User login

Blood biomarkers predict TBI disability and mortality

, new research suggests.

In new data from the TRACK-TBI study group, high levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) proteins found in glial cells and neurons, respectively, correlated with death and severe injury. Investigators note that measuring these biomarkers may give a more accurate assessment of a patient’s prognosis following TBI.

This study is the “first report of the accuracy of a blood test that can be obtained rapidly on the day of injury to predict neurological recovery at 6 months after injury,” lead author Frederick Korley, MD, PhD, associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in a news release.

The findings were published online in the Lancet Neurology.

Added value

The researchers measured GFAP and UCH-L1 in blood samples taken from 1,696 patients with TBI on the day of their injury, and they assessed patient recovery 6 months later.

The markers were measured using the i-STAT TBI Plasma test (Abbott Labs). The test was approved in 2021 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to determine which patients with mild TBI should undergo computed tomography scans.

About two-thirds of the study population were men, and the average age was 39 years. All patients were evaluated at Level I trauma centers for injuries caused primarily by traffic accidents or falls.

Six months following injury, 7% of the patients had died and 14% had an unfavorable outcome, ranging from vegetative state to severe disability requiring daily support. In addition, 67% had incomplete recovery, ranging from moderate disabilities requiring assistance outside of the home to minor disabling neurological or psychological deficits.

Day-of-injury GFAP and UCH-L1 levels had a high probability of predicting death (87% for GFAP and 89% for UCH-L1) and severe disability (86% for both GFAP and UCH-L1) at 6 months, the investigators reported.

The biomarkers were less accurate in predicting incomplete recovery (62% for GFAP and 61% for UCH-L1).

The researchers also assessed the added value of combining the blood biomarkers to current TBI prognostic models that take into account variables such as age, motor score, pupil reactivity, and CT characteristics.

In patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 3-12, adding GFAP and UCH-L1 alone or combined to each of the three International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials in TBI (IMPACT) models significantly increased their accuracy for predicting death (range, 90%-94%) and unfavorable outcome (range, 83%-89%).

In patients with milder TBI (GCS score, 13-15), adding GFAP and UCH-L1 to the UPFRONT prognostic model modestly increased accuracy for predicting incomplete recovery (69%).

‘Important’ findings

Commenting on the study, Cyrus A. Raji, MD, PhD, assistant professor of radiology and neurology, Washington University, St. Louis, said this “critical” study shows that these biomarkers can “predict key outcomes,” including mortality and severe disability. “Thus, in conjunction with clinical evaluations and related data such as neuroimaging, these tests may warrant translation to broader clinical practice, particularly in acute settings,” said Dr. Raji, who was not involved in the research.

Also weighing in, Heidi Fusco, MD, assistant director of the traumatic brain injury program at NYU Langone Rusk Rehabilitation, said the findings are “important.”

“Prognosis after brain injury often is based on the initial presentation, ongoing clinical exams, and neuroimaging; and the addition of biomarkers would contribute to creating a more objective prognostic model,” Dr. Fusco said.

She noted “it’s unclear” whether clinical hospital laboratories would be able to accommodate this type of laboratory drawing.

“It is imperative that clinicians still use the patient history [and] clinical and radiological exam when making clinical decisions for a patient and not just lab values. It would be best to incorporate the GFAP and UCH-L1 into a preexisting prognostic model,” Dr. Fusco said.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke, the U.S. Department of Defense, One Mind, and U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command. Dr. Korley reported having previously consulted for Abbott Laboratories and has received research funding from Abbott Laboratories, which makes the assays used in the study. Dr. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader ApS and Neurevolution. Dr. Fusco has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

In new data from the TRACK-TBI study group, high levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) proteins found in glial cells and neurons, respectively, correlated with death and severe injury. Investigators note that measuring these biomarkers may give a more accurate assessment of a patient’s prognosis following TBI.

This study is the “first report of the accuracy of a blood test that can be obtained rapidly on the day of injury to predict neurological recovery at 6 months after injury,” lead author Frederick Korley, MD, PhD, associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in a news release.

The findings were published online in the Lancet Neurology.

Added value

The researchers measured GFAP and UCH-L1 in blood samples taken from 1,696 patients with TBI on the day of their injury, and they assessed patient recovery 6 months later.

The markers were measured using the i-STAT TBI Plasma test (Abbott Labs). The test was approved in 2021 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to determine which patients with mild TBI should undergo computed tomography scans.

About two-thirds of the study population were men, and the average age was 39 years. All patients were evaluated at Level I trauma centers for injuries caused primarily by traffic accidents or falls.

Six months following injury, 7% of the patients had died and 14% had an unfavorable outcome, ranging from vegetative state to severe disability requiring daily support. In addition, 67% had incomplete recovery, ranging from moderate disabilities requiring assistance outside of the home to minor disabling neurological or psychological deficits.

Day-of-injury GFAP and UCH-L1 levels had a high probability of predicting death (87% for GFAP and 89% for UCH-L1) and severe disability (86% for both GFAP and UCH-L1) at 6 months, the investigators reported.

The biomarkers were less accurate in predicting incomplete recovery (62% for GFAP and 61% for UCH-L1).

The researchers also assessed the added value of combining the blood biomarkers to current TBI prognostic models that take into account variables such as age, motor score, pupil reactivity, and CT characteristics.

In patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 3-12, adding GFAP and UCH-L1 alone or combined to each of the three International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials in TBI (IMPACT) models significantly increased their accuracy for predicting death (range, 90%-94%) and unfavorable outcome (range, 83%-89%).

In patients with milder TBI (GCS score, 13-15), adding GFAP and UCH-L1 to the UPFRONT prognostic model modestly increased accuracy for predicting incomplete recovery (69%).

‘Important’ findings

Commenting on the study, Cyrus A. Raji, MD, PhD, assistant professor of radiology and neurology, Washington University, St. Louis, said this “critical” study shows that these biomarkers can “predict key outcomes,” including mortality and severe disability. “Thus, in conjunction with clinical evaluations and related data such as neuroimaging, these tests may warrant translation to broader clinical practice, particularly in acute settings,” said Dr. Raji, who was not involved in the research.

Also weighing in, Heidi Fusco, MD, assistant director of the traumatic brain injury program at NYU Langone Rusk Rehabilitation, said the findings are “important.”

“Prognosis after brain injury often is based on the initial presentation, ongoing clinical exams, and neuroimaging; and the addition of biomarkers would contribute to creating a more objective prognostic model,” Dr. Fusco said.

She noted “it’s unclear” whether clinical hospital laboratories would be able to accommodate this type of laboratory drawing.

“It is imperative that clinicians still use the patient history [and] clinical and radiological exam when making clinical decisions for a patient and not just lab values. It would be best to incorporate the GFAP and UCH-L1 into a preexisting prognostic model,” Dr. Fusco said.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke, the U.S. Department of Defense, One Mind, and U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command. Dr. Korley reported having previously consulted for Abbott Laboratories and has received research funding from Abbott Laboratories, which makes the assays used in the study. Dr. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader ApS and Neurevolution. Dr. Fusco has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

In new data from the TRACK-TBI study group, high levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) proteins found in glial cells and neurons, respectively, correlated with death and severe injury. Investigators note that measuring these biomarkers may give a more accurate assessment of a patient’s prognosis following TBI.

This study is the “first report of the accuracy of a blood test that can be obtained rapidly on the day of injury to predict neurological recovery at 6 months after injury,” lead author Frederick Korley, MD, PhD, associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in a news release.

The findings were published online in the Lancet Neurology.

Added value

The researchers measured GFAP and UCH-L1 in blood samples taken from 1,696 patients with TBI on the day of their injury, and they assessed patient recovery 6 months later.

