User login

COMMENTARY—Adding CBT Adds Value If Patients Are Receptive

Increasing numbers of adolescents are presenting to physicians for management of concussions. This is mainly because of much greater awareness of the signs, symptoms, and potential adverse effects. While the majority of concussed teens recover in less than two weeks, 10% to 15% will have prolonged symptoms (greater than one month), which has significant negative impact on their health, mood, social functioning, and academic performance. This is the first study to provide evidence-based guidance for treating these slow-to-recover teens.

I definitely believe there is value in adding CBT to postconcussive therapy for teens. I have seen CBT help a large number of my own patients who are suffering from prolonged postconcussion symptoms, so it is good to see the results of this well-done study support this approach. One caveat with CBT is that its success hinges on the patient's being receptive to the idea of CBT and consistent with applying it in daily life, so it may not work for teens who are not motivated to learn and apply its techniques.

I am not surprised by the results of the study. A large proportion of the adolescents I treat for concussions are referred by their pediatricians because they are suffering from prolonged symptoms. We have anecdotally noted that when a collaborative care model is applied, similar to what was provided for the intervention group in this study, including CBT, patients experience more rapid decrease in symptoms, improved mood, and smoother transition back to baseline functioning, especially in school. I suspect this is because CBT teaches them effective coping skills, and the bonus is that these skills are incredibly useful across one's lifetime, not just for concussion recovery.

Adolescents who are slow to recover from a concussion commonly experience depressive symptoms. This study suggests CBT is a promising treatment for improving mood and facilitating recovery for these teens. However, a larger study is needed with more diverse subject population. This study included only 49 subjects, and the majority of them were white females. A larger study is needed to determine whether CBT is as feasible and effective for other populations of teens with prolonged concussion symptoms. Also, longer-term longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the etiology of persistent postconcussive symptoms and long-term effects 10 to 20 years down the road.

—Cynthia LaBella, MD

Director of the Concussion Program

Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago

Increasing numbers of adolescents are presenting to physicians for management of concussions. This is mainly because of much greater awareness of the signs, symptoms, and potential adverse effects. While the majority of concussed teens recover in less than two weeks, 10% to 15% will have prolonged symptoms (greater than one month), which has significant negative impact on their health, mood, social functioning, and academic performance. This is the first study to provide evidence-based guidance for treating these slow-to-recover teens.

I definitely believe there is value in adding CBT to postconcussive therapy for teens. I have seen CBT help a large number of my own patients who are suffering from prolonged postconcussion symptoms, so it is good to see the results of this well-done study support this approach. One caveat with CBT is that its success hinges on the patient's being receptive to the idea of CBT and consistent with applying it in daily life, so it may not work for teens who are not motivated to learn and apply its techniques.

I am not surprised by the results of the study. A large proportion of the adolescents I treat for concussions are referred by their pediatricians because they are suffering from prolonged symptoms. We have anecdotally noted that when a collaborative care model is applied, similar to what was provided for the intervention group in this study, including CBT, patients experience more rapid decrease in symptoms, improved mood, and smoother transition back to baseline functioning, especially in school. I suspect this is because CBT teaches them effective coping skills, and the bonus is that these skills are incredibly useful across one's lifetime, not just for concussion recovery.

Adolescents who are slow to recover from a concussion commonly experience depressive symptoms. This study suggests CBT is a promising treatment for improving mood and facilitating recovery for these teens. However, a larger study is needed with more diverse subject population. This study included only 49 subjects, and the majority of them were white females. A larger study is needed to determine whether CBT is as feasible and effective for other populations of teens with prolonged concussion symptoms. Also, longer-term longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the etiology of persistent postconcussive symptoms and long-term effects 10 to 20 years down the road.

—Cynthia LaBella, MD

Director of the Concussion Program

Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago

Increasing numbers of adolescents are presenting to physicians for management of concussions. This is mainly because of much greater awareness of the signs, symptoms, and potential adverse effects. While the majority of concussed teens recover in less than two weeks, 10% to 15% will have prolonged symptoms (greater than one month), which has significant negative impact on their health, mood, social functioning, and academic performance. This is the first study to provide evidence-based guidance for treating these slow-to-recover teens.

I definitely believe there is value in adding CBT to postconcussive therapy for teens. I have seen CBT help a large number of my own patients who are suffering from prolonged postconcussion symptoms, so it is good to see the results of this well-done study support this approach. One caveat with CBT is that its success hinges on the patient's being receptive to the idea of CBT and consistent with applying it in daily life, so it may not work for teens who are not motivated to learn and apply its techniques.

I am not surprised by the results of the study. A large proportion of the adolescents I treat for concussions are referred by their pediatricians because they are suffering from prolonged symptoms. We have anecdotally noted that when a collaborative care model is applied, similar to what was provided for the intervention group in this study, including CBT, patients experience more rapid decrease in symptoms, improved mood, and smoother transition back to baseline functioning, especially in school. I suspect this is because CBT teaches them effective coping skills, and the bonus is that these skills are incredibly useful across one's lifetime, not just for concussion recovery.

Adolescents who are slow to recover from a concussion commonly experience depressive symptoms. This study suggests CBT is a promising treatment for improving mood and facilitating recovery for these teens. However, a larger study is needed with more diverse subject population. This study included only 49 subjects, and the majority of them were white females. A larger study is needed to determine whether CBT is as feasible and effective for other populations of teens with prolonged concussion symptoms. Also, longer-term longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the etiology of persistent postconcussive symptoms and long-term effects 10 to 20 years down the road.

—Cynthia LaBella, MD

Director of the Concussion Program

Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago

A job to love

I would like to think it was the culmination of a series of clever decisions, but finding myself in a job that I enjoyed was more than likely the result of blind luck. Even as I filled out medical school applications during my senior year in college, I had no intention of actually becoming a physician. I was more focused on not becoming cannon fodder in Vietnam. I am hesitant to use the word love to describe my affection for a job I did for 40 years. But I can’t imagine any work I could have enjoyed more than being a general pediatrician in a small town.

Were there moments when I would have rather been watching one of my children play in a postseason soccer game than see a patient in the office? Sure, but I can’t recall a morning when I dreaded going to work. Having listened to many other people, including my father, complain about their work, I consider myself fortunate to have discovered a job that wasn’t just tolerable and a way to support my family, but one that I actually enjoyed enough to not mind working nights and weekends.

What was it about being a pediatrician that fueled my affection for it? Social scientists have asked the same question, and one of the answers they discovered is that jobs that offer a degree of autonomy and contribute positively to society are more likely to have satisfied workers (“The Incalculable Value of Finding a Job You Love,” by Robert Frank, the New York Times, July 22, 2016). If one assumes that the mission of pediatrics is to help children become and stay healthy, then when I was practicing solo or in a small physician-owned practice, my job easily met these two criteria. But autonomy and a good cause don’t necessarily pay the rent. However, unless I had foolishly chosen to open a practice in an area already saturated with physicians, doing pediatrics meant I would have an adequate income.

