User login

Evidence-Based Apps: Is it possible to diagnose epileptic seizure digitally?

A new app seems to help nonneurologist health care workers diagnose seizures as epileptic or nonepileptic, findings from a small study to be presented at the American Academy of Neurology meeting suggest.

The epilepsy app, which will be called Epilepsy Diagnosis when it becomes available, was created by neurologist Victor Patterson of Belfast, Northern Ireland, and built by a contracted company. He asked 67 patients at an epilepsy clinic in Nepal (51 of whom had epileptic seizures) 26 questions about their seizures and incorporated into the app the 11 most helpful questions and answers for predicting an epileptic seizure.

Nonphysician health care workers and a few physicians-in-training tested the app on 132 patients attending epilepsy clinics in Nepal and India. They either used the app before a formal diagnosis was made or were blinded to the patient’s clinical diagnosis.

The app was informative in 87% of cases (115 patients), and app results ultimately agreed with a physician’s diagnosis of epileptic or nonepileptic seizure in 97% of those cases (112 patients), according to Dr. Patterson. In addition to developing the app, he has been a visiting neurologist or teleneurologist for nonprofit international aid organizations or for hospitals in Nepal and Sudan, he said in an interview.

Using the app, health care providers were able to separate epileptic from nonepileptic seizures with "near-complete reliability," according to the abstract for his upcoming poster presentation on May 1 at the American Academy of Neurology annual meeting in Philadelphia. "Nondoctors were able to use it with minimal training."

Helping health care workers diagnose epileptic seizures could "save precious medical time," he said. "The diagnosis of episodes of altered consciousness as epileptic seizures is key to the management of epilepsy."

Neurologists typically distinguish an epileptic seizure from a nonepileptic one by taking a careful history of the attack both from the patient and an eyewitness and then use their medical knowledge to decide whether the episode is epileptic or not, Dr. Patterson said in an interview. The app uses what he considered to be the 11 most helpful questions in diagnosing Nepalese patients to take a history from the patient and an eyewitness. The app is programmed to analyze the answers and give a probability of the episode being epileptic.

"It’s the same process, with the app substituting for the neurologist," he said.

Primary care physicians, nurses, and other nonneurologist health care workers in more developed countries (like the United States) might be able to use the app in areas where neurologists are in short supply, but Dr. Patterson cautioned that the app was programmed based on the population in Nepal, which may be different from the U.S. population. For example, the rate of convulsive seizures or other conditions may differ between the two countries.

"I recommend physicians in different parts of the world to test this to see if it works for them," he said.

Health workers in resource-poor areas of the world will be able to get the app for free but a fee will be charged to physicians. Any profits will go toward more research into methods for "closing the epilepsy treatment gap," he added.

Dr. Patterson reported having no financial disclosures other than those disclosed above.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

A new app seems to help nonneurologist health care workers diagnose seizures as epileptic or nonepileptic, findings from a small study to be presented at the American Academy of Neurology meeting suggest.

The epilepsy app, which will be called Epilepsy Diagnosis when it becomes available, was created by neurologist Victor Patterson of Belfast, Northern Ireland, and built by a contracted company. He asked 67 patients at an epilepsy clinic in Nepal (51 of whom had epileptic seizures) 26 questions about their seizures and incorporated into the app the 11 most helpful questions and answers for predicting an epileptic seizure.

Nonphysician health care workers and a few physicians-in-training tested the app on 132 patients attending epilepsy clinics in Nepal and India. They either used the app before a formal diagnosis was made or were blinded to the patient’s clinical diagnosis.

The app was informative in 87% of cases (115 patients), and app results ultimately agreed with a physician’s diagnosis of epileptic or nonepileptic seizure in 97% of those cases (112 patients), according to Dr. Patterson. In addition to developing the app, he has been a visiting neurologist or teleneurologist for nonprofit international aid organizations or for hospitals in Nepal and Sudan, he said in an interview.

Using the app, health care providers were able to separate epileptic from nonepileptic seizures with "near-complete reliability," according to the abstract for his upcoming poster presentation on May 1 at the American Academy of Neurology annual meeting in Philadelphia. "Nondoctors were able to use it with minimal training."

Helping health care workers diagnose epileptic seizures could "save precious medical time," he said. "The diagnosis of episodes of altered consciousness as epileptic seizures is key to the management of epilepsy."

Neurologists typically distinguish an epileptic seizure from a nonepileptic one by taking a careful history of the attack both from the patient and an eyewitness and then use their medical knowledge to decide whether the episode is epileptic or not, Dr. Patterson said in an interview. The app uses what he considered to be the 11 most helpful questions in diagnosing Nepalese patients to take a history from the patient and an eyewitness. The app is programmed to analyze the answers and give a probability of the episode being epileptic.

"It’s the same process, with the app substituting for the neurologist," he said.

Primary care physicians, nurses, and other nonneurologist health care workers in more developed countries (like the United States) might be able to use the app in areas where neurologists are in short supply, but Dr. Patterson cautioned that the app was programmed based on the population in Nepal, which may be different from the U.S. population. For example, the rate of convulsive seizures or other conditions may differ between the two countries.

"I recommend physicians in different parts of the world to test this to see if it works for them," he said.

Health workers in resource-poor areas of the world will be able to get the app for free but a fee will be charged to physicians. Any profits will go toward more research into methods for "closing the epilepsy treatment gap," he added.

Dr. Patterson reported having no financial disclosures other than those disclosed above.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

A new app seems to help nonneurologist health care workers diagnose seizures as epileptic or nonepileptic, findings from a small study to be presented at the American Academy of Neurology meeting suggest.

The epilepsy app, which will be called Epilepsy Diagnosis when it becomes available, was created by neurologist Victor Patterson of Belfast, Northern Ireland, and built by a contracted company. He asked 67 patients at an epilepsy clinic in Nepal (51 of whom had epileptic seizures) 26 questions about their seizures and incorporated into the app the 11 most helpful questions and answers for predicting an epileptic seizure.

Nonphysician health care workers and a few physicians-in-training tested the app on 132 patients attending epilepsy clinics in Nepal and India. They either used the app before a formal diagnosis was made or were blinded to the patient’s clinical diagnosis.

The app was informative in 87% of cases (115 patients), and app results ultimately agreed with a physician’s diagnosis of epileptic or nonepileptic seizure in 97% of those cases (112 patients), according to Dr. Patterson. In addition to developing the app, he has been a visiting neurologist or teleneurologist for nonprofit international aid organizations or for hospitals in Nepal and Sudan, he said in an interview.

Using the app, health care providers were able to separate epileptic from nonepileptic seizures with "near-complete reliability," according to the abstract for his upcoming poster presentation on May 1 at the American Academy of Neurology annual meeting in Philadelphia. "Nondoctors were able to use it with minimal training."

Helping health care workers diagnose epileptic seizures could "save precious medical time," he said. "The diagnosis of episodes of altered consciousness as epileptic seizures is key to the management of epilepsy."

Neurologists typically distinguish an epileptic seizure from a nonepileptic one by taking a careful history of the attack both from the patient and an eyewitness and then use their medical knowledge to decide whether the episode is epileptic or not, Dr. Patterson said in an interview. The app uses what he considered to be the 11 most helpful questions in diagnosing Nepalese patients to take a history from the patient and an eyewitness. The app is programmed to analyze the answers and give a probability of the episode being epileptic.

"It’s the same process, with the app substituting for the neurologist," he said.

