User login

Advances in IV nutrition for very low birth weight neonates

Premature neonates are at high risk for growth failure and a host of morbidities including sepsis, chronic lung disease, necrotizing enterocolitis, retinopathy of prematurity, cholestasis, and neurodevelopmental impairment. Nutrition plays an important role in modulating disease. Virtually all extremely low birth weight neonates (birth weight less than 1 kg) receive parenteral nutrition and intravenous lipids in order to promote optimal nutrition and growth. Intravenous lipids provide nonprotein calories and the essential fatty acids linoleic acid (an omega-6 fatty acid) and alpha-linoleic acid (an omega-3 fatty acid). High omega-6:omega-3 fatty acid ratios promote inflammation and have been associated with various adult-onset diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer.

Currently, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved lipid emulsion is entirely soybean based (Intralipid). This lipid emulsion contains a high omega-6:omega-3 fatty acid ratio, high concentrations of linoleic and alpha-linoleic acid, and lacks arachidonic acid (ARA, an omega-6 fatty acid) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, an omega-3 fatty acid). Moreover, soybean oil contains a small amount of vitamin E, an antioxidant which helps prevent lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress. A non–FDA approved lipid emulsion (SMOFlipid) is currently being prescribed to children, including preterm neonates, in Europe. SMOFlipid contains a “mix” of various oils (30% soy, 15% fish, 30% coconut, and 25% olive oil) and a higher concentration of Vitamin E (48 mg/dL vs. 38 mg/dL). In comparison with soybean oil, SMOFlipid’s fatty acid content more closely resembles breast milk with a more physiologically appropriate omega-6:omega-3 fatty acid ratio. As a result, SMOFlipid theoretically may have the capability to modulate disease by decreasing systemic inflammation and tissue injury.

In small retrospective and randomized controlled trials, preterm neonates who received SMOFlipid have increased ARA, DHA, and vitamin E concentrations and decreased markers of oxidative stress, compared with neonates who received standard soybean oil1-3. Improving the DHA and ARA status in preterm neonates has several theoretical advantages. DHA and ARA are preferentially transferred to the fetus during the third trimester of pregnancy, and found in significant quantities in the brain, retina, and breast milk. Under normal physiological conditions, linoleic and alpha-linoleic acid, which cannot be synthesized de novo, are metabolized to ARA and DHA. Despite being provided with linoleic and alpha-linoleic acid in intravenous soybean oil, preterm neonates develop ARA and DHA deficiencies. Preterm neonates lack the necessary enzymatic machinery (due to immature livers) to convert these essential fatty acids into their downstream products. ARA and DHA deficiencies have been linked to the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and retinopathy of prematurity. Infant formulas now contain DHA and ARA, and have been associated with improved visual and cognitive outcomes. Because very low birth weight neonates are at high risk for growth failure and neurological impairment along with other comorbidities, many people believe that intravenous lipids should contain pre-formed ARA and DHA. However, it remains to be determined if an improved fatty acid profile in this population translates into better long-term outcomes.

Soybean-based lipids also have been heavily criticized for their high concentrations of hepatotoxic phytosterols, which have been linked to parenteral nutrition associated liver disease (PNALD). Neonates are at high risk for PNALD because of immature livers and the need for prolonged courses of parenteral nutrition. Twenty percent to 60% of premature neonates and children with gastrointestinal disorders will develop PNALD. In neonates with short bowel syndrome, the highest-risk subgroup, 70% will develop PNALD and 20% will progress to liver failure. Once end-stage liver disease develops, an isolated liver or combined small bowel-liver transplant may be the only life-saving measure. Due to the high mortality of end-stage PNALD, small size of transplant candidates, and shortage of organ donors, 50% of children awaiting a transplant will not survive. Five-year post-transplant survival is 60%-70% and fraught with a complex lifestyle. Transplants also carry a high price tag with an estimated cost of $1.5-$1.9 million in the first year.

In comparison with soybean oil, SMOFlipid has a reduced concentration of phytosterols (48 mg/L vs. 343 mg/L). Phytosterols are only found in plant food sources and approximately 5%-10% of phytosterols are absorbed in the intestine. As a result, in a healthy child, they are present at minimal concentrations in the bloodstream. Children receiving parenteral nutrition and with PNALD have higher concentrations of phytosterols, compared with controls. High concentrations of phytosterol reduce the expression of hepatic bilirubin and bile acid transporters. As a result, as phytosterol concentrations rise, bile acids and bilirubin are retained in the liver, causing cholestasis. Like phytosterols, cytokines cause a decrease in biliary flow. Hence, soybean oil’s high concentration of phytosterols and omega-6 fatty acids, which causes a shift toward a proinflammatory state, act synergistically to promote liver injury. SMOFlipid’s reduced phytosterol content potentially may have important implications with regards to the development and progression of PNALD. In randomized controlled trials, neonates who received SMOFlipid had decreased phytosterol concentrations and improved liver function tests, compared with neonates who received soybean oil. Larger studies are needed to determine if SMOFlipid reduces the incidence or severity of PNALD.

In children with advanced PNALD, low dose fish oil monotherapy (Omegaven) has been shown to biochemically reverse cholestasis4,5. Like SMOFlipid, Omegaven is not FDA approved and its use is restricted throughout the United States. Omegaven is dosed at 1 g/kg per day, lacks phytosterols, and contains high concentrations of the anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids DHA and eicosapentaenoic acid, and vitamin E. Based on the assumption that reducing the liver’s exposure to phytosterols and omega-6 fatty acids treats PNALD, it has now become common clinical practice in many neonatal intensive care units to prescribe low dose soybean oil for PNALD prevention. While observational data suggests low dose soybean oil (1 g/kg per day or less) reduces the incidence of PNALD, randomized controlled trials have not demonstrated a change in cholestasis. Lipid sparing (fish or soy) is not without risks, particularly in high-risk populations such as preterm neonates. Inadequate lipid intake during a period of rapid growth and development could cause a fatty acid deficiency and impair growth and neurodevelopment. The central nervous system contains high concentrations of lipids, which are important for cell structure and function and gene transcription. One of the advantages of SMOFlipid is that it can be dosed at 3 g/kg per day, unlike Omegaven, and may be more likely to meet the lipid requirement of neonates.

In summary, the current FDA-approved soy-based lipid product was not designed to meet the nutritional needs of the preterm infant. An ideal lipid emulsion would provide adequate concentrations of polyunsaturated fatty acids, promote growth, be free of phytosterols, and minimize inflammation and other adverse sequelae. SMOFlipid may be more likely to meet the DHA and ARA requirement of the premature neonate. A mixed lipid emulsion dosed at 3 g/kg per day may improve growth and long-term neurodevelopment and reduce the incidence of parenteral nutrition associated liver disease along with other common neonatal diseases. In turn, this may reduce health care related costs. Appropriately powered, well-designed randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up are needed to evaluate this new lipid emulsion.

References

1. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010 Oct;51(4):514-21.

2. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012 Dec;27(6):817-24.

3. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Apr;58(4):417-27.

4. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016 Mar;40(3):374-82.

5. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014 Aug;38(6):682-92.

Dr. Calkins is an assistant professor of pediatrics in the division of neonatology at the University of California, Los Angeles. She receives research funding from Fresenius Kabi, the German manufacturer of the products described in this article. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed by UCLA in accordance with its conflict of interest policy. Because there is only one manufacturer for some of the products discussed in this article, for clarity we have chosen to use brand names rather than generic names. Email Dr. Calkins at [email protected].

