User login

Bariatric surgery and alcohol use disorder

As obesity continues to ravage the health of the United States, bariatric surgery offers an effective strategy for individual patients suffering from medical complications.

When performed in adults with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2, bariatric surgery is associated with a mean weight loss of 20%-35% of baseline weight at 2-3 years. Bariatric surgery is associated with greater reductions in obesity comorbidities, compared with lifestyle intervention and supervised weight loss. Contemporary bariatric surgeries include Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, sleeve gastrectomy, and mini–gastric bypass.

Bariatric surgical procedures affect weight loss through two mechanisms: malabsorption and restriction. Such alterations in human physiology can change the absorption of common drugs of addiction, such as alcohol. This can increase the risk for problem drinking behaviors.

Wendy C. King, Ph.D., of the department of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh and her colleagues conducted an analysis of data from 1,945 patients in a cohort who underwent bariatric surgery in 10 U.S. hospitals. Symptoms of alcohol use disorder (AUD) were assessed pre- and postoperatively (JAMA 2012;307:2516-25).

The prevalence of AUD was significantly higher at 2 years postoperatively (9.6%), compared with the preoperative period (7.6%; P less than .01). Factors associated with a higher risk of postoperative AUD included male gender, younger age, smoking, regular alcohol consumption, a history of AUD, recreational drug use, low social support, and receiving Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

AUD can disqualify patients from bariatric surgery – but 7.6% of patients in this survey (taken independently of clinical care) reported it. The authors noted that a 2% increase in AUD associated with bariatric surgery translates into 2,000 additional people with AUD each year.

This is particularly problematic for this population, because a large number of calories are associated with alcohol intake, and alcohol intake can lower inhibitions for other types of eating behaviors – all of which can lead to weight regain.

So, what do we do?

I think it may be helpful to take alcohol use histories in the patients we are seeing in bariatric surgery follow-up, especially those who appear to be regaining weight. Some patients may not be aware of this connection. For the patients who I have told about this relationship, they recognize it, which may be the first step toward dealing with it.

Dr. Ebbert is a professor of medicine and a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author. He reports no disclosures.

As obesity continues to ravage the health of the United States, bariatric surgery offers an effective strategy for individual patients suffering from medical complications.

When performed in adults with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2, bariatric surgery is associated with a mean weight loss of 20%-35% of baseline weight at 2-3 years. Bariatric surgery is associated with greater reductions in obesity comorbidities, compared with lifestyle intervention and supervised weight loss. Contemporary bariatric surgeries include Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, sleeve gastrectomy, and mini–gastric bypass.

Bariatric surgical procedures affect weight loss through two mechanisms: malabsorption and restriction. Such alterations in human physiology can change the absorption of common drugs of addiction, such as alcohol. This can increase the risk for problem drinking behaviors.

Wendy C. King, Ph.D., of the department of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh and her colleagues conducted an analysis of data from 1,945 patients in a cohort who underwent bariatric surgery in 10 U.S. hospitals. Symptoms of alcohol use disorder (AUD) were assessed pre- and postoperatively (JAMA 2012;307:2516-25).

The prevalence of AUD was significantly higher at 2 years postoperatively (9.6%), compared with the preoperative period (7.6%; P less than .01). Factors associated with a higher risk of postoperative AUD included male gender, younger age, smoking, regular alcohol consumption, a history of AUD, recreational drug use, low social support, and receiving Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

AUD can disqualify patients from bariatric surgery – but 7.6% of patients in this survey (taken independently of clinical care) reported it. The authors noted that a 2% increase in AUD associated with bariatric surgery translates into 2,000 additional people with AUD each year.

This is particularly problematic for this population, because a large number of calories are associated with alcohol intake, and alcohol intake can lower inhibitions for other types of eating behaviors – all of which can lead to weight regain.

So, what do we do?

I think it may be helpful to take alcohol use histories in the patients we are seeing in bariatric surgery follow-up, especially those who appear to be regaining weight. Some patients may not be aware of this connection. For the patients who I have told about this relationship, they recognize it, which may be the first step toward dealing with it.

Dr. Ebbert is a professor of medicine and a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author. He reports no disclosures.

As obesity continues to ravage the health of the United States, bariatric surgery offers an effective strategy for individual patients suffering from medical complications.

When performed in adults with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2, bariatric surgery is associated with a mean weight loss of 20%-35% of baseline weight at 2-3 years. Bariatric surgery is associated with greater reductions in obesity comorbidities, compared with lifestyle intervention and supervised weight loss. Contemporary bariatric surgeries include Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, sleeve gastrectomy, and mini–gastric bypass.

Bariatric surgical procedures affect weight loss through two mechanisms: malabsorption and restriction. Such alterations in human physiology can change the absorption of common drugs of addiction, such as alcohol. This can increase the risk for problem drinking behaviors.

Wendy C. King, Ph.D., of the department of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh and her colleagues conducted an analysis of data from 1,945 patients in a cohort who underwent bariatric surgery in 10 U.S. hospitals. Symptoms of alcohol use disorder (AUD) were assessed pre- and postoperatively (JAMA 2012;307:2516-25).

The prevalence of AUD was significantly higher at 2 years postoperatively (9.6%), compared with the preoperative period (7.6%; P less than .01). Factors associated with a higher risk of postoperative AUD included male gender, younger age, smoking, regular alcohol consumption, a history of AUD, recreational drug use, low social support, and receiving Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

AUD can disqualify patients from bariatric surgery – but 7.6% of patients in this survey (taken independently of clinical care) reported it. The authors noted that a 2% increase in AUD associated with bariatric surgery translates into 2,000 additional people with AUD each year.

This is particularly problematic for this population, because a large number of calories are associated with alcohol intake, and alcohol intake can lower inhibitions for other types of eating behaviors – all of which can lead to weight regain.

So, what do we do?

I think it may be helpful to take alcohol use histories in the patients we are seeing in bariatric surgery follow-up, especially those who appear to be regaining weight. Some patients may not be aware of this connection. For the patients who I have told about this relationship, they recognize it, which may be the first step toward dealing with it.

Dr. Ebbert is a professor of medicine and a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author. He reports no disclosures.

HACs may not tell the whole story

The Affordable Care Act has essentially overhauled Medicare’s payment system for hospitals in an effort to improve quality while minimizing wasteful spending.

One such change centers on HACs, or hospital-acquired conditions. These conditions were deemed potentially preventable by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in 2009 and are a major target for Medicare payment penalties and hospital quality initiatives. Hospitalizations that are complicated by one of these conditions, for instance, the development of diabetic ketoacidosis from poor glycemic control, do not qualify for higher paying diagnosis-related group payment, leaving a gaping hole between the cost of care delivered and the amount reimbursed by Medicare.

Yet to come in fiscal year 2015, Medicare payments for all discharges will be cut by 1% for those hospitals that score in the top quartile for the rate of hospital-acquired conditions, compared with national average.

Upon initially hearing about this provision in the ACA, I was shocked and felt it was both unfair and realistic, but as time has passed, it is clear that a variety of innovative hospital-based quality initiatives have made significant headway into minimizing at least some of the HACs.

Help is also available through the government. The Medicare Shared Savings and Pioneer ACO Models offer participating hospitals a share of the savings if they can reduce spending below historical benchmarks. A healthier bottom line for our hospitals has the potential to ultimately translate into improved resources and support systems to enhance our ability to provide excellent care for our patients, while making our days run more smoothly.

