User login

Is burnout on the rise and what are the signs ObGyns should be on the lookout for?

In a peer-to-peer audiocast, Ms. DiVenere probed Dr. Smith for the problem areas that appear in the early to late stages of burnout. He spoke to the stressors that residents experience in the learning situation and that ObGyns must deal with in practice, as well as described strategies to deal with that stress.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Have you read "ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim," by Lucia DiVenere, MA (September 2016)?

In a peer-to-peer audiocast, Ms. DiVenere probed Dr. Smith for the problem areas that appear in the early to late stages of burnout. He spoke to the stressors that residents experience in the learning situation and that ObGyns must deal with in practice, as well as described strategies to deal with that stress.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Have you read "ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim," by Lucia DiVenere, MA (September 2016)?

In a peer-to-peer audiocast, Ms. DiVenere probed Dr. Smith for the problem areas that appear in the early to late stages of burnout. He spoke to the stressors that residents experience in the learning situation and that ObGyns must deal with in practice, as well as described strategies to deal with that stress.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Have you read "ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim," by Lucia DiVenere, MA (September 2016)?

Should risk-reducing gynecologic surgery for BRCA mutation carriers include hysterectomy?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Although RRSO is routinely recommended to decrease the risk of ovarian as well as breast cancer in women who harbor BRCA mutations, whether or not surgery should include hysterectomy has not been clear. Shu and colleagues prospectively evaluated the risk of uterine cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers who underwent RRSO without hysterectomy at 1 of 9 centers in the United States or the United Kingdom, comparing it with rates expected from national surveillance data.

Details of the study

Among 1,083 women (median age, 45.6 years at the time of RRSO; median follow-up, 5.1 years), 8 incident uterine cancers were observed (4.3 were expected; observed to expected [O:E] ratio, 1.9; P = .09). In an analysis stratified by tumor subtype, no elevated risk for endometrioid endometrial cancer or sarcoma was noted. Five serous and/or serous-like endometrial cancers were observed after RRSO. Four were found in BRCA1 carriers and 1 in a BRCA2 carrier, with the O:E ratio of 22.2 (P<.001) for BRCA1 and 6.4 (P = .15) for BRCA2 carriers.

Details of the accompanying editorial

Commenting on the study, Leath and colleagues noted that while the number of cases was small, the study demonstrated a link between the presence of BRCA mutations (particularly BRCA1 mutations) and a "small but not null risk of endometrial cancer." Many of these uterine cancers have a serous histology, a concern due to the likelihood of worse outcomes compared with the more common endometrioid variant.

The authors suggest that clinicians make patients with BRCA mutations undergoing RRSO aware of the potential risks and benefits of concomitant hysterectomy and work to make an individualized decision based on the limitations of available data. They state, "Perhaps it is time to consider that the line for risk-reducing gynecologic surgery in patients with BRCA mutations not stop at the ovaries and fallopian tubes. Thus, concomitant hysterectomy with RRSO, when performed with a minimally invasive surgical approach, particularly for women with a BRCA1 mutation, should be able to be performed with minimum morbidity and allow for use of estrogen-only hormone therapy after surgery, if needed."

Although adding hysterectomy to RRSO increases the perioperative risks, these risks should be attenuated by the use of minimally invasive surgical approaches. Women diagnosed with serous endometrial cancer have worse outcomes than those with the more common endometrioid endometrial tumors, even when they are diagnosed with early stage disease. Future risk of any uterine malignancy is essentially eliminated when hysterectomy is performed.

Risk-reducing gynecologic surgery in BRCA carriers is optimally performed prior to age 40, meaning that unless hormone therapy is used, severe menopausal symptoms likely will occur, and women are at elevated risk for osteoporosis and cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Given that hysterectomy allows estrogen (little or no impact on breast cancer risk) to be prescribed without progestin (small elevation in breast cancer risk), hysterectomy has particular advantages for younger mutation carriers undergoing risk-reducing gynecologic surgery.

I agree with the editorialists who provided an accompanying comment on the study that—provided a minimally invasive approach is used—we should encourage hysterectomy as part of risk-reducing surgery for women with BRCA mutations.

—ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Although RRSO is routinely recommended to decrease the risk of ovarian as well as breast cancer in women who harbor BRCA mutations, whether or not surgery should include hysterectomy has not been clear. Shu and colleagues prospectively evaluated the risk of uterine cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers who underwent RRSO without hysterectomy at 1 of 9 centers in the United States or the United Kingdom, comparing it with rates expected from national surveillance data.

Details of the study

Among 1,083 women (median age, 45.6 years at the time of RRSO; median follow-up, 5.1 years), 8 incident uterine cancers were observed (4.3 were expected; observed to expected [O:E] ratio, 1.9; P = .09). In an analysis stratified by tumor subtype, no elevated risk for endometrioid endometrial cancer or sarcoma was noted. Five serous and/or serous-like endometrial cancers were observed after RRSO. Four were found in BRCA1 carriers and 1 in a BRCA2 carrier, with the O:E ratio of 22.2 (P<.001) for BRCA1 and 6.4 (P = .15) for BRCA2 carriers.

Details of the accompanying editorial

Commenting on the study, Leath and colleagues noted that while the number of cases was small, the study demonstrated a link between the presence of BRCA mutations (particularly BRCA1 mutations) and a "small but not null risk of endometrial cancer." Many of these uterine cancers have a serous histology, a concern due to the likelihood of worse outcomes compared with the more common endometrioid variant.

The authors suggest that clinicians make patients with BRCA mutations undergoing RRSO aware of the potential risks and benefits of concomitant hysterectomy and work to make an individualized decision based on the limitations of available data. They state, "Perhaps it is time to consider that the line for risk-reducing gynecologic surgery in patients with BRCA mutations not stop at the ovaries and fallopian tubes. Thus, concomitant hysterectomy with RRSO, when performed with a minimally invasive surgical approach, particularly for women with a BRCA1 mutation, should be able to be performed with minimum morbidity and allow for use of estrogen-only hormone therapy after surgery, if needed."

Although adding hysterectomy to RRSO increases the perioperative risks, these risks should be attenuated by the use of minimally invasive surgical approaches. Women diagnosed with serous endometrial cancer have worse outcomes than those with the more common endometrioid endometrial tumors, even when they are diagnosed with early stage disease. Future risk of any uterine malignancy is essentially eliminated when hysterectomy is performed.

Risk-reducing gynecologic surgery in BRCA carriers is optimally performed prior to age 40, meaning that unless hormone therapy is used, severe menopausal symptoms likely will occur, and women are at elevated risk for osteoporosis and cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Given that hysterectomy allows estrogen (little or no impact on breast cancer risk) to be prescribed without progestin (small elevation in breast cancer risk), hysterectomy has particular advantages for younger mutation carriers undergoing risk-reducing gynecologic surgery.

I agree with the editorialists who provided an accompanying comment on the study that—provided a minimally invasive approach is used—we should encourage hysterectomy as part of risk-reducing surgery for women with BRCA mutations.

—ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Although RRSO is routinely recommended to decrease the risk of ovarian as well as breast cancer in women who harbor BRCA mutations, whether or not surgery should include hysterectomy has not been clear. Shu and colleagues prospectively evaluated the risk of uterine cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers who underwent RRSO without hysterectomy at 1 of 9 centers in the United States or the United Kingdom, comparing it with rates expected from national surveillance data.

Details of the study

Among 1,083 women (median age, 45.6 years at the time of RRSO; median follow-up, 5.1 years), 8 incident uterine cancers were observed (4.3 were expected; observed to expected [O:E] ratio, 1.9; P = .09). In an analysis stratified by tumor subtype, no elevated risk for endometrioid endometrial cancer or sarcoma was noted. Five serous and/or serous-like endometrial cancers were observed after RRSO. Four were found in BRCA1 carriers and 1 in a BRCA2 carrier, with the O:E ratio of 22.2 (P<.001) for BRCA1 and 6.4 (P = .15) for BRCA2 carriers.

Details of the accompanying editorial

Commenting on the study, Leath and colleagues noted that while the number of cases was small, the study demonstrated a link between the presence of BRCA mutations (particularly BRCA1 mutations) and a "small but not null risk of endometrial cancer." Many of these uterine cancers have a serous histology, a concern due to the likelihood of worse outcomes compared with the more common endometrioid variant.

