User login

Human frailty is a cash cow

Doctor, if you are caring for patients with diabetes, I sure hope you know more about it than I do. The longer I live, it seems, the less I understand.

In a free society, people can do what they want, and that’s great except when it isn’t. That’s why societies develop ethics and even public laws if ethics are not strong enough to protect us from ourselves and others.

Sugar, sugar

When I was growing up in small-town Alabama during the Depression and World War II, we called it sugar diabetes. Eat too much sugar, you got fat; your blood sugar went up, and you spilled sugar into your urine. Diabetes was fairly rare, and so was obesity. Doctors treated it by limiting the intake of sugar (and various sweet foods), along with attempting weight loss. If that didn’t do the trick, insulin injections.

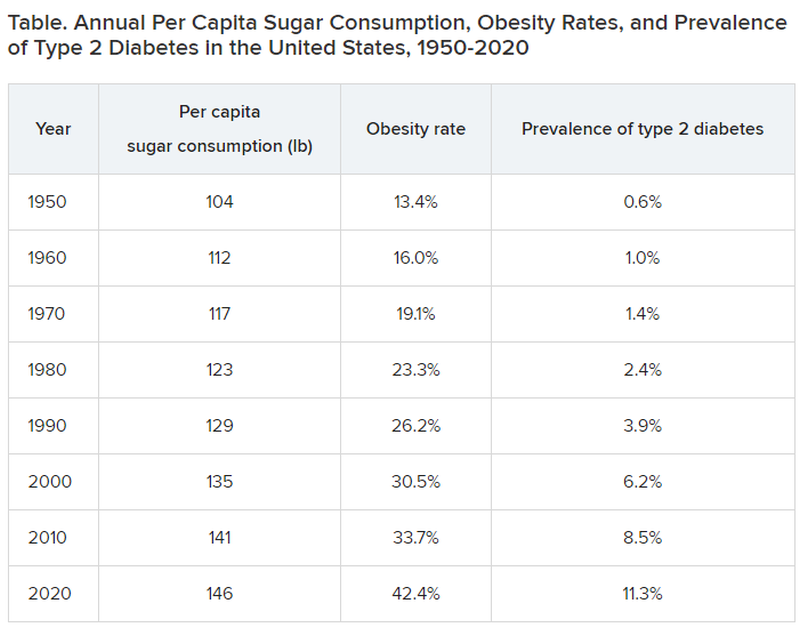

From then until now, note these trends.

Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed even more infrequently before 1950:

- 1920: 0.2% of the population

- 1930: 0.3% of the population

- 1940: 0.4% of the population

In 2020, although 11.3% of the population was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, the unknown undiagnosed proportion could be much higher.

Notice a correlation between sugar consumption and prevalence of diabetes? Of course, correlation is not causation, but at the same time, it sure as hell is not negation. Such concordance can be considered hypothesis generating. It may not be true causation, but it’s a good bet when 89% of people with diabetes have overweight or obesity.

What did the entire medical, public health, government, agriculture, nursing, food manufacturing, marketing, advertising, restaurant, and education constituencies do about this as it was happening? They observed, documented, gave lip service, and wrung their hands in public a bit. I do not believe that this is an organized active conspiracy; it would take too many players cooperating over too long a period of time. But it certainly may be a passive conspiracy, and primary care physicians and their patients are trapped.

The proper daily practice of medicine consists of one patient, one physician, one moment, and one decision. Let it be a shared decision, informed by the best evidence and taking cost into consideration. That encounter represents an opportunity, a responsibility, and a conundrum.

Individual health is subsumed under the collective health of the public. As such, a patient’s health is out of the control of both physician and patient; instead, patients are the beneficiaries or victims of the “marketplace.” Humans are frail and easily taken advantage of by the brilliant and highly motivated strategic planning and execution of Big Agriculture, Big Food, Big Pharma, Big Marketing, and Big Money-Driven Medicine and generally failed by Big Government, Big Public Health, Big Education, Big Psychology, and Big Religion.

Rethinking diabetes

Consider diabetes as one of many examples. What a terrific deal for capitalism. then it discovers (invents) long-term, very expensive, compelling treatments to slim us down, with no end in sight, and still without ever understanding the true nature of diabetes.

Gary Taubes’s great new book, “Rethinking Diabetes: What Science Reveals About Diet, Insulin, and Successful Treatments,” is being published by Alfred A. Knopf in early 2024.

It is 404 pages of (dense) text, with 401 numbered references and footnotes, a bibliography of 790 references, alphabetically arranged for easy cross-checking, and a 25-page index.

Remember Mr. Taubes’s earlier definitive historical treatises: “Good Calories, Bad Calories” (2007), “Why We Get Fat” (2010), “The Case Against Sugar” (2016), and “The Case for Keto” (2020)?

This new book is more like “Good Calories, Bad Calories”: long, dense, detailed, definitive, and of great historical reference value, including original research information from other countries in other languages. The author told me that the many early research reference sources were available only in German and that his use of generative artificial intelligence as an assistant researcher was of great value.

Nonphysician author Mr. Taubes uses his deep understanding of science and history to inform his long-honed talents of impartial investigative journalism as he attempts to understand and then explain why after all these years, the medical scientific community still does not have a sound consensus about the essence of diabetes, diet, insulin, and proper prevention and treatment at a level that is actually effective – amazing and so sad.

To signal these evolved and evolving conflicts, the book includes the following chapters:

- “Rise of the Carbohydrate-Rich and Very-Low-Carbohydrate Diets”

- “The Fear of Fat and High-Fat Diets”

- “Insulin and The End of Carbohydrate Restriction and Low Blood Sugar”

Yes, it is difficult. Imagine the bookend segments: “The Nature of Medical Knowledge” and “The Conflicts of Evidence-Based Medicine.” There is also a detailed discussion of good versus bad science spanning three long chapters.

If all that reads like a greatly confused mess to you then you’re beginning to understand. If you are a fan of an unbiased explication of the evolution of understanding the ins and outs of scientific history in richly documented detail, this is a book for you. It’s not a quick nor easy read. And don’t expect to discover whether the newest wonder drugs for weight loss and control of diabetes will be the long-term solution for people with obesity and diabetes worldwide.

Obesity and overweight are major risk factors for type 2 diabetes. About 90% of patients with diabetes have either overweight or obesity. Thus, the complications of these two conditions, which largely overlap, include atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; myocardial infarction; stroke; hypertension; metabolic syndrome; lower-extremity gangrene; chronic kidney disease; retinopathy; glaucoma; cataracts; disabling osteoarthritis; breast, endometrial, colon, and other cancers; fatty liver; sleep apnea; and peripheral neuropathy. These diseases create a major lucrative business for a wide swathe of medical and surgical specialties, plus hospital, clinic, device, pharmaceutical, and food industries.

In summary, we’ve just been through 40 years of failure to recognize the sugar-elephant in the room and intervene with serious preventive efforts. Forty years of fleshing out both the populace and the American medical-industrial complex (AMIC). Talk about a sweet spot. The only successful long-term treatment of obesity (and with it, diabetes) is prevention. Don’t emphasize losing weight. Focus on preventing excessive weight gain, right now, for the population, beginning with yourselves. Otherwise, we continue openly to perpetuate a terrific deal for the AMIC, a travesty for everyone else. Time for some industrial grade penance and a course correction.

Meanwhile, here we are living out Big Pharma’s dream of a big populace, produced by the agriculture and food industries, enjoyed by capitalism after failures of education, medicine, and public health: a seemingly endless supply of people living with big complications who are ready for big (expensive, new) medications to fix the world’s big health problems.

Dr. Lundberg is editor in chief, Cancer Commons. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctor, if you are caring for patients with diabetes, I sure hope you know more about it than I do. The longer I live, it seems, the less I understand.

In a free society, people can do what they want, and that’s great except when it isn’t. That’s why societies develop ethics and even public laws if ethics are not strong enough to protect us from ourselves and others.

