User login

Bad blood: Could brain bleeds be contagious?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

How do you tell if a condition is caused by an infection?

It seems like an obvious question, right? In the post–van Leeuwenhoek era we can look at whatever part of the body is diseased under a microscope and see microbes – you know, the usual suspects.

Except when we can’t. And there are plenty of cases where we can’t: where the microbe is too small to be seen without more advanced imaging techniques, like with viruses; or when the pathogen is sparsely populated or hard to culture, like Mycobacterium.

Finding out that a condition is the result of an infection is not only an exercise for 19th century physicians. After all, it was 2008 when Barry Marshall and Robin Warren won their Nobel Prize for proving that stomach ulcers, long thought to be due to “stress,” were actually caused by a tiny microbe called Helicobacter pylori.

And this week, we are looking at a study which, once again, begins to suggest that a condition thought to be more or less random – cerebral amyloid angiopathy – may actually be the result of an infectious disease.

We’re talking about this paper, appearing in JAMA, which is just a great example of old-fashioned shoe-leather epidemiology. But let’s get up to speed on cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) first.

CAA is characterized by the deposition of amyloid protein in the brain. While there are some genetic causes, they are quite rare, and most cases are thought to be idiopathic. Recent analyses suggest that somewhere between 5% and 7% of cognitively normal older adults have CAA, but the rate is much higher among those with intracerebral hemorrhage – brain bleeds. In fact, CAA is the second-most common cause of bleeding in the brain, second only to severe hypertension.

An article in Nature highlights cases that seemed to develop after the administration of cadaveric pituitary hormone.

Other studies have shown potential transmission via dura mater grafts and neurosurgical instruments. But despite those clues, no infectious organism has been identified. Some have suggested that the long latent period and difficulty of finding a responsible microbe points to a prion-like disease not yet known. But these studies are more or less case series. The new JAMA paper gives us, if not a smoking gun, a pretty decent set of fingerprints.

Here’s the idea: If CAA is caused by some infectious agent, it may be transmitted in the blood. We know that a decent percentage of people who have spontaneous brain bleeds have CAA. If those people donated blood in the past, maybe the people who received that blood would be at risk for brain bleeds too.

Of course, to really test that hypothesis, you’d need to know who every blood donor in a country was and every person who received that blood and all their subsequent diagnoses for basically their entire lives. No one has that kind of data, right?

Well, if you’ve been watching this space, you’ll know that a few countries do. Enter Sweden and Denmark, with their national electronic health record that captures all of this information, and much more, on every single person who lives or has lived in those countries since before 1970. Unbelievable.

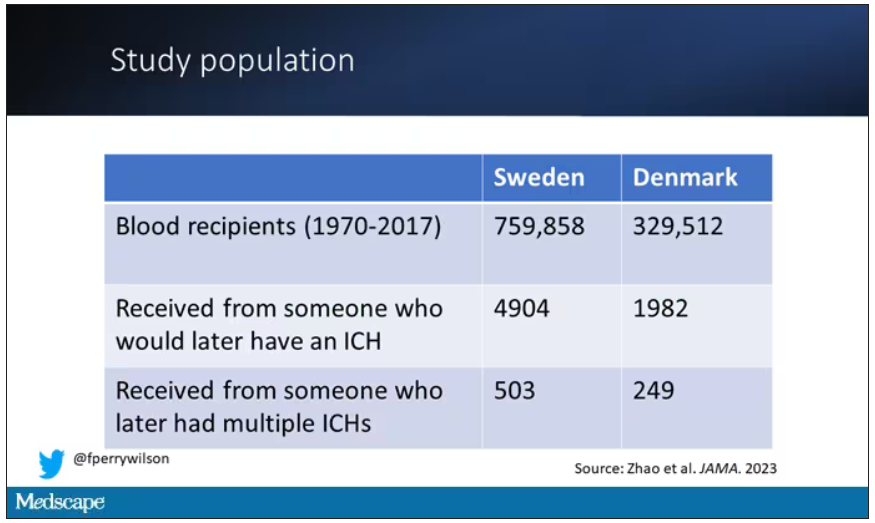

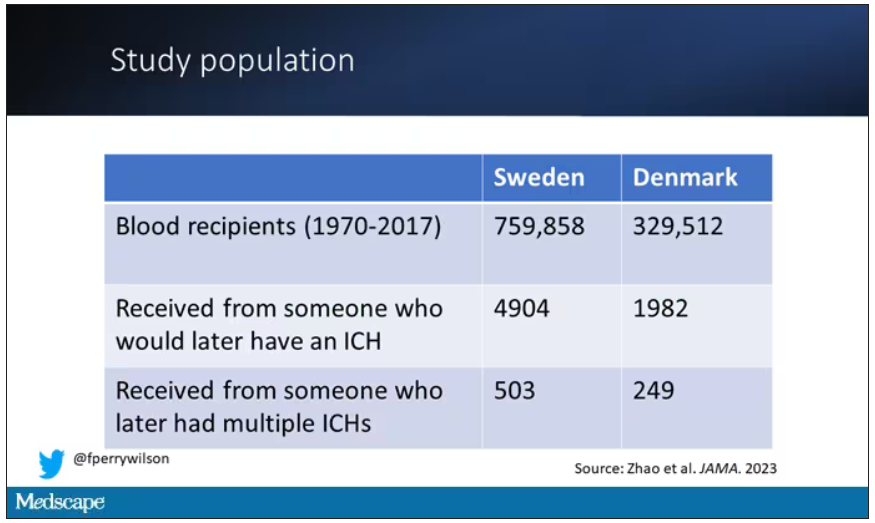

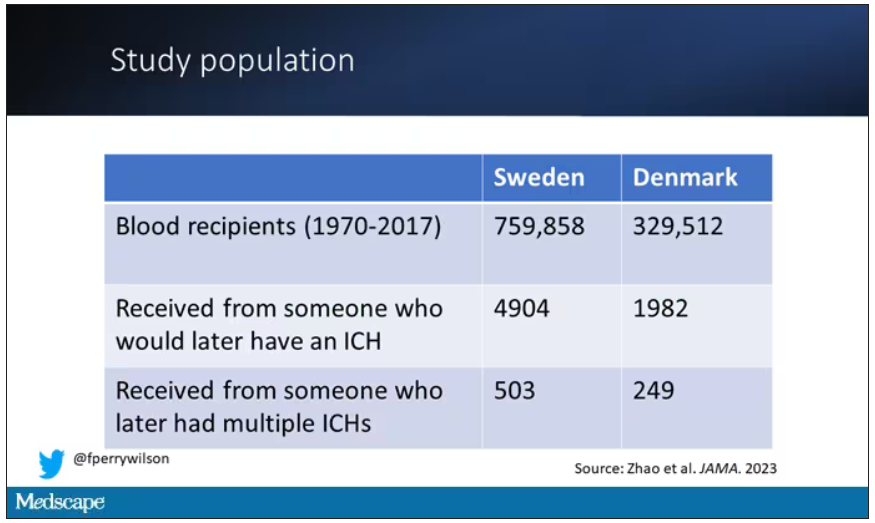

So that’s exactly what the researchers, led by Jingchen Zhao at Karolinska (Sweden) University, did. They identified roughly 760,000 individuals in Sweden and 330,000 people in Denmark who had received a blood transfusion between 1970 and 2017.

Of course, most of those blood donors – 99% of them, actually – never went on to have any bleeding in the brain. It is a rare thing, fortunately.

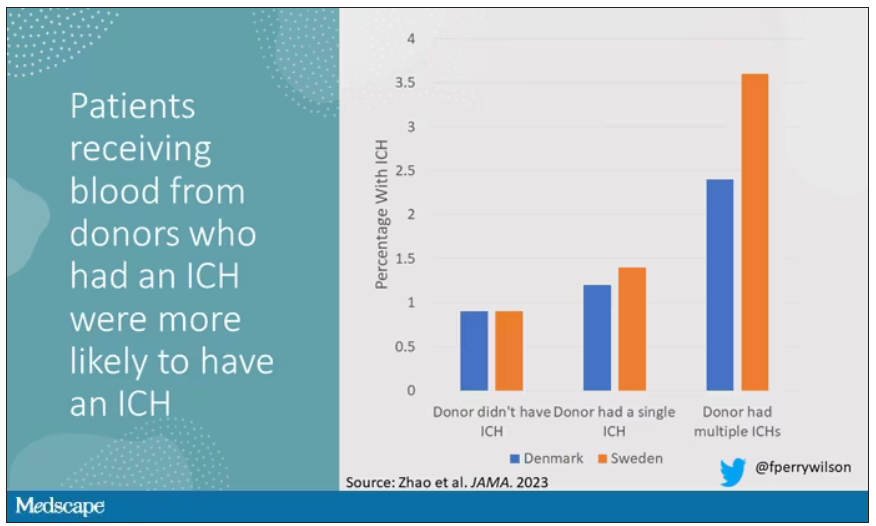

But some of the donors did, on average within about 5 years of the time they donated blood. The researchers characterized each donor as either never having a brain bleed, having a single bleed, or having multiple bleeds. The latter is most strongly associated with CAA.