The authors suggest that clinicians make patients with BRCA mutations undergoing RRSO aware of the potential risks and benefits of concomitant hysterectomy and work to make an individualized decision based on the limitations of available data. They state, "Perhaps it is time to consider that the line for risk-reducing gynecologic surgery in patients with BRCA mutations not stop at the ovaries and fallopian tubes. Thus, concomitant hysterectomy with RRSO, when performed with a minimally invasive surgical approach, particularly for women with a BRCA1 mutation, should be able to be performed with minimum morbidity and allow for use of estrogen-only hormone therapy after surgery, if needed."

Although adding hysterectomy to RRSO increases the perioperative risks, these risks should be attenuated by the use of minimally invasive surgical approaches. Women diagnosed with serous endometrial cancer have worse outcomes than those with the more common endometrioid endometrial tumors, even when they are diagnosed with early stage disease. Future risk of any uterine malignancy is essentially eliminated when hysterectomy is performed.

Risk-reducing gynecologic surgery in BRCA carriers is optimally performed prior to age 40, meaning that unless hormone therapy is used, severe menopausal symptoms likely will occur, and women are at elevated risk for osteoporosis and cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Given that hysterectomy allows estrogen (little or no impact on breast cancer risk) to be prescribed without progestin (small elevation in breast cancer risk), hysterectomy has particular advantages for younger mutation carriers undergoing risk-reducing gynecologic surgery.

I agree with the editorialists who provided an accompanying comment on the study that—provided a minimally invasive approach is used—we should encourage hysterectomy as part of risk-reducing surgery for women with BRCA mutations.

—ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

STOP using instruments to assist with delivery of the head at cesarean

Rates of cesarean delivery in the second stage of labor have increased dramatically over the past few years.1 Compared with cesarean delivery prior to labor, second-stage labor cesarean is associated with a higher risk to both the mother and the fetus; risks include excessive bleeding, lower uterine segment extensions, injuries to the maternal ureters or bladder, and injury to the fetus.2−4 The risk is increased even further if the fetal head is deeply impacted in the pelvis. What can we do to avoid and manage such situations?

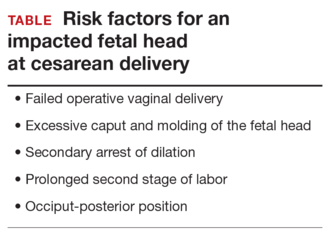

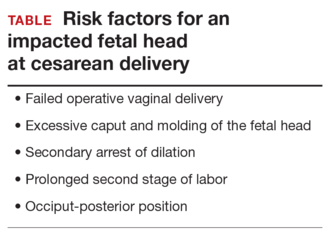

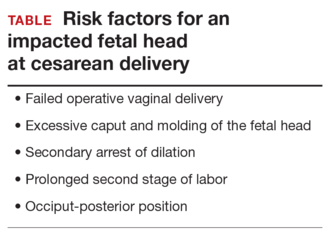

Anticipate an impacted fetal headThe true incidence of an impacted fetal head at the time of cesarean is not known, although a number of risk factors have been described (TABLE). Obstetric care providers should be aware of these risk factors and anticipate the likelihood of a difficult delivery of the fetal head at cesarean.

Options for managing an impacted fetal head at cesareanSeveral techniques have been reported in the literature for managing the delivery of a deeply engaged head, including:

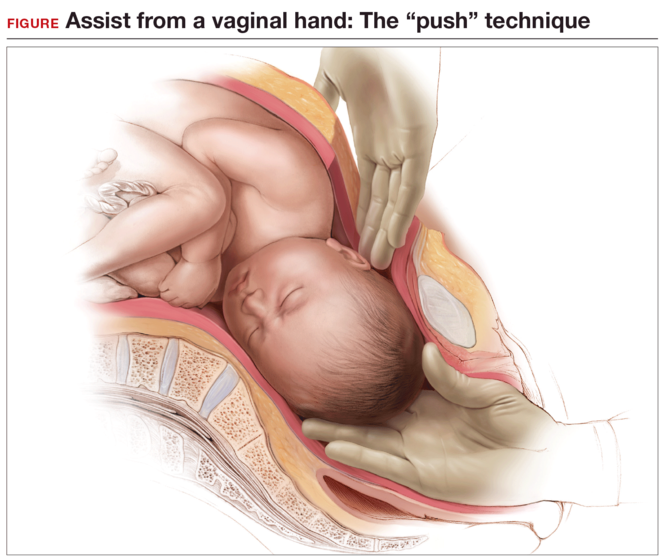

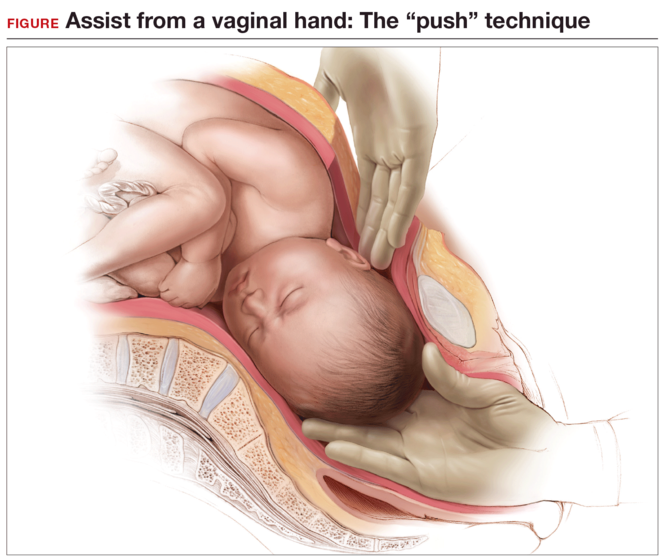

Using an assistant to push the fetus’s head up using a hand in the vagina (“push” technique). This can cause trauma to the fetus, since the force required to push the fetus up from below is uncontrolled.5,6

The reverse breech extraction (“pull” technique) involves pulling the infant out feet first through the uterine incision.7

Use of an instrument. The most common instrument used is a vacuum extractor,8 although a number of other devices have been developed, including the Murless fetal head extractor (an instrument with a hinged shaft and sliding collar lock),9 the C-Snorkel impacted fetal head release device (the device’s tip contains ventilation ports to facilitate airflow and release of the vacuum/suction created by the impacted fetal head),10 and the Fetal Pillow (a balloon device inserted in the vagina and inflated with sterile saline to disimpact an engaged fetal head before cesarean delivery).11

While all of these techniques can cause injury to the mother and the fetus, available data favor use of the reverse breech extraction (pull) technique, since it is associated with fewer maternal risks, including lower rates of uterine incision extension, infection, and postpartum hemorrhage and a shorter operative time.12−18

Stop use of vacuum to deliver the fetal head at cesarean

Placement of a vacuum can be effective in assisting with delivery of the fetal head at cesarean. For this reason, vacuum-assisted deliveries at cesarean are becoming more common. While the rate of complications caused by vacuum extraction of the fetal head at cesarean is not known, injuries have been reported.19,20 As such, routine use of vacuum extraction at the time of cesarean delivery cannot be recommended.

Start disengaging the fetal head prior to cesarean

One useful technique in planning a cesarean in the second stage of labor or when an impacted fetal head is anticipated is to disengage the fetal head vaginally prior to skin incision. This can be done in the delivery room or in the operating room immediately prior to surgery with the help of an assistant.