However, a recent study shows that HACs do not appear to be the bottom line in hospital savings after all. Identifying hospital-wide harm associated with increased cost, length of stay, and mortality in U.S. hospitals, was recently released by the Premier health care alliance, and was based on peer-reviewed research in the American Journal of Medical Quality.

Premier evaluated more than 5.5 million deidentified ICD-9 discharge records from hospitals and medical centers in 47 states. They identified 86 potential inpatient complications that were associated with higher cost, increased length of stay, and/or higher mortality.

Surprisingly, this study concluded that the current HACs used by the CMS cover only a fraction of the complications and that of the 86 high-impact conditions they evaluated, only 22 are addressed through the CMS’s federal payment policies. Conditions such as acute renal failure, which was associated with close to $490 million in costs, and hypotension, which had $200 million in costs in this study were far more significant than were the HACs such as air embolism and blood incompatibility, seen in 23 and 8 patients, respectively, in more than 5 million records.

While some of the 86 conditions identified may not be easy to prevent, others, such as acute renal failure and hypotension, have the potential to be significantly reduced through vigilant monitoring of parameters such as nephrotoxin use and blood pressure trends.

Dr. A. Maria Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

The Affordable Care Act has essentially overhauled Medicare’s payment system for hospitals in an effort to improve quality while minimizing wasteful spending.

One such change centers on HACs, or hospital-acquired conditions. These conditions were deemed potentially preventable by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in 2009 and are a major target for Medicare payment penalties and hospital quality initiatives. Hospitalizations that are complicated by one of these conditions, for instance, the development of diabetic ketoacidosis from poor glycemic control, do not qualify for higher paying diagnosis-related group payment, leaving a gaping hole between the cost of care delivered and the amount reimbursed by Medicare.

Yet to come in fiscal year 2015, Medicare payments for all discharges will be cut by 1% for those hospitals that score in the top quartile for the rate of hospital-acquired conditions, compared with national average.

Upon initially hearing about this provision in the ACA, I was shocked and felt it was both unfair and realistic, but as time has passed, it is clear that a variety of innovative hospital-based quality initiatives have made significant headway into minimizing at least some of the HACs.

Help is also available through the government. The Medicare Shared Savings and Pioneer ACO Models offer participating hospitals a share of the savings if they can reduce spending below historical benchmarks. A healthier bottom line for our hospitals has the potential to ultimately translate into improved resources and support systems to enhance our ability to provide excellent care for our patients, while making our days run more smoothly.

However, a recent study shows that HACs do not appear to be the bottom line in hospital savings after all. Identifying hospital-wide harm associated with increased cost, length of stay, and mortality in U.S. hospitals, was recently released by the Premier health care alliance, and was based on peer-reviewed research in the American Journal of Medical Quality.

Premier evaluated more than 5.5 million deidentified ICD-9 discharge records from hospitals and medical centers in 47 states. They identified 86 potential inpatient complications that were associated with higher cost, increased length of stay, and/or higher mortality.

Surprisingly, this study concluded that the current HACs used by the CMS cover only a fraction of the complications and that of the 86 high-impact conditions they evaluated, only 22 are addressed through the CMS’s federal payment policies. Conditions such as acute renal failure, which was associated with close to $490 million in costs, and hypotension, which had $200 million in costs in this study were far more significant than were the HACs such as air embolism and blood incompatibility, seen in 23 and 8 patients, respectively, in more than 5 million records.

While some of the 86 conditions identified may not be easy to prevent, others, such as acute renal failure and hypotension, have the potential to be significantly reduced through vigilant monitoring of parameters such as nephrotoxin use and blood pressure trends.

Dr. A. Maria Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

The Affordable Care Act has essentially overhauled Medicare’s payment system for hospitals in an effort to improve quality while minimizing wasteful spending.

One such change centers on HACs, or hospital-acquired conditions. These conditions were deemed potentially preventable by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in 2009 and are a major target for Medicare payment penalties and hospital quality initiatives. Hospitalizations that are complicated by one of these conditions, for instance, the development of diabetic ketoacidosis from poor glycemic control, do not qualify for higher paying diagnosis-related group payment, leaving a gaping hole between the cost of care delivered and the amount reimbursed by Medicare.

Yet to come in fiscal year 2015, Medicare payments for all discharges will be cut by 1% for those hospitals that score in the top quartile for the rate of hospital-acquired conditions, compared with national average.

Upon initially hearing about this provision in the ACA, I was shocked and felt it was both unfair and realistic, but as time has passed, it is clear that a variety of innovative hospital-based quality initiatives have made significant headway into minimizing at least some of the HACs.

Help is also available through the government. The Medicare Shared Savings and Pioneer ACO Models offer participating hospitals a share of the savings if they can reduce spending below historical benchmarks. A healthier bottom line for our hospitals has the potential to ultimately translate into improved resources and support systems to enhance our ability to provide excellent care for our patients, while making our days run more smoothly.

However, a recent study shows that HACs do not appear to be the bottom line in hospital savings after all. Identifying hospital-wide harm associated with increased cost, length of stay, and mortality in U.S. hospitals, was recently released by the Premier health care alliance, and was based on peer-reviewed research in the American Journal of Medical Quality.

Premier evaluated more than 5.5 million deidentified ICD-9 discharge records from hospitals and medical centers in 47 states. They identified 86 potential inpatient complications that were associated with higher cost, increased length of stay, and/or higher mortality.

Surprisingly, this study concluded that the current HACs used by the CMS cover only a fraction of the complications and that of the 86 high-impact conditions they evaluated, only 22 are addressed through the CMS’s federal payment policies. Conditions such as acute renal failure, which was associated with close to $490 million in costs, and hypotension, which had $200 million in costs in this study were far more significant than were the HACs such as air embolism and blood incompatibility, seen in 23 and 8 patients, respectively, in more than 5 million records.

While some of the 86 conditions identified may not be easy to prevent, others, such as acute renal failure and hypotension, have the potential to be significantly reduced through vigilant monitoring of parameters such as nephrotoxin use and blood pressure trends.

Dr. A. Maria Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Not in the guidelines: A year in review

As I reflect on my 1 year of writing for this newspaper and my first year as an attending, some things stand out as being, for me, consistently challenging and others, consistently rewarding. Time has seemed to go by much faster than during residency. So, without further ado, here is a list of those things that I have, continue to, and may always either struggle with or find joy in.

The checkout e-mail

What I feared the most about becoming an attending – managing a team day to day and teaching students and residents – has come easier than I thought. What has brought me the most angst, however, is passing my team off to my partners. As I write my "checkout e-mail," I am often plagued by doubt and worry that I have overlooked something. I worry I have ordered too many/not enough studies, consulted too often/not enough, or discharged too early/not early enough.

For the first half, and most emotionally pathologic part, of the year, I would log in each day after coming off-service, to see how my partners had changed things, to see what I had missed, and to see how the patients were progressing. I would even text my partners and residents to "see how Mr. X is doing" or to ask "How is the team doing?" This would often result in me second-guessing myself and ruining my day off. I don’t do this anymore.

Now I give myself several healthy days of "no team contact" before I log in to finish notes and inevitably check in on patients. I know that there must be a balance of educational follow-up, feedback, and a healthy forgiving mind, but I still struggle to find it.

Placement

Though there are some scoring systems that help the clinician know which patients need to be hospitalized, who needs the ICU, and who can go home, a lot of this falls in evidence-based medicine’s gray zone. One of the learning curves for me was to know which patients I should insist go to the unit, insist be evaluated by the unit, or who, though sick, can be managed on the floor. In the end, I have found that my gut feeling and the first 15 seconds of my encounter with the patient help me more with placement than any scoring system or guideline.