The big question: Would recipients who got blood from individuals who later on had brain bleeds, have brain bleeds themselves?

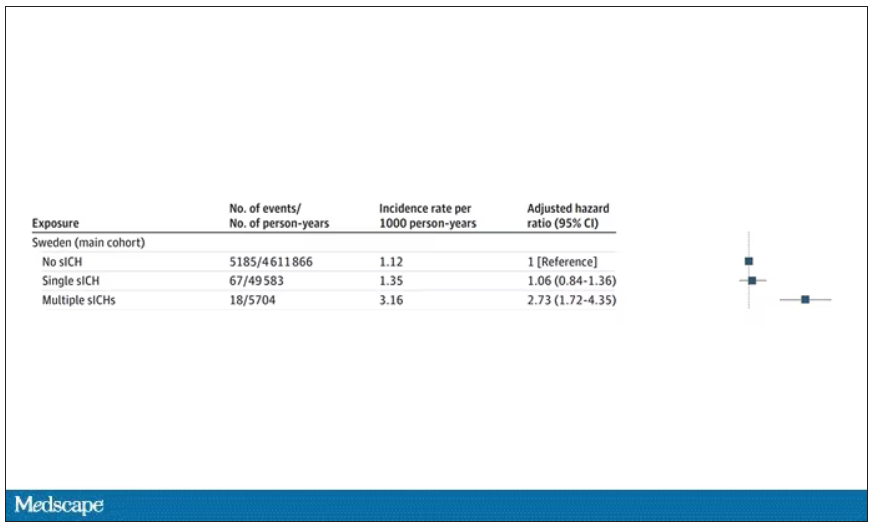

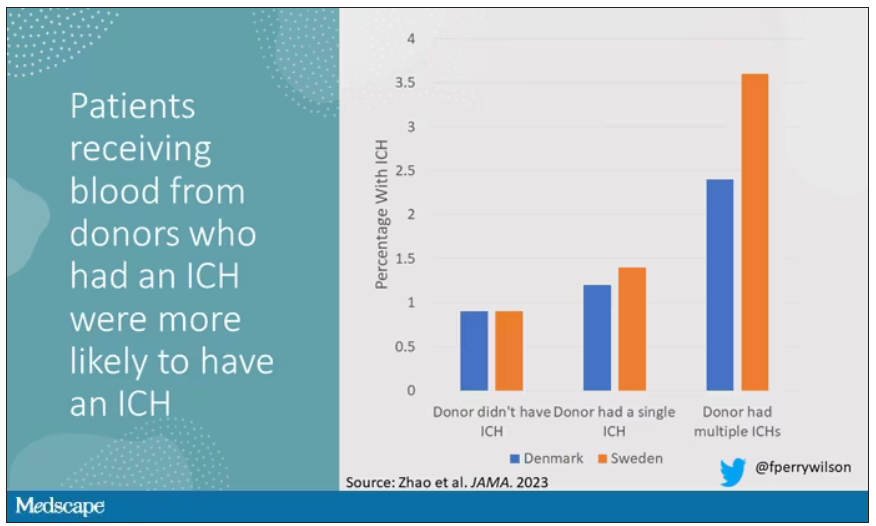

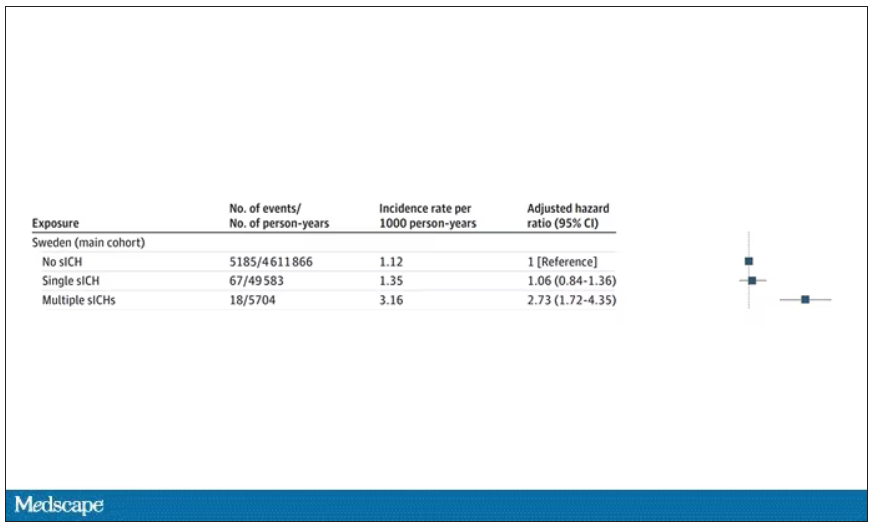

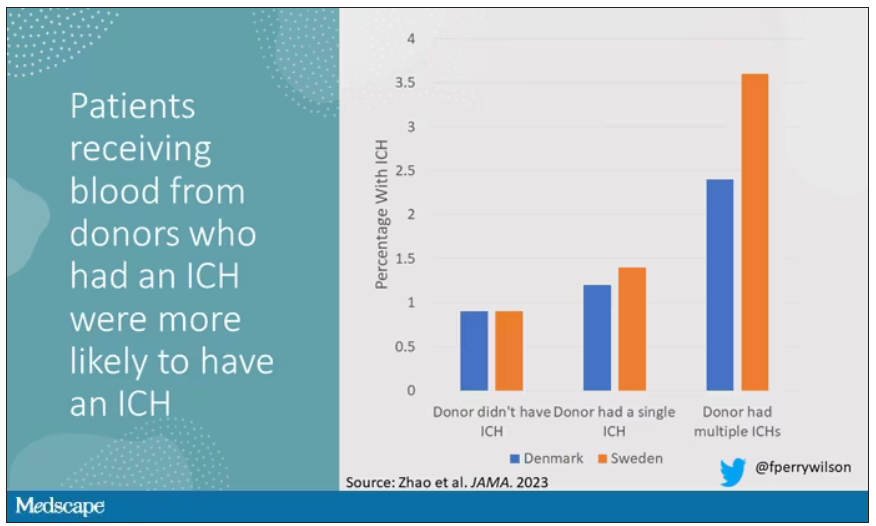

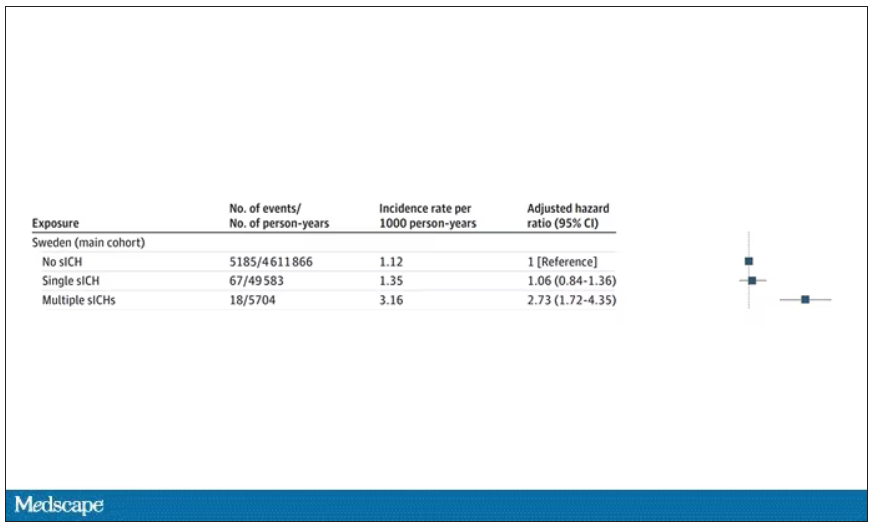

The answer is yes, though with an asterisk. You can see the results here. The risk of recipients having a brain bleed was lowest if the blood they received was from people who never had a brain bleed, higher if the individual had a single brain bleed, and highest if they got blood from a donor who would go on to have multiple brain bleeds.

All in all, individuals who received blood from someone who would later have multiple hemorrhages were three times more likely to themselves develop bleeds themselves. It’s fairly compelling evidence of a transmissible agent.

Of course, there are some potential confounders to consider here. Whose blood you get is not totally random. If, for example, people with type O blood are just more likely to have brain bleeds, then you could get results like this, as type O tends to donate to type O and both groups would have higher risk after donation. But the authors adjusted for blood type. They also adjusted for number of transfusions, calendar year, age, sex, and indication for transfusion.

Perhaps most compelling, and most clever, is that they used ischemic stroke as a negative control. Would people who received blood from someone who later had an ischemic stroke themselves be more likely to go on to have an ischemic stroke? No signal at all. It does not appear that there is a transmissible agent associated with ischemic stroke – only the brain bleeds.

