editorial is being written on Veterans Day. Likely you will read it when the stores and streets are lined with holiday decorations. Thanksgiving will have come and gone. All these celebrations have the common themes of giving and gratitude, and among the many requests clamoring for your attention at this season are care package collections for active-duty service members and donations for disadvantaged veterans. These efforts are well intentioned on the part of givers and appreciated on the part of those who receive them. Yet these themes remind me of the hackneyed saying we likely have all heard, and many of us have said: Thank you for your service.

Many of you may recall the controversy that emerged surrounding this seemingly innocuous cliché. It has had an Internet resurgence on this day set out to honor those who wore or are in uniform.1 For those who don’t remember the phenomenon, I will briefly summarize. A journalist was interviewing a combat veteran from Afghanistan on a different subject but knowing he had been in the military and the reporter thinking he was being kind and respectful, like so many of us, thanked him for his service. The astute journalist could tell from the expression on the veteran’s face that the comment had touched a wound he never expected to open. But he cared enough to try and understand how the veteran heard these words from out of the depths of his memories of war.

The emotions that emerged from the interview and the online blogs and comments that followed reflect the toll that war takes: anger, anguish, alienation, which these “have a nice day” words seem to evoke, even though they are never meant to create distance, dismissal, or dishonor. This interaction was a painful one for the veteran, and even for the journalist, and created what psychologists call cognitive dissonance, “a condition of conflict or anxiety resulting from inconsistency between belief and action.”2

The reason those 5 words strike a raw nerve in some—but by no means all—who were or are in the armed forces is that those to whom they are spoken know in a deep and personal way, that we who say them usually do not know what we are talking about. I can see this reaction when I watch several of my VA colleagues who actually are combat veterans say the words but from a different theory of mind, a theory of mind they share. Theory of mind is another psychological concept that is at the core of interpersonal and communication skills, the ability to see and feel the world as another person sees it. When someone who has never fought or even served says “thank you for your service,” some veterans feel that their individual experience of combat or even of being in the military is being expressed inauthentically, even perhaps insincerely.

“To these vets, thanking soldiers for their service symbolizes the ease of sending a volunteer army to wage war at great distance—physically, spiritually, economically,” journalist Matt Richtel writes. “It raises questions of the meaning of patriotism, shared purpose and, pointedly, what you’re supposed to say to those who put their lives on the line and are uncomfortable about being thanked for it.”2

My father, a World War II combat veteran and career army physician, told me when I was young that there were 3 experiences that could never be understood unless you lived them: pregnancy, medical school, and combat. I’m not sure why or how he chose these although I am sure they were not original, but having gone through the second, I believe it was because these events are of such personal intensity, such immediate contact with the human condition in all its suffering and resilience that they cannot be faithfully replicated in any in vitro simulation but only in vivo.

Which brings me to the title of the column. How can we say thank you to our friends and family members, our coworkers, and our patients who went to war and returned, who enlisted ready to go into combat even if the fates did not send them? Reading the comments of these men and women in response to the superficial phrase with which we habitually acknowledge their sacrifice leaves me wondering what to say to express our obligation to those who struggled through foreign tribulations while we remained safe at home. Their reflections offer some surprising suggestions that seem prophetic as we as a country process the results of the recent election with grief, triumph, or indifference.

We can say thank you through voting, donations, or advocacy as long as we act to promote the most fundamental good for humanity. We say thank you when we act to help a veteran to live a decent and rewarding life, to have a safe place to live, to grow through education, to share life with companions, and to find a job or another way to contribute to society. Actions to improve the living conditions of veterans now and a better future for those who leave the ranks are seeds of gratitude that come to fruition long after the empty phrases are forgotten.

We say thank you when we think and question long and hard until it hurts, until we too experience cognitive dissonance, until our theory of mind is stretched beyond its comfortable boundaries about the purpose of war in general and the justification for any particular conflict in which our government contemplates sending the young and brave to fight and die. Acting and thinking honor sacrifice as words never can.

1. Korzen DM. One veteran’s unease when hearing, “Thanks for your service.” Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com /opinion/op-ed/la-oe-korzen-veterans-thank-you-20161111-story.html. Published November 11, 2016. Accessed November 14, 2016.

2. Richtel M. Please don’t thank me for my service.” The New York Times. http://www.nytimes .com/2015/02/22/sunday-review/please-dont-thank -me-for-my-service.html?_r=0. Published February 21, 2015. Accessed November 14, 2016.

And remember: you must never, under any circumstances, despair. To hope and to act, these are our duties in misfortune.

—Boris Pasternak, Doctor Zhivago

This editorial is being written on Veterans Day. Likely you will read it when the stores and streets are lined with holiday decorations. Thanksgiving will have come and gone. All these celebrations have the common themes of giving and gratitude, and among the many requests clamoring for your attention at this season are care package collections for active-duty service members and donations for disadvantaged veterans. These efforts are well intentioned on the part of givers and appreciated on the part of those who receive them. Yet these themes remind me of the hackneyed saying we likely have all heard, and many of us have said: Thank you for your service.

Many of you may recall the controversy that emerged surrounding this seemingly innocuous cliché. It has had an Internet resurgence on this day set out to honor those who wore or are in uniform.1 For those who don’t remember the phenomenon, I will briefly summarize. A journalist was interviewing a combat veteran from Afghanistan on a different subject but knowing he had been in the military and the reporter thinking he was being kind and respectful, like so many of us, thanked him for his service. The astute journalist could tell from the expression on the veteran’s face that the comment had touched a wound he never expected to open. But he cared enough to try and understand how the veteran heard these words from out of the depths of his memories of war.

The emotions that emerged from the interview and the online blogs and comments that followed reflect the toll that war takes: anger, anguish, alienation, which these “have a nice day” words seem to evoke, even though they are never meant to create distance, dismissal, or dishonor. This interaction was a painful one for the veteran, and even for the journalist, and created what psychologists call cognitive dissonance, “a condition of conflict or anxiety resulting from inconsistency between belief and action.”2

The reason those 5 words strike a raw nerve in some—but by no means all—who were or are in the armed forces is that those to whom they are spoken know in a deep and personal way, that we who say them usually do not know what we are talking about. I can see this reaction when I watch several of my VA colleagues who actually are combat veterans say the words but from a different theory of mind, a theory of mind they share. Theory of mind is another psychological concept that is at the core of interpersonal and communication skills, the ability to see and feel the world as another person sees it. When someone who has never fought or even served says “thank you for your service,” some veterans feel that their individual experience of combat or even of being in the military is being expressed inauthentically, even perhaps insincerely.

