User login

Dispensing with expert testimony

Question: When a doctor could not find a dislodged biopsy guide wire, he abandoned his search after informing the patient of his intention to retrieve it at a later date. Two months later, he was successful in locating and removing the foreign body, but the patient alleged she suffered pain and anxiety in the interim. She filed a negligence lawsuit and, based on the “obvious” nature of her injuries, called no expert witness to testify on her behalf.

Which of the following choices is best?

A. Expert testimony is always needed to establish the applicable standard of care in medical negligence lawsuits.

B. Although a plaintiff is not qualified to expound on medical matters, he/she can offer evidence from learned treatises and medical texts.

C. The jury is the one who determines whether a plaintiff can invoke either the res ipsa loquitur doctrine or the “common knowledge” rule to obviate the need for an expert witness.

D. This patient will likely win her case.

E. All are incorrect.

Answer: E. It is well-established law that the question of negligence must be decided by reference to relevant medical standards of care for which the plaintiff carries the burden of proving through expert medical testimony. Only a professional, duly qualified by the court as an expert witness, is allowed to offer medical testimony – whereas the plaintiff typically will be disqualified from playing this role because of the complexity of issues involved.

However, under either the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur (“the thing speaks for itself”) or the “common knowledge” rule, a court (i.e., the judge) may allow the jury to infer negligence in the absence of expert testimony.

The res doctrine is invoked where there is only circumstantial but no direct evidence, and three conditions are met: 1) The injury would not have occurred in the absence of someone’s negligence; 2) the plaintiff was not at fault; and 3) the defendant had total control of the instrumentality that led to the injury.

The closely related “common knowledge” rule relies on the everyday knowledge and experience of the layperson to identify plain and obvious negligent conduct, which then allows the judge to waive the expert requirement.

The two principles are frequently used interchangeably, ultimately favoring the plaintiff by dispensing with the difficult and expensive task of securing a qualified expert willing to testify against a doctor defendant.

The best example of res in action is the surgeon who inadvertently leaves behind a sponge or instrument inside a body cavity. Other successfully litigated examples include a cardiac arrest in the operating room, hypoxia in the recovery room, burns to the buttock, gangrene after the accidental injection of penicillin into an artery, air trapped subcutaneously from a displaced needle, and a pierced eyeball during a procedure.

A particularly well-known example is Ybarra v. Spangard, in which the patient developed shoulder injuries during an appendectomy.1 The Supreme Court of California felt it was appropriate to place the burden on the operating room defendants to explain how the patient, unconscious under general anesthesia throughout the procedure, sustained the shoulder injury.

The scenario provided in the opening question is taken from a 2013 New York case, James v. Wormuth, in which the plaintiff relied on the res doctrine.2 The defendant doctor had left a guide wire in the plaintiff’s chest following a biopsy and was unable to locate it after a 20-minute search. However, he was able to retrieve the wire 2 months later under C-arm imaging.

The plaintiff sued the doctor for pain and anxiety, but did not call any expert witness, relying instead on the “foreign object” basis for invoking the res doctrine. The lower court ruled for the doctor, and the court of appeals affirmed.

It reasoned that the object was left behind deliberately, not unintentionally, and that under the circumstances of the case, an expert witness was needed to set out the applicable standard of care, without which a jury could not determine whether the doctor’s professional judgment breached the requisite standard. The court also ruled that the plaintiff failed to satisfy the “exclusive control” requirement of the res doctrine, because several other individuals participated to an extent in the medical procedure.

Hawaii’s case of Barbee v. Queen’s Medical Center is illustrative of the “common knowledge” rule.3 Mr. Barbee, age 75 years, underwent laparoscopic nephrectomy for a malignancy. Massive bleeding complicated his postoperative course, the hemoglobin falling into the 3 range, and he required emergent reoperation. Over the next 18 months, the patient progressively deteriorated, eventually requiring dialysis and dying from a stroke and intestinal volvulus.

Notwithstanding an initial jury verdict in favor of the plaintiff’s children, awarding each of the three children $365,000, the defendants filed a so-called JNOV motion (current term is “judgment as a matter of law”) to negate the jury verdict, on the basis that the plaintiffs failed to present competent expert testimony at trial to prove causation.

The plaintiffs countered that the cause of death was within the realm of common knowledge, thus no expert was necessary. They asserted that “any lay person can easily grasp the concept that a person dies from losing so much blood that multiple organs fail to perform their functions.” Mr. Barbee’s death thus was not “of such a technical nature that lay persons are incompetent to draw their own conclusions from facts presented without aid.”

Hawaii’s Intermediate Court of Appeals disagreed with the plaintiffs, holding that although “Hawaii does recognize a ‘common knowledge’ exception to the requirement that a plaintiff must introduce expert medical testimony on causation … this exception is rare in application.” The court asserted that the causal link between any alleged negligence and Mr. Barbee’s death 17 months later is not within the realm of common knowledge.

It reasoned that the long-term effects of internal bleeding are not so widely known as to be analogous to leaving a sponge within a patient or removing the wrong limb during an amputation. Moreover, Mr. Barbee had a long history of preexisting conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. He also suffered numerous and serious postoperative medical conditions, including a stroke and surgery to remove part of his intestine, which had become gangrenous.

Thus, the role that preexisting conditions and/or the subsequent complications of this type played in Mr. Barbee’s death was not within the knowledge of the average layperson.

The “common knowledge” rule is aligned with, though not identical to, the res doctrine, but courts are known to conflate the two legal principles, often using them interchangeably.4

Strictly speaking, the “common knowledge” waiver comes into play where direct evidence of negligent conduct lies within the realm of everyday lay knowledge that the physician had deviated from common practice. It may or may not address the causation issue.

On the other hand, res is successfully invoked when, despite no direct evidence of negligence and causation, the circumstances surrounding the injury are such that the plaintiff’s case can go to the jury without expert testimony.

References

1. Ybarra v. Spangard, 154 P.2d 687 (Cal. 1944).

2. James v. Wormuth, 997 N.E.2d 133 (N.Y. 2013).

3. Barbee v. Queen’s Medical Center, 119 Haw 136 (2008).

4. Spinner, Amanda E. Common Ignorance: Medical Malpractice Law and the Misconceived Application of the “Common Knowledge” and “Res Ipsa Loquitur” Doctrines.” Touro Law Review: Vol. 31: No. 3, Article 15. Available at http://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol31/iss3/15.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and currently directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: When a doctor could not find a dislodged biopsy guide wire, he abandoned his search after informing the patient of his intention to retrieve it at a later date. Two months later, he was successful in locating and removing the foreign body, but the patient alleged she suffered pain and anxiety in the interim. She filed a negligence lawsuit and, based on the “obvious” nature of her injuries, called no expert witness to testify on her behalf.

Which of the following choices is best?

A. Expert testimony is always needed to establish the applicable standard of care in medical negligence lawsuits.

B. Although a plaintiff is not qualified to expound on medical matters, he/she can offer evidence from learned treatises and medical texts.

C. The jury is the one who determines whether a plaintiff can invoke either the res ipsa loquitur doctrine or the “common knowledge” rule to obviate the need for an expert witness.

D. This patient will likely win her case.

E. All are incorrect.

Answer: E. It is well-established law that the question of negligence must be decided by reference to relevant medical standards of care for which the plaintiff carries the burden of proving through expert medical testimony. Only a professional, duly qualified by the court as an expert witness, is allowed to offer medical testimony – whereas the plaintiff typically will be disqualified from playing this role because of the complexity of issues involved.