I know what you’re thinking. What’s the agent? What’s the microbe, or virus, or prion, or toxin? The study gives us no insight there. These nationwide databases are awesome but they can only do so much. Because of the vagaries of medical coding and the difficulty of making the CAA diagnosis, the authors are using brain bleeds as a proxy here; we don’t even know for sure whether these were CAA-associated brain bleeds.

It’s also worth noting that there’s little we can do about this. None of the blood donors in this study had a brain bleed prior to donation; it’s not like we could screen people out of donating in the future. We have no test for whatever this agent is, if it even exists, nor do we have a potential treatment. Fortunately, whatever it is, it is extremely rare.

Still, this paper feels like a shot across the bow. At this point, the probability has shifted strongly away from CAA being a purely random disease and toward it being an infectious one. It may be time to round up some of the unusual suspects.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

How do you tell if a condition is caused by an infection?

It seems like an obvious question, right? In the post–van Leeuwenhoek era we can look at whatever part of the body is diseased under a microscope and see microbes – you know, the usual suspects.

Except when we can’t. And there are plenty of cases where we can’t: where the microbe is too small to be seen without more advanced imaging techniques, like with viruses; or when the pathogen is sparsely populated or hard to culture, like Mycobacterium.

Finding out that a condition is the result of an infection is not only an exercise for 19th century physicians. After all, it was 2008 when Barry Marshall and Robin Warren won their Nobel Prize for proving that stomach ulcers, long thought to be due to “stress,” were actually caused by a tiny microbe called Helicobacter pylori.

And this week, we are looking at a study which, once again, begins to suggest that a condition thought to be more or less random – cerebral amyloid angiopathy – may actually be the result of an infectious disease.

We’re talking about this paper, appearing in JAMA, which is just a great example of old-fashioned shoe-leather epidemiology. But let’s get up to speed on cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) first.

CAA is characterized by the deposition of amyloid protein in the brain. While there are some genetic causes, they are quite rare, and most cases are thought to be idiopathic. Recent analyses suggest that somewhere between 5% and 7% of cognitively normal older adults have CAA, but the rate is much higher among those with intracerebral hemorrhage – brain bleeds. In fact, CAA is the second-most common cause of bleeding in the brain, second only to severe hypertension.

An article in Nature highlights cases that seemed to develop after the administration of cadaveric pituitary hormone.

Other studies have shown potential transmission via dura mater grafts and neurosurgical instruments. But despite those clues, no infectious organism has been identified. Some have suggested that the long latent period and difficulty of finding a responsible microbe points to a prion-like disease not yet known. But these studies are more or less case series. The new JAMA paper gives us, if not a smoking gun, a pretty decent set of fingerprints.

Here’s the idea: If CAA is caused by some infectious agent, it may be transmitted in the blood. We know that a decent percentage of people who have spontaneous brain bleeds have CAA. If those people donated blood in the past, maybe the people who received that blood would be at risk for brain bleeds too.

Of course, to really test that hypothesis, you’d need to know who every blood donor in a country was and every person who received that blood and all their subsequent diagnoses for basically their entire lives. No one has that kind of data, right?

Well, if you’ve been watching this space, you’ll know that a few countries do. Enter Sweden and Denmark, with their national electronic health record that captures all of this information, and much more, on every single person who lives or has lived in those countries since before 1970. Unbelievable.

So that’s exactly what the researchers, led by Jingchen Zhao at Karolinska (Sweden) University, did. They identified roughly 760,000 individuals in Sweden and 330,000 people in Denmark who had received a blood transfusion between 1970 and 2017.

Of course, most of those blood donors – 99% of them, actually – never went on to have any bleeding in the brain. It is a rare thing, fortunately.

But some of the donors did, on average within about 5 years of the time they donated blood. The researchers characterized each donor as either never having a brain bleed, having a single bleed, or having multiple bleeds. The latter is most strongly associated with CAA.

The big question: Would recipients who got blood from individuals who later on had brain bleeds, have brain bleeds themselves?

The answer is yes, though with an asterisk. You can see the results here. The risk of recipients having a brain bleed was lowest if the blood they received was from people who never had a brain bleed, higher if the individual had a single brain bleed, and highest if they got blood from a donor who would go on to have multiple brain bleeds.

All in all, individuals who received blood from someone who would later have multiple hemorrhages were three times more likely to themselves develop bleeds themselves. It’s fairly compelling evidence of a transmissible agent.

Of course, there are some potential confounders to consider here. Whose blood you get is not totally random. If, for example, people with type O blood are just more likely to have brain bleeds, then you could get results like this, as type O tends to donate to type O and both groups would have higher risk after donation. But the authors adjusted for blood type. They also adjusted for number of transfusions, calendar year, age, sex, and indication for transfusion.

Perhaps most compelling, and most clever, is that they used ischemic stroke as a negative control. Would people who received blood from someone who later had an ischemic stroke themselves be more likely to go on to have an ischemic stroke? No signal at all. It does not appear that there is a transmissible agent associated with ischemic stroke – only the brain bleeds.

I know what you’re thinking. What’s the agent? What’s the microbe, or virus, or prion, or toxin? The study gives us no insight there. These nationwide databases are awesome but they can only do so much. Because of the vagaries of medical coding and the difficulty of making the CAA diagnosis, the authors are using brain bleeds as a proxy here; we don’t even know for sure whether these were CAA-associated brain bleeds.

It’s also worth noting that there’s little we can do about this. None of the blood donors in this study had a brain bleed prior to donation; it’s not like we could screen people out of donating in the future. We have no test for whatever this agent is, if it even exists, nor do we have a potential treatment. Fortunately, whatever it is, it is extremely rare.

Still, this paper feels like a shot across the bow. At this point, the probability has shifted strongly away from CAA being a purely random disease and toward it being an infectious one. It may be time to round up some of the unusual suspects.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

How do you tell if a condition is caused by an infection?

It seems like an obvious question, right? In the post–van Leeuwenhoek era we can look at whatever part of the body is diseased under a microscope and see microbes – you know, the usual suspects.

Except when we can’t. And there are plenty of cases where we can’t: where the microbe is too small to be seen without more advanced imaging techniques, like with viruses; or when the pathogen is sparsely populated or hard to culture, like Mycobacterium.

Finding out that a condition is the result of an infection is not only an exercise for 19th century physicians. After all, it was 2008 when Barry Marshall and Robin Warren won their Nobel Prize for proving that stomach ulcers, long thought to be due to “stress,” were actually caused by a tiny microbe called Helicobacter pylori.

And this week, we are looking at a study which, once again, begins to suggest that a condition thought to be more or less random – cerebral amyloid angiopathy – may actually be the result of an infectious disease.

We’re talking about this paper, appearing in JAMA, which is just a great example of old-fashioned shoe-leather epidemiology. But let’s get up to speed on cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) first.

CAA is characterized by the deposition of amyloid protein in the brain. While there are some genetic causes, they are quite rare, and most cases are thought to be idiopathic. Recent analyses suggest that somewhere between 5% and 7% of cognitively normal older adults have CAA, but the rate is much higher among those with intracerebral hemorrhage – brain bleeds. In fact, CAA is the second-most common cause of bleeding in the brain, second only to severe hypertension.

An article in Nature highlights cases that seemed to develop after the administration of cadaveric pituitary hormone.

Other studies have shown potential transmission via dura mater grafts and neurosurgical instruments. But despite those clues, no infectious organism has been identified. Some have suggested that the long latent period and difficulty of finding a responsible microbe points to a prion-like disease not yet known. But these studies are more or less case series. The new JAMA paper gives us, if not a smoking gun, a pretty decent set of fingerprints.

Here’s the idea: If CAA is caused by some infectious agent, it may be transmitted in the blood. We know that a decent percentage of people who have spontaneous brain bleeds have CAA. If those people donated blood in the past, maybe the people who received that blood would be at risk for brain bleeds too.

Of course, to really test that hypothesis, you’d need to know who every blood donor in a country was and every person who received that blood and all their subsequent diagnoses for basically their entire lives. No one has that kind of data, right?

Well, if you’ve been watching this space, you’ll know that a few countries do. Enter Sweden and Denmark, with their national electronic health record that captures all of this information, and much more, on every single person who lives or has lived in those countries since before 1970. Unbelievable.

So that’s exactly what the researchers, led by Jingchen Zhao at Karolinska (Sweden) University, did. They identified roughly 760,000 individuals in Sweden and 330,000 people in Denmark who had received a blood transfusion between 1970 and 2017.

Of course, most of those blood donors – 99% of them, actually – never went on to have any bleeding in the brain. It is a rare thing, fortunately.

But some of the donors did, on average within about 5 years of the time they donated blood. The researchers characterized each donor as either never having a brain bleed, having a single bleed, or having multiple bleeds. The latter is most strongly associated with CAA.

The big question: Would recipients who got blood from individuals who later on had brain bleeds, have brain bleeds themselves?

The answer is yes, though with an asterisk. You can see the results here. The risk of recipients having a brain bleed was lowest if the blood they received was from people who never had a brain bleed, higher if the individual had a single brain bleed, and highest if they got blood from a donor who would go on to have multiple brain bleeds.

