User login

Does the discontinuation of menopausal hormone therapy affect a woman’s cardiovascular risk?

This recently published study from Finland generated headlines when its authors concluded that stopping HT elevates the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD), including cardiac and cerebrovascular events. Using nationwide data, investigators compared the CVD mortality rate among women who discontinued HT during the years 1994 through 2009 (n = 332,202) with expected (not actual) CVD mortality rates in the background population.

Within the first year after HT discontinuation, elevations in death rates from cardiac events and stroke were noted (standardized mortality ratio, 1.26 and 1.63, respectively), while in the subsequent year, reductions in such mortality were observed (P<.05 for all comparisons).

The absolute increased risk of death from cardiac events reported within the first year after discontinuation of HT was 4 deaths per 10,000 woman-years of exposure. The absolute risk of death from stroke was 5 additional events per 10,000 woman-years. This level of risk is considered to be rare.

How these data compare to those of other studiesIn contrast with these Finnish data, findings from the Women’s Health Initiative—the largest randomized trial of menopausal HT—do not indicate an increase in mortality or an increase in coronary heart or stroke events among women stopping HT.1,2

It seems likely that limitations associated with the Finnish observational data account for this discordance. For example, Mikkola and colleagues did not know why women discontinued HT, raising the possibility that women with symptoms suggestive of CVD or development of new risk factors preferentially stopped HT, potentially introducing important bias into the Finnish analysis.

What this evidence means for practiceWomen and their clinicians should make decisions regarding whether to continue, reduce the dose, or discontinue HT through shared decision making, focusing on individual patient quality of life parameters as well as changing risk concerns related to such entities as cancer, CVD, and osteoporosis.3 Dramatic as they are, findings from this Finnish report should not impact how we counsel women regarding use or discontinuation of HT.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH; and Cynthia A. Stuenkel, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson GL, et al; WHI investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036–1045.

- LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, et al; WHI investigators. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1305–1314.

- Kaunitz AM. Extended duration use of menopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2014;21(6):679–68.

This recently published study from Finland generated headlines when its authors concluded that stopping HT elevates the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD), including cardiac and cerebrovascular events. Using nationwide data, investigators compared the CVD mortality rate among women who discontinued HT during the years 1994 through 2009 (n = 332,202) with expected (not actual) CVD mortality rates in the background population.

Within the first year after HT discontinuation, elevations in death rates from cardiac events and stroke were noted (standardized mortality ratio, 1.26 and 1.63, respectively), while in the subsequent year, reductions in such mortality were observed (P<.05 for all comparisons).

The absolute increased risk of death from cardiac events reported within the first year after discontinuation of HT was 4 deaths per 10,000 woman-years of exposure. The absolute risk of death from stroke was 5 additional events per 10,000 woman-years. This level of risk is considered to be rare.

How these data compare to those of other studiesIn contrast with these Finnish data, findings from the Women’s Health Initiative—the largest randomized trial of menopausal HT—do not indicate an increase in mortality or an increase in coronary heart or stroke events among women stopping HT.1,2

It seems likely that limitations associated with the Finnish observational data account for this discordance. For example, Mikkola and colleagues did not know why women discontinued HT, raising the possibility that women with symptoms suggestive of CVD or development of new risk factors preferentially stopped HT, potentially introducing important bias into the Finnish analysis.

What this evidence means for practiceWomen and their clinicians should make decisions regarding whether to continue, reduce the dose, or discontinue HT through shared decision making, focusing on individual patient quality of life parameters as well as changing risk concerns related to such entities as cancer, CVD, and osteoporosis.3 Dramatic as they are, findings from this Finnish report should not impact how we counsel women regarding use or discontinuation of HT.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH; and Cynthia A. Stuenkel, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This recently published study from Finland generated headlines when its authors concluded that stopping HT elevates the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD), including cardiac and cerebrovascular events. Using nationwide data, investigators compared the CVD mortality rate among women who discontinued HT during the years 1994 through 2009 (n = 332,202) with expected (not actual) CVD mortality rates in the background population.

Within the first year after HT discontinuation, elevations in death rates from cardiac events and stroke were noted (standardized mortality ratio, 1.26 and 1.63, respectively), while in the subsequent year, reductions in such mortality were observed (P<.05 for all comparisons).

The absolute increased risk of death from cardiac events reported within the first year after discontinuation of HT was 4 deaths per 10,000 woman-years of exposure. The absolute risk of death from stroke was 5 additional events per 10,000 woman-years. This level of risk is considered to be rare.

How these data compare to those of other studiesIn contrast with these Finnish data, findings from the Women’s Health Initiative—the largest randomized trial of menopausal HT—do not indicate an increase in mortality or an increase in coronary heart or stroke events among women stopping HT.1,2

It seems likely that limitations associated with the Finnish observational data account for this discordance. For example, Mikkola and colleagues did not know why women discontinued HT, raising the possibility that women with symptoms suggestive of CVD or development of new risk factors preferentially stopped HT, potentially introducing important bias into the Finnish analysis.

What this evidence means for practiceWomen and their clinicians should make decisions regarding whether to continue, reduce the dose, or discontinue HT through shared decision making, focusing on individual patient quality of life parameters as well as changing risk concerns related to such entities as cancer, CVD, and osteoporosis.3 Dramatic as they are, findings from this Finnish report should not impact how we counsel women regarding use or discontinuation of HT.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH; and Cynthia A. Stuenkel, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson GL, et al; WHI investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036–1045.

- LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, et al; WHI investigators. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1305–1314.

- Kaunitz AM. Extended duration use of menopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2014;21(6):679–68.

- Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson GL, et al; WHI investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036–1045.

- LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, et al; WHI investigators. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1305–1314.

- Kaunitz AM. Extended duration use of menopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2014;21(6):679–68.

Poor Continuity of Patient Care Increases Work for Hospitalist Groups

I think every hospitalist group should diligently try to maximize hospitalist-patient continuity, but many seem to adopt schedules and other operational practices that erode it. Let’s walk through the issue of continuity, starting with some history.

Inpatient Continuity in Old Healthcare System

Proudly carrying a pager nearly the size of a loaf of bread and wearing a white shirt and pants with Converse All Stars, I served as a hospital orderly in the 1970s. This position involved things like getting patients out of bed, placing Foley catheters, performing chest compressions during codes, and transporting the bodies of the deceased to the morgue. I really enjoyed the work, and the experience serves as one of my historical frames of reference for how hospital care has evolved since then.

The way I remember it, nearly everyone at the hospital worked a predictable schedule. RN staffing was the same each day; it didn’t vary based on census. Each full-time RN worked five shifts a week, eight hours each. Most or all would work alternate weekends and would have two compensatory days off during the following work week. This resulted in terrific continuity between nurse and patient, and the long length of stays meant patients and nurses got to know one another really well.

Continuity Takes a Hit

But things have changed. Nurse-patient continuity seems to have declined significantly as a result of two main forces: the hospital’s efforts to reduce staffing costs by varying nurse staffing to match daily patient volume, and nurses’ desire for a wide variety of work schedules. Asking a bedside nurse in today’s hospital whether the patient’s confusion, diarrhea, or appetite is meaningfully different today than yesterday typically yields the same reply. “This is my first day with the patient; I’ll have to look at the chart.”