The markers were measured using the i-STAT TBI Plasma test (Abbott Labs). The test was approved in 2021 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to determine which patients with mild TBI should undergo computed tomography scans.

About two-thirds of the study population were men, and the average age was 39 years. All patients were evaluated at Level I trauma centers for injuries caused primarily by traffic accidents or falls.

Six months following injury, 7% of the patients had died and 14% had an unfavorable outcome, ranging from vegetative state to severe disability requiring daily support. In addition, 67% had incomplete recovery, ranging from moderate disabilities requiring assistance outside of the home to minor disabling neurological or psychological deficits.

Day-of-injury GFAP and UCH-L1 levels had a high probability of predicting death (87% for GFAP and 89% for UCH-L1) and severe disability (86% for both GFAP and UCH-L1) at 6 months, the investigators reported.

The biomarkers were less accurate in predicting incomplete recovery (62% for GFAP and 61% for UCH-L1).

The researchers also assessed the added value of combining the blood biomarkers to current TBI prognostic models that take into account variables such as age, motor score, pupil reactivity, and CT characteristics.

In patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 3-12, adding GFAP and UCH-L1 alone or combined to each of the three International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials in TBI (IMPACT) models significantly increased their accuracy for predicting death (range, 90%-94%) and unfavorable outcome (range, 83%-89%).

In patients with milder TBI (GCS score, 13-15), adding GFAP and UCH-L1 to the UPFRONT prognostic model modestly increased accuracy for predicting incomplete recovery (69%).

‘Important’ findings

Commenting on the study, Cyrus A. Raji, MD, PhD, assistant professor of radiology and neurology, Washington University, St. Louis, said this “critical” study shows that these biomarkers can “predict key outcomes,” including mortality and severe disability. “Thus, in conjunction with clinical evaluations and related data such as neuroimaging, these tests may warrant translation to broader clinical practice, particularly in acute settings,” said Dr. Raji, who was not involved in the research.

Also weighing in, Heidi Fusco, MD, assistant director of the traumatic brain injury program at NYU Langone Rusk Rehabilitation, said the findings are “important.”

“Prognosis after brain injury often is based on the initial presentation, ongoing clinical exams, and neuroimaging; and the addition of biomarkers would contribute to creating a more objective prognostic model,” Dr. Fusco said.

She noted “it’s unclear” whether clinical hospital laboratories would be able to accommodate this type of laboratory drawing.

“It is imperative that clinicians still use the patient history [and] clinical and radiological exam when making clinical decisions for a patient and not just lab values. It would be best to incorporate the GFAP and UCH-L1 into a preexisting prognostic model,” Dr. Fusco said.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke, the U.S. Department of Defense, One Mind, and U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command. Dr. Korley reported having previously consulted for Abbott Laboratories and has received research funding from Abbott Laboratories, which makes the assays used in the study. Dr. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader ApS and Neurevolution. Dr. Fusco has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET NEUROLOGY

Digital therapy may ‘rewire’ the brain to improve tinnitus

, new research suggests. In a randomized controlled trial, results at 12 weeks showed patients with tinnitus reported clinically meaningful reductions in ratings of annoyance, inability to ignore, unpleasantness, and loudness after using a digital polytherapeutic app prototype that focuses on relief, relaxation, and attention-focused retraining. In addition, their improvements were significantly greater than for the control group, which received a common white noise app.

Researchers called the results “promising” for a condition that has no cure and few successful treatments. “What this therapy does is essentially rewire the brain in a way that de-emphasizes the sound of the tinnitus to a background noise that has no meaning or relevance to the listener,” lead author Grant Searchfield, PhD, associate professor of audiology at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, said in a press release.

The findings were published online in Frontiers in Neurology.

Worldwide problem

A recent study showed more than 740 million adults worldwide (nearly 15% of the population) have experienced at least one symptom of tinnitus – and about 120 million are severely affected. Tinnitus is the perception of a ringing, buzzing, whistling, or hissing noise in one or both ears when no external source of the sound is present. Often caused by damage to the auditory system, tinnitus can also be a symptom of a wide range of medical conditions and has been identified as a side effect of COVID-19 vaccination. In its most severe form, which is associated with hearing loss, tinnitus can also affect a patient’s mental, emotional, and social health.

For the current study, participants with tinnitus were randomly assigned to a popular app that uses white noise (control group, n = 30) or to the UpSilent app (n = 31). The UpSilent group received a smartphone app, Bluetooth bone conduction headphones, a Bluetooth neck pillow speaker for sleep, and written counseling materials. Participants in the control group received a widely available app called “White Noise” and in-ear wired headphones.

‘Quicker and more effective’

Both groups reported reductions in ratings of annoyance, inability to ignore, unpleasantness, and loudness at 12 weeks. But significantly more of the UpSilent group reported clinically meaningful improvement compared with the control group (65% vs. 43%, respectively; P = .049).

“Earlier trials have found white noise, goal-based counseling, goal-oriented games, and other technology-based therapies are effective for some people some of the time,” Dr. Searchfield said. “This is quicker and more effective, taking 12 weeks rather than 12 months for more individuals to gain some control,” he added.

The investigators noted that the study was not designed to determine which of the app’s functions of passive listening, active listening, or counseling contributed to symptom improvement.

The next step will be to refine the prototype and proceed to larger local and international trials with a view toward approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, they reported.

The researchers hope the app will be clinically available in about 6 months.

The study was funded by Return on Science, Auckland UniServices. Dr. Searchfield is a founder and scientific officer for TrueSilence, a spinout company of the University of Auckland, and has a financial interest in TrueSilence. His coauthor has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests. In a randomized controlled trial, results at 12 weeks showed patients with tinnitus reported clinically meaningful reductions in ratings of annoyance, inability to ignore, unpleasantness, and loudness after using a digital polytherapeutic app prototype that focuses on relief, relaxation, and attention-focused retraining. In addition, their improvements were significantly greater than for the control group, which received a common white noise app.

Researchers called the results “promising” for a condition that has no cure and few successful treatments. “What this therapy does is essentially rewire the brain in a way that de-emphasizes the sound of the tinnitus to a background noise that has no meaning or relevance to the listener,” lead author Grant Searchfield, PhD, associate professor of audiology at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, said in a press release.

The findings were published online in Frontiers in Neurology.

Worldwide problem

A recent study showed more than 740 million adults worldwide (nearly 15% of the population) have experienced at least one symptom of tinnitus – and about 120 million are severely affected. Tinnitus is the perception of a ringing, buzzing, whistling, or hissing noise in one or both ears when no external source of the sound is present. Often caused by damage to the auditory system, tinnitus can also be a symptom of a wide range of medical conditions and has been identified as a side effect of COVID-19 vaccination. In its most severe form, which is associated with hearing loss, tinnitus can also affect a patient’s mental, emotional, and social health.

For the current study, participants with tinnitus were randomly assigned to a popular app that uses white noise (control group, n = 30) or to the UpSilent app (n = 31). The UpSilent group received a smartphone app, Bluetooth bone conduction headphones, a Bluetooth neck pillow speaker for sleep, and written counseling materials. Participants in the control group received a widely available app called “White Noise” and in-ear wired headphones.

‘Quicker and more effective’

Both groups reported reductions in ratings of annoyance, inability to ignore, unpleasantness, and loudness at 12 weeks. But significantly more of the UpSilent group reported clinically meaningful improvement compared with the control group (65% vs. 43%, respectively; P = .049).

