User login

Pride profile: Keshav Khanijow, MD

Keshav Khanijow, MD, is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and assistant professor at Northwestern University, Chicago. Originally from the San Francisco Bay area, he studied anthropology as an undergrad at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, then went to medical school at the University of California, San Francisco, followed by internal medicine residency and a hospital medicine fellowship at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. He came out as gay in 2006 as an undergrad. He is a founding member of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s LGBTQ+ Task Force and is involved with SHM’s Diversity and Inclusion Special Interest Group.

What challenges have you faced because of your sexual orientation in the different stages of your career, from training to now as a practicing physician?

In my early training, there weren’t a lot of accessible LGBTQ role models to talk about balancing my personal identities with my professional aspirations. Being a double minority as both South Asian and a gay male, made it that much more difficult. “What is it like to work in health care as a gay cismale? Will being out on my personal statement affect my entry into medical school? Should I list my LGBTQ activism activities or not?” Those were important to me.

And did you make your activism known?

Thankfully, I did. I joke that my application might as well have been printed on rainbow paper, if you will. I decided to be out because I wanted to be part of an environment that would accept me for who I was. But it was a difficult decision.

In medical school at UCSF, it’s San Francisco, so they were a little ahead of the game. They had a lot of social networking opportunities with LGBTQ and ally faculty. Those connections were important in helping me explore different fields, and I even got to write my first publication. That said, networking could sometimes be challenging, especially when it came to residency interviews. While many people would talk about family activities and engagements, I’d only been out to my family for a few years. As such, there would be somewhat of a disconnect. On the flip side, there were LGBTQ celebrations and cultural concepts important to me, but I couldn’t always connect on those fronts either.

When it comes to patients, I do have a bit of a higher-pitched voice, and my mannerisms can be gender nonconforming. While it did make me the target of some cruel middle school humor, I’ve come to be proud of myself, mannerisms and all. That said, I have had patients make remarks to me about being gay, whether it be positive or negative. For LGBTQ patients, they’re like, “this is great, I have a gay doctor. They’ll know a bit more about what I’m talking about or be able to relate to the community pressures I face.”

But sometimes homophobic patients can be a bit more cold. I’ve never had anyone say that they don’t want to have me as their physician, but I definitely have patients who disagree with me and say, essentially, “oh well, you don’t know what you’re talking about because you’re gay.” Of course, there have also been comments based on my ethnicity as well.

What specific progress could you point to that you’ve seen over the course of your training and your career so far with regard to LGBTQ health care workers’ experience and LGBTQ patients?

When I was in college, there was a case in 2007 where a woman wasn’t able to see her partner or children before dying in a Florida hospital. Since then, there’s been great strides with a 2011 executive order extending hospital visitation rights to LGBTQ families. In 2013, there was the legalization of same-sex marriage. More recently, in June 2020, the Supreme Court extended protections against workplace discrimination to LGBTQ employees.

But there are certain things that continue to be problems, such as the recent Final Rule from the Department of Health & Human Services that fails to protect our LGBTQ patients and friends against discrimination in health care.

Can you remember a specific episode with a patient who was in the LGBTQ community that was particularly satisfying or moving?

There are two that I think about. In medical school, I was working in a more conservative area of California, and there was a patient who identified as lesbian. She felt more able to talk about her fears of raising a family in a conservative area. She even said, “I feel you can understand the stuff, I can talk to you a bit more about it freely, which is really nice.” Later on, I was able to see them on another rotation I was on, after she’d had a baby with her partner. I was honored that they considered me a part of their family’s journey.

A couple years ago as an attending hospitalist, I had a gay male patient that came in for hepatitis A treatment. Although we typically think of hepatitis A as a foodborne illness, oral-anal sex (rimming) is also a risk factor. After having an open discussion with him about his sexual practices, I said, “it was probably an STI in your case,” and was able to give him guidelines on how to prevent giving it to anyone else during the recovery period. He was very appreciative, and I was glad to have been there for that patient.

What is SHM’s role in regard to improving the care of LGBTQ patients, improving inclusiveness for LGBTQ health professionals?

Continuing to have educational activities, whether it be lectures at the annual conference or online learning modules, will be critical to care for our LGBTQ patients. With regard to membership, we need to make sure that hospitalists feel included and protected. To this end, our Diversity and Inclusion Special Interest Group was working toward having gender-neutral bathrooms and personal pronoun tags for the in-person 2020 annual conference before it was converted to an online format.

Does it ever get tiring for you to work on “social issues” in addition to strictly medical issues?

I will say I definitely experienced a moment in time during residency where I had to take a step back and recenter myself. Sometimes, realizing how much work needs to get done, coupled with the challenges of one’s personal life, can be daunting. That said, I can only stare at a problem so long before needing to work on creating a solution. At the end of the day I didn’t want to run away from these newfound problems of exclusion – I wanted to be a part of the solution.

In my hospital medicine fellowship, I was lucky to have Flora Kisuule, MD, as a mentor who encouraged me to take my prior work with LGBTQ health and leverage it into hospital medicine projects. As such, I was able to combine a topic I was passionate about with my interests in research and teaching so that they work synergistically. After all, the social issues affect our medical histories, just as our medical issues affect our social being. They go hand in hand.

Keshav Khanijow, MD, is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and assistant professor at Northwestern University, Chicago. Originally from the San Francisco Bay area, he studied anthropology as an undergrad at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, then went to medical school at the University of California, San Francisco, followed by internal medicine residency and a hospital medicine fellowship at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. He came out as gay in 2006 as an undergrad. He is a founding member of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s LGBTQ+ Task Force and is involved with SHM’s Diversity and Inclusion Special Interest Group.

What challenges have you faced because of your sexual orientation in the different stages of your career, from training to now as a practicing physician?

In my early training, there weren’t a lot of accessible LGBTQ role models to talk about balancing my personal identities with my professional aspirations. Being a double minority as both South Asian and a gay male, made it that much more difficult. “What is it like to work in health care as a gay cismale? Will being out on my personal statement affect my entry into medical school? Should I list my LGBTQ activism activities or not?” Those were important to me.

And did you make your activism known?

Thankfully, I did. I joke that my application might as well have been printed on rainbow paper, if you will. I decided to be out because I wanted to be part of an environment that would accept me for who I was. But it was a difficult decision.

In medical school at UCSF, it’s San Francisco, so they were a little ahead of the game. They had a lot of social networking opportunities with LGBTQ and ally faculty. Those connections were important in helping me explore different fields, and I even got to write my first publication. That said, networking could sometimes be challenging, especially when it came to residency interviews. While many people would talk about family activities and engagements, I’d only been out to my family for a few years. As such, there would be somewhat of a disconnect. On the flip side, there were LGBTQ celebrations and cultural concepts important to me, but I couldn’t always connect on those fronts either.

When it comes to patients, I do have a bit of a higher-pitched voice, and my mannerisms can be gender nonconforming. While it did make me the target of some cruel middle school humor, I’ve come to be proud of myself, mannerisms and all. That said, I have had patients make remarks to me about being gay, whether it be positive or negative. For LGBTQ patients, they’re like, “this is great, I have a gay doctor. They’ll know a bit more about what I’m talking about or be able to relate to the community pressures I face.”

But sometimes homophobic patients can be a bit more cold. I’ve never had anyone say that they don’t want to have me as their physician, but I definitely have patients who disagree with me and say, essentially, “oh well, you don’t know what you’re talking about because you’re gay.” Of course, there have also been comments based on my ethnicity as well.

What specific progress could you point to that you’ve seen over the course of your training and your career so far with regard to LGBTQ health care workers’ experience and LGBTQ patients?