Premature neonates are at high risk for growth failure and a host of morbidities including sepsis, chronic lung disease, necrotizing enterocolitis, retinopathy of prematurity, cholestasis, and neurodevelopmental impairment. Nutrition plays an important role in modulating disease. Virtually all extremely low birth weight neonates (birth weight less than 1 kg) receive parenteral nutrition and intravenous lipids in order to promote optimal nutrition and growth. Intravenous lipids provide nonprotein calories and the essential fatty acids linoleic acid (an omega-6 fatty acid) and alpha-linoleic acid (an omega-3 fatty acid). High omega-6:omega-3 fatty acid ratios promote inflammation and have been associated with various adult-onset diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer.

Currently, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved lipid emulsion is entirely soybean based (Intralipid). This lipid emulsion contains a high omega-6:omega-3 fatty acid ratio, high concentrations of linoleic and alpha-linoleic acid, and lacks arachidonic acid (ARA, an omega-6 fatty acid) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, an omega-3 fatty acid). Moreover, soybean oil contains a small amount of vitamin E, an antioxidant which helps prevent lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress. A non–FDA approved lipid emulsion (SMOFlipid) is currently being prescribed to children, including preterm neonates, in Europe. SMOFlipid contains a “mix” of various oils (30% soy, 15% fish, 30% coconut, and 25% olive oil) and a higher concentration of Vitamin E (48 mg/dL vs. 38 mg/dL). In comparison with soybean oil, SMOFlipid’s fatty acid content more closely resembles breast milk with a more physiologically appropriate omega-6:omega-3 fatty acid ratio. As a result, SMOFlipid theoretically may have the capability to modulate disease by decreasing systemic inflammation and tissue injury.

In small retrospective and randomized controlled trials, preterm neonates who received SMOFlipid have increased ARA, DHA, and vitamin E concentrations and decreased markers of oxidative stress, compared with neonates who received standard soybean oil1-3. Improving the DHA and ARA status in preterm neonates has several theoretical advantages. DHA and ARA are preferentially transferred to the fetus during the third trimester of pregnancy, and found in significant quantities in the brain, retina, and breast milk. Under normal physiological conditions, linoleic and alpha-linoleic acid, which cannot be synthesized de novo, are metabolized to ARA and DHA. Despite being provided with linoleic and alpha-linoleic acid in intravenous soybean oil, preterm neonates develop ARA and DHA deficiencies. Preterm neonates lack the necessary enzymatic machinery (due to immature livers) to convert these essential fatty acids into their downstream products. ARA and DHA deficiencies have been linked to the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and retinopathy of prematurity. Infant formulas now contain DHA and ARA, and have been associated with improved visual and cognitive outcomes. Because very low birth weight neonates are at high risk for growth failure and neurological impairment along with other comorbidities, many people believe that intravenous lipids should contain pre-formed ARA and DHA. However, it remains to be determined if an improved fatty acid profile in this population translates into better long-term outcomes.

Soybean-based lipids also have been heavily criticized for their high concentrations of hepatotoxic phytosterols, which have been linked to parenteral nutrition associated liver disease (PNALD). Neonates are at high risk for PNALD because of immature livers and the need for prolonged courses of parenteral nutrition. Twenty percent to 60% of premature neonates and children with gastrointestinal disorders will develop PNALD. In neonates with short bowel syndrome, the highest-risk subgroup, 70% will develop PNALD and 20% will progress to liver failure. Once end-stage liver disease develops, an isolated liver or combined small bowel-liver transplant may be the only life-saving measure. Due to the high mortality of end-stage PNALD, small size of transplant candidates, and shortage of organ donors, 50% of children awaiting a transplant will not survive. Five-year post-transplant survival is 60%-70% and fraught with a complex lifestyle. Transplants also carry a high price tag with an estimated cost of $1.5-$1.9 million in the first year.

In comparison with soybean oil, SMOFlipid has a reduced concentration of phytosterols (48 mg/L vs. 343 mg/L). Phytosterols are only found in plant food sources and approximately 5%-10% of phytosterols are absorbed in the intestine. As a result, in a healthy child, they are present at minimal concentrations in the bloodstream. Children receiving parenteral nutrition and with PNALD have higher concentrations of phytosterols, compared with controls. High concentrations of phytosterol reduce the expression of hepatic bilirubin and bile acid transporters. As a result, as phytosterol concentrations rise, bile acids and bilirubin are retained in the liver, causing cholestasis. Like phytosterols, cytokines cause a decrease in biliary flow. Hence, soybean oil’s high concentration of phytosterols and omega-6 fatty acids, which causes a shift toward a proinflammatory state, act synergistically to promote liver injury. SMOFlipid’s reduced phytosterol content potentially may have important implications with regards to the development and progression of PNALD. In randomized controlled trials, neonates who received SMOFlipid had decreased phytosterol concentrations and improved liver function tests, compared with neonates who received soybean oil. Larger studies are needed to determine if SMOFlipid reduces the incidence or severity of PNALD.

In children with advanced PNALD, low dose fish oil monotherapy (Omegaven) has been shown to biochemically reverse cholestasis4,5. Like SMOFlipid, Omegaven is not FDA approved and its use is restricted throughout the United States. Omegaven is dosed at 1 g/kg per day, lacks phytosterols, and contains high concentrations of the anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids DHA and eicosapentaenoic acid, and vitamin E. Based on the assumption that reducing the liver’s exposure to phytosterols and omega-6 fatty acids treats PNALD, it has now become common clinical practice in many neonatal intensive care units to prescribe low dose soybean oil for PNALD prevention. While observational data suggests low dose soybean oil (1 g/kg per day or less) reduces the incidence of PNALD, randomized controlled trials have not demonstrated a change in cholestasis. Lipid sparing (fish or soy) is not without risks, particularly in high-risk populations such as preterm neonates. Inadequate lipid intake during a period of rapid growth and development could cause a fatty acid deficiency and impair growth and neurodevelopment. The central nervous system contains high concentrations of lipids, which are important for cell structure and function and gene transcription. One of the advantages of SMOFlipid is that it can be dosed at 3 g/kg per day, unlike Omegaven, and may be more likely to meet the lipid requirement of neonates.

In summary, the current FDA-approved soy-based lipid product was not designed to meet the nutritional needs of the preterm infant. An ideal lipid emulsion would provide adequate concentrations of polyunsaturated fatty acids, promote growth, be free of phytosterols, and minimize inflammation and other adverse sequelae. SMOFlipid may be more likely to meet the DHA and ARA requirement of the premature neonate. A mixed lipid emulsion dosed at 3 g/kg per day may improve growth and long-term neurodevelopment and reduce the incidence of parenteral nutrition associated liver disease along with other common neonatal diseases. In turn, this may reduce health care related costs. Appropriately powered, well-designed randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up are needed to evaluate this new lipid emulsion.

References

1. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010 Oct;51(4):514-21.

2. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012 Dec;27(6):817-24.

3. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Apr;58(4):417-27.

4. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016 Mar;40(3):374-82.

5. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014 Aug;38(6):682-92.

Dr. Calkins is an assistant professor of pediatrics in the division of neonatology at the University of California, Los Angeles. She receives research funding from Fresenius Kabi, the German manufacturer of the products described in this article. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed by UCLA in accordance with its conflict of interest policy. Because there is only one manufacturer for some of the products discussed in this article, for clarity we have chosen to use brand names rather than generic names. Email Dr. Calkins at [email protected].