However, under either the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur (“the thing speaks for itself”) or the “common knowledge” rule, a court (i.e., the judge) may allow the jury to infer negligence in the absence of expert testimony.

The res doctrine is invoked where there is only circumstantial but no direct evidence, and three conditions are met: 1) The injury would not have occurred in the absence of someone’s negligence; 2) the plaintiff was not at fault; and 3) the defendant had total control of the instrumentality that led to the injury.

The closely related “common knowledge” rule relies on the everyday knowledge and experience of the layperson to identify plain and obvious negligent conduct, which then allows the judge to waive the expert requirement.

The two principles are frequently used interchangeably, ultimately favoring the plaintiff by dispensing with the difficult and expensive task of securing a qualified expert willing to testify against a doctor defendant.

The best example of res in action is the surgeon who inadvertently leaves behind a sponge or instrument inside a body cavity. Other successfully litigated examples include a cardiac arrest in the operating room, hypoxia in the recovery room, burns to the buttock, gangrene after the accidental injection of penicillin into an artery, air trapped subcutaneously from a displaced needle, and a pierced eyeball during a procedure.

A particularly well-known example is Ybarra v. Spangard, in which the patient developed shoulder injuries during an appendectomy.1 The Supreme Court of California felt it was appropriate to place the burden on the operating room defendants to explain how the patient, unconscious under general anesthesia throughout the procedure, sustained the shoulder injury.

The scenario provided in the opening question is taken from a 2013 New York case, James v. Wormuth, in which the plaintiff relied on the res doctrine.2 The defendant doctor had left a guide wire in the plaintiff’s chest following a biopsy and was unable to locate it after a 20-minute search. However, he was able to retrieve the wire 2 months later under C-arm imaging.

The plaintiff sued the doctor for pain and anxiety, but did not call any expert witness, relying instead on the “foreign object” basis for invoking the res doctrine. The lower court ruled for the doctor, and the court of appeals affirmed.

It reasoned that the object was left behind deliberately, not unintentionally, and that under the circumstances of the case, an expert witness was needed to set out the applicable standard of care, without which a jury could not determine whether the doctor’s professional judgment breached the requisite standard. The court also ruled that the plaintiff failed to satisfy the “exclusive control” requirement of the res doctrine, because several other individuals participated to an extent in the medical procedure.

Hawaii’s case of Barbee v. Queen’s Medical Center is illustrative of the “common knowledge” rule.3 Mr. Barbee, age 75 years, underwent laparoscopic nephrectomy for a malignancy. Massive bleeding complicated his postoperative course, the hemoglobin falling into the 3 range, and he required emergent reoperation. Over the next 18 months, the patient progressively deteriorated, eventually requiring dialysis and dying from a stroke and intestinal volvulus.

Notwithstanding an initial jury verdict in favor of the plaintiff’s children, awarding each of the three children $365,000, the defendants filed a so-called JNOV motion (current term is “judgment as a matter of law”) to negate the jury verdict, on the basis that the plaintiffs failed to present competent expert testimony at trial to prove causation.

The plaintiffs countered that the cause of death was within the realm of common knowledge, thus no expert was necessary. They asserted that “any lay person can easily grasp the concept that a person dies from losing so much blood that multiple organs fail to perform their functions.” Mr. Barbee’s death thus was not “of such a technical nature that lay persons are incompetent to draw their own conclusions from facts presented without aid.”

Hawaii’s Intermediate Court of Appeals disagreed with the plaintiffs, holding that although “Hawaii does recognize a ‘common knowledge’ exception to the requirement that a plaintiff must introduce expert medical testimony on causation … this exception is rare in application.” The court asserted that the causal link between any alleged negligence and Mr. Barbee’s death 17 months later is not within the realm of common knowledge.

It reasoned that the long-term effects of internal bleeding are not so widely known as to be analogous to leaving a sponge within a patient or removing the wrong limb during an amputation. Moreover, Mr. Barbee had a long history of preexisting conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. He also suffered numerous and serious postoperative medical conditions, including a stroke and surgery to remove part of his intestine, which had become gangrenous.

Thus, the role that preexisting conditions and/or the subsequent complications of this type played in Mr. Barbee’s death was not within the knowledge of the average layperson.

The “common knowledge” rule is aligned with, though not identical to, the res doctrine, but courts are known to conflate the two legal principles, often using them interchangeably.4

Strictly speaking, the “common knowledge” waiver comes into play where direct evidence of negligent conduct lies within the realm of everyday lay knowledge that the physician had deviated from common practice. It may or may not address the causation issue.

On the other hand, res is successfully invoked when, despite no direct evidence of negligence and causation, the circumstances surrounding the injury are such that the plaintiff’s case can go to the jury without expert testimony.

References

1. Ybarra v. Spangard, 154 P.2d 687 (Cal. 1944).

2. James v. Wormuth, 997 N.E.2d 133 (N.Y. 2013).

3. Barbee v. Queen’s Medical Center, 119 Haw 136 (2008).

4. Spinner, Amanda E. Common Ignorance: Medical Malpractice Law and the Misconceived Application of the “Common Knowledge” and “Res Ipsa Loquitur” Doctrines.” Touro Law Review: Vol. 31: No. 3, Article 15. Available at http://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol31/iss3/15.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and currently directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: When a doctor could not find a dislodged biopsy guide wire, he abandoned his search after informing the patient of his intention to retrieve it at a later date. Two months later, he was successful in locating and removing the foreign body, but the patient alleged she suffered pain and anxiety in the interim. She filed a negligence lawsuit and, based on the “obvious” nature of her injuries, called no expert witness to testify on her behalf.

Which of the following choices is best?

A. Expert testimony is always needed to establish the applicable standard of care in medical negligence lawsuits.

B. Although a plaintiff is not qualified to expound on medical matters, he/she can offer evidence from learned treatises and medical texts.

C. The jury is the one who determines whether a plaintiff can invoke either the res ipsa loquitur doctrine or the “common knowledge” rule to obviate the need for an expert witness.

D. This patient will likely win her case.

E. All are incorrect.

Answer: E. It is well-established law that the question of negligence must be decided by reference to relevant medical standards of care for which the plaintiff carries the burden of proving through expert medical testimony. Only a professional, duly qualified by the court as an expert witness, is allowed to offer medical testimony – whereas the plaintiff typically will be disqualified from playing this role because of the complexity of issues involved.

However, under either the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur (“the thing speaks for itself”) or the “common knowledge” rule, a court (i.e., the judge) may allow the jury to infer negligence in the absence of expert testimony.

The res doctrine is invoked where there is only circumstantial but no direct evidence, and three conditions are met: 1) The injury would not have occurred in the absence of someone’s negligence; 2) the plaintiff was not at fault; and 3) the defendant had total control of the instrumentality that led to the injury.

The closely related “common knowledge” rule relies on the everyday knowledge and experience of the layperson to identify plain and obvious negligent conduct, which then allows the judge to waive the expert requirement.

The two principles are frequently used interchangeably, ultimately favoring the plaintiff by dispensing with the difficult and expensive task of securing a qualified expert willing to testify against a doctor defendant.

The best example of res in action is the surgeon who inadvertently leaves behind a sponge or instrument inside a body cavity. Other successfully litigated examples include a cardiac arrest in the operating room, hypoxia in the recovery room, burns to the buttock, gangrene after the accidental injection of penicillin into an artery, air trapped subcutaneously from a displaced needle, and a pierced eyeball during a procedure.