Sugar, sugar

When I was growing up in small-town Alabama during the Depression and World War II, we called it sugar diabetes. Eat too much sugar, you got fat; your blood sugar went up, and you spilled sugar into your urine. Diabetes was fairly rare, and so was obesity. Doctors treated it by limiting the intake of sugar (and various sweet foods), along with attempting weight loss. If that didn’t do the trick, insulin injections.

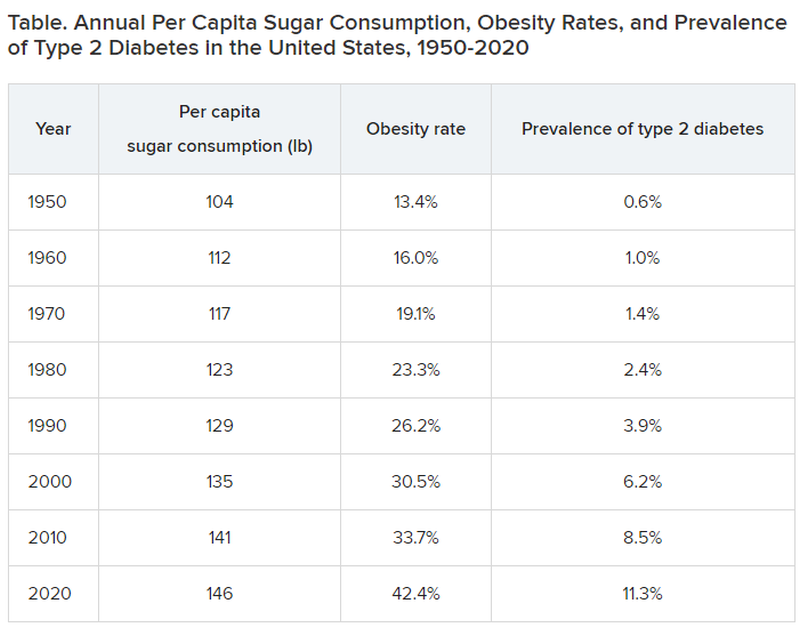

From then until now, note these trends.

Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed even more infrequently before 1950:

- 1920: 0.2% of the population

- 1930: 0.3% of the population

- 1940: 0.4% of the population

In 2020, although 11.3% of the population was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, the unknown undiagnosed proportion could be much higher.

Notice a correlation between sugar consumption and prevalence of diabetes? Of course, correlation is not causation, but at the same time, it sure as hell is not negation. Such concordance can be considered hypothesis generating. It may not be true causation, but it’s a good bet when 89% of people with diabetes have overweight or obesity.

What did the entire medical, public health, government, agriculture, nursing, food manufacturing, marketing, advertising, restaurant, and education constituencies do about this as it was happening? They observed, documented, gave lip service, and wrung their hands in public a bit. I do not believe that this is an organized active conspiracy; it would take too many players cooperating over too long a period of time. But it certainly may be a passive conspiracy, and primary care physicians and their patients are trapped.

The proper daily practice of medicine consists of one patient, one physician, one moment, and one decision. Let it be a shared decision, informed by the best evidence and taking cost into consideration. That encounter represents an opportunity, a responsibility, and a conundrum.

Individual health is subsumed under the collective health of the public. As such, a patient’s health is out of the control of both physician and patient; instead, patients are the beneficiaries or victims of the “marketplace.” Humans are frail and easily taken advantage of by the brilliant and highly motivated strategic planning and execution of Big Agriculture, Big Food, Big Pharma, Big Marketing, and Big Money-Driven Medicine and generally failed by Big Government, Big Public Health, Big Education, Big Psychology, and Big Religion.

Rethinking diabetes

Consider diabetes as one of many examples. What a terrific deal for capitalism. then it discovers (invents) long-term, very expensive, compelling treatments to slim us down, with no end in sight, and still without ever understanding the true nature of diabetes.

Gary Taubes’s great new book, “Rethinking Diabetes: What Science Reveals About Diet, Insulin, and Successful Treatments,” is being published by Alfred A. Knopf in early 2024.

It is 404 pages of (dense) text, with 401 numbered references and footnotes, a bibliography of 790 references, alphabetically arranged for easy cross-checking, and a 25-page index.

Remember Mr. Taubes’s earlier definitive historical treatises: “Good Calories, Bad Calories” (2007), “Why We Get Fat” (2010), “The Case Against Sugar” (2016), and “The Case for Keto” (2020)?

This new book is more like “Good Calories, Bad Calories”: long, dense, detailed, definitive, and of great historical reference value, including original research information from other countries in other languages. The author told me that the many early research reference sources were available only in German and that his use of generative artificial intelligence as an assistant researcher was of great value.

Nonphysician author Mr. Taubes uses his deep understanding of science and history to inform his long-honed talents of impartial investigative journalism as he attempts to understand and then explain why after all these years, the medical scientific community still does not have a sound consensus about the essence of diabetes, diet, insulin, and proper prevention and treatment at a level that is actually effective – amazing and so sad.

To signal these evolved and evolving conflicts, the book includes the following chapters:

- “Rise of the Carbohydrate-Rich and Very-Low-Carbohydrate Diets”

- “The Fear of Fat and High-Fat Diets”

- “Insulin and The End of Carbohydrate Restriction and Low Blood Sugar”

Yes, it is difficult. Imagine the bookend segments: “The Nature of Medical Knowledge” and “The Conflicts of Evidence-Based Medicine.” There is also a detailed discussion of good versus bad science spanning three long chapters.

If all that reads like a greatly confused mess to you then you’re beginning to understand. If you are a fan of an unbiased explication of the evolution of understanding the ins and outs of scientific history in richly documented detail, this is a book for you. It’s not a quick nor easy read. And don’t expect to discover whether the newest wonder drugs for weight loss and control of diabetes will be the long-term solution for people with obesity and diabetes worldwide.

Obesity and overweight are major risk factors for type 2 diabetes. About 90% of patients with diabetes have either overweight or obesity. Thus, the complications of these two conditions, which largely overlap, include atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; myocardial infarction; stroke; hypertension; metabolic syndrome; lower-extremity gangrene; chronic kidney disease; retinopathy; glaucoma; cataracts; disabling osteoarthritis; breast, endometrial, colon, and other cancers; fatty liver; sleep apnea; and peripheral neuropathy. These diseases create a major lucrative business for a wide swathe of medical and surgical specialties, plus hospital, clinic, device, pharmaceutical, and food industries.

In summary, we’ve just been through 40 years of failure to recognize the sugar-elephant in the room and intervene with serious preventive efforts. Forty years of fleshing out both the populace and the American medical-industrial complex (AMIC). Talk about a sweet spot. The only successful long-term treatment of obesity (and with it, diabetes) is prevention. Don’t emphasize losing weight. Focus on preventing excessive weight gain, right now, for the population, beginning with yourselves. Otherwise, we continue openly to perpetuate a terrific deal for the AMIC, a travesty for everyone else. Time for some industrial grade penance and a course correction.

Meanwhile, here we are living out Big Pharma’s dream of a big populace, produced by the agriculture and food industries, enjoyed by capitalism after failures of education, medicine, and public health: a seemingly endless supply of people living with big complications who are ready for big (expensive, new) medications to fix the world’s big health problems.

Dr. Lundberg is editor in chief, Cancer Commons. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctor, if you are caring for patients with diabetes, I sure hope you know more about it than I do. The longer I live, it seems, the less I understand.

In a free society, people can do what they want, and that’s great except when it isn’t. That’s why societies develop ethics and even public laws if ethics are not strong enough to protect us from ourselves and others.

Sugar, sugar

When I was growing up in small-town Alabama during the Depression and World War II, we called it sugar diabetes. Eat too much sugar, you got fat; your blood sugar went up, and you spilled sugar into your urine. Diabetes was fairly rare, and so was obesity. Doctors treated it by limiting the intake of sugar (and various sweet foods), along with attempting weight loss. If that didn’t do the trick, insulin injections.

