User login

Tissue extraction: Can the pendulum change direction?

On April 17, 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a safety communication that discouraged the use of laparoscopic power morcellation during hysterectomy or myomectomy for the treatment of women with uterine fibroids. This recommendation was based mainly on the premise that fibroids may contain an underlying malignancy (in 1 in 350 women) that laparoscopic power morcellation could spread, thereby potentially worsening a cancer prognosis.1 Whether we liked it or not, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery as we knew it had changed forever on that fateful day.

During the last 2 years, the implications of that initial safety communication, along with its update in November of 2014,2 have been far reaching. From a health care industry perspective, the largest manufacturer of power morcellators, Johnson & Johnson, completely pulled its device out of the market within months of the initial FDA safety communication.3 Although several other companies remained in the market, health insurers such as Highmark and Aetna took the stance of not paying for the routine use of a power morcellator.4,5 Soon government officials became involved in the campaign against power morcellators and trial lawyers made this surgical device the latest “hot target.”6,7

The power morcellator’s absence impactFor clinicians, the narrative painted had moved the pendulum so far against power morcellation that it did not come as a surprise that practice patterns were significantly impacted. Harris and colleagues recently measured that impact by evaluating practice patterns and postoperative complications before and after the FDA safety communication on power morcellation. In their retrospective cohort study of patients within the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, utilization of minimally invasive hysterectomy decreased and major surgical, nontransfusion complications and 30-day hospital readmission rates increased after release of the safety communication.8

Further support of this change in practice patterns was demonstrated in a recent survey conducted by the AAGL and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Collaborative Ambulatory Research Network (ACOG CARN). In this survey study, Lum and colleagues were able to show that power morcellation use decreased among AAGL and ACOG CARN members after the FDA warnings, and rates of laparotomy increased.9

Critical to the discussion, yet apparently overlooked during the formulation of the initial FDA warning, was the potential clinical significance of the downstream impact of converting minimally invasive surgical cases to more invasive laparotomies. A decision-tree analysis published by Siedhoff and colleagues highlighted this point by predicting fewer overall deaths for laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation compared with abdominal hysterectomy.10 An ability to weigh the benefits and risks of procedure-related complications that are associated with laparotomy, including death, should have been part of the conversation from the beginning.

There is a silver lining emergingBased on this domino effect, it would seem that the damage done to minimally invasive gynecologic surgery over the past 2 years is irreparable. So is there any silver lining to the current state of affairs in tissue extraction? I would argue yes.

We have updated estimates for incidence of unsuspected leiomyosarcoma. First of all, discussions surrounding the FDA’s estimated 1 in 350 risk of encountering an unsuspected uterine sarcoma during the treatment of fibroids prompted a more critical evaluation of the scientific literature. In fact, Parker and colleagues, in a commentary published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, summarized very nicely the flawed methodology in the FDA’s determination of risk and in turn presented several updated calculations and studies that placed the prevalence somewhere in the range of 2 in 8,720 (0.023%) to 1 in 1,550 (0.064%).11

We are speaking with the FDA. Channels of communication with the FDA have since been developed and societies such as the AAGL were invited by the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) at the FDA to serve in their Network of Experts. This Network of Experts is an FDA-vetted group of non−FDA affiliated scientists, clinicians, and engineers who provide the CDRH at the FDA with rapid access to scientific, engineering, and medical expertise when it is needed to supplement existing knowledge and expertise within the CDRH. By developing these lines of communication, the CDRH is able to broaden its exposure to scientific viewpoints without the influence of external, or non−FDA, policy advice or opinions.

We have been innovating our techniques. Clinicians also began to develop innovative techniques for tissue extraction that also included contained, in-bag power morcellation. Vargas and colleagues showed similar perioperative outcomes when comparing open power morcellation with contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag. The mean operative time was prolonged by only 26 minutes with in-bag morcellation.12

Although the initial experience of surgeons involved various containment systems that were off label in their usage and not designed to be paired with a power morcellator, it allowed for the identification of potential limitations, such as the risk of leakage. Cohen and colleagues, in their published experience, demonstrated a 9.2% spillage in 76 patients who underwent contained power morcellation.13

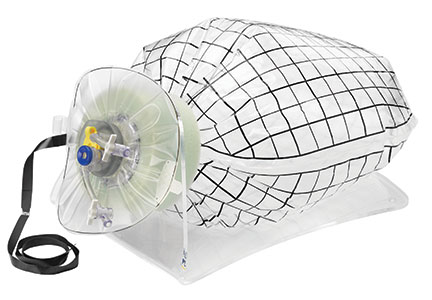

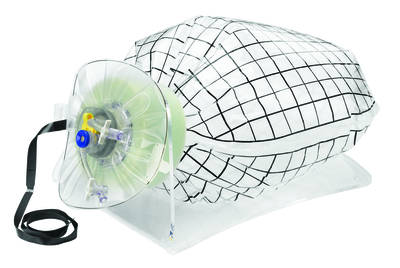

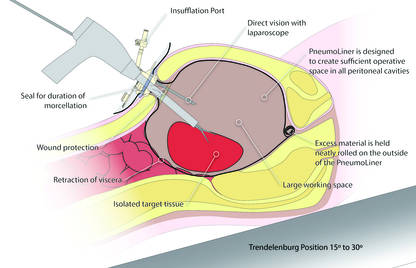

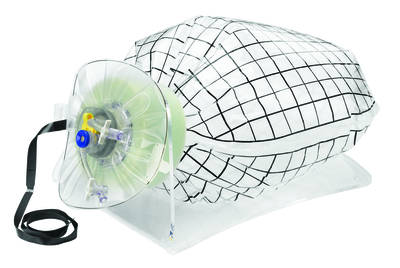

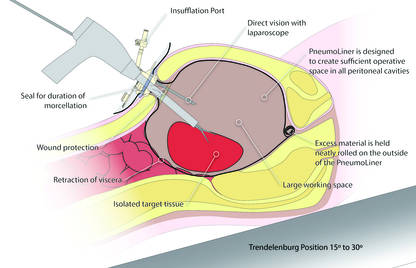

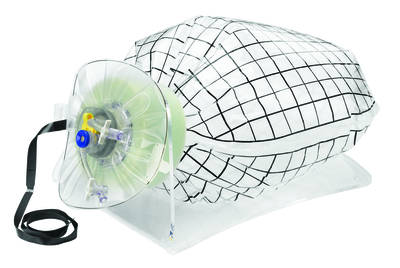

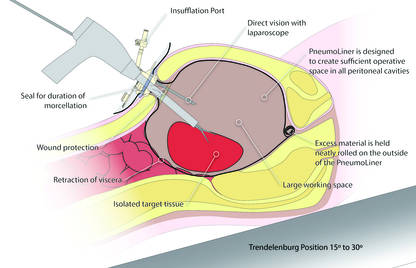

Could a new FDA approval turn the tide?In an interesting turn of events, the FDA, on April 7, 2016, nearly 2 years after their initial warning about power morcellation, gave de novo classification clearance to Advanced Surgical Concepts for its PneumoLiner device.14 This first-of-a-kind medical device was developed for the purpose of completely containing fluid, cells, and tissue fragments during laparoscopic power morcellation, isolating uterine tissue that is not suspected to contain cancer (FIGURES 1 and 2). It is important to note, however, that it has not been shown to reduce the risk of spreading cancer during this procedure. Although a surprise to some, the approval of such a product is in keeping with the FDA’s safety communication update in November 2014 that encouraged the development of containment systems designed specifically for gynecologic surgery.

| FIGURE 1 PneumoLiner tissue containment device | FIGURE 2 PneumoLiner device placement | |

|

|

Currently, the PneumoLiner is not yet available for purchase until Olympus, who will be the exclusive distributor, finalizes its formal training program rollout for ensuring safe and effective use of the device by gynecologic surgeons. As part of the FDA approval process, a training protocol was validated in a laboratory setting by surgeons with varying levels of experience in order to demonstrate that adherence to this process showed no damage to any of the containment systems used during the study.