Like any craft, practicing pediatrics became easier and more enjoyable as I gained experience. I made fewer time-gobbling errors and had more therapeutic successes. It’s not that more children got better or better quicker under my care. They were going to get better, regardless of what I did. But over time, an increasing number of parents and patients seemed to be appreciative of my role in educating and reassuring them.

So what happened? I retired from office practice 3 years ago. Had I fallen out of love with pediatrics? My physical stamina was and still is good. I just go to bed earlier. But as my practice was swallowed by larger and larger entities, I lost most of the autonomy that had been so appealing. Practicing medicine has always been a business. It has to be unless you are living off an inherited trust fund. But despite praiseworthy mission statements, corporate decisions were being made that were no longer consistent with the kind of individualized care I thought the patients deserved. It was frustrating to hear families who I had been seeing for decades complain that the care delivery system in our office had taken several steps back.

At the risk of whipping the same old tired horse, I must say that it was the impending introduction of a third new and increasingly less-patient and physician-friendly EHR that made it too difficult to accept the accumulation of negatives in exchange for the wonderful feeling at the end of the workday during which at least one person had thanked me or told me I had done a good job.

For those of you that remain on the job, I urge you to fight the good fight to preserve what it is about practicing pediatrics that allows you to get up in the morning and head off to work without grumbling. It won’t be easy, but if you can make it into a job you love, the patients are going to benefit along with you.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

I would like to think it was the culmination of a series of clever decisions, but finding myself in a job that I enjoyed was more than likely the result of blind luck. Even as I filled out medical school applications during my senior year in college, I had no intention of actually becoming a physician. I was more focused on not becoming cannon fodder in Vietnam. I am hesitant to use the word love to describe my affection for a job I did for 40 years. But I can’t imagine any work I could have enjoyed more than being a general pediatrician in a small town.

Were there moments when I would have rather been watching one of my children play in a postseason soccer game than see a patient in the office? Sure, but I can’t recall a morning when I dreaded going to work. Having listened to many other people, including my father, complain about their work, I consider myself fortunate to have discovered a job that wasn’t just tolerable and a way to support my family, but one that I actually enjoyed enough to not mind working nights and weekends.

What was it about being a pediatrician that fueled my affection for it? Social scientists have asked the same question, and one of the answers they discovered is that jobs that offer a degree of autonomy and contribute positively to society are more likely to have satisfied workers (“The Incalculable Value of Finding a Job You Love,” by Robert Frank, the New York Times, July 22, 2016). If one assumes that the mission of pediatrics is to help children become and stay healthy, then when I was practicing solo or in a small physician-owned practice, my job easily met these two criteria. But autonomy and a good cause don’t necessarily pay the rent. However, unless I had foolishly chosen to open a practice in an area already saturated with physicians, doing pediatrics meant I would have an adequate income.

Like any craft, practicing pediatrics became easier and more enjoyable as I gained experience. I made fewer time-gobbling errors and had more therapeutic successes. It’s not that more children got better or better quicker under my care. They were going to get better, regardless of what I did. But over time, an increasing number of parents and patients seemed to be appreciative of my role in educating and reassuring them.

So what happened? I retired from office practice 3 years ago. Had I fallen out of love with pediatrics? My physical stamina was and still is good. I just go to bed earlier. But as my practice was swallowed by larger and larger entities, I lost most of the autonomy that had been so appealing. Practicing medicine has always been a business. It has to be unless you are living off an inherited trust fund. But despite praiseworthy mission statements, corporate decisions were being made that were no longer consistent with the kind of individualized care I thought the patients deserved. It was frustrating to hear families who I had been seeing for decades complain that the care delivery system in our office had taken several steps back.

At the risk of whipping the same old tired horse, I must say that it was the impending introduction of a third new and increasingly less-patient and physician-friendly EHR that made it too difficult to accept the accumulation of negatives in exchange for the wonderful feeling at the end of the workday during which at least one person had thanked me or told me I had done a good job.

For those of you that remain on the job, I urge you to fight the good fight to preserve what it is about practicing pediatrics that allows you to get up in the morning and head off to work without grumbling. It won’t be easy, but if you can make it into a job you love, the patients are going to benefit along with you.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

I would like to think it was the culmination of a series of clever decisions, but finding myself in a job that I enjoyed was more than likely the result of blind luck. Even as I filled out medical school applications during my senior year in college, I had no intention of actually becoming a physician. I was more focused on not becoming cannon fodder in Vietnam. I am hesitant to use the word love to describe my affection for a job I did for 40 years. But I can’t imagine any work I could have enjoyed more than being a general pediatrician in a small town.

Were there moments when I would have rather been watching one of my children play in a postseason soccer game than see a patient in the office? Sure, but I can’t recall a morning when I dreaded going to work. Having listened to many other people, including my father, complain about their work, I consider myself fortunate to have discovered a job that wasn’t just tolerable and a way to support my family, but one that I actually enjoyed enough to not mind working nights and weekends.

What was it about being a pediatrician that fueled my affection for it? Social scientists have asked the same question, and one of the answers they discovered is that jobs that offer a degree of autonomy and contribute positively to society are more likely to have satisfied workers (“The Incalculable Value of Finding a Job You Love,” by Robert Frank, the New York Times, July 22, 2016). If one assumes that the mission of pediatrics is to help children become and stay healthy, then when I was practicing solo or in a small physician-owned practice, my job easily met these two criteria. But autonomy and a good cause don’t necessarily pay the rent. However, unless I had foolishly chosen to open a practice in an area already saturated with physicians, doing pediatrics meant I would have an adequate income.

Like any craft, practicing pediatrics became easier and more enjoyable as I gained experience. I made fewer time-gobbling errors and had more therapeutic successes. It’s not that more children got better or better quicker under my care. They were going to get better, regardless of what I did. But over time, an increasing number of parents and patients seemed to be appreciative of my role in educating and reassuring them.

So what happened? I retired from office practice 3 years ago. Had I fallen out of love with pediatrics? My physical stamina was and still is good. I just go to bed earlier. But as my practice was swallowed by larger and larger entities, I lost most of the autonomy that had been so appealing. Practicing medicine has always been a business. It has to be unless you are living off an inherited trust fund. But despite praiseworthy mission statements, corporate decisions were being made that were no longer consistent with the kind of individualized care I thought the patients deserved. It was frustrating to hear families who I had been seeing for decades complain that the care delivery system in our office had taken several steps back.

At the risk of whipping the same old tired horse, I must say that it was the impending introduction of a third new and increasingly less-patient and physician-friendly EHR that made it too difficult to accept the accumulation of negatives in exchange for the wonderful feeling at the end of the workday during which at least one person had thanked me or told me I had done a good job.