“Earlier trials have found white noise, goal-based counseling, goal-oriented games, and other technology-based therapies are effective for some people some of the time,” Dr. Searchfield said. “This is quicker and more effective, taking 12 weeks rather than 12 months for more individuals to gain some control,” he added.

The investigators noted that the study was not designed to determine which of the app’s functions of passive listening, active listening, or counseling contributed to symptom improvement.

The next step will be to refine the prototype and proceed to larger local and international trials with a view toward approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, they reported.

The researchers hope the app will be clinically available in about 6 months.

The study was funded by Return on Science, Auckland UniServices. Dr. Searchfield is a founder and scientific officer for TrueSilence, a spinout company of the University of Auckland, and has a financial interest in TrueSilence. His coauthor has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests. In a randomized controlled trial, results at 12 weeks showed patients with tinnitus reported clinically meaningful reductions in ratings of annoyance, inability to ignore, unpleasantness, and loudness after using a digital polytherapeutic app prototype that focuses on relief, relaxation, and attention-focused retraining. In addition, their improvements were significantly greater than for the control group, which received a common white noise app.

Researchers called the results “promising” for a condition that has no cure and few successful treatments. “What this therapy does is essentially rewire the brain in a way that de-emphasizes the sound of the tinnitus to a background noise that has no meaning or relevance to the listener,” lead author Grant Searchfield, PhD, associate professor of audiology at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, said in a press release.

The findings were published online in Frontiers in Neurology.

Worldwide problem

A recent study showed more than 740 million adults worldwide (nearly 15% of the population) have experienced at least one symptom of tinnitus – and about 120 million are severely affected. Tinnitus is the perception of a ringing, buzzing, whistling, or hissing noise in one or both ears when no external source of the sound is present. Often caused by damage to the auditory system, tinnitus can also be a symptom of a wide range of medical conditions and has been identified as a side effect of COVID-19 vaccination. In its most severe form, which is associated with hearing loss, tinnitus can also affect a patient’s mental, emotional, and social health.

For the current study, participants with tinnitus were randomly assigned to a popular app that uses white noise (control group, n = 30) or to the UpSilent app (n = 31). The UpSilent group received a smartphone app, Bluetooth bone conduction headphones, a Bluetooth neck pillow speaker for sleep, and written counseling materials. Participants in the control group received a widely available app called “White Noise” and in-ear wired headphones.

‘Quicker and more effective’

Both groups reported reductions in ratings of annoyance, inability to ignore, unpleasantness, and loudness at 12 weeks. But significantly more of the UpSilent group reported clinically meaningful improvement compared with the control group (65% vs. 43%, respectively; P = .049).

“Earlier trials have found white noise, goal-based counseling, goal-oriented games, and other technology-based therapies are effective for some people some of the time,” Dr. Searchfield said. “This is quicker and more effective, taking 12 weeks rather than 12 months for more individuals to gain some control,” he added.

The investigators noted that the study was not designed to determine which of the app’s functions of passive listening, active listening, or counseling contributed to symptom improvement.

The next step will be to refine the prototype and proceed to larger local and international trials with a view toward approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, they reported.

The researchers hope the app will be clinically available in about 6 months.

The study was funded by Return on Science, Auckland UniServices. Dr. Searchfield is a founder and scientific officer for TrueSilence, a spinout company of the University of Auckland, and has a financial interest in TrueSilence. His coauthor has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM FRONTIERS IN NEUROLOGY

Incomplete recovery common 6 months after mild TBI

, new data from the TRACK-TBI study shows.

“Seeing that more than half of the GCS [Glasgow Coma Score] 15, CT-negative TBI cohort in our study were not back to their preinjury baseline at 6 months was surprising and impacts the millions of Americans who suffer from concussions annually,” said lead author Debbie Madhok, MD, with department of emergency medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

“These results highlight the importance of improving care pathways for concussion, particularly from the emergency department,” Dr. Madhok said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

The short- and long-term outcomes in the large group of patients who come into the ED with TBI, a GCS of 15, and without acute intracranial traumatic injury (defined as a negative head CT scan) remain poorly understood, the investigators noted. To investigate further, they evaluated outcomes at 2 weeks and 6 months in 991 of these patients (mean age, 38 years; 64% men) from the TRACK-TBI study.

Among the 751 (76%) participants followed up at 2 weeks after the injury, only 204 (27%) had functional recovery – with a Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended (GOS-E) score of 8. The remaining 547 (73%) had incomplete recovery (GOS-E scores < 8).

Among the 659 patients (66%) followed up at 6 months after the injury, 287 (44%) had functional recovery and 372 (56%) had incomplete recovery.

Most patients who failed to recover completely reported they had not returned to their preinjury life (88%). They described trouble returning to social activities outside the home and disruptions in family relationships and friendships.

The researchers noted that the study population had a high rate of preinjury psychiatric comorbidities, and these patients were more likely to have incomplete recovery than those without psychiatric comorbidities. This aligns with results from previous studies, they added.

The investigators also noted that patients with mild TBI without acute intracranial trauma are typically managed by ED personnel.

“These findings highlight the importance of ED clinicians being aware of the risk of incomplete recovery for patients with a mild TBI (that is, GCS score of 15 and negative head CT scan) and providing accurate education and timely referral information before ED discharge,” they wrote.

The study was funded by grants from the National Foundation of Emergency Medicine, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the U.S. Department of Defense Traumatic Brain Injury Endpoints Development Initiative. Dr. Madhok has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new data from the TRACK-TBI study shows.

“Seeing that more than half of the GCS [Glasgow Coma Score] 15, CT-negative TBI cohort in our study were not back to their preinjury baseline at 6 months was surprising and impacts the millions of Americans who suffer from concussions annually,” said lead author Debbie Madhok, MD, with department of emergency medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

“These results highlight the importance of improving care pathways for concussion, particularly from the emergency department,” Dr. Madhok said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

The short- and long-term outcomes in the large group of patients who come into the ED with TBI, a GCS of 15, and without acute intracranial traumatic injury (defined as a negative head CT scan) remain poorly understood, the investigators noted. To investigate further, they evaluated outcomes at 2 weeks and 6 months in 991 of these patients (mean age, 38 years; 64% men) from the TRACK-TBI study.

Among the 751 (76%) participants followed up at 2 weeks after the injury, only 204 (27%) had functional recovery – with a Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended (GOS-E) score of 8. The remaining 547 (73%) had incomplete recovery (GOS-E scores < 8).

Among the 659 patients (66%) followed up at 6 months after the injury, 287 (44%) had functional recovery and 372 (56%) had incomplete recovery.

Most patients who failed to recover completely reported they had not returned to their preinjury life (88%). They described trouble returning to social activities outside the home and disruptions in family relationships and friendships.

The researchers noted that the study population had a high rate of preinjury psychiatric comorbidities, and these patients were more likely to have incomplete recovery than those without psychiatric comorbidities. This aligns with results from previous studies, they added.

The investigators also noted that patients with mild TBI without acute intracranial trauma are typically managed by ED personnel.

“These findings highlight the importance of ED clinicians being aware of the risk of incomplete recovery for patients with a mild TBI (that is, GCS score of 15 and negative head CT scan) and providing accurate education and timely referral information before ED discharge,” they wrote.

The study was funded by grants from the National Foundation of Emergency Medicine, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the U.S. Department of Defense Traumatic Brain Injury Endpoints Development Initiative. Dr. Madhok has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new data from the TRACK-TBI study shows.