As I look forward to the opportunity to learn more about this new containment system and potentially incorporate it into my surgical armamentarium, several questions immediately come to mind.

- Will hospitals, many of which pulled morcellators off their shelves in the wake of the FDA safety communication, be willing to embrace such innovative new containment technology and make it available to their surgeons?

- Will the litigious landscape painted by trial lawyers prevent surgeons from offering this option to their patients?

- Can surgeons undo much of the misinformation being propagated by the media as it relates to tissue extraction and the risk of encountering a malignancy?

I hope the answer to all of these questions is yes.

I do believe the pendulum can change directionAs surgeons it is our duty to evaluate potentially innovative solutions to the surgical challenges we face in clinical practice while maintaining an evidence-based approach. Most importantly, all of this must be balanced by sound clinical judgment that no technology can replace. With these guiding principles in mind, I believe that the pendulum regarding tissue extraction can change direction.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication. April 17, 2014. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm393576.htm. Updated November 24, 2014. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- Updated laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication. November 24, 2014. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm424443.htm. Updated April 7, 2014. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- Kamp J, Levitz J. Johnson & Johnson pulls hysterectomy device from hospitals. The Wall Street Journal. July 30, 2014. http://www.wsj.com/articles/johnson-johnson-to-call-for-voluntary-return-of-morcellators-1406754350. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Levitz J. Health insurer to stop covering uterine procedure. The Wall Street Journal. August 2, 2014. http://www.wsj.com/articles/health-insurer-to-stop-covering-uterine-procedure-1406999176. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Kamp J. Aetna to stop covering routine use of power morcellator. The Wall Street Journal. May 5, 2015. http://www.wsj.com/articles/aetna-to-stop-covering-routine-use-of-power-morcellator-1430838666. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Kamp J. Senators want more companies to pull surgical device from market. The Wall Street Journal. August 19, 2014. http://www.wsj.com/articles/senators-want-more-companies-to-pull-surgical-device-from-market-1408405349. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Silverman E. Power morcellators are the latest hot target among trial lawyers. The Wall Street Journal. December 2, 2014. http://blogs.wsj.com/pharmalot/2014/12/02/power-morcellators-are-the-latest-hot-target-among-trial-lawyers/. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Harris JA, Swenson CW, Uppal S, et al. Practice patterns and postoperative complications before and after the US Food and Drug Administration safety communication on power morcellation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(1):98.e1−e13.

- Lum DA, Sokol ER, Berek JS, et al. Impact of the 2014 Food and Drug Administration warnings against power morcellation. J Minim Invasiv Gynecol. 2016;23(4):548−556.

- Siedhoff M, Wheeler SB, Rutstein SE, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation vs abdominal hysterectomy for presumed fibroid tumors in premenopausal women: a decision analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):591.e1−e8.

- Parker WH, Kaunitz AM, Pritts EA, et al; Leiomyoma Morcellation Review Group. US Food and Drug Administration’s guidance regarding morcellation of leiomyomas: well-intentioned, but is it harmful for women? Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(1):18−22.

- Vargas MV, Cohen SL, Fuchs-Weizman N, et al. Open power morcellation versus contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag: comparison of perioperative outcomes. J Minim Invasiv Gynecol. 2015;22(3):433−438.

- Cohen SL, Morris SN, Brown DN, et al. Contained tissue extraction using power morcellation: prospective evaluation of leakage parameters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(2):257.e1−e6.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA allows marketing of first-of-kind tissue containment system for use with certain laparoscopic power morcellators in select patients. April 7, 2016. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm494650.htm. Updated April 7, 2016. Accessed May 24, 2016.

On April 17, 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a safety communication that discouraged the use of laparoscopic power morcellation during hysterectomy or myomectomy for the treatment of women with uterine fibroids. This recommendation was based mainly on the premise that fibroids may contain an underlying malignancy (in 1 in 350 women) that laparoscopic power morcellation could spread, thereby potentially worsening a cancer prognosis.1 Whether we liked it or not, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery as we knew it had changed forever on that fateful day.

During the last 2 years, the implications of that initial safety communication, along with its update in November of 2014,2 have been far reaching. From a health care industry perspective, the largest manufacturer of power morcellators, Johnson & Johnson, completely pulled its device out of the market within months of the initial FDA safety communication.3 Although several other companies remained in the market, health insurers such as Highmark and Aetna took the stance of not paying for the routine use of a power morcellator.4,5 Soon government officials became involved in the campaign against power morcellators and trial lawyers made this surgical device the latest “hot target.”6,7

The power morcellator’s absence impactFor clinicians, the narrative painted had moved the pendulum so far against power morcellation that it did not come as a surprise that practice patterns were significantly impacted. Harris and colleagues recently measured that impact by evaluating practice patterns and postoperative complications before and after the FDA safety communication on power morcellation. In their retrospective cohort study of patients within the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, utilization of minimally invasive hysterectomy decreased and major surgical, nontransfusion complications and 30-day hospital readmission rates increased after release of the safety communication.8

Further support of this change in practice patterns was demonstrated in a recent survey conducted by the AAGL and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Collaborative Ambulatory Research Network (ACOG CARN). In this survey study, Lum and colleagues were able to show that power morcellation use decreased among AAGL and ACOG CARN members after the FDA warnings, and rates of laparotomy increased.9

Critical to the discussion, yet apparently overlooked during the formulation of the initial FDA warning, was the potential clinical significance of the downstream impact of converting minimally invasive surgical cases to more invasive laparotomies. A decision-tree analysis published by Siedhoff and colleagues highlighted this point by predicting fewer overall deaths for laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation compared with abdominal hysterectomy.10 An ability to weigh the benefits and risks of procedure-related complications that are associated with laparotomy, including death, should have been part of the conversation from the beginning.

There is a silver lining emergingBased on this domino effect, it would seem that the damage done to minimally invasive gynecologic surgery over the past 2 years is irreparable. So is there any silver lining to the current state of affairs in tissue extraction? I would argue yes.

We have updated estimates for incidence of unsuspected leiomyosarcoma. First of all, discussions surrounding the FDA’s estimated 1 in 350 risk of encountering an unsuspected uterine sarcoma during the treatment of fibroids prompted a more critical evaluation of the scientific literature. In fact, Parker and colleagues, in a commentary published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, summarized very nicely the flawed methodology in the FDA’s determination of risk and in turn presented several updated calculations and studies that placed the prevalence somewhere in the range of 2 in 8,720 (0.023%) to 1 in 1,550 (0.064%).11

We are speaking with the FDA. Channels of communication with the FDA have since been developed and societies such as the AAGL were invited by the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) at the FDA to serve in their Network of Experts. This Network of Experts is an FDA-vetted group of non−FDA affiliated scientists, clinicians, and engineers who provide the CDRH at the FDA with rapid access to scientific, engineering, and medical expertise when it is needed to supplement existing knowledge and expertise within the CDRH. By developing these lines of communication, the CDRH is able to broaden its exposure to scientific viewpoints without the influence of external, or non−FDA, policy advice or opinions.