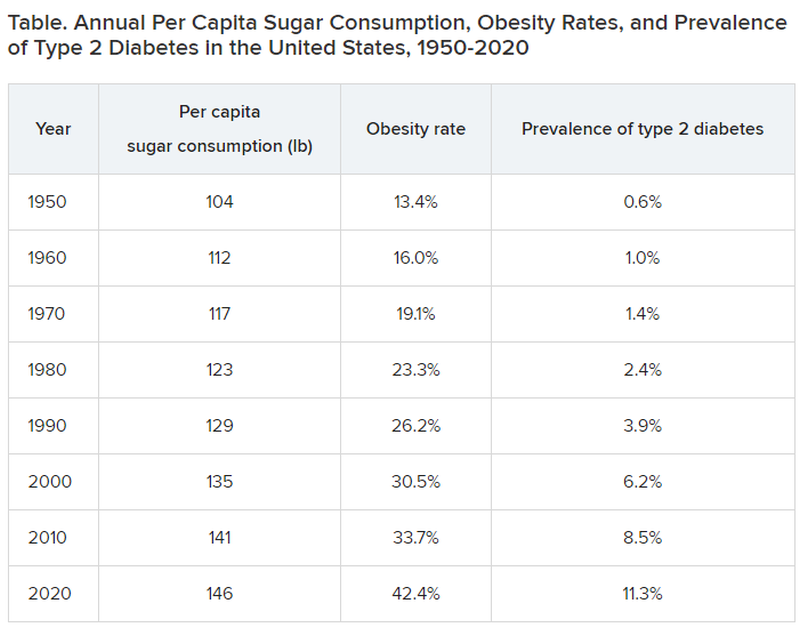

From then until now, note these trends.

Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed even more infrequently before 1950:

- 1920: 0.2% of the population

- 1930: 0.3% of the population

- 1940: 0.4% of the population

In 2020, although 11.3% of the population was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, the unknown undiagnosed proportion could be much higher.

Notice a correlation between sugar consumption and prevalence of diabetes? Of course, correlation is not causation, but at the same time, it sure as hell is not negation. Such concordance can be considered hypothesis generating. It may not be true causation, but it’s a good bet when 89% of people with diabetes have overweight or obesity.

What did the entire medical, public health, government, agriculture, nursing, food manufacturing, marketing, advertising, restaurant, and education constituencies do about this as it was happening? They observed, documented, gave lip service, and wrung their hands in public a bit. I do not believe that this is an organized active conspiracy; it would take too many players cooperating over too long a period of time. But it certainly may be a passive conspiracy, and primary care physicians and their patients are trapped.

The proper daily practice of medicine consists of one patient, one physician, one moment, and one decision. Let it be a shared decision, informed by the best evidence and taking cost into consideration. That encounter represents an opportunity, a responsibility, and a conundrum.

Individual health is subsumed under the collective health of the public. As such, a patient’s health is out of the control of both physician and patient; instead, patients are the beneficiaries or victims of the “marketplace.” Humans are frail and easily taken advantage of by the brilliant and highly motivated strategic planning and execution of Big Agriculture, Big Food, Big Pharma, Big Marketing, and Big Money-Driven Medicine and generally failed by Big Government, Big Public Health, Big Education, Big Psychology, and Big Religion.

Rethinking diabetes

Consider diabetes as one of many examples. What a terrific deal for capitalism. then it discovers (invents) long-term, very expensive, compelling treatments to slim us down, with no end in sight, and still without ever understanding the true nature of diabetes.

Gary Taubes’s great new book, “Rethinking Diabetes: What Science Reveals About Diet, Insulin, and Successful Treatments,” is being published by Alfred A. Knopf in early 2024.

It is 404 pages of (dense) text, with 401 numbered references and footnotes, a bibliography of 790 references, alphabetically arranged for easy cross-checking, and a 25-page index.

Remember Mr. Taubes’s earlier definitive historical treatises: “Good Calories, Bad Calories” (2007), “Why We Get Fat” (2010), “The Case Against Sugar” (2016), and “The Case for Keto” (2020)?

This new book is more like “Good Calories, Bad Calories”: long, dense, detailed, definitive, and of great historical reference value, including original research information from other countries in other languages. The author told me that the many early research reference sources were available only in German and that his use of generative artificial intelligence as an assistant researcher was of great value.

Nonphysician author Mr. Taubes uses his deep understanding of science and history to inform his long-honed talents of impartial investigative journalism as he attempts to understand and then explain why after all these years, the medical scientific community still does not have a sound consensus about the essence of diabetes, diet, insulin, and proper prevention and treatment at a level that is actually effective – amazing and so sad.

To signal these evolved and evolving conflicts, the book includes the following chapters:

- “Rise of the Carbohydrate-Rich and Very-Low-Carbohydrate Diets”

- “The Fear of Fat and High-Fat Diets”

- “Insulin and The End of Carbohydrate Restriction and Low Blood Sugar”

Yes, it is difficult. Imagine the bookend segments: “The Nature of Medical Knowledge” and “The Conflicts of Evidence-Based Medicine.” There is also a detailed discussion of good versus bad science spanning three long chapters.

If all that reads like a greatly confused mess to you then you’re beginning to understand. If you are a fan of an unbiased explication of the evolution of understanding the ins and outs of scientific history in richly documented detail, this is a book for you. It’s not a quick nor easy read. And don’t expect to discover whether the newest wonder drugs for weight loss and control of diabetes will be the long-term solution for people with obesity and diabetes worldwide.

Obesity and overweight are major risk factors for type 2 diabetes. About 90% of patients with diabetes have either overweight or obesity. Thus, the complications of these two conditions, which largely overlap, include atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; myocardial infarction; stroke; hypertension; metabolic syndrome; lower-extremity gangrene; chronic kidney disease; retinopathy; glaucoma; cataracts; disabling osteoarthritis; breast, endometrial, colon, and other cancers; fatty liver; sleep apnea; and peripheral neuropathy. These diseases create a major lucrative business for a wide swathe of medical and surgical specialties, plus hospital, clinic, device, pharmaceutical, and food industries.

In summary, we’ve just been through 40 years of failure to recognize the sugar-elephant in the room and intervene with serious preventive efforts. Forty years of fleshing out both the populace and the American medical-industrial complex (AMIC). Talk about a sweet spot. The only successful long-term treatment of obesity (and with it, diabetes) is prevention. Don’t emphasize losing weight. Focus on preventing excessive weight gain, right now, for the population, beginning with yourselves. Otherwise, we continue openly to perpetuate a terrific deal for the AMIC, a travesty for everyone else. Time for some industrial grade penance and a course correction.

Meanwhile, here we are living out Big Pharma’s dream of a big populace, produced by the agriculture and food industries, enjoyed by capitalism after failures of education, medicine, and public health: a seemingly endless supply of people living with big complications who are ready for big (expensive, new) medications to fix the world’s big health problems.

Dr. Lundberg is editor in chief, Cancer Commons. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Mothers in medicine: What can we learn when worlds collide?

Across all industries, studies by the U.S. Department of Labor have shown that women, on average, earn 83.7 percent of what their male peers earn. While a lot has been written about the struggles women face in medicine, there have been decidedly fewer analyses that focus on women who choose to become mothers while working in medicine.

I’ve been privileged to work with medical students and residents for the last 8 years as the director of graduate and medical student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. Often, the women I see as patients speak about their struggles with the elusive goal of “having it all.” While both men and women in medicine have difficulty maintaining a work-life balance, I’ve learned, both personally and professionally, that many women face a unique set of challenges.

No matter what their professional status, our society often views a woman as the default parent. For example, the teacher often calls the mothers first. The camp nurse calls me first, not my husband, when our child scrapes a knee. After-school play dates are arranged by the mothers, not fathers.

But mothers also bring to medicine a wealth of unique experiences, ideas, and viewpoints. They learn firsthand how to foster affect regulation and frustration tolerance in their kids and become efficient at managing the constant, conflicting tug of war of demands.

Some may argue that, over time, women end up earning significantly less than their male counterparts because they leave the workforce while on maternity leave, ultimately delaying their upward career progression. It’s likely a much more complex problem. Many of my patients believe that, in our male-dominated society (and workforce), women are punished for being aggressive or stating bold opinions, while men are rewarded for the same actions. While a man may sound forceful and in charge, a women will likely be thought of as brusque and unappreciative.