“Seeing that more than half of the GCS [Glasgow Coma Score] 15, CT-negative TBI cohort in our study were not back to their preinjury baseline at 6 months was surprising and impacts the millions of Americans who suffer from concussions annually,” said lead author Debbie Madhok, MD, with department of emergency medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

“These results highlight the importance of improving care pathways for concussion, particularly from the emergency department,” Dr. Madhok said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

The short- and long-term outcomes in the large group of patients who come into the ED with TBI, a GCS of 15, and without acute intracranial traumatic injury (defined as a negative head CT scan) remain poorly understood, the investigators noted. To investigate further, they evaluated outcomes at 2 weeks and 6 months in 991 of these patients (mean age, 38 years; 64% men) from the TRACK-TBI study.

Among the 751 (76%) participants followed up at 2 weeks after the injury, only 204 (27%) had functional recovery – with a Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended (GOS-E) score of 8. The remaining 547 (73%) had incomplete recovery (GOS-E scores < 8).

Among the 659 patients (66%) followed up at 6 months after the injury, 287 (44%) had functional recovery and 372 (56%) had incomplete recovery.

Most patients who failed to recover completely reported they had not returned to their preinjury life (88%). They described trouble returning to social activities outside the home and disruptions in family relationships and friendships.

The researchers noted that the study population had a high rate of preinjury psychiatric comorbidities, and these patients were more likely to have incomplete recovery than those without psychiatric comorbidities. This aligns with results from previous studies, they added.

The investigators also noted that patients with mild TBI without acute intracranial trauma are typically managed by ED personnel.

“These findings highlight the importance of ED clinicians being aware of the risk of incomplete recovery for patients with a mild TBI (that is, GCS score of 15 and negative head CT scan) and providing accurate education and timely referral information before ED discharge,” they wrote.

The study was funded by grants from the National Foundation of Emergency Medicine, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the U.S. Department of Defense Traumatic Brain Injury Endpoints Development Initiative. Dr. Madhok has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

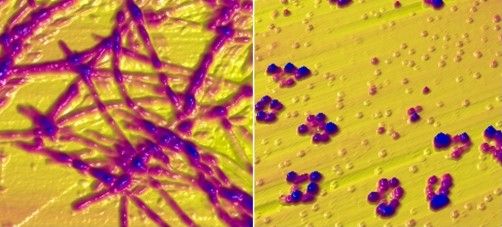

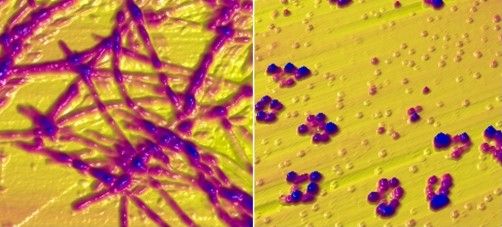

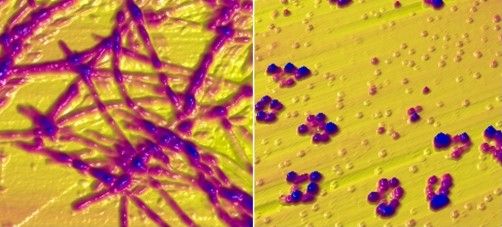

Mechanistic link between herpes virus, Alzheimer’s revealed?

, new research suggests.

“Our results suggest one pathway to Alzheimer’s disease, caused by a VZV infection which creates inflammatory triggers that awaken HSV in the brain,” lead author Dana Cairns, PhD, research associate, department of biomedical engineering at Tufts University, Boston, said in a news release.

The findings were published online in Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

‘One-two punch’

Previous research has suggested a correlation between HSV-1 and AD and involvement of VZV. However, the sequence of events that the viruses create to set the disease in motion has been unclear.

“We think we now have evidence of those events,” co–senior author David Kaplan, PhD, chair of the department of biomedical engineering at Tufts, said in the release.

Working with co–senior author Ruth Itzhaki, PhD, University of Oxford, United Kingdom, the researchers infected human-induced neural stem cells (hiNSCs) and 3D brain tissue models with HSV-1 and/or VZV. Dr. Itzhaki was one of the first to hypothesize a connection between herpes virus and AD.

The investigators found that HSV-1 infection of hiNSCs induces amyloid-beta and P-tau accumulation: the main components of AD plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, respectively.

On the other hand, VZV infection of cultured hiNSCs did not lead to amyloid-beta and P-tau accumulation but instead resulted in gliosis and increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines.

“Strikingly,” VZV infection of cells quiescently infected with HSV-1 caused reactivation of HSV-1, leading to AD-like changes, including amyloid-beta and P-tau accumulation, the investigators report.

This suggests that VZV is unlikely to be a direct cause of AD but rather acts indirectly via reactivation of HSV-1, they add.

Similar findings emerged in similar experiments using 3D human brain tissue models.

“It’s a one-two punch of two viruses that are very common and usually harmless, but the lab studies suggest that if a new exposure to VZV wakes up dormant HSV-1, they could cause trouble,” Dr. Cairns said.

The researchers note that vaccination against VZV has been shown previously to reduce risk for dementia. It is possible, they add, that the vaccine is helping to stop the cycle of viral reactivation, inflammation, and neuronal damage.

‘A first step’

Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of Medical & Scientific Relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, said that the study “is using artificial systems with the goal of more clearly and more deeply understanding” the assessed associations.

She added that although it is a first step, it may provide valuable direction for follow-up research.

“This is preliminary work that first needs replication, validation, and further development to understand if any association that is uncovered between viruses and Alzheimer’s/dementia has a mechanistic link,” said Dr. Snyder.

She noted that several past studies have sought to help the research field better understand the links between different viruses and Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

“There have been some challenges in evaluating these associations in our current model systems or in individuals for a number of reasons,” said Dr. Snyder.

However, “the COVID-19 pandemic has created an opportunity to examine and investigate the relationships between different viruses and Alzheimer’s and other dementias by following individuals in more common and well-established ways,” she added.

She reported that her organization is “leading and working with a large global network of studies and investigators to address some of these questions” from during and after the COVID pandemic.

“The lessons we learn and share may inform our understanding of how other viruses are, or are not, connected to Alzheimer’s and other dementia,” Dr. Snyder said.

More information on the Alzheimer’s Association International Cohort Study of Chronic Neurological Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 is available online.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Cairns, Dr. Kaplan, Dr. Itzhaki, and Dr. Snyder have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

“Our results suggest one pathway to Alzheimer’s disease, caused by a VZV infection which creates inflammatory triggers that awaken HSV in the brain,” lead author Dana Cairns, PhD, research associate, department of biomedical engineering at Tufts University, Boston, said in a news release.

The findings were published online in Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

‘One-two punch’

Previous research has suggested a correlation between HSV-1 and AD and involvement of VZV. However, the sequence of events that the viruses create to set the disease in motion has been unclear.

“We think we now have evidence of those events,” co–senior author David Kaplan, PhD, chair of the department of biomedical engineering at Tufts, said in the release.

Working with co–senior author Ruth Itzhaki, PhD, University of Oxford, United Kingdom, the researchers infected human-induced neural stem cells (hiNSCs) and 3D brain tissue models with HSV-1 and/or VZV. Dr. Itzhaki was one of the first to hypothesize a connection between herpes virus and AD.

The investigators found that HSV-1 infection of hiNSCs induces amyloid-beta and P-tau accumulation: the main components of AD plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, respectively.

On the other hand, VZV infection of cultured hiNSCs did not lead to amyloid-beta and P-tau accumulation but instead resulted in gliosis and increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines.

“Strikingly,” VZV infection of cells quiescently infected with HSV-1 caused reactivation of HSV-1, leading to AD-like changes, including amyloid-beta and P-tau accumulation, the investigators report.

This suggests that VZV is unlikely to be a direct cause of AD but rather acts indirectly via reactivation of HSV-1, they add.

Similar findings emerged in similar experiments using 3D human brain tissue models.