We have been innovating our techniques. Clinicians also began to develop innovative techniques for tissue extraction that also included contained, in-bag power morcellation. Vargas and colleagues showed similar perioperative outcomes when comparing open power morcellation with contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag. The mean operative time was prolonged by only 26 minutes with in-bag morcellation.12

Although the initial experience of surgeons involved various containment systems that were off label in their usage and not designed to be paired with a power morcellator, it allowed for the identification of potential limitations, such as the risk of leakage. Cohen and colleagues, in their published experience, demonstrated a 9.2% spillage in 76 patients who underwent contained power morcellation.13

Could a new FDA approval turn the tide?In an interesting turn of events, the FDA, on April 7, 2016, nearly 2 years after their initial warning about power morcellation, gave de novo classification clearance to Advanced Surgical Concepts for its PneumoLiner device.14 This first-of-a-kind medical device was developed for the purpose of completely containing fluid, cells, and tissue fragments during laparoscopic power morcellation, isolating uterine tissue that is not suspected to contain cancer (FIGURES 1 and 2). It is important to note, however, that it has not been shown to reduce the risk of spreading cancer during this procedure. Although a surprise to some, the approval of such a product is in keeping with the FDA’s safety communication update in November 2014 that encouraged the development of containment systems designed specifically for gynecologic surgery.

| FIGURE 1 PneumoLiner tissue containment device | FIGURE 2 PneumoLiner device placement | |

|

|

Currently, the PneumoLiner is not yet available for purchase until Olympus, who will be the exclusive distributor, finalizes its formal training program rollout for ensuring safe and effective use of the device by gynecologic surgeons. As part of the FDA approval process, a training protocol was validated in a laboratory setting by surgeons with varying levels of experience in order to demonstrate that adherence to this process showed no damage to any of the containment systems used during the study.

As I look forward to the opportunity to learn more about this new containment system and potentially incorporate it into my surgical armamentarium, several questions immediately come to mind.

- Will hospitals, many of which pulled morcellators off their shelves in the wake of the FDA safety communication, be willing to embrace such innovative new containment technology and make it available to their surgeons?

- Will the litigious landscape painted by trial lawyers prevent surgeons from offering this option to their patients?

- Can surgeons undo much of the misinformation being propagated by the media as it relates to tissue extraction and the risk of encountering a malignancy?

I hope the answer to all of these questions is yes.

I do believe the pendulum can change directionAs surgeons it is our duty to evaluate potentially innovative solutions to the surgical challenges we face in clinical practice while maintaining an evidence-based approach. Most importantly, all of this must be balanced by sound clinical judgment that no technology can replace. With these guiding principles in mind, I believe that the pendulum regarding tissue extraction can change direction.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

On April 17, 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a safety communication that discouraged the use of laparoscopic power morcellation during hysterectomy or myomectomy for the treatment of women with uterine fibroids. This recommendation was based mainly on the premise that fibroids may contain an underlying malignancy (in 1 in 350 women) that laparoscopic power morcellation could spread, thereby potentially worsening a cancer prognosis.1 Whether we liked it or not, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery as we knew it had changed forever on that fateful day.

During the last 2 years, the implications of that initial safety communication, along with its update in November of 2014,2 have been far reaching. From a health care industry perspective, the largest manufacturer of power morcellators, Johnson & Johnson, completely pulled its device out of the market within months of the initial FDA safety communication.3 Although several other companies remained in the market, health insurers such as Highmark and Aetna took the stance of not paying for the routine use of a power morcellator.4,5 Soon government officials became involved in the campaign against power morcellators and trial lawyers made this surgical device the latest “hot target.”6,7

The power morcellator’s absence impactFor clinicians, the narrative painted had moved the pendulum so far against power morcellation that it did not come as a surprise that practice patterns were significantly impacted. Harris and colleagues recently measured that impact by evaluating practice patterns and postoperative complications before and after the FDA safety communication on power morcellation. In their retrospective cohort study of patients within the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, utilization of minimally invasive hysterectomy decreased and major surgical, nontransfusion complications and 30-day hospital readmission rates increased after release of the safety communication.8

Further support of this change in practice patterns was demonstrated in a recent survey conducted by the AAGL and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Collaborative Ambulatory Research Network (ACOG CARN). In this survey study, Lum and colleagues were able to show that power morcellation use decreased among AAGL and ACOG CARN members after the FDA warnings, and rates of laparotomy increased.9

Critical to the discussion, yet apparently overlooked during the formulation of the initial FDA warning, was the potential clinical significance of the downstream impact of converting minimally invasive surgical cases to more invasive laparotomies. A decision-tree analysis published by Siedhoff and colleagues highlighted this point by predicting fewer overall deaths for laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation compared with abdominal hysterectomy.10 An ability to weigh the benefits and risks of procedure-related complications that are associated with laparotomy, including death, should have been part of the conversation from the beginning.

There is a silver lining emergingBased on this domino effect, it would seem that the damage done to minimally invasive gynecologic surgery over the past 2 years is irreparable. So is there any silver lining to the current state of affairs in tissue extraction? I would argue yes.

We have updated estimates for incidence of unsuspected leiomyosarcoma. First of all, discussions surrounding the FDA’s estimated 1 in 350 risk of encountering an unsuspected uterine sarcoma during the treatment of fibroids prompted a more critical evaluation of the scientific literature. In fact, Parker and colleagues, in a commentary published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, summarized very nicely the flawed methodology in the FDA’s determination of risk and in turn presented several updated calculations and studies that placed the prevalence somewhere in the range of 2 in 8,720 (0.023%) to 1 in 1,550 (0.064%).11

We are speaking with the FDA. Channels of communication with the FDA have since been developed and societies such as the AAGL were invited by the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) at the FDA to serve in their Network of Experts. This Network of Experts is an FDA-vetted group of non−FDA affiliated scientists, clinicians, and engineers who provide the CDRH at the FDA with rapid access to scientific, engineering, and medical expertise when it is needed to supplement existing knowledge and expertise within the CDRH. By developing these lines of communication, the CDRH is able to broaden its exposure to scientific viewpoints without the influence of external, or non−FDA, policy advice or opinions.

We have been innovating our techniques. Clinicians also began to develop innovative techniques for tissue extraction that also included contained, in-bag power morcellation. Vargas and colleagues showed similar perioperative outcomes when comparing open power morcellation with contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag. The mean operative time was prolonged by only 26 minutes with in-bag morcellation.12

Although the initial experience of surgeons involved various containment systems that were off label in their usage and not designed to be paired with a power morcellator, it allowed for the identification of potential limitations, such as the risk of leakage. Cohen and colleagues, in their published experience, demonstrated a 9.2% spillage in 76 patients who underwent contained power morcellation.13

Could a new FDA approval turn the tide?In an interesting turn of events, the FDA, on April 7, 2016, nearly 2 years after their initial warning about power morcellation, gave de novo classification clearance to Advanced Surgical Concepts for its PneumoLiner device.14 This first-of-a-kind medical device was developed for the purpose of completely containing fluid, cells, and tissue fragments during laparoscopic power morcellation, isolating uterine tissue that is not suspected to contain cancer (FIGURES 1 and 2). It is important to note, however, that it has not been shown to reduce the risk of spreading cancer during this procedure. Although a surprise to some, the approval of such a product is in keeping with the FDA’s safety communication update in November 2014 that encouraged the development of containment systems designed specifically for gynecologic surgery.

| FIGURE 1 PneumoLiner tissue containment device | FIGURE 2 PneumoLiner device placement | |

|

|

Currently, the PneumoLiner is not yet available for purchase until Olympus, who will be the exclusive distributor, finalizes its formal training program rollout for ensuring safe and effective use of the device by gynecologic surgeons. As part of the FDA approval process, a training protocol was validated in a laboratory setting by surgeons with varying levels of experience in order to demonstrate that adherence to this process showed no damage to any of the containment systems used during the study.

As I look forward to the opportunity to learn more about this new containment system and potentially incorporate it into my surgical armamentarium, several questions immediately come to mind.

- Will hospitals, many of which pulled morcellators off their shelves in the wake of the FDA safety communication, be willing to embrace such innovative new containment technology and make it available to their surgeons?

- Will the litigious landscape painted by trial lawyers prevent surgeons from offering this option to their patients?

- Can surgeons undo much of the misinformation being propagated by the media as it relates to tissue extraction and the risk of encountering a malignancy?

I hope the answer to all of these questions is yes.

