User login

Silent Epidemic: Loneliness a Serious Threat to Both Brain and Body

In a world that is more connected than ever, a silent epidemic is taking its toll. Overall, one in three US adults report chronic loneliness — a condition so detrimental that it rivals smoking and obesity with respect to its negative effect on health and well-being. From anxiety and depression to life-threatening conditions like cardiovascular disease, stroke, and Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, loneliness is more than an emotion — it’s a serious threat to both the brain and body.

In 2023, a US Surgeon General advisory raised the alarm about the national problem of loneliness and isolation, describing it as an epidemic.

“Given the significant health consequences of loneliness and isolation, we must prioritize building social connection in the same way we have prioritized other critical public health issues such as tobacco, obesity, and substance use disorders. Together, we can build a country that’s healthier, more resilient, less lonely, and more connected,” the report concluded.

But how, exactly, does chronic loneliness affect the physiology and function of the brain? What does the latest research reveal about the link between loneliness and neurologic and psychiatric illness, and what can clinicians do to address the issue?

This news organization spoke to multiple experts in the field to explore these issues.

A Major Risk Factor

Anna Finley, PhD, assistant professor of psychology at North Dakota State University, Fargo, explained that loneliness and social isolation are different entities. Social isolation is an objective measure of the number of people someone interacts with on a regular basis, whereas loneliness is a subjective feeling that occurs when close connections are lacking.

“These two things are not actually as related as you think they would be. People can feel lonely in a crowd or feel well connected with only a few friendships. It’s more about the quality of the connection and the quality of your perception of it. So someone could be in some very supportive relationships but still feel that there’s something missing,” she said in an interview.

So what do we know about how loneliness affects health? Evidence supporting the hypothesis that loneliness is an emerging risk factor for many diseases is steadily building.

Recently, the American Heart Association published a statement summarizing the evidence for a direct association between social isolation and loneliness and coronary heart disease and stroke mortality.

In addition, many studies have shown that individuals experiencing social isolation or loneliness have an increased risk for anxiety and depression, dementia, infectious disease, hospitalization, and all-cause death, even after adjusting for age and many other traditional risk factors.

One study revealed that eliminating loneliness has the potential to prevent nearly 20% of cases of depression in adults aged 50 years or older.

Indu Subramanian, MD, professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues conducted a study involving patients with Parkinson’s disease, which showed that the negative impact of loneliness on disease severity was as significant as the positive effects of 30 minutes of daily exercise.

“The importance of loneliness is under-recognized and undervalued, and it poses a major risk for health outcomes and quality of life,” said Subramanian.

Subramanian noted that loneliness is stigmatizing, causing people to feel unlikable and blame themselves, which prevents them from opening up to doctors or loved ones about their struggle. At the same time, healthcare providers may not think to ask about loneliness or know about potential interventions. She emphasized that much more work is needed to address this issue.

Early Mortality Risk

Julianne Holt-Lunstad, PhD, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, is the author of two large meta-analyses that suggest loneliness, social isolation, or living alone are independent risk factors for early mortality, increasing this risk by about a third — the equivalent to the risk of smoking 15 cigarettes per day.

“We have quite robust evidence across a number of health outcomes implicating the harmful effects of loneliness and social isolation. While these are observational studies and show mainly associations, we do have evidence from longitudinal studies that show lacking social connection, whether that be loneliness or social isolation, predicts subsequent worse outcomes, and most of these studies have adjusted for alternative kinds of explanations, like age, initial health status, lifestyle factors,” Holt-Lunstad said.

There is some evidence to suggest that isolation is more predictive of physical health outcomes, whereas loneliness is more predictive of mental health outcomes. That said, both isolation and loneliness have significant effects on mental and physical health outcomes, she noted.

There is also the question of whether loneliness is causing poor health or whether people who are in poor health feel lonely because poor health can lead to social isolation.

Finley said there’s probably a bit of both going on, but longitudinal studies, where loneliness is measured at a fixed timepoint then health outcomes are reported a few years later, suggest that loneliness is contributing to these adverse outcomes.

She added that there is also some evidence in animal models to suggest that loneliness is a causal risk factor for adverse health outcomes. “But you can’t ask a mouse or rat how lonely they’re feeling. All you can do is house them individually — removing them from social connection. This isn’t necessarily the same thing as loneliness in humans.”

Finley is studying mechanisms in the brain that may be involved in mediating the adverse health consequences of loneliness.

“What I’ve been seeing in the data so far is that it tends to be the self-report of how lonely folks are feeling that has the associations with differences in the brain, as opposed to the number of social connections people have. It does seem to be the more subjective, emotional perception of loneliness that is important.”

In a review of potential mechanisms involved, she concluded that it is dysregulated emotions and altered perceptions of social interactions that has profound impacts on the brain, suggesting that people who are lonely may have a tendency to interpret social cues in a negative way, preventing them from forming productive positive relationships.

Lack of Trust

One researcher who has studied this phenomenon is Dirk Scheele, PhD, professor of social neuroscience at Ruhr University Bochum in Germany.

“We were interested to find out why people remained lonely,” he said in an interview. “Loneliness is an unpleasant experience, and there are so many opportunities for social contacts nowadays, it’s not really clear at first sight why people are chronically lonely.”

To examine this question, Scheele and his team conducted a study in which functional MRI was used to examine the brain in otherwise healthy individuals with high or low loneliness scores while they played a trust game.

They also simulated a positive social interaction between participants and researchers, in which they talked about plans for a fictitious lottery win, and about their hobbies and interests, during which mood was measured with questionnaires, and saliva samples were collected to measure hormone levels.

Results showed that the high-lonely individuals had reduced activation in the insula cortex during the trust decisions. “This area of the brain is involved in the processing of bodily signals, such as ‘gut feelings.’ So reduced activity here could be interpreted as fewer gut feelings on who can be trusted,” Scheele explained.

The high-lonely individuals also had reduced responsiveness to the positive social interaction with a lower release of oxytocin and a smaller elevation in mood compared with the control individuals.

Scheele pointed out that there is some evidence that oxytocin might increase trust, and there is reduced release of endogenous oxytocin in high loneliness.

“Our results are consistent with the idea that loneliness is associated with negative biases about other people. So if we expect negative things from other people — for instance, that they cannot be trusted — then that would hamper further social interactions and could lead to loneliness,” he added.

A Role for Oxytocin?

In another study, the same researchers tested short-term (five weekly sessions) group psychotherapy to reduce loneliness using established techniques to target these negative biases. They also investigated whether the effects of this group psychotherapy could be augmented by administering intranasal oxytocin (vs placebo) before the group psychotherapy sessions.

Results showed that the group psychotherapy intervention reduced trait loneliness (loneliness experienced over a prolonged period). The oxytocin did not show a significant effect on trait loneliness, but there was a suggestion that it may enhance the reduction in state loneliness (how someone is feeling at a specific time) brought about by the psychotherapy sessions.

“We found that bonding within the groups was experienced as more positive in the oxytocin treated groups. It is possible that a longer intervention would be helpful for longer-term results,” Scheele concluded. “It’s not going to be a quick fix for loneliness, but there may be a role for oxytocin as an adjunct to psychotherapy.”

A Basic Human Need

Another loneliness researcher, Livia Tomova, PhD, assistant professor of psychology at Cardiff University in Wales, has used social isolation to induce loneliness in young people and found that this intervention was linked to brain patterns similar to those associated with hunger.

“We know that the drive to eat food is a very basic human need. We know quite well how it is represented in the brain,” she explained.

The researchers tested how the brains of the participants responded to seeing pictures of social interactions after they underwent a prolonged period of social isolation. In a subsequent session, the same people were asked to undergo food fasting and then underwent brain scans when looking at pictures of food. Results showed that the neural patterns were similar in the two situations with increased activity in the substantia nigra area within the midbrain.

“This area of the brain processes rewards and motivation. It consists primarily of dopamine neurons and increased activity corresponds to a feeling of craving something. So this area of the brain that controls essential homeostatic needs is activated when people feel lonely, suggesting that our need for social contact with others is potentially a very basic need similar to eating,” Tomova said.