Outside of work, many women may have more on their plate. A 2020 Gallup poll of more than 3,000 heterosexual couples found that women are responsible for the majority of household chores. Women continue to handle more of the emotional labor within their families, regardless of income, age, or professional status. This is sometimes called the “Mental Load’ or “Second Shift.” As our society continues to view women as the default parent for childcare, medical issues, and overarching social and emotional tasks vital to raising happy, healthy children, the struggle a female medical professional feels is palpable.

Raising kids requires a parent to consistently dole out control, predictability, and reassurance for a child to thrive. Good limit and boundary setting leads to healthy development from a young age.

Psychiatric patients (and perhaps all patients) also require control, predictability, and reassurance from their doctor. The lessons learned in being a good mother can be directly applied in patient care, and vice versa. The cross-pollination of this relationship continues to grow more powerful as a woman’s children grow and her career matures.

Pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s idea of a “good enough” mother cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Women who self-select into the world of medicine often hold themselves to a higher standard than “good enough.” Acknowledging that the demands from both home and work will fluctuate is key to achieving success both personally and professionally, and lessons from home can and should be utilized to become a more effective physician. The notion of having it all, and the definition of success, must evolve over time.

Dr. Maymind is director of medical and graduate student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. She has no relevant disclosures.

Across all industries, studies by the U.S. Department of Labor have shown that women, on average, earn 83.7 percent of what their male peers earn. While a lot has been written about the struggles women face in medicine, there have been decidedly fewer analyses that focus on women who choose to become mothers while working in medicine.

I’ve been privileged to work with medical students and residents for the last 8 years as the director of graduate and medical student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. Often, the women I see as patients speak about their struggles with the elusive goal of “having it all.” While both men and women in medicine have difficulty maintaining a work-life balance, I’ve learned, both personally and professionally, that many women face a unique set of challenges.

No matter what their professional status, our society often views a woman as the default parent. For example, the teacher often calls the mothers first. The camp nurse calls me first, not my husband, when our child scrapes a knee. After-school play dates are arranged by the mothers, not fathers.

But mothers also bring to medicine a wealth of unique experiences, ideas, and viewpoints. They learn firsthand how to foster affect regulation and frustration tolerance in their kids and become efficient at managing the constant, conflicting tug of war of demands.

Some may argue that, over time, women end up earning significantly less than their male counterparts because they leave the workforce while on maternity leave, ultimately delaying their upward career progression. It’s likely a much more complex problem. Many of my patients believe that, in our male-dominated society (and workforce), women are punished for being aggressive or stating bold opinions, while men are rewarded for the same actions. While a man may sound forceful and in charge, a women will likely be thought of as brusque and unappreciative.

Outside of work, many women may have more on their plate. A 2020 Gallup poll of more than 3,000 heterosexual couples found that women are responsible for the majority of household chores. Women continue to handle more of the emotional labor within their families, regardless of income, age, or professional status. This is sometimes called the “Mental Load’ or “Second Shift.” As our society continues to view women as the default parent for childcare, medical issues, and overarching social and emotional tasks vital to raising happy, healthy children, the struggle a female medical professional feels is palpable.

Raising kids requires a parent to consistently dole out control, predictability, and reassurance for a child to thrive. Good limit and boundary setting leads to healthy development from a young age.

Psychiatric patients (and perhaps all patients) also require control, predictability, and reassurance from their doctor. The lessons learned in being a good mother can be directly applied in patient care, and vice versa. The cross-pollination of this relationship continues to grow more powerful as a woman’s children grow and her career matures.

Pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s idea of a “good enough” mother cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Women who self-select into the world of medicine often hold themselves to a higher standard than “good enough.” Acknowledging that the demands from both home and work will fluctuate is key to achieving success both personally and professionally, and lessons from home can and should be utilized to become a more effective physician. The notion of having it all, and the definition of success, must evolve over time.

Dr. Maymind is director of medical and graduate student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. She has no relevant disclosures.

Across all industries, studies by the U.S. Department of Labor have shown that women, on average, earn 83.7 percent of what their male peers earn. While a lot has been written about the struggles women face in medicine, there have been decidedly fewer analyses that focus on women who choose to become mothers while working in medicine.

I’ve been privileged to work with medical students and residents for the last 8 years as the director of graduate and medical student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. Often, the women I see as patients speak about their struggles with the elusive goal of “having it all.” While both men and women in medicine have difficulty maintaining a work-life balance, I’ve learned, both personally and professionally, that many women face a unique set of challenges.

No matter what their professional status, our society often views a woman as the default parent. For example, the teacher often calls the mothers first. The camp nurse calls me first, not my husband, when our child scrapes a knee. After-school play dates are arranged by the mothers, not fathers.

But mothers also bring to medicine a wealth of unique experiences, ideas, and viewpoints. They learn firsthand how to foster affect regulation and frustration tolerance in their kids and become efficient at managing the constant, conflicting tug of war of demands.

Some may argue that, over time, women end up earning significantly less than their male counterparts because they leave the workforce while on maternity leave, ultimately delaying their upward career progression. It’s likely a much more complex problem. Many of my patients believe that, in our male-dominated society (and workforce), women are punished for being aggressive or stating bold opinions, while men are rewarded for the same actions. While a man may sound forceful and in charge, a women will likely be thought of as brusque and unappreciative.

Outside of work, many women may have more on their plate. A 2020 Gallup poll of more than 3,000 heterosexual couples found that women are responsible for the majority of household chores. Women continue to handle more of the emotional labor within their families, regardless of income, age, or professional status. This is sometimes called the “Mental Load’ or “Second Shift.” As our society continues to view women as the default parent for childcare, medical issues, and overarching social and emotional tasks vital to raising happy, healthy children, the struggle a female medical professional feels is palpable.

Raising kids requires a parent to consistently dole out control, predictability, and reassurance for a child to thrive. Good limit and boundary setting leads to healthy development from a young age.

Psychiatric patients (and perhaps all patients) also require control, predictability, and reassurance from their doctor. The lessons learned in being a good mother can be directly applied in patient care, and vice versa. The cross-pollination of this relationship continues to grow more powerful as a woman’s children grow and her career matures.

Pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s idea of a “good enough” mother cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Women who self-select into the world of medicine often hold themselves to a higher standard than “good enough.” Acknowledging that the demands from both home and work will fluctuate is key to achieving success both personally and professionally, and lessons from home can and should be utilized to become a more effective physician. The notion of having it all, and the definition of success, must evolve over time.

Dr. Maymind is director of medical and graduate student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. She has no relevant disclosures.

ChatGPT in Dermatology Clinical Practice: Potential Uses and Pitfalls

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has increasingly been incorporated in medicine. In dermatology, AI has been used to detect and diagnose skin lesions, including skin cancer.1 ChatGPT (OpenAI) is a novel, highly popular development in generative AI technology. A large language model released in 2022, ChatGPT is a chatbot designed to mimic human conversation and generate specific detailed information when prompted. Free and publicly available, it has been used by millions of people. ChatGPT’s application in the medical field currently is being evaluated across several specialties, including plastic surgery, radiology, and urology.2-4 ChatGPT has the potential to assist health care professionals, including dermatologists, though its use raises important ethical considerations. Herein, we focus on the potential benefits as well as the pitfalls of using ChatGPT in dermatology clinical practice.

Potential Uses of ChatGPT in Practice

A major benefit of ChatGPT is its ability to improve clinical efficiency. First, ChatGPT can provide quick access to general medical information, similar to a search engine but with more natural language processing and contextual understanding to synthesize information.5 This function is useful for rapid concise answers to specific and directed questions. ChatGPT also can interact with its user by asking follow-up questions to produce more precise and relevant responses; this feature may help dermatologists form more accurate differential diagnoses. Additionally, ChatGPT can increase efficiency in clinical practice by drafting generic medical documents,2 including templates for after-visit summaries, postprocedure instructions, referrals, prior authorization appeal letters, and educational handouts. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. Another useful feature of ChatGPT is its ability to output information modeling human conversation. Because of this feature, ChatGPT also could be employed in clinical practice to serve as an interpreter for patients during clinic visits. Currently, the use of virtual translators can be cumbersome and subject to technical constraints. ChatGPT can provide accurate and conversational translations for patients and dermatologists, improving the patient-provider relationship.