I do believe the pendulum can change directionAs surgeons it is our duty to evaluate potentially innovative solutions to the surgical challenges we face in clinical practice while maintaining an evidence-based approach. Most importantly, all of this must be balanced by sound clinical judgment that no technology can replace. With these guiding principles in mind, I believe that the pendulum regarding tissue extraction can change direction.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication. April 17, 2014. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm393576.htm. Updated November 24, 2014. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- Updated laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication. November 24, 2014. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm424443.htm. Updated April 7, 2014. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- Kamp J, Levitz J. Johnson & Johnson pulls hysterectomy device from hospitals. The Wall Street Journal. July 30, 2014. http://www.wsj.com/articles/johnson-johnson-to-call-for-voluntary-return-of-morcellators-1406754350. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Levitz J. Health insurer to stop covering uterine procedure. The Wall Street Journal. August 2, 2014. http://www.wsj.com/articles/health-insurer-to-stop-covering-uterine-procedure-1406999176. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Kamp J. Aetna to stop covering routine use of power morcellator. The Wall Street Journal. May 5, 2015. http://www.wsj.com/articles/aetna-to-stop-covering-routine-use-of-power-morcellator-1430838666. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Kamp J. Senators want more companies to pull surgical device from market. The Wall Street Journal. August 19, 2014. http://www.wsj.com/articles/senators-want-more-companies-to-pull-surgical-device-from-market-1408405349. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Silverman E. Power morcellators are the latest hot target among trial lawyers. The Wall Street Journal. December 2, 2014. http://blogs.wsj.com/pharmalot/2014/12/02/power-morcellators-are-the-latest-hot-target-among-trial-lawyers/. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Harris JA, Swenson CW, Uppal S, et al. Practice patterns and postoperative complications before and after the US Food and Drug Administration safety communication on power morcellation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(1):98.e1−e13.

- Lum DA, Sokol ER, Berek JS, et al. Impact of the 2014 Food and Drug Administration warnings against power morcellation. J Minim Invasiv Gynecol. 2016;23(4):548−556.

- Siedhoff M, Wheeler SB, Rutstein SE, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation vs abdominal hysterectomy for presumed fibroid tumors in premenopausal women: a decision analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):591.e1−e8.

- Parker WH, Kaunitz AM, Pritts EA, et al; Leiomyoma Morcellation Review Group. US Food and Drug Administration’s guidance regarding morcellation of leiomyomas: well-intentioned, but is it harmful for women? Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(1):18−22.

- Vargas MV, Cohen SL, Fuchs-Weizman N, et al. Open power morcellation versus contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag: comparison of perioperative outcomes. J Minim Invasiv Gynecol. 2015;22(3):433−438.

- Cohen SL, Morris SN, Brown DN, et al. Contained tissue extraction using power morcellation: prospective evaluation of leakage parameters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(2):257.e1−e6.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA allows marketing of first-of-kind tissue containment system for use with certain laparoscopic power morcellators in select patients. April 7, 2016. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm494650.htm. Updated April 7, 2016. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication. April 17, 2014. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm393576.htm. Updated November 24, 2014. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- Updated laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication. November 24, 2014. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm424443.htm. Updated April 7, 2014. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- Kamp J, Levitz J. Johnson & Johnson pulls hysterectomy device from hospitals. The Wall Street Journal. July 30, 2014. http://www.wsj.com/articles/johnson-johnson-to-call-for-voluntary-return-of-morcellators-1406754350. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Levitz J. Health insurer to stop covering uterine procedure. The Wall Street Journal. August 2, 2014. http://www.wsj.com/articles/health-insurer-to-stop-covering-uterine-procedure-1406999176. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Kamp J. Aetna to stop covering routine use of power morcellator. The Wall Street Journal. May 5, 2015. http://www.wsj.com/articles/aetna-to-stop-covering-routine-use-of-power-morcellator-1430838666. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Kamp J. Senators want more companies to pull surgical device from market. The Wall Street Journal. August 19, 2014. http://www.wsj.com/articles/senators-want-more-companies-to-pull-surgical-device-from-market-1408405349. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Silverman E. Power morcellators are the latest hot target among trial lawyers. The Wall Street Journal. December 2, 2014. http://blogs.wsj.com/pharmalot/2014/12/02/power-morcellators-are-the-latest-hot-target-among-trial-lawyers/. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- Harris JA, Swenson CW, Uppal S, et al. Practice patterns and postoperative complications before and after the US Food and Drug Administration safety communication on power morcellation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(1):98.e1−e13.

- Lum DA, Sokol ER, Berek JS, et al. Impact of the 2014 Food and Drug Administration warnings against power morcellation. J Minim Invasiv Gynecol. 2016;23(4):548−556.

- Siedhoff M, Wheeler SB, Rutstein SE, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation vs abdominal hysterectomy for presumed fibroid tumors in premenopausal women: a decision analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):591.e1−e8.

- Parker WH, Kaunitz AM, Pritts EA, et al; Leiomyoma Morcellation Review Group. US Food and Drug Administration’s guidance regarding morcellation of leiomyomas: well-intentioned, but is it harmful for women? Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(1):18−22.

- Vargas MV, Cohen SL, Fuchs-Weizman N, et al. Open power morcellation versus contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag: comparison of perioperative outcomes. J Minim Invasiv Gynecol. 2015;22(3):433−438.

- Cohen SL, Morris SN, Brown DN, et al. Contained tissue extraction using power morcellation: prospective evaluation of leakage parameters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(2):257.e1−e6.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA allows marketing of first-of-kind tissue containment system for use with certain laparoscopic power morcellators in select patients. April 7, 2016. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm494650.htm. Updated April 7, 2016. Accessed May 24, 2016.

When could use of antenatal corticosteroids in the late preterm birth period be beneficial?

The use of antenatal corticosteroids for preterm deliveries between 24 and 34 weeks has been standard of care in obstetric practice. But approximately 70% of preterm deliveries in the United States occur after 34 weeks, in the so-called late preterm period (34 weeks 0 days to 36 weeks 6 days). Recently, Gyamfi-Bannerman and colleagues at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network completed a trial that examined the use of antenatal betamethasone in women at risk for delivery in the late preterm period.

Details of the study

The Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that included women with a singleton gestation between 34 weeks 0 days and 36 weeks 5 days who had a high probability risk of delivery in the late preterm period. The authors defined “high probability of delivery” as spontaneous labor with cervical change (at least 3-cm dilation or 75% effacement), preterm premature rupture of the membranes, or a planned delivery scheduled in the late preterm period for specific obstetric indications, such as oligohydramnios, preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and intrauterine growth restriction.

Women were excluded from the study if they had previously received a course of steroids or had multiple gestations, pregestational diabetes, chorioamnionitis, or were expected to deliver in less than 12 hours due to advanced labor, vaginal bleeding, or nonreassuring fetal status.

Study participants were randomly assigned to receive 2 doses (12 mg intramuscularly) of betamethasone 24 hours apart (1,429 participants) or identical-appearing placebo (1,402 participants). Tocolysis was not allowed in the protocol.

Positive outcomes for neonates

The use of corticosteroids was associated with a significant reduction in the primary outcome of need for respiratory support in the first 72 hours of life (14.4% in the placebo group vs 11.6% in the betamethasone group; relative risk [RR], 0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66–0.97; P = .02). Steroid use also decreased the incidence of severe respiratory complications, the need for resuscitation at birth, the need for surfactant therapy, the incidence of transient tachypnea of the newborn, and the incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Neonatal hypoglycemia was more frequent among infants exposed to betamethasone (24% vs 15%; RR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.37–1.87; P<.001).