The consult

It has been a bit painful learning to juggle the nuances of consultant services preferences (who always wants to be involved vs. who rarely does), attending preferences (some want to know when any of their patients are in-house), and what is my own comfort level. I think, for the most part, I have erred on the overconsult side this year, and though I have felt embarrassed a couple of times, it has been the safer route as I become comfortable as a hospitalist.

Discharge

As with The Placement, there is virtually no evidence to help The Discharge. As a resident, an earlier discharge usually was better, but as an attending, The Discharge is where the complex intertwinement of disease, social situation, physical therapy, and unfortunately, day of the week manifests (see previous column: "Closed on weekends?" Hospitalist News, May 2014). Also, like The Placement, this often ends up being a gut feeling supported by close follow-up, a good conversation with the patient and family, and some hopeful finger-crossing.

Being a people pleaser

This personality trait has helped me to be a good student, a responsive employee, and sometimes a good doctor. But it has also caused me a good amount of suffering. Thus, when despite my best efforts a patient or family continues to be upset with how quickly or slowly things are being done, which services are or are not involved, etc., I feel bad. Maybe this will change in the coming years. Maybe not.

Teaching

I have always liked teaching, but as a resident this often played second fiddle to grunt work and "res-interning." As an attending, however, I have finally been able to make this a significant part of every day. I enjoy it, and I think my residents and medical students enjoy that I enjoy it. This has been one of the true pleasures of my first year as an attending.

Connection

As an attending I now benefit from much more time to enjoy my patient connections. Less tired and harried, I have longer conversations and enjoy actively practicing communication. I have the ability to have more in-depth conversations about goals of care, and have found that often these conversations end with a decrease in anxiety and a sense of peace.

I now also have a business card with an e-mail address that receives occasional thank-you notes. Yesterday, I received an e-mail that said simply, "Thank you for your great service." How incredibly fulfilling. Talk about unexpected joy.

Dr. Horton completed his residency in internal medicine and pediatrics at the University of Utah and Primary Children’s Medical Center, both in Salt Lake City, in July 2013, and joined the faculty there. He is sharing his new-career experiences with Hospitalist News.

As I reflect on my 1 year of writing for this newspaper and my first year as an attending, some things stand out as being, for me, consistently challenging and others, consistently rewarding. Time has seemed to go by much faster than during residency. So, without further ado, here is a list of those things that I have, continue to, and may always either struggle with or find joy in.

The checkout e-mail

What I feared the most about becoming an attending – managing a team day to day and teaching students and residents – has come easier than I thought. What has brought me the most angst, however, is passing my team off to my partners. As I write my "checkout e-mail," I am often plagued by doubt and worry that I have overlooked something. I worry I have ordered too many/not enough studies, consulted too often/not enough, or discharged too early/not early enough.

For the first half, and most emotionally pathologic part, of the year, I would log in each day after coming off-service, to see how my partners had changed things, to see what I had missed, and to see how the patients were progressing. I would even text my partners and residents to "see how Mr. X is doing" or to ask "How is the team doing?" This would often result in me second-guessing myself and ruining my day off. I don’t do this anymore.

Now I give myself several healthy days of "no team contact" before I log in to finish notes and inevitably check in on patients. I know that there must be a balance of educational follow-up, feedback, and a healthy forgiving mind, but I still struggle to find it.

Placement

Though there are some scoring systems that help the clinician know which patients need to be hospitalized, who needs the ICU, and who can go home, a lot of this falls in evidence-based medicine’s gray zone. One of the learning curves for me was to know which patients I should insist go to the unit, insist be evaluated by the unit, or who, though sick, can be managed on the floor. In the end, I have found that my gut feeling and the first 15 seconds of my encounter with the patient help me more with placement than any scoring system or guideline.

The consult

It has been a bit painful learning to juggle the nuances of consultant services preferences (who always wants to be involved vs. who rarely does), attending preferences (some want to know when any of their patients are in-house), and what is my own comfort level. I think, for the most part, I have erred on the overconsult side this year, and though I have felt embarrassed a couple of times, it has been the safer route as I become comfortable as a hospitalist.

Discharge

As with The Placement, there is virtually no evidence to help The Discharge. As a resident, an earlier discharge usually was better, but as an attending, The Discharge is where the complex intertwinement of disease, social situation, physical therapy, and unfortunately, day of the week manifests (see previous column: "Closed on weekends?" Hospitalist News, May 2014). Also, like The Placement, this often ends up being a gut feeling supported by close follow-up, a good conversation with the patient and family, and some hopeful finger-crossing.

Being a people pleaser

This personality trait has helped me to be a good student, a responsive employee, and sometimes a good doctor. But it has also caused me a good amount of suffering. Thus, when despite my best efforts a patient or family continues to be upset with how quickly or slowly things are being done, which services are or are not involved, etc., I feel bad. Maybe this will change in the coming years. Maybe not.

Teaching

I have always liked teaching, but as a resident this often played second fiddle to grunt work and "res-interning." As an attending, however, I have finally been able to make this a significant part of every day. I enjoy it, and I think my residents and medical students enjoy that I enjoy it. This has been one of the true pleasures of my first year as an attending.

Connection

As an attending I now benefit from much more time to enjoy my patient connections. Less tired and harried, I have longer conversations and enjoy actively practicing communication. I have the ability to have more in-depth conversations about goals of care, and have found that often these conversations end with a decrease in anxiety and a sense of peace.

I now also have a business card with an e-mail address that receives occasional thank-you notes. Yesterday, I received an e-mail that said simply, "Thank you for your great service." How incredibly fulfilling. Talk about unexpected joy.

Dr. Horton completed his residency in internal medicine and pediatrics at the University of Utah and Primary Children’s Medical Center, both in Salt Lake City, in July 2013, and joined the faculty there. He is sharing his new-career experiences with Hospitalist News.

As I reflect on my 1 year of writing for this newspaper and my first year as an attending, some things stand out as being, for me, consistently challenging and others, consistently rewarding. Time has seemed to go by much faster than during residency. So, without further ado, here is a list of those things that I have, continue to, and may always either struggle with or find joy in.

The checkout e-mail

What I feared the most about becoming an attending – managing a team day to day and teaching students and residents – has come easier than I thought. What has brought me the most angst, however, is passing my team off to my partners. As I write my "checkout e-mail," I am often plagued by doubt and worry that I have overlooked something. I worry I have ordered too many/not enough studies, consulted too often/not enough, or discharged too early/not early enough.

For the first half, and most emotionally pathologic part, of the year, I would log in each day after coming off-service, to see how my partners had changed things, to see what I had missed, and to see how the patients were progressing. I would even text my partners and residents to "see how Mr. X is doing" or to ask "How is the team doing?" This would often result in me second-guessing myself and ruining my day off. I don’t do this anymore.

Now I give myself several healthy days of "no team contact" before I log in to finish notes and inevitably check in on patients. I know that there must be a balance of educational follow-up, feedback, and a healthy forgiving mind, but I still struggle to find it.

Placement

Though there are some scoring systems that help the clinician know which patients need to be hospitalized, who needs the ICU, and who can go home, a lot of this falls in evidence-based medicine’s gray zone. One of the learning curves for me was to know which patients I should insist go to the unit, insist be evaluated by the unit, or who, though sick, can be managed on the floor. In the end, I have found that my gut feeling and the first 15 seconds of my encounter with the patient help me more with placement than any scoring system or guideline.