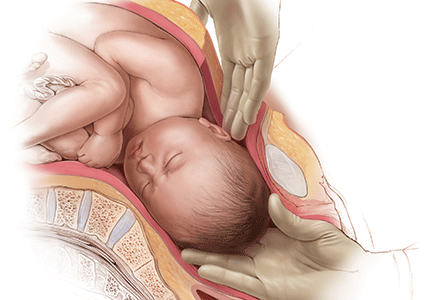

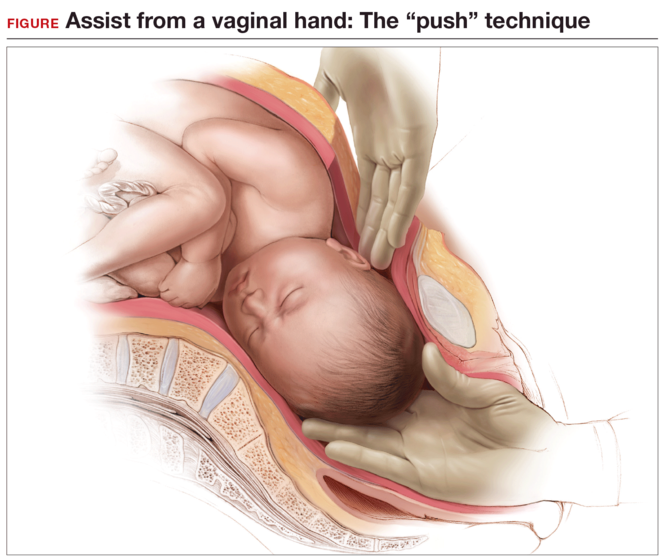

While supporting the patient’s legs, the assistant inserts a hand into the vagina and pushes upward on the fetal head with gentle, sustained effort. The assistant should use a cupped hand or the palm of the hand while attempting to both elevate and flex the fetal head. It is best to avoid using 1 or 2 fingers to elevate the head, as this may cause excessive pressure at a single point and lead to injury, such as a skull fracture (FIGURE). The assistant should disengage his or her hand only when the operating surgeon is able to reach down and secure the fetal head from above.

Elevating the fetal head prior to skin incision offers 3 major advantages:

- It avoids the embarrassing situation of having the fetus deliver vaginally before it can be pulled out through the abdominal incision. Although rare, this has been known to happen, because the dense regional anesthesia further relaxes the pelvic floor musculature, leading to flexion and rotation of the fetal head, which then descends and delivers. Performing a final bimanual examination in the operating room after the establishment of surgical level anesthesia and immediately prior to skin incision will avoid this situation.

- It elevates the fetal head, thereby creating additional space between the bony pelvis and fetal presenting part for the provider’s hand to fit. This helps minimize injury to the fetus and to the maternal soft tissues at the time of cesarean.

- Lastly, it provides additional information about the extent to which the fetal head is impacted in the pelvis and may influence decision making around the time of cesarean. For example, if the fetal head were deeply impacted in the pelvis and could not be disimpacted vaginally, the surgeon may choose to make a different uterine incision (such as a low vertical hysterotomy), administer a uterine relaxant (an inhaled anesthetic agent or nitric oxide), ask for additional instrumentation, and/or ask an assistant to be ready to elevate the fetal head vaginally should this be necessary.21

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Spencer C, Murphy D, Bewley S. Caesarean delivery in the second stage of labour. BMJ. 2006;333(7569):613–614.

- Häger RM, Daltviet AK, Hofoss D, et al. Complications of cesarean deliveries: rates and risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(2):428–434.

- Murphy DJ, Liebling RE, Verity L, Swingler R, Patel R. Early maternal and neonatal morbidity associated with operative delivery in second stage of labour: a cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358(9289):1203–1207.

- Pergialiotis V, Vlachos DG, Rodolakis A, Haidopoulos D, Thomakos N, Vlachos GD. First versus second stage C/S maternal and neonatal morbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;175:15–24.

- Lippert TH. Bimanual delivery of the fetal head at cesarean section with the fetal head in the midcavity. Arch Gynecol. 1983;234(1):59–60.

- Landesman R, Graber EA. Abdominovaginal delivery: modification of the cesarean section operation to facilitate delivery of the impacted head. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148(6):707–710.

- Fong YF, Arulkumaran S. Breech extraction—an alternative method of delivering a deeply engaged head at cesarean section. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;56(2):183–184.

- Arad I, Linder N, Bercovici B. Vacuum extraction at cesarean section—neonatal outcome. J Perinat Med. 1986;14(2):137–140.

- Murless BC. Lower-segment caesarean section; a new head extractor. BMJ. 1948;1(4564):1234.

- C-Snorkle impacted fetal head release device. Clinical Innovations website. http://clinicalinnovations.com /portfolio-items/c-snorkel/. Accessed July 22, 2016.

- Seal SL, Dey A, Barman SC, Kamilya G, Mukherji J, Onwude JL. Randomized controlled trial of elevation of the fetal head with a fetal pillow during cesarean delivery at full cervical dilatation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;133(2):178–182.

- Fasubaa OB, Ezechi OC, Orji EO, et al. Delivery of the impacted head of the fetus at caesarean section after prolonged obstructed labour: a randomised comparative study of two methods. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22(4):375–378.

- Levy R, Chernomoretz T, Appelman Z, Levin D, Or Y, Hagay ZJ. Head pushing versus reverse breech extraction in cases of impacted fetal head during Cesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;121(1):24–26.

- Chopra S, Bagga R, Keepanasseril A, Jain V, Kalra J, Suri V. Disengagement of the deeply engaged fetal head during cesarean section in advanced labor: conventional method versus reverse breech extraction. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(10):1163–1166.

- Veisi F, Zangeneh M, Malekkhosravi S, Rezavand N. Comparison of “push” and “pull” methods for impacted fetal head extraction during cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;118(1):4–6.

- Bastani P, Pourabolghasem S, Abbasalizadeh F, Motvalli L. ComparisonColor/Black of neonatal and maternal outcomes associated with head-pushing and head-pulling methods for impacted fetal head extraction during cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;118(1):1–3.

- Waterfall H, Grivell RM, Dodd JM. Techniques for assisting difficult delivery at caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;1:CD004944.

- Jeve YB, Navti OB, Konje JC. Comparison of techniques used to deliver a deeply impacted fetal head at full dilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2016;123(3): 337–345.

- Clark SL, Vines VL, Belfort MA. Fetal injury associated with routine vacuum use during cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):e4.

- Fareeduddin R, Schifrin BS. Subgaleal hemorrhage after the use of a vacuum extractor during elective cesarean delivery: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(10):809–810.

- Barbieri RL. Difficult fetal extraction at cesarean delivery: What should you do? OBG Manag. 2012;24(1):8–12.

Rates of cesarean delivery in the second stage of labor have increased dramatically over the past few years.1 Compared with cesarean delivery prior to labor, second-stage labor cesarean is associated with a higher risk to both the mother and the fetus; risks include excessive bleeding, lower uterine segment extensions, injuries to the maternal ureters or bladder, and injury to the fetus.2−4 The risk is increased even further if the fetal head is deeply impacted in the pelvis. What can we do to avoid and manage such situations?

Anticipate an impacted fetal headThe true incidence of an impacted fetal head at the time of cesarean is not known, although a number of risk factors have been described (TABLE). Obstetric care providers should be aware of these risk factors and anticipate the likelihood of a difficult delivery of the fetal head at cesarean.

Options for managing an impacted fetal head at cesareanSeveral techniques have been reported in the literature for managing the delivery of a deeply engaged head, including:

Using an assistant to push the fetus’s head up using a hand in the vagina (“push” technique). This can cause trauma to the fetus, since the force required to push the fetus up from below is uncontrolled.5,6

The reverse breech extraction (“pull” technique) involves pulling the infant out feet first through the uterine incision.7

Use of an instrument. The most common instrument used is a vacuum extractor,8 although a number of other devices have been developed, including the Murless fetal head extractor (an instrument with a hinged shaft and sliding collar lock),9 the C-Snorkel impacted fetal head release device (the device’s tip contains ventilation ports to facilitate airflow and release of the vacuum/suction created by the impacted fetal head),10 and the Fetal Pillow (a balloon device inserted in the vagina and inflated with sterile saline to disimpact an engaged fetal head before cesarean delivery).11

While all of these techniques can cause injury to the mother and the fetus, available data favor use of the reverse breech extraction (pull) technique, since it is associated with fewer maternal risks, including lower rates of uterine incision extension, infection, and postpartum hemorrhage and a shorter operative time.12−18

Stop use of vacuum to deliver the fetal head at cesarean

Placement of a vacuum can be effective in assisting with delivery of the fetal head at cesarean. For this reason, vacuum-assisted deliveries at cesarean are becoming more common. While the rate of complications caused by vacuum extraction of the fetal head at cesarean is not known, injuries have been reported.19,20 As such, routine use of vacuum extraction at the time of cesarean delivery cannot be recommended.

Start disengaging the fetal head prior to cesarean

One useful technique in planning a cesarean in the second stage of labor or when an impacted fetal head is anticipated is to disengage the fetal head vaginally prior to skin incision. This can be done in the delivery room or in the operating room immediately prior to surgery with the help of an assistant.