When I was in college, there was a case in 2007 where a woman wasn’t able to see her partner or children before dying in a Florida hospital. Since then, there’s been great strides with a 2011 executive order extending hospital visitation rights to LGBTQ families. In 2013, there was the legalization of same-sex marriage. More recently, in June 2020, the Supreme Court extended protections against workplace discrimination to LGBTQ employees.

But there are certain things that continue to be problems, such as the recent Final Rule from the Department of Health & Human Services that fails to protect our LGBTQ patients and friends against discrimination in health care.

Can you remember a specific episode with a patient who was in the LGBTQ community that was particularly satisfying or moving?

There are two that I think about. In medical school, I was working in a more conservative area of California, and there was a patient who identified as lesbian. She felt more able to talk about her fears of raising a family in a conservative area. She even said, “I feel you can understand the stuff, I can talk to you a bit more about it freely, which is really nice.” Later on, I was able to see them on another rotation I was on, after she’d had a baby with her partner. I was honored that they considered me a part of their family’s journey.

A couple years ago as an attending hospitalist, I had a gay male patient that came in for hepatitis A treatment. Although we typically think of hepatitis A as a foodborne illness, oral-anal sex (rimming) is also a risk factor. After having an open discussion with him about his sexual practices, I said, “it was probably an STI in your case,” and was able to give him guidelines on how to prevent giving it to anyone else during the recovery period. He was very appreciative, and I was glad to have been there for that patient.

What is SHM’s role in regard to improving the care of LGBTQ patients, improving inclusiveness for LGBTQ health professionals?

Continuing to have educational activities, whether it be lectures at the annual conference or online learning modules, will be critical to care for our LGBTQ patients. With regard to membership, we need to make sure that hospitalists feel included and protected. To this end, our Diversity and Inclusion Special Interest Group was working toward having gender-neutral bathrooms and personal pronoun tags for the in-person 2020 annual conference before it was converted to an online format.

Does it ever get tiring for you to work on “social issues” in addition to strictly medical issues?

I will say I definitely experienced a moment in time during residency where I had to take a step back and recenter myself. Sometimes, realizing how much work needs to get done, coupled with the challenges of one’s personal life, can be daunting. That said, I can only stare at a problem so long before needing to work on creating a solution. At the end of the day I didn’t want to run away from these newfound problems of exclusion – I wanted to be a part of the solution.

In my hospital medicine fellowship, I was lucky to have Flora Kisuule, MD, as a mentor who encouraged me to take my prior work with LGBTQ health and leverage it into hospital medicine projects. As such, I was able to combine a topic I was passionate about with my interests in research and teaching so that they work synergistically. After all, the social issues affect our medical histories, just as our medical issues affect our social being. They go hand in hand.

Keshav Khanijow, MD, is a hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and assistant professor at Northwestern University, Chicago. Originally from the San Francisco Bay area, he studied anthropology as an undergrad at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, then went to medical school at the University of California, San Francisco, followed by internal medicine residency and a hospital medicine fellowship at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. He came out as gay in 2006 as an undergrad. He is a founding member of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s LGBTQ+ Task Force and is involved with SHM’s Diversity and Inclusion Special Interest Group.

What challenges have you faced because of your sexual orientation in the different stages of your career, from training to now as a practicing physician?

In my early training, there weren’t a lot of accessible LGBTQ role models to talk about balancing my personal identities with my professional aspirations. Being a double minority as both South Asian and a gay male, made it that much more difficult. “What is it like to work in health care as a gay cismale? Will being out on my personal statement affect my entry into medical school? Should I list my LGBTQ activism activities or not?” Those were important to me.

And did you make your activism known?

Thankfully, I did. I joke that my application might as well have been printed on rainbow paper, if you will. I decided to be out because I wanted to be part of an environment that would accept me for who I was. But it was a difficult decision.

In medical school at UCSF, it’s San Francisco, so they were a little ahead of the game. They had a lot of social networking opportunities with LGBTQ and ally faculty. Those connections were important in helping me explore different fields, and I even got to write my first publication. That said, networking could sometimes be challenging, especially when it came to residency interviews. While many people would talk about family activities and engagements, I’d only been out to my family for a few years. As such, there would be somewhat of a disconnect. On the flip side, there were LGBTQ celebrations and cultural concepts important to me, but I couldn’t always connect on those fronts either.

When it comes to patients, I do have a bit of a higher-pitched voice, and my mannerisms can be gender nonconforming. While it did make me the target of some cruel middle school humor, I’ve come to be proud of myself, mannerisms and all. That said, I have had patients make remarks to me about being gay, whether it be positive or negative. For LGBTQ patients, they’re like, “this is great, I have a gay doctor. They’ll know a bit more about what I’m talking about or be able to relate to the community pressures I face.”

But sometimes homophobic patients can be a bit more cold. I’ve never had anyone say that they don’t want to have me as their physician, but I definitely have patients who disagree with me and say, essentially, “oh well, you don’t know what you’re talking about because you’re gay.” Of course, there have also been comments based on my ethnicity as well.

What specific progress could you point to that you’ve seen over the course of your training and your career so far with regard to LGBTQ health care workers’ experience and LGBTQ patients?

When I was in college, there was a case in 2007 where a woman wasn’t able to see her partner or children before dying in a Florida hospital. Since then, there’s been great strides with a 2011 executive order extending hospital visitation rights to LGBTQ families. In 2013, there was the legalization of same-sex marriage. More recently, in June 2020, the Supreme Court extended protections against workplace discrimination to LGBTQ employees.

But there are certain things that continue to be problems, such as the recent Final Rule from the Department of Health & Human Services that fails to protect our LGBTQ patients and friends against discrimination in health care.

Can you remember a specific episode with a patient who was in the LGBTQ community that was particularly satisfying or moving?

There are two that I think about. In medical school, I was working in a more conservative area of California, and there was a patient who identified as lesbian. She felt more able to talk about her fears of raising a family in a conservative area. She even said, “I feel you can understand the stuff, I can talk to you a bit more about it freely, which is really nice.” Later on, I was able to see them on another rotation I was on, after she’d had a baby with her partner. I was honored that they considered me a part of their family’s journey.

A couple years ago as an attending hospitalist, I had a gay male patient that came in for hepatitis A treatment. Although we typically think of hepatitis A as a foodborne illness, oral-anal sex (rimming) is also a risk factor. After having an open discussion with him about his sexual practices, I said, “it was probably an STI in your case,” and was able to give him guidelines on how to prevent giving it to anyone else during the recovery period. He was very appreciative, and I was glad to have been there for that patient.

What is SHM’s role in regard to improving the care of LGBTQ patients, improving inclusiveness for LGBTQ health professionals?

Continuing to have educational activities, whether it be lectures at the annual conference or online learning modules, will be critical to care for our LGBTQ patients. With regard to membership, we need to make sure that hospitalists feel included and protected. To this end, our Diversity and Inclusion Special Interest Group was working toward having gender-neutral bathrooms and personal pronoun tags for the in-person 2020 annual conference before it was converted to an online format.

Does it ever get tiring for you to work on “social issues” in addition to strictly medical issues?

I will say I definitely experienced a moment in time during residency where I had to take a step back and recenter myself. Sometimes, realizing how much work needs to get done, coupled with the challenges of one’s personal life, can be daunting. That said, I can only stare at a problem so long before needing to work on creating a solution. At the end of the day I didn’t want to run away from these newfound problems of exclusion – I wanted to be a part of the solution.

In my hospital medicine fellowship, I was lucky to have Flora Kisuule, MD, as a mentor who encouraged me to take my prior work with LGBTQ health and leverage it into hospital medicine projects. As such, I was able to combine a topic I was passionate about with my interests in research and teaching so that they work synergistically. After all, the social issues affect our medical histories, just as our medical issues affect our social being. They go hand in hand.

Treatment developments in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (oHCM)

Background: oHCM is characterized by mutations in sarcomeric proteins. Mavacamten is a small-molecule modulator of cardiac myosin, commonly affected in oHCM.