Lower Gray Matter Volumes in Key Brain Areas

And another group from Germany has found that higher loneliness scores are negatively associated with specific brain regions responsible for memory, emotion regulation, and social processing.

Sandra Düzel, PhD, and colleagues from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, both in Berlin, Germany, reported a study in which individuals who reported higher loneliness had smaller gray matter volumes in brain regions such as the left amygdala, anterior hippocampus, and cerebellum, regions which are crucial for both emotional regulation and higher-order cognitive processes, such as self-reflection and executive function.

Düzel believes that possible mechanisms behind the link between loneliness and brain volume differences could include stress-related damage, with prolonged loneliness associated with elevated levels of stress hormones, which can damage the hippocampus over time, and reduced cognitive and social stimulation, which may contribute to brain volume reductions in regions critical for memory and emotional processing.

“Loneliness is often characterized by reduced social and environmental diversity, leading to less engagement with novel experiences and potentially lower hippocampal-striatal connectivity.

Since novelty-seeking and environmental diversity are associated with positive emotional states, individuals experiencing loneliness might benefit from increased exposure to new environments which could stimulate the brain’s reward circuits, fostering positive affect and potentially mitigating the emotional burden of loneliness,” she said.

Is Social Prescribing the Answer?

So are there enough data now to act and attempt to develop interventions to reduce loneliness? Most of these researchers believe so.

“I think we have enough information to act on this now. There are a number of national academies consensus reports, which suggest that, while certainly there are still gaps in our evidence and more to be learned, there is sufficient evidence that a concerning portion of the population seems to lack connection, and that the consequences are serious enough that we need to do something about it,” said Holt-Lunstad.

Some countries have introduced social prescribing where doctors can prescribe a group activity or a regular visit or telephone conversation with a supportive person.

Subramanian pointed out that it’s easier to implement in countries with national health services and may be more difficult to embrace in the US healthcare system.

“We are not so encouraged from a financial perspective to think about preventive care in the US. We don’t have an easy way to recognize in any tangible way the downstream of such activities in terms of preventing future problems. That is something we need to work on,” she said.

Finley cautioned that to work well, social prescribing will require an understanding of each person’s individual situation.

“Some people may only receive benefit of interacting with others if they are also getting some sort of support to address the social and emotional concerns that are tagging along with loneliness. I’m not sure that just telling people to go join their local gardening club or whatever will be the correct answer for everyone.”

She pointed out that many people will have issues in their life that are making it hard for them to be social. These could be mobility or financial challenges, care responsibilities, or concerns about illnesses or life events. “We need to figure out what would have the most bang for the person’s buck, so to speak, as an intervention. That could mean connecting them to a group relevant to their individual situation.”

Opportunity to Connect Not Enough?

Tomova believes that training people in social skills may be a better option. “It appears that some people who are chronically lonely seem to struggle to make relationships with others. So just encouraging them to interact with others more will not necessarily help. We need to better understand the pathways involved and who are the people who become ill. We can then develop and target better interventions and teach people coping strategies for that situation.”

Scheele agreed. “While just giving people the opportunity to connect may work for some, others who are experiencing really chronic loneliness may not benefit very much from this unless their negative belief systems are addressed.” He suggested some sort of psychotherapy may be helpful in this situation.

But at least all seem to agree that healthcare providers need to be more aware of loneliness as a health risk factor, try to identify people at risk, and to think about how best to support them.

Holt-Lunstad noted that one of the recommendations in the US Surgeon General’s advisory was to increase the education, training, and resources on loneliness for healthcare providers.

“If we want this to be addressed, we need to give healthcare providers the time, resources, and training in order to do that, otherwise, we are adding one more thing to an already overburdened system. They need to understand how important it is, and how it might help them take care of the patient.”

“Our hope is that we can start to reverse some of the trends that we are seeing, both in terms of the prevalence rates of loneliness, but also that we could start seeing improvements in health and other kinds of outcomes,” she concluded.

Progress is being made in increasing awareness about the dangers of chronic loneliness. It’s now recognized as a serious health risk, but there are actionable steps that can help. Loneliness doesn’t have to be a permanent condition for anyone, said Scheele.

Holt-Lunstad served as an adviser for Foundation for Social Connection, Global Initiative on Loneliness and Connection, and Nextdoor Neighborhood Vitality Board and received research grants/income from Templeton Foundation, Eventbrite, Foundation for Social Connection, and Triple-S Foundation. Subramanian served as a speaker bureau for Acorda Pharma. The other researchers reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a world that is more connected than ever, a silent epidemic is taking its toll. Overall, one in three US adults report chronic loneliness — a condition so detrimental that it rivals smoking and obesity with respect to its negative effect on health and well-being. From anxiety and depression to life-threatening conditions like cardiovascular disease, stroke, and Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, loneliness is more than an emotion — it’s a serious threat to both the brain and body.

In 2023, a US Surgeon General advisory raised the alarm about the national problem of loneliness and isolation, describing it as an epidemic.

“Given the significant health consequences of loneliness and isolation, we must prioritize building social connection in the same way we have prioritized other critical public health issues such as tobacco, obesity, and substance use disorders. Together, we can build a country that’s healthier, more resilient, less lonely, and more connected,” the report concluded.

But how, exactly, does chronic loneliness affect the physiology and function of the brain? What does the latest research reveal about the link between loneliness and neurologic and psychiatric illness, and what can clinicians do to address the issue?

This news organization spoke to multiple experts in the field to explore these issues.

A Major Risk Factor

Anna Finley, PhD, assistant professor of psychology at North Dakota State University, Fargo, explained that loneliness and social isolation are different entities. Social isolation is an objective measure of the number of people someone interacts with on a regular basis, whereas loneliness is a subjective feeling that occurs when close connections are lacking.

“These two things are not actually as related as you think they would be. People can feel lonely in a crowd or feel well connected with only a few friendships. It’s more about the quality of the connection and the quality of your perception of it. So someone could be in some very supportive relationships but still feel that there’s something missing,” she said in an interview.

So what do we know about how loneliness affects health? Evidence supporting the hypothesis that loneliness is an emerging risk factor for many diseases is steadily building.

Recently, the American Heart Association published a statement summarizing the evidence for a direct association between social isolation and loneliness and coronary heart disease and stroke mortality.

In addition, many studies have shown that individuals experiencing social isolation or loneliness have an increased risk for anxiety and depression, dementia, infectious disease, hospitalization, and all-cause death, even after adjusting for age and many other traditional risk factors.

One study revealed that eliminating loneliness has the potential to prevent nearly 20% of cases of depression in adults aged 50 years or older.

Indu Subramanian, MD, professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues conducted a study involving patients with Parkinson’s disease, which showed that the negative impact of loneliness on disease severity was as significant as the positive effects of 30 minutes of daily exercise.

“The importance of loneliness is under-recognized and undervalued, and it poses a major risk for health outcomes and quality of life,” said Subramanian.

Subramanian noted that loneliness is stigmatizing, causing people to feel unlikable and blame themselves, which prevents them from opening up to doctors or loved ones about their struggle. At the same time, healthcare providers may not think to ask about loneliness or know about potential interventions. She emphasized that much more work is needed to address this issue.

Early Mortality Risk

Julianne Holt-Lunstad, PhD, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, is the author of two large meta-analyses that suggest loneliness, social isolation, or living alone are independent risk factors for early mortality, increasing this risk by about a third — the equivalent to the risk of smoking 15 cigarettes per day.

“We have quite robust evidence across a number of health outcomes implicating the harmful effects of loneliness and social isolation. While these are observational studies and show mainly associations, we do have evidence from longitudinal studies that show lacking social connection, whether that be loneliness or social isolation, predicts subsequent worse outcomes, and most of these studies have adjusted for alternative kinds of explanations, like age, initial health status, lifestyle factors,” Holt-Lunstad said.