While supporting the patient’s legs, the assistant inserts a hand into the vagina and pushes upward on the fetal head with gentle, sustained effort. The assistant should use a cupped hand or the palm of the hand while attempting to both elevate and flex the fetal head. It is best to avoid using 1 or 2 fingers to elevate the head, as this may cause excessive pressure at a single point and lead to injury, such as a skull fracture (FIGURE). The assistant should disengage his or her hand only when the operating surgeon is able to reach down and secure the fetal head from above.

Elevating the fetal head prior to skin incision offers 3 major advantages:

- It avoids the embarrassing situation of having the fetus deliver vaginally before it can be pulled out through the abdominal incision. Although rare, this has been known to happen, because the dense regional anesthesia further relaxes the pelvic floor musculature, leading to flexion and rotation of the fetal head, which then descends and delivers. Performing a final bimanual examination in the operating room after the establishment of surgical level anesthesia and immediately prior to skin incision will avoid this situation.

- It elevates the fetal head, thereby creating additional space between the bony pelvis and fetal presenting part for the provider’s hand to fit. This helps minimize injury to the fetus and to the maternal soft tissues at the time of cesarean.

- Lastly, it provides additional information about the extent to which the fetal head is impacted in the pelvis and may influence decision making around the time of cesarean. For example, if the fetal head were deeply impacted in the pelvis and could not be disimpacted vaginally, the surgeon may choose to make a different uterine incision (such as a low vertical hysterotomy), administer a uterine relaxant (an inhaled anesthetic agent or nitric oxide), ask for additional instrumentation, and/or ask an assistant to be ready to elevate the fetal head vaginally should this be necessary.21

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Rates of cesarean delivery in the second stage of labor have increased dramatically over the past few years.1 Compared with cesarean delivery prior to labor, second-stage labor cesarean is associated with a higher risk to both the mother and the fetus; risks include excessive bleeding, lower uterine segment extensions, injuries to the maternal ureters or bladder, and injury to the fetus.2−4 The risk is increased even further if the fetal head is deeply impacted in the pelvis. What can we do to avoid and manage such situations?

Anticipate an impacted fetal headThe true incidence of an impacted fetal head at the time of cesarean is not known, although a number of risk factors have been described (TABLE). Obstetric care providers should be aware of these risk factors and anticipate the likelihood of a difficult delivery of the fetal head at cesarean.

Options for managing an impacted fetal head at cesareanSeveral techniques have been reported in the literature for managing the delivery of a deeply engaged head, including:

Using an assistant to push the fetus’s head up using a hand in the vagina (“push” technique). This can cause trauma to the fetus, since the force required to push the fetus up from below is uncontrolled.5,6

The reverse breech extraction (“pull” technique) involves pulling the infant out feet first through the uterine incision.7

Use of an instrument. The most common instrument used is a vacuum extractor,8 although a number of other devices have been developed, including the Murless fetal head extractor (an instrument with a hinged shaft and sliding collar lock),9 the C-Snorkel impacted fetal head release device (the device’s tip contains ventilation ports to facilitate airflow and release of the vacuum/suction created by the impacted fetal head),10 and the Fetal Pillow (a balloon device inserted in the vagina and inflated with sterile saline to disimpact an engaged fetal head before cesarean delivery).11

While all of these techniques can cause injury to the mother and the fetus, available data favor use of the reverse breech extraction (pull) technique, since it is associated with fewer maternal risks, including lower rates of uterine incision extension, infection, and postpartum hemorrhage and a shorter operative time.12−18

Stop use of vacuum to deliver the fetal head at cesarean

Placement of a vacuum can be effective in assisting with delivery of the fetal head at cesarean. For this reason, vacuum-assisted deliveries at cesarean are becoming more common. While the rate of complications caused by vacuum extraction of the fetal head at cesarean is not known, injuries have been reported.19,20 As such, routine use of vacuum extraction at the time of cesarean delivery cannot be recommended.

Start disengaging the fetal head prior to cesarean

One useful technique in planning a cesarean in the second stage of labor or when an impacted fetal head is anticipated is to disengage the fetal head vaginally prior to skin incision. This can be done in the delivery room or in the operating room immediately prior to surgery with the help of an assistant.

While supporting the patient’s legs, the assistant inserts a hand into the vagina and pushes upward on the fetal head with gentle, sustained effort. The assistant should use a cupped hand or the palm of the hand while attempting to both elevate and flex the fetal head. It is best to avoid using 1 or 2 fingers to elevate the head, as this may cause excessive pressure at a single point and lead to injury, such as a skull fracture (FIGURE). The assistant should disengage his or her hand only when the operating surgeon is able to reach down and secure the fetal head from above.

Elevating the fetal head prior to skin incision offers 3 major advantages:

- It avoids the embarrassing situation of having the fetus deliver vaginally before it can be pulled out through the abdominal incision. Although rare, this has been known to happen, because the dense regional anesthesia further relaxes the pelvic floor musculature, leading to flexion and rotation of the fetal head, which then descends and delivers. Performing a final bimanual examination in the operating room after the establishment of surgical level anesthesia and immediately prior to skin incision will avoid this situation.

- It elevates the fetal head, thereby creating additional space between the bony pelvis and fetal presenting part for the provider’s hand to fit. This helps minimize injury to the fetus and to the maternal soft tissues at the time of cesarean.

- Lastly, it provides additional information about the extent to which the fetal head is impacted in the pelvis and may influence decision making around the time of cesarean. For example, if the fetal head were deeply impacted in the pelvis and could not be disimpacted vaginally, the surgeon may choose to make a different uterine incision (such as a low vertical hysterotomy), administer a uterine relaxant (an inhaled anesthetic agent or nitric oxide), ask for additional instrumentation, and/or ask an assistant to be ready to elevate the fetal head vaginally should this be necessary.21

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Spencer C, Murphy D, Bewley S. Caesarean delivery in the second stage of labour. BMJ. 2006;333(7569):613–614.

- Häger RM, Daltviet AK, Hofoss D, et al. Complications of cesarean deliveries: rates and risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(2):428–434.

- Murphy DJ, Liebling RE, Verity L, Swingler R, Patel R. Early maternal and neonatal morbidity associated with operative delivery in second stage of labour: a cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358(9289):1203–1207.

- Pergialiotis V, Vlachos DG, Rodolakis A, Haidopoulos D, Thomakos N, Vlachos GD. First versus second stage C/S maternal and neonatal morbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;175:15–24.

- Lippert TH. Bimanual delivery of the fetal head at cesarean section with the fetal head in the midcavity. Arch Gynecol. 1983;234(1):59–60.

- Landesman R, Graber EA. Abdominovaginal delivery: modification of the cesarean section operation to facilitate delivery of the impacted head. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148(6):707–710.

- Fong YF, Arulkumaran S. Breech extraction—an alternative method of delivering a deeply engaged head at cesarean section. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;56(2):183–184.

- Arad I, Linder N, Bercovici B. Vacuum extraction at cesarean section—neonatal outcome. J Perinat Med. 1986;14(2):137–140.

- Murless BC. Lower-segment caesarean section; a new head extractor. BMJ. 1948;1(4564):1234.

- C-Snorkle impacted fetal head release device. Clinical Innovations website. http://clinicalinnovations.com /portfolio-items/c-snorkel/. Accessed July 22, 2016.

- Seal SL, Dey A, Barman SC, Kamilya G, Mukherji J, Onwude JL. Randomized controlled trial of elevation of the fetal head with a fetal pillow during cesarean delivery at full cervical dilatation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;133(2):178–182.

- Fasubaa OB, Ezechi OC, Orji EO, et al. Delivery of the impacted head of the fetus at caesarean section after prolonged obstructed labour: a randomised comparative study of two methods. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22(4):375–378.

- Levy R, Chernomoretz T, Appelman Z, Levin D, Or Y, Hagay ZJ. Head pushing versus reverse breech extraction in cases of impacted fetal head during Cesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;121(1):24–26.

- Chopra S, Bagga R, Keepanasseril A, Jain V, Kalra J, Suri V. Disengagement of the deeply engaged fetal head during cesarean section in advanced labor: conventional method versus reverse breech extraction. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(10):1163–1166.

- Veisi F, Zangeneh M, Malekkhosravi S, Rezavand N. Comparison of “push” and “pull” methods for impacted fetal head extraction during cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;118(1):4–6.