Primary care physicians, nurses, and other nonneurologist health care workers in more developed countries (like the United States) might be able to use the app in areas where neurologists are in short supply, but Dr. Patterson cautioned that the app was programmed based on the population in Nepal, which may be different from the U.S. population. For example, the rate of convulsive seizures or other conditions may differ between the two countries.

"I recommend physicians in different parts of the world to test this to see if it works for them," he said.

Health workers in resource-poor areas of the world will be able to get the app for free but a fee will be charged to physicians. Any profits will go toward more research into methods for "closing the epilepsy treatment gap," he added.

Dr. Patterson reported having no financial disclosures other than those disclosed above.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Where’s the evidence that medical apps are clinically useful?

The idea that smartphones, tablets, apps, and mobile technology might improve medical care certainly is appealing, but is there any evidence that these are useful clinical tools and not just glamorous new toys?

Welcome to our newest column – Evidence-Based Apps – in which we’ll track the growing field of mobile-device medicine for you and deliver the data that you need to decide whether an app might complement your clinical practice.

First, here’s the definition we’ll use: A medical app, or application, is software running on a phone, computer, some other electronic device, or the Internet that’s intended to improve health outcomes or act as a medical device. This may include products that you download to your phone or tablet, text-messaging interventions aimed at motivating patients, or small electronic devices and software that could replace larger, older, costlier medical technology.

Does that smartphone app for mental health decrease depression or anxiety? Can a smart skin patch replace Holter monitors? Will texts or other electronic reminders improve patient adherence to medication regimens? And will any of those ultimately improve patient health in the long term, increase convenience, or reduce medical costs? The developers of these devices would like you to think so, but here’s our mantra for this column: Show me the data!

A review of 1,500 health apps that cost between 69 cents and $999 found that 331 claimed to treat or cure medical problems, but all were disputed by medical experts, according to the New England Center for Investigative Reporting. Twelve of these apps relied on cell-phone light for "treatment," two said that the phone’s vibrations were therapeutic, and a whopping 43% claimed that cell-phone sounds were treatments.

Mobile health products (also called mHealth) are a booming field, and we’re now starting to see studies of apps that report clinical outcomes. The Food and Drug Administration regulates more than 100 apps that it sees as stand-ins for previously approved medical devices, and hospitals have put their own brands on more than 200 apps so far.

At least 9% of all U.S. adults have at least one health app on a smartphone, according to the Pew Research Center’s "Mobile Health 2012" report. Most popular are health apps to track and promote exercise, healthful diet, and weight loss.

In 2013, 95 million Americans accessed health information or tools through mobile phones, 27% more than in 2012, according to a report by Manhattan Research. Patients with the following diseases were most likely to be doing this, Manhattan Research said: cystic fibrosis, growth hormone deficiency, acne, ADD or ADHD, hepatitis C virus infection, migraine, Crohn’s disease, chronic kidney disease, generalized anxiety disorder, and bipolar disorder.

Makers of digital health products have lagged in conducting studies to verify the efficacy of these products, but it’s a problem that’s common to medicine, Forbes.com contributor David Shaywitz noted in a recent post. An estimated 40% of current medical practices aren’t backed by evidence from good clinical trials.

This column will offer reports on which of the more than 40,000 health and medical apps on the marketplace have some clinical trial evidence behind them. If there are any particular apps or topics you’d like us to cover, we’d love to hear from you!

On Twitter @sherryboschert

The idea that smartphones, tablets, apps, and mobile technology might improve medical care certainly is appealing, but is there any evidence that these are useful clinical tools and not just glamorous new toys?

Welcome to our newest column – Evidence-Based Apps – in which we’ll track the growing field of mobile-device medicine for you and deliver the data that you need to decide whether an app might complement your clinical practice.

First, here’s the definition we’ll use: A medical app, or application, is software running on a phone, computer, some other electronic device, or the Internet that’s intended to improve health outcomes or act as a medical device. This may include products that you download to your phone or tablet, text-messaging interventions aimed at motivating patients, or small electronic devices and software that could replace larger, older, costlier medical technology.

Does that smartphone app for mental health decrease depression or anxiety? Can a smart skin patch replace Holter monitors? Will texts or other electronic reminders improve patient adherence to medication regimens? And will any of those ultimately improve patient health in the long term, increase convenience, or reduce medical costs? The developers of these devices would like you to think so, but here’s our mantra for this column: Show me the data!

A review of 1,500 health apps that cost between 69 cents and $999 found that 331 claimed to treat or cure medical problems, but all were disputed by medical experts, according to the New England Center for Investigative Reporting. Twelve of these apps relied on cell-phone light for "treatment," two said that the phone’s vibrations were therapeutic, and a whopping 43% claimed that cell-phone sounds were treatments.

Mobile health products (also called mHealth) are a booming field, and we’re now starting to see studies of apps that report clinical outcomes. The Food and Drug Administration regulates more than 100 apps that it sees as stand-ins for previously approved medical devices, and hospitals have put their own brands on more than 200 apps so far.

At least 9% of all U.S. adults have at least one health app on a smartphone, according to the Pew Research Center’s "Mobile Health 2012" report. Most popular are health apps to track and promote exercise, healthful diet, and weight loss.

In 2013, 95 million Americans accessed health information or tools through mobile phones, 27% more than in 2012, according to a report by Manhattan Research. Patients with the following diseases were most likely to be doing this, Manhattan Research said: cystic fibrosis, growth hormone deficiency, acne, ADD or ADHD, hepatitis C virus infection, migraine, Crohn’s disease, chronic kidney disease, generalized anxiety disorder, and bipolar disorder.

Makers of digital health products have lagged in conducting studies to verify the efficacy of these products, but it’s a problem that’s common to medicine, Forbes.com contributor David Shaywitz noted in a recent post. An estimated 40% of current medical practices aren’t backed by evidence from good clinical trials.

This column will offer reports on which of the more than 40,000 health and medical apps on the marketplace have some clinical trial evidence behind them. If there are any particular apps or topics you’d like us to cover, we’d love to hear from you!

On Twitter @sherryboschert

The idea that smartphones, tablets, apps, and mobile technology might improve medical care certainly is appealing, but is there any evidence that these are useful clinical tools and not just glamorous new toys?

Welcome to our newest column – Evidence-Based Apps – in which we’ll track the growing field of mobile-device medicine for you and deliver the data that you need to decide whether an app might complement your clinical practice.

First, here’s the definition we’ll use: A medical app, or application, is software running on a phone, computer, some other electronic device, or the Internet that’s intended to improve health outcomes or act as a medical device. This may include products that you download to your phone or tablet, text-messaging interventions aimed at motivating patients, or small electronic devices and software that could replace larger, older, costlier medical technology.

Does that smartphone app for mental health decrease depression or anxiety? Can a smart skin patch replace Holter monitors? Will texts or other electronic reminders improve patient adherence to medication regimens? And will any of those ultimately improve patient health in the long term, increase convenience, or reduce medical costs? The developers of these devices would like you to think so, but here’s our mantra for this column: Show me the data!

A review of 1,500 health apps that cost between 69 cents and $999 found that 331 claimed to treat or cure medical problems, but all were disputed by medical experts, according to the New England Center for Investigative Reporting. Twelve of these apps relied on cell-phone light for "treatment," two said that the phone’s vibrations were therapeutic, and a whopping 43% claimed that cell-phone sounds were treatments.

Mobile health products (also called mHealth) are a booming field, and we’re now starting to see studies of apps that report clinical outcomes. The Food and Drug Administration regulates more than 100 apps that it sees as stand-ins for previously approved medical devices, and hospitals have put their own brands on more than 200 apps so far.