For those of you that remain on the job, I urge you to fight the good fight to preserve what it is about practicing pediatrics that allows you to get up in the morning and head off to work without grumbling. It won’t be easy, but if you can make it into a job you love, the patients are going to benefit along with you.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Here on Earth

We live inundated with promises that technology will solve our most challenging problems, yet we are regularly disappointed when it does not. New technological solutions seem to appear daily, and we feel like we are falling behind if we do not jump to join the people who are implementing, selling, or imposing new solutions. Often these solutions are offered before the problem is even fully understood, and no assessment has been made to determine if the solution actually helps to solve the challenge identified. With 80% of us now having transitioned to EHRs, we know full well their benefits as well as their pitfalls. While we have mostly accommodated to electronic documentation, we are now at the point where we are beginning to explore some of the most exciting potential benefits of our EHRs – population health, enhanced data on medication adherence, and improved patient communication. As we look at this next stage of growth, we are reminded of a lesson from an old joke:

A rabbi dies and goes to heaven. When he gets there he is given an old robe and a wooden walking stick and is told to get in line to the entrance to heaven. While the rabbi waits in the long line, a taxi driver walks up and is greeted by a group of angels blowing their horns announcing his arrival. One of the angels walks over to the driver and gives him a flowing white satin robe and a golden walking stick. Another angel then escorts him to the front of the line.

The angel turned toward him, smiled, and shook his head. “Yes, yes,” the angel replied, “We know all that. But, here in heaven we care about results, not intent. While you gave your sermons, people slept. When the cab driver drove, people prayed.”

As we look ahead to the next generation of electronic health records, there are going to be many creative ideas of how to use them to help patients improve their health and take care of their diseases. One of the more notable new technologies over the last 5 years is the development of wearable health devices. Innovations like the Apple Watch, Fitbit, and other wearables allow us to track our activity and diet, and encourage us to behave better. They do this by providing constant feedback on how we are doing, and they offer the ability to use social groups to encourage sustained behavioral change. Some devices tell us regularly how far we have walked while others let us know when we have been sitting too long. As we input information about diet, the devices and their associated apps give us feedback on how we are adhering to our dietary goals. Some even allow data to be funneled into the EHR so that physicians can review the behavioral changes and track patient progress. The challenge that arises is that the technology itself is so fascinating and so filled with promise that it is easy to forget what is most important: ensuring it works not just to keep us engaged and busy but also to help us accomplish the real goals we have defined for its use.

Wearable technology is now the most recent and dramatic example of how the excitement over technology may be outpacing its utility. Most of us have tried (or have patients, friends and family who have tried) wearable technology solutions to track and encourage behavioral change. A recent article published in JAMA looked at more than 400 individuals randomized to a standard behavioral weight-loss intervention vs. a technology-enhanced weight loss intervention using a wearable device over 24 months. It was fairly obvious that the group with the wearable device would do better, and have improved fitness and more weight loss. It was obvious … except that is not what happened. Both groups improved equally in fitness, and the standard intervention group lost significantly more weight over 24 months than did the wearable technology group.

There are many reasons that this might have happened. It may be that the idea of this quick feedback loop is in itself flawed, or it may be that the devices and/or the dietary input is simply imprecise, causing people to think that they are doing better than they really are (and then modifying their behavior in the wrong direction). Whatever the explanation, seeing those results, I think again of the moral handed down though generations by that old joke – that here on earth we need to care less about intent and more about results.

Reference

Jakicic JM, et al. Effect of Wearable Technology Combined With a Lifestyle Intervention on Long-term Weight Loss The IDEA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316[11]:1161-71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12858

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

We live inundated with promises that technology will solve our most challenging problems, yet we are regularly disappointed when it does not. New technological solutions seem to appear daily, and we feel like we are falling behind if we do not jump to join the people who are implementing, selling, or imposing new solutions. Often these solutions are offered before the problem is even fully understood, and no assessment has been made to determine if the solution actually helps to solve the challenge identified. With 80% of us now having transitioned to EHRs, we know full well their benefits as well as their pitfalls. While we have mostly accommodated to electronic documentation, we are now at the point where we are beginning to explore some of the most exciting potential benefits of our EHRs – population health, enhanced data on medication adherence, and improved patient communication. As we look at this next stage of growth, we are reminded of a lesson from an old joke:

A rabbi dies and goes to heaven. When he gets there he is given an old robe and a wooden walking stick and is told to get in line to the entrance to heaven. While the rabbi waits in the long line, a taxi driver walks up and is greeted by a group of angels blowing their horns announcing his arrival. One of the angels walks over to the driver and gives him a flowing white satin robe and a golden walking stick. Another angel then escorts him to the front of the line.

The angel turned toward him, smiled, and shook his head. “Yes, yes,” the angel replied, “We know all that. But, here in heaven we care about results, not intent. While you gave your sermons, people slept. When the cab driver drove, people prayed.”

As we look ahead to the next generation of electronic health records, there are going to be many creative ideas of how to use them to help patients improve their health and take care of their diseases. One of the more notable new technologies over the last 5 years is the development of wearable health devices. Innovations like the Apple Watch, Fitbit, and other wearables allow us to track our activity and diet, and encourage us to behave better. They do this by providing constant feedback on how we are doing, and they offer the ability to use social groups to encourage sustained behavioral change. Some devices tell us regularly how far we have walked while others let us know when we have been sitting too long. As we input information about diet, the devices and their associated apps give us feedback on how we are adhering to our dietary goals. Some even allow data to be funneled into the EHR so that physicians can review the behavioral changes and track patient progress. The challenge that arises is that the technology itself is so fascinating and so filled with promise that it is easy to forget what is most important: ensuring it works not just to keep us engaged and busy but also to help us accomplish the real goals we have defined for its use.

Wearable technology is now the most recent and dramatic example of how the excitement over technology may be outpacing its utility. Most of us have tried (or have patients, friends and family who have tried) wearable technology solutions to track and encourage behavioral change. A recent article published in JAMA looked at more than 400 individuals randomized to a standard behavioral weight-loss intervention vs. a technology-enhanced weight loss intervention using a wearable device over 24 months. It was fairly obvious that the group with the wearable device would do better, and have improved fitness and more weight loss. It was obvious … except that is not what happened. Both groups improved equally in fitness, and the standard intervention group lost significantly more weight over 24 months than did the wearable technology group.

There are many reasons that this might have happened. It may be that the idea of this quick feedback loop is in itself flawed, or it may be that the devices and/or the dietary input is simply imprecise, causing people to think that they are doing better than they really are (and then modifying their behavior in the wrong direction). Whatever the explanation, seeing those results, I think again of the moral handed down though generations by that old joke – that here on earth we need to care less about intent and more about results.

Reference

Jakicic JM, et al. Effect of Wearable Technology Combined With a Lifestyle Intervention on Long-term Weight Loss The IDEA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316[11]:1161-71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12858

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

We live inundated with promises that technology will solve our most challenging problems, yet we are regularly disappointed when it does not. New technological solutions seem to appear daily, and we feel like we are falling behind if we do not jump to join the people who are implementing, selling, or imposing new solutions. Often these solutions are offered before the problem is even fully understood, and no assessment has been made to determine if the solution actually helps to solve the challenge identified. With 80% of us now having transitioned to EHRs, we know full well their benefits as well as their pitfalls. While we have mostly accommodated to electronic documentation, we are now at the point where we are beginning to explore some of the most exciting potential benefits of our EHRs – population health, enhanced data on medication adherence, and improved patient communication. As we look at this next stage of growth, we are reminded of a lesson from an old joke:

A rabbi dies and goes to heaven. When he gets there he is given an old robe and a wooden walking stick and is told to get in line to the entrance to heaven. While the rabbi waits in the long line, a taxi driver walks up and is greeted by a group of angels blowing their horns announcing his arrival. One of the angels walks over to the driver and gives him a flowing white satin robe and a golden walking stick. Another angel then escorts him to the front of the line.