The consult

It has been a bit painful learning to juggle the nuances of consultant services preferences (who always wants to be involved vs. who rarely does), attending preferences (some want to know when any of their patients are in-house), and what is my own comfort level. I think, for the most part, I have erred on the overconsult side this year, and though I have felt embarrassed a couple of times, it has been the safer route as I become comfortable as a hospitalist.

Discharge

As with The Placement, there is virtually no evidence to help The Discharge. As a resident, an earlier discharge usually was better, but as an attending, The Discharge is where the complex intertwinement of disease, social situation, physical therapy, and unfortunately, day of the week manifests (see previous column: "Closed on weekends?" Hospitalist News, May 2014). Also, like The Placement, this often ends up being a gut feeling supported by close follow-up, a good conversation with the patient and family, and some hopeful finger-crossing.

Being a people pleaser

This personality trait has helped me to be a good student, a responsive employee, and sometimes a good doctor. But it has also caused me a good amount of suffering. Thus, when despite my best efforts a patient or family continues to be upset with how quickly or slowly things are being done, which services are or are not involved, etc., I feel bad. Maybe this will change in the coming years. Maybe not.

Teaching

I have always liked teaching, but as a resident this often played second fiddle to grunt work and "res-interning." As an attending, however, I have finally been able to make this a significant part of every day. I enjoy it, and I think my residents and medical students enjoy that I enjoy it. This has been one of the true pleasures of my first year as an attending.

Connection

As an attending I now benefit from much more time to enjoy my patient connections. Less tired and harried, I have longer conversations and enjoy actively practicing communication. I have the ability to have more in-depth conversations about goals of care, and have found that often these conversations end with a decrease in anxiety and a sense of peace.

I now also have a business card with an e-mail address that receives occasional thank-you notes. Yesterday, I received an e-mail that said simply, "Thank you for your great service." How incredibly fulfilling. Talk about unexpected joy.

Dr. Horton completed his residency in internal medicine and pediatrics at the University of Utah and Primary Children’s Medical Center, both in Salt Lake City, in July 2013, and joined the faculty there. He is sharing his new-career experiences with Hospitalist News.

Receiving Medicare pay for concierge care, cash-only referrals

In my area, there are several internists who run cash-pay practices. Only one of them refers to me, and that’s just when he can’t get them to see the Mayo Clinic folks fast enough.

I’m not a cash-only concierge neurologist for a number of reasons I’ve previously mentioned. I don’t really try to cultivate these referrals, and the concierge physicians don’t really want me to see their patients.

Why would I not be bending over backward to get more patients? I take Medicare (and other insurances), so whether you want to pay cash or not, if you’re on Medicare, I can’t accept it. It’s a crime. I can only take what Washington says I can. Maybe that law will change someday, but I doubt it.

So the patient who’s paying $3,000 per year to see Dr. Concierge down the street and cash for every visit after that isn’t financially any more special to me than the guy who’s living on a fixed income and only has Medicare. I get paid the same for both.

About a year ago, a representative from a cash-only practice came by, asking me to be the "designated neurologist" for them. In return, I’d have to agree to the following conditions:

• All patients from them would be seen within 24 hours of calling my office.

• I’d have to give my cell and home phone numbers to all of their patients, so I’d be available. ("Our patients want a lot of hand-holding" is what he said.)

• If needed, I’d meet them on weekends, either at my office or by making house calls, at the patient’s request.

There were a few other requests. I politely said, "No, thank you" and handed his "designated specialist" paperwork back to him.

My practice right now is pretty egalitarian. Uncle Sam pays me the same for your visit regardless of how much money you have or what your social standing is. I also value my privacy and home life. My patients know how to reach the doc on call in an emergency, and know it may not be me.

So, if you’re a concierge physician and don’t feel I’m going the extra mile to get your patients in at the drop of a hat, or to make sure a double-soy latte is ready for them on arrival, I’m sorry. They may be paying you a lot for these perks, but not me. The only thing I have to offer at my practice is the best patient care I can – to all equally.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

In my area, there are several internists who run cash-pay practices. Only one of them refers to me, and that’s just when he can’t get them to see the Mayo Clinic folks fast enough.

I’m not a cash-only concierge neurologist for a number of reasons I’ve previously mentioned. I don’t really try to cultivate these referrals, and the concierge physicians don’t really want me to see their patients.

Why would I not be bending over backward to get more patients? I take Medicare (and other insurances), so whether you want to pay cash or not, if you’re on Medicare, I can’t accept it. It’s a crime. I can only take what Washington says I can. Maybe that law will change someday, but I doubt it.

So the patient who’s paying $3,000 per year to see Dr. Concierge down the street and cash for every visit after that isn’t financially any more special to me than the guy who’s living on a fixed income and only has Medicare. I get paid the same for both.

About a year ago, a representative from a cash-only practice came by, asking me to be the "designated neurologist" for them. In return, I’d have to agree to the following conditions:

• All patients from them would be seen within 24 hours of calling my office.

• I’d have to give my cell and home phone numbers to all of their patients, so I’d be available. ("Our patients want a lot of hand-holding" is what he said.)

• If needed, I’d meet them on weekends, either at my office or by making house calls, at the patient’s request.

There were a few other requests. I politely said, "No, thank you" and handed his "designated specialist" paperwork back to him.

My practice right now is pretty egalitarian. Uncle Sam pays me the same for your visit regardless of how much money you have or what your social standing is. I also value my privacy and home life. My patients know how to reach the doc on call in an emergency, and know it may not be me.

So, if you’re a concierge physician and don’t feel I’m going the extra mile to get your patients in at the drop of a hat, or to make sure a double-soy latte is ready for them on arrival, I’m sorry. They may be paying you a lot for these perks, but not me. The only thing I have to offer at my practice is the best patient care I can – to all equally.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

In my area, there are several internists who run cash-pay practices. Only one of them refers to me, and that’s just when he can’t get them to see the Mayo Clinic folks fast enough.

I’m not a cash-only concierge neurologist for a number of reasons I’ve previously mentioned. I don’t really try to cultivate these referrals, and the concierge physicians don’t really want me to see their patients.

Why would I not be bending over backward to get more patients? I take Medicare (and other insurances), so whether you want to pay cash or not, if you’re on Medicare, I can’t accept it. It’s a crime. I can only take what Washington says I can. Maybe that law will change someday, but I doubt it.

So the patient who’s paying $3,000 per year to see Dr. Concierge down the street and cash for every visit after that isn’t financially any more special to me than the guy who’s living on a fixed income and only has Medicare. I get paid the same for both.

About a year ago, a representative from a cash-only practice came by, asking me to be the "designated neurologist" for them. In return, I’d have to agree to the following conditions:

• All patients from them would be seen within 24 hours of calling my office.

• I’d have to give my cell and home phone numbers to all of their patients, so I’d be available. ("Our patients want a lot of hand-holding" is what he said.)

• If needed, I’d meet them on weekends, either at my office or by making house calls, at the patient’s request.

There were a few other requests. I politely said, "No, thank you" and handed his "designated specialist" paperwork back to him.

My practice right now is pretty egalitarian. Uncle Sam pays me the same for your visit regardless of how much money you have or what your social standing is. I also value my privacy and home life. My patients know how to reach the doc on call in an emergency, and know it may not be me.