New guidelines issued

The ALPS study is the largest randomized trial to evaluate the benefit of antenatal steroids during the late preterm period. The study’s findings certainly will change clinical practice. Based on the study’s large sample size, rigorous design and protocol, and a cohort generalizable to the US population, SMFM has issued new recommendations for practitioners on using antenatal steroids in the late preterm period in women at risk for preterm delivery.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

In light of the new SMFM recommendations, in my practice, I will adhere to the inclusion criteria used in the ALPS study, and be careful not to apply the same approach used before 34 weeks, when delivery is often delayed intentionally in order to achieve steroid benefit. If considering adoption of this same practice, clinicians should not use tocolytics when administering corticosteroids in the late preterm period. When indicated, such as in women with severe preeclampsia or ruptured membranes, delivery should not be delayed. A patient with high probability of delivery in the late preterm period is eligible for treatment as long as the clinician thinks that she is not going to deliver within 12 hours. On the other hand, clinicians should not overtreat women, and should maintain a high suspicion for delivery in patients with preterm labor (a cervix that is at least 3 cm dilated or 75% effaced).

The ALPS trial did not allow the administration of more than one course of steroids. The eligibility criteria for corticosteroid use in the late preterm period should not be extended to include subpopulations that were not studied in the trial (including patients with multiple gestations, pregestational diabetes, or those who already had received a complete course of steroids).

— Luis Pacheco, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The use of antenatal corticosteroids for preterm deliveries between 24 and 34 weeks has been standard of care in obstetric practice. But approximately 70% of preterm deliveries in the United States occur after 34 weeks, in the so-called late preterm period (34 weeks 0 days to 36 weeks 6 days). Recently, Gyamfi-Bannerman and colleagues at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network completed a trial that examined the use of antenatal betamethasone in women at risk for delivery in the late preterm period.

Details of the study

The Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that included women with a singleton gestation between 34 weeks 0 days and 36 weeks 5 days who had a high probability risk of delivery in the late preterm period. The authors defined “high probability of delivery” as spontaneous labor with cervical change (at least 3-cm dilation or 75% effacement), preterm premature rupture of the membranes, or a planned delivery scheduled in the late preterm period for specific obstetric indications, such as oligohydramnios, preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and intrauterine growth restriction.

Women were excluded from the study if they had previously received a course of steroids or had multiple gestations, pregestational diabetes, chorioamnionitis, or were expected to deliver in less than 12 hours due to advanced labor, vaginal bleeding, or nonreassuring fetal status.

Study participants were randomly assigned to receive 2 doses (12 mg intramuscularly) of betamethasone 24 hours apart (1,429 participants) or identical-appearing placebo (1,402 participants). Tocolysis was not allowed in the protocol.

Positive outcomes for neonates

The use of corticosteroids was associated with a significant reduction in the primary outcome of need for respiratory support in the first 72 hours of life (14.4% in the placebo group vs 11.6% in the betamethasone group; relative risk [RR], 0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66–0.97; P = .02). Steroid use also decreased the incidence of severe respiratory complications, the need for resuscitation at birth, the need for surfactant therapy, the incidence of transient tachypnea of the newborn, and the incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Neonatal hypoglycemia was more frequent among infants exposed to betamethasone (24% vs 15%; RR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.37–1.87; P<.001).

New guidelines issued

The ALPS study is the largest randomized trial to evaluate the benefit of antenatal steroids during the late preterm period. The study’s findings certainly will change clinical practice. Based on the study’s large sample size, rigorous design and protocol, and a cohort generalizable to the US population, SMFM has issued new recommendations for practitioners on using antenatal steroids in the late preterm period in women at risk for preterm delivery.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

In light of the new SMFM recommendations, in my practice, I will adhere to the inclusion criteria used in the ALPS study, and be careful not to apply the same approach used before 34 weeks, when delivery is often delayed intentionally in order to achieve steroid benefit. If considering adoption of this same practice, clinicians should not use tocolytics when administering corticosteroids in the late preterm period. When indicated, such as in women with severe preeclampsia or ruptured membranes, delivery should not be delayed. A patient with high probability of delivery in the late preterm period is eligible for treatment as long as the clinician thinks that she is not going to deliver within 12 hours. On the other hand, clinicians should not overtreat women, and should maintain a high suspicion for delivery in patients with preterm labor (a cervix that is at least 3 cm dilated or 75% effaced).

The ALPS trial did not allow the administration of more than one course of steroids. The eligibility criteria for corticosteroid use in the late preterm period should not be extended to include subpopulations that were not studied in the trial (including patients with multiple gestations, pregestational diabetes, or those who already had received a complete course of steroids).

— Luis Pacheco, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The use of antenatal corticosteroids for preterm deliveries between 24 and 34 weeks has been standard of care in obstetric practice. But approximately 70% of preterm deliveries in the United States occur after 34 weeks, in the so-called late preterm period (34 weeks 0 days to 36 weeks 6 days). Recently, Gyamfi-Bannerman and colleagues at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network completed a trial that examined the use of antenatal betamethasone in women at risk for delivery in the late preterm period.

Details of the study

The Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that included women with a singleton gestation between 34 weeks 0 days and 36 weeks 5 days who had a high probability risk of delivery in the late preterm period. The authors defined “high probability of delivery” as spontaneous labor with cervical change (at least 3-cm dilation or 75% effacement), preterm premature rupture of the membranes, or a planned delivery scheduled in the late preterm period for specific obstetric indications, such as oligohydramnios, preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and intrauterine growth restriction.

Women were excluded from the study if they had previously received a course of steroids or had multiple gestations, pregestational diabetes, chorioamnionitis, or were expected to deliver in less than 12 hours due to advanced labor, vaginal bleeding, or nonreassuring fetal status.

Study participants were randomly assigned to receive 2 doses (12 mg intramuscularly) of betamethasone 24 hours apart (1,429 participants) or identical-appearing placebo (1,402 participants). Tocolysis was not allowed in the protocol.

Positive outcomes for neonates

The use of corticosteroids was associated with a significant reduction in the primary outcome of need for respiratory support in the first 72 hours of life (14.4% in the placebo group vs 11.6% in the betamethasone group; relative risk [RR], 0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66–0.97; P = .02). Steroid use also decreased the incidence of severe respiratory complications, the need for resuscitation at birth, the need for surfactant therapy, the incidence of transient tachypnea of the newborn, and the incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Neonatal hypoglycemia was more frequent among infants exposed to betamethasone (24% vs 15%; RR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.37–1.87; P<.001).

New guidelines issued

The ALPS study is the largest randomized trial to evaluate the benefit of antenatal steroids during the late preterm period. The study’s findings certainly will change clinical practice. Based on the study’s large sample size, rigorous design and protocol, and a cohort generalizable to the US population, SMFM has issued new recommendations for practitioners on using antenatal steroids in the late preterm period in women at risk for preterm delivery.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

In light of the new SMFM recommendations, in my practice, I will adhere to the inclusion criteria used in the ALPS study, and be careful not to apply the same approach used before 34 weeks, when delivery is often delayed intentionally in order to achieve steroid benefit. If considering adoption of this same practice, clinicians should not use tocolytics when administering corticosteroids in the late preterm period. When indicated, such as in women with severe preeclampsia or ruptured membranes, delivery should not be delayed. A patient with high probability of delivery in the late preterm period is eligible for treatment as long as the clinician thinks that she is not going to deliver within 12 hours. On the other hand, clinicians should not overtreat women, and should maintain a high suspicion for delivery in patients with preterm labor (a cervix that is at least 3 cm dilated or 75% effaced).

The ALPS trial did not allow the administration of more than one course of steroids. The eligibility criteria for corticosteroid use in the late preterm period should not be extended to include subpopulations that were not studied in the trial (including patients with multiple gestations, pregestational diabetes, or those who already had received a complete course of steroids).