Study design: Open-label, nonrandomized phase 2 trial.

Setting: Five academic medical centers.

Synopsis: A total of 21 patients with oHCM were randomized to cohort A, high-dose mavacamten without additional therapy (beta-blockers, CCBs), or cohort B, low-dose mavacamten plus additional medical therapy. The LVOT gradient at 12 weeks improved in both cohorts: Cohort A had a mean change of –89.5 mm Hg (95% confidence interval, –138.3 to –40.7; P = .008) and cohort B –25.0 mm Hg (95% CI, –47.1 to –3.0, P = .020).

Bottom line: This phase 2 trial provides proof of concept and identified a plasma concentration of mavacamten needed to decrease the LVOT significantly. Phase 3 trials hold significant promise.

Citation: Heitner SB et al. Mavacamten treatment for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 30. doi: 10.7326/M18-3016.

Dr. Blount is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: oHCM is characterized by mutations in sarcomeric proteins. Mavacamten is a small-molecule modulator of cardiac myosin, commonly affected in oHCM.

Study design: Open-label, nonrandomized phase 2 trial.

Setting: Five academic medical centers.

Synopsis: A total of 21 patients with oHCM were randomized to cohort A, high-dose mavacamten without additional therapy (beta-blockers, CCBs), or cohort B, low-dose mavacamten plus additional medical therapy. The LVOT gradient at 12 weeks improved in both cohorts: Cohort A had a mean change of –89.5 mm Hg (95% confidence interval, –138.3 to –40.7; P = .008) and cohort B –25.0 mm Hg (95% CI, –47.1 to –3.0, P = .020).

Bottom line: This phase 2 trial provides proof of concept and identified a plasma concentration of mavacamten needed to decrease the LVOT significantly. Phase 3 trials hold significant promise.

Citation: Heitner SB et al. Mavacamten treatment for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 30. doi: 10.7326/M18-3016.

Dr. Blount is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: oHCM is characterized by mutations in sarcomeric proteins. Mavacamten is a small-molecule modulator of cardiac myosin, commonly affected in oHCM.

Study design: Open-label, nonrandomized phase 2 trial.

Setting: Five academic medical centers.

Synopsis: A total of 21 patients with oHCM were randomized to cohort A, high-dose mavacamten without additional therapy (beta-blockers, CCBs), or cohort B, low-dose mavacamten plus additional medical therapy. The LVOT gradient at 12 weeks improved in both cohorts: Cohort A had a mean change of –89.5 mm Hg (95% confidence interval, –138.3 to –40.7; P = .008) and cohort B –25.0 mm Hg (95% CI, –47.1 to –3.0, P = .020).

Bottom line: This phase 2 trial provides proof of concept and identified a plasma concentration of mavacamten needed to decrease the LVOT significantly. Phase 3 trials hold significant promise.

Citation: Heitner SB et al. Mavacamten treatment for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 30. doi: 10.7326/M18-3016.

Dr. Blount is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Manage the pandemic with a multidisciplinary coalition

Implement a 6-P framework

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, arguably the biggest public health and economic catastrophe of modern times, elevated multiple deficiencies in public health infrastructures across the world, such as a slow or delayed response to suppress and mitigate the virus, an inadequately prepared and protected health care and public health workforce, and decentralized, siloed efforts.1 COVID-19 further highlighted the vulnerabilities of the health care, public health, and economic sectors.2,3 Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading and deadly infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and the patients they serve to a breaking point.

Hospital systems in the United States are not only at the crux of the current pandemic but are also well positioned to lead the response to the pandemic. Hospital administrators oversee nearly 33% of national health expenditure that amounts to the hospital-based care in the United States. Additionally, they may have an impact on nearly 30% of the expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities.4

The two primary goals underlying our proposed framework to target COVID-19 are based on the World Health Organization recommendations and lessons learned from countries such as South Korea that have successfully implemented these recommendations.5

1. Flatten the curve. According to the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, flattening the curve means that we must do everything that will help us to slow down the rate of infection, so the number of cases do not exceed the capacity of health systems.

2. Establish a standardized, interdisciplinary approach to flattening the curve. Pandemics can have major adverse consequences beyond health outcomes (e.g., economy) that can impact adherence to advisories and introduce multiple unintended consequences (e.g., deferred chronic care, unemployment). Managing the current pandemic and thoughtful consideration of and action regarding its ripple effects is heavily dependent on a standardized, interdisciplinary approach that is monitored, implemented, and evaluated well.

To achieve these two goals, we recommend establishing an interdisciplinary coalition representing multiple sectors. Our 6-P framework described below is intended to guide hospital administrators, to build the coalition, and to achieve these goals.

Structure of the pandemic coalition

A successful coalition invites a collaborative partnership involving senior members of respective disciplines, who would provide valuable, complementary perspectives in the coalition. We recommend hospital administrators take a lead in the formation of such a coalition. While we present the stakeholders and their roles below based on their intended influence and impact on the overall outcome of COVID-19, the basic guiding principles behind our 6-P framework remain true for any large-scale population health intervention.