Premature neonates are at high risk for growth failure and a host of morbidities including sepsis, chronic lung disease, necrotizing enterocolitis, retinopathy of prematurity, cholestasis, and neurodevelopmental impairment. Nutrition plays an important role in modulating disease. Virtually all extremely low birth weight neonates (birth weight less than 1 kg) receive parenteral nutrition and intravenous lipids in order to promote optimal nutrition and growth. Intravenous lipids provide nonprotein calories and the essential fatty acids linoleic acid (an omega-6 fatty acid) and alpha-linoleic acid (an omega-3 fatty acid). High omega-6:omega-3 fatty acid ratios promote inflammation and have been associated with various adult-onset diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer.

Currently, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved lipid emulsion is entirely soybean based (Intralipid). This lipid emulsion contains a high omega-6:omega-3 fatty acid ratio, high concentrations of linoleic and alpha-linoleic acid, and lacks arachidonic acid (ARA, an omega-6 fatty acid) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, an omega-3 fatty acid). Moreover, soybean oil contains a small amount of vitamin E, an antioxidant which helps prevent lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress. A non–FDA approved lipid emulsion (SMOFlipid) is currently being prescribed to children, including preterm neonates, in Europe. SMOFlipid contains a “mix” of various oils (30% soy, 15% fish, 30% coconut, and 25% olive oil) and a higher concentration of Vitamin E (48 mg/dL vs. 38 mg/dL). In comparison with soybean oil, SMOFlipid’s fatty acid content more closely resembles breast milk with a more physiologically appropriate omega-6:omega-3 fatty acid ratio. As a result, SMOFlipid theoretically may have the capability to modulate disease by decreasing systemic inflammation and tissue injury.

In small retrospective and randomized controlled trials, preterm neonates who received SMOFlipid have increased ARA, DHA, and vitamin E concentrations and decreased markers of oxidative stress, compared with neonates who received standard soybean oil1-3. Improving the DHA and ARA status in preterm neonates has several theoretical advantages. DHA and ARA are preferentially transferred to the fetus during the third trimester of pregnancy, and found in significant quantities in the brain, retina, and breast milk. Under normal physiological conditions, linoleic and alpha-linoleic acid, which cannot be synthesized de novo, are metabolized to ARA and DHA. Despite being provided with linoleic and alpha-linoleic acid in intravenous soybean oil, preterm neonates develop ARA and DHA deficiencies. Preterm neonates lack the necessary enzymatic machinery (due to immature livers) to convert these essential fatty acids into their downstream products. ARA and DHA deficiencies have been linked to the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and retinopathy of prematurity. Infant formulas now contain DHA and ARA, and have been associated with improved visual and cognitive outcomes. Because very low birth weight neonates are at high risk for growth failure and neurological impairment along with other comorbidities, many people believe that intravenous lipids should contain pre-formed ARA and DHA. However, it remains to be determined if an improved fatty acid profile in this population translates into better long-term outcomes.

Soybean-based lipids also have been heavily criticized for their high concentrations of hepatotoxic phytosterols, which have been linked to parenteral nutrition associated liver disease (PNALD). Neonates are at high risk for PNALD because of immature livers and the need for prolonged courses of parenteral nutrition. Twenty percent to 60% of premature neonates and children with gastrointestinal disorders will develop PNALD. In neonates with short bowel syndrome, the highest-risk subgroup, 70% will develop PNALD and 20% will progress to liver failure. Once end-stage liver disease develops, an isolated liver or combined small bowel-liver transplant may be the only life-saving measure. Due to the high mortality of end-stage PNALD, small size of transplant candidates, and shortage of organ donors, 50% of children awaiting a transplant will not survive. Five-year post-transplant survival is 60%-70% and fraught with a complex lifestyle. Transplants also carry a high price tag with an estimated cost of $1.5-$1.9 million in the first year.

In comparison with soybean oil, SMOFlipid has a reduced concentration of phytosterols (48 mg/L vs. 343 mg/L). Phytosterols are only found in plant food sources and approximately 5%-10% of phytosterols are absorbed in the intestine. As a result, in a healthy child, they are present at minimal concentrations in the bloodstream. Children receiving parenteral nutrition and with PNALD have higher concentrations of phytosterols, compared with controls. High concentrations of phytosterol reduce the expression of hepatic bilirubin and bile acid transporters. As a result, as phytosterol concentrations rise, bile acids and bilirubin are retained in the liver, causing cholestasis. Like phytosterols, cytokines cause a decrease in biliary flow. Hence, soybean oil’s high concentration of phytosterols and omega-6 fatty acids, which causes a shift toward a proinflammatory state, act synergistically to promote liver injury. SMOFlipid’s reduced phytosterol content potentially may have important implications with regards to the development and progression of PNALD. In randomized controlled trials, neonates who received SMOFlipid had decreased phytosterol concentrations and improved liver function tests, compared with neonates who received soybean oil. Larger studies are needed to determine if SMOFlipid reduces the incidence or severity of PNALD.

In children with advanced PNALD, low dose fish oil monotherapy (Omegaven) has been shown to biochemically reverse cholestasis4,5. Like SMOFlipid, Omegaven is not FDA approved and its use is restricted throughout the United States. Omegaven is dosed at 1 g/kg per day, lacks phytosterols, and contains high concentrations of the anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids DHA and eicosapentaenoic acid, and vitamin E. Based on the assumption that reducing the liver’s exposure to phytosterols and omega-6 fatty acids treats PNALD, it has now become common clinical practice in many neonatal intensive care units to prescribe low dose soybean oil for PNALD prevention. While observational data suggests low dose soybean oil (1 g/kg per day or less) reduces the incidence of PNALD, randomized controlled trials have not demonstrated a change in cholestasis. Lipid sparing (fish or soy) is not without risks, particularly in high-risk populations such as preterm neonates. Inadequate lipid intake during a period of rapid growth and development could cause a fatty acid deficiency and impair growth and neurodevelopment. The central nervous system contains high concentrations of lipids, which are important for cell structure and function and gene transcription. One of the advantages of SMOFlipid is that it can be dosed at 3 g/kg per day, unlike Omegaven, and may be more likely to meet the lipid requirement of neonates.

In summary, the current FDA-approved soy-based lipid product was not designed to meet the nutritional needs of the preterm infant. An ideal lipid emulsion would provide adequate concentrations of polyunsaturated fatty acids, promote growth, be free of phytosterols, and minimize inflammation and other adverse sequelae. SMOFlipid may be more likely to meet the DHA and ARA requirement of the premature neonate. A mixed lipid emulsion dosed at 3 g/kg per day may improve growth and long-term neurodevelopment and reduce the incidence of parenteral nutrition associated liver disease along with other common neonatal diseases. In turn, this may reduce health care related costs. Appropriately powered, well-designed randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up are needed to evaluate this new lipid emulsion.

References

1. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010 Oct;51(4):514-21.

2. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012 Dec;27(6):817-24.

3. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Apr;58(4):417-27.

4. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016 Mar;40(3):374-82.

5. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014 Aug;38(6):682-92.

Dr. Calkins is an assistant professor of pediatrics in the division of neonatology at the University of California, Los Angeles. She receives research funding from Fresenius Kabi, the German manufacturer of the products described in this article. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed by UCLA in accordance with its conflict of interest policy. Because there is only one manufacturer for some of the products discussed in this article, for clarity we have chosen to use brand names rather than generic names. Email Dr. Calkins at [email protected].