So, if you’re a concierge physician and don’t feel I’m going the extra mile to get your patients in at the drop of a hat, or to make sure a double-soy latte is ready for them on arrival, I’m sorry. They may be paying you a lot for these perks, but not me. The only thing I have to offer at my practice is the best patient care I can – to all equally.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Obesity and gynecologic surgery, part 2

As previously reported, obesity poses many challenges to gynecologic surgery, from open to minimally invasive to vaginal surgery (Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2012;22:76-81; Gynecol. Oncol. 2008;111:41-5; J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:259-65). Concerns relevant to operative management in the obese include difficulty with patient positioning, access to the abdominal cavity, visualization, and ventilation. This article will review tips for overcoming these challenges.

Positioning of obese patients often requires specialized equipment including bariatric beds, large padded stirrups, bed extenders, and arm sleds. Extra time and care should be taken while positioning obese patients given the increased propensity for pressure ulcers and nerve injuries. The basics of positioning begin with requesting additional help for patient moving and positioning as needed.

With regard to minimally invasive surgery, the use of antislip devices such as egg crate, gel pad, or a surgical beanbag is important for prevention of slippage when the patient is placed in the Trendelenburg position (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:182-95). The best laparoscopic positioning for these patients is in low lithotomy, with both arms tucked at the side in the military position and with liberal corporeal padding (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;191:669-74). When placing the patient in lithotomy, care should be taken to avoid hyperflexion of the hip, as obese patients are particularly prone to femoral nerve stretch injuries in this position.

Access to the abdominal cavity can be difficult because of the thickness of the abdominal wall in these patients. In open surgery, this is overcome with deep blades on retractors. In minimally invasive surgery, this requires longer trocars and Veress needles, which are now routinely available. If there is difficulty accessing the abdominal cavity with a Veress needle, a Hassan entry technique or ports with see-through trocars also can be used to ensure safe entry into the abdomen.

It is important to remember that the abdominal wall is the thinnest at the umbilical stalk. Additionally, using the upper abdomen can help assist with entry as the abdominal wall is often thinner above the umbilicus than below. For this reason, a left upper quadrant entry is often utilized at Palmer’s point. Care should be taken that entry is not so high as to limit the operator’s ability to reach the deep pelvis with laparoscopic instruments. Further, anesthesia must decompress the stomach prior to port placement in order to avoid a gastric injury.

Obese patients have a higher concentration of intraperitoneal and visceral fat, which can cause decreased visualization in the pelvis. In addition, the thick abdominal wall creates more torque on laparoscopic instruments, which can impair a surgeon’s ability to easily maneuver instruments. To decrease torque, trocars should be placed in the direction of the operative field. Draping the omentum over the liver can help to increase visualization, and always consider additional trocar placement to assist in visualization (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;191:669-74). Robotic instruments may further assist with feasibility of laparoscopy in the obese by obviating the role of abdominal wall torque.

Finally, patients can be difficult to ventilate in steep Trendelenburg required for laparoscopic surgery, as the weight of the breasts and abdomen shifts onto the thorax (J. Anesth. 2012;26:758-65; Ann. Surg. 2005;241:219-26; Anesth. Analg. 2002;94:1345-50). By slowly tilting the patient into steep Trendelenburg, the body has a chance to acclimate to ventilation in this position. One needs to remember to insufflate the abdomen in the supine position prior to proceeding with Trendelenburg.

Of course, one should always consider that vaginal surgery provides a "minimally invasive" approach without the difficulty of ventilating an obese patient in steep Trendelenburg position. A recent review of the effect of obesity on vaginal surgery concludes that obesity increases the difficulty of vaginal surgery and may be best performed by high-volume surgeons, given the difficulties that are often encountered (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:168-75).

As the obesity epidemic continues, figuring out safe and effective ways to provide surgical care will continue to remain a challenge to surgeons. Utilizing these tips is a start, but continued innovation and experience will be required to provide optimal care to our ever-growing population.

Dr. Clark is a chief resident in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Clark and Dr. Gehrig said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

As previously reported, obesity poses many challenges to gynecologic surgery, from open to minimally invasive to vaginal surgery (Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2012;22:76-81; Gynecol. Oncol. 2008;111:41-5; J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:259-65). Concerns relevant to operative management in the obese include difficulty with patient positioning, access to the abdominal cavity, visualization, and ventilation. This article will review tips for overcoming these challenges.

Positioning of obese patients often requires specialized equipment including bariatric beds, large padded stirrups, bed extenders, and arm sleds. Extra time and care should be taken while positioning obese patients given the increased propensity for pressure ulcers and nerve injuries. The basics of positioning begin with requesting additional help for patient moving and positioning as needed.

With regard to minimally invasive surgery, the use of antislip devices such as egg crate, gel pad, or a surgical beanbag is important for prevention of slippage when the patient is placed in the Trendelenburg position (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:182-95). The best laparoscopic positioning for these patients is in low lithotomy, with both arms tucked at the side in the military position and with liberal corporeal padding (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;191:669-74). When placing the patient in lithotomy, care should be taken to avoid hyperflexion of the hip, as obese patients are particularly prone to femoral nerve stretch injuries in this position.

Access to the abdominal cavity can be difficult because of the thickness of the abdominal wall in these patients. In open surgery, this is overcome with deep blades on retractors. In minimally invasive surgery, this requires longer trocars and Veress needles, which are now routinely available. If there is difficulty accessing the abdominal cavity with a Veress needle, a Hassan entry technique or ports with see-through trocars also can be used to ensure safe entry into the abdomen.

It is important to remember that the abdominal wall is the thinnest at the umbilical stalk. Additionally, using the upper abdomen can help assist with entry as the abdominal wall is often thinner above the umbilicus than below. For this reason, a left upper quadrant entry is often utilized at Palmer’s point. Care should be taken that entry is not so high as to limit the operator’s ability to reach the deep pelvis with laparoscopic instruments. Further, anesthesia must decompress the stomach prior to port placement in order to avoid a gastric injury.

Obese patients have a higher concentration of intraperitoneal and visceral fat, which can cause decreased visualization in the pelvis. In addition, the thick abdominal wall creates more torque on laparoscopic instruments, which can impair a surgeon’s ability to easily maneuver instruments. To decrease torque, trocars should be placed in the direction of the operative field. Draping the omentum over the liver can help to increase visualization, and always consider additional trocar placement to assist in visualization (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;191:669-74). Robotic instruments may further assist with feasibility of laparoscopy in the obese by obviating the role of abdominal wall torque.

Finally, patients can be difficult to ventilate in steep Trendelenburg required for laparoscopic surgery, as the weight of the breasts and abdomen shifts onto the thorax (J. Anesth. 2012;26:758-65; Ann. Surg. 2005;241:219-26; Anesth. Analg. 2002;94:1345-50). By slowly tilting the patient into steep Trendelenburg, the body has a chance to acclimate to ventilation in this position. One needs to remember to insufflate the abdomen in the supine position prior to proceeding with Trendelenburg.

Of course, one should always consider that vaginal surgery provides a "minimally invasive" approach without the difficulty of ventilating an obese patient in steep Trendelenburg position. A recent review of the effect of obesity on vaginal surgery concludes that obesity increases the difficulty of vaginal surgery and may be best performed by high-volume surgeons, given the difficulties that are often encountered (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:168-75).