“It’s a one-two punch of two viruses that are very common and usually harmless, but the lab studies suggest that if a new exposure to VZV wakes up dormant HSV-1, they could cause trouble,” Dr. Cairns said.

The researchers note that vaccination against VZV has been shown previously to reduce risk for dementia. It is possible, they add, that the vaccine is helping to stop the cycle of viral reactivation, inflammation, and neuronal damage.

‘A first step’

Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of Medical & Scientific Relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, said that the study “is using artificial systems with the goal of more clearly and more deeply understanding” the assessed associations.

She added that although it is a first step, it may provide valuable direction for follow-up research.

“This is preliminary work that first needs replication, validation, and further development to understand if any association that is uncovered between viruses and Alzheimer’s/dementia has a mechanistic link,” said Dr. Snyder.

She noted that several past studies have sought to help the research field better understand the links between different viruses and Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

“There have been some challenges in evaluating these associations in our current model systems or in individuals for a number of reasons,” said Dr. Snyder.

However, “the COVID-19 pandemic has created an opportunity to examine and investigate the relationships between different viruses and Alzheimer’s and other dementias by following individuals in more common and well-established ways,” she added.

She reported that her organization is “leading and working with a large global network of studies and investigators to address some of these questions” from during and after the COVID pandemic.

“The lessons we learn and share may inform our understanding of how other viruses are, or are not, connected to Alzheimer’s and other dementia,” Dr. Snyder said.

More information on the Alzheimer’s Association International Cohort Study of Chronic Neurological Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 is available online.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Cairns, Dr. Kaplan, Dr. Itzhaki, and Dr. Snyder have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

“Our results suggest one pathway to Alzheimer’s disease, caused by a VZV infection which creates inflammatory triggers that awaken HSV in the brain,” lead author Dana Cairns, PhD, research associate, department of biomedical engineering at Tufts University, Boston, said in a news release.

The findings were published online in Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

‘One-two punch’

Previous research has suggested a correlation between HSV-1 and AD and involvement of VZV. However, the sequence of events that the viruses create to set the disease in motion has been unclear.

“We think we now have evidence of those events,” co–senior author David Kaplan, PhD, chair of the department of biomedical engineering at Tufts, said in the release.

Working with co–senior author Ruth Itzhaki, PhD, University of Oxford, United Kingdom, the researchers infected human-induced neural stem cells (hiNSCs) and 3D brain tissue models with HSV-1 and/or VZV. Dr. Itzhaki was one of the first to hypothesize a connection between herpes virus and AD.

The investigators found that HSV-1 infection of hiNSCs induces amyloid-beta and P-tau accumulation: the main components of AD plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, respectively.

On the other hand, VZV infection of cultured hiNSCs did not lead to amyloid-beta and P-tau accumulation but instead resulted in gliosis and increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines.

“Strikingly,” VZV infection of cells quiescently infected with HSV-1 caused reactivation of HSV-1, leading to AD-like changes, including amyloid-beta and P-tau accumulation, the investigators report.

This suggests that VZV is unlikely to be a direct cause of AD but rather acts indirectly via reactivation of HSV-1, they add.

Similar findings emerged in similar experiments using 3D human brain tissue models.

“It’s a one-two punch of two viruses that are very common and usually harmless, but the lab studies suggest that if a new exposure to VZV wakes up dormant HSV-1, they could cause trouble,” Dr. Cairns said.

The researchers note that vaccination against VZV has been shown previously to reduce risk for dementia. It is possible, they add, that the vaccine is helping to stop the cycle of viral reactivation, inflammation, and neuronal damage.

‘A first step’

Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of Medical & Scientific Relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, said that the study “is using artificial systems with the goal of more clearly and more deeply understanding” the assessed associations.

She added that although it is a first step, it may provide valuable direction for follow-up research.

“This is preliminary work that first needs replication, validation, and further development to understand if any association that is uncovered between viruses and Alzheimer’s/dementia has a mechanistic link,” said Dr. Snyder.

She noted that several past studies have sought to help the research field better understand the links between different viruses and Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

“There have been some challenges in evaluating these associations in our current model systems or in individuals for a number of reasons,” said Dr. Snyder.

However, “the COVID-19 pandemic has created an opportunity to examine and investigate the relationships between different viruses and Alzheimer’s and other dementias by following individuals in more common and well-established ways,” she added.

She reported that her organization is “leading and working with a large global network of studies and investigators to address some of these questions” from during and after the COVID pandemic.

“The lessons we learn and share may inform our understanding of how other viruses are, or are not, connected to Alzheimer’s and other dementia,” Dr. Snyder said.

More information on the Alzheimer’s Association International Cohort Study of Chronic Neurological Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 is available online.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Cairns, Dr. Kaplan, Dr. Itzhaki, and Dr. Snyder have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Drug-resistant epilepsy needs earlier surgical referral

, according to expert consensus recommendations from the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) published in the journal Epilepsia.

Comprehensive epilepsy care

Such a referral is not ”a commitment to undergo brain surgery,” wrote the authors of the new recommendations study, but surgical evaluations offer patients an opportunity to learn about the range of therapies available to them and to have their diagnosis verified, as well as learning about the cause and type of epilepsy they have, even if they ultimately do not pursue surgery.

”In fact, most patients with drug-resistant epilepsy do not end up undergoing surgery after referral, but still benefit from comprehensive epilepsy care improving quality of life and lowering mortality,” wrote lead author Lara Jehi, MD, professor of neurology and epilepsy specialist at Cleveland Clinic, and her colleagues. “A better characterization of the epilepsy can also help optimize medical therapy and address somatic, cognitive, behavioral, and psychiatric comorbidities.”

Is the diagnosis correct?

They noted that about one-third of patients referred to epilepsy centers with an apparent diagnosis of drug-resistant epilepsy actually have psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) – not epilepsy – and an early, accurate diagnosis of PNES can ensure they receive psychotherapy, stop taking antiseizure medications, and have better outcomes.

“These recommendations are necessary, as the delay to surgery and the overall underutilization of surgery have not improved much over the last 20 years,” said Selim R. Benbadis, MD, professor of neurology and director of the comprehensive epilepsy program at the University of South Florida and Tampa General Hospital. “Comprehensive epilepsy centers offer more than surgery, including correct and precise diagnosis, drug options, three [Food and Drug Administration]–approved neurostimulation options, and more,” said Dr. Benbadis, who was not involved in the development of these recommendations.

Consensus recommendations

On behalf of the the ILAE’s Surgical Therapies Commission, the authors used the Delphi consensus process to develop expert consensus recommendations on when to refer patients with epilepsy to surgery. They conducted three Delphi rounds on 51 clinical scenarios with 61 epileptologists (38% of participants), epilepsy neurosurgeons (34%), neurologists (23%), neuropsychiatrists (2%), and neuropsychologists (3%) from 28 countries. Most of clinicians focused on adults (39%) or adults and children (41%) while 20% focused only on pediatric epilepsy.

The physicians involved had a median 22 years of practice and represented all six ILAE regions: 30% from North America, 28% from Europe, 18% from Asia/Oceania, 13% from Latin America, 7% from the Eastern Mediterranean, and 4% from Africa.

The result of these rounds were three key recommendations arising from the consensus of experts consulted. First, every patient up to 70 years old who has drug-resistant epilepsy should be offered the option of a surgical evaluation as soon as it’s apparent that they have drug resistance. The option for surgical evaluation should be provided independent of their sex or socioeconomic status and regardless of how long they have had epilepsy, their seizure type, their epilepsy type, localization, and their comorbidities, ”including severe psychiatric comorbidity like psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) or substance abuse if patients are cooperative with management,” the authors wrote.