Quality Improvement in Clinical Practice

As Director for Quality Improvement in an academic department, I frequently remind my colleagues that "quality" is not a 4-letter word. Unfortunately, quality is linked in many physicians’ minds to increasing practice complexity and an alphabet soup of acronyms, such as PQRS (Physician Quality Reporting System), MU (meaningful use), and MOC (Maintenance of Certification), among others. Quality improvement (QI) can and should be driven by a desire to improve patient outcomes, professional satisfaction, and operational efficiency, so how should dermatologists respond?

It is helpful to consider why measures of quality are increasingly tied to payment. Conventional wisdom suggests that the American health care system provides poor value. In 2014, total health care expenditures in the United States were $3.0 trillion ($9523 per person), representing 17.5% of the gross domestic product.1 In 1999, the Institute of Medicine estimated that 44,000 to 98,000 individuals die each year due to hospital-based medical errors.2 Noting poor outcomes and high costs, Berwick et al3 proposed the triple aim of improving the experience of care, improving health of populations, and reducing cost. If health care is too expensive and if quality includes outcomes and safety, then improved value of health care must couple cost reduction to QI. Although the future of health care reform is uncertain, it is reasonable to assume that physicians will be expected to care for more patients with fewer dollars. In that context, maximizing operational efficiency and thus economic viability is key. Our challenge is to remain focused on our patients and to identify opportunities to improve the value of their care, both by reducing costs and improving quality.

Health care systems, however, cannot improve with an unhappy and burned-out workforce. Recent data demonstrate high rates of professional burnout among physicians, including dermatologists.4 Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 propose the quadruple aim, which adds improving physician and staff work-life balance to the elements of the triple aim. Burned-out physicians cannot constructively participate in achieving the goals of the triple aim, and physician and staff satisfaction must be a component of any QI paradigm.

The Institute of Medicine has proposed 6 specific aims for improving health care systems: health care should be safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.6 These aims, taken together with the quadruple aim, can serve as a foundation for developing QI projects for practices and health systems.

Patient safety is a well-recognized issue in dermatology.7-9 Specimen labeling errors, medication errors, wrong-site surgery, and postprocedure complications are examples of safety issues. Quality improvement directed toward improved professional satisfaction for physicians and staff also is critical. The suggestions offered by Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 are directed to primary care providers but are applicable to many dermatology practices. The American Medical Association’s STEPS Forward initiative provides online tutorials that guide practice improvements aimed at improving professional satisfaction and operational efficiency.10

Patient-centered care need not focus solely on patient satisfaction. Clearly, a physician’s duty is to do what is best for each patient, but patient satisfaction and experience are increasingly common measures of quality. Although evidence suggests that measures of physician-patient communication correlate with patient compliance,11 higher patient satisfaction scores may also correlate with higher cost and increased mortality.12 A practice without happy patients is unlikely to thrive, but initiatives aimed at improving patient-centered care might do well to maximize the quality of communication with patients, rather than to focus solely on satisfaction.

Effective care can be particularly challenging to measure in the absence of widely accepted clinical quality measures. DataDerm measures, appropriate use criteria, and clinical guidelines all may serve to inspire QI projects for a broad range of practice settings. Diagnostic error is particularly challenging, but approaches to improving diagnostic accuracy have been published.13,14 Case reviews may reduce diagnostic errors, and dermatopathologists may consider second-opinion pathologic review of challenging cases.15

Promotion of equitable care is often overlooked as a QI opportunity. Lower socioeconomic status correlates with poorer medical outcomes. For example, melanoma patients who are uninsured or covered by Medicaid present with higher-stage disease, are less likely to be treated, and demonstrate worse survival compared to non-Medicaid insured patients.16 It is important to recognize inequity in health care access and outcomes, and dermatologists can participate in addressing disparities in care.

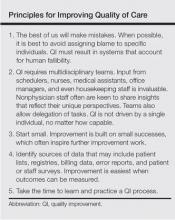

How can an individual physician proceed? There are general principles that can guide physicians in any practice setting (Table).

Any of us can be forgiven for being frustrated by ever-increasing mandates that purport to address quality and for feeling paralyzed when asked to do our part to improve the value of the American health care system. The key to successful QI is to continually identify small processes that can be improved while focusing on one’s patients, colleagues, staff, and community. A well-designed process can and will result in better care, lower costs, and happier physicians and staff. With time, disparate and coordinated efforts among physicians and systems can inform and promote national QI efforts.

1. Martin AB, Hartman M, Benson J, et al. National health spending in 2014: faster growth driven by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:150-160.

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Vol 627. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

3. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:759-769.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general us working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1600-1613.

5. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:573-576.

6. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

7. Elston DM, Taylor JS, Coldiron B, et al. Part I. patient safety and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:179-190.

8. Elston DM, Stratman E, Johnson-Jahangir H, et al. Part II. opportunities for improvement in patient safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:193-205.

9. Watson AJ, Redbord K, Taylor JS, et al. Medical error in dermatology practice: development of a classification system to drive priority setting in patient safety efforts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;68:729-737.

10. American Medical Association. STEPS Forward website. http://www.stepsforward.org. Accessed March 8, 2016.

11. Zolnierick KB, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826-834.

12. Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, et al. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405-411.

13. Dunbar M, Helms SE, Brodell RT. Reducing cognitive errors in dermatology: can anything be done? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:810-813.

14. Groszkruger D. Diagnostic error: untapped potential for improving patient safety. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2014;34:38-43.

15. Middleton LP, Feeley TW, Albright HW, et al. Second-opinion pathologic review is a patient safety mechanism that helps reduce error and decrease waste. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:275-280.

16. Amini A, Rusthoven CG, Waxweiler TV, et al. Association of health insurance with outcomes in adults ages 18-64 years with melanoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:309-316.

As Director for Quality Improvement in an academic department, I frequently remind my colleagues that "quality" is not a 4-letter word. Unfortunately, quality is linked in many physicians’ minds to increasing practice complexity and an alphabet soup of acronyms, such as PQRS (Physician Quality Reporting System), MU (meaningful use), and MOC (Maintenance of Certification), among others. Quality improvement (QI) can and should be driven by a desire to improve patient outcomes, professional satisfaction, and operational efficiency, so how should dermatologists respond?

It is helpful to consider why measures of quality are increasingly tied to payment. Conventional wisdom suggests that the American health care system provides poor value. In 2014, total health care expenditures in the United States were $3.0 trillion ($9523 per person), representing 17.5% of the gross domestic product.1 In 1999, the Institute of Medicine estimated that 44,000 to 98,000 individuals die each year due to hospital-based medical errors.2 Noting poor outcomes and high costs, Berwick et al3 proposed the triple aim of improving the experience of care, improving health of populations, and reducing cost. If health care is too expensive and if quality includes outcomes and safety, then improved value of health care must couple cost reduction to QI. Although the future of health care reform is uncertain, it is reasonable to assume that physicians will be expected to care for more patients with fewer dollars. In that context, maximizing operational efficiency and thus economic viability is key. Our challenge is to remain focused on our patients and to identify opportunities to improve the value of their care, both by reducing costs and improving quality.

Health care systems, however, cannot improve with an unhappy and burned-out workforce. Recent data demonstrate high rates of professional burnout among physicians, including dermatologists.4 Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 propose the quadruple aim, which adds improving physician and staff work-life balance to the elements of the triple aim. Burned-out physicians cannot constructively participate in achieving the goals of the triple aim, and physician and staff satisfaction must be a component of any QI paradigm.