I couldn’t find many research articles or editorials regarding hospital nurse-patient continuity from one day to the next. But several researchers seem to have begun studying this issue and have recently published a proposed framework for assessing it, and I found one study showing it wasn’t correlated with rates of pressure ulcers.1,2.

My anecdotal experience tells me continuity between the patient and caregivers of all stripes matters a lot. Research will be valuable in helping us to better understand its most significant costs and benefits, but I’m already convinced “Continuity is King” and should be one of the most important factors in the design of work schedules and patient allocation models for nurses and hospitalists alike.

While some might say we should wait for randomized trials of continuity to determine its importance, I’m inclined to see it like the authors of “Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials.” As a ding against those who insist on research data when common sense may be sufficient, they concluded “…that everyone might benefit if the most radical protagonists of evidence-based medicine organised and participated in a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of the parachute.3

Continuity and Hospitalists

On top of what I see as erosion in nurse-patient continuity, the arrival of hospitalists disrupted doctor-patient continuity across the inpatient and outpatient setting. While there was significant concern about this when our field first took off in the 1990s, it seems to be getting a great deal less attention over the last few years. In many hospitalist groups I work with, it is one of the last factors considered when creating a work schedule. Factors that are examined include the following:

- Solely for provider convenience, a group might regularly schedule a provider for only two or three consecutive daytime shifts, or sometimes only single days;

- Groups that use unit-based hospital (a.k.a. “geographic”) staffing might have a patient transfer to a different attending hospitalist solely as a result of moving to a room in a different nursing unit; and

- As part of morning load leveling, some groups reassign existing patients to a new hospitalist.

I think all groups should work hard to avoid doing these things. And while I seem to be a real outlier on this one, I think the benefits of a separate daytime hospitalist admitter shift are not worth the cost of having different doctors always do the admission and first follow-up visit. Most groups should consider moving the admitter into an additional rounder position and allocating daytime admissions across all hospitalists.

One study found that hospitalist discontinuity was not associated with adverse events, and another found it was associated with higher length of stay for selected diagnoses.4,5 But there is too little research to draw hard conclusions. I’m convinced poor continuity increases the possibility of handoff-related errors, likely results in lower patient satisfaction, and increases the overall work of the hospitalist group, because more providers have to take the time to get to know the patient.

Although there will always be some tension between terrific continuity and a sustainable hospitalist lifestyle—a person can work only so many consecutive days before wearing out—every group should thoughtfully consider whether they are doing everything reasonable to maximize continuity. After all, continuity is king.

References

- Stifter J, Yao Y, Lopez KC, Khokhar A, Wilkie DJ, Keenan GM. Proposing a new conceptual model and an exemplar measure using health information technology to examine the impact of relational nurse continuity on hospital-acquired pressure ulcers. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2015;38(3):241-251.

- Stifter J, Yao Y, Lodhi MK, et al. Nurse continuity and hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: a comparative analysis using an electronic health record “big data” set. Nurs Res. 2015;64(5):361-371.

- Smith GC, Pell JP. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2003;327(7429):1459-1461.

- O’Leary KJ, Turner J, Christensen N, et al. The effect of hospitalist discontinuity on adverse events. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):147-151.

- Epstein K, Juarez E, Epstein A, Loya K, Singer A. The impact of fragmentation of hospitalist care on length of stay. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):335-338.

I think every hospitalist group should diligently try to maximize hospitalist-patient continuity, but many seem to adopt schedules and other operational practices that erode it. Let’s walk through the issue of continuity, starting with some history.

Inpatient Continuity in Old Healthcare System

Proudly carrying a pager nearly the size of a loaf of bread and wearing a white shirt and pants with Converse All Stars, I served as a hospital orderly in the 1970s. This position involved things like getting patients out of bed, placing Foley catheters, performing chest compressions during codes, and transporting the bodies of the deceased to the morgue. I really enjoyed the work, and the experience serves as one of my historical frames of reference for how hospital care has evolved since then.

The way I remember it, nearly everyone at the hospital worked a predictable schedule. RN staffing was the same each day; it didn’t vary based on census. Each full-time RN worked five shifts a week, eight hours each. Most or all would work alternate weekends and would have two compensatory days off during the following work week. This resulted in terrific continuity between nurse and patient, and the long length of stays meant patients and nurses got to know one another really well.

Continuity Takes a Hit

But things have changed. Nurse-patient continuity seems to have declined significantly as a result of two main forces: the hospital’s efforts to reduce staffing costs by varying nurse staffing to match daily patient volume, and nurses’ desire for a wide variety of work schedules. Asking a bedside nurse in today’s hospital whether the patient’s confusion, diarrhea, or appetite is meaningfully different today than yesterday typically yields the same reply. “This is my first day with the patient; I’ll have to look at the chart.”

I couldn’t find many research articles or editorials regarding hospital nurse-patient continuity from one day to the next. But several researchers seem to have begun studying this issue and have recently published a proposed framework for assessing it, and I found one study showing it wasn’t correlated with rates of pressure ulcers.1,2.

My anecdotal experience tells me continuity between the patient and caregivers of all stripes matters a lot. Research will be valuable in helping us to better understand its most significant costs and benefits, but I’m already convinced “Continuity is King” and should be one of the most important factors in the design of work schedules and patient allocation models for nurses and hospitalists alike.

While some might say we should wait for randomized trials of continuity to determine its importance, I’m inclined to see it like the authors of “Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials.” As a ding against those who insist on research data when common sense may be sufficient, they concluded “…that everyone might benefit if the most radical protagonists of evidence-based medicine organised and participated in a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of the parachute.3

Continuity and Hospitalists

On top of what I see as erosion in nurse-patient continuity, the arrival of hospitalists disrupted doctor-patient continuity across the inpatient and outpatient setting. While there was significant concern about this when our field first took off in the 1990s, it seems to be getting a great deal less attention over the last few years. In many hospitalist groups I work with, it is one of the last factors considered when creating a work schedule. Factors that are examined include the following:

- Solely for provider convenience, a group might regularly schedule a provider for only two or three consecutive daytime shifts, or sometimes only single days;

- Groups that use unit-based hospital (a.k.a. “geographic”) staffing might have a patient transfer to a different attending hospitalist solely as a result of moving to a room in a different nursing unit; and

- As part of morning load leveling, some groups reassign existing patients to a new hospitalist.

I think all groups should work hard to avoid doing these things. And while I seem to be a real outlier on this one, I think the benefits of a separate daytime hospitalist admitter shift are not worth the cost of having different doctors always do the admission and first follow-up visit. Most groups should consider moving the admitter into an additional rounder position and allocating daytime admissions across all hospitalists.

One study found that hospitalist discontinuity was not associated with adverse events, and another found it was associated with higher length of stay for selected diagnoses.4,5 But there is too little research to draw hard conclusions. I’m convinced poor continuity increases the possibility of handoff-related errors, likely results in lower patient satisfaction, and increases the overall work of the hospitalist group, because more providers have to take the time to get to know the patient.

Although there will always be some tension between terrific continuity and a sustainable hospitalist lifestyle—a person can work only so many consecutive days before wearing out—every group should thoughtfully consider whether they are doing everything reasonable to maximize continuity. After all, continuity is king.

References

- Stifter J, Yao Y, Lopez KC, Khokhar A, Wilkie DJ, Keenan GM. Proposing a new conceptual model and an exemplar measure using health information technology to examine the impact of relational nurse continuity on hospital-acquired pressure ulcers. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2015;38(3):241-251.