— Luis Pacheco, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Things Hospitalists Want Hospital Administrators to Know

I think it is really cool that this publication has a series of articles on “What Cardiologists [or infection disease specialists, nephrologists, etc.] Want Hospitalists to Know.” I’m always interested to see which clinical topics made the list and which I’m already reasonably familiar with versus know little about. I’ve added this series to my list of things that are always worth the time to read, along with the “What’s New” section in UpToDate, review articles in major journals, and the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Not long ago, I worked with a hospitalist group that had agreed to cardiologists’ request that new hospitalists round with a cardiologist for something like three days as part of their orientation. This seems like they’ve taken the idea of “What Cardiologists Want Hospitalists to Know” a lot further than I had ever considered. I’m sure it would have value on many levels, including positioning the new hospitalist to work more effectively with the cardiologists, but I’m not sure it’s worth the cost. And I’m really concerned it sends a signal that the relationship is one way—that is, the hospitalists need to understand what the cardiologists do and want from them and not the reverse. For many reasons, I think this should be a reciprocal relationship, and it seems reasonable that new cardiologists should orient by rounding with hospitalists.

Same goes for the “… Want Hospitalists to Know” series. I’d like to see articles enumerating what hospitalists want doctors in other fields to know either in this magazine or its counterpart in the other specialty. What follows is the first of these. It is my take on non-clinical topics hospitalists want hospital leaders to know, and I’ll leave it to others to write about clinical topics.

We Aren’t on ‘Vacation’ Every Other Week

If you always think of our days off as a vacation, as in, “Those hospitalists get 26 weeks of vacation a year,” you’re making a mistake. A significant portion of our weekdays off are just like your weekends; they’re days to take a breather.

And you’re likely forgetting how many weekends we work.

And maybe lots of nights also.

You probably work more hours annually, but having more days for a breather are one offset for our weekends and nights.

Insisting Hospitalists Work an Entire Shift (12 Hours) Doesn’t Make a Lot of Sense on Slow Days

Staying around after completing clinical work yields no value. Too often, the time is spent watching YouTube or similar activities. And it means the doctor will be much more frustrated, and more likely to lobby for overtime compensation, when needing to stay beyond the scheduled end of the shift on busy days.

Avoid measuring work effort in hours. And in many cases, it is best to avoid precise determinations of when a day shift ends. At most hospitals, you do need at least one daytime doctor to stay on duty until the next shift arrives, but it rarely makes sense to have all of the hospitalists stay.

Your hospitalists need to be professional enough not to dash out the door the minute they’ve put notes on every patient’s chart. Instead, rather than leaving at the first opportunity on slow days, they could do all of the discharge preparation (med rec, discharge summary, etc.) for patients likely ready for discharge the next day; this can help a lot to discharge patients early the next day. Or they could make “secondary” rounds focused on patient satisfaction, etc.

Obs Patients Usually Are No Less Complicated—or Labor-Intensive—to Care For

It’s best to think of observation as solely a payor classification and not a good indicator of risk, complexity, or work required. Unfortunately “observation” is often thought of as shorthand for simple, not sick, easy to manage, etc. While true for a small subset of observation patients, such as younger people with a single problem such as atypical chest pain, it isn’t true for older (Medicare) patients with multiple chronic illnesses, on multiple medications, and with complex social situations.

Shouldn’t We Measure Length of Stay for All Patients in Hours Rather Than Days?

Then we could better understand throughput issues such as whether afternoon discharges for inpatients are late discharges or really very early discharges that weren’t held until the next morning.

Even High-Performing Hospitalist Groups Are Likely to Have Patient Satisfaction Scores on the Lower End of Doctors at Your Hospital

Don’t decide that just because they have much lower scores than the orthopedists, cardiologists, obstetricians, and other specialties, it is the hospitalists who are falling furthest below their potential. It may be the cardiologists who have a long way to go to achieve great scores for their specialty.

This isn’t an excuse. Just about every hospitalist group can do better and should work to make it happen. And because in nearly every hospital more HCAHPS surveys are attributed to hospitalists than any other specialty by a wide margin, our scores have a huge impact on the overall hospital averages. But you should keep in mind that, for a variety of reasons, hospitalists everywhere have physician communication scores that are lower than many or most other specialties.

To my knowledge, there isn’t a data set that provides patient satisfaction scores by specialty. And scores seem to vary a lot by geographic region, e.g., they’re nearly always higher in the South than other parts of the country. So there isn’t a good way to control for all the variables and know you’re setting appropriate improvement goals for each specialty. But your hospitalists will appreciate it if you acknowledge it may be unreasonable to set the same goals across specialties.

We’d Love Your Help Getting Rid of Pagers

Secure text messaging between all caregivers seems to be the way to go, and we will look to the hospital to make an investment in technology to make it possible and train users to ensure that by making messaging easier the volume of messages (interruptions) doesn’t just skyrocket. We, the hospitalists at your hospital, are happy to help with all of this, from vendor selection to plans for implementation. Please ask! TH

I think it is really cool that this publication has a series of articles on “What Cardiologists [or infection disease specialists, nephrologists, etc.] Want Hospitalists to Know.” I’m always interested to see which clinical topics made the list and which I’m already reasonably familiar with versus know little about. I’ve added this series to my list of things that are always worth the time to read, along with the “What’s New” section in UpToDate, review articles in major journals, and the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Not long ago, I worked with a hospitalist group that had agreed to cardiologists’ request that new hospitalists round with a cardiologist for something like three days as part of their orientation. This seems like they’ve taken the idea of “What Cardiologists Want Hospitalists to Know” a lot further than I had ever considered. I’m sure it would have value on many levels, including positioning the new hospitalist to work more effectively with the cardiologists, but I’m not sure it’s worth the cost. And I’m really concerned it sends a signal that the relationship is one way—that is, the hospitalists need to understand what the cardiologists do and want from them and not the reverse. For many reasons, I think this should be a reciprocal relationship, and it seems reasonable that new cardiologists should orient by rounding with hospitalists.

Same goes for the “… Want Hospitalists to Know” series. I’d like to see articles enumerating what hospitalists want doctors in other fields to know either in this magazine or its counterpart in the other specialty. What follows is the first of these. It is my take on non-clinical topics hospitalists want hospital leaders to know, and I’ll leave it to others to write about clinical topics.

We Aren’t on ‘Vacation’ Every Other Week

If you always think of our days off as a vacation, as in, “Those hospitalists get 26 weeks of vacation a year,” you’re making a mistake. A significant portion of our weekdays off are just like your weekends; they’re days to take a breather.

And you’re likely forgetting how many weekends we work.

And maybe lots of nights also.

You probably work more hours annually, but having more days for a breather are one offset for our weekends and nights.

Insisting Hospitalists Work an Entire Shift (12 Hours) Doesn’t Make a Lot of Sense on Slow Days

Staying around after completing clinical work yields no value. Too often, the time is spent watching YouTube or similar activities. And it means the doctor will be much more frustrated, and more likely to lobby for overtime compensation, when needing to stay beyond the scheduled end of the shift on busy days.

Avoid measuring work effort in hours. And in many cases, it is best to avoid precise determinations of when a day shift ends. At most hospitals, you do need at least one daytime doctor to stay on duty until the next shift arrives, but it rarely makes sense to have all of the hospitalists stay.

Your hospitalists need to be professional enough not to dash out the door the minute they’ve put notes on every patient’s chart. Instead, rather than leaving at the first opportunity on slow days, they could do all of the discharge preparation (med rec, discharge summary, etc.) for patients likely ready for discharge the next day; this can help a lot to discharge patients early the next day. Or they could make “secondary” rounds focused on patient satisfaction, etc.

Obs Patients Usually Are No Less Complicated—or Labor-Intensive—to Care For

It’s best to think of observation as solely a payor classification and not a good indicator of risk, complexity, or work required. Unfortunately “observation” is often thought of as shorthand for simple, not sick, easy to manage, etc. While true for a small subset of observation patients, such as younger people with a single problem such as atypical chest pain, it isn’t true for older (Medicare) patients with multiple chronic illnesses, on multiple medications, and with complex social situations.

Shouldn’t We Measure Length of Stay for All Patients in Hours Rather Than Days?

Then we could better understand throughput issues such as whether afternoon discharges for inpatients are late discharges or really very early discharges that weren’t held until the next morning.