The Institute of Medicine has proposed 6 specific aims for improving health care systems: health care should be safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.6 These aims, taken together with the quadruple aim, can serve as a foundation for developing QI projects for practices and health systems.

Patient safety is a well-recognized issue in dermatology.7-9 Specimen labeling errors, medication errors, wrong-site surgery, and postprocedure complications are examples of safety issues. Quality improvement directed toward improved professional satisfaction for physicians and staff also is critical. The suggestions offered by Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 are directed to primary care providers but are applicable to many dermatology practices. The American Medical Association’s STEPS Forward initiative provides online tutorials that guide practice improvements aimed at improving professional satisfaction and operational efficiency.10

Patient-centered care need not focus solely on patient satisfaction. Clearly, a physician’s duty is to do what is best for each patient, but patient satisfaction and experience are increasingly common measures of quality. Although evidence suggests that measures of physician-patient communication correlate with patient compliance,11 higher patient satisfaction scores may also correlate with higher cost and increased mortality.12 A practice without happy patients is unlikely to thrive, but initiatives aimed at improving patient-centered care might do well to maximize the quality of communication with patients, rather than to focus solely on satisfaction.

Effective care can be particularly challenging to measure in the absence of widely accepted clinical quality measures. DataDerm measures, appropriate use criteria, and clinical guidelines all may serve to inspire QI projects for a broad range of practice settings. Diagnostic error is particularly challenging, but approaches to improving diagnostic accuracy have been published.13,14 Case reviews may reduce diagnostic errors, and dermatopathologists may consider second-opinion pathologic review of challenging cases.15

Promotion of equitable care is often overlooked as a QI opportunity. Lower socioeconomic status correlates with poorer medical outcomes. For example, melanoma patients who are uninsured or covered by Medicaid present with higher-stage disease, are less likely to be treated, and demonstrate worse survival compared to non-Medicaid insured patients.16 It is important to recognize inequity in health care access and outcomes, and dermatologists can participate in addressing disparities in care.

How can an individual physician proceed? There are general principles that can guide physicians in any practice setting (Table).

Any of us can be forgiven for being frustrated by ever-increasing mandates that purport to address quality and for feeling paralyzed when asked to do our part to improve the value of the American health care system. The key to successful QI is to continually identify small processes that can be improved while focusing on one’s patients, colleagues, staff, and community. A well-designed process can and will result in better care, lower costs, and happier physicians and staff. With time, disparate and coordinated efforts among physicians and systems can inform and promote national QI efforts.

As Director for Quality Improvement in an academic department, I frequently remind my colleagues that "quality" is not a 4-letter word. Unfortunately, quality is linked in many physicians’ minds to increasing practice complexity and an alphabet soup of acronyms, such as PQRS (Physician Quality Reporting System), MU (meaningful use), and MOC (Maintenance of Certification), among others. Quality improvement (QI) can and should be driven by a desire to improve patient outcomes, professional satisfaction, and operational efficiency, so how should dermatologists respond?

It is helpful to consider why measures of quality are increasingly tied to payment. Conventional wisdom suggests that the American health care system provides poor value. In 2014, total health care expenditures in the United States were $3.0 trillion ($9523 per person), representing 17.5% of the gross domestic product.1 In 1999, the Institute of Medicine estimated that 44,000 to 98,000 individuals die each year due to hospital-based medical errors.2 Noting poor outcomes and high costs, Berwick et al3 proposed the triple aim of improving the experience of care, improving health of populations, and reducing cost. If health care is too expensive and if quality includes outcomes and safety, then improved value of health care must couple cost reduction to QI. Although the future of health care reform is uncertain, it is reasonable to assume that physicians will be expected to care for more patients with fewer dollars. In that context, maximizing operational efficiency and thus economic viability is key. Our challenge is to remain focused on our patients and to identify opportunities to improve the value of their care, both by reducing costs and improving quality.

Health care systems, however, cannot improve with an unhappy and burned-out workforce. Recent data demonstrate high rates of professional burnout among physicians, including dermatologists.4 Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 propose the quadruple aim, which adds improving physician and staff work-life balance to the elements of the triple aim. Burned-out physicians cannot constructively participate in achieving the goals of the triple aim, and physician and staff satisfaction must be a component of any QI paradigm.

The Institute of Medicine has proposed 6 specific aims for improving health care systems: health care should be safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.6 These aims, taken together with the quadruple aim, can serve as a foundation for developing QI projects for practices and health systems.

Patient safety is a well-recognized issue in dermatology.7-9 Specimen labeling errors, medication errors, wrong-site surgery, and postprocedure complications are examples of safety issues. Quality improvement directed toward improved professional satisfaction for physicians and staff also is critical. The suggestions offered by Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 are directed to primary care providers but are applicable to many dermatology practices. The American Medical Association’s STEPS Forward initiative provides online tutorials that guide practice improvements aimed at improving professional satisfaction and operational efficiency.10

Patient-centered care need not focus solely on patient satisfaction. Clearly, a physician’s duty is to do what is best for each patient, but patient satisfaction and experience are increasingly common measures of quality. Although evidence suggests that measures of physician-patient communication correlate with patient compliance,11 higher patient satisfaction scores may also correlate with higher cost and increased mortality.12 A practice without happy patients is unlikely to thrive, but initiatives aimed at improving patient-centered care might do well to maximize the quality of communication with patients, rather than to focus solely on satisfaction.

Effective care can be particularly challenging to measure in the absence of widely accepted clinical quality measures. DataDerm measures, appropriate use criteria, and clinical guidelines all may serve to inspire QI projects for a broad range of practice settings. Diagnostic error is particularly challenging, but approaches to improving diagnostic accuracy have been published.13,14 Case reviews may reduce diagnostic errors, and dermatopathologists may consider second-opinion pathologic review of challenging cases.15

Promotion of equitable care is often overlooked as a QI opportunity. Lower socioeconomic status correlates with poorer medical outcomes. For example, melanoma patients who are uninsured or covered by Medicaid present with higher-stage disease, are less likely to be treated, and demonstrate worse survival compared to non-Medicaid insured patients.16 It is important to recognize inequity in health care access and outcomes, and dermatologists can participate in addressing disparities in care.

How can an individual physician proceed? There are general principles that can guide physicians in any practice setting (Table).

Any of us can be forgiven for being frustrated by ever-increasing mandates that purport to address quality and for feeling paralyzed when asked to do our part to improve the value of the American health care system. The key to successful QI is to continually identify small processes that can be improved while focusing on one’s patients, colleagues, staff, and community. A well-designed process can and will result in better care, lower costs, and happier physicians and staff. With time, disparate and coordinated efforts among physicians and systems can inform and promote national QI efforts.

1. Martin AB, Hartman M, Benson J, et al. National health spending in 2014: faster growth driven by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:150-160.

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Vol 627. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

3. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:759-769.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general us working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1600-1613.

5. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:573-576.

6. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

7. Elston DM, Taylor JS, Coldiron B, et al. Part I. patient safety and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:179-190.

8. Elston DM, Stratman E, Johnson-Jahangir H, et al. Part II. opportunities for improvement in patient safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:193-205.

9. Watson AJ, Redbord K, Taylor JS, et al. Medical error in dermatology practice: development of a classification system to drive priority setting in patient safety efforts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;68:729-737.

10. American Medical Association. STEPS Forward website. http://www.stepsforward.org. Accessed March 8, 2016.

11. Zolnierick KB, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826-834.

12. Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, et al. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405-411.