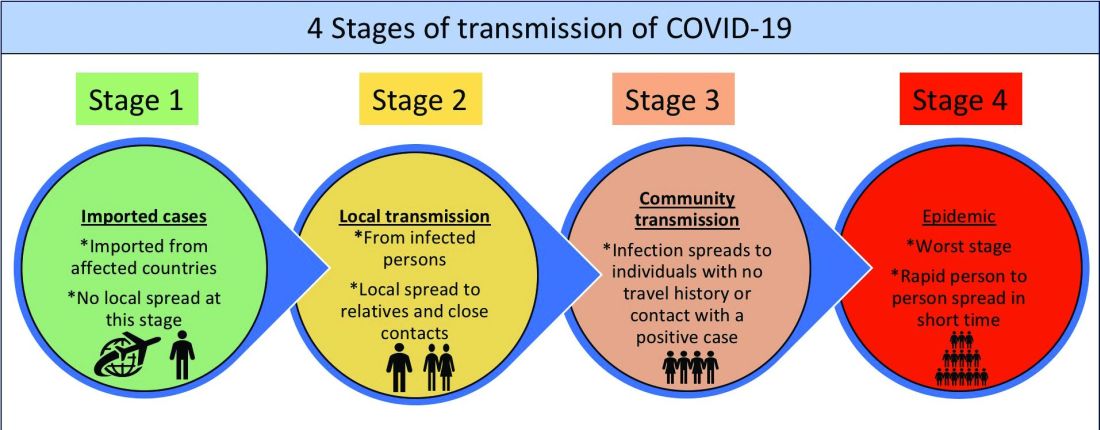

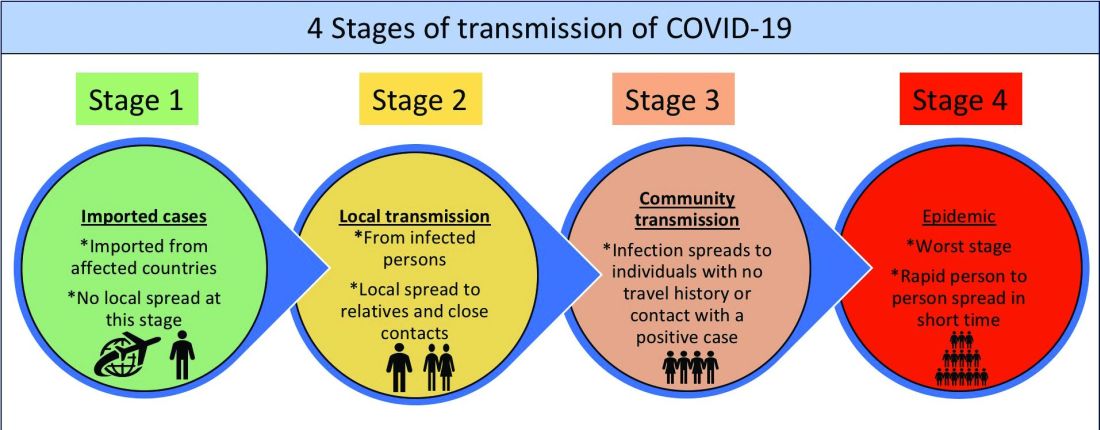

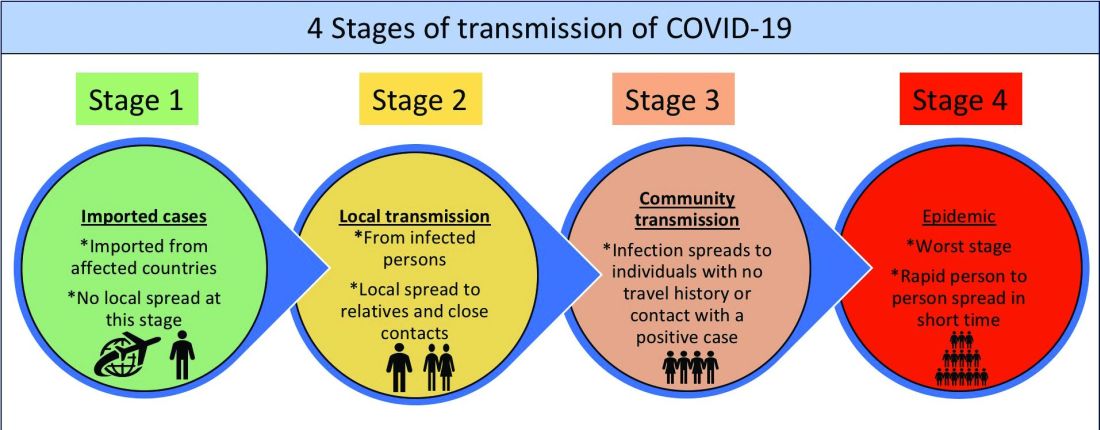

Although several models for staging the transmission of COVID-19 are available, we adopted a four-stage model followed by the Indian Council for Medical Research.6 Irrespective of the origin of the infection, we believe that the four-stage model can cultivate situational awareness that can help guide the strategic design and systematic implementation of interventions.

Our 6-P framework integrates the four-stage model of COVID-19 transmission to identify action items for each stakeholder group and appropriate strategies selected based on the stages targeted.

1. Policy makers: Policy makers at all levels are critical in establishing policies, orders, and advisories, as well as dedicating resources and infrastructure, to enhance adherence to recommendations and guidelines at the community and population levels.7 They can assist hospitals in workforce expansion across county/state/discipline lines (e.g., accelerate the licensing and credentialing process, authorize graduate medical trainees, nurse practitioners, and other allied health professionals). Policy revisions for data sharing, privacy, communication, liability, and telehealth expansion.82. Providers: The health of the health care workforce itself is at risk because of their frontline services. Their buy-in will be crucial in both the formulation and implementation of evidence- and practice-based guidelines.9 Rapid adoption of telehealth for care continuum, policy revisions for elective procedures, visitor restriction, surge, resurge planning, capacity expansion, effective population health management, and working with employee unions, professional staff organizations are few, but very important action items that need to be implemented.

3. Public health authorities: Representation of public health authorities will be crucial in standardizing data collection, management, and reporting; providing up-to-date guidelines and advisories; developing, implementing, and evaluating short- and long-term public health interventions; and preparing and helping communities throughout the course of the pandemic. They also play a key role in identifying and reducing barriers related to the expansion of testing and contact tracing efforts.

4. Payers: In the United States, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services oversees primary federally funded programs and serves as a point of reference for the American health care system. Having representation from all payer sources is crucial for achieving uniformity and standardization of the care process during the pandemic, with particular priority given to individuals and families who may have recently lost their health insurance because of job loss from COVID-19–related business furloughs, layoffs, and closures. Customer outreach initiatives, revision of patients’ out of pocket responsibilities, rapid claim settlement and denial management services, expansion of telehealth, elimination of prior authorization barriers, rapid credentialing of providers, data sharing, and assisting hospital systems in chronic disease management are examples of time-sensitive initiatives that are vital for population health management.

5. Partners: Establishing partnerships with pharma, health IT, labs, device industries, and other ancillary services is important to facilitate rapid innovation, production, and supply of essential medical devices and resources. These partners directly influence the outcomes of the pandemic and long-term health of the society through expansion of testing capability, contact tracing, leveraging technology for expanding access to COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 care, home monitoring of cases, innovation of treatment and prevention, and data sharing. Partners should consider options such as flexible medication delivery, electronic prescription services, and use of drones in supply chain to deliver test kits, test samples, medication, and blood products.

6. People/patients: Lastly and perhaps most critically, the trust, buy-in, and needs of the overall population are needed to enhance adherence to guidelines and recommendations. Many millions more than those who test positive for COVID-19 have and will continue to experience the crippling adverse economic, social, physical, and mental health effects of stay-at-home advisories, business and school closures, and physical distancing orders. Members of each community need to be heard in voicing their concerns and priorities and providing input on public health interventions to enhance acceptance and adherence (e.g., wear mask/face coverings in public, engage in physical distancing, etc.). Special attention should be given to managing chronic or existing medical problems and seek care when needed (e.g., avoid delaying of medical care).

An interdisciplinary and multipronged approach is necessary to address a complex, widespread, disruptive, and deadly pandemic such as COVID-19. The suggested activities put forth in our table are by no means exhaustive, nor do we expect all coalitions to be able to carry them all out. Our intention is that the 6-P framework encourages cross-sector collaboration to facilitate the design, implementation, evaluation, and scalability of preventive and intervention efforts based on the menu of items we have provided. Each coalition may determine which strategies they are able to prioritize and when within the context of specific national, regional, and local advisories, resulting in a tailored approach for each community or region that is thus better positioned for success.

Dr. Lingisetty is a hospitalist and physician executive at Baptist Health System, Little Rock, Ark. He is cofounder/president of SHM’s Arkansas chapter. Dr. Wang is assistant professor in the department of community health sciences at Boston University and adjunct assistant professor of health policy and management at the Harvard School of Public Health. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management and physician advisory services, at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson. He is an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist at the University of Mississippi.

References

1. Powles J, Comim F. Public health infrastructure and knowledge, in Smith R et al. “Global Public Goods for Health.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2. Lombardi P, Petroni G. Virus outbreak pushes Italy’s health care system to the brink. Wall Street Journal. 2020 Mar 12. https://www.wsj.com/articles/virus-outbreak-pushes-italys-healthcare-system-to-the-brink-11583968769

3. Davies, R. How coronavirus is affecting the global economy. The Guardian. 2020 Feb 5. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/05/coronavirus-global-economy

4. National Center for Health Statistics. FastStats. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm.

5. World Health Organization. Country & Technical Guidance–Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance

6. Indian Council of Medical Research. Stages of transmission of COVID-19. https://main.icmr.nic.in/content/covid-19

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) – Prevention & treatment. 2020 Apr 24. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

8. Ostriker R. Cutbacks for some doctors and nurses as they battle on the front line. Boston Globe. 2020 Mar 27. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/03/27/metro/coronavirus-rages-doctors-hit-with-cuts-compensation/

9. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. News alert. 2020 Mar 26. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-news-alert-march-26-2020

Implement a 6-P framework

Implement a 6-P framework

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, arguably the biggest public health and economic catastrophe of modern times, elevated multiple deficiencies in public health infrastructures across the world, such as a slow or delayed response to suppress and mitigate the virus, an inadequately prepared and protected health care and public health workforce, and decentralized, siloed efforts.1 COVID-19 further highlighted the vulnerabilities of the health care, public health, and economic sectors.2,3 Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading and deadly infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and the patients they serve to a breaking point.