All in all, individuals who received blood from someone who would later have multiple hemorrhages were three times more likely to themselves develop bleeds themselves. It’s fairly compelling evidence of a transmissible agent.

Of course, there are some potential confounders to consider here. Whose blood you get is not totally random. If, for example, people with type O blood are just more likely to have brain bleeds, then you could get results like this, as type O tends to donate to type O and both groups would have higher risk after donation. But the authors adjusted for blood type. They also adjusted for number of transfusions, calendar year, age, sex, and indication for transfusion.

Perhaps most compelling, and most clever, is that they used ischemic stroke as a negative control. Would people who received blood from someone who later had an ischemic stroke themselves be more likely to go on to have an ischemic stroke? No signal at all. It does not appear that there is a transmissible agent associated with ischemic stroke – only the brain bleeds.

I know what you’re thinking. What’s the agent? What’s the microbe, or virus, or prion, or toxin? The study gives us no insight there. These nationwide databases are awesome but they can only do so much. Because of the vagaries of medical coding and the difficulty of making the CAA diagnosis, the authors are using brain bleeds as a proxy here; we don’t even know for sure whether these were CAA-associated brain bleeds.

It’s also worth noting that there’s little we can do about this. None of the blood donors in this study had a brain bleed prior to donation; it’s not like we could screen people out of donating in the future. We have no test for whatever this agent is, if it even exists, nor do we have a potential treatment. Fortunately, whatever it is, it is extremely rare.

Still, this paper feels like a shot across the bow. At this point, the probability has shifted strongly away from CAA being a purely random disease and toward it being an infectious one. It may be time to round up some of the unusual suspects.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Disenfranchised grief: What it looks like, where it goes

What happens to grief when those around you don’t understand it? Where does it go? How do you process it?

Disenfranchised grief, when someone or society more generally doesn’t see a loss as worthy of mourning, can deprive people of experiencing or processing their sadness. This grief, which may be triggered by the death of an ex-spouse, a pet, a failed adoption, can be painful and long-lasting.

Suzanne Cole, MD: ‘I didn’t feel the right to grieve’

During the COVID-19 pandemic, my little sister unexpectedly died. Though she was not one of the nearly 7 million people who died of the virus, in 2021 she became another type of statistic: one of the 109,699 people in the United State who died from a drug overdose. Hers was from fentanyl laced with methamphetamines.

Her death unraveled me. I felt deep guilt that I could not pull her from the sweeping current that had wrenched her from mainstream society into the underbelly of sex work and toward the solace of mind-altering drugs.

But I did not feel the right to grieve for her as I have grieved for other loved ones who were not blamed for their exit from this world. My sister was living a sordid life on the fringes of society. My grief felt invalid, undeserved. Yet, in the eyes of other “upstanding citizens,” her life was not as worth grieving – or so I thought. I tucked my sorrow into a small corner of my soul so no one would see, and I carried on.

To this day, the shame I feel robbed me of the ability to freely talk about her or share the searing pain I feel. Tears still prick my eyes when I think of her, but I have become adept at swallowing them, shaking off the waves of grief as though nothing happened. Even now, I cannot shake the pervasive feeling that my silent tears don’t deserve to be wept.

Don S. Dizon, MD: Working through tragedy

As a medical student, I worked with an outpatient physician as part of a third-year rotation. When we met, the first thing that struck me was how disheveled he looked. His clothes were wrinkled, and his pants were baggy. He took cigarette breaks, which I found disturbing.

But I quickly came to admire him. Despite my first impression, he was the type of doctor I aspired to be. He didn’t need to look at a patient’s chart to recall who they were. He just knew them. He greeted patients warmly, asked about their family. He even remembered the special occasions his patients had mentioned since their past visit. He epitomized empathy and connectedness.

Spending one day in clinic brought to light the challenges of forming such bonds with patients. A man came into the cancer clinic reporting chest pain and was triaged to an exam room. Soon after, the patient was found unresponsive on the floor. Nurses were yelling for help, and the doctor ran in and started CPR while minutes ticked by waiting for an ambulance that could take him to the ED.

By the time help arrived, the patient was blue.

He had died in the clinic in the middle of the day, as the waiting room filled. After the body was taken away, the doctor went into the bathroom. About 20 minutes later, he came out, eyes bloodshot, and continued with the rest of his day, ensuring each patient was seen and cared for.

As a medical student, it hit me how hard it must be to see something so tragic like the end of a life and then continue with your day as if nothing had happened. This is an experience of grief I later came to know well after nearly 30 years treating patients with advanced cancers: compartmentalizing it and carrying on.

A space for grieving: The Schwartz Center Rounds

Disenfranchised grief, the grief that is hard to share and often seems wrong to feel in the first place, can be triggered in many situations. Losing a person others don’t believe deserve to be grieved, such as an abusive partner or someone who committed a crime; losing someone you cared for in a professional role; a loss experienced in a breakup or same-sex partnership, if that relationship was not accepted by one’s family; loss from infertility, miscarriage, stillbirth, or failed adoption; loss that may be taboo or stigmatized, such as deaths via suicide or abortion; and loss of a job, home, or possession that you treasure.

Many of us have had similar situations or will, and the feeling that no one understands the need to mourn can be paralyzing and alienating. In the early days, intense, crushing feelings can cause intrusive, distracting thoughts, and over time, that grief can linger and find a permanent place in our minds.

More and more, though, we are being given opportunities to reflect on these sad moments.

The Schwartz Rounds are an example of such an opportunity. In these rounds, we gather to talk about the experience of caring for people, not the science of medicine.

During one particularly powerful rounds, I spoke to my colleagues about my initial meeting with a patient who was very sick. I detailed the experience of telling her children and her at that initial consult how I thought she was dying and that I did not recommend therapy. I remember how they cried. And I remembered how powerless I felt.

As I recalled that memory during Schwartz Rounds, I could not stop from crying. The unfairness of being a physician meeting someone for the first time and having to tell them such bad news overwhelmed me.

Even more poignant, I had the chance to reconnect with this woman’s children, who were present that day, not as audience members but as participants. Their presence may have brought my emotions to the surface more strongly. In that moment, I could show them the feelings I had bottled up for the sake of professionalism. Ultimately, I felt relieved, freer somehow, as if this burden my soul was carrying had been lifted.

Although we are both grateful for forums like this, these opportunities to share and express the grief we may have hidden away are not as common as they should be.

As physicians, we may express grief by shedding tears at the bedside of a patient nearing the end of life or through the anxiety we feel when our patient suffers a severe reaction to treatment. But we tend to put it away, to go on with our day, because there are others to be seen and cared for and more work to be done. Somehow, we move forward, shedding tears in one room and celebrating victories in another.

We need to create more spaces to express and feel grief, so we don’t get lost in it. Because understanding how grief impacts us, as people and as providers, is one of the most important realizations we can make as we go about our time-honored profession as healers.

Dr. Dizon is the director of women’s cancers at Lifespan Cancer Institute, director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Brown University, all in Providence. He reported conflicts of interest with Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Kazia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What happens to grief when those around you don’t understand it? Where does it go? How do you process it?

Disenfranchised grief, when someone or society more generally doesn’t see a loss as worthy of mourning, can deprive people of experiencing or processing their sadness. This grief, which may be triggered by the death of an ex-spouse, a pet, a failed adoption, can be painful and long-lasting.

Suzanne Cole, MD: ‘I didn’t feel the right to grieve’

During the COVID-19 pandemic, my little sister unexpectedly died. Though she was not one of the nearly 7 million people who died of the virus, in 2021 she became another type of statistic: one of the 109,699 people in the United State who died from a drug overdose. Hers was from fentanyl laced with methamphetamines.

Her death unraveled me. I felt deep guilt that I could not pull her from the sweeping current that had wrenched her from mainstream society into the underbelly of sex work and toward the solace of mind-altering drugs.

But I did not feel the right to grieve for her as I have grieved for other loved ones who were not blamed for their exit from this world. My sister was living a sordid life on the fringes of society. My grief felt invalid, undeserved. Yet, in the eyes of other “upstanding citizens,” her life was not as worth grieving – or so I thought. I tucked my sorrow into a small corner of my soul so no one would see, and I carried on.

To this day, the shame I feel robbed me of the ability to freely talk about her or share the searing pain I feel. Tears still prick my eyes when I think of her, but I have become adept at swallowing them, shaking off the waves of grief as though nothing happened. Even now, I cannot shake the pervasive feeling that my silent tears don’t deserve to be wept.

Don S. Dizon, MD: Working through tragedy

As a medical student, I worked with an outpatient physician as part of a third-year rotation. When we met, the first thing that struck me was how disheveled he looked. His clothes were wrinkled, and his pants were baggy. He took cigarette breaks, which I found disturbing.

But I quickly came to admire him. Despite my first impression, he was the type of doctor I aspired to be. He didn’t need to look at a patient’s chart to recall who they were. He just knew them. He greeted patients warmly, asked about their family. He even remembered the special occasions his patients had mentioned since their past visit. He epitomized empathy and connectedness.