- Bastani P, Pourabolghasem S, Abbasalizadeh F, Motvalli L. ComparisonColor/Black of neonatal and maternal outcomes associated with head-pushing and head-pulling methods for impacted fetal head extraction during cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;118(1):1–3.

- Waterfall H, Grivell RM, Dodd JM. Techniques for assisting difficult delivery at caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;1:CD004944.

- Jeve YB, Navti OB, Konje JC. Comparison of techniques used to deliver a deeply impacted fetal head at full dilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2016;123(3): 337–345.

- Clark SL, Vines VL, Belfort MA. Fetal injury associated with routine vacuum use during cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):e4.

- Fareeduddin R, Schifrin BS. Subgaleal hemorrhage after the use of a vacuum extractor during elective cesarean delivery: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(10):809–810.

- Barbieri RL. Difficult fetal extraction at cesarean delivery: What should you do? OBG Manag. 2012;24(1):8–12.

- Spencer C, Murphy D, Bewley S. Caesarean delivery in the second stage of labour. BMJ. 2006;333(7569):613–614.

- Häger RM, Daltviet AK, Hofoss D, et al. Complications of cesarean deliveries: rates and risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(2):428–434.

- Murphy DJ, Liebling RE, Verity L, Swingler R, Patel R. Early maternal and neonatal morbidity associated with operative delivery in second stage of labour: a cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358(9289):1203–1207.

- Pergialiotis V, Vlachos DG, Rodolakis A, Haidopoulos D, Thomakos N, Vlachos GD. First versus second stage C/S maternal and neonatal morbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;175:15–24.

- Lippert TH. Bimanual delivery of the fetal head at cesarean section with the fetal head in the midcavity. Arch Gynecol. 1983;234(1):59–60.

- Landesman R, Graber EA. Abdominovaginal delivery: modification of the cesarean section operation to facilitate delivery of the impacted head. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148(6):707–710.

- Fong YF, Arulkumaran S. Breech extraction—an alternative method of delivering a deeply engaged head at cesarean section. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;56(2):183–184.

- Arad I, Linder N, Bercovici B. Vacuum extraction at cesarean section—neonatal outcome. J Perinat Med. 1986;14(2):137–140.

- Murless BC. Lower-segment caesarean section; a new head extractor. BMJ. 1948;1(4564):1234.

- C-Snorkle impacted fetal head release device. Clinical Innovations website. http://clinicalinnovations.com /portfolio-items/c-snorkel/. Accessed July 22, 2016.

- Seal SL, Dey A, Barman SC, Kamilya G, Mukherji J, Onwude JL. Randomized controlled trial of elevation of the fetal head with a fetal pillow during cesarean delivery at full cervical dilatation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;133(2):178–182.

- Fasubaa OB, Ezechi OC, Orji EO, et al. Delivery of the impacted head of the fetus at caesarean section after prolonged obstructed labour: a randomised comparative study of two methods. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22(4):375–378.

- Levy R, Chernomoretz T, Appelman Z, Levin D, Or Y, Hagay ZJ. Head pushing versus reverse breech extraction in cases of impacted fetal head during Cesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;121(1):24–26.

- Chopra S, Bagga R, Keepanasseril A, Jain V, Kalra J, Suri V. Disengagement of the deeply engaged fetal head during cesarean section in advanced labor: conventional method versus reverse breech extraction. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(10):1163–1166.

- Veisi F, Zangeneh M, Malekkhosravi S, Rezavand N. Comparison of “push” and “pull” methods for impacted fetal head extraction during cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;118(1):4–6.

- Bastani P, Pourabolghasem S, Abbasalizadeh F, Motvalli L. ComparisonColor/Black of neonatal and maternal outcomes associated with head-pushing and head-pulling methods for impacted fetal head extraction during cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;118(1):1–3.

- Waterfall H, Grivell RM, Dodd JM. Techniques for assisting difficult delivery at caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;1:CD004944.

- Jeve YB, Navti OB, Konje JC. Comparison of techniques used to deliver a deeply impacted fetal head at full dilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2016;123(3): 337–345.

- Clark SL, Vines VL, Belfort MA. Fetal injury associated with routine vacuum use during cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):e4.

- Fareeduddin R, Schifrin BS. Subgaleal hemorrhage after the use of a vacuum extractor during elective cesarean delivery: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(10):809–810.

- Barbieri RL. Difficult fetal extraction at cesarean delivery: What should you do? OBG Manag. 2012;24(1):8–12.

In this Article

- Risk factors for impacted fetal head

- Advantages to elevating fetal head

Does extending aromatase-inhibitor use from 5 to 10 years benefit menopausal women with hormone-positive breast cancer?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Since the current treatment choice for hormone-receptor–positive early breast cancer in postmenopausal women is 5 years of aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy, or AI therapy following initial tamoxifen treatment, could 10 years of an AI be beneficial to cancer recurrence? Goss and colleagues analyzed this question in the MA.17R trial, a North American Breast Cancer Group trial coordinated by the Canadian Cancer Trials Group. (Results of the prior MA.17 trial were published in 2003.1)

The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the effect of 5 years of extended AI (letrozole 2.5 mg) treatment compared with placebo in menopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer who had previously received 5 years of hormonal adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen alone or plus AIs. Of note, this study was funded in part by Novartis, the pharmaceutical manufacturer of letrozole, though the company had no role in either study design or writing of the manuscript. Seven of the 20 authors disclosed some sort of relationship with industry (some with the manufacturer of letrozole), including membership on advisory boards, board of directors, steering committees, or data and safety monitoring committees or receiving lecturer or consulting fees or grant support.

The trial’s primary end point was DFS. Secondary end points included overall survival, the incidence of contralateral breast cancer, quality of life (QOL), and long-term safety.

Details of the studyWomen were eligible to participate in the study if they were disease free after having completed 4.5 to 6 years of therapy with any AI and if their primary tumor was hormone-receptor positive. A total of 1,918 women were included in the trial and were randomly assigned to receive either letrozole treatment (n = 959) or placebo (n = 959).

Clinical evaluation was performed annually and included assessments of new bone fracture and new-onset osteoporosis, blood tests, mammography, and assessment of toxic effects. QOL measures were assessed with a validated health survey and a menopause-specific questionnaire. The Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0, was used to assess adverse events.

Impact on disease free, overall survivalThe rate of 5-year DFS was statistically improved in the letrozole group compared with the placebo group, 95% (95% confidence interval [CI], 93–96) versus 91% (95% CI, 89–93), respectively, a 4% improvement in DFS. However, there was no impact on disease-specific mortality and no benefit in overall survival (93% [95% CI, 92–95] with letrozole and 94% [95% CI, 92–95] with placebo), as competing causes of death become increasingly important in this older population. Among women who died during the study follow-up, more than half died of causes not related to breast cancer.

QOL measures. More than 85% of participants completed the QOL assessments at each time point. There was no difference in the various QOL measures between the letrozole and the placebo group.

Adverse effects. Expected adverse effects due to AIs were significantly higher in the letrozole group. For example, new-onset osteoporosis occurred in 109 (11%) of letrozole-treated women and in 54 (6%) of the placebo group (P<.001), and bone fracture occurred in 133 (14%) of the letrozole group and 88 (9%) of the placebo group (P = .001).

Of note, however, fewer toxicities/adverse effects were seen in the AI group in this study than in previously published reports. The authors suggested that these adverse effect data may be lower than expected because the majority of women eligible for this study likely had prior exposure to AIs, and those with significant adverse effects with aromatase inhibitor therapy may have self-selected out of this trial.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICEWhile the study authors selected DFS as the primary outcome, the lack of overall survival, adverse effect profile, and the drug cost (average wholesale price, ~$33,050 for 5 years2) make the choice to routinely continue AIs in menopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer less clear, and counseling on both the benefits and limitations of continuing hormonal adjuvant therapy will be important for these women.

Continued follow-up of the study participants over time would be useful to determine if, after 10 to 15 years, the benefit of extending AI therapy for an additional 5 years would provide an overall benefit in longevity, as competing causes of death (bone fracture, cardiovascular risk) actually may increase over time in the extended-treatment group compared with the placebo group.

— Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1793–1802.