There is some evidence to suggest that isolation is more predictive of physical health outcomes, whereas loneliness is more predictive of mental health outcomes. That said, both isolation and loneliness have significant effects on mental and physical health outcomes, she noted.

There is also the question of whether loneliness is causing poor health or whether people who are in poor health feel lonely because poor health can lead to social isolation.

Finley said there’s probably a bit of both going on, but longitudinal studies, where loneliness is measured at a fixed timepoint then health outcomes are reported a few years later, suggest that loneliness is contributing to these adverse outcomes.

She added that there is also some evidence in animal models to suggest that loneliness is a causal risk factor for adverse health outcomes. “But you can’t ask a mouse or rat how lonely they’re feeling. All you can do is house them individually — removing them from social connection. This isn’t necessarily the same thing as loneliness in humans.”

Finley is studying mechanisms in the brain that may be involved in mediating the adverse health consequences of loneliness.

“What I’ve been seeing in the data so far is that it tends to be the self-report of how lonely folks are feeling that has the associations with differences in the brain, as opposed to the number of social connections people have. It does seem to be the more subjective, emotional perception of loneliness that is important.”

In a review of potential mechanisms involved, she concluded that it is dysregulated emotions and altered perceptions of social interactions that has profound impacts on the brain, suggesting that people who are lonely may have a tendency to interpret social cues in a negative way, preventing them from forming productive positive relationships.

Lack of Trust

One researcher who has studied this phenomenon is Dirk Scheele, PhD, professor of social neuroscience at Ruhr University Bochum in Germany.

“We were interested to find out why people remained lonely,” he said in an interview. “Loneliness is an unpleasant experience, and there are so many opportunities for social contacts nowadays, it’s not really clear at first sight why people are chronically lonely.”

To examine this question, Scheele and his team conducted a study in which functional MRI was used to examine the brain in otherwise healthy individuals with high or low loneliness scores while they played a trust game.

They also simulated a positive social interaction between participants and researchers, in which they talked about plans for a fictitious lottery win, and about their hobbies and interests, during which mood was measured with questionnaires, and saliva samples were collected to measure hormone levels.

Results showed that the high-lonely individuals had reduced activation in the insula cortex during the trust decisions. “This area of the brain is involved in the processing of bodily signals, such as ‘gut feelings.’ So reduced activity here could be interpreted as fewer gut feelings on who can be trusted,” Scheele explained.

The high-lonely individuals also had reduced responsiveness to the positive social interaction with a lower release of oxytocin and a smaller elevation in mood compared with the control individuals.

Scheele pointed out that there is some evidence that oxytocin might increase trust, and there is reduced release of endogenous oxytocin in high loneliness.

“Our results are consistent with the idea that loneliness is associated with negative biases about other people. So if we expect negative things from other people — for instance, that they cannot be trusted — then that would hamper further social interactions and could lead to loneliness,” he added.

A Role for Oxytocin?

In another study, the same researchers tested short-term (five weekly sessions) group psychotherapy to reduce loneliness using established techniques to target these negative biases. They also investigated whether the effects of this group psychotherapy could be augmented by administering intranasal oxytocin (vs placebo) before the group psychotherapy sessions.

Results showed that the group psychotherapy intervention reduced trait loneliness (loneliness experienced over a prolonged period). The oxytocin did not show a significant effect on trait loneliness, but there was a suggestion that it may enhance the reduction in state loneliness (how someone is feeling at a specific time) brought about by the psychotherapy sessions.

“We found that bonding within the groups was experienced as more positive in the oxytocin treated groups. It is possible that a longer intervention would be helpful for longer-term results,” Scheele concluded. “It’s not going to be a quick fix for loneliness, but there may be a role for oxytocin as an adjunct to psychotherapy.”

A Basic Human Need

Another loneliness researcher, Livia Tomova, PhD, assistant professor of psychology at Cardiff University in Wales, has used social isolation to induce loneliness in young people and found that this intervention was linked to brain patterns similar to those associated with hunger.

“We know that the drive to eat food is a very basic human need. We know quite well how it is represented in the brain,” she explained.

The researchers tested how the brains of the participants responded to seeing pictures of social interactions after they underwent a prolonged period of social isolation. In a subsequent session, the same people were asked to undergo food fasting and then underwent brain scans when looking at pictures of food. Results showed that the neural patterns were similar in the two situations with increased activity in the substantia nigra area within the midbrain.

“This area of the brain processes rewards and motivation. It consists primarily of dopamine neurons and increased activity corresponds to a feeling of craving something. So this area of the brain that controls essential homeostatic needs is activated when people feel lonely, suggesting that our need for social contact with others is potentially a very basic need similar to eating,” Tomova said.

Lower Gray Matter Volumes in Key Brain Areas

And another group from Germany has found that higher loneliness scores are negatively associated with specific brain regions responsible for memory, emotion regulation, and social processing.

Sandra Düzel, PhD, and colleagues from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, both in Berlin, Germany, reported a study in which individuals who reported higher loneliness had smaller gray matter volumes in brain regions such as the left amygdala, anterior hippocampus, and cerebellum, regions which are crucial for both emotional regulation and higher-order cognitive processes, such as self-reflection and executive function.

Düzel believes that possible mechanisms behind the link between loneliness and brain volume differences could include stress-related damage, with prolonged loneliness associated with elevated levels of stress hormones, which can damage the hippocampus over time, and reduced cognitive and social stimulation, which may contribute to brain volume reductions in regions critical for memory and emotional processing.

“Loneliness is often characterized by reduced social and environmental diversity, leading to less engagement with novel experiences and potentially lower hippocampal-striatal connectivity.

Since novelty-seeking and environmental diversity are associated with positive emotional states, individuals experiencing loneliness might benefit from increased exposure to new environments which could stimulate the brain’s reward circuits, fostering positive affect and potentially mitigating the emotional burden of loneliness,” she said.

Is Social Prescribing the Answer?

So are there enough data now to act and attempt to develop interventions to reduce loneliness? Most of these researchers believe so.

“I think we have enough information to act on this now. There are a number of national academies consensus reports, which suggest that, while certainly there are still gaps in our evidence and more to be learned, there is sufficient evidence that a concerning portion of the population seems to lack connection, and that the consequences are serious enough that we need to do something about it,” said Holt-Lunstad.

Some countries have introduced social prescribing where doctors can prescribe a group activity or a regular visit or telephone conversation with a supportive person.

Subramanian pointed out that it’s easier to implement in countries with national health services and may be more difficult to embrace in the US healthcare system.

“We are not so encouraged from a financial perspective to think about preventive care in the US. We don’t have an easy way to recognize in any tangible way the downstream of such activities in terms of preventing future problems. That is something we need to work on,” she said.

Finley cautioned that to work well, social prescribing will require an understanding of each person’s individual situation.

“Some people may only receive benefit of interacting with others if they are also getting some sort of support to address the social and emotional concerns that are tagging along with loneliness. I’m not sure that just telling people to go join their local gardening club or whatever will be the correct answer for everyone.”

She pointed out that many people will have issues in their life that are making it hard for them to be social. These could be mobility or financial challenges, care responsibilities, or concerns about illnesses or life events. “We need to figure out what would have the most bang for the person’s buck, so to speak, as an intervention. That could mean connecting them to a group relevant to their individual situation.”

Opportunity to Connect Not Enough?

Tomova believes that training people in social skills may be a better option. “It appears that some people who are chronically lonely seem to struggle to make relationships with others. So just encouraging them to interact with others more will not necessarily help. We need to better understand the pathways involved and who are the people who become ill. We can then develop and target better interventions and teach people coping strategies for that situation.”

Scheele agreed. “While just giving people the opportunity to connect may work for some, others who are experiencing really chronic loneliness may not benefit very much from this unless their negative belief systems are addressed.” He suggested some sort of psychotherapy may be helpful in this situation.

But at least all seem to agree that healthcare providers need to be more aware of loneliness as a health risk factor, try to identify people at risk, and to think about how best to support them.

Holt-Lunstad noted that one of the recommendations in the US Surgeon General’s advisory was to increase the education, training, and resources on loneliness for healthcare providers.