Spending one day in clinic brought to light the challenges of forming such bonds with patients. A man came into the cancer clinic reporting chest pain and was triaged to an exam room. Soon after, the patient was found unresponsive on the floor. Nurses were yelling for help, and the doctor ran in and started CPR while minutes ticked by waiting for an ambulance that could take him to the ED.

By the time help arrived, the patient was blue.

He had died in the clinic in the middle of the day, as the waiting room filled. After the body was taken away, the doctor went into the bathroom. About 20 minutes later, he came out, eyes bloodshot, and continued with the rest of his day, ensuring each patient was seen and cared for.

As a medical student, it hit me how hard it must be to see something so tragic like the end of a life and then continue with your day as if nothing had happened. This is an experience of grief I later came to know well after nearly 30 years treating patients with advanced cancers: compartmentalizing it and carrying on.

A space for grieving: The Schwartz Center Rounds

Disenfranchised grief, the grief that is hard to share and often seems wrong to feel in the first place, can be triggered in many situations. Losing a person others don’t believe deserve to be grieved, such as an abusive partner or someone who committed a crime; losing someone you cared for in a professional role; a loss experienced in a breakup or same-sex partnership, if that relationship was not accepted by one’s family; loss from infertility, miscarriage, stillbirth, or failed adoption; loss that may be taboo or stigmatized, such as deaths via suicide or abortion; and loss of a job, home, or possession that you treasure.

Many of us have had similar situations or will, and the feeling that no one understands the need to mourn can be paralyzing and alienating. In the early days, intense, crushing feelings can cause intrusive, distracting thoughts, and over time, that grief can linger and find a permanent place in our minds.

More and more, though, we are being given opportunities to reflect on these sad moments.

The Schwartz Rounds are an example of such an opportunity. In these rounds, we gather to talk about the experience of caring for people, not the science of medicine.

During one particularly powerful rounds, I spoke to my colleagues about my initial meeting with a patient who was very sick. I detailed the experience of telling her children and her at that initial consult how I thought she was dying and that I did not recommend therapy. I remember how they cried. And I remembered how powerless I felt.

As I recalled that memory during Schwartz Rounds, I could not stop from crying. The unfairness of being a physician meeting someone for the first time and having to tell them such bad news overwhelmed me.

Even more poignant, I had the chance to reconnect with this woman’s children, who were present that day, not as audience members but as participants. Their presence may have brought my emotions to the surface more strongly. In that moment, I could show them the feelings I had bottled up for the sake of professionalism. Ultimately, I felt relieved, freer somehow, as if this burden my soul was carrying had been lifted.

Although we are both grateful for forums like this, these opportunities to share and express the grief we may have hidden away are not as common as they should be.

As physicians, we may express grief by shedding tears at the bedside of a patient nearing the end of life or through the anxiety we feel when our patient suffers a severe reaction to treatment. But we tend to put it away, to go on with our day, because there are others to be seen and cared for and more work to be done. Somehow, we move forward, shedding tears in one room and celebrating victories in another.

We need to create more spaces to express and feel grief, so we don’t get lost in it. Because understanding how grief impacts us, as people and as providers, is one of the most important realizations we can make as we go about our time-honored profession as healers.

Dr. Dizon is the director of women’s cancers at Lifespan Cancer Institute, director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Brown University, all in Providence. He reported conflicts of interest with Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Kazia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What happens to grief when those around you don’t understand it? Where does it go? How do you process it?

Disenfranchised grief, when someone or society more generally doesn’t see a loss as worthy of mourning, can deprive people of experiencing or processing their sadness. This grief, which may be triggered by the death of an ex-spouse, a pet, a failed adoption, can be painful and long-lasting.

Suzanne Cole, MD: ‘I didn’t feel the right to grieve’

During the COVID-19 pandemic, my little sister unexpectedly died. Though she was not one of the nearly 7 million people who died of the virus, in 2021 she became another type of statistic: one of the 109,699 people in the United State who died from a drug overdose. Hers was from fentanyl laced with methamphetamines.

Her death unraveled me. I felt deep guilt that I could not pull her from the sweeping current that had wrenched her from mainstream society into the underbelly of sex work and toward the solace of mind-altering drugs.

But I did not feel the right to grieve for her as I have grieved for other loved ones who were not blamed for their exit from this world. My sister was living a sordid life on the fringes of society. My grief felt invalid, undeserved. Yet, in the eyes of other “upstanding citizens,” her life was not as worth grieving – or so I thought. I tucked my sorrow into a small corner of my soul so no one would see, and I carried on.

To this day, the shame I feel robbed me of the ability to freely talk about her or share the searing pain I feel. Tears still prick my eyes when I think of her, but I have become adept at swallowing them, shaking off the waves of grief as though nothing happened. Even now, I cannot shake the pervasive feeling that my silent tears don’t deserve to be wept.

Don S. Dizon, MD: Working through tragedy

As a medical student, I worked with an outpatient physician as part of a third-year rotation. When we met, the first thing that struck me was how disheveled he looked. His clothes were wrinkled, and his pants were baggy. He took cigarette breaks, which I found disturbing.

But I quickly came to admire him. Despite my first impression, he was the type of doctor I aspired to be. He didn’t need to look at a patient’s chart to recall who they were. He just knew them. He greeted patients warmly, asked about their family. He even remembered the special occasions his patients had mentioned since their past visit. He epitomized empathy and connectedness.

Spending one day in clinic brought to light the challenges of forming such bonds with patients. A man came into the cancer clinic reporting chest pain and was triaged to an exam room. Soon after, the patient was found unresponsive on the floor. Nurses were yelling for help, and the doctor ran in and started CPR while minutes ticked by waiting for an ambulance that could take him to the ED.

By the time help arrived, the patient was blue.

He had died in the clinic in the middle of the day, as the waiting room filled. After the body was taken away, the doctor went into the bathroom. About 20 minutes later, he came out, eyes bloodshot, and continued with the rest of his day, ensuring each patient was seen and cared for.

As a medical student, it hit me how hard it must be to see something so tragic like the end of a life and then continue with your day as if nothing had happened. This is an experience of grief I later came to know well after nearly 30 years treating patients with advanced cancers: compartmentalizing it and carrying on.

A space for grieving: The Schwartz Center Rounds

Disenfranchised grief, the grief that is hard to share and often seems wrong to feel in the first place, can be triggered in many situations. Losing a person others don’t believe deserve to be grieved, such as an abusive partner or someone who committed a crime; losing someone you cared for in a professional role; a loss experienced in a breakup or same-sex partnership, if that relationship was not accepted by one’s family; loss from infertility, miscarriage, stillbirth, or failed adoption; loss that may be taboo or stigmatized, such as deaths via suicide or abortion; and loss of a job, home, or possession that you treasure.

Many of us have had similar situations or will, and the feeling that no one understands the need to mourn can be paralyzing and alienating. In the early days, intense, crushing feelings can cause intrusive, distracting thoughts, and over time, that grief can linger and find a permanent place in our minds.

More and more, though, we are being given opportunities to reflect on these sad moments.

The Schwartz Rounds are an example of such an opportunity. In these rounds, we gather to talk about the experience of caring for people, not the science of medicine.

During one particularly powerful rounds, I spoke to my colleagues about my initial meeting with a patient who was very sick. I detailed the experience of telling her children and her at that initial consult how I thought she was dying and that I did not recommend therapy. I remember how they cried. And I remembered how powerless I felt.

As I recalled that memory during Schwartz Rounds, I could not stop from crying. The unfairness of being a physician meeting someone for the first time and having to tell them such bad news overwhelmed me.

Even more poignant, I had the chance to reconnect with this woman’s children, who were present that day, not as audience members but as participants. Their presence may have brought my emotions to the surface more strongly. In that moment, I could show them the feelings I had bottled up for the sake of professionalism. Ultimately, I felt relieved, freer somehow, as if this burden my soul was carrying had been lifted.

Although we are both grateful for forums like this, these opportunities to share and express the grief we may have hidden away are not as common as they should be.

As physicians, we may express grief by shedding tears at the bedside of a patient nearing the end of life or through the anxiety we feel when our patient suffers a severe reaction to treatment. But we tend to put it away, to go on with our day, because there are others to be seen and cared for and more work to be done. Somehow, we move forward, shedding tears in one room and celebrating victories in another.

We need to create more spaces to express and feel grief, so we don’t get lost in it. Because understanding how grief impacts us, as people and as providers, is one of the most important realizations we can make as we go about our time-honored profession as healers.

Dr. Dizon is the director of women’s cancers at Lifespan Cancer Institute, director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Brown University, all in Providence. He reported conflicts of interest with Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Kazia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Universal anxiety screening recommendation is a good start

A very good thing happened this summer for patients with anxiety and the psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health professionals who provide treatment for them. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended anxiety screening for all adults younger than 65.