“To these vets, thanking soldiers for their service symbolizes the ease of sending a volunteer army to wage war at great distance—physically, spiritually, economically,” journalist Matt Richtel writes. “It raises questions of the meaning of patriotism, shared purpose and, pointedly, what you’re supposed to say to those who put their lives on the line and are uncomfortable about being thanked for it.”2

My father, a World War II combat veteran and career army physician, told me when I was young that there were 3 experiences that could never be understood unless you lived them: pregnancy, medical school, and combat. I’m not sure why or how he chose these although I am sure they were not original, but having gone through the second, I believe it was because these events are of such personal intensity, such immediate contact with the human condition in all its suffering and resilience that they cannot be faithfully replicated in any in vitro simulation but only in vivo.

Which brings me to the title of the column. How can we say thank you to our friends and family members, our coworkers, and our patients who went to war and returned, who enlisted ready to go into combat even if the fates did not send them? Reading the comments of these men and women in response to the superficial phrase with which we habitually acknowledge their sacrifice leaves me wondering what to say to express our obligation to those who struggled through foreign tribulations while we remained safe at home. Their reflections offer some surprising suggestions that seem prophetic as we as a country process the results of the recent election with grief, triumph, or indifference.

We can say thank you through voting, donations, or advocacy as long as we act to promote the most fundamental good for humanity. We say thank you when we act to help a veteran to live a decent and rewarding life, to have a safe place to live, to grow through education, to share life with companions, and to find a job or another way to contribute to society. Actions to improve the living conditions of veterans now and a better future for those who leave the ranks are seeds of gratitude that come to fruition long after the empty phrases are forgotten.

We say thank you when we think and question long and hard until it hurts, until we too experience cognitive dissonance, until our theory of mind is stretched beyond its comfortable boundaries about the purpose of war in general and the justification for any particular conflict in which our government contemplates sending the young and brave to fight and die. Acting and thinking honor sacrifice as words never can.

And remember: you must never, under any circumstances, despair. To hope and to act, these are our duties in misfortune.

—Boris Pasternak, Doctor Zhivago

This editorial is being written on Veterans Day. Likely you will read it when the stores and streets are lined with holiday decorations. Thanksgiving will have come and gone. All these celebrations have the common themes of giving and gratitude, and among the many requests clamoring for your attention at this season are care package collections for active-duty service members and donations for disadvantaged veterans. These efforts are well intentioned on the part of givers and appreciated on the part of those who receive them. Yet these themes remind me of the hackneyed saying we likely have all heard, and many of us have said: Thank you for your service.

Many of you may recall the controversy that emerged surrounding this seemingly innocuous cliché. It has had an Internet resurgence on this day set out to honor those who wore or are in uniform.1 For those who don’t remember the phenomenon, I will briefly summarize. A journalist was interviewing a combat veteran from Afghanistan on a different subject but knowing he had been in the military and the reporter thinking he was being kind and respectful, like so many of us, thanked him for his service. The astute journalist could tell from the expression on the veteran’s face that the comment had touched a wound he never expected to open. But he cared enough to try and understand how the veteran heard these words from out of the depths of his memories of war.

The emotions that emerged from the interview and the online blogs and comments that followed reflect the toll that war takes: anger, anguish, alienation, which these “have a nice day” words seem to evoke, even though they are never meant to create distance, dismissal, or dishonor. This interaction was a painful one for the veteran, and even for the journalist, and created what psychologists call cognitive dissonance, “a condition of conflict or anxiety resulting from inconsistency between belief and action.”2

The reason those 5 words strike a raw nerve in some—but by no means all—who were or are in the armed forces is that those to whom they are spoken know in a deep and personal way, that we who say them usually do not know what we are talking about. I can see this reaction when I watch several of my VA colleagues who actually are combat veterans say the words but from a different theory of mind, a theory of mind they share. Theory of mind is another psychological concept that is at the core of interpersonal and communication skills, the ability to see and feel the world as another person sees it. When someone who has never fought or even served says “thank you for your service,” some veterans feel that their individual experience of combat or even of being in the military is being expressed inauthentically, even perhaps insincerely.

“To these vets, thanking soldiers for their service symbolizes the ease of sending a volunteer army to wage war at great distance—physically, spiritually, economically,” journalist Matt Richtel writes. “It raises questions of the meaning of patriotism, shared purpose and, pointedly, what you’re supposed to say to those who put their lives on the line and are uncomfortable about being thanked for it.”2

My father, a World War II combat veteran and career army physician, told me when I was young that there were 3 experiences that could never be understood unless you lived them: pregnancy, medical school, and combat. I’m not sure why or how he chose these although I am sure they were not original, but having gone through the second, I believe it was because these events are of such personal intensity, such immediate contact with the human condition in all its suffering and resilience that they cannot be faithfully replicated in any in vitro simulation but only in vivo.

Which brings me to the title of the column. How can we say thank you to our friends and family members, our coworkers, and our patients who went to war and returned, who enlisted ready to go into combat even if the fates did not send them? Reading the comments of these men and women in response to the superficial phrase with which we habitually acknowledge their sacrifice leaves me wondering what to say to express our obligation to those who struggled through foreign tribulations while we remained safe at home. Their reflections offer some surprising suggestions that seem prophetic as we as a country process the results of the recent election with grief, triumph, or indifference.

We can say thank you through voting, donations, or advocacy as long as we act to promote the most fundamental good for humanity. We say thank you when we act to help a veteran to live a decent and rewarding life, to have a safe place to live, to grow through education, to share life with companions, and to find a job or another way to contribute to society. Actions to improve the living conditions of veterans now and a better future for those who leave the ranks are seeds of gratitude that come to fruition long after the empty phrases are forgotten.

We say thank you when we think and question long and hard until it hurts, until we too experience cognitive dissonance, until our theory of mind is stretched beyond its comfortable boundaries about the purpose of war in general and the justification for any particular conflict in which our government contemplates sending the young and brave to fight and die. Acting and thinking honor sacrifice as words never can.

1. Korzen DM. One veteran’s unease when hearing, “Thanks for your service.” Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com /opinion/op-ed/la-oe-korzen-veterans-thank-you-20161111-story.html. Published November 11, 2016. Accessed November 14, 2016.

2. Richtel M. Please don’t thank me for my service.” The New York Times. http://www.nytimes .com/2015/02/22/sunday-review/please-dont-thank -me-for-my-service.html?_r=0. Published February 21, 2015. Accessed November 14, 2016.

1. Korzen DM. One veteran’s unease when hearing, “Thanks for your service.” Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com /opinion/op-ed/la-oe-korzen-veterans-thank-you-20161111-story.html. Published November 11, 2016. Accessed November 14, 2016.