- Stifter J, Yao Y, Lodhi MK, et al. Nurse continuity and hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: a comparative analysis using an electronic health record “big data” set. Nurs Res. 2015;64(5):361-371.

- Smith GC, Pell JP. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2003;327(7429):1459-1461.

- O’Leary KJ, Turner J, Christensen N, et al. The effect of hospitalist discontinuity on adverse events. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):147-151.

- Epstein K, Juarez E, Epstein A, Loya K, Singer A. The impact of fragmentation of hospitalist care on length of stay. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):335-338.

I think every hospitalist group should diligently try to maximize hospitalist-patient continuity, but many seem to adopt schedules and other operational practices that erode it. Let’s walk through the issue of continuity, starting with some history.

Inpatient Continuity in Old Healthcare System

Proudly carrying a pager nearly the size of a loaf of bread and wearing a white shirt and pants with Converse All Stars, I served as a hospital orderly in the 1970s. This position involved things like getting patients out of bed, placing Foley catheters, performing chest compressions during codes, and transporting the bodies of the deceased to the morgue. I really enjoyed the work, and the experience serves as one of my historical frames of reference for how hospital care has evolved since then.

The way I remember it, nearly everyone at the hospital worked a predictable schedule. RN staffing was the same each day; it didn’t vary based on census. Each full-time RN worked five shifts a week, eight hours each. Most or all would work alternate weekends and would have two compensatory days off during the following work week. This resulted in terrific continuity between nurse and patient, and the long length of stays meant patients and nurses got to know one another really well.

Continuity Takes a Hit

But things have changed. Nurse-patient continuity seems to have declined significantly as a result of two main forces: the hospital’s efforts to reduce staffing costs by varying nurse staffing to match daily patient volume, and nurses’ desire for a wide variety of work schedules. Asking a bedside nurse in today’s hospital whether the patient’s confusion, diarrhea, or appetite is meaningfully different today than yesterday typically yields the same reply. “This is my first day with the patient; I’ll have to look at the chart.”

I couldn’t find many research articles or editorials regarding hospital nurse-patient continuity from one day to the next. But several researchers seem to have begun studying this issue and have recently published a proposed framework for assessing it, and I found one study showing it wasn’t correlated with rates of pressure ulcers.1,2.

My anecdotal experience tells me continuity between the patient and caregivers of all stripes matters a lot. Research will be valuable in helping us to better understand its most significant costs and benefits, but I’m already convinced “Continuity is King” and should be one of the most important factors in the design of work schedules and patient allocation models for nurses and hospitalists alike.

While some might say we should wait for randomized trials of continuity to determine its importance, I’m inclined to see it like the authors of “Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials.” As a ding against those who insist on research data when common sense may be sufficient, they concluded “…that everyone might benefit if the most radical protagonists of evidence-based medicine organised and participated in a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of the parachute.3

Continuity and Hospitalists

On top of what I see as erosion in nurse-patient continuity, the arrival of hospitalists disrupted doctor-patient continuity across the inpatient and outpatient setting. While there was significant concern about this when our field first took off in the 1990s, it seems to be getting a great deal less attention over the last few years. In many hospitalist groups I work with, it is one of the last factors considered when creating a work schedule. Factors that are examined include the following:

- Solely for provider convenience, a group might regularly schedule a provider for only two or three consecutive daytime shifts, or sometimes only single days;

- Groups that use unit-based hospital (a.k.a. “geographic”) staffing might have a patient transfer to a different attending hospitalist solely as a result of moving to a room in a different nursing unit; and

- As part of morning load leveling, some groups reassign existing patients to a new hospitalist.

I think all groups should work hard to avoid doing these things. And while I seem to be a real outlier on this one, I think the benefits of a separate daytime hospitalist admitter shift are not worth the cost of having different doctors always do the admission and first follow-up visit. Most groups should consider moving the admitter into an additional rounder position and allocating daytime admissions across all hospitalists.

One study found that hospitalist discontinuity was not associated with adverse events, and another found it was associated with higher length of stay for selected diagnoses.4,5 But there is too little research to draw hard conclusions. I’m convinced poor continuity increases the possibility of handoff-related errors, likely results in lower patient satisfaction, and increases the overall work of the hospitalist group, because more providers have to take the time to get to know the patient.

Although there will always be some tension between terrific continuity and a sustainable hospitalist lifestyle—a person can work only so many consecutive days before wearing out—every group should thoughtfully consider whether they are doing everything reasonable to maximize continuity. After all, continuity is king.

References

- Stifter J, Yao Y, Lopez KC, Khokhar A, Wilkie DJ, Keenan GM. Proposing a new conceptual model and an exemplar measure using health information technology to examine the impact of relational nurse continuity on hospital-acquired pressure ulcers. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2015;38(3):241-251.

- Stifter J, Yao Y, Lodhi MK, et al. Nurse continuity and hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: a comparative analysis using an electronic health record “big data” set. Nurs Res. 2015;64(5):361-371.

- Smith GC, Pell JP. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2003;327(7429):1459-1461.

- O’Leary KJ, Turner J, Christensen N, et al. The effect of hospitalist discontinuity on adverse events. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):147-151.

- Epstein K, Juarez E, Epstein A, Loya K, Singer A. The impact of fragmentation of hospitalist care on length of stay. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):335-338.

My response to ACOG’s emphasis on vaginal hysterectomy first

Recorded November 17, 2015, at the AAGL Global Congress in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Recorded November 17, 2015, at the AAGL Global Congress in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Recorded November 17, 2015, at the AAGL Global Congress in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Is a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy for Gyn cancer utilized equally in all racial and income groups?

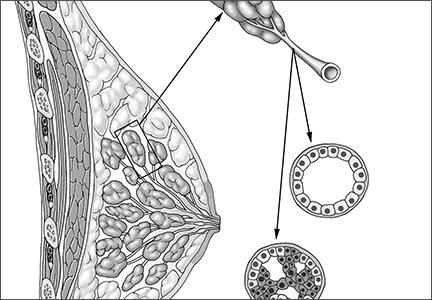

The minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy (laparoscopic, robot-assisted, or vaginal) is associated with less blood loss, a shorter length of stay, and quicker recovery than the abdominal approach (laparotomy). In this study, Esselen and colleagues drew from the 2012 National Inpatient Sample, the largest national all-payer database of hospital discharges, which samples some 20% of hospital discharges. Of an estimated 28,160 hysterectomies performed in 2012 for endometrial cancer, 50% were abdominal and 50% involved MIS (38% robot-assisted, 11% laparoscopic, and 1% vaginal).

MIS was used less often for black women (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.50) and Native American women (0.56), compared with white women. Similarly, Medicaid patients were less likely to undergo MIS (adjusted OR, 0.58) than those who were covered by commercial medical insurance.

MIS was used 3.68 times more often in women cared for in urban teaching hospitals, compared with women undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial cancer in rural hospitals (P<.04 for all comparisons).

Length of stay was substantially longer and total costs were higher for women undergoing abdominal hysterectomy.

Study did not control for stage of cancer at presentation

These striking findings parallel higher cancer-specific mortality and other disparities faced by minority patients. Esselen and colleagues point out that higher stage at presentation sometimes mandates use of an abdominal approach for hysterectomy and that minority and low-income women often present with higher-stage disease; accordingly, their inability to control for stage represents an important limitation.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

This report indicates that, for US women of different ethnic and socioeconomic status, important differences are present with respect to access to MIS for gynecologic malignancy.

— Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy (laparoscopic, robot-assisted, or vaginal) is associated with less blood loss, a shorter length of stay, and quicker recovery than the abdominal approach (laparotomy). In this study, Esselen and colleagues drew from the 2012 National Inpatient Sample, the largest national all-payer database of hospital discharges, which samples some 20% of hospital discharges. Of an estimated 28,160 hysterectomies performed in 2012 for endometrial cancer, 50% were abdominal and 50% involved MIS (38% robot-assisted, 11% laparoscopic, and 1% vaginal).

MIS was used less often for black women (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.50) and Native American women (0.56), compared with white women. Similarly, Medicaid patients were less likely to undergo MIS (adjusted OR, 0.58) than those who were covered by commercial medical insurance.

MIS was used 3.68 times more often in women cared for in urban teaching hospitals, compared with women undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial cancer in rural hospitals (P<.04 for all comparisons).

Length of stay was substantially longer and total costs were higher for women undergoing abdominal hysterectomy.

Study did not control for stage of cancer at presentation

These striking findings parallel higher cancer-specific mortality and other disparities faced by minority patients. Esselen and colleagues point out that higher stage at presentation sometimes mandates use of an abdominal approach for hysterectomy and that minority and low-income women often present with higher-stage disease; accordingly, their inability to control for stage represents an important limitation.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

This report indicates that, for US women of different ethnic and socioeconomic status, important differences are present with respect to access to MIS for gynecologic malignancy.

— Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy (laparoscopic, robot-assisted, or vaginal) is associated with less blood loss, a shorter length of stay, and quicker recovery than the abdominal approach (laparotomy). In this study, Esselen and colleagues drew from the 2012 National Inpatient Sample, the largest national all-payer database of hospital discharges, which samples some 20% of hospital discharges. Of an estimated 28,160 hysterectomies performed in 2012 for endometrial cancer, 50% were abdominal and 50% involved MIS (38% robot-assisted, 11% laparoscopic, and 1% vaginal).

MIS was used less often for black women (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.50) and Native American women (0.56), compared with white women. Similarly, Medicaid patients were less likely to undergo MIS (adjusted OR, 0.58) than those who were covered by commercial medical insurance.

MIS was used 3.68 times more often in women cared for in urban teaching hospitals, compared with women undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial cancer in rural hospitals (P<.04 for all comparisons).

Length of stay was substantially longer and total costs were higher for women undergoing abdominal hysterectomy.

Study did not control for stage of cancer at presentation

These striking findings parallel higher cancer-specific mortality and other disparities faced by minority patients. Esselen and colleagues point out that higher stage at presentation sometimes mandates use of an abdominal approach for hysterectomy and that minority and low-income women often present with higher-stage disease; accordingly, their inability to control for stage represents an important limitation.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

This report indicates that, for US women of different ethnic and socioeconomic status, important differences are present with respect to access to MIS for gynecologic malignancy.

— Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Dengue disease is here and U.S. physicians need to get to know it

SAN DIEGO – With dengue disease now knocking on the door of the United States, it’s a good time for American physicians to get up to speed regarding the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease in the world.

That’s a particularly sound idea if they – or their patients – plan to visit anywhere in the Caribbean, Central America, Brazil, East Asia, or large swathes of Africa, where the disease is a major and rapidly growing public health problem. The World Health Organization estimates 3.6 billion people worldwide are at risk for dengue disease, with up to 100 million symptomatic infections occurring annually, 250,000-500,000 cases of severe dengue, and 21,000 deaths due to the disease. There have been recent outbreaks in South Florida, Texas, and Hawaii, Dr. Federico Narvaez noted at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The most important thing for clinicians to know about dengue disease is how to identify the subset of up to 10% of symptomatic dengue patients who – absent appropriate intervention – will progress to severe disease marked by pronounced plasma leakage leading to shock, respiratory failure, severe hemorrhage, and/or organ failure, he stressed. This is a disease that can cause death within the space of 24-48 hours in a person who was healthy just a few days before. And there are a handful of warning signs that predictably occur on day 3 or 4 of the illness, when the initial high fever comes down, before things take a dramatic turn for the worse.

“Timely diagnosis improves prognosis. If properly managed, the case fatality rate of severe dengue is less than 1%,” said Dr. Narvaez of the National Pediatric Reference Hospital and the Nicaragua Ministry of Health in Managua.

The traditional WHO classification for dengue into self-limited dengue fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever, and dengue shock syndrome was replaced in 2009 by a system that Dr. Narvaez and other experts consider a big step forward in guiding clinical management. Under the revised WHO classification, dengue disease is divided into dengue without warning signs, dengue with warning signs, and severe dengue.

In a study of 544 laboratory-confirmed cases of pediatric dengue in Managua, Dr. Narvaez and coinvestigators compared the former and revised WHO classifications and demonstrated that the 2009 revised system boosted the positive predictive value for need for inpatient care from 43% to 67% (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011 Nov;5[11]:e1397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001397. Epub 2011 Nov 8).

Some key points about dengue disease: It has two distinct mosquito vectors, Aedis aegypti and A. albonictus. There are four cocirculating serotypes; infection with one doesn’t protect against infection with the others. Three-quarters of infections are asymptomatic. Symptomatic infections follow a three-stage course: the febrile, critical, and recovery phases. And the primary pathophysiology of dengue disease is plasma leakage.

The febrile phase is marked by abrupt onset of high fever plus various combinations of severe headache, facial flushing, a transient macular or maculopapular rash, retro-orbital pain, and/or the intense arthralgias/myalgias which have led to dengue being known as ‘breakbone fever.’

The critical phase begins around the time of defervescence. This is when clinically significant plasma leakage can occur, with resultant compensated or decompensated shock and other severe complications. The critical phase is the time for vigilance regarding the appearance of the 2009 WHO warning signs of increased risk for shock: abdominal pain, an abrupt rise in hematocrit concurrent with a rapid drop in platelets, mucosal bleeding, development of ascites or other clinically apparent fluid accumulation, liver enlargement of more than 2 cm, persistent vomiting, and restlessness/lethargy.

In a soon-to-be-published study of 812 Nicaraguan dengue patients, 220 of whom developed shock, Dr. Narvaez and coworkers found that the presence of any of the warning signs except persistent vomiting was associated with significantly increased likelihood of subsequent shock, with the magnitude of increased risk ranging from 1.31 to 2.3. Moreover, other studies have demonstrated that by acting upon these warning signs by means of cautious administration of intravenous fluids and other supportive measures, the risk of developing shock is reduced.

The WHO warning signs are particularly valuable in the often resource-poor countries where dengue is most common. In such settings most front-line primary care physicians lack ready access to ultrasound imaging of the gallbladder looking for evidence of wall thickening. A thickened gallbladder wall is an expression of subclinical plasma leakage, which has been shown in multiple studies to be even better at identifying patients at risk for severe dengue than the WHO warning signs.

For example, a prospective hospital-based study in which Dutch and Indonesian investigators utilized serial daily bedside ultrasonography with a hand-held imaging device found that gallbladder wall edema at enrollment had a 35% positive predictive value and a 90% negative predictive value for subsequent severe dengue (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013 Jun 13;7[6]:e2277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002277).