The angel turned toward him, smiled, and shook his head. “Yes, yes,” the angel replied, “We know all that. But, here in heaven we care about results, not intent. While you gave your sermons, people slept. When the cab driver drove, people prayed.”

As we look ahead to the next generation of electronic health records, there are going to be many creative ideas of how to use them to help patients improve their health and take care of their diseases. One of the more notable new technologies over the last 5 years is the development of wearable health devices. Innovations like the Apple Watch, Fitbit, and other wearables allow us to track our activity and diet, and encourage us to behave better. They do this by providing constant feedback on how we are doing, and they offer the ability to use social groups to encourage sustained behavioral change. Some devices tell us regularly how far we have walked while others let us know when we have been sitting too long. As we input information about diet, the devices and their associated apps give us feedback on how we are adhering to our dietary goals. Some even allow data to be funneled into the EHR so that physicians can review the behavioral changes and track patient progress. The challenge that arises is that the technology itself is so fascinating and so filled with promise that it is easy to forget what is most important: ensuring it works not just to keep us engaged and busy but also to help us accomplish the real goals we have defined for its use.

Wearable technology is now the most recent and dramatic example of how the excitement over technology may be outpacing its utility. Most of us have tried (or have patients, friends and family who have tried) wearable technology solutions to track and encourage behavioral change. A recent article published in JAMA looked at more than 400 individuals randomized to a standard behavioral weight-loss intervention vs. a technology-enhanced weight loss intervention using a wearable device over 24 months. It was fairly obvious that the group with the wearable device would do better, and have improved fitness and more weight loss. It was obvious … except that is not what happened. Both groups improved equally in fitness, and the standard intervention group lost significantly more weight over 24 months than did the wearable technology group.

There are many reasons that this might have happened. It may be that the idea of this quick feedback loop is in itself flawed, or it may be that the devices and/or the dietary input is simply imprecise, causing people to think that they are doing better than they really are (and then modifying their behavior in the wrong direction). Whatever the explanation, seeing those results, I think again of the moral handed down though generations by that old joke – that here on earth we need to care less about intent and more about results.

Reference

Jakicic JM, et al. Effect of Wearable Technology Combined With a Lifestyle Intervention on Long-term Weight Loss The IDEA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316[11]:1161-71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12858

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

What Makes Feedback Productive?

When my youngest daughter returns home from acting or dancing rehearsals, she talks about “notes” that she or the company received that day. Discussing them with her, I appreciate that giving notes to performers after rehearsal or even after a show is standard theater practice. The notes may be from the assistant stage director commenting on lines that were missed, mangled, or perfected. They also could be from the director concerning stage position or behaviors, or they may be about character development or a clarification about the emotions in a particular scene. They are written out as specific references to a certain line or segment of the script. Some directors write them on sticky memos so that they can actually be added to the actor’s script. Others keep their notes on index cards that can be sorted and handed out to the designated performer. My daughter works hard during the first part of the rehearsal process to get as few notes as possible, but at the end of the rehearsal process or during the run of the show, she likes getting notes as a reflection of how she is being perceived and to facilitate fine-tuning her performance.

Giving written notes in our offices to our colleagues, trainees, and staff after a day’s work is not likely to be productive; however, there are parts of this process that dermatologists can utilize. The notes give feedback that is timely and specific. They can be given to individuals or to the entire troupe. I also noticed that my daughter appeared to have a positive relationship with the note givers and looked for their feedback to improve her performance. When residents are on a procedural rotation with me, I endeavor to give them feedback every day about some part of their surgical technique to help them finesse their skills. I am not, however, as rigorous about giving feedback concerning other aspects of the practice, and so this editorial serves the purpose of reminding me that giving feedback is an important skill that we can and should use on a daily basis.

There are many guides for giving feedback. The Center for Creative Leadership developed a feedback technique called Situation-Behavior-Impact (S-B-I).1 Similar to performance notes, it is simple, direct, and timely. Step 1: Capture the situation (S). Step 2: Describe the behavior (B). Step 3: Deliver the impact (I). For example, I have given the following feedback to many fellows when they are working with the resident: (S) “This morning when you two were finishing the repair, (B) you were talking about the lack of efficiency of the clinic in another hospital. (I) It made me uncomfortable because I believe the patient is the center of attention, and yet this was not a conversation that included him. I also worried that he would become nervous or anxious to hear about problems in a medical facility.” Another conversation could go: (S) “This morning with the patient with the eyelid tumor, (B) you told the patient that you would send the eye surgeon a photo so she could be prepared for the repair, and (I) I noticed the patient’s hands immediately relaxed.”

These are straightforward examples. There are more complicated situations that seem to require longer analysis; however, if we acquire the habit of immediate and specific feedback, there will be less need for more difficult conversations. Situation-Behavior-Impact is about behavior; it is not judgmental of the person, and it leaves room for the recipient to think about what happened without being defensive and to take action to create productive behaviors and improve performance. The Center for Creative Leadership recommends that feedback be framed as an observation, which further diminishes the development of a defensive rejection of the information.1

Feedback is such an important loop for all of us professionally and personally because it is the mechanism that gives us the opportunity to improve our performance, so why don’t we always hear it in a constructive thought-provoking way? Stone and Heen2 point out 3 triggers that escalate rejection of feedback: truth, relationship, and identity. They also can be described as immediate reactions: “You are wrong about your assessment,” “I don’t like you anyway,” and “You’re messing with who I am.” For those of you who want to up your game in any of your professional or personal arenas, Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well2 will open you up to seek out and take in feedback. Feedback-seeking behavior has been linked to higher job satisfaction, greater creativity on the job, and faster adaptation to change, while negative feedback has been linked to improved job performance.3 Interestingly, it also helps in our personal lives; a husband’s openness to influence and

In an effort to decrease resistance to hearing feedback, there are proponents of the sandwich technique in which a positive comment is made, then the negative feedback is given, followed by another positive comment. In my experience, this technique does not work. First, you have to give some thought to the appropriate items to bring to the discussion, so the conversation might be delayed long enough to obscure the memory of the details involved in the situations. Second, if you employ it often, the receiver tenses up with the first positive comment, knowing a negative comment will ensue, and so he/she is primed to reject the feedback before it is even offered. Finally, it confuses the priorities for the conversation. However, working over time to give more positive feedback than negative feedback (an average of 4–5 to 1) allows for the development of trust and mutual respect and quiets the urge to immediately reject the negative messages. In my experience, positive feedback is especially effective in creating engagement as well as validating and promoting desirable behaviors. Physicians may have to work deliberately to offer positive feedback because it is more natural for us to diagnose problems than to identify good health.

What impresses me most about the theater culture surrounding notes is that giving and receiving feedback is an expected element of the artistic process. As practitioners, wouldn’t we as well as our patients benefit if the culture of medicine also expected that we were giving each other feedback on a daily basis?