Hospital systems in the United States are not only at the crux of the current pandemic but are also well positioned to lead the response to the pandemic. Hospital administrators oversee nearly 33% of national health expenditure that amounts to the hospital-based care in the United States. Additionally, they may have an impact on nearly 30% of the expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities.4

The two primary goals underlying our proposed framework to target COVID-19 are based on the World Health Organization recommendations and lessons learned from countries such as South Korea that have successfully implemented these recommendations.5

1. Flatten the curve. According to the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, flattening the curve means that we must do everything that will help us to slow down the rate of infection, so the number of cases do not exceed the capacity of health systems.

2. Establish a standardized, interdisciplinary approach to flattening the curve. Pandemics can have major adverse consequences beyond health outcomes (e.g., economy) that can impact adherence to advisories and introduce multiple unintended consequences (e.g., deferred chronic care, unemployment). Managing the current pandemic and thoughtful consideration of and action regarding its ripple effects is heavily dependent on a standardized, interdisciplinary approach that is monitored, implemented, and evaluated well.

To achieve these two goals, we recommend establishing an interdisciplinary coalition representing multiple sectors. Our 6-P framework described below is intended to guide hospital administrators, to build the coalition, and to achieve these goals.

Structure of the pandemic coalition

A successful coalition invites a collaborative partnership involving senior members of respective disciplines, who would provide valuable, complementary perspectives in the coalition. We recommend hospital administrators take a lead in the formation of such a coalition. While we present the stakeholders and their roles below based on their intended influence and impact on the overall outcome of COVID-19, the basic guiding principles behind our 6-P framework remain true for any large-scale population health intervention.

Although several models for staging the transmission of COVID-19 are available, we adopted a four-stage model followed by the Indian Council for Medical Research.6 Irrespective of the origin of the infection, we believe that the four-stage model can cultivate situational awareness that can help guide the strategic design and systematic implementation of interventions.

Our 6-P framework integrates the four-stage model of COVID-19 transmission to identify action items for each stakeholder group and appropriate strategies selected based on the stages targeted.

1. Policy makers: Policy makers at all levels are critical in establishing policies, orders, and advisories, as well as dedicating resources and infrastructure, to enhance adherence to recommendations and guidelines at the community and population levels.7 They can assist hospitals in workforce expansion across county/state/discipline lines (e.g., accelerate the licensing and credentialing process, authorize graduate medical trainees, nurse practitioners, and other allied health professionals). Policy revisions for data sharing, privacy, communication, liability, and telehealth expansion.82. Providers: The health of the health care workforce itself is at risk because of their frontline services. Their buy-in will be crucial in both the formulation and implementation of evidence- and practice-based guidelines.9 Rapid adoption of telehealth for care continuum, policy revisions for elective procedures, visitor restriction, surge, resurge planning, capacity expansion, effective population health management, and working with employee unions, professional staff organizations are few, but very important action items that need to be implemented.

3. Public health authorities: Representation of public health authorities will be crucial in standardizing data collection, management, and reporting; providing up-to-date guidelines and advisories; developing, implementing, and evaluating short- and long-term public health interventions; and preparing and helping communities throughout the course of the pandemic. They also play a key role in identifying and reducing barriers related to the expansion of testing and contact tracing efforts.

4. Payers: In the United States, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services oversees primary federally funded programs and serves as a point of reference for the American health care system. Having representation from all payer sources is crucial for achieving uniformity and standardization of the care process during the pandemic, with particular priority given to individuals and families who may have recently lost their health insurance because of job loss from COVID-19–related business furloughs, layoffs, and closures. Customer outreach initiatives, revision of patients’ out of pocket responsibilities, rapid claim settlement and denial management services, expansion of telehealth, elimination of prior authorization barriers, rapid credentialing of providers, data sharing, and assisting hospital systems in chronic disease management are examples of time-sensitive initiatives that are vital for population health management.

5. Partners: Establishing partnerships with pharma, health IT, labs, device industries, and other ancillary services is important to facilitate rapid innovation, production, and supply of essential medical devices and resources. These partners directly influence the outcomes of the pandemic and long-term health of the society through expansion of testing capability, contact tracing, leveraging technology for expanding access to COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 care, home monitoring of cases, innovation of treatment and prevention, and data sharing. Partners should consider options such as flexible medication delivery, electronic prescription services, and use of drones in supply chain to deliver test kits, test samples, medication, and blood products.

6. People/patients: Lastly and perhaps most critically, the trust, buy-in, and needs of the overall population are needed to enhance adherence to guidelines and recommendations. Many millions more than those who test positive for COVID-19 have and will continue to experience the crippling adverse economic, social, physical, and mental health effects of stay-at-home advisories, business and school closures, and physical distancing orders. Members of each community need to be heard in voicing their concerns and priorities and providing input on public health interventions to enhance acceptance and adherence (e.g., wear mask/face coverings in public, engage in physical distancing, etc.). Special attention should be given to managing chronic or existing medical problems and seek care when needed (e.g., avoid delaying of medical care).

An interdisciplinary and multipronged approach is necessary to address a complex, widespread, disruptive, and deadly pandemic such as COVID-19. The suggested activities put forth in our table are by no means exhaustive, nor do we expect all coalitions to be able to carry them all out. Our intention is that the 6-P framework encourages cross-sector collaboration to facilitate the design, implementation, evaluation, and scalability of preventive and intervention efforts based on the menu of items we have provided. Each coalition may determine which strategies they are able to prioritize and when within the context of specific national, regional, and local advisories, resulting in a tailored approach for each community or region that is thus better positioned for success.

Dr. Lingisetty is a hospitalist and physician executive at Baptist Health System, Little Rock, Ark. He is cofounder/president of SHM’s Arkansas chapter. Dr. Wang is assistant professor in the department of community health sciences at Boston University and adjunct assistant professor of health policy and management at the Harvard School of Public Health. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management and physician advisory services, at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson. He is an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist at the University of Mississippi.

References

1. Powles J, Comim F. Public health infrastructure and knowledge, in Smith R et al. “Global Public Goods for Health.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2. Lombardi P, Petroni G. Virus outbreak pushes Italy’s health care system to the brink. Wall Street Journal. 2020 Mar 12. https://www.wsj.com/articles/virus-outbreak-pushes-italys-healthcare-system-to-the-brink-11583968769

3. Davies, R. How coronavirus is affecting the global economy. The Guardian. 2020 Feb 5. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/05/coronavirus-global-economy

4. National Center for Health Statistics. FastStats. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm.

5. World Health Organization. Country & Technical Guidance–Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance

6. Indian Council of Medical Research. Stages of transmission of COVID-19. https://main.icmr.nic.in/content/covid-19

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) – Prevention & treatment. 2020 Apr 24. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

8. Ostriker R. Cutbacks for some doctors and nurses as they battle on the front line. Boston Globe. 2020 Mar 27. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/03/27/metro/coronavirus-rages-doctors-hit-with-cuts-compensation/

9. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. News alert. 2020 Mar 26. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-news-alert-march-26-2020

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, arguably the biggest public health and economic catastrophe of modern times, elevated multiple deficiencies in public health infrastructures across the world, such as a slow or delayed response to suppress and mitigate the virus, an inadequately prepared and protected health care and public health workforce, and decentralized, siloed efforts.1 COVID-19 further highlighted the vulnerabilities of the health care, public health, and economic sectors.2,3 Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading and deadly infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and the patients they serve to a breaking point.