2. Richtel M. Please don’t thank me for my service.” The New York Times. http://www.nytimes .com/2015/02/22/sunday-review/please-dont-thank -me-for-my-service.html?_r=0. Published February 21, 2015. Accessed November 14, 2016.

The merits of buprenorphine for pregnant women with opioid use disorder; A possible solution to the ‘shrinking’ workforce

The merits of buprenorphine for pregnant women with opioid use disorder

Several medication-assisted treatments (MATs) for opioid use disorder were highlighted in “What clinicians need to know about treating opioid use disorder,” (Evidence-Based Reviews,

The landmark study, the Maternal Opioid Treatment: Human Experimental Research, a 2010 multicenter randomized controlled trial compared buprenorphine with methadone in pregnant women with opioid use disorder. The results revealed that neonates exposed to buprenorphine needed 89% less morphine to treat neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), 43% shorter hospital stay, and 58% shorter duration of medical treatment for NAS compared with those receiving methadone. Other advantages of buprenorphine over methadone are lower risk of overdose, fewer drug–drug interactions, and the option of receiving treatment in an outpatient setting, rather than a licensed treatment program, such as a methadone maintenance treatment program, which is more tightly controlled.1-3

The previous recommendation was to consider buprenorphine for patients who refused methadone or were unable to take it, or when a methadone treatment program wasn’t available. This study highlighted some clear advantages for treating this subpopulation with methadone instead of buprenorphine: only 18% of patients receiving methadone discontinued treatment, compared with 33% of those receiving buprenorphine,1-3 and methadone had a lower risk of diversion.3 The accepted practice has been to recommend methadone treatment for patients with mental, physical, or social stressors because of the structure of opioid treatment programs (OTP) (also known as methadone maintenance treatment programs). However, buprenorphine can be dispensed through an OTP, following the same stringent rules and regulations.4

The single agent, buprenorphine—not buprenorphine/naloxone—is recommended to prevent prenatal exposure to naloxone. It is thought that exposure to naloxone in utero might produce hormonal changes in the fetus.1,5 O'Connor et al5 noted methadone’s suitability during breast-feeding because of its low concentration in breast milk. Buprenorphine is excreted at breast milk to plasma ratio of 1:1, but because of buprenorphine’s poor oral bioavailability, infant exposure has little impact on the NAS score, therefore it’s suitable for breast-feeding mothers.5

Adegboyega Oyemade, MD, FAPA

Addiction Psychiatrist

Kaiser Permanente

Baltimore, Maryland

References

1. Lori W. Buprenorphine during pregnancy reduces neonate distress. https://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/nida-notes/2012/07/buprenorphine- during-pregnancy-reduces-neonate-distress. Published July 6, 2016. Accessed September 9, 2016.

2. Jones HE, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after methadone or buprenorphine exposure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(24):2320-2331.

3. ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women; American Society of Addiction Medicine. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524: Opioid abuse, dependence, and addiction in pregnancy. Obest Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1070-1076.

4. Addiction Treatment Forum. Methadone vs. buprenorphine: how do OTPs and patients make the choice? http://atforum.com/2013/11/methadone-vs-buprenorphine-how-do-otps-and-patients-make-the-choice. Published November 15, 2013. Accessed September 9, 2016.

5. O’Connor A, Alto W, Musgrave K, et al. Observational study of buprenorphine treatment of opioid-dependent pregnancy women in a family medicine residency: reports on maternal and infant outcomes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(2):194-201.

A possible solution to the 'shrinking' workforce

I would like to offer another pragmatic, easy, and quick solution for dealing with the shrinking psychiatrist workforce (The psychiatry workforce pool is shrinking. What are we doing about it? From the Editor.

The United States is short approximately 45,000 psychiatrists.1 Burnout—a silent epidemic among physicians—is prevalent in psychiatry. What consumes time and leads to burn out? “Scut work.”

There are thousands of unmatched residency graduates.2 Most of these graduates have clinical experience in the United States. Psychiatry residency programs should give these unmatched graduates 6 months of training in psychiatry and use them as our primary workforce. These assistant physicians could be paired with 2 to 3 psychiatrists to perform the menial tasks, including, but not limited to, phone calls, prescriptions, prior authorizations, chart review, and other clinical and administrative paper work. This way, psychiatrists can focus on the interview, diagnoses, and treatment, major medical decision-making, and see more patients.

Employing assistant physicians to provide care has been suggested as a solution.3 Arkansas, Kansas, and Missouri have passed laws that allow medical school graduates who did not match with a residency program to work in underserved areas with a collaborating physician.

Because 1 out of 4 individuals have a mental illness and more of them are seeking help because of increasing awareness and the Affordable Care Act, the construct of “assistant physicians” could ease psychiatrists’ workload allowing them to deliver better care to more people.

Maju Mathew Koola, MD

Associate Professor

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

George Washington University

School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Washington, DC

References

1. Carlat D. 45,000 More psychiatrists, anyone? Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/45000-more-psychiatrists-anyone-0.Published August 3, 2010. Accessed November 11, 2016.

2. The Match: National Resident Matching Program. results and data: 2016 main residency match. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Main-Match-Results-and-Data-2016.pdf. Published April 2016. Accessed November 11, 2016.

3. Miller JG, Peterson DJ. Employing nurse practitioners and physician assistants to provide access to care as the psychiatrist shortage continues. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):685-686.

Concerns in psychiatry

The August 2016 editorial (Unresolved questions about the specialty lurk in the cortext of psychiatrists.

Denis F. Darko, MD

CEO

NeuroSci R&D Consultancy, LLC

Maple Grove, Minnesota

The merits of buprenorphine for pregnant women with opioid use disorder

Several medication-assisted treatments (MATs) for opioid use disorder were highlighted in “What clinicians need to know about treating opioid use disorder,” (Evidence-Based Reviews,

The landmark study, the Maternal Opioid Treatment: Human Experimental Research, a 2010 multicenter randomized controlled trial compared buprenorphine with methadone in pregnant women with opioid use disorder. The results revealed that neonates exposed to buprenorphine needed 89% less morphine to treat neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), 43% shorter hospital stay, and 58% shorter duration of medical treatment for NAS compared with those receiving methadone. Other advantages of buprenorphine over methadone are lower risk of overdose, fewer drug–drug interactions, and the option of receiving treatment in an outpatient setting, rather than a licensed treatment program, such as a methadone maintenance treatment program, which is more tightly controlled.1-3