At least 9% of all U.S. adults have at least one health app on a smartphone, according to the Pew Research Center’s "Mobile Health 2012" report. Most popular are health apps to track and promote exercise, healthful diet, and weight loss.

In 2013, 95 million Americans accessed health information or tools through mobile phones, 27% more than in 2012, according to a report by Manhattan Research. Patients with the following diseases were most likely to be doing this, Manhattan Research said: cystic fibrosis, growth hormone deficiency, acne, ADD or ADHD, hepatitis C virus infection, migraine, Crohn’s disease, chronic kidney disease, generalized anxiety disorder, and bipolar disorder.

Makers of digital health products have lagged in conducting studies to verify the efficacy of these products, but it’s a problem that’s common to medicine, Forbes.com contributor David Shaywitz noted in a recent post. An estimated 40% of current medical practices aren’t backed by evidence from good clinical trials.

This column will offer reports on which of the more than 40,000 health and medical apps on the marketplace have some clinical trial evidence behind them. If there are any particular apps or topics you’d like us to cover, we’d love to hear from you!

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Negotiation: Priceless in good communication

The Society of Hospital Medicine held its annual meeting recently in Las Vegas, and Stephen had the opportunity to speak on the topic of "Family Meetings: The Art and the Evidence." As a special edition of Palliatively Speaking, we thought we would highlight one aspect of this subject, with other elements forthcoming in future pieces.

As a hospitalist, I stumbled and stuttered through many family meetings until I eventually found myself on more comfortable ground. Overall, I found them rewarding when they went well but stressful and deflating when they did not. The latter sensation was enough to create some avoidant behavior on my part.

After a few years of practice, my hospitalist group began shadowing one another periodically on rounds to provide feedback to our colleagues in the hope of improving the quality of our communication skills. It was then that I noticed that one of my partners was a master at these meetings. A real Rembrandt. He had the ability to deliver bad or difficult news without the dynamic in the room becoming inflammatory or out of control.

I will never forget watching him mediate a disagreement between a nurse and a patient suspected of using illicit substances while hospitalized. He flipped an antagonistic, heated situation into one where the patient, nurse, and physician all agreed on putting the past to rest and forging ahead with his proposed plan. We all left the room with a genuine sense that we had mutual purpose. In my admiration I realized that some of these skills must be teachable.

While I didn’t act on learning those communication techniques immediately after that encounter, I would eventually be formally exposed to them during my palliative medicine training. As it turns out, I still have some uncomfortable meetings with patients and families, but they come around much less frequently and when they do I now have a variety of tools to deal with challenges.

My appreciation of these tools doesn’t stop when I walk through the hospital doors each evening. I have found them to be invaluable in my personal life. In fact, learning to communicate better has been a source of renewal for me at work and staves off burnout. These techniques include active listening, motivational interviewing, demonstration of empathy, conflict resolution, and also negotiation. For the Society of Hospital Medicine meeting audience, I dissected negotiation, citing how it and the other skills can inject vitality into your interactions.

In any negotiation, it’s all about the other party. You are the smallest person in the room, the least important.

This is counterintuitive. Oftentimes at work we are trying to convince everyone how important we are. The readmissions committee should implement your plan to reduce recurrent hospitalizations. Your fellow hospitalists should recognize your value and make you the leader of the group. Patients show their appreciation for you making the right diagnosis and averting a medical calamity for them. But when you enter a family meeting, the patient and his or her loved ones are the center stage. To be successful you have to listen more and talk less. Get to understand the pictures in their heads and then summarize those thoughts and ideas back to them to show you’ve listened.

Make emotional payments. I don’t get into the meat of the meeting until I’ve done that with the patient and every family member in the room. No one holds family meetings for patients who are thriving and have outstanding outcomes. We have family meetings to figure out goals in the face of terrible diseases, when elder abuse is a possibility, when insurance-funded resources are depleted, and for a host of other difficult reasons.

This means that everyone in the room is suffering, sacrificing, scared, confused, or worried. Acknowledge them. Hold them up. Thank them. Reflect on similar moments in your life and demonstrate empathy. Apologize when things haven’t gone right for them at your hospital. These payments will pay handsome dividends as your relationship evolves.

Not manipulation. The term negotiation might bring up images of used car salespeople. I strongly disagree. In manipulation, one side wins and the other doesn’t. In negotiation, the goal is improved communication and understanding. Manipulation is about one side of the equation having knowledge that the other side is lacking and using that to achieve its means. Negotiators hope everyone at the table has the same knowledge.

This leads to two key principles of negotiations: transparency and genuineness. Patients and families are excellent at taking the temperature of the room when you sit down to meet with them. Share knowledge. Don’t have any hidden agendas. Following this principle builds trust.

Be incremental. Taking patients from comfortable, familiar territory into that which is uncomfortable or unfamiliar should not be done in one giant leap. Let’s use code status (CS) as an example because of the frequency with which it comes up (though I rarely talk about CS without first understanding the patient’s goals and hopes).

Some patients refuse to talk about CS, so I think incrementally. I ask that they consider talking about CS with me in the future. Very few people refuse to consider something. Two or three days later I ask, "Have you considered talking to me about CS?" That by itself opens up the topic for conversation. In the extremely unusual case where they still won’t engage, I then ask them, "What would it take for you to consider talking to me about this?" More incrementalism.

While this is not nearly an exhaustive list of negotiation techniques, we hope it is stimulating enough that you might be curious enough to learn more on your own and try incorporating this into your practice. If you’re motivated to do so, please feel free to contact us for reading suggestions: E-mail [email protected].

Dr. Bekanich and Dr. Fredholm are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

The Society of Hospital Medicine held its annual meeting recently in Las Vegas, and Stephen had the opportunity to speak on the topic of "Family Meetings: The Art and the Evidence." As a special edition of Palliatively Speaking, we thought we would highlight one aspect of this subject, with other elements forthcoming in future pieces.

As a hospitalist, I stumbled and stuttered through many family meetings until I eventually found myself on more comfortable ground. Overall, I found them rewarding when they went well but stressful and deflating when they did not. The latter sensation was enough to create some avoidant behavior on my part.

After a few years of practice, my hospitalist group began shadowing one another periodically on rounds to provide feedback to our colleagues in the hope of improving the quality of our communication skills. It was then that I noticed that one of my partners was a master at these meetings. A real Rembrandt. He had the ability to deliver bad or difficult news without the dynamic in the room becoming inflammatory or out of control.

I will never forget watching him mediate a disagreement between a nurse and a patient suspected of using illicit substances while hospitalized. He flipped an antagonistic, heated situation into one where the patient, nurse, and physician all agreed on putting the past to rest and forging ahead with his proposed plan. We all left the room with a genuine sense that we had mutual purpose. In my admiration I realized that some of these skills must be teachable.

While I didn’t act on learning those communication techniques immediately after that encounter, I would eventually be formally exposed to them during my palliative medicine training. As it turns out, I still have some uncomfortable meetings with patients and families, but they come around much less frequently and when they do I now have a variety of tools to deal with challenges.

My appreciation of these tools doesn’t stop when I walk through the hospital doors each evening. I have found them to be invaluable in my personal life. In fact, learning to communicate better has been a source of renewal for me at work and staves off burnout. These techniques include active listening, motivational interviewing, demonstration of empathy, conflict resolution, and also negotiation. For the Society of Hospital Medicine meeting audience, I dissected negotiation, citing how it and the other skills can inject vitality into your interactions.