Hospital systems in the United States are not only at the crux of the current pandemic but are also well positioned to lead the response to the pandemic. Hospital administrators oversee nearly 33% of national health expenditure that amounts to the hospital-based care in the United States. Additionally, they may have an impact on nearly 30% of the expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities.4

The two primary goals underlying our proposed framework to target COVID-19 are based on the World Health Organization recommendations and lessons learned from countries such as South Korea that have successfully implemented these recommendations.5

1. Flatten the curve. According to the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, flattening the curve means that we must do everything that will help us to slow down the rate of infection, so the number of cases do not exceed the capacity of health systems.

2. Establish a standardized, interdisciplinary approach to flattening the curve. Pandemics can have major adverse consequences beyond health outcomes (e.g., economy) that can impact adherence to advisories and introduce multiple unintended consequences (e.g., deferred chronic care, unemployment). Managing the current pandemic and thoughtful consideration of and action regarding its ripple effects is heavily dependent on a standardized, interdisciplinary approach that is monitored, implemented, and evaluated well.

To achieve these two goals, we recommend establishing an interdisciplinary coalition representing multiple sectors. Our 6-P framework described below is intended to guide hospital administrators, to build the coalition, and to achieve these goals.

Structure of the pandemic coalition

A successful coalition invites a collaborative partnership involving senior members of respective disciplines, who would provide valuable, complementary perspectives in the coalition. We recommend hospital administrators take a lead in the formation of such a coalition. While we present the stakeholders and their roles below based on their intended influence and impact on the overall outcome of COVID-19, the basic guiding principles behind our 6-P framework remain true for any large-scale population health intervention.

Although several models for staging the transmission of COVID-19 are available, we adopted a four-stage model followed by the Indian Council for Medical Research.6 Irrespective of the origin of the infection, we believe that the four-stage model can cultivate situational awareness that can help guide the strategic design and systematic implementation of interventions.

Our 6-P framework integrates the four-stage model of COVID-19 transmission to identify action items for each stakeholder group and appropriate strategies selected based on the stages targeted.

1. Policy makers: Policy makers at all levels are critical in establishing policies, orders, and advisories, as well as dedicating resources and infrastructure, to enhance adherence to recommendations and guidelines at the community and population levels.7 They can assist hospitals in workforce expansion across county/state/discipline lines (e.g., accelerate the licensing and credentialing process, authorize graduate medical trainees, nurse practitioners, and other allied health professionals). Policy revisions for data sharing, privacy, communication, liability, and telehealth expansion.82. Providers: The health of the health care workforce itself is at risk because of their frontline services. Their buy-in will be crucial in both the formulation and implementation of evidence- and practice-based guidelines.9 Rapid adoption of telehealth for care continuum, policy revisions for elective procedures, visitor restriction, surge, resurge planning, capacity expansion, effective population health management, and working with employee unions, professional staff organizations are few, but very important action items that need to be implemented.

3. Public health authorities: Representation of public health authorities will be crucial in standardizing data collection, management, and reporting; providing up-to-date guidelines and advisories; developing, implementing, and evaluating short- and long-term public health interventions; and preparing and helping communities throughout the course of the pandemic. They also play a key role in identifying and reducing barriers related to the expansion of testing and contact tracing efforts.

4. Payers: In the United States, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services oversees primary federally funded programs and serves as a point of reference for the American health care system. Having representation from all payer sources is crucial for achieving uniformity and standardization of the care process during the pandemic, with particular priority given to individuals and families who may have recently lost their health insurance because of job loss from COVID-19–related business furloughs, layoffs, and closures. Customer outreach initiatives, revision of patients’ out of pocket responsibilities, rapid claim settlement and denial management services, expansion of telehealth, elimination of prior authorization barriers, rapid credentialing of providers, data sharing, and assisting hospital systems in chronic disease management are examples of time-sensitive initiatives that are vital for population health management.

5. Partners: Establishing partnerships with pharma, health IT, labs, device industries, and other ancillary services is important to facilitate rapid innovation, production, and supply of essential medical devices and resources. These partners directly influence the outcomes of the pandemic and long-term health of the society through expansion of testing capability, contact tracing, leveraging technology for expanding access to COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 care, home monitoring of cases, innovation of treatment and prevention, and data sharing. Partners should consider options such as flexible medication delivery, electronic prescription services, and use of drones in supply chain to deliver test kits, test samples, medication, and blood products.

6. People/patients: Lastly and perhaps most critically, the trust, buy-in, and needs of the overall population are needed to enhance adherence to guidelines and recommendations. Many millions more than those who test positive for COVID-19 have and will continue to experience the crippling adverse economic, social, physical, and mental health effects of stay-at-home advisories, business and school closures, and physical distancing orders. Members of each community need to be heard in voicing their concerns and priorities and providing input on public health interventions to enhance acceptance and adherence (e.g., wear mask/face coverings in public, engage in physical distancing, etc.). Special attention should be given to managing chronic or existing medical problems and seek care when needed (e.g., avoid delaying of medical care).

An interdisciplinary and multipronged approach is necessary to address a complex, widespread, disruptive, and deadly pandemic such as COVID-19. The suggested activities put forth in our table are by no means exhaustive, nor do we expect all coalitions to be able to carry them all out. Our intention is that the 6-P framework encourages cross-sector collaboration to facilitate the design, implementation, evaluation, and scalability of preventive and intervention efforts based on the menu of items we have provided. Each coalition may determine which strategies they are able to prioritize and when within the context of specific national, regional, and local advisories, resulting in a tailored approach for each community or region that is thus better positioned for success.

Dr. Lingisetty is a hospitalist and physician executive at Baptist Health System, Little Rock, Ark. He is cofounder/president of SHM’s Arkansas chapter. Dr. Wang is assistant professor in the department of community health sciences at Boston University and adjunct assistant professor of health policy and management at the Harvard School of Public Health. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management and physician advisory services, at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson. He is an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist at the University of Mississippi.

References

1. Powles J, Comim F. Public health infrastructure and knowledge, in Smith R et al. “Global Public Goods for Health.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2. Lombardi P, Petroni G. Virus outbreak pushes Italy’s health care system to the brink. Wall Street Journal. 2020 Mar 12. https://www.wsj.com/articles/virus-outbreak-pushes-italys-healthcare-system-to-the-brink-11583968769

3. Davies, R. How coronavirus is affecting the global economy. The Guardian. 2020 Feb 5. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/05/coronavirus-global-economy

4. National Center for Health Statistics. FastStats. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm.

5. World Health Organization. Country & Technical Guidance–Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance

6. Indian Council of Medical Research. Stages of transmission of COVID-19. https://main.icmr.nic.in/content/covid-19

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) – Prevention & treatment. 2020 Apr 24. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

8. Ostriker R. Cutbacks for some doctors and nurses as they battle on the front line. Boston Globe. 2020 Mar 27. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/03/27/metro/coronavirus-rages-doctors-hit-with-cuts-compensation/

9. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. News alert. 2020 Mar 26. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-news-alert-march-26-2020

Suboptimal statin response predicts future risk

Background: Rates of LDL-C reduction with statin therapy vary based on biological and genetic factors, as well as adherence. In a general primary prevention population at cardiovascular risk, little is known about the extent of this variability or its impact on outcomes.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Primary care practices in England and Wales.

Synopsis: Across a cohort of 183,213 patients, 51.2% had a suboptimal response, defined as a less than 40% proportional reduction in LDL-C. During more than 1 million person-years of follow-up, suboptimal statin response at 2 years was associated with a 20% higher hazard ratio for incident cardiovascular disease.Bottom line: Half of patients do not have a sufficient response to statins, with higher attendant future risk.

Citation: Akyea RK et al. Suboptimal cholesterol response to initiation of statins and future risk of cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2019 Apr 15;0:1-7. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314253.

Dr. Anderson is chief, hospital medicine section, and deputy chief, medicine service, at the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Health Care System, Aurora.