- Weitzel SR. Feedback That Works: How to Build and Deliver Your Message. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership; 2000.

- Stone D, Heen S. Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2015:16-30.

- Crommelinck M, Anseel F. Understanding and encouraging feedback-seeking behavior: a literature review. Med Educ. 2013;47:232-241.

- Carrère S, Buehlman KT, Gottman JM, et al. Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. J Fam Psychol. 2000;14:42-58.

When my youngest daughter returns home from acting or dancing rehearsals, she talks about “notes” that she or the company received that day. Discussing them with her, I appreciate that giving notes to performers after rehearsal or even after a show is standard theater practice. The notes may be from the assistant stage director commenting on lines that were missed, mangled, or perfected. They also could be from the director concerning stage position or behaviors, or they may be about character development or a clarification about the emotions in a particular scene. They are written out as specific references to a certain line or segment of the script. Some directors write them on sticky memos so that they can actually be added to the actor’s script. Others keep their notes on index cards that can be sorted and handed out to the designated performer. My daughter works hard during the first part of the rehearsal process to get as few notes as possible, but at the end of the rehearsal process or during the run of the show, she likes getting notes as a reflection of how she is being perceived and to facilitate fine-tuning her performance.

Giving written notes in our offices to our colleagues, trainees, and staff after a day’s work is not likely to be productive; however, there are parts of this process that dermatologists can utilize. The notes give feedback that is timely and specific. They can be given to individuals or to the entire troupe. I also noticed that my daughter appeared to have a positive relationship with the note givers and looked for their feedback to improve her performance. When residents are on a procedural rotation with me, I endeavor to give them feedback every day about some part of their surgical technique to help them finesse their skills. I am not, however, as rigorous about giving feedback concerning other aspects of the practice, and so this editorial serves the purpose of reminding me that giving feedback is an important skill that we can and should use on a daily basis.

There are many guides for giving feedback. The Center for Creative Leadership developed a feedback technique called Situation-Behavior-Impact (S-B-I).1 Similar to performance notes, it is simple, direct, and timely. Step 1: Capture the situation (S). Step 2: Describe the behavior (B). Step 3: Deliver the impact (I). For example, I have given the following feedback to many fellows when they are working with the resident: (S) “This morning when you two were finishing the repair, (B) you were talking about the lack of efficiency of the clinic in another hospital. (I) It made me uncomfortable because I believe the patient is the center of attention, and yet this was not a conversation that included him. I also worried that he would become nervous or anxious to hear about problems in a medical facility.” Another conversation could go: (S) “This morning with the patient with the eyelid tumor, (B) you told the patient that you would send the eye surgeon a photo so she could be prepared for the repair, and (I) I noticed the patient’s hands immediately relaxed.”

These are straightforward examples. There are more complicated situations that seem to require longer analysis; however, if we acquire the habit of immediate and specific feedback, there will be less need for more difficult conversations. Situation-Behavior-Impact is about behavior; it is not judgmental of the person, and it leaves room for the recipient to think about what happened without being defensive and to take action to create productive behaviors and improve performance. The Center for Creative Leadership recommends that feedback be framed as an observation, which further diminishes the development of a defensive rejection of the information.1

Feedback is such an important loop for all of us professionally and personally because it is the mechanism that gives us the opportunity to improve our performance, so why don’t we always hear it in a constructive thought-provoking way? Stone and Heen2 point out 3 triggers that escalate rejection of feedback: truth, relationship, and identity. They also can be described as immediate reactions: “You are wrong about your assessment,” “I don’t like you anyway,” and “You’re messing with who I am.” For those of you who want to up your game in any of your professional or personal arenas, Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well2 will open you up to seek out and take in feedback. Feedback-seeking behavior has been linked to higher job satisfaction, greater creativity on the job, and faster adaptation to change, while negative feedback has been linked to improved job performance.3 Interestingly, it also helps in our personal lives; a husband’s openness to influence and

In an effort to decrease resistance to hearing feedback, there are proponents of the sandwich technique in which a positive comment is made, then the negative feedback is given, followed by another positive comment. In my experience, this technique does not work. First, you have to give some thought to the appropriate items to bring to the discussion, so the conversation might be delayed long enough to obscure the memory of the details involved in the situations. Second, if you employ it often, the receiver tenses up with the first positive comment, knowing a negative comment will ensue, and so he/she is primed to reject the feedback before it is even offered. Finally, it confuses the priorities for the conversation. However, working over time to give more positive feedback than negative feedback (an average of 4–5 to 1) allows for the development of trust and mutual respect and quiets the urge to immediately reject the negative messages. In my experience, positive feedback is especially effective in creating engagement as well as validating and promoting desirable behaviors. Physicians may have to work deliberately to offer positive feedback because it is more natural for us to diagnose problems than to identify good health.

What impresses me most about the theater culture surrounding notes is that giving and receiving feedback is an expected element of the artistic process. As practitioners, wouldn’t we as well as our patients benefit if the culture of medicine also expected that we were giving each other feedback on a daily basis?

When my youngest daughter returns home from acting or dancing rehearsals, she talks about “notes” that she or the company received that day. Discussing them with her, I appreciate that giving notes to performers after rehearsal or even after a show is standard theater practice. The notes may be from the assistant stage director commenting on lines that were missed, mangled, or perfected. They also could be from the director concerning stage position or behaviors, or they may be about character development or a clarification about the emotions in a particular scene. They are written out as specific references to a certain line or segment of the script. Some directors write them on sticky memos so that they can actually be added to the actor’s script. Others keep their notes on index cards that can be sorted and handed out to the designated performer. My daughter works hard during the first part of the rehearsal process to get as few notes as possible, but at the end of the rehearsal process or during the run of the show, she likes getting notes as a reflection of how she is being perceived and to facilitate fine-tuning her performance.

Giving written notes in our offices to our colleagues, trainees, and staff after a day’s work is not likely to be productive; however, there are parts of this process that dermatologists can utilize. The notes give feedback that is timely and specific. They can be given to individuals or to the entire troupe. I also noticed that my daughter appeared to have a positive relationship with the note givers and looked for their feedback to improve her performance. When residents are on a procedural rotation with me, I endeavor to give them feedback every day about some part of their surgical technique to help them finesse their skills. I am not, however, as rigorous about giving feedback concerning other aspects of the practice, and so this editorial serves the purpose of reminding me that giving feedback is an important skill that we can and should use on a daily basis.

There are many guides for giving feedback. The Center for Creative Leadership developed a feedback technique called Situation-Behavior-Impact (S-B-I).1 Similar to performance notes, it is simple, direct, and timely. Step 1: Capture the situation (S). Step 2: Describe the behavior (B). Step 3: Deliver the impact (I). For example, I have given the following feedback to many fellows when they are working with the resident: (S) “This morning when you two were finishing the repair, (B) you were talking about the lack of efficiency of the clinic in another hospital. (I) It made me uncomfortable because I believe the patient is the center of attention, and yet this was not a conversation that included him. I also worried that he would become nervous or anxious to hear about problems in a medical facility.” Another conversation could go: (S) “This morning with the patient with the eyelid tumor, (B) you told the patient that you would send the eye surgeon a photo so she could be prepared for the repair, and (I) I noticed the patient’s hands immediately relaxed.”