On the surface, this is a great recommendation for recognition and caring for those who deal with and suffer from an anxiety disorder or multiple anxiety disorders. Although the USPSTF recommendations are independent of the U.S. government and are not an official position of the Department of Health & Human Services, they are a wonderful start at recognizing the importance of mental health care.

After all, anxiety disorders are the most commonly experienced and diagnosed mental disorders, according to the DSM-5.

They range mainly from generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), to panic attacks and panic disorder, separation anxiety, specific type phobias (bridges, tunnels, insects, snakes, and the list goes on), to other phobias, including agoraphobia, social phobia, and of course, anxiety caused by medical conditions. GAD alone occurs in, at least, more than 3% of the population.

Those of us who have been treating anxiety disorders for decades recognize them as an issue affecting both mental and physical well-being, not only because of the emotional causes but the physical distress and illnesses that anxiety may precipitate or worsen.

For example, blood pressure– and heart-related issues, GI disorders, and musculoskeletal issues are just a few examples of how our bodies and organ systems are affected by anxiety. Just the momentary physical symptoms of tachycardia or the “runs” before an exam are fine examples of how anxiety may affect patients physically, and an ongoing, consistent anxiety is potentially more harmful.

In fact, a first panic attack or episode of generalized anxiety may be so serious that an emergency department or physician visit is necessary to rule out a heart attack, asthma, or breathing issues – even a hormone or thyroid emergency, or a cardiac arrhythmia. Panic attacks alone create a high number of ED visits.

Treatments mainly include medication management and a variety of psychotherapy techniques. Currently, the most preferred, first-choice medications are the SSRI antidepressants, which are Food and Drug Administration approved for anxiety as well. These include Zoloft (sertraline), Prozac/Sarafem (fluoxetine), Celexa (citalopram), and Lexapro (escitalopram).

For many years, benzodiazepines (that is, tranquillizers) such as Valium (diazepam), Ativan (lorazepam), and Klonopin/Rivotril (clonazepam) to name a few, were the mainstay of anxiety treatment, but they have proven addictive and may affect cognition and memory. As the current opioid epidemic has shown, when combined with opioids, benzodiazepines are a potentially lethal combination and when used, they need to be for shorter-term care and monitored very judiciously.

It should be noted that after ongoing long-term use of an SSRI for anxiety or depression, it should not be stopped abruptly, as a variety of physical symptoms (for example, flu-like symptoms) may occur.

Benefits of nonmedicinal therapies

There are a variety of talk therapies, from dynamic psychotherapies to cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), plus relaxation techniques and guided imagery that have all had a good amount of success in treating generalized anxiety, panic disorder, as well as various types of phobias.

When medications are stopped, the anxiety symptoms may well return. But when using nonmedicinal therapies, clinicians have discovered that when patients develop a new perspective on the anxiety problem or have a new technique to treat anxiety, it may well be long lasting.

For me, using CBT, relaxation techniques, hypnosis, and guided imagery has been very successful in treating anxiety disorders with long-lasting results. Once a person learns to relax, whether it’s from deep breathing exercises, hypnosis (which is not sleep), mindfulness, or meditation, a strategy of guided imagery can be taught, which allows a person to practice as well as control their anxiety as a lifetime process. For example, I like imagining a large movie screen to desensitize and project anxieties.

In many instances, a combination of a medication and a talk therapy approach works best, but there are an equal number of instances in which just medication or just talk therapy is needed. Once again, knowledge, clinical judgment, and the art of care are required to make these assessments.

In other words, recognizing and treating anxiety requires highly specialized training, which is why I thought the USPSTF recommendations raise a few critical questions.

Questions and concerns

One issue, of course, is the exclusion of those patients over age 65 because of a lack of “data.” Why such an exclusion? Does this mean that data are lacking for this age group?

The concept of using solely evidenced-based data in psychiatry is itself an interesting concept because our profession, like many other medical specialties, requires practitioners to use a combination of art and science. And much can be said either way about the clarity of accuracy in the diversity of issues that arise when treating emotional disorders.

When looking at the over-65 population, has anyone thought of clinical knowledge, judgment, experience, observation, and, of course, common sense?

Just consider the worry (a cardinal feature of anxiety) that besets people over 65 when it comes to issues such as retirement, financial security, “empty nesting,” physical health issues, decreased socialization that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, and the perpetual loss of relatives and friends.

In addition, as we age, anxiety can come simply from the loss of identity as active lifestyles decrease and the reality of nearing life’s end becomes more of a reality. It would seem that this population would benefit enormously from anxiety screening and possible treatment.

Another major concern is that the screening and potential treatment of patients is aimed at primary care physicians. Putting the sole responsibility of providing mental health care on these overworked PCPs defies common sense unless we’re okay with 1- to 2-minute assessments of mental health issues and no doubt, a pharmacology-only approach.

If this follows the same route as well-intentioned PCPs treating depression, where 5-minute medication management is far too common, the only proper diagnostic course – the in-depth interview necessary to make a proper diagnosis – is often missing.

For example, in depression alone, it takes psychiatric experience and time to differentiate a major depressive disorder from a bipolar depression and to provide the appropriate medication and treatment plan with careful follow-up. In my experience, this usually does not happen in the exceedingly overworked, time-driven day of a PCP.

Anxiety disorders and depression can prove debilitating, and if a PCP wants the responsibility of treatment, a mandated mental health program should be followed – just as here in New York, prescribers are mandated to take a pain control, opioid, and infection control CME course to keep our licenses up to date.

Short of mandating a mental health program for PCPs, it should be part of training and CME courses that Psychiatry is a super specialty, much like orthopedics and ophthalmology, and primary care physicians should never hesitate to make referrals to the specialist.

The big picture for me, and I hope for us all, is that the USPSTF has started things rolling by making it clear that PCPs and other health care clinicians need to screen for anxiety as a disabling disorder that is quite treatable.

This approach will help to advance the destigmatization of mental health disorders. But as result, with more patients diagnosed, there will be a need for more psychiatrists – and psychologists with PhDs or PsyDs – to fill the gaps in mental health care.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist and has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

A very good thing happened this summer for patients with anxiety and the psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health professionals who provide treatment for them. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended anxiety screening for all adults younger than 65.

On the surface, this is a great recommendation for recognition and caring for those who deal with and suffer from an anxiety disorder or multiple anxiety disorders. Although the USPSTF recommendations are independent of the U.S. government and are not an official position of the Department of Health & Human Services, they are a wonderful start at recognizing the importance of mental health care.

After all, anxiety disorders are the most commonly experienced and diagnosed mental disorders, according to the DSM-5.

They range mainly from generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), to panic attacks and panic disorder, separation anxiety, specific type phobias (bridges, tunnels, insects, snakes, and the list goes on), to other phobias, including agoraphobia, social phobia, and of course, anxiety caused by medical conditions. GAD alone occurs in, at least, more than 3% of the population.

Those of us who have been treating anxiety disorders for decades recognize them as an issue affecting both mental and physical well-being, not only because of the emotional causes but the physical distress and illnesses that anxiety may precipitate or worsen.

For example, blood pressure– and heart-related issues, GI disorders, and musculoskeletal issues are just a few examples of how our bodies and organ systems are affected by anxiety. Just the momentary physical symptoms of tachycardia or the “runs” before an exam are fine examples of how anxiety may affect patients physically, and an ongoing, consistent anxiety is potentially more harmful.

In fact, a first panic attack or episode of generalized anxiety may be so serious that an emergency department or physician visit is necessary to rule out a heart attack, asthma, or breathing issues – even a hormone or thyroid emergency, or a cardiac arrhythmia. Panic attacks alone create a high number of ED visits.

Treatments mainly include medication management and a variety of psychotherapy techniques. Currently, the most preferred, first-choice medications are the SSRI antidepressants, which are Food and Drug Administration approved for anxiety as well. These include Zoloft (sertraline), Prozac/Sarafem (fluoxetine), Celexa (citalopram), and Lexapro (escitalopram).

For many years, benzodiazepines (that is, tranquillizers) such as Valium (diazepam), Ativan (lorazepam), and Klonopin/Rivotril (clonazepam) to name a few, were the mainstay of anxiety treatment, but they have proven addictive and may affect cognition and memory. As the current opioid epidemic has shown, when combined with opioids, benzodiazepines are a potentially lethal combination and when used, they need to be for shorter-term care and monitored very judiciously.

It should be noted that after ongoing long-term use of an SSRI for anxiety or depression, it should not be stopped abruptly, as a variety of physical symptoms (for example, flu-like symptoms) may occur.

Benefits of nonmedicinal therapies

There are a variety of talk therapies, from dynamic psychotherapies to cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), plus relaxation techniques and guided imagery that have all had a good amount of success in treating generalized anxiety, panic disorder, as well as various types of phobias.

When medications are stopped, the anxiety symptoms may well return. But when using nonmedicinal therapies, clinicians have discovered that when patients develop a new perspective on the anxiety problem or have a new technique to treat anxiety, it may well be long lasting.