A particularly well-known example is Ybarra v. Spangard, in which the patient developed shoulder injuries during an appendectomy.1 The Supreme Court of California felt it was appropriate to place the burden on the operating room defendants to explain how the patient, unconscious under general anesthesia throughout the procedure, sustained the shoulder injury.

The scenario provided in the opening question is taken from a 2013 New York case, James v. Wormuth, in which the plaintiff relied on the res doctrine.2 The defendant doctor had left a guide wire in the plaintiff’s chest following a biopsy and was unable to locate it after a 20-minute search. However, he was able to retrieve the wire 2 months later under C-arm imaging.

The plaintiff sued the doctor for pain and anxiety, but did not call any expert witness, relying instead on the “foreign object” basis for invoking the res doctrine. The lower court ruled for the doctor, and the court of appeals affirmed.

It reasoned that the object was left behind deliberately, not unintentionally, and that under the circumstances of the case, an expert witness was needed to set out the applicable standard of care, without which a jury could not determine whether the doctor’s professional judgment breached the requisite standard. The court also ruled that the plaintiff failed to satisfy the “exclusive control” requirement of the res doctrine, because several other individuals participated to an extent in the medical procedure.

Hawaii’s case of Barbee v. Queen’s Medical Center is illustrative of the “common knowledge” rule.3 Mr. Barbee, age 75 years, underwent laparoscopic nephrectomy for a malignancy. Massive bleeding complicated his postoperative course, the hemoglobin falling into the 3 range, and he required emergent reoperation. Over the next 18 months, the patient progressively deteriorated, eventually requiring dialysis and dying from a stroke and intestinal volvulus.

Notwithstanding an initial jury verdict in favor of the plaintiff’s children, awarding each of the three children $365,000, the defendants filed a so-called JNOV motion (current term is “judgment as a matter of law”) to negate the jury verdict, on the basis that the plaintiffs failed to present competent expert testimony at trial to prove causation.

The plaintiffs countered that the cause of death was within the realm of common knowledge, thus no expert was necessary. They asserted that “any lay person can easily grasp the concept that a person dies from losing so much blood that multiple organs fail to perform their functions.” Mr. Barbee’s death thus was not “of such a technical nature that lay persons are incompetent to draw their own conclusions from facts presented without aid.”

Hawaii’s Intermediate Court of Appeals disagreed with the plaintiffs, holding that although “Hawaii does recognize a ‘common knowledge’ exception to the requirement that a plaintiff must introduce expert medical testimony on causation … this exception is rare in application.” The court asserted that the causal link between any alleged negligence and Mr. Barbee’s death 17 months later is not within the realm of common knowledge.

It reasoned that the long-term effects of internal bleeding are not so widely known as to be analogous to leaving a sponge within a patient or removing the wrong limb during an amputation. Moreover, Mr. Barbee had a long history of preexisting conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. He also suffered numerous and serious postoperative medical conditions, including a stroke and surgery to remove part of his intestine, which had become gangrenous.

Thus, the role that preexisting conditions and/or the subsequent complications of this type played in Mr. Barbee’s death was not within the knowledge of the average layperson.

The “common knowledge” rule is aligned with, though not identical to, the res doctrine, but courts are known to conflate the two legal principles, often using them interchangeably.4

Strictly speaking, the “common knowledge” waiver comes into play where direct evidence of negligent conduct lies within the realm of everyday lay knowledge that the physician had deviated from common practice. It may or may not address the causation issue.

On the other hand, res is successfully invoked when, despite no direct evidence of negligence and causation, the circumstances surrounding the injury are such that the plaintiff’s case can go to the jury without expert testimony.

References

1. Ybarra v. Spangard, 154 P.2d 687 (Cal. 1944).

2. James v. Wormuth, 997 N.E.2d 133 (N.Y. 2013).

3. Barbee v. Queen’s Medical Center, 119 Haw 136 (2008).

4. Spinner, Amanda E. Common Ignorance: Medical Malpractice Law and the Misconceived Application of the “Common Knowledge” and “Res Ipsa Loquitur” Doctrines.” Touro Law Review: Vol. 31: No. 3, Article 15. Available at http://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol31/iss3/15.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and currently directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Allegations: Current Trends in Medical Malpractice, Part 2

Most medical malpractice cases are still resolved in a courtroom—typically after years of preparation and personal torment. Yet, overall rates of paid medical malpractice claims among all physicians have been steadily decreasing over the past two decades, with reports showing decreases of 30% to 50% in paid claims since 2000.1-3 At the same time, while median payments and insurance premiums continued to increase until the mid-2000s, they now appear to have plateaued.1

None of these changes occurred in isolation. More than 30 states now have caps on noneconomic or total damages.2 As noted in part 1, since 2000, some states have enacted comprehensive tort reform.4 However, whether these changes in malpractice patterns can be attributed directly to specific policy changes remains a hotly contested issue.

Malpractice Risk in Emergency Medicine

To what extent do the trends in medical malpractice apply to emergency medicine (EM)? While emergency physicians’ (EPs’) perception of malpractice risk ranks higher than any other medical specialty,5 in a review of a large sample of malpractice claims from 1991 through 2005, EPs ranked in the middle among specialties with respect to annual risk of a malpractice claim.6 Moreover, the annual risk of a claim for EPs is just under 8%, compared to 7.4% for all physicians. Yet, for neurosurgery and cardiothoracic surgery—the specialties with the highest overall risk of malpractice claims—the annual risk approaches 20%.6 Regarding payout statistics, less than one-fifth of the claims against EPs resulted in payment.6 In a review of a separate insurance database of closed claims, EPs were named as the primary defendant in only 19% of cases.7

Despite the discrepancies between perceived risk and absolute risk of malpractice claims among EPs, malpractice lawsuits continue to affect the practice of EM. This is evidenced in several surveys, in which the majority of EP participants admitted to practicing “defensive medicine” by ordering tests that were felt to be unnecessary and did so in response to perceived malpractice risk.8-10 Perceived risk also accounts for the significant variation in decision-making in the ED with respect to diagnostic testing and hospitalization of patients.11 One would expect that lowering malpractice risk would result in less so-called unnecessary testing, but whether or not this is truly the case remains to be seen.

Effects of Malpractice Reform

A study by Waxman et al12 on the effects of significant malpractice tort reform in ED care in Texas, Georgia, and South Carolina found no difference in rates of imaging studies, charges, or patient admissions. Furthermore, legislation reform did not increase plaintiff onus to prove proximate “gross negligence” rather than simply a breach from “reasonably skillful and careful” medicine.12 These findings suggest that perception of malpractice risk might simply be serving as a proxy for physicians’ underlying risk tolerance, and be less subject to influence by external forces.