In any negotiation, it’s all about the other party. You are the smallest person in the room, the least important.

This is counterintuitive. Oftentimes at work we are trying to convince everyone how important we are. The readmissions committee should implement your plan to reduce recurrent hospitalizations. Your fellow hospitalists should recognize your value and make you the leader of the group. Patients show their appreciation for you making the right diagnosis and averting a medical calamity for them. But when you enter a family meeting, the patient and his or her loved ones are the center stage. To be successful you have to listen more and talk less. Get to understand the pictures in their heads and then summarize those thoughts and ideas back to them to show you’ve listened.

Make emotional payments. I don’t get into the meat of the meeting until I’ve done that with the patient and every family member in the room. No one holds family meetings for patients who are thriving and have outstanding outcomes. We have family meetings to figure out goals in the face of terrible diseases, when elder abuse is a possibility, when insurance-funded resources are depleted, and for a host of other difficult reasons.

This means that everyone in the room is suffering, sacrificing, scared, confused, or worried. Acknowledge them. Hold them up. Thank them. Reflect on similar moments in your life and demonstrate empathy. Apologize when things haven’t gone right for them at your hospital. These payments will pay handsome dividends as your relationship evolves.

Not manipulation. The term negotiation might bring up images of used car salespeople. I strongly disagree. In manipulation, one side wins and the other doesn’t. In negotiation, the goal is improved communication and understanding. Manipulation is about one side of the equation having knowledge that the other side is lacking and using that to achieve its means. Negotiators hope everyone at the table has the same knowledge.

This leads to two key principles of negotiations: transparency and genuineness. Patients and families are excellent at taking the temperature of the room when you sit down to meet with them. Share knowledge. Don’t have any hidden agendas. Following this principle builds trust.

Be incremental. Taking patients from comfortable, familiar territory into that which is uncomfortable or unfamiliar should not be done in one giant leap. Let’s use code status (CS) as an example because of the frequency with which it comes up (though I rarely talk about CS without first understanding the patient’s goals and hopes).

Some patients refuse to talk about CS, so I think incrementally. I ask that they consider talking about CS with me in the future. Very few people refuse to consider something. Two or three days later I ask, "Have you considered talking to me about CS?" That by itself opens up the topic for conversation. In the extremely unusual case where they still won’t engage, I then ask them, "What would it take for you to consider talking to me about this?" More incrementalism.

While this is not nearly an exhaustive list of negotiation techniques, we hope it is stimulating enough that you might be curious enough to learn more on your own and try incorporating this into your practice. If you’re motivated to do so, please feel free to contact us for reading suggestions: E-mail [email protected].

Dr. Bekanich and Dr. Fredholm are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

The Society of Hospital Medicine held its annual meeting recently in Las Vegas, and Stephen had the opportunity to speak on the topic of "Family Meetings: The Art and the Evidence." As a special edition of Palliatively Speaking, we thought we would highlight one aspect of this subject, with other elements forthcoming in future pieces.

As a hospitalist, I stumbled and stuttered through many family meetings until I eventually found myself on more comfortable ground. Overall, I found them rewarding when they went well but stressful and deflating when they did not. The latter sensation was enough to create some avoidant behavior on my part.

After a few years of practice, my hospitalist group began shadowing one another periodically on rounds to provide feedback to our colleagues in the hope of improving the quality of our communication skills. It was then that I noticed that one of my partners was a master at these meetings. A real Rembrandt. He had the ability to deliver bad or difficult news without the dynamic in the room becoming inflammatory or out of control.

I will never forget watching him mediate a disagreement between a nurse and a patient suspected of using illicit substances while hospitalized. He flipped an antagonistic, heated situation into one where the patient, nurse, and physician all agreed on putting the past to rest and forging ahead with his proposed plan. We all left the room with a genuine sense that we had mutual purpose. In my admiration I realized that some of these skills must be teachable.

While I didn’t act on learning those communication techniques immediately after that encounter, I would eventually be formally exposed to them during my palliative medicine training. As it turns out, I still have some uncomfortable meetings with patients and families, but they come around much less frequently and when they do I now have a variety of tools to deal with challenges.

My appreciation of these tools doesn’t stop when I walk through the hospital doors each evening. I have found them to be invaluable in my personal life. In fact, learning to communicate better has been a source of renewal for me at work and staves off burnout. These techniques include active listening, motivational interviewing, demonstration of empathy, conflict resolution, and also negotiation. For the Society of Hospital Medicine meeting audience, I dissected negotiation, citing how it and the other skills can inject vitality into your interactions.

In any negotiation, it’s all about the other party. You are the smallest person in the room, the least important.

This is counterintuitive. Oftentimes at work we are trying to convince everyone how important we are. The readmissions committee should implement your plan to reduce recurrent hospitalizations. Your fellow hospitalists should recognize your value and make you the leader of the group. Patients show their appreciation for you making the right diagnosis and averting a medical calamity for them. But when you enter a family meeting, the patient and his or her loved ones are the center stage. To be successful you have to listen more and talk less. Get to understand the pictures in their heads and then summarize those thoughts and ideas back to them to show you’ve listened.

Make emotional payments. I don’t get into the meat of the meeting until I’ve done that with the patient and every family member in the room. No one holds family meetings for patients who are thriving and have outstanding outcomes. We have family meetings to figure out goals in the face of terrible diseases, when elder abuse is a possibility, when insurance-funded resources are depleted, and for a host of other difficult reasons.

This means that everyone in the room is suffering, sacrificing, scared, confused, or worried. Acknowledge them. Hold them up. Thank them. Reflect on similar moments in your life and demonstrate empathy. Apologize when things haven’t gone right for them at your hospital. These payments will pay handsome dividends as your relationship evolves.

Not manipulation. The term negotiation might bring up images of used car salespeople. I strongly disagree. In manipulation, one side wins and the other doesn’t. In negotiation, the goal is improved communication and understanding. Manipulation is about one side of the equation having knowledge that the other side is lacking and using that to achieve its means. Negotiators hope everyone at the table has the same knowledge.

This leads to two key principles of negotiations: transparency and genuineness. Patients and families are excellent at taking the temperature of the room when you sit down to meet with them. Share knowledge. Don’t have any hidden agendas. Following this principle builds trust.

Be incremental. Taking patients from comfortable, familiar territory into that which is uncomfortable or unfamiliar should not be done in one giant leap. Let’s use code status (CS) as an example because of the frequency with which it comes up (though I rarely talk about CS without first understanding the patient’s goals and hopes).

Some patients refuse to talk about CS, so I think incrementally. I ask that they consider talking about CS with me in the future. Very few people refuse to consider something. Two or three days later I ask, "Have you considered talking to me about CS?" That by itself opens up the topic for conversation. In the extremely unusual case where they still won’t engage, I then ask them, "What would it take for you to consider talking to me about this?" More incrementalism.

While this is not nearly an exhaustive list of negotiation techniques, we hope it is stimulating enough that you might be curious enough to learn more on your own and try incorporating this into your practice. If you’re motivated to do so, please feel free to contact us for reading suggestions: E-mail [email protected].

Dr. Bekanich and Dr. Fredholm are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

Evidence-Based Apps: Texting reminders improved pediatric asthma control

A small study presented at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology meeting in San Diego adds to a growing body of evidence that texting patients reminders to take their medication may improve asthma control.