Background: Rates of LDL-C reduction with statin therapy vary based on biological and genetic factors, as well as adherence. In a general primary prevention population at cardiovascular risk, little is known about the extent of this variability or its impact on outcomes.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Primary care practices in England and Wales.

Synopsis: Across a cohort of 183,213 patients, 51.2% had a suboptimal response, defined as a less than 40% proportional reduction in LDL-C. During more than 1 million person-years of follow-up, suboptimal statin response at 2 years was associated with a 20% higher hazard ratio for incident cardiovascular disease.Bottom line: Half of patients do not have a sufficient response to statins, with higher attendant future risk.

Citation: Akyea RK et al. Suboptimal cholesterol response to initiation of statins and future risk of cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2019 Apr 15;0:1-7. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314253.

Dr. Anderson is chief, hospital medicine section, and deputy chief, medicine service, at the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Health Care System, Aurora.

Background: Rates of LDL-C reduction with statin therapy vary based on biological and genetic factors, as well as adherence. In a general primary prevention population at cardiovascular risk, little is known about the extent of this variability or its impact on outcomes.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Primary care practices in England and Wales.

Synopsis: Across a cohort of 183,213 patients, 51.2% had a suboptimal response, defined as a less than 40% proportional reduction in LDL-C. During more than 1 million person-years of follow-up, suboptimal statin response at 2 years was associated with a 20% higher hazard ratio for incident cardiovascular disease.Bottom line: Half of patients do not have a sufficient response to statins, with higher attendant future risk.

Citation: Akyea RK et al. Suboptimal cholesterol response to initiation of statins and future risk of cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2019 Apr 15;0:1-7. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314253.

Dr. Anderson is chief, hospital medicine section, and deputy chief, medicine service, at the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Health Care System, Aurora.

PAP use associated with lower mortality

Background: OSA is a key modifiable risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes and is increasingly prevalent in older populations. PAP improves OSA severity, increases oxygenation, and reduces daytime sleepiness. Its effect on major adverse cardiovascular outcomes remains uncertain.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study of the Sleep Heart Health Study.

Setting: Nine existing U.S. epidemiologic studies.

Synopsis: Of the 392 patients analyzed, 81 were prescribed PAP and 311 were not. Investigators controlled for OSA severity, history of stroke or MI, hypertension, diabetes, weight, smoking, and alcohol intake. The adjusted hazard ratio for death at mean 11 years was 42% lower for those prescribed PAP.

Bottom line: PAP markedly lowers mortality in OSA, with survival curves separating at 6-7 years.

Citation: Lisan Q et al. Association of positive airway pressure prescription with mortality in patients with obesity and severe obstructive sleep apnea. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Apr 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0281.

Dr. Anderson is chief, hospital medicine section, and deputy chief, medicine service, at the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Health Care System, Aurora.

Background: OSA is a key modifiable risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes and is increasingly prevalent in older populations. PAP improves OSA severity, increases oxygenation, and reduces daytime sleepiness. Its effect on major adverse cardiovascular outcomes remains uncertain.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study of the Sleep Heart Health Study.

Setting: Nine existing U.S. epidemiologic studies.

Synopsis: Of the 392 patients analyzed, 81 were prescribed PAP and 311 were not. Investigators controlled for OSA severity, history of stroke or MI, hypertension, diabetes, weight, smoking, and alcohol intake. The adjusted hazard ratio for death at mean 11 years was 42% lower for those prescribed PAP.

Bottom line: PAP markedly lowers mortality in OSA, with survival curves separating at 6-7 years.

Citation: Lisan Q et al. Association of positive airway pressure prescription with mortality in patients with obesity and severe obstructive sleep apnea. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Apr 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0281.

Dr. Anderson is chief, hospital medicine section, and deputy chief, medicine service, at the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Health Care System, Aurora.

Background: OSA is a key modifiable risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes and is increasingly prevalent in older populations. PAP improves OSA severity, increases oxygenation, and reduces daytime sleepiness. Its effect on major adverse cardiovascular outcomes remains uncertain.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study of the Sleep Heart Health Study.

Setting: Nine existing U.S. epidemiologic studies.

Synopsis: Of the 392 patients analyzed, 81 were prescribed PAP and 311 were not. Investigators controlled for OSA severity, history of stroke or MI, hypertension, diabetes, weight, smoking, and alcohol intake. The adjusted hazard ratio for death at mean 11 years was 42% lower for those prescribed PAP.

Bottom line: PAP markedly lowers mortality in OSA, with survival curves separating at 6-7 years.

Citation: Lisan Q et al. Association of positive airway pressure prescription with mortality in patients with obesity and severe obstructive sleep apnea. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Apr 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0281.

Dr. Anderson is chief, hospital medicine section, and deputy chief, medicine service, at the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Health Care System, Aurora.

SHM responds to racism in the United States

The Society of Hospital Medicine deplores the negative impact of racism in our nation and will always strive to remedy racial inequities in our health care system. Racism in our society cannot be ignored. Nor will SHM ignore racism’s impact on public health. SHM enthusiastically supports its members working to promote equity and reduce the adverse impact of racism. We are committed to using our platform to improve the health of patients everywhere.

SHM would like to reaffirm its long-valued dedication to diversity and inclusion. We remain committed to promoting healthy discussions and action throughout our publications, resources and member communities, as outlined by our diversity and inclusion statement.

SHM Diversity and Inclusion Statement

Hospitalists are charged with treating individuals at their most vulnerable moments, when being respected as a whole person is crucial to advance patients’ healing and wellness. Within our workforce, diversity is a strength in all its forms, which helps us learn about the human experience, grow as leaders, and ultimately create a respectful environment for all regardless of age, race, religion, national origin, gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, appearance, or ability.

To this end, the Society of Hospital Medicine will work to eliminate health disparities for our patients and foster inclusive and equitable cultures across our care teams and institutions with the goal of moving medicine and humanity forward.

The Society of Hospital Medicine deplores the negative impact of racism in our nation and will always strive to remedy racial inequities in our health care system. Racism in our society cannot be ignored. Nor will SHM ignore racism’s impact on public health. SHM enthusiastically supports its members working to promote equity and reduce the adverse impact of racism. We are committed to using our platform to improve the health of patients everywhere.

SHM would like to reaffirm its long-valued dedication to diversity and inclusion. We remain committed to promoting healthy discussions and action throughout our publications, resources and member communities, as outlined by our diversity and inclusion statement.

SHM Diversity and Inclusion Statement

Hospitalists are charged with treating individuals at their most vulnerable moments, when being respected as a whole person is crucial to advance patients’ healing and wellness. Within our workforce, diversity is a strength in all its forms, which helps us learn about the human experience, grow as leaders, and ultimately create a respectful environment for all regardless of age, race, religion, national origin, gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, appearance, or ability.

To this end, the Society of Hospital Medicine will work to eliminate health disparities for our patients and foster inclusive and equitable cultures across our care teams and institutions with the goal of moving medicine and humanity forward.

The Society of Hospital Medicine deplores the negative impact of racism in our nation and will always strive to remedy racial inequities in our health care system. Racism in our society cannot be ignored. Nor will SHM ignore racism’s impact on public health. SHM enthusiastically supports its members working to promote equity and reduce the adverse impact of racism. We are committed to using our platform to improve the health of patients everywhere.

SHM would like to reaffirm its long-valued dedication to diversity and inclusion. We remain committed to promoting healthy discussions and action throughout our publications, resources and member communities, as outlined by our diversity and inclusion statement.

SHM Diversity and Inclusion Statement

Hospitalists are charged with treating individuals at their most vulnerable moments, when being respected as a whole person is crucial to advance patients’ healing and wellness. Within our workforce, diversity is a strength in all its forms, which helps us learn about the human experience, grow as leaders, and ultimately create a respectful environment for all regardless of age, race, religion, national origin, gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, appearance, or ability.