For me, using CBT, relaxation techniques, hypnosis, and guided imagery has been very successful in treating anxiety disorders with long-lasting results. Once a person learns to relax, whether it’s from deep breathing exercises, hypnosis (which is not sleep), mindfulness, or meditation, a strategy of guided imagery can be taught, which allows a person to practice as well as control their anxiety as a lifetime process. For example, I like imagining a large movie screen to desensitize and project anxieties.

In many instances, a combination of a medication and a talk therapy approach works best, but there are an equal number of instances in which just medication or just talk therapy is needed. Once again, knowledge, clinical judgment, and the art of care are required to make these assessments.

In other words, recognizing and treating anxiety requires highly specialized training, which is why I thought the USPSTF recommendations raise a few critical questions.

Questions and concerns

One issue, of course, is the exclusion of those patients over age 65 because of a lack of “data.” Why such an exclusion? Does this mean that data are lacking for this age group?

The concept of using solely evidenced-based data in psychiatry is itself an interesting concept because our profession, like many other medical specialties, requires practitioners to use a combination of art and science. And much can be said either way about the clarity of accuracy in the diversity of issues that arise when treating emotional disorders.

When looking at the over-65 population, has anyone thought of clinical knowledge, judgment, experience, observation, and, of course, common sense?

Just consider the worry (a cardinal feature of anxiety) that besets people over 65 when it comes to issues such as retirement, financial security, “empty nesting,” physical health issues, decreased socialization that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, and the perpetual loss of relatives and friends.

In addition, as we age, anxiety can come simply from the loss of identity as active lifestyles decrease and the reality of nearing life’s end becomes more of a reality. It would seem that this population would benefit enormously from anxiety screening and possible treatment.

Another major concern is that the screening and potential treatment of patients is aimed at primary care physicians. Putting the sole responsibility of providing mental health care on these overworked PCPs defies common sense unless we’re okay with 1- to 2-minute assessments of mental health issues and no doubt, a pharmacology-only approach.

If this follows the same route as well-intentioned PCPs treating depression, where 5-minute medication management is far too common, the only proper diagnostic course – the in-depth interview necessary to make a proper diagnosis – is often missing.

For example, in depression alone, it takes psychiatric experience and time to differentiate a major depressive disorder from a bipolar depression and to provide the appropriate medication and treatment plan with careful follow-up. In my experience, this usually does not happen in the exceedingly overworked, time-driven day of a PCP.

Anxiety disorders and depression can prove debilitating, and if a PCP wants the responsibility of treatment, a mandated mental health program should be followed – just as here in New York, prescribers are mandated to take a pain control, opioid, and infection control CME course to keep our licenses up to date.

Short of mandating a mental health program for PCPs, it should be part of training and CME courses that Psychiatry is a super specialty, much like orthopedics and ophthalmology, and primary care physicians should never hesitate to make referrals to the specialist.

The big picture for me, and I hope for us all, is that the USPSTF has started things rolling by making it clear that PCPs and other health care clinicians need to screen for anxiety as a disabling disorder that is quite treatable.

This approach will help to advance the destigmatization of mental health disorders. But as result, with more patients diagnosed, there will be a need for more psychiatrists – and psychologists with PhDs or PsyDs – to fill the gaps in mental health care.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist and has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

A very good thing happened this summer for patients with anxiety and the psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health professionals who provide treatment for them. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended anxiety screening for all adults younger than 65.

On the surface, this is a great recommendation for recognition and caring for those who deal with and suffer from an anxiety disorder or multiple anxiety disorders. Although the USPSTF recommendations are independent of the U.S. government and are not an official position of the Department of Health & Human Services, they are a wonderful start at recognizing the importance of mental health care.

After all, anxiety disorders are the most commonly experienced and diagnosed mental disorders, according to the DSM-5.

They range mainly from generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), to panic attacks and panic disorder, separation anxiety, specific type phobias (bridges, tunnels, insects, snakes, and the list goes on), to other phobias, including agoraphobia, social phobia, and of course, anxiety caused by medical conditions. GAD alone occurs in, at least, more than 3% of the population.

Those of us who have been treating anxiety disorders for decades recognize them as an issue affecting both mental and physical well-being, not only because of the emotional causes but the physical distress and illnesses that anxiety may precipitate or worsen.

For example, blood pressure– and heart-related issues, GI disorders, and musculoskeletal issues are just a few examples of how our bodies and organ systems are affected by anxiety. Just the momentary physical symptoms of tachycardia or the “runs” before an exam are fine examples of how anxiety may affect patients physically, and an ongoing, consistent anxiety is potentially more harmful.

In fact, a first panic attack or episode of generalized anxiety may be so serious that an emergency department or physician visit is necessary to rule out a heart attack, asthma, or breathing issues – even a hormone or thyroid emergency, or a cardiac arrhythmia. Panic attacks alone create a high number of ED visits.

Treatments mainly include medication management and a variety of psychotherapy techniques. Currently, the most preferred, first-choice medications are the SSRI antidepressants, which are Food and Drug Administration approved for anxiety as well. These include Zoloft (sertraline), Prozac/Sarafem (fluoxetine), Celexa (citalopram), and Lexapro (escitalopram).

For many years, benzodiazepines (that is, tranquillizers) such as Valium (diazepam), Ativan (lorazepam), and Klonopin/Rivotril (clonazepam) to name a few, were the mainstay of anxiety treatment, but they have proven addictive and may affect cognition and memory. As the current opioid epidemic has shown, when combined with opioids, benzodiazepines are a potentially lethal combination and when used, they need to be for shorter-term care and monitored very judiciously.

It should be noted that after ongoing long-term use of an SSRI for anxiety or depression, it should not be stopped abruptly, as a variety of physical symptoms (for example, flu-like symptoms) may occur.

Benefits of nonmedicinal therapies

There are a variety of talk therapies, from dynamic psychotherapies to cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), plus relaxation techniques and guided imagery that have all had a good amount of success in treating generalized anxiety, panic disorder, as well as various types of phobias.

When medications are stopped, the anxiety symptoms may well return. But when using nonmedicinal therapies, clinicians have discovered that when patients develop a new perspective on the anxiety problem or have a new technique to treat anxiety, it may well be long lasting.

For me, using CBT, relaxation techniques, hypnosis, and guided imagery has been very successful in treating anxiety disorders with long-lasting results. Once a person learns to relax, whether it’s from deep breathing exercises, hypnosis (which is not sleep), mindfulness, or meditation, a strategy of guided imagery can be taught, which allows a person to practice as well as control their anxiety as a lifetime process. For example, I like imagining a large movie screen to desensitize and project anxieties.

In many instances, a combination of a medication and a talk therapy approach works best, but there are an equal number of instances in which just medication or just talk therapy is needed. Once again, knowledge, clinical judgment, and the art of care are required to make these assessments.

In other words, recognizing and treating anxiety requires highly specialized training, which is why I thought the USPSTF recommendations raise a few critical questions.

Questions and concerns

One issue, of course, is the exclusion of those patients over age 65 because of a lack of “data.” Why such an exclusion? Does this mean that data are lacking for this age group?

The concept of using solely evidenced-based data in psychiatry is itself an interesting concept because our profession, like many other medical specialties, requires practitioners to use a combination of art and science. And much can be said either way about the clarity of accuracy in the diversity of issues that arise when treating emotional disorders.

When looking at the over-65 population, has anyone thought of clinical knowledge, judgment, experience, observation, and, of course, common sense?

Just consider the worry (a cardinal feature of anxiety) that besets people over 65 when it comes to issues such as retirement, financial security, “empty nesting,” physical health issues, decreased socialization that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, and the perpetual loss of relatives and friends.

In addition, as we age, anxiety can come simply from the loss of identity as active lifestyles decrease and the reality of nearing life’s end becomes more of a reality. It would seem that this population would benefit enormously from anxiety screening and possible treatment.

Another major concern is that the screening and potential treatment of patients is aimed at primary care physicians. Putting the sole responsibility of providing mental health care on these overworked PCPs defies common sense unless we’re okay with 1- to 2-minute assessments of mental health issues and no doubt, a pharmacology-only approach.

If this follows the same route as well-intentioned PCPs treating depression, where 5-minute medication management is far too common, the only proper diagnostic course – the in-depth interview necessary to make a proper diagnosis – is often missing.

For example, in depression alone, it takes psychiatric experience and time to differentiate a major depressive disorder from a bipolar depression and to provide the appropriate medication and treatment plan with careful follow-up. In my experience, this usually does not happen in the exceedingly overworked, time-driven day of a PCP.

Anxiety disorders and depression can prove debilitating, and if a PCP wants the responsibility of treatment, a mandated mental health program should be followed – just as here in New York, prescribers are mandated to take a pain control, opioid, and infection control CME course to keep our licenses up to date.

Short of mandating a mental health program for PCPs, it should be part of training and CME courses that Psychiatry is a super specialty, much like orthopedics and ophthalmology, and primary care physicians should never hesitate to make referrals to the specialist.

The big picture for me, and I hope for us all, is that the USPSTF has started things rolling by making it clear that PCPs and other health care clinicians need to screen for anxiety as a disabling disorder that is quite treatable.