Dr. Humaa M. Bhatti’s ongoing study is one of the few so far to look not just at medication adherence but at health outcomes. But, like similar studies before it, the trial’s small size and short duration so far preclude any definitive pronouncements about the effectiveness of using text messages (also known as short message service) via mobile phones to influence patient behavior. A couple of recent reviews of the literature, however, show mostly positive results.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Starting in April 2013, Dr. Bhatti and her associates recruited 37 patients up to 18 years of age with asthma to receive twice-daily texts from a research assistant reminding them to take medication. Texts went to the parents of children and/or directly to the adolescents. Patients or parents also could reply to communicate with the research assistant.

For the 29 patients who received 3-9 months of texting at the time of preliminary analysis of results (8 patients dropped out), records showed that 21 patients had two or more steroid bursts in the 12 months prior to the start of texting (72%), 28 had at least one urgent visit (96%) in that year, and 28 had been hospitalized for asthma at least once (96%).

The number of asthma exacerbations requiring prednisone decreased from a mean of 3.4/patient before the trial to 1.6/patient with texted reminders. Hospitalizations decreased from a mean of 1.6/patient before the trial to 0.8/patient. Urgent or emergency visits decreased from a mean of 3/patient before the trial to 1.4/patient. Those differences were statistically significant, reported Dr. Bhatti, an allergy and immunology fellow at the Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Detroit.

Since the texting started, 16 of the 29 patients (55%) had no steroid bursts, emergency department visits, or hospitalizations. Similar results were seen for 25 patients who were added to the study since November 2013, a preliminary analysis found.

The study soon will open to all patients with asthma at the hospital to see if results remain positive and are sustained over longer periods. With more patients to text, the investigators are considering using an automated text-sending program that would not allow the recipients to reply, and patients may be randomized to receive texts from either the research assistant or the text program to see if there is a difference in outcomes.

A separate systematic review of the literature found five randomized controlled trials and one "pragmatic" randomized controlled trial reporting evidence that daily technology-based reminders improved asthma medication adherence. None of these trials documented improved clinical outcomes or changes in asthma-related quality of life. The reminder systems studied included text messages, automated phone calls, or audiovisual reminder devices. The median follow-up time was 16 weeks (J. Asthma 2014 Feb. 13 [doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.888572]).

Texting also looked good in another literature review that found 13 controlled clinical trials of interventions using text messages, audiovisual reminders from electronic reminder devices, or pagers for patients on chronic medication. Of the four studies using texting, medication adherence improved in the one study of asthma and in two studies of HIV, but made no difference in one study of women on oral contraceptives (J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2012 [doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-00748]). The one study on patients with asthma in that review was, again, a small, short study of 26 adults. Adherence to treatment improved after 12 weeks by an absolute rate of 18% in the texting group compared with controls (Respir. Med. 2010;104:166-71).

There are hints elsewhere that texting may not always help. At the 2011 meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, Dr. Jennifer S. Lee reported that two of seven patients aged 6-17 years improved their asthma control after receiving text message reminders. Texting influenced children but not adolescents, according to news interviews with Dr. Lee, an allergist and ear, nose, and throat specialist in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Dr. Bhatti had no financial disclosures.

A small study presented at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology meeting in San Diego adds to a growing body of evidence that texting patients reminders to take their medication may improve asthma control.

Dr. Humaa M. Bhatti’s ongoing study is one of the few so far to look not just at medication adherence but at health outcomes. But, like similar studies before it, the trial’s small size and short duration so far preclude any definitive pronouncements about the effectiveness of using text messages (also known as short message service) via mobile phones to influence patient behavior. A couple of recent reviews of the literature, however, show mostly positive results.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Starting in April 2013, Dr. Bhatti and her associates recruited 37 patients up to 18 years of age with asthma to receive twice-daily texts from a research assistant reminding them to take medication. Texts went to the parents of children and/or directly to the adolescents. Patients or parents also could reply to communicate with the research assistant.

For the 29 patients who received 3-9 months of texting at the time of preliminary analysis of results (8 patients dropped out), records showed that 21 patients had two or more steroid bursts in the 12 months prior to the start of texting (72%), 28 had at least one urgent visit (96%) in that year, and 28 had been hospitalized for asthma at least once (96%).

The number of asthma exacerbations requiring prednisone decreased from a mean of 3.4/patient before the trial to 1.6/patient with texted reminders. Hospitalizations decreased from a mean of 1.6/patient before the trial to 0.8/patient. Urgent or emergency visits decreased from a mean of 3/patient before the trial to 1.4/patient. Those differences were statistically significant, reported Dr. Bhatti, an allergy and immunology fellow at the Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Detroit.

Since the texting started, 16 of the 29 patients (55%) had no steroid bursts, emergency department visits, or hospitalizations. Similar results were seen for 25 patients who were added to the study since November 2013, a preliminary analysis found.

The study soon will open to all patients with asthma at the hospital to see if results remain positive and are sustained over longer periods. With more patients to text, the investigators are considering using an automated text-sending program that would not allow the recipients to reply, and patients may be randomized to receive texts from either the research assistant or the text program to see if there is a difference in outcomes.

A separate systematic review of the literature found five randomized controlled trials and one "pragmatic" randomized controlled trial reporting evidence that daily technology-based reminders improved asthma medication adherence. None of these trials documented improved clinical outcomes or changes in asthma-related quality of life. The reminder systems studied included text messages, automated phone calls, or audiovisual reminder devices. The median follow-up time was 16 weeks (J. Asthma 2014 Feb. 13 [doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.888572]).

Texting also looked good in another literature review that found 13 controlled clinical trials of interventions using text messages, audiovisual reminders from electronic reminder devices, or pagers for patients on chronic medication. Of the four studies using texting, medication adherence improved in the one study of asthma and in two studies of HIV, but made no difference in one study of women on oral contraceptives (J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2012 [doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-00748]). The one study on patients with asthma in that review was, again, a small, short study of 26 adults. Adherence to treatment improved after 12 weeks by an absolute rate of 18% in the texting group compared with controls (Respir. Med. 2010;104:166-71).

There are hints elsewhere that texting may not always help. At the 2011 meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, Dr. Jennifer S. Lee reported that two of seven patients aged 6-17 years improved their asthma control after receiving text message reminders. Texting influenced children but not adolescents, according to news interviews with Dr. Lee, an allergist and ear, nose, and throat specialist in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Dr. Bhatti had no financial disclosures.

A small study presented at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology meeting in San Diego adds to a growing body of evidence that texting patients reminders to take their medication may improve asthma control.

Dr. Humaa M. Bhatti’s ongoing study is one of the few so far to look not just at medication adherence but at health outcomes. But, like similar studies before it, the trial’s small size and short duration so far preclude any definitive pronouncements about the effectiveness of using text messages (also known as short message service) via mobile phones to influence patient behavior. A couple of recent reviews of the literature, however, show mostly positive results.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Starting in April 2013, Dr. Bhatti and her associates recruited 37 patients up to 18 years of age with asthma to receive twice-daily texts from a research assistant reminding them to take medication. Texts went to the parents of children and/or directly to the adolescents. Patients or parents also could reply to communicate with the research assistant.

For the 29 patients who received 3-9 months of texting at the time of preliminary analysis of results (8 patients dropped out), records showed that 21 patients had two or more steroid bursts in the 12 months prior to the start of texting (72%), 28 had at least one urgent visit (96%) in that year, and 28 had been hospitalized for asthma at least once (96%).

The number of asthma exacerbations requiring prednisone decreased from a mean of 3.4/patient before the trial to 1.6/patient with texted reminders. Hospitalizations decreased from a mean of 1.6/patient before the trial to 0.8/patient. Urgent or emergency visits decreased from a mean of 3/patient before the trial to 1.4/patient. Those differences were statistically significant, reported Dr. Bhatti, an allergy and immunology fellow at the Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Detroit.