To this end, the Society of Hospital Medicine will work to eliminate health disparities for our patients and foster inclusive and equitable cultures across our care teams and institutions with the goal of moving medicine and humanity forward.

What COVID-19 has taught us about senior care

Across the globe, there are marked differences in how countries responded to the COVID-19 outbreak, with varying degrees of success in limiting the spread of the virus. Some countries learned important lessons from previous outbreaks, including SARS and MERS, and put policies in place that contributed to lower infection and death rates from COVID-19 in these countries. Others struggled to respond appropriately to the outbreak.

The United States and most of the world was not affected significantly by SARS and MERS. Hence there is a need for different perspectives and observations on lessons that can be learned from this outbreak to help develop effective strategies and policies for the future. It also makes sense to focus intently on the demographic most affected by COVID-19 – the elderly.

Medical care, for the most part, is governed by protocols that clearly detail processes to be followed for the prevention and treatment of disease. Caring for older patients requires going above and beyond the protocols. That is one of the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic – a wake-up call for a more proactive approach for at-risk patients, in this case everyone over the age of 60 years.

In this context, it is important for medical outreach to continue with the senior population long after the pandemic has run its course. Many seniors, particularly those susceptible to other illnesses or exhibiting ongoing issues, would benefit from a consistent and preplanned pattern of contacts by medical professionals and agencies that work with the aging population. These proactive follow-ups can facilitate prevention and treatment and, at the same time, reduce costs that would otherwise increase when health care is reactive.

Lessons in infectious disease containment

As COVID-19 spread globally, there were contrasting responses from individual countries in their efforts to contain the disease. Unfortunately, Italy suffered from its decision to lock down only specific regions of the country initially. The leadership in Italy may have ignored the advice of medical experts and been caught off guard by the intensity of the spread of COVID-19. In fact, they might not have taken strict actions right away because they did not want their responses to be viewed as an overreaction to the disease.

The government decided to shut down areas where the infection rates were high (“red zones”) rather than implement restrictions nationally. This may have inadvertently increased the spread as Italians vacated those “red zones” for other areas of the country not yet affected by COVID-19. Italy’s decentralized health care system also played a part in the effects of the disease, with some regions demonstrating more success in slowing the reach of the disease. According to an article in the Harvard Business Review, the neighboring regions of Lombardy and Veneto applied similar approaches to social distancing and retail closures. Veneto was more proactive, and its response to the outbreak was multipronged, including putting a “strong emphasis on home diagnosis and care” and “specific efforts to monitor and protect health care and other essential workers.” These measures most likely contributed to a slowdown of the spread of the disease in Veneto’s health care facilities, which lessened the load on medical providers.1

Conversely, Taiwan implemented proactive measures swiftly after learning about COVID-19. Taiwan was impacted adversely by the SARS outbreak in 2003 and, afterward, revised their medical policies and procedures to respond quickly to future infectious disease crises. In the beginning, little was known about COVID-19 or how it spread. However, Taiwan’s swift public health response to COVID-19 included early travel restrictions, patient screening, and quarantining of symptomatic patients. The government emphasized education and created real-time digital updates and alerts sent to their citizens, as well as partnering with media to broadcast crucial proactive health information and quickly disproving false information related to COVID-19. They coordinated with organizations throughout the country to increase supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE).2

Although countries and even cities within a country differ in terms of population demographics, health resources, government policies, and cultural practices, initial success stories have some similarities, including the following:

- Early travel restrictions from countries with positive cases, with some circumstances requiring compulsory quarantine periods and testing before entry.

- Extensive testing and proactive tracing of symptomatic cases early. Contacts of people testing positive were also tested, irrespective of being symptomatic or asymptomatic. If testing kits were unavailable, the contacts were self-quarantined.

- Emphasis on avoiding overburdening hospitals by having the public health infrastructure to divert people exhibiting symptoms, including using public health hotlines to send patients to dedicated testing sites and drive-through testing, rather than have patients presenting to emergency rooms and hospitals. This approach protected medical staff from exposure and allowed the focus to remain on treating severe symptomatic patients.

The vastly different response to the COVID-19 outbreak in these two countries illuminates the need for better preparation in the United States. At the onset of this outbreak, emergency room medical professionals, hospitalists, and outpatient primary care providers did not know how to screen for or treat this virus. Additionally, there was limited information on the most effective contact protocols for medical professionals, patients, and visitors. Finally, the lack of PPE and COVID-19 test kits hindered the U.S. response. Once the country is on the road to recovery from COVID-19, it is imperative to set the groundwork to prepare for future outbreaks and create mechanisms to quickly identify vulnerable populations when outbreaks occur.

Senior care in future infectious disease outbreaks

How can medical providers translate lessons learned from this outbreak into improving the quality of care for seniors? The National Institute on Aging (NIA) maintains a website with information about healthy aging. Seniors and their caregivers can use this website to learn more about chronic diseases, lifestyle modifications, disease prevention, and mental health.

In times of a pandemic, this website provides consistent and accurate information and education. One recommendation for reaching the elderly population during future outbreaks is for NIA to develop and implement strategies to increase the use of the website, including adding more audio and visual interfaces and developing a mobile app. Other recommendations for improving the quality of care for seniors include the following:

1. Identify which populations may be most affected when future outbreaks occur.

2. Consider nontraditional platforms, including social media, for communicating with the general population and for medical providers worldwide to learn from each other about new diseases, including the signs, symptoms, and treatment plans. Some medical professionals created specific WhatsApp groups to communicate, and the World Health Organization sent updated information about COVID-19 to anyone who texted them via WhatsApp.3

3. Create a checklist of signs and symptoms related to current infectious diseases and assess every vulnerable patient.

4. Share these guidelines with medical facilities that treat these populations, such as senior care, assisted living and rehabilitation facilities, hospitals, and outpatient treatment centers. Teach the staff at these medical facilities how to screen patients for signs and symptoms of the disease.

5. Implement social isolation strategies, travel and visitor restrictions, and testing and screening as soon as possible at these medical facilities.

6. Recognize that these strategies may affect the psychological and emotional well-being of seniors, increasing their risk for depression and anxiety and negatively affecting their immunity and mental health. Additionally, the use of PPE, either by the medical providers or the patient, may cause anxiety in seniors and those with mild cognitive impairment.

7. Encourage these medical facilities to improve coping strategies with older patients, such as incorporating communication technology that helps seniors stay connected with their families, and participating in physical and mental exercise, as well as religious activities.

8. Ask these medical facilities to create isolation or quarantine rooms for infected seniors.

9. Work with family members to proactively report to medical professionals any symptoms noticed in their senior relatives. Educate seniors to report symptoms earlier.

10. Offer incentives for medical professionals to conduct on-site testing in primary care offices or senior care facilities instead of sending patients to hospital emergency rooms for evaluation. This will only be effective if there are enough test kits available.

11. Urge insurance companies and Medicare to allow additional medical visits for screening vulnerable populations. Encourage the use of telemedicine in place of in-office visits (preferably billed at the same rate as an in-office visit) where appropriate, especially with nonambulatory patients or those with transportation issues. Many insurance companies, including Medicare, approved COVID-19–related coverage of telemedicine in place of office visits to limit the spread of the disease.

12. Provide community health care and integration and better coordination of local, state, and national health care.

13. Hold regular epidemic and pandemic preparedness exercises in every hospital, nursing home, and assisted living facility.

Proactive health care outreach

It is easier to identify the signs and symptoms of already identified infectious diseases as opposed to a novel one like COVID-19. The United States faced a steep learning curve with COVID-19. Hospitalists and other medical professionals were not able to learn about COVID-19 in a journal. At first, they did not know how to screen patients coming into the ER, how to protect staff, or what the treatment plan was for this new disease. As a result, the medical system experienced disorder and confusion. Investing in community health care and better coordination of local, state, and national health care resources is a priority.