This approach will help to advance the destigmatization of mental health disorders. But as result, with more patients diagnosed, there will be a need for more psychiatrists – and psychologists with PhDs or PsyDs – to fill the gaps in mental health care.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist and has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

A White male presented with a purulent erythematous edematous plaque with central necrosis and ulceration on his right flank

Lyme disease is the most commonly transmitted tick-borne illness in the United States. This infection is typically transmitted through a bite by the Ixodes tick commonly found in the Midwest, Northeast, and mid-Atlantic regions; however, the geographical distribution continues to expand over time in the United States. Ticks must be attached for 24-48 hours to transmit the pathogen. There are three general stages of the disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated.

The most common presentation is the early localized disease, which manifests between 3 and 30 days after an infected tick bite. Approximately 70%-80% of cases feature a targetlike lesion that expands centrifugally at the site of the bite. Most commonly, lesions appear on the abdomen, groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa. The diagnosis of ECM requires lesions at least 5 cm in size. Lesions may be asymptomatic, although burning may occur in half of patients. Atypical presentations include bullous, vesicular, hemorrhagic, or necrotic lesions. Up to half of patients may develop multiple ECM lesions. Palms and soles are spared. Differential diagnoses include arthropod reactions, pyoderma gangrenosum, cellulitis, herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus, contact dermatitis, or granuloma annulare. The rash is often accompanied by systemic symptoms including fatigue, myalgia, headache, and fever.

The next two stages include early and late disseminated infection. Early disseminated infection often occurs 3-12 weeks after infection and is characterized by muscle pain, dizziness, headache, and cardiac symptoms. CNS involvement occurs in about 20% of patients. Joint involvement may include the knee, ankle, and wrist. If symptoms are only in one joint, septic arthritis is part of the differential diagnosis, so clinical correlation and labs must be considered. Late disseminated infection occurs months or years after initial infection and includes neurologic and rheumatologic symptoms including meningitis, Bell’s palsy, arthritis, and dysesthesia. Knee arthritis is a key feature of this stage. Patients commonly have radicular pain and fibromyalgia-type pain. More severe disease processes include encephalomyelitis, arrhythmias, and heart block.

ECM is often a clinical diagnosis because serologic testing may not be positive during the first 2 weeks of infection. The screening serologic test is the ELISA, and a Western blot confirms the results. Skin histopathology for Lyme disease is often nonspecific and reveals a perivascular infiltrate of histiocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. Silver stain or antibody testing may be used to identify the spirochete. In acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, late Lyme disease presenting on the distal extremities, lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates are present. In borrelial lymphocytoma, a dense dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is present.

The standard for treatment of early localized disease is oral doxycycline in adults. Alternatives may be used if a patient is allergic or for children under 9. Disseminated disease may be treated with IV ceftriaxone and topical steroids are used if ocular symptoms are involved. Early treatment is often curative.

This patient’s antibodies were negative initially, but became positive after 6 weeks. He was treated empirically at the time of his office visit with doxycycline for 1 month.

This case and the photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Susannah Berke, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/Dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Carriveau A et al. Nurs Clin North Am. 2019 Jun;54(2):261-75.

Skar GL and Simonsen KA. Lyme Disease. [Updated 2023 May 31]. In: “StatPearls” [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

Tiger JB et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Oct;71(4):e133-4.

Lyme disease is the most commonly transmitted tick-borne illness in the United States. This infection is typically transmitted through a bite by the Ixodes tick commonly found in the Midwest, Northeast, and mid-Atlantic regions; however, the geographical distribution continues to expand over time in the United States. Ticks must be attached for 24-48 hours to transmit the pathogen. There are three general stages of the disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated.

The most common presentation is the early localized disease, which manifests between 3 and 30 days after an infected tick bite. Approximately 70%-80% of cases feature a targetlike lesion that expands centrifugally at the site of the bite. Most commonly, lesions appear on the abdomen, groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa. The diagnosis of ECM requires lesions at least 5 cm in size. Lesions may be asymptomatic, although burning may occur in half of patients. Atypical presentations include bullous, vesicular, hemorrhagic, or necrotic lesions. Up to half of patients may develop multiple ECM lesions. Palms and soles are spared. Differential diagnoses include arthropod reactions, pyoderma gangrenosum, cellulitis, herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus, contact dermatitis, or granuloma annulare. The rash is often accompanied by systemic symptoms including fatigue, myalgia, headache, and fever.

The next two stages include early and late disseminated infection. Early disseminated infection often occurs 3-12 weeks after infection and is characterized by muscle pain, dizziness, headache, and cardiac symptoms. CNS involvement occurs in about 20% of patients. Joint involvement may include the knee, ankle, and wrist. If symptoms are only in one joint, septic arthritis is part of the differential diagnosis, so clinical correlation and labs must be considered. Late disseminated infection occurs months or years after initial infection and includes neurologic and rheumatologic symptoms including meningitis, Bell’s palsy, arthritis, and dysesthesia. Knee arthritis is a key feature of this stage. Patients commonly have radicular pain and fibromyalgia-type pain. More severe disease processes include encephalomyelitis, arrhythmias, and heart block.

ECM is often a clinical diagnosis because serologic testing may not be positive during the first 2 weeks of infection. The screening serologic test is the ELISA, and a Western blot confirms the results. Skin histopathology for Lyme disease is often nonspecific and reveals a perivascular infiltrate of histiocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. Silver stain or antibody testing may be used to identify the spirochete. In acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, late Lyme disease presenting on the distal extremities, lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates are present. In borrelial lymphocytoma, a dense dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is present.

The standard for treatment of early localized disease is oral doxycycline in adults. Alternatives may be used if a patient is allergic or for children under 9. Disseminated disease may be treated with IV ceftriaxone and topical steroids are used if ocular symptoms are involved. Early treatment is often curative.

This patient’s antibodies were negative initially, but became positive after 6 weeks. He was treated empirically at the time of his office visit with doxycycline for 1 month.

This case and the photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Susannah Berke, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/Dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Carriveau A et al. Nurs Clin North Am. 2019 Jun;54(2):261-75.

Skar GL and Simonsen KA. Lyme Disease. [Updated 2023 May 31]. In: “StatPearls” [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

Tiger JB et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Oct;71(4):e133-4.

Lyme disease is the most commonly transmitted tick-borne illness in the United States. This infection is typically transmitted through a bite by the Ixodes tick commonly found in the Midwest, Northeast, and mid-Atlantic regions; however, the geographical distribution continues to expand over time in the United States. Ticks must be attached for 24-48 hours to transmit the pathogen. There are three general stages of the disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated.

The most common presentation is the early localized disease, which manifests between 3 and 30 days after an infected tick bite. Approximately 70%-80% of cases feature a targetlike lesion that expands centrifugally at the site of the bite. Most commonly, lesions appear on the abdomen, groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa. The diagnosis of ECM requires lesions at least 5 cm in size. Lesions may be asymptomatic, although burning may occur in half of patients. Atypical presentations include bullous, vesicular, hemorrhagic, or necrotic lesions. Up to half of patients may develop multiple ECM lesions. Palms and soles are spared. Differential diagnoses include arthropod reactions, pyoderma gangrenosum, cellulitis, herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus, contact dermatitis, or granuloma annulare. The rash is often accompanied by systemic symptoms including fatigue, myalgia, headache, and fever.

The next two stages include early and late disseminated infection. Early disseminated infection often occurs 3-12 weeks after infection and is characterized by muscle pain, dizziness, headache, and cardiac symptoms. CNS involvement occurs in about 20% of patients. Joint involvement may include the knee, ankle, and wrist. If symptoms are only in one joint, septic arthritis is part of the differential diagnosis, so clinical correlation and labs must be considered. Late disseminated infection occurs months or years after initial infection and includes neurologic and rheumatologic symptoms including meningitis, Bell’s palsy, arthritis, and dysesthesia. Knee arthritis is a key feature of this stage. Patients commonly have radicular pain and fibromyalgia-type pain. More severe disease processes include encephalomyelitis, arrhythmias, and heart block.

ECM is often a clinical diagnosis because serologic testing may not be positive during the first 2 weeks of infection. The screening serologic test is the ELISA, and a Western blot confirms the results. Skin histopathology for Lyme disease is often nonspecific and reveals a perivascular infiltrate of histiocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. Silver stain or antibody testing may be used to identify the spirochete. In acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, late Lyme disease presenting on the distal extremities, lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates are present. In borrelial lymphocytoma, a dense dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is present.

The standard for treatment of early localized disease is oral doxycycline in adults. Alternatives may be used if a patient is allergic or for children under 9. Disseminated disease may be treated with IV ceftriaxone and topical steroids are used if ocular symptoms are involved. Early treatment is often curative.

This patient’s antibodies were negative initially, but became positive after 6 weeks. He was treated empirically at the time of his office visit with doxycycline for 1 month.

This case and the photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Susannah Berke, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/Dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References