Even High-Performing Hospitalist Groups Are Likely to Have Patient Satisfaction Scores on the Lower End of Doctors at Your Hospital

Don’t decide that just because they have much lower scores than the orthopedists, cardiologists, obstetricians, and other specialties, it is the hospitalists who are falling furthest below their potential. It may be the cardiologists who have a long way to go to achieve great scores for their specialty.

This isn’t an excuse. Just about every hospitalist group can do better and should work to make it happen. And because in nearly every hospital more HCAHPS surveys are attributed to hospitalists than any other specialty by a wide margin, our scores have a huge impact on the overall hospital averages. But you should keep in mind that, for a variety of reasons, hospitalists everywhere have physician communication scores that are lower than many or most other specialties.

To my knowledge, there isn’t a data set that provides patient satisfaction scores by specialty. And scores seem to vary a lot by geographic region, e.g., they’re nearly always higher in the South than other parts of the country. So there isn’t a good way to control for all the variables and know you’re setting appropriate improvement goals for each specialty. But your hospitalists will appreciate it if you acknowledge it may be unreasonable to set the same goals across specialties.

We’d Love Your Help Getting Rid of Pagers

Secure text messaging between all caregivers seems to be the way to go, and we will look to the hospital to make an investment in technology to make it possible and train users to ensure that by making messaging easier the volume of messages (interruptions) doesn’t just skyrocket. We, the hospitalists at your hospital, are happy to help with all of this, from vendor selection to plans for implementation. Please ask! TH

I think it is really cool that this publication has a series of articles on “What Cardiologists [or infection disease specialists, nephrologists, etc.] Want Hospitalists to Know.” I’m always interested to see which clinical topics made the list and which I’m already reasonably familiar with versus know little about. I’ve added this series to my list of things that are always worth the time to read, along with the “What’s New” section in UpToDate, review articles in major journals, and the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Not long ago, I worked with a hospitalist group that had agreed to cardiologists’ request that new hospitalists round with a cardiologist for something like three days as part of their orientation. This seems like they’ve taken the idea of “What Cardiologists Want Hospitalists to Know” a lot further than I had ever considered. I’m sure it would have value on many levels, including positioning the new hospitalist to work more effectively with the cardiologists, but I’m not sure it’s worth the cost. And I’m really concerned it sends a signal that the relationship is one way—that is, the hospitalists need to understand what the cardiologists do and want from them and not the reverse. For many reasons, I think this should be a reciprocal relationship, and it seems reasonable that new cardiologists should orient by rounding with hospitalists.

Same goes for the “… Want Hospitalists to Know” series. I’d like to see articles enumerating what hospitalists want doctors in other fields to know either in this magazine or its counterpart in the other specialty. What follows is the first of these. It is my take on non-clinical topics hospitalists want hospital leaders to know, and I’ll leave it to others to write about clinical topics.

We Aren’t on ‘Vacation’ Every Other Week

If you always think of our days off as a vacation, as in, “Those hospitalists get 26 weeks of vacation a year,” you’re making a mistake. A significant portion of our weekdays off are just like your weekends; they’re days to take a breather.

And you’re likely forgetting how many weekends we work.

And maybe lots of nights also.

You probably work more hours annually, but having more days for a breather are one offset for our weekends and nights.

Insisting Hospitalists Work an Entire Shift (12 Hours) Doesn’t Make a Lot of Sense on Slow Days

Staying around after completing clinical work yields no value. Too often, the time is spent watching YouTube or similar activities. And it means the doctor will be much more frustrated, and more likely to lobby for overtime compensation, when needing to stay beyond the scheduled end of the shift on busy days.

Avoid measuring work effort in hours. And in many cases, it is best to avoid precise determinations of when a day shift ends. At most hospitals, you do need at least one daytime doctor to stay on duty until the next shift arrives, but it rarely makes sense to have all of the hospitalists stay.

Your hospitalists need to be professional enough not to dash out the door the minute they’ve put notes on every patient’s chart. Instead, rather than leaving at the first opportunity on slow days, they could do all of the discharge preparation (med rec, discharge summary, etc.) for patients likely ready for discharge the next day; this can help a lot to discharge patients early the next day. Or they could make “secondary” rounds focused on patient satisfaction, etc.

Obs Patients Usually Are No Less Complicated—or Labor-Intensive—to Care For

It’s best to think of observation as solely a payor classification and not a good indicator of risk, complexity, or work required. Unfortunately “observation” is often thought of as shorthand for simple, not sick, easy to manage, etc. While true for a small subset of observation patients, such as younger people with a single problem such as atypical chest pain, it isn’t true for older (Medicare) patients with multiple chronic illnesses, on multiple medications, and with complex social situations.

Shouldn’t We Measure Length of Stay for All Patients in Hours Rather Than Days?

Then we could better understand throughput issues such as whether afternoon discharges for inpatients are late discharges or really very early discharges that weren’t held until the next morning.

Even High-Performing Hospitalist Groups Are Likely to Have Patient Satisfaction Scores on the Lower End of Doctors at Your Hospital

Don’t decide that just because they have much lower scores than the orthopedists, cardiologists, obstetricians, and other specialties, it is the hospitalists who are falling furthest below their potential. It may be the cardiologists who have a long way to go to achieve great scores for their specialty.

This isn’t an excuse. Just about every hospitalist group can do better and should work to make it happen. And because in nearly every hospital more HCAHPS surveys are attributed to hospitalists than any other specialty by a wide margin, our scores have a huge impact on the overall hospital averages. But you should keep in mind that, for a variety of reasons, hospitalists everywhere have physician communication scores that are lower than many or most other specialties.

To my knowledge, there isn’t a data set that provides patient satisfaction scores by specialty. And scores seem to vary a lot by geographic region, e.g., they’re nearly always higher in the South than other parts of the country. So there isn’t a good way to control for all the variables and know you’re setting appropriate improvement goals for each specialty. But your hospitalists will appreciate it if you acknowledge it may be unreasonable to set the same goals across specialties.

We’d Love Your Help Getting Rid of Pagers

Secure text messaging between all caregivers seems to be the way to go, and we will look to the hospital to make an investment in technology to make it possible and train users to ensure that by making messaging easier the volume of messages (interruptions) doesn’t just skyrocket. We, the hospitalists at your hospital, are happy to help with all of this, from vendor selection to plans for implementation. Please ask! TH

Medical errors: Caring for the second victim (you)

What insect repellents are safe during pregnancy?

With summer almost upon us, and the weather warming in many parts of the country, we have received questions from colleagues about the best over-the-counter insect repellants to advise their pregnant patients to use.

The preferred insect repellent for skin coverate is DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) (TABLE). Oil of lemon/eucalyptus/para-menthane-diol and IR3535 are also acceptable repellents to use on the skin that are safe for use in pregnancy. In addition, patients should be instructed to spray permethrin on their clothing or buy clothing (boots, pants, socks) that has been pretreated with permethrin.1,2

| Repellent | Product | Manufacturer | Notes |

| DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide)

| Off! | SC Johnson | Preferred repellent for use on the skin |

| Repel 100 | Spectrum Brands | ||

| Ultra 30 Liposome Controlled Release | Sawyer | ||

| Oil of lemon/eucalyptus/ para-menthane-diol | Repel Lemon Eucalyptus Insect Repellent | Spectrum Brands | Acceptable option for skin use |

| IR3535 | Skin So Soft Bug Guard Plus IR3535 Expedition | Avon | Acceptable option for skin use |

| Permethrin | Repel Permethrin Clothing & Gear Aerosol | Spectrum Brands | For use on clothing |

| Permethrin Pump Spray | Sawyer | ||

| Abbreviations: OTC, over the counter | |||

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Peterson EE, Staples JE, Meaney-Delman D, et al. Interim guidelines for pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak – United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(2):30-33.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Features: Avoid mosquito bites. http://www.cdc.gov/Features/stopmosquitoes/index.html. Updated March 18, 2016. Accessed May 10, 2016.