“If we want this to be addressed, we need to give healthcare providers the time, resources, and training in order to do that, otherwise, we are adding one more thing to an already overburdened system. They need to understand how important it is, and how it might help them take care of the patient.”

“Our hope is that we can start to reverse some of the trends that we are seeing, both in terms of the prevalence rates of loneliness, but also that we could start seeing improvements in health and other kinds of outcomes,” she concluded.

Progress is being made in increasing awareness about the dangers of chronic loneliness. It’s now recognized as a serious health risk, but there are actionable steps that can help. Loneliness doesn’t have to be a permanent condition for anyone, said Scheele.

Holt-Lunstad served as an adviser for Foundation for Social Connection, Global Initiative on Loneliness and Connection, and Nextdoor Neighborhood Vitality Board and received research grants/income from Templeton Foundation, Eventbrite, Foundation for Social Connection, and Triple-S Foundation. Subramanian served as a speaker bureau for Acorda Pharma. The other researchers reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a world that is more connected than ever, a silent epidemic is taking its toll. Overall, one in three US adults report chronic loneliness — a condition so detrimental that it rivals smoking and obesity with respect to its negative effect on health and well-being. From anxiety and depression to life-threatening conditions like cardiovascular disease, stroke, and Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, loneliness is more than an emotion — it’s a serious threat to both the brain and body.

In 2023, a US Surgeon General advisory raised the alarm about the national problem of loneliness and isolation, describing it as an epidemic.

“Given the significant health consequences of loneliness and isolation, we must prioritize building social connection in the same way we have prioritized other critical public health issues such as tobacco, obesity, and substance use disorders. Together, we can build a country that’s healthier, more resilient, less lonely, and more connected,” the report concluded.

But how, exactly, does chronic loneliness affect the physiology and function of the brain? What does the latest research reveal about the link between loneliness and neurologic and psychiatric illness, and what can clinicians do to address the issue?

This news organization spoke to multiple experts in the field to explore these issues.

A Major Risk Factor

Anna Finley, PhD, assistant professor of psychology at North Dakota State University, Fargo, explained that loneliness and social isolation are different entities. Social isolation is an objective measure of the number of people someone interacts with on a regular basis, whereas loneliness is a subjective feeling that occurs when close connections are lacking.

“These two things are not actually as related as you think they would be. People can feel lonely in a crowd or feel well connected with only a few friendships. It’s more about the quality of the connection and the quality of your perception of it. So someone could be in some very supportive relationships but still feel that there’s something missing,” she said in an interview.

So what do we know about how loneliness affects health? Evidence supporting the hypothesis that loneliness is an emerging risk factor for many diseases is steadily building.

Recently, the American Heart Association published a statement summarizing the evidence for a direct association between social isolation and loneliness and coronary heart disease and stroke mortality.

In addition, many studies have shown that individuals experiencing social isolation or loneliness have an increased risk for anxiety and depression, dementia, infectious disease, hospitalization, and all-cause death, even after adjusting for age and many other traditional risk factors.

One study revealed that eliminating loneliness has the potential to prevent nearly 20% of cases of depression in adults aged 50 years or older.

Indu Subramanian, MD, professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues conducted a study involving patients with Parkinson’s disease, which showed that the negative impact of loneliness on disease severity was as significant as the positive effects of 30 minutes of daily exercise.

“The importance of loneliness is under-recognized and undervalued, and it poses a major risk for health outcomes and quality of life,” said Subramanian.

Subramanian noted that loneliness is stigmatizing, causing people to feel unlikable and blame themselves, which prevents them from opening up to doctors or loved ones about their struggle. At the same time, healthcare providers may not think to ask about loneliness or know about potential interventions. She emphasized that much more work is needed to address this issue.

Early Mortality Risk

Julianne Holt-Lunstad, PhD, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, is the author of two large meta-analyses that suggest loneliness, social isolation, or living alone are independent risk factors for early mortality, increasing this risk by about a third — the equivalent to the risk of smoking 15 cigarettes per day.

“We have quite robust evidence across a number of health outcomes implicating the harmful effects of loneliness and social isolation. While these are observational studies and show mainly associations, we do have evidence from longitudinal studies that show lacking social connection, whether that be loneliness or social isolation, predicts subsequent worse outcomes, and most of these studies have adjusted for alternative kinds of explanations, like age, initial health status, lifestyle factors,” Holt-Lunstad said.

There is some evidence to suggest that isolation is more predictive of physical health outcomes, whereas loneliness is more predictive of mental health outcomes. That said, both isolation and loneliness have significant effects on mental and physical health outcomes, she noted.

There is also the question of whether loneliness is causing poor health or whether people who are in poor health feel lonely because poor health can lead to social isolation.

Finley said there’s probably a bit of both going on, but longitudinal studies, where loneliness is measured at a fixed timepoint then health outcomes are reported a few years later, suggest that loneliness is contributing to these adverse outcomes.

She added that there is also some evidence in animal models to suggest that loneliness is a causal risk factor for adverse health outcomes. “But you can’t ask a mouse or rat how lonely they’re feeling. All you can do is house them individually — removing them from social connection. This isn’t necessarily the same thing as loneliness in humans.”

Finley is studying mechanisms in the brain that may be involved in mediating the adverse health consequences of loneliness.

“What I’ve been seeing in the data so far is that it tends to be the self-report of how lonely folks are feeling that has the associations with differences in the brain, as opposed to the number of social connections people have. It does seem to be the more subjective, emotional perception of loneliness that is important.”

In a review of potential mechanisms involved, she concluded that it is dysregulated emotions and altered perceptions of social interactions that has profound impacts on the brain, suggesting that people who are lonely may have a tendency to interpret social cues in a negative way, preventing them from forming productive positive relationships.

Lack of Trust

One researcher who has studied this phenomenon is Dirk Scheele, PhD, professor of social neuroscience at Ruhr University Bochum in Germany.

“We were interested to find out why people remained lonely,” he said in an interview. “Loneliness is an unpleasant experience, and there are so many opportunities for social contacts nowadays, it’s not really clear at first sight why people are chronically lonely.”

To examine this question, Scheele and his team conducted a study in which functional MRI was used to examine the brain in otherwise healthy individuals with high or low loneliness scores while they played a trust game.

They also simulated a positive social interaction between participants and researchers, in which they talked about plans for a fictitious lottery win, and about their hobbies and interests, during which mood was measured with questionnaires, and saliva samples were collected to measure hormone levels.

Results showed that the high-lonely individuals had reduced activation in the insula cortex during the trust decisions. “This area of the brain is involved in the processing of bodily signals, such as ‘gut feelings.’ So reduced activity here could be interpreted as fewer gut feelings on who can be trusted,” Scheele explained.

The high-lonely individuals also had reduced responsiveness to the positive social interaction with a lower release of oxytocin and a smaller elevation in mood compared with the control individuals.

Scheele pointed out that there is some evidence that oxytocin might increase trust, and there is reduced release of endogenous oxytocin in high loneliness.

“Our results are consistent with the idea that loneliness is associated with negative biases about other people. So if we expect negative things from other people — for instance, that they cannot be trusted — then that would hamper further social interactions and could lead to loneliness,” he added.

A Role for Oxytocin?

In another study, the same researchers tested short-term (five weekly sessions) group psychotherapy to reduce loneliness using established techniques to target these negative biases. They also investigated whether the effects of this group psychotherapy could be augmented by administering intranasal oxytocin (vs placebo) before the group psychotherapy sessions.

Results showed that the group psychotherapy intervention reduced trait loneliness (loneliness experienced over a prolonged period). The oxytocin did not show a significant effect on trait loneliness, but there was a suggestion that it may enhance the reduction in state loneliness (how someone is feeling at a specific time) brought about by the psychotherapy sessions.

“We found that bonding within the groups was experienced as more positive in the oxytocin treated groups. It is possible that a longer intervention would be helpful for longer-term results,” Scheele concluded. “It’s not going to be a quick fix for loneliness, but there may be a role for oxytocin as an adjunct to psychotherapy.”