The previous recommendation was to consider buprenorphine for patients who refused methadone or were unable to take it, or when a methadone treatment program wasn’t available. This study highlighted some clear advantages for treating this subpopulation with methadone instead of buprenorphine: only 18% of patients receiving methadone discontinued treatment, compared with 33% of those receiving buprenorphine,1-3 and methadone had a lower risk of diversion.3 The accepted practice has been to recommend methadone treatment for patients with mental, physical, or social stressors because of the structure of opioid treatment programs (OTP) (also known as methadone maintenance treatment programs). However, buprenorphine can be dispensed through an OTP, following the same stringent rules and regulations.4

The single agent, buprenorphine—not buprenorphine/naloxone—is recommended to prevent prenatal exposure to naloxone. It is thought that exposure to naloxone in utero might produce hormonal changes in the fetus.1,5 O'Connor et al5 noted methadone’s suitability during breast-feeding because of its low concentration in breast milk. Buprenorphine is excreted at breast milk to plasma ratio of 1:1, but because of buprenorphine’s poor oral bioavailability, infant exposure has little impact on the NAS score, therefore it’s suitable for breast-feeding mothers.5

Adegboyega Oyemade, MD, FAPA

Addiction Psychiatrist

Kaiser Permanente

Baltimore, Maryland

References

1. Lori W. Buprenorphine during pregnancy reduces neonate distress. https://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/nida-notes/2012/07/buprenorphine- during-pregnancy-reduces-neonate-distress. Published July 6, 2016. Accessed September 9, 2016.

2. Jones HE, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after methadone or buprenorphine exposure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(24):2320-2331.

3. ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women; American Society of Addiction Medicine. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524: Opioid abuse, dependence, and addiction in pregnancy. Obest Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1070-1076.

4. Addiction Treatment Forum. Methadone vs. buprenorphine: how do OTPs and patients make the choice? http://atforum.com/2013/11/methadone-vs-buprenorphine-how-do-otps-and-patients-make-the-choice. Published November 15, 2013. Accessed September 9, 2016.

5. O’Connor A, Alto W, Musgrave K, et al. Observational study of buprenorphine treatment of opioid-dependent pregnancy women in a family medicine residency: reports on maternal and infant outcomes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(2):194-201.

A possible solution to the 'shrinking' workforce

I would like to offer another pragmatic, easy, and quick solution for dealing with the shrinking psychiatrist workforce (The psychiatry workforce pool is shrinking. What are we doing about it? From the Editor.

The United States is short approximately 45,000 psychiatrists.1 Burnout—a silent epidemic among physicians—is prevalent in psychiatry. What consumes time and leads to burn out? “Scut work.”

There are thousands of unmatched residency graduates.2 Most of these graduates have clinical experience in the United States. Psychiatry residency programs should give these unmatched graduates 6 months of training in psychiatry and use them as our primary workforce. These assistant physicians could be paired with 2 to 3 psychiatrists to perform the menial tasks, including, but not limited to, phone calls, prescriptions, prior authorizations, chart review, and other clinical and administrative paper work. This way, psychiatrists can focus on the interview, diagnoses, and treatment, major medical decision-making, and see more patients.

Employing assistant physicians to provide care has been suggested as a solution.3 Arkansas, Kansas, and Missouri have passed laws that allow medical school graduates who did not match with a residency program to work in underserved areas with a collaborating physician.

Because 1 out of 4 individuals have a mental illness and more of them are seeking help because of increasing awareness and the Affordable Care Act, the construct of “assistant physicians” could ease psychiatrists’ workload allowing them to deliver better care to more people.

Maju Mathew Koola, MD

Associate Professor

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

George Washington University

School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Washington, DC

References

1. Carlat D. 45,000 More psychiatrists, anyone? Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/45000-more-psychiatrists-anyone-0.Published August 3, 2010. Accessed November 11, 2016.

2. The Match: National Resident Matching Program. results and data: 2016 main residency match. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Main-Match-Results-and-Data-2016.pdf. Published April 2016. Accessed November 11, 2016.

3. Miller JG, Peterson DJ. Employing nurse practitioners and physician assistants to provide access to care as the psychiatrist shortage continues. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):685-686.

Concerns in psychiatry

The August 2016 editorial (Unresolved questions about the specialty lurk in the cortext of psychiatrists.

Denis F. Darko, MD

CEO

NeuroSci R&D Consultancy, LLC

Maple Grove, Minnesota

The merits of buprenorphine for pregnant women with opioid use disorder

Several medication-assisted treatments (MATs) for opioid use disorder were highlighted in “What clinicians need to know about treating opioid use disorder,” (Evidence-Based Reviews,

The landmark study, the Maternal Opioid Treatment: Human Experimental Research, a 2010 multicenter randomized controlled trial compared buprenorphine with methadone in pregnant women with opioid use disorder. The results revealed that neonates exposed to buprenorphine needed 89% less morphine to treat neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), 43% shorter hospital stay, and 58% shorter duration of medical treatment for NAS compared with those receiving methadone. Other advantages of buprenorphine over methadone are lower risk of overdose, fewer drug–drug interactions, and the option of receiving treatment in an outpatient setting, rather than a licensed treatment program, such as a methadone maintenance treatment program, which is more tightly controlled.1-3

The previous recommendation was to consider buprenorphine for patients who refused methadone or were unable to take it, or when a methadone treatment program wasn’t available. This study highlighted some clear advantages for treating this subpopulation with methadone instead of buprenorphine: only 18% of patients receiving methadone discontinued treatment, compared with 33% of those receiving buprenorphine,1-3 and methadone had a lower risk of diversion.3 The accepted practice has been to recommend methadone treatment for patients with mental, physical, or social stressors because of the structure of opioid treatment programs (OTP) (also known as methadone maintenance treatment programs). However, buprenorphine can be dispensed through an OTP, following the same stringent rules and regulations.4

The single agent, buprenorphine—not buprenorphine/naloxone—is recommended to prevent prenatal exposure to naloxone. It is thought that exposure to naloxone in utero might produce hormonal changes in the fetus.1,5 O'Connor et al5 noted methadone’s suitability during breast-feeding because of its low concentration in breast milk. Buprenorphine is excreted at breast milk to plasma ratio of 1:1, but because of buprenorphine’s poor oral bioavailability, infant exposure has little impact on the NAS score, therefore it’s suitable for breast-feeding mothers.5

Adegboyega Oyemade, MD, FAPA

Addiction Psychiatrist

Kaiser Permanente

Baltimore, Maryland

References

1. Lori W. Buprenorphine during pregnancy reduces neonate distress. https://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/nida-notes/2012/07/buprenorphine- during-pregnancy-reduces-neonate-distress. Published July 6, 2016. Accessed September 9, 2016.