With summer almost upon us, and the weather warming in many parts of the country, we have received questions from colleagues about the best over-the-counter insect repellants to advise their pregnant patients to use.

The preferred insect repellent for skin coverate is DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) (TABLE). Oil of lemon/eucalyptus/para-menthane-diol and IR3535 are also acceptable repellents to use on the skin that are safe for use in pregnancy. In addition, patients should be instructed to spray permethrin on their clothing or buy clothing (boots, pants, socks) that has been pretreated with permethrin.1,2

| Repellent | Product | Manufacturer | Notes |

| DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide)

| Off! | SC Johnson | Preferred repellent for use on the skin |

| Repel 100 | Spectrum Brands | ||

| Ultra 30 Liposome Controlled Release | Sawyer | ||

| Oil of lemon/eucalyptus/ para-menthane-diol | Repel Lemon Eucalyptus Insect Repellent | Spectrum Brands | Acceptable option for skin use |

| IR3535 | Skin So Soft Bug Guard Plus IR3535 Expedition | Avon | Acceptable option for skin use |

| Permethrin | Repel Permethrin Clothing & Gear Aerosol | Spectrum Brands | For use on clothing |

| Permethrin Pump Spray | Sawyer | ||

| Abbreviations: OTC, over the counter | |||

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

With summer almost upon us, and the weather warming in many parts of the country, we have received questions from colleagues about the best over-the-counter insect repellants to advise their pregnant patients to use.

The preferred insect repellent for skin coverate is DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) (TABLE). Oil of lemon/eucalyptus/para-menthane-diol and IR3535 are also acceptable repellents to use on the skin that are safe for use in pregnancy. In addition, patients should be instructed to spray permethrin on their clothing or buy clothing (boots, pants, socks) that has been pretreated with permethrin.1,2

| Repellent | Product | Manufacturer | Notes |

| DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide)

| Off! | SC Johnson | Preferred repellent for use on the skin |

| Repel 100 | Spectrum Brands | ||

| Ultra 30 Liposome Controlled Release | Sawyer | ||

| Oil of lemon/eucalyptus/ para-menthane-diol | Repel Lemon Eucalyptus Insect Repellent | Spectrum Brands | Acceptable option for skin use |

| IR3535 | Skin So Soft Bug Guard Plus IR3535 Expedition | Avon | Acceptable option for skin use |

| Permethrin | Repel Permethrin Clothing & Gear Aerosol | Spectrum Brands | For use on clothing |

| Permethrin Pump Spray | Sawyer | ||

| Abbreviations: OTC, over the counter | |||

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Peterson EE, Staples JE, Meaney-Delman D, et al. Interim guidelines for pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak – United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(2):30-33.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Features: Avoid mosquito bites. http://www.cdc.gov/Features/stopmosquitoes/index.html. Updated March 18, 2016. Accessed May 10, 2016.

- Peterson EE, Staples JE, Meaney-Delman D, et al. Interim guidelines for pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak – United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(2):30-33.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Features: Avoid mosquito bites. http://www.cdc.gov/Features/stopmosquitoes/index.html. Updated March 18, 2016. Accessed May 10, 2016.

How to help your patients control gestational weight gain

Resource:

Choosemyplate.org

Resource:

Choosemyplate.org

Resource:

Choosemyplate.org

8 Lessons for Hospitalists Turned Entrepreneurs

If you are a hospitalist, you are an entrepreneur almost by definition. All hospitalists are continuously engaged in improving the hospital experience for our patients. For some of us, the inner entrepreneur may grow to a point where we seriously consider a part-time or full-time commitment to an entrepreneurial dream. Combining our years of immersion in hospital patient care with an inventive streak can be a potent recipe for an innovative product or service idea.

It may be that the burgeoning startup scene in healthcare has inspired your dream. From coast to coast, there are startup incubators such as Rock Health, Healthbox, Blueprint Health, StartUp Health, Health Wildcatters, The Iron Yard, and TechSpring. These outfits support entrepreneurs with mentorship, funding, workspace, and/or information, such as how to deal with HIPAA or the FDA. Most of us have had at least a passing fascination with Steve Jobs–type characters, individuals who changed the world through their vision and force of will or who just seemed to enjoy a freedom that those who work for “The Man” will never know.

A few years ago, I caught the entrepreneurial bug. Initially, I continued with my day job and worked nights and weekends on my side project. Eventually, I made the leap to work full-time at an early-stage healthcare company. Since then, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to improve my new practice as a full-time entrepreneur, working as hard as ever, trying to be an effective innovator. Every day seems to bring new lessons—some more hard-earned than others—and there’s a lifetime of them still ahead. I’d like to share some of the insights I have learned on this journey. By the way, I still make time for patient care since that remains a priority for me.

Patience Is a Virtue, but Persistence and Positivity Count Even More

As Henry David Thoreau wrote, “Go confidently in the direction of your dreams.” Don’t postpone action indefinitely just because there are obstacles. Stop making excuses, make a start, and build momentum every day. Commit.

Becoming an entrepreneur is a long-term effort fueled by dedication and optimism, but first you have to make a start. You can’t win if you don’t play.

Action and Learning Matter More than Ideation

Start with your idea and a rough plan, but above all, believe in yourself, especially your ability to problem-solve. Many of the qualities that have fueled our success as physicians—precision, thoughtfulness, error aversion, and compulsiveness—might be constraints in a startup environment. Startups are hostile places for perfectionists and those who require complete information before proceeding. Have a bias for action and become comfortable with ambiguity. Entrepreneurs turn little things into big things by making progress every day.

Perhaps contrary to what we learn as physicians, entrepreneurs understand progress is measured more by authentic learning than by getting particular results. Entrepreneurs must quickly learn how to fail. In fact, progress often resembles multiple experiments that allow you to fail (and learn) faster. For entrepreneurs, perfection truly is the enemy of the good.

Learn, make adjustments, and progress will follow.

Guidance Is More Valuable than Money

Commercializing an idea is a challenging proposition. First-timers need advice, support, and help. For advice, find a mentor who has successfully launched a startup. Most of the successful people I know have had the wisdom or good fortune to have a mentor to provide guidance.

Startup incubators can be another source of support. Nearly all large cities and many medium and small cities now have business incubators or accelerators. Attend an event and get involved. They will provide many of the tools you will need to get started.

There are lots of opportunities for innovation in healthcare. But commercializing an idea will be one of the most challenging things you’ll ever do. Surround yourself with people who have skills that complement yours. Physician entrepreneurs need to be part of a viable team.

Sell, Sell, Sell

In business, as in life, “we’re all in sales.” We sell our ideas, our work product, ourselves. Even as physicians we have to sell patients and colleagues on our thought processes to be successful. Successful entrepreneurs are comfortable selling and put their best foot forward when trying to recruit a resource or persuade a potential customer.

Conflicts of Interest

“There is no interest without conflict.” If you look hard enough, you’ll see that we all have conflicts of interest. The key is to recognize them and disclose them. Of course, there are certain conflicts that are deal breakers. They must be avoided. If you remain employed, most of them are spelled out in your employer’s conflict of interest and intellectual property policies.

HIPAA Is an Innovation Killer

If your idea involves technology or services that address protected health information, become a HIPAA savant as soon as possible. The good news is that if you can effectively navigate the HIPAA challenge, you will have an advantage over your competitors.

Pure ‘Tech’ Plays Are Difficult

If you want to try to build the next killer app for healthcare and hope it will go viral, good luck. Based on my experience, it is difficult to get market traction with a pure technology offering. The strategy with a higher likelihood of success is to provide services with a technology platform that supports those services. As a provider of a service, you can provide immediate value to the customer and become “sticky” as you build your business (and software).

Enjoy the Journey, No Matter What