As the obesity epidemic continues, figuring out safe and effective ways to provide surgical care will continue to remain a challenge to surgeons. Utilizing these tips is a start, but continued innovation and experience will be required to provide optimal care to our ever-growing population.

Dr. Clark is a chief resident in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Clark and Dr. Gehrig said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

As previously reported, obesity poses many challenges to gynecologic surgery, from open to minimally invasive to vaginal surgery (Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2012;22:76-81; Gynecol. Oncol. 2008;111:41-5; J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:259-65). Concerns relevant to operative management in the obese include difficulty with patient positioning, access to the abdominal cavity, visualization, and ventilation. This article will review tips for overcoming these challenges.

Positioning of obese patients often requires specialized equipment including bariatric beds, large padded stirrups, bed extenders, and arm sleds. Extra time and care should be taken while positioning obese patients given the increased propensity for pressure ulcers and nerve injuries. The basics of positioning begin with requesting additional help for patient moving and positioning as needed.

With regard to minimally invasive surgery, the use of antislip devices such as egg crate, gel pad, or a surgical beanbag is important for prevention of slippage when the patient is placed in the Trendelenburg position (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:182-95). The best laparoscopic positioning for these patients is in low lithotomy, with both arms tucked at the side in the military position and with liberal corporeal padding (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;191:669-74). When placing the patient in lithotomy, care should be taken to avoid hyperflexion of the hip, as obese patients are particularly prone to femoral nerve stretch injuries in this position.

Access to the abdominal cavity can be difficult because of the thickness of the abdominal wall in these patients. In open surgery, this is overcome with deep blades on retractors. In minimally invasive surgery, this requires longer trocars and Veress needles, which are now routinely available. If there is difficulty accessing the abdominal cavity with a Veress needle, a Hassan entry technique or ports with see-through trocars also can be used to ensure safe entry into the abdomen.

It is important to remember that the abdominal wall is the thinnest at the umbilical stalk. Additionally, using the upper abdomen can help assist with entry as the abdominal wall is often thinner above the umbilicus than below. For this reason, a left upper quadrant entry is often utilized at Palmer’s point. Care should be taken that entry is not so high as to limit the operator’s ability to reach the deep pelvis with laparoscopic instruments. Further, anesthesia must decompress the stomach prior to port placement in order to avoid a gastric injury.

Obese patients have a higher concentration of intraperitoneal and visceral fat, which can cause decreased visualization in the pelvis. In addition, the thick abdominal wall creates more torque on laparoscopic instruments, which can impair a surgeon’s ability to easily maneuver instruments. To decrease torque, trocars should be placed in the direction of the operative field. Draping the omentum over the liver can help to increase visualization, and always consider additional trocar placement to assist in visualization (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;191:669-74). Robotic instruments may further assist with feasibility of laparoscopy in the obese by obviating the role of abdominal wall torque.

Finally, patients can be difficult to ventilate in steep Trendelenburg required for laparoscopic surgery, as the weight of the breasts and abdomen shifts onto the thorax (J. Anesth. 2012;26:758-65; Ann. Surg. 2005;241:219-26; Anesth. Analg. 2002;94:1345-50). By slowly tilting the patient into steep Trendelenburg, the body has a chance to acclimate to ventilation in this position. One needs to remember to insufflate the abdomen in the supine position prior to proceeding with Trendelenburg.

Of course, one should always consider that vaginal surgery provides a "minimally invasive" approach without the difficulty of ventilating an obese patient in steep Trendelenburg position. A recent review of the effect of obesity on vaginal surgery concludes that obesity increases the difficulty of vaginal surgery and may be best performed by high-volume surgeons, given the difficulties that are often encountered (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:168-75).

As the obesity epidemic continues, figuring out safe and effective ways to provide surgical care will continue to remain a challenge to surgeons. Utilizing these tips is a start, but continued innovation and experience will be required to provide optimal care to our ever-growing population.

Dr. Clark is a chief resident in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Clark and Dr. Gehrig said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

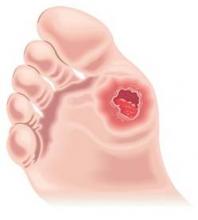

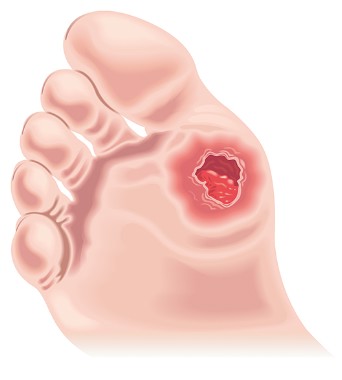

A diabetic foot infection progresses to amputation

The story

KL was a 56-year-old man with multiple comorbidities, including obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, insulin-dependent diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and dyslipidemia. He presented to Hospital A with fever and chills, along with an open wound on the bottom of his left foot. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 14,000 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 3.1 mg/dL. KL was admitted by Dr. Hospitalist for cellulitis and an infected diabetic foot ulcer.

KL was started on intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam and blood cultures were drawn. A bone scan was negative for osteomyelitis. Blood cultures did not grow any bacteria, but a wound culture from his foot ulcer grew Klebsiella. Dr. Hospitalist consulted inpatient podiatry for wound debridement, but KL apparently refused in favor of being seen by his own podiatrist as an outpatient. By hospital day 2, KL was afebrile, eating well, and he was discharged on oral ciprofloxacin later that same day.

Two days after discharge, KL followed up with his primary care physician (PCP). KL was again febrile and his foot ulcer looked worse. The PCP recommended hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics, but KL was reluctant to return to the hospital. The PCP arranged for midline placement and KL was referred to a local wound clinic for intravenous vancomycin to begin the next day. KL remained on the oral ciprofloxacin.

Over the next 3 days, KL received daily intravenous vancomycin at the wound clinic. However, the foot ulcer continued to drain purulent material with associated cellulitis and advancing erythema across the forefoot. The wound nurse contacted the PCP who had sent KL to the emergency department of Hospital B. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 18,300 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 2.2 mg/dL. KL was informed that he needed wound debridement and was offered the same podiatrist that he refused at Hospital A. Once again, KL deferred in favor of his own podiatrist who apparently was on vacation. Blood and wound cultures were obtained and KL received a dose of intravenous amoxicillin/sulbactam in the ED, but because of his refusal to receive wound debridement and care at Hospital A or B, he was sent home that same afternoon.

KL left Hospital B and drove 2 hours to the ED of Hospital C. He was immediately admitted and intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were begun. Plain films of the foot were consistent with osteomyelitis. An MRI of the foot demonstrated cellulitis, myositis, and a forefoot abscess. Within 24 hours of admission, KL developed chest pain and was subsequently ruled-in for a non–ST-elevation MI. KL ended up getting a left heart catheterization, and this delayed surgical debridement of his infected foot. Ultimately, KL did have debridement of his foot, but the infection had an advanced to the point that a below-the-knee amputation was required. Surgical pathology cultures were positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Complaint

KL was now facing life without his left leg, and he was angry and felt that the medical system had let him down. A complaint was quickly filed and alleged multiple breaches in the standard of care against multiple providers. The complaint included Dr. Hospitalist and asserted that he failed to obtain an MRI of the left foot from the very start, stopped intravenous vancomycin inappropriately, and failed to obtain infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults.

The complaint further asserted that the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B were negligent for not readmitting KL and obtaining infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults. If the providers in this case had continued intravenous vancomycin throughout his case and otherwise obtained appropriate specialty care, KL’s leg would have been saved.