2. Jones HE, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after methadone or buprenorphine exposure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(24):2320-2331.

3. ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women; American Society of Addiction Medicine. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524: Opioid abuse, dependence, and addiction in pregnancy. Obest Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1070-1076.

4. Addiction Treatment Forum. Methadone vs. buprenorphine: how do OTPs and patients make the choice? http://atforum.com/2013/11/methadone-vs-buprenorphine-how-do-otps-and-patients-make-the-choice. Published November 15, 2013. Accessed September 9, 2016.

5. O’Connor A, Alto W, Musgrave K, et al. Observational study of buprenorphine treatment of opioid-dependent pregnancy women in a family medicine residency: reports on maternal and infant outcomes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(2):194-201.

A possible solution to the 'shrinking' workforce

I would like to offer another pragmatic, easy, and quick solution for dealing with the shrinking psychiatrist workforce (The psychiatry workforce pool is shrinking. What are we doing about it? From the Editor.

The United States is short approximately 45,000 psychiatrists.1 Burnout—a silent epidemic among physicians—is prevalent in psychiatry. What consumes time and leads to burn out? “Scut work.”

There are thousands of unmatched residency graduates.2 Most of these graduates have clinical experience in the United States. Psychiatry residency programs should give these unmatched graduates 6 months of training in psychiatry and use them as our primary workforce. These assistant physicians could be paired with 2 to 3 psychiatrists to perform the menial tasks, including, but not limited to, phone calls, prescriptions, prior authorizations, chart review, and other clinical and administrative paper work. This way, psychiatrists can focus on the interview, diagnoses, and treatment, major medical decision-making, and see more patients.

Employing assistant physicians to provide care has been suggested as a solution.3 Arkansas, Kansas, and Missouri have passed laws that allow medical school graduates who did not match with a residency program to work in underserved areas with a collaborating physician.

Because 1 out of 4 individuals have a mental illness and more of them are seeking help because of increasing awareness and the Affordable Care Act, the construct of “assistant physicians” could ease psychiatrists’ workload allowing them to deliver better care to more people.

Maju Mathew Koola, MD

Associate Professor

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

George Washington University

School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Washington, DC

References

1. Carlat D. 45,000 More psychiatrists, anyone? Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/45000-more-psychiatrists-anyone-0.Published August 3, 2010. Accessed November 11, 2016.

2. The Match: National Resident Matching Program. results and data: 2016 main residency match. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Main-Match-Results-and-Data-2016.pdf. Published April 2016. Accessed November 11, 2016.

3. Miller JG, Peterson DJ. Employing nurse practitioners and physician assistants to provide access to care as the psychiatrist shortage continues. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):685-686.

Concerns in psychiatry

The August 2016 editorial (Unresolved questions about the specialty lurk in the cortext of psychiatrists.

Denis F. Darko, MD

CEO

NeuroSci R&D Consultancy, LLC

Maple Grove, Minnesota

6 steps to take when a patient insists on that antibiotic

In this issue of JFP, Wiskirchen and colleagues discuss the appropriate use of antibiotics in outpatient settings, providing stewardship advice for several conditions we frequently see in primary care practice.

One of the symptoms for which we most frequently battle requests for antibiotics is acute cough. Despite the fact that more than 90% of cases of acute cough illness (aka acute bronchitis) are caused by viruses, the prescribing rate for it in the United States remains about 70%.1

Over the years, I’ve honed a “spiel” that I use with patients with acute cough illness to help keep my antibiotic prescribing to a minimum. It must be working; my prescribing rate is less than 20%. What follows are some of my catch phrases and techniques.

1. Acknowledge the patient’s misery. “Sounds like you have a really bad bug."

2. Tell the patient what he or she doesn’t have. “Your lungs sound good, and your throat does not look too bad, so that means you don’t have strep throat or pneumonia. That’s good news.”

3. Explain what viruses are “making the rounds.” If you have surveillance data, that’s even better. “I have seen several other patients with symptoms just like yours this week.” Over 25 years ago, Jon Temte, an FP from Wisconsin, drove down prescribing rates for acute bronchitis below 20% in family medicine residencies by providing feedback to physicians and patients about the viruses circulating in their communities.2

4. Set realistic expectations. Tell patients how long their cough is likely to last. The duration of the typical cough is (unfortunately) about 17 days.3 Most patients (and even some doctors) think a bad cold should be gone in 7 days.3

5. Choose your terms carefully. Don’t use the term “acute bronchitis.” It sounds bad and worthy of an antibiotic. “Chest cold” sounds much more benign; patients are less likely to think they need an antibiotic for a chest cold.4

6. When all else fails, consider a delayed prescription. I reserve this strategy for patients who are insistent on getting an antibiotic even though their illness is clearly viral. Randomized trials of the delayed strategy show that fewer than 50% of patients actually fill the prescription.5

Develop your own spiel to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing. You’ll find that it works a good deal of the time.

1. Barnett ML, Linder JA. Antibiotic prescribing for adults with acute bronchitis in the United States, 1996-2010. JAMA. 2014;311:2020-2022.

2. Temte JL, Shult PA, Kirk CJ, et al. Effects of viral respiratory disease education and surveillance on antibiotic prescribing. Fam Med. 1999;31:101-106.

3. Ebell MH, Lundgren J, Youngpairoj S. How long does a cough last? Comparing patients’ expectations with data from a systematic review of the literature. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:5-13.

4. Phillips TG, Hickner J. Calling acute bronchitis a chest cold may improve patient satisfaction with appropriate antibiotic use. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:459-463.

5. Spurling GK, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, et al. Delayed antibiotics for respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD004417.

In this issue of JFP, Wiskirchen and colleagues discuss the appropriate use of antibiotics in outpatient settings, providing stewardship advice for several conditions we frequently see in primary care practice.

One of the symptoms for which we most frequently battle requests for antibiotics is acute cough. Despite the fact that more than 90% of cases of acute cough illness (aka acute bronchitis) are caused by viruses, the prescribing rate for it in the United States remains about 70%.1

Over the years, I’ve honed a “spiel” that I use with patients with acute cough illness to help keep my antibiotic prescribing to a minimum. It must be working; my prescribing rate is less than 20%. What follows are some of my catch phrases and techniques.

1. Acknowledge the patient’s misery. “Sounds like you have a really bad bug."

2. Tell the patient what he or she doesn’t have. “Your lungs sound good, and your throat does not look too bad, so that means you don’t have strep throat or pneumonia. That’s good news.”