Areas Associated With Malpractice Risk

A number of closed-claim databases attempted to identify the characteristics of patient encounters that can lead to malpractice claims, including patient conditions and sources of error. Diagnostic errors have consistently been found to be the leading cause of malpractice claims, accounting for 28% to 65% of claims, followed by inappropriate management of medical treatment and improper performance of a procedure.7,13-16 A January 2016 benchmarking system report by CRICO Strategies found that 30% of 23,658 medical malpractice claims filed between 2009 through 2013 cited failures in communication as a factor.17 The report also revealed that among these failed communications, those that occurred between health care providers are more likely to result in payout compared to miscommunications between providers and patients.17 This report further noted 70% to 80% of claims closed without payment.7,16 Closed claims were significantly more likely to involve serious injuries or death.7,18 Leading conditions that resulted in claims include myocardial infarction, nonspecific chest pain, symptoms involving the abdomen or pelvis, appendicitis, and orthopedic injuries.7,13,16

Diagnostic Errors

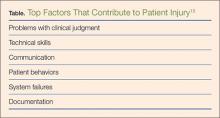

Errors in diagnosis have been attributed to multiple factors in the ED. The two most common factors were failure to order tests and failure to perform an adequate history and physical examination, both of which contribute to rationalization of the practice of defensive medicine under the current tort system.13 Other significant factors associated with errors in diagnosis include misinterpretation of test results or imaging studies and failure to obtain an appropriate consultation. Processes contributing to each of these potential errors include mistakes in judgment, lack of knowledge, miscommunication, and insufficient documentation (Table).15

Strategies for Reducing Malpractice Risk

In part 1, we listed several strategies EPs could adopt to help reduce malpractice risk. In this section, we will discuss in further detail how these strategies help mitigate malpractice claims.

Patient Communication

Open communication with patients is paramount in reducing the risk of a malpractice allegation. Patients are more likely to become angry or frustrated if they sense a physician is not listening to or addressing their concerns. These patients are in turn more likely to file a complaint if they are harmed or experience a bad outcome during their stay in the ED.

Situations in which patients are unable to provide pertinent information also place the EP at significant risk, as the provider must make decisions without full knowledge of the case. Communication with potential resources such as nursing home staff, the patient’s family, and emergency medical service providers to obtain additional information can help reduce risk.

Of course, when evaluating and treating patients, the EP should always take the time to listen to the patient’s concerns during the encounter to ensure his or her needs have been addressed. In the event of a patient allegation or complaint, the EP should make the effort to explore and de-escalate the situation before the patient is discharged.

Discharge Care and Instructions

According to CRICO, premature discharge as a factor in medical malpractice liability results from inadequate assessment and missed opportunities in 41% of diagnosis-related ED cases.16 The following situation illustrates a brief example of such a missed opportunity: A provider makes a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in a patient presenting with fever and abdominal pain but whose urinalysis is suspect for contamination and in whom no pelvic examination was performed to rule out other etiologies. When the same patient later returns to the ED with worse abdominal pain, a sterile urine culture invalidates the diagnosis of UTI, and further evaluation leads to a final diagnosis of ruptured appendix.

Prior to discharging any patient, the EP should provide clear and concise at-home care instructions in a manner in which the patient can understand. Clear instructions on how the patient is to manage his or her care after discharge are vital, and failure to do so in terms the patient can understand can create problems if a harmful result occurs. This is especially important in patients with whom there is a communication barrier—eg, language barrier, hearing impairment, cognitive deficit, intoxication, or violent or irrational behavior. In these situations, the EP should always take advantage of available resources and tools such as language lines, interpreters, discharge planners, psychiatric staff, and supportive family members to help reconcile any communication barriers. These measures will in turn optimize patient outcome and reduce the risk of a later malpractice allegation.

Board Certification

All physicians should maintain their respective board certification and specialty training requirements. Efforts in this area help providers to stay up to date in current practice standards and new developments, thus reducing one’s risk of incurring a malpractice claim.

Patient Safety

All members of the care team should engender an environment that is focused on patient safety, including open communication between providers and with nursing staff and technical support teams. Although interruptions can be detrimental to patient care, simply having an understanding of this phenomenon among all staff members can alleviate some of the working stressors in the ED. Effort must be made to create an environment that allows for clarification between nursing staff and physicians without causing undue antagonism. Fostering supportive communication, having a questioning attitude, and seeking clarification can only enhance patient safety.

The importance of the supervisory role of attending physicians to trainees, physician extenders, and nursing staff must be emphasized, and appropriate guidance from the ED attending is germane in keeping patients safe in teaching environments. Additionally, in departments that suffer the burden of high numbers of admitted patient boarders in the ED, attention must be given to the transitional period between decision to admit and termination of ED care and the acquisition of care of the admitting physician. A clear plan of responsibility must be in place for these high-risk situations.

Policies and Procedures

Departmental policies and procedures should be designed to identify and address all late laboratory results data, radiological discrepancies, and culture results in a timely and uniform manner. Since unaddressed results and discrepancies can result in patient harm, patient-callback processes should be designed to reduce risk by addressing these hazards regularly, thoroughly, and in a timely fashion.

Cognitive Biases

An awareness of inherent biases in the medical decision-making process is also helpful to maintain mindfulness in the routine practice of EM and avoid medical errors. The EP should take care not to be influenced by recent events and diagnostic information that is easy to recall or common, and to ensure the differential addresses possibilities beyond the readily available diagnoses. Further, reliance on an existing opinion may be misleading if subsequent judgments are based on this “anchor,” whether it is true or false.

If the data points of the case do not line up as expected, or if there are unexplained outliers, the EP should expand the frame of reference to seek more appropriate possibilities, and avoid attempts to make the data fit a preferred or favored conclusion.

When one fails to recognize that data do not fit the diagnostic presumption, the true diagnosis can be undermined. Such confirmation bias in turn challenges diagnostic success. Hasty judgment without considering and seeking out relevant information can set up diagnostic failure and premature closure.

Remembering the Basics

Finally, providers should follow the basic principles for every patient. Vital signs are vital for a reason, and all abnormal data must be accounted for prior to patient hand off or discharge. Patient turnover is a high-risk occasion, and demands careful attention to case details between the off-going physician, the accepting physician, and the patient.

All patients presenting to the ED for care should leave the ED at their baseline functional level (ie, if they walk independently, they should still walk independently at discharge). If not, the reason should be sought out and clarified with appropriate recommendations for treatment and follow-up.

Patients and staff should always be treated with respect, which in turn will encourage effective communication. Providers should be honest with patients, document truthfully, respect privacy and confidentiality, practice within one’s competence, confirm information, and avoid assumptions. Compassion goes hand in hand with respectful and open communication. Physicians perceived as compassionate and trustworthy are less likely to be the target of a malpractice suit, even when harm has occurred.

Conclusion

Even though the number of paid medical malpractice claims has continued to decrease over the past 20 years, a discrepancy between perceived and absolute risk persists among EPs—one that perpetuates the practice of defensive medicine and continues to affect EM. Despite the current perceptions and climate, EPs can allay their risk of incurring a malpractice claim by employing the strategies outlined above.

1. Mello MM, Studdert DM, Kachalia A. The medical liability climate and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2014;312(20):2146-2155.

2. Paik M, Black B, Hyman DA. The receding tide of medical malpractice: part 1 - national trends. J Empirical Leg Stud. 2013;10(4):612-638.

3. Bishop TF, Ryan AM, Caslino LP. Paid malpractice claims for adverse events in inpatient and outpatient settings. JAMA. 2011;305(23):2427-2431.

4. Kachalia A, Mello MM. New directions in medical liability reform. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):

1564-1572.

5. Carrier ER, Reschovsky JD, Mello MM, Mayrell RC, Katz D. Physicians’ fears of malpractice lawsuits are not assured by tort reforms. Health Aff. 2010;29(9):1585-1592.

6. Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):629-636.

7. Brown TW, McCarthy ML, Kelen GD, Levy F. An epidemiologic study of closed emergency department malpractice claims in a national database of physician malpractice insurers. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):553-560.

8. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617.

9. Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. Physicians’ views on defensive medicine: a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(12):1081-1083.