A Basic Human Need

Another loneliness researcher, Livia Tomova, PhD, assistant professor of psychology at Cardiff University in Wales, has used social isolation to induce loneliness in young people and found that this intervention was linked to brain patterns similar to those associated with hunger.

“We know that the drive to eat food is a very basic human need. We know quite well how it is represented in the brain,” she explained.

The researchers tested how the brains of the participants responded to seeing pictures of social interactions after they underwent a prolonged period of social isolation. In a subsequent session, the same people were asked to undergo food fasting and then underwent brain scans when looking at pictures of food. Results showed that the neural patterns were similar in the two situations with increased activity in the substantia nigra area within the midbrain.

“This area of the brain processes rewards and motivation. It consists primarily of dopamine neurons and increased activity corresponds to a feeling of craving something. So this area of the brain that controls essential homeostatic needs is activated when people feel lonely, suggesting that our need for social contact with others is potentially a very basic need similar to eating,” Tomova said.

Lower Gray Matter Volumes in Key Brain Areas

And another group from Germany has found that higher loneliness scores are negatively associated with specific brain regions responsible for memory, emotion regulation, and social processing.

Sandra Düzel, PhD, and colleagues from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, both in Berlin, Germany, reported a study in which individuals who reported higher loneliness had smaller gray matter volumes in brain regions such as the left amygdala, anterior hippocampus, and cerebellum, regions which are crucial for both emotional regulation and higher-order cognitive processes, such as self-reflection and executive function.

Düzel believes that possible mechanisms behind the link between loneliness and brain volume differences could include stress-related damage, with prolonged loneliness associated with elevated levels of stress hormones, which can damage the hippocampus over time, and reduced cognitive and social stimulation, which may contribute to brain volume reductions in regions critical for memory and emotional processing.

“Loneliness is often characterized by reduced social and environmental diversity, leading to less engagement with novel experiences and potentially lower hippocampal-striatal connectivity.

Since novelty-seeking and environmental diversity are associated with positive emotional states, individuals experiencing loneliness might benefit from increased exposure to new environments which could stimulate the brain’s reward circuits, fostering positive affect and potentially mitigating the emotional burden of loneliness,” she said.

Is Social Prescribing the Answer?

So are there enough data now to act and attempt to develop interventions to reduce loneliness? Most of these researchers believe so.

“I think we have enough information to act on this now. There are a number of national academies consensus reports, which suggest that, while certainly there are still gaps in our evidence and more to be learned, there is sufficient evidence that a concerning portion of the population seems to lack connection, and that the consequences are serious enough that we need to do something about it,” said Holt-Lunstad.

Some countries have introduced social prescribing where doctors can prescribe a group activity or a regular visit or telephone conversation with a supportive person.

Subramanian pointed out that it’s easier to implement in countries with national health services and may be more difficult to embrace in the US healthcare system.

“We are not so encouraged from a financial perspective to think about preventive care in the US. We don’t have an easy way to recognize in any tangible way the downstream of such activities in terms of preventing future problems. That is something we need to work on,” she said.

Finley cautioned that to work well, social prescribing will require an understanding of each person’s individual situation.

“Some people may only receive benefit of interacting with others if they are also getting some sort of support to address the social and emotional concerns that are tagging along with loneliness. I’m not sure that just telling people to go join their local gardening club or whatever will be the correct answer for everyone.”

She pointed out that many people will have issues in their life that are making it hard for them to be social. These could be mobility or financial challenges, care responsibilities, or concerns about illnesses or life events. “We need to figure out what would have the most bang for the person’s buck, so to speak, as an intervention. That could mean connecting them to a group relevant to their individual situation.”

Opportunity to Connect Not Enough?

Tomova believes that training people in social skills may be a better option. “It appears that some people who are chronically lonely seem to struggle to make relationships with others. So just encouraging them to interact with others more will not necessarily help. We need to better understand the pathways involved and who are the people who become ill. We can then develop and target better interventions and teach people coping strategies for that situation.”

Scheele agreed. “While just giving people the opportunity to connect may work for some, others who are experiencing really chronic loneliness may not benefit very much from this unless their negative belief systems are addressed.” He suggested some sort of psychotherapy may be helpful in this situation.

But at least all seem to agree that healthcare providers need to be more aware of loneliness as a health risk factor, try to identify people at risk, and to think about how best to support them.

Holt-Lunstad noted that one of the recommendations in the US Surgeon General’s advisory was to increase the education, training, and resources on loneliness for healthcare providers.

“If we want this to be addressed, we need to give healthcare providers the time, resources, and training in order to do that, otherwise, we are adding one more thing to an already overburdened system. They need to understand how important it is, and how it might help them take care of the patient.”

“Our hope is that we can start to reverse some of the trends that we are seeing, both in terms of the prevalence rates of loneliness, but also that we could start seeing improvements in health and other kinds of outcomes,” she concluded.

Progress is being made in increasing awareness about the dangers of chronic loneliness. It’s now recognized as a serious health risk, but there are actionable steps that can help. Loneliness doesn’t have to be a permanent condition for anyone, said Scheele.

Holt-Lunstad served as an adviser for Foundation for Social Connection, Global Initiative on Loneliness and Connection, and Nextdoor Neighborhood Vitality Board and received research grants/income from Templeton Foundation, Eventbrite, Foundation for Social Connection, and Triple-S Foundation. Subramanian served as a speaker bureau for Acorda Pharma. The other researchers reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

IBS: Understanding a Common Yet Misunderstood Condition

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common conditions encountered by both primary care providers and gastroenterologists, with a pooled global prevalence of 11.2%. This functional bowel disorder is characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort, diarrhea and/or constipation, and bloating.

Unfortunately, , according to Alan Desmond, MB, consultant in gastroenterology and general internal medicine, Torbay Hospital, UK National Health Service.

Desmond regularly sees patients who either haven’t been accurately diagnosed or have been told, “Don’t worry, it’s ‘just’ irritable bowel syndrome,” he said at the recent International Conference on Nutrition in Medicine.

A 2017 study involving nearly 2000 patients with a history of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms found that 43.1% of those who met the criteria for IBS were undiagnosed, and among those who were diagnosed, 26% were not receiving treatment.

“Many clinicians vastly underestimate the impact functional GI symptoms have on our patients in lack of productivity, becoming homebound or losing employment, the inability to enjoy a meal with friends or family, and always needing to know where the nearest bathroom is, for example,” Desmond said in an interview.

IBS can profoundly affect patients’ mental health. One study found that 38% of patients with IBS attending a tertiary care clinic contemplated suicide because they felt hopeless about ever achieving symptom relief.

Today, several dietary, pharmacologic, and psychological/behavioral approaches are available to treat patients with IBS, noted William D. Chey, MD, AGAF, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

“Each individual patient may need a different combination of these foundational treatments,” he said. “One size doesn’t fit all.”

Diagnostic Pathway

One reason IBS is so hard to diagnose is that it’s a “symptom-based disorder, with identification of the condition predicated upon certain key characteristics that are heterogeneous,” Chey said in an interview. “IBS in patient ‘A’ may not present the same way as IBS in patient ‘B,’ although there are certain foundational common characteristics.”

IBS involves “abnormalities in the motility and contractility of the GI tract,” he said. It can present with diarrhea (IBS-D), constipation (IBS-C), or a mixture or alternation of diarrhea and constipation (IBS-M).

Patients with IBS-D often have an exaggerated gastro-colonic response, while those with IBS-C often have a blunted response.

Beyond stool abnormalities and abdominal pain/discomfort, patients often report bloating/distension, low backache, lethargy, nausea, thigh pain, and urinary and gynecologic symptoms.