13. Dunbar M, Helms SE, Brodell RT. Reducing cognitive errors in dermatology: can anything be done? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:810-813.

14. Groszkruger D. Diagnostic error: untapped potential for improving patient safety. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2014;34:38-43.

15. Middleton LP, Feeley TW, Albright HW, et al. Second-opinion pathologic review is a patient safety mechanism that helps reduce error and decrease waste. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:275-280.

16. Amini A, Rusthoven CG, Waxweiler TV, et al. Association of health insurance with outcomes in adults ages 18-64 years with melanoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:309-316.

1. Martin AB, Hartman M, Benson J, et al. National health spending in 2014: faster growth driven by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:150-160.

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Vol 627. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

3. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:759-769.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general us working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1600-1613.

5. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:573-576.

6. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

7. Elston DM, Taylor JS, Coldiron B, et al. Part I. patient safety and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:179-190.

8. Elston DM, Stratman E, Johnson-Jahangir H, et al. Part II. opportunities for improvement in patient safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:193-205.

9. Watson AJ, Redbord K, Taylor JS, et al. Medical error in dermatology practice: development of a classification system to drive priority setting in patient safety efforts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;68:729-737.

10. American Medical Association. STEPS Forward website. http://www.stepsforward.org. Accessed March 8, 2016.

11. Zolnierick KB, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826-834.

12. Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, et al. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405-411.

13. Dunbar M, Helms SE, Brodell RT. Reducing cognitive errors in dermatology: can anything be done? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:810-813.

14. Groszkruger D. Diagnostic error: untapped potential for improving patient safety. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2014;34:38-43.

15. Middleton LP, Feeley TW, Albright HW, et al. Second-opinion pathologic review is a patient safety mechanism that helps reduce error and decrease waste. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:275-280.

16. Amini A, Rusthoven CG, Waxweiler TV, et al. Association of health insurance with outcomes in adults ages 18-64 years with melanoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:309-316.

It’s imperative to protect adolescents with HPV vaccine

Low vaccination rates in the United States are in large part due to parental and religious objections to this vaccination that can be overcome by better education and support by pediatricians. It’s been demonstrated that physicians encourage the HPV vaccine less strongly than the other adolescent vaccinations such as Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine1. In addition, there is a lack of legislation promoting this vaccine. There are only two states and Washington, D.C., that currently have opt-out state mandates for HPV immunization, compared with 46 states plus Washington, D.C., with similar policies for Tdap2. The HPV vaccine is safe, efficacious, and has been demonstrated to reduce mortality and morbidity in our population. It is imperative that we, as pediatricians, strongly encourage and provide these vaccinations to our adolescent patients to help protect our community.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine was approved for girls in 2008 and for boys in 20113. However, the adoption rate for HPV immunization in the United States has been dismal. Data from 2014 show only 60% of adolescent girls have received at least one HPV vaccine dose, and only 40% have received three doses4. The rates for boys are far worse, with 42% of adolescent boys receiving at least one dose, and only 22% receiving three doses4.

HPV is currently the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, with an estimated 14 million new infections per year3. Of these, approximately 11,000 will progress to cervical cancers and 9,000 to male anogenital cancers each year. Annually there are about 4,000 cervical cancer deaths in the United States3.

Three vaccines are approved by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent HPV infection: Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Cervarix. All three vaccines prevent infections with HPV types 16 and 18, two high-risk HPVs that cause about 70% of cervical cancers (as well as oropharyngeal and other anogenital cancers). Gardasil also prevents infection with HPV types 6 and 11, associated with approximately 90% of anogenital warts. Gardasil 9 prevents infection with the same four HPV types plus five other high-risk HPV types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58); it is called a nonavalent, or 9-valent, vaccine.

The HPV vaccines have the ability to reduce mortality and morbidity in our patients. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011 demonstrated that vaccination with the full HPV series in males 16-26 years prior to HPV exposure led to a 90% efficacy in preventing HPV-related disease5, compared with a 60% efficacy if given after HPV exposure or if the individual received an incomplete dose series.

A recent Pediatrics study reported data since initiation of the vaccination program in American adolescent and young adult women6. The data showed a reduction in HPV-related disease of 64% in the 14- to 19-year age group and a reduction of 34% in the older age group (aged 20-24 years). This is impressive given our currently low vaccination rates.

A Lancet meta-analysis shows evidence of herd immunity and cross-protective effects when vaccination rates are greater than 50% in the population7. This allows groups that aren’t currently approved for vaccination to have a reduction in disease and allows for some protection against HPV types that aren’t currently covered by the vaccines.

So we pediatricians have a job to do in protecting our patients by encouraging HPV immunization.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137(2):1-9.

3. www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/clinician-factsheet.html

5. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):401-11.

6. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):1-9.

7. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):565-80.

Dr. Denby is a second-year internal medicine/pediatrics resident at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

Low vaccination rates in the United States are in large part due to parental and religious objections to this vaccination that can be overcome by better education and support by pediatricians. It’s been demonstrated that physicians encourage the HPV vaccine less strongly than the other adolescent vaccinations such as Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine1. In addition, there is a lack of legislation promoting this vaccine. There are only two states and Washington, D.C., that currently have opt-out state mandates for HPV immunization, compared with 46 states plus Washington, D.C., with similar policies for Tdap2. The HPV vaccine is safe, efficacious, and has been demonstrated to reduce mortality and morbidity in our population. It is imperative that we, as pediatricians, strongly encourage and provide these vaccinations to our adolescent patients to help protect our community.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine was approved for girls in 2008 and for boys in 20113. However, the adoption rate for HPV immunization in the United States has been dismal. Data from 2014 show only 60% of adolescent girls have received at least one HPV vaccine dose, and only 40% have received three doses4. The rates for boys are far worse, with 42% of adolescent boys receiving at least one dose, and only 22% receiving three doses4.

HPV is currently the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, with an estimated 14 million new infections per year3. Of these, approximately 11,000 will progress to cervical cancers and 9,000 to male anogenital cancers each year. Annually there are about 4,000 cervical cancer deaths in the United States3.

Three vaccines are approved by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent HPV infection: Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Cervarix. All three vaccines prevent infections with HPV types 16 and 18, two high-risk HPVs that cause about 70% of cervical cancers (as well as oropharyngeal and other anogenital cancers). Gardasil also prevents infection with HPV types 6 and 11, associated with approximately 90% of anogenital warts. Gardasil 9 prevents infection with the same four HPV types plus five other high-risk HPV types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58); it is called a nonavalent, or 9-valent, vaccine.

The HPV vaccines have the ability to reduce mortality and morbidity in our patients. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011 demonstrated that vaccination with the full HPV series in males 16-26 years prior to HPV exposure led to a 90% efficacy in preventing HPV-related disease5, compared with a 60% efficacy if given after HPV exposure or if the individual received an incomplete dose series.

A recent Pediatrics study reported data since initiation of the vaccination program in American adolescent and young adult women6. The data showed a reduction in HPV-related disease of 64% in the 14- to 19-year age group and a reduction of 34% in the older age group (aged 20-24 years). This is impressive given our currently low vaccination rates.

A Lancet meta-analysis shows evidence of herd immunity and cross-protective effects when vaccination rates are greater than 50% in the population7. This allows groups that aren’t currently approved for vaccination to have a reduction in disease and allows for some protection against HPV types that aren’t currently covered by the vaccines.