ChatGPT also can contribute to major advancements in the field of dermatology beyond the clinical setting. Because of its ability to draw from extensive data that have already been uploaded, there are some uses of ChatGPT in a research context: to assist in finding resources for research and reviews, formulating hypotheses, drafting study protocols, and collecting large amounts of data within seconds.6

ChatGPT also has potential in advancing medical education. It could be used by medical schools to model interactive patient encounters to help students practice taking a patient’s history and creating differential diagnoses.6 This application of ChatGPT may help medical students hone their clinical skills in a low-stress environment without the restrictions that can come with hiring and training standardized patients, especially when mimicking dermatologic clinical encounters.

Other possibilities for ChatGPT in dermatologic practice include survey administration, clinical trial recruitment, and even automatic high-risk medication monitoring. Despite the many potential applications of ChatGPT in clinical practice, the question raised in each scenario is the quality, accuracy, and safety of what it produces.

Potential Pitfalls of ChatGPT in Practice and Possible Mitigation Strategies

A main concern in using ChatGPT in clinical practice is its potential to produce inaccurate or biased information. When prompted to create a research abstract based on previously published research, ChatGPT drafted abstracts that were clear and digestible but supplemented with incorrect data.7 A group of medical researchers who reviewed these ChatGPT-generated abstracts mistook 32% of the abstracts as having been written by human researchers. The implications of this finding are worrisome. If inaccurate or false information is used by ChatGPT in documents sent to insurance companies or patients, the patient’s safety as well as the dermatologist’s license and credibility are at stake. Thus, dermatologists looking to use ChatGPT to draft generic medical documents should actively review the output to ensure that the information is accurate. Importantly, ChatGPT also is only currently programmed with information up to 2021, limiting its access to recently published research articles and updated International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes.5 The continued development of ChatGPT will lead to regular updates by OpenAI that resolve this shortcoming in the future. Further, AI models may encode and perpetuate harmful stereotypes and social biases that are present in training data.8

When considering its potential in clinical practice, ChatGPT itself states that it can aid in clinical decision-making by processing patient information, including history, current symptoms, and biopsy and test results. This is uncharted territory, and providers who use ChatGPT at this stage to aid in decision-making should regard it similarly to information retrieved from a search engine. The information produced by ChatGPT should be used to substantiate but not definitively confirm a diagnosis or dictate management. Clinical suspicion by the dermatologist should always trump ChatGPT output. If physicians recommend ChatGPT output over their own advice, it can become a liability, as the technology is not regulated to any degree. Patients also should be cautious when seeking and following medical advice from ChatGPT, as it could be misleading or incorrect and could undermine the patient-physician relationship.6

Additionally, the specific use of ChatGPT to evaluate patient health records raises concerns related to patient privacy and confidentiality. Providers should never enter patient information protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act into ChatGPT or anywhere else on the internet. Mitigation of this risk is not currently possible; ChatGPT requires more development and further understanding to even consider its integration into current electronic health records without compromising patient confidentiality.

The Bottom Line

Overall, ChatGPT has the potential to improve efficiency in clinical practice by assisting with informational searches and document drafting. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. However, dermatologists should carefully weigh the ethical issues of nonmaleficence and justice in evaluating ChatGPT for accuracy, biases, and the protection of patient confidentiality.

Finally, we asked ChatGPT on February 28, 2023, what it thinks:

User: Should dermatologists use ChatGPT in clinical practice?

ChatGPT: As an AI language model, ChatGPT can be a useful tool in dermatology clinical practice, but it should be used with caution in conjunction with other sources of information and clinical judgement.

Dermatologists should be aware of the potential benefits and risks of using ChatGPT and make informed decisions about how to integrate it into their clinical practice. It’s important to remember that ChatGPT is not a substitute for clinical expertise or human interaction with patients, and it should only be used as a supplement to enhance the quality of patient care.

Dermatologists who choose to use ChatGPT should also be aware of its limitations and potential risks, such as limited accuracy, lack of context, and liability issues if it provides incorrect information or recommendations that lead to patient harm. Dermatologists should use their professional judgement and consult with other health care professionals when making important decisions regarding patient care.

- Thomsen K, Iversen L, Titlestad TL, et al. Systematic review of machine learning for diagnosis and prognosis in dermatology. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;31:496-510. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1682500

- Shen Y, Heacock L, Elias J, et al. ChatGPT and other large language models are double-edged swords. Radiology. 2023;307:E230163. doi:10.1148/radiol.230163

- Gupta R, Pande P, Herzog I, et al. Application of ChatGPT in cosmetic plastic surgery: ally or antagonist? Aesthet Surg J. 2023;43:NP587-NP590. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjad042

- Gabrielson AT, Odisho AY, Canes D. Harnessing generative artificial intelligence to improve efficiency among urologists: welcome ChatGPT. J Urol. 2023;209:827-829. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003383

- What is ChatGPT? OpenAI. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://help.openai.com/en/articles/6783457-chatgpt-general-faq

- Haupt CE, Marks M. AI-generated medical advice—GPT and beyond. JAMA. 2023;329:1349-1350. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5321

- Gao CA, Howard FM, Markov NS, et al. Comparing Scientific Abstracts Generated by ChatGPT to Original Abstracts Using an Artificial Intelligence Output Detector, Plagiarism Detector, and Blinded Human Reviewers. Scientific Communication and Education; 2022. doi:10.1101/2022.12.23.521610

- Weidinger L, Mellor J, Rauh M, et al. Ethical and social risks of harm from language models. arXiv. Preprint posted online December 8, 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.04359

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has increasingly been incorporated in medicine. In dermatology, AI has been used to detect and diagnose skin lesions, including skin cancer.1 ChatGPT (OpenAI) is a novel, highly popular development in generative AI technology. A large language model released in 2022, ChatGPT is a chatbot designed to mimic human conversation and generate specific detailed information when prompted. Free and publicly available, it has been used by millions of people. ChatGPT’s application in the medical field currently is being evaluated across several specialties, including plastic surgery, radiology, and urology.2-4 ChatGPT has the potential to assist health care professionals, including dermatologists, though its use raises important ethical considerations. Herein, we focus on the potential benefits as well as the pitfalls of using ChatGPT in dermatology clinical practice.

Potential Uses of ChatGPT in Practice

A major benefit of ChatGPT is its ability to improve clinical efficiency. First, ChatGPT can provide quick access to general medical information, similar to a search engine but with more natural language processing and contextual understanding to synthesize information.5 This function is useful for rapid concise answers to specific and directed questions. ChatGPT also can interact with its user by asking follow-up questions to produce more precise and relevant responses; this feature may help dermatologists form more accurate differential diagnoses. Additionally, ChatGPT can increase efficiency in clinical practice by drafting generic medical documents,2 including templates for after-visit summaries, postprocedure instructions, referrals, prior authorization appeal letters, and educational handouts. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. Another useful feature of ChatGPT is its ability to output information modeling human conversation. Because of this feature, ChatGPT also could be employed in clinical practice to serve as an interpreter for patients during clinic visits. Currently, the use of virtual translators can be cumbersome and subject to technical constraints. ChatGPT can provide accurate and conversational translations for patients and dermatologists, improving the patient-provider relationship.

ChatGPT also can contribute to major advancements in the field of dermatology beyond the clinical setting. Because of its ability to draw from extensive data that have already been uploaded, there are some uses of ChatGPT in a research context: to assist in finding resources for research and reviews, formulating hypotheses, drafting study protocols, and collecting large amounts of data within seconds.6

ChatGPT also has potential in advancing medical education. It could be used by medical schools to model interactive patient encounters to help students practice taking a patient’s history and creating differential diagnoses.6 This application of ChatGPT may help medical students hone their clinical skills in a low-stress environment without the restrictions that can come with hiring and training standardized patients, especially when mimicking dermatologic clinical encounters.