- Average Wholesale Price (AWP) Policy. Truven Health Analytics. Red Book. http://sites.truvenhealth.com/redbook /awp/. Accessed July 18, 2016.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Since the current treatment choice for hormone-receptor–positive early breast cancer in postmenopausal women is 5 years of aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy, or AI therapy following initial tamoxifen treatment, could 10 years of an AI be beneficial to cancer recurrence? Goss and colleagues analyzed this question in the MA.17R trial, a North American Breast Cancer Group trial coordinated by the Canadian Cancer Trials Group. (Results of the prior MA.17 trial were published in 2003.1)

The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the effect of 5 years of extended AI (letrozole 2.5 mg) treatment compared with placebo in menopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer who had previously received 5 years of hormonal adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen alone or plus AIs. Of note, this study was funded in part by Novartis, the pharmaceutical manufacturer of letrozole, though the company had no role in either study design or writing of the manuscript. Seven of the 20 authors disclosed some sort of relationship with industry (some with the manufacturer of letrozole), including membership on advisory boards, board of directors, steering committees, or data and safety monitoring committees or receiving lecturer or consulting fees or grant support.

The trial’s primary end point was DFS. Secondary end points included overall survival, the incidence of contralateral breast cancer, quality of life (QOL), and long-term safety.

Details of the studyWomen were eligible to participate in the study if they were disease free after having completed 4.5 to 6 years of therapy with any AI and if their primary tumor was hormone-receptor positive. A total of 1,918 women were included in the trial and were randomly assigned to receive either letrozole treatment (n = 959) or placebo (n = 959).

Clinical evaluation was performed annually and included assessments of new bone fracture and new-onset osteoporosis, blood tests, mammography, and assessment of toxic effects. QOL measures were assessed with a validated health survey and a menopause-specific questionnaire. The Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0, was used to assess adverse events.

Impact on disease free, overall survivalThe rate of 5-year DFS was statistically improved in the letrozole group compared with the placebo group, 95% (95% confidence interval [CI], 93–96) versus 91% (95% CI, 89–93), respectively, a 4% improvement in DFS. However, there was no impact on disease-specific mortality and no benefit in overall survival (93% [95% CI, 92–95] with letrozole and 94% [95% CI, 92–95] with placebo), as competing causes of death become increasingly important in this older population. Among women who died during the study follow-up, more than half died of causes not related to breast cancer.

QOL measures. More than 85% of participants completed the QOL assessments at each time point. There was no difference in the various QOL measures between the letrozole and the placebo group.

Adverse effects. Expected adverse effects due to AIs were significantly higher in the letrozole group. For example, new-onset osteoporosis occurred in 109 (11%) of letrozole-treated women and in 54 (6%) of the placebo group (P<.001), and bone fracture occurred in 133 (14%) of the letrozole group and 88 (9%) of the placebo group (P = .001).

Of note, however, fewer toxicities/adverse effects were seen in the AI group in this study than in previously published reports. The authors suggested that these adverse effect data may be lower than expected because the majority of women eligible for this study likely had prior exposure to AIs, and those with significant adverse effects with aromatase inhibitor therapy may have self-selected out of this trial.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICEWhile the study authors selected DFS as the primary outcome, the lack of overall survival, adverse effect profile, and the drug cost (average wholesale price, ~$33,050 for 5 years2) make the choice to routinely continue AIs in menopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer less clear, and counseling on both the benefits and limitations of continuing hormonal adjuvant therapy will be important for these women.

Continued follow-up of the study participants over time would be useful to determine if, after 10 to 15 years, the benefit of extending AI therapy for an additional 5 years would provide an overall benefit in longevity, as competing causes of death (bone fracture, cardiovascular risk) actually may increase over time in the extended-treatment group compared with the placebo group.

— Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Since the current treatment choice for hormone-receptor–positive early breast cancer in postmenopausal women is 5 years of aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy, or AI therapy following initial tamoxifen treatment, could 10 years of an AI be beneficial to cancer recurrence? Goss and colleagues analyzed this question in the MA.17R trial, a North American Breast Cancer Group trial coordinated by the Canadian Cancer Trials Group. (Results of the prior MA.17 trial were published in 2003.1)

The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the effect of 5 years of extended AI (letrozole 2.5 mg) treatment compared with placebo in menopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer who had previously received 5 years of hormonal adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen alone or plus AIs. Of note, this study was funded in part by Novartis, the pharmaceutical manufacturer of letrozole, though the company had no role in either study design or writing of the manuscript. Seven of the 20 authors disclosed some sort of relationship with industry (some with the manufacturer of letrozole), including membership on advisory boards, board of directors, steering committees, or data and safety monitoring committees or receiving lecturer or consulting fees or grant support.

The trial’s primary end point was DFS. Secondary end points included overall survival, the incidence of contralateral breast cancer, quality of life (QOL), and long-term safety.

Details of the studyWomen were eligible to participate in the study if they were disease free after having completed 4.5 to 6 years of therapy with any AI and if their primary tumor was hormone-receptor positive. A total of 1,918 women were included in the trial and were randomly assigned to receive either letrozole treatment (n = 959) or placebo (n = 959).

Clinical evaluation was performed annually and included assessments of new bone fracture and new-onset osteoporosis, blood tests, mammography, and assessment of toxic effects. QOL measures were assessed with a validated health survey and a menopause-specific questionnaire. The Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0, was used to assess adverse events.

Impact on disease free, overall survivalThe rate of 5-year DFS was statistically improved in the letrozole group compared with the placebo group, 95% (95% confidence interval [CI], 93–96) versus 91% (95% CI, 89–93), respectively, a 4% improvement in DFS. However, there was no impact on disease-specific mortality and no benefit in overall survival (93% [95% CI, 92–95] with letrozole and 94% [95% CI, 92–95] with placebo), as competing causes of death become increasingly important in this older population. Among women who died during the study follow-up, more than half died of causes not related to breast cancer.

QOL measures. More than 85% of participants completed the QOL assessments at each time point. There was no difference in the various QOL measures between the letrozole and the placebo group.

Adverse effects. Expected adverse effects due to AIs were significantly higher in the letrozole group. For example, new-onset osteoporosis occurred in 109 (11%) of letrozole-treated women and in 54 (6%) of the placebo group (P<.001), and bone fracture occurred in 133 (14%) of the letrozole group and 88 (9%) of the placebo group (P = .001).

Of note, however, fewer toxicities/adverse effects were seen in the AI group in this study than in previously published reports. The authors suggested that these adverse effect data may be lower than expected because the majority of women eligible for this study likely had prior exposure to AIs, and those with significant adverse effects with aromatase inhibitor therapy may have self-selected out of this trial.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICEWhile the study authors selected DFS as the primary outcome, the lack of overall survival, adverse effect profile, and the drug cost (average wholesale price, ~$33,050 for 5 years2) make the choice to routinely continue AIs in menopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer less clear, and counseling on both the benefits and limitations of continuing hormonal adjuvant therapy will be important for these women.

Continued follow-up of the study participants over time would be useful to determine if, after 10 to 15 years, the benefit of extending AI therapy for an additional 5 years would provide an overall benefit in longevity, as competing causes of death (bone fracture, cardiovascular risk) actually may increase over time in the extended-treatment group compared with the placebo group.

— Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1793–1802.

- Average Wholesale Price (AWP) Policy. Truven Health Analytics. Red Book. http://sites.truvenhealth.com/redbook /awp/. Accessed July 18, 2016.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1793–1802.

- Average Wholesale Price (AWP) Policy. Truven Health Analytics. Red Book. http://sites.truvenhealth.com/redbook /awp/. Accessed July 18, 2016.

Simple Strategy for Addressing Problematic Patient Behavior

Linden Spital, NP, a psychiatric mental-health nurse practitioner, staffs the Psychiatric Consultation Liaison Service at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Nearly every hospital larger than about 200 beds, she says, could benefit from a similar service, and hospitalists could play an important role in creating it.

I wrote about the idea for a generally similar service in my April 2015 column, but at the time, I didn’t know of an institution that had something like this in place.

Along with her hospitalist colleagues, Anupama (Anu) Goyal, MBChB, and Rob Chang, MD, Linden has launched a service to provide assistance to bedside caregivers dealing with very difficult patients (eg, those who are verbally or physically threatening to staff, unreasonably demanding and angry, have bizarre behavior, etc.).