Since the texting started, 16 of the 29 patients (55%) had no steroid bursts, emergency department visits, or hospitalizations. Similar results were seen for 25 patients who were added to the study since November 2013, a preliminary analysis found.

The study soon will open to all patients with asthma at the hospital to see if results remain positive and are sustained over longer periods. With more patients to text, the investigators are considering using an automated text-sending program that would not allow the recipients to reply, and patients may be randomized to receive texts from either the research assistant or the text program to see if there is a difference in outcomes.

A separate systematic review of the literature found five randomized controlled trials and one "pragmatic" randomized controlled trial reporting evidence that daily technology-based reminders improved asthma medication adherence. None of these trials documented improved clinical outcomes or changes in asthma-related quality of life. The reminder systems studied included text messages, automated phone calls, or audiovisual reminder devices. The median follow-up time was 16 weeks (J. Asthma 2014 Feb. 13 [doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.888572]).

Texting also looked good in another literature review that found 13 controlled clinical trials of interventions using text messages, audiovisual reminders from electronic reminder devices, or pagers for patients on chronic medication. Of the four studies using texting, medication adherence improved in the one study of asthma and in two studies of HIV, but made no difference in one study of women on oral contraceptives (J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2012 [doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-00748]). The one study on patients with asthma in that review was, again, a small, short study of 26 adults. Adherence to treatment improved after 12 weeks by an absolute rate of 18% in the texting group compared with controls (Respir. Med. 2010;104:166-71).

There are hints elsewhere that texting may not always help. At the 2011 meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, Dr. Jennifer S. Lee reported that two of seven patients aged 6-17 years improved their asthma control after receiving text message reminders. Texting influenced children but not adolescents, according to news interviews with Dr. Lee, an allergist and ear, nose, and throat specialist in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Dr. Bhatti had no financial disclosures.

They love me, they love me not ...

It was the worst of days. It was the best of days.

When I opened the mail one day last week, I found a letter from someone I’ll call Thelma. It read, in part:

"Last Monday you were kind enough to look at my rash, which you thought was just eczema. You gave me cream and asked me to e-mail you Thursday about my condition. When I did and said I was still itchy, you said I should stick with the same and that I could come back Monday, but I couldn’t wait because I itched so bad I couldn’t take it anymore. I saw another doctor Friday who said the patch was host to something called pityriasis rosea. He said the rash was so textbook it should have been picked up immediately. I had to be put on an oral steroid right away.

"I am so upset that I’m sending you back your bill [for a $15 co-pay] because I had to go to another doctor who could really help me."

I thought of a few choice words for my esteemed Friday colleague, but kept them to myself. A single scaly patch is a textbook case of pityriasis rosea? Oral steroids for pityriasis? Really?

As far as this patient is concerned, I must be a bum. Thirty-five years on the job, and I haven’t mastered the textbook yet.

Sunk in gloom, I opened an e-mail sent to my website by a patient I’ll call Louise:

"I suffer from psoriasis and have been to countless dermatologists since I was 8 years old. I recently had a terrible outbreak and was really hesitant to even go to a dermatologist because I’ve never been satisfied with any of them. Your associate is wonderful! I can’t say enough about her. She is warm, thorough, and really takes the time to sit with you and listen. You can tell she truly cares about her patients and loves her job."

I looked at the patient’s chart. What was the wonderful and satisfying treatment that my associate had prescribed to deal with this patient’s lifelong, recalcitrant psoriasis?

Betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05%. Wow.

I e-mailed my associate at once and we shared a gratified chuckle. Guess no one ever thought of treating Louise’s psoriasis with a topical steroid before. We must be geniuses, right out there on the cutting edge.

So which are we, dear colleagues – geniuses or bums?

We’re neither, of course, which doesn’t stop our patients from forming firm opinions one way or the other. Which they can share by angry letter, fulsome e-mail, or, of course, any on-line reviews they can slip past the mysterious algorithms of the Yelps and Angie’s Lists of the world.

When I get messages like Thelma’s and Louise’s, I show them to my students and make three suggestions:

• Don’t try to look smart at someone else’s expense. Next time around a patient will be in somebody else’s office calling you a fool.

• Don’t respond to snippy patients’ complaints by contacting the complainer and trying to justify yourself. Learn something if you can, and move on.

• Be grateful for praise. Just don’t take it too seriously.

In the meantime, the insurers and assorted bureaucrats who run our lives these days are busy defining good care and claiming to measure it so they can reward quality and punish inefficiency. I’m sure they think they’re doing a fine job, although I remain deeply skeptical that what they choose to measure has much relevance to what actually goes on in offices like ours.

I could, of course, try to tell them why I think so. (I have tried, in fact.) Getting through to people with a completely different way of looking at things than yours is not very rewarding, even when large sums of money are not involved. I would have as good a chance of winning them over as I would of convincing Thelma that a scaly patch is not textbook pityriasis that needs prednisone and Louise that betamethasone cream is not the breakthrough that will change her life.

So: Not the best of times. Not the worst of times. Just another day at the office.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since 1997.

It was the worst of days. It was the best of days.

When I opened the mail one day last week, I found a letter from someone I’ll call Thelma. It read, in part:

"Last Monday you were kind enough to look at my rash, which you thought was just eczema. You gave me cream and asked me to e-mail you Thursday about my condition. When I did and said I was still itchy, you said I should stick with the same and that I could come back Monday, but I couldn’t wait because I itched so bad I couldn’t take it anymore. I saw another doctor Friday who said the patch was host to something called pityriasis rosea. He said the rash was so textbook it should have been picked up immediately. I had to be put on an oral steroid right away.

"I am so upset that I’m sending you back your bill [for a $15 co-pay] because I had to go to another doctor who could really help me."

I thought of a few choice words for my esteemed Friday colleague, but kept them to myself. A single scaly patch is a textbook case of pityriasis rosea? Oral steroids for pityriasis? Really?

As far as this patient is concerned, I must be a bum. Thirty-five years on the job, and I haven’t mastered the textbook yet.

Sunk in gloom, I opened an e-mail sent to my website by a patient I’ll call Louise:

"I suffer from psoriasis and have been to countless dermatologists since I was 8 years old. I recently had a terrible outbreak and was really hesitant to even go to a dermatologist because I’ve never been satisfied with any of them. Your associate is wonderful! I can’t say enough about her. She is warm, thorough, and really takes the time to sit with you and listen. You can tell she truly cares about her patients and loves her job."

I looked at the patient’s chart. What was the wonderful and satisfying treatment that my associate had prescribed to deal with this patient’s lifelong, recalcitrant psoriasis?

Betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05%. Wow.

I e-mailed my associate at once and we shared a gratified chuckle. Guess no one ever thought of treating Louise’s psoriasis with a topical steroid before. We must be geniuses, right out there on the cutting edge.

So which are we, dear colleagues – geniuses or bums?

We’re neither, of course, which doesn’t stop our patients from forming firm opinions one way or the other. Which they can share by angry letter, fulsome e-mail, or, of course, any on-line reviews they can slip past the mysterious algorithms of the Yelps and Angie’s Lists of the world.

When I get messages like Thelma’s and Louise’s, I show them to my students and make three suggestions:

• Don’t try to look smart at someone else’s expense. Next time around a patient will be in somebody else’s office calling you a fool.