These are straightforward examples. There are more complicated situations that seem to require longer analysis; however, if we acquire the habit of immediate and specific feedback, there will be less need for more difficult conversations. Situation-Behavior-Impact is about behavior; it is not judgmental of the person, and it leaves room for the recipient to think about what happened without being defensive and to take action to create productive behaviors and improve performance. The Center for Creative Leadership recommends that feedback be framed as an observation, which further diminishes the development of a defensive rejection of the information.1

Feedback is such an important loop for all of us professionally and personally because it is the mechanism that gives us the opportunity to improve our performance, so why don’t we always hear it in a constructive thought-provoking way? Stone and Heen2 point out 3 triggers that escalate rejection of feedback: truth, relationship, and identity. They also can be described as immediate reactions: “You are wrong about your assessment,” “I don’t like you anyway,” and “You’re messing with who I am.” For those of you who want to up your game in any of your professional or personal arenas, Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well2 will open you up to seek out and take in feedback. Feedback-seeking behavior has been linked to higher job satisfaction, greater creativity on the job, and faster adaptation to change, while negative feedback has been linked to improved job performance.3 Interestingly, it also helps in our personal lives; a husband’s openness to influence and

In an effort to decrease resistance to hearing feedback, there are proponents of the sandwich technique in which a positive comment is made, then the negative feedback is given, followed by another positive comment. In my experience, this technique does not work. First, you have to give some thought to the appropriate items to bring to the discussion, so the conversation might be delayed long enough to obscure the memory of the details involved in the situations. Second, if you employ it often, the receiver tenses up with the first positive comment, knowing a negative comment will ensue, and so he/she is primed to reject the feedback before it is even offered. Finally, it confuses the priorities for the conversation. However, working over time to give more positive feedback than negative feedback (an average of 4–5 to 1) allows for the development of trust and mutual respect and quiets the urge to immediately reject the negative messages. In my experience, positive feedback is especially effective in creating engagement as well as validating and promoting desirable behaviors. Physicians may have to work deliberately to offer positive feedback because it is more natural for us to diagnose problems than to identify good health.

What impresses me most about the theater culture surrounding notes is that giving and receiving feedback is an expected element of the artistic process. As practitioners, wouldn’t we as well as our patients benefit if the culture of medicine also expected that we were giving each other feedback on a daily basis?

- Weitzel SR. Feedback That Works: How to Build and Deliver Your Message. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership; 2000.

- Stone D, Heen S. Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2015:16-30.

- Crommelinck M, Anseel F. Understanding and encouraging feedback-seeking behavior: a literature review. Med Educ. 2013;47:232-241.

- Carrère S, Buehlman KT, Gottman JM, et al. Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. J Fam Psychol. 2000;14:42-58.

- Weitzel SR. Feedback That Works: How to Build and Deliver Your Message. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership; 2000.

- Stone D, Heen S. Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2015:16-30.

- Crommelinck M, Anseel F. Understanding and encouraging feedback-seeking behavior: a literature review. Med Educ. 2013;47:232-241.

- Carrère S, Buehlman KT, Gottman JM, et al. Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. J Fam Psychol. 2000;14:42-58.

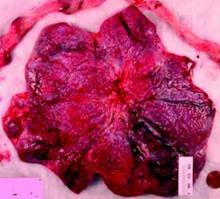

Sentinel lymph node technique in endometrial cancer, Part 2

As reviewed in Part 1, surgery is indicated for the staging and treatment of endometrial cancer. Lymph node status is one of the most important factors in determining prognosis and the need for adjuvant treatment. The extent of lymph node evaluation is controversial as full lymphadenectomy carries risks, including increased operative time, blood loss, nerve injury, and lymphedema.

Two trials have found no survival benefit from lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer; however, other evidence suggests that women without known nodal status may be more likely to receive radiotherapy.1,2,3

Given these issues, the sentinel lymph node technique strikes a balance between the risks and benefits of lymph node evaluation in endometrial cancer.

Sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) are the first nodes to drain a tumor site, and thus, are typically the first to demonstrate occult malignancy. The use of the SLN technique as an alternative to complete lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer has been well described, although its accuracy and the validity of its use are still debated.

The viability of the SLN technique is predicated on the ability to achieve mapping of dye or tracer from the tumor to the first lymph node to drain the tumor. The lymphatic drainage of the endometrium is complex and unlike vulvar or breast cancer, endometrial cancer is less accessible for peritumoral injection. Several injection techniques have been described; cervical injection is the easiest to achieve and has been found to have similar or higher SLN detection than hysteroscopic or fundal injections.4,5

There are a number of techniques for SLN detection, each with unique benefits and risks. Visual identification of blue dye, most frequently isosulfan blue, is the “colorimetric method” and has been used most commonly with cervical injection for endometrial cancer. Injection of isosulfan blue does not require specialized equipment, however visualization in obese patients is inferior.6

Technetium sulfur colloid (Tc) is a radioactive tracer that can be detected by gamma probes. A preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and a handheld gamma probe are used to map lymphatics. This technique has limitations, including the additional time and coordination of procedures, as well as some evidence of poor correlation between lymphoscintigraphy and surgical SLN mapping.7

Indocyanine green (ICG) is a fluorescent dye that has excellent signal penetration and allows for real-time visual identification using near-infrared fluorescence imaging. The bilateral detection rate with ICG appears comparable or better than blue dye.8 Combinations of dye, either ICG plus Tc or Tc plus blue dye, may be also used to increase SLN detection.

The accuracy of the SLN technique is the cornerstone to its success. In a prospective multicenter study – Senti-Endo – patients with early-stage disease underwent pelvic SLN assessment with cervical injection of a combination of dyes followed by systematic pelvic node dissection. The overall negative predictive value was 97% with three patients who had positive lymph nodes that were not detected, all of whom had a type 2 endometrial cancer.9

With the uptake of the SLN technique, many institutions have protocols surrounding the technique to ensure appropriate SLN detection and evaluation. Physicians using this technique should adhere to protocols supported by National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, taking care to remove any suspicious lymph nodes and perform a full side-specific lymphadenectomy if bilateral mapping is not achieved.

The extent of lymphadenectomy and application of the SLN technique in high-risk endometrial cancer remains controversial. These patients are at higher risk for unsuccessful mapping and isolated para-aortic metastasis. Retrospective series have suggested equivalent oncologic outcomes for women with high-grade cancers who have been staged by SLN biopsy, compared with selective or complete lymphadenectomy.10,11

We await the results of a large prospective trial in which patients undergo comprehensive lymphadenectomy in addition to SLN biopsy to assess the accuracy of the technique (NCT01673022).

Pathologic evaluation of SLNs is frequently done with ultrastaging, which describes additional sectioning and staining of the node. This technique frequently identifies isolated tumor cells and micrometastasis (collectively called low-volume disease) in addition to macrometastasis. The clinical and prognostic significance of low-volume disease is unknown and additional investigation is urgently needed to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and follow-up for these patients.