3. Explain what viruses are “making the rounds.” If you have surveillance data, that’s even better. “I have seen several other patients with symptoms just like yours this week.” Over 25 years ago, Jon Temte, an FP from Wisconsin, drove down prescribing rates for acute bronchitis below 20% in family medicine residencies by providing feedback to physicians and patients about the viruses circulating in their communities.2

4. Set realistic expectations. Tell patients how long their cough is likely to last. The duration of the typical cough is (unfortunately) about 17 days.3 Most patients (and even some doctors) think a bad cold should be gone in 7 days.3

5. Choose your terms carefully. Don’t use the term “acute bronchitis.” It sounds bad and worthy of an antibiotic. “Chest cold” sounds much more benign; patients are less likely to think they need an antibiotic for a chest cold.4

6. When all else fails, consider a delayed prescription. I reserve this strategy for patients who are insistent on getting an antibiotic even though their illness is clearly viral. Randomized trials of the delayed strategy show that fewer than 50% of patients actually fill the prescription.5

Develop your own spiel to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing. You’ll find that it works a good deal of the time.

In this issue of JFP, Wiskirchen and colleagues discuss the appropriate use of antibiotics in outpatient settings, providing stewardship advice for several conditions we frequently see in primary care practice.

One of the symptoms for which we most frequently battle requests for antibiotics is acute cough. Despite the fact that more than 90% of cases of acute cough illness (aka acute bronchitis) are caused by viruses, the prescribing rate for it in the United States remains about 70%.1

Over the years, I’ve honed a “spiel” that I use with patients with acute cough illness to help keep my antibiotic prescribing to a minimum. It must be working; my prescribing rate is less than 20%. What follows are some of my catch phrases and techniques.

1. Acknowledge the patient’s misery. “Sounds like you have a really bad bug."

2. Tell the patient what he or she doesn’t have. “Your lungs sound good, and your throat does not look too bad, so that means you don’t have strep throat or pneumonia. That’s good news.”

3. Explain what viruses are “making the rounds.” If you have surveillance data, that’s even better. “I have seen several other patients with symptoms just like yours this week.” Over 25 years ago, Jon Temte, an FP from Wisconsin, drove down prescribing rates for acute bronchitis below 20% in family medicine residencies by providing feedback to physicians and patients about the viruses circulating in their communities.2

4. Set realistic expectations. Tell patients how long their cough is likely to last. The duration of the typical cough is (unfortunately) about 17 days.3 Most patients (and even some doctors) think a bad cold should be gone in 7 days.3

5. Choose your terms carefully. Don’t use the term “acute bronchitis.” It sounds bad and worthy of an antibiotic. “Chest cold” sounds much more benign; patients are less likely to think they need an antibiotic for a chest cold.4

6. When all else fails, consider a delayed prescription. I reserve this strategy for patients who are insistent on getting an antibiotic even though their illness is clearly viral. Randomized trials of the delayed strategy show that fewer than 50% of patients actually fill the prescription.5

Develop your own spiel to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing. You’ll find that it works a good deal of the time.

1. Barnett ML, Linder JA. Antibiotic prescribing for adults with acute bronchitis in the United States, 1996-2010. JAMA. 2014;311:2020-2022.

2. Temte JL, Shult PA, Kirk CJ, et al. Effects of viral respiratory disease education and surveillance on antibiotic prescribing. Fam Med. 1999;31:101-106.

3. Ebell MH, Lundgren J, Youngpairoj S. How long does a cough last? Comparing patients’ expectations with data from a systematic review of the literature. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:5-13.

4. Phillips TG, Hickner J. Calling acute bronchitis a chest cold may improve patient satisfaction with appropriate antibiotic use. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:459-463.

5. Spurling GK, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, et al. Delayed antibiotics for respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD004417.

1. Barnett ML, Linder JA. Antibiotic prescribing for adults with acute bronchitis in the United States, 1996-2010. JAMA. 2014;311:2020-2022.

2. Temte JL, Shult PA, Kirk CJ, et al. Effects of viral respiratory disease education and surveillance on antibiotic prescribing. Fam Med. 1999;31:101-106.

3. Ebell MH, Lundgren J, Youngpairoj S. How long does a cough last? Comparing patients’ expectations with data from a systematic review of the literature. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:5-13.

4. Phillips TG, Hickner J. Calling acute bronchitis a chest cold may improve patient satisfaction with appropriate antibiotic use. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:459-463.

5. Spurling GK, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, et al. Delayed antibiotics for respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD004417.

Mental Health: A Forgotten Facet of Primary Care

One of the biggest disparities in health care today is the separate treatment of mind and body, despite their known integration.1 While mental and behavioral health conditions are frequently diagnosed and treated within primary care settings, fragmentation persists between the mental and physical health care systems—creating barriers in the quality, outcome, and efficiency of care.2 Since half of Americans with mental health conditions go without essential care, reform of our nation’s mental health system is a priority issue for NPs and PAs and the patients we serve.

Some progress has been made to implement change—the Now Is the Time initiative, launched in 2013, increased federal funding for behavioral health care workforce training in an effort to support more providers in mental and substance use disorder treatment. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has worked to improve behavioral health coverage for Americans in three ways: ending insurance company discrimination based on pre-existing conditions, requiring health insurance coverage for mental and substance use disorder services, and expanding mental health parity. This has improved coverage and access to mental and substance abuse services for more than 60 million Americans.3 In January 2016, President Obama proposed a $500 million investment to increase access to mental health care.4 The most recent presidential election creates an uncertain future for

Regardless, more work has to be done to guarantee that Americans have the access they need. Sadly, even with these advancements in behavioral health coverage, only about half of children and less than half of adults with diagnosable mental health disorders get the treatment they need.4 A 2016 report from the Rural Health Research Center revealed that more than 15 million Americans face behavioral health issues without access to the necessary care.5

Psychiatric providers (like most other specialists) tend to be located in urban areas, limiting access in rural areas and even some underserved urban communities. Only 43% of family physicians in this country provide mental health care.6 The team-based care that NPs and PAs provide has great potential for bridging this gap in mental health coverage.

NPs and PAs are an important but underutilized resource for improving mental health care access—but how can primary care NPs and PAs work to enhance the delivery of mental health care in our country? In the preprofessional area, it would be prudent to entice qualified individuals in the mental health field—particularly those who are licensed clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors, or marriage and family therapists—into NP and PA programs with preference.

Clinical rotations in behavioral health (BH)/psychiatry should be encouraged—even mandated—in professional education. We should ensure this content is taught in the didactic portion of NP/PA professional education, as well as bolstering psychiatric pharmacology in coursework.