”Resective surgery can improve quality of life and cognitive outcomes and is the only treatment demonstrated to improve survival and reverse excess mortality attributed to drug-resistant epilepsy,” the authors wrote. Evidence supports that surgical evaluation is the most cost-effective approach to treating drug-resistant epilepsy, they added. Yet, it still takes about 20 years with epilepsy before an adult patient might be referred, ”and the neurology community remains ambivalent due to ongoing barriers and misconceptions about epilepsy surgery,” they wrote.

The second recommendation is to consider a surgical referral for older patients with drug-resistant epilepsy who have no surgical contraindication. Physicians can also consider a referral for patients of any age who are seizure free while taking one to two antiseizure drugs but who have a brain lesion in the noneloquent cortex.

The third recommendation is not to offer surgery if a patient has an active substance dependency and is not cooperative with management.

“Although there is some evidence that seizure outcomes are no different in individuals with active substance use disorder who have epilepsy surgery, the literature suggests increased perioperative surgical and anesthetic risk in this cohort,” the authors wrote. ”Patients with active substance abuse are more likely to be nonadherent with their seizure medications, and to leave the hospital against medical advice.”

One area where the participants did not reach consensus was regarding whether to refer patients who did not become seizure-free after trying just one “tolerated and appropriately chosen” antiseizure medication. Half (49%) said they would be unlikely to refer or would never refer that patient while 44% said they would likely or always refer them, and 7% weren’t sure.

The ‘next level’ of epilepsy care

“Similar recommendations have been published before, by the National Association of Epilepsy Centers, more than once, and have not changed the referral patterns,” Dr. Benbadis said. “They are not implemented by the average general neurologist.” While there are many reasons for this, one with a relativity simple fix is to adjust the language doctors use to when talking with patients about getting an evaluation, Dr. Benbadis said. ”The key is to rephrase: Instead of referrals ‘for surgery,’ which can be scary to many neurologists and patients, we should use more general terms, like referrals for the ‘next level of care by epilepsy specialists,’ ” said Dr. Benbadis, who advocated for this change in terminology in a 2019 editorial. Such language is less frightening and can ease patients’ concerns about going to an epilepsy center where they can learn about more options than just surgery.

Further, surgical options have expanded in recent years, including the development of laser interstitial thermal therapy and neuromodulation. “Identifying candidacy for any of these approaches starts with a surgical referral, so a timely evaluation is key,” the authors wrote.

Referral delays persist

Despite the strong evidence for timely referrals, delays have persisted for decades, said Dr. Benbadis, echoing what the authors describe. ”Despite the results of two randomized controlled trials showing that surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy in adults, and resective surgery in children, is superior to continued antiseizure medications both in terms of seizure freedom and improved quality of life, the mean epilepsy duration to temporal lobe resection has persisted at over 20 years,” the authors wrote. ”Although drug resistance is reached with a mean latency of 9 years in epilepsy surgery candidates, these patients have experienced a decade of unabating seizures with detrimental effects including cognitive and psychiatric comorbidities, poor psychosocial outcomes, potential injuries, and risk of death.”

Surgery is not a ‘dangerous last resort’

The authors point out a variety of likely reasons for these delays, including patients experiencing temporary remissions with a new drug, lack of adequate health care access, overestimating surgery risks, and underestimating the seriousness and risk of death from ongoing seizures.

Dr. Benbadis agreed, referring to a “combination of lack of knowledge and unrealistic views about surgery outcomes and complications.” Patients and their neurologists think surgery is a “dangerous last resort, fraught with complications, and they don’t know the outcome, so it’s mainly that they are not very well-educated about epilepsy surgery,” he said. Complacency about a patient’s infrequent seizures plays a role as well, he added. “Their patient is having one seizure every 2 months, and they might say, ‘well, that’s okay, that’s not that bad,’ but it is when we can cure it.”

Similar factors are barriers to epilepsy surgery: “lack of knowledge or misconceptions about surgical risks, negative behaviors, or cultural issues and access issues.”

Another major barrier, both within neurology and throughout medicine in general, is that large academic centers that accept referrals, including epilepsy centers, have poor communication, follow-up, and scheduling, Dr. Benbadis said.

The authors provided a table with suggestions on potential solutions to those barriers, including identifying online resources to help doctors identify possible surgery candidates, such as www.toolsforepilepsy.com, and a range of educational resources. Ways to improve access and cost include mobile clinics, telehealth, coordinating with an epilepsy organization, and employing a multidisciplinary team that includes a social worker to help with support such as transportation and health insurance.

, according to expert consensus recommendations from the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) published in the journal Epilepsia.

Comprehensive epilepsy care

Such a referral is not ”a commitment to undergo brain surgery,” wrote the authors of the new recommendations study, but surgical evaluations offer patients an opportunity to learn about the range of therapies available to them and to have their diagnosis verified, as well as learning about the cause and type of epilepsy they have, even if they ultimately do not pursue surgery.

”In fact, most patients with drug-resistant epilepsy do not end up undergoing surgery after referral, but still benefit from comprehensive epilepsy care improving quality of life and lowering mortality,” wrote lead author Lara Jehi, MD, professor of neurology and epilepsy specialist at Cleveland Clinic, and her colleagues. “A better characterization of the epilepsy can also help optimize medical therapy and address somatic, cognitive, behavioral, and psychiatric comorbidities.”

Is the diagnosis correct?

They noted that about one-third of patients referred to epilepsy centers with an apparent diagnosis of drug-resistant epilepsy actually have psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) – not epilepsy – and an early, accurate diagnosis of PNES can ensure they receive psychotherapy, stop taking antiseizure medications, and have better outcomes.

“These recommendations are necessary, as the delay to surgery and the overall underutilization of surgery have not improved much over the last 20 years,” said Selim R. Benbadis, MD, professor of neurology and director of the comprehensive epilepsy program at the University of South Florida and Tampa General Hospital. “Comprehensive epilepsy centers offer more than surgery, including correct and precise diagnosis, drug options, three [Food and Drug Administration]–approved neurostimulation options, and more,” said Dr. Benbadis, who was not involved in the development of these recommendations.

Consensus recommendations

On behalf of the the ILAE’s Surgical Therapies Commission, the authors used the Delphi consensus process to develop expert consensus recommendations on when to refer patients with epilepsy to surgery. They conducted three Delphi rounds on 51 clinical scenarios with 61 epileptologists (38% of participants), epilepsy neurosurgeons (34%), neurologists (23%), neuropsychiatrists (2%), and neuropsychologists (3%) from 28 countries. Most of clinicians focused on adults (39%) or adults and children (41%) while 20% focused only on pediatric epilepsy.

The physicians involved had a median 22 years of practice and represented all six ILAE regions: 30% from North America, 28% from Europe, 18% from Asia/Oceania, 13% from Latin America, 7% from the Eastern Mediterranean, and 4% from Africa.

The result of these rounds were three key recommendations arising from the consensus of experts consulted. First, every patient up to 70 years old who has drug-resistant epilepsy should be offered the option of a surgical evaluation as soon as it’s apparent that they have drug resistance. The option for surgical evaluation should be provided independent of their sex or socioeconomic status and regardless of how long they have had epilepsy, their seizure type, their epilepsy type, localization, and their comorbidities, ”including severe psychiatric comorbidity like psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) or substance abuse if patients are cooperative with management,” the authors wrote.

”Resective surgery can improve quality of life and cognitive outcomes and is the only treatment demonstrated to improve survival and reverse excess mortality attributed to drug-resistant epilepsy,” the authors wrote. Evidence supports that surgical evaluation is the most cost-effective approach to treating drug-resistant epilepsy, they added. Yet, it still takes about 20 years with epilepsy before an adult patient might be referred, ”and the neurology community remains ambivalent due to ongoing barriers and misconceptions about epilepsy surgery,” they wrote.