The SLN technique is an acceptable approach to assess clinical stage I endometrial cancer. Physicians should consider adding the SLN biopsy to their routine staging techniques prior to exclusively adopting the new technique. They should take care to adhere to SLN algorithms and monitor outcomes.

References

1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1707-16.

2. Lancet. 2009 Jan;373(9658):125-36.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;205(6):562.e1–9.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 Nov;131(2):299-303.

5. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Nov;23(9):1704-11.

6. Gynecol Oncol 2014 Aug;134(2):281-6.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Feb;112(2):348-352.

8. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 May;133(2):274-7.

9. Lancet Oncol. 2011 May;12(5):469-76.

10. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Jan;23(1):196-202.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Mar;140(3):394-9.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Sullivan is a clinical fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi and Dr. Sullivan reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

As reviewed in Part 1, surgery is indicated for the staging and treatment of endometrial cancer. Lymph node status is one of the most important factors in determining prognosis and the need for adjuvant treatment. The extent of lymph node evaluation is controversial as full lymphadenectomy carries risks, including increased operative time, blood loss, nerve injury, and lymphedema.

Two trials have found no survival benefit from lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer; however, other evidence suggests that women without known nodal status may be more likely to receive radiotherapy.1,2,3

Given these issues, the sentinel lymph node technique strikes a balance between the risks and benefits of lymph node evaluation in endometrial cancer.

Sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) are the first nodes to drain a tumor site, and thus, are typically the first to demonstrate occult malignancy. The use of the SLN technique as an alternative to complete lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer has been well described, although its accuracy and the validity of its use are still debated.

The viability of the SLN technique is predicated on the ability to achieve mapping of dye or tracer from the tumor to the first lymph node to drain the tumor. The lymphatic drainage of the endometrium is complex and unlike vulvar or breast cancer, endometrial cancer is less accessible for peritumoral injection. Several injection techniques have been described; cervical injection is the easiest to achieve and has been found to have similar or higher SLN detection than hysteroscopic or fundal injections.4,5

There are a number of techniques for SLN detection, each with unique benefits and risks. Visual identification of blue dye, most frequently isosulfan blue, is the “colorimetric method” and has been used most commonly with cervical injection for endometrial cancer. Injection of isosulfan blue does not require specialized equipment, however visualization in obese patients is inferior.6

Technetium sulfur colloid (Tc) is a radioactive tracer that can be detected by gamma probes. A preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and a handheld gamma probe are used to map lymphatics. This technique has limitations, including the additional time and coordination of procedures, as well as some evidence of poor correlation between lymphoscintigraphy and surgical SLN mapping.7

Indocyanine green (ICG) is a fluorescent dye that has excellent signal penetration and allows for real-time visual identification using near-infrared fluorescence imaging. The bilateral detection rate with ICG appears comparable or better than blue dye.8 Combinations of dye, either ICG plus Tc or Tc plus blue dye, may be also used to increase SLN detection.

The accuracy of the SLN technique is the cornerstone to its success. In a prospective multicenter study – Senti-Endo – patients with early-stage disease underwent pelvic SLN assessment with cervical injection of a combination of dyes followed by systematic pelvic node dissection. The overall negative predictive value was 97% with three patients who had positive lymph nodes that were not detected, all of whom had a type 2 endometrial cancer.9

With the uptake of the SLN technique, many institutions have protocols surrounding the technique to ensure appropriate SLN detection and evaluation. Physicians using this technique should adhere to protocols supported by National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, taking care to remove any suspicious lymph nodes and perform a full side-specific lymphadenectomy if bilateral mapping is not achieved.

The extent of lymphadenectomy and application of the SLN technique in high-risk endometrial cancer remains controversial. These patients are at higher risk for unsuccessful mapping and isolated para-aortic metastasis. Retrospective series have suggested equivalent oncologic outcomes for women with high-grade cancers who have been staged by SLN biopsy, compared with selective or complete lymphadenectomy.10,11

We await the results of a large prospective trial in which patients undergo comprehensive lymphadenectomy in addition to SLN biopsy to assess the accuracy of the technique (NCT01673022).

Pathologic evaluation of SLNs is frequently done with ultrastaging, which describes additional sectioning and staining of the node. This technique frequently identifies isolated tumor cells and micrometastasis (collectively called low-volume disease) in addition to macrometastasis. The clinical and prognostic significance of low-volume disease is unknown and additional investigation is urgently needed to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and follow-up for these patients.

The SLN technique is an acceptable approach to assess clinical stage I endometrial cancer. Physicians should consider adding the SLN biopsy to their routine staging techniques prior to exclusively adopting the new technique. They should take care to adhere to SLN algorithms and monitor outcomes.

References

1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1707-16.

2. Lancet. 2009 Jan;373(9658):125-36.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;205(6):562.e1–9.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 Nov;131(2):299-303.

5. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Nov;23(9):1704-11.

6. Gynecol Oncol 2014 Aug;134(2):281-6.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Feb;112(2):348-352.

8. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 May;133(2):274-7.

9. Lancet Oncol. 2011 May;12(5):469-76.

10. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Jan;23(1):196-202.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Mar;140(3):394-9.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Sullivan is a clinical fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi and Dr. Sullivan reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

As reviewed in Part 1, surgery is indicated for the staging and treatment of endometrial cancer. Lymph node status is one of the most important factors in determining prognosis and the need for adjuvant treatment. The extent of lymph node evaluation is controversial as full lymphadenectomy carries risks, including increased operative time, blood loss, nerve injury, and lymphedema.

Two trials have found no survival benefit from lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer; however, other evidence suggests that women without known nodal status may be more likely to receive radiotherapy.1,2,3

Given these issues, the sentinel lymph node technique strikes a balance between the risks and benefits of lymph node evaluation in endometrial cancer.

Sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) are the first nodes to drain a tumor site, and thus, are typically the first to demonstrate occult malignancy. The use of the SLN technique as an alternative to complete lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer has been well described, although its accuracy and the validity of its use are still debated.

The viability of the SLN technique is predicated on the ability to achieve mapping of dye or tracer from the tumor to the first lymph node to drain the tumor. The lymphatic drainage of the endometrium is complex and unlike vulvar or breast cancer, endometrial cancer is less accessible for peritumoral injection. Several injection techniques have been described; cervical injection is the easiest to achieve and has been found to have similar or higher SLN detection than hysteroscopic or fundal injections.4,5

There are a number of techniques for SLN detection, each with unique benefits and risks. Visual identification of blue dye, most frequently isosulfan blue, is the “colorimetric method” and has been used most commonly with cervical injection for endometrial cancer. Injection of isosulfan blue does not require specialized equipment, however visualization in obese patients is inferior.6

Technetium sulfur colloid (Tc) is a radioactive tracer that can be detected by gamma probes. A preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and a handheld gamma probe are used to map lymphatics. This technique has limitations, including the additional time and coordination of procedures, as well as some evidence of poor correlation between lymphoscintigraphy and surgical SLN mapping.7

Indocyanine green (ICG) is a fluorescent dye that has excellent signal penetration and allows for real-time visual identification using near-infrared fluorescence imaging. The bilateral detection rate with ICG appears comparable or better than blue dye.8 Combinations of dye, either ICG plus Tc or Tc plus blue dye, may be also used to increase SLN detection.