So we pediatricians have a job to do in protecting our patients by encouraging HPV immunization.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137(2):1-9.

3. www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/clinician-factsheet.html

5. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):401-11.

6. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):1-9.

7. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):565-80.

Dr. Denby is a second-year internal medicine/pediatrics resident at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

Low vaccination rates in the United States are in large part due to parental and religious objections to this vaccination that can be overcome by better education and support by pediatricians. It’s been demonstrated that physicians encourage the HPV vaccine less strongly than the other adolescent vaccinations such as Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine1. In addition, there is a lack of legislation promoting this vaccine. There are only two states and Washington, D.C., that currently have opt-out state mandates for HPV immunization, compared with 46 states plus Washington, D.C., with similar policies for Tdap2. The HPV vaccine is safe, efficacious, and has been demonstrated to reduce mortality and morbidity in our population. It is imperative that we, as pediatricians, strongly encourage and provide these vaccinations to our adolescent patients to help protect our community.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine was approved for girls in 2008 and for boys in 20113. However, the adoption rate for HPV immunization in the United States has been dismal. Data from 2014 show only 60% of adolescent girls have received at least one HPV vaccine dose, and only 40% have received three doses4. The rates for boys are far worse, with 42% of adolescent boys receiving at least one dose, and only 22% receiving three doses4.

HPV is currently the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, with an estimated 14 million new infections per year3. Of these, approximately 11,000 will progress to cervical cancers and 9,000 to male anogenital cancers each year. Annually there are about 4,000 cervical cancer deaths in the United States3.

Three vaccines are approved by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent HPV infection: Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Cervarix. All three vaccines prevent infections with HPV types 16 and 18, two high-risk HPVs that cause about 70% of cervical cancers (as well as oropharyngeal and other anogenital cancers). Gardasil also prevents infection with HPV types 6 and 11, associated with approximately 90% of anogenital warts. Gardasil 9 prevents infection with the same four HPV types plus five other high-risk HPV types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58); it is called a nonavalent, or 9-valent, vaccine.

The HPV vaccines have the ability to reduce mortality and morbidity in our patients. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011 demonstrated that vaccination with the full HPV series in males 16-26 years prior to HPV exposure led to a 90% efficacy in preventing HPV-related disease5, compared with a 60% efficacy if given after HPV exposure or if the individual received an incomplete dose series.

A recent Pediatrics study reported data since initiation of the vaccination program in American adolescent and young adult women6. The data showed a reduction in HPV-related disease of 64% in the 14- to 19-year age group and a reduction of 34% in the older age group (aged 20-24 years). This is impressive given our currently low vaccination rates.

A Lancet meta-analysis shows evidence of herd immunity and cross-protective effects when vaccination rates are greater than 50% in the population7. This allows groups that aren’t currently approved for vaccination to have a reduction in disease and allows for some protection against HPV types that aren’t currently covered by the vaccines.

So we pediatricians have a job to do in protecting our patients by encouraging HPV immunization.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137(2):1-9.

3. www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/clinician-factsheet.html

5. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):401-11.

6. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):1-9.

7. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):565-80.

Dr. Denby is a second-year internal medicine/pediatrics resident at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

It’s imperative to protect adolescents with HPV vaccine

Low vaccination rates in the United States are in large part due to parental and religious objections to this vaccination that can be overcome by better education and support by pediatricians. It’s been demonstrated that physicians encourage the HPV vaccine less strongly than the other adolescent vaccinations such as Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine1. In addition, there is a lack of legislation promoting this vaccine. There are only two states and Washington, D.C., that currently have opt-out state mandates for HPV immunization, compared with 46 states plus Washington, D.C., with similar policies for Tdap2. The HPV vaccine is safe, efficacious, and has been demonstrated to reduce mortality and morbidity in our population. It is imperative that we, as pediatricians, strongly encourage and provide these vaccinations to our adolescent patients to help protect our community.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine was approved for girls in 2008 and for boys in 20113. However, the adoption rate for HPV immunization in the United States has been dismal. Data from 2014 show only 60% of adolescent girls have received at least one HPV vaccine dose, and only 40% have received three doses4. The rates for boys are far worse, with 42% of adolescent boys receiving at least one dose, and only 22% receiving three doses4.

HPV is currently the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, with an estimated 14 million new infections per year3. Of these, approximately 11,000 will progress to cervical cancers and 9,000 to male anogenital cancers each year. Annually there are about 4,000 cervical cancer deaths in the United States3.

Three vaccines are approved by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent HPV infection: Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Cervarix. All three vaccines prevent infections with HPV types 16 and 18, two high-risk HPVs that cause about 70% of cervical cancers (as well as oropharyngeal and other anogenital cancers). Gardasil also prevents infection with HPV types 6 and 11, associated with approximately 90% of anogenital warts. Gardasil 9 prevents infection with the same four HPV types plus five other high-risk HPV types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58); it is called a nonavalent, or 9-valent, vaccine.

The HPV vaccines have the ability to reduce mortality and morbidity in our patients. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011 demonstrated that vaccination with the full HPV series in males 16-26 years prior to HPV exposure led to a 90% efficacy in preventing HPV-related disease5, compared with a 60% efficacy if given after HPV exposure or if the individual received an incomplete dose series.

A recent Pediatrics study reported data since initiation of the vaccination program in American adolescent and young adult women6. The data showed a reduction in HPV-related disease of 64% in the 14- to 19-year age group and a reduction of 34% in the older age group (aged 20-24 years). This is impressive given our currently low vaccination rates.

A Lancet meta-analysis shows evidence of herd immunity and cross-protective effects when vaccination rates are greater than 50% in the population7. This allows groups that aren’t currently approved for vaccination to have a reduction in disease and allows for some protection against HPV types that aren’t currently covered by the vaccines.

So we pediatricians have a job to do in protecting our patients by encouraging HPV immunization.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137(2):1-9.

3. www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/clinician-factsheet.html

5. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):401-11.

6. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):1-9.

7. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):565-80.

Dr. Denby is a second-year internal medicine/pediatrics resident at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

Low vaccination rates in the United States are in large part due to parental and religious objections to this vaccination that can be overcome by better education and support by pediatricians. It’s been demonstrated that physicians encourage the HPV vaccine less strongly than the other adolescent vaccinations such as Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine1. In addition, there is a lack of legislation promoting this vaccine. There are only two states and Washington, D.C., that currently have opt-out state mandates for HPV immunization, compared with 46 states plus Washington, D.C., with similar policies for Tdap2. The HPV vaccine is safe, efficacious, and has been demonstrated to reduce mortality and morbidity in our population. It is imperative that we, as pediatricians, strongly encourage and provide these vaccinations to our adolescent patients to help protect our community.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine was approved for girls in 2008 and for boys in 20113. However, the adoption rate for HPV immunization in the United States has been dismal. Data from 2014 show only 60% of adolescent girls have received at least one HPV vaccine dose, and only 40% have received three doses4. The rates for boys are far worse, with 42% of adolescent boys receiving at least one dose, and only 22% receiving three doses4.

HPV is currently the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, with an estimated 14 million new infections per year3. Of these, approximately 11,000 will progress to cervical cancers and 9,000 to male anogenital cancers each year. Annually there are about 4,000 cervical cancer deaths in the United States3.