Scientific principles

Diabetic foot infections are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Important risk factors for development of diabetic foot infections include neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, and poor glycemic control. Most diabetic foot infections are polymicrobial, but MRSA is a common pathogen. Although severe diabetic foot infections warrant hospitalization for urgent surgical consultation, antimicrobial administration, and medical stabilization, most mild infections and many moderate infections can be managed in the outpatient setting with close follow-up.

The possibility of osteomyelitis should be considered in diabetic patients with foot wounds associated with signs of infection in the deeper soft tissues and in patients with chronic ulcers. Many patients with confirmed osteomyelitis of the foot benefit from surgical resection.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Although Dr. Hospitalist had a negative bone scan result, he should have considered MRSA as a pathogen for KL despite a wound culture growing Klebsiella only. Most experts agreed, however, that it would be pure speculation as to what an MRI would have shown so early in KL’s course and ultimately, Dr. Hospitalist was defensible because KL did have appropriate follow-up just 48 hours after discharge. In fact, more than 21 days from original presentation to his amputation, KL only had 3 days off of intravenous vancomycin.

As a result, defense experts focused on the failure of KL to obtain debridement as the main reason for his injury. Dr. Hospitalist, the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B, all documented KL’s refusal to allow debridement by a podiatrist other than his own. KL denied this allegation, but the chart was consistent in this regard.

Conclusion

In the era of patient-centered care, patient wishes and preferences are important to integrate into the overall care plan. But when a patient’s wishes and preferences delay or otherwise subvert optimal care, it is vital that the hospitalist document the circumstances in their entirety. Documentation should confirm that the patient has capacity for decision making and that care recommendation benefits, risks for not following said recommendations, and care recommendation alternatives have been fully reviewed.

It is also helpful to have such discussions witnessed by other providers (that is, the nurse) so that the documentation is corroborated. The PCP and Hospital B were dismissed from the case. Hospital A settled with the plaintiff by waiving all hospital charges from his original hospitalization.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

The story

KL was a 56-year-old man with multiple comorbidities, including obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, insulin-dependent diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and dyslipidemia. He presented to Hospital A with fever and chills, along with an open wound on the bottom of his left foot. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 14,000 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 3.1 mg/dL. KL was admitted by Dr. Hospitalist for cellulitis and an infected diabetic foot ulcer.

KL was started on intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam and blood cultures were drawn. A bone scan was negative for osteomyelitis. Blood cultures did not grow any bacteria, but a wound culture from his foot ulcer grew Klebsiella. Dr. Hospitalist consulted inpatient podiatry for wound debridement, but KL apparently refused in favor of being seen by his own podiatrist as an outpatient. By hospital day 2, KL was afebrile, eating well, and he was discharged on oral ciprofloxacin later that same day.

Two days after discharge, KL followed up with his primary care physician (PCP). KL was again febrile and his foot ulcer looked worse. The PCP recommended hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics, but KL was reluctant to return to the hospital. The PCP arranged for midline placement and KL was referred to a local wound clinic for intravenous vancomycin to begin the next day. KL remained on the oral ciprofloxacin.

Over the next 3 days, KL received daily intravenous vancomycin at the wound clinic. However, the foot ulcer continued to drain purulent material with associated cellulitis and advancing erythema across the forefoot. The wound nurse contacted the PCP who had sent KL to the emergency department of Hospital B. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 18,300 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 2.2 mg/dL. KL was informed that he needed wound debridement and was offered the same podiatrist that he refused at Hospital A. Once again, KL deferred in favor of his own podiatrist who apparently was on vacation. Blood and wound cultures were obtained and KL received a dose of intravenous amoxicillin/sulbactam in the ED, but because of his refusal to receive wound debridement and care at Hospital A or B, he was sent home that same afternoon.

KL left Hospital B and drove 2 hours to the ED of Hospital C. He was immediately admitted and intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were begun. Plain films of the foot were consistent with osteomyelitis. An MRI of the foot demonstrated cellulitis, myositis, and a forefoot abscess. Within 24 hours of admission, KL developed chest pain and was subsequently ruled-in for a non–ST-elevation MI. KL ended up getting a left heart catheterization, and this delayed surgical debridement of his infected foot. Ultimately, KL did have debridement of his foot, but the infection had an advanced to the point that a below-the-knee amputation was required. Surgical pathology cultures were positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Complaint

KL was now facing life without his left leg, and he was angry and felt that the medical system had let him down. A complaint was quickly filed and alleged multiple breaches in the standard of care against multiple providers. The complaint included Dr. Hospitalist and asserted that he failed to obtain an MRI of the left foot from the very start, stopped intravenous vancomycin inappropriately, and failed to obtain infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults.

The complaint further asserted that the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B were negligent for not readmitting KL and obtaining infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults. If the providers in this case had continued intravenous vancomycin throughout his case and otherwise obtained appropriate specialty care, KL’s leg would have been saved.

Scientific principles

Diabetic foot infections are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Important risk factors for development of diabetic foot infections include neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, and poor glycemic control. Most diabetic foot infections are polymicrobial, but MRSA is a common pathogen. Although severe diabetic foot infections warrant hospitalization for urgent surgical consultation, antimicrobial administration, and medical stabilization, most mild infections and many moderate infections can be managed in the outpatient setting with close follow-up.

The possibility of osteomyelitis should be considered in diabetic patients with foot wounds associated with signs of infection in the deeper soft tissues and in patients with chronic ulcers. Many patients with confirmed osteomyelitis of the foot benefit from surgical resection.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Although Dr. Hospitalist had a negative bone scan result, he should have considered MRSA as a pathogen for KL despite a wound culture growing Klebsiella only. Most experts agreed, however, that it would be pure speculation as to what an MRI would have shown so early in KL’s course and ultimately, Dr. Hospitalist was defensible because KL did have appropriate follow-up just 48 hours after discharge. In fact, more than 21 days from original presentation to his amputation, KL only had 3 days off of intravenous vancomycin.

As a result, defense experts focused on the failure of KL to obtain debridement as the main reason for his injury. Dr. Hospitalist, the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B, all documented KL’s refusal to allow debridement by a podiatrist other than his own. KL denied this allegation, but the chart was consistent in this regard.

Conclusion

In the era of patient-centered care, patient wishes and preferences are important to integrate into the overall care plan. But when a patient’s wishes and preferences delay or otherwise subvert optimal care, it is vital that the hospitalist document the circumstances in their entirety. Documentation should confirm that the patient has capacity for decision making and that care recommendation benefits, risks for not following said recommendations, and care recommendation alternatives have been fully reviewed.

It is also helpful to have such discussions witnessed by other providers (that is, the nurse) so that the documentation is corroborated. The PCP and Hospital B were dismissed from the case. Hospital A settled with the plaintiff by waiving all hospital charges from his original hospitalization.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

The story

KL was a 56-year-old man with multiple comorbidities, including obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, insulin-dependent diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and dyslipidemia. He presented to Hospital A with fever and chills, along with an open wound on the bottom of his left foot. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 14,000 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 3.1 mg/dL. KL was admitted by Dr. Hospitalist for cellulitis and an infected diabetic foot ulcer.

KL was started on intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam and blood cultures were drawn. A bone scan was negative for osteomyelitis. Blood cultures did not grow any bacteria, but a wound culture from his foot ulcer grew Klebsiella. Dr. Hospitalist consulted inpatient podiatry for wound debridement, but KL apparently refused in favor of being seen by his own podiatrist as an outpatient. By hospital day 2, KL was afebrile, eating well, and he was discharged on oral ciprofloxacin later that same day.