The second recommendation is to consider a surgical referral for older patients with drug-resistant epilepsy who have no surgical contraindication. Physicians can also consider a referral for patients of any age who are seizure free while taking one to two antiseizure drugs but who have a brain lesion in the noneloquent cortex.

The third recommendation is not to offer surgery if a patient has an active substance dependency and is not cooperative with management.

“Although there is some evidence that seizure outcomes are no different in individuals with active substance use disorder who have epilepsy surgery, the literature suggests increased perioperative surgical and anesthetic risk in this cohort,” the authors wrote. ”Patients with active substance abuse are more likely to be nonadherent with their seizure medications, and to leave the hospital against medical advice.”

One area where the participants did not reach consensus was regarding whether to refer patients who did not become seizure-free after trying just one “tolerated and appropriately chosen” antiseizure medication. Half (49%) said they would be unlikely to refer or would never refer that patient while 44% said they would likely or always refer them, and 7% weren’t sure.

The ‘next level’ of epilepsy care

“Similar recommendations have been published before, by the National Association of Epilepsy Centers, more than once, and have not changed the referral patterns,” Dr. Benbadis said. “They are not implemented by the average general neurologist.” While there are many reasons for this, one with a relativity simple fix is to adjust the language doctors use to when talking with patients about getting an evaluation, Dr. Benbadis said. ”The key is to rephrase: Instead of referrals ‘for surgery,’ which can be scary to many neurologists and patients, we should use more general terms, like referrals for the ‘next level of care by epilepsy specialists,’ ” said Dr. Benbadis, who advocated for this change in terminology in a 2019 editorial. Such language is less frightening and can ease patients’ concerns about going to an epilepsy center where they can learn about more options than just surgery.

Further, surgical options have expanded in recent years, including the development of laser interstitial thermal therapy and neuromodulation. “Identifying candidacy for any of these approaches starts with a surgical referral, so a timely evaluation is key,” the authors wrote.

Referral delays persist

Despite the strong evidence for timely referrals, delays have persisted for decades, said Dr. Benbadis, echoing what the authors describe. ”Despite the results of two randomized controlled trials showing that surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy in adults, and resective surgery in children, is superior to continued antiseizure medications both in terms of seizure freedom and improved quality of life, the mean epilepsy duration to temporal lobe resection has persisted at over 20 years,” the authors wrote. ”Although drug resistance is reached with a mean latency of 9 years in epilepsy surgery candidates, these patients have experienced a decade of unabating seizures with detrimental effects including cognitive and psychiatric comorbidities, poor psychosocial outcomes, potential injuries, and risk of death.”

Surgery is not a ‘dangerous last resort’

The authors point out a variety of likely reasons for these delays, including patients experiencing temporary remissions with a new drug, lack of adequate health care access, overestimating surgery risks, and underestimating the seriousness and risk of death from ongoing seizures.

Dr. Benbadis agreed, referring to a “combination of lack of knowledge and unrealistic views about surgery outcomes and complications.” Patients and their neurologists think surgery is a “dangerous last resort, fraught with complications, and they don’t know the outcome, so it’s mainly that they are not very well-educated about epilepsy surgery,” he said. Complacency about a patient’s infrequent seizures plays a role as well, he added. “Their patient is having one seizure every 2 months, and they might say, ‘well, that’s okay, that’s not that bad,’ but it is when we can cure it.”

Similar factors are barriers to epilepsy surgery: “lack of knowledge or misconceptions about surgical risks, negative behaviors, or cultural issues and access issues.”

Another major barrier, both within neurology and throughout medicine in general, is that large academic centers that accept referrals, including epilepsy centers, have poor communication, follow-up, and scheduling, Dr. Benbadis said.

The authors provided a table with suggestions on potential solutions to those barriers, including identifying online resources to help doctors identify possible surgery candidates, such as www.toolsforepilepsy.com, and a range of educational resources. Ways to improve access and cost include mobile clinics, telehealth, coordinating with an epilepsy organization, and employing a multidisciplinary team that includes a social worker to help with support such as transportation and health insurance.

, according to expert consensus recommendations from the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) published in the journal Epilepsia.

Comprehensive epilepsy care

Such a referral is not ”a commitment to undergo brain surgery,” wrote the authors of the new recommendations study, but surgical evaluations offer patients an opportunity to learn about the range of therapies available to them and to have their diagnosis verified, as well as learning about the cause and type of epilepsy they have, even if they ultimately do not pursue surgery.

”In fact, most patients with drug-resistant epilepsy do not end up undergoing surgery after referral, but still benefit from comprehensive epilepsy care improving quality of life and lowering mortality,” wrote lead author Lara Jehi, MD, professor of neurology and epilepsy specialist at Cleveland Clinic, and her colleagues. “A better characterization of the epilepsy can also help optimize medical therapy and address somatic, cognitive, behavioral, and psychiatric comorbidities.”

Is the diagnosis correct?

They noted that about one-third of patients referred to epilepsy centers with an apparent diagnosis of drug-resistant epilepsy actually have psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) – not epilepsy – and an early, accurate diagnosis of PNES can ensure they receive psychotherapy, stop taking antiseizure medications, and have better outcomes.

“These recommendations are necessary, as the delay to surgery and the overall underutilization of surgery have not improved much over the last 20 years,” said Selim R. Benbadis, MD, professor of neurology and director of the comprehensive epilepsy program at the University of South Florida and Tampa General Hospital. “Comprehensive epilepsy centers offer more than surgery, including correct and precise diagnosis, drug options, three [Food and Drug Administration]–approved neurostimulation options, and more,” said Dr. Benbadis, who was not involved in the development of these recommendations.

Consensus recommendations

On behalf of the the ILAE’s Surgical Therapies Commission, the authors used the Delphi consensus process to develop expert consensus recommendations on when to refer patients with epilepsy to surgery. They conducted three Delphi rounds on 51 clinical scenarios with 61 epileptologists (38% of participants), epilepsy neurosurgeons (34%), neurologists (23%), neuropsychiatrists (2%), and neuropsychologists (3%) from 28 countries. Most of clinicians focused on adults (39%) or adults and children (41%) while 20% focused only on pediatric epilepsy.

The physicians involved had a median 22 years of practice and represented all six ILAE regions: 30% from North America, 28% from Europe, 18% from Asia/Oceania, 13% from Latin America, 7% from the Eastern Mediterranean, and 4% from Africa.

The result of these rounds were three key recommendations arising from the consensus of experts consulted. First, every patient up to 70 years old who has drug-resistant epilepsy should be offered the option of a surgical evaluation as soon as it’s apparent that they have drug resistance. The option for surgical evaluation should be provided independent of their sex or socioeconomic status and regardless of how long they have had epilepsy, their seizure type, their epilepsy type, localization, and their comorbidities, ”including severe psychiatric comorbidity like psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) or substance abuse if patients are cooperative with management,” the authors wrote.

”Resective surgery can improve quality of life and cognitive outcomes and is the only treatment demonstrated to improve survival and reverse excess mortality attributed to drug-resistant epilepsy,” the authors wrote. Evidence supports that surgical evaluation is the most cost-effective approach to treating drug-resistant epilepsy, they added. Yet, it still takes about 20 years with epilepsy before an adult patient might be referred, ”and the neurology community remains ambivalent due to ongoing barriers and misconceptions about epilepsy surgery,” they wrote.