Postprofessional education should encourage primary care NPs and PAs to gain additional self-directed education in BH/psychiatry. This can be achieved via a focused psychiatry “boot camp” (for PAs following the CAQ blueprint, found at www.nccpa.net/psychiatry) or a competency-based online postprofessional certificate in BH/psychiatry (such as—shameless plug—the one offered at my institution; www.atsu.edu/postgraduate-certificate-in-psychiatry-and-behavioral-health-online).7,8

This psychiatric background is fundamental throughout primary care but is crucial in community health centers, correctional health care centers, and Veterans Administration hospitals. Of course, in order to make a difference, we must remove the barriers that prevent psychiatric NPs and PAs from being considered mental health providers and adjust reimbursement accordingly.

Do you have ideas on how to increase the knowledge base of primary care NPs and PAs and enhance the provision of mental health services in this country? Will the political change in leadership in January 2017 increase opportunities to make a difference in mental health care? Please share your thoughts by contacting me at [email protected].

1. deGruy F. Mental health care in the primary care setting. In: Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN, Vanselow NA, eds. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 1996.

2. Simon GE, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(10): 1638-1644.

3. Enomoto K. Improving access to mental health services - President’s FY 2017 Budget proposes new investments to increase access. http://abilitychicagoinfo.blogspot.com/2016/02/improving-access-to-mental-health.html. Accessed November 3, 2016.

4. Enomoto K. Improving access to mental health services. www.hhs.gov/blog/2016/02/09/improving-access-mental-health-services.html. Accessed November 3, 2016.

5. Rural Health Research Center. Supply and distribution of the behavioral health workforce in rural America. http://depts.washington.edu/fammed/rhrc/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/09/RHRC_DB160_Larson.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2016.

6. Miller BF, Druss B. The role of family physicians in mental health care delivery in the United States: implications for health reform. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(2): 111-113.

7. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Psychiatry CAQ. www.nccpa.net/psychiatry. Accessed November 3, 2016.

8. A.T. Still University. Postgraduate certificate in psychiatry and behavioral health online. www.atsu.edu/postgraduate-certificate-in-psychiatry-and-behavioral-health-online. Accessed November 3, 2016.

One of the biggest disparities in health care today is the separate treatment of mind and body, despite their known integration.1 While mental and behavioral health conditions are frequently diagnosed and treated within primary care settings, fragmentation persists between the mental and physical health care systems—creating barriers in the quality, outcome, and efficiency of care.2 Since half of Americans with mental health conditions go without essential care, reform of our nation’s mental health system is a priority issue for NPs and PAs and the patients we serve.

Some progress has been made to implement change—the Now Is the Time initiative, launched in 2013, increased federal funding for behavioral health care workforce training in an effort to support more providers in mental and substance use disorder treatment. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has worked to improve behavioral health coverage for Americans in three ways: ending insurance company discrimination based on pre-existing conditions, requiring health insurance coverage for mental and substance use disorder services, and expanding mental health parity. This has improved coverage and access to mental and substance abuse services for more than 60 million Americans.3 In January 2016, President Obama proposed a $500 million investment to increase access to mental health care.4 The most recent presidential election creates an uncertain future for

Regardless, more work has to be done to guarantee that Americans have the access they need. Sadly, even with these advancements in behavioral health coverage, only about half of children and less than half of adults with diagnosable mental health disorders get the treatment they need.4 A 2016 report from the Rural Health Research Center revealed that more than 15 million Americans face behavioral health issues without access to the necessary care.5

Psychiatric providers (like most other specialists) tend to be located in urban areas, limiting access in rural areas and even some underserved urban communities. Only 43% of family physicians in this country provide mental health care.6 The team-based care that NPs and PAs provide has great potential for bridging this gap in mental health coverage.

NPs and PAs are an important but underutilized resource for improving mental health care access—but how can primary care NPs and PAs work to enhance the delivery of mental health care in our country? In the preprofessional area, it would be prudent to entice qualified individuals in the mental health field—particularly those who are licensed clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors, or marriage and family therapists—into NP and PA programs with preference.

Clinical rotations in behavioral health (BH)/psychiatry should be encouraged—even mandated—in professional education. We should ensure this content is taught in the didactic portion of NP/PA professional education, as well as bolstering psychiatric pharmacology in coursework.

Postprofessional education should encourage primary care NPs and PAs to gain additional self-directed education in BH/psychiatry. This can be achieved via a focused psychiatry “boot camp” (for PAs following the CAQ blueprint, found at www.nccpa.net/psychiatry) or a competency-based online postprofessional certificate in BH/psychiatry (such as—shameless plug—the one offered at my institution; www.atsu.edu/postgraduate-certificate-in-psychiatry-and-behavioral-health-online).7,8

This psychiatric background is fundamental throughout primary care but is crucial in community health centers, correctional health care centers, and Veterans Administration hospitals. Of course, in order to make a difference, we must remove the barriers that prevent psychiatric NPs and PAs from being considered mental health providers and adjust reimbursement accordingly.

Do you have ideas on how to increase the knowledge base of primary care NPs and PAs and enhance the provision of mental health services in this country? Will the political change in leadership in January 2017 increase opportunities to make a difference in mental health care? Please share your thoughts by contacting me at [email protected].

One of the biggest disparities in health care today is the separate treatment of mind and body, despite their known integration.1 While mental and behavioral health conditions are frequently diagnosed and treated within primary care settings, fragmentation persists between the mental and physical health care systems—creating barriers in the quality, outcome, and efficiency of care.2 Since half of Americans with mental health conditions go without essential care, reform of our nation’s mental health system is a priority issue for NPs and PAs and the patients we serve.

Some progress has been made to implement change—the Now Is the Time initiative, launched in 2013, increased federal funding for behavioral health care workforce training in an effort to support more providers in mental and substance use disorder treatment. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has worked to improve behavioral health coverage for Americans in three ways: ending insurance company discrimination based on pre-existing conditions, requiring health insurance coverage for mental and substance use disorder services, and expanding mental health parity. This has improved coverage and access to mental and substance abuse services for more than 60 million Americans.3 In January 2016, President Obama proposed a $500 million investment to increase access to mental health care.4 The most recent presidential election creates an uncertain future for

Regardless, more work has to be done to guarantee that Americans have the access they need. Sadly, even with these advancements in behavioral health coverage, only about half of children and less than half of adults with diagnosable mental health disorders get the treatment they need.4 A 2016 report from the Rural Health Research Center revealed that more than 15 million Americans face behavioral health issues without access to the necessary care.5

Psychiatric providers (like most other specialists) tend to be located in urban areas, limiting access in rural areas and even some underserved urban communities. Only 43% of family physicians in this country provide mental health care.6 The team-based care that NPs and PAs provide has great potential for bridging this gap in mental health coverage.