The accuracy of the SLN technique is the cornerstone to its success. In a prospective multicenter study – Senti-Endo – patients with early-stage disease underwent pelvic SLN assessment with cervical injection of a combination of dyes followed by systematic pelvic node dissection. The overall negative predictive value was 97% with three patients who had positive lymph nodes that were not detected, all of whom had a type 2 endometrial cancer.9

With the uptake of the SLN technique, many institutions have protocols surrounding the technique to ensure appropriate SLN detection and evaluation. Physicians using this technique should adhere to protocols supported by National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, taking care to remove any suspicious lymph nodes and perform a full side-specific lymphadenectomy if bilateral mapping is not achieved.

The extent of lymphadenectomy and application of the SLN technique in high-risk endometrial cancer remains controversial. These patients are at higher risk for unsuccessful mapping and isolated para-aortic metastasis. Retrospective series have suggested equivalent oncologic outcomes for women with high-grade cancers who have been staged by SLN biopsy, compared with selective or complete lymphadenectomy.10,11

We await the results of a large prospective trial in which patients undergo comprehensive lymphadenectomy in addition to SLN biopsy to assess the accuracy of the technique (NCT01673022).

Pathologic evaluation of SLNs is frequently done with ultrastaging, which describes additional sectioning and staining of the node. This technique frequently identifies isolated tumor cells and micrometastasis (collectively called low-volume disease) in addition to macrometastasis. The clinical and prognostic significance of low-volume disease is unknown and additional investigation is urgently needed to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and follow-up for these patients.

The SLN technique is an acceptable approach to assess clinical stage I endometrial cancer. Physicians should consider adding the SLN biopsy to their routine staging techniques prior to exclusively adopting the new technique. They should take care to adhere to SLN algorithms and monitor outcomes.

References

1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1707-16.

2. Lancet. 2009 Jan;373(9658):125-36.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;205(6):562.e1–9.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 Nov;131(2):299-303.

5. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Nov;23(9):1704-11.

6. Gynecol Oncol 2014 Aug;134(2):281-6.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Feb;112(2):348-352.

8. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 May;133(2):274-7.

9. Lancet Oncol. 2011 May;12(5):469-76.

10. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Jan;23(1):196-202.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Mar;140(3):394-9.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Sullivan is a clinical fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi and Dr. Sullivan reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

New FASD diagnosis guidelines: Comprehensive or overly broad?

One of the most challenging elements in making a diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders is obtaining a thorough history of the mother’s drinking during pregnancy. This is something that ob.gyns. have struggled with for many years, and while there are ways to improve the collection of this information, it’s often an uncomfortable conversation that yields unreliable answers.

In August, a group of experts on fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), organized by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, proposed new clinical guidelines for diagnosing these disorders, the first update since 2005 (Pediatrics. 2016;138[2]:e20154256). The update creates a more inclusive definition of FASD and puts a greater emphasis on the sometimes subtle physical and behavioral changes that occur in children.

Growth restriction

The updated diagnosis begins with the acknowledgment of maternal drinking during pregnancy and growth restriction in the infant, which the new guidelines set at the 10th percentile. That’s an important change because it significantly increases sensitivity, expanding the number of infants who could be diagnosed by raising the growth restriction threshold from the third percentile. Clinicians must take into account other factors, such as the size of the natural parents and whether growth restriction could be caused by other conditions.

Facial changes

A key component on the FASD diagnosis is the assessment of facial changes. The three typical facial changes that have been used to make this diagnosis since the 1970s include short palpebral fissures, a shallow or lack of philtrum, and a thin vermilion border of the upper lip. Previously, if all three of these facial features were present, a history of maternal drinking was not needed in the diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome. If two of the three features were present, it was considered partial fetal alcohol syndrome. Now, if maternal drinking has been determined, it’s not necessary to have all three facial features to make a diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome.

For the first time, the guidelines describe other facial changes common in FASD that can be used to diagnose partial fetal alcohol syndrome, including a flat nasal bridge, epicanthal folds, and other signs. Again, the guidelines increase sensitivity and make it likely that more cases will be picked up through these criteria.

Neurobehavioral changes

The most devastating part of FASD are the complex neurobehavioral changes, resulting from damage to the fetal brain. Under the updated guidelines, the authors relaxed the criteria so that children can be diagnosed if they have domains of either intellectual impairment or behavioral changes that are 1.5 standard deviations below the age-adjusted mean, rather than the previous 2 standard deviations.

The challenge with making this change is that unlike with the facial changes, there’s a lack of specificity in assessing intellectual impairment and behavioral changes. In addition, these issues often emerge with other conditions unrelated to fetal exposure to alcohol.

Sensitivity vs. specificity

Statistically, the authors of the updated guidelines have moved to increase sensitivity, reaching more children who need interventions for the devastating manifestations of FASD. But the price of this expansion of the diagnostic criteria is a decrease in specificity. The authors seek to combat this potential lack of specificity by emphasizing that an FASD diagnosis should be made not by a single clinician but by a multidisciplinary team that includes physicians, a psychologist, social worker, and speech and language specialists.

While a specialized team will certainly help to make a better diagnosis, the literature shows very large variability in obtaining FASD diagnosis by using different guidelines. A May 2016 paper in Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research found wide diagnostic variation of between roughly 5% (using guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and 60% (using 2006 guidelines from Hoyme et al.) in the same group of alcohol- and drug-exposed children, when five different guidelines were used (doi: 10.1111/acer.13032). This type of variation would not be acceptable in other conditions, such as autism or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and it highlights a serious unresolved gap in advancing FASD.

Ob.gyn. role

The role for the ob.gyn. is a complicated one, both in terms of diagnosis and prevention of FASD. Quite often the mother is abusing both alcohol and drugs and the infant may be at risk for neonatal abstinence syndrome in addition to FASD. And because alcohol abuse is often chronic, this is an issue that could affect future children.

While there are still many unanswered questions on the genetics of FASD, we do know that it’s not an equal opportunity condition. Mothers who have had a child with the syndrome have a higher likelihood of its occurring with a second child, compared with mothers who drink heavily but did not have a previous child with FASD.

For now, it’s imperative that ob.gyns. continue to ask about drinking in a nonjudgmental way and that they ask this question of all their patients, not just ones they consider to be in high risk populations.

Dr. Koren is professor of physiology/pharmacology at Western University in Ontario. He is the founder of the Motherisk Program. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

One of the most challenging elements in making a diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders is obtaining a thorough history of the mother’s drinking during pregnancy. This is something that ob.gyns. have struggled with for many years, and while there are ways to improve the collection of this information, it’s often an uncomfortable conversation that yields unreliable answers.

In August, a group of experts on fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), organized by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, proposed new clinical guidelines for diagnosing these disorders, the first update since 2005 (Pediatrics. 2016;138[2]:e20154256). The update creates a more inclusive definition of FASD and puts a greater emphasis on the sometimes subtle physical and behavioral changes that occur in children.

Growth restriction