Other possibilities for ChatGPT in dermatologic practice include survey administration, clinical trial recruitment, and even automatic high-risk medication monitoring. Despite the many potential applications of ChatGPT in clinical practice, the question raised in each scenario is the quality, accuracy, and safety of what it produces.

Potential Pitfalls of ChatGPT in Practice and Possible Mitigation Strategies

A main concern in using ChatGPT in clinical practice is its potential to produce inaccurate or biased information. When prompted to create a research abstract based on previously published research, ChatGPT drafted abstracts that were clear and digestible but supplemented with incorrect data.7 A group of medical researchers who reviewed these ChatGPT-generated abstracts mistook 32% of the abstracts as having been written by human researchers. The implications of this finding are worrisome. If inaccurate or false information is used by ChatGPT in documents sent to insurance companies or patients, the patient’s safety as well as the dermatologist’s license and credibility are at stake. Thus, dermatologists looking to use ChatGPT to draft generic medical documents should actively review the output to ensure that the information is accurate. Importantly, ChatGPT also is only currently programmed with information up to 2021, limiting its access to recently published research articles and updated International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes.5 The continued development of ChatGPT will lead to regular updates by OpenAI that resolve this shortcoming in the future. Further, AI models may encode and perpetuate harmful stereotypes and social biases that are present in training data.8

When considering its potential in clinical practice, ChatGPT itself states that it can aid in clinical decision-making by processing patient information, including history, current symptoms, and biopsy and test results. This is uncharted territory, and providers who use ChatGPT at this stage to aid in decision-making should regard it similarly to information retrieved from a search engine. The information produced by ChatGPT should be used to substantiate but not definitively confirm a diagnosis or dictate management. Clinical suspicion by the dermatologist should always trump ChatGPT output. If physicians recommend ChatGPT output over their own advice, it can become a liability, as the technology is not regulated to any degree. Patients also should be cautious when seeking and following medical advice from ChatGPT, as it could be misleading or incorrect and could undermine the patient-physician relationship.6

Additionally, the specific use of ChatGPT to evaluate patient health records raises concerns related to patient privacy and confidentiality. Providers should never enter patient information protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act into ChatGPT or anywhere else on the internet. Mitigation of this risk is not currently possible; ChatGPT requires more development and further understanding to even consider its integration into current electronic health records without compromising patient confidentiality.

The Bottom Line

Overall, ChatGPT has the potential to improve efficiency in clinical practice by assisting with informational searches and document drafting. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. However, dermatologists should carefully weigh the ethical issues of nonmaleficence and justice in evaluating ChatGPT for accuracy, biases, and the protection of patient confidentiality.

Finally, we asked ChatGPT on February 28, 2023, what it thinks:

User: Should dermatologists use ChatGPT in clinical practice?

ChatGPT: As an AI language model, ChatGPT can be a useful tool in dermatology clinical practice, but it should be used with caution in conjunction with other sources of information and clinical judgement.

Dermatologists should be aware of the potential benefits and risks of using ChatGPT and make informed decisions about how to integrate it into their clinical practice. It’s important to remember that ChatGPT is not a substitute for clinical expertise or human interaction with patients, and it should only be used as a supplement to enhance the quality of patient care.

Dermatologists who choose to use ChatGPT should also be aware of its limitations and potential risks, such as limited accuracy, lack of context, and liability issues if it provides incorrect information or recommendations that lead to patient harm. Dermatologists should use their professional judgement and consult with other health care professionals when making important decisions regarding patient care.

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has increasingly been incorporated in medicine. In dermatology, AI has been used to detect and diagnose skin lesions, including skin cancer.1 ChatGPT (OpenAI) is a novel, highly popular development in generative AI technology. A large language model released in 2022, ChatGPT is a chatbot designed to mimic human conversation and generate specific detailed information when prompted. Free and publicly available, it has been used by millions of people. ChatGPT’s application in the medical field currently is being evaluated across several specialties, including plastic surgery, radiology, and urology.2-4 ChatGPT has the potential to assist health care professionals, including dermatologists, though its use raises important ethical considerations. Herein, we focus on the potential benefits as well as the pitfalls of using ChatGPT in dermatology clinical practice.

Potential Uses of ChatGPT in Practice

A major benefit of ChatGPT is its ability to improve clinical efficiency. First, ChatGPT can provide quick access to general medical information, similar to a search engine but with more natural language processing and contextual understanding to synthesize information.5 This function is useful for rapid concise answers to specific and directed questions. ChatGPT also can interact with its user by asking follow-up questions to produce more precise and relevant responses; this feature may help dermatologists form more accurate differential diagnoses. Additionally, ChatGPT can increase efficiency in clinical practice by drafting generic medical documents,2 including templates for after-visit summaries, postprocedure instructions, referrals, prior authorization appeal letters, and educational handouts. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. Another useful feature of ChatGPT is its ability to output information modeling human conversation. Because of this feature, ChatGPT also could be employed in clinical practice to serve as an interpreter for patients during clinic visits. Currently, the use of virtual translators can be cumbersome and subject to technical constraints. ChatGPT can provide accurate and conversational translations for patients and dermatologists, improving the patient-provider relationship.

ChatGPT also can contribute to major advancements in the field of dermatology beyond the clinical setting. Because of its ability to draw from extensive data that have already been uploaded, there are some uses of ChatGPT in a research context: to assist in finding resources for research and reviews, formulating hypotheses, drafting study protocols, and collecting large amounts of data within seconds.6

ChatGPT also has potential in advancing medical education. It could be used by medical schools to model interactive patient encounters to help students practice taking a patient’s history and creating differential diagnoses.6 This application of ChatGPT may help medical students hone their clinical skills in a low-stress environment without the restrictions that can come with hiring and training standardized patients, especially when mimicking dermatologic clinical encounters.

Other possibilities for ChatGPT in dermatologic practice include survey administration, clinical trial recruitment, and even automatic high-risk medication monitoring. Despite the many potential applications of ChatGPT in clinical practice, the question raised in each scenario is the quality, accuracy, and safety of what it produces.

Potential Pitfalls of ChatGPT in Practice and Possible Mitigation Strategies

A main concern in using ChatGPT in clinical practice is its potential to produce inaccurate or biased information. When prompted to create a research abstract based on previously published research, ChatGPT drafted abstracts that were clear and digestible but supplemented with incorrect data.7 A group of medical researchers who reviewed these ChatGPT-generated abstracts mistook 32% of the abstracts as having been written by human researchers. The implications of this finding are worrisome. If inaccurate or false information is used by ChatGPT in documents sent to insurance companies or patients, the patient’s safety as well as the dermatologist’s license and credibility are at stake. Thus, dermatologists looking to use ChatGPT to draft generic medical documents should actively review the output to ensure that the information is accurate. Importantly, ChatGPT also is only currently programmed with information up to 2021, limiting its access to recently published research articles and updated International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes.5 The continued development of ChatGPT will lead to regular updates by OpenAI that resolve this shortcoming in the future. Further, AI models may encode and perpetuate harmful stereotypes and social biases that are present in training data.8

When considering its potential in clinical practice, ChatGPT itself states that it can aid in clinical decision-making by processing patient information, including history, current symptoms, and biopsy and test results. This is uncharted territory, and providers who use ChatGPT at this stage to aid in decision-making should regard it similarly to information retrieved from a search engine. The information produced by ChatGPT should be used to substantiate but not definitively confirm a diagnosis or dictate management. Clinical suspicion by the dermatologist should always trump ChatGPT output. If physicians recommend ChatGPT output over their own advice, it can become a liability, as the technology is not regulated to any degree. Patients also should be cautious when seeking and following medical advice from ChatGPT, as it could be misleading or incorrect and could undermine the patient-physician relationship.6

Additionally, the specific use of ChatGPT to evaluate patient health records raises concerns related to patient privacy and confidentiality. Providers should never enter patient information protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act into ChatGPT or anywhere else on the internet. Mitigation of this risk is not currently possible; ChatGPT requires more development and further understanding to even consider its integration into current electronic health records without compromising patient confidentiality.