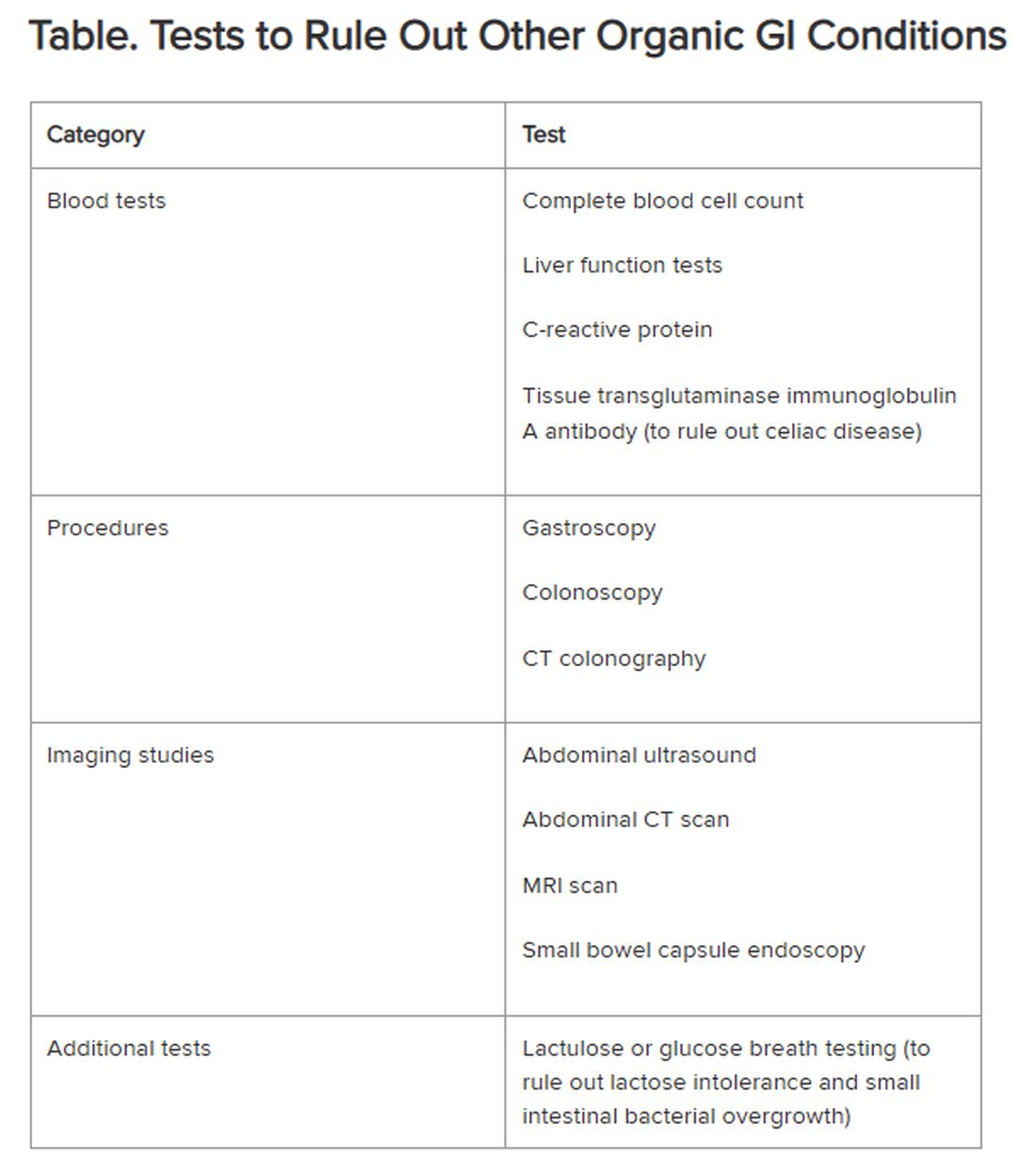

Historically, IBS has been regarded as a “diagnosis of exclusion” because classic diagnostic tests typically yield no concrete findings. Desmond noted that several blood tests, procedures, imaging studies, and other tests are available to rule out other organic GI conditions, as outlined in the Table.

If the patient comes from a geographical region where giardia is endemic, clinicians also should consider testing for the parasite, Chey said.

New Understanding of IBS Etiology

Now, advances in the understanding of IBS are changing the approach to the disease.

“The field is moving away from seeing IBS as a ‘wastebasket diagnosis,’ recognizing that there are other causes of a patient’s symptoms,” Mark Pimentel, MD, associate professor of medicine and gastroenterology, Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, said in an interview. “What’s made IBS so difficult to diagnose has been the absence of biological markers and hallmark findings on endoscopy.”

Recent research points to novel bacterial causes as culprits in the development of IBS. In particular, altered small bowel microbiota can be triggered by acute gastroenteritis.

Food poisoning can trigger the onset of IBS — a phenomenon called “postinfectious IBS (PI-IBS),” said Pimentel, who is also executive director of the Medically Associated Science and Technology Program at Cedars-Sinai. PI-IBS almost always takes the form of IBS-D, with up to 60% of patients with IBS-D suffering the long-term sequelae of food poisoning.

The types of bacteria most commonly associated with gastroenteritis are Shigella, Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Escherichia coli, Pimentel said. All of them release cytolethal distending toxin B (CdtB), causing the body to produce antibodies to the toxin.

CdtB resembles vinculin, a naturally occurring protein critical for healthy gut function. “Because of this molecular resemblance, the immune system often mistakes one for the other, producing anti-vinculin,” Pimentel explained.

This autoimmune response leads to disruptions in the gut microbiome, ultimately resulting in PI-IBS. The chain of events “doesn’t necessarily happen immediately,” Pimentel said. “You might have developed food poisoning at a party weeks or months ago.”

Acute gastroenteritis is common, affecting as many as 179 million people in the United States annually. A meta-analysis of 47 studies, incorporating 28,270 patients, found that those who had experienced acute gastroenteritis had a fourfold higher risk of developing IBS compared with nonexposed controls.

“The problem isn’t only the IBS itself, but the fact that people with PI-IBS are four times as likely to contract food poisoning again, which can further exacerbate IBS symptoms,” Pimentel said.

Diarrhea-predominant IBS can be detected through the presence of two blood biomarkers — anti-CdtB and anti-vinculin — in a blood test developed by Pimentel and his group.

“Elevation in either of these biomarkers establishes the diagnosis,” Pimentel said. “This is a breakthrough because it represents the first test that can make IBS a ‘diagnosis of inclusion.’”

The blood test also can identify IBS-M but not IBS-C.

Pimentel said that IBS-C is associated with increased levels of methanogenic archaea, which can be diagnosed by a positive methane breath test. “Methane gas slows intestinal contractility, which might result in constipation,” he said.

Diet as a Treatment Option

Diet is usually the starting point for IBS treatment, Chey said. “The standard dietary recommendations, as defined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guidance for managing IBS, are reasonable and common sense — eating three meals a day, avoiding carbonated beverages, excess alcohol, and excess caffeine, and avoiding hard-to-digest foods that can be gas producing.”

A diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs), which are carbohydrates that aren’t completely absorbed in the intestines, has been shown to be effective in alleviating GI distress in as many as 86% of patients with IBS, leading to improvements in overall GI symptoms as well as individual symptoms (eg, abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, diarrhea, and flatulence).

Desmond recommends the low FODMAP program delineated by Monash University in Australia. The diet should be undertaken only under the supervision of a dietitian, he warned. Moreover, following it on a long-term basis can have an adverse impact on dietary quality and the gut microbiome. Therefore, “it’s important to embark on stepwise reintroduction of FODMAPS under supervision to find acceptable thresholds that don’t cause a return of symptoms.”

A growing body of research suggests that following the Mediterranean diet can be helpful in reducing IBS symptoms. Chey said that some patients who tend to over-restrict their eating might benefit from a less restrictive diet than the typical low FODMAPs diet. For them, the Mediterranean diet may be a good option.

Pharmacotherapy for IBS

Nutritional approaches aren’t for everyone, Chey noted. “Some people don’t want to be on a highly restricted diet.” For them, medications addressing symptoms might be a better option.