Sample Cases

Two recent cases illustrate the role of the service. A female patient in her 60s had several admissions characterized by what many caregivers agreed were unreasonably precise demands regarding how her care should be delivered. She was verbally abusive of caregivers, especially those who were young or of a different race, and her family member tended to reinforce these maladaptive behaviors. Staff found it very stressful to care for her and had concerns that her care suffered as a result.

Linden served as a resource and support for staff, plus worked with providers to set limits on the patient and family behavior and to separate patient behaviors that were and weren’t modifiable. Linden’s efforts helped clarify the goals for the patient’s care and reduced staff distress. Even though the patient’s behavior didn’t change significantly, staff anecdotally reported less distress and concern that the patient’s care suffered as a result.

Another case involved a man in his 50s who had a progressive neurodegenerative disease and was admitted because of increasingly aggressive behavior in his skilled-nursing facility (SNF). Providers at the SNF attributed the poor behavior to changes in medications. His behavior was very difficult to manage, and staff asked for Linden’s help. She worked with the patient and realized much of his difficult behavior stemmed from his frustration with communicating verbally because of his neurologic disease. Rather than pursue increasing psychotropics, Linden promoted efforts to develop a system of hand signals the patient could use to communicate needs. His behavior improved, presumably by reducing his own frustration and improving his autonomy.

Atypical Consults

This psychiatric consultation liaison service has some overlap with traditional inpatient psychiatry services, but it is configured so that the caregiver is essentially embedded on the medical units of the hospital and assists in the care of patients who wouldn’t typically be appropriate for a psychiatry consult. For example, patients and/or families who act out because of anger over being on observation status are appropriate for this service but would usually not be appropriate for a psychiatry consult. The two examples above aren’t ideal cases for a standard psychiatry consult; however, the attending hospitalist needed help nonetheless.

Operational Details

The liaison service started with a successful trial on two hospital units in 2013. Linden began serving as the sole clinician on the service in January 2015. She is available during the daytime on weekdays, and any staff can request her participation in the care of a patient. Her visits are billed when appropriate, but many aren’t billed (for example, if her primary work was to conference with staff regarding management of a patient).

Consults can be requested by anyone (nurses, etc., as well as physicians, though only the latter would be billable) via an electronic health record entry that helps ensure whether the request is for this service versus the inpatient psychiatry service. The order includes a standard list of potential reasons for consult that can be selected and amplified with free text comments. She also receives verbal consult requests as she moves through the hospital.

Linden’s position is budgeted through the psychiatry department and funded by the hospital with only modest professional fee collections.

An Idea That Is Catching On?

Anu Goyal made me aware of a study from 2004 that summarized findings from experience with a similar service at Washington University in St. Louis, but the service was cancelled after a short time due to its cost.1 She also found a few studies from the 1990s and a 2001 study from Australia that report on a similar service.

But maybe the idea is catching on again, at least a little.

On April 25, The Wall Street Journal published an article titled “Hospitals Test Putting Psychiatrists on Medical Wards.”2 It described programs at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, and NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center in New York City. They share some similarities with the service at the University of Michigan. However, according to the article, the three big-city programs tilt more toward a traditional consultation model than what Linden does.

I think every hospital should be thinking about a service other than traditional consult psychiatry that could help with challenging patient behavior. The University of Michigan model or similar ones seem like a good place to start. TH

Reference

- Yakimo R, Kurlowicz L, Murray R. Evaluation of outcomes in psychiatric consultation-liaison nursing practice. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2004;18(6):215-227.

2. Ladnado L. Hospitals test putting psychiatrists on medical wards. The Wall Street Journal website. Accessed July 3, 2016.

Linden Spital, NP, a psychiatric mental-health nurse practitioner, staffs the Psychiatric Consultation Liaison Service at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Nearly every hospital larger than about 200 beds, she says, could benefit from a similar service, and hospitalists could play an important role in creating it.

I wrote about the idea for a generally similar service in my April 2015 column, but at the time, I didn’t know of an institution that had something like this in place.

Along with her hospitalist colleagues, Anupama (Anu) Goyal, MBChB, and Rob Chang, MD, Linden has launched a service to provide assistance to bedside caregivers dealing with very difficult patients (eg, those who are verbally or physically threatening to staff, unreasonably demanding and angry, have bizarre behavior, etc.).

Sample Cases

Two recent cases illustrate the role of the service. A female patient in her 60s had several admissions characterized by what many caregivers agreed were unreasonably precise demands regarding how her care should be delivered. She was verbally abusive of caregivers, especially those who were young or of a different race, and her family member tended to reinforce these maladaptive behaviors. Staff found it very stressful to care for her and had concerns that her care suffered as a result.

Linden served as a resource and support for staff, plus worked with providers to set limits on the patient and family behavior and to separate patient behaviors that were and weren’t modifiable. Linden’s efforts helped clarify the goals for the patient’s care and reduced staff distress. Even though the patient’s behavior didn’t change significantly, staff anecdotally reported less distress and concern that the patient’s care suffered as a result.

Another case involved a man in his 50s who had a progressive neurodegenerative disease and was admitted because of increasingly aggressive behavior in his skilled-nursing facility (SNF). Providers at the SNF attributed the poor behavior to changes in medications. His behavior was very difficult to manage, and staff asked for Linden’s help. She worked with the patient and realized much of his difficult behavior stemmed from his frustration with communicating verbally because of his neurologic disease. Rather than pursue increasing psychotropics, Linden promoted efforts to develop a system of hand signals the patient could use to communicate needs. His behavior improved, presumably by reducing his own frustration and improving his autonomy.

Atypical Consults

This psychiatric consultation liaison service has some overlap with traditional inpatient psychiatry services, but it is configured so that the caregiver is essentially embedded on the medical units of the hospital and assists in the care of patients who wouldn’t typically be appropriate for a psychiatry consult. For example, patients and/or families who act out because of anger over being on observation status are appropriate for this service but would usually not be appropriate for a psychiatry consult. The two examples above aren’t ideal cases for a standard psychiatry consult; however, the attending hospitalist needed help nonetheless.

Operational Details

The liaison service started with a successful trial on two hospital units in 2013. Linden began serving as the sole clinician on the service in January 2015. She is available during the daytime on weekdays, and any staff can request her participation in the care of a patient. Her visits are billed when appropriate, but many aren’t billed (for example, if her primary work was to conference with staff regarding management of a patient).

Consults can be requested by anyone (nurses, etc., as well as physicians, though only the latter would be billable) via an electronic health record entry that helps ensure whether the request is for this service versus the inpatient psychiatry service. The order includes a standard list of potential reasons for consult that can be selected and amplified with free text comments. She also receives verbal consult requests as she moves through the hospital.

Linden’s position is budgeted through the psychiatry department and funded by the hospital with only modest professional fee collections.

An Idea That Is Catching On?

Anu Goyal made me aware of a study from 2004 that summarized findings from experience with a similar service at Washington University in St. Louis, but the service was cancelled after a short time due to its cost.1 She also found a few studies from the 1990s and a 2001 study from Australia that report on a similar service.

But maybe the idea is catching on again, at least a little.

On April 25, The Wall Street Journal published an article titled “Hospitals Test Putting Psychiatrists on Medical Wards.”2 It described programs at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, and NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center in New York City. They share some similarities with the service at the University of Michigan. However, according to the article, the three big-city programs tilt more toward a traditional consultation model than what Linden does.

I think every hospital should be thinking about a service other than traditional consult psychiatry that could help with challenging patient behavior. The University of Michigan model or similar ones seem like a good place to start. TH

Reference

- Yakimo R, Kurlowicz L, Murray R. Evaluation of outcomes in psychiatric consultation-liaison nursing practice. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2004;18(6):215-227.

2. Ladnado L. Hospitals test putting psychiatrists on medical wards. The Wall Street Journal website. Accessed July 3, 2016.

Linden Spital, NP, a psychiatric mental-health nurse practitioner, staffs the Psychiatric Consultation Liaison Service at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Nearly every hospital larger than about 200 beds, she says, could benefit from a similar service, and hospitalists could play an important role in creating it.

I wrote about the idea for a generally similar service in my April 2015 column, but at the time, I didn’t know of an institution that had something like this in place.

Along with her hospitalist colleagues, Anupama (Anu) Goyal, MBChB, and Rob Chang, MD, Linden has launched a service to provide assistance to bedside caregivers dealing with very difficult patients (eg, those who are verbally or physically threatening to staff, unreasonably demanding and angry, have bizarre behavior, etc.).