The Bottom Line

Overall, ChatGPT has the potential to improve efficiency in clinical practice by assisting with informational searches and document drafting. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. However, dermatologists should carefully weigh the ethical issues of nonmaleficence and justice in evaluating ChatGPT for accuracy, biases, and the protection of patient confidentiality.

Finally, we asked ChatGPT on February 28, 2023, what it thinks:

User: Should dermatologists use ChatGPT in clinical practice?

ChatGPT: As an AI language model, ChatGPT can be a useful tool in dermatology clinical practice, but it should be used with caution in conjunction with other sources of information and clinical judgement.

Dermatologists should be aware of the potential benefits and risks of using ChatGPT and make informed decisions about how to integrate it into their clinical practice. It’s important to remember that ChatGPT is not a substitute for clinical expertise or human interaction with patients, and it should only be used as a supplement to enhance the quality of patient care.

Dermatologists who choose to use ChatGPT should also be aware of its limitations and potential risks, such as limited accuracy, lack of context, and liability issues if it provides incorrect information or recommendations that lead to patient harm. Dermatologists should use their professional judgement and consult with other health care professionals when making important decisions regarding patient care.

- Thomsen K, Iversen L, Titlestad TL, et al. Systematic review of machine learning for diagnosis and prognosis in dermatology. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;31:496-510. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1682500

- Shen Y, Heacock L, Elias J, et al. ChatGPT and other large language models are double-edged swords. Radiology. 2023;307:E230163. doi:10.1148/radiol.230163

- Gupta R, Pande P, Herzog I, et al. Application of ChatGPT in cosmetic plastic surgery: ally or antagonist? Aesthet Surg J. 2023;43:NP587-NP590. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjad042

- Gabrielson AT, Odisho AY, Canes D. Harnessing generative artificial intelligence to improve efficiency among urologists: welcome ChatGPT. J Urol. 2023;209:827-829. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003383

- What is ChatGPT? OpenAI. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://help.openai.com/en/articles/6783457-chatgpt-general-faq

- Haupt CE, Marks M. AI-generated medical advice—GPT and beyond. JAMA. 2023;329:1349-1350. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5321

- Gao CA, Howard FM, Markov NS, et al. Comparing Scientific Abstracts Generated by ChatGPT to Original Abstracts Using an Artificial Intelligence Output Detector, Plagiarism Detector, and Blinded Human Reviewers. Scientific Communication and Education; 2022. doi:10.1101/2022.12.23.521610

- Weidinger L, Mellor J, Rauh M, et al. Ethical and social risks of harm from language models. arXiv. Preprint posted online December 8, 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.04359

- Thomsen K, Iversen L, Titlestad TL, et al. Systematic review of machine learning for diagnosis and prognosis in dermatology. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;31:496-510. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1682500

- Shen Y, Heacock L, Elias J, et al. ChatGPT and other large language models are double-edged swords. Radiology. 2023;307:E230163. doi:10.1148/radiol.230163

- Gupta R, Pande P, Herzog I, et al. Application of ChatGPT in cosmetic plastic surgery: ally or antagonist? Aesthet Surg J. 2023;43:NP587-NP590. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjad042

- Gabrielson AT, Odisho AY, Canes D. Harnessing generative artificial intelligence to improve efficiency among urologists: welcome ChatGPT. J Urol. 2023;209:827-829. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003383

- What is ChatGPT? OpenAI. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://help.openai.com/en/articles/6783457-chatgpt-general-faq

- Haupt CE, Marks M. AI-generated medical advice—GPT and beyond. JAMA. 2023;329:1349-1350. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5321

- Gao CA, Howard FM, Markov NS, et al. Comparing Scientific Abstracts Generated by ChatGPT to Original Abstracts Using an Artificial Intelligence Output Detector, Plagiarism Detector, and Blinded Human Reviewers. Scientific Communication and Education; 2022. doi:10.1101/2022.12.23.521610

- Weidinger L, Mellor J, Rauh M, et al. Ethical and social risks of harm from language models. arXiv. Preprint posted online December 8, 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.04359

Practice Points

- ChatGPT potentially can play a beneficial role in dermatologic practice by quickly accessing and synthesizing information, drafting generic medical documents, interpreting visits, advancing medical education, and more.

- Dermatologists using ChatGPT should be extremely cautious, as it can produce false or biased information, perpetuate harmful stereotypes, and present information that is not up-to-date.

Parental bias about a doctor can’t trump a patient’s health

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’d like to present you today with a case that raised a large amount of discussion and debate. I got involved as an ethics consultant on the case. I think you’ll find it very interesting and I also think there are going to be some differences of opinion about how to manage the case. I’ll be looking forward to getting comments and feedback on this.

The case involved a 14-year-old boy who had been brought into the hospital by his parents, suffering from severe bouts of anxiety that were just almost overwhelming to him. When he was brought in, he was assigned a health care provider who had a West African last name. Prior to meeting the patient, I have to say that the father of this kid told the intake department nurse that he requested someone else. He saw the name – he hadn’t even met the provider – and he said he wanted someone who might be Catholic.

The parents are both from the Dominican Republic. They identified as White, but they appeared to be non-White Latinx to the nurse who was doing some of the initial intake. They got reassigned to a different provider in the department who identified as African American.

The first month of treatment for the young boy went very well, and he seemed to be getting along extremely well with his provider. He was reporting relief to both parents of some of his anxiety, and the provider felt very connected to the child. A good doctor-patient alliance had been formed.

Nevertheless, at the end of the first month, the father connected back to one of the administrators at the hospital and complained, saying he still wanted a different provider. When asked why, he said, “Well, I don’t really want to answer that,” but getting pressed, he basically said he wasn’t comfortable with having an African American doctor take care of his child. He eventually went back to the argument that what he wanted was someone with a Catholic background, although I don’t know that he knew whether this particular provider was religious – Catholic or anything else.

Some people felt that, as the father in charge of the child’s care, if we could accommodate what he wanted in terms of the parents being comfortable, then that’s something we should do. I absolutely did not agree.

My view is that in a situation where a strong provider-patient relationship has been established, where trust is going both ways, where there are no issues coming up between this 14-year-old and the provider, and when a serious mental health issue is being adequately addressed, the patient’s interest must come first.

Once that therapeutic alliance had been established and both the patient and the provider felt satisfied, I don’t think the father’s wishes made any sense. He may have been acting more out of bigotry or just discomfort about difference in terms of who the provider was. I don’t think that’s something that any health system should have to accommodate unless it is getting in the way of patient care.

I hope that we treat all physicians as properly trained to deal with all kinds of patients, regardless of their religion, ethnicity, or skin color. They should have the skills to manage and do well with any patient. There may be situations where it just doesn’t work or where people don’t get along. Yes, I think we then should try, perhaps, to shift the doctor, get a different nurse, or have a different person do an exam. That’s because of the inability to get the patient’s health interests addressed.

Listening to this dad about what he preferred in terms of religion or ethnicity seemed to me to be interfering with medical success. Could I stop him from moving this patient out entirely from the care setting? Probably not, but I think the way to manage this is to try to talk to him – and, by the way, to talk to the mother.

When we did bring the mom into the situation, she was very happy with the health care provider. She didn’t agree with the dad and wanted to have a meeting with the social worker, the dad, and her to get him to get over the worries, concerns, and maybe even biases he was bringing in about the kind of provider he wanted. That’s exactly what we did.

I know that there are many instances where patients may say, “I don’t want a particular doctor or a particular type.” My view is that we shouldn’t accommodate that. We should say that our doctors are trained to help and care for all manner of people. Unless we can think of some reason that there might be a gap or a problem in the actual delivery of the quality of care, we are not going to accommodate racism, bigotry, or bias.