The critical phase typically lasts from day 3 or 4 through day 6 of the illness. This is followed by the recovery phase, marked by reabsorption of extravasated fluid over the course of 48-72 hours, increased diuresis, and stabilization of hemodynamic status. The appearance of a highly pruritic and erythematous rash with small islands of normal skin is another common finding that indicates the patient’s condition will continue to improve. A temporary bradycardia is also quite common during the recovery phase, according to Dr. Narvaez.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SAN DIEGO – With dengue disease now knocking on the door of the United States, it’s a good time for American physicians to get up to speed regarding the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease in the world.

That’s a particularly sound idea if they – or their patients – plan to visit anywhere in the Caribbean, Central America, Brazil, East Asia, or large swathes of Africa, where the disease is a major and rapidly growing public health problem. The World Health Organization estimates 3.6 billion people worldwide are at risk for dengue disease, with up to 100 million symptomatic infections occurring annually, 250,000-500,000 cases of severe dengue, and 21,000 deaths due to the disease. There have been recent outbreaks in South Florida, Texas, and Hawaii, Dr. Federico Narvaez noted at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The most important thing for clinicians to know about dengue disease is how to identify the subset of up to 10% of symptomatic dengue patients who – absent appropriate intervention – will progress to severe disease marked by pronounced plasma leakage leading to shock, respiratory failure, severe hemorrhage, and/or organ failure, he stressed. This is a disease that can cause death within the space of 24-48 hours in a person who was healthy just a few days before. And there are a handful of warning signs that predictably occur on day 3 or 4 of the illness, when the initial high fever comes down, before things take a dramatic turn for the worse.

“Timely diagnosis improves prognosis. If properly managed, the case fatality rate of severe dengue is less than 1%,” said Dr. Narvaez of the National Pediatric Reference Hospital and the Nicaragua Ministry of Health in Managua.

The traditional WHO classification for dengue into self-limited dengue fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever, and dengue shock syndrome was replaced in 2009 by a system that Dr. Narvaez and other experts consider a big step forward in guiding clinical management. Under the revised WHO classification, dengue disease is divided into dengue without warning signs, dengue with warning signs, and severe dengue.

In a study of 544 laboratory-confirmed cases of pediatric dengue in Managua, Dr. Narvaez and coinvestigators compared the former and revised WHO classifications and demonstrated that the 2009 revised system boosted the positive predictive value for need for inpatient care from 43% to 67% (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011 Nov;5[11]:e1397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001397. Epub 2011 Nov 8).

Some key points about dengue disease: It has two distinct mosquito vectors, Aedis aegypti and A. albonictus. There are four cocirculating serotypes; infection with one doesn’t protect against infection with the others. Three-quarters of infections are asymptomatic. Symptomatic infections follow a three-stage course: the febrile, critical, and recovery phases. And the primary pathophysiology of dengue disease is plasma leakage.

The febrile phase is marked by abrupt onset of high fever plus various combinations of severe headache, facial flushing, a transient macular or maculopapular rash, retro-orbital pain, and/or the intense arthralgias/myalgias which have led to dengue being known as ‘breakbone fever.’

The critical phase begins around the time of defervescence. This is when clinically significant plasma leakage can occur, with resultant compensated or decompensated shock and other severe complications. The critical phase is the time for vigilance regarding the appearance of the 2009 WHO warning signs of increased risk for shock: abdominal pain, an abrupt rise in hematocrit concurrent with a rapid drop in platelets, mucosal bleeding, development of ascites or other clinically apparent fluid accumulation, liver enlargement of more than 2 cm, persistent vomiting, and restlessness/lethargy.

In a soon-to-be-published study of 812 Nicaraguan dengue patients, 220 of whom developed shock, Dr. Narvaez and coworkers found that the presence of any of the warning signs except persistent vomiting was associated with significantly increased likelihood of subsequent shock, with the magnitude of increased risk ranging from 1.31 to 2.3. Moreover, other studies have demonstrated that by acting upon these warning signs by means of cautious administration of intravenous fluids and other supportive measures, the risk of developing shock is reduced.

The WHO warning signs are particularly valuable in the often resource-poor countries where dengue is most common. In such settings most front-line primary care physicians lack ready access to ultrasound imaging of the gallbladder looking for evidence of wall thickening. A thickened gallbladder wall is an expression of subclinical plasma leakage, which has been shown in multiple studies to be even better at identifying patients at risk for severe dengue than the WHO warning signs.

For example, a prospective hospital-based study in which Dutch and Indonesian investigators utilized serial daily bedside ultrasonography with a hand-held imaging device found that gallbladder wall edema at enrollment had a 35% positive predictive value and a 90% negative predictive value for subsequent severe dengue (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013 Jun 13;7[6]:e2277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002277).

The critical phase typically lasts from day 3 or 4 through day 6 of the illness. This is followed by the recovery phase, marked by reabsorption of extravasated fluid over the course of 48-72 hours, increased diuresis, and stabilization of hemodynamic status. The appearance of a highly pruritic and erythematous rash with small islands of normal skin is another common finding that indicates the patient’s condition will continue to improve. A temporary bradycardia is also quite common during the recovery phase, according to Dr. Narvaez.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SAN DIEGO – With dengue disease now knocking on the door of the United States, it’s a good time for American physicians to get up to speed regarding the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease in the world.

That’s a particularly sound idea if they – or their patients – plan to visit anywhere in the Caribbean, Central America, Brazil, East Asia, or large swathes of Africa, where the disease is a major and rapidly growing public health problem. The World Health Organization estimates 3.6 billion people worldwide are at risk for dengue disease, with up to 100 million symptomatic infections occurring annually, 250,000-500,000 cases of severe dengue, and 21,000 deaths due to the disease. There have been recent outbreaks in South Florida, Texas, and Hawaii, Dr. Federico Narvaez noted at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The most important thing for clinicians to know about dengue disease is how to identify the subset of up to 10% of symptomatic dengue patients who – absent appropriate intervention – will progress to severe disease marked by pronounced plasma leakage leading to shock, respiratory failure, severe hemorrhage, and/or organ failure, he stressed. This is a disease that can cause death within the space of 24-48 hours in a person who was healthy just a few days before. And there are a handful of warning signs that predictably occur on day 3 or 4 of the illness, when the initial high fever comes down, before things take a dramatic turn for the worse.

“Timely diagnosis improves prognosis. If properly managed, the case fatality rate of severe dengue is less than 1%,” said Dr. Narvaez of the National Pediatric Reference Hospital and the Nicaragua Ministry of Health in Managua.

The traditional WHO classification for dengue into self-limited dengue fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever, and dengue shock syndrome was replaced in 2009 by a system that Dr. Narvaez and other experts consider a big step forward in guiding clinical management. Under the revised WHO classification, dengue disease is divided into dengue without warning signs, dengue with warning signs, and severe dengue.

In a study of 544 laboratory-confirmed cases of pediatric dengue in Managua, Dr. Narvaez and coinvestigators compared the former and revised WHO classifications and demonstrated that the 2009 revised system boosted the positive predictive value for need for inpatient care from 43% to 67% (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011 Nov;5[11]:e1397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001397. Epub 2011 Nov 8).