The second recommendation is to consider a surgical referral for older patients with drug-resistant epilepsy who have no surgical contraindication. Physicians can also consider a referral for patients of any age who are seizure free while taking one to two antiseizure drugs but who have a brain lesion in the noneloquent cortex.

The third recommendation is not to offer surgery if a patient has an active substance dependency and is not cooperative with management.

“Although there is some evidence that seizure outcomes are no different in individuals with active substance use disorder who have epilepsy surgery, the literature suggests increased perioperative surgical and anesthetic risk in this cohort,” the authors wrote. ”Patients with active substance abuse are more likely to be nonadherent with their seizure medications, and to leave the hospital against medical advice.”

One area where the participants did not reach consensus was regarding whether to refer patients who did not become seizure-free after trying just one “tolerated and appropriately chosen” antiseizure medication. Half (49%) said they would be unlikely to refer or would never refer that patient while 44% said they would likely or always refer them, and 7% weren’t sure.

The ‘next level’ of epilepsy care

“Similar recommendations have been published before, by the National Association of Epilepsy Centers, more than once, and have not changed the referral patterns,” Dr. Benbadis said. “They are not implemented by the average general neurologist.” While there are many reasons for this, one with a relativity simple fix is to adjust the language doctors use to when talking with patients about getting an evaluation, Dr. Benbadis said. ”The key is to rephrase: Instead of referrals ‘for surgery,’ which can be scary to many neurologists and patients, we should use more general terms, like referrals for the ‘next level of care by epilepsy specialists,’ ” said Dr. Benbadis, who advocated for this change in terminology in a 2019 editorial. Such language is less frightening and can ease patients’ concerns about going to an epilepsy center where they can learn about more options than just surgery.

Further, surgical options have expanded in recent years, including the development of laser interstitial thermal therapy and neuromodulation. “Identifying candidacy for any of these approaches starts with a surgical referral, so a timely evaluation is key,” the authors wrote.

Referral delays persist

Despite the strong evidence for timely referrals, delays have persisted for decades, said Dr. Benbadis, echoing what the authors describe. ”Despite the results of two randomized controlled trials showing that surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy in adults, and resective surgery in children, is superior to continued antiseizure medications both in terms of seizure freedom and improved quality of life, the mean epilepsy duration to temporal lobe resection has persisted at over 20 years,” the authors wrote. ”Although drug resistance is reached with a mean latency of 9 years in epilepsy surgery candidates, these patients have experienced a decade of unabating seizures with detrimental effects including cognitive and psychiatric comorbidities, poor psychosocial outcomes, potential injuries, and risk of death.”

Surgery is not a ‘dangerous last resort’

The authors point out a variety of likely reasons for these delays, including patients experiencing temporary remissions with a new drug, lack of adequate health care access, overestimating surgery risks, and underestimating the seriousness and risk of death from ongoing seizures.

Dr. Benbadis agreed, referring to a “combination of lack of knowledge and unrealistic views about surgery outcomes and complications.” Patients and their neurologists think surgery is a “dangerous last resort, fraught with complications, and they don’t know the outcome, so it’s mainly that they are not very well-educated about epilepsy surgery,” he said. Complacency about a patient’s infrequent seizures plays a role as well, he added. “Their patient is having one seizure every 2 months, and they might say, ‘well, that’s okay, that’s not that bad,’ but it is when we can cure it.”

Similar factors are barriers to epilepsy surgery: “lack of knowledge or misconceptions about surgical risks, negative behaviors, or cultural issues and access issues.”

Another major barrier, both within neurology and throughout medicine in general, is that large academic centers that accept referrals, including epilepsy centers, have poor communication, follow-up, and scheduling, Dr. Benbadis said.

The authors provided a table with suggestions on potential solutions to those barriers, including identifying online resources to help doctors identify possible surgery candidates, such as www.toolsforepilepsy.com, and a range of educational resources. Ways to improve access and cost include mobile clinics, telehealth, coordinating with an epilepsy organization, and employing a multidisciplinary team that includes a social worker to help with support such as transportation and health insurance.

FROM EPILEPSIA

How retraining your brain could help with lower back pain

Are you among the hundreds of millions of people worldwide with low back pain? If so, you may be familiar with standard treatments like surgery, shots, medications, and spinal manipulations. But new research suggests the solution for the world’s leading cause of disability may lie in fixing how the brain and the body communicate.

Setting out to challenge traditional treatments for chronic back pain, scientists across Australia, Europe, and the United States came together to test the effectiveness of altering how neural networks recognize pain for new research published this week in JAMA.

The randomized clinical trial recruited two groups of 138 participants with chronic low back pain, testing one group with a novel method called graded sensorimotor retraining intervention (RESOLVE) and the other with things like mock laser therapy and noninvasive brain stimulation.

The researchers found the RESOLVE 12-week training course resulted in a statistically significant improvement in pain intensity at 18 weeks.

“What we observed in our trial was a clinically meaningful effect on pain intensity and a clinically meaningful effect on disability. People were happier, they reported their backs felt better, and their quality of life was better,” the study’s lead author, James McAuley, PhD, said in a statement. “This is the first new treatment of its kind for back pain.”

Brainy talk

Communication between your brain and back changes over time when you have chronic lower back pain, leading the brain to interpret signals from the back differently and change how you move. It is thought that these neural changes make recovery from pain slower and more complicated , according to Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA), a nonprofit research institute in Sydney.

“Over time, the back becomes less fit, and the way the back and brain communicate is disrupted in ways that seem to reinforce the notion that the back is vulnerable and needs protecting,” said Dr. McAuley, a professor at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, and a NeuRA senior research scientist. “The treatment we devised aims to break this self-sustaining cycle.”

RESOLVE treatment focuses on improving this transformed brain-back communication by slowly retraining the body and the brain without the use of opioids or surgery. People in the study have reported improved quality of life 1 year later, according to Dr. McAuley.

The researchers said the pain improvement was “modest,” and the method will need to be tested on other patients and conditions. They hope to introduce this new treatment to doctors and physiotherapists within the next 6-9 months and have already enlisted partner organizations to start this process, according to NeuRA.

A version of this article first appeared on Webmd.com.

Are you among the hundreds of millions of people worldwide with low back pain? If so, you may be familiar with standard treatments like surgery, shots, medications, and spinal manipulations. But new research suggests the solution for the world’s leading cause of disability may lie in fixing how the brain and the body communicate.

Setting out to challenge traditional treatments for chronic back pain, scientists across Australia, Europe, and the United States came together to test the effectiveness of altering how neural networks recognize pain for new research published this week in JAMA.

The randomized clinical trial recruited two groups of 138 participants with chronic low back pain, testing one group with a novel method called graded sensorimotor retraining intervention (RESOLVE) and the other with things like mock laser therapy and noninvasive brain stimulation.

The researchers found the RESOLVE 12-week training course resulted in a statistically significant improvement in pain intensity at 18 weeks.

“What we observed in our trial was a clinically meaningful effect on pain intensity and a clinically meaningful effect on disability. People were happier, they reported their backs felt better, and their quality of life was better,” the study’s lead author, James McAuley, PhD, said in a statement. “This is the first new treatment of its kind for back pain.”

Brainy talk

Communication between your brain and back changes over time when you have chronic lower back pain, leading the brain to interpret signals from the back differently and change how you move. It is thought that these neural changes make recovery from pain slower and more complicated , according to Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA), a nonprofit research institute in Sydney.

“Over time, the back becomes less fit, and the way the back and brain communicate is disrupted in ways that seem to reinforce the notion that the back is vulnerable and needs protecting,” said Dr. McAuley, a professor at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, and a NeuRA senior research scientist. “The treatment we devised aims to break this self-sustaining cycle.”