Sample Cases

Two recent cases illustrate the role of the service. A female patient in her 60s had several admissions characterized by what many caregivers agreed were unreasonably precise demands regarding how her care should be delivered. She was verbally abusive of caregivers, especially those who were young or of a different race, and her family member tended to reinforce these maladaptive behaviors. Staff found it very stressful to care for her and had concerns that her care suffered as a result.

Linden served as a resource and support for staff, plus worked with providers to set limits on the patient and family behavior and to separate patient behaviors that were and weren’t modifiable. Linden’s efforts helped clarify the goals for the patient’s care and reduced staff distress. Even though the patient’s behavior didn’t change significantly, staff anecdotally reported less distress and concern that the patient’s care suffered as a result.

Another case involved a man in his 50s who had a progressive neurodegenerative disease and was admitted because of increasingly aggressive behavior in his skilled-nursing facility (SNF). Providers at the SNF attributed the poor behavior to changes in medications. His behavior was very difficult to manage, and staff asked for Linden’s help. She worked with the patient and realized much of his difficult behavior stemmed from his frustration with communicating verbally because of his neurologic disease. Rather than pursue increasing psychotropics, Linden promoted efforts to develop a system of hand signals the patient could use to communicate needs. His behavior improved, presumably by reducing his own frustration and improving his autonomy.

Atypical Consults

This psychiatric consultation liaison service has some overlap with traditional inpatient psychiatry services, but it is configured so that the caregiver is essentially embedded on the medical units of the hospital and assists in the care of patients who wouldn’t typically be appropriate for a psychiatry consult. For example, patients and/or families who act out because of anger over being on observation status are appropriate for this service but would usually not be appropriate for a psychiatry consult. The two examples above aren’t ideal cases for a standard psychiatry consult; however, the attending hospitalist needed help nonetheless.

Operational Details

The liaison service started with a successful trial on two hospital units in 2013. Linden began serving as the sole clinician on the service in January 2015. She is available during the daytime on weekdays, and any staff can request her participation in the care of a patient. Her visits are billed when appropriate, but many aren’t billed (for example, if her primary work was to conference with staff regarding management of a patient).

Consults can be requested by anyone (nurses, etc., as well as physicians, though only the latter would be billable) via an electronic health record entry that helps ensure whether the request is for this service versus the inpatient psychiatry service. The order includes a standard list of potential reasons for consult that can be selected and amplified with free text comments. She also receives verbal consult requests as she moves through the hospital.

Linden’s position is budgeted through the psychiatry department and funded by the hospital with only modest professional fee collections.

An Idea That Is Catching On?

Anu Goyal made me aware of a study from 2004 that summarized findings from experience with a similar service at Washington University in St. Louis, but the service was cancelled after a short time due to its cost.1 She also found a few studies from the 1990s and a 2001 study from Australia that report on a similar service.

But maybe the idea is catching on again, at least a little.

On April 25, The Wall Street Journal published an article titled “Hospitals Test Putting Psychiatrists on Medical Wards.”2 It described programs at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, and NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center in New York City. They share some similarities with the service at the University of Michigan. However, according to the article, the three big-city programs tilt more toward a traditional consultation model than what Linden does.

I think every hospital should be thinking about a service other than traditional consult psychiatry that could help with challenging patient behavior. The University of Michigan model or similar ones seem like a good place to start. TH

Reference

- Yakimo R, Kurlowicz L, Murray R. Evaluation of outcomes in psychiatric consultation-liaison nursing practice. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2004;18(6):215-227.

2. Ladnado L. Hospitals test putting psychiatrists on medical wards. The Wall Street Journal website. Accessed July 3, 2016.

Skin rash in recent traveler? Think dengue fever

BOSTON – Maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever among individuals with recent travel to endemic areas who present with a rash and other signs and symptoms of infection, an expert advised at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

Dengue fever accounts for nearly 10% of skin rashes among individuals returning from endemic areas, and related illness can range from mild to fatal, said Jose Dario Martinez, MD, chief of the Internal Medicine Clinic at University Hospital “J.E. Gonzalez,” UANL Monterrey, Mexico.

“This is the most prevalent arthropod-borne virus in the world at this time, and it is a resurgent disease in some countries, like Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia,” he noted.

Worldwide, more than 2.5 billion people are at risk of dengue infection, and between 50 million and 100 million cases occur each year, while about 250,000 to 500,000 cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever occur each year, and about 25,000 related deaths occur.

In 2005, there was a dengue outbreak in Texas, where 25 cases occurred; and in southern Florida, an outbreak of 90 cases was reported in 2009 and 2010. More recently, in 2015, there was an outbreak of 107 cases of locally-acquired dengue on the Big Island, Hawaii (MMWR). But in Mexico, 18,000 new cases occurred in 2015, Dr. Martinez said.

Of the RNA virus serotypes 1-4, type 1 (DENV1) is the most common, and DENV2 and 3 are the most severe, but up to 40% of cases are asymptomatic, he noted, adding that the virus has an incubation period of 2-8 days. When symptoms occur, they are representative of acute febrile illness, and may include headache, high fever, myalgia, arthralgia, retro-orbital pain, and fatigue. A faint, itchy, macular rash commonly occurs at 2-6 days into the illness. According to the World Health Organization, a probable dengue fever case includes acute febrile illness and at least two of either headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, arthralgia, rash, hemorrhagic manifestations, leukopenia, or supportive serology.

“Sometimes the nose bleeds, the gums bleed, and there is bruising in the patient,” Dr. Martinez said. “Most important are retro-orbital pain and hemorrhagic manifestations, but also supportive serology.”

About 1% of patients progress to dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome during the critical phase (days 4-7) of illness. This is most likely in those with serotypes 2 and 3, but can occur with all serotypes. Warning signs of such severe disease include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, pleural effusion or ascites, and of particular importance – mucosal bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

By the WHO definition, a diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever requires the presence of fever for at least 2-7 days, hemorrhagic tendencies, thrombocytopenia, and evidence and signs of plasma leakage; dengue shock syndrome requires these, as well as evidence of circulatory failure, such as rapid and weak pulse, narrow pulse pressure, hypotension, and shock.

It is important to maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever, particularly in anyone who has traveled to an endemic area in the 2 weeks before presentation. Serologic tests are important to detect anti-dengue antibodies. IgG is important, because its presence could suggest recurrent infection and thus the potential for severe disease, Dr. Martinez said. Polymerase chain reaction can be used for detection in the first 4-5 days of infection, and the NS1 rapid test can be positive on the first day, he noted.

The differential diagnosis for dengue fever is broad, and can include chikungunya fever, malaria, leptospirosis, meningococcemia, drug eruption, and Zika fever.

Management of dengue fever includes bed rest, liquids, and mosquito net isolation to prevent re-infection, as more severe disease can occur after re-infection. Acetaminophen can be used for pain relief; aspirin should be avoided due to risk of bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

Hospitalization and supportive care are required for those with dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome. Intensive care unit admission may be required.

Of note, a vaccine against dengue fever has shown promise in phase III trials. The vaccine has been approved in Mexico and Brazil, but not yet in the U.S.

Dr Martinez reported having no disclosures.

BOSTON – Maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever among individuals with recent travel to endemic areas who present with a rash and other signs and symptoms of infection, an expert advised at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

Dengue fever accounts for nearly 10% of skin rashes among individuals returning from endemic areas, and related illness can range from mild to fatal, said Jose Dario Martinez, MD, chief of the Internal Medicine Clinic at University Hospital “J.E. Gonzalez,” UANL Monterrey, Mexico.

“This is the most prevalent arthropod-borne virus in the world at this time, and it is a resurgent disease in some countries, like Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia,” he noted.

Worldwide, more than 2.5 billion people are at risk of dengue infection, and between 50 million and 100 million cases occur each year, while about 250,000 to 500,000 cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever occur each year, and about 25,000 related deaths occur.

In 2005, there was a dengue outbreak in Texas, where 25 cases occurred; and in southern Florida, an outbreak of 90 cases was reported in 2009 and 2010. More recently, in 2015, there was an outbreak of 107 cases of locally-acquired dengue on the Big Island, Hawaii (MMWR). But in Mexico, 18,000 new cases occurred in 2015, Dr. Martinez said.