Two days after discharge, KL followed up with his primary care physician (PCP). KL was again febrile and his foot ulcer looked worse. The PCP recommended hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics, but KL was reluctant to return to the hospital. The PCP arranged for midline placement and KL was referred to a local wound clinic for intravenous vancomycin to begin the next day. KL remained on the oral ciprofloxacin.

Over the next 3 days, KL received daily intravenous vancomycin at the wound clinic. However, the foot ulcer continued to drain purulent material with associated cellulitis and advancing erythema across the forefoot. The wound nurse contacted the PCP who had sent KL to the emergency department of Hospital B. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 18,300 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 2.2 mg/dL. KL was informed that he needed wound debridement and was offered the same podiatrist that he refused at Hospital A. Once again, KL deferred in favor of his own podiatrist who apparently was on vacation. Blood and wound cultures were obtained and KL received a dose of intravenous amoxicillin/sulbactam in the ED, but because of his refusal to receive wound debridement and care at Hospital A or B, he was sent home that same afternoon.

KL left Hospital B and drove 2 hours to the ED of Hospital C. He was immediately admitted and intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were begun. Plain films of the foot were consistent with osteomyelitis. An MRI of the foot demonstrated cellulitis, myositis, and a forefoot abscess. Within 24 hours of admission, KL developed chest pain and was subsequently ruled-in for a non–ST-elevation MI. KL ended up getting a left heart catheterization, and this delayed surgical debridement of his infected foot. Ultimately, KL did have debridement of his foot, but the infection had an advanced to the point that a below-the-knee amputation was required. Surgical pathology cultures were positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Complaint

KL was now facing life without his left leg, and he was angry and felt that the medical system had let him down. A complaint was quickly filed and alleged multiple breaches in the standard of care against multiple providers. The complaint included Dr. Hospitalist and asserted that he failed to obtain an MRI of the left foot from the very start, stopped intravenous vancomycin inappropriately, and failed to obtain infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults.

The complaint further asserted that the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B were negligent for not readmitting KL and obtaining infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults. If the providers in this case had continued intravenous vancomycin throughout his case and otherwise obtained appropriate specialty care, KL’s leg would have been saved.

Scientific principles

Diabetic foot infections are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Important risk factors for development of diabetic foot infections include neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, and poor glycemic control. Most diabetic foot infections are polymicrobial, but MRSA is a common pathogen. Although severe diabetic foot infections warrant hospitalization for urgent surgical consultation, antimicrobial administration, and medical stabilization, most mild infections and many moderate infections can be managed in the outpatient setting with close follow-up.

The possibility of osteomyelitis should be considered in diabetic patients with foot wounds associated with signs of infection in the deeper soft tissues and in patients with chronic ulcers. Many patients with confirmed osteomyelitis of the foot benefit from surgical resection.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Although Dr. Hospitalist had a negative bone scan result, he should have considered MRSA as a pathogen for KL despite a wound culture growing Klebsiella only. Most experts agreed, however, that it would be pure speculation as to what an MRI would have shown so early in KL’s course and ultimately, Dr. Hospitalist was defensible because KL did have appropriate follow-up just 48 hours after discharge. In fact, more than 21 days from original presentation to his amputation, KL only had 3 days off of intravenous vancomycin.

As a result, defense experts focused on the failure of KL to obtain debridement as the main reason for his injury. Dr. Hospitalist, the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B, all documented KL’s refusal to allow debridement by a podiatrist other than his own. KL denied this allegation, but the chart was consistent in this regard.

Conclusion

In the era of patient-centered care, patient wishes and preferences are important to integrate into the overall care plan. But when a patient’s wishes and preferences delay or otherwise subvert optimal care, it is vital that the hospitalist document the circumstances in their entirety. Documentation should confirm that the patient has capacity for decision making and that care recommendation benefits, risks for not following said recommendations, and care recommendation alternatives have been fully reviewed.

It is also helpful to have such discussions witnessed by other providers (that is, the nurse) so that the documentation is corroborated. The PCP and Hospital B were dismissed from the case. Hospital A settled with the plaintiff by waiving all hospital charges from his original hospitalization.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

Homesick

I don’t think that my kids appreciate how good they have it when it comes to summer camp. When I was their age, there was just one kind of camp: the kind with a mosquito-clouded lake, flatulent horses, and songs the other campers all seemed to know. No one asked what your interests were; it was assumed you had always dreamed of expressing yourself in the form of a lanyard keychain.

Now my children can choose between DJ camp, computer gaming camp, and, I kid you not, LEGO camp. They literally have camps just for the stuff you had to leave at home when you were at camp. I can’t wait for the letters home: “Today we programmed mosquitoes for our lake in Minecraft. Since I did so well, my counselor said I could join some of the older campers tomorrow and help them figure out how to design virtual horses that pass gas....”

Soap opera

With five kids, two dogs, and a cat, I’ve had to adjust my standards for what constitutes a clean house. Are the dust bunnies hidden behind piles of mismatched socks? Then it’s clean. Are the dirty dishes all within a yard of the sink? Clean. Do the roaches scatter within 2 seconds of the light coming on? We’re good. Three seconds is bad. At least we’re doing our part to fight allergies and asthma, according to a new report, which I’m sure is around here...ah, right under that wet towel!

Dr. Robert Wood, chief of allergy and immunology at Johns Hopkins Children's Center, Baltimore, wondered why studies seemed to show that dirt and bacteria protect rural children from developing allergies when other studies implicate roach droppings and animal dander in promoting allergies in urban settings. How can city dirt be so bad when urban music is so much better than country?

As it turns out, it’s all about the timing. A review of exposures and allergy and asthma symptoms among 467 children in four cities demonstrated that kids exposed to increased levels of mouse and cat dander, cockroach droppings, and house-dust harboring Firmicutes and Bacteriodetes bacteria enjoyed protection from wheezing so long as that exposure occurred in the first year of life. The implications are clear: Either we need to develop a strain of bacteria-encrusted urban cats that harbor mice infested with cockroaches, or I should tour America’s cities giving housekeeping tips.

Too cool

The study that I’ve been waiting for since 7th grade is finally out! We now have scientific proof that being a...what did they used call me...a geek? Nerd? Dork? Weirdo? Dweeb? Wonk? Bookworm? Poindexter? Grind? Hey-you-with-the-glasses? Well, anyway, over the long run we do better than those cool kids with their admittedly impressive vocabulary of insults.

Publishing in Child Behavior, University of Virginia psychologist Joseph Allen evaluated 184 adolescents’ use of “pseudomature behavior” to impress their peers. He questioned kids, their families, and their peers over 10 years, as the subjects matured from age 13 to 23. Early on, those kids who experimented with cigarettes, alcohol, and sex were indeed rated as “cool” by their peers, who also secretly seethed with resentment. (Dr. Allen did not report that last part, but I just know, okay?)

By age 22, however, those same kids were experiencing increased trouble with alcohol, substance abuse, and criminality compared to their peers. Their classmates, in the meantime (at least those who hadn’t managed to get out of that dusty little town and pursue their dreams in the big city), rated the “cool” kids as being less socially competent and less mature. Whether they were also starting to lose some hair and get a little thick around the middle is, again, unreported, but we know, because we may wear glasses, but we can see just fine, thank you.

The whole truth