Antispasmodics — either anticholinergics (hyoscine and dicyclomine) or smooth muscle relaxants (alverine, mebeverine, and peppermint oil) — can be helpful, although they can worsen constipation in a dose-dependent manner. It is advisable to use them on an as-needed rather than long-term basis.

Antidiarrheal agents include loperamide and diphenoxylate.

For constipation, laxatives (eg, senna, bisacodyl, polyethylene glycol, and sodium picosulfate) can be helpful.

Desmond noted that the American Gastroenterological Association does not recommend routine use of probiotics for most GI disorders, including IBS. Exceptions include prevention of Clostridioides difficile, ulcerative colitis, and pouchitis.

Targeting the Gut-Brain Relationship

Stress plays a role in exacerbating symptoms in patients with IBS and is an important target for intervention.

“If patients are living with a level of stress that’s impairing, we won’t be able to solve their gut issues until we resolve their stress issues,” Desmond said. “We need to calm the gut-microbiome-brain axis, which is multidimensional and bidirectional.”

Many people — even those without IBS — experience queasiness or diarrhea prior to a major event they’re nervous about, Chey noted. These events activate the brain, which activates the nervous system, which interacts with the GI tract. Indeed, IBS is now recognized as a disorder of gut-brain interaction, he said.

“We now know that the microbiome in the GI tract influences cognition and emotional function, depression, and anxiety. One might say that the gut is the ‘center of the universe’ to human beings,” Chey said.

Evidence-based psychological approaches for stress reduction in patients with IBS include cognitive behavioral therapy, specifically tailored to helping the patient identify associations between IBS symptoms and thoughts, emotions, and actions, as well as learning new behaviors and engaging in stress management. Psychodynamic (interpersonal) therapy enables patients to understand the connection between GI symptoms and interpersonal conflicts, emotional factors, or relationship difficulties.

Gut-directed hypnotherapy (GDH) is a “proven modality for IBS,” Desmond said. Unlike other forms of hypnotherapy, GDH focuses specifically on controlling and normalizing GI function. Studies have shown a reduction of ≥ 30% in abdominal pain in two thirds of participants, with overall response rates up to 85%. It can be delivered in an individual or group setting or via a smartphone.

Desmond recommends mindfulness-based therapy (MBT) for IBS. MBT focuses on the “cultivation of mindfulness, defined as intentional, nonjudgmental, present-focused awareness.” It has been found effective in reducing flares and the markers of gut inflammation in ulcerative colitis, as well as reducing symptoms of IBS.

Chey noted that an emerging body of literature supports the potential role of acupuncture in treating IBS, and his clinic employs it. “I would like to see further research into other areas of CAM [complementary and alternative medicine], including herbal approaches to IBS symptoms as well as stress.”

Finally, all the experts agree that more research is needed.

“The real tragedy is that the NIH invests next to nothing in IBS, in contrast to inflammatory bowel disease and many other conditions,” Pimentel said. “Yet IBS is 45 times more common than inflammatory bowel disease.”

Pimentel hopes that with enough advocacy and recognition that IBS isn’t “just stress-related,” more resources will be devoted to understanding this debilitating condition.

Desmond is the author of a book on the benefits of a plant-based diet. He has also received honoraria, speaking, and consultancy fees from the European Space Agency, Dyson Institute of Engineering and Technology, Riverford Organic Farmers, Ltd., Salesforce Inc., Sentara Healthcare, Saudi Sports for All Federation, the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, The Plantrician Project, Doctors for Nutrition, and The Happy Pear.

Pimentel is a consultant for Bausch Health, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, and Ardelyx. He holds equity in and is also a consultant for Dieta Health, Salvo Health, Cylinder Health, and Gemelli Biotech. Cedars-Sinai has a licensing agreement with Gemelli Biotech and Hobbs Medical.

Chey is a consultant to AbbVie, Ardelyx, Atmo, Biomerica, Gemelli Biotech, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Nestlé, QOL Medical, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Redhill, Salix/Valeant, Takeda, and Vibrant. He receives grant/research funding from Commonwealth Diagnostics International, Inc., US Food and Drug Administration, National Institutes of Health, QOL Medical, and Salix/Valeant. He holds stock options in Coprata, Dieta Health, Evinature, FoodMarble, Kiwi Biosciences, and ModifyHealth. He is a board or advisory panel member of the American College of Gastroenterology, GI Health Foundation, International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders, Rome. He holds patents on My Nutrition Health, Digital Manometry, and Rectal Expulsion Device.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common conditions encountered by both primary care providers and gastroenterologists, with a pooled global prevalence of 11.2%. This functional bowel disorder is characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort, diarrhea and/or constipation, and bloating.

Unfortunately, , according to Alan Desmond, MB, consultant in gastroenterology and general internal medicine, Torbay Hospital, UK National Health Service.

Desmond regularly sees patients who either haven’t been accurately diagnosed or have been told, “Don’t worry, it’s ‘just’ irritable bowel syndrome,” he said at the recent International Conference on Nutrition in Medicine.

A 2017 study involving nearly 2000 patients with a history of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms found that 43.1% of those who met the criteria for IBS were undiagnosed, and among those who were diagnosed, 26% were not receiving treatment.

“Many clinicians vastly underestimate the impact functional GI symptoms have on our patients in lack of productivity, becoming homebound or losing employment, the inability to enjoy a meal with friends or family, and always needing to know where the nearest bathroom is, for example,” Desmond said in an interview.

IBS can profoundly affect patients’ mental health. One study found that 38% of patients with IBS attending a tertiary care clinic contemplated suicide because they felt hopeless about ever achieving symptom relief.

Today, several dietary, pharmacologic, and psychological/behavioral approaches are available to treat patients with IBS, noted William D. Chey, MD, AGAF, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

“Each individual patient may need a different combination of these foundational treatments,” he said. “One size doesn’t fit all.”

Diagnostic Pathway

One reason IBS is so hard to diagnose is that it’s a “symptom-based disorder, with identification of the condition predicated upon certain key characteristics that are heterogeneous,” Chey said in an interview. “IBS in patient ‘A’ may not present the same way as IBS in patient ‘B,’ although there are certain foundational common characteristics.”

IBS involves “abnormalities in the motility and contractility of the GI tract,” he said. It can present with diarrhea (IBS-D), constipation (IBS-C), or a mixture or alternation of diarrhea and constipation (IBS-M).

Patients with IBS-D often have an exaggerated gastro-colonic response, while those with IBS-C often have a blunted response.

Beyond stool abnormalities and abdominal pain/discomfort, patients often report bloating/distension, low backache, lethargy, nausea, thigh pain, and urinary and gynecologic symptoms.

Historically, IBS has been regarded as a “diagnosis of exclusion” because classic diagnostic tests typically yield no concrete findings. Desmond noted that several blood tests, procedures, imaging studies, and other tests are available to rule out other organic GI conditions, as outlined in the Table.

If the patient comes from a geographical region where giardia is endemic, clinicians also should consider testing for the parasite, Chey said.

New Understanding of IBS Etiology

Now, advances in the understanding of IBS are changing the approach to the disease.

“The field is moving away from seeing IBS as a ‘wastebasket diagnosis,’ recognizing that there are other causes of a patient’s symptoms,” Mark Pimentel, MD, associate professor of medicine and gastroenterology, Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, said in an interview. “What’s made IBS so difficult to diagnose has been the absence of biological markers and hallmark findings on endoscopy.”

Recent research points to novel bacterial causes as culprits in the development of IBS. In particular, altered small bowel microbiota can be triggered by acute gastroenteritis.

Food poisoning can trigger the onset of IBS — a phenomenon called “postinfectious IBS (PI-IBS),” said Pimentel, who is also executive director of the Medically Associated Science and Technology Program at Cedars-Sinai. PI-IBS almost always takes the form of IBS-D, with up to 60% of patients with IBS-D suffering the long-term sequelae of food poisoning.

The types of bacteria most commonly associated with gastroenteritis are Shigella, Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Escherichia coli, Pimentel said. All of them release cytolethal distending toxin B (CdtB), causing the body to produce antibodies to the toxin.