Some key points about dengue disease: It has two distinct mosquito vectors, Aedis aegypti and A. albonictus. There are four cocirculating serotypes; infection with one doesn’t protect against infection with the others. Three-quarters of infections are asymptomatic. Symptomatic infections follow a three-stage course: the febrile, critical, and recovery phases. And the primary pathophysiology of dengue disease is plasma leakage.

The febrile phase is marked by abrupt onset of high fever plus various combinations of severe headache, facial flushing, a transient macular or maculopapular rash, retro-orbital pain, and/or the intense arthralgias/myalgias which have led to dengue being known as ‘breakbone fever.’

The critical phase begins around the time of defervescence. This is when clinically significant plasma leakage can occur, with resultant compensated or decompensated shock and other severe complications. The critical phase is the time for vigilance regarding the appearance of the 2009 WHO warning signs of increased risk for shock: abdominal pain, an abrupt rise in hematocrit concurrent with a rapid drop in platelets, mucosal bleeding, development of ascites or other clinically apparent fluid accumulation, liver enlargement of more than 2 cm, persistent vomiting, and restlessness/lethargy.

In a soon-to-be-published study of 812 Nicaraguan dengue patients, 220 of whom developed shock, Dr. Narvaez and coworkers found that the presence of any of the warning signs except persistent vomiting was associated with significantly increased likelihood of subsequent shock, with the magnitude of increased risk ranging from 1.31 to 2.3. Moreover, other studies have demonstrated that by acting upon these warning signs by means of cautious administration of intravenous fluids and other supportive measures, the risk of developing shock is reduced.

The WHO warning signs are particularly valuable in the often resource-poor countries where dengue is most common. In such settings most front-line primary care physicians lack ready access to ultrasound imaging of the gallbladder looking for evidence of wall thickening. A thickened gallbladder wall is an expression of subclinical plasma leakage, which has been shown in multiple studies to be even better at identifying patients at risk for severe dengue than the WHO warning signs.

For example, a prospective hospital-based study in which Dutch and Indonesian investigators utilized serial daily bedside ultrasonography with a hand-held imaging device found that gallbladder wall edema at enrollment had a 35% positive predictive value and a 90% negative predictive value for subsequent severe dengue (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013 Jun 13;7[6]:e2277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002277).

The critical phase typically lasts from day 3 or 4 through day 6 of the illness. This is followed by the recovery phase, marked by reabsorption of extravasated fluid over the course of 48-72 hours, increased diuresis, and stabilization of hemodynamic status. The appearance of a highly pruritic and erythematous rash with small islands of normal skin is another common finding that indicates the patient’s condition will continue to improve. A temporary bradycardia is also quite common during the recovery phase, according to Dr. Narvaez.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ICAAC 2015

VIDEO: HFSA Roundtable, part 3: Acute heart failure decompensations pose uncertain consequences

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – “There may be more to acute heart failure than meets the eye,” Hani N. Sabbah, Ph.D., said in a discussion during the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

What remains unclear about acute decompensation episodes in patients with chronic heart failure is whether these events themselves exert a detrimental effect or if decompensation episodes merely flag patients in the worst clinical condition and are part of the natural history of worsening heart failure, said Dr. Sabbah, professor and director of cardiovascular research at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

The importance of acute heart failure decompensations seems comparable to acute MIs, episodes in which incremental declines in heart-muscle function contribute to additional long-term worsening of heart failure, said Dr. Jay N. Cohn, another member of a discussion panel that also included Dr. Sidney Goldstein and Dr. Prakash Deedwania.

The risk from acute decompensations of heart failure highlights the importance of taking steps to cut the incidence of decompensations, said Dr. Cohn. Usual triggers of decompensation that could be targets for prevention are uncontrolled blood pressure and dietary indiscretions, Dr. Deedwania noted. Troponin leaks, a marker of myocardial-cell death, constitute another indicator of acute decompensation that may offer further insight into how to manage these episodes, he said.

Dr. Goldstein had no disclosures. Dr. Deedwania had no disclosures. Dr. Cohn receives royalties from Arbor Pharmaceuticals related to his work on hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate. Dr. Sabbah is a consultant to Boston Scientific and an advisor to BioControl Medical and he has received research grants from both companies.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – “There may be more to acute heart failure than meets the eye,” Hani N. Sabbah, Ph.D., said in a discussion during the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

What remains unclear about acute decompensation episodes in patients with chronic heart failure is whether these events themselves exert a detrimental effect or if decompensation episodes merely flag patients in the worst clinical condition and are part of the natural history of worsening heart failure, said Dr. Sabbah, professor and director of cardiovascular research at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

The importance of acute heart failure decompensations seems comparable to acute MIs, episodes in which incremental declines in heart-muscle function contribute to additional long-term worsening of heart failure, said Dr. Jay N. Cohn, another member of a discussion panel that also included Dr. Sidney Goldstein and Dr. Prakash Deedwania.

The risk from acute decompensations of heart failure highlights the importance of taking steps to cut the incidence of decompensations, said Dr. Cohn. Usual triggers of decompensation that could be targets for prevention are uncontrolled blood pressure and dietary indiscretions, Dr. Deedwania noted. Troponin leaks, a marker of myocardial-cell death, constitute another indicator of acute decompensation that may offer further insight into how to manage these episodes, he said.

Dr. Goldstein had no disclosures. Dr. Deedwania had no disclosures. Dr. Cohn receives royalties from Arbor Pharmaceuticals related to his work on hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate. Dr. Sabbah is a consultant to Boston Scientific and an advisor to BioControl Medical and he has received research grants from both companies.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – “There may be more to acute heart failure than meets the eye,” Hani N. Sabbah, Ph.D., said in a discussion during the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

What remains unclear about acute decompensation episodes in patients with chronic heart failure is whether these events themselves exert a detrimental effect or if decompensation episodes merely flag patients in the worst clinical condition and are part of the natural history of worsening heart failure, said Dr. Sabbah, professor and director of cardiovascular research at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

The importance of acute heart failure decompensations seems comparable to acute MIs, episodes in which incremental declines in heart-muscle function contribute to additional long-term worsening of heart failure, said Dr. Jay N. Cohn, another member of a discussion panel that also included Dr. Sidney Goldstein and Dr. Prakash Deedwania.

The risk from acute decompensations of heart failure highlights the importance of taking steps to cut the incidence of decompensations, said Dr. Cohn. Usual triggers of decompensation that could be targets for prevention are uncontrolled blood pressure and dietary indiscretions, Dr. Deedwania noted. Troponin leaks, a marker of myocardial-cell death, constitute another indicator of acute decompensation that may offer further insight into how to manage these episodes, he said.

Dr. Goldstein had no disclosures. Dr. Deedwania had no disclosures. Dr. Cohn receives royalties from Arbor Pharmaceuticals related to his work on hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate. Dr. Sabbah is a consultant to Boston Scientific and an advisor to BioControl Medical and he has received research grants from both companies.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE HFSA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC MEETING

Eliminations Hospitalist Groups Should Consider

Editor’s note: Second in a continuing series of articles exploring ways hospitalist groups can cut back.

In last month’s column, I made the case that most hospitalist groups should think about doing away with a morning meeting to distribute overnight admissions and changing a daytime admitter shift into another rounder and having all of the day rounders share admissions. Here I’ll describe additional things in place at some hospitalist groups that should probably be eliminated.