Three vaccines are approved by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent HPV infection: Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Cervarix. All three vaccines prevent infections with HPV types 16 and 18, two high-risk HPVs that cause about 70% of cervical cancers (as well as oropharyngeal and other anogenital cancers). Gardasil also prevents infection with HPV types 6 and 11, associated with approximately 90% of anogenital warts. Gardasil 9 prevents infection with the same four HPV types plus five other high-risk HPV types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58); it is called a nonavalent, or 9-valent, vaccine.

The HPV vaccines have the ability to reduce mortality and morbidity in our patients. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011 demonstrated that vaccination with the full HPV series in males 16-26 years prior to HPV exposure led to a 90% efficacy in preventing HPV-related disease5, compared with a 60% efficacy if given after HPV exposure or if the individual received an incomplete dose series.

A recent Pediatrics study reported data since initiation of the vaccination program in American adolescent and young adult women6. The data showed a reduction in HPV-related disease of 64% in the 14- to 19-year age group and a reduction of 34% in the older age group (aged 20-24 years). This is impressive given our currently low vaccination rates.

A Lancet meta-analysis shows evidence of herd immunity and cross-protective effects when vaccination rates are greater than 50% in the population7. This allows groups that aren’t currently approved for vaccination to have a reduction in disease and allows for some protection against HPV types that aren’t currently covered by the vaccines.

So we pediatricians have a job to do in protecting our patients by encouraging HPV immunization.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137(2):1-9.

3. www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/clinician-factsheet.html

5. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):401-11.

6. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):1-9.

7. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):565-80.

Dr. Denby is a second-year internal medicine/pediatrics resident at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

Low vaccination rates in the United States are in large part due to parental and religious objections to this vaccination that can be overcome by better education and support by pediatricians. It’s been demonstrated that physicians encourage the HPV vaccine less strongly than the other adolescent vaccinations such as Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine1. In addition, there is a lack of legislation promoting this vaccine. There are only two states and Washington, D.C., that currently have opt-out state mandates for HPV immunization, compared with 46 states plus Washington, D.C., with similar policies for Tdap2. The HPV vaccine is safe, efficacious, and has been demonstrated to reduce mortality and morbidity in our population. It is imperative that we, as pediatricians, strongly encourage and provide these vaccinations to our adolescent patients to help protect our community.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine was approved for girls in 2008 and for boys in 20113. However, the adoption rate for HPV immunization in the United States has been dismal. Data from 2014 show only 60% of adolescent girls have received at least one HPV vaccine dose, and only 40% have received three doses4. The rates for boys are far worse, with 42% of adolescent boys receiving at least one dose, and only 22% receiving three doses4.

HPV is currently the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, with an estimated 14 million new infections per year3. Of these, approximately 11,000 will progress to cervical cancers and 9,000 to male anogenital cancers each year. Annually there are about 4,000 cervical cancer deaths in the United States3.

Three vaccines are approved by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent HPV infection: Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Cervarix. All three vaccines prevent infections with HPV types 16 and 18, two high-risk HPVs that cause about 70% of cervical cancers (as well as oropharyngeal and other anogenital cancers). Gardasil also prevents infection with HPV types 6 and 11, associated with approximately 90% of anogenital warts. Gardasil 9 prevents infection with the same four HPV types plus five other high-risk HPV types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58); it is called a nonavalent, or 9-valent, vaccine.

The HPV vaccines have the ability to reduce mortality and morbidity in our patients. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011 demonstrated that vaccination with the full HPV series in males 16-26 years prior to HPV exposure led to a 90% efficacy in preventing HPV-related disease5, compared with a 60% efficacy if given after HPV exposure or if the individual received an incomplete dose series.

A recent Pediatrics study reported data since initiation of the vaccination program in American adolescent and young adult women6. The data showed a reduction in HPV-related disease of 64% in the 14- to 19-year age group and a reduction of 34% in the older age group (aged 20-24 years). This is impressive given our currently low vaccination rates.

A Lancet meta-analysis shows evidence of herd immunity and cross-protective effects when vaccination rates are greater than 50% in the population7. This allows groups that aren’t currently approved for vaccination to have a reduction in disease and allows for some protection against HPV types that aren’t currently covered by the vaccines.

So we pediatricians have a job to do in protecting our patients by encouraging HPV immunization.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137(2):1-9.

3. www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/clinician-factsheet.html

5. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):401-11.

6. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):1-9.

7. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):565-80.

Dr. Denby is a second-year internal medicine/pediatrics resident at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

Marine ingredients and the skin

Just as we learned early in life that 70% of the human body is composed of water, water covers approximately the same percentage of the earth’s surface. While fishing and harvesting of algae have occurred throughout human history,1 it has only been since the 1970s that widespread scientific interest in the great biological and chemical diversity of the vast oceans of the world has led to investigations into medical and cosmetic applications of the rich life beneath the sea.2 During this period, the marine environment has been found to boast multiple organisms with unique metabolisms adapted for survival in challenging conditions, yielding secondary metabolites, some of which have become valuable in the pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical markets.3,4 Thus, the inclusion of bioactive substances from the sea in drugs and cosmetic products is primarily a recent phenomenon.1 In fact, marine ingredients in cosmetics are thought to confer various benefits to skin health, including antioxidant, anti-acne, anti-wrinkle, and anti-tyrosinase activity.

Chemistry and biologic activity

Several marine microbial natural products have been found to display antimicrobial, antitumor, and anti-inflammatory activity.2,5 And seaweed extracts (green, brown, and red algal compounds that include constituents such as phlorotannins, sulfated polysaccharides, and tyrosinase inhibitors) have been incorporated into cosmeceutical products, with a long history of traditional folk uses for various health – including skin – conditions.3,6,7 Kim and Li reviewed the beneficial health effects of marine fungi-derived terpenoids in 2012, reporting that hundreds of these compounds have been discovered in the last few decades, with many exhibiting anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antimicrobial, and antioxidant activity.8,9 Terpenoids, or isoprenoids, are a subclass of prenyllipids, which include prenylquinones, sterols, and terpenes, the largest class of natural substances.10

The terpenes are the largest group of biologically diverse marine compounds, and include the pseudopterosins, which are structurally discrete active metabolites of the Caribbean gorgonian soft coral Pseudopterogorgia elisabethae, which is native to the waters of the Caribbean Sea, Central Bahamas, Bermuda, the West Indies, and the Florida keys.11,12 The most common gorgonian corals are diterpenes.13 Twenty-six derivatives of the octocoral P. elisabethae (designated PsA-PsZ), also known as the sea whip, sea fan, or sea plume, have been isolated.11,12,14 Pseudopterosins were first isolated in 1986.14,15

Based on the identified biologic activities, particularly anti-inflammatory capacity, of pseudopterosins, researchers have investigated their potential for treatment of various conditions including asthma, cancer, contact dermatitis, dermatoheliosis, HIV, photodamage, psoriasis, and rheumatoid arthritis.1,11

After decades of extensive research of pseudopterosins, these tricyclic diterpene glycosides are thought to provide superior anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties, compared to standard anti-inflammatory treatments, without inducing adverse side effects; they also offer marked antimicrobial and wound-healing effects.3,11,14,16-19

Other marine diterpene glycosides include eleutherobins and fucosides, which also exhibit notable biologic activity.15 In particular, the anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of pseudopterosins have been found to be concentration- and dose-dependently more potent than the standard-bearing indomethacin.11,14,17

Marine ingredients in topical formulations

The first product to include pseudopterosins was the skin formulation Resilience marketed by Estée Lauder over a decade ago.19,20 Natural marine ingredients have since been incorporated into a few more products, such as Imedeen, an oral skin care preparation that contains Marine Complex.21