We certainly shouldn’t be accommodating that once a successful therapeutic relationship is established. Even when it’s a child, I would argue that the patient’s best interest has to trump parental desires, parental worries, and parental concerns about the background, ethnicity, and religion of the provider.

Dr. Caplan is director of the division of medical ethics at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York. He disclosed a conflict of interest with Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’d like to present you today with a case that raised a large amount of discussion and debate. I got involved as an ethics consultant on the case. I think you’ll find it very interesting and I also think there are going to be some differences of opinion about how to manage the case. I’ll be looking forward to getting comments and feedback on this.

The case involved a 14-year-old boy who had been brought into the hospital by his parents, suffering from severe bouts of anxiety that were just almost overwhelming to him. When he was brought in, he was assigned a health care provider who had a West African last name. Prior to meeting the patient, I have to say that the father of this kid told the intake department nurse that he requested someone else. He saw the name – he hadn’t even met the provider – and he said he wanted someone who might be Catholic.

The parents are both from the Dominican Republic. They identified as White, but they appeared to be non-White Latinx to the nurse who was doing some of the initial intake. They got reassigned to a different provider in the department who identified as African American.

The first month of treatment for the young boy went very well, and he seemed to be getting along extremely well with his provider. He was reporting relief to both parents of some of his anxiety, and the provider felt very connected to the child. A good doctor-patient alliance had been formed.

Nevertheless, at the end of the first month, the father connected back to one of the administrators at the hospital and complained, saying he still wanted a different provider. When asked why, he said, “Well, I don’t really want to answer that,” but getting pressed, he basically said he wasn’t comfortable with having an African American doctor take care of his child. He eventually went back to the argument that what he wanted was someone with a Catholic background, although I don’t know that he knew whether this particular provider was religious – Catholic or anything else.

Some people felt that, as the father in charge of the child’s care, if we could accommodate what he wanted in terms of the parents being comfortable, then that’s something we should do. I absolutely did not agree.

My view is that in a situation where a strong provider-patient relationship has been established, where trust is going both ways, where there are no issues coming up between this 14-year-old and the provider, and when a serious mental health issue is being adequately addressed, the patient’s interest must come first.

Once that therapeutic alliance had been established and both the patient and the provider felt satisfied, I don’t think the father’s wishes made any sense. He may have been acting more out of bigotry or just discomfort about difference in terms of who the provider was. I don’t think that’s something that any health system should have to accommodate unless it is getting in the way of patient care.

I hope that we treat all physicians as properly trained to deal with all kinds of patients, regardless of their religion, ethnicity, or skin color. They should have the skills to manage and do well with any patient. There may be situations where it just doesn’t work or where people don’t get along. Yes, I think we then should try, perhaps, to shift the doctor, get a different nurse, or have a different person do an exam. That’s because of the inability to get the patient’s health interests addressed.

Listening to this dad about what he preferred in terms of religion or ethnicity seemed to me to be interfering with medical success. Could I stop him from moving this patient out entirely from the care setting? Probably not, but I think the way to manage this is to try to talk to him – and, by the way, to talk to the mother.

When we did bring the mom into the situation, she was very happy with the health care provider. She didn’t agree with the dad and wanted to have a meeting with the social worker, the dad, and her to get him to get over the worries, concerns, and maybe even biases he was bringing in about the kind of provider he wanted. That’s exactly what we did.

I know that there are many instances where patients may say, “I don’t want a particular doctor or a particular type.” My view is that we shouldn’t accommodate that. We should say that our doctors are trained to help and care for all manner of people. Unless we can think of some reason that there might be a gap or a problem in the actual delivery of the quality of care, we are not going to accommodate racism, bigotry, or bias.

We certainly shouldn’t be accommodating that once a successful therapeutic relationship is established. Even when it’s a child, I would argue that the patient’s best interest has to trump parental desires, parental worries, and parental concerns about the background, ethnicity, and religion of the provider.

Dr. Caplan is director of the division of medical ethics at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York. He disclosed a conflict of interest with Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’d like to present you today with a case that raised a large amount of discussion and debate. I got involved as an ethics consultant on the case. I think you’ll find it very interesting and I also think there are going to be some differences of opinion about how to manage the case. I’ll be looking forward to getting comments and feedback on this.

The case involved a 14-year-old boy who had been brought into the hospital by his parents, suffering from severe bouts of anxiety that were just almost overwhelming to him. When he was brought in, he was assigned a health care provider who had a West African last name. Prior to meeting the patient, I have to say that the father of this kid told the intake department nurse that he requested someone else. He saw the name – he hadn’t even met the provider – and he said he wanted someone who might be Catholic.

The parents are both from the Dominican Republic. They identified as White, but they appeared to be non-White Latinx to the nurse who was doing some of the initial intake. They got reassigned to a different provider in the department who identified as African American.

The first month of treatment for the young boy went very well, and he seemed to be getting along extremely well with his provider. He was reporting relief to both parents of some of his anxiety, and the provider felt very connected to the child. A good doctor-patient alliance had been formed.

Nevertheless, at the end of the first month, the father connected back to one of the administrators at the hospital and complained, saying he still wanted a different provider. When asked why, he said, “Well, I don’t really want to answer that,” but getting pressed, he basically said he wasn’t comfortable with having an African American doctor take care of his child. He eventually went back to the argument that what he wanted was someone with a Catholic background, although I don’t know that he knew whether this particular provider was religious – Catholic or anything else.

Some people felt that, as the father in charge of the child’s care, if we could accommodate what he wanted in terms of the parents being comfortable, then that’s something we should do. I absolutely did not agree.

My view is that in a situation where a strong provider-patient relationship has been established, where trust is going both ways, where there are no issues coming up between this 14-year-old and the provider, and when a serious mental health issue is being adequately addressed, the patient’s interest must come first.

Once that therapeutic alliance had been established and both the patient and the provider felt satisfied, I don’t think the father’s wishes made any sense. He may have been acting more out of bigotry or just discomfort about difference in terms of who the provider was. I don’t think that’s something that any health system should have to accommodate unless it is getting in the way of patient care.

I hope that we treat all physicians as properly trained to deal with all kinds of patients, regardless of their religion, ethnicity, or skin color. They should have the skills to manage and do well with any patient. There may be situations where it just doesn’t work or where people don’t get along. Yes, I think we then should try, perhaps, to shift the doctor, get a different nurse, or have a different person do an exam. That’s because of the inability to get the patient’s health interests addressed.

Listening to this dad about what he preferred in terms of religion or ethnicity seemed to me to be interfering with medical success. Could I stop him from moving this patient out entirely from the care setting? Probably not, but I think the way to manage this is to try to talk to him – and, by the way, to talk to the mother.

When we did bring the mom into the situation, she was very happy with the health care provider. She didn’t agree with the dad and wanted to have a meeting with the social worker, the dad, and her to get him to get over the worries, concerns, and maybe even biases he was bringing in about the kind of provider he wanted. That’s exactly what we did.

I know that there are many instances where patients may say, “I don’t want a particular doctor or a particular type.” My view is that we shouldn’t accommodate that. We should say that our doctors are trained to help and care for all manner of people. Unless we can think of some reason that there might be a gap or a problem in the actual delivery of the quality of care, we are not going to accommodate racism, bigotry, or bias.

We certainly shouldn’t be accommodating that once a successful therapeutic relationship is established. Even when it’s a child, I would argue that the patient’s best interest has to trump parental desires, parental worries, and parental concerns about the background, ethnicity, and religion of the provider.

Dr. Caplan is director of the division of medical ethics at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York. He disclosed a conflict of interest with Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Buyer beware

The invitation came to my house, addressed to “residential customer.” It was for my wife and me to attend a free dinner at a swanky local restaurant to learn about “revolutionary” treatments for memory loss. It was presented by a “wellness expert.”

Of course, I just had to check out the website.

The dinner was hosted by an internist pushing an unproven (except for the usual small noncontrolled studies) treatment. Although not stated, I’m sure when you call you’ll find out this is not covered by insurance; not Food and Drug Administration approved to treat, cure, diagnose, prevent any disease; your mileage may vary, etc.