CdtB resembles vinculin, a naturally occurring protein critical for healthy gut function. “Because of this molecular resemblance, the immune system often mistakes one for the other, producing anti-vinculin,” Pimentel explained.

This autoimmune response leads to disruptions in the gut microbiome, ultimately resulting in PI-IBS. The chain of events “doesn’t necessarily happen immediately,” Pimentel said. “You might have developed food poisoning at a party weeks or months ago.”

Acute gastroenteritis is common, affecting as many as 179 million people in the United States annually. A meta-analysis of 47 studies, incorporating 28,270 patients, found that those who had experienced acute gastroenteritis had a fourfold higher risk of developing IBS compared with nonexposed controls.

“The problem isn’t only the IBS itself, but the fact that people with PI-IBS are four times as likely to contract food poisoning again, which can further exacerbate IBS symptoms,” Pimentel said.

Diarrhea-predominant IBS can be detected through the presence of two blood biomarkers — anti-CdtB and anti-vinculin — in a blood test developed by Pimentel and his group.

“Elevation in either of these biomarkers establishes the diagnosis,” Pimentel said. “This is a breakthrough because it represents the first test that can make IBS a ‘diagnosis of inclusion.’”

The blood test also can identify IBS-M but not IBS-C.

Pimentel said that IBS-C is associated with increased levels of methanogenic archaea, which can be diagnosed by a positive methane breath test. “Methane gas slows intestinal contractility, which might result in constipation,” he said.

Diet as a Treatment Option

Diet is usually the starting point for IBS treatment, Chey said. “The standard dietary recommendations, as defined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guidance for managing IBS, are reasonable and common sense — eating three meals a day, avoiding carbonated beverages, excess alcohol, and excess caffeine, and avoiding hard-to-digest foods that can be gas producing.”

A diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs), which are carbohydrates that aren’t completely absorbed in the intestines, has been shown to be effective in alleviating GI distress in as many as 86% of patients with IBS, leading to improvements in overall GI symptoms as well as individual symptoms (eg, abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, diarrhea, and flatulence).

Desmond recommends the low FODMAP program delineated by Monash University in Australia. The diet should be undertaken only under the supervision of a dietitian, he warned. Moreover, following it on a long-term basis can have an adverse impact on dietary quality and the gut microbiome. Therefore, “it’s important to embark on stepwise reintroduction of FODMAPS under supervision to find acceptable thresholds that don’t cause a return of symptoms.”

A growing body of research suggests that following the Mediterranean diet can be helpful in reducing IBS symptoms. Chey said that some patients who tend to over-restrict their eating might benefit from a less restrictive diet than the typical low FODMAPs diet. For them, the Mediterranean diet may be a good option.

Pharmacotherapy for IBS

Nutritional approaches aren’t for everyone, Chey noted. “Some people don’t want to be on a highly restricted diet.” For them, medications addressing symptoms might be a better option.

Antispasmodics — either anticholinergics (hyoscine and dicyclomine) or smooth muscle relaxants (alverine, mebeverine, and peppermint oil) — can be helpful, although they can worsen constipation in a dose-dependent manner. It is advisable to use them on an as-needed rather than long-term basis.

Antidiarrheal agents include loperamide and diphenoxylate.

For constipation, laxatives (eg, senna, bisacodyl, polyethylene glycol, and sodium picosulfate) can be helpful.

Desmond noted that the American Gastroenterological Association does not recommend routine use of probiotics for most GI disorders, including IBS. Exceptions include prevention of Clostridioides difficile, ulcerative colitis, and pouchitis.

Targeting the Gut-Brain Relationship

Stress plays a role in exacerbating symptoms in patients with IBS and is an important target for intervention.

“If patients are living with a level of stress that’s impairing, we won’t be able to solve their gut issues until we resolve their stress issues,” Desmond said. “We need to calm the gut-microbiome-brain axis, which is multidimensional and bidirectional.”

Many people — even those without IBS — experience queasiness or diarrhea prior to a major event they’re nervous about, Chey noted. These events activate the brain, which activates the nervous system, which interacts with the GI tract. Indeed, IBS is now recognized as a disorder of gut-brain interaction, he said.

“We now know that the microbiome in the GI tract influences cognition and emotional function, depression, and anxiety. One might say that the gut is the ‘center of the universe’ to human beings,” Chey said.

Evidence-based psychological approaches for stress reduction in patients with IBS include cognitive behavioral therapy, specifically tailored to helping the patient identify associations between IBS symptoms and thoughts, emotions, and actions, as well as learning new behaviors and engaging in stress management. Psychodynamic (interpersonal) therapy enables patients to understand the connection between GI symptoms and interpersonal conflicts, emotional factors, or relationship difficulties.

Gut-directed hypnotherapy (GDH) is a “proven modality for IBS,” Desmond said. Unlike other forms of hypnotherapy, GDH focuses specifically on controlling and normalizing GI function. Studies have shown a reduction of ≥ 30% in abdominal pain in two thirds of participants, with overall response rates up to 85%. It can be delivered in an individual or group setting or via a smartphone.

Desmond recommends mindfulness-based therapy (MBT) for IBS. MBT focuses on the “cultivation of mindfulness, defined as intentional, nonjudgmental, present-focused awareness.” It has been found effective in reducing flares and the markers of gut inflammation in ulcerative colitis, as well as reducing symptoms of IBS.

Chey noted that an emerging body of literature supports the potential role of acupuncture in treating IBS, and his clinic employs it. “I would like to see further research into other areas of CAM [complementary and alternative medicine], including herbal approaches to IBS symptoms as well as stress.”

Finally, all the experts agree that more research is needed.

“The real tragedy is that the NIH invests next to nothing in IBS, in contrast to inflammatory bowel disease and many other conditions,” Pimentel said. “Yet IBS is 45 times more common than inflammatory bowel disease.”

Pimentel hopes that with enough advocacy and recognition that IBS isn’t “just stress-related,” more resources will be devoted to understanding this debilitating condition.

Desmond is the author of a book on the benefits of a plant-based diet. He has also received honoraria, speaking, and consultancy fees from the European Space Agency, Dyson Institute of Engineering and Technology, Riverford Organic Farmers, Ltd., Salesforce Inc., Sentara Healthcare, Saudi Sports for All Federation, the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, The Plantrician Project, Doctors for Nutrition, and The Happy Pear.

Pimentel is a consultant for Bausch Health, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, and Ardelyx. He holds equity in and is also a consultant for Dieta Health, Salvo Health, Cylinder Health, and Gemelli Biotech. Cedars-Sinai has a licensing agreement with Gemelli Biotech and Hobbs Medical.

Chey is a consultant to AbbVie, Ardelyx, Atmo, Biomerica, Gemelli Biotech, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Nestlé, QOL Medical, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Redhill, Salix/Valeant, Takeda, and Vibrant. He receives grant/research funding from Commonwealth Diagnostics International, Inc., US Food and Drug Administration, National Institutes of Health, QOL Medical, and Salix/Valeant. He holds stock options in Coprata, Dieta Health, Evinature, FoodMarble, Kiwi Biosciences, and ModifyHealth. He is a board or advisory panel member of the American College of Gastroenterology, GI Health Foundation, International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders, Rome. He holds patents on My Nutrition Health, Digital Manometry, and Rectal Expulsion Device.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common conditions encountered by both primary care providers and gastroenterologists, with a pooled global prevalence of 11.2%. This functional bowel disorder is characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort, diarrhea and/or constipation, and bloating.

Unfortunately, , according to Alan Desmond, MB, consultant in gastroenterology and general internal medicine, Torbay Hospital, UK National Health Service.

Desmond regularly sees patients who either haven’t been accurately diagnosed or have been told, “Don’t worry, it’s ‘just’ irritable bowel syndrome,” he said at the recent International Conference on Nutrition in Medicine.

A 2017 study involving nearly 2000 patients with a history of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms found that 43.1% of those who met the criteria for IBS were undiagnosed, and among those who were diagnosed, 26% were not receiving treatment.