10. Massachusetts Medical Society. Investigation of defensive medicine in Massachusetts. November 2008. Available at http://www.massmed.org/defensivemedicine. Accessed March 16, 2016.

11. Katz DA, Williams GC, Brown RL, et al. Emergency physicians’ fear of malpractice in evaluating patient with possible acute cardiac ischemia. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(6):525-533.

12. Waxman DA, Greenberg MD, Ridgely MS, Kellermann AL, Heaton P. The effect of malpractice reform on emergency department care. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1518-1525.

13. Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196-205.

14. Saber Tehrani AS, Lee H, Mathews SC, et al. 25-Year summary of US malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986-2010: an analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(8):672-680.

15. Ross J, Ranum D, Troxel DB. Emergency medicine closed claims study. The Doctors Company. Available at http://www.thedoctors.com/ecm/groups/public/@tdc/@web/@kc/@patientsafety/documents/article/con_id_004776.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2016.

16. Ruoff G, ed. 2011 Annual benchmarking report: malpractice risks in emergency medicine. CRICO strategies. 2012. Available at https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/Strategies/Home/Products-and-Services/Comparative-Data/Annual-Benchmark-Reports. Accessed March 16, 2016.

17. Failures in communication contribute to medical malpractice. January 31, 2016. https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/About-CRICO/Media/Press-Releases/News/2016/February/Failures-in-Communication-Contribute-to-Medical-Malpractice.

18. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024-2033. Accessed March 16, 2016.

Most medical malpractice cases are still resolved in a courtroom—typically after years of preparation and personal torment. Yet, overall rates of paid medical malpractice claims among all physicians have been steadily decreasing over the past two decades, with reports showing decreases of 30% to 50% in paid claims since 2000.1-3 At the same time, while median payments and insurance premiums continued to increase until the mid-2000s, they now appear to have plateaued.1

None of these changes occurred in isolation. More than 30 states now have caps on noneconomic or total damages.2 As noted in part 1, since 2000, some states have enacted comprehensive tort reform.4 However, whether these changes in malpractice patterns can be attributed directly to specific policy changes remains a hotly contested issue.

Malpractice Risk in Emergency Medicine

To what extent do the trends in medical malpractice apply to emergency medicine (EM)? While emergency physicians’ (EPs’) perception of malpractice risk ranks higher than any other medical specialty,5 in a review of a large sample of malpractice claims from 1991 through 2005, EPs ranked in the middle among specialties with respect to annual risk of a malpractice claim.6 Moreover, the annual risk of a claim for EPs is just under 8%, compared to 7.4% for all physicians. Yet, for neurosurgery and cardiothoracic surgery—the specialties with the highest overall risk of malpractice claims—the annual risk approaches 20%.6 Regarding payout statistics, less than one-fifth of the claims against EPs resulted in payment.6 In a review of a separate insurance database of closed claims, EPs were named as the primary defendant in only 19% of cases.7

Despite the discrepancies between perceived risk and absolute risk of malpractice claims among EPs, malpractice lawsuits continue to affect the practice of EM. This is evidenced in several surveys, in which the majority of EP participants admitted to practicing “defensive medicine” by ordering tests that were felt to be unnecessary and did so in response to perceived malpractice risk.8-10 Perceived risk also accounts for the significant variation in decision-making in the ED with respect to diagnostic testing and hospitalization of patients.11 One would expect that lowering malpractice risk would result in less so-called unnecessary testing, but whether or not this is truly the case remains to be seen.

Effects of Malpractice Reform

A study by Waxman et al12 on the effects of significant malpractice tort reform in ED care in Texas, Georgia, and South Carolina found no difference in rates of imaging studies, charges, or patient admissions. Furthermore, legislation reform did not increase plaintiff onus to prove proximate “gross negligence” rather than simply a breach from “reasonably skillful and careful” medicine.12 These findings suggest that perception of malpractice risk might simply be serving as a proxy for physicians’ underlying risk tolerance, and be less subject to influence by external forces.

Areas Associated With Malpractice Risk

A number of closed-claim databases attempted to identify the characteristics of patient encounters that can lead to malpractice claims, including patient conditions and sources of error. Diagnostic errors have consistently been found to be the leading cause of malpractice claims, accounting for 28% to 65% of claims, followed by inappropriate management of medical treatment and improper performance of a procedure.7,13-16 A January 2016 benchmarking system report by CRICO Strategies found that 30% of 23,658 medical malpractice claims filed between 2009 through 2013 cited failures in communication as a factor.17 The report also revealed that among these failed communications, those that occurred between health care providers are more likely to result in payout compared to miscommunications between providers and patients.17 This report further noted 70% to 80% of claims closed without payment.7,16 Closed claims were significantly more likely to involve serious injuries or death.7,18 Leading conditions that resulted in claims include myocardial infarction, nonspecific chest pain, symptoms involving the abdomen or pelvis, appendicitis, and orthopedic injuries.7,13,16

Diagnostic Errors

Errors in diagnosis have been attributed to multiple factors in the ED. The two most common factors were failure to order tests and failure to perform an adequate history and physical examination, both of which contribute to rationalization of the practice of defensive medicine under the current tort system.13 Other significant factors associated with errors in diagnosis include misinterpretation of test results or imaging studies and failure to obtain an appropriate consultation. Processes contributing to each of these potential errors include mistakes in judgment, lack of knowledge, miscommunication, and insufficient documentation (Table).15

Strategies for Reducing Malpractice Risk

In part 1, we listed several strategies EPs could adopt to help reduce malpractice risk. In this section, we will discuss in further detail how these strategies help mitigate malpractice claims.

Patient Communication

Open communication with patients is paramount in reducing the risk of a malpractice allegation. Patients are more likely to become angry or frustrated if they sense a physician is not listening to or addressing their concerns. These patients are in turn more likely to file a complaint if they are harmed or experience a bad outcome during their stay in the ED.

Situations in which patients are unable to provide pertinent information also place the EP at significant risk, as the provider must make decisions without full knowledge of the case. Communication with potential resources such as nursing home staff, the patient’s family, and emergency medical service providers to obtain additional information can help reduce risk.

Of course, when evaluating and treating patients, the EP should always take the time to listen to the patient’s concerns during the encounter to ensure his or her needs have been addressed. In the event of a patient allegation or complaint, the EP should make the effort to explore and de-escalate the situation before the patient is discharged.

Discharge Care and Instructions

According to CRICO, premature discharge as a factor in medical malpractice liability results from inadequate assessment and missed opportunities in 41% of diagnosis-related ED cases.16 The following situation illustrates a brief example of such a missed opportunity: A provider makes a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in a patient presenting with fever and abdominal pain but whose urinalysis is suspect for contamination and in whom no pelvic examination was performed to rule out other etiologies. When the same patient later returns to the ED with worse abdominal pain, a sterile urine culture invalidates the diagnosis of UTI, and further evaluation leads to a final diagnosis of ruptured appendix.

Prior to discharging any patient, the EP should provide clear and concise at-home care instructions in a manner in which the patient can understand. Clear instructions on how the patient is to manage his or her care after discharge are vital, and failure to do so in terms the patient can understand can create problems if a harmful result occurs. This is especially important in patients with whom there is a communication barrier—eg, language barrier, hearing impairment, cognitive deficit, intoxication, or violent or irrational behavior. In these situations, the EP should always take advantage of available resources and tools such as language lines, interpreters, discharge planners, psychiatric staff, and supportive family members to help reconcile any communication barriers. These measures will in turn optimize patient outcome and reduce the risk of a later malpractice allegation.