Obscuring Attending Hospitalist Name

Some hospitalist groups admit patients to the “blue team” or “gold team” or use a similar system. I encountered one place that had a fuchsia team. Such designations typically take the place of the attending physician’s name and can be convenient when one hospitalist goes off service and is replaced by another; the team name stays the same. Even if the attending hospitalist makes up the entire team (i.e., no residents or students), some groups use the “team” name rather than the attending hospitalist name.

But when the patient’s chart, sign on the door, and other identifying materials all refer only to the team that is caring for the patient, the patients, their families, and most hospital staff don’t have an easy way to identify the responsible physician. Say a worried daughter steps into the hall to ask the nurse, “Which doctor is taking care of my dad?” The nurse might readily see that the blue team is responsible but may not know which hospitalist is working on the blue team today and might have to walk back to the nursing station to look over a sheet of paper (a “decoder ring”) to figure out the hospitalist’s name.

This scenario has all kinds of drawbacks. To the daughter, the name of the doctor in charge is a big deal. It doesn’t inspire confidence if the nurse can’t readily say who that is. And the busy nurse might forget to investigate and provide the name to the daughter in a timely way.

I think groups using a system like this should seriously consider replacing team names with the attending hospitalist name and updating that name in the medical record, whether that is an EHR, a paper chart, or some other form, every time that doctor rotates off service and is replaced by another. Hospital staff, patients, and families should always see the name of the attending physician and not an uninformative color or nondescript team name.

It will require work for someone, the hospitalist in many cases, to go into the EHR and write an order or send a message to ensure that the hospitalist name is kept current every time one doctor replaces another. But it’s worth the effort.

Day Hospitalists Should Round on Patients Admitted after Midnight

Although not exactly common, I’ve come across this scenario often enough that it’s worth mentioning.

Hospitalists, sometimes with a hint of indignity or even chest thumping, have told me they don’t visit or round on patients admitted after midnight by their night doctor. “You can’t bill for a second visit on the same calendar day,” they explain, firmly. “So if I can’t get paid to see the patient, then I won’t.”

This is just crazy.

For one thing, these same doctors are typically employed by the hospital and are being paid to provide whatever care patients need. I think they’ve just latched onto the “can’t bill another visit” as an excuse to get out of some work.

Don’t forget that many of these patients may wait over 30 hours from their admitting visit to the first follow-up visit; this delay is at the beginning of their hospital stay, when they might be most unstable. And it delays initiation of discharge planning and other important steps in patient care.

I don’t see any room for meaningful debate on this. The rounder who picks up a patient admitted the night before should always make a full rounding visit, even if the admission was after midnight.

But if the visit isn’t billable, you are freed from the typical billing-related documentation requirements. No need to document detail in the note that doesn’t meaningfully contribute to the care of the patient. For example, you might omit a chief complaint for this encounter.

Daytime Triage Doctor

Practices larger than about 20 full-time equivalents often have one daytime doctor hold a “triage” or “hot” pager, which others call to make a new referral. This triage doctor will hear about all referrals and keep track of and contact the hospitalist responsible for the next new patient. This can be a very busy job and often comes on top of a full clinical load for that doctor.

As I mentioned in my July 2015 and December 2010 articles, in many or most groups, a clerical person could take over this function, at least during business hours.

Vacation Time

In many or most cases, hospitalists that have specified vacation time are not getting a better deal than those that have no vacation time. What really matters is how many shifts you’re responsible for in a year. For the days you aren’t on shift, in most hospitalist groups it really doesn’t matter whether you label some of them as vacation days or CME days.

I discussed this issue in greater detail in my March 2007 article.

But if you’re in the 30% of hospitalist groups that have a vacation (or PTO) provision currently and it works well, then there certainly isn’t a compelling reason to change or do away with it.

Editor’s note: Second in a continuing series of articles exploring ways hospitalist groups can cut back.

In last month’s column, I made the case that most hospitalist groups should think about doing away with a morning meeting to distribute overnight admissions and changing a daytime admitter shift into another rounder and having all of the day rounders share admissions. Here I’ll describe additional things in place at some hospitalist groups that should probably be eliminated.

Obscuring Attending Hospitalist Name

Some hospitalist groups admit patients to the “blue team” or “gold team” or use a similar system. I encountered one place that had a fuchsia team. Such designations typically take the place of the attending physician’s name and can be convenient when one hospitalist goes off service and is replaced by another; the team name stays the same. Even if the attending hospitalist makes up the entire team (i.e., no residents or students), some groups use the “team” name rather than the attending hospitalist name.

But when the patient’s chart, sign on the door, and other identifying materials all refer only to the team that is caring for the patient, the patients, their families, and most hospital staff don’t have an easy way to identify the responsible physician. Say a worried daughter steps into the hall to ask the nurse, “Which doctor is taking care of my dad?” The nurse might readily see that the blue team is responsible but may not know which hospitalist is working on the blue team today and might have to walk back to the nursing station to look over a sheet of paper (a “decoder ring”) to figure out the hospitalist’s name.

This scenario has all kinds of drawbacks. To the daughter, the name of the doctor in charge is a big deal. It doesn’t inspire confidence if the nurse can’t readily say who that is. And the busy nurse might forget to investigate and provide the name to the daughter in a timely way.

I think groups using a system like this should seriously consider replacing team names with the attending hospitalist name and updating that name in the medical record, whether that is an EHR, a paper chart, or some other form, every time that doctor rotates off service and is replaced by another. Hospital staff, patients, and families should always see the name of the attending physician and not an uninformative color or nondescript team name.

It will require work for someone, the hospitalist in many cases, to go into the EHR and write an order or send a message to ensure that the hospitalist name is kept current every time one doctor replaces another. But it’s worth the effort.

Day Hospitalists Should Round on Patients Admitted after Midnight

Although not exactly common, I’ve come across this scenario often enough that it’s worth mentioning.

Hospitalists, sometimes with a hint of indignity or even chest thumping, have told me they don’t visit or round on patients admitted after midnight by their night doctor. “You can’t bill for a second visit on the same calendar day,” they explain, firmly. “So if I can’t get paid to see the patient, then I won’t.”

This is just crazy.

For one thing, these same doctors are typically employed by the hospital and are being paid to provide whatever care patients need. I think they’ve just latched onto the “can’t bill another visit” as an excuse to get out of some work.

Don’t forget that many of these patients may wait over 30 hours from their admitting visit to the first follow-up visit; this delay is at the beginning of their hospital stay, when they might be most unstable. And it delays initiation of discharge planning and other important steps in patient care.

I don’t see any room for meaningful debate on this. The rounder who picks up a patient admitted the night before should always make a full rounding visit, even if the admission was after midnight.

But if the visit isn’t billable, you are freed from the typical billing-related documentation requirements. No need to document detail in the note that doesn’t meaningfully contribute to the care of the patient. For example, you might omit a chief complaint for this encounter.

Daytime Triage Doctor

Practices larger than about 20 full-time equivalents often have one daytime doctor hold a “triage” or “hot” pager, which others call to make a new referral. This triage doctor will hear about all referrals and keep track of and contact the hospitalist responsible for the next new patient. This can be a very busy job and often comes on top of a full clinical load for that doctor.

As I mentioned in my July 2015 and December 2010 articles, in many or most groups, a clerical person could take over this function, at least during business hours.