• Don’t respond to snippy patients’ complaints by contacting the complainer and trying to justify yourself. Learn something if you can, and move on.

• Be grateful for praise. Just don’t take it too seriously.

In the meantime, the insurers and assorted bureaucrats who run our lives these days are busy defining good care and claiming to measure it so they can reward quality and punish inefficiency. I’m sure they think they’re doing a fine job, although I remain deeply skeptical that what they choose to measure has much relevance to what actually goes on in offices like ours.

I could, of course, try to tell them why I think so. (I have tried, in fact.) Getting through to people with a completely different way of looking at things than yours is not very rewarding, even when large sums of money are not involved. I would have as good a chance of winning them over as I would of convincing Thelma that a scaly patch is not textbook pityriasis that needs prednisone and Louise that betamethasone cream is not the breakthrough that will change her life.

So: Not the best of times. Not the worst of times. Just another day at the office.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since 1997.

It was the worst of days. It was the best of days.

When I opened the mail one day last week, I found a letter from someone I’ll call Thelma. It read, in part:

"Last Monday you were kind enough to look at my rash, which you thought was just eczema. You gave me cream and asked me to e-mail you Thursday about my condition. When I did and said I was still itchy, you said I should stick with the same and that I could come back Monday, but I couldn’t wait because I itched so bad I couldn’t take it anymore. I saw another doctor Friday who said the patch was host to something called pityriasis rosea. He said the rash was so textbook it should have been picked up immediately. I had to be put on an oral steroid right away.

"I am so upset that I’m sending you back your bill [for a $15 co-pay] because I had to go to another doctor who could really help me."

I thought of a few choice words for my esteemed Friday colleague, but kept them to myself. A single scaly patch is a textbook case of pityriasis rosea? Oral steroids for pityriasis? Really?

As far as this patient is concerned, I must be a bum. Thirty-five years on the job, and I haven’t mastered the textbook yet.

Sunk in gloom, I opened an e-mail sent to my website by a patient I’ll call Louise:

"I suffer from psoriasis and have been to countless dermatologists since I was 8 years old. I recently had a terrible outbreak and was really hesitant to even go to a dermatologist because I’ve never been satisfied with any of them. Your associate is wonderful! I can’t say enough about her. She is warm, thorough, and really takes the time to sit with you and listen. You can tell she truly cares about her patients and loves her job."

I looked at the patient’s chart. What was the wonderful and satisfying treatment that my associate had prescribed to deal with this patient’s lifelong, recalcitrant psoriasis?

Betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05%. Wow.

I e-mailed my associate at once and we shared a gratified chuckle. Guess no one ever thought of treating Louise’s psoriasis with a topical steroid before. We must be geniuses, right out there on the cutting edge.

So which are we, dear colleagues – geniuses or bums?

We’re neither, of course, which doesn’t stop our patients from forming firm opinions one way or the other. Which they can share by angry letter, fulsome e-mail, or, of course, any on-line reviews they can slip past the mysterious algorithms of the Yelps and Angie’s Lists of the world.

When I get messages like Thelma’s and Louise’s, I show them to my students and make three suggestions:

• Don’t try to look smart at someone else’s expense. Next time around a patient will be in somebody else’s office calling you a fool.

• Don’t respond to snippy patients’ complaints by contacting the complainer and trying to justify yourself. Learn something if you can, and move on.

• Be grateful for praise. Just don’t take it too seriously.

In the meantime, the insurers and assorted bureaucrats who run our lives these days are busy defining good care and claiming to measure it so they can reward quality and punish inefficiency. I’m sure they think they’re doing a fine job, although I remain deeply skeptical that what they choose to measure has much relevance to what actually goes on in offices like ours.

I could, of course, try to tell them why I think so. (I have tried, in fact.) Getting through to people with a completely different way of looking at things than yours is not very rewarding, even when large sums of money are not involved. I would have as good a chance of winning them over as I would of convincing Thelma that a scaly patch is not textbook pityriasis that needs prednisone and Louise that betamethasone cream is not the breakthrough that will change her life.

So: Not the best of times. Not the worst of times. Just another day at the office.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since 1997.

Clostridium difficile: Not just for adults

The true prevalence and meaning of Clostridium difficile detection in children remains an issue despite a known high prevalence of asymptomatic colonization in children during the first 3 years of life. Distinguishing C. difficile disease from colonization is difficult. Endoscopy can identify some severe C. difficile disease, but what about mild to moderate C. difficile infection?

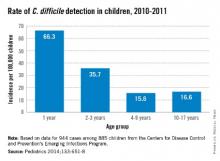

A passive Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance study (Pediatrics 2014;133:651-8) helps in understanding C. difficile prevalence by documenting the relatively high prevalence of community-acquired C. difficile often associated with use of common oral antibiotics and possibly because of the emergence of the NAP1 strain, which is also emerging in adults. But distinguishing infection from colonization remains an issue. The data have implications for everyday pediatric care.

Methods

Children aged 1-17 years from 10 U.S. states were studied during 2011-2012. C. difficile "cases" were defined via a positive toxin or a molecular test ordered as part of standard care. Standard of care testing for other selected gastrointestinal pathogens and data from medical records were collected. Within 3-6 months of the C. difficile–positive test, a convenience sample of families (about 9%) underwent a telephone interview.

Factors in C. difficile detection

C. difficile was detected in 944 stools from 885 children with no gender difference. The highest rates per 100,000 by race were in whites (23.9) vs. nonwhites (17.4), and in 12- to 23-month-olds (66.3). Overall, 71% of detections were categorized from charted data as community acquired. Only 17% were associated with outpatient health care and 12% with inpatient care.

Antibiotic use in the 14 days before a C. difficile–positive stool was 33% among all cases with no age group differences. Cephalosporins (41%) and amoxicillin/clavulanate (28%) were most common. Among 84 cases also later interviewed by phone, antibiotic use was more frequent (73%); penicillins (39%) and cephalosporins (44%) were the antibiotics most commonly used in this subset of patients. Indications were most often otitis, sinusitis, or upper respiratory infection. In the phone interviews, outpatient office visits were a more frequent (97%) health care exposure than in the overall case population.

Signs and symptoms were mild and similar in all age groups. Diarrhea was not present in 28%. Coinfection with another enteric pathogen was identified in 3% of 535 tested samples: bacterial (n = 12), protozoal (n = 4), and viral (n = 1) – and more common in 2- to 9-year-olds (P = .03). Peripheral WBC counts were abnormal (greater than 15, 000/mm3) in only 7%. There was radiographic evidence of ileus in three and pseudomembranous colitis developed in five cases. Cases were defined as severe in 8% with no age preponderance. There were no deaths.

Infection vs. colonization?

The authors reason that similar clinical presentations and symptom severity at all ages means that detection of C. difficile "likely represents infection" but not colonization. They explain that they expect milder symptoms in the youngest cases if they were only colonized. Is this reasonable?

One could counterargue that in the absence of testing for the most common diarrheagenic pathogen in the United States (norovirus), that diarrhea in at least some of these C. difficile–positive children was likely caused by undetected norovirus. That could partially explain why symptoms were not significantly different by age. One viral coinfection in nearly 500 diarrhea stools (even preselected by C. difficile positivity) seems low. Even if norovirus is not the wildcard here, the similar "disease" at all ages could suggest that something other than C. difficile is the cause. Norovirus and other viral agents testing of samples that were cultured for C. difficile could increase understanding of coinfection rates. Another issue is that 28% of C. difficile children did not have diarrhea, raising concern that these were colonized children.