Board Certification

All physicians should maintain their respective board certification and specialty training requirements. Efforts in this area help providers to stay up to date in current practice standards and new developments, thus reducing one’s risk of incurring a malpractice claim.

Patient Safety

All members of the care team should engender an environment that is focused on patient safety, including open communication between providers and with nursing staff and technical support teams. Although interruptions can be detrimental to patient care, simply having an understanding of this phenomenon among all staff members can alleviate some of the working stressors in the ED. Effort must be made to create an environment that allows for clarification between nursing staff and physicians without causing undue antagonism. Fostering supportive communication, having a questioning attitude, and seeking clarification can only enhance patient safety.

The importance of the supervisory role of attending physicians to trainees, physician extenders, and nursing staff must be emphasized, and appropriate guidance from the ED attending is germane in keeping patients safe in teaching environments. Additionally, in departments that suffer the burden of high numbers of admitted patient boarders in the ED, attention must be given to the transitional period between decision to admit and termination of ED care and the acquisition of care of the admitting physician. A clear plan of responsibility must be in place for these high-risk situations.

Policies and Procedures

Departmental policies and procedures should be designed to identify and address all late laboratory results data, radiological discrepancies, and culture results in a timely and uniform manner. Since unaddressed results and discrepancies can result in patient harm, patient-callback processes should be designed to reduce risk by addressing these hazards regularly, thoroughly, and in a timely fashion.

Cognitive Biases

An awareness of inherent biases in the medical decision-making process is also helpful to maintain mindfulness in the routine practice of EM and avoid medical errors. The EP should take care not to be influenced by recent events and diagnostic information that is easy to recall or common, and to ensure the differential addresses possibilities beyond the readily available diagnoses. Further, reliance on an existing opinion may be misleading if subsequent judgments are based on this “anchor,” whether it is true or false.

If the data points of the case do not line up as expected, or if there are unexplained outliers, the EP should expand the frame of reference to seek more appropriate possibilities, and avoid attempts to make the data fit a preferred or favored conclusion.

When one fails to recognize that data do not fit the diagnostic presumption, the true diagnosis can be undermined. Such confirmation bias in turn challenges diagnostic success. Hasty judgment without considering and seeking out relevant information can set up diagnostic failure and premature closure.

Remembering the Basics

Finally, providers should follow the basic principles for every patient. Vital signs are vital for a reason, and all abnormal data must be accounted for prior to patient hand off or discharge. Patient turnover is a high-risk occasion, and demands careful attention to case details between the off-going physician, the accepting physician, and the patient.

All patients presenting to the ED for care should leave the ED at their baseline functional level (ie, if they walk independently, they should still walk independently at discharge). If not, the reason should be sought out and clarified with appropriate recommendations for treatment and follow-up.

Patients and staff should always be treated with respect, which in turn will encourage effective communication. Providers should be honest with patients, document truthfully, respect privacy and confidentiality, practice within one’s competence, confirm information, and avoid assumptions. Compassion goes hand in hand with respectful and open communication. Physicians perceived as compassionate and trustworthy are less likely to be the target of a malpractice suit, even when harm has occurred.

Conclusion

Even though the number of paid medical malpractice claims has continued to decrease over the past 20 years, a discrepancy between perceived and absolute risk persists among EPs—one that perpetuates the practice of defensive medicine and continues to affect EM. Despite the current perceptions and climate, EPs can allay their risk of incurring a malpractice claim by employing the strategies outlined above.

Most medical malpractice cases are still resolved in a courtroom—typically after years of preparation and personal torment. Yet, overall rates of paid medical malpractice claims among all physicians have been steadily decreasing over the past two decades, with reports showing decreases of 30% to 50% in paid claims since 2000.1-3 At the same time, while median payments and insurance premiums continued to increase until the mid-2000s, they now appear to have plateaued.1

None of these changes occurred in isolation. More than 30 states now have caps on noneconomic or total damages.2 As noted in part 1, since 2000, some states have enacted comprehensive tort reform.4 However, whether these changes in malpractice patterns can be attributed directly to specific policy changes remains a hotly contested issue.

Malpractice Risk in Emergency Medicine

To what extent do the trends in medical malpractice apply to emergency medicine (EM)? While emergency physicians’ (EPs’) perception of malpractice risk ranks higher than any other medical specialty,5 in a review of a large sample of malpractice claims from 1991 through 2005, EPs ranked in the middle among specialties with respect to annual risk of a malpractice claim.6 Moreover, the annual risk of a claim for EPs is just under 8%, compared to 7.4% for all physicians. Yet, for neurosurgery and cardiothoracic surgery—the specialties with the highest overall risk of malpractice claims—the annual risk approaches 20%.6 Regarding payout statistics, less than one-fifth of the claims against EPs resulted in payment.6 In a review of a separate insurance database of closed claims, EPs were named as the primary defendant in only 19% of cases.7

Despite the discrepancies between perceived risk and absolute risk of malpractice claims among EPs, malpractice lawsuits continue to affect the practice of EM. This is evidenced in several surveys, in which the majority of EP participants admitted to practicing “defensive medicine” by ordering tests that were felt to be unnecessary and did so in response to perceived malpractice risk.8-10 Perceived risk also accounts for the significant variation in decision-making in the ED with respect to diagnostic testing and hospitalization of patients.11 One would expect that lowering malpractice risk would result in less so-called unnecessary testing, but whether or not this is truly the case remains to be seen.

Effects of Malpractice Reform

A study by Waxman et al12 on the effects of significant malpractice tort reform in ED care in Texas, Georgia, and South Carolina found no difference in rates of imaging studies, charges, or patient admissions. Furthermore, legislation reform did not increase plaintiff onus to prove proximate “gross negligence” rather than simply a breach from “reasonably skillful and careful” medicine.12 These findings suggest that perception of malpractice risk might simply be serving as a proxy for physicians’ underlying risk tolerance, and be less subject to influence by external forces.

Areas Associated With Malpractice Risk

A number of closed-claim databases attempted to identify the characteristics of patient encounters that can lead to malpractice claims, including patient conditions and sources of error. Diagnostic errors have consistently been found to be the leading cause of malpractice claims, accounting for 28% to 65% of claims, followed by inappropriate management of medical treatment and improper performance of a procedure.7,13-16 A January 2016 benchmarking system report by CRICO Strategies found that 30% of 23,658 medical malpractice claims filed between 2009 through 2013 cited failures in communication as a factor.17 The report also revealed that among these failed communications, those that occurred between health care providers are more likely to result in payout compared to miscommunications between providers and patients.17 This report further noted 70% to 80% of claims closed without payment.7,16 Closed claims were significantly more likely to involve serious injuries or death.7,18 Leading conditions that resulted in claims include myocardial infarction, nonspecific chest pain, symptoms involving the abdomen or pelvis, appendicitis, and orthopedic injuries.7,13,16

Diagnostic Errors

Errors in diagnosis have been attributed to multiple factors in the ED. The two most common factors were failure to order tests and failure to perform an adequate history and physical examination, both of which contribute to rationalization of the practice of defensive medicine under the current tort system.13 Other significant factors associated with errors in diagnosis include misinterpretation of test results or imaging studies and failure to obtain an appropriate consultation. Processes contributing to each of these potential errors include mistakes in judgment, lack of knowledge, miscommunication, and insufficient documentation (Table).15

Strategies for Reducing Malpractice Risk

In part 1, we listed several strategies EPs could adopt to help reduce malpractice risk. In this section, we will discuss in further detail how these strategies help mitigate malpractice claims.