Vacation Time

In many or most cases, hospitalists that have specified vacation time are not getting a better deal than those that have no vacation time. What really matters is how many shifts you’re responsible for in a year. For the days you aren’t on shift, in most hospitalist groups it really doesn’t matter whether you label some of them as vacation days or CME days.

I discussed this issue in greater detail in my March 2007 article.

But if you’re in the 30% of hospitalist groups that have a vacation (or PTO) provision currently and it works well, then there certainly isn’t a compelling reason to change or do away with it.

Editor’s note: Second in a continuing series of articles exploring ways hospitalist groups can cut back.

In last month’s column, I made the case that most hospitalist groups should think about doing away with a morning meeting to distribute overnight admissions and changing a daytime admitter shift into another rounder and having all of the day rounders share admissions. Here I’ll describe additional things in place at some hospitalist groups that should probably be eliminated.

Obscuring Attending Hospitalist Name

Some hospitalist groups admit patients to the “blue team” or “gold team” or use a similar system. I encountered one place that had a fuchsia team. Such designations typically take the place of the attending physician’s name and can be convenient when one hospitalist goes off service and is replaced by another; the team name stays the same. Even if the attending hospitalist makes up the entire team (i.e., no residents or students), some groups use the “team” name rather than the attending hospitalist name.

But when the patient’s chart, sign on the door, and other identifying materials all refer only to the team that is caring for the patient, the patients, their families, and most hospital staff don’t have an easy way to identify the responsible physician. Say a worried daughter steps into the hall to ask the nurse, “Which doctor is taking care of my dad?” The nurse might readily see that the blue team is responsible but may not know which hospitalist is working on the blue team today and might have to walk back to the nursing station to look over a sheet of paper (a “decoder ring”) to figure out the hospitalist’s name.

This scenario has all kinds of drawbacks. To the daughter, the name of the doctor in charge is a big deal. It doesn’t inspire confidence if the nurse can’t readily say who that is. And the busy nurse might forget to investigate and provide the name to the daughter in a timely way.

I think groups using a system like this should seriously consider replacing team names with the attending hospitalist name and updating that name in the medical record, whether that is an EHR, a paper chart, or some other form, every time that doctor rotates off service and is replaced by another. Hospital staff, patients, and families should always see the name of the attending physician and not an uninformative color or nondescript team name.

It will require work for someone, the hospitalist in many cases, to go into the EHR and write an order or send a message to ensure that the hospitalist name is kept current every time one doctor replaces another. But it’s worth the effort.

Day Hospitalists Should Round on Patients Admitted after Midnight

Although not exactly common, I’ve come across this scenario often enough that it’s worth mentioning.

Hospitalists, sometimes with a hint of indignity or even chest thumping, have told me they don’t visit or round on patients admitted after midnight by their night doctor. “You can’t bill for a second visit on the same calendar day,” they explain, firmly. “So if I can’t get paid to see the patient, then I won’t.”

This is just crazy.

For one thing, these same doctors are typically employed by the hospital and are being paid to provide whatever care patients need. I think they’ve just latched onto the “can’t bill another visit” as an excuse to get out of some work.

Don’t forget that many of these patients may wait over 30 hours from their admitting visit to the first follow-up visit; this delay is at the beginning of their hospital stay, when they might be most unstable. And it delays initiation of discharge planning and other important steps in patient care.

I don’t see any room for meaningful debate on this. The rounder who picks up a patient admitted the night before should always make a full rounding visit, even if the admission was after midnight.

But if the visit isn’t billable, you are freed from the typical billing-related documentation requirements. No need to document detail in the note that doesn’t meaningfully contribute to the care of the patient. For example, you might omit a chief complaint for this encounter.

Daytime Triage Doctor

Practices larger than about 20 full-time equivalents often have one daytime doctor hold a “triage” or “hot” pager, which others call to make a new referral. This triage doctor will hear about all referrals and keep track of and contact the hospitalist responsible for the next new patient. This can be a very busy job and often comes on top of a full clinical load for that doctor.

As I mentioned in my July 2015 and December 2010 articles, in many or most groups, a clerical person could take over this function, at least during business hours.

Vacation Time

In many or most cases, hospitalists that have specified vacation time are not getting a better deal than those that have no vacation time. What really matters is how many shifts you’re responsible for in a year. For the days you aren’t on shift, in most hospitalist groups it really doesn’t matter whether you label some of them as vacation days or CME days.

I discussed this issue in greater detail in my March 2007 article.

But if you’re in the 30% of hospitalist groups that have a vacation (or PTO) provision currently and it works well, then there certainly isn’t a compelling reason to change or do away with it.

When is cell-free DNA best used as a primary screen?

Cell-free DNA screening, or so-called noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT), has had greatly increased utilization recently as advances in technology have elevated it almost to the level of a diagnostic test for detection of certain aneuploidies. Although it is still considered a screening test, recent interest has arisen regarding population screening and whether or not this test should be universally used as first-line or whether it should still be restricted to specific high-risk populations.

In the current study, Kaimal and colleagues attempted to determine the best strategy for utilization of NIPT using a decision-analytic model. For their study many assumptions had to be made in order to allow for calculation of detection rates and for determination of cost and quality-adjusted life years. (The model followed a theoretical cohort of women desiring prenatal testing [screening or diagnostic or both] from the time of their initial test through the end of their pregnancy, the birth of their neonate, and the remainder of their own life expectancy.)

The conclusion of the authors is that traditional multiple marker screening remains the optimal choice for most women (those aged 20 to 38 years) but that NIPT becomes the optimal strategy at age 38. The goal of this study was not just to determine cost-effectiveness but also to attempt to devise a strategy that would optimize detection of aneuploidy and minimize the need for the performance of diagnostic procedures.

Data not available in this study included such things as population differences with respect to the acceptance of pregnancy termination as an option, and the potential utility of first-trimester ultrasound screening for structural defects that might not be accounted for with NIPT (such as thickened nuchal translucency, altered cardiac axis, cranial defects, and abdominal wall defects).

What this evidence means for practice

For now, the best approach would be to adhere to current recommendations as outlined in the 2015 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee Opinion.1 Summarized, these are:

- Do not utilize NIPT in low-risk populations (although this opinion also suggests that patients may opt to have this test performed regardless of risk status with the understanding that detection rates are lower in low-risk populations and insurance coverage may be different).

- Offer NIPT to high-risk women as a first-line screen, as is suggested in the current study with respect to maternal age criteria (ACOG uses an age cut-off of 35 years, not 38).

- Utilize NIPT as a follow-up test after conventional testing suggests increased risk status in those patients wishing to avoid invasive diagnostic testing.

- The ACOG position remains that all women, regardless of age, who desire the most comprehensive information available regarding fetal chromosomal abnormalities should be offered diagnostic testing (chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis).

Also, as mentioned in the committee opinion, this technology is evolving rapidly and all practitioners should closely follow this evolution with respect to changing efficacy and changing cost.

—John T. Repke, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 640. Cell-free DNA screening for fetal aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):e31–e37.

Cell-free DNA screening, or so-called noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT), has had greatly increased utilization recently as advances in technology have elevated it almost to the level of a diagnostic test for detection of certain aneuploidies. Although it is still considered a screening test, recent interest has arisen regarding population screening and whether or not this test should be universally used as first-line or whether it should still be restricted to specific high-risk populations.