NPs and PAs are an important but underutilized resource for improving mental health care access—but how can primary care NPs and PAs work to enhance the delivery of mental health care in our country? In the preprofessional area, it would be prudent to entice qualified individuals in the mental health field—particularly those who are licensed clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors, or marriage and family therapists—into NP and PA programs with preference.

Clinical rotations in behavioral health (BH)/psychiatry should be encouraged—even mandated—in professional education. We should ensure this content is taught in the didactic portion of NP/PA professional education, as well as bolstering psychiatric pharmacology in coursework.

Postprofessional education should encourage primary care NPs and PAs to gain additional self-directed education in BH/psychiatry. This can be achieved via a focused psychiatry “boot camp” (for PAs following the CAQ blueprint, found at www.nccpa.net/psychiatry) or a competency-based online postprofessional certificate in BH/psychiatry (such as—shameless plug—the one offered at my institution; www.atsu.edu/postgraduate-certificate-in-psychiatry-and-behavioral-health-online).7,8

This psychiatric background is fundamental throughout primary care but is crucial in community health centers, correctional health care centers, and Veterans Administration hospitals. Of course, in order to make a difference, we must remove the barriers that prevent psychiatric NPs and PAs from being considered mental health providers and adjust reimbursement accordingly.

Do you have ideas on how to increase the knowledge base of primary care NPs and PAs and enhance the provision of mental health services in this country? Will the political change in leadership in January 2017 increase opportunities to make a difference in mental health care? Please share your thoughts by contacting me at [email protected].

1. deGruy F. Mental health care in the primary care setting. In: Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN, Vanselow NA, eds. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 1996.

2. Simon GE, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(10): 1638-1644.

3. Enomoto K. Improving access to mental health services - President’s FY 2017 Budget proposes new investments to increase access. http://abilitychicagoinfo.blogspot.com/2016/02/improving-access-to-mental-health.html. Accessed November 3, 2016.

4. Enomoto K. Improving access to mental health services. www.hhs.gov/blog/2016/02/09/improving-access-mental-health-services.html. Accessed November 3, 2016.

5. Rural Health Research Center. Supply and distribution of the behavioral health workforce in rural America. http://depts.washington.edu/fammed/rhrc/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/09/RHRC_DB160_Larson.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2016.

6. Miller BF, Druss B. The role of family physicians in mental health care delivery in the United States: implications for health reform. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(2): 111-113.

7. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Psychiatry CAQ. www.nccpa.net/psychiatry. Accessed November 3, 2016.

8. A.T. Still University. Postgraduate certificate in psychiatry and behavioral health online. www.atsu.edu/postgraduate-certificate-in-psychiatry-and-behavioral-health-online. Accessed November 3, 2016.

1. deGruy F. Mental health care in the primary care setting. In: Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN, Vanselow NA, eds. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 1996.

2. Simon GE, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(10): 1638-1644.

3. Enomoto K. Improving access to mental health services - President’s FY 2017 Budget proposes new investments to increase access. http://abilitychicagoinfo.blogspot.com/2016/02/improving-access-to-mental-health.html. Accessed November 3, 2016.

4. Enomoto K. Improving access to mental health services. www.hhs.gov/blog/2016/02/09/improving-access-mental-health-services.html. Accessed November 3, 2016.

5. Rural Health Research Center. Supply and distribution of the behavioral health workforce in rural America. http://depts.washington.edu/fammed/rhrc/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/09/RHRC_DB160_Larson.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2016.

6. Miller BF, Druss B. The role of family physicians in mental health care delivery in the United States: implications for health reform. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(2): 111-113.

7. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Psychiatry CAQ. www.nccpa.net/psychiatry. Accessed November 3, 2016.

8. A.T. Still University. Postgraduate certificate in psychiatry and behavioral health online. www.atsu.edu/postgraduate-certificate-in-psychiatry-and-behavioral-health-online. Accessed November 3, 2016.

Physicians Must Encourage HPV Vaccine

Despite overwhelming evidence indicating vaccines are safe and effective at preventing diseases,1 physicians are still faced with the dilemma of convincing patients to receive their recommended vaccinations. The topic comes up regularly on television talk shows; presidential debates; or in new documentary films, such as “Vaxxed: From Cover-up to Catastrophe,” which was pulled from the Tribeca Film Festival in March 2016.2 The central debate over vaccines traces back almost 20 years to the study published in The Lancet regarding the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine and the link to autism. Although the article was retracted in 2010 and no evidence has been found linking vaccines with autism,1,3 vaccination coverage gaps still exist. These gaps can leave communities vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases.4 This lack of protection is especially glaring for the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, putting health care professionals including dermatologists in the position of educating parents and guardians to have their children immunized.

More than 10 years after the federal government approved the first vaccines to fight the cancer-causing HPV, less than half of adolescent girls and only a fifth of adolescent boys are getting immunized. The reasons for the low vaccination rates are particularly complicated because they play not only into fears over vaccines but also over a perceived risk the vaccine may encourage sexual activity in adolescents, which has not been proven.5 Another factor is reluctance on the part of physicians to discuss the vaccine with patients and to fully embrace its lifesaving potential. A recent study showed how physicians are contributing to the low rate.6 “The single biggest barrier to increasing HPV vaccination is not receiving a health care provider’s recommendation,” said Harvard University researcher Melissa Gilkey.7

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as of 2014, only 40% of adolescent girls aged 13 to 17 years had completed the 3-dose course of the HPV vaccine and just 22% of adolescent boys,8 which is short of the 80% public health goal set in 2010 by the federal government.9 Vexingly, HPV vaccination rates lag behind the other 2 vaccines recommended in the same age group: the tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis booster (88%) and the vaccine to prevent meningococcal disease (79%).8

Malo et al6 surveyed 776 primary care physicians and reported that more than a quarter of primary care respondents (27%) do not strongly endorse the HPV vaccine when talking with their patients’ families. Nearly 2 in 5 physicians (39%) did not recommend on-time HPV vaccination for their male patients compared to 26% for female patients.6

The starkest findings, however, related to how the physicians approached their discussions with parents and guardians. Only half recommended the vaccine the same day they discussed it, and 59% said they approached discussions by assessing the child’s risk for contracting the disease rather than consistently recommending it to all children as a routine immunization.6