Patient Communication

Open communication with patients is paramount in reducing the risk of a malpractice allegation. Patients are more likely to become angry or frustrated if they sense a physician is not listening to or addressing their concerns. These patients are in turn more likely to file a complaint if they are harmed or experience a bad outcome during their stay in the ED.

Situations in which patients are unable to provide pertinent information also place the EP at significant risk, as the provider must make decisions without full knowledge of the case. Communication with potential resources such as nursing home staff, the patient’s family, and emergency medical service providers to obtain additional information can help reduce risk.

Of course, when evaluating and treating patients, the EP should always take the time to listen to the patient’s concerns during the encounter to ensure his or her needs have been addressed. In the event of a patient allegation or complaint, the EP should make the effort to explore and de-escalate the situation before the patient is discharged.

Discharge Care and Instructions

According to CRICO, premature discharge as a factor in medical malpractice liability results from inadequate assessment and missed opportunities in 41% of diagnosis-related ED cases.16 The following situation illustrates a brief example of such a missed opportunity: A provider makes a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in a patient presenting with fever and abdominal pain but whose urinalysis is suspect for contamination and in whom no pelvic examination was performed to rule out other etiologies. When the same patient later returns to the ED with worse abdominal pain, a sterile urine culture invalidates the diagnosis of UTI, and further evaluation leads to a final diagnosis of ruptured appendix.

Prior to discharging any patient, the EP should provide clear and concise at-home care instructions in a manner in which the patient can understand. Clear instructions on how the patient is to manage his or her care after discharge are vital, and failure to do so in terms the patient can understand can create problems if a harmful result occurs. This is especially important in patients with whom there is a communication barrier—eg, language barrier, hearing impairment, cognitive deficit, intoxication, or violent or irrational behavior. In these situations, the EP should always take advantage of available resources and tools such as language lines, interpreters, discharge planners, psychiatric staff, and supportive family members to help reconcile any communication barriers. These measures will in turn optimize patient outcome and reduce the risk of a later malpractice allegation.

Board Certification

All physicians should maintain their respective board certification and specialty training requirements. Efforts in this area help providers to stay up to date in current practice standards and new developments, thus reducing one’s risk of incurring a malpractice claim.

Patient Safety

All members of the care team should engender an environment that is focused on patient safety, including open communication between providers and with nursing staff and technical support teams. Although interruptions can be detrimental to patient care, simply having an understanding of this phenomenon among all staff members can alleviate some of the working stressors in the ED. Effort must be made to create an environment that allows for clarification between nursing staff and physicians without causing undue antagonism. Fostering supportive communication, having a questioning attitude, and seeking clarification can only enhance patient safety.

The importance of the supervisory role of attending physicians to trainees, physician extenders, and nursing staff must be emphasized, and appropriate guidance from the ED attending is germane in keeping patients safe in teaching environments. Additionally, in departments that suffer the burden of high numbers of admitted patient boarders in the ED, attention must be given to the transitional period between decision to admit and termination of ED care and the acquisition of care of the admitting physician. A clear plan of responsibility must be in place for these high-risk situations.

Policies and Procedures

Departmental policies and procedures should be designed to identify and address all late laboratory results data, radiological discrepancies, and culture results in a timely and uniform manner. Since unaddressed results and discrepancies can result in patient harm, patient-callback processes should be designed to reduce risk by addressing these hazards regularly, thoroughly, and in a timely fashion.

Cognitive Biases

An awareness of inherent biases in the medical decision-making process is also helpful to maintain mindfulness in the routine practice of EM and avoid medical errors. The EP should take care not to be influenced by recent events and diagnostic information that is easy to recall or common, and to ensure the differential addresses possibilities beyond the readily available diagnoses. Further, reliance on an existing opinion may be misleading if subsequent judgments are based on this “anchor,” whether it is true or false.

If the data points of the case do not line up as expected, or if there are unexplained outliers, the EP should expand the frame of reference to seek more appropriate possibilities, and avoid attempts to make the data fit a preferred or favored conclusion.

When one fails to recognize that data do not fit the diagnostic presumption, the true diagnosis can be undermined. Such confirmation bias in turn challenges diagnostic success. Hasty judgment without considering and seeking out relevant information can set up diagnostic failure and premature closure.

Remembering the Basics

Finally, providers should follow the basic principles for every patient. Vital signs are vital for a reason, and all abnormal data must be accounted for prior to patient hand off or discharge. Patient turnover is a high-risk occasion, and demands careful attention to case details between the off-going physician, the accepting physician, and the patient.

All patients presenting to the ED for care should leave the ED at their baseline functional level (ie, if they walk independently, they should still walk independently at discharge). If not, the reason should be sought out and clarified with appropriate recommendations for treatment and follow-up.

Patients and staff should always be treated with respect, which in turn will encourage effective communication. Providers should be honest with patients, document truthfully, respect privacy and confidentiality, practice within one’s competence, confirm information, and avoid assumptions. Compassion goes hand in hand with respectful and open communication. Physicians perceived as compassionate and trustworthy are less likely to be the target of a malpractice suit, even when harm has occurred.

Conclusion

Even though the number of paid medical malpractice claims has continued to decrease over the past 20 years, a discrepancy between perceived and absolute risk persists among EPs—one that perpetuates the practice of defensive medicine and continues to affect EM. Despite the current perceptions and climate, EPs can allay their risk of incurring a malpractice claim by employing the strategies outlined above.

1. Mello MM, Studdert DM, Kachalia A. The medical liability climate and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2014;312(20):2146-2155.

2. Paik M, Black B, Hyman DA. The receding tide of medical malpractice: part 1 - national trends. J Empirical Leg Stud. 2013;10(4):612-638.

3. Bishop TF, Ryan AM, Caslino LP. Paid malpractice claims for adverse events in inpatient and outpatient settings. JAMA. 2011;305(23):2427-2431.

4. Kachalia A, Mello MM. New directions in medical liability reform. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):

1564-1572.

5. Carrier ER, Reschovsky JD, Mello MM, Mayrell RC, Katz D. Physicians’ fears of malpractice lawsuits are not assured by tort reforms. Health Aff. 2010;29(9):1585-1592.

6. Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):629-636.

7. Brown TW, McCarthy ML, Kelen GD, Levy F. An epidemiologic study of closed emergency department malpractice claims in a national database of physician malpractice insurers. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):553-560.

8. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617.

9. Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. Physicians’ views on defensive medicine: a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(12):1081-1083.

10. Massachusetts Medical Society. Investigation of defensive medicine in Massachusetts. November 2008. Available at http://www.massmed.org/defensivemedicine. Accessed March 16, 2016.

11. Katz DA, Williams GC, Brown RL, et al. Emergency physicians’ fear of malpractice in evaluating patient with possible acute cardiac ischemia. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(6):525-533.

12. Waxman DA, Greenberg MD, Ridgely MS, Kellermann AL, Heaton P. The effect of malpractice reform on emergency department care. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1518-1525.

13. Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196-205.

14. Saber Tehrani AS, Lee H, Mathews SC, et al. 25-Year summary of US malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986-2010: an analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(8):672-680.

15. Ross J, Ranum D, Troxel DB. Emergency medicine closed claims study. The Doctors Company. Available at http://www.thedoctors.com/ecm/groups/public/@tdc/@web/@kc/@patientsafety/documents/article/con_id_004776.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2016.