The authors state that high antibiotic use (73% in phone interviewees) might have contributed to the high C. difficile detection rates. This seems logical, but the phone-derived data came from only about 8% of the total population. The original charted data from the entire population showed 33% antibiotic use. The charted data may have been more reliable because it was collected at the time of the C. difficile–positive stool, not 3-6 months later. Nevertheless, it seems apparent that common outpatient antibiotics could be a factor. If the data were compared with antibiotic use rates for C. difficile–negative children of the same ages, the conclusion would be more powerful.

Children less than 1year of age were not included because up to 73% (Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1989;8:390-3) of infants have been reported as asymptomatically colonized. In similar studies, colonized infants were frequent (25% between 6 days and 6 months) up to about 3 years of age when rates dropped off to less than 3%, similar to adults. Inclusion of children in the second and third year of life likely means that not all detections were infections. But there is no way to definitively distinguish infection from colonization in this study.

A further step in filling the knowledge gap on C. difficile would be prospective surveillance with improved definitions of infection vs. colonization and a more complete search for potential concurrent causes of diarrhea. Undoubtedly, many of these C. difficile–positive children had true infection, but it also seems likely that some were colonized, particularly in the second and third year of life. It would be interesting to compare results from healthy controls vs. those with diarrhea using new multiplex molecular assays to gain a better understanding of what proportion of all children have detectable C. difficile with and without other pathogens.

Bottom line

NAP1 C. difficile is emerging in children. C. difficile detection, whether infected or colonized, in this many children is new. These data suggest that our best contributions to reducing the spread of C. difficile are the use of amoxicillin without clavulanate as first line – if antibiotics are needed for acute otitis media and for acute sinusitis – while we refrain from antibiotics for viral upper respiratory infections. As the old knight told Indiana Jones, "Choose wisely."

Factors associated with C. difficile detection in children

1. White race. Question more frequent health care and antibiotic exposure.

2. Age 12 to 23 months. Question whether the population is mix of colonized and infected children. This needs more study.

3. Amoxicillin/clavulanate or oral cephalosporin use for common outpatient infection. Is narrower spectrum, amoxicillin alone better?

4. A recent outpatient health care visit may be a cofactor with #1 and #3.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. Dr. Harrison said he has no relevant financial disclosures. E-mail him at [email protected].

The true prevalence and meaning of Clostridium difficile detection in children remains an issue despite a known high prevalence of asymptomatic colonization in children during the first 3 years of life. Distinguishing C. difficile disease from colonization is difficult. Endoscopy can identify some severe C. difficile disease, but what about mild to moderate C. difficile infection?

A passive Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance study (Pediatrics 2014;133:651-8) helps in understanding C. difficile prevalence by documenting the relatively high prevalence of community-acquired C. difficile often associated with use of common oral antibiotics and possibly because of the emergence of the NAP1 strain, which is also emerging in adults. But distinguishing infection from colonization remains an issue. The data have implications for everyday pediatric care.

Methods

Children aged 1-17 years from 10 U.S. states were studied during 2011-2012. C. difficile "cases" were defined via a positive toxin or a molecular test ordered as part of standard care. Standard of care testing for other selected gastrointestinal pathogens and data from medical records were collected. Within 3-6 months of the C. difficile–positive test, a convenience sample of families (about 9%) underwent a telephone interview.

Factors in C. difficile detection

C. difficile was detected in 944 stools from 885 children with no gender difference. The highest rates per 100,000 by race were in whites (23.9) vs. nonwhites (17.4), and in 12- to 23-month-olds (66.3). Overall, 71% of detections were categorized from charted data as community acquired. Only 17% were associated with outpatient health care and 12% with inpatient care.

Antibiotic use in the 14 days before a C. difficile–positive stool was 33% among all cases with no age group differences. Cephalosporins (41%) and amoxicillin/clavulanate (28%) were most common. Among 84 cases also later interviewed by phone, antibiotic use was more frequent (73%); penicillins (39%) and cephalosporins (44%) were the antibiotics most commonly used in this subset of patients. Indications were most often otitis, sinusitis, or upper respiratory infection. In the phone interviews, outpatient office visits were a more frequent (97%) health care exposure than in the overall case population.

Signs and symptoms were mild and similar in all age groups. Diarrhea was not present in 28%. Coinfection with another enteric pathogen was identified in 3% of 535 tested samples: bacterial (n = 12), protozoal (n = 4), and viral (n = 1) – and more common in 2- to 9-year-olds (P = .03). Peripheral WBC counts were abnormal (greater than 15, 000/mm3) in only 7%. There was radiographic evidence of ileus in three and pseudomembranous colitis developed in five cases. Cases were defined as severe in 8% with no age preponderance. There were no deaths.

Infection vs. colonization?

The authors reason that similar clinical presentations and symptom severity at all ages means that detection of C. difficile "likely represents infection" but not colonization. They explain that they expect milder symptoms in the youngest cases if they were only colonized. Is this reasonable?

One could counterargue that in the absence of testing for the most common diarrheagenic pathogen in the United States (norovirus), that diarrhea in at least some of these C. difficile–positive children was likely caused by undetected norovirus. That could partially explain why symptoms were not significantly different by age. One viral coinfection in nearly 500 diarrhea stools (even preselected by C. difficile positivity) seems low. Even if norovirus is not the wildcard here, the similar "disease" at all ages could suggest that something other than C. difficile is the cause. Norovirus and other viral agents testing of samples that were cultured for C. difficile could increase understanding of coinfection rates. Another issue is that 28% of C. difficile children did not have diarrhea, raising concern that these were colonized children.

The authors state that high antibiotic use (73% in phone interviewees) might have contributed to the high C. difficile detection rates. This seems logical, but the phone-derived data came from only about 8% of the total population. The original charted data from the entire population showed 33% antibiotic use. The charted data may have been more reliable because it was collected at the time of the C. difficile–positive stool, not 3-6 months later. Nevertheless, it seems apparent that common outpatient antibiotics could be a factor. If the data were compared with antibiotic use rates for C. difficile–negative children of the same ages, the conclusion would be more powerful.

Children less than 1year of age were not included because up to 73% (Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1989;8:390-3) of infants have been reported as asymptomatically colonized. In similar studies, colonized infants were frequent (25% between 6 days and 6 months) up to about 3 years of age when rates dropped off to less than 3%, similar to adults. Inclusion of children in the second and third year of life likely means that not all detections were infections. But there is no way to definitively distinguish infection from colonization in this study.

A further step in filling the knowledge gap on C. difficile would be prospective surveillance with improved definitions of infection vs. colonization and a more complete search for potential concurrent causes of diarrhea. Undoubtedly, many of these C. difficile–positive children had true infection, but it also seems likely that some were colonized, particularly in the second and third year of life. It would be interesting to compare results from healthy controls vs. those with diarrhea using new multiplex molecular assays to gain a better understanding of what proportion of all children have detectable C. difficile with and without other pathogens.

Bottom line

NAP1 C. difficile is emerging in children. C. difficile detection, whether infected or colonized, in this many children is new. These data suggest that our best contributions to reducing the spread of C. difficile are the use of amoxicillin without clavulanate as first line – if antibiotics are needed for acute otitis media and for acute sinusitis – while we refrain from antibiotics for viral upper respiratory infections. As the old knight told Indiana Jones, "Choose wisely."

Factors associated with C. difficile detection in children

1. White race. Question more frequent health care and antibiotic exposure.

2. Age 12 to 23 months. Question whether the population is mix of colonized and infected children. This needs more study.