16. Ruoff G, ed. 2011 Annual benchmarking report: malpractice risks in emergency medicine. CRICO strategies. 2012. Available at https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/Strategies/Home/Products-and-Services/Comparative-Data/Annual-Benchmark-Reports. Accessed March 16, 2016.

17. Failures in communication contribute to medical malpractice. January 31, 2016. https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/About-CRICO/Media/Press-Releases/News/2016/February/Failures-in-Communication-Contribute-to-Medical-Malpractice.

18. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024-2033. Accessed March 16, 2016.

1. Mello MM, Studdert DM, Kachalia A. The medical liability climate and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2014;312(20):2146-2155.

2. Paik M, Black B, Hyman DA. The receding tide of medical malpractice: part 1 - national trends. J Empirical Leg Stud. 2013;10(4):612-638.

3. Bishop TF, Ryan AM, Caslino LP. Paid malpractice claims for adverse events in inpatient and outpatient settings. JAMA. 2011;305(23):2427-2431.

4. Kachalia A, Mello MM. New directions in medical liability reform. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):

1564-1572.

5. Carrier ER, Reschovsky JD, Mello MM, Mayrell RC, Katz D. Physicians’ fears of malpractice lawsuits are not assured by tort reforms. Health Aff. 2010;29(9):1585-1592.

6. Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):629-636.

7. Brown TW, McCarthy ML, Kelen GD, Levy F. An epidemiologic study of closed emergency department malpractice claims in a national database of physician malpractice insurers. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):553-560.

8. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617.

9. Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. Physicians’ views on defensive medicine: a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(12):1081-1083.

10. Massachusetts Medical Society. Investigation of defensive medicine in Massachusetts. November 2008. Available at http://www.massmed.org/defensivemedicine. Accessed March 16, 2016.

11. Katz DA, Williams GC, Brown RL, et al. Emergency physicians’ fear of malpractice in evaluating patient with possible acute cardiac ischemia. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(6):525-533.

12. Waxman DA, Greenberg MD, Ridgely MS, Kellermann AL, Heaton P. The effect of malpractice reform on emergency department care. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1518-1525.

13. Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196-205.

14. Saber Tehrani AS, Lee H, Mathews SC, et al. 25-Year summary of US malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986-2010: an analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(8):672-680.

15. Ross J, Ranum D, Troxel DB. Emergency medicine closed claims study. The Doctors Company. Available at http://www.thedoctors.com/ecm/groups/public/@tdc/@web/@kc/@patientsafety/documents/article/con_id_004776.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2016.

16. Ruoff G, ed. 2011 Annual benchmarking report: malpractice risks in emergency medicine. CRICO strategies. 2012. Available at https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/Strategies/Home/Products-and-Services/Comparative-Data/Annual-Benchmark-Reports. Accessed March 16, 2016.

17. Failures in communication contribute to medical malpractice. January 31, 2016. https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/About-CRICO/Media/Press-Releases/News/2016/February/Failures-in-Communication-Contribute-to-Medical-Malpractice.

18. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024-2033. Accessed March 16, 2016.

Echocardiogram goes unread ... Call to help line is too late

Echocardiograms were done, but who was reading them?

A 67-YEAR-OLD MAN had been under the care of his primary care physician for aortic stenosis. The physician was aware of this diagnosis and did periodic echocardiograms to monitor the patient’s heart. The patient was sent to a cardiologist for additional care. Over the next year and a half, the decedent’s condition worsened, and he died of heart failure.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The defendants deviated from the standard of care in not reading the echocardiograms. If they had, they could have treated him and extended his life.

THE DEFENSE The cardiologist said it was not up to him to read the echocardiogram. The primary care physician acknowledged that he deviated from the standard of care.

VERDICT $3 million Connecticut verdict.

COMMENT This is a clear case of failure to take responsibility. I suspect the failure was based on the assumption by both physicians that the other physician was monitoring the patient’s status.

This happened to me with a patient who gradually drifted into acute heart failure while I assumed the nephrologist was managing his diuretics. A phone call and more furosemide would have prevented that hospital admission. (Luckily, my patient recovered uneventfully.)

Don’t assume the specialist has taken charge; verify or manage the patient yourself.

Third call to help line finally leads to office visit, but it’s too late

A 42-YEAR-OLD WOMAN called a phone help line and told a nurse that she had a fever, chills, sore throat, and severe chest pain. The next day she called again and spoke with a nurse who routed her call to a physician. The physician diagnosed the woman with influenza during their 4-minute conversation. She called again the next day and was told to come in for examination. The woman did so and was admitted. One day later, she died of sepsis secondary to pneumonia.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The standard of care required immediate examination by the time of the second call.

THE DEFENSE The plaintiff did not actually report chest pain until the second call, and she contracted an unusually fast-acting strain of pneumonia.

VERDICT $3.5 million California arbitration award.

COMMENT Delayed diagnosis is one of the main reasons family physicians are successfully sued. Management of this patient may have been reasonable the first day. The second call should have prompted a same day visit or instructions to go to the emergency department or at least an urgent care facility. The third call was too late.

Echocardiograms were done, but who was reading them?

A 67-YEAR-OLD MAN had been under the care of his primary care physician for aortic stenosis. The physician was aware of this diagnosis and did periodic echocardiograms to monitor the patient’s heart. The patient was sent to a cardiologist for additional care. Over the next year and a half, the decedent’s condition worsened, and he died of heart failure.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The defendants deviated from the standard of care in not reading the echocardiograms. If they had, they could have treated him and extended his life.

THE DEFENSE The cardiologist said it was not up to him to read the echocardiogram. The primary care physician acknowledged that he deviated from the standard of care.

VERDICT $3 million Connecticut verdict.

COMMENT This is a clear case of failure to take responsibility. I suspect the failure was based on the assumption by both physicians that the other physician was monitoring the patient’s status.

This happened to me with a patient who gradually drifted into acute heart failure while I assumed the nephrologist was managing his diuretics. A phone call and more furosemide would have prevented that hospital admission. (Luckily, my patient recovered uneventfully.)

Don’t assume the specialist has taken charge; verify or manage the patient yourself.

Third call to help line finally leads to office visit, but it’s too late

A 42-YEAR-OLD WOMAN called a phone help line and told a nurse that she had a fever, chills, sore throat, and severe chest pain. The next day she called again and spoke with a nurse who routed her call to a physician. The physician diagnosed the woman with influenza during their 4-minute conversation. She called again the next day and was told to come in for examination. The woman did so and was admitted. One day later, she died of sepsis secondary to pneumonia.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The standard of care required immediate examination by the time of the second call.

THE DEFENSE The plaintiff did not actually report chest pain until the second call, and she contracted an unusually fast-acting strain of pneumonia.

VERDICT $3.5 million California arbitration award.

COMMENT Delayed diagnosis is one of the main reasons family physicians are successfully sued. Management of this patient may have been reasonable the first day. The second call should have prompted a same day visit or instructions to go to the emergency department or at least an urgent care facility. The third call was too late.

Echocardiograms were done, but who was reading them?

A 67-YEAR-OLD MAN had been under the care of his primary care physician for aortic stenosis. The physician was aware of this diagnosis and did periodic echocardiograms to monitor the patient’s heart. The patient was sent to a cardiologist for additional care. Over the next year and a half, the decedent’s condition worsened, and he died of heart failure.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The defendants deviated from the standard of care in not reading the echocardiograms. If they had